User login

The etiology of premenstrual dysphoric disorder: 5 interwoven pieces

In an age when psychiatry strives to identify the biologic causes of disease, studying endocrine-related mood disorders is particularly intriguing. DSM-5 defines premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) as a depressive disorder, with a 12-month prevalence ranging from 1.8% to 5.8% among women who menstruate.1-3 Factors that differentiate PMDD from other affective disorders include etiology, duration, and temporal relationship with the menstrual cycle.

PMDD is a disorder of consistent yet intermittent change in mental health and functionality. Therefore, it may be underdiagnosed and consequently undertreated if a psychiatric evaluation does not coincide with symptom occurrence or if patients do not understand that intermittent symptoms are treatable.

This article summarizes what is known about the etiology of PMDD. Although there are several treatments for PMDD, many women experience adverse effects or incomplete effectiveness. Further understanding of this disorder may lead to more efficacious treatments. Additionally, understanding the pathophysiology of PMDD might shed a light on the etiology of other disorders that are temporally related to reproductive life changes, such as pregnancy-, postpartum-, or menopause-related affective dysregulation.

Making the diagnosis

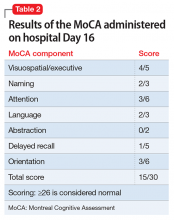

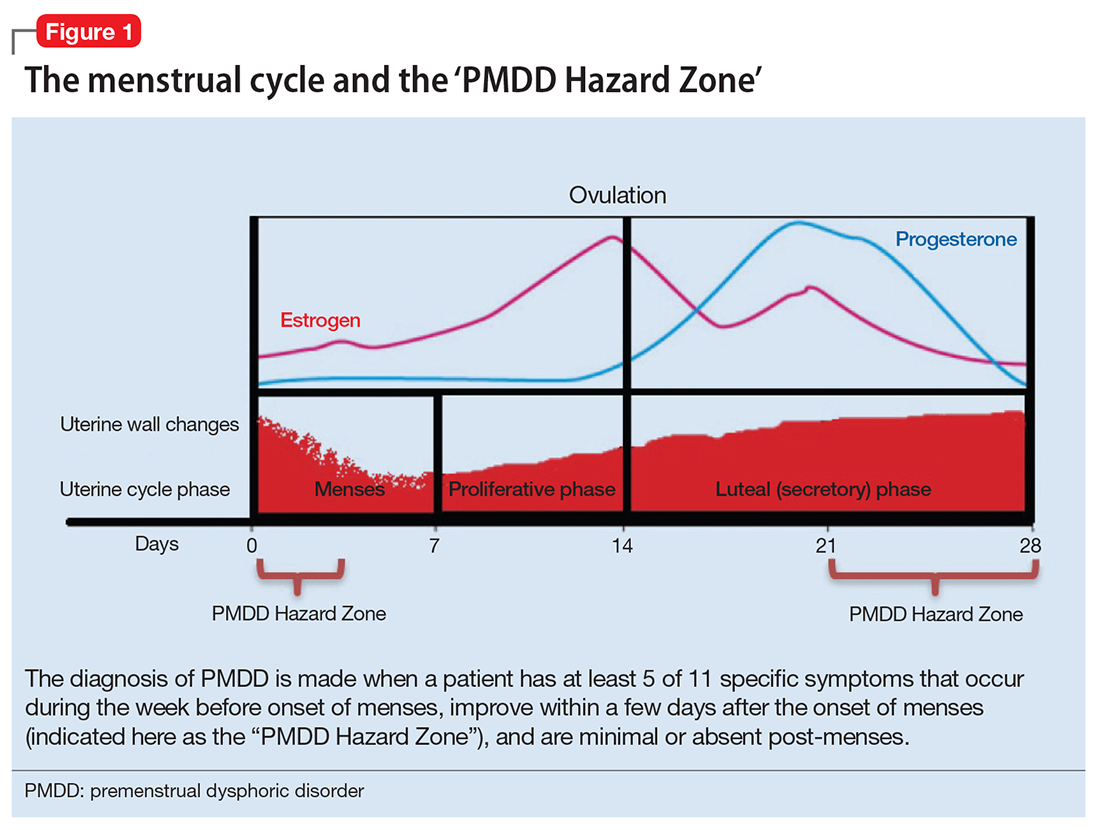

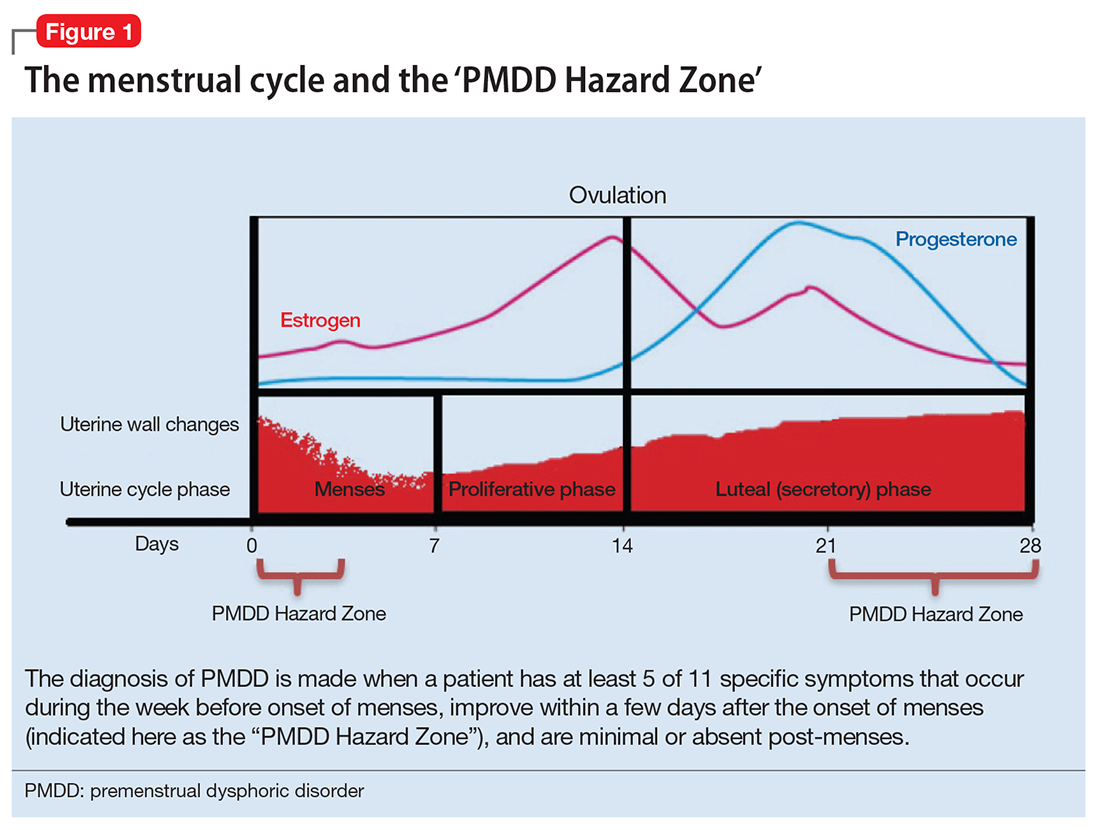

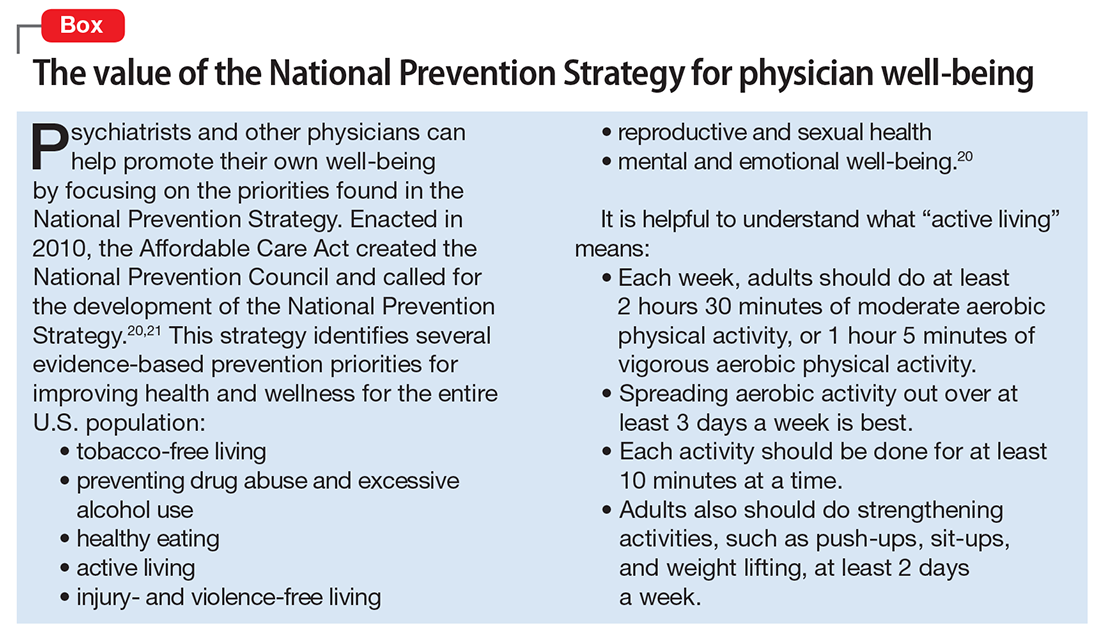

The diagnosis of PMDD is made when a patient has at least 5 of 11 specific symptoms that occur during the week before onset of menses, improve within a few days after the onset of menses (shown as the “PMDD Hazard Zone” in Figure 1), and are minimal or absent post-menses.3 Symptoms should be tracked prospectively for at least 2 menstrual cycles in order to confirm the diagnosis (one must be an affective symptom and another must be a behavioral/cognitive symptom).3

The affective symptoms are:

- lability of affect (eg, sudden sadness, tearfulness, or sensitivity to rejection)

- irritability, anger, or increased interpersonal conflicts

- depressed mood, hopelessness, or self- deprecating thoughts

- anxiety or tension, feeling “keyed up” or “on edge.”

The behavioral/cognitive symptoms are:

- decreased interest in usual activities (eg, work, hobbies, friends, school)

- difficulty concentrating

- lethargy, low energy, easy fatigability

- change in appetite, overeating, food cravings

- hypersomnia or insomnia

- feeling overwhelmed or out of control

- physical symptoms (breast tenderness or swelling, headache, joint or muscle pain, bloating, weight gain).

