User login

Benlysta approved for children with SLE

The B-lymphocyte stimulator–inhibitor called Benlysta already is approved for use in adults alongside standard therapy for SLE, and this approval marks the first such treatment available for children. Although there are regulatory submissions for use of this drug among children elsewhere, the United States is the first to approve its use among this age group, according to a press release from GSK. According to an FDA press announcement, the agency expedited the review and approval because belimumab could fulfill an unmet need.

The approval is based on a 1-year postapproval commitment study, which assessed efficacy, safety, and pharmacokinetics of 10 mg/kg belimumab plus standard therapy versus placebo plus standard therapy among children with SLE aged 5-11 years (n = 13) and those aged 12-17 years (n = 80). Although the study was not fully powered because of the rarity of the disease in this age group, it did find numerically higher SLE responder index response rates over 1 year among children treated with belimumab plus standard therapy (53%) than in those treated with placebo and standard therapy (44%).

Adverse reactions seen among this age group were consistent with those seen in adults, including nausea, diarrhea, pyrexia, nasopharyngitis, and bronchitis. The most common serious adverse reactions were serious infections. Belimumab has not been studied in combination with certain other drugs, such as other biologics or cyclophosphamide; therefore, combining it with such treatments is not recommended. Acute hypersensitivity reactions – including anaphylaxis and death – have been observed, even among patients who had previously tolerated belimumab.

Infusion reactions were common, so pretreat patients with an antihistamine. Also, do not administer the drug with live vaccines, the FDA noted.

More information can be found in the press announcement on the FDA website.

The B-lymphocyte stimulator–inhibitor called Benlysta already is approved for use in adults alongside standard therapy for SLE, and this approval marks the first such treatment available for children. Although there are regulatory submissions for use of this drug among children elsewhere, the United States is the first to approve its use among this age group, according to a press release from GSK. According to an FDA press announcement, the agency expedited the review and approval because belimumab could fulfill an unmet need.

The approval is based on a 1-year postapproval commitment study, which assessed efficacy, safety, and pharmacokinetics of 10 mg/kg belimumab plus standard therapy versus placebo plus standard therapy among children with SLE aged 5-11 years (n = 13) and those aged 12-17 years (n = 80). Although the study was not fully powered because of the rarity of the disease in this age group, it did find numerically higher SLE responder index response rates over 1 year among children treated with belimumab plus standard therapy (53%) than in those treated with placebo and standard therapy (44%).

Adverse reactions seen among this age group were consistent with those seen in adults, including nausea, diarrhea, pyrexia, nasopharyngitis, and bronchitis. The most common serious adverse reactions were serious infections. Belimumab has not been studied in combination with certain other drugs, such as other biologics or cyclophosphamide; therefore, combining it with such treatments is not recommended. Acute hypersensitivity reactions – including anaphylaxis and death – have been observed, even among patients who had previously tolerated belimumab.

Infusion reactions were common, so pretreat patients with an antihistamine. Also, do not administer the drug with live vaccines, the FDA noted.

More information can be found in the press announcement on the FDA website.

The B-lymphocyte stimulator–inhibitor called Benlysta already is approved for use in adults alongside standard therapy for SLE, and this approval marks the first such treatment available for children. Although there are regulatory submissions for use of this drug among children elsewhere, the United States is the first to approve its use among this age group, according to a press release from GSK. According to an FDA press announcement, the agency expedited the review and approval because belimumab could fulfill an unmet need.

The approval is based on a 1-year postapproval commitment study, which assessed efficacy, safety, and pharmacokinetics of 10 mg/kg belimumab plus standard therapy versus placebo plus standard therapy among children with SLE aged 5-11 years (n = 13) and those aged 12-17 years (n = 80). Although the study was not fully powered because of the rarity of the disease in this age group, it did find numerically higher SLE responder index response rates over 1 year among children treated with belimumab plus standard therapy (53%) than in those treated with placebo and standard therapy (44%).

Adverse reactions seen among this age group were consistent with those seen in adults, including nausea, diarrhea, pyrexia, nasopharyngitis, and bronchitis. The most common serious adverse reactions were serious infections. Belimumab has not been studied in combination with certain other drugs, such as other biologics or cyclophosphamide; therefore, combining it with such treatments is not recommended. Acute hypersensitivity reactions – including anaphylaxis and death – have been observed, even among patients who had previously tolerated belimumab.

Infusion reactions were common, so pretreat patients with an antihistamine. Also, do not administer the drug with live vaccines, the FDA noted.

More information can be found in the press announcement on the FDA website.

Statute of limitations in malpractice actions

Question: Regarding the statute of limitations, which of the following is incorrect?

A. The statute stipulates the time period from knowledge of injury to when a lawsuit must be filed, beyond which it will be forever barred.

B. This time period is usually 2 years but varies somewhat from jurisdiction to jurisdiction.

C. It starts to “run” when the cause of action accrues, i.e., when the claimant knew or should have known of the injury, not when the negligent act took place.

D. In the case of minors, disability, and concealment, the statute may be tolled, thereby giving the plaintiff more time to file his/her claim.

E. In some U.S. jurisdictions, the judge may exercise discretion and waive the statutory time period.

Answer: E. At common law, there was no time limit that barred a plaintiff from bringing a claim, although there was a so-called “doctrine of laches” that foreclosed an action that had long lapsed. However, statutory changes in the law now require that complaints be brought in a timely manner so that the evidence remains fresh, accurate, and reliable. Another reason is to provide repose to the wrongdoer, i.e., relief from worrying for an indefinite period of time whether a lawsuit will be brought. It is 2 years for the tort of negligence in most jurisdictions, although states like California and Tennessee place a 1-year limit on medical malpractice claims under some circumstances. In England, actions for negligence-based personal injury have a limitation period of 3 years. Additionally, section 33 allows the court to use its discretion to extend this time period, something that is not available in other common law jurisdictions such as Singapore and the United States.

The statute of limitations does not start to run from the date of the negligent act or omission. For example, if there is a failure to timely diagnose and treat a cancerous condition and the patient suffers harm several years later, time starts to accrue from the date of discovering the injury, not the date of misdiagnosis. The term “discovery rule” defines the accrual period, which begins from the date the injury is discovered or should have been discovered if the party had exercised reasonable diligence. In cases of fraudulent concealment of a right of action, the statute may be tolled (halted) during the period of concealment. Tolling also may apply during legal disability.

In malpractice actions involving minors, the running of the time period may be tolled until the minor reaches a certain age, such as the age of majority, or by the minor’s 10th birthday (Hawaii law). Chaffin v. Nicosia1 dealt with such a situation. As the result of negligent forceps delivery, which injured the optic nerve, the plaintiff became blind in the right eye in early infancy. He brought suit when he was 22 years old. Indiana had two statutes on the issue, one requiring a malpractice suit to be brought within 2 years of the incident, and the other allowing a minor to sue no later than 2 years after reaching the age of 21. The Indiana Supreme Court allowed the case to go forward, reversing the lower court’s decision barring the action.

Courts are apt to closely scrutinize attempts to use the statute of limitations to prevent recovery as taking such actions could deprive the injured plaintiff of an otherwise legitimate claim. In one example, the defendants sought to dismiss the case (so-called motion for summary judgment) by arguing that the plaintiff filed suit some 32 months after she had developed Sheehan syndrome from postpartum hemorrhagic shock, and this exceeded the 2-year statute of limitations. The court ruled: “Since reasonable minds could differ as to when the injury and its operative cause should have been discovered by a reasonably diligent patient, the timeliness of the plaintiff’s claims should be decided by a jury and the motions for summary judgment will therefore be denied.”2

Two very recent cases are illustrative of litigation over statutes of limitations. In the first case, the District of Columbia’s highest court held that BKW, a patient-plaintiff, did not qualify for an extension and rejected his untimely suit against the hospital.3 The patient’s injuries stemmed from alleged unsuccessful venipunctures, and his complaint contained six causes of action, including negligent and intentional infliction of emotional distress and unnecessary pain, suffering, and bodily injury. In the District of Columbia, a plaintiff must serve the defendant with notice of intention to file suit (pre-suit notice) not less than 90 days prior to filing the action. The plaintiff must then file the complaint itself within the 3-year limitations period, with an extension allowed to take into account the 90-day pre-suit notice requirement. The case centered on the “within 90 days” requirement to trigger the statute of limitations extension. BKW, acting on one’s own behalf, conceded that the 3-year period applicable to his claims had lapsed, but because his complaint was filed “within 90 days” after the limitation period expired, it was eligible for an extension. The Court disagreed and dismissed the case, holding that to be eligible for the 90-day extension, a plaintiff must serve the pre-suit notice within 90 days before the limitation period expired.

