User login

COVID-19: Adjusting practice in acute leukemia care

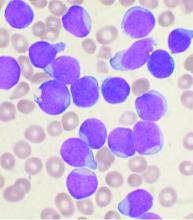

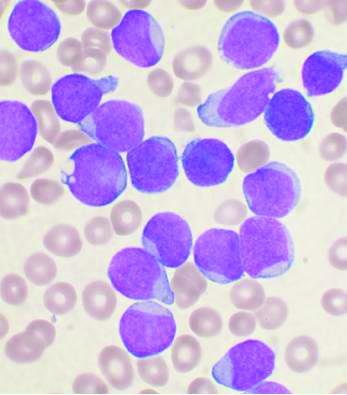

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic poses significant risks to leukemia patients and their providers, impacting every aspect of care from diagnosis through therapy, according to an editorial letter published online in Leukemia Research.

One key concern to be considered is the risk of missed or delayed diagnosis due to the pandemic conditions. An estimated 50%-75% of patients with acute leukemia are febrile at diagnosis and this puts them at high risk of a misdiagnosis of COVID-19 upon initial evaluation. As with other oncological conditions (primary mediastinal lymphoma or lung cancer, for example), which often present with a cough with or without fever, their symptoms “are likely to be considered trivial after a negative SARS-CoV-2 test,” with patients then being sent home without further assessment. In a rapidly progressing disease such as acute leukemia, this could lead to critical delays in therapeutic intervention.

The authors, from the Service and Central Laboratory of Hematology, Lausanne (Switzerland) University Hospital, also discussed the problems that might occur with regard to most standard forms of therapy. In particular, they addressed potential impacts of the pandemic on chemotherapy, bone marrow transplantation, maintenance treatments, supportive measures, and targeted therapies.

Of particular concern, “most patients may suffer from postponed chemotherapy, due to a shortage of isolation beds and blood products or the wish to avoid immunosuppressive treatments,” the authors noted, warning that “delay in chemotherapy initiation may negatively affect prognosis, [particularly in patients under age 60] with favorable- or intermediate-risk disease.”

With regard to stem cell transplantation, the authors detail the many potential difficulties with regard to procedures involving both donors and recipients, and warn that in some cases, delay in transplant could result in the reappearance of a significant minimal residual disease, which has a well-established negative impact on survival.

The authors also noted that blood product shortages have already begun in most affected countries, and how, in response, transfusion societies have called for conservative transfusion policies in strict adherence to evidence-based guidelines for patient’s blood management.

“COVID-19 will result in numerous casualties. Acute leukemia patients are at a higher risk of severe complications,” the authors stated. In particular, physicians should especially be aware of how treatment for acute leukemia may have “interactions with other drugs used to treat SARS-CoV-2–related infections/complications such as antibiotics, antiviral drugs, and various other drugs that prolong QTc or impact targeted-therapy pharmacokinetics,” they concluded.

The authors reported that they received no government or private funding for this research, and that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Gavillet M et al. Leuk. Res. 2020. doi.org/10.1016/j.leukres.2020.106353.

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic poses significant risks to leukemia patients and their providers, impacting every aspect of care from diagnosis through therapy, according to an editorial letter published online in Leukemia Research.

One key concern to be considered is the risk of missed or delayed diagnosis due to the pandemic conditions. An estimated 50%-75% of patients with acute leukemia are febrile at diagnosis and this puts them at high risk of a misdiagnosis of COVID-19 upon initial evaluation. As with other oncological conditions (primary mediastinal lymphoma or lung cancer, for example), which often present with a cough with or without fever, their symptoms “are likely to be considered trivial after a negative SARS-CoV-2 test,” with patients then being sent home without further assessment. In a rapidly progressing disease such as acute leukemia, this could lead to critical delays in therapeutic intervention.

The authors, from the Service and Central Laboratory of Hematology, Lausanne (Switzerland) University Hospital, also discussed the problems that might occur with regard to most standard forms of therapy. In particular, they addressed potential impacts of the pandemic on chemotherapy, bone marrow transplantation, maintenance treatments, supportive measures, and targeted therapies.

Of particular concern, “most patients may suffer from postponed chemotherapy, due to a shortage of isolation beds and blood products or the wish to avoid immunosuppressive treatments,” the authors noted, warning that “delay in chemotherapy initiation may negatively affect prognosis, [particularly in patients under age 60] with favorable- or intermediate-risk disease.”

With regard to stem cell transplantation, the authors detail the many potential difficulties with regard to procedures involving both donors and recipients, and warn that in some cases, delay in transplant could result in the reappearance of a significant minimal residual disease, which has a well-established negative impact on survival.

The authors also noted that blood product shortages have already begun in most affected countries, and how, in response, transfusion societies have called for conservative transfusion policies in strict adherence to evidence-based guidelines for patient’s blood management.

“COVID-19 will result in numerous casualties. Acute leukemia patients are at a higher risk of severe complications,” the authors stated. In particular, physicians should especially be aware of how treatment for acute leukemia may have “interactions with other drugs used to treat SARS-CoV-2–related infections/complications such as antibiotics, antiviral drugs, and various other drugs that prolong QTc or impact targeted-therapy pharmacokinetics,” they concluded.

The authors reported that they received no government or private funding for this research, and that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Gavillet M et al. Leuk. Res. 2020. doi.org/10.1016/j.leukres.2020.106353.

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic poses significant risks to leukemia patients and their providers, impacting every aspect of care from diagnosis through therapy, according to an editorial letter published online in Leukemia Research.

One key concern to be considered is the risk of missed or delayed diagnosis due to the pandemic conditions. An estimated 50%-75% of patients with acute leukemia are febrile at diagnosis and this puts them at high risk of a misdiagnosis of COVID-19 upon initial evaluation. As with other oncological conditions (primary mediastinal lymphoma or lung cancer, for example), which often present with a cough with or without fever, their symptoms “are likely to be considered trivial after a negative SARS-CoV-2 test,” with patients then being sent home without further assessment. In a rapidly progressing disease such as acute leukemia, this could lead to critical delays in therapeutic intervention.

The authors, from the Service and Central Laboratory of Hematology, Lausanne (Switzerland) University Hospital, also discussed the problems that might occur with regard to most standard forms of therapy. In particular, they addressed potential impacts of the pandemic on chemotherapy, bone marrow transplantation, maintenance treatments, supportive measures, and targeted therapies.

Of particular concern, “most patients may suffer from postponed chemotherapy, due to a shortage of isolation beds and blood products or the wish to avoid immunosuppressive treatments,” the authors noted, warning that “delay in chemotherapy initiation may negatively affect prognosis, [particularly in patients under age 60] with favorable- or intermediate-risk disease.”

With regard to stem cell transplantation, the authors detail the many potential difficulties with regard to procedures involving both donors and recipients, and warn that in some cases, delay in transplant could result in the reappearance of a significant minimal residual disease, which has a well-established negative impact on survival.

The authors also noted that blood product shortages have already begun in most affected countries, and how, in response, transfusion societies have called for conservative transfusion policies in strict adherence to evidence-based guidelines for patient’s blood management.

“COVID-19 will result in numerous casualties. Acute leukemia patients are at a higher risk of severe complications,” the authors stated. In particular, physicians should especially be aware of how treatment for acute leukemia may have “interactions with other drugs used to treat SARS-CoV-2–related infections/complications such as antibiotics, antiviral drugs, and various other drugs that prolong QTc or impact targeted-therapy pharmacokinetics,” they concluded.

The authors reported that they received no government or private funding for this research, and that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Gavillet M et al. Leuk. Res. 2020. doi.org/10.1016/j.leukres.2020.106353.