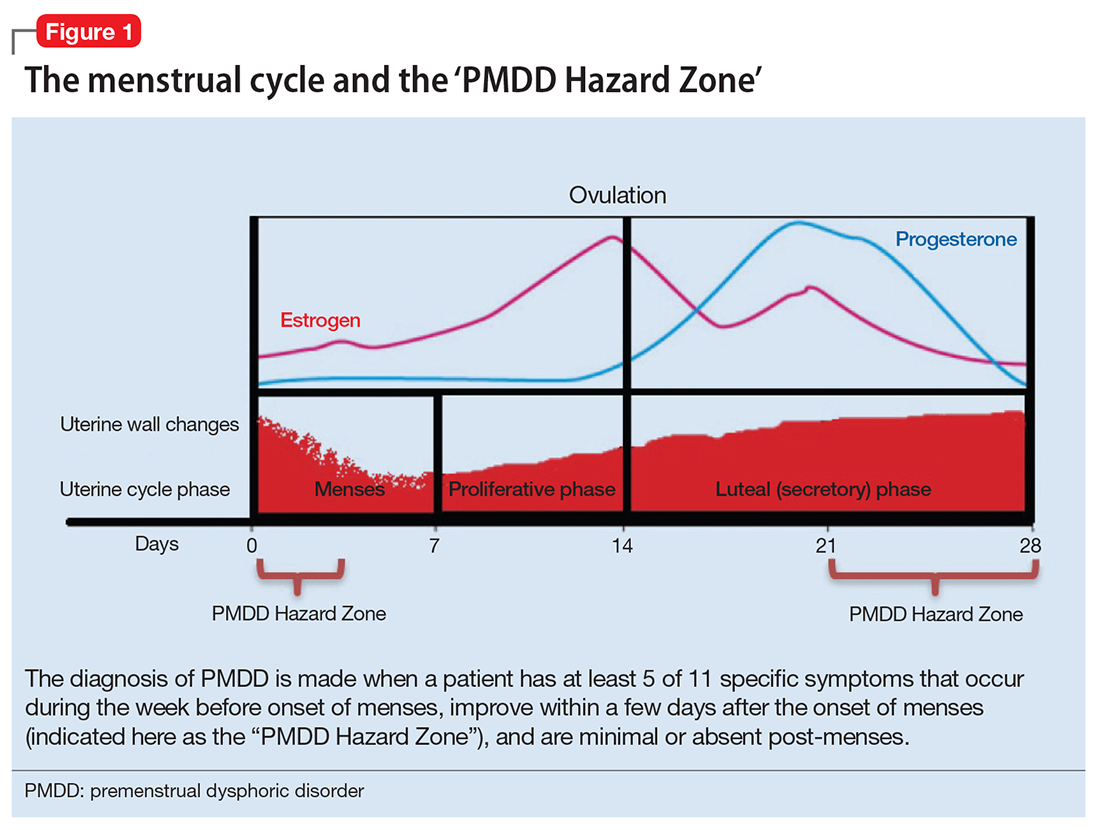

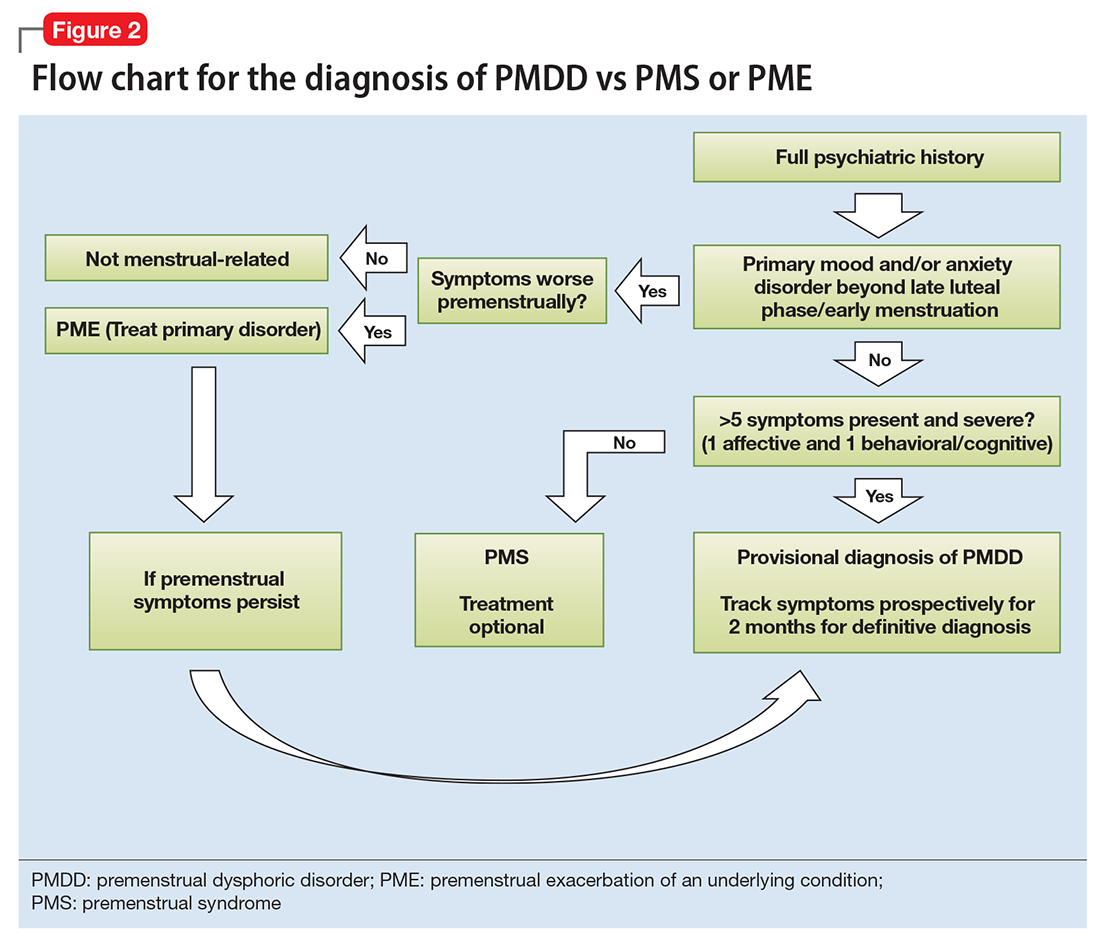

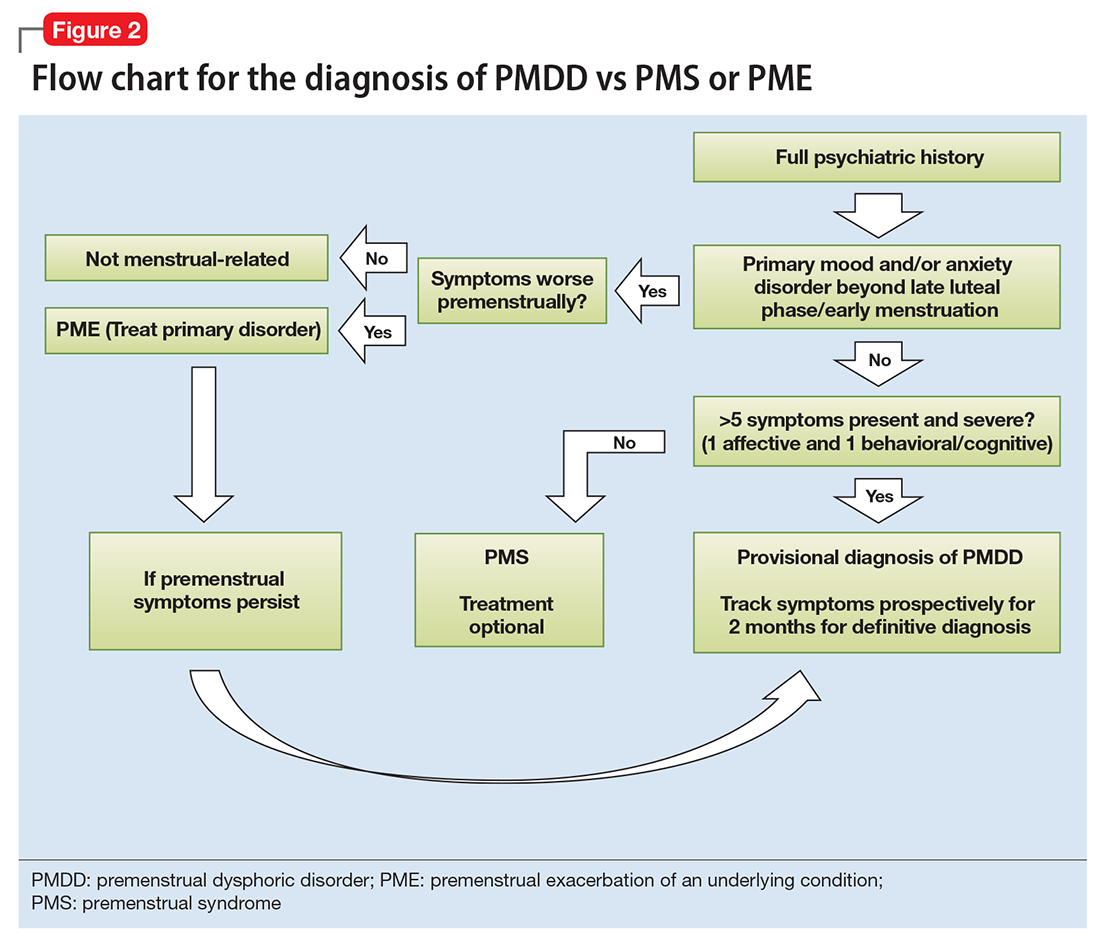

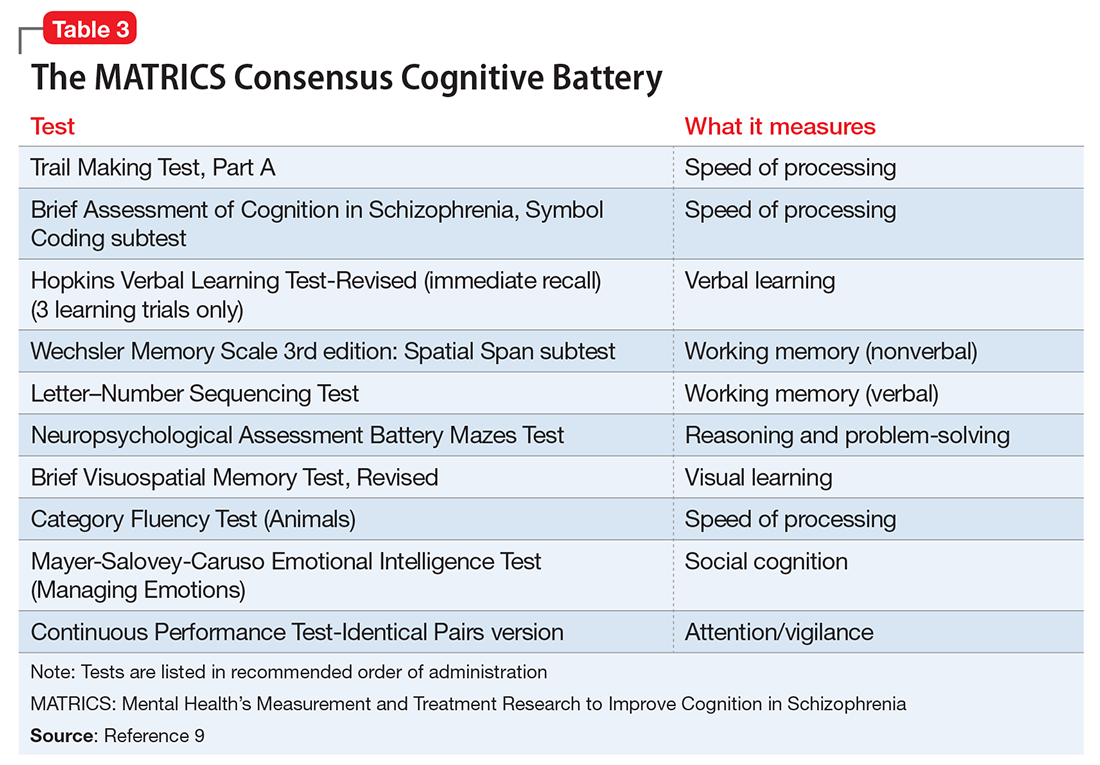

Ruling out premenstrual exacerbation (PME). Perhaps the most common cause for misdiagnosis of PMDD is failing to rule out PME of another underlying or comorbid condition (Figure 2). In many women who have a primary mood or anxiety disorder, the late luteal phase is a vulnerable time. A patient might be coping with untreated anxiety, for example, but the symptoms become unbearable the week before menstruation begins, which is likely when she seeks help. At this stage, a diagnosis of PMDD should be provisional at best. Often, PME is treated by treating the underlying condition. Therefore, a full diagnostic psychiatric interview is important to first rule out other underlying psychiatric disorders. PMDD is diagnosed if the premenstrual symptoms persist for 2 consecutive months after treating the suspected mood or anxiety disorder. Patients can use one of many PMDD daily symptom charts available online. Alternatively, they can use a cycle-tracking mobile phone application to correlate their symptoms with their cycle and share this information with their providers.

