User login

Experts call to revise the Uniform Determination of Death Act

, according to an editorial published online Dec. 24, 2019, in Annals of Internal Medicine. Proposed revisions would identify the standards for determining death by neurologic criteria and address the question of whether consent is required to make this determination. If accepted, the revisions would enhance public trust in the determination of death by neurologic criteria, the authors said.

“There is a disconnect between the medical and legal standards for brain death,” said Ariane K. Lewis, MD, associate professor of neurology and neurosurgery at New York University and lead author of the editorial. The discrepancy must be remedied because it has led to lawsuits and has proved to be problematic from a societal standpoint, she added.

“We defend changing the law to match medical practice, rather than changing medical practice to match the law,” said Thaddeus Mason Pope, JD, PhD, director of the Health Law Institute at Mitchell Hamline School of Law in Saint Paul, Minnesota, and an author of the editorial.

Accepted medical standards are unclear

The UDDA was drafted in 1981 to establish a uniform legal standard for death by neurologic criteria. A person with “irreversible cessation of all functions of the entire brain, including the brainstem,” is dead, according to the statute. A determination of death, it adds, “must be made in accordance with accepted medical standards.”

But the medical standards used to determine death by neurologic cause have not been uniform. In 2015, the Supreme Court of Nevada ruled that it was not clear that the standard published by the American Academy of Neurology (AAN), which had been used in the case at issue, was the “accepted medical standard.” An AAN summit later affirmed that the accepted medical standards for determination of death by neurologic cause are the 2010 AAN standard for determination of brain death in adults and the 2011 Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM), American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and Child Neurology Society (CNS) standard for determination of brain death in children. The Nevada legislature amended the state UDDA to identify these standards as the accepted standards. A revised UDDA also should identify these standards and grant an administrative agency (i.e., the board of medicine) the power to review and update the accepted medical standards as needed, according to the editorial.

To the extent that hospitals are not following the AAN or SCCM/AAP/CNS standards for determining death by neurologic cause, “enshrining” these standards in a revised UDDA “should increase uniformity and consistency” in hospitals’ policies on brain death, Dr. Pope said.

The question of hormonal function

Lawsuits in California and Nevada raised the question of whether the pituitary gland and hypothalamus are parts of the brain. If so, then the accepted medical standards for death by neurologic cause are not consistent with the statutory requirements for the determination of death, since the former do not test for cessation of hormonal function.

The current edition of the adult standards for determining death by neurologic cause were published in 2010. “Whenever we measure brain death, we’re not measuring the cessation of all functions of the entire brain,” Dr. Pope said. “That’s not a new thing; that’s been the case for a long time.”

To address the discrepancy between medical practice and the legal statute, Dr. Lewis and colleagues proposed that the UDDA’s reference to “irreversible cessation of functions of the entire brain” be followed by the following clause: “including the brainstem, leading to unresponsive coma with loss of capacity for consciousness, brainstem areflexia, and the inability to breathe spontaneously.” An alternative revision would be to add the briefer phrase “... with the exception of hormonal function.”

Authors say consent is not required for testing

Other complications have arisen from the UDDA’s failure to specify whether consent is required for a determination of death by neurologic cause. Court rulings on this question have not been consistent. Dr. Lewis and colleagues propose adding the following text to the UDDA: “Reasonable efforts should be made to notify a patient’s legally authorized decision-maker before performing a determination of death by neurologic criteria, but consent is not required to initiate such an evaluation.”

The proposed revisions to the UDDA “might give [clinicians] more confidence to proceed with brain death testing, because it would clarify that they don’t need the parents’ [or the patient’s legally authorized decision-maker] consent to do the tests,” said Dr. Pope. “If anything, they might even have a duty to do the tests.”

The final problem with the UDDA that Dr. Lewis and colleagues cited is that it does not provide clear guidance about how to respond to religious objections to discontinuation of organ support after a determination of death by neurologic cause. “Because the issue is rather complicated, we have not advocated for a singular position related to this [question] in our revised UDDA,” Dr. Lewis said. “Rather, we recommended the need for a multidisciplinary group to come together to determine what is the best approach. In an ideal world, this [approach] would be universal throughout the country.”

Although a revised UDDA would provide greater clarity to physicians and promote uniformity of practice, it would not resolve ongoing theological and philosophical debates about whether brain death is biological death, Dr. Pope said. “The key thing is that it would give clinicians a green light or certainty and clarity that they may proceed to do the test in the first place. If the tests are positive and the patient really is dead, then they could proceed to organ procurement or to move to the morgue.”

Dr. Lewis is a member of various AAN committees and working groups but receives no compensation for her role. A coauthor received personal fees from the AAN that were unrelated to the editorial.

SOURCE: Lewis A et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Dec 24. doi: 10.7326/M19-2731.

, according to an editorial published online Dec. 24, 2019, in Annals of Internal Medicine. Proposed revisions would identify the standards for determining death by neurologic criteria and address the question of whether consent is required to make this determination. If accepted, the revisions would enhance public trust in the determination of death by neurologic criteria, the authors said.

“There is a disconnect between the medical and legal standards for brain death,” said Ariane K. Lewis, MD, associate professor of neurology and neurosurgery at New York University and lead author of the editorial. The discrepancy must be remedied because it has led to lawsuits and has proved to be problematic from a societal standpoint, she added.

“We defend changing the law to match medical practice, rather than changing medical practice to match the law,” said Thaddeus Mason Pope, JD, PhD, director of the Health Law Institute at Mitchell Hamline School of Law in Saint Paul, Minnesota, and an author of the editorial.

Accepted medical standards are unclear

The UDDA was drafted in 1981 to establish a uniform legal standard for death by neurologic criteria. A person with “irreversible cessation of all functions of the entire brain, including the brainstem,” is dead, according to the statute. A determination of death, it adds, “must be made in accordance with accepted medical standards.”

But the medical standards used to determine death by neurologic cause have not been uniform. In 2015, the Supreme Court of Nevada ruled that it was not clear that the standard published by the American Academy of Neurology (AAN), which had been used in the case at issue, was the “accepted medical standard.” An AAN summit later affirmed that the accepted medical standards for determination of death by neurologic cause are the 2010 AAN standard for determination of brain death in adults and the 2011 Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM), American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and Child Neurology Society (CNS) standard for determination of brain death in children. The Nevada legislature amended the state UDDA to identify these standards as the accepted standards. A revised UDDA also should identify these standards and grant an administrative agency (i.e., the board of medicine) the power to review and update the accepted medical standards as needed, according to the editorial.

To the extent that hospitals are not following the AAN or SCCM/AAP/CNS standards for determining death by neurologic cause, “enshrining” these standards in a revised UDDA “should increase uniformity and consistency” in hospitals’ policies on brain death, Dr. Pope said.

The question of hormonal function

Lawsuits in California and Nevada raised the question of whether the pituitary gland and hypothalamus are parts of the brain. If so, then the accepted medical standards for death by neurologic cause are not consistent with the statutory requirements for the determination of death, since the former do not test for cessation of hormonal function.

The current edition of the adult standards for determining death by neurologic cause were published in 2010. “Whenever we measure brain death, we’re not measuring the cessation of all functions of the entire brain,” Dr. Pope said. “That’s not a new thing; that’s been the case for a long time.”

To address the discrepancy between medical practice and the legal statute, Dr. Lewis and colleagues proposed that the UDDA’s reference to “irreversible cessation of functions of the entire brain” be followed by the following clause: “including the brainstem, leading to unresponsive coma with loss of capacity for consciousness, brainstem areflexia, and the inability to breathe spontaneously.” An alternative revision would be to add the briefer phrase “... with the exception of hormonal function.”

Authors say consent is not required for testing

Other complications have arisen from the UDDA’s failure to specify whether consent is required for a determination of death by neurologic cause. Court rulings on this question have not been consistent. Dr. Lewis and colleagues propose adding the following text to the UDDA: “Reasonable efforts should be made to notify a patient’s legally authorized decision-maker before performing a determination of death by neurologic criteria, but consent is not required to initiate such an evaluation.”

The proposed revisions to the UDDA “might give [clinicians] more confidence to proceed with brain death testing, because it would clarify that they don’t need the parents’ [or the patient’s legally authorized decision-maker] consent to do the tests,” said Dr. Pope. “If anything, they might even have a duty to do the tests.”

The final problem with the UDDA that Dr. Lewis and colleagues cited is that it does not provide clear guidance about how to respond to religious objections to discontinuation of organ support after a determination of death by neurologic cause. “Because the issue is rather complicated, we have not advocated for a singular position related to this [question] in our revised UDDA,” Dr. Lewis said. “Rather, we recommended the need for a multidisciplinary group to come together to determine what is the best approach. In an ideal world, this [approach] would be universal throughout the country.”

Although a revised UDDA would provide greater clarity to physicians and promote uniformity of practice, it would not resolve ongoing theological and philosophical debates about whether brain death is biological death, Dr. Pope said. “The key thing is that it would give clinicians a green light or certainty and clarity that they may proceed to do the test in the first place. If the tests are positive and the patient really is dead, then they could proceed to organ procurement or to move to the morgue.”

Dr. Lewis is a member of various AAN committees and working groups but receives no compensation for her role. A coauthor received personal fees from the AAN that were unrelated to the editorial.

SOURCE: Lewis A et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Dec 24. doi: 10.7326/M19-2731.

, according to an editorial published online Dec. 24, 2019, in Annals of Internal Medicine. Proposed revisions would identify the standards for determining death by neurologic criteria and address the question of whether consent is required to make this determination. If accepted, the revisions would enhance public trust in the determination of death by neurologic criteria, the authors said.

