User login

Acquiring a REDcap data entry skill set

Editor’s Note: The Society of Hospital Medicine’s (SHM’s) Physician in Training Committee launched a scholarship program in 2015 for medical students to help transform health care and revolutionize patient care. The program has been expanded for the 2017-2018 year, offering two options for students to receive funding and engage in scholarly work during their first, second, and third years of medical school. As a part of the program, recipients are required to write about their experience on a biweekly basis.

To give a status update on my project, I am almost finished collecting data for the Emergency ICU Transfer cases in Cincinnati Children’s Hospital. The project timeline is going as planned, and I should be finishing my data collection within the next week or so. I have begun to match control subjects by age strata, time of transfer and hospital unit to the Emergency ICU Transfer cases, and hope to finish that within the next week as well.

To streamline data collection and make it available for analysis in the near future, I set up a REDcap data entry form for my project. This was initially a challenge because even though I have entered data using this online tool before, I had no experience creating my own forms. With a lot of help from Google, people who worked around me, and our campus REDcap administrators, I was able to set this up pretty quickly and independently. I have noticed that this tool is widely used for clinical research, and am glad that being able create project instruments within REDcap is now part of my skill set. This was a unique learning experience for me that I wasn’t expecting to gain. It helped me understand what needs to be done specifically in order to execute a clinical research project, such as the one I’m working on alongside my mentor.

I have also learned a little medical knowledge from reading patient charts as I’m collecting data. For example, for procedures such as intubation, I have been seeing what specific medications are being administered for the pediatric patient. It has been interesting to learn some medical details behind lifesaving procedures, before even having clinical exposure in my medical training.

Farah Hussain is a 2nd-year medical student at University of Cincinnati College of Medicine and student researcher at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. Her research interests involve bettering patient care to vulnerable populations.

Editor’s Note: The Society of Hospital Medicine’s (SHM’s) Physician in Training Committee launched a scholarship program in 2015 for medical students to help transform health care and revolutionize patient care. The program has been expanded for the 2017-2018 year, offering two options for students to receive funding and engage in scholarly work during their first, second, and third years of medical school. As a part of the program, recipients are required to write about their experience on a biweekly basis.

To give a status update on my project, I am almost finished collecting data for the Emergency ICU Transfer cases in Cincinnati Children’s Hospital. The project timeline is going as planned, and I should be finishing my data collection within the next week or so. I have begun to match control subjects by age strata, time of transfer and hospital unit to the Emergency ICU Transfer cases, and hope to finish that within the next week as well.

To streamline data collection and make it available for analysis in the near future, I set up a REDcap data entry form for my project. This was initially a challenge because even though I have entered data using this online tool before, I had no experience creating my own forms. With a lot of help from Google, people who worked around me, and our campus REDcap administrators, I was able to set this up pretty quickly and independently. I have noticed that this tool is widely used for clinical research, and am glad that being able create project instruments within REDcap is now part of my skill set. This was a unique learning experience for me that I wasn’t expecting to gain. It helped me understand what needs to be done specifically in order to execute a clinical research project, such as the one I’m working on alongside my mentor.

I have also learned a little medical knowledge from reading patient charts as I’m collecting data. For example, for procedures such as intubation, I have been seeing what specific medications are being administered for the pediatric patient. It has been interesting to learn some medical details behind lifesaving procedures, before even having clinical exposure in my medical training.

Farah Hussain is a 2nd-year medical student at University of Cincinnati College of Medicine and student researcher at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. Her research interests involve bettering patient care to vulnerable populations.

Editor’s Note: The Society of Hospital Medicine’s (SHM’s) Physician in Training Committee launched a scholarship program in 2015 for medical students to help transform health care and revolutionize patient care. The program has been expanded for the 2017-2018 year, offering two options for students to receive funding and engage in scholarly work during their first, second, and third years of medical school. As a part of the program, recipients are required to write about their experience on a biweekly basis.

To give a status update on my project, I am almost finished collecting data for the Emergency ICU Transfer cases in Cincinnati Children’s Hospital. The project timeline is going as planned, and I should be finishing my data collection within the next week or so. I have begun to match control subjects by age strata, time of transfer and hospital unit to the Emergency ICU Transfer cases, and hope to finish that within the next week as well.

To streamline data collection and make it available for analysis in the near future, I set up a REDcap data entry form for my project. This was initially a challenge because even though I have entered data using this online tool before, I had no experience creating my own forms. With a lot of help from Google, people who worked around me, and our campus REDcap administrators, I was able to set this up pretty quickly and independently. I have noticed that this tool is widely used for clinical research, and am glad that being able create project instruments within REDcap is now part of my skill set. This was a unique learning experience for me that I wasn’t expecting to gain. It helped me understand what needs to be done specifically in order to execute a clinical research project, such as the one I’m working on alongside my mentor.

I have also learned a little medical knowledge from reading patient charts as I’m collecting data. For example, for procedures such as intubation, I have been seeing what specific medications are being administered for the pediatric patient. It has been interesting to learn some medical details behind lifesaving procedures, before even having clinical exposure in my medical training.

Farah Hussain is a 2nd-year medical student at University of Cincinnati College of Medicine and student researcher at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. Her research interests involve bettering patient care to vulnerable populations.

HPV vaccine pioneers win 2017 Lasker-DeBakey Clinical Medical Research Award

Douglas R. Lowy, MD, and John T. Schiller, PhD, received the 2017 Lasker-DeBakey Clinical Medical Research Award for their development of the virus-like particle technology used to create the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine. Their team discovered that proteins making up the outer shell of HPV could form virus-like particles that closely resemble the original virus but are not infectious, and these particles could trigger the immune system to produce protective antibodies that could neutralize HPV in a later infection. These particles eventually became the basis of the HPV vaccines Gardasil, Gardasil 9, and Cervarix.

HPV causes cervical cancer and other cancers such as cancer of the vulva, vagina, penis, or anus, as well as oropharyngeal cancer. Two of the high-risk types of HPV – HPV-16 and HPV-18 – cause about 70% of cervical cancers worldwide; it ranks 14th in frequency in the United States, according to the National Cancer Institute. The HPV vaccines are very effective in preventing persistent infections with HPV-16 and HPV-18. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices continues to recommend routine HPV vaccination for girls and boys at age 11 or 12 years, with a second vaccine given 6-12 months later.

Douglas R. Lowy, MD, and John T. Schiller, PhD, received the 2017 Lasker-DeBakey Clinical Medical Research Award for their development of the virus-like particle technology used to create the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine. Their team discovered that proteins making up the outer shell of HPV could form virus-like particles that closely resemble the original virus but are not infectious, and these particles could trigger the immune system to produce protective antibodies that could neutralize HPV in a later infection. These particles eventually became the basis of the HPV vaccines Gardasil, Gardasil 9, and Cervarix.

HPV causes cervical cancer and other cancers such as cancer of the vulva, vagina, penis, or anus, as well as oropharyngeal cancer. Two of the high-risk types of HPV – HPV-16 and HPV-18 – cause about 70% of cervical cancers worldwide; it ranks 14th in frequency in the United States, according to the National Cancer Institute. The HPV vaccines are very effective in preventing persistent infections with HPV-16 and HPV-18. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices continues to recommend routine HPV vaccination for girls and boys at age 11 or 12 years, with a second vaccine given 6-12 months later.

Douglas R. Lowy, MD, and John T. Schiller, PhD, received the 2017 Lasker-DeBakey Clinical Medical Research Award for their development of the virus-like particle technology used to create the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine. Their team discovered that proteins making up the outer shell of HPV could form virus-like particles that closely resemble the original virus but are not infectious, and these particles could trigger the immune system to produce protective antibodies that could neutralize HPV in a later infection. These particles eventually became the basis of the HPV vaccines Gardasil, Gardasil 9, and Cervarix.

HPV causes cervical cancer and other cancers such as cancer of the vulva, vagina, penis, or anus, as well as oropharyngeal cancer. Two of the high-risk types of HPV – HPV-16 and HPV-18 – cause about 70% of cervical cancers worldwide; it ranks 14th in frequency in the United States, according to the National Cancer Institute. The HPV vaccines are very effective in preventing persistent infections with HPV-16 and HPV-18. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices continues to recommend routine HPV vaccination for girls and boys at age 11 or 12 years, with a second vaccine given 6-12 months later.

