User login

Navigators improve medication adherence in HFrEF

PHILADELPHIA – Treatment guidelines are clear about optimal treatment of heart failure in patients with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), but adherence breakdowns often occur.

So, Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston implemented a navigator-administered patient outreach program that led to improved medication adherence over usual care, according to study results reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Although the study was done at a major academic center, the findings have implications for community practitioners, lead study author Akshay S. Desai, MD, MPH, said in an interview. “The impact of the intervention is clearly greater in those practitioners who manage heart failure and have the least support around them,” he said.

“Our sense is that the kind of population where this intervention would have the greater impact would be a community-dwelling heart failure population managed by community cardiologists, where the infrastructure to provide longitudinal heart failure care is less robust than may be in an academic center,” Dr. Desai said.

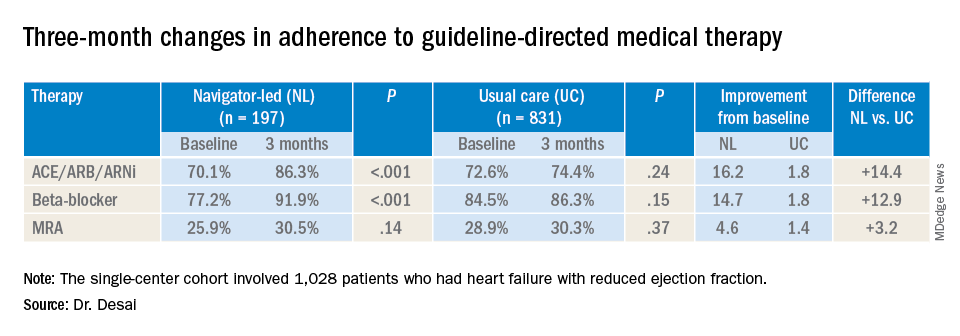

The study evaluated adherence in guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT) at 3 months. “The navigator-led remote medication optimization strategy improved utilization and dosing of all categories of GDMP and was associated with a lower rate of adverse events,” Dr. Desai said. “The impact was more pronounced in patients followed by general practitioners than by a HF specialist.” In the outreach, health navigators contacted patients by phone and managed medications based on remote surveillance of labs, blood pressure, and symptoms under supervision of a pharmacist, nurse practitioner, and heart failure specialist.

The study included 1,028 patients with chronic HFrEF who’d visited a cardiologist at Brigham and Women’s in the year prior to the study: 197 patients and their providers consented to participate in the program with the remainder serving as the reference usual-care group. Most HF specialists at Brigham and Women’s declined to participate in the navigator-led program, Dr. Desai said.

Treating providers were approached for consent to adjust medical therapy according to a sequential, stepped titration algorithm modeled on the current American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association HF Guidelines. The study population did not include patients with end-stage HF, those with a severe noncardiac illness with a life expectancy of less than a year, and patients with a pattern of nonadherence. Baseline characteristics of the two groups were well balanced, Dr. Desai said.

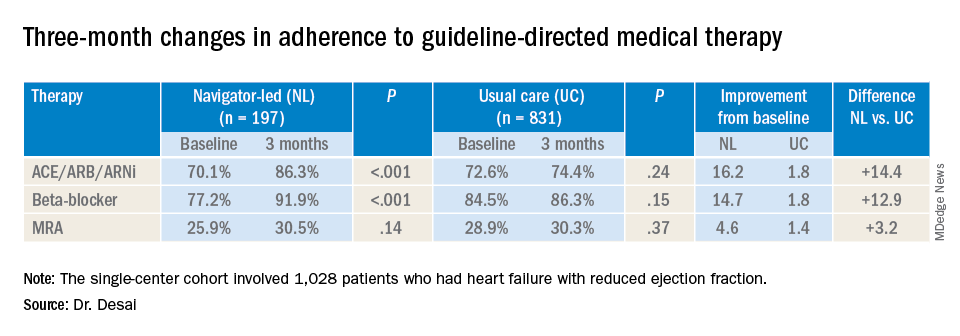

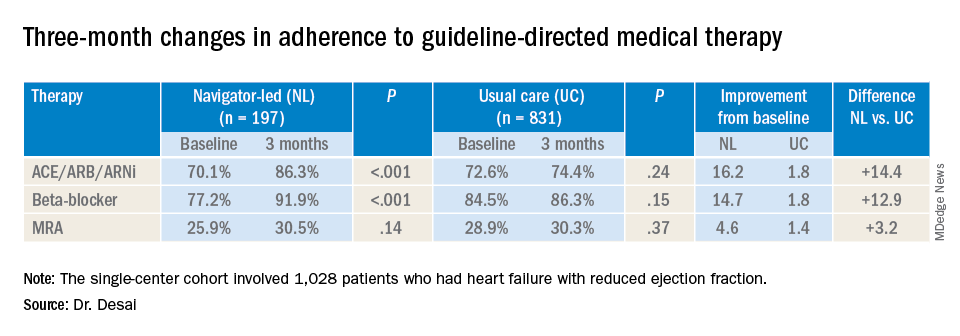

At baseline, 74% (759) participants were treated with ACE inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers/angiotensin-receptor neprilysin inhibitors (ACE/ARB/ARNi), 73% (746) with guideline-directed beta-blockers, and 29% (303) with mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs), with 10% (107) and 11% (117) treated with target doses of ACE/ARB/ARNi and beta-blockers, respectively.

In the navigator-led group, beta-blocker adherence improved from 77.2% at baseline to 91.9% at 3 months (P less than 0.001) compared with an increase from 84.5% to 86.3% in the usual-care patients (P = 0.15), Dr. Desai said. ACE/ARB/ARNi adherence increased 16.2 percentage points to 86.3% (P less than 0.001) in the navigator-group versus 1.8 percentage points to 74.4% (P = 0.24) for usual care. In the MRA subgroup, 3-month adherence to GDMT was almost identical: 30.5% (P = 0.14) and 30.3% (P = 0.37) for the two treatment groups, respectively, although the navigator-led patients averaged a larger increase of 4.6 versus 1.4 percentage points from baseline.

Adverse event rates were similar in both groups, although the navigator group had “slightly higher rates” of hypotension and hyperkalemia but no serious events, Dr. Desai said. This group also had similarly higher rates of worsening renal function, but most were asymptomatic change in creatinine that was addressed with medication changes, he said. There were no hospitalizations for adverse events.

He said the navigator-led optimization has potential in a community setting because the referral nature of Brigham and Women’s HF population “reflects potentially a worst-case scenario for such a program.” The greatest impact was seen in patients managed by general cardiologists, he said. “If we were to move this forward, which we hope to do with scale, the impact might be greater in a community population where there are fewer specialists and less severe illnesses present.”

This study represents a proof of concept, Dr. Desai said in an interview. “What we would like to do is demonstrate that this can be done on a larger scale,” he said. “That might involve partnership with a payer or health care system to see if we can replicate these findings across a broader range of providers.”

Dr. Desai disclosed financial relationships with Novartis, AstraZeneca, Abbott, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Coston Scientific, Biofourmis, DalCor, Relypsa, Regeneron, and Alnylam. Novartis provided an unrestricted grant for the investigator-initiated trial.

SOURCE: Desai AS. AHA 2019 Featured Science session AOS.07.

PHILADELPHIA – Treatment guidelines are clear about optimal treatment of heart failure in patients with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), but adherence breakdowns often occur.

So, Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston implemented a navigator-administered patient outreach program that led to improved medication adherence over usual care, according to study results reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Although the study was done at a major academic center, the findings have implications for community practitioners, lead study author Akshay S. Desai, MD, MPH, said in an interview. “The impact of the intervention is clearly greater in those practitioners who manage heart failure and have the least support around them,” he said.

“Our sense is that the kind of population where this intervention would have the greater impact would be a community-dwelling heart failure population managed by community cardiologists, where the infrastructure to provide longitudinal heart failure care is less robust than may be in an academic center,” Dr. Desai said.

