User login

Thalidomide Analogue Drug Eruption Along the Lines of Blaschko

To the Editor:

Lenalidomide is a thalidomide analogue used to treat various hematologic malignancies, including non-Hodgkin lymphoma, myelodysplastic syndrome, and multiple myeloma (MM).1 Lenalidomide is referred to as a degrader therapeutic because it induces targeted protein degradation of disease-relevant proteins (eg, Ikaros family zinc finger protein 1 [IKZF1], Ikaros family zinc finger protein 3 [IKZF3], and casein kinase I isoform-α [CK1α]) as its primary mechanism of action.1,2 Although cutaneous adverse events are relatively common among thalidomide analogues, the morphologic and histopathologic descriptions of these drug eruptions have not been fully elucidated.3,4 We report a novel pityriasiform drug eruption followed by a clinical eruption suggestive of blaschkitis in a patient with MM who was being treated with lenalidomide.

A 76-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic with a progressive, mildly pruritic eruption on the chest and axillae of 1 year’s duration. He had a medical history of chronic hepatitis B, malignant carcinoid tumor of the colon, prostate cancer, and MM. The eruption emerged 1 to 2 weeks after the patient started oral lenalidomide 10 mg/d and oral dexamethasone40 mg/wk following autologous stem cell transplantation for MM. The patient had not received any other therapy for MM.

