User login

CMS suspends advance payment program to clinicians for COVID-19 relief

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services will suspend its Medicare advance payment program for clinicians and is reevaluating how much to pay to hospitals going forward through particular COVID-19 relief initiatives. CMS announced the changes on April 26. Physicians and others who use the accelerated and advance Medicare payments program repay these advances, and they are typically given 1 year or less to repay the funding.

CMS said in a news release it will not accept new applications for the advanced Medicare payment, and it will be reevaluating all pending and new applications “in light of historical direct payments made available through the Department of Health & Human Services’ (HHS) Provider Relief Fund.”

The advance Medicare payment program predates COVID-19, although it previously was used on a much smaller scale. In the past 5 years, CMS approved about 100 total requests for advanced Medicare payment, with most being tied to natural disasters such as hurricanes.

CMS said it has approved, since March, more than 21,000 applications for advanced Medicare payment, totaling $59.6 billion, for hospitals and other organizations that bill its Part A program. In addition, CMS approved almost 24,000 applications for its Part B program, advancing $40.4 billion for physicians, other clinicians, and medical equipment suppliers.

CMS noted that Congress also has provided $175 billion in aid for the medical community that clinicians and medical organizations would not need to repay. The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act enacted in March included $100 billion, and the Paycheck Protection Program and Health Care Enhancement Act, enacted March 24, includes another $75 billion.

A version of this article was originally published on Medscape.com.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services will suspend its Medicare advance payment program for clinicians and is reevaluating how much to pay to hospitals going forward through particular COVID-19 relief initiatives. CMS announced the changes on April 26. Physicians and others who use the accelerated and advance Medicare payments program repay these advances, and they are typically given 1 year or less to repay the funding.

CMS said in a news release it will not accept new applications for the advanced Medicare payment, and it will be reevaluating all pending and new applications “in light of historical direct payments made available through the Department of Health & Human Services’ (HHS) Provider Relief Fund.”

The advance Medicare payment program predates COVID-19, although it previously was used on a much smaller scale. In the past 5 years, CMS approved about 100 total requests for advanced Medicare payment, with most being tied to natural disasters such as hurricanes.

CMS said it has approved, since March, more than 21,000 applications for advanced Medicare payment, totaling $59.6 billion, for hospitals and other organizations that bill its Part A program. In addition, CMS approved almost 24,000 applications for its Part B program, advancing $40.4 billion for physicians, other clinicians, and medical equipment suppliers.

CMS noted that Congress also has provided $175 billion in aid for the medical community that clinicians and medical organizations would not need to repay. The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act enacted in March included $100 billion, and the Paycheck Protection Program and Health Care Enhancement Act, enacted March 24, includes another $75 billion.

A version of this article was originally published on Medscape.com.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services will suspend its Medicare advance payment program for clinicians and is reevaluating how much to pay to hospitals going forward through particular COVID-19 relief initiatives. CMS announced the changes on April 26. Physicians and others who use the accelerated and advance Medicare payments program repay these advances, and they are typically given 1 year or less to repay the funding.

CMS said in a news release it will not accept new applications for the advanced Medicare payment, and it will be reevaluating all pending and new applications “in light of historical direct payments made available through the Department of Health & Human Services’ (HHS) Provider Relief Fund.”

The advance Medicare payment program predates COVID-19, although it previously was used on a much smaller scale. In the past 5 years, CMS approved about 100 total requests for advanced Medicare payment, with most being tied to natural disasters such as hurricanes.

CMS said it has approved, since March, more than 21,000 applications for advanced Medicare payment, totaling $59.6 billion, for hospitals and other organizations that bill its Part A program. In addition, CMS approved almost 24,000 applications for its Part B program, advancing $40.4 billion for physicians, other clinicians, and medical equipment suppliers.

CMS noted that Congress also has provided $175 billion in aid for the medical community that clinicians and medical organizations would not need to repay. The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act enacted in March included $100 billion, and the Paycheck Protection Program and Health Care Enhancement Act, enacted March 24, includes another $75 billion.

A version of this article was originally published on Medscape.com.

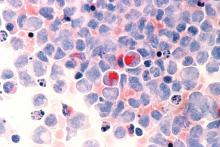

EHA webinar addresses treating AML patients with COVID-19

A hematologist in Italy shared his personal experience addressing the intersection of COVID-19 and the care of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients during a webinar hosted by the European Hematology Association (EHA).

Felicetto Ferrara, MD, of Cardarelli Hospital in Naples, Italy, discussed the main difficulties in administering optimal treatment for AML patients who become infected with SARS-CoV-2.

The major problems include the need to isolate patients while simultaneously allowing for collaboration with pulmonologists and intensivists, the delays in AML treatment caused by COVID-19, and the risk of drug-drug interactions while treating AML patients with COVID-19.

The need to isolate AML patients with COVID-19 is paramount, according to Dr. Ferrara. Isolation can be accomplished, ideally, by the creation of a dedicated COVID-19 unit or, alternatively, with the use of single-patient negative pressure rooms. Dr. Ferrara stressed that all patients with AML should be tested for COVID-19 before admission.

Delaying or reducing AML treatment

Treatment delays are of particular concern, according to Dr. Ferrara, and some patients may require dose reductions, especially for AML treatments that might have a detrimental effect on the immune system.

Decisions must be made as to whether planned approaches to induction or consolidation therapy should be changed, and special concern has to be paid to elderly AML patients, who have the highest risks of bad COVID-19 outcomes.

Specific attention should be paid to patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia as well, according to Dr. Ferrara. These patients are of concern in the COVID-19 era because of their risk of differentiation syndrome, which can induce respiratory distress.

In all cases, autologous or allogeneic stem cell transplant should be deferred until confirmed COVID-19–negative test results are obtained.

Continuing AML treatment

Of particular concern is the fact that, without a standard therapy for COVID-19, many different drugs might be used in treatment efforts. This raises the potential for serious drug-drug interactions with the patient’s AML medications, so close attention should be paid to an individual patient’s medications.

In terms of continuing AML treatment for younger adults (less than 65 years) who are positive for COVID-19, symptomatic and asymptomatic patients should be treated differently, Dr. Ferarra said.

Symptomatic patients should be given hydroxyurea until symptom resolution, and unless urgent, any further AML treatments should be delayed. However, if treatment is needed immediately, it should be given in a COVID-19–dedicated unit.

The restrictions are much looser for young adult asymptomatic COVID-19 patients with AML. Standard induction therapy should be given, with intermediate-dose cytarabine used as consolidation therapy.

Therapy in elderly patients with AML and COVID-19 should be based on symptom status as well, said Dr. Ferrara.

Asymptomatic but otherwise fit elderly patients should have standard induction therapy if they are in the European Leukemia Network favorable genetic subgroup. Asymptomatic elderly patients with high-risk molecular disease can receive venetoclax with a hypomethylating agent.

Symptomatic elderly patients should continue with hydroxyurea until symptom resolution, and any other treatments should be delayed in nonemergency cases.

Relapsed AML patients with COVID-19 should have their treatments postponed until they obtain negative COVID-19 test results whenever possible, Dr. Ferarra said. However, if treatment is necessary, molecularly targeted therapies (gilteritinib, ivosidenib, and enasidenib) are preferable to high-dose chemotherapy.

In all cases, treatment decisions should be made in conjunction with pulmonologists and intensivists, Dr. Ferrera noted.

Webinar moderator Francesco Cerisoli, MD, head of research and mentoring at EHA, highlighted the fact that EHA has published specific recommendations for treating AML patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. The majority of these were discussed by and are aligned with the recommendations presented by Dr. Ferrara.

The EHA webinar contains a disclaimer that the content discussed was based on the personal experiences and opinions of the speakers and that no general, evidence-based guidance could be derived from the discussion. There were no disclosures given.

