User login

Research on statin for preeclampsia prevention advances

WASHINGTON – with a large National Institutes of Health–funded trial currently recruiting women with a prior history of the disorder with preterm delivery at less than 34 weeks, Maged Costantine, MD, said at the biennial Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America meeting.

More should be learned about low-dose aspirin, in the meantime, once the outcomes of a global study involving first-trimester initiation are published, said another speaker, Cynthia Gyamfi-Bannerman, MD, MS. Low-dose aspirin currently is recommended for preeclampsia prevention starting between 12 and 28 weeks, optimally before 16 weeks.

The biological plausibility of using pravastatin for preeclampsia prevention stems from the overlapping pathophysiology of preeclampsia with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease – endothelial dysfunction and inflammation are common key mechanisms – as well as common risk factors, including diabetes and obesity, said Dr. Costantine, director of the division of maternal-fetal medicine at Ohio State University, Columbus, who is chairing the study.

In animal models of preeclampsia, pravastatin has been shown to upregulate placental growth factor, reduce antiangiogenic factors such as soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFlt1), and upregulate endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Mice have shown improved vascular reactivity, decreased proteinuria, decreased oxidative stress, and other positive effects, without any detrimental outcomes.

A pilot randomized controlled trial conducted with the Obstetric-Fetal Pharmacology Research Units Network and published in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology in 2016 assigned 10 women to 10 mg daily pravastatin and 10 women to placebo. The drug reduced maternal cholesterol concentrations but there were no differences in birth weight or umbilical cord cholesterol concentrations between the two groups.

Women in the pravastatin group were less likely to develop preeclampsia (none, compared with four in the placebo group), less likely to have an indicated preterm delivery (one, compared with five in the placebo group), and less likely to have their neonates admitted to the neonatal ICU.

There were no differences in side effects, congenital anomalies, or other adverse events. Dr. Costantine, principal investigator of the pilot study, and his colleagues wrote in the paper that the “favorable risk-benefit analysis justifies continued research with a dose escalation” (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Jun;214[6]:720.e1-17).

The new multicenter randomized controlled trial is randomizing 1,550 women to either 20 mg pravastatin or placebo starting between 12 weeks 0 days and 16 weeks 6 days. The primary outcome is a composite of preeclampsia, maternal death, or fetal loss. Secondary outcomes include a composite of severe maternal morbidity and various measures representing preeclampsia severity and complications, as well as preterm delivery less than 37 weeks and less than 34 weeks and various fetal/neonatal outcomes.

“In addition, we’ll look at development,” Dr. Costantine said, with offspring assessed at 2 and 5 years of age. The trial is sponsored by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

In the meantime, he said, the use of pravastatin to ameliorate early-onset preeclampsia is being tested in a small European proof-of-concept trial that has randomized women with early-onset preeclampsia (between 24 and 31 6/7 weeks) to 40 mg pravastatin or placebo. The primary outcome is reduction of antiangiogenic markers. Results are expected in another year or 2, he said.

The aspirin trial referred to by Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman has been looking at the 81-mg dose of aspirin initiated between 6 0/7 and 13 6/7 weeks in nulliparous women who had no more than two previous pregnancy losses. The key question of the Aspirin Supplementation for Pregnancy Indicated Risk Reduction in Nulliparas (ASPIRIN) trial – conducted in the NICHD Global Network for Women’s and Children’s Health – is whether low-dose aspirin can reduce the rate of preterm birth. Preeclampsia is a secondary outcome (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02409680).

“It may eventually be that the use of baby aspirin is further expanded to reduce the risk of preterm birth,” she said.

Overall, “we need more data on first-trimester use [of low-dose aspirin] and long-term outcomes,” Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman said. And with respect to preeclampsia prevention specifically, more research is needed looking at risk reduction levels within specific groups of patients.

Since 2014, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) has called for low-dose aspirin at 81 mg/day in women who have one or more high-risk factors for preeclampsia (including type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus), and consideration of such treatment in patients with several moderate-risk factors. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ recommendation varies slightly in that it advises treatment in patients with more than one (versus several) moderate-level risk factors (Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132[1]:e44-52).

Moderate-level risk factors include nulliparity, obesity, family history of preeclampsia, a baseline demographic risk (African-American or low socioeconomic status), and prior poor history (intrauterine growth restriction/small-for-gestational-age, previous poor outcome). “This is just about everyone I see,” Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman said.

Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman said she’d “love to see more data on higher doses” of low-dose aspirin – data that compares 81 mg/day with 150 mg/day, for instance.

A study published in 2017 in the New England Journal of Medicine randomized 1,776 women at high risk for preeclampsia to 150 mg/day or placebo and found a significant reduction in preterm preeclampsia (4.3% vs. 1.6%) in the aspirin group. Women in this European trial were deemed to be at high risk, however, based on a first-trimester screening algorithm that incorporated serum markers (maternal serum pregnancy-associated plasma protein A and placental growth factor) and uterine artery Doppler measures (N Engl J Med. 2017 Aug 17;377[7]:613-22).

“So it was a very interesting study, very provocative, but it’s hard to know how it would translate to the U.S. population [given that such screening practices] are not the way most of us are practicing here,” said Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman, codirector of the Preterm Birth Prevention Center at Columbia University, New York, and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the university.

The USPSTF based its recommendations on a systematic review that pooled data from 15 high-quality randomized controlled trials, including 13 that reported preeclampsia incidence among women at highest risk of disease. They found a 24% reduction in preeclampsia, but the actual risk reduction depends on the baseline population risk and may be closer to 10%, she said.

In a presentation on gaps in knowledge, Leslie Myatt, PhD, of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, emphasized that preeclampsia is a syndrome with a heterogeneity of presentation and pathophysiology. “We don’t completely understand the pathophysiology,” he said.

Research needs to be “directed at the existence of multiple pathways [and subtypes],” he said, such that future therapies can be targeted and personalized.

Dr. Costantine did not report any disclosures. Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman reported a Society of Maternal Fetal Medicine/AMAG Pharmaceuticals unrestricted grant and Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development/National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute funding. Dr. Myatt reported that he has no financial or other ties that pose a conflict of interest.

WASHINGTON – with a large National Institutes of Health–funded trial currently recruiting women with a prior history of the disorder with preterm delivery at less than 34 weeks, Maged Costantine, MD, said at the biennial Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America meeting.

More should be learned about low-dose aspirin, in the meantime, once the outcomes of a global study involving first-trimester initiation are published, said another speaker, Cynthia Gyamfi-Bannerman, MD, MS. Low-dose aspirin currently is recommended for preeclampsia prevention starting between 12 and 28 weeks, optimally before 16 weeks.

The biological plausibility of using pravastatin for preeclampsia prevention stems from the overlapping pathophysiology of preeclampsia with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease – endothelial dysfunction and inflammation are common key mechanisms – as well as common risk factors, including diabetes and obesity, said Dr. Costantine, director of the division of maternal-fetal medicine at Ohio State University, Columbus, who is chairing the study.

In animal models of preeclampsia, pravastatin has been shown to upregulate placental growth factor, reduce antiangiogenic factors such as soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFlt1), and upregulate endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Mice have shown improved vascular reactivity, decreased proteinuria, decreased oxidative stress, and other positive effects, without any detrimental outcomes.

A pilot randomized controlled trial conducted with the Obstetric-Fetal Pharmacology Research Units Network and published in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology in 2016 assigned 10 women to 10 mg daily pravastatin and 10 women to placebo. The drug reduced maternal cholesterol concentrations but there were no differences in birth weight or umbilical cord cholesterol concentrations between the two groups.

