User login

CML: Biomarkers can predict relapse in patients on treatment-free remission

Key clinical point: Biomarkers can predict relapse in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) who are eligible for a controlled treatment interruption.

Major finding: Predictors of CML relapse after treatment interruptions were low levels of cytotoxic cells such as CD56+ with low expression of CD16 and CD94/NKG2 receptors and CD8± T cells expressing TCRγβ+; low expression of activating receptors on the surface of natural killer (NK) and NK T cells; impaired synthesis of proinflammatory cytokines or proteases from NK cells; and HLA-E*0103 homozygosis and KIR haplotype BX.

Study details: The data come from an observational, cross-sectional study of 93 patients with chronic phase CML and 20 age- and gender-matched controls. Among patients with CML, 45 were on treatment with tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), 27 on sustained treatment-free remission (off TKIs), 15 had a relapse, and 6 had newly diagnosed CML.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the Foundation for Biomedical Research of the Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal, the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness, and the Spanish AIDS Research Network. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Vigón L et al. J Clin Med. 2020 Dec 25. doi: 10.3390/jcm10010042.

Key clinical point: Biomarkers can predict relapse in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) who are eligible for a controlled treatment interruption.

Major finding: Predictors of CML relapse after treatment interruptions were low levels of cytotoxic cells such as CD56+ with low expression of CD16 and CD94/NKG2 receptors and CD8± T cells expressing TCRγβ+; low expression of activating receptors on the surface of natural killer (NK) and NK T cells; impaired synthesis of proinflammatory cytokines or proteases from NK cells; and HLA-E*0103 homozygosis and KIR haplotype BX.

Study details: The data come from an observational, cross-sectional study of 93 patients with chronic phase CML and 20 age- and gender-matched controls. Among patients with CML, 45 were on treatment with tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), 27 on sustained treatment-free remission (off TKIs), 15 had a relapse, and 6 had newly diagnosed CML.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the Foundation for Biomedical Research of the Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal, the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness, and the Spanish AIDS Research Network. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Vigón L et al. J Clin Med. 2020 Dec 25. doi: 10.3390/jcm10010042.

Key clinical point: Biomarkers can predict relapse in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) who are eligible for a controlled treatment interruption.

Major finding: Predictors of CML relapse after treatment interruptions were low levels of cytotoxic cells such as CD56+ with low expression of CD16 and CD94/NKG2 receptors and CD8± T cells expressing TCRγβ+; low expression of activating receptors on the surface of natural killer (NK) and NK T cells; impaired synthesis of proinflammatory cytokines or proteases from NK cells; and HLA-E*0103 homozygosis and KIR haplotype BX.

Study details: The data come from an observational, cross-sectional study of 93 patients with chronic phase CML and 20 age- and gender-matched controls. Among patients with CML, 45 were on treatment with tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), 27 on sustained treatment-free remission (off TKIs), 15 had a relapse, and 6 had newly diagnosed CML.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the Foundation for Biomedical Research of the Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal, the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness, and the Spanish AIDS Research Network. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Vigón L et al. J Clin Med. 2020 Dec 25. doi: 10.3390/jcm10010042.

Risk factors for COVID-19 mortality in patients with CML

Key clinical point: Older age and imatinib therapy were associated with a higher mortality rate in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) who contracted COVID-19. However, imatinib could be a confounding factor.

Major finding: Outcome was favorable and fatal in 86% and 14% of patients, respectively. COVID-19 mortality rate was higher in patients aged 75 years vs. less than 75 years (60% vs. 7%; P less than .001) and in those on imatinib vs. second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) vs. no TKIs (25% vs. 3% vs. 0%; P = .003). However, 25% vs. 0% of patients treated with imatinib vs. second-generation TKIs were more than 75 years old.

Study details: The CANDID study evaluated 110 cases of COVID-19 in patients with CML reported by physicians to the International CML Foundation until July 1, 2020 across 20 countries.

Disclosures: No study sponsor was identified. The lead author reported ties with BMS, Incyte, Novartis, and Pfizer. Some co-authors also reported ties with various pharmaceutical companies.

Source: Rea D et al. ASH 2020. 2020 Dec 7. Abstract 649.

Key clinical point: Older age and imatinib therapy were associated with a higher mortality rate in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) who contracted COVID-19. However, imatinib could be a confounding factor.

Major finding: Outcome was favorable and fatal in 86% and 14% of patients, respectively. COVID-19 mortality rate was higher in patients aged 75 years vs. less than 75 years (60% vs. 7%; P less than .001) and in those on imatinib vs. second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) vs. no TKIs (25% vs. 3% vs. 0%; P = .003). However, 25% vs. 0% of patients treated with imatinib vs. second-generation TKIs were more than 75 years old.

Study details: The CANDID study evaluated 110 cases of COVID-19 in patients with CML reported by physicians to the International CML Foundation until July 1, 2020 across 20 countries.

Disclosures: No study sponsor was identified. The lead author reported ties with BMS, Incyte, Novartis, and Pfizer. Some co-authors also reported ties with various pharmaceutical companies.

Source: Rea D et al. ASH 2020. 2020 Dec 7. Abstract 649.

Key clinical point: Older age and imatinib therapy were associated with a higher mortality rate in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) who contracted COVID-19. However, imatinib could be a confounding factor.

Major finding: Outcome was favorable and fatal in 86% and 14% of patients, respectively. COVID-19 mortality rate was higher in patients aged 75 years vs. less than 75 years (60% vs. 7%; P less than .001) and in those on imatinib vs. second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) vs. no TKIs (25% vs. 3% vs. 0%; P = .003). However, 25% vs. 0% of patients treated with imatinib vs. second-generation TKIs were more than 75 years old.

Study details: The CANDID study evaluated 110 cases of COVID-19 in patients with CML reported by physicians to the International CML Foundation until July 1, 2020 across 20 countries.

Disclosures: No study sponsor was identified. The lead author reported ties with BMS, Incyte, Novartis, and Pfizer. Some co-authors also reported ties with various pharmaceutical companies.