The study evaluated adherence in guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT) at 3 months. “The navigator-led remote medication optimization strategy improved utilization and dosing of all categories of GDMP and was associated with a lower rate of adverse events,” Dr. Desai said. “The impact was more pronounced in patients followed by general practitioners than by a HF specialist.” In the outreach, health navigators contacted patients by phone and managed medications based on remote surveillance of labs, blood pressure, and symptoms under supervision of a pharmacist, nurse practitioner, and heart failure specialist.

The study included 1,028 patients with chronic HFrEF who’d visited a cardiologist at Brigham and Women’s in the year prior to the study: 197 patients and their providers consented to participate in the program with the remainder serving as the reference usual-care group. Most HF specialists at Brigham and Women’s declined to participate in the navigator-led program, Dr. Desai said.

Treating providers were approached for consent to adjust medical therapy according to a sequential, stepped titration algorithm modeled on the current American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association HF Guidelines. The study population did not include patients with end-stage HF, those with a severe noncardiac illness with a life expectancy of less than a year, and patients with a pattern of nonadherence. Baseline characteristics of the two groups were well balanced, Dr. Desai said.

At baseline, 74% (759) participants were treated with ACE inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers/angiotensin-receptor neprilysin inhibitors (ACE/ARB/ARNi), 73% (746) with guideline-directed beta-blockers, and 29% (303) with mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs), with 10% (107) and 11% (117) treated with target doses of ACE/ARB/ARNi and beta-blockers, respectively.

In the navigator-led group, beta-blocker adherence improved from 77.2% at baseline to 91.9% at 3 months (P less than 0.001) compared with an increase from 84.5% to 86.3% in the usual-care patients (P = 0.15), Dr. Desai said. ACE/ARB/ARNi adherence increased 16.2 percentage points to 86.3% (P less than 0.001) in the navigator-group versus 1.8 percentage points to 74.4% (P = 0.24) for usual care. In the MRA subgroup, 3-month adherence to GDMT was almost identical: 30.5% (P = 0.14) and 30.3% (P = 0.37) for the two treatment groups, respectively, although the navigator-led patients averaged a larger increase of 4.6 versus 1.4 percentage points from baseline.

Adverse event rates were similar in both groups, although the navigator group had “slightly higher rates” of hypotension and hyperkalemia but no serious events, Dr. Desai said. This group also had similarly higher rates of worsening renal function, but most were asymptomatic change in creatinine that was addressed with medication changes, he said. There were no hospitalizations for adverse events.

He said the navigator-led optimization has potential in a community setting because the referral nature of Brigham and Women’s HF population “reflects potentially a worst-case scenario for such a program.” The greatest impact was seen in patients managed by general cardiologists, he said. “If we were to move this forward, which we hope to do with scale, the impact might be greater in a community population where there are fewer specialists and less severe illnesses present.”

This study represents a proof of concept, Dr. Desai said in an interview. “What we would like to do is demonstrate that this can be done on a larger scale,” he said. “That might involve partnership with a payer or health care system to see if we can replicate these findings across a broader range of providers.”

Dr. Desai disclosed financial relationships with Novartis, AstraZeneca, Abbott, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Coston Scientific, Biofourmis, DalCor, Relypsa, Regeneron, and Alnylam. Novartis provided an unrestricted grant for the investigator-initiated trial.

SOURCE: Desai AS. AHA 2019 Featured Science session AOS.07.

PHILADELPHIA – Treatment guidelines are clear about optimal treatment of heart failure in patients with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), but adherence breakdowns often occur.

So, Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston implemented a navigator-administered patient outreach program that led to improved medication adherence over usual care, according to study results reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Although the study was done at a major academic center, the findings have implications for community practitioners, lead study author Akshay S. Desai, MD, MPH, said in an interview. “The impact of the intervention is clearly greater in those practitioners who manage heart failure and have the least support around them,” he said.

“Our sense is that the kind of population where this intervention would have the greater impact would be a community-dwelling heart failure population managed by community cardiologists, where the infrastructure to provide longitudinal heart failure care is less robust than may be in an academic center,” Dr. Desai said.

The study evaluated adherence in guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT) at 3 months. “The navigator-led remote medication optimization strategy improved utilization and dosing of all categories of GDMP and was associated with a lower rate of adverse events,” Dr. Desai said. “The impact was more pronounced in patients followed by general practitioners than by a HF specialist.” In the outreach, health navigators contacted patients by phone and managed medications based on remote surveillance of labs, blood pressure, and symptoms under supervision of a pharmacist, nurse practitioner, and heart failure specialist.

The study included 1,028 patients with chronic HFrEF who’d visited a cardiologist at Brigham and Women’s in the year prior to the study: 197 patients and their providers consented to participate in the program with the remainder serving as the reference usual-care group. Most HF specialists at Brigham and Women’s declined to participate in the navigator-led program, Dr. Desai said.

Treating providers were approached for consent to adjust medical therapy according to a sequential, stepped titration algorithm modeled on the current American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association HF Guidelines. The study population did not include patients with end-stage HF, those with a severe noncardiac illness with a life expectancy of less than a year, and patients with a pattern of nonadherence. Baseline characteristics of the two groups were well balanced, Dr. Desai said.

At baseline, 74% (759) participants were treated with ACE inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers/angiotensin-receptor neprilysin inhibitors (ACE/ARB/ARNi), 73% (746) with guideline-directed beta-blockers, and 29% (303) with mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs), with 10% (107) and 11% (117) treated with target doses of ACE/ARB/ARNi and beta-blockers, respectively.

In the navigator-led group, beta-blocker adherence improved from 77.2% at baseline to 91.9% at 3 months (P less than 0.001) compared with an increase from 84.5% to 86.3% in the usual-care patients (P = 0.15), Dr. Desai said. ACE/ARB/ARNi adherence increased 16.2 percentage points to 86.3% (P less than 0.001) in the navigator-group versus 1.8 percentage points to 74.4% (P = 0.24) for usual care. In the MRA subgroup, 3-month adherence to GDMT was almost identical: 30.5% (P = 0.14) and 30.3% (P = 0.37) for the two treatment groups, respectively, although the navigator-led patients averaged a larger increase of 4.6 versus 1.4 percentage points from baseline.

Adverse event rates were similar in both groups, although the navigator group had “slightly higher rates” of hypotension and hyperkalemia but no serious events, Dr. Desai said. This group also had similarly higher rates of worsening renal function, but most were asymptomatic change in creatinine that was addressed with medication changes, he said. There were no hospitalizations for adverse events.

He said the navigator-led optimization has potential in a community setting because the referral nature of Brigham and Women’s HF population “reflects potentially a worst-case scenario for such a program.” The greatest impact was seen in patients managed by general cardiologists, he said. “If we were to move this forward, which we hope to do with scale, the impact might be greater in a community population where there are fewer specialists and less severe illnesses present.”

This study represents a proof of concept, Dr. Desai said in an interview. “What we would like to do is demonstrate that this can be done on a larger scale,” he said. “That might involve partnership with a payer or health care system to see if we can replicate these findings across a broader range of providers.”

Dr. Desai disclosed financial relationships with Novartis, AstraZeneca, Abbott, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Coston Scientific, Biofourmis, DalCor, Relypsa, Regeneron, and Alnylam. Novartis provided an unrestricted grant for the investigator-initiated trial.

SOURCE: Desai AS. AHA 2019 Featured Science session AOS.07.

REPORTING FROM AHA 2019

New guideline provides recommendations for radiation therapy of basal cell, squamous cell cancers

who are not candidates for surgery, according to a new guideline from an American Society for Radiation Oncology task force.

“We hope that the dermatology community will find this guideline helpful, especially when it comes to defining clinical and pathological characteristics that may necessitate a discussion about the merits of postoperative radiation therapy,” said lead author Anna Likhacheva, MD, of the Sutter Medical Center in Sacramento, Calif., in an email. The guideline was published in Practical Radiation Oncology.

To address five key questions in regard to radiation therapy (RT) for the two most common skin cancers, the American Society for Radiation Oncology convened a task force of radiation, medical, and surgical oncologists; dermatopathologists; a radiation oncology resident; a medical physicist; and a dermatologist. They reviewed studies of adults with nonmetastatic, invasive basal cell carcinoma (BCC) or cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) that were published between May 1998 and June 2018, with the caveat that “there are limited, well-conducted modern randomized trials” in this area. As such, the majority of the recommendations have low to moderate quality of evidence designations.

