User login

Most neurologists live within their means, are savers

An important caveat, however, is that data for this year’s report were collected prior to Feb. 11, 2020, as part of the Medscape Physician Compensation Report 2020. The financial picture has changed for many physicians since then because of COVID-19’s impact on medical practices.

While it will be some time before medical practices become accustomed to a new version of normal, the report data provide a picture of the debt load and net worth of neurologists.

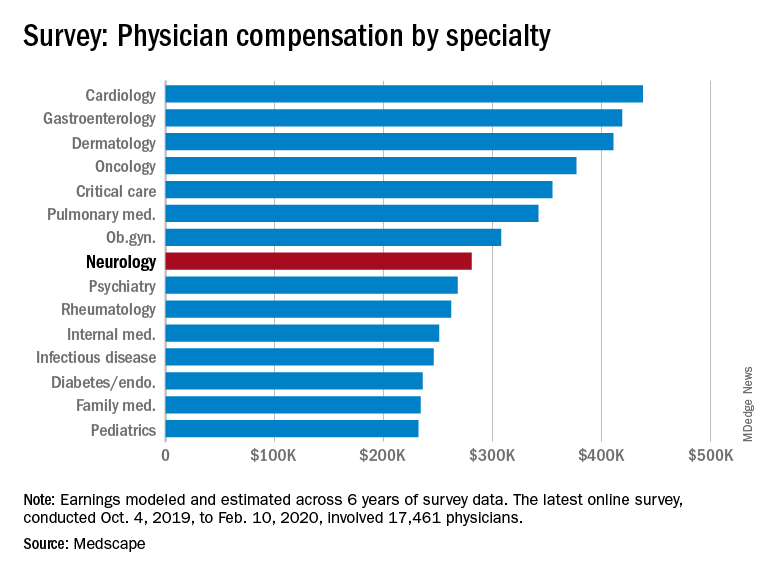

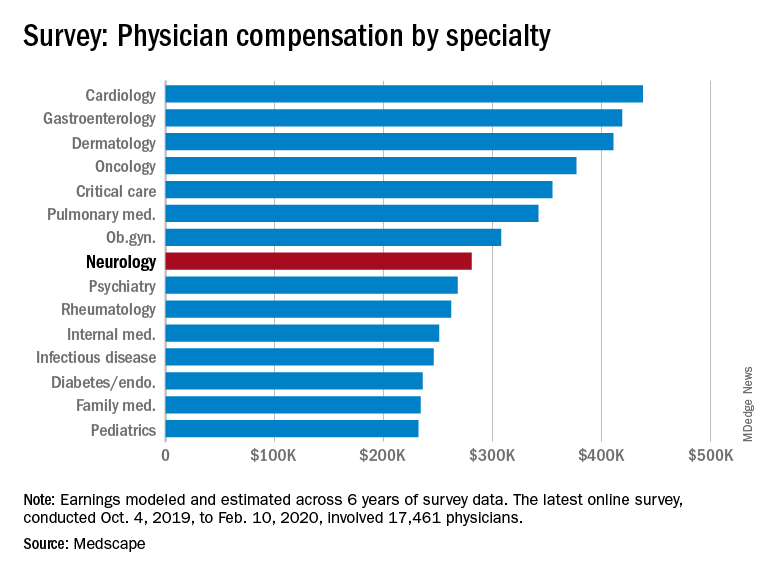

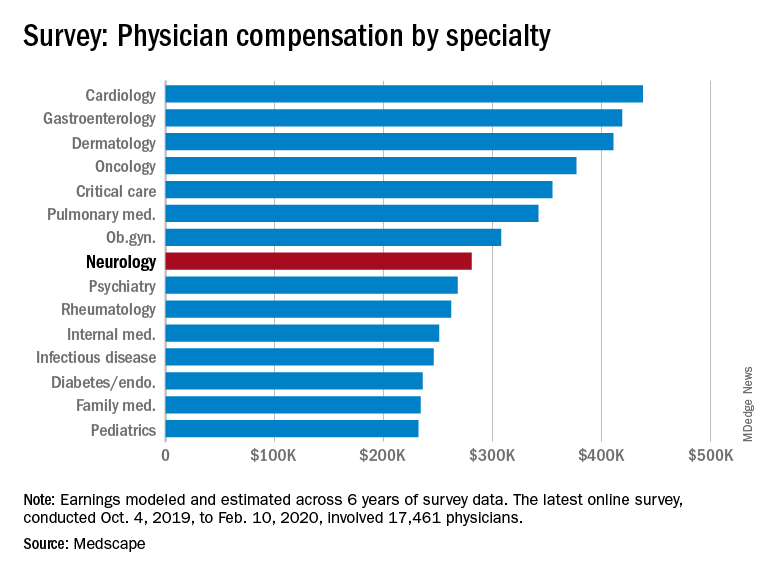

Below the middle earners

According to the Medscape Neurologist Compensation Report 2020, neurologists are below the middle earners of all physicians, earning $280,000 on average this year. That’s up from $267,000 last year. More than half of neurologists (58%) report a net worth (total assets minus total liabilities) of less than $1 million (52% men, 70% women), while 36% have a net worth between $1 and $5 million (40% men, 29% women), and 6% top $5 million in net worth (8% men, 1% women).

Among specialists, orthopedists are most likely to top the $5 million level (at 19%), followed by plastic surgeons and gastroenterologists (both at 16%), according to the Medscape Physician Debt and Net Worth Report 2020.

Conversely, about two in five neurologists (41%) have a net worth under $500,000, just below family medicine physicians (46%) and pediatricians (44%).

For roughly two thirds of neurologists (64%), their major expense is mortgage payment on their primary residence. Around one third of neurologists have a mortgage of $300,000 or less, 28% have no mortgage or a mortgage that is paid off, and 17% have a mortgage topping $500,000. Six in 10 neurologists live in a house that is 3000 square feet or smaller.

Mortgage aside, other top ongoing expenses for neurologists are car payments (35%), credit card debt (28%), school loans (25%), and childcare (19%). At 25%, neurologists are in the middle of the list when it comes to physicians still paying off loans for education.

Spender or saver?

The average American has four credit cards, according to the credit reporting agency Experian. Among neurologists, more than half said they have four or fewer credit cards, including 37% with three to four cards, 16% with one to two cards, and 1% with no cards. A little more than a quarter of neurologists (28%) have five to six credit cards and 18% have more than seven at their disposal.

Only a small percentage of neurologists (7%) say they live above their means; 57% live at their means and 35% live below their means.

More than half (59%) of neurologists contribute $1,000 or more to a tax-deferred retirement or college savings account each month, while 12% do not do this on a regular basis. About two thirds of neurologists make contributions to a taxable savings account, a tool many use when tax-deferred contributions have reached their limit.

Nearly half of neurologists (48%) rely on a “mental budget” for personal expenses, while 18% rely on a written budget or use software or an app for budgeting; 34% do not have a budget for personal expenses.

Nearly three quarters of neurologists did not experience a financial loss in 2019. Of those that did, the main causes were bad investments (10%) and practice-related issues (9%), followed by legal fees (5%), real estate loss (4%), and divorce (1%).

Among neurologists with joint finances with a spouse or partner, 62% pool their income to pay household expenses. For 12%, the person who earns more pays more of the bills and/or expenses. Only a small percentage divide bills and expenses equally (4%).

Forty-three percent of neurologists said they currently work with a financial planner or had in the past, 38% never did, and 19% met with a financial planner but did not pursue working with that person.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

An important caveat, however, is that data for this year’s report were collected prior to Feb. 11, 2020, as part of the Medscape Physician Compensation Report 2020. The financial picture has changed for many physicians since then because of COVID-19’s impact on medical practices.

While it will be some time before medical practices become accustomed to a new version of normal, the report data provide a picture of the debt load and net worth of neurologists.

Below the middle earners

According to the Medscape Neurologist Compensation Report 2020, neurologists are below the middle earners of all physicians, earning $280,000 on average this year. That’s up from $267,000 last year. More than half of neurologists (58%) report a net worth (total assets minus total liabilities) of less than $1 million (52% men, 70% women), while 36% have a net worth between $1 and $5 million (40% men, 29% women), and 6% top $5 million in net worth (8% men, 1% women).

Among specialists, orthopedists are most likely to top the $5 million level (at 19%), followed by plastic surgeons and gastroenterologists (both at 16%), according to the Medscape Physician Debt and Net Worth Report 2020.

Conversely, about two in five neurologists (41%) have a net worth under $500,000, just below family medicine physicians (46%) and pediatricians (44%).

For roughly two thirds of neurologists (64%), their major expense is mortgage payment on their primary residence. Around one third of neurologists have a mortgage of $300,000 or less, 28% have no mortgage or a mortgage that is paid off, and 17% have a mortgage topping $500,000. Six in 10 neurologists live in a house that is 3000 square feet or smaller.

Mortgage aside, other top ongoing expenses for neurologists are car payments (35%), credit card debt (28%), school loans (25%), and childcare (19%). At 25%, neurologists are in the middle of the list when it comes to physicians still paying off loans for education.

Spender or saver?

The average American has four credit cards, according to the credit reporting agency Experian. Among neurologists, more than half said they have four or fewer credit cards, including 37% with three to four cards, 16% with one to two cards, and 1% with no cards. A little more than a quarter of neurologists (28%) have five to six credit cards and 18% have more than seven at their disposal.

Only a small percentage of neurologists (7%) say they live above their means; 57% live at their means and 35% live below their means.

More than half (59%) of neurologists contribute $1,000 or more to a tax-deferred retirement or college savings account each month, while 12% do not do this on a regular basis. About two thirds of neurologists make contributions to a taxable savings account, a tool many use when tax-deferred contributions have reached their limit.

Nearly half of neurologists (48%) rely on a “mental budget” for personal expenses, while 18% rely on a written budget or use software or an app for budgeting; 34% do not have a budget for personal expenses.

Nearly three quarters of neurologists did not experience a financial loss in 2019. Of those that did, the main causes were bad investments (10%) and practice-related issues (9%), followed by legal fees (5%), real estate loss (4%), and divorce (1%).

Among neurologists with joint finances with a spouse or partner, 62% pool their income to pay household expenses. For 12%, the person who earns more pays more of the bills and/or expenses. Only a small percentage divide bills and expenses equally (4%).

Forty-three percent of neurologists said they currently work with a financial planner or had in the past, 38% never did, and 19% met with a financial planner but did not pursue working with that person.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

An important caveat, however, is that data for this year’s report were collected prior to Feb. 11, 2020, as part of the Medscape Physician Compensation Report 2020. The financial picture has changed for many physicians since then because of COVID-19’s impact on medical practices.

