User login

What is your diagnosis? - May 2019

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug–induced diaphragm disease

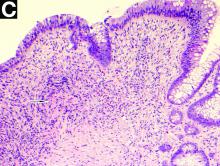

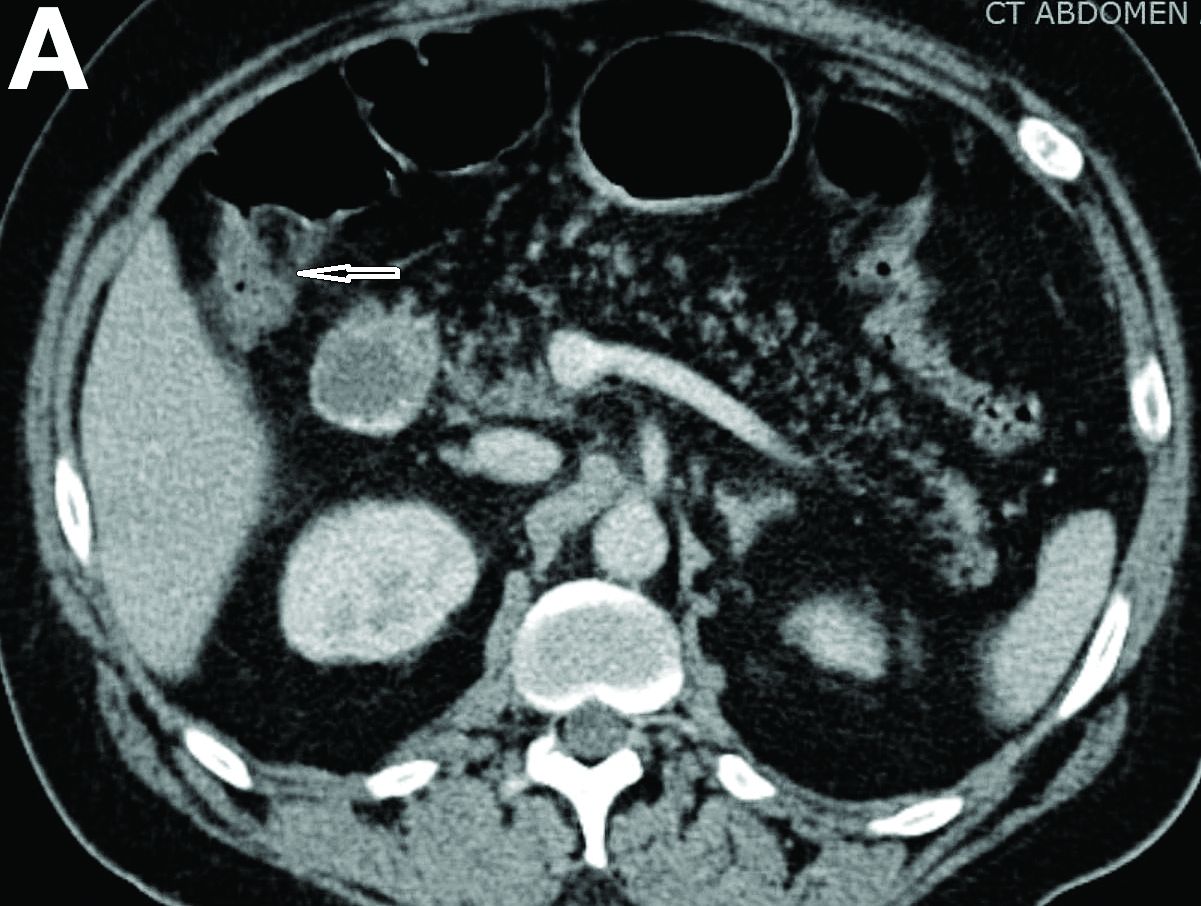

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID)–induced diaphragm disease is a rare cause of colonic stricture. To date, only about 50 cases have been reported. Diaphragm-like strictures occur predominantly in the right colon. The most common clinical presentations are obstructive symptoms and gastrointestinal bleeding after taking traditional NSAIDs or cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors for more than 1 year.1 The thin diaphragm strictures are difficult to detect on imaging studies. They are seen during endoscopy or surgery. Concentric strictures in the right colon in the setting of chronic NSAID use are almost diagnostic of colonic diaphragm disease.2 Histopathology demonstrates submucosal fibrosis on resection specimens. Endoscopic biopsies may show lamina propria fibrosis, increased eosinophils with relative paucity of neutrophils, and even crypt distortion. The mechanism is thought to be due to contraction of scar tissue from healing concentric ulceration resulting in diaphragm-like strictures. Discontinuation of NSAIDs is recommended. Surgery is required to relieve obstruction in 75% of reported cases. Some have reported success with endoscopic balloon dilation.3

Using a 15-mm balloon, we performed endoscopic through-the-scope balloon dilation under fluoroscopy (Figures D, E). After dilation, the colonoscopy was completed to the distal ileum. There were two additional proximal concentric colonic strictures that allowed passage of the colonoscope and did not require dilation (Figure F). The patient was advised to stop diclofenac. He had no further gastrointestinal symptoms at the 3-month follow-up visit.

References

1. Wang Y-Z, Sun G, Cai F-C et al. Clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment strategies of gastrointestinal diaphragm disease associated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2016;2016:3679741

2. Püspök A, Kiener HP, Oberhuber G. Clinical, endoscopic, and histologic spectrum of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced lesions in the colon. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:685-91.

3. Smith JA, Pineau BC. Endoscopic therapy of NSAID-induced colonic diaphragm disease: two cases and a review of published reports. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:120-5.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug–induced diaphragm disease

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID)–induced diaphragm disease is a rare cause of colonic stricture. To date, only about 50 cases have been reported. Diaphragm-like strictures occur predominantly in the right colon. The most common clinical presentations are obstructive symptoms and gastrointestinal bleeding after taking traditional NSAIDs or cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors for more than 1 year.1 The thin diaphragm strictures are difficult to detect on imaging studies. They are seen during endoscopy or surgery. Concentric strictures in the right colon in the setting of chronic NSAID use are almost diagnostic of colonic diaphragm disease.2 Histopathology demonstrates submucosal fibrosis on resection specimens. Endoscopic biopsies may show lamina propria fibrosis, increased eosinophils with relative paucity of neutrophils, and even crypt distortion. The mechanism is thought to be due to contraction of scar tissue from healing concentric ulceration resulting in diaphragm-like strictures. Discontinuation of NSAIDs is recommended. Surgery is required to relieve obstruction in 75% of reported cases. Some have reported success with endoscopic balloon dilation.3

Using a 15-mm balloon, we performed endoscopic through-the-scope balloon dilation under fluoroscopy (Figures D, E). After dilation, the colonoscopy was completed to the distal ileum. There were two additional proximal concentric colonic strictures that allowed passage of the colonoscope and did not require dilation (Figure F). The patient was advised to stop diclofenac. He had no further gastrointestinal symptoms at the 3-month follow-up visit.

References

1. Wang Y-Z, Sun G, Cai F-C et al. Clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment strategies of gastrointestinal diaphragm disease associated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2016;2016:3679741

2. Püspök A, Kiener HP, Oberhuber G. Clinical, endoscopic, and histologic spectrum of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced lesions in the colon. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:685-91.

3. Smith JA, Pineau BC. Endoscopic therapy of NSAID-induced colonic diaphragm disease: two cases and a review of published reports. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:120-5.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug–induced diaphragm disease

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID)–induced diaphragm disease is a rare cause of colonic stricture. To date, only about 50 cases have been reported. Diaphragm-like strictures occur predominantly in the right colon. The most common clinical presentations are obstructive symptoms and gastrointestinal bleeding after taking traditional NSAIDs or cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors for more than 1 year.1 The thin diaphragm strictures are difficult to detect on imaging studies. They are seen during endoscopy or surgery. Concentric strictures in the right colon in the setting of chronic NSAID use are almost diagnostic of colonic diaphragm disease.2 Histopathology demonstrates submucosal fibrosis on resection specimens. Endoscopic biopsies may show lamina propria fibrosis, increased eosinophils with relative paucity of neutrophils, and even crypt distortion. The mechanism is thought to be due to contraction of scar tissue from healing concentric ulceration resulting in diaphragm-like strictures. Discontinuation of NSAIDs is recommended. Surgery is required to relieve obstruction in 75% of reported cases. Some have reported success with endoscopic balloon dilation.3

Using a 15-mm balloon, we performed endoscopic through-the-scope balloon dilation under fluoroscopy (Figures D, E). After dilation, the colonoscopy was completed to the distal ileum. There were two additional proximal concentric colonic strictures that allowed passage of the colonoscope and did not require dilation (Figure F). The patient was advised to stop diclofenac. He had no further gastrointestinal symptoms at the 3-month follow-up visit.

