User login

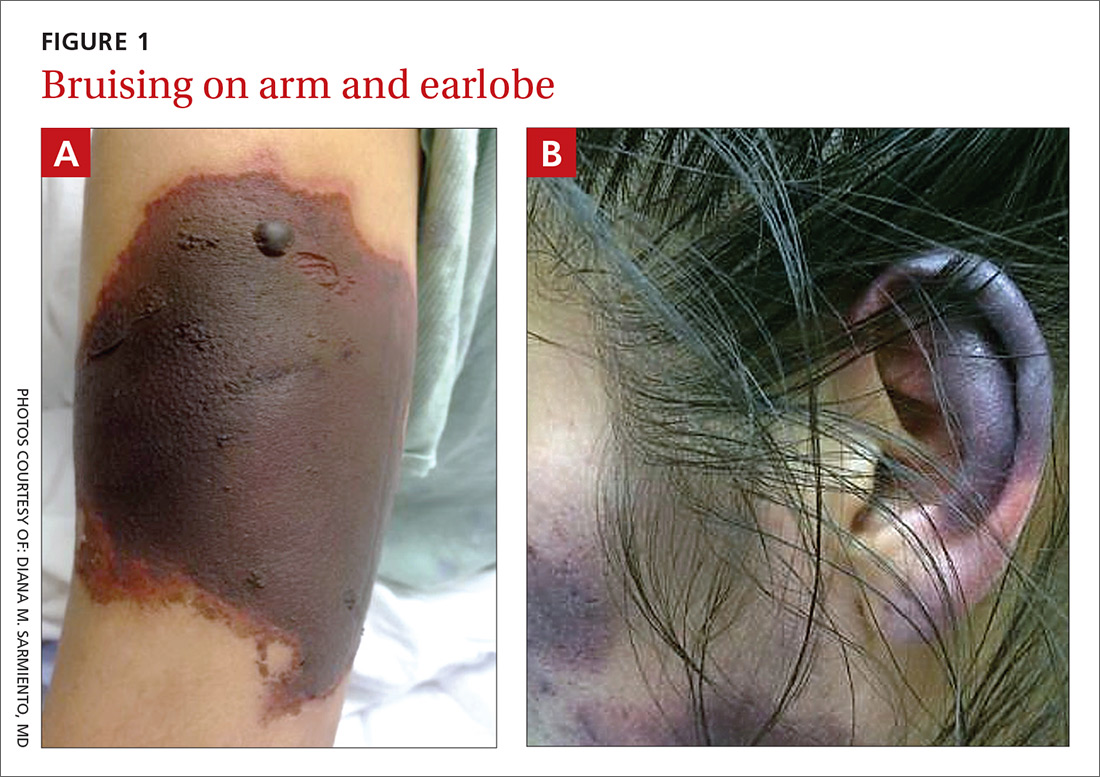

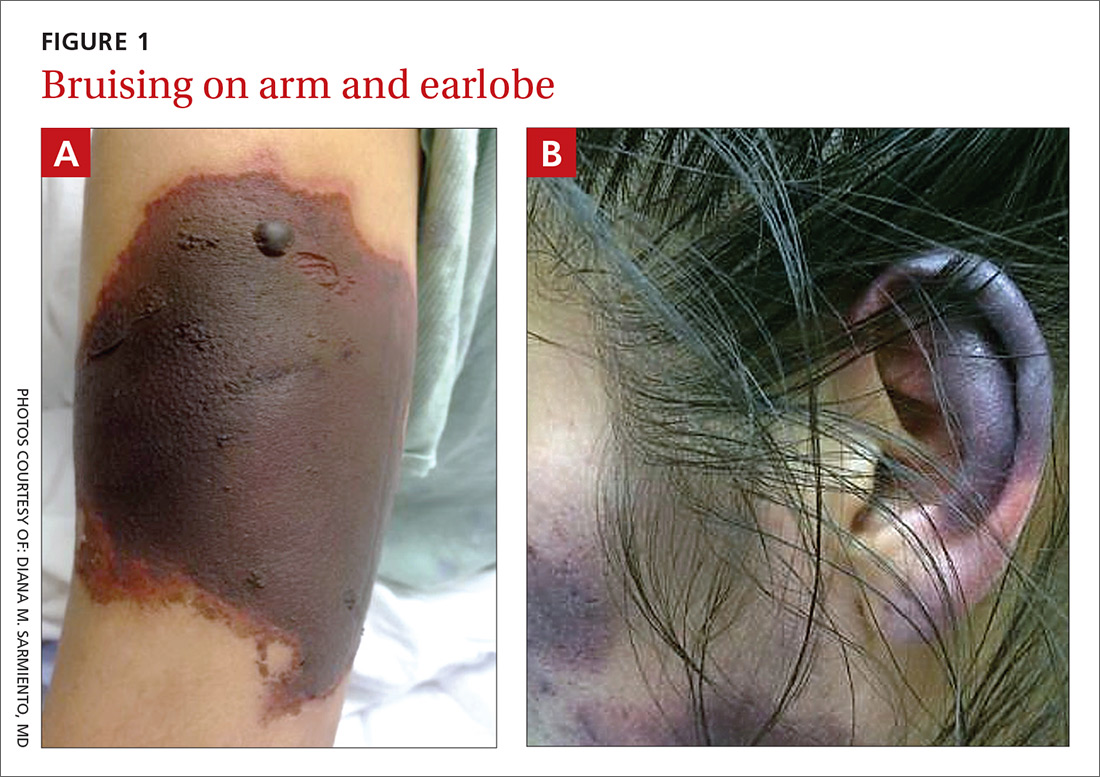

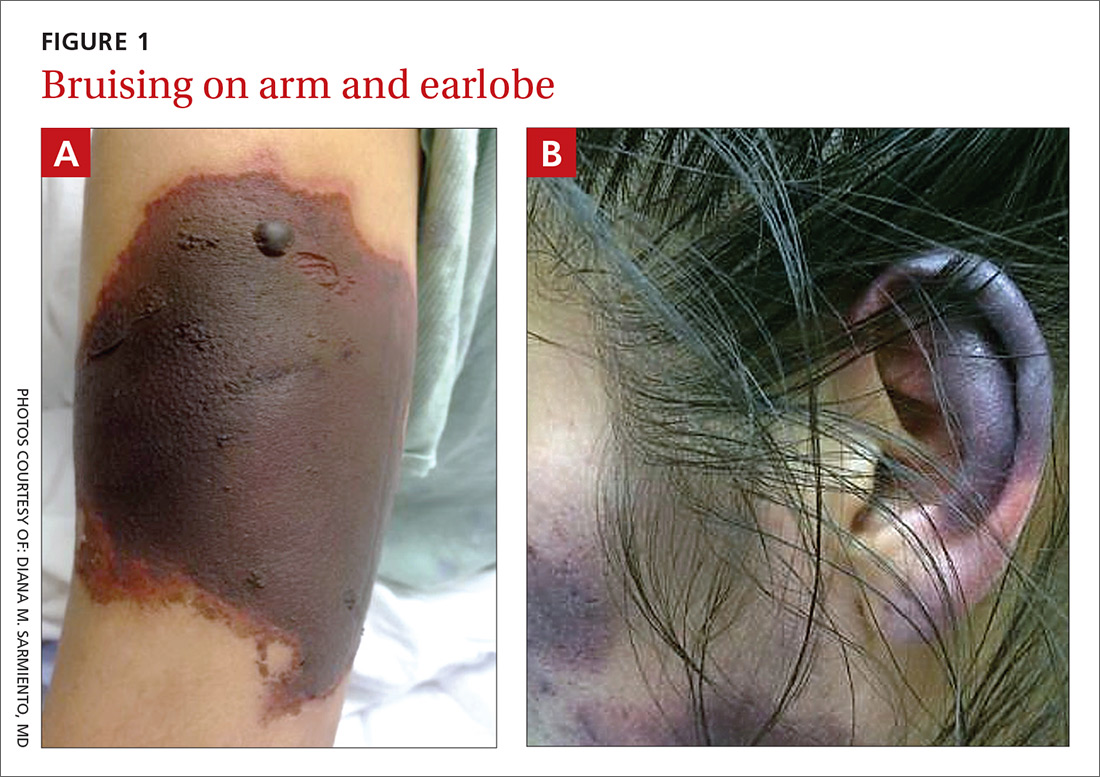

Inflammatory masses on boy’s scalp

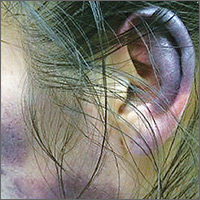

The patient was given a diagnosis of tinea capitis (ringworm of the scalp) based on the clinical presentation. (His brother and sister were told that they had tinea corporis and tinea faciei, which our patient also had on his face.)

Tinea capitis is a fungal infection of the scalp that usually starts as flaky and crusty patches of skin, broken-off hair, erythema, scaling, and pustules on the scalp. This can quickly deteriorate into a boggy and pruritic mass of inflamed tissue known as a kerion, which can become severely inflamed and develop regional lymphadenopathy. Hypersensitive and highly inflammatory reactions that look similar to a bacterial infection may be found when the infection is caused by a zoophilic dermatophyte.

Tinea capitis primarily affects children younger than 10 years of age, with a peak incidence among African American boys. Because US public health agencies no longer require physicians to report cases of tinea capitis, its true incidence in the United States is unknown, but it is believed to be increasing.

Tinea capitis is treated with systemic antifungal medication. Oral antifungal agents, such as griseofulvin, itraconazole, terbinafine, and fluconazole, are effective. Oral fluconazole is typically administered at a dosage of 5 to 6 mg/kg/d for 3 to 6 weeks; an alternative regimen, 8 mg/kg once weekly for 8 to 12 weeks, is safe, effective, and associated with high compliance. Short-duration therapy with fluconazole 6 mg/kg/d for 2 weeks is also effective.

This patient was treated with oral fluconazole 50 mg/d for 2 weeks and showed rapid improvement. Fluconazole was continued at 150 mg weekly for another 2 weeks, and at 6 weeks, his scalp lesions had completely resolved. The patient’s siblings were initially treated with topical itraconazole, without effect. They were switched to oral fluconazole 50 mg/d and improved.

Adapted from: Kim K. Inflammatory masses on boy’s scalp. J Fam Pract. 2015;64:367-369

The patient was given a diagnosis of tinea capitis (ringworm of the scalp) based on the clinical presentation. (His brother and sister were told that they had tinea corporis and tinea faciei, which our patient also had on his face.)

Tinea capitis is a fungal infection of the scalp that usually starts as flaky and crusty patches of skin, broken-off hair, erythema, scaling, and pustules on the scalp. This can quickly deteriorate into a boggy and pruritic mass of inflamed tissue known as a kerion, which can become severely inflamed and develop regional lymphadenopathy. Hypersensitive and highly inflammatory reactions that look similar to a bacterial infection may be found when the infection is caused by a zoophilic dermatophyte.

Tinea capitis primarily affects children younger than 10 years of age, with a peak incidence among African American boys. Because US public health agencies no longer require physicians to report cases of tinea capitis, its true incidence in the United States is unknown, but it is believed to be increasing.

Tinea capitis is treated with systemic antifungal medication. Oral antifungal agents, such as griseofulvin, itraconazole, terbinafine, and fluconazole, are effective. Oral fluconazole is typically administered at a dosage of 5 to 6 mg/kg/d for 3 to 6 weeks; an alternative regimen, 8 mg/kg once weekly for 8 to 12 weeks, is safe, effective, and associated with high compliance. Short-duration therapy with fluconazole 6 mg/kg/d for 2 weeks is also effective.

This patient was treated with oral fluconazole 50 mg/d for 2 weeks and showed rapid improvement. Fluconazole was continued at 150 mg weekly for another 2 weeks, and at 6 weeks, his scalp lesions had completely resolved. The patient’s siblings were initially treated with topical itraconazole, without effect. They were switched to oral fluconazole 50 mg/d and improved.

Adapted from: Kim K. Inflammatory masses on boy’s scalp. J Fam Pract. 2015;64:367-369

The patient was given a diagnosis of tinea capitis (ringworm of the scalp) based on the clinical presentation. (His brother and sister were told that they had tinea corporis and tinea faciei, which our patient also had on his face.)

Tinea capitis is a fungal infection of the scalp that usually starts as flaky and crusty patches of skin, broken-off hair, erythema, scaling, and pustules on the scalp. This can quickly deteriorate into a boggy and pruritic mass of inflamed tissue known as a kerion, which can become severely inflamed and develop regional lymphadenopathy. Hypersensitive and highly inflammatory reactions that look similar to a bacterial infection may be found when the infection is caused by a zoophilic dermatophyte.

Tinea capitis primarily affects children younger than 10 years of age, with a peak incidence among African American boys. Because US public health agencies no longer require physicians to report cases of tinea capitis, its true incidence in the United States is unknown, but it is believed to be increasing.

Tinea capitis is treated with systemic antifungal medication. Oral antifungal agents, such as griseofulvin, itraconazole, terbinafine, and fluconazole, are effective. Oral fluconazole is typically administered at a dosage of 5 to 6 mg/kg/d for 3 to 6 weeks; an alternative regimen, 8 mg/kg once weekly for 8 to 12 weeks, is safe, effective, and associated with high compliance. Short-duration therapy with fluconazole 6 mg/kg/d for 2 weeks is also effective.

This patient was treated with oral fluconazole 50 mg/d for 2 weeks and showed rapid improvement. Fluconazole was continued at 150 mg weekly for another 2 weeks, and at 6 weeks, his scalp lesions had completely resolved. The patient’s siblings were initially treated with topical itraconazole, without effect. They were switched to oral fluconazole 50 mg/d and improved.

