User login

Autism, pain, and the NMDA receptor

Ms. G, a 36-year-old woman, presented to the emergency department (ED) requesting a neurologic evaluation. She told clinicians she had “NMDA receptor encephalitis.”

Ms. G reported successful self-treatment of “life-long” body pain that was precipitated by multiple external stimuli (food, social encounters, interpersonal conflict, etc.). Through her own research, she had learned that both ketamine and magnesium could alter nociception in rats through N-methyl-

In the ED, Ms. G had a labile affect, pressured speech, and flight of ideas. She denied any history of psychiatric treatment, suicide attempts, or substance abuse. Ms. G’s family reported she had been unusually social, talkative, and impulsive. She was admitted to the inpatient psychiatric unit with a diagnosis of mania.

On psychiatric evaluation, Ms. G was grandiose, irritable, and perseverative about her aberrant symptoms. She felt she did not experience the world as other people did, but found relief from her chronic pain after taking Delsym. She was not taking other medications. Ms. G did not report a family history of bipolar disorder or psychosis. Her laboratory results, including a comprehensive metabolic panel, complete blood count, lipid panel, thyroid studies, urine drug screening, and urinalysis, were unremarkable. Her blood pressure was mildly elevated (141/82 mm Hg).

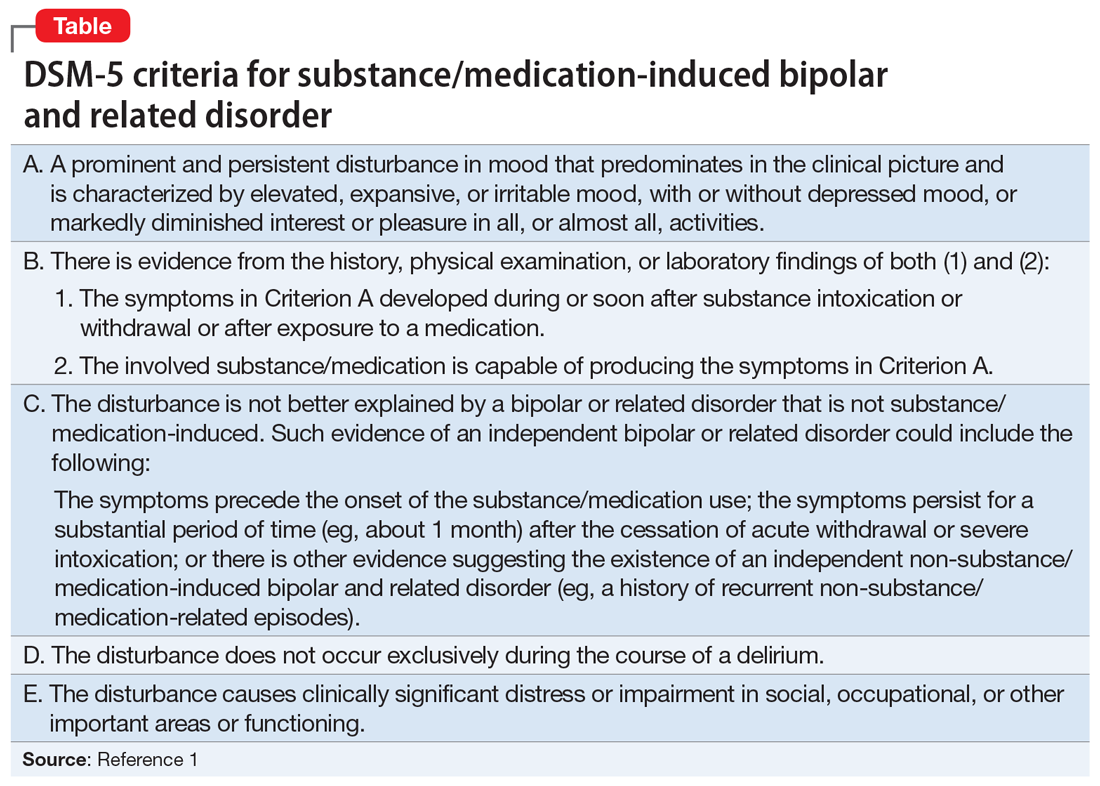

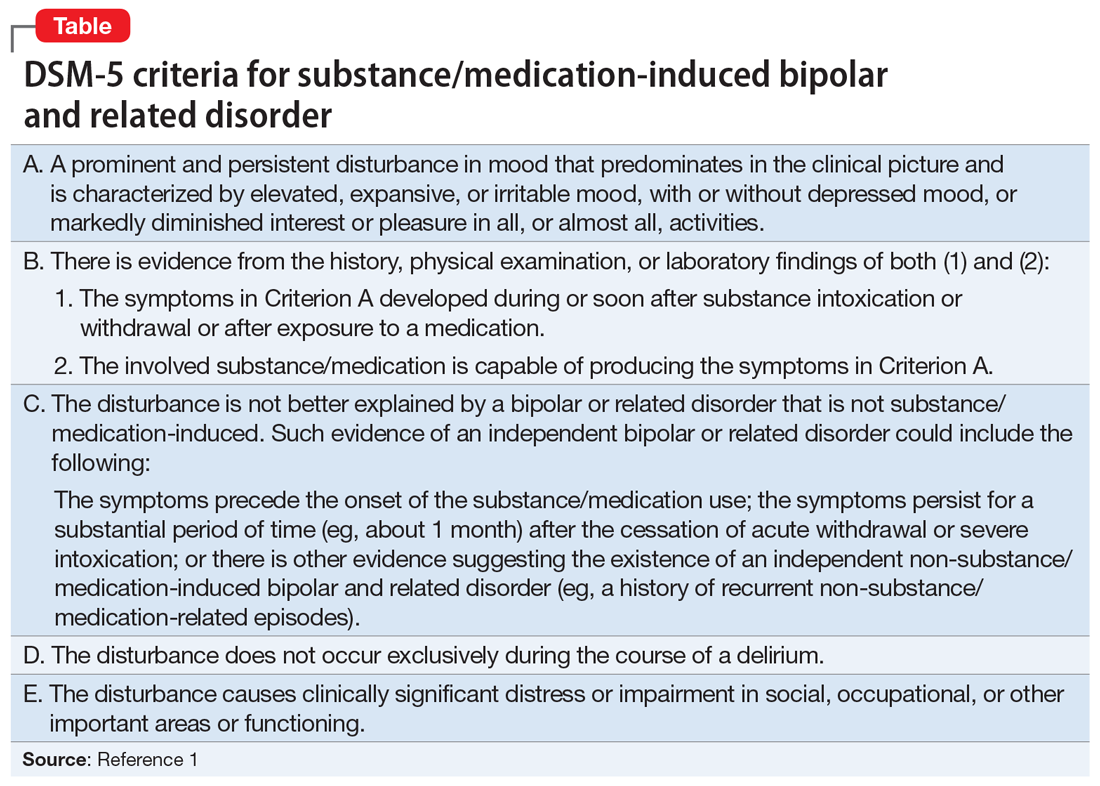

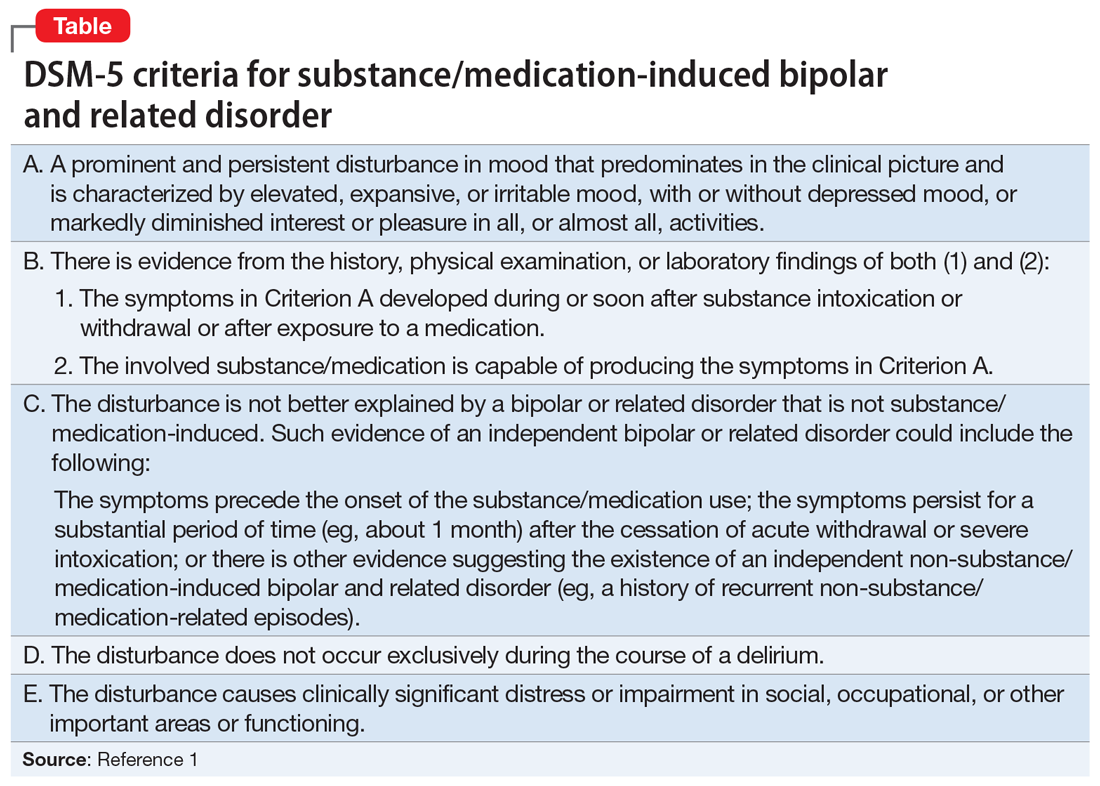

Ms. G’s eventual diagnosis was substance-induced mania (DXM). The DXM-containing cough syrup and magnesium were discontinued in the hospital. She was stabilized on lithium extended-release, 900 mg/d (blood level 0.8 mmol/L), and olanzapine, 10 mg/d at bedtime. However, after discharge, Ms. G resumed using Delsym, which resulted in 3 subsequent psychiatric hospitalizations for mania during the next year.

