User login

Telltale dermoscopic features of melanomas lacking pigment reviewed

by familiarity with a handful of dermoscopic features specific to melanomas lacking significant pigment, Steven Q. Wang, MD, said at MedscapeLive’s annual Las Vegas Dermatology Seminar, held virtually this year.

These features emerged from a major study conducted on five continents by members of the International Dermoscopy Society. The investigators developed a simple, eight-variable model, which demonstrated a sensitivity of 70% and specificity of 56% for diagnosis of melanoma. And while that’s a markedly worse performance than when dermoscopy is used for detection of pigmented melanomas, where sensitivities in excess of 90% and specificities greater than 70% are typical, it’s nonetheless a significant improvement over naked-eye evaluation of these challenging pigment-deprived melanomas, noted Dr. Wang, director of dermatologic surgery and dermatology at Memorial Sloan Kettering Basking Ridge (N.J.)

Using the predictive model developed in the international study to evaluate lesions lacking pigment, a diagnosis of melanoma is made provided two conditions are met: The lesion can have no more than three milia-like cysts, and it has to possess one or more of seven positive dermoscopic findings. The strongest predictor of melanoma in the study was the presence of a blue-white veil, which in univariate analysis was associated with a 13-fold increased likelihood of melanoma.

The other positive predictors were irregularly shaped depigmentation, more than one shade of pink, predominant central vessels, irregularly sized or distributed brown dots or globules, multiple blue-gray dots, and dotted and linear irregular vessels.

Dr. Wang emphasized that, when dermoscopy and clinical skin examination of a featureless hypomelanotic or amelanotic lesion yield ambiguous findings, frequent vigilant follow-up is a viable strategy to detect early melanoma – provided the lesion is superficial.

“The reality is not all melanomas are the same. The superficial spreading melanomas and lentigo melanomas grow very, very slowly: less than 0.1 mm per month. Those are the types of lesions you can monitor. But there is one type of lesion you should never, ever monitor: nodular lesions. They are the type of lesions that can do your patient harm because nodular melanomas can grow really fast. So my key takeaway message is, if you see a nodule and you don’t know what it is, take it off,” the dermatologist said.

Dermoscopy in the hands of experienced users has repeatedly been shown to improve diagnostic accuracy by more than 25%. But there is an additional very important reason to embrace dermoscopy in daily clinical practice, according to Dr. Wang: “When you put the scope on an individual, you slow down the exam and patients feels like you’re paying more attention to them.”

That’s worthwhile because the No. 1 complaint voiced by patients who make their way to Sloan Kettering for a second opinion is that their prior skin examination by an outside physician wasn’t thorough. They’re often angry about it. And while it’s true that incorporating dermoscopy does make for a lengthier skin examination, the additional time involved is actually minimal. Dr. Wang cited a randomized, prospective, multicenter study which documented that the median time required to conduct a thorough complete skin examination without dermoscopy was 70 seconds versus 142 seconds with dermoscopy.

Dr. Wang reported having no financial conflicts regarding his presentation.

MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

by familiarity with a handful of dermoscopic features specific to melanomas lacking significant pigment, Steven Q. Wang, MD, said at MedscapeLive’s annual Las Vegas Dermatology Seminar, held virtually this year.

These features emerged from a major study conducted on five continents by members of the International Dermoscopy Society. The investigators developed a simple, eight-variable model, which demonstrated a sensitivity of 70% and specificity of 56% for diagnosis of melanoma. And while that’s a markedly worse performance than when dermoscopy is used for detection of pigmented melanomas, where sensitivities in excess of 90% and specificities greater than 70% are typical, it’s nonetheless a significant improvement over naked-eye evaluation of these challenging pigment-deprived melanomas, noted Dr. Wang, director of dermatologic surgery and dermatology at Memorial Sloan Kettering Basking Ridge (N.J.)

Using the predictive model developed in the international study to evaluate lesions lacking pigment, a diagnosis of melanoma is made provided two conditions are met: The lesion can have no more than three milia-like cysts, and it has to possess one or more of seven positive dermoscopic findings. The strongest predictor of melanoma in the study was the presence of a blue-white veil, which in univariate analysis was associated with a 13-fold increased likelihood of melanoma.

The other positive predictors were irregularly shaped depigmentation, more than one shade of pink, predominant central vessels, irregularly sized or distributed brown dots or globules, multiple blue-gray dots, and dotted and linear irregular vessels.

Dr. Wang emphasized that, when dermoscopy and clinical skin examination of a featureless hypomelanotic or amelanotic lesion yield ambiguous findings, frequent vigilant follow-up is a viable strategy to detect early melanoma – provided the lesion is superficial.

“The reality is not all melanomas are the same. The superficial spreading melanomas and lentigo melanomas grow very, very slowly: less than 0.1 mm per month. Those are the types of lesions you can monitor. But there is one type of lesion you should never, ever monitor: nodular lesions. They are the type of lesions that can do your patient harm because nodular melanomas can grow really fast. So my key takeaway message is, if you see a nodule and you don’t know what it is, take it off,” the dermatologist said.

Dermoscopy in the hands of experienced users has repeatedly been shown to improve diagnostic accuracy by more than 25%. But there is an additional very important reason to embrace dermoscopy in daily clinical practice, according to Dr. Wang: “When you put the scope on an individual, you slow down the exam and patients feels like you’re paying more attention to them.”

That’s worthwhile because the No. 1 complaint voiced by patients who make their way to Sloan Kettering for a second opinion is that their prior skin examination by an outside physician wasn’t thorough. They’re often angry about it. And while it’s true that incorporating dermoscopy does make for a lengthier skin examination, the additional time involved is actually minimal. Dr. Wang cited a randomized, prospective, multicenter study which documented that the median time required to conduct a thorough complete skin examination without dermoscopy was 70 seconds versus 142 seconds with dermoscopy.

Dr. Wang reported having no financial conflicts regarding his presentation.

MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

by familiarity with a handful of dermoscopic features specific to melanomas lacking significant pigment, Steven Q. Wang, MD, said at MedscapeLive’s annual Las Vegas Dermatology Seminar, held virtually this year.

These features emerged from a major study conducted on five continents by members of the International Dermoscopy Society. The investigators developed a simple, eight-variable model, which demonstrated a sensitivity of 70% and specificity of 56% for diagnosis of melanoma. And while that’s a markedly worse performance than when dermoscopy is used for detection of pigmented melanomas, where sensitivities in excess of 90% and specificities greater than 70% are typical, it’s nonetheless a significant improvement over naked-eye evaluation of these challenging pigment-deprived melanomas, noted Dr. Wang, director of dermatologic surgery and dermatology at Memorial Sloan Kettering Basking Ridge (N.J.)

Using the predictive model developed in the international study to evaluate lesions lacking pigment, a diagnosis of melanoma is made provided two conditions are met: The lesion can have no more than three milia-like cysts, and it has to possess one or more of seven positive dermoscopic findings. The strongest predictor of melanoma in the study was the presence of a blue-white veil, which in univariate analysis was associated with a 13-fold increased likelihood of melanoma.

The other positive predictors were irregularly shaped depigmentation, more than one shade of pink, predominant central vessels, irregularly sized or distributed brown dots or globules, multiple blue-gray dots, and dotted and linear irregular vessels.

Dr. Wang emphasized that, when dermoscopy and clinical skin examination of a featureless hypomelanotic or amelanotic lesion yield ambiguous findings, frequent vigilant follow-up is a viable strategy to detect early melanoma – provided the lesion is superficial.

“The reality is not all melanomas are the same. The superficial spreading melanomas and lentigo melanomas grow very, very slowly: less than 0.1 mm per month. Those are the types of lesions you can monitor. But there is one type of lesion you should never, ever monitor: nodular lesions. They are the type of lesions that can do your patient harm because nodular melanomas can grow really fast. So my key takeaway message is, if you see a nodule and you don’t know what it is, take it off,” the dermatologist said.

Dermoscopy in the hands of experienced users has repeatedly been shown to improve diagnostic accuracy by more than 25%. But there is an additional very important reason to embrace dermoscopy in daily clinical practice, according to Dr. Wang: “When you put the scope on an individual, you slow down the exam and patients feels like you’re paying more attention to them.”

That’s worthwhile because the No. 1 complaint voiced by patients who make their way to Sloan Kettering for a second opinion is that their prior skin examination by an outside physician wasn’t thorough. They’re often angry about it. And while it’s true that incorporating dermoscopy does make for a lengthier skin examination, the additional time involved is actually minimal. Dr. Wang cited a randomized, prospective, multicenter study which documented that the median time required to conduct a thorough complete skin examination without dermoscopy was 70 seconds versus 142 seconds with dermoscopy.