Adapted from: Kim K. Inflammatory masses on boy’s scalp. J Fam Pract. 2015;64:367-369

FDA approves drug to treat CRS induced by CAR T-cell therapy

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved tocilizumab (Actemra®) for the treatment of patients age 2 and older who have severe or life-threatening cytokine release syndrome (CRS) induced by chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy.

Tocilizumab is a humanized interleukin-6 receptor antagonist.

The drug is also FDA-approved to treat adults with rheumatoid arthritis or giant cell arteritis and patients age 2 and older with polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis or systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

The full prescribing information for tocilizumab, which includes a boxed warning about the risk of serious infections, is available at http://www.actemra.com. The drug is jointly developed by Genentech (a member of the Roche Group) and Chugai Pharmaceutical Co.

The FDA’s latest approval of tocilizumab coincided with the FDA’s approval of the CAR T-cell therapy tisagenlecleucel (Kymriah, formerly CTL019) to treat pediatric and young adult patients with relapsed or refractory B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

According to Genentech, the FDA’s decision to expand the approval of tocilizumab is based on a retrospective analysis of pooled outcome data from clinical trials of CAR T-cell therapies in patients with hematologic malignancies.

For this analysis, researchers assessed 45 pediatric and adult patients treated with tocilizumab, with or without additional high-dose corticosteroids, for severe or life-threatening CRS.

Thirty-one patients (69%) achieved a response, defined as resolution of CRS within 14 days of the first dose of tocilizumab.

No more than 2 doses of tocilizumab were needed, and no drugs other than tocilizumab and corticosteroids were used for treatment.

No adverse reactions related to tocilizumab were reported. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved tocilizumab (Actemra®) for the treatment of patients age 2 and older who have severe or life-threatening cytokine release syndrome (CRS) induced by chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy.

Tocilizumab is a humanized interleukin-6 receptor antagonist.

The drug is also FDA-approved to treat adults with rheumatoid arthritis or giant cell arteritis and patients age 2 and older with polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis or systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

The full prescribing information for tocilizumab, which includes a boxed warning about the risk of serious infections, is available at http://www.actemra.com. The drug is jointly developed by Genentech (a member of the Roche Group) and Chugai Pharmaceutical Co.

The FDA’s latest approval of tocilizumab coincided with the FDA’s approval of the CAR T-cell therapy tisagenlecleucel (Kymriah, formerly CTL019) to treat pediatric and young adult patients with relapsed or refractory B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

According to Genentech, the FDA’s decision to expand the approval of tocilizumab is based on a retrospective analysis of pooled outcome data from clinical trials of CAR T-cell therapies in patients with hematologic malignancies.

For this analysis, researchers assessed 45 pediatric and adult patients treated with tocilizumab, with or without additional high-dose corticosteroids, for severe or life-threatening CRS.

Thirty-one patients (69%) achieved a response, defined as resolution of CRS within 14 days of the first dose of tocilizumab.

No more than 2 doses of tocilizumab were needed, and no drugs other than tocilizumab and corticosteroids were used for treatment.

No adverse reactions related to tocilizumab were reported. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved tocilizumab (Actemra®) for the treatment of patients age 2 and older who have severe or life-threatening cytokine release syndrome (CRS) induced by chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy.

Tocilizumab is a humanized interleukin-6 receptor antagonist.

The drug is also FDA-approved to treat adults with rheumatoid arthritis or giant cell arteritis and patients age 2 and older with polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis or systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

The full prescribing information for tocilizumab, which includes a boxed warning about the risk of serious infections, is available at http://www.actemra.com. The drug is jointly developed by Genentech (a member of the Roche Group) and Chugai Pharmaceutical Co.

The FDA’s latest approval of tocilizumab coincided with the FDA’s approval of the CAR T-cell therapy tisagenlecleucel (Kymriah, formerly CTL019) to treat pediatric and young adult patients with relapsed or refractory B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

According to Genentech, the FDA’s decision to expand the approval of tocilizumab is based on a retrospective analysis of pooled outcome data from clinical trials of CAR T-cell therapies in patients with hematologic malignancies.

For this analysis, researchers assessed 45 pediatric and adult patients treated with tocilizumab, with or without additional high-dose corticosteroids, for severe or life-threatening CRS.

Thirty-one patients (69%) achieved a response, defined as resolution of CRS within 14 days of the first dose of tocilizumab.

No more than 2 doses of tocilizumab were needed, and no drugs other than tocilizumab and corticosteroids were used for treatment.

No adverse reactions related to tocilizumab were reported. ![]()

Hypertension treatment strategies for older adults

CASE 1 An 82-year-old black woman comes in for an annual exam. She has no medical concerns. She volunteers at a hospice, walks daily, and maintains a healthy diet. Her past medical history (PMH) includes osteopenia and osteoarthritis, and her medications include acetaminophen as needed and vitamin D. She has no drug allergies. Her exam reveals a blood pressure (BP) of 148/70 mm Hg, a body mass index of 31, and a heart rate (HR) of 71 beats per minute (bpm). Cardiac and pulmonary exams are normal, and she shows no signs of peripheral edema.

CASE 2 An 88-year-old white man presents to the office for a 3-month follow-up of his hypertension. His systolic BP at home has ranged from 140 to 170 mm Hg. He denies chest pain, shortness of breath, or lower extremity edema. He lives with his wife and frequently swims for exercise. His PMH is significant for depression and degenerative disc disease. His medications include hydrochlorothiazide 12.5 mg/d, sertraline 50 mg/d, and naproxen 250 mg bid. His BP is 160/80 mm Hg and his HR is 70 bpm with normal cardiovascular (CV) and pulmonary exams.

CASE 3 An 80-year-old white man with diabetes mellitus (DM), hypertension, and chronic kidney disease (CKD) presents for a 3-month follow-up visit. His home systolic BP has been in the 140s to 150s. He is functional in all of his activities of daily living (ADLs), but is starting to require assistance with medications, finances, and transportation. He takes aspirin 81 mg/d, chlorthalidone 25 mg/d, and atenolol 50 mg/d. Remarkable laboratory test results include a hemoglobin A1c of 8.6%, a serum creatinine of 1.9 mg/dL (normal range: 0.6-1.2 mg/dL), and an albumin-creatinine ratio of 250 mg/g (normal range: <30 mg/g). During the exam, his BP is 143/70 mm Hg, his HR is 70 bpm, he is alert and oriented to person, place, and time, and he has normal CV and pulmonary exams with no signs of peripheral edema. He has decreased sensation in his feet, but normal reflexes.

How would you proceed with the care of these 3 patients?

Hypertension is the most common diagnosis made during physician office visits in the United States.1 Nearly one-third of the population has hypertension, and its prevalence increases with age, such that 67% of men and 79% of women ≥75 years of age have the condition.2