I first treated Ms. G as an outpatient after her second hospitalization. At that point, she was stable. Her mental status was calm and cooperative, and she had a linear thought process. At her baseline, in the absence of mania, she had a blunted affect. She understood that DXM caused her to have manic symptoms, but she continued to believe that Delsym and magnesium cured her physical suffering and social inhibition. I noticed Ms. G would use figurative language inappropriately. I later learned she had sensitivities to food textures and a specialized interest in electronics. Because of this, I suspected Ms. G was on the autism spectrum; she met several DSM-5 criteria for autism spectrum disorder (ASD), particularly deficits in social-emotional reciprocity, highly restricted interests, and hyperreactivity to sensory input.

Upon routine lab screening, Ms. G was found to have hypothyroidism, with a thyroid-stimulating hormone level of 6.67 mcIU/mL. This resolved after discontinuing lithium. Olanzapine caused adverse metabolic effects and also was discontinued. Ms. G remained euthymic without any mood-stabilizing medication, except during periods when she abused DXM, when she would again become manic. Eventually, her motivation to avoid hospitalization would promote her abstinence.

Continue to: Implications of NMDA receptor antagonism

Implications of NMDA receptor antagonism

The use of ketamine as an NMDA receptor antagonist for treating depression and other psychiatric illnesses has gained momentum. Esketamine, the S-enantiomer of racemic ketamine, is now available as an FDA-approved intranasal formulation for treatment-resistant depression. Ketamine stops afferent nociception to the brain and is used as an analgesic (at low concentrations) and anesthetic (at high concentrations).1

Dextromethorphan is abused as a recreational drug because at high doses it works similarly to both ketamine and phencyclidine. Individuals who abuse DXM can develop psychosis, motor/cognitive impairment, agitation, fevers, hypertension, tachycardia, and death.2 In patients with ASD, researchers have identified genetic variations of NMDA receptors that are linked to dysfunction of these receptors.3 In animal models, as well as in humans, researchers have found that suppression or excitation of the NMDA receptor can ameliorate ASD symptoms, including social withdrawal and repetitive behaviors.3

Many individuals with ASD suffer from sensory abnormalities, including a reduced sensitivity to pain or a crippling sensitivity to various stimuli. Patients with ASD may have difficulty describing these abnormalities, and as a result, they may be misdiagnosed. One case report described a 15-year-old girl diagnosed with social anxiety and chronic generalized pain when in social situations.4 Pediatric rheumatologists had diagnosed her with “amplified pain syndrome.” When she presented to a mental health clinic for a neurodevelopmental evaluation, she explained to clinicians how she simply “did not ‘get’ people; they are just empty shells” and subsequently was given a diagnosis of ASD.4

In psychiatric patients who have comorbid substance use disorders, it is vital for clinicians to not only detect the presence of substance misuse, but also to understand what drives the patient toward abuse. Ms. G’s case, with its combination of substance abuse and ASD, illustrates the importance of listening to our patients for more precise diagnostic formulations, which then shape our treatment recommendations.

1. Vadivelu N, Schermer E, Kodumudi V, et al. Role of ketamine for analgesia in adults and children. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2016;32(3):298-306.

2. Martinak B, Bolis R, Black J, et al. Dextromethorphan in cough syrup: the poor man’s psychosis. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2017;47(4):59-63.

3. Lee E, Choi S, Kim E. NMDA receptor dysfunction in autism spectrum disorders. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2015;20:8-13.

4. Clarke C. Autism spectrum disorder and amplified pain. Case Rep Psychiatry. 2015;2015:930874. doi: 10.1155/2015/930874.

Ms. G, a 36-year-old woman, presented to the emergency department (ED) requesting a neurologic evaluation. She told clinicians she had “NMDA receptor encephalitis.”

Ms. G reported successful self-treatment of “life-long” body pain that was precipitated by multiple external stimuli (food, social encounters, interpersonal conflict, etc.). Through her own research, she had learned that both ketamine and magnesium could alter nociception in rats through N-methyl-

In the ED, Ms. G had a labile affect, pressured speech, and flight of ideas. She denied any history of psychiatric treatment, suicide attempts, or substance abuse. Ms. G’s family reported she had been unusually social, talkative, and impulsive. She was admitted to the inpatient psychiatric unit with a diagnosis of mania.

On psychiatric evaluation, Ms. G was grandiose, irritable, and perseverative about her aberrant symptoms. She felt she did not experience the world as other people did, but found relief from her chronic pain after taking Delsym. She was not taking other medications. Ms. G did not report a family history of bipolar disorder or psychosis. Her laboratory results, including a comprehensive metabolic panel, complete blood count, lipid panel, thyroid studies, urine drug screening, and urinalysis, were unremarkable. Her blood pressure was mildly elevated (141/82 mm Hg).

Ms. G’s eventual diagnosis was substance-induced mania (DXM). The DXM-containing cough syrup and magnesium were discontinued in the hospital. She was stabilized on lithium extended-release, 900 mg/d (blood level 0.8 mmol/L), and olanzapine, 10 mg/d at bedtime. However, after discharge, Ms. G resumed using Delsym, which resulted in 3 subsequent psychiatric hospitalizations for mania during the next year.

I first treated Ms. G as an outpatient after her second hospitalization. At that point, she was stable. Her mental status was calm and cooperative, and she had a linear thought process. At her baseline, in the absence of mania, she had a blunted affect. She understood that DXM caused her to have manic symptoms, but she continued to believe that Delsym and magnesium cured her physical suffering and social inhibition. I noticed Ms. G would use figurative language inappropriately. I later learned she had sensitivities to food textures and a specialized interest in electronics. Because of this, I suspected Ms. G was on the autism spectrum; she met several DSM-5 criteria for autism spectrum disorder (ASD), particularly deficits in social-emotional reciprocity, highly restricted interests, and hyperreactivity to sensory input.

Upon routine lab screening, Ms. G was found to have hypothyroidism, with a thyroid-stimulating hormone level of 6.67 mcIU/mL. This resolved after discontinuing lithium. Olanzapine caused adverse metabolic effects and also was discontinued. Ms. G remained euthymic without any mood-stabilizing medication, except during periods when she abused DXM, when she would again become manic. Eventually, her motivation to avoid hospitalization would promote her abstinence.

Continue to: Implications of NMDA receptor antagonism

Implications of NMDA receptor antagonism

The use of ketamine as an NMDA receptor antagonist for treating depression and other psychiatric illnesses has gained momentum. Esketamine, the S-enantiomer of racemic ketamine, is now available as an FDA-approved intranasal formulation for treatment-resistant depression. Ketamine stops afferent nociception to the brain and is used as an analgesic (at low concentrations) and anesthetic (at high concentrations).1

Dextromethorphan is abused as a recreational drug because at high doses it works similarly to both ketamine and phencyclidine. Individuals who abuse DXM can develop psychosis, motor/cognitive impairment, agitation, fevers, hypertension, tachycardia, and death.2 In patients with ASD, researchers have identified genetic variations of NMDA receptors that are linked to dysfunction of these receptors.3 In animal models, as well as in humans, researchers have found that suppression or excitation of the NMDA receptor can ameliorate ASD symptoms, including social withdrawal and repetitive behaviors.3

Many individuals with ASD suffer from sensory abnormalities, including a reduced sensitivity to pain or a crippling sensitivity to various stimuli. Patients with ASD may have difficulty describing these abnormalities, and as a result, they may be misdiagnosed. One case report described a 15-year-old girl diagnosed with social anxiety and chronic generalized pain when in social situations.4 Pediatric rheumatologists had diagnosed her with “amplified pain syndrome.” When she presented to a mental health clinic for a neurodevelopmental evaluation, she explained to clinicians how she simply “did not ‘get’ people; they are just empty shells” and subsequently was given a diagnosis of ASD.4

In psychiatric patients who have comorbid substance use disorders, it is vital for clinicians to not only detect the presence of substance misuse, but also to understand what drives the patient toward abuse. Ms. G’s case, with its combination of substance abuse and ASD, illustrates the importance of listening to our patients for more precise diagnostic formulations, which then shape our treatment recommendations.

Ms. G, a 36-year-old woman, presented to the emergency department (ED) requesting a neurologic evaluation. She told clinicians she had “NMDA receptor encephalitis.”

Ms. G reported successful self-treatment of “life-long” body pain that was precipitated by multiple external stimuli (food, social encounters, interpersonal conflict, etc.). Through her own research, she had learned that both ketamine and magnesium could alter nociception in rats through N-methyl-

In the ED, Ms. G had a labile affect, pressured speech, and flight of ideas. She denied any history of psychiatric treatment, suicide attempts, or substance abuse. Ms. G’s family reported she had been unusually social, talkative, and impulsive. She was admitted to the inpatient psychiatric unit with a diagnosis of mania.

On psychiatric evaluation, Ms. G was grandiose, irritable, and perseverative about her aberrant symptoms. She felt she did not experience the world as other people did, but found relief from her chronic pain after taking Delsym. She was not taking other medications. Ms. G did not report a family history of bipolar disorder or psychosis. Her laboratory results, including a comprehensive metabolic panel, complete blood count, lipid panel, thyroid studies, urine drug screening, and urinalysis, were unremarkable. Her blood pressure was mildly elevated (141/82 mm Hg).

Ms. G’s eventual diagnosis was substance-induced mania (DXM). The DXM-containing cough syrup and magnesium were discontinued in the hospital. She was stabilized on lithium extended-release, 900 mg/d (blood level 0.8 mmol/L), and olanzapine, 10 mg/d at bedtime. However, after discharge, Ms. G resumed using Delsym, which resulted in 3 subsequent psychiatric hospitalizations for mania during the next year.

I first treated Ms. G as an outpatient after her second hospitalization. At that point, she was stable. Her mental status was calm and cooperative, and she had a linear thought process. At her baseline, in the absence of mania, she had a blunted affect. She understood that DXM caused her to have manic symptoms, but she continued to believe that Delsym and magnesium cured her physical suffering and social inhibition. I noticed Ms. G would use figurative language inappropriately. I later learned she had sensitivities to food textures and a specialized interest in electronics. Because of this, I suspected Ms. G was on the autism spectrum; she met several DSM-5 criteria for autism spectrum disorder (ASD), particularly deficits in social-emotional reciprocity, highly restricted interests, and hyperreactivity to sensory input.

Upon routine lab screening, Ms. G was found to have hypothyroidism, with a thyroid-stimulating hormone level of 6.67 mcIU/mL. This resolved after discontinuing lithium. Olanzapine caused adverse metabolic effects and also was discontinued. Ms. G remained euthymic without any mood-stabilizing medication, except during periods when she abused DXM, when she would again become manic. Eventually, her motivation to avoid hospitalization would promote her abstinence.

