User login

Oligoclonal Bands May Predict MS Relapses and Progression

NASHVILLE—Patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) and 10 or more oligoclonal bands (OCBs) in CSF may have significantly more clinical and radiographic relapses and clinical progression during short-term follow-up than those who have fewer OCBs, according to data described at the 2018 CMSC Annual Meeting. OCBs may have greater diagnostic weight in the future, and their quantity may be important to consider during the selection of disease-modifying therapies, said the investigators.

Data Suggest the Predictive Value of OCBs

OCBs in the CSF are a common laboratory abnormality in MS. More than 90% of patients with MS have this finding. Previous research has suggested that OCBs predict the likelihood of progressing from clinically isolated syndrome to clinically definite MS. When observed early in the disease course, OCBs indicate a worse prognosis. Reflecting this emerging research, the latest version of the McDonald Criteria for MS diagnosis has incorporated OCBs.

Yet the predictive value of OCBs has been incompletely explored, said Christopher Perrone, MD, a resident at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, and colleagues. “While most studies examine the presence or absence of OCBs with regard to prognosis, only a few small studies have investigated correlations between the number of OCBs on single disease metrics,” he added.

OCBs May Predict Need for Assistive Devices

In their retrospective study, Dr. Perrone and colleagues intended to examine relationships between the number of OCBs and markers of clinical and radiographic relapses and progression in two-year follow-up. They screened 1,270 patients receiving MS disease-modifying therapies for OCB testing. Further selection criteria included a diagnosis of relapsing-remitting MS and adherence to a DMT with two years of follow-up clinical visits and imaging. In all, 128 patients met the inclusion criteria.

The study’s primary outcome measures were clinical relapses (defined as the number of steroid prescriptions) and radiographic relapses (defined as the number of new lesions on MRI) at two-year follow-up. Secondary outcome measures were clinical progression (categorized as independent, cane, walker, or wheelchair) and radiographic progression (net changes in third ventricular width, lateral ventricular width, and cortical width). Unpaired, two-tailed t tests were used for comparative analyses.

At two years, the number of clinical relapses was significantly greater in patients with 10 or more OCBs, compared with patients with fewer than 10 OCBs. Similarly, patients with 10 or more OCBs were more likely to have radiographic relapses, with nearly twice the number of new lesions on MRI at two years, compared with patients with fewer than 10 OCBs. Although the investigators found no significant difference between groups at baseline in the use of an assistive device, within-subjects analysis demonstrated that the use of a new assistive device was more common for patients with 10 or more OCBs. While lateral ventricular width increased more in patients with 10 or more OCBs, changes in third ventricular width and cortical width were not significantly different between groups.

NASHVILLE—Patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) and 10 or more oligoclonal bands (OCBs) in CSF may have significantly more clinical and radiographic relapses and clinical progression during short-term follow-up than those who have fewer OCBs, according to data described at the 2018 CMSC Annual Meeting. OCBs may have greater diagnostic weight in the future, and their quantity may be important to consider during the selection of disease-modifying therapies, said the investigators.

Data Suggest the Predictive Value of OCBs

OCBs in the CSF are a common laboratory abnormality in MS. More than 90% of patients with MS have this finding. Previous research has suggested that OCBs predict the likelihood of progressing from clinically isolated syndrome to clinically definite MS. When observed early in the disease course, OCBs indicate a worse prognosis. Reflecting this emerging research, the latest version of the McDonald Criteria for MS diagnosis has incorporated OCBs.

Yet the predictive value of OCBs has been incompletely explored, said Christopher Perrone, MD, a resident at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, and colleagues. “While most studies examine the presence or absence of OCBs with regard to prognosis, only a few small studies have investigated correlations between the number of OCBs on single disease metrics,” he added.

OCBs May Predict Need for Assistive Devices

In their retrospective study, Dr. Perrone and colleagues intended to examine relationships between the number of OCBs and markers of clinical and radiographic relapses and progression in two-year follow-up. They screened 1,270 patients receiving MS disease-modifying therapies for OCB testing. Further selection criteria included a diagnosis of relapsing-remitting MS and adherence to a DMT with two years of follow-up clinical visits and imaging. In all, 128 patients met the inclusion criteria.

The study’s primary outcome measures were clinical relapses (defined as the number of steroid prescriptions) and radiographic relapses (defined as the number of new lesions on MRI) at two-year follow-up. Secondary outcome measures were clinical progression (categorized as independent, cane, walker, or wheelchair) and radiographic progression (net changes in third ventricular width, lateral ventricular width, and cortical width). Unpaired, two-tailed t tests were used for comparative analyses.

At two years, the number of clinical relapses was significantly greater in patients with 10 or more OCBs, compared with patients with fewer than 10 OCBs. Similarly, patients with 10 or more OCBs were more likely to have radiographic relapses, with nearly twice the number of new lesions on MRI at two years, compared with patients with fewer than 10 OCBs. Although the investigators found no significant difference between groups at baseline in the use of an assistive device, within-subjects analysis demonstrated that the use of a new assistive device was more common for patients with 10 or more OCBs. While lateral ventricular width increased more in patients with 10 or more OCBs, changes in third ventricular width and cortical width were not significantly different between groups.

NASHVILLE—Patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) and 10 or more oligoclonal bands (OCBs) in CSF may have significantly more clinical and radiographic relapses and clinical progression during short-term follow-up than those who have fewer OCBs, according to data described at the 2018 CMSC Annual Meeting. OCBs may have greater diagnostic weight in the future, and their quantity may be important to consider during the selection of disease-modifying therapies, said the investigators.

Data Suggest the Predictive Value of OCBs

OCBs in the CSF are a common laboratory abnormality in MS. More than 90% of patients with MS have this finding. Previous research has suggested that OCBs predict the likelihood of progressing from clinically isolated syndrome to clinically definite MS. When observed early in the disease course, OCBs indicate a worse prognosis. Reflecting this emerging research, the latest version of the McDonald Criteria for MS diagnosis has incorporated OCBs.

Yet the predictive value of OCBs has been incompletely explored, said Christopher Perrone, MD, a resident at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, and colleagues. “While most studies examine the presence or absence of OCBs with regard to prognosis, only a few small studies have investigated correlations between the number of OCBs on single disease metrics,” he added.

OCBs May Predict Need for Assistive Devices

In their retrospective study, Dr. Perrone and colleagues intended to examine relationships between the number of OCBs and markers of clinical and radiographic relapses and progression in two-year follow-up. They screened 1,270 patients receiving MS disease-modifying therapies for OCB testing. Further selection criteria included a diagnosis of relapsing-remitting MS and adherence to a DMT with two years of follow-up clinical visits and imaging. In all, 128 patients met the inclusion criteria.

The study’s primary outcome measures were clinical relapses (defined as the number of steroid prescriptions) and radiographic relapses (defined as the number of new lesions on MRI) at two-year follow-up. Secondary outcome measures were clinical progression (categorized as independent, cane, walker, or wheelchair) and radiographic progression (net changes in third ventricular width, lateral ventricular width, and cortical width). Unpaired, two-tailed t tests were used for comparative analyses.

At two years, the number of clinical relapses was significantly greater in patients with 10 or more OCBs, compared with patients with fewer than 10 OCBs. Similarly, patients with 10 or more OCBs were more likely to have radiographic relapses, with nearly twice the number of new lesions on MRI at two years, compared with patients with fewer than 10 OCBs. Although the investigators found no significant difference between groups at baseline in the use of an assistive device, within-subjects analysis demonstrated that the use of a new assistive device was more common for patients with 10 or more OCBs. While lateral ventricular width increased more in patients with 10 or more OCBs, changes in third ventricular width and cortical width were not significantly different between groups.

Rapid Foot-Tapping Task Distinguishes Between MS Subtypes

NASHVILLE—A rapid foot-tapping task can distinguish between healthy controls and people with multiple sclerosis (MS), as well as between MS subtypes, according to a study presented at the 2018 CMSC Annual Meeting. “The associations between foot-tap speed and mobility measures such as the Timed Up and Go [TUG] test and the 25-Foot Walk test [25FWT] suggest that rapid foot tapping may be a useful marker for tracking or predicting progression of mobility dysfunction in people with MS, regardless of their ability to ambulate,” said Sumire Sato, a graduate student in the Neuroscience and Behavior Program at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, and colleagues.

The TUG test and the 25FWT are common clinical measurements that require ambulation and are used to assess mobility in people with MS. Not all people with MS are ambulatory, however. Preliminary, unpublished work by Ms. Sato and colleagues suggests that while the TUG test and the 25FWT can distinguish individuals with MS from controls without MS, they cannot distinguish between nonprogressive (MS-NP) and progressive (MS-P) MS subtypes. “Therefore, there is a critical need to identify a sensitive and nonambulatory task that can distinguish MS subtypes,” said the investigators.

Ms. Sato and colleagues recruited 30 participants with MS-NP, 30 participants with MS-P, and 17 age- and sex-matched controls for a study to determine whether rapid foot tapping ability can distinguish people with MS from controls and between MS subtypes. Each participant wore inertial sensors (manufactured by APDM) on the foot to measure angular velocity and acceleration. Participants were instructed to tap one foot as fast as possible for 10 seconds. Participants performed three trials on each foot while seated with self-selected knee and ankle angle.