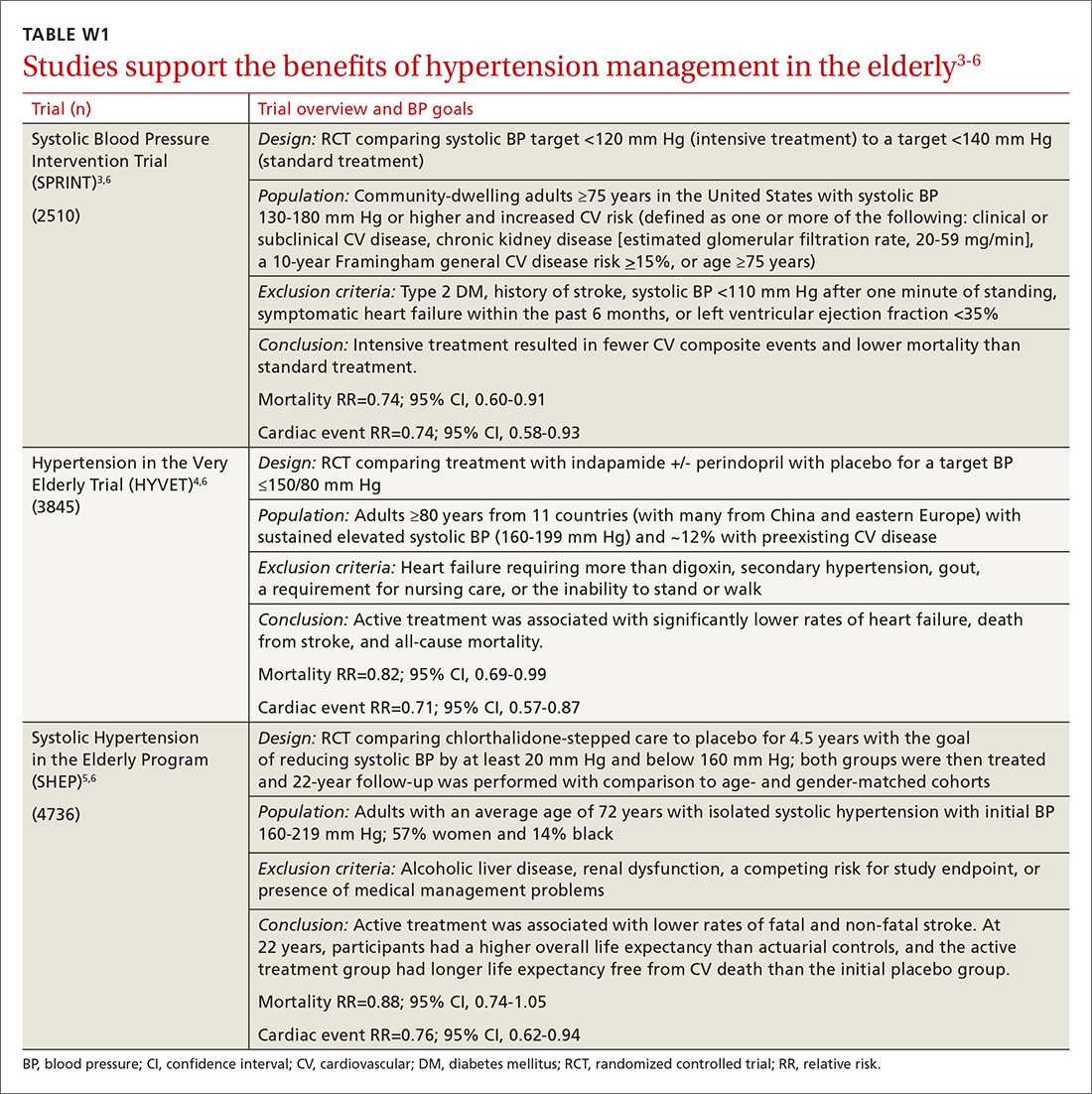

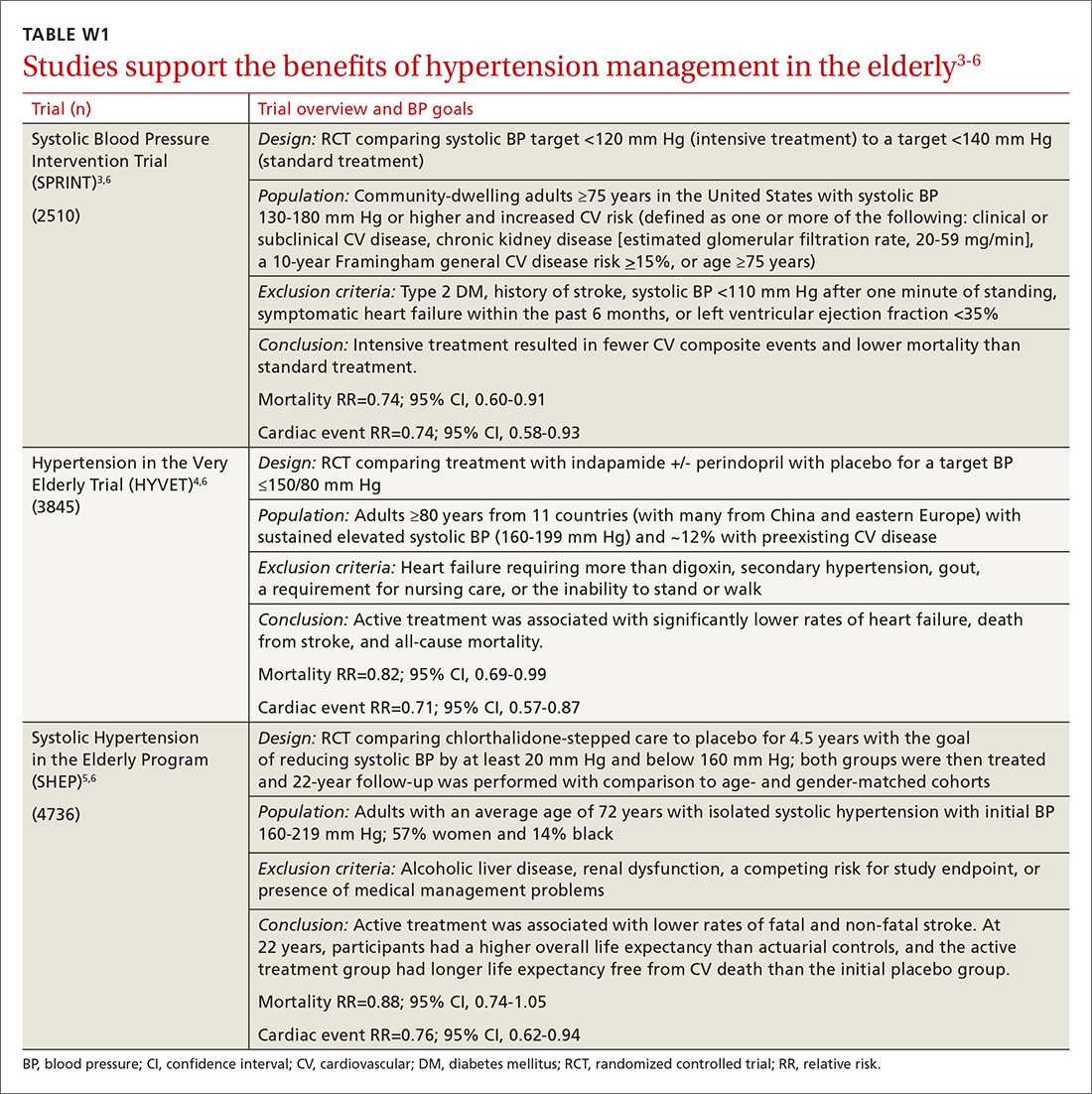

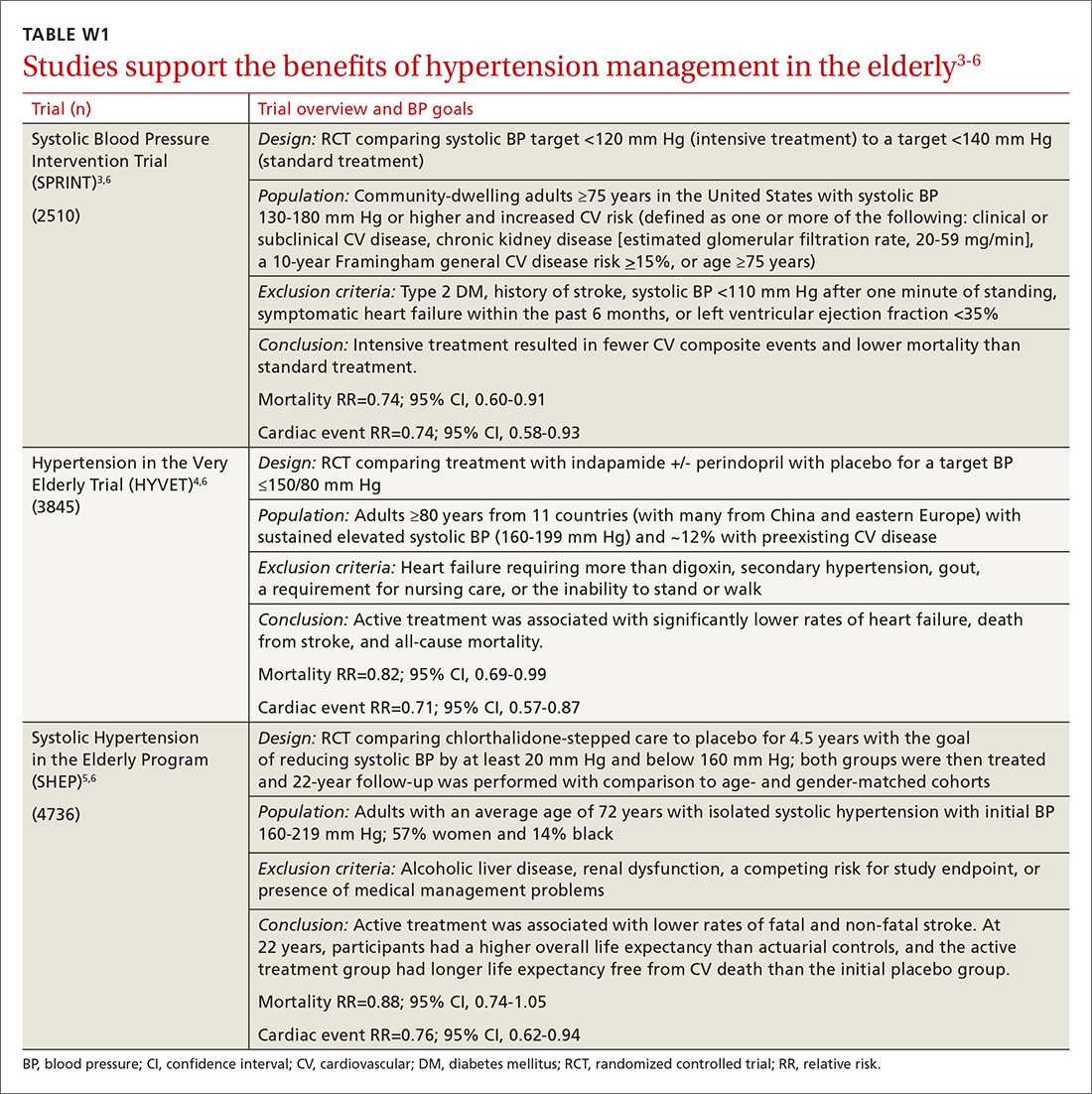

Evidence indicates that hypertension is a modifiable risk factor for CV and all-cause mortality (TABLE W13-6). All adults ≥75 years of age are at increased CV risk based on Framingham criteria,7 making hypertension management paramount. Complicating the situation are findings that indicate nearly half of adults with hypertension have inadequate BP control.2

Clinicians require clear direction about optimal BP targets, how best to adjust antihypertensive medications for comorbidities, and how to incorporate frailty and cognitive impairment into management strategies. This article presents recommendations derived from recent evidence and consensus guidelines regarding the management of hypertension in adults ≥75 years of age.

[polldaddy:9818133]

Diagnosing hypertension

According to the seventh report of the Joint National Committee (JNC 7), hypertension is defined as a systolic BP ≥140 mm Hg and/or a diastolic BP ≥90 mm Hg.8 The JNC’s more recent report (JNC 8), however, does not define hypertension; instead, it sets forth treatment thresholds (eg, that there is strong evidence to support treating individuals ≥60 years of age when BP ≥150/90 mm Hg).9

It starts with an accurate BP measurement. Ensuring the accuracy of a BP measurement requires multiple readings over time. White coat hypertension and masked hypertension can complicate BP measurement. Home measurements better correlate with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk than do office measurements.10-12 In fact, the US Preventive Services Task Force recommends obtaining measurements outside of the clinic setting prior to initiating treatment for hypertension.13

