User login

Evidence for endoscopic GERD treatments approaching critical mass

SAN FRANCISCO – It is now reasonable to conclude that many of the endoscopic devices and procedures developed for the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) offer good short-term efficacy, leaving only the task to understand how these fit with competing options to improve quality of life long term, according to a state-of-the-art summary at the 2019 AGA Tech Summit, sponsored by the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology.

“The quality of the data for many of these devices has improved substantially, putting us in a much better place than we were in 4 or 5 years ago in considering their role,” reported Michael F. Vaezi, MD, PhD, professor of medicine, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn.

Over the past 15 years, an array of endoscopic approaches to treatment of GERD has received FDA approval. Examples of the very different techniques include plication devices that can suture, staple, or otherwise prevent reflux at the gastroesophageal junction (GEJ), and interventions aimed at the lower esophageal sphincter (LES), where placement of magnets or radiofrequency ablation has been employed to achieve a tighter defense against transient reflux episodes.

Despite FDA approval, the supportive evidence for many of these endoscopic interventions was criticized. In some cases, the number of patients evaluated in pivotal studies was considered too small. In others, there were objections to methodology, particularly to the choice of control arm. In all cases, there has been concern that follow-up was insufficient to confirm persistent benefit. Many of these criticisms are dissipating under the weight of more data.

“For most of the currently available, FDA-approved devices, there is now a substantial body of at least short-term data showing efficacy and safety,” reported Dr. Vaezi, who is a coauthor of an expert review now being prepared for publication. “This includes evidence that they improve quality of life, reduce the need for acid-suppressing therapy, and reduce esophageal acid exposure.”

Additional follow-up represents the final hurdle for understanding how these endoscopic interventions fit for extended symptom control. The long-term efficacy of the current standards of chronic proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy and surgical fundoplication has been established. Among these options, the choice is indefinite pharmacologic therapy or a surgical procedure. Endoscopic devices add additional options, but not with clear conclusions to be drawn on persistence of benefit.

Patient selection is an important consideration. Dr. Vaezi outlined three groups of patients: Patients who have responded to once-daily PPIs and are doing well, but would prefer not to take them indefinitely; PPI non-responders; and patients with improved heartburn but no improvement in regurgitation. Responders are reasonable candidates for endoscopic interventions, but non-responders are not, according to Dr. Vaezi. “You’re exposing the patient to the risk without the benefit, because they don’t have reflux. It’s something else,” he said.

Patients with improved heartburn but no change in regurgitation may be a candidate for endoscopic devices, as long as the clinician rules out non-reflux causes such as achalasia or gastroparesis.

“In patients being considered for alternative nonmedical therapy, it is essential to show that their symptoms are acid related. Those who do not respond to a PPI have traditionally not been good surgical candidates because the lack of a response suggests that acid reflux is not the source of their complaints. For patients being considered for an endoscopic treatment, we must apply the same time proven strategy. At this point, what is uncertain about the device therapies is the long-term durability for reflux control,” Dr. Vaezi said.

PPIs are effective for acid control, so the reason to consider an invasive treatment strategy is to avoid chronic PPI treatment. This is an increasingly attractive goal for many patients as a result of well-publicized case-control studies associating PPI use with a variety of increased risks, such as osteoporosis, chronic kidney disease, and gastrointestinal infections, but many gastroenterologists have been slow to recommend endoscopic interventions due to enduring concerns about safety and efficacy.

From his survey of the evidence, Dr. Vaezi characterized himself as “cautiously optimistic” that many of the endoscopic interventions will be included among standard options for durable GERD treatment.

SAN FRANCISCO – It is now reasonable to conclude that many of the endoscopic devices and procedures developed for the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) offer good short-term efficacy, leaving only the task to understand how these fit with competing options to improve quality of life long term, according to a state-of-the-art summary at the 2019 AGA Tech Summit, sponsored by the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology.

“The quality of the data for many of these devices has improved substantially, putting us in a much better place than we were in 4 or 5 years ago in considering their role,” reported Michael F. Vaezi, MD, PhD, professor of medicine, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn.

Over the past 15 years, an array of endoscopic approaches to treatment of GERD has received FDA approval. Examples of the very different techniques include plication devices that can suture, staple, or otherwise prevent reflux at the gastroesophageal junction (GEJ), and interventions aimed at the lower esophageal sphincter (LES), where placement of magnets or radiofrequency ablation has been employed to achieve a tighter defense against transient reflux episodes.

Despite FDA approval, the supportive evidence for many of these endoscopic interventions was criticized. In some cases, the number of patients evaluated in pivotal studies was considered too small. In others, there were objections to methodology, particularly to the choice of control arm. In all cases, there has been concern that follow-up was insufficient to confirm persistent benefit. Many of these criticisms are dissipating under the weight of more data.

“For most of the currently available, FDA-approved devices, there is now a substantial body of at least short-term data showing efficacy and safety,” reported Dr. Vaezi, who is a coauthor of an expert review now being prepared for publication. “This includes evidence that they improve quality of life, reduce the need for acid-suppressing therapy, and reduce esophageal acid exposure.”

Additional follow-up represents the final hurdle for understanding how these endoscopic interventions fit for extended symptom control. The long-term efficacy of the current standards of chronic proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy and surgical fundoplication has been established. Among these options, the choice is indefinite pharmacologic therapy or a surgical procedure. Endoscopic devices add additional options, but not with clear conclusions to be drawn on persistence of benefit.

Patient selection is an important consideration. Dr. Vaezi outlined three groups of patients: Patients who have responded to once-daily PPIs and are doing well, but would prefer not to take them indefinitely; PPI non-responders; and patients with improved heartburn but no improvement in regurgitation. Responders are reasonable candidates for endoscopic interventions, but non-responders are not, according to Dr. Vaezi. “You’re exposing the patient to the risk without the benefit, because they don’t have reflux. It’s something else,” he said.

Patients with improved heartburn but no change in regurgitation may be a candidate for endoscopic devices, as long as the clinician rules out non-reflux causes such as achalasia or gastroparesis.

“In patients being considered for alternative nonmedical therapy, it is essential to show that their symptoms are acid related. Those who do not respond to a PPI have traditionally not been good surgical candidates because the lack of a response suggests that acid reflux is not the source of their complaints. For patients being considered for an endoscopic treatment, we must apply the same time proven strategy. At this point, what is uncertain about the device therapies is the long-term durability for reflux control,” Dr. Vaezi said.

PPIs are effective for acid control, so the reason to consider an invasive treatment strategy is to avoid chronic PPI treatment. This is an increasingly attractive goal for many patients as a result of well-publicized case-control studies associating PPI use with a variety of increased risks, such as osteoporosis, chronic kidney disease, and gastrointestinal infections, but many gastroenterologists have been slow to recommend endoscopic interventions due to enduring concerns about safety and efficacy.

From his survey of the evidence, Dr. Vaezi characterized himself as “cautiously optimistic” that many of the endoscopic interventions will be included among standard options for durable GERD treatment.

SAN FRANCISCO – It is now reasonable to conclude that many of the endoscopic devices and procedures developed for the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) offer good short-term efficacy, leaving only the task to understand how these fit with competing options to improve quality of life long term, according to a state-of-the-art summary at the 2019 AGA Tech Summit, sponsored by the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology.

“The quality of the data for many of these devices has improved substantially, putting us in a much better place than we were in 4 or 5 years ago in considering their role,” reported Michael F. Vaezi, MD, PhD, professor of medicine, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn.

Over the past 15 years, an array of endoscopic approaches to treatment of GERD has received FDA approval. Examples of the very different techniques include plication devices that can suture, staple, or otherwise prevent reflux at the gastroesophageal junction (GEJ), and interventions aimed at the lower esophageal sphincter (LES), where placement of magnets or radiofrequency ablation has been employed to achieve a tighter defense against transient reflux episodes.

Despite FDA approval, the supportive evidence for many of these endoscopic interventions was criticized. In some cases, the number of patients evaluated in pivotal studies was considered too small. In others, there were objections to methodology, particularly to the choice of control arm. In all cases, there has been concern that follow-up was insufficient to confirm persistent benefit. Many of these criticisms are dissipating under the weight of more data.

“For most of the currently available, FDA-approved devices, there is now a substantial body of at least short-term data showing efficacy and safety,” reported Dr. Vaezi, who is a coauthor of an expert review now being prepared for publication. “This includes evidence that they improve quality of life, reduce the need for acid-suppressing therapy, and reduce esophageal acid exposure.”

