User login

Washington State removes exemption for MMR vaccine

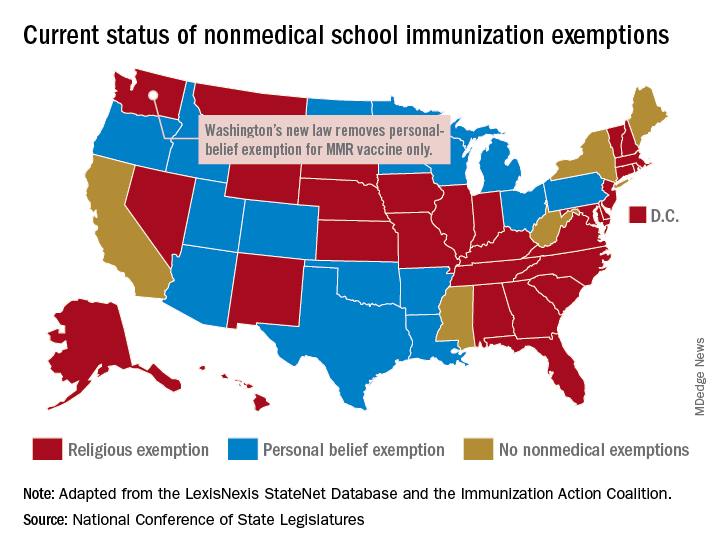

Washington state parents may no longer cite personal or philosophical objections to refuse the MMR vaccine for their children, effective July 28, according to the state’s department of health.

“In Washington state we believe in our doctors. We believe in our nurses. We believe in our educators. We believe in science and we love our children,” Gov. Jay Inslee (D) said when he signed the bill into law on May 10. “And that is why in Washington State, we are against measles.”

The new law applies only to the MMR vaccine and “does not change religious and medical exemption laws. Children who have one of these types of exemptions on file are not affected by the new law,” the health department said.

Washington is one of 45 states that allows religious exemptions from school immunization requirements, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures, which also reported that 15 of those states allow personal-belief exemptions.

The five states that do not allow any form of nonmedical exemption are California, Maine, Mississippi, New York, and West Virginia.

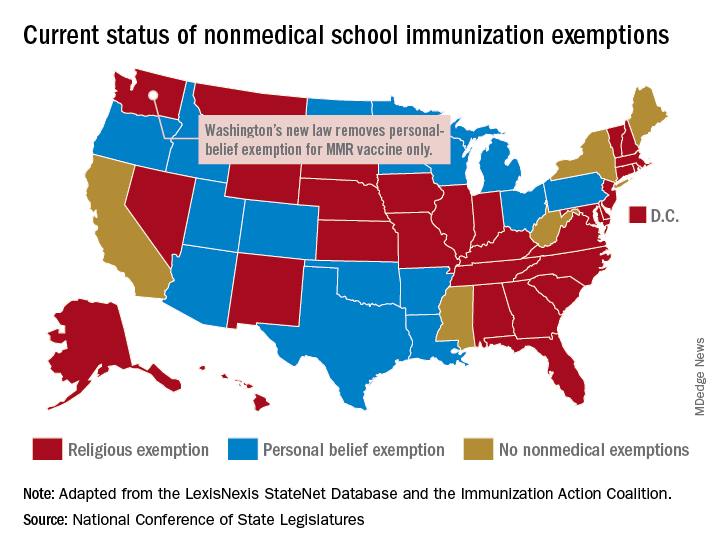

Washington state parents may no longer cite personal or philosophical objections to refuse the MMR vaccine for their children, effective July 28, according to the state’s department of health.

“In Washington state we believe in our doctors. We believe in our nurses. We believe in our educators. We believe in science and we love our children,” Gov. Jay Inslee (D) said when he signed the bill into law on May 10. “And that is why in Washington State, we are against measles.”

The new law applies only to the MMR vaccine and “does not change religious and medical exemption laws. Children who have one of these types of exemptions on file are not affected by the new law,” the health department said.

Washington is one of 45 states that allows religious exemptions from school immunization requirements, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures, which also reported that 15 of those states allow personal-belief exemptions.

The five states that do not allow any form of nonmedical exemption are California, Maine, Mississippi, New York, and West Virginia.

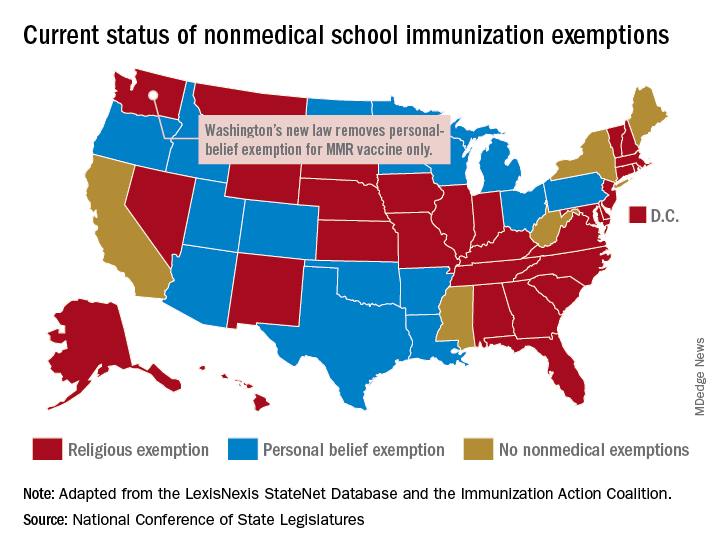

Washington state parents may no longer cite personal or philosophical objections to refuse the MMR vaccine for their children, effective July 28, according to the state’s department of health.

“In Washington state we believe in our doctors. We believe in our nurses. We believe in our educators. We believe in science and we love our children,” Gov. Jay Inslee (D) said when he signed the bill into law on May 10. “And that is why in Washington State, we are against measles.”

The new law applies only to the MMR vaccine and “does not change religious and medical exemption laws. Children who have one of these types of exemptions on file are not affected by the new law,” the health department said.

Washington is one of 45 states that allows religious exemptions from school immunization requirements, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures, which also reported that 15 of those states allow personal-belief exemptions.

The five states that do not allow any form of nonmedical exemption are California, Maine, Mississippi, New York, and West Virginia.

Inflammation diminishes quality of life in NAFLD, not fibrosis

A variety of demographic and disease-related factors contribute to poorer quality of life in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), based on questionnaires involving 304 European patients.

In contrast with previous research, lobular inflammation, but not hepatic fibrosis, was associated with worse quality of life, reported to lead author Yvonne Huber, MD, of Johannes Gutenberg University in Mainz, Germany, and colleagues. Women and those with advanced disease or comorbidities had the lowest health-related quality of life (HRQL) scores. The investigators suggested that these findings could be used for treatment planning at a population and patient level.

“With the emergence of medical therapy for [nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH)], it will be of importance to identify patients with the highest unmet need for treatment,” the investigators wrote in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, emphasizing that therapies targeting inflammation could provide the greatest relief.

To determine which patients with NAFLD were most affected by their condition, the investigators used the Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire (CLDQ), which assesses physical, mental, social, and emotional function, with lower scores indicating poorer health-related quality of life. “[The CLDQ] more specifically addresses symptoms of patients with chronic liver disease, including extrahepatic manifestations, compared with traditional HRQL measures such as the [Short Form–36 (SF-36)] Health Survey Questionnaire,” the investigators explained. Recent research has used the CLDQ to reveal a variety of findings, the investigators noted, such as a 2016 study by Alt and colleagues outlining the most common symptoms in noninfectious chronic liver disease (abdominal discomfort, fatigue, and anxiety), and two studies by Younossi and colleagues describing quality of life improvements after curing hepatitis C virus, and negative impacts of viremia and hepatic inflammation in patients with hepatitis B.

The current study involved 304 patients with histologically confirmed NAFLD who were prospectively entered into the European NAFLD registry via centers in Germany (n = 133), the United Kingdom (n = 154), and Spain (n = 17). Patient data included demographic factors, laboratory findings, and histologic features. Within 6 months of liver biopsy, patients completed the CLDQ.

The mean patient age was 52.3 years, with slightly more men than women (53.3% vs. 46.7%). Most patients (75%) were obese, leading to a median body mass index of 33.3 kg/m2. More than two-thirds of patients (69.1%) had NASH, while approximately half of the population (51.4%) had moderate steatosis, no or low-grade fibrosis (F0-2, 58.2%), and no or low-grade lobular inflammation (grade 0 or 1, 54.7%). The three countries had significantly different population profiles; for example, the United Kingdom had an approximately 10% higher prevalence of type 2 diabetes and obesity compared with the entire cohort, but a decreased arterial hypertension rate of a similar magnitude. The United Kingdom also had a significantly lower mean CLDQ score than that of the study population as a whole (4.73 vs. 4.99).