Women in the pravastatin group were less likely to develop preeclampsia (none, compared with four in the placebo group), less likely to have an indicated preterm delivery (one, compared with five in the placebo group), and less likely to have their neonates admitted to the neonatal ICU.

There were no differences in side effects, congenital anomalies, or other adverse events. Dr. Costantine, principal investigator of the pilot study, and his colleagues wrote in the paper that the “favorable risk-benefit analysis justifies continued research with a dose escalation” (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Jun;214[6]:720.e1-17).

The new multicenter randomized controlled trial is randomizing 1,550 women to either 20 mg pravastatin or placebo starting between 12 weeks 0 days and 16 weeks 6 days. The primary outcome is a composite of preeclampsia, maternal death, or fetal loss. Secondary outcomes include a composite of severe maternal morbidity and various measures representing preeclampsia severity and complications, as well as preterm delivery less than 37 weeks and less than 34 weeks and various fetal/neonatal outcomes.

“In addition, we’ll look at development,” Dr. Costantine said, with offspring assessed at 2 and 5 years of age. The trial is sponsored by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

In the meantime, he said, the use of pravastatin to ameliorate early-onset preeclampsia is being tested in a small European proof-of-concept trial that has randomized women with early-onset preeclampsia (between 24 and 31 6/7 weeks) to 40 mg pravastatin or placebo. The primary outcome is reduction of antiangiogenic markers. Results are expected in another year or 2, he said.

The aspirin trial referred to by Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman has been looking at the 81-mg dose of aspirin initiated between 6 0/7 and 13 6/7 weeks in nulliparous women who had no more than two previous pregnancy losses. The key question of the Aspirin Supplementation for Pregnancy Indicated Risk Reduction in Nulliparas (ASPIRIN) trial – conducted in the NICHD Global Network for Women’s and Children’s Health – is whether low-dose aspirin can reduce the rate of preterm birth. Preeclampsia is a secondary outcome (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02409680).

“It may eventually be that the use of baby aspirin is further expanded to reduce the risk of preterm birth,” she said.

Overall, “we need more data on first-trimester use [of low-dose aspirin] and long-term outcomes,” Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman said. And with respect to preeclampsia prevention specifically, more research is needed looking at risk reduction levels within specific groups of patients.

Since 2014, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) has called for low-dose aspirin at 81 mg/day in women who have one or more high-risk factors for preeclampsia (including type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus), and consideration of such treatment in patients with several moderate-risk factors. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ recommendation varies slightly in that it advises treatment in patients with more than one (versus several) moderate-level risk factors (Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132[1]:e44-52).

Moderate-level risk factors include nulliparity, obesity, family history of preeclampsia, a baseline demographic risk (African-American or low socioeconomic status), and prior poor history (intrauterine growth restriction/small-for-gestational-age, previous poor outcome). “This is just about everyone I see,” Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman said.

Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman said she’d “love to see more data on higher doses” of low-dose aspirin – data that compares 81 mg/day with 150 mg/day, for instance.

A study published in 2017 in the New England Journal of Medicine randomized 1,776 women at high risk for preeclampsia to 150 mg/day or placebo and found a significant reduction in preterm preeclampsia (4.3% vs. 1.6%) in the aspirin group. Women in this European trial were deemed to be at high risk, however, based on a first-trimester screening algorithm that incorporated serum markers (maternal serum pregnancy-associated plasma protein A and placental growth factor) and uterine artery Doppler measures (N Engl J Med. 2017 Aug 17;377[7]:613-22).

“So it was a very interesting study, very provocative, but it’s hard to know how it would translate to the U.S. population [given that such screening practices] are not the way most of us are practicing here,” said Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman, codirector of the Preterm Birth Prevention Center at Columbia University, New York, and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the university.

The USPSTF based its recommendations on a systematic review that pooled data from 15 high-quality randomized controlled trials, including 13 that reported preeclampsia incidence among women at highest risk of disease. They found a 24% reduction in preeclampsia, but the actual risk reduction depends on the baseline population risk and may be closer to 10%, she said.

In a presentation on gaps in knowledge, Leslie Myatt, PhD, of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, emphasized that preeclampsia is a syndrome with a heterogeneity of presentation and pathophysiology. “We don’t completely understand the pathophysiology,” he said.

Research needs to be “directed at the existence of multiple pathways [and subtypes],” he said, such that future therapies can be targeted and personalized.

Dr. Costantine did not report any disclosures. Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman reported a Society of Maternal Fetal Medicine/AMAG Pharmaceuticals unrestricted grant and Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development/National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute funding. Dr. Myatt reported that he has no financial or other ties that pose a conflict of interest.

WASHINGTON – with a large National Institutes of Health–funded trial currently recruiting women with a prior history of the disorder with preterm delivery at less than 34 weeks, Maged Costantine, MD, said at the biennial Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America meeting.

More should be learned about low-dose aspirin, in the meantime, once the outcomes of a global study involving first-trimester initiation are published, said another speaker, Cynthia Gyamfi-Bannerman, MD, MS. Low-dose aspirin currently is recommended for preeclampsia prevention starting between 12 and 28 weeks, optimally before 16 weeks.

The biological plausibility of using pravastatin for preeclampsia prevention stems from the overlapping pathophysiology of preeclampsia with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease – endothelial dysfunction and inflammation are common key mechanisms – as well as common risk factors, including diabetes and obesity, said Dr. Costantine, director of the division of maternal-fetal medicine at Ohio State University, Columbus, who is chairing the study.

In animal models of preeclampsia, pravastatin has been shown to upregulate placental growth factor, reduce antiangiogenic factors such as soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFlt1), and upregulate endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Mice have shown improved vascular reactivity, decreased proteinuria, decreased oxidative stress, and other positive effects, without any detrimental outcomes.

A pilot randomized controlled trial conducted with the Obstetric-Fetal Pharmacology Research Units Network and published in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology in 2016 assigned 10 women to 10 mg daily pravastatin and 10 women to placebo. The drug reduced maternal cholesterol concentrations but there were no differences in birth weight or umbilical cord cholesterol concentrations between the two groups.

Women in the pravastatin group were less likely to develop preeclampsia (none, compared with four in the placebo group), less likely to have an indicated preterm delivery (one, compared with five in the placebo group), and less likely to have their neonates admitted to the neonatal ICU.

There were no differences in side effects, congenital anomalies, or other adverse events. Dr. Costantine, principal investigator of the pilot study, and his colleagues wrote in the paper that the “favorable risk-benefit analysis justifies continued research with a dose escalation” (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Jun;214[6]:720.e1-17).

The new multicenter randomized controlled trial is randomizing 1,550 women to either 20 mg pravastatin or placebo starting between 12 weeks 0 days and 16 weeks 6 days. The primary outcome is a composite of preeclampsia, maternal death, or fetal loss. Secondary outcomes include a composite of severe maternal morbidity and various measures representing preeclampsia severity and complications, as well as preterm delivery less than 37 weeks and less than 34 weeks and various fetal/neonatal outcomes.

“In addition, we’ll look at development,” Dr. Costantine said, with offspring assessed at 2 and 5 years of age. The trial is sponsored by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

In the meantime, he said, the use of pravastatin to ameliorate early-onset preeclampsia is being tested in a small European proof-of-concept trial that has randomized women with early-onset preeclampsia (between 24 and 31 6/7 weeks) to 40 mg pravastatin or placebo. The primary outcome is reduction of antiangiogenic markers. Results are expected in another year or 2, he said.

The aspirin trial referred to by Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman has been looking at the 81-mg dose of aspirin initiated between 6 0/7 and 13 6/7 weeks in nulliparous women who had no more than two previous pregnancy losses. The key question of the Aspirin Supplementation for Pregnancy Indicated Risk Reduction in Nulliparas (ASPIRIN) trial – conducted in the NICHD Global Network for Women’s and Children’s Health – is whether low-dose aspirin can reduce the rate of preterm birth. Preeclampsia is a secondary outcome (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02409680).