Briviact gets monotherapy approval for partial-onset seizures

A supplemental new drug application for Briviact (brivaracetam) CV as a monotherapy treatment for partial-onset seizures in patients aged 16 years and older with epilepsy received approval from the Food and Drug Administration on Sept. 15, according to an announcement from its manufacturer, UCB.

Brivaracetam is already approved in the United States as an adjunctive treatment for partial-onset seizures in patients in this age group. As a result, adults and adolescents aged 16 years and older with partial-onset seizures in the United States can now be initiated on brivaracetam as monotherapy or adjunctive therapy.

Brivaracetam is the newest antiepileptic drug (AED) in the ‘racetam’ class of medicines and demonstrates a high and selective affinity for synaptic vesicle protein 2A (SV2A) in the brain, which may contribute to its anticonvulsant effects. Gradual dose escalation is not required when initiating treatment with brivaracetam for monotherapy or adjunctive therapy. According to the prescribing information, it is available in three formulations: film-coated tablets (10-mg, 25-mg, 50-mg, 75-mg, and 100-mg strengths), oral solution (10 mg/mL), and injection (50 mg in a 5-mL single-dose vial).

Common adverse reactions reported in at least 5% of brivaracetam users and at least 2% more frequently than placebo are somnolence and sedation, dizziness, fatigue, and nausea and vomiting.

“This new monotherapy indication builds on an already strong and compelling clinical profile for Briviact, providing doctors the flexibility to tailor their choice of AED to match individual patient needs and circumstances,” explained Pavel Klein, MD, director of the Mid-Atlantic Epilepsy and Sleep Center, Bethesda, Md., in the UCB announcement. “In helping to progress their journey towards seizure freedom by providing a choice of treatment which can be initiated as monotherapy, at a therapeutic dose, from day 1, Briviact provides an additional treatment choice for neurologists and their patients.”

A supplemental new drug application for Briviact (brivaracetam) CV as a monotherapy treatment for partial-onset seizures in patients aged 16 years and older with epilepsy received approval from the Food and Drug Administration on Sept. 15, according to an announcement from its manufacturer, UCB.

Brivaracetam is already approved in the United States as an adjunctive treatment for partial-onset seizures in patients in this age group. As a result, adults and adolescents aged 16 years and older with partial-onset seizures in the United States can now be initiated on brivaracetam as monotherapy or adjunctive therapy.

Brivaracetam is the newest antiepileptic drug (AED) in the ‘racetam’ class of medicines and demonstrates a high and selective affinity for synaptic vesicle protein 2A (SV2A) in the brain, which may contribute to its anticonvulsant effects. Gradual dose escalation is not required when initiating treatment with brivaracetam for monotherapy or adjunctive therapy. According to the prescribing information, it is available in three formulations: film-coated tablets (10-mg, 25-mg, 50-mg, 75-mg, and 100-mg strengths), oral solution (10 mg/mL), and injection (50 mg in a 5-mL single-dose vial).

Common adverse reactions reported in at least 5% of brivaracetam users and at least 2% more frequently than placebo are somnolence and sedation, dizziness, fatigue, and nausea and vomiting.

“This new monotherapy indication builds on an already strong and compelling clinical profile for Briviact, providing doctors the flexibility to tailor their choice of AED to match individual patient needs and circumstances,” explained Pavel Klein, MD, director of the Mid-Atlantic Epilepsy and Sleep Center, Bethesda, Md., in the UCB announcement. “In helping to progress their journey towards seizure freedom by providing a choice of treatment which can be initiated as monotherapy, at a therapeutic dose, from day 1, Briviact provides an additional treatment choice for neurologists and their patients.”

A supplemental new drug application for Briviact (brivaracetam) CV as a monotherapy treatment for partial-onset seizures in patients aged 16 years and older with epilepsy received approval from the Food and Drug Administration on Sept. 15, according to an announcement from its manufacturer, UCB.

Brivaracetam is already approved in the United States as an adjunctive treatment for partial-onset seizures in patients in this age group. As a result, adults and adolescents aged 16 years and older with partial-onset seizures in the United States can now be initiated on brivaracetam as monotherapy or adjunctive therapy.

Brivaracetam is the newest antiepileptic drug (AED) in the ‘racetam’ class of medicines and demonstrates a high and selective affinity for synaptic vesicle protein 2A (SV2A) in the brain, which may contribute to its anticonvulsant effects. Gradual dose escalation is not required when initiating treatment with brivaracetam for monotherapy or adjunctive therapy. According to the prescribing information, it is available in three formulations: film-coated tablets (10-mg, 25-mg, 50-mg, 75-mg, and 100-mg strengths), oral solution (10 mg/mL), and injection (50 mg in a 5-mL single-dose vial).

Common adverse reactions reported in at least 5% of brivaracetam users and at least 2% more frequently than placebo are somnolence and sedation, dizziness, fatigue, and nausea and vomiting.

“This new monotherapy indication builds on an already strong and compelling clinical profile for Briviact, providing doctors the flexibility to tailor their choice of AED to match individual patient needs and circumstances,” explained Pavel Klein, MD, director of the Mid-Atlantic Epilepsy and Sleep Center, Bethesda, Md., in the UCB announcement. “In helping to progress their journey towards seizure freedom by providing a choice of treatment which can be initiated as monotherapy, at a therapeutic dose, from day 1, Briviact provides an additional treatment choice for neurologists and their patients.”

VIDEO: What’s new in AAP’s pediatric hypertension guidelines

SAN FRANCISCO – The American Academy of Pediatrics recently released new hypertension guidelines for children and adolescents.

Some of the advice is similar to the group’s last effort in 2004, but there are a few key changes that clinicians need to know, according to lead author Joseph Flynn, MD, professor of pediatrics and chief of nephrology at Seattle Children’s Hospital. He explained what they are, and the reasons behind them, in an interview at the joint hypertension scientific sessions sponsored by the American Heart Association and the American Society of Hypertension (Pediatrics. 2017 Aug 21. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-1904).

The prevalence of pediatric hypertension, he said, now rivals asthma.

SAN FRANCISCO – The American Academy of Pediatrics recently released new hypertension guidelines for children and adolescents.

Some of the advice is similar to the group’s last effort in 2004, but there are a few key changes that clinicians need to know, according to lead author Joseph Flynn, MD, professor of pediatrics and chief of nephrology at Seattle Children’s Hospital. He explained what they are, and the reasons behind them, in an interview at the joint hypertension scientific sessions sponsored by the American Heart Association and the American Society of Hypertension (Pediatrics. 2017 Aug 21. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-1904).

The prevalence of pediatric hypertension, he said, now rivals asthma.

SAN FRANCISCO – The American Academy of Pediatrics recently released new hypertension guidelines for children and adolescents.

Some of the advice is similar to the group’s last effort in 2004, but there are a few key changes that clinicians need to know, according to lead author Joseph Flynn, MD, professor of pediatrics and chief of nephrology at Seattle Children’s Hospital. He explained what they are, and the reasons behind them, in an interview at the joint hypertension scientific sessions sponsored by the American Heart Association and the American Society of Hypertension (Pediatrics. 2017 Aug 21. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-1904).

