User login

AHA promises practice-changing late breakers

Of the trials chosen for the six Late-Breaking Clinical Trial sessions, all being presented in the first 2 days of the American Heart Association scientific sessions in Chicago Nov. 10-12. Here are some of the most potentially practice-changing studies to look out for.

Saturday

- REDUCE-IT: Relative to placebo, the fish oil derivative AMR101 (icosapent-ethyl) evaluated in the REDUCE-IT trial was associated with a 25% reduction in a primary composite endpoint of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), according top-line data released in September. A highly purified ethyl ester of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), AMR101 (Vascepa, Amarin) was studied on top of statin therapy in both primary and secondary prevention cohorts among the 8,000 patients randomized. Relative efficacy for primary and secondary prevention was not described in the initial release of data and will be of particular when the full results are released on Saturday, Nov. 10 at 2:00 p.m.

- DECLARE TIMI58: In top line results from DECLARE TIMI58, which randomized more than 17,000 participants with type 2 diabetes an experimental arm or placebo, the SGLT2 inhibitor dapagliflozin (Farxiga, AstraZeneca) was linked to a reduction in the composite endpoint of hospitalization for heart failure or cardiovascular death. In the early release of results, no mention was made of the effect of this agent on a composite of cardiovascular death, MI, or ischemic stroke, which was a secondary co-primary endpoint. This and the impact of dapagliflozin on an array of secondary endpoints will be revealed when the full results are made available in the Saturday late-breaker session at 2:00 p.m.

- VITAL: The relative effect of vitamin D, fish oil, or both on body composition was compared in the VITAL study, which randomized more than 20,000 patients. Fish oil plus vitamin D, fish oil plus placebo, vitamin D plus placebo, and two placebos were compared in a 2 x 2 factorial design. The primary outcome includes total body fat and lean mass as well as these components in the abdomen and other anatomic sites. Body mass index, waist circumference, and waist-to-hip ratio are among secondary outcomes. In addition, the relative effects of these treatments on lipids, blood glucose, and other aspects of metabolism were followed over the 2 years of the study, to presented at 2 p.m. on Saturday.

- CIRT: Responding to the evidence that inflammation is a crucial contributor to atherothrombosis, the CIRT trial tested whether the anti-inflammatory agent methotrexate reduces rates of MI, stroke, and cardiovascular death relative to placebo in patients with stable coronary artery disease and either type 2 diabetes or metabolic syndrome. The study enrolled about 7,000 patients and will have follow-up of nearly 6 years. Secondary endpoints, such as the impact of methotrexate on rates of coronary revascularization, peripheral artery disease, venous thromboembolism, and aortic stenosis, may provide insight about the ways in which control of inflammation affects vascular pathology. The presentation is at 2 p.m. on Saturday.

- Also on Saturday, diverse trial hypotheses are being tested. For example, the cost effectiveness of a PCSK9 inhibitor will be the focus of the ODYSSEY OUTCOMES economics study, presented at the 2:00 session. The results of YOGA-CaRe, a multicenter trial of a yoga-based cardiac rehabilitation program, will be presented in a subsequent Saturday late-breaking session. Of highlights of the third Saturday late-breaking session, ALERT-AF will determine whether a computerized decision protocol affected anticoagulation management in hospitalized patients with atrial fibrillation.

Sunday

- PIONEER-HF: It has been previously shown that sacubitril/valsartan improves outcome in stable heart failure patients with a reduced ejection fraction (HRrEF), but PIONEER-HF will test the tolerability of this strategy when this treatment is initiated prior to hospital discharge. Patients with a left ventricular ejection fraction of 40% or less and elevated N-terminal pro hormone BNP (NT-proBNP) will be randomized to sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto, Novartis) or the ACE inhibitor enalapril. The primary outcome of the trial, which enrolled more than 700 patients, is the time-averaged percentage change in NT-proBNP from baseline. Secondary outcome measures included the proportion of patients with symptomatic hypotension, hyperkalemia, and angioedema. Presentation will be at the Sunday 10:45 a.m. session.

- TICAB: The hypothesis that ticagrelor is superior to aspirin for preventing a composite MACE endpoint of CV death, myocardial infarction, target vessel revascularization, and stroke in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting is the basis for the TICAB trial. The nearly 1,900 patients were randomized to 90 mg of ticagrelor twice daily or 100 mg of aspirin twice daily. Major bleeding events, CV death, and all cause death are key secondary outcomes. Relative benefit in context of safety, particularly bleeding risk, will be of interest when the final results are revealed at 5:30 p.m. on Sunday.

All-in-all, the Sunday late-breaking sessions are no less crowded with potentially practice-changing studies, including T-TIME, an evaluation of low-dose alteplase during primary percutaneous intervention at 9:00 a.m., TRED-HF, a study of withdrawal of heart failure therapy in patients who have recovered from dilated cardiomyopathy at 10:45 a.m., and ISAR TEST 4, which will provide 10-year outcomes after coronary stents with biodegradable versus permanent polymer coated devices, at 5:30 p.m.

Of the trials chosen for the six Late-Breaking Clinical Trial sessions, all being presented in the first 2 days of the American Heart Association scientific sessions in Chicago Nov. 10-12. Here are some of the most potentially practice-changing studies to look out for.

Saturday

- REDUCE-IT: Relative to placebo, the fish oil derivative AMR101 (icosapent-ethyl) evaluated in the REDUCE-IT trial was associated with a 25% reduction in a primary composite endpoint of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), according top-line data released in September. A highly purified ethyl ester of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), AMR101 (Vascepa, Amarin) was studied on top of statin therapy in both primary and secondary prevention cohorts among the 8,000 patients randomized. Relative efficacy for primary and secondary prevention was not described in the initial release of data and will be of particular when the full results are released on Saturday, Nov. 10 at 2:00 p.m.

- DECLARE TIMI58: In top line results from DECLARE TIMI58, which randomized more than 17,000 participants with type 2 diabetes an experimental arm or placebo, the SGLT2 inhibitor dapagliflozin (Farxiga, AstraZeneca) was linked to a reduction in the composite endpoint of hospitalization for heart failure or cardiovascular death. In the early release of results, no mention was made of the effect of this agent on a composite of cardiovascular death, MI, or ischemic stroke, which was a secondary co-primary endpoint. This and the impact of dapagliflozin on an array of secondary endpoints will be revealed when the full results are made available in the Saturday late-breaker session at 2:00 p.m.

- VITAL: The relative effect of vitamin D, fish oil, or both on body composition was compared in the VITAL study, which randomized more than 20,000 patients. Fish oil plus vitamin D, fish oil plus placebo, vitamin D plus placebo, and two placebos were compared in a 2 x 2 factorial design. The primary outcome includes total body fat and lean mass as well as these components in the abdomen and other anatomic sites. Body mass index, waist circumference, and waist-to-hip ratio are among secondary outcomes. In addition, the relative effects of these treatments on lipids, blood glucose, and other aspects of metabolism were followed over the 2 years of the study, to presented at 2 p.m. on Saturday.

- CIRT: Responding to the evidence that inflammation is a crucial contributor to atherothrombosis, the CIRT trial tested whether the anti-inflammatory agent methotrexate reduces rates of MI, stroke, and cardiovascular death relative to placebo in patients with stable coronary artery disease and either type 2 diabetes or metabolic syndrome. The study enrolled about 7,000 patients and will have follow-up of nearly 6 years. Secondary endpoints, such as the impact of methotrexate on rates of coronary revascularization, peripheral artery disease, venous thromboembolism, and aortic stenosis, may provide insight about the ways in which control of inflammation affects vascular pathology. The presentation is at 2 p.m. on Saturday.

- Also on Saturday, diverse trial hypotheses are being tested. For example, the cost effectiveness of a PCSK9 inhibitor will be the focus of the ODYSSEY OUTCOMES economics study, presented at the 2:00 session. The results of YOGA-CaRe, a multicenter trial of a yoga-based cardiac rehabilitation program, will be presented in a subsequent Saturday late-breaking session. Of highlights of the third Saturday late-breaking session, ALERT-AF will determine whether a computerized decision protocol affected anticoagulation management in hospitalized patients with atrial fibrillation.