“There is a disconnect between the medical and legal standards for brain death,” said Ariane K. Lewis, MD, associate professor of neurology and neurosurgery at New York University and lead author of the editorial. The discrepancy must be remedied because it has led to lawsuits and has proved to be problematic from a societal standpoint, she added.

“We defend changing the law to match medical practice, rather than changing medical practice to match the law,” said Thaddeus Mason Pope, JD, PhD, director of the Health Law Institute at Mitchell Hamline School of Law in Saint Paul, Minnesota, and an author of the editorial.

Accepted medical standards are unclear

The UDDA was drafted in 1981 to establish a uniform legal standard for death by neurologic criteria. A person with “irreversible cessation of all functions of the entire brain, including the brainstem,” is dead, according to the statute. A determination of death, it adds, “must be made in accordance with accepted medical standards.”

But the medical standards used to determine death by neurologic cause have not been uniform. In 2015, the Supreme Court of Nevada ruled that it was not clear that the standard published by the American Academy of Neurology (AAN), which had been used in the case at issue, was the “accepted medical standard.” An AAN summit later affirmed that the accepted medical standards for determination of death by neurologic cause are the 2010 AAN standard for determination of brain death in adults and the 2011 Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM), American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and Child Neurology Society (CNS) standard for determination of brain death in children. The Nevada legislature amended the state UDDA to identify these standards as the accepted standards. A revised UDDA also should identify these standards and grant an administrative agency (i.e., the board of medicine) the power to review and update the accepted medical standards as needed, according to the editorial.

To the extent that hospitals are not following the AAN or SCCM/AAP/CNS standards for determining death by neurologic cause, “enshrining” these standards in a revised UDDA “should increase uniformity and consistency” in hospitals’ policies on brain death, Dr. Pope said.

The question of hormonal function

Lawsuits in California and Nevada raised the question of whether the pituitary gland and hypothalamus are parts of the brain. If so, then the accepted medical standards for death by neurologic cause are not consistent with the statutory requirements for the determination of death, since the former do not test for cessation of hormonal function.

The current edition of the adult standards for determining death by neurologic cause were published in 2010. “Whenever we measure brain death, we’re not measuring the cessation of all functions of the entire brain,” Dr. Pope said. “That’s not a new thing; that’s been the case for a long time.”

To address the discrepancy between medical practice and the legal statute, Dr. Lewis and colleagues proposed that the UDDA’s reference to “irreversible cessation of functions of the entire brain” be followed by the following clause: “including the brainstem, leading to unresponsive coma with loss of capacity for consciousness, brainstem areflexia, and the inability to breathe spontaneously.” An alternative revision would be to add the briefer phrase “... with the exception of hormonal function.”

Authors say consent is not required for testing

Other complications have arisen from the UDDA’s failure to specify whether consent is required for a determination of death by neurologic cause. Court rulings on this question have not been consistent. Dr. Lewis and colleagues propose adding the following text to the UDDA: “Reasonable efforts should be made to notify a patient’s legally authorized decision-maker before performing a determination of death by neurologic criteria, but consent is not required to initiate such an evaluation.”

The proposed revisions to the UDDA “might give [clinicians] more confidence to proceed with brain death testing, because it would clarify that they don’t need the parents’ [or the patient’s legally authorized decision-maker] consent to do the tests,” said Dr. Pope. “If anything, they might even have a duty to do the tests.”

The final problem with the UDDA that Dr. Lewis and colleagues cited is that it does not provide clear guidance about how to respond to religious objections to discontinuation of organ support after a determination of death by neurologic cause. “Because the issue is rather complicated, we have not advocated for a singular position related to this [question] in our revised UDDA,” Dr. Lewis said. “Rather, we recommended the need for a multidisciplinary group to come together to determine what is the best approach. In an ideal world, this [approach] would be universal throughout the country.”

Although a revised UDDA would provide greater clarity to physicians and promote uniformity of practice, it would not resolve ongoing theological and philosophical debates about whether brain death is biological death, Dr. Pope said. “The key thing is that it would give clinicians a green light or certainty and clarity that they may proceed to do the test in the first place. If the tests are positive and the patient really is dead, then they could proceed to organ procurement or to move to the morgue.”

Dr. Lewis is a member of various AAN committees and working groups but receives no compensation for her role. A coauthor received personal fees from the AAN that were unrelated to the editorial.

SOURCE: Lewis A et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Dec 24. doi: 10.7326/M19-2731.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Patient poaching: High on practices’ dirty tricks list

Years ago, I wrote about patient poaching – the practice of stealing another practice’s patients without the patient or other physician realizing what’s going on.

This is high on the dirty tricks list of some practices. It’s certainly not illegal, but seems pretty unethical. Fortunately, it’s infrequent (at least where I work), but still occurs.

Recently, I encountered a particularly egregious example.

One of my patients, a nice lady in her 70s, had a syncopal event and landed in a hospital I don’t cover. A neurologist who saw her there did a brain MRI and head/neck MR angiogram, which were fine. A cardiology evaluation was also fine, so she was sent home. The neurologist there told her to follow-up with him at his office.

As my nurse says, “some people just do whatever they’re told, they don’t want to make a doctor angry.” So my patient did, and at the other doctor’s office had a four-limb electromyogram test and nerve conduction study, carotid Dopplers, transcranial Dopplers, and an EEG. He also made changes in her medications.

The first time I found out about it was when the patient scheduled an unrelated procedure, and I got a clearance request to take her off a medication in advance of it. Since I hadn’t started her on the medication (or was even aware she was on it) I refused, saying they’d have to contact the physician who prescribed it.

This got back to the patient, who was under the impression I’d been aware of all this the whole time, and she called the other neurologist to have his records sent to me.

When I got them, I was surprised to find he’d documented that I’d asked him to assume her outpatient care and do these studies for me. I have no recollection of such a conversation, and I would not have agreed to such a thing unless the patient had informed me she was transferring care to him (in which case it’s no longer my concern). Unless I was in a coma at the time this conversation occurred, I’m pretty sure it didn’t happen.

Basically, what the other doctor did was perform a walletectomy (or, in this case insurance-ectomy) on the patient under the guise (to her) that he was doing this as a favor to me.

How do you look yourself in mirror each day when you do stuff like this? Apparently, it’s easier for some doctors than it is for me.

I’ll do my best to keep it that way, too. I can’t change others, but I can do my best to take the high road.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Years ago, I wrote about patient poaching – the practice of stealing another practice’s patients without the patient or other physician realizing what’s going on.

This is high on the dirty tricks list of some practices. It’s certainly not illegal, but seems pretty unethical. Fortunately, it’s infrequent (at least where I work), but still occurs.

Recently, I encountered a particularly egregious example.

One of my patients, a nice lady in her 70s, had a syncopal event and landed in a hospital I don’t cover. A neurologist who saw her there did a brain MRI and head/neck MR angiogram, which were fine. A cardiology evaluation was also fine, so she was sent home. The neurologist there told her to follow-up with him at his office.

As my nurse says, “some people just do whatever they’re told, they don’t want to make a doctor angry.” So my patient did, and at the other doctor’s office had a four-limb electromyogram test and nerve conduction study, carotid Dopplers, transcranial Dopplers, and an EEG. He also made changes in her medications.

The first time I found out about it was when the patient scheduled an unrelated procedure, and I got a clearance request to take her off a medication in advance of it. Since I hadn’t started her on the medication (or was even aware she was on it) I refused, saying they’d have to contact the physician who prescribed it.

This got back to the patient, who was under the impression I’d been aware of all this the whole time, and she called the other neurologist to have his records sent to me.

When I got them, I was surprised to find he’d documented that I’d asked him to assume her outpatient care and do these studies for me. I have no recollection of such a conversation, and I would not have agreed to such a thing unless the patient had informed me she was transferring care to him (in which case it’s no longer my concern). Unless I was in a coma at the time this conversation occurred, I’m pretty sure it didn’t happen.

Basically, what the other doctor did was perform a walletectomy (or, in this case insurance-ectomy) on the patient under the guise (to her) that he was doing this as a favor to me.

How do you look yourself in mirror each day when you do stuff like this? Apparently, it’s easier for some doctors than it is for me.

I’ll do my best to keep it that way, too. I can’t change others, but I can do my best to take the high road.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Years ago, I wrote about patient poaching – the practice of stealing another practice’s patients without the patient or other physician realizing what’s going on.

This is high on the dirty tricks list of some practices. It’s certainly not illegal, but seems pretty unethical. Fortunately, it’s infrequent (at least where I work), but still occurs.

Recently, I encountered a particularly egregious example.

One of my patients, a nice lady in her 70s, had a syncopal event and landed in a hospital I don’t cover. A neurologist who saw her there did a brain MRI and head/neck MR angiogram, which were fine. A cardiology evaluation was also fine, so she was sent home. The neurologist there told her to follow-up with him at his office.

As my nurse says, “some people just do whatever they’re told, they don’t want to make a doctor angry.” So my patient did, and at the other doctor’s office had a four-limb electromyogram test and nerve conduction study, carotid Dopplers, transcranial Dopplers, and an EEG. He also made changes in her medications.

The first time I found out about it was when the patient scheduled an unrelated procedure, and I got a clearance request to take her off a medication in advance of it. Since I hadn’t started her on the medication (or was even aware she was on it) I refused, saying they’d have to contact the physician who prescribed it.