“It may eventually be that the use of baby aspirin is further expanded to reduce the risk of preterm birth,” she said.

Overall, “we need more data on first-trimester use [of low-dose aspirin] and long-term outcomes,” Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman said. And with respect to preeclampsia prevention specifically, more research is needed looking at risk reduction levels within specific groups of patients.

Since 2014, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) has called for low-dose aspirin at 81 mg/day in women who have one or more high-risk factors for preeclampsia (including type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus), and consideration of such treatment in patients with several moderate-risk factors. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ recommendation varies slightly in that it advises treatment in patients with more than one (versus several) moderate-level risk factors (Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132[1]:e44-52).

Moderate-level risk factors include nulliparity, obesity, family history of preeclampsia, a baseline demographic risk (African-American or low socioeconomic status), and prior poor history (intrauterine growth restriction/small-for-gestational-age, previous poor outcome). “This is just about everyone I see,” Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman said.

Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman said she’d “love to see more data on higher doses” of low-dose aspirin – data that compares 81 mg/day with 150 mg/day, for instance.

A study published in 2017 in the New England Journal of Medicine randomized 1,776 women at high risk for preeclampsia to 150 mg/day or placebo and found a significant reduction in preterm preeclampsia (4.3% vs. 1.6%) in the aspirin group. Women in this European trial were deemed to be at high risk, however, based on a first-trimester screening algorithm that incorporated serum markers (maternal serum pregnancy-associated plasma protein A and placental growth factor) and uterine artery Doppler measures (N Engl J Med. 2017 Aug 17;377[7]:613-22).

“So it was a very interesting study, very provocative, but it’s hard to know how it would translate to the U.S. population [given that such screening practices] are not the way most of us are practicing here,” said Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman, codirector of the Preterm Birth Prevention Center at Columbia University, New York, and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the university.

The USPSTF based its recommendations on a systematic review that pooled data from 15 high-quality randomized controlled trials, including 13 that reported preeclampsia incidence among women at highest risk of disease. They found a 24% reduction in preeclampsia, but the actual risk reduction depends on the baseline population risk and may be closer to 10%, she said.

In a presentation on gaps in knowledge, Leslie Myatt, PhD, of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, emphasized that preeclampsia is a syndrome with a heterogeneity of presentation and pathophysiology. “We don’t completely understand the pathophysiology,” he said.

Research needs to be “directed at the existence of multiple pathways [and subtypes],” he said, such that future therapies can be targeted and personalized.

Dr. Costantine did not report any disclosures. Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman reported a Society of Maternal Fetal Medicine/AMAG Pharmaceuticals unrestricted grant and Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development/National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute funding. Dr. Myatt reported that he has no financial or other ties that pose a conflict of interest.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE DPSG-NA 2019

SimLEARN Musculoskeletal Training for VHA Primary Care Providers and Health Professions Educators

Diseases of the musculoskeletal (MSK) system are common, accounting for some of the most frequent visits to primary care clinics.1-3 In addition, care for patients with chronic MSK diseases represents a substantial economic burden.4-6

In response to this clinical training need, the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) developed a portfolio of educational experiences for VHA health care providers and trainees, including both the Salt Lake City and National MSK “mini-residencies.”17-19 These programs have educated more than 800 individuals. Early observations show a progressive increase in the number of joint injections performed at participant’s VHA clinics as well as a reduction in unnecessary magnetic resonance imaging orders of the knee.20,21 These findings may be interpreted as markers for improved access to care for veterans as well as cost savings for the health care system.

The success of these early initiatives was recognized by the medical leadership of the VHA Simulation Learning, Education and Research Network (SimLEARN), who requested the Mini-Residency course directors to implement a similar educational program at the National Simulation Center in Orlando, Florida. SimLEARN was created to promote best practices in learning and education and provides a high-tech immersive environment for the development and delivery of simulation-based training curricula to facilitate workforce development.22 This article describes the initial experience of the VHA SimLEARN MSK continuing professional development (CPD) training programs, including curriculum design and educational impact on early learners, and how this informed additional CPD needs to continue advancing MSK education and care.

Methods

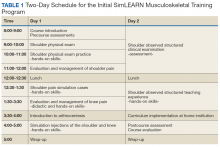

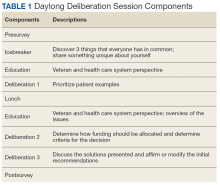

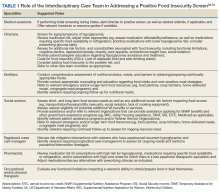

The initial vision was inspired by the national MSK Mini-Residency initiative for PCPs, which involved 13 US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers; its development, dissemination, and validity evidence for assessment methods have been previously described.17,18,23 SimLEARN leadership attended a Mini-Residency, observing the educational experience and identifying learning objectives most aligned with national goals. The director and codirector of the MSK Mini-Residency (MJB, AMB) then worked with SimLEARN using its educational platform and train-the-trainer model to create a condensed 2-day course, centered on primary care evaluation and management of shoulder and knee pain. The course also included elements supporting educational leaders in providing similar trainings at their local facility (Table 1).

Curriculum was introduced through didactics and reinforced in hands-on sessions enhanced by peer-teaching, arthrocentesis task trainers, and simulated patient experiences. At the end of day 1, participants engaged in critical reflection, reviewing knowledge and skills they had acquired.

On day 2, each participant was evaluated using an observed structured clinical examination (OSCE) for the shoulder, followed by an observed structured teaching experience (OSTE). Given the complexity of the physical examination and the greater potential for appropriate interpretation of clinical findings to influence best practice care, the shoulder was emphasized for these experiences. Time constraints of a 2-day program based on SimLEARN format requirements prevented including an additional OSCE for the knee. At the conclusion of the course, faculty and participants discussed strategies for bringing this educational experience to learners at their local facilities as well as for avoiding potential barriers to implementation. The course was accredited through the VHA Employee Education System (EES), and participants received 16 hours of CPD credit.

Participants

Opportunity to attend was communicated through national, regional, and local VHA organizational networks. Participants self-registered online through the VHA Talent Management System, the main learning resource for VHA employee education, and registration was open to both PCPs and clinician educators. Class size was limited to 10 to facilitate detailed faculty observation during skill acquisition experiences, simulations, and assessment exercises.

Program Evaluation

A standard process for evaluating and measuring learning objectives was performed through VHA EES. Self-assessment surveys and OSCEs were used to assess the activity.

Self-assessment surveys were administered at the beginning and end of the program. Content was adapted from that used in the national MSK Mini-Residency initiative and revised by experts in survey design.18,24,25 Pre- and postcourse surveys asked participants to rate how important it was for them to be competent in evaluating shoulder and knee pain and in performing related joint injections, as well as to rate their level of confidence in their ability to evaluate and manage these conditions. The survey used 5 construct-specific response options distributed equally on a visual scale. Participants’ learning goals were collected on the precourse survey.

Participants’ competence in performing and interpreting a systematic and thorough physical examination of the shoulder and in suggesting a reasonable plan of management were assessed using a single-station OSCE. This tool, which presented learners with a simulated case depicting rotator cuff pathology, has been described in multiple educational settings, and validity evidence supporting its use has been published.18,19,23 Course faculty conducted the OSCE, one as the simulated patient, the other as the rater. Immediately following the examination, both faculty conducted a debriefing session with each participant. The OSCE was scored using the validated checklist for specific elements of the shoulder exam, followed by a structured sequence of questions exploring participants’ interpretation of findings, diagnostic impressions, and recommendations for initial management. Scores for participants’ differential diagnosis were based on the completeness and specificity of diagnoses given; scores for management plans were based on appropriateness and accuracy of both the primary and secondary approach to treatment or further diagnostic efforts. A global rating (range 1 to 9) was assigned, independent of scores in other domains.