While it will be some time before medical practices become accustomed to a new version of normal, the report data provide a picture of the debt load and net worth of neurologists.

Below the middle earners

According to the Medscape Neurologist Compensation Report 2020, neurologists are below the middle earners of all physicians, earning $280,000 on average this year. That’s up from $267,000 last year. More than half of neurologists (58%) report a net worth (total assets minus total liabilities) of less than $1 million (52% men, 70% women), while 36% have a net worth between $1 and $5 million (40% men, 29% women), and 6% top $5 million in net worth (8% men, 1% women).

Among specialists, orthopedists are most likely to top the $5 million level (at 19%), followed by plastic surgeons and gastroenterologists (both at 16%), according to the Medscape Physician Debt and Net Worth Report 2020.

Conversely, about two in five neurologists (41%) have a net worth under $500,000, just below family medicine physicians (46%) and pediatricians (44%).

For roughly two thirds of neurologists (64%), their major expense is mortgage payment on their primary residence. Around one third of neurologists have a mortgage of $300,000 or less, 28% have no mortgage or a mortgage that is paid off, and 17% have a mortgage topping $500,000. Six in 10 neurologists live in a house that is 3000 square feet or smaller.

Mortgage aside, other top ongoing expenses for neurologists are car payments (35%), credit card debt (28%), school loans (25%), and childcare (19%). At 25%, neurologists are in the middle of the list when it comes to physicians still paying off loans for education.

Spender or saver?

The average American has four credit cards, according to the credit reporting agency Experian. Among neurologists, more than half said they have four or fewer credit cards, including 37% with three to four cards, 16% with one to two cards, and 1% with no cards. A little more than a quarter of neurologists (28%) have five to six credit cards and 18% have more than seven at their disposal.

Only a small percentage of neurologists (7%) say they live above their means; 57% live at their means and 35% live below their means.

More than half (59%) of neurologists contribute $1,000 or more to a tax-deferred retirement or college savings account each month, while 12% do not do this on a regular basis. About two thirds of neurologists make contributions to a taxable savings account, a tool many use when tax-deferred contributions have reached their limit.

Nearly half of neurologists (48%) rely on a “mental budget” for personal expenses, while 18% rely on a written budget or use software or an app for budgeting; 34% do not have a budget for personal expenses.

Nearly three quarters of neurologists did not experience a financial loss in 2019. Of those that did, the main causes were bad investments (10%) and practice-related issues (9%), followed by legal fees (5%), real estate loss (4%), and divorce (1%).

Among neurologists with joint finances with a spouse or partner, 62% pool their income to pay household expenses. For 12%, the person who earns more pays more of the bills and/or expenses. Only a small percentage divide bills and expenses equally (4%).

Forty-three percent of neurologists said they currently work with a financial planner or had in the past, 38% never did, and 19% met with a financial planner but did not pursue working with that person.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Erythematous Plaque on the Scalp With Alopecia

