User login

Vermont tops America’s Health Rankings for 2019

The award for healthiest state goes to Vermont in 2019, marking the fifth time the Green Mountain State has taken the top spot in the 30-year span of America’s Health Rankings.

The New England states took 3 of the top 5 spots and 4 of the top 10, while last year’s winner, Hawaii, dropped to third and missed out on the title for only the second time in the last 8 years, according to the America’s Heath Rankings annual report.

Another rankings tradition lived on, however, as Mississippi and Louisiana continued their battle to be the state with the “greatest opportunity for improvement.” In 2019, Mississippi managed to take that dishonor away from Louisiana, which had finished 50th in 2018. The two states have occupied the 49th and 50th spots in the rankings for the last 5 years, with Mississippi ahead 3-2 on 50th-place finishes, based on data from the AHR website.

Alaska (2019 rank, 27th), Virginia (15th), and Wyoming (19th) made the largest improvements, each moving up five spots since 2018, while Maine dropped from 16th to 21st for the largest decline among the states. A look back to the original rankings from 1990 puts New York on top of the list of improvers with a +29 over 30 years and shows Kansas to be the largest decliner with a change of –21, the report said.

At the national level, the report noted some key long-term health improvements and challenges:

- Smoking among adults is down 45% since 1990.

- Infant mortality declined by 43% and decreased in all 50 states.

- Diabetes prevalence has risen by 166% in adults since 1996.

- Obesity has increased by 166% since 1990.

The model used by AHR ranks states using 35 measures of public health in five broad categories: behaviors (Utah, 1st; La., 50th), community and environment (N.H., 1st; La. 50th), policy (Mass., 1st; Tex., 50th), clinical care (Mass., 1st; Miss. 50th), and health outcomes (Hawaii, 1st; Ala., 50th). Health measures include rates of excessive drinking, occupational fatalities, uninsured, preventable hospitalizations, and infant mortality.

America’s Health Rankings are produced by the American Public Health Association and the private, not-for-profit United Health Foundation, which was founded by UnitedHealth Group, operator of UnitedHealthcare.

The award for healthiest state goes to Vermont in 2019, marking the fifth time the Green Mountain State has taken the top spot in the 30-year span of America’s Health Rankings.

The New England states took 3 of the top 5 spots and 4 of the top 10, while last year’s winner, Hawaii, dropped to third and missed out on the title for only the second time in the last 8 years, according to the America’s Heath Rankings annual report.

Another rankings tradition lived on, however, as Mississippi and Louisiana continued their battle to be the state with the “greatest opportunity for improvement.” In 2019, Mississippi managed to take that dishonor away from Louisiana, which had finished 50th in 2018. The two states have occupied the 49th and 50th spots in the rankings for the last 5 years, with Mississippi ahead 3-2 on 50th-place finishes, based on data from the AHR website.

Alaska (2019 rank, 27th), Virginia (15th), and Wyoming (19th) made the largest improvements, each moving up five spots since 2018, while Maine dropped from 16th to 21st for the largest decline among the states. A look back to the original rankings from 1990 puts New York on top of the list of improvers with a +29 over 30 years and shows Kansas to be the largest decliner with a change of –21, the report said.

At the national level, the report noted some key long-term health improvements and challenges:

- Smoking among adults is down 45% since 1990.

- Infant mortality declined by 43% and decreased in all 50 states.

- Diabetes prevalence has risen by 166% in adults since 1996.

- Obesity has increased by 166% since 1990.

The model used by AHR ranks states using 35 measures of public health in five broad categories: behaviors (Utah, 1st; La., 50th), community and environment (N.H., 1st; La. 50th), policy (Mass., 1st; Tex., 50th), clinical care (Mass., 1st; Miss. 50th), and health outcomes (Hawaii, 1st; Ala., 50th). Health measures include rates of excessive drinking, occupational fatalities, uninsured, preventable hospitalizations, and infant mortality.

America’s Health Rankings are produced by the American Public Health Association and the private, not-for-profit United Health Foundation, which was founded by UnitedHealth Group, operator of UnitedHealthcare.

The award for healthiest state goes to Vermont in 2019, marking the fifth time the Green Mountain State has taken the top spot in the 30-year span of America’s Health Rankings.

The New England states took 3 of the top 5 spots and 4 of the top 10, while last year’s winner, Hawaii, dropped to third and missed out on the title for only the second time in the last 8 years, according to the America’s Heath Rankings annual report.

Another rankings tradition lived on, however, as Mississippi and Louisiana continued their battle to be the state with the “greatest opportunity for improvement.” In 2019, Mississippi managed to take that dishonor away from Louisiana, which had finished 50th in 2018. The two states have occupied the 49th and 50th spots in the rankings for the last 5 years, with Mississippi ahead 3-2 on 50th-place finishes, based on data from the AHR website.

Alaska (2019 rank, 27th), Virginia (15th), and Wyoming (19th) made the largest improvements, each moving up five spots since 2018, while Maine dropped from 16th to 21st for the largest decline among the states. A look back to the original rankings from 1990 puts New York on top of the list of improvers with a +29 over 30 years and shows Kansas to be the largest decliner with a change of –21, the report said.

At the national level, the report noted some key long-term health improvements and challenges:

- Smoking among adults is down 45% since 1990.

- Infant mortality declined by 43% and decreased in all 50 states.

- Diabetes prevalence has risen by 166% in adults since 1996.

- Obesity has increased by 166% since 1990.

The model used by AHR ranks states using 35 measures of public health in five broad categories: behaviors (Utah, 1st; La., 50th), community and environment (N.H., 1st; La. 50th), policy (Mass., 1st; Tex., 50th), clinical care (Mass., 1st; Miss. 50th), and health outcomes (Hawaii, 1st; Ala., 50th). Health measures include rates of excessive drinking, occupational fatalities, uninsured, preventable hospitalizations, and infant mortality.

America’s Health Rankings are produced by the American Public Health Association and the private, not-for-profit United Health Foundation, which was founded by UnitedHealth Group, operator of UnitedHealthcare.

Administrative data can help drive quality improvement in breast cancer care

Quality indicators of breast cancer care were successfully computed for more than 15,000 incident cases of breast cancer using electronic administrative databases in a project led by five regional oncology networks in Italy.

The project has shown that, despite some limitations in the use of administrative data to measure health care performance, “evaluating the quality of breast cancer care at a population level is possible,” investigators reported in the Journal of Oncology Practice.

The data obtained “from multiple administrative databases gathered in a real-world setting across five Italian regions” highlighted regional variations in breast cancer care and ways in which clinical guidelines were being overlooked, they wrote.

In doing so, the project confirmed that administrative data is “suitable” for measuring performance in health care and potentially useful for guiding quality improvement interventions. For instance, the project identified extensive use of blood tumor markers in breast cancer follow-up, wrote Valentina Guarneri, PhD, MD, of the University of Padova (Italy) and the Istituto Oncologico Veneto, also in Padova, and coauthors.

Oncologists and epidemiologists from the Italian regional oncology networks identified 46 clinically relevant indicators (9 structure indicators, 29 dealing with process, and 8 outcome indicators) by comparing pathways of care established by each network and identifying commonalities.

Of the 46 indicators, 22 were considered by the project leaders to be “potentially computable” from information retrieved by regional administrative databases. And of these 22 designed to be extractable, 9 (2 indicators of structure and 7 of process) were found to be actually evaluable for 15,342 cases of newly diagnosed invasive and/or in situ breast cancer diagnosed during 2016.

Blood tumor markers were tested in 44.2%-64.5% of patients in the first year after surgery – higher than the benchmark of 20% or less that was established to account for stage IV patients and other specific conditions in which markers might be indicated. National, international, and regional guidelines “discourage the use of blood tumor markers” in breast cancer follow-up, the investigators wrote.

The extensive use of these markers – observed across all five regions – is “a starting point to understanding how to improve clinical practice,” they added.

Other quality indicators that were evaluable included radiotherapy within 12 weeks after surgery if adjuvant chemotherapy is not administered (42%-83.8% in the project, compared with the benchmark of 90% or greater) and mammography 6-18 months after surgery (administered in 55.1%-72.6%, compared with the benchmark of 90% or greater), as well as the proportion of patients starting adjuvant systemic treatment (chemotherapy or endocrine therapy) within 60 days of surgery (for patients receiving systemic treatment).

To calculate the indicators, each regional cancer network used computerized sources of information including hospital discharge forms, outpatient records of diagnostic and therapeutic procedures, prescriptions of drugs reimbursed by the National Health Service in the hospital and outpatient settings, regional health registries, and the regional mortality registries.