“The conspicuous lack of prospective and randomized data should serve as a reminder to open clinical trials and collect outcomes data in a prospective fashion,” added Dr. Likhacheva, noting that “improving the quality of data on this topic will ultimately serve our common goal of improving patient outcomes.”

Their first recommendation was to strongly consider definitive RT as an alternative to surgery for BCC and cSCC, especially in areas where a surgical procedure would potentially compromise function or cosmesis. However, they did discourage its use in patients with genetic conditions associated with increased radiosensitivity.

Their second recommendation was to strongly consider postoperative radiation therapy for clinically or radiologically apparent gross perineural spread. They also strongly recommended PORT for cSCC patients with close or positive margins, with T3 or T4 tumors, or with desmoplastic or infiltrative tumors.

Their third recommendation was to strongly consider therapeutic lymphadenectomy followed by adjuvant RT in patients with cSCC or BCC that has metastasized to the regional lymph nodes. They also recommended definitive RT in medically inoperable patients with the same metastasized cSCC or BCC. In addition, patients with BCC or cSCC undergoing adjuvant RT after therapeutic lymphadenectomy were recommended a dose of 6,000-6,600 cGy, while patients with cSCC undergoing elective RT without a lymphadenectomy were recommended a dose of 5,000-5,400 cGy.

Their fourth recommendation focused on techniques and dose-fractionation schedules for RT in the definitive or postoperative setting. For patients with BCC and cSCC receiving definitive RT, the biologically effective dose (BED10) range for conventional fractionation – defined as 180-200 cGy/fraction – should be 70-93.5 and the BED10 range for hypofractionation – defined as 210-500 cGy/fraction – should be 56-88. For patients with BCC and cSCC receiving postoperative RT, the BED10 range for conventional fractionation should be 59.5-79.2 and the BED10 range for hypofractionation should be 56-70.2.

Finally, their fifth recommendation was to not add concurrent carboplatin to adjuvant RT in patients with resected, locally advanced cSCC. They also conditionally recommended adding concurrent drug therapies to definitive RT in patients with unresected, locally advanced cSCC.

Several of the authors reported receiving honoraria and travel expenses from medical and pharmaceutical companies, along with serving on their advisory boards. The others reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Likhacheva A et al. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2019 Dec 9. doi: 10.1016/j.prro.2019.10.014.

who are not candidates for surgery, according to a new guideline from an American Society for Radiation Oncology task force.

“We hope that the dermatology community will find this guideline helpful, especially when it comes to defining clinical and pathological characteristics that may necessitate a discussion about the merits of postoperative radiation therapy,” said lead author Anna Likhacheva, MD, of the Sutter Medical Center in Sacramento, Calif., in an email. The guideline was published in Practical Radiation Oncology.

To address five key questions in regard to radiation therapy (RT) for the two most common skin cancers, the American Society for Radiation Oncology convened a task force of radiation, medical, and surgical oncologists; dermatopathologists; a radiation oncology resident; a medical physicist; and a dermatologist. They reviewed studies of adults with nonmetastatic, invasive basal cell carcinoma (BCC) or cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) that were published between May 1998 and June 2018, with the caveat that “there are limited, well-conducted modern randomized trials” in this area. As such, the majority of the recommendations have low to moderate quality of evidence designations.

“The conspicuous lack of prospective and randomized data should serve as a reminder to open clinical trials and collect outcomes data in a prospective fashion,” added Dr. Likhacheva, noting that “improving the quality of data on this topic will ultimately serve our common goal of improving patient outcomes.”

Their first recommendation was to strongly consider definitive RT as an alternative to surgery for BCC and cSCC, especially in areas where a surgical procedure would potentially compromise function or cosmesis. However, they did discourage its use in patients with genetic conditions associated with increased radiosensitivity.

Their second recommendation was to strongly consider postoperative radiation therapy for clinically or radiologically apparent gross perineural spread. They also strongly recommended PORT for cSCC patients with close or positive margins, with T3 or T4 tumors, or with desmoplastic or infiltrative tumors.

Their third recommendation was to strongly consider therapeutic lymphadenectomy followed by adjuvant RT in patients with cSCC or BCC that has metastasized to the regional lymph nodes. They also recommended definitive RT in medically inoperable patients with the same metastasized cSCC or BCC. In addition, patients with BCC or cSCC undergoing adjuvant RT after therapeutic lymphadenectomy were recommended a dose of 6,000-6,600 cGy, while patients with cSCC undergoing elective RT without a lymphadenectomy were recommended a dose of 5,000-5,400 cGy.

Their fourth recommendation focused on techniques and dose-fractionation schedules for RT in the definitive or postoperative setting. For patients with BCC and cSCC receiving definitive RT, the biologically effective dose (BED10) range for conventional fractionation – defined as 180-200 cGy/fraction – should be 70-93.5 and the BED10 range for hypofractionation – defined as 210-500 cGy/fraction – should be 56-88. For patients with BCC and cSCC receiving postoperative RT, the BED10 range for conventional fractionation should be 59.5-79.2 and the BED10 range for hypofractionation should be 56-70.2.

Finally, their fifth recommendation was to not add concurrent carboplatin to adjuvant RT in patients with resected, locally advanced cSCC. They also conditionally recommended adding concurrent drug therapies to definitive RT in patients with unresected, locally advanced cSCC.

Several of the authors reported receiving honoraria and travel expenses from medical and pharmaceutical companies, along with serving on their advisory boards. The others reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Likhacheva A et al. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2019 Dec 9. doi: 10.1016/j.prro.2019.10.014.

who are not candidates for surgery, according to a new guideline from an American Society for Radiation Oncology task force.

“We hope that the dermatology community will find this guideline helpful, especially when it comes to defining clinical and pathological characteristics that may necessitate a discussion about the merits of postoperative radiation therapy,” said lead author Anna Likhacheva, MD, of the Sutter Medical Center in Sacramento, Calif., in an email. The guideline was published in Practical Radiation Oncology.

To address five key questions in regard to radiation therapy (RT) for the two most common skin cancers, the American Society for Radiation Oncology convened a task force of radiation, medical, and surgical oncologists; dermatopathologists; a radiation oncology resident; a medical physicist; and a dermatologist. They reviewed studies of adults with nonmetastatic, invasive basal cell carcinoma (BCC) or cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) that were published between May 1998 and June 2018, with the caveat that “there are limited, well-conducted modern randomized trials” in this area. As such, the majority of the recommendations have low to moderate quality of evidence designations.

“The conspicuous lack of prospective and randomized data should serve as a reminder to open clinical trials and collect outcomes data in a prospective fashion,” added Dr. Likhacheva, noting that “improving the quality of data on this topic will ultimately serve our common goal of improving patient outcomes.”

Their first recommendation was to strongly consider definitive RT as an alternative to surgery for BCC and cSCC, especially in areas where a surgical procedure would potentially compromise function or cosmesis. However, they did discourage its use in patients with genetic conditions associated with increased radiosensitivity.

Their second recommendation was to strongly consider postoperative radiation therapy for clinically or radiologically apparent gross perineural spread. They also strongly recommended PORT for cSCC patients with close or positive margins, with T3 or T4 tumors, or with desmoplastic or infiltrative tumors.

Their third recommendation was to strongly consider therapeutic lymphadenectomy followed by adjuvant RT in patients with cSCC or BCC that has metastasized to the regional lymph nodes. They also recommended definitive RT in medically inoperable patients with the same metastasized cSCC or BCC. In addition, patients with BCC or cSCC undergoing adjuvant RT after therapeutic lymphadenectomy were recommended a dose of 6,000-6,600 cGy, while patients with cSCC undergoing elective RT without a lymphadenectomy were recommended a dose of 5,000-5,400 cGy.

Their fourth recommendation focused on techniques and dose-fractionation schedules for RT in the definitive or postoperative setting. For patients with BCC and cSCC receiving definitive RT, the biologically effective dose (BED10) range for conventional fractionation – defined as 180-200 cGy/fraction – should be 70-93.5 and the BED10 range for hypofractionation – defined as 210-500 cGy/fraction – should be 56-88. For patients with BCC and cSCC receiving postoperative RT, the BED10 range for conventional fractionation should be 59.5-79.2 and the BED10 range for hypofractionation should be 56-70.2.

