User login

Aligning scheduling and satisfaction

Research reveals counterintuitive results

Hospitalist work schedules have been the subject of much reporting – and recent research. Studies have shown that control over work hours and schedule flexibility are predictors of clinicians’ career satisfaction and burnout, factors linked to quality of patient care and retention.

Starting in January 2017, an academic hospital medicine group at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, undertook a scheduling redesign using improvement methodology, combined with purchased scheduling software. Tyler Anstett, DO, a hospitalist and assistant professor at the university, and colleagues presented the results in an abstract published during the SHM 2019 annual conference last March.

“We wrote this abstract as a report of the work that we did over several years in our hospital medicine group to improve hospitalist satisfaction with their schedules,” said Dr. Anstett. “We identified that, despite not following the traditional seven-on, seven-off model and 100% fulfillment of individual schedule requests, the majority of clinicians were dissatisfied with the scheduling process and their overall clinical schedules. Further, building these complex, individualized schedules resulted in a heavy administrative burden. We strove to provide better alignment of schedule satisfaction and the administrative burden of incorporating individualized schedule requests.”

Prior to January 2017, service stretches had ranged from 5 to 9 days, and there were few limits on time-off requests.

“Through sequential interventions, we standardized service stretches to 7 days (Tuesday-Monday), introduced a limited number of guaranteed 7-day time-off requests (Tuesday-Monday), and added a limited number of nonguaranteed 3-day flexible time-off requests,” according to the authors. “This simplification improved the automation of the scheduling software, which increased the schedule release lead time to an average of 16 weeks. Further, despite standardizing service stretches to 7 days and limiting time-off requests, physicians surveyed reported improved satisfaction with both their scheduling process (34% of participants ‘satisfied’ in 2017 to 67% in 2018) and their overall clinical schedules (50% of participants ‘satisfied’ in 2017 to 75% in 2018).”So counterintuitively, creating individualized schedules may not result in improved satisfaction and likely results in heavy administrative burden, Dr. Anstett said. “Standardization of schedule creation with allowance of a ‘free-market’ system, allowing clinicians to self-individualize their schedules may also result in less administrative burden and improved satisfaction.”

Reference

1. Anstett T et al. K.I.S.S. (Keep It Simple … Schedules): How Standardization and Simplification Can Improve Scheduling and Physician Satisfaction. SHM 2019, Abstract 112. Accessed June 4, 2019.

Research reveals counterintuitive results

Research reveals counterintuitive results

Hospitalist work schedules have been the subject of much reporting – and recent research. Studies have shown that control over work hours and schedule flexibility are predictors of clinicians’ career satisfaction and burnout, factors linked to quality of patient care and retention.

Starting in January 2017, an academic hospital medicine group at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, undertook a scheduling redesign using improvement methodology, combined with purchased scheduling software. Tyler Anstett, DO, a hospitalist and assistant professor at the university, and colleagues presented the results in an abstract published during the SHM 2019 annual conference last March.

“We wrote this abstract as a report of the work that we did over several years in our hospital medicine group to improve hospitalist satisfaction with their schedules,” said Dr. Anstett. “We identified that, despite not following the traditional seven-on, seven-off model and 100% fulfillment of individual schedule requests, the majority of clinicians were dissatisfied with the scheduling process and their overall clinical schedules. Further, building these complex, individualized schedules resulted in a heavy administrative burden. We strove to provide better alignment of schedule satisfaction and the administrative burden of incorporating individualized schedule requests.”

Prior to January 2017, service stretches had ranged from 5 to 9 days, and there were few limits on time-off requests.

“Through sequential interventions, we standardized service stretches to 7 days (Tuesday-Monday), introduced a limited number of guaranteed 7-day time-off requests (Tuesday-Monday), and added a limited number of nonguaranteed 3-day flexible time-off requests,” according to the authors. “This simplification improved the automation of the scheduling software, which increased the schedule release lead time to an average of 16 weeks. Further, despite standardizing service stretches to 7 days and limiting time-off requests, physicians surveyed reported improved satisfaction with both their scheduling process (34% of participants ‘satisfied’ in 2017 to 67% in 2018) and their overall clinical schedules (50% of participants ‘satisfied’ in 2017 to 75% in 2018).”So counterintuitively, creating individualized schedules may not result in improved satisfaction and likely results in heavy administrative burden, Dr. Anstett said. “Standardization of schedule creation with allowance of a ‘free-market’ system, allowing clinicians to self-individualize their schedules may also result in less administrative burden and improved satisfaction.”

Reference

1. Anstett T et al. K.I.S.S. (Keep It Simple … Schedules): How Standardization and Simplification Can Improve Scheduling and Physician Satisfaction. SHM 2019, Abstract 112. Accessed June 4, 2019.

Hospitalist work schedules have been the subject of much reporting – and recent research. Studies have shown that control over work hours and schedule flexibility are predictors of clinicians’ career satisfaction and burnout, factors linked to quality of patient care and retention.

Starting in January 2017, an academic hospital medicine group at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, undertook a scheduling redesign using improvement methodology, combined with purchased scheduling software. Tyler Anstett, DO, a hospitalist and assistant professor at the university, and colleagues presented the results in an abstract published during the SHM 2019 annual conference last March.

“We wrote this abstract as a report of the work that we did over several years in our hospital medicine group to improve hospitalist satisfaction with their schedules,” said Dr. Anstett. “We identified that, despite not following the traditional seven-on, seven-off model and 100% fulfillment of individual schedule requests, the majority of clinicians were dissatisfied with the scheduling process and their overall clinical schedules. Further, building these complex, individualized schedules resulted in a heavy administrative burden. We strove to provide better alignment of schedule satisfaction and the administrative burden of incorporating individualized schedule requests.”

Prior to January 2017, service stretches had ranged from 5 to 9 days, and there were few limits on time-off requests.

“Through sequential interventions, we standardized service stretches to 7 days (Tuesday-Monday), introduced a limited number of guaranteed 7-day time-off requests (Tuesday-Monday), and added a limited number of nonguaranteed 3-day flexible time-off requests,” according to the authors. “This simplification improved the automation of the scheduling software, which increased the schedule release lead time to an average of 16 weeks. Further, despite standardizing service stretches to 7 days and limiting time-off requests, physicians surveyed reported improved satisfaction with both their scheduling process (34% of participants ‘satisfied’ in 2017 to 67% in 2018) and their overall clinical schedules (50% of participants ‘satisfied’ in 2017 to 75% in 2018).”So counterintuitively, creating individualized schedules may not result in improved satisfaction and likely results in heavy administrative burden, Dr. Anstett said. “Standardization of schedule creation with allowance of a ‘free-market’ system, allowing clinicians to self-individualize their schedules may also result in less administrative burden and improved satisfaction.”

Reference

1. Anstett T et al. K.I.S.S. (Keep It Simple … Schedules): How Standardization and Simplification Can Improve Scheduling and Physician Satisfaction. SHM 2019, Abstract 112. Accessed June 4, 2019.

Top AGA Community patient cases

Physicians with difficult patient scenarios regularly bring their questions to the AGA Community (https://community.gastro.org) to seek advice from colleagues about therapy and disease management options, best practices, and diagnoses. In case you missed it, here are the most popular clinical discussions shared in the forum recently:

1. Possible congestive heart failure, tuberculosis (http://ow.ly/QdmG30pZqqo) – Join the GI community in discussing the echocardiogram results of a Holocaust survivor with a history of diabetes, hypothyroidism, benign prostate hyperplasia and hypercholesterolemia, and whose daughter was recently found to be QuantiFERON Gold positive.

2. Recurrent diarrhea in Behcet’s disease patient (http://ow.ly/YX6L30pZqws) – A 42-year-old patient diagnosed with Behcet’s disease at age 13 presented with recurrent diarrhea; a colonoscopy revealed terminal ileal and cecal ulcerations.

3. Gastroparesis patient unable to take anti-emetics (http://ow.ly/E5jD30pZqw4) – Help your colleague address a tricky patient with prolonged QT and gastroparesis.