All data used in the project came from regional repositories, which collect data from all National Health Service providers in the region, and not from single institutional repositories, the investigators noted.

More than half of the indicators expected to be assessable – but not found to be – were not computable as a result of data being unavailable (for example, pathology data) or incomplete, and as a result of data not being reliable for various reasons. The fact that examinations paid for directly by patients are not reported by the management systems of the National Health System was another complicating factor, they reported.

The authors disclosed funding and relationships with various pharmaceutical companies. The research was supported by the Periplo Association.

SOURCE: Guarneri V et al. J Oncol Pract. 2019 Dec 19. doi: 10.1200/JOP.19.00466.

Quality indicators of breast cancer care were successfully computed for more than 15,000 incident cases of breast cancer using electronic administrative databases in a project led by five regional oncology networks in Italy.

The project has shown that, despite some limitations in the use of administrative data to measure health care performance, “evaluating the quality of breast cancer care at a population level is possible,” investigators reported in the Journal of Oncology Practice.

The data obtained “from multiple administrative databases gathered in a real-world setting across five Italian regions” highlighted regional variations in breast cancer care and ways in which clinical guidelines were being overlooked, they wrote.

In doing so, the project confirmed that administrative data is “suitable” for measuring performance in health care and potentially useful for guiding quality improvement interventions. For instance, the project identified extensive use of blood tumor markers in breast cancer follow-up, wrote Valentina Guarneri, PhD, MD, of the University of Padova (Italy) and the Istituto Oncologico Veneto, also in Padova, and coauthors.

Oncologists and epidemiologists from the Italian regional oncology networks identified 46 clinically relevant indicators (9 structure indicators, 29 dealing with process, and 8 outcome indicators) by comparing pathways of care established by each network and identifying commonalities.

Of the 46 indicators, 22 were considered by the project leaders to be “potentially computable” from information retrieved by regional administrative databases. And of these 22 designed to be extractable, 9 (2 indicators of structure and 7 of process) were found to be actually evaluable for 15,342 cases of newly diagnosed invasive and/or in situ breast cancer diagnosed during 2016.

Blood tumor markers were tested in 44.2%-64.5% of patients in the first year after surgery – higher than the benchmark of 20% or less that was established to account for stage IV patients and other specific conditions in which markers might be indicated. National, international, and regional guidelines “discourage the use of blood tumor markers” in breast cancer follow-up, the investigators wrote.

The extensive use of these markers – observed across all five regions – is “a starting point to understanding how to improve clinical practice,” they added.

Other quality indicators that were evaluable included radiotherapy within 12 weeks after surgery if adjuvant chemotherapy is not administered (42%-83.8% in the project, compared with the benchmark of 90% or greater) and mammography 6-18 months after surgery (administered in 55.1%-72.6%, compared with the benchmark of 90% or greater), as well as the proportion of patients starting adjuvant systemic treatment (chemotherapy or endocrine therapy) within 60 days of surgery (for patients receiving systemic treatment).

To calculate the indicators, each regional cancer network used computerized sources of information including hospital discharge forms, outpatient records of diagnostic and therapeutic procedures, prescriptions of drugs reimbursed by the National Health Service in the hospital and outpatient settings, regional health registries, and the regional mortality registries.

All data used in the project came from regional repositories, which collect data from all National Health Service providers in the region, and not from single institutional repositories, the investigators noted.

More than half of the indicators expected to be assessable – but not found to be – were not computable as a result of data being unavailable (for example, pathology data) or incomplete, and as a result of data not being reliable for various reasons. The fact that examinations paid for directly by patients are not reported by the management systems of the National Health System was another complicating factor, they reported.

The authors disclosed funding and relationships with various pharmaceutical companies. The research was supported by the Periplo Association.

SOURCE: Guarneri V et al. J Oncol Pract. 2019 Dec 19. doi: 10.1200/JOP.19.00466.

Quality indicators of breast cancer care were successfully computed for more than 15,000 incident cases of breast cancer using electronic administrative databases in a project led by five regional oncology networks in Italy.

The project has shown that, despite some limitations in the use of administrative data to measure health care performance, “evaluating the quality of breast cancer care at a population level is possible,” investigators reported in the Journal of Oncology Practice.

The data obtained “from multiple administrative databases gathered in a real-world setting across five Italian regions” highlighted regional variations in breast cancer care and ways in which clinical guidelines were being overlooked, they wrote.

In doing so, the project confirmed that administrative data is “suitable” for measuring performance in health care and potentially useful for guiding quality improvement interventions. For instance, the project identified extensive use of blood tumor markers in breast cancer follow-up, wrote Valentina Guarneri, PhD, MD, of the University of Padova (Italy) and the Istituto Oncologico Veneto, also in Padova, and coauthors.

Oncologists and epidemiologists from the Italian regional oncology networks identified 46 clinically relevant indicators (9 structure indicators, 29 dealing with process, and 8 outcome indicators) by comparing pathways of care established by each network and identifying commonalities.

Of the 46 indicators, 22 were considered by the project leaders to be “potentially computable” from information retrieved by regional administrative databases. And of these 22 designed to be extractable, 9 (2 indicators of structure and 7 of process) were found to be actually evaluable for 15,342 cases of newly diagnosed invasive and/or in situ breast cancer diagnosed during 2016.

Blood tumor markers were tested in 44.2%-64.5% of patients in the first year after surgery – higher than the benchmark of 20% or less that was established to account for stage IV patients and other specific conditions in which markers might be indicated. National, international, and regional guidelines “discourage the use of blood tumor markers” in breast cancer follow-up, the investigators wrote.

The extensive use of these markers – observed across all five regions – is “a starting point to understanding how to improve clinical practice,” they added.

Other quality indicators that were evaluable included radiotherapy within 12 weeks after surgery if adjuvant chemotherapy is not administered (42%-83.8% in the project, compared with the benchmark of 90% or greater) and mammography 6-18 months after surgery (administered in 55.1%-72.6%, compared with the benchmark of 90% or greater), as well as the proportion of patients starting adjuvant systemic treatment (chemotherapy or endocrine therapy) within 60 days of surgery (for patients receiving systemic treatment).

To calculate the indicators, each regional cancer network used computerized sources of information including hospital discharge forms, outpatient records of diagnostic and therapeutic procedures, prescriptions of drugs reimbursed by the National Health Service in the hospital and outpatient settings, regional health registries, and the regional mortality registries.

All data used in the project came from regional repositories, which collect data from all National Health Service providers in the region, and not from single institutional repositories, the investigators noted.

More than half of the indicators expected to be assessable – but not found to be – were not computable as a result of data being unavailable (for example, pathology data) or incomplete, and as a result of data not being reliable for various reasons. The fact that examinations paid for directly by patients are not reported by the management systems of the National Health System was another complicating factor, they reported.

The authors disclosed funding and relationships with various pharmaceutical companies. The research was supported by the Periplo Association.

SOURCE: Guarneri V et al. J Oncol Pract. 2019 Dec 19. doi: 10.1200/JOP.19.00466.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF ONCOLOGY PRACTICE

Dual e-cigarette and combustible tobacco use compound respiratory disease risk

according to recent longitudinal analysis published in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine.

E-cigarettes have been promoted as a safer alternative to combustible tobacco, and until recently, there has been little and conflicting evidence by which to test this hypothesis. This study conducted by Dharma N. Bhatta, PhD, and Stanton A. Glantz, PhD, of the Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education at the University of California, San Francisco, is one of the first longitudinal examinations of e-cigarette use and controlling for combustible tobacco use.

Dr. Bhatta and Dr. Glantz performed a multivariable, logistic regression analysis of adults enrolled in the nationally representative, population-based, longitudinal Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health study. The researchers analyzed the tobacco use of adults in the study in three waves, following them through wave 1 (September 2013 to December 2014), wave 2 (October 2014 to October 2015), and wave 3 (October 2015 to October 2016), analyzing the data between 2018 and 2019. Overall, wave 1 began with 32,320 participants, and 15.1% of adults reported respiratory disease at baseline.

Lung or respiratory disease was assessed by asking participants whether they had been told by a health professional that they had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic bronchitis, emphysema, or asthma. The researchers defined e-cigarette and combustible tobacco use as participants who never, currently, or formerly used e-cigarettes or smoked combustible tobacco. Participants who indicated they used e-cigarettes or combustible tobacco frequently or infrequently were placed in the current-user group, while past users were those participants who said they used to, but no longer use e-cigarettes or combustible tobacco.