FROM LEUKEMIA RESEARCH

Noninvasive fibrosis scores not sensitive in people with fatty liver disease and T2D

Noninvasive fibrosis scores, which are widely used to predict advanced fibrosis in people with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), do not do a good job of picking up advanced fibrosis in patients with underlying diabetes, according to a new study.

Advanced fibrosis is associated with an increased risk of cirrhosis, end-stage liver disease, and liver failure. Underlying diabetes is a risk factor for both advanced fibrosis and death in patients with NAFLD.

While liver biopsy remains the gold standard for detecting advanced fibrosis, high costs and risks limit its use. Noninvasive scores such as the AST/ALT ratio; AST to platelet ratio index (APRI); fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) index; and NAFLD fibrosis score (NFS) have gained popularity in recent years, as they offer the compelling advantage of using easily and cheaply attained clinical and laboratory measures to assess likelihood of disease.

But their accuracy has come into question, particularly for people with diabetes.

In research published in the Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology, Amandeep Singh, MD, and colleagues at the Cleveland Clinic looked at their center’s records for 1,157 patients with type 2 diabetes (65% women, 88% white, 85% with obesity) who had undergone a liver biopsy for suspected advanced fibrosis between 2000 and 2015. Biopsy results revealed that a third of the cohort (32%) was positive for advanced fibrosis.

The investigators then pulled patients’ laboratory results for AST, ALT, cholesterol, triglycerides, fasting glucose, hemoglobin A1c, bilirubin, albumin, platelet count, alkaline phosphatase, albumin, and lipid levels, all collected within a year of biopsy. After plugging these into the algorithms of four different scoring systems for advanced fibrosis, they compared results with results from the biopsies.

The scores of AST/ALT greater than 1.4, APRI of at least 1.5, NFS greater than 0.676, and FIB-4 index greater than 2.67 had high specificities of 84%, 97%, 70%, and 93%, respectively, but sensitivities of only 27%, 17%, 64%, and 44%. Even when the cutoff measures were tightened, the scoring systems still missed a lot of disease. This suggests, Dr. Singh and colleagues wrote, that “the presence of diabetes could decrease the predictive value of these scores to detect advanced disease in NAFLD patients.” Reliable noninvasive biomarkers are “urgently needed” for this patient population.

In an interview, Dr. Singh advised that clinicians continue to use current noninvasive scores in patients with diabetes – preferably the NFS – “until we have a better scoring system.” If clinicians suspect advanced fibrosis based on lab tests and clinical data, then “liver biopsy should be considered,” he said.

The investigators described among the limitations of their study its retrospective, single-center design, with patients who were mostly white and from one geographic region.

Dr. Singh and colleagues reported no conflicts of interest or outside funding for their study.

SOURCE: Singh A et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2020 Mar 11. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001339.

Noninvasive fibrosis scores, which are widely used to predict advanced fibrosis in people with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), do not do a good job of picking up advanced fibrosis in patients with underlying diabetes, according to a new study.

Advanced fibrosis is associated with an increased risk of cirrhosis, end-stage liver disease, and liver failure. Underlying diabetes is a risk factor for both advanced fibrosis and death in patients with NAFLD.

While liver biopsy remains the gold standard for detecting advanced fibrosis, high costs and risks limit its use. Noninvasive scores such as the AST/ALT ratio; AST to platelet ratio index (APRI); fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) index; and NAFLD fibrosis score (NFS) have gained popularity in recent years, as they offer the compelling advantage of using easily and cheaply attained clinical and laboratory measures to assess likelihood of disease.

But their accuracy has come into question, particularly for people with diabetes.

In research published in the Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology, Amandeep Singh, MD, and colleagues at the Cleveland Clinic looked at their center’s records for 1,157 patients with type 2 diabetes (65% women, 88% white, 85% with obesity) who had undergone a liver biopsy for suspected advanced fibrosis between 2000 and 2015. Biopsy results revealed that a third of the cohort (32%) was positive for advanced fibrosis.

The investigators then pulled patients’ laboratory results for AST, ALT, cholesterol, triglycerides, fasting glucose, hemoglobin A1c, bilirubin, albumin, platelet count, alkaline phosphatase, albumin, and lipid levels, all collected within a year of biopsy. After plugging these into the algorithms of four different scoring systems for advanced fibrosis, they compared results with results from the biopsies.

The scores of AST/ALT greater than 1.4, APRI of at least 1.5, NFS greater than 0.676, and FIB-4 index greater than 2.67 had high specificities of 84%, 97%, 70%, and 93%, respectively, but sensitivities of only 27%, 17%, 64%, and 44%. Even when the cutoff measures were tightened, the scoring systems still missed a lot of disease. This suggests, Dr. Singh and colleagues wrote, that “the presence of diabetes could decrease the predictive value of these scores to detect advanced disease in NAFLD patients.” Reliable noninvasive biomarkers are “urgently needed” for this patient population.

In an interview, Dr. Singh advised that clinicians continue to use current noninvasive scores in patients with diabetes – preferably the NFS – “until we have a better scoring system.” If clinicians suspect advanced fibrosis based on lab tests and clinical data, then “liver biopsy should be considered,” he said.

The investigators described among the limitations of their study its retrospective, single-center design, with patients who were mostly white and from one geographic region.

Dr. Singh and colleagues reported no conflicts of interest or outside funding for their study.

SOURCE: Singh A et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2020 Mar 11. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001339.

Noninvasive fibrosis scores, which are widely used to predict advanced fibrosis in people with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), do not do a good job of picking up advanced fibrosis in patients with underlying diabetes, according to a new study.

Advanced fibrosis is associated with an increased risk of cirrhosis, end-stage liver disease, and liver failure. Underlying diabetes is a risk factor for both advanced fibrosis and death in patients with NAFLD.

While liver biopsy remains the gold standard for detecting advanced fibrosis, high costs and risks limit its use. Noninvasive scores such as the AST/ALT ratio; AST to platelet ratio index (APRI); fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) index; and NAFLD fibrosis score (NFS) have gained popularity in recent years, as they offer the compelling advantage of using easily and cheaply attained clinical and laboratory measures to assess likelihood of disease.

But their accuracy has come into question, particularly for people with diabetes.

In research published in the Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology, Amandeep Singh, MD, and colleagues at the Cleveland Clinic looked at their center’s records for 1,157 patients with type 2 diabetes (65% women, 88% white, 85% with obesity) who had undergone a liver biopsy for suspected advanced fibrosis between 2000 and 2015. Biopsy results revealed that a third of the cohort (32%) was positive for advanced fibrosis.

The investigators then pulled patients’ laboratory results for AST, ALT, cholesterol, triglycerides, fasting glucose, hemoglobin A1c, bilirubin, albumin, platelet count, alkaline phosphatase, albumin, and lipid levels, all collected within a year of biopsy. After plugging these into the algorithms of four different scoring systems for advanced fibrosis, they compared results with results from the biopsies.

The scores of AST/ALT greater than 1.4, APRI of at least 1.5, NFS greater than 0.676, and FIB-4 index greater than 2.67 had high specificities of 84%, 97%, 70%, and 93%, respectively, but sensitivities of only 27%, 17%, 64%, and 44%. Even when the cutoff measures were tightened, the scoring systems still missed a lot of disease. This suggests, Dr. Singh and colleagues wrote, that “the presence of diabetes could decrease the predictive value of these scores to detect advanced disease in NAFLD patients.” Reliable noninvasive biomarkers are “urgently needed” for this patient population.

In an interview, Dr. Singh advised that clinicians continue to use current noninvasive scores in patients with diabetes – preferably the NFS – “until we have a better scoring system.” If clinicians suspect advanced fibrosis based on lab tests and clinical data, then “liver biopsy should be considered,” he said.

The investigators described among the limitations of their study its retrospective, single-center design, with patients who were mostly white and from one geographic region.

Dr. Singh and colleagues reported no conflicts of interest or outside funding for their study.