Additional follow-up represents the final hurdle for understanding how these endoscopic interventions fit for extended symptom control. The long-term efficacy of the current standards of chronic proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy and surgical fundoplication has been established. Among these options, the choice is indefinite pharmacologic therapy or a surgical procedure. Endoscopic devices add additional options, but not with clear conclusions to be drawn on persistence of benefit.

Patient selection is an important consideration. Dr. Vaezi outlined three groups of patients: Patients who have responded to once-daily PPIs and are doing well, but would prefer not to take them indefinitely; PPI non-responders; and patients with improved heartburn but no improvement in regurgitation. Responders are reasonable candidates for endoscopic interventions, but non-responders are not, according to Dr. Vaezi. “You’re exposing the patient to the risk without the benefit, because they don’t have reflux. It’s something else,” he said.

Patients with improved heartburn but no change in regurgitation may be a candidate for endoscopic devices, as long as the clinician rules out non-reflux causes such as achalasia or gastroparesis.

“In patients being considered for alternative nonmedical therapy, it is essential to show that their symptoms are acid related. Those who do not respond to a PPI have traditionally not been good surgical candidates because the lack of a response suggests that acid reflux is not the source of their complaints. For patients being considered for an endoscopic treatment, we must apply the same time proven strategy. At this point, what is uncertain about the device therapies is the long-term durability for reflux control,” Dr. Vaezi said.

PPIs are effective for acid control, so the reason to consider an invasive treatment strategy is to avoid chronic PPI treatment. This is an increasingly attractive goal for many patients as a result of well-publicized case-control studies associating PPI use with a variety of increased risks, such as osteoporosis, chronic kidney disease, and gastrointestinal infections, but many gastroenterologists have been slow to recommend endoscopic interventions due to enduring concerns about safety and efficacy.

From his survey of the evidence, Dr. Vaezi characterized himself as “cautiously optimistic” that many of the endoscopic interventions will be included among standard options for durable GERD treatment.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM 2019 AGA TECH SUMMIT

Cost gap widens between brand-name, generic drugs

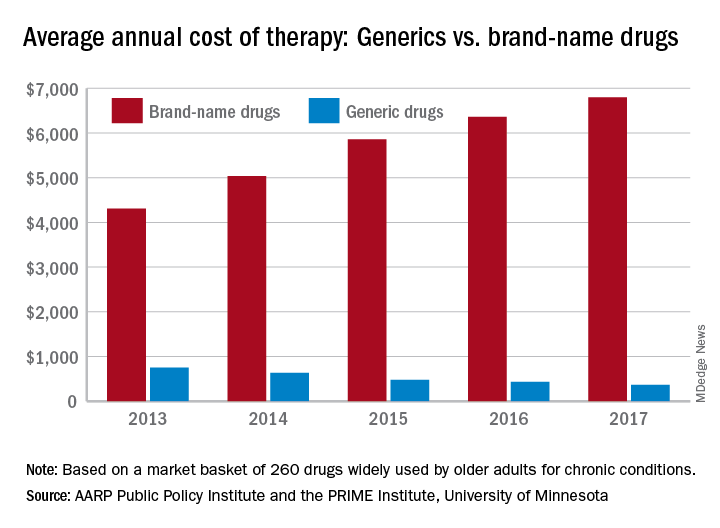

In 2017, the average retail cost of 260 generic drugs widely used by older adults for chronic conditions was $365 for a year of therapy, compared with $6,798 for brand-name drugs. In 2013, that same year of therapy with an average brand-name drug ($4,308) was only 5.7 times more expensive than the generic ($751), the AARP wrote in the report, produced in collaboration with the PRIME Institute at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis.

“Generics account for nearly 9 out of every 10 prescriptions filled in the U.S. but represent less than a quarter of the country’s drug spending. These results highlight the importance of eliminating anticompetitive behavior by brand-name drug companies so that we get more lower-priced generic drugs on the market,” Debra Whitman, executive vice president and chief public policy officer at AARP, said in a written statement.

The average retail cost of a larger group of 390 generic drugs used by older adults fell by 9.3% from 2016 to 2017, compared with an increase of 8.4% for a group of 267 brand-name prescription drugs. Over that same time, the general inflation rate rose by 2.1%, the AARP noted.

The AARP’s annual Rx Price Watch Report is based on data from the Truven Health MarketScan research databases.

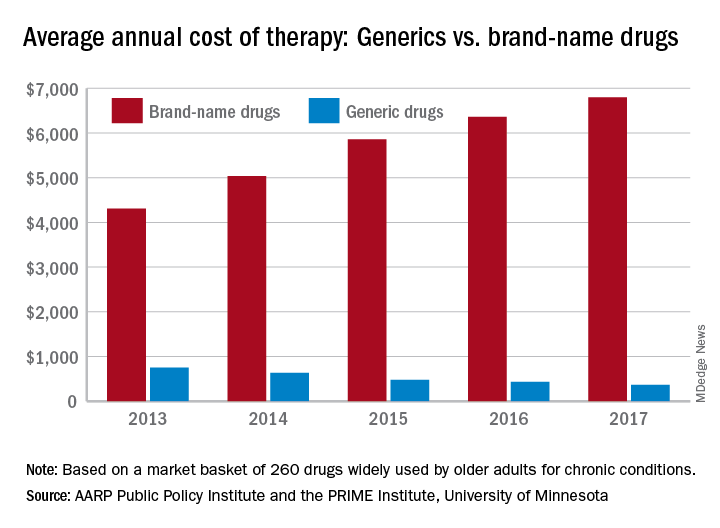

In 2017, the average retail cost of 260 generic drugs widely used by older adults for chronic conditions was $365 for a year of therapy, compared with $6,798 for brand-name drugs. In 2013, that same year of therapy with an average brand-name drug ($4,308) was only 5.7 times more expensive than the generic ($751), the AARP wrote in the report, produced in collaboration with the PRIME Institute at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis.

“Generics account for nearly 9 out of every 10 prescriptions filled in the U.S. but represent less than a quarter of the country’s drug spending. These results highlight the importance of eliminating anticompetitive behavior by brand-name drug companies so that we get more lower-priced generic drugs on the market,” Debra Whitman, executive vice president and chief public policy officer at AARP, said in a written statement.

The average retail cost of a larger group of 390 generic drugs used by older adults fell by 9.3% from 2016 to 2017, compared with an increase of 8.4% for a group of 267 brand-name prescription drugs. Over that same time, the general inflation rate rose by 2.1%, the AARP noted.

The AARP’s annual Rx Price Watch Report is based on data from the Truven Health MarketScan research databases.

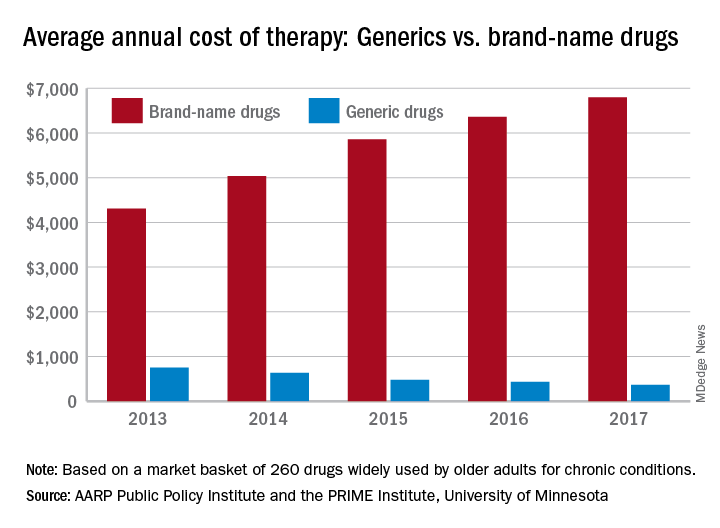

In 2017, the average retail cost of 260 generic drugs widely used by older adults for chronic conditions was $365 for a year of therapy, compared with $6,798 for brand-name drugs. In 2013, that same year of therapy with an average brand-name drug ($4,308) was only 5.7 times more expensive than the generic ($751), the AARP wrote in the report, produced in collaboration with the PRIME Institute at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis.

“Generics account for nearly 9 out of every 10 prescriptions filled in the U.S. but represent less than a quarter of the country’s drug spending. These results highlight the importance of eliminating anticompetitive behavior by brand-name drug companies so that we get more lower-priced generic drugs on the market,” Debra Whitman, executive vice president and chief public policy officer at AARP, said in a written statement.

The average retail cost of a larger group of 390 generic drugs used by older adults fell by 9.3% from 2016 to 2017, compared with an increase of 8.4% for a group of 267 brand-name prescription drugs. Over that same time, the general inflation rate rose by 2.1%, the AARP noted.