The second case4 alleged malpractice in the care of a patient who died of anaphylaxis after a nurse infused him with iron dextran. The nurse had allegedly left the patient’s room too soon and did not adequately monitor his reaction to the drug. The patient was admitted to the hospital for removal of a colonic tumor and was to receive treatment for iron deficiency anemia. The nurse, identified in the chart as Agency Nurse RN 104, administered the prescribed intravenous 25-mg test-dose of iron dextran over a 5-minute period, but when the patient began having an anaphylactic-type allergic reaction, the nurse was allegedly not in the patient’s room. The plaintiff and her attorney attempted, on several occasions and without success, to discover the actual identity of the nurse from the hospital’s representatives. Consequently, the complaint designated the nurse as “Agency Nurse RN 104,” and the plaintiff did not provide the name of the nurse, even though doing so was legally required; the exclusion of the nurse’s name would have resulted in case dismissal since the statute of limitations had lapsed. However, the court ruled, “we are satisfied that plaintiff and her attorney acted with reasonable diligence in attempting – with no avail – to ascertain the true identity of “Agency Nurse RN 104” before filing suit and before the 2-year limitations statute ran ...”

Dr. Tan is emeritus professor of medicine and former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii, Honolulu. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. Portions of this article had been previously published in a 2010 issue of Internal Medicine News. For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected]

References

1. Chaffin v. Nicosia, 310 N.E.2d 867 (Ind. 1974).

2. Lomeo v. Davis, 53 Pa. D. & C. 4th 49 (Pa. Com. Pl. Jul 24, 2001).

3. Waugh v. Medstar Georgetown University Hospital, District of Columbia Court of Appeals No. 18-CV-329. Decided March 14, 2019.

4. Rosenberg v. Watts, Superior Court N.J. Appellate Div., Docket No. A-4525-16T4. Decided March 21, 2019.

Question: Regarding the statute of limitations, which of the following is incorrect?

A. The statute stipulates the time period from knowledge of injury to when a lawsuit must be filed, beyond which it will be forever barred.

B. This time period is usually 2 years but varies somewhat from jurisdiction to jurisdiction.

C. It starts to “run” when the cause of action accrues, i.e., when the claimant knew or should have known of the injury, not when the negligent act took place.

D. In the case of minors, disability, and concealment, the statute may be tolled, thereby giving the plaintiff more time to file his/her claim.

E. In some U.S. jurisdictions, the judge may exercise discretion and waive the statutory time period.

Answer: E. At common law, there was no time limit that barred a plaintiff from bringing a claim, although there was a so-called “doctrine of laches” that foreclosed an action that had long lapsed. However, statutory changes in the law now require that complaints be brought in a timely manner so that the evidence remains fresh, accurate, and reliable. Another reason is to provide repose to the wrongdoer, i.e., relief from worrying for an indefinite period of time whether a lawsuit will be brought. It is 2 years for the tort of negligence in most jurisdictions, although states like California and Tennessee place a 1-year limit on medical malpractice claims under some circumstances. In England, actions for negligence-based personal injury have a limitation period of 3 years. Additionally, section 33 allows the court to use its discretion to extend this time period, something that is not available in other common law jurisdictions such as Singapore and the United States.

The statute of limitations does not start to run from the date of the negligent act or omission. For example, if there is a failure to timely diagnose and treat a cancerous condition and the patient suffers harm several years later, time starts to accrue from the date of discovering the injury, not the date of misdiagnosis. The term “discovery rule” defines the accrual period, which begins from the date the injury is discovered or should have been discovered if the party had exercised reasonable diligence. In cases of fraudulent concealment of a right of action, the statute may be tolled (halted) during the period of concealment. Tolling also may apply during legal disability.

In malpractice actions involving minors, the running of the time period may be tolled until the minor reaches a certain age, such as the age of majority, or by the minor’s 10th birthday (Hawaii law). Chaffin v. Nicosia1 dealt with such a situation. As the result of negligent forceps delivery, which injured the optic nerve, the plaintiff became blind in the right eye in early infancy. He brought suit when he was 22 years old. Indiana had two statutes on the issue, one requiring a malpractice suit to be brought within 2 years of the incident, and the other allowing a minor to sue no later than 2 years after reaching the age of 21. The Indiana Supreme Court allowed the case to go forward, reversing the lower court’s decision barring the action.

Courts are apt to closely scrutinize attempts to use the statute of limitations to prevent recovery as taking such actions could deprive the injured plaintiff of an otherwise legitimate claim. In one example, the defendants sought to dismiss the case (so-called motion for summary judgment) by arguing that the plaintiff filed suit some 32 months after she had developed Sheehan syndrome from postpartum hemorrhagic shock, and this exceeded the 2-year statute of limitations. The court ruled: “Since reasonable minds could differ as to when the injury and its operative cause should have been discovered by a reasonably diligent patient, the timeliness of the plaintiff’s claims should be decided by a jury and the motions for summary judgment will therefore be denied.”2

Two very recent cases are illustrative of litigation over statutes of limitations. In the first case, the District of Columbia’s highest court held that BKW, a patient-plaintiff, did not qualify for an extension and rejected his untimely suit against the hospital.3 The patient’s injuries stemmed from alleged unsuccessful venipunctures, and his complaint contained six causes of action, including negligent and intentional infliction of emotional distress and unnecessary pain, suffering, and bodily injury. In the District of Columbia, a plaintiff must serve the defendant with notice of intention to file suit (pre-suit notice) not less than 90 days prior to filing the action. The plaintiff must then file the complaint itself within the 3-year limitations period, with an extension allowed to take into account the 90-day pre-suit notice requirement. The case centered on the “within 90 days” requirement to trigger the statute of limitations extension. BKW, acting on one’s own behalf, conceded that the 3-year period applicable to his claims had lapsed, but because his complaint was filed “within 90 days” after the limitation period expired, it was eligible for an extension. The Court disagreed and dismissed the case, holding that to be eligible for the 90-day extension, a plaintiff must serve the pre-suit notice within 90 days before the limitation period expired.

The second case4 alleged malpractice in the care of a patient who died of anaphylaxis after a nurse infused him with iron dextran. The nurse had allegedly left the patient’s room too soon and did not adequately monitor his reaction to the drug. The patient was admitted to the hospital for removal of a colonic tumor and was to receive treatment for iron deficiency anemia. The nurse, identified in the chart as Agency Nurse RN 104, administered the prescribed intravenous 25-mg test-dose of iron dextran over a 5-minute period, but when the patient began having an anaphylactic-type allergic reaction, the nurse was allegedly not in the patient’s room. The plaintiff and her attorney attempted, on several occasions and without success, to discover the actual identity of the nurse from the hospital’s representatives. Consequently, the complaint designated the nurse as “Agency Nurse RN 104,” and the plaintiff did not provide the name of the nurse, even though doing so was legally required; the exclusion of the nurse’s name would have resulted in case dismissal since the statute of limitations had lapsed. However, the court ruled, “we are satisfied that plaintiff and her attorney acted with reasonable diligence in attempting – with no avail – to ascertain the true identity of “Agency Nurse RN 104” before filing suit and before the 2-year limitations statute ran ...”

Dr. Tan is emeritus professor of medicine and former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii, Honolulu. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. Portions of this article had been previously published in a 2010 issue of Internal Medicine News. For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected]

References

1. Chaffin v. Nicosia, 310 N.E.2d 867 (Ind. 1974).

2. Lomeo v. Davis, 53 Pa. D. & C. 4th 49 (Pa. Com. Pl. Jul 24, 2001).

3. Waugh v. Medstar Georgetown University Hospital, District of Columbia Court of Appeals No. 18-CV-329. Decided March 14, 2019.

4. Rosenberg v. Watts, Superior Court N.J. Appellate Div., Docket No. A-4525-16T4. Decided March 21, 2019.

Question: Regarding the statute of limitations, which of the following is incorrect?

A. The statute stipulates the time period from knowledge of injury to when a lawsuit must be filed, beyond which it will be forever barred.

B. This time period is usually 2 years but varies somewhat from jurisdiction to jurisdiction.

C. It starts to “run” when the cause of action accrues, i.e., when the claimant knew or should have known of the injury, not when the negligent act took place.

D. In the case of minors, disability, and concealment, the statute may be tolled, thereby giving the plaintiff more time to file his/her claim.