Dr. Wang reported having no financial conflicts regarding his presentation.

MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

FROM MEDSCAPELIVE LAS VEGAS DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

Higher dose maximizes effects of magnesium sulfate for obese women

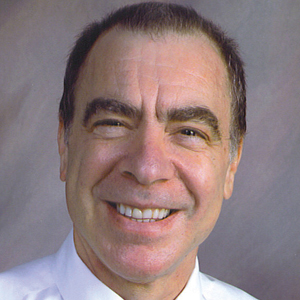

Obese women may benefit from a higher dose of magnesium sulfate to protect against preeclampsia, based on data from a randomized trial.

Pharmacokinetic models have shown that, “in women who received a 4-g intravenous loading dose followed by a 2-g/h IV maintenance dose, obese women took approximately twice as long as women of mean body weight in the sample to achieve these previously accepted therapeutic serum magnesium concentrations,” which suggests the need for alternate dosing based on body mass index, wrote Kathleen F. Brookfield, MD, of Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, and colleagues.

In a study published in Obstetrics & Gynecology, the researchers randomized 37 women aged 15-45 years with a BMI of 35 kg/m2 or higher who were at least 32 weeks’ gestation to receive the standard Zuspan regimen of magnesium sulfate (4 g intravenous loading dose, followed by a 1-g/hour infusion) or to higher dosing (6 g IV loading dose, followed by a 2-g/hour infusion).

Higher dose increases effectiveness

Serum magnesium concentrations were measured at baseline, and after administration of magnesium sulfate at 1 hour, 4 hours, and delivery; the primary outcome was the proportion of women with subtherapeutic serum magnesium concentrations (less than 4.8 mg/dL) 4 hours after administration.

After 4 hours, the average magnesium sulfate concentrations were significantly higher for women in the high-dose group vs. the standard group (4.41 mg/dL vs. 3.53 mg/dL). In addition, 100% of women in the standard group had subtherapeutic serum magnesium concentrations compared with 63% of the high-dose group.

No significant differences in maternal side effects or neonatal outcomes occurred between the groups. However, rates of nausea and flushing were higher in the higher dose group, compared with the standard group (10.5% vs. 5.5% and 5.2% vs. 0%, respectively).

The study findings were limited by several factors including the lack of statistical power to evaluate clinical outcomes and lack of generalizability to extremely obese patients, as well as to settings in which the higher-dose regimen is already the standard treatment, the researchers noted. However, the results were strengthened by the use of prospective pharmacokinetic data to determine dosing.

The researchers also noted that the study was not powered to examine preeclampsia as an outcome “and there is no evidence to date to suggest women in the United States with higher BMIs are more likely to experience eclampsia,” they said. “Therefore, we caution against universally applying the study findings to obese women without also considering the potential for increased toxicity with higher dosing regimens,” they added.

Current results may not affect practice

The study objectives are unclear, as they do not change the dosing for magnesium sulfate already in use, said Baha M. Sibai, MD, of the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, in an interview.

Dr. Sibai said he was not surprised by the findings. “This information has been known for almost 30 years as to serum levels with different dosing irrespective of BMI,” he said. Based on current evidence, Dr. Sibai advised clinicians “not to change your practice, since there are no therapeutic levels for preventing seizures.” In fact, “the largest trial that included 10,000 women showed no difference in the rate of eclampsia between 4 grams loading with 1 g/hour [magnesium sulfate] and 6 g loading and 2 g/hour,” he explained.

Future research should focus on different outcomes, said Dr. Sibai. “The outcome should be eclampsia and not serum levels. This requires studying over 6,000 women,” he emphasized.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health Loan Repayment Program and a Mission Support Award from Oregon Health & Science University to Dr. Brookfield and by the Oregon Clinical & Translational Research Institute grant. Dr. Brookfield also disclosed funding from the World Health Organization. Dr. Sibai had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Brookfield KF et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Dec. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004137.

Obese women may benefit from a higher dose of magnesium sulfate to protect against preeclampsia, based on data from a randomized trial.

Pharmacokinetic models have shown that, “in women who received a 4-g intravenous loading dose followed by a 2-g/h IV maintenance dose, obese women took approximately twice as long as women of mean body weight in the sample to achieve these previously accepted therapeutic serum magnesium concentrations,” which suggests the need for alternate dosing based on body mass index, wrote Kathleen F. Brookfield, MD, of Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, and colleagues.

In a study published in Obstetrics & Gynecology, the researchers randomized 37 women aged 15-45 years with a BMI of 35 kg/m2 or higher who were at least 32 weeks’ gestation to receive the standard Zuspan regimen of magnesium sulfate (4 g intravenous loading dose, followed by a 1-g/hour infusion) or to higher dosing (6 g IV loading dose, followed by a 2-g/hour infusion).

Higher dose increases effectiveness

Serum magnesium concentrations were measured at baseline, and after administration of magnesium sulfate at 1 hour, 4 hours, and delivery; the primary outcome was the proportion of women with subtherapeutic serum magnesium concentrations (less than 4.8 mg/dL) 4 hours after administration.

After 4 hours, the average magnesium sulfate concentrations were significantly higher for women in the high-dose group vs. the standard group (4.41 mg/dL vs. 3.53 mg/dL). In addition, 100% of women in the standard group had subtherapeutic serum magnesium concentrations compared with 63% of the high-dose group.

No significant differences in maternal side effects or neonatal outcomes occurred between the groups. However, rates of nausea and flushing were higher in the higher dose group, compared with the standard group (10.5% vs. 5.5% and 5.2% vs. 0%, respectively).

The study findings were limited by several factors including the lack of statistical power to evaluate clinical outcomes and lack of generalizability to extremely obese patients, as well as to settings in which the higher-dose regimen is already the standard treatment, the researchers noted. However, the results were strengthened by the use of prospective pharmacokinetic data to determine dosing.

The researchers also noted that the study was not powered to examine preeclampsia as an outcome “and there is no evidence to date to suggest women in the United States with higher BMIs are more likely to experience eclampsia,” they said. “Therefore, we caution against universally applying the study findings to obese women without also considering the potential for increased toxicity with higher dosing regimens,” they added.

Current results may not affect practice

The study objectives are unclear, as they do not change the dosing for magnesium sulfate already in use, said Baha M. Sibai, MD, of the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, in an interview.

Dr. Sibai said he was not surprised by the findings. “This information has been known for almost 30 years as to serum levels with different dosing irrespective of BMI,” he said. Based on current evidence, Dr. Sibai advised clinicians “not to change your practice, since there are no therapeutic levels for preventing seizures.” In fact, “the largest trial that included 10,000 women showed no difference in the rate of eclampsia between 4 grams loading with 1 g/hour [magnesium sulfate] and 6 g loading and 2 g/hour,” he explained.

Future research should focus on different outcomes, said Dr. Sibai. “The outcome should be eclampsia and not serum levels. This requires studying over 6,000 women,” he emphasized.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health Loan Repayment Program and a Mission Support Award from Oregon Health & Science University to Dr. Brookfield and by the Oregon Clinical & Translational Research Institute grant. Dr. Brookfield also disclosed funding from the World Health Organization. Dr. Sibai had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Brookfield KF et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Dec. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004137.

Obese women may benefit from a higher dose of magnesium sulfate to protect against preeclampsia, based on data from a randomized trial.

Pharmacokinetic models have shown that, “in women who received a 4-g intravenous loading dose followed by a 2-g/h IV maintenance dose, obese women took approximately twice as long as women of mean body weight in the sample to achieve these previously accepted therapeutic serum magnesium concentrations,” which suggests the need for alternate dosing based on body mass index, wrote Kathleen F. Brookfield, MD, of Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, and colleagues.

In a study published in Obstetrics & Gynecology, the researchers randomized 37 women aged 15-45 years with a BMI of 35 kg/m2 or higher who were at least 32 weeks’ gestation to receive the standard Zuspan regimen of magnesium sulfate (4 g intravenous loading dose, followed by a 1-g/hour infusion) or to higher dosing (6 g IV loading dose, followed by a 2-g/hour infusion).

Higher dose increases effectiveness

Serum magnesium concentrations were measured at baseline, and after administration of magnesium sulfate at 1 hour, 4 hours, and delivery; the primary outcome was the proportion of women with subtherapeutic serum magnesium concentrations (less than 4.8 mg/dL) 4 hours after administration.

After 4 hours, the average magnesium sulfate concentrations were significantly higher for women in the high-dose group vs. the standard group (4.41 mg/dL vs. 3.53 mg/dL). In addition, 100% of women in the standard group had subtherapeutic serum magnesium concentrations compared with 63% of the high-dose group.