Continue to: Implications of NMDA receptor antagonism

Implications of NMDA receptor antagonism

The use of ketamine as an NMDA receptor antagonist for treating depression and other psychiatric illnesses has gained momentum. Esketamine, the S-enantiomer of racemic ketamine, is now available as an FDA-approved intranasal formulation for treatment-resistant depression. Ketamine stops afferent nociception to the brain and is used as an analgesic (at low concentrations) and anesthetic (at high concentrations).1

Dextromethorphan is abused as a recreational drug because at high doses it works similarly to both ketamine and phencyclidine. Individuals who abuse DXM can develop psychosis, motor/cognitive impairment, agitation, fevers, hypertension, tachycardia, and death.2 In patients with ASD, researchers have identified genetic variations of NMDA receptors that are linked to dysfunction of these receptors.3 In animal models, as well as in humans, researchers have found that suppression or excitation of the NMDA receptor can ameliorate ASD symptoms, including social withdrawal and repetitive behaviors.3

Many individuals with ASD suffer from sensory abnormalities, including a reduced sensitivity to pain or a crippling sensitivity to various stimuli. Patients with ASD may have difficulty describing these abnormalities, and as a result, they may be misdiagnosed. One case report described a 15-year-old girl diagnosed with social anxiety and chronic generalized pain when in social situations.4 Pediatric rheumatologists had diagnosed her with “amplified pain syndrome.” When she presented to a mental health clinic for a neurodevelopmental evaluation, she explained to clinicians how she simply “did not ‘get’ people; they are just empty shells” and subsequently was given a diagnosis of ASD.4

In psychiatric patients who have comorbid substance use disorders, it is vital for clinicians to not only detect the presence of substance misuse, but also to understand what drives the patient toward abuse. Ms. G’s case, with its combination of substance abuse and ASD, illustrates the importance of listening to our patients for more precise diagnostic formulations, which then shape our treatment recommendations.

1. Vadivelu N, Schermer E, Kodumudi V, et al. Role of ketamine for analgesia in adults and children. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2016;32(3):298-306.

2. Martinak B, Bolis R, Black J, et al. Dextromethorphan in cough syrup: the poor man’s psychosis. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2017;47(4):59-63.

3. Lee E, Choi S, Kim E. NMDA receptor dysfunction in autism spectrum disorders. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2015;20:8-13.

4. Clarke C. Autism spectrum disorder and amplified pain. Case Rep Psychiatry. 2015;2015:930874. doi: 10.1155/2015/930874.

1. Vadivelu N, Schermer E, Kodumudi V, et al. Role of ketamine for analgesia in adults and children. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2016;32(3):298-306.

2. Martinak B, Bolis R, Black J, et al. Dextromethorphan in cough syrup: the poor man’s psychosis. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2017;47(4):59-63.

3. Lee E, Choi S, Kim E. NMDA receptor dysfunction in autism spectrum disorders. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2015;20:8-13.

4. Clarke C. Autism spectrum disorder and amplified pain. Case Rep Psychiatry. 2015;2015:930874. doi: 10.1155/2015/930874.

Premature mortality across most psychiatric disorders

The evidence is robust and disheartening: As if the personal suffering and societal stigma of mental illness are not bad enough, psychiatric patients also have a shorter lifespan.1 In the past, most studies have focused on early mortality and loss of potential life-years in schizophrenia,2 but many subsequent reports indicate that premature death occurs in all major psychiatric disorders.

Here is a summary of the sobering facts:

- Schizophrenia. In a study of 30,210 patients with schizophrenia, compared with >5 million individuals in the general population in Denmark (where they have an excellent registry), mortality was 16-fold higher among patients with schizophrenia if they had a single somatic illness.3 The illnesses were mostly respiratory, gastrointestinal, or cardiovascular).3 The loss of potential years of life was staggeringly high: 18.7 years for men, 16.3 years for women.4 A study conducted in 8 US states reported a loss of 2 to 3 decades of life across each of these states.5 The causes of death in patients with schizophrenia were mainly heart disease, cancer, stroke, and pulmonary diseases. A national database in Sweden found that unmedicated patients with schizophrenia had a significantly higher death rate than those receiving antipsychotics.6,7 Similar findings were reported by researchers in Finland.8 The Swedish study by Tiihonen et al6 also found that mortality was highest in patients receiving benzodiazepines along with antipsychotics, but there was no increased mortality among patients with schizophrenia receiving antidepressants.

- Bipolar disorder. A shorter life expectancy has also been reported in bipolar disorder,9 with a loss of 13.6 years for men and 12.1 years for women. Early death was caused by physical illness (even when suicide deaths were excluded), especially cardiovascular disease.10

- Major depressive disorder (MDD). A reduction of life expectancy in persons with MDD (unipolar depression) has been reported, with a loss of 14 years in men and 10 years in women.11 Although suicide contributed to the shorter lifespan, death due to accidents was 500% higher among persons with unipolar depression; the largest causes of death were physical illnesses. Further, Zubenko et al12 reported alarming findings about excess mortality among first- and second-degree relatives of persons with early-onset depression (some of whom were bipolar). The relatives died an average of 8 years earlier than the local population, and 40% died before reaching age 65. Also, there was a 5-fold increase in infant mortality (in the first year of life) among the relatives. The most common causes of death in adult relatives were heart disease, cancer, and stroke. It is obvious that MDD has a significant negative impact on health and longevity in both patients and their relatives.

- Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). A 220% increase in mortality was reported in persons with ADHD at all ages.13 Accidents were the most common cause of death. The mortality rate ratio (MRR) was 1.86 for ADHD before age 6, 1.58 for ADHD between age 6 to 17, and 4.25 for those age ≥18. The rate of early mortality was higher in girls and women (MRR = 2.85) than boys and men (MRR = 1.27).

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). A study from Denmark of 10,155 persons with OCD followed for 10 years reported a significantly higher risk of death from both natural (MRR = 1.68) and unnatural causes (MRR = 2.61), compared with the general population.14 Patients with OCD and comorbid depression, anxiety, or substance use had a further increase in mortality risk, but the mortality risk of individuals with OCD without psychiatric comorbidity was still 200% higher than that of the general population.

- Anxiety disorders. One study found no increase in mortality among patients who have generalized anxiety, unless it was associated with depression.15 Another study reported that the presence of anxiety reduced the risk of cardiovascular mortality in persons with depression.16 The absence of increased mortality in anxiety disorders was also confirmed in a meta-analysis of 36 studies.17 However, a study of postmenopausal women with panic attacks found a 3-fold increase in coronary artery disease and stroke in that cohort,18 which confirmed the findings of an older study19 that demonstrated a 2-fold increase of mortality among 155 men with panic disorder after a 12-year follow-up. Also, a 25-year follow-up study found that suicide accounted for 20% of deaths in the anxiety group compared with 16.2% in the depression group,20 showing a significant risk of suicide in panic disorder, even exceeding that of depression.

- Oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) and conduct disorder (CD). In a 12-year follow-up study of 9,495 individuals with “disruptive behavioral disorders,” which included ODD and CD, the mortality rate was >400% higher in these patients compared with 1.92 million individuals in the general population (9.66 vs 2.22 per 10,000 person-years).21 Comorbid substance use disorder and ADHD further increased the mortality rate in this cohort.

- Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Studies show that there is a significantly increased risk of early cardiovascular mortality in PTSD,22 and that the death rate may be associated with accelerated “DNA methylation age” that leads to a 13% increased risk for all-cause mortality.23

- Borderline personality disorder (BPD). A recent longitudinal study (24 years of follow-up with evaluation every 2 years) reported a significantly higher mortality in patients with BPD compared with those with other personality disorders. The age range when the study started was 18 to 35. The rate of suicide death was Palatino LT Std>400% higher in BPD (5.9% vs 1.4%). Also, non-suicidal death was 250% higher in BPD (14% vs 5.5%). The causes of non-suicidal death included cardiovascular disease, substance-related complications, cancer, and accidents.24

- Other personality disorders. Certain personality traits have been associated with shorter leukocyte telomeres, which signal early death. These traits include neuroticism, conscientiousness, harm avoidance, and reward dependence.25 Another study found shorter telomeres in persons with high neuroticism and low agreeableness26 regardless of age or sex. Short telomeres, which reflect accelerated cellular senescence and aging, have also been reported in several major psychiatric disorders (schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, MDD, and anxiety).27-29 The cumulative evidence is unassailable; psychiatric brain disorders are not only associated with premature death due to high suicide rates, but also with multiple medical diseases that lead to early mortality and a shorter lifespan. The shortened telomeres reflect high oxidative stress and inflammation, and both those toxic processes are known to be associated with major psychiatric disorders. Compounding the dismal facts about early mortality due to mental illness are the additional grave medical consequences of alcohol and substance use, which are highly comorbid with most psychiatric disorders, further exacerbating the premature death rates among psychiatric patients.

Continue to: There is an important take-home message...

There is an important take-home message in all of this: Our patients are at high risk for potentially fatal medical conditions that require early detection, and intensive ongoing treatment by a primary care clinician (not “provider”; I abhor the widespread use of that term for physicians or nurse practitioners) is an indispensable component of psychiatric care. Thus, collaborative care is vital to protect our psychiatric patients from early mortality and a shortened lifespan. Psychiatrists and psychiatric nurse practitioners must not only win the battle against mental illness, but also diligently avoid losing the war of life and death.

1. Walker ER, McGee RE, Druss BG. Mortality in mental disorders and global disease burden implications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(4):334-341.

2. Laursen TM, Wahlbeck K, Hällgren J, et al. Life expectancy and death by diseases of the circulatory system in patients with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia in the Nordic countries. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e67133. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067133.

3. Kugathasan P, Stubbs B, Aagaard J, et al. Increased mortality from somatic multimorbidity in patients with schizophrenia: a Danish nationwide cohort study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2019. doi: 10.1111/acps.13076.

4. Laursen TM. Life expectancy among persons with schizophrenia or bipolar affective disorder. Schizophr Res. 2011;131(1-3):101-104.

5. Colton CW, Manderscheid RW. Congruencies in increased mortality rates, years of potential life lost, and causes of death among public mental health clients in eight states. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;3(2):A42.

6. Tiihonen J, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Torniainen M, et al. Mortality and cumulative exposure to antipsychotics, antidepressants, and benzodiazepines in patients with schizophrenia: an observational follow-up study. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(6):600-606.