References

1. Wang Y-Z, Sun G, Cai F-C et al. Clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment strategies of gastrointestinal diaphragm disease associated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2016;2016:3679741

2. Püspök A, Kiener HP, Oberhuber G. Clinical, endoscopic, and histologic spectrum of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced lesions in the colon. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:685-91.

3. Smith JA, Pineau BC. Endoscopic therapy of NSAID-induced colonic diaphragm disease: two cases and a review of published reports. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:120-5.

A 57-year-old man presented to our hospital with a week of generalized weakness and abdominal pain.

Relevant medications included diclofenac 75 mg twice daily, aspirin 81 mg, and clopidogrel 75 mg/d. Vital signs were normal. Physical examination showed mild diffuse abdominal tenderness.

Admission blood work revealed a hemoglobin of 8.8 g/dL, decreased from a baseline hemoglobin of 12 g/dL. The patient did not have overt gastrointestinal bleeding, but tested positive for fecal occult blood. A computed tomography scan demonstrated luminal narrowing at the hepatic flexure without bowel wall thickening or obstruction (Figure A). Esophagogastroduodenoscopy was normal. Colonoscopy revealed a circumferential stricture in the right colon with an estimated diameter of 8 mm (Figure B).

Biopsies of the stricture showed significant lamina propria fibrosis, eosinophilic infiltration, and mild crypt distortion (Figure C).

Positive psoriatic arthritis screens occur often in psoriasis patients

One out of eight patients with psoriasis had a positive screen for possibly undiagnosed psoriatic arthritis, according to an analysis of data from a prospective registry.

The finding highlights the need for better psoriatic arthritis screening among patients with psoriasis, said Philip J. Mease, MD, of the University of Washington, Seattle, and associates. The simple, five-question Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool (PEST) used in this study could be deployed in general or dermatology practices to identify psoriasis patients who might need a rheumatology referral, they wrote. The report is in the Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

Up to 30% of patients with psoriasis have comorbid psoriatic arthritis, but many such cases go undiagnosed, and even a 6-month diagnostic delay can worsen peripheral joint erosion and physical disability.

This study included 1,516 patients with psoriasis seen at 114 private and academic practices in 34 states that participate in the independent, prospective Corrona Psoriasis Registry. A total of 904 patients without dermatologist-reported psoriatic arthritis responded to the validated PEST, which assesses risk of psoriatic arthritis by asking whether the test taker has been told by a doctor that he or she has arthritis and whether they have experienced swollen joints, heel pain, pronounced and unexplained swelling of a finger or toe, and pitting of the fingernails or toenails. Each “yes” response is worth 1 point, and total scores of 3 or higher indicate risk of psoriatic arthritis. A total of 112 (12.4%) had a score of 3 or higher.

The average age of patients who met this threshold was 53 years, 4 years older than those who did not (P = .02). Patients with PEST scores of 3 or more also had a significantly longer duration of psoriasis and were significantly more likely to have nail disease and a family history of psoriasis. Demographically, they were more likely to be white, female, and unemployed. They had significantly higher rates of several comorbidities, including depression and anxiety, cardiovascular disease, obesity, and serious infections. Finally, they reported having significantly more pain and fatigue and significantly worse health-related quality of life.

The study did not account for possible confounding. “Further research is needed to characterize patients by individual PEST score and to assess outcomes over time,” the researchers wrote. “The use of screening tools can be beneficial in the detection of psoriatic arthritis, and comprehensive efforts to validate them in multiple clinical settings must continue, along with collection of critical feedback from patients and clinicians.”

Corrona and Novartis designed and helped conduct the study. Novartis, the chief funder, participated in data analysis and manuscript review. Dr. Mease disclosed research funding from Novartis and several other pharmaceutical companies. He also disclosed consulting and speakers bureau fees from Novartis, Corrona, and several other companies.

SOURCE: Mease PJ et al. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019 Mar 5. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15443.

One out of eight patients with psoriasis had a positive screen for possibly undiagnosed psoriatic arthritis, according to an analysis of data from a prospective registry.

The finding highlights the need for better psoriatic arthritis screening among patients with psoriasis, said Philip J. Mease, MD, of the University of Washington, Seattle, and associates. The simple, five-question Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool (PEST) used in this study could be deployed in general or dermatology practices to identify psoriasis patients who might need a rheumatology referral, they wrote. The report is in the Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

Up to 30% of patients with psoriasis have comorbid psoriatic arthritis, but many such cases go undiagnosed, and even a 6-month diagnostic delay can worsen peripheral joint erosion and physical disability.

This study included 1,516 patients with psoriasis seen at 114 private and academic practices in 34 states that participate in the independent, prospective Corrona Psoriasis Registry. A total of 904 patients without dermatologist-reported psoriatic arthritis responded to the validated PEST, which assesses risk of psoriatic arthritis by asking whether the test taker has been told by a doctor that he or she has arthritis and whether they have experienced swollen joints, heel pain, pronounced and unexplained swelling of a finger or toe, and pitting of the fingernails or toenails. Each “yes” response is worth 1 point, and total scores of 3 or higher indicate risk of psoriatic arthritis. A total of 112 (12.4%) had a score of 3 or higher.

The average age of patients who met this threshold was 53 years, 4 years older than those who did not (P = .02). Patients with PEST scores of 3 or more also had a significantly longer duration of psoriasis and were significantly more likely to have nail disease and a family history of psoriasis. Demographically, they were more likely to be white, female, and unemployed. They had significantly higher rates of several comorbidities, including depression and anxiety, cardiovascular disease, obesity, and serious infections. Finally, they reported having significantly more pain and fatigue and significantly worse health-related quality of life.

The study did not account for possible confounding. “Further research is needed to characterize patients by individual PEST score and to assess outcomes over time,” the researchers wrote. “The use of screening tools can be beneficial in the detection of psoriatic arthritis, and comprehensive efforts to validate them in multiple clinical settings must continue, along with collection of critical feedback from patients and clinicians.”

Corrona and Novartis designed and helped conduct the study. Novartis, the chief funder, participated in data analysis and manuscript review. Dr. Mease disclosed research funding from Novartis and several other pharmaceutical companies. He also disclosed consulting and speakers bureau fees from Novartis, Corrona, and several other companies.

SOURCE: Mease PJ et al. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019 Mar 5. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15443.

One out of eight patients with psoriasis had a positive screen for possibly undiagnosed psoriatic arthritis, according to an analysis of data from a prospective registry.

The finding highlights the need for better psoriatic arthritis screening among patients with psoriasis, said Philip J. Mease, MD, of the University of Washington, Seattle, and associates. The simple, five-question Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool (PEST) used in this study could be deployed in general or dermatology practices to identify psoriasis patients who might need a rheumatology referral, they wrote. The report is in the Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

Up to 30% of patients with psoriasis have comorbid psoriatic arthritis, but many such cases go undiagnosed, and even a 6-month diagnostic delay can worsen peripheral joint erosion and physical disability.

This study included 1,516 patients with psoriasis seen at 114 private and academic practices in 34 states that participate in the independent, prospective Corrona Psoriasis Registry. A total of 904 patients without dermatologist-reported psoriatic arthritis responded to the validated PEST, which assesses risk of psoriatic arthritis by asking whether the test taker has been told by a doctor that he or she has arthritis and whether they have experienced swollen joints, heel pain, pronounced and unexplained swelling of a finger or toe, and pitting of the fingernails or toenails. Each “yes” response is worth 1 point, and total scores of 3 or higher indicate risk of psoriatic arthritis. A total of 112 (12.4%) had a score of 3 or higher.

The average age of patients who met this threshold was 53 years, 4 years older than those who did not (P = .02). Patients with PEST scores of 3 or more also had a significantly longer duration of psoriasis and were significantly more likely to have nail disease and a family history of psoriasis. Demographically, they were more likely to be white, female, and unemployed. They had significantly higher rates of several comorbidities, including depression and anxiety, cardiovascular disease, obesity, and serious infections. Finally, they reported having significantly more pain and fatigue and significantly worse health-related quality of life.