The researchers analyzed sensor data using a custom MATLAB program that identified taps as acceleration peaks that occurred after every other zero-crossing of angular velocity. They administered the TUG test and 25FWT to participants to compare mobility to rapid foot tapping. Analysis of variance was used to analyze main effects of group and to make pairwise comparisons between groups. Ms. Sato and colleagues evaluated associations between foot tap count and mobility measures in MS groups using Spearman’s rho.

The researchers observed a main effect of group for foot-tap count, such that tap count differed between controls and participants with MS-NP and MS-P. The tap count also differed between participants with MS-NP and those with MS-P. Foot-tap count was negatively correlated with the 25FWT and the TUG test, thus indicating an association between the slowing of tapping speed and mobility measures.

NASHVILLE—A rapid foot-tapping task can distinguish between healthy controls and people with multiple sclerosis (MS), as well as between MS subtypes, according to a study presented at the 2018 CMSC Annual Meeting. “The associations between foot-tap speed and mobility measures such as the Timed Up and Go [TUG] test and the 25-Foot Walk test [25FWT] suggest that rapid foot tapping may be a useful marker for tracking or predicting progression of mobility dysfunction in people with MS, regardless of their ability to ambulate,” said Sumire Sato, a graduate student in the Neuroscience and Behavior Program at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, and colleagues.

The TUG test and the 25FWT are common clinical measurements that require ambulation and are used to assess mobility in people with MS. Not all people with MS are ambulatory, however. Preliminary, unpublished work by Ms. Sato and colleagues suggests that while the TUG test and the 25FWT can distinguish individuals with MS from controls without MS, they cannot distinguish between nonprogressive (MS-NP) and progressive (MS-P) MS subtypes. “Therefore, there is a critical need to identify a sensitive and nonambulatory task that can distinguish MS subtypes,” said the investigators.

Ms. Sato and colleagues recruited 30 participants with MS-NP, 30 participants with MS-P, and 17 age- and sex-matched controls for a study to determine whether rapid foot tapping ability can distinguish people with MS from controls and between MS subtypes. Each participant wore inertial sensors (manufactured by APDM) on the foot to measure angular velocity and acceleration. Participants were instructed to tap one foot as fast as possible for 10 seconds. Participants performed three trials on each foot while seated with self-selected knee and ankle angle.

The researchers analyzed sensor data using a custom MATLAB program that identified taps as acceleration peaks that occurred after every other zero-crossing of angular velocity. They administered the TUG test and 25FWT to participants to compare mobility to rapid foot tapping. Analysis of variance was used to analyze main effects of group and to make pairwise comparisons between groups. Ms. Sato and colleagues evaluated associations between foot tap count and mobility measures in MS groups using Spearman’s rho.

The researchers observed a main effect of group for foot-tap count, such that tap count differed between controls and participants with MS-NP and MS-P. The tap count also differed between participants with MS-NP and those with MS-P. Foot-tap count was negatively correlated with the 25FWT and the TUG test, thus indicating an association between the slowing of tapping speed and mobility measures.

NASHVILLE—A rapid foot-tapping task can distinguish between healthy controls and people with multiple sclerosis (MS), as well as between MS subtypes, according to a study presented at the 2018 CMSC Annual Meeting. “The associations between foot-tap speed and mobility measures such as the Timed Up and Go [TUG] test and the 25-Foot Walk test [25FWT] suggest that rapid foot tapping may be a useful marker for tracking or predicting progression of mobility dysfunction in people with MS, regardless of their ability to ambulate,” said Sumire Sato, a graduate student in the Neuroscience and Behavior Program at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, and colleagues.

The TUG test and the 25FWT are common clinical measurements that require ambulation and are used to assess mobility in people with MS. Not all people with MS are ambulatory, however. Preliminary, unpublished work by Ms. Sato and colleagues suggests that while the TUG test and the 25FWT can distinguish individuals with MS from controls without MS, they cannot distinguish between nonprogressive (MS-NP) and progressive (MS-P) MS subtypes. “Therefore, there is a critical need to identify a sensitive and nonambulatory task that can distinguish MS subtypes,” said the investigators.

Ms. Sato and colleagues recruited 30 participants with MS-NP, 30 participants with MS-P, and 17 age- and sex-matched controls for a study to determine whether rapid foot tapping ability can distinguish people with MS from controls and between MS subtypes. Each participant wore inertial sensors (manufactured by APDM) on the foot to measure angular velocity and acceleration. Participants were instructed to tap one foot as fast as possible for 10 seconds. Participants performed three trials on each foot while seated with self-selected knee and ankle angle.

The researchers analyzed sensor data using a custom MATLAB program that identified taps as acceleration peaks that occurred after every other zero-crossing of angular velocity. They administered the TUG test and 25FWT to participants to compare mobility to rapid foot tapping. Analysis of variance was used to analyze main effects of group and to make pairwise comparisons between groups. Ms. Sato and colleagues evaluated associations between foot tap count and mobility measures in MS groups using Spearman’s rho.

The researchers observed a main effect of group for foot-tap count, such that tap count differed between controls and participants with MS-NP and MS-P. The tap count also differed between participants with MS-NP and those with MS-P. Foot-tap count was negatively correlated with the 25FWT and the TUG test, thus indicating an association between the slowing of tapping speed and mobility measures.

Value of alemtuzumab demonstrated in RRMS patients with prior IFNB-1a treatment

LOS ANGELES – Patients with multiple sclerosis in the CARE-MS II study who switched from interferon beta-1a therapy to the humanized monoclonal antibody alemtuzumab experienced continued reductions in brain volume loss and lesions on MRI through 5 years, according to follow-up data from the CARE-MS II extension study known as TOPAZ.

These outcomes support core findings from the CARE-MS II study, and suggest that alemtuzumab (Lemtrada) provides a unique treatment approach for patients with prior subcutaneous interferon beta-1a (IFNB-1a) treatment, Daniel Pelletier, MD, reported in a poster discussion session at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

In CARE-MS II, relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis patients with inadequate response to prior therapy experienced improvements in MRI lesions and brain volume loss with two courses of alemtuzumab versus IFNB-1a through 2 years, and in a 4-year extension in which participants discontinued subcutaneous IFNB-1a and initiated alemtuzumab at 12 mg/day, they experienced durable efficacy in the absence of continuous treatment, explained Dr. Pelletier, a professor of neurology at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

In the extension, patients could receive alemtuzumab retreatment as needed for relapse/MRI activity or receive other disease-modifying therapies at the investigator’s discretion. Patients completing the extension could enter the 5-year TOPAZ study for further evaluation, he said.

Of 119 patients who completed TOPAZ year 1, and thus had 5 years of follow-up after initiating alemtuzumab, 78% were free of new, gadolinium-enhancing lesions in IFNB-1a year 2; this increased significantly to 92% in post-alemtuzumab year 2, and remained high at 85%-89% in years 3-5. Additionally, 48% of patients were free of new/enlarging T2 lesions in IFNB-1a year 2; this increased significantly to 81% in post-alemtuzumab year 2 and remained high in years 3-5.

Further, 47% of the TOPAZ patients were MRI disease activity–free in IFNB-1a year 2; this increased significantly to 81% in post-alemtuzumab year 2, and remained high at 67%-72% in years 3-5.

“Perhaps for me what makes even more sense is looking at the yearly brain parenchymal fraction change,” Dr. Pelletier said, noting that the median annual reductions in years 1-5, respectively, were 0.02%, 0.04%, 0.15%, 0.14%, and 0.08%, compared with –0.33% for subcutaneous IFNB-1a at year 2 in CARE-MS II. The median brain parenchymal fraction change from baseline to post-alemtuzumab year 5 was –1.40%.

In 61% of patients, no further treatment was given after the second course of alemtuzumab.

The findings suggest that alemtuzumab provides durable efficacy without continuous treatment, he concluded.

This study was supported by Sanofi and Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Pelletier has received personal compensation for consulting, serving on a scientific advisory board, speaking, or other activities with Biogen, Merck Serono, Novartis, Roche, and Sanofi, as well as research support from Biogen, Merck Serono, Novartis, Roche, and Sanofi.

SOURCE: Pelletier D et al. Neurology. 2018 Apr 10. 90(15 Suppl.):P5.031.

LOS ANGELES – Patients with multiple sclerosis in the CARE-MS II study who switched from interferon beta-1a therapy to the humanized monoclonal antibody alemtuzumab experienced continued reductions in brain volume loss and lesions on MRI through 5 years, according to follow-up data from the CARE-MS II extension study known as TOPAZ.