7. Torniainen M, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Tanskanen A, et al. Antipsychotic treatment and mortality in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2015;41(3):656-663.

8. Tiihonen J, Lönnqvist J, Wahlbeck K, et al. 11-year follow-up of mortality in patients with schizophrenia: a population-based cohort study (FIN11 study). Lancet. 2009;374(9690):620-627.

9. Wilson R, Gaughran F, Whitburn T, et al. Place of death and other factors associated with unnatural mortality in patients with serious mental disorders: population-based retrospective cohort study. BJPsych Open. 2019;5(2):e23. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2019.5.

10. Ösby U, Westman J, Hällgren J, et al. Mortality trends in cardiovascular causes in schizophrenia, bipolar and unipolar mood disorder in Sweden 1987-2010. Eur J Public Health. 2016;26(5):867-871.

11. Laursen TM, Musliner KL, Benros ME, et al. Mortality and life expectancy in persons with severe unipolar depression. J Affect Disord. 2016;193:203-207.

12. Zubenko GS, Zubenko WN, Spiker DG, et al. Malignancy of recurrent, early-onset major depression: a family study. Am J Med Genet. 2001;105(8):690-699.

13. Dalsgaard S, Østergaard SD, Leckman JF, et al. Mortality in children, adolescents, and adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a nationwide cohort study. Lancet. 2015;385(9983):2190-2196.

14. Meier SM, Mattheisen M, Mors O, et al. Mortality among persons with obsessive-compulsive disorder in Denmark. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(3):268-274.

15. Holwerda TJ, Schoevers RA, Dekker J, et al. The relationship between generalized anxiety disorder, depression and mortality in old age. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22(3):241-249.

16. Ivanovs R, Kivite A, Ziedonis D, et al. Association of depression and anxiety with the 10-year risk of cardiovascular mortality in a primary care population of Latvia using the SCORE system. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:276.

17. Miloyan B, Bulley A, Bandeen-Roche K, et al. Anxiety disorders and all-cause mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2016;51(11):1467-1475.

18. Smoller JW, Pollack MH, Wassertheil-Smoller S, et al. Panic attacks and risk of incident cardiovascular events among postmenopausal women in the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(10):1153-1160.

19. Coryell W, Noyes R Jr, House JD. Mortality among outpatients with anxiety disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143(4):508-510.

20. Coryell W, Noyes R, Clancy J. Excess mortality in panic disorder. A comparison with primary unipolar depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1982;39(6):701-703.

21. Scott JG, Giørtz Pedersen M, Erskine HE, et al. Mortality in individuals with disruptive behavior disorders diagnosed by specialist services - a nationwide cohort study. Psychiatry Res. 2017;251:255-260.

22. Burg MM, Soufer R. Post-traumatic stress disorder and cardiovascular disease. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2016;18(10):94.

23. Wolf EJ, Logue MW, Stoop TB, et al. Accelerated DNA methylation age: associations with PTSD and mortality. Psychosom Med. 2017. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000506.

24. Temes CM, Frankenburg FR, Fitzmaurice MC, et al. Deaths by suicide and other causes among patients with borderline personality disorder and personality-disordered comparison subjects over 24 years of prospective follow-up. J Clin Psychiatry. 2019;80(1). doi: 10.4088/JCP.18m12436.

25. Sadahiro R, Suzuki A, Enokido M, et al. Relationship between leukocyte telomere length and personality traits in healthy subjects. Eur Psychiatry. 2015;30(2):291-295.

26. Schoormans D, Verhoeven JE, Denollet J, et al. Leukocyte telomere length and personality: associations with the Big Five and Type D personality traits. Psychol Med. 2018;48(6):1008-1019.

27. Muneer A, Minhas FA. Telomere biology in mood disorders: an updated, comprehensive review of the literature. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2019;17(3):343-363.

28. Vakonaki E, Tsiminikaki K, Plaitis S, et al. Common mental disorders and association with telomere length. Biomed Rep. 2018;8(2):111-116.

29. Malouff

The evidence is robust and disheartening: As if the personal suffering and societal stigma of mental illness are not bad enough, psychiatric patients also have a shorter lifespan.1 In the past, most studies have focused on early mortality and loss of potential life-years in schizophrenia,2 but many subsequent reports indicate that premature death occurs in all major psychiatric disorders.

Here is a summary of the sobering facts:

- Schizophrenia. In a study of 30,210 patients with schizophrenia, compared with >5 million individuals in the general population in Denmark (where they have an excellent registry), mortality was 16-fold higher among patients with schizophrenia if they had a single somatic illness.3 The illnesses were mostly respiratory, gastrointestinal, or cardiovascular).3 The loss of potential years of life was staggeringly high: 18.7 years for men, 16.3 years for women.4 A study conducted in 8 US states reported a loss of 2 to 3 decades of life across each of these states.5 The causes of death in patients with schizophrenia were mainly heart disease, cancer, stroke, and pulmonary diseases. A national database in Sweden found that unmedicated patients with schizophrenia had a significantly higher death rate than those receiving antipsychotics.6,7 Similar findings were reported by researchers in Finland.8 The Swedish study by Tiihonen et al6 also found that mortality was highest in patients receiving benzodiazepines along with antipsychotics, but there was no increased mortality among patients with schizophrenia receiving antidepressants.

- Bipolar disorder. A shorter life expectancy has also been reported in bipolar disorder,9 with a loss of 13.6 years for men and 12.1 years for women. Early death was caused by physical illness (even when suicide deaths were excluded), especially cardiovascular disease.10

- Major depressive disorder (MDD). A reduction of life expectancy in persons with MDD (unipolar depression) has been reported, with a loss of 14 years in men and 10 years in women.11 Although suicide contributed to the shorter lifespan, death due to accidents was 500% higher among persons with unipolar depression; the largest causes of death were physical illnesses. Further, Zubenko et al12 reported alarming findings about excess mortality among first- and second-degree relatives of persons with early-onset depression (some of whom were bipolar). The relatives died an average of 8 years earlier than the local population, and 40% died before reaching age 65. Also, there was a 5-fold increase in infant mortality (in the first year of life) among the relatives. The most common causes of death in adult relatives were heart disease, cancer, and stroke. It is obvious that MDD has a significant negative impact on health and longevity in both patients and their relatives.

- Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). A 220% increase in mortality was reported in persons with ADHD at all ages.13 Accidents were the most common cause of death. The mortality rate ratio (MRR) was 1.86 for ADHD before age 6, 1.58 for ADHD between age 6 to 17, and 4.25 for those age ≥18. The rate of early mortality was higher in girls and women (MRR = 2.85) than boys and men (MRR = 1.27).

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). A study from Denmark of 10,155 persons with OCD followed for 10 years reported a significantly higher risk of death from both natural (MRR = 1.68) and unnatural causes (MRR = 2.61), compared with the general population.14 Patients with OCD and comorbid depression, anxiety, or substance use had a further increase in mortality risk, but the mortality risk of individuals with OCD without psychiatric comorbidity was still 200% higher than that of the general population.

- Anxiety disorders. One study found no increase in mortality among patients who have generalized anxiety, unless it was associated with depression.15 Another study reported that the presence of anxiety reduced the risk of cardiovascular mortality in persons with depression.16 The absence of increased mortality in anxiety disorders was also confirmed in a meta-analysis of 36 studies.17 However, a study of postmenopausal women with panic attacks found a 3-fold increase in coronary artery disease and stroke in that cohort,18 which confirmed the findings of an older study19 that demonstrated a 2-fold increase of mortality among 155 men with panic disorder after a 12-year follow-up. Also, a 25-year follow-up study found that suicide accounted for 20% of deaths in the anxiety group compared with 16.2% in the depression group,20 showing a significant risk of suicide in panic disorder, even exceeding that of depression.

- Oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) and conduct disorder (CD). In a 12-year follow-up study of 9,495 individuals with “disruptive behavioral disorders,” which included ODD and CD, the mortality rate was >400% higher in these patients compared with 1.92 million individuals in the general population (9.66 vs 2.22 per 10,000 person-years).21 Comorbid substance use disorder and ADHD further increased the mortality rate in this cohort.

- Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Studies show that there is a significantly increased risk of early cardiovascular mortality in PTSD,22 and that the death rate may be associated with accelerated “DNA methylation age” that leads to a 13% increased risk for all-cause mortality.23

- Borderline personality disorder (BPD). A recent longitudinal study (24 years of follow-up with evaluation every 2 years) reported a significantly higher mortality in patients with BPD compared with those with other personality disorders. The age range when the study started was 18 to 35. The rate of suicide death was Palatino LT Std>400% higher in BPD (5.9% vs 1.4%). Also, non-suicidal death was 250% higher in BPD (14% vs 5.5%). The causes of non-suicidal death included cardiovascular disease, substance-related complications, cancer, and accidents.24

- Other personality disorders. Certain personality traits have been associated with shorter leukocyte telomeres, which signal early death. These traits include neuroticism, conscientiousness, harm avoidance, and reward dependence.25 Another study found shorter telomeres in persons with high neuroticism and low agreeableness26 regardless of age or sex. Short telomeres, which reflect accelerated cellular senescence and aging, have also been reported in several major psychiatric disorders (schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, MDD, and anxiety).27-29 The cumulative evidence is unassailable; psychiatric brain disorders are not only associated with premature death due to high suicide rates, but also with multiple medical diseases that lead to early mortality and a shorter lifespan. The shortened telomeres reflect high oxidative stress and inflammation, and both those toxic processes are known to be associated with major psychiatric disorders. Compounding the dismal facts about early mortality due to mental illness are the additional grave medical consequences of alcohol and substance use, which are highly comorbid with most psychiatric disorders, further exacerbating the premature death rates among psychiatric patients.

Continue to: There is an important take-home message...

There is an important take-home message in all of this: Our patients are at high risk for potentially fatal medical conditions that require early detection, and intensive ongoing treatment by a primary care clinician (not “provider”; I abhor the widespread use of that term for physicians or nurse practitioners) is an indispensable component of psychiatric care. Thus, collaborative care is vital to protect our psychiatric patients from early mortality and a shortened lifespan. Psychiatrists and psychiatric nurse practitioners must not only win the battle against mental illness, but also diligently avoid losing the war of life and death.

The evidence is robust and disheartening: As if the personal suffering and societal stigma of mental illness are not bad enough, psychiatric patients also have a shorter lifespan.1 In the past, most studies have focused on early mortality and loss of potential life-years in schizophrenia,2 but many subsequent reports indicate that premature death occurs in all major psychiatric disorders.