The AARP’s annual Rx Price Watch Report is based on data from the Truven Health MarketScan research databases.

ACP leaders explain why they value telehealth

PHILADELPHIA – according to the recently announced results of a questionnaire by the American College of Physicians.

The survey participants included 233 members of the ACP, who provided their responses between October 2018 and January 2019. ACP President Ana Maria Lopez, MD, as well as Tabassum Salam, MD, vice president for medical education, announced the survey’s results at a press briefing at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians.

Dr. Lopez and Dr. Salam highlighted some of the findings and expressed their enthusiasm about the recent increases in the use of telemedicine in a video interview. They also explained how telehealth benefits patients and the barriers to more widespread use of telemedicine.

Dr. Lopez and Dr. Salam did not disclose any relevant conflicts of interest.

PHILADELPHIA – according to the recently announced results of a questionnaire by the American College of Physicians.

The survey participants included 233 members of the ACP, who provided their responses between October 2018 and January 2019. ACP President Ana Maria Lopez, MD, as well as Tabassum Salam, MD, vice president for medical education, announced the survey’s results at a press briefing at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians.

Dr. Lopez and Dr. Salam highlighted some of the findings and expressed their enthusiasm about the recent increases in the use of telemedicine in a video interview. They also explained how telehealth benefits patients and the barriers to more widespread use of telemedicine.

Dr. Lopez and Dr. Salam did not disclose any relevant conflicts of interest.

PHILADELPHIA – according to the recently announced results of a questionnaire by the American College of Physicians.

The survey participants included 233 members of the ACP, who provided their responses between October 2018 and January 2019. ACP President Ana Maria Lopez, MD, as well as Tabassum Salam, MD, vice president for medical education, announced the survey’s results at a press briefing at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians.

Dr. Lopez and Dr. Salam highlighted some of the findings and expressed their enthusiasm about the recent increases in the use of telemedicine in a video interview. They also explained how telehealth benefits patients and the barriers to more widespread use of telemedicine.

Dr. Lopez and Dr. Salam did not disclose any relevant conflicts of interest.

REPORTING FROM INTERNAL MEDICINE 2019

Gilteritinib prolonged survival in FLT3-mutated AML

ATLANTA – The FLT3 inhibitor gilteritinib (Xospata) significantly prolonged overall survival, compared with salvage chemotherapy, in patients with FLT3-mutated relapsed/refractory acute myeloid leukemia, Alexander E. Perl, MD, from the Abramson Cancer Center at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia reported at the 2019 annual meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR).

In a video interview, Dr. Perl discussed the results of the ADMIRAL global phase 3 randomized trial and described the current state of therapy for patients with relapsed/refractory AML bearing FLT3 mutations. Up to 70% of patients with acute myeloid leukemia will experience a relapse, and up to 40% may have disease that is resistant to induction chemotherapy. Survival for these patients is generally poor.

In particular, patients with acute myeloid leukemia and FLT3-activating mutations are at increased risk for early relapse and poor overall survival.

The ADMIRAL trial is funded by Astellas Pharma. Dr. Perl disclosed advisory board participation, consulting fees, and institutional support from Astellas and others.

ATLANTA – The FLT3 inhibitor gilteritinib (Xospata) significantly prolonged overall survival, compared with salvage chemotherapy, in patients with FLT3-mutated relapsed/refractory acute myeloid leukemia, Alexander E. Perl, MD, from the Abramson Cancer Center at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia reported at the 2019 annual meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR).

In a video interview, Dr. Perl discussed the results of the ADMIRAL global phase 3 randomized trial and described the current state of therapy for patients with relapsed/refractory AML bearing FLT3 mutations. Up to 70% of patients with acute myeloid leukemia will experience a relapse, and up to 40% may have disease that is resistant to induction chemotherapy. Survival for these patients is generally poor.

In particular, patients with acute myeloid leukemia and FLT3-activating mutations are at increased risk for early relapse and poor overall survival.

The ADMIRAL trial is funded by Astellas Pharma. Dr. Perl disclosed advisory board participation, consulting fees, and institutional support from Astellas and others.

ATLANTA – The FLT3 inhibitor gilteritinib (Xospata) significantly prolonged overall survival, compared with salvage chemotherapy, in patients with FLT3-mutated relapsed/refractory acute myeloid leukemia, Alexander E. Perl, MD, from the Abramson Cancer Center at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia reported at the 2019 annual meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR).

In a video interview, Dr. Perl discussed the results of the ADMIRAL global phase 3 randomized trial and described the current state of therapy for patients with relapsed/refractory AML bearing FLT3 mutations. Up to 70% of patients with acute myeloid leukemia will experience a relapse, and up to 40% may have disease that is resistant to induction chemotherapy. Survival for these patients is generally poor.

In particular, patients with acute myeloid leukemia and FLT3-activating mutations are at increased risk for early relapse and poor overall survival.

The ADMIRAL trial is funded by Astellas Pharma. Dr. Perl disclosed advisory board participation, consulting fees, and institutional support from Astellas and others.

REPORTING FROM AACR 2019

Pooled KEYNOTE data support pembro for elderly patients with NSCLC

GENEVA – Pembrolizumab monotherapy is as safe and effective in elderly patients with non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) as it is younger patients, according to investigators.

They reached this conclusion after analyzing pooled data from 264 patients 75 years or older involved in the KEYNOTE-010, KEYNOTE-024, and KEYNOTE-042 phase 3 trials, reported lead author Kaname Nosaki, MD, of the National Hospital Organization Kyushu Cancer Center in Fukuoka, Japan, and his colleagues.

“Approximately 70% of newly-diagnosed NSCLC cases occur in the elderly, and more than half are locally advanced or metastatic,” the investigators noted in their abstract. Despite this, patients aged 75 years or older are underrepresented in clinical trials, Dr. Nosaki said during a presentation at the European Lung Cancer Conference.

All patients in the three KEYNOTE trials had PD-L1 positive NSCLC, with variations between studies with respect to PD-L1 tumor proportion score (TPS) and dosing regimen. While KEYNOTE-010 and KEYNOTE-042 involved patients with a TPS of at least 1%, KEYNOTE-024 raised the minimum TPS threshold to 50%. KEYNOTE-010 pembrolizumab dose was set at 2 mg/kg or 10 mg/kg, compared with the other two studies, which set a consistent dose of the checkpoint inhibitor at 200 mg.

As with younger patients, higher TPS expression generally predicted better outcomes. Independent of treatment line, elderly patients with a TPS of at least 50% had a hazard ratio of 0.40 in favor of pembrolizumab over chemotherapy, compared with all PD-L1-positive elderly patients, who had a hazard ratio of 0.76.

Generally, adverse events were comparable between age groups, with 68% of elderly patients experiencing at least one treatment-related adverse event, compared with 65% of younger patients. Grade 3 or 4 adverse events were slightly more common among elderly patients than younger patients (23% vs. 16%), with a mild concomitant increase in adverse event–related treatment discontinuations (11% vs. 7%). The rate of immune-mediated adverse events and infusion reactions, however, held steady regardless of age group, occurring in one out of four patients (25%). In contrast with these similarities, almost all elderly patients receiving chemotherapy (94%) had adverse events, compared with two out of three elderly patients receiving pembrolizumab. Rates of grade 3 or 4 adverse events also favored pembrolizumab over chemotherapy (23% vs. 59%).

“These data support the use of pembrolizumab monotherapy in elderly patients more than 75 years old with advanced PD-L1-expressing NSCLC,” Dr. Nosaki concluded.

Invited discussant Sanjay Popat, PhD, of Imperial College London, described the knowledge gap addressed by this study. “If we look at U.S. statistics, we see that lung cancer is the leading cause of death for patients above the age of 80, both for males and females,” Dr. Popat said at the meeting, presented by the European Society for Medical Oncology. “The real question is should this group of patients be getting any form of checkpoint inhibitors at all, and if so, what is the benefit to risk ratio?

“Our patients are getting older, we’re all living slightly longer, and the burden of geriatric oncology is predicted to rise quite markedly with age, so it’s important to get a good feel for how we should be managing our senior population,” he added.

According to Dr. Popat, elderly patients naturally undergo immune senescence, meaning the immune system deteriorates with age, and this phenomenon could theoretically mitigate efficacy of immunotherapies; however, previous studies have not found decreased efficacy among elderly patients. Still, some “so-called elderly population subsets we’ve been analyzing are actually around the median age [of diagnosis with NSCLC],” Dr. Popat said, noting that among these studies, those with wider age ranges offer more reliable data.