Finally, their fifth recommendation was to not add concurrent carboplatin to adjuvant RT in patients with resected, locally advanced cSCC. They also conditionally recommended adding concurrent drug therapies to definitive RT in patients with unresected, locally advanced cSCC.

Several of the authors reported receiving honoraria and travel expenses from medical and pharmaceutical companies, along with serving on their advisory boards. The others reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Likhacheva A et al. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2019 Dec 9. doi: 10.1016/j.prro.2019.10.014.

FROM PRACTICAL RADIATION ONCOLOGY

Makeup is contaminated with pathogenic bacteria

Recalcitrant acne is a common, unwavering problem in dermatology practices nationwide. However, both gram positive and gram negative infections of the skin can go undiagnosed in patients with acne resistant to the armamentarium of oral and topical therapeutics. Although I often use isotretinoin in patients with cystic or recalcitrant acne, I almost always do a culture prior to initiating therapy, and more often than not, have discovered patients have gram negative and gram positive skin infections resistant to antibiotics commonly used to treat acne.

In a study by Bashir and Lambert published in the Journal of Applied Microbiology, 70%-90% of makeup products tested – including lipstick, lip gloss, beauty blenders, eyeliners, and mascara – were found to be contaminated with bacteria. Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Escherichia coli were the most common culprits, and the product with the highest contamination rates were beauty blenders (the small sponges used to apply makeup), which also had high rates of fungal contamination.

Expiration dates on cosmetic products are used to indicate the length of time a preservative in a product can control bacterial contamination. They are printed on packaging as an open jar symbol with the 3M, 6M, 9M, and 12M label for the number of months the product can be opened and used. Unfortunately and unknowingly, most consumers use products beyond the expiration date, and the most common offender is mascara.

Gram positive and gram negative skin infections should be ruled out in all cases of recalcitrant acne. A reminder to note on all culture requisitions to grow gram negatives because not all labs will grow gram negatives on a skin swab. Counseling should also be given to those patients who wear makeup, which should include techniques to clean and sanitize makeup applicators including brushes, tools, and towels. Blenders are known to be used “wet” and are not dried when washed.

It is my recommendation that blenders be a one-time-use-only tool and disposed of after EVERY application. Instructions provided in my clinic are to wash all devices and brushes once a week with hot soapy water, and blow dry with a hair dryer immediately afterward. Lipsticks, mascara wands, and lip glosses should be sanitized with alcohol once a month. Finally, all products need to be disposed of after their expiry.

Dr. Talakoub and Dr. Wesley are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

Resource

Basher A, Lambert P. J Appl Microbiol. 2019. doi: 10.1111/jam.14479.

Recalcitrant acne is a common, unwavering problem in dermatology practices nationwide. However, both gram positive and gram negative infections of the skin can go undiagnosed in patients with acne resistant to the armamentarium of oral and topical therapeutics. Although I often use isotretinoin in patients with cystic or recalcitrant acne, I almost always do a culture prior to initiating therapy, and more often than not, have discovered patients have gram negative and gram positive skin infections resistant to antibiotics commonly used to treat acne.

In a study by Bashir and Lambert published in the Journal of Applied Microbiology, 70%-90% of makeup products tested – including lipstick, lip gloss, beauty blenders, eyeliners, and mascara – were found to be contaminated with bacteria. Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Escherichia coli were the most common culprits, and the product with the highest contamination rates were beauty blenders (the small sponges used to apply makeup), which also had high rates of fungal contamination.

Expiration dates on cosmetic products are used to indicate the length of time a preservative in a product can control bacterial contamination. They are printed on packaging as an open jar symbol with the 3M, 6M, 9M, and 12M label for the number of months the product can be opened and used. Unfortunately and unknowingly, most consumers use products beyond the expiration date, and the most common offender is mascara.

Gram positive and gram negative skin infections should be ruled out in all cases of recalcitrant acne. A reminder to note on all culture requisitions to grow gram negatives because not all labs will grow gram negatives on a skin swab. Counseling should also be given to those patients who wear makeup, which should include techniques to clean and sanitize makeup applicators including brushes, tools, and towels. Blenders are known to be used “wet” and are not dried when washed.

It is my recommendation that blenders be a one-time-use-only tool and disposed of after EVERY application. Instructions provided in my clinic are to wash all devices and brushes once a week with hot soapy water, and blow dry with a hair dryer immediately afterward. Lipsticks, mascara wands, and lip glosses should be sanitized with alcohol once a month. Finally, all products need to be disposed of after their expiry.

Dr. Talakoub and Dr. Wesley are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

Resource

Basher A, Lambert P. J Appl Microbiol. 2019. doi: 10.1111/jam.14479.

Recalcitrant acne is a common, unwavering problem in dermatology practices nationwide. However, both gram positive and gram negative infections of the skin can go undiagnosed in patients with acne resistant to the armamentarium of oral and topical therapeutics. Although I often use isotretinoin in patients with cystic or recalcitrant acne, I almost always do a culture prior to initiating therapy, and more often than not, have discovered patients have gram negative and gram positive skin infections resistant to antibiotics commonly used to treat acne.

In a study by Bashir and Lambert published in the Journal of Applied Microbiology, 70%-90% of makeup products tested – including lipstick, lip gloss, beauty blenders, eyeliners, and mascara – were found to be contaminated with bacteria. Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Escherichia coli were the most common culprits, and the product with the highest contamination rates were beauty blenders (the small sponges used to apply makeup), which also had high rates of fungal contamination.

Expiration dates on cosmetic products are used to indicate the length of time a preservative in a product can control bacterial contamination. They are printed on packaging as an open jar symbol with the 3M, 6M, 9M, and 12M label for the number of months the product can be opened and used. Unfortunately and unknowingly, most consumers use products beyond the expiration date, and the most common offender is mascara.

Gram positive and gram negative skin infections should be ruled out in all cases of recalcitrant acne. A reminder to note on all culture requisitions to grow gram negatives because not all labs will grow gram negatives on a skin swab. Counseling should also be given to those patients who wear makeup, which should include techniques to clean and sanitize makeup applicators including brushes, tools, and towels. Blenders are known to be used “wet” and are not dried when washed.

It is my recommendation that blenders be a one-time-use-only tool and disposed of after EVERY application. Instructions provided in my clinic are to wash all devices and brushes once a week with hot soapy water, and blow dry with a hair dryer immediately afterward. Lipsticks, mascara wands, and lip glosses should be sanitized with alcohol once a month. Finally, all products need to be disposed of after their expiry.

Dr. Talakoub and Dr. Wesley are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

Resource

Basher A, Lambert P. J Appl Microbiol. 2019. doi: 10.1111/jam.14479.

Well-tolerated topical capsaicin formulation reduces knee OA pain

ATLANTA – Use of high-concentration topical capsaicin was associated with reduced pain, a longer duration of clinical response, and was well tolerated in patients with knee osteoarthritis, compared with lower concentrations of capsaicin and placebo, according to recent research presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

While the ACR has recommended topical capsaicin for the relief of hand and knee OA pain, there are issues with using low-dose capsaicin, including the need for multiple applications and burning, stinging sensations at applications sites. As repeat exposure to capsaicin results in depletion of pain neurotransmitters and a reduction in nerve fibers in a dose-dependent fashion, higher doses of topical capsaicin are a potential topical treatment for OA pain relief, but their tolerability is low, Tim Warneke, vice president of clinical operations at Vizuri Health Sciences in Columbia, Md., said in his presentation.

“[P]oor tolerability has limited the ability to maximize the analgesic effect of capsaicin,” Mr. Warneke said. “While [over-the-counter] preparations of capsaicin provide some pain relief, poor tolerability with higher doses has really left us wondering if we haven’t maximized capsaicin’s ability to provide pain relief.”