Sunday

- PIONEER-HF: It has been previously shown that sacubitril/valsartan improves outcome in stable heart failure patients with a reduced ejection fraction (HRrEF), but PIONEER-HF will test the tolerability of this strategy when this treatment is initiated prior to hospital discharge. Patients with a left ventricular ejection fraction of 40% or less and elevated N-terminal pro hormone BNP (NT-proBNP) will be randomized to sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto, Novartis) or the ACE inhibitor enalapril. The primary outcome of the trial, which enrolled more than 700 patients, is the time-averaged percentage change in NT-proBNP from baseline. Secondary outcome measures included the proportion of patients with symptomatic hypotension, hyperkalemia, and angioedema. Presentation will be at the Sunday 10:45 a.m. session.

- TICAB: The hypothesis that ticagrelor is superior to aspirin for preventing a composite MACE endpoint of CV death, myocardial infarction, target vessel revascularization, and stroke in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting is the basis for the TICAB trial. The nearly 1,900 patients were randomized to 90 mg of ticagrelor twice daily or 100 mg of aspirin twice daily. Major bleeding events, CV death, and all cause death are key secondary outcomes. Relative benefit in context of safety, particularly bleeding risk, will be of interest when the final results are revealed at 5:30 p.m. on Sunday.

All-in-all, the Sunday late-breaking sessions are no less crowded with potentially practice-changing studies, including T-TIME, an evaluation of low-dose alteplase during primary percutaneous intervention at 9:00 a.m., TRED-HF, a study of withdrawal of heart failure therapy in patients who have recovered from dilated cardiomyopathy at 10:45 a.m., and ISAR TEST 4, which will provide 10-year outcomes after coronary stents with biodegradable versus permanent polymer coated devices, at 5:30 p.m.

Of the trials chosen for the six Late-Breaking Clinical Trial sessions, all being presented in the first 2 days of the American Heart Association scientific sessions in Chicago Nov. 10-12. Here are some of the most potentially practice-changing studies to look out for.

Saturday

- REDUCE-IT: Relative to placebo, the fish oil derivative AMR101 (icosapent-ethyl) evaluated in the REDUCE-IT trial was associated with a 25% reduction in a primary composite endpoint of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), according top-line data released in September. A highly purified ethyl ester of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), AMR101 (Vascepa, Amarin) was studied on top of statin therapy in both primary and secondary prevention cohorts among the 8,000 patients randomized. Relative efficacy for primary and secondary prevention was not described in the initial release of data and will be of particular when the full results are released on Saturday, Nov. 10 at 2:00 p.m.

- DECLARE TIMI58: In top line results from DECLARE TIMI58, which randomized more than 17,000 participants with type 2 diabetes an experimental arm or placebo, the SGLT2 inhibitor dapagliflozin (Farxiga, AstraZeneca) was linked to a reduction in the composite endpoint of hospitalization for heart failure or cardiovascular death. In the early release of results, no mention was made of the effect of this agent on a composite of cardiovascular death, MI, or ischemic stroke, which was a secondary co-primary endpoint. This and the impact of dapagliflozin on an array of secondary endpoints will be revealed when the full results are made available in the Saturday late-breaker session at 2:00 p.m.

- VITAL: The relative effect of vitamin D, fish oil, or both on body composition was compared in the VITAL study, which randomized more than 20,000 patients. Fish oil plus vitamin D, fish oil plus placebo, vitamin D plus placebo, and two placebos were compared in a 2 x 2 factorial design. The primary outcome includes total body fat and lean mass as well as these components in the abdomen and other anatomic sites. Body mass index, waist circumference, and waist-to-hip ratio are among secondary outcomes. In addition, the relative effects of these treatments on lipids, blood glucose, and other aspects of metabolism were followed over the 2 years of the study, to presented at 2 p.m. on Saturday.

- CIRT: Responding to the evidence that inflammation is a crucial contributor to atherothrombosis, the CIRT trial tested whether the anti-inflammatory agent methotrexate reduces rates of MI, stroke, and cardiovascular death relative to placebo in patients with stable coronary artery disease and either type 2 diabetes or metabolic syndrome. The study enrolled about 7,000 patients and will have follow-up of nearly 6 years. Secondary endpoints, such as the impact of methotrexate on rates of coronary revascularization, peripheral artery disease, venous thromboembolism, and aortic stenosis, may provide insight about the ways in which control of inflammation affects vascular pathology. The presentation is at 2 p.m. on Saturday.

- Also on Saturday, diverse trial hypotheses are being tested. For example, the cost effectiveness of a PCSK9 inhibitor will be the focus of the ODYSSEY OUTCOMES economics study, presented at the 2:00 session. The results of YOGA-CaRe, a multicenter trial of a yoga-based cardiac rehabilitation program, will be presented in a subsequent Saturday late-breaking session. Of highlights of the third Saturday late-breaking session, ALERT-AF will determine whether a computerized decision protocol affected anticoagulation management in hospitalized patients with atrial fibrillation.

Sunday

- PIONEER-HF: It has been previously shown that sacubitril/valsartan improves outcome in stable heart failure patients with a reduced ejection fraction (HRrEF), but PIONEER-HF will test the tolerability of this strategy when this treatment is initiated prior to hospital discharge. Patients with a left ventricular ejection fraction of 40% or less and elevated N-terminal pro hormone BNP (NT-proBNP) will be randomized to sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto, Novartis) or the ACE inhibitor enalapril. The primary outcome of the trial, which enrolled more than 700 patients, is the time-averaged percentage change in NT-proBNP from baseline. Secondary outcome measures included the proportion of patients with symptomatic hypotension, hyperkalemia, and angioedema. Presentation will be at the Sunday 10:45 a.m. session.

- TICAB: The hypothesis that ticagrelor is superior to aspirin for preventing a composite MACE endpoint of CV death, myocardial infarction, target vessel revascularization, and stroke in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting is the basis for the TICAB trial. The nearly 1,900 patients were randomized to 90 mg of ticagrelor twice daily or 100 mg of aspirin twice daily. Major bleeding events, CV death, and all cause death are key secondary outcomes. Relative benefit in context of safety, particularly bleeding risk, will be of interest when the final results are revealed at 5:30 p.m. on Sunday.

All-in-all, the Sunday late-breaking sessions are no less crowded with potentially practice-changing studies, including T-TIME, an evaluation of low-dose alteplase during primary percutaneous intervention at 9:00 a.m., TRED-HF, a study of withdrawal of heart failure therapy in patients who have recovered from dilated cardiomyopathy at 10:45 a.m., and ISAR TEST 4, which will provide 10-year outcomes after coronary stents with biodegradable versus permanent polymer coated devices, at 5:30 p.m.

Robin Williams’ widow recounts ‘terror’ of late husband’s Lewy body dementia

ATLANTA –

“With our medical team’s care, for the next 10 months we chased symptoms, but they were so elusive,” Mr. Williams’ widow, Susan Schneider Williams, said during a keynote address at the annual meeting of the American Neurological Association. “One hallmark of LBD is that symptoms appear and disappear randomly. The game whack-a-mole comes to mind. As soon as you think you are about to figure out a symptom, it disappears, and another one pops up.”

Mr. Williams’ medical team included one general physician, one neurologist, one motor specialist, two psychiatrists, one hypnotherapist, one physical trainer, and assorted alternative specialists. “We had been celebrating our second wedding anniversary when Robin started having gut discomfort,” Ms. Williams recalled. “He was tested for diverticulitis [but] the results came back negative. The pain eventually subsided but what was alarming was Robin’s reaction to it. He had a sudden and sustained spike in fear and anxiety unlike anything I’d seen before. By that point, we’d been by each other’s side long enough that I knew his normal baseline moods, fears, and anxieties. This was totally out of character, and I wondered privately: ‘Is my husband a hypochondriac?’ What I know now is that he was exhibiting a notable hallmark of LBD: new onset anxiety, sustained.” Lewy body disease is characterized by more than 40 symptoms, she continued, “and Robin experienced nearly all of them. He was particularly debilitated by fear, anxiety, delusions, paranoia, and as I came to find out later, hallucinations.”

The medical team continued running all sorts of tests, but everything kept came back negative, except for a very high cortisol count. By the late spring of 2014, however, Mr. Williams was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. “I was relieved to find out we finally had an answer, but I could tell, Robin was not buying it,” said Ms. Williams, who is a California-based fine artist, author, and brain health advocate. “The motor specialist said it was early and mild and that he’d be feeling better once he adjusted to the medications, [that] he had another 10 good years.”