Consider these 5 interwoven pieces

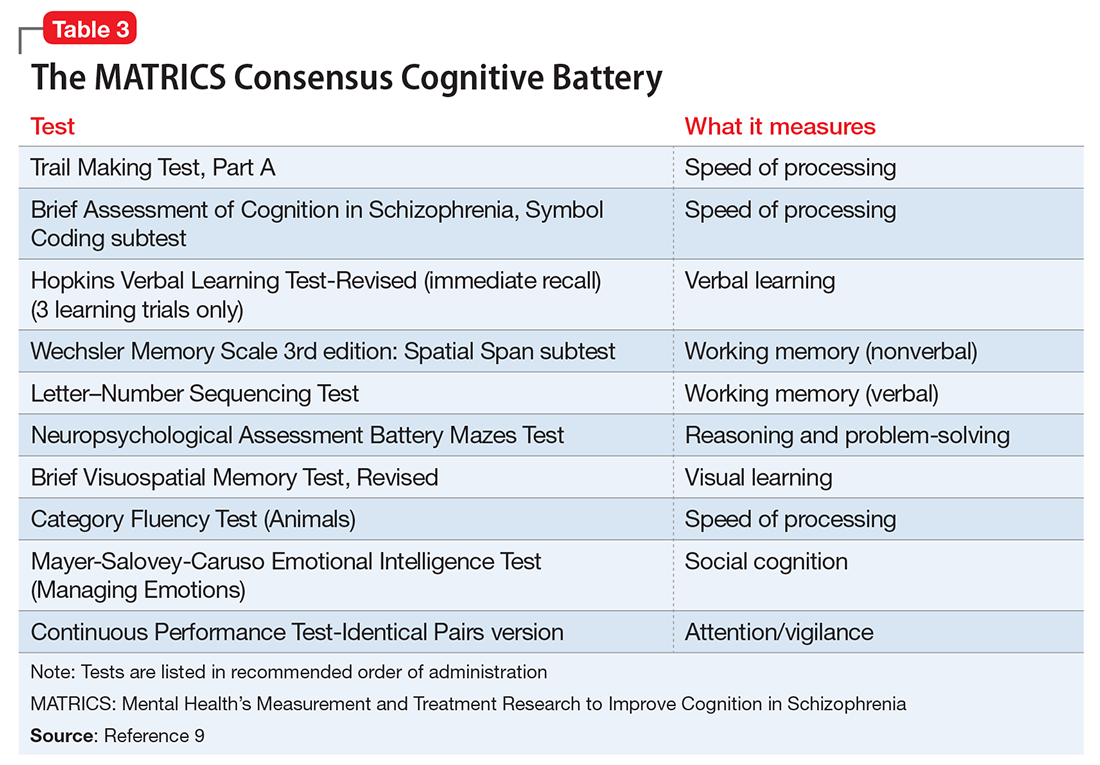

The many variables that contribute to the pathophysiology of PMDD overlap and should be considered connecting pieces in the puzzle that is the etiology of this disorder (Figure 3). In reviewing the literature, we have identified 5 topics likely to be major contributors to this disorder:

- genetic susceptibility

- progesterone and allopregnanolone (ALLO)

- estrogen, serotonin, and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF)

- putative brain structural and functional differences

- further involvement of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis and hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal (HPG) axis: trauma, resiliency, and inflammation.

Genetic susceptibility. PMDD is thought to have a heritability range between 30% to 80%.3 This is demonstrated by family and twin studies4-7 and specific genetic studies.8 The involvement of genetics means an underlying neurobiologic pathophysiology is in place.

Estrogen receptor alpha (ESR1) gene. Huo et al8 found an associated variation in ESR1 in women with PMDD compared with controls. They speculated that because ESR1 is important for arousal, if dysfunctional, this gene could be implicated in somatic as well as affective and cognitive deficits in PMDD patients. In another study, investigators reported a relationship between PMDD and heritable personality traits, as well as a link between these traits and ESR1 polymorphic variants.1 They suggested that personality traits (independent of affective state) might be used to distinguish patients with PMDD from controls.1

Studies on serotonin gene polymorphism and serotonin transporter genotype. Although a study of serotonin gene polymorphism did not find an association between serotonin1A gene polymorphism and PMDD, it did show that the presence of at least 1 C allele was associated with a 2.5-fold increased risk of PMDD.9 Another study did not find an association between the serotonin transporter genotype 5-HTTLPR and PMDD.10 However, it showed lower frontocingulate cortex activation during the luteal phase of PMDD patients compared with controls, suggesting that PMDD is linked to impaired frontocingulate cortex activation induced by emotions during the luteal phase.10

Seasonal affective disorder (SAD) and PMDD have shared clinical features. A polymorphism in the serotonin transporter promoter gene 5-HTTLPR has been associated with SAD. One study found that patients with comorbid SAD and PMDD are genetically more vulnerable to comorbid affective disorders compared with patients who have SAD only.11

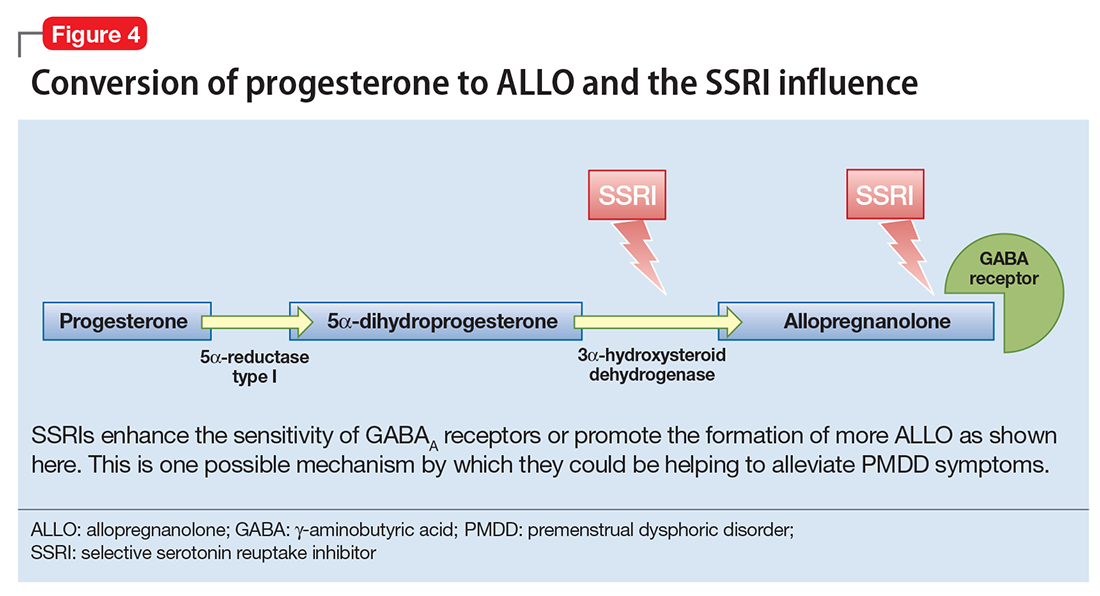

Progesterone and ALLO. Chronic exposure to progesterone and ALLO (a main progesterone metabolite) and rapid withdrawal from ovarian hormones may play a role in the etiology of PMDD. Much like alcohol or benzodiazepines, ALLO is a potent positive allosteric modulator of GABAA receptors and has sedative, anesthetic, and anxiolytic properties. In times of acute stress, increased ALLO is known to provide relief.12,13 However, in women with PMDD, this typical ALLO increase might not occur.14

Patients with PMDD have been reported to have decreased levels of ALLO in the luteal phase.15-17 In one study, women with highly symptomatic PMDD had lower levels of ALLO compared with women with less symptomatic PMDD.14 A gonadotropin-releasing hormone challenge study showed the increase in ALLO response was less in PMDD patients compared with controls.17 Luteal-phase ALLO concentrations are reported to be lower in women with premenstrual syndrome (PMS), a milder form of PMDD.14,17

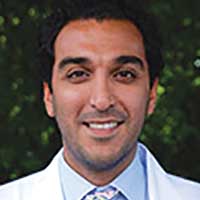

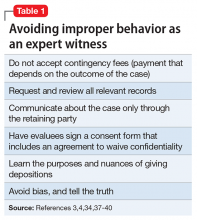

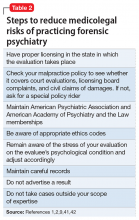

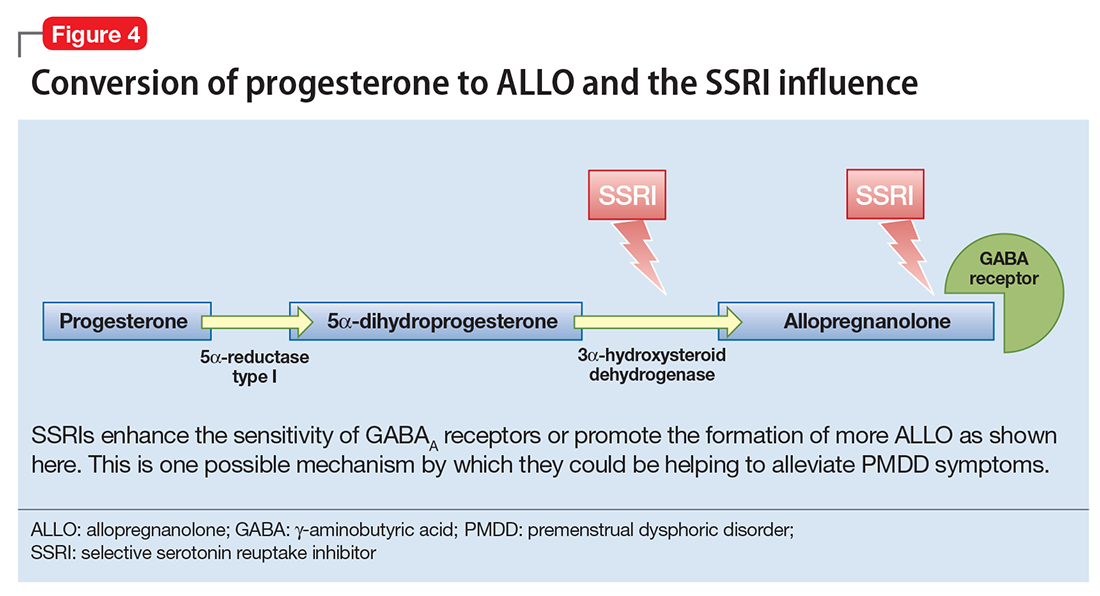

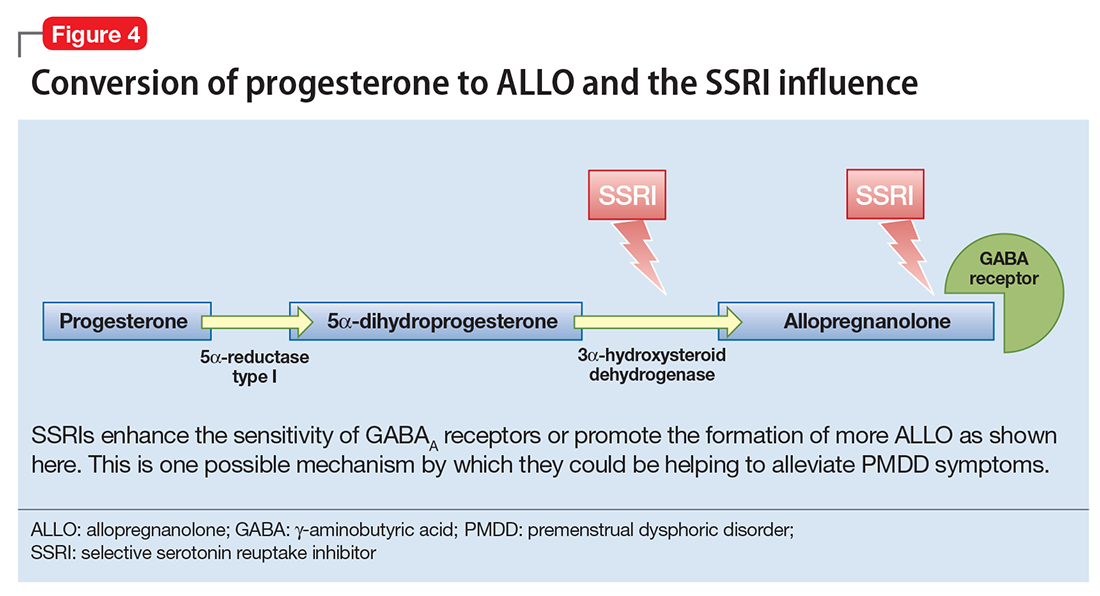

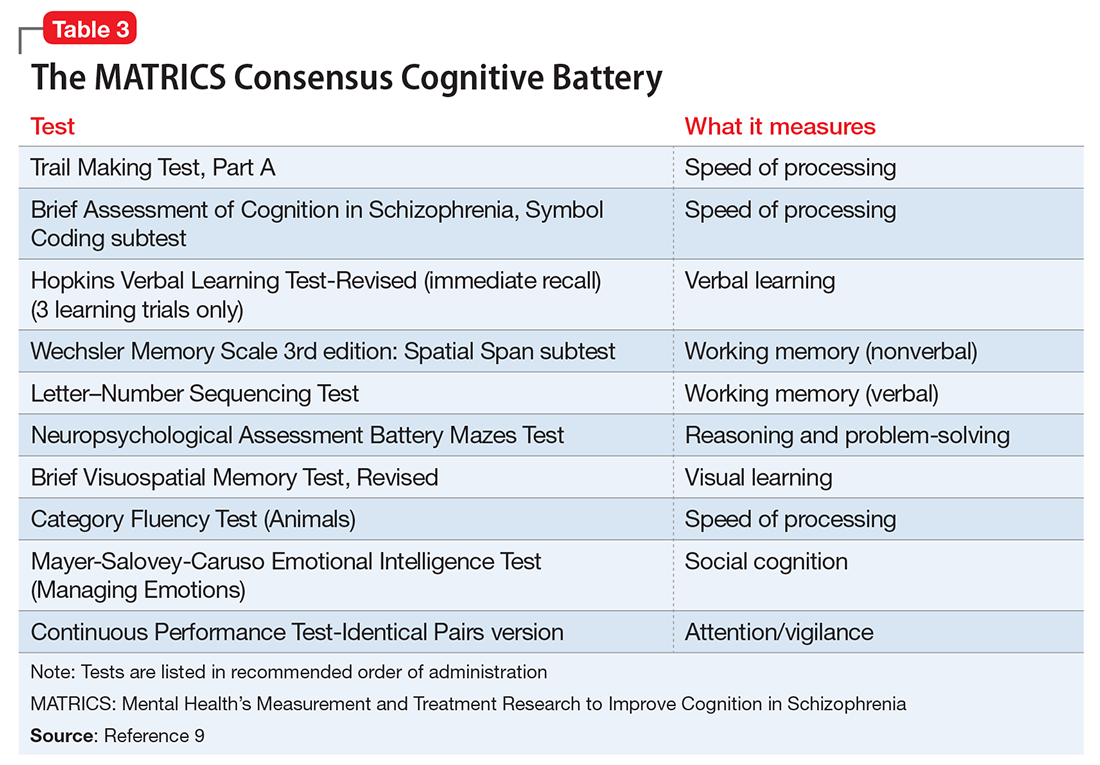

The efficacy of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) for treating PMDD could be the result of the interaction of these medications with neuroactive steroids,18 possibly because SSRIs enhance the sensitivity of GABAA receptors or promote the formation of more ALLO (Figure 4).19-21

Estrogen, serotonin, and BDNF. Estrogen affects multiple neurotransmitter systems that regulate mood, cognition, sleep, and eating.22 Studying estrogen in context of PMDD is important because women with PMDD can have low mood, specific food cravings, and impaired cognitive function.