These outcomes support core findings from the CARE-MS II study, and suggest that alemtuzumab (Lemtrada) provides a unique treatment approach for patients with prior subcutaneous interferon beta-1a (IFNB-1a) treatment, Daniel Pelletier, MD, reported in a poster discussion session at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

In CARE-MS II, relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis patients with inadequate response to prior therapy experienced improvements in MRI lesions and brain volume loss with two courses of alemtuzumab versus IFNB-1a through 2 years, and in a 4-year extension in which participants discontinued subcutaneous IFNB-1a and initiated alemtuzumab at 12 mg/day, they experienced durable efficacy in the absence of continuous treatment, explained Dr. Pelletier, a professor of neurology at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

In the extension, patients could receive alemtuzumab retreatment as needed for relapse/MRI activity or receive other disease-modifying therapies at the investigator’s discretion. Patients completing the extension could enter the 5-year TOPAZ study for further evaluation, he said.

Of 119 patients who completed TOPAZ year 1, and thus had 5 years of follow-up after initiating alemtuzumab, 78% were free of new, gadolinium-enhancing lesions in IFNB-1a year 2; this increased significantly to 92% in post-alemtuzumab year 2, and remained high at 85%-89% in years 3-5. Additionally, 48% of patients were free of new/enlarging T2 lesions in IFNB-1a year 2; this increased significantly to 81% in post-alemtuzumab year 2 and remained high in years 3-5.

Further, 47% of the TOPAZ patients were MRI disease activity–free in IFNB-1a year 2; this increased significantly to 81% in post-alemtuzumab year 2, and remained high at 67%-72% in years 3-5.

“Perhaps for me what makes even more sense is looking at the yearly brain parenchymal fraction change,” Dr. Pelletier said, noting that the median annual reductions in years 1-5, respectively, were 0.02%, 0.04%, 0.15%, 0.14%, and 0.08%, compared with –0.33% for subcutaneous IFNB-1a at year 2 in CARE-MS II. The median brain parenchymal fraction change from baseline to post-alemtuzumab year 5 was –1.40%.

In 61% of patients, no further treatment was given after the second course of alemtuzumab.

The findings suggest that alemtuzumab provides durable efficacy without continuous treatment, he concluded.

This study was supported by Sanofi and Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Pelletier has received personal compensation for consulting, serving on a scientific advisory board, speaking, or other activities with Biogen, Merck Serono, Novartis, Roche, and Sanofi, as well as research support from Biogen, Merck Serono, Novartis, Roche, and Sanofi.

SOURCE: Pelletier D et al. Neurology. 2018 Apr 10. 90(15 Suppl.):P5.031.

LOS ANGELES – Patients with multiple sclerosis in the CARE-MS II study who switched from interferon beta-1a therapy to the humanized monoclonal antibody alemtuzumab experienced continued reductions in brain volume loss and lesions on MRI through 5 years, according to follow-up data from the CARE-MS II extension study known as TOPAZ.

These outcomes support core findings from the CARE-MS II study, and suggest that alemtuzumab (Lemtrada) provides a unique treatment approach for patients with prior subcutaneous interferon beta-1a (IFNB-1a) treatment, Daniel Pelletier, MD, reported in a poster discussion session at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

In CARE-MS II, relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis patients with inadequate response to prior therapy experienced improvements in MRI lesions and brain volume loss with two courses of alemtuzumab versus IFNB-1a through 2 years, and in a 4-year extension in which participants discontinued subcutaneous IFNB-1a and initiated alemtuzumab at 12 mg/day, they experienced durable efficacy in the absence of continuous treatment, explained Dr. Pelletier, a professor of neurology at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

In the extension, patients could receive alemtuzumab retreatment as needed for relapse/MRI activity or receive other disease-modifying therapies at the investigator’s discretion. Patients completing the extension could enter the 5-year TOPAZ study for further evaluation, he said.

Of 119 patients who completed TOPAZ year 1, and thus had 5 years of follow-up after initiating alemtuzumab, 78% were free of new, gadolinium-enhancing lesions in IFNB-1a year 2; this increased significantly to 92% in post-alemtuzumab year 2, and remained high at 85%-89% in years 3-5. Additionally, 48% of patients were free of new/enlarging T2 lesions in IFNB-1a year 2; this increased significantly to 81% in post-alemtuzumab year 2 and remained high in years 3-5.

Further, 47% of the TOPAZ patients were MRI disease activity–free in IFNB-1a year 2; this increased significantly to 81% in post-alemtuzumab year 2, and remained high at 67%-72% in years 3-5.

“Perhaps for me what makes even more sense is looking at the yearly brain parenchymal fraction change,” Dr. Pelletier said, noting that the median annual reductions in years 1-5, respectively, were 0.02%, 0.04%, 0.15%, 0.14%, and 0.08%, compared with –0.33% for subcutaneous IFNB-1a at year 2 in CARE-MS II. The median brain parenchymal fraction change from baseline to post-alemtuzumab year 5 was –1.40%.

In 61% of patients, no further treatment was given after the second course of alemtuzumab.

The findings suggest that alemtuzumab provides durable efficacy without continuous treatment, he concluded.

This study was supported by Sanofi and Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Pelletier has received personal compensation for consulting, serving on a scientific advisory board, speaking, or other activities with Biogen, Merck Serono, Novartis, Roche, and Sanofi, as well as research support from Biogen, Merck Serono, Novartis, Roche, and Sanofi.

SOURCE: Pelletier D et al. Neurology. 2018 Apr 10. 90(15 Suppl.):P5.031.

REPORTING FROM AAN 2018

Key clinical point: Alemtuzumab appears to provide durable efficacy without continuous treatment.

Major finding: Brain parenchymal fraction reductions with alemtuzumab in years 1-5, respectively, were 0.02%, 0.04%, 0.15%, 0.14%, and 0.08%.

Study details: A total of 119 patients who completed CARE-MS II and its 4-year extension, as well as 1 year of the TOPAZ study.

Disclosures: This study was supported by Sanofi and Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Pelletier has received personal compensation for consulting, serving on a scientific advisory board, speaking, or other activities with Biogen, Merck Serono, Novartis, Roche, and Sanofi, as well as research support from Biogen, Merck Serono, Novartis, Roche, and Sanofi.

Source: Pelletier D et al. Neurology. 2018 Apr 10. 90(15 Suppl.):P5.031.

Research on exercise in MS needs to build up some muscle

NASHVILLE, TENN. – Physical activity appears to have profound rehabilitative effects – both physical and cognitive – upon patients with multiple sclerosis, but the body of evidence remains largely based on small, sometimes problematic studies, Alan Thompson, MD, said at the annual meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers.

There are compelling animal data that exercise promotes a number of beneficial neuronal changes that improve patient-reported outcomes, said Dr. Thompson, the Garfield Weston Professor of Clinical Neurology and Neurorehabilitation at University College London (England).

“A lot of animal work suggests that exercise can have a major impact on repair and recovery in neurons, synaptic signaling, dendritic branching, long-term potentiation,” and can beneficially affect inflammation and demyelination, he said. Besides the direct effect on nerves, exercise builds up muscle mass, strengthens connective tissue, improves movement, and reduces cardiovascular risk. “Exercise improves inactivity, but also may improve the underlying disease process,” he said. “The effect can be quite profound, and we are building a very good evidence base to support the use of exercise in MS.”

Unfortunately, the existing body of literature remains unimpressive, Dr. Thompson admitted. He compared research in physical activity to that of medicinal therapeutics. Disease-modifying therapeutics research is highly regulated, very well funded, adequately powered and replicated, and – once it shows positive results – receives substantial marketing and sales effort. “As a result, there can be a substantial impact on care.”

Research on rehabilitation and symptom management, with physical activity and other similar interventions, is not well funded, relies on diverse outcome measures, has small cohort numbers, and often is unreplicated. Even positive results “are just left to lie there,” he said. “Thus, it has a modest impact on care. I would like to see equal resources for both research areas.”

The recent surge in stroke rehabilitation is an excellent example of how academic focus can change practice for neurologic illness, he said. A 2017 research letter in Lancet Neurology described the current state of research on exercise in MS (Lancet Neurol. 2017;16[10];848-56). An accompanying editorial compared the MS literature to that in stroke (Lancet Neurol. 2017;16[10]:768-9).

During 1990-2005, there were almost no clinical studies in rehabilitation for stroke, Parkinson’s disease, spinal cord injury, and MS. Around 2005, things began to change in stroke, with close to 60 publications in just 1 year. During 2010-2015, the pace of research accelerated dramatically. Researchers, clinicians, and patients began to see the immediate and long-term benefits of early poststroke rehabilitation. These interventions have now been encoded in practice guidelines and are a core part of clinical care, Dr. Thompson said.

The picture in MS, Parkinson’s, and spinal cord injury remained almost unchanged, although there has been a very slight increase in these studies since 2010.

“We are way behind the stroke research,” Dr. Thompson said. “We need global collaboration to correct this.”

That may be coming. Dr. Thompson described a newly minted, multinational study sponsored by the Canadian Multiple Sclerosis Society. The four-armed “Improving Cognition in People with Progressive MS” study will determine whether cognitive rehabilitation and exercise are effective treatments for cognitive dysfunction in people with progressive MS. It seeks to enroll 360 patients in six countries. They will be randomized to a wait list, exercise plus cognitive rehabilitation, exercise only, or cognitive rehabilitation only.

