User login

Tofacitinib retreatment effective for ulcerative colitis

Retreatment with tofacitinib after a period of treatment interruption was well tolerated and effective in patients with ulcerative colitis who had shown a previous response to tofacitinib induction, according to an analysis of data from the OCTAVE extension trial.

“Clinical response was recaptured in most patients by month 2, and about half of patients by month 36, irrespective of prior anti–[tumor necrosis factor] status,” said lead researcher Edward V. Loftus Jr, MD, from the Mayo Medical School, Rochester, Minn.

A temporary suspension of treatment with the oral, small-molecule Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor might be necessary for a number of reasons, such as if a patient has to undergo surgery, experiences adverse events, or becomes pregnant.

For their study, Dr. Loftus and colleagues set out to assess the safety and efficacy of retreatment after a period of interruption.

“The population we’re interested in are patients who received tofacitinib during induction and placebo during maintenance” in the original OCTAVE trials, said Dr. Loftus. “They then either completed the trial or flared and rolled over to the open-label extension.”

The researchers looked at the 100 patients who had achieved a clinical response after 8 weeks of treatment with tofacitinib 10 mg twice-daily in the OCTAVE Induction 1 and OCTAVE Induction 2 trials and then received placebo in the OCTAVE Sustain trial and experienced treatment failure between week 8 and week 52. These patients went on to receive tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily as part of the ongoing, open-label, long-term extension OCTAVE Open trial.

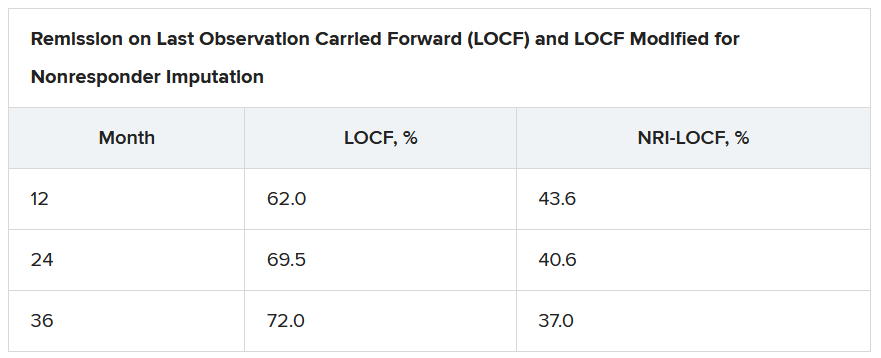

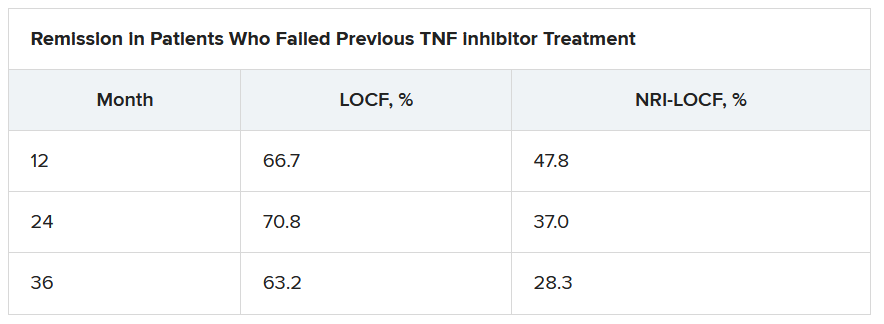

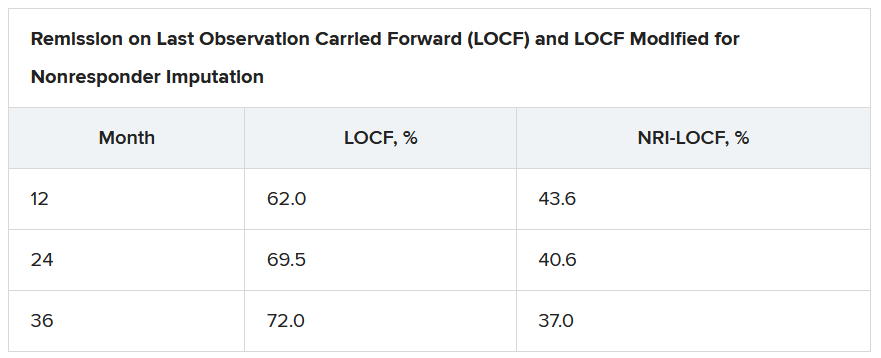

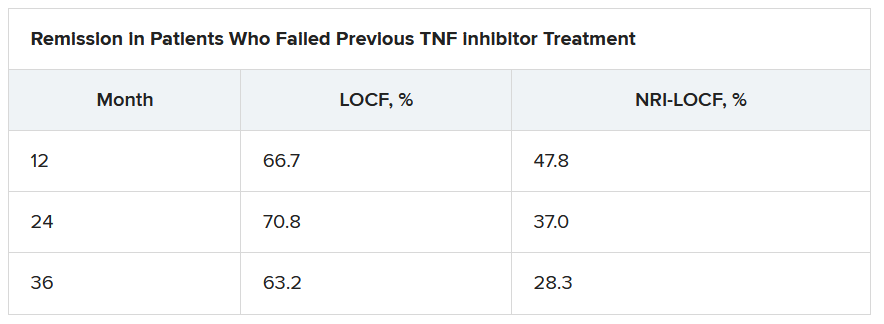

Treatment failure was defined as an increase of at least 3 points from the baseline total Mayo score achieved in OCTAVE Sustain, plus an increase of at least 1 point in rectal bleeding and endoscopic subscores and an absolute endoscopic subscore of at least 2 points after at least 8 weeks of treatment. Efficacy was evaluated for up to 36 months in the open-label extension; adverse events were assessed throughout the study period.

The median time to treatment failure was 135 days, Dr. Loftus reported during his award-winning presentation at the virtual annual meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology.

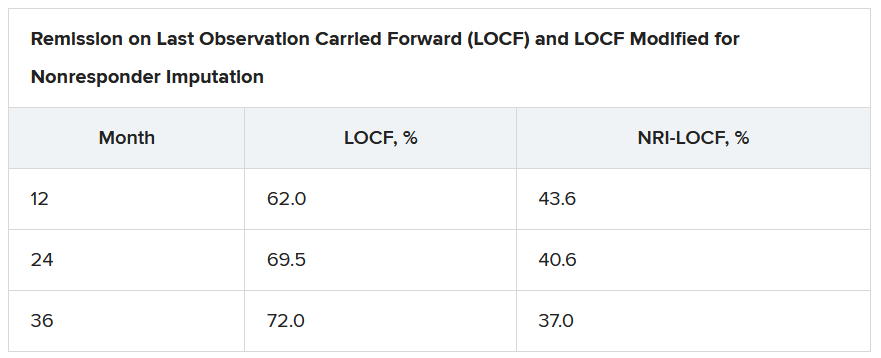

On last observation carried forward (LOCF) analysis, or observed data, 85.2% of the patients had recaptured clinical response by month 2. That rate fell to 74.3% when the analysis was modified for nonresponder imputation (NRI).

“The truth lies somewhere in between,” Dr. Loftus said.

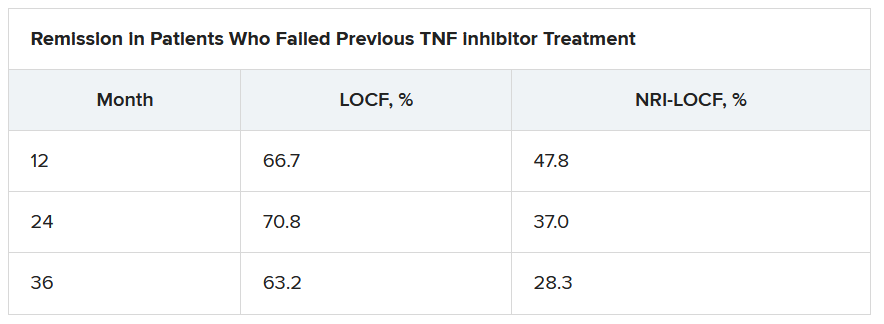

Of interest, a clinical response to tofacitinib retreatment at month 2 was achieved by 92.5% (observed data) and 80.4% (NRI-LOCF) of patients who experienced treatment failure after tumor necrosis factor inhibitor therapy.

“Many patients were able to regain response with tofacitinib and then maintain that over time,” said Dr. Loftus.

Study supports retreatment, which is good news for patients

Incidence rates of adverse events were comparable in the retreatment population and in the overall extension cohort. “There are no signals jumping out, saying that safety events were higher or more frequent in this retreatment population, which is reassuring,” Dr. Loftus added.

Findings such as these are to be expected given the mechanism of action and pharmacologic features of tofacitinib, said Gionata Fiorino, MD, from Humanitas University in Milan, who was not involved in the study.