Estrogen–serotonin interactions are thought to be involved in hormone-related mood disorders such as perimenopausal depression and PMDD.23,24 However, the nature of their relationship is not yet fully understood. Ovariectomized animals have shown estrogen-induced changes related to serotonin metabolism, binding, and transmission in the regions of the brain involved in regulation of affect and cognition. Research in menopausal women also has provided some support for this interaction.24

Positron emission tomography studies in humans have found increased cortical serotonin binding modulated by levels of estrogen, similar to those previously seen in rat studies.24-27 One study showed an increased binding potential of serotonin in the cerebral cortex with estrogen treatment. This study further showed an even greater binding potential with estrogen plus progesterone, signaling a synergistic effect of the 2 hormones.28

SSRIs are an effective treatment for the irritability, anxiety, and mood swings of PMDD.29-30 Although the exact mechanism of action is unknown, the serotonergic properties are certainly of primary attention. For some PMDD patients, SSRIs work within hours to days, as opposed to days or weeks for patients with depression or anxiety, which suggests a separate or co-occurring mechanism of action is in place. In a double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study, researchers administered the serotonin receptor antagonist metergoline to women with PMDD whose symptoms had remitted during treatment with fluoxetine and a group of healthy controls who were not receiving any medication.31 The women with PMDD experienced a return of symptoms 24 hours after treatment with metergoline but not with placebo; the controls experienced no mood changes.31

BDNF is a neurotransmitter linked to estrogen and likely related to PMDD. BDNF is critical for neurogenesis and is expressed in brain regions involved in learning and memory and also affects regulation.32 BDNF levels are increased by serotonergic antidepressants, affected by estradiol, and have cyclicity throughout the menstrual cycle.33-35

Putative brain structural and functional differences. Imaging studies have suggested differences in brain structure in women with PMDD, with a focus on the amygdala and the prefrontal cortex. Women with PMDD have greater gray matter volume in the posterior cerebellum,36 greater gray matter density of hippocampal cortex, and lower gray matter density in the parahippocampal cortex.37

Some studies have shown a functional variability of the amygdala’s response to stress in women with PMDD vs healthy controls.38,39 A proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H-MRS) study of the displays the possibility of an altered GABAergic function in patients with PMDD.40

Patients will PMDD have enhanced dorsolateral prefrontal cortex reactivity when anticipating negative stimuli (but not to the actual exposure) during the luteal phase. A positive correlation between this reactivity and progesterone levels also was observed.41 Some researchers have suggested that prefrontal cortex dysfunction may be a risk factor for PMDD.42

HPA axis and HPG axis: Trauma, resiliency, inflammation. Altered cortisol levels (higher during the luteal phase43 and lower during times of stress14,44) suggest a possibly altered HPA axis in some women with PMDD. However, studies on this topic have been few and inconsistent.

Dysregulation of the HPG axis could cause vasomotor symptoms, sleep dysregulation, and mood symptoms during menopause; women with PMDD can also experience these symptoms. The influence of estrogen and progesterone on mood is also highly dependent on this axis.

Ultimately, the interplay between the HPA axis and the HPG axis is important. One study found that women with PMDD who had high serum ALLO levels (HPG-related) had blunted nocturnal cortisol levels (HPA-related) compared with healthy controls who had low ALLO levels.45

Significant stress and trauma exposure have been associated with PMDD. A study of 3,968 women found a history of trauma and PTSD were independently associated with PMDD.46 Another study of approximately 3,000 women found a strong correlation between abuse and PMS.47 However, a third study found no correlations between PMDD and trauma.48

Patients with a predisposition to PMDD may be more vulnerable to develop a posttraumatic stress-related disorder, perhaps due to decreased biologic resiliency. For example, the startle response (hypervigilance) has been shown to be different in women with PMDD. One study suggested that suboptimal production of premenstrual ALLO may lead to increased arousal and increased stress reactivity to psychosocial or environmental triggers.49

The possible role of inflammation in PMDD deserves further investigation. The luteal phase entails an increase in the production of proinflammatory markers.50,51 A 10-fold increase in progesterone is correlated with a 20% to 23% increase in C-reactive protein levels.52,53 Women with inflammatory diseases (eg, gingivitis or irritable bowel syndrome) show worsening of symptoms prior to menstruation.54-56 One study found increased levels of proinflammatory markers in women with PMDD compared with controls.57

Putting together the 5 pieces of the puzzle

Because PMDD is heritable, it must have an underlying neurobiologic pathophysiology. Brain imaging studies show differences in structure and function in women with PMDD across the menstrual cycle. Conversion of progesterone to ALLO and the GABAergic influence of this metabolite is a topic of interest in current research. Similarly, the role of estrogen and its connection to serotonin and other neurotransmitters such as BDNF have been implicated.

The link between a history of stress, trauma, and PMDD raises the question of biologic resiliency and illness in these patients, as it connects to the HPA and HPG axis and production of inflammatory stress hormones and steroid hormones and their metabolites. PMDD can be conceptualized as variable sensitivity to hormonal response to stress,58 thus contextualizing biochemical and psychological resiliency.

Further research is needed to clarify the possibility of a shared pathophysiology between endocrine-related mood disorders such as postpartum depression (PPD) and PMDD because current research is controversial.59,60 In PPD, women who are exposed to high levels of progesterone and estrogen during pregnancy (just like in the mid-luteal phase) have a sudden drop in these hormones postpartum.

The ‘withdrawal theory.’ The affective symptoms of PMDD resolve almost instantaneously after the start of menstruation. Perhaps this type of immediate relief is akin to substance use disorders and symptoms of withdrawal. It could be that reinstatement of a certain amount of gonadal steroids in the follicular phase of the cycle diminishes a withdrawal-like response to these steroids.

Currently, the main leading theory is that PMDD is a result of “an abnormal response to normal hormonal changes.”61 A new study also has shown that the change in estradiol/progesterone levels (vs the steady state) was associated with PMDD symptoms.62 Thinking of PMDD as a disorder of withdrawal offers an alternative (yet complementary) perspective to the current theory: PMDD may be caused by the absence or diminishing of the above-named hormones and their metabolites in the late luteal phase (in the context of developed “tolerance” during the early- to mid-luteal phase).

Considering the interplay between neurotransmitters and neurosteroids, both a “serotonin withdrawal theory” (caused by a drop in steroid hormones) and a “GABAergic withdrawal theory” (due to the decline in progesterone) could be proposed. This theory would be supported by the fact that SSRIs seem to mitigate symptoms of PMDD as well as the genetic association between PMDD and ESR1. It is more than likely that the “withdrawal” is caused by the interactions between estrogen-serotonin, progesterone-ALLO, and GABA receptors, and the complementary fashion in which progesterone and estrogen influence each other.

1. Miller A, Vo H, Huo L, et al. Estrogen receptor alpha (ESR-1) associations with psychological traits in women with PMDD and controls. J Psychiatr Res. 2010;44(12):788-794.

2. Epperson CN, Steiner M, Hartlage SA, et al. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder: evidence for a new category for DSM-5. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(5):465-475.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

4. Wilson CA, Turner CW, Keye WR Jr. Firstborn adolescent daughters and mothers with and without premenstrual syndrome: a comparison. J Adolesc Health. 1991;12(2):130-137.

5. Kendler KS, Silberg JL, Neale MC, et al. Genetic and environmental factors in the aetiology of menstrual, premenstrual and neurotic symptoms: a population-based twin study. Psychol Med. 1992;22(1):85-100.

6. Condon JT. The premenstrual syndrome: a twin study. Br J Psychiatry. 1993;162:481-486.

7. Kendler KS, Karkowski LM, Corey LA, et al. Longitudinal population-based twin study of retrospectively reported premenstrual symptoms and lifetime major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155(9):1234-1240.

8. Huo L, Straub RE, Roca C, et al. Risk for premenstrual dysphoric disorder is associated with genetic variation in ESR1, the estrogen receptor alpha gene. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62(8):925-933.

9. Dhingra V, Magnay JL, O’Brien PM, et al. Serotonin receptor 1A C(-1019)G polymorphism associated with premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(4):788-792.

10. Comasco E, Hahn A, Ganger S, et al. Emotional fronto-cingulate cortex activation and brain derived neurotrophic factor polymorphism in premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Hum Brain Mapp. 2014;35(9):4450-4458.

11. Praschak-Rieder N, Willeit M, Winkler D, et al. Role of family history and 5-HTTLPR polymorphism in female seasonal affective disorder patients with and without premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2002;12(2):129-134.

12. Klatzkin RR, Morrow AL, Light KC, et al. Associations of histories of depression and PMDD diagnosis with allopregnanolone concentrations following the oral administration of micronized progesterone. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2006;31(10):1208-1219.

13. Crowley SK, Girdler SS. Neurosteroid, GABAergic and hypothalamic pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis regulation: what is the current state of knowledge in humans? Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2014;231(17):3619-3634.

14. Girdler SS, Straneva PA, Light KC, et al. Allopregnanolone levels and reactivity to mental stress in premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;49(9):788-797.

15. Rapkin AJ, Morgan M, Goldman L, et al. Progesterone metabolite allopregnanolone in women with premenstrual syndrome. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90(5):709-714.

16. Bicíková M, Dibbelt L, Hill M, et al. Allopregnanolone in women with premenstrual syndrome. Horm Metab Res. 1998;30(4):227-230.

17. Monteleone P, Luisi S, Tonetti A, et al. Allopregnanolone concentrations and premenstrual syndrome. Eur J Endocrinol. 2000;142(3):269-273.

18. Steiner M, Steinberg S, Stewart D, et al. Fluoxetine in the treatment of premenstrual dysphoria. Canadian Fluoxetine/Premenstrual Dysphoria Collaborative Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(23):1529-1534.

19. Sundström I, Bäckström T. Citalopram increases pregnanolone sensitivity in patients with premenstrual syndrome: an open trial. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1998;23(1):73-88.

20. Griffin LD, Mellon SH. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors directly alter activity of neurosteroidogenic enzymes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(23):13512-13517.

21. Trauger JW, Jiang A, Stearns BA, et al. Kinetics of allopregnanolone formation catalyzed by human 3 alpha-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type III (AKR1C2). Biochemistry. 2002;41(45):13451-13459.

22. Shanmugan S, Epperson CN. Estrogen and the prefrontal cortex: towards a new understanding of estrogen’s effects on executive functions in the menopause transition. Hum Brain Mapp. 2014;35(3):847-865.

23. Rubinow DR, Schmidt PJ, Roca CA. Estrogen-serotonin interactions: implications for affective regulation. Biol Psychiatry. 1998;44(9):839-850.

24. Amin Z, Canli T, Epperson CN. Effect of estrogen-serotonin interactions on mood and cognition. Behav Cogn Neurosci Rev. 2005;4(1):43-58.

25. Cyr M, Bossé R, Di Paolo T. Gonadal hormones modulate 5-hydroxytryptamine2A receptors: emphasis on the rat frontal cortex. Neuroscience. 1998;83(3):829-836.

26. Fink G, Sumner BE, Rosie R, et al. Estrogen control of central neurotransmission: effect on mood, mental state, and memory. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 1996;16(3):325-344.