The study did not account for possible confounding. “Further research is needed to characterize patients by individual PEST score and to assess outcomes over time,” the researchers wrote. “The use of screening tools can be beneficial in the detection of psoriatic arthritis, and comprehensive efforts to validate them in multiple clinical settings must continue, along with collection of critical feedback from patients and clinicians.”

Corrona and Novartis designed and helped conduct the study. Novartis, the chief funder, participated in data analysis and manuscript review. Dr. Mease disclosed research funding from Novartis and several other pharmaceutical companies. He also disclosed consulting and speakers bureau fees from Novartis, Corrona, and several other companies.

SOURCE: Mease PJ et al. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019 Mar 5. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15443.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE EUROPEAN ACADEMY OF DERMATOLOGY AND VENEREOLOGY

Retail neurosis

When I stopped by last August to pick up new eyeglass lenses, Harold the optician sat alone in his shop.

“Business slow in the summer?” I asked.

Harold looked morose. “I knew it would be like this when I bought the business,” he said. “We’re open Saturdays, but summers I close at 2. Everybody’s at the Cape.”

Working in retail makes people more neurotic than necessary. I should know. I’ve been in retail for 40 years.

My patient Myrtle once explained to me how retail induces neurosis by deforming incentives. Myrtle used to work in management at a big department store. (Older readers may recall going to stores in buildings to buy things. The same readers may recall newspapers.)

“The month between Thanksgiving and Christmas makes or breaks the whole year,” Myrtle said. “If you do worse than last year, you feel bad. But if you do better than last year you also feel bad, because you worry you won’t be able to top it next year.”

She paused. “I guess that’s not a very healthy way to live, is it?”

I was too polite to agree.

Early in my career I had few patients on my schedule, maybe five on a good day. Then three of them would cancel. That was the start of my retail neurosis. Of course, I was a solo practitioner who started my own practice. The likes of me will someday be found in a museum, stuffed and mounted, along with other extinct species, under the label Medicus Cutaneous Solipsisticus (North America c. 20th century).

Over time, I got busier and dropped each of my eleven part-time jobs. By now I’ve been busy for decades, even though I’ve never had much of a waiting list. Don’t know why that is, but it no longer matters.

Except it does, psychologically. You won’t find this code in the DSM, but my working definition for the malady I describe is as follows:

Retail Neurosis (billable ICD-10 code F48.8. Other unspecified nonpsychotic mental disorders, along with writer’s block and psychasthenia):

Definition: The unquenchable fear that even the tiniest break in an endless churn of patients means that all patients will disappear later this afternoon, reverting the practice to the empty, formless void from whence it came. Other than retirement, there is no treatment for this disorder. And maybe not then either.

You might think to classify Retail Neurosis under Financial Insecurity, but that disorder has a different code. (F40.248, Fear of Failing, Life-Circumstance Problem). After all, a single well-remunerated patient (53 actinic keratoses!) can outreimburse half a dozen others with only E/M codes and big deductibles. Treat one of the former, take the rest of the hour off, and you’re financially just as well off, or even better. Yes?

No. Taking the rest of the hour off leaves you with too much time to ponder what every retailer knows: Each idle minute is another lost chance to make another sale and generate revenue. That minute (and revenue) can never be retrieved. Never!

As Myrtle would say, “Not a very healthy way to live, is it?”

Maybe not, but here as elsewhere, knowing something and fixing it are different things. Besides, brisk retail business brings a buzz, along with a sense of mastery and accomplishment, which is pleasantly addictive. Until it isn’t.

New generations of physicians and other medical providers will work in different settings than mine; they will be wage-earners in large organizations. These conglomerations bring their own neurosis-inducing incentives. Their managers measure providers’ productivity in various deforming and crazy-making ways. (See RVU-penia, ICD-10 M26.56: “Nonworking side interference.” This is actually a dental code that refers to jaw position, but billing demands creativity.) Practitioner anxieties will center on being docked for not generating enough relative value units or for failure to bundle enough comorbidities for maximizing capitation payments (e.g., Plaque Psoriasis plus Morbid Obesity plus Writer’s Block). But the youngsters will learn to get along. They’ll have to.

“Taking any time off this summer?” I asked my optician Harold.

“My wife and daughter are going out to Michigan in mid-August,” he said.

“Aren’t you going with them?”

“I can’t swing it that week,” he said. “By then, people are coming back to town, getting their kids ready for school. If I go away, I would miss some customers.”

Harold, you are my kind of guy!

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass., and is a longtime contributor to Dermatology News. He serves on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. His second book, “Act Like a Doctor, Think Like a Patient,” is available at amazon.com and barnesandnoble.com. Write to him at [email protected].

When I stopped by last August to pick up new eyeglass lenses, Harold the optician sat alone in his shop.

“Business slow in the summer?” I asked.

Harold looked morose. “I knew it would be like this when I bought the business,” he said. “We’re open Saturdays, but summers I close at 2. Everybody’s at the Cape.”

Working in retail makes people more neurotic than necessary. I should know. I’ve been in retail for 40 years.

My patient Myrtle once explained to me how retail induces neurosis by deforming incentives. Myrtle used to work in management at a big department store. (Older readers may recall going to stores in buildings to buy things. The same readers may recall newspapers.)

“The month between Thanksgiving and Christmas makes or breaks the whole year,” Myrtle said. “If you do worse than last year, you feel bad. But if you do better than last year you also feel bad, because you worry you won’t be able to top it next year.”

She paused. “I guess that’s not a very healthy way to live, is it?”

I was too polite to agree.

Early in my career I had few patients on my schedule, maybe five on a good day. Then three of them would cancel. That was the start of my retail neurosis. Of course, I was a solo practitioner who started my own practice. The likes of me will someday be found in a museum, stuffed and mounted, along with other extinct species, under the label Medicus Cutaneous Solipsisticus (North America c. 20th century).

Over time, I got busier and dropped each of my eleven part-time jobs. By now I’ve been busy for decades, even though I’ve never had much of a waiting list. Don’t know why that is, but it no longer matters.

Except it does, psychologically. You won’t find this code in the DSM, but my working definition for the malady I describe is as follows:

Retail Neurosis (billable ICD-10 code F48.8. Other unspecified nonpsychotic mental disorders, along with writer’s block and psychasthenia):

Definition: The unquenchable fear that even the tiniest break in an endless churn of patients means that all patients will disappear later this afternoon, reverting the practice to the empty, formless void from whence it came. Other than retirement, there is no treatment for this disorder. And maybe not then either.

You might think to classify Retail Neurosis under Financial Insecurity, but that disorder has a different code. (F40.248, Fear of Failing, Life-Circumstance Problem). After all, a single well-remunerated patient (53 actinic keratoses!) can outreimburse half a dozen others with only E/M codes and big deductibles. Treat one of the former, take the rest of the hour off, and you’re financially just as well off, or even better. Yes?

No. Taking the rest of the hour off leaves you with too much time to ponder what every retailer knows: Each idle minute is another lost chance to make another sale and generate revenue. That minute (and revenue) can never be retrieved. Never!

As Myrtle would say, “Not a very healthy way to live, is it?”

Maybe not, but here as elsewhere, knowing something and fixing it are different things. Besides, brisk retail business brings a buzz, along with a sense of mastery and accomplishment, which is pleasantly addictive. Until it isn’t.

New generations of physicians and other medical providers will work in different settings than mine; they will be wage-earners in large organizations. These conglomerations bring their own neurosis-inducing incentives. Their managers measure providers’ productivity in various deforming and crazy-making ways. (See RVU-penia, ICD-10 M26.56: “Nonworking side interference.” This is actually a dental code that refers to jaw position, but billing demands creativity.) Practitioner anxieties will center on being docked for not generating enough relative value units or for failure to bundle enough comorbidities for maximizing capitation payments (e.g., Plaque Psoriasis plus Morbid Obesity plus Writer’s Block). But the youngsters will learn to get along. They’ll have to.

“Taking any time off this summer?” I asked my optician Harold.

“My wife and daughter are going out to Michigan in mid-August,” he said.

“Aren’t you going with them?”

“I can’t swing it that week,” he said. “By then, people are coming back to town, getting their kids ready for school. If I go away, I would miss some customers.”

Harold, you are my kind of guy!

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass., and is a longtime contributor to Dermatology News. He serves on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. His second book, “Act Like a Doctor, Think Like a Patient,” is available at amazon.com and barnesandnoble.com. Write to him at [email protected].

When I stopped by last August to pick up new eyeglass lenses, Harold the optician sat alone in his shop.