“I think this is important for patients who need to stop therapy for several reasons – pregnancy, adverse events that do not require permanent withdrawal of the drug, or surgical interventions – and experience a flare after drug withdrawal,” he said in an interview.

“There are several other therapeutic options for these patients, but I have experienced many patients who do not respond to other mechanisms of action apart from JAK [inhibitors],” he added. “And, in the case of a patient who has stopped the drug after having achieved remission, this study clearly supports retreatment, which is good news, especially for patients.”

This study was funded by Pfizer. Dr. Loftus reported financial relationships with AbbVie, Allergan, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Celltrion, Eli Lilly, Exact Sciences, Genentech, Gilead, Janssen, Pfizer, Robarts Clinical Trials, Takeda, and UCB. Dr. Fiorino reports financial relationships with MSD, Takeda, AbbVie, Janssen, Pfizer, Celltrion, Sandoz, AlfaSigma, Samsung, Amgen, Roche, and Ferring.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Retreatment with tofacitinib after a period of treatment interruption was well tolerated and effective in patients with ulcerative colitis who had shown a previous response to tofacitinib induction, according to an analysis of data from the OCTAVE extension trial.

“Clinical response was recaptured in most patients by month 2, and about half of patients by month 36, irrespective of prior anti–[tumor necrosis factor] status,” said lead researcher Edward V. Loftus Jr, MD, from the Mayo Medical School, Rochester, Minn.

A temporary suspension of treatment with the oral, small-molecule Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor might be necessary for a number of reasons, such as if a patient has to undergo surgery, experiences adverse events, or becomes pregnant.

For their study, Dr. Loftus and colleagues set out to assess the safety and efficacy of retreatment after a period of interruption.

“The population we’re interested in are patients who received tofacitinib during induction and placebo during maintenance” in the original OCTAVE trials, said Dr. Loftus. “They then either completed the trial or flared and rolled over to the open-label extension.”

The researchers looked at the 100 patients who had achieved a clinical response after 8 weeks of treatment with tofacitinib 10 mg twice-daily in the OCTAVE Induction 1 and OCTAVE Induction 2 trials and then received placebo in the OCTAVE Sustain trial and experienced treatment failure between week 8 and week 52. These patients went on to receive tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily as part of the ongoing, open-label, long-term extension OCTAVE Open trial.

Treatment failure was defined as an increase of at least 3 points from the baseline total Mayo score achieved in OCTAVE Sustain, plus an increase of at least 1 point in rectal bleeding and endoscopic subscores and an absolute endoscopic subscore of at least 2 points after at least 8 weeks of treatment. Efficacy was evaluated for up to 36 months in the open-label extension; adverse events were assessed throughout the study period.

The median time to treatment failure was 135 days, Dr. Loftus reported during his award-winning presentation at the virtual annual meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology.

On last observation carried forward (LOCF) analysis, or observed data, 85.2% of the patients had recaptured clinical response by month 2. That rate fell to 74.3% when the analysis was modified for nonresponder imputation (NRI).

“The truth lies somewhere in between,” Dr. Loftus said.

Of interest, a clinical response to tofacitinib retreatment at month 2 was achieved by 92.5% (observed data) and 80.4% (NRI-LOCF) of patients who experienced treatment failure after tumor necrosis factor inhibitor therapy.

“Many patients were able to regain response with tofacitinib and then maintain that over time,” said Dr. Loftus.

Study supports retreatment, which is good news for patients

Incidence rates of adverse events were comparable in the retreatment population and in the overall extension cohort. “There are no signals jumping out, saying that safety events were higher or more frequent in this retreatment population, which is reassuring,” Dr. Loftus added.

Findings such as these are to be expected given the mechanism of action and pharmacologic features of tofacitinib, said Gionata Fiorino, MD, from Humanitas University in Milan, who was not involved in the study.

“I think this is important for patients who need to stop therapy for several reasons – pregnancy, adverse events that do not require permanent withdrawal of the drug, or surgical interventions – and experience a flare after drug withdrawal,” he said in an interview.

“There are several other therapeutic options for these patients, but I have experienced many patients who do not respond to other mechanisms of action apart from JAK [inhibitors],” he added. “And, in the case of a patient who has stopped the drug after having achieved remission, this study clearly supports retreatment, which is good news, especially for patients.”

This study was funded by Pfizer. Dr. Loftus reported financial relationships with AbbVie, Allergan, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Celltrion, Eli Lilly, Exact Sciences, Genentech, Gilead, Janssen, Pfizer, Robarts Clinical Trials, Takeda, and UCB. Dr. Fiorino reports financial relationships with MSD, Takeda, AbbVie, Janssen, Pfizer, Celltrion, Sandoz, AlfaSigma, Samsung, Amgen, Roche, and Ferring.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Retreatment with tofacitinib after a period of treatment interruption was well tolerated and effective in patients with ulcerative colitis who had shown a previous response to tofacitinib induction, according to an analysis of data from the OCTAVE extension trial.

“Clinical response was recaptured in most patients by month 2, and about half of patients by month 36, irrespective of prior anti–[tumor necrosis factor] status,” said lead researcher Edward V. Loftus Jr, MD, from the Mayo Medical School, Rochester, Minn.

A temporary suspension of treatment with the oral, small-molecule Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor might be necessary for a number of reasons, such as if a patient has to undergo surgery, experiences adverse events, or becomes pregnant.

For their study, Dr. Loftus and colleagues set out to assess the safety and efficacy of retreatment after a period of interruption.

“The population we’re interested in are patients who received tofacitinib during induction and placebo during maintenance” in the original OCTAVE trials, said Dr. Loftus. “They then either completed the trial or flared and rolled over to the open-label extension.”

The researchers looked at the 100 patients who had achieved a clinical response after 8 weeks of treatment with tofacitinib 10 mg twice-daily in the OCTAVE Induction 1 and OCTAVE Induction 2 trials and then received placebo in the OCTAVE Sustain trial and experienced treatment failure between week 8 and week 52. These patients went on to receive tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily as part of the ongoing, open-label, long-term extension OCTAVE Open trial.

Treatment failure was defined as an increase of at least 3 points from the baseline total Mayo score achieved in OCTAVE Sustain, plus an increase of at least 1 point in rectal bleeding and endoscopic subscores and an absolute endoscopic subscore of at least 2 points after at least 8 weeks of treatment. Efficacy was evaluated for up to 36 months in the open-label extension; adverse events were assessed throughout the study period.

The median time to treatment failure was 135 days, Dr. Loftus reported during his award-winning presentation at the virtual annual meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology.

On last observation carried forward (LOCF) analysis, or observed data, 85.2% of the patients had recaptured clinical response by month 2. That rate fell to 74.3% when the analysis was modified for nonresponder imputation (NRI).

“The truth lies somewhere in between,” Dr. Loftus said.

Of interest, a clinical response to tofacitinib retreatment at month 2 was achieved by 92.5% (observed data) and 80.4% (NRI-LOCF) of patients who experienced treatment failure after tumor necrosis factor inhibitor therapy.

“Many patients were able to regain response with tofacitinib and then maintain that over time,” said Dr. Loftus.

Study supports retreatment, which is good news for patients

Incidence rates of adverse events were comparable in the retreatment population and in the overall extension cohort. “There are no signals jumping out, saying that safety events were higher or more frequent in this retreatment population, which is reassuring,” Dr. Loftus added.

Findings such as these are to be expected given the mechanism of action and pharmacologic features of tofacitinib, said Gionata Fiorino, MD, from Humanitas University in Milan, who was not involved in the study.

“I think this is important for patients who need to stop therapy for several reasons – pregnancy, adverse events that do not require permanent withdrawal of the drug, or surgical interventions – and experience a flare after drug withdrawal,” he said in an interview.

“There are several other therapeutic options for these patients, but I have experienced many patients who do not respond to other mechanisms of action apart from JAK [inhibitors],” he added. “And, in the case of a patient who has stopped the drug after having achieved remission, this study clearly supports retreatment, which is good news, especially for patients.”

This study was funded by Pfizer. Dr. Loftus reported financial relationships with AbbVie, Allergan, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Celltrion, Eli Lilly, Exact Sciences, Genentech, Gilead, Janssen, Pfizer, Robarts Clinical Trials, Takeda, and UCB. Dr. Fiorino reports financial relationships with MSD, Takeda, AbbVie, Janssen, Pfizer, Celltrion, Sandoz, AlfaSigma, Samsung, Amgen, Roche, and Ferring.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Trump signs CR with Medicare loan relief

President Trump on Oct. 1 signed a bill to keep the federal government running through Dec. 11. This “continuing resolution” (CR), which was approved by the House by a 359-57 vote and the Senate by a 84-10 vote, includes provisions to delay repayment by physicians of pandemic-related Medicare loans and to reduce the loans’ interest rate.