This got back to the patient, who was under the impression I’d been aware of all this the whole time, and she called the other neurologist to have his records sent to me.

When I got them, I was surprised to find he’d documented that I’d asked him to assume her outpatient care and do these studies for me. I have no recollection of such a conversation, and I would not have agreed to such a thing unless the patient had informed me she was transferring care to him (in which case it’s no longer my concern). Unless I was in a coma at the time this conversation occurred, I’m pretty sure it didn’t happen.

Basically, what the other doctor did was perform a walletectomy (or, in this case insurance-ectomy) on the patient under the guise (to her) that he was doing this as a favor to me.

How do you look yourself in mirror each day when you do stuff like this? Apparently, it’s easier for some doctors than it is for me.

I’ll do my best to keep it that way, too. I can’t change others, but I can do my best to take the high road.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

2020 Directory of VA and DoD Facilities

Click here to access The 2020 Directory of VA and DoD Facilities

Table of Contents

- Letter From the Publisher

- Explanatory Notes and Abbreviation Key

- Veterans Integrated Service Network (VISN) Guide

- Department of Veterans Affairs Health Care Facilities

- TRICARE Region Guide

- Department of Defense Health Care Facilities

Click here to access The 2020 Directory of VA and DoD Facilities

Table of Contents

- Letter From the Publisher

- Explanatory Notes and Abbreviation Key

- Veterans Integrated Service Network (VISN) Guide

- Department of Veterans Affairs Health Care Facilities

- TRICARE Region Guide

- Department of Defense Health Care Facilities

Click here to access The 2020 Directory of VA and DoD Facilities

Table of Contents

- Letter From the Publisher

- Explanatory Notes and Abbreviation Key

- Veterans Integrated Service Network (VISN) Guide

- Department of Veterans Affairs Health Care Facilities

- TRICARE Region Guide

- Department of Defense Health Care Facilities

FDA targets flavored cartridge-based e-cigarettes, but says it is not a ‘ban’

but states it is not a “ban.”

On Jan. 2, the agency issued enforcement guidance alerting companies that manufacture, distribute, and sell unauthorized flavored cartridge-based e-cigarettes within the next 30 days will risk FDA enforcement action.

FDA has had the authority to require premarket authorization of all e-cigarettes and other electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) since August 2016, but thus far has exercised enforcement discretion regarding the need for premarket authorization for these types of products.

“By prioritizing enforcement against the products that are most widely used by children, our action today seeks to strike the right public health balance by maintaining e-cigarettes as a potential off-ramp for adults using combustible tobacco while ensuring these products don’t provide an on-ramp to nicotine addiction for our youth,” Department of Health & Human Services Secretary Alex Azar said in a statement.

The action comes in the wake of more than 2,500 vaping-related injuries being reported, including more than 50 deaths associated with vaping reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (although many are related to the use of tetrahydrocannabinol [THC] within vaping products) and a continued rise in youth use of e-cigarettes noted in government surveys.

The agency noted in a Jan. 2 statement announcing the enforcement action that, to date, no ENDS products have received a premarket authorization, “meaning that all ENDS products currently on the market are considered illegally marketed and are subject to enforcement, at any time, in the FDA’s discretion.”

FDA said it is prioritizing enforcement in 30 days against:

- Any flavored, cartridge-based ENDS product, other than those with a tobacco or menthol flavoring.

- All other ENDS products for which manufacturers are failing to take adequate measures to prevent access by minors.

- Any ENDS product that is targeted to minors or is likely to promote use by minors.

In the last category, this might include labeling or advertising resembling “kid-friendly food and drinks such as juice boxes or kid-friendly cereal; products marketed directly to minors by promoting ease of concealing the product or disguising it as another product; and products marketed with characters designed to appeal to youth,” according to the FDA statement.

As of May 12, FDA also will prioritize enforcement against any ENDS product for which the manufacturer has not submitted a premarket application. The agency will continue to exercise enforcement discretion for up to 1 year on these products if an application has been submitted, pending the review of that application.

“By not prioritizing enforcement against other flavored ENDS products in the same way as flavored cartridge-based ENDS products, the FDA has attempted to balance the public health concerns related to youth use of ENDS products with consideration regarding addicted adult cigarette smokers who may try to use ENDS products to transition away from combustible tobacco products,” the agency stated, adding that cartridge-based ENDS products are most commonly used among youth.

The FDA statement noted that the enforcement priorities outlined in the guidance document were not a “ban” on flavored or cartridge-based ENDS, noting the agency “has already accepted and begun review of several premarket applications for flavored ENDS products through the pathway that Congress established in the Tobacco Control Act. ... If a company can demonstrate to the FDA that a specific product meets the applicable standard set forth by Congress, including considering how the marketing of the product may affect youth initiation and use, then the FDA could authorize that product for sale.”

“Coupled with the recently signed legislation increasing the minimum age of sale of tobacco to 21, we believe this policy balances the urgency with which we must address the public health threat of youth use of e-cigarette products with the potential role that e-cigarettes may play in helping adult smokers transition completely away from combustible tobacco to a potentially less risky form of nicotine delivery,” FDA Commissioner Stephen Hahn, MD, said in a statement. “While we expect that responsible members of industry will comply with premarket requirements, we’re ready to take action against any unauthorized e-cigarette products as outlined in our priorities. We’ll also closely monitor the use rates of all e-cigarette products and take additional steps to address youth use as necessary.”

The American Medical Association criticized the action as not going far enough, even though it was a step in the right direction.

“The AMA is disappointed that menthol flavors, one of the most popular, will still be allowed, and that flavored e-liquids will remain on the market, leaving young people with easy access to alternative flavored e-cigarette products,” AMA President Patrice A. Harris, MD, said in a statement. “If we are serious about tackling this epidemic and keeping these harmful products out of the hands of young people, a total ban on all flavored e-cigarettes, in all forms and at all locations, is prudent and urgently needed. We are pleased the administration committed today to closely monitoring the situation and trends in e-cigarette use among young people, and to taking further action if needed.”

but states it is not a “ban.”

On Jan. 2, the agency issued enforcement guidance alerting companies that manufacture, distribute, and sell unauthorized flavored cartridge-based e-cigarettes within the next 30 days will risk FDA enforcement action.

FDA has had the authority to require premarket authorization of all e-cigarettes and other electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) since August 2016, but thus far has exercised enforcement discretion regarding the need for premarket authorization for these types of products.

“By prioritizing enforcement against the products that are most widely used by children, our action today seeks to strike the right public health balance by maintaining e-cigarettes as a potential off-ramp for adults using combustible tobacco while ensuring these products don’t provide an on-ramp to nicotine addiction for our youth,” Department of Health & Human Services Secretary Alex Azar said in a statement.

The action comes in the wake of more than 2,500 vaping-related injuries being reported, including more than 50 deaths associated with vaping reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (although many are related to the use of tetrahydrocannabinol [THC] within vaping products) and a continued rise in youth use of e-cigarettes noted in government surveys.

The agency noted in a Jan. 2 statement announcing the enforcement action that, to date, no ENDS products have received a premarket authorization, “meaning that all ENDS products currently on the market are considered illegally marketed and are subject to enforcement, at any time, in the FDA’s discretion.”

FDA said it is prioritizing enforcement in 30 days against:

- Any flavored, cartridge-based ENDS product, other than those with a tobacco or menthol flavoring.

- All other ENDS products for which manufacturers are failing to take adequate measures to prevent access by minors.

- Any ENDS product that is targeted to minors or is likely to promote use by minors.

In the last category, this might include labeling or advertising resembling “kid-friendly food and drinks such as juice boxes or kid-friendly cereal; products marketed directly to minors by promoting ease of concealing the product or disguising it as another product; and products marketed with characters designed to appeal to youth,” according to the FDA statement.

As of May 12, FDA also will prioritize enforcement against any ENDS product for which the manufacturer has not submitted a premarket application. The agency will continue to exercise enforcement discretion for up to 1 year on these products if an application has been submitted, pending the review of that application.

“By not prioritizing enforcement against other flavored ENDS products in the same way as flavored cartridge-based ENDS products, the FDA has attempted to balance the public health concerns related to youth use of ENDS products with consideration regarding addicted adult cigarette smokers who may try to use ENDS products to transition away from combustible tobacco products,” the agency stated, adding that cartridge-based ENDS products are most commonly used among youth.

The FDA statement noted that the enforcement priorities outlined in the guidance document were not a “ban” on flavored or cartridge-based ENDS, noting the agency “has already accepted and begun review of several premarket applications for flavored ENDS products through the pathway that Congress established in the Tobacco Control Act. ... If a company can demonstrate to the FDA that a specific product meets the applicable standard set forth by Congress, including considering how the marketing of the product may affect youth initiation and use, then the FDA could authorize that product for sale.”

“Coupled with the recently signed legislation increasing the minimum age of sale of tobacco to 21, we believe this policy balances the urgency with which we must address the public health threat of youth use of e-cigarette products with the potential role that e-cigarettes may play in helping adult smokers transition completely away from combustible tobacco to a potentially less risky form of nicotine delivery,” FDA Commissioner Stephen Hahn, MD, said in a statement. “While we expect that responsible members of industry will comply with premarket requirements, we’re ready to take action against any unauthorized e-cigarette products as outlined in our priorities. We’ll also closely monitor the use rates of all e-cigarette products and take additional steps to address youth use as necessary.”

The American Medical Association criticized the action as not going far enough, even though it was a step in the right direction.