No significant differences in maternal side effects or neonatal outcomes occurred between the groups. However, rates of nausea and flushing were higher in the higher dose group, compared with the standard group (10.5% vs. 5.5% and 5.2% vs. 0%, respectively).

The study findings were limited by several factors including the lack of statistical power to evaluate clinical outcomes and lack of generalizability to extremely obese patients, as well as to settings in which the higher-dose regimen is already the standard treatment, the researchers noted. However, the results were strengthened by the use of prospective pharmacokinetic data to determine dosing.

The researchers also noted that the study was not powered to examine preeclampsia as an outcome “and there is no evidence to date to suggest women in the United States with higher BMIs are more likely to experience eclampsia,” they said. “Therefore, we caution against universally applying the study findings to obese women without also considering the potential for increased toxicity with higher dosing regimens,” they added.

Current results may not affect practice

The study objectives are unclear, as they do not change the dosing for magnesium sulfate already in use, said Baha M. Sibai, MD, of the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, in an interview.

Dr. Sibai said he was not surprised by the findings. “This information has been known for almost 30 years as to serum levels with different dosing irrespective of BMI,” he said. Based on current evidence, Dr. Sibai advised clinicians “not to change your practice, since there are no therapeutic levels for preventing seizures.” In fact, “the largest trial that included 10,000 women showed no difference in the rate of eclampsia between 4 grams loading with 1 g/hour [magnesium sulfate] and 6 g loading and 2 g/hour,” he explained.

Future research should focus on different outcomes, said Dr. Sibai. “The outcome should be eclampsia and not serum levels. This requires studying over 6,000 women,” he emphasized.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health Loan Repayment Program and a Mission Support Award from Oregon Health & Science University to Dr. Brookfield and by the Oregon Clinical & Translational Research Institute grant. Dr. Brookfield also disclosed funding from the World Health Organization. Dr. Sibai had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Brookfield KF et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Dec. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004137.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Caring for Patients at a COVID-19 Field Hospital

During the initial peak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) cases, US models suggested hospital bed shortages, hinting at the dire possibility of an overwhelmed healthcare system.1,2 Such projections invoked widespread uncertainty and fear of massive loss of life secondary to an undersupply of treatment resources. This led many state governments to rush into a series of historically unprecedented interventions, including the rapid deployment of field hospitals. US state governments, in partnership with the Army Corps of Engineers, invested more than $660 million to transform convention halls, university campus buildings, and even abandoned industrial warehouses, into overflow hospitals for the care of COVID-19 patients.1 Such a national scale of field hospital construction is truly historic, never before having occurred at this speed and on this scale. The only other time field hospitals were deployed nearly as widely in the United States was during the Civil War.3

FIELD HOSPITALS DURING THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC

The use of COVID-19 field hospital resources has been variable, with patient volumes ranging from 0 at many to more than 1,000 at the Javits Center field hospital in New York City.1 In fact, most field hospitals did not treat any patients because early public health measures, such as stay-at-home orders, helped contain the virus in most states.1 As of this writing, the United States has seen a dramatic surge in COVID-19 transmission and hospitalizations. This has led many states to re-introduce field hospitals into their COVID emergency response.

Our site, the Baltimore Convention Center Field Hospital (BCCFH), is one of few sites that is still operational and, to our knowledge, is the longest-running US COVID-19 field hospital. We have cared for 543 patients since opening and have had no cardiac arrests or on-site deaths. To safely offload lower-acuity COVID-19 patients from Maryland hospitals, we designed admission criteria and care processes to provide medical care on site until patients are ready for discharge. However, we anticipated that some patients would decompensate and need to return to a higher level of care. Here, we share our experience with identifying, assessing, resuscitating, and transporting unstable patients. We believe that this process has allowed us to treat about 80% of our patients in place with successful discharge to outpatient care. We have safely transferred about 20% to a higher level of care, having learned from our early cases to refine and improve our rapid response process.

CASES

Case 1

A 39-year-old man was transferred to the BCCFH on his 9th day of symptoms following a 3-day hospital admission for COVID-19. On BCCFH day 1, he developed an oxygen requirement of 2 L/min and a fever of 39.9 oC. Testing revealed worsening hyponatremia and new proteinuria, and a chest radiograph showed increased bilateral interstitial infiltrates. Cefdinir and fluid restriction were initiated. On BCCFH day 2, the patient developed hypotension (88/55 mm Hg), tachycardia (180 bpm), an oxygen requirement of 3 L/min, and a brief syncopal episode while sitting in bed. The charge physician and nurse were directed to the bedside. They instructed staff to bring a stretcher and intravenous (IV) supplies. Unable to locate these supplies in the triage bay, the staff found them in various locations. An IV line was inserted, and fluids administered, after which vital signs improved. Emergency medical services (EMS), which were on standby outside the field hospital, were alerted via radio; they donned personal protective equipment (PPE) and arrived at the triage bay. They were redirected to patient bedside, whence they transported the patient to the hospital.

Case 2

A 64-year-old man with a history of homelessness, myocardial infarctions, cerebrovascular accident, and paroxysmal atrial fibrillation was transferred to the BCCFH on his 6th day of symptoms after a 2-day hospitalization with COVID-19 respiratory illness. On BCCFH day 1, he had a temperature of 39.3 oC and atypical chest pain. A laboratory workup was unrevealing. On BCCFH day 2, he had asymptomatic hypotension and a heart rate of 60-85 bpm while receiving his usual metoprolol dose. On BCCFH day 3, he reported dizziness and was found to be hypotensive (83/41 mm Hg) and febrile (38.6 oC). The rapid response team (RRT) was called over radio, and they quickly assessed the patient and transported him to the triage bay. EMS, signaled through the RRT radio announcement, arrived at the triage bay and transported the patient to a traditional hospital.

ABOUT THE BCCFH

The BCCFH, which opened in April 2020, is a 252-bed facility that’s spread over a single exhibit hall floor and cares for stable adult COVID-19 patients from any hospital or emergency department in Maryland (Appendix A). The site offers basic laboratory tests, radiography, a limited on-site pharmacy, and spot vital sign monitoring without telemetry. Both EMS and a certified registered nurse anesthetist are on standby in the nonclinical area and must don PPE before entering the patient care area when called. The appendices show the patient beds (Appendix B) and triage area (Appendix C) used for patient evaluation and resuscitation. Unlike conventional hospitals, the BCCFH has limited consultant access, and there are frequent changes in clinical teams. In addition to clinicians, our site has physical therapists, occupational therapists, and social work teams to assist in patient care and discharge planning. As of this writing, we have cared for 543 patients, sent to us from one-third of Maryland’s hospitals. Use during the first wave of COVID was variable, with some hospitals sending us just a few patients. One Baltimore hospital sent us 8% of its COVID-19 patients. Because the patients have an average 5-day stay, the BCCFH has offloaded 2,600 bed-days of care from acute hospitals.

ROLE OF THE RRT IN A FIELD HOSPITAL

COVID-19 field hospitals must be prepared to respond effectively to decompensating patients. In our experience, effective RRTs provide a standard and reproducible approach to patient emergencies. In the conventional hospital setting, these teams consist of clinicians who can be called on by any healthcare worker to quickly assess deteriorating patients and intervene with treatment. The purpose of an RRT is to provide immediate care to a patient before progression to respiratory or cardiac arrest. RRTs proliferated in US hospitals after 2004 when the Institute for Healthcare Improvement in Boston, Massachusetts, recommended such teams for improved quality of care. Though studies report conflicting findings on the impact of RRTs on mortality rates, these studies were performed in traditional hospitals with ample resources, consultants, and clinicians familiar with their patients rather than in resource-limited field hospitals.4-13 Our field hospital has found RRTs, and the principles behind them, useful in the identification and management of decompensating COVID-19 patients.

A FOUR-STEP RAPID RESPONSE FRAMEWORK: CASE CORRELATION

An approach to managing decompensating patients in a COVID-19 field hospital can be considered in four phases: identification, assessment, resuscitation, and transport. Referring to these phases, the first case shows opportunities for improvement in resuscitation and transport. Although decompensation was identified, the patient was not transported to the triage bay for resuscitation, and there was confusion when trying to obtain the proper equipment. Additionally, EMS awaited the patient in the triage bay, while he remained in his cubicle, which delayed transport to an acute care hospital. The second case shows opportunities for improvement in identification and assessment. The patient had signs of impending decompensation that were not immediately recognized and treated. However, once decompensation occurred, the RRT was called and the patient was transported quickly to the triage bay, and then to the hospital via EMS.