The results showed former e-cigarette use (adjusted odds ratio, 1.34; 95% confidence interval, 1.23-1.46) and current e-cigarette use (aOR, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.17-1.49) were associated with an increased risk of having incident respiratory disease.

The data showed a not unexpected statistically significant association between former combustible tobacco use (aOR, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.14-1.47) as well as current combustible tobacco use (aOR, 1.61; 95% CI, 1.42-1.82) and incident respiratory disease risk.

There was a statistically significant association between respiratory disease and former or current e-cigarette use for adults who did not have respiratory disease at baseline, after adjusting for factors such as current combustible tobacco use, clinical variables, and demographic differences. Participants in wave 1 who reported former (aOR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.07-1.60) or current e-cigarette use (aOR, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.03-1.61) had a significantly higher risk of developing incident respiratory disease in subsequent waves. There was also a statistically significant association between use of combustible tobacco and subsequent respiratory disease in later waves of the study (aOR, 2.56; 95% CI, 1.92-3.41), which the researchers noted was independent of the usual risks associated with combustible tobacco.

The investigators also looked at the link between dual use of e-cigarettes and combustible tobacco and respiratory disease risk. “The much more common pattern is dual use, in which an e-cigarette user continues to smoke combusted tobacco products at the same time (93.7% of e-cigarette users at wave 2 and 91.2% at wave 3 also used combustible tobacco; 73.3% of e-cigarette users at wave 2 and 64.9% at wave 3 also smoked cigarettes),” they wrote.

The odds of developing respiratory disease for participants who used both e-cigarettes and combustible tobacco were 3.30, compared with a participant who never used e-cigarettes, with similar results seen when comparing e-cigarettes and cigarettes.

“Although switching from combustible tobacco, including cigarettes, to e-cigarettes theoretically could reduce the risk of developing respiratory disease, current evidence indicates a high prevalence of dual use, which is associated with in-creased risk beyond combustible tobacco use,” the investigators wrote.

Harold J. Farber, MD, FCCP, professor of pediatrics in the pulmonary section at Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Children’s Hospital, both in Houston, said in an interview that the increased respiratory risk among dual users, who are likely using e-cigarettes and combustible tobacco together as a way to quit smoking, is particularly concerning.

“There is substantial reason to be concerned about efficacy of electronic cigarette products. Real-world observational studies have shown that, on average, tobacco smokers who use electronic cigarettes are less likely to stop smoking than those who do not use electronic cigarettes,” he said. “People who have stopped tobacco smoking but use electronic cigarettes are more likely to relapse to tobacco smoking than those who do not use electronic cigarettes.”

Dr. Farber noted that there are other Food and Drug Administration–approved medications for treating tobacco addiction. In addition, the World Health Organization, American Medical Association, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and FDA have all advised that e-cigarettes should not be used as smoking cessation aids, he said, especially in light of current outbreak of life-threatening e-cigarette and vaping lung injuries currently being investigated by the CDC and FDA.

“These study results suggest that the CDC reports of e-cigarette, or vaping, product use–associated lung injury are likely to be just the tip of the iceberg,” he said. “Although the CDC has identified vitamin E acetate–containing products as an important culprit, it is unlikely to be the only one. There are many substances in the emissions of e-cigarettes that have known irritant and/or toxic effects on the airways.”

Dr. Bhatta and Dr. Glantz acknowledged several limitations in their analysis, including the possibility of recall bias, not distinguishing between nondaily and daily e-cigarette or combustible tobacco use, and combining respiratory conditions together to achieve adequate power. The study shows an association, but the mechanism by which e-cigarettes may contribute to the development of lung disease remains under investigation.

This study was supported by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse; the National Cancer Institute; the FDA Center for Tobacco Products; the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; and the University of California, San Francisco Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center Global Cancer Program. Dr. Bhatta and Dr. Glantz reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Bhatta DN, Glantz SA. Am J Prev Med. 2019 Dec 16. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2019.07.028.

according to recent longitudinal analysis published in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine.

E-cigarettes have been promoted as a safer alternative to combustible tobacco, and until recently, there has been little and conflicting evidence by which to test this hypothesis. This study conducted by Dharma N. Bhatta, PhD, and Stanton A. Glantz, PhD, of the Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education at the University of California, San Francisco, is one of the first longitudinal examinations of e-cigarette use and controlling for combustible tobacco use.

Dr. Bhatta and Dr. Glantz performed a multivariable, logistic regression analysis of adults enrolled in the nationally representative, population-based, longitudinal Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health study. The researchers analyzed the tobacco use of adults in the study in three waves, following them through wave 1 (September 2013 to December 2014), wave 2 (October 2014 to October 2015), and wave 3 (October 2015 to October 2016), analyzing the data between 2018 and 2019. Overall, wave 1 began with 32,320 participants, and 15.1% of adults reported respiratory disease at baseline.

Lung or respiratory disease was assessed by asking participants whether they had been told by a health professional that they had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic bronchitis, emphysema, or asthma. The researchers defined e-cigarette and combustible tobacco use as participants who never, currently, or formerly used e-cigarettes or smoked combustible tobacco. Participants who indicated they used e-cigarettes or combustible tobacco frequently or infrequently were placed in the current-user group, while past users were those participants who said they used to, but no longer use e-cigarettes or combustible tobacco.

The results showed former e-cigarette use (adjusted odds ratio, 1.34; 95% confidence interval, 1.23-1.46) and current e-cigarette use (aOR, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.17-1.49) were associated with an increased risk of having incident respiratory disease.

The data showed a not unexpected statistically significant association between former combustible tobacco use (aOR, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.14-1.47) as well as current combustible tobacco use (aOR, 1.61; 95% CI, 1.42-1.82) and incident respiratory disease risk.

There was a statistically significant association between respiratory disease and former or current e-cigarette use for adults who did not have respiratory disease at baseline, after adjusting for factors such as current combustible tobacco use, clinical variables, and demographic differences. Participants in wave 1 who reported former (aOR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.07-1.60) or current e-cigarette use (aOR, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.03-1.61) had a significantly higher risk of developing incident respiratory disease in subsequent waves. There was also a statistically significant association between use of combustible tobacco and subsequent respiratory disease in later waves of the study (aOR, 2.56; 95% CI, 1.92-3.41), which the researchers noted was independent of the usual risks associated with combustible tobacco.

The investigators also looked at the link between dual use of e-cigarettes and combustible tobacco and respiratory disease risk. “The much more common pattern is dual use, in which an e-cigarette user continues to smoke combusted tobacco products at the same time (93.7% of e-cigarette users at wave 2 and 91.2% at wave 3 also used combustible tobacco; 73.3% of e-cigarette users at wave 2 and 64.9% at wave 3 also smoked cigarettes),” they wrote.

The odds of developing respiratory disease for participants who used both e-cigarettes and combustible tobacco were 3.30, compared with a participant who never used e-cigarettes, with similar results seen when comparing e-cigarettes and cigarettes.

“Although switching from combustible tobacco, including cigarettes, to e-cigarettes theoretically could reduce the risk of developing respiratory disease, current evidence indicates a high prevalence of dual use, which is associated with in-creased risk beyond combustible tobacco use,” the investigators wrote.

Harold J. Farber, MD, FCCP, professor of pediatrics in the pulmonary section at Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Children’s Hospital, both in Houston, said in an interview that the increased respiratory risk among dual users, who are likely using e-cigarettes and combustible tobacco together as a way to quit smoking, is particularly concerning.

“There is substantial reason to be concerned about efficacy of electronic cigarette products. Real-world observational studies have shown that, on average, tobacco smokers who use electronic cigarettes are less likely to stop smoking than those who do not use electronic cigarettes,” he said. “People who have stopped tobacco smoking but use electronic cigarettes are more likely to relapse to tobacco smoking than those who do not use electronic cigarettes.”

Dr. Farber noted that there are other Food and Drug Administration–approved medications for treating tobacco addiction. In addition, the World Health Organization, American Medical Association, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and FDA have all advised that e-cigarettes should not be used as smoking cessation aids, he said, especially in light of current outbreak of life-threatening e-cigarette and vaping lung injuries currently being investigated by the CDC and FDA.

“These study results suggest that the CDC reports of e-cigarette, or vaping, product use–associated lung injury are likely to be just the tip of the iceberg,” he said. “Although the CDC has identified vitamin E acetate–containing products as an important culprit, it is unlikely to be the only one. There are many substances in the emissions of e-cigarettes that have known irritant and/or toxic effects on the airways.”