In an earlier news release, the American Medical Association reported that Congress and the White House had agreed to include the provisions on Medicare loans in the CR.

Under Medicare’s Accelerated and Advance Payments (AAP) Program, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) advanced funds to physicians who were financially impacted by the pandemic.

Revisions were made under the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act to broaden the existing program to supply provider relief related to the public health emergency. The program was revised in March but suspended accepting new applications related to the pandemic in late April.

Physicians who received APP loans were required to begin repayment within 120 days after the loan disbursement. CMS planned to recoup the advances by offsetting them against Medicare claims payments due to physicians. Practices had up to 210 days (7 months) to repay the loans through this process before being asked to repay them directly with a 10.25 % interest rate.

For practices that received these advances, their Medicare cash flow was scheduled to dry up, starting in August. However, CMS quietly abstained from collecting these payments when they came due, according to Modern Healthcare.

New terms

Under the new loan repayment terms in the CR, repayment of the disbursed funds is postponed until 365 days after the date on which a practice received the money. The balance is due by September 2022.

The amount to be recouped from each claim is reduced from 100% to 25% of the claim for the first 11 months and to 50% of claims withheld for an additional 6 months. If the loan is not repaid in full by then, the provider must pay the balance with an interest rate of 4%.

More than 80% of the $100 billion that CMS loaned to health care providers through May 2 went to hospitals, Modern Healthcare calculated. Of the remainder, specialty or multispecialty practices received $3.5 billion, internal medicine specialists got $24 million, family physicians were loaned $15 million, and federally qualified health centers received $20 million.

In the AMA’s news release, AMA President Susan Bailey, MD, who assumed the post in June, called the original loan repayment plan an “economic sword hanging over physician practices.”

The American Gastroenterological Association has been advocating for more flexibility for the financial assistance programs, such as the Accelerated and Advanced Payment Program and the Paycheck Protection Program, that physicians have utilized. It is critical to give physicians leeway on these loans given that many practices are still not operating at full capacity.

Based on reporting from Medscape.com.

President Trump on Oct. 1 signed a bill to keep the federal government running through Dec. 11. This “continuing resolution” (CR), which was approved by the House by a 359-57 vote and the Senate by a 84-10 vote, includes provisions to delay repayment by physicians of pandemic-related Medicare loans and to reduce the loans’ interest rate.

In an earlier news release, the American Medical Association reported that Congress and the White House had agreed to include the provisions on Medicare loans in the CR.

Under Medicare’s Accelerated and Advance Payments (AAP) Program, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) advanced funds to physicians who were financially impacted by the pandemic.

Revisions were made under the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act to broaden the existing program to supply provider relief related to the public health emergency. The program was revised in March but suspended accepting new applications related to the pandemic in late April.

Physicians who received APP loans were required to begin repayment within 120 days after the loan disbursement. CMS planned to recoup the advances by offsetting them against Medicare claims payments due to physicians. Practices had up to 210 days (7 months) to repay the loans through this process before being asked to repay them directly with a 10.25 % interest rate.

For practices that received these advances, their Medicare cash flow was scheduled to dry up, starting in August. However, CMS quietly abstained from collecting these payments when they came due, according to Modern Healthcare.

New terms

Under the new loan repayment terms in the CR, repayment of the disbursed funds is postponed until 365 days after the date on which a practice received the money. The balance is due by September 2022.

The amount to be recouped from each claim is reduced from 100% to 25% of the claim for the first 11 months and to 50% of claims withheld for an additional 6 months. If the loan is not repaid in full by then, the provider must pay the balance with an interest rate of 4%.

More than 80% of the $100 billion that CMS loaned to health care providers through May 2 went to hospitals, Modern Healthcare calculated. Of the remainder, specialty or multispecialty practices received $3.5 billion, internal medicine specialists got $24 million, family physicians were loaned $15 million, and federally qualified health centers received $20 million.

In the AMA’s news release, AMA President Susan Bailey, MD, who assumed the post in June, called the original loan repayment plan an “economic sword hanging over physician practices.”

The American Gastroenterological Association has been advocating for more flexibility for the financial assistance programs, such as the Accelerated and Advanced Payment Program and the Paycheck Protection Program, that physicians have utilized. It is critical to give physicians leeway on these loans given that many practices are still not operating at full capacity.

Based on reporting from Medscape.com.

President Trump on Oct. 1 signed a bill to keep the federal government running through Dec. 11. This “continuing resolution” (CR), which was approved by the House by a 359-57 vote and the Senate by a 84-10 vote, includes provisions to delay repayment by physicians of pandemic-related Medicare loans and to reduce the loans’ interest rate.

In an earlier news release, the American Medical Association reported that Congress and the White House had agreed to include the provisions on Medicare loans in the CR.

Under Medicare’s Accelerated and Advance Payments (AAP) Program, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) advanced funds to physicians who were financially impacted by the pandemic.

Revisions were made under the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act to broaden the existing program to supply provider relief related to the public health emergency. The program was revised in March but suspended accepting new applications related to the pandemic in late April.

Physicians who received APP loans were required to begin repayment within 120 days after the loan disbursement. CMS planned to recoup the advances by offsetting them against Medicare claims payments due to physicians. Practices had up to 210 days (7 months) to repay the loans through this process before being asked to repay them directly with a 10.25 % interest rate.

For practices that received these advances, their Medicare cash flow was scheduled to dry up, starting in August. However, CMS quietly abstained from collecting these payments when they came due, according to Modern Healthcare.

New terms

Under the new loan repayment terms in the CR, repayment of the disbursed funds is postponed until 365 days after the date on which a practice received the money. The balance is due by September 2022.

The amount to be recouped from each claim is reduced from 100% to 25% of the claim for the first 11 months and to 50% of claims withheld for an additional 6 months. If the loan is not repaid in full by then, the provider must pay the balance with an interest rate of 4%.

More than 80% of the $100 billion that CMS loaned to health care providers through May 2 went to hospitals, Modern Healthcare calculated. Of the remainder, specialty or multispecialty practices received $3.5 billion, internal medicine specialists got $24 million, family physicians were loaned $15 million, and federally qualified health centers received $20 million.

In the AMA’s news release, AMA President Susan Bailey, MD, who assumed the post in June, called the original loan repayment plan an “economic sword hanging over physician practices.”

The American Gastroenterological Association has been advocating for more flexibility for the financial assistance programs, such as the Accelerated and Advanced Payment Program and the Paycheck Protection Program, that physicians have utilized. It is critical to give physicians leeway on these loans given that many practices are still not operating at full capacity.

Based on reporting from Medscape.com.

Cannabis may improve liver function in patients with obesity

Cannabis use is associated with a decrease in the prevalence of steatohepatitis and a slowing of its progression in patients with obesity, results from a retrospective cohort study show.

This suggests “that the anti-inflammatory effects of cannabis may be leading to reduced prevalence of steatohepatitis in cannabis users,” said Ikechukwu Achebe, MD, from the John H. Stroger, Jr. Hospital of Cook County in Chicago.

Liver injuries such as nonalcoholic steatohepatitis are characterized by hepatocellular injury and inflammation, which combine to contribute to an increase in the risk for liver failure, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma.

“This is where cannabis comes in,” said Dr. Achebe, who presented the study results at the virtual annual meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology. “It is the most commonly used psychoactive substance worldwide and has been shown to reduce hepatic myofibroblast and stellate cell injury. Studies using mouse models have demonstrated reduced liver fibrosis and cirrhosis as a consequence of cannabis exposure.”

Given this possible connection, Dr. Achebe and colleagues set out to determine whether cannabis use affects the prevalence and progression of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) in obese patients.

To do so, they analyzed the discharge records of 879,952 obese adults in the 2016 Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project National Inpatient Sample. The primary outcome was the prevalence of the four presentations of NAFLD: steatosis, steatohepatitis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma.

The researchers compared disease stages in cannabis users and nonusers. In the study cohort of 14,236 patients, 1.6% used cannabis. Steatohepatitis was less common among cannabis users than among nonusers (0.4% vs. 0.7%; P < .001), as was cirrhosis (1.1% vs. 1.5%; P < .001).

After propensity matching, the association between cannabis use and lower rates of steatohepatitis remained significant (0.4% vs. 0.5%; P = .035), but the association between cannabis use and the prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma did not.

These results might be partly explained by the protective effect of cannabis on hepatocytes regulated by the endocannabinoid system, the researchers concluded.

More studies are needed to explore this relation, said Dr. Achebe.

The challenge of self-reported use

The study is “incredibly interesting,” said Nancy S. Reau, MD, from Rush Medical College, Chicago. However, the association between cannabis and nonalcoholic fatty liver needs to be further investigated before clinicians can counsel their patients to use the agent to prevent progression.

It is difficult in a study such as this to tease out other lifestyle factors that might be linked to cannabis use, she explained. For example, “is it possible that the cannabis users exercise more, drink more coffee, or eat differently?”