Analysis of the entire cohort revealed that a variety of demographic and disease-related factors negatively impacted health-related quality of life. Women had a significantly lower mean CLDQ score than that of men (5.31 vs. 4.62; P less than .001), more often reporting abdominal symptoms, fatigue, systemic symptoms, reduced activity, diminished emotional functioning, and worry. CLDQ overall score was negatively influenced by obesity (4.83 vs. 5.46), type 2 diabetes (4.74 vs. 5.25), and hyperlipidemia (4.84 vs. 5.24), but not hypertension. Laboratory findings that negatively correlated with CLDQ included aspartate transaminase (AST) and HbA1c, whereas ferritin was positively correlated.

Generally, patients with NASH reported worse quality of life than that of those with just NAFLD (4.85 vs. 5.31). Factors contributing most to this disparity were fatigue, systemic symptoms, activity, and worry. On a histologic level, hepatic steatosis, ballooning, and lobular inflammation predicted poorer quality of life; although advanced fibrosis and compensated cirrhosis were associated with a trend toward reduced quality of life, this pattern lacked statistical significance. Multivariate analysis, which accounted for age, sex, body mass index, country, and type 2 diabetes, revealed independent associations between reduced quality of life and type 2 diabetes, sex, age, body mass index, and hepatic inflammation, but not fibrosis.

“The striking finding of the current analysis in this well-characterized European cohort was that, in contrast to the published data on predictors of overall and liver-specific mortality, lobular inflammation correlated independently with HRQL,” the investigators wrote. “These results differ from the NASH [Clinical Research Network] cohort, which found lower HRQL using the generic [SF-36 Health Survey Questionnaire] in NASH compared with a healthy U.S. population and a significant effect in cirrhosis only.” The investigators suggested that mechanistic differences in disease progression could explain this discordance.

Although hepatic fibrosis has been tied with quality of life by some studies, the investigators pointed out that patients with chronic hepatitis B or C have reported improved quality of life after viral elimination or suppression, which reduce inflammation, but not fibrosis. “On the basis of the current analysis, it can be expected that improvement of steatohepatitis, and in particular lobular inflammation, will have measurable influence on HRQL even independently of fibrosis improvement,” the investigators concluded.

The study was funded by H2020. The investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Huber Y et al. CGH. 2018 Dec 20. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.12.016.

A variety of demographic and disease-related factors contribute to poorer quality of life in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), based on questionnaires involving 304 European patients.

In contrast with previous research, lobular inflammation, but not hepatic fibrosis, was associated with worse quality of life, reported to lead author Yvonne Huber, MD, of Johannes Gutenberg University in Mainz, Germany, and colleagues. Women and those with advanced disease or comorbidities had the lowest health-related quality of life (HRQL) scores. The investigators suggested that these findings could be used for treatment planning at a population and patient level.

“With the emergence of medical therapy for [nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH)], it will be of importance to identify patients with the highest unmet need for treatment,” the investigators wrote in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, emphasizing that therapies targeting inflammation could provide the greatest relief.

To determine which patients with NAFLD were most affected by their condition, the investigators used the Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire (CLDQ), which assesses physical, mental, social, and emotional function, with lower scores indicating poorer health-related quality of life. “[The CLDQ] more specifically addresses symptoms of patients with chronic liver disease, including extrahepatic manifestations, compared with traditional HRQL measures such as the [Short Form–36 (SF-36)] Health Survey Questionnaire,” the investigators explained. Recent research has used the CLDQ to reveal a variety of findings, the investigators noted, such as a 2016 study by Alt and colleagues outlining the most common symptoms in noninfectious chronic liver disease (abdominal discomfort, fatigue, and anxiety), and two studies by Younossi and colleagues describing quality of life improvements after curing hepatitis C virus, and negative impacts of viremia and hepatic inflammation in patients with hepatitis B.

The current study involved 304 patients with histologically confirmed NAFLD who were prospectively entered into the European NAFLD registry via centers in Germany (n = 133), the United Kingdom (n = 154), and Spain (n = 17). Patient data included demographic factors, laboratory findings, and histologic features. Within 6 months of liver biopsy, patients completed the CLDQ.

The mean patient age was 52.3 years, with slightly more men than women (53.3% vs. 46.7%). Most patients (75%) were obese, leading to a median body mass index of 33.3 kg/m2. More than two-thirds of patients (69.1%) had NASH, while approximately half of the population (51.4%) had moderate steatosis, no or low-grade fibrosis (F0-2, 58.2%), and no or low-grade lobular inflammation (grade 0 or 1, 54.7%). The three countries had significantly different population profiles; for example, the United Kingdom had an approximately 10% higher prevalence of type 2 diabetes and obesity compared with the entire cohort, but a decreased arterial hypertension rate of a similar magnitude. The United Kingdom also had a significantly lower mean CLDQ score than that of the study population as a whole (4.73 vs. 4.99).

Analysis of the entire cohort revealed that a variety of demographic and disease-related factors negatively impacted health-related quality of life. Women had a significantly lower mean CLDQ score than that of men (5.31 vs. 4.62; P less than .001), more often reporting abdominal symptoms, fatigue, systemic symptoms, reduced activity, diminished emotional functioning, and worry. CLDQ overall score was negatively influenced by obesity (4.83 vs. 5.46), type 2 diabetes (4.74 vs. 5.25), and hyperlipidemia (4.84 vs. 5.24), but not hypertension. Laboratory findings that negatively correlated with CLDQ included aspartate transaminase (AST) and HbA1c, whereas ferritin was positively correlated.

Generally, patients with NASH reported worse quality of life than that of those with just NAFLD (4.85 vs. 5.31). Factors contributing most to this disparity were fatigue, systemic symptoms, activity, and worry. On a histologic level, hepatic steatosis, ballooning, and lobular inflammation predicted poorer quality of life; although advanced fibrosis and compensated cirrhosis were associated with a trend toward reduced quality of life, this pattern lacked statistical significance. Multivariate analysis, which accounted for age, sex, body mass index, country, and type 2 diabetes, revealed independent associations between reduced quality of life and type 2 diabetes, sex, age, body mass index, and hepatic inflammation, but not fibrosis.

“The striking finding of the current analysis in this well-characterized European cohort was that, in contrast to the published data on predictors of overall and liver-specific mortality, lobular inflammation correlated independently with HRQL,” the investigators wrote. “These results differ from the NASH [Clinical Research Network] cohort, which found lower HRQL using the generic [SF-36 Health Survey Questionnaire] in NASH compared with a healthy U.S. population and a significant effect in cirrhosis only.” The investigators suggested that mechanistic differences in disease progression could explain this discordance.

Although hepatic fibrosis has been tied with quality of life by some studies, the investigators pointed out that patients with chronic hepatitis B or C have reported improved quality of life after viral elimination or suppression, which reduce inflammation, but not fibrosis. “On the basis of the current analysis, it can be expected that improvement of steatohepatitis, and in particular lobular inflammation, will have measurable influence on HRQL even independently of fibrosis improvement,” the investigators concluded.

The study was funded by H2020. The investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Huber Y et al. CGH. 2018 Dec 20. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.12.016.

A variety of demographic and disease-related factors contribute to poorer quality of life in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), based on questionnaires involving 304 European patients.

In contrast with previous research, lobular inflammation, but not hepatic fibrosis, was associated with worse quality of life, reported to lead author Yvonne Huber, MD, of Johannes Gutenberg University in Mainz, Germany, and colleagues. Women and those with advanced disease or comorbidities had the lowest health-related quality of life (HRQL) scores. The investigators suggested that these findings could be used for treatment planning at a population and patient level.

“With the emergence of medical therapy for [nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH)], it will be of importance to identify patients with the highest unmet need for treatment,” the investigators wrote in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, emphasizing that therapies targeting inflammation could provide the greatest relief.