SOURCE: Singh A et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2020 Mar 11. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001339.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY

AASLD: Liver transplants should proceed despite COVID-19

In liver transplant recipients or patients with autoimmune hepatitis on immunosuppressive therapy, acute cellular rejection or disease flare should not be presumed in the face of active coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), according to the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD).

Signs that would normally be interpreted as flare or rejection need to be considered more cautiously now because the virus attacks the liver, and elevated aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, and slightly elevated bilirubin are common, ranging from a prevalence of 14% to 53% in COVID-19 patients. Acute liver injury is possible, especially in more severe cases, the group said.

The advice comes from a recently released document from AASLD, called “Clinical Insights for Hepatology and Liver Transplant Providers During the Covid-19 Pandemic,” to help hepatologists and liver transplant providers negotiate the pandemic, according to the latest data. It’s a far-ranging work that contains a lot of now familiar steps for providers to take to protect themselves and patients from the virus, but also much advice specific to liver medicine.

For instance, the group said it’s important to keep in mind that experimental treatments for the infection, including statins, remdesivir, and tocilizumab, can be hepatotoxic. Abnormal liver biochemistries are not a contraindication, but liver biochemistries need to be followed regularly in COVID-19 patients, especially those treated with remdesivir or tocilizumab, regardless of baseline values.

Also, lopinavir/ritonavir is a potent inhibitor of cytochrome P450 enzymes involved with calcineurin inhibitor metabolism, so if it’s used, AASLD said to reduce tacrolimus dosages to 1/20–1/50 of baseline.

The group cautioned against anticipatory adjustments to immunosuppressive drugs or dosages in patients without COVID-19, but if immunosuppressed liver disease patients do get the infection, prednisone doses should be reduced but kept above 10 mg/day to avoid adrenal insufficiency. In the setting of lymphopenia, fever, or worsening COVID-19 pneumonia, it advised reduction of azathioprine and mycophenolate dosages and reduction of, but not stopping, calcineurin inhibitors.

Liver transplants should not be postponed. However, to minimize exposure to the hospital environment, AASLD advised to “consider evaluating only patients with HCC [hepatocellular carcinoma] or those patients with severe disease and high MELD [model for end-stage liver disease] scores who are likely to benefit from immediate liver transplant.”

“An argument that has been put forward to justify deferring some transplants is concern about immunosuppressing patients during the COVID-19 pandemic,” the group said, but “data suggest the innate immune response may be the main driver for pulmonary injury due to COVID-19 and [that] immunosuppression may be protective. ... Posttransplant immunosuppression was not a risk factor for mortality associated with” the severe acute respiratory syndrome pandemic in 2003-2004 or the ongoing Middle East respiratory syndrome pandemic, both also caused by coronaviruses.

AASLD advised against reducing immunosuppression or stopping mycophenolate for asymptomatic patients after transplant, but COVID-19 prevention measures should be emphasized, including frequent hand washing and staying away from large crowds.

People who test positive for COVID-19 are ineligible for organ donation. Bronchoalveolar lavage is the most sensitive test (93%), followed by nasal swabs (63%) and pharyngeal swabs (32%).

In general, the group said elective procedures should be postponed, but urgent ones, such as biliary surgery and transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts for bleeding varices, in addition to liver transplants, should not.

Also, HCC patients “should not wait until the pandemic abates to undergo [surveillance] imaging because the prospective duration of the pandemic is unknown. ... An arbitrary delay of 2 months is reasonable” for imaging based on patient and facility circumstances, but otherwise, “proceed with HCC treatments rather than delaying them due to the pandemic,” the group said.

As for who to bring into the office for an initial consult, “consider seeing in person only new adult and pediatric patients with urgent issues and clinically significant liver disease (e.g., jaundice, elevated ALT or AST above 500 U/L, recent onset of hepatic decompensation),” AASLD said.

In liver transplant recipients or patients with autoimmune hepatitis on immunosuppressive therapy, acute cellular rejection or disease flare should not be presumed in the face of active coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), according to the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD).

Signs that would normally be interpreted as flare or rejection need to be considered more cautiously now because the virus attacks the liver, and elevated aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, and slightly elevated bilirubin are common, ranging from a prevalence of 14% to 53% in COVID-19 patients. Acute liver injury is possible, especially in more severe cases, the group said.

The advice comes from a recently released document from AASLD, called “Clinical Insights for Hepatology and Liver Transplant Providers During the Covid-19 Pandemic,” to help hepatologists and liver transplant providers negotiate the pandemic, according to the latest data. It’s a far-ranging work that contains a lot of now familiar steps for providers to take to protect themselves and patients from the virus, but also much advice specific to liver medicine.

For instance, the group said it’s important to keep in mind that experimental treatments for the infection, including statins, remdesivir, and tocilizumab, can be hepatotoxic. Abnormal liver biochemistries are not a contraindication, but liver biochemistries need to be followed regularly in COVID-19 patients, especially those treated with remdesivir or tocilizumab, regardless of baseline values.

Also, lopinavir/ritonavir is a potent inhibitor of cytochrome P450 enzymes involved with calcineurin inhibitor metabolism, so if it’s used, AASLD said to reduce tacrolimus dosages to 1/20–1/50 of baseline.

The group cautioned against anticipatory adjustments to immunosuppressive drugs or dosages in patients without COVID-19, but if immunosuppressed liver disease patients do get the infection, prednisone doses should be reduced but kept above 10 mg/day to avoid adrenal insufficiency. In the setting of lymphopenia, fever, or worsening COVID-19 pneumonia, it advised reduction of azathioprine and mycophenolate dosages and reduction of, but not stopping, calcineurin inhibitors.

Liver transplants should not be postponed. However, to minimize exposure to the hospital environment, AASLD advised to “consider evaluating only patients with HCC [hepatocellular carcinoma] or those patients with severe disease and high MELD [model for end-stage liver disease] scores who are likely to benefit from immediate liver transplant.”

“An argument that has been put forward to justify deferring some transplants is concern about immunosuppressing patients during the COVID-19 pandemic,” the group said, but “data suggest the innate immune response may be the main driver for pulmonary injury due to COVID-19 and [that] immunosuppression may be protective. ... Posttransplant immunosuppression was not a risk factor for mortality associated with” the severe acute respiratory syndrome pandemic in 2003-2004 or the ongoing Middle East respiratory syndrome pandemic, both also caused by coronaviruses.

AASLD advised against reducing immunosuppression or stopping mycophenolate for asymptomatic patients after transplant, but COVID-19 prevention measures should be emphasized, including frequent hand washing and staying away from large crowds.

People who test positive for COVID-19 are ineligible for organ donation. Bronchoalveolar lavage is the most sensitive test (93%), followed by nasal swabs (63%) and pharyngeal swabs (32%).

In general, the group said elective procedures should be postponed, but urgent ones, such as biliary surgery and transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts for bleeding varices, in addition to liver transplants, should not.

Also, HCC patients “should not wait until the pandemic abates to undergo [surveillance] imaging because the prospective duration of the pandemic is unknown. ... An arbitrary delay of 2 months is reasonable” for imaging based on patient and facility circumstances, but otherwise, “proceed with HCC treatments rather than delaying them due to the pandemic,” the group said.

As for who to bring into the office for an initial consult, “consider seeing in person only new adult and pediatric patients with urgent issues and clinically significant liver disease (e.g., jaundice, elevated ALT or AST above 500 U/L, recent onset of hepatic decompensation),” AASLD said.

In liver transplant recipients or patients with autoimmune hepatitis on immunosuppressive therapy, acute cellular rejection or disease flare should not be presumed in the face of active coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), according to the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD).

Signs that would normally be interpreted as flare or rejection need to be considered more cautiously now because the virus attacks the liver, and elevated aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, and slightly elevated bilirubin are common, ranging from a prevalence of 14% to 53% in COVID-19 patients. Acute liver injury is possible, especially in more severe cases, the group said.