Dr. Bhatta and Dr. Glantz acknowledged several limitations in their analysis, including the possibility of recall bias, not distinguishing between nondaily and daily e-cigarette or combustible tobacco use, and combining respiratory conditions together to achieve adequate power. The study shows an association, but the mechanism by which e-cigarettes may contribute to the development of lung disease remains under investigation.

This study was supported by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse; the National Cancer Institute; the FDA Center for Tobacco Products; the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; and the University of California, San Francisco Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center Global Cancer Program. Dr. Bhatta and Dr. Glantz reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Bhatta DN, Glantz SA. Am J Prev Med. 2019 Dec 16. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2019.07.028.

according to recent longitudinal analysis published in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine.

E-cigarettes have been promoted as a safer alternative to combustible tobacco, and until recently, there has been little and conflicting evidence by which to test this hypothesis. This study conducted by Dharma N. Bhatta, PhD, and Stanton A. Glantz, PhD, of the Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education at the University of California, San Francisco, is one of the first longitudinal examinations of e-cigarette use and controlling for combustible tobacco use.

Dr. Bhatta and Dr. Glantz performed a multivariable, logistic regression analysis of adults enrolled in the nationally representative, population-based, longitudinal Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health study. The researchers analyzed the tobacco use of adults in the study in three waves, following them through wave 1 (September 2013 to December 2014), wave 2 (October 2014 to October 2015), and wave 3 (October 2015 to October 2016), analyzing the data between 2018 and 2019. Overall, wave 1 began with 32,320 participants, and 15.1% of adults reported respiratory disease at baseline.

Lung or respiratory disease was assessed by asking participants whether they had been told by a health professional that they had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic bronchitis, emphysema, or asthma. The researchers defined e-cigarette and combustible tobacco use as participants who never, currently, or formerly used e-cigarettes or smoked combustible tobacco. Participants who indicated they used e-cigarettes or combustible tobacco frequently or infrequently were placed in the current-user group, while past users were those participants who said they used to, but no longer use e-cigarettes or combustible tobacco.

The results showed former e-cigarette use (adjusted odds ratio, 1.34; 95% confidence interval, 1.23-1.46) and current e-cigarette use (aOR, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.17-1.49) were associated with an increased risk of having incident respiratory disease.

The data showed a not unexpected statistically significant association between former combustible tobacco use (aOR, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.14-1.47) as well as current combustible tobacco use (aOR, 1.61; 95% CI, 1.42-1.82) and incident respiratory disease risk.

There was a statistically significant association between respiratory disease and former or current e-cigarette use for adults who did not have respiratory disease at baseline, after adjusting for factors such as current combustible tobacco use, clinical variables, and demographic differences. Participants in wave 1 who reported former (aOR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.07-1.60) or current e-cigarette use (aOR, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.03-1.61) had a significantly higher risk of developing incident respiratory disease in subsequent waves. There was also a statistically significant association between use of combustible tobacco and subsequent respiratory disease in later waves of the study (aOR, 2.56; 95% CI, 1.92-3.41), which the researchers noted was independent of the usual risks associated with combustible tobacco.

The investigators also looked at the link between dual use of e-cigarettes and combustible tobacco and respiratory disease risk. “The much more common pattern is dual use, in which an e-cigarette user continues to smoke combusted tobacco products at the same time (93.7% of e-cigarette users at wave 2 and 91.2% at wave 3 also used combustible tobacco; 73.3% of e-cigarette users at wave 2 and 64.9% at wave 3 also smoked cigarettes),” they wrote.

The odds of developing respiratory disease for participants who used both e-cigarettes and combustible tobacco were 3.30, compared with a participant who never used e-cigarettes, with similar results seen when comparing e-cigarettes and cigarettes.

“Although switching from combustible tobacco, including cigarettes, to e-cigarettes theoretically could reduce the risk of developing respiratory disease, current evidence indicates a high prevalence of dual use, which is associated with in-creased risk beyond combustible tobacco use,” the investigators wrote.

Harold J. Farber, MD, FCCP, professor of pediatrics in the pulmonary section at Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Children’s Hospital, both in Houston, said in an interview that the increased respiratory risk among dual users, who are likely using e-cigarettes and combustible tobacco together as a way to quit smoking, is particularly concerning.

“There is substantial reason to be concerned about efficacy of electronic cigarette products. Real-world observational studies have shown that, on average, tobacco smokers who use electronic cigarettes are less likely to stop smoking than those who do not use electronic cigarettes,” he said. “People who have stopped tobacco smoking but use electronic cigarettes are more likely to relapse to tobacco smoking than those who do not use electronic cigarettes.”

Dr. Farber noted that there are other Food and Drug Administration–approved medications for treating tobacco addiction. In addition, the World Health Organization, American Medical Association, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and FDA have all advised that e-cigarettes should not be used as smoking cessation aids, he said, especially in light of current outbreak of life-threatening e-cigarette and vaping lung injuries currently being investigated by the CDC and FDA.

“These study results suggest that the CDC reports of e-cigarette, or vaping, product use–associated lung injury are likely to be just the tip of the iceberg,” he said. “Although the CDC has identified vitamin E acetate–containing products as an important culprit, it is unlikely to be the only one. There are many substances in the emissions of e-cigarettes that have known irritant and/or toxic effects on the airways.”

Dr. Bhatta and Dr. Glantz acknowledged several limitations in their analysis, including the possibility of recall bias, not distinguishing between nondaily and daily e-cigarette or combustible tobacco use, and combining respiratory conditions together to achieve adequate power. The study shows an association, but the mechanism by which e-cigarettes may contribute to the development of lung disease remains under investigation.

This study was supported by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse; the National Cancer Institute; the FDA Center for Tobacco Products; the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; and the University of California, San Francisco Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center Global Cancer Program. Dr. Bhatta and Dr. Glantz reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Bhatta DN, Glantz SA. Am J Prev Med. 2019 Dec 16. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2019.07.028.

FROM THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF PREVENTIVE MEDICINE

Moffitt announces new chief digital innovation officer

Edmondo Robinson, MD, is the new senior vice president and chief digital innovation officer at Moffitt Cancer Center in Tampa, Fla. In this newly created position, Dr. Robinson will “oversee Moffitt’s portfolio of digital innovation, including the development and commercialization of health products, tools, and technology.”

Dr. Robinson is also associate professor of medicine at Thomas Jefferson University’s Sidney Kimmel Medical College in Philadelphia. He was previously the chief transformation officer and senior vice-president of consumerism at ChristianaCare, a health system based in Wilmington, Del. Dr. Robinson’s research is focused on health services, particularly care transitions and how technology impacts care delivery.

In other news, Elizabeth Fox, MD, has been named senior vice president of clinical trials research at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tenn. She will also serve as the associate director for clinical research in the St. Jude Comprehensive Cancer Center. Dr. Fox will take on these roles in January 2020.

Dr. Fox was previously director of developmental therapeutics in oncology and professor of pediatrics at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. According to St. Jude, Dr. Fox is an expert in integrating clinical and preclinical pharmacology in clinical trial design.

The International Society of Gastrointestinal Oncology has appointed Weijing Sun, MD, as its president-elect. After his 2-year term as president-elect, Dr. Sun will take over as president from Ghassan Abou-Alfa, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

Dr. Sun is director of the division of medical oncology and associate director for clinical research at the University of Kansas Cancer Center in Kansas City. He is a gastrointestinal medical oncologist with a research focus on the development of new treatments for pancreatic, gastroesophageal, hepatobiliary, and colorectal cancers.

Finally, Elizabeth Plimack, MD, has been elected to the American Society of Clinical Oncology’s board of directors for a term of 4 years. She will begin this appointment in June 2020.

Dr. Plimack is a professor and chief of the division of genitourinary medical oncology at Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia. Dr. Plimack’s clinical practice is focused on the treatment of kidney, bladder, prostate, and testicular cancer. Her research is focused on developing new therapies for bladder and kidney cancers.

Edmondo Robinson, MD, is the new senior vice president and chief digital innovation officer at Moffitt Cancer Center in Tampa, Fla. In this newly created position, Dr. Robinson will “oversee Moffitt’s portfolio of digital innovation, including the development and commercialization of health products, tools, and technology.”

Dr. Robinson is also associate professor of medicine at Thomas Jefferson University’s Sidney Kimmel Medical College in Philadelphia. He was previously the chief transformation officer and senior vice-president of consumerism at ChristianaCare, a health system based in Wilmington, Del. Dr. Robinson’s research is focused on health services, particularly care transitions and how technology impacts care delivery.