To determine which patients with NAFLD were most affected by their condition, the investigators used the Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire (CLDQ), which assesses physical, mental, social, and emotional function, with lower scores indicating poorer health-related quality of life. “[The CLDQ] more specifically addresses symptoms of patients with chronic liver disease, including extrahepatic manifestations, compared with traditional HRQL measures such as the [Short Form–36 (SF-36)] Health Survey Questionnaire,” the investigators explained. Recent research has used the CLDQ to reveal a variety of findings, the investigators noted, such as a 2016 study by Alt and colleagues outlining the most common symptoms in noninfectious chronic liver disease (abdominal discomfort, fatigue, and anxiety), and two studies by Younossi and colleagues describing quality of life improvements after curing hepatitis C virus, and negative impacts of viremia and hepatic inflammation in patients with hepatitis B.

The current study involved 304 patients with histologically confirmed NAFLD who were prospectively entered into the European NAFLD registry via centers in Germany (n = 133), the United Kingdom (n = 154), and Spain (n = 17). Patient data included demographic factors, laboratory findings, and histologic features. Within 6 months of liver biopsy, patients completed the CLDQ.

The mean patient age was 52.3 years, with slightly more men than women (53.3% vs. 46.7%). Most patients (75%) were obese, leading to a median body mass index of 33.3 kg/m2. More than two-thirds of patients (69.1%) had NASH, while approximately half of the population (51.4%) had moderate steatosis, no or low-grade fibrosis (F0-2, 58.2%), and no or low-grade lobular inflammation (grade 0 or 1, 54.7%). The three countries had significantly different population profiles; for example, the United Kingdom had an approximately 10% higher prevalence of type 2 diabetes and obesity compared with the entire cohort, but a decreased arterial hypertension rate of a similar magnitude. The United Kingdom also had a significantly lower mean CLDQ score than that of the study population as a whole (4.73 vs. 4.99).

Analysis of the entire cohort revealed that a variety of demographic and disease-related factors negatively impacted health-related quality of life. Women had a significantly lower mean CLDQ score than that of men (5.31 vs. 4.62; P less than .001), more often reporting abdominal symptoms, fatigue, systemic symptoms, reduced activity, diminished emotional functioning, and worry. CLDQ overall score was negatively influenced by obesity (4.83 vs. 5.46), type 2 diabetes (4.74 vs. 5.25), and hyperlipidemia (4.84 vs. 5.24), but not hypertension. Laboratory findings that negatively correlated with CLDQ included aspartate transaminase (AST) and HbA1c, whereas ferritin was positively correlated.

Generally, patients with NASH reported worse quality of life than that of those with just NAFLD (4.85 vs. 5.31). Factors contributing most to this disparity were fatigue, systemic symptoms, activity, and worry. On a histologic level, hepatic steatosis, ballooning, and lobular inflammation predicted poorer quality of life; although advanced fibrosis and compensated cirrhosis were associated with a trend toward reduced quality of life, this pattern lacked statistical significance. Multivariate analysis, which accounted for age, sex, body mass index, country, and type 2 diabetes, revealed independent associations between reduced quality of life and type 2 diabetes, sex, age, body mass index, and hepatic inflammation, but not fibrosis.

“The striking finding of the current analysis in this well-characterized European cohort was that, in contrast to the published data on predictors of overall and liver-specific mortality, lobular inflammation correlated independently with HRQL,” the investigators wrote. “These results differ from the NASH [Clinical Research Network] cohort, which found lower HRQL using the generic [SF-36 Health Survey Questionnaire] in NASH compared with a healthy U.S. population and a significant effect in cirrhosis only.” The investigators suggested that mechanistic differences in disease progression could explain this discordance.

Although hepatic fibrosis has been tied with quality of life by some studies, the investigators pointed out that patients with chronic hepatitis B or C have reported improved quality of life after viral elimination or suppression, which reduce inflammation, but not fibrosis. “On the basis of the current analysis, it can be expected that improvement of steatohepatitis, and in particular lobular inflammation, will have measurable influence on HRQL even independently of fibrosis improvement,” the investigators concluded.

The study was funded by H2020. The investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Huber Y et al. CGH. 2018 Dec 20. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.12.016.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

RNA interference drug fitusiran looks effective in both hemophilia A and B

MELBOURNE – An investigational RNA interference therapeutic that suppresses the production of antithrombin has shown significant reductions in bleeding rates with no major safety events, according to findings presented at the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis congress.

Fitusiran is a once-monthly, fixed-dose subcutaneous therapy that uses RNA interference to silence the gene for the endogenous anticoagulant antithrombin.

“The therapeutic hypothesis is based on the fact that hemophilia A and B are essentially thrombin-deficiency disorders, so if we lack factor VIII or factor IX, we can’t generate enough thrombin and we can’t produce a significant and substantial blood clot,” John Pasi, MBChB, PhD, of the Royal London Haemophilia Centre, Barts Health NHS Trust. “If we, however, administer fitusiran, which will suppress antithrombin production, we can rebalance coagulation, generate more thrombin and form a much more substantial clot.”

Dr. Pasi presented results of an interim analysis of safety and efficacy data from an open-label, phase 2 extension study in 34 individuals with hemophilia A or B, with or without inhibitors, who were treated either with 50-mg or 80-mg doses of fitusiran for a median of at least 2 years.

Researchers saw significant declines in annualized bleeding rates in patients with hemophilia A and B, with and without inhibitors. Among those without inhibitors, the median annualized bleeding rate declined from 2.00 in patients already on hemophilia prophylaxis and 12.00 in those using on-demand treatment to 1.08 overall. In patients with inhibitors, the median annualized bleeding rate dropped from 42.00 to 1.04.

The treatment was also associated with substantial reductions in antithrombin production and increases in thrombin generation.

One patient in the phase 1 study experienced a fatal cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, which subsequently led to introduction of a bleed management protocol.

“Following that last case, we revised and reviewed the bleed management guidelines in view of the fact that there might potentially be an interaction between the amount of replacement therapy and thrombin generation,” Dr. Pasi said. Since introduction of that protocol, there have been no related thrombotic events.

The majority of adverse events reported were mild and deemed not related to the study drug, Dr. Pasi said. These included headache, injection site erythema, and arthralgia. A total of 14 subjects – all of whom were positive for hepatitis C at baseline – experienced rises in ALT levels but these were asymptomatic and resolved spontaneously.

One patient with chronic active hepatitis C infection also showed significant ALT/AST elevation which led to discontinuation of treatment.

In an interview, Dr. Pasi said one of the biggest advantages of fitusiran was that it could be used in patients with hemophilia A and B. “You’ve got patients with hemophilia B who’ve got no options at the moment. That would be an obvious specific group that would gain from this.”

Another advantage was fitusiran’s stability and dosing, he said, pointing out that the treatment was fixed dosing and stable at room temperature. Fitusiran is now undergoing phase 3 trials.

The study was funded by Sanofi Genzyme and Alnylam Pharmaceuticals, and six authors were employees of Sanofi Genzyme. Dr. Pasi reported financial relationships with pharmaceutical companies, including Alnylam.

SOURCE: Pasi J et al. 2019 ISTH Congress, Abstract OC 11.3.

MELBOURNE – An investigational RNA interference therapeutic that suppresses the production of antithrombin has shown significant reductions in bleeding rates with no major safety events, according to findings presented at the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis congress.

Fitusiran is a once-monthly, fixed-dose subcutaneous therapy that uses RNA interference to silence the gene for the endogenous anticoagulant antithrombin.

“The therapeutic hypothesis is based on the fact that hemophilia A and B are essentially thrombin-deficiency disorders, so if we lack factor VIII or factor IX, we can’t generate enough thrombin and we can’t produce a significant and substantial blood clot,” John Pasi, MBChB, PhD, of the Royal London Haemophilia Centre, Barts Health NHS Trust. “If we, however, administer fitusiran, which will suppress antithrombin production, we can rebalance coagulation, generate more thrombin and form a much more substantial clot.”

Dr. Pasi presented results of an interim analysis of safety and efficacy data from an open-label, phase 2 extension study in 34 individuals with hemophilia A or B, with or without inhibitors, who were treated either with 50-mg or 80-mg doses of fitusiran for a median of at least 2 years.

Researchers saw significant declines in annualized bleeding rates in patients with hemophilia A and B, with and without inhibitors. Among those without inhibitors, the median annualized bleeding rate declined from 2.00 in patients already on hemophilia prophylaxis and 12.00 in those using on-demand treatment to 1.08 overall. In patients with inhibitors, the median annualized bleeding rate dropped from 42.00 to 1.04.

The treatment was also associated with substantial reductions in antithrombin production and increases in thrombin generation.

One patient in the phase 1 study experienced a fatal cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, which subsequently led to introduction of a bleed management protocol.

“Following that last case, we revised and reviewed the bleed management guidelines in view of the fact that there might potentially be an interaction between the amount of replacement therapy and thrombin generation,” Dr. Pasi said. Since introduction of that protocol, there have been no related thrombotic events.