Access these clinical cases and more discussions at https://community.gastro.org/discussions.

Physicians with difficult patient scenarios regularly bring their questions to the AGA Community (https://community.gastro.org) to seek advice from colleagues about therapy and disease management options, best practices, and diagnoses. In case you missed it, here are the most popular clinical discussions shared in the forum recently:

1. Possible congestive heart failure, tuberculosis (http://ow.ly/QdmG30pZqqo) – Join the GI community in discussing the echocardiogram results of a Holocaust survivor with a history of diabetes, hypothyroidism, benign prostate hyperplasia and hypercholesterolemia, and whose daughter was recently found to be QuantiFERON Gold positive.

2. Recurrent diarrhea in Behcet’s disease patient (http://ow.ly/YX6L30pZqws) – A 42-year-old patient diagnosed with Behcet’s disease at age 13 presented with recurrent diarrhea; a colonoscopy revealed terminal ileal and cecal ulcerations.

3. Gastroparesis patient unable to take anti-emetics (http://ow.ly/E5jD30pZqw4) – Help your colleague address a tricky patient with prolonged QT and gastroparesis.

Access these clinical cases and more discussions at https://community.gastro.org/discussions.

Physicians with difficult patient scenarios regularly bring their questions to the AGA Community (https://community.gastro.org) to seek advice from colleagues about therapy and disease management options, best practices, and diagnoses. In case you missed it, here are the most popular clinical discussions shared in the forum recently:

1. Possible congestive heart failure, tuberculosis (http://ow.ly/QdmG30pZqqo) – Join the GI community in discussing the echocardiogram results of a Holocaust survivor with a history of diabetes, hypothyroidism, benign prostate hyperplasia and hypercholesterolemia, and whose daughter was recently found to be QuantiFERON Gold positive.

2. Recurrent diarrhea in Behcet’s disease patient (http://ow.ly/YX6L30pZqws) – A 42-year-old patient diagnosed with Behcet’s disease at age 13 presented with recurrent diarrhea; a colonoscopy revealed terminal ileal and cecal ulcerations.

3. Gastroparesis patient unable to take anti-emetics (http://ow.ly/E5jD30pZqw4) – Help your colleague address a tricky patient with prolonged QT and gastroparesis.

Access these clinical cases and more discussions at https://community.gastro.org/discussions.

Simple ways to create your legacy

Creating a legacy of giving is easier than you think. As the new year begins, take some time to start creating your legacy while supporting the AGA Research Foundation. Gifts to charitable organizations, such as the AGA Research Foundation, in your future plans ensure your support for our mission continues even after your lifetime.

Here are two ideas to help you get started.

Name the AGA Research Foundation as a beneficiary. This arrangement is one of the most tax-smart ways to support the AGA Research Foundation after your lifetime. When you leave retirement plan assets to us, we bypass any taxes and receive the full amount.

Include the AGA Research Foundation in your will or living trust. This gift can be made by including as little as one sentence in your will or living trust. Plus, your gift can be modified throughout your lifetime as circumstances change.

Want to learn more about including a gift to the AGA Research Foundation in your future plans? Visit our website at https://gastro.planmylegacy.org or contact Harmony Excellent at 301-272-1602 or [email protected].

Creating a legacy of giving is easier than you think. As the new year begins, take some time to start creating your legacy while supporting the AGA Research Foundation. Gifts to charitable organizations, such as the AGA Research Foundation, in your future plans ensure your support for our mission continues even after your lifetime.

Here are two ideas to help you get started.

Name the AGA Research Foundation as a beneficiary. This arrangement is one of the most tax-smart ways to support the AGA Research Foundation after your lifetime. When you leave retirement plan assets to us, we bypass any taxes and receive the full amount.

Include the AGA Research Foundation in your will or living trust. This gift can be made by including as little as one sentence in your will or living trust. Plus, your gift can be modified throughout your lifetime as circumstances change.

Want to learn more about including a gift to the AGA Research Foundation in your future plans? Visit our website at https://gastro.planmylegacy.org or contact Harmony Excellent at 301-272-1602 or [email protected].

Creating a legacy of giving is easier than you think. As the new year begins, take some time to start creating your legacy while supporting the AGA Research Foundation. Gifts to charitable organizations, such as the AGA Research Foundation, in your future plans ensure your support for our mission continues even after your lifetime.

Here are two ideas to help you get started.

Name the AGA Research Foundation as a beneficiary. This arrangement is one of the most tax-smart ways to support the AGA Research Foundation after your lifetime. When you leave retirement plan assets to us, we bypass any taxes and receive the full amount.

Include the AGA Research Foundation in your will or living trust. This gift can be made by including as little as one sentence in your will or living trust. Plus, your gift can be modified throughout your lifetime as circumstances change.

Want to learn more about including a gift to the AGA Research Foundation in your future plans? Visit our website at https://gastro.planmylegacy.org or contact Harmony Excellent at 301-272-1602 or [email protected].

Talk to your patients about the current state of prebiotics

Bridgette Wilson, PhD, RD, postdoctoral research associate in nutritional sciences, and Kevin Whelan, PhD, RD, professor of dietetics, King’s College London, England, share talking points to help your patients understand what is currently known about the use of prebiotics for GI disorders.

Explaining prebiotics for GI disorders

Different prebiotic supplements have different effects on gut symptoms. For example, lower doses of noninulin type fructans (e.g., beta-galacto-oligosaccharides [GOS], pectin, partially hydrolyzed guar gum) are likely to be better tolerated in patients with functional gut symptoms, including irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

Though prebiotic-containing foods are thought to benefit gut health in general, some prebiotics are FODMAPs that have been associated with symptoms in IBS patients. Individual patients on restrictive diets should systematically introduce prebiotic foods to identify the type and quantity they can tolerate.

Prebiotic supplementation of more than 10 g/d may soften stools and increase bowel movements in patients with defecation difficulty or constipation.

Prebiotic supplementation may worsen symptoms in Crohn’s disease but is well tolerated in ulcerative colitis, although there is no effect on disease activity.

These tips are from “The current state of prebiotics,” the third article of a four-part CME series on prebiotics. This activity is supported by an educational grant from GlaxoSmithKline. Part one, “Prebiotics 101,” and part two, “Diet vs. Prebiotics,” are available through AGA University (agau.gastro.org).

AGA also has educational materials for patients on probiotics, which can be accessed at www.gastro.org/probiotics in English and Spanish.

Bridgette Wilson, PhD, RD, postdoctoral research associate in nutritional sciences, and Kevin Whelan, PhD, RD, professor of dietetics, King’s College London, England, share talking points to help your patients understand what is currently known about the use of prebiotics for GI disorders.

Explaining prebiotics for GI disorders

Different prebiotic supplements have different effects on gut symptoms. For example, lower doses of noninulin type fructans (e.g., beta-galacto-oligosaccharides [GOS], pectin, partially hydrolyzed guar gum) are likely to be better tolerated in patients with functional gut symptoms, including irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

Though prebiotic-containing foods are thought to benefit gut health in general, some prebiotics are FODMAPs that have been associated with symptoms in IBS patients. Individual patients on restrictive diets should systematically introduce prebiotic foods to identify the type and quantity they can tolerate.

Prebiotic supplementation of more than 10 g/d may soften stools and increase bowel movements in patients with defecation difficulty or constipation.

Prebiotic supplementation may worsen symptoms in Crohn’s disease but is well tolerated in ulcerative colitis, although there is no effect on disease activity.

These tips are from “The current state of prebiotics,” the third article of a four-part CME series on prebiotics. This activity is supported by an educational grant from GlaxoSmithKline. Part one, “Prebiotics 101,” and part two, “Diet vs. Prebiotics,” are available through AGA University (agau.gastro.org).

AGA also has educational materials for patients on probiotics, which can be accessed at www.gastro.org/probiotics in English and Spanish.

