User login

A refined strategy for confirming diagnosis in suspected NSTEMI

ORLANDO – A novel diagnostic strategy of performing CT angiography or cardiovascular MRI first in patients with suspected non-ST-elevation MI safely improved appropriate selection for invasive coronary angiography in the Dutch randomized CARMENTA trial.

The strategy of using noninvasive imaging first significantly cut down on the high proportion of diagnostic invasive angiography procedures that end up showing no significant obstructive coronary artery disease in the current era of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin assays, Martijn W. Smulders, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

CARMENTA (Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Computed Tomography Angiography) was a single-center, prospective, randomized trial including 207 patients with suspected NSTEMI on the basis of acute chest pain, an elevated high-sensitivity cardiac troponin level, and an inconclusive ECG. They were randomized to one of three diagnostic strategies: a routine invasive strategy in which they were sent straight to the cardiac catheterization lab for invasive coronary angiography, or either CTA- or CMR-first as gatekeeper strategies in which referral for invasive angiography was reserved for only those patients whose noninvasive imaging demonstrated myocardial ischemia, infarction, or obstructive CAD with at least a 70% stenosis.

The impetus for the trial was the investigators’ concern that widespread embrace of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin assays has resulted in a serious clinical problem: Although these assays offer very high sensitivity for rapid detection of acute MI, their positive predictive value is only 56%, compared with 76% for the older troponin assays.

“That means almost one out of two patients with acute chest pain and an elevated high-sensitivity troponin level does not have a type 1 MI. We see a twofold higher incidence of elevated troponin levels with these assays, so there has been a significant increase in referrals for invasive angiography – and up to one-third of these patients with suspected NSTEMI don’t have an obstructive stenosis. We need a strategy to improve patient selection,” explained Dr. Smulders of Maastricht (the Netherlands) University.

The CARMENTA strategy worked. The primary outcome – the proportion of patients with suspected NSTEMI who underwent invasive coronary angiography during their initial hospitalization – was 65% in the CTA-first group and 77% in the CMR group, compared with 100% in the routine invasive-strategy control group. Moreover, fully 38% of patients in the control group turned out not to have obstructive CAD, compared with 15% who were sent for invasive angiography only after CTA and 31% who first had CMR.

Procedure-related complications, a secondary outcome, occurred in 12% of the CMR-first group, 13% of the CTA-first group, and 16% of patients in the routine invasive strategy control group. Major adverse cardiac events during 1 year of follow-up, which was the other secondary outcome, occurred in 9% of the CMR group, 6% of the CTA group, and 9% of the control group.

A limitation of the CARMENTA trial was that, even though it was scheduled to enroll 288 patients to achieve strong statistical power, the study’s data safety monitoring committee recommended on the basis of an interim analysis that the trial be halted early. The reasoning was that the experience of the first 200 enrollees made it clear that the noninvasive-imaging-first strategy would achieve the goal of reducing the volume of referrals to invasive angiography for suspected NSTEMI.

Session cochair Stefan D. Anker, MD, was irked by the trial’s early termination, which weakened the strength of the conclusions, especially with regard to the safety of the novel strategy.

“I agree that this imaging-first strategy reduces procedures, but the use of the word ‘safely’ is premature,” said Dr. Anker, professor of homeostasis and cachexia at Charite Medical School in Berlin.

“I totally agree with you,” Dr. Smulders replied. “We need a bigger trial to confirm our results – preferably a multicenter trial.”

“How can you do a bigger trial when your data safety monitoring board didn’t allow you to complete even this trial? They killed your trial. That’s the way I see it,” Dr. Anker said.

The CARMENTA trial was funded by the Dutch Heart Foundation. Dr. Smulders reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Smulders M. ACC 18.

ORLANDO – A novel diagnostic strategy of performing CT angiography or cardiovascular MRI first in patients with suspected non-ST-elevation MI safely improved appropriate selection for invasive coronary angiography in the Dutch randomized CARMENTA trial.

The strategy of using noninvasive imaging first significantly cut down on the high proportion of diagnostic invasive angiography procedures that end up showing no significant obstructive coronary artery disease in the current era of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin assays, Martijn W. Smulders, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

CARMENTA (Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Computed Tomography Angiography) was a single-center, prospective, randomized trial including 207 patients with suspected NSTEMI on the basis of acute chest pain, an elevated high-sensitivity cardiac troponin level, and an inconclusive ECG. They were randomized to one of three diagnostic strategies: a routine invasive strategy in which they were sent straight to the cardiac catheterization lab for invasive coronary angiography, or either CTA- or CMR-first as gatekeeper strategies in which referral for invasive angiography was reserved for only those patients whose noninvasive imaging demonstrated myocardial ischemia, infarction, or obstructive CAD with at least a 70% stenosis.

The impetus for the trial was the investigators’ concern that widespread embrace of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin assays has resulted in a serious clinical problem: Although these assays offer very high sensitivity for rapid detection of acute MI, their positive predictive value is only 56%, compared with 76% for the older troponin assays.

“That means almost one out of two patients with acute chest pain and an elevated high-sensitivity troponin level does not have a type 1 MI. We see a twofold higher incidence of elevated troponin levels with these assays, so there has been a significant increase in referrals for invasive angiography – and up to one-third of these patients with suspected NSTEMI don’t have an obstructive stenosis. We need a strategy to improve patient selection,” explained Dr. Smulders of Maastricht (the Netherlands) University.

The CARMENTA strategy worked. The primary outcome – the proportion of patients with suspected NSTEMI who underwent invasive coronary angiography during their initial hospitalization – was 65% in the CTA-first group and 77% in the CMR group, compared with 100% in the routine invasive-strategy control group. Moreover, fully 38% of patients in the control group turned out not to have obstructive CAD, compared with 15% who were sent for invasive angiography only after CTA and 31% who first had CMR.

Procedure-related complications, a secondary outcome, occurred in 12% of the CMR-first group, 13% of the CTA-first group, and 16% of patients in the routine invasive strategy control group. Major adverse cardiac events during 1 year of follow-up, which was the other secondary outcome, occurred in 9% of the CMR group, 6% of the CTA group, and 9% of the control group.

A limitation of the CARMENTA trial was that, even though it was scheduled to enroll 288 patients to achieve strong statistical power, the study’s data safety monitoring committee recommended on the basis of an interim analysis that the trial be halted early. The reasoning was that the experience of the first 200 enrollees made it clear that the noninvasive-imaging-first strategy would achieve the goal of reducing the volume of referrals to invasive angiography for suspected NSTEMI.

Session cochair Stefan D. Anker, MD, was irked by the trial’s early termination, which weakened the strength of the conclusions, especially with regard to the safety of the novel strategy.

“I agree that this imaging-first strategy reduces procedures, but the use of the word ‘safely’ is premature,” said Dr. Anker, professor of homeostasis and cachexia at Charite Medical School in Berlin.

“I totally agree with you,” Dr. Smulders replied. “We need a bigger trial to confirm our results – preferably a multicenter trial.”

“How can you do a bigger trial when your data safety monitoring board didn’t allow you to complete even this trial? They killed your trial. That’s the way I see it,” Dr. Anker said.

The CARMENTA trial was funded by the Dutch Heart Foundation. Dr. Smulders reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Smulders M. ACC 18.

ORLANDO – A novel diagnostic strategy of performing CT angiography or cardiovascular MRI first in patients with suspected non-ST-elevation MI safely improved appropriate selection for invasive coronary angiography in the Dutch randomized CARMENTA trial.

The strategy of using noninvasive imaging first significantly cut down on the high proportion of diagnostic invasive angiography procedures that end up showing no significant obstructive coronary artery disease in the current era of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin assays, Martijn W. Smulders, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

CARMENTA (Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Computed Tomography Angiography) was a single-center, prospective, randomized trial including 207 patients with suspected NSTEMI on the basis of acute chest pain, an elevated high-sensitivity cardiac troponin level, and an inconclusive ECG. They were randomized to one of three diagnostic strategies: a routine invasive strategy in which they were sent straight to the cardiac catheterization lab for invasive coronary angiography, or either CTA- or CMR-first as gatekeeper strategies in which referral for invasive angiography was reserved for only those patients whose noninvasive imaging demonstrated myocardial ischemia, infarction, or obstructive CAD with at least a 70% stenosis.

The impetus for the trial was the investigators’ concern that widespread embrace of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin assays has resulted in a serious clinical problem: Although these assays offer very high sensitivity for rapid detection of acute MI, their positive predictive value is only 56%, compared with 76% for the older troponin assays.

“That means almost one out of two patients with acute chest pain and an elevated high-sensitivity troponin level does not have a type 1 MI. We see a twofold higher incidence of elevated troponin levels with these assays, so there has been a significant increase in referrals for invasive angiography – and up to one-third of these patients with suspected NSTEMI don’t have an obstructive stenosis. We need a strategy to improve patient selection,” explained Dr. Smulders of Maastricht (the Netherlands) University.

The CARMENTA strategy worked. The primary outcome – the proportion of patients with suspected NSTEMI who underwent invasive coronary angiography during their initial hospitalization – was 65% in the CTA-first group and 77% in the CMR group, compared with 100% in the routine invasive-strategy control group. Moreover, fully 38% of patients in the control group turned out not to have obstructive CAD, compared with 15% who were sent for invasive angiography only after CTA and 31% who first had CMR.

Procedure-related complications, a secondary outcome, occurred in 12% of the CMR-first group, 13% of the CTA-first group, and 16% of patients in the routine invasive strategy control group. Major adverse cardiac events during 1 year of follow-up, which was the other secondary outcome, occurred in 9% of the CMR group, 6% of the CTA group, and 9% of the control group.

A limitation of the CARMENTA trial was that, even though it was scheduled to enroll 288 patients to achieve strong statistical power, the study’s data safety monitoring committee recommended on the basis of an interim analysis that the trial be halted early. The reasoning was that the experience of the first 200 enrollees made it clear that the noninvasive-imaging-first strategy would achieve the goal of reducing the volume of referrals to invasive angiography for suspected NSTEMI.

Session cochair Stefan D. Anker, MD, was irked by the trial’s early termination, which weakened the strength of the conclusions, especially with regard to the safety of the novel strategy.

“I agree that this imaging-first strategy reduces procedures, but the use of the word ‘safely’ is premature,” said Dr. Anker, professor of homeostasis and cachexia at Charite Medical School in Berlin.

“I totally agree with you,” Dr. Smulders replied. “We need a bigger trial to confirm our results – preferably a multicenter trial.”

“How can you do a bigger trial when your data safety monitoring board didn’t allow you to complete even this trial? They killed your trial. That’s the way I see it,” Dr. Anker said.

The CARMENTA trial was funded by the Dutch Heart Foundation. Dr. Smulders reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Smulders M. ACC 18.

REPORTING FROM ACC 18

Key clinical point: Dutch cardiologists have come up with a novel way to reduce the high rate of negative diagnostic coronary angiography in patients with suspected NSTEMI.

Major finding: Reserving invasive coronary angiography for only those patients with suspected NSTEMI who first showed positive findings on noninvasive CT angiography reduced invasive angiography volume by 35%.

Study details: This single-center, randomized, prospective, three-arm clinical trial included 207 patients with suspected NSTEMI.

Disclosures: The CARMENTA trial was funded by the Dutch Heart Foundation. The presenter reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

Source: Smulders M. ACC 18.

Commentary—Could Prazosin Play a Role in Treating Chronic Posttraumatic Headache?

Headache is a common symptom after any severity traumatic brain injury in the civilian and military populations. Currently, there is no evidence-based treatment protocol for posttraumatic headache, and management largely is based on therapies used in the primary headache disorders.

There is a complex interaction between mood disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), sleep disorders, and headache. Depression and PTSD are frequently seen in civilian and military populations accompanying chronic posttraumatic headache. In civilians, about one-third of patients with posttraumatic headache meet criteria for depression and PTSD. A longitudinal study of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans followed over three years found that co-occurrence of depression, PTSD, or both would increase the risk of chronic posttraumatic headache more than TBI alone. Another meta-analysis of civilian and military TBI found that, though PTSD could affect intensity and severity of chronic posttraumatic headache, TBI was an independent risk factor for chronic posttraumatic headache. PTSD and depression can cause sleep disruption and intensify pain syndromes, including headache.

Though prazosin had been shown to be effective in decreasing nightmares, improving sleep, or decreasing daytime sleepiness in many prior studies, the PACT trial, a randomized, double-blind controlled trial of 304 participants at Veterans Affairs medical centers, did not meet its primary end points of less frequent and less intense trauma-related nightmares, greater improvement in sleep quality, and overall clinical status among veterans assigned to prazosin, compared with veterans assigned to placebo. While disappointing, and surprising given the results of the preceding studies, do these results predict a similar failure in the use of prazosin for treatment of posttraumatic headache?

In an observational study of 126 veterans with blast-related mild TBI during Operation Iraqi Freedom or Operation Enduring Freedom, 82% of participants had co-occurring conditions, including frequent, severe headache, neurologic exam abnormalities, or cognitive disorders. This pilot study found that treatment with prazosin and sleep hygiene counseling improved sleep, but also decreased headache pain and frequency, as well as improved cognitive function over nine weeks. Improvements were maintained for six months. Though difficult to determine the interplay of sleep, posttraumatic headache, and depression, could prazosin independently reduce the burden of headache? Currently, a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial in veterans is examining the effectiveness of prazosin as a preventive agent in treating combat-related posttraumatic headache. This study was scheduled to enroll its last patient at the end of 2017, and results may be out soon.

There may be specific pharmacologic properties that make prazosin a useful drug for headache treatment. Prazosin is a very potent, selective alpha 1-adrenergic antagonist that passes through the blood–brain barrier. It is highly protein bound (97%), so absolute amounts in the CNS are likely to be low. Its use in the treatment of hypertension is based on decreased peripheral vascular resistance as a result of arteriolar and venous receptor blockade. It also can act in the CNS to decrease sympathetic outflow. While an effect on headache could be central, peripheral, or both, other drugs with alpha-adrenergic blocking effects have been used in the treatment of migraine for decades. The ergots, for example, were the first alpha-adrenergic agents to be discovered acting as partial agonists or antagonists at adrenergic, tryptaminergic, and dopaminergic receptors. The hydrogenated ergot alkaloids are among the most potent alpha-adrenergic blocking agents, but adverse effects prevent doses that can cause more than minimal blockade. Chlorpromazine and other dopamine (D2) receptor antagonists, which are highly effective in acute treatment of migraine, particularly with parenteral delivery, also produce significant alpha-adrenergic receptor blockade, while trazodone, amitriptyline, and the atypical antipsychotics, with various levels of alpha-adrenergic antagonism, have found some success in migraine prevention.