The prevalence of pediatric hypertension, he said, now rivals asthma.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE AHA/ASH JOINT SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

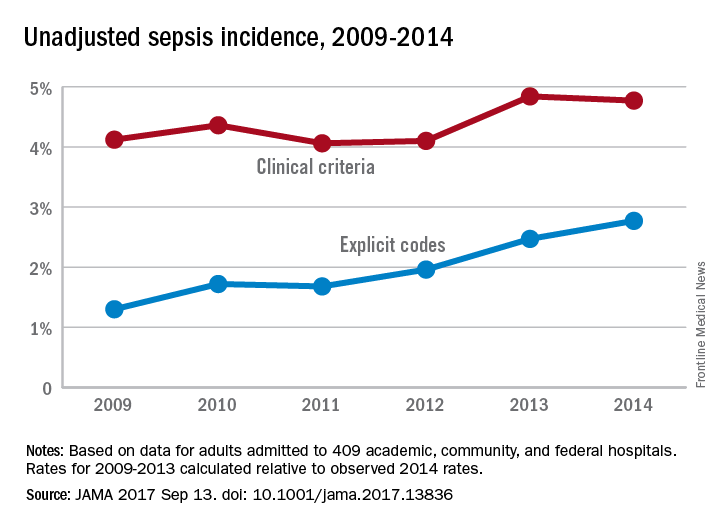

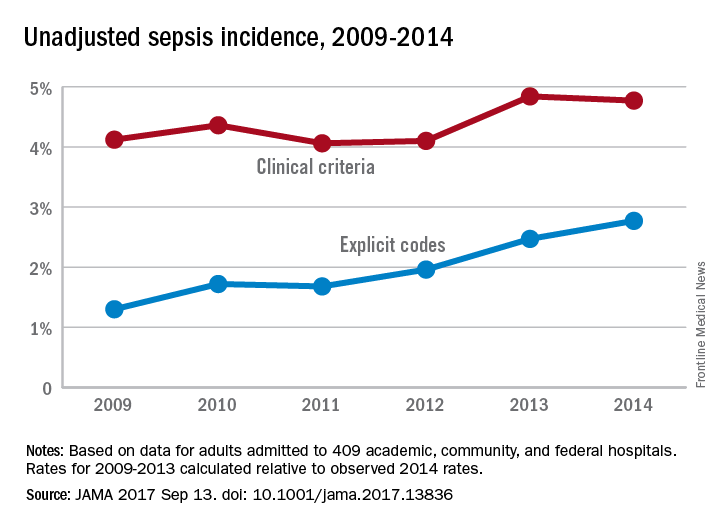

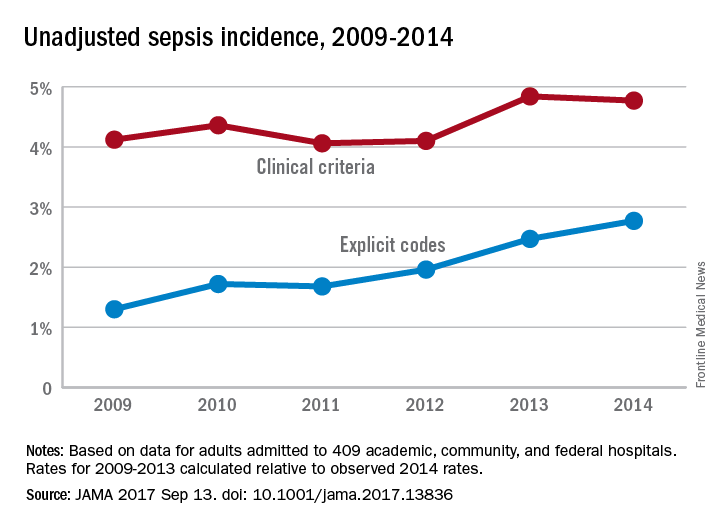

Increase in sepsis incidence stable from 2009 to 2014

The trend for sepsis incidence from 2009 to 2014, “calculated relative to the observed 2014 rates,” was a stable increase of 0.6% per year using the more accurate of two forms of analysis, investigators reported.

The incidence of sepsis was an adjusted 5.9% among hospitalized adults in 2014, with in-hospital mortality of 15%, according to a retrospective cohort study published online Sept. 13 in JAMA.

“Most studies [of sepsis incidence] have used claims data, but increasing clinical awareness, changes in diagnosis and coding practices, and variable definitions have led to uncertainty about the accuracy of reported trends,” wrote Chanu Rhee, MD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and his associates (JAMA. 2017 Sep 13. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.13836).

They used two methods – one involving claims-based estimates using ICD-9-CM codes and the other based on clinical data from electronic health records (EHRs) – to analyze data for more than 2.9 million adults admitted to 409 U.S. academic, community, and federal acute-care hospitals in 2014. The claims-based “explicit-codes” approach used discharge diagnoses of severe sepsis (995.92) or septic shock (785.52), while the EHR-based, clinical-criteria method included blood cultures, antibiotics, and concurrent organ dysfunction with or without the criterion of a lactate level of 2.0 mmol/L or greater, the investigators said.

The explicit-codes approach produced an increase of 10.3% per year in sepsis incidence from 2009 to 2014, compared with 0.6% per year for the clinical-criteria approach, while in-hospital mortality declined by 7% a year using explicit codes and 3.3% using clinical criteria, Dr. Rhee and his associates reported.

“EHR-based criteria were more sensitive than explicit sepsis codes on medical record review, with comparable [positive predictive value]; EHR-based criteria had similar sensitivity to implicit or explicit codes combined but higher [positive predictive value],” they said.

The estimates provided by Dr. Rhee and his associates provide “a clearer understanding of trends in the incidence and mortality of sepsis in the United States but also a better understanding of the challenges in improving ICD coding to accurately document the global burden of sepsis,” Kristina E. Rudd, MD, of the University of Washington, Seattle, and her associates said in an editorial (JAMA 2017 Sep 13. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.13697).

The study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, National Institutes of Health, Department of Veterans Affairs, National Institutes of Health Clinical Center, and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Three of Dr. Rhee’s associates reported receiving personal fees from private companies or serving on advisory boards or as consultants. No other authors reported disclosures. Dr. Rudd and her associates had no conflicts of interest to report.

The trend for sepsis incidence from 2009 to 2014, “calculated relative to the observed 2014 rates,” was a stable increase of 0.6% per year using the more accurate of two forms of analysis, investigators reported.

The incidence of sepsis was an adjusted 5.9% among hospitalized adults in 2014, with in-hospital mortality of 15%, according to a retrospective cohort study published online Sept. 13 in JAMA.

“Most studies [of sepsis incidence] have used claims data, but increasing clinical awareness, changes in diagnosis and coding practices, and variable definitions have led to uncertainty about the accuracy of reported trends,” wrote Chanu Rhee, MD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and his associates (JAMA. 2017 Sep 13. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.13836).

They used two methods – one involving claims-based estimates using ICD-9-CM codes and the other based on clinical data from electronic health records (EHRs) – to analyze data for more than 2.9 million adults admitted to 409 U.S. academic, community, and federal acute-care hospitals in 2014. The claims-based “explicit-codes” approach used discharge diagnoses of severe sepsis (995.92) or septic shock (785.52), while the EHR-based, clinical-criteria method included blood cultures, antibiotics, and concurrent organ dysfunction with or without the criterion of a lactate level of 2.0 mmol/L or greater, the investigators said.

The explicit-codes approach produced an increase of 10.3% per year in sepsis incidence from 2009 to 2014, compared with 0.6% per year for the clinical-criteria approach, while in-hospital mortality declined by 7% a year using explicit codes and 3.3% using clinical criteria, Dr. Rhee and his associates reported.

“EHR-based criteria were more sensitive than explicit sepsis codes on medical record review, with comparable [positive predictive value]; EHR-based criteria had similar sensitivity to implicit or explicit codes combined but higher [positive predictive value],” they said.

The estimates provided by Dr. Rhee and his associates provide “a clearer understanding of trends in the incidence and mortality of sepsis in the United States but also a better understanding of the challenges in improving ICD coding to accurately document the global burden of sepsis,” Kristina E. Rudd, MD, of the University of Washington, Seattle, and her associates said in an editorial (JAMA 2017 Sep 13. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.13697).

The study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, National Institutes of Health, Department of Veterans Affairs, National Institutes of Health Clinical Center, and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Three of Dr. Rhee’s associates reported receiving personal fees from private companies or serving on advisory boards or as consultants. No other authors reported disclosures. Dr. Rudd and her associates had no conflicts of interest to report.

The trend for sepsis incidence from 2009 to 2014, “calculated relative to the observed 2014 rates,” was a stable increase of 0.6% per year using the more accurate of two forms of analysis, investigators reported.