E. In some U.S. jurisdictions, the judge may exercise discretion and waive the statutory time period.

Answer: E. At common law, there was no time limit that barred a plaintiff from bringing a claim, although there was a so-called “doctrine of laches” that foreclosed an action that had long lapsed. However, statutory changes in the law now require that complaints be brought in a timely manner so that the evidence remains fresh, accurate, and reliable. Another reason is to provide repose to the wrongdoer, i.e., relief from worrying for an indefinite period of time whether a lawsuit will be brought. It is 2 years for the tort of negligence in most jurisdictions, although states like California and Tennessee place a 1-year limit on medical malpractice claims under some circumstances. In England, actions for negligence-based personal injury have a limitation period of 3 years. Additionally, section 33 allows the court to use its discretion to extend this time period, something that is not available in other common law jurisdictions such as Singapore and the United States.

The statute of limitations does not start to run from the date of the negligent act or omission. For example, if there is a failure to timely diagnose and treat a cancerous condition and the patient suffers harm several years later, time starts to accrue from the date of discovering the injury, not the date of misdiagnosis. The term “discovery rule” defines the accrual period, which begins from the date the injury is discovered or should have been discovered if the party had exercised reasonable diligence. In cases of fraudulent concealment of a right of action, the statute may be tolled (halted) during the period of concealment. Tolling also may apply during legal disability.

In malpractice actions involving minors, the running of the time period may be tolled until the minor reaches a certain age, such as the age of majority, or by the minor’s 10th birthday (Hawaii law). Chaffin v. Nicosia1 dealt with such a situation. As the result of negligent forceps delivery, which injured the optic nerve, the plaintiff became blind in the right eye in early infancy. He brought suit when he was 22 years old. Indiana had two statutes on the issue, one requiring a malpractice suit to be brought within 2 years of the incident, and the other allowing a minor to sue no later than 2 years after reaching the age of 21. The Indiana Supreme Court allowed the case to go forward, reversing the lower court’s decision barring the action.

Courts are apt to closely scrutinize attempts to use the statute of limitations to prevent recovery as taking such actions could deprive the injured plaintiff of an otherwise legitimate claim. In one example, the defendants sought to dismiss the case (so-called motion for summary judgment) by arguing that the plaintiff filed suit some 32 months after she had developed Sheehan syndrome from postpartum hemorrhagic shock, and this exceeded the 2-year statute of limitations. The court ruled: “Since reasonable minds could differ as to when the injury and its operative cause should have been discovered by a reasonably diligent patient, the timeliness of the plaintiff’s claims should be decided by a jury and the motions for summary judgment will therefore be denied.”2

Two very recent cases are illustrative of litigation over statutes of limitations. In the first case, the District of Columbia’s highest court held that BKW, a patient-plaintiff, did not qualify for an extension and rejected his untimely suit against the hospital.3 The patient’s injuries stemmed from alleged unsuccessful venipunctures, and his complaint contained six causes of action, including negligent and intentional infliction of emotional distress and unnecessary pain, suffering, and bodily injury. In the District of Columbia, a plaintiff must serve the defendant with notice of intention to file suit (pre-suit notice) not less than 90 days prior to filing the action. The plaintiff must then file the complaint itself within the 3-year limitations period, with an extension allowed to take into account the 90-day pre-suit notice requirement. The case centered on the “within 90 days” requirement to trigger the statute of limitations extension. BKW, acting on one’s own behalf, conceded that the 3-year period applicable to his claims had lapsed, but because his complaint was filed “within 90 days” after the limitation period expired, it was eligible for an extension. The Court disagreed and dismissed the case, holding that to be eligible for the 90-day extension, a plaintiff must serve the pre-suit notice within 90 days before the limitation period expired.

The second case4 alleged malpractice in the care of a patient who died of anaphylaxis after a nurse infused him with iron dextran. The nurse had allegedly left the patient’s room too soon and did not adequately monitor his reaction to the drug. The patient was admitted to the hospital for removal of a colonic tumor and was to receive treatment for iron deficiency anemia. The nurse, identified in the chart as Agency Nurse RN 104, administered the prescribed intravenous 25-mg test-dose of iron dextran over a 5-minute period, but when the patient began having an anaphylactic-type allergic reaction, the nurse was allegedly not in the patient’s room. The plaintiff and her attorney attempted, on several occasions and without success, to discover the actual identity of the nurse from the hospital’s representatives. Consequently, the complaint designated the nurse as “Agency Nurse RN 104,” and the plaintiff did not provide the name of the nurse, even though doing so was legally required; the exclusion of the nurse’s name would have resulted in case dismissal since the statute of limitations had lapsed. However, the court ruled, “we are satisfied that plaintiff and her attorney acted with reasonable diligence in attempting – with no avail – to ascertain the true identity of “Agency Nurse RN 104” before filing suit and before the 2-year limitations statute ran ...”

Dr. Tan is emeritus professor of medicine and former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii, Honolulu. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. Portions of this article had been previously published in a 2010 issue of Internal Medicine News. For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected]

References

1. Chaffin v. Nicosia, 310 N.E.2d 867 (Ind. 1974).

2. Lomeo v. Davis, 53 Pa. D. & C. 4th 49 (Pa. Com. Pl. Jul 24, 2001).

3. Waugh v. Medstar Georgetown University Hospital, District of Columbia Court of Appeals No. 18-CV-329. Decided March 14, 2019.

4. Rosenberg v. Watts, Superior Court N.J. Appellate Div., Docket No. A-4525-16T4. Decided March 21, 2019.

Psoriatic Arthritis Journal Scan: April 2019

Systematic review of depression and anxiety in psoriatic arthritis.

Kamalaraj N, El-Haddad C, Hay P, Pile K. Int J Rheum Dis. 2019 Apr 26.

This is the first systematic review of point prevalence of depression and anxiety in patients with psoriatic arthritis. There is a moderate point prevalence of both depression and anxiety in patients with psoriatic arthritis, which is similar or slightly higher than the general population and comparable to that seen in other rheumatic diseases. The effects of treatment for psoriatic arthritis on comorbid depression and anxiety remain unclear.

Amplifying the concept of psoriatic arthritis: The role of autoimmunity in systemic psoriatic disease.

Chimenti MS, Caso F, Alivernini S, et al. Autoimmun Rev. 2019 Apr 5.

Recently, an autoimmune footprint of PsA pathogenesis has been demonstrated with the presence of autoantigens and related autoantibodies in PsA patients' sera. The purpose of this review is to describe the new pathogenetic mechanisms and the different clinical pictures of systemic psoriatic disease, with the ultimate goal of improving the knowledge of this heterogeneous chronic inflammatory condition.

Cardiac and cardiovascular morbidities in patients with psoriatic arthritis: a population-based case control study.

Kibari A, Cohen AD, Gazitt T, et al. Clin Rheumatol. 2019 Apr 1.

A retrospective case control study assessed the prevalence of risk factors associated with cardiovascular disease (CVD) and CVD-related morbidity in a large Middle-Eastern psoriatic arthritis (PsA) cohort. The results emphasize the importance of clinician awareness of the increased risk for CVD-related complications in PsA patients.

Exploring Dimensions of Stiffness in Rheumatoid and Psoriatic Arthritis: The ARAD and OMERACT Stiffness Special Interest Group collaboration.

Sinnathura P, Bartlett SJ, Halls S, et al. J Rheumatol. 2019 Apr 1.

The aims of this study were to: 1) compare stiffness in psoriatic arthritis (PsA) and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) using patient-reported outcomes, 2) explore how dimensions of stiffness are associated with each other and reflect the patient experience, 3) explore how different dimensions of stiffness are associated with physical function.

Acrodermatitis Continua of Hallopeau with Psoriatic Arthritis.

Khosravi-Hafshejani T, Zhou Y, Dutz JP. J Rheumatol. 2019 Apr;46(4):437-438.

Acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau (ACH) is a form of localized pustular psoriasis that can be associated with psoriatic arthritis. This case report examines a 53-year-old male presented with a 1-year history of fingernail and toenail dystrophy and pustules on the distal toes.

Systematic review of depression and anxiety in psoriatic arthritis.

Kamalaraj N, El-Haddad C, Hay P, Pile K. Int J Rheum Dis. 2019 Apr 26.

This is the first systematic review of point prevalence of depression and anxiety in patients with psoriatic arthritis. There is a moderate point prevalence of both depression and anxiety in patients with psoriatic arthritis, which is similar or slightly higher than the general population and comparable to that seen in other rheumatic diseases. The effects of treatment for psoriatic arthritis on comorbid depression and anxiety remain unclear.

Amplifying the concept of psoriatic arthritis: The role of autoimmunity in systemic psoriatic disease.

Chimenti MS, Caso F, Alivernini S, et al. Autoimmun Rev. 2019 Apr 5.