Clinical experience has shown that there is wide response variability to acute and chronic medication for migraine. Genetic studies of patients with migraine, though at an early stage, have identified genes involved with vascular and neuronal function. It is likely that clinical observation will be borne out by individual responses to drug classes based on individual genetic profiles, so that subtypes of patients in clinical trial populations may show efficacy based on these profiles. It is likely that prazosin will be useful in certain patient subtypes for the treatment of headache. Posttraumatic headache, which may share some similar pathways of headache physiology with primary headache disorders, adds another layer of response complexity.

—Sylvia Lucas, MD, PhD

Clinical Professor of Neurology and Neurological Surgery

University of Washington

Seattle

Suggested Reading

Nampiaparampil DE. Prevalence of chronic pain after traumatic brain injury: a systematic review. JAMA. 2008;300(6):711-719.

Peterlin BL, Nijjar SS, Tietjen GE. Post-traumatic stress disorder and migraine: epidemiology, sex differences, and potential mechanisms. Headache. 2011;51(6):860-868.

Ruff RL, Riechers RG, Wang XF, et al. For veterans with mild traumatic brain injury, improved posttraumatic stress disorder severity and sleep correlated with symptomatic improvement. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2012;49(9):1305-1320.

Headache is a common symptom after any severity traumatic brain injury in the civilian and military populations. Currently, there is no evidence-based treatment protocol for posttraumatic headache, and management largely is based on therapies used in the primary headache disorders.

There is a complex interaction between mood disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), sleep disorders, and headache. Depression and PTSD are frequently seen in civilian and military populations accompanying chronic posttraumatic headache. In civilians, about one-third of patients with posttraumatic headache meet criteria for depression and PTSD. A longitudinal study of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans followed over three years found that co-occurrence of depression, PTSD, or both would increase the risk of chronic posttraumatic headache more than TBI alone. Another meta-analysis of civilian and military TBI found that, though PTSD could affect intensity and severity of chronic posttraumatic headache, TBI was an independent risk factor for chronic posttraumatic headache. PTSD and depression can cause sleep disruption and intensify pain syndromes, including headache.

Though prazosin had been shown to be effective in decreasing nightmares, improving sleep, or decreasing daytime sleepiness in many prior studies, the PACT trial, a randomized, double-blind controlled trial of 304 participants at Veterans Affairs medical centers, did not meet its primary end points of less frequent and less intense trauma-related nightmares, greater improvement in sleep quality, and overall clinical status among veterans assigned to prazosin, compared with veterans assigned to placebo. While disappointing, and surprising given the results of the preceding studies, do these results predict a similar failure in the use of prazosin for treatment of posttraumatic headache?

In an observational study of 126 veterans with blast-related mild TBI during Operation Iraqi Freedom or Operation Enduring Freedom, 82% of participants had co-occurring conditions, including frequent, severe headache, neurologic exam abnormalities, or cognitive disorders. This pilot study found that treatment with prazosin and sleep hygiene counseling improved sleep, but also decreased headache pain and frequency, as well as improved cognitive function over nine weeks. Improvements were maintained for six months. Though difficult to determine the interplay of sleep, posttraumatic headache, and depression, could prazosin independently reduce the burden of headache? Currently, a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial in veterans is examining the effectiveness of prazosin as a preventive agent in treating combat-related posttraumatic headache. This study was scheduled to enroll its last patient at the end of 2017, and results may be out soon.

There may be specific pharmacologic properties that make prazosin a useful drug for headache treatment. Prazosin is a very potent, selective alpha 1-adrenergic antagonist that passes through the blood–brain barrier. It is highly protein bound (97%), so absolute amounts in the CNS are likely to be low. Its use in the treatment of hypertension is based on decreased peripheral vascular resistance as a result of arteriolar and venous receptor blockade. It also can act in the CNS to decrease sympathetic outflow. While an effect on headache could be central, peripheral, or both, other drugs with alpha-adrenergic blocking effects have been used in the treatment of migraine for decades. The ergots, for example, were the first alpha-adrenergic agents to be discovered acting as partial agonists or antagonists at adrenergic, tryptaminergic, and dopaminergic receptors. The hydrogenated ergot alkaloids are among the most potent alpha-adrenergic blocking agents, but adverse effects prevent doses that can cause more than minimal blockade. Chlorpromazine and other dopamine (D2) receptor antagonists, which are highly effective in acute treatment of migraine, particularly with parenteral delivery, also produce significant alpha-adrenergic receptor blockade, while trazodone, amitriptyline, and the atypical antipsychotics, with various levels of alpha-adrenergic antagonism, have found some success in migraine prevention.

Clinical experience has shown that there is wide response variability to acute and chronic medication for migraine. Genetic studies of patients with migraine, though at an early stage, have identified genes involved with vascular and neuronal function. It is likely that clinical observation will be borne out by individual responses to drug classes based on individual genetic profiles, so that subtypes of patients in clinical trial populations may show efficacy based on these profiles. It is likely that prazosin will be useful in certain patient subtypes for the treatment of headache. Posttraumatic headache, which may share some similar pathways of headache physiology with primary headache disorders, adds another layer of response complexity.

—Sylvia Lucas, MD, PhD

Clinical Professor of Neurology and Neurological Surgery

University of Washington

Seattle

Suggested Reading

Nampiaparampil DE. Prevalence of chronic pain after traumatic brain injury: a systematic review. JAMA. 2008;300(6):711-719.

Peterlin BL, Nijjar SS, Tietjen GE. Post-traumatic stress disorder and migraine: epidemiology, sex differences, and potential mechanisms. Headache. 2011;51(6):860-868.

Ruff RL, Riechers RG, Wang XF, et al. For veterans with mild traumatic brain injury, improved posttraumatic stress disorder severity and sleep correlated with symptomatic improvement. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2012;49(9):1305-1320.

Headache is a common symptom after any severity traumatic brain injury in the civilian and military populations. Currently, there is no evidence-based treatment protocol for posttraumatic headache, and management largely is based on therapies used in the primary headache disorders.

There is a complex interaction between mood disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), sleep disorders, and headache. Depression and PTSD are frequently seen in civilian and military populations accompanying chronic posttraumatic headache. In civilians, about one-third of patients with posttraumatic headache meet criteria for depression and PTSD. A longitudinal study of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans followed over three years found that co-occurrence of depression, PTSD, or both would increase the risk of chronic posttraumatic headache more than TBI alone. Another meta-analysis of civilian and military TBI found that, though PTSD could affect intensity and severity of chronic posttraumatic headache, TBI was an independent risk factor for chronic posttraumatic headache. PTSD and depression can cause sleep disruption and intensify pain syndromes, including headache.

Though prazosin had been shown to be effective in decreasing nightmares, improving sleep, or decreasing daytime sleepiness in many prior studies, the PACT trial, a randomized, double-blind controlled trial of 304 participants at Veterans Affairs medical centers, did not meet its primary end points of less frequent and less intense trauma-related nightmares, greater improvement in sleep quality, and overall clinical status among veterans assigned to prazosin, compared with veterans assigned to placebo. While disappointing, and surprising given the results of the preceding studies, do these results predict a similar failure in the use of prazosin for treatment of posttraumatic headache?

In an observational study of 126 veterans with blast-related mild TBI during Operation Iraqi Freedom or Operation Enduring Freedom, 82% of participants had co-occurring conditions, including frequent, severe headache, neurologic exam abnormalities, or cognitive disorders. This pilot study found that treatment with prazosin and sleep hygiene counseling improved sleep, but also decreased headache pain and frequency, as well as improved cognitive function over nine weeks. Improvements were maintained for six months. Though difficult to determine the interplay of sleep, posttraumatic headache, and depression, could prazosin independently reduce the burden of headache? Currently, a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial in veterans is examining the effectiveness of prazosin as a preventive agent in treating combat-related posttraumatic headache. This study was scheduled to enroll its last patient at the end of 2017, and results may be out soon.

There may be specific pharmacologic properties that make prazosin a useful drug for headache treatment. Prazosin is a very potent, selective alpha 1-adrenergic antagonist that passes through the blood–brain barrier. It is highly protein bound (97%), so absolute amounts in the CNS are likely to be low. Its use in the treatment of hypertension is based on decreased peripheral vascular resistance as a result of arteriolar and venous receptor blockade. It also can act in the CNS to decrease sympathetic outflow. While an effect on headache could be central, peripheral, or both, other drugs with alpha-adrenergic blocking effects have been used in the treatment of migraine for decades. The ergots, for example, were the first alpha-adrenergic agents to be discovered acting as partial agonists or antagonists at adrenergic, tryptaminergic, and dopaminergic receptors. The hydrogenated ergot alkaloids are among the most potent alpha-adrenergic blocking agents, but adverse effects prevent doses that can cause more than minimal blockade. Chlorpromazine and other dopamine (D2) receptor antagonists, which are highly effective in acute treatment of migraine, particularly with parenteral delivery, also produce significant alpha-adrenergic receptor blockade, while trazodone, amitriptyline, and the atypical antipsychotics, with various levels of alpha-adrenergic antagonism, have found some success in migraine prevention.

Clinical experience has shown that there is wide response variability to acute and chronic medication for migraine. Genetic studies of patients with migraine, though at an early stage, have identified genes involved with vascular and neuronal function. It is likely that clinical observation will be borne out by individual responses to drug classes based on individual genetic profiles, so that subtypes of patients in clinical trial populations may show efficacy based on these profiles. It is likely that prazosin will be useful in certain patient subtypes for the treatment of headache. Posttraumatic headache, which may share some similar pathways of headache physiology with primary headache disorders, adds another layer of response complexity.

—Sylvia Lucas, MD, PhD

Clinical Professor of Neurology and Neurological Surgery

University of Washington

Seattle

Suggested Reading

Nampiaparampil DE. Prevalence of chronic pain after traumatic brain injury: a systematic review. JAMA. 2008;300(6):711-719.

Peterlin BL, Nijjar SS, Tietjen GE. Post-traumatic stress disorder and migraine: epidemiology, sex differences, and potential mechanisms. Headache. 2011;51(6):860-868.

Ruff RL, Riechers RG, Wang XF, et al. For veterans with mild traumatic brain injury, improved posttraumatic stress disorder severity and sleep correlated with symptomatic improvement. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2012;49(9):1305-1320.

Does Prazosin Benefit Patients With Posttraumatic Stress Disorder?

Among military veterans with chronic posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and frequent nightmares, prazosin does not alleviate distressing dreams or improve sleep quality, according to trial results published in the February 8 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine.

Prior single-center trials found that prazosin, an alpha 1-adrenoreceptor antagonist, may alleviate nightmares associated with PTSD and improve overall clinical status. The present study’s eligibility criteria may have led to selection bias that contributed to its negative results, the researchers said.

The PACT Trial

To investigate the efficacy of prazosin in patients with chronic combat-related PTSD and frequent nightmares, Murray A. Raskind, MD, and colleagues conducted the Prazosin and Combat Trauma PTSD (PACT) trial. Dr. Raskind is the Director of the Veterans Affairs (VA) Northwest Network Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center and Professor and Vice Chair of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at the University of Washington School of Medicine in Seattle.

The 26-week, double-blind, randomized, controlled trial included 304 veterans from 12 VA medical centers. Participants met DSM-IV criteria for PTSD; had a total score of at least 50 on the 17-item Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS); had been exposed to one or more traumatic, life-threatening events in a war zone before the onset of recurrent nightmares; could recall combat-related nightmares; had a frequency score of at least 2 and a cumulative score of at least 5 on CAPS item B2 (ie, “recurrent distressing dreams”); and, for at least four weeks before randomization, were receiving a stable dose of nonexcluded medications or supportive psychotherapy. Exclusion criteria included unstable medical illness, a systolic blood pressure of less than 110 mm Hg in the supine position, active suicidal or homicidal ideation with plan or intent, and psychosocial instability.

Of 413 people screened, 304 underwent randomization (about 98% male; average age, 52); 152 patients were assigned to each treatment group. The two groups’ patient characteristics did not differ significantly at baseline. Researchers administered prazosin or placebo in escalating divided doses over five weeks to a daily maximum of 20 mg in men and 12 mg in women.

Primary Outcome Measures

The three primary outcome measures were change in score from baseline to 10 weeks on the CAPS item B2, change in score from baseline to 10 weeks on the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, and the Clinical Global Impression of Change score at 10 weeks. None of the primary outcome measures significantly differed between the groups at 10 weeks. The groups’ outcome measures at 26 weeks and other secondary outcomes also were not significantly different.

The number of serious adverse events did not differ significantly by group. Of the adverse events, dizziness, lightheadedness, and urinary incontinence were significantly more common in the prazosin group, compared with the placebo group, whereas new or worsening suicidal ideation was significantly less common among participants who received prazosin, compared with patients who received placebo (8% vs 15%, respectively).

The investigators enrolled patients who were mainly in clinically stable condition, which may have led the trial to include patients whose distressing dreams were unlikely to respond to prazosin, Dr. Raskind and colleagues said.

Future Directions

“The failure of this new, large, multisite trial to replicate the previous studies is surprising and disappointing,” said Kerry J. Ressler, MD, PhD, Chief of the Division of Depression and Anxiety Disorders at McLean Hospital in Belmont, Massachusetts, and Professor of Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School in Boston, in an accompanying editorial. “PTSD remains a psychiatric malady that in some respects seems understandable and treatable on the basis of known neurobiologic pathways. Yet it is a complex syndrome with innumerable subtypes and variations…. There is a need to define clinical subtypes of PTSD on the basis of biologic markers.”