Following the OSCE, participants rotated through a 3-cycle OSTE where they practiced the roles of simulated patient, learner, and educator. Faculty observed each OSTE and led focused debriefing sessions immediately following each rotation to facilitate participants’ critical reflection of their involvement in these elements of the course. This exercise was formative without quantitative assessment of performance.

Statistical Analysis

Pre- and postsurvey data were analyzed using a paired Student t test. Comparisons between multiple variables (eg, OSCE scores by years of experience or level of credentials) were analyzed using analysis of variance. Relationships between variables were analyzed with a Pearson correlation. All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS, Version 24 (Armonk, NY).

This project was reviewed by the institutional review board of the University of Utah and the Salt Lake City VA and was determined to be exempt from review because the work did not meet the definition of research with human subjects and was considered a quality improvement study.

Results

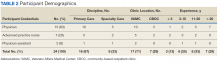

Twenty-four participants completed the program over 3 course offerings between February and May 2016, and all completed pre- and postcourse self-assessment surveys (Table 2). Self-ratings of the importance of competence in shoulder and knee MSK skills remained high before and after the course, and confidence improved significantly across all learning objectives. Despite the emphasis on the evaluation and management of shoulder pain, participants’ self-confidence still improved significantly with the knee—though these improvements were generally smaller in scale compared with those of the shoulder.

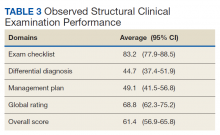

Overall OSCE scores and scores by domain were not found to be statistically different based on either years of experience or by level of credential or specialty (advanced practice registered nurse/physician assistant, PCP, or specialty care physician)(Table 3). However, there was a trend toward higher performance among the specialty care physician group, and a trend toward lower performance among participants with less than 3 years’ experience.

Discussion

Building on the foundation of other successful innovations in MSK education, the first year of the SimLEARN National MSK Training Program demonstrated the feasibility of a 2-day centralized national course as a method to increase participants’ confidence and competence in evaluating and managing MSK problems, and to disseminate a portable curriculum to a range of clinician educators. Although this course focused on developing competence for shoulder skills, including an OSCE on day 2, self-perceived improvements in participants’ ability to evaluate and manage knee pain were observed. Future program refinement and follow-up of participants’ experience and needs may lead to increased time allocated to the knee exam as well as objective measures of competence for knee skills.

In comparing our findings to the work that others have previously described, we looked for reports of CPD programs in 2 contexts: those that focused on acquisition of MSK skills relevant to clinical practice, and those designed as clinician educator or faculty development initiatives. Although there are few reports of MSK-themed CPD experiences designed specifically for nurses and allied health professionals, a recent effort to survey members of these disciplines in the United Kingdom was an important contribution to a systematic needs assessment.26-28 Increased support from leadership, mostly in terms of time allowance and budgetary support, was identified as an important driver to facilitate participation in MSK CPD experiences. Through SimLEARN, the VHA is investing in CPD, providing the MSK Training Programs and other courses at no cost to its employees.

Most published reports on physician education have not evaluated content knowledge or physical examination skills with measures for which validity evidence has been published.19,29,30 One notable exception is the 2000 Canadian Viscosupplementation Injector Preceptor experience, in which Bellamy and colleagues examined patient outcomes in evaluating their program.31

Our experience is congruent with the work of Macedo and colleagues and Sturpe and colleagues, who described the effectiveness and acceptability of an OSTE for faculty development.32,33 These studies emphasize debriefing, a critical element in faculty development identified by Steinert and colleagues in a 2006 best evidence medical education (BEME) review.34 The shoulder OSTE was one of the most well-received elements of our course, and each debrief was critical to facilitating rich discussions between educators and practitioners playing the role of teacher or student during this simulated experience, gaining insight into each other’s perspectives.

This program has several significant strengths: First, this is the most recent step in the development of a portfolio of innovative MSK CPD programs that were envisioned through a systematic process involving projections of cost-effectiveness, local pilot testing, and national expansion.17,18,35 Second, the SimLEARN program uses assessment tools for which validity evidence has been published, made available for reflective critique by educational scholars.19,23 This supports a national consortium of MSK educators, advancing clinical teaching and educational scholarship, and creating opportunities for interprofessional collaboration in congruence with the vision expressed in the 2010 Institute of Medicine report, “Redesigning Continuing Education in the Health Professions,” as well as the 2016 update of the BEME recommendations for faculty development.36,37

Our experience with the SimLEARN National MSK Training Program demonstrates need for 2 distinct courses: (1) the MSK Clinician—serving PCPs seeking to develop their skills in evaluating and managing patients with MSK problems; and (2), the MSK Master Educator—for those with preexisting content expertise who would value the introduction to a national curriculum and connections with other MSK master educators. Both of these are now offered regularly through SimLEARN for VHA and US Department of Defense employees. The MSK Clinician program establishes competence in systematically evaluating and managing shoulder and knee MSK problems in an educational setting and prepares participants for subsequent clinical experiences where they can perform related procedures if desired, under appropriate supervision. The Master Educator program introduces partici pants to the clinician curriculum and provides the opportunity to develop an individualized plan for implementation of an MSK educational program at their home institutions. Participants are selected through a competitive application process, and funding for travel to attend the Master Educator program is provided by SimLEARN for participants who are accepted. Additionally, the Master Educator program serves as a repository for potential future SimLEARN MSK Clinician course faculty.

Limitations

The small number of participants may limit the validity of our conclusions. Although we included an OSCE to measure competence in performing and interpreting the shoulder exam, the durability of these skills is not known. Periodic postcourse OSCEs could help determine this and refresh and preserve accuracy in the performance of specific maneuvers. Second, although this experience was rated highly by participants, we do not know the impact of the program on their daily work or career trajectory. Sustained follow-up of learners, perhaps developed on the model of the Long-Term Career Outcome Study, may increase the value of this experience for future participants.38 This program appealed to a diverse pool of learners, with a broad range of precourse expertise and varied expectations of how course experiences would impact their future work and career development. Some clinical educator attendees came from tertiary care facilities affiliated with academic medical centers, held specialist or subspecialist credentials, and had formal responsibilities as leaders in HPE. Other clinical practitioner participants were solitary PCPs, often in rural or home-based settings; although they may have been eager to apply new knowledge and skills in patient care, they neither anticipated nor desired any role as an educator.

Conclusion

The initial SimLEARN MSK Training Program provides PCPs and clinician educators with rich learning experiences, increasing confidence in addressing MSK problems and competence in performing and interpreting a systematic physical examination of the shoulder. The success of this program has created new opportunities for practitioners seeking to strengthen clinical skills and for leaders in health professions education looking to disseminate similar trainings and connect with a national group of educators.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the faculty and staff at the Veterans Health Administration SimLEARN National Simulation Center, the faculty of the Salt Lake City Musculoskeletal Mini-Residency program, the supportive leadership of the George E. Wahlen Salt Lake City Veterans Affairs Medical Center, and the efforts of Danielle Blake for logistical support and data entry.

1. Helmick CG, Felson DT, Lawrence RC, et al; National Arthritis Data Workgroup. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part I. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(1):15-25.

2. Lawrence RC, Felson DT, Helmick CG, et al; National Arthritis Data Workgroup. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part II. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(1):26-35.

3. Sacks JJ, Luo YH, Helmick CG. Prevalence of specific types of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the ambulatory health care system in the United States, 2001-2005. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2010;62(4):460-464.