The incidence of sepsis was an adjusted 5.9% among hospitalized adults in 2014, with in-hospital mortality of 15%, according to a retrospective cohort study published online Sept. 13 in JAMA.

“Most studies [of sepsis incidence] have used claims data, but increasing clinical awareness, changes in diagnosis and coding practices, and variable definitions have led to uncertainty about the accuracy of reported trends,” wrote Chanu Rhee, MD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and his associates (JAMA. 2017 Sep 13. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.13836).

They used two methods – one involving claims-based estimates using ICD-9-CM codes and the other based on clinical data from electronic health records (EHRs) – to analyze data for more than 2.9 million adults admitted to 409 U.S. academic, community, and federal acute-care hospitals in 2014. The claims-based “explicit-codes” approach used discharge diagnoses of severe sepsis (995.92) or septic shock (785.52), while the EHR-based, clinical-criteria method included blood cultures, antibiotics, and concurrent organ dysfunction with or without the criterion of a lactate level of 2.0 mmol/L or greater, the investigators said.

The explicit-codes approach produced an increase of 10.3% per year in sepsis incidence from 2009 to 2014, compared with 0.6% per year for the clinical-criteria approach, while in-hospital mortality declined by 7% a year using explicit codes and 3.3% using clinical criteria, Dr. Rhee and his associates reported.

“EHR-based criteria were more sensitive than explicit sepsis codes on medical record review, with comparable [positive predictive value]; EHR-based criteria had similar sensitivity to implicit or explicit codes combined but higher [positive predictive value],” they said.

The estimates provided by Dr. Rhee and his associates provide “a clearer understanding of trends in the incidence and mortality of sepsis in the United States but also a better understanding of the challenges in improving ICD coding to accurately document the global burden of sepsis,” Kristina E. Rudd, MD, of the University of Washington, Seattle, and her associates said in an editorial (JAMA 2017 Sep 13. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.13697).

The study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, National Institutes of Health, Department of Veterans Affairs, National Institutes of Health Clinical Center, and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Three of Dr. Rhee’s associates reported receiving personal fees from private companies or serving on advisory boards or as consultants. No other authors reported disclosures. Dr. Rudd and her associates had no conflicts of interest to report.

FROM JAMA

Sleep Strategies

The definition of mild obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) has varied over the years depending upon several factors, but based upon all definitions, it is highly prevalent. Depending upon presence of symptoms and gender, the prevalence may be as high 28% in men and 26% in women. (Young et al. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1230).

Typically, a combination of symptoms and frequency of respiratory events is required to make the diagnosis. Based upon the International Classification of Sleep Disorders-3rd edition (ICSD-3), the threshold apnea hypopnea index (AHI) for diagnosis depends upon the presence or absence of symptoms. If an individual has no symptoms, an AHI of 15 events per hour or more is required to make a diagnosis of OSA. However, there are several concerns about whether or not an individual may be “symptomatic.” This is most relevant when driving privileges may be at risk, such as with a commercial drivers’ licensing.

The presence of other comorbid disease can be used as criteria, including hypertension, mood disorder, cognitive dysfunction, coronary artery disease, stroke, congestive heart failure, atrial fibrillation, and type 2 diabetes mellitus. If no signs, symptoms, or comorbid diseases are present, then an AHI greater than 15 events per hour or more is required to make the diagnosis of OSA (Chowdrui et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193:e37).

There is still debate regarding the association of mild OSA and cardiovascular disease and whether treatment may prevent or reduce cardiovascular outcomes. The four main clinical outcomes typically reported are hypertension, cardiovascular events, cardiovascular and all-cause mortality, and arrhythmias.

A large clinical cohort of patients referred for sleep studies showed no association of mild OSA with different composite outcomes. Kendzerska and colleagues evaluated a composite outcome (myocardial infarction, stroke, CHF, revascularization procedures, or death from any cause) during a median follow-up of 68 months. No association of mild OSA with the composite cardiovascular endpoint was identified compared with those without OSA (Kendzerska et al. PLoS Med. 2014;11[2]:e1001599). Only one population-based study (MrOS Sleep Study) looked at the association between mild OSA and nocturnal arrhythmias in elderly men. The study did not find an increased risk for atrial fibrillation or complex ventricular ectopy in patients with mild OSA vs no OSA (Mehra et al. Arch Intern Med. 2009; 169:1147).

Several cohort studies have reported mild OSA is not associated with increased cardiovascular mortality. In the 18-year follow-up of the Wisconsin Cohort Study, it was found that mild OSA was not associated with cardiovascular mortality (HR, 1.8; 95% CI, 0.7–4.9). All-cause mortality was also not significantly increased in the mild OSA group compared with the no-OSA group in the Wisconsin cohort after 8 years of follow-up (adjusted HR, 1.6; 95% CI, 0.8–2.8). In summary, compared with subjects without OSA, available evidence from population-based longitudinal studies indicates that mild OSA is not associated with increased cardiovascular or all-cause mortality.

Does treatment of mild OSA vs no treatment change cardiovascular or mortality outcomes? This is still debated with no definitive answer. There have been several studies that have examined different therapies for OSA to reduce cardiovascular events. Typical events include coronary artery disease, hypertension, heart failure, stroke, arrhythmias, and cardiovascular disease-related mortality. However, most studies have examined cohorts with moderate to severe OSA with limited evaluation in the mild OSA category.

An observational study evaluated the effects of CPAP specifically in patients with mild OSA. There was no significant difference in the risk of developing hypertension among those patients ineligible for CPAP therapy, active on therapy, or those who declined therapy (Marin et al. JAMA. 2012; 307:2169). In contrast, a retrospective longitudinal cohort with normal blood pressure at baseline (mild OSA without preexisting cardiovascular disease, diabetes, or hyperlipidemia) did show decrease in mean arterial blood pressure of 2 mm Hg in the treatment group (Jaimchariyatam et al. Sleep Med. 2010;11:837). The MOSAIC trial was a multicenter randomized trial that evaluated the effects of CPAP on cardiac function in minimally symptomatic patients with OSA. The use of CPAP reduced the oxygen desaturation index (ODI) and Epworth Sleepiness Scale values. However, 6 months of therapy did not change functional or structural parameters measured by echocardiogram or cardiac magnetic resonance scanning in patients with mild to moderate OSA (Craig et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2015;11[9]:967). A single retrospective study reported the effects of CPAP in patients with mild OSA and all-cause mortality. The study compared treatment with patients using CPAP more than 4 hours vs a combined group of nonadherent and those who refused therapy (Hudgel et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2012;8:9). There was no significant difference in all-cause mortality in the two groups. However, this study did not analyze the impact of therapy on cardiovascular-specific mortality.

To date, there have been no studies that have evaluated the impact of treatment of mild OSA on cardiovascular events, arrhythmias, or stroke. In addition, there have been no randomized studies assessing treatment of mild OSA on fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular events. There is inadequate evidence regarding the effect of mild OSA on elevated blood pressure, neurologic cognition, quality of life, and cardiovascular consequences. Future research is needed to investigate the impact of mild OSA on these outcomes.

In summary, mild OSA is a very prevalent disease but the association with hypertension remains unclear and the literature to date suggests no association with other cardiovascular outcomes. In addition, no clear prevention of cardiovascular outcomes with treatment has been proven in the setting of mild OSA.

Dr. Duthuluru is Assistant Professor, Dr. Nazir is Assistant Professor, and Dr. Stevens is Associate Professor at the University of Kansas Medical Center.

The definition of mild obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) has varied over the years depending upon several factors, but based upon all definitions, it is highly prevalent. Depending upon presence of symptoms and gender, the prevalence may be as high 28% in men and 26% in women. (Young et al. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1230).

Typically, a combination of symptoms and frequency of respiratory events is required to make the diagnosis. Based upon the International Classification of Sleep Disorders-3rd edition (ICSD-3), the threshold apnea hypopnea index (AHI) for diagnosis depends upon the presence or absence of symptoms. If an individual has no symptoms, an AHI of 15 events per hour or more is required to make a diagnosis of OSA. However, there are several concerns about whether or not an individual may be “symptomatic.” This is most relevant when driving privileges may be at risk, such as with a commercial drivers’ licensing.