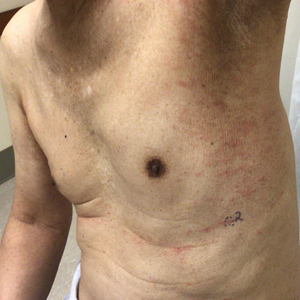

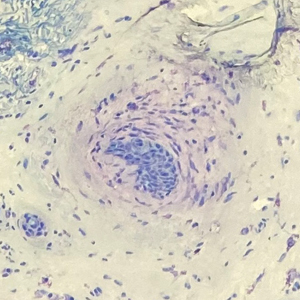

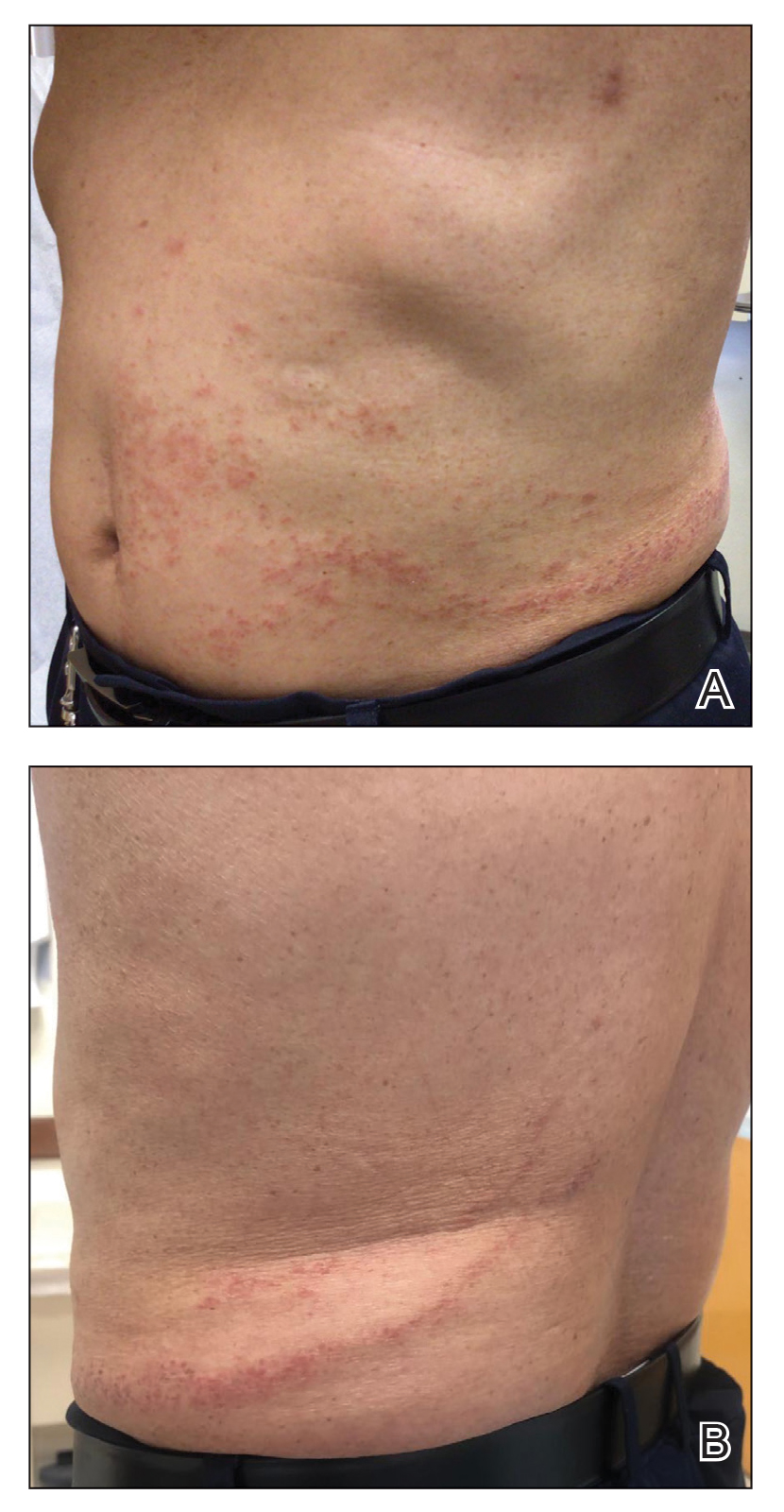

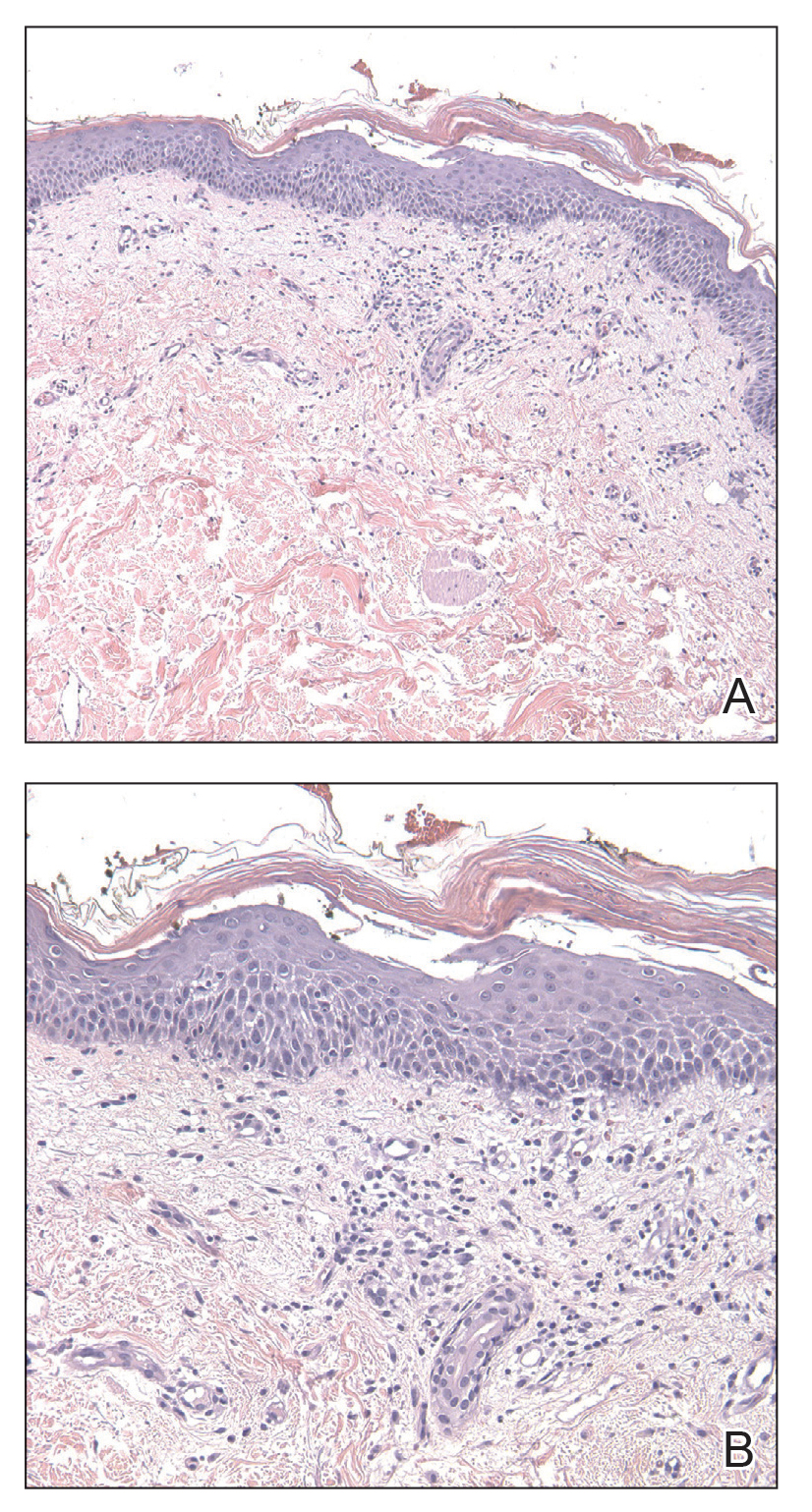

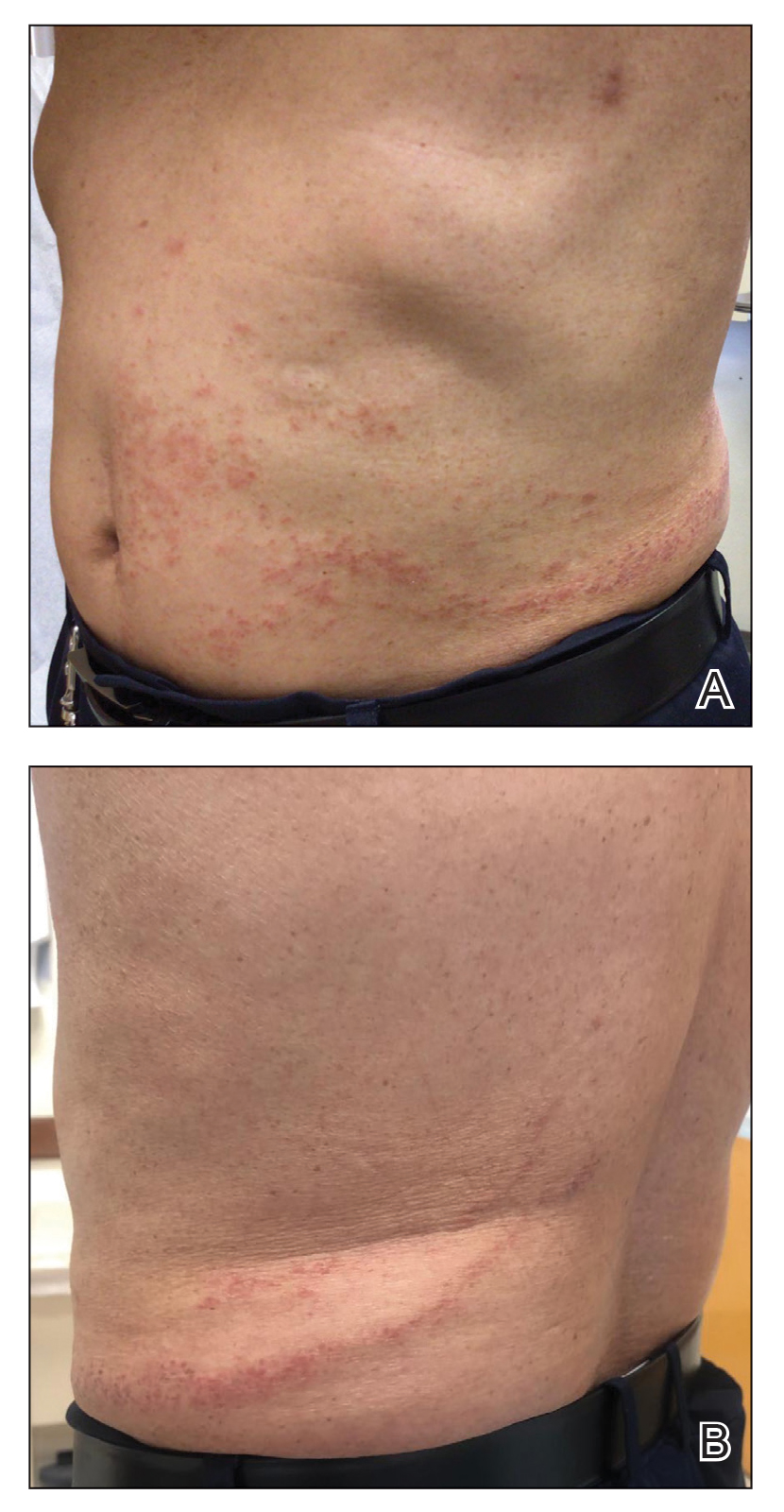

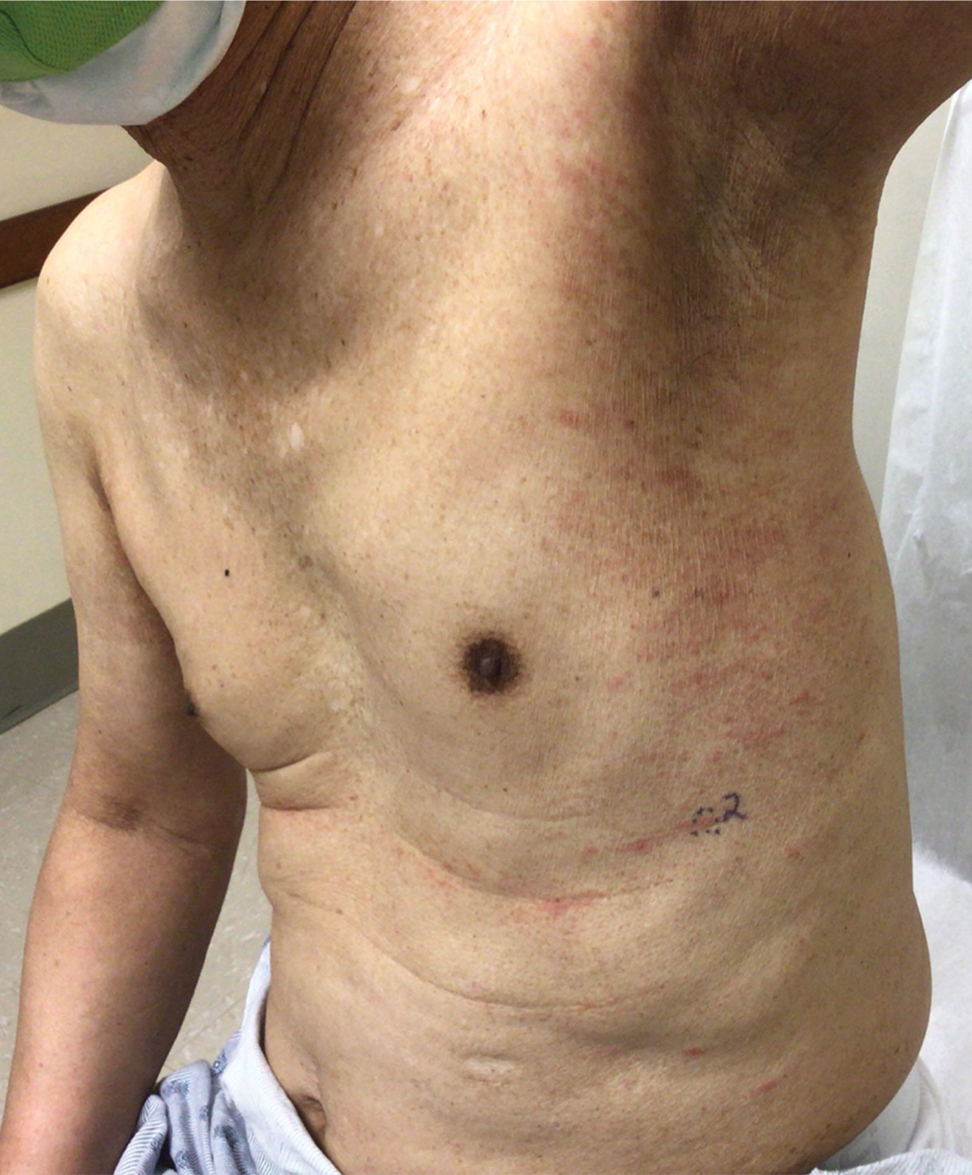

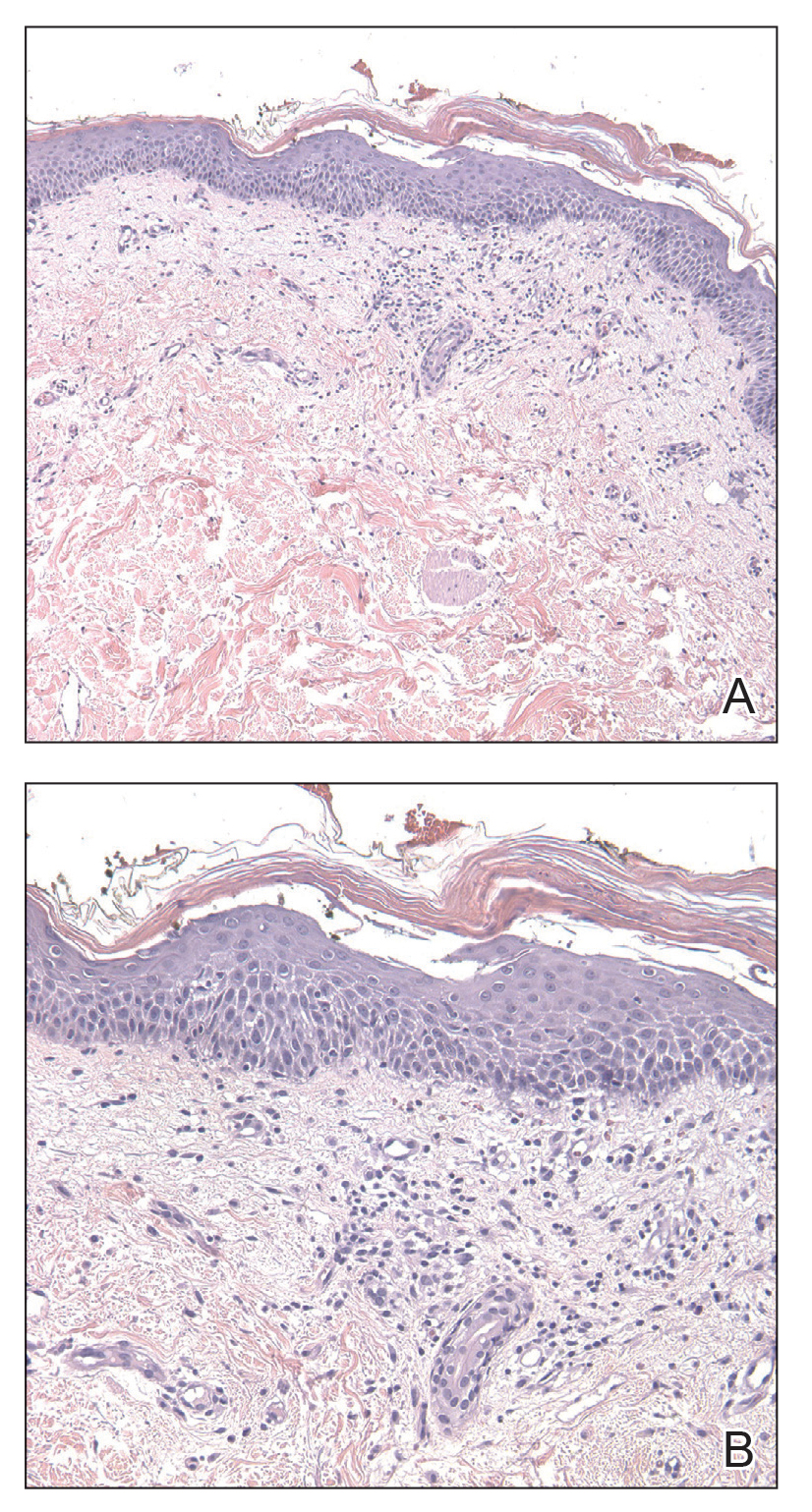

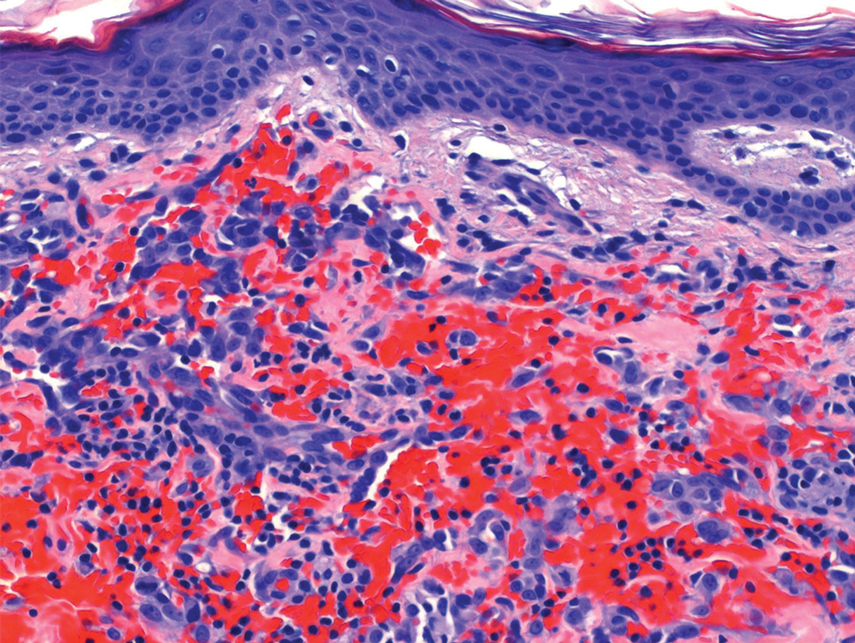

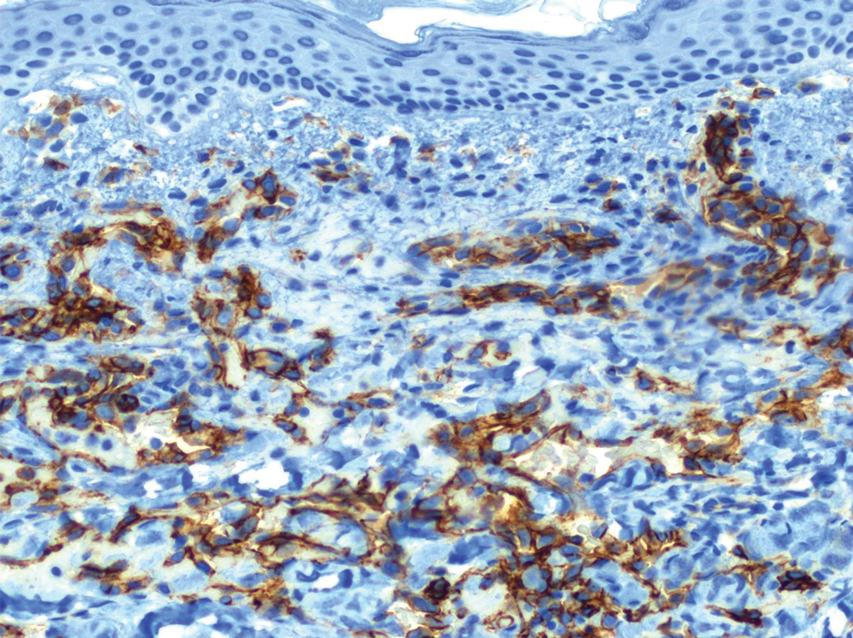

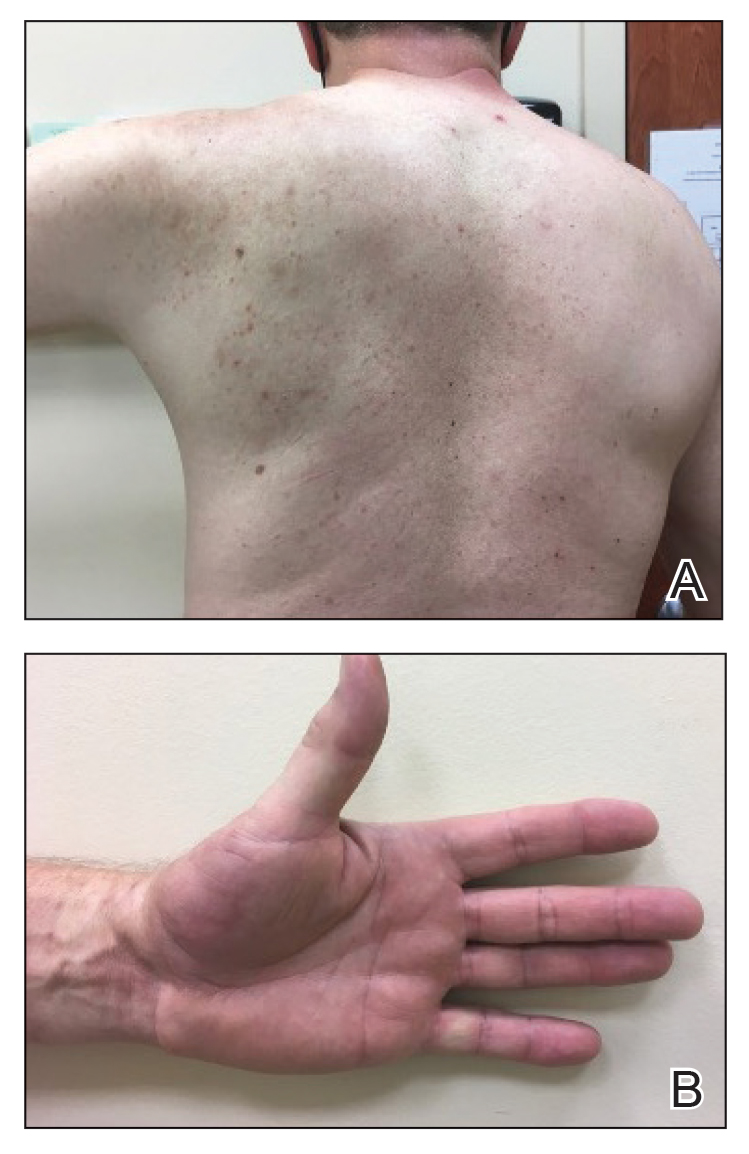

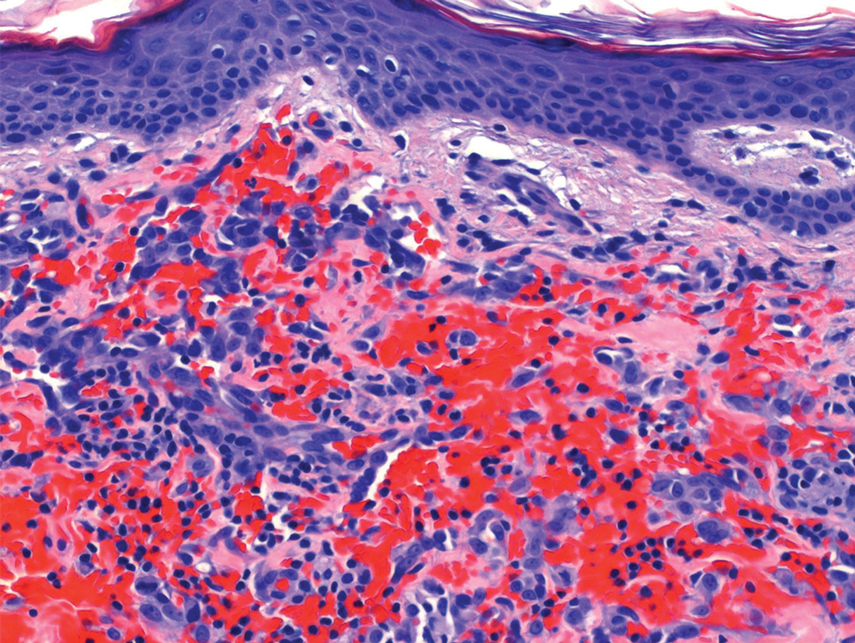

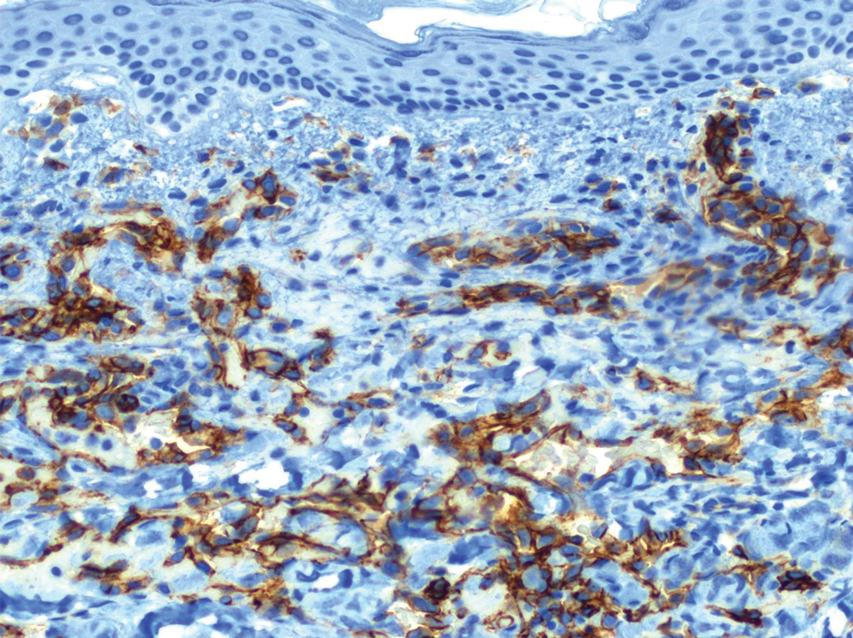

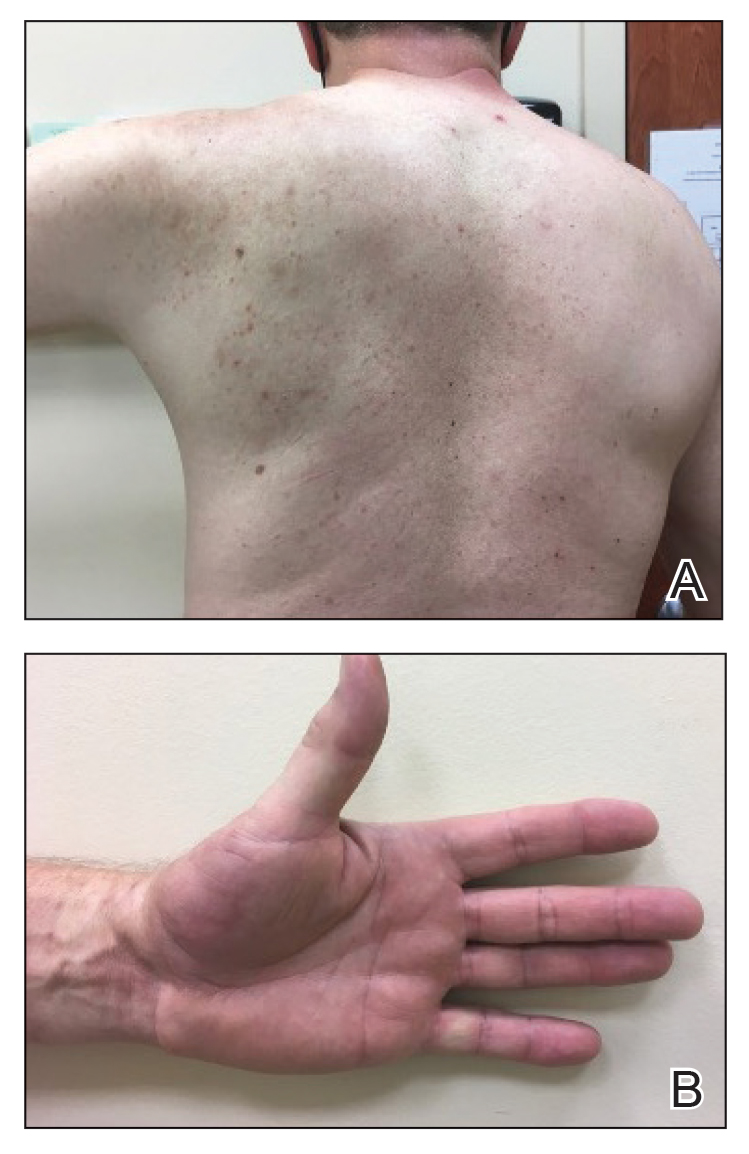

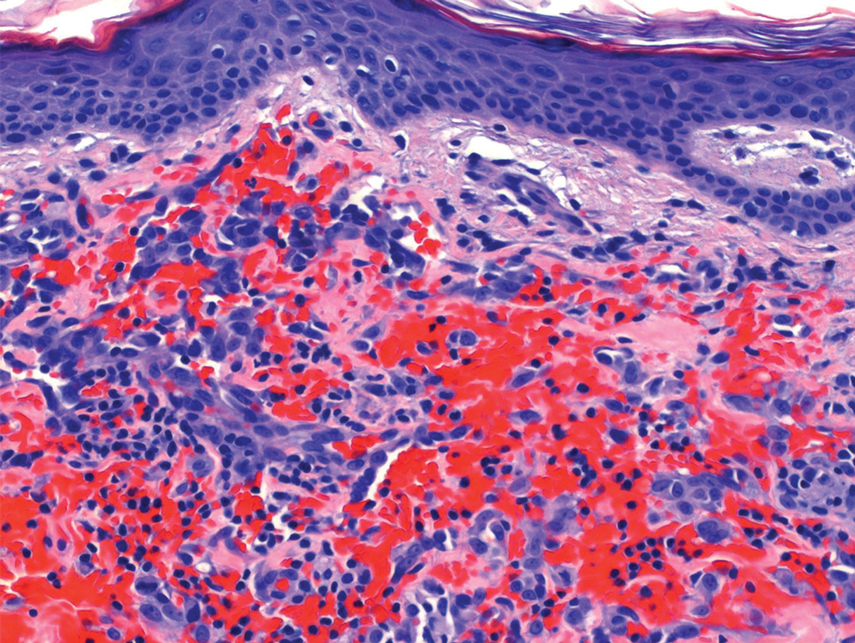

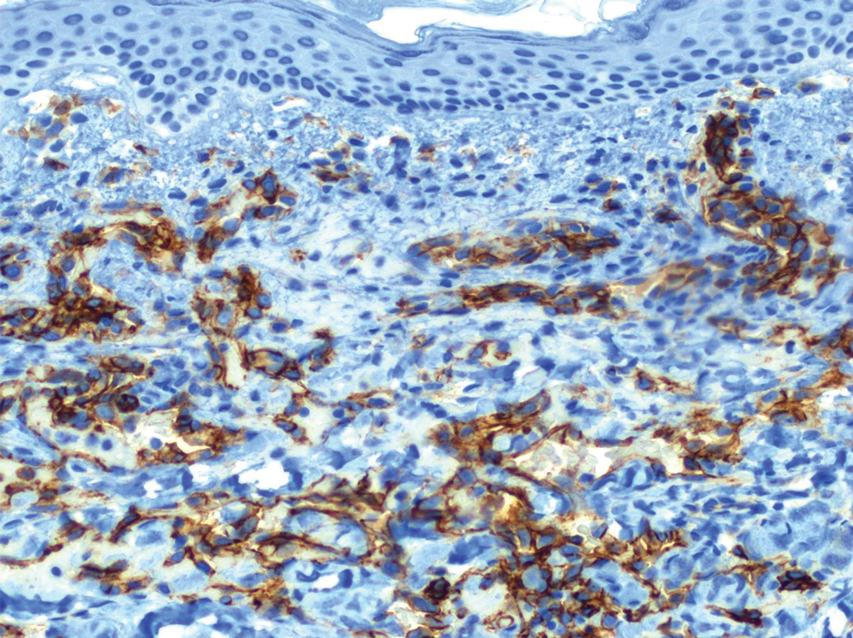

Physical examination revealed multiple erythematous, hyperpigmented, scaly papules and plaques on the lateral chest and within the axillae (Figure 1). A skin biopsy from the left axilla demonstrated a mild lichenoid and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with scattered eosinophils, neutrophils, and extravasated erythrocytes. The overlying epidermis showed spongiosis with parakeratosis in addition to lymphocytic exocytosis (Figure 2). No fungal organisms were highlighted on periodic acid–Schiff staining. After this evaluation, we recommended that the patient discontinue lenalidomide and start taking a topical over-the-counter corticosteroid for 2 weeks. Over time, he noted marked improvement in the eruption and associated pruritus.

After a drug holiday of 2 months, the patient resumed a maintenance dosage of oral lenalidomide 10 mg/d. Four or 5 days after restarting lenalidomide, a pruritic eruption appeared that involved the axillae and the left lower abdomen, circling around to the left lower back. The axillary eruption resolved with a topical over-the-counter corticosteroid; the abdominal eruption persisted.