In an attempt to treat the Parkinson’s and what was assumed to be depression, his care plan involved adjusting Parkinson’s medications, combined with an antidepressant. His physician also recommended a visit to the Dan Anderson Renewal Center in Minnesota, “for enhanced 12-step work to augment his sobriety,” Ms. Williams said. “The hope was this might help with fear and anxiety. Robin was clean and sober for 8 continuous years when he passed. I watched how he gained spiritually in so many ways from all the work he’d been doing, but his brain biology was going in the exact opposite direction. He tried desperately to join the parts of his heart, mind, and spirit, but his brain was pulling him apart. I felt like I was watching my husband disintegrate before my eyes, and there was nothing anyone could do about it. There came a day when we were getting ready to go to one of our dear friend’s birthday party. I came and saw Robin as he lay on our bed, imprisoned by fear and anxiety. Through tears, he pleaded, ‘I just want to reboot my brain!’ I promised him, ‘I know, honey. I swear we’re going to get to the bottom of this.’ ”

The couple was about a week away from choosing which neurocognitive testing facility to go to for further evaluation when Mr. Williams took his own life in his Paradise Cay, Calif., home on Aug. 11, 2014. “Robin was exhausted from the terror coming from his brain,” Ms. Williams said. “He took [his own life] before it could take any more of him.”

About 3 months later, the underlying cause of death was revealed: diffuse Lewy body dementia, “one of the worst cases they’d ever seen,” she said. “Because Robin’s disease pathway was extreme and unfolded the way it did, it highlights quite strikingly this disease spectrum. He had a perfusion of Lewy bodies, the essential underlying shared biology between Parkinson’s and Lewy body disease, scattered throughout his entire brain and brain stem.” She added that her husband’s prior history of depression from earlier in life “added to the challenge of getting a proper diagnosis. That single symptom of depression was being treated as its own illness, rather than part of the larger neurocognitive disease. It seems that one of the biggest challenges to getting an accurate diagnosis is that LBD symptoms have tremendous crossover with normal human psychology and behavior, mood, cognition and sleep issues. All of us experience fear, stress, anxiety, paranoia, trouble sleeping, mild depression, and other issues from time to time. We would hardly be human if we didn’t. The challenge of LBD is seeing the giant constellation that it is, rather than just a few of its stars.”

In early 2016, Ms. Williams received the “Commitment to Cures Award” from American Brain Foundation, honoring work she’s done raising awareness for Lewy body disease since her husband’s death. “The day I accepted that award and told our story to a room full of neurologists, my path was forever changed,” she said. “The ABF’s mission of connecting donors to researchers and curing brain disease was an alignment with my mission and hope.” She currently serves as vice chair of the ABF’s board of directors.

“From my own research and from the myriad of letters and information that has come to me, I have distilled what I think are the top three overlooked ideas in this disease space,” Ms. Williams said. “1. Diagnosis: The norm seems to be misdiagnosis, switched diagnosis, or no diagnosis at all. 2. Symptoms: They are being treated independently, apart from the neurological disorder. 3. Suicides: If more autopsies were done, more suicides would be attributed to this disease.”

She concluded her address by reflecting on the impact of her husband’s death has had in bringing an international spotlight to LBD. “When I meet individuals who have lost someone they loved to LBD, I see the pain in their eyes, but I hear the determination in their voice as they chart their own course toward making a difference,” Ms. Williams said. “I have been blessed to learn over and over again that I am not alone. I believe that Robin’s death in this battle against these diseases holds a profound purpose. There was tremendous power in what he suffered, and I saw that power up close. I’m here doing all that I can to see that power transformed into something good.”

ATLANTA –

“With our medical team’s care, for the next 10 months we chased symptoms, but they were so elusive,” Mr. Williams’ widow, Susan Schneider Williams, said during a keynote address at the annual meeting of the American Neurological Association. “One hallmark of LBD is that symptoms appear and disappear randomly. The game whack-a-mole comes to mind. As soon as you think you are about to figure out a symptom, it disappears, and another one pops up.”

Mr. Williams’ medical team included one general physician, one neurologist, one motor specialist, two psychiatrists, one hypnotherapist, one physical trainer, and assorted alternative specialists. “We had been celebrating our second wedding anniversary when Robin started having gut discomfort,” Ms. Williams recalled. “He was tested for diverticulitis [but] the results came back negative. The pain eventually subsided but what was alarming was Robin’s reaction to it. He had a sudden and sustained spike in fear and anxiety unlike anything I’d seen before. By that point, we’d been by each other’s side long enough that I knew his normal baseline moods, fears, and anxieties. This was totally out of character, and I wondered privately: ‘Is my husband a hypochondriac?’ What I know now is that he was exhibiting a notable hallmark of LBD: new onset anxiety, sustained.” Lewy body disease is characterized by more than 40 symptoms, she continued, “and Robin experienced nearly all of them. He was particularly debilitated by fear, anxiety, delusions, paranoia, and as I came to find out later, hallucinations.”

The medical team continued running all sorts of tests, but everything kept came back negative, except for a very high cortisol count. By the late spring of 2014, however, Mr. Williams was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. “I was relieved to find out we finally had an answer, but I could tell, Robin was not buying it,” said Ms. Williams, who is a California-based fine artist, author, and brain health advocate. “The motor specialist said it was early and mild and that he’d be feeling better once he adjusted to the medications, [that] he had another 10 good years.”

In an attempt to treat the Parkinson’s and what was assumed to be depression, his care plan involved adjusting Parkinson’s medications, combined with an antidepressant. His physician also recommended a visit to the Dan Anderson Renewal Center in Minnesota, “for enhanced 12-step work to augment his sobriety,” Ms. Williams said. “The hope was this might help with fear and anxiety. Robin was clean and sober for 8 continuous years when he passed. I watched how he gained spiritually in so many ways from all the work he’d been doing, but his brain biology was going in the exact opposite direction. He tried desperately to join the parts of his heart, mind, and spirit, but his brain was pulling him apart. I felt like I was watching my husband disintegrate before my eyes, and there was nothing anyone could do about it. There came a day when we were getting ready to go to one of our dear friend’s birthday party. I came and saw Robin as he lay on our bed, imprisoned by fear and anxiety. Through tears, he pleaded, ‘I just want to reboot my brain!’ I promised him, ‘I know, honey. I swear we’re going to get to the bottom of this.’ ”

The couple was about a week away from choosing which neurocognitive testing facility to go to for further evaluation when Mr. Williams took his own life in his Paradise Cay, Calif., home on Aug. 11, 2014. “Robin was exhausted from the terror coming from his brain,” Ms. Williams said. “He took [his own life] before it could take any more of him.”

About 3 months later, the underlying cause of death was revealed: diffuse Lewy body dementia, “one of the worst cases they’d ever seen,” she said. “Because Robin’s disease pathway was extreme and unfolded the way it did, it highlights quite strikingly this disease spectrum. He had a perfusion of Lewy bodies, the essential underlying shared biology between Parkinson’s and Lewy body disease, scattered throughout his entire brain and brain stem.” She added that her husband’s prior history of depression from earlier in life “added to the challenge of getting a proper diagnosis. That single symptom of depression was being treated as its own illness, rather than part of the larger neurocognitive disease. It seems that one of the biggest challenges to getting an accurate diagnosis is that LBD symptoms have tremendous crossover with normal human psychology and behavior, mood, cognition and sleep issues. All of us experience fear, stress, anxiety, paranoia, trouble sleeping, mild depression, and other issues from time to time. We would hardly be human if we didn’t. The challenge of LBD is seeing the giant constellation that it is, rather than just a few of its stars.”

In early 2016, Ms. Williams received the “Commitment to Cures Award” from American Brain Foundation, honoring work she’s done raising awareness for Lewy body disease since her husband’s death. “The day I accepted that award and told our story to a room full of neurologists, my path was forever changed,” she said. “The ABF’s mission of connecting donors to researchers and curing brain disease was an alignment with my mission and hope.” She currently serves as vice chair of the ABF’s board of directors.

“From my own research and from the myriad of letters and information that has come to me, I have distilled what I think are the top three overlooked ideas in this disease space,” Ms. Williams said. “1. Diagnosis: The norm seems to be misdiagnosis, switched diagnosis, or no diagnosis at all. 2. Symptoms: They are being treated independently, apart from the neurological disorder. 3. Suicides: If more autopsies were done, more suicides would be attributed to this disease.”

