User login

High objective response rate, OS seen with ATA129 in PTLD

SALT LAKE CITY, UTAH – An allogeneic off-the-shelf Epstein-Barr virus–targeted cytotoxic T lymphocyte–cell product known as ATA129 (tabelecleucel), is associated with a high response rate and a low rate of serious adverse events in patients with posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD), according to interim findings from an ongoing multicenter study.

The objective response rate at a median of 3.3 months among patients who were treated with ATA129 and who had sufficient follow-up to assess response was 80% in six patients treated following hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT), and 83% in six who were treated after solid organ transplant (SOT), Susan E. Prockop, MD, reported at the combined annual meetings of the Center for International Blood & Marrow Transplant Research and the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation.

Study participants included those with or without underlying immune deficiency with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)–positive PTLD, EBV-positive lymphoma, EBV-positive hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, or EBV viremia, and they had to have measurable disease. All had adequate organ function and performance status. The overall median age of the cohort was 41 years, and among the transplant recipients the median age was 24.5 years. They received a median of 5 weeks of therapy (2.1 months among post-HCT patients and 12.9 months among post-SOT patients), she said.

Patients in the trial underwent the adoptive T cell therapy with partially human leukocyte antigen (HLA)–matched ATA129 that shared at least 2 of 10 HLA alleles at high resolution, including at least 1 through which ATA129 exerted cytotoxicity, or “HLA restriction,” Dr. Prockop said, noting that the product was licensed and obtained breakthrough designation in February 2015.

The ATA129 dose was 1.6-2 million T cells/kg infused on days 1, 8, and 15 of every 35-day cycle. Those without toxicity were eligible to receive additional cycles, and patients with progressive disease after one cycle were allowed to switch to an ATA129 product with a different HLA restriction, she noted.

Treatment-emergent adverse events occurred in 21 patients, including 17 who experienced grade 3 or greater adverse events or serious adverse events. Six were treatment related; one of those was grade 3 or greater, and five were considered serious adverse events. One patient had a grade 5 treatment-emergent adverse event (disease progression); two in the post-HCT group experienced graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), including one with grade 3 skin GVHD after sun exposure, which resolved with topical therapy; and one had grade 4 GVHD of the gastrointestinal tract and liver. One patient had a tumor flare that resolved, Dr. Prockop said.

“The most common safety events were GI disorders in seven patients, infections and infestations in five patients, and general disorders and administration site conditions in four,” she said. “No events have been categorized as drug reactions.”

PTLD, an EBV-driven lymphoproliferative disorder, is a life-threatening condition typically involving aggressive, clonal, diffuse large B cell lymphomas. Survival without therapy is a median of 31 days, she explained. Patients at high risk have a mortality rate of 72%, and these included those over age 30 years, those with GVHD at the time of diagnosis, and those with extranodal disease, three or more sites of disease involved, or central nervous system disease.

Although some patients respond to single-agent rituximab (Rituxan) therapy, those with rituximab-refractory disease have a median overall survival of 16-56 days, she said.

SOT recipients who develop indolent PTLD may respond to reduction of immunosuppression. Two-year risk-based survival in these patients is 88% with zero or one risk factors, and 0% with three or more risk factors, which include older age, poor performance status at diagnosis, high lactate dehydrogenase, CNS involvement, and short time from transplant to development of PTLD.

Rituximab monotherapy response rates are 76% in those with early lesions, and 47% in those with high-grade lesions, she said.

“Two-year overall survival in this patient population is 33%, reflecting their eligibility for multiagent chemotherapy, although this approach comes with significant morbidity,” she added, noting that patients failing rituximab experience increased chemotherapy-induced treatment-related mortality, compared with other lymphoma patients.

The benefit-risk profile observed in this multicenter trial is favorable with maximum response rates being reached after two cycles of therapy, and the findings confirm those from prior single-center studies, she said, noting that based on those earlier findings in patients treated with both primary and third-party donor EBV-cytotoxic T lymphocytes, the therapy is now an established National Comprehensive Cancer Network guideline therapeutic alternative for PTLD.

“Further evaluation in rituximab-refractory PTLD is ongoing in phase 3 registration trials,” she said.

Atara Biotherapeutics sponsored the trial. Dr. Prockop reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Prockop S et al. BMT Tandem Meetings Abstract 21.

SALT LAKE CITY, UTAH – An allogeneic off-the-shelf Epstein-Barr virus–targeted cytotoxic T lymphocyte–cell product known as ATA129 (tabelecleucel), is associated with a high response rate and a low rate of serious adverse events in patients with posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD), according to interim findings from an ongoing multicenter study.

The objective response rate at a median of 3.3 months among patients who were treated with ATA129 and who had sufficient follow-up to assess response was 80% in six patients treated following hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT), and 83% in six who were treated after solid organ transplant (SOT), Susan E. Prockop, MD, reported at the combined annual meetings of the Center for International Blood & Marrow Transplant Research and the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation.

Study participants included those with or without underlying immune deficiency with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)–positive PTLD, EBV-positive lymphoma, EBV-positive hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, or EBV viremia, and they had to have measurable disease. All had adequate organ function and performance status. The overall median age of the cohort was 41 years, and among the transplant recipients the median age was 24.5 years. They received a median of 5 weeks of therapy (2.1 months among post-HCT patients and 12.9 months among post-SOT patients), she said.

Patients in the trial underwent the adoptive T cell therapy with partially human leukocyte antigen (HLA)–matched ATA129 that shared at least 2 of 10 HLA alleles at high resolution, including at least 1 through which ATA129 exerted cytotoxicity, or “HLA restriction,” Dr. Prockop said, noting that the product was licensed and obtained breakthrough designation in February 2015.

The ATA129 dose was 1.6-2 million T cells/kg infused on days 1, 8, and 15 of every 35-day cycle. Those without toxicity were eligible to receive additional cycles, and patients with progressive disease after one cycle were allowed to switch to an ATA129 product with a different HLA restriction, she noted.

Treatment-emergent adverse events occurred in 21 patients, including 17 who experienced grade 3 or greater adverse events or serious adverse events. Six were treatment related; one of those was grade 3 or greater, and five were considered serious adverse events. One patient had a grade 5 treatment-emergent adverse event (disease progression); two in the post-HCT group experienced graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), including one with grade 3 skin GVHD after sun exposure, which resolved with topical therapy; and one had grade 4 GVHD of the gastrointestinal tract and liver. One patient had a tumor flare that resolved, Dr. Prockop said.

“The most common safety events were GI disorders in seven patients, infections and infestations in five patients, and general disorders and administration site conditions in four,” she said. “No events have been categorized as drug reactions.”

PTLD, an EBV-driven lymphoproliferative disorder, is a life-threatening condition typically involving aggressive, clonal, diffuse large B cell lymphomas. Survival without therapy is a median of 31 days, she explained. Patients at high risk have a mortality rate of 72%, and these included those over age 30 years, those with GVHD at the time of diagnosis, and those with extranodal disease, three or more sites of disease involved, or central nervous system disease.

Although some patients respond to single-agent rituximab (Rituxan) therapy, those with rituximab-refractory disease have a median overall survival of 16-56 days, she said.

SOT recipients who develop indolent PTLD may respond to reduction of immunosuppression. Two-year risk-based survival in these patients is 88% with zero or one risk factors, and 0% with three or more risk factors, which include older age, poor performance status at diagnosis, high lactate dehydrogenase, CNS involvement, and short time from transplant to development of PTLD.

Rituximab monotherapy response rates are 76% in those with early lesions, and 47% in those with high-grade lesions, she said.

“Two-year overall survival in this patient population is 33%, reflecting their eligibility for multiagent chemotherapy, although this approach comes with significant morbidity,” she added, noting that patients failing rituximab experience increased chemotherapy-induced treatment-related mortality, compared with other lymphoma patients.

The benefit-risk profile observed in this multicenter trial is favorable with maximum response rates being reached after two cycles of therapy, and the findings confirm those from prior single-center studies, she said, noting that based on those earlier findings in patients treated with both primary and third-party donor EBV-cytotoxic T lymphocytes, the therapy is now an established National Comprehensive Cancer Network guideline therapeutic alternative for PTLD.

“Further evaluation in rituximab-refractory PTLD is ongoing in phase 3 registration trials,” she said.

Atara Biotherapeutics sponsored the trial. Dr. Prockop reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Prockop S et al. BMT Tandem Meetings Abstract 21.