In other news, Elizabeth Fox, MD, has been named senior vice president of clinical trials research at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tenn. She will also serve as the associate director for clinical research in the St. Jude Comprehensive Cancer Center. Dr. Fox will take on these roles in January 2020.

Dr. Fox was previously director of developmental therapeutics in oncology and professor of pediatrics at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. According to St. Jude, Dr. Fox is an expert in integrating clinical and preclinical pharmacology in clinical trial design.

The International Society of Gastrointestinal Oncology has appointed Weijing Sun, MD, as its president-elect. After his 2-year term as president-elect, Dr. Sun will take over as president from Ghassan Abou-Alfa, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

Dr. Sun is director of the division of medical oncology and associate director for clinical research at the University of Kansas Cancer Center in Kansas City. He is a gastrointestinal medical oncologist with a research focus on the development of new treatments for pancreatic, gastroesophageal, hepatobiliary, and colorectal cancers.

Finally, Elizabeth Plimack, MD, has been elected to the American Society of Clinical Oncology’s board of directors for a term of 4 years. She will begin this appointment in June 2020.

Dr. Plimack is a professor and chief of the division of genitourinary medical oncology at Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia. Dr. Plimack’s clinical practice is focused on the treatment of kidney, bladder, prostate, and testicular cancer. Her research is focused on developing new therapies for bladder and kidney cancers.

Edmondo Robinson, MD, is the new senior vice president and chief digital innovation officer at Moffitt Cancer Center in Tampa, Fla. In this newly created position, Dr. Robinson will “oversee Moffitt’s portfolio of digital innovation, including the development and commercialization of health products, tools, and technology.”

Dr. Robinson is also associate professor of medicine at Thomas Jefferson University’s Sidney Kimmel Medical College in Philadelphia. He was previously the chief transformation officer and senior vice-president of consumerism at ChristianaCare, a health system based in Wilmington, Del. Dr. Robinson’s research is focused on health services, particularly care transitions and how technology impacts care delivery.

In other news, Elizabeth Fox, MD, has been named senior vice president of clinical trials research at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tenn. She will also serve as the associate director for clinical research in the St. Jude Comprehensive Cancer Center. Dr. Fox will take on these roles in January 2020.

Dr. Fox was previously director of developmental therapeutics in oncology and professor of pediatrics at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. According to St. Jude, Dr. Fox is an expert in integrating clinical and preclinical pharmacology in clinical trial design.

The International Society of Gastrointestinal Oncology has appointed Weijing Sun, MD, as its president-elect. After his 2-year term as president-elect, Dr. Sun will take over as president from Ghassan Abou-Alfa, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

Dr. Sun is director of the division of medical oncology and associate director for clinical research at the University of Kansas Cancer Center in Kansas City. He is a gastrointestinal medical oncologist with a research focus on the development of new treatments for pancreatic, gastroesophageal, hepatobiliary, and colorectal cancers.

Finally, Elizabeth Plimack, MD, has been elected to the American Society of Clinical Oncology’s board of directors for a term of 4 years. She will begin this appointment in June 2020.

Dr. Plimack is a professor and chief of the division of genitourinary medical oncology at Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia. Dr. Plimack’s clinical practice is focused on the treatment of kidney, bladder, prostate, and testicular cancer. Her research is focused on developing new therapies for bladder and kidney cancers.

Withdrawal of candidacy for APA President-Elect

To the readers of Current Psychiatry,

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) informed me on 12-27-19 that my editorial in the December issue about my candidacy for APA President-Elect was unfair to the other candidates because they should have been invited to publish their own statements side-by-side with mine. I was not aware of this because the APA election rules allow a candidate to blog or write on all social media or to send a mass mailing unilaterally. I take full responsibility for my mistake and decided to inform the APA Board of Trustees that I am withdrawing my candidacy for APA President-Elect. I hope the elections will go smoothly and wish the APA well.

Please note that my loyalty to the APA is very strong. That’s why my January 2020 editorial strongly urges all psychiatrists to join (or rejoin) the APA because unity will make it more possible for us to advocate for our patients, increase access to mental health, eliminate stigma, achieve true parity, and raise the profile of psychiatry as a medical discipline.

As you may have read in my campaign statement, one of my major goals as a candidate was to change the name of the APA to the American Psychiatric Physicians Association, or APPA. This name change is critical so that the public knows our medical identity. It also will differentiate us from the other APA (American Psychological Association), which is the first to appear when anyone enters APA on Google or other search engines. I will lobby vigorously with the current APA president, the APA CEO, and whoever becomes President-Elect to get this name change approved by the Board of Trustees. I am very sure that the vast majority of psychiatrists will support such a name change.

Thank you and I hope 2020 will be a happy and healthy year for all of you, and for all our psychiatric patients.

To the readers of Current Psychiatry,

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) informed me on 12-27-19 that my editorial in the December issue about my candidacy for APA President-Elect was unfair to the other candidates because they should have been invited to publish their own statements side-by-side with mine. I was not aware of this because the APA election rules allow a candidate to blog or write on all social media or to send a mass mailing unilaterally. I take full responsibility for my mistake and decided to inform the APA Board of Trustees that I am withdrawing my candidacy for APA President-Elect. I hope the elections will go smoothly and wish the APA well.

Please note that my loyalty to the APA is very strong. That’s why my January 2020 editorial strongly urges all psychiatrists to join (or rejoin) the APA because unity will make it more possible for us to advocate for our patients, increase access to mental health, eliminate stigma, achieve true parity, and raise the profile of psychiatry as a medical discipline.

As you may have read in my campaign statement, one of my major goals as a candidate was to change the name of the APA to the American Psychiatric Physicians Association, or APPA. This name change is critical so that the public knows our medical identity. It also will differentiate us from the other APA (American Psychological Association), which is the first to appear when anyone enters APA on Google or other search engines. I will lobby vigorously with the current APA president, the APA CEO, and whoever becomes President-Elect to get this name change approved by the Board of Trustees. I am very sure that the vast majority of psychiatrists will support such a name change.

Thank you and I hope 2020 will be a happy and healthy year for all of you, and for all our psychiatric patients.

To the readers of Current Psychiatry,

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) informed me on 12-27-19 that my editorial in the December issue about my candidacy for APA President-Elect was unfair to the other candidates because they should have been invited to publish their own statements side-by-side with mine. I was not aware of this because the APA election rules allow a candidate to blog or write on all social media or to send a mass mailing unilaterally. I take full responsibility for my mistake and decided to inform the APA Board of Trustees that I am withdrawing my candidacy for APA President-Elect. I hope the elections will go smoothly and wish the APA well.

Please note that my loyalty to the APA is very strong. That’s why my January 2020 editorial strongly urges all psychiatrists to join (or rejoin) the APA because unity will make it more possible for us to advocate for our patients, increase access to mental health, eliminate stigma, achieve true parity, and raise the profile of psychiatry as a medical discipline.

As you may have read in my campaign statement, one of my major goals as a candidate was to change the name of the APA to the American Psychiatric Physicians Association, or APPA. This name change is critical so that the public knows our medical identity. It also will differentiate us from the other APA (American Psychological Association), which is the first to appear when anyone enters APA on Google or other search engines. I will lobby vigorously with the current APA president, the APA CEO, and whoever becomes President-Elect to get this name change approved by the Board of Trustees. I am very sure that the vast majority of psychiatrists will support such a name change.

Thank you and I hope 2020 will be a happy and healthy year for all of you, and for all our psychiatric patients.