A hematologist in Italy shared his personal experience addressing the intersection of COVID-19 and the care of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients during a webinar hosted by the European Hematology Association (EHA).

Felicetto Ferrara, MD, of Cardarelli Hospital in Naples, Italy, discussed the main difficulties in administering optimal treatment for AML patients who become infected with SARS-CoV-2.

The major problems include the need to isolate patients while simultaneously allowing for collaboration with pulmonologists and intensivists, the delays in AML treatment caused by COVID-19, and the risk of drug-drug interactions while treating AML patients with COVID-19.

The need to isolate AML patients with COVID-19 is paramount, according to Dr. Ferrara. Isolation can be accomplished, ideally, by the creation of a dedicated COVID-19 unit or, alternatively, with the use of single-patient negative pressure rooms. Dr. Ferrara stressed that all patients with AML should be tested for COVID-19 before admission.

Delaying or reducing AML treatment

Treatment delays are of particular concern, according to Dr. Ferrara, and some patients may require dose reductions, especially for AML treatments that might have a detrimental effect on the immune system.

Decisions must be made as to whether planned approaches to induction or consolidation therapy should be changed, and special concern has to be paid to elderly AML patients, who have the highest risks of bad COVID-19 outcomes.

Specific attention should be paid to patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia as well, according to Dr. Ferrara. These patients are of concern in the COVID-19 era because of their risk of differentiation syndrome, which can induce respiratory distress.

In all cases, autologous or allogeneic stem cell transplant should be deferred until confirmed COVID-19–negative test results are obtained.

Continuing AML treatment

Of particular concern is the fact that, without a standard therapy for COVID-19, many different drugs might be used in treatment efforts. This raises the potential for serious drug-drug interactions with the patient’s AML medications, so close attention should be paid to an individual patient’s medications.

In terms of continuing AML treatment for younger adults (less than 65 years) who are positive for COVID-19, symptomatic and asymptomatic patients should be treated differently, Dr. Ferarra said.

Symptomatic patients should be given hydroxyurea until symptom resolution, and unless urgent, any further AML treatments should be delayed. However, if treatment is needed immediately, it should be given in a COVID-19–dedicated unit.

The restrictions are much looser for young adult asymptomatic COVID-19 patients with AML. Standard induction therapy should be given, with intermediate-dose cytarabine used as consolidation therapy.

Therapy in elderly patients with AML and COVID-19 should be based on symptom status as well, said Dr. Ferrara.

Asymptomatic but otherwise fit elderly patients should have standard induction therapy if they are in the European Leukemia Network favorable genetic subgroup. Asymptomatic elderly patients with high-risk molecular disease can receive venetoclax with a hypomethylating agent.

Symptomatic elderly patients should continue with hydroxyurea until symptom resolution, and any other treatments should be delayed in nonemergency cases.

Relapsed AML patients with COVID-19 should have their treatments postponed until they obtain negative COVID-19 test results whenever possible, Dr. Ferarra said. However, if treatment is necessary, molecularly targeted therapies (gilteritinib, ivosidenib, and enasidenib) are preferable to high-dose chemotherapy.

In all cases, treatment decisions should be made in conjunction with pulmonologists and intensivists, Dr. Ferrera noted.

Webinar moderator Francesco Cerisoli, MD, head of research and mentoring at EHA, highlighted the fact that EHA has published specific recommendations for treating AML patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. The majority of these were discussed by and are aligned with the recommendations presented by Dr. Ferrara.

The EHA webinar contains a disclaimer that the content discussed was based on the personal experiences and opinions of the speakers and that no general, evidence-based guidance could be derived from the discussion. There were no disclosures given.

A hematologist in Italy shared his personal experience addressing the intersection of COVID-19 and the care of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients during a webinar hosted by the European Hematology Association (EHA).

Felicetto Ferrara, MD, of Cardarelli Hospital in Naples, Italy, discussed the main difficulties in administering optimal treatment for AML patients who become infected with SARS-CoV-2.

The major problems include the need to isolate patients while simultaneously allowing for collaboration with pulmonologists and intensivists, the delays in AML treatment caused by COVID-19, and the risk of drug-drug interactions while treating AML patients with COVID-19.

The need to isolate AML patients with COVID-19 is paramount, according to Dr. Ferrara. Isolation can be accomplished, ideally, by the creation of a dedicated COVID-19 unit or, alternatively, with the use of single-patient negative pressure rooms. Dr. Ferrara stressed that all patients with AML should be tested for COVID-19 before admission.

Delaying or reducing AML treatment

Treatment delays are of particular concern, according to Dr. Ferrara, and some patients may require dose reductions, especially for AML treatments that might have a detrimental effect on the immune system.

Decisions must be made as to whether planned approaches to induction or consolidation therapy should be changed, and special concern has to be paid to elderly AML patients, who have the highest risks of bad COVID-19 outcomes.

Specific attention should be paid to patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia as well, according to Dr. Ferrara. These patients are of concern in the COVID-19 era because of their risk of differentiation syndrome, which can induce respiratory distress.

In all cases, autologous or allogeneic stem cell transplant should be deferred until confirmed COVID-19–negative test results are obtained.

Continuing AML treatment

Of particular concern is the fact that, without a standard therapy for COVID-19, many different drugs might be used in treatment efforts. This raises the potential for serious drug-drug interactions with the patient’s AML medications, so close attention should be paid to an individual patient’s medications.

In terms of continuing AML treatment for younger adults (less than 65 years) who are positive for COVID-19, symptomatic and asymptomatic patients should be treated differently, Dr. Ferarra said.

Symptomatic patients should be given hydroxyurea until symptom resolution, and unless urgent, any further AML treatments should be delayed. However, if treatment is needed immediately, it should be given in a COVID-19–dedicated unit.

The restrictions are much looser for young adult asymptomatic COVID-19 patients with AML. Standard induction therapy should be given, with intermediate-dose cytarabine used as consolidation therapy.

Therapy in elderly patients with AML and COVID-19 should be based on symptom status as well, said Dr. Ferrara.

Asymptomatic but otherwise fit elderly patients should have standard induction therapy if they are in the European Leukemia Network favorable genetic subgroup. Asymptomatic elderly patients with high-risk molecular disease can receive venetoclax with a hypomethylating agent.

Symptomatic elderly patients should continue with hydroxyurea until symptom resolution, and any other treatments should be delayed in nonemergency cases.

Relapsed AML patients with COVID-19 should have their treatments postponed until they obtain negative COVID-19 test results whenever possible, Dr. Ferarra said. However, if treatment is necessary, molecularly targeted therapies (gilteritinib, ivosidenib, and enasidenib) are preferable to high-dose chemotherapy.

In all cases, treatment decisions should be made in conjunction with pulmonologists and intensivists, Dr. Ferrera noted.

Webinar moderator Francesco Cerisoli, MD, head of research and mentoring at EHA, highlighted the fact that EHA has published specific recommendations for treating AML patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. The majority of these were discussed by and are aligned with the recommendations presented by Dr. Ferrara.

The EHA webinar contains a disclaimer that the content discussed was based on the personal experiences and opinions of the speakers and that no general, evidence-based guidance could be derived from the discussion. There were no disclosures given.

COVID-19: Defer ‘bread and butter’ procedure for thyroid nodules

With a few notable exceptions, the majority of fine needle aspiration (FNA) biopsies of thyroid nodules should be delayed until the risk of COVID-19, and the burden on resources, has lessened, according to expert consensus.

“Our group recommends that FNA biopsy of most asymptomatic thyroid nodules – taking into account the sonographic characteristics and patients’ clinical picture – be deferred to a later time, when risk of exposure to COVID-19 is more manageable and resource restriction is no longer a concern,” said the endocrinologists, writing in a guest editorial in Clinical Thyroidology.