Recently, an autoimmune footprint of PsA pathogenesis has been demonstrated with the presence of autoantigens and related autoantibodies in PsA patients' sera. The purpose of this review is to describe the new pathogenetic mechanisms and the different clinical pictures of systemic psoriatic disease, with the ultimate goal of improving the knowledge of this heterogeneous chronic inflammatory condition.

Cardiac and cardiovascular morbidities in patients with psoriatic arthritis: a population-based case control study.

Kibari A, Cohen AD, Gazitt T, et al. Clin Rheumatol. 2019 Apr 1.

A retrospective case control study assessed the prevalence of risk factors associated with cardiovascular disease (CVD) and CVD-related morbidity in a large Middle-Eastern psoriatic arthritis (PsA) cohort. The results emphasize the importance of clinician awareness of the increased risk for CVD-related complications in PsA patients.

Exploring Dimensions of Stiffness in Rheumatoid and Psoriatic Arthritis: The ARAD and OMERACT Stiffness Special Interest Group collaboration.

Sinnathura P, Bartlett SJ, Halls S, et al. J Rheumatol. 2019 Apr 1.

The aims of this study were to: 1) compare stiffness in psoriatic arthritis (PsA) and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) using patient-reported outcomes, 2) explore how dimensions of stiffness are associated with each other and reflect the patient experience, 3) explore how different dimensions of stiffness are associated with physical function.

Acrodermatitis Continua of Hallopeau with Psoriatic Arthritis.

Khosravi-Hafshejani T, Zhou Y, Dutz JP. J Rheumatol. 2019 Apr;46(4):437-438.

Acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau (ACH) is a form of localized pustular psoriasis that can be associated with psoriatic arthritis. This case report examines a 53-year-old male presented with a 1-year history of fingernail and toenail dystrophy and pustules on the distal toes.

Systematic review of depression and anxiety in psoriatic arthritis.

Kamalaraj N, El-Haddad C, Hay P, Pile K. Int J Rheum Dis. 2019 Apr 26.

This is the first systematic review of point prevalence of depression and anxiety in patients with psoriatic arthritis. There is a moderate point prevalence of both depression and anxiety in patients with psoriatic arthritis, which is similar or slightly higher than the general population and comparable to that seen in other rheumatic diseases. The effects of treatment for psoriatic arthritis on comorbid depression and anxiety remain unclear.

Amplifying the concept of psoriatic arthritis: The role of autoimmunity in systemic psoriatic disease.

Chimenti MS, Caso F, Alivernini S, et al. Autoimmun Rev. 2019 Apr 5.

Recently, an autoimmune footprint of PsA pathogenesis has been demonstrated with the presence of autoantigens and related autoantibodies in PsA patients' sera. The purpose of this review is to describe the new pathogenetic mechanisms and the different clinical pictures of systemic psoriatic disease, with the ultimate goal of improving the knowledge of this heterogeneous chronic inflammatory condition.

Cardiac and cardiovascular morbidities in patients with psoriatic arthritis: a population-based case control study.

Kibari A, Cohen AD, Gazitt T, et al. Clin Rheumatol. 2019 Apr 1.

A retrospective case control study assessed the prevalence of risk factors associated with cardiovascular disease (CVD) and CVD-related morbidity in a large Middle-Eastern psoriatic arthritis (PsA) cohort. The results emphasize the importance of clinician awareness of the increased risk for CVD-related complications in PsA patients.

Exploring Dimensions of Stiffness in Rheumatoid and Psoriatic Arthritis: The ARAD and OMERACT Stiffness Special Interest Group collaboration.

Sinnathura P, Bartlett SJ, Halls S, et al. J Rheumatol. 2019 Apr 1.

The aims of this study were to: 1) compare stiffness in psoriatic arthritis (PsA) and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) using patient-reported outcomes, 2) explore how dimensions of stiffness are associated with each other and reflect the patient experience, 3) explore how different dimensions of stiffness are associated with physical function.

Acrodermatitis Continua of Hallopeau with Psoriatic Arthritis.

Khosravi-Hafshejani T, Zhou Y, Dutz JP. J Rheumatol. 2019 Apr;46(4):437-438.

Acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau (ACH) is a form of localized pustular psoriasis that can be associated with psoriatic arthritis. This case report examines a 53-year-old male presented with a 1-year history of fingernail and toenail dystrophy and pustules on the distal toes.

Head and neck cancer cost analysis yields simple bundled payment model

While many factors can influence cost in head and neck cancer, a simple bundled payments model for the disease can be developed based solely on treatment types, researchers reported.

The number of treatment modalities was the biggest driver of cost in an analysis of 150 head and neck cancer patients. Whether those patients needed single-modality, bimodality, or trimodality treatment was in turn driven by the stage of the disease; by contrast, patient factors had no significant cost impacts, the investigators found.

Based on those findings, they developed a three-tiered cost model in which surgery or radiation was the least costly, chemoradiation or surgery plus radiation was next, and surgery plus chemoradiation was associated with the highest cost.

Basing bundled payments on treatment modality is a “simple but clinically robust model” for payment selection in head and neck cancer patients, wrote senior author Matthew C. Ward, MD, of the Levine Cancer Institute at Atrium Health in Charlotte, N.C., and coauthors.

“A tiered system driven by treatment complexity will aid providers who seek to stratify financial risk in a simple and meaningful manner,” Dr. Ward and colleagues wrote in the Journal of Oncology Practice.

As cancer costs rise, bundled payment models seek to “incentivize value and reduce administrative waste” with a single payment per episode of care, shared by all providers contributing to that episode, they wrote. However, there have been few cancer-specific bundled payment programs described to date.

The tiered approach was based on an analysis of 150 patients with stage 0 to IVB head and neck cancer, excluding those with recurrent or metastatic disease and those treated with palliative intent. Most (58%) had stage IVA disease and the oropharynx was the tumor subsite in 48%.

Direct costs could not be published because of institutional policy, according to Dr. Ward and coauthors, who instead reported overall costs of treatment as relative median costs, or the ratio of the cost of a specific treatment versus the cost of surgery alone.

Specifically, surgery plus chemoradiation was the most costly versus surgery alone, with a relative median cost of 3.13 (P less than .001), followed by chemoradiation at 2.18 (P less than .001) surgery and radiation at 1.98 (P less than .001), and radiation alone at 1.66 (P = .013).

The treatment modalities used were driven by groups of stages, the investigators wrote. Compared with stages 0 to I, stages II to IVA were 33% more expensive, while stage IVB was 60% more expensive. Patient factors such as age, smoking, or comorbidities were not associated with cost.

Previous reported studies of cancer-specific bundled payment models have shown decreased costs and favorable outcomes, according to the researchers. Among those is an University of Texas MD Anderson Center report showing that a four-tiered model, based on treatments received and stratified by comorbidities, was feasible in a 1-year pilot study.

The current report validates those previous findings, with some differences, Dr. Ward and coauthors wrote. In particular, the three-tiered model was not stratified by Charlson comorbidity index, which did not correlate with cost in the present analysis, and it included less common disease sites than in the MD Anderson model.

“We felt it important to be inclusive of all patients seen by our multidisciplinary head and neck cancer team to keep the proposed bundled payments model as practical and simple as possible,” they wrote.

Dr. Ward reported a consulting or advisory role with AstraZeneca. Study coauthors provided disclosures related to Blue Earth Diagnostics, Merck, Varian Medical Systems, UpToDate, Gerson Lehrman Group, Osler, AlignRT, Chrysalis Biotherapeutics, and others.

SOURCE: Tom MC et al. J Oncol Pract. 2019 Apr 22. doi: 10.1200/JOP.18.00665.

While many factors can influence cost in head and neck cancer, a simple bundled payments model for the disease can be developed based solely on treatment types, researchers reported.

The number of treatment modalities was the biggest driver of cost in an analysis of 150 head and neck cancer patients. Whether those patients needed single-modality, bimodality, or trimodality treatment was in turn driven by the stage of the disease; by contrast, patient factors had no significant cost impacts, the investigators found.

Based on those findings, they developed a three-tiered cost model in which surgery or radiation was the least costly, chemoradiation or surgery plus radiation was next, and surgery plus chemoradiation was associated with the highest cost.

Basing bundled payments on treatment modality is a “simple but clinically robust model” for payment selection in head and neck cancer patients, wrote senior author Matthew C. Ward, MD, of the Levine Cancer Institute at Atrium Health in Charlotte, N.C., and coauthors.

“A tiered system driven by treatment complexity will aid providers who seek to stratify financial risk in a simple and meaningful manner,” Dr. Ward and colleagues wrote in the Journal of Oncology Practice.