The majority of adverse events reported were mild and deemed not related to the study drug, Dr. Pasi said. These included headache, injection site erythema, and arthralgia. A total of 14 subjects – all of whom were positive for hepatitis C at baseline – experienced rises in ALT levels but these were asymptomatic and resolved spontaneously.

One patient with chronic active hepatitis C infection also showed significant ALT/AST elevation which led to discontinuation of treatment.

In an interview, Dr. Pasi said one of the biggest advantages of fitusiran was that it could be used in patients with hemophilia A and B. “You’ve got patients with hemophilia B who’ve got no options at the moment. That would be an obvious specific group that would gain from this.”

Another advantage was fitusiran’s stability and dosing, he said, pointing out that the treatment was fixed dosing and stable at room temperature. Fitusiran is now undergoing phase 3 trials.

The study was funded by Sanofi Genzyme and Alnylam Pharmaceuticals, and six authors were employees of Sanofi Genzyme. Dr. Pasi reported financial relationships with pharmaceutical companies, including Alnylam.

SOURCE: Pasi J et al. 2019 ISTH Congress, Abstract OC 11.3.

MELBOURNE – An investigational RNA interference therapeutic that suppresses the production of antithrombin has shown significant reductions in bleeding rates with no major safety events, according to findings presented at the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis congress.

Fitusiran is a once-monthly, fixed-dose subcutaneous therapy that uses RNA interference to silence the gene for the endogenous anticoagulant antithrombin.

“The therapeutic hypothesis is based on the fact that hemophilia A and B are essentially thrombin-deficiency disorders, so if we lack factor VIII or factor IX, we can’t generate enough thrombin and we can’t produce a significant and substantial blood clot,” John Pasi, MBChB, PhD, of the Royal London Haemophilia Centre, Barts Health NHS Trust. “If we, however, administer fitusiran, which will suppress antithrombin production, we can rebalance coagulation, generate more thrombin and form a much more substantial clot.”

Dr. Pasi presented results of an interim analysis of safety and efficacy data from an open-label, phase 2 extension study in 34 individuals with hemophilia A or B, with or without inhibitors, who were treated either with 50-mg or 80-mg doses of fitusiran for a median of at least 2 years.

Researchers saw significant declines in annualized bleeding rates in patients with hemophilia A and B, with and without inhibitors. Among those without inhibitors, the median annualized bleeding rate declined from 2.00 in patients already on hemophilia prophylaxis and 12.00 in those using on-demand treatment to 1.08 overall. In patients with inhibitors, the median annualized bleeding rate dropped from 42.00 to 1.04.

The treatment was also associated with substantial reductions in antithrombin production and increases in thrombin generation.

One patient in the phase 1 study experienced a fatal cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, which subsequently led to introduction of a bleed management protocol.

“Following that last case, we revised and reviewed the bleed management guidelines in view of the fact that there might potentially be an interaction between the amount of replacement therapy and thrombin generation,” Dr. Pasi said. Since introduction of that protocol, there have been no related thrombotic events.

The majority of adverse events reported were mild and deemed not related to the study drug, Dr. Pasi said. These included headache, injection site erythema, and arthralgia. A total of 14 subjects – all of whom were positive for hepatitis C at baseline – experienced rises in ALT levels but these were asymptomatic and resolved spontaneously.

One patient with chronic active hepatitis C infection also showed significant ALT/AST elevation which led to discontinuation of treatment.

In an interview, Dr. Pasi said one of the biggest advantages of fitusiran was that it could be used in patients with hemophilia A and B. “You’ve got patients with hemophilia B who’ve got no options at the moment. That would be an obvious specific group that would gain from this.”

Another advantage was fitusiran’s stability and dosing, he said, pointing out that the treatment was fixed dosing and stable at room temperature. Fitusiran is now undergoing phase 3 trials.

The study was funded by Sanofi Genzyme and Alnylam Pharmaceuticals, and six authors were employees of Sanofi Genzyme. Dr. Pasi reported financial relationships with pharmaceutical companies, including Alnylam.

SOURCE: Pasi J et al. 2019 ISTH Congress, Abstract OC 11.3.

REPORTING FROM 2019 ISTH CONGRESS

Gram-negative bacteremia: Cultures, drugs, and duration

Are we doing it right?

Case

A 42-year-old woman with uncontrolled diabetes presents to the ED with fever, chills, dysuria, and flank pain for 3 days. On exam, she is febrile and tachycardic. Lab results show leukocytosis and urinalysis is consistent with infection. CT scan shows acute pyelonephritis without complication. She is admitted to the hospital and started on ceftriaxone 2 g/24 hrs. On hospital day 2, her blood cultures show gram-negative bacteria.

Brief overview

Management of gram-negative (GN) bacteremia remains a challenging clinical situation for inpatient providers. With the push for high-value care and reductions in length of stay, recent literature has focused on reviewing current practices and attempting to standardize care. Despite this, no overarching guidelines exist to direct practice and clinicians are left to make decisions based on prior experience and expert opinion. Three key clinical questions exist when caring for a hospitalized patient with GN bacteremia: Should blood cultures be repeated? When is transition to oral antibiotics appropriate? And for what duration should antibiotics be given?

Overview of the data

When considering repeating blood cultures, it is important to understand that current literature does not support the practice for all GN bacteremias.

Canzoneri et al. retrospectively studied GN bacteremia and found that it took 17 repeat blood cultures being drawn to yield 1 positive result, which suggests that they are not necessary in all cases.1 Furthermore, repeat blood cultures increase cost of hospitalization, length of stay, and inconvenience to patients.2

However, Mushtaq et al. noted that repeating blood cultures can provide valuable information to confirm the response to treatment in patients with endovascular infection. Furthermore, they found that repeated blood cultures are also reasonable when the following scenarios are suspected: endocarditis or central line–associated infection, concern for multidrug resistant GN bacilli, and ongoing evidence of sepsis or patient decompensation.3

Consideration of a transition from intravenous to oral antibiotics is a key decision point in the care of GN bacteremia. Without guidelines, clinicians are left to evaluate patients on a case-by-case basis.4 Studies have suggested that the transition should be guided by the condition of the patient, the type of infection, and the culture-derived sensitivities.5 Additionally, bioavailability of antibiotics (see Table 1) is an important consideration and a recent examination of oral antibiotic failure rates demonstrated that lower bioavailability antibiotics have an increased risk of failure (2% vs. 16%).6

In their study, Kutob et al. highlighted the importance of choosing not only an antibiotic of high bioavailability, but also an antibiotic dose which will support a high concentration of the antibiotic in the bloodstream.6 For example, they identify ciprofloxacin as a moderate bioavailability medication, but note that most cases they examined utilized 500 mg b.i.d., where the concentration-dependent killing and dose-dependent bioavailability would advocate for the use of 750 mg b.i.d. or 500 mg every 8 hours.

The heterogeneity of GN bloodstream infections also creates difficulty in standardization of care. The literature suggests that infection source plays a significant role in the type of GN bacteria isolated.6,7 The best data for the transition to oral antibiotics exists with urologic sources and it remains unclear whether bacteria from other sources have higher risks of oral antibiotic failure.8

One recent study of 66 patients examined bacteremia in the setting of cholangitis and found that, once patients had stabilized, a switch from intravenous to oral antibiotics was noninferior, but randomized, prospective trials have not been performed. Notably, patients were transitioned to orals only after they were found to have a fluoroquinolone-sensitive infection, allowing the study authors to use higher-bioavailability agents for the transition to orals.9 Multiple studies have highlighted the unique care required for certain infections, such as pseudomonal infections, which most experts agree requires a more conservative approach.5,6

Fluoroquinolones are the bedrock of therapy for GN bacteremia because of historic in vivo experience and in vitro findings about bioavailability and dose-dependent killing, but they are also the antibiotic class associated with the highest hospitalization rates for antibiotic-associated adverse events.8 A recent noninferiority trial comparing the use of beta-lactams with fluoroquinolones found that beta-lactams were noninferior, though the study was flawed by the limited number of beta-lactam–using patients identified.8 It is clear that more investigation is needed before recommendations can be made regarding ideal oral antibiotics for GN bacteremia.