Mr. Warneke and colleagues conducted a phase 2, multicenter, double-blind, parallel-group, vehicle-controlled trial where 120 patients with knee OA were randomized in a 1:1:1 ratio to receive 5% capsaicin topical liquid (CGS-200-5), 1% capsaicin topical liquid (CGS-200-1), or vehicle (CGS-200-0) and then followed up to 90 days. “The CGS-200 vehicle was developed to mitigate the burning, stinging pain of capsaicin,” Mr. Warneke said. “It allows the 5% concentration to be well tolerated, which opens the door for increased efficacy, including durability of response.”

Inclusion criteria were radiographically confirmed knee OA using 1986 ACR classification criteria, a Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) pain score of 250 mm or greater, and more than 3 months of chronic knee pain. While patients were excluded for use of topical, oral, or injectable corticosteroids in the month prior to enrollment, they were allowed to continue using analgesics such as NSAIDs if they maintained their daily dose throughout the trial. Mr. Warneke noted the study population was typical of an OA population with a mostly female, mostly Caucasian cohort who had a median age of 60 years and a body mass index of 30 kg/m2. Patients had moderate to severe OA and were refractory to previous pain treatments.

The interventions consisted of a single 60-minute application of capsaicin or vehicle to both knees once per day for 4 consecutive days, and patients performed the applications in the clinic. The investigators compared change in WOMAC pain scores between the groups at 31 days, 60 days, and 90 days post dose.

The results at 31 days showed a 46.2% reduction in WOMAC pain scores from baseline for patients using CGS-200-5, compared with a 28.3% reduction in the vehicle group (P = .02). At 60 days, there was a 49.1% reduction in WOMAC pain scores in the CGS-200-5 group, compared with 21.5% in patients using vehicle (P = .0001), and a 42.8% reduction for patients in the CGS-200-5 group at 90 days, compared with 22.8% in the vehicle group (P = .01). The CGS-200-1 group did not reach the primary efficacy WOMAC pain endpoint, compared with vehicle.

A post hoc analysis showed that there was a significantly greater mean reduction in WOMAC total score for patients using CGS-200-5, compared with vehicle at 31 days (P = .02), 60 days (P = .0005), and 90 days post dose (P = .005). “This durability of clinical response for single applications seems to be a promising feature of CGS-200-5,” Mr. Warneke said.

Concerning safety and tolerability, there were no serious adverse events, and one patient discontinued treatment in the CGS-200-5 group. When assessing tolerability at predose, 15-minute, 30-minute, 60-minute, and 90-minute postdose time intervals, the investigators found patients experienced mild or moderate adverse events such as erythema, edema, scaling, and pruritus, with symptoms decreasing by the fourth consecutive day of application.

Mr. Warneke acknowledged the “robust placebo response” in the trial and noted it is not unusual to see in pain studies. “It’s something that is a challenge for all of us who are in this space to overcome, but we still have significant differences here and they are statistically significant as well,” he said. “You have to be pretty good these days to beat the wonder drug placebo, it appears.”

Four authors in addition to Mr. Warneke reported being employees of Vizuri Health Sciences, the company developing CGS-200-5. One author reported being a former consultant for Vizuri. Three authors reported they were current or former employees of CT Clinical Trial & Consulting, a contract research organization employed by Vizuri to execute and manage the study, perform data analysis, and create reports.

SOURCE: Warneke T et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(suppl 10), Abstract 2760.

ATLANTA – Use of high-concentration topical capsaicin was associated with reduced pain, a longer duration of clinical response, and was well tolerated in patients with knee osteoarthritis, compared with lower concentrations of capsaicin and placebo, according to recent research presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

While the ACR has recommended topical capsaicin for the relief of hand and knee OA pain, there are issues with using low-dose capsaicin, including the need for multiple applications and burning, stinging sensations at applications sites. As repeat exposure to capsaicin results in depletion of pain neurotransmitters and a reduction in nerve fibers in a dose-dependent fashion, higher doses of topical capsaicin are a potential topical treatment for OA pain relief, but their tolerability is low, Tim Warneke, vice president of clinical operations at Vizuri Health Sciences in Columbia, Md., said in his presentation.

“[P]oor tolerability has limited the ability to maximize the analgesic effect of capsaicin,” Mr. Warneke said. “While [over-the-counter] preparations of capsaicin provide some pain relief, poor tolerability with higher doses has really left us wondering if we haven’t maximized capsaicin’s ability to provide pain relief.”

Mr. Warneke and colleagues conducted a phase 2, multicenter, double-blind, parallel-group, vehicle-controlled trial where 120 patients with knee OA were randomized in a 1:1:1 ratio to receive 5% capsaicin topical liquid (CGS-200-5), 1% capsaicin topical liquid (CGS-200-1), or vehicle (CGS-200-0) and then followed up to 90 days. “The CGS-200 vehicle was developed to mitigate the burning, stinging pain of capsaicin,” Mr. Warneke said. “It allows the 5% concentration to be well tolerated, which opens the door for increased efficacy, including durability of response.”

Inclusion criteria were radiographically confirmed knee OA using 1986 ACR classification criteria, a Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) pain score of 250 mm or greater, and more than 3 months of chronic knee pain. While patients were excluded for use of topical, oral, or injectable corticosteroids in the month prior to enrollment, they were allowed to continue using analgesics such as NSAIDs if they maintained their daily dose throughout the trial. Mr. Warneke noted the study population was typical of an OA population with a mostly female, mostly Caucasian cohort who had a median age of 60 years and a body mass index of 30 kg/m2. Patients had moderate to severe OA and were refractory to previous pain treatments.

The interventions consisted of a single 60-minute application of capsaicin or vehicle to both knees once per day for 4 consecutive days, and patients performed the applications in the clinic. The investigators compared change in WOMAC pain scores between the groups at 31 days, 60 days, and 90 days post dose.

The results at 31 days showed a 46.2% reduction in WOMAC pain scores from baseline for patients using CGS-200-5, compared with a 28.3% reduction in the vehicle group (P = .02). At 60 days, there was a 49.1% reduction in WOMAC pain scores in the CGS-200-5 group, compared with 21.5% in patients using vehicle (P = .0001), and a 42.8% reduction for patients in the CGS-200-5 group at 90 days, compared with 22.8% in the vehicle group (P = .01). The CGS-200-1 group did not reach the primary efficacy WOMAC pain endpoint, compared with vehicle.

A post hoc analysis showed that there was a significantly greater mean reduction in WOMAC total score for patients using CGS-200-5, compared with vehicle at 31 days (P = .02), 60 days (P = .0005), and 90 days post dose (P = .005). “This durability of clinical response for single applications seems to be a promising feature of CGS-200-5,” Mr. Warneke said.

Concerning safety and tolerability, there were no serious adverse events, and one patient discontinued treatment in the CGS-200-5 group. When assessing tolerability at predose, 15-minute, 30-minute, 60-minute, and 90-minute postdose time intervals, the investigators found patients experienced mild or moderate adverse events such as erythema, edema, scaling, and pruritus, with symptoms decreasing by the fourth consecutive day of application.

Mr. Warneke acknowledged the “robust placebo response” in the trial and noted it is not unusual to see in pain studies. “It’s something that is a challenge for all of us who are in this space to overcome, but we still have significant differences here and they are statistically significant as well,” he said. “You have to be pretty good these days to beat the wonder drug placebo, it appears.”

Four authors in addition to Mr. Warneke reported being employees of Vizuri Health Sciences, the company developing CGS-200-5. One author reported being a former consultant for Vizuri. Three authors reported they were current or former employees of CT Clinical Trial & Consulting, a contract research organization employed by Vizuri to execute and manage the study, perform data analysis, and create reports.

SOURCE: Warneke T et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(suppl 10), Abstract 2760.

ATLANTA – Use of high-concentration topical capsaicin was associated with reduced pain, a longer duration of clinical response, and was well tolerated in patients with knee osteoarthritis, compared with lower concentrations of capsaicin and placebo, according to recent research presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

While the ACR has recommended topical capsaicin for the relief of hand and knee OA pain, there are issues with using low-dose capsaicin, including the need for multiple applications and burning, stinging sensations at applications sites. As repeat exposure to capsaicin results in depletion of pain neurotransmitters and a reduction in nerve fibers in a dose-dependent fashion, higher doses of topical capsaicin are a potential topical treatment for OA pain relief, but their tolerability is low, Tim Warneke, vice president of clinical operations at Vizuri Health Sciences in Columbia, Md., said in his presentation.