SALT LAKE CITY, UTAH – An allogeneic off-the-shelf Epstein-Barr virus–targeted cytotoxic T lymphocyte–cell product known as ATA129 (tabelecleucel), is associated with a high response rate and a low rate of serious adverse events in patients with posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD), according to interim findings from an ongoing multicenter study.

The objective response rate at a median of 3.3 months among patients who were treated with ATA129 and who had sufficient follow-up to assess response was 80% in six patients treated following hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT), and 83% in six who were treated after solid organ transplant (SOT), Susan E. Prockop, MD, reported at the combined annual meetings of the Center for International Blood & Marrow Transplant Research and the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation.

Study participants included those with or without underlying immune deficiency with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)–positive PTLD, EBV-positive lymphoma, EBV-positive hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, or EBV viremia, and they had to have measurable disease. All had adequate organ function and performance status. The overall median age of the cohort was 41 years, and among the transplant recipients the median age was 24.5 years. They received a median of 5 weeks of therapy (2.1 months among post-HCT patients and 12.9 months among post-SOT patients), she said.

Patients in the trial underwent the adoptive T cell therapy with partially human leukocyte antigen (HLA)–matched ATA129 that shared at least 2 of 10 HLA alleles at high resolution, including at least 1 through which ATA129 exerted cytotoxicity, or “HLA restriction,” Dr. Prockop said, noting that the product was licensed and obtained breakthrough designation in February 2015.

The ATA129 dose was 1.6-2 million T cells/kg infused on days 1, 8, and 15 of every 35-day cycle. Those without toxicity were eligible to receive additional cycles, and patients with progressive disease after one cycle were allowed to switch to an ATA129 product with a different HLA restriction, she noted.

Treatment-emergent adverse events occurred in 21 patients, including 17 who experienced grade 3 or greater adverse events or serious adverse events. Six were treatment related; one of those was grade 3 or greater, and five were considered serious adverse events. One patient had a grade 5 treatment-emergent adverse event (disease progression); two in the post-HCT group experienced graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), including one with grade 3 skin GVHD after sun exposure, which resolved with topical therapy; and one had grade 4 GVHD of the gastrointestinal tract and liver. One patient had a tumor flare that resolved, Dr. Prockop said.

“The most common safety events were GI disorders in seven patients, infections and infestations in five patients, and general disorders and administration site conditions in four,” she said. “No events have been categorized as drug reactions.”

PTLD, an EBV-driven lymphoproliferative disorder, is a life-threatening condition typically involving aggressive, clonal, diffuse large B cell lymphomas. Survival without therapy is a median of 31 days, she explained. Patients at high risk have a mortality rate of 72%, and these included those over age 30 years, those with GVHD at the time of diagnosis, and those with extranodal disease, three or more sites of disease involved, or central nervous system disease.

Although some patients respond to single-agent rituximab (Rituxan) therapy, those with rituximab-refractory disease have a median overall survival of 16-56 days, she said.

SOT recipients who develop indolent PTLD may respond to reduction of immunosuppression. Two-year risk-based survival in these patients is 88% with zero or one risk factors, and 0% with three or more risk factors, which include older age, poor performance status at diagnosis, high lactate dehydrogenase, CNS involvement, and short time from transplant to development of PTLD.

Rituximab monotherapy response rates are 76% in those with early lesions, and 47% in those with high-grade lesions, she said.

“Two-year overall survival in this patient population is 33%, reflecting their eligibility for multiagent chemotherapy, although this approach comes with significant morbidity,” she added, noting that patients failing rituximab experience increased chemotherapy-induced treatment-related mortality, compared with other lymphoma patients.

The benefit-risk profile observed in this multicenter trial is favorable with maximum response rates being reached after two cycles of therapy, and the findings confirm those from prior single-center studies, she said, noting that based on those earlier findings in patients treated with both primary and third-party donor EBV-cytotoxic T lymphocytes, the therapy is now an established National Comprehensive Cancer Network guideline therapeutic alternative for PTLD.

“Further evaluation in rituximab-refractory PTLD is ongoing in phase 3 registration trials,” she said.

Atara Biotherapeutics sponsored the trial. Dr. Prockop reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Prockop S et al. BMT Tandem Meetings Abstract 21.

REPORTING FROM THE 2018 BMT TANDEM MEETINGS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Overall 1-year survival was 90.3%.

Study details: Interim results in 23 patients from a multicenter study.

Disclosures: Atara Biotherapeutics sponsored the trial. Dr. Prockop reported having no disclosures.

Source: Prockop S et al. BMT Tandem Meetings Abstract 21.

Dual kinase inhibitor performs well in its first safety, efficacy study for atopic dermatitis

SAN DIEGO – A novel molecule that inhibits two major inflammatory pathways acquitted itself well in its first safety and efficacy clinical trial in patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis.

After 29 days, 100% of those taking the highest dose of the molecule, ASN002, achieved a 50% improvement in skin involvement.

“This is an interesting molecule,” Robert Bissonnette, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology. “By targeting the entire JAK family, it inhibits cytokine signaling through IL-4 [interleukin-4], IL-13, IL-23, and thymic stromal lymphopoietin,” which plays a role in maturing T cells. The SYK inhibition targets IL-17, increases the terminal differentiation of keratinocytes, and inhibits B-cell signaling.

Dr. Bissonnette, president of Innovaderm Research presented the results in a late-breaking session at the meeting. Innovaderm designs, conducts, and analyzes dermatology clinical trials, and ran the study for Asana BioSciences.

In an Asana press release about the study results, CEO Sandeep Gupta, PhD, said that ASN002 “is the only oral compound in clinical development targeting JAK [including Tyk2] and SYK signaling, two clinically validated mechanisms.” He added that inhibition of JAK and SYK pathways “diminishes cytokine production and signaling including those mediated by Th2 and Th22 cytokines. Dysregulation of Th2 and Th22 cytokine pathways is implicated in the pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis.”

Safety was the primary endpoint in the phase 1b dose-ranging trial, but there were also several efficacy endpoints, Dr. Bissonnette said at the meeting. The study comprised 36 patients separated into three 12-patient groups. In each group, nine received the active drug every day, and three received a placebo. The first group received 20 mg ASN002 or placebo for 28 days, followed by the 14-day safety period. The next group received 40 mg ASN002 or placebo for 28 days, followed by the safety analysis. The third group followed the same treatment pattern, but received 80 mg of the drug.

All patients were aged 29-42 years. The Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) was imbalanced among the groups, ranging from 21 in the placebo group and 40-mg group, to 29 in the 20-mg and 80-mg groups. The Body Surface Area (BSA) index also differed between groups: 25% among the placebo patients, 45% in the 20-mg group, 32% in the 40-mg group, and 29% in the 80-mg group. The average Investigator Global Assessment (IGA) score was 3.

A pharmacokinetic analysis showed rapid uptake of the drug with a half-life of 10-14 hours depending on dose.

There were no concerning safety signals, Dr. Bissonnette said and no thromboembolic events, serious infections, or opportunistic infections. The most common adverse event was headache, which occurred at equal rates among the groups. The single serious adverse event was anxiety, which occurred in one patient taking 80 mg ASN002, 4 days after the medication was stopped, and was judged unrelated to ASN002.

There were no significant changes in any lab parameters, no changes in lipid profiles, and no hematologic abnormalities. One patient experienced an increase in creatinine phosphokinase, something that has been seen in other studies of JAK inhibitors, Dr. Bissonnette said.

The molecule performed well on secondary efficacy endpoints. By day 15, 63% of the 40-mg group and 75% of the 80-mg group had achieved EASI-50, and by day 29, these rates were 88% and 100%, respectively. These doses also performed well on the EASI-75 endpoint. By day 29, 63% of the 40-mg group and 50% of the 80-mg group had achieved a 75% improvement in EASI score.

The 40- and 80-mg groups also did well with regards to BSA improvement. By day 29, the 80-mg group had achieved a mean BSA reduction of 58%, and the 40-mg group a mean reduction of 64%. IGA tracked that improvement, with 25% of the 80-mg group and 38% of the 40-mg group achieving an IGA score of 1 or 0.

Itching responded well to ASN002, but here, the 20-mg dose threw investigators a bit of a curve ball. Pruritus decreased most in the 80-mg group (about 70% by the end of the study). But at 3 weeks, patients taking 20 mg and 40 mg were experiencing the same 30% decrease in itch. By 4 weeks, however, the scores had separated, with the 40-mg group landing at about a 40% reduction, and the 20-mg group rebounding to about a 20% reduction.

“I would say that this first trial of ASN002 showed clear efficacy in patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis, with rapid improvement itch and a large proportion of patients reaching EASI-50 as early as 2 weeks,” Dr. Bissonnette said.