In our experience at the BCCFH, identification is a key phase in COVID-19 care at a field hospital. Identification involves recognizing impending deterioration, as well as understanding risk factors for decompensation. For COVID-19 specifically, this requires heightened awareness of patients who are in the 2nd to 3rd week of symptoms. Data from Wuhan, China, suggest that decompensation occurs predictably around symptom day 9.14,15 At the BCCFH, the median symptom duration for patients who decompensated and returned to a hospital was 13 days. In both introductory cases, patients were in the high-risk 2nd week of symptoms when decompensation occurred. Clinicians at the BCCFH now discuss patient symptom day during their handoffs, when rounding, and when making decisions regarding acute care transfer. Our team has also integrated clinical information from our electronic health record to create a dashboard describing those patients requiring acute care transfer to assist in identifying other trends or predictive factors (Appendix D).

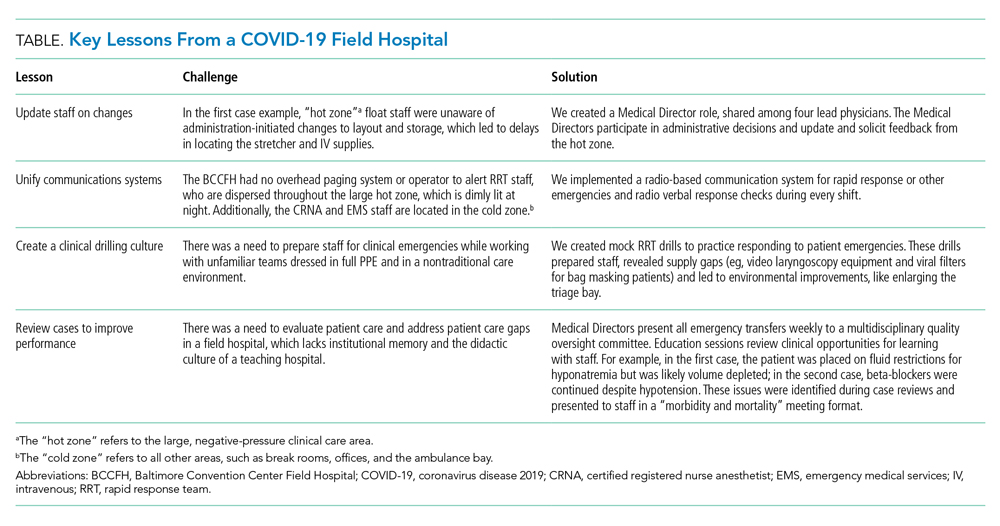

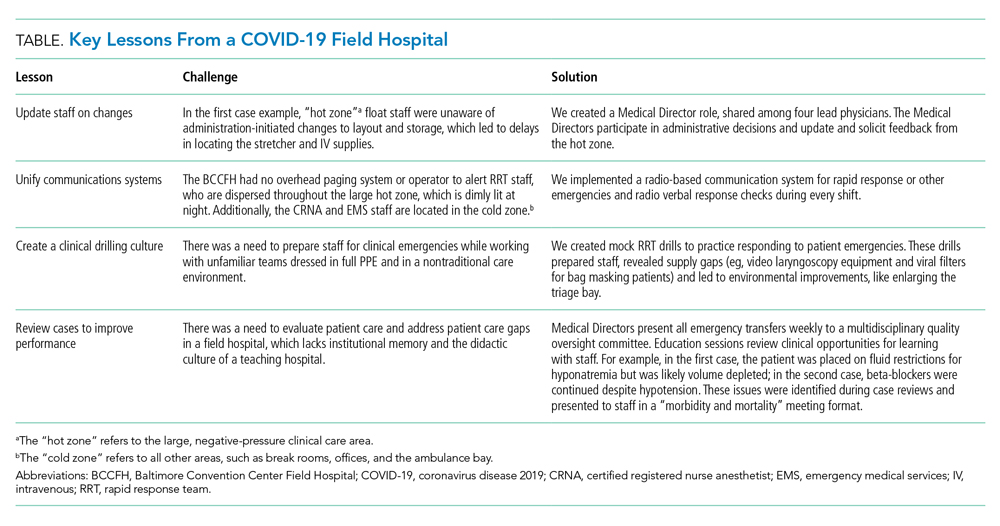

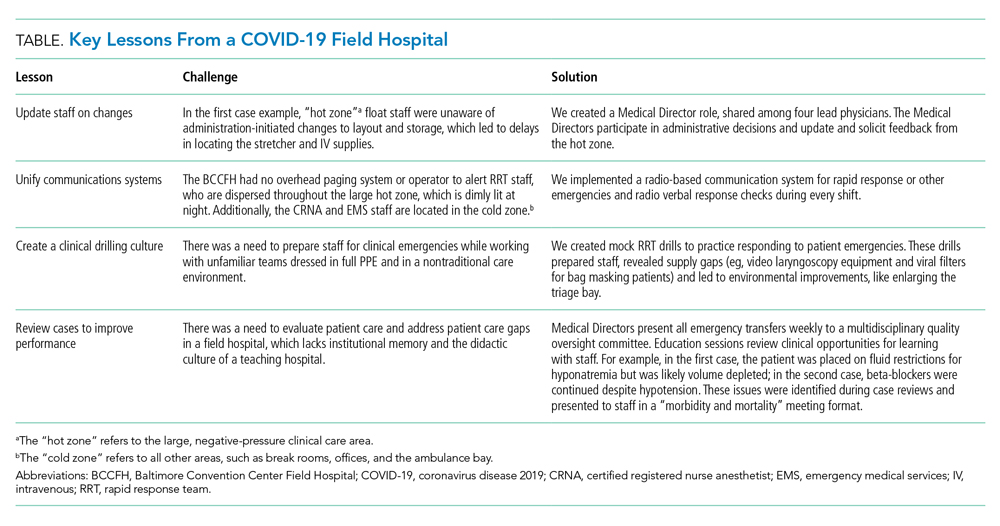

LESSONS FROM THE FIELD HOSPITAL: IMPROVING CLINICAL PERFORMANCE

Although RRTs are designed to activate when an individual patient decompensates, they should fit within a larger operational framework for patient safety. Our experience with emergencies at the BCCFH has yielded four opportunities for learning relevant to COVID-19 care in nontraditional settings (Table). These lessons include how to update staff on clinical process changes, unify communication systems, create a clinical drilling culture, and review cases to improve performance. They illustrate the importance of standardizing emergency processes, conducting frequent updates and drills, and ensuring continuous improvement. We found that, while caring for patients with an unpredictable, novel disease in a nontraditional setting and while wearing PPE and working with new colleagues during every shift, the best approach to support patients and staff is to anticipate emergencies rather than relying on individual staff to develop on-the-spot solutions.

CONCLUSION

The COVID-19 era has seen the unprecedented construction and utilization of emergency field hospital facilities. Such facilities can serve to offload some COVID-19 patients from strained healthcare infrastructure and provide essential care to these patients. We share many of the unique physical and logistical considerations specific to a nontraditional site. We optimized our space, our equipment, and our communication system. We learned how to identify, assess, resuscitate, and transport decompensating COVID-19 patients. Ultimately, our field hospital has been well utilized and successful at caring for patients because of its adaptability, accessibility, and safety record. Of the 15% of patients we transferred to a hospital for care, 81% were successfully stabilized and were willing to return to the BCCFH to complete their care. Our design included supportive care such as social work, physical and occupational therapy, and treatment of comorbidities, such as diabetes and substance use disorder. Our model demonstrates an effective nonhospital option for the care of lower-acuity, medically complex COVID-19 patients. If such facilities are used in subsequent COVID-19 outbreaks, we advise structured planning for the care of decompensating patients that takes into account the need for effective communication, drilling, and ongoing process improvement.

1. Rose J. U.S. Field Hospitals Stand Down, Most Without Treating Any COVID-19 Patients. All Things Considered. NPR; May 7, 2020. Accessed July 21, 2020. https://www.npr.org/2020/05/07/851712311/u-s-field-hospitals-stand-down-most-without-treating-any-covid-19-patients

2. Chen S, Zhang Z, Yang J, et al. Fangcang shelter hospitals: a novel concept for responding to public health emergencies. Lancet. 2020;395(10232):1305-1314. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30744-3

3. Reilly RF. Medical and surgical care during the American Civil War, 1861-1865. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2016;29(2):138-142. https://doi.org/10.1080/08998280.2016.11929390

4. Bellomo R, Goldsmith D, Uchino S, et al. Prospective controlled trial of effect of medical emergency team on postoperative morbidity and mortality rates. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(4):916-21. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ccm.0000119428.02968.9e

5. Bellomo R, Goldsmith D, Uchino S, et al. A prospective before-and-after trial of a medical emergency team. Med J Aust. 2003;179(6):283-287.