“[P]oor tolerability has limited the ability to maximize the analgesic effect of capsaicin,” Mr. Warneke said. “While [over-the-counter] preparations of capsaicin provide some pain relief, poor tolerability with higher doses has really left us wondering if we haven’t maximized capsaicin’s ability to provide pain relief.”

Mr. Warneke and colleagues conducted a phase 2, multicenter, double-blind, parallel-group, vehicle-controlled trial where 120 patients with knee OA were randomized in a 1:1:1 ratio to receive 5% capsaicin topical liquid (CGS-200-5), 1% capsaicin topical liquid (CGS-200-1), or vehicle (CGS-200-0) and then followed up to 90 days. “The CGS-200 vehicle was developed to mitigate the burning, stinging pain of capsaicin,” Mr. Warneke said. “It allows the 5% concentration to be well tolerated, which opens the door for increased efficacy, including durability of response.”

Inclusion criteria were radiographically confirmed knee OA using 1986 ACR classification criteria, a Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) pain score of 250 mm or greater, and more than 3 months of chronic knee pain. While patients were excluded for use of topical, oral, or injectable corticosteroids in the month prior to enrollment, they were allowed to continue using analgesics such as NSAIDs if they maintained their daily dose throughout the trial. Mr. Warneke noted the study population was typical of an OA population with a mostly female, mostly Caucasian cohort who had a median age of 60 years and a body mass index of 30 kg/m2. Patients had moderate to severe OA and were refractory to previous pain treatments.

The interventions consisted of a single 60-minute application of capsaicin or vehicle to both knees once per day for 4 consecutive days, and patients performed the applications in the clinic. The investigators compared change in WOMAC pain scores between the groups at 31 days, 60 days, and 90 days post dose.

The results at 31 days showed a 46.2% reduction in WOMAC pain scores from baseline for patients using CGS-200-5, compared with a 28.3% reduction in the vehicle group (P = .02). At 60 days, there was a 49.1% reduction in WOMAC pain scores in the CGS-200-5 group, compared with 21.5% in patients using vehicle (P = .0001), and a 42.8% reduction for patients in the CGS-200-5 group at 90 days, compared with 22.8% in the vehicle group (P = .01). The CGS-200-1 group did not reach the primary efficacy WOMAC pain endpoint, compared with vehicle.

A post hoc analysis showed that there was a significantly greater mean reduction in WOMAC total score for patients using CGS-200-5, compared with vehicle at 31 days (P = .02), 60 days (P = .0005), and 90 days post dose (P = .005). “This durability of clinical response for single applications seems to be a promising feature of CGS-200-5,” Mr. Warneke said.

Concerning safety and tolerability, there were no serious adverse events, and one patient discontinued treatment in the CGS-200-5 group. When assessing tolerability at predose, 15-minute, 30-minute, 60-minute, and 90-minute postdose time intervals, the investigators found patients experienced mild or moderate adverse events such as erythema, edema, scaling, and pruritus, with symptoms decreasing by the fourth consecutive day of application.

Mr. Warneke acknowledged the “robust placebo response” in the trial and noted it is not unusual to see in pain studies. “It’s something that is a challenge for all of us who are in this space to overcome, but we still have significant differences here and they are statistically significant as well,” he said. “You have to be pretty good these days to beat the wonder drug placebo, it appears.”

Four authors in addition to Mr. Warneke reported being employees of Vizuri Health Sciences, the company developing CGS-200-5. One author reported being a former consultant for Vizuri. Three authors reported they were current or former employees of CT Clinical Trial & Consulting, a contract research organization employed by Vizuri to execute and manage the study, perform data analysis, and create reports.

SOURCE: Warneke T et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(suppl 10), Abstract 2760.

REPORTING FROM ACR 2019

HHS drug importation proposals aim to address high costs

The Department of Health & Human Services is taking the first steps in allowing drugs to be imported into the United States.

HHS proposes to offer two different pathways for importation: One allowing states to design programs to import certain drugs directly from Canada and another allowing manufacturers to obtain a new National Drug Code (NDC) number to import their own Food and Drug Administration–approved products manufactured outside of the United States.

“The importation proposals we are rolling out ... are a historic step forward in efforts to bring down drug prices and out-of-pocket costs,” HHS Secretary Alex Azar said during a Dec. 17, 2019, press conference. “New pathways for importation can move us toward a more open and competitive marketplace that supplies American patients with safe, effective, affordable prescription drugs.”

The proposals were made public on Dec. 18, the day the House Rules committee was scheduled to vote on impeaching President Trump.

He emphasized that these proposals “are both important steps in advancing the FDA’s safe-importation action plan, [which] aims to insure that importation is done in a way that prioritizes safety and includes elements to help insure importation does not put patients or the U.S. drug supply chain at risk.”

The pathway for states to import drugs from Canada will be proposed through the federal regulatory process. The notice of proposed rulemaking, which implements authority for FDA regulation of importation granted in the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003, will outline a process by which states, potentially working with wholesalers and/or pharmacies, will submit proposals for FDA review and approval on how they would implement an importation program.

Only certain drugs would be eligible for importation from Canada under this proposal. The drugs would need to be approved in Canada and, except for Canadian labeling, need to meet the conditions of an FDA-approved new drug application or abbreviated new drug application.

Controlled substances, biologics, intravenously injected drugs, drugs with a risk evaluation and management strategy, and drugs injected into the spinal column or eye would be excluded from importation.

Drugs coming in from Canada would be relabeled with U.S.-approved labels and would be subject to testing to ensure they are authentic, not degraded, and compliant with U.S. standards.

States would be required to show that importing drugs poses no additional risk in public health and safety and it would result in the reduction of costs, according to information provided by HHS.

Many of the most expensive drugs, as well as insulins, would not be eligible for importation under this pathway, Mr. Azar acknowledged, adding that “I would envision that as we demonstrate the safety as well as the cost savings from this pathway, [this could serve as] a pilot and a proof of concept that Congress could then look to and potentially take up for more complex molecules that involve cold-chain storage and more complex distribution channels.”

The proposed regulations do not offer any estimates on how much savings could be achieved. He said that there is no way to estimate which states might develop importation plans and how those plans might work.

The second proposed pathway would involve FDA guidance to manufacturers allowing them to import their own FDA-approved products manufactured abroad. Under this proposal, there would be no restriction on which type or kind of FDA-approved product to be imported.

“The FDA has become aware that manufacturers of some brand-name drugs want to offer their drugs at lower costs in the U.S. market but, due to certain challenges in the private market, are not readily [able] to do so without obtaining a different national drug code for their drugs,” Adm. Brett Giroir, MD, HHS assistant secretary for health, said during the press conference.

Obtaining a separate NDC for imported drugs could address the challenges, particularly those posed by the incentives to raise list prices and offer higher rebates to pharmacy benefit managers, Mr. Azar said.

The draft guidance outlines procedures manufacturers could follow to get that NDC for those products and how manufacturers can demonstrate that these products meet U.S. regulatory standards. Products imported in this pathway could be made available to patients in hospitals, physician offices, and pharmacies. Generic drugs are not part of this guidance, but the proposed guidance asked for feedback on whether a similar approach is needed for generic products.

“This would potentially allow for the sale of these drugs at lower prices than currently offered to American consumers, giving drugmakers new flexibility to reduce list prices,” Mr. Azar said.

The proposed regulation on state-level importation will have a 75-day comment period from the day it is published in the Federal Register, and Mr. Azar said that the FDA is committing resources to getting the comments analyzed and reflected in the final rule.

“We will be moving as quickly as we possibly can,” Mr. Azar said, adding that the FDA guidance to manufacturers may move more quickly through its approval process because it is not a formal rule.

The Department of Health & Human Services is taking the first steps in allowing drugs to be imported into the United States.

HHS proposes to offer two different pathways for importation: One allowing states to design programs to import certain drugs directly from Canada and another allowing manufacturers to obtain a new National Drug Code (NDC) number to import their own Food and Drug Administration–approved products manufactured outside of the United States.