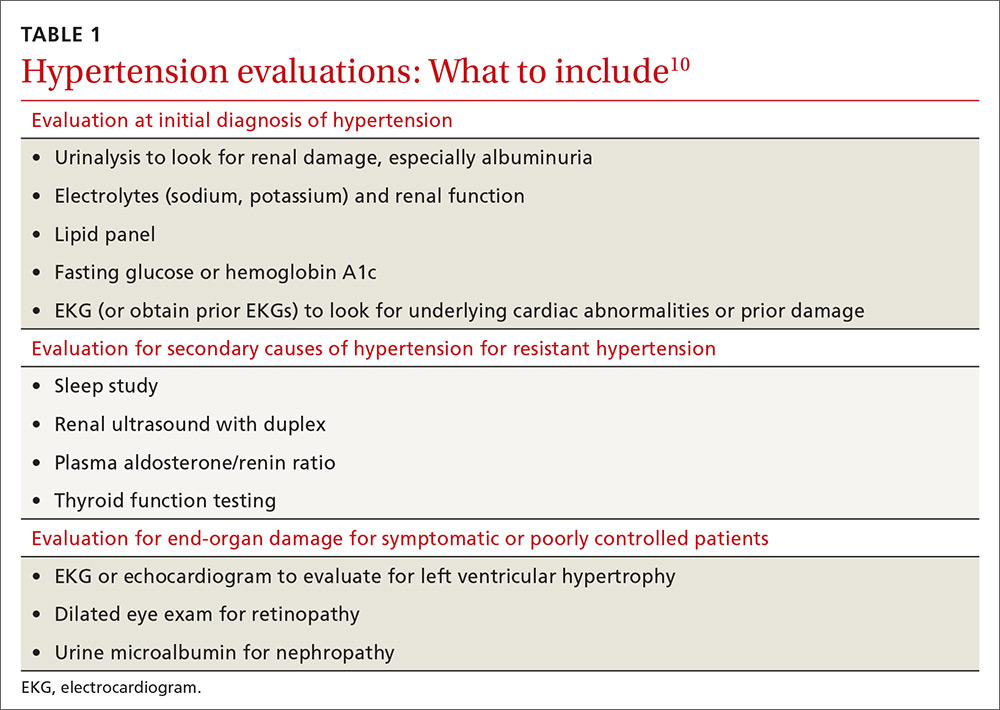

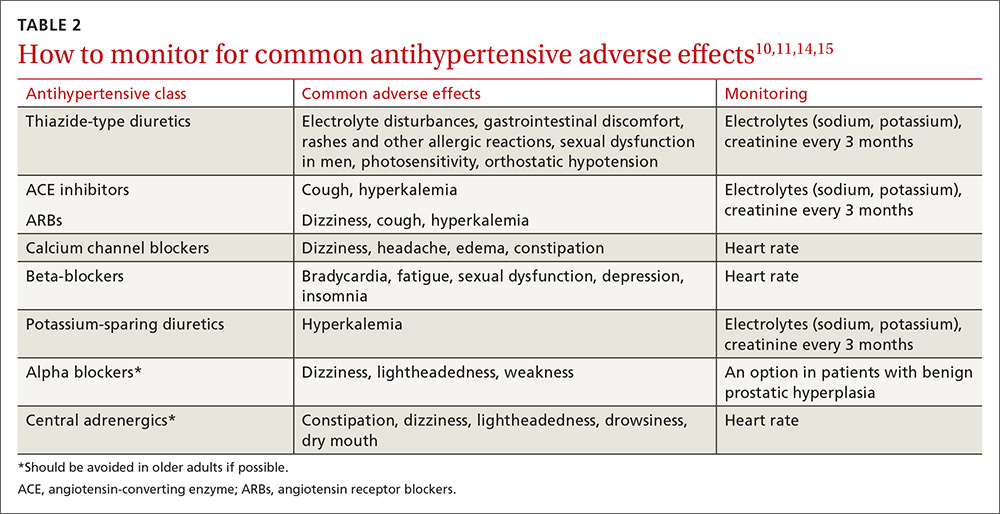

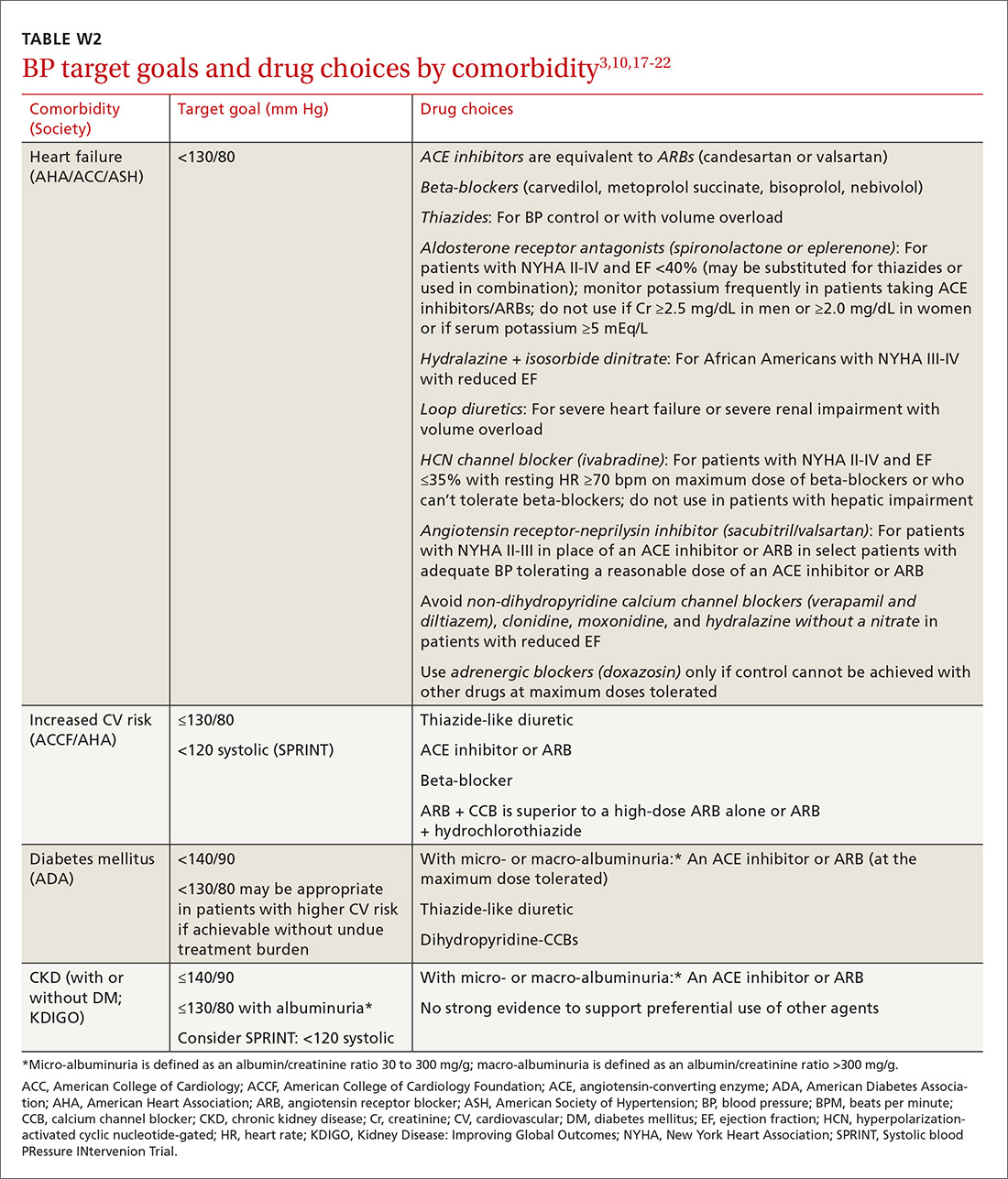

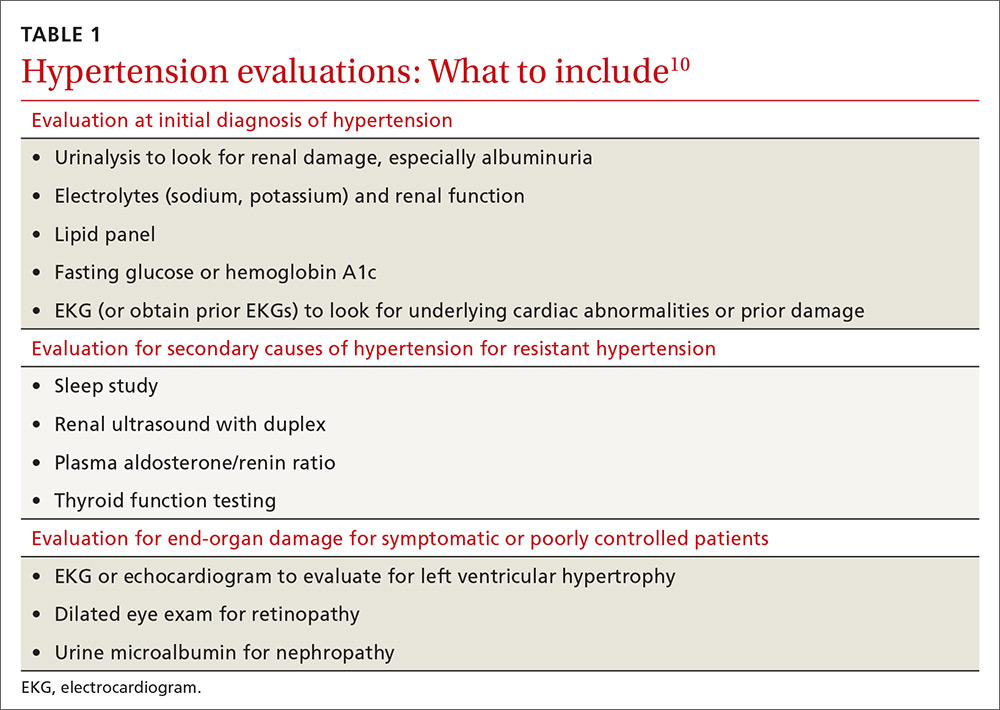

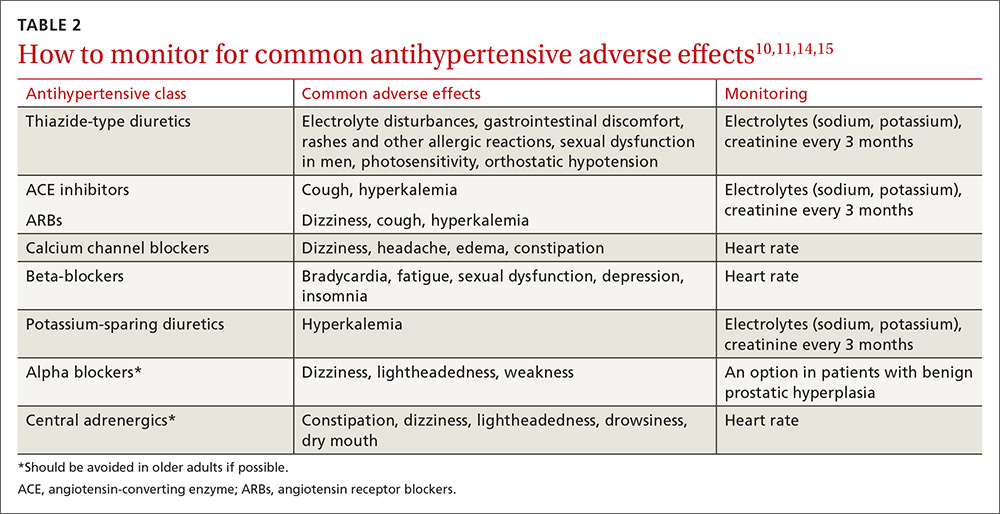

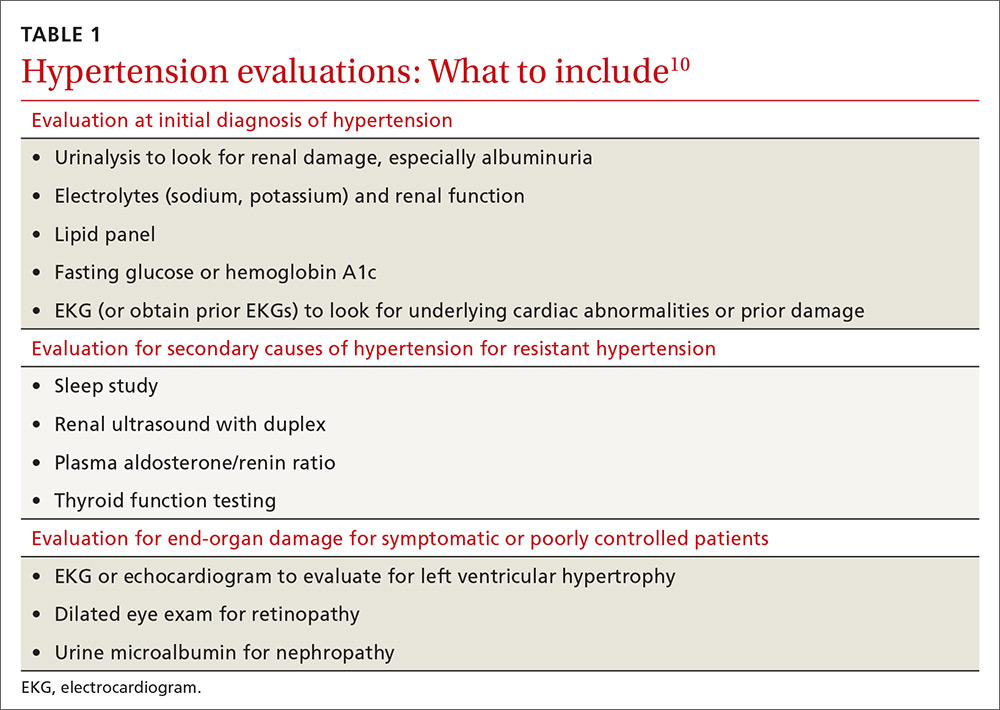

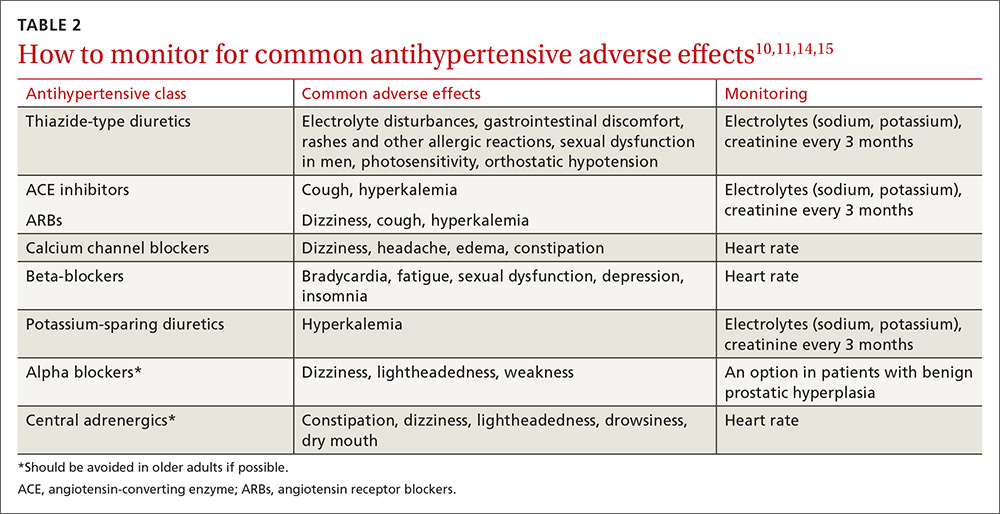

Educate staff on the proper technique for obtaining BP measurements in the office (ie, taking measurements using an appropriately sized cuff when patients have been seated for at least 5 minutes with feet uncrossed and with their arm supported at heart level). Cold temperatures, coffee consumption, talking, and recent tobacco use can transiently raise BP. TABLE 110 outlines the initial work-up after confirming the diagnosis of hypertension. No other routine tests are recommended for the management of hypertension except those associated with medication monitoring (outlined in TABLE 210,11,14,15).

What’s the optimal BP target for older patients? No consensus exists on an optimal BP target for older patients. JNC 8 recommends a target BP <150/90 mm Hg in patients ≥60 years of age.9 The American College of Physicians recommends a systolic BP target <140 mm Hg in patients ≥60 years of age with increased stroke or CV risk.11 A subgroup analysis of patients ≥75 years of age from the Systolic BP Intervention Trial (SPRINT)3 was stopped early because of the clear composite CV and mortality benefits associated with targeting a systolic BP <120 mm Hg as compared with <140 mm Hg (TABLE W13-6). Although a criticism of this trial and its results is that the researchers included only adults with high CV risk, all adults ≥75 years of age are considered to have high CV risk by the SPRINT study.3 Another criticism is that early suspension of the trial may have exaggerated treatment effects.6

Lastly, results were seemingly discrepant from previous trials, most notably, the Action to Control CV Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD) trial.6,16 However, on closer review, the ACCORD trial16 included only patients with DM, while the SPRINT3 trial excluded patients with DM, and ACCORD comprised a younger population than the SPRINT subgroup analysis. Also, the ACCORD trial did demonstrate stroke reduction and non-significant reduction in CV events, albeit, at the cost of increased adverse events, such as hypotension, bradycardia, and hypokalemia, with tighter BP control.16

Population differences presumably explain the discrepancy in results, and a systolic BP target of <120 mm Hg is appropriate in community-dwelling, non-diabetic adults ≥75 years of age. If this target goal cannot be achieved without undue burden (ie, without syncope, hypotension, bradycardia, electrolyte disturbance, renal impairment, or substantial medication burden), a recent meta-analysis found evidence that a systolic BP goal <140 mm Hg also provides benefit.6