4. Gupta S, Hawker GA, Laporte A, Croxford R, Coyte PC. The economic burden of disabling hip and knee osteoarthritis (OA) from the perspective of individuals living with this condition. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2005;44(12):1531-1537.

5. Gore M, Tai KS, Sadosky A, Leslie D, Stacey BR. Clinical comorbidities, treatment patterns, and direct medical costs of patients with osteoarthritis in usual care: a retrospective claims database analysis. J Med Econ. 2011;14(4):497-507.

6. Rabenda V, Manette C, Lemmens R, Mariani AM, Struvay N, Reginster JY. Direct and indirect costs attributable to osteoarthritis in active subjects. J Rheumatol. 2006;33(6):1152-1158.

7. Day CS, Yeh AC. Evidence of educational inadequacies in region-specific musculoskeletal medicine. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466(10):2542-2547.

8. Glazier RH, Dalby DM, Badley EM, Hawker GA, Bell MJ, Buchbinder R. Determinants of physician confidence in the primary care management of musculoskeletal disorders. J Rheumatol. 1996;23(2):351-356.

9. Haywood BL, Porter SL, Grana WA. Assessment of musculoskeletal knowledge in primary care residents. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2006;35(6):273-275.

10. Monrad SU, Zeller JL, Craig CL, Diponio LA. Musculoskeletal education in US medical schools: lessons from the past and suggestions for the future. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2011;4(3):91-98.

11. O’Dunn-Orto A, Hartling L, Campbell S, Oswald AE. Teaching musculoskeletal clinical skills to medical trainees and physicians: a Best Evidence in Medical Education systematic review of strategies and their effectiveness: BEME Guide No. 18. Med Teach. 2012;34(2):93-102.

12. Wilcox T, Oyler J, Harada C, Utset T. Musculoskeletal exam and joint injection training for internal medicine residents. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(5):521-523.

13. Petron DJ, Greis PE, Aoki SK, et al. Use of knee magnetic resonance imaging by primary care physicians in patients aged 40 years and older. Sports Health. 2010;2(5):385-390.

14. Roberts TT, Singer N, Hushmendy S, et al. MRI for the evaluation of knee pain: comparison of ordering practices of primary care physicians and orthopaedic surgeons. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97(9):709-714.

15. Wylie JD, Crim JR, Working ZM, Schmidt RL, Burks RT. Physician provider type influences utilization and diagnostic utility of magnetic resonance imaging of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97(1):56-62.

16. Smith M, Saunders R, Stuckhardt L, McGinnis JM, eds. Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America. Washington, DC; 2013.

17. Battistone MJ, Barker AM, Lawrence P, Grotzke MP, Cannon GW. Mini-residency in musculoskeletal care: an interprofessional, mixed-methods educational initiative for primary care providers. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2016;68(2):275-279.

18. Battistone MJ, Barker AM, Grotzke MP, Beck JP, Lawrence P, Cannon GW. “Mini-residency” in musculoskeletal care: a national continuing professional development program for primary care providers. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(11):1301-1307.

19. Battistone MJ, Barker AM, Grotzke MP, et al. Effectiveness of an interprofessional and multidisciplinary musculoskeletal training program. J Grad Med Educ. 2016;8(3):398-404.

20. Battistone MJ, Barker AM, Lawrence P, Grotzke M, Cannon GW. Two-year impact of a continuing professional education program to train primary care providers to perform arthrocentesis. Presented at: 2017 ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting [Abstract 909]. https://acrabstracts.org/abstract/two-year-impact-of-a-continuing-professional-education-program-to-train-primary-care-providers-to-perform-arthrocentesis. Accessed November 14, 2019.

21. Call MR, Barker AM, Lawrence P, Cannon GW, Battistone MJ. Impact of a musculoskeltal “mini-residency” continuing professional education program on knee mri orders by primary care providers. Presented at: 2015 ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting [Abstract 1011]. https://acrabstracts.org/abstract/impact-of-a-musculoskeletal-aeoemini-residencyae%ef%bf%bd-continuing-professional-education-program-on-knee-mri-orders-by-primary-care-providers. Accessed November 14, 2019.

22. US Department of Veterans Affairs. VHA SimLEARN. https://www.simlearn.va.gov/SIMLEARN/about_us.asp. Updated January 24, 2019. Accessed November 13, 2019.

23. Battistone MJ, Barker AM, Beck JP, Tashjian RZ, Cannon GW. Validity evidence for two objective structured clinical examination stations to evaluate core skills of the shoulder and knee assessment. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17(1):13.

24. Artino AR Jr, La Rochelle JS, Dezee KJ, Gehlbach H. Developing questionnaires for educational research: AMEE Guide No. 87. Med Teach. 2014;36(6):463-474.

25. Gehlbach H, Artino AR Jr. The survey checklist (Manifesto). Acad Med. 2018;93(3):360-366.

26. Haywood H, Pain H, Ryan S, Adams J. The continuing professional development for nurses and allied health professionals working within musculoskeletal services: a national UK survey. Musculoskeletal Care. 2013;11(2):63-70.

27. Haywood H, Pain H, Ryan S, Adams J. Continuing professional development: issues raised by nurses and allied health professionals working in musculoskeletal settings. Musculoskeletal Care. 2013;11(3):136-144.

28. Warburton L. Continuing professional development in musculoskeletal domains. Musculoskeletal Care. 2012;10(3):125-126.

29. Stansfield RB, Diponio L, Craig C, et al. Assessing musculoskeletal examination skills and diagnostic reasoning of 4th year medical students using a novel objective structured clinical exam. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16(1):268.

30. Hose MK, Fontanesi J, Woytowitz M, Jarrin D, Quan A. Competency based clinical shoulder examination training improves physical exam, confidence, and knowledge in common shoulder conditions. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(11):1261-1265.

31. Bellamy N, Goldstein LD, Tekanoff RA. Continuing medical education-driven skills acquisition and impact on improved patient outcomes in family practice setting. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2000;20(1):52-61.

32. Macedo L, Sturpe DA, Haines ST, Layson-Wolf C, Tofade TS, McPherson ML. An objective structured teaching exercise (OSTE) for preceptor development. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2015;7(5):627-634.

33. Sturpe DA, Schaivone KA. A primer for objective structured teaching exercises. Am J Pharm Educ. 2014;78(5):104.

34. Steinert Y, Mann K, Centeno A, et al. A systematic review of faculty development initiatives designed to improve teaching effectiveness in medical education: BEME Guide No. 8. Med Teach. 2006;28(6):497-526.

35. Nelson SD, Nelson RE, Cannon GW, et al. Cost-effectiveness of training rural providers to identify and treat patients at risk for fragility fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2014;25(12):2701-2707.

36. Steinert Y, Mann K, Anderson B, et al. A systematic review of faculty development initiatives designed to enhance teaching effectiveness: A 10-year update: BEME Guide No. 40. Med Teach. 2016;38(8):769-786.

37. Institute of Medicine. Redesigning Continuing Education in the Health Professions. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2010.

38. Durning SJ, Dong T, LaRochelle JL, et al. The long-term career outcome study: lessons learned and implications for educational practice. Mil Med. 2015;180(suppl 4):164-170.

Diseases of the musculoskeletal (MSK) system are common, accounting for some of the most frequent visits to primary care clinics.1-3 In addition, care for patients with chronic MSK diseases represents a substantial economic burden.4-6

In response to this clinical training need, the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) developed a portfolio of educational experiences for VHA health care providers and trainees, including both the Salt Lake City and National MSK “mini-residencies.”17-19 These programs have educated more than 800 individuals. Early observations show a progressive increase in the number of joint injections performed at participant’s VHA clinics as well as a reduction in unnecessary magnetic resonance imaging orders of the knee.20,21 These findings may be interpreted as markers for improved access to care for veterans as well as cost savings for the health care system.