Bridgette Wilson, PhD, RD, postdoctoral research associate in nutritional sciences, and Kevin Whelan, PhD, RD, professor of dietetics, King’s College London, England, share talking points to help your patients understand what is currently known about the use of prebiotics for GI disorders.

Explaining prebiotics for GI disorders

Different prebiotic supplements have different effects on gut symptoms. For example, lower doses of noninulin type fructans (e.g., beta-galacto-oligosaccharides [GOS], pectin, partially hydrolyzed guar gum) are likely to be better tolerated in patients with functional gut symptoms, including irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

Though prebiotic-containing foods are thought to benefit gut health in general, some prebiotics are FODMAPs that have been associated with symptoms in IBS patients. Individual patients on restrictive diets should systematically introduce prebiotic foods to identify the type and quantity they can tolerate.

Prebiotic supplementation of more than 10 g/d may soften stools and increase bowel movements in patients with defecation difficulty or constipation.

Prebiotic supplementation may worsen symptoms in Crohn’s disease but is well tolerated in ulcerative colitis, although there is no effect on disease activity.

These tips are from “The current state of prebiotics,” the third article of a four-part CME series on prebiotics. This activity is supported by an educational grant from GlaxoSmithKline. Part one, “Prebiotics 101,” and part two, “Diet vs. Prebiotics,” are available through AGA University (agau.gastro.org).

AGA also has educational materials for patients on probiotics, which can be accessed at www.gastro.org/probiotics in English and Spanish.

Step Therapy National Day of Advocacy

AGA and 17 other specialty physician and patient advocacy organizations partnered with the Digestive Disease National Coalition (DDNC) on an advocacy day focused on the need for step therapy reform.

We met with congressional offices to seek support for patient protection guardrails in step therapy and to encourage co-sponsorship of the Safe Step Act. This bipartisan legislation would create a clear process for a patient or physician to request an exception to a step therapy protocol. It also would require insurers to grant exemptions to step therapy in the following situations:

- Patient already tried and failed on a required treatment

- Delayed treatment will cause irreversible damage

- Required treatment will cause harm to the patient

- Required treatment will prevent a patient from working or fulling daily activities

- Patient is stable on their current treatment

AGA representatives and patient advocates met with the congressional offices of these legislators who serve on key committees that have jurisdiction over this issue.

Sen. Chris Van Hollen, D-Md

Sen. Tim Scott, R-S.C.

Sen. Thom Tillis, R-N.C.

Sen. Lamar Alexander, R-N.C.

Rep. Alma Adams, D-N.C.

Rep. Mark Walker, R-N.C.

Rep. Tim Walberg, R-Mich

A special thanks to AGA members who contacted your legislators online. A combination of 344 tweets and emails were sent urging federal legislators to support the Safe Step Act.

Sharing is caring

Legislators and their staff are always asking us for real-life examples from constituents about step therapy burdens to humanize the issue. Contact AGA staff at [email protected] to share your story.

AGA and 17 other specialty physician and patient advocacy organizations partnered with the Digestive Disease National Coalition (DDNC) on an advocacy day focused on the need for step therapy reform.

We met with congressional offices to seek support for patient protection guardrails in step therapy and to encourage co-sponsorship of the Safe Step Act. This bipartisan legislation would create a clear process for a patient or physician to request an exception to a step therapy protocol. It also would require insurers to grant exemptions to step therapy in the following situations:

- Patient already tried and failed on a required treatment

- Delayed treatment will cause irreversible damage

- Required treatment will cause harm to the patient

- Required treatment will prevent a patient from working or fulling daily activities

- Patient is stable on their current treatment

AGA representatives and patient advocates met with the congressional offices of these legislators who serve on key committees that have jurisdiction over this issue.

Sen. Chris Van Hollen, D-Md

Sen. Tim Scott, R-S.C.

Sen. Thom Tillis, R-N.C.

Sen. Lamar Alexander, R-N.C.

Rep. Alma Adams, D-N.C.

Rep. Mark Walker, R-N.C.

Rep. Tim Walberg, R-Mich

A special thanks to AGA members who contacted your legislators online. A combination of 344 tweets and emails were sent urging federal legislators to support the Safe Step Act.

Sharing is caring

Legislators and their staff are always asking us for real-life examples from constituents about step therapy burdens to humanize the issue. Contact AGA staff at [email protected] to share your story.

AGA and 17 other specialty physician and patient advocacy organizations partnered with the Digestive Disease National Coalition (DDNC) on an advocacy day focused on the need for step therapy reform.

We met with congressional offices to seek support for patient protection guardrails in step therapy and to encourage co-sponsorship of the Safe Step Act. This bipartisan legislation would create a clear process for a patient or physician to request an exception to a step therapy protocol. It also would require insurers to grant exemptions to step therapy in the following situations:

- Patient already tried and failed on a required treatment

- Delayed treatment will cause irreversible damage

- Required treatment will cause harm to the patient

- Required treatment will prevent a patient from working or fulling daily activities

- Patient is stable on their current treatment

AGA representatives and patient advocates met with the congressional offices of these legislators who serve on key committees that have jurisdiction over this issue.

Sen. Chris Van Hollen, D-Md

Sen. Tim Scott, R-S.C.

Sen. Thom Tillis, R-N.C.

Sen. Lamar Alexander, R-N.C.

Rep. Alma Adams, D-N.C.

Rep. Mark Walker, R-N.C.

Rep. Tim Walberg, R-Mich

A special thanks to AGA members who contacted your legislators online. A combination of 344 tweets and emails were sent urging federal legislators to support the Safe Step Act.

Sharing is caring

Legislators and their staff are always asking us for real-life examples from constituents about step therapy burdens to humanize the issue. Contact AGA staff at [email protected] to share your story.

GI societies advise FDA on duodenoscope reprocessing

AGA, ACG, ASGE and SAGES were represented by three physicians who made oral remarks to the panel: Michael Kochman, MD, AGAF, Wilmott Professor of Medicine and Surgery at the University of Pennsylvania; Bret Petersen, MD, FASGE, professor of medicine and advanced endoscopist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. and Danielle Walsh, MD, associate professor of surgery at East Carolina University.

The GI societies over-arching goal is to ensure patient safety and ready access to clinically indicated procedures employing duodenoscopes and other elevator-channel endoscopes.

The panel discussed the adequacy/margin of safety for high-level disinfection, as well as the challenges and benefits of sterilization for routine for duodenoscope reprocessing. The panel’s consensus was that cleaning is the most important step in duodenoscope reprocessing. The panel noted that in properly cleaned duodenoscopes, high-level disinfection is appropriate; however, panel members acknowledged that reports indicate that duodenoscopes are not properly cleaned. The panel also discussed the challenges of implementing sterilization of duodenoscopes, such as potential decreased patient access to endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and increased costs.

On behalf of the GI societies, Dr. Kochman and Dr. Petersen proposed several overarching principles for the future evolution of our clinical practices focusing on patient safety and outcomes:

We encourage embracing multiple solutions, using a measured step-wise approach to the transition with both iterative and novel devices and processes.

We encourage data-based solutions addressing real-world efficacy while incorporating ongoing surveillance of processes and performance to ensure that early trouble signals are detected.

We believe that device or reprocessing transitions can be incorporated over the lifecycle of current instrumentation, to eliminate the potential for gaps in accessibility of care and to ensure that there is adequate efficacy and safety data to support the adoption of new technology.

We accept minimizing extensive premarket studies, while expecting vigilant post-market surveillance, for technologies or device changes made exclusively with intent to convert to conceptually more safe designs without significant changes in mechanism or function.

We support the addition of durability testing for devices undergoing both standard reprocessing and, in particular, those undergoing sterilization.

Our societies are prepared to support and participate in continued discussion regarding:

Mandatory servicing and inspections.

Mandatory device retirement for reusable devices.

Assessment of the role and standards for third-party inspection and repair.

Our societies strongly support the importance and oversight of succinct, practical, reproducible, user-friendly guidance in manufacturers’ instructions for use (IFUs), which should incorporate post-market validation studies and updates.