All elective procedures have been canceled under guidance of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in conjunction with the U.S. surgeon general, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, thyroid nodule FNAs, though elective, fall into the category of being considered medically necessary and potentially prolonging life expectancy

Yet, with approximately 90% of asymptomatic thyroid nodules turning out to be benign and little evidence that early detection and treatment affects disease outcomes, there is a strong argument for deferral in most cases, stressed Ming Lee, MD, and colleagues, of the endocrinology division at Phoenix (Ariz.) Veterans Affairs Health Care System (PVAHCS), who convened a multidisciplinary meeting to address the urgent issue.

Patients should instead be interviewed by an endocrinologist (preferably via telehealth) to collect their clinical history as well as assess their perception of the disease and risk of malignancy, senior author S. Mitchell Harman, MD, chief of PVAHCS, said in an interview.

“The principal guiding factor should be the objectively assessed likelihood of malignancy of the individual patient’s nodule(s),” he said.

“In my opinion, we should also factor in the patient’s level of anxiety, since some patients are more sanguine about risk than others and our goal is to provide relief of anxiety as well as to determine need for, and course of, subsequent treatment,” Dr. Harman added.

Vast majority of malignant thyroid nodules are DTC, which is ‘indolent’

Dr. Lee and colleagues noted that, even of the 10% of thyroid nodules that do prove to be malignant, the vast majority of these (90%) are differentiated thyroid cancers (DTC). In general, patients with DTC “follow an indolent course and have excellent outcomes.”

“There is little evidence that early detection and treatment of DTC significantly alters disease outcomes as the overall mortality rate for DTC has remained low, at around 0.5%,” they wrote.

They also noted that ultrasound features of thyroid nodules can help guide priority for the future timing of an FNA procedure, but should not be the sole basis for deciding on immediate thyroid FNA or surgery.

Exceptions to the rule

Exceptions for considering FNA include more urgent thyroid disease diagnoses, including those that are symptomatic:

Suspected medullary thyroid cancer

“Regarding medullary thyroid cancer (MTC), early diagnosis and surgery do significantly improve outcomes, therefore, delaying FNA of nodules harboring MTC could be potentially injurious,” the authors said.

They suggested, however, measuring calcitonin levels instead, which they noted “is still controversial” in the United States, but “we feel it would be justified in patients with thyroid nodules that would usually be indicated for FNA.”

Those with a family history of MTC, or nodules located in the posterior upper third of lateral lobes (the usual location of MTC), should have calcitonin levels measured.

If calcitonin levels are above 10 pg/mL, “FNA should be offered as early as possible.”

“Significantly elevated serum calcitonin levels (e.g., > 100 pg/mL) should be considered an indication for surgery without cytologic confirmation by FNA,” they added.

Anaplastic thyroid cancer

Anaplastic thyroid cancer, though rare, “is one of the few occasions when thyroid surgery should be performed on an urgent basis, as this condition can worsen very rapidly.

“Patients typically present with a rapidly enlarging thyroid mass that is associated with compressive symptoms, such as dysphagia and dyspnea,” they observed.

In this instance, although FNA is part of the preoperative work-up, it is often nondiagnostic and could require additional sampling.

“At the time of this pandemic, it is reasonable that after a multidisciplinary discussion, such patients with the appropriate clinical scenario be referred for thyroid surgery, with or without prior FNA, based on the team’s judgment,” the authors recommended.

Long-standing thyroid masses

These are usually large and/or closely associated with vital structures, such as the trachea and esophagus, and when such masses cause compressive symptoms, thyroid surgery typically is warranted.

And although prior FNA is helpful to obtain a cytologic diagnosis, as this may change the extent of surgery, it may not always be essential.

Broadly, symptomatic patients with compressive symptoms threatening vital structures can be directly referred to a surgeon, with the timing for surgery jointly decided based on the severity of symptoms, rapidity of disease progression, local COVID-19 status, and available resources.

“During the pandemic, we believe that the vast majority of thyroid FNAs should be considered optional, and extent of surgery can be determined by pathological analysis of frozen sections intraoperatively,” they wrote.

“The value of FNA in these situations is less compelling in the current COVID-19 setting, as the basis of decision for surgery has been already determined,” the authors explained.

If urgent FNA needed, screen patient for COVID-19 and use PPE

Should the need for an urgent thyroid FNA occur, patients should be screened and tested for COVID-19 by a clinician wearing personal protective equipment (PPE), said Dr. Lee and colleagues.

“It is crucial to carefully weigh the risks of COVID-19 exposure, availability of resources, and urgency of these procedures for each patient in our individual practice settings,” they noted.

As restrictions eventually loosen, precautions will still be necessary to some degree, Dr. Harman said.

“I do not consider FNA a ‘high-risk’ procedure in the era of COVID-19, since it does not routinely result in profuse aerosolization of respiratory fluids,” he said in an interview.

“However, patients do sometimes cough or choke due to pressure on the neck and the operator is, of necessity, very close to the patient’s face. Therefore, when we resume FNA, patients will be screened for symptoms of COVID-19 infection and both the operator and the patient will be masked,” Dr. Harman continued.

“We routinely wear gloves, [and] whether the operator will wear a surgical or an N95 mask, disposable gown, etc, will depend on CDC guidance and guidance received from our VA infectious disease experts as it is applied specifically to each patient evaluation.”

The authors have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

With a few notable exceptions, the majority of fine needle aspiration (FNA) biopsies of thyroid nodules should be delayed until the risk of COVID-19, and the burden on resources, has lessened, according to expert consensus.

“Our group recommends that FNA biopsy of most asymptomatic thyroid nodules – taking into account the sonographic characteristics and patients’ clinical picture – be deferred to a later time, when risk of exposure to COVID-19 is more manageable and resource restriction is no longer a concern,” said the endocrinologists, writing in a guest editorial in Clinical Thyroidology.

All elective procedures have been canceled under guidance of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in conjunction with the U.S. surgeon general, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, thyroid nodule FNAs, though elective, fall into the category of being considered medically necessary and potentially prolonging life expectancy

Yet, with approximately 90% of asymptomatic thyroid nodules turning out to be benign and little evidence that early detection and treatment affects disease outcomes, there is a strong argument for deferral in most cases, stressed Ming Lee, MD, and colleagues, of the endocrinology division at Phoenix (Ariz.) Veterans Affairs Health Care System (PVAHCS), who convened a multidisciplinary meeting to address the urgent issue.

Patients should instead be interviewed by an endocrinologist (preferably via telehealth) to collect their clinical history as well as assess their perception of the disease and risk of malignancy, senior author S. Mitchell Harman, MD, chief of PVAHCS, said in an interview.

“The principal guiding factor should be the objectively assessed likelihood of malignancy of the individual patient’s nodule(s),” he said.

“In my opinion, we should also factor in the patient’s level of anxiety, since some patients are more sanguine about risk than others and our goal is to provide relief of anxiety as well as to determine need for, and course of, subsequent treatment,” Dr. Harman added.

Vast majority of malignant thyroid nodules are DTC, which is ‘indolent’

Dr. Lee and colleagues noted that, even of the 10% of thyroid nodules that do prove to be malignant, the vast majority of these (90%) are differentiated thyroid cancers (DTC). In general, patients with DTC “follow an indolent course and have excellent outcomes.”

“There is little evidence that early detection and treatment of DTC significantly alters disease outcomes as the overall mortality rate for DTC has remained low, at around 0.5%,” they wrote.

They also noted that ultrasound features of thyroid nodules can help guide priority for the future timing of an FNA procedure, but should not be the sole basis for deciding on immediate thyroid FNA or surgery.

Exceptions to the rule

Exceptions for considering FNA include more urgent thyroid disease diagnoses, including those that are symptomatic:

Suspected medullary thyroid cancer

“Regarding medullary thyroid cancer (MTC), early diagnosis and surgery do significantly improve outcomes, therefore, delaying FNA of nodules harboring MTC could be potentially injurious,” the authors said.