Studies of prazosin for the treatment of other conditions are under way. Investigators have initiated trials to examine whether prazosin reduces the frequency of chronic postconcussive headaches, compared with placebo.

—Jake Remaly

Suggested Reading

Raskind MA, Peskind ER, Chow B, et al. Trial of prazosin for post-traumatic stress disorder in military veterans. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(6):507-517.

Raskind MA, Peterson K, Williams T, et al. A trial of prazosin for combat trauma PTSD with nightmares in active-duty soldiers returned from Iraq and Afghanistan. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(9):1003-1010.

Ressler KJ. Alpha-adrenergic receptors in PTSD - Failure or time for precision medicine? N Engl J Med. 2018; 378(6):575-576.

Among military veterans with chronic posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and frequent nightmares, prazosin does not alleviate distressing dreams or improve sleep quality, according to trial results published in the February 8 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine.

Prior single-center trials found that prazosin, an alpha 1-adrenoreceptor antagonist, may alleviate nightmares associated with PTSD and improve overall clinical status. The present study’s eligibility criteria may have led to selection bias that contributed to its negative results, the researchers said.

The PACT Trial

To investigate the efficacy of prazosin in patients with chronic combat-related PTSD and frequent nightmares, Murray A. Raskind, MD, and colleagues conducted the Prazosin and Combat Trauma PTSD (PACT) trial. Dr. Raskind is the Director of the Veterans Affairs (VA) Northwest Network Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center and Professor and Vice Chair of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at the University of Washington School of Medicine in Seattle.

The 26-week, double-blind, randomized, controlled trial included 304 veterans from 12 VA medical centers. Participants met DSM-IV criteria for PTSD; had a total score of at least 50 on the 17-item Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS); had been exposed to one or more traumatic, life-threatening events in a war zone before the onset of recurrent nightmares; could recall combat-related nightmares; had a frequency score of at least 2 and a cumulative score of at least 5 on CAPS item B2 (ie, “recurrent distressing dreams”); and, for at least four weeks before randomization, were receiving a stable dose of nonexcluded medications or supportive psychotherapy. Exclusion criteria included unstable medical illness, a systolic blood pressure of less than 110 mm Hg in the supine position, active suicidal or homicidal ideation with plan or intent, and psychosocial instability.

Of 413 people screened, 304 underwent randomization (about 98% male; average age, 52); 152 patients were assigned to each treatment group. The two groups’ patient characteristics did not differ significantly at baseline. Researchers administered prazosin or placebo in escalating divided doses over five weeks to a daily maximum of 20 mg in men and 12 mg in women.

Primary Outcome Measures

The three primary outcome measures were change in score from baseline to 10 weeks on the CAPS item B2, change in score from baseline to 10 weeks on the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, and the Clinical Global Impression of Change score at 10 weeks. None of the primary outcome measures significantly differed between the groups at 10 weeks. The groups’ outcome measures at 26 weeks and other secondary outcomes also were not significantly different.

The number of serious adverse events did not differ significantly by group. Of the adverse events, dizziness, lightheadedness, and urinary incontinence were significantly more common in the prazosin group, compared with the placebo group, whereas new or worsening suicidal ideation was significantly less common among participants who received prazosin, compared with patients who received placebo (8% vs 15%, respectively).

The investigators enrolled patients who were mainly in clinically stable condition, which may have led the trial to include patients whose distressing dreams were unlikely to respond to prazosin, Dr. Raskind and colleagues said.

Future Directions

“The failure of this new, large, multisite trial to replicate the previous studies is surprising and disappointing,” said Kerry J. Ressler, MD, PhD, Chief of the Division of Depression and Anxiety Disorders at McLean Hospital in Belmont, Massachusetts, and Professor of Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School in Boston, in an accompanying editorial. “PTSD remains a psychiatric malady that in some respects seems understandable and treatable on the basis of known neurobiologic pathways. Yet it is a complex syndrome with innumerable subtypes and variations…. There is a need to define clinical subtypes of PTSD on the basis of biologic markers.”

Studies of prazosin for the treatment of other conditions are under way. Investigators have initiated trials to examine whether prazosin reduces the frequency of chronic postconcussive headaches, compared with placebo.

—Jake Remaly

Suggested Reading

Raskind MA, Peskind ER, Chow B, et al. Trial of prazosin for post-traumatic stress disorder in military veterans. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(6):507-517.

Raskind MA, Peterson K, Williams T, et al. A trial of prazosin for combat trauma PTSD with nightmares in active-duty soldiers returned from Iraq and Afghanistan. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(9):1003-1010.

Ressler KJ. Alpha-adrenergic receptors in PTSD - Failure or time for precision medicine? N Engl J Med. 2018; 378(6):575-576.

Among military veterans with chronic posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and frequent nightmares, prazosin does not alleviate distressing dreams or improve sleep quality, according to trial results published in the February 8 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine.

Prior single-center trials found that prazosin, an alpha 1-adrenoreceptor antagonist, may alleviate nightmares associated with PTSD and improve overall clinical status. The present study’s eligibility criteria may have led to selection bias that contributed to its negative results, the researchers said.

The PACT Trial

To investigate the efficacy of prazosin in patients with chronic combat-related PTSD and frequent nightmares, Murray A. Raskind, MD, and colleagues conducted the Prazosin and Combat Trauma PTSD (PACT) trial. Dr. Raskind is the Director of the Veterans Affairs (VA) Northwest Network Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center and Professor and Vice Chair of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at the University of Washington School of Medicine in Seattle.

The 26-week, double-blind, randomized, controlled trial included 304 veterans from 12 VA medical centers. Participants met DSM-IV criteria for PTSD; had a total score of at least 50 on the 17-item Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS); had been exposed to one or more traumatic, life-threatening events in a war zone before the onset of recurrent nightmares; could recall combat-related nightmares; had a frequency score of at least 2 and a cumulative score of at least 5 on CAPS item B2 (ie, “recurrent distressing dreams”); and, for at least four weeks before randomization, were receiving a stable dose of nonexcluded medications or supportive psychotherapy. Exclusion criteria included unstable medical illness, a systolic blood pressure of less than 110 mm Hg in the supine position, active suicidal or homicidal ideation with plan or intent, and psychosocial instability.

Of 413 people screened, 304 underwent randomization (about 98% male; average age, 52); 152 patients were assigned to each treatment group. The two groups’ patient characteristics did not differ significantly at baseline. Researchers administered prazosin or placebo in escalating divided doses over five weeks to a daily maximum of 20 mg in men and 12 mg in women.

Primary Outcome Measures

The three primary outcome measures were change in score from baseline to 10 weeks on the CAPS item B2, change in score from baseline to 10 weeks on the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, and the Clinical Global Impression of Change score at 10 weeks. None of the primary outcome measures significantly differed between the groups at 10 weeks. The groups’ outcome measures at 26 weeks and other secondary outcomes also were not significantly different.

The number of serious adverse events did not differ significantly by group. Of the adverse events, dizziness, lightheadedness, and urinary incontinence were significantly more common in the prazosin group, compared with the placebo group, whereas new or worsening suicidal ideation was significantly less common among participants who received prazosin, compared with patients who received placebo (8% vs 15%, respectively).

The investigators enrolled patients who were mainly in clinically stable condition, which may have led the trial to include patients whose distressing dreams were unlikely to respond to prazosin, Dr. Raskind and colleagues said.

Future Directions

“The failure of this new, large, multisite trial to replicate the previous studies is surprising and disappointing,” said Kerry J. Ressler, MD, PhD, Chief of the Division of Depression and Anxiety Disorders at McLean Hospital in Belmont, Massachusetts, and Professor of Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School in Boston, in an accompanying editorial. “PTSD remains a psychiatric malady that in some respects seems understandable and treatable on the basis of known neurobiologic pathways. Yet it is a complex syndrome with innumerable subtypes and variations…. There is a need to define clinical subtypes of PTSD on the basis of biologic markers.”

Studies of prazosin for the treatment of other conditions are under way. Investigators have initiated trials to examine whether prazosin reduces the frequency of chronic postconcussive headaches, compared with placebo.

—Jake Remaly

Suggested Reading

Raskind MA, Peskind ER, Chow B, et al. Trial of prazosin for post-traumatic stress disorder in military veterans. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(6):507-517.

Raskind MA, Peterson K, Williams T, et al. A trial of prazosin for combat trauma PTSD with nightmares in active-duty soldiers returned from Iraq and Afghanistan. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(9):1003-1010.

Ressler KJ. Alpha-adrenergic receptors in PTSD - Failure or time for precision medicine? N Engl J Med. 2018; 378(6):575-576.

Perianal Condyloma Acuminatum-like Plaque

The Diagnosis: Metastatic Crohn Disease

Crohn disease (CD), a chronic inflammatory granulomatous disease of the gastrointestinal tract, has a wide spectrum of presentations.1 The condition may affect the vulva, perineum, or perianal skin by direct extension from the gastrointestinal tract or may appear as a separate and distinct cutaneous focus of disease referred to as metastatic Crohn disease (MCD).2

Cutaneous lesions of MCD include ulcers, fissures, sinus tracts, abscesses, and vegetative plaques, which typically extend in continuity with sites of intra-abdominal disease to the perineum, buttocks, or abdominal wall, as well as ostomy sites or incisional scars. Erythema nodosum and pyoderma gangrenosum are the most common nonspecific cutaneous manifestations. Other cutaneous lesions described in CD include polyarteritis nodosa, psoriasis, erythema multiforme, erythema elevatum diutinum, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, acne fulminans, pyoderma faciale, neutrophilic lobular panniculitis, granulomatous vasculitis, and porokeratosis.3

Perianal skin is the most common site of cutaneous involvement in individuals with CD. It is a marker of more severe disease and is associated with multiple surgical interventions and frequent relapses and has been reported in 22% of patients with CD.4 Most already had an existing diagnosis of gastrointestinal CD, which was active in one-third of individuals; however, 20% presented with disease at nongastrointestinal sites 2 months to 4 years prior to developing the gastrointestinal CD manifestations.5 Our patient presented with lesions on the perianal skin of 2 years' duration and a 6-month history of diarrhea. A colonoscopy demonstrated shallow ulcers involving the ileocecal portion of the gut, colon, and rectum. A biopsy from intestinal mucosal tissue showed acute and chronic inflammation with necrosis mixed with granulomatous inflammation, suggestive of CD.