“The AMA is disappointed that menthol flavors, one of the most popular, will still be allowed, and that flavored e-liquids will remain on the market, leaving young people with easy access to alternative flavored e-cigarette products,” AMA President Patrice A. Harris, MD, said in a statement. “If we are serious about tackling this epidemic and keeping these harmful products out of the hands of young people, a total ban on all flavored e-cigarettes, in all forms and at all locations, is prudent and urgently needed. We are pleased the administration committed today to closely monitoring the situation and trends in e-cigarette use among young people, and to taking further action if needed.”

but states it is not a “ban.”

On Jan. 2, the agency issued enforcement guidance alerting companies that manufacture, distribute, and sell unauthorized flavored cartridge-based e-cigarettes within the next 30 days will risk FDA enforcement action.

FDA has had the authority to require premarket authorization of all e-cigarettes and other electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) since August 2016, but thus far has exercised enforcement discretion regarding the need for premarket authorization for these types of products.

“By prioritizing enforcement against the products that are most widely used by children, our action today seeks to strike the right public health balance by maintaining e-cigarettes as a potential off-ramp for adults using combustible tobacco while ensuring these products don’t provide an on-ramp to nicotine addiction for our youth,” Department of Health & Human Services Secretary Alex Azar said in a statement.

The action comes in the wake of more than 2,500 vaping-related injuries being reported, including more than 50 deaths associated with vaping reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (although many are related to the use of tetrahydrocannabinol [THC] within vaping products) and a continued rise in youth use of e-cigarettes noted in government surveys.

The agency noted in a Jan. 2 statement announcing the enforcement action that, to date, no ENDS products have received a premarket authorization, “meaning that all ENDS products currently on the market are considered illegally marketed and are subject to enforcement, at any time, in the FDA’s discretion.”

FDA said it is prioritizing enforcement in 30 days against:

- Any flavored, cartridge-based ENDS product, other than those with a tobacco or menthol flavoring.

- All other ENDS products for which manufacturers are failing to take adequate measures to prevent access by minors.

- Any ENDS product that is targeted to minors or is likely to promote use by minors.

In the last category, this might include labeling or advertising resembling “kid-friendly food and drinks such as juice boxes or kid-friendly cereal; products marketed directly to minors by promoting ease of concealing the product or disguising it as another product; and products marketed with characters designed to appeal to youth,” according to the FDA statement.

As of May 12, FDA also will prioritize enforcement against any ENDS product for which the manufacturer has not submitted a premarket application. The agency will continue to exercise enforcement discretion for up to 1 year on these products if an application has been submitted, pending the review of that application.

“By not prioritizing enforcement against other flavored ENDS products in the same way as flavored cartridge-based ENDS products, the FDA has attempted to balance the public health concerns related to youth use of ENDS products with consideration regarding addicted adult cigarette smokers who may try to use ENDS products to transition away from combustible tobacco products,” the agency stated, adding that cartridge-based ENDS products are most commonly used among youth.

The FDA statement noted that the enforcement priorities outlined in the guidance document were not a “ban” on flavored or cartridge-based ENDS, noting the agency “has already accepted and begun review of several premarket applications for flavored ENDS products through the pathway that Congress established in the Tobacco Control Act. ... If a company can demonstrate to the FDA that a specific product meets the applicable standard set forth by Congress, including considering how the marketing of the product may affect youth initiation and use, then the FDA could authorize that product for sale.”

“Coupled with the recently signed legislation increasing the minimum age of sale of tobacco to 21, we believe this policy balances the urgency with which we must address the public health threat of youth use of e-cigarette products with the potential role that e-cigarettes may play in helping adult smokers transition completely away from combustible tobacco to a potentially less risky form of nicotine delivery,” FDA Commissioner Stephen Hahn, MD, said in a statement. “While we expect that responsible members of industry will comply with premarket requirements, we’re ready to take action against any unauthorized e-cigarette products as outlined in our priorities. We’ll also closely monitor the use rates of all e-cigarette products and take additional steps to address youth use as necessary.”

The American Medical Association criticized the action as not going far enough, even though it was a step in the right direction.

“The AMA is disappointed that menthol flavors, one of the most popular, will still be allowed, and that flavored e-liquids will remain on the market, leaving young people with easy access to alternative flavored e-cigarette products,” AMA President Patrice A. Harris, MD, said in a statement. “If we are serious about tackling this epidemic and keeping these harmful products out of the hands of young people, a total ban on all flavored e-cigarettes, in all forms and at all locations, is prudent and urgently needed. We are pleased the administration committed today to closely monitoring the situation and trends in e-cigarette use among young people, and to taking further action if needed.”

Down syndrome arthritis: Distinct from JIA and missed in the clinic

ATLANTA – Pediatric Down syndrome arthritis is more aggressive and severe than juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), but it’s underrecognized and undertreated, according to reports at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

“The vast majority of parents don’t know their kids are at risk for arthritis,” and a lot of doctors don’t realize it, either. Meanwhile, children show up in the clinic a year or more into the process with irreversible joint damage, said pediatric rheumatologist Jordan Jones, DO, an assistant professor at the University of Missouri, Kansas City, and the lead investigator on a review of 36 children with Down syndrome (DS) in the national Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance (CARRA) registry.

One solution is to add routine musculoskeletal exams to American Academy of Pediatrics DS guidelines, something Dr. Jones said he and his colleagues are hoping to do.

Part of the problem is that children with DS have a hard time articulating and localizing pain, and it’s easy to attribute functional issues to DS itself. Charlene Foley, MD, PhD, from the National Centre for Paediatric Rheumatology in Dublin, said she’s seen “loads of cases” in which parents were told that their children were acting up, probably because of the DS, when they didn’t want to walk down stairs anymore or hold their parent’s hand.

She was the lead investigator on an Irish program that screened 503 DS children, about one-third of the country’s pediatric DS population, for arthritis; 33 cases were identified, including 18 new ones. Most of the children had polyarticular, rheumatoid factor–negative arthritis, and all of them were antinuclear antibody negative.

A key take-home from the work is that DS arthritis preferentially attacks the hands and wrists and was present exclusively in the hands and wrists of about one-third of the Irish cohort. “So, if you only have a second to examine a child or you can’t get them to sit still, just go straight for the hands, and have a low threshold for imaging,” Dr. Foley said.

DS arthritis is often considered a subtype of JIA, but findings from the studies call that into question and suggest the need for novel therapeutic targets, the investigators said.

The Irish team found that 42% of their subjects (14 of 33) had joint erosions, far more than the 14% of JIA children (3 of 21) who served as controls, and Dr. Foley and colleagues didn’t think that was solely because of delayed diagnosis. Also, at about 20 cases per 1,000, they estimated that arthritis was far more prevalent in DS than was JIA in the general pediatrics population.

Disease onset was at a mean of 7.1 years in Dr. Jones’ CARRA registry review, and mean delay to diagnosis was 11.5 months. The 36 children presented with an average of four affected joints. Only 22% (8 of 36) had elevated inflammatory markers; just one-third were positive for antinuclear antibody, and 17% for human leukocyte antigen B27. It means that “these kids can present with normal labs, even with very aggressive disease. The threshold of concern for arthritis has to be very high when you evaluate these children,” Dr. Jones said.

Treatment was initiated with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) in two-thirds of the registry children, often with a concomitant biologic, most commonly etanercept. Over half had at least one switch during a mean follow-up of 4.5 years; methotrexate was a leading culprit, frequently discontinued because of nausea and other problems, and biologics were changed for lack of effect. Active joint counts and physician assessments improved, but there were no significant changes in limited joint counts and health assessments.

In short, “the current therapies for JIA appear to be poorly tolerated, more toxic, and less effective in patients with Down syndrome. These kids don’t respond the same. They have a very high disease burden despite being treated aggressively,” Dr. Jones said.

That finding adds additional weight to the idea that DS arthritis is a distinct disease entity, with unique therapeutic targets. “Down syndrome has a lot of immunologic issues associated with it; maybe that’s it. I think in the next few years, we will be able to show that this is a different disease,” Dr. Jones said.

There was a boost in that direction from benchwork, also led and presented by Dr. Foley, that found significant immunologic, histologic, and genetic differences between JIA and DS arthritis, including lower CD19- and CD20-positive B-cell counts in DS arthritis and higher interferon-gamma and tumor necrosis factor–alpha production, greater synovial lining hyperplasia, and different minor allele frequencies.

There was no industry funding for the studies, and the investigators didn’t have any industry disclosures.

SOURCES: Jones J et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(suppl 10), Abstract 2722; Foley C et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(suppl 10), Abstract 1817; and Foley C et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(suppl 10), Abstract 781

ATLANTA – Pediatric Down syndrome arthritis is more aggressive and severe than juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), but it’s underrecognized and undertreated, according to reports at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

“The vast majority of parents don’t know their kids are at risk for arthritis,” and a lot of doctors don’t realize it, either. Meanwhile, children show up in the clinic a year or more into the process with irreversible joint damage, said pediatric rheumatologist Jordan Jones, DO, an assistant professor at the University of Missouri, Kansas City, and the lead investigator on a review of 36 children with Down syndrome (DS) in the national Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance (CARRA) registry.

One solution is to add routine musculoskeletal exams to American Academy of Pediatrics DS guidelines, something Dr. Jones said he and his colleagues are hoping to do.

Part of the problem is that children with DS have a hard time articulating and localizing pain, and it’s easy to attribute functional issues to DS itself. Charlene Foley, MD, PhD, from the National Centre for Paediatric Rheumatology in Dublin, said she’s seen “loads of cases” in which parents were told that their children were acting up, probably because of the DS, when they didn’t want to walk down stairs anymore or hold their parent’s hand.