The presence of other comorbid disease can be used as criteria, including hypertension, mood disorder, cognitive dysfunction, coronary artery disease, stroke, congestive heart failure, atrial fibrillation, and type 2 diabetes mellitus. If no signs, symptoms, or comorbid diseases are present, then an AHI greater than 15 events per hour or more is required to make the diagnosis of OSA (Chowdrui et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193:e37).

There is still debate regarding the association of mild OSA and cardiovascular disease and whether treatment may prevent or reduce cardiovascular outcomes. The four main clinical outcomes typically reported are hypertension, cardiovascular events, cardiovascular and all-cause mortality, and arrhythmias.

A large clinical cohort of patients referred for sleep studies showed no association of mild OSA with different composite outcomes. Kendzerska and colleagues evaluated a composite outcome (myocardial infarction, stroke, CHF, revascularization procedures, or death from any cause) during a median follow-up of 68 months. No association of mild OSA with the composite cardiovascular endpoint was identified compared with those without OSA (Kendzerska et al. PLoS Med. 2014;11[2]:e1001599). Only one population-based study (MrOS Sleep Study) looked at the association between mild OSA and nocturnal arrhythmias in elderly men. The study did not find an increased risk for atrial fibrillation or complex ventricular ectopy in patients with mild OSA vs no OSA (Mehra et al. Arch Intern Med. 2009; 169:1147).

Several cohort studies have reported mild OSA is not associated with increased cardiovascular mortality. In the 18-year follow-up of the Wisconsin Cohort Study, it was found that mild OSA was not associated with cardiovascular mortality (HR, 1.8; 95% CI, 0.7–4.9). All-cause mortality was also not significantly increased in the mild OSA group compared with the no-OSA group in the Wisconsin cohort after 8 years of follow-up (adjusted HR, 1.6; 95% CI, 0.8–2.8). In summary, compared with subjects without OSA, available evidence from population-based longitudinal studies indicates that mild OSA is not associated with increased cardiovascular or all-cause mortality.

Does treatment of mild OSA vs no treatment change cardiovascular or mortality outcomes? This is still debated with no definitive answer. There have been several studies that have examined different therapies for OSA to reduce cardiovascular events. Typical events include coronary artery disease, hypertension, heart failure, stroke, arrhythmias, and cardiovascular disease-related mortality. However, most studies have examined cohorts with moderate to severe OSA with limited evaluation in the mild OSA category.

An observational study evaluated the effects of CPAP specifically in patients with mild OSA. There was no significant difference in the risk of developing hypertension among those patients ineligible for CPAP therapy, active on therapy, or those who declined therapy (Marin et al. JAMA. 2012; 307:2169). In contrast, a retrospective longitudinal cohort with normal blood pressure at baseline (mild OSA without preexisting cardiovascular disease, diabetes, or hyperlipidemia) did show decrease in mean arterial blood pressure of 2 mm Hg in the treatment group (Jaimchariyatam et al. Sleep Med. 2010;11:837). The MOSAIC trial was a multicenter randomized trial that evaluated the effects of CPAP on cardiac function in minimally symptomatic patients with OSA. The use of CPAP reduced the oxygen desaturation index (ODI) and Epworth Sleepiness Scale values. However, 6 months of therapy did not change functional or structural parameters measured by echocardiogram or cardiac magnetic resonance scanning in patients with mild to moderate OSA (Craig et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2015;11[9]:967). A single retrospective study reported the effects of CPAP in patients with mild OSA and all-cause mortality. The study compared treatment with patients using CPAP more than 4 hours vs a combined group of nonadherent and those who refused therapy (Hudgel et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2012;8:9). There was no significant difference in all-cause mortality in the two groups. However, this study did not analyze the impact of therapy on cardiovascular-specific mortality.

To date, there have been no studies that have evaluated the impact of treatment of mild OSA on cardiovascular events, arrhythmias, or stroke. In addition, there have been no randomized studies assessing treatment of mild OSA on fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular events. There is inadequate evidence regarding the effect of mild OSA on elevated blood pressure, neurologic cognition, quality of life, and cardiovascular consequences. Future research is needed to investigate the impact of mild OSA on these outcomes.

In summary, mild OSA is a very prevalent disease but the association with hypertension remains unclear and the literature to date suggests no association with other cardiovascular outcomes. In addition, no clear prevention of cardiovascular outcomes with treatment has been proven in the setting of mild OSA.

Dr. Duthuluru is Assistant Professor, Dr. Nazir is Assistant Professor, and Dr. Stevens is Associate Professor at the University of Kansas Medical Center.

The definition of mild obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) has varied over the years depending upon several factors, but based upon all definitions, it is highly prevalent. Depending upon presence of symptoms and gender, the prevalence may be as high 28% in men and 26% in women. (Young et al. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1230).

Typically, a combination of symptoms and frequency of respiratory events is required to make the diagnosis. Based upon the International Classification of Sleep Disorders-3rd edition (ICSD-3), the threshold apnea hypopnea index (AHI) for diagnosis depends upon the presence or absence of symptoms. If an individual has no symptoms, an AHI of 15 events per hour or more is required to make a diagnosis of OSA. However, there are several concerns about whether or not an individual may be “symptomatic.” This is most relevant when driving privileges may be at risk, such as with a commercial drivers’ licensing.

The presence of other comorbid disease can be used as criteria, including hypertension, mood disorder, cognitive dysfunction, coronary artery disease, stroke, congestive heart failure, atrial fibrillation, and type 2 diabetes mellitus. If no signs, symptoms, or comorbid diseases are present, then an AHI greater than 15 events per hour or more is required to make the diagnosis of OSA (Chowdrui et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193:e37).

There is still debate regarding the association of mild OSA and cardiovascular disease and whether treatment may prevent or reduce cardiovascular outcomes. The four main clinical outcomes typically reported are hypertension, cardiovascular events, cardiovascular and all-cause mortality, and arrhythmias.

A large clinical cohort of patients referred for sleep studies showed no association of mild OSA with different composite outcomes. Kendzerska and colleagues evaluated a composite outcome (myocardial infarction, stroke, CHF, revascularization procedures, or death from any cause) during a median follow-up of 68 months. No association of mild OSA with the composite cardiovascular endpoint was identified compared with those without OSA (Kendzerska et al. PLoS Med. 2014;11[2]:e1001599). Only one population-based study (MrOS Sleep Study) looked at the association between mild OSA and nocturnal arrhythmias in elderly men. The study did not find an increased risk for atrial fibrillation or complex ventricular ectopy in patients with mild OSA vs no OSA (Mehra et al. Arch Intern Med. 2009; 169:1147).

Several cohort studies have reported mild OSA is not associated with increased cardiovascular mortality. In the 18-year follow-up of the Wisconsin Cohort Study, it was found that mild OSA was not associated with cardiovascular mortality (HR, 1.8; 95% CI, 0.7–4.9). All-cause mortality was also not significantly increased in the mild OSA group compared with the no-OSA group in the Wisconsin cohort after 8 years of follow-up (adjusted HR, 1.6; 95% CI, 0.8–2.8). In summary, compared with subjects without OSA, available evidence from population-based longitudinal studies indicates that mild OSA is not associated with increased cardiovascular or all-cause mortality.

Does treatment of mild OSA vs no treatment change cardiovascular or mortality outcomes? This is still debated with no definitive answer. There have been several studies that have examined different therapies for OSA to reduce cardiovascular events. Typical events include coronary artery disease, hypertension, heart failure, stroke, arrhythmias, and cardiovascular disease-related mortality. However, most studies have examined cohorts with moderate to severe OSA with limited evaluation in the mild OSA category.