They suggested, however, measuring calcitonin levels instead, which they noted “is still controversial” in the United States, but “we feel it would be justified in patients with thyroid nodules that would usually be indicated for FNA.”

Those with a family history of MTC, or nodules located in the posterior upper third of lateral lobes (the usual location of MTC), should have calcitonin levels measured.

If calcitonin levels are above 10 pg/mL, “FNA should be offered as early as possible.”

“Significantly elevated serum calcitonin levels (e.g., > 100 pg/mL) should be considered an indication for surgery without cytologic confirmation by FNA,” they added.

Anaplastic thyroid cancer

Anaplastic thyroid cancer, though rare, “is one of the few occasions when thyroid surgery should be performed on an urgent basis, as this condition can worsen very rapidly.

“Patients typically present with a rapidly enlarging thyroid mass that is associated with compressive symptoms, such as dysphagia and dyspnea,” they observed.

In this instance, although FNA is part of the preoperative work-up, it is often nondiagnostic and could require additional sampling.

“At the time of this pandemic, it is reasonable that after a multidisciplinary discussion, such patients with the appropriate clinical scenario be referred for thyroid surgery, with or without prior FNA, based on the team’s judgment,” the authors recommended.

Long-standing thyroid masses

These are usually large and/or closely associated with vital structures, such as the trachea and esophagus, and when such masses cause compressive symptoms, thyroid surgery typically is warranted.

And although prior FNA is helpful to obtain a cytologic diagnosis, as this may change the extent of surgery, it may not always be essential.

Broadly, symptomatic patients with compressive symptoms threatening vital structures can be directly referred to a surgeon, with the timing for surgery jointly decided based on the severity of symptoms, rapidity of disease progression, local COVID-19 status, and available resources.

“During the pandemic, we believe that the vast majority of thyroid FNAs should be considered optional, and extent of surgery can be determined by pathological analysis of frozen sections intraoperatively,” they wrote.

“The value of FNA in these situations is less compelling in the current COVID-19 setting, as the basis of decision for surgery has been already determined,” the authors explained.

If urgent FNA needed, screen patient for COVID-19 and use PPE

Should the need for an urgent thyroid FNA occur, patients should be screened and tested for COVID-19 by a clinician wearing personal protective equipment (PPE), said Dr. Lee and colleagues.

“It is crucial to carefully weigh the risks of COVID-19 exposure, availability of resources, and urgency of these procedures for each patient in our individual practice settings,” they noted.

As restrictions eventually loosen, precautions will still be necessary to some degree, Dr. Harman said.

“I do not consider FNA a ‘high-risk’ procedure in the era of COVID-19, since it does not routinely result in profuse aerosolization of respiratory fluids,” he said in an interview.

“However, patients do sometimes cough or choke due to pressure on the neck and the operator is, of necessity, very close to the patient’s face. Therefore, when we resume FNA, patients will be screened for symptoms of COVID-19 infection and both the operator and the patient will be masked,” Dr. Harman continued.

“We routinely wear gloves, [and] whether the operator will wear a surgical or an N95 mask, disposable gown, etc, will depend on CDC guidance and guidance received from our VA infectious disease experts as it is applied specifically to each patient evaluation.”

The authors have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

With a few notable exceptions, the majority of fine needle aspiration (FNA) biopsies of thyroid nodules should be delayed until the risk of COVID-19, and the burden on resources, has lessened, according to expert consensus.

“Our group recommends that FNA biopsy of most asymptomatic thyroid nodules – taking into account the sonographic characteristics and patients’ clinical picture – be deferred to a later time, when risk of exposure to COVID-19 is more manageable and resource restriction is no longer a concern,” said the endocrinologists, writing in a guest editorial in Clinical Thyroidology.

All elective procedures have been canceled under guidance of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in conjunction with the U.S. surgeon general, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, thyroid nodule FNAs, though elective, fall into the category of being considered medically necessary and potentially prolonging life expectancy

Yet, with approximately 90% of asymptomatic thyroid nodules turning out to be benign and little evidence that early detection and treatment affects disease outcomes, there is a strong argument for deferral in most cases, stressed Ming Lee, MD, and colleagues, of the endocrinology division at Phoenix (Ariz.) Veterans Affairs Health Care System (PVAHCS), who convened a multidisciplinary meeting to address the urgent issue.

Patients should instead be interviewed by an endocrinologist (preferably via telehealth) to collect their clinical history as well as assess their perception of the disease and risk of malignancy, senior author S. Mitchell Harman, MD, chief of PVAHCS, said in an interview.

“The principal guiding factor should be the objectively assessed likelihood of malignancy of the individual patient’s nodule(s),” he said.

“In my opinion, we should also factor in the patient’s level of anxiety, since some patients are more sanguine about risk than others and our goal is to provide relief of anxiety as well as to determine need for, and course of, subsequent treatment,” Dr. Harman added.

Vast majority of malignant thyroid nodules are DTC, which is ‘indolent’

Dr. Lee and colleagues noted that, even of the 10% of thyroid nodules that do prove to be malignant, the vast majority of these (90%) are differentiated thyroid cancers (DTC). In general, patients with DTC “follow an indolent course and have excellent outcomes.”

“There is little evidence that early detection and treatment of DTC significantly alters disease outcomes as the overall mortality rate for DTC has remained low, at around 0.5%,” they wrote.

They also noted that ultrasound features of thyroid nodules can help guide priority for the future timing of an FNA procedure, but should not be the sole basis for deciding on immediate thyroid FNA or surgery.

Exceptions to the rule

Exceptions for considering FNA include more urgent thyroid disease diagnoses, including those that are symptomatic:

Suspected medullary thyroid cancer

“Regarding medullary thyroid cancer (MTC), early diagnosis and surgery do significantly improve outcomes, therefore, delaying FNA of nodules harboring MTC could be potentially injurious,” the authors said.

They suggested, however, measuring calcitonin levels instead, which they noted “is still controversial” in the United States, but “we feel it would be justified in patients with thyroid nodules that would usually be indicated for FNA.”

Those with a family history of MTC, or nodules located in the posterior upper third of lateral lobes (the usual location of MTC), should have calcitonin levels measured.

If calcitonin levels are above 10 pg/mL, “FNA should be offered as early as possible.”

“Significantly elevated serum calcitonin levels (e.g., > 100 pg/mL) should be considered an indication for surgery without cytologic confirmation by FNA,” they added.

Anaplastic thyroid cancer

Anaplastic thyroid cancer, though rare, “is one of the few occasions when thyroid surgery should be performed on an urgent basis, as this condition can worsen very rapidly.

“Patients typically present with a rapidly enlarging thyroid mass that is associated with compressive symptoms, such as dysphagia and dyspnea,” they observed.

In this instance, although FNA is part of the preoperative work-up, it is often nondiagnostic and could require additional sampling.

“At the time of this pandemic, it is reasonable that after a multidisciplinary discussion, such patients with the appropriate clinical scenario be referred for thyroid surgery, with or without prior FNA, based on the team’s judgment,” the authors recommended.

Long-standing thyroid masses

These are usually large and/or closely associated with vital structures, such as the trachea and esophagus, and when such masses cause compressive symptoms, thyroid surgery typically is warranted.

And although prior FNA is helpful to obtain a cytologic diagnosis, as this may change the extent of surgery, it may not always be essential.

Broadly, symptomatic patients with compressive symptoms threatening vital structures can be directly referred to a surgeon, with the timing for surgery jointly decided based on the severity of symptoms, rapidity of disease progression, local COVID-19 status, and available resources.

“During the pandemic, we believe that the vast majority of thyroid FNAs should be considered optional, and extent of surgery can be determined by pathological analysis of frozen sections intraoperatively,” they wrote.