We recommend that devices that incorporate programmable features (AERs, washers, sterilizers) should have lock-down mechanisms in place to prevent both user and manufacturer from deviating from the FDA-cleared IFU parameters for the device.

Our societies, as well as numerous guidelines, include high-level disinfection as a currently acceptable option for endoscope reprocessing, assuming use of enhanced washing and drying standards of practice.

Finally, we support the FDA in its efforts to convey to companies the necessary endpoints and goals for performance and expectations relative to post-market review and development of new data to ensure efficacy in the community.

Our societies appreciated this opportunity to comment on the complex and critical topic at hand. Our over-arching goal as physicians remains that of ensuring patient safety and ready access to clinically indicated procedures employing duodenoscopes and other elevator-channel endoscopes.

AGA, ACG, ASGE and SAGES were represented by three physicians who made oral remarks to the panel: Michael Kochman, MD, AGAF, Wilmott Professor of Medicine and Surgery at the University of Pennsylvania; Bret Petersen, MD, FASGE, professor of medicine and advanced endoscopist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. and Danielle Walsh, MD, associate professor of surgery at East Carolina University.

The GI societies over-arching goal is to ensure patient safety and ready access to clinically indicated procedures employing duodenoscopes and other elevator-channel endoscopes.

The panel discussed the adequacy/margin of safety for high-level disinfection, as well as the challenges and benefits of sterilization for routine for duodenoscope reprocessing. The panel’s consensus was that cleaning is the most important step in duodenoscope reprocessing. The panel noted that in properly cleaned duodenoscopes, high-level disinfection is appropriate; however, panel members acknowledged that reports indicate that duodenoscopes are not properly cleaned. The panel also discussed the challenges of implementing sterilization of duodenoscopes, such as potential decreased patient access to endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and increased costs.

On behalf of the GI societies, Dr. Kochman and Dr. Petersen proposed several overarching principles for the future evolution of our clinical practices focusing on patient safety and outcomes:

We encourage embracing multiple solutions, using a measured step-wise approach to the transition with both iterative and novel devices and processes.

We encourage data-based solutions addressing real-world efficacy while incorporating ongoing surveillance of processes and performance to ensure that early trouble signals are detected.

We believe that device or reprocessing transitions can be incorporated over the lifecycle of current instrumentation, to eliminate the potential for gaps in accessibility of care and to ensure that there is adequate efficacy and safety data to support the adoption of new technology.

We accept minimizing extensive premarket studies, while expecting vigilant post-market surveillance, for technologies or device changes made exclusively with intent to convert to conceptually more safe designs without significant changes in mechanism or function.

We support the addition of durability testing for devices undergoing both standard reprocessing and, in particular, those undergoing sterilization.

Our societies are prepared to support and participate in continued discussion regarding:

Mandatory servicing and inspections.

Mandatory device retirement for reusable devices.

Assessment of the role and standards for third-party inspection and repair.

Our societies strongly support the importance and oversight of succinct, practical, reproducible, user-friendly guidance in manufacturers’ instructions for use (IFUs), which should incorporate post-market validation studies and updates.

We recommend that devices that incorporate programmable features (AERs, washers, sterilizers) should have lock-down mechanisms in place to prevent both user and manufacturer from deviating from the FDA-cleared IFU parameters for the device.

Our societies, as well as numerous guidelines, include high-level disinfection as a currently acceptable option for endoscope reprocessing, assuming use of enhanced washing and drying standards of practice.

Finally, we support the FDA in its efforts to convey to companies the necessary endpoints and goals for performance and expectations relative to post-market review and development of new data to ensure efficacy in the community.

Our societies appreciated this opportunity to comment on the complex and critical topic at hand. Our over-arching goal as physicians remains that of ensuring patient safety and ready access to clinically indicated procedures employing duodenoscopes and other elevator-channel endoscopes.

AGA, ACG, ASGE and SAGES were represented by three physicians who made oral remarks to the panel: Michael Kochman, MD, AGAF, Wilmott Professor of Medicine and Surgery at the University of Pennsylvania; Bret Petersen, MD, FASGE, professor of medicine and advanced endoscopist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. and Danielle Walsh, MD, associate professor of surgery at East Carolina University.

The GI societies over-arching goal is to ensure patient safety and ready access to clinically indicated procedures employing duodenoscopes and other elevator-channel endoscopes.

The panel discussed the adequacy/margin of safety for high-level disinfection, as well as the challenges and benefits of sterilization for routine for duodenoscope reprocessing. The panel’s consensus was that cleaning is the most important step in duodenoscope reprocessing. The panel noted that in properly cleaned duodenoscopes, high-level disinfection is appropriate; however, panel members acknowledged that reports indicate that duodenoscopes are not properly cleaned. The panel also discussed the challenges of implementing sterilization of duodenoscopes, such as potential decreased patient access to endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and increased costs.

On behalf of the GI societies, Dr. Kochman and Dr. Petersen proposed several overarching principles for the future evolution of our clinical practices focusing on patient safety and outcomes:

We encourage embracing multiple solutions, using a measured step-wise approach to the transition with both iterative and novel devices and processes.

We encourage data-based solutions addressing real-world efficacy while incorporating ongoing surveillance of processes and performance to ensure that early trouble signals are detected.

We believe that device or reprocessing transitions can be incorporated over the lifecycle of current instrumentation, to eliminate the potential for gaps in accessibility of care and to ensure that there is adequate efficacy and safety data to support the adoption of new technology.

We accept minimizing extensive premarket studies, while expecting vigilant post-market surveillance, for technologies or device changes made exclusively with intent to convert to conceptually more safe designs without significant changes in mechanism or function.

We support the addition of durability testing for devices undergoing both standard reprocessing and, in particular, those undergoing sterilization.

Our societies are prepared to support and participate in continued discussion regarding:

Mandatory servicing and inspections.

Mandatory device retirement for reusable devices.

Assessment of the role and standards for third-party inspection and repair.

Our societies strongly support the importance and oversight of succinct, practical, reproducible, user-friendly guidance in manufacturers’ instructions for use (IFUs), which should incorporate post-market validation studies and updates.

We recommend that devices that incorporate programmable features (AERs, washers, sterilizers) should have lock-down mechanisms in place to prevent both user and manufacturer from deviating from the FDA-cleared IFU parameters for the device.

Our societies, as well as numerous guidelines, include high-level disinfection as a currently acceptable option for endoscope reprocessing, assuming use of enhanced washing and drying standards of practice.

Finally, we support the FDA in its efforts to convey to companies the necessary endpoints and goals for performance and expectations relative to post-market review and development of new data to ensure efficacy in the community.

Our societies appreciated this opportunity to comment on the complex and critical topic at hand. Our over-arching goal as physicians remains that of ensuring patient safety and ready access to clinically indicated procedures employing duodenoscopes and other elevator-channel endoscopes.

Caution about ‘miracle cures’; more

Caution about ‘miracle cures’

I thank Drs. Katherine Epstein and Helen Farrell for the balanced approach in their article “‘Miracle cures’ in psychiatry?” (Psychiatry 2.0,

We need to pay serious attention to the small sample sizes and limited criteria for patient selection in trials of ketamine and MDMA, as well as to what sort of “psychotherapy” follows treatment with these agents. Many of us in psychiatric practice for the past 40 years have been humbled by patients’ idiosyncratic reactions to standard medications, let alone novel ones. Those of us who practiced psychiatry in the heyday of “party drugs” have seen many idiosyncratic reactions. Most early research with cannabinoids and lysergic acid diethylamide (and even Strassman’s trials with N,N-dimethyltryptamine [DMT]1-5) highlighted the significance of response by drug-naïve patients vs drug-savvy individuals. Apart from Veterans Affairs trials for posttraumatic stress disorder, many trials of these drugs for treatment-resistant depression or end-of-life care have attracted non-naïve participants.6-8 Private use of entheogens is quite different from medicalizing their use. This requires our best scrutiny. Our earnest interest in improving outcomes must not be influenced by the promise of a quick fix, let alone a miracle cure.