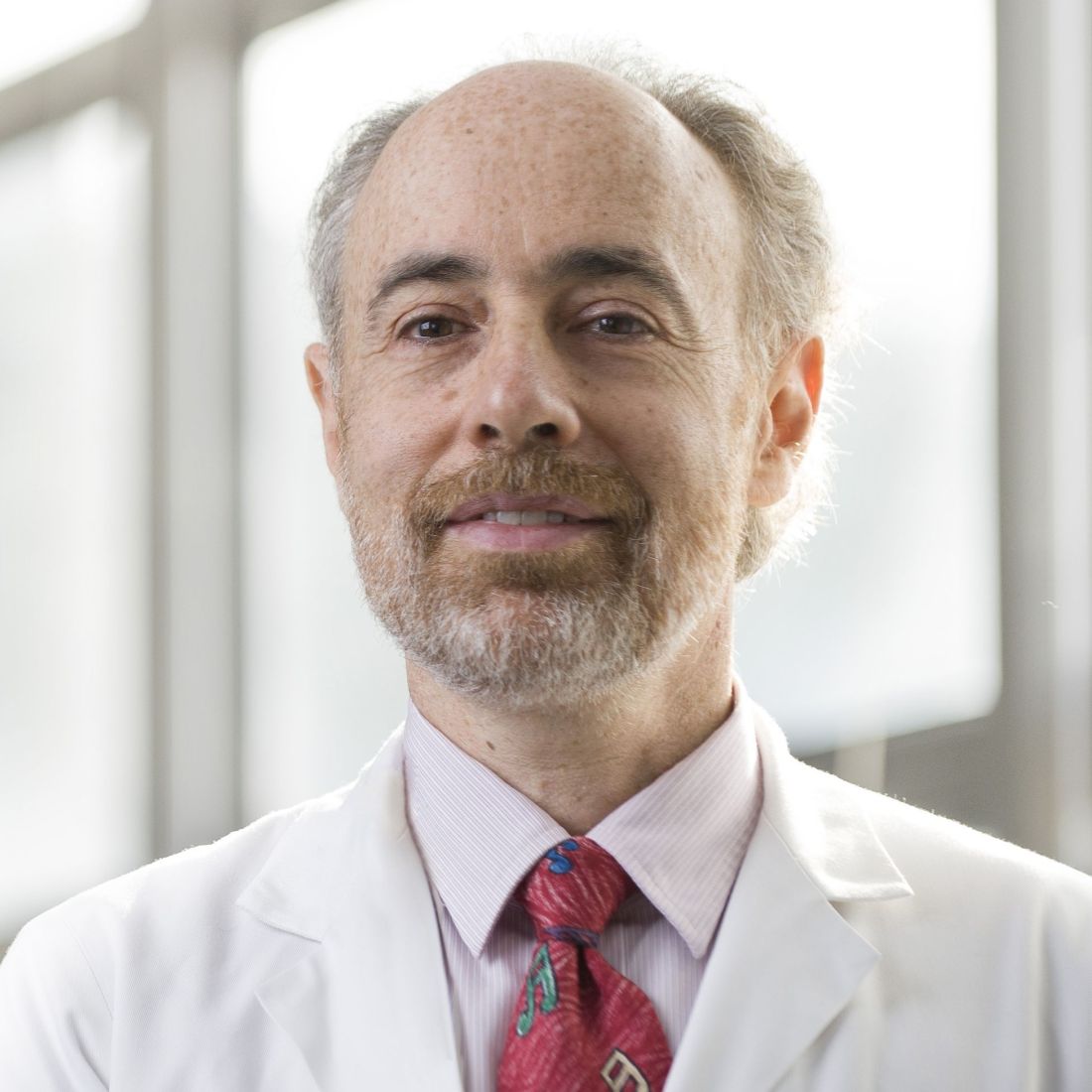

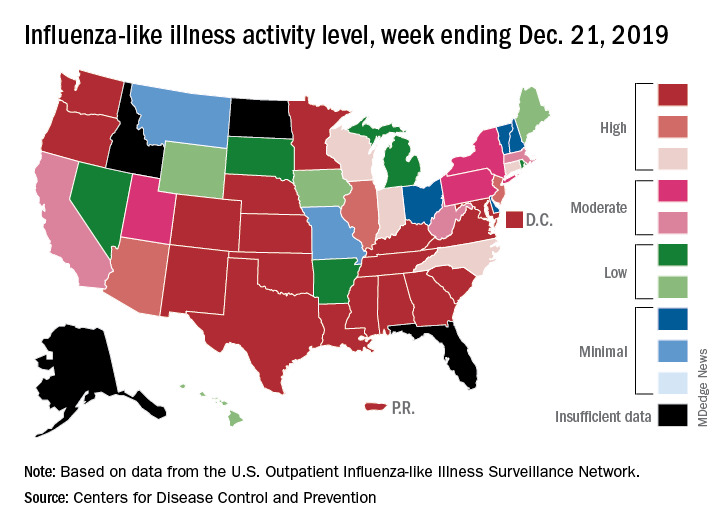

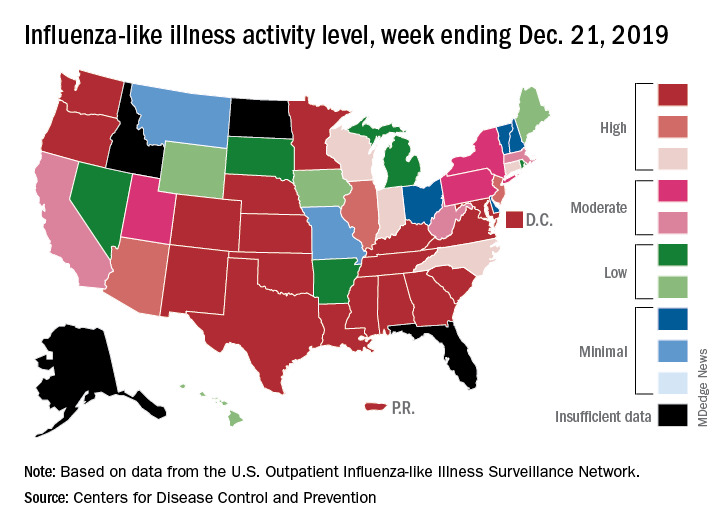

Early increase in flu activity shows no signs of slowing

An important measure of U.S. flu activity for the 2019-2020 season has already surpassed last season’s high, and more than half the states are experiencing high levels of activity, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

reported Dec. 27.

The last time the outpatient visit rate was higher than that was in February of the 2017-2018 season, when it peaked at 7.5%. The peak month of flu activity occurs most often – about once every 3 years – in February, and the odds of a December peak are about one in five, the CDC has said.

Outpatient illness activity also increased at the state level during the week ending Dec. 21. There were 20 jurisdictions – 18 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico – at level 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale of activity, compared with 13 the previous week, and the number of jurisdictions in the “high” range (levels 8-10) jumped from 21 to 28, the CDC data show.

The influenza division estimated that there have been 4.6 million flu illnesses so far this season, nearly a million more than the total after last week, along with 39,000 hospitalizations. The overall hospitalization rate for the season is up to 6.6 per 100,000 population, which is about average at this point. The proportion of deaths attributed to pneumonia and influenza increased to 5.7%, which is below the epidemic threshold, the CDC said.

Three pediatric deaths related to influenza-like illness were reported during the week ending Dec. 21, two of which occurred in an earlier week. For the 2019-2020 season so far, a total of 22 pediatric deaths have been reported to the CDC.

An important measure of U.S. flu activity for the 2019-2020 season has already surpassed last season’s high, and more than half the states are experiencing high levels of activity, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

reported Dec. 27.

The last time the outpatient visit rate was higher than that was in February of the 2017-2018 season, when it peaked at 7.5%. The peak month of flu activity occurs most often – about once every 3 years – in February, and the odds of a December peak are about one in five, the CDC has said.

Outpatient illness activity also increased at the state level during the week ending Dec. 21. There were 20 jurisdictions – 18 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico – at level 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale of activity, compared with 13 the previous week, and the number of jurisdictions in the “high” range (levels 8-10) jumped from 21 to 28, the CDC data show.

The influenza division estimated that there have been 4.6 million flu illnesses so far this season, nearly a million more than the total after last week, along with 39,000 hospitalizations. The overall hospitalization rate for the season is up to 6.6 per 100,000 population, which is about average at this point. The proportion of deaths attributed to pneumonia and influenza increased to 5.7%, which is below the epidemic threshold, the CDC said.

Three pediatric deaths related to influenza-like illness were reported during the week ending Dec. 21, two of which occurred in an earlier week. For the 2019-2020 season so far, a total of 22 pediatric deaths have been reported to the CDC.

An important measure of U.S. flu activity for the 2019-2020 season has already surpassed last season’s high, and more than half the states are experiencing high levels of activity, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

reported Dec. 27.

The last time the outpatient visit rate was higher than that was in February of the 2017-2018 season, when it peaked at 7.5%. The peak month of flu activity occurs most often – about once every 3 years – in February, and the odds of a December peak are about one in five, the CDC has said.

Outpatient illness activity also increased at the state level during the week ending Dec. 21. There were 20 jurisdictions – 18 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico – at level 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale of activity, compared with 13 the previous week, and the number of jurisdictions in the “high” range (levels 8-10) jumped from 21 to 28, the CDC data show.