An observational study evaluated the effects of CPAP specifically in patients with mild OSA. There was no significant difference in the risk of developing hypertension among those patients ineligible for CPAP therapy, active on therapy, or those who declined therapy (Marin et al. JAMA. 2012; 307:2169). In contrast, a retrospective longitudinal cohort with normal blood pressure at baseline (mild OSA without preexisting cardiovascular disease, diabetes, or hyperlipidemia) did show decrease in mean arterial blood pressure of 2 mm Hg in the treatment group (Jaimchariyatam et al. Sleep Med. 2010;11:837). The MOSAIC trial was a multicenter randomized trial that evaluated the effects of CPAP on cardiac function in minimally symptomatic patients with OSA. The use of CPAP reduced the oxygen desaturation index (ODI) and Epworth Sleepiness Scale values. However, 6 months of therapy did not change functional or structural parameters measured by echocardiogram or cardiac magnetic resonance scanning in patients with mild to moderate OSA (Craig et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2015;11[9]:967). A single retrospective study reported the effects of CPAP in patients with mild OSA and all-cause mortality. The study compared treatment with patients using CPAP more than 4 hours vs a combined group of nonadherent and those who refused therapy (Hudgel et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2012;8:9). There was no significant difference in all-cause mortality in the two groups. However, this study did not analyze the impact of therapy on cardiovascular-specific mortality.

To date, there have been no studies that have evaluated the impact of treatment of mild OSA on cardiovascular events, arrhythmias, or stroke. In addition, there have been no randomized studies assessing treatment of mild OSA on fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular events. There is inadequate evidence regarding the effect of mild OSA on elevated blood pressure, neurologic cognition, quality of life, and cardiovascular consequences. Future research is needed to investigate the impact of mild OSA on these outcomes.

In summary, mild OSA is a very prevalent disease but the association with hypertension remains unclear and the literature to date suggests no association with other cardiovascular outcomes. In addition, no clear prevention of cardiovascular outcomes with treatment has been proven in the setting of mild OSA.

Dr. Duthuluru is Assistant Professor, Dr. Nazir is Assistant Professor, and Dr. Stevens is Associate Professor at the University of Kansas Medical Center.

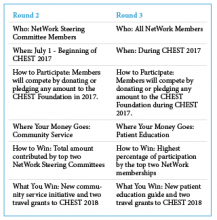

CHEST Foundation NetWorks Challenge

The CHEST Foundation is proud to announce the winners of the first round of the 2017 NetWorks Challenge! Our first place winner, Home-Based Mechanical Ventilation and Neuromuscular Disease NetWork, and our second place finisher, Women’s Health NetWork, both receive session time at CHEST 2017 on a topic of their choice and two travel grants to help their NetWork members attend CHEST 2017.

The Women’s Health NetWork was directly behind our first place finishers with more than 90% participation. Their session, “Care of the Critically Ill Pregnant Woman: Balancing Two Patients and Two Lives” will be on Monday, October 30, 1:30

Don’t forget, there is still time to win Round 2 and Round 3 of the NetWorks Challenge.

Learn more about the challenge at chestfoundation.org/networkschallenge.

The CHEST Foundation is proud to announce the winners of the first round of the 2017 NetWorks Challenge! Our first place winner, Home-Based Mechanical Ventilation and Neuromuscular Disease NetWork, and our second place finisher, Women’s Health NetWork, both receive session time at CHEST 2017 on a topic of their choice and two travel grants to help their NetWork members attend CHEST 2017.

The Women’s Health NetWork was directly behind our first place finishers with more than 90% participation. Their session, “Care of the Critically Ill Pregnant Woman: Balancing Two Patients and Two Lives” will be on Monday, October 30, 1:30

Don’t forget, there is still time to win Round 2 and Round 3 of the NetWorks Challenge.

Learn more about the challenge at chestfoundation.org/networkschallenge.

The CHEST Foundation is proud to announce the winners of the first round of the 2017 NetWorks Challenge! Our first place winner, Home-Based Mechanical Ventilation and Neuromuscular Disease NetWork, and our second place finisher, Women’s Health NetWork, both receive session time at CHEST 2017 on a topic of their choice and two travel grants to help their NetWork members attend CHEST 2017.

The Women’s Health NetWork was directly behind our first place finishers with more than 90% participation. Their session, “Care of the Critically Ill Pregnant Woman: Balancing Two Patients and Two Lives” will be on Monday, October 30, 1:30

Don’t forget, there is still time to win Round 2 and Round 3 of the NetWorks Challenge.

Learn more about the challenge at chestfoundation.org/networkschallenge.

Aptiom approved for pediatric partial-onset seizures

The Food and Drug Administration has approved Aptiom (eslicarbazepine acetate) for the treatment of partial-onset seizures in children aged 4-17 years, according to an announcement from Sunovion Pharmaceuticals.

The approval was based on results of three clinical trials where eslicarbazepine was shown to be safe and well tolerated in pediatric populations. The efficacy of eslicarbazepine has been illustrated in clinical trials in adult populations, and data were extrapolated to support usage in pediatric patients. Eslicarbazepine has previously been approved to treat partial-onset seizures in adults.

Pediatric dosing of eslicarbazepine is based on weight, and the tablets, available in 200-mg, 400-mg, 600-mg, and 800-mg strengths, can be taken whole or crushed, with or without food, according to the prescribing information.

“The unpredictable nature of seizures can be disruptive in the lives of these young people and their families, friends, and community. It is important that physicians have additional treatment options that address patient needs,” Steven Wolf, MD, director of pediatric epilepsy at Mount Sinai Health System, said in the announcement.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved Aptiom (eslicarbazepine acetate) for the treatment of partial-onset seizures in children aged 4-17 years, according to an announcement from Sunovion Pharmaceuticals.

The approval was based on results of three clinical trials where eslicarbazepine was shown to be safe and well tolerated in pediatric populations. The efficacy of eslicarbazepine has been illustrated in clinical trials in adult populations, and data were extrapolated to support usage in pediatric patients. Eslicarbazepine has previously been approved to treat partial-onset seizures in adults.

Pediatric dosing of eslicarbazepine is based on weight, and the tablets, available in 200-mg, 400-mg, 600-mg, and 800-mg strengths, can be taken whole or crushed, with or without food, according to the prescribing information.

“The unpredictable nature of seizures can be disruptive in the lives of these young people and their families, friends, and community. It is important that physicians have additional treatment options that address patient needs,” Steven Wolf, MD, director of pediatric epilepsy at Mount Sinai Health System, said in the announcement.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved Aptiom (eslicarbazepine acetate) for the treatment of partial-onset seizures in children aged 4-17 years, according to an announcement from Sunovion Pharmaceuticals.

The approval was based on results of three clinical trials where eslicarbazepine was shown to be safe and well tolerated in pediatric populations. The efficacy of eslicarbazepine has been illustrated in clinical trials in adult populations, and data were extrapolated to support usage in pediatric patients. Eslicarbazepine has previously been approved to treat partial-onset seizures in adults.

Pediatric dosing of eslicarbazepine is based on weight, and the tablets, available in 200-mg, 400-mg, 600-mg, and 800-mg strengths, can be taken whole or crushed, with or without food, according to the prescribing information.

“The unpredictable nature of seizures can be disruptive in the lives of these young people and their families, friends, and community. It is important that physicians have additional treatment options that address patient needs,” Steven Wolf, MD, director of pediatric epilepsy at Mount Sinai Health System, said in the announcement.

NetWorks

Gender Disparities in Occupational Health

Over the past few decades, the presence of women in the workforce has changed significantly. According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics Current Population Survey, in 2015, 46.8% of the workforce included women compared with 28.6% in 1948. Along with this change, there has been an increased focus on gender disparities in occupational health.

Gender differences in occupational asthma were also seen in snow crab processing plant workers. Women were significantly more likely to have occupational asthma than men. However, they found that overall, women had a greater cumulative exposure to crab allergens, which may be a major contributor to this disparity (Howse et al. Environ Res. 2006;101[2]:163).

Although several occupational health studies are beginning to highlight gender disparities, a major confounding factor is that of occupational segregation, meaning the under-representation of one gender in some jobs and over-representation in others. Differences in jobs and tasks even within the same job title between men and women are often major contributors to gender disparities [WHO Dept of Gender, Women and Health, 2006]. Also, several studies suggest that more women should be included in toxicology and occupational cancer studies, since currently, they have included mostly men (Sorrentino et al. Ann Ist Super Sanità. 2016;52[2]:190). Perhaps future studies can improve the overall understanding of these important contributing factors to gender disparities in occupational health.