She was the lead investigator on an Irish program that screened 503 DS children, about one-third of the country’s pediatric DS population, for arthritis; 33 cases were identified, including 18 new ones. Most of the children had polyarticular, rheumatoid factor–negative arthritis, and all of them were antinuclear antibody negative.

A key take-home from the work is that DS arthritis preferentially attacks the hands and wrists and was present exclusively in the hands and wrists of about one-third of the Irish cohort. “So, if you only have a second to examine a child or you can’t get them to sit still, just go straight for the hands, and have a low threshold for imaging,” Dr. Foley said.

DS arthritis is often considered a subtype of JIA, but findings from the studies call that into question and suggest the need for novel therapeutic targets, the investigators said.

The Irish team found that 42% of their subjects (14 of 33) had joint erosions, far more than the 14% of JIA children (3 of 21) who served as controls, and Dr. Foley and colleagues didn’t think that was solely because of delayed diagnosis. Also, at about 20 cases per 1,000, they estimated that arthritis was far more prevalent in DS than was JIA in the general pediatrics population.

Disease onset was at a mean of 7.1 years in Dr. Jones’ CARRA registry review, and mean delay to diagnosis was 11.5 months. The 36 children presented with an average of four affected joints. Only 22% (8 of 36) had elevated inflammatory markers; just one-third were positive for antinuclear antibody, and 17% for human leukocyte antigen B27. It means that “these kids can present with normal labs, even with very aggressive disease. The threshold of concern for arthritis has to be very high when you evaluate these children,” Dr. Jones said.

Treatment was initiated with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) in two-thirds of the registry children, often with a concomitant biologic, most commonly etanercept. Over half had at least one switch during a mean follow-up of 4.5 years; methotrexate was a leading culprit, frequently discontinued because of nausea and other problems, and biologics were changed for lack of effect. Active joint counts and physician assessments improved, but there were no significant changes in limited joint counts and health assessments.

In short, “the current therapies for JIA appear to be poorly tolerated, more toxic, and less effective in patients with Down syndrome. These kids don’t respond the same. They have a very high disease burden despite being treated aggressively,” Dr. Jones said.

That finding adds additional weight to the idea that DS arthritis is a distinct disease entity, with unique therapeutic targets. “Down syndrome has a lot of immunologic issues associated with it; maybe that’s it. I think in the next few years, we will be able to show that this is a different disease,” Dr. Jones said.

There was a boost in that direction from benchwork, also led and presented by Dr. Foley, that found significant immunologic, histologic, and genetic differences between JIA and DS arthritis, including lower CD19- and CD20-positive B-cell counts in DS arthritis and higher interferon-gamma and tumor necrosis factor–alpha production, greater synovial lining hyperplasia, and different minor allele frequencies.

There was no industry funding for the studies, and the investigators didn’t have any industry disclosures.

SOURCES: Jones J et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(suppl 10), Abstract 2722; Foley C et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(suppl 10), Abstract 1817; and Foley C et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(suppl 10), Abstract 781

ATLANTA – Pediatric Down syndrome arthritis is more aggressive and severe than juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), but it’s underrecognized and undertreated, according to reports at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

“The vast majority of parents don’t know their kids are at risk for arthritis,” and a lot of doctors don’t realize it, either. Meanwhile, children show up in the clinic a year or more into the process with irreversible joint damage, said pediatric rheumatologist Jordan Jones, DO, an assistant professor at the University of Missouri, Kansas City, and the lead investigator on a review of 36 children with Down syndrome (DS) in the national Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance (CARRA) registry.

One solution is to add routine musculoskeletal exams to American Academy of Pediatrics DS guidelines, something Dr. Jones said he and his colleagues are hoping to do.

Part of the problem is that children with DS have a hard time articulating and localizing pain, and it’s easy to attribute functional issues to DS itself. Charlene Foley, MD, PhD, from the National Centre for Paediatric Rheumatology in Dublin, said she’s seen “loads of cases” in which parents were told that their children were acting up, probably because of the DS, when they didn’t want to walk down stairs anymore or hold their parent’s hand.

She was the lead investigator on an Irish program that screened 503 DS children, about one-third of the country’s pediatric DS population, for arthritis; 33 cases were identified, including 18 new ones. Most of the children had polyarticular, rheumatoid factor–negative arthritis, and all of them were antinuclear antibody negative.

A key take-home from the work is that DS arthritis preferentially attacks the hands and wrists and was present exclusively in the hands and wrists of about one-third of the Irish cohort. “So, if you only have a second to examine a child or you can’t get them to sit still, just go straight for the hands, and have a low threshold for imaging,” Dr. Foley said.

DS arthritis is often considered a subtype of JIA, but findings from the studies call that into question and suggest the need for novel therapeutic targets, the investigators said.

The Irish team found that 42% of their subjects (14 of 33) had joint erosions, far more than the 14% of JIA children (3 of 21) who served as controls, and Dr. Foley and colleagues didn’t think that was solely because of delayed diagnosis. Also, at about 20 cases per 1,000, they estimated that arthritis was far more prevalent in DS than was JIA in the general pediatrics population.

Disease onset was at a mean of 7.1 years in Dr. Jones’ CARRA registry review, and mean delay to diagnosis was 11.5 months. The 36 children presented with an average of four affected joints. Only 22% (8 of 36) had elevated inflammatory markers; just one-third were positive for antinuclear antibody, and 17% for human leukocyte antigen B27. It means that “these kids can present with normal labs, even with very aggressive disease. The threshold of concern for arthritis has to be very high when you evaluate these children,” Dr. Jones said.

Treatment was initiated with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) in two-thirds of the registry children, often with a concomitant biologic, most commonly etanercept. Over half had at least one switch during a mean follow-up of 4.5 years; methotrexate was a leading culprit, frequently discontinued because of nausea and other problems, and biologics were changed for lack of effect. Active joint counts and physician assessments improved, but there were no significant changes in limited joint counts and health assessments.

In short, “the current therapies for JIA appear to be poorly tolerated, more toxic, and less effective in patients with Down syndrome. These kids don’t respond the same. They have a very high disease burden despite being treated aggressively,” Dr. Jones said.

That finding adds additional weight to the idea that DS arthritis is a distinct disease entity, with unique therapeutic targets. “Down syndrome has a lot of immunologic issues associated with it; maybe that’s it. I think in the next few years, we will be able to show that this is a different disease,” Dr. Jones said.

There was a boost in that direction from benchwork, also led and presented by Dr. Foley, that found significant immunologic, histologic, and genetic differences between JIA and DS arthritis, including lower CD19- and CD20-positive B-cell counts in DS arthritis and higher interferon-gamma and tumor necrosis factor–alpha production, greater synovial lining hyperplasia, and different minor allele frequencies.

There was no industry funding for the studies, and the investigators didn’t have any industry disclosures.

SOURCES: Jones J et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(suppl 10), Abstract 2722; Foley C et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(suppl 10), Abstract 1817; and Foley C et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(suppl 10), Abstract 781