The influenza division estimated that there have been 4.6 million flu illnesses so far this season, nearly a million more than the total after last week, along with 39,000 hospitalizations. The overall hospitalization rate for the season is up to 6.6 per 100,000 population, which is about average at this point. The proportion of deaths attributed to pneumonia and influenza increased to 5.7%, which is below the epidemic threshold, the CDC said.

Three pediatric deaths related to influenza-like illness were reported during the week ending Dec. 21, two of which occurred in an earlier week. For the 2019-2020 season so far, a total of 22 pediatric deaths have been reported to the CDC.

Calif. woman poisoned by methylmercury-containing skin cream

The first known case of contamination of skin-lightening cream with methylmercury was identified in July 2019 in a Mexican American woman in Sacramento, Calif., according to Anita Mudan, MD, of the department of emergency medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, and associates.

The woman, aged 47 years, sought medical care for dysesthesias and weakness in the upper extremities, the investigators wrote in a report published in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

This progressed to dysarthria, blurry vision, and unsteady gait over a 2-week period, leading to her hospitalization. Over the next 2 weeks, she declined into an agitated delirium; screening blood and urine tests detected levels of mercury exceeding the upper limit of quantification.

Oral dimercaptosuccinic acid at 10 mg/kg every 8 hours was administered via feeding tube. The California Department of Public Health (CDPH) conducted interviews with the patient’s family, discovering that the patient had used a skin-lightening cream obtained from Mexico for the past 7 years. The cream was analyzed and found to contain mercury at a concentration of 12,000 ppm. A Raman spectral analysis showed that the sample contained the organic compound methylmercury iodide.

Typically, contaminated skin-lightening creams contain inorganic mercury at levels up to 200,000 ppm; the significantly lower mercury content of the cream in this case “underscores the far higher toxicity of organic mercury compounds,” the investigators wrote.

The patient has undergone extensive chelation therapy, but remains unable to verbalize or care for herself, requiring continued tube feeding for nutritional support, Dr. Mudan and associates noted.

“CDPH is actively working to warn the public of this health risk, actively screening other skin lightening cream samples for mercury, and is investigating the case of a family member with likely exposure but less severe illness,” the investigators concluded.

The study authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Mudan A et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019 Dec 20. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6850a4.

The first known case of contamination of skin-lightening cream with methylmercury was identified in July 2019 in a Mexican American woman in Sacramento, Calif., according to Anita Mudan, MD, of the department of emergency medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, and associates.

The woman, aged 47 years, sought medical care for dysesthesias and weakness in the upper extremities, the investigators wrote in a report published in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

This progressed to dysarthria, blurry vision, and unsteady gait over a 2-week period, leading to her hospitalization. Over the next 2 weeks, she declined into an agitated delirium; screening blood and urine tests detected levels of mercury exceeding the upper limit of quantification.

Oral dimercaptosuccinic acid at 10 mg/kg every 8 hours was administered via feeding tube. The California Department of Public Health (CDPH) conducted interviews with the patient’s family, discovering that the patient had used a skin-lightening cream obtained from Mexico for the past 7 years. The cream was analyzed and found to contain mercury at a concentration of 12,000 ppm. A Raman spectral analysis showed that the sample contained the organic compound methylmercury iodide.

Typically, contaminated skin-lightening creams contain inorganic mercury at levels up to 200,000 ppm; the significantly lower mercury content of the cream in this case “underscores the far higher toxicity of organic mercury compounds,” the investigators wrote.

The patient has undergone extensive chelation therapy, but remains unable to verbalize or care for herself, requiring continued tube feeding for nutritional support, Dr. Mudan and associates noted.

“CDPH is actively working to warn the public of this health risk, actively screening other skin lightening cream samples for mercury, and is investigating the case of a family member with likely exposure but less severe illness,” the investigators concluded.

The study authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Mudan A et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019 Dec 20. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6850a4.

The first known case of contamination of skin-lightening cream with methylmercury was identified in July 2019 in a Mexican American woman in Sacramento, Calif., according to Anita Mudan, MD, of the department of emergency medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, and associates.

The woman, aged 47 years, sought medical care for dysesthesias and weakness in the upper extremities, the investigators wrote in a report published in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

This progressed to dysarthria, blurry vision, and unsteady gait over a 2-week period, leading to her hospitalization. Over the next 2 weeks, she declined into an agitated delirium; screening blood and urine tests detected levels of mercury exceeding the upper limit of quantification.

Oral dimercaptosuccinic acid at 10 mg/kg every 8 hours was administered via feeding tube. The California Department of Public Health (CDPH) conducted interviews with the patient’s family, discovering that the patient had used a skin-lightening cream obtained from Mexico for the past 7 years. The cream was analyzed and found to contain mercury at a concentration of 12,000 ppm. A Raman spectral analysis showed that the sample contained the organic compound methylmercury iodide.

Typically, contaminated skin-lightening creams contain inorganic mercury at levels up to 200,000 ppm; the significantly lower mercury content of the cream in this case “underscores the far higher toxicity of organic mercury compounds,” the investigators wrote.

The patient has undergone extensive chelation therapy, but remains unable to verbalize or care for herself, requiring continued tube feeding for nutritional support, Dr. Mudan and associates noted.

“CDPH is actively working to warn the public of this health risk, actively screening other skin lightening cream samples for mercury, and is investigating the case of a family member with likely exposure but less severe illness,” the investigators concluded.

The study authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Mudan A et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019 Dec 20. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6850a4.

FROM MMWR

Replacement meals boost nutrient intake by pregnant women with obesity

LAS VEGAS – Pregnant women with overweight or obesity who replaced two meals a day with bars or shakes starting at their second trimester not only had a significantly reduced rate of gestational weight gain but also benefited from significant improvements in their intake of several micronutrients, in a randomized study of 211 women who completed the regimen.

Further research needs “to examine the generalizability and effectiveness of this prenatal lifestyle modification program in improving micronutrient sufficiency in other populations and settings,” Suzanne Phelan, PhD, said at a meeting presented by The Obesity Society and the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. The study she presented ran at two U.S. sites, in California and Rhode Island, and enrolled a population that was 42% Hispanic/Latina. Despite uncertainty about the applicability of the findings to other populations, the results suggested that partial meal replacement is a way to better control gestational weight gain in women with overweight or obesity while simultaneously increasing micronutrient intake, said Dr. Phelan, a clinical psychologist and professor of kinesiology and public health at the California Polytechnic State University in San Luis Obispo.

She reported data from the Healthy Beginnings/Comienzos Saludables (Preventing Excessive Gestational Weight Gain in Obese Women) study, which enrolled 257 women with overweight or obesity (body mass index of at least 25 kg/m2) at week 9-16 of pregnancy and randomized them to either a multifactorial behavioral lifestyle intervention that included two daily meal replacements, or to “enhanced” usual care. About 80% of participants in both arms, a total of 211 women, completed the study with final follow-up at 35-36 weeks’ gestational age, after enrolling at an average gestational age of just under 14 weeks. In addition to eating nutrition bars or drinking nutrition shakes as the replacement meal options, participants also ate one conventional meal daily as well as 2-4 healthy snacks. The enrolled women included 41% with overweight and 59% with obesity.

The study’s primary endpoint was the rate of gestational weight gain per week, which was 0.33 kg in the intervention group and 0.39 kg in the controls, a statistically significant difference. The proportion of women who exceeded the Institute of Medicine’s recommended maximum gestational weight gain maximum was 41% among those in the intervention group and 54% among the controls, also a statistically significant difference (Am J Clin Nutr. 2018 Feb;107[2]:183-94).

The secondary micronutrient analysis that Dr. Phelan reported documented the high prevalence of micronutrient deficiencies among the study participants at baseline. More than 90% had deficient intake of vitamin D and fiber, more than 80% had inadequate dietary levels of iron, vitamin E, and choline, and more than half had too little dietary magnesium, vitamin K, and folate. There were additional deficiencies for other micronutrients in lesser proportions of study participants.

The analysis also showed how the behavioral and diet intervention through the end of the third trimester normalized many of these deficiencies, compared with the placebo arm. For example, the prevalence of a magnesium dietary deficiency in the intervention arm dropped from 69% at baseline to 37% at follow-up, compared with hardly any change in the control arm, so that women in the intervention group had a 64% reduced rate of magnesium deficiency compared with the controls, a statistically significant difference.