The primary investigator is Anthony Feinstein, MBBCh, PhD, a psychiatrist at the University of Toronto.

Dr. Thompson had no disclosures relevant to his discussion.

NASHVILLE, TENN. – Physical activity appears to have profound rehabilitative effects – both physical and cognitive – upon patients with multiple sclerosis, but the body of evidence remains largely based on small, sometimes problematic studies, Alan Thompson, MD, said at the annual meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers.

There are compelling animal data that exercise promotes a number of beneficial neuronal changes that improve patient-reported outcomes, said Dr. Thompson, the Garfield Weston Professor of Clinical Neurology and Neurorehabilitation at University College London (England).

“A lot of animal work suggests that exercise can have a major impact on repair and recovery in neurons, synaptic signaling, dendritic branching, long-term potentiation,” and can beneficially affect inflammation and demyelination, he said. Besides the direct effect on nerves, exercise builds up muscle mass, strengthens connective tissue, improves movement, and reduces cardiovascular risk. “Exercise improves inactivity, but also may improve the underlying disease process,” he said. “The effect can be quite profound, and we are building a very good evidence base to support the use of exercise in MS.”

Unfortunately, the existing body of literature remains unimpressive, Dr. Thompson admitted. He compared research in physical activity to that of medicinal therapeutics. Disease-modifying therapeutics research is highly regulated, very well funded, adequately powered and replicated, and – once it shows positive results – receives substantial marketing and sales effort. “As a result, there can be a substantial impact on care.”

Research on rehabilitation and symptom management, with physical activity and other similar interventions, is not well funded, relies on diverse outcome measures, has small cohort numbers, and often is unreplicated. Even positive results “are just left to lie there,” he said. “Thus, it has a modest impact on care. I would like to see equal resources for both research areas.”

The recent surge in stroke rehabilitation is an excellent example of how academic focus can change practice for neurologic illness, he said. A 2017 research letter in Lancet Neurology described the current state of research on exercise in MS (Lancet Neurol. 2017;16[10];848-56). An accompanying editorial compared the MS literature to that in stroke (Lancet Neurol. 2017;16[10]:768-9).

During 1990-2005, there were almost no clinical studies in rehabilitation for stroke, Parkinson’s disease, spinal cord injury, and MS. Around 2005, things began to change in stroke, with close to 60 publications in just 1 year. During 2010-2015, the pace of research accelerated dramatically. Researchers, clinicians, and patients began to see the immediate and long-term benefits of early poststroke rehabilitation. These interventions have now been encoded in practice guidelines and are a core part of clinical care, Dr. Thompson said.

The picture in MS, Parkinson’s, and spinal cord injury remained almost unchanged, although there has been a very slight increase in these studies since 2010.

“We are way behind the stroke research,” Dr. Thompson said. “We need global collaboration to correct this.”

That may be coming. Dr. Thompson described a newly minted, multinational study sponsored by the Canadian Multiple Sclerosis Society. The four-armed “Improving Cognition in People with Progressive MS” study will determine whether cognitive rehabilitation and exercise are effective treatments for cognitive dysfunction in people with progressive MS. It seeks to enroll 360 patients in six countries. They will be randomized to a wait list, exercise plus cognitive rehabilitation, exercise only, or cognitive rehabilitation only.

The primary investigator is Anthony Feinstein, MBBCh, PhD, a psychiatrist at the University of Toronto.

Dr. Thompson had no disclosures relevant to his discussion.

NASHVILLE, TENN. – Physical activity appears to have profound rehabilitative effects – both physical and cognitive – upon patients with multiple sclerosis, but the body of evidence remains largely based on small, sometimes problematic studies, Alan Thompson, MD, said at the annual meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers.

There are compelling animal data that exercise promotes a number of beneficial neuronal changes that improve patient-reported outcomes, said Dr. Thompson, the Garfield Weston Professor of Clinical Neurology and Neurorehabilitation at University College London (England).

“A lot of animal work suggests that exercise can have a major impact on repair and recovery in neurons, synaptic signaling, dendritic branching, long-term potentiation,” and can beneficially affect inflammation and demyelination, he said. Besides the direct effect on nerves, exercise builds up muscle mass, strengthens connective tissue, improves movement, and reduces cardiovascular risk. “Exercise improves inactivity, but also may improve the underlying disease process,” he said. “The effect can be quite profound, and we are building a very good evidence base to support the use of exercise in MS.”

Unfortunately, the existing body of literature remains unimpressive, Dr. Thompson admitted. He compared research in physical activity to that of medicinal therapeutics. Disease-modifying therapeutics research is highly regulated, very well funded, adequately powered and replicated, and – once it shows positive results – receives substantial marketing and sales effort. “As a result, there can be a substantial impact on care.”

Research on rehabilitation and symptom management, with physical activity and other similar interventions, is not well funded, relies on diverse outcome measures, has small cohort numbers, and often is unreplicated. Even positive results “are just left to lie there,” he said. “Thus, it has a modest impact on care. I would like to see equal resources for both research areas.”

The recent surge in stroke rehabilitation is an excellent example of how academic focus can change practice for neurologic illness, he said. A 2017 research letter in Lancet Neurology described the current state of research on exercise in MS (Lancet Neurol. 2017;16[10];848-56). An accompanying editorial compared the MS literature to that in stroke (Lancet Neurol. 2017;16[10]:768-9).

During 1990-2005, there were almost no clinical studies in rehabilitation for stroke, Parkinson’s disease, spinal cord injury, and MS. Around 2005, things began to change in stroke, with close to 60 publications in just 1 year. During 2010-2015, the pace of research accelerated dramatically. Researchers, clinicians, and patients began to see the immediate and long-term benefits of early poststroke rehabilitation. These interventions have now been encoded in practice guidelines and are a core part of clinical care, Dr. Thompson said.

The picture in MS, Parkinson’s, and spinal cord injury remained almost unchanged, although there has been a very slight increase in these studies since 2010.

“We are way behind the stroke research,” Dr. Thompson said. “We need global collaboration to correct this.”

That may be coming. Dr. Thompson described a newly minted, multinational study sponsored by the Canadian Multiple Sclerosis Society. The four-armed “Improving Cognition in People with Progressive MS” study will determine whether cognitive rehabilitation and exercise are effective treatments for cognitive dysfunction in people with progressive MS. It seeks to enroll 360 patients in six countries. They will be randomized to a wait list, exercise plus cognitive rehabilitation, exercise only, or cognitive rehabilitation only.

The primary investigator is Anthony Feinstein, MBBCh, PhD, a psychiatrist at the University of Toronto.

Dr. Thompson had no disclosures relevant to his discussion.

REPORTING FROM THE CMSC ANNUAL MEETING

In CRC patients, chemo yields more toxicities in women than in men

Compared with men, women receiving fluorouracil-based chemotherapy for colorectal cancer had higher rates of treatment-emergent adverse events, a retrospective analysis shows.

Women had statistically significant and clinically relevant increased risks of multiple hematologic and nonhematologic toxicities in the analysis, which was based on data from the PETACC-3 trial conducted by the EORTC Gastrointestinal Group.

The findings suggest that drug targets may be different between women and men, as may be the optimal doses needed to hit those targets with acceptable levels of adverse events, said Valerie Cristina, MD, of Lausanne (Switzerland) University Hospital, and her coinvestigators.

“In an age of personalized medicine, and also considering growing knowledge about sex-related differences in molecular profiles and disease biology, the potential effect of sex on efficacy and toxic effects of systemic treatments in oncology deserves more awareness and further investigation,” the researchers wrote. The report was published in JAMA Oncology.

Patients in this retrospective study had stage II-III colorectal cancer and had received treatment with either adjuvant fluorouracil/leucovorin or leucovorin, fluorouracil, and irinotecan (FOLFIRI). Of 2,974 patients, 1,656 (55.7%) were men and 1,318 (44.3%) were women.

The primary analysis in the study was a comparison by sex of treatment-emergent adverse events of any grade. The investigators found women had significantly higher rates of all-grade alopecia, anemia, cholinergic syndrome, constipation, cramping, lethargy, leukopenia, nausea, neutropenia, stomatitis, and vomiting.

Significant differences were reported for hematologic adverse events such as leukopenia of any grade, which was seen in 49.6% of women and 38.9% of men (P less than .001), and nonhematologic adverse events, such as nausea of any grade, seen in 61.8% of women and 53.7% of men (P less than .001).

More serious toxicities (grade 3 or 4) occurring significantly more often in women were alopecia, anemia, diarrhea, leukopenia, nausea, neutropenia, and stomatitis, according to the report.

Treatment with FOLFIRI was associated with higher rates of toxicity overall, and numerically increased differences in incidence between women and men, the investigators said. They noted that incidence of grade 3 or 4 alopecia, diarrhea, lethargy, and stomatitis were all significantly higher among FOLFIRI-treated women.

This was the largest systematic analysis of sex-related differences in adverse effects related to standard fluorouracil with or without irinotecan, according to the researchers, who noted that a previous study had identified female sex as a risk factor for irinotecan-induced neutropenia.