The advice comes from a recently released document from AASLD, called “Clinical Insights for Hepatology and Liver Transplant Providers During the Covid-19 Pandemic,” to help hepatologists and liver transplant providers negotiate the pandemic, according to the latest data. It’s a far-ranging work that contains a lot of now familiar steps for providers to take to protect themselves and patients from the virus, but also much advice specific to liver medicine.

For instance, the group said it’s important to keep in mind that experimental treatments for the infection, including statins, remdesivir, and tocilizumab, can be hepatotoxic. Abnormal liver biochemistries are not a contraindication, but liver biochemistries need to be followed regularly in COVID-19 patients, especially those treated with remdesivir or tocilizumab, regardless of baseline values.

Also, lopinavir/ritonavir is a potent inhibitor of cytochrome P450 enzymes involved with calcineurin inhibitor metabolism, so if it’s used, AASLD said to reduce tacrolimus dosages to 1/20–1/50 of baseline.

The group cautioned against anticipatory adjustments to immunosuppressive drugs or dosages in patients without COVID-19, but if immunosuppressed liver disease patients do get the infection, prednisone doses should be reduced but kept above 10 mg/day to avoid adrenal insufficiency. In the setting of lymphopenia, fever, or worsening COVID-19 pneumonia, it advised reduction of azathioprine and mycophenolate dosages and reduction of, but not stopping, calcineurin inhibitors.

Liver transplants should not be postponed. However, to minimize exposure to the hospital environment, AASLD advised to “consider evaluating only patients with HCC [hepatocellular carcinoma] or those patients with severe disease and high MELD [model for end-stage liver disease] scores who are likely to benefit from immediate liver transplant.”

“An argument that has been put forward to justify deferring some transplants is concern about immunosuppressing patients during the COVID-19 pandemic,” the group said, but “data suggest the innate immune response may be the main driver for pulmonary injury due to COVID-19 and [that] immunosuppression may be protective. ... Posttransplant immunosuppression was not a risk factor for mortality associated with” the severe acute respiratory syndrome pandemic in 2003-2004 or the ongoing Middle East respiratory syndrome pandemic, both also caused by coronaviruses.

AASLD advised against reducing immunosuppression or stopping mycophenolate for asymptomatic patients after transplant, but COVID-19 prevention measures should be emphasized, including frequent hand washing and staying away from large crowds.

People who test positive for COVID-19 are ineligible for organ donation. Bronchoalveolar lavage is the most sensitive test (93%), followed by nasal swabs (63%) and pharyngeal swabs (32%).

In general, the group said elective procedures should be postponed, but urgent ones, such as biliary surgery and transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts for bleeding varices, in addition to liver transplants, should not.

Also, HCC patients “should not wait until the pandemic abates to undergo [surveillance] imaging because the prospective duration of the pandemic is unknown. ... An arbitrary delay of 2 months is reasonable” for imaging based on patient and facility circumstances, but otherwise, “proceed with HCC treatments rather than delaying them due to the pandemic,” the group said.

As for who to bring into the office for an initial consult, “consider seeing in person only new adult and pediatric patients with urgent issues and clinically significant liver disease (e.g., jaundice, elevated ALT or AST above 500 U/L, recent onset of hepatic decompensation),” AASLD said.

COVID-19 experiences from the ob.gyn. front line

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to spread across the United States, several members of the Ob.Gyn. News Editorial Advisory Board shared their experiences.

Catherine Cansino, MD, MPH, who is an associate clinical professor in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of California, Davis, discussed the changes COVID-19 has had on local and regional practice in Sacramento and northern California.

There has been a dramatic increase in telehealth, using video, phone, and apps such as Zoom. Although ob.gyns. at the university are limiting outpatient appointments to essential visits only, we are continuing to offer telehealth to a few nonessential visits. This will be readdressed when the COVID-19 cases peak, Dr. Cansino said.

All patients admitted to labor & delivery undergo COVID-19 testing regardless of symptoms. For patients in the clinic who are expected to be induced or scheduled for cesarean delivery, we are screening them within 72 hours before admission.

In gynecology, only essential or urgent surgeries at UC Davis are being performed and include indications such as cancer, serious benign conditions unresponsive to conservative treatment (e.g., tubo-ovarian abscess, large symptomatic adnexal mass), and pregnancy termination. We are preserving access to abortion and reproductive health services since these are essential services.

We limit the number of providers involved in direct contact with inpatients to one or two, including a physician, nurse, and/or resident, Dr. Cansino said in an interview. Based on recent Liaison Committee on Medical Education policies related to concerns about educational experience during the pandemic, no medical students are allowed at the hospital at present. We also severely restrict the number of visitors in the inpatient and outpatient settings, including only two attendants (partner, doula, and such) during labor and delivery, and consider the impact on patients’ well-being when we restrict their visitors.

We are following University of California guidelines regarding face mask use, which have been in evolution over the last month. Face masks are used for patients and the health care providers primarily when patients either have known COVID-19 infection or are considered as patients under investigation or if the employee had a high-risk exposure. The use of face masks is becoming more permissive, rather than mandatory, to conserve personal protective equipment (PPE) for when the surge arrives.

Education is ongoing about caring for our families and ourselves if we get infected and need to isolate within our own homes. The department and health system is trying to balance the challenges of urgent patient care needs against the wellness concerns for the faculty, staff, and residents. Many physicians are also struggling with childcare problems, which add to our personal stress. There is anxiety among many physicians about exposure to asymptomatic carriers, including themselves, patients, and their families, Dr. Cansino said.

David Forstein, DO, dean and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Touro College of Osteopathic Medicine, New York, said in an interview that the COVID-19 pandemic has “totally disrupted medical education. At almost all medical schools, didactics have moved completely online – ZOOM sessions abound, but labs become demonstrations, if at all, during the preclinical years. The clinical years have been put on hold, as well as student rotations suspended, out of caution for the students because hospitals needed to conserve PPE for the essential personnel and because administrators knew there would be less time for teaching. After initially requesting a pause, many hospitals now are asking students to come back because so many physicians, nurses, and residents have become ill with COVID-19 and either are quarantined or are patients in the hospital themselves.

“There has been a state-by-state call to consider graduating health professions students early, and press them into service, before their residencies actually begin. Some locations are looking for these new graduates to volunteer; some are willing to pay them a resident’s salary level. Medical schools are auditing their student records now to see which students would qualify to graduate early,” Dr. Forstein noted.

David M. Jaspan, DO, chairman of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the Einstein Health Care Network in Philadelphia, described in an email interview how COVID-19 has changed practice.

To minimize the number of providers on the front line, we have developed a Monday to Friday rotating schedule of three teams of five members, he explained. There will be a hospital-based team, an office-based team, and a telehealth-based team who will provide their services from home. On-call responsibilities remain the same.

The hospital team, working 7 a.m. to 5 p.m., will rotate through assignments each day:

- One person will cover labor and delivery.

- One person will cover triage and help on labor and delivery.

- One person will be assigned to the resident office.

- One person will be assigned to cover the team of the post call attending (Sunday through Thursday call).

- One person will be assigned to gynecology coverage, consults, and postpartum rounds.

To further minimize the patient interactions, when possible, each patient should be seen by the attending physician with the resident. This is a change from usual practice, where the patient is first seen by the resident, who reports back to the attending, and then both physicians see the patient together.

The network’s offices now open from 9 a.m. (many offices had been offering early-morning hours starting at 7 a.m.), and the physicians and advanced practice providers will work through the last scheduled patient appointment, Dr. Jaspan explained. “The office-based team will preferentially see in-person visits.”

Several offices have been closed so that ob.gyns. and staff can be reassigned to telehealth. The remaining five offices generally have one attending physician and one advanced practice provider.