“Today we looked at the novel cutoff, this 75-year group cutoff, which I very much welcome,” Dr. Popat said, “because this much more reflects what we see in routine clinical care.”

Regarding the results, Dr. Popat suggested that chemotherapy leads to an “excess of mortality” among elderly patients, “likely due to toxicities,” thereby explaining part of the relative advantage provided by pembrolizumab. Considering these findings in addition to previous experiences with pembrolizumab in the elderly, Dr. Popat said that “if you choose your patient population well, fit patients well enough to go to a trial, they don’t have an excess of toxicities regardless of their age.”

Taken as a whole, the present analysis supports the routine use of pembrolizumab in fit, elderly patients, Dr. Popat said.

The study was funded by MSD. The investigators reported financial relationships with AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Taiho, Chugai, and others.

SOURCE: Nosaki et al. ELCC 2019. Abstract 103O_PR.

GENEVA – Pembrolizumab monotherapy is as safe and effective in elderly patients with non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) as it is younger patients, according to investigators.

They reached this conclusion after analyzing pooled data from 264 patients 75 years or older involved in the KEYNOTE-010, KEYNOTE-024, and KEYNOTE-042 phase 3 trials, reported lead author Kaname Nosaki, MD, of the National Hospital Organization Kyushu Cancer Center in Fukuoka, Japan, and his colleagues.

“Approximately 70% of newly-diagnosed NSCLC cases occur in the elderly, and more than half are locally advanced or metastatic,” the investigators noted in their abstract. Despite this, patients aged 75 years or older are underrepresented in clinical trials, Dr. Nosaki said during a presentation at the European Lung Cancer Conference.

All patients in the three KEYNOTE trials had PD-L1 positive NSCLC, with variations between studies with respect to PD-L1 tumor proportion score (TPS) and dosing regimen. While KEYNOTE-010 and KEYNOTE-042 involved patients with a TPS of at least 1%, KEYNOTE-024 raised the minimum TPS threshold to 50%. KEYNOTE-010 pembrolizumab dose was set at 2 mg/kg or 10 mg/kg, compared with the other two studies, which set a consistent dose of the checkpoint inhibitor at 200 mg.

As with younger patients, higher TPS expression generally predicted better outcomes. Independent of treatment line, elderly patients with a TPS of at least 50% had a hazard ratio of 0.40 in favor of pembrolizumab over chemotherapy, compared with all PD-L1-positive elderly patients, who had a hazard ratio of 0.76.

Generally, adverse events were comparable between age groups, with 68% of elderly patients experiencing at least one treatment-related adverse event, compared with 65% of younger patients. Grade 3 or 4 adverse events were slightly more common among elderly patients than younger patients (23% vs. 16%), with a mild concomitant increase in adverse event–related treatment discontinuations (11% vs. 7%). The rate of immune-mediated adverse events and infusion reactions, however, held steady regardless of age group, occurring in one out of four patients (25%). In contrast with these similarities, almost all elderly patients receiving chemotherapy (94%) had adverse events, compared with two out of three elderly patients receiving pembrolizumab. Rates of grade 3 or 4 adverse events also favored pembrolizumab over chemotherapy (23% vs. 59%).

“These data support the use of pembrolizumab monotherapy in elderly patients more than 75 years old with advanced PD-L1-expressing NSCLC,” Dr. Nosaki concluded.

Invited discussant Sanjay Popat, PhD, of Imperial College London, described the knowledge gap addressed by this study. “If we look at U.S. statistics, we see that lung cancer is the leading cause of death for patients above the age of 80, both for males and females,” Dr. Popat said at the meeting, presented by the European Society for Medical Oncology. “The real question is should this group of patients be getting any form of checkpoint inhibitors at all, and if so, what is the benefit to risk ratio?

“Our patients are getting older, we’re all living slightly longer, and the burden of geriatric oncology is predicted to rise quite markedly with age, so it’s important to get a good feel for how we should be managing our senior population,” he added.

According to Dr. Popat, elderly patients naturally undergo immune senescence, meaning the immune system deteriorates with age, and this phenomenon could theoretically mitigate efficacy of immunotherapies; however, previous studies have not found decreased efficacy among elderly patients. Still, some “so-called elderly population subsets we’ve been analyzing are actually around the median age [of diagnosis with NSCLC],” Dr. Popat said, noting that among these studies, those with wider age ranges offer more reliable data.

“Today we looked at the novel cutoff, this 75-year group cutoff, which I very much welcome,” Dr. Popat said, “because this much more reflects what we see in routine clinical care.”

Regarding the results, Dr. Popat suggested that chemotherapy leads to an “excess of mortality” among elderly patients, “likely due to toxicities,” thereby explaining part of the relative advantage provided by pembrolizumab. Considering these findings in addition to previous experiences with pembrolizumab in the elderly, Dr. Popat said that “if you choose your patient population well, fit patients well enough to go to a trial, they don’t have an excess of toxicities regardless of their age.”

Taken as a whole, the present analysis supports the routine use of pembrolizumab in fit, elderly patients, Dr. Popat said.

The study was funded by MSD. The investigators reported financial relationships with AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Taiho, Chugai, and others.

SOURCE: Nosaki et al. ELCC 2019. Abstract 103O_PR.

GENEVA – Pembrolizumab monotherapy is as safe and effective in elderly patients with non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) as it is younger patients, according to investigators.

They reached this conclusion after analyzing pooled data from 264 patients 75 years or older involved in the KEYNOTE-010, KEYNOTE-024, and KEYNOTE-042 phase 3 trials, reported lead author Kaname Nosaki, MD, of the National Hospital Organization Kyushu Cancer Center in Fukuoka, Japan, and his colleagues.

“Approximately 70% of newly-diagnosed NSCLC cases occur in the elderly, and more than half are locally advanced or metastatic,” the investigators noted in their abstract. Despite this, patients aged 75 years or older are underrepresented in clinical trials, Dr. Nosaki said during a presentation at the European Lung Cancer Conference.

All patients in the three KEYNOTE trials had PD-L1 positive NSCLC, with variations between studies with respect to PD-L1 tumor proportion score (TPS) and dosing regimen. While KEYNOTE-010 and KEYNOTE-042 involved patients with a TPS of at least 1%, KEYNOTE-024 raised the minimum TPS threshold to 50%. KEYNOTE-010 pembrolizumab dose was set at 2 mg/kg or 10 mg/kg, compared with the other two studies, which set a consistent dose of the checkpoint inhibitor at 200 mg.

As with younger patients, higher TPS expression generally predicted better outcomes. Independent of treatment line, elderly patients with a TPS of at least 50% had a hazard ratio of 0.40 in favor of pembrolizumab over chemotherapy, compared with all PD-L1-positive elderly patients, who had a hazard ratio of 0.76.

Generally, adverse events were comparable between age groups, with 68% of elderly patients experiencing at least one treatment-related adverse event, compared with 65% of younger patients. Grade 3 or 4 adverse events were slightly more common among elderly patients than younger patients (23% vs. 16%), with a mild concomitant increase in adverse event–related treatment discontinuations (11% vs. 7%). The rate of immune-mediated adverse events and infusion reactions, however, held steady regardless of age group, occurring in one out of four patients (25%). In contrast with these similarities, almost all elderly patients receiving chemotherapy (94%) had adverse events, compared with two out of three elderly patients receiving pembrolizumab. Rates of grade 3 or 4 adverse events also favored pembrolizumab over chemotherapy (23% vs. 59%).

“These data support the use of pembrolizumab monotherapy in elderly patients more than 75 years old with advanced PD-L1-expressing NSCLC,” Dr. Nosaki concluded.

Invited discussant Sanjay Popat, PhD, of Imperial College London, described the knowledge gap addressed by this study. “If we look at U.S. statistics, we see that lung cancer is the leading cause of death for patients above the age of 80, both for males and females,” Dr. Popat said at the meeting, presented by the European Society for Medical Oncology. “The real question is should this group of patients be getting any form of checkpoint inhibitors at all, and if so, what is the benefit to risk ratio?

“Our patients are getting older, we’re all living slightly longer, and the burden of geriatric oncology is predicted to rise quite markedly with age, so it’s important to get a good feel for how we should be managing our senior population,” he added.

According to Dr. Popat, elderly patients naturally undergo immune senescence, meaning the immune system deteriorates with age, and this phenomenon could theoretically mitigate efficacy of immunotherapies; however, previous studies have not found decreased efficacy among elderly patients. Still, some “so-called elderly population subsets we’ve been analyzing are actually around the median age [of diagnosis with NSCLC],” Dr. Popat said, noting that among these studies, those with wider age ranges offer more reliable data.