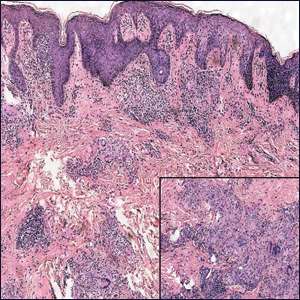

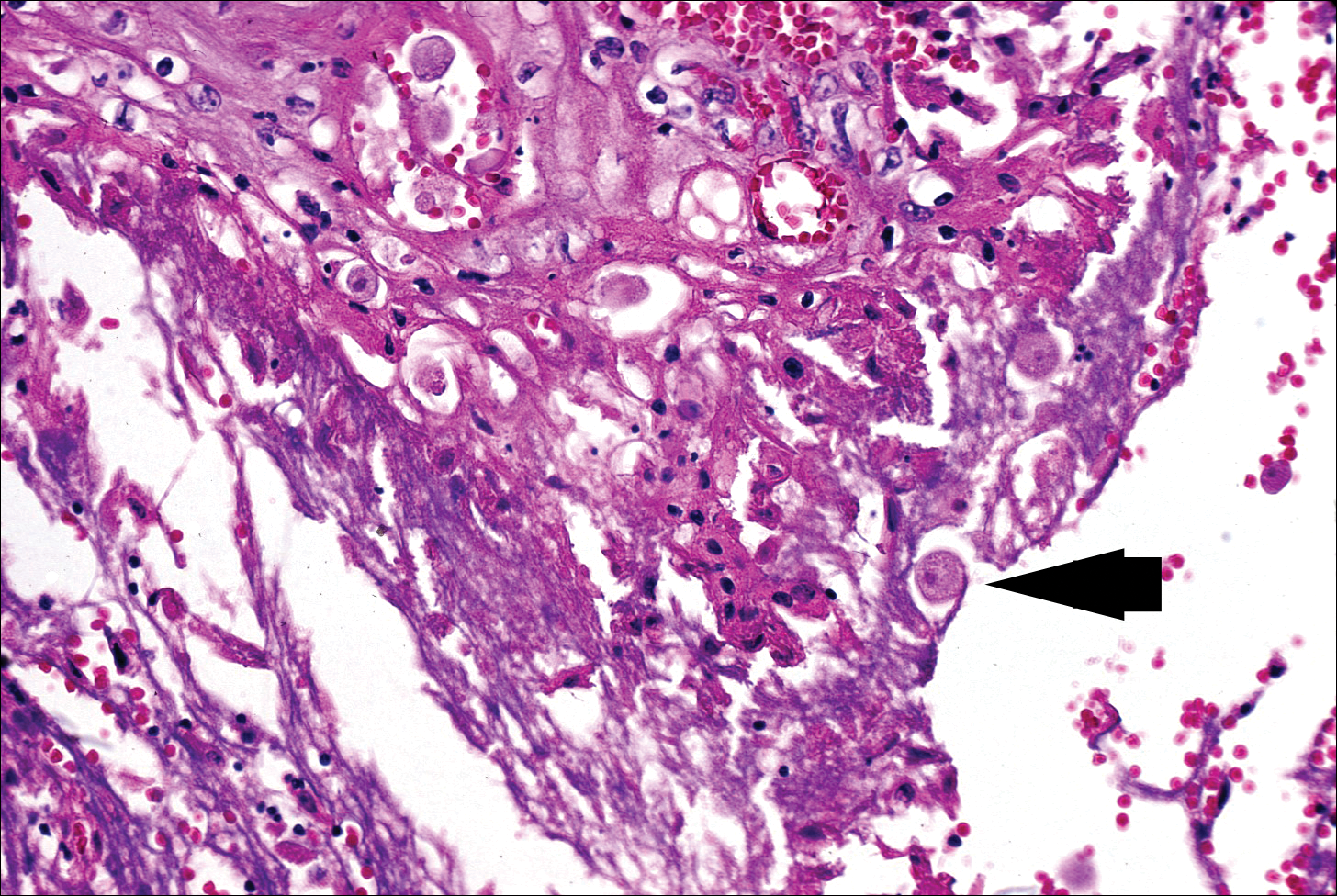

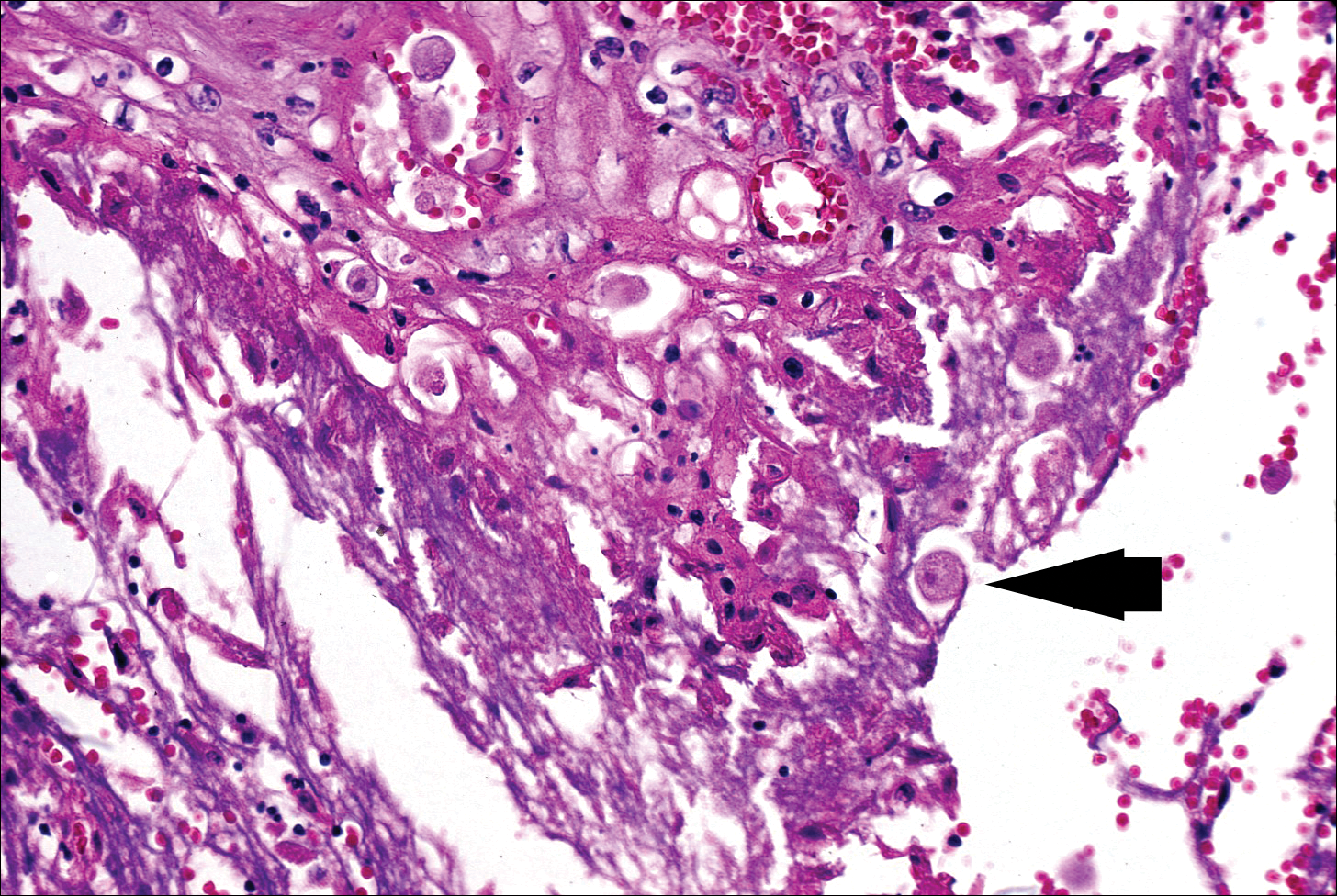

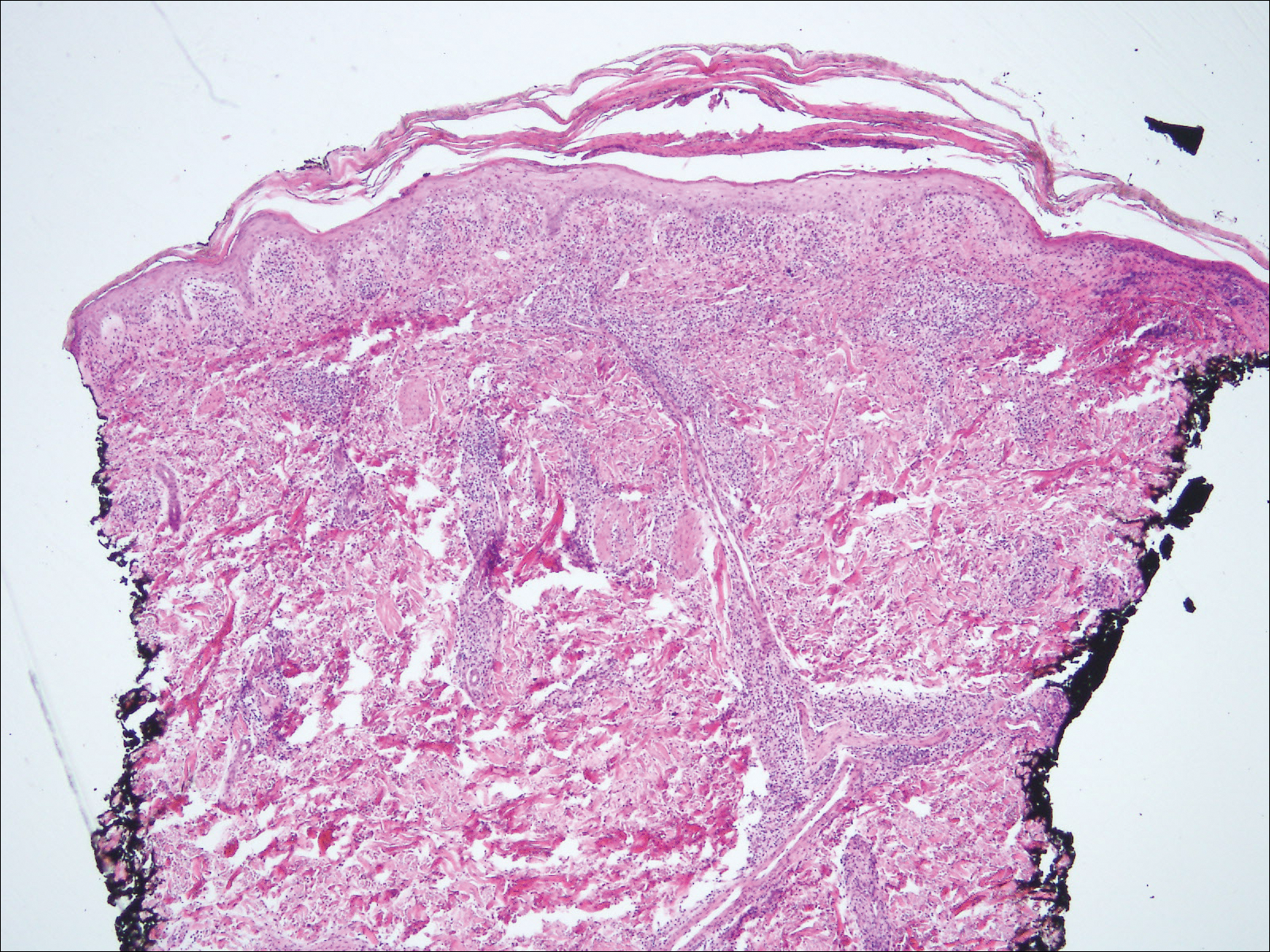

Microscopically, the dominant histologic features of MCD are similar to those of bowel lesions, including an inflammatory infiltrate commonly consisting of sterile noncaseating sarcoidal granulomas, foreign body and Langhans giant cells, epithelioid histiocytes, and plasma cells surrounded by numerous mononuclear cells within the dermis with occasional extension into the subcutis (quiz image). Less common features include collagen degeneration, an infiltrate rich in eosinophils, dermal edema, and mixed lichenoid and granulomatous dermatitis.6

Metastatic CD often is misdiagnosed. A detailed history and physical examination may help narrow the differential; however, biopsy is necessary to establish a diagnosis of MCD. The histologic differential diagnosis of sarcoidal granulomatous inflammation of genital skin includes sarcoidosis, rheumatoid arthritis, leprosy or other mycobacterial and parasitic infection, granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), and granulomatous infiltrate associated with certain exogenous material (eg, silica, zirconium, beryllium, tattoo pigment).

Sarcoidosis is a multiorgan disease that most frequently affects the lungs, skin, and lymph nodes. Its etiopathogenesis has not been clearly elucidated.7 Cutaneous lesions are present in 20% to 35% of patients.8 Given the wide variability of clinical manifestations, cutaneous sarcoidosis is another one of the great imitators. Cutaneous lesions are classified as specific and nonspecific depending on the presence of noncaseating granulomas on histologic studies and include maculopapules, plaques, nodules, lupus pernio, scar infiltration, alopecia, ulcerative lesions, and hypopigmentation. The most common nonspecific lesion of cutaneous sarcoidosis is erythema nodosum. Other manifestations include calcifications, prurigo, erythema multiforme, nail clubbing, and Sweet syndrome.9