And “self-reported use is challenging,” Dr. Reau said in an interview. “This cannot differentiate someone who occasionally uses from someone who is a heavy daily user. There must be some minimum level of exposure needed for it to have protective effects, if they exist.”

This study was honored at the meeting as an ACG Newsworthy Abstract and an ACG Outstanding Poster Presenter.

Dr. Achebe disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Reau reported receiving research support from Genfit and having a consultant relationship with Intercept Pharmaceuticals.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Cannabis use is associated with a decrease in the prevalence of steatohepatitis and a slowing of its progression in patients with obesity, results from a retrospective cohort study show.

This suggests “that the anti-inflammatory effects of cannabis may be leading to reduced prevalence of steatohepatitis in cannabis users,” said Ikechukwu Achebe, MD, from the John H. Stroger, Jr. Hospital of Cook County in Chicago.

Liver injuries such as nonalcoholic steatohepatitis are characterized by hepatocellular injury and inflammation, which combine to contribute to an increase in the risk for liver failure, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma.

“This is where cannabis comes in,” said Dr. Achebe, who presented the study results at the virtual annual meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology. “It is the most commonly used psychoactive substance worldwide and has been shown to reduce hepatic myofibroblast and stellate cell injury. Studies using mouse models have demonstrated reduced liver fibrosis and cirrhosis as a consequence of cannabis exposure.”

Given this possible connection, Dr. Achebe and colleagues set out to determine whether cannabis use affects the prevalence and progression of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) in obese patients.

To do so, they analyzed the discharge records of 879,952 obese adults in the 2016 Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project National Inpatient Sample. The primary outcome was the prevalence of the four presentations of NAFLD: steatosis, steatohepatitis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma.

The researchers compared disease stages in cannabis users and nonusers. In the study cohort of 14,236 patients, 1.6% used cannabis. Steatohepatitis was less common among cannabis users than among nonusers (0.4% vs. 0.7%; P < .001), as was cirrhosis (1.1% vs. 1.5%; P < .001).

After propensity matching, the association between cannabis use and lower rates of steatohepatitis remained significant (0.4% vs. 0.5%; P = .035), but the association between cannabis use and the prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma did not.

These results might be partly explained by the protective effect of cannabis on hepatocytes regulated by the endocannabinoid system, the researchers concluded.

More studies are needed to explore this relation, said Dr. Achebe.

The challenge of self-reported use

The study is “incredibly interesting,” said Nancy S. Reau, MD, from Rush Medical College, Chicago. However, the association between cannabis and nonalcoholic fatty liver needs to be further investigated before clinicians can counsel their patients to use the agent to prevent progression.

It is difficult in a study such as this to tease out other lifestyle factors that might be linked to cannabis use, she explained. For example, “is it possible that the cannabis users exercise more, drink more coffee, or eat differently?”

And “self-reported use is challenging,” Dr. Reau said in an interview. “This cannot differentiate someone who occasionally uses from someone who is a heavy daily user. There must be some minimum level of exposure needed for it to have protective effects, if they exist.”

This study was honored at the meeting as an ACG Newsworthy Abstract and an ACG Outstanding Poster Presenter.

Dr. Achebe disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Reau reported receiving research support from Genfit and having a consultant relationship with Intercept Pharmaceuticals.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Cannabis use is associated with a decrease in the prevalence of steatohepatitis and a slowing of its progression in patients with obesity, results from a retrospective cohort study show.

This suggests “that the anti-inflammatory effects of cannabis may be leading to reduced prevalence of steatohepatitis in cannabis users,” said Ikechukwu Achebe, MD, from the John H. Stroger, Jr. Hospital of Cook County in Chicago.

Liver injuries such as nonalcoholic steatohepatitis are characterized by hepatocellular injury and inflammation, which combine to contribute to an increase in the risk for liver failure, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma.

“This is where cannabis comes in,” said Dr. Achebe, who presented the study results at the virtual annual meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology. “It is the most commonly used psychoactive substance worldwide and has been shown to reduce hepatic myofibroblast and stellate cell injury. Studies using mouse models have demonstrated reduced liver fibrosis and cirrhosis as a consequence of cannabis exposure.”

Given this possible connection, Dr. Achebe and colleagues set out to determine whether cannabis use affects the prevalence and progression of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) in obese patients.

To do so, they analyzed the discharge records of 879,952 obese adults in the 2016 Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project National Inpatient Sample. The primary outcome was the prevalence of the four presentations of NAFLD: steatosis, steatohepatitis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma.

The researchers compared disease stages in cannabis users and nonusers. In the study cohort of 14,236 patients, 1.6% used cannabis. Steatohepatitis was less common among cannabis users than among nonusers (0.4% vs. 0.7%; P < .001), as was cirrhosis (1.1% vs. 1.5%; P < .001).

After propensity matching, the association between cannabis use and lower rates of steatohepatitis remained significant (0.4% vs. 0.5%; P = .035), but the association between cannabis use and the prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma did not.

These results might be partly explained by the protective effect of cannabis on hepatocytes regulated by the endocannabinoid system, the researchers concluded.

More studies are needed to explore this relation, said Dr. Achebe.

The challenge of self-reported use

The study is “incredibly interesting,” said Nancy S. Reau, MD, from Rush Medical College, Chicago. However, the association between cannabis and nonalcoholic fatty liver needs to be further investigated before clinicians can counsel their patients to use the agent to prevent progression.

It is difficult in a study such as this to tease out other lifestyle factors that might be linked to cannabis use, she explained. For example, “is it possible that the cannabis users exercise more, drink more coffee, or eat differently?”

And “self-reported use is challenging,” Dr. Reau said in an interview. “This cannot differentiate someone who occasionally uses from someone who is a heavy daily user. There must be some minimum level of exposure needed for it to have protective effects, if they exist.”

This study was honored at the meeting as an ACG Newsworthy Abstract and an ACG Outstanding Poster Presenter.

Dr. Achebe disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Reau reported receiving research support from Genfit and having a consultant relationship with Intercept Pharmaceuticals.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ACG 2020

Menstrual irregularity appears to be predictor of early death

than women with regular or short cycles, reported Yi-Xin Wang, PhD, of Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, Boston, and associates. This is particularly true in the presence of cardiovascular disease and a history of smoking.

In a peer-reviewed observational study of 79,505 premenopausal women enrolled in the Nurses’ Health Study II, the researchers sought to determine whether a life-long history of irregular or long menstrual cycles was associated with premature death. Patients averaged a mean age of 37.7 years and had no history of cardiovascular disease, cancer, or diabetes at enrollment.

Although irregular and long menstrual cycles are common and frequently linked with an increased risk of major chronic diseases – such as ovarian cancer, coronary heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and mental health problems – in women of reproductive age, actual evidence linking irregular or long menstrual cycles with mortality is scant, the researchers noted in the BMJ.

During the study, participants checked in at ages 14-17 years, 18-22 years, and 29-46 years to report the usual length and regularity of their menstrual cycles. Over 24 years of follow-up, a total of 1,975 premature deaths were noted, including 894 from cancer and 172 from cardiovascular disease.

Irregular cycles appear to bring risks

After considering other possible factors of influence, including age, weight, lifestyle, and family medical history, Dr. Wang and associates noted higher rates of mortality among those consistently reporting irregular cycles than women in the same age ranges with very regular cycles. Specifically, women aged 18-22 years and 29-46 years with cycles of 40 days or more were at greater risk of dying prematurely than were those in the same age ranges with cycles of 26-31 days.

Cardiovascular disease was a stronger predictor of death than cancer or other causes. Also included in the higher-risk group were those who currently smoked.

Among women reporting very regular cycles and women reporting always irregular cycles, mortality rates per 1,000 person-years were 1.05 and 1.23 at ages 14-17 years, 1.00 and 1.37 at ages 18-22 years, and 1.00 and 1.68 at ages 29-46 years, respectively.

The study also found that women reporting irregular cycles or no periods had a higher body mass indexes (28.2 vs. 25.0 kg/m2); were more likely to have conditions including hypertension (13.2% vs. 6.2%), high blood cholesterol levels (23.9% vs. 14.9%), hirsutism (8.4%

vs. 1.8%), or endometriosis (5.9% vs. 4.5%); and uterine fibroids (10.0% vs. 7.8%); and a higher prevalence of family history of diabetes (19.4% vs. 15.8%).

Dr. Wang and associates also observed – using multivariable Cox models – a greater risk of premature death across all categories and all age ranges in women with decreasing menstrual cycle regularity. In models that were fully adjusted, cycle lengths that were 40 days or more or too irregular to estimate from ages 18-22 and 29-46 expressed hazard ratios for premature death at the time of follow-up of 1.34 and 1.40, compared with women in the same age ranges reporting cycle lengths of 26-31 days.