Dr. Cristina had no conflicts of interest to disclose. Coauthors reported disclosures related to Amgen, Bayer, Boehringer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Ipsen, Lilly, Merck, Merck KgA, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi, Servier, and Shire.

SOURCE: Cristina V et al. JAMA Oncol. 2018 May 24. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.1080.

Compared with men, women receiving fluorouracil-based chemotherapy for colorectal cancer had higher rates of treatment-emergent adverse events, a retrospective analysis shows.

Women had statistically significant and clinically relevant increased risks of multiple hematologic and nonhematologic toxicities in the analysis, which was based on data from the PETACC-3 trial conducted by the EORTC Gastrointestinal Group.

The findings suggest that drug targets may be different between women and men, as may be the optimal doses needed to hit those targets with acceptable levels of adverse events, said Valerie Cristina, MD, of Lausanne (Switzerland) University Hospital, and her coinvestigators.

“In an age of personalized medicine, and also considering growing knowledge about sex-related differences in molecular profiles and disease biology, the potential effect of sex on efficacy and toxic effects of systemic treatments in oncology deserves more awareness and further investigation,” the researchers wrote. The report was published in JAMA Oncology.

Patients in this retrospective study had stage II-III colorectal cancer and had received treatment with either adjuvant fluorouracil/leucovorin or leucovorin, fluorouracil, and irinotecan (FOLFIRI). Of 2,974 patients, 1,656 (55.7%) were men and 1,318 (44.3%) were women.

The primary analysis in the study was a comparison by sex of treatment-emergent adverse events of any grade. The investigators found women had significantly higher rates of all-grade alopecia, anemia, cholinergic syndrome, constipation, cramping, lethargy, leukopenia, nausea, neutropenia, stomatitis, and vomiting.

Significant differences were reported for hematologic adverse events such as leukopenia of any grade, which was seen in 49.6% of women and 38.9% of men (P less than .001), and nonhematologic adverse events, such as nausea of any grade, seen in 61.8% of women and 53.7% of men (P less than .001).

More serious toxicities (grade 3 or 4) occurring significantly more often in women were alopecia, anemia, diarrhea, leukopenia, nausea, neutropenia, and stomatitis, according to the report.

Treatment with FOLFIRI was associated with higher rates of toxicity overall, and numerically increased differences in incidence between women and men, the investigators said. They noted that incidence of grade 3 or 4 alopecia, diarrhea, lethargy, and stomatitis were all significantly higher among FOLFIRI-treated women.

This was the largest systematic analysis of sex-related differences in adverse effects related to standard fluorouracil with or without irinotecan, according to the researchers, who noted that a previous study had identified female sex as a risk factor for irinotecan-induced neutropenia.

Dr. Cristina had no conflicts of interest to disclose. Coauthors reported disclosures related to Amgen, Bayer, Boehringer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Ipsen, Lilly, Merck, Merck KgA, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi, Servier, and Shire.

SOURCE: Cristina V et al. JAMA Oncol. 2018 May 24. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.1080.

Compared with men, women receiving fluorouracil-based chemotherapy for colorectal cancer had higher rates of treatment-emergent adverse events, a retrospective analysis shows.

Women had statistically significant and clinically relevant increased risks of multiple hematologic and nonhematologic toxicities in the analysis, which was based on data from the PETACC-3 trial conducted by the EORTC Gastrointestinal Group.

The findings suggest that drug targets may be different between women and men, as may be the optimal doses needed to hit those targets with acceptable levels of adverse events, said Valerie Cristina, MD, of Lausanne (Switzerland) University Hospital, and her coinvestigators.

“In an age of personalized medicine, and also considering growing knowledge about sex-related differences in molecular profiles and disease biology, the potential effect of sex on efficacy and toxic effects of systemic treatments in oncology deserves more awareness and further investigation,” the researchers wrote. The report was published in JAMA Oncology.

Patients in this retrospective study had stage II-III colorectal cancer and had received treatment with either adjuvant fluorouracil/leucovorin or leucovorin, fluorouracil, and irinotecan (FOLFIRI). Of 2,974 patients, 1,656 (55.7%) were men and 1,318 (44.3%) were women.

The primary analysis in the study was a comparison by sex of treatment-emergent adverse events of any grade. The investigators found women had significantly higher rates of all-grade alopecia, anemia, cholinergic syndrome, constipation, cramping, lethargy, leukopenia, nausea, neutropenia, stomatitis, and vomiting.

Significant differences were reported for hematologic adverse events such as leukopenia of any grade, which was seen in 49.6% of women and 38.9% of men (P less than .001), and nonhematologic adverse events, such as nausea of any grade, seen in 61.8% of women and 53.7% of men (P less than .001).

More serious toxicities (grade 3 or 4) occurring significantly more often in women were alopecia, anemia, diarrhea, leukopenia, nausea, neutropenia, and stomatitis, according to the report.

Treatment with FOLFIRI was associated with higher rates of toxicity overall, and numerically increased differences in incidence between women and men, the investigators said. They noted that incidence of grade 3 or 4 alopecia, diarrhea, lethargy, and stomatitis were all significantly higher among FOLFIRI-treated women.

This was the largest systematic analysis of sex-related differences in adverse effects related to standard fluorouracil with or without irinotecan, according to the researchers, who noted that a previous study had identified female sex as a risk factor for irinotecan-induced neutropenia.

Dr. Cristina had no conflicts of interest to disclose. Coauthors reported disclosures related to Amgen, Bayer, Boehringer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Ipsen, Lilly, Merck, Merck KgA, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi, Servier, and Shire.

SOURCE: Cristina V et al. JAMA Oncol. 2018 May 24. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.1080.

FROM JAMA ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: Risks of adverse events were significantly higher in women treated with fluorouracil with or without irinotecan.

Major finding: Compared with men, women had significantly higher rates of all-grade alopecia, anemia, cholinergic syndrome, constipation, cramping, lethargy, leukopenia, nausea, neutropenia, stomatitis, and vomiting.

Study details: A retrospective analysis of treatment-emergent adverse events for 2,974 participants in the PETACC-3 trial conducted by the EORTC Gastrointestinal Group.

Disclosures: The authors reported disclosures related to Amgen, Bayer, Boehringer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Ipsen, Lilly, Merck, Merck KgA, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi, Servier, and Shire.

Source: Cristina V et al. JAMA Oncol. 2018 May 24. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.1080.

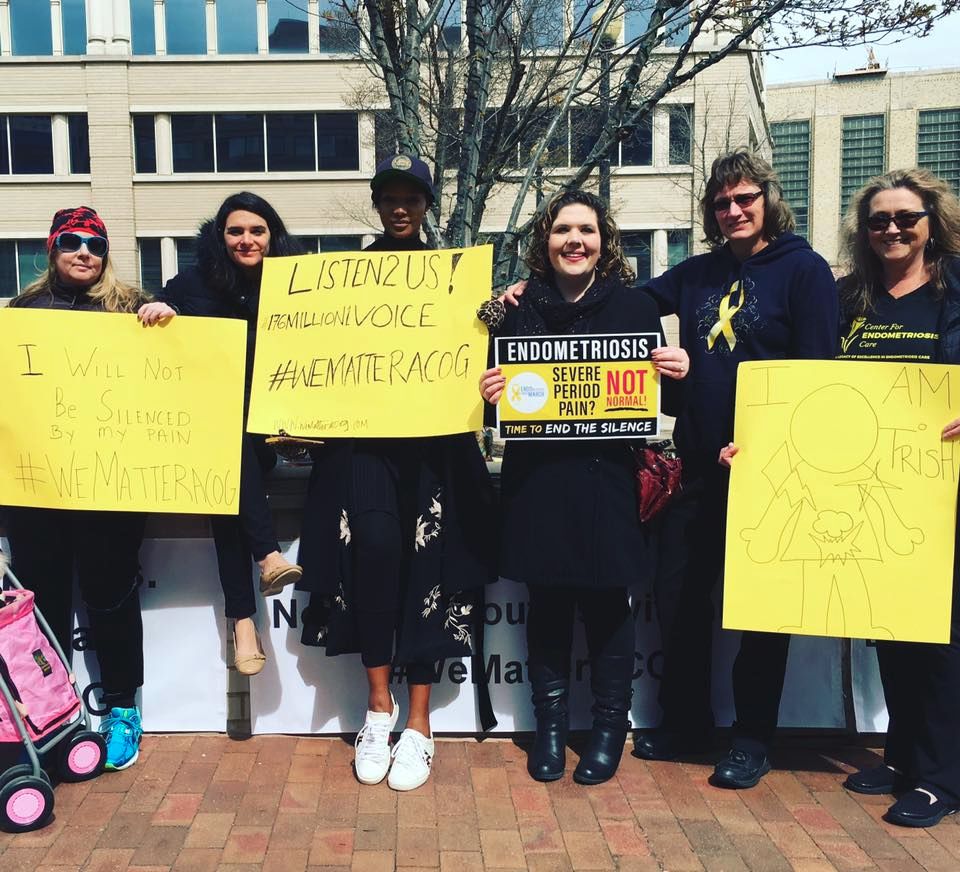

Gyn surgeons’ EndoMarch empowers patients

Empowering women through a grassroots approach is what Camran Nezhat, MD, a gynecologic surgeon in Palo Alto, Calif., had in mind when he founded the Worldwide Endometriosis March, or EndoMarch, some years ago. In March 2018, the 5th annual international day of marches and calls to action took place across at least eight U.S. cities and dozens of locations across Europe, Africa, the Middle East, and Asia.