The success of these early initiatives was recognized by the medical leadership of the VHA Simulation Learning, Education and Research Network (SimLEARN), who requested the Mini-Residency course directors to implement a similar educational program at the National Simulation Center in Orlando, Florida. SimLEARN was created to promote best practices in learning and education and provides a high-tech immersive environment for the development and delivery of simulation-based training curricula to facilitate workforce development.22 This article describes the initial experience of the VHA SimLEARN MSK continuing professional development (CPD) training programs, including curriculum design and educational impact on early learners, and how this informed additional CPD needs to continue advancing MSK education and care.

Methods

The initial vision was inspired by the national MSK Mini-Residency initiative for PCPs, which involved 13 US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers; its development, dissemination, and validity evidence for assessment methods have been previously described.17,18,23 SimLEARN leadership attended a Mini-Residency, observing the educational experience and identifying learning objectives most aligned with national goals. The director and codirector of the MSK Mini-Residency (MJB, AMB) then worked with SimLEARN using its educational platform and train-the-trainer model to create a condensed 2-day course, centered on primary care evaluation and management of shoulder and knee pain. The course also included elements supporting educational leaders in providing similar trainings at their local facility (Table 1).

Curriculum was introduced through didactics and reinforced in hands-on sessions enhanced by peer-teaching, arthrocentesis task trainers, and simulated patient experiences. At the end of day 1, participants engaged in critical reflection, reviewing knowledge and skills they had acquired.

On day 2, each participant was evaluated using an observed structured clinical examination (OSCE) for the shoulder, followed by an observed structured teaching experience (OSTE). Given the complexity of the physical examination and the greater potential for appropriate interpretation of clinical findings to influence best practice care, the shoulder was emphasized for these experiences. Time constraints of a 2-day program based on SimLEARN format requirements prevented including an additional OSCE for the knee. At the conclusion of the course, faculty and participants discussed strategies for bringing this educational experience to learners at their local facilities as well as for avoiding potential barriers to implementation. The course was accredited through the VHA Employee Education System (EES), and participants received 16 hours of CPD credit.

Participants

Opportunity to attend was communicated through national, regional, and local VHA organizational networks. Participants self-registered online through the VHA Talent Management System, the main learning resource for VHA employee education, and registration was open to both PCPs and clinician educators. Class size was limited to 10 to facilitate detailed faculty observation during skill acquisition experiences, simulations, and assessment exercises.

Program Evaluation

A standard process for evaluating and measuring learning objectives was performed through VHA EES. Self-assessment surveys and OSCEs were used to assess the activity.

Self-assessment surveys were administered at the beginning and end of the program. Content was adapted from that used in the national MSK Mini-Residency initiative and revised by experts in survey design.18,24,25 Pre- and postcourse surveys asked participants to rate how important it was for them to be competent in evaluating shoulder and knee pain and in performing related joint injections, as well as to rate their level of confidence in their ability to evaluate and manage these conditions. The survey used 5 construct-specific response options distributed equally on a visual scale. Participants’ learning goals were collected on the precourse survey.

Participants’ competence in performing and interpreting a systematic and thorough physical examination of the shoulder and in suggesting a reasonable plan of management were assessed using a single-station OSCE. This tool, which presented learners with a simulated case depicting rotator cuff pathology, has been described in multiple educational settings, and validity evidence supporting its use has been published.18,19,23 Course faculty conducted the OSCE, one as the simulated patient, the other as the rater. Immediately following the examination, both faculty conducted a debriefing session with each participant. The OSCE was scored using the validated checklist for specific elements of the shoulder exam, followed by a structured sequence of questions exploring participants’ interpretation of findings, diagnostic impressions, and recommendations for initial management. Scores for participants’ differential diagnosis were based on the completeness and specificity of diagnoses given; scores for management plans were based on appropriateness and accuracy of both the primary and secondary approach to treatment or further diagnostic efforts. A global rating (range 1 to 9) was assigned, independent of scores in other domains.

Following the OSCE, participants rotated through a 3-cycle OSTE where they practiced the roles of simulated patient, learner, and educator. Faculty observed each OSTE and led focused debriefing sessions immediately following each rotation to facilitate participants’ critical reflection of their involvement in these elements of the course. This exercise was formative without quantitative assessment of performance.

Statistical Analysis

Pre- and postsurvey data were analyzed using a paired Student t test. Comparisons between multiple variables (eg, OSCE scores by years of experience or level of credentials) were analyzed using analysis of variance. Relationships between variables were analyzed with a Pearson correlation. All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS, Version 24 (Armonk, NY).

This project was reviewed by the institutional review board of the University of Utah and the Salt Lake City VA and was determined to be exempt from review because the work did not meet the definition of research with human subjects and was considered a quality improvement study.

Results

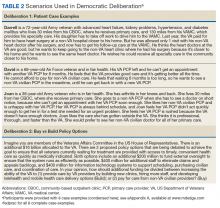

Twenty-four participants completed the program over 3 course offerings between February and May 2016, and all completed pre- and postcourse self-assessment surveys (Table 2). Self-ratings of the importance of competence in shoulder and knee MSK skills remained high before and after the course, and confidence improved significantly across all learning objectives. Despite the emphasis on the evaluation and management of shoulder pain, participants’ self-confidence still improved significantly with the knee—though these improvements were generally smaller in scale compared with those of the shoulder.

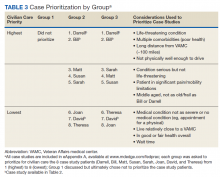

Overall OSCE scores and scores by domain were not found to be statistically different based on either years of experience or by level of credential or specialty (advanced practice registered nurse/physician assistant, PCP, or specialty care physician)(Table 3). However, there was a trend toward higher performance among the specialty care physician group, and a trend toward lower performance among participants with less than 3 years’ experience.

Discussion

Building on the foundation of other successful innovations in MSK education, the first year of the SimLEARN National MSK Training Program demonstrated the feasibility of a 2-day centralized national course as a method to increase participants’ confidence and competence in evaluating and managing MSK problems, and to disseminate a portable curriculum to a range of clinician educators. Although this course focused on developing competence for shoulder skills, including an OSCE on day 2, self-perceived improvements in participants’ ability to evaluate and manage knee pain were observed. Future program refinement and follow-up of participants’ experience and needs may lead to increased time allocated to the knee exam as well as objective measures of competence for knee skills.

In comparing our findings to the work that others have previously described, we looked for reports of CPD programs in 2 contexts: those that focused on acquisition of MSK skills relevant to clinical practice, and those designed as clinician educator or faculty development initiatives. Although there are few reports of MSK-themed CPD experiences designed specifically for nurses and allied health professionals, a recent effort to survey members of these disciplines in the United Kingdom was an important contribution to a systematic needs assessment.26-28 Increased support from leadership, mostly in terms of time allowance and budgetary support, was identified as an important driver to facilitate participation in MSK CPD experiences. Through SimLEARN, the VHA is investing in CPD, providing the MSK Training Programs and other courses at no cost to its employees.

Most published reports on physician education have not evaluated content knowledge or physical examination skills with measures for which validity evidence has been published.19,29,30 One notable exception is the 2000 Canadian Viscosupplementation Injector Preceptor experience, in which Bellamy and colleagues examined patient outcomes in evaluating their program.31

Our experience is congruent with the work of Macedo and colleagues and Sturpe and colleagues, who described the effectiveness and acceptability of an OSTE for faculty development.32,33 These studies emphasize debriefing, a critical element in faculty development identified by Steinert and colleagues in a 2006 best evidence medical education (BEME) review.34 The shoulder OSTE was one of the most well-received elements of our course, and each debrief was critical to facilitating rich discussions between educators and practitioners playing the role of teacher or student during this simulated experience, gaining insight into each other’s perspectives.