The Diagnosis: Tufted Hair Folliculitis

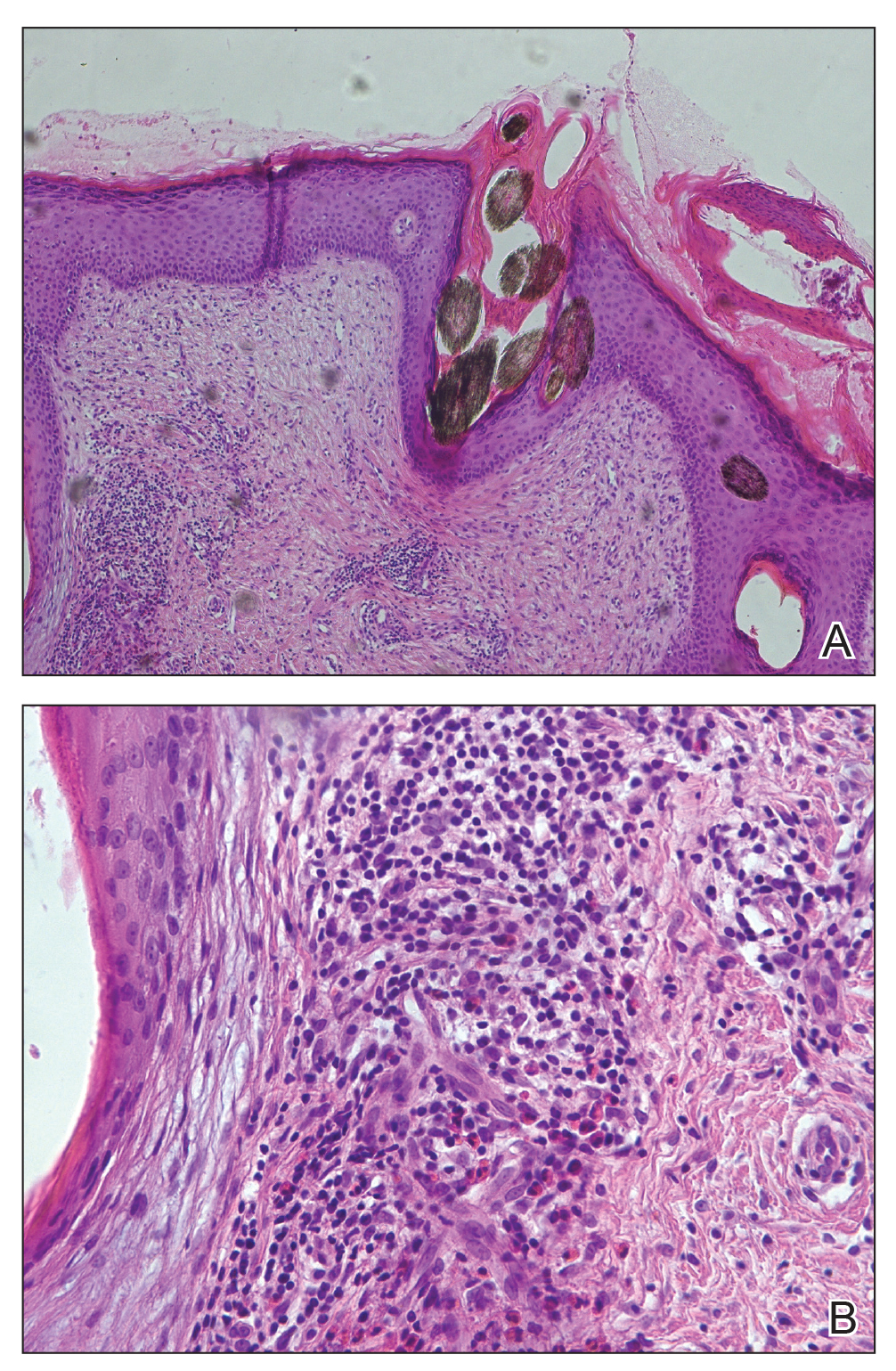

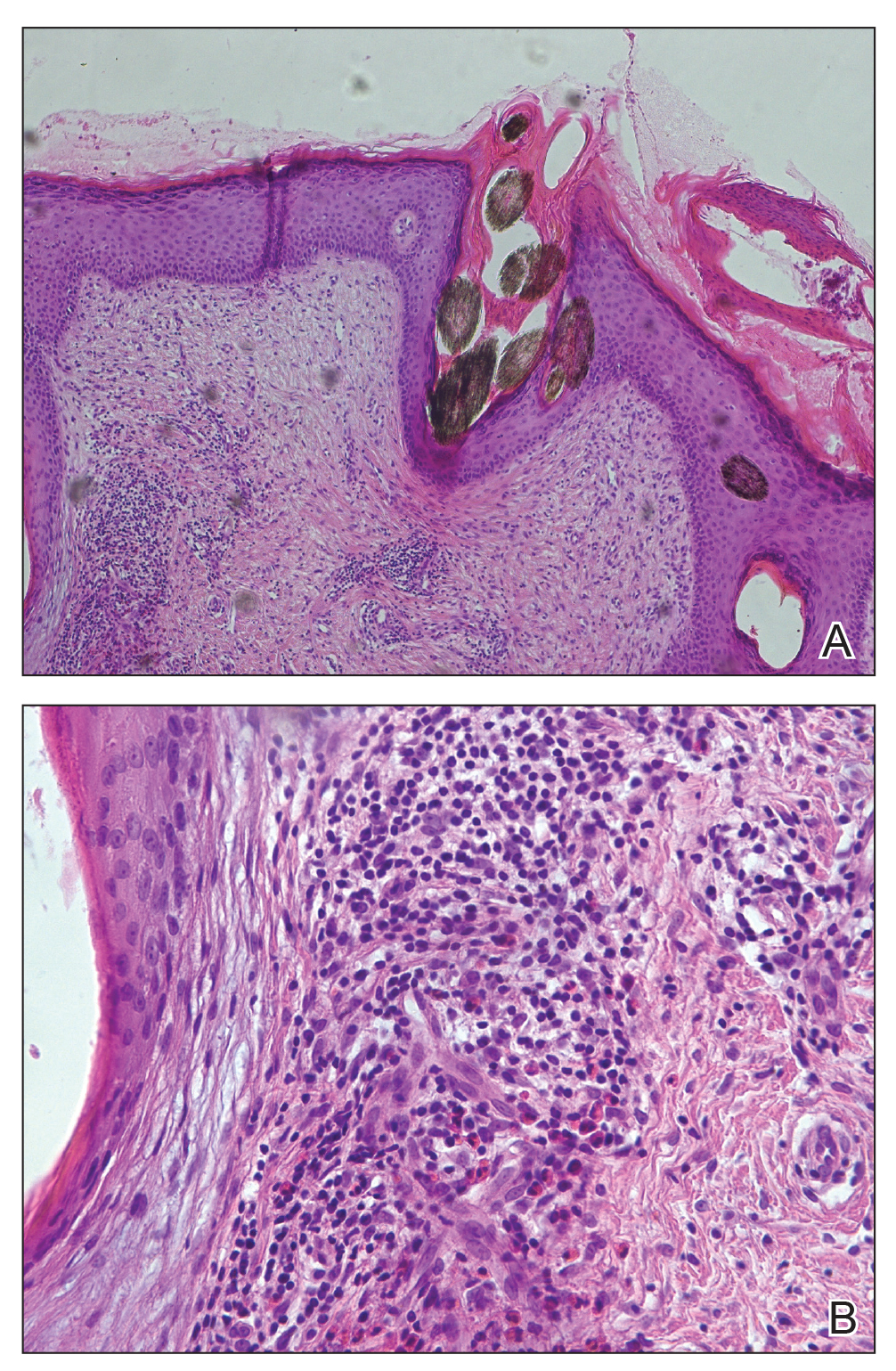

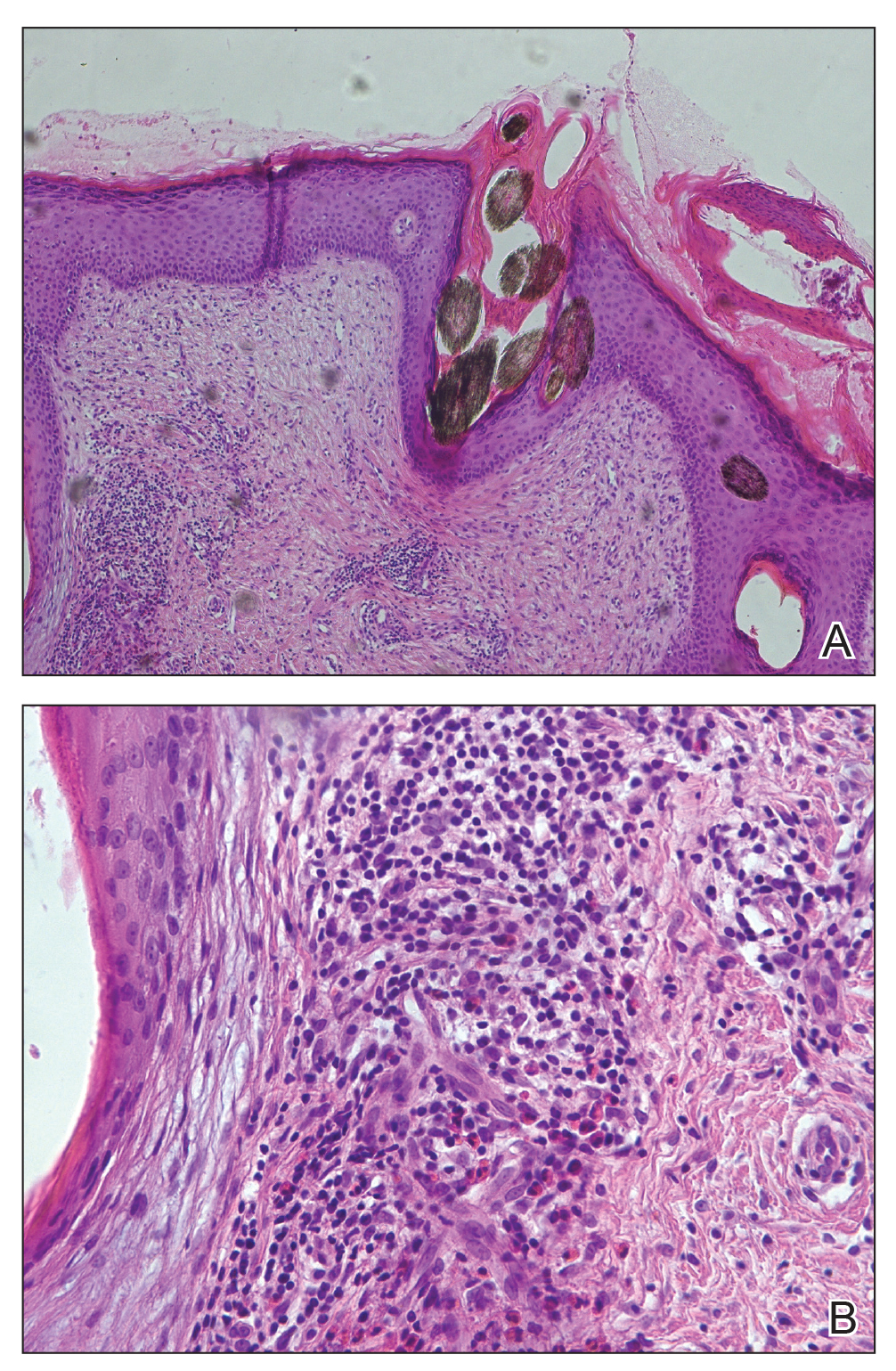

Dermoscopic examination revealed multiple hair tufts of 5 to 20 normal hairs emerging from single dilated follicular openings (Figure 1). The density of hair follicles was reduced with adherent yellow-white scales that encircled the dilated follicular orifices. Histopathology revealed hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis in the stratum corneum. Infiltration of lymphocytes, neutrophils, plasma cells, and eosinophils around the upper portions of the follicles also was found. Multiple hairs emerging from a single dilated follicular ostia with prominent fibrosis of the dermis were seen (Figure 2). Based on the clinical and histopathological findings, the patient was diagnosed with tufted hair folliculitis (THF). She was treated with minocycline 100 mg once daily and an intralesional betamethasone injection 5 mg once daily. After 2 weeks of treatment, the lesion improved and decreased in size to 1×1 cm in diameter; however, the hair tufts and scarring alopecia remained.

Tufted hair folliculitis is a rare inflammatory condition of the scalp characterized by a peculiar tufting of hair that was first described by Smith and Sanderson1 in 1978. Most patients present with a patch or plaque on the parietal or occipital region of the scalp. The condition may lead to the destruction of follicular units, resulting in permanent scarring alopecia.2 Histopathology in our patient revealed perifollicular inflammation, and several follicles could be seen converging toward a common follicular duct with a widely dilated opening, consistent with the diagnosis of THF.

The pathogenic mechanisms of THF are unclear. Primary hair tufting, local trauma, tinea capitis, nevoid malformation, and Staphylococcus aureus infection have been proposed as causative pathomechanisms.3 Typically there is no history of underlying disease or trauma on the scalp; however, secondary changes may have occurred following unrecognized trauma or repeated stimuli. Staphylococcal infections may play a notable role in inducing THF. Ekmekci and Koslu4 reported that a local inflammatory process led to the destruction of adjacent follicles, which subsequently amalgamated to form a common follicular duct due to local fibrosis and scarring. However, Powell et al5 found no evidence of local immune suppression or immune failure that could explain the abnormal host response to a certain presumptive superantigen. In our patient, the inflammatory injury was mild, and no purulent exudation was found from the dilated follicular openings. Because the patient had applied an antibiotic ointment prior to presentation, bacterial cultures from biopsy specimens were not appropriate.

The differential diagnosis of THF includes folliculitis decalvans, folliculitis keloidalis nuchae, dissecting cellulitis of the scalp, and follicular lichen planus.6 In our patient, folliculitis keloidalis nuchae and dissecting cellulitis of the scalp were excluded because no keloid or purulent inflammation was found. The diagnosis of follicular lichen planus was not taken into consideration because characteristic pathology such as liquefaction degeneration of basal cells was not observed. Folliculitis decalvans was considered to be a possible cause of the alopecia in our patient. It also was suggested that hair tufting could be a secondary phenomenon, occurring in several inflammatory disorders of the scalp. Powell et al5 concluded that THF should be considered as a distinctive clinicohistologic variant of folliculitis decalvans characterized by multiple hair tufts with patches of scarring alopecia. This hypothesis corresponded with our patient's clinical manifestation and histopathology.

Conventional treatment of THF includes topical antiseptics and oral antibiotics (eg, flucloxacillin, erythromycin, tetracycline, doxycycline), but reduction in hair bundling rarely has been observed after antibiotic treatment. Although good prognosis has been reported after surgical excision of the involved areas, it can only be performed in small lesions.6 Pranteda et al7 reported that combination therapy with oral rifampin and oral clindamycin can prevent relapse long-term. Combination therapy for 10 weeks also was effective in 10 of 18 patients with THF.5 Rifampin is an effective therapeutic modality to control the progression of THF as well as prevent relapse; however, long-term use should be avoided to prevent hepatic or renal side effects.7 Our patient was successfully treated with intralesional betamethasone and oral minocycline to reduce the inflammation and prevent the expansion of scarring alopecia.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Xue Chen, MD (Beijing, China), for writing support.

- Smith NP, Sanderson KV. Tufted folliculitis of the scalp. J R Soc Med. 1978;71:606-608.

- Broshtilova V, Bardarov E, Kazandjieva J, et al. Tufted hair folliculitis: a case report and literature review. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2011;20:27-29.

- Gungor S, Yuksel T, Topal I. Tufted hair folliculitis associated with Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome and hidradenitis suppurativa. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2014;80:484-487.

- Ekmekci TR, Koslu A. Tufted hair folliculitis causing skullcap-pattern cicatricial alopecia. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:227-229.

- Powell JJ, Dawber RP, Gatter K. Folliculitis decalvans including tufted folliculitis: clinical, histological and therapeutic findings. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:328-333.

- Baroni A, Romano F. Tufted hair folliculitis in a patient affected by pachydermoperiostosis: case report and videodermoscopic features. Skinmed. 2011;9:186-188.

- Pranteda G, Grimaldi M, Palese E, et al. Tufted hair folliculitis: complete enduring response after treatment with rifampicin. J Dermatolog Treat. 2004;15:396-398.

The Diagnosis: Tufted Hair Folliculitis

Dermoscopic examination revealed multiple hair tufts of 5 to 20 normal hairs emerging from single dilated follicular openings (Figure 1). The density of hair follicles was reduced with adherent yellow-white scales that encircled the dilated follicular orifices. Histopathology revealed hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis in the stratum corneum. Infiltration of lymphocytes, neutrophils, plasma cells, and eosinophils around the upper portions of the follicles also was found. Multiple hairs emerging from a single dilated follicular ostia with prominent fibrosis of the dermis were seen (Figure 2). Based on the clinical and histopathological findings, the patient was diagnosed with tufted hair folliculitis (THF). She was treated with minocycline 100 mg once daily and an intralesional betamethasone injection 5 mg once daily. After 2 weeks of treatment, the lesion improved and decreased in size to 1×1 cm in diameter; however, the hair tufts and scarring alopecia remained.

Tufted hair folliculitis is a rare inflammatory condition of the scalp characterized by a peculiar tufting of hair that was first described by Smith and Sanderson1 in 1978. Most patients present with a patch or plaque on the parietal or occipital region of the scalp. The condition may lead to the destruction of follicular units, resulting in permanent scarring alopecia.2 Histopathology in our patient revealed perifollicular inflammation, and several follicles could be seen converging toward a common follicular duct with a widely dilated opening, consistent with the diagnosis of THF.