Sara Hartley, MD

Clinical Faculty

Interim Head of Admissions

UC Berkley/UCSF Joint Medical Program

Berkeley, California

Disclosure: The author reports no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article, or with manufacturers of competing products.

References

1. Strassman RJ. Human psychopharmacology of N,N-dimethyltryptamine. Behav Brain Res. 1996;73(1-2):121-124.

2. Strassman RJ. DMT: the spirit molecule. A doctor’s revolutionary research into the biology of near-death and mystical experiences. Rochester, VT: Park Street Press; 2001.

3. Strassman RJ, Qualls CR. Dose-response study of N,N-dimethyltryptamine in humans. I. Neuroendocrine, autonomic, and cardiovascular effects. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51(2):85-97.

4. Strassman RJ, Qualls CR, Berg LM. Differential tolerance to biological and subjective effects of four closely spaced doses of N,N-dimethyltryptamine in humans. Biol Psychiatry. 1996;39(9):784-795.

5. Strassman RJ, Qualls CR, Uhlenhuth EH, et al. Dose-response study of N,N-dimethyltryptamine in humans. II. Subjective effects and preliminary results of a new rating scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51(2):98-108.

6. Albott CS, et al. Improvement in suicidal ideation after repeated ketamine infusions: Relationship to reductions in symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and pain. Presented at: The Anxiety and Depression Association of America Annual Conference; Mar. 28-31, 2019; Chicago.

7. Abdallah CG, Sanacora G, Duman RS, et al. Ketamine and rapid-acting antidepressants: a window into a new neurobiology for mood disorder therapeutics. Annu Rev Med. 2015;66:509-523.

8. Mithoefer MC, Mithoefer AT, Feduccia AA, et al. 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA)-assisted psychotherapy for post-traumatic stress disorder in military veterans, firefighters, and police officers: a randomised, double-blind, dose-response, phase 2 clinical trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(6):486-497.

Continue to: Physician assistants and the psychiatrist shortage

Physician assistants and the psychiatrist shortage

J. Michael Smith’s article “Physician assistants in psychiatry: Helping to meet America’s mental health needs” (Commentary,

There needs to be a multifocal approach to incentivize medical students to choose psychiatry as a specialty. Several factors have discouraged medical students from going into psychiatry. The low reimbursement rates by insurance companies force psychiatrists to not accept insurances or to work for hospital or clinic organizations, where they become a part of the “medication management industry.” This scenario was created by the pharmaceutical industry and often leaves psychotherapy to other types of clinicians. In the not-too-distant future, advances in both neuroscience and artificial intelligence technologies will further reduce the role of medically trained psychiatrists, and might lead to them being replaced by other emerging professions (eg, psychiatric PAs) that are concentrated in urban settings where they are most profitable.

What can possibly be left for the future of the medically trained psychiatrist if a PA can diagnose and treat psychiatric patients? Why would we need more psychiatrists?

Marco T. Carpio, MD

Psychiatrist, private practice

Lynbrook, New York

Disclosure: The author reports no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article, or with manufacturers of competing products.

The author responds

I appreciate Dr. Carpio’s comments, and I agree that the shortage of psychiatrists will not be addressed solely by the addition of other types of clinicians, such as PAs and nurse practitioners. However, the use of well-trained health care providers such as PAs will go a long way towards helping patients receive timely and appropriate access to care. Unfortunately, no single plan or method will be adequate to solve the shortage of psychiatrists in the United States, but that does not negate the need for utilizing all available options to improve access to quality mental health care. Physician assistants are well-trained to support this endeavor.

J. Michael Smith, DHSc, MPAS, PA-C, CAQ-Psychiatry

Post-Graduate PA Mental Health Residency Training Director

Physician Assistant, ACCESS Clinic, GMHC

Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center

Houston, Texas

Continue to: Additional anathemas in psychiatry

Additional anathemas in psychiatry

While reading Dr. Nasrallah’s “Anathemas of psychiatric practice” (From the Editor,

- Cash-only suboxone clinics. Suboxone was never intended to be used in “suboxone clinics”; it was meant to be part of an integrated treatment provided in an office-based practice. Nevertheless, this treatment has been used as such in this country. As part of this trend, an anathema has grown: cash-only suboxone clinics. Patients with severe substance use disorders can be found in every socioeconomic layer of our society, but many struggle with significant psychosocial adversity and outright poverty. Cash-only suboxone clinics put many patients in a bind. Patients spend their last dollars on a needed treatment or sell these medications to maintain their addiction, or even to purchase food.

- “Medical” marijuana. There is no credible evidence based upon methodologically sound research that cannabis has benefit for treating any mental illness. In fact, there is evidence to the contrary.1 Yet, in many states, physicians—including psychiatrists—are supporting the approval of medical marijuana. I remember taking my Hippocratic Oath when I graduated from medical school, pledging to continue educating myself and my patients about evidenced-based medical science that benefits us all. I have not yet found credible evidence supporting medical marijuana.

Greed in general is a strong anathema in medicine.

Leo Bastiaens, MD

Clinical Associate Professor of Psychiatry

University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Disclosure: The author reports no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article, or with manufacturers of competing products.

Reference

1. Radhakrishnan R, Ranganathan M, D'Souza DC. Medical marijuana: what physicians need to know. J Clin Psychiatry. 2019;80(5):45-47.

Caution about ‘miracle cures’

I thank Drs. Katherine Epstein and Helen Farrell for the balanced approach in their article “‘Miracle cures’ in psychiatry?” (Psychiatry 2.0,

We need to pay serious attention to the small sample sizes and limited criteria for patient selection in trials of ketamine and MDMA, as well as to what sort of “psychotherapy” follows treatment with these agents. Many of us in psychiatric practice for the past 40 years have been humbled by patients’ idiosyncratic reactions to standard medications, let alone novel ones. Those of us who practiced psychiatry in the heyday of “party drugs” have seen many idiosyncratic reactions. Most early research with cannabinoids and lysergic acid diethylamide (and even Strassman’s trials with N,N-dimethyltryptamine [DMT]1-5) highlighted the significance of response by drug-naïve patients vs drug-savvy individuals. Apart from Veterans Affairs trials for posttraumatic stress disorder, many trials of these drugs for treatment-resistant depression or end-of-life care have attracted non-naïve participants.6-8 Private use of entheogens is quite different from medicalizing their use. This requires our best scrutiny. Our earnest interest in improving outcomes must not be influenced by the promise of a quick fix, let alone a miracle cure.

Sara Hartley, MD

Clinical Faculty

Interim Head of Admissions

UC Berkley/UCSF Joint Medical Program

Berkeley, California

Disclosure: The author reports no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article, or with manufacturers of competing products.

References

1. Strassman RJ. Human psychopharmacology of N,N-dimethyltryptamine. Behav Brain Res. 1996;73(1-2):121-124.

2. Strassman RJ. DMT: the spirit molecule. A doctor’s revolutionary research into the biology of near-death and mystical experiences. Rochester, VT: Park Street Press; 2001.

3. Strassman RJ, Qualls CR. Dose-response study of N,N-dimethyltryptamine in humans. I. Neuroendocrine, autonomic, and cardiovascular effects. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51(2):85-97.

4. Strassman RJ, Qualls CR, Berg LM. Differential tolerance to biological and subjective effects of four closely spaced doses of N,N-dimethyltryptamine in humans. Biol Psychiatry. 1996;39(9):784-795.

5. Strassman RJ, Qualls CR, Uhlenhuth EH, et al. Dose-response study of N,N-dimethyltryptamine in humans. II. Subjective effects and preliminary results of a new rating scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51(2):98-108.

6. Albott CS, et al. Improvement in suicidal ideation after repeated ketamine infusions: Relationship to reductions in symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and pain. Presented at: The Anxiety and Depression Association of America Annual Conference; Mar. 28-31, 2019; Chicago.