Krystal Cleven, MD

Fellow-in-Training Member

Does Beta-agonist Therapy With Albuterol Cause Lactic Acidosis?

Cohen and associates (Clin Sci Mol Med. 1977;53:405) suggested that lactic acidosis can occur in at least two different physiologic clinical presentations. Type A occurs when oxygen delivery to the tissues is compromised. Dodda and Spiro (Respir Care. 2012;57[12]:2115) indicated that type A lactic acidosis was due to hypoxemia, as seen in inadequate tissue oxygenation during an exacerbation of asthma. In severe asthma, pulsus paradoxus and air trapping (causing intrinsic positive end-expiratory pressure, or PEEP) served to decrease tissue oxygenation by decreasing cardiac output and venous return, leading to type A lactic acidosis. Bates and associates (Pediatrics. 2014;133[4]:e1087) considered the role of intrapulmonary arteriovenous anastomoses (IPAVs) when a status asthmaticus patient improved after cessation of beta-agonist therapy. Type B lactic acidosis occurs when lactate production was increased or lactate removal was decreased even when oxygen was delivered to tissue. Amaducci (http://www.emresident.org/gasping-air-albuterol-induced-lactic-acidosis/) explained how high dosages of albuterol, beyond 1 mg/kg, created an increased adrenergic state that, with reduced tissue perfusion, increased glycolysis and pyruvate production, resulting in measurable hyperlactatemia. The authors (Br J Med Pract. 2011;4[2]:a420) noted that lactic acidosis also occurs in acute severe asthma due to inadequate oxygen delivery to the respiratory muscles to meet an elevated oxygen demand or due to fatiguing respiratory muscles. Ganaie and Hughes reported a case of lactic acidosis caused by treatment with salbutamol. Salbutamol is the most commonly used short-acting beta-agonist. Stimulation of beta-adrenergic receptors leads to a variety of metabolic effects, including increase in glycogenolysis, gluconeogenesis, and lipolysis, thus contributing to lactic acidosis. All authors agreed that the mechanism of albuterol-caused lactic acidosis was poorly understood.

Douglas E. Masini, EdD, FCCP

Steering Committee Member

Withdrawal of OSA Screening Regulation for Commercial Motor Vehicle Operators

Compared with the general US population, the prevalence of sleep apnea (SA) is higher among commercial motor vehicle (CMV) drivers (Berger et al. J Occup Environ Med. 2012;54[8]:1017). Additionally, the risk of motor vehicle accidents is higher among individuals with SA compared with those without SA (Tregear et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5[6]:573), and treatment of SA is associated with a reduction in this risk (Mahssa et al. Sleep. 2015;38[3]341).

However, after reviewing the public input and data, the FRA and FMCSA recently announced that there was “not enough information available to support moving forward with a rulemaking action,” and, therefore, they are no longer pursuing the regulation that would require SA screening for truck drivers and train engineers (Federal Register August 2017;49 CFR 391,240,242). See CHEST’s press release at www.chestnet.org/News/Press-Releases/2017/08/American-College-of-Chest-Physicians-Responds-to-DOT-Withdrawal-of-Sleep-Apnea-Screening. The FMCSA endorses existing resources,such as the North American Fatigue Management Program (NAFMP) (www.nafmp.org), which is a web-based program designed to reduce driver fatigue and includes information on SA screening and treatment. The medical examiners, however, will have the ultimate responsibility to screen, diagnose, and treat SA based on their medical knowledge and clinical experience.

Vaishnavi Kundel, MD

NetWork Member

Steering Committee Member

Corrections to previous NetWork articles

July 2017

Clinical Research

Mohsin Ijaz’s name was misspelled.

August 2017

Transplant

The name under Shruti Gadre’s photograph is wrong. It says Dr. Ahya instead of Dr. Gadre.

The authorship of the article at the end of the article is incorrect. It says Vivek Ahya, instead of Shruti Gadre and Marie Budev.

Gender Disparities in Occupational Health

Over the past few decades, the presence of women in the workforce has changed significantly. According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics Current Population Survey, in 2015, 46.8% of the workforce included women compared with 28.6% in 1948. Along with this change, there has been an increased focus on gender disparities in occupational health.

Gender differences in occupational asthma were also seen in snow crab processing plant workers. Women were significantly more likely to have occupational asthma than men. However, they found that overall, women had a greater cumulative exposure to crab allergens, which may be a major contributor to this disparity (Howse et al. Environ Res. 2006;101[2]:163).

Although several occupational health studies are beginning to highlight gender disparities, a major confounding factor is that of occupational segregation, meaning the under-representation of one gender in some jobs and over-representation in others. Differences in jobs and tasks even within the same job title between men and women are often major contributors to gender disparities [WHO Dept of Gender, Women and Health, 2006]. Also, several studies suggest that more women should be included in toxicology and occupational cancer studies, since currently, they have included mostly men (Sorrentino et al. Ann Ist Super Sanità. 2016;52[2]:190). Perhaps future studies can improve the overall understanding of these important contributing factors to gender disparities in occupational health.

Krystal Cleven, MD

Fellow-in-Training Member

Does Beta-agonist Therapy With Albuterol Cause Lactic Acidosis?

Cohen and associates (Clin Sci Mol Med. 1977;53:405) suggested that lactic acidosis can occur in at least two different physiologic clinical presentations. Type A occurs when oxygen delivery to the tissues is compromised. Dodda and Spiro (Respir Care. 2012;57[12]:2115) indicated that type A lactic acidosis was due to hypoxemia, as seen in inadequate tissue oxygenation during an exacerbation of asthma. In severe asthma, pulsus paradoxus and air trapping (causing intrinsic positive end-expiratory pressure, or PEEP) served to decrease tissue oxygenation by decreasing cardiac output and venous return, leading to type A lactic acidosis. Bates and associates (Pediatrics. 2014;133[4]:e1087) considered the role of intrapulmonary arteriovenous anastomoses (IPAVs) when a status asthmaticus patient improved after cessation of beta-agonist therapy. Type B lactic acidosis occurs when lactate production was increased or lactate removal was decreased even when oxygen was delivered to tissue. Amaducci (http://www.emresident.org/gasping-air-albuterol-induced-lactic-acidosis/) explained how high dosages of albuterol, beyond 1 mg/kg, created an increased adrenergic state that, with reduced tissue perfusion, increased glycolysis and pyruvate production, resulting in measurable hyperlactatemia. The authors (Br J Med Pract. 2011;4[2]:a420) noted that lactic acidosis also occurs in acute severe asthma due to inadequate oxygen delivery to the respiratory muscles to meet an elevated oxygen demand or due to fatiguing respiratory muscles. Ganaie and Hughes reported a case of lactic acidosis caused by treatment with salbutamol. Salbutamol is the most commonly used short-acting beta-agonist. Stimulation of beta-adrenergic receptors leads to a variety of metabolic effects, including increase in glycogenolysis, gluconeogenesis, and lipolysis, thus contributing to lactic acidosis. All authors agreed that the mechanism of albuterol-caused lactic acidosis was poorly understood.

Douglas E. Masini, EdD, FCCP

Steering Committee Member

Withdrawal of OSA Screening Regulation for Commercial Motor Vehicle Operators

Compared with the general US population, the prevalence of sleep apnea (SA) is higher among commercial motor vehicle (CMV) drivers (Berger et al. J Occup Environ Med. 2012;54[8]:1017). Additionally, the risk of motor vehicle accidents is higher among individuals with SA compared with those without SA (Tregear et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5[6]:573), and treatment of SA is associated with a reduction in this risk (Mahssa et al. Sleep. 2015;38[3]341).