The pathogenic mechanisms of THF are unclear. Primary hair tufting, local trauma, tinea capitis, nevoid malformation, and Staphylococcus aureus infection have been proposed as causative pathomechanisms.3 Typically there is no history of underlying disease or trauma on the scalp; however, secondary changes may have occurred following unrecognized trauma or repeated stimuli. Staphylococcal infections may play a notable role in inducing THF. Ekmekci and Koslu4 reported that a local inflammatory process led to the destruction of adjacent follicles, which subsequently amalgamated to form a common follicular duct due to local fibrosis and scarring. However, Powell et al5 found no evidence of local immune suppression or immune failure that could explain the abnormal host response to a certain presumptive superantigen. In our patient, the inflammatory injury was mild, and no purulent exudation was found from the dilated follicular openings. Because the patient had applied an antibiotic ointment prior to presentation, bacterial cultures from biopsy specimens were not appropriate.

The differential diagnosis of THF includes folliculitis decalvans, folliculitis keloidalis nuchae, dissecting cellulitis of the scalp, and follicular lichen planus.6 In our patient, folliculitis keloidalis nuchae and dissecting cellulitis of the scalp were excluded because no keloid or purulent inflammation was found. The diagnosis of follicular lichen planus was not taken into consideration because characteristic pathology such as liquefaction degeneration of basal cells was not observed. Folliculitis decalvans was considered to be a possible cause of the alopecia in our patient. It also was suggested that hair tufting could be a secondary phenomenon, occurring in several inflammatory disorders of the scalp. Powell et al5 concluded that THF should be considered as a distinctive clinicohistologic variant of folliculitis decalvans characterized by multiple hair tufts with patches of scarring alopecia. This hypothesis corresponded with our patient's clinical manifestation and histopathology.

Conventional treatment of THF includes topical antiseptics and oral antibiotics (eg, flucloxacillin, erythromycin, tetracycline, doxycycline), but reduction in hair bundling rarely has been observed after antibiotic treatment. Although good prognosis has been reported after surgical excision of the involved areas, it can only be performed in small lesions.6 Pranteda et al7 reported that combination therapy with oral rifampin and oral clindamycin can prevent relapse long-term. Combination therapy for 10 weeks also was effective in 10 of 18 patients with THF.5 Rifampin is an effective therapeutic modality to control the progression of THF as well as prevent relapse; however, long-term use should be avoided to prevent hepatic or renal side effects.7 Our patient was successfully treated with intralesional betamethasone and oral minocycline to reduce the inflammation and prevent the expansion of scarring alopecia.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Xue Chen, MD (Beijing, China), for writing support.

The Diagnosis: Tufted Hair Folliculitis

Dermoscopic examination revealed multiple hair tufts of 5 to 20 normal hairs emerging from single dilated follicular openings (Figure 1). The density of hair follicles was reduced with adherent yellow-white scales that encircled the dilated follicular orifices. Histopathology revealed hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis in the stratum corneum. Infiltration of lymphocytes, neutrophils, plasma cells, and eosinophils around the upper portions of the follicles also was found. Multiple hairs emerging from a single dilated follicular ostia with prominent fibrosis of the dermis were seen (Figure 2). Based on the clinical and histopathological findings, the patient was diagnosed with tufted hair folliculitis (THF). She was treated with minocycline 100 mg once daily and an intralesional betamethasone injection 5 mg once daily. After 2 weeks of treatment, the lesion improved and decreased in size to 1×1 cm in diameter; however, the hair tufts and scarring alopecia remained.

Tufted hair folliculitis is a rare inflammatory condition of the scalp characterized by a peculiar tufting of hair that was first described by Smith and Sanderson1 in 1978. Most patients present with a patch or plaque on the parietal or occipital region of the scalp. The condition may lead to the destruction of follicular units, resulting in permanent scarring alopecia.2 Histopathology in our patient revealed perifollicular inflammation, and several follicles could be seen converging toward a common follicular duct with a widely dilated opening, consistent with the diagnosis of THF.

The pathogenic mechanisms of THF are unclear. Primary hair tufting, local trauma, tinea capitis, nevoid malformation, and Staphylococcus aureus infection have been proposed as causative pathomechanisms.3 Typically there is no history of underlying disease or trauma on the scalp; however, secondary changes may have occurred following unrecognized trauma or repeated stimuli. Staphylococcal infections may play a notable role in inducing THF. Ekmekci and Koslu4 reported that a local inflammatory process led to the destruction of adjacent follicles, which subsequently amalgamated to form a common follicular duct due to local fibrosis and scarring. However, Powell et al5 found no evidence of local immune suppression or immune failure that could explain the abnormal host response to a certain presumptive superantigen. In our patient, the inflammatory injury was mild, and no purulent exudation was found from the dilated follicular openings. Because the patient had applied an antibiotic ointment prior to presentation, bacterial cultures from biopsy specimens were not appropriate.

The differential diagnosis of THF includes folliculitis decalvans, folliculitis keloidalis nuchae, dissecting cellulitis of the scalp, and follicular lichen planus.6 In our patient, folliculitis keloidalis nuchae and dissecting cellulitis of the scalp were excluded because no keloid or purulent inflammation was found. The diagnosis of follicular lichen planus was not taken into consideration because characteristic pathology such as liquefaction degeneration of basal cells was not observed. Folliculitis decalvans was considered to be a possible cause of the alopecia in our patient. It also was suggested that hair tufting could be a secondary phenomenon, occurring in several inflammatory disorders of the scalp. Powell et al5 concluded that THF should be considered as a distinctive clinicohistologic variant of folliculitis decalvans characterized by multiple hair tufts with patches of scarring alopecia. This hypothesis corresponded with our patient's clinical manifestation and histopathology.

Conventional treatment of THF includes topical antiseptics and oral antibiotics (eg, flucloxacillin, erythromycin, tetracycline, doxycycline), but reduction in hair bundling rarely has been observed after antibiotic treatment. Although good prognosis has been reported after surgical excision of the involved areas, it can only be performed in small lesions.6 Pranteda et al7 reported that combination therapy with oral rifampin and oral clindamycin can prevent relapse long-term. Combination therapy for 10 weeks also was effective in 10 of 18 patients with THF.5 Rifampin is an effective therapeutic modality to control the progression of THF as well as prevent relapse; however, long-term use should be avoided to prevent hepatic or renal side effects.7 Our patient was successfully treated with intralesional betamethasone and oral minocycline to reduce the inflammation and prevent the expansion of scarring alopecia.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Xue Chen, MD (Beijing, China), for writing support.

- Smith NP, Sanderson KV. Tufted folliculitis of the scalp. J R Soc Med. 1978;71:606-608.

- Broshtilova V, Bardarov E, Kazandjieva J, et al. Tufted hair folliculitis: a case report and literature review. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2011;20:27-29.

- Gungor S, Yuksel T, Topal I. Tufted hair folliculitis associated with Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome and hidradenitis suppurativa. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2014;80:484-487.

- Ekmekci TR, Koslu A. Tufted hair folliculitis causing skullcap-pattern cicatricial alopecia. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:227-229.

- Powell JJ, Dawber RP, Gatter K. Folliculitis decalvans including tufted folliculitis: clinical, histological and therapeutic findings. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:328-333.

- Baroni A, Romano F. Tufted hair folliculitis in a patient affected by pachydermoperiostosis: case report and videodermoscopic features. Skinmed. 2011;9:186-188.

- Pranteda G, Grimaldi M, Palese E, et al. Tufted hair folliculitis: complete enduring response after treatment with rifampicin. J Dermatolog Treat. 2004;15:396-398.

- Smith NP, Sanderson KV. Tufted folliculitis of the scalp. J R Soc Med. 1978;71:606-608.

- Broshtilova V, Bardarov E, Kazandjieva J, et al. Tufted hair folliculitis: a case report and literature review. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2011;20:27-29.

- Gungor S, Yuksel T, Topal I. Tufted hair folliculitis associated with Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome and hidradenitis suppurativa. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2014;80:484-487.

- Ekmekci TR, Koslu A. Tufted hair folliculitis causing skullcap-pattern cicatricial alopecia. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:227-229.

- Powell JJ, Dawber RP, Gatter K. Folliculitis decalvans including tufted folliculitis: clinical, histological and therapeutic findings. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:328-333.

- Baroni A, Romano F. Tufted hair folliculitis in a patient affected by pachydermoperiostosis: case report and videodermoscopic features. Skinmed. 2011;9:186-188.

- Pranteda G, Grimaldi M, Palese E, et al. Tufted hair folliculitis: complete enduring response after treatment with rifampicin. J Dermatolog Treat. 2004;15:396-398.

A 37-year-old woman presented with a 2×6-cm, firm, erythematous plaque on the parietal region of the scalp of 1 year’s duration. No history of injury to the scalp was noted. The patient noticed hair loss in the affected area in the month prior to presentation. She was afebrile and otherwise asymptomatic. She denied a family history of similar scalp disorders.

MM patients with concurrent AL show poor survival when coupled to cardiac dysfunction

Cardiac dysfunction is a major determinant of poor survival in multiple myeloma (MM) patients with concurrently developed light chain amyloidosis (AL), according to the results of a small cohort study conducted at a single institution.

A total of 53 patients in whom MM and AL were initially diagnosed from July 2006 to June 2016, The cohort comprised 36 men and 17 women with a median age of 59 years; main organ involvement was kidney (72%) and heart (62%). A bortezomib-based regimen was used in 22 patients whose response rate was better than the other 21 patients who received nonbortezomib-based regimens (64% vs. 29%). The median overall survival for the total cohort was 12 months (P < .05), according to the report published in Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma & Leukemia.

Of particular note, the researchers found that cardiac involvement significantly and adversely affected overall survival (6 vs. 40 months), as did low systolic blood pressure (<90 mm Hg, 3 vs. 8.5 months), according to Yuanyuan Yu and colleagues at the Multiple Myeloma Medical Center of Beijing, Beijing Chao-yang Hospital.

“Although MM-concurrent AL is rare, AL has a negative impact on survival. This study determined that cardiovascular dysfunction caused by AL is the main determinant of shortening survival in patients with MM complicated with AL, and the necessary interventions should be taken to prevent cardiovascular risk,” the researchers concluded.

The work was supported by the Beijing Municipal Health Commission. The authors reported that they had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Yu Y et al. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2020;20(8):519-25.

Cardiac dysfunction is a major determinant of poor survival in multiple myeloma (MM) patients with concurrently developed light chain amyloidosis (AL), according to the results of a small cohort study conducted at a single institution.