Source: Rea D et al. ASH 2020. 2020 Dec 7. Abstract 649.

TNF inhibitors may slow spinal progression in axial spondyloarthritis

Patients with axial spondyloarthritis showed reduced spinal radiographic progression after treatment with tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors, based on data from 314 adults in a prospective cohort study.

Evidence of a link between inflammation and axial damage in patients with axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) has been reported, and these patients are routinely treated with NSAIDs and TNF inhibitors (TNFi), wrote Alexandre Sepriano, MD, PhD, of Leiden (the Netherlands) University Medical Center, and colleagues.

“However, and despite significant efforts, it remains to be clarified whether there is also an effect of these drugs on axial damage accrual,” they noted.

In a study published in Arthritis & Rheumatology, the researchers recruited consecutive patients from rheumatology practices in Northern Alberta to enroll in the Follow Up Research Cohort in Ankylosing Spondylitis Treatment (ALBERTA FORCAST) observational cohort study. The average age of the patients was 41 years, 74% were men, 83% were HLA-B27 positive, and the average duration of symptoms was 18 years.

Progression was measured via spine radiographs every 2 years for up to 10 years; the radiographs were scored using the modified Stoke Ankylosing Spondylitis Spine Score (mSASSS). In addition, the researchers assessed the interaction between TNFi exposure and clinical disease activity using the Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS) and the impact on mSASSS every 2 years. The analysis included 442 2-year intervals.

Overall, the researchers found a significant interaction between ASDAS and TNFi at the start of the interval, followed by gradient effect of ASDAS at the start of the interval on mSASSS 2 years later, which was more than twice as high in patients never treated with TNFi (beta = 0.41), compared with patients who were continuously treated with a TNFi (beta = 0.16).

“Similarly, patients treated with TNFi were 30% less likely to develop a new syndesmophyte 2 years later compared to those not treated,” the researchers said.

TNFi also directly slowed progression, as treated patients averaged 0.85 mSASSS units less 2 years later, compared with untreated patients.

Of note, “treatment with NSAIDs during follow-up was neither associated with the outcome nor did it modify or confound the association between TNFi and mSASSS,” the researchers said. In addition, “the direct effect of TNFi on mSASSS was still present after adjusting for a propensity score,” they wrote.

The study results were limited by several factors including the observational design, lack of data on long-term treatment effects, and inability to assess individual TNFi drugs separately, the researchers noted.

However, “the present study informs the rheumatology community by addressing the question as to whether or not TNFi inhibit radiographic progression in axSpA and if this effect is mediated solely by their effects on inflammation, as measured by the ASDAS, or whether additional mechanisms may be relevant,” they emphasized.

“A better understanding of these mechanisms might open avenues to further treatment strategies that might finally lead to effective disease modification in axial SpA,” they concluded.

The ALBERTA FORCAST study was supported by AbbVie. Several authors disclosed financial relationships with AbbVie and other manufacturers of TNFi.

Patients with axial spondyloarthritis showed reduced spinal radiographic progression after treatment with tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors, based on data from 314 adults in a prospective cohort study.

Evidence of a link between inflammation and axial damage in patients with axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) has been reported, and these patients are routinely treated with NSAIDs and TNF inhibitors (TNFi), wrote Alexandre Sepriano, MD, PhD, of Leiden (the Netherlands) University Medical Center, and colleagues.

“However, and despite significant efforts, it remains to be clarified whether there is also an effect of these drugs on axial damage accrual,” they noted.

In a study published in Arthritis & Rheumatology, the researchers recruited consecutive patients from rheumatology practices in Northern Alberta to enroll in the Follow Up Research Cohort in Ankylosing Spondylitis Treatment (ALBERTA FORCAST) observational cohort study. The average age of the patients was 41 years, 74% were men, 83% were HLA-B27 positive, and the average duration of symptoms was 18 years.

Progression was measured via spine radiographs every 2 years for up to 10 years; the radiographs were scored using the modified Stoke Ankylosing Spondylitis Spine Score (mSASSS). In addition, the researchers assessed the interaction between TNFi exposure and clinical disease activity using the Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS) and the impact on mSASSS every 2 years. The analysis included 442 2-year intervals.

Overall, the researchers found a significant interaction between ASDAS and TNFi at the start of the interval, followed by gradient effect of ASDAS at the start of the interval on mSASSS 2 years later, which was more than twice as high in patients never treated with TNFi (beta = 0.41), compared with patients who were continuously treated with a TNFi (beta = 0.16).

“Similarly, patients treated with TNFi were 30% less likely to develop a new syndesmophyte 2 years later compared to those not treated,” the researchers said.

TNFi also directly slowed progression, as treated patients averaged 0.85 mSASSS units less 2 years later, compared with untreated patients.

Of note, “treatment with NSAIDs during follow-up was neither associated with the outcome nor did it modify or confound the association between TNFi and mSASSS,” the researchers said. In addition, “the direct effect of TNFi on mSASSS was still present after adjusting for a propensity score,” they wrote.

The study results were limited by several factors including the observational design, lack of data on long-term treatment effects, and inability to assess individual TNFi drugs separately, the researchers noted.

However, “the present study informs the rheumatology community by addressing the question as to whether or not TNFi inhibit radiographic progression in axSpA and if this effect is mediated solely by their effects on inflammation, as measured by the ASDAS, or whether additional mechanisms may be relevant,” they emphasized.

“A better understanding of these mechanisms might open avenues to further treatment strategies that might finally lead to effective disease modification in axial SpA,” they concluded.

The ALBERTA FORCAST study was supported by AbbVie. Several authors disclosed financial relationships with AbbVie and other manufacturers of TNFi.

Patients with axial spondyloarthritis showed reduced spinal radiographic progression after treatment with tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors, based on data from 314 adults in a prospective cohort study.