“The importation proposals we are rolling out ... are a historic step forward in efforts to bring down drug prices and out-of-pocket costs,” HHS Secretary Alex Azar said during a Dec. 17, 2019, press conference. “New pathways for importation can move us toward a more open and competitive marketplace that supplies American patients with safe, effective, affordable prescription drugs.”

The proposals were made public on Dec. 18, the day the House Rules committee was scheduled to vote on impeaching President Trump.

He emphasized that these proposals “are both important steps in advancing the FDA’s safe-importation action plan, [which] aims to insure that importation is done in a way that prioritizes safety and includes elements to help insure importation does not put patients or the U.S. drug supply chain at risk.”

The pathway for states to import drugs from Canada will be proposed through the federal regulatory process. The notice of proposed rulemaking, which implements authority for FDA regulation of importation granted in the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003, will outline a process by which states, potentially working with wholesalers and/or pharmacies, will submit proposals for FDA review and approval on how they would implement an importation program.

Only certain drugs would be eligible for importation from Canada under this proposal. The drugs would need to be approved in Canada and, except for Canadian labeling, need to meet the conditions of an FDA-approved new drug application or abbreviated new drug application.

Controlled substances, biologics, intravenously injected drugs, drugs with a risk evaluation and management strategy, and drugs injected into the spinal column or eye would be excluded from importation.

Drugs coming in from Canada would be relabeled with U.S.-approved labels and would be subject to testing to ensure they are authentic, not degraded, and compliant with U.S. standards.

States would be required to show that importing drugs poses no additional risk in public health and safety and it would result in the reduction of costs, according to information provided by HHS.

Many of the most expensive drugs, as well as insulins, would not be eligible for importation under this pathway, Mr. Azar acknowledged, adding that “I would envision that as we demonstrate the safety as well as the cost savings from this pathway, [this could serve as] a pilot and a proof of concept that Congress could then look to and potentially take up for more complex molecules that involve cold-chain storage and more complex distribution channels.”

The proposed regulations do not offer any estimates on how much savings could be achieved. He said that there is no way to estimate which states might develop importation plans and how those plans might work.

The second proposed pathway would involve FDA guidance to manufacturers allowing them to import their own FDA-approved products manufactured abroad. Under this proposal, there would be no restriction on which type or kind of FDA-approved product to be imported.

“The FDA has become aware that manufacturers of some brand-name drugs want to offer their drugs at lower costs in the U.S. market but, due to certain challenges in the private market, are not readily [able] to do so without obtaining a different national drug code for their drugs,” Adm. Brett Giroir, MD, HHS assistant secretary for health, said during the press conference.

Obtaining a separate NDC for imported drugs could address the challenges, particularly those posed by the incentives to raise list prices and offer higher rebates to pharmacy benefit managers, Mr. Azar said.

The draft guidance outlines procedures manufacturers could follow to get that NDC for those products and how manufacturers can demonstrate that these products meet U.S. regulatory standards. Products imported in this pathway could be made available to patients in hospitals, physician offices, and pharmacies. Generic drugs are not part of this guidance, but the proposed guidance asked for feedback on whether a similar approach is needed for generic products.

“This would potentially allow for the sale of these drugs at lower prices than currently offered to American consumers, giving drugmakers new flexibility to reduce list prices,” Mr. Azar said.

The proposed regulation on state-level importation will have a 75-day comment period from the day it is published in the Federal Register, and Mr. Azar said that the FDA is committing resources to getting the comments analyzed and reflected in the final rule.

“We will be moving as quickly as we possibly can,” Mr. Azar said, adding that the FDA guidance to manufacturers may move more quickly through its approval process because it is not a formal rule.

The Department of Health & Human Services is taking the first steps in allowing drugs to be imported into the United States.

HHS proposes to offer two different pathways for importation: One allowing states to design programs to import certain drugs directly from Canada and another allowing manufacturers to obtain a new National Drug Code (NDC) number to import their own Food and Drug Administration–approved products manufactured outside of the United States.

“The importation proposals we are rolling out ... are a historic step forward in efforts to bring down drug prices and out-of-pocket costs,” HHS Secretary Alex Azar said during a Dec. 17, 2019, press conference. “New pathways for importation can move us toward a more open and competitive marketplace that supplies American patients with safe, effective, affordable prescription drugs.”

The proposals were made public on Dec. 18, the day the House Rules committee was scheduled to vote on impeaching President Trump.

He emphasized that these proposals “are both important steps in advancing the FDA’s safe-importation action plan, [which] aims to insure that importation is done in a way that prioritizes safety and includes elements to help insure importation does not put patients or the U.S. drug supply chain at risk.”

The pathway for states to import drugs from Canada will be proposed through the federal regulatory process. The notice of proposed rulemaking, which implements authority for FDA regulation of importation granted in the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003, will outline a process by which states, potentially working with wholesalers and/or pharmacies, will submit proposals for FDA review and approval on how they would implement an importation program.

Only certain drugs would be eligible for importation from Canada under this proposal. The drugs would need to be approved in Canada and, except for Canadian labeling, need to meet the conditions of an FDA-approved new drug application or abbreviated new drug application.

Controlled substances, biologics, intravenously injected drugs, drugs with a risk evaluation and management strategy, and drugs injected into the spinal column or eye would be excluded from importation.

Drugs coming in from Canada would be relabeled with U.S.-approved labels and would be subject to testing to ensure they are authentic, not degraded, and compliant with U.S. standards.

States would be required to show that importing drugs poses no additional risk in public health and safety and it would result in the reduction of costs, according to information provided by HHS.

Many of the most expensive drugs, as well as insulins, would not be eligible for importation under this pathway, Mr. Azar acknowledged, adding that “I would envision that as we demonstrate the safety as well as the cost savings from this pathway, [this could serve as] a pilot and a proof of concept that Congress could then look to and potentially take up for more complex molecules that involve cold-chain storage and more complex distribution channels.”

The proposed regulations do not offer any estimates on how much savings could be achieved. He said that there is no way to estimate which states might develop importation plans and how those plans might work.

The second proposed pathway would involve FDA guidance to manufacturers allowing them to import their own FDA-approved products manufactured abroad. Under this proposal, there would be no restriction on which type or kind of FDA-approved product to be imported.

“The FDA has become aware that manufacturers of some brand-name drugs want to offer their drugs at lower costs in the U.S. market but, due to certain challenges in the private market, are not readily [able] to do so without obtaining a different national drug code for their drugs,” Adm. Brett Giroir, MD, HHS assistant secretary for health, said during the press conference.

Obtaining a separate NDC for imported drugs could address the challenges, particularly those posed by the incentives to raise list prices and offer higher rebates to pharmacy benefit managers, Mr. Azar said.

The draft guidance outlines procedures manufacturers could follow to get that NDC for those products and how manufacturers can demonstrate that these products meet U.S. regulatory standards. Products imported in this pathway could be made available to patients in hospitals, physician offices, and pharmacies. Generic drugs are not part of this guidance, but the proposed guidance asked for feedback on whether a similar approach is needed for generic products.

“This would potentially allow for the sale of these drugs at lower prices than currently offered to American consumers, giving drugmakers new flexibility to reduce list prices,” Mr. Azar said.

The proposed regulation on state-level importation will have a 75-day comment period from the day it is published in the Federal Register, and Mr. Azar said that the FDA is committing resources to getting the comments analyzed and reflected in the final rule.

“We will be moving as quickly as we possibly can,” Mr. Azar said, adding that the FDA guidance to manufacturers may move more quickly through its approval process because it is not a formal rule.

Chasing Hope: When Are Requests for Hospital Transfer a Place for Palliative Care Integration?

“I don’t think she’ll ever make it home again.”

I stood at the nursing station with two staff nurses from our medical ward. The patient, a woman with metastatic cancer and acute respiratory failure, had just arrived by a medical helicopter from an out-of-state community hospital. At the previous hospital, days had stretched into weeks, and she was not getting better. Limited documentation told us that the patient’s family sought further options at our facility. Beyond that, we knew little about the conversations that had transpired. The transfer had been arranged and off she went, arriving on our helipad in worsening respiratory distress, now needing a higher level of supplemental oxygen and teetering on the edge of endotracheal intubation. Above all, she was extremely uncomfortable from shortness of breath, and an urgent palliative care consult was placed a few hours after she touched down.