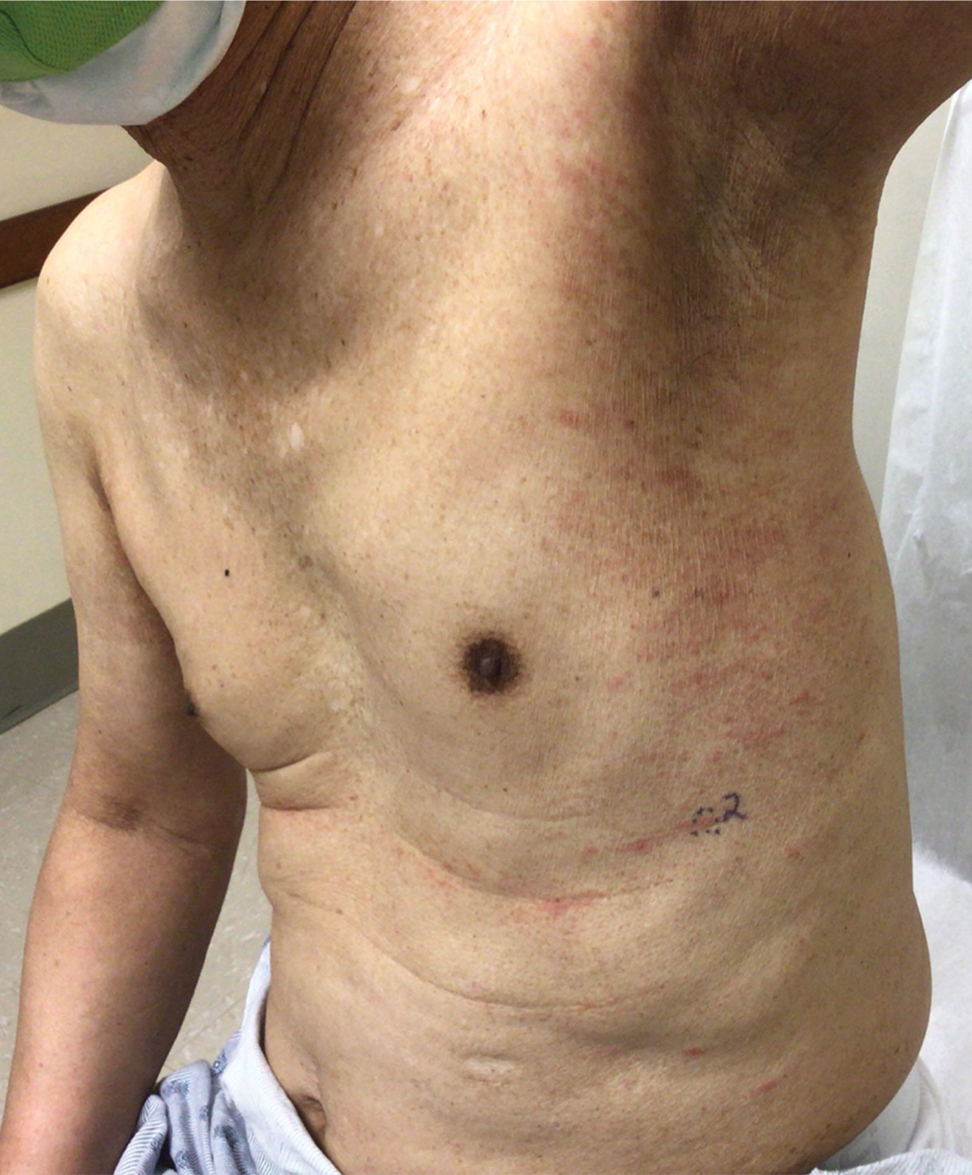

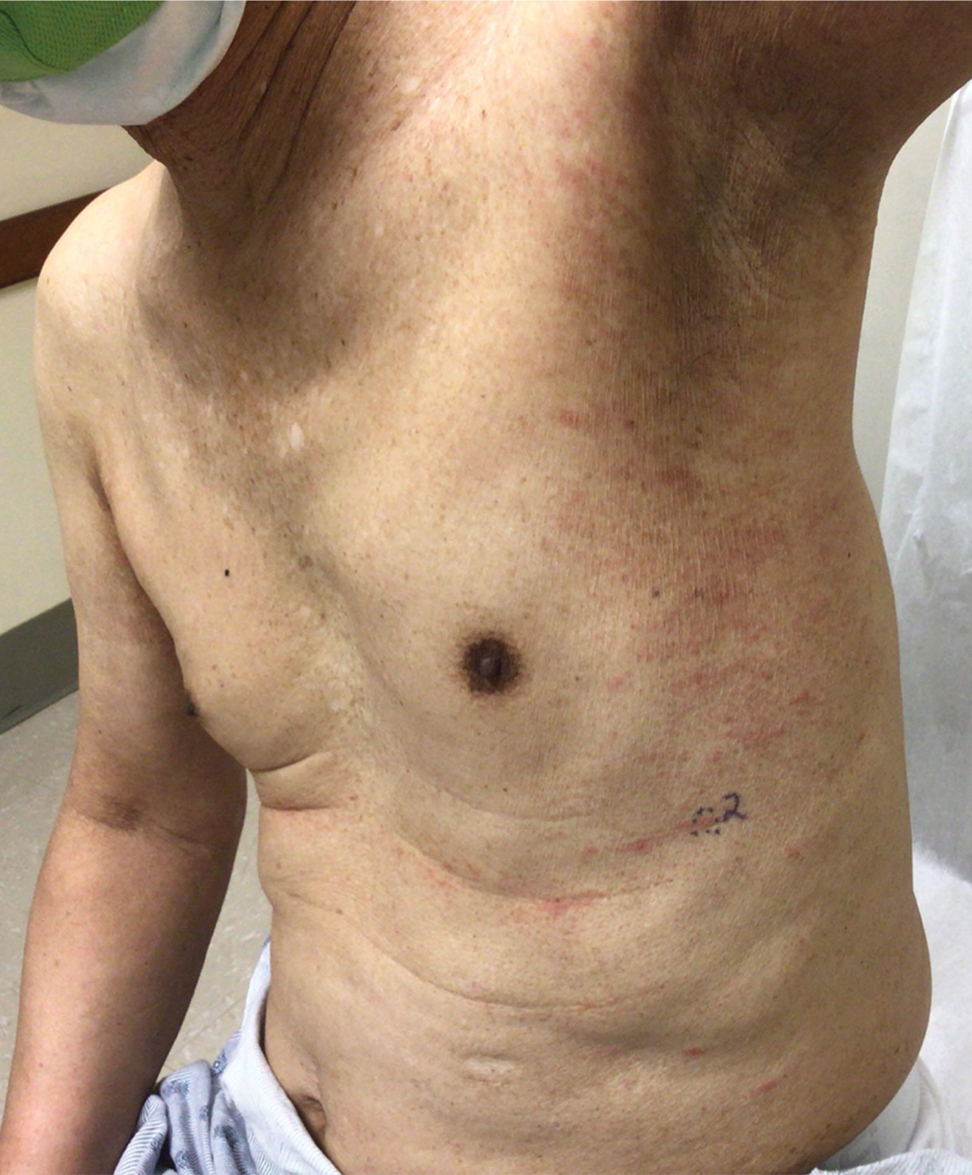

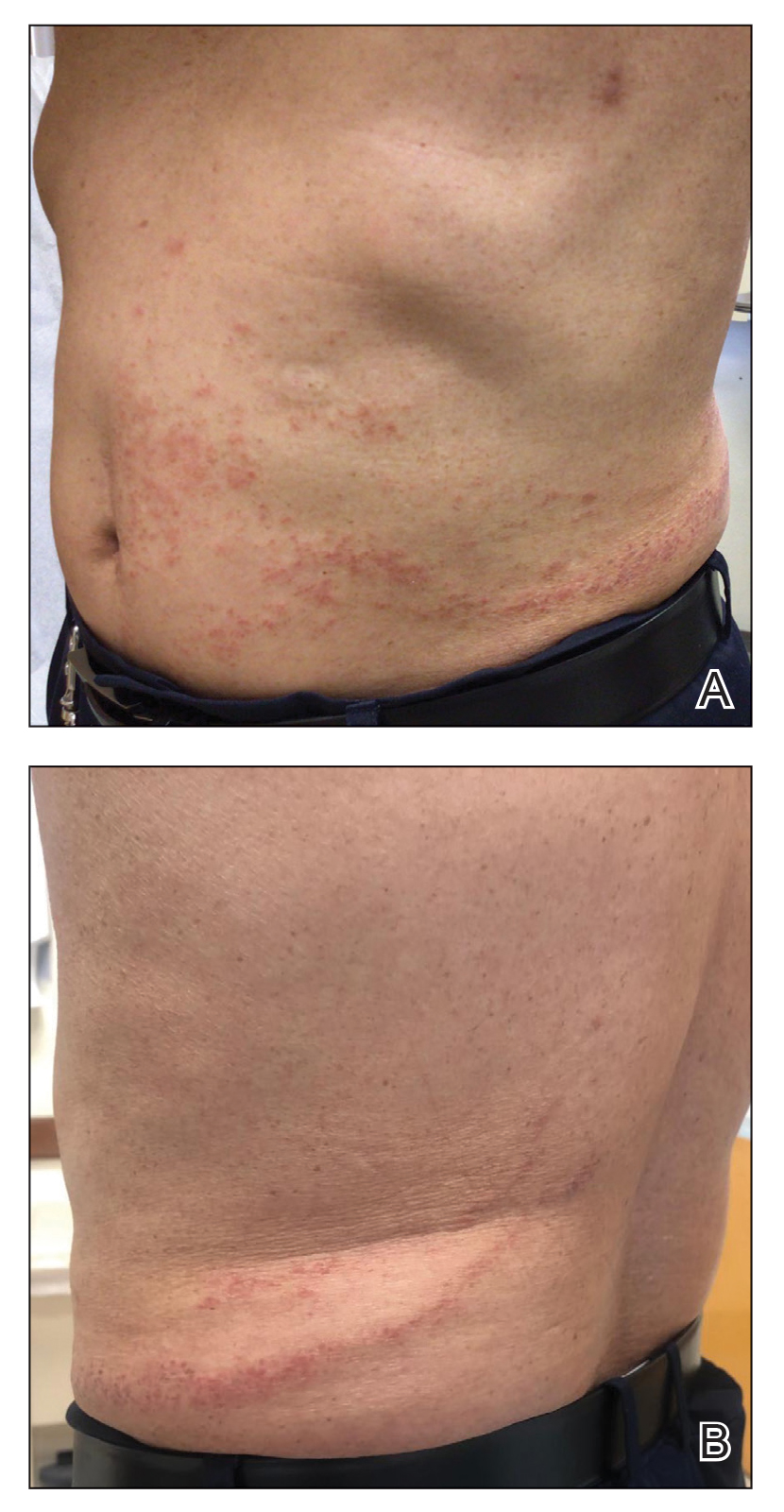

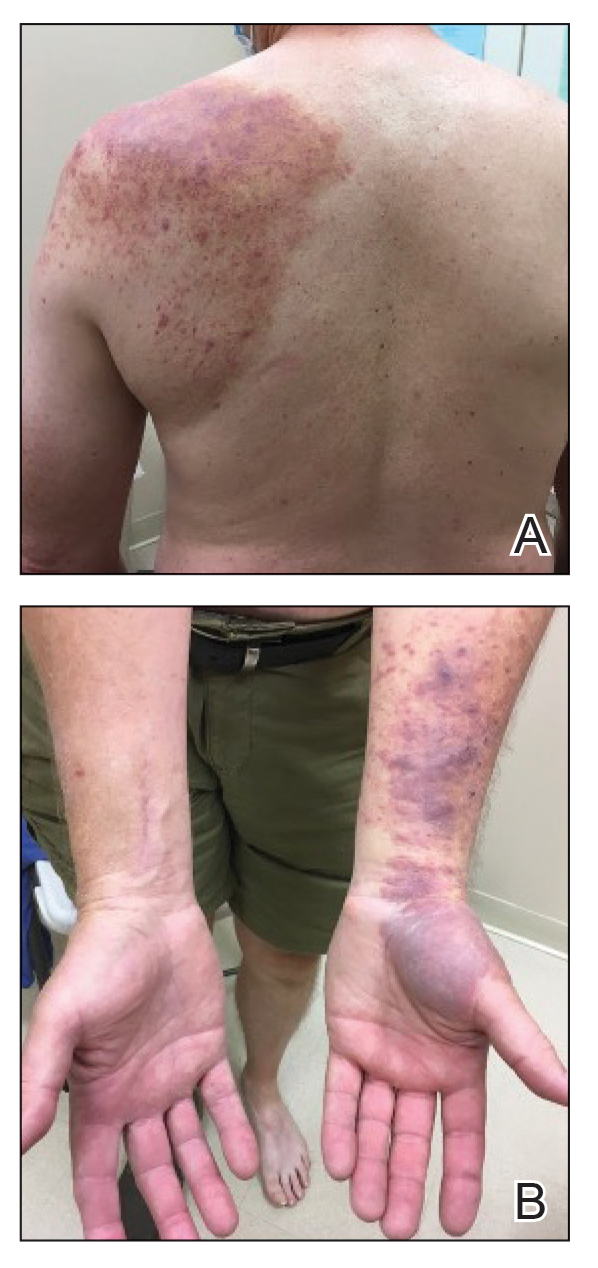

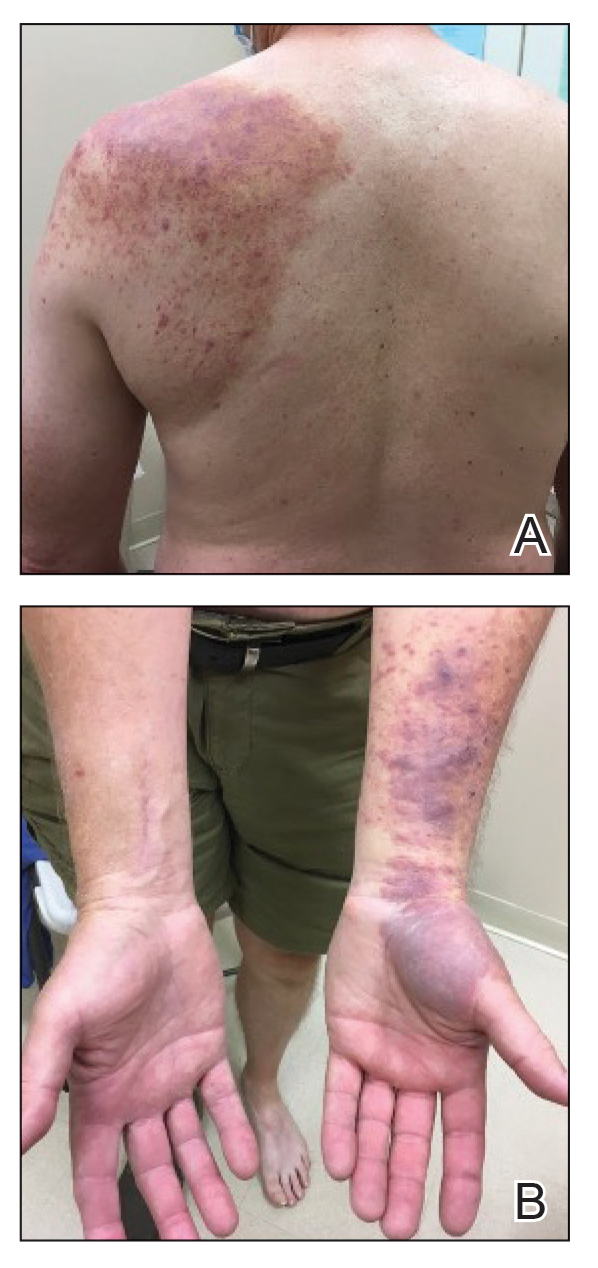

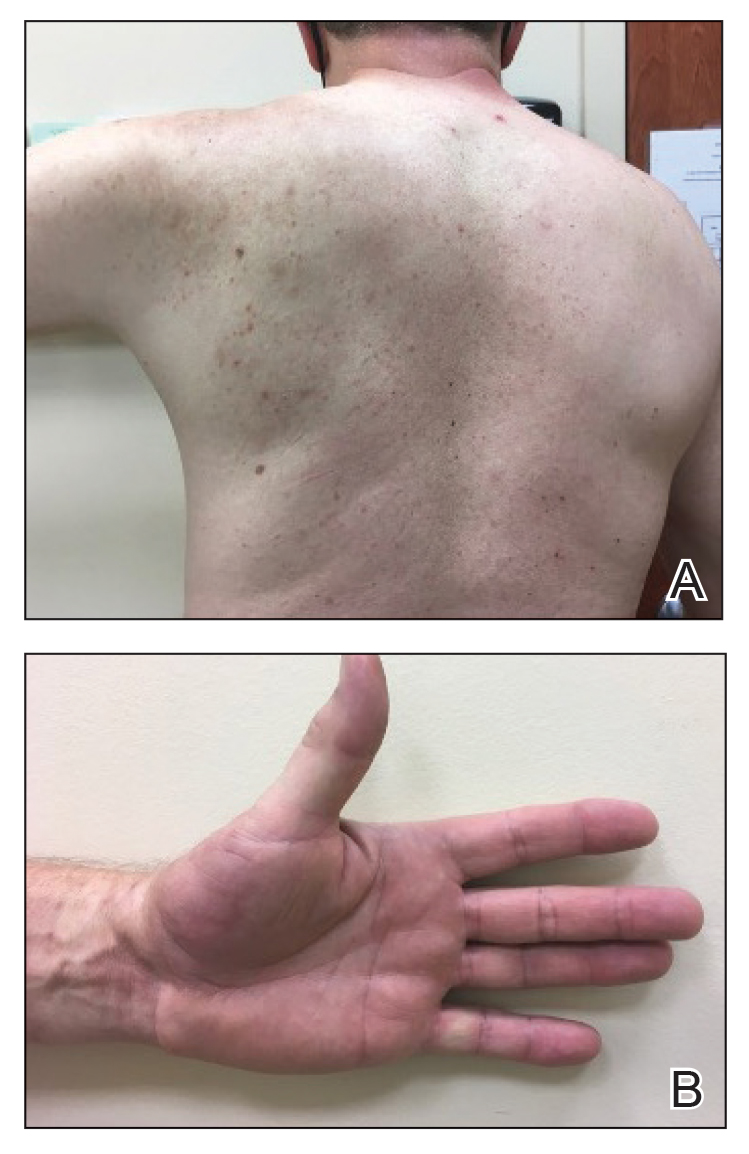

At the 3-month follow-up visit, physical examination revealed erythematous macules and papules that coalesced over a salmon-colored base along the lines of Blaschko extending from the left lower abdominal quadrant, crossing the left flank, and continuing to the left lower back without crossing the midline (Figure 3).

We recommended that the patient continue treatment through this eruption; he was instructed to apply a corticosteroid cream and resume lenalidomide at the maintenance dosage. A month later, he reported that the eruption and associated pruritus resolved with the corticosteroid cream and resumption of the maintenance dose of lenalidomide. The patient noted no further spread of the eruption.

Cutaneous adverse events are common following lenalidomide. In prior trials, the overall incidence of any-grade rash following lenalidomide exposure was 22% to 33%.5 A meta-analysis of 10 trials determined the overall incidence of all-grade and high-grade cutaneous adverse events after exposure to lenalidomide was 27.2% and 3.6%, respectively.6 Our case represents a pityriasiform eruption due to lenalidomide followed by a secondary eruption suggestive of blaschkitis.

The rash due to lenalidomide has been described as morbilliform, urticarial, dermatitic, acneform, and undefined.7 Lenalidomide-induced rash typically develops during the first month of therapy, similar to our patient’s presentation. It has even been observed in the first week of therapy.8 Severe reactions such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis have been reported.5,6 Risk factors associated with rash secondary to lenalidomide include advanced age (≥70 years), presence of Bence-Jones protein-type MM in urine, and no prior chemotherapy.8 Our patient had 2 of these risk factors: advanced age and no prior chemotherapy for MM. The exact pathogenesis by which lenalidomide leads to a pityriasiform eruption, as in our patient, or to a rash in general is unclear. Studies have hypothesized that a lenalidomide-induced rash could be attributable to a delayed hypersensitivity type IV reaction or to a reaction related to the molecular mechanism of action of the drug.9

At the molecular level, the antimyeloma effects of lenalidomide include promoting degradation of transcription factors IKZF1 and IKZF3, which subsequently increases production of IL-2.1,2,9 Recombinant IL-2 has been associated with an increased incidence of rash in other cancers.9 Overexpression of programmed death 1(PD-1) and its ligand (PD-L1) has been demonstrated in MM; lenalidomide has been shown to downregulate both PD-1 and PD-L1. Patients receiving PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors commonly have developed rash.9 However, the association between lenalidomide and its downregulation of PD-1 and PD-L1 leading to rash has not been fully elucidated. Given the multiple malignancies in our patient—MM, prostate cancer, malignant carcinoid tumor—an underlying paraneoplastic phenomenon may be possible. Additionally, because our patient initially received dexamethasone along with lenalidomide, the manifestation of the initial pityriasiform rash may have been less severe due to the steroid use. Although our patient underwent a 2-month drug holiday following the initial pityriasiform eruption, most lenalidomide-induced rashes do not necessitate discontinuation of the drug.5,7

Our patient’s secondary drug eruption was clinically suggestive of lenalidomide-induced blaschkitis. A report of a German patient with plasmacytoma described a unilateral papular exanthem that developed 4 months after lenalidomide was initiated.10 The papular exanthem following the lines of Blaschko lines extended from that patient’s posterior left foot to the calf and on to the thigh and flank,10 which was more extensive than our patient’s eruption. Blaschkitis in this patient resolved with a corticosteroid cream and UV light therapy10; lenalidomide was not discontinued, similar to our patient.

The pathogenesis of our patient’s secondary eruption that preferentially involved the lines of Blaschko is unclear. After the initial pityriasiform eruption, the secondary eruption was blaschkitis. Distinguishing dermatomes from the lines of Blaschko, which are thought to represent pathways of epidermal cell migration and proliferation during embryologic development, is important. Genodermatoses such as incontinentia pigmenti and hypomelanosis of Ito involve the lines of Blaschko11; other disorders in the differential diagnosis of linear configurations include linear lichen planus, linear cutaneous lupus erythematosus, linear morphea, and lichen striatus.11 Notably, drug-induced blaschkitis is rare.

Cutaneous adverse reactions from thalidomide analogues are relatively common. Our case of lenalidomide-associated blaschkitis that developed following an initial pityriasiform drug eruption in a patient with MM highlights that dermatologists need to collaborate with the oncologist regarding the severity of drug eruptions to determine if the patient should continue treatment through the cutaneous eruptions or discontinue a vital medication.

- Jan M, Sperling AS, Ebert BL. Cancer therapies based on targeted protein degradation—lessons learned with lenalidomide. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2021;18:401-417. doi:10.1038/s41571-021-00479-z

- Shah UA, Mailankody S. Emerging immunotherapies in multiple myeloma. BMJ. 2020;370:3176. doi:10.1136/BMJ.M3176

- Richardson PG, Blood E, Mitsiades CS, et al. A randomized phase 2 study of lenalidomide therapy for patients with relapsed or relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma. Blood. 2006;108:3458-3464. doi:10.1182/BLOOD-2006-04-015909

- Benboubker L, Dimopoulos MA, Dispenzieri A, et al. Lenalidomide and dexamethasone in transplant-ineligible patients with myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:906-917. doi:10.1056/NEJMOA1402551

- Tinsley SM, Kurtin SE, Ridgeway JA. Practical management of lenalidomide-related rash. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2015;15(suppl):S64-S69. doi:10.1016/J.CLML.2015.02.008

- Nardone B, Wu S, Garden BC, et al. Risk of rash associated with lenalidomide in cancer patients: a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2013;13:424-429. doi:10.1016/J.CLML.2013.03.006

- Sviggum HP, Davis MDP, Rajkumar SV, et al. Dermatologic adverse effects of lenalidomide therapy for amyloidosis and multiple myeloma. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1298-1302. doi:10.1001/ARCHDERM.142.10.1298

- Sugi T, Nishigami Y, Saigo H, et al. Analysis of risk factors for lenalidomide-associated skin rash in patients with multiple myeloma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2021;62:1405-1410. doi:10.1080/10428194.2021.1876867

- Barley K, He W, Agarwal S, et al. Outcomes and management of lenalidomide-associated rash in patients with multiple myeloma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2016;57:2510-2515. doi:10.3109/10428194.2016.1151507

- Grape J, Frosch P. Papular drug eruption along the lines of Blaschko caused by lenalidomide [in German]. Hautarzt. 2011;62:618-620. doi:10.1007/S00105-010-2121-6

- Bolognia JL, Orlow SJ, Glick SA. Lines of Blaschko. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31(2 pt 1):157-190. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(94)70143-1

To the Editor:

Lenalidomide is a thalidomide analogue used to treat various hematologic malignancies, including non-Hodgkin lymphoma, myelodysplastic syndrome, and multiple myeloma (MM).1 Lenalidomide is referred to as a degrader therapeutic because it induces targeted protein degradation of disease-relevant proteins (eg, Ikaros family zinc finger protein 1 [IKZF1], Ikaros family zinc finger protein 3 [IKZF3], and casein kinase I isoform-α [CK1α]) as its primary mechanism of action.1,2 Although cutaneous adverse events are relatively common among thalidomide analogues, the morphologic and histopathologic descriptions of these drug eruptions have not been fully elucidated.3,4 We report a novel pityriasiform drug eruption followed by a clinical eruption suggestive of blaschkitis in a patient with MM who was being treated with lenalidomide.

A 76-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic with a progressive, mildly pruritic eruption on the chest and axillae of 1 year’s duration. He had a medical history of chronic hepatitis B, malignant carcinoid tumor of the colon, prostate cancer, and MM. The eruption emerged 1 to 2 weeks after the patient started oral lenalidomide 10 mg/d and oral dexamethasone40 mg/wk following autologous stem cell transplantation for MM. The patient had not received any other therapy for MM.

Physical examination revealed multiple erythematous, hyperpigmented, scaly papules and plaques on the lateral chest and within the axillae (Figure 1). A skin biopsy from the left axilla demonstrated a mild lichenoid and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with scattered eosinophils, neutrophils, and extravasated erythrocytes. The overlying epidermis showed spongiosis with parakeratosis in addition to lymphocytic exocytosis (Figure 2). No fungal organisms were highlighted on periodic acid–Schiff staining. After this evaluation, we recommended that the patient discontinue lenalidomide and start taking a topical over-the-counter corticosteroid for 2 weeks. Over time, he noted marked improvement in the eruption and associated pruritus.

After a drug holiday of 2 months, the patient resumed a maintenance dosage of oral lenalidomide 10 mg/d. Four or 5 days after restarting lenalidomide, a pruritic eruption appeared that involved the axillae and the left lower abdomen, circling around to the left lower back. The axillary eruption resolved with a topical over-the-counter corticosteroid; the abdominal eruption persisted.

At the 3-month follow-up visit, physical examination revealed erythematous macules and papules that coalesced over a salmon-colored base along the lines of Blaschko extending from the left lower abdominal quadrant, crossing the left flank, and continuing to the left lower back without crossing the midline (Figure 3).

We recommended that the patient continue treatment through this eruption; he was instructed to apply a corticosteroid cream and resume lenalidomide at the maintenance dosage. A month later, he reported that the eruption and associated pruritus resolved with the corticosteroid cream and resumption of the maintenance dose of lenalidomide. The patient noted no further spread of the eruption.