6. Bristow PJ, Hillman KM, Chey T, et al. Rates of in-hospital arrests, deaths and intensive care admissions: the effect of a medical emergency team. Med J Aust. 2000;173(5):236-240.

7. Buist MD, Moore GE, Bernard SA, Waxman BP, Anderson JN, Nguyen TV. Effects of a medical emergency team on reduction of incidence of and mortality from unexpected cardiac arrests in hospital: preliminary study. BMJ. 2002;324(7334):387-390. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.324.7334.387

8. DeVita MA, Braithwaite RS, Mahidhara R, Stuart S, Foraida M, Simmons RL; Medical Emergency Response Improvement Team (MERIT). Use of medical emergency team responses to reduce hospital cardiopulmonary arrests. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13(4):251-254. https://doi.org/10.1136/qhc.13.4.251

9. Goldhill DR, Worthington L, Mulcahy A, Tarling M, Sumner A. The patient-at-risk team: identifying and managing seriously ill ward patients. Anaesthesia. 1999;54(9):853-860. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2044.1999.00996.x

10. Hillman K, Chen J, Cretikos M, et al; MERIT study investigators. Introduction of the medical emergency team (MET) system: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;365(9477):2091-2097. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(05)66733-5

11. Kenward G, Castle N, Hodgetts T, Shaikh L. Evaluation of a medical emergency team one year after implementation. Resuscitation. 2004;61(3):257-263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2004.01.021

12. Pittard AJ. Out of our reach? assessing the impact of introducing a critical care outreach service. Anaesthesia. 2003;58(9):882-885. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2044.2003.03331.x

13. Priestley G, Watson W, Rashidian A, et al. Introducing critical care outreach: a ward-randomised trial of phased introduction in a general hospital. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30(7):1398-1404. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-004-2268-7

14. Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054-1062. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30566-3

15. Zhou Y, Li W, Wang D, et al. Clinical time course of COVID-19, its neurological manifestation and some thoughts on its management. Stroke Vasc Neurol. 2020;5(2):177-179. https://doi.org/10.1136/svn-2020-000398

During the initial peak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) cases, US models suggested hospital bed shortages, hinting at the dire possibility of an overwhelmed healthcare system.1,2 Such projections invoked widespread uncertainty and fear of massive loss of life secondary to an undersupply of treatment resources. This led many state governments to rush into a series of historically unprecedented interventions, including the rapid deployment of field hospitals. US state governments, in partnership with the Army Corps of Engineers, invested more than $660 million to transform convention halls, university campus buildings, and even abandoned industrial warehouses, into overflow hospitals for the care of COVID-19 patients.1 Such a national scale of field hospital construction is truly historic, never before having occurred at this speed and on this scale. The only other time field hospitals were deployed nearly as widely in the United States was during the Civil War.3

FIELD HOSPITALS DURING THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC

The use of COVID-19 field hospital resources has been variable, with patient volumes ranging from 0 at many to more than 1,000 at the Javits Center field hospital in New York City.1 In fact, most field hospitals did not treat any patients because early public health measures, such as stay-at-home orders, helped contain the virus in most states.1 As of this writing, the United States has seen a dramatic surge in COVID-19 transmission and hospitalizations. This has led many states to re-introduce field hospitals into their COVID emergency response.

Our site, the Baltimore Convention Center Field Hospital (BCCFH), is one of few sites that is still operational and, to our knowledge, is the longest-running US COVID-19 field hospital. We have cared for 543 patients since opening and have had no cardiac arrests or on-site deaths. To safely offload lower-acuity COVID-19 patients from Maryland hospitals, we designed admission criteria and care processes to provide medical care on site until patients are ready for discharge. However, we anticipated that some patients would decompensate and need to return to a higher level of care. Here, we share our experience with identifying, assessing, resuscitating, and transporting unstable patients. We believe that this process has allowed us to treat about 80% of our patients in place with successful discharge to outpatient care. We have safely transferred about 20% to a higher level of care, having learned from our early cases to refine and improve our rapid response process.

CASES

Case 1

A 39-year-old man was transferred to the BCCFH on his 9th day of symptoms following a 3-day hospital admission for COVID-19. On BCCFH day 1, he developed an oxygen requirement of 2 L/min and a fever of 39.9 oC. Testing revealed worsening hyponatremia and new proteinuria, and a chest radiograph showed increased bilateral interstitial infiltrates. Cefdinir and fluid restriction were initiated. On BCCFH day 2, the patient developed hypotension (88/55 mm Hg), tachycardia (180 bpm), an oxygen requirement of 3 L/min, and a brief syncopal episode while sitting in bed. The charge physician and nurse were directed to the bedside. They instructed staff to bring a stretcher and intravenous (IV) supplies. Unable to locate these supplies in the triage bay, the staff found them in various locations. An IV line was inserted, and fluids administered, after which vital signs improved. Emergency medical services (EMS), which were on standby outside the field hospital, were alerted via radio; they donned personal protective equipment (PPE) and arrived at the triage bay. They were redirected to patient bedside, whence they transported the patient to the hospital.

Case 2

A 64-year-old man with a history of homelessness, myocardial infarctions, cerebrovascular accident, and paroxysmal atrial fibrillation was transferred to the BCCFH on his 6th day of symptoms after a 2-day hospitalization with COVID-19 respiratory illness. On BCCFH day 1, he had a temperature of 39.3 oC and atypical chest pain. A laboratory workup was unrevealing. On BCCFH day 2, he had asymptomatic hypotension and a heart rate of 60-85 bpm while receiving his usual metoprolol dose. On BCCFH day 3, he reported dizziness and was found to be hypotensive (83/41 mm Hg) and febrile (38.6 oC). The rapid response team (RRT) was called over radio, and they quickly assessed the patient and transported him to the triage bay. EMS, signaled through the RRT radio announcement, arrived at the triage bay and transported the patient to a traditional hospital.

ABOUT THE BCCFH

The BCCFH, which opened in April 2020, is a 252-bed facility that’s spread over a single exhibit hall floor and cares for stable adult COVID-19 patients from any hospital or emergency department in Maryland (Appendix A). The site offers basic laboratory tests, radiography, a limited on-site pharmacy, and spot vital sign monitoring without telemetry. Both EMS and a certified registered nurse anesthetist are on standby in the nonclinical area and must don PPE before entering the patient care area when called. The appendices show the patient beds (Appendix B) and triage area (Appendix C) used for patient evaluation and resuscitation. Unlike conventional hospitals, the BCCFH has limited consultant access, and there are frequent changes in clinical teams. In addition to clinicians, our site has physical therapists, occupational therapists, and social work teams to assist in patient care and discharge planning. As of this writing, we have cared for 543 patients, sent to us from one-third of Maryland’s hospitals. Use during the first wave of COVID was variable, with some hospitals sending us just a few patients. One Baltimore hospital sent us 8% of its COVID-19 patients. Because the patients have an average 5-day stay, the BCCFH has offloaded 2,600 bed-days of care from acute hospitals.

ROLE OF THE RRT IN A FIELD HOSPITAL

COVID-19 field hospitals must be prepared to respond effectively to decompensating patients. In our experience, effective RRTs provide a standard and reproducible approach to patient emergencies. In the conventional hospital setting, these teams consist of clinicians who can be called on by any healthcare worker to quickly assess deteriorating patients and intervene with treatment. The purpose of an RRT is to provide immediate care to a patient before progression to respiratory or cardiac arrest. RRTs proliferated in US hospitals after 2004 when the Institute for Healthcare Improvement in Boston, Massachusetts, recommended such teams for improved quality of care. Though studies report conflicting findings on the impact of RRTs on mortality rates, these studies were performed in traditional hospitals with ample resources, consultants, and clinicians familiar with their patients rather than in resource-limited field hospitals.4-13 Our field hospital has found RRTs, and the principles behind them, useful in the identification and management of decompensating COVID-19 patients.

A FOUR-STEP RAPID RESPONSE FRAMEWORK: CASE CORRELATION

An approach to managing decompensating patients in a COVID-19 field hospital can be considered in four phases: identification, assessment, resuscitation, and transport. Referring to these phases, the first case shows opportunities for improvement in resuscitation and transport. Although decompensation was identified, the patient was not transported to the triage bay for resuscitation, and there was confusion when trying to obtain the proper equipment. Additionally, EMS awaited the patient in the triage bay, while he remained in his cubicle, which delayed transport to an acute care hospital. The second case shows opportunities for improvement in identification and assessment. The patient had signs of impending decompensation that were not immediately recognized and treated. However, once decompensation occurred, the RRT was called and the patient was transported quickly to the triage bay, and then to the hospital via EMS.