Here is a summary of the sobering facts:

- Schizophrenia. In a study of 30,210 patients with schizophrenia, compared with >5 million individuals in the general population in Denmark (where they have an excellent registry), mortality was 16-fold higher among patients with schizophrenia if they had a single somatic illness.3 The illnesses were mostly respiratory, gastrointestinal, or cardiovascular).3 The loss of potential years of life was staggeringly high: 18.7 years for men, 16.3 years for women.4 A study conducted in 8 US states reported a loss of 2 to 3 decades of life across each of these states.5 The causes of death in patients with schizophrenia were mainly heart disease, cancer, stroke, and pulmonary diseases. A national database in Sweden found that unmedicated patients with schizophrenia had a significantly higher death rate than those receiving antipsychotics.6,7 Similar findings were reported by researchers in Finland.8 The Swedish study by Tiihonen et al6 also found that mortality was highest in patients receiving benzodiazepines along with antipsychotics, but there was no increased mortality among patients with schizophrenia receiving antidepressants.

- Bipolar disorder. A shorter life expectancy has also been reported in bipolar disorder,9 with a loss of 13.6 years for men and 12.1 years for women. Early death was caused by physical illness (even when suicide deaths were excluded), especially cardiovascular disease.10

- Major depressive disorder (MDD). A reduction of life expectancy in persons with MDD (unipolar depression) has been reported, with a loss of 14 years in men and 10 years in women.11 Although suicide contributed to the shorter lifespan, death due to accidents was 500% higher among persons with unipolar depression; the largest causes of death were physical illnesses. Further, Zubenko et al12 reported alarming findings about excess mortality among first- and second-degree relatives of persons with early-onset depression (some of whom were bipolar). The relatives died an average of 8 years earlier than the local population, and 40% died before reaching age 65. Also, there was a 5-fold increase in infant mortality (in the first year of life) among the relatives. The most common causes of death in adult relatives were heart disease, cancer, and stroke. It is obvious that MDD has a significant negative impact on health and longevity in both patients and their relatives.

- Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). A 220% increase in mortality was reported in persons with ADHD at all ages.13 Accidents were the most common cause of death. The mortality rate ratio (MRR) was 1.86 for ADHD before age 6, 1.58 for ADHD between age 6 to 17, and 4.25 for those age ≥18. The rate of early mortality was higher in girls and women (MRR = 2.85) than boys and men (MRR = 1.27).

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). A study from Denmark of 10,155 persons with OCD followed for 10 years reported a significantly higher risk of death from both natural (MRR = 1.68) and unnatural causes (MRR = 2.61), compared with the general population.14 Patients with OCD and comorbid depression, anxiety, or substance use had a further increase in mortality risk, but the mortality risk of individuals with OCD without psychiatric comorbidity was still 200% higher than that of the general population.

- Anxiety disorders. One study found no increase in mortality among patients who have generalized anxiety, unless it was associated with depression.15 Another study reported that the presence of anxiety reduced the risk of cardiovascular mortality in persons with depression.16 The absence of increased mortality in anxiety disorders was also confirmed in a meta-analysis of 36 studies.17 However, a study of postmenopausal women with panic attacks found a 3-fold increase in coronary artery disease and stroke in that cohort,18 which confirmed the findings of an older study19 that demonstrated a 2-fold increase of mortality among 155 men with panic disorder after a 12-year follow-up. Also, a 25-year follow-up study found that suicide accounted for 20% of deaths in the anxiety group compared with 16.2% in the depression group,20 showing a significant risk of suicide in panic disorder, even exceeding that of depression.

- Oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) and conduct disorder (CD). In a 12-year follow-up study of 9,495 individuals with “disruptive behavioral disorders,” which included ODD and CD, the mortality rate was >400% higher in these patients compared with 1.92 million individuals in the general population (9.66 vs 2.22 per 10,000 person-years).21 Comorbid substance use disorder and ADHD further increased the mortality rate in this cohort.

- Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Studies show that there is a significantly increased risk of early cardiovascular mortality in PTSD,22 and that the death rate may be associated with accelerated “DNA methylation age” that leads to a 13% increased risk for all-cause mortality.23

- Borderline personality disorder (BPD). A recent longitudinal study (24 years of follow-up with evaluation every 2 years) reported a significantly higher mortality in patients with BPD compared with those with other personality disorders. The age range when the study started was 18 to 35. The rate of suicide death was Palatino LT Std>400% higher in BPD (5.9% vs 1.4%). Also, non-suicidal death was 250% higher in BPD (14% vs 5.5%). The causes of non-suicidal death included cardiovascular disease, substance-related complications, cancer, and accidents.24

- Other personality disorders. Certain personality traits have been associated with shorter leukocyte telomeres, which signal early death. These traits include neuroticism, conscientiousness, harm avoidance, and reward dependence.25 Another study found shorter telomeres in persons with high neuroticism and low agreeableness26 regardless of age or sex. Short telomeres, which reflect accelerated cellular senescence and aging, have also been reported in several major psychiatric disorders (schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, MDD, and anxiety).27-29 The cumulative evidence is unassailable; psychiatric brain disorders are not only associated with premature death due to high suicide rates, but also with multiple medical diseases that lead to early mortality and a shorter lifespan. The shortened telomeres reflect high oxidative stress and inflammation, and both those toxic processes are known to be associated with major psychiatric disorders. Compounding the dismal facts about early mortality due to mental illness are the additional grave medical consequences of alcohol and substance use, which are highly comorbid with most psychiatric disorders, further exacerbating the premature death rates among psychiatric patients.

Continue to: There is an important take-home message...

There is an important take-home message in all of this: Our patients are at high risk for potentially fatal medical conditions that require early detection, and intensive ongoing treatment by a primary care clinician (not “provider”; I abhor the widespread use of that term for physicians or nurse practitioners) is an indispensable component of psychiatric care. Thus, collaborative care is vital to protect our psychiatric patients from early mortality and a shortened lifespan. Psychiatrists and psychiatric nurse practitioners must not only win the battle against mental illness, but also diligently avoid losing the war of life and death.

1. Walker ER, McGee RE, Druss BG. Mortality in mental disorders and global disease burden implications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(4):334-341.

2. Laursen TM, Wahlbeck K, Hällgren J, et al. Life expectancy and death by diseases of the circulatory system in patients with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia in the Nordic countries. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e67133. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067133.

3. Kugathasan P, Stubbs B, Aagaard J, et al. Increased mortality from somatic multimorbidity in patients with schizophrenia: a Danish nationwide cohort study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2019. doi: 10.1111/acps.13076.

4. Laursen TM. Life expectancy among persons with schizophrenia or bipolar affective disorder. Schizophr Res. 2011;131(1-3):101-104.

5. Colton CW, Manderscheid RW. Congruencies in increased mortality rates, years of potential life lost, and causes of death among public mental health clients in eight states. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;3(2):A42.

6. Tiihonen J, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Torniainen M, et al. Mortality and cumulative exposure to antipsychotics, antidepressants, and benzodiazepines in patients with schizophrenia: an observational follow-up study. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(6):600-606.

7. Torniainen M, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Tanskanen A, et al. Antipsychotic treatment and mortality in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2015;41(3):656-663.

8. Tiihonen J, Lönnqvist J, Wahlbeck K, et al. 11-year follow-up of mortality in patients with schizophrenia: a population-based cohort study (FIN11 study). Lancet. 2009;374(9690):620-627.

9. Wilson R, Gaughran F, Whitburn T, et al. Place of death and other factors associated with unnatural mortality in patients with serious mental disorders: population-based retrospective cohort study. BJPsych Open. 2019;5(2):e23. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2019.5.

10. Ösby U, Westman J, Hällgren J, et al. Mortality trends in cardiovascular causes in schizophrenia, bipolar and unipolar mood disorder in Sweden 1987-2010. Eur J Public Health. 2016;26(5):867-871.

11. Laursen TM, Musliner KL, Benros ME, et al. Mortality and life expectancy in persons with severe unipolar depression. J Affect Disord. 2016;193:203-207.

12. Zubenko GS, Zubenko WN, Spiker DG, et al. Malignancy of recurrent, early-onset major depression: a family study. Am J Med Genet. 2001;105(8):690-699.

13. Dalsgaard S, Østergaard SD, Leckman JF, et al. Mortality in children, adolescents, and adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a nationwide cohort study. Lancet. 2015;385(9983):2190-2196.

14. Meier SM, Mattheisen M, Mors O, et al. Mortality among persons with obsessive-compulsive disorder in Denmark. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(3):268-274.

15. Holwerda TJ, Schoevers RA, Dekker J, et al. The relationship between generalized anxiety disorder, depression and mortality in old age. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22(3):241-249.

16. Ivanovs R, Kivite A, Ziedonis D, et al. Association of depression and anxiety with the 10-year risk of cardiovascular mortality in a primary care population of Latvia using the SCORE system. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:276.

17. Miloyan B, Bulley A, Bandeen-Roche K, et al. Anxiety disorders and all-cause mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2016;51(11):1467-1475.

18. Smoller JW, Pollack MH, Wassertheil-Smoller S, et al. Panic attacks and risk of incident cardiovascular events among postmenopausal women in the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(10):1153-1160.

19. Coryell W, Noyes R Jr, House JD. Mortality among outpatients with anxiety disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143(4):508-510.

20. Coryell W, Noyes R, Clancy J. Excess mortality in panic disorder. A comparison with primary unipolar depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1982;39(6):701-703.

21. Scott JG, Giørtz Pedersen M, Erskine HE, et al. Mortality in individuals with disruptive behavior disorders diagnosed by specialist services - a nationwide cohort study. Psychiatry Res. 2017;251:255-260.

22. Burg MM, Soufer R. Post-traumatic stress disorder and cardiovascular disease. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2016;18(10):94.

23. Wolf EJ, Logue MW, Stoop TB, et al. Accelerated DNA methylation age: associations with PTSD and mortality. Psychosom Med. 2017. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000506.

24. Temes CM, Frankenburg FR, Fitzmaurice MC, et al. Deaths by suicide and other causes among patients with borderline personality disorder and personality-disordered comparison subjects over 24 years of prospective follow-up. J Clin Psychiatry. 2019;80(1). doi: 10.4088/JCP.18m12436.

25. Sadahiro R, Suzuki A, Enokido M, et al. Relationship between leukocyte telomere length and personality traits in healthy subjects. Eur Psychiatry. 2015;30(2):291-295.