REPORTING FROM ACR 2019

Numerous Flesh-Colored Nodules on the Trunk

The Diagnosis: Steatocystoma Multiplex

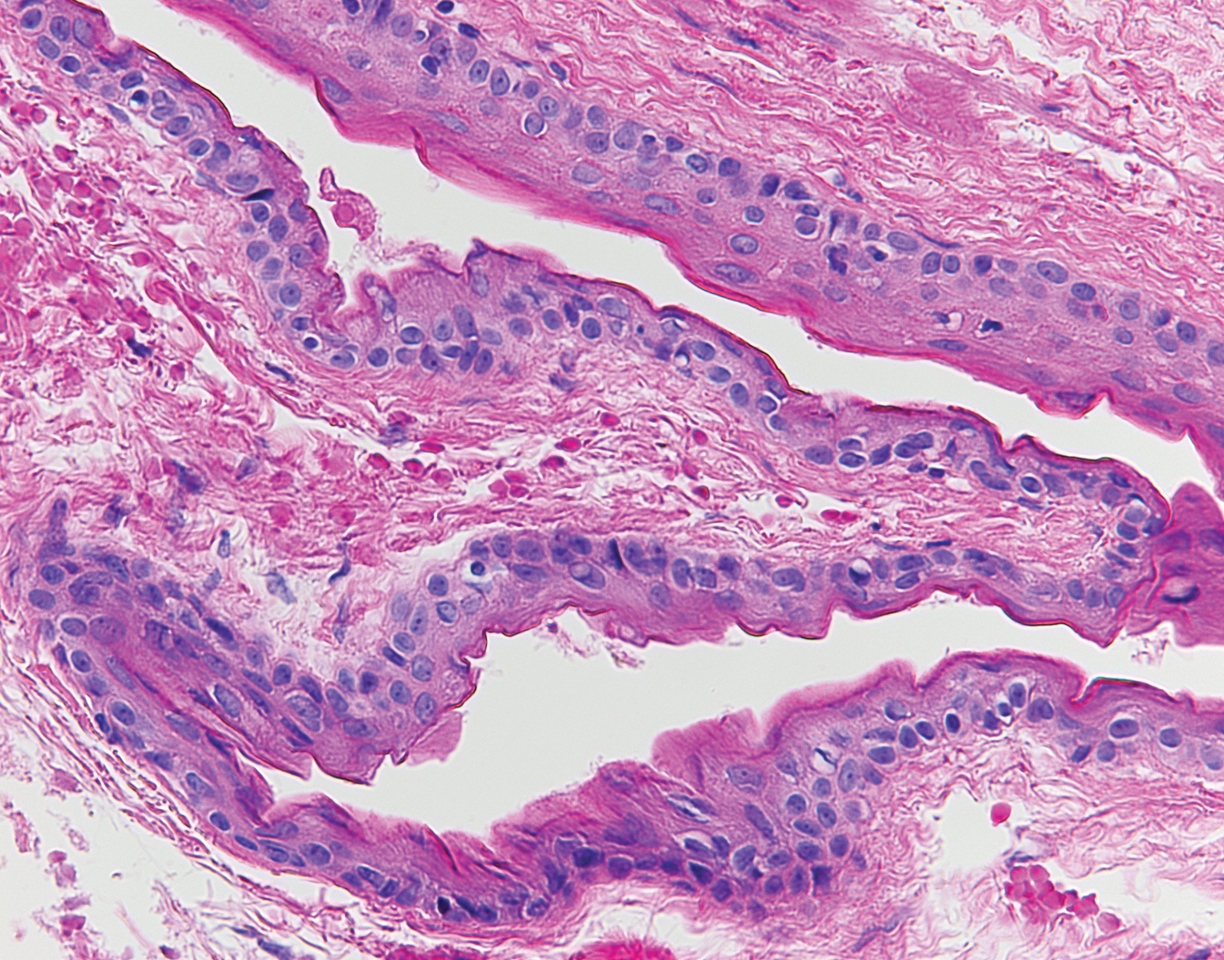

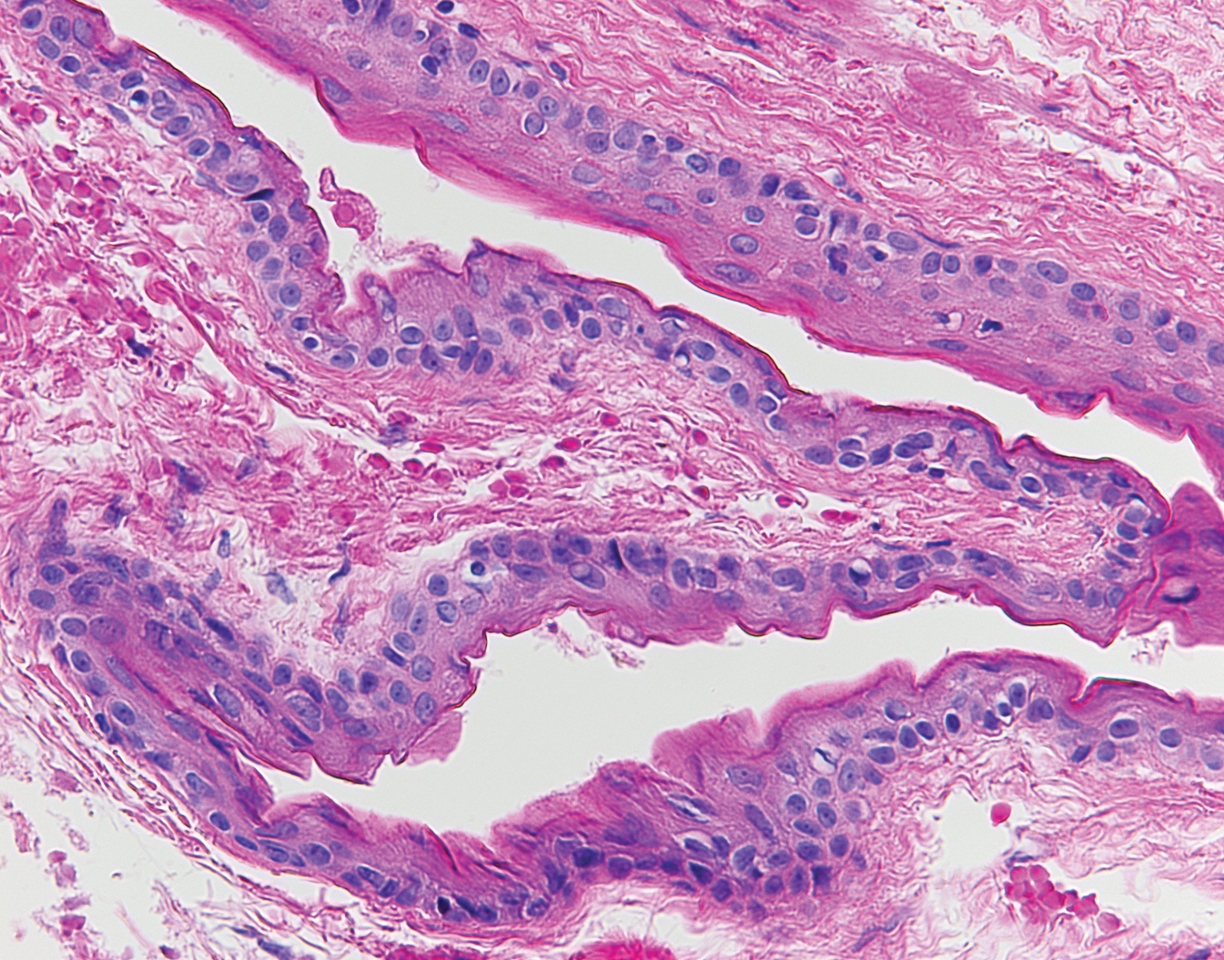

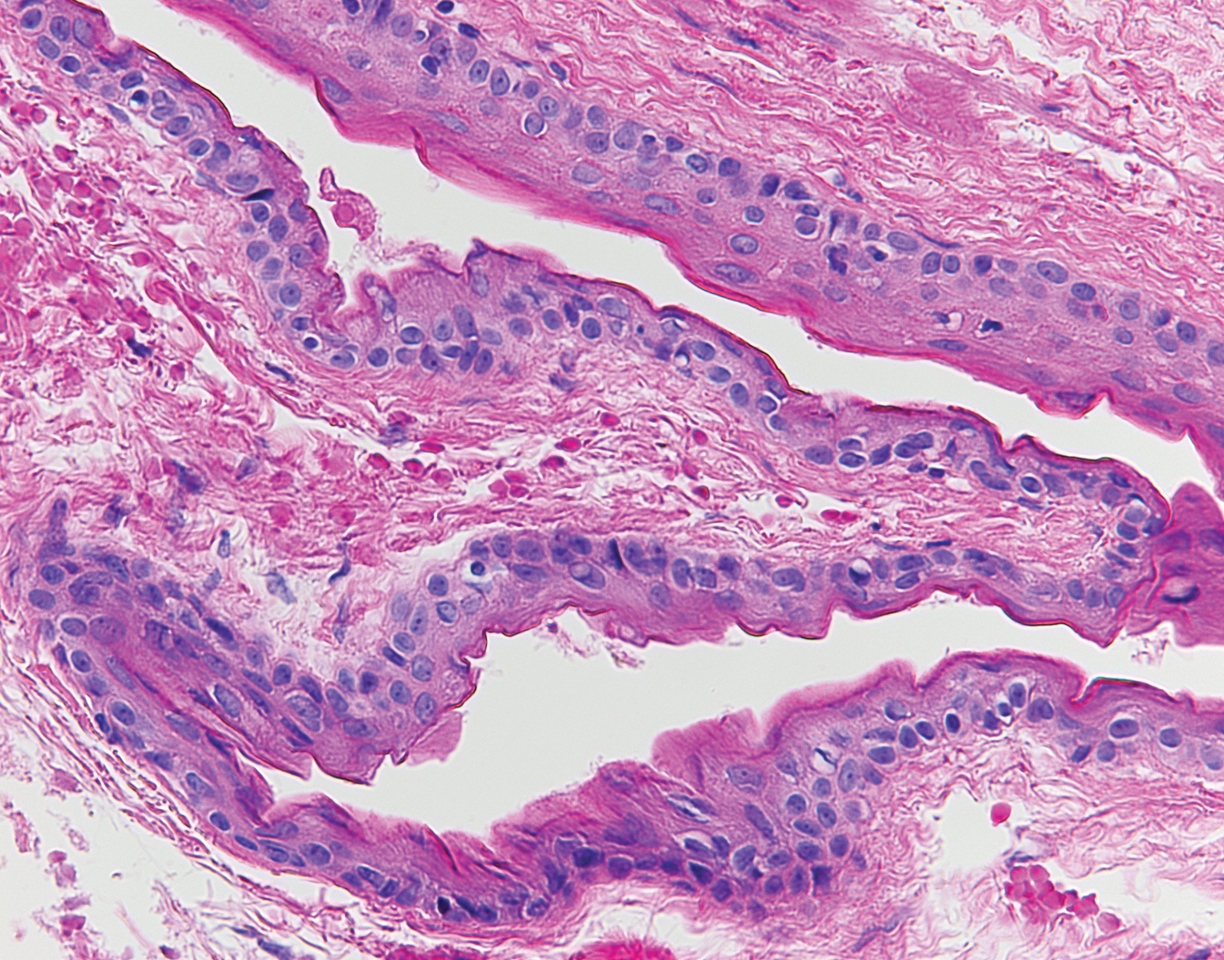

The punch biopsy of an abdominal lesion demonstrated a folded cyst wall with a wavy eosinophilic cuticle (Figure), characteristics consistent with steatocystoma multiplex (SM).