“Today we looked at the novel cutoff, this 75-year group cutoff, which I very much welcome,” Dr. Popat said, “because this much more reflects what we see in routine clinical care.”

Regarding the results, Dr. Popat suggested that chemotherapy leads to an “excess of mortality” among elderly patients, “likely due to toxicities,” thereby explaining part of the relative advantage provided by pembrolizumab. Considering these findings in addition to previous experiences with pembrolizumab in the elderly, Dr. Popat said that “if you choose your patient population well, fit patients well enough to go to a trial, they don’t have an excess of toxicities regardless of their age.”

Taken as a whole, the present analysis supports the routine use of pembrolizumab in fit, elderly patients, Dr. Popat said.

The study was funded by MSD. The investigators reported financial relationships with AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Taiho, Chugai, and others.

SOURCE: Nosaki et al. ELCC 2019. Abstract 103O_PR.

REPORTING FROM ELCC 2019

Interest renewed in targeting gluten in schizophrenia

ORLANDO – Going gluten free shows a benefit for a subset of schizophrenia patients, and it offers a new array of potential intervention – suggesting that knowing what some patients consume or interrupting newly identified mechanisms could make real differences in symptom severity, an expert said at the annual congress of the Schizophrenia International Research Society.

Deanna L. Kelly, PharmD, director of the Treatment Research Program at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, said that if she’d been told 10 years ago that she’d be studying links between diet and schizophrenia, “I would have probably not believed you.”

Interest in the link between wheat, which contains gluten, and schizophrenia is not brand new. Research published in the 1960s found that, as wheat consumption fell in Scandinavia during World War II, so did hospital admissions for schizophrenia. In the United States, schizophrenia admissions rose as wheat consumption rose. But interest in the topic died off in the 1980s, when links between a gluten-free diet and schizophrenia symptoms were found to be weak or nonexistent.

Dr. Kelly said that’s because that research looked at all comers without a finely tuned schizophrenia population.

a protein that helps bread rise during baking and is hard to digest. Researchers have found that antibodies to other gluten proteins – such as anti–tissue transglutaminase antibodies, used to diagnose celiac disease – are not elevated in schizophrenia patients, compared with healthy controls (Schizophr Res. 2018 May;195:585-6). But native gliadin antibodies (AGA IgG) are significantly elevated – this is seen in about 30% of patients, compared with about 10% in controls, Dr. Kelly said.

Elevated AGA IgG is also correlated to higher levels of peripheral inflammation and higher levels of peripheral kynurenine, a metabolite of tryptophan linked to schizophrenia.

In a feasibility study with 16 patients published this year, researchers randomized patients with elevated AGA IgG to a gluten-free diet – they were fed with certified gluten-free shakes – or a diet that wasn’t gluten free over 5 weeks. Patients stayed at a hospital to ensure adherence to the diet and for close monitoring. They found that those who were gluten free showed significant improvement in negative symptoms, measured by the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms, compared with those who continued eating gluten. These symptoms included the inability to experience pleasure, inability to speak, lack of initiative, and inability to express emotion (J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2019 Mar 27;44[3]:1-9).

“Removing gliadin may improve negative symptoms in schizophrenia,” Dr. Kelly said.

Those on the gluten-free diet also showed improvement in gastrointestinal symptoms and improvement in certain cognitive traits, such as attention and verbal learning.

Her research team is now conducting on a larger trial comparing the two diets, this time with the gluten-containing diet involving a higher amount of gluten, which researchers think better reflects real-life diets.

Researchers are still not sure how gliadin intake affects schizophrenia symptoms, but it could involve problems with the blood brain barrier, the permeability of the gut, or the effects on the microbiome, she said. But the importance of gliadin and gluten to this group of schizophrenia patients raises the possibility of treatment with ongoing dietary changes, anti-inflammatory treatments, blocking absorption of gluten, improving how it’s digested or by blocking gliadin antibodies.

“We’re trying to learn about disease states themselves, but each person should find their best lives,” Dr. Kelly said. “Everyone deserves optimized and personalized treatment.”

Dr. Kelly reported financial relationships with Lundbeck and HLS Therapeutics.

ORLANDO – Going gluten free shows a benefit for a subset of schizophrenia patients, and it offers a new array of potential intervention – suggesting that knowing what some patients consume or interrupting newly identified mechanisms could make real differences in symptom severity, an expert said at the annual congress of the Schizophrenia International Research Society.

Deanna L. Kelly, PharmD, director of the Treatment Research Program at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, said that if she’d been told 10 years ago that she’d be studying links between diet and schizophrenia, “I would have probably not believed you.”

Interest in the link between wheat, which contains gluten, and schizophrenia is not brand new. Research published in the 1960s found that, as wheat consumption fell in Scandinavia during World War II, so did hospital admissions for schizophrenia. In the United States, schizophrenia admissions rose as wheat consumption rose. But interest in the topic died off in the 1980s, when links between a gluten-free diet and schizophrenia symptoms were found to be weak or nonexistent.

Dr. Kelly said that’s because that research looked at all comers without a finely tuned schizophrenia population.

a protein that helps bread rise during baking and is hard to digest. Researchers have found that antibodies to other gluten proteins – such as anti–tissue transglutaminase antibodies, used to diagnose celiac disease – are not elevated in schizophrenia patients, compared with healthy controls (Schizophr Res. 2018 May;195:585-6). But native gliadin antibodies (AGA IgG) are significantly elevated – this is seen in about 30% of patients, compared with about 10% in controls, Dr. Kelly said.

Elevated AGA IgG is also correlated to higher levels of peripheral inflammation and higher levels of peripheral kynurenine, a metabolite of tryptophan linked to schizophrenia.

In a feasibility study with 16 patients published this year, researchers randomized patients with elevated AGA IgG to a gluten-free diet – they were fed with certified gluten-free shakes – or a diet that wasn’t gluten free over 5 weeks. Patients stayed at a hospital to ensure adherence to the diet and for close monitoring. They found that those who were gluten free showed significant improvement in negative symptoms, measured by the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms, compared with those who continued eating gluten. These symptoms included the inability to experience pleasure, inability to speak, lack of initiative, and inability to express emotion (J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2019 Mar 27;44[3]:1-9).

“Removing gliadin may improve negative symptoms in schizophrenia,” Dr. Kelly said.

Those on the gluten-free diet also showed improvement in gastrointestinal symptoms and improvement in certain cognitive traits, such as attention and verbal learning.

Her research team is now conducting on a larger trial comparing the two diets, this time with the gluten-containing diet involving a higher amount of gluten, which researchers think better reflects real-life diets.

Researchers are still not sure how gliadin intake affects schizophrenia symptoms, but it could involve problems with the blood brain barrier, the permeability of the gut, or the effects on the microbiome, she said. But the importance of gliadin and gluten to this group of schizophrenia patients raises the possibility of treatment with ongoing dietary changes, anti-inflammatory treatments, blocking absorption of gluten, improving how it’s digested or by blocking gliadin antibodies.

“We’re trying to learn about disease states themselves, but each person should find their best lives,” Dr. Kelly said. “Everyone deserves optimized and personalized treatment.”

Dr. Kelly reported financial relationships with Lundbeck and HLS Therapeutics.

ORLANDO – Going gluten free shows a benefit for a subset of schizophrenia patients, and it offers a new array of potential intervention – suggesting that knowing what some patients consume or interrupting newly identified mechanisms could make real differences in symptom severity, an expert said at the annual congress of the Schizophrenia International Research Society.

Deanna L. Kelly, PharmD, director of the Treatment Research Program at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, said that if she’d been told 10 years ago that she’d be studying links between diet and schizophrenia, “I would have probably not believed you.”

Interest in the link between wheat, which contains gluten, and schizophrenia is not brand new. Research published in the 1960s found that, as wheat consumption fell in Scandinavia during World War II, so did hospital admissions for schizophrenia. In the United States, schizophrenia admissions rose as wheat consumption rose. But interest in the topic died off in the 1980s, when links between a gluten-free diet and schizophrenia symptoms were found to be weak or nonexistent.

Dr. Kelly said that’s because that research looked at all comers without a finely tuned schizophrenia population.

a protein that helps bread rise during baking and is hard to digest. Researchers have found that antibodies to other gluten proteins – such as anti–tissue transglutaminase antibodies, used to diagnose celiac disease – are not elevated in schizophrenia patients, compared with healthy controls (Schizophr Res. 2018 May;195:585-6). But native gliadin antibodies (AGA IgG) are significantly elevated – this is seen in about 30% of patients, compared with about 10% in controls, Dr. Kelly said.

Elevated AGA IgG is also correlated to higher levels of peripheral inflammation and higher levels of peripheral kynurenine, a metabolite of tryptophan linked to schizophrenia.