Dr. Nezhat founded the 501(c)(3) public charity nonprofit along with his brothers, Farr Nezhat, MD, and Ceana Nezhat, MD; his niece Azadeh Nezhat, MD; and Barbara Page, a graduate of the University of California, Berkeley, who was working in his practice at the time.

“We’d published so much on the disease [in the medical literature], we didn’t know what else to do ... to help these women. We practice in one of the most advanced cultures for medical care ... and yet women come to us who’ve been told it’s all in their heads, or that they have PID [pelvic inflammatory disease] or depression,” Dr. Camran Nezhat said. “We’d get together and talk about this ... and we thought about how not much changed [with civil rights] in this country until people marched and took matters into their own hands.”

A final catalyst was a lengthy account and reflection on the history of endometriosis that the Nezhat brothers wrote, titled “Endometriosis: Ancient disease, ancient treatments” (Fertil Steril. 2012;98[6 Suppl]:S1-62). They dedicated their research to their mother, who suffered from endometriosis during her life in Iran and who inspired them to pursue medicine and become gynecologic surgeons.

Each year’s EndoMarch events are organized by EndoMarch chapters that are run by volunteers, many of whom have used the annual events to network and fuel year-round advocacy. Chapters have played important roles, for instance, in a national, government-sponsored awareness campaign launched in 2016 in France to alert the public through ads at bus stops and on TV and other media that pain during menstruation is “not natural” and may be a sign of endometriosis.

In Australia, EndoMarch advocates also helped drive plans in December 2017 to create a federally funded “national action plan” for endometriosis. In announcing the plan, Australian health minister Greg Hunt apologized, saying that the disease should have been acknowledged and acted upon “long ago.”

Empowering women through a grassroots approach is what Camran Nezhat, MD, a gynecologic surgeon in Palo Alto, Calif., had in mind when he founded the Worldwide Endometriosis March, or EndoMarch, some years ago. In March 2018, the 5th annual international day of marches and calls to action took place across at least eight U.S. cities and dozens of locations across Europe, Africa, the Middle East, and Asia.

Dr. Nezhat founded the 501(c)(3) public charity nonprofit along with his brothers, Farr Nezhat, MD, and Ceana Nezhat, MD; his niece Azadeh Nezhat, MD; and Barbara Page, a graduate of the University of California, Berkeley, who was working in his practice at the time.

“We’d published so much on the disease [in the medical literature], we didn’t know what else to do ... to help these women. We practice in one of the most advanced cultures for medical care ... and yet women come to us who’ve been told it’s all in their heads, or that they have PID [pelvic inflammatory disease] or depression,” Dr. Camran Nezhat said. “We’d get together and talk about this ... and we thought about how not much changed [with civil rights] in this country until people marched and took matters into their own hands.”

A final catalyst was a lengthy account and reflection on the history of endometriosis that the Nezhat brothers wrote, titled “Endometriosis: Ancient disease, ancient treatments” (Fertil Steril. 2012;98[6 Suppl]:S1-62). They dedicated their research to their mother, who suffered from endometriosis during her life in Iran and who inspired them to pursue medicine and become gynecologic surgeons.

Each year’s EndoMarch events are organized by EndoMarch chapters that are run by volunteers, many of whom have used the annual events to network and fuel year-round advocacy. Chapters have played important roles, for instance, in a national, government-sponsored awareness campaign launched in 2016 in France to alert the public through ads at bus stops and on TV and other media that pain during menstruation is “not natural” and may be a sign of endometriosis.

In Australia, EndoMarch advocates also helped drive plans in December 2017 to create a federally funded “national action plan” for endometriosis. In announcing the plan, Australian health minister Greg Hunt apologized, saying that the disease should have been acknowledged and acted upon “long ago.”

Empowering women through a grassroots approach is what Camran Nezhat, MD, a gynecologic surgeon in Palo Alto, Calif., had in mind when he founded the Worldwide Endometriosis March, or EndoMarch, some years ago. In March 2018, the 5th annual international day of marches and calls to action took place across at least eight U.S. cities and dozens of locations across Europe, Africa, the Middle East, and Asia.

Dr. Nezhat founded the 501(c)(3) public charity nonprofit along with his brothers, Farr Nezhat, MD, and Ceana Nezhat, MD; his niece Azadeh Nezhat, MD; and Barbara Page, a graduate of the University of California, Berkeley, who was working in his practice at the time.

“We’d published so much on the disease [in the medical literature], we didn’t know what else to do ... to help these women. We practice in one of the most advanced cultures for medical care ... and yet women come to us who’ve been told it’s all in their heads, or that they have PID [pelvic inflammatory disease] or depression,” Dr. Camran Nezhat said. “We’d get together and talk about this ... and we thought about how not much changed [with civil rights] in this country until people marched and took matters into their own hands.”

A final catalyst was a lengthy account and reflection on the history of endometriosis that the Nezhat brothers wrote, titled “Endometriosis: Ancient disease, ancient treatments” (Fertil Steril. 2012;98[6 Suppl]:S1-62). They dedicated their research to their mother, who suffered from endometriosis during her life in Iran and who inspired them to pursue medicine and become gynecologic surgeons.

Each year’s EndoMarch events are organized by EndoMarch chapters that are run by volunteers, many of whom have used the annual events to network and fuel year-round advocacy. Chapters have played important roles, for instance, in a national, government-sponsored awareness campaign launched in 2016 in France to alert the public through ads at bus stops and on TV and other media that pain during menstruation is “not natural” and may be a sign of endometriosis.

In Australia, EndoMarch advocates also helped drive plans in December 2017 to create a federally funded “national action plan” for endometriosis. In announcing the plan, Australian health minister Greg Hunt apologized, saying that the disease should have been acknowledged and acted upon “long ago.”

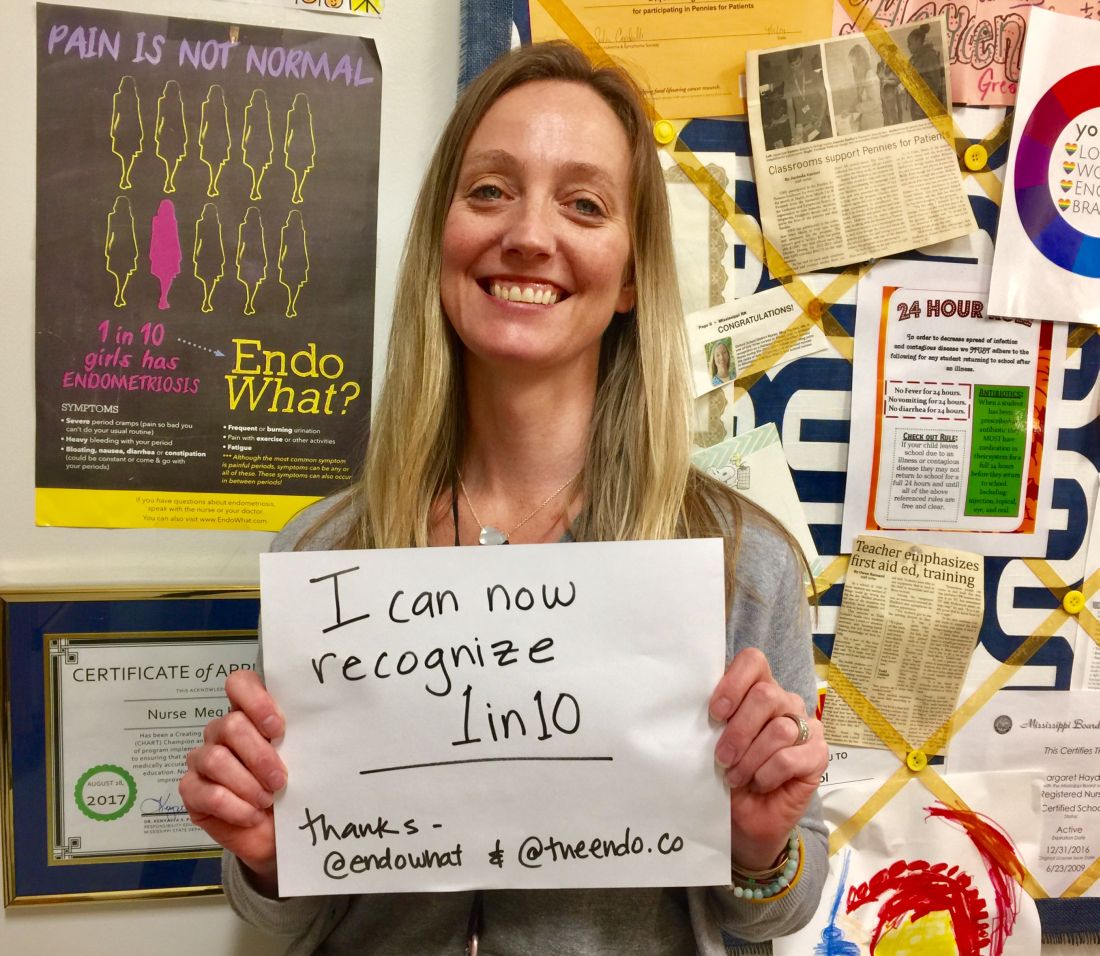

The push is on to recognize endometriosis in adolescents

Meg Hayden, RN, a school nurse in Oxford, Miss., used to be a labor and delivery nurse and considers herself more attuned to women’s health issues than other school nurses are. Still, a new educational initiative on endometriosis that stresses that menstrual pain is not normal – and that teenagers are not too young to have endometriosis – has helped her “connect the dots.”