Asana will soon initiate a phase 2b study of ASN002 in moderate to severe atopic dermatitis patients. Clinical studies in other dermatologic and autoimmune indications are under consideration, according to the company website.

Dr. Bissonnette is the president of Innovaderm Research, which was paid to run the ASN002 study.

SOURCE: Bissonnette R et al. AAD 2018, Abstract 6777

SAN DIEGO – A novel molecule that inhibits two major inflammatory pathways acquitted itself well in its first safety and efficacy clinical trial in patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis.

After 29 days, 100% of those taking the highest dose of the molecule, ASN002, achieved a 50% improvement in skin involvement.

“This is an interesting molecule,” Robert Bissonnette, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology. “By targeting the entire JAK family, it inhibits cytokine signaling through IL-4 [interleukin-4], IL-13, IL-23, and thymic stromal lymphopoietin,” which plays a role in maturing T cells. The SYK inhibition targets IL-17, increases the terminal differentiation of keratinocytes, and inhibits B-cell signaling.

Dr. Bissonnette, president of Innovaderm Research presented the results in a late-breaking session at the meeting. Innovaderm designs, conducts, and analyzes dermatology clinical trials, and ran the study for Asana BioSciences.

In an Asana press release about the study results, CEO Sandeep Gupta, PhD, said that ASN002 “is the only oral compound in clinical development targeting JAK [including Tyk2] and SYK signaling, two clinically validated mechanisms.” He added that inhibition of JAK and SYK pathways “diminishes cytokine production and signaling including those mediated by Th2 and Th22 cytokines. Dysregulation of Th2 and Th22 cytokine pathways is implicated in the pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis.”

Safety was the primary endpoint in the phase 1b dose-ranging trial, but there were also several efficacy endpoints, Dr. Bissonnette said at the meeting. The study comprised 36 patients separated into three 12-patient groups. In each group, nine received the active drug every day, and three received a placebo. The first group received 20 mg ASN002 or placebo for 28 days, followed by the 14-day safety period. The next group received 40 mg ASN002 or placebo for 28 days, followed by the safety analysis. The third group followed the same treatment pattern, but received 80 mg of the drug.

All patients were aged 29-42 years. The Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) was imbalanced among the groups, ranging from 21 in the placebo group and 40-mg group, to 29 in the 20-mg and 80-mg groups. The Body Surface Area (BSA) index also differed between groups: 25% among the placebo patients, 45% in the 20-mg group, 32% in the 40-mg group, and 29% in the 80-mg group. The average Investigator Global Assessment (IGA) score was 3.

A pharmacokinetic analysis showed rapid uptake of the drug with a half-life of 10-14 hours depending on dose.

There were no concerning safety signals, Dr. Bissonnette said and no thromboembolic events, serious infections, or opportunistic infections. The most common adverse event was headache, which occurred at equal rates among the groups. The single serious adverse event was anxiety, which occurred in one patient taking 80 mg ASN002, 4 days after the medication was stopped, and was judged unrelated to ASN002.

There were no significant changes in any lab parameters, no changes in lipid profiles, and no hematologic abnormalities. One patient experienced an increase in creatinine phosphokinase, something that has been seen in other studies of JAK inhibitors, Dr. Bissonnette said.

The molecule performed well on secondary efficacy endpoints. By day 15, 63% of the 40-mg group and 75% of the 80-mg group had achieved EASI-50, and by day 29, these rates were 88% and 100%, respectively. These doses also performed well on the EASI-75 endpoint. By day 29, 63% of the 40-mg group and 50% of the 80-mg group had achieved a 75% improvement in EASI score.

The 40- and 80-mg groups also did well with regards to BSA improvement. By day 29, the 80-mg group had achieved a mean BSA reduction of 58%, and the 40-mg group a mean reduction of 64%. IGA tracked that improvement, with 25% of the 80-mg group and 38% of the 40-mg group achieving an IGA score of 1 or 0.

Itching responded well to ASN002, but here, the 20-mg dose threw investigators a bit of a curve ball. Pruritus decreased most in the 80-mg group (about 70% by the end of the study). But at 3 weeks, patients taking 20 mg and 40 mg were experiencing the same 30% decrease in itch. By 4 weeks, however, the scores had separated, with the 40-mg group landing at about a 40% reduction, and the 20-mg group rebounding to about a 20% reduction.

“I would say that this first trial of ASN002 showed clear efficacy in patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis, with rapid improvement itch and a large proportion of patients reaching EASI-50 as early as 2 weeks,” Dr. Bissonnette said.

Asana will soon initiate a phase 2b study of ASN002 in moderate to severe atopic dermatitis patients. Clinical studies in other dermatologic and autoimmune indications are under consideration, according to the company website.

Dr. Bissonnette is the president of Innovaderm Research, which was paid to run the ASN002 study.

SOURCE: Bissonnette R et al. AAD 2018, Abstract 6777

SAN DIEGO – A novel molecule that inhibits two major inflammatory pathways acquitted itself well in its first safety and efficacy clinical trial in patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis.

After 29 days, 100% of those taking the highest dose of the molecule, ASN002, achieved a 50% improvement in skin involvement.

“This is an interesting molecule,” Robert Bissonnette, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology. “By targeting the entire JAK family, it inhibits cytokine signaling through IL-4 [interleukin-4], IL-13, IL-23, and thymic stromal lymphopoietin,” which plays a role in maturing T cells. The SYK inhibition targets IL-17, increases the terminal differentiation of keratinocytes, and inhibits B-cell signaling.

Dr. Bissonnette, president of Innovaderm Research presented the results in a late-breaking session at the meeting. Innovaderm designs, conducts, and analyzes dermatology clinical trials, and ran the study for Asana BioSciences.

In an Asana press release about the study results, CEO Sandeep Gupta, PhD, said that ASN002 “is the only oral compound in clinical development targeting JAK [including Tyk2] and SYK signaling, two clinically validated mechanisms.” He added that inhibition of JAK and SYK pathways “diminishes cytokine production and signaling including those mediated by Th2 and Th22 cytokines. Dysregulation of Th2 and Th22 cytokine pathways is implicated in the pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis.”

Safety was the primary endpoint in the phase 1b dose-ranging trial, but there were also several efficacy endpoints, Dr. Bissonnette said at the meeting. The study comprised 36 patients separated into three 12-patient groups. In each group, nine received the active drug every day, and three received a placebo. The first group received 20 mg ASN002 or placebo for 28 days, followed by the 14-day safety period. The next group received 40 mg ASN002 or placebo for 28 days, followed by the safety analysis. The third group followed the same treatment pattern, but received 80 mg of the drug.

All patients were aged 29-42 years. The Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) was imbalanced among the groups, ranging from 21 in the placebo group and 40-mg group, to 29 in the 20-mg and 80-mg groups. The Body Surface Area (BSA) index also differed between groups: 25% among the placebo patients, 45% in the 20-mg group, 32% in the 40-mg group, and 29% in the 80-mg group. The average Investigator Global Assessment (IGA) score was 3.

A pharmacokinetic analysis showed rapid uptake of the drug with a half-life of 10-14 hours depending on dose.

There were no concerning safety signals, Dr. Bissonnette said and no thromboembolic events, serious infections, or opportunistic infections. The most common adverse event was headache, which occurred at equal rates among the groups. The single serious adverse event was anxiety, which occurred in one patient taking 80 mg ASN002, 4 days after the medication was stopped, and was judged unrelated to ASN002.

There were no significant changes in any lab parameters, no changes in lipid profiles, and no hematologic abnormalities. One patient experienced an increase in creatinine phosphokinase, something that has been seen in other studies of JAK inhibitors, Dr. Bissonnette said.

The molecule performed well on secondary efficacy endpoints. By day 15, 63% of the 40-mg group and 75% of the 80-mg group had achieved EASI-50, and by day 29, these rates were 88% and 100%, respectively. These doses also performed well on the EASI-75 endpoint. By day 29, 63% of the 40-mg group and 50% of the 80-mg group had achieved a 75% improvement in EASI score.

The 40- and 80-mg groups also did well with regards to BSA improvement. By day 29, the 80-mg group had achieved a mean BSA reduction of 58%, and the 40-mg group a mean reduction of 64%. IGA tracked that improvement, with 25% of the 80-mg group and 38% of the 40-mg group achieving an IGA score of 1 or 0.