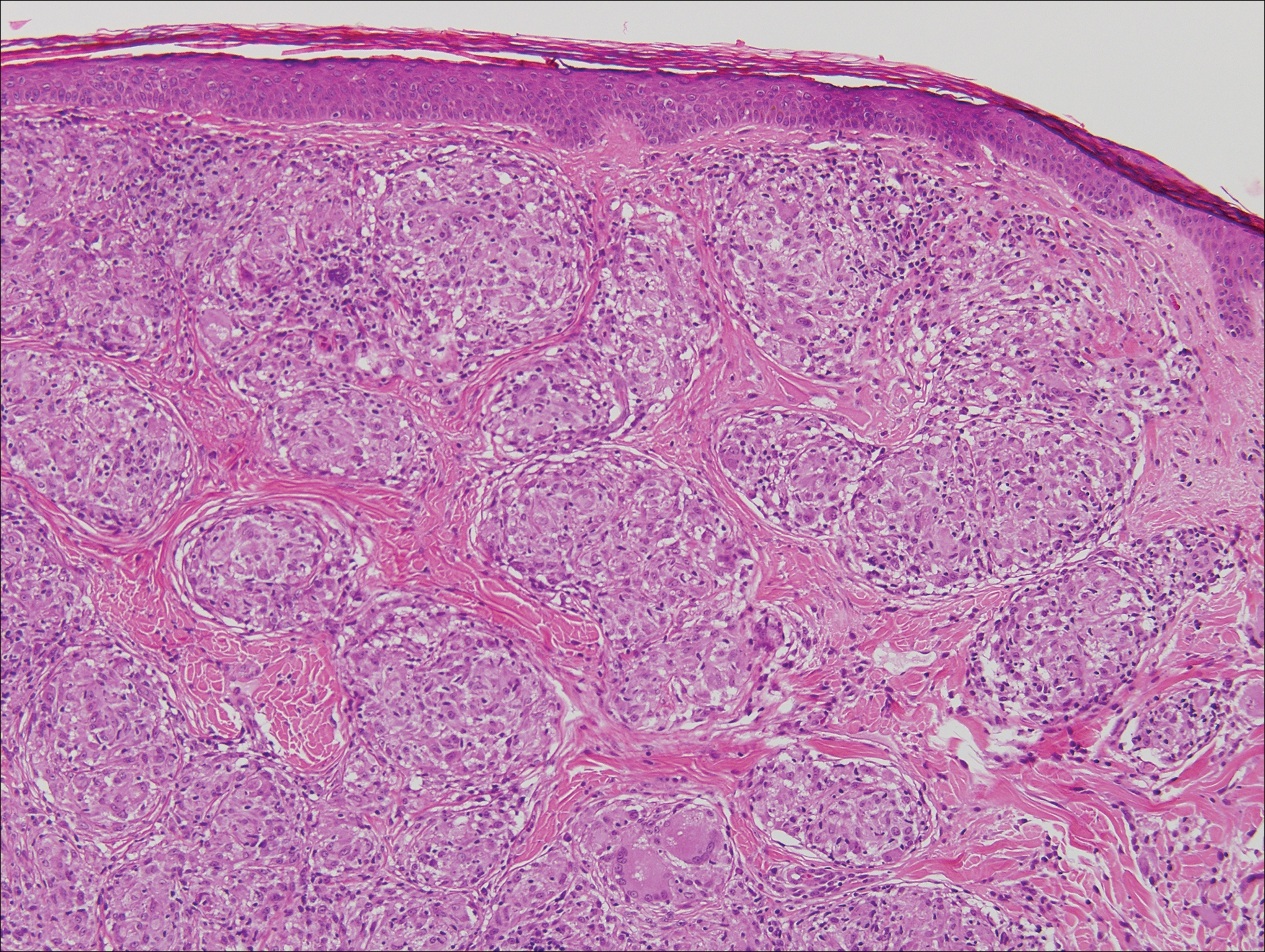

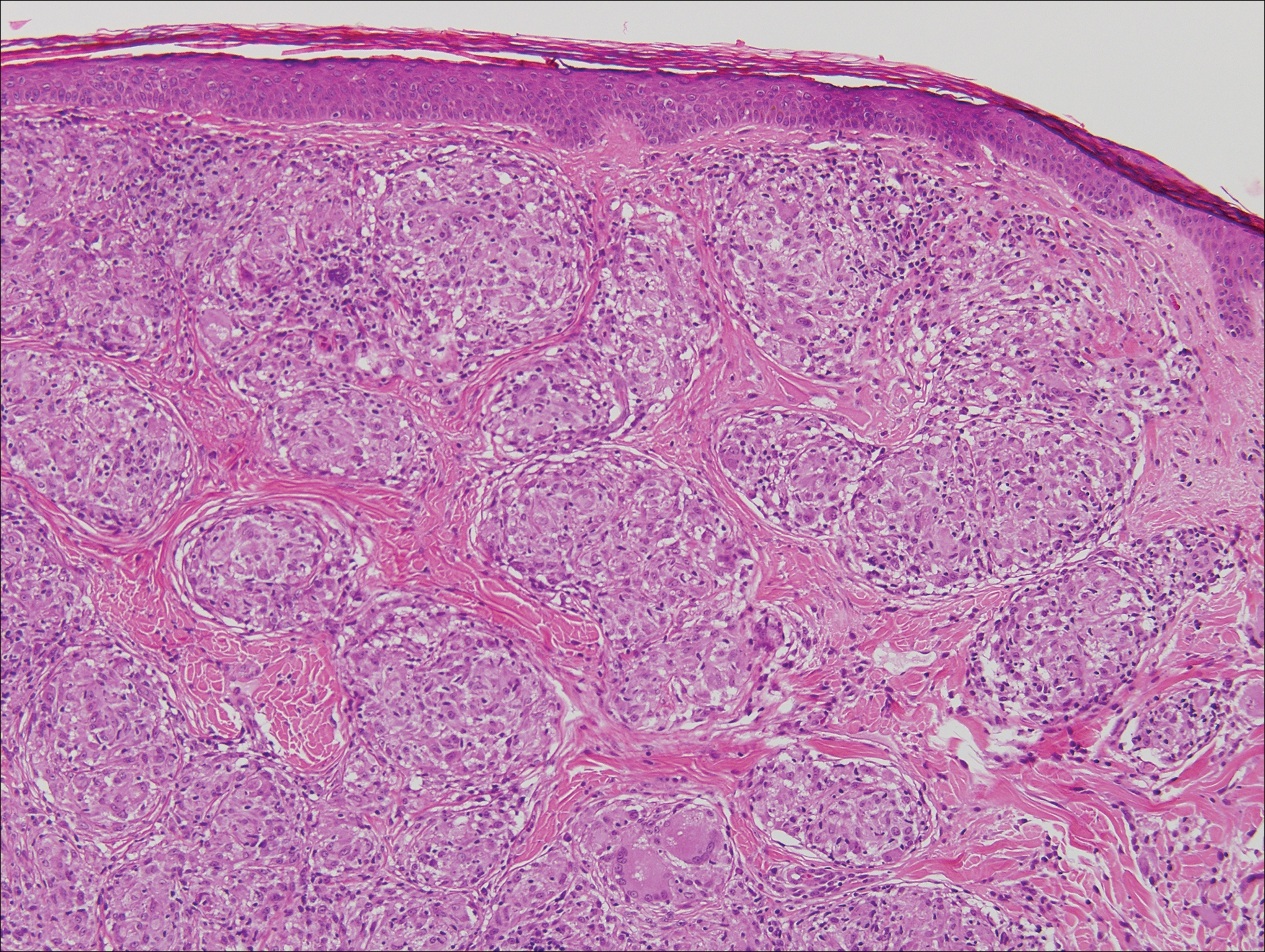

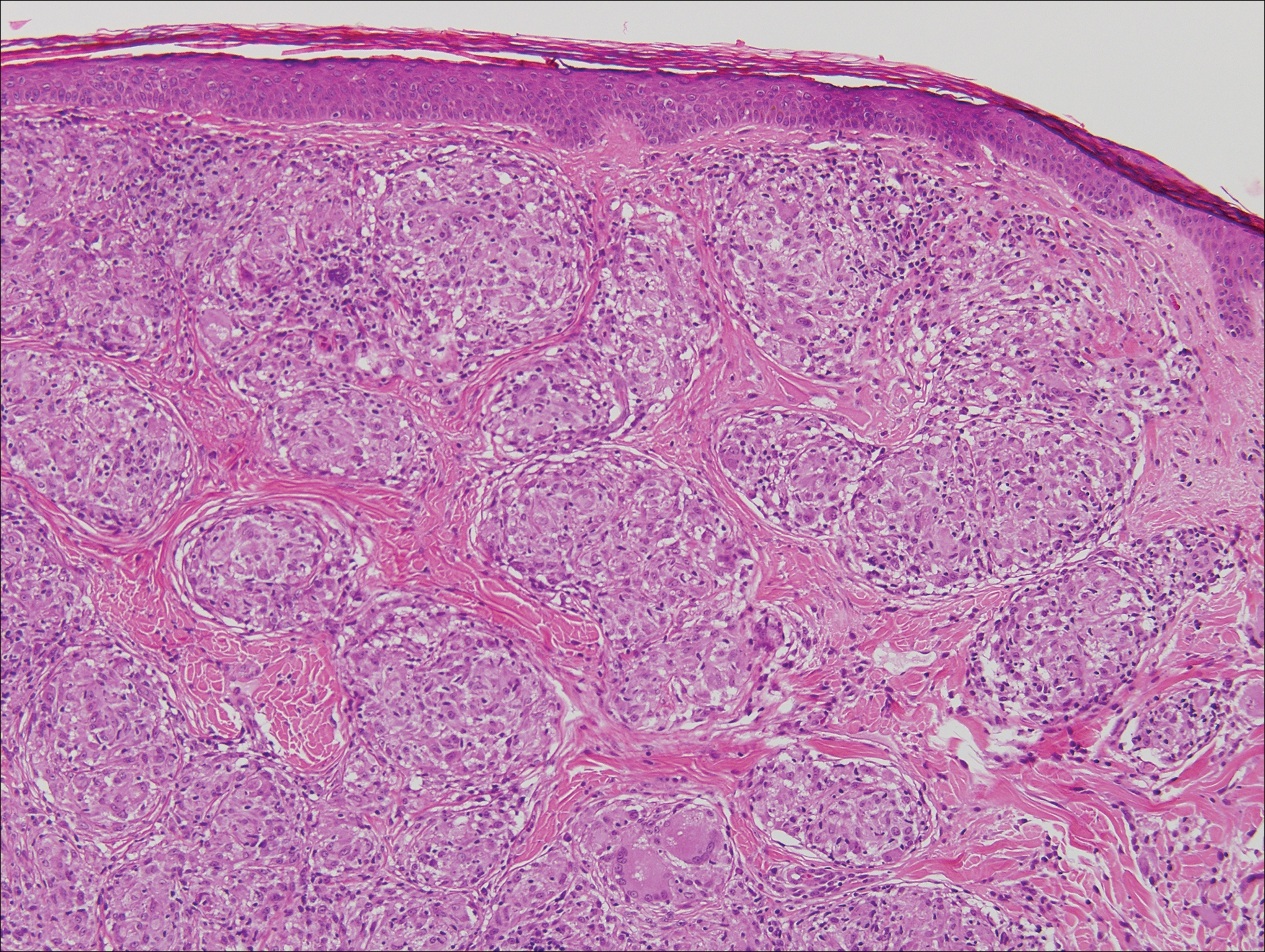

Histologic findings in sarcoidosis generally are independent of the respective organ and clinical disease presentation. The epidermis usually remains unchanged, whereas the dermis shows a superficial and deep nodular granulomatous infiltrate. Granulomas consist of epithelioid cells with only few giant cells and no surrounding lymphocytes or a very sparse lymphocytic infiltrate ("naked" granuloma)(Figure 1). Foreign bodies, including silica, are known to be able to induce sarcoid granulomas, especially in patients with sarcoidosis. A sarcoidal reaction in long-standing scar tissue points to a diagnosis of sarcoidosis.10

Cutaneous tuberculosis primarily is caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis and less frequently Mycobacterium bovis.11,12 The manifestations of cutaneous tuberculosis depends on various factors such as the type of infection, mode of dissemination, host immunity, and whether it is a first-time infection or a recurrence. In Europe, the head and neck regions are most frequently affected.13 Lesions present as red-brown papules coalescing into a plaque. The tissue, especially in central parts of the lesion, is fragile (probe phenomenon). Diascopy shows the typical apple jelly-like color.