As cancer costs rise, bundled payment models seek to “incentivize value and reduce administrative waste” with a single payment per episode of care, shared by all providers contributing to that episode, they wrote. However, there have been few cancer-specific bundled payment programs described to date.

The tiered approach was based on an analysis of 150 patients with stage 0 to IVB head and neck cancer, excluding those with recurrent or metastatic disease and those treated with palliative intent. Most (58%) had stage IVA disease and the oropharynx was the tumor subsite in 48%.

Direct costs could not be published because of institutional policy, according to Dr. Ward and coauthors, who instead reported overall costs of treatment as relative median costs, or the ratio of the cost of a specific treatment versus the cost of surgery alone.

Specifically, surgery plus chemoradiation was the most costly versus surgery alone, with a relative median cost of 3.13 (P less than .001), followed by chemoradiation at 2.18 (P less than .001) surgery and radiation at 1.98 (P less than .001), and radiation alone at 1.66 (P = .013).

The treatment modalities used were driven by groups of stages, the investigators wrote. Compared with stages 0 to I, stages II to IVA were 33% more expensive, while stage IVB was 60% more expensive. Patient factors such as age, smoking, or comorbidities were not associated with cost.

Previous reported studies of cancer-specific bundled payment models have shown decreased costs and favorable outcomes, according to the researchers. Among those is an University of Texas MD Anderson Center report showing that a four-tiered model, based on treatments received and stratified by comorbidities, was feasible in a 1-year pilot study.

The current report validates those previous findings, with some differences, Dr. Ward and coauthors wrote. In particular, the three-tiered model was not stratified by Charlson comorbidity index, which did not correlate with cost in the present analysis, and it included less common disease sites than in the MD Anderson model.

“We felt it important to be inclusive of all patients seen by our multidisciplinary head and neck cancer team to keep the proposed bundled payments model as practical and simple as possible,” they wrote.

Dr. Ward reported a consulting or advisory role with AstraZeneca. Study coauthors provided disclosures related to Blue Earth Diagnostics, Merck, Varian Medical Systems, UpToDate, Gerson Lehrman Group, Osler, AlignRT, Chrysalis Biotherapeutics, and others.

SOURCE: Tom MC et al. J Oncol Pract. 2019 Apr 22. doi: 10.1200/JOP.18.00665.

While many factors can influence cost in head and neck cancer, a simple bundled payments model for the disease can be developed based solely on treatment types, researchers reported.

The number of treatment modalities was the biggest driver of cost in an analysis of 150 head and neck cancer patients. Whether those patients needed single-modality, bimodality, or trimodality treatment was in turn driven by the stage of the disease; by contrast, patient factors had no significant cost impacts, the investigators found.

Based on those findings, they developed a three-tiered cost model in which surgery or radiation was the least costly, chemoradiation or surgery plus radiation was next, and surgery plus chemoradiation was associated with the highest cost.

Basing bundled payments on treatment modality is a “simple but clinically robust model” for payment selection in head and neck cancer patients, wrote senior author Matthew C. Ward, MD, of the Levine Cancer Institute at Atrium Health in Charlotte, N.C., and coauthors.

“A tiered system driven by treatment complexity will aid providers who seek to stratify financial risk in a simple and meaningful manner,” Dr. Ward and colleagues wrote in the Journal of Oncology Practice.

As cancer costs rise, bundled payment models seek to “incentivize value and reduce administrative waste” with a single payment per episode of care, shared by all providers contributing to that episode, they wrote. However, there have been few cancer-specific bundled payment programs described to date.

The tiered approach was based on an analysis of 150 patients with stage 0 to IVB head and neck cancer, excluding those with recurrent or metastatic disease and those treated with palliative intent. Most (58%) had stage IVA disease and the oropharynx was the tumor subsite in 48%.

Direct costs could not be published because of institutional policy, according to Dr. Ward and coauthors, who instead reported overall costs of treatment as relative median costs, or the ratio of the cost of a specific treatment versus the cost of surgery alone.

Specifically, surgery plus chemoradiation was the most costly versus surgery alone, with a relative median cost of 3.13 (P less than .001), followed by chemoradiation at 2.18 (P less than .001) surgery and radiation at 1.98 (P less than .001), and radiation alone at 1.66 (P = .013).

The treatment modalities used were driven by groups of stages, the investigators wrote. Compared with stages 0 to I, stages II to IVA were 33% more expensive, while stage IVB was 60% more expensive. Patient factors such as age, smoking, or comorbidities were not associated with cost.

Previous reported studies of cancer-specific bundled payment models have shown decreased costs and favorable outcomes, according to the researchers. Among those is an University of Texas MD Anderson Center report showing that a four-tiered model, based on treatments received and stratified by comorbidities, was feasible in a 1-year pilot study.

The current report validates those previous findings, with some differences, Dr. Ward and coauthors wrote. In particular, the three-tiered model was not stratified by Charlson comorbidity index, which did not correlate with cost in the present analysis, and it included less common disease sites than in the MD Anderson model.

“We felt it important to be inclusive of all patients seen by our multidisciplinary head and neck cancer team to keep the proposed bundled payments model as practical and simple as possible,” they wrote.

Dr. Ward reported a consulting or advisory role with AstraZeneca. Study coauthors provided disclosures related to Blue Earth Diagnostics, Merck, Varian Medical Systems, UpToDate, Gerson Lehrman Group, Osler, AlignRT, Chrysalis Biotherapeutics, and others.

SOURCE: Tom MC et al. J Oncol Pract. 2019 Apr 22. doi: 10.1200/JOP.18.00665.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF ONCOLOGY PRACTICE

Good Notes Can Deter Litigation

At 11:15

While in the ED, the patient was examined and treated by a PA. At approximately 12:13

Given the lack of any positive pertinent findings, the PA irrigated the patient’s wounds and applied 1% lidocaine to all affected fingers so that pain would not mask any potential physical exam findings. He also used single-layer absorbable sutures to repair the injured digits. In addition, the PA tested the plaintiff for both distal interphalangeal (DIP) and proximal interphalangeal (PIP) flexion function and recorded normal results.

The PA discharged the patient from the ED at 5:56

The PA provided no further care or treatment to the patient following the visit to the hospital’s ED. However, the patient contended that he suffered an injury to the tendons of his right hand, which ultimately required several surgical procedures. He sued the hospital, the PA, the PA’s medical office, his supervising physician, and the physician who performed the later surgical procedures. The supervising physician and the surgeon were ultimately let out of the case by summary judgment motions. The hospital, which was named as a defendant under a respondeat superior theory, was also dismissed from the case when it was established that the PA was employed by his medical office and not by the hospital directly. The PA stipulated that he was within his course and scope of employment at the time he treated the plaintiff.

Continue to: Plaintiff's counsel contended...

Plaintiff’s counsel contended that the defendant PA was negligent in his examination and evaluation of the plaintiff’s digit lacerations and that he was negligent for failing to splint the plaintiff’s hand. Counsel also contended that the defendant was negligent for failing to refer the plaintiff to a hand surgeon (either directly or through the plaintiff’s primary care provider) and/or for failing to seek the assistance of his supervising physician, who was on site at the hospital’s ED and available for consultation.

Defense counsel argued that the defendant met the applicable standard of care at all times, in all aspects of his visit with the plaintiff in the early morning hours of September 1, 2014, and that there was nothing that he either did or did not do that was a substantial factor in causing the plaintiff’s alleged injuries and damages. The defendant claimed that upon his arrival at the patient’s bedside, the plaintiff verbally indicated to him that he could move his fingers (extension and flexion). He also claimed that he visualized the plaintiff moving his fingers while they were wrapped in the dressing that the plaintiff had placed on himself after the injury-producing event. However, the plaintiff disputed the defendant’s claim, denying ever being asked to extend and flex his fingers. The plaintiff also claimed that he never was able to make a full fist with his fingers on the night in question while in the ED, either by way of passive or active flexion.

Defense counsel noted that the defendant’s dictated ED note stated that the range of motion of all the plaintiff’s phalanges were normal, with no deficits, at all times while in the ED. The defendant testified about how he tested and evaluated the plaintiff’s DIP function. He also testified that he had the plaintiff lay his hand on the table, palm side up, and then laid his own hand across the plaintiff’s hand so as to isolate the DIP joint on each finger. He explained that he then had the plaintiff flex his fingers, which allowed him to determine whether there had been any kind of injury to the flexor digitorum profundus tendon (responsible for DIP function in the hand). The defendant claimed that he did the test for all the lacerated fingers and characterized them as active (as opposed to passive) flexion. Thus, he claimed that his physical exam findings were that the plaintiff had full range of motion (ROM) intact following the DIP function testing, which helped him conclude that the plaintiff did not have completely lacerated tendons as of that visit.