In our experience at the BCCFH, identification is a key phase in COVID-19 care at a field hospital. Identification involves recognizing impending deterioration, as well as understanding risk factors for decompensation. For COVID-19 specifically, this requires heightened awareness of patients who are in the 2nd to 3rd week of symptoms. Data from Wuhan, China, suggest that decompensation occurs predictably around symptom day 9.14,15 At the BCCFH, the median symptom duration for patients who decompensated and returned to a hospital was 13 days. In both introductory cases, patients were in the high-risk 2nd week of symptoms when decompensation occurred. Clinicians at the BCCFH now discuss patient symptom day during their handoffs, when rounding, and when making decisions regarding acute care transfer. Our team has also integrated clinical information from our electronic health record to create a dashboard describing those patients requiring acute care transfer to assist in identifying other trends or predictive factors (Appendix D).

LESSONS FROM THE FIELD HOSPITAL: IMPROVING CLINICAL PERFORMANCE

Although RRTs are designed to activate when an individual patient decompensates, they should fit within a larger operational framework for patient safety. Our experience with emergencies at the BCCFH has yielded four opportunities for learning relevant to COVID-19 care in nontraditional settings (Table). These lessons include how to update staff on clinical process changes, unify communication systems, create a clinical drilling culture, and review cases to improve performance. They illustrate the importance of standardizing emergency processes, conducting frequent updates and drills, and ensuring continuous improvement. We found that, while caring for patients with an unpredictable, novel disease in a nontraditional setting and while wearing PPE and working with new colleagues during every shift, the best approach to support patients and staff is to anticipate emergencies rather than relying on individual staff to develop on-the-spot solutions.

CONCLUSION

The COVID-19 era has seen the unprecedented construction and utilization of emergency field hospital facilities. Such facilities can serve to offload some COVID-19 patients from strained healthcare infrastructure and provide essential care to these patients. We share many of the unique physical and logistical considerations specific to a nontraditional site. We optimized our space, our equipment, and our communication system. We learned how to identify, assess, resuscitate, and transport decompensating COVID-19 patients. Ultimately, our field hospital has been well utilized and successful at caring for patients because of its adaptability, accessibility, and safety record. Of the 15% of patients we transferred to a hospital for care, 81% were successfully stabilized and were willing to return to the BCCFH to complete their care. Our design included supportive care such as social work, physical and occupational therapy, and treatment of comorbidities, such as diabetes and substance use disorder. Our model demonstrates an effective nonhospital option for the care of lower-acuity, medically complex COVID-19 patients. If such facilities are used in subsequent COVID-19 outbreaks, we advise structured planning for the care of decompensating patients that takes into account the need for effective communication, drilling, and ongoing process improvement.

During the initial peak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) cases, US models suggested hospital bed shortages, hinting at the dire possibility of an overwhelmed healthcare system.1,2 Such projections invoked widespread uncertainty and fear of massive loss of life secondary to an undersupply of treatment resources. This led many state governments to rush into a series of historically unprecedented interventions, including the rapid deployment of field hospitals. US state governments, in partnership with the Army Corps of Engineers, invested more than $660 million to transform convention halls, university campus buildings, and even abandoned industrial warehouses, into overflow hospitals for the care of COVID-19 patients.1 Such a national scale of field hospital construction is truly historic, never before having occurred at this speed and on this scale. The only other time field hospitals were deployed nearly as widely in the United States was during the Civil War.3

FIELD HOSPITALS DURING THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC

The use of COVID-19 field hospital resources has been variable, with patient volumes ranging from 0 at many to more than 1,000 at the Javits Center field hospital in New York City.1 In fact, most field hospitals did not treat any patients because early public health measures, such as stay-at-home orders, helped contain the virus in most states.1 As of this writing, the United States has seen a dramatic surge in COVID-19 transmission and hospitalizations. This has led many states to re-introduce field hospitals into their COVID emergency response.

Our site, the Baltimore Convention Center Field Hospital (BCCFH), is one of few sites that is still operational and, to our knowledge, is the longest-running US COVID-19 field hospital. We have cared for 543 patients since opening and have had no cardiac arrests or on-site deaths. To safely offload lower-acuity COVID-19 patients from Maryland hospitals, we designed admission criteria and care processes to provide medical care on site until patients are ready for discharge. However, we anticipated that some patients would decompensate and need to return to a higher level of care. Here, we share our experience with identifying, assessing, resuscitating, and transporting unstable patients. We believe that this process has allowed us to treat about 80% of our patients in place with successful discharge to outpatient care. We have safely transferred about 20% to a higher level of care, having learned from our early cases to refine and improve our rapid response process.

CASES

Case 1

A 39-year-old man was transferred to the BCCFH on his 9th day of symptoms following a 3-day hospital admission for COVID-19. On BCCFH day 1, he developed an oxygen requirement of 2 L/min and a fever of 39.9 oC. Testing revealed worsening hyponatremia and new proteinuria, and a chest radiograph showed increased bilateral interstitial infiltrates. Cefdinir and fluid restriction were initiated. On BCCFH day 2, the patient developed hypotension (88/55 mm Hg), tachycardia (180 bpm), an oxygen requirement of 3 L/min, and a brief syncopal episode while sitting in bed. The charge physician and nurse were directed to the bedside. They instructed staff to bring a stretcher and intravenous (IV) supplies. Unable to locate these supplies in the triage bay, the staff found them in various locations. An IV line was inserted, and fluids administered, after which vital signs improved. Emergency medical services (EMS), which were on standby outside the field hospital, were alerted via radio; they donned personal protective equipment (PPE) and arrived at the triage bay. They were redirected to patient bedside, whence they transported the patient to the hospital.

Case 2

A 64-year-old man with a history of homelessness, myocardial infarctions, cerebrovascular accident, and paroxysmal atrial fibrillation was transferred to the BCCFH on his 6th day of symptoms after a 2-day hospitalization with COVID-19 respiratory illness. On BCCFH day 1, he had a temperature of 39.3 oC and atypical chest pain. A laboratory workup was unrevealing. On BCCFH day 2, he had asymptomatic hypotension and a heart rate of 60-85 bpm while receiving his usual metoprolol dose. On BCCFH day 3, he reported dizziness and was found to be hypotensive (83/41 mm Hg) and febrile (38.6 oC). The rapid response team (RRT) was called over radio, and they quickly assessed the patient and transported him to the triage bay. EMS, signaled through the RRT radio announcement, arrived at the triage bay and transported the patient to a traditional hospital.

ABOUT THE BCCFH

The BCCFH, which opened in April 2020, is a 252-bed facility that’s spread over a single exhibit hall floor and cares for stable adult COVID-19 patients from any hospital or emergency department in Maryland (Appendix A). The site offers basic laboratory tests, radiography, a limited on-site pharmacy, and spot vital sign monitoring without telemetry. Both EMS and a certified registered nurse anesthetist are on standby in the nonclinical area and must don PPE before entering the patient care area when called. The appendices show the patient beds (Appendix B) and triage area (Appendix C) used for patient evaluation and resuscitation. Unlike conventional hospitals, the BCCFH has limited consultant access, and there are frequent changes in clinical teams. In addition to clinicians, our site has physical therapists, occupational therapists, and social work teams to assist in patient care and discharge planning. As of this writing, we have cared for 543 patients, sent to us from one-third of Maryland’s hospitals. Use during the first wave of COVID was variable, with some hospitals sending us just a few patients. One Baltimore hospital sent us 8% of its COVID-19 patients. Because the patients have an average 5-day stay, the BCCFH has offloaded 2,600 bed-days of care from acute hospitals.

ROLE OF THE RRT IN A FIELD HOSPITAL

COVID-19 field hospitals must be prepared to respond effectively to decompensating patients. In our experience, effective RRTs provide a standard and reproducible approach to patient emergencies. In the conventional hospital setting, these teams consist of clinicians who can be called on by any healthcare worker to quickly assess deteriorating patients and intervene with treatment. The purpose of an RRT is to provide immediate care to a patient before progression to respiratory or cardiac arrest. RRTs proliferated in US hospitals after 2004 when the Institute for Healthcare Improvement in Boston, Massachusetts, recommended such teams for improved quality of care. Though studies report conflicting findings on the impact of RRTs on mortality rates, these studies were performed in traditional hospitals with ample resources, consultants, and clinicians familiar with their patients rather than in resource-limited field hospitals.4-13 Our field hospital has found RRTs, and the principles behind them, useful in the identification and management of decompensating COVID-19 patients.