26. Schoormans D, Verhoeven JE, Denollet J, et al. Leukocyte telomere length and personality: associations with the Big Five and Type D personality traits. Psychol Med. 2018;48(6):1008-1019.

27. Muneer A, Minhas FA. Telomere biology in mood disorders: an updated, comprehensive review of the literature. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2019;17(3):343-363.

28. Vakonaki E, Tsiminikaki K, Plaitis S, et al. Common mental disorders and association with telomere length. Biomed Rep. 2018;8(2):111-116.

29. Malouff

1. Walker ER, McGee RE, Druss BG. Mortality in mental disorders and global disease burden implications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(4):334-341.

2. Laursen TM, Wahlbeck K, Hällgren J, et al. Life expectancy and death by diseases of the circulatory system in patients with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia in the Nordic countries. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e67133. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067133.

3. Kugathasan P, Stubbs B, Aagaard J, et al. Increased mortality from somatic multimorbidity in patients with schizophrenia: a Danish nationwide cohort study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2019. doi: 10.1111/acps.13076.

4. Laursen TM. Life expectancy among persons with schizophrenia or bipolar affective disorder. Schizophr Res. 2011;131(1-3):101-104.

5. Colton CW, Manderscheid RW. Congruencies in increased mortality rates, years of potential life lost, and causes of death among public mental health clients in eight states. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;3(2):A42.

6. Tiihonen J, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Torniainen M, et al. Mortality and cumulative exposure to antipsychotics, antidepressants, and benzodiazepines in patients with schizophrenia: an observational follow-up study. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(6):600-606.

7. Torniainen M, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Tanskanen A, et al. Antipsychotic treatment and mortality in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2015;41(3):656-663.

8. Tiihonen J, Lönnqvist J, Wahlbeck K, et al. 11-year follow-up of mortality in patients with schizophrenia: a population-based cohort study (FIN11 study). Lancet. 2009;374(9690):620-627.

9. Wilson R, Gaughran F, Whitburn T, et al. Place of death and other factors associated with unnatural mortality in patients with serious mental disorders: population-based retrospective cohort study. BJPsych Open. 2019;5(2):e23. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2019.5.

10. Ösby U, Westman J, Hällgren J, et al. Mortality trends in cardiovascular causes in schizophrenia, bipolar and unipolar mood disorder in Sweden 1987-2010. Eur J Public Health. 2016;26(5):867-871.

11. Laursen TM, Musliner KL, Benros ME, et al. Mortality and life expectancy in persons with severe unipolar depression. J Affect Disord. 2016;193:203-207.

12. Zubenko GS, Zubenko WN, Spiker DG, et al. Malignancy of recurrent, early-onset major depression: a family study. Am J Med Genet. 2001;105(8):690-699.

13. Dalsgaard S, Østergaard SD, Leckman JF, et al. Mortality in children, adolescents, and adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a nationwide cohort study. Lancet. 2015;385(9983):2190-2196.

14. Meier SM, Mattheisen M, Mors O, et al. Mortality among persons with obsessive-compulsive disorder in Denmark. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(3):268-274.

15. Holwerda TJ, Schoevers RA, Dekker J, et al. The relationship between generalized anxiety disorder, depression and mortality in old age. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22(3):241-249.

16. Ivanovs R, Kivite A, Ziedonis D, et al. Association of depression and anxiety with the 10-year risk of cardiovascular mortality in a primary care population of Latvia using the SCORE system. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:276.

17. Miloyan B, Bulley A, Bandeen-Roche K, et al. Anxiety disorders and all-cause mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2016;51(11):1467-1475.

18. Smoller JW, Pollack MH, Wassertheil-Smoller S, et al. Panic attacks and risk of incident cardiovascular events among postmenopausal women in the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(10):1153-1160.

19. Coryell W, Noyes R Jr, House JD. Mortality among outpatients with anxiety disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143(4):508-510.

20. Coryell W, Noyes R, Clancy J. Excess mortality in panic disorder. A comparison with primary unipolar depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1982;39(6):701-703.

21. Scott JG, Giørtz Pedersen M, Erskine HE, et al. Mortality in individuals with disruptive behavior disorders diagnosed by specialist services - a nationwide cohort study. Psychiatry Res. 2017;251:255-260.

22. Burg MM, Soufer R. Post-traumatic stress disorder and cardiovascular disease. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2016;18(10):94.

23. Wolf EJ, Logue MW, Stoop TB, et al. Accelerated DNA methylation age: associations with PTSD and mortality. Psychosom Med. 2017. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000506.

24. Temes CM, Frankenburg FR, Fitzmaurice MC, et al. Deaths by suicide and other causes among patients with borderline personality disorder and personality-disordered comparison subjects over 24 years of prospective follow-up. J Clin Psychiatry. 2019;80(1). doi: 10.4088/JCP.18m12436.

25. Sadahiro R, Suzuki A, Enokido M, et al. Relationship between leukocyte telomere length and personality traits in healthy subjects. Eur Psychiatry. 2015;30(2):291-295.

26. Schoormans D, Verhoeven JE, Denollet J, et al. Leukocyte telomere length and personality: associations with the Big Five and Type D personality traits. Psychol Med. 2018;48(6):1008-1019.

27. Muneer A, Minhas FA. Telomere biology in mood disorders: an updated, comprehensive review of the literature. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2019;17(3):343-363.

28. Vakonaki E, Tsiminikaki K, Plaitis S, et al. Common mental disorders and association with telomere length. Biomed Rep. 2018;8(2):111-116.