Also known as eruptive steatocystoma, SM consists of numerous flesh-colored, dome-shaped papules and nodules that most commonly arise during adolescence, with a median age of onset of 26 years.1 These hamartomatous nevoid malformations arise in areas with well-developed pilosebaceous units, such as the upper extremities, neck, axillae, and trunk.1,2 They occur less commonly on the scalp, face, and acral surfaces.2-5 The lesions range in size from 2 to 30 mm6 and usually are asymptomatic.1 Occasionally, steatocystomas become tender or can rupture.7

Steatocystoma multiplex may arise sporadically or may be inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion. Mutations in exon 1 of the keratin 17 gene, KRT17, have been identified in autosomal-dominant SM.6,8 KRT17 mutations also are responsible for pachyonychia congenita type 2, which is associated with SM.9 Some patients with pachyonychia congenita type 2 who have prominent SM and mild nail findings may be misdiagnosed as having pure SM.2

The histopathologic features of SM were described in a study by Cho and colleagues1 of 64 patients. Steatocystomas have cyst walls that may be either intricately folded or round/oval, comprised of an average of 4.9 epithelial cell layers. In most cases, the cyst wall contains sebaceous lobules. In all cases, an acellular eosinophilic cuticle was present, and no granular layer was seen. Few vellus hairs may be observed in the cystic cavity.1

The differential diagnosis of SM includes eruptive vellus hair cysts, lipomas, Muir-Torre syndrome, and Gardner syndrome. Some have suggested that eruptive vellus hair cysts and SM exist on a disease spectrum because of their similar clinical presentation.10 In contrast to SM, however, eruptive vellus hair cysts originate in the infundibulum of the hair shaft rather than the sebaceous duct, and more numerous vellus hair shafts are seen on histopathology.1

Various treatment modalities have been described, including isotretinoin for inflamed lesions,11 cryotherapy for noninflamed lesions,11 aspiration of lesions smallerthan 1 cm,12 and electrocautery combined with topical retinoids.13 Laser treatment has been described, with a 1450-nm diode laser used to target the abnormal sebaceous glands and a 1550-nm fractionated erbium-doped fiber laser used to target the dermal cysts.14 Carbon dioxide lasers also may be used to open the cyst for drainage.15 Surgical excision or mini-incision also may be performed.16,17

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Garth Fraga, MD (Kansas City, Kansas), for his assistance with interpretation of the dermatopathology in this case.

- Cho S, Chang SE, Choi JH, et al. Clinical and histologic features of 64 cases of steatocystoma multiplex. J Dermatol. 2002;29:152-156.

- Rollins T, Levin RM, Heymann WR. Acral steatocystoma multiplex.J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(2, pt 2):396-399.

- Setoyama M, Mizoguchi S, Usuki K, et al. Steatocystoma multiplex: a case with unusual clinical and histological manifestation. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:89-92.

- Cole LA. Steatocystoma multiplex. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:1437-1439.

- Marzano AV, Tavecchio S, Balice Y, et al. Acral subcutaneous steatocystoma multiplex: a distinct subtype of the disease? Australas J Dermatol. 2012;53:198-201.

- Liu Q, Wu W, Lu J, et al. Steatocystoma multiplex is associated with the R94C mutation in the KRTl7 gene. Mol Med Rep. 2015;12:5072-5076.

- Egbert BM, Price NM, Segal RJ. Steatocystoma multiplex. Report of a florid case and a review. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:334-335.

- Covello SP, Smith FJ, Sillevis Smitt JH, et al. Keratin 17 mutations cause either steatocystoma multiplex or pachyonychia congenita type 2. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:475-480.

- McLean WH, Rugg EL, Lunny DP, et al. Keratin 16 and keratin 17 mutations cause pachyonychia congenita. Nat Genet. 1995;9:273-278.

- Ohtake N, Kubota Y, Takayama O, et al. Relationship between steatocystoma multiplex and eruptive vellus hair cysts. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26(5, pt 2):876-878.

- Apaydin R, Bilen N, Bayramgurler D, et al. Steatocystoma multiplex suppurativum: oral isotretinoin treatment combined with cryotherapy. Australas J Dermatol. 2000;41:98-100.

- Sato K, Shibuya K, Taguchi H, et al. Aspiration therapy in steatocystoma multiplex. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:35-37.

- Papakonstantinou E, Franke I, Gollnick H. Facial steatocystoma multiplex combined with eruptive vellus hair cysts: a hybrid? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:2051-2053.

- Moody MN, Landau JM, Goldberg LH, et al. 1,450-nm diode laser in combination with the 1550-nm fractionated erbium-doped fiber laser for the treatment of steatocystoma multiplex: a case report. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38(7, pt 1):1104-1106.

- Rossi R, Cappugi P, Battini M, et al. CO2 laser therapy in a case of steatocystoma multiplex with prominent nodules on the face and neck. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:302-304.

- Schmook T, Burg G, Hafner J. Surgical pearl: mini-incisions for the extraction of steatocystoma multiplex. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:1041-1042.

- Adams BB, Mutasim DF, Nordlund JJ. Steatocystoma multiplex: a quick removal technique. Cutis. 1999;64:127-130.

The Diagnosis: Steatocystoma Multiplex

The punch biopsy of an abdominal lesion demonstrated a folded cyst wall with a wavy eosinophilic cuticle (Figure), characteristics consistent with steatocystoma multiplex (SM).

Also known as eruptive steatocystoma, SM consists of numerous flesh-colored, dome-shaped papules and nodules that most commonly arise during adolescence, with a median age of onset of 26 years.1 These hamartomatous nevoid malformations arise in areas with well-developed pilosebaceous units, such as the upper extremities, neck, axillae, and trunk.1,2 They occur less commonly on the scalp, face, and acral surfaces.2-5 The lesions range in size from 2 to 30 mm6 and usually are asymptomatic.1 Occasionally, steatocystomas become tender or can rupture.7

Steatocystoma multiplex may arise sporadically or may be inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion. Mutations in exon 1 of the keratin 17 gene, KRT17, have been identified in autosomal-dominant SM.6,8 KRT17 mutations also are responsible for pachyonychia congenita type 2, which is associated with SM.9 Some patients with pachyonychia congenita type 2 who have prominent SM and mild nail findings may be misdiagnosed as having pure SM.2

The histopathologic features of SM were described in a study by Cho and colleagues1 of 64 patients. Steatocystomas have cyst walls that may be either intricately folded or round/oval, comprised of an average of 4.9 epithelial cell layers. In most cases, the cyst wall contains sebaceous lobules. In all cases, an acellular eosinophilic cuticle was present, and no granular layer was seen. Few vellus hairs may be observed in the cystic cavity.1

The differential diagnosis of SM includes eruptive vellus hair cysts, lipomas, Muir-Torre syndrome, and Gardner syndrome. Some have suggested that eruptive vellus hair cysts and SM exist on a disease spectrum because of their similar clinical presentation.10 In contrast to SM, however, eruptive vellus hair cysts originate in the infundibulum of the hair shaft rather than the sebaceous duct, and more numerous vellus hair shafts are seen on histopathology.1

Various treatment modalities have been described, including isotretinoin for inflamed lesions,11 cryotherapy for noninflamed lesions,11 aspiration of lesions smallerthan 1 cm,12 and electrocautery combined with topical retinoids.13 Laser treatment has been described, with a 1450-nm diode laser used to target the abnormal sebaceous glands and a 1550-nm fractionated erbium-doped fiber laser used to target the dermal cysts.14 Carbon dioxide lasers also may be used to open the cyst for drainage.15 Surgical excision or mini-incision also may be performed.16,17

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Garth Fraga, MD (Kansas City, Kansas), for his assistance with interpretation of the dermatopathology in this case.

The Diagnosis: Steatocystoma Multiplex

The punch biopsy of an abdominal lesion demonstrated a folded cyst wall with a wavy eosinophilic cuticle (Figure), characteristics consistent with steatocystoma multiplex (SM).

Also known as eruptive steatocystoma, SM consists of numerous flesh-colored, dome-shaped papules and nodules that most commonly arise during adolescence, with a median age of onset of 26 years.1 These hamartomatous nevoid malformations arise in areas with well-developed pilosebaceous units, such as the upper extremities, neck, axillae, and trunk.1,2 They occur less commonly on the scalp, face, and acral surfaces.2-5 The lesions range in size from 2 to 30 mm6 and usually are asymptomatic.1 Occasionally, steatocystomas become tender or can rupture.7

Steatocystoma multiplex may arise sporadically or may be inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion. Mutations in exon 1 of the keratin 17 gene, KRT17, have been identified in autosomal-dominant SM.6,8 KRT17 mutations also are responsible for pachyonychia congenita type 2, which is associated with SM.9 Some patients with pachyonychia congenita type 2 who have prominent SM and mild nail findings may be misdiagnosed as having pure SM.2

The histopathologic features of SM were described in a study by Cho and colleagues1 of 64 patients. Steatocystomas have cyst walls that may be either intricately folded or round/oval, comprised of an average of 4.9 epithelial cell layers. In most cases, the cyst wall contains sebaceous lobules. In all cases, an acellular eosinophilic cuticle was present, and no granular layer was seen. Few vellus hairs may be observed in the cystic cavity.1

The differential diagnosis of SM includes eruptive vellus hair cysts, lipomas, Muir-Torre syndrome, and Gardner syndrome. Some have suggested that eruptive vellus hair cysts and SM exist on a disease spectrum because of their similar clinical presentation.10 In contrast to SM, however, eruptive vellus hair cysts originate in the infundibulum of the hair shaft rather than the sebaceous duct, and more numerous vellus hair shafts are seen on histopathology.1

Various treatment modalities have been described, including isotretinoin for inflamed lesions,11 cryotherapy for noninflamed lesions,11 aspiration of lesions smallerthan 1 cm,12 and electrocautery combined with topical retinoids.13 Laser treatment has been described, with a 1450-nm diode laser used to target the abnormal sebaceous glands and a 1550-nm fractionated erbium-doped fiber laser used to target the dermal cysts.14 Carbon dioxide lasers also may be used to open the cyst for drainage.15 Surgical excision or mini-incision also may be performed.16,17

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Garth Fraga, MD (Kansas City, Kansas), for his assistance with interpretation of the dermatopathology in this case.