Itching responded well to ASN002, but here, the 20-mg dose threw investigators a bit of a curve ball. Pruritus decreased most in the 80-mg group (about 70% by the end of the study). But at 3 weeks, patients taking 20 mg and 40 mg were experiencing the same 30% decrease in itch. By 4 weeks, however, the scores had separated, with the 40-mg group landing at about a 40% reduction, and the 20-mg group rebounding to about a 20% reduction.

“I would say that this first trial of ASN002 showed clear efficacy in patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis, with rapid improvement itch and a large proportion of patients reaching EASI-50 as early as 2 weeks,” Dr. Bissonnette said.

Asana will soon initiate a phase 2b study of ASN002 in moderate to severe atopic dermatitis patients. Clinical studies in other dermatologic and autoimmune indications are under consideration, according to the company website.

Dr. Bissonnette is the president of Innovaderm Research, which was paid to run the ASN002 study.

SOURCE: Bissonnette R et al. AAD 2018, Abstract 6777

REPORTING FROM AAD 2018

Key clinical point: ASN002 calmed itch, improved skin involvement in moderate to severe atopic dermatitis.

Major finding: After 29 days, 100% of those taking 80-mg doses of ASN002 daily achieved a 50% improvement in EASI.

Study details: The randomized dose-escalation phase 1b study comprised 36 patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis.

Disclosures: Asana BioSciences sponsored the study. Dr. Bissonnette is CEO of Innovaderm Research, Montreal, which conducted the trial.

Source: Bissonnette R et al. AAD 2018, Abstract 6777.

Perfusion-only scan rules out PE in pregnancy

For pregnant women with suspected pulmonary embolism (PE), (CTPA), according to authors of a recent retrospective study.

Pulmonary embolism causes 9% of maternal deaths in the United States, according to the authors of the study, which was published online in the journal CHEST®. While it’s clear that perfusion scans yield lower radiation exposure than CTPA, to date, there has only been limited study of its diagnostic performance in women with suspected PE.

The low-dose perfusion scan offered comparable diagnostic efficacy while potentially limiting radiation exposure, according to the single-center cohort study.

The retrospective study included pregnant women (mean age, 27.3 years) who underwent imaging for pulmonary embolism at Montefiore Medical Center, New York, between 2008 and 2013. A total of 225 women underwent perfusion-only scans, while 97 underwent CTPA.

Chest pain and dyspnea were the most common symptoms for patients in both groups: 136 of the patients (60.4%) in the low-dose perfusion group reported chest pain versus 40 patients (41.2%) in the CTPA group. About half of the patients in both groups had dyspnea.

Tachycardia was found in 43 of patients (44.3%) who underwent CTPA, compared with 77 of patients (34.2% ) who underwent the diagnostic test involving less radiation exposure.

Imaging was negative for PE in 198 of the patients (88.0%) who were scanned with low-dose perfusion, while 84 of patients (86.6%) who had CTPAs were negative for PE. For both groups of patients, the percentage who had indeterminate imaging was 9.3%. Only one study participant had a deep vein thrombosis at the time she presented with PE symptoms.

The primary end point of the study, negative predictive value, was 100% for the perfusion-only group and 97.5% for CTPA, according to the report. It was determined by a diagnosis of venous thromboembolism within 90 days of evaluation.

Those “indistinguishable” negative predictive values suggest that low-dose perfusion scintigraphy performs comparably to CTPA, making it an appropriate first diagnostic modality for pregnant women who are suspected of having pulmonary embolism, Dr. Sheen and her colleagues wrote.

The negative predictive value was a particularly important endpoint to evaluate because pulmonary embolism is rare among pregnant women and most perfusion-only imaging is negative, the authors stated.

Of the women in the study, 252 (89%) of those who tested negative for PE – either by a low-dose perfusion scan or a CTPA – returned to the medical center for follow-up 90 days later. Thromboembolic events occurred in two of the women who previously had a negative CTPA, but none occurred in patients who had been tested for PE with low-dose perfusion scan. The two thromboembolic events were detected in women who were no longer pregnant.

Ten patients in the study (3.1%) were treated for pulmonary embolism, the authors reported. The PE diagnoses were based on four positive low-dose perfusion scans and six positive CTPAs “in conjunction with clinical suspicion.” These patients’ most common symptoms were chest pain and dyspnea, and one of these patients had recently been diagnosed with a deep vein thrombosis.

When perfusion defects are found, they should be interpreted cautiously, particularly in asthmatic patients, according to authors: “Segmental perfusion defects secondary to abnormal ventilation cannot be distinguished from PE without a ventilation scan,”they noted.

Three of the patients diagnosed with a PE had asthma. In a subanalysis of the 77 patients with asthma who participated in this study, the negative predictive values were 100% for both those who received a low-dose perfusion scan and those who received a CTPA. For patients in this subgroup, the negative rates of PE from low-dose perfusion scan and CTPA were 74.1% and 87.1%, respectively.

“Maternal-fetal radiation exposure should be of utmost importance when considering the choice of diagnostic test,” the authors wrote. “When available, [a low-dose perfusion scan] is a reasonable first choice modality for suspected pulmonary embolism in pregnant women with a negative chest radiograph.”

One study coauthor is on an advisory panel for Jubilant DraxImage, and another has a spouse who is a board member of Kyron Pharma Consulting. The remaining authors, including Dr. Sheen,reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Sheen JJ et al. Chest. 2018 Feb. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.08.005.

Nirmal Sharma, MD, comments: During pregnancy, all radiation is bad radiation, but when it was really needed, we did use this low-radiation perfusion scan quite a bit at my past institution. This article definitely shines light on the utility/validity of this technique because most centers still use a computed tomographic pulmonary angiography study in pregnant females (with shielding methods) if suspicion of pulmonary embolism is high. The downside to low-dose perfusion scintigraphy is that it cannot be used in patients with grossly abnormal chest x-rays.

Nirmal Sharma, MD, comments: During pregnancy, all radiation is bad radiation, but when it was really needed, we did use this low-radiation perfusion scan quite a bit at my past institution. This article definitely shines light on the utility/validity of this technique because most centers still use a computed tomographic pulmonary angiography study in pregnant females (with shielding methods) if suspicion of pulmonary embolism is high. The downside to low-dose perfusion scintigraphy is that it cannot be used in patients with grossly abnormal chest x-rays.

Nirmal Sharma, MD, comments: During pregnancy, all radiation is bad radiation, but when it was really needed, we did use this low-radiation perfusion scan quite a bit at my past institution. This article definitely shines light on the utility/validity of this technique because most centers still use a computed tomographic pulmonary angiography study in pregnant females (with shielding methods) if suspicion of pulmonary embolism is high. The downside to low-dose perfusion scintigraphy is that it cannot be used in patients with grossly abnormal chest x-rays.

For pregnant women with suspected pulmonary embolism (PE), (CTPA), according to authors of a recent retrospective study.

Pulmonary embolism causes 9% of maternal deaths in the United States, according to the authors of the study, which was published online in the journal CHEST®. While it’s clear that perfusion scans yield lower radiation exposure than CTPA, to date, there has only been limited study of its diagnostic performance in women with suspected PE.

The low-dose perfusion scan offered comparable diagnostic efficacy while potentially limiting radiation exposure, according to the single-center cohort study.

The retrospective study included pregnant women (mean age, 27.3 years) who underwent imaging for pulmonary embolism at Montefiore Medical Center, New York, between 2008 and 2013. A total of 225 women underwent perfusion-only scans, while 97 underwent CTPA.

Chest pain and dyspnea were the most common symptoms for patients in both groups: 136 of the patients (60.4%) in the low-dose perfusion group reported chest pain versus 40 patients (41.2%) in the CTPA group. About half of the patients in both groups had dyspnea.

Tachycardia was found in 43 of patients (44.3%) who underwent CTPA, compared with 77 of patients (34.2% ) who underwent the diagnostic test involving less radiation exposure.

Imaging was negative for PE in 198 of the patients (88.0%) who were scanned with low-dose perfusion, while 84 of patients (86.6%) who had CTPAs were negative for PE. For both groups of patients, the percentage who had indeterminate imaging was 9.3%. Only one study participant had a deep vein thrombosis at the time she presented with PE symptoms.

The primary end point of the study, negative predictive value, was 100% for the perfusion-only group and 97.5% for CTPA, according to the report. It was determined by a diagnosis of venous thromboembolism within 90 days of evaluation.

Those “indistinguishable” negative predictive values suggest that low-dose perfusion scintigraphy performs comparably to CTPA, making it an appropriate first diagnostic modality for pregnant women who are suspected of having pulmonary embolism, Dr. Sheen and her colleagues wrote.