However, after reviewing the public input and data, the FRA and FMCSA recently announced that there was “not enough information available to support moving forward with a rulemaking action,” and, therefore, they are no longer pursuing the regulation that would require SA screening for truck drivers and train engineers (Federal Register August 2017;49 CFR 391,240,242). See CHEST’s press release at www.chestnet.org/News/Press-Releases/2017/08/American-College-of-Chest-Physicians-Responds-to-DOT-Withdrawal-of-Sleep-Apnea-Screening. The FMCSA endorses existing resources,such as the North American Fatigue Management Program (NAFMP) (www.nafmp.org), which is a web-based program designed to reduce driver fatigue and includes information on SA screening and treatment. The medical examiners, however, will have the ultimate responsibility to screen, diagnose, and treat SA based on their medical knowledge and clinical experience.

Vaishnavi Kundel, MD

NetWork Member

Steering Committee Member

Corrections to previous NetWork articles

July 2017

Clinical Research

Mohsin Ijaz’s name was misspelled.

August 2017

Transplant

The name under Shruti Gadre’s photograph is wrong. It says Dr. Ahya instead of Dr. Gadre.

The authorship of the article at the end of the article is incorrect. It says Vivek Ahya, instead of Shruti Gadre and Marie Budev.

Gender Disparities in Occupational Health

Over the past few decades, the presence of women in the workforce has changed significantly. According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics Current Population Survey, in 2015, 46.8% of the workforce included women compared with 28.6% in 1948. Along with this change, there has been an increased focus on gender disparities in occupational health.

Gender differences in occupational asthma were also seen in snow crab processing plant workers. Women were significantly more likely to have occupational asthma than men. However, they found that overall, women had a greater cumulative exposure to crab allergens, which may be a major contributor to this disparity (Howse et al. Environ Res. 2006;101[2]:163).

Although several occupational health studies are beginning to highlight gender disparities, a major confounding factor is that of occupational segregation, meaning the under-representation of one gender in some jobs and over-representation in others. Differences in jobs and tasks even within the same job title between men and women are often major contributors to gender disparities [WHO Dept of Gender, Women and Health, 2006]. Also, several studies suggest that more women should be included in toxicology and occupational cancer studies, since currently, they have included mostly men (Sorrentino et al. Ann Ist Super Sanità. 2016;52[2]:190). Perhaps future studies can improve the overall understanding of these important contributing factors to gender disparities in occupational health.

Krystal Cleven, MD

Fellow-in-Training Member

Does Beta-agonist Therapy With Albuterol Cause Lactic Acidosis?

Cohen and associates (Clin Sci Mol Med. 1977;53:405) suggested that lactic acidosis can occur in at least two different physiologic clinical presentations. Type A occurs when oxygen delivery to the tissues is compromised. Dodda and Spiro (Respir Care. 2012;57[12]:2115) indicated that type A lactic acidosis was due to hypoxemia, as seen in inadequate tissue oxygenation during an exacerbation of asthma. In severe asthma, pulsus paradoxus and air trapping (causing intrinsic positive end-expiratory pressure, or PEEP) served to decrease tissue oxygenation by decreasing cardiac output and venous return, leading to type A lactic acidosis. Bates and associates (Pediatrics. 2014;133[4]:e1087) considered the role of intrapulmonary arteriovenous anastomoses (IPAVs) when a status asthmaticus patient improved after cessation of beta-agonist therapy. Type B lactic acidosis occurs when lactate production was increased or lactate removal was decreased even when oxygen was delivered to tissue. Amaducci (http://www.emresident.org/gasping-air-albuterol-induced-lactic-acidosis/) explained how high dosages of albuterol, beyond 1 mg/kg, created an increased adrenergic state that, with reduced tissue perfusion, increased glycolysis and pyruvate production, resulting in measurable hyperlactatemia. The authors (Br J Med Pract. 2011;4[2]:a420) noted that lactic acidosis also occurs in acute severe asthma due to inadequate oxygen delivery to the respiratory muscles to meet an elevated oxygen demand or due to fatiguing respiratory muscles. Ganaie and Hughes reported a case of lactic acidosis caused by treatment with salbutamol. Salbutamol is the most commonly used short-acting beta-agonist. Stimulation of beta-adrenergic receptors leads to a variety of metabolic effects, including increase in glycogenolysis, gluconeogenesis, and lipolysis, thus contributing to lactic acidosis. All authors agreed that the mechanism of albuterol-caused lactic acidosis was poorly understood.

Douglas E. Masini, EdD, FCCP

Steering Committee Member

Withdrawal of OSA Screening Regulation for Commercial Motor Vehicle Operators

Compared with the general US population, the prevalence of sleep apnea (SA) is higher among commercial motor vehicle (CMV) drivers (Berger et al. J Occup Environ Med. 2012;54[8]:1017). Additionally, the risk of motor vehicle accidents is higher among individuals with SA compared with those without SA (Tregear et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5[6]:573), and treatment of SA is associated with a reduction in this risk (Mahssa et al. Sleep. 2015;38[3]341).

However, after reviewing the public input and data, the FRA and FMCSA recently announced that there was “not enough information available to support moving forward with a rulemaking action,” and, therefore, they are no longer pursuing the regulation that would require SA screening for truck drivers and train engineers (Federal Register August 2017;49 CFR 391,240,242). See CHEST’s press release at www.chestnet.org/News/Press-Releases/2017/08/American-College-of-Chest-Physicians-Responds-to-DOT-Withdrawal-of-Sleep-Apnea-Screening. The FMCSA endorses existing resources,such as the North American Fatigue Management Program (NAFMP) (www.nafmp.org), which is a web-based program designed to reduce driver fatigue and includes information on SA screening and treatment. The medical examiners, however, will have the ultimate responsibility to screen, diagnose, and treat SA based on their medical knowledge and clinical experience.

Vaishnavi Kundel, MD

NetWork Member

Steering Committee Member

Corrections to previous NetWork articles

July 2017

Clinical Research

Mohsin Ijaz’s name was misspelled.

August 2017

Transplant

The name under Shruti Gadre’s photograph is wrong. It says Dr. Ahya instead of Dr. Gadre.

The authorship of the article at the end of the article is incorrect. It says Vivek Ahya, instead of Shruti Gadre and Marie Budev.

This month in CHEST : Editor’s picks

Giants in Chest Medicine

Jack Hirsh, MD, FCCP.

By Dr. S. Z. Goldhaber.

Original Research

IVIg for Treatment of Severe Refractory Heparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia.

By Dr. A. Padmanabhan et al.

The Impact of Statin Drug Use on All-Cause Mortality in Patients With COPD:

A Population-Based Cohort Study.

By Dr. A. J. Raymakers et al.

Pathologic Findings and Prognosis in a Large Prospective Cohort of Chronic Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis.

By Dr. P. Wang et al.

Evidence-based Medicine

Etiologies of Chronic Cough in Pediatric Cohorts: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report.

By Dr. A. B. Chang et al, on behalf of the CHEST Expert Cough Panel.

Giants in Chest Medicine

Jack Hirsh, MD, FCCP.

By Dr. S. Z. Goldhaber.

Original Research

IVIg for Treatment of Severe Refractory Heparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia.

By Dr. A. Padmanabhan et al.

The Impact of Statin Drug Use on All-Cause Mortality in Patients With COPD:

A Population-Based Cohort Study.

By Dr. A. J. Raymakers et al.

Pathologic Findings and Prognosis in a Large Prospective Cohort of Chronic Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis.

By Dr. P. Wang et al.

Evidence-based Medicine

Etiologies of Chronic Cough in Pediatric Cohorts: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report.

By Dr. A. B. Chang et al, on behalf of the CHEST Expert Cough Panel.

Giants in Chest Medicine

Jack Hirsh, MD, FCCP.

By Dr. S. Z. Goldhaber.

Original Research

IVIg for Treatment of Severe Refractory Heparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia.

By Dr. A. Padmanabhan et al.

The Impact of Statin Drug Use on All-Cause Mortality in Patients With COPD:

A Population-Based Cohort Study.

By Dr. A. J. Raymakers et al.

Pathologic Findings and Prognosis in a Large Prospective Cohort of Chronic Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis.

By Dr. P. Wang et al.

Evidence-based Medicine

Etiologies of Chronic Cough in Pediatric Cohorts: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report.

By Dr. A. B. Chang et al, on behalf of the CHEST Expert Cough Panel.