The transition to oral is reasonable given the following criteria: the patient has improved on intravenous antibiotics and source control has been achieved; the culture data have demonstrated sensitivity to the oral antibiotic of choice, with special care given to higher-risk bacteria such as Pseudomonas; the patient is able to take the oral antibiotic; and the oral antibiotic of choice has the highest bioavailability possible and is given at an appropriate dose to reach its highest killing and bioavailability concentrations.7

After evaluating the appropriateness of transition to oral antibiotics, the final decision is about duration of antibiotic therapy. Current Infectious Disease Society of America guidelines are based on expert opinion and recommend 7-14 days of therapy. As with many common infections, recent studies have focused on evaluating reduction in antibiotic durations.

Chotiprasitsakul et al. demonstrated no difference in mortality or morbidity in 385 propensity-matched pairs with treatment of Enterobacteriaceae bacteremia for 8 versus 15 days.10 A mixed meta-analysis performed in 2011 evaluated 24 randomized, controlled trials and found shorter durations (5-7 days) had similar outcomes to prolonged durations (7-21 days).11 Recently, Yahav et al. performed a randomized control trial comparing 7- and 14-day regimens for uncomplicated GN bacteremia and found a 7-day course to be noninferior if patients were clinically stable by day 5 and had source control.12

It should be noted that not all studies have found that reduced durations are without harm. Nelson et al. performed a retrospective cohort analysis and found that reduced durations of antibiotics (7-10 days) increased mortality and recurrent infection when compared with a longer course (greater than 10 days).13 These contrary findings highlight the need for provider discretion in selecting a course of antibiotics as well as the need for further studies about optimal duration of antibiotics.

Application of the data

Returning to our case, on day 3, the patient’s fever had resolved and leukocytosis improved. In the absence of concern for persistent infection, repeat blood cultures were not performed. On day 4 initial blood cultures showed pan-sensitive Escherichia coli. The patient was transitioned to 750 mg oral ciprofloxacin b.i.d. to complete a 10-day course from first dose of ceftriaxone and was discharged from the hospital.

Bottom line

Management of GN bacteremia requires individualized care based on clinical presentation, but the data presented above can be used as broad guidelines to help reduce excess blood cultures, avoid prolonged use of intravenous antibiotics, and limit the duration of antibiotic exposure.

Dr. Imber is an assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, and director of the Internal Medicine Simulation Education and Hospitalist Procedural Certification. Dr. Burns is an assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine at the University of New Mexico. Dr. Chan is currently a chief resident in the department of internal medicine at the University of New Mexico.

References

1. Canzoneri CN et al. Follow-up blood cultures in gram-negative bacteremia: Are they needed? Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65(11):1776-9. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix648.

2. Kang CK et al. Can a routine follow-up blood culture be justified in Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia? A retrospective case-control study. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:365. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-365.

3. Mushtaq A et al. Repeating blood cultures after an initial bacteremia: When and how often? Cleve Clin J Med. 2019;86(2):89-92. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.86a.18001.

4. Nimmich EB et al. Development of institutional guidelines for management of gram-negative bloodstream infections: Incorporating local evidence. Hosp Pharm. 2017;52(10):691-7. doi: 10.1177/0018578717720506.

5. Hale AJ et al. When are oral antibiotics a safe and effective choice for bacterial bloodstream infections? An evidence-based narrative review. J Hosp Med. 2018 May. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2949.

6. Kutob LF et al. Effectiveness of oral antibiotics for definitive therapy of gram-negative bloodstream infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2016.07.013.

7. Tamma PD et al. Association of 30-day mortality with oral step-down vs. continued intravenous therapy in patients hospitalized with Enterobacteriaceae bacteremia. JAMA Intern Med. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6226.

8. Mercuro NJ et al. Retrospective analysis comparing oral stepdown therapy for enterobacteriaceae bloodstream infections: fluoroquinolones vs. B-lactams. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2017.12.007.

9. Park TY et al. Early oral antibiotic switch compared with conventional intravenous antibiotic therapy for acute cholangitis with bacteremia. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59:2790-6. doi: 10.1007/s10620-014-3233-0.

10. Chotiprasitsakul D et al. Comparing the outcomes of adults with Enterobacteriaceae bacteremia receiving short-course versus prolonged-course antibiotic therapy in a multicenter, propensity score-matched cohort. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66(2):172-7. doi:10.1093/cid/cix767.

11. Havey TC et al. Duration of antibiotic therapy for bacteremia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2011;15(6):R267. doi:10.1186/cc10545.

12. Yahav D et al. Seven versus fourteen days of antibiotic therapy for uncomplicated gram-negative bacteremia: A noninferiority randomized controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2018 Dec. doi:10.1093/cid/ciy1054.

13. Nelson AN et al. Optimal duration of antimicrobial therapy for uncomplicated gram-negative bloodstream infections. Infection. 2017;45(5):613-20. doi:10.1007/s15010-017-1020-5.

Are we doing it right?

Are we doing it right?

Case

A 42-year-old woman with uncontrolled diabetes presents to the ED with fever, chills, dysuria, and flank pain for 3 days. On exam, she is febrile and tachycardic. Lab results show leukocytosis and urinalysis is consistent with infection. CT scan shows acute pyelonephritis without complication. She is admitted to the hospital and started on ceftriaxone 2 g/24 hrs. On hospital day 2, her blood cultures show gram-negative bacteria.

Brief overview

Management of gram-negative (GN) bacteremia remains a challenging clinical situation for inpatient providers. With the push for high-value care and reductions in length of stay, recent literature has focused on reviewing current practices and attempting to standardize care. Despite this, no overarching guidelines exist to direct practice and clinicians are left to make decisions based on prior experience and expert opinion. Three key clinical questions exist when caring for a hospitalized patient with GN bacteremia: Should blood cultures be repeated? When is transition to oral antibiotics appropriate? And for what duration should antibiotics be given?

Overview of the data

When considering repeating blood cultures, it is important to understand that current literature does not support the practice for all GN bacteremias.

Canzoneri et al. retrospectively studied GN bacteremia and found that it took 17 repeat blood cultures being drawn to yield 1 positive result, which suggests that they are not necessary in all cases.1 Furthermore, repeat blood cultures increase cost of hospitalization, length of stay, and inconvenience to patients.2

However, Mushtaq et al. noted that repeating blood cultures can provide valuable information to confirm the response to treatment in patients with endovascular infection. Furthermore, they found that repeated blood cultures are also reasonable when the following scenarios are suspected: endocarditis or central line–associated infection, concern for multidrug resistant GN bacilli, and ongoing evidence of sepsis or patient decompensation.3

Consideration of a transition from intravenous to oral antibiotics is a key decision point in the care of GN bacteremia. Without guidelines, clinicians are left to evaluate patients on a case-by-case basis.4 Studies have suggested that the transition should be guided by the condition of the patient, the type of infection, and the culture-derived sensitivities.5 Additionally, bioavailability of antibiotics (see Table 1) is an important consideration and a recent examination of oral antibiotic failure rates demonstrated that lower bioavailability antibiotics have an increased risk of failure (2% vs. 16%).6

In their study, Kutob et al. highlighted the importance of choosing not only an antibiotic of high bioavailability, but also an antibiotic dose which will support a high concentration of the antibiotic in the bloodstream.6 For example, they identify ciprofloxacin as a moderate bioavailability medication, but note that most cases they examined utilized 500 mg b.i.d., where the concentration-dependent killing and dose-dependent bioavailability would advocate for the use of 750 mg b.i.d. or 500 mg every 8 hours.

The heterogeneity of GN bloodstream infections also creates difficulty in standardization of care. The literature suggests that infection source plays a significant role in the type of GN bacteria isolated.6,7 The best data for the transition to oral antibiotics exists with urologic sources and it remains unclear whether bacteria from other sources have higher risks of oral antibiotic failure.8

One recent study of 66 patients examined bacteremia in the setting of cholangitis and found that, once patients had stabilized, a switch from intravenous to oral antibiotics was noninferior, but randomized, prospective trials have not been performed. Notably, patients were transitioned to orals only after they were found to have a fluoroquinolone-sensitive infection, allowing the study authors to use higher-bioavailability agents for the transition to orals.9 Multiple studies have highlighted the unique care required for certain infections, such as pseudomonal infections, which most experts agree requires a more conservative approach.5,6

Fluoroquinolones are the bedrock of therapy for GN bacteremia because of historic in vivo experience and in vitro findings about bioavailability and dose-dependent killing, but they are also the antibiotic class associated with the highest hospitalization rates for antibiotic-associated adverse events.8 A recent noninferiority trial comparing the use of beta-lactams with fluoroquinolones found that beta-lactams were noninferior, though the study was flawed by the limited number of beta-lactam–using patients identified.8 It is clear that more investigation is needed before recommendations can be made regarding ideal oral antibiotics for GN bacteremia.