27. Sumner BE, Grant KE, Rosie R, et al. Effects of tamoxifen on serotonin transporter and 5-hydroxytryptamine(2A) receptor binding sites and mRNA levels in the brain of ovariectomized rats with or without acute estradiol replacement. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1999;73(1-2):119-128.

28. Moses-Kolko EL, Berga SL, Greer PJ, et al. Widespread increases of cortical serotonin type 2A receptor availability after hormone therapy in euthymic postmenopausal women. Fertil Steril. 2003;80(3):554-559.

29. Su TP, Schmidt PJ, Danaceau MA, et al. Fluoxetine in the treatment of premenstrual dysphoria. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1997;16(5):346-356.

30. Steinberg EM, Cardoso GM, Martinez PE, et al. Rapid response to fluoxetine in women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Depress Anxiety. 2012;29(6):531-540.

31. Roca CA, Schmidt PJ, Smith MJ, et al. Effects of metergoline on symptoms in women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(11):1876-1881.

32. Gray JD, Milner TA, McEwen BS. Dynamic plasticity: the role of glucocorticoids, brain-derived neurotrophic factor and other trophic factors. Neuroscience. 2013;239:214-227.

33. Carbone DL, Handa RJ. Sex and stress hormone influences on the expression and activity of brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Neuroscience. 2013;239:295-303.

34. Pilar-Cuéllar F, Vidal R, Pazos A. Subchronic treatment with fluoxetine and ketanserin increases hippocampal brain-derived neurotrophic factor, β-catenin and antidepressant-like effects. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;165(4b):1046-1057.

35. Deuschle M, Gilles M, Scharnholz B, et al. Changes of serum concentrations of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) during treatment with venlafaxine and mirtazapine: role of medication and response to treatment. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2013;46(2):54-58.

36. Berman SM, London ED, Morgan M, et al. Elevated gray matter volume of the emotional cerebellum in women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder. J Affect Disord. 2013;146(2):266-271.

37. Jeong HG, Ham BJ, Yeo HB, et al. Gray matter abnormalities in patients with premenstrual dysphoric disorder: an optimized voxel-based morphometry. J Affect Disord. 2012;140(3):260-267.

38. Protopopescu X, Tuescher O, Pan H, et al. Toward a functional neuroanatomy of premenstrual dysphoric disorder. J Affect Disord. 2008;108(1-2):87-94.

39. Gingnell M, Morell A, Bannbers E, et al. Menstrual cycle effects on amygdala reactivity to emotional stimulation in premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Horm Behav. 2012;62(4):400-406.

40. Epperson CN, Haga K, Mason GF, et al. Cortical gamma-aminobutyric acid levels across the menstrual cycle in healthy women and those with premenstrual dysphoric disorder: a proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(9):851-858.

41. Gingnell M, Bannbers E, Wikström J, et al. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder and prefrontal reactivity during anticipation of emotional stimuli. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;23(11):1474-1483.

42. Baller EB, Wei SM, Kohn PD, et al. Abnormalities of dorsolateral prefrontal function in women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder: a multimodal neuroimaging study. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(3):305-314.

43. Rasgon N, McGuire M, Tanavoli S, et al. Neuroendocrine response to an intravenous L-tryptophan challenge in women with premenstrual syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2000;73(1):144-149.

44. Huang Y, Zhou R, Wu M, et al. Premenstrual syndrome is associated with blunted cortisol reactivity to the TSST. Stress. 2015;18(2):160-168.

45. Segebladh B, Bannbers E, Moby L, et al. Allopregnanolone serum concentrations and diurnal cortisol secretion in women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2013;16(2):131-137.

46. Pilver CE, Levy BR, Libby DJ, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and trauma characteristics are correlates of premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2011;14(5):383-393.

47. Bertone-Johnson ER, Whitcomb BW, Missmer SA, et al. Early life emotional, physical, and sexual abuse and the development of premenstrual syndrome: a longitudinal study. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2014;23(9):729-739.

48. Segebladh B, Bannbers E, Kask K, et al. Prevalence of violence exposure in women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder in comparison with other gynecological patients and asymptomatic controls. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2011;90(7):746-752.

49. Kask K, Gulinello M, Bäckström T, et al. Patients with premenstrual dysphoric disorder have increased startle response across both cycle phases and lower levels of prepulse inhibition during the late luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33(9):2283-2290.

50. O’Brien SM, Fitzgerald P, Scully P, et al. Impact of gender and menstrual cycle phase on plasma cytokine concentrations. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2007;14(2):84-90.

51. Northoff H, Symons S, Zieker D, et al. Gender- and menstrual phase dependent regulation of inflammatory gene expression in response to aerobic exercise. Exerc Immunol Rev. 2008;14:86-103.

52. Gaskins AJ, Wilchesky M, Mumford SL, et al. Endogenous reproductive hormones and C-reactive protein across the menstrual cycle: the BioCycle Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;175(5):423-431.

53. Wander K, Brindle E, O’Connor KA. C-reactive protein across the menstrual cycle. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2008;136(2):138-146.

54. Jane ZY, Chang CC, Lin HK, et al. The association between the exacerbation of irritable bowel syndrome and menstrual symptoms in young Taiwanese women. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2011;34(4):277-286.

55. Kane SV, Sable K, Hanauer SB. The menstrual cycle and its effect on inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome: a prevalence study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93(10):1867-1872.

56. Shourie V, Dwarakanath CD, Prashanth GV, et al. The effect of menstrual cycle on periodontal health - a clinical and microbiological study. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2012;10(2):185-192.

57. Hantsoo L, Epperson CN. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder: epidemiology and treatment. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2015;17(11):87.

58. Maeng LY, Milad MR. Sex differences in anxiety disorders: Interactions between fear, stress, and gonadal hormones. Horm Behav. 2015;76:106-117.

59. Lee YJ, Yi SW, Ju DH, et al. Correlation between postpartum depression and premenstrual dysphoric disorder: single center study. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2015;58(5):353-358.

60. Kepple AL, Lee EE, Haq N, et al. History of postpartum depression in a clinic-based sample of women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(4):e415-e420.

61. Schmidt PJ, Nieman LK, Danaceau MA, et al. Differential behavioral effects of gonadal steroids in women with and in those without premenstrual syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(4):209-216.

62. Schmidt PJ, Martinez PE, Nieman LK, et al. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder symptoms following ovarian suppression: Triggered by change in ovarian steroid levels but not continuous stable levels. Am J Psychiatry. [published online April 21, 2017]. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.16101113.

In an age when psychiatry strives to identify the biologic causes of disease, studying endocrine-related mood disorders is particularly intriguing. DSM-5 defines premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) as a depressive disorder, with a 12-month prevalence ranging from 1.8% to 5.8% among women who menstruate.1-3 Factors that differentiate PMDD from other affective disorders include etiology, duration, and temporal relationship with the menstrual cycle.

PMDD is a disorder of consistent yet intermittent change in mental health and functionality. Therefore, it may be underdiagnosed and consequently undertreated if a psychiatric evaluation does not coincide with symptom occurrence or if patients do not understand that intermittent symptoms are treatable.

This article summarizes what is known about the etiology of PMDD. Although there are several treatments for PMDD, many women experience adverse effects or incomplete effectiveness. Further understanding of this disorder may lead to more efficacious treatments. Additionally, understanding the pathophysiology of PMDD might shed a light on the etiology of other disorders that are temporally related to reproductive life changes, such as pregnancy-, postpartum-, or menopause-related affective dysregulation.

Making the diagnosis

The diagnosis of PMDD is made when a patient has at least 5 of 11 specific symptoms that occur during the week before onset of menses, improve within a few days after the onset of menses (shown as the “PMDD Hazard Zone” in Figure 1), and are minimal or absent post-menses.3 Symptoms should be tracked prospectively for at least 2 menstrual cycles in order to confirm the diagnosis (one must be an affective symptom and another must be a behavioral/cognitive symptom).3

The affective symptoms are:

- lability of affect (eg, sudden sadness, tearfulness, or sensitivity to rejection)

- irritability, anger, or increased interpersonal conflicts

- depressed mood, hopelessness, or self- deprecating thoughts

- anxiety or tension, feeling “keyed up” or “on edge.”

The behavioral/cognitive symptoms are:

- decreased interest in usual activities (eg, work, hobbies, friends, school)

- difficulty concentrating

- lethargy, low energy, easy fatigability

- change in appetite, overeating, food cravings

- hypersomnia or insomnia

- feeling overwhelmed or out of control

- physical symptoms (breast tenderness or swelling, headache, joint or muscle pain, bloating, weight gain).

Ruling out premenstrual exacerbation (PME). Perhaps the most common cause for misdiagnosis of PMDD is failing to rule out PME of another underlying or comorbid condition (Figure 2). In many women who have a primary mood or anxiety disorder, the late luteal phase is a vulnerable time. A patient might be coping with untreated anxiety, for example, but the symptoms become unbearable the week before menstruation begins, which is likely when she seeks help. At this stage, a diagnosis of PMDD should be provisional at best. Often, PME is treated by treating the underlying condition. Therefore, a full diagnostic psychiatric interview is important to first rule out other underlying psychiatric disorders. PMDD is diagnosed if the premenstrual symptoms persist for 2 consecutive months after treating the suspected mood or anxiety disorder. Patients can use one of many PMDD daily symptom charts available online. Alternatively, they can use a cycle-tracking mobile phone application to correlate their symptoms with their cycle and share this information with their providers.

Consider these 5 interwoven pieces

The many variables that contribute to the pathophysiology of PMDD overlap and should be considered connecting pieces in the puzzle that is the etiology of this disorder (Figure 3). In reviewing the literature, we have identified 5 topics likely to be major contributors to this disorder:

- genetic susceptibility

- progesterone and allopregnanolone (ALLO)

- estrogen, serotonin, and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF)

- putative brain structural and functional differences

- further involvement of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis and hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal (HPG) axis: trauma, resiliency, and inflammation.

Genetic susceptibility. PMDD is thought to have a heritability range between 30% to 80%.3 This is demonstrated by family and twin studies4-7 and specific genetic studies.8 The involvement of genetics means an underlying neurobiologic pathophysiology is in place.

Estrogen receptor alpha (ESR1) gene. Huo et al8 found an associated variation in ESR1 in women with PMDD compared with controls. They speculated that because ESR1 is important for arousal, if dysfunctional, this gene could be implicated in somatic as well as affective and cognitive deficits in PMDD patients. In another study, investigators reported a relationship between PMDD and heritable personality traits, as well as a link between these traits and ESR1 polymorphic variants.1 They suggested that personality traits (independent of affective state) might be used to distinguish patients with PMDD from controls.1

Studies on serotonin gene polymorphism and serotonin transporter genotype. Although a study of serotonin gene polymorphism did not find an association between serotonin1A gene polymorphism and PMDD, it did show that the presence of at least 1 C allele was associated with a 2.5-fold increased risk of PMDD.9 Another study did not find an association between the serotonin transporter genotype 5-HTTLPR and PMDD.10 However, it showed lower frontocingulate cortex activation during the luteal phase of PMDD patients compared with controls, suggesting that PMDD is linked to impaired frontocingulate cortex activation induced by emotions during the luteal phase.10

Seasonal affective disorder (SAD) and PMDD have shared clinical features. A polymorphism in the serotonin transporter promoter gene 5-HTTLPR has been associated with SAD. One study found that patients with comorbid SAD and PMDD are genetically more vulnerable to comorbid affective disorders compared with patients who have SAD only.11

Progesterone and ALLO. Chronic exposure to progesterone and ALLO (a main progesterone metabolite) and rapid withdrawal from ovarian hormones may play a role in the etiology of PMDD. Much like alcohol or benzodiazepines, ALLO is a potent positive allosteric modulator of GABAA receptors and has sedative, anesthetic, and anxiolytic properties. In times of acute stress, increased ALLO is known to provide relief.12,13 However, in women with PMDD, this typical ALLO increase might not occur.14

Patients with PMDD have been reported to have decreased levels of ALLO in the luteal phase.15-17 In one study, women with highly symptomatic PMDD had lower levels of ALLO compared with women with less symptomatic PMDD.14 A gonadotropin-releasing hormone challenge study showed the increase in ALLO response was less in PMDD patients compared with controls.17 Luteal-phase ALLO concentrations are reported to be lower in women with premenstrual syndrome (PMS), a milder form of PMDD.14,17

The efficacy of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) for treating PMDD could be the result of the interaction of these medications with neuroactive steroids,18 possibly because SSRIs enhance the sensitivity of GABAA receptors or promote the formation of more ALLO (Figure 4).19-21

Estrogen, serotonin, and BDNF. Estrogen affects multiple neurotransmitter systems that regulate mood, cognition, sleep, and eating.22 Studying estrogen in context of PMDD is important because women with PMDD can have low mood, specific food cravings, and impaired cognitive function.