A total of 53 patients in whom MM and AL were initially diagnosed from July 2006 to June 2016, The cohort comprised 36 men and 17 women with a median age of 59 years; main organ involvement was kidney (72%) and heart (62%). A bortezomib-based regimen was used in 22 patients whose response rate was better than the other 21 patients who received nonbortezomib-based regimens (64% vs. 29%). The median overall survival for the total cohort was 12 months (P < .05), according to the report published in Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma & Leukemia.

Of particular note, the researchers found that cardiac involvement significantly and adversely affected overall survival (6 vs. 40 months), as did low systolic blood pressure (<90 mm Hg, 3 vs. 8.5 months), according to Yuanyuan Yu and colleagues at the Multiple Myeloma Medical Center of Beijing, Beijing Chao-yang Hospital.

“Although MM-concurrent AL is rare, AL has a negative impact on survival. This study determined that cardiovascular dysfunction caused by AL is the main determinant of shortening survival in patients with MM complicated with AL, and the necessary interventions should be taken to prevent cardiovascular risk,” the researchers concluded.

The work was supported by the Beijing Municipal Health Commission. The authors reported that they had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Yu Y et al. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2020;20(8):519-25.

Cardiac dysfunction is a major determinant of poor survival in multiple myeloma (MM) patients with concurrently developed light chain amyloidosis (AL), according to the results of a small cohort study conducted at a single institution.

A total of 53 patients in whom MM and AL were initially diagnosed from July 2006 to June 2016, The cohort comprised 36 men and 17 women with a median age of 59 years; main organ involvement was kidney (72%) and heart (62%). A bortezomib-based regimen was used in 22 patients whose response rate was better than the other 21 patients who received nonbortezomib-based regimens (64% vs. 29%). The median overall survival for the total cohort was 12 months (P < .05), according to the report published in Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma & Leukemia.

Of particular note, the researchers found that cardiac involvement significantly and adversely affected overall survival (6 vs. 40 months), as did low systolic blood pressure (<90 mm Hg, 3 vs. 8.5 months), according to Yuanyuan Yu and colleagues at the Multiple Myeloma Medical Center of Beijing, Beijing Chao-yang Hospital.

“Although MM-concurrent AL is rare, AL has a negative impact on survival. This study determined that cardiovascular dysfunction caused by AL is the main determinant of shortening survival in patients with MM complicated with AL, and the necessary interventions should be taken to prevent cardiovascular risk,” the researchers concluded.

The work was supported by the Beijing Municipal Health Commission. The authors reported that they had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Yu Y et al. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2020;20(8):519-25.

FROM CLINICAL LYMPHOMA, MYELOMA & LEUKEMIA

Low-dose prasugrel preserves efficacy but lowers bleeding in elderly

In elderly or low-weight patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS), a reduced dose of prasugrel relative to a full-dose of ticagrelor is associated with lower numerical rates of ischemic events and bleeding events, according to a prespecified substudy of the ISAR-REACT 5 trial.

“The present study provides the strongest support for reduced-dose prasugrel as the standard for elderly and low-weight patients with ACS undergoing an invasive treatment strategy,” according to the senior author, Adnan Kastrati, MD, professor of cardiology and head of the Catheterization Laboratory at Deutsches Herzzentrum, Technical University of Munich.

The main results of ISAR-REACT 5, an open-label, head-to-head comparison of prasugrel and ticagrelor in patients with ACS, showed that the risk of the composite primary endpoint of death, myocardial infarction, or stroke 1 year after randomization was significantly higher for those on ticagrelor than prasugrel (hazard ratio, 1.39; P = .006). The bleeding risk on ticagrelor was also higher but not significantly different (5.4% vs. 4.8%; P = .46) (Schüpke S et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Oct;381:1524-34).

In this substudy newly published in Annals of Internal Medicine, outcomes were compared in the 1,099 patients who were 75 years or older or weighed less than 60 kg. In this group, unlike those younger or weighing more, patients were randomized to receive a reduced maintenance dose of 5 mg of once-daily prasugrel (rather than 10 mg) or full dose ticagrelor (90 mg twice daily).

At 1 year, the low-dose prasugrel strategy relative to ticagrelor was associated with a lower rate of events (12.7% vs. 14.6%) and a lower rate of bleeding (8.1% vs. 10.6%), defined as Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) type 3-5 events.

Neither the 18% reduction for the efficacy endpoint (HR, 0.82; 95% CI 0.60-1.14) nor the 28% reduction in the bleeding endpoint (HR, 0.72; 95% CI 0.46-1.12) reached significance, but Dr. Kastrati reported that there was a significant “treatment effect-by-study-group interaction” for BARC 1-5 bleeding (P = .004) favoring prasugrel. This supports low-dose prasugrel as a strategy to prevent the excess bleeding risk previously observed with the standard 10-mg dose of prasugrel.

In other words, a reduced dose of prasugrel, compared with the standard dose of ticagrelor, in low-weight and elderly patients “is associated with maintained anti-ischemic efficacy while protecting these patients against the excess risk of bleeding,” he and his coinvestigators concluded.

Low-weight and older patients represented 27% of those enrolled in ISAR-REACT 5. When compared to the study population as a whole, the risk for both ischemic and bleeding events was at least twice as high, the authors of an accompanying editorial observed. They praised this effort to refine the optimal antiplatelet regimen in a very-high-risk ACS population.

“The current analysis suggests that the prasugrel dose reduction regimen for elderly or underweight patients with ACS is effective and safe,” according to the editorial coauthors, David Conen, MD, and P.J. Devereaux, MD, PhD, who are affiliated with the Population Health Research Institute, Hamilton, Ontario.

This substudy was underpowered to show superiority for the efficacy and safety outcomes in elderly and low-weight ACS patients, which makes these results “hypothesis generating,” but the authors believe that they provide the best available evidence for selecting antiplatelet therapy in this challenging subgroup. Although the exclusion of patients at very high risk of bleeding from ISAR-REACT 5 suggest findings might not be relevant to all elderly and low-weight individuals, the investigators believe the data do inform clinical practice.

“Our study is the first head-to-head randomized comparison of the reduced dose of prasugrel against standard dose of ticagrelor in elderly and low-weight patients,” said Dr. Kastrati in an interview. “Specifically designed studies for this subset of patients are very unlikely to be conducted in the future.”

Dr. Kastrati reported no potential conflicts of interest relevant to this study.

SOURCE: Menichelli M et al. Ann Intern Med. 2020 Jul 21. doi: 10.7326/M20-1806.

In elderly or low-weight patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS), a reduced dose of prasugrel relative to a full-dose of ticagrelor is associated with lower numerical rates of ischemic events and bleeding events, according to a prespecified substudy of the ISAR-REACT 5 trial.

“The present study provides the strongest support for reduced-dose prasugrel as the standard for elderly and low-weight patients with ACS undergoing an invasive treatment strategy,” according to the senior author, Adnan Kastrati, MD, professor of cardiology and head of the Catheterization Laboratory at Deutsches Herzzentrum, Technical University of Munich.

The main results of ISAR-REACT 5, an open-label, head-to-head comparison of prasugrel and ticagrelor in patients with ACS, showed that the risk of the composite primary endpoint of death, myocardial infarction, or stroke 1 year after randomization was significantly higher for those on ticagrelor than prasugrel (hazard ratio, 1.39; P = .006). The bleeding risk on ticagrelor was also higher but not significantly different (5.4% vs. 4.8%; P = .46) (Schüpke S et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Oct;381:1524-34).

In this substudy newly published in Annals of Internal Medicine, outcomes were compared in the 1,099 patients who were 75 years or older or weighed less than 60 kg. In this group, unlike those younger or weighing more, patients were randomized to receive a reduced maintenance dose of 5 mg of once-daily prasugrel (rather than 10 mg) or full dose ticagrelor (90 mg twice daily).

At 1 year, the low-dose prasugrel strategy relative to ticagrelor was associated with a lower rate of events (12.7% vs. 14.6%) and a lower rate of bleeding (8.1% vs. 10.6%), defined as Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) type 3-5 events.

Neither the 18% reduction for the efficacy endpoint (HR, 0.82; 95% CI 0.60-1.14) nor the 28% reduction in the bleeding endpoint (HR, 0.72; 95% CI 0.46-1.12) reached significance, but Dr. Kastrati reported that there was a significant “treatment effect-by-study-group interaction” for BARC 1-5 bleeding (P = .004) favoring prasugrel. This supports low-dose prasugrel as a strategy to prevent the excess bleeding risk previously observed with the standard 10-mg dose of prasugrel.

In other words, a reduced dose of prasugrel, compared with the standard dose of ticagrelor, in low-weight and elderly patients “is associated with maintained anti-ischemic efficacy while protecting these patients against the excess risk of bleeding,” he and his coinvestigators concluded.

Low-weight and older patients represented 27% of those enrolled in ISAR-REACT 5. When compared to the study population as a whole, the risk for both ischemic and bleeding events was at least twice as high, the authors of an accompanying editorial observed. They praised this effort to refine the optimal antiplatelet regimen in a very-high-risk ACS population.

“The current analysis suggests that the prasugrel dose reduction regimen for elderly or underweight patients with ACS is effective and safe,” according to the editorial coauthors, David Conen, MD, and P.J. Devereaux, MD, PhD, who are affiliated with the Population Health Research Institute, Hamilton, Ontario.

This substudy was underpowered to show superiority for the efficacy and safety outcomes in elderly and low-weight ACS patients, which makes these results “hypothesis generating,” but the authors believe that they provide the best available evidence for selecting antiplatelet therapy in this challenging subgroup. Although the exclusion of patients at very high risk of bleeding from ISAR-REACT 5 suggest findings might not be relevant to all elderly and low-weight individuals, the investigators believe the data do inform clinical practice.

“Our study is the first head-to-head randomized comparison of the reduced dose of prasugrel against standard dose of ticagrelor in elderly and low-weight patients,” said Dr. Kastrati in an interview. “Specifically designed studies for this subset of patients are very unlikely to be conducted in the future.”

Dr. Kastrati reported no potential conflicts of interest relevant to this study.

SOURCE: Menichelli M et al. Ann Intern Med. 2020 Jul 21. doi: 10.7326/M20-1806.

In elderly or low-weight patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS), a reduced dose of prasugrel relative to a full-dose of ticagrelor is associated with lower numerical rates of ischemic events and bleeding events, according to a prespecified substudy of the ISAR-REACT 5 trial.