A FOUR-STEP RAPID RESPONSE FRAMEWORK: CASE CORRELATION

An approach to managing decompensating patients in a COVID-19 field hospital can be considered in four phases: identification, assessment, resuscitation, and transport. Referring to these phases, the first case shows opportunities for improvement in resuscitation and transport. Although decompensation was identified, the patient was not transported to the triage bay for resuscitation, and there was confusion when trying to obtain the proper equipment. Additionally, EMS awaited the patient in the triage bay, while he remained in his cubicle, which delayed transport to an acute care hospital. The second case shows opportunities for improvement in identification and assessment. The patient had signs of impending decompensation that were not immediately recognized and treated. However, once decompensation occurred, the RRT was called and the patient was transported quickly to the triage bay, and then to the hospital via EMS.

In our experience at the BCCFH, identification is a key phase in COVID-19 care at a field hospital. Identification involves recognizing impending deterioration, as well as understanding risk factors for decompensation. For COVID-19 specifically, this requires heightened awareness of patients who are in the 2nd to 3rd week of symptoms. Data from Wuhan, China, suggest that decompensation occurs predictably around symptom day 9.14,15 At the BCCFH, the median symptom duration for patients who decompensated and returned to a hospital was 13 days. In both introductory cases, patients were in the high-risk 2nd week of symptoms when decompensation occurred. Clinicians at the BCCFH now discuss patient symptom day during their handoffs, when rounding, and when making decisions regarding acute care transfer. Our team has also integrated clinical information from our electronic health record to create a dashboard describing those patients requiring acute care transfer to assist in identifying other trends or predictive factors (Appendix D).

LESSONS FROM THE FIELD HOSPITAL: IMPROVING CLINICAL PERFORMANCE

Although RRTs are designed to activate when an individual patient decompensates, they should fit within a larger operational framework for patient safety. Our experience with emergencies at the BCCFH has yielded four opportunities for learning relevant to COVID-19 care in nontraditional settings (Table). These lessons include how to update staff on clinical process changes, unify communication systems, create a clinical drilling culture, and review cases to improve performance. They illustrate the importance of standardizing emergency processes, conducting frequent updates and drills, and ensuring continuous improvement. We found that, while caring for patients with an unpredictable, novel disease in a nontraditional setting and while wearing PPE and working with new colleagues during every shift, the best approach to support patients and staff is to anticipate emergencies rather than relying on individual staff to develop on-the-spot solutions.

CONCLUSION

The COVID-19 era has seen the unprecedented construction and utilization of emergency field hospital facilities. Such facilities can serve to offload some COVID-19 patients from strained healthcare infrastructure and provide essential care to these patients. We share many of the unique physical and logistical considerations specific to a nontraditional site. We optimized our space, our equipment, and our communication system. We learned how to identify, assess, resuscitate, and transport decompensating COVID-19 patients. Ultimately, our field hospital has been well utilized and successful at caring for patients because of its adaptability, accessibility, and safety record. Of the 15% of patients we transferred to a hospital for care, 81% were successfully stabilized and were willing to return to the BCCFH to complete their care. Our design included supportive care such as social work, physical and occupational therapy, and treatment of comorbidities, such as diabetes and substance use disorder. Our model demonstrates an effective nonhospital option for the care of lower-acuity, medically complex COVID-19 patients. If such facilities are used in subsequent COVID-19 outbreaks, we advise structured planning for the care of decompensating patients that takes into account the need for effective communication, drilling, and ongoing process improvement.

1. Rose J. U.S. Field Hospitals Stand Down, Most Without Treating Any COVID-19 Patients. All Things Considered. NPR; May 7, 2020. Accessed July 21, 2020. https://www.npr.org/2020/05/07/851712311/u-s-field-hospitals-stand-down-most-without-treating-any-covid-19-patients

2. Chen S, Zhang Z, Yang J, et al. Fangcang shelter hospitals: a novel concept for responding to public health emergencies. Lancet. 2020;395(10232):1305-1314. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30744-3

3. Reilly RF. Medical and surgical care during the American Civil War, 1861-1865. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2016;29(2):138-142. https://doi.org/10.1080/08998280.2016.11929390

4. Bellomo R, Goldsmith D, Uchino S, et al. Prospective controlled trial of effect of medical emergency team on postoperative morbidity and mortality rates. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(4):916-21. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ccm.0000119428.02968.9e

5. Bellomo R, Goldsmith D, Uchino S, et al. A prospective before-and-after trial of a medical emergency team. Med J Aust. 2003;179(6):283-287.

6. Bristow PJ, Hillman KM, Chey T, et al. Rates of in-hospital arrests, deaths and intensive care admissions: the effect of a medical emergency team. Med J Aust. 2000;173(5):236-240.

7. Buist MD, Moore GE, Bernard SA, Waxman BP, Anderson JN, Nguyen TV. Effects of a medical emergency team on reduction of incidence of and mortality from unexpected cardiac arrests in hospital: preliminary study. BMJ. 2002;324(7334):387-390. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.324.7334.387

8. DeVita MA, Braithwaite RS, Mahidhara R, Stuart S, Foraida M, Simmons RL; Medical Emergency Response Improvement Team (MERIT). Use of medical emergency team responses to reduce hospital cardiopulmonary arrests. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13(4):251-254. https://doi.org/10.1136/qhc.13.4.251

9. Goldhill DR, Worthington L, Mulcahy A, Tarling M, Sumner A. The patient-at-risk team: identifying and managing seriously ill ward patients. Anaesthesia. 1999;54(9):853-860. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2044.1999.00996.x

10. Hillman K, Chen J, Cretikos M, et al; MERIT study investigators. Introduction of the medical emergency team (MET) system: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;365(9477):2091-2097. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(05)66733-5

11. Kenward G, Castle N, Hodgetts T, Shaikh L. Evaluation of a medical emergency team one year after implementation. Resuscitation. 2004;61(3):257-263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2004.01.021

12. Pittard AJ. Out of our reach? assessing the impact of introducing a critical care outreach service. Anaesthesia. 2003;58(9):882-885. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2044.2003.03331.x

13. Priestley G, Watson W, Rashidian A, et al. Introducing critical care outreach: a ward-randomised trial of phased introduction in a general hospital. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30(7):1398-1404. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-004-2268-7

14. Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054-1062. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30566-3

15. Zhou Y, Li W, Wang D, et al. Clinical time course of COVID-19, its neurological manifestation and some thoughts on its management. Stroke Vasc Neurol. 2020;5(2):177-179. https://doi.org/10.1136/svn-2020-000398

1. Rose J. U.S. Field Hospitals Stand Down, Most Without Treating Any COVID-19 Patients. All Things Considered. NPR; May 7, 2020. Accessed July 21, 2020. https://www.npr.org/2020/05/07/851712311/u-s-field-hospitals-stand-down-most-without-treating-any-covid-19-patients

2. Chen S, Zhang Z, Yang J, et al. Fangcang shelter hospitals: a novel concept for responding to public health emergencies. Lancet. 2020;395(10232):1305-1314. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30744-3

3. Reilly RF. Medical and surgical care during the American Civil War, 1861-1865. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2016;29(2):138-142. https://doi.org/10.1080/08998280.2016.11929390

4. Bellomo R, Goldsmith D, Uchino S, et al. Prospective controlled trial of effect of medical emergency team on postoperative morbidity and mortality rates. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(4):916-21. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ccm.0000119428.02968.9e

5. Bellomo R, Goldsmith D, Uchino S, et al. A prospective before-and-after trial of a medical emergency team. Med J Aust. 2003;179(6):283-287.

6. Bristow PJ, Hillman KM, Chey T, et al. Rates of in-hospital arrests, deaths and intensive care admissions: the effect of a medical emergency team. Med J Aust. 2000;173(5):236-240.