The defendant further explained that if the tendons were completely lacerated, the plaintiff would have had nonexistent DIP functioning on examination. The defendant testified that if he suspected a tendon laceration in a patient such as the plaintiff, his practice would be to notify his supervising physician in the ED and then either refer the patient to a primary care provider for an orthopedic hand surgeon referral or directly refer the patient to an orthopedic hand surgeon. He claimed that he took no such actions because there was no indication, from his perspective, that the plaintiff had suffered any tendon damage based on his physical exam findings, the plaintiff’s ability to make a fist, and the x-ray results.

Continue to: VERDICT

VERDICT

After a 5-day trial and 7 hours of deliberation, the jury found in favor of the defendants.

COMMENTARY

As human beings, we do a lot with our hands. They are vulnerable to injury, and misdiagnosis may result in life-altering debility. The impact is even greater when one’s livelihood requires fine dexterity. Thus, tendon lacerations are relatively common and must be managed properly.

In this case, we are told that the PA documented in his notes that the plaintiff had range of motion in all phalanges and no deficits. We are also told the defendant testified regarding his procedure for hand examination. But we are not told that his note included the details of his exam—and by inference, we have reason to suspect it did not.

You might think, “The jury found in favor of the defense, so why does this matter?” Because a well-documented chart may prevent liability.

If you wish to avoid lawsuits, it is helpful to understand how they originate: An aggrieved patient contacts a plaintiff’s lawyer, insists he or she has been wronged, and asks the lawyer to take the case. Often faced with the ticking clock of statute of limitations (the absolute deadline to file), plaintiff’s counsel will review whatever records are available (which may not be all of them), looking for perceived deficiencies of care. The case may also be reviewed by a medical professional (generally a physician) prior to filing; some states require an affidavit of merit—an attestation that there is just cause to bring the action.

Whether reviewed only by plaintiff’s counsel or with the aid of an expert, a well-documented medical record may prevent a case from being filed. Medical malpractice cases are a huge gamble for plaintiff firms: They are expensive, time consuming, difficult to litigate, document heavy, and technically complex—falling outside the experience of most lawyers. They are also less likely than other cases to be settled, thanks to National Practitioner Data Bank recording requirements and (in several states) automatic medical board inquiry for potential adverse action against a medical or nursing professional following settlement. Clinicians will often fight tooth and nail to avoid an adverse recording, hospital credentialing woes, and state investigation. A medical malpractice case can be a trap for both the clinician and the plaintiff’s attorney stuck with a bad case.

Continue to: In the early stages...

In the early stages of potential litigation, before a case is filed in court, do yourself a favor: Help plaintiff’s counsel realize it will be a losing case. You actually start the process much earlier, by conducting the proper exam and documenting lavishly. This is particularly important with specialty exams, such as the hand exam in this case.

Here, simply noting “positive ROM and distal CSM [circulation, sensation, and motion] intact” is inadequate. Why? Because it is a conclusion, not evidence of the specialty examination that was diligently performed. The mechanism of injury and initial presentation roused the clinician’s suspicions sufficiently to conduct a thorough hand examination—but the mechanics of the exam were not included, only conclusions. The trouble is, those conclusions may have been based on sound medical evidence or they may have been hastily and improvidently drawn. A plaintiff’s firm deciding whether to take this case doesn’t know but will bet on the latter.

The clinician testified he performed a detailed and thorough examination of the plaintiff’s hand. Had plaintiff’s counsel been confronted with the full details of the exam—which showed the defendant PA tested all the PIPs and DIPs by isolating each finger—early on, this case may never have been filed. Thus, conduct and document specialty exams fully. If you need a cheat sheet for exams you don’t do often, use one—that is still solid practice. If you don’t do many pelvic exams or mental status exams, make sure you aren’t missing anything. Practicing medicine is an open-book exam; if you need materials, use them.

Good documentation leads to good defense, and any good defense lawyer will recommend the Jerry Maguire rule: “Help me help you.” Solid records make a case easier to defend and win at all phases of litigation. Of course, this is not a universal cure that will prevent all lawsuits. But even if the case is filed, the strength of your records may have convinced stronger, more capable medical malpractice firms to turn it down. This is something of value: It is “you helping you” and potent proof that your human head weighs more than 8 lb.

IN SUMMARY

A well-documented chart may prevent liability by showcasing the strength of your care and preventing no-win lawsuits from being filed. Help the plaintiff’s attorney realize, early on, that he or she is facing a costly uphill battle. The key word is early, when the medical records are first reviewed—not 18 months later, when the attorney hears your testimony at deposition and realizes that he or she has invested time and sweat in a case only to learn that your care was fabulous. Showcase that fabulous care early and short circuit the whole process by detailing the substance of a key exam (not just conclusions) in the record. Detailed notes may spare you from a visit by a sheriff you don’t know holding papers you don’t want.

At 11:15

While in the ED, the patient was examined and treated by a PA. At approximately 12:13

Given the lack of any positive pertinent findings, the PA irrigated the patient’s wounds and applied 1% lidocaine to all affected fingers so that pain would not mask any potential physical exam findings. He also used single-layer absorbable sutures to repair the injured digits. In addition, the PA tested the plaintiff for both distal interphalangeal (DIP) and proximal interphalangeal (PIP) flexion function and recorded normal results.

The PA discharged the patient from the ED at 5:56

The PA provided no further care or treatment to the patient following the visit to the hospital’s ED. However, the patient contended that he suffered an injury to the tendons of his right hand, which ultimately required several surgical procedures. He sued the hospital, the PA, the PA’s medical office, his supervising physician, and the physician who performed the later surgical procedures. The supervising physician and the surgeon were ultimately let out of the case by summary judgment motions. The hospital, which was named as a defendant under a respondeat superior theory, was also dismissed from the case when it was established that the PA was employed by his medical office and not by the hospital directly. The PA stipulated that he was within his course and scope of employment at the time he treated the plaintiff.

Continue to: Plaintiff's counsel contended...

Plaintiff’s counsel contended that the defendant PA was negligent in his examination and evaluation of the plaintiff’s digit lacerations and that he was negligent for failing to splint the plaintiff’s hand. Counsel also contended that the defendant was negligent for failing to refer the plaintiff to a hand surgeon (either directly or through the plaintiff’s primary care provider) and/or for failing to seek the assistance of his supervising physician, who was on site at the hospital’s ED and available for consultation.

Defense counsel argued that the defendant met the applicable standard of care at all times, in all aspects of his visit with the plaintiff in the early morning hours of September 1, 2014, and that there was nothing that he either did or did not do that was a substantial factor in causing the plaintiff’s alleged injuries and damages. The defendant claimed that upon his arrival at the patient’s bedside, the plaintiff verbally indicated to him that he could move his fingers (extension and flexion). He also claimed that he visualized the plaintiff moving his fingers while they were wrapped in the dressing that the plaintiff had placed on himself after the injury-producing event. However, the plaintiff disputed the defendant’s claim, denying ever being asked to extend and flex his fingers. The plaintiff also claimed that he never was able to make a full fist with his fingers on the night in question while in the ED, either by way of passive or active flexion.

Defense counsel noted that the defendant’s dictated ED note stated that the range of motion of all the plaintiff’s phalanges were normal, with no deficits, at all times while in the ED. The defendant testified about how he tested and evaluated the plaintiff’s DIP function. He also testified that he had the plaintiff lay his hand on the table, palm side up, and then laid his own hand across the plaintiff’s hand so as to isolate the DIP joint on each finger. He explained that he then had the plaintiff flex his fingers, which allowed him to determine whether there had been any kind of injury to the flexor digitorum profundus tendon (responsible for DIP function in the hand). The defendant claimed that he did the test for all the lacerated fingers and characterized them as active (as opposed to passive) flexion. Thus, he claimed that his physical exam findings were that the plaintiff had full range of motion (ROM) intact following the DIP function testing, which helped him conclude that the plaintiff did not have completely lacerated tendons as of that visit.

The defendant further explained that if the tendons were completely lacerated, the plaintiff would have had nonexistent DIP functioning on examination. The defendant testified that if he suspected a tendon laceration in a patient such as the plaintiff, his practice would be to notify his supervising physician in the ED and then either refer the patient to a primary care provider for an orthopedic hand surgeon referral or directly refer the patient to an orthopedic hand surgeon. He claimed that he took no such actions because there was no indication, from his perspective, that the plaintiff had suffered any tendon damage based on his physical exam findings, the plaintiff’s ability to make a fist, and the x-ray results.

Continue to: VERDICT

VERDICT

After a 5-day trial and 7 hours of deliberation, the jury found in favor of the defendants.