“It’s a good reminder for me to look at patterns” and advise those girls who have repeated episodes of pelvic pain and other symptoms to “keep a diary” and to seek care, Ms. Hayden said.

They are demanding that serious diagnostic delays be rectified – that disease symptoms be better recognized by gynecologists, pediatricians, and other primary care physicians – and then, that the disease be better managed.

Some of the advocacy groups have petitioned the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists to involve patients and endometriosis experts in creating new standards of care. And at press time, activist Shannon Cohn, who developed the School Nurse initiative after producing a documentary film titled Endo What?, was working with Sen. Orrin Hatch (R-Utah) and Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) on finalizing plans for a national public service announcement campaign. (Sen. Hatch wrote an opinion piece for CNN in late March describing his granddaughter’s experience with the disease and calling the widespread prevalence of the disease – and the lack of any long-term treatment options – “nothing short of a public health emergency.”)

Estimates vary, but the average interval between presentation of symptoms and definitive diagnosis of endometriosis by laparoscopy (and usually) biopsy is commonly reported as 7-10 years. The disease can cause incapacitating pain, missed days of school and work, and increasing morbidities over time, including infertility and organ damage both inside and outside the pelvic cavity. A majority of women with endometriosis – two-thirds, according to one survey of more than 4,300 women with surgically diagnosed disease (Fertil Steril. 2009;91:32-9) – report first experiencing symptoms during adolescence.

Yet, too often, adolescents believe or are told that “periods are supposed to hurt,” and other symptoms of the disease – such as gastrointestinal symptoms – are overlooked.

“If we can diagnose endometriosis in its early stages, we could prevent a lifetime of pain and suffering, and decrease rates of infertility ... hopefully stopping disease progression before it does damage,” said Marc R. Laufer, MD, chief of gynecology at Boston Children’s Hospital and professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology at Harvard Medical School, also in Boston. “If we don’t, we’re missing a huge opportunity because we know that endometriosis affects 10% of women.”

Atypical symptoms and presentation

Endometriosis is an enigmatic disease. It traditionally has been associated with retrograde menstruation, but today, there are more nuanced and likely overlapping theories of etiology. Identified in girls even prior to the onset of menses, the disease is generally believed to be progressive, but perhaps not all the time. Patients with significant amounts of disease may have tremendous pain or they may have very little discomfort.

While adolescents can have advanced endometriosis, most have early-stage disease, experts say. Still, adolescence offers its own complexities. Preteen and teen patients with endometriosis tend to present more often with atypical symptoms and with much more subtle and variable laparoscopic findings than do adult patients. Dr. Laufer reported more than 20 years ago that only 9.7% of 46 girls presented classically with dysmenorrhea. In 63%, pain was both acyclic and cyclic, and in 28%, pain was acyclic only (J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 1997;10:199-202).

In a more recent report on adolescents treated by gynecologic surgeon Ceana Nezhat, MD, 64% had dysmenorrhea, 44% had menorrhagia, 60% had abnormal or irregular uterine bleeding, 56% had at least one gastrointestinal symptom, and 52% had at least one genitourinary symptom. The girls had seen a mean of three physicians, including psychiatrists and orthopedic surgeons, and had received diagnoses of pelvic inflammatory disease, irritable bowel syndrome, dysmenorrhea, appendicitis, ovarian cysts, and musculoskeletal pain (JSLS. 2015;19:e2015.00019). Notably, 56% had a family history of endometriosis, Dr. Nezhat, of the Atlanta Center for Minimally Invasive Surgery and Reproductive Medicine, and his colleagues found.

To address levels of pain, Dr. Laufer usually asks young women if they feel they’re at a disadvantage to other young women or to men. This opens the door to learning more about school absences, missed activities, and decreased quality of life. Pain, he emphasizes, is only part of the picture. “It’s also about fatigue and energy levels, social interaction, depression, sexual function if they’re sexually active, body image issues, and bowel and bladder functionality.”

If the new generation of school nurse programs and other educational initiatives are successful, teens will increasingly come to appointments with notes in hand. Ms. Hayden counsels students on what to discuss with the doctor. And high school students in New York who have been educated through the Endometriosis Foundation of America’s 5-year-old ENPOWR Project for endometriosis education are urged to keep a journal or use a symptom tracker app if they are experiencing pain or other symptoms associated with endometriosis.

“We tell them that, with a record, you can show that the second week of every month I’m in terrible pain, for instance, or I’ve fainted twice in the last month, or here’s when my nausea is really aggressive,” said Nina Baker, outreach coordinator for the foundation. “We’re very honest about how often this is dismissed ... and we assure them that by no means are you wrong about your pain.”

ENPOWR lessons have been taught in more than 165 schools thus far (mostly in health classes in New York schools and largely by foundation-trained educators), and a recently developed online package of educational materials for schools – the Endo EduKit – is expanding the foundation’s geographical reach to other states. Students are encouraged during the training to see a gynecologist if they’re concerned about endometriosis, Ms. Baker said.

In Mississippi, Ms. Hayden suggests that younger high-schoolers see their pediatrician, but after that, “I feel like they should go to the gynecologist.” (ACOG recommends a first visit to the gynecologist between the ages of 13 and 15 for anticipatory guidance.) The year-old School Nurse Initiative has sent toolkits, posters, and DVD copies of the “Endo What?” film to nurses in 652 schools thus far. “Our goal,” said Ms. Cohn, a lawyer, filmmaker, and an endometriosis patient, “is to educate every school nurse in middle and high schools across the country.”

Treatment dilemmas

The first-line treatment for dysmenorrhea and for suspected endometriosis in adolescents has long been empiric treatment with NSAIDs and oral contraceptive pills. Experts commonly recommend today that combined oral contraceptive pills (COCPs) be started cyclically and then changed to continuous dosing if necessary with the goal of inducing amenorrhea.

If symptoms are not well controlled within 3-6 months of compliant medication management with COCPs and NSAIDs and endometriosis is suspected, then laparoscopy by a physician who is familiar with adolescent endometriosis and can simultaneously diagnose and treat the disease should be considered, according to Dr. Laufer and several other experts in pediatric and adolescent gynecology who spoke with Ob.Gyn. News.

“If someone still has pain on one COCP, then switching to another COCP is not going to solve the problem – there is no study that shows that one pill is better than another,” Dr. Laufer said.

Yet extra months and sometimes years of pill-switching and empiric therapy with other medications – rather than surgical evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment – is not uncommon. “Usually, by the time a patient comes to me, they’ve already been on multiple birth control pills, they’ve failed NSAIDs, and they’ve often tried other medications as well,” such as progestins and gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists, said Iris Kerin Orbuch, MD, director of the Advanced Gynecologic Laparoscopy Centers in New York and Los Angeles.

Some also have had diagnostic laparoscopies and been wrongly told that nothing is wrong. Endometriosis is “not all powder-burn lesions and chocolate cysts, which is what we’re taught in medical school,” she said. “It can have many appearances, especially in teens and adolescents. It can be clear vesicles, white, fibrotic, yellow, blue, and brown ... and quite commonly there can simply be areas of increased vascularity. I only learned this in my fellowship.”

Dr. Orbuch, who routinely treats adolescents with endometriosis, takes a holistic approach to the disease that includes working with patients – often before surgery and in partnership with other providers – to downregulate the central nervous system and to alleviate pelvic floor dysfunction that often develops secondary to the disease. When she does operate and finds endometriosis, she performs excisional surgery, in contrast with ablative techniques such as cauterization or desiccation that are used by many physicians.

Treatment of endometriosis is rife with dilemmas, controversies, and shortcomings. Medical treatments can improve pain, but as ACOG’s current Practice Bulletin (No. 114) points out, recurrence rates are high after medication is discontinued – and there is concern among some experts that hormone therapy may not keep the disease from progressing. In adolescents, there is concern about the significant side effects of gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists, which are sometimes chosen if COCPs and NSAIDs fail to relieve symptoms. COCPs themselves may be problematic, causing premature closure of growth plates.