The remaining team of ob.gyns. provides telehealth with the help of staff members. This involves an initial call to the patient by staff letting them know the doctor will be calling, checking them in, verifying insurance, and collecting payment, followed by the actual telehealth visit. If follow-up is needed, the staff member schedules the follow-up.

Dr. Jaspan called the new approach to prenatal care because of COVID-19 a “cataclysmic change in how we care for our patients. We have decided to further limit our obstetrical in-person visits. It is our feeling that these changes will enable patients to remain outside of the office and in the safety of their homes, provide appropriate social distancing, and diminish potential exposures to the office staff providers and patients.”

In-person visits will occur at: the initial visit, between 24 and 28 weeks, at 32 weeks, and at 36 or 37 weeks; if the patient at 36/37 has a blood pressure cuff, they will not have additional scheduled in-patient visits. We have partnered with the insurance companies to provide more than 88% of obstetrical patients with home blood pressure cuffs.

Obstetrical visits via telehealth will continue at our standard intervals: monthly until 26 weeks; twice monthly during 26-36 weeks; and weekly from 37 weeks to delivery. These visits should use a video component such as Zoom, Doxy.me, or FaceTime.

“If the patient has concerns or problems, we will see them at any time. However, the new standard will be telehealth visits and the exception will be the in-person visit,” Dr. Jaspan said.

In addition, we have worked our division of maternal-fetal medicine to adjust the antenatal testing schedules, and we have curtailed the frequency of ultrasound, he noted.

He emphasized the importance of documenting telehealth interactions with obstetrical patients, in addition to “providing adequate teaching and education for patients regarding kick counts to ensure fetal well-being.” It also is key to “properly document conversations with patients regarding bleeding, rupture of membranes, fetal movement, headache, visual changes, fevers, cough, nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, fatigue, muscle aches, etc.”

The residents’ schedule also has been modified to diminish their exposure. Within our new paradigm, we have scheduled video conferences to enable our program to maintain our commitment to academics.

It is imperative that we keep our patients safe, and it is critical to protect our staff members. Those who provide women’s health cannot be replaced by other nurses or physicians.

Mark P. Trolice, MD, is director of Fertility CARE: the IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, Orlando. He related in an email interview that, on March 17, 2020, the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) released “Patient Management and Clinical Recommendations During the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic.” This document serves as guidance on fertility care during the current crisis. Specifically, the recommendations include the following:

- Suspend initiation of new treatment cycles, including ovulation induction, intrauterine inseminations, in vitro fertilization including retrievals and frozen embryo transfers, and nonurgent gamete cryopreservation.

- Strongly consider cancellation of all embryo transfers, whether fresh or frozen.

- Continue to care for patients who are currently “in cycle” or who require urgent stimulation and cryopreservation.

- Suspend elective surgeries and nonurgent diagnostic procedures.

- Minimize in-person interactions and increase utilization of telehealth.

As a member of ASRM for more than 2 decades and a participant of several of their committees, my practice immediately ceased treatment cycles to comply with this guidance.

Then on March 20, 2020, the Florida governor’s executive order 20-72 was released, stating, “All hospitals, ambulatory surgical centers, office surgery centers, dental, orthodontic and endodontic offices, and other health care practitioners’ offices in the State of Florida are prohibited from providing any medically unnecessary, nonurgent or nonemergency procedure or surgery which, if delayed, does not place a patient’s immediate health, safety, or well-being at risk, or will, if delayed, not contribute to the worsening of a serious or life-threatening medical condition.”

As a result, my practice has been limited to telemedicine consultations. While the ASRM guidance and the gubernatorial executive order pose a significant financial hardship on my center and all applicable medical clinics in my state, resulting in expected layoffs, salary reductions, and requests for government stimulus loans, the greater good takes priority and we pray for all the victims of this devastating pandemic.

The governor’s current executive order is set to expire on May 9, 2020, unless it is extended.

ASRM released an update of their guidance on March 30, 2020, offering no change from their prior recommendations. The organization plans to reevaluate the guidance at 2-week intervals.

Sangeeta Sinha, MD, an ob.gyn. in private practice at Stone Springs Hospital Center, Dulles, Va. said in an interview, “COVID 19 has put fear in all aspects of our daily activities which we are attempting to cope with.”

She related several changes made to her office and hospital environments. “In our office, we are now wearing a mask at all times, gloves to examine every patient. We have staggered physicians in the office to take televisits and in-office patients. We are screening all new patients on the phone to determine if they are sick, have traveled to high-risk, hot spot areas of the country, or have had contact with someone who tested positive for COVID-19. We are only seeing our pregnant women and have also pushed out their return appointments to 4 weeks if possible. There are several staff who are not working due to fear or are in self quarantine so we have shortage of staff in the office. At the hospital as well we are wearing a mask at all times, using personal protective equipment for deliveries and C-sections.

“We have had several scares, including a new transfer of an 18-year-old pregnant patient at 30 weeks with cough and sore throat, who later reported that her roommate is very sick and he works with someone who has tested positive for COVID-19. Thankfully she is healthy and well. We learned several lessons from this one.”

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to spread across the United States, several members of the Ob.Gyn. News Editorial Advisory Board shared their experiences.

Catherine Cansino, MD, MPH, who is an associate clinical professor in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of California, Davis, discussed the changes COVID-19 has had on local and regional practice in Sacramento and northern California.

There has been a dramatic increase in telehealth, using video, phone, and apps such as Zoom. Although ob.gyns. at the university are limiting outpatient appointments to essential visits only, we are continuing to offer telehealth to a few nonessential visits. This will be readdressed when the COVID-19 cases peak, Dr. Cansino said.

All patients admitted to labor & delivery undergo COVID-19 testing regardless of symptoms. For patients in the clinic who are expected to be induced or scheduled for cesarean delivery, we are screening them within 72 hours before admission.

In gynecology, only essential or urgent surgeries at UC Davis are being performed and include indications such as cancer, serious benign conditions unresponsive to conservative treatment (e.g., tubo-ovarian abscess, large symptomatic adnexal mass), and pregnancy termination. We are preserving access to abortion and reproductive health services since these are essential services.

We limit the number of providers involved in direct contact with inpatients to one or two, including a physician, nurse, and/or resident, Dr. Cansino said in an interview. Based on recent Liaison Committee on Medical Education policies related to concerns about educational experience during the pandemic, no medical students are allowed at the hospital at present. We also severely restrict the number of visitors in the inpatient and outpatient settings, including only two attendants (partner, doula, and such) during labor and delivery, and consider the impact on patients’ well-being when we restrict their visitors.

We are following University of California guidelines regarding face mask use, which have been in evolution over the last month. Face masks are used for patients and the health care providers primarily when patients either have known COVID-19 infection or are considered as patients under investigation or if the employee had a high-risk exposure. The use of face masks is becoming more permissive, rather than mandatory, to conserve personal protective equipment (PPE) for when the surge arrives.

Education is ongoing about caring for our families and ourselves if we get infected and need to isolate within our own homes. The department and health system is trying to balance the challenges of urgent patient care needs against the wellness concerns for the faculty, staff, and residents. Many physicians are also struggling with childcare problems, which add to our personal stress. There is anxiety among many physicians about exposure to asymptomatic carriers, including themselves, patients, and their families, Dr. Cansino said.

David Forstein, DO, dean and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Touro College of Osteopathic Medicine, New York, said in an interview that the COVID-19 pandemic has “totally disrupted medical education. At almost all medical schools, didactics have moved completely online – ZOOM sessions abound, but labs become demonstrations, if at all, during the preclinical years. The clinical years have been put on hold, as well as student rotations suspended, out of caution for the students because hospitals needed to conserve PPE for the essential personnel and because administrators knew there would be less time for teaching. After initially requesting a pause, many hospitals now are asking students to come back because so many physicians, nurses, and residents have become ill with COVID-19 and either are quarantined or are patients in the hospital themselves.