“The present study provides the strongest support for reduced-dose prasugrel as the standard for elderly and low-weight patients with ACS undergoing an invasive treatment strategy,” according to the senior author, Adnan Kastrati, MD, professor of cardiology and head of the Catheterization Laboratory at Deutsches Herzzentrum, Technical University of Munich.

The main results of ISAR-REACT 5, an open-label, head-to-head comparison of prasugrel and ticagrelor in patients with ACS, showed that the risk of the composite primary endpoint of death, myocardial infarction, or stroke 1 year after randomization was significantly higher for those on ticagrelor than prasugrel (hazard ratio, 1.39; P = .006). The bleeding risk on ticagrelor was also higher but not significantly different (5.4% vs. 4.8%; P = .46) (Schüpke S et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Oct;381:1524-34).

In this substudy newly published in Annals of Internal Medicine, outcomes were compared in the 1,099 patients who were 75 years or older or weighed less than 60 kg. In this group, unlike those younger or weighing more, patients were randomized to receive a reduced maintenance dose of 5 mg of once-daily prasugrel (rather than 10 mg) or full dose ticagrelor (90 mg twice daily).

At 1 year, the low-dose prasugrel strategy relative to ticagrelor was associated with a lower rate of events (12.7% vs. 14.6%) and a lower rate of bleeding (8.1% vs. 10.6%), defined as Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) type 3-5 events.

Neither the 18% reduction for the efficacy endpoint (HR, 0.82; 95% CI 0.60-1.14) nor the 28% reduction in the bleeding endpoint (HR, 0.72; 95% CI 0.46-1.12) reached significance, but Dr. Kastrati reported that there was a significant “treatment effect-by-study-group interaction” for BARC 1-5 bleeding (P = .004) favoring prasugrel. This supports low-dose prasugrel as a strategy to prevent the excess bleeding risk previously observed with the standard 10-mg dose of prasugrel.

In other words, a reduced dose of prasugrel, compared with the standard dose of ticagrelor, in low-weight and elderly patients “is associated with maintained anti-ischemic efficacy while protecting these patients against the excess risk of bleeding,” he and his coinvestigators concluded.

Low-weight and older patients represented 27% of those enrolled in ISAR-REACT 5. When compared to the study population as a whole, the risk for both ischemic and bleeding events was at least twice as high, the authors of an accompanying editorial observed. They praised this effort to refine the optimal antiplatelet regimen in a very-high-risk ACS population.

“The current analysis suggests that the prasugrel dose reduction regimen for elderly or underweight patients with ACS is effective and safe,” according to the editorial coauthors, David Conen, MD, and P.J. Devereaux, MD, PhD, who are affiliated with the Population Health Research Institute, Hamilton, Ontario.

This substudy was underpowered to show superiority for the efficacy and safety outcomes in elderly and low-weight ACS patients, which makes these results “hypothesis generating,” but the authors believe that they provide the best available evidence for selecting antiplatelet therapy in this challenging subgroup. Although the exclusion of patients at very high risk of bleeding from ISAR-REACT 5 suggest findings might not be relevant to all elderly and low-weight individuals, the investigators believe the data do inform clinical practice.

“Our study is the first head-to-head randomized comparison of the reduced dose of prasugrel against standard dose of ticagrelor in elderly and low-weight patients,” said Dr. Kastrati in an interview. “Specifically designed studies for this subset of patients are very unlikely to be conducted in the future.”

Dr. Kastrati reported no potential conflicts of interest relevant to this study.

SOURCE: Menichelli M et al. Ann Intern Med. 2020 Jul 21. doi: 10.7326/M20-1806.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

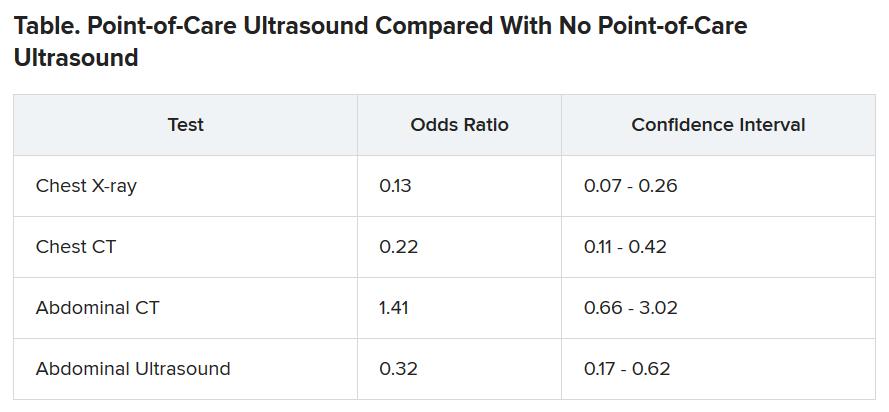

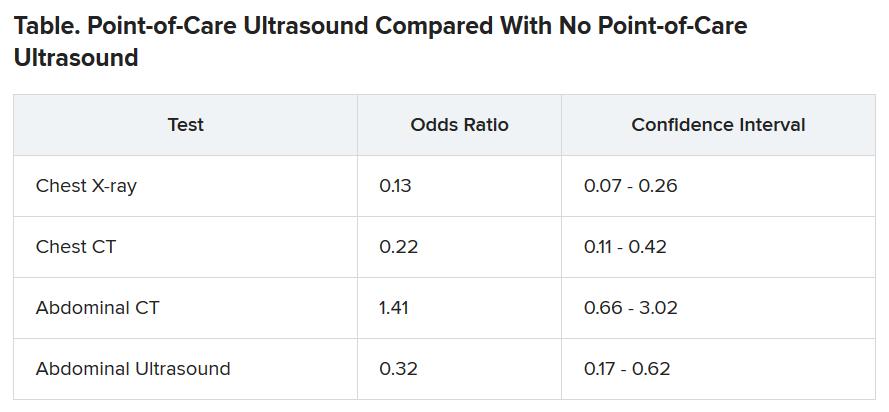

Internists’ use of ultrasound can reduce radiology referrals

researchers say.

“It’s a safe and very useful tool,” Marco Barchiesi, MD, an internal medicine resident at Luigi Sacco Hospital in Milan, said in an interview. “We had a great reduction in chest x-rays because of the use of ultrasound.”

The finding addresses concerns that ultrasound used in primary care could consume more health care resources or put patients at risk.

Dr. Barchiesi and colleagues published their findings July 20 in the European Journal of Internal Medicine.

Point-of-care ultrasound has become increasingly common as miniaturization of devices has made them more portable. The approach has caught on particularly in emergency departments where quick decisions are of the essence.

Its use in internal medicine has been more controversial, with concerns raised that improperly trained practitioners may miss diagnoses or refer patients for unnecessary tests as a result of uncertainty about their findings.

To measure the effect of point-of-care ultrasound in an internal medicine hospital ward, Dr. Barchiesi and colleagues alternated months when point-of-care ultrasound was allowed with months when it was not allowed, for a total of 4 months each, on an internal medicine unit. They allowed the ultrasound to be used for invasive procedures and excluded patients whose critical condition made point-of-care ultrasound crucial.

The researchers analyzed data on 263 patients in the “on” months when point-of-care ultrasound was used, and 255 in the “off” months when it wasn’t used. The two groups were well balanced in age, sex, comorbidity, and clinical impairment.

During the on months, the internists ordered 113 diagnostic tests (0.43 per patient). During the off months they ordered 329 tests (1.29 per patient).

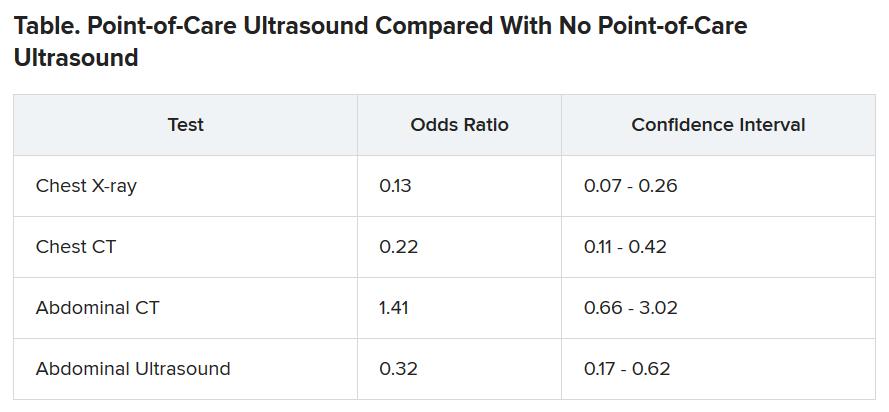

The odds of being referred for a chest x-ray were 87% less in the “on” months, compared with the off months, a statistically significant finding (P < .001). The risk for a chest CT scan and abdominal ultrasound were also reduced during the on months, but the risk for an abdominal CT was increased.

Nineteen patients died during the o” months and 10 during the off months, a difference that was not statistically significant (P = .15). The median length of stay in the hospital was almost the same for the two groups: 9 days for the on months and 9 days for the off months. The difference was also not statistically significant (P = .094).

Point-of-care ultrasound is particularly accurate in identifying cardiac abnormalities and pleural fluid and pneumonia, and it can be used effectively for monitoring heart conditions, the researchers wrote. This could explain the reduction in chest x-rays and CT scans.

On the other hand, ultrasound cannot address such questions as staging in an abdominal malignancy, and unexpected findings are more common with abdominal than chest ultrasound. This could explain why the point-of-care ultrasound did not reduce the use of abdominal CT, the researchers speculated.

They acknowledged that the patients in their sample had an average age of 81 years, raising questions about how well their data could be applied to a younger population. And they noted that they used point-of-care ultrasound frequently, so they were particularly adept with it. “We use it almost every day in our clinical practice,” said Dr. Barchiesi.

Those factors may have played a key role in the success of point-of-care ultrasound in this study, said Michael Wagner, MD, an assistant professor of medicine at the University of South Carolina, Greenville, who has helped colleagues incorporate ultrasound into their practices.

Elderly patients often present with multiple comorbidities and atypical signs and symptoms, he said. “Sometimes they can be very confusing as to the underlying clinical picture. Ultrasound is being used frequently to better assess these complicated patients.”

Dr. Wagner said extensive training is required to use point-of-care ultrasound accurately.

Dr. Barchiesi also acknowledged that the devices used in this study were large portable machines, not the simpler and less expensive hand-held versions that are also available for similar purposes.