She concluded her address by reflecting on the impact of her husband’s death has had in bringing an international spotlight to LBD. “When I meet individuals who have lost someone they loved to LBD, I see the pain in their eyes, but I hear the determination in their voice as they chart their own course toward making a difference,” Ms. Williams said. “I have been blessed to learn over and over again that I am not alone. I believe that Robin’s death in this battle against these diseases holds a profound purpose. There was tremendous power in what he suffered, and I saw that power up close. I’m here doing all that I can to see that power transformed into something good.”

ATLANTA –

“With our medical team’s care, for the next 10 months we chased symptoms, but they were so elusive,” Mr. Williams’ widow, Susan Schneider Williams, said during a keynote address at the annual meeting of the American Neurological Association. “One hallmark of LBD is that symptoms appear and disappear randomly. The game whack-a-mole comes to mind. As soon as you think you are about to figure out a symptom, it disappears, and another one pops up.”

Mr. Williams’ medical team included one general physician, one neurologist, one motor specialist, two psychiatrists, one hypnotherapist, one physical trainer, and assorted alternative specialists. “We had been celebrating our second wedding anniversary when Robin started having gut discomfort,” Ms. Williams recalled. “He was tested for diverticulitis [but] the results came back negative. The pain eventually subsided but what was alarming was Robin’s reaction to it. He had a sudden and sustained spike in fear and anxiety unlike anything I’d seen before. By that point, we’d been by each other’s side long enough that I knew his normal baseline moods, fears, and anxieties. This was totally out of character, and I wondered privately: ‘Is my husband a hypochondriac?’ What I know now is that he was exhibiting a notable hallmark of LBD: new onset anxiety, sustained.” Lewy body disease is characterized by more than 40 symptoms, she continued, “and Robin experienced nearly all of them. He was particularly debilitated by fear, anxiety, delusions, paranoia, and as I came to find out later, hallucinations.”

The medical team continued running all sorts of tests, but everything kept came back negative, except for a very high cortisol count. By the late spring of 2014, however, Mr. Williams was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. “I was relieved to find out we finally had an answer, but I could tell, Robin was not buying it,” said Ms. Williams, who is a California-based fine artist, author, and brain health advocate. “The motor specialist said it was early and mild and that he’d be feeling better once he adjusted to the medications, [that] he had another 10 good years.”

In an attempt to treat the Parkinson’s and what was assumed to be depression, his care plan involved adjusting Parkinson’s medications, combined with an antidepressant. His physician also recommended a visit to the Dan Anderson Renewal Center in Minnesota, “for enhanced 12-step work to augment his sobriety,” Ms. Williams said. “The hope was this might help with fear and anxiety. Robin was clean and sober for 8 continuous years when he passed. I watched how he gained spiritually in so many ways from all the work he’d been doing, but his brain biology was going in the exact opposite direction. He tried desperately to join the parts of his heart, mind, and spirit, but his brain was pulling him apart. I felt like I was watching my husband disintegrate before my eyes, and there was nothing anyone could do about it. There came a day when we were getting ready to go to one of our dear friend’s birthday party. I came and saw Robin as he lay on our bed, imprisoned by fear and anxiety. Through tears, he pleaded, ‘I just want to reboot my brain!’ I promised him, ‘I know, honey. I swear we’re going to get to the bottom of this.’ ”

The couple was about a week away from choosing which neurocognitive testing facility to go to for further evaluation when Mr. Williams took his own life in his Paradise Cay, Calif., home on Aug. 11, 2014. “Robin was exhausted from the terror coming from his brain,” Ms. Williams said. “He took [his own life] before it could take any more of him.”

About 3 months later, the underlying cause of death was revealed: diffuse Lewy body dementia, “one of the worst cases they’d ever seen,” she said. “Because Robin’s disease pathway was extreme and unfolded the way it did, it highlights quite strikingly this disease spectrum. He had a perfusion of Lewy bodies, the essential underlying shared biology between Parkinson’s and Lewy body disease, scattered throughout his entire brain and brain stem.” She added that her husband’s prior history of depression from earlier in life “added to the challenge of getting a proper diagnosis. That single symptom of depression was being treated as its own illness, rather than part of the larger neurocognitive disease. It seems that one of the biggest challenges to getting an accurate diagnosis is that LBD symptoms have tremendous crossover with normal human psychology and behavior, mood, cognition and sleep issues. All of us experience fear, stress, anxiety, paranoia, trouble sleeping, mild depression, and other issues from time to time. We would hardly be human if we didn’t. The challenge of LBD is seeing the giant constellation that it is, rather than just a few of its stars.”

In early 2016, Ms. Williams received the “Commitment to Cures Award” from American Brain Foundation, honoring work she’s done raising awareness for Lewy body disease since her husband’s death. “The day I accepted that award and told our story to a room full of neurologists, my path was forever changed,” she said. “The ABF’s mission of connecting donors to researchers and curing brain disease was an alignment with my mission and hope.” She currently serves as vice chair of the ABF’s board of directors.

“From my own research and from the myriad of letters and information that has come to me, I have distilled what I think are the top three overlooked ideas in this disease space,” Ms. Williams said. “1. Diagnosis: The norm seems to be misdiagnosis, switched diagnosis, or no diagnosis at all. 2. Symptoms: They are being treated independently, apart from the neurological disorder. 3. Suicides: If more autopsies were done, more suicides would be attributed to this disease.”

She concluded her address by reflecting on the impact of her husband’s death has had in bringing an international spotlight to LBD. “When I meet individuals who have lost someone they loved to LBD, I see the pain in their eyes, but I hear the determination in their voice as they chart their own course toward making a difference,” Ms. Williams said. “I have been blessed to learn over and over again that I am not alone. I believe that Robin’s death in this battle against these diseases holds a profound purpose. There was tremendous power in what he suffered, and I saw that power up close. I’m here doing all that I can to see that power transformed into something good.”

REPORTING FROM ANA 2018

Struggling to reach an HCV vaccine

Currently, there is no effective hepatitis C virus (HCV) vaccine available despite numerous ongoing studies, according to the results of a review published in Gastroenterology.

In their article, Justin R. Bailey, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and his colleagues reviewed the limited feasibility of applying traditional vaccine design to HCV and the problem of genetic diversity in the virus, as well as trials of vaccines designed to elicit T-cell responses.

One profound difficulty in the development and testing of an HCV vaccine is that the cohort most predictably at risk for high infection levels, people who inject drugs, are notoriously difficult to recruit, maintain consistent treatment, and follow up on – all necessary aspects of an appropriate vaccine trial.

Thus, at present, adjuvant envelope or core protein and virus-vectored nonstructural antigen vaccines have been tested only in healthy volunteers who are not at risk for HCV infection; viral vectors encoding nonstructural proteins remain the only vaccine strategy tested in truly at-risk individuals, according to Dr. Bailey and his colleagues.

“Although pharmaceutical companies invest in drug development, vaccine development requires investment from sources beyond government and charitable foundations. A prophylactic HCV vaccine is an important part of a successful strategy for global control. Although development is not easy, the quest is a worthy challenge,” Dr. Bailey and his colleagues concluded.

The authors reported having no conflicts.

SOURCE: Bailey JR et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 Sep 27. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.08.060.

Currently, there is no effective hepatitis C virus (HCV) vaccine available despite numerous ongoing studies, according to the results of a review published in Gastroenterology.

In their article, Justin R. Bailey, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and his colleagues reviewed the limited feasibility of applying traditional vaccine design to HCV and the problem of genetic diversity in the virus, as well as trials of vaccines designed to elicit T-cell responses.

One profound difficulty in the development and testing of an HCV vaccine is that the cohort most predictably at risk for high infection levels, people who inject drugs, are notoriously difficult to recruit, maintain consistent treatment, and follow up on – all necessary aspects of an appropriate vaccine trial.

Thus, at present, adjuvant envelope or core protein and virus-vectored nonstructural antigen vaccines have been tested only in healthy volunteers who are not at risk for HCV infection; viral vectors encoding nonstructural proteins remain the only vaccine strategy tested in truly at-risk individuals, according to Dr. Bailey and his colleagues.

“Although pharmaceutical companies invest in drug development, vaccine development requires investment from sources beyond government and charitable foundations. A prophylactic HCV vaccine is an important part of a successful strategy for global control. Although development is not easy, the quest is a worthy challenge,” Dr. Bailey and his colleagues concluded.