Evidence of a link between inflammation and axial damage in patients with axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) has been reported, and these patients are routinely treated with NSAIDs and TNF inhibitors (TNFi), wrote Alexandre Sepriano, MD, PhD, of Leiden (the Netherlands) University Medical Center, and colleagues.

“However, and despite significant efforts, it remains to be clarified whether there is also an effect of these drugs on axial damage accrual,” they noted.

In a study published in Arthritis & Rheumatology, the researchers recruited consecutive patients from rheumatology practices in Northern Alberta to enroll in the Follow Up Research Cohort in Ankylosing Spondylitis Treatment (ALBERTA FORCAST) observational cohort study. The average age of the patients was 41 years, 74% were men, 83% were HLA-B27 positive, and the average duration of symptoms was 18 years.

Progression was measured via spine radiographs every 2 years for up to 10 years; the radiographs were scored using the modified Stoke Ankylosing Spondylitis Spine Score (mSASSS). In addition, the researchers assessed the interaction between TNFi exposure and clinical disease activity using the Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS) and the impact on mSASSS every 2 years. The analysis included 442 2-year intervals.

Overall, the researchers found a significant interaction between ASDAS and TNFi at the start of the interval, followed by gradient effect of ASDAS at the start of the interval on mSASSS 2 years later, which was more than twice as high in patients never treated with TNFi (beta = 0.41), compared with patients who were continuously treated with a TNFi (beta = 0.16).

“Similarly, patients treated with TNFi were 30% less likely to develop a new syndesmophyte 2 years later compared to those not treated,” the researchers said.

TNFi also directly slowed progression, as treated patients averaged 0.85 mSASSS units less 2 years later, compared with untreated patients.

Of note, “treatment with NSAIDs during follow-up was neither associated with the outcome nor did it modify or confound the association between TNFi and mSASSS,” the researchers said. In addition, “the direct effect of TNFi on mSASSS was still present after adjusting for a propensity score,” they wrote.

The study results were limited by several factors including the observational design, lack of data on long-term treatment effects, and inability to assess individual TNFi drugs separately, the researchers noted.

However, “the present study informs the rheumatology community by addressing the question as to whether or not TNFi inhibit radiographic progression in axSpA and if this effect is mediated solely by their effects on inflammation, as measured by the ASDAS, or whether additional mechanisms may be relevant,” they emphasized.

“A better understanding of these mechanisms might open avenues to further treatment strategies that might finally lead to effective disease modification in axial SpA,” they concluded.

The ALBERTA FORCAST study was supported by AbbVie. Several authors disclosed financial relationships with AbbVie and other manufacturers of TNFi.

FROM ARTHRITIS & RHEUMATOLOGY

Which behavioral health screening tool should you use—and when?