COMMENTARY

As human beings, we do a lot with our hands. They are vulnerable to injury, and misdiagnosis may result in life-altering debility. The impact is even greater when one’s livelihood requires fine dexterity. Thus, tendon lacerations are relatively common and must be managed properly.

In this case, we are told that the PA documented in his notes that the plaintiff had range of motion in all phalanges and no deficits. We are also told the defendant testified regarding his procedure for hand examination. But we are not told that his note included the details of his exam—and by inference, we have reason to suspect it did not.

You might think, “The jury found in favor of the defense, so why does this matter?” Because a well-documented chart may prevent liability.

If you wish to avoid lawsuits, it is helpful to understand how they originate: An aggrieved patient contacts a plaintiff’s lawyer, insists he or she has been wronged, and asks the lawyer to take the case. Often faced with the ticking clock of statute of limitations (the absolute deadline to file), plaintiff’s counsel will review whatever records are available (which may not be all of them), looking for perceived deficiencies of care. The case may also be reviewed by a medical professional (generally a physician) prior to filing; some states require an affidavit of merit—an attestation that there is just cause to bring the action.

Whether reviewed only by plaintiff’s counsel or with the aid of an expert, a well-documented medical record may prevent a case from being filed. Medical malpractice cases are a huge gamble for plaintiff firms: They are expensive, time consuming, difficult to litigate, document heavy, and technically complex—falling outside the experience of most lawyers. They are also less likely than other cases to be settled, thanks to National Practitioner Data Bank recording requirements and (in several states) automatic medical board inquiry for potential adverse action against a medical or nursing professional following settlement. Clinicians will often fight tooth and nail to avoid an adverse recording, hospital credentialing woes, and state investigation. A medical malpractice case can be a trap for both the clinician and the plaintiff’s attorney stuck with a bad case.

Continue to: In the early stages...

In the early stages of potential litigation, before a case is filed in court, do yourself a favor: Help plaintiff’s counsel realize it will be a losing case. You actually start the process much earlier, by conducting the proper exam and documenting lavishly. This is particularly important with specialty exams, such as the hand exam in this case.

Here, simply noting “positive ROM and distal CSM [circulation, sensation, and motion] intact” is inadequate. Why? Because it is a conclusion, not evidence of the specialty examination that was diligently performed. The mechanism of injury and initial presentation roused the clinician’s suspicions sufficiently to conduct a thorough hand examination—but the mechanics of the exam were not included, only conclusions. The trouble is, those conclusions may have been based on sound medical evidence or they may have been hastily and improvidently drawn. A plaintiff’s firm deciding whether to take this case doesn’t know but will bet on the latter.

The clinician testified he performed a detailed and thorough examination of the plaintiff’s hand. Had plaintiff’s counsel been confronted with the full details of the exam—which showed the defendant PA tested all the PIPs and DIPs by isolating each finger—early on, this case may never have been filed. Thus, conduct and document specialty exams fully. If you need a cheat sheet for exams you don’t do often, use one—that is still solid practice. If you don’t do many pelvic exams or mental status exams, make sure you aren’t missing anything. Practicing medicine is an open-book exam; if you need materials, use them.

Good documentation leads to good defense, and any good defense lawyer will recommend the Jerry Maguire rule: “Help me help you.” Solid records make a case easier to defend and win at all phases of litigation. Of course, this is not a universal cure that will prevent all lawsuits. But even if the case is filed, the strength of your records may have convinced stronger, more capable medical malpractice firms to turn it down. This is something of value: It is “you helping you” and potent proof that your human head weighs more than 8 lb.

IN SUMMARY

A well-documented chart may prevent liability by showcasing the strength of your care and preventing no-win lawsuits from being filed. Help the plaintiff’s attorney realize, early on, that he or she is facing a costly uphill battle. The key word is early, when the medical records are first reviewed—not 18 months later, when the attorney hears your testimony at deposition and realizes that he or she has invested time and sweat in a case only to learn that your care was fabulous. Showcase that fabulous care early and short circuit the whole process by detailing the substance of a key exam (not just conclusions) in the record. Detailed notes may spare you from a visit by a sheriff you don’t know holding papers you don’t want.

At 11:15

While in the ED, the patient was examined and treated by a PA. At approximately 12:13

Given the lack of any positive pertinent findings, the PA irrigated the patient’s wounds and applied 1% lidocaine to all affected fingers so that pain would not mask any potential physical exam findings. He also used single-layer absorbable sutures to repair the injured digits. In addition, the PA tested the plaintiff for both distal interphalangeal (DIP) and proximal interphalangeal (PIP) flexion function and recorded normal results.

The PA discharged the patient from the ED at 5:56

The PA provided no further care or treatment to the patient following the visit to the hospital’s ED. However, the patient contended that he suffered an injury to the tendons of his right hand, which ultimately required several surgical procedures. He sued the hospital, the PA, the PA’s medical office, his supervising physician, and the physician who performed the later surgical procedures. The supervising physician and the surgeon were ultimately let out of the case by summary judgment motions. The hospital, which was named as a defendant under a respondeat superior theory, was also dismissed from the case when it was established that the PA was employed by his medical office and not by the hospital directly. The PA stipulated that he was within his course and scope of employment at the time he treated the plaintiff.

Continue to: Plaintiff's counsel contended...

Plaintiff’s counsel contended that the defendant PA was negligent in his examination and evaluation of the plaintiff’s digit lacerations and that he was negligent for failing to splint the plaintiff’s hand. Counsel also contended that the defendant was negligent for failing to refer the plaintiff to a hand surgeon (either directly or through the plaintiff’s primary care provider) and/or for failing to seek the assistance of his supervising physician, who was on site at the hospital’s ED and available for consultation.

Defense counsel argued that the defendant met the applicable standard of care at all times, in all aspects of his visit with the plaintiff in the early morning hours of September 1, 2014, and that there was nothing that he either did or did not do that was a substantial factor in causing the plaintiff’s alleged injuries and damages. The defendant claimed that upon his arrival at the patient’s bedside, the plaintiff verbally indicated to him that he could move his fingers (extension and flexion). He also claimed that he visualized the plaintiff moving his fingers while they were wrapped in the dressing that the plaintiff had placed on himself after the injury-producing event. However, the plaintiff disputed the defendant’s claim, denying ever being asked to extend and flex his fingers. The plaintiff also claimed that he never was able to make a full fist with his fingers on the night in question while in the ED, either by way of passive or active flexion.

Defense counsel noted that the defendant’s dictated ED note stated that the range of motion of all the plaintiff’s phalanges were normal, with no deficits, at all times while in the ED. The defendant testified about how he tested and evaluated the plaintiff’s DIP function. He also testified that he had the plaintiff lay his hand on the table, palm side up, and then laid his own hand across the plaintiff’s hand so as to isolate the DIP joint on each finger. He explained that he then had the plaintiff flex his fingers, which allowed him to determine whether there had been any kind of injury to the flexor digitorum profundus tendon (responsible for DIP function in the hand). The defendant claimed that he did the test for all the lacerated fingers and characterized them as active (as opposed to passive) flexion. Thus, he claimed that his physical exam findings were that the plaintiff had full range of motion (ROM) intact following the DIP function testing, which helped him conclude that the plaintiff did not have completely lacerated tendons as of that visit.

The defendant further explained that if the tendons were completely lacerated, the plaintiff would have had nonexistent DIP functioning on examination. The defendant testified that if he suspected a tendon laceration in a patient such as the plaintiff, his practice would be to notify his supervising physician in the ED and then either refer the patient to a primary care provider for an orthopedic hand surgeon referral or directly refer the patient to an orthopedic hand surgeon. He claimed that he took no such actions because there was no indication, from his perspective, that the plaintiff had suffered any tendon damage based on his physical exam findings, the plaintiff’s ability to make a fist, and the x-ray results.

Continue to: VERDICT

VERDICT

After a 5-day trial and 7 hours of deliberation, the jury found in favor of the defendants.

COMMENTARY

As human beings, we do a lot with our hands. They are vulnerable to injury, and misdiagnosis may result in life-altering debility. The impact is even greater when one’s livelihood requires fine dexterity. Thus, tendon lacerations are relatively common and must be managed properly.

In this case, we are told that the PA documented in his notes that the plaintiff had range of motion in all phalanges and no deficits. We are also told the defendant testified regarding his procedure for hand examination. But we are not told that his note included the details of his exam—and by inference, we have reason to suspect it did not.

You might think, “The jury found in favor of the defense, so why does this matter?” Because a well-documented chart may prevent liability.