“Business slow in the summer?” I asked.

Harold looked morose. “I knew it would be like this when I bought the business,” he said. “We’re open Saturdays, but summers I close at 2. Everybody’s at the Cape.”

Working in retail makes people more neurotic than necessary. I should know. I’ve been in retail for 40 years.

My patient Myrtle once explained to me how retail induces neurosis by deforming incentives. Myrtle used to work in management at a big department store. (Older readers may recall going to stores in buildings to buy things. The same readers may recall newspapers.)

“The month between Thanksgiving and Christmas makes or breaks the whole year,” Myrtle said. “If you do worse than last year, you feel bad. But if you do better than last year you also feel bad, because you worry you won’t be able to top it next year.”

She paused. “I guess that’s not a very healthy way to live, is it?”

I was too polite to agree.

Early in my career I had few patients on my schedule, maybe five on a good day. Then three of them would cancel. That was the start of my retail neurosis. Of course, I was a solo practitioner who started my own practice. The likes of me will someday be found in a museum, stuffed and mounted, along with other extinct species, under the label Medicus Cutaneous Solipsisticus (North America c. 20th century).

Over time, I got busier and dropped each of my eleven part-time jobs. By now I’ve been busy for decades, even though I’ve never had much of a waiting list. Don’t know why that is, but it no longer matters.

Except it does, psychologically. You won’t find this code in the DSM, but my working definition for the malady I describe is as follows:

Retail Neurosis (billable ICD-10 code F48.8. Other unspecified nonpsychotic mental disorders, along with writer’s block and psychasthenia):

Definition: The unquenchable fear that even the tiniest break in an endless churn of patients means that all patients will disappear later this afternoon, reverting the practice to the empty, formless void from whence it came. Other than retirement, there is no treatment for this disorder. And maybe not then either.

You might think to classify Retail Neurosis under Financial Insecurity, but that disorder has a different code. (F40.248, Fear of Failing, Life-Circumstance Problem). After all, a single well-remunerated patient (53 actinic keratoses!) can outreimburse half a dozen others with only E/M codes and big deductibles. Treat one of the former, take the rest of the hour off, and you’re financially just as well off, or even better. Yes?

No. Taking the rest of the hour off leaves you with too much time to ponder what every retailer knows: Each idle minute is another lost chance to make another sale and generate revenue. That minute (and revenue) can never be retrieved. Never!

As Myrtle would say, “Not a very healthy way to live, is it?”

Maybe not, but here as elsewhere, knowing something and fixing it are different things. Besides, brisk retail business brings a buzz, along with a sense of mastery and accomplishment, which is pleasantly addictive. Until it isn’t.

New generations of physicians and other medical providers will work in different settings than mine; they will be wage-earners in large organizations. These conglomerations bring their own neurosis-inducing incentives. Their managers measure providers’ productivity in various deforming and crazy-making ways. (See RVU-penia, ICD-10 M26.56: “Nonworking side interference.” This is actually a dental code that refers to jaw position, but billing demands creativity.) Practitioner anxieties will center on being docked for not generating enough relative value units or for failure to bundle enough comorbidities for maximizing capitation payments (e.g., Plaque Psoriasis plus Morbid Obesity plus Writer’s Block). But the youngsters will learn to get along. They’ll have to.

“Taking any time off this summer?” I asked my optician Harold.

“My wife and daughter are going out to Michigan in mid-August,” he said.

“Aren’t you going with them?”

“I can’t swing it that week,” he said. “By then, people are coming back to town, getting their kids ready for school. If I go away, I would miss some customers.”

Harold, you are my kind of guy!

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass., and is a longtime contributor to Dermatology News. He serves on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. His second book, “Act Like a Doctor, Think Like a Patient,” is available at amazon.com and barnesandnoble.com. Write to him at [email protected].

8-week yoga wellness program feasible, beneficial in ob.gyn trainees

A yoga-based wellness program was associated with reductions in blood pressure and measures of depersonalization in a pilot study of ob.gyn. trainees, according to Shilpa Babbar, MD, of Saint Louis University, and associates.

The wellness program consisted of weekly 1-hour yoga classes over an 8-week period as well as weekly physical and nutritional challenges. The 29 people recruited to participate had their blood pressures, heart rates, and weights measured at baseline; they also took the abbreviated Maslach Burnout Inventory, the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale, and the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire. These tests were repeated after the 8-week study period.

Of the 29 people who were recruited, 25 completed the study and 26 attended at least one class. Those who completed the program attended a mean of 3.8 classes, and 68% of participants attended at least half of the classes; no participant attended all classes. Participation in the weekly challenges was slightly less common, with 80% of participants engaging in at least one nutrition challenge and 60% of participants engaging in at least one physical challenge.

After the program had ended, participants had a significant decrease in the depersonalization component of burnout (P = .04), anxiety (P = .02), and systolic (P = .01) and diastolic (P = .01) blood pressures. In addition, those who attended more than 50% of classes had significantly lower systolic and diastolic blood pressures, compared with those who attended less frequently (P = .02 and P = .04, respectively). Participants also expressed increased camaraderie, appreciation, motivation, and overall training experience in a postprogram survey.

“ and overall health care system performance,” the investigators concluded.

One coauthor reported consulting with Health Insights Collaborative; no other conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Babbar S et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2019 May;133(5):994-1001.

A yoga-based wellness program was associated with reductions in blood pressure and measures of depersonalization in a pilot study of ob.gyn. trainees, according to Shilpa Babbar, MD, of Saint Louis University, and associates.

The wellness program consisted of weekly 1-hour yoga classes over an 8-week period as well as weekly physical and nutritional challenges. The 29 people recruited to participate had their blood pressures, heart rates, and weights measured at baseline; they also took the abbreviated Maslach Burnout Inventory, the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale, and the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire. These tests were repeated after the 8-week study period.

Of the 29 people who were recruited, 25 completed the study and 26 attended at least one class. Those who completed the program attended a mean of 3.8 classes, and 68% of participants attended at least half of the classes; no participant attended all classes. Participation in the weekly challenges was slightly less common, with 80% of participants engaging in at least one nutrition challenge and 60% of participants engaging in at least one physical challenge.

After the program had ended, participants had a significant decrease in the depersonalization component of burnout (P = .04), anxiety (P = .02), and systolic (P = .01) and diastolic (P = .01) blood pressures. In addition, those who attended more than 50% of classes had significantly lower systolic and diastolic blood pressures, compared with those who attended less frequently (P = .02 and P = .04, respectively). Participants also expressed increased camaraderie, appreciation, motivation, and overall training experience in a postprogram survey.

“ and overall health care system performance,” the investigators concluded.

One coauthor reported consulting with Health Insights Collaborative; no other conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Babbar S et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2019 May;133(5):994-1001.

A yoga-based wellness program was associated with reductions in blood pressure and measures of depersonalization in a pilot study of ob.gyn. trainees, according to Shilpa Babbar, MD, of Saint Louis University, and associates.

The wellness program consisted of weekly 1-hour yoga classes over an 8-week period as well as weekly physical and nutritional challenges. The 29 people recruited to participate had their blood pressures, heart rates, and weights measured at baseline; they also took the abbreviated Maslach Burnout Inventory, the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale, and the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire. These tests were repeated after the 8-week study period.

Of the 29 people who were recruited, 25 completed the study and 26 attended at least one class. Those who completed the program attended a mean of 3.8 classes, and 68% of participants attended at least half of the classes; no participant attended all classes. Participation in the weekly challenges was slightly less common, with 80% of participants engaging in at least one nutrition challenge and 60% of participants engaging in at least one physical challenge.

After the program had ended, participants had a significant decrease in the depersonalization component of burnout (P = .04), anxiety (P = .02), and systolic (P = .01) and diastolic (P = .01) blood pressures. In addition, those who attended more than 50% of classes had significantly lower systolic and diastolic blood pressures, compared with those who attended less frequently (P = .02 and P = .04, respectively). Participants also expressed increased camaraderie, appreciation, motivation, and overall training experience in a postprogram survey.

“ and overall health care system performance,” the investigators concluded.

One coauthor reported consulting with Health Insights Collaborative; no other conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Babbar S et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2019 May;133(5):994-1001.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Sleep apnea is linked with tau accumulation in the brain

PHILADELPHIA – according to data that will be presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology. Tau accumulation is a biomarker of Alzheimer’s disease, and the finding suggests a possible explanation for the apparent association between sleep disruption and dementia.