The negative predictive value was a particularly important endpoint to evaluate because pulmonary embolism is rare among pregnant women and most perfusion-only imaging is negative, the authors stated.

Of the women in the study, 252 (89%) of those who tested negative for PE – either by a low-dose perfusion scan or a CTPA – returned to the medical center for follow-up 90 days later. Thromboembolic events occurred in two of the women who previously had a negative CTPA, but none occurred in patients who had been tested for PE with low-dose perfusion scan. The two thromboembolic events were detected in women who were no longer pregnant.

Ten patients in the study (3.1%) were treated for pulmonary embolism, the authors reported. The PE diagnoses were based on four positive low-dose perfusion scans and six positive CTPAs “in conjunction with clinical suspicion.” These patients’ most common symptoms were chest pain and dyspnea, and one of these patients had recently been diagnosed with a deep vein thrombosis.

When perfusion defects are found, they should be interpreted cautiously, particularly in asthmatic patients, according to authors: “Segmental perfusion defects secondary to abnormal ventilation cannot be distinguished from PE without a ventilation scan,”they noted.

Three of the patients diagnosed with a PE had asthma. In a subanalysis of the 77 patients with asthma who participated in this study, the negative predictive values were 100% for both those who received a low-dose perfusion scan and those who received a CTPA. For patients in this subgroup, the negative rates of PE from low-dose perfusion scan and CTPA were 74.1% and 87.1%, respectively.

“Maternal-fetal radiation exposure should be of utmost importance when considering the choice of diagnostic test,” the authors wrote. “When available, [a low-dose perfusion scan] is a reasonable first choice modality for suspected pulmonary embolism in pregnant women with a negative chest radiograph.”

One study coauthor is on an advisory panel for Jubilant DraxImage, and another has a spouse who is a board member of Kyron Pharma Consulting. The remaining authors, including Dr. Sheen,reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Sheen JJ et al. Chest. 2018 Feb. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.08.005.

For pregnant women with suspected pulmonary embolism (PE), (CTPA), according to authors of a recent retrospective study.

Pulmonary embolism causes 9% of maternal deaths in the United States, according to the authors of the study, which was published online in the journal CHEST®. While it’s clear that perfusion scans yield lower radiation exposure than CTPA, to date, there has only been limited study of its diagnostic performance in women with suspected PE.

The low-dose perfusion scan offered comparable diagnostic efficacy while potentially limiting radiation exposure, according to the single-center cohort study.

The retrospective study included pregnant women (mean age, 27.3 years) who underwent imaging for pulmonary embolism at Montefiore Medical Center, New York, between 2008 and 2013. A total of 225 women underwent perfusion-only scans, while 97 underwent CTPA.

Chest pain and dyspnea were the most common symptoms for patients in both groups: 136 of the patients (60.4%) in the low-dose perfusion group reported chest pain versus 40 patients (41.2%) in the CTPA group. About half of the patients in both groups had dyspnea.

Tachycardia was found in 43 of patients (44.3%) who underwent CTPA, compared with 77 of patients (34.2% ) who underwent the diagnostic test involving less radiation exposure.

Imaging was negative for PE in 198 of the patients (88.0%) who were scanned with low-dose perfusion, while 84 of patients (86.6%) who had CTPAs were negative for PE. For both groups of patients, the percentage who had indeterminate imaging was 9.3%. Only one study participant had a deep vein thrombosis at the time she presented with PE symptoms.

The primary end point of the study, negative predictive value, was 100% for the perfusion-only group and 97.5% for CTPA, according to the report. It was determined by a diagnosis of venous thromboembolism within 90 days of evaluation.

Those “indistinguishable” negative predictive values suggest that low-dose perfusion scintigraphy performs comparably to CTPA, making it an appropriate first diagnostic modality for pregnant women who are suspected of having pulmonary embolism, Dr. Sheen and her colleagues wrote.

The negative predictive value was a particularly important endpoint to evaluate because pulmonary embolism is rare among pregnant women and most perfusion-only imaging is negative, the authors stated.

Of the women in the study, 252 (89%) of those who tested negative for PE – either by a low-dose perfusion scan or a CTPA – returned to the medical center for follow-up 90 days later. Thromboembolic events occurred in two of the women who previously had a negative CTPA, but none occurred in patients who had been tested for PE with low-dose perfusion scan. The two thromboembolic events were detected in women who were no longer pregnant.

Ten patients in the study (3.1%) were treated for pulmonary embolism, the authors reported. The PE diagnoses were based on four positive low-dose perfusion scans and six positive CTPAs “in conjunction with clinical suspicion.” These patients’ most common symptoms were chest pain and dyspnea, and one of these patients had recently been diagnosed with a deep vein thrombosis.

When perfusion defects are found, they should be interpreted cautiously, particularly in asthmatic patients, according to authors: “Segmental perfusion defects secondary to abnormal ventilation cannot be distinguished from PE without a ventilation scan,”they noted.

Three of the patients diagnosed with a PE had asthma. In a subanalysis of the 77 patients with asthma who participated in this study, the negative predictive values were 100% for both those who received a low-dose perfusion scan and those who received a CTPA. For patients in this subgroup, the negative rates of PE from low-dose perfusion scan and CTPA were 74.1% and 87.1%, respectively.

“Maternal-fetal radiation exposure should be of utmost importance when considering the choice of diagnostic test,” the authors wrote. “When available, [a low-dose perfusion scan] is a reasonable first choice modality for suspected pulmonary embolism in pregnant women with a negative chest radiograph.”

One study coauthor is on an advisory panel for Jubilant DraxImage, and another has a spouse who is a board member of Kyron Pharma Consulting. The remaining authors, including Dr. Sheen,reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Sheen JJ et al. Chest. 2018 Feb. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.08.005.

FROM CHEST®

Key clinical point: In the evaluation of pregnant women with suspected pulmonary embolism, low-dose perfusion scintigraphy may offer diagnostic performance that’s comparable to CTPA.

Major finding: The negative predictive value of a pulmonary embolism was 100% for the low dose perfusion scan, compared with 97.5% for CTPA.

Study details: A retrospective, single-center cohort study including 322 pregnant women who underwent imaging studies for suspected pulmonary embolism.

Disclosures: One study coauthor is on an advisory panel for Jubilant DraxImage, and another has a spouse who is a board member of Kyron Pharma Consulting. The remaining authors, including Dr. Sheen,reported no conflicts of interest.

Source: Sheen JJ et al. Chest. 2018 Feb. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.08.005.

Tryptophan depletion may explain high rate of eating disorders in women

TAMPA, FLA. – The far higher rate of eating disorders in women than men appears to be explained at least in part by a greater acute depletion of tryptophan, which is essential for the formation of serotonin, a key mediator of risk, according to a research review presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Psychiatrists.

“The specific vulnerability of women to eating disorders relates to the fact that women’s brains are much more sensitive to dietary intake of tryptophan than are men’s brains,” explained Allan S. Kaplan, MD, senior scientist at the Center for Addiction and Mental Health at the University of Toronto.

“Women are more likely than men to be dieting,” said Dr. Kaplan, walking through the evidence. “Low-calorie diets tend to be high in protein and low in cholesterol and fat. Such diets lead to tryptophan depletion and decreased serotonin synthesis in the brain. Because of lower levels of central serotonin, women are more vulnerable to mood and eating disorders than men.”

Not all women who diet may be vulnerable to this sequence of events. Genetics are likely to be a factor, according to Dr. Kaplan, who said, “Genes load the gun; the environment pulls the trigger.”

However, women do appear to be more susceptible for a number of reasons. For one, the mean rate of serotonin synthesis is 52% higher in normal males than normal females, giving them a greater buffer when dietary intake of tryptophan is low. For another, there is evidence that intake of nutrients most rich in tryptophan, particularly proteins, is typically lower in women than men.

The ratio of females to males for both anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa is about 10:1. Although the female-to-male ratio of binge eating is lower at 2:1, women dominate these psychiatric diagnoses. Several environmental factors associated with eating disorders are more closely associated with women than men, including a history of sexual or physical abuse and female preoccupation with body image, but acute tryptophan depletion may be an important factor participating in the translation of risk to an active disease, according to Dr. Kaplan.

Acute tryptophan deficiency may also explain why treatment of eating disorders with SSRIs has been disappointing. With low levels of tryptophan leading to serotonin depletion, “there is no substrate” for drugs administered to increase serotonin-mediated signaling, Dr. Kaplan explained.