7. Abdallah CG, Sanacora G, Duman RS, et al. Ketamine and rapid-acting antidepressants: a window into a new neurobiology for mood disorder therapeutics. Annu Rev Med. 2015;66:509-523.

8. Mithoefer MC, Mithoefer AT, Feduccia AA, et al. 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA)-assisted psychotherapy for post-traumatic stress disorder in military veterans, firefighters, and police officers: a randomised, double-blind, dose-response, phase 2 clinical trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(6):486-497.

Continue to: Physician assistants and the psychiatrist shortage

Physician assistants and the psychiatrist shortage

J. Michael Smith’s article “Physician assistants in psychiatry: Helping to meet America’s mental health needs” (Commentary,

There needs to be a multifocal approach to incentivize medical students to choose psychiatry as a specialty. Several factors have discouraged medical students from going into psychiatry. The low reimbursement rates by insurance companies force psychiatrists to not accept insurances or to work for hospital or clinic organizations, where they become a part of the “medication management industry.” This scenario was created by the pharmaceutical industry and often leaves psychotherapy to other types of clinicians. In the not-too-distant future, advances in both neuroscience and artificial intelligence technologies will further reduce the role of medically trained psychiatrists, and might lead to them being replaced by other emerging professions (eg, psychiatric PAs) that are concentrated in urban settings where they are most profitable.

What can possibly be left for the future of the medically trained psychiatrist if a PA can diagnose and treat psychiatric patients? Why would we need more psychiatrists?

Marco T. Carpio, MD

Psychiatrist, private practice

Lynbrook, New York

Disclosure: The author reports no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article, or with manufacturers of competing products.

The author responds

I appreciate Dr. Carpio’s comments, and I agree that the shortage of psychiatrists will not be addressed solely by the addition of other types of clinicians, such as PAs and nurse practitioners. However, the use of well-trained health care providers such as PAs will go a long way towards helping patients receive timely and appropriate access to care. Unfortunately, no single plan or method will be adequate to solve the shortage of psychiatrists in the United States, but that does not negate the need for utilizing all available options to improve access to quality mental health care. Physician assistants are well-trained to support this endeavor.

J. Michael Smith, DHSc, MPAS, PA-C, CAQ-Psychiatry

Post-Graduate PA Mental Health Residency Training Director

Physician Assistant, ACCESS Clinic, GMHC

Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center

Houston, Texas

Continue to: Additional anathemas in psychiatry

Additional anathemas in psychiatry

While reading Dr. Nasrallah’s “Anathemas of psychiatric practice” (From the Editor,

- Cash-only suboxone clinics. Suboxone was never intended to be used in “suboxone clinics”; it was meant to be part of an integrated treatment provided in an office-based practice. Nevertheless, this treatment has been used as such in this country. As part of this trend, an anathema has grown: cash-only suboxone clinics. Patients with severe substance use disorders can be found in every socioeconomic layer of our society, but many struggle with significant psychosocial adversity and outright poverty. Cash-only suboxone clinics put many patients in a bind. Patients spend their last dollars on a needed treatment or sell these medications to maintain their addiction, or even to purchase food.

- “Medical” marijuana. There is no credible evidence based upon methodologically sound research that cannabis has benefit for treating any mental illness. In fact, there is evidence to the contrary.1 Yet, in many states, physicians—including psychiatrists—are supporting the approval of medical marijuana. I remember taking my Hippocratic Oath when I graduated from medical school, pledging to continue educating myself and my patients about evidenced-based medical science that benefits us all. I have not yet found credible evidence supporting medical marijuana.

Greed in general is a strong anathema in medicine.

Leo Bastiaens, MD

Clinical Associate Professor of Psychiatry

University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Disclosure: The author reports no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article, or with manufacturers of competing products.

Reference

1. Radhakrishnan R, Ranganathan M, D'Souza DC. Medical marijuana: what physicians need to know. J Clin Psychiatry. 2019;80(5):45-47.

Caution about ‘miracle cures’

I thank Drs. Katherine Epstein and Helen Farrell for the balanced approach in their article “‘Miracle cures’ in psychiatry?” (Psychiatry 2.0,

We need to pay serious attention to the small sample sizes and limited criteria for patient selection in trials of ketamine and MDMA, as well as to what sort of “psychotherapy” follows treatment with these agents. Many of us in psychiatric practice for the past 40 years have been humbled by patients’ idiosyncratic reactions to standard medications, let alone novel ones. Those of us who practiced psychiatry in the heyday of “party drugs” have seen many idiosyncratic reactions. Most early research with cannabinoids and lysergic acid diethylamide (and even Strassman’s trials with N,N-dimethyltryptamine [DMT]1-5) highlighted the significance of response by drug-naïve patients vs drug-savvy individuals. Apart from Veterans Affairs trials for posttraumatic stress disorder, many trials of these drugs for treatment-resistant depression or end-of-life care have attracted non-naïve participants.6-8 Private use of entheogens is quite different from medicalizing their use. This requires our best scrutiny. Our earnest interest in improving outcomes must not be influenced by the promise of a quick fix, let alone a miracle cure.

Sara Hartley, MD

Clinical Faculty

Interim Head of Admissions

UC Berkley/UCSF Joint Medical Program

Berkeley, California

Disclosure: The author reports no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article, or with manufacturers of competing products.

References

1. Strassman RJ. Human psychopharmacology of N,N-dimethyltryptamine. Behav Brain Res. 1996;73(1-2):121-124.

2. Strassman RJ. DMT: the spirit molecule. A doctor’s revolutionary research into the biology of near-death and mystical experiences. Rochester, VT: Park Street Press; 2001.

3. Strassman RJ, Qualls CR. Dose-response study of N,N-dimethyltryptamine in humans. I. Neuroendocrine, autonomic, and cardiovascular effects. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51(2):85-97.

4. Strassman RJ, Qualls CR, Berg LM. Differential tolerance to biological and subjective effects of four closely spaced doses of N,N-dimethyltryptamine in humans. Biol Psychiatry. 1996;39(9):784-795.

5. Strassman RJ, Qualls CR, Uhlenhuth EH, et al. Dose-response study of N,N-dimethyltryptamine in humans. II. Subjective effects and preliminary results of a new rating scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51(2):98-108.

6. Albott CS, et al. Improvement in suicidal ideation after repeated ketamine infusions: Relationship to reductions in symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and pain. Presented at: The Anxiety and Depression Association of America Annual Conference; Mar. 28-31, 2019; Chicago.

7. Abdallah CG, Sanacora G, Duman RS, et al. Ketamine and rapid-acting antidepressants: a window into a new neurobiology for mood disorder therapeutics. Annu Rev Med. 2015;66:509-523.

8. Mithoefer MC, Mithoefer AT, Feduccia AA, et al. 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA)-assisted psychotherapy for post-traumatic stress disorder in military veterans, firefighters, and police officers: a randomised, double-blind, dose-response, phase 2 clinical trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(6):486-497.

Continue to: Physician assistants and the psychiatrist shortage

Physician assistants and the psychiatrist shortage

J. Michael Smith’s article “Physician assistants in psychiatry: Helping to meet America’s mental health needs” (Commentary,

There needs to be a multifocal approach to incentivize medical students to choose psychiatry as a specialty. Several factors have discouraged medical students from going into psychiatry. The low reimbursement rates by insurance companies force psychiatrists to not accept insurances or to work for hospital or clinic organizations, where they become a part of the “medication management industry.” This scenario was created by the pharmaceutical industry and often leaves psychotherapy to other types of clinicians. In the not-too-distant future, advances in both neuroscience and artificial intelligence technologies will further reduce the role of medically trained psychiatrists, and might lead to them being replaced by other emerging professions (eg, psychiatric PAs) that are concentrated in urban settings where they are most profitable.

What can possibly be left for the future of the medically trained psychiatrist if a PA can diagnose and treat psychiatric patients? Why would we need more psychiatrists?

Marco T. Carpio, MD

Psychiatrist, private practice

Lynbrook, New York

Disclosure: The author reports no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article, or with manufacturers of competing products.