Initiate treatment, watch for age-related changes

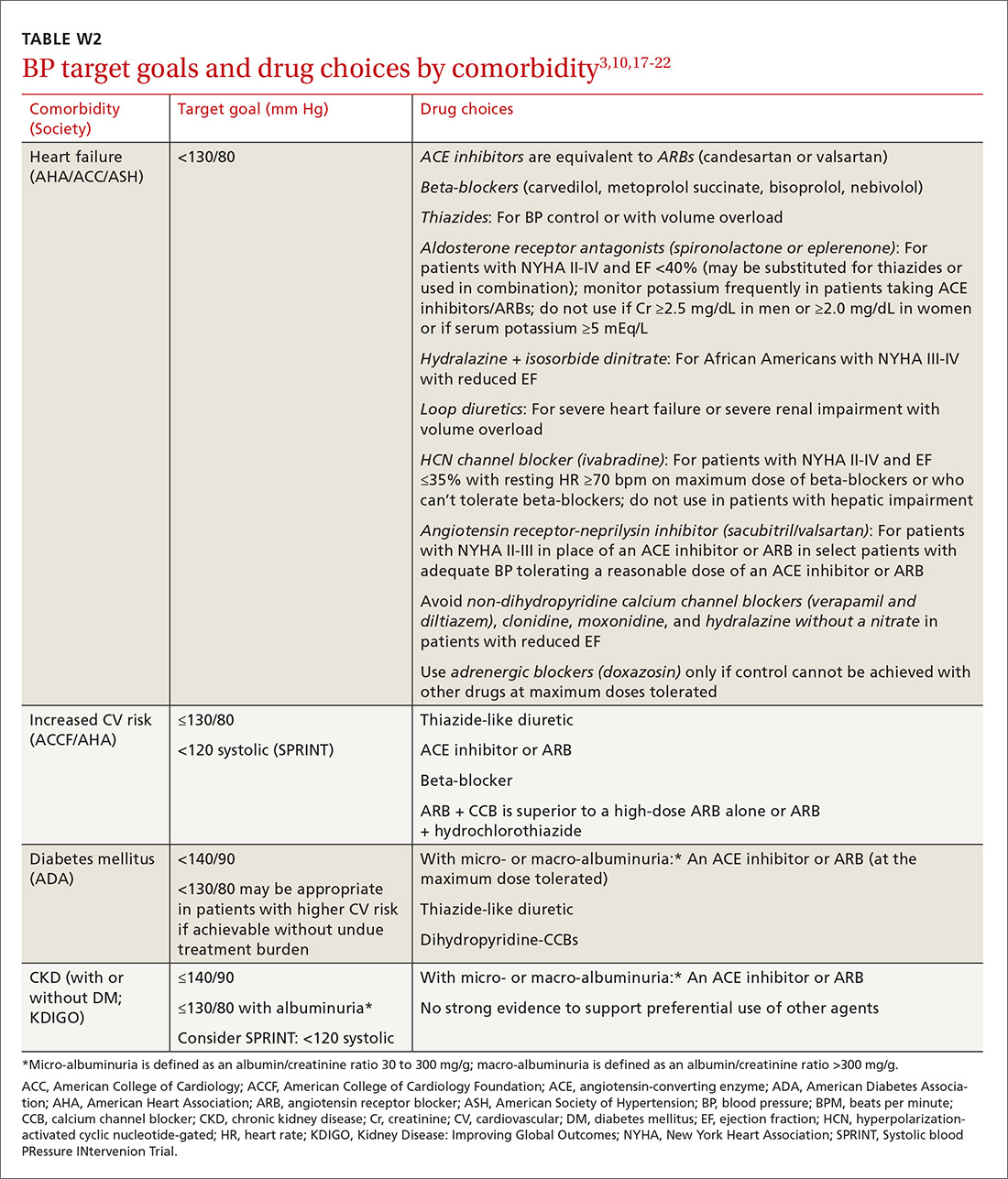

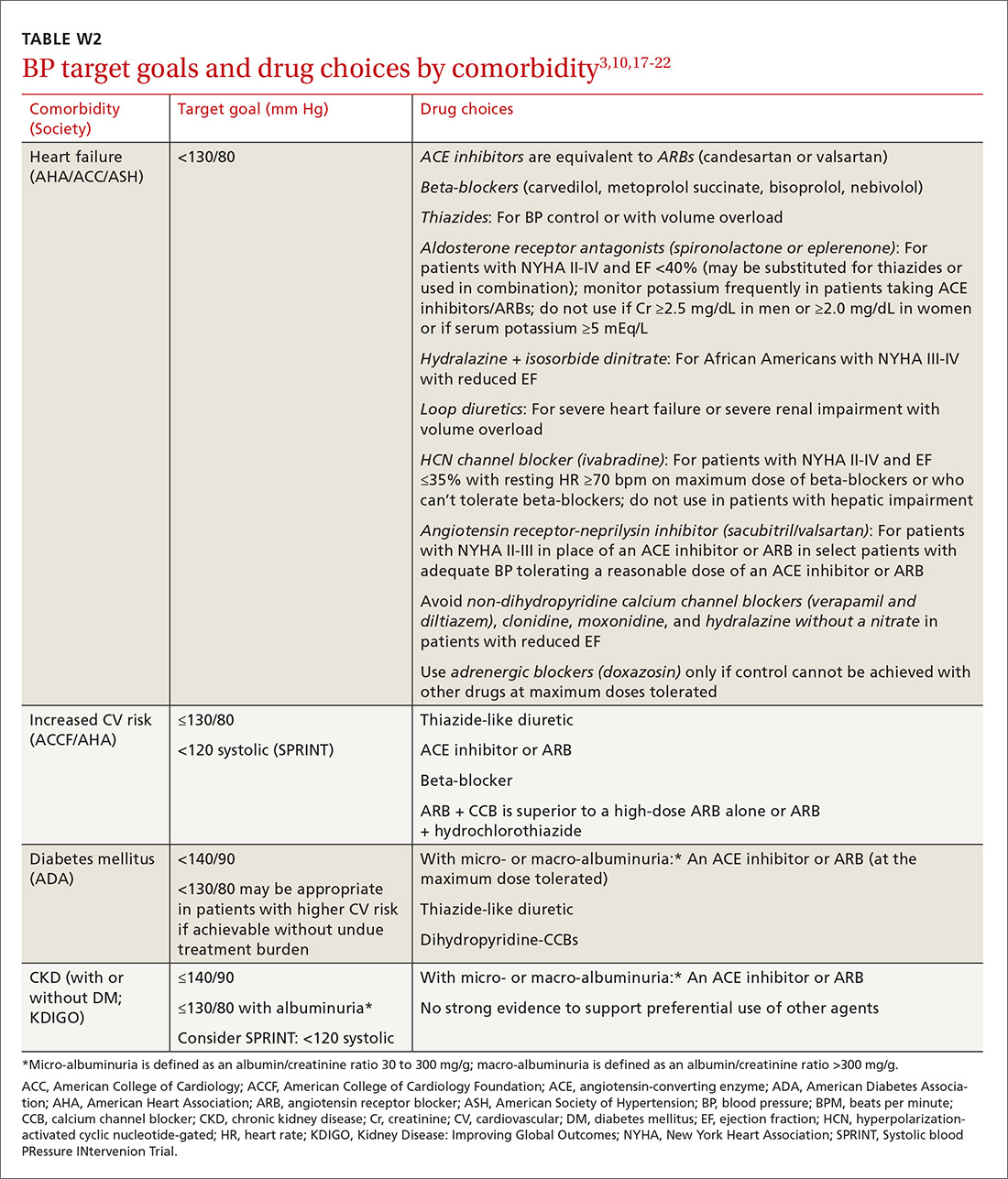

Lifestyle modifications (including appropriate weight loss; reduced caffeine, salt, and alcohol intake; increased physical activity; and smoking cessation) are important in the initial and ongoing management of hypertension.10,11,17,18 JNC 8 recommends initial treatment with a thiazide-type diuretic, calcium channel blocker (CCB), angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor, or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) in the nonblack population, and a CCB or thiazide diuretic in the black population.9 Specific initial medication choices for comorbid conditions are outlined in TABLE W23,10,17-22. JNC 8 recommends against the use of a beta-blocker or alpha blocker for initial treatment of hypertension.9

Start a second drug instead of maximizing the dose of the first

If the target BP cannot be achieved within one month of initiating medication, JNC 8 recommends increasing the dose of the initial drug or adding a second drug without preference for one strategy over the other.9 However, a meta-analysis demonstrates that approximately 80% of the antihypertensive effect of a drug can be achieved with half of the standard dose of the medication; this is true for thiazide-type diuretics, ACE inhibitors/ARBs, beta-blockers, and CCBs.23

Furthermore, due to fewer adverse effects and positive synergies, studies show that combining low doses of 2 medications is more beneficial than high-dose monotherapy.19,23,24 Prescribing combination pills can be helpful to limit pill burden. It is appropriate to combine any of the 4 classes of medications recommended as initial therapy by JNC 8 except for an ACE inhibitor combined with an ARB. If the target BP cannot be achieved with 3 drugs in those classes, other medications such as potassium-sparing diuretics or beta-blockers can be added.9

Changes associated with aging

Changes associated with aging include atherosclerosis and stiffening of blood vessels, increased systolic BP, widened pulse pressure, reduced glomerular filtration rate, reduced sodium elimination and volume expansion, sinoatrial node cellular dropout, and decreased sensitivity of baroreceptors.10 Because of these alterations, antihypertensive requirements may change, and resistant hypertension may develop. In addition, older patients may be more susceptible to orthostatic hypotension, heart block, electrolyte derangements, and other antihypertensive adverse effects.

When hypertension is difficult to control. Resistant hypertension is defined as hypertension that cannot be controlled with 3 drugs from 3 different antihypertensive classes, one of which is a diuretic. Cognitive impairment, polypharmacy, and multimorbidity may contribute to difficult-to-control hypertension in older adults and should be assessed prior to work-up for other secondary causes of poorly controlled hypertension.

- Cognitive impairment is often unrecognized and may impact medication adherence, which can masquerade as treatment failure. Assess for cognitive impairment on an ongoing basis with the aging patient, especially when medication adherence appears poor.

- Polypharmacy may also contribute to uncontrolled BP. Common pharmacotherapeutic contributors to uncontrolled BP include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), glucocorticoids, high-dose decongestants, and selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors.25

- Multimorbidity describes 2 or more chronic medical conditions in one patient. These patients are medically complex. Comorbidities can increase pill burden and make medication adherence difficult for patients. Other poorly controlled disease states can worsen hypertension (eg, renal dysfunction secondary to diabetes). Optimize treatment of comorbid conditions.

Secondary causes. If resistant hypertension persists despite confirming medication adherence and eliminating offending medications, a work-up should ensue for secondary causes of hypertension, as well as end-organ damage. Causes of secondary hypertension include sleep apnea (see this month's HelpDesk), renal dysfunction (renal artery stenosis), aldosterone-mediated hypertension (often with hypokalemia), and thyroid disease. Evaluation for secondary causes of hypertension and end-organ damage is outlined in TABLE 1.10 Patients with well-controlled hypertension do not require repeated assessments for end-organ damage unless new symptoms—such as chest pain or edema—develop.

Consider comorbidities

Clinical trials implicitly or explicitly exclude patients with multiple comorbidities. JNC 8 provided minimal guidance for adjusting BP targets based on comorbidity with only nondiabetic CKD and DM specifically addressed.9 Guidelines from specialty organizations and recent trials provide some additional guidance in these situations and are outlined in TABLE W23,10,17-22.

Heart failure. Hypertension is a major risk factor for heart failure. Long-term treatment of systolic and diastolic hypertension can reduce the incidence of heart failure by approximately half with increased benefit in patients with prior myocardial infarction.22 Research demonstrates clear mortality benefits of certain antihypertensive drug classes, including diuretics, beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors, ARBs, aldosterone antagonists, combination hydralazine and nitrates, and angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitors.21,22 The overall treatment goal in heart failure is to optimize drugs with mortality benefit, while lowering BP to a goal <130/80 mm Hg in patients ≥75 years of age.22

Increased risk for CV disease. The SPRINT trial3 defined high risk of CV disease as clinical or subclinical CV disease, CKD, 10-year ASCVD risk of ≥15%, or age ≥75 years. SPRINT supports a systolic BP goal <120 mm Hg, but, as a reminder, SPRINT excluded patients with diabetes. The American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force and the American Heart Association define high CV risk as a 10-year ASCVD risk ≥10% and recommend a BP goal <130/80 mm Hg.10

Diabetes mellitus. A BP >115/75 mm Hg is associated with increased CV events and mortality in patients with DM.18 The American Diabetes Association (ADA) and JNC 8 recommend a BP target <140/90 mm Hg.9,18 ADA suggests a lower target of 130/80 mm Hg in patients with high CV risk if it is achievable without undue burden.18

Studies show increased mortality associated with initiating additional treatment once a systolic goal <140 mm Hg has been achieved in patients with DM.26 The ACCORD trial found increased adverse events with aggressive BP lowering to <120/80 mm Hg.16

For patients with DM requiring more than one antihypertensive agent, there are CV mortality benefits associated with administering at least one antihypertensive drug at night, likely related to the beneficial effect of physiologic nocturnal dipping.27

Chronic kidney disease. JNC 8 specifically recommends an ACE inhibitor or ARB for initial or add-on treatment in patients with CKD and a BP goal <140/90 mm Hg.9 The Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Blood Pressure Work Group recommends a BP target ≤140/90 mm Hg in patients without albuminuria and ≤130/80 mm Hg in patients with albuminuria to protect against the progression of nephropathy.17 The SPRINT trial3 included patients with CKD, and KDIGO has not yet updated its guidelines to reflect SPRINT.

Frailty is a clinical syndrome that has been defined as a state of increased vulnerability that is associated with a decline in reserve and function.28 The largest hypertension studies in older adults address frailty, although often the most frail patients are excluded from these studies (TABLE W13-6).

The Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial (HYVET) categorized patients as frail, pre-frail, or robust and found a consistent benefit of antihypertensive treatment on stroke, CV events, and total mortality—regardless of baseline frailty status.29 The SPRINT trial included only community-dwelling adults.3 Other studies suggest that hypertension actually has a protective effect by lowering overall mortality in frail older adults, especially in the frailest and oldest nursing home populations.30,31

Although there is a paucity of data to direct the management of hypertension in frail older patients, physicians should prioritize the condition and focus on adverse events from antihypertensives and on slow titration of medications. The JNC 8 BP target of <150/90 mm Hg is a reasonable BP goal in this population, given the lack of evidence for lower or higher targets.9 Many frail patients have one or more of the comorbidities described earlier, and it is reasonable to strive for the comorbidity-specific target, provided it can be achieved without undue burden.

Cognitive impairment and dementia. The association between hypertension and dementia/cognitive impairment is evolving. Hypertension may impact various forms of dementia, such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) or vascular dementia, differently. There is evidence linking hypertension to AD.32 The relationship between BP and brain perfusion is complex with the potential existence of an age-adjusted relationship such that mid-life hypertension may increase the risk of dementia while late-life hypertension may not.33

A number of studies reveal the evolving nature of our understanding of these 2 conditions:

- A recent systematic review and meta-analysis examining intensive BP treatments in older adults demonstrated that lower BP targets did not increase cognitive decline.6

- HYVET’s cognitive function assessment did not find a significant reduction in the incidence of dementia with BP reduction over a short follow-up period, but when results were combined in a meta-analysis with other placebo-controlled, double-blind trials of antihypertensive treatments, there was significant reduction in incident dementia in patients randomized to antihypertensive treatment.34

- The ACCORD Memory in Diabetes trial (ACCORD-MIND) had the unexpected outcome that intensive lowering of systolic BP to a target <120 mm Hg resulted in a greater decline in total brain volume, compared with the standard BP goal <140 mm Hg. This was measured with magnetic resonance imaging in older adults with type 2 DM.35

- Results from the SPRINT sub-analysis Memory and Cognition in Decreased Hypertension trial are forthcoming and aim to determine the effects of BP reduction on dementia.36

The JNC 89 BP target <150/90 mm Hg or a comorbidity-specific target, if achievable without undue burden, is reasonable in patients with dementia. In a systematic review of observational studies in patients with hypertension and dementia, diuretics, CCBs, ACE inhibitors/ARBs, and beta-blockers were commonly used medications with a trend toward prescribing CCBs and ACE inhibitors/ARBs.37

As previously highlighted, cognitive impairment may lead to problems with medication adherence and even inadvertent improper medication use, potentially resulting in adverse events from antihypertensives. If cognitive impairment or dementia is suspected, ensure additional measures (such as medication assistance or supervision) are in place before prescribing antihypertensives.

Certain diseases, such as Parkinson’s-related dementia and multiple system atrophy, can cause autonomic instability, which can increase the risk of falls and complicate hypertension management. Carefully monitor patients for signs of orthostasis.

CASE 1 Repeat the BP measurement in the office once the patient has been seated for ≥5 minutes, and have the patient monitor her BP at home; schedule a follow-up visit in 2 weeks. If hypertension is confirmed with home measurements, then, in addition to lifestyle modifications, initiate treatment with a CCB or thiazide diuretic to achieve a systolic BP goal <120 mm Hg. Titrate medications slowly while monitoring for adverse effects.