Point-of-care ultrasound is a promising innovation, said Thomas Melgar, MD, a professor of medicine at Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo. “The advantage is that the exam is being done by someone who knows the patient and specifically what they’re looking for. It’s done at the bedside so you don’t have to move the patient.”

The study could help address opposition to internal medicine residents being trained in the technique, he said, adding that “I think it’s very exciting.”

The study was partially supported by Philips, which provided the ultrasound devices. Dr. Barchiesi, Dr. Melgar, and Dr. Wagner disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

researchers say.

“It’s a safe and very useful tool,” Marco Barchiesi, MD, an internal medicine resident at Luigi Sacco Hospital in Milan, said in an interview. “We had a great reduction in chest x-rays because of the use of ultrasound.”

The finding addresses concerns that ultrasound used in primary care could consume more health care resources or put patients at risk.

Dr. Barchiesi and colleagues published their findings July 20 in the European Journal of Internal Medicine.

Point-of-care ultrasound has become increasingly common as miniaturization of devices has made them more portable. The approach has caught on particularly in emergency departments where quick decisions are of the essence.

Its use in internal medicine has been more controversial, with concerns raised that improperly trained practitioners may miss diagnoses or refer patients for unnecessary tests as a result of uncertainty about their findings.

To measure the effect of point-of-care ultrasound in an internal medicine hospital ward, Dr. Barchiesi and colleagues alternated months when point-of-care ultrasound was allowed with months when it was not allowed, for a total of 4 months each, on an internal medicine unit. They allowed the ultrasound to be used for invasive procedures and excluded patients whose critical condition made point-of-care ultrasound crucial.

The researchers analyzed data on 263 patients in the “on” months when point-of-care ultrasound was used, and 255 in the “off” months when it wasn’t used. The two groups were well balanced in age, sex, comorbidity, and clinical impairment.

During the on months, the internists ordered 113 diagnostic tests (0.43 per patient). During the off months they ordered 329 tests (1.29 per patient).

The odds of being referred for a chest x-ray were 87% less in the “on” months, compared with the off months, a statistically significant finding (P < .001). The risk for a chest CT scan and abdominal ultrasound were also reduced during the on months, but the risk for an abdominal CT was increased.

Nineteen patients died during the o” months and 10 during the off months, a difference that was not statistically significant (P = .15). The median length of stay in the hospital was almost the same for the two groups: 9 days for the on months and 9 days for the off months. The difference was also not statistically significant (P = .094).

Point-of-care ultrasound is particularly accurate in identifying cardiac abnormalities and pleural fluid and pneumonia, and it can be used effectively for monitoring heart conditions, the researchers wrote. This could explain the reduction in chest x-rays and CT scans.

On the other hand, ultrasound cannot address such questions as staging in an abdominal malignancy, and unexpected findings are more common with abdominal than chest ultrasound. This could explain why the point-of-care ultrasound did not reduce the use of abdominal CT, the researchers speculated.

They acknowledged that the patients in their sample had an average age of 81 years, raising questions about how well their data could be applied to a younger population. And they noted that they used point-of-care ultrasound frequently, so they were particularly adept with it. “We use it almost every day in our clinical practice,” said Dr. Barchiesi.

Those factors may have played a key role in the success of point-of-care ultrasound in this study, said Michael Wagner, MD, an assistant professor of medicine at the University of South Carolina, Greenville, who has helped colleagues incorporate ultrasound into their practices.

Elderly patients often present with multiple comorbidities and atypical signs and symptoms, he said. “Sometimes they can be very confusing as to the underlying clinical picture. Ultrasound is being used frequently to better assess these complicated patients.”

Dr. Wagner said extensive training is required to use point-of-care ultrasound accurately.

Dr. Barchiesi also acknowledged that the devices used in this study were large portable machines, not the simpler and less expensive hand-held versions that are also available for similar purposes.

Point-of-care ultrasound is a promising innovation, said Thomas Melgar, MD, a professor of medicine at Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo. “The advantage is that the exam is being done by someone who knows the patient and specifically what they’re looking for. It’s done at the bedside so you don’t have to move the patient.”

The study could help address opposition to internal medicine residents being trained in the technique, he said, adding that “I think it’s very exciting.”

The study was partially supported by Philips, which provided the ultrasound devices. Dr. Barchiesi, Dr. Melgar, and Dr. Wagner disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

researchers say.

“It’s a safe and very useful tool,” Marco Barchiesi, MD, an internal medicine resident at Luigi Sacco Hospital in Milan, said in an interview. “We had a great reduction in chest x-rays because of the use of ultrasound.”

The finding addresses concerns that ultrasound used in primary care could consume more health care resources or put patients at risk.

Dr. Barchiesi and colleagues published their findings July 20 in the European Journal of Internal Medicine.

Point-of-care ultrasound has become increasingly common as miniaturization of devices has made them more portable. The approach has caught on particularly in emergency departments where quick decisions are of the essence.

Its use in internal medicine has been more controversial, with concerns raised that improperly trained practitioners may miss diagnoses or refer patients for unnecessary tests as a result of uncertainty about their findings.

To measure the effect of point-of-care ultrasound in an internal medicine hospital ward, Dr. Barchiesi and colleagues alternated months when point-of-care ultrasound was allowed with months when it was not allowed, for a total of 4 months each, on an internal medicine unit. They allowed the ultrasound to be used for invasive procedures and excluded patients whose critical condition made point-of-care ultrasound crucial.

The researchers analyzed data on 263 patients in the “on” months when point-of-care ultrasound was used, and 255 in the “off” months when it wasn’t used. The two groups were well balanced in age, sex, comorbidity, and clinical impairment.

During the on months, the internists ordered 113 diagnostic tests (0.43 per patient). During the off months they ordered 329 tests (1.29 per patient).

The odds of being referred for a chest x-ray were 87% less in the “on” months, compared with the off months, a statistically significant finding (P < .001). The risk for a chest CT scan and abdominal ultrasound were also reduced during the on months, but the risk for an abdominal CT was increased.

Nineteen patients died during the o” months and 10 during the off months, a difference that was not statistically significant (P = .15). The median length of stay in the hospital was almost the same for the two groups: 9 days for the on months and 9 days for the off months. The difference was also not statistically significant (P = .094).

Point-of-care ultrasound is particularly accurate in identifying cardiac abnormalities and pleural fluid and pneumonia, and it can be used effectively for monitoring heart conditions, the researchers wrote. This could explain the reduction in chest x-rays and CT scans.

On the other hand, ultrasound cannot address such questions as staging in an abdominal malignancy, and unexpected findings are more common with abdominal than chest ultrasound. This could explain why the point-of-care ultrasound did not reduce the use of abdominal CT, the researchers speculated.

They acknowledged that the patients in their sample had an average age of 81 years, raising questions about how well their data could be applied to a younger population. And they noted that they used point-of-care ultrasound frequently, so they were particularly adept with it. “We use it almost every day in our clinical practice,” said Dr. Barchiesi.

Those factors may have played a key role in the success of point-of-care ultrasound in this study, said Michael Wagner, MD, an assistant professor of medicine at the University of South Carolina, Greenville, who has helped colleagues incorporate ultrasound into their practices.

Elderly patients often present with multiple comorbidities and atypical signs and symptoms, he said. “Sometimes they can be very confusing as to the underlying clinical picture. Ultrasound is being used frequently to better assess these complicated patients.”

Dr. Wagner said extensive training is required to use point-of-care ultrasound accurately.

Dr. Barchiesi also acknowledged that the devices used in this study were large portable machines, not the simpler and less expensive hand-held versions that are also available for similar purposes.

Point-of-care ultrasound is a promising innovation, said Thomas Melgar, MD, a professor of medicine at Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo. “The advantage is that the exam is being done by someone who knows the patient and specifically what they’re looking for. It’s done at the bedside so you don’t have to move the patient.”

The study could help address opposition to internal medicine residents being trained in the technique, he said, adding that “I think it’s very exciting.”

The study was partially supported by Philips, which provided the ultrasound devices. Dr. Barchiesi, Dr. Melgar, and Dr. Wagner disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Ob.gyns. struggle to keep pace with changing COVID-19 knowledge

In early April, Maura Quinlan, MD, was working nights on the labor and delivery unit at Northwestern Medicine Prentice Women’s Hospital in Chicago. At the time, hospital policy was to test only patients with known COVID-19 symptoms for SARS-CoV-2. Women in labor wore N95 masks, but only while pushing – and practitioners didn’t always don proper protection in time.

Babies came and families rejoiced. But Dr. Quinlan looks back on those weeks with a degree of horror. “We were laboring a bunch of patients that probably had COVID,” she said, and they were doing so without proper protection.

She’s probably right. According to one study in the New England Journal of Medicine, 13.7% of 211 women who came into the labor and delivery unit at one New York City hospital between March 22 and April 2 were asymptomatic but infected, potentially putting staff and doctors at risk.

Dr. Quinlan already knew she and her fellow ob.gyns. had been walking a thin line and, upon seeing that research, her heart sank. In the middle of a pandemic, they had been racing to keep up with the reality of delivering babies. But despite their efforts to protect both practitioners and patients, some aspects slipped through the cracks. Today, every laboring patient admitted to Northwestern is now tested for the novel coronavirus.

Across the country, hospital labor and delivery wards have been working to find a careful and informed balance among multiple competing interests: the safety of their health care workers, the health of tiny and vulnerable new humans, and the stability of a birthing mother. Each hospital has been making the best decisions it can based on available data. The result is a patchwork of policies, but all of them center around rapid testing and appropriate protection.

Shifting recommendations

One case study of women in a New York City hospital during the height of the city’s surge found that, of seven confirmed COVID-19–positive patients, two were asymptomatic upon admission to the obstetrical service, and these same two patients ultimately required unplanned ICU admission. The women’s care prior to their positive diagnosis had exposed multiple health care workers, all of whom lacked appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE), the study authors wrote. “Further, five of seven confirmed COVID-19–positive women were afebrile on initial screen, and four did not first report a cough. In some locations where testing availability remains limited, the minimal symptoms reported for some of these cases might have been insufficient to prompt COVID-19 testing.”

As studies like this pour in, societies continue to update their recommendations accordingly. The latest guidance from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists came on July 1. The group suggests testing all labor and delivery patients, particularly in high-prevalence areas. If tests are in short supply, it recommends prioritizing testing pregnant women with suspected COVID-19 and those who develop symptoms during admission.

At Northwestern, the hospital requests patients stay home and quarantine for the weeks leading up to their delivery date. Then, they rapidly test every patient who comes in for delivery and aim to have results available within a few hours.