If you wish to avoid lawsuits, it is helpful to understand how they originate: An aggrieved patient contacts a plaintiff’s lawyer, insists he or she has been wronged, and asks the lawyer to take the case. Often faced with the ticking clock of statute of limitations (the absolute deadline to file), plaintiff’s counsel will review whatever records are available (which may not be all of them), looking for perceived deficiencies of care. The case may also be reviewed by a medical professional (generally a physician) prior to filing; some states require an affidavit of merit—an attestation that there is just cause to bring the action.

Whether reviewed only by plaintiff’s counsel or with the aid of an expert, a well-documented medical record may prevent a case from being filed. Medical malpractice cases are a huge gamble for plaintiff firms: They are expensive, time consuming, difficult to litigate, document heavy, and technically complex—falling outside the experience of most lawyers. They are also less likely than other cases to be settled, thanks to National Practitioner Data Bank recording requirements and (in several states) automatic medical board inquiry for potential adverse action against a medical or nursing professional following settlement. Clinicians will often fight tooth and nail to avoid an adverse recording, hospital credentialing woes, and state investigation. A medical malpractice case can be a trap for both the clinician and the plaintiff’s attorney stuck with a bad case.

Continue to: In the early stages...

In the early stages of potential litigation, before a case is filed in court, do yourself a favor: Help plaintiff’s counsel realize it will be a losing case. You actually start the process much earlier, by conducting the proper exam and documenting lavishly. This is particularly important with specialty exams, such as the hand exam in this case.

Here, simply noting “positive ROM and distal CSM [circulation, sensation, and motion] intact” is inadequate. Why? Because it is a conclusion, not evidence of the specialty examination that was diligently performed. The mechanism of injury and initial presentation roused the clinician’s suspicions sufficiently to conduct a thorough hand examination—but the mechanics of the exam were not included, only conclusions. The trouble is, those conclusions may have been based on sound medical evidence or they may have been hastily and improvidently drawn. A plaintiff’s firm deciding whether to take this case doesn’t know but will bet on the latter.

The clinician testified he performed a detailed and thorough examination of the plaintiff’s hand. Had plaintiff’s counsel been confronted with the full details of the exam—which showed the defendant PA tested all the PIPs and DIPs by isolating each finger—early on, this case may never have been filed. Thus, conduct and document specialty exams fully. If you need a cheat sheet for exams you don’t do often, use one—that is still solid practice. If you don’t do many pelvic exams or mental status exams, make sure you aren’t missing anything. Practicing medicine is an open-book exam; if you need materials, use them.

Good documentation leads to good defense, and any good defense lawyer will recommend the Jerry Maguire rule: “Help me help you.” Solid records make a case easier to defend and win at all phases of litigation. Of course, this is not a universal cure that will prevent all lawsuits. But even if the case is filed, the strength of your records may have convinced stronger, more capable medical malpractice firms to turn it down. This is something of value: It is “you helping you” and potent proof that your human head weighs more than 8 lb.

IN SUMMARY

A well-documented chart may prevent liability by showcasing the strength of your care and preventing no-win lawsuits from being filed. Help the plaintiff’s attorney realize, early on, that he or she is facing a costly uphill battle. The key word is early, when the medical records are first reviewed—not 18 months later, when the attorney hears your testimony at deposition and realizes that he or she has invested time and sweat in a case only to learn that your care was fabulous. Showcase that fabulous care early and short circuit the whole process by detailing the substance of a key exam (not just conclusions) in the record. Detailed notes may spare you from a visit by a sheriff you don’t know holding papers you don’t want.

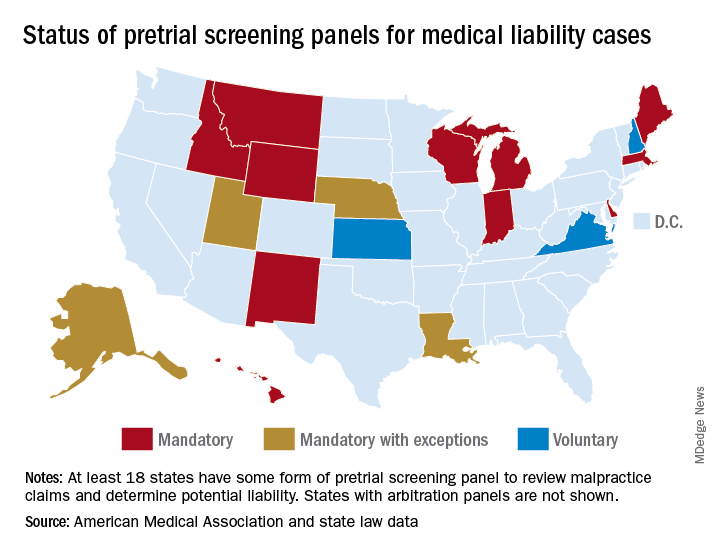

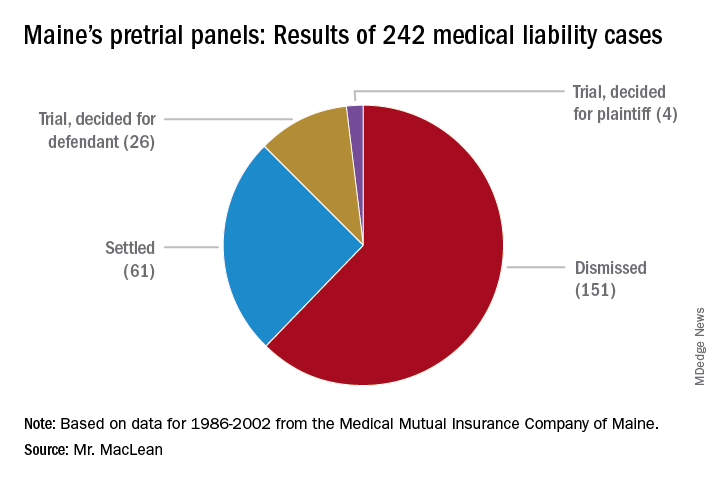

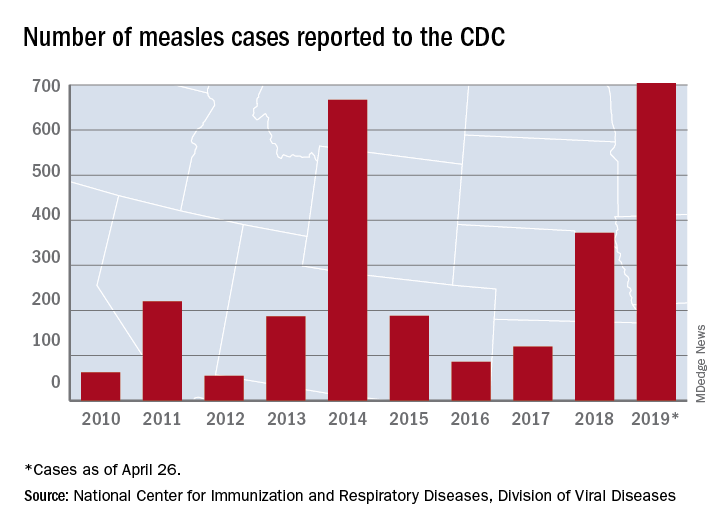

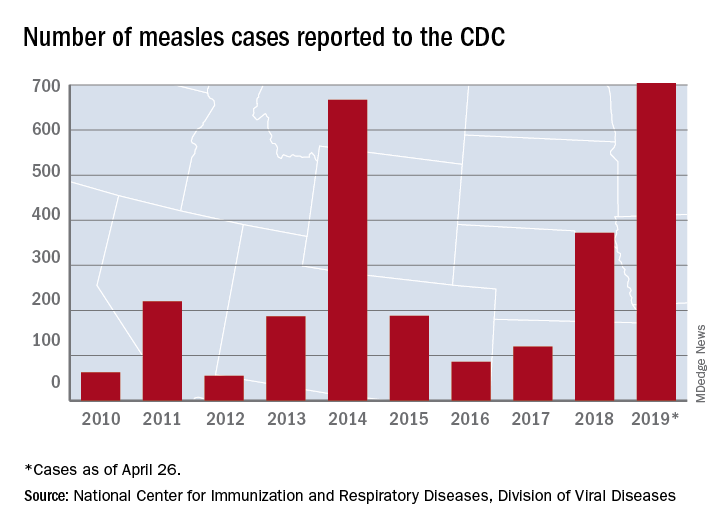

Pretrial screening panels: Do they reduce frivolous claims?

The liability climate for Kentucky physicians has long been bleak, according to Bruce A. Scott, MD, president of the Kentucky Medical Association. Insurance premiums are high, few doctors want to relocate to the Bluegrass State, and an overriding fear of lawsuits weighs heavily on the minds of physicians practicing there.