Of note, Dr. Wang and colleagues unexpectedly discovered an increased risk of premature death in women who had used contraceptives between 14-17 years. They suggested that a greater number of women self-reporting contraceptive use in adolescence may have been using contraceptives to manage symptoms of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) and other conditions such as endometriosis.

Relying on the potential inaccuracy inherent in patient recall of their menstrual cycle characteristics, and the likelihood for other unmeasured factors, may have affected study results. Study strengths included the significant number of participants who had a high follow-up rate over many years, and the availability of menstrual cycle data at three different points across the reproductive lifespan.

Because the mechanisms underlying these associations are likely related to the disrupted hormonal environment, the study results “emphasize the need for primary care providers to include menstrual cycle characteristics throughout the reproductive life span as additional vital signs in assessing women’s general health status,” Dr. Wang and colleagues cautioned.

Expert suggests a probable underlying link

“Irregular menstrual cycles in women have long been known to be associated with significant morbidities, including the leading causes of mortality worldwide such as cardiovascular disease and cancer,” Reshef Tal, MD, PhD, assistant professor of obstetrics, gynecology & reproductive sciences at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., said in an interview. “The findings of this large study that irregular menstrual cycles are associated with premature death, most strongly from cardiovascular causes, are therefore not surprising.”

Dr. Tal acknowledged that one probable underlying link is PCOS, which is recognized as the most common hormonal disorder affecting women of reproductive age. The irregular periods that characterize PCOS are tied to a number of metabolic risk factors, including obesity, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and hypertension, which increase the long-term risk of cardiovascular disease and cancer of the uterus.

“The study did not have information on patients’ pelvic ultrasound findings and male hormone levels, which would have helped to establish PCOS diagnosis. However, women in this study who had irregular cycles tended to have more hirsutism, high cholesterol, hypertension as well as higher BMI, suggesting that PCOS is at least partly responsible for the observed association with cardiovascular disease. Interestingly, the association between irregular cycles and early mortality was independent of BMI, indicating that mechanisms other than metabolic factors may also play a role,” observed Dr. Tal, who was asked to comment on the study.

“Irregular periods are a symptom and not a disease, so it is important to identify underlying metabolic risk factors. Furthermore, physicians are advised to counsel patients experiencing menstrual irregularity, [to advise them to] maintain a healthy lifestyle and be alert to health changes,” Dr. Tal suggested.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The investigators had no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Tal said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Chavarro J et al. BMJ. 2020. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3464.

than women with regular or short cycles, reported Yi-Xin Wang, PhD, of Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, Boston, and associates. This is particularly true in the presence of cardiovascular disease and a history of smoking.

In a peer-reviewed observational study of 79,505 premenopausal women enrolled in the Nurses’ Health Study II, the researchers sought to determine whether a life-long history of irregular or long menstrual cycles was associated with premature death. Patients averaged a mean age of 37.7 years and had no history of cardiovascular disease, cancer, or diabetes at enrollment.

Although irregular and long menstrual cycles are common and frequently linked with an increased risk of major chronic diseases – such as ovarian cancer, coronary heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and mental health problems – in women of reproductive age, actual evidence linking irregular or long menstrual cycles with mortality is scant, the researchers noted in the BMJ.

During the study, participants checked in at ages 14-17 years, 18-22 years, and 29-46 years to report the usual length and regularity of their menstrual cycles. Over 24 years of follow-up, a total of 1,975 premature deaths were noted, including 894 from cancer and 172 from cardiovascular disease.

Irregular cycles appear to bring risks

After considering other possible factors of influence, including age, weight, lifestyle, and family medical history, Dr. Wang and associates noted higher rates of mortality among those consistently reporting irregular cycles than women in the same age ranges with very regular cycles. Specifically, women aged 18-22 years and 29-46 years with cycles of 40 days or more were at greater risk of dying prematurely than were those in the same age ranges with cycles of 26-31 days.

Cardiovascular disease was a stronger predictor of death than cancer or other causes. Also included in the higher-risk group were those who currently smoked.

Among women reporting very regular cycles and women reporting always irregular cycles, mortality rates per 1,000 person-years were 1.05 and 1.23 at ages 14-17 years, 1.00 and 1.37 at ages 18-22 years, and 1.00 and 1.68 at ages 29-46 years, respectively.

The study also found that women reporting irregular cycles or no periods had a higher body mass indexes (28.2 vs. 25.0 kg/m2); were more likely to have conditions including hypertension (13.2% vs. 6.2%), high blood cholesterol levels (23.9% vs. 14.9%), hirsutism (8.4%

vs. 1.8%), or endometriosis (5.9% vs. 4.5%); and uterine fibroids (10.0% vs. 7.8%); and a higher prevalence of family history of diabetes (19.4% vs. 15.8%).

Dr. Wang and associates also observed – using multivariable Cox models – a greater risk of premature death across all categories and all age ranges in women with decreasing menstrual cycle regularity. In models that were fully adjusted, cycle lengths that were 40 days or more or too irregular to estimate from ages 18-22 and 29-46 expressed hazard ratios for premature death at the time of follow-up of 1.34 and 1.40, compared with women in the same age ranges reporting cycle lengths of 26-31 days.

Of note, Dr. Wang and colleagues unexpectedly discovered an increased risk of premature death in women who had used contraceptives between 14-17 years. They suggested that a greater number of women self-reporting contraceptive use in adolescence may have been using contraceptives to manage symptoms of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) and other conditions such as endometriosis.

Relying on the potential inaccuracy inherent in patient recall of their menstrual cycle characteristics, and the likelihood for other unmeasured factors, may have affected study results. Study strengths included the significant number of participants who had a high follow-up rate over many years, and the availability of menstrual cycle data at three different points across the reproductive lifespan.

Because the mechanisms underlying these associations are likely related to the disrupted hormonal environment, the study results “emphasize the need for primary care providers to include menstrual cycle characteristics throughout the reproductive life span as additional vital signs in assessing women’s general health status,” Dr. Wang and colleagues cautioned.

Expert suggests a probable underlying link

“Irregular menstrual cycles in women have long been known to be associated with significant morbidities, including the leading causes of mortality worldwide such as cardiovascular disease and cancer,” Reshef Tal, MD, PhD, assistant professor of obstetrics, gynecology & reproductive sciences at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., said in an interview. “The findings of this large study that irregular menstrual cycles are associated with premature death, most strongly from cardiovascular causes, are therefore not surprising.”

Dr. Tal acknowledged that one probable underlying link is PCOS, which is recognized as the most common hormonal disorder affecting women of reproductive age. The irregular periods that characterize PCOS are tied to a number of metabolic risk factors, including obesity, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and hypertension, which increase the long-term risk of cardiovascular disease and cancer of the uterus.

“The study did not have information on patients’ pelvic ultrasound findings and male hormone levels, which would have helped to establish PCOS diagnosis. However, women in this study who had irregular cycles tended to have more hirsutism, high cholesterol, hypertension as well as higher BMI, suggesting that PCOS is at least partly responsible for the observed association with cardiovascular disease. Interestingly, the association between irregular cycles and early mortality was independent of BMI, indicating that mechanisms other than metabolic factors may also play a role,” observed Dr. Tal, who was asked to comment on the study.

“Irregular periods are a symptom and not a disease, so it is important to identify underlying metabolic risk factors. Furthermore, physicians are advised to counsel patients experiencing menstrual irregularity, [to advise them to] maintain a healthy lifestyle and be alert to health changes,” Dr. Tal suggested.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The investigators had no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Tal said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Chavarro J et al. BMJ. 2020. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3464.

than women with regular or short cycles, reported Yi-Xin Wang, PhD, of Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, Boston, and associates. This is particularly true in the presence of cardiovascular disease and a history of smoking.

In a peer-reviewed observational study of 79,505 premenopausal women enrolled in the Nurses’ Health Study II, the researchers sought to determine whether a life-long history of irregular or long menstrual cycles was associated with premature death. Patients averaged a mean age of 37.7 years and had no history of cardiovascular disease, cancer, or diabetes at enrollment.

Although irregular and long menstrual cycles are common and frequently linked with an increased risk of major chronic diseases – such as ovarian cancer, coronary heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and mental health problems – in women of reproductive age, actual evidence linking irregular or long menstrual cycles with mortality is scant, the researchers noted in the BMJ.

During the study, participants checked in at ages 14-17 years, 18-22 years, and 29-46 years to report the usual length and regularity of their menstrual cycles. Over 24 years of follow-up, a total of 1,975 premature deaths were noted, including 894 from cancer and 172 from cardiovascular disease.

Irregular cycles appear to bring risks

After considering other possible factors of influence, including age, weight, lifestyle, and family medical history, Dr. Wang and associates noted higher rates of mortality among those consistently reporting irregular cycles than women in the same age ranges with very regular cycles. Specifically, women aged 18-22 years and 29-46 years with cycles of 40 days or more were at greater risk of dying prematurely than were those in the same age ranges with cycles of 26-31 days.