Cutaneous adverse events are common following lenalidomide. In prior trials, the overall incidence of any-grade rash following lenalidomide exposure was 22% to 33%.5 A meta-analysis of 10 trials determined the overall incidence of all-grade and high-grade cutaneous adverse events after exposure to lenalidomide was 27.2% and 3.6%, respectively.6 Our case represents a pityriasiform eruption due to lenalidomide followed by a secondary eruption suggestive of blaschkitis.

The rash due to lenalidomide has been described as morbilliform, urticarial, dermatitic, acneform, and undefined.7 Lenalidomide-induced rash typically develops during the first month of therapy, similar to our patient’s presentation. It has even been observed in the first week of therapy.8 Severe reactions such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis have been reported.5,6 Risk factors associated with rash secondary to lenalidomide include advanced age (≥70 years), presence of Bence-Jones protein-type MM in urine, and no prior chemotherapy.8 Our patient had 2 of these risk factors: advanced age and no prior chemotherapy for MM. The exact pathogenesis by which lenalidomide leads to a pityriasiform eruption, as in our patient, or to a rash in general is unclear. Studies have hypothesized that a lenalidomide-induced rash could be attributable to a delayed hypersensitivity type IV reaction or to a reaction related to the molecular mechanism of action of the drug.9

At the molecular level, the antimyeloma effects of lenalidomide include promoting degradation of transcription factors IKZF1 and IKZF3, which subsequently increases production of IL-2.1,2,9 Recombinant IL-2 has been associated with an increased incidence of rash in other cancers.9 Overexpression of programmed death 1(PD-1) and its ligand (PD-L1) has been demonstrated in MM; lenalidomide has been shown to downregulate both PD-1 and PD-L1. Patients receiving PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors commonly have developed rash.9 However, the association between lenalidomide and its downregulation of PD-1 and PD-L1 leading to rash has not been fully elucidated. Given the multiple malignancies in our patient—MM, prostate cancer, malignant carcinoid tumor—an underlying paraneoplastic phenomenon may be possible. Additionally, because our patient initially received dexamethasone along with lenalidomide, the manifestation of the initial pityriasiform rash may have been less severe due to the steroid use. Although our patient underwent a 2-month drug holiday following the initial pityriasiform eruption, most lenalidomide-induced rashes do not necessitate discontinuation of the drug.5,7

Our patient’s secondary drug eruption was clinically suggestive of lenalidomide-induced blaschkitis. A report of a German patient with plasmacytoma described a unilateral papular exanthem that developed 4 months after lenalidomide was initiated.10 The papular exanthem following the lines of Blaschko lines extended from that patient’s posterior left foot to the calf and on to the thigh and flank,10 which was more extensive than our patient’s eruption. Blaschkitis in this patient resolved with a corticosteroid cream and UV light therapy10; lenalidomide was not discontinued, similar to our patient.

The pathogenesis of our patient’s secondary eruption that preferentially involved the lines of Blaschko is unclear. After the initial pityriasiform eruption, the secondary eruption was blaschkitis. Distinguishing dermatomes from the lines of Blaschko, which are thought to represent pathways of epidermal cell migration and proliferation during embryologic development, is important. Genodermatoses such as incontinentia pigmenti and hypomelanosis of Ito involve the lines of Blaschko11; other disorders in the differential diagnosis of linear configurations include linear lichen planus, linear cutaneous lupus erythematosus, linear morphea, and lichen striatus.11 Notably, drug-induced blaschkitis is rare.

Cutaneous adverse reactions from thalidomide analogues are relatively common. Our case of lenalidomide-associated blaschkitis that developed following an initial pityriasiform drug eruption in a patient with MM highlights that dermatologists need to collaborate with the oncologist regarding the severity of drug eruptions to determine if the patient should continue treatment through the cutaneous eruptions or discontinue a vital medication.

To the Editor:

Lenalidomide is a thalidomide analogue used to treat various hematologic malignancies, including non-Hodgkin lymphoma, myelodysplastic syndrome, and multiple myeloma (MM).1 Lenalidomide is referred to as a degrader therapeutic because it induces targeted protein degradation of disease-relevant proteins (eg, Ikaros family zinc finger protein 1 [IKZF1], Ikaros family zinc finger protein 3 [IKZF3], and casein kinase I isoform-α [CK1α]) as its primary mechanism of action.1,2 Although cutaneous adverse events are relatively common among thalidomide analogues, the morphologic and histopathologic descriptions of these drug eruptions have not been fully elucidated.3,4 We report a novel pityriasiform drug eruption followed by a clinical eruption suggestive of blaschkitis in a patient with MM who was being treated with lenalidomide.

A 76-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic with a progressive, mildly pruritic eruption on the chest and axillae of 1 year’s duration. He had a medical history of chronic hepatitis B, malignant carcinoid tumor of the colon, prostate cancer, and MM. The eruption emerged 1 to 2 weeks after the patient started oral lenalidomide 10 mg/d and oral dexamethasone40 mg/wk following autologous stem cell transplantation for MM. The patient had not received any other therapy for MM.

Physical examination revealed multiple erythematous, hyperpigmented, scaly papules and plaques on the lateral chest and within the axillae (Figure 1). A skin biopsy from the left axilla demonstrated a mild lichenoid and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with scattered eosinophils, neutrophils, and extravasated erythrocytes. The overlying epidermis showed spongiosis with parakeratosis in addition to lymphocytic exocytosis (Figure 2). No fungal organisms were highlighted on periodic acid–Schiff staining. After this evaluation, we recommended that the patient discontinue lenalidomide and start taking a topical over-the-counter corticosteroid for 2 weeks. Over time, he noted marked improvement in the eruption and associated pruritus.

After a drug holiday of 2 months, the patient resumed a maintenance dosage of oral lenalidomide 10 mg/d. Four or 5 days after restarting lenalidomide, a pruritic eruption appeared that involved the axillae and the left lower abdomen, circling around to the left lower back. The axillary eruption resolved with a topical over-the-counter corticosteroid; the abdominal eruption persisted.

At the 3-month follow-up visit, physical examination revealed erythematous macules and papules that coalesced over a salmon-colored base along the lines of Blaschko extending from the left lower abdominal quadrant, crossing the left flank, and continuing to the left lower back without crossing the midline (Figure 3).

We recommended that the patient continue treatment through this eruption; he was instructed to apply a corticosteroid cream and resume lenalidomide at the maintenance dosage. A month later, he reported that the eruption and associated pruritus resolved with the corticosteroid cream and resumption of the maintenance dose of lenalidomide. The patient noted no further spread of the eruption.

Cutaneous adverse events are common following lenalidomide. In prior trials, the overall incidence of any-grade rash following lenalidomide exposure was 22% to 33%.5 A meta-analysis of 10 trials determined the overall incidence of all-grade and high-grade cutaneous adverse events after exposure to lenalidomide was 27.2% and 3.6%, respectively.6 Our case represents a pityriasiform eruption due to lenalidomide followed by a secondary eruption suggestive of blaschkitis.

The rash due to lenalidomide has been described as morbilliform, urticarial, dermatitic, acneform, and undefined.7 Lenalidomide-induced rash typically develops during the first month of therapy, similar to our patient’s presentation. It has even been observed in the first week of therapy.8 Severe reactions such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis have been reported.5,6 Risk factors associated with rash secondary to lenalidomide include advanced age (≥70 years), presence of Bence-Jones protein-type MM in urine, and no prior chemotherapy.8 Our patient had 2 of these risk factors: advanced age and no prior chemotherapy for MM. The exact pathogenesis by which lenalidomide leads to a pityriasiform eruption, as in our patient, or to a rash in general is unclear. Studies have hypothesized that a lenalidomide-induced rash could be attributable to a delayed hypersensitivity type IV reaction or to a reaction related to the molecular mechanism of action of the drug.9

At the molecular level, the antimyeloma effects of lenalidomide include promoting degradation of transcription factors IKZF1 and IKZF3, which subsequently increases production of IL-2.1,2,9 Recombinant IL-2 has been associated with an increased incidence of rash in other cancers.9 Overexpression of programmed death 1(PD-1) and its ligand (PD-L1) has been demonstrated in MM; lenalidomide has been shown to downregulate both PD-1 and PD-L1. Patients receiving PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors commonly have developed rash.9 However, the association between lenalidomide and its downregulation of PD-1 and PD-L1 leading to rash has not been fully elucidated. Given the multiple malignancies in our patient—MM, prostate cancer, malignant carcinoid tumor—an underlying paraneoplastic phenomenon may be possible. Additionally, because our patient initially received dexamethasone along with lenalidomide, the manifestation of the initial pityriasiform rash may have been less severe due to the steroid use. Although our patient underwent a 2-month drug holiday following the initial pityriasiform eruption, most lenalidomide-induced rashes do not necessitate discontinuation of the drug.5,7

Our patient’s secondary drug eruption was clinically suggestive of lenalidomide-induced blaschkitis. A report of a German patient with plasmacytoma described a unilateral papular exanthem that developed 4 months after lenalidomide was initiated.10 The papular exanthem following the lines of Blaschko lines extended from that patient’s posterior left foot to the calf and on to the thigh and flank,10 which was more extensive than our patient’s eruption. Blaschkitis in this patient resolved with a corticosteroid cream and UV light therapy10; lenalidomide was not discontinued, similar to our patient.

The pathogenesis of our patient’s secondary eruption that preferentially involved the lines of Blaschko is unclear. After the initial pityriasiform eruption, the secondary eruption was blaschkitis. Distinguishing dermatomes from the lines of Blaschko, which are thought to represent pathways of epidermal cell migration and proliferation during embryologic development, is important. Genodermatoses such as incontinentia pigmenti and hypomelanosis of Ito involve the lines of Blaschko11; other disorders in the differential diagnosis of linear configurations include linear lichen planus, linear cutaneous lupus erythematosus, linear morphea, and lichen striatus.11 Notably, drug-induced blaschkitis is rare.

Cutaneous adverse reactions from thalidomide analogues are relatively common. Our case of lenalidomide-associated blaschkitis that developed following an initial pityriasiform drug eruption in a patient with MM highlights that dermatologists need to collaborate with the oncologist regarding the severity of drug eruptions to determine if the patient should continue treatment through the cutaneous eruptions or discontinue a vital medication.

- Jan M, Sperling AS, Ebert BL. Cancer therapies based on targeted protein degradation—lessons learned with lenalidomide. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2021;18:401-417. doi:10.1038/s41571-021-00479-z

- Shah UA, Mailankody S. Emerging immunotherapies in multiple myeloma. BMJ. 2020;370:3176. doi:10.1136/BMJ.M3176

- Richardson PG, Blood E, Mitsiades CS, et al. A randomized phase 2 study of lenalidomide therapy for patients with relapsed or relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma. Blood. 2006;108:3458-3464. doi:10.1182/BLOOD-2006-04-015909

- Benboubker L, Dimopoulos MA, Dispenzieri A, et al. Lenalidomide and dexamethasone in transplant-ineligible patients with myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:906-917. doi:10.1056/NEJMOA1402551

- Tinsley SM, Kurtin SE, Ridgeway JA. Practical management of lenalidomide-related rash. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2015;15(suppl):S64-S69. doi:10.1016/J.CLML.2015.02.008

- Nardone B, Wu S, Garden BC, et al. Risk of rash associated with lenalidomide in cancer patients: a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2013;13:424-429. doi:10.1016/J.CLML.2013.03.006

- Sviggum HP, Davis MDP, Rajkumar SV, et al. Dermatologic adverse effects of lenalidomide therapy for amyloidosis and multiple myeloma. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1298-1302. doi:10.1001/ARCHDERM.142.10.1298

- Sugi T, Nishigami Y, Saigo H, et al. Analysis of risk factors for lenalidomide-associated skin rash in patients with multiple myeloma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2021;62:1405-1410. doi:10.1080/10428194.2021.1876867

- Barley K, He W, Agarwal S, et al. Outcomes and management of lenalidomide-associated rash in patients with multiple myeloma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2016;57:2510-2515. doi:10.3109/10428194.2016.1151507

- Grape J, Frosch P. Papular drug eruption along the lines of Blaschko caused by lenalidomide [in German]. Hautarzt. 2011;62:618-620. doi:10.1007/S00105-010-2121-6

- Bolognia JL, Orlow SJ, Glick SA. Lines of Blaschko. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31(2 pt 1):157-190. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(94)70143-1

- Jan M, Sperling AS, Ebert BL. Cancer therapies based on targeted protein degradation—lessons learned with lenalidomide. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2021;18:401-417. doi:10.1038/s41571-021-00479-z

- Shah UA, Mailankody S. Emerging immunotherapies in multiple myeloma. BMJ. 2020;370:3176. doi:10.1136/BMJ.M3176

- Richardson PG, Blood E, Mitsiades CS, et al. A randomized phase 2 study of lenalidomide therapy for patients with relapsed or relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma. Blood. 2006;108:3458-3464. doi:10.1182/BLOOD-2006-04-015909

- Benboubker L, Dimopoulos MA, Dispenzieri A, et al. Lenalidomide and dexamethasone in transplant-ineligible patients with myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:906-917. doi:10.1056/NEJMOA1402551

- Tinsley SM, Kurtin SE, Ridgeway JA. Practical management of lenalidomide-related rash. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2015;15(suppl):S64-S69. doi:10.1016/J.CLML.2015.02.008

- Nardone B, Wu S, Garden BC, et al. Risk of rash associated with lenalidomide in cancer patients: a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2013;13:424-429. doi:10.1016/J.CLML.2013.03.006

- Sviggum HP, Davis MDP, Rajkumar SV, et al. Dermatologic adverse effects of lenalidomide therapy for amyloidosis and multiple myeloma. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1298-1302. doi:10.1001/ARCHDERM.142.10.1298

- Sugi T, Nishigami Y, Saigo H, et al. Analysis of risk factors for lenalidomide-associated skin rash in patients with multiple myeloma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2021;62:1405-1410. doi:10.1080/10428194.2021.1876867

- Barley K, He W, Agarwal S, et al. Outcomes and management of lenalidomide-associated rash in patients with multiple myeloma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2016;57:2510-2515. doi:10.3109/10428194.2016.1151507

- Grape J, Frosch P. Papular drug eruption along the lines of Blaschko caused by lenalidomide [in German]. Hautarzt. 2011;62:618-620. doi:10.1007/S00105-010-2121-6

- Bolognia JL, Orlow SJ, Glick SA. Lines of Blaschko. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31(2 pt 1):157-190. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(94)70143-1

Practice Points

- Dermatologists should be aware of the variety of cutaneous adverse events that can arise from the use of immunotherapeutic agents for hematologic malignancies.

- Some cutaneous reactions to immunotherapeutic medications, such as pityriasiform eruption and blaschkitis, generally are benign and may not necessitate halting an important therapy.

The Role of Toluidine Blue in Mohs Micrographic Surgery: A Systematic Review

Toluidine blue (TB), a dye with metachromatic staining properties, was developed in 1856 by William Henry Perkin.1 Metachromasia is a perceptible change in the color of staining of living tissue due to the electrochemical properties of the tissue. Tissues that contain high concentrations of ionized sulfate and phosphate groups (high concentrations of free electronegative groups) form polymeric aggregates of the basic dye solution that alter the absorbed wavelengths of light.2 The function of this characteristic is to use a single dye to highlight different structures in tissue based on their relative chemical differences.3

Toluidine blue primarily was used within the dye industry until the 1960s, when it was first used in vital staining of the oral mucosa.2 Because of the tissue absorption potential, this technique was used to detect the location of oral malignancies.4 Since then, TB has progressively been used for staining fresh frozen sections in Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS). In a 2003 survey study (N=310), 16.8% of surgeons performing MMS reported using TB in their laboratory.5 We sought to systematically review the published literature describing the uses of TB in the setting of fresh frozen sections and MMS.

Methods

We conducted a systematic search of the PubMed and Cochrane databases for articles published before December 1, 2019, to identify any relevant studies in English. Electronic searches were performed using the terms toluidine blue and Mohs or Mohs micrographic surgery. We manually checked the bibliographies of the identified articles to further identify eligible studies.

Eligibility Criteria—The inclusion criteria were articles that (1) considered TB in the context of MMS, (2) were published in peer-reviewed journals, (3) were published in English, and (4) were available as full text. Systematic reviews were excluded.

Data Extraction and Outcomes—All relevant information regarding the study characteristics, including design, level of evidence, methodologic quality of evidence, pathology examined, and outcome measures, were collected by 2 independent reviewers (T.L. and A.D.) using a predetermined data sheet. The same 2 reviewers were used for all steps of the review process, data were independently obtained, and any discrepancy was introduced for a third opinion (D.H.) and agreed upon by the majority.

Quality Assessment—The level of evidence was evaluated based on the criteria of the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. Two reviewers (T.L. and A.D.) graded each article included in the review.