“Our research results raise the possibility that sleep apnea affects tau accumulation,” said Diego Z. Carvalho, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., in a press release. “But it is also possible that higher levels of tau in other regions may predispose a person to sleep apnea, so longer studies are now needed to solve this chicken-and-egg problem.”

Previous research had suggested an association between sleep disruption and increased risk of dementia. Obstructive sleep apnea in particular has been associated with this increased risk. The pathological processes that account for this association are unknown, however.

Dr. Carvalho and colleagues decided to evaluate whether apneas during sleep, reported by the patient or an informant, were associated with high levels of tau in cognitively normal elderly individuals. The investigators identified 288 participants in the Mayo Clinic Study of Aging for their analysis. Eligible participants were aged 65 years or older, had no cognitive impairment, had undergone tau PET and amyloid PET scans, and had completed a questionnaire that solicited information about witnessed apneas during sleep (either from patients or bed partners). Dr. Carvalho’s group took the entorhinal cortex as its region of interest because it is highly susceptible to tau accumulation. The entorhinal cortex is involved in memory, navigation, and the perception of time. They chose the cerebellum crus as their reference region.

The investigators created a linear model to evaluate the association between tau in the entorhinal cortex and witnessed apneas. They controlled the data for age, sex, years of education, body mass index, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, reduced sleep, excessive daytime sleepiness, and global amyloid.

In all, 43 participants (15%) had witnessed apneas during sleep. Witnessed apneas were significantly associated with tau in the entorhinal cortex. After controlling for potential confounders, Dr. Carvalho and colleagues estimated a 0.049 elevation in the entorhinal cortex tau standardized uptake value ratio (95% confidence interval, 0.011–0.087; P = 0.012).

The study had a relatively small sample size, and its results require validation. Other important limitations include the absence of sleep studies to confirm the presence and severity of sleep apnea and a lack of information about whether participants already were receiving treatment for sleep apnea.

The National Institutes of Health supported the study.

SOURCE: Carvalho D et al. AAN 2019, Abstract P3.6-021.

PHILADELPHIA – according to data that will be presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology. Tau accumulation is a biomarker of Alzheimer’s disease, and the finding suggests a possible explanation for the apparent association between sleep disruption and dementia.

“Our research results raise the possibility that sleep apnea affects tau accumulation,” said Diego Z. Carvalho, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., in a press release. “But it is also possible that higher levels of tau in other regions may predispose a person to sleep apnea, so longer studies are now needed to solve this chicken-and-egg problem.”

Previous research had suggested an association between sleep disruption and increased risk of dementia. Obstructive sleep apnea in particular has been associated with this increased risk. The pathological processes that account for this association are unknown, however.

Dr. Carvalho and colleagues decided to evaluate whether apneas during sleep, reported by the patient or an informant, were associated with high levels of tau in cognitively normal elderly individuals. The investigators identified 288 participants in the Mayo Clinic Study of Aging for their analysis. Eligible participants were aged 65 years or older, had no cognitive impairment, had undergone tau PET and amyloid PET scans, and had completed a questionnaire that solicited information about witnessed apneas during sleep (either from patients or bed partners). Dr. Carvalho’s group took the entorhinal cortex as its region of interest because it is highly susceptible to tau accumulation. The entorhinal cortex is involved in memory, navigation, and the perception of time. They chose the cerebellum crus as their reference region.

The investigators created a linear model to evaluate the association between tau in the entorhinal cortex and witnessed apneas. They controlled the data for age, sex, years of education, body mass index, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, reduced sleep, excessive daytime sleepiness, and global amyloid.

In all, 43 participants (15%) had witnessed apneas during sleep. Witnessed apneas were significantly associated with tau in the entorhinal cortex. After controlling for potential confounders, Dr. Carvalho and colleagues estimated a 0.049 elevation in the entorhinal cortex tau standardized uptake value ratio (95% confidence interval, 0.011–0.087; P = 0.012).

The study had a relatively small sample size, and its results require validation. Other important limitations include the absence of sleep studies to confirm the presence and severity of sleep apnea and a lack of information about whether participants already were receiving treatment for sleep apnea.

The National Institutes of Health supported the study.

SOURCE: Carvalho D et al. AAN 2019, Abstract P3.6-021.

PHILADELPHIA – according to data that will be presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology. Tau accumulation is a biomarker of Alzheimer’s disease, and the finding suggests a possible explanation for the apparent association between sleep disruption and dementia.

“Our research results raise the possibility that sleep apnea affects tau accumulation,” said Diego Z. Carvalho, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., in a press release. “But it is also possible that higher levels of tau in other regions may predispose a person to sleep apnea, so longer studies are now needed to solve this chicken-and-egg problem.”

Previous research had suggested an association between sleep disruption and increased risk of dementia. Obstructive sleep apnea in particular has been associated with this increased risk. The pathological processes that account for this association are unknown, however.

Dr. Carvalho and colleagues decided to evaluate whether apneas during sleep, reported by the patient or an informant, were associated with high levels of tau in cognitively normal elderly individuals. The investigators identified 288 participants in the Mayo Clinic Study of Aging for their analysis. Eligible participants were aged 65 years or older, had no cognitive impairment, had undergone tau PET and amyloid PET scans, and had completed a questionnaire that solicited information about witnessed apneas during sleep (either from patients or bed partners). Dr. Carvalho’s group took the entorhinal cortex as its region of interest because it is highly susceptible to tau accumulation. The entorhinal cortex is involved in memory, navigation, and the perception of time. They chose the cerebellum crus as their reference region.

The investigators created a linear model to evaluate the association between tau in the entorhinal cortex and witnessed apneas. They controlled the data for age, sex, years of education, body mass index, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, reduced sleep, excessive daytime sleepiness, and global amyloid.

In all, 43 participants (15%) had witnessed apneas during sleep. Witnessed apneas were significantly associated with tau in the entorhinal cortex. After controlling for potential confounders, Dr. Carvalho and colleagues estimated a 0.049 elevation in the entorhinal cortex tau standardized uptake value ratio (95% confidence interval, 0.011–0.087; P = 0.012).

The study had a relatively small sample size, and its results require validation. Other important limitations include the absence of sleep studies to confirm the presence and severity of sleep apnea and a lack of information about whether participants already were receiving treatment for sleep apnea.

The National Institutes of Health supported the study.

SOURCE: Carvalho D et al. AAN 2019, Abstract P3.6-021.

FROM AAN 2019

Technology and the evolution of medical knowledge: What’s happening in the background

“Knowledge comes, but wisdom lingers. It may not be difficult to store up in the mind a vast quantity of facts within a comparatively short time, but the ability to form judgments requires the severe discipline of hard work and the tempering heat of experience and maturity.” – Calvin Coolidge

The information we use every day in patient care comes from one of two sources: personal experience (our own or that of another clinician) or a research study. Up until a hundred years ago, medicine was primarily a trade in which more experienced clinicians passed along their wisdom to younger clinicians, teaching them the things that they had learned during their long and difficult careers. Knowledge accrued slowly, influenced by the biased observations of each practicing doctor. People tended to remember their successes or unusual outcomes more than their failures or ordinary outcomes. Eventually, doctors realized that their knowledge base would be more accurate and accumulate more efficiently if they looked at the outcomes of many patients given the same treatment. Thus, the observational trial emerged.

As promising and important as the dawn of observational research was, it quickly became apparent that these trials had important limitations. The most notable limitations were the potential for bias and confounding variables to influence the results. Bias occurs when the opinion of the researcher influences how the result is interpreted. Confounders occur when an outcome is generated by some unexpected aspect of the patient, environment, or medication, rather than the thing that is being studied. An example of this might be a study that finds a higher mortality rate in a city by the sea than a city located inland. From these results, one might initially conclude that the sea is unhealthy. After realizing more retired people lived in the city by the sea; however, an individual would probably change his or her mind. In this example, the older age of this city’s population would be a confounding variable that drove the increased mortality in the city by the sea.

To solve the inherent problems with observational trials, the randomized, controlled trial was developed. Our reliance on information from RCTs runs so deep that it is hard to believe that the first modern clinical trial was not reported until 1948, in a paper on streptomycin in the treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis. It followed that faith in the randomized, controlled trial reached almost religious proportions, and the belief that information that does not come from an RCT should not be relied on was held by many, until recently. Why have things changed and what does this have to do with technology?