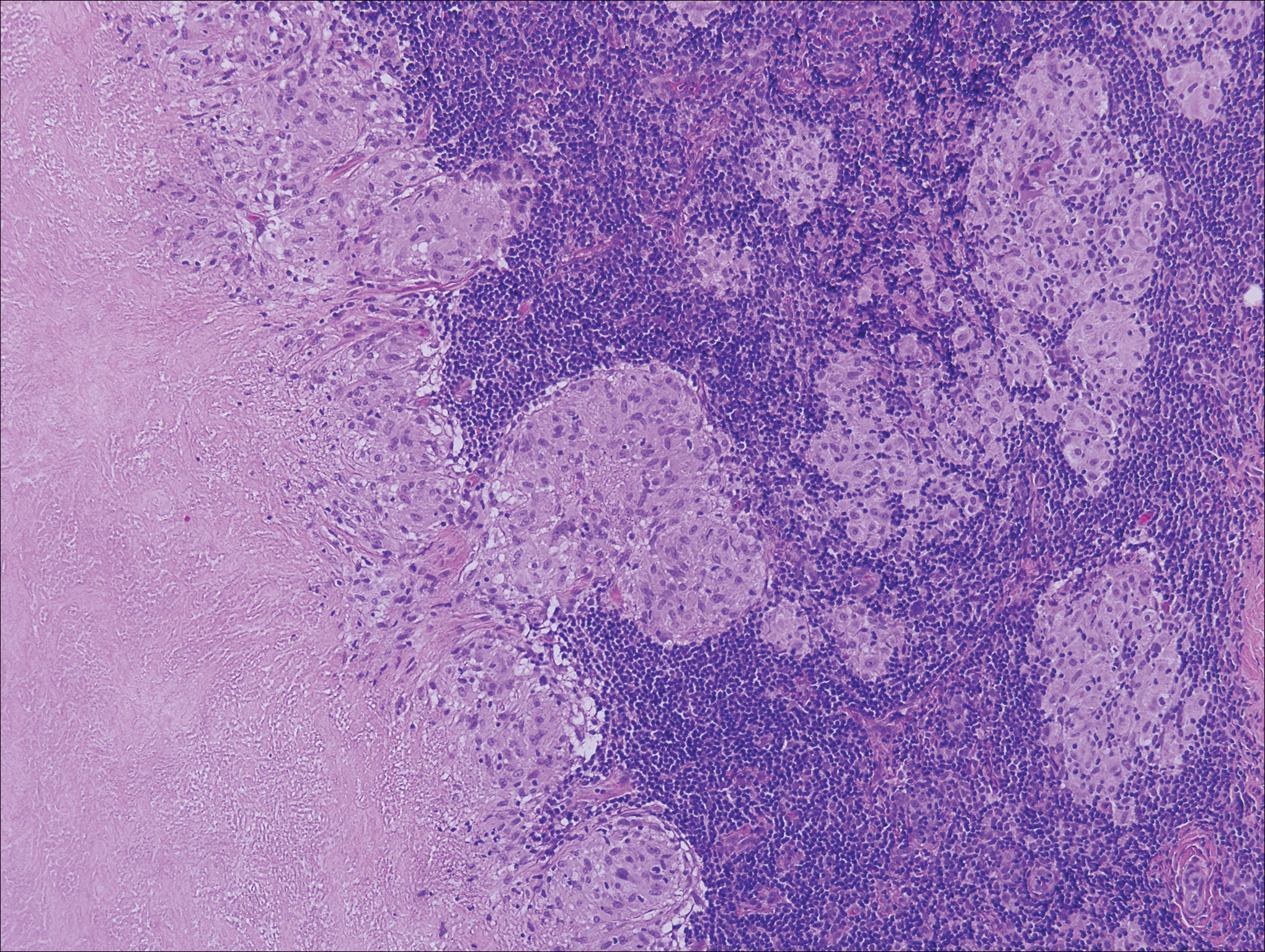

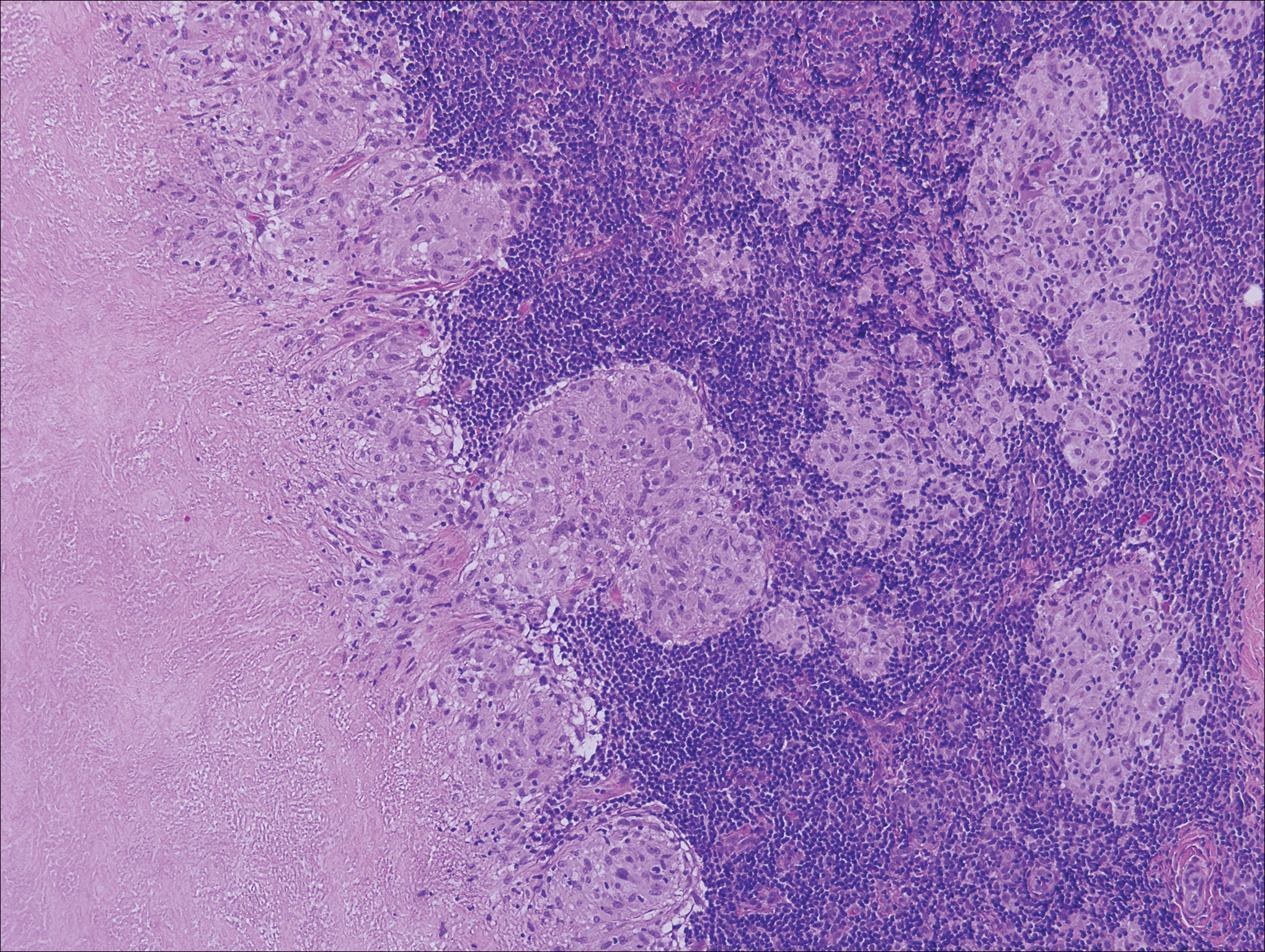

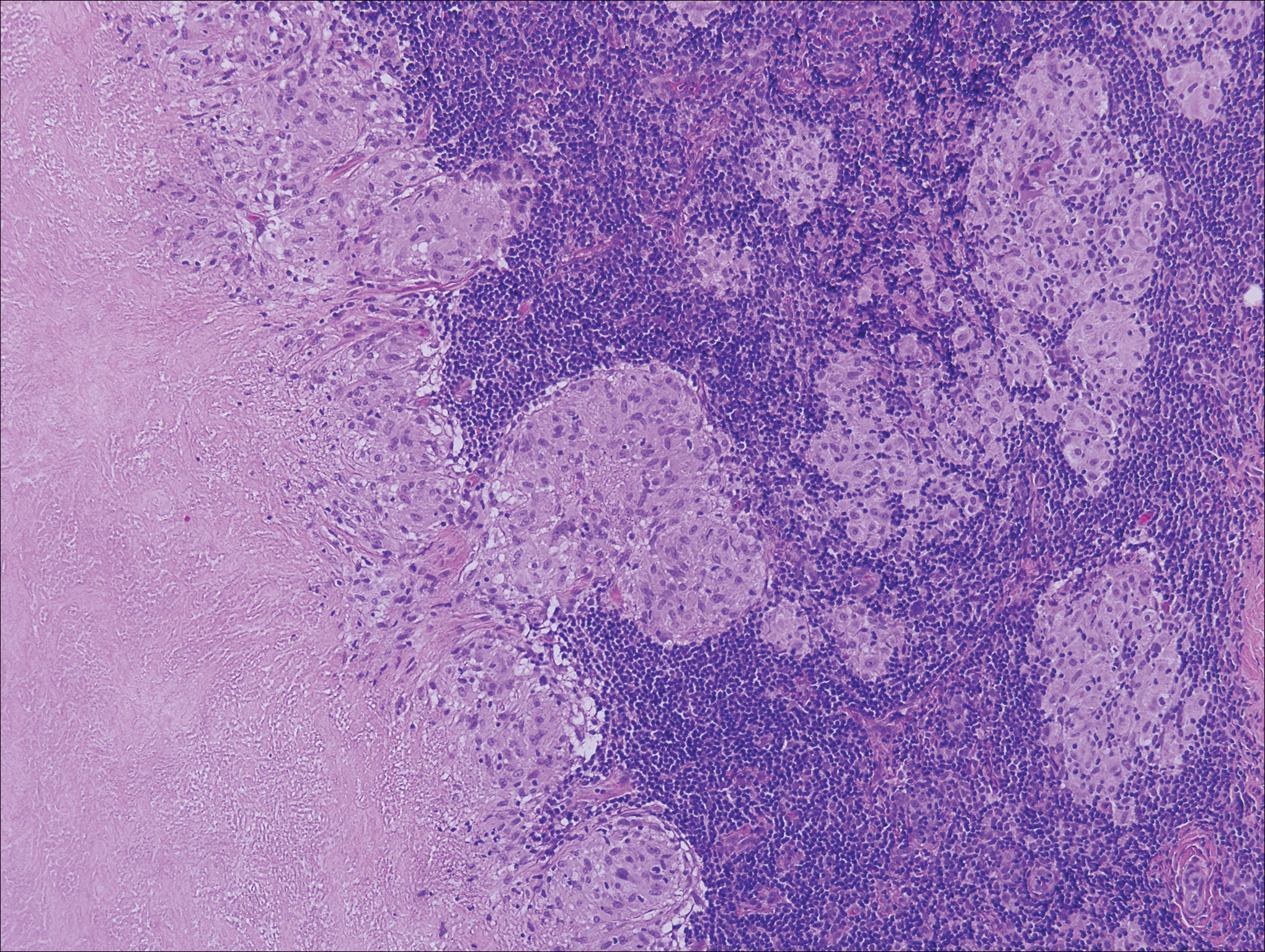

Histologically, cutaneous tuberculosis is characterized by typical tuberculoid granulomas with epithelioid cells and Langhans giant cells at the center surrounded by lymphocytes (Figure 2). Caseous necrosis as well as fibrosis may occur,14,15 and the granulomas tend to coalesce.

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis, formerly known as Wegener granulomatosis, is a complex, multisystemic disease with varying manifestations. The condition has been defined as a necrotizing granulomatous inflammation usually involving the upper and lower respiratory tracts and necrotizing vasculitis affecting predominantly small- to medium-sized vessels.16 The etiology of GPA is thought to be linked to environmental and infectious triggers inciting onset of disease in genetically predisposed individuals. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies play an important role in the pathogenesis of this disease. Cutaneous vasculitis secondary to GPA can present as papules, nodules, palpable purpura, ulcers resembling pyoderma gangrenosum, or necrotizing lesions leading to gangrene.17