And when it comes to surgical treatment, there’s often sharp debate over which operative approaches are best for endometriosis. Advocates of excision – including many of the patient advocacy groups – say that ablation too often causes scar tissue and leaves behind disease, leading to recurrent symptoms and multiple surgeries. Critics of excisional surgery express concern about excision-induced adhesions and scar tissue, and about some excisional surgery being too “radical,” particularly when it is performed for earlier-stage disease in adolescents. Research is limited, comprised largely of small retrospective reports and single-institution cohort studies.

Meredith Loveless, MD, a pediatric and adolescent gynecologist who chairs ACOG’s Committee on Adolescent Health Care, is leading the development of a new ACOG committee opinion on dysmenorrhea and endometriosis in adolescents. The laparoscopic appearance of endometriosis in young patients and the need “for fertility preservation as a priority” in surgery will be among the points discussed in ACOG’s upcoming guidance, she said.

“Somebody who manages adult endometriosis and who does extremely aggressive surgical work may actually be harming an adolescent rather than helping them,” said Dr. Loveless of the Norton Children’s Hospital in Louisville, Ky. (Dr. Loveless has also worked with the American Academy of Pediatrics and notes that the academy provides education on dysmenorrhea and endometriosis as part of its national conference.)

Nicole Donnellan, MD, of the University of Pittsburgh Magee–Womens Hospital, said that fertility preservation is always a goal – and is possible – regardless of age. “A lot of us who are advanced laparoscopic surgeons are passionate about excision because (with other approaches) you’re not fully exploring the extent of the disease – what’s behind the superficial things you see,” she said. “Whether you’re 38 and wanting to preserve your fertility, or whether you’re 18, I’m still going to use the same approach. I want to make sure you have a functioning tube, ovaries, and uterus.”

Ken R. Sinervo, MD, medical director of the Center for Endometriosis Care in Atlanta, which has followed patients postsurgically for an average of 7-8 years, said adhesions can occur "whether you're ablating the disease or excising it," and that in his excisional surgeries, he successfully prevents adhesion formation with the use of various intraoperative adhesion barriers as well as bioregenerative medicine to facilitate healing. The key to avoiding repeat surgeries is to "remove all the disease that is present," he emphasized, adding that the "great majority of young patients will have peritoneal disease and very little ovarian involvement."*

ACOG under fire

Dr. Sinervo and Dr. Orbuch are among the gynecologic surgeons, other providers, and patients who have signed a petition to ACOG urging it to involve both educated patients and expert, multidisciplinary endometriosis providers in improving their guidance and policies on endometriosis to facilitate earlier diagnosis and more effective treatment.

The petition was organized by advocate Casey Berna in July and supported by more than a half-dozen endometriosis advocacy groups; in early May, it had almost 8,700 signatures. Ms. Berna also co-organized a demonstration outside ACOG headquarters on April 5-6 as leaders were reviewing practice bulletins and deciding which need revision – and a virtual protest (#WeMatterACOG) – to push for better guidelines.

Ms. Berna, Ms. Cohn, and others have also expressed concern that ob.gyns.’ management of endometriosis – and the development of guidelines – is colored by financial conflicts of interest. The petition, moreover, calls upon ACOG to help create coding specific for excision surgery; currently, because of the lack of reimbursement, many surgeons operate out of network and patients struggle with treatment costs.

In a statement issued in response to the protests, ACOG chief executive officer and executive vice president Hal Lawrence, MD, said that “ACOG is aware of the sensitivities and concerns surrounding timely and accurate diagnosis and treatment of endometriosis. We are always working diligently to review all the available literature and ensure that our guidance to members is accurate and up to date. It’s our aim that [diagnosis and care] are both evidence based and patient centered. To that end, we recognize that patient voices and advocacy are an important part of ensuring we are meeting these high standards.”

In an interview before the protests, Dr. Lawrence said the Committee on Practice Bulletins–Gynecology will revise its guidelines on the management of endometriosis, which were last revised in 2010 and reaffirmed in 2016. He said that he had spoken at length with Ms. Berna on the phone and had passed on a file of research and other materials to the Committee for their consideration.

On April 5, ACOG also joined the American Society for Reproductive Medicine and seven other organizations in sending a letter to the U.S. Senate and House calling for more research on and attention to the disease. NIH research dollars for the disease have dropped from $16 million in 2010 to $7 million in 2018, and “there are too few treatment options available to patients,” the letter says. “We urge you to [prioritize endometriosis] as an important women’s health issue.”

*This article was updated June 5, 2018. An earlier version of this article misstated Dr. Ken R. Sinervo’s name.

Meg Hayden, RN, a school nurse in Oxford, Miss., used to be a labor and delivery nurse and considers herself more attuned to women’s health issues than other school nurses are. Still, a new educational initiative on endometriosis that stresses that menstrual pain is not normal – and that teenagers are not too young to have endometriosis – has helped her “connect the dots.”

“It’s a good reminder for me to look at patterns” and advise those girls who have repeated episodes of pelvic pain and other symptoms to “keep a diary” and to seek care, Ms. Hayden said.

They are demanding that serious diagnostic delays be rectified – that disease symptoms be better recognized by gynecologists, pediatricians, and other primary care physicians – and then, that the disease be better managed.

Some of the advocacy groups have petitioned the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists to involve patients and endometriosis experts in creating new standards of care. And at press time, activist Shannon Cohn, who developed the School Nurse initiative after producing a documentary film titled Endo What?, was working with Sen. Orrin Hatch (R-Utah) and Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) on finalizing plans for a national public service announcement campaign. (Sen. Hatch wrote an opinion piece for CNN in late March describing his granddaughter’s experience with the disease and calling the widespread prevalence of the disease – and the lack of any long-term treatment options – “nothing short of a public health emergency.”)

Estimates vary, but the average interval between presentation of symptoms and definitive diagnosis of endometriosis by laparoscopy (and usually) biopsy is commonly reported as 7-10 years. The disease can cause incapacitating pain, missed days of school and work, and increasing morbidities over time, including infertility and organ damage both inside and outside the pelvic cavity. A majority of women with endometriosis – two-thirds, according to one survey of more than 4,300 women with surgically diagnosed disease (Fertil Steril. 2009;91:32-9) – report first experiencing symptoms during adolescence.

Yet, too often, adolescents believe or are told that “periods are supposed to hurt,” and other symptoms of the disease – such as gastrointestinal symptoms – are overlooked.

“If we can diagnose endometriosis in its early stages, we could prevent a lifetime of pain and suffering, and decrease rates of infertility ... hopefully stopping disease progression before it does damage,” said Marc R. Laufer, MD, chief of gynecology at Boston Children’s Hospital and professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology at Harvard Medical School, also in Boston. “If we don’t, we’re missing a huge opportunity because we know that endometriosis affects 10% of women.”

Atypical symptoms and presentation

Endometriosis is an enigmatic disease. It traditionally has been associated with retrograde menstruation, but today, there are more nuanced and likely overlapping theories of etiology. Identified in girls even prior to the onset of menses, the disease is generally believed to be progressive, but perhaps not all the time. Patients with significant amounts of disease may have tremendous pain or they may have very little discomfort.

While adolescents can have advanced endometriosis, most have early-stage disease, experts say. Still, adolescence offers its own complexities. Preteen and teen patients with endometriosis tend to present more often with atypical symptoms and with much more subtle and variable laparoscopic findings than do adult patients. Dr. Laufer reported more than 20 years ago that only 9.7% of 46 girls presented classically with dysmenorrhea. In 63%, pain was both acyclic and cyclic, and in 28%, pain was acyclic only (J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 1997;10:199-202).

In a more recent report on adolescents treated by gynecologic surgeon Ceana Nezhat, MD, 64% had dysmenorrhea, 44% had menorrhagia, 60% had abnormal or irregular uterine bleeding, 56% had at least one gastrointestinal symptom, and 52% had at least one genitourinary symptom. The girls had seen a mean of three physicians, including psychiatrists and orthopedic surgeons, and had received diagnoses of pelvic inflammatory disease, irritable bowel syndrome, dysmenorrhea, appendicitis, ovarian cysts, and musculoskeletal pain (JSLS. 2015;19:e2015.00019). Notably, 56% had a family history of endometriosis, Dr. Nezhat, of the Atlanta Center for Minimally Invasive Surgery and Reproductive Medicine, and his colleagues found.

To address levels of pain, Dr. Laufer usually asks young women if they feel they’re at a disadvantage to other young women or to men. This opens the door to learning more about school absences, missed activities, and decreased quality of life. Pain, he emphasizes, is only part of the picture. “It’s also about fatigue and energy levels, social interaction, depression, sexual function if they’re sexually active, body image issues, and bowel and bladder functionality.”

If the new generation of school nurse programs and other educational initiatives are successful, teens will increasingly come to appointments with notes in hand. Ms. Hayden counsels students on what to discuss with the doctor. And high school students in New York who have been educated through the Endometriosis Foundation of America’s 5-year-old ENPOWR Project for endometriosis education are urged to keep a journal or use a symptom tracker app if they are experiencing pain or other symptoms associated with endometriosis.