Cardiovascular disease was a stronger predictor of death than cancer or other causes. Also included in the higher-risk group were those who currently smoked.

Among women reporting very regular cycles and women reporting always irregular cycles, mortality rates per 1,000 person-years were 1.05 and 1.23 at ages 14-17 years, 1.00 and 1.37 at ages 18-22 years, and 1.00 and 1.68 at ages 29-46 years, respectively.

The study also found that women reporting irregular cycles or no periods had a higher body mass indexes (28.2 vs. 25.0 kg/m2); were more likely to have conditions including hypertension (13.2% vs. 6.2%), high blood cholesterol levels (23.9% vs. 14.9%), hirsutism (8.4%

vs. 1.8%), or endometriosis (5.9% vs. 4.5%); and uterine fibroids (10.0% vs. 7.8%); and a higher prevalence of family history of diabetes (19.4% vs. 15.8%).

Dr. Wang and associates also observed – using multivariable Cox models – a greater risk of premature death across all categories and all age ranges in women with decreasing menstrual cycle regularity. In models that were fully adjusted, cycle lengths that were 40 days or more or too irregular to estimate from ages 18-22 and 29-46 expressed hazard ratios for premature death at the time of follow-up of 1.34 and 1.40, compared with women in the same age ranges reporting cycle lengths of 26-31 days.

Of note, Dr. Wang and colleagues unexpectedly discovered an increased risk of premature death in women who had used contraceptives between 14-17 years. They suggested that a greater number of women self-reporting contraceptive use in adolescence may have been using contraceptives to manage symptoms of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) and other conditions such as endometriosis.

Relying on the potential inaccuracy inherent in patient recall of their menstrual cycle characteristics, and the likelihood for other unmeasured factors, may have affected study results. Study strengths included the significant number of participants who had a high follow-up rate over many years, and the availability of menstrual cycle data at three different points across the reproductive lifespan.

Because the mechanisms underlying these associations are likely related to the disrupted hormonal environment, the study results “emphasize the need for primary care providers to include menstrual cycle characteristics throughout the reproductive life span as additional vital signs in assessing women’s general health status,” Dr. Wang and colleagues cautioned.

Expert suggests a probable underlying link

“Irregular menstrual cycles in women have long been known to be associated with significant morbidities, including the leading causes of mortality worldwide such as cardiovascular disease and cancer,” Reshef Tal, MD, PhD, assistant professor of obstetrics, gynecology & reproductive sciences at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., said in an interview. “The findings of this large study that irregular menstrual cycles are associated with premature death, most strongly from cardiovascular causes, are therefore not surprising.”

Dr. Tal acknowledged that one probable underlying link is PCOS, which is recognized as the most common hormonal disorder affecting women of reproductive age. The irregular periods that characterize PCOS are tied to a number of metabolic risk factors, including obesity, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and hypertension, which increase the long-term risk of cardiovascular disease and cancer of the uterus.

“The study did not have information on patients’ pelvic ultrasound findings and male hormone levels, which would have helped to establish PCOS diagnosis. However, women in this study who had irregular cycles tended to have more hirsutism, high cholesterol, hypertension as well as higher BMI, suggesting that PCOS is at least partly responsible for the observed association with cardiovascular disease. Interestingly, the association between irregular cycles and early mortality was independent of BMI, indicating that mechanisms other than metabolic factors may also play a role,” observed Dr. Tal, who was asked to comment on the study.

“Irregular periods are a symptom and not a disease, so it is important to identify underlying metabolic risk factors. Furthermore, physicians are advised to counsel patients experiencing menstrual irregularity, [to advise them to] maintain a healthy lifestyle and be alert to health changes,” Dr. Tal suggested.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The investigators had no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Tal said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Chavarro J et al. BMJ. 2020. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3464.

FROM THE BMJ

‘Tour de force’ study reveals therapeutic targets in 38% of cancer patients

The effort is the National Cancer Institute Molecular Analysis for Therapy Choice (NCI-MATCH) trial. For this study, researchers performed next-generation sequencing on tumor biopsy specimens to identify therapeutically actionable molecular alterations in patients with “underexplored” cancer types.

The trial included 5,954 patients with cancers that had progressed on standard treatments or rare cancers for which there is no standard treatment. If actionable alterations were found in these patients, they could receive new drugs in development that showed promise in other clinical trials or drugs that were approved by the Food and Drug Administration to treat at least one cancer type.

Data newly reported in the Journal of Clinical Oncology showed that 37.6% of patients had alterations that could be matched to targeted drugs, and 17.8% of patients were assigned to targeted treatment. Multiple actionable tumor mutations were seen in 11.9% of specimens, and resistance-conferring mutations were seen in 71.3% of specimens.

“The bottom line from this report is that next-generation sequencing is an efficient way to identify both approved and promising investigational therapies. For this reason, it should be considered standard of care for patients with advanced cancers,” said study chair Keith T. Flaherty, MD, director of the Henri and Belinda Termeer Center for Targeted Therapy at Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center in Boston.

“This study sets the benchmark for the ‘actionability’ of next-generation sequencing,” Dr. Flaherty added. “We expect this number [of actionable alterations] will continue to rise steadily as further advances are made in the development of therapies that target some of the genetic alterations for which we could not offer treatment options in NCI-MATCH.”

Relapsed/refractory vs. primary tumors

The NCI-MATCH researchers focused on the most commonly found genetic alterations and performed biopsies at study entry to provide the most accurate picture of the genetic landscape of relapsed/refractory cancer patients. That makes this cohort distinct from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), a database of patients with mostly untreated primary tumors, and other published cohorts that include genetic analysis of primary tumors and biopsies from the time of initial metastatic recurrence.

The researchers compared the tumor gene makeup of NCI-MATCH and TCGA patients with seven cancer types – breast, bile duct, cervix, colorectal, lung, pancreas, and prostate.

“Perhaps the biggest surprise was the relatively minimal change in the genetic alterations found in these relapsed/refractory patients, compared to primary tumors,” Dr. Flaherty said. “These findings suggest that it is very reasonable to perform next-generation sequencing at the time of initial metastatic cancer diagnosis and to rely on those findings for the purposes of considering FDA-approved therapies and clinical trial participation.”

Multiple alterations and resistance

The complex genetics of cancers has led researchers to explore combinations of targeted and other therapies to address multiple defects at the same time.

“Not surprisingly, the most common collision of multiple genetic alterations within the same tumor was in the commonly altered tumor suppressor genes: TP53, APC, and PTEN,” Dr. Flaherty said.

“An increasing body of evidence supports a role for loss-of-function alterations in these genes to confer resistance to many targeted therapies,” he added. “While we don’t have targeted therapies yet established to directly counter this form of therapeutic resistance, we hypothesize that various types of combination therapy may be able to indirectly undercut resistance and enhance the benefit of many targeted therapies.”

The NCI-MATCH researchers will continue to mine this large dataset to better understand the many small, genetically defined cancer subpopulations.

“We will continue to report the outcome of the individual treatment subprotocols, and combining this genetic analysis with those outcomes will likely inform the next clinical trials,” Dr. Flaherty said.

Actionable mutations make a difference

Precision oncology experts agree that NCI-MATCH results are impressive and add a fuller appreciation that actionable mutations make a clinical difference.

“This is a powerful, extremely well-designed study, a tour de force of collaborative science,” said Stephen Gruber, MD, PhD, director of the Center for Precision Medicine at City of Hope National Medical Center in Duarte, Calif.

“The future holds even more promise,” he added. “Our ability to interrogate the genomic landscape of cancer is improving rapidly. Tumor testing helps get the right drug to the right tumor faster than a guidelines-based approach from historical data of combination chemotherapy. This is a likely game changer for the way oncologists will practice in the future, especially as we learn more results of subset trials. The NCI-MATCH researchers have taken a laser-focused look at the current data, but we now know we can look far more comprehensively at genomic profiles of tumors.”

From the viewpoint of the practicing oncologist, co-occurring resistance mutations make a difference in defining what combinations are likely and, more importantly, less likely to be effective. “When we see two mutations and one is likely to confer resistance, we can make a choice to avoid a drug that is not likely to work,” Dr. Gruber said.

“The NCI-MATCH trial allows both approved and investigational agents, which expands the possibility of matching patients to newer agents. This is especially relevant if there are no FDA-approved drugs yet for some molecular aberrations,” said Lillian L. Siu, MD, a senior medical oncologist at the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre in Toronto. “This trial enables such evaluations under the auspice of a clinical trial to provide important knowledge.”

Both experts agree that in-depth biological interrogations of cancer will move the field of precision oncology forward. Dr. Gruber said that “studies have not yet fully addressed the power of germline genetic testing of DNA. Inherited susceptibility will drive therapeutic choices – for example, PARP inhibitors that access homologous recombination deficiency for breast, ovarian, and prostate cancer. We will learn more about treatment choices for those cancers.”