The transition to oral is reasonable given the following criteria: the patient has improved on intravenous antibiotics and source control has been achieved; the culture data have demonstrated sensitivity to the oral antibiotic of choice, with special care given to higher-risk bacteria such as Pseudomonas; the patient is able to take the oral antibiotic; and the oral antibiotic of choice has the highest bioavailability possible and is given at an appropriate dose to reach its highest killing and bioavailability concentrations.7

After evaluating the appropriateness of transition to oral antibiotics, the final decision is about duration of antibiotic therapy. Current Infectious Disease Society of America guidelines are based on expert opinion and recommend 7-14 days of therapy. As with many common infections, recent studies have focused on evaluating reduction in antibiotic durations.

Chotiprasitsakul et al. demonstrated no difference in mortality or morbidity in 385 propensity-matched pairs with treatment of Enterobacteriaceae bacteremia for 8 versus 15 days.10 A mixed meta-analysis performed in 2011 evaluated 24 randomized, controlled trials and found shorter durations (5-7 days) had similar outcomes to prolonged durations (7-21 days).11 Recently, Yahav et al. performed a randomized control trial comparing 7- and 14-day regimens for uncomplicated GN bacteremia and found a 7-day course to be noninferior if patients were clinically stable by day 5 and had source control.12

It should be noted that not all studies have found that reduced durations are without harm. Nelson et al. performed a retrospective cohort analysis and found that reduced durations of antibiotics (7-10 days) increased mortality and recurrent infection when compared with a longer course (greater than 10 days).13 These contrary findings highlight the need for provider discretion in selecting a course of antibiotics as well as the need for further studies about optimal duration of antibiotics.

Application of the data

Returning to our case, on day 3, the patient’s fever had resolved and leukocytosis improved. In the absence of concern for persistent infection, repeat blood cultures were not performed. On day 4 initial blood cultures showed pan-sensitive Escherichia coli. The patient was transitioned to 750 mg oral ciprofloxacin b.i.d. to complete a 10-day course from first dose of ceftriaxone and was discharged from the hospital.

Bottom line

Management of GN bacteremia requires individualized care based on clinical presentation, but the data presented above can be used as broad guidelines to help reduce excess blood cultures, avoid prolonged use of intravenous antibiotics, and limit the duration of antibiotic exposure.

Dr. Imber is an assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, and director of the Internal Medicine Simulation Education and Hospitalist Procedural Certification. Dr. Burns is an assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine at the University of New Mexico. Dr. Chan is currently a chief resident in the department of internal medicine at the University of New Mexico.

References

1. Canzoneri CN et al. Follow-up blood cultures in gram-negative bacteremia: Are they needed? Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65(11):1776-9. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix648.

2. Kang CK et al. Can a routine follow-up blood culture be justified in Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia? A retrospective case-control study. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:365. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-365.

3. Mushtaq A et al. Repeating blood cultures after an initial bacteremia: When and how often? Cleve Clin J Med. 2019;86(2):89-92. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.86a.18001.

4. Nimmich EB et al. Development of institutional guidelines for management of gram-negative bloodstream infections: Incorporating local evidence. Hosp Pharm. 2017;52(10):691-7. doi: 10.1177/0018578717720506.

5. Hale AJ et al. When are oral antibiotics a safe and effective choice for bacterial bloodstream infections? An evidence-based narrative review. J Hosp Med. 2018 May. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2949.

6. Kutob LF et al. Effectiveness of oral antibiotics for definitive therapy of gram-negative bloodstream infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2016.07.013.

7. Tamma PD et al. Association of 30-day mortality with oral step-down vs. continued intravenous therapy in patients hospitalized with Enterobacteriaceae bacteremia. JAMA Intern Med. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6226.

8. Mercuro NJ et al. Retrospective analysis comparing oral stepdown therapy for enterobacteriaceae bloodstream infections: fluoroquinolones vs. B-lactams. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2017.12.007.

9. Park TY et al. Early oral antibiotic switch compared with conventional intravenous antibiotic therapy for acute cholangitis with bacteremia. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59:2790-6. doi: 10.1007/s10620-014-3233-0.

10. Chotiprasitsakul D et al. Comparing the outcomes of adults with Enterobacteriaceae bacteremia receiving short-course versus prolonged-course antibiotic therapy in a multicenter, propensity score-matched cohort. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66(2):172-7. doi:10.1093/cid/cix767.

11. Havey TC et al. Duration of antibiotic therapy for bacteremia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2011;15(6):R267. doi:10.1186/cc10545.

12. Yahav D et al. Seven versus fourteen days of antibiotic therapy for uncomplicated gram-negative bacteremia: A noninferiority randomized controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2018 Dec. doi:10.1093/cid/ciy1054.

13. Nelson AN et al. Optimal duration of antimicrobial therapy for uncomplicated gram-negative bloodstream infections. Infection. 2017;45(5):613-20. doi:10.1007/s15010-017-1020-5.

Case

A 42-year-old woman with uncontrolled diabetes presents to the ED with fever, chills, dysuria, and flank pain for 3 days. On exam, she is febrile and tachycardic. Lab results show leukocytosis and urinalysis is consistent with infection. CT scan shows acute pyelonephritis without complication. She is admitted to the hospital and started on ceftriaxone 2 g/24 hrs. On hospital day 2, her blood cultures show gram-negative bacteria.

Brief overview

Management of gram-negative (GN) bacteremia remains a challenging clinical situation for inpatient providers. With the push for high-value care and reductions in length of stay, recent literature has focused on reviewing current practices and attempting to standardize care. Despite this, no overarching guidelines exist to direct practice and clinicians are left to make decisions based on prior experience and expert opinion. Three key clinical questions exist when caring for a hospitalized patient with GN bacteremia: Should blood cultures be repeated? When is transition to oral antibiotics appropriate? And for what duration should antibiotics be given?

Overview of the data

When considering repeating blood cultures, it is important to understand that current literature does not support the practice for all GN bacteremias.

Canzoneri et al. retrospectively studied GN bacteremia and found that it took 17 repeat blood cultures being drawn to yield 1 positive result, which suggests that they are not necessary in all cases.1 Furthermore, repeat blood cultures increase cost of hospitalization, length of stay, and inconvenience to patients.2

However, Mushtaq et al. noted that repeating blood cultures can provide valuable information to confirm the response to treatment in patients with endovascular infection. Furthermore, they found that repeated blood cultures are also reasonable when the following scenarios are suspected: endocarditis or central line–associated infection, concern for multidrug resistant GN bacilli, and ongoing evidence of sepsis or patient decompensation.3

Consideration of a transition from intravenous to oral antibiotics is a key decision point in the care of GN bacteremia. Without guidelines, clinicians are left to evaluate patients on a case-by-case basis.4 Studies have suggested that the transition should be guided by the condition of the patient, the type of infection, and the culture-derived sensitivities.5 Additionally, bioavailability of antibiotics (see Table 1) is an important consideration and a recent examination of oral antibiotic failure rates demonstrated that lower bioavailability antibiotics have an increased risk of failure (2% vs. 16%).6

In their study, Kutob et al. highlighted the importance of choosing not only an antibiotic of high bioavailability, but also an antibiotic dose which will support a high concentration of the antibiotic in the bloodstream.6 For example, they identify ciprofloxacin as a moderate bioavailability medication, but note that most cases they examined utilized 500 mg b.i.d., where the concentration-dependent killing and dose-dependent bioavailability would advocate for the use of 750 mg b.i.d. or 500 mg every 8 hours.

The heterogeneity of GN bloodstream infections also creates difficulty in standardization of care. The literature suggests that infection source plays a significant role in the type of GN bacteria isolated.6,7 The best data for the transition to oral antibiotics exists with urologic sources and it remains unclear whether bacteria from other sources have higher risks of oral antibiotic failure.8

One recent study of 66 patients examined bacteremia in the setting of cholangitis and found that, once patients had stabilized, a switch from intravenous to oral antibiotics was noninferior, but randomized, prospective trials have not been performed. Notably, patients were transitioned to orals only after they were found to have a fluoroquinolone-sensitive infection, allowing the study authors to use higher-bioavailability agents for the transition to orals.9 Multiple studies have highlighted the unique care required for certain infections, such as pseudomonal infections, which most experts agree requires a more conservative approach.5,6

Fluoroquinolones are the bedrock of therapy for GN bacteremia because of historic in vivo experience and in vitro findings about bioavailability and dose-dependent killing, but they are also the antibiotic class associated with the highest hospitalization rates for antibiotic-associated adverse events.8 A recent noninferiority trial comparing the use of beta-lactams with fluoroquinolones found that beta-lactams were noninferior, though the study was flawed by the limited number of beta-lactam–using patients identified.8 It is clear that more investigation is needed before recommendations can be made regarding ideal oral antibiotics for GN bacteremia.