The author responds

I appreciate Dr. Carpio’s comments, and I agree that the shortage of psychiatrists will not be addressed solely by the addition of other types of clinicians, such as PAs and nurse practitioners. However, the use of well-trained health care providers such as PAs will go a long way towards helping patients receive timely and appropriate access to care. Unfortunately, no single plan or method will be adequate to solve the shortage of psychiatrists in the United States, but that does not negate the need for utilizing all available options to improve access to quality mental health care. Physician assistants are well-trained to support this endeavor.

J. Michael Smith, DHSc, MPAS, PA-C, CAQ-Psychiatry

Post-Graduate PA Mental Health Residency Training Director

Physician Assistant, ACCESS Clinic, GMHC

Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center

Houston, Texas

Continue to: Additional anathemas in psychiatry

Additional anathemas in psychiatry

While reading Dr. Nasrallah’s “Anathemas of psychiatric practice” (From the Editor,

- Cash-only suboxone clinics. Suboxone was never intended to be used in “suboxone clinics”; it was meant to be part of an integrated treatment provided in an office-based practice. Nevertheless, this treatment has been used as such in this country. As part of this trend, an anathema has grown: cash-only suboxone clinics. Patients with severe substance use disorders can be found in every socioeconomic layer of our society, but many struggle with significant psychosocial adversity and outright poverty. Cash-only suboxone clinics put many patients in a bind. Patients spend their last dollars on a needed treatment or sell these medications to maintain their addiction, or even to purchase food.

- “Medical” marijuana. There is no credible evidence based upon methodologically sound research that cannabis has benefit for treating any mental illness. In fact, there is evidence to the contrary.1 Yet, in many states, physicians—including psychiatrists—are supporting the approval of medical marijuana. I remember taking my Hippocratic Oath when I graduated from medical school, pledging to continue educating myself and my patients about evidenced-based medical science that benefits us all. I have not yet found credible evidence supporting medical marijuana.

Greed in general is a strong anathema in medicine.

Leo Bastiaens, MD

Clinical Associate Professor of Psychiatry

University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Disclosure: The author reports no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article, or with manufacturers of competing products.

Reference

1. Radhakrishnan R, Ranganathan M, D'Souza DC. Medical marijuana: what physicians need to know. J Clin Psychiatry. 2019;80(5):45-47.

Called to court? Tips for testifying

As a psychiatrist, you could be called to court to testify as a fact witness in a hearing or trial. Your role as a fact witness would differ from that of an expert witness in that you would likely testify about the information that you have gathered through direct observation of patients or others. Fact witnesses are generally not asked to give expert opinions regarding forensic issues, and treating psychiatrists should not do so about their patients. As a fact witness, depending on the form of litigation, you might be in one of the following 4 roles1:

- Observer. As the term implies, you have observed an event. For example, you are asked to testify about a fight that you witnessed between another clinician’s patient and a nurse while you were making your rounds on an inpatient unit.

- Non-defendant treater. You are the treating psychiatrist for a patient who is involved in litigation to recover damages for injuries sustained from a third party. For example, you are asked to testify about your patient’s premorbid functioning before a claimed injury that spurred the lawsuit.

- Plaintiff. You are suing someone else and may be claiming your own damages. For example, in your attempt to claim damages as a plaintiff, you use your clinical knowledge to testify about your own mental health symptoms and the adverse impact these have had on you.

- Defendant treater. You are being sued by one of your patients. For example, a patient brings a malpractice case against you for allegations of not meeting the standard of care. You testify about your direct observations of the patient, the diagnoses you provided, and your rationale for the implemented treatment plan.

Preparing yourself as a fact witness

For many psychiatrists, testifying can be an intimidating process. Although there are similarities between testifying in a courtroom and giving a deposition, there are also significant differences. For guidelines on providing depositions, see Knoll and Resnick’s “Deposition dos and don’ts: How to answer 8 tricky questions” (

Don’t panic. Although your first reaction may be to panic upon receiving a subpoena or court order, you should “keep your cool” and remember that the observations you made or treatment provided have already taken place.1 Your role as a fact witness is to inform the judge and jury about what you saw and did.1

Continue to: Refresh your memory and practice

Refresh your memory and practice. Gather all required information (eg, medical records, your notes, etc.) and review it before testifying. This will help you to recall the facts more accurately when you are asked a question. Consider practicing your testimony with the attorney who requested you to get feedback on how you present yourself.1 However, do not try to memorize what you are going to say because this could make your testimony sound rehearsed and unconvincing.

Plan ahead, and have a pretrial conference. Because court proceedings are unpredictable, you should clear your schedule to allow enough time to appear in court. Before your court appearance, meet with the attorney who requested you to discuss any new facts or issues as well as learn what the attorney aims to accomplish with your testimony.1

Speak clearly in your own words, and avoid jargon. Courtroom officials are unlikely to understand psychiatric jargon. Therefore, you should explain psychiatric terms in language that laypeople would comprehend. Because the court stenographer will require you to use actual words for the court transcripts, you should answer clearly and verbally or respond with a definitive “yes” or “no” (and not by nodding or shaking your head).

Testimony is also not a time for guessing. If you don’t know the answer, you should say “I don’t know.”

1. Gutheil TG. The psychiatrist in court: a survival guide. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc.; 1998.

2. Knoll JL, Resnick PJ. Deposition dos and don’ts: how to answer 8 tricky questions. Current Psychiatry. 2008;7(3):25-28,36,39-40.

As a psychiatrist, you could be called to court to testify as a fact witness in a hearing or trial. Your role as a fact witness would differ from that of an expert witness in that you would likely testify about the information that you have gathered through direct observation of patients or others. Fact witnesses are generally not asked to give expert opinions regarding forensic issues, and treating psychiatrists should not do so about their patients. As a fact witness, depending on the form of litigation, you might be in one of the following 4 roles1:

- Observer. As the term implies, you have observed an event. For example, you are asked to testify about a fight that you witnessed between another clinician’s patient and a nurse while you were making your rounds on an inpatient unit.

- Non-defendant treater. You are the treating psychiatrist for a patient who is involved in litigation to recover damages for injuries sustained from a third party. For example, you are asked to testify about your patient’s premorbid functioning before a claimed injury that spurred the lawsuit.

- Plaintiff. You are suing someone else and may be claiming your own damages. For example, in your attempt to claim damages as a plaintiff, you use your clinical knowledge to testify about your own mental health symptoms and the adverse impact these have had on you.

- Defendant treater. You are being sued by one of your patients. For example, a patient brings a malpractice case against you for allegations of not meeting the standard of care. You testify about your direct observations of the patient, the diagnoses you provided, and your rationale for the implemented treatment plan.

Preparing yourself as a fact witness

For many psychiatrists, testifying can be an intimidating process. Although there are similarities between testifying in a courtroom and giving a deposition, there are also significant differences. For guidelines on providing depositions, see Knoll and Resnick’s “Deposition dos and don’ts: How to answer 8 tricky questions” (

Don’t panic. Although your first reaction may be to panic upon receiving a subpoena or court order, you should “keep your cool” and remember that the observations you made or treatment provided have already taken place.1 Your role as a fact witness is to inform the judge and jury about what you saw and did.1

Continue to: Refresh your memory and practice

Refresh your memory and practice. Gather all required information (eg, medical records, your notes, etc.) and review it before testifying. This will help you to recall the facts more accurately when you are asked a question. Consider practicing your testimony with the attorney who requested you to get feedback on how you present yourself.1 However, do not try to memorize what you are going to say because this could make your testimony sound rehearsed and unconvincing.

Plan ahead, and have a pretrial conference. Because court proceedings are unpredictable, you should clear your schedule to allow enough time to appear in court. Before your court appearance, meet with the attorney who requested you to discuss any new facts or issues as well as learn what the attorney aims to accomplish with your testimony.1

Speak clearly in your own words, and avoid jargon. Courtroom officials are unlikely to understand psychiatric jargon. Therefore, you should explain psychiatric terms in language that laypeople would comprehend. Because the court stenographer will require you to use actual words for the court transcripts, you should answer clearly and verbally or respond with a definitive “yes” or “no” (and not by nodding or shaking your head).