This program has several significant strengths: First, this is the most recent step in the development of a portfolio of innovative MSK CPD programs that were envisioned through a systematic process involving projections of cost-effectiveness, local pilot testing, and national expansion.17,18,35 Second, the SimLEARN program uses assessment tools for which validity evidence has been published, made available for reflective critique by educational scholars.19,23 This supports a national consortium of MSK educators, advancing clinical teaching and educational scholarship, and creating opportunities for interprofessional collaboration in congruence with the vision expressed in the 2010 Institute of Medicine report, “Redesigning Continuing Education in the Health Professions,” as well as the 2016 update of the BEME recommendations for faculty development.36,37

Our experience with the SimLEARN National MSK Training Program demonstrates need for 2 distinct courses: (1) the MSK Clinician—serving PCPs seeking to develop their skills in evaluating and managing patients with MSK problems; and (2), the MSK Master Educator—for those with preexisting content expertise who would value the introduction to a national curriculum and connections with other MSK master educators. Both of these are now offered regularly through SimLEARN for VHA and US Department of Defense employees. The MSK Clinician program establishes competence in systematically evaluating and managing shoulder and knee MSK problems in an educational setting and prepares participants for subsequent clinical experiences where they can perform related procedures if desired, under appropriate supervision. The Master Educator program introduces partici pants to the clinician curriculum and provides the opportunity to develop an individualized plan for implementation of an MSK educational program at their home institutions. Participants are selected through a competitive application process, and funding for travel to attend the Master Educator program is provided by SimLEARN for participants who are accepted. Additionally, the Master Educator program serves as a repository for potential future SimLEARN MSK Clinician course faculty.

Limitations

The small number of participants may limit the validity of our conclusions. Although we included an OSCE to measure competence in performing and interpreting the shoulder exam, the durability of these skills is not known. Periodic postcourse OSCEs could help determine this and refresh and preserve accuracy in the performance of specific maneuvers. Second, although this experience was rated highly by participants, we do not know the impact of the program on their daily work or career trajectory. Sustained follow-up of learners, perhaps developed on the model of the Long-Term Career Outcome Study, may increase the value of this experience for future participants.38 This program appealed to a diverse pool of learners, with a broad range of precourse expertise and varied expectations of how course experiences would impact their future work and career development. Some clinical educator attendees came from tertiary care facilities affiliated with academic medical centers, held specialist or subspecialist credentials, and had formal responsibilities as leaders in HPE. Other clinical practitioner participants were solitary PCPs, often in rural or home-based settings; although they may have been eager to apply new knowledge and skills in patient care, they neither anticipated nor desired any role as an educator.

Conclusion

The initial SimLEARN MSK Training Program provides PCPs and clinician educators with rich learning experiences, increasing confidence in addressing MSK problems and competence in performing and interpreting a systematic physical examination of the shoulder. The success of this program has created new opportunities for practitioners seeking to strengthen clinical skills and for leaders in health professions education looking to disseminate similar trainings and connect with a national group of educators.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the faculty and staff at the Veterans Health Administration SimLEARN National Simulation Center, the faculty of the Salt Lake City Musculoskeletal Mini-Residency program, the supportive leadership of the George E. Wahlen Salt Lake City Veterans Affairs Medical Center, and the efforts of Danielle Blake for logistical support and data entry.

Diseases of the musculoskeletal (MSK) system are common, accounting for some of the most frequent visits to primary care clinics.1-3 In addition, care for patients with chronic MSK diseases represents a substantial economic burden.4-6

In response to this clinical training need, the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) developed a portfolio of educational experiences for VHA health care providers and trainees, including both the Salt Lake City and National MSK “mini-residencies.”17-19 These programs have educated more than 800 individuals. Early observations show a progressive increase in the number of joint injections performed at participant’s VHA clinics as well as a reduction in unnecessary magnetic resonance imaging orders of the knee.20,21 These findings may be interpreted as markers for improved access to care for veterans as well as cost savings for the health care system.

The success of these early initiatives was recognized by the medical leadership of the VHA Simulation Learning, Education and Research Network (SimLEARN), who requested the Mini-Residency course directors to implement a similar educational program at the National Simulation Center in Orlando, Florida. SimLEARN was created to promote best practices in learning and education and provides a high-tech immersive environment for the development and delivery of simulation-based training curricula to facilitate workforce development.22 This article describes the initial experience of the VHA SimLEARN MSK continuing professional development (CPD) training programs, including curriculum design and educational impact on early learners, and how this informed additional CPD needs to continue advancing MSK education and care.

Methods

The initial vision was inspired by the national MSK Mini-Residency initiative for PCPs, which involved 13 US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers; its development, dissemination, and validity evidence for assessment methods have been previously described.17,18,23 SimLEARN leadership attended a Mini-Residency, observing the educational experience and identifying learning objectives most aligned with national goals. The director and codirector of the MSK Mini-Residency (MJB, AMB) then worked with SimLEARN using its educational platform and train-the-trainer model to create a condensed 2-day course, centered on primary care evaluation and management of shoulder and knee pain. The course also included elements supporting educational leaders in providing similar trainings at their local facility (Table 1).

Curriculum was introduced through didactics and reinforced in hands-on sessions enhanced by peer-teaching, arthrocentesis task trainers, and simulated patient experiences. At the end of day 1, participants engaged in critical reflection, reviewing knowledge and skills they had acquired.

On day 2, each participant was evaluated using an observed structured clinical examination (OSCE) for the shoulder, followed by an observed structured teaching experience (OSTE). Given the complexity of the physical examination and the greater potential for appropriate interpretation of clinical findings to influence best practice care, the shoulder was emphasized for these experiences. Time constraints of a 2-day program based on SimLEARN format requirements prevented including an additional OSCE for the knee. At the conclusion of the course, faculty and participants discussed strategies for bringing this educational experience to learners at their local facilities as well as for avoiding potential barriers to implementation. The course was accredited through the VHA Employee Education System (EES), and participants received 16 hours of CPD credit.

Participants

Opportunity to attend was communicated through national, regional, and local VHA organizational networks. Participants self-registered online through the VHA Talent Management System, the main learning resource for VHA employee education, and registration was open to both PCPs and clinician educators. Class size was limited to 10 to facilitate detailed faculty observation during skill acquisition experiences, simulations, and assessment exercises.

Program Evaluation

A standard process for evaluating and measuring learning objectives was performed through VHA EES. Self-assessment surveys and OSCEs were used to assess the activity.

Self-assessment surveys were administered at the beginning and end of the program. Content was adapted from that used in the national MSK Mini-Residency initiative and revised by experts in survey design.18,24,25 Pre- and postcourse surveys asked participants to rate how important it was for them to be competent in evaluating shoulder and knee pain and in performing related joint injections, as well as to rate their level of confidence in their ability to evaluate and manage these conditions. The survey used 5 construct-specific response options distributed equally on a visual scale. Participants’ learning goals were collected on the precourse survey.

Participants’ competence in performing and interpreting a systematic and thorough physical examination of the shoulder and in suggesting a reasonable plan of management were assessed using a single-station OSCE. This tool, which presented learners with a simulated case depicting rotator cuff pathology, has been described in multiple educational settings, and validity evidence supporting its use has been published.18,19,23 Course faculty conducted the OSCE, one as the simulated patient, the other as the rater. Immediately following the examination, both faculty conducted a debriefing session with each participant. The OSCE was scored using the validated checklist for specific elements of the shoulder exam, followed by a structured sequence of questions exploring participants’ interpretation of findings, diagnostic impressions, and recommendations for initial management. Scores for participants’ differential diagnosis were based on the completeness and specificity of diagnoses given; scores for management plans were based on appropriateness and accuracy of both the primary and secondary approach to treatment or further diagnostic efforts. A global rating (range 1 to 9) was assigned, independent of scores in other domains.