The transition to oral is reasonable given the following criteria: the patient has improved on intravenous antibiotics and source control has been achieved; the culture data have demonstrated sensitivity to the oral antibiotic of choice, with special care given to higher-risk bacteria such as Pseudomonas; the patient is able to take the oral antibiotic; and the oral antibiotic of choice has the highest bioavailability possible and is given at an appropriate dose to reach its highest killing and bioavailability concentrations.7

After evaluating the appropriateness of transition to oral antibiotics, the final decision is about duration of antibiotic therapy. Current Infectious Disease Society of America guidelines are based on expert opinion and recommend 7-14 days of therapy. As with many common infections, recent studies have focused on evaluating reduction in antibiotic durations.

Chotiprasitsakul et al. demonstrated no difference in mortality or morbidity in 385 propensity-matched pairs with treatment of Enterobacteriaceae bacteremia for 8 versus 15 days.10 A mixed meta-analysis performed in 2011 evaluated 24 randomized, controlled trials and found shorter durations (5-7 days) had similar outcomes to prolonged durations (7-21 days).11 Recently, Yahav et al. performed a randomized control trial comparing 7- and 14-day regimens for uncomplicated GN bacteremia and found a 7-day course to be noninferior if patients were clinically stable by day 5 and had source control.12

It should be noted that not all studies have found that reduced durations are without harm. Nelson et al. performed a retrospective cohort analysis and found that reduced durations of antibiotics (7-10 days) increased mortality and recurrent infection when compared with a longer course (greater than 10 days).13 These contrary findings highlight the need for provider discretion in selecting a course of antibiotics as well as the need for further studies about optimal duration of antibiotics.

Application of the data

Returning to our case, on day 3, the patient’s fever had resolved and leukocytosis improved. In the absence of concern for persistent infection, repeat blood cultures were not performed. On day 4 initial blood cultures showed pan-sensitive Escherichia coli. The patient was transitioned to 750 mg oral ciprofloxacin b.i.d. to complete a 10-day course from first dose of ceftriaxone and was discharged from the hospital.

Bottom line

Management of GN bacteremia requires individualized care based on clinical presentation, but the data presented above can be used as broad guidelines to help reduce excess blood cultures, avoid prolonged use of intravenous antibiotics, and limit the duration of antibiotic exposure.

Dr. Imber is an assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, and director of the Internal Medicine Simulation Education and Hospitalist Procedural Certification. Dr. Burns is an assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine at the University of New Mexico. Dr. Chan is currently a chief resident in the department of internal medicine at the University of New Mexico.

References

1. Canzoneri CN et al. Follow-up blood cultures in gram-negative bacteremia: Are they needed? Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65(11):1776-9. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix648.

2. Kang CK et al. Can a routine follow-up blood culture be justified in Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia? A retrospective case-control study. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:365. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-365.

3. Mushtaq A et al. Repeating blood cultures after an initial bacteremia: When and how often? Cleve Clin J Med. 2019;86(2):89-92. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.86a.18001.

4. Nimmich EB et al. Development of institutional guidelines for management of gram-negative bloodstream infections: Incorporating local evidence. Hosp Pharm. 2017;52(10):691-7. doi: 10.1177/0018578717720506.

5. Hale AJ et al. When are oral antibiotics a safe and effective choice for bacterial bloodstream infections? An evidence-based narrative review. J Hosp Med. 2018 May. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2949.

6. Kutob LF et al. Effectiveness of oral antibiotics for definitive therapy of gram-negative bloodstream infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2016.07.013.

7. Tamma PD et al. Association of 30-day mortality with oral step-down vs. continued intravenous therapy in patients hospitalized with Enterobacteriaceae bacteremia. JAMA Intern Med. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6226.

8. Mercuro NJ et al. Retrospective analysis comparing oral stepdown therapy for enterobacteriaceae bloodstream infections: fluoroquinolones vs. B-lactams. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2017.12.007.

9. Park TY et al. Early oral antibiotic switch compared with conventional intravenous antibiotic therapy for acute cholangitis with bacteremia. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59:2790-6. doi: 10.1007/s10620-014-3233-0.

10. Chotiprasitsakul D et al. Comparing the outcomes of adults with Enterobacteriaceae bacteremia receiving short-course versus prolonged-course antibiotic therapy in a multicenter, propensity score-matched cohort. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66(2):172-7. doi:10.1093/cid/cix767.

11. Havey TC et al. Duration of antibiotic therapy for bacteremia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2011;15(6):R267. doi:10.1186/cc10545.

12. Yahav D et al. Seven versus fourteen days of antibiotic therapy for uncomplicated gram-negative bacteremia: A noninferiority randomized controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2018 Dec. doi:10.1093/cid/ciy1054.

13. Nelson AN et al. Optimal duration of antimicrobial therapy for uncomplicated gram-negative bloodstream infections. Infection. 2017;45(5):613-20. doi:10.1007/s15010-017-1020-5.

Hadlima approved as fourth adalimumab biosimilar in U.S.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the Humira biosimilar Hadlima (adalimumab-bwwd), making it the fourth adalimumab biosimilar approved in the United States, the agency announced.

Hadlima is approved for seven of the reference product’s indications, which include rheumatoid arthritis, polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis, plaque psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, adult Crohn’s disease, and ulcerative colitis.

The product will launch in the United States on June 30, 2023. Other FDA-approved adalimumab biosimilars – Amjevita (adalimunab-atto), Cyltezo (adalimumab-adbm), Hyrimoz (adalimumab-adaz) – similarly will not reach the U.S. market until 2023.

Hadlima is developed by Samsung Bioepis and commercialized by Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co.

Visit the AGA GI Patient Center for information to share with your patients about biologics and biosimilars at https://www.gastro.org/practice-guidance/gi-patient-center/topic/biosimilars.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the Humira biosimilar Hadlima (adalimumab-bwwd), making it the fourth adalimumab biosimilar approved in the United States, the agency announced.

Hadlima is approved for seven of the reference product’s indications, which include rheumatoid arthritis, polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis, plaque psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, adult Crohn’s disease, and ulcerative colitis.

The product will launch in the United States on June 30, 2023. Other FDA-approved adalimumab biosimilars – Amjevita (adalimunab-atto), Cyltezo (adalimumab-adbm), Hyrimoz (adalimumab-adaz) – similarly will not reach the U.S. market until 2023.

Hadlima is developed by Samsung Bioepis and commercialized by Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co.

Visit the AGA GI Patient Center for information to share with your patients about biologics and biosimilars at https://www.gastro.org/practice-guidance/gi-patient-center/topic/biosimilars.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the Humira biosimilar Hadlima (adalimumab-bwwd), making it the fourth adalimumab biosimilar approved in the United States, the agency announced.

Hadlima is approved for seven of the reference product’s indications, which include rheumatoid arthritis, polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis, plaque psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, adult Crohn’s disease, and ulcerative colitis.

The product will launch in the United States on June 30, 2023. Other FDA-approved adalimumab biosimilars – Amjevita (adalimunab-atto), Cyltezo (adalimumab-adbm), Hyrimoz (adalimumab-adaz) – similarly will not reach the U.S. market until 2023.

Hadlima is developed by Samsung Bioepis and commercialized by Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co.

Visit the AGA GI Patient Center for information to share with your patients about biologics and biosimilars at https://www.gastro.org/practice-guidance/gi-patient-center/topic/biosimilars.

Early phase trial shows durable responses to gene therapy for hemophilia A

MELBOURNE – A gene therapy treatment for hemophilia A has shown sustained reductions in bleeding rates 3 years after treatment, with no major safety issues, according to findings presented at the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis congress.

Valoctocogene roxaparvovec is an investigational gene therapy that involves using an adenovirus-associated virus to deliver the gene for clotting factor VIII.

John Pasi, MBChB, PhD, of the Royal London Haemophilia Centre, Barts Health NHS Trust, presented the 3-year efficacy and safety results from the phase 1/2 trial of the therapy, involving 15 men with hemophilia A without inhibitors who received a single intravenous dose – either 4 x 1013 vector genomes (vg) per kg or 6 x 1013 vg/kg – of the therapy.