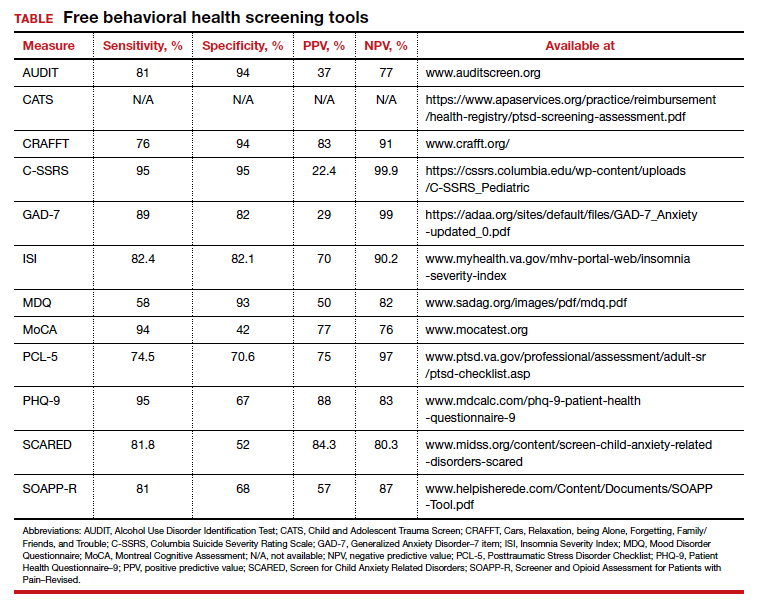

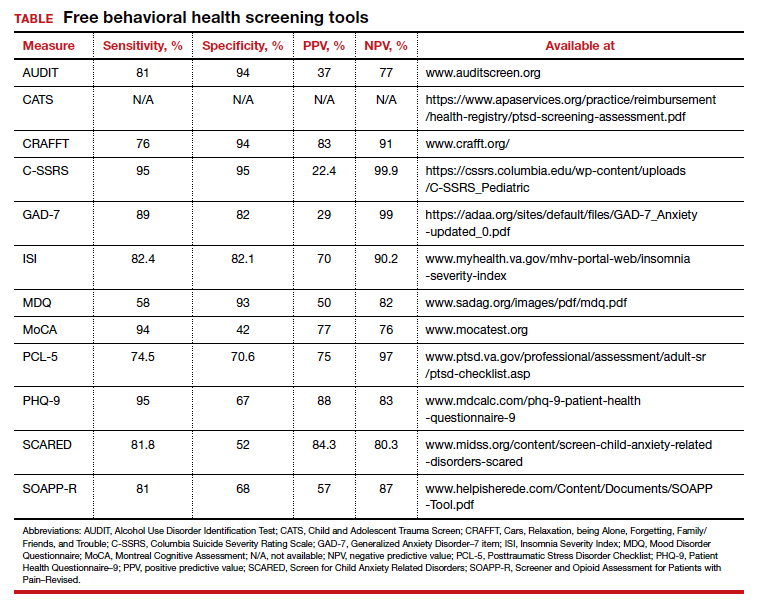

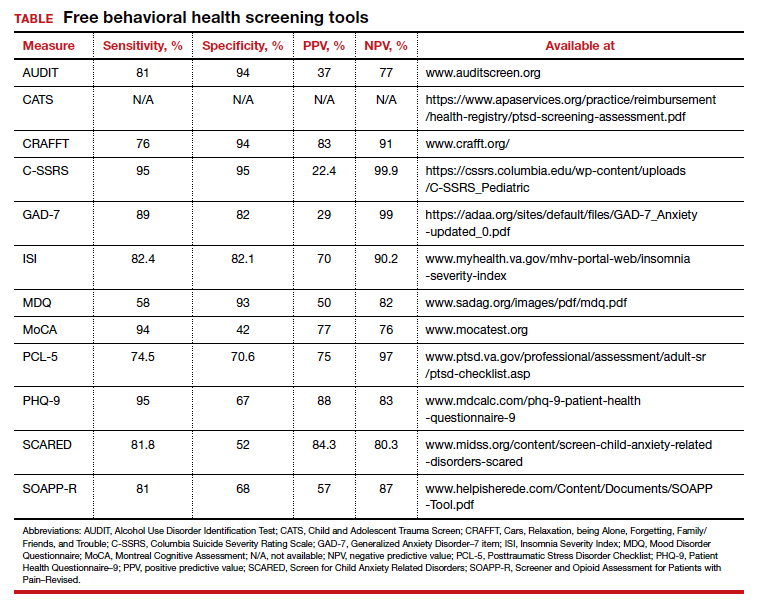

Many screening tools are available in the public domain to assess a variety of symptoms related to impaired mental health. These tools can be used to quickly evaluate for mood, suicidal ideation or behavior, anxiety, sleep, substance use, pain, trauma, memory, and cognition (TABLE). Individuals with poor mental health incur high health care costs. Those suffering from anxiety and posttraumatic stress have more outpatient and emergency department visits and hospitalizations than patients without these disorders,1,2 although use of mental health care services has been related to a decrease in the overutilization of health care services in general.3

Here we review several screening tools that can help you to identify symptoms of mental illnesses and thus, provide prompt early intervention, including referrals to psychological and psychiatric services.

Mood disorders

Most patients with mood disorders are treated in primary care settings.4 Quickly measuring patients’ mood symptoms can expedite treatment for those who need it. Many primary care clinics use the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) to screen for depression.5 The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) has recommended screening for depression with adequate systems to ensure accurate diagnoses, effective treatment, and follow-up. Although the USPSTF did not specially endorse screening for bipolar disorder, it followed that recommendation with the qualifying statement, “positive screening results [for depression] should lead to additional assessment that considers severity of depression and comorbid psychological problems, alternate diagnoses, and medical conditions.”6 Thus, following a positive screen result for depression, consider using a screening tool for mood disorders to provide diagnostic clarification.

The Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ) is a validated 15-item, self-administered questionnaire that takes only 5 minutes to use in screening adult patients for bipolar I disorder.7 The MDQ assesses specific behaviors related to bipolar disorder, symptom co-occurrence, and functional impairment. The MDQ has low sensitivity (58%) but good specificity (93%) in a primary care setting.8 However, the MDQ is not a diagnostic instrument. A positive screen result should prompt a more thorough clinical evaluation, if necessary, by a professional trained in psychiatric disorders.

We recommend completing the MDQ prior to prescribing antidepressants. You can also monitor a patient’s response to treatment with serial MDQ testing. The MDQ is useful, too, when a patient has unclear mood symptoms that may have features overlapping with bipolar disorder. Furthermore, we recommend screening for bipolar disorder with every patient who reports symptoms of depression, given that some pharmacologic treatments (predominately selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) can induce mania in patients who actually have unrecognized bipolar disorder.9

Continue to: Suicide...

Suicide

Suicide is the 10th leading cause of death among the general population. All demographic groups are impacted by suicide; however, the most vulnerable are men ages 45 to 64 years.10 Given the imminent risk to individuals who experience suicidal ideation, properly assessing and targeting suicidal risk is paramount.

The Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) can be completed in an interview format or as a patient self-report. Versions of the C-SSRS are available for children, adolescents, and adults. It can be used in practice with any patient who may be at risk for suicide. Specifically, consider using the C-SSRS when a patient scores 1 or greater on the PHQ-9 or when risk is revealed with another brief screening tool that includes suicidal ideation.

The C-SSRS covers 10 categories related to suicidal ideation and behavior that the clinician explores with questions requiring only Yes/No responses. The C-SSRS demonstrates moderate-to-strong internal consistency and reliability, and it has shown a high degree of sensitivity (95%) and specificity (95%) for suicidal ideation.11

Anxiety and physiologic arousal

Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) is one of the most common anxiety disorders, with an estimated prevalence of 2.8% to 8.5% among primary care patients.12 Brief, validated screening tools such as the Generalized Anxiety Disorder–7 item (GAD-7) scale can be effective in identifying anxiety and other related disorders in primary care settings.

The GAD-7 comprises 7 items inquiring about symptoms experienced in the past 2 weeks. Scores range from 0 to 21, with cutoffs of 5, 10, and 15 indicating mild, moderate, and severe anxiety, respectively. This questionnaire is appropriate for use with adults and has strong specificity, internal consistency, and test-retest reliability.12 Specificity and sensitivity of the GAD-7 are maximized at a cutoff score of 10 or greater, both exceeding 80%.12 The GAD-7 can be used when patients report symptoms of anxiety or when one needs to screen for anxiety with new patients or more clearly understand symptoms among patients who have complex mental health concerns.

The Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders (SCARED) is a 41-item self-report measure of anxiety for children ages 8 to 18. The SCARED questionnaire yields an overall anxiety score, as well as subscales for panic disorder or significant somatic symptoms, generalized anxiety disorder, separation anxiety, social anxiety disorder, and significant school avoidance.13 There is also a 5-item version of the SCARED, which can be useful for brief screening in fast-paced settings when no anxiety disorder is suspected, or for children who may have anxiety but exhibit reduced verbal capacity. The SCARED has been found to have moderate sensitivity (81.8%) and specificity (52%) for diagnosing anxiety disorders in a community sample, with an optimal cutoff point of 22 on the total scale.14

Sleep

Sleep concerns are common, with the prevalence of insomnia among adults in the United States estimated to be 19.2%.15 The importance of assessing these concerns cannot be overstated, and primary care providers are the ones patients consult most often.16 The gold standard in assessing sleep disorders is a structured clinical interview, polysomnography, sleep diary, and actigraphy (home-based monitoring of movement through a device, often worn on the wrist).17,18 However, this work-up is expensive, time-intensive, and impractical in integrated care settings; thus the need for a brief, self-report screening tool to guide further assessment and intervention.

The Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) assesses patients’ perceptions of their insomnia. The ISI was developed to aid both in the clinical evaluation of patients with insomnia and to measure treatment outcomes. Administration of the ISI takes approximately 5 minutes, and scoring takes less than 1 minute.

The ISI is composed of 7 items that measure the severity of sleep onset and sleep maintenance difficulties, satisfaction with current sleep, impact on daily functioning, impairment observable to others, and degree of distress caused by the sleep problems. Each item is scored on a 0 to 4 Likert-type scale, and the individual items are summed for a total score of 0 to 28, with higher scores suggesting more severe insomnia. Evidence-based guidelines recommend cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) as the first-line treatment for adults with primary insomnia.19

Several validation studies have found the ISI to be a reliable measure of perceived insomnia severity, and one that is sensitive to changes in patients’ perceptions of treatment outcomes.20,21 An additional validation study confirmed that in primary care settings, a cutoff score of 14 should be used to indicate the likely presence of clinical insomnia22 and to guide further assessment and intervention.

The percentage of insomniac patients correctly identified with the ISI was 82.2%, with moderate sensitivity (82.4%) and specificity (82.1%).22 A positive predictive value of 70% was found, meaning that an insomnia disorder is probable when the ISI total score is 14 or higher; conversely, the negative predictive value was 90.2%.

Continue to: Substance use and pain...

Substance use and pain

The evaluation of alcohol and drug use is an integral part of assessing risky health behaviors. The 10-item Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT) is a self-report tool developed by the World Health Organization.23,24 Validated in medical settings, scores of 8 or higher suggest problematic drinking.25,26 The AUDIT has demonstrated high specificity (94%) and moderate sensitivity (81%) in primary care settings.27 The AUDIT-C (items 1, 2, and 3 of the AUDIT) has also demonstrated comparable sensitivity, although slightly lower specificity, than the full AUDIT, suggesting that this 3-question screen can also be used in primary care settings.27

Opioid medications, frequently prescribed for chronic pain, present serious risks for many patients. The Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain–Revised (SOAPP-R) is a 24-item self-reporting scale that can be completed in approximately 10 minutes.28 A score of 18 or higher has identified 81% of patients at high risk for opioid misuse in a clinical setting, with moderate specificity (68%). Although other factors should be considered when assessing risk of opioid misuse, the SOAPP-R is a helpful and quick addition to an opioid risk assessment.

The CRAFFT Screening Tool for Adolescent Substance Use is administered by the clinician for youths ages 14 to 21. The first 3 questions ask about use of alcohol, marijuana, or other substances during the past 12 months. What follows are questions related to the young person’s specific experiences with substances in relation to Cars, Relaxation, being Alone, Forgetting, Family/Friends, and Trouble (CRAFFT). The CRAFFT has shown moderate sensitivity (76%) and good specificity (94%) for identifying any problem with substance use.29 These measures may be administered to clarify or confirm substance use patterns (ie, duration, frequency), or to determine the severity of problems related to substance use (ie, social or legal problems).

Trauma and PTSD

Approximately 7.7 million adults per year will experience posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms, although PTSD can affect individuals of any age.30 Given the impact that trauma can have, assess for PTSD in patients who have a history of trauma or who otherwise seem to be at risk. The Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist (PCL-5) is a 20-item self-report questionnaire that screens for symptoms directly from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5) criteria for PTSD. One limitation is that the questionnaire is only validated for adults ages 18 years or older. Completion of the PCL-5 takes 5 to 10 minutes. The PCL-5 has strong internal consistency reliability (94%) and test-retest reliability (82%).31 With a cutoff score of 33 or higher, the sensitivity and specificity have been shown to be moderately high (74.5% and 70.6%, respectively).32

The Child and Adolescent Trauma Screen (CATS) is used to assess for potentially traumatic events and PTSD symptoms in children and adolescents. These symptoms are based on the DSM-5, and therefore the CATS can act as a useful diagnostic aid. The CATS is also available in Spanish, with both caregiver-report (for children ages 3-6 years or 7-17 years) and self-report (for ages 7-17 years) versions. Practical use of the PCL-5 and the CATS involves screening for PTSD symptoms, supporting a provisional diagnosis of PTSD, and monitoring PTSD symptom changes during and after treatment.

Memory and cognition

Cognitive screening is a first step in evaluating possible dementia and other neuropsychological disorders. The importance of brief cognitive screening in primary care cannot be understated, especially for an aging patient population. Although the Mini Mental Status Exam (MMSE) has been widely used among health care providers and researchers, we recommend the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA).

The MoCA is a simple, standalone cognitive screening tool validated for adults ages 55 to 85 years.33 The MoCA addresses many important cognitive domains, fits on one page, and can be administered by a trained provider in 10 minutes. Research also suggests that it has strong test-retest reliability and positive and negative predictive values for mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer dementia, and it has been found to be more sensitive than the MMSE.34 We additionally recommend the MoCA as it measures several cognitive skills that are not addressed on the MMSE, including verbal fluency and abstraction.34 Scores below 25 are suggestive of cognitive impairment and should lead to a referral for neuropsychological testing.

The MoCA’s sensitivity for detecting cognitive impairment is high (94%), and specificity is low (42%).35 To ensure consistency and accuracy in administering the MoCA, certification is now required via an online training program through www.mocatest.org.