CASE 2 Consistent with the office measurement, the patient has home BP readings that are above the BP target (<120 mm Hg systolic). He has been taking a single antihypertensive for longer than one month. Discontinue his NSAID prior to adding any new medications. If his BP is still above target without NSAIDs, then add a second agent, such as a low dose of an ACE inhibitor, ARB, or CCB, rather than maximizing the dose of hydrochlorothiazide.

CASE 3 Given the patient’s diabetes, CKD, and albuminuria, a target BP goal <130/80 mm Hg is reasonable. An ACE inhibitor or ARB is a better medication choice than atenolol in this patient with albuminuria. Because of the deterioration in his ADLs, careful assessment of mobility, functionality, comorbidities, frailty, and cognitive function should take place at each office visit and inform adjustments to the patient’s BP target. Employ cautious medication titration with monitoring for adverse effects, especially hypotension and syncope. If his functional status declines, adverse effects develop, or the medication regimen becomes burdensome, relax the target BP goal to 150/90 mm Hg.

CORRESPONDENCE

Julienne K. Kirk, PharmD, Family and Community Medicine, Wake Forest School of Medicine, Medical Center Boulevard, Winston-Salem, NC 27157-1084; [email protected].

1. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2013 State and National Summary Tables. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/namcs_summary/2013_namcs_web_tables.pdf. Accessed May 29, 2017.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. High blood pressure facts. Available at: https://cdc.gov/bloodpressure/facts.htm. Accessed May 29, 2017.

3. Williamson JD, Suplano MA, Applegate WB, et al. Intensive vs standard blood pressure control and cardiovascular disease outcomes in adults aged ≥75 years: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315:2673-2682.

4. Beckett NS, Peters R, Fletcher AE, et al. Treatment of hypertension in patients 80 years of age or older. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1887-1898.

5. Kostis WJ, Cabrera J, Messerli FH, et al. Competing cardiovascular and noncardiovascular risks and longevity in the systolic hypertension in the elderly program. Am J Cardiol. 2014;113:676-681.

6. Weiss J, Freeman M, Low A, et al. Benefits and harms of intensive blood pressure treatment in adults aged 60 years or older: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:419-429.

7. Framingham Heart Study. Available at: https://www.framinghamheartstudy.org/risk-functions/cardiovascular-disease/10-year-risk.php. Accessed May 29, 2017.

8. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. The seventh report of the Joint National Committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003;289:2560-2572.

9. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311:507-520.

10. Aronow WS, Fleg JL, Pepine CJ, et al. ACCF/AHA 2011 expert consensus document on hypertension in the elderly: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on clinical expert consensus documents developed in collaboration with the American Academy of Neurology, American Geriatrics Society, American Society for Preventive Cardiology, American Society of Hypertension, American Society of Nephrology, Association of Black Cardiologists, and European Society of Hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:2037-2114.

11. Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Rich R, et al. Pharmacological treatment of hypertension in adults aged 60 years or older to higher versus lower blood pressure targets: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Academy of Family Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:430-437.

12. Sega R, Facchetti R, Bombelli M, et al. Prognostic value of ambulatory and home blood pressures compared with office blood pressure in the general population: follow-up results from the Pressioni Arteriose Monitorate e Loro Associazioni (PAMELA) study. Circulation. 2005;111:1777-1783.

13. US Preventive Services Task Force. Final recommendation statement: high blood pressure in adults: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/high-blood-pressure-in-adults-screening. Accessed May 29, 2017.

14. Steinman MA, Miao Y, Boscardin WJ, et al. Prescribing quality in older veterans: a multifocal approach. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29:1379-1386.

15. Schwartz JB. Primary prevention: do the very elderly require a different approach. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2015:25:228-239.

16. Accord Study Group, Cushman WC, Evans GW, Byington RP, et al. Effects of intensive blood-pressure control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1575-1585.

17. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Blood Pressure Work Group. KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Blood Pressure in Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int. 2012;2:337-414.

18. American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2017. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(suppl 1):S1-S135.

19. Ogawa H, Kim-Mitsuyama S, Matsui K, et al, OSCAR Study Group. Angiotensin II receptor blocker-based therapy in Japanese elderly, high-risk, hypertensive patients. Am J Med. 2012;125:981-990.

20. Rosendorff C, Lackland DT, Allison M, et al. AHA/ACC/ASH Scientific Statement. Treatment of hypertension in patients with coronary heart disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology, and American Society of Hypertension. Hypertension. 2015;65:1372-1407.

21. Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2013;128:e240-e327.

22. Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA focused update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on clinical practice guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America. Circulation. 2017;136:e137-e161.

23. Law MR, Wald MJ, Morris JK, et al. Value of low dose combination treatment with blood pressure lowering drugs: analysis of 354 randomised trials. BMJ. 2003;326:1427.

24. Wald DS, Law M, Morris JK, et al. Combination therapy versus monotherapy in reducing blood pressure: meta-analysis on 11,000 participants from 42 trials. Am J Med. 2009;122:290-300.

25. Mukete BN, Ferdinand KC. Polypharmacy in older adults with hypertension: a comprehensive review. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2016;18:10-18.

26. Brunstrom M, Carlberg B. Effect of antihypertensive treatment at different blood pressure levels in patients with diabetes mellitus: systematic review and meta-analyses. BMJ. 2016;352:i717.

27. Hermida RC, Ayala DE, Mojón A, et al. Influence of time of day of blood pressure-lowering treatment on cardiovascular risk in hypertensive patients with type 2 diabetes. Diab Care. 2011;34:1270-1276.

28. Xue QL. The frailty syndrome: definition and natural history. Clin Geriatr Med. 2011;27:1-15.

29. Warwick J, Falashcetti E, Rockwood K, et al. No evidence that frailty modifies the positive impact of antihypertensive treatment in very elderly people: an investigation of the impact of frailty upon treatment effect in the Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial (HYVET) study, a double-blind, placebo-controlled study of antihypertensives in people with hypertension aged 80 and over. BMC Med. 2015;13:78.

30. Zhang XE, Cheng B, Wang Q. Relationship between high blood pressure and cardiovascular outcomes in elderly frail patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Geriatric Nurs. 2016;37:385-392.

31. Benetos A, Rossignol P, Cherbuini A, et al. Polypharmacy in the aging patient: management of hypertension in octogenarians. JAMA. 2015;314:170-180.

32. de Bruijn R, Ikram MA. Cardiovascular risk factors and future risk of Alzheimer’s disease. BMC Med. 2014;12:130.

33. Joas E, Bäckman K, Gustafson D, et al. Blood pressure trajectories from midlife to late life in relation to dementia in women followed for 37 years. Hypertension. 2012;59:796-801.

34. Peters R, Beckett N, Forette F, et al. Incident dementia and blood pressure lowering in the Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial cognitive function assessment (HYVET-COG): a double-blind, placebo controlled trial. Lanc Neurol. 2008;7:683-689.

35. Williamson JD, Launer LJ, Bryan RN, et al. Cognitive function and brain structure in persons with type 2 diabetes mellitus after intensive lowering of blood pressure and lipid levels: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:324-333.

36. Tom Wade, MD. Methods of the SPRINT MIND Trial—how they did it + why it matters to primary care physicians. Available at: /www.tomwademd.net/methods-of-the-sprint-mind-trial-how-they-did-it-why-it-matters-to-primary-care-physicians/. Accessed August 11, 2017.

37. Welsh TJ, Gladman JR, Gordon AL. The treatment of hypertension in people with dementia: a systematic review of observational studies. BMC Geriatr. 2014;14:19.

CASE 1 An 82-year-old black woman comes in for an annual exam. She has no medical concerns. She volunteers at a hospice, walks daily, and maintains a healthy diet. Her past medical history (PMH) includes osteopenia and osteoarthritis, and her medications include acetaminophen as needed and vitamin D. She has no drug allergies. Her exam reveals a blood pressure (BP) of 148/70 mm Hg, a body mass index of 31, and a heart rate (HR) of 71 beats per minute (bpm). Cardiac and pulmonary exams are normal, and she shows no signs of peripheral edema.

CASE 2 An 88-year-old white man presents to the office for a 3-month follow-up of his hypertension. His systolic BP at home has ranged from 140 to 170 mm Hg. He denies chest pain, shortness of breath, or lower extremity edema. He lives with his wife and frequently swims for exercise. His PMH is significant for depression and degenerative disc disease. His medications include hydrochlorothiazide 12.5 mg/d, sertraline 50 mg/d, and naproxen 250 mg bid. His BP is 160/80 mm Hg and his HR is 70 bpm with normal cardiovascular (CV) and pulmonary exams.

CASE 3 An 80-year-old white man with diabetes mellitus (DM), hypertension, and chronic kidney disease (CKD) presents for a 3-month follow-up visit. His home systolic BP has been in the 140s to 150s. He is functional in all of his activities of daily living (ADLs), but is starting to require assistance with medications, finances, and transportation. He takes aspirin 81 mg/d, chlorthalidone 25 mg/d, and atenolol 50 mg/d. Remarkable laboratory test results include a hemoglobin A1c of 8.6%, a serum creatinine of 1.9 mg/dL (normal range: 0.6-1.2 mg/dL), and an albumin-creatinine ratio of 250 mg/g (normal range: <30 mg/g). During the exam, his BP is 143/70 mm Hg, his HR is 70 bpm, he is alert and oriented to person, place, and time, and he has normal CV and pulmonary exams with no signs of peripheral edema. He has decreased sensation in his feet, but normal reflexes.

How would you proceed with the care of these 3 patients?

Hypertension is the most common diagnosis made during physician office visits in the United States.1 Nearly one-third of the population has hypertension, and its prevalence increases with age, such that 67% of men and 79% of women ≥75 years of age have the condition.2

Evidence indicates that hypertension is a modifiable risk factor for CV and all-cause mortality (TABLE W13-6). All adults ≥75 years of age are at increased CV risk based on Framingham criteria,7 making hypertension management paramount. Complicating the situation are findings that indicate nearly half of adults with hypertension have inadequate BP control.2

Clinicians require clear direction about optimal BP targets, how best to adjust antihypertensive medications for comorbidities, and how to incorporate frailty and cognitive impairment into management strategies. This article presents recommendations derived from recent evidence and consensus guidelines regarding the management of hypertension in adults ≥75 years of age.

[polldaddy:9818133]

Diagnosing hypertension

According to the seventh report of the Joint National Committee (JNC 7), hypertension is defined as a systolic BP ≥140 mm Hg and/or a diastolic BP ≥90 mm Hg.8 The JNC’s more recent report (JNC 8), however, does not define hypertension; instead, it sets forth treatment thresholds (eg, that there is strong evidence to support treating individuals ≥60 years of age when BP ≥150/90 mm Hg).9

It starts with an accurate BP measurement. Ensuring the accuracy of a BP measurement requires multiple readings over time. White coat hypertension and masked hypertension can complicate BP measurement. Home measurements better correlate with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk than do office measurements.10-12 In fact, the US Preventive Services Task Force recommends obtaining measurements outside of the clinic setting prior to initiating treatment for hypertension.13

Educate staff on the proper technique for obtaining BP measurements in the office (ie, taking measurements using an appropriately sized cuff when patients have been seated for at least 5 minutes with feet uncrossed and with their arm supported at heart level). Cold temperatures, coffee consumption, talking, and recent tobacco use can transiently raise BP. TABLE 110 outlines the initial work-up after confirming the diagnosis of hypertension. No other routine tests are recommended for the management of hypertension except those associated with medication monitoring (outlined in TABLE 210,11,14,15).

What’s the optimal BP target for older patients? No consensus exists on an optimal BP target for older patients. JNC 8 recommends a target BP <150/90 mm Hg in patients ≥60 years of age.9 The American College of Physicians recommends a systolic BP target <140 mm Hg in patients ≥60 years of age with increased stroke or CV risk.11 A subgroup analysis of patients ≥75 years of age from the Systolic BP Intervention Trial (SPRINT)3 was stopped early because of the clear composite CV and mortality benefits associated with targeting a systolic BP <120 mm Hg as compared with <140 mm Hg (TABLE W13-6). Although a criticism of this trial and its results is that the researchers included only adults with high CV risk, all adults ≥75 years of age are considered to have high CV risk by the SPRINT study.3 Another criticism is that early suspension of the trial may have exaggerated treatment effects.6

Lastly, results were seemingly discrepant from previous trials, most notably, the Action to Control CV Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD) trial.6,16 However, on closer review, the ACCORD trial16 included only patients with DM, while the SPRINT3 trial excluded patients with DM, and ACCORD comprised a younger population than the SPRINT subgroup analysis. Also, the ACCORD trial did demonstrate stroke reduction and non-significant reduction in CV events, albeit, at the cost of increased adverse events, such as hypotension, bradycardia, and hypokalemia, with tighter BP control.16

Population differences presumably explain the discrepancy in results, and a systolic BP target of <120 mm Hg is appropriate in community-dwelling, non-diabetic adults ≥75 years of age. If this target goal cannot be achieved without undue burden (ie, without syncope, hypotension, bradycardia, electrolyte disturbance, renal impairment, or substantial medication burden), a recent meta-analysis found evidence that a systolic BP goal <140 mm Hg also provides benefit.6

Initiate treatment, watch for age-related changes

Lifestyle modifications (including appropriate weight loss; reduced caffeine, salt, and alcohol intake; increased physical activity; and smoking cessation) are important in the initial and ongoing management of hypertension.10,11,17,18 JNC 8 recommends initial treatment with a thiazide-type diuretic, calcium channel blocker (CCB), angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor, or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) in the nonblack population, and a CCB or thiazide diuretic in the black population.9 Specific initial medication choices for comorbid conditions are outlined in TABLE W23,10,17-22. JNC 8 recommends against the use of a beta-blocker or alpha blocker for initial treatment of hypertension.9

Start a second drug instead of maximizing the dose of the first

If the target BP cannot be achieved within one month of initiating medication, JNC 8 recommends increasing the dose of the initial drug or adding a second drug without preference for one strategy over the other.9 However, a meta-analysis demonstrates that approximately 80% of the antihypertensive effect of a drug can be achieved with half of the standard dose of the medication; this is true for thiazide-type diuretics, ACE inhibitors/ARBs, beta-blockers, and CCBs.23

Furthermore, due to fewer adverse effects and positive synergies, studies show that combining low doses of 2 medications is more beneficial than high-dose monotherapy.19,23,24 Prescribing combination pills can be helpful to limit pill burden. It is appropriate to combine any of the 4 classes of medications recommended as initial therapy by JNC 8 except for an ACE inhibitor combined with an ARB. If the target BP cannot be achieved with 3 drugs in those classes, other medications such as potassium-sparing diuretics or beta-blockers can be added.9

Changes associated with aging

Changes associated with aging include atherosclerosis and stiffening of blood vessels, increased systolic BP, widened pulse pressure, reduced glomerular filtration rate, reduced sodium elimination and volume expansion, sinoatrial node cellular dropout, and decreased sensitivity of baroreceptors.10 Because of these alterations, antihypertensive requirements may change, and resistant hypertension may develop. In addition, older patients may be more susceptible to orthostatic hypotension, heart block, electrolyte derangements, and other antihypertensive adverse effects.