Participants’ mean annualized bleeding rate at baseline ranged from 6.5 among men who had been receiving prophylactic therapy to 25 among those who had been historically been treated on demand.

The treatment was associated with a substantial, significant reduction in mean annualized bleed rates; a 96% reduction in the 6 x 1013 vg/kg group by year 3, and 92% reduction in the 4 x 1013 vg/kg group by year 2.

By year 3, 86% of patients in the higher dose group had not experienced a bleed in the prior 12 months, all patients were off prophylaxis, and all had experienced resolution of target joints.

Mean factor VIII usage also decreased significantly, with a 96% reduction by year 3 in the higher dose cohort, and a 97% reduction by year 2 in the lower dose cohort.

The study also showed significant improvements in quality of life across all domains, Dr. Pasi reported.

There were no significant safety concerns raised during the study. Several patients experienced mild to moderate, transient rises in alanine aminotransferase levels at around 8-16 weeks after treatment, but there was no significant impact on liver function or on corticosteroid use. Two patients reported mild infusion reactions, which resolved within 48 hours with altering treatment.

The researchers also examined durability of factor VIII activity levels following the gene therapy, which was monitored using chromogenic assays. This revealed that after the initial increase following therapy, the factor VIII levels plateaued between years 2 and 3.

“We’ve got what we feel is really good clinical evidence of a persistent effect and we think this is dramatic,” Dr. Pasi said. A phase 3 trial is now underway.

A commenter from the audience, who remarked that the data were incredible and would make a huge difference for patients, asked about whether this represented a possible cure for the disease.

It’s premature to talk about a cure, Dr. Pasi said.

“It’s like watching paint dry; it’s going to take years before we know where we are,” he said in an interview.

However, this could represent massive and transformational change in the management of hemophilia A, he added.

On the question of whether this approach might also work in patients with inhibitors, Dr. Pasi said there were animal data suggesting that gene therapy could work in individuals with inhibitors, but the focus for the moment was on patients without inhibitors.

“But for patients that previously had a history of inhibitors and are now tolerant, that’s quite a significant group of patients that we were going to have to think about how we deal with that in due course,” he said.

The study was sponsored by manufacturer BioMarin Pharmaceutical. Dr. Pasi reported financial relationships with the study sponsor and other companies.

SOURCE: Pasi KJ et al. 2019 ISTH Congress, Abstract LB 01.2.

MELBOURNE – A gene therapy treatment for hemophilia A has shown sustained reductions in bleeding rates 3 years after treatment, with no major safety issues, according to findings presented at the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis congress.

Valoctocogene roxaparvovec is an investigational gene therapy that involves using an adenovirus-associated virus to deliver the gene for clotting factor VIII.

John Pasi, MBChB, PhD, of the Royal London Haemophilia Centre, Barts Health NHS Trust, presented the 3-year efficacy and safety results from the phase 1/2 trial of the therapy, involving 15 men with hemophilia A without inhibitors who received a single intravenous dose – either 4 x 1013 vector genomes (vg) per kg or 6 x 1013 vg/kg – of the therapy.

Participants’ mean annualized bleeding rate at baseline ranged from 6.5 among men who had been receiving prophylactic therapy to 25 among those who had been historically been treated on demand.

The treatment was associated with a substantial, significant reduction in mean annualized bleed rates; a 96% reduction in the 6 x 1013 vg/kg group by year 3, and 92% reduction in the 4 x 1013 vg/kg group by year 2.

By year 3, 86% of patients in the higher dose group had not experienced a bleed in the prior 12 months, all patients were off prophylaxis, and all had experienced resolution of target joints.

Mean factor VIII usage also decreased significantly, with a 96% reduction by year 3 in the higher dose cohort, and a 97% reduction by year 2 in the lower dose cohort.

The study also showed significant improvements in quality of life across all domains, Dr. Pasi reported.

There were no significant safety concerns raised during the study. Several patients experienced mild to moderate, transient rises in alanine aminotransferase levels at around 8-16 weeks after treatment, but there was no significant impact on liver function or on corticosteroid use. Two patients reported mild infusion reactions, which resolved within 48 hours with altering treatment.

The researchers also examined durability of factor VIII activity levels following the gene therapy, which was monitored using chromogenic assays. This revealed that after the initial increase following therapy, the factor VIII levels plateaued between years 2 and 3.

“We’ve got what we feel is really good clinical evidence of a persistent effect and we think this is dramatic,” Dr. Pasi said. A phase 3 trial is now underway.

A commenter from the audience, who remarked that the data were incredible and would make a huge difference for patients, asked about whether this represented a possible cure for the disease.

It’s premature to talk about a cure, Dr. Pasi said.

“It’s like watching paint dry; it’s going to take years before we know where we are,” he said in an interview.

However, this could represent massive and transformational change in the management of hemophilia A, he added.

On the question of whether this approach might also work in patients with inhibitors, Dr. Pasi said there were animal data suggesting that gene therapy could work in individuals with inhibitors, but the focus for the moment was on patients without inhibitors.

“But for patients that previously had a history of inhibitors and are now tolerant, that’s quite a significant group of patients that we were going to have to think about how we deal with that in due course,” he said.

The study was sponsored by manufacturer BioMarin Pharmaceutical. Dr. Pasi reported financial relationships with the study sponsor and other companies.

SOURCE: Pasi KJ et al. 2019 ISTH Congress, Abstract LB 01.2.

MELBOURNE – A gene therapy treatment for hemophilia A has shown sustained reductions in bleeding rates 3 years after treatment, with no major safety issues, according to findings presented at the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis congress.

Valoctocogene roxaparvovec is an investigational gene therapy that involves using an adenovirus-associated virus to deliver the gene for clotting factor VIII.

John Pasi, MBChB, PhD, of the Royal London Haemophilia Centre, Barts Health NHS Trust, presented the 3-year efficacy and safety results from the phase 1/2 trial of the therapy, involving 15 men with hemophilia A without inhibitors who received a single intravenous dose – either 4 x 1013 vector genomes (vg) per kg or 6 x 1013 vg/kg – of the therapy.

Participants’ mean annualized bleeding rate at baseline ranged from 6.5 among men who had been receiving prophylactic therapy to 25 among those who had been historically been treated on demand.

The treatment was associated with a substantial, significant reduction in mean annualized bleed rates; a 96% reduction in the 6 x 1013 vg/kg group by year 3, and 92% reduction in the 4 x 1013 vg/kg group by year 2.

By year 3, 86% of patients in the higher dose group had not experienced a bleed in the prior 12 months, all patients were off prophylaxis, and all had experienced resolution of target joints.

Mean factor VIII usage also decreased significantly, with a 96% reduction by year 3 in the higher dose cohort, and a 97% reduction by year 2 in the lower dose cohort.

The study also showed significant improvements in quality of life across all domains, Dr. Pasi reported.

There were no significant safety concerns raised during the study. Several patients experienced mild to moderate, transient rises in alanine aminotransferase levels at around 8-16 weeks after treatment, but there was no significant impact on liver function or on corticosteroid use. Two patients reported mild infusion reactions, which resolved within 48 hours with altering treatment.

The researchers also examined durability of factor VIII activity levels following the gene therapy, which was monitored using chromogenic assays. This revealed that after the initial increase following therapy, the factor VIII levels plateaued between years 2 and 3.

“We’ve got what we feel is really good clinical evidence of a persistent effect and we think this is dramatic,” Dr. Pasi said. A phase 3 trial is now underway.

A commenter from the audience, who remarked that the data were incredible and would make a huge difference for patients, asked about whether this represented a possible cure for the disease.

It’s premature to talk about a cure, Dr. Pasi said.

“It’s like watching paint dry; it’s going to take years before we know where we are,” he said in an interview.

However, this could represent massive and transformational change in the management of hemophilia A, he added.

On the question of whether this approach might also work in patients with inhibitors, Dr. Pasi said there were animal data suggesting that gene therapy could work in individuals with inhibitors, but the focus for the moment was on patients without inhibitors.

“But for patients that previously had a history of inhibitors and are now tolerant, that’s quite a significant group of patients that we were going to have to think about how we deal with that in due course,” he said.

The study was sponsored by manufacturer BioMarin Pharmaceutical. Dr. Pasi reported financial relationships with the study sponsor and other companies.

SOURCE: Pasi KJ et al. 2019 ISTH Congress, Abstract LB 01.2.

REPORTING FROM 2019 ISTH CONGRESS

Probiotic protects against aspirin-related intestinal damage

Source: American Gastroenterological Association