In a feasibility study with 16 patients published this year, researchers randomized patients with elevated AGA IgG to a gluten-free diet – they were fed with certified gluten-free shakes – or a diet that wasn’t gluten free over 5 weeks. Patients stayed at a hospital to ensure adherence to the diet and for close monitoring. They found that those who were gluten free showed significant improvement in negative symptoms, measured by the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms, compared with those who continued eating gluten. These symptoms included the inability to experience pleasure, inability to speak, lack of initiative, and inability to express emotion (J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2019 Mar 27;44[3]:1-9).

“Removing gliadin may improve negative symptoms in schizophrenia,” Dr. Kelly said.

Those on the gluten-free diet also showed improvement in gastrointestinal symptoms and improvement in certain cognitive traits, such as attention and verbal learning.

Her research team is now conducting on a larger trial comparing the two diets, this time with the gluten-containing diet involving a higher amount of gluten, which researchers think better reflects real-life diets.

Researchers are still not sure how gliadin intake affects schizophrenia symptoms, but it could involve problems with the blood brain barrier, the permeability of the gut, or the effects on the microbiome, she said. But the importance of gliadin and gluten to this group of schizophrenia patients raises the possibility of treatment with ongoing dietary changes, anti-inflammatory treatments, blocking absorption of gluten, improving how it’s digested or by blocking gliadin antibodies.

“We’re trying to learn about disease states themselves, but each person should find their best lives,” Dr. Kelly said. “Everyone deserves optimized and personalized treatment.”

Dr. Kelly reported financial relationships with Lundbeck and HLS Therapeutics.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM SIRS 2019

Highlights from the ‘Updates in ACS’ session (VIDEO)

Hospital Medicine 2019 attendees outlined their key takeaways from the Updates in Acute Coronary Syndrome session, presented by Jeffrey Trost, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Dr. Trost’s discussion focused on the relationship between dual antiplatelet therapy, in-stent thrombosis, and in-stent restenosis. He also explored the diagnostic role of fractional flow reserve, and he outlined effective approaches to PCSK9 inhibitor use.

Hospital Medicine 2019 attendees outlined their key takeaways from the Updates in Acute Coronary Syndrome session, presented by Jeffrey Trost, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Dr. Trost’s discussion focused on the relationship between dual antiplatelet therapy, in-stent thrombosis, and in-stent restenosis. He also explored the diagnostic role of fractional flow reserve, and he outlined effective approaches to PCSK9 inhibitor use.

Hospital Medicine 2019 attendees outlined their key takeaways from the Updates in Acute Coronary Syndrome session, presented by Jeffrey Trost, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Dr. Trost’s discussion focused on the relationship between dual antiplatelet therapy, in-stent thrombosis, and in-stent restenosis. He also explored the diagnostic role of fractional flow reserve, and he outlined effective approaches to PCSK9 inhibitor use.

REPORTING FROM HM19

Tumor-treating fields boost chemo for mesothelioma

GENEVA – For patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma, adding tumor-treating fields (TTFields) to standard pemetrexed plus platinum compound chemotherapy could boost median overall survival by about 6 months, according to final results from the phase 2 STELLAR trial.

The survival benefit of TTFields was greatest among patients with epithelioid mesothelioma, reported lead author Giovanni Luca Ceresoli, MD, of Humanitas Gavazzeni in Bergamo, Italy. According to Dr. Ceresoli, who presented findings at the at the European Lung Cancer Conference, TTFields offer a safe way to improve mesothelioma outcomes without increasing the risk of serious adverse events.

“TTFields are a locoregional treatment comprising low-intensity alternating electric fields delivered through a portable medical device,” Dr. Ceresoli explained at the meeting, presented by the European Society for Medical Oncology. “Their main mode of action is an anti-mitotic mechanism.” He noted that TTFields are already approved by the Food and Drug Administration for newly diagnosed glioblastoma.

The STELLAR trial involved 80 patients with mesothelioma who were treated with TTFields in combination with standard first-line chemotherapy, a combination of pemetrexed with cisplatin or carboplatin. Patients were instructed to self-administer continuous 150 kHz TTFields for at least 18 hours a day. Eligibility required an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0 to 1. Both ECOG status and cancer-related pain were followed with a visual analog scale until disease progression. Median overall survival (OS) was the primary endpoint.

The patient population was predominantly male (84%), with median age of 67 years. About 44% of the patients had an ECOG performance status of 1 and 66% had epithelioid histology. Median treatment time per day was 16.3 hours.

After a minimum follow-up of 1 year, patients treated with TTFields in combination with standard chemotherapy had a median overall survival of 18.2 months, compared with 12.1 months for standard chemotherapy alone, which Dr. Ceresoli cited as the historical benchmark. The survival benefit was 3 months longer among patients with epithelioid mesothelioma, who had a median overall survival of 21.2 months.

In addition to survival benefits, the investigators found that median time to decreased performance status was just over 1 year (13.1 months), and that pain did not increase to a clinically significant degree (33%) until an average of 8.4 months. Although no device-related serious adverse events occurred, 37 patients (46%) experienced TTFields-related dermatitis; 4 of these patients had grade 3 dermatitis. Dr. Ceresoli noted that dermatitis was typically “easily managed” with topical application of a corticosteroid, while patients with severe dermatitis took short treatment breaks.

“In conclusion, in the STELLAR trial, TTFields in combination with standard chemotherapy were effective and safe for first-line treatment of unresectable malignant pleural mesothelioma, and median overall survival was significantly longer as compared to historical controls,” Dr. Ceresoli said, pointing out better survival than in recent trials MAPS and LUME-Meso.

When asked by the invited discussant about future research, Dr. Ceresoli described a narrower focus for upcoming TTFields studies for mesothelioma. “As you well know, most patients have epithelioid histology, and in our hands, the patients with epithelioid histology had better prognoses,” he said. “So, in the future, I think we will focus on epithelioid tumors.”

Dr. Ceresoli disclosed travel funding from Novocure.

SOURCE: Ceresoli et al. ELCC 2019. Abstract 55O.

GENEVA – For patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma, adding tumor-treating fields (TTFields) to standard pemetrexed plus platinum compound chemotherapy could boost median overall survival by about 6 months, according to final results from the phase 2 STELLAR trial.

The survival benefit of TTFields was greatest among patients with epithelioid mesothelioma, reported lead author Giovanni Luca Ceresoli, MD, of Humanitas Gavazzeni in Bergamo, Italy. According to Dr. Ceresoli, who presented findings at the at the European Lung Cancer Conference, TTFields offer a safe way to improve mesothelioma outcomes without increasing the risk of serious adverse events.

“TTFields are a locoregional treatment comprising low-intensity alternating electric fields delivered through a portable medical device,” Dr. Ceresoli explained at the meeting, presented by the European Society for Medical Oncology. “Their main mode of action is an anti-mitotic mechanism.” He noted that TTFields are already approved by the Food and Drug Administration for newly diagnosed glioblastoma.

The STELLAR trial involved 80 patients with mesothelioma who were treated with TTFields in combination with standard first-line chemotherapy, a combination of pemetrexed with cisplatin or carboplatin. Patients were instructed to self-administer continuous 150 kHz TTFields for at least 18 hours a day. Eligibility required an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0 to 1. Both ECOG status and cancer-related pain were followed with a visual analog scale until disease progression. Median overall survival (OS) was the primary endpoint.

The patient population was predominantly male (84%), with median age of 67 years. About 44% of the patients had an ECOG performance status of 1 and 66% had epithelioid histology. Median treatment time per day was 16.3 hours.

After a minimum follow-up of 1 year, patients treated with TTFields in combination with standard chemotherapy had a median overall survival of 18.2 months, compared with 12.1 months for standard chemotherapy alone, which Dr. Ceresoli cited as the historical benchmark. The survival benefit was 3 months longer among patients with epithelioid mesothelioma, who had a median overall survival of 21.2 months.

In addition to survival benefits, the investigators found that median time to decreased performance status was just over 1 year (13.1 months), and that pain did not increase to a clinically significant degree (33%) until an average of 8.4 months. Although no device-related serious adverse events occurred, 37 patients (46%) experienced TTFields-related dermatitis; 4 of these patients had grade 3 dermatitis. Dr. Ceresoli noted that dermatitis was typically “easily managed” with topical application of a corticosteroid, while patients with severe dermatitis took short treatment breaks.

“In conclusion, in the STELLAR trial, TTFields in combination with standard chemotherapy were effective and safe for first-line treatment of unresectable malignant pleural mesothelioma, and median overall survival was significantly longer as compared to historical controls,” Dr. Ceresoli said, pointing out better survival than in recent trials MAPS and LUME-Meso.