“The value of FNA in these situations is less compelling in the current COVID-19 setting, as the basis of decision for surgery has been already determined,” the authors explained.

If urgent FNA needed, screen patient for COVID-19 and use PPE

Should the need for an urgent thyroid FNA occur, patients should be screened and tested for COVID-19 by a clinician wearing personal protective equipment (PPE), said Dr. Lee and colleagues.

“It is crucial to carefully weigh the risks of COVID-19 exposure, availability of resources, and urgency of these procedures for each patient in our individual practice settings,” they noted.

As restrictions eventually loosen, precautions will still be necessary to some degree, Dr. Harman said.

“I do not consider FNA a ‘high-risk’ procedure in the era of COVID-19, since it does not routinely result in profuse aerosolization of respiratory fluids,” he said in an interview.

“However, patients do sometimes cough or choke due to pressure on the neck and the operator is, of necessity, very close to the patient’s face. Therefore, when we resume FNA, patients will be screened for symptoms of COVID-19 infection and both the operator and the patient will be masked,” Dr. Harman continued.

“We routinely wear gloves, [and] whether the operator will wear a surgical or an N95 mask, disposable gown, etc, will depend on CDC guidance and guidance received from our VA infectious disease experts as it is applied specifically to each patient evaluation.”

The authors have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Changing habits, sleep patterns, and home duties during the pandemic

Like you, I’m not sure when this weird Twilight Zone world of coronavirus will end. Even when it does, its effects will be with us for a long time to come.

But in some ways, they may be for the better. Hopefully some of these changes will stick. Like every new situation, I try to take away something of value from it.

As pithy as it sounds, I used to obsess (sort of) over the daily mail delivery. My secretary would check it mid-afternoon, and if it wasn’t there either she or I would run down again before we left. If it still wasn’t there I’d swing by the box when I came in early the next morning. On Saturdays, I’d sometimes drive in just to get the mail.

There certainly are things that come in that are important: payments, bills, medical records, legal cases to review ... but realistically a lot of mail is junk. Office-supply catalogs, CME or pharmaceutical ads, credit card promotions, and so on.

Now? I just don’t care. If I go several days without seeing patients at the office, the mail is at the back of my mind. It’s in a locked box and isn’t going anywhere. Why worry about it? Next time I’m there I can deal with it. It’s not worth thinking about, it’s just the mail. It’s not worth a special trip.

Sleep is another thing. For years my internal alarm has had me up around 4:00 a.m. (I don’t even bother to set one on my phone), and I get up and go in to get started on the day.

Now? I don’t think I’ve ever slept this much. If I have to go to my office, I’m much less rushed. Many days I don’t even have to do that. I walk down to my home office, call up my charts and the day’s video appointment schedule, and we’re off. Granted, once things return to speed, this will probably be back to normal.

My kids are all home from college, so I have the extra time at home to enjoy them and our dogs. My wife, an oncology infusion nurse, doesn’t get home until 6:00 each night, so for now I’ve become a stay-at-home dad. This is actually something I’ve always liked (in high school, I was voted “most likely to to be a house husband”). So I do the laundry and am in charge of dinner each night. I’m enjoying the last, as I get to pick things out, go through recipes, and cook. I won’t say I’m a great cook, but I’m learning and having fun. As strange as it sounds, being a house husband has always been something I wanted to do, so I’m appreciating the opportunity while it lasts.

I think all of us have come to accept this strange pause button that’s been pushed, and I’ll try to learn what I can from it and take that with me as I move forward.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz. He has no relevant disclosures.

Like you, I’m not sure when this weird Twilight Zone world of coronavirus will end. Even when it does, its effects will be with us for a long time to come.

But in some ways, they may be for the better. Hopefully some of these changes will stick. Like every new situation, I try to take away something of value from it.

As pithy as it sounds, I used to obsess (sort of) over the daily mail delivery. My secretary would check it mid-afternoon, and if it wasn’t there either she or I would run down again before we left. If it still wasn’t there I’d swing by the box when I came in early the next morning. On Saturdays, I’d sometimes drive in just to get the mail.

There certainly are things that come in that are important: payments, bills, medical records, legal cases to review ... but realistically a lot of mail is junk. Office-supply catalogs, CME or pharmaceutical ads, credit card promotions, and so on.

Now? I just don’t care. If I go several days without seeing patients at the office, the mail is at the back of my mind. It’s in a locked box and isn’t going anywhere. Why worry about it? Next time I’m there I can deal with it. It’s not worth thinking about, it’s just the mail. It’s not worth a special trip.

Sleep is another thing. For years my internal alarm has had me up around 4:00 a.m. (I don’t even bother to set one on my phone), and I get up and go in to get started on the day.

Now? I don’t think I’ve ever slept this much. If I have to go to my office, I’m much less rushed. Many days I don’t even have to do that. I walk down to my home office, call up my charts and the day’s video appointment schedule, and we’re off. Granted, once things return to speed, this will probably be back to normal.

My kids are all home from college, so I have the extra time at home to enjoy them and our dogs. My wife, an oncology infusion nurse, doesn’t get home until 6:00 each night, so for now I’ve become a stay-at-home dad. This is actually something I’ve always liked (in high school, I was voted “most likely to to be a house husband”). So I do the laundry and am in charge of dinner each night. I’m enjoying the last, as I get to pick things out, go through recipes, and cook. I won’t say I’m a great cook, but I’m learning and having fun. As strange as it sounds, being a house husband has always been something I wanted to do, so I’m appreciating the opportunity while it lasts.

I think all of us have come to accept this strange pause button that’s been pushed, and I’ll try to learn what I can from it and take that with me as I move forward.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz. He has no relevant disclosures.

Like you, I’m not sure when this weird Twilight Zone world of coronavirus will end. Even when it does, its effects will be with us for a long time to come.

But in some ways, they may be for the better. Hopefully some of these changes will stick. Like every new situation, I try to take away something of value from it.

As pithy as it sounds, I used to obsess (sort of) over the daily mail delivery. My secretary would check it mid-afternoon, and if it wasn’t there either she or I would run down again before we left. If it still wasn’t there I’d swing by the box when I came in early the next morning. On Saturdays, I’d sometimes drive in just to get the mail.

There certainly are things that come in that are important: payments, bills, medical records, legal cases to review ... but realistically a lot of mail is junk. Office-supply catalogs, CME or pharmaceutical ads, credit card promotions, and so on.

Now? I just don’t care. If I go several days without seeing patients at the office, the mail is at the back of my mind. It’s in a locked box and isn’t going anywhere. Why worry about it? Next time I’m there I can deal with it. It’s not worth thinking about, it’s just the mail. It’s not worth a special trip.

Sleep is another thing. For years my internal alarm has had me up around 4:00 a.m. (I don’t even bother to set one on my phone), and I get up and go in to get started on the day.

Now? I don’t think I’ve ever slept this much. If I have to go to my office, I’m much less rushed. Many days I don’t even have to do that. I walk down to my home office, call up my charts and the day’s video appointment schedule, and we’re off. Granted, once things return to speed, this will probably be back to normal.

My kids are all home from college, so I have the extra time at home to enjoy them and our dogs. My wife, an oncology infusion nurse, doesn’t get home until 6:00 each night, so for now I’ve become a stay-at-home dad. This is actually something I’ve always liked (in high school, I was voted “most likely to to be a house husband”). So I do the laundry and am in charge of dinner each night. I’m enjoying the last, as I get to pick things out, go through recipes, and cook. I won’t say I’m a great cook, but I’m learning and having fun. As strange as it sounds, being a house husband has always been something I wanted to do, so I’m appreciating the opportunity while it lasts.

I think all of us have come to accept this strange pause button that’s been pushed, and I’ll try to learn what I can from it and take that with me as I move forward.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz. He has no relevant disclosures.