I arrived at the bedside to meet the patient and family. In these circumstances, I often feel that a palliative care consult is not the miracle that patients seek, but the grim consolation prize behind door two of a tragic and exhausting game show of a hospital transfer. I read the family’s dismayed facial expressions as they gazed at my badge reading “Palliative Care” and imagined that they would have preferred a different answer to their question that led them here: “Is this all that can be done?”

The hope of patients and families is a precious thing. As a palliative care physician, I recognize that my role is never to take away hope but rather reframe the wish for recovery into the realm of the achievable. Some people can pivot when the hospital transfer happens. They feel that they have “done all they could” and searched the earth for the reversal of their medical circumstances. I empathize with the wish to try everything and respect the motivation that lies behind it. I also see the cost of chasing hope.

In 2017, 1.5 million patients were transferred, comprising 3.5% of all hospital admissions.1 Although the majority of hospital transfers are medically appropriate and hold the possibility of treatment options unavailable at smaller facilities, there are also significant drawbacks. Transfers have been identified as risky times for adverse events, are often expensive, and are associated with higher mortality and longer length of stay.2 There are often lapses in documentation and provider communication, and handoff practices vary widely between hospitals.3 Some transferred seriously ill patients become functionally trapped in the accepting hospital. Patients arrive too sick to undergo any meaningful disease-directed therapy and too medically tenuous to return to their home community.

When patients and families seem overly hopeful about what a transfer might provide, the request for transfer may indicate a deeper need for empathic understanding. Clinical conversations about “what can be done” typically focus on medical aspects and often miss a critical element—a complete exploration of a seriously ill patient’s prognostic awareness.

In palliative care, we use the term prognostic awareness to define patients’ dynamic understanding of their prognosis in terms of likely longevity and quality of life. Accurate prognostic awareness—where there is concordance between a patient’s worries and the medical facts as understood by their treatment team—has been associated with enhanced quality of life and mood when patients have enough emotional reserve to actively cope with the illness; for example, by reframing things in a positive light.4,5 However, when patients are struggling to cope, talking about the prognosis is hard for patients and for their clinicians, who often accurately perceive their patient’s struggle and delay conversations, hoping that more time will help their patient better adapt and prepare to talk about it.6,7 However, delaying conversations makes it even harder for patients and families to develop accurate prognostic awareness, leaving them unprepared when medical decisions arise.8 Such delays have a particularly strong impact in nononcology care, where a more unpredictable illness trajectory makes it even harder for patients to understand and prepare for what might happen.

When seriously ill patients and families consider transfer to a tertiary medical center in a situation of medical crisis, it can be a good time to pause. Palliative care specialists are trained to communicate around these difficult points of transition, but generalist clinicians already involved in the patient’s care can also sensitively explore patients’ prognostic awareness as it relates to the hospital transfer.9 In the Table, The phrases mentioned suggest language that is helpful in broaching such discussions, which assesses the patient’s illness understanding, hopes, and worries. Asking about patients’ hopes for their illness enables clinicians to quickly know some of their most important priorities. Giving patients the permission to be future-oriented and positive also supports them to cope in these challenging conversations. Asking patients to identify two or three hopes places their most optimistic hopes within a larger context and can lead to a discussion of the potential tradeoffs of the transfer.10 For example, the hope for a little more time from treatments available through transfer may be at odds with the hope to spend as much time as possible with family. Once the patient’s hopes are better understood, the clinician can then ask about worries. Most seriously ill patients are deeply (often silently) worried about the future, and when asked, can articulate worries about dying that can be the foundation for an honest conversation about the likely course of the hospital transfer.

With empathic assessment, several patients can speak honestly with their clinicians about their illness, including the pros and cons of hospital transfer. However, some continue to struggle, often asking clinicians to remain positive and not endorsing any worry. We describe these patients as having low prognostic awareness.11 With such patients, palliative care expertise may be needed to ensure that patients and their families have the information they need to engage in informed medical decision-making. There are emerging models for distance palliative care integration, which may be helpful in these situations.12 If these technologies became common in practice, frontline clinicians may increasingly find virtual consultation helpful in working with patients to develop more accurate prognostic awareness. There is also the possibility of clinician-to-clinician electronic consultation, or peer coaching, where the patient is not seen directly by the consultant, but expert advice is offered to the local provider.13 Although both these innovations offer service that currently may not be available in certain care settings, in-person consultation remains the gold standard. If a nuanced discussion cannot be had, palliative care expertise may be the reason for transfer.

Back at our hospital, I met with the patient and her partner. There were tradeoffs to be made and hard truths to be acknowledged. In this unfamiliar place, with caregivers she had met just hours before, the patient changed her resuscitation order to allow for a natural death. She passed away later that evening, surrounded by her immediate family but far away from the community that had held her throughout her illness. I reflect on the loss that can come with choosing “everything” when efforts are often better spent on ensuring comfort. Although hospital transfer is often the right answer for seriously ill patients seeking diagnostic and therapeutic options unavailable at their home medical centers, the question should also be an impetus for a nuanced assessment of patients’ prognostic awareness to prepare patients if things do not go as hoped or to enlist palliative care expertise for those struggling to cope. As there is a workforce shortage of palliative care providers, particularly in smaller and rural American hospitals, frontline hospitalist clinicians may find themselves increasingly playing a critical role in discussions where transfer is considered. By assessing patients’ prognostic awareness through thoughtful, compassionate inquiry in these moments of transition, we can support informed medical decision-making.

1. Hernandez-Boussard T, Davies S, McDonald K, Wang NE. Interhospital facility transfers in the United States: a nationwide outcomes study. J Patient Saf. 2017;13(4):187-191. https://doi.org/10.1097/PTS.0000000000000148.

2. Ligtenberg JJ, Arnold LG, Stienstra Y, et al. Quality of inter‐hospital transport of critically ill patients: a prospective audit. Crit Care. 2005;9(4):R446-R451. https://doi.org/10.1097/PTS.0000000000000148.

3. Payne CE, Stein JM, Leong T, Dressler DD. Avoiding handover fumbles: a controlled trial of a structured handover tool versus traditional handover methods. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21(11):925-932. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2011-000308.

4. Nipp RD, Greer JA, El-Jawahri A, et al. Coping and prognostic awareness in patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Onc. 2017;1(22):2551-2557. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2016.71.3404.

5. El-Jawahri A, Traeger L, Park, et al. Associations among prognostic understanding, quality of life, and mood in patients with advanced cancer. Cancer. 2014;120(2):278-285. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.28369.

6. Temel JS, Greer JA, Admane S, et al. Longitudinal perceptions of prognosis and goals of therapy in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: results of a randomized study of early palliative care. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(17):2319-2326. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2010.32.4459.

7. Bernacki R, Paladino J, Neville BA, et al. Effect of the serious illness care program in outpatient oncology: a cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;2019179(6):751-759. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0077.

8. Jackson VA, Jacobsen J, Greer JA, et al. The cultivation of prognostic awareness through the provision of early palliative care in the ambulatory setting: a communication guide. J Palliat Med. 2013;16(8):894-900. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2012.0547.

9. Lakin JR, Jacobsen J. Softening our approach to discussing prognosis. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(1):5-6. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.5786.

10. Nipp RD, El-Jawahri A, Fishbein JN, et al. The relationship between coping strategies, quality of life, and mood in patients with incurable cancer. Cancer. 2016;122(13):2110-2116. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.30025.

11. El-Jawahri A, Traeger L, Park ER, et al. Associations among prognostic understanding, quality of life, and mood in patients with advanced cancer. Cancer. 2014;120(2):278-285. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.28369.

12. Tasneem S, Kim A, Bagheri A, Lebret J. Telemedicine video visits for patients receiving palliative care: A qualitative study. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2019;36(9):789-794. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909119846843.

13. Lustbader D, Mudra M, Romano C, et al. The impact of a home-based palliative care program in an accountable care organization. J Palliat Med. 2017;20:23-28. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2016.0265.

“I don’t think she’ll ever make it home again.”