When hypertension is difficult to control. Resistant hypertension is defined as hypertension that cannot be controlled with 3 drugs from 3 different antihypertensive classes, one of which is a diuretic. Cognitive impairment, polypharmacy, and multimorbidity may contribute to difficult-to-control hypertension in older adults and should be assessed prior to work-up for other secondary causes of poorly controlled hypertension.

- Cognitive impairment is often unrecognized and may impact medication adherence, which can masquerade as treatment failure. Assess for cognitive impairment on an ongoing basis with the aging patient, especially when medication adherence appears poor.

- Polypharmacy may also contribute to uncontrolled BP. Common pharmacotherapeutic contributors to uncontrolled BP include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), glucocorticoids, high-dose decongestants, and selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors.25

- Multimorbidity describes 2 or more chronic medical conditions in one patient. These patients are medically complex. Comorbidities can increase pill burden and make medication adherence difficult for patients. Other poorly controlled disease states can worsen hypertension (eg, renal dysfunction secondary to diabetes). Optimize treatment of comorbid conditions.

Secondary causes. If resistant hypertension persists despite confirming medication adherence and eliminating offending medications, a work-up should ensue for secondary causes of hypertension, as well as end-organ damage. Causes of secondary hypertension include sleep apnea (see this month's HelpDesk), renal dysfunction (renal artery stenosis), aldosterone-mediated hypertension (often with hypokalemia), and thyroid disease. Evaluation for secondary causes of hypertension and end-organ damage is outlined in TABLE 1.10 Patients with well-controlled hypertension do not require repeated assessments for end-organ damage unless new symptoms—such as chest pain or edema—develop.

Consider comorbidities

Clinical trials implicitly or explicitly exclude patients with multiple comorbidities. JNC 8 provided minimal guidance for adjusting BP targets based on comorbidity with only nondiabetic CKD and DM specifically addressed.9 Guidelines from specialty organizations and recent trials provide some additional guidance in these situations and are outlined in TABLE W23,10,17-22.

Heart failure. Hypertension is a major risk factor for heart failure. Long-term treatment of systolic and diastolic hypertension can reduce the incidence of heart failure by approximately half with increased benefit in patients with prior myocardial infarction.22 Research demonstrates clear mortality benefits of certain antihypertensive drug classes, including diuretics, beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors, ARBs, aldosterone antagonists, combination hydralazine and nitrates, and angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitors.21,22 The overall treatment goal in heart failure is to optimize drugs with mortality benefit, while lowering BP to a goal <130/80 mm Hg in patients ≥75 years of age.22

Increased risk for CV disease. The SPRINT trial3 defined high risk of CV disease as clinical or subclinical CV disease, CKD, 10-year ASCVD risk of ≥15%, or age ≥75 years. SPRINT supports a systolic BP goal <120 mm Hg, but, as a reminder, SPRINT excluded patients with diabetes. The American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force and the American Heart Association define high CV risk as a 10-year ASCVD risk ≥10% and recommend a BP goal <130/80 mm Hg.10

Diabetes mellitus. A BP >115/75 mm Hg is associated with increased CV events and mortality in patients with DM.18 The American Diabetes Association (ADA) and JNC 8 recommend a BP target <140/90 mm Hg.9,18 ADA suggests a lower target of 130/80 mm Hg in patients with high CV risk if it is achievable without undue burden.18

Studies show increased mortality associated with initiating additional treatment once a systolic goal <140 mm Hg has been achieved in patients with DM.26 The ACCORD trial found increased adverse events with aggressive BP lowering to <120/80 mm Hg.16

For patients with DM requiring more than one antihypertensive agent, there are CV mortality benefits associated with administering at least one antihypertensive drug at night, likely related to the beneficial effect of physiologic nocturnal dipping.27

Chronic kidney disease. JNC 8 specifically recommends an ACE inhibitor or ARB for initial or add-on treatment in patients with CKD and a BP goal <140/90 mm Hg.9 The Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Blood Pressure Work Group recommends a BP target ≤140/90 mm Hg in patients without albuminuria and ≤130/80 mm Hg in patients with albuminuria to protect against the progression of nephropathy.17 The SPRINT trial3 included patients with CKD, and KDIGO has not yet updated its guidelines to reflect SPRINT.

Frailty is a clinical syndrome that has been defined as a state of increased vulnerability that is associated with a decline in reserve and function.28 The largest hypertension studies in older adults address frailty, although often the most frail patients are excluded from these studies (TABLE W13-6).

The Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial (HYVET) categorized patients as frail, pre-frail, or robust and found a consistent benefit of antihypertensive treatment on stroke, CV events, and total mortality—regardless of baseline frailty status.29 The SPRINT trial included only community-dwelling adults.3 Other studies suggest that hypertension actually has a protective effect by lowering overall mortality in frail older adults, especially in the frailest and oldest nursing home populations.30,31

Although there is a paucity of data to direct the management of hypertension in frail older patients, physicians should prioritize the condition and focus on adverse events from antihypertensives and on slow titration of medications. The JNC 8 BP target of <150/90 mm Hg is a reasonable BP goal in this population, given the lack of evidence for lower or higher targets.9 Many frail patients have one or more of the comorbidities described earlier, and it is reasonable to strive for the comorbidity-specific target, provided it can be achieved without undue burden.

Cognitive impairment and dementia. The association between hypertension and dementia/cognitive impairment is evolving. Hypertension may impact various forms of dementia, such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) or vascular dementia, differently. There is evidence linking hypertension to AD.32 The relationship between BP and brain perfusion is complex with the potential existence of an age-adjusted relationship such that mid-life hypertension may increase the risk of dementia while late-life hypertension may not.33

A number of studies reveal the evolving nature of our understanding of these 2 conditions:

- A recent systematic review and meta-analysis examining intensive BP treatments in older adults demonstrated that lower BP targets did not increase cognitive decline.6

- HYVET’s cognitive function assessment did not find a significant reduction in the incidence of dementia with BP reduction over a short follow-up period, but when results were combined in a meta-analysis with other placebo-controlled, double-blind trials of antihypertensive treatments, there was significant reduction in incident dementia in patients randomized to antihypertensive treatment.34

- The ACCORD Memory in Diabetes trial (ACCORD-MIND) had the unexpected outcome that intensive lowering of systolic BP to a target <120 mm Hg resulted in a greater decline in total brain volume, compared with the standard BP goal <140 mm Hg. This was measured with magnetic resonance imaging in older adults with type 2 DM.35

- Results from the SPRINT sub-analysis Memory and Cognition in Decreased Hypertension trial are forthcoming and aim to determine the effects of BP reduction on dementia.36

The JNC 89 BP target <150/90 mm Hg or a comorbidity-specific target, if achievable without undue burden, is reasonable in patients with dementia. In a systematic review of observational studies in patients with hypertension and dementia, diuretics, CCBs, ACE inhibitors/ARBs, and beta-blockers were commonly used medications with a trend toward prescribing CCBs and ACE inhibitors/ARBs.37

As previously highlighted, cognitive impairment may lead to problems with medication adherence and even inadvertent improper medication use, potentially resulting in adverse events from antihypertensives. If cognitive impairment or dementia is suspected, ensure additional measures (such as medication assistance or supervision) are in place before prescribing antihypertensives.

Certain diseases, such as Parkinson’s-related dementia and multiple system atrophy, can cause autonomic instability, which can increase the risk of falls and complicate hypertension management. Carefully monitor patients for signs of orthostasis.

CASE 1 Repeat the BP measurement in the office once the patient has been seated for ≥5 minutes, and have the patient monitor her BP at home; schedule a follow-up visit in 2 weeks. If hypertension is confirmed with home measurements, then, in addition to lifestyle modifications, initiate treatment with a CCB or thiazide diuretic to achieve a systolic BP goal <120 mm Hg. Titrate medications slowly while monitoring for adverse effects.

CASE 2 Consistent with the office measurement, the patient has home BP readings that are above the BP target (<120 mm Hg systolic). He has been taking a single antihypertensive for longer than one month. Discontinue his NSAID prior to adding any new medications. If his BP is still above target without NSAIDs, then add a second agent, such as a low dose of an ACE inhibitor, ARB, or CCB, rather than maximizing the dose of hydrochlorothiazide.

CASE 3 Given the patient’s diabetes, CKD, and albuminuria, a target BP goal <130/80 mm Hg is reasonable. An ACE inhibitor or ARB is a better medication choice than atenolol in this patient with albuminuria. Because of the deterioration in his ADLs, careful assessment of mobility, functionality, comorbidities, frailty, and cognitive function should take place at each office visit and inform adjustments to the patient’s BP target. Employ cautious medication titration with monitoring for adverse effects, especially hypotension and syncope. If his functional status declines, adverse effects develop, or the medication regimen becomes burdensome, relax the target BP goal to 150/90 mm Hg.

CORRESPONDENCE

Julienne K. Kirk, PharmD, Family and Community Medicine, Wake Forest School of Medicine, Medical Center Boulevard, Winston-Salem, NC 27157-1084; [email protected].

CASE 1 An 82-year-old black woman comes in for an annual exam. She has no medical concerns. She volunteers at a hospice, walks daily, and maintains a healthy diet. Her past medical history (PMH) includes osteopenia and osteoarthritis, and her medications include acetaminophen as needed and vitamin D. She has no drug allergies. Her exam reveals a blood pressure (BP) of 148/70 mm Hg, a body mass index of 31, and a heart rate (HR) of 71 beats per minute (bpm). Cardiac and pulmonary exams are normal, and she shows no signs of peripheral edema.

CASE 2 An 88-year-old white man presents to the office for a 3-month follow-up of his hypertension. His systolic BP at home has ranged from 140 to 170 mm Hg. He denies chest pain, shortness of breath, or lower extremity edema. He lives with his wife and frequently swims for exercise. His PMH is significant for depression and degenerative disc disease. His medications include hydrochlorothiazide 12.5 mg/d, sertraline 50 mg/d, and naproxen 250 mg bid. His BP is 160/80 mm Hg and his HR is 70 bpm with normal cardiovascular (CV) and pulmonary exams.

CASE 3 An 80-year-old white man with diabetes mellitus (DM), hypertension, and chronic kidney disease (CKD) presents for a 3-month follow-up visit. His home systolic BP has been in the 140s to 150s. He is functional in all of his activities of daily living (ADLs), but is starting to require assistance with medications, finances, and transportation. He takes aspirin 81 mg/d, chlorthalidone 25 mg/d, and atenolol 50 mg/d. Remarkable laboratory test results include a hemoglobin A1c of 8.6%, a serum creatinine of 1.9 mg/dL (normal range: 0.6-1.2 mg/dL), and an albumin-creatinine ratio of 250 mg/g (normal range: <30 mg/g). During the exam, his BP is 143/70 mm Hg, his HR is 70 bpm, he is alert and oriented to person, place, and time, and he has normal CV and pulmonary exams with no signs of peripheral edema. He has decreased sensation in his feet, but normal reflexes.

How would you proceed with the care of these 3 patients?

Hypertension is the most common diagnosis made during physician office visits in the United States.1 Nearly one-third of the population has hypertension, and its prevalence increases with age, such that 67% of men and 79% of women ≥75 years of age have the condition.2

Evidence indicates that hypertension is a modifiable risk factor for CV and all-cause mortality (TABLE W13-6). All adults ≥75 years of age are at increased CV risk based on Framingham criteria,7 making hypertension management paramount. Complicating the situation are findings that indicate nearly half of adults with hypertension have inadequate BP control.2

Clinicians require clear direction about optimal BP targets, how best to adjust antihypertensive medications for comorbidities, and how to incorporate frailty and cognitive impairment into management strategies. This article presents recommendations derived from recent evidence and consensus guidelines regarding the management of hypertension in adults ≥75 years of age.