Observation pathway safely reduces acute pancreatitis hospitalization rate

For patients diagnosed with mild acute pancreatitis (AP) in the ED, an observation pathway may significantly reduce hospitalization rate and associated costs without compromising patient safety or quality of care, according to investigators.

Over a 2-year period, the observation pathway at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, reduced hospitalizations by 31.2%, reported lead author Awais Ahmed, MD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and colleagues.

“AP carries a significant burden on the health care system, accounting for the third most common reason for gastrointestinal-related admissions in the United States,” the investigators wrote in the Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology. “As such, streamlining care for AP patients to reduce admissions can reduce the associated financial burden.”

The investigators’ efforts to reduce admissions for patients with AP began in 2016, when they first implemented an observation pathway at Beth Israel. This 6-month pilot study demonstrated proof of concept because it reduced admissions by 22.2% and shortened average length of stay without negatively affecting rates of mortality or readmission.

Based on these encouraging results, the hospital implemented the observation pathway as a standard of care. The present study analyzed 2 years of data from patients diagnosed with AP following the end of the pilot study. The primary outcome was hospitalization rate. Secondary outcomes included health care utilization, 30-day mortality rate, 30-day readmission rate, and median length of stay.

Patients with mild AP entered the observation pathway at the discretion of the supervising clinician, as well as based on absence of exclusion criteria, such as end organ damage, chronic pancreatitis, cholangitis, and other considerations.

Over 2 years, 165 patients were diagnosed with AP in the ED, of whom 118 (71.5%) had mild AP. From this latter group, 54 (45.8%) entered the observation pathway, while 64 (54.2%) were admitted as inpatients, primarily (n = 58) because of exclusion criteria. Within the observation group, 45 out of 54 patients (83.3%) successfully completed the pathway and were discharged. Six of these patients were readmitted within 30 days. Among the 9 patients who did not complete the pathway, 6 failed to meet discharge criteria, resulting in admission, whereas 3 patients left the hospital against medical advice.

Combining data from this 2-year period and the pilot study, the hospitalization rate for mild AP was reduced by 31.2%. In the present study, hospitalization was reduced by 27% for patients with AP of any severity. This figure was steady over a 3-year period, at 25.8%.

Median length of stay for patients with mild AP was significantly shorter in the present study’s observation pathway than in a historical cohort (19.9 vs. 72.0 hours); this remained significant when also including patients from the pilot study (21.2 vs. 72.0 hours). Compared with the historic cohort, patients in the observation had significantly fewer radiographic studies, and more patients were discharged in less than 24 hours. Meanwhile, 30-day readmission and mortality rates remained unchanged.

“In summary, our long-term data of a single center emergency department–based observation management pathway for mild AP demonstrates durability over more than 2 years in maintaining its objective of reducing hospitalization,” the investigators concluded. “This is associated with a [shorter] length of stay, and reduced health care resource utilization, suggesting a possible decrease in financial cost of managing mild AP, without affecting readmission rates or mortality.”

These findings encourage further research, the investigators suggested, while noting that the observation pathway may not be appropriate for all treatment centers.

“The generalizability of the pathway is limited, given its single center location, and tertiary environment,” the investigators wrote. “Smaller hospitals, lacking multidisciplinary support for complications of AP, may find it challenging to implement such a pathway, and thus triage these patients for inpatient admission at their facility or to nearby tertiary centers.”The investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Ahmed A et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2020 Apr 14. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001354.

For patients diagnosed with mild acute pancreatitis (AP) in the ED, an observation pathway may significantly reduce hospitalization rate and associated costs without compromising patient safety or quality of care, according to investigators.

Over a 2-year period, the observation pathway at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, reduced hospitalizations by 31.2%, reported lead author Awais Ahmed, MD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and colleagues.

“AP carries a significant burden on the health care system, accounting for the third most common reason for gastrointestinal-related admissions in the United States,” the investigators wrote in the Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology. “As such, streamlining care for AP patients to reduce admissions can reduce the associated financial burden.”

The investigators’ efforts to reduce admissions for patients with AP began in 2016, when they first implemented an observation pathway at Beth Israel. This 6-month pilot study demonstrated proof of concept because it reduced admissions by 22.2% and shortened average length of stay without negatively affecting rates of mortality or readmission.

Based on these encouraging results, the hospital implemented the observation pathway as a standard of care. The present study analyzed 2 years of data from patients diagnosed with AP following the end of the pilot study. The primary outcome was hospitalization rate. Secondary outcomes included health care utilization, 30-day mortality rate, 30-day readmission rate, and median length of stay.

Patients with mild AP entered the observation pathway at the discretion of the supervising clinician, as well as based on absence of exclusion criteria, such as end organ damage, chronic pancreatitis, cholangitis, and other considerations.

Over 2 years, 165 patients were diagnosed with AP in the ED, of whom 118 (71.5%) had mild AP. From this latter group, 54 (45.8%) entered the observation pathway, while 64 (54.2%) were admitted as inpatients, primarily (n = 58) because of exclusion criteria. Within the observation group, 45 out of 54 patients (83.3%) successfully completed the pathway and were discharged. Six of these patients were readmitted within 30 days. Among the 9 patients who did not complete the pathway, 6 failed to meet discharge criteria, resulting in admission, whereas 3 patients left the hospital against medical advice.

Combining data from this 2-year period and the pilot study, the hospitalization rate for mild AP was reduced by 31.2%. In the present study, hospitalization was reduced by 27% for patients with AP of any severity. This figure was steady over a 3-year period, at 25.8%.

Median length of stay for patients with mild AP was significantly shorter in the present study’s observation pathway than in a historical cohort (19.9 vs. 72.0 hours); this remained significant when also including patients from the pilot study (21.2 vs. 72.0 hours). Compared with the historic cohort, patients in the observation had significantly fewer radiographic studies, and more patients were discharged in less than 24 hours. Meanwhile, 30-day readmission and mortality rates remained unchanged.

“In summary, our long-term data of a single center emergency department–based observation management pathway for mild AP demonstrates durability over more than 2 years in maintaining its objective of reducing hospitalization,” the investigators concluded. “This is associated with a [shorter] length of stay, and reduced health care resource utilization, suggesting a possible decrease in financial cost of managing mild AP, without affecting readmission rates or mortality.”

These findings encourage further research, the investigators suggested, while noting that the observation pathway may not be appropriate for all treatment centers.

“The generalizability of the pathway is limited, given its single center location, and tertiary environment,” the investigators wrote. “Smaller hospitals, lacking multidisciplinary support for complications of AP, may find it challenging to implement such a pathway, and thus triage these patients for inpatient admission at their facility or to nearby tertiary centers.”The investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Ahmed A et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2020 Apr 14. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001354.

For patients diagnosed with mild acute pancreatitis (AP) in the ED, an observation pathway may significantly reduce hospitalization rate and associated costs without compromising patient safety or quality of care, according to investigators.

Over a 2-year period, the observation pathway at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, reduced hospitalizations by 31.2%, reported lead author Awais Ahmed, MD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and colleagues.

“AP carries a significant burden on the health care system, accounting for the third most common reason for gastrointestinal-related admissions in the United States,” the investigators wrote in the Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology. “As such, streamlining care for AP patients to reduce admissions can reduce the associated financial burden.”

The investigators’ efforts to reduce admissions for patients with AP began in 2016, when they first implemented an observation pathway at Beth Israel. This 6-month pilot study demonstrated proof of concept because it reduced admissions by 22.2% and shortened average length of stay without negatively affecting rates of mortality or readmission.

Based on these encouraging results, the hospital implemented the observation pathway as a standard of care. The present study analyzed 2 years of data from patients diagnosed with AP following the end of the pilot study. The primary outcome was hospitalization rate. Secondary outcomes included health care utilization, 30-day mortality rate, 30-day readmission rate, and median length of stay.