Estrogen–serotonin interactions are thought to be involved in hormone-related mood disorders such as perimenopausal depression and PMDD.23,24 However, the nature of their relationship is not yet fully understood. Ovariectomized animals have shown estrogen-induced changes related to serotonin metabolism, binding, and transmission in the regions of the brain involved in regulation of affect and cognition. Research in menopausal women also has provided some support for this interaction.24

Positron emission tomography studies in humans have found increased cortical serotonin binding modulated by levels of estrogen, similar to those previously seen in rat studies.24-27 One study showed an increased binding potential of serotonin in the cerebral cortex with estrogen treatment. This study further showed an even greater binding potential with estrogen plus progesterone, signaling a synergistic effect of the 2 hormones.28

SSRIs are an effective treatment for the irritability, anxiety, and mood swings of PMDD.29-30 Although the exact mechanism of action is unknown, the serotonergic properties are certainly of primary attention. For some PMDD patients, SSRIs work within hours to days, as opposed to days or weeks for patients with depression or anxiety, which suggests a separate or co-occurring mechanism of action is in place. In a double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study, researchers administered the serotonin receptor antagonist metergoline to women with PMDD whose symptoms had remitted during treatment with fluoxetine and a group of healthy controls who were not receiving any medication.31 The women with PMDD experienced a return of symptoms 24 hours after treatment with metergoline but not with placebo; the controls experienced no mood changes.31

BDNF is a neurotransmitter linked to estrogen and likely related to PMDD. BDNF is critical for neurogenesis and is expressed in brain regions involved in learning and memory and also affects regulation.32 BDNF levels are increased by serotonergic antidepressants, affected by estradiol, and have cyclicity throughout the menstrual cycle.33-35

Putative brain structural and functional differences. Imaging studies have suggested differences in brain structure in women with PMDD, with a focus on the amygdala and the prefrontal cortex. Women with PMDD have greater gray matter volume in the posterior cerebellum,36 greater gray matter density of hippocampal cortex, and lower gray matter density in the parahippocampal cortex.37

Some studies have shown a functional variability of the amygdala’s response to stress in women with PMDD vs healthy controls.38,39 A proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H-MRS) study of the displays the possibility of an altered GABAergic function in patients with PMDD.40

Patients will PMDD have enhanced dorsolateral prefrontal cortex reactivity when anticipating negative stimuli (but not to the actual exposure) during the luteal phase. A positive correlation between this reactivity and progesterone levels also was observed.41 Some researchers have suggested that prefrontal cortex dysfunction may be a risk factor for PMDD.42

HPA axis and HPG axis: Trauma, resiliency, inflammation. Altered cortisol levels (higher during the luteal phase43 and lower during times of stress14,44) suggest a possibly altered HPA axis in some women with PMDD. However, studies on this topic have been few and inconsistent.

Dysregulation of the HPG axis could cause vasomotor symptoms, sleep dysregulation, and mood symptoms during menopause; women with PMDD can also experience these symptoms. The influence of estrogen and progesterone on mood is also highly dependent on this axis.

Ultimately, the interplay between the HPA axis and the HPG axis is important. One study found that women with PMDD who had high serum ALLO levels (HPG-related) had blunted nocturnal cortisol levels (HPA-related) compared with healthy controls who had low ALLO levels.45

Significant stress and trauma exposure have been associated with PMDD. A study of 3,968 women found a history of trauma and PTSD were independently associated with PMDD.46 Another study of approximately 3,000 women found a strong correlation between abuse and PMS.47 However, a third study found no correlations between PMDD and trauma.48

Patients with a predisposition to PMDD may be more vulnerable to develop a posttraumatic stress-related disorder, perhaps due to decreased biologic resiliency. For example, the startle response (hypervigilance) has been shown to be different in women with PMDD. One study suggested that suboptimal production of premenstrual ALLO may lead to increased arousal and increased stress reactivity to psychosocial or environmental triggers.49

The possible role of inflammation in PMDD deserves further investigation. The luteal phase entails an increase in the production of proinflammatory markers.50,51 A 10-fold increase in progesterone is correlated with a 20% to 23% increase in C-reactive protein levels.52,53 Women with inflammatory diseases (eg, gingivitis or irritable bowel syndrome) show worsening of symptoms prior to menstruation.54-56 One study found increased levels of proinflammatory markers in women with PMDD compared with controls.57

Putting together the 5 pieces of the puzzle

Because PMDD is heritable, it must have an underlying neurobiologic pathophysiology. Brain imaging studies show differences in structure and function in women with PMDD across the menstrual cycle. Conversion of progesterone to ALLO and the GABAergic influence of this metabolite is a topic of interest in current research. Similarly, the role of estrogen and its connection to serotonin and other neurotransmitters such as BDNF have been implicated.

The link between a history of stress, trauma, and PMDD raises the question of biologic resiliency and illness in these patients, as it connects to the HPA and HPG axis and production of inflammatory stress hormones and steroid hormones and their metabolites. PMDD can be conceptualized as variable sensitivity to hormonal response to stress,58 thus contextualizing biochemical and psychological resiliency.

Further research is needed to clarify the possibility of a shared pathophysiology between endocrine-related mood disorders such as postpartum depression (PPD) and PMDD because current research is controversial.59,60 In PPD, women who are exposed to high levels of progesterone and estrogen during pregnancy (just like in the mid-luteal phase) have a sudden drop in these hormones postpartum.

The ‘withdrawal theory.’ The affective symptoms of PMDD resolve almost instantaneously after the start of menstruation. Perhaps this type of immediate relief is akin to substance use disorders and symptoms of withdrawal. It could be that reinstatement of a certain amount of gonadal steroids in the follicular phase of the cycle diminishes a withdrawal-like response to these steroids.

Currently, the main leading theory is that PMDD is a result of “an abnormal response to normal hormonal changes.”61 A new study also has shown that the change in estradiol/progesterone levels (vs the steady state) was associated with PMDD symptoms.62 Thinking of PMDD as a disorder of withdrawal offers an alternative (yet complementary) perspective to the current theory: PMDD may be caused by the absence or diminishing of the above-named hormones and their metabolites in the late luteal phase (in the context of developed “tolerance” during the early- to mid-luteal phase).

Considering the interplay between neurotransmitters and neurosteroids, both a “serotonin withdrawal theory” (caused by a drop in steroid hormones) and a “GABAergic withdrawal theory” (due to the decline in progesterone) could be proposed. This theory would be supported by the fact that SSRIs seem to mitigate symptoms of PMDD as well as the genetic association between PMDD and ESR1. It is more than likely that the “withdrawal” is caused by the interactions between estrogen-serotonin, progesterone-ALLO, and GABA receptors, and the complementary fashion in which progesterone and estrogen influence each other.

In an age when psychiatry strives to identify the biologic causes of disease, studying endocrine-related mood disorders is particularly intriguing. DSM-5 defines premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) as a depressive disorder, with a 12-month prevalence ranging from 1.8% to 5.8% among women who menstruate.1-3 Factors that differentiate PMDD from other affective disorders include etiology, duration, and temporal relationship with the menstrual cycle.

PMDD is a disorder of consistent yet intermittent change in mental health and functionality. Therefore, it may be underdiagnosed and consequently undertreated if a psychiatric evaluation does not coincide with symptom occurrence or if patients do not understand that intermittent symptoms are treatable.

This article summarizes what is known about the etiology of PMDD. Although there are several treatments for PMDD, many women experience adverse effects or incomplete effectiveness. Further understanding of this disorder may lead to more efficacious treatments. Additionally, understanding the pathophysiology of PMDD might shed a light on the etiology of other disorders that are temporally related to reproductive life changes, such as pregnancy-, postpartum-, or menopause-related affective dysregulation.

Making the diagnosis

The diagnosis of PMDD is made when a patient has at least 5 of 11 specific symptoms that occur during the week before onset of menses, improve within a few days after the onset of menses (shown as the “PMDD Hazard Zone” in Figure 1), and are minimal or absent post-menses.3 Symptoms should be tracked prospectively for at least 2 menstrual cycles in order to confirm the diagnosis (one must be an affective symptom and another must be a behavioral/cognitive symptom).3

The affective symptoms are:

- lability of affect (eg, sudden sadness, tearfulness, or sensitivity to rejection)

- irritability, anger, or increased interpersonal conflicts

- depressed mood, hopelessness, or self- deprecating thoughts

- anxiety or tension, feeling “keyed up” or “on edge.”

The behavioral/cognitive symptoms are:

- decreased interest in usual activities (eg, work, hobbies, friends, school)

- difficulty concentrating

- lethargy, low energy, easy fatigability

- change in appetite, overeating, food cravings

- hypersomnia or insomnia

- feeling overwhelmed or out of control

- physical symptoms (breast tenderness or swelling, headache, joint or muscle pain, bloating, weight gain).

Ruling out premenstrual exacerbation (PME). Perhaps the most common cause for misdiagnosis of PMDD is failing to rule out PME of another underlying or comorbid condition (Figure 2). In many women who have a primary mood or anxiety disorder, the late luteal phase is a vulnerable time. A patient might be coping with untreated anxiety, for example, but the symptoms become unbearable the week before menstruation begins, which is likely when she seeks help. At this stage, a diagnosis of PMDD should be provisional at best. Often, PME is treated by treating the underlying condition. Therefore, a full diagnostic psychiatric interview is important to first rule out other underlying psychiatric disorders. PMDD is diagnosed if the premenstrual symptoms persist for 2 consecutive months after treating the suspected mood or anxiety disorder. Patients can use one of many PMDD daily symptom charts available online. Alternatively, they can use a cycle-tracking mobile phone application to correlate their symptoms with their cycle and share this information with their providers.

Consider these 5 interwoven pieces

The many variables that contribute to the pathophysiology of PMDD overlap and should be considered connecting pieces in the puzzle that is the etiology of this disorder (Figure 3). In reviewing the literature, we have identified 5 topics likely to be major contributors to this disorder:

- genetic susceptibility

- progesterone and allopregnanolone (ALLO)

- estrogen, serotonin, and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF)

- putative brain structural and functional differences

- further involvement of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis and hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal (HPG) axis: trauma, resiliency, and inflammation.

Genetic susceptibility. PMDD is thought to have a heritability range between 30% to 80%.3 This is demonstrated by family and twin studies4-7 and specific genetic studies.8 The involvement of genetics means an underlying neurobiologic pathophysiology is in place.

Estrogen receptor alpha (ESR1) gene. Huo et al8 found an associated variation in ESR1 in women with PMDD compared with controls. They speculated that because ESR1 is important for arousal, if dysfunctional, this gene could be implicated in somatic as well as affective and cognitive deficits in PMDD patients. In another study, investigators reported a relationship between PMDD and heritable personality traits, as well as a link between these traits and ESR1 polymorphic variants.1 They suggested that personality traits (independent of affective state) might be used to distinguish patients with PMDD from controls.1

Studies on serotonin gene polymorphism and serotonin transporter genotype. Although a study of serotonin gene polymorphism did not find an association between serotonin1A gene polymorphism and PMDD, it did show that the presence of at least 1 C allele was associated with a 2.5-fold increased risk of PMDD.9 Another study did not find an association between the serotonin transporter genotype 5-HTTLPR and PMDD.10 However, it showed lower frontocingulate cortex activation during the luteal phase of PMDD patients compared with controls, suggesting that PMDD is linked to impaired frontocingulate cortex activation induced by emotions during the luteal phase.10

Seasonal affective disorder (SAD) and PMDD have shared clinical features. A polymorphism in the serotonin transporter promoter gene 5-HTTLPR has been associated with SAD. One study found that patients with comorbid SAD and PMDD are genetically more vulnerable to comorbid affective disorders compared with patients who have SAD only.11

Progesterone and ALLO. Chronic exposure to progesterone and ALLO (a main progesterone metabolite) and rapid withdrawal from ovarian hormones may play a role in the etiology of PMDD. Much like alcohol or benzodiazepines, ALLO is a potent positive allosteric modulator of GABAA receptors and has sedative, anesthetic, and anxiolytic properties. In times of acute stress, increased ALLO is known to provide relief.12,13 However, in women with PMDD, this typical ALLO increase might not occur.14

Patients with PMDD have been reported to have decreased levels of ALLO in the luteal phase.15-17 In one study, women with highly symptomatic PMDD had lower levels of ALLO compared with women with less symptomatic PMDD.14 A gonadotropin-releasing hormone challenge study showed the increase in ALLO response was less in PMDD patients compared with controls.17 Luteal-phase ALLO concentrations are reported to be lower in women with premenstrual syndrome (PMS), a milder form of PMDD.14,17

The efficacy of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) for treating PMDD could be the result of the interaction of these medications with neuroactive steroids,18 possibly because SSRIs enhance the sensitivity of GABAA receptors or promote the formation of more ALLO (Figure 4).19-21

Estrogen, serotonin, and BDNF. Estrogen affects multiple neurotransmitter systems that regulate mood, cognition, sleep, and eating.22 Studying estrogen in context of PMDD is important because women with PMDD can have low mood, specific food cravings, and impaired cognitive function.