Other micronutrients that had significant drops in deficiency rate included calcium, with a 63% relative reduction in the deficiency prevalence, vitamin A with a 61% cut, vitamin E with an 83% relative reduction, and vitamin K with a 51% relative drop. Other micronutrient intake levels that showed statistically significant increases during the study compared with controls included vitamin D and copper, but choline showed an inexplicable drop in consumption in the intervention group, a “potential concern,” Dr. Phelan said. The intervention also significantly reduced sodium intake. Dr. Phelan and her associates published these findings (Nutrients. 2019 May 14;11[5]:1071; doi: 10.3390/nu11051071).

“The diet quality of many of the pregnant women we have studied was poor, often eating less than half the recommended amounts of fruits and vegetables,” said Leanne M. Redman, PhD, a professor at Louisiana State University and director of the Reproductive Endocrinology and Women’s Health Laboratory at the university’s Pennington Biomedical Research Center in Baton Rouge. “Meal replacement with bars and shakes will be really important for future efforts at improving diet quality” in pregnant women with obesity, predicted Dr. Redman, who did not collaborate on the study Dr. Phelan reported.

SOURCE: Phelan S et al. Obesity Week 2019. Abstract T-OR-2081.

LAS VEGAS – Pregnant women with overweight or obesity who replaced two meals a day with bars or shakes starting at their second trimester not only had a significantly reduced rate of gestational weight gain but also benefited from significant improvements in their intake of several micronutrients, in a randomized study of 211 women who completed the regimen.

Further research needs “to examine the generalizability and effectiveness of this prenatal lifestyle modification program in improving micronutrient sufficiency in other populations and settings,” Suzanne Phelan, PhD, said at a meeting presented by The Obesity Society and the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. The study she presented ran at two U.S. sites, in California and Rhode Island, and enrolled a population that was 42% Hispanic/Latina. Despite uncertainty about the applicability of the findings to other populations, the results suggested that partial meal replacement is a way to better control gestational weight gain in women with overweight or obesity while simultaneously increasing micronutrient intake, said Dr. Phelan, a clinical psychologist and professor of kinesiology and public health at the California Polytechnic State University in San Luis Obispo.

She reported data from the Healthy Beginnings/Comienzos Saludables (Preventing Excessive Gestational Weight Gain in Obese Women) study, which enrolled 257 women with overweight or obesity (body mass index of at least 25 kg/m2) at week 9-16 of pregnancy and randomized them to either a multifactorial behavioral lifestyle intervention that included two daily meal replacements, or to “enhanced” usual care. About 80% of participants in both arms, a total of 211 women, completed the study with final follow-up at 35-36 weeks’ gestational age, after enrolling at an average gestational age of just under 14 weeks. In addition to eating nutrition bars or drinking nutrition shakes as the replacement meal options, participants also ate one conventional meal daily as well as 2-4 healthy snacks. The enrolled women included 41% with overweight and 59% with obesity.

The study’s primary endpoint was the rate of gestational weight gain per week, which was 0.33 kg in the intervention group and 0.39 kg in the controls, a statistically significant difference. The proportion of women who exceeded the Institute of Medicine’s recommended maximum gestational weight gain maximum was 41% among those in the intervention group and 54% among the controls, also a statistically significant difference (Am J Clin Nutr. 2018 Feb;107[2]:183-94).

The secondary micronutrient analysis that Dr. Phelan reported documented the high prevalence of micronutrient deficiencies among the study participants at baseline. More than 90% had deficient intake of vitamin D and fiber, more than 80% had inadequate dietary levels of iron, vitamin E, and choline, and more than half had too little dietary magnesium, vitamin K, and folate. There were additional deficiencies for other micronutrients in lesser proportions of study participants.

The analysis also showed how the behavioral and diet intervention through the end of the third trimester normalized many of these deficiencies, compared with the placebo arm. For example, the prevalence of a magnesium dietary deficiency in the intervention arm dropped from 69% at baseline to 37% at follow-up, compared with hardly any change in the control arm, so that women in the intervention group had a 64% reduced rate of magnesium deficiency compared with the controls, a statistically significant difference.

Other micronutrients that had significant drops in deficiency rate included calcium, with a 63% relative reduction in the deficiency prevalence, vitamin A with a 61% cut, vitamin E with an 83% relative reduction, and vitamin K with a 51% relative drop. Other micronutrient intake levels that showed statistically significant increases during the study compared with controls included vitamin D and copper, but choline showed an inexplicable drop in consumption in the intervention group, a “potential concern,” Dr. Phelan said. The intervention also significantly reduced sodium intake. Dr. Phelan and her associates published these findings (Nutrients. 2019 May 14;11[5]:1071; doi: 10.3390/nu11051071).

“The diet quality of many of the pregnant women we have studied was poor, often eating less than half the recommended amounts of fruits and vegetables,” said Leanne M. Redman, PhD, a professor at Louisiana State University and director of the Reproductive Endocrinology and Women’s Health Laboratory at the university’s Pennington Biomedical Research Center in Baton Rouge. “Meal replacement with bars and shakes will be really important for future efforts at improving diet quality” in pregnant women with obesity, predicted Dr. Redman, who did not collaborate on the study Dr. Phelan reported.

SOURCE: Phelan S et al. Obesity Week 2019. Abstract T-OR-2081.

LAS VEGAS – Pregnant women with overweight or obesity who replaced two meals a day with bars or shakes starting at their second trimester not only had a significantly reduced rate of gestational weight gain but also benefited from significant improvements in their intake of several micronutrients, in a randomized study of 211 women who completed the regimen.

Further research needs “to examine the generalizability and effectiveness of this prenatal lifestyle modification program in improving micronutrient sufficiency in other populations and settings,” Suzanne Phelan, PhD, said at a meeting presented by The Obesity Society and the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. The study she presented ran at two U.S. sites, in California and Rhode Island, and enrolled a population that was 42% Hispanic/Latina. Despite uncertainty about the applicability of the findings to other populations, the results suggested that partial meal replacement is a way to better control gestational weight gain in women with overweight or obesity while simultaneously increasing micronutrient intake, said Dr. Phelan, a clinical psychologist and professor of kinesiology and public health at the California Polytechnic State University in San Luis Obispo.

She reported data from the Healthy Beginnings/Comienzos Saludables (Preventing Excessive Gestational Weight Gain in Obese Women) study, which enrolled 257 women with overweight or obesity (body mass index of at least 25 kg/m2) at week 9-16 of pregnancy and randomized them to either a multifactorial behavioral lifestyle intervention that included two daily meal replacements, or to “enhanced” usual care. About 80% of participants in both arms, a total of 211 women, completed the study with final follow-up at 35-36 weeks’ gestational age, after enrolling at an average gestational age of just under 14 weeks. In addition to eating nutrition bars or drinking nutrition shakes as the replacement meal options, participants also ate one conventional meal daily as well as 2-4 healthy snacks. The enrolled women included 41% with overweight and 59% with obesity.

The study’s primary endpoint was the rate of gestational weight gain per week, which was 0.33 kg in the intervention group and 0.39 kg in the controls, a statistically significant difference. The proportion of women who exceeded the Institute of Medicine’s recommended maximum gestational weight gain maximum was 41% among those in the intervention group and 54% among the controls, also a statistically significant difference (Am J Clin Nutr. 2018 Feb;107[2]:183-94).

The secondary micronutrient analysis that Dr. Phelan reported documented the high prevalence of micronutrient deficiencies among the study participants at baseline. More than 90% had deficient intake of vitamin D and fiber, more than 80% had inadequate dietary levels of iron, vitamin E, and choline, and more than half had too little dietary magnesium, vitamin K, and folate. There were additional deficiencies for other micronutrients in lesser proportions of study participants.

The analysis also showed how the behavioral and diet intervention through the end of the third trimester normalized many of these deficiencies, compared with the placebo arm. For example, the prevalence of a magnesium dietary deficiency in the intervention arm dropped from 69% at baseline to 37% at follow-up, compared with hardly any change in the control arm, so that women in the intervention group had a 64% reduced rate of magnesium deficiency compared with the controls, a statistically significant difference.

Other micronutrients that had significant drops in deficiency rate included calcium, with a 63% relative reduction in the deficiency prevalence, vitamin A with a 61% cut, vitamin E with an 83% relative reduction, and vitamin K with a 51% relative drop. Other micronutrient intake levels that showed statistically significant increases during the study compared with controls included vitamin D and copper, but choline showed an inexplicable drop in consumption in the intervention group, a “potential concern,” Dr. Phelan said. The intervention also significantly reduced sodium intake. Dr. Phelan and her associates published these findings (Nutrients. 2019 May 14;11[5]:1071; doi: 10.3390/nu11051071).