Patients with mild AP entered the observation pathway at the discretion of the supervising clinician, as well as based on absence of exclusion criteria, such as end organ damage, chronic pancreatitis, cholangitis, and other considerations.

Over 2 years, 165 patients were diagnosed with AP in the ED, of whom 118 (71.5%) had mild AP. From this latter group, 54 (45.8%) entered the observation pathway, while 64 (54.2%) were admitted as inpatients, primarily (n = 58) because of exclusion criteria. Within the observation group, 45 out of 54 patients (83.3%) successfully completed the pathway and were discharged. Six of these patients were readmitted within 30 days. Among the 9 patients who did not complete the pathway, 6 failed to meet discharge criteria, resulting in admission, whereas 3 patients left the hospital against medical advice.

Combining data from this 2-year period and the pilot study, the hospitalization rate for mild AP was reduced by 31.2%. In the present study, hospitalization was reduced by 27% for patients with AP of any severity. This figure was steady over a 3-year period, at 25.8%.

Median length of stay for patients with mild AP was significantly shorter in the present study’s observation pathway than in a historical cohort (19.9 vs. 72.0 hours); this remained significant when also including patients from the pilot study (21.2 vs. 72.0 hours). Compared with the historic cohort, patients in the observation had significantly fewer radiographic studies, and more patients were discharged in less than 24 hours. Meanwhile, 30-day readmission and mortality rates remained unchanged.

“In summary, our long-term data of a single center emergency department–based observation management pathway for mild AP demonstrates durability over more than 2 years in maintaining its objective of reducing hospitalization,” the investigators concluded. “This is associated with a [shorter] length of stay, and reduced health care resource utilization, suggesting a possible decrease in financial cost of managing mild AP, without affecting readmission rates or mortality.”

These findings encourage further research, the investigators suggested, while noting that the observation pathway may not be appropriate for all treatment centers.

“The generalizability of the pathway is limited, given its single center location, and tertiary environment,” the investigators wrote. “Smaller hospitals, lacking multidisciplinary support for complications of AP, may find it challenging to implement such a pathway, and thus triage these patients for inpatient admission at their facility or to nearby tertiary centers.”The investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Ahmed A et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2020 Apr 14. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001354.

FROM JOURNAL OF CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY

FDA grants Breakthrough Therapy status to sotatercept for PAH treatment

Approval for sotatercept, “a selective ligand trap for members of the TGF-beta [transforming growth factor-beta] superfamily which rebalances BMPR-II [bone morphogenetic protein receptor type II] signaling,” was based on two types of research. It was based on results of preclinical research indicating “reversed pulmonary vessel muscularization and improved indicators of right heart failure,” as well as results of the phase 2, placebo-controlled PULSAR study, in which sotatercept showed positive results, meeting primary and secondary endpoints.

Adverse events during PULSAR “were consistent with previously published data on sotatercept” in other diseases. The drug is also under investigation in the phase 2 SPECTRA trial, which includes patients with PAH.

“We believe that sotatercept has the potential to shift the current treatment paradigm and provide significant benefit to patients with PAH on top of currently available therapies. Thus, we’re thrilled that the FDA has granted this Breakthrough Therapy designation – a first for an Acceleron-discovered medicine and for a therapeutic candidate in PAH – as it supports and aligns with our mission to deliver novel therapeutic options to patients in need as quickly as possible,” Habib Dable, president and CEO of Acceleron Pharma, said in the press release.

Approval for sotatercept, “a selective ligand trap for members of the TGF-beta [transforming growth factor-beta] superfamily which rebalances BMPR-II [bone morphogenetic protein receptor type II] signaling,” was based on two types of research. It was based on results of preclinical research indicating “reversed pulmonary vessel muscularization and improved indicators of right heart failure,” as well as results of the phase 2, placebo-controlled PULSAR study, in which sotatercept showed positive results, meeting primary and secondary endpoints.

Adverse events during PULSAR “were consistent with previously published data on sotatercept” in other diseases. The drug is also under investigation in the phase 2 SPECTRA trial, which includes patients with PAH.

“We believe that sotatercept has the potential to shift the current treatment paradigm and provide significant benefit to patients with PAH on top of currently available therapies. Thus, we’re thrilled that the FDA has granted this Breakthrough Therapy designation – a first for an Acceleron-discovered medicine and for a therapeutic candidate in PAH – as it supports and aligns with our mission to deliver novel therapeutic options to patients in need as quickly as possible,” Habib Dable, president and CEO of Acceleron Pharma, said in the press release.

Approval for sotatercept, “a selective ligand trap for members of the TGF-beta [transforming growth factor-beta] superfamily which rebalances BMPR-II [bone morphogenetic protein receptor type II] signaling,” was based on two types of research. It was based on results of preclinical research indicating “reversed pulmonary vessel muscularization and improved indicators of right heart failure,” as well as results of the phase 2, placebo-controlled PULSAR study, in which sotatercept showed positive results, meeting primary and secondary endpoints.

Adverse events during PULSAR “were consistent with previously published data on sotatercept” in other diseases. The drug is also under investigation in the phase 2 SPECTRA trial, which includes patients with PAH.

“We believe that sotatercept has the potential to shift the current treatment paradigm and provide significant benefit to patients with PAH on top of currently available therapies. Thus, we’re thrilled that the FDA has granted this Breakthrough Therapy designation – a first for an Acceleron-discovered medicine and for a therapeutic candidate in PAH – as it supports and aligns with our mission to deliver novel therapeutic options to patients in need as quickly as possible,” Habib Dable, president and CEO of Acceleron Pharma, said in the press release.

Evidence on spironolactone safety, COVID-19 reassuring for acne patients

according to a report in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

The virus needs androgens to infect cells, and uses androgen-dependent transmembrane protease serine 2 to prime viral protein spikes to anchor onto ACE2 receptors. Without that step, the virus can’t enter cells. Androgens are the only known activator in humans, so androgen blockers like spironolactone probably short-circuit the process, said the report’s lead author Carlos Wambier, MD, PhD, of the department of dermatology at Brown University, Providence, R.I (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Apr 10. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.032).

The lack of androgens could be a possible explanation as to why mortality is so rare among children with COVID-19, and why fatalities among men are higher than among women with COVID-19, he said in an interview.

There are a lot of androgen blocker candidates, but he said spironolactone – a mainstay of acne treatment – might well be the best for the pandemic because of its concomitant lung and heart benefits.

The message counters a post on Instagram in March from a New York City dermatologist in private practice, Ellen Marmur, MD, that raised a question about spironolactone. Concerned about the situation in New York, she reviewed the literature and found a 2005 study that reported that macrophages drawn from 10 heart failure patients had increased ACE2 activity and increased messenger RNA expression after the subjects had been on spironolactone 25 mg per day for a month.

In an interview, she said she has been sharing her concerns with patients on spironolactone and offering them an alternative, such as minocycline, until this issue is better elucidated. To date, she has had one young patient who declined to switch to another treatment, and about six patients who were comfortable switching to another treatment for 1-2 months. She said that she is “clearly cautious yet uncertain about the influence of chronic spironolactone for acne on COVID infection in acne patients,” and that eventually she would be interested in seeing retrospective data on outcomes of patients on spironolactone for hypertension versus acne during the pandemic.

Dr. Marmur’s post was spread on social media and was picked up by a few online news outlets.

In an interview, Adam Friedman, MD, professor and interim chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, said he’s been addressing concerns about spironolactone in educational webinars because of it.

He tells his audience that “you can’t make any claims” for COVID-19 based on the 2005 study. It was a small clinical study in heart failure patients and only assessed ACE2 expression on macrophages, not respiratory, cardiac, or mesangial cells, which are the relevant locations for viral invasion and damage. In fact, there are studies showing that spironolactone reduced ACE2 in renal mesangial cells. Also of note, spironolactone has been used with no indication of virus risk since the 1950s, he pointed out. The American Academy of Dermatology has not said to stop spironolactone.