Estrogen–serotonin interactions are thought to be involved in hormone-related mood disorders such as perimenopausal depression and PMDD.23,24 However, the nature of their relationship is not yet fully understood. Ovariectomized animals have shown estrogen-induced changes related to serotonin metabolism, binding, and transmission in the regions of the brain involved in regulation of affect and cognition. Research in menopausal women also has provided some support for this interaction.24

Positron emission tomography studies in humans have found increased cortical serotonin binding modulated by levels of estrogen, similar to those previously seen in rat studies.24-27 One study showed an increased binding potential of serotonin in the cerebral cortex with estrogen treatment. This study further showed an even greater binding potential with estrogen plus progesterone, signaling a synergistic effect of the 2 hormones.28

SSRIs are an effective treatment for the irritability, anxiety, and mood swings of PMDD.29-30 Although the exact mechanism of action is unknown, the serotonergic properties are certainly of primary attention. For some PMDD patients, SSRIs work within hours to days, as opposed to days or weeks for patients with depression or anxiety, which suggests a separate or co-occurring mechanism of action is in place. In a double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study, researchers administered the serotonin receptor antagonist metergoline to women with PMDD whose symptoms had remitted during treatment with fluoxetine and a group of healthy controls who were not receiving any medication.31 The women with PMDD experienced a return of symptoms 24 hours after treatment with metergoline but not with placebo; the controls experienced no mood changes.31

BDNF is a neurotransmitter linked to estrogen and likely related to PMDD. BDNF is critical for neurogenesis and is expressed in brain regions involved in learning and memory and also affects regulation.32 BDNF levels are increased by serotonergic antidepressants, affected by estradiol, and have cyclicity throughout the menstrual cycle.33-35

Putative brain structural and functional differences. Imaging studies have suggested differences in brain structure in women with PMDD, with a focus on the amygdala and the prefrontal cortex. Women with PMDD have greater gray matter volume in the posterior cerebellum,36 greater gray matter density of hippocampal cortex, and lower gray matter density in the parahippocampal cortex.37

Some studies have shown a functional variability of the amygdala’s response to stress in women with PMDD vs healthy controls.38,39 A proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H-MRS) study of the displays the possibility of an altered GABAergic function in patients with PMDD.40

Patients will PMDD have enhanced dorsolateral prefrontal cortex reactivity when anticipating negative stimuli (but not to the actual exposure) during the luteal phase. A positive correlation between this reactivity and progesterone levels also was observed.41 Some researchers have suggested that prefrontal cortex dysfunction may be a risk factor for PMDD.42

HPA axis and HPG axis: Trauma, resiliency, inflammation. Altered cortisol levels (higher during the luteal phase43 and lower during times of stress14,44) suggest a possibly altered HPA axis in some women with PMDD. However, studies on this topic have been few and inconsistent.

Dysregulation of the HPG axis could cause vasomotor symptoms, sleep dysregulation, and mood symptoms during menopause; women with PMDD can also experience these symptoms. The influence of estrogen and progesterone on mood is also highly dependent on this axis.

Ultimately, the interplay between the HPA axis and the HPG axis is important. One study found that women with PMDD who had high serum ALLO levels (HPG-related) had blunted nocturnal cortisol levels (HPA-related) compared with healthy controls who had low ALLO levels.45

Significant stress and trauma exposure have been associated with PMDD. A study of 3,968 women found a history of trauma and PTSD were independently associated with PMDD.46 Another study of approximately 3,000 women found a strong correlation between abuse and PMS.47 However, a third study found no correlations between PMDD and trauma.48

Patients with a predisposition to PMDD may be more vulnerable to develop a posttraumatic stress-related disorder, perhaps due to decreased biologic resiliency. For example, the startle response (hypervigilance) has been shown to be different in women with PMDD. One study suggested that suboptimal production of premenstrual ALLO may lead to increased arousal and increased stress reactivity to psychosocial or environmental triggers.49

The possible role of inflammation in PMDD deserves further investigation. The luteal phase entails an increase in the production of proinflammatory markers.50,51 A 10-fold increase in progesterone is correlated with a 20% to 23% increase in C-reactive protein levels.52,53 Women with inflammatory diseases (eg, gingivitis or irritable bowel syndrome) show worsening of symptoms prior to menstruation.54-56 One study found increased levels of proinflammatory markers in women with PMDD compared with controls.57

Putting together the 5 pieces of the puzzle

Because PMDD is heritable, it must have an underlying neurobiologic pathophysiology. Brain imaging studies show differences in structure and function in women with PMDD across the menstrual cycle. Conversion of progesterone to ALLO and the GABAergic influence of this metabolite is a topic of interest in current research. Similarly, the role of estrogen and its connection to serotonin and other neurotransmitters such as BDNF have been implicated.

The link between a history of stress, trauma, and PMDD raises the question of biologic resiliency and illness in these patients, as it connects to the HPA and HPG axis and production of inflammatory stress hormones and steroid hormones and their metabolites. PMDD can be conceptualized as variable sensitivity to hormonal response to stress,58 thus contextualizing biochemical and psychological resiliency.

Further research is needed to clarify the possibility of a shared pathophysiology between endocrine-related mood disorders such as postpartum depression (PPD) and PMDD because current research is controversial.59,60 In PPD, women who are exposed to high levels of progesterone and estrogen during pregnancy (just like in the mid-luteal phase) have a sudden drop in these hormones postpartum.

The ‘withdrawal theory.’ The affective symptoms of PMDD resolve almost instantaneously after the start of menstruation. Perhaps this type of immediate relief is akin to substance use disorders and symptoms of withdrawal. It could be that reinstatement of a certain amount of gonadal steroids in the follicular phase of the cycle diminishes a withdrawal-like response to these steroids.

Currently, the main leading theory is that PMDD is a result of “an abnormal response to normal hormonal changes.”61 A new study also has shown that the change in estradiol/progesterone levels (vs the steady state) was associated with PMDD symptoms.62 Thinking of PMDD as a disorder of withdrawal offers an alternative (yet complementary) perspective to the current theory: PMDD may be caused by the absence or diminishing of the above-named hormones and their metabolites in the late luteal phase (in the context of developed “tolerance” during the early- to mid-luteal phase).

Considering the interplay between neurotransmitters and neurosteroids, both a “serotonin withdrawal theory” (caused by a drop in steroid hormones) and a “GABAergic withdrawal theory” (due to the decline in progesterone) could be proposed. This theory would be supported by the fact that SSRIs seem to mitigate symptoms of PMDD as well as the genetic association between PMDD and ESR1. It is more than likely that the “withdrawal” is caused by the interactions between estrogen-serotonin, progesterone-ALLO, and GABA receptors, and the complementary fashion in which progesterone and estrogen influence each other.

1. Miller A, Vo H, Huo L, et al. Estrogen receptor alpha (ESR-1) associations with psychological traits in women with PMDD and controls. J Psychiatr Res. 2010;44(12):788-794.

2. Epperson CN, Steiner M, Hartlage SA, et al. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder: evidence for a new category for DSM-5. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(5):465-475.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

4. Wilson CA, Turner CW, Keye WR Jr. Firstborn adolescent daughters and mothers with and without premenstrual syndrome: a comparison. J Adolesc Health. 1991;12(2):130-137.

5. Kendler KS, Silberg JL, Neale MC, et al. Genetic and environmental factors in the aetiology of menstrual, premenstrual and neurotic symptoms: a population-based twin study. Psychol Med. 1992;22(1):85-100.

6. Condon JT. The premenstrual syndrome: a twin study. Br J Psychiatry. 1993;162:481-486.

7. Kendler KS, Karkowski LM, Corey LA, et al. Longitudinal population-based twin study of retrospectively reported premenstrual symptoms and lifetime major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155(9):1234-1240.

8. Huo L, Straub RE, Roca C, et al. Risk for premenstrual dysphoric disorder is associated with genetic variation in ESR1, the estrogen receptor alpha gene. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62(8):925-933.

9. Dhingra V, Magnay JL, O’Brien PM, et al. Serotonin receptor 1A C(-1019)G polymorphism associated with premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(4):788-792.

10. Comasco E, Hahn A, Ganger S, et al. Emotional fronto-cingulate cortex activation and brain derived neurotrophic factor polymorphism in premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Hum Brain Mapp. 2014;35(9):4450-4458.

11. Praschak-Rieder N, Willeit M, Winkler D, et al. Role of family history and 5-HTTLPR polymorphism in female seasonal affective disorder patients with and without premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2002;12(2):129-134.

12. Klatzkin RR, Morrow AL, Light KC, et al. Associations of histories of depression and PMDD diagnosis with allopregnanolone concentrations following the oral administration of micronized progesterone. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2006;31(10):1208-1219.

13. Crowley SK, Girdler SS. Neurosteroid, GABAergic and hypothalamic pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis regulation: what is the current state of knowledge in humans? Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2014;231(17):3619-3634.

14. Girdler SS, Straneva PA, Light KC, et al. Allopregnanolone levels and reactivity to mental stress in premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;49(9):788-797.

15. Rapkin AJ, Morgan M, Goldman L, et al. Progesterone metabolite allopregnanolone in women with premenstrual syndrome. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90(5):709-714.

16. Bicíková M, Dibbelt L, Hill M, et al. Allopregnanolone in women with premenstrual syndrome. Horm Metab Res. 1998;30(4):227-230.

17. Monteleone P, Luisi S, Tonetti A, et al. Allopregnanolone concentrations and premenstrual syndrome. Eur J Endocrinol. 2000;142(3):269-273.

18. Steiner M, Steinberg S, Stewart D, et al. Fluoxetine in the treatment of premenstrual dysphoria. Canadian Fluoxetine/Premenstrual Dysphoria Collaborative Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(23):1529-1534.

19. Sundström I, Bäckström T. Citalopram increases pregnanolone sensitivity in patients with premenstrual syndrome: an open trial. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1998;23(1):73-88.

20. Griffin LD, Mellon SH. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors directly alter activity of neurosteroidogenic enzymes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(23):13512-13517.

21. Trauger JW, Jiang A, Stearns BA, et al. Kinetics of allopregnanolone formation catalyzed by human 3 alpha-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type III (AKR1C2). Biochemistry. 2002;41(45):13451-13459.

22. Shanmugan S, Epperson CN. Estrogen and the prefrontal cortex: towards a new understanding of estrogen’s effects on executive functions in the menopause transition. Hum Brain Mapp. 2014;35(3):847-865.

23. Rubinow DR, Schmidt PJ, Roca CA. Estrogen-serotonin interactions: implications for affective regulation. Biol Psychiatry. 1998;44(9):839-850.

24. Amin Z, Canli T, Epperson CN. Effect of estrogen-serotonin interactions on mood and cognition. Behav Cogn Neurosci Rev. 2005;4(1):43-58.

25. Cyr M, Bossé R, Di Paolo T. Gonadal hormones modulate 5-hydroxytryptamine2A receptors: emphasis on the rat frontal cortex. Neuroscience. 1998;83(3):829-836.

26. Fink G, Sumner BE, Rosie R, et al. Estrogen control of central neurotransmission: effect on mood, mental state, and memory. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 1996;16(3):325-344.

27. Sumner BE, Grant KE, Rosie R, et al. Effects of tamoxifen on serotonin transporter and 5-hydroxytryptamine(2A) receptor binding sites and mRNA levels in the brain of ovariectomized rats with or without acute estradiol replacement. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1999;73(1-2):119-128.

28. Moses-Kolko EL, Berga SL, Greer PJ, et al. Widespread increases of cortical serotonin type 2A receptor availability after hormone therapy in euthymic postmenopausal women. Fertil Steril. 2003;80(3):554-559.

29. Su TP, Schmidt PJ, Danaceau MA, et al. Fluoxetine in the treatment of premenstrual dysphoria. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1997;16(5):346-356.

30. Steinberg EM, Cardoso GM, Martinez PE, et al. Rapid response to fluoxetine in women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Depress Anxiety. 2012;29(6):531-540.

31. Roca CA, Schmidt PJ, Smith MJ, et al. Effects of metergoline on symptoms in women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(11):1876-1881.