The authors reported having no conflicts.

SOURCE: Bailey JR et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 Sep 27. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.08.060.

Currently, there is no effective hepatitis C virus (HCV) vaccine available despite numerous ongoing studies, according to the results of a review published in Gastroenterology.

In their article, Justin R. Bailey, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and his colleagues reviewed the limited feasibility of applying traditional vaccine design to HCV and the problem of genetic diversity in the virus, as well as trials of vaccines designed to elicit T-cell responses.

One profound difficulty in the development and testing of an HCV vaccine is that the cohort most predictably at risk for high infection levels, people who inject drugs, are notoriously difficult to recruit, maintain consistent treatment, and follow up on – all necessary aspects of an appropriate vaccine trial.

Thus, at present, adjuvant envelope or core protein and virus-vectored nonstructural antigen vaccines have been tested only in healthy volunteers who are not at risk for HCV infection; viral vectors encoding nonstructural proteins remain the only vaccine strategy tested in truly at-risk individuals, according to Dr. Bailey and his colleagues.

“Although pharmaceutical companies invest in drug development, vaccine development requires investment from sources beyond government and charitable foundations. A prophylactic HCV vaccine is an important part of a successful strategy for global control. Although development is not easy, the quest is a worthy challenge,” Dr. Bailey and his colleagues concluded.

The authors reported having no conflicts.

SOURCE: Bailey JR et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 Sep 27. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.08.060.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Reviewing the state of HCV and HBV in children

The natural histories of hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) are very different in children, compared with their progress in adults, and depends on age at time of infection, mode of acquisition, ethnicity, and genotype, according to a review in a special pediatric issue of Clinics in Liver Disease.

Most children infected perinatally or vertically continue to be asymptomatic but are at uniquely higher risk of developing chronic viral hepatitis and progressing to liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), according to Krupa R. Mysore, MD, and Daniel H. Leung, MD, both of the Baylor College of Medicine, Houston. In addition, because the risk of progression to cancer along with such other liver damage is high in children, the reviewers stated that HCV and HBV can be classified as oncoviruses.

Their article assessed overall epidemiology, viral characteristics, and immune responses, as well as prevention, clinical manifestations, and current advances in the treatment of hepatitis B and C in children.

Because of the introduction of universal infant vaccination for HBV in the United States in 1991, the incidence of acute hepatitis B in U.S. children (those aged less than 19 years) has decreased from approximately 13.80/100,000 population (in children aged 10-19 years) in the 1980s to 0.34/100,000 population in 2002, Dr. Mysore and Dr. Leung wrote.

However, they added that those children who have chronic HBV remain at high risk for HCC, with a 100-fold greater incidence, compared with the HBV-negative population.

Similarly, HCV is a significant problem in children, with an estimated prevalence in the United States of 0.2% and 0.4% for children aged 6-11 years and 12-19 years, respectively. Vertical transmission from the mother is responsible for more than 60% of pediatric HCV infection and adds approximately 7,200 new cases in the United States yearly. Older children can acquire the virus through intravenous and intranasal drug use and high-risk sexual activity, they stated.

“Our understanding of the pathobiology and immunology of hepatitis B and C is unprecedented. As new antiviral therapies are being developed for the pediatric population, the differences in management and monitoring between children and adults with HBV and HCV are beginning to narrow but are still important,” the authors wrote.

They pointed out that soon-to-be-available treatments for HCV will be curative in children aged as young as 3 years. “[T]his will change the natural history of HCV and the prevalence of hepatocellular carcinoma over the next several decades for the better,” Dr. Mysore and Dr. Leung concluded.

They reported that they had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

SOURCE: Mysore KR et al. Clin Liver Dis. 2018; 22:703-22.

The natural histories of hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) are very different in children, compared with their progress in adults, and depends on age at time of infection, mode of acquisition, ethnicity, and genotype, according to a review in a special pediatric issue of Clinics in Liver Disease.

Most children infected perinatally or vertically continue to be asymptomatic but are at uniquely higher risk of developing chronic viral hepatitis and progressing to liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), according to Krupa R. Mysore, MD, and Daniel H. Leung, MD, both of the Baylor College of Medicine, Houston. In addition, because the risk of progression to cancer along with such other liver damage is high in children, the reviewers stated that HCV and HBV can be classified as oncoviruses.

Their article assessed overall epidemiology, viral characteristics, and immune responses, as well as prevention, clinical manifestations, and current advances in the treatment of hepatitis B and C in children.

Because of the introduction of universal infant vaccination for HBV in the United States in 1991, the incidence of acute hepatitis B in U.S. children (those aged less than 19 years) has decreased from approximately 13.80/100,000 population (in children aged 10-19 years) in the 1980s to 0.34/100,000 population in 2002, Dr. Mysore and Dr. Leung wrote.

However, they added that those children who have chronic HBV remain at high risk for HCC, with a 100-fold greater incidence, compared with the HBV-negative population.

Similarly, HCV is a significant problem in children, with an estimated prevalence in the United States of 0.2% and 0.4% for children aged 6-11 years and 12-19 years, respectively. Vertical transmission from the mother is responsible for more than 60% of pediatric HCV infection and adds approximately 7,200 new cases in the United States yearly. Older children can acquire the virus through intravenous and intranasal drug use and high-risk sexual activity, they stated.

“Our understanding of the pathobiology and immunology of hepatitis B and C is unprecedented. As new antiviral therapies are being developed for the pediatric population, the differences in management and monitoring between children and adults with HBV and HCV are beginning to narrow but are still important,” the authors wrote.

They pointed out that soon-to-be-available treatments for HCV will be curative in children aged as young as 3 years. “[T]his will change the natural history of HCV and the prevalence of hepatocellular carcinoma over the next several decades for the better,” Dr. Mysore and Dr. Leung concluded.

They reported that they had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

SOURCE: Mysore KR et al. Clin Liver Dis. 2018; 22:703-22.

The natural histories of hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) are very different in children, compared with their progress in adults, and depends on age at time of infection, mode of acquisition, ethnicity, and genotype, according to a review in a special pediatric issue of Clinics in Liver Disease.

Most children infected perinatally or vertically continue to be asymptomatic but are at uniquely higher risk of developing chronic viral hepatitis and progressing to liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), according to Krupa R. Mysore, MD, and Daniel H. Leung, MD, both of the Baylor College of Medicine, Houston. In addition, because the risk of progression to cancer along with such other liver damage is high in children, the reviewers stated that HCV and HBV can be classified as oncoviruses.

Their article assessed overall epidemiology, viral characteristics, and immune responses, as well as prevention, clinical manifestations, and current advances in the treatment of hepatitis B and C in children.

Because of the introduction of universal infant vaccination for HBV in the United States in 1991, the incidence of acute hepatitis B in U.S. children (those aged less than 19 years) has decreased from approximately 13.80/100,000 population (in children aged 10-19 years) in the 1980s to 0.34/100,000 population in 2002, Dr. Mysore and Dr. Leung wrote.

However, they added that those children who have chronic HBV remain at high risk for HCC, with a 100-fold greater incidence, compared with the HBV-negative population.

Similarly, HCV is a significant problem in children, with an estimated prevalence in the United States of 0.2% and 0.4% for children aged 6-11 years and 12-19 years, respectively. Vertical transmission from the mother is responsible for more than 60% of pediatric HCV infection and adds approximately 7,200 new cases in the United States yearly. Older children can acquire the virus through intravenous and intranasal drug use and high-risk sexual activity, they stated.

“Our understanding of the pathobiology and immunology of hepatitis B and C is unprecedented. As new antiviral therapies are being developed for the pediatric population, the differences in management and monitoring between children and adults with HBV and HCV are beginning to narrow but are still important,” the authors wrote.

They pointed out that soon-to-be-available treatments for HCV will be curative in children aged as young as 3 years. “[T]his will change the natural history of HCV and the prevalence of hepatocellular carcinoma over the next several decades for the better,” Dr. Mysore and Dr. Leung concluded.

They reported that they had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

SOURCE: Mysore KR et al. Clin Liver Dis. 2018; 22:703-22.

FROM CLINICS IN LIVER DISEASE

Dueling SLE classification criteria: And the winner is...