Results

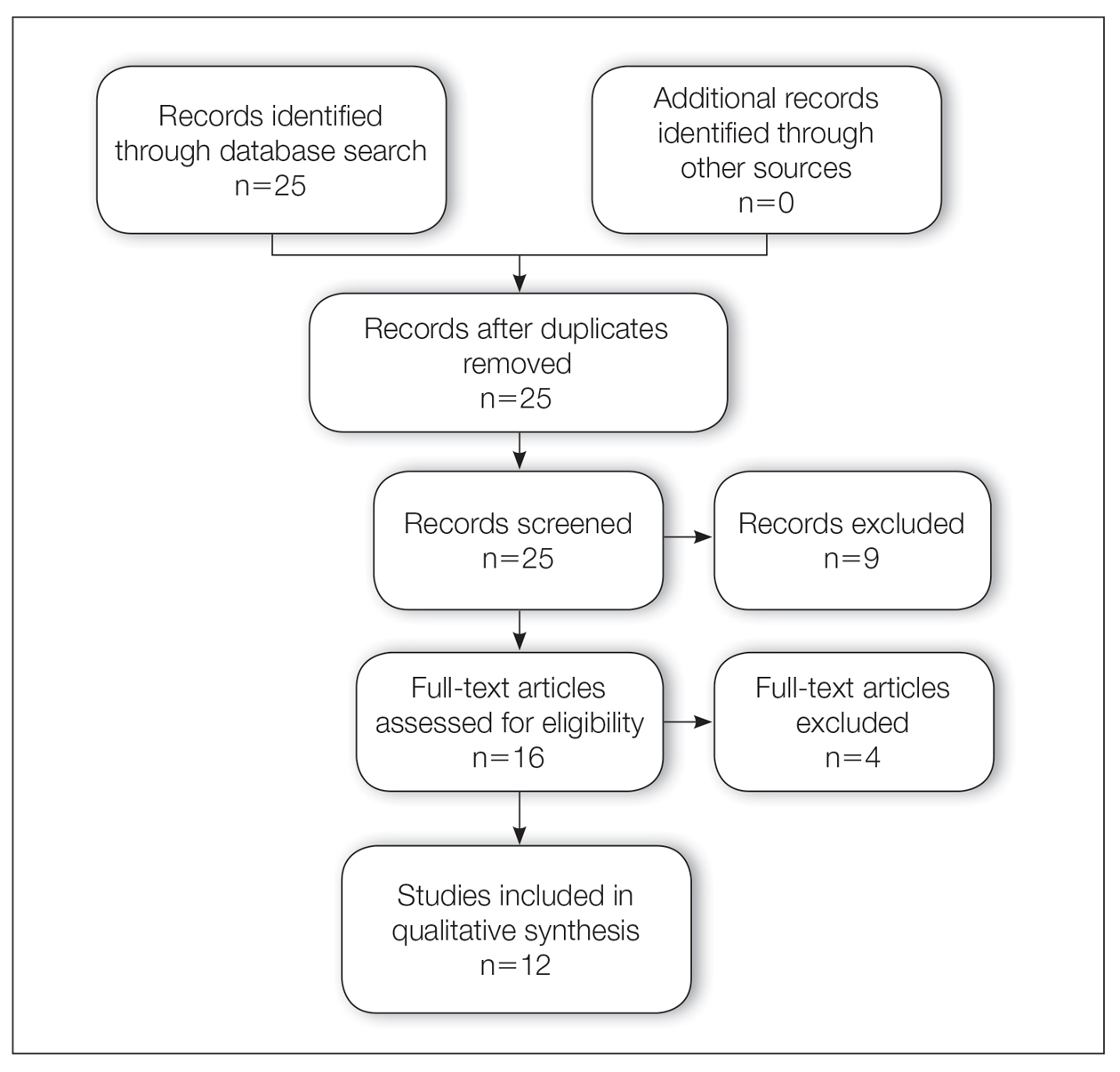

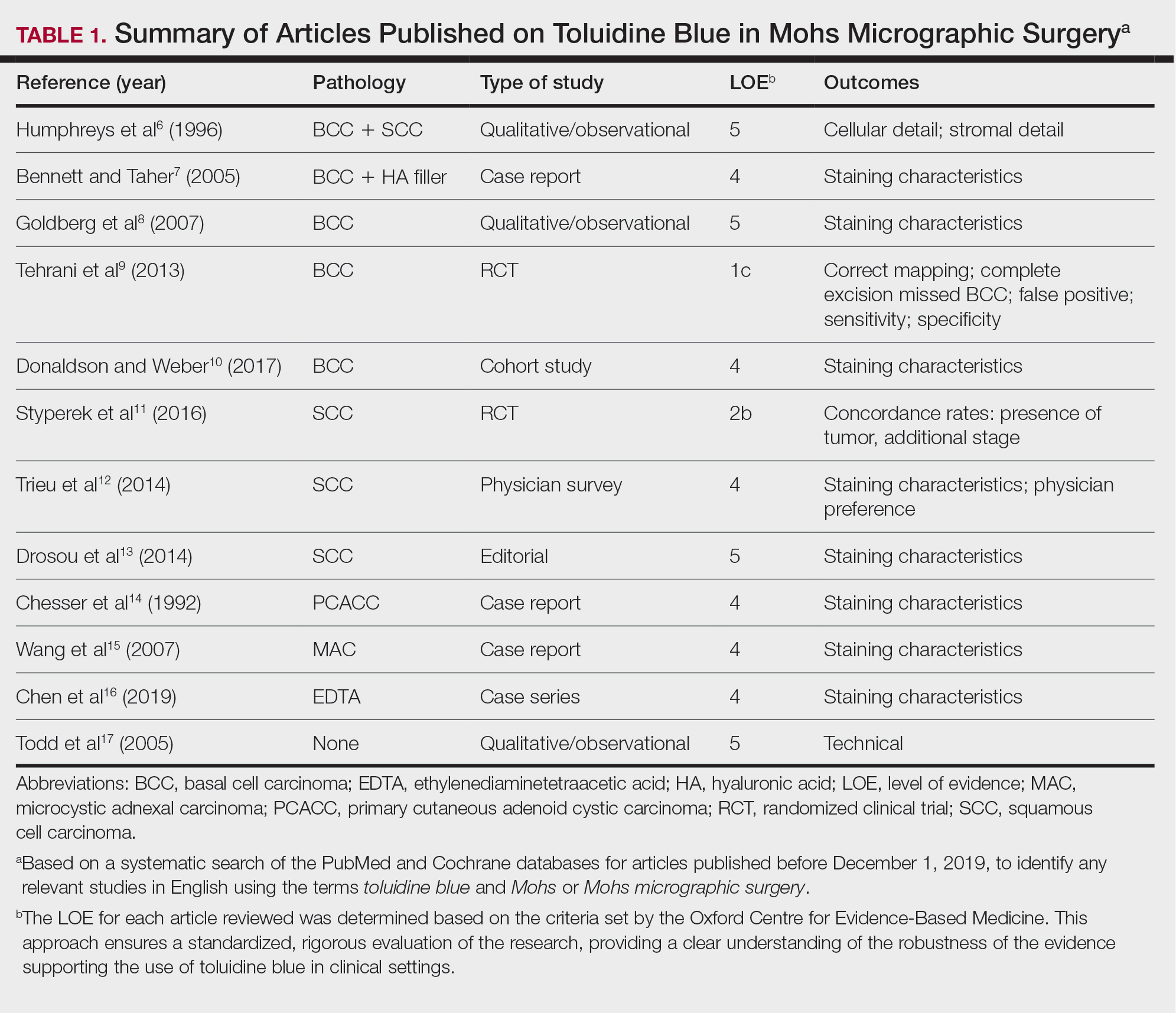

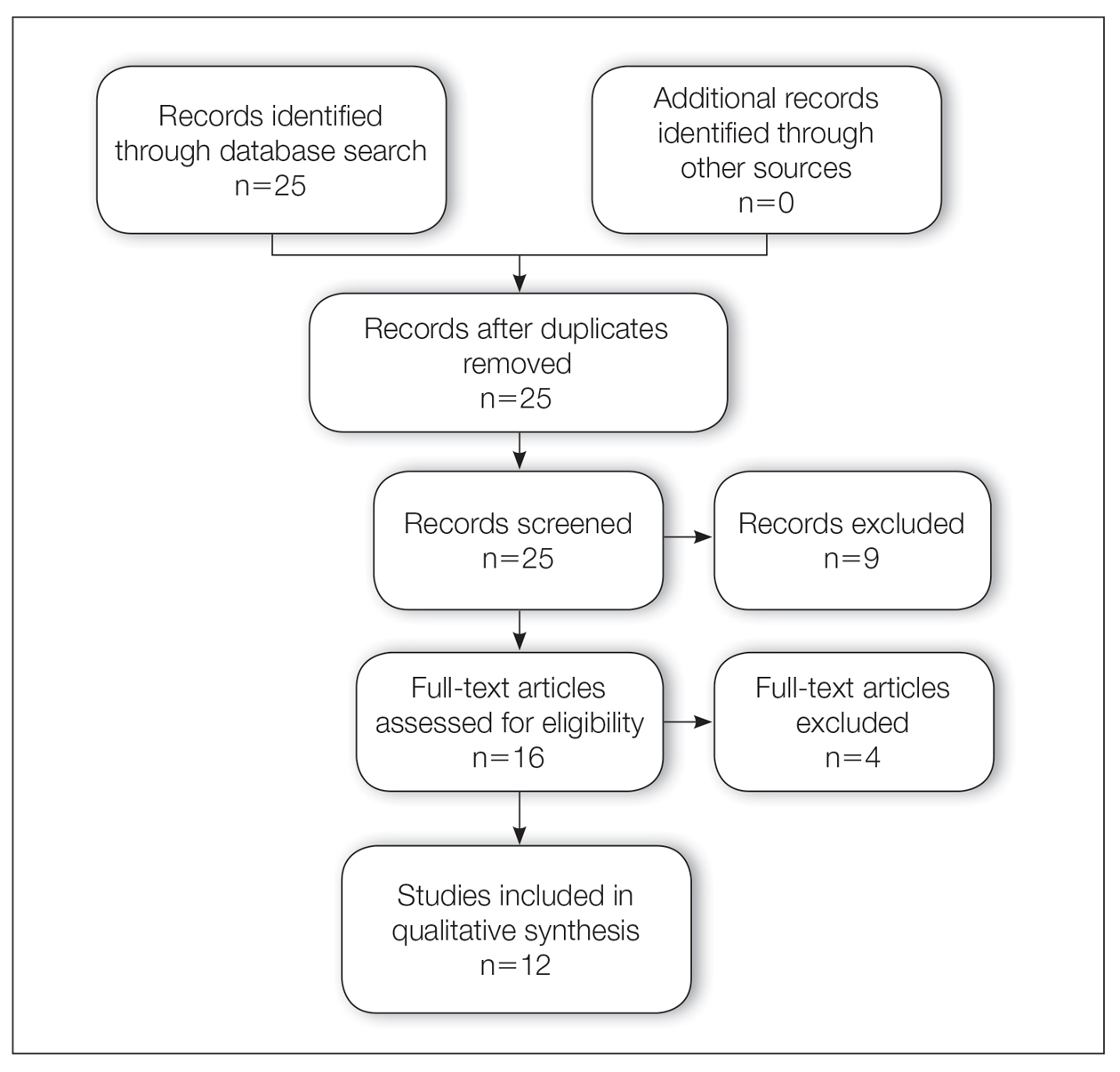

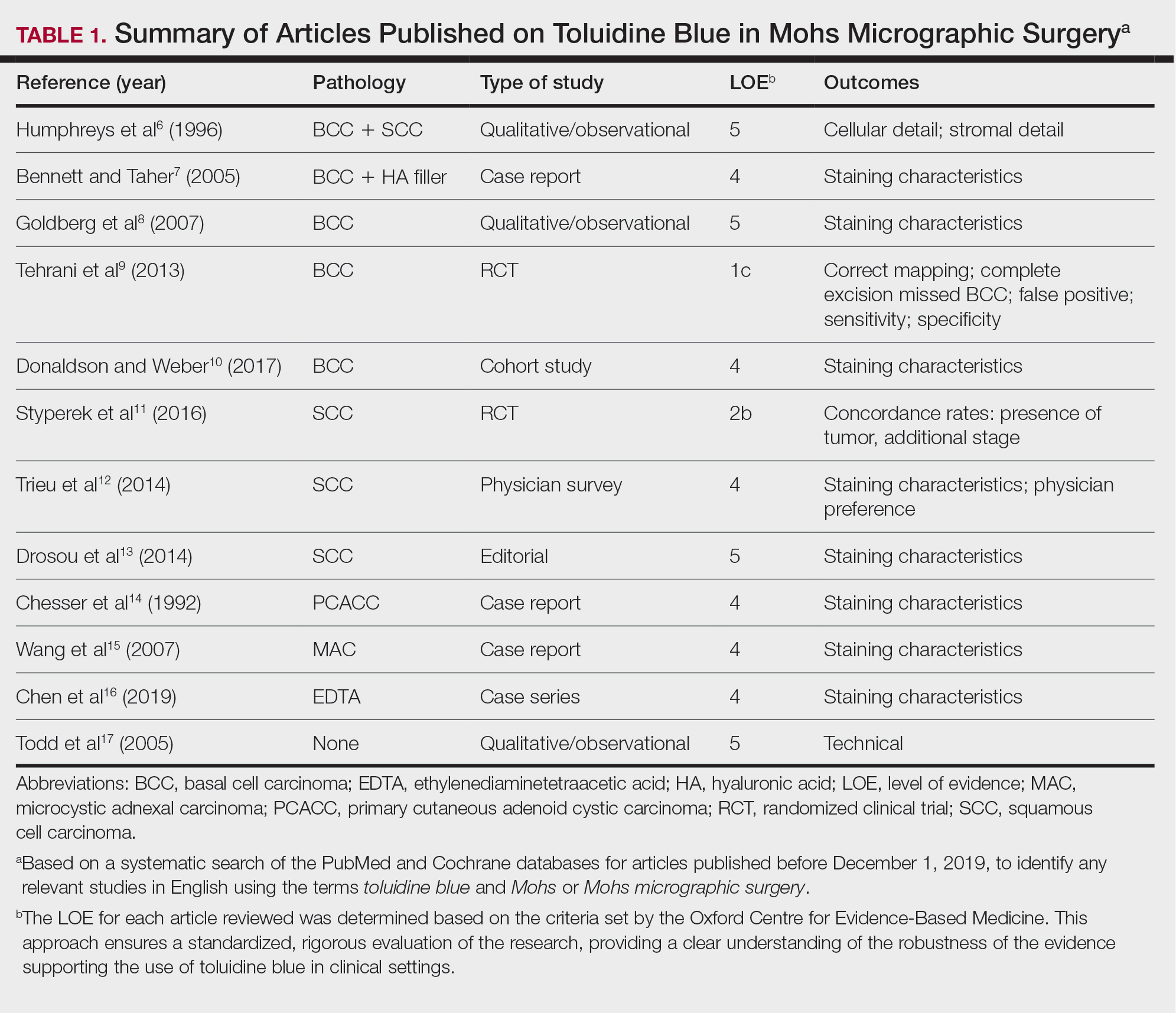

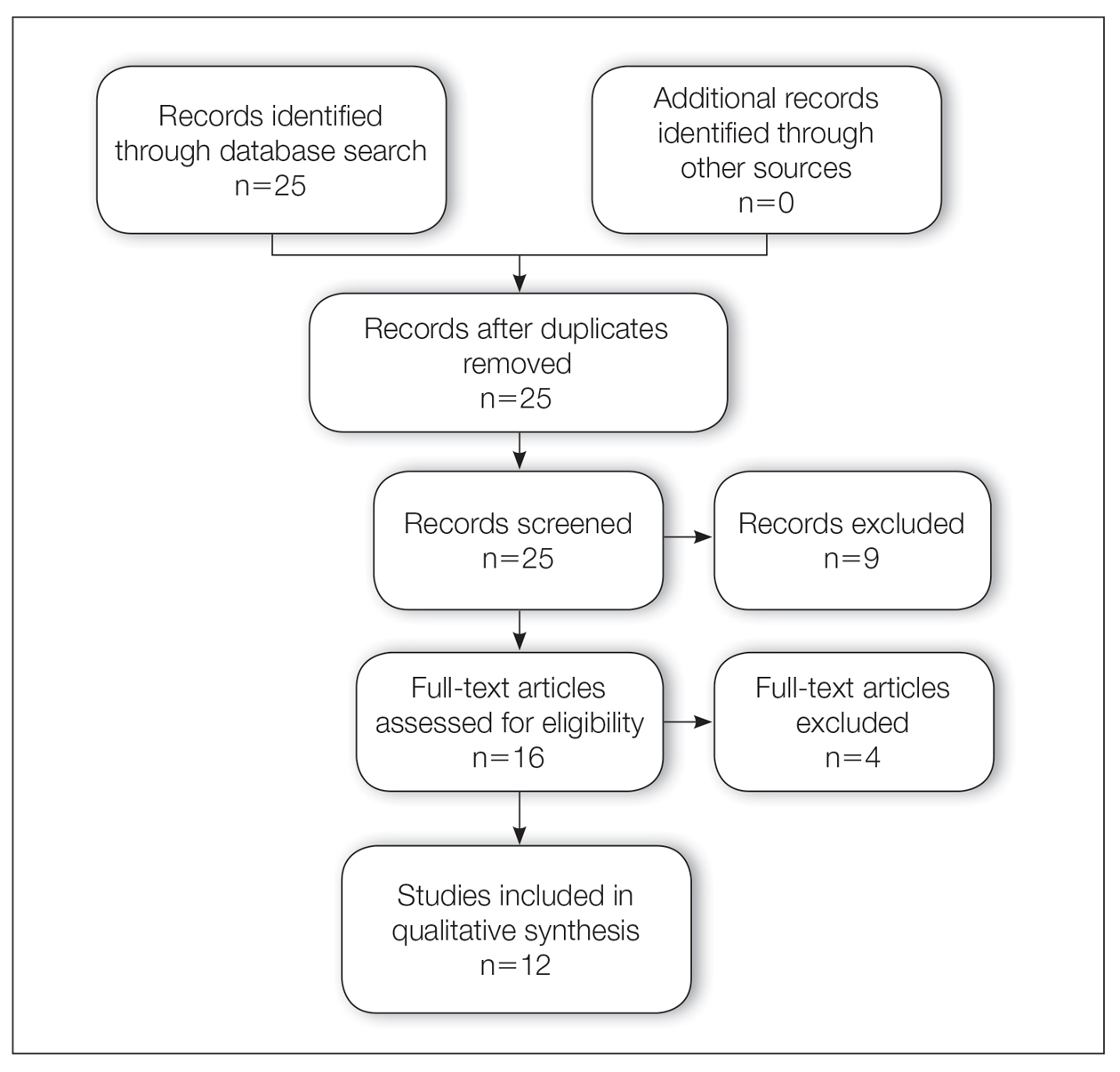

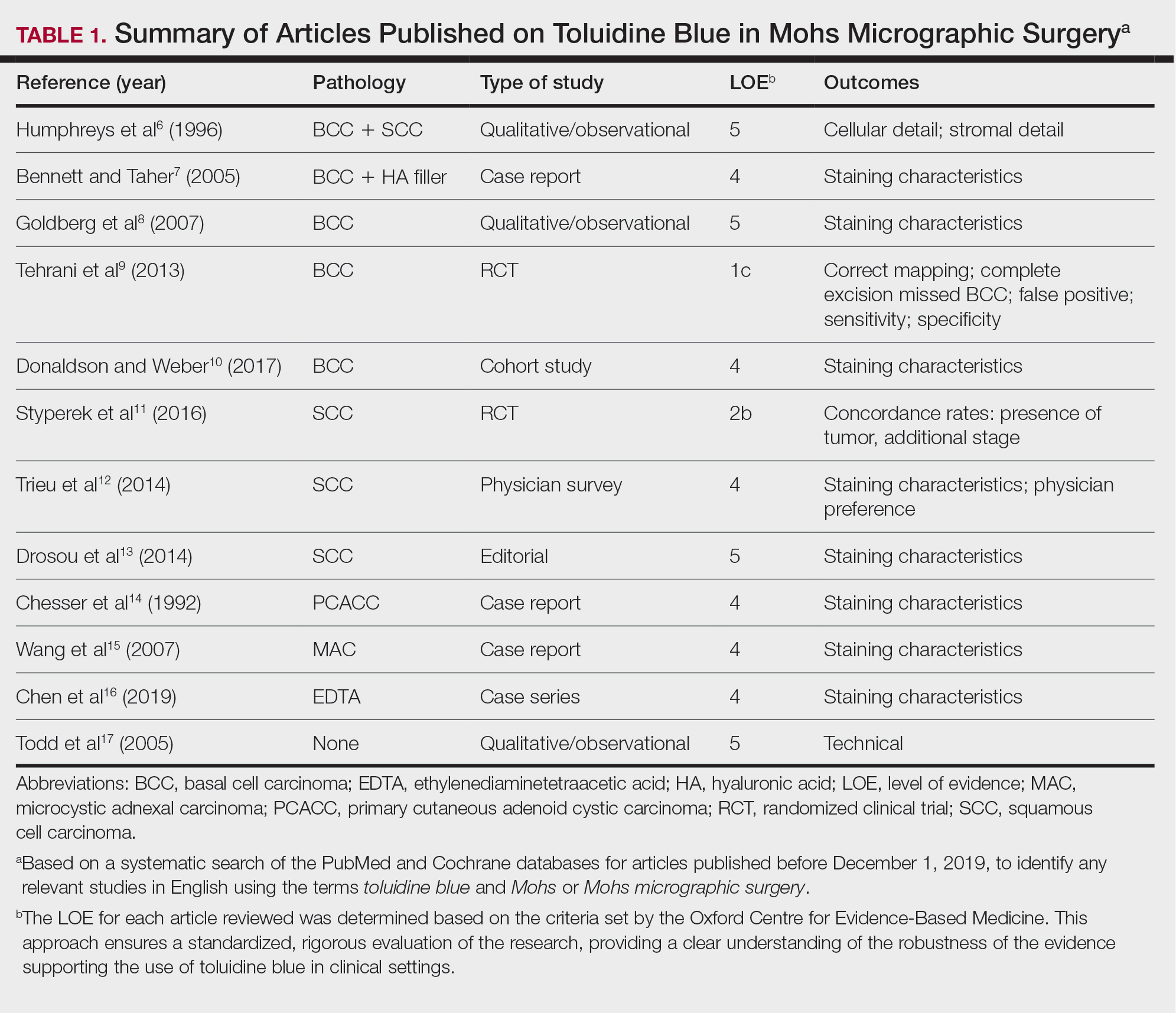

A total of 25 articles were reviewed. After the titles and abstracts were screened for relevance, 12 articles remained (Figure 1). Of these, 1 compared basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), 4 were related to BCC, 3 were related to SCC, 1 was related to microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC), 1 was related to primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma (PCACC), and 2 were related to technical aspects of the staining process (Table 1).

A majority of the articles included in this review were qualitative and observational in nature, describing the staining characteristics of TB. Study characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Comment