At least one study is underway to see if spironolactone is beneficial: 100 mg twice a day for 5 days is being pitted against placebo in Turkey among people hospitalized with acute respiratory distress. The study will evaluate the effect of spironolactone on oxygenation.

“There’s no evidence to show spironolactone can increase mortality levels,” Dr. Wambier said. He is using it more now in patients with acne – a sign of androgen hyperactivity – convinced that it will protect against COVID-19. He even started his sister on it to help with androgenic hair loss, and maybe the virus.

Observations in Spain – increased prevalence of androgenic alopecia among hospitalized patients – support the androgen link; 29 of 41 men (71%) hospitalized with bilateral pneumonia had male pattern baldness, which was severe in 16 (39%), according to a recent report (J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020 Apr 16. doi: 10.1111/jocd.13443). The expected prevalence in a similar age-matched population is 31%-53%.

“Based on the scientific rationale combined with this preliminary observation, we believe investigating the potential association between androgens and COVID‐19 disease severity warrants further merit,” concluded the authors, who included Dr. Wambier, and other dermatologists from the United States, as well as Spain, Australia, Croatia, and Switzerland. “If such an association is confirmed, antiandrogens could be evaluated as a potential treatment for COVID‐19 infection,” they wrote.

The numbers are holding up in a larger series from three Spanish hospitals, and also showing a greater prevalence of androgenic hair loss among hospitalized women, Dr. Wambier said in the interview.

Authors of the two studies include an employee of Applied Biology. No conflicts were declared in the Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology study; no disclosures were listed in the JAAD study. Dr. Friedman had no disclosures.

according to a report in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

The virus needs androgens to infect cells, and uses androgen-dependent transmembrane protease serine 2 to prime viral protein spikes to anchor onto ACE2 receptors. Without that step, the virus can’t enter cells. Androgens are the only known activator in humans, so androgen blockers like spironolactone probably short-circuit the process, said the report’s lead author Carlos Wambier, MD, PhD, of the department of dermatology at Brown University, Providence, R.I (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Apr 10. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.032).

The lack of androgens could be a possible explanation as to why mortality is so rare among children with COVID-19, and why fatalities among men are higher than among women with COVID-19, he said in an interview.

There are a lot of androgen blocker candidates, but he said spironolactone – a mainstay of acne treatment – might well be the best for the pandemic because of its concomitant lung and heart benefits.

The message counters a post on Instagram in March from a New York City dermatologist in private practice, Ellen Marmur, MD, that raised a question about spironolactone. Concerned about the situation in New York, she reviewed the literature and found a 2005 study that reported that macrophages drawn from 10 heart failure patients had increased ACE2 activity and increased messenger RNA expression after the subjects had been on spironolactone 25 mg per day for a month.

In an interview, she said she has been sharing her concerns with patients on spironolactone and offering them an alternative, such as minocycline, until this issue is better elucidated. To date, she has had one young patient who declined to switch to another treatment, and about six patients who were comfortable switching to another treatment for 1-2 months. She said that she is “clearly cautious yet uncertain about the influence of chronic spironolactone for acne on COVID infection in acne patients,” and that eventually she would be interested in seeing retrospective data on outcomes of patients on spironolactone for hypertension versus acne during the pandemic.

Dr. Marmur’s post was spread on social media and was picked up by a few online news outlets.

In an interview, Adam Friedman, MD, professor and interim chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, said he’s been addressing concerns about spironolactone in educational webinars because of it.

He tells his audience that “you can’t make any claims” for COVID-19 based on the 2005 study. It was a small clinical study in heart failure patients and only assessed ACE2 expression on macrophages, not respiratory, cardiac, or mesangial cells, which are the relevant locations for viral invasion and damage. In fact, there are studies showing that spironolactone reduced ACE2 in renal mesangial cells. Also of note, spironolactone has been used with no indication of virus risk since the 1950s, he pointed out. The American Academy of Dermatology has not said to stop spironolactone.

At least one study is underway to see if spironolactone is beneficial: 100 mg twice a day for 5 days is being pitted against placebo in Turkey among people hospitalized with acute respiratory distress. The study will evaluate the effect of spironolactone on oxygenation.

“There’s no evidence to show spironolactone can increase mortality levels,” Dr. Wambier said. He is using it more now in patients with acne – a sign of androgen hyperactivity – convinced that it will protect against COVID-19. He even started his sister on it to help with androgenic hair loss, and maybe the virus.

Observations in Spain – increased prevalence of androgenic alopecia among hospitalized patients – support the androgen link; 29 of 41 men (71%) hospitalized with bilateral pneumonia had male pattern baldness, which was severe in 16 (39%), according to a recent report (J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020 Apr 16. doi: 10.1111/jocd.13443). The expected prevalence in a similar age-matched population is 31%-53%.

“Based on the scientific rationale combined with this preliminary observation, we believe investigating the potential association between androgens and COVID‐19 disease severity warrants further merit,” concluded the authors, who included Dr. Wambier, and other dermatologists from the United States, as well as Spain, Australia, Croatia, and Switzerland. “If such an association is confirmed, antiandrogens could be evaluated as a potential treatment for COVID‐19 infection,” they wrote.

The numbers are holding up in a larger series from three Spanish hospitals, and also showing a greater prevalence of androgenic hair loss among hospitalized women, Dr. Wambier said in the interview.

Authors of the two studies include an employee of Applied Biology. No conflicts were declared in the Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology study; no disclosures were listed in the JAAD study. Dr. Friedman had no disclosures.

according to a report in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

The virus needs androgens to infect cells, and uses androgen-dependent transmembrane protease serine 2 to prime viral protein spikes to anchor onto ACE2 receptors. Without that step, the virus can’t enter cells. Androgens are the only known activator in humans, so androgen blockers like spironolactone probably short-circuit the process, said the report’s lead author Carlos Wambier, MD, PhD, of the department of dermatology at Brown University, Providence, R.I (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Apr 10. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.032).

The lack of androgens could be a possible explanation as to why mortality is so rare among children with COVID-19, and why fatalities among men are higher than among women with COVID-19, he said in an interview.

There are a lot of androgen blocker candidates, but he said spironolactone – a mainstay of acne treatment – might well be the best for the pandemic because of its concomitant lung and heart benefits.

The message counters a post on Instagram in March from a New York City dermatologist in private practice, Ellen Marmur, MD, that raised a question about spironolactone. Concerned about the situation in New York, she reviewed the literature and found a 2005 study that reported that macrophages drawn from 10 heart failure patients had increased ACE2 activity and increased messenger RNA expression after the subjects had been on spironolactone 25 mg per day for a month.

In an interview, she said she has been sharing her concerns with patients on spironolactone and offering them an alternative, such as minocycline, until this issue is better elucidated. To date, she has had one young patient who declined to switch to another treatment, and about six patients who were comfortable switching to another treatment for 1-2 months. She said that she is “clearly cautious yet uncertain about the influence of chronic spironolactone for acne on COVID infection in acne patients,” and that eventually she would be interested in seeing retrospective data on outcomes of patients on spironolactone for hypertension versus acne during the pandemic.

Dr. Marmur’s post was spread on social media and was picked up by a few online news outlets.

In an interview, Adam Friedman, MD, professor and interim chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, said he’s been addressing concerns about spironolactone in educational webinars because of it.

He tells his audience that “you can’t make any claims” for COVID-19 based on the 2005 study. It was a small clinical study in heart failure patients and only assessed ACE2 expression on macrophages, not respiratory, cardiac, or mesangial cells, which are the relevant locations for viral invasion and damage. In fact, there are studies showing that spironolactone reduced ACE2 in renal mesangial cells. Also of note, spironolactone has been used with no indication of virus risk since the 1950s, he pointed out. The American Academy of Dermatology has not said to stop spironolactone.