The hospital’s 30-room labor and delivery wing remains reserved for patients who test negative. Those with positive COVID-19 results are sent to a 6-bed COVID labor and delivery unit elsewhere in the hospital. “We were lucky we had the space to do that, because smaller community hospitals wouldn’t have a separate unused unit where they could put these women,” Dr. Quinlan said.

In the COVID unit, women deliver without a support person – no partner, doula, or family member can join. Doctors and nurses wear full PPE and work only in that ward. And because some research shows that pregnant women who are asymptomatic or presymptomatic may develop symptoms quickly after starting labor with no measurable illness, Dr. Quinlan must decide on a case-by-case basis what to do, if anything at all.

Delaying an induction could allow the infection to resolve or it could result in her patient moving from presymptomatic disease to full-blown pneumonia. Accelerating labor could bring on symptoms or it could allow a mother to deliver safely and get out of the hospital as quickly as possible. “There is an advantage to having the baby now if you feel okay – even if it’s alone – and getting home,” Dr. Quinlan said.

The hospital also tests the partners of women who are COVID-19 positive. Those with negative results can take the newborn home and try to maintain distance until the mother is no longer symptomatic.

In different parts of the country, hospitals have developed different approaches. Southern California is experiencing its own surge, but at the Ronald Reagan University of California, Los Angeles, Medical Center there still haven’t been enough COVID-19 patients to warrant a separate labor and delivery unit.

At UCLA, staff swab patients when they enter the labor and delivery ward — those who test positive have specific room designations. For both COVID-19–positive patients and women who progress faster than test results can be returned, the goals are the same, said Rashmi Rao, MD, an ob.gyn. at UCLA: Deliver in the safest way possible for both mother and baby.

All women, positive or negative, must wear masks during labor – as much as they can tolerate, at least. For patients who are only mildly ill or asymptomatic, the only difference is that everyone wears protective gear. But if a patient’s oxygen levels dip, or her baby is in distress, the team moves more quickly to a cesarean delivery than they’d do with a healthy patient.

Just as hospital policies have been evolving, rules for visitors have been constantly changing too. Initially, UCLA allowed a support person to be present during delivery but had to leave immediately following. Now, each new mother is allowed one visitor for the duration of their stay. And the hospital suggests that patients who are COVID-19 positive recover in separate rooms from their babies and encourages them to maintain distance from their infants, except when breastfeeding.

“We respect and understand that this is a joyous occasion and we’re trying to keep families together as much as possible,” Dr. Rao said.

Care conundrums

How hospitals protect their smallest charges keeps changing too. Reports have been circulating about newborns being taken away from COVID-19-positive mothers, especially in marginalized communities. The stories have led many to worry they’d be forcibly separated from their babies. Most hospitals, however, leave it up to the woman and her doctors to decide how much separation is needed. “After delivery, it depends on how someone is feeling,” Dr. Rao said.

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that mothers who are COVID-19–positive pump breast milk and have a healthy caregiver use that milk, or formula, to bottle-feed the baby, with the new mother remaining 6 feet away from the child as much as she can. If that’s not possible, she should wear gloves and a mask while breastfeeding until she has been naturally afebrile for 72 hours and at least 1 week removed from the first appearance of her symptoms.

“It’s tragically hard,” said Dr. Quinlan, to keep a COVID-19–positive mother even 6 feet away from her newborn baby. “If a mother declines separation, we ask the acting pediatric team to discuss the theoretical risks and paucity of data.”

Until recently, research indicated that SARS-CoV-2 wasn’t being transmitted through the uterus from mothers to their babies. And despite a recent case study reporting transplacental transmission between a mother and her fetus in France, researchers still say that the risk of transference is low. To ensure newborn risk remains as low as possible, UCLA’s policy is to swab the baby when he/she is 24 hours old and keep watch for signs of infection: increased lethargy, difficulty waking, or gastrointestinal symptoms like vomiting.

Transmission via breast milk has also, to date, proven relatively unlikely. One study in The Lancet detected the novel coronavirus in breast milk, although it’s not clear that the virus can be passed on in the fluid, says Christina Chambers, PhD, a professor of pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Chambers is studying breast milk to see if the virus or antibodies to it are present. She is also investigating how infection with SARS-CoV-2 impacts women at different times in pregnancy, something that’s still an open question.

“[In] pregnant women with a deteriorating infection, the decisions are the same you would make with any delivery: Save the mom and save the baby,” Dr. Chambers said. “Beyond that, I am encouraged to see that pregnant women are prioritized to being tested,” something that will help researchers understand prevalence of disease in order to better understand whether some symptoms are more dangerous than others.

The situation is evolving so quickly that hospitals and providers are simply trying to stay abreast of the flood of new research. In the absence of definitive answers, they are using the information available and adjusting on the fly. “We are cautiously waiting for more data,” said Dr. Rao. “With the information we have we are doing the best we can to keep our patients safe. And we’re just going to keep at it.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

In early April, Maura Quinlan, MD, was working nights on the labor and delivery unit at Northwestern Medicine Prentice Women’s Hospital in Chicago. At the time, hospital policy was to test only patients with known COVID-19 symptoms for SARS-CoV-2. Women in labor wore N95 masks, but only while pushing – and practitioners didn’t always don proper protection in time.

Babies came and families rejoiced. But Dr. Quinlan looks back on those weeks with a degree of horror. “We were laboring a bunch of patients that probably had COVID,” she said, and they were doing so without proper protection.

She’s probably right. According to one study in the New England Journal of Medicine, 13.7% of 211 women who came into the labor and delivery unit at one New York City hospital between March 22 and April 2 were asymptomatic but infected, potentially putting staff and doctors at risk.

Dr. Quinlan already knew she and her fellow ob.gyns. had been walking a thin line and, upon seeing that research, her heart sank. In the middle of a pandemic, they had been racing to keep up with the reality of delivering babies. But despite their efforts to protect both practitioners and patients, some aspects slipped through the cracks. Today, every laboring patient admitted to Northwestern is now tested for the novel coronavirus.

Across the country, hospital labor and delivery wards have been working to find a careful and informed balance among multiple competing interests: the safety of their health care workers, the health of tiny and vulnerable new humans, and the stability of a birthing mother. Each hospital has been making the best decisions it can based on available data. The result is a patchwork of policies, but all of them center around rapid testing and appropriate protection.

Shifting recommendations

One case study of women in a New York City hospital during the height of the city’s surge found that, of seven confirmed COVID-19–positive patients, two were asymptomatic upon admission to the obstetrical service, and these same two patients ultimately required unplanned ICU admission. The women’s care prior to their positive diagnosis had exposed multiple health care workers, all of whom lacked appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE), the study authors wrote. “Further, five of seven confirmed COVID-19–positive women were afebrile on initial screen, and four did not first report a cough. In some locations where testing availability remains limited, the minimal symptoms reported for some of these cases might have been insufficient to prompt COVID-19 testing.”

As studies like this pour in, societies continue to update their recommendations accordingly. The latest guidance from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists came on July 1. The group suggests testing all labor and delivery patients, particularly in high-prevalence areas. If tests are in short supply, it recommends prioritizing testing pregnant women with suspected COVID-19 and those who develop symptoms during admission.

At Northwestern, the hospital requests patients stay home and quarantine for the weeks leading up to their delivery date. Then, they rapidly test every patient who comes in for delivery and aim to have results available within a few hours.

The hospital’s 30-room labor and delivery wing remains reserved for patients who test negative. Those with positive COVID-19 results are sent to a 6-bed COVID labor and delivery unit elsewhere in the hospital. “We were lucky we had the space to do that, because smaller community hospitals wouldn’t have a separate unused unit where they could put these women,” Dr. Quinlan said.

In the COVID unit, women deliver without a support person – no partner, doula, or family member can join. Doctors and nurses wear full PPE and work only in that ward. And because some research shows that pregnant women who are asymptomatic or presymptomatic may develop symptoms quickly after starting labor with no measurable illness, Dr. Quinlan must decide on a case-by-case basis what to do, if anything at all.

Delaying an induction could allow the infection to resolve or it could result in her patient moving from presymptomatic disease to full-blown pneumonia. Accelerating labor could bring on symptoms or it could allow a mother to deliver safely and get out of the hospital as quickly as possible. “There is an advantage to having the baby now if you feel okay – even if it’s alone – and getting home,” Dr. Quinlan said.

The hospital also tests the partners of women who are COVID-19 positive. Those with negative results can take the newborn home and try to maintain distance until the mother is no longer symptomatic.

In different parts of the country, hospitals have developed different approaches. Southern California is experiencing its own surge, but at the Ronald Reagan University of California, Los Angeles, Medical Center there still haven’t been enough COVID-19 patients to warrant a separate labor and delivery unit.

At UCLA, staff swab patients when they enter the labor and delivery ward — those who test positive have specific room designations. For both COVID-19–positive patients and women who progress faster than test results can be returned, the goals are the same, said Rashmi Rao, MD, an ob.gyn. at UCLA: Deliver in the safest way possible for both mother and baby.

All women, positive or negative, must wear masks during labor – as much as they can tolerate, at least. For patients who are only mildly ill or asymptomatic, the only difference is that everyone wears protective gear. But if a patient’s oxygen levels dip, or her baby is in distress, the team moves more quickly to a cesarean delivery than they’d do with a healthy patient.

Just as hospital policies have been evolving, rules for visitors have been constantly changing too. Initially, UCLA allowed a support person to be present during delivery but had to leave immediately following. Now, each new mother is allowed one visitor for the duration of their stay. And the hospital suggests that patients who are COVID-19 positive recover in separate rooms from their babies and encourages them to maintain distance from their infants, except when breastfeeding.

“We respect and understand that this is a joyous occasion and we’re trying to keep families together as much as possible,” Dr. Rao said.

Care conundrums

How hospitals protect their smallest charges keeps changing too. Reports have been circulating about newborns being taken away from COVID-19-positive mothers, especially in marginalized communities. The stories have led many to worry they’d be forcibly separated from their babies. Most hospitals, however, leave it up to the woman and her doctors to decide how much separation is needed. “After delivery, it depends on how someone is feeling,” Dr. Rao said.

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that mothers who are COVID-19–positive pump breast milk and have a healthy caregiver use that milk, or formula, to bottle-feed the baby, with the new mother remaining 6 feet away from the child as much as she can. If that’s not possible, she should wear gloves and a mask while breastfeeding until she has been naturally afebrile for 72 hours and at least 1 week removed from the first appearance of her symptoms.