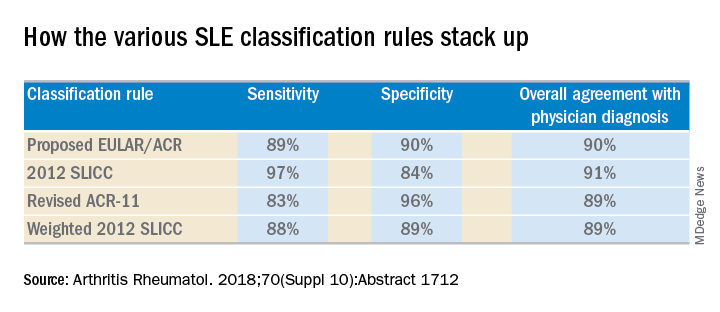

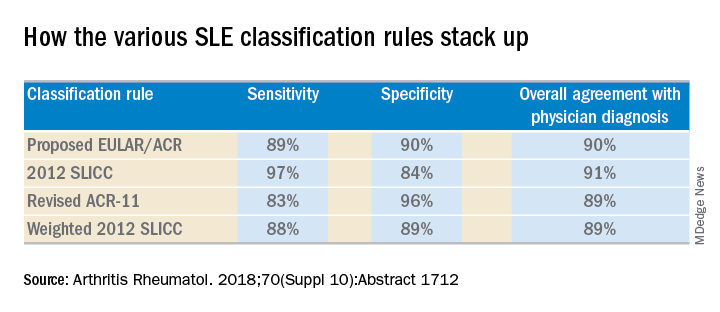

CHICAGO – Newer isn’t necessarily better – especially when it comes to the plethora of SLE classification criteria, according to Michelle A. Petri, MD, professor of medicine and director of the Hopkins Lupus Center at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

“We have an embarrassment of criteria for lupus right now, and everyone wants to know if one is better than the others,” the rheumatologist said at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

She and several coinvestigators who are members of the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics (SLICC) set out to learn the answer. They developed a new, modified, weighted version of the 2012 SLICC criteria and compared its sensitivity and specificity for SLE diagnosis by 690 physicians with three other major classification systems: the 1997 update to ACR-11 criteria, the nonweighted SLICC 2012 criteria, and the proposed EULAR/ACR criteria, which uses a differentially weighted approach in which the various possible disease manifestations are each assigned a different point score. In contrast, the revised ACR-11 and SLICC 2012 criteria count each SLE manifestation equally.

Long story short: “The two newly derived weighted classification rules did not perform better than the existing list-based rules in terms of overall agreement,” according to Dr. Petri.

“We don’t think that weighting all the criteria, which is what the EULAR/ACR and weighted SLICC 2012 rules do, adds to the performance of the criteria set, and in fact it makes it much more difficult for clinicians to use when there’s a complicated weighting system, unless it’s web-based or there’s an app for it. And to be honest, clinicians are so busy that they’re probably not going to take time out in a clinic visit to go use the web or an app. Our criteria need to be user friendly,” she continued.

So which of the four classification systems is most user friendly? The EULAR/ACR criteria can be dismissed on that score because they are supposed to be used only for research, according to the rheumatologist.

“I think the SLICC 2012 criteria are very useful for clinicians because they have the highest sensitivity. And what a clinician wants is not to miss a diagnosis and to start treatment early,” Dr. Petri said.

To develop the weighted SLICC criteria, whose future at this point doesn’t look bright, she and her coinvestigators redeployed the same physician-rated patient scenarios used to develop the nonweighted 2012 SLICC classification criteria and assigned each of the potential manifestations of SLE a specific point score. For example, acute cutaneous manifestations received 16 points, serositis 9, oral ulcers 16, thrombocytopenia 15, and so forth. Under this system, a patient with a score of at least 56 points, or lupus nephritis, or least one clinical and one immunologic component of SLE was classified as having the disease.

Dr. Petri reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study, supported by the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Petri MA et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70(Suppl 10): Abstract 1712.

CHICAGO – Newer isn’t necessarily better – especially when it comes to the plethora of SLE classification criteria, according to Michelle A. Petri, MD, professor of medicine and director of the Hopkins Lupus Center at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

“We have an embarrassment of criteria for lupus right now, and everyone wants to know if one is better than the others,” the rheumatologist said at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

She and several coinvestigators who are members of the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics (SLICC) set out to learn the answer. They developed a new, modified, weighted version of the 2012 SLICC criteria and compared its sensitivity and specificity for SLE diagnosis by 690 physicians with three other major classification systems: the 1997 update to ACR-11 criteria, the nonweighted SLICC 2012 criteria, and the proposed EULAR/ACR criteria, which uses a differentially weighted approach in which the various possible disease manifestations are each assigned a different point score. In contrast, the revised ACR-11 and SLICC 2012 criteria count each SLE manifestation equally.

Long story short: “The two newly derived weighted classification rules did not perform better than the existing list-based rules in terms of overall agreement,” according to Dr. Petri.

“We don’t think that weighting all the criteria, which is what the EULAR/ACR and weighted SLICC 2012 rules do, adds to the performance of the criteria set, and in fact it makes it much more difficult for clinicians to use when there’s a complicated weighting system, unless it’s web-based or there’s an app for it. And to be honest, clinicians are so busy that they’re probably not going to take time out in a clinic visit to go use the web or an app. Our criteria need to be user friendly,” she continued.

So which of the four classification systems is most user friendly? The EULAR/ACR criteria can be dismissed on that score because they are supposed to be used only for research, according to the rheumatologist.

“I think the SLICC 2012 criteria are very useful for clinicians because they have the highest sensitivity. And what a clinician wants is not to miss a diagnosis and to start treatment early,” Dr. Petri said.

To develop the weighted SLICC criteria, whose future at this point doesn’t look bright, she and her coinvestigators redeployed the same physician-rated patient scenarios used to develop the nonweighted 2012 SLICC classification criteria and assigned each of the potential manifestations of SLE a specific point score. For example, acute cutaneous manifestations received 16 points, serositis 9, oral ulcers 16, thrombocytopenia 15, and so forth. Under this system, a patient with a score of at least 56 points, or lupus nephritis, or least one clinical and one immunologic component of SLE was classified as having the disease.

Dr. Petri reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study, supported by the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Petri MA et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70(Suppl 10): Abstract 1712.

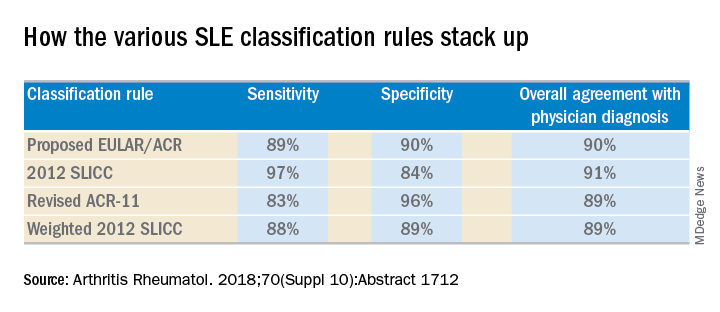

CHICAGO – Newer isn’t necessarily better – especially when it comes to the plethora of SLE classification criteria, according to Michelle A. Petri, MD, professor of medicine and director of the Hopkins Lupus Center at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

“We have an embarrassment of criteria for lupus right now, and everyone wants to know if one is better than the others,” the rheumatologist said at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

She and several coinvestigators who are members of the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics (SLICC) set out to learn the answer. They developed a new, modified, weighted version of the 2012 SLICC criteria and compared its sensitivity and specificity for SLE diagnosis by 690 physicians with three other major classification systems: the 1997 update to ACR-11 criteria, the nonweighted SLICC 2012 criteria, and the proposed EULAR/ACR criteria, which uses a differentially weighted approach in which the various possible disease manifestations are each assigned a different point score. In contrast, the revised ACR-11 and SLICC 2012 criteria count each SLE manifestation equally.

Long story short: “The two newly derived weighted classification rules did not perform better than the existing list-based rules in terms of overall agreement,” according to Dr. Petri.

“We don’t think that weighting all the criteria, which is what the EULAR/ACR and weighted SLICC 2012 rules do, adds to the performance of the criteria set, and in fact it makes it much more difficult for clinicians to use when there’s a complicated weighting system, unless it’s web-based or there’s an app for it. And to be honest, clinicians are so busy that they’re probably not going to take time out in a clinic visit to go use the web or an app. Our criteria need to be user friendly,” she continued.