Ensuring adequate dietary intake of tryptophan, which is “found mainly in high-protein animal foods,” may be important, even though Dr. Kaplan warned that achieving optimal levels of serotonin “can be challenging from food alone.” Nevertheless, behavioral therapies are commonly effective for eating disorders, presumably at least partially as a result of their ability to normalize diet.

Overall, the tryptophan hypothesis has provided a major shift in the understanding of eating disorders, according to Dr. Kaplan. Further studies are needed, but he said that the key message is that, “For women’s brains, you are what you eat.”

Dr. Kaplan reported no conflicts of interest relevant to this topic.

This story was updated on 2/25/2018.

TAMPA, FLA. – The far higher rate of eating disorders in women than men appears to be explained at least in part by a greater acute depletion of tryptophan, which is essential for the formation of serotonin, a key mediator of risk, according to a research review presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Psychiatrists.

“The specific vulnerability of women to eating disorders relates to the fact that women’s brains are much more sensitive to dietary intake of tryptophan than are men’s brains,” explained Allan S. Kaplan, MD, senior scientist at the Center for Addiction and Mental Health at the University of Toronto.

“Women are more likely than men to be dieting,” said Dr. Kaplan, walking through the evidence. “Low-calorie diets tend to be high in protein and low in cholesterol and fat. Such diets lead to tryptophan depletion and decreased serotonin synthesis in the brain. Because of lower levels of central serotonin, women are more vulnerable to mood and eating disorders than men.”

Not all women who diet may be vulnerable to this sequence of events. Genetics are likely to be a factor, according to Dr. Kaplan, who said, “Genes load the gun; the environment pulls the trigger.”

However, women do appear to be more susceptible for a number of reasons. For one, the mean rate of serotonin synthesis is 52% higher in normal males than normal females, giving them a greater buffer when dietary intake of tryptophan is low. For another, there is evidence that intake of nutrients most rich in tryptophan, particularly proteins, is typically lower in women than men.

The ratio of females to males for both anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa is about 10:1. Although the female-to-male ratio of binge eating is lower at 2:1, women dominate these psychiatric diagnoses. Several environmental factors associated with eating disorders are more closely associated with women than men, including a history of sexual or physical abuse and female preoccupation with body image, but acute tryptophan depletion may be an important factor participating in the translation of risk to an active disease, according to Dr. Kaplan.

Acute tryptophan deficiency may also explain why treatment of eating disorders with SSRIs has been disappointing. With low levels of tryptophan leading to serotonin depletion, “there is no substrate” for drugs administered to increase serotonin-mediated signaling, Dr. Kaplan explained.

Ensuring adequate dietary intake of tryptophan, which is “found mainly in high-protein animal foods,” may be important, even though Dr. Kaplan warned that achieving optimal levels of serotonin “can be challenging from food alone.” Nevertheless, behavioral therapies are commonly effective for eating disorders, presumably at least partially as a result of their ability to normalize diet.

Overall, the tryptophan hypothesis has provided a major shift in the understanding of eating disorders, according to Dr. Kaplan. Further studies are needed, but he said that the key message is that, “For women’s brains, you are what you eat.”

Dr. Kaplan reported no conflicts of interest relevant to this topic.

This story was updated on 2/25/2018.

TAMPA, FLA. – The far higher rate of eating disorders in women than men appears to be explained at least in part by a greater acute depletion of tryptophan, which is essential for the formation of serotonin, a key mediator of risk, according to a research review presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Psychiatrists.

“The specific vulnerability of women to eating disorders relates to the fact that women’s brains are much more sensitive to dietary intake of tryptophan than are men’s brains,” explained Allan S. Kaplan, MD, senior scientist at the Center for Addiction and Mental Health at the University of Toronto.

“Women are more likely than men to be dieting,” said Dr. Kaplan, walking through the evidence. “Low-calorie diets tend to be high in protein and low in cholesterol and fat. Such diets lead to tryptophan depletion and decreased serotonin synthesis in the brain. Because of lower levels of central serotonin, women are more vulnerable to mood and eating disorders than men.”

Not all women who diet may be vulnerable to this sequence of events. Genetics are likely to be a factor, according to Dr. Kaplan, who said, “Genes load the gun; the environment pulls the trigger.”

However, women do appear to be more susceptible for a number of reasons. For one, the mean rate of serotonin synthesis is 52% higher in normal males than normal females, giving them a greater buffer when dietary intake of tryptophan is low. For another, there is evidence that intake of nutrients most rich in tryptophan, particularly proteins, is typically lower in women than men.

The ratio of females to males for both anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa is about 10:1. Although the female-to-male ratio of binge eating is lower at 2:1, women dominate these psychiatric diagnoses. Several environmental factors associated with eating disorders are more closely associated with women than men, including a history of sexual or physical abuse and female preoccupation with body image, but acute tryptophan depletion may be an important factor participating in the translation of risk to an active disease, according to Dr. Kaplan.

Acute tryptophan deficiency may also explain why treatment of eating disorders with SSRIs has been disappointing. With low levels of tryptophan leading to serotonin depletion, “there is no substrate” for drugs administered to increase serotonin-mediated signaling, Dr. Kaplan explained.

Ensuring adequate dietary intake of tryptophan, which is “found mainly in high-protein animal foods,” may be important, even though Dr. Kaplan warned that achieving optimal levels of serotonin “can be challenging from food alone.” Nevertheless, behavioral therapies are commonly effective for eating disorders, presumably at least partially as a result of their ability to normalize diet.

Overall, the tryptophan hypothesis has provided a major shift in the understanding of eating disorders, according to Dr. Kaplan. Further studies are needed, but he said that the key message is that, “For women’s brains, you are what you eat.”

Dr. Kaplan reported no conflicts of interest relevant to this topic.

This story was updated on 2/25/2018.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE COLLEGE 2018

Flu season shows signs of slowing

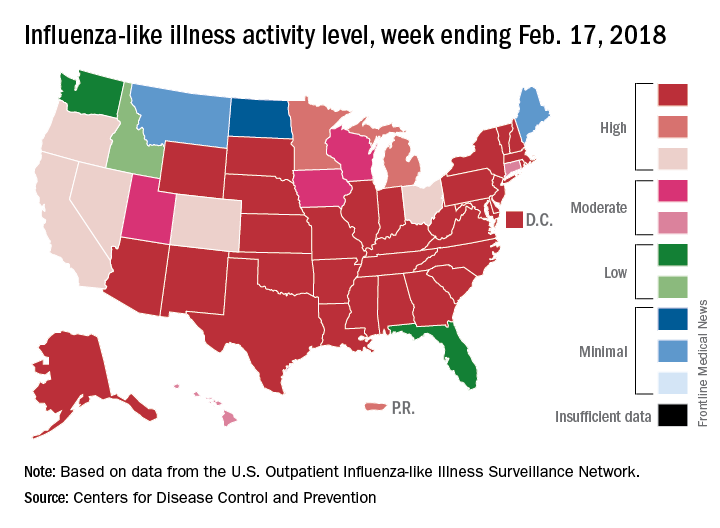

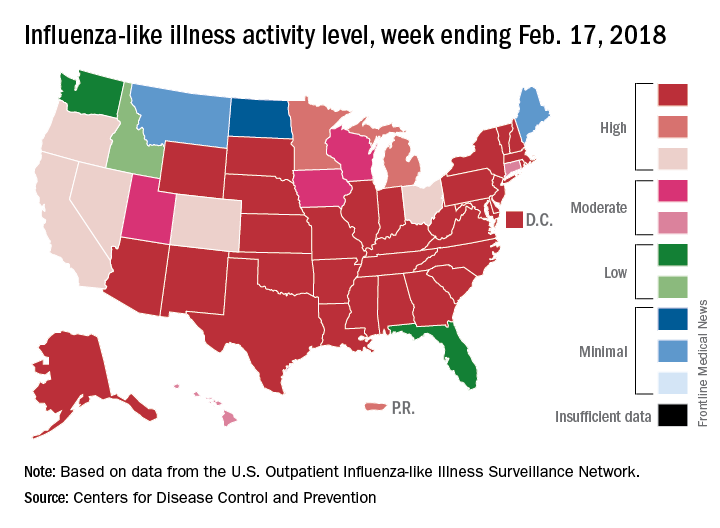

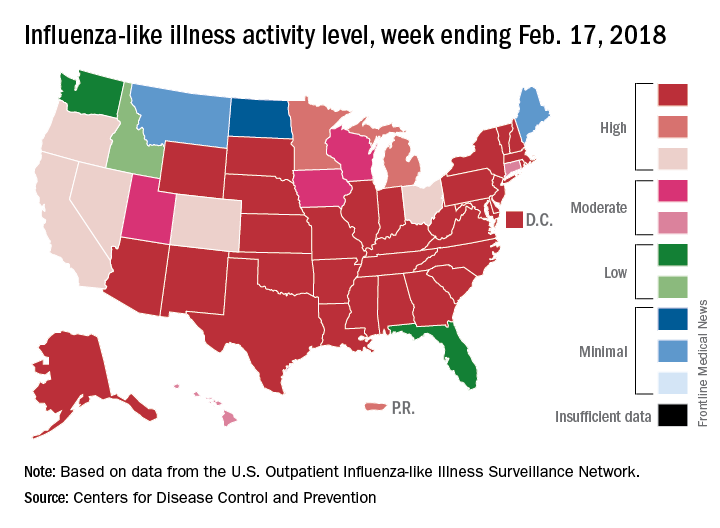

Flu-related outpatient activity dropped for the second week in a row as the cumulative hospitalization rate continues to rise, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