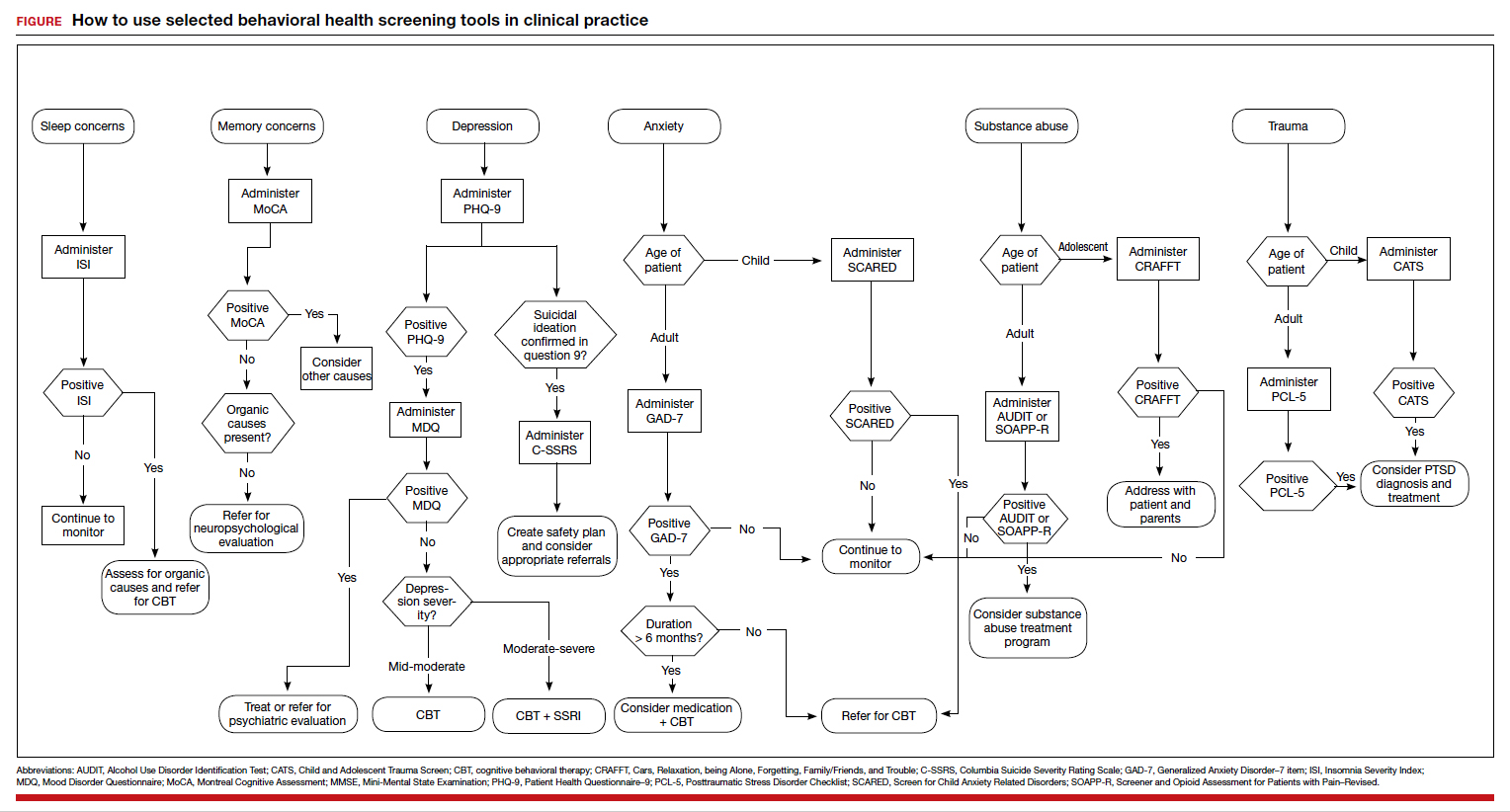

Adapting these screening tools to practice

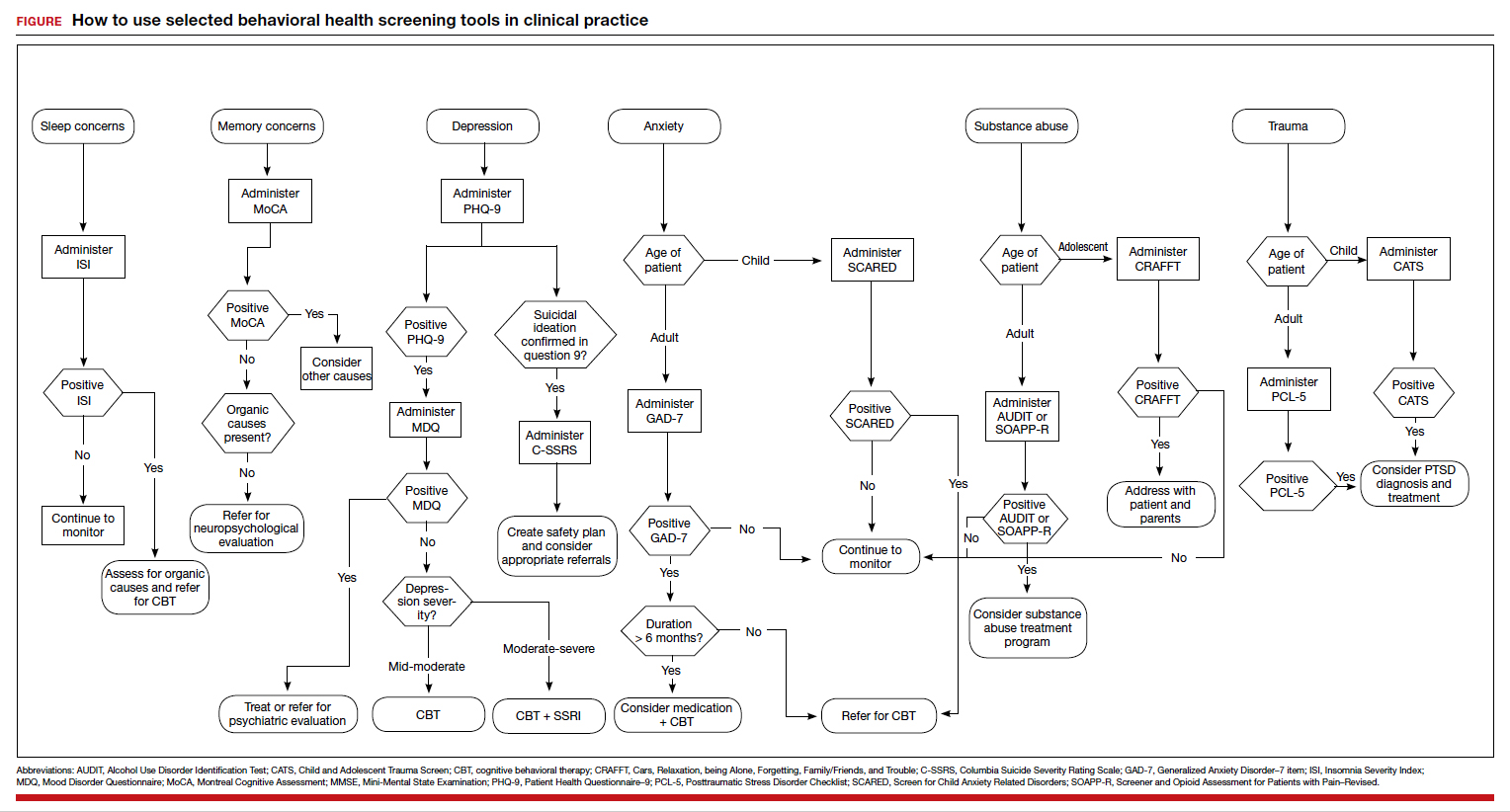

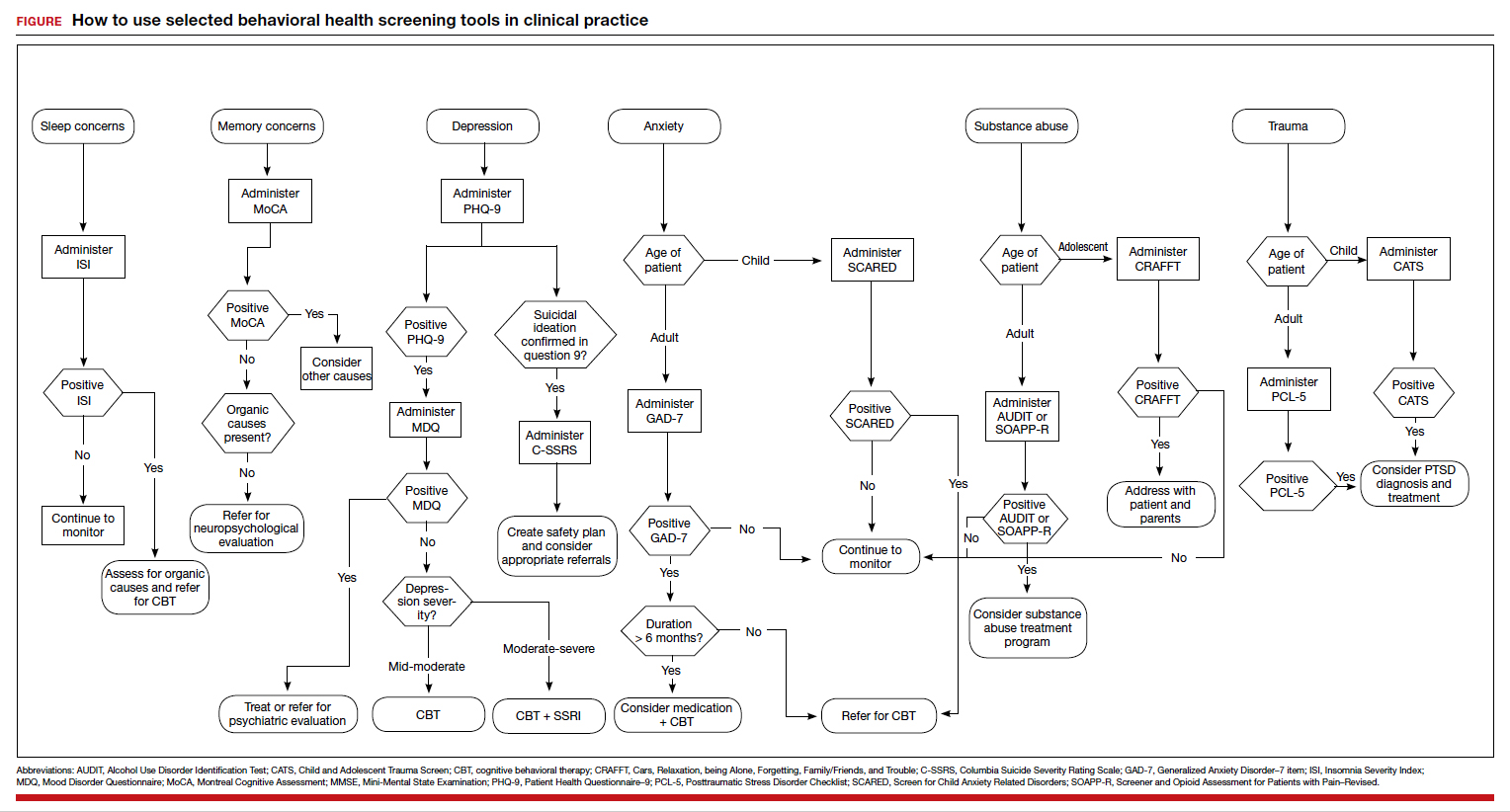

These tools are not meant to be used at every appointment. Every practice is different, and each clinic or physician can tailor the use of these screening tools to the needs of the patient population, as concerns arise, or in collaboration with other providers. Additionally, these screening tools can be used in both integrated care and in private practice, to prompt a more thorough assessment or to aid in—and inform—treatment. Although some physicians choose to administer certain screening tools at each clinic visit, knowing about the availability of other tools can be useful in assessing various issues. The FIGURE can be used to aid in the clinical decision-making process.