32. Gray JD, Milner TA, McEwen BS. Dynamic plasticity: the role of glucocorticoids, brain-derived neurotrophic factor and other trophic factors. Neuroscience. 2013;239:214-227.

33. Carbone DL, Handa RJ. Sex and stress hormone influences on the expression and activity of brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Neuroscience. 2013;239:295-303.

34. Pilar-Cuéllar F, Vidal R, Pazos A. Subchronic treatment with fluoxetine and ketanserin increases hippocampal brain-derived neurotrophic factor, β-catenin and antidepressant-like effects. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;165(4b):1046-1057.

35. Deuschle M, Gilles M, Scharnholz B, et al. Changes of serum concentrations of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) during treatment with venlafaxine and mirtazapine: role of medication and response to treatment. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2013;46(2):54-58.

36. Berman SM, London ED, Morgan M, et al. Elevated gray matter volume of the emotional cerebellum in women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder. J Affect Disord. 2013;146(2):266-271.

37. Jeong HG, Ham BJ, Yeo HB, et al. Gray matter abnormalities in patients with premenstrual dysphoric disorder: an optimized voxel-based morphometry. J Affect Disord. 2012;140(3):260-267.

38. Protopopescu X, Tuescher O, Pan H, et al. Toward a functional neuroanatomy of premenstrual dysphoric disorder. J Affect Disord. 2008;108(1-2):87-94.

39. Gingnell M, Morell A, Bannbers E, et al. Menstrual cycle effects on amygdala reactivity to emotional stimulation in premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Horm Behav. 2012;62(4):400-406.

40. Epperson CN, Haga K, Mason GF, et al. Cortical gamma-aminobutyric acid levels across the menstrual cycle in healthy women and those with premenstrual dysphoric disorder: a proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(9):851-858.

41. Gingnell M, Bannbers E, Wikström J, et al. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder and prefrontal reactivity during anticipation of emotional stimuli. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;23(11):1474-1483.

42. Baller EB, Wei SM, Kohn PD, et al. Abnormalities of dorsolateral prefrontal function in women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder: a multimodal neuroimaging study. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(3):305-314.

43. Rasgon N, McGuire M, Tanavoli S, et al. Neuroendocrine response to an intravenous L-tryptophan challenge in women with premenstrual syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2000;73(1):144-149.

44. Huang Y, Zhou R, Wu M, et al. Premenstrual syndrome is associated with blunted cortisol reactivity to the TSST. Stress. 2015;18(2):160-168.

45. Segebladh B, Bannbers E, Moby L, et al. Allopregnanolone serum concentrations and diurnal cortisol secretion in women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2013;16(2):131-137.

46. Pilver CE, Levy BR, Libby DJ, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and trauma characteristics are correlates of premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2011;14(5):383-393.

47. Bertone-Johnson ER, Whitcomb BW, Missmer SA, et al. Early life emotional, physical, and sexual abuse and the development of premenstrual syndrome: a longitudinal study. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2014;23(9):729-739.

48. Segebladh B, Bannbers E, Kask K, et al. Prevalence of violence exposure in women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder in comparison with other gynecological patients and asymptomatic controls. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2011;90(7):746-752.

49. Kask K, Gulinello M, Bäckström T, et al. Patients with premenstrual dysphoric disorder have increased startle response across both cycle phases and lower levels of prepulse inhibition during the late luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33(9):2283-2290.

50. O’Brien SM, Fitzgerald P, Scully P, et al. Impact of gender and menstrual cycle phase on plasma cytokine concentrations. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2007;14(2):84-90.

51. Northoff H, Symons S, Zieker D, et al. Gender- and menstrual phase dependent regulation of inflammatory gene expression in response to aerobic exercise. Exerc Immunol Rev. 2008;14:86-103.

52. Gaskins AJ, Wilchesky M, Mumford SL, et al. Endogenous reproductive hormones and C-reactive protein across the menstrual cycle: the BioCycle Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;175(5):423-431.

53. Wander K, Brindle E, O’Connor KA. C-reactive protein across the menstrual cycle. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2008;136(2):138-146.

54. Jane ZY, Chang CC, Lin HK, et al. The association between the exacerbation of irritable bowel syndrome and menstrual symptoms in young Taiwanese women. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2011;34(4):277-286.

55. Kane SV, Sable K, Hanauer SB. The menstrual cycle and its effect on inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome: a prevalence study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93(10):1867-1872.

56. Shourie V, Dwarakanath CD, Prashanth GV, et al. The effect of menstrual cycle on periodontal health - a clinical and microbiological study. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2012;10(2):185-192.

57. Hantsoo L, Epperson CN. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder: epidemiology and treatment. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2015;17(11):87.

58. Maeng LY, Milad MR. Sex differences in anxiety disorders: Interactions between fear, stress, and gonadal hormones. Horm Behav. 2015;76:106-117.

59. Lee YJ, Yi SW, Ju DH, et al. Correlation between postpartum depression and premenstrual dysphoric disorder: single center study. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2015;58(5):353-358.

60. Kepple AL, Lee EE, Haq N, et al. History of postpartum depression in a clinic-based sample of women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(4):e415-e420.

61. Schmidt PJ, Nieman LK, Danaceau MA, et al. Differential behavioral effects of gonadal steroids in women with and in those without premenstrual syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(4):209-216.

62. Schmidt PJ, Martinez PE, Nieman LK, et al. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder symptoms following ovarian suppression: Triggered by change in ovarian steroid levels but not continuous stable levels. Am J Psychiatry. [published online April 21, 2017]. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.16101113.

1. Miller A, Vo H, Huo L, et al. Estrogen receptor alpha (ESR-1) associations with psychological traits in women with PMDD and controls. J Psychiatr Res. 2010;44(12):788-794.

2. Epperson CN, Steiner M, Hartlage SA, et al. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder: evidence for a new category for DSM-5. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(5):465-475.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

4. Wilson CA, Turner CW, Keye WR Jr. Firstborn adolescent daughters and mothers with and without premenstrual syndrome: a comparison. J Adolesc Health. 1991;12(2):130-137.

5. Kendler KS, Silberg JL, Neale MC, et al. Genetic and environmental factors in the aetiology of menstrual, premenstrual and neurotic symptoms: a population-based twin study. Psychol Med. 1992;22(1):85-100.

6. Condon JT. The premenstrual syndrome: a twin study. Br J Psychiatry. 1993;162:481-486.

7. Kendler KS, Karkowski LM, Corey LA, et al. Longitudinal population-based twin study of retrospectively reported premenstrual symptoms and lifetime major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155(9):1234-1240.

8. Huo L, Straub RE, Roca C, et al. Risk for premenstrual dysphoric disorder is associated with genetic variation in ESR1, the estrogen receptor alpha gene. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62(8):925-933.

9. Dhingra V, Magnay JL, O’Brien PM, et al. Serotonin receptor 1A C(-1019)G polymorphism associated with premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(4):788-792.

10. Comasco E, Hahn A, Ganger S, et al. Emotional fronto-cingulate cortex activation and brain derived neurotrophic factor polymorphism in premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Hum Brain Mapp. 2014;35(9):4450-4458.

11. Praschak-Rieder N, Willeit M, Winkler D, et al. Role of family history and 5-HTTLPR polymorphism in female seasonal affective disorder patients with and without premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2002;12(2):129-134.

12. Klatzkin RR, Morrow AL, Light KC, et al. Associations of histories of depression and PMDD diagnosis with allopregnanolone concentrations following the oral administration of micronized progesterone. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2006;31(10):1208-1219.

13. Crowley SK, Girdler SS. Neurosteroid, GABAergic and hypothalamic pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis regulation: what is the current state of knowledge in humans? Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2014;231(17):3619-3634.

14. Girdler SS, Straneva PA, Light KC, et al. Allopregnanolone levels and reactivity to mental stress in premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;49(9):788-797.

15. Rapkin AJ, Morgan M, Goldman L, et al. Progesterone metabolite allopregnanolone in women with premenstrual syndrome. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90(5):709-714.

16. Bicíková M, Dibbelt L, Hill M, et al. Allopregnanolone in women with premenstrual syndrome. Horm Metab Res. 1998;30(4):227-230.

17. Monteleone P, Luisi S, Tonetti A, et al. Allopregnanolone concentrations and premenstrual syndrome. Eur J Endocrinol. 2000;142(3):269-273.

18. Steiner M, Steinberg S, Stewart D, et al. Fluoxetine in the treatment of premenstrual dysphoria. Canadian Fluoxetine/Premenstrual Dysphoria Collaborative Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(23):1529-1534.

19. Sundström I, Bäckström T. Citalopram increases pregnanolone sensitivity in patients with premenstrual syndrome: an open trial. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1998;23(1):73-88.

20. Griffin LD, Mellon SH. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors directly alter activity of neurosteroidogenic enzymes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(23):13512-13517.

21. Trauger JW, Jiang A, Stearns BA, et al. Kinetics of allopregnanolone formation catalyzed by human 3 alpha-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type III (AKR1C2). Biochemistry. 2002;41(45):13451-13459.

22. Shanmugan S, Epperson CN. Estrogen and the prefrontal cortex: towards a new understanding of estrogen’s effects on executive functions in the menopause transition. Hum Brain Mapp. 2014;35(3):847-865.

23. Rubinow DR, Schmidt PJ, Roca CA. Estrogen-serotonin interactions: implications for affective regulation. Biol Psychiatry. 1998;44(9):839-850.

24. Amin Z, Canli T, Epperson CN. Effect of estrogen-serotonin interactions on mood and cognition. Behav Cogn Neurosci Rev. 2005;4(1):43-58.

25. Cyr M, Bossé R, Di Paolo T. Gonadal hormones modulate 5-hydroxytryptamine2A receptors: emphasis on the rat frontal cortex. Neuroscience. 1998;83(3):829-836.

26. Fink G, Sumner BE, Rosie R, et al. Estrogen control of central neurotransmission: effect on mood, mental state, and memory. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 1996;16(3):325-344.

27. Sumner BE, Grant KE, Rosie R, et al. Effects of tamoxifen on serotonin transporter and 5-hydroxytryptamine(2A) receptor binding sites and mRNA levels in the brain of ovariectomized rats with or without acute estradiol replacement. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1999;73(1-2):119-128.

28. Moses-Kolko EL, Berga SL, Greer PJ, et al. Widespread increases of cortical serotonin type 2A receptor availability after hormone therapy in euthymic postmenopausal women. Fertil Steril. 2003;80(3):554-559.

29. Su TP, Schmidt PJ, Danaceau MA, et al. Fluoxetine in the treatment of premenstrual dysphoria. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1997;16(5):346-356.

30. Steinberg EM, Cardoso GM, Martinez PE, et al. Rapid response to fluoxetine in women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Depress Anxiety. 2012;29(6):531-540.

31. Roca CA, Schmidt PJ, Smith MJ, et al. Effects of metergoline on symptoms in women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(11):1876-1881.

32. Gray JD, Milner TA, McEwen BS. Dynamic plasticity: the role of glucocorticoids, brain-derived neurotrophic factor and other trophic factors. Neuroscience. 2013;239:214-227.

33. Carbone DL, Handa RJ. Sex and stress hormone influences on the expression and activity of brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Neuroscience. 2013;239:295-303.

34. Pilar-Cuéllar F, Vidal R, Pazos A. Subchronic treatment with fluoxetine and ketanserin increases hippocampal brain-derived neurotrophic factor, β-catenin and antidepressant-like effects. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;165(4b):1046-1057.

35. Deuschle M, Gilles M, Scharnholz B, et al. Changes of serum concentrations of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) during treatment with venlafaxine and mirtazapine: role of medication and response to treatment. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2013;46(2):54-58.

36. Berman SM, London ED, Morgan M, et al. Elevated gray matter volume of the emotional cerebellum in women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder. J Affect Disord. 2013;146(2):266-271.

37. Jeong HG, Ham BJ, Yeo HB, et al. Gray matter abnormalities in patients with premenstrual dysphoric disorder: an optimized voxel-based morphometry. J Affect Disord. 2012;140(3):260-267.

38. Protopopescu X, Tuescher O, Pan H, et al. Toward a functional neuroanatomy of premenstrual dysphoric disorder. J Affect Disord. 2008;108(1-2):87-94.

39. Gingnell M, Morell A, Bannbers E, et al. Menstrual cycle effects on amygdala reactivity to emotional stimulation in premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Horm Behav. 2012;62(4):400-406.

40. Epperson CN, Haga K, Mason GF, et al. Cortical gamma-aminobutyric acid levels across the menstrual cycle in healthy women and those with premenstrual dysphoric disorder: a proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(9):851-858.

41. Gingnell M, Bannbers E, Wikström J, et al. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder and prefrontal reactivity during anticipation of emotional stimuli. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;23(11):1474-1483.