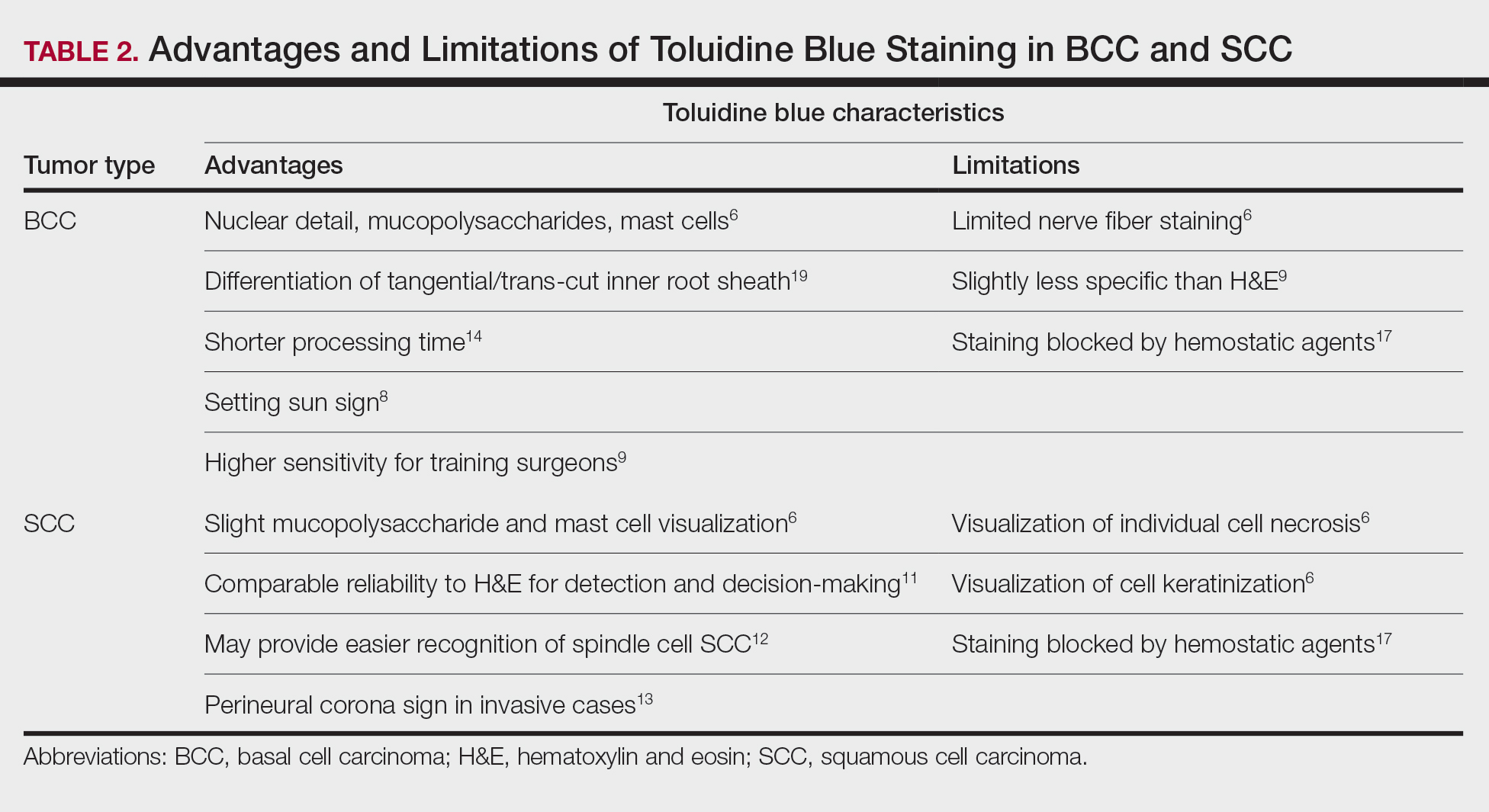

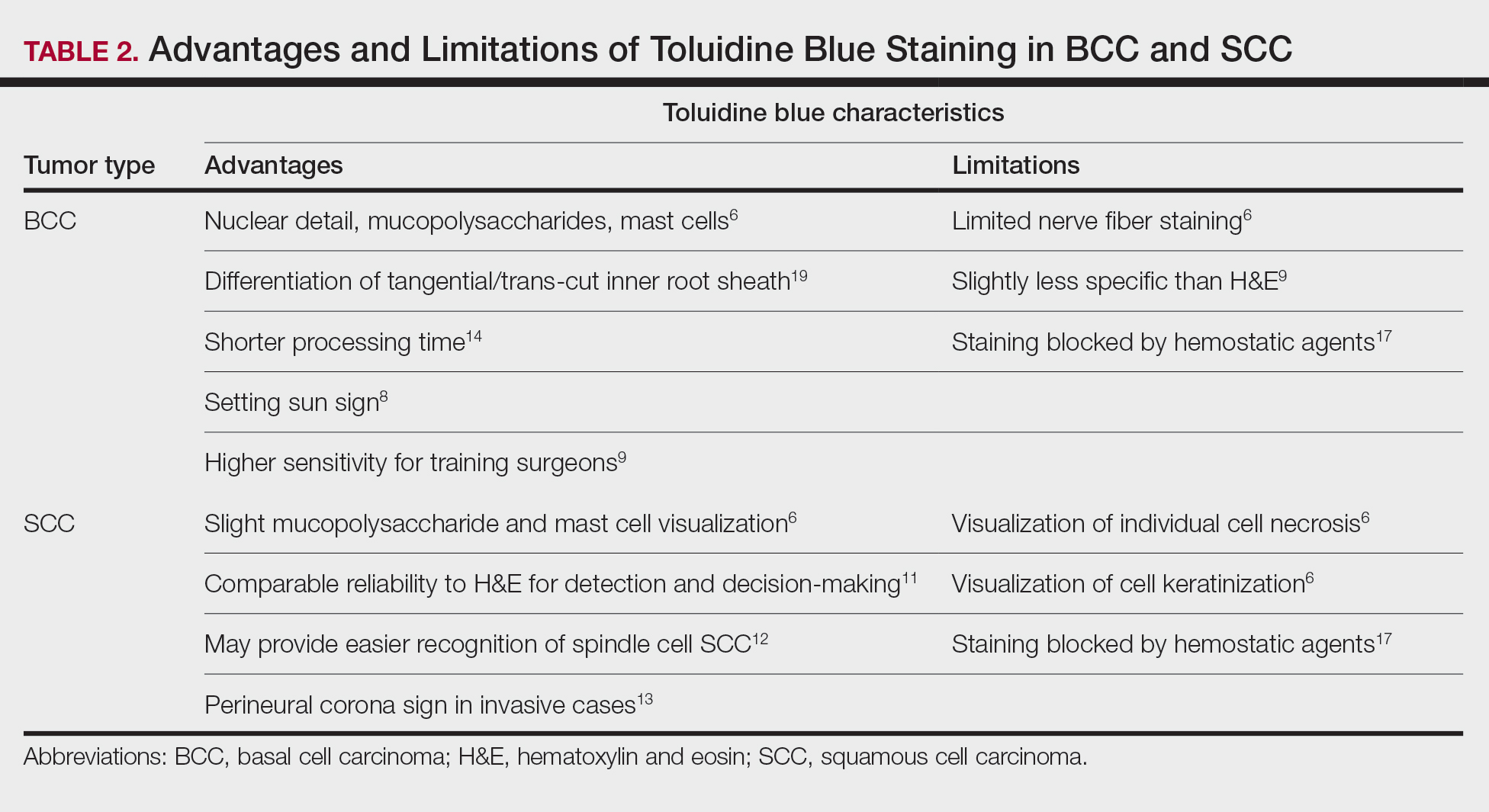

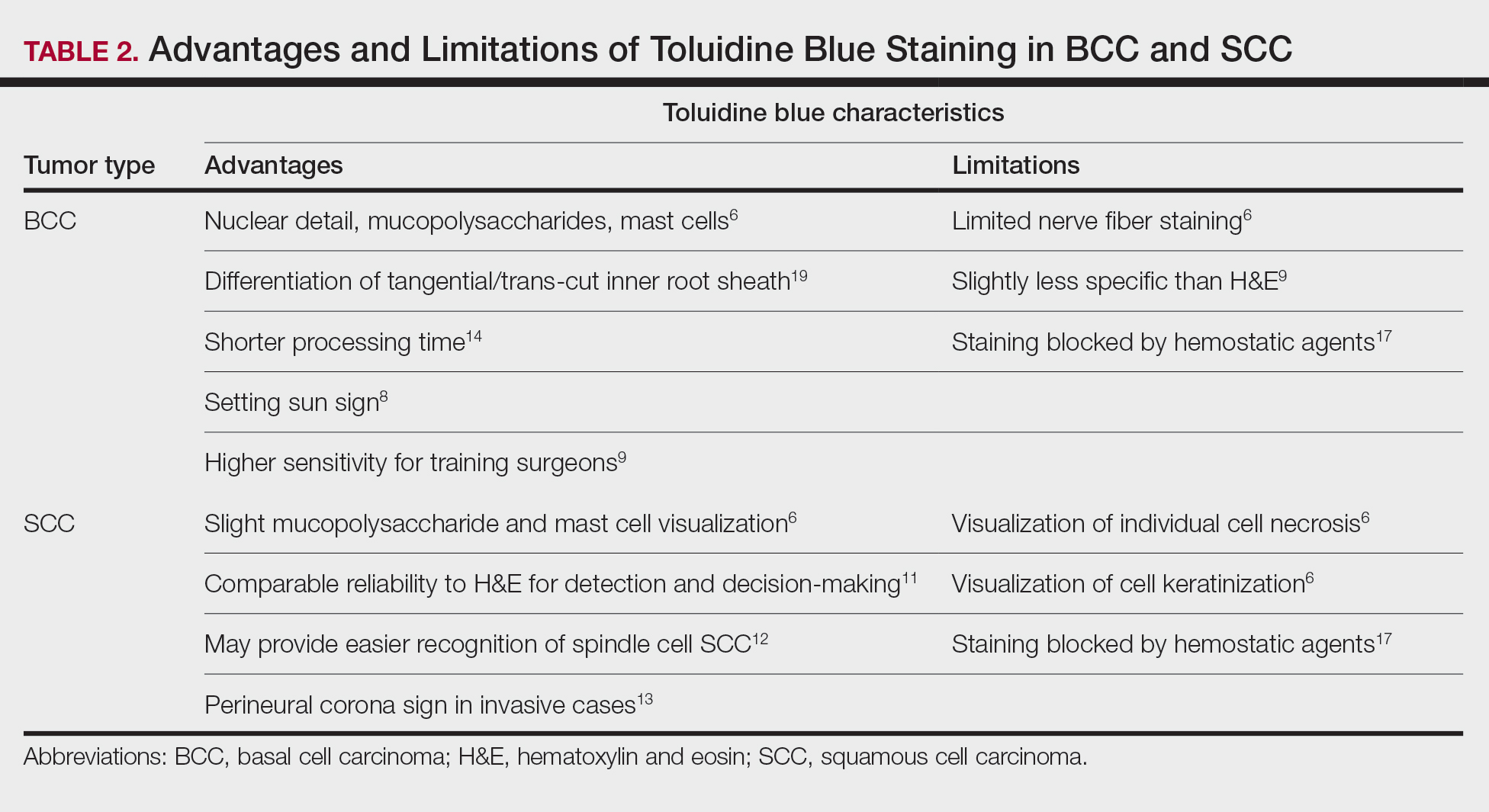

Basal Cell Carcinoma—Toluidine blue staining characteristics help to identify BCC nests by differentiating them from hair follicles in frozen sections. The metachromatic characteristic of TB stains the inner root sheath deep blue and highlights the surrounding stromal mucin of BCC a magenta color.18,19 In hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stains, these 2 distinct structures can be differentiated by cleft formation around tumor nests, mitotic figures, and the lack of a fibrous sheath present in BCC tumors.20 The advantages and limitations of TB staining of BCC are presented in Table 2.

Humphreys et al6 suggested a noticeable difference between H&E and TB in the staining of cellular and stromal components. The nuclear detail of tumor cells was subjectively sharper and clearer with TB staining. The staining of stromal components may provide the most assistance in locating BCC islands. Mucopolysaccharide staining may be absent in H&E but stain a deep magenta with TB. Although the presence of mucopolysaccharides does not specifically indicate a tumor, it may prompt further attention and provide an indicator for sparse and infiltrative tumor cells.6 The metachromatic stromal change may indicate a narrow tumor-free margin where additional deeper sections often reveal tumor that may warrant additional resection margin in more aggressive malignancies. In particular, sclerosing/morpheaform BCCs have been shown to induce glycosaminoglycan synthesis and are highlighted more readily with TB than with H&E when compared to surrounding tissue.21 This differentiation in staining has remained a popular reason to routinely incorporate TB into the staining of infiltrative and morpheaform variants of BCC. Additionally, stromal mast cells are believed to be more abundant in the stroma of BCC and are more readily visualized in tissue specimens stained with TB, appearing as bright purple metachromatic granules. These granules are larger than normal and are increased in number.6

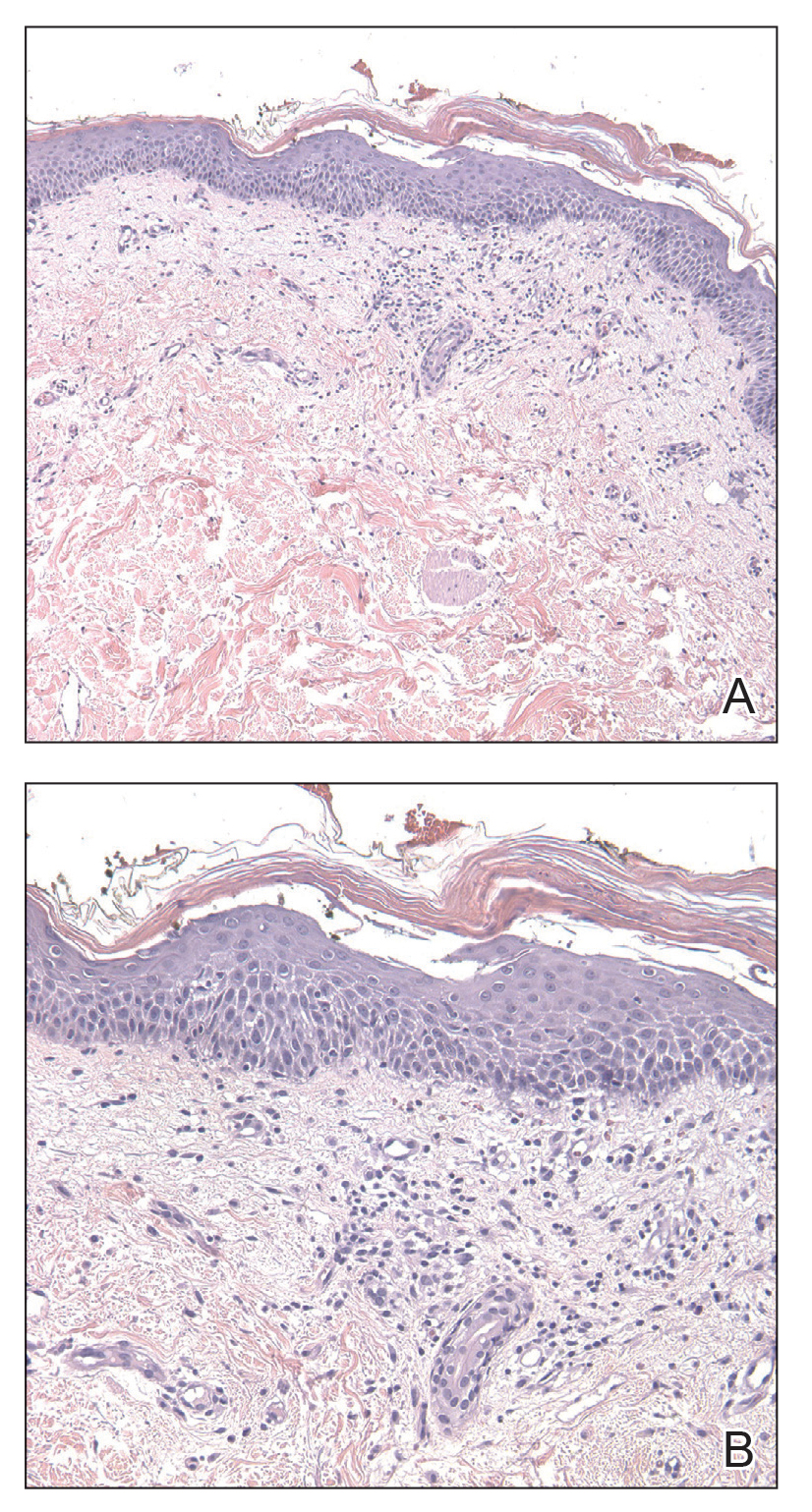

The margin behavior of BCC stained with TB was further characterized by Goldberg et al,8 who coined the term setting sun sign, which may be present in sequential sections of a disappearing nodule of a BCC tumor. Stroma, inflammatory infiltrate, and mast cells produce a magenta glow surrounding BCC tumors that is reminiscent of a setting sun (Figure 2). Invasive BCC is considered variable in this presentation, primarily because of zones of cell-free fluid and edema or the second area of inflammatory cells. This unique sign may benefit the inspecting Mohs surgeon by providing a clue to an underlying process that may have residual BCC tumors. The setting sun sign also may assist in identifying exact surgical margins.8

The nasal surface has a predilection for BCC.22 The skin of the nose has numerous look-alike structures to consider for complete tumor removal and avoidance of unnecessary removal. One challenge is distinguishing follicular basaloid proliferations (FBP) from BCC, a scenario that is more common on the nose.22 When TB staining was used, the sensitivity for detecting FBP reached 100% in 34 cases reviewed by Donaldson and Weber.10 None of the cases examined showed TB metachromasia surrounding FBP, thus indicating that TB can dependably identify this benign entity. Conversely, 5% (N=279) of BCCs confirmed on H&E did not exhibit surrounding TB metachromasia. This finding is concerning regarding the specificity of TB staining for BCC, but the authors of this study suggested the possibility that these exceptions were benign “simulants” (ie, trichoepithelioma) of BCC.10

The use of TB also has been shown to be statistically beneficial in Mohs training. In a single-center, single-fellow experiment, the sensitivity and specificity of using TB for BCC were extrapolated.9 Using TB as an adjunct in deep sections showed superior sensitivity to H&E alone in identifying BCC, increasing sensitivity from 96.3% to 99.7%. In a cohort of 352 BCC excisions and frozen sections, only 1 BCC was not completely excised. If H&E only had been performed, the fellow would have missed 13 residual BCC tumors.9

Bennett and Taher7 described a case in which hyaluronic acid (HA) from a filler injection was confused with the HA surrounding BCC tumor nests. They found that when TB is used as an adjunct, the HA filler is easier to differentiate from the HA surrounding the BCC tumor nests. In frozen sections stained with TB, the HA filler appeared as an amorphous, metachromatic, reddish-purple, whereas the HA surrounding the BCC tumor nests appeared as a well-defined red. These findings were less obvious in the same sections stained with H&E alone.7

Squamous Cell Carcinoma—In early investigations, the utility of TB in identifying SCC in frozen sections was thought to be limited. The description by Humphreys and colleagues6 of staining characteristics in SCC suggested that the nuclear detail that H&E provides is more easily recognized. The deep aqua nuclear staining produced with TB was considered more difficult to observe than the cytoplasmic eosinophilia of pyknotic and keratinizing cells in H&E.6

Toluidine blue may be beneficial in providing unique staining characteristics to further detail tumors that are difficult to interpret, such as spindle cell SCC and perineural invasion of aggressive SCC. In H&E, squamous cells of spindle cell SCC (scSCC) blend into the background of inflammatory cells and can be perceptibly difficult to locate. A small cohort of 3 Mohs surgeons who routinely use H&E were surveyed on their ability to detect a proven scSCC in H&E or TB by photograph.12 All 3 were able to detect the scSCC in the TB photographs, but only 2 of 3 were able to detect it in H&E photographs. All 3 surgeons agreed that TB was preferable to H&E for this tumor type. These findings suggested that TB may be superior and preferred over H&E for visualizing tumor cells of scSCC.12 The TB staining characteristics of perineural invasion of aggressive SCC have been referred to as the perineural corona sign because of the bright magenta stain that forms around affected nerves.13 Drosou et al13 suggested that TB may enhance the diagnostic accuracy for perineural SCC.

Rare Tumors—The adjunctive use of TB with H&E has been examined in rare tumors. Published reports have highlighted its use in MMS for treating MAC and PCACC. Toluidine blue exhibits staining advantages for these tumors. It may render isolated nests and perineural invasion of MAC more easily visible on frozen section.15

Although PCACC is rare, the recurrence rate is high.23 Toluidine blue has been used with MMS to ensure complete removal and higher cure rates. The metachromatic nature of TB is advantageous in staining the HA present in these tumors. Those who have reported the use of TB for PCACC prefer it to H&E for frozen sections.14