7. Buist MD, Moore GE, Bernard SA, Waxman BP, Anderson JN, Nguyen TV. Effects of a medical emergency team on reduction of incidence of and mortality from unexpected cardiac arrests in hospital: preliminary study. BMJ. 2002;324(7334):387-390. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.324.7334.387

8. DeVita MA, Braithwaite RS, Mahidhara R, Stuart S, Foraida M, Simmons RL; Medical Emergency Response Improvement Team (MERIT). Use of medical emergency team responses to reduce hospital cardiopulmonary arrests. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13(4):251-254. https://doi.org/10.1136/qhc.13.4.251

9. Goldhill DR, Worthington L, Mulcahy A, Tarling M, Sumner A. The patient-at-risk team: identifying and managing seriously ill ward patients. Anaesthesia. 1999;54(9):853-860. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2044.1999.00996.x

10. Hillman K, Chen J, Cretikos M, et al; MERIT study investigators. Introduction of the medical emergency team (MET) system: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;365(9477):2091-2097. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(05)66733-5

11. Kenward G, Castle N, Hodgetts T, Shaikh L. Evaluation of a medical emergency team one year after implementation. Resuscitation. 2004;61(3):257-263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2004.01.021

12. Pittard AJ. Out of our reach? assessing the impact of introducing a critical care outreach service. Anaesthesia. 2003;58(9):882-885. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2044.2003.03331.x

13. Priestley G, Watson W, Rashidian A, et al. Introducing critical care outreach: a ward-randomised trial of phased introduction in a general hospital. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30(7):1398-1404. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-004-2268-7

14. Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054-1062. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30566-3

15. Zhou Y, Li W, Wang D, et al. Clinical time course of COVID-19, its neurological manifestation and some thoughts on its management. Stroke Vasc Neurol. 2020;5(2):177-179. https://doi.org/10.1136/svn-2020-000398

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine

ADHD through the retrospectoscope

Isolation in response to COVID-19 pandemic has driven many people to reestablish long forgotten connections between old friends and geographically distant relatives. Fed by the ease in which Zoom and other electronic miracles can bring once familiar voices and faces into our homes, we no longer need to wait until our high school or college reunions to reconnect.

The Class of 1962 at Pleasantville (N.Y.) High School has always attracted an unusually large number of attendees at its reunions, and its exuberant response to pandemic-fueled mini Zoom reunions is not surprising. With each virtual gathering we learn and relearn more about each other. I had always felt that because my birthday was in December that I was among the very youngest in my class. (New York’s school enrollment calendar cutoff is in December.) However, I recently learned that some of my classmates were even younger, having been born in the following spring.

This revelation prompted a discussion among the younger septuagenarians about whether we felt that our relative immaturity, at least as measured by the calendar, affected us. It was generally agreed that for the women, being younger seemed to present little problem. For, the men there were a few for whom immaturity put them at an athletic disadvantage. But, there was uniform agreement that social immaturity made dating an uncomfortable adventure. No one felt that his or her immaturity placed them at an academic disadvantage. Of course, all of these observations are heavily colored by the bias of those who have chosen to maintain contact with classmates.

A recent flurry of papers and commentaries about relative age at school entry and the diagnosis of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder prompted me to ask my Zoom mates if they could recall anyone whom they would label as having exhibited the behavior we have all come to associate with ADHD (Vuori M et al. Children’s relative age and ADHD medication use: A Finnish population-based study. Pediatrics 2020 Oct. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-4046, and Butter EM. Keeping relative age effects and ADHD care in context. Pediatrics. 2020;146[4]:e2020022798).

We could all recall classmates who struggled academically and seemed to not be paying attention. However, when one includes the hyperactivity descriptor we couldn’t recall anyone whose in-classroom physical activity drew our attention. Of course, there were many shared anecdotes about note passing, spitball throwing, and out-of-class shenanigans. But, from the perspective of behavior that disrupted the classroom there were very few. And, not surprisingly, given the intervening 6 decades, none of us could make an association between immaturity and the behavior.

While I have very few memories of what happened when I was in grade school, many of my classmates have vivid recollections of events both mundane and dramatic even as far back as first and second grade. Why do none of them recall classmates whose behavior would in current terminology be labeled as ADHD?

Were most of us that age bouncing off the walls and so there were no outliers? Were the teachers more tolerant because they expected that many children, particularly the younger ones, would be more physically active? Or, maybe we arrived at school, even those who were chronologically less mature, having already been settled down by home environments that neither fostered nor tolerated hyperactivity?

If you ask a pediatrician over the age of 70 if he or she recalls being taught anything about ADHD in medical school or seeing any children in his or her first years of practice who would fit the current diagnostic criteria, you will see them simply shrug. ADHD was simply not on our radar in the 1970s and 1980s. And it’s not because radar hadn’t been invented. We pediatricians were paying attention, and I trust in my high school classmates’ observations. I am sure there were isolated cases that could easily have been labeled as ADHD if the term had existed. But, the volume of hyperactive children a pediatrician sees today in the course of a normal office day just didn’t exist.

I have trouble believing that this dramatic increase in frequency is the result of accumulating genetic damage from Teflon cookware or climate change or air pollution. Although I am open to any serious attempt to explain the phenomenon I think we should look first into the home environment in which children are being raised. Sleep schedules, activity, and amusement opportunities as well as discipline styles – just to name a few – are far different now than before the ADHD diagnosis overtook the landscape.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

Isolation in response to COVID-19 pandemic has driven many people to reestablish long forgotten connections between old friends and geographically distant relatives. Fed by the ease in which Zoom and other electronic miracles can bring once familiar voices and faces into our homes, we no longer need to wait until our high school or college reunions to reconnect.

The Class of 1962 at Pleasantville (N.Y.) High School has always attracted an unusually large number of attendees at its reunions, and its exuberant response to pandemic-fueled mini Zoom reunions is not surprising. With each virtual gathering we learn and relearn more about each other. I had always felt that because my birthday was in December that I was among the very youngest in my class. (New York’s school enrollment calendar cutoff is in December.) However, I recently learned that some of my classmates were even younger, having been born in the following spring.

This revelation prompted a discussion among the younger septuagenarians about whether we felt that our relative immaturity, at least as measured by the calendar, affected us. It was generally agreed that for the women, being younger seemed to present little problem. For, the men there were a few for whom immaturity put them at an athletic disadvantage. But, there was uniform agreement that social immaturity made dating an uncomfortable adventure. No one felt that his or her immaturity placed them at an academic disadvantage. Of course, all of these observations are heavily colored by the bias of those who have chosen to maintain contact with classmates.

A recent flurry of papers and commentaries about relative age at school entry and the diagnosis of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder prompted me to ask my Zoom mates if they could recall anyone whom they would label as having exhibited the behavior we have all come to associate with ADHD (Vuori M et al. Children’s relative age and ADHD medication use: A Finnish population-based study. Pediatrics 2020 Oct. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-4046, and Butter EM. Keeping relative age effects and ADHD care in context. Pediatrics. 2020;146[4]:e2020022798).

We could all recall classmates who struggled academically and seemed to not be paying attention. However, when one includes the hyperactivity descriptor we couldn’t recall anyone whose in-classroom physical activity drew our attention. Of course, there were many shared anecdotes about note passing, spitball throwing, and out-of-class shenanigans. But, from the perspective of behavior that disrupted the classroom there were very few. And, not surprisingly, given the intervening 6 decades, none of us could make an association between immaturity and the behavior.

While I have very few memories of what happened when I was in grade school, many of my classmates have vivid recollections of events both mundane and dramatic even as far back as first and second grade. Why do none of them recall classmates whose behavior would in current terminology be labeled as ADHD?

Were most of us that age bouncing off the walls and so there were no outliers? Were the teachers more tolerant because they expected that many children, particularly the younger ones, would be more physically active? Or, maybe we arrived at school, even those who were chronologically less mature, having already been settled down by home environments that neither fostered nor tolerated hyperactivity?

If you ask a pediatrician over the age of 70 if he or she recalls being taught anything about ADHD in medical school or seeing any children in his or her first years of practice who would fit the current diagnostic criteria, you will see them simply shrug. ADHD was simply not on our radar in the 1970s and 1980s. And it’s not because radar hadn’t been invented. We pediatricians were paying attention, and I trust in my high school classmates’ observations. I am sure there were isolated cases that could easily have been labeled as ADHD if the term had existed. But, the volume of hyperactive children a pediatrician sees today in the course of a normal office day just didn’t exist.

I have trouble believing that this dramatic increase in frequency is the result of accumulating genetic damage from Teflon cookware or climate change or air pollution. Although I am open to any serious attempt to explain the phenomenon I think we should look first into the home environment in which children are being raised. Sleep schedules, activity, and amusement opportunities as well as discipline styles – just to name a few – are far different now than before the ADHD diagnosis overtook the landscape.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

Isolation in response to COVID-19 pandemic has driven many people to reestablish long forgotten connections between old friends and geographically distant relatives. Fed by the ease in which Zoom and other electronic miracles can bring once familiar voices and faces into our homes, we no longer need to wait until our high school or college reunions to reconnect.

The Class of 1962 at Pleasantville (N.Y.) High School has always attracted an unusually large number of attendees at its reunions, and its exuberant response to pandemic-fueled mini Zoom reunions is not surprising. With each virtual gathering we learn and relearn more about each other. I had always felt that because my birthday was in December that I was among the very youngest in my class. (New York’s school enrollment calendar cutoff is in December.) However, I recently learned that some of my classmates were even younger, having been born in the following spring.