“There has been a state-by-state call to consider graduating health professions students early, and press them into service, before their residencies actually begin. Some locations are looking for these new graduates to volunteer; some are willing to pay them a resident’s salary level. Medical schools are auditing their student records now to see which students would qualify to graduate early,” Dr. Forstein noted.

David M. Jaspan, DO, chairman of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the Einstein Health Care Network in Philadelphia, described in an email interview how COVID-19 has changed practice.

To minimize the number of providers on the front line, we have developed a Monday to Friday rotating schedule of three teams of five members, he explained. There will be a hospital-based team, an office-based team, and a telehealth-based team who will provide their services from home. On-call responsibilities remain the same.

The hospital team, working 7 a.m. to 5 p.m., will rotate through assignments each day:

- One person will cover labor and delivery.

- One person will cover triage and help on labor and delivery.

- One person will be assigned to the resident office.

- One person will be assigned to cover the team of the post call attending (Sunday through Thursday call).

- One person will be assigned to gynecology coverage, consults, and postpartum rounds.

To further minimize the patient interactions, when possible, each patient should be seen by the attending physician with the resident. This is a change from usual practice, where the patient is first seen by the resident, who reports back to the attending, and then both physicians see the patient together.

The network’s offices now open from 9 a.m. (many offices had been offering early-morning hours starting at 7 a.m.), and the physicians and advanced practice providers will work through the last scheduled patient appointment, Dr. Jaspan explained. “The office-based team will preferentially see in-person visits.”

Several offices have been closed so that ob.gyns. and staff can be reassigned to telehealth. The remaining five offices generally have one attending physician and one advanced practice provider.

The remaining team of ob.gyns. provides telehealth with the help of staff members. This involves an initial call to the patient by staff letting them know the doctor will be calling, checking them in, verifying insurance, and collecting payment, followed by the actual telehealth visit. If follow-up is needed, the staff member schedules the follow-up.

Dr. Jaspan called the new approach to prenatal care because of COVID-19 a “cataclysmic change in how we care for our patients. We have decided to further limit our obstetrical in-person visits. It is our feeling that these changes will enable patients to remain outside of the office and in the safety of their homes, provide appropriate social distancing, and diminish potential exposures to the office staff providers and patients.”

In-person visits will occur at: the initial visit, between 24 and 28 weeks, at 32 weeks, and at 36 or 37 weeks; if the patient at 36/37 has a blood pressure cuff, they will not have additional scheduled in-patient visits. We have partnered with the insurance companies to provide more than 88% of obstetrical patients with home blood pressure cuffs.

Obstetrical visits via telehealth will continue at our standard intervals: monthly until 26 weeks; twice monthly during 26-36 weeks; and weekly from 37 weeks to delivery. These visits should use a video component such as Zoom, Doxy.me, or FaceTime.

“If the patient has concerns or problems, we will see them at any time. However, the new standard will be telehealth visits and the exception will be the in-person visit,” Dr. Jaspan said.

In addition, we have worked our division of maternal-fetal medicine to adjust the antenatal testing schedules, and we have curtailed the frequency of ultrasound, he noted.

He emphasized the importance of documenting telehealth interactions with obstetrical patients, in addition to “providing adequate teaching and education for patients regarding kick counts to ensure fetal well-being.” It also is key to “properly document conversations with patients regarding bleeding, rupture of membranes, fetal movement, headache, visual changes, fevers, cough, nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, fatigue, muscle aches, etc.”

The residents’ schedule also has been modified to diminish their exposure. Within our new paradigm, we have scheduled video conferences to enable our program to maintain our commitment to academics.

It is imperative that we keep our patients safe, and it is critical to protect our staff members. Those who provide women’s health cannot be replaced by other nurses or physicians.

Mark P. Trolice, MD, is director of Fertility CARE: the IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, Orlando. He related in an email interview that, on March 17, 2020, the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) released “Patient Management and Clinical Recommendations During the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic.” This document serves as guidance on fertility care during the current crisis. Specifically, the recommendations include the following:

- Suspend initiation of new treatment cycles, including ovulation induction, intrauterine inseminations, in vitro fertilization including retrievals and frozen embryo transfers, and nonurgent gamete cryopreservation.

- Strongly consider cancellation of all embryo transfers, whether fresh or frozen.

- Continue to care for patients who are currently “in cycle” or who require urgent stimulation and cryopreservation.

- Suspend elective surgeries and nonurgent diagnostic procedures.

- Minimize in-person interactions and increase utilization of telehealth.

As a member of ASRM for more than 2 decades and a participant of several of their committees, my practice immediately ceased treatment cycles to comply with this guidance.

Then on March 20, 2020, the Florida governor’s executive order 20-72 was released, stating, “All hospitals, ambulatory surgical centers, office surgery centers, dental, orthodontic and endodontic offices, and other health care practitioners’ offices in the State of Florida are prohibited from providing any medically unnecessary, nonurgent or nonemergency procedure or surgery which, if delayed, does not place a patient’s immediate health, safety, or well-being at risk, or will, if delayed, not contribute to the worsening of a serious or life-threatening medical condition.”

As a result, my practice has been limited to telemedicine consultations. While the ASRM guidance and the gubernatorial executive order pose a significant financial hardship on my center and all applicable medical clinics in my state, resulting in expected layoffs, salary reductions, and requests for government stimulus loans, the greater good takes priority and we pray for all the victims of this devastating pandemic.

The governor’s current executive order is set to expire on May 9, 2020, unless it is extended.

ASRM released an update of their guidance on March 30, 2020, offering no change from their prior recommendations. The organization plans to reevaluate the guidance at 2-week intervals.

Sangeeta Sinha, MD, an ob.gyn. in private practice at Stone Springs Hospital Center, Dulles, Va. said in an interview, “COVID 19 has put fear in all aspects of our daily activities which we are attempting to cope with.”

She related several changes made to her office and hospital environments. “In our office, we are now wearing a mask at all times, gloves to examine every patient. We have staggered physicians in the office to take televisits and in-office patients. We are screening all new patients on the phone to determine if they are sick, have traveled to high-risk, hot spot areas of the country, or have had contact with someone who tested positive for COVID-19. We are only seeing our pregnant women and have also pushed out their return appointments to 4 weeks if possible. There are several staff who are not working due to fear or are in self quarantine so we have shortage of staff in the office. At the hospital as well we are wearing a mask at all times, using personal protective equipment for deliveries and C-sections.

“We have had several scares, including a new transfer of an 18-year-old pregnant patient at 30 weeks with cough and sore throat, who later reported that her roommate is very sick and he works with someone who has tested positive for COVID-19. Thankfully she is healthy and well. We learned several lessons from this one.”

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to spread across the United States, several members of the Ob.Gyn. News Editorial Advisory Board shared their experiences.

Catherine Cansino, MD, MPH, who is an associate clinical professor in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of California, Davis, discussed the changes COVID-19 has had on local and regional practice in Sacramento and northern California.

There has been a dramatic increase in telehealth, using video, phone, and apps such as Zoom. Although ob.gyns. at the university are limiting outpatient appointments to essential visits only, we are continuing to offer telehealth to a few nonessential visits. This will be readdressed when the COVID-19 cases peak, Dr. Cansino said.

All patients admitted to labor & delivery undergo COVID-19 testing regardless of symptoms. For patients in the clinic who are expected to be induced or scheduled for cesarean delivery, we are screening them within 72 hours before admission.

In gynecology, only essential or urgent surgeries at UC Davis are being performed and include indications such as cancer, serious benign conditions unresponsive to conservative treatment (e.g., tubo-ovarian abscess, large symptomatic adnexal mass), and pregnancy termination. We are preserving access to abortion and reproductive health services since these are essential services.