Testimony is also not a time for guessing. If you don’t know the answer, you should say “I don’t know.”

As a psychiatrist, you could be called to court to testify as a fact witness in a hearing or trial. Your role as a fact witness would differ from that of an expert witness in that you would likely testify about the information that you have gathered through direct observation of patients or others. Fact witnesses are generally not asked to give expert opinions regarding forensic issues, and treating psychiatrists should not do so about their patients. As a fact witness, depending on the form of litigation, you might be in one of the following 4 roles1:

- Observer. As the term implies, you have observed an event. For example, you are asked to testify about a fight that you witnessed between another clinician’s patient and a nurse while you were making your rounds on an inpatient unit.

- Non-defendant treater. You are the treating psychiatrist for a patient who is involved in litigation to recover damages for injuries sustained from a third party. For example, you are asked to testify about your patient’s premorbid functioning before a claimed injury that spurred the lawsuit.

- Plaintiff. You are suing someone else and may be claiming your own damages. For example, in your attempt to claim damages as a plaintiff, you use your clinical knowledge to testify about your own mental health symptoms and the adverse impact these have had on you.

- Defendant treater. You are being sued by one of your patients. For example, a patient brings a malpractice case against you for allegations of not meeting the standard of care. You testify about your direct observations of the patient, the diagnoses you provided, and your rationale for the implemented treatment plan.

Preparing yourself as a fact witness

For many psychiatrists, testifying can be an intimidating process. Although there are similarities between testifying in a courtroom and giving a deposition, there are also significant differences. For guidelines on providing depositions, see Knoll and Resnick’s “Deposition dos and don’ts: How to answer 8 tricky questions” (

Don’t panic. Although your first reaction may be to panic upon receiving a subpoena or court order, you should “keep your cool” and remember that the observations you made or treatment provided have already taken place.1 Your role as a fact witness is to inform the judge and jury about what you saw and did.1

Continue to: Refresh your memory and practice

Refresh your memory and practice. Gather all required information (eg, medical records, your notes, etc.) and review it before testifying. This will help you to recall the facts more accurately when you are asked a question. Consider practicing your testimony with the attorney who requested you to get feedback on how you present yourself.1 However, do not try to memorize what you are going to say because this could make your testimony sound rehearsed and unconvincing.

Plan ahead, and have a pretrial conference. Because court proceedings are unpredictable, you should clear your schedule to allow enough time to appear in court. Before your court appearance, meet with the attorney who requested you to discuss any new facts or issues as well as learn what the attorney aims to accomplish with your testimony.1

Speak clearly in your own words, and avoid jargon. Courtroom officials are unlikely to understand psychiatric jargon. Therefore, you should explain psychiatric terms in language that laypeople would comprehend. Because the court stenographer will require you to use actual words for the court transcripts, you should answer clearly and verbally or respond with a definitive “yes” or “no” (and not by nodding or shaking your head).

Testimony is also not a time for guessing. If you don’t know the answer, you should say “I don’t know.”

1. Gutheil TG. The psychiatrist in court: a survival guide. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc.; 1998.

2. Knoll JL, Resnick PJ. Deposition dos and don’ts: how to answer 8 tricky questions. Current Psychiatry. 2008;7(3):25-28,36,39-40.

1. Gutheil TG. The psychiatrist in court: a survival guide. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc.; 1998.

2. Knoll JL, Resnick PJ. Deposition dos and don’ts: how to answer 8 tricky questions. Current Psychiatry. 2008;7(3):25-28,36,39-40.

The evolution of manic and hypomanic symptoms

Since publication of the first Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) in 1952,1 the diagnosis of manic and hypomanic symptoms has evolved significantly. This evolution has changed my approach to patients who exhibit these symptoms, which include increased goal-directed activity, decreased need for sleep, and racing thoughts. Here I outline these diagnostic changes in each edition of the DSM and discuss their therapeutic importance and the possibility of future changes.

DSM-I (1952) described manic symptoms as having psychotic features.1 The term “manic episode” was not used, but manic symptoms were described as having a “tendency to remission and recurrence.”1

DSM-II (1968) introduced the term “manic episode” as having psychotic features.2 Manic episodes were characterized by symptoms of excessive elation, irritability, talkativeness, flight of ideas, and accelerated speech and motor activity.2

DSM-III (1980) explained that a manic episode could occur without psychotic features.3 The term “hypomanic episode” was introduced. It described manic features that do not meet criteria for a manic episode.3

DSM-IV (1994) reiterated the criteria for a manic episode.4 In addition, it established criteria for a hypomanic episode as lasting at least 4 days and requires ≥3 symptoms.4

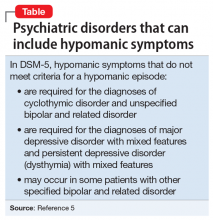

DSM-5 (2013) describes hypomanic symptoms that do not meet criteria for a hypomanic episode (Table).5 These symptoms may require treatment with a mood stabilizer or antipsychotic medication.5

Suggested changes for the next DSM

Although DSM-5 does not discuss the duration of different manic or hypomanic symptoms in the same patient, these can vary widely.6 The same patient may have increased activity for 2 days, increased irritability for 2 weeks, and racing thoughts every day. Future versions of the DSM could include the varying durations of different manic or hypomanic symptoms in the same patient.

Continue to: Racing thoughts without...

Racing thoughts without increased energy or activity occur frequently and often go unnoticed.7 They can be mistaken for severe worrying or obsessive ideation. Depending on the severity of the patient’s racing thoughts, treatment might include a mood stabilizer or antipsychotic. All 5 DSM-5 diagnoses listed in the Table5 may include this symptom pattern, but do not specifically mention it. A diagnosis or specifier, such as “racing thoughts without increased energy or activity,” might help clinicians better recognize and treat this symptom pattern.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1952:24-25.

2. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1968:35-37.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1980:208-210,223.

4. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994:332,338.

5. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013:139-140,148-149,169,184-185.

6. Wilf TJ. When to treat subthreshold hypomanic episodes. Current Psychiatry. 2012;11(8):55.

7. Benazzi F. Unipolar depression with racing thoughts: a bipolar spectrum disorder? Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;59(5):570-575.

Since publication of the first Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) in 1952,1 the diagnosis of manic and hypomanic symptoms has evolved significantly. This evolution has changed my approach to patients who exhibit these symptoms, which include increased goal-directed activity, decreased need for sleep, and racing thoughts. Here I outline these diagnostic changes in each edition of the DSM and discuss their therapeutic importance and the possibility of future changes.

DSM-I (1952) described manic symptoms as having psychotic features.1 The term “manic episode” was not used, but manic symptoms were described as having a “tendency to remission and recurrence.”1

DSM-II (1968) introduced the term “manic episode” as having psychotic features.2 Manic episodes were characterized by symptoms of excessive elation, irritability, talkativeness, flight of ideas, and accelerated speech and motor activity.2

DSM-III (1980) explained that a manic episode could occur without psychotic features.3 The term “hypomanic episode” was introduced. It described manic features that do not meet criteria for a manic episode.3

DSM-IV (1994) reiterated the criteria for a manic episode.4 In addition, it established criteria for a hypomanic episode as lasting at least 4 days and requires ≥3 symptoms.4

DSM-5 (2013) describes hypomanic symptoms that do not meet criteria for a hypomanic episode (Table).5 These symptoms may require treatment with a mood stabilizer or antipsychotic medication.5

Suggested changes for the next DSM

Although DSM-5 does not discuss the duration of different manic or hypomanic symptoms in the same patient, these can vary widely.6 The same patient may have increased activity for 2 days, increased irritability for 2 weeks, and racing thoughts every day. Future versions of the DSM could include the varying durations of different manic or hypomanic symptoms in the same patient.

Continue to: Racing thoughts without...