For the week ending Feb. 17, the proportion of outpatient visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) was 6.4%, which was down from 7.4% the previous week (Feb. 10) and down from the seasonal high of 7.5% set 2 weeks earlier, the CDC said in its weekly flu surveillance report. The rate for the week ending Feb. 10 was reported last week as 7.5%, but it has been revised downward.

State reports of ILI activity support the decreases seen in the national outpatient rate. There were 33 states at level 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale for the week ending Feb. 17 – down from 39 the week before – and a total of 41 states in the “high” range from levels 8-10, compared with 45 the previous week, CDC’s FluView website shows.

Reports of flu-related pediatric deaths continued: 13 deaths were reported during the week, although 9 occurred in previous weeks. The total for the 2017-2018 season is now 97. There were 110 pediatric deaths in the entire 2016-2017 season, 93 during the 2015-2016 season, and 149 in 2014-2015, the CDC said.

Flu-related outpatient activity dropped for the second week in a row as the cumulative hospitalization rate continues to rise, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

For the week ending Feb. 17, the proportion of outpatient visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) was 6.4%, which was down from 7.4% the previous week (Feb. 10) and down from the seasonal high of 7.5% set 2 weeks earlier, the CDC said in its weekly flu surveillance report. The rate for the week ending Feb. 10 was reported last week as 7.5%, but it has been revised downward.

State reports of ILI activity support the decreases seen in the national outpatient rate. There were 33 states at level 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale for the week ending Feb. 17 – down from 39 the week before – and a total of 41 states in the “high” range from levels 8-10, compared with 45 the previous week, CDC’s FluView website shows.

Reports of flu-related pediatric deaths continued: 13 deaths were reported during the week, although 9 occurred in previous weeks. The total for the 2017-2018 season is now 97. There were 110 pediatric deaths in the entire 2016-2017 season, 93 during the 2015-2016 season, and 149 in 2014-2015, the CDC said.

Flu-related outpatient activity dropped for the second week in a row as the cumulative hospitalization rate continues to rise, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

For the week ending Feb. 17, the proportion of outpatient visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) was 6.4%, which was down from 7.4% the previous week (Feb. 10) and down from the seasonal high of 7.5% set 2 weeks earlier, the CDC said in its weekly flu surveillance report. The rate for the week ending Feb. 10 was reported last week as 7.5%, but it has been revised downward.

State reports of ILI activity support the decreases seen in the national outpatient rate. There were 33 states at level 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale for the week ending Feb. 17 – down from 39 the week before – and a total of 41 states in the “high” range from levels 8-10, compared with 45 the previous week, CDC’s FluView website shows.

Reports of flu-related pediatric deaths continued: 13 deaths were reported during the week, although 9 occurred in previous weeks. The total for the 2017-2018 season is now 97. There were 110 pediatric deaths in the entire 2016-2017 season, 93 during the 2015-2016 season, and 149 in 2014-2015, the CDC said.

Sleep disturbance not linked to age or IQ in early ASD

Sleep disturbance is not associated with age and IQ in young children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and disruptive behaviors, according to Cynthia R. Johnson, PhD, and her associates.

They assessed 177 children aged 3-7 who were participating in the Research Units on Behavioral Intervention study, a 24-week trial. All of the children had a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder, based on DSM-IV criteria. The diagnoses were corroborated by the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule and the Autism Diagnostic Interview–Revised.

The children were randomized into a parent training group or a parent education group. After getting parents to complete several forms, including the Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire, Dr. Johnson and her associates found no age differences between children who fell into the category of “good sleepers” (n = 52), and those characterized as “poor sleepers” (n = 46) (P = .57). In both sleep groups, more than 70% of the children had an IQ of 70 or above, and no significant difference was found in good sleepers, compared with poor sleepers, in IQ variable (P = .87) (Sleep Med. 2018. 44:61-6).

In addition, the researchers found that poor sleepers had significantly higher scores on the Aberrant Behavior Checklist subscales of irritability, hyperactivity, stereotypic behavior, and social withdrawal/lethargy, compared with good sleepers. All subscales of the parenting stress index and the PSI total score also were significantly higher in the poor sleepers group, compared with children in the good sleepers group, reported Dr. Johnson of the University of Florida, Gainesville, and her associates.

Additional studies are needed within a “comprehensive biopsychosocial model” to advance the understanding of why some children with autism experience disrupted sleep patterns and others do not. “, regardless of age and cognitive level,” Dr. Johnson and her associates concluded. “With improved sleep, better outcomes for children with ASD could be expected.”

Read the full study in Sleep Medicine

Sleep disturbance is not associated with age and IQ in young children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and disruptive behaviors, according to Cynthia R. Johnson, PhD, and her associates.

They assessed 177 children aged 3-7 who were participating in the Research Units on Behavioral Intervention study, a 24-week trial. All of the children had a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder, based on DSM-IV criteria. The diagnoses were corroborated by the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule and the Autism Diagnostic Interview–Revised.

The children were randomized into a parent training group or a parent education group. After getting parents to complete several forms, including the Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire, Dr. Johnson and her associates found no age differences between children who fell into the category of “good sleepers” (n = 52), and those characterized as “poor sleepers” (n = 46) (P = .57). In both sleep groups, more than 70% of the children had an IQ of 70 or above, and no significant difference was found in good sleepers, compared with poor sleepers, in IQ variable (P = .87) (Sleep Med. 2018. 44:61-6).

In addition, the researchers found that poor sleepers had significantly higher scores on the Aberrant Behavior Checklist subscales of irritability, hyperactivity, stereotypic behavior, and social withdrawal/lethargy, compared with good sleepers. All subscales of the parenting stress index and the PSI total score also were significantly higher in the poor sleepers group, compared with children in the good sleepers group, reported Dr. Johnson of the University of Florida, Gainesville, and her associates.

Additional studies are needed within a “comprehensive biopsychosocial model” to advance the understanding of why some children with autism experience disrupted sleep patterns and others do not. “, regardless of age and cognitive level,” Dr. Johnson and her associates concluded. “With improved sleep, better outcomes for children with ASD could be expected.”

Read the full study in Sleep Medicine

Sleep disturbance is not associated with age and IQ in young children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and disruptive behaviors, according to Cynthia R. Johnson, PhD, and her associates.

They assessed 177 children aged 3-7 who were participating in the Research Units on Behavioral Intervention study, a 24-week trial. All of the children had a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder, based on DSM-IV criteria. The diagnoses were corroborated by the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule and the Autism Diagnostic Interview–Revised.

The children were randomized into a parent training group or a parent education group. After getting parents to complete several forms, including the Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire, Dr. Johnson and her associates found no age differences between children who fell into the category of “good sleepers” (n = 52), and those characterized as “poor sleepers” (n = 46) (P = .57). In both sleep groups, more than 70% of the children had an IQ of 70 or above, and no significant difference was found in good sleepers, compared with poor sleepers, in IQ variable (P = .87) (Sleep Med. 2018. 44:61-6).

In addition, the researchers found that poor sleepers had significantly higher scores on the Aberrant Behavior Checklist subscales of irritability, hyperactivity, stereotypic behavior, and social withdrawal/lethargy, compared with good sleepers. All subscales of the parenting stress index and the PSI total score also were significantly higher in the poor sleepers group, compared with children in the good sleepers group, reported Dr. Johnson of the University of Florida, Gainesville, and her associates.

Additional studies are needed within a “comprehensive biopsychosocial model” to advance the understanding of why some children with autism experience disrupted sleep patterns and others do not. “, regardless of age and cognitive level,” Dr. Johnson and her associates concluded. “With improved sleep, better outcomes for children with ASD could be expected.”