We limit the number of providers involved in direct contact with inpatients to one or two, including a physician, nurse, and/or resident, Dr. Cansino said in an interview. Based on recent Liaison Committee on Medical Education policies related to concerns about educational experience during the pandemic, no medical students are allowed at the hospital at present. We also severely restrict the number of visitors in the inpatient and outpatient settings, including only two attendants (partner, doula, and such) during labor and delivery, and consider the impact on patients’ well-being when we restrict their visitors.

We are following University of California guidelines regarding face mask use, which have been in evolution over the last month. Face masks are used for patients and the health care providers primarily when patients either have known COVID-19 infection or are considered as patients under investigation or if the employee had a high-risk exposure. The use of face masks is becoming more permissive, rather than mandatory, to conserve personal protective equipment (PPE) for when the surge arrives.

Education is ongoing about caring for our families and ourselves if we get infected and need to isolate within our own homes. The department and health system is trying to balance the challenges of urgent patient care needs against the wellness concerns for the faculty, staff, and residents. Many physicians are also struggling with childcare problems, which add to our personal stress. There is anxiety among many physicians about exposure to asymptomatic carriers, including themselves, patients, and their families, Dr. Cansino said.

David Forstein, DO, dean and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Touro College of Osteopathic Medicine, New York, said in an interview that the COVID-19 pandemic has “totally disrupted medical education. At almost all medical schools, didactics have moved completely online – ZOOM sessions abound, but labs become demonstrations, if at all, during the preclinical years. The clinical years have been put on hold, as well as student rotations suspended, out of caution for the students because hospitals needed to conserve PPE for the essential personnel and because administrators knew there would be less time for teaching. After initially requesting a pause, many hospitals now are asking students to come back because so many physicians, nurses, and residents have become ill with COVID-19 and either are quarantined or are patients in the hospital themselves.

“There has been a state-by-state call to consider graduating health professions students early, and press them into service, before their residencies actually begin. Some locations are looking for these new graduates to volunteer; some are willing to pay them a resident’s salary level. Medical schools are auditing their student records now to see which students would qualify to graduate early,” Dr. Forstein noted.

David M. Jaspan, DO, chairman of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the Einstein Health Care Network in Philadelphia, described in an email interview how COVID-19 has changed practice.

To minimize the number of providers on the front line, we have developed a Monday to Friday rotating schedule of three teams of five members, he explained. There will be a hospital-based team, an office-based team, and a telehealth-based team who will provide their services from home. On-call responsibilities remain the same.

The hospital team, working 7 a.m. to 5 p.m., will rotate through assignments each day:

- One person will cover labor and delivery.

- One person will cover triage and help on labor and delivery.

- One person will be assigned to the resident office.

- One person will be assigned to cover the team of the post call attending (Sunday through Thursday call).

- One person will be assigned to gynecology coverage, consults, and postpartum rounds.

To further minimize the patient interactions, when possible, each patient should be seen by the attending physician with the resident. This is a change from usual practice, where the patient is first seen by the resident, who reports back to the attending, and then both physicians see the patient together.

The network’s offices now open from 9 a.m. (many offices had been offering early-morning hours starting at 7 a.m.), and the physicians and advanced practice providers will work through the last scheduled patient appointment, Dr. Jaspan explained. “The office-based team will preferentially see in-person visits.”

Several offices have been closed so that ob.gyns. and staff can be reassigned to telehealth. The remaining five offices generally have one attending physician and one advanced practice provider.

The remaining team of ob.gyns. provides telehealth with the help of staff members. This involves an initial call to the patient by staff letting them know the doctor will be calling, checking them in, verifying insurance, and collecting payment, followed by the actual telehealth visit. If follow-up is needed, the staff member schedules the follow-up.

Dr. Jaspan called the new approach to prenatal care because of COVID-19 a “cataclysmic change in how we care for our patients. We have decided to further limit our obstetrical in-person visits. It is our feeling that these changes will enable patients to remain outside of the office and in the safety of their homes, provide appropriate social distancing, and diminish potential exposures to the office staff providers and patients.”

In-person visits will occur at: the initial visit, between 24 and 28 weeks, at 32 weeks, and at 36 or 37 weeks; if the patient at 36/37 has a blood pressure cuff, they will not have additional scheduled in-patient visits. We have partnered with the insurance companies to provide more than 88% of obstetrical patients with home blood pressure cuffs.

Obstetrical visits via telehealth will continue at our standard intervals: monthly until 26 weeks; twice monthly during 26-36 weeks; and weekly from 37 weeks to delivery. These visits should use a video component such as Zoom, Doxy.me, or FaceTime.

“If the patient has concerns or problems, we will see them at any time. However, the new standard will be telehealth visits and the exception will be the in-person visit,” Dr. Jaspan said.

In addition, we have worked our division of maternal-fetal medicine to adjust the antenatal testing schedules, and we have curtailed the frequency of ultrasound, he noted.

He emphasized the importance of documenting telehealth interactions with obstetrical patients, in addition to “providing adequate teaching and education for patients regarding kick counts to ensure fetal well-being.” It also is key to “properly document conversations with patients regarding bleeding, rupture of membranes, fetal movement, headache, visual changes, fevers, cough, nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, fatigue, muscle aches, etc.”

The residents’ schedule also has been modified to diminish their exposure. Within our new paradigm, we have scheduled video conferences to enable our program to maintain our commitment to academics.

It is imperative that we keep our patients safe, and it is critical to protect our staff members. Those who provide women’s health cannot be replaced by other nurses or physicians.

Mark P. Trolice, MD, is director of Fertility CARE: the IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, Orlando. He related in an email interview that, on March 17, 2020, the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) released “Patient Management and Clinical Recommendations During the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic.” This document serves as guidance on fertility care during the current crisis. Specifically, the recommendations include the following:

- Suspend initiation of new treatment cycles, including ovulation induction, intrauterine inseminations, in vitro fertilization including retrievals and frozen embryo transfers, and nonurgent gamete cryopreservation.

- Strongly consider cancellation of all embryo transfers, whether fresh or frozen.

- Continue to care for patients who are currently “in cycle” or who require urgent stimulation and cryopreservation.

- Suspend elective surgeries and nonurgent diagnostic procedures.

- Minimize in-person interactions and increase utilization of telehealth.

As a member of ASRM for more than 2 decades and a participant of several of their committees, my practice immediately ceased treatment cycles to comply with this guidance.

Then on March 20, 2020, the Florida governor’s executive order 20-72 was released, stating, “All hospitals, ambulatory surgical centers, office surgery centers, dental, orthodontic and endodontic offices, and other health care practitioners’ offices in the State of Florida are prohibited from providing any medically unnecessary, nonurgent or nonemergency procedure or surgery which, if delayed, does not place a patient’s immediate health, safety, or well-being at risk, or will, if delayed, not contribute to the worsening of a serious or life-threatening medical condition.”

As a result, my practice has been limited to telemedicine consultations. While the ASRM guidance and the gubernatorial executive order pose a significant financial hardship on my center and all applicable medical clinics in my state, resulting in expected layoffs, salary reductions, and requests for government stimulus loans, the greater good takes priority and we pray for all the victims of this devastating pandemic.

The governor’s current executive order is set to expire on May 9, 2020, unless it is extended.

ASRM released an update of their guidance on March 30, 2020, offering no change from their prior recommendations. The organization plans to reevaluate the guidance at 2-week intervals.

Sangeeta Sinha, MD, an ob.gyn. in private practice at Stone Springs Hospital Center, Dulles, Va. said in an interview, “COVID 19 has put fear in all aspects of our daily activities which we are attempting to cope with.”