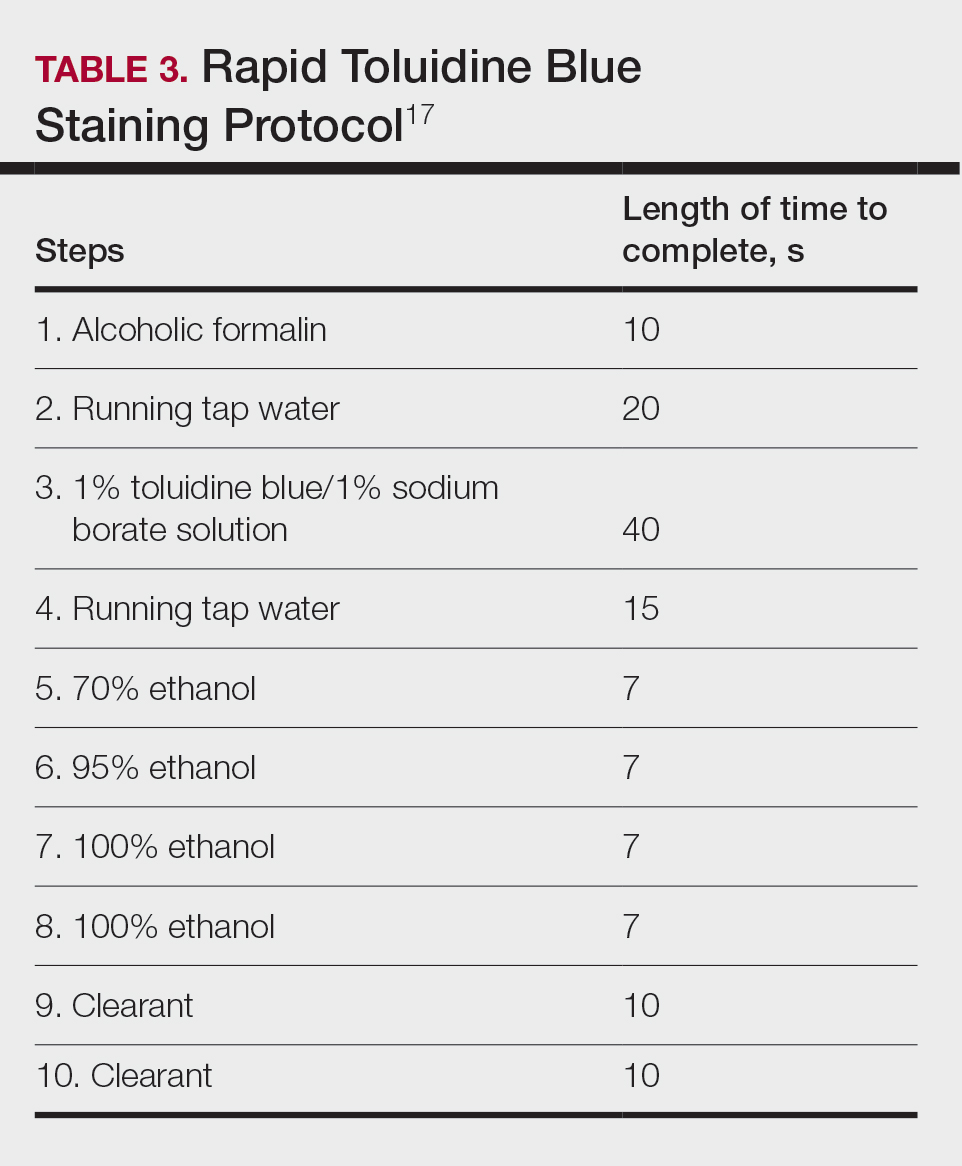

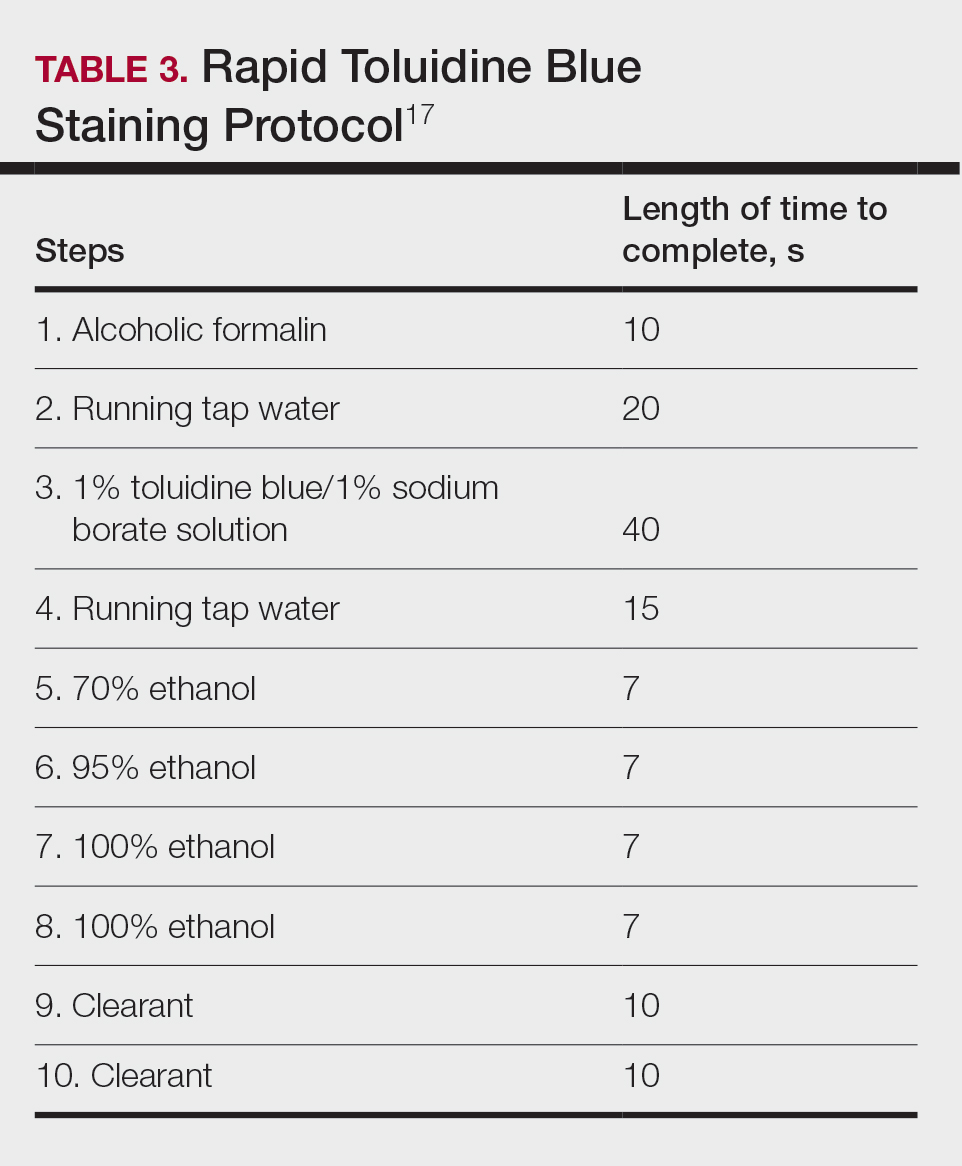

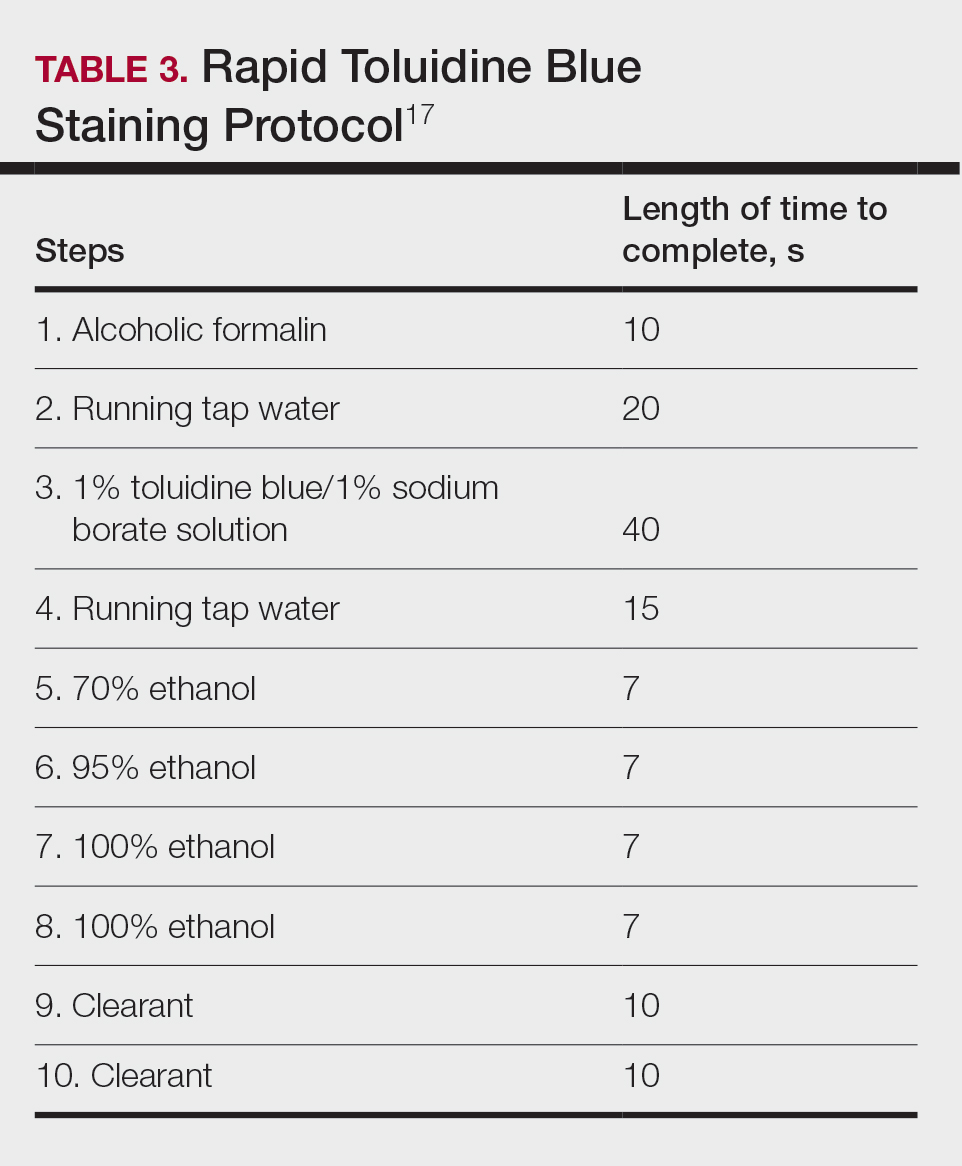

Technical Aspects—The staining time for TB-treated slides is reduced compared to H&E staining; staining can be efficiently done in frozen sections in less than 2.5 minutes using the method shown in Table 3.17 In comparison, typical H&E staining takes 9 minutes, and older TB techniques take 7 minutes.6

Conclusion

Toluidine blue may play an important and helpful role in the successful diagnosis and treatment of particular cutaneous tumors by providing additional diagnostic information. Although surgeons performing MMS will continue using the staining protocols with which they are most comfortable, adjunctive use of TB over time may provide an additional benefit at low risk for disrupting practice efficiency or workflow. Many Mohs surgeons are accustomed to using this stain, even preferring to interpret only TB-stained slides for cutaneous malignancy. Most published studies on this topic have been observational in nature, and additional controlled trials may be warranted to determine the effects on outcomes in real-world practice.

- Culling CF, Allison TR. Cellular Pathology Technique. 4th ed. Butterworths; 1985.

- Bergeron JA, Singer M. Metachromasy: an experimental and theoretical reevaluation. J Biophys Biochem Cytol. 1958;4:433-457. doi:10.1083/jcb.4.4.433

- Epstein JB, Scully C, Spinelli J. Toluidine blue and Lugol’s iodine application in the assessment of oral malignant disease and lesions at risk of malignancy. J Oral Pathol Med. 1992;21:160-163. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0714.1992.tb00094.x

- Warnakulasuriya KA, Johnson NW. Sensitivity and specificity of OraScan (R) toluidine blue mouthrinse in the detection of oral cancer and precancer. J Oral Pathol Med. 1996;25:97-103. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0714.1996.tb00201.x

- Silapunt S, Peterson SR, Alcalay J, et al. Mohs tissue mapping and processing: a survey study. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:1109-1112; discussion 1112.

- Humphreys TR, Nemeth A, McCrevey S, et al. A pilot study comparing toluidine blue and hematoxylin and eosin staining of basal cell and squamous cell carcinoma during Mohs surgery. Dermatol Surg. 1996;22:693-697. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.1996.tb00619.x

- Bennett R, Taher M. Restylane persistent for 23 months found during Mohs micrographic surgery: a source of confusion with hyaluronic acid surrounding basal cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:1366-1369. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2005.31223

- Goldberg LH, Wang SQ, Kimyai-Asadi A. The setting sun sign: visualizing the margins of a basal cell carcinoma on serial frozen sections stained with toluidine blue. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:761-763. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.33158.x

- Tehrani H, May K, Morris A, et al. Does the dual use of toluidine blue and hematoxylin and eosin staining improve basal cell carcinoma detection by Mohs surgery trainees? Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:995-1000. doi:10.1111/dsu.12180

- Donaldson MR, Weber LA. Toluidine blue supports differentiation of folliculocentric basaloid proliferation from basal cell carcinoma on frozen sections in a small single-practice cohort. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:1303-1306. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001107

- Styperek AR, Goldberg LH, Goldschmidt LE, et al. Toluidine blue and hematoxylin and eosin stains are comparable in evaluating squamous cell carcinoma during Mohs. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:1279-1284. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000872

- Trieu D, Drosou A, Goldberg LH, et al. Detecting spindle cell squamous cell carcinomas with toluidine blue on frozen sections. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:1259-1260. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000147

- Drosou A, Trieu D, Goldberg LH, et al. The perineural corona sign: enhancing detection of perineural squamous cell carcinoma during Mohs micrographic surgery with toluidine blue stain. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:826-827. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.04.076

- Chesser RS, Bertler DE, Fitzpatrick JE, et al. Primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma treated with Mohs micrographic surgery toluidine blue technique. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1992;18:175-176. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.1992.tb02794.x

- Wang SQ, Goldberg LH, Nemeth A. The merits of adding toluidine blue-stained slides in Mohs surgery in the treatment of a microcystic adnexal carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:1067-1069. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2007.01.008

- Chen CL, Wilson S, Afzalneia R, et al. Topical aluminum chloride and Monsel’s solution block toluidine blue staining in Mohs frozen sections: mechanism and solution. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:1019-1025. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001761

- Todd MM, Lee JW, Marks VJ. Rapid toluidine blue stain for Mohs’ micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:244-245. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2005.31053

- Picoto AM, Picoto A. Technical procedures for Mohs fresh tissue surgery. J Derm Surg Oncol. 1986;12:134-138. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.1986.tb01442.x

- Sperling LC, Winton GB. The transverse anatomy of androgenic alopecia. J Derm Surg Oncol. 1990;16:1127-1133. doi:10.1111/j.1524 -4725.1990.tb00024.x

- Smith-Zagone MJ, Schwartz MR. Frozen section of skin specimens. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2005;129:1536-1543. doi:10.5858/2005-129-1536-FSOSS

- Moy RL, Potter TS, Uitto J. Increased glycosaminoglycans production in sclerosing basal cell carcinoma–derived fibroblasts and stimulation of normal skin fibroblast glycosaminoglycans production by a cytokine-derived from sclerosing basal cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2000;26:1029-1036. doi:10.1046/j.1524-4725.2000.0260111029.x

- Leshin B, White WL. Folliculocentric basaloid proliferation. The bulge (der Wulst) revisited. Arch Dermatol. 1990;126:900-906. doi:10.1001/archderm.126.7.900

- Seab JA, Graham JH. Primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma.J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:113-118. doi:10.1016/s0190 -9622(87)70182-0

Toluidine blue (TB), a dye with metachromatic staining properties, was developed in 1856 by William Henry Perkin.1 Metachromasia is a perceptible change in the color of staining of living tissue due to the electrochemical properties of the tissue. Tissues that contain high concentrations of ionized sulfate and phosphate groups (high concentrations of free electronegative groups) form polymeric aggregates of the basic dye solution that alter the absorbed wavelengths of light.2 The function of this characteristic is to use a single dye to highlight different structures in tissue based on their relative chemical differences.3

Toluidine blue primarily was used within the dye industry until the 1960s, when it was first used in vital staining of the oral mucosa.2 Because of the tissue absorption potential, this technique was used to detect the location of oral malignancies.4 Since then, TB has progressively been used for staining fresh frozen sections in Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS). In a 2003 survey study (N=310), 16.8% of surgeons performing MMS reported using TB in their laboratory.5 We sought to systematically review the published literature describing the uses of TB in the setting of fresh frozen sections and MMS.

Methods

We conducted a systematic search of the PubMed and Cochrane databases for articles published before December 1, 2019, to identify any relevant studies in English. Electronic searches were performed using the terms toluidine blue and Mohs or Mohs micrographic surgery. We manually checked the bibliographies of the identified articles to further identify eligible studies.

Eligibility Criteria—The inclusion criteria were articles that (1) considered TB in the context of MMS, (2) were published in peer-reviewed journals, (3) were published in English, and (4) were available as full text. Systematic reviews were excluded.

Data Extraction and Outcomes—All relevant information regarding the study characteristics, including design, level of evidence, methodologic quality of evidence, pathology examined, and outcome measures, were collected by 2 independent reviewers (T.L. and A.D.) using a predetermined data sheet. The same 2 reviewers were used for all steps of the review process, data were independently obtained, and any discrepancy was introduced for a third opinion (D.H.) and agreed upon by the majority.

Quality Assessment—The level of evidence was evaluated based on the criteria of the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. Two reviewers (T.L. and A.D.) graded each article included in the review.

Results

A total of 25 articles were reviewed. After the titles and abstracts were screened for relevance, 12 articles remained (Figure 1). Of these, 1 compared basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), 4 were related to BCC, 3 were related to SCC, 1 was related to microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC), 1 was related to primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma (PCACC), and 2 were related to technical aspects of the staining process (Table 1).

A majority of the articles included in this review were qualitative and observational in nature, describing the staining characteristics of TB. Study characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Comment

Basal Cell Carcinoma—Toluidine blue staining characteristics help to identify BCC nests by differentiating them from hair follicles in frozen sections. The metachromatic characteristic of TB stains the inner root sheath deep blue and highlights the surrounding stromal mucin of BCC a magenta color.18,19 In hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stains, these 2 distinct structures can be differentiated by cleft formation around tumor nests, mitotic figures, and the lack of a fibrous sheath present in BCC tumors.20 The advantages and limitations of TB staining of BCC are presented in Table 2.

Humphreys et al6 suggested a noticeable difference between H&E and TB in the staining of cellular and stromal components. The nuclear detail of tumor cells was subjectively sharper and clearer with TB staining. The staining of stromal components may provide the most assistance in locating BCC islands. Mucopolysaccharide staining may be absent in H&E but stain a deep magenta with TB. Although the presence of mucopolysaccharides does not specifically indicate a tumor, it may prompt further attention and provide an indicator for sparse and infiltrative tumor cells.6 The metachromatic stromal change may indicate a narrow tumor-free margin where additional deeper sections often reveal tumor that may warrant additional resection margin in more aggressive malignancies. In particular, sclerosing/morpheaform BCCs have been shown to induce glycosaminoglycan synthesis and are highlighted more readily with TB than with H&E when compared to surrounding tissue.21 This differentiation in staining has remained a popular reason to routinely incorporate TB into the staining of infiltrative and morpheaform variants of BCC. Additionally, stromal mast cells are believed to be more abundant in the stroma of BCC and are more readily visualized in tissue specimens stained with TB, appearing as bright purple metachromatic granules. These granules are larger than normal and are increased in number.6

The margin behavior of BCC stained with TB was further characterized by Goldberg et al,8 who coined the term setting sun sign, which may be present in sequential sections of a disappearing nodule of a BCC tumor. Stroma, inflammatory infiltrate, and mast cells produce a magenta glow surrounding BCC tumors that is reminiscent of a setting sun (Figure 2). Invasive BCC is considered variable in this presentation, primarily because of zones of cell-free fluid and edema or the second area of inflammatory cells. This unique sign may benefit the inspecting Mohs surgeon by providing a clue to an underlying process that may have residual BCC tumors. The setting sun sign also may assist in identifying exact surgical margins.8

The nasal surface has a predilection for BCC.22 The skin of the nose has numerous look-alike structures to consider for complete tumor removal and avoidance of unnecessary removal. One challenge is distinguishing follicular basaloid proliferations (FBP) from BCC, a scenario that is more common on the nose.22 When TB staining was used, the sensitivity for detecting FBP reached 100% in 34 cases reviewed by Donaldson and Weber.10 None of the cases examined showed TB metachromasia surrounding FBP, thus indicating that TB can dependably identify this benign entity. Conversely, 5% (N=279) of BCCs confirmed on H&E did not exhibit surrounding TB metachromasia. This finding is concerning regarding the specificity of TB staining for BCC, but the authors of this study suggested the possibility that these exceptions were benign “simulants” (ie, trichoepithelioma) of BCC.10

The use of TB also has been shown to be statistically beneficial in Mohs training. In a single-center, single-fellow experiment, the sensitivity and specificity of using TB for BCC were extrapolated.9 Using TB as an adjunct in deep sections showed superior sensitivity to H&E alone in identifying BCC, increasing sensitivity from 96.3% to 99.7%. In a cohort of 352 BCC excisions and frozen sections, only 1 BCC was not completely excised. If H&E only had been performed, the fellow would have missed 13 residual BCC tumors.9

Bennett and Taher7 described a case in which hyaluronic acid (HA) from a filler injection was confused with the HA surrounding BCC tumor nests. They found that when TB is used as an adjunct, the HA filler is easier to differentiate from the HA surrounding the BCC tumor nests. In frozen sections stained with TB, the HA filler appeared as an amorphous, metachromatic, reddish-purple, whereas the HA surrounding the BCC tumor nests appeared as a well-defined red. These findings were less obvious in the same sections stained with H&E alone.7

Squamous Cell Carcinoma—In early investigations, the utility of TB in identifying SCC in frozen sections was thought to be limited. The description by Humphreys and colleagues6 of staining characteristics in SCC suggested that the nuclear detail that H&E provides is more easily recognized. The deep aqua nuclear staining produced with TB was considered more difficult to observe than the cytoplasmic eosinophilia of pyknotic and keratinizing cells in H&E.6

Toluidine blue may be beneficial in providing unique staining characteristics to further detail tumors that are difficult to interpret, such as spindle cell SCC and perineural invasion of aggressive SCC. In H&E, squamous cells of spindle cell SCC (scSCC) blend into the background of inflammatory cells and can be perceptibly difficult to locate. A small cohort of 3 Mohs surgeons who routinely use H&E were surveyed on their ability to detect a proven scSCC in H&E or TB by photograph.12 All 3 were able to detect the scSCC in the TB photographs, but only 2 of 3 were able to detect it in H&E photographs. All 3 surgeons agreed that TB was preferable to H&E for this tumor type. These findings suggested that TB may be superior and preferred over H&E for visualizing tumor cells of scSCC.12 The TB staining characteristics of perineural invasion of aggressive SCC have been referred to as the perineural corona sign because of the bright magenta stain that forms around affected nerves.13 Drosou et al13 suggested that TB may enhance the diagnostic accuracy for perineural SCC.

Rare Tumors—The adjunctive use of TB with H&E has been examined in rare tumors. Published reports have highlighted its use in MMS for treating MAC and PCACC. Toluidine blue exhibits staining advantages for these tumors. It may render isolated nests and perineural invasion of MAC more easily visible on frozen section.15

Although PCACC is rare, the recurrence rate is high.23 Toluidine blue has been used with MMS to ensure complete removal and higher cure rates. The metachromatic nature of TB is advantageous in staining the HA present in these tumors. Those who have reported the use of TB for PCACC prefer it to H&E for frozen sections.14

Technical Aspects—The staining time for TB-treated slides is reduced compared to H&E staining; staining can be efficiently done in frozen sections in less than 2.5 minutes using the method shown in Table 3.17 In comparison, typical H&E staining takes 9 minutes, and older TB techniques take 7 minutes.6

Conclusion

Toluidine blue may play an important and helpful role in the successful diagnosis and treatment of particular cutaneous tumors by providing additional diagnostic information. Although surgeons performing MMS will continue using the staining protocols with which they are most comfortable, adjunctive use of TB over time may provide an additional benefit at low risk for disrupting practice efficiency or workflow. Many Mohs surgeons are accustomed to using this stain, even preferring to interpret only TB-stained slides for cutaneous malignancy. Most published studies on this topic have been observational in nature, and additional controlled trials may be warranted to determine the effects on outcomes in real-world practice.