When asked by the invited discussant about future research, Dr. Ceresoli described a narrower focus for upcoming TTFields studies for mesothelioma. “As you well know, most patients have epithelioid histology, and in our hands, the patients with epithelioid histology had better prognoses,” he said. “So, in the future, I think we will focus on epithelioid tumors.”

Dr. Ceresoli disclosed travel funding from Novocure.

SOURCE: Ceresoli et al. ELCC 2019. Abstract 55O.

GENEVA – For patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma, adding tumor-treating fields (TTFields) to standard pemetrexed plus platinum compound chemotherapy could boost median overall survival by about 6 months, according to final results from the phase 2 STELLAR trial.

The survival benefit of TTFields was greatest among patients with epithelioid mesothelioma, reported lead author Giovanni Luca Ceresoli, MD, of Humanitas Gavazzeni in Bergamo, Italy. According to Dr. Ceresoli, who presented findings at the at the European Lung Cancer Conference, TTFields offer a safe way to improve mesothelioma outcomes without increasing the risk of serious adverse events.

“TTFields are a locoregional treatment comprising low-intensity alternating electric fields delivered through a portable medical device,” Dr. Ceresoli explained at the meeting, presented by the European Society for Medical Oncology. “Their main mode of action is an anti-mitotic mechanism.” He noted that TTFields are already approved by the Food and Drug Administration for newly diagnosed glioblastoma.

The STELLAR trial involved 80 patients with mesothelioma who were treated with TTFields in combination with standard first-line chemotherapy, a combination of pemetrexed with cisplatin or carboplatin. Patients were instructed to self-administer continuous 150 kHz TTFields for at least 18 hours a day. Eligibility required an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0 to 1. Both ECOG status and cancer-related pain were followed with a visual analog scale until disease progression. Median overall survival (OS) was the primary endpoint.

The patient population was predominantly male (84%), with median age of 67 years. About 44% of the patients had an ECOG performance status of 1 and 66% had epithelioid histology. Median treatment time per day was 16.3 hours.

After a minimum follow-up of 1 year, patients treated with TTFields in combination with standard chemotherapy had a median overall survival of 18.2 months, compared with 12.1 months for standard chemotherapy alone, which Dr. Ceresoli cited as the historical benchmark. The survival benefit was 3 months longer among patients with epithelioid mesothelioma, who had a median overall survival of 21.2 months.

In addition to survival benefits, the investigators found that median time to decreased performance status was just over 1 year (13.1 months), and that pain did not increase to a clinically significant degree (33%) until an average of 8.4 months. Although no device-related serious adverse events occurred, 37 patients (46%) experienced TTFields-related dermatitis; 4 of these patients had grade 3 dermatitis. Dr. Ceresoli noted that dermatitis was typically “easily managed” with topical application of a corticosteroid, while patients with severe dermatitis took short treatment breaks.

“In conclusion, in the STELLAR trial, TTFields in combination with standard chemotherapy were effective and safe for first-line treatment of unresectable malignant pleural mesothelioma, and median overall survival was significantly longer as compared to historical controls,” Dr. Ceresoli said, pointing out better survival than in recent trials MAPS and LUME-Meso.

When asked by the invited discussant about future research, Dr. Ceresoli described a narrower focus for upcoming TTFields studies for mesothelioma. “As you well know, most patients have epithelioid histology, and in our hands, the patients with epithelioid histology had better prognoses,” he said. “So, in the future, I think we will focus on epithelioid tumors.”

Dr. Ceresoli disclosed travel funding from Novocure.

SOURCE: Ceresoli et al. ELCC 2019. Abstract 55O.

At ELCC 2019

Treating the pregnant patient with opioid addiction

OBG Management : How has the opioid crisis affected women in general?

Mishka Terplan, MD: Everyone is aware that we are experiencing a massive opioid crisis in the United States, and from a historical perspective, this is at least the third or fourth significant opioid epidemic in our nation’s history.1 It is similar in some ways to the very first one, which also featured a large proportion of women and also was driven initially by physician prescribing practices. However, the magnitude of this crisis is unparalleled compared with prior opioid epidemics.

There are lots of reasons why women are overrepresented in this crisis. There are gender-based differences in pain—chronic pain syndromes are more common in women. In addition, we have a gender bias in prescribing opioids and prescribe more opioids to women (especially older women) than to men. Cultural differences also contribute. As providers, we tend not to think of women as people who use drugs or people who develop addictions the same way as we think of these risks and behaviors for men. Therefore, compared with men, we are less likely to screen, assess, or refer women for substance use, misuse, and addiction. All of this adds up to creating a crisis in which women are increasingly the face of the epidemic.

OBG Management : What are the concerns about opioid addiction and pregnant women specifically?

Dr. Terplan: Addiction is a chronic condition, just like diabetes or depression, and the same principles that we think of in terms of optimizing maternal and newborn health apply to addiction. Ideally, we want, for women with chronic diseases to have stable disease at the time of conception and through pregnancy. We know this maximizes birth outcomes.

Unfortunately, there is a massive treatment gap in the United States. Most people with addiction receive no treatment. Only 11% of people with a substance use disorder report receipt of treatment. By contrast, more than 70% of people with depression, hypertension, or diabetes receive care. This treatment gap is also present in pregnancy. Among use disorders, treatment receipt is highest for opioid use disorder; however, nationally, at best, 25% of pregnant women with opioid addiction receive any care.

In other words, when we encounter addiction clinically, it is often untreated addiction. Therefore, many times providers will have women presenting to care who are both pregnant and have untreated addiction. From both a public health and a clinical practice perspective, the salient distinction is not between people with addiction and those without but between people with treated disease and people with untreated disease.

Untreated addiction is a serious medical condition. It is associated with preterm delivery and low birth weight infants. It is associated with acquisition and transmission of HIV and hepatitis C. It is associated with overdose and overdose death. By contrast, treated addiction is associated with term delivery and normal weight infants. Pharmacotherapies for opioid use disorder stabilize the intrauterine environment and allow for normal fetal growth. Pharmacotherapies for opioid use disorder help to structure and stabilize the mom’s social circumstance, providing a platform to deliver prenatal care and essential social services. And pharmacotherapies for opioid use disorder protect women and their fetuses from overdose and from overdose deaths. The goal of management of addiction in pregnancy is treatment of the underlying condition, treating the addiction.

Continue to: OBG Management...

OBG Management : What should the ObGyn do when faced with a patient who might have an addiction?

Dr. Terplan: The good news is that there are lots of recently published guidance documents from the World Health Organization,2 the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG),3 and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA),4 and there have been a whole series of trainings throughout the United States organized by both ACOG and SAMHSA.

There is also a collaboration between ACOG and the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) to provide buprenorphine waiver trainings specifically designed for ObGyns. Check both the ACOG and ASAM pages for details. I encourage every provider to get a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine. There are about 30 ObGyns who are also board certified in addiction medicine in the United States, and all of us are more than happy to help our colleagues in the clinical care of this population, a population that all of us really enjoy taking care of.

Although care in pregnancy is important, we must not forget about the postpartum period. Generally speaking, women do quite well during pregnancy in terms of treatment. Postpartum, however, is a vulnerable period, where relapse happens, where gaps in care happen, where child welfare involvement and sometimes child removal happens, which can be very stressful for anyone much less somebody with a substance use disorder. Recent data demonstrate that one of the leading causes of maternal mortality in the US in from overdose, and most of these deaths occur in the postpartum period.5 Regardless of what happens during pregnancy, it is essential that we be able to link and continue care for women with opioid use disorder throughout the postpartum period.

OBG Management : How do you treat opioid use disorder in pregnancy?

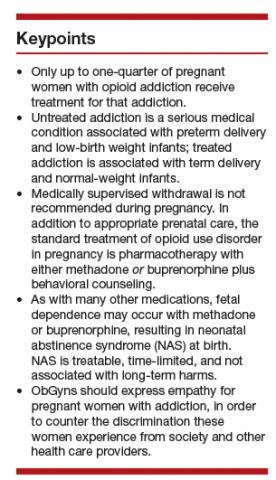

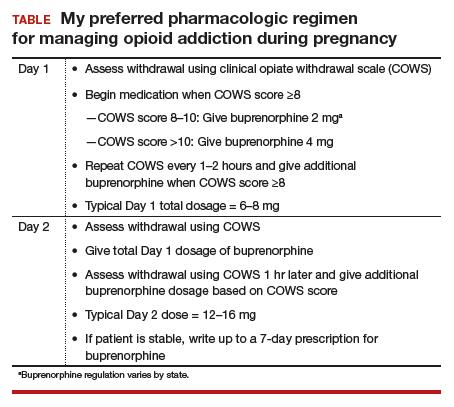

Dr. Terplan: The standard of care for treatment of opioid use disorder in pregnancy is pharmacotherapy with either methadone or buprenorphine (TABLE) plus behavioral counseling—ideally, co-located with prenatal care. The evidence base for pharmacotherapy for opioid use disorder in pregnancy is supported by every single professional society that has ever issued guidance on this, from the World Health Organization to ACOG, to ASAM, to the Royal College in the UK as well as Canadian and Australian obstetrics and gynecology societies; literally every single professional society supports medication.