29. Malouff

Psychotherapy for psychiatric disorders: A review of 4 studies

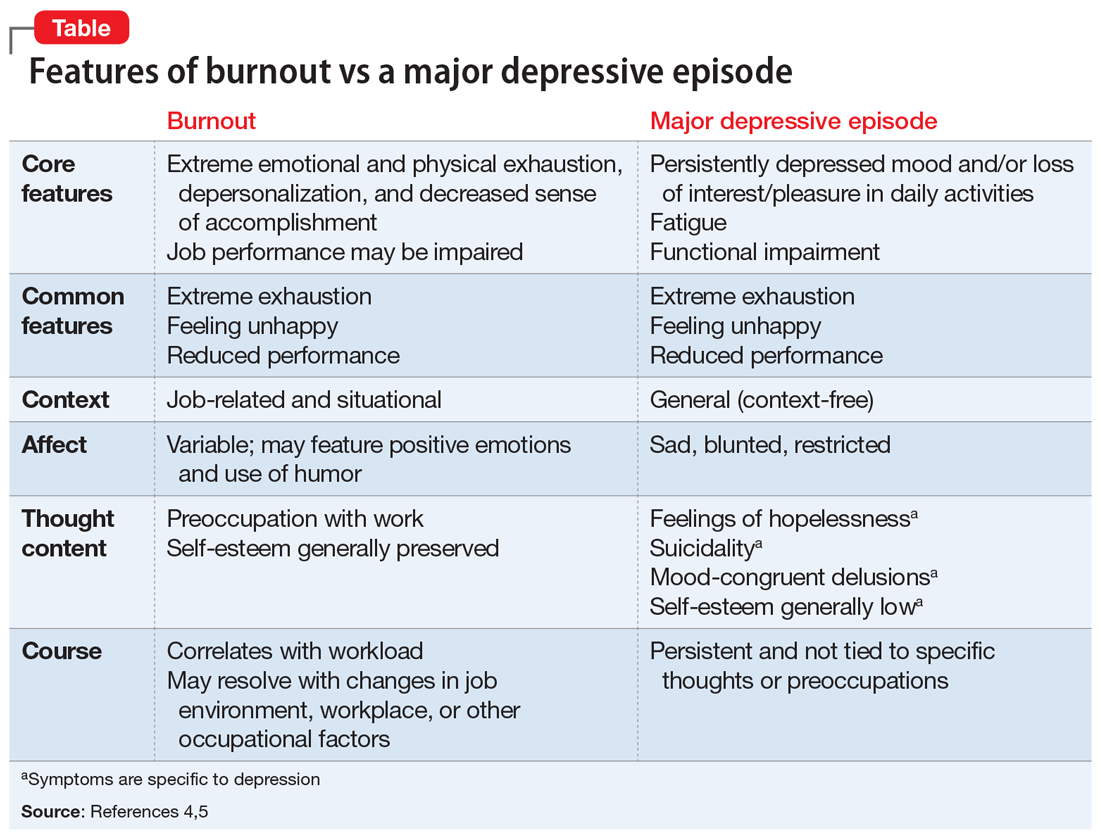

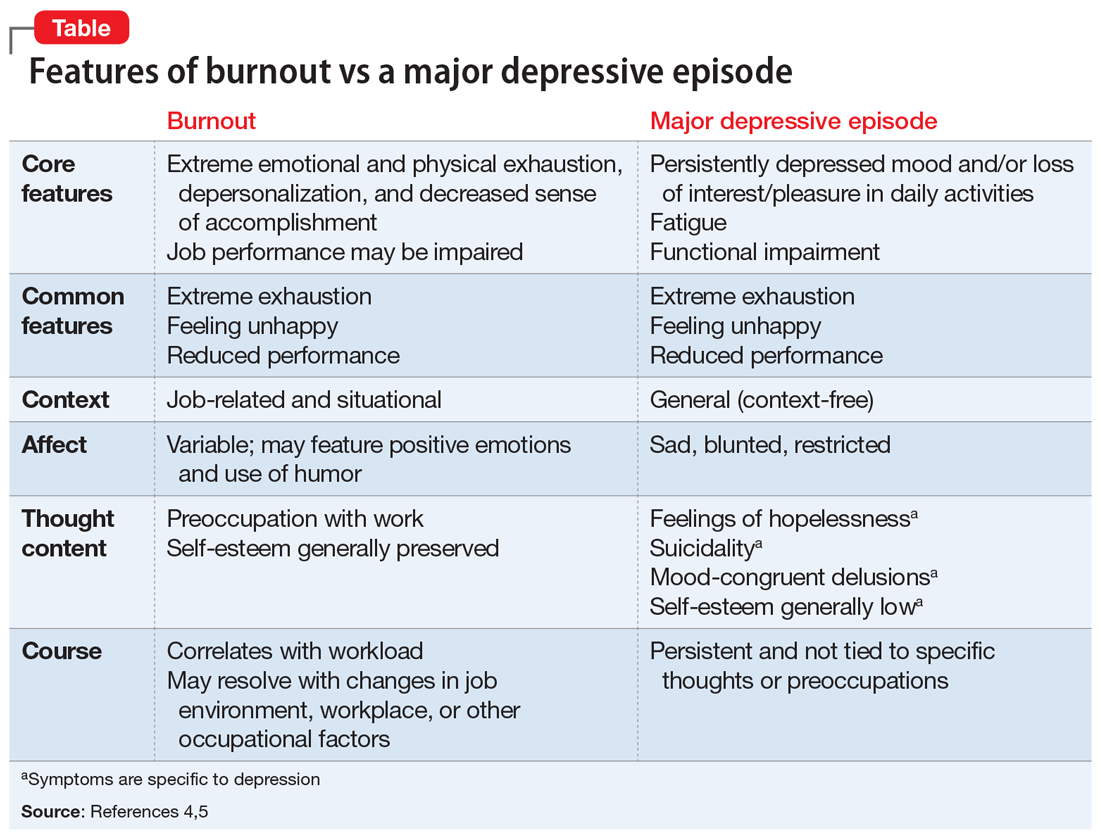

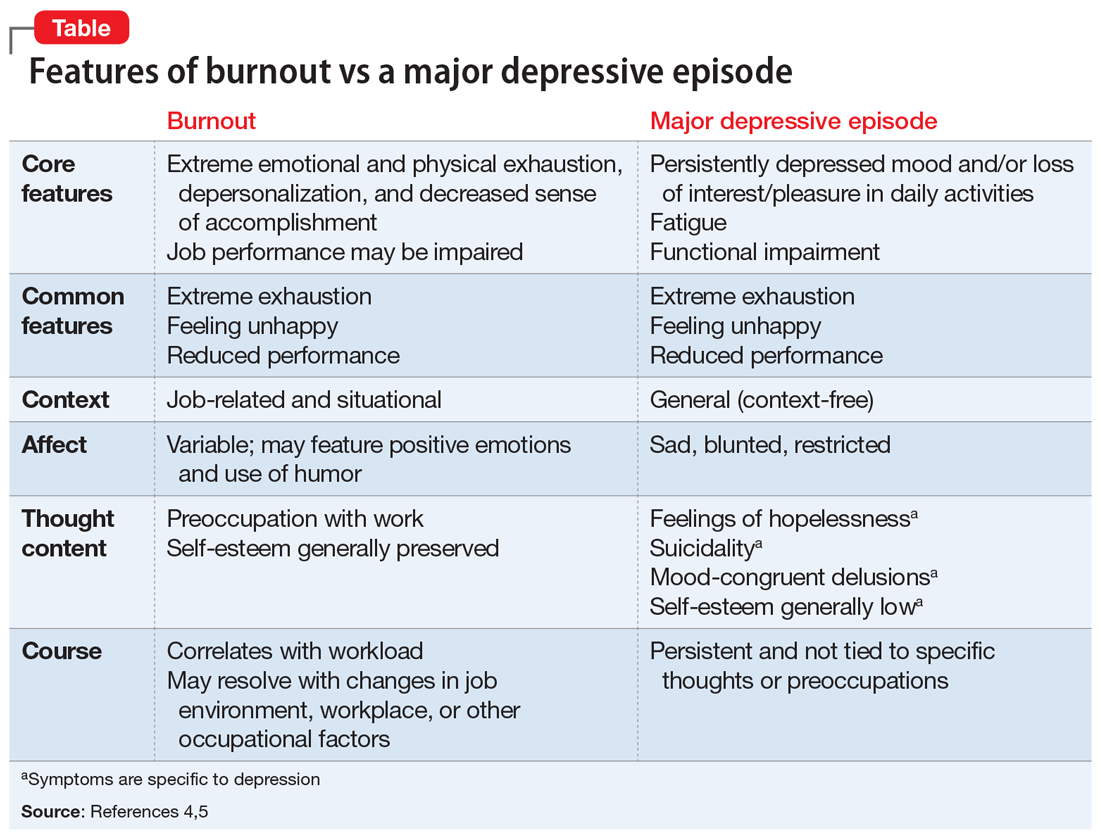

Psychotherapy is among the evidence-based treatment options for treating various psychiatric disorders. How we approach psychiatric disorders via psychotherapy has been shaped by numerous theories of personality and psychopathology, including psychodynamic, behavioral, cognitive, systems, and existential-humanistic approaches. Whether used as primary treatment or in conjunction with medication, psychotherapy has played a pivotal role in shaping psychiatric disease management and treatment. Several evidence-based therapy modalities have been used throughout the years and continue to significantly improve and impact our patients’ lives. In the armamentarium of treatment modalities, therapy takes the leading role for several conditions. Here we review 4 studies from current psychotherapy literature; these studies are summarized in the Table.1-4

1.

Panic disorder has a lifetime prevalence of 3.7% in the general population. Three treatment modalities recommended for patients with panic disorder are psychological therapy, pharmacologic therapy, and self-help. Among the psychological therapies, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is one of the most widely used.1

Cognitive-behavioral therapy for panic disorder has been proven to be an efficacious and impactful treatment. For panic disorder, CBT may consist of different combinations of several therapeutic components, such as relaxation, breathing retraining, cognitive restructuring, interoceptive exposure, and/or in vivo exposure. It is therefore important, both theoretically and clinically, to examine whether specific components of CBT or their combinations are superior to others for treating panic disorder.1

Pompoli et al1 conducted a component network meta-analysis (NMA) of 72 studies in order to determine which CBT components were the most efficacious in treating patients with panic disorder. Component NMA is an extension of standard NMA; it is used to disentangle the treatment effects of different components included in composite interventions.1

The aim of this study was to determine which specific component or combination of components was superior to others when treating panic disorder.1

Study design

- Researchers reviewed 2,526 references from Medline, EMBASE, PsycINFO, and Cochrane Central and selected 72 studies that included 4,064 patients with panic disorder.1

- The primary outcome was remission of panic disorder with or without agoraphobia in the short term (3 to 6 months). Remission was defined as achieving a score of ≤7 on the Panic Disorder Severity Scale (PDSS).1

- Secondary outcomes included response (≥40% reduction in PDSS score from baseline) and dropout for any reason in the short term.1

Continue to: Outcomes

Outcomes

- Using component NMA, researchers determined that interoceptive exposure and face-to-face setting (administration of therapeutic components in a face-to-face setting rather than through self-help means) led to better efficacy and acceptability. Muscle relaxation and virtual reality exposure corresponded to lower efficacy. Breathing retraining and in vivo exposure improved treatment acceptability, but had small effects on efficacy.1

- Based on an analysis of remission rates, the most efficacious CBT incorporated cognitive restructuring and interoceptive exposure. The least efficacious CBT incorporated breathing retraining, muscle relaxation, in vivo exposure, and virtual reality exposure.1

- Application of cognitive and behavioral therapeutic elements was superior to administration of behavioral elements alone. When administering CBT, face-to-face therapy led to better outcomes in response and remission rates. Dropout rates occurred at a lower frequency when CBT was administered face-to-face when compared with self-help groups. The placebo effect was associated with the highest dropout rate.1

Conclusion

- Findings from this meta-analysis have high practical utility. Which CBT components are used can significantly alter CBT’s efficacy and acceptability in patients with panic disorder.1

- The “most efficacious CBT” would include cognitive restructuring and interoceptive exposure delivered in a face-to-face setting. Breathing retraining, muscle relaxation, and virtual reality may have a minimal or even negative impact.1

- Limitations of this meta-analysis include the high number of studies used for the data analysis, complex statistical analysis, inability to include unpublished studies, and limited relevant studies. A future implication of this study is the consideration of formal methodology based on the clinical application of efficacious CBT components when treating patients with panic disorder.1

2. Sloan DM, Marx BP, Lee DJ, et al. A brief exposure-based treatment vs cognitive processing therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized noninferiority clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(3):233-239.

Psychotherapy is also a useful modality for treating posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Sloan et al2 compared brief exposure-based treatment with cognitive processing therapy (CPT) for PTSD.

Clinical practice guidelines for the management of PTSD and acute stress disorder recommend the use of individual, trauma-focused therapies that focus on exposure and cognitive restructuring, such as prolonged exposure, CPT, and written narrative exposure.5

Continue to: One type of written narrative...

One type of written narrative exposure treatment is written exposure therapy (WET), which consists of 5 sessions during which patients write about their trauma. The first session is comprised of psychoeducation about PTSD and a review of treatment reasoning, followed by 30 minutes of writing. The therapist provides feedback and instructions. Written exposure therapy requires less therapist training and less supervision than prolonged exposure or CPT. Prior studies have suggested that WET can significantly reduce PTSD symptoms in various trauma survivors.2

Although efficacious for PTSD, WET had not been compared with CPT, which is the most commonly used first-line treatment of PTSD. The aim of this study was to determine whether WET is noninferior to CPT.2

Study design

- In this randomized noninferiority clinical trial conducted in Boston, Massachusetts from February 28, 2013 to November 6, 2016, 126 veterans and non-veteran adults were randomized to WET or CPT. Participants met DSM-5 criteria for PTSD and were taking stable doses of their medications for at least 4 weeks.2

- Participants assigned to CPT (n = 63) underwent 12 sessions, and participants assigned to WET (n = 63) received 5 sessions. Cognitive processing therapy was conducted over 60-minute weekly sessions. Written exposure therapy consisted of an initial session that was 60 minutes long and four 40-minute follow-up sessions.2

- Interviews were conducted by 4 independent evaluators at baseline and 6, 12, 24, and 36 weeks. During the WET sessions, participants wrote about a traumatic event while focusing on details, thoughts, and feelings associated with the event.2

- Cognitive processing therapy involved 12 trauma-focused therapy sessions during which participants learn how to become aware of and address problematic cognitions about the trauma as well as thoughts about themselves and others. Between sessions, participants were required to write 2 trauma accounts and complete other assignments.2

Outcomes

- The primary outcome was change in total score on the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5). The CAPS-5 scores for participants in the WET group were noninferior to those for participants in the CPT group at all assessment points.2

- Participants did not significantly differ in age, education, income, or PTSD severity. Participants in the 2 groups did not differ in treatment expectations or level of satisfaction with treatment. Individuals assigned to CPT were more likely to drop out of the study: 20 participants in the CPT group dropped out in the first 5 sessions, whereas only 4 dropped out of the WET group. The dropout rate in the CPT group was 39.7%. Improvements in PTSD symptoms in the WET group were noninferior to improvements in the CPT group.2

- Written exposure therapy showed no difference compared with CPT in decreasing PTSD symptoms. Furthermore, this study demonstrated that PTSD symptoms can decrease with a smaller number of shorter therapeutic sessions.2

Conclusion

- This study demonstrated noninferiority between an established, commonly used PTSD therapy (CPT) and a version of exposure therapy that is briefer, simpler, and requires less homework and less therapist training and expertise. This “lower-dose” approach may improve access for the expanding number of patients who require treatment for PTSD, especially in the Veterans Affairs system.2

- In summary, WET is well tolerated and time-efficient. Although it requires fewer sessions, WET was noninferior to CPT.2

Continue to: Multisystemic therapy versus management as usual...