Toluidine blue (TB), a dye with metachromatic staining properties, was developed in 1856 by William Henry Perkin.1 Metachromasia is a perceptible change in the color of staining of living tissue due to the electrochemical properties of the tissue. Tissues that contain high concentrations of ionized sulfate and phosphate groups (high concentrations of free electronegative groups) form polymeric aggregates of the basic dye solution that alter the absorbed wavelengths of light.2 The function of this characteristic is to use a single dye to highlight different structures in tissue based on their relative chemical differences.3

Toluidine blue primarily was used within the dye industry until the 1960s, when it was first used in vital staining of the oral mucosa.2 Because of the tissue absorption potential, this technique was used to detect the location of oral malignancies.4 Since then, TB has progressively been used for staining fresh frozen sections in Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS). In a 2003 survey study (N=310), 16.8% of surgeons performing MMS reported using TB in their laboratory.5 We sought to systematically review the published literature describing the uses of TB in the setting of fresh frozen sections and MMS.

Methods

We conducted a systematic search of the PubMed and Cochrane databases for articles published before December 1, 2019, to identify any relevant studies in English. Electronic searches were performed using the terms toluidine blue and Mohs or Mohs micrographic surgery. We manually checked the bibliographies of the identified articles to further identify eligible studies.

Eligibility Criteria—The inclusion criteria were articles that (1) considered TB in the context of MMS, (2) were published in peer-reviewed journals, (3) were published in English, and (4) were available as full text. Systematic reviews were excluded.

Data Extraction and Outcomes—All relevant information regarding the study characteristics, including design, level of evidence, methodologic quality of evidence, pathology examined, and outcome measures, were collected by 2 independent reviewers (T.L. and A.D.) using a predetermined data sheet. The same 2 reviewers were used for all steps of the review process, data were independently obtained, and any discrepancy was introduced for a third opinion (D.H.) and agreed upon by the majority.

Quality Assessment—The level of evidence was evaluated based on the criteria of the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. Two reviewers (T.L. and A.D.) graded each article included in the review.

Results

A total of 25 articles were reviewed. After the titles and abstracts were screened for relevance, 12 articles remained (Figure 1). Of these, 1 compared basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), 4 were related to BCC, 3 were related to SCC, 1 was related to microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC), 1 was related to primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma (PCACC), and 2 were related to technical aspects of the staining process (Table 1).

A majority of the articles included in this review were qualitative and observational in nature, describing the staining characteristics of TB. Study characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Comment

Basal Cell Carcinoma—Toluidine blue staining characteristics help to identify BCC nests by differentiating them from hair follicles in frozen sections. The metachromatic characteristic of TB stains the inner root sheath deep blue and highlights the surrounding stromal mucin of BCC a magenta color.18,19 In hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stains, these 2 distinct structures can be differentiated by cleft formation around tumor nests, mitotic figures, and the lack of a fibrous sheath present in BCC tumors.20 The advantages and limitations of TB staining of BCC are presented in Table 2.

Humphreys et al6 suggested a noticeable difference between H&E and TB in the staining of cellular and stromal components. The nuclear detail of tumor cells was subjectively sharper and clearer with TB staining. The staining of stromal components may provide the most assistance in locating BCC islands. Mucopolysaccharide staining may be absent in H&E but stain a deep magenta with TB. Although the presence of mucopolysaccharides does not specifically indicate a tumor, it may prompt further attention and provide an indicator for sparse and infiltrative tumor cells.6 The metachromatic stromal change may indicate a narrow tumor-free margin where additional deeper sections often reveal tumor that may warrant additional resection margin in more aggressive malignancies. In particular, sclerosing/morpheaform BCCs have been shown to induce glycosaminoglycan synthesis and are highlighted more readily with TB than with H&E when compared to surrounding tissue.21 This differentiation in staining has remained a popular reason to routinely incorporate TB into the staining of infiltrative and morpheaform variants of BCC. Additionally, stromal mast cells are believed to be more abundant in the stroma of BCC and are more readily visualized in tissue specimens stained with TB, appearing as bright purple metachromatic granules. These granules are larger than normal and are increased in number.6

The margin behavior of BCC stained with TB was further characterized by Goldberg et al,8 who coined the term setting sun sign, which may be present in sequential sections of a disappearing nodule of a BCC tumor. Stroma, inflammatory infiltrate, and mast cells produce a magenta glow surrounding BCC tumors that is reminiscent of a setting sun (Figure 2). Invasive BCC is considered variable in this presentation, primarily because of zones of cell-free fluid and edema or the second area of inflammatory cells. This unique sign may benefit the inspecting Mohs surgeon by providing a clue to an underlying process that may have residual BCC tumors. The setting sun sign also may assist in identifying exact surgical margins.8

The nasal surface has a predilection for BCC.22 The skin of the nose has numerous look-alike structures to consider for complete tumor removal and avoidance of unnecessary removal. One challenge is distinguishing follicular basaloid proliferations (FBP) from BCC, a scenario that is more common on the nose.22 When TB staining was used, the sensitivity for detecting FBP reached 100% in 34 cases reviewed by Donaldson and Weber.10 None of the cases examined showed TB metachromasia surrounding FBP, thus indicating that TB can dependably identify this benign entity. Conversely, 5% (N=279) of BCCs confirmed on H&E did not exhibit surrounding TB metachromasia. This finding is concerning regarding the specificity of TB staining for BCC, but the authors of this study suggested the possibility that these exceptions were benign “simulants” (ie, trichoepithelioma) of BCC.10

The use of TB also has been shown to be statistically beneficial in Mohs training. In a single-center, single-fellow experiment, the sensitivity and specificity of using TB for BCC were extrapolated.9 Using TB as an adjunct in deep sections showed superior sensitivity to H&E alone in identifying BCC, increasing sensitivity from 96.3% to 99.7%. In a cohort of 352 BCC excisions and frozen sections, only 1 BCC was not completely excised. If H&E only had been performed, the fellow would have missed 13 residual BCC tumors.9

Bennett and Taher7 described a case in which hyaluronic acid (HA) from a filler injection was confused with the HA surrounding BCC tumor nests. They found that when TB is used as an adjunct, the HA filler is easier to differentiate from the HA surrounding the BCC tumor nests. In frozen sections stained with TB, the HA filler appeared as an amorphous, metachromatic, reddish-purple, whereas the HA surrounding the BCC tumor nests appeared as a well-defined red. These findings were less obvious in the same sections stained with H&E alone.7

Squamous Cell Carcinoma—In early investigations, the utility of TB in identifying SCC in frozen sections was thought to be limited. The description by Humphreys and colleagues6 of staining characteristics in SCC suggested that the nuclear detail that H&E provides is more easily recognized. The deep aqua nuclear staining produced with TB was considered more difficult to observe than the cytoplasmic eosinophilia of pyknotic and keratinizing cells in H&E.6

Toluidine blue may be beneficial in providing unique staining characteristics to further detail tumors that are difficult to interpret, such as spindle cell SCC and perineural invasion of aggressive SCC. In H&E, squamous cells of spindle cell SCC (scSCC) blend into the background of inflammatory cells and can be perceptibly difficult to locate. A small cohort of 3 Mohs surgeons who routinely use H&E were surveyed on their ability to detect a proven scSCC in H&E or TB by photograph.12 All 3 were able to detect the scSCC in the TB photographs, but only 2 of 3 were able to detect it in H&E photographs. All 3 surgeons agreed that TB was preferable to H&E for this tumor type. These findings suggested that TB may be superior and preferred over H&E for visualizing tumor cells of scSCC.12 The TB staining characteristics of perineural invasion of aggressive SCC have been referred to as the perineural corona sign because of the bright magenta stain that forms around affected nerves.13 Drosou et al13 suggested that TB may enhance the diagnostic accuracy for perineural SCC.

Rare Tumors—The adjunctive use of TB with H&E has been examined in rare tumors. Published reports have highlighted its use in MMS for treating MAC and PCACC. Toluidine blue exhibits staining advantages for these tumors. It may render isolated nests and perineural invasion of MAC more easily visible on frozen section.15

Although PCACC is rare, the recurrence rate is high.23 Toluidine blue has been used with MMS to ensure complete removal and higher cure rates. The metachromatic nature of TB is advantageous in staining the HA present in these tumors. Those who have reported the use of TB for PCACC prefer it to H&E for frozen sections.14

Technical Aspects—The staining time for TB-treated slides is reduced compared to H&E staining; staining can be efficiently done in frozen sections in less than 2.5 minutes using the method shown in Table 3.17 In comparison, typical H&E staining takes 9 minutes, and older TB techniques take 7 minutes.6

Conclusion

Toluidine blue may play an important and helpful role in the successful diagnosis and treatment of particular cutaneous tumors by providing additional diagnostic information. Although surgeons performing MMS will continue using the staining protocols with which they are most comfortable, adjunctive use of TB over time may provide an additional benefit at low risk for disrupting practice efficiency or workflow. Many Mohs surgeons are accustomed to using this stain, even preferring to interpret only TB-stained slides for cutaneous malignancy. Most published studies on this topic have been observational in nature, and additional controlled trials may be warranted to determine the effects on outcomes in real-world practice.

- Culling CF, Allison TR. Cellular Pathology Technique. 4th ed. Butterworths; 1985.

- Bergeron JA, Singer M. Metachromasy: an experimental and theoretical reevaluation. J Biophys Biochem Cytol. 1958;4:433-457. doi:10.1083/jcb.4.4.433

- Epstein JB, Scully C, Spinelli J. Toluidine blue and Lugol’s iodine application in the assessment of oral malignant disease and lesions at risk of malignancy. J Oral Pathol Med. 1992;21:160-163. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0714.1992.tb00094.x

- Warnakulasuriya KA, Johnson NW. Sensitivity and specificity of OraScan (R) toluidine blue mouthrinse in the detection of oral cancer and precancer. J Oral Pathol Med. 1996;25:97-103. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0714.1996.tb00201.x

- Silapunt S, Peterson SR, Alcalay J, et al. Mohs tissue mapping and processing: a survey study. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:1109-1112; discussion 1112.

- Humphreys TR, Nemeth A, McCrevey S, et al. A pilot study comparing toluidine blue and hematoxylin and eosin staining of basal cell and squamous cell carcinoma during Mohs surgery. Dermatol Surg. 1996;22:693-697. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.1996.tb00619.x

- Bennett R, Taher M. Restylane persistent for 23 months found during Mohs micrographic surgery: a source of confusion with hyaluronic acid surrounding basal cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:1366-1369. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2005.31223

- Goldberg LH, Wang SQ, Kimyai-Asadi A. The setting sun sign: visualizing the margins of a basal cell carcinoma on serial frozen sections stained with toluidine blue. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:761-763. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.33158.x

- Tehrani H, May K, Morris A, et al. Does the dual use of toluidine blue and hematoxylin and eosin staining improve basal cell carcinoma detection by Mohs surgery trainees? Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:995-1000. doi:10.1111/dsu.12180

- Donaldson MR, Weber LA. Toluidine blue supports differentiation of folliculocentric basaloid proliferation from basal cell carcinoma on frozen sections in a small single-practice cohort. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:1303-1306. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001107

- Styperek AR, Goldberg LH, Goldschmidt LE, et al. Toluidine blue and hematoxylin and eosin stains are comparable in evaluating squamous cell carcinoma during Mohs. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:1279-1284. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000872

- Trieu D, Drosou A, Goldberg LH, et al. Detecting spindle cell squamous cell carcinomas with toluidine blue on frozen sections. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:1259-1260. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000147

- Drosou A, Trieu D, Goldberg LH, et al. The perineural corona sign: enhancing detection of perineural squamous cell carcinoma during Mohs micrographic surgery with toluidine blue stain. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:826-827. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.04.076

- Chesser RS, Bertler DE, Fitzpatrick JE, et al. Primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma treated with Mohs micrographic surgery toluidine blue technique. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1992;18:175-176. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.1992.tb02794.x

- Wang SQ, Goldberg LH, Nemeth A. The merits of adding toluidine blue-stained slides in Mohs surgery in the treatment of a microcystic adnexal carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:1067-1069. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2007.01.008

- Chen CL, Wilson S, Afzalneia R, et al. Topical aluminum chloride and Monsel’s solution block toluidine blue staining in Mohs frozen sections: mechanism and solution. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:1019-1025. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001761

- Todd MM, Lee JW, Marks VJ. Rapid toluidine blue stain for Mohs’ micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:244-245. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2005.31053

- Picoto AM, Picoto A. Technical procedures for Mohs fresh tissue surgery. J Derm Surg Oncol. 1986;12:134-138. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.1986.tb01442.x

- Sperling LC, Winton GB. The transverse anatomy of androgenic alopecia. J Derm Surg Oncol. 1990;16:1127-1133. doi:10.1111/j.1524 -4725.1990.tb00024.x

- Smith-Zagone MJ, Schwartz MR. Frozen section of skin specimens. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2005;129:1536-1543. doi:10.5858/2005-129-1536-FSOSS

- Moy RL, Potter TS, Uitto J. Increased glycosaminoglycans production in sclerosing basal cell carcinoma–derived fibroblasts and stimulation of normal skin fibroblast glycosaminoglycans production by a cytokine-derived from sclerosing basal cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2000;26:1029-1036. doi:10.1046/j.1524-4725.2000.0260111029.x

- Leshin B, White WL. Folliculocentric basaloid proliferation. The bulge (der Wulst) revisited. Arch Dermatol. 1990;126:900-906. doi:10.1001/archderm.126.7.900

- Seab JA, Graham JH. Primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma.J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:113-118. doi:10.1016/s0190 -9622(87)70182-0

- Culling CF, Allison TR. Cellular Pathology Technique. 4th ed. Butterworths; 1985.

- Bergeron JA, Singer M. Metachromasy: an experimental and theoretical reevaluation. J Biophys Biochem Cytol. 1958;4:433-457. doi:10.1083/jcb.4.4.433

- Epstein JB, Scully C, Spinelli J. Toluidine blue and Lugol’s iodine application in the assessment of oral malignant disease and lesions at risk of malignancy. J Oral Pathol Med. 1992;21:160-163. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0714.1992.tb00094.x

- Warnakulasuriya KA, Johnson NW. Sensitivity and specificity of OraScan (R) toluidine blue mouthrinse in the detection of oral cancer and precancer. J Oral Pathol Med. 1996;25:97-103. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0714.1996.tb00201.x

- Silapunt S, Peterson SR, Alcalay J, et al. Mohs tissue mapping and processing: a survey study. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:1109-1112; discussion 1112.

- Humphreys TR, Nemeth A, McCrevey S, et al. A pilot study comparing toluidine blue and hematoxylin and eosin staining of basal cell and squamous cell carcinoma during Mohs surgery. Dermatol Surg. 1996;22:693-697. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.1996.tb00619.x

- Bennett R, Taher M. Restylane persistent for 23 months found during Mohs micrographic surgery: a source of confusion with hyaluronic acid surrounding basal cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:1366-1369. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2005.31223

- Goldberg LH, Wang SQ, Kimyai-Asadi A. The setting sun sign: visualizing the margins of a basal cell carcinoma on serial frozen sections stained with toluidine blue. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:761-763. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.33158.x

- Tehrani H, May K, Morris A, et al. Does the dual use of toluidine blue and hematoxylin and eosin staining improve basal cell carcinoma detection by Mohs surgery trainees? Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:995-1000. doi:10.1111/dsu.12180

- Donaldson MR, Weber LA. Toluidine blue supports differentiation of folliculocentric basaloid proliferation from basal cell carcinoma on frozen sections in a small single-practice cohort. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:1303-1306. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001107

- Styperek AR, Goldberg LH, Goldschmidt LE, et al. Toluidine blue and hematoxylin and eosin stains are comparable in evaluating squamous cell carcinoma during Mohs. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:1279-1284. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000872

- Trieu D, Drosou A, Goldberg LH, et al. Detecting spindle cell squamous cell carcinomas with toluidine blue on frozen sections. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:1259-1260. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000147

- Drosou A, Trieu D, Goldberg LH, et al. The perineural corona sign: enhancing detection of perineural squamous cell carcinoma during Mohs micrographic surgery with toluidine blue stain. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:826-827. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.04.076

- Chesser RS, Bertler DE, Fitzpatrick JE, et al. Primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma treated with Mohs micrographic surgery toluidine blue technique. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1992;18:175-176. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.1992.tb02794.x

- Wang SQ, Goldberg LH, Nemeth A. The merits of adding toluidine blue-stained slides in Mohs surgery in the treatment of a microcystic adnexal carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:1067-1069. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2007.01.008

- Chen CL, Wilson S, Afzalneia R, et al. Topical aluminum chloride and Monsel’s solution block toluidine blue staining in Mohs frozen sections: mechanism and solution. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:1019-1025. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001761

- Todd MM, Lee JW, Marks VJ. Rapid toluidine blue stain for Mohs’ micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:244-245. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2005.31053

- Picoto AM, Picoto A. Technical procedures for Mohs fresh tissue surgery. J Derm Surg Oncol. 1986;12:134-138. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.1986.tb01442.x

- Sperling LC, Winton GB. The transverse anatomy of androgenic alopecia. J Derm Surg Oncol. 1990;16:1127-1133. doi:10.1111/j.1524 -4725.1990.tb00024.x

- Smith-Zagone MJ, Schwartz MR. Frozen section of skin specimens. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2005;129:1536-1543. doi:10.5858/2005-129-1536-FSOSS

- Moy RL, Potter TS, Uitto J. Increased glycosaminoglycans production in sclerosing basal cell carcinoma–derived fibroblasts and stimulation of normal skin fibroblast glycosaminoglycans production by a cytokine-derived from sclerosing basal cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2000;26:1029-1036. doi:10.1046/j.1524-4725.2000.0260111029.x

- Leshin B, White WL. Folliculocentric basaloid proliferation. The bulge (der Wulst) revisited. Arch Dermatol. 1990;126:900-906. doi:10.1001/archderm.126.7.900

- Seab JA, Graham JH. Primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma.J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:113-118. doi:10.1016/s0190 -9622(87)70182-0

Practice Points

- Toluidine blue (TB) staining can be integrated into Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) for enhanced diagnosis of cutaneous tumors. Its metachromatic properties can aid in differentiating tumor cells from surrounding tissues, especially in basal cell carcinomas and squamous cell carcinomas.

- It is important to develop expertise in interpreting TB-stained sections, as it may offer clearer visualization of nuclear details and stromal components, potentially leading to more accurate diagnosis and effective tumor margin identification.

- Toluidine blue staining can be incorporated into routine MMS practice considering its quick staining process and low disruption to workflow. This can potentially improve diagnostic efficiency without significantly lengthening surgery time.

Reactive Angioendotheliomatosis Following Ad26.COV2.S Vaccination

To the Editor:

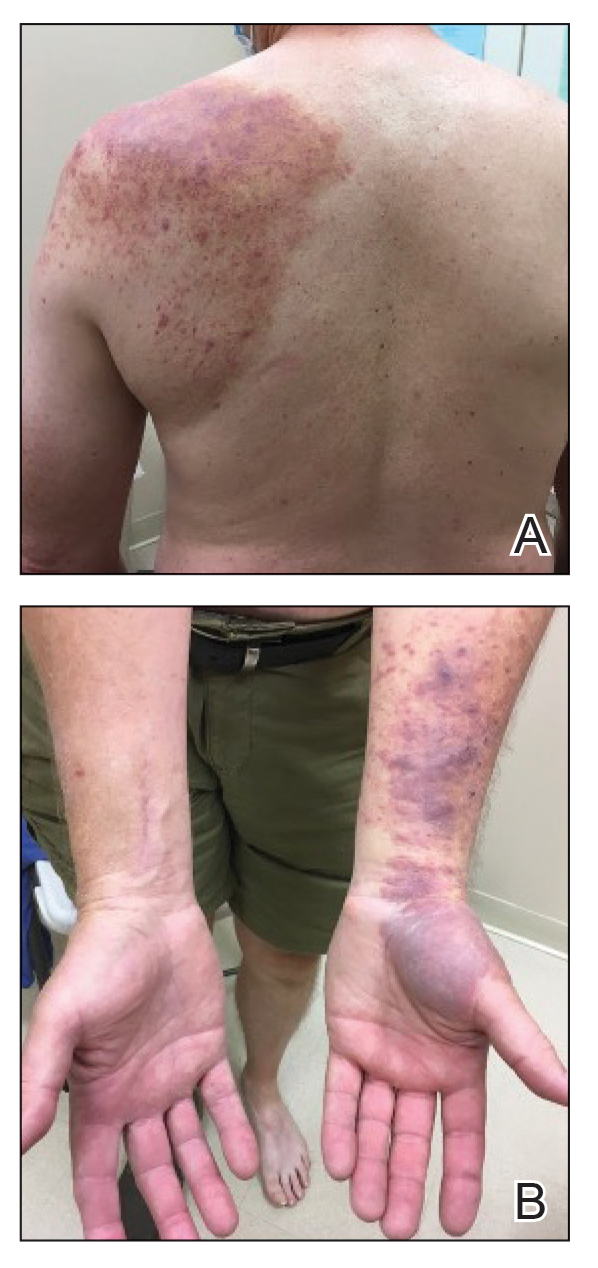

Reactive angioendotheliomatosis (RAE) is a rare self-limited cutaneous vascular proliferation of endothelial cells within blood vessels that manifests clinically as infiltrated red-blue patches and plaques with purpura that can progress to occlude vascular lumina. The etiology of RAE is mostly idiopathic; however, the disorder typically occurs in association with a range of systemic diseases, including infection, cryoglobulinemia, leukemia, antiphospholipid syndrome, peripheral vascular disease, and arteriovenous fistula. Histopathologic examination of these lesions shows marked proliferation of endothelial cells, including occlusion of the lumen of blood vessels over wide areas.

After ruling out malignancy, treatment of RAE focuses on targeting the underlying cause or disease, if any is present; 75% of reported cases occur in association with systemic disease.1 Onset can occur at any age without predilection for sex. Reactive angioendotheliomatosis commonly manifests on the extremities but may occur on the head and neck in rare instances.2