Dr. Siu added: “I truly believe that liquid biopsies [circulating tumor DNA] will help us perform target-drug matching in a less invasive way. We need to explore beyond the genome to look at the transcriptome, proteome, epigenome, and immunome, among others. It is likely that multiomic predictors are going to be able to identify more therapeutic options compared to single genomic predictors.”

Dr. Flaherty noted that all tumor samples from patients assigned to treatment are being subjected to whole-exome sequencing to further the discovery of the genetic features of responsive and nonresponsive tumors.

NCI-MATCH was funded by the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Flaherty disclosed relationships with Clovis Oncology, Loxo, X4 Pharma, and many other companies. His coauthors disclosed many conflicts as well. Dr. Gruber is cofounder of Brogent International. Dr. Siu disclosed relationships with Agios, Treadwell Therapeutics, Merck, Pfizer, and many other companies.

SOURCE: Flaherty KT et al. J Clin Oncol. 2020 Oct 13. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.03010.

The effort is the National Cancer Institute Molecular Analysis for Therapy Choice (NCI-MATCH) trial. For this study, researchers performed next-generation sequencing on tumor biopsy specimens to identify therapeutically actionable molecular alterations in patients with “underexplored” cancer types.

The trial included 5,954 patients with cancers that had progressed on standard treatments or rare cancers for which there is no standard treatment. If actionable alterations were found in these patients, they could receive new drugs in development that showed promise in other clinical trials or drugs that were approved by the Food and Drug Administration to treat at least one cancer type.

Data newly reported in the Journal of Clinical Oncology showed that 37.6% of patients had alterations that could be matched to targeted drugs, and 17.8% of patients were assigned to targeted treatment. Multiple actionable tumor mutations were seen in 11.9% of specimens, and resistance-conferring mutations were seen in 71.3% of specimens.

“The bottom line from this report is that next-generation sequencing is an efficient way to identify both approved and promising investigational therapies. For this reason, it should be considered standard of care for patients with advanced cancers,” said study chair Keith T. Flaherty, MD, director of the Henri and Belinda Termeer Center for Targeted Therapy at Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center in Boston.

“This study sets the benchmark for the ‘actionability’ of next-generation sequencing,” Dr. Flaherty added. “We expect this number [of actionable alterations] will continue to rise steadily as further advances are made in the development of therapies that target some of the genetic alterations for which we could not offer treatment options in NCI-MATCH.”

Relapsed/refractory vs. primary tumors

The NCI-MATCH researchers focused on the most commonly found genetic alterations and performed biopsies at study entry to provide the most accurate picture of the genetic landscape of relapsed/refractory cancer patients. That makes this cohort distinct from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), a database of patients with mostly untreated primary tumors, and other published cohorts that include genetic analysis of primary tumors and biopsies from the time of initial metastatic recurrence.

The researchers compared the tumor gene makeup of NCI-MATCH and TCGA patients with seven cancer types – breast, bile duct, cervix, colorectal, lung, pancreas, and prostate.

“Perhaps the biggest surprise was the relatively minimal change in the genetic alterations found in these relapsed/refractory patients, compared to primary tumors,” Dr. Flaherty said. “These findings suggest that it is very reasonable to perform next-generation sequencing at the time of initial metastatic cancer diagnosis and to rely on those findings for the purposes of considering FDA-approved therapies and clinical trial participation.”

Multiple alterations and resistance

The complex genetics of cancers has led researchers to explore combinations of targeted and other therapies to address multiple defects at the same time.

“Not surprisingly, the most common collision of multiple genetic alterations within the same tumor was in the commonly altered tumor suppressor genes: TP53, APC, and PTEN,” Dr. Flaherty said.

“An increasing body of evidence supports a role for loss-of-function alterations in these genes to confer resistance to many targeted therapies,” he added. “While we don’t have targeted therapies yet established to directly counter this form of therapeutic resistance, we hypothesize that various types of combination therapy may be able to indirectly undercut resistance and enhance the benefit of many targeted therapies.”

The NCI-MATCH researchers will continue to mine this large dataset to better understand the many small, genetically defined cancer subpopulations.

“We will continue to report the outcome of the individual treatment subprotocols, and combining this genetic analysis with those outcomes will likely inform the next clinical trials,” Dr. Flaherty said.

Actionable mutations make a difference

Precision oncology experts agree that NCI-MATCH results are impressive and add a fuller appreciation that actionable mutations make a clinical difference.

“This is a powerful, extremely well-designed study, a tour de force of collaborative science,” said Stephen Gruber, MD, PhD, director of the Center for Precision Medicine at City of Hope National Medical Center in Duarte, Calif.

“The future holds even more promise,” he added. “Our ability to interrogate the genomic landscape of cancer is improving rapidly. Tumor testing helps get the right drug to the right tumor faster than a guidelines-based approach from historical data of combination chemotherapy. This is a likely game changer for the way oncologists will practice in the future, especially as we learn more results of subset trials. The NCI-MATCH researchers have taken a laser-focused look at the current data, but we now know we can look far more comprehensively at genomic profiles of tumors.”

From the viewpoint of the practicing oncologist, co-occurring resistance mutations make a difference in defining what combinations are likely and, more importantly, less likely to be effective. “When we see two mutations and one is likely to confer resistance, we can make a choice to avoid a drug that is not likely to work,” Dr. Gruber said.

“The NCI-MATCH trial allows both approved and investigational agents, which expands the possibility of matching patients to newer agents. This is especially relevant if there are no FDA-approved drugs yet for some molecular aberrations,” said Lillian L. Siu, MD, a senior medical oncologist at the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre in Toronto. “This trial enables such evaluations under the auspice of a clinical trial to provide important knowledge.”

Both experts agree that in-depth biological interrogations of cancer will move the field of precision oncology forward. Dr. Gruber said that “studies have not yet fully addressed the power of germline genetic testing of DNA. Inherited susceptibility will drive therapeutic choices – for example, PARP inhibitors that access homologous recombination deficiency for breast, ovarian, and prostate cancer. We will learn more about treatment choices for those cancers.”

Dr. Siu added: “I truly believe that liquid biopsies [circulating tumor DNA] will help us perform target-drug matching in a less invasive way. We need to explore beyond the genome to look at the transcriptome, proteome, epigenome, and immunome, among others. It is likely that multiomic predictors are going to be able to identify more therapeutic options compared to single genomic predictors.”

Dr. Flaherty noted that all tumor samples from patients assigned to treatment are being subjected to whole-exome sequencing to further the discovery of the genetic features of responsive and nonresponsive tumors.

NCI-MATCH was funded by the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Flaherty disclosed relationships with Clovis Oncology, Loxo, X4 Pharma, and many other companies. His coauthors disclosed many conflicts as well. Dr. Gruber is cofounder of Brogent International. Dr. Siu disclosed relationships with Agios, Treadwell Therapeutics, Merck, Pfizer, and many other companies.

SOURCE: Flaherty KT et al. J Clin Oncol. 2020 Oct 13. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.03010.

The effort is the National Cancer Institute Molecular Analysis for Therapy Choice (NCI-MATCH) trial. For this study, researchers performed next-generation sequencing on tumor biopsy specimens to identify therapeutically actionable molecular alterations in patients with “underexplored” cancer types.

The trial included 5,954 patients with cancers that had progressed on standard treatments or rare cancers for which there is no standard treatment. If actionable alterations were found in these patients, they could receive new drugs in development that showed promise in other clinical trials or drugs that were approved by the Food and Drug Administration to treat at least one cancer type.

Data newly reported in the Journal of Clinical Oncology showed that 37.6% of patients had alterations that could be matched to targeted drugs, and 17.8% of patients were assigned to targeted treatment. Multiple actionable tumor mutations were seen in 11.9% of specimens, and resistance-conferring mutations were seen in 71.3% of specimens.

“The bottom line from this report is that next-generation sequencing is an efficient way to identify both approved and promising investigational therapies. For this reason, it should be considered standard of care for patients with advanced cancers,” said study chair Keith T. Flaherty, MD, director of the Henri and Belinda Termeer Center for Targeted Therapy at Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center in Boston.

“This study sets the benchmark for the ‘actionability’ of next-generation sequencing,” Dr. Flaherty added. “We expect this number [of actionable alterations] will continue to rise steadily as further advances are made in the development of therapies that target some of the genetic alterations for which we could not offer treatment options in NCI-MATCH.”

Relapsed/refractory vs. primary tumors

The NCI-MATCH researchers focused on the most commonly found genetic alterations and performed biopsies at study entry to provide the most accurate picture of the genetic landscape of relapsed/refractory cancer patients. That makes this cohort distinct from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), a database of patients with mostly untreated primary tumors, and other published cohorts that include genetic analysis of primary tumors and biopsies from the time of initial metastatic recurrence.