The core principle of maternal fetal medicine rests upon the fact that chronic conditions need to be treated and that treated illness improves birth outcomes. For both maternal and fetal health, treated addiction is way better than untreated addiction. One concern people have regarding methadone and buprenorphine is the development of dependence. Dependence is a physiologic effect of medication and occurs with opioids, as well as with many other medications, such as antidepressants and most hypertensive agents. For the fetus, dependence means that at the time of delivery, the infant may go into withdrawal, which is also called neonatal abstinence syndrome. Neonatal abstinence syndrome is an expected outcome of in-utero opioid exposure. It is a time-limited and treatable condition. Prospective data do not demonstrate any long-term harms among infants whose mothers received pharmacotherapy for opioid use disorder during pregnancy.6

The treatment for neonatal abstinence syndrome is costly, especially when in a neonatal intensive care unit. It can be quite concerning to a new mother to have an infant that has to spend extra time in the hospital and sometimes be medicated for management of withdrawal.

There has been a renewed interest amongst ObGyns in investigating medically-supervised withdrawal during pregnancy. Although there are remaining questions, overall, the literature does not support withdrawal during pregnancy—mostly because withdrawal is associated with relapse, and relapse is associated with cessation of care (both prenatal care and addiction treatment), acquisition and transmission of HIV and Hepatitis C, and overdose and overdose death. The pertinent clinical and public health goal is the treatment of the chronic condition of addiction during pregnancy. The standard of care remains pharmacotherapy plus behavioral counseling for the treatment of opioid use disorder in pregnancy.

Clinical care, however, is both evidence-based and person-centered. All of us who have worked in this field, long before there was attention to the opioid crisis, all of us have provided medically-supervised withdrawal of a pregnant person, and that is because we understand the principles of care. When evidence-based care conflicts with person-centered care, the ethical course is the provision of person-centered care. Patients have the right of refusal. If someone wants to discontinue medication, I have tapered the medication during pregnancy, but continued to provide (and often increase) behavioral counseling and prenatal care.

Treated addiction is better for the fetus than untreated addiction. Untreated opioid addiction is associated with preterm birth and low birth weight. These obstetric risks are not because of the opioid per se, but because of the repeated cycles of withdrawal that an individual with untreated addiction experiences. People with untreated addiction are not getting “high” when they use, they are just becoming a little bit less sick. It is this repeated cycle of withdrawal that stresses the fetus, which leads to preterm delivery and low birth weight.

Medications for opioid use disorder are long-acting and dosed daily. In contrast to the repeated cycles of fetal withdrawal in untreated addiction, pharmacotherapy stabilizes the intrauterine environment. There is no cyclic, repeated, stressful withdrawal, and consequentially, the fetus grows normally and delivers at term. Obstetric risk is from repeated cyclic withdrawal more than from opioid exposure itself.

Continue to: OBG Management...

OBG Management : Research reports that women are not using all of the opioids that are prescribed to them after a cesarean delivery. What are the risks for addiction in this setting?

Dr. Terplan: I mark a distinction between use (ie, using something as prescribed) and misuse, which means using a prescribed medication not in the manner in which it was prescribed, or using somebody else’s medications, or using an illicit substance. And I differentiate use and misuse from addiction, which is a behavioral condition, a disease. There has been a lot of attention paid to opioid prescribing in general and in particular postdelivery and post–cesarean delivery, which is one of the most common operative procedures in the United States.

It seems clear from the literature that we have overprescribed opioids postdelivery, and a small number of women, about 1 in 300 will continue an opioid script.7 This means that 1 in 300 women who received an opioid prescription following delivery present for care and get another opioid prescription filled. Now, that is a small number at the level of the individual, but because we do so many cesarean deliveries, this is a large number of women at the level of the population. This does not mean, however, that 1 in 300 women who received opioids after cesarean delivery are going to become addicted to them. It just means that 1 in 300 will continue the prescription. Prescription continuation is a risk factor for opioid misuse, and opioid misuse is on the pathway toward addiction.

Most people who use substances do not develop an addiction to that substance. We know from the opioid literature that at most only 10% of people who receive chronic opioid therapy will meet criteria for opioid use disorder.8 Now 10% is not 100%, nor is it 0%, but because we prescribed so many opioids to so many people for so long, the absolute number of people with opioid use disorder from physician opioid prescribing is large, even though the risk at the level of the individual is not as large as people think.

OBG Management : From your experience in treating addiction during pregnancy, are there clinical pearls you would like to share with ObGyns?

Dr. Terplan: There are a couple of takeaways. One is that all women are motivated to maximize their health and that of their baby to be, and every pregnant woman engages in behavioral change; in fact most women quit or cutback substance use during pregnancy. But some can’t. Those that can’t likely have a substance use disorder. We think of addiction as a chronic condition, centered in the brain, but the primary symptoms of addiction are behaviors. The salient feature of addiction is continued use despite adverse consequences; using something that you know is harming yourself and others but you can’t stop using it. In other words, continuing substance use during pregnancy. When we see clinically a pregnant woman who is using a substance, 99% of the time we are seeing a pregnant woman who has the condition of addiction, and what she needs is treatment. She does not need to be told that injecting heroin is unsafe for her and her fetus, she knows that. What she needs is treatment.

The second point is that pregnant women who use drugs and pregnant women with addiction experience a real specific and strong form of discrimination by providers, by other people with addiction, by the legal system, and by their friends and families. Caring for people who have substance use disorder is grounded in human rights, which means treating people with dignity and respect. It is important for providers to have empathy, especially for pregnant people who use drugs, to counter the discrimination they experience from society and from other health care providers.

Continue to: OBG Management...

OBG Management : Are there specific ways in which ObGyns can show empathy when speaking with a pregnant woman who likely has addiction?

Dr. Terplan: In general when we talk to people about drug use, it is important to ask their permission to talk about it. For example, “Is it okay if I ask you some questions about smoking, drinking, and other drugs?” If someone says, “No, I don’t want you to ask those questions,” we have to respect that. Assessment of substance use should be a universal part of all medical care, as substance use, misuse, and addiction are essential domains of wellness, but I think we should ask permission before screening.

One of the really good things about prenatal care is that people come back; we have multiple visits across the gestational period. The behavioral work of addiction treatment rests upon a strong therapeutic alliance. If you do not respect your patient, then there is no way you can achieve a therapeutic alliance. Asking permission, and then respecting somebody’s answers, I think goes a really long way to establishing a strong therapeutic alliance, which is the basis of any medical care.

- Terplan M. Women and the opioid crisis: historical context and public health solutions. Fertil Steril. 2017;108:195-199.

- Management of substance abuse. World Health Organization website. https://www.who.int/substance_abuse/activities/treatment_opioid_dependence/en/. Accessed March 20, 2019.

- Committee on Obstetric Practice. Committee Opinion No. 711: Opioid use and opioid use disorder in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(2):e81-e94.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Clinical guidance for treating pregnant and parenting women with opioid use disorder and their infants. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 18-5054. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2018.

- Metz TD, Royner P, Hoffman MC, et al. Maternal deaths from suicide and overdose in Colorado, 2004-2012. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:1233-1240.

- Kaltenbach K, O’Grady E, Heil SH, et al. Prenatal exposure to methadone or buprenorphine: early childhood developmental outcomes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;185:40-49.

- Bateman BT, Franklin JM, Bykov K, et al. Persistent opioid use following cesarean delivery: patterns and predictors among opioid-naive women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215:353.e1-353.e18.

OBG Management : How has the opioid crisis affected women in general?

Mishka Terplan, MD: Everyone is aware that we are experiencing a massive opioid crisis in the United States, and from a historical perspective, this is at least the third or fourth significant opioid epidemic in our nation’s history.1 It is similar in some ways to the very first one, which also featured a large proportion of women and also was driven initially by physician prescribing practices. However, the magnitude of this crisis is unparalleled compared with prior opioid epidemics.