So which of the four classification systems is most user friendly? The EULAR/ACR criteria can be dismissed on that score because they are supposed to be used only for research, according to the rheumatologist.

“I think the SLICC 2012 criteria are very useful for clinicians because they have the highest sensitivity. And what a clinician wants is not to miss a diagnosis and to start treatment early,” Dr. Petri said.

To develop the weighted SLICC criteria, whose future at this point doesn’t look bright, she and her coinvestigators redeployed the same physician-rated patient scenarios used to develop the nonweighted 2012 SLICC classification criteria and assigned each of the potential manifestations of SLE a specific point score. For example, acute cutaneous manifestations received 16 points, serositis 9, oral ulcers 16, thrombocytopenia 15, and so forth. Under this system, a patient with a score of at least 56 points, or lupus nephritis, or least one clinical and one immunologic component of SLE was classified as having the disease.

Dr. Petri reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study, supported by the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Petri MA et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70(Suppl 10): Abstract 1712.

REPORTING FROM THE ACR ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: The 2012 SLICC SLE classification criteria are best suited for clinical practice.

Major finding:

Study details: This study compared the sensitivity, specificity, and overall agreement with physician diagnosis of four different sets of SLE classification criteria.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health. The presenter reported having no financial conflicts.

Source: Petri MA et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70(Suppl 10): Abstract 1712.

Tumor burden in active surveillance for mRCC may inform treatment decisions

suggests an Italian cohort study.

Investigators led by Davide Bimbatti, MD, of Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Integrata in Verona, Italy, retrospectively studied 52 patients with mRCC who started active surveillance as their initial strategy for disease management. They assessed three predictors of outcomes: International Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium (IMDC) risk class, number of metastatic sites, and tumor burden.

Patients remained on active surveillance for a median of 18.3 months and had a median total overall survival of 80.1 months, according to study results published in Urologic Oncology. Fully 69.2% started first-line systemic therapy during a median follow-up of 38.5 months.

The only baseline factor predicting time on active surveillance was IMDC class (hazard ratio, 2.15; P = .011).

An increasing number of metastatic sites during active surveillance was associated with poorer total overall survival (HR, 2.86; P = .010) and a trend toward poorer postsurveillance overall survival (HR, 2.37; P = .060).

Increasing tumor burden, measured as the sum in millimeters of the longest tumor diameter of each measurable lesion, during active surveillance was associated with both poorer total overall survival (HR, 1.16; P = .024) and poorer postsurveillance overall survival (HR, 1.21; P = .004).

Finally, an IMDC class of good or intermediate versus poor at the start of systemic therapy was a favorable predictor (HR, 0.07; P = .010; and HR, 0.12; P = .044, respectively) and an increase in tumor burden was an unfavorable predictor (HR, 1.26; P = .005) of postsurveillance overall survival.

“Our study confirms that active surveillance is a safe option for certain patients, with a median time on surveillance of 1.5 years delaying the beginning of systemic therapies and avoiding drug-related toxicities, with a median overall survival greater than 6.5 years,” wrote Dr. Bimbatti and coinvestigators.

“During active surveillance, patients rarely show any deterioration of the IMDC prognostic class. Meanwhile, the tumor burden changes, more than the increase of metastatic sites, account for the heterogeneity of the disease and may help physicians to make decisions about the early termination of active surveillance and the start of systemic therapy,” they concluded.

SOURCE: Bimbatti D et al. Urol Oncol. 2018 Oct 6. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2018.08.018.

suggests an Italian cohort study.

Investigators led by Davide Bimbatti, MD, of Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Integrata in Verona, Italy, retrospectively studied 52 patients with mRCC who started active surveillance as their initial strategy for disease management. They assessed three predictors of outcomes: International Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium (IMDC) risk class, number of metastatic sites, and tumor burden.

Patients remained on active surveillance for a median of 18.3 months and had a median total overall survival of 80.1 months, according to study results published in Urologic Oncology. Fully 69.2% started first-line systemic therapy during a median follow-up of 38.5 months.

The only baseline factor predicting time on active surveillance was IMDC class (hazard ratio, 2.15; P = .011).

An increasing number of metastatic sites during active surveillance was associated with poorer total overall survival (HR, 2.86; P = .010) and a trend toward poorer postsurveillance overall survival (HR, 2.37; P = .060).

Increasing tumor burden, measured as the sum in millimeters of the longest tumor diameter of each measurable lesion, during active surveillance was associated with both poorer total overall survival (HR, 1.16; P = .024) and poorer postsurveillance overall survival (HR, 1.21; P = .004).

Finally, an IMDC class of good or intermediate versus poor at the start of systemic therapy was a favorable predictor (HR, 0.07; P = .010; and HR, 0.12; P = .044, respectively) and an increase in tumor burden was an unfavorable predictor (HR, 1.26; P = .005) of postsurveillance overall survival.

“Our study confirms that active surveillance is a safe option for certain patients, with a median time on surveillance of 1.5 years delaying the beginning of systemic therapies and avoiding drug-related toxicities, with a median overall survival greater than 6.5 years,” wrote Dr. Bimbatti and coinvestigators.

“During active surveillance, patients rarely show any deterioration of the IMDC prognostic class. Meanwhile, the tumor burden changes, more than the increase of metastatic sites, account for the heterogeneity of the disease and may help physicians to make decisions about the early termination of active surveillance and the start of systemic therapy,” they concluded.

SOURCE: Bimbatti D et al. Urol Oncol. 2018 Oct 6. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2018.08.018.

suggests an Italian cohort study.

Investigators led by Davide Bimbatti, MD, of Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Integrata in Verona, Italy, retrospectively studied 52 patients with mRCC who started active surveillance as their initial strategy for disease management. They assessed three predictors of outcomes: International Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium (IMDC) risk class, number of metastatic sites, and tumor burden.

Patients remained on active surveillance for a median of 18.3 months and had a median total overall survival of 80.1 months, according to study results published in Urologic Oncology. Fully 69.2% started first-line systemic therapy during a median follow-up of 38.5 months.

The only baseline factor predicting time on active surveillance was IMDC class (hazard ratio, 2.15; P = .011).

An increasing number of metastatic sites during active surveillance was associated with poorer total overall survival (HR, 2.86; P = .010) and a trend toward poorer postsurveillance overall survival (HR, 2.37; P = .060).

Increasing tumor burden, measured as the sum in millimeters of the longest tumor diameter of each measurable lesion, during active surveillance was associated with both poorer total overall survival (HR, 1.16; P = .024) and poorer postsurveillance overall survival (HR, 1.21; P = .004).

Finally, an IMDC class of good or intermediate versus poor at the start of systemic therapy was a favorable predictor (HR, 0.07; P = .010; and HR, 0.12; P = .044, respectively) and an increase in tumor burden was an unfavorable predictor (HR, 1.26; P = .005) of postsurveillance overall survival.

“Our study confirms that active surveillance is a safe option for certain patients, with a median time on surveillance of 1.5 years delaying the beginning of systemic therapies and avoiding drug-related toxicities, with a median overall survival greater than 6.5 years,” wrote Dr. Bimbatti and coinvestigators.

“During active surveillance, patients rarely show any deterioration of the IMDC prognostic class. Meanwhile, the tumor burden changes, more than the increase of metastatic sites, account for the heterogeneity of the disease and may help physicians to make decisions about the early termination of active surveillance and the start of systemic therapy,” they concluded.

SOURCE: Bimbatti D et al. Urol Oncol. 2018 Oct 6. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2018.08.018.

FROM UROLOGIC ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: Change in tumor burden during active surveillance for metastatic RCC is prognostic.

Major finding: Each millimeter increase in total tumor burden during surveillance was associated with a 16% higher risk of death overall and a 21% increase in risk of death after stopping surveillance and starting first-line systemic therapy.

Study details: Retrospective cohort study of 52 patients with metastatic RCC who started with active surveillance.

Disclosures: The authors declared having no conflicts of interest.

Source: Bimbatti D et al. Urol Oncol. 2018 Oct 6. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2018.08.018.

Bradycardia guideline sets new bar for shared decision-making in pacemaker placement

A new clinical practice guideline on the management of bradycardia and cardiac conduction system disorders in adults emphasizes the importance of patient-centered care and “shared decision-making” between patient and clinician, particularly with regard to patients who have indications for pacemaker implantation.