The first is an increasing recognition that, for all of their advantages, randomized trials have one nagging but critical limitation – generalizability. Randomized trials have strict inclusion and exclusion criteria. We do not have such inclusion and exclusion criteria when we take care of patients in our offices. For example, a recent trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine (2018 Dec 4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1814468.), entitled “Apixaban to prevent venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer,” concluded that apixaban therapy resulted in a lower rate of venous thromboembolism than did placebo in patients starting chemotherapy for cancer. This was a large trial with more than 500 patients enrolled, and it reached an important conclusion with significant clinical implications. When you look at the details of the article, more than 1,800 patients were assessed to find the 500 patients who were eventually included in the trial. This is fairly typical of clinical trials and raises an important point: We need to be careful about how well the results of these clinical trials can be generalized to apply to the patient in front of us. This leads us to the second development that is something happening behind the scenes that each of us has contributed to.

Real-world research

As we see each patient and type information into the EHR, we add to an enormous database of medical information. That database is increasingly being used to advance our knowledge of how medicines actually work in the real world with real patients, and has already started providing answers that supplement, clarify, and even change our perspectives. The information will provide observations derived from real populations that have not been selected or influenced by the way in which a study is conducted. This new field of research is called “real-world research.”

An example of the difference between randomized controlled trial results and real-world research was published in Diabetes Care. This article examined the effectiveness of dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitors vs. glucagonlike peptide–1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) in the treatment of patients with diabetes. The goal of the study was to assess the difference in change in hemoglobin A1c between real-world evidence and randomized-trial evidence after initiation of a GLP-1 RA or a DPP-4 inhibitor. In RCTs, GLP-1 RAs decreased HbA1c by about 1.3% while DPP-4 inhibitors decreased HbA1c by about 0.68% (i.e., DPP-4 inhibitors were about half as effective). However, when the effects of these two diabetes drugs were examined using clinical databases in the real world, the two classes of medications had almost the same effect, each decreasing HbA1c by about 0.5%. This difference between RCT and real-world evidence might have been caused by the differential adherence to the two classes of medications, one being an injectable with significant GI side effects, and the other being a pill with few side effects.

The important take-home point is that we are now all contributing to a massive database that can be queried to give quicker, more accurate, more relevant information. Along with personal experience and randomized trials, this third source of clinical information, when used with wisdom, will provide us with the information we need to take ever better care of patients.

References

Carls GS et al. Understanding the gap between efficacy in randomized controlled trials and effectiveness in real-world use of GLP-1 RA and DPP-4 therapies in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2017;40:1469-78.

Blonde L et al. Interpretation and impact of real-world clinical data for the practicing clinician. Adv Ther. 2018 Nov;35:1763-74.

“Knowledge comes, but wisdom lingers. It may not be difficult to store up in the mind a vast quantity of facts within a comparatively short time, but the ability to form judgments requires the severe discipline of hard work and the tempering heat of experience and maturity.” – Calvin Coolidge

The information we use every day in patient care comes from one of two sources: personal experience (our own or that of another clinician) or a research study. Up until a hundred years ago, medicine was primarily a trade in which more experienced clinicians passed along their wisdom to younger clinicians, teaching them the things that they had learned during their long and difficult careers. Knowledge accrued slowly, influenced by the biased observations of each practicing doctor. People tended to remember their successes or unusual outcomes more than their failures or ordinary outcomes. Eventually, doctors realized that their knowledge base would be more accurate and accumulate more efficiently if they looked at the outcomes of many patients given the same treatment. Thus, the observational trial emerged.

As promising and important as the dawn of observational research was, it quickly became apparent that these trials had important limitations. The most notable limitations were the potential for bias and confounding variables to influence the results. Bias occurs when the opinion of the researcher influences how the result is interpreted. Confounders occur when an outcome is generated by some unexpected aspect of the patient, environment, or medication, rather than the thing that is being studied. An example of this might be a study that finds a higher mortality rate in a city by the sea than a city located inland. From these results, one might initially conclude that the sea is unhealthy. After realizing more retired people lived in the city by the sea; however, an individual would probably change his or her mind. In this example, the older age of this city’s population would be a confounding variable that drove the increased mortality in the city by the sea.

To solve the inherent problems with observational trials, the randomized, controlled trial was developed. Our reliance on information from RCTs runs so deep that it is hard to believe that the first modern clinical trial was not reported until 1948, in a paper on streptomycin in the treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis. It followed that faith in the randomized, controlled trial reached almost religious proportions, and the belief that information that does not come from an RCT should not be relied on was held by many, until recently. Why have things changed and what does this have to do with technology?

The first is an increasing recognition that, for all of their advantages, randomized trials have one nagging but critical limitation – generalizability. Randomized trials have strict inclusion and exclusion criteria. We do not have such inclusion and exclusion criteria when we take care of patients in our offices. For example, a recent trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine (2018 Dec 4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1814468.), entitled “Apixaban to prevent venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer,” concluded that apixaban therapy resulted in a lower rate of venous thromboembolism than did placebo in patients starting chemotherapy for cancer. This was a large trial with more than 500 patients enrolled, and it reached an important conclusion with significant clinical implications. When you look at the details of the article, more than 1,800 patients were assessed to find the 500 patients who were eventually included in the trial. This is fairly typical of clinical trials and raises an important point: We need to be careful about how well the results of these clinical trials can be generalized to apply to the patient in front of us. This leads us to the second development that is something happening behind the scenes that each of us has contributed to.

Real-world research

As we see each patient and type information into the EHR, we add to an enormous database of medical information. That database is increasingly being used to advance our knowledge of how medicines actually work in the real world with real patients, and has already started providing answers that supplement, clarify, and even change our perspectives. The information will provide observations derived from real populations that have not been selected or influenced by the way in which a study is conducted. This new field of research is called “real-world research.”

An example of the difference between randomized controlled trial results and real-world research was published in Diabetes Care. This article examined the effectiveness of dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitors vs. glucagonlike peptide–1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) in the treatment of patients with diabetes. The goal of the study was to assess the difference in change in hemoglobin A1c between real-world evidence and randomized-trial evidence after initiation of a GLP-1 RA or a DPP-4 inhibitor. In RCTs, GLP-1 RAs decreased HbA1c by about 1.3% while DPP-4 inhibitors decreased HbA1c by about 0.68% (i.e., DPP-4 inhibitors were about half as effective). However, when the effects of these two diabetes drugs were examined using clinical databases in the real world, the two classes of medications had almost the same effect, each decreasing HbA1c by about 0.5%. This difference between RCT and real-world evidence might have been caused by the differential adherence to the two classes of medications, one being an injectable with significant GI side effects, and the other being a pill with few side effects.

The important take-home point is that we are now all contributing to a massive database that can be queried to give quicker, more accurate, more relevant information. Along with personal experience and randomized trials, this third source of clinical information, when used with wisdom, will provide us with the information we need to take ever better care of patients.

References

Carls GS et al. Understanding the gap between efficacy in randomized controlled trials and effectiveness in real-world use of GLP-1 RA and DPP-4 therapies in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2017;40:1469-78.

Blonde L et al. Interpretation and impact of real-world clinical data for the practicing clinician. Adv Ther. 2018 Nov;35:1763-74.

“Knowledge comes, but wisdom lingers. It may not be difficult to store up in the mind a vast quantity of facts within a comparatively short time, but the ability to form judgments requires the severe discipline of hard work and the tempering heat of experience and maturity.” – Calvin Coolidge

The information we use every day in patient care comes from one of two sources: personal experience (our own or that of another clinician) or a research study. Up until a hundred years ago, medicine was primarily a trade in which more experienced clinicians passed along their wisdom to younger clinicians, teaching them the things that they had learned during their long and difficult careers. Knowledge accrued slowly, influenced by the biased observations of each practicing doctor. People tended to remember their successes or unusual outcomes more than their failures or ordinary outcomes. Eventually, doctors realized that their knowledge base would be more accurate and accumulate more efficiently if they looked at the outcomes of many patients given the same treatment. Thus, the observational trial emerged.

As promising and important as the dawn of observational research was, it quickly became apparent that these trials had important limitations. The most notable limitations were the potential for bias and confounding variables to influence the results. Bias occurs when the opinion of the researcher influences how the result is interpreted. Confounders occur when an outcome is generated by some unexpected aspect of the patient, environment, or medication, rather than the thing that is being studied. An example of this might be a study that finds a higher mortality rate in a city by the sea than a city located inland. From these results, one might initially conclude that the sea is unhealthy. After realizing more retired people lived in the city by the sea; however, an individual would probably change his or her mind. In this example, the older age of this city’s population would be a confounding variable that drove the increased mortality in the city by the sea.