The researchers compared the tumor gene makeup of NCI-MATCH and TCGA patients with seven cancer types – breast, bile duct, cervix, colorectal, lung, pancreas, and prostate.

“Perhaps the biggest surprise was the relatively minimal change in the genetic alterations found in these relapsed/refractory patients, compared to primary tumors,” Dr. Flaherty said. “These findings suggest that it is very reasonable to perform next-generation sequencing at the time of initial metastatic cancer diagnosis and to rely on those findings for the purposes of considering FDA-approved therapies and clinical trial participation.”

Multiple alterations and resistance

The complex genetics of cancers has led researchers to explore combinations of targeted and other therapies to address multiple defects at the same time.

“Not surprisingly, the most common collision of multiple genetic alterations within the same tumor was in the commonly altered tumor suppressor genes: TP53, APC, and PTEN,” Dr. Flaherty said.

“An increasing body of evidence supports a role for loss-of-function alterations in these genes to confer resistance to many targeted therapies,” he added. “While we don’t have targeted therapies yet established to directly counter this form of therapeutic resistance, we hypothesize that various types of combination therapy may be able to indirectly undercut resistance and enhance the benefit of many targeted therapies.”

The NCI-MATCH researchers will continue to mine this large dataset to better understand the many small, genetically defined cancer subpopulations.

“We will continue to report the outcome of the individual treatment subprotocols, and combining this genetic analysis with those outcomes will likely inform the next clinical trials,” Dr. Flaherty said.

Actionable mutations make a difference

Precision oncology experts agree that NCI-MATCH results are impressive and add a fuller appreciation that actionable mutations make a clinical difference.

“This is a powerful, extremely well-designed study, a tour de force of collaborative science,” said Stephen Gruber, MD, PhD, director of the Center for Precision Medicine at City of Hope National Medical Center in Duarte, Calif.

“The future holds even more promise,” he added. “Our ability to interrogate the genomic landscape of cancer is improving rapidly. Tumor testing helps get the right drug to the right tumor faster than a guidelines-based approach from historical data of combination chemotherapy. This is a likely game changer for the way oncologists will practice in the future, especially as we learn more results of subset trials. The NCI-MATCH researchers have taken a laser-focused look at the current data, but we now know we can look far more comprehensively at genomic profiles of tumors.”

From the viewpoint of the practicing oncologist, co-occurring resistance mutations make a difference in defining what combinations are likely and, more importantly, less likely to be effective. “When we see two mutations and one is likely to confer resistance, we can make a choice to avoid a drug that is not likely to work,” Dr. Gruber said.

“The NCI-MATCH trial allows both approved and investigational agents, which expands the possibility of matching patients to newer agents. This is especially relevant if there are no FDA-approved drugs yet for some molecular aberrations,” said Lillian L. Siu, MD, a senior medical oncologist at the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre in Toronto. “This trial enables such evaluations under the auspice of a clinical trial to provide important knowledge.”

Both experts agree that in-depth biological interrogations of cancer will move the field of precision oncology forward. Dr. Gruber said that “studies have not yet fully addressed the power of germline genetic testing of DNA. Inherited susceptibility will drive therapeutic choices – for example, PARP inhibitors that access homologous recombination deficiency for breast, ovarian, and prostate cancer. We will learn more about treatment choices for those cancers.”

Dr. Siu added: “I truly believe that liquid biopsies [circulating tumor DNA] will help us perform target-drug matching in a less invasive way. We need to explore beyond the genome to look at the transcriptome, proteome, epigenome, and immunome, among others. It is likely that multiomic predictors are going to be able to identify more therapeutic options compared to single genomic predictors.”

Dr. Flaherty noted that all tumor samples from patients assigned to treatment are being subjected to whole-exome sequencing to further the discovery of the genetic features of responsive and nonresponsive tumors.

NCI-MATCH was funded by the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Flaherty disclosed relationships with Clovis Oncology, Loxo, X4 Pharma, and many other companies. His coauthors disclosed many conflicts as well. Dr. Gruber is cofounder of Brogent International. Dr. Siu disclosed relationships with Agios, Treadwell Therapeutics, Merck, Pfizer, and many other companies.

SOURCE: Flaherty KT et al. J Clin Oncol. 2020 Oct 13. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.03010.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

POP surgeries not tied to decreased sexual functioning

Danielle D. Antosh, MD, of the Houston Methodist Hospital and colleagues reported in a systematic review of prospective comparative studies on pelvic organ prolapse surgery, which was published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

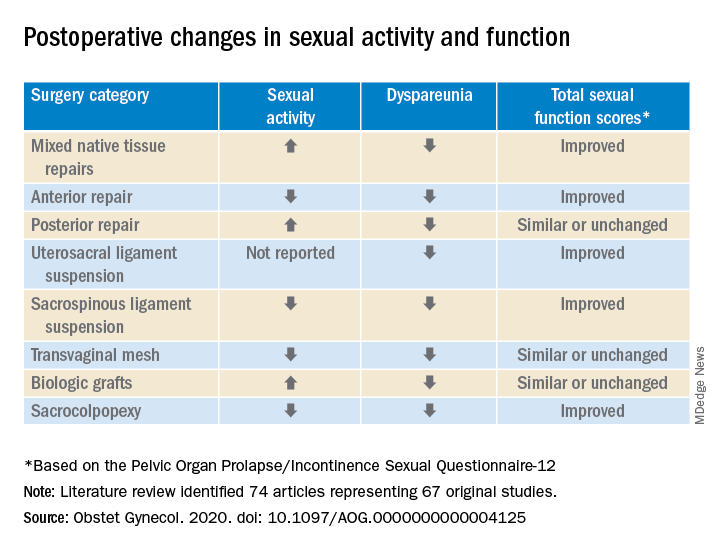

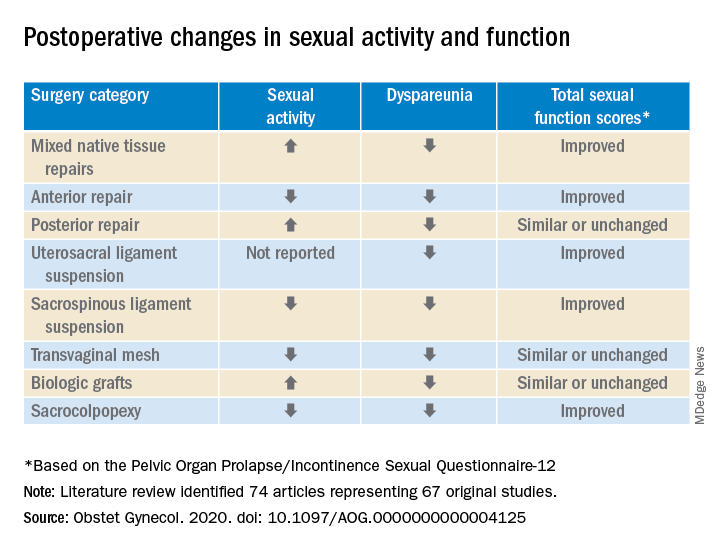

In a preliminary search of 3,124 citations, Dr. Antosh and her colleagues, who are members of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons Systematic Review Group responsible for the study, identified and accepted 74 articles representing 67 original studies. Ten of these were ancillary studies with different reported outcomes or follow-up times, and 44 were randomized control trials. They compared the pre- and postoperative effects of pelvic organ prolapse (POP) surgery on sexual function for changes in sexual activity and function across eight different prolapse surgery categories: mixed native tissue repairs, anterior repair, posterior repair, uterosacral ligament suspension, sacrospinous ligament suspension, transvaginal mesh, biologic grafts, and sacrocolpopexy. In only three categories – posterior repair, transvaginal mesh, and biological grafts – postoperative changes in sexual function scores were similar or remained unchanged. In all other categories, total sexual function scores improved. Dyspareunia was lower after surgery for all prolapse surgery types.

“Although sexual function improves in the majority of women, it is important to note that a small proportion of women can develop de novo (new onset) dyspareunia after surgery. The rate of this ranges from 0%-9% for prolapse surgeries. However, there is limited data on posterior repairs,” Dr. Antosh said in a later interview.*

POP surgeries positively impact sexual function, dyspareunia outcomes

The researchers determined that there is “moderate to high quality data” supporting the influence of POP on sexual activity and function. They also observed a lower prevalence of dyspareunia postoperatively across all surgery types, compared with baseline. Additionally, no decrease in sexual function was reported across surgical categories; in fact, sexual activity and function improved or stayed the same after POP surgery in this review.

Across most POP surgery groups, Dr. Antosh and colleagues found that with the exception of the sacrospinous ligament suspension, transvaginal mesh, and sacrocolpopexy groups, the rate of postoperative sexual activity was modestly higher. Several studies attributed this finding to a lack of partner or partner-related issues. Another 16 studies (7.7%) cited pain as the primary factor for postoperative sexual inactivity.