[polldaddy:9818133]

Diagnosing hypertension

According to the seventh report of the Joint National Committee (JNC 7), hypertension is defined as a systolic BP ≥140 mm Hg and/or a diastolic BP ≥90 mm Hg.8 The JNC’s more recent report (JNC 8), however, does not define hypertension; instead, it sets forth treatment thresholds (eg, that there is strong evidence to support treating individuals ≥60 years of age when BP ≥150/90 mm Hg).9

It starts with an accurate BP measurement. Ensuring the accuracy of a BP measurement requires multiple readings over time. White coat hypertension and masked hypertension can complicate BP measurement. Home measurements better correlate with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk than do office measurements.10-12 In fact, the US Preventive Services Task Force recommends obtaining measurements outside of the clinic setting prior to initiating treatment for hypertension.13

Educate staff on the proper technique for obtaining BP measurements in the office (ie, taking measurements using an appropriately sized cuff when patients have been seated for at least 5 minutes with feet uncrossed and with their arm supported at heart level). Cold temperatures, coffee consumption, talking, and recent tobacco use can transiently raise BP. TABLE 110 outlines the initial work-up after confirming the diagnosis of hypertension. No other routine tests are recommended for the management of hypertension except those associated with medication monitoring (outlined in TABLE 210,11,14,15).

What’s the optimal BP target for older patients? No consensus exists on an optimal BP target for older patients. JNC 8 recommends a target BP <150/90 mm Hg in patients ≥60 years of age.9 The American College of Physicians recommends a systolic BP target <140 mm Hg in patients ≥60 years of age with increased stroke or CV risk.11 A subgroup analysis of patients ≥75 years of age from the Systolic BP Intervention Trial (SPRINT)3 was stopped early because of the clear composite CV and mortality benefits associated with targeting a systolic BP <120 mm Hg as compared with <140 mm Hg (TABLE W13-6). Although a criticism of this trial and its results is that the researchers included only adults with high CV risk, all adults ≥75 years of age are considered to have high CV risk by the SPRINT study.3 Another criticism is that early suspension of the trial may have exaggerated treatment effects.6

Lastly, results were seemingly discrepant from previous trials, most notably, the Action to Control CV Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD) trial.6,16 However, on closer review, the ACCORD trial16 included only patients with DM, while the SPRINT3 trial excluded patients with DM, and ACCORD comprised a younger population than the SPRINT subgroup analysis. Also, the ACCORD trial did demonstrate stroke reduction and non-significant reduction in CV events, albeit, at the cost of increased adverse events, such as hypotension, bradycardia, and hypokalemia, with tighter BP control.16

Population differences presumably explain the discrepancy in results, and a systolic BP target of <120 mm Hg is appropriate in community-dwelling, non-diabetic adults ≥75 years of age. If this target goal cannot be achieved without undue burden (ie, without syncope, hypotension, bradycardia, electrolyte disturbance, renal impairment, or substantial medication burden), a recent meta-analysis found evidence that a systolic BP goal <140 mm Hg also provides benefit.6

Initiate treatment, watch for age-related changes

Lifestyle modifications (including appropriate weight loss; reduced caffeine, salt, and alcohol intake; increased physical activity; and smoking cessation) are important in the initial and ongoing management of hypertension.10,11,17,18 JNC 8 recommends initial treatment with a thiazide-type diuretic, calcium channel blocker (CCB), angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor, or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) in the nonblack population, and a CCB or thiazide diuretic in the black population.9 Specific initial medication choices for comorbid conditions are outlined in TABLE W23,10,17-22. JNC 8 recommends against the use of a beta-blocker or alpha blocker for initial treatment of hypertension.9

Start a second drug instead of maximizing the dose of the first

If the target BP cannot be achieved within one month of initiating medication, JNC 8 recommends increasing the dose of the initial drug or adding a second drug without preference for one strategy over the other.9 However, a meta-analysis demonstrates that approximately 80% of the antihypertensive effect of a drug can be achieved with half of the standard dose of the medication; this is true for thiazide-type diuretics, ACE inhibitors/ARBs, beta-blockers, and CCBs.23

Furthermore, due to fewer adverse effects and positive synergies, studies show that combining low doses of 2 medications is more beneficial than high-dose monotherapy.19,23,24 Prescribing combination pills can be helpful to limit pill burden. It is appropriate to combine any of the 4 classes of medications recommended as initial therapy by JNC 8 except for an ACE inhibitor combined with an ARB. If the target BP cannot be achieved with 3 drugs in those classes, other medications such as potassium-sparing diuretics or beta-blockers can be added.9

Changes associated with aging

Changes associated with aging include atherosclerosis and stiffening of blood vessels, increased systolic BP, widened pulse pressure, reduced glomerular filtration rate, reduced sodium elimination and volume expansion, sinoatrial node cellular dropout, and decreased sensitivity of baroreceptors.10 Because of these alterations, antihypertensive requirements may change, and resistant hypertension may develop. In addition, older patients may be more susceptible to orthostatic hypotension, heart block, electrolyte derangements, and other antihypertensive adverse effects.

When hypertension is difficult to control. Resistant hypertension is defined as hypertension that cannot be controlled with 3 drugs from 3 different antihypertensive classes, one of which is a diuretic. Cognitive impairment, polypharmacy, and multimorbidity may contribute to difficult-to-control hypertension in older adults and should be assessed prior to work-up for other secondary causes of poorly controlled hypertension.

- Cognitive impairment is often unrecognized and may impact medication adherence, which can masquerade as treatment failure. Assess for cognitive impairment on an ongoing basis with the aging patient, especially when medication adherence appears poor.

- Polypharmacy may also contribute to uncontrolled BP. Common pharmacotherapeutic contributors to uncontrolled BP include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), glucocorticoids, high-dose decongestants, and selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors.25

- Multimorbidity describes 2 or more chronic medical conditions in one patient. These patients are medically complex. Comorbidities can increase pill burden and make medication adherence difficult for patients. Other poorly controlled disease states can worsen hypertension (eg, renal dysfunction secondary to diabetes). Optimize treatment of comorbid conditions.

Secondary causes. If resistant hypertension persists despite confirming medication adherence and eliminating offending medications, a work-up should ensue for secondary causes of hypertension, as well as end-organ damage. Causes of secondary hypertension include sleep apnea (see this month's HelpDesk), renal dysfunction (renal artery stenosis), aldosterone-mediated hypertension (often with hypokalemia), and thyroid disease. Evaluation for secondary causes of hypertension and end-organ damage is outlined in TABLE 1.10 Patients with well-controlled hypertension do not require repeated assessments for end-organ damage unless new symptoms—such as chest pain or edema—develop.

Consider comorbidities

Clinical trials implicitly or explicitly exclude patients with multiple comorbidities. JNC 8 provided minimal guidance for adjusting BP targets based on comorbidity with only nondiabetic CKD and DM specifically addressed.9 Guidelines from specialty organizations and recent trials provide some additional guidance in these situations and are outlined in TABLE W23,10,17-22.

Heart failure. Hypertension is a major risk factor for heart failure. Long-term treatment of systolic and diastolic hypertension can reduce the incidence of heart failure by approximately half with increased benefit in patients with prior myocardial infarction.22 Research demonstrates clear mortality benefits of certain antihypertensive drug classes, including diuretics, beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors, ARBs, aldosterone antagonists, combination hydralazine and nitrates, and angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitors.21,22 The overall treatment goal in heart failure is to optimize drugs with mortality benefit, while lowering BP to a goal <130/80 mm Hg in patients ≥75 years of age.22

Increased risk for CV disease. The SPRINT trial3 defined high risk of CV disease as clinical or subclinical CV disease, CKD, 10-year ASCVD risk of ≥15%, or age ≥75 years. SPRINT supports a systolic BP goal <120 mm Hg, but, as a reminder, SPRINT excluded patients with diabetes. The American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force and the American Heart Association define high CV risk as a 10-year ASCVD risk ≥10% and recommend a BP goal <130/80 mm Hg.10

Diabetes mellitus. A BP >115/75 mm Hg is associated with increased CV events and mortality in patients with DM.18 The American Diabetes Association (ADA) and JNC 8 recommend a BP target <140/90 mm Hg.9,18 ADA suggests a lower target of 130/80 mm Hg in patients with high CV risk if it is achievable without undue burden.18

Studies show increased mortality associated with initiating additional treatment once a systolic goal <140 mm Hg has been achieved in patients with DM.26 The ACCORD trial found increased adverse events with aggressive BP lowering to <120/80 mm Hg.16

For patients with DM requiring more than one antihypertensive agent, there are CV mortality benefits associated with administering at least one antihypertensive drug at night, likely related to the beneficial effect of physiologic nocturnal dipping.27

Chronic kidney disease. JNC 8 specifically recommends an ACE inhibitor or ARB for initial or add-on treatment in patients with CKD and a BP goal <140/90 mm Hg.9 The Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Blood Pressure Work Group recommends a BP target ≤140/90 mm Hg in patients without albuminuria and ≤130/80 mm Hg in patients with albuminuria to protect against the progression of nephropathy.17 The SPRINT trial3 included patients with CKD, and KDIGO has not yet updated its guidelines to reflect SPRINT.

Frailty is a clinical syndrome that has been defined as a state of increased vulnerability that is associated with a decline in reserve and function.28 The largest hypertension studies in older adults address frailty, although often the most frail patients are excluded from these studies (TABLE W13-6).

The Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial (HYVET) categorized patients as frail, pre-frail, or robust and found a consistent benefit of antihypertensive treatment on stroke, CV events, and total mortality—regardless of baseline frailty status.29 The SPRINT trial included only community-dwelling adults.3 Other studies suggest that hypertension actually has a protective effect by lowering overall mortality in frail older adults, especially in the frailest and oldest nursing home populations.30,31

Although there is a paucity of data to direct the management of hypertension in frail older patients, physicians should prioritize the condition and focus on adverse events from antihypertensives and on slow titration of medications. The JNC 8 BP target of <150/90 mm Hg is a reasonable BP goal in this population, given the lack of evidence for lower or higher targets.9 Many frail patients have one or more of the comorbidities described earlier, and it is reasonable to strive for the comorbidity-specific target, provided it can be achieved without undue burden.

Cognitive impairment and dementia. The association between hypertension and dementia/cognitive impairment is evolving. Hypertension may impact various forms of dementia, such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) or vascular dementia, differently. There is evidence linking hypertension to AD.32 The relationship between BP and brain perfusion is complex with the potential existence of an age-adjusted relationship such that mid-life hypertension may increase the risk of dementia while late-life hypertension may not.33

A number of studies reveal the evolving nature of our understanding of these 2 conditions:

- A recent systematic review and meta-analysis examining intensive BP treatments in older adults demonstrated that lower BP targets did not increase cognitive decline.6

- HYVET’s cognitive function assessment did not find a significant reduction in the incidence of dementia with BP reduction over a short follow-up period, but when results were combined in a meta-analysis with other placebo-controlled, double-blind trials of antihypertensive treatments, there was significant reduction in incident dementia in patients randomized to antihypertensive treatment.34

- The ACCORD Memory in Diabetes trial (ACCORD-MIND) had the unexpected outcome that intensive lowering of systolic BP to a target <120 mm Hg resulted in a greater decline in total brain volume, compared with the standard BP goal <140 mm Hg. This was measured with magnetic resonance imaging in older adults with type 2 DM.35

- Results from the SPRINT sub-analysis Memory and Cognition in Decreased Hypertension trial are forthcoming and aim to determine the effects of BP reduction on dementia.36

The JNC 89 BP target <150/90 mm Hg or a comorbidity-specific target, if achievable without undue burden, is reasonable in patients with dementia. In a systematic review of observational studies in patients with hypertension and dementia, diuretics, CCBs, ACE inhibitors/ARBs, and beta-blockers were commonly used medications with a trend toward prescribing CCBs and ACE inhibitors/ARBs.37

As previously highlighted, cognitive impairment may lead to problems with medication adherence and even inadvertent improper medication use, potentially resulting in adverse events from antihypertensives. If cognitive impairment or dementia is suspected, ensure additional measures (such as medication assistance or supervision) are in place before prescribing antihypertensives.

Certain diseases, such as Parkinson’s-related dementia and multiple system atrophy, can cause autonomic instability, which can increase the risk of falls and complicate hypertension management. Carefully monitor patients for signs of orthostasis.

CASE 1 Repeat the BP measurement in the office once the patient has been seated for ≥5 minutes, and have the patient monitor her BP at home; schedule a follow-up visit in 2 weeks. If hypertension is confirmed with home measurements, then, in addition to lifestyle modifications, initiate treatment with a CCB or thiazide diuretic to achieve a systolic BP goal <120 mm Hg. Titrate medications slowly while monitoring for adverse effects.

CASE 2 Consistent with the office measurement, the patient has home BP readings that are above the BP target (<120 mm Hg systolic). He has been taking a single antihypertensive for longer than one month. Discontinue his NSAID prior to adding any new medications. If his BP is still above target without NSAIDs, then add a second agent, such as a low dose of an ACE inhibitor, ARB, or CCB, rather than maximizing the dose of hydrochlorothiazide.

CASE 3 Given the patient’s diabetes, CKD, and albuminuria, a target BP goal <130/80 mm Hg is reasonable. An ACE inhibitor or ARB is a better medication choice than atenolol in this patient with albuminuria. Because of the deterioration in his ADLs, careful assessment of mobility, functionality, comorbidities, frailty, and cognitive function should take place at each office visit and inform adjustments to the patient’s BP target. Employ cautious medication titration with monitoring for adverse effects, especially hypotension and syncope. If his functional status declines, adverse effects develop, or the medication regimen becomes burdensome, relax the target BP goal to 150/90 mm Hg.

CORRESPONDENCE

Julienne K. Kirk, PharmD, Family and Community Medicine, Wake Forest School of Medicine, Medical Center Boulevard, Winston-Salem, NC 27157-1084; [email protected].

1. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2013 State and National Summary Tables. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/namcs_summary/2013_namcs_web_tables.pdf. Accessed May 29, 2017.