To solve the inherent problems with observational trials, the randomized, controlled trial was developed. Our reliance on information from RCTs runs so deep that it is hard to believe that the first modern clinical trial was not reported until 1948, in a paper on streptomycin in the treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis. It followed that faith in the randomized, controlled trial reached almost religious proportions, and the belief that information that does not come from an RCT should not be relied on was held by many, until recently. Why have things changed and what does this have to do with technology?

The first is an increasing recognition that, for all of their advantages, randomized trials have one nagging but critical limitation – generalizability. Randomized trials have strict inclusion and exclusion criteria. We do not have such inclusion and exclusion criteria when we take care of patients in our offices. For example, a recent trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine (2018 Dec 4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1814468.), entitled “Apixaban to prevent venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer,” concluded that apixaban therapy resulted in a lower rate of venous thromboembolism than did placebo in patients starting chemotherapy for cancer. This was a large trial with more than 500 patients enrolled, and it reached an important conclusion with significant clinical implications. When you look at the details of the article, more than 1,800 patients were assessed to find the 500 patients who were eventually included in the trial. This is fairly typical of clinical trials and raises an important point: We need to be careful about how well the results of these clinical trials can be generalized to apply to the patient in front of us. This leads us to the second development that is something happening behind the scenes that each of us has contributed to.

Real-world research

As we see each patient and type information into the EHR, we add to an enormous database of medical information. That database is increasingly being used to advance our knowledge of how medicines actually work in the real world with real patients, and has already started providing answers that supplement, clarify, and even change our perspectives. The information will provide observations derived from real populations that have not been selected or influenced by the way in which a study is conducted. This new field of research is called “real-world research.”

An example of the difference between randomized controlled trial results and real-world research was published in Diabetes Care. This article examined the effectiveness of dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitors vs. glucagonlike peptide–1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) in the treatment of patients with diabetes. The goal of the study was to assess the difference in change in hemoglobin A1c between real-world evidence and randomized-trial evidence after initiation of a GLP-1 RA or a DPP-4 inhibitor. In RCTs, GLP-1 RAs decreased HbA1c by about 1.3% while DPP-4 inhibitors decreased HbA1c by about 0.68% (i.e., DPP-4 inhibitors were about half as effective). However, when the effects of these two diabetes drugs were examined using clinical databases in the real world, the two classes of medications had almost the same effect, each decreasing HbA1c by about 0.5%. This difference between RCT and real-world evidence might have been caused by the differential adherence to the two classes of medications, one being an injectable with significant GI side effects, and the other being a pill with few side effects.

The important take-home point is that we are now all contributing to a massive database that can be queried to give quicker, more accurate, more relevant information. Along with personal experience and randomized trials, this third source of clinical information, when used with wisdom, will provide us with the information we need to take ever better care of patients.

References

Carls GS et al. Understanding the gap between efficacy in randomized controlled trials and effectiveness in real-world use of GLP-1 RA and DPP-4 therapies in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2017;40:1469-78.

Blonde L et al. Interpretation and impact of real-world clinical data for the practicing clinician. Adv Ther. 2018 Nov;35:1763-74.

Using Social Media to Talk About Public Health Issues

Public health organizations have learned that when it comes to sharing important information, it pays to capitalize on social media. Platforms like Facebook can not only reach multitudes, but also spread a message far more widely than conventional media can. But what is the best way to leverage social media for public health messages? Researchers from University of Sydney in Australia analyzed 20 Facebook pages on skin cancer, smoking, and other public health issues to find out the most effective strategies for getting users to engage.

The researchers coded 360 days of posts for each page, ending up with 5,356 posts. They categorized the communication techniques as informative, call-to-action, instructive, positive emotive appeal, fear appeal, testimonial, and humor. They also looked at marketing elements, such as whether the page used branding, celebrities or persons of authority, mascots, competitions or giveaways, sponsorships, or vouchers and other offers.

Almost all pages were administered by a nongovernment organization. Mental health and cancer prevention were the most common public health issues. Most posts were photos; the next most common were links (but only 1% of users actually clicked on the links). The most common communication techniques were positive emotional appeal and testimonial. Fear appeal was the least common.

Video posts engaged the most users, getting the most likes and shares, the researchers say. Videos received nearly 4 times as many shares as photo posts; links and text received 30% and 69% fewer shares, respectively. Video and text-only posts received more comments than photo posts. However, the researchers add, this could reflect the Facebook algorithm, which may favor videos over other post types. They also note that only 3% of all posts they coded were videos, “suggesting that public health organizations are trailing behind conventional marketers.”

Posts with positive emotional appeal drew 18% more likes than call-to-action posts, but 27% fewer shares. Informative posts received more than twice as many shares. Fear appeal and humorous posts received more comments than call-to-action posts (perhaps because they are more controversial, the researchers suggest), and instructive posts received fewer.

Conventional marketing, such as using sponsorships or “persons of authority,” generally did not have much engagement. Celebrities and sports figures, though, got 62% more likes, more than double the shares, and 64% more comments than posts without celebrities and sportspeople.

Still, regardless of the post type, communication technique, or marketing element, the researchers say, only 2% to 6% of potential customers engaged with it in some way.

Public health organizations have learned that when it comes to sharing important information, it pays to capitalize on social media. Platforms like Facebook can not only reach multitudes, but also spread a message far more widely than conventional media can. But what is the best way to leverage social media for public health messages? Researchers from University of Sydney in Australia analyzed 20 Facebook pages on skin cancer, smoking, and other public health issues to find out the most effective strategies for getting users to engage.

The researchers coded 360 days of posts for each page, ending up with 5,356 posts. They categorized the communication techniques as informative, call-to-action, instructive, positive emotive appeal, fear appeal, testimonial, and humor. They also looked at marketing elements, such as whether the page used branding, celebrities or persons of authority, mascots, competitions or giveaways, sponsorships, or vouchers and other offers.

Almost all pages were administered by a nongovernment organization. Mental health and cancer prevention were the most common public health issues. Most posts were photos; the next most common were links (but only 1% of users actually clicked on the links). The most common communication techniques were positive emotional appeal and testimonial. Fear appeal was the least common.

Video posts engaged the most users, getting the most likes and shares, the researchers say. Videos received nearly 4 times as many shares as photo posts; links and text received 30% and 69% fewer shares, respectively. Video and text-only posts received more comments than photo posts. However, the researchers add, this could reflect the Facebook algorithm, which may favor videos over other post types. They also note that only 3% of all posts they coded were videos, “suggesting that public health organizations are trailing behind conventional marketers.”

Posts with positive emotional appeal drew 18% more likes than call-to-action posts, but 27% fewer shares. Informative posts received more than twice as many shares. Fear appeal and humorous posts received more comments than call-to-action posts (perhaps because they are more controversial, the researchers suggest), and instructive posts received fewer.

Conventional marketing, such as using sponsorships or “persons of authority,” generally did not have much engagement. Celebrities and sports figures, though, got 62% more likes, more than double the shares, and 64% more comments than posts without celebrities and sportspeople.

Still, regardless of the post type, communication technique, or marketing element, the researchers say, only 2% to 6% of potential customers engaged with it in some way.

Public health organizations have learned that when it comes to sharing important information, it pays to capitalize on social media. Platforms like Facebook can not only reach multitudes, but also spread a message far more widely than conventional media can. But what is the best way to leverage social media for public health messages? Researchers from University of Sydney in Australia analyzed 20 Facebook pages on skin cancer, smoking, and other public health issues to find out the most effective strategies for getting users to engage.

The researchers coded 360 days of posts for each page, ending up with 5,356 posts. They categorized the communication techniques as informative, call-to-action, instructive, positive emotive appeal, fear appeal, testimonial, and humor. They also looked at marketing elements, such as whether the page used branding, celebrities or persons of authority, mascots, competitions or giveaways, sponsorships, or vouchers and other offers.

Almost all pages were administered by a nongovernment organization. Mental health and cancer prevention were the most common public health issues. Most posts were photos; the next most common were links (but only 1% of users actually clicked on the links). The most common communication techniques were positive emotional appeal and testimonial. Fear appeal was the least common.

Video posts engaged the most users, getting the most likes and shares, the researchers say. Videos received nearly 4 times as many shares as photo posts; links and text received 30% and 69% fewer shares, respectively. Video and text-only posts received more comments than photo posts. However, the researchers add, this could reflect the Facebook algorithm, which may favor videos over other post types. They also note that only 3% of all posts they coded were videos, “suggesting that public health organizations are trailing behind conventional marketers.”