Read the full study in Sleep Medicine

FROM SLEEP MEDICINE

Suicidal behaviors are associated with discordant sexual orientation in teens

Teenagers with discordant sexual orientation are more likely to experience nonfatal suicidal behaviors, according to results of a study published in the American Journal of Preventative Medicine.

“In this study, discordance refers to reporting sexual contact that is inconsistent with a respondent’s sexual identity. ... Discrimination, stigma, prejudice, rejection, and societal norms may put pressure on sexual minorities to present a sexual identity inconsistent with their true sexual identity or to act in a manner inconsistent with their sexual identity,” said Francis Annor, PhD, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and fellow investigators.

“In considering the health and well-being of youth, sexual identity and sexual behavior and their intersection should be considered for their association with the mental health and well-being of adolescents,” according to Dr. Annor and his colleagues. “Some adolescents reporting discordance may have needs that should be considered when developing and implementing suicide prevention programs.”

For this study, investigators analyzed survey questions from 6,790 high school students queried during the 2015 national Youth Risk Behavior Survey.

Sexual discordance was measured by asking students their sexual orientation and the gender of any sexual partners they may have had. Students who responded as being bisexual or who had not experienced sexual contact before were excluded from final analysis.

Students were majority male (56% vs. 44%), white (54.8%), and heterosexual (97.8%), and sexually concordant (96.1%).

When analyzing suicidal tendencies among students, teens who were sexually discordant were 70% more likely to report thinking about, or planning, suicide. High risk for nonfatal suicidal behaviors was significantly more common among discordant students, compared with concordant students (46.3% vs .22.4%, P less than .0001). Students who were gay or lesbian were significantly more likely to report sexual orientation discordance than heterosexual students (32% vs. 3%, P less than .001).

Sexual discordance also was common among students who were female, black, bullied on school property, used marijuana, or physically forced to have sexual intercourse.

Dr. Annor and fellow investigators theorized that the association between discordance and suicidal ideation may stem from self-discrepancy, which can lead to increased anxiety, stress, or depression.

Another theory was that the stress was induced from being a minority, which is supported by the increased number of nonfatal suicidal behaviors in students who were discordant, female, or gay or lesbian, according to investigators. “The minority stress theory suggests that stigma experienced by sexual minorities may cause chronic, cumulative stress that may negatively impact both mental and physical health,” Dr. Francis and associates explained. “Minority stress has been associated with increased depression, overall poor physical health, and increased risk of chronic disease diagnosis.”

To help prevent these suicidal tendencies, Dr. Annor and colleagues suggested using a multipronged public health approach, including using CDC suicide prevention materials, creating safe spaces for kids to understand their developing sexual identities, and further studies to examine risk among discordant teens and nonfatal suicidal behaviors.

The findings of this study are limited by the use of only high school students, which excludes what may be a significant part of the population. Certain aspects of the survey, including no specific definition of sexual contact, as well as the self-reported nature of the information, might have affected findings. Finally, some of those involved in the study may not have been fully aware of their sexual preference at this age and may have experimented with those of the opposite sex as their reported sexual preference, and this may not have been associated with distress, the researchers said.

Dr. Annor and associates reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Annor F et al. Am J Prev Med. 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.01.013

Teenagers with discordant sexual orientation are more likely to experience nonfatal suicidal behaviors, according to results of a study published in the American Journal of Preventative Medicine.

“In this study, discordance refers to reporting sexual contact that is inconsistent with a respondent’s sexual identity. ... Discrimination, stigma, prejudice, rejection, and societal norms may put pressure on sexual minorities to present a sexual identity inconsistent with their true sexual identity or to act in a manner inconsistent with their sexual identity,” said Francis Annor, PhD, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and fellow investigators.

“In considering the health and well-being of youth, sexual identity and sexual behavior and their intersection should be considered for their association with the mental health and well-being of adolescents,” according to Dr. Annor and his colleagues. “Some adolescents reporting discordance may have needs that should be considered when developing and implementing suicide prevention programs.”

For this study, investigators analyzed survey questions from 6,790 high school students queried during the 2015 national Youth Risk Behavior Survey.

Sexual discordance was measured by asking students their sexual orientation and the gender of any sexual partners they may have had. Students who responded as being bisexual or who had not experienced sexual contact before were excluded from final analysis.

Students were majority male (56% vs. 44%), white (54.8%), and heterosexual (97.8%), and sexually concordant (96.1%).

When analyzing suicidal tendencies among students, teens who were sexually discordant were 70% more likely to report thinking about, or planning, suicide. High risk for nonfatal suicidal behaviors was significantly more common among discordant students, compared with concordant students (46.3% vs .22.4%, P less than .0001). Students who were gay or lesbian were significantly more likely to report sexual orientation discordance than heterosexual students (32% vs. 3%, P less than .001).

Sexual discordance also was common among students who were female, black, bullied on school property, used marijuana, or physically forced to have sexual intercourse.

Dr. Annor and fellow investigators theorized that the association between discordance and suicidal ideation may stem from self-discrepancy, which can lead to increased anxiety, stress, or depression.

Another theory was that the stress was induced from being a minority, which is supported by the increased number of nonfatal suicidal behaviors in students who were discordant, female, or gay or lesbian, according to investigators. “The minority stress theory suggests that stigma experienced by sexual minorities may cause chronic, cumulative stress that may negatively impact both mental and physical health,” Dr. Francis and associates explained. “Minority stress has been associated with increased depression, overall poor physical health, and increased risk of chronic disease diagnosis.”

To help prevent these suicidal tendencies, Dr. Annor and colleagues suggested using a multipronged public health approach, including using CDC suicide prevention materials, creating safe spaces for kids to understand their developing sexual identities, and further studies to examine risk among discordant teens and nonfatal suicidal behaviors.

The findings of this study are limited by the use of only high school students, which excludes what may be a significant part of the population. Certain aspects of the survey, including no specific definition of sexual contact, as well as the self-reported nature of the information, might have affected findings. Finally, some of those involved in the study may not have been fully aware of their sexual preference at this age and may have experimented with those of the opposite sex as their reported sexual preference, and this may not have been associated with distress, the researchers said.

Dr. Annor and associates reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Annor F et al. Am J Prev Med. 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.01.013

Teenagers with discordant sexual orientation are more likely to experience nonfatal suicidal behaviors, according to results of a study published in the American Journal of Preventative Medicine.

“In this study, discordance refers to reporting sexual contact that is inconsistent with a respondent’s sexual identity. ... Discrimination, stigma, prejudice, rejection, and societal norms may put pressure on sexual minorities to present a sexual identity inconsistent with their true sexual identity or to act in a manner inconsistent with their sexual identity,” said Francis Annor, PhD, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and fellow investigators.

“In considering the health and well-being of youth, sexual identity and sexual behavior and their intersection should be considered for their association with the mental health and well-being of adolescents,” according to Dr. Annor and his colleagues. “Some adolescents reporting discordance may have needs that should be considered when developing and implementing suicide prevention programs.”

For this study, investigators analyzed survey questions from 6,790 high school students queried during the 2015 national Youth Risk Behavior Survey.

Sexual discordance was measured by asking students their sexual orientation and the gender of any sexual partners they may have had. Students who responded as being bisexual or who had not experienced sexual contact before were excluded from final analysis.

Students were majority male (56% vs. 44%), white (54.8%), and heterosexual (97.8%), and sexually concordant (96.1%).

When analyzing suicidal tendencies among students, teens who were sexually discordant were 70% more likely to report thinking about, or planning, suicide. High risk for nonfatal suicidal behaviors was significantly more common among discordant students, compared with concordant students (46.3% vs .22.4%, P less than .0001). Students who were gay or lesbian were significantly more likely to report sexual orientation discordance than heterosexual students (32% vs. 3%, P less than .001).

Sexual discordance also was common among students who were female, black, bullied on school property, used marijuana, or physically forced to have sexual intercourse.

Dr. Annor and fellow investigators theorized that the association between discordance and suicidal ideation may stem from self-discrepancy, which can lead to increased anxiety, stress, or depression.

Another theory was that the stress was induced from being a minority, which is supported by the increased number of nonfatal suicidal behaviors in students who were discordant, female, or gay or lesbian, according to investigators. “The minority stress theory suggests that stigma experienced by sexual minorities may cause chronic, cumulative stress that may negatively impact both mental and physical health,” Dr. Francis and associates explained. “Minority stress has been associated with increased depression, overall poor physical health, and increased risk of chronic disease diagnosis.”