Shared decision-making extends to the end-of-life setting where “complex” informed consent and refusal of care decisions need to be patient-specific, and must involve all stakeholders, according to the new 2018 guidelines from the American College of Cardiology (ACC), American Heart Association (AHA), and Heart Rhythm Society (HRS).

“Patients with decision-making capacity or his/her legally defined surrogate has the right to refuse or request withdrawal of pacemaker therapy, even if the patient is pacemaker dependent, which should be considered palliative, end-of-life care, and not physician-assisted suicide,” the guidelines read.

The guidelines additionally update the evaluation and treatment of sinus node dysfunction, atrioventricular block, and conduction disorders, based in part on a comprehensive evidence review conducted from January to September 2017. They supersede a 2008 guideline from the three societies on device-based therapy of cardiac rhythm abnormalities, and the focused update to that guideline published in 2012.

These guidelines will be useful not only to arrhythmia specialists, but also to internists and family physicians, cardiologists, surgeons, emergency physicians, and anesthesiologists, according to the guideline writing committee, which included representativens of ACC, AHA, HRS, and several other national organizations. The committee included cardiac electrophysiologists, cardiologists, surgeons, an anesthesiologist, and other clinicians, as well as a patient/lay representative, and was chaired by Fred M. Kusumoto, MD, of Mayo Clinic Florida in Jacksonville.

For sinus node dysfunction, no minimum heart rate or pause duration has been determined for which permanent pacing would be recommended, the guidelines state. To determine whether permanent pacing is necessary in those patients, clinicians should work to establish a temporal correlation bewteen bradycardia and symptoms, according to the guideline authors.

Left bundle branch block, when found on echocardiogram, greatly increases the chances of underlying structural heart disease and of a left ventricular systolic dysfunction diagnosis, according to the guidelines, which state that echocardiography is the most appropriate initial screening test for left ventricular systolic dysfunction and other structural heart disease.

Permanent pacing is recommended for certain types of atrioventricular (AV) block, according to the guidelines, which include high-grade AV block, acquired second-degree Mobitz type II AV block, and third-degree AV block not related to reversible or physiologic causes.

Treatment of sleep apnea can reduce frequency of nocturnal bradycardia and may provide a cardiovascular benefit, the guideline authors state. Patients with nocturnal bradycardias should be screened for sleep apnea, though authors cautioned that these arrhythmias are not, in and of themselves, an indication for permanent pacing.

“Treatment decisions are based not only on the best available evidence, but also on the patient’s goals of care and preferences,” Dr. Kusumoto said in a press release jointly issued by the ACC, AHA, and HRS. Toward that end, patients should receive “trusted material” to help them understand the consequences and risks of any proposed management decision.

Emerging pacing technologies such as His bundle pacing and transcatheter leadless pacing systems need more study to determine which patient populations will benefit most from them, the guidelines state.

“Regardless of technology, for the foreseeable future, pacing therapy requires implantation of a medical device,” Dr. Kusumoto said in the release. “Future studies are warranted to focus on the long-term implications associated with lifelong therapy.”

The 2018 ACC/AHA/HRS Guideline on the Evaluation and Management of Patients With Bradycardia and Cardiac Conduction Delay is now published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, and simultaneously in the journals Circulation and HeartRhythm.

Dr. Kusumoto reported no relationships with industry or other entities. Guideline co-authors provided disclosures related to Boston Scientific, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Medtronic, Daiichi-Sankyo, Sanofi-Aventis, St. Jude Medical, and Abbott, among others.

SOURCE: Kusumoto FM, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Nov 6.

A new clinical practice guideline on the management of bradycardia and cardiac conduction system disorders in adults emphasizes the importance of patient-centered care and “shared decision-making” between patient and clinician, particularly with regard to patients who have indications for pacemaker implantation.

Shared decision-making extends to the end-of-life setting where “complex” informed consent and refusal of care decisions need to be patient-specific, and must involve all stakeholders, according to the new 2018 guidelines from the American College of Cardiology (ACC), American Heart Association (AHA), and Heart Rhythm Society (HRS).

“Patients with decision-making capacity or his/her legally defined surrogate has the right to refuse or request withdrawal of pacemaker therapy, even if the patient is pacemaker dependent, which should be considered palliative, end-of-life care, and not physician-assisted suicide,” the guidelines read.

The guidelines additionally update the evaluation and treatment of sinus node dysfunction, atrioventricular block, and conduction disorders, based in part on a comprehensive evidence review conducted from January to September 2017. They supersede a 2008 guideline from the three societies on device-based therapy of cardiac rhythm abnormalities, and the focused update to that guideline published in 2012.

These guidelines will be useful not only to arrhythmia specialists, but also to internists and family physicians, cardiologists, surgeons, emergency physicians, and anesthesiologists, according to the guideline writing committee, which included representativens of ACC, AHA, HRS, and several other national organizations. The committee included cardiac electrophysiologists, cardiologists, surgeons, an anesthesiologist, and other clinicians, as well as a patient/lay representative, and was chaired by Fred M. Kusumoto, MD, of Mayo Clinic Florida in Jacksonville.

For sinus node dysfunction, no minimum heart rate or pause duration has been determined for which permanent pacing would be recommended, the guidelines state. To determine whether permanent pacing is necessary in those patients, clinicians should work to establish a temporal correlation bewteen bradycardia and symptoms, according to the guideline authors.

Left bundle branch block, when found on echocardiogram, greatly increases the chances of underlying structural heart disease and of a left ventricular systolic dysfunction diagnosis, according to the guidelines, which state that echocardiography is the most appropriate initial screening test for left ventricular systolic dysfunction and other structural heart disease.

Permanent pacing is recommended for certain types of atrioventricular (AV) block, according to the guidelines, which include high-grade AV block, acquired second-degree Mobitz type II AV block, and third-degree AV block not related to reversible or physiologic causes.

Treatment of sleep apnea can reduce frequency of nocturnal bradycardia and may provide a cardiovascular benefit, the guideline authors state. Patients with nocturnal bradycardias should be screened for sleep apnea, though authors cautioned that these arrhythmias are not, in and of themselves, an indication for permanent pacing.

“Treatment decisions are based not only on the best available evidence, but also on the patient’s goals of care and preferences,” Dr. Kusumoto said in a press release jointly issued by the ACC, AHA, and HRS. Toward that end, patients should receive “trusted material” to help them understand the consequences and risks of any proposed management decision.

Emerging pacing technologies such as His bundle pacing and transcatheter leadless pacing systems need more study to determine which patient populations will benefit most from them, the guidelines state.

“Regardless of technology, for the foreseeable future, pacing therapy requires implantation of a medical device,” Dr. Kusumoto said in the release. “Future studies are warranted to focus on the long-term implications associated with lifelong therapy.”

The 2018 ACC/AHA/HRS Guideline on the Evaluation and Management of Patients With Bradycardia and Cardiac Conduction Delay is now published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, and simultaneously in the journals Circulation and HeartRhythm.

Dr. Kusumoto reported no relationships with industry or other entities. Guideline co-authors provided disclosures related to Boston Scientific, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Medtronic, Daiichi-Sankyo, Sanofi-Aventis, St. Jude Medical, and Abbott, among others.

SOURCE: Kusumoto FM, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Nov 6.

A new clinical practice guideline on the management of bradycardia and cardiac conduction system disorders in adults emphasizes the importance of patient-centered care and “shared decision-making” between patient and clinician, particularly with regard to patients who have indications for pacemaker implantation.

Shared decision-making extends to the end-of-life setting where “complex” informed consent and refusal of care decisions need to be patient-specific, and must involve all stakeholders, according to the new 2018 guidelines from the American College of Cardiology (ACC), American Heart Association (AHA), and Heart Rhythm Society (HRS).

“Patients with decision-making capacity or his/her legally defined surrogate has the right to refuse or request withdrawal of pacemaker therapy, even if the patient is pacemaker dependent, which should be considered palliative, end-of-life care, and not physician-assisted suicide,” the guidelines read.

The guidelines additionally update the evaluation and treatment of sinus node dysfunction, atrioventricular block, and conduction disorders, based in part on a comprehensive evidence review conducted from January to September 2017. They supersede a 2008 guideline from the three societies on device-based therapy of cardiac rhythm abnormalities, and the focused update to that guideline published in 2012.