- Robinson RL, Grabner M, Palli SR, et al. Covariates of depression and high utilizers of healthcare: impact on resource use and costs. J Psychosom Res. 2016,85:35-43.

- Fogarty CT, Sharma S, Chetty VK, et al. Mental health conditions are associated with increased health care utilization among urban family medicine patients. J Am Board Fam Med. 2008,21:398-407.

- Weissman JD, Russell D, Beasley J, et al. Relationships between adult emotional states and indicators of health care utilization: findings from the National Health Interview Survey 2006–2014. J Psychosom Res. 2016,91:75-81.

- Haddad M, Walters P. Mood disorders in primary care. Psychiatry. 2009,8:71-75.

- Mitchell AJ, Yadegarfar M, Gill J, et al. Case finding and screening clinical utility of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9 and PHQ-2) for depression in primary care: a diagnostic metaanalysis of 40 studies. BJPsych Open. 2016,2:127-138.

- Siu AL and US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for depression in adults. JAMA. 2016;315:380-387.

- Hirschfeld RM, Williams JB, Spitzer RL, et al. Development and validation of a screening instrument for bipolar spectrum disorder: the Mood Disorder Questionnaire. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1873-1875.

- Hirschfeld RM, Cass AR, Holt DC, et al. Screening for bipolar disorder in patients treated for depression in a family medicine clinic. J Am Board Fam Med. 2005;18:233-239.

- Das AK, Olfson M, Gameroff MJ, et al. Screening for bipolar disorder in a primary care practice. JAMA. 2005;293:956-963.

- CDC. Suicide mortality in the United States, 1999-2017. www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db330.htm. Accessed October 23, 2020.

- Viguera AC, Milano N, Ralston L, et al. Comparison of electronic screening for suicidal risk with Patient Health Questionnaire Item 9 and the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale in an outpatient psychiatric clinic. Psychosomatics. 2015;56:460-469.

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092-1097.

- Birmaher B, Khetarpal S, Brent D, et al. The Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED): scale construction and psychometric characteristics. J Am Acad Chil Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:545-553.

- DeSousa DA, Salum GA, Isolan LR, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED): a community-based study. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2013;44:391-399.

- Ford ES, Cunningham TJ, Giles WH, et al. Trends in insomnia and excessive daytime sleepiness among U.S. adults from 2002 to 2012. Sleep Med. 2015;16:372-378.

- Morin CM, LeBlanc M, Daley M, et al. Epidemiology of insomnia: prevalence, self-help treatments, consultations, and determinants of help-seeking behaviors. Sleep Med. 2006;7:123-130.

- Buysse DJ, Ancoli-Israel S, Edinger JD, et al. Recommendations for a standard research assessment of insomnia. Sleep. 2006;29:1155-1173.

- Martin JL, Hakim AD. Wrist actigraphy. Chest. 2011;139:1514-1527.

- Riemann D, Baglioni C, Bassetti C, et al. European guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of insomnia. J Sleep Res. 2017;26:675-700.

- Bastien CH, Vallières A, Morin CM. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med. 2001;2:297-307.

- Wong ML, Lau KNT, Espie CA, et al. Psychometric properties of the Sleep Condition Indicator and Insomnia Severity Index in the evaluation of insomnia disorder. Sleep Med. 2017;33:76-81.

- Gagnon C, Bélanger L, Ivers H, et al. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index in primary care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2013;26:701-710.

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, et al. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO Collaborative Project on Early Detection of Persons with Harmful Alcohol Consumption. Addiction. 1993;88:791-804.

- Selin KH. Test-retest reliability of the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test in a general population sample. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:1428-1435.

- Bohn MJ, Babor TF, Kranzler HR. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): validation of a screening instrument for use in medical settings. J Stud Alcohol. 1995;56:423-432.

- Conigrave KM, Hall WD, Saunders JB. The AUDIT questionnaire: choosing a cut-off score. Addiction. 1995;90:1349-1356.

- Gomez A, Conde A, Santana JM, et al. Diagnostic usefulness of brief versions of Alcohol Use Identification Test (AUDIT) for detecting hazardous drinkers in primary care settings. J Stud Alcohol. 2005;66:305-308.

- Butler SF, Fernandez K, Benoit C, et al. Validation of the revised Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain (SOAPPR). J Pain. 2008;9:360-372.

- Knight JR, Sherritt L, Shrier LA, et al. Validity of the CRAFFT substance abuse screening test among adolescent clinic patients. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:607-614.

- DHHS. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). https://archives.nih.gov/asites/report/09-09-2019/report.nih.gov/nihfactsheets/ViewFactSheetfdf8.html?csid=58&key=P#P. Accessed October 23,2020.

- Blevins CA, Weathers FW, Davis MT, et al. The Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): development and initial psychometric evaluation. J Trauma Stress. 2015;28:489-498.

- Verhey R, Chilbanda D, Gibson L, et al. Validation of the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist- 5 (PCL-5) in a primary care population with high HIV prevalence in Zimbabwe. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18:109.

- Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:695-699.

- Stewart S, O’Riley A, Edelstein B, et al. A preliminary comparison of three cognitive screening instruments in long term care: the MMSE, SLUMS, and MoCA. Clin Gerontol. 2012;35:57-75.

- Godefroy O, Fickl A, Roussel M, et al. Is the Montreal Cognitive Assessment superior to the Mini-Mental State Examination to detect poststroke cognitive impairment? A study with neuropsychological evaluation. Stroke. 2011;42:1712-1716.

Many screening tools