She related several changes made to her office and hospital environments. “In our office, we are now wearing a mask at all times, gloves to examine every patient. We have staggered physicians in the office to take televisits and in-office patients. We are screening all new patients on the phone to determine if they are sick, have traveled to high-risk, hot spot areas of the country, or have had contact with someone who tested positive for COVID-19. We are only seeing our pregnant women and have also pushed out their return appointments to 4 weeks if possible. There are several staff who are not working due to fear or are in self quarantine so we have shortage of staff in the office. At the hospital as well we are wearing a mask at all times, using personal protective equipment for deliveries and C-sections.

“We have had several scares, including a new transfer of an 18-year-old pregnant patient at 30 weeks with cough and sore throat, who later reported that her roommate is very sick and he works with someone who has tested positive for COVID-19. Thankfully she is healthy and well. We learned several lessons from this one.”

Patients with preexisting diabetes benefit less from bariatric surgery

according to a retrospective review of patients receiving both sleeve gastrectomy and gastric bypass.

The difference was particularly pronounced and persistent for patients who had gastric bypass, Yingying Luo, MD, said during a virtual news conference held by the Endocrine Society. The study was slated for presentation during ENDO 2020, the society’s annual meeting, which was canceled because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Our findings demonstrated that having bariatric surgery before developing diabetes may result in greater weight loss from the surgery, especially within the first 3 years after surgery and in patients undergoing gastric bypass surgery,” said Dr. Luo.

More than a third of U.S. adults have obesity, and more than half the population is overweight or has obesity, said Dr. Luo, citing data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Bariatric surgery not only reduces body weight, but also “can lead to remission of many metabolic disorders, including diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia,” said Dr. Luo, a visiting scholar at the University of Michigan’s division of metabolism, endocrinology, and diabetes. However, until now, it has not been known how diabetes interacts with bariatric surgery to affect weight loss outcomes.

To address that question, Dr. Luo and her colleagues looked at patients in the Michigan Bariatric Surgery Cohort who were at least 18 years old and had a body mass index (BMI) of more than 40 kg/m2, or of more than 35 kg/m2 with comorbidities.

The researchers followed 380 patients who received gastric bypass and 334 who received sleeve gastrectomy for at least 5 years. Over time, sleeve gastrectomy became the predominant type of surgery conducted, noted Dr. Luo.

At baseline, and yearly for 5 years thereafter, the researchers recorded participants’ BMI as well as their lipid levels and other laboratory values. Medication use was also tracked. Patients with a diagnosis of diabetes also had their hemoglobin A1c levels recorded at each visit.

Overall, patients in the sleeve gastrectomy group were more overweight, and those in the gastric bypass group had higher HbA1c and total cholesterol levels. The mean baseline weight for the sleeve gastrectomy recipients was 141.5 kg, compared with 133.5 kg for those receiving gastric bypass (BMI, 49.9 vs. 47.3 kg/m2, respectively; P < .01 for both measures). Mean HbA1c was 6.5% for the gastric bypass group, compared with 6.3% for the sleeve gastrectomy group (P = .03).

At baseline, 149 (39.2%) of the gastric bypass patients had diabetes, compared with 108 (32.3%) of the sleeve gastrectomy patients, but the difference was not statistically significant.

About two-thirds of the full cohort were tracked for at least 5 years, which is still considered “a good follow-up rate in a real-world study,” said Dr. Luo.

Total weight loss was defined as the difference between initial weight and postoperative weight at a given point in time. Excess weight was the difference between initial weight and an individual’s ideal weight, that is, what their weight would have been if they had a BMI of 25 kg/m2.

“The probability of achieving a BMI of less than 30 kg/m2 or excess weight loss of 50% or more was higher in patients who did not have diabetes diagnosis at baseline. We found that the presence of diabetes at baseline substantially impacted the probability of achieving both indicators,” said Dr. Luo. “Individuals without diabetes had a 1.5 times higher chance of achieving a BMI of under 30 kg/m2, and … [they also] had a 1.6 times higher chance of achieving excess body weight loss of 50%, or more.” Both of those differences were statistically significant on univariate analysis (P = .0249 and .0021, respectively).

The researchers conducted further statistical analysis – adjusted for age, gender, surgery type, and baseline weight – to examine whether diabetes still predicted future weight loss after bariatric surgery. After those adjustments, they still found that “the presence of diabetes before surgery is an indicator of future weight loss outcomes,” said Dr. Luo.

The differences in outcomes for those with and without diabetes tended to diminish over time in looking at the cohort as a whole. However, greater BMI reduction for those without diabetes persisted for the full 5 years of follow-up for the gastric bypass recipients. Those trends held when the researchers looked at the proportion of patients whose BMI dropped to below 30 kg/m2, and those who achieved excess weight loss of more than 50%.

Dr. Luo acknowledged that an ideal study would track patients for longer than 5 years and that studies involving more patients would also be useful. Still, she said, “our study opens the door for further research to understand why diabetes diminishes the weight loss effect of bariatric surgery.”

The research will be published in a special supplemental issue of the Journal of the Endocrine Society. In addition to a series of news conferences on March 30-31, the society will host ENDO Online 2020 during June 8-22, which will present programming for clinicians and researchers.

Dr. Luo reported no outside sources of funding and no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Luo Y et al. ENDO 2020, Abstract 590.

according to a retrospective review of patients receiving both sleeve gastrectomy and gastric bypass.

The difference was particularly pronounced and persistent for patients who had gastric bypass, Yingying Luo, MD, said during a virtual news conference held by the Endocrine Society. The study was slated for presentation during ENDO 2020, the society’s annual meeting, which was canceled because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Our findings demonstrated that having bariatric surgery before developing diabetes may result in greater weight loss from the surgery, especially within the first 3 years after surgery and in patients undergoing gastric bypass surgery,” said Dr. Luo.

More than a third of U.S. adults have obesity, and more than half the population is overweight or has obesity, said Dr. Luo, citing data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Bariatric surgery not only reduces body weight, but also “can lead to remission of many metabolic disorders, including diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia,” said Dr. Luo, a visiting scholar at the University of Michigan’s division of metabolism, endocrinology, and diabetes. However, until now, it has not been known how diabetes interacts with bariatric surgery to affect weight loss outcomes.

To address that question, Dr. Luo and her colleagues looked at patients in the Michigan Bariatric Surgery Cohort who were at least 18 years old and had a body mass index (BMI) of more than 40 kg/m2, or of more than 35 kg/m2 with comorbidities.

The researchers followed 380 patients who received gastric bypass and 334 who received sleeve gastrectomy for at least 5 years. Over time, sleeve gastrectomy became the predominant type of surgery conducted, noted Dr. Luo.

At baseline, and yearly for 5 years thereafter, the researchers recorded participants’ BMI as well as their lipid levels and other laboratory values. Medication use was also tracked. Patients with a diagnosis of diabetes also had their hemoglobin A1c levels recorded at each visit.

Overall, patients in the sleeve gastrectomy group were more overweight, and those in the gastric bypass group had higher HbA1c and total cholesterol levels. The mean baseline weight for the sleeve gastrectomy recipients was 141.5 kg, compared with 133.5 kg for those receiving gastric bypass (BMI, 49.9 vs. 47.3 kg/m2, respectively; P < .01 for both measures). Mean HbA1c was 6.5% for the gastric bypass group, compared with 6.3% for the sleeve gastrectomy group (P = .03).

At baseline, 149 (39.2%) of the gastric bypass patients had diabetes, compared with 108 (32.3%) of the sleeve gastrectomy patients, but the difference was not statistically significant.

About two-thirds of the full cohort were tracked for at least 5 years, which is still considered “a good follow-up rate in a real-world study,” said Dr. Luo.

Total weight loss was defined as the difference between initial weight and postoperative weight at a given point in time. Excess weight was the difference between initial weight and an individual’s ideal weight, that is, what their weight would have been if they had a BMI of 25 kg/m2.