- Cho S, Chang SE, Choi JH, et al. Clinical and histologic features of 64 cases of steatocystoma multiplex. J Dermatol. 2002;29:152-156.

- Rollins T, Levin RM, Heymann WR. Acral steatocystoma multiplex.J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(2, pt 2):396-399.

- Setoyama M, Mizoguchi S, Usuki K, et al. Steatocystoma multiplex: a case with unusual clinical and histological manifestation. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:89-92.

- Cole LA. Steatocystoma multiplex. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:1437-1439.

- Marzano AV, Tavecchio S, Balice Y, et al. Acral subcutaneous steatocystoma multiplex: a distinct subtype of the disease? Australas J Dermatol. 2012;53:198-201.

- Liu Q, Wu W, Lu J, et al. Steatocystoma multiplex is associated with the R94C mutation in the KRTl7 gene. Mol Med Rep. 2015;12:5072-5076.

- Egbert BM, Price NM, Segal RJ. Steatocystoma multiplex. Report of a florid case and a review. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:334-335.

- Covello SP, Smith FJ, Sillevis Smitt JH, et al. Keratin 17 mutations cause either steatocystoma multiplex or pachyonychia congenita type 2. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:475-480.

- McLean WH, Rugg EL, Lunny DP, et al. Keratin 16 and keratin 17 mutations cause pachyonychia congenita. Nat Genet. 1995;9:273-278.

- Ohtake N, Kubota Y, Takayama O, et al. Relationship between steatocystoma multiplex and eruptive vellus hair cysts. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26(5, pt 2):876-878.

- Apaydin R, Bilen N, Bayramgurler D, et al. Steatocystoma multiplex suppurativum: oral isotretinoin treatment combined with cryotherapy. Australas J Dermatol. 2000;41:98-100.

- Sato K, Shibuya K, Taguchi H, et al. Aspiration therapy in steatocystoma multiplex. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:35-37.

- Papakonstantinou E, Franke I, Gollnick H. Facial steatocystoma multiplex combined with eruptive vellus hair cysts: a hybrid? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:2051-2053.

- Moody MN, Landau JM, Goldberg LH, et al. 1,450-nm diode laser in combination with the 1550-nm fractionated erbium-doped fiber laser for the treatment of steatocystoma multiplex: a case report. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38(7, pt 1):1104-1106.

- Rossi R, Cappugi P, Battini M, et al. CO2 laser therapy in a case of steatocystoma multiplex with prominent nodules on the face and neck. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:302-304.

- Schmook T, Burg G, Hafner J. Surgical pearl: mini-incisions for the extraction of steatocystoma multiplex. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:1041-1042.

- Adams BB, Mutasim DF, Nordlund JJ. Steatocystoma multiplex: a quick removal technique. Cutis. 1999;64:127-130.

- Cho S, Chang SE, Choi JH, et al. Clinical and histologic features of 64 cases of steatocystoma multiplex. J Dermatol. 2002;29:152-156.

- Rollins T, Levin RM, Heymann WR. Acral steatocystoma multiplex.J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(2, pt 2):396-399.

- Setoyama M, Mizoguchi S, Usuki K, et al. Steatocystoma multiplex: a case with unusual clinical and histological manifestation. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:89-92.

- Cole LA. Steatocystoma multiplex. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:1437-1439.

- Marzano AV, Tavecchio S, Balice Y, et al. Acral subcutaneous steatocystoma multiplex: a distinct subtype of the disease? Australas J Dermatol. 2012;53:198-201.

- Liu Q, Wu W, Lu J, et al. Steatocystoma multiplex is associated with the R94C mutation in the KRTl7 gene. Mol Med Rep. 2015;12:5072-5076.

- Egbert BM, Price NM, Segal RJ. Steatocystoma multiplex. Report of a florid case and a review. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:334-335.

- Covello SP, Smith FJ, Sillevis Smitt JH, et al. Keratin 17 mutations cause either steatocystoma multiplex or pachyonychia congenita type 2. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:475-480.

- McLean WH, Rugg EL, Lunny DP, et al. Keratin 16 and keratin 17 mutations cause pachyonychia congenita. Nat Genet. 1995;9:273-278.

- Ohtake N, Kubota Y, Takayama O, et al. Relationship between steatocystoma multiplex and eruptive vellus hair cysts. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26(5, pt 2):876-878.

- Apaydin R, Bilen N, Bayramgurler D, et al. Steatocystoma multiplex suppurativum: oral isotretinoin treatment combined with cryotherapy. Australas J Dermatol. 2000;41:98-100.

- Sato K, Shibuya K, Taguchi H, et al. Aspiration therapy in steatocystoma multiplex. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:35-37.

- Papakonstantinou E, Franke I, Gollnick H. Facial steatocystoma multiplex combined with eruptive vellus hair cysts: a hybrid? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:2051-2053.

- Moody MN, Landau JM, Goldberg LH, et al. 1,450-nm diode laser in combination with the 1550-nm fractionated erbium-doped fiber laser for the treatment of steatocystoma multiplex: a case report. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38(7, pt 1):1104-1106.

- Rossi R, Cappugi P, Battini M, et al. CO2 laser therapy in a case of steatocystoma multiplex with prominent nodules on the face and neck. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:302-304.

- Schmook T, Burg G, Hafner J. Surgical pearl: mini-incisions for the extraction of steatocystoma multiplex. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:1041-1042.

- Adams BB, Mutasim DF, Nordlund JJ. Steatocystoma multiplex: a quick removal technique. Cutis. 1999;64:127-130.

A 33-year-old woman presented with numerous firm, noncompressible, flesh-colored nodules that measured 3 to 4 mm and were distributed across the abdomen, chest, back, and neck. The lesions had been present for approximately 10 years. The patient denied any lesion-associated pain, itching, or bleeding, and there was no family history of similar lesions. A punch biopsy of a lesion on the central abdomen was obtained.

New ustekinumab response predictor in Crohn’s called ‘brilliant’

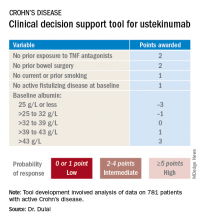

SAN ANTONIO – The probability of achieving clinical remission of Crohn’s disease in response to ustekinumab can now be readily estimated by using a clinical prediction tool, Parambir S. Dulai, MBBS, announced at the annual meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology.

This new clinical decision support tool also provides individualized stratification of the rapidity with which symptoms will be reduced in response to the anti-interleukin-12/23 biologic, added Dr. Dulai, a gastroenterologist at the University of California, San Diego.

He and his coinvestigators developed the prediction tool through analysis of detailed data on 781 patients with active Crohn’s disease treated with ustekinumab (Stelara) during both the induction and maintenance portions of the phase 3 UNITI randomized trials conducted in the biologic’s development program. The researchers identified a series of baseline features associated with clinical remission as defined by a Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (CDAI) score below 150 by week 16 of treatment. Through statistical manipulation, they transformed the data into a predictive model and then went one step further by turning the model into a decision support tool with points given for the individual predictive variables (see graphic).

Patients with 5 or more total points were categorized as having a high probability of week-16 clinical remission. Patients with 0 or 1 point were deemed low probability, and a score of 2-4 indicated an intermediate likelihood of clinical remission.

Next, the investigators applied their new clinical decision support tool to the 781 ustekinumab-treated patients included in the derivation analysis. The tool performed well: The high-probability group had a 57% clinical remission rate, significantly better than the 34% rate in the intermediate-probability group, which in turn was significantly better than the 21% rate of clinical remission in the group with a baseline score of 0 or 1.

In addition, onset of treatment benefit was significantly faster in the group having a score of 5 or more. They had a significantly higher clinical remission rate than the intermediate- and low-probability groups at all scheduled assessments, which were conducted at weeks 3, 6, 8, and 16. Indeed, by week 3 the high-probability group experienced a mean 69-point drop from baseline in CDAI and a 94-point drop by week 8, as compared with week-8 reductions of 54 and 40 points in the intermediate- and low-probability groups, respectively.

In an exploratory analysis involving the 122 patients who underwent week-8 endoscopy, endoscopic remission was documented in 12% of patients whose baseline scores placed them in the high-probability group, 10% in the intermediate group, and 8% of those in the low-probability group.

The high-probability group had significantly higher ustekinumab trough concentrations than did the intermediate- and low-probability groups when measured at weeks 3, 6, 8, and 16.

An external validation study conducted in a large cohort of Crohn’s disease patients seen in routine clinical practice has recently been completed, with the results now being analyzed, according to Dr. Dulai.

Miguel Requeiro, MD, chairman of gastroenterology and hepatology at the Cleveland Clinic, rose from the audience to declare the creation of the decision support tool to be “brilliant work.” He asked if it has changed clinical practice for Dr. Dulai and his coworkers.