Posts with positive emotional appeal drew 18% more likes than call-to-action posts, but 27% fewer shares. Informative posts received more than twice as many shares. Fear appeal and humorous posts received more comments than call-to-action posts (perhaps because they are more controversial, the researchers suggest), and instructive posts received fewer.

Conventional marketing, such as using sponsorships or “persons of authority,” generally did not have much engagement. Celebrities and sports figures, though, got 62% more likes, more than double the shares, and 64% more comments than posts without celebrities and sportspeople.

Still, regardless of the post type, communication technique, or marketing element, the researchers say, only 2% to 6% of potential customers engaged with it in some way.

Chronic abdominal pain, career options in industry, coding basics, and more

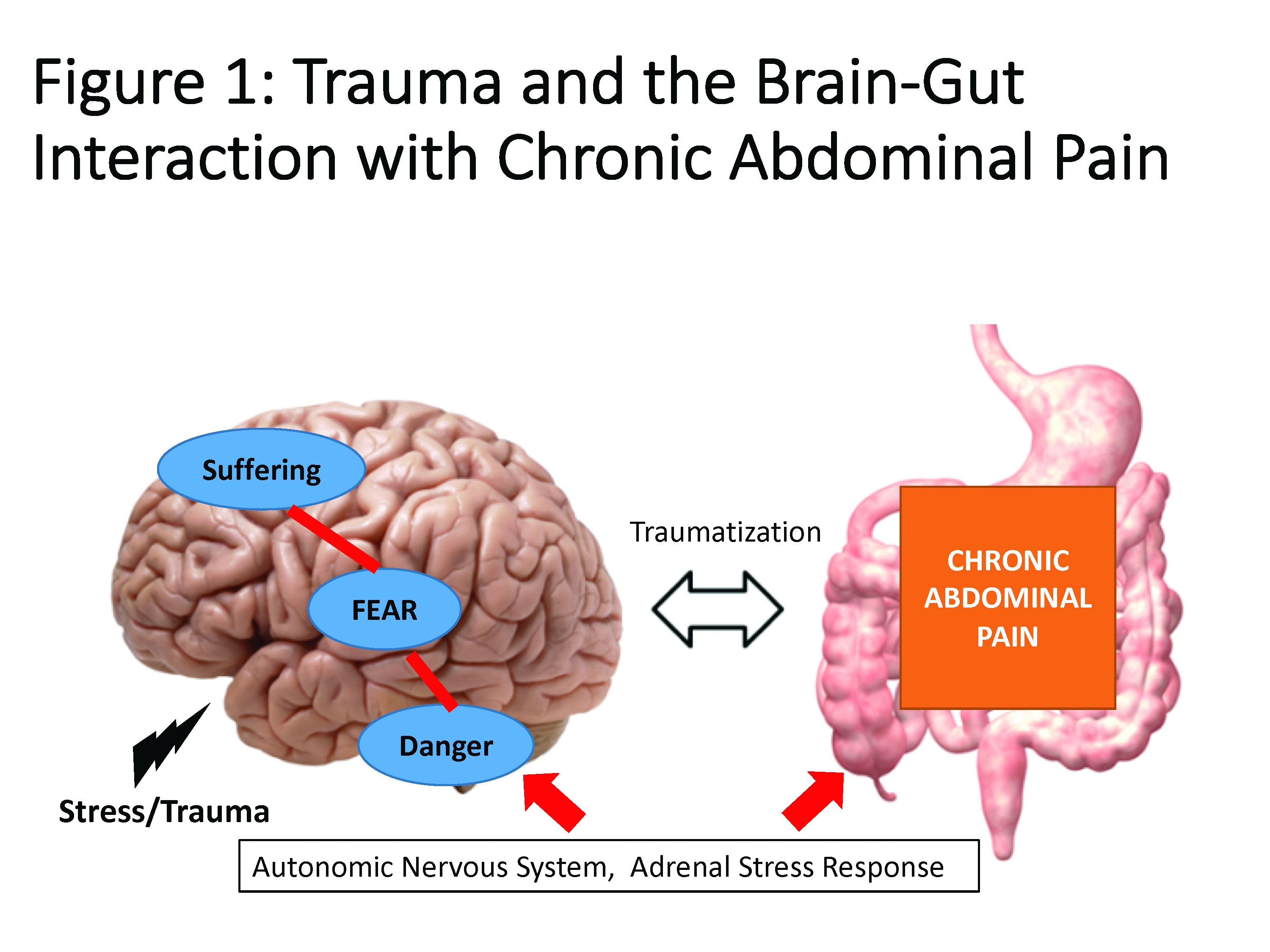

As many of us see patients with abdominal pain on an almost daily basis, it becomes easy to overlook the substantial long-term effects this chronic pain can have on patients. In this quarter’s In Focus article, Emily Weaver and Eva Szigethy (UPMC) explore how to utilize a multidisciplinary approach to effectively treat chronic abdominal pain, and they also highlight how chronic abdominal pain can truly be a traumatic experience for patients. This article is definitely a must-read for all practitioners.

Also in this issue of The New Gastroenterologist, Matthew Whitson (Hofstra-Northwell) provides some advice on becoming an effective educator, which is critically important, especially when making the transition from being a trainee to now having to teach trainees. Additionally, Erica Cohen and Gil Melmed (Cedars-Sinai) provide some important lessons about attempting to start an investigator-led clinical trial, which is a difficult task regardless of what career stage you’re in.

In this quarter’s DHPA-cosponsored private practice perspective, Marc Sonenshine (Atlanta Gastroenterology Associates) provides some tips for how to develop a specialized niche in private practice. And in our postfellowship pathway section, Mark Sostek (Orphomed) provides an enlightening overview of some career options in industry.

Finally, Kathleen Mueller (AskMueller Consulting, LLC) gives an overview of some coding basics, which is important knowledge, especially for trainees, and Latha Alaparthi (Gastroenterology Center of Connecticut/Yale/Quinnipiac) provides an overview of some advanced degree programs you may consider when contemplating a career change.

Interested in contributing to The New Gastroenterologist? Have ideas for future issues? If so, please contact me at [email protected] or the managing editor, Ryan Farrell, at [email protected].

Sincerely,

Bryson W. Katona, MD, PhD

Editor in Chief

Dr. Katona is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

As many of us see patients with abdominal pain on an almost daily basis, it becomes easy to overlook the substantial long-term effects this chronic pain can have on patients. In this quarter’s In Focus article, Emily Weaver and Eva Szigethy (UPMC) explore how to utilize a multidisciplinary approach to effectively treat chronic abdominal pain, and they also highlight how chronic abdominal pain can truly be a traumatic experience for patients. This article is definitely a must-read for all practitioners.

Also in this issue of The New Gastroenterologist, Matthew Whitson (Hofstra-Northwell) provides some advice on becoming an effective educator, which is critically important, especially when making the transition from being a trainee to now having to teach trainees. Additionally, Erica Cohen and Gil Melmed (Cedars-Sinai) provide some important lessons about attempting to start an investigator-led clinical trial, which is a difficult task regardless of what career stage you’re in.

In this quarter’s DHPA-cosponsored private practice perspective, Marc Sonenshine (Atlanta Gastroenterology Associates) provides some tips for how to develop a specialized niche in private practice. And in our postfellowship pathway section, Mark Sostek (Orphomed) provides an enlightening overview of some career options in industry.

Finally, Kathleen Mueller (AskMueller Consulting, LLC) gives an overview of some coding basics, which is important knowledge, especially for trainees, and Latha Alaparthi (Gastroenterology Center of Connecticut/Yale/Quinnipiac) provides an overview of some advanced degree programs you may consider when contemplating a career change.

Interested in contributing to The New Gastroenterologist? Have ideas for future issues? If so, please contact me at [email protected] or the managing editor, Ryan Farrell, at [email protected].

Sincerely,

Bryson W. Katona, MD, PhD

Editor in Chief

Dr. Katona is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

As many of us see patients with abdominal pain on an almost daily basis, it becomes easy to overlook the substantial long-term effects this chronic pain can have on patients. In this quarter’s In Focus article, Emily Weaver and Eva Szigethy (UPMC) explore how to utilize a multidisciplinary approach to effectively treat chronic abdominal pain, and they also highlight how chronic abdominal pain can truly be a traumatic experience for patients. This article is definitely a must-read for all practitioners.