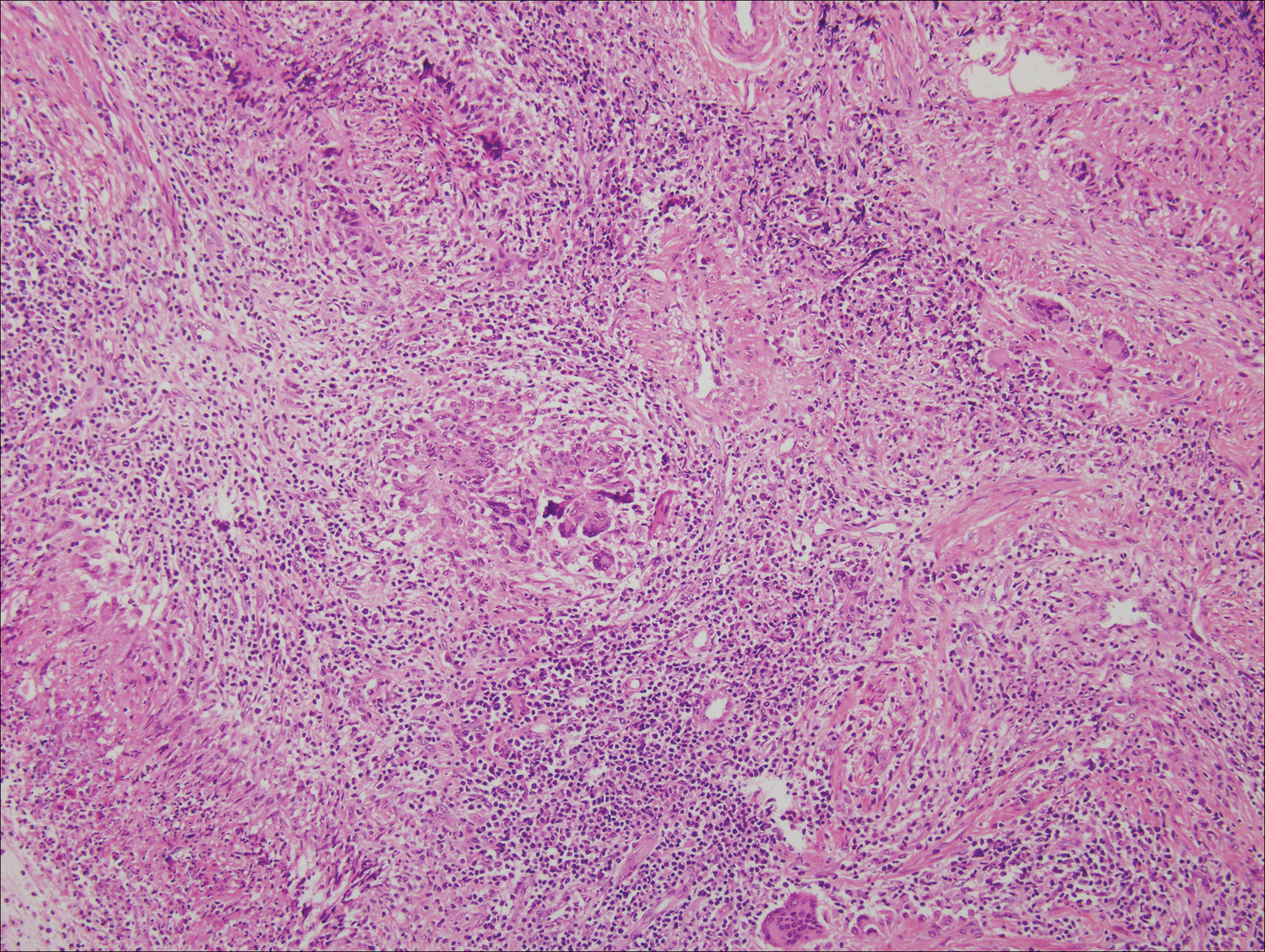

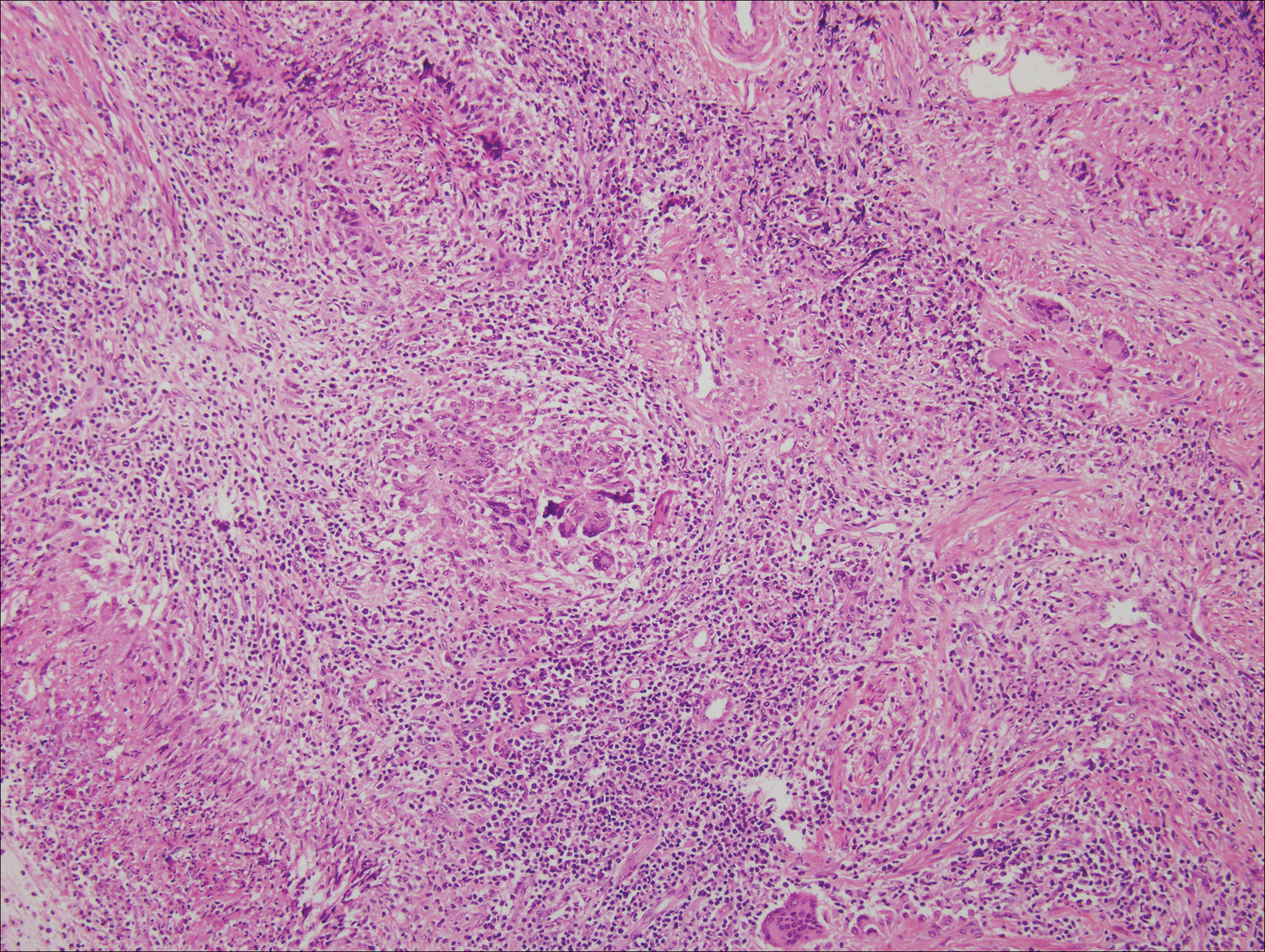

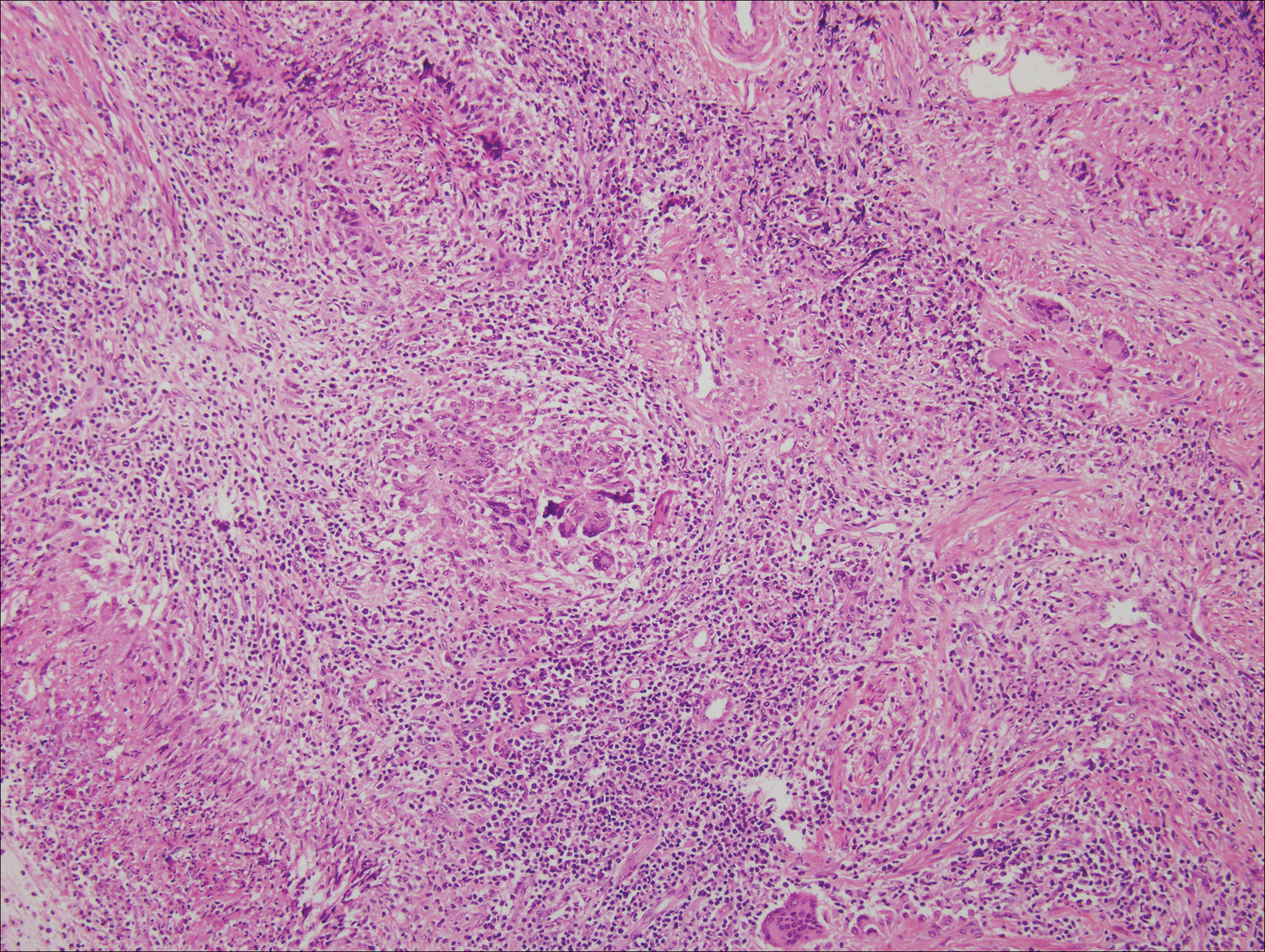

The predominant histopathologic pattern in cutaneous lesions of GPA is leukocytoclastic vasculitis, which is present in up to 50% of biopsies.18 Characteristic findings that aid in establishing the diagnosis include histologic evidence of focal necrosis, fibrinoid degeneration, palisading granuloma surrounding neutrophils (Figure 3), and granulomatous vasculitis involving muscular vessel walls.19 Nonpalisading foci of necrosis or fibrinoid degeneration may precede the development of the typical palisading granuloma.20

The typical histopathologic pattern of cutaneous amebiasis is ulceration with vascular necrosis (Figure 4).21 The organisms have prominent round nuclei and nucleoli and the cytoplasm may have a scalloped border.

- Crohn BB, Ginzburg L, Oppenheimer GD. Landmark article Oct 25, 1932. regional ileitis. a pathologic and clinical entity. by Burril B. Crohn, Leon Gonzburg and Gordon D. Oppenheimer. JAMA. 1984;251:73-79.

- Parks AG, Morson BC, Pegum JS. Crohn's disease with cutaneous involvement. Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58:241-242.

- Weedon D. Miscellaneous conditions. Skin Pathology. 2nd ed. London, England: Churchill Livingstone; 2002:554.

- Samitz MH, Dana Jr AS, Rosenberg P. Cutaneous vasculitis in association with Crohn's disease. Cutis. 1970;6:51-56.

- Palamaras I, El-Jabbour J, Pietropaolo N, et al. Metastatic Crohn's disease: a review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1033-1043.

- Aberumand B, Howard J, Howard J. Metastatic Crohn's disease: an approach to an uncommon but important cutaneous disorder: a review [published online January 3, 2017]. BioMed Res Int. 2017;2017:8192150.

- Mahony J, Helms SE, Brodell RT. The sarcoidal granuloma: a unifying hypothesis for an enigmatic response. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:654-659.

- Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolf K, et al. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. 6th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2003.

- Fernandez-Faith E, McDonnell J. Cutaneous sarcoidosis: differential diagnosis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:276-287.

- Walsh NM, Hanly JG, Tremaine R, et al. Cutaneous sarcoidosis and foreign bodies. Am J Dermatopathol. 1993;15:203-207.

- Semaan R, Traboulsi R, Kanj S. Primary Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex cutaneous infection: report of two cases and literature review. Int J Infect Dis. 2008;12:472-477.

- Lai-Cheong JE, Perez A, Tang V, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of tuberculosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007;32:461-466.

- Marcoval J, Servitje O, Moreno A, et al. Lupus vulgaris. clinical, histopathologic, and bacteriologic study of 10 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:404-407.

- Tronnier M, Wolff H. Dermatosen mit granulomatöser Entzündung. Histopathologie der Haut. In: Kerl H, Garbe C, Cerroni L, et al, eds. New York, NY: Springer; 2003.

- Min KW, Ko JY, Park CK. Histopathological spectrum of cutaneous tuberculosis and non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:582-595.

- Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Bacon PA, et al. 2012 Revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference nomenclature of vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:1-11.

- Comfere NI, Macaron NC, Gibson LE. Cutaneous manifestations of Wegener's granulomatosis: a clinicopathologic study of 17 patients and correlation to antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody status. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:739-747.

- Marzano AV, Vezzoli P, Berti E. Skin involvement in cutaneous and systemic vasculitis. Autoimmun Rev. 2012;12:467-476.

- Bramsiepe I, Danz B, Heine R, et al. Primary cutaneous manifestation of Wegener's granulomatosis [in German]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2008;27:1429-1432.

- Daoud MS, Gibson LE, DeRemee RA, et al. Cutaneous Wegener's granulomatosis: clinical, histopathologic, and immunopathologic features of thirty patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:605-612.

- Guidry JA, Downing C, Tyring SK. Deep fungal infections, blastomycosis-like pyoderma, and granulomatous sexually transmitted infections. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:595-607.

The Diagnosis: Metastatic Crohn Disease

Crohn disease (CD), a chronic inflammatory granulomatous disease of the gastrointestinal tract, has a wide spectrum of presentations.1 The condition may affect the vulva, perineum, or perianal skin by direct extension from the gastrointestinal tract or may appear as a separate and distinct cutaneous focus of disease referred to as metastatic Crohn disease (MCD).2

Cutaneous lesions of MCD include ulcers, fissures, sinus tracts, abscesses, and vegetative plaques, which typically extend in continuity with sites of intra-abdominal disease to the perineum, buttocks, or abdominal wall, as well as ostomy sites or incisional scars. Erythema nodosum and pyoderma gangrenosum are the most common nonspecific cutaneous manifestations. Other cutaneous lesions described in CD include polyarteritis nodosa, psoriasis, erythema multiforme, erythema elevatum diutinum, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, acne fulminans, pyoderma faciale, neutrophilic lobular panniculitis, granulomatous vasculitis, and porokeratosis.3

Perianal skin is the most common site of cutaneous involvement in individuals with CD. It is a marker of more severe disease and is associated with multiple surgical interventions and frequent relapses and has been reported in 22% of patients with CD.4 Most already had an existing diagnosis of gastrointestinal CD, which was active in one-third of individuals; however, 20% presented with disease at nongastrointestinal sites 2 months to 4 years prior to developing the gastrointestinal CD manifestations.5 Our patient presented with lesions on the perianal skin of 2 years' duration and a 6-month history of diarrhea. A colonoscopy demonstrated shallow ulcers involving the ileocecal portion of the gut, colon, and rectum. A biopsy from intestinal mucosal tissue showed acute and chronic inflammation with necrosis mixed with granulomatous inflammation, suggestive of CD.

Microscopically, the dominant histologic features of MCD are similar to those of bowel lesions, including an inflammatory infiltrate commonly consisting of sterile noncaseating sarcoidal granulomas, foreign body and Langhans giant cells, epithelioid histiocytes, and plasma cells surrounded by numerous mononuclear cells within the dermis with occasional extension into the subcutis (quiz image). Less common features include collagen degeneration, an infiltrate rich in eosinophils, dermal edema, and mixed lichenoid and granulomatous dermatitis.6

Metastatic CD often is misdiagnosed. A detailed history and physical examination may help narrow the differential; however, biopsy is necessary to establish a diagnosis of MCD. The histologic differential diagnosis of sarcoidal granulomatous inflammation of genital skin includes sarcoidosis, rheumatoid arthritis, leprosy or other mycobacterial and parasitic infection, granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), and granulomatous infiltrate associated with certain exogenous material (eg, silica, zirconium, beryllium, tattoo pigment).

Sarcoidosis is a multiorgan disease that most frequently affects the lungs, skin, and lymph nodes. Its etiopathogenesis has not been clearly elucidated.7 Cutaneous lesions are present in 20% to 35% of patients.8 Given the wide variability of clinical manifestations, cutaneous sarcoidosis is another one of the great imitators. Cutaneous lesions are classified as specific and nonspecific depending on the presence of noncaseating granulomas on histologic studies and include maculopapules, plaques, nodules, lupus pernio, scar infiltration, alopecia, ulcerative lesions, and hypopigmentation. The most common nonspecific lesion of cutaneous sarcoidosis is erythema nodosum. Other manifestations include calcifications, prurigo, erythema multiforme, nail clubbing, and Sweet syndrome.9

Histologic findings in sarcoidosis generally are independent of the respective organ and clinical disease presentation. The epidermis usually remains unchanged, whereas the dermis shows a superficial and deep nodular granulomatous infiltrate. Granulomas consist of epithelioid cells with only few giant cells and no surrounding lymphocytes or a very sparse lymphocytic infiltrate ("naked" granuloma)(Figure 1). Foreign bodies, including silica, are known to be able to induce sarcoid granulomas, especially in patients with sarcoidosis. A sarcoidal reaction in long-standing scar tissue points to a diagnosis of sarcoidosis.10

Cutaneous tuberculosis primarily is caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis and less frequently Mycobacterium bovis.11,12 The manifestations of cutaneous tuberculosis depends on various factors such as the type of infection, mode of dissemination, host immunity, and whether it is a first-time infection or a recurrence. In Europe, the head and neck regions are most frequently affected.13 Lesions present as red-brown papules coalescing into a plaque. The tissue, especially in central parts of the lesion, is fragile (probe phenomenon). Diascopy shows the typical apple jelly-like color.

Histologically, cutaneous tuberculosis is characterized by typical tuberculoid granulomas with epithelioid cells and Langhans giant cells at the center surrounded by lymphocytes (Figure 2). Caseous necrosis as well as fibrosis may occur,14,15 and the granulomas tend to coalesce.

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis, formerly known as Wegener granulomatosis, is a complex, multisystemic disease with varying manifestations. The condition has been defined as a necrotizing granulomatous inflammation usually involving the upper and lower respiratory tracts and necrotizing vasculitis affecting predominantly small- to medium-sized vessels.16 The etiology of GPA is thought to be linked to environmental and infectious triggers inciting onset of disease in genetically predisposed individuals. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies play an important role in the pathogenesis of this disease. Cutaneous vasculitis secondary to GPA can present as papules, nodules, palpable purpura, ulcers resembling pyoderma gangrenosum, or necrotizing lesions leading to gangrene.17

The predominant histopathologic pattern in cutaneous lesions of GPA is leukocytoclastic vasculitis, which is present in up to 50% of biopsies.18 Characteristic findings that aid in establishing the diagnosis include histologic evidence of focal necrosis, fibrinoid degeneration, palisading granuloma surrounding neutrophils (Figure 3), and granulomatous vasculitis involving muscular vessel walls.19 Nonpalisading foci of necrosis or fibrinoid degeneration may precede the development of the typical palisading granuloma.20

The typical histopathologic pattern of cutaneous amebiasis is ulceration with vascular necrosis (Figure 4).21 The organisms have prominent round nuclei and nucleoli and the cytoplasm may have a scalloped border.