Following the OSCE, participants rotated through a 3-cycle OSTE where they practiced the roles of simulated patient, learner, and educator. Faculty observed each OSTE and led focused debriefing sessions immediately following each rotation to facilitate participants’ critical reflection of their involvement in these elements of the course. This exercise was formative without quantitative assessment of performance.

Statistical Analysis

Pre- and postsurvey data were analyzed using a paired Student t test. Comparisons between multiple variables (eg, OSCE scores by years of experience or level of credentials) were analyzed using analysis of variance. Relationships between variables were analyzed with a Pearson correlation. All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS, Version 24 (Armonk, NY).

This project was reviewed by the institutional review board of the University of Utah and the Salt Lake City VA and was determined to be exempt from review because the work did not meet the definition of research with human subjects and was considered a quality improvement study.

Results

Twenty-four participants completed the program over 3 course offerings between February and May 2016, and all completed pre- and postcourse self-assessment surveys (Table 2). Self-ratings of the importance of competence in shoulder and knee MSK skills remained high before and after the course, and confidence improved significantly across all learning objectives. Despite the emphasis on the evaluation and management of shoulder pain, participants’ self-confidence still improved significantly with the knee—though these improvements were generally smaller in scale compared with those of the shoulder.

Overall OSCE scores and scores by domain were not found to be statistically different based on either years of experience or by level of credential or specialty (advanced practice registered nurse/physician assistant, PCP, or specialty care physician)(Table 3). However, there was a trend toward higher performance among the specialty care physician group, and a trend toward lower performance among participants with less than 3 years’ experience.

Discussion

Building on the foundation of other successful innovations in MSK education, the first year of the SimLEARN National MSK Training Program demonstrated the feasibility of a 2-day centralized national course as a method to increase participants’ confidence and competence in evaluating and managing MSK problems, and to disseminate a portable curriculum to a range of clinician educators. Although this course focused on developing competence for shoulder skills, including an OSCE on day 2, self-perceived improvements in participants’ ability to evaluate and manage knee pain were observed. Future program refinement and follow-up of participants’ experience and needs may lead to increased time allocated to the knee exam as well as objective measures of competence for knee skills.

In comparing our findings to the work that others have previously described, we looked for reports of CPD programs in 2 contexts: those that focused on acquisition of MSK skills relevant to clinical practice, and those designed as clinician educator or faculty development initiatives. Although there are few reports of MSK-themed CPD experiences designed specifically for nurses and allied health professionals, a recent effort to survey members of these disciplines in the United Kingdom was an important contribution to a systematic needs assessment.26-28 Increased support from leadership, mostly in terms of time allowance and budgetary support, was identified as an important driver to facilitate participation in MSK CPD experiences. Through SimLEARN, the VHA is investing in CPD, providing the MSK Training Programs and other courses at no cost to its employees.

Most published reports on physician education have not evaluated content knowledge or physical examination skills with measures for which validity evidence has been published.19,29,30 One notable exception is the 2000 Canadian Viscosupplementation Injector Preceptor experience, in which Bellamy and colleagues examined patient outcomes in evaluating their program.31

Our experience is congruent with the work of Macedo and colleagues and Sturpe and colleagues, who described the effectiveness and acceptability of an OSTE for faculty development.32,33 These studies emphasize debriefing, a critical element in faculty development identified by Steinert and colleagues in a 2006 best evidence medical education (BEME) review.34 The shoulder OSTE was one of the most well-received elements of our course, and each debrief was critical to facilitating rich discussions between educators and practitioners playing the role of teacher or student during this simulated experience, gaining insight into each other’s perspectives.

This program has several significant strengths: First, this is the most recent step in the development of a portfolio of innovative MSK CPD programs that were envisioned through a systematic process involving projections of cost-effectiveness, local pilot testing, and national expansion.17,18,35 Second, the SimLEARN program uses assessment tools for which validity evidence has been published, made available for reflective critique by educational scholars.19,23 This supports a national consortium of MSK educators, advancing clinical teaching and educational scholarship, and creating opportunities for interprofessional collaboration in congruence with the vision expressed in the 2010 Institute of Medicine report, “Redesigning Continuing Education in the Health Professions,” as well as the 2016 update of the BEME recommendations for faculty development.36,37

Our experience with the SimLEARN National MSK Training Program demonstrates need for 2 distinct courses: (1) the MSK Clinician—serving PCPs seeking to develop their skills in evaluating and managing patients with MSK problems; and (2), the MSK Master Educator—for those with preexisting content expertise who would value the introduction to a national curriculum and connections with other MSK master educators. Both of these are now offered regularly through SimLEARN for VHA and US Department of Defense employees. The MSK Clinician program establishes competence in systematically evaluating and managing shoulder and knee MSK problems in an educational setting and prepares participants for subsequent clinical experiences where they can perform related procedures if desired, under appropriate supervision. The Master Educator program introduces partici pants to the clinician curriculum and provides the opportunity to develop an individualized plan for implementation of an MSK educational program at their home institutions. Participants are selected through a competitive application process, and funding for travel to attend the Master Educator program is provided by SimLEARN for participants who are accepted. Additionally, the Master Educator program serves as a repository for potential future SimLEARN MSK Clinician course faculty.

Limitations

The small number of participants may limit the validity of our conclusions. Although we included an OSCE to measure competence in performing and interpreting the shoulder exam, the durability of these skills is not known. Periodic postcourse OSCEs could help determine this and refresh and preserve accuracy in the performance of specific maneuvers. Second, although this experience was rated highly by participants, we do not know the impact of the program on their daily work or career trajectory. Sustained follow-up of learners, perhaps developed on the model of the Long-Term Career Outcome Study, may increase the value of this experience for future participants.38 This program appealed to a diverse pool of learners, with a broad range of precourse expertise and varied expectations of how course experiences would impact their future work and career development. Some clinical educator attendees came from tertiary care facilities affiliated with academic medical centers, held specialist or subspecialist credentials, and had formal responsibilities as leaders in HPE. Other clinical practitioner participants were solitary PCPs, often in rural or home-based settings; although they may have been eager to apply new knowledge and skills in patient care, they neither anticipated nor desired any role as an educator.

Conclusion

The initial SimLEARN MSK Training Program provides PCPs and clinician educators with rich learning experiences, increasing confidence in addressing MSK problems and competence in performing and interpreting a systematic physical examination of the shoulder. The success of this program has created new opportunities for practitioners seeking to strengthen clinical skills and for leaders in health professions education looking to disseminate similar trainings and connect with a national group of educators.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the faculty and staff at the Veterans Health Administration SimLEARN National Simulation Center, the faculty of the Salt Lake City Musculoskeletal Mini-Residency program, the supportive leadership of the George E. Wahlen Salt Lake City Veterans Affairs Medical Center, and the efforts of Danielle Blake for logistical support and data entry.

1. Helmick CG, Felson DT, Lawrence RC, et al; National Arthritis Data Workgroup. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part I. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(1):15-25.

2. Lawrence RC, Felson DT, Helmick CG, et al; National Arthritis Data Workgroup. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part II. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(1):26-35.

3. Sacks JJ, Luo YH, Helmick CG. Prevalence of specific types of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the ambulatory health care system in the United States, 2001-2005. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2010;62(4):460-464.