3. Fonagy P, Butler S, Cottrell D, et al. Multisystemic therapy versus management as usual in the treatment of adolescent antisocial behaviour (START): a pragmatic, randomised controlled, superiority trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(2):119-133.

Multisystemic therapy (MST) is an intensive, family-based, home-based intervention for young people with serious antisocial behavior. It has been found effective for childhood conduct disorders in the United States. However, previous studies that supported its efficacy were conducted by the therapy’s developers and used noncomprehensive comparators, such as individual therapy. Fonagy et al3 assessed the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of MST vs management as usual for treating adolescent antisocial behavior. This is the first study that was performed by independent investigators and used a comprehensive control.3

Study design

- This 18-month, multisite, pragmatic, randomized controlled superiority trial was conducted in England.3

- Participants were age 11 to 17, with moderate to severe antisocial behavior. They had at least 3 severity criteria indicating difficulties across several settings and at least one of the 5 inclusion criteria for antisocial behavior. Six hundred eighty-four families were randomly assigned to MST or management as usual, and 491 families completed the study.3

- For the MST intervention, therapists worked with the adolescent’s caregiver 3 times a week for 3 to 5 months to improve parenting skills, enhance family relationships, increase support from social networks, develop skills and resources, address communication problems, increase school attendance and achievement, and reduce the adolescent’s association with delinquent peers.3

- For the management as usual intervention, management was based on local services for young people and was designed to be in line with current community practice.3

Outcomes

- The primary outcome was the proportion of participants in out-of-home placements at 18 months. The secondary outcomes were time to first criminal offense and the total number of offenses.3

- In terms of the risk of out-of-home placement, MST had no effect: 13% of participants in the MST group had out-of-home placement at 18 months, compared with 11% in the management-as-usual group.3

- Multisystemic therapy also did not significantly delay the time to first offense (hazard ratio, 1.06; 95% confidence interval, 0.84 to 1.33). Also, at 18-month follow-up, participants in the MST group had committed more offenses than those in the management-as-usual group, although the difference was not statistically significant.3

- Parents in the MST group reported increased parental support and involvement and reduced problems at 6 months, but the adolescents’ reports of parenting behavior indicated no significant effect for MST vs management as usual at any time point.3

Conclusion

- Multisystemic therapy was not superior to management as usual in reducing out-of-home placements. Although the parents believed that MST brought about a rapid and effective change, this was not reflected in objective indicators of antisocial behavior. These results are contrary to previous studies in the United States. The substantial improvements observed in both groups reflected the effectiveness of routinely offered interventions for this group of young people, at least when observed in clinical trials.3

Continue to: Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy...

4. Janssen L, Kan CC, Carpentier PJ, et al. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy v. treatment as usual in adults with ADHD: a multicentre, single-blind, randomised controlled trial. Psychol Med. 2019;49(1):55-65.

There is empirical support for using psychotherapy to treat attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Although medication management plays a leading role in treating ADHD, Janssen et al4 conducted a multicenter, single-blind trial comparing mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) vs treatment as usual (TAU) for ADHD.

The aim of this study was to determine the efficacy of MBCT plus TAU vs TAU only in decreasing symptoms of adults with ADHD.4

Study design

- This multicenter, single-blind randomized controlled trial was conducted in the Netherlands. Participants (N = 120) met criteria for ADHD and were age ≥18. Patients were randomly assigned to MBCT plus TAU (n = 60) or TAU only (n = 60). Patients in the MBCT plus TAU group received weekly group therapy sessions, meditation exercises, psychoeducation, and group discussions. Patients in the TAU-only group received pharmacotherapy and psychoeducation.4

- Blinded clinicians used the Connors’ Adult ADHD Rating Scale to assess ADHD symptoms.4

- Secondary outcomes were determined by self-reported questionnaires that patients completed online.4

- All statistical analyses were performed on an intention-to-treat sample as well as the per protocol sample.4

Outcomes

- The primary outcome was ADHD symptoms rated by clinicians. Secondary outcomes included self-reported ADHD symptoms, executive functioning, mindfulness skills, positive mental health, and general functioning. Outcomes were examined at baseline and then at post treatment and 3- and 6-month follow-up.4

- Patients in the MBCT plus TAU group had a significant decrease in clinician-rated ADHD symptoms that was maintained at 6-month follow-up. More patients in the MBCT plus TAU group (27%) vs patients in the TAU group (4%) showed a ≥30% reduction in ADHD symptoms. Compared with patients in the TAU group, patients in the MBCT plus TAU group had significant improvements in ADHD symptoms, mindfulness skills, and positive mental health at post treatment and at 6-month follow-up. Compared with those receiving TAU only, patients treated with MBCT plus TAU reported no improvement in executive functioning at post treatment, but did improve at 6-month follow-up.4

Continue to: Conclusion

Conclusion

- Compared with TAU only, MBCT plus TAU is more effective in reducing ADHD symptoms, with a lasting effect at 6-month follow-up. In terms of secondary outcomes, MBCT plus TAU proved to be effective in improving mindfulness, self-compassion, positive mental health, and executive functioning. The results of this trial demonstrate that psychosocial treatments can be effective in addition to TAU in patients with ADHD, and MBCT holds promise for adult ADHD.4

1. Pompoli A, Furukawa TA, Efthimiou O, et al. Dismantling cognitive-behaviour therapy for panic disorder: a systematic review and component network meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2018;48(12):1945-1953.

2. Sloan DM, Marx BP, Lee DJ, et al. A brief exposure-based treatment vs cognitive processing therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized noninferiority clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(3):233-239.

3. Fonagy P, Butler S, Cottrell D, et al. Multisystemic therapy versus management as usual in the treatment of adolescent antisocial behaviour (START): a pragmatic, randomised controlled, superiority trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(2):119-133.

4. Janssen L, Kan CC, Carpentier PJ, et al. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy v. treatment as usual in adults with ADHD: a multicentre, single-blind, randomised controlled trial. Psychol Med. 2019;49(1):55-65.

5. US Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the management of posttraumatic stress disorder and acute stress disorder . https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/ptsd/VADoDPTSDCPGFinal082917.pdf. Published June 2017. Accessed September 8, 2019.

Psychotherapy is among the evidence-based treatment options for treating various psychiatric disorders. How we approach psychiatric disorders via psychotherapy has been shaped by numerous theories of personality and psychopathology, including psychodynamic, behavioral, cognitive, systems, and existential-humanistic approaches. Whether used as primary treatment or in conjunction with medication, psychotherapy has played a pivotal role in shaping psychiatric disease management and treatment. Several evidence-based therapy modalities have been used throughout the years and continue to significantly improve and impact our patients’ lives. In the armamentarium of treatment modalities, therapy takes the leading role for several conditions. Here we review 4 studies from current psychotherapy literature; these studies are summarized in the Table.1-4

1.

Panic disorder has a lifetime prevalence of 3.7% in the general population. Three treatment modalities recommended for patients with panic disorder are psychological therapy, pharmacologic therapy, and self-help. Among the psychological therapies, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is one of the most widely used.1

Cognitive-behavioral therapy for panic disorder has been proven to be an efficacious and impactful treatment. For panic disorder, CBT may consist of different combinations of several therapeutic components, such as relaxation, breathing retraining, cognitive restructuring, interoceptive exposure, and/or in vivo exposure. It is therefore important, both theoretically and clinically, to examine whether specific components of CBT or their combinations are superior to others for treating panic disorder.1

Pompoli et al1 conducted a component network meta-analysis (NMA) of 72 studies in order to determine which CBT components were the most efficacious in treating patients with panic disorder. Component NMA is an extension of standard NMA; it is used to disentangle the treatment effects of different components included in composite interventions.1

The aim of this study was to determine which specific component or combination of components was superior to others when treating panic disorder.1

Study design

- Researchers reviewed 2,526 references from Medline, EMBASE, PsycINFO, and Cochrane Central and selected 72 studies that included 4,064 patients with panic disorder.1

- The primary outcome was remission of panic disorder with or without agoraphobia in the short term (3 to 6 months). Remission was defined as achieving a score of ≤7 on the Panic Disorder Severity Scale (PDSS).1

- Secondary outcomes included response (≥40% reduction in PDSS score from baseline) and dropout for any reason in the short term.1

Continue to: Outcomes

Outcomes

- Using component NMA, researchers determined that interoceptive exposure and face-to-face setting (administration of therapeutic components in a face-to-face setting rather than through self-help means) led to better efficacy and acceptability. Muscle relaxation and virtual reality exposure corresponded to lower efficacy. Breathing retraining and in vivo exposure improved treatment acceptability, but had small effects on efficacy.1

- Based on an analysis of remission rates, the most efficacious CBT incorporated cognitive restructuring and interoceptive exposure. The least efficacious CBT incorporated breathing retraining, muscle relaxation, in vivo exposure, and virtual reality exposure.1

- Application of cognitive and behavioral therapeutic elements was superior to administration of behavioral elements alone. When administering CBT, face-to-face therapy led to better outcomes in response and remission rates. Dropout rates occurred at a lower frequency when CBT was administered face-to-face when compared with self-help groups. The placebo effect was associated with the highest dropout rate.1

Conclusion

- Findings from this meta-analysis have high practical utility. Which CBT components are used can significantly alter CBT’s efficacy and acceptability in patients with panic disorder.1

- The “most efficacious CBT” would include cognitive restructuring and interoceptive exposure delivered in a face-to-face setting. Breathing retraining, muscle relaxation, and virtual reality may have a minimal or even negative impact.1

- Limitations of this meta-analysis include the high number of studies used for the data analysis, complex statistical analysis, inability to include unpublished studies, and limited relevant studies. A future implication of this study is the consideration of formal methodology based on the clinical application of efficacious CBT components when treating patients with panic disorder.1

2. Sloan DM, Marx BP, Lee DJ, et al. A brief exposure-based treatment vs cognitive processing therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized noninferiority clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(3):233-239.