The Diagnosis: Metastatic Crohn Disease

Crohn disease (CD), a chronic inflammatory granulomatous disease of the gastrointestinal tract, has a wide spectrum of presentations.1 The condition may affect the vulva, perineum, or perianal skin by direct extension from the gastrointestinal tract or may appear as a separate and distinct cutaneous focus of disease referred to as metastatic Crohn disease (MCD).2

Cutaneous lesions of MCD include ulcers, fissures, sinus tracts, abscesses, and vegetative plaques, which typically extend in continuity with sites of intra-abdominal disease to the perineum, buttocks, or abdominal wall, as well as ostomy sites or incisional scars. Erythema nodosum and pyoderma gangrenosum are the most common nonspecific cutaneous manifestations. Other cutaneous lesions described in CD include polyarteritis nodosa, psoriasis, erythema multiforme, erythema elevatum diutinum, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, acne fulminans, pyoderma faciale, neutrophilic lobular panniculitis, granulomatous vasculitis, and porokeratosis.3

Perianal skin is the most common site of cutaneous involvement in individuals with CD. It is a marker of more severe disease and is associated with multiple surgical interventions and frequent relapses and has been reported in 22% of patients with CD.4 Most already had an existing diagnosis of gastrointestinal CD, which was active in one-third of individuals; however, 20% presented with disease at nongastrointestinal sites 2 months to 4 years prior to developing the gastrointestinal CD manifestations.5 Our patient presented with lesions on the perianal skin of 2 years' duration and a 6-month history of diarrhea. A colonoscopy demonstrated shallow ulcers involving the ileocecal portion of the gut, colon, and rectum. A biopsy from intestinal mucosal tissue showed acute and chronic inflammation with necrosis mixed with granulomatous inflammation, suggestive of CD.

Microscopically, the dominant histologic features of MCD are similar to those of bowel lesions, including an inflammatory infiltrate commonly consisting of sterile noncaseating sarcoidal granulomas, foreign body and Langhans giant cells, epithelioid histiocytes, and plasma cells surrounded by numerous mononuclear cells within the dermis with occasional extension into the subcutis (quiz image). Less common features include collagen degeneration, an infiltrate rich in eosinophils, dermal edema, and mixed lichenoid and granulomatous dermatitis.6

Metastatic CD often is misdiagnosed. A detailed history and physical examination may help narrow the differential; however, biopsy is necessary to establish a diagnosis of MCD. The histologic differential diagnosis of sarcoidal granulomatous inflammation of genital skin includes sarcoidosis, rheumatoid arthritis, leprosy or other mycobacterial and parasitic infection, granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), and granulomatous infiltrate associated with certain exogenous material (eg, silica, zirconium, beryllium, tattoo pigment).

Sarcoidosis is a multiorgan disease that most frequently affects the lungs, skin, and lymph nodes. Its etiopathogenesis has not been clearly elucidated.7 Cutaneous lesions are present in 20% to 35% of patients.8 Given the wide variability of clinical manifestations, cutaneous sarcoidosis is another one of the great imitators. Cutaneous lesions are classified as specific and nonspecific depending on the presence of noncaseating granulomas on histologic studies and include maculopapules, plaques, nodules, lupus pernio, scar infiltration, alopecia, ulcerative lesions, and hypopigmentation. The most common nonspecific lesion of cutaneous sarcoidosis is erythema nodosum. Other manifestations include calcifications, prurigo, erythema multiforme, nail clubbing, and Sweet syndrome.9

Histologic findings in sarcoidosis generally are independent of the respective organ and clinical disease presentation. The epidermis usually remains unchanged, whereas the dermis shows a superficial and deep nodular granulomatous infiltrate. Granulomas consist of epithelioid cells with only few giant cells and no surrounding lymphocytes or a very sparse lymphocytic infiltrate ("naked" granuloma)(Figure 1). Foreign bodies, including silica, are known to be able to induce sarcoid granulomas, especially in patients with sarcoidosis. A sarcoidal reaction in long-standing scar tissue points to a diagnosis of sarcoidosis.10

Cutaneous tuberculosis primarily is caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis and less frequently Mycobacterium bovis.11,12 The manifestations of cutaneous tuberculosis depends on various factors such as the type of infection, mode of dissemination, host immunity, and whether it is a first-time infection or a recurrence. In Europe, the head and neck regions are most frequently affected.13 Lesions present as red-brown papules coalescing into a plaque. The tissue, especially in central parts of the lesion, is fragile (probe phenomenon). Diascopy shows the typical apple jelly-like color.

Histologically, cutaneous tuberculosis is characterized by typical tuberculoid granulomas with epithelioid cells and Langhans giant cells at the center surrounded by lymphocytes (Figure 2). Caseous necrosis as well as fibrosis may occur,14,15 and the granulomas tend to coalesce.

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis, formerly known as Wegener granulomatosis, is a complex, multisystemic disease with varying manifestations. The condition has been defined as a necrotizing granulomatous inflammation usually involving the upper and lower respiratory tracts and necrotizing vasculitis affecting predominantly small- to medium-sized vessels.16 The etiology of GPA is thought to be linked to environmental and infectious triggers inciting onset of disease in genetically predisposed individuals. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies play an important role in the pathogenesis of this disease. Cutaneous vasculitis secondary to GPA can present as papules, nodules, palpable purpura, ulcers resembling pyoderma gangrenosum, or necrotizing lesions leading to gangrene.17

The predominant histopathologic pattern in cutaneous lesions of GPA is leukocytoclastic vasculitis, which is present in up to 50% of biopsies.18 Characteristic findings that aid in establishing the diagnosis include histologic evidence of focal necrosis, fibrinoid degeneration, palisading granuloma surrounding neutrophils (Figure 3), and granulomatous vasculitis involving muscular vessel walls.19 Nonpalisading foci of necrosis or fibrinoid degeneration may precede the development of the typical palisading granuloma.20

The typical histopathologic pattern of cutaneous amebiasis is ulceration with vascular necrosis (Figure 4).21 The organisms have prominent round nuclei and nucleoli and the cytoplasm may have a scalloped border.

- Crohn BB, Ginzburg L, Oppenheimer GD. Landmark article Oct 25, 1932. regional ileitis. a pathologic and clinical entity. by Burril B. Crohn, Leon Gonzburg and Gordon D. Oppenheimer. JAMA. 1984;251:73-79.

- Parks AG, Morson BC, Pegum JS. Crohn's disease with cutaneous involvement. Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58:241-242.

- Weedon D. Miscellaneous conditions. Skin Pathology. 2nd ed. London, England: Churchill Livingstone; 2002:554.

- Samitz MH, Dana Jr AS, Rosenberg P. Cutaneous vasculitis in association with Crohn's disease. Cutis. 1970;6:51-56.

- Palamaras I, El-Jabbour J, Pietropaolo N, et al. Metastatic Crohn's disease: a review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1033-1043.

- Aberumand B, Howard J, Howard J. Metastatic Crohn's disease: an approach to an uncommon but important cutaneous disorder: a review [published online January 3, 2017]. BioMed Res Int. 2017;2017:8192150.

- Mahony J, Helms SE, Brodell RT. The sarcoidal granuloma: a unifying hypothesis for an enigmatic response. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:654-659.

- Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolf K, et al. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. 6th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2003.

- Fernandez-Faith E, McDonnell J. Cutaneous sarcoidosis: differential diagnosis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:276-287.

- Walsh NM, Hanly JG, Tremaine R, et al. Cutaneous sarcoidosis and foreign bodies. Am J Dermatopathol. 1993;15:203-207.

- Semaan R, Traboulsi R, Kanj S. Primary Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex cutaneous infection: report of two cases and literature review. Int J Infect Dis. 2008;12:472-477.

- Lai-Cheong JE, Perez A, Tang V, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of tuberculosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007;32:461-466.

- Marcoval J, Servitje O, Moreno A, et al. Lupus vulgaris. clinical, histopathologic, and bacteriologic study of 10 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:404-407.

- Tronnier M, Wolff H. Dermatosen mit granulomatöser Entzündung. Histopathologie der Haut. In: Kerl H, Garbe C, Cerroni L, et al, eds. New York, NY: Springer; 2003.

- Min KW, Ko JY, Park CK. Histopathological spectrum of cutaneous tuberculosis and non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:582-595.

- Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Bacon PA, et al. 2012 Revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference nomenclature of vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:1-11.

- Comfere NI, Macaron NC, Gibson LE. Cutaneous manifestations of Wegener's granulomatosis: a clinicopathologic study of 17 patients and correlation to antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody status. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:739-747.

- Marzano AV, Vezzoli P, Berti E. Skin involvement in cutaneous and systemic vasculitis. Autoimmun Rev. 2012;12:467-476.

- Bramsiepe I, Danz B, Heine R, et al. Primary cutaneous manifestation of Wegener's granulomatosis [in German]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2008;27:1429-1432.

- Daoud MS, Gibson LE, DeRemee RA, et al. Cutaneous Wegener's granulomatosis: clinical, histopathologic, and immunopathologic features of thirty patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:605-612.

- Guidry JA, Downing C, Tyring SK. Deep fungal infections, blastomycosis-like pyoderma, and granulomatous sexually transmitted infections. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:595-607.

- Crohn BB, Ginzburg L, Oppenheimer GD. Landmark article Oct 25, 1932. regional ileitis. a pathologic and clinical entity. by Burril B. Crohn, Leon Gonzburg and Gordon D. Oppenheimer. JAMA. 1984;251:73-79.

- Parks AG, Morson BC, Pegum JS. Crohn's disease with cutaneous involvement. Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58:241-242.

- Weedon D. Miscellaneous conditions. Skin Pathology. 2nd ed. London, England: Churchill Livingstone; 2002:554.

- Samitz MH, Dana Jr AS, Rosenberg P. Cutaneous vasculitis in association with Crohn's disease. Cutis. 1970;6:51-56.

- Palamaras I, El-Jabbour J, Pietropaolo N, et al. Metastatic Crohn's disease: a review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1033-1043.

- Aberumand B, Howard J, Howard J. Metastatic Crohn's disease: an approach to an uncommon but important cutaneous disorder: a review [published online January 3, 2017]. BioMed Res Int. 2017;2017:8192150.

- Mahony J, Helms SE, Brodell RT. The sarcoidal granuloma: a unifying hypothesis for an enigmatic response. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:654-659.

- Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolf K, et al. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. 6th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2003.

- Fernandez-Faith E, McDonnell J. Cutaneous sarcoidosis: differential diagnosis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:276-287.

- Walsh NM, Hanly JG, Tremaine R, et al. Cutaneous sarcoidosis and foreign bodies. Am J Dermatopathol. 1993;15:203-207.

- Semaan R, Traboulsi R, Kanj S. Primary Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex cutaneous infection: report of two cases and literature review. Int J Infect Dis. 2008;12:472-477.

- Lai-Cheong JE, Perez A, Tang V, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of tuberculosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007;32:461-466.

- Marcoval J, Servitje O, Moreno A, et al. Lupus vulgaris. clinical, histopathologic, and bacteriologic study of 10 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:404-407.

- Tronnier M, Wolff H. Dermatosen mit granulomatöser Entzündung. Histopathologie der Haut. In: Kerl H, Garbe C, Cerroni L, et al, eds. New York, NY: Springer; 2003.

- Min KW, Ko JY, Park CK. Histopathological spectrum of cutaneous tuberculosis and non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:582-595.

- Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Bacon PA, et al. 2012 Revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference nomenclature of vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:1-11.

- Comfere NI, Macaron NC, Gibson LE. Cutaneous manifestations of Wegener's granulomatosis: a clinicopathologic study of 17 patients and correlation to antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody status. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:739-747.

- Marzano AV, Vezzoli P, Berti E. Skin involvement in cutaneous and systemic vasculitis. Autoimmun Rev. 2012;12:467-476.

- Bramsiepe I, Danz B, Heine R, et al. Primary cutaneous manifestation of Wegener's granulomatosis [in German]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2008;27:1429-1432.

- Daoud MS, Gibson LE, DeRemee RA, et al. Cutaneous Wegener's granulomatosis: clinical, histopathologic, and immunopathologic features of thirty patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:605-612.

- Guidry JA, Downing C, Tyring SK. Deep fungal infections, blastomycosis-like pyoderma, and granulomatous sexually transmitted infections. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:595-607.

A 19-year-old man presented with a perianal condyloma acuminatum-like plaque of 2 years' duration and a 6-month history of diarrhea.

Aspirin Reduces Stroke Risk Associated With Preeclampsia

LOS ANGELES—Women with a history of preeclampsia have a significantly increased risk for early-onset stroke, but that risk is reduced in women taking aspirin, according to research described at the International Stroke Conference 2018.

The results came from an epidemiologic analysis of data for 83,790 women in the California Teachers Study. Among the 4,072 women with a history of preeclampsia, 3,003 were not on aspirin. During follow-up, these women had an incidence of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke before age 60 of greater than 1%. Their incidence rate was 40% higher than that of the approximately 60,000 women without a history of preeclampsia who were not taking aspirin. The difference between groups remained statistically significant after the researchers adjusted the data for demographics, smoking, obesity, diabetes, and hypertension, said Eliza C. Miller, MD, a vascular neurologist at Columbia University in New York.

The findings suggest that an aspirin prevention trial in women at high risk for stroke, such as women with a history of preeclampsia, is warranted, said Dr. Miller. Cardiovascular risk prediction models such as the Framingham Risk Score could be modified to account for a history of preeclampsia, she added.

Dr. Miller’s analysis focused on women who entered the California Teachers Study when they were younger than 60, had no history of stroke, and provided data on their history of preeclampsia. The prevalence of a history of preeclampsia was 4.9% overall and 6.1% among women who had been pregnant at least once. This incidence rate was similar to those of other large populations of women, said Dr. Miller.

The average age was 44 among women with preeclampsia and 46 among women without preeclampsia. Women with a history of preeclampsia also had higher prevalence rates of obesity, hypertension, diabetes, and chronic kidney disease. About a quarter of all women regularly took aspirin.

After data adjustment, women with a history of preeclampsia had a 20% higher overall rate of stroke before age 60. The difference between groups was not significant in an analysis that included women taking aspirin and those not taking it. When the analysis examined only women not taking aspirin, the stroke rate in women with a history of preeclampsia was 40% higher than that in women without a history of preeclampsia, a statistically significant difference. In contrast, among women taking aspirin, women with and without a history of preeclampsia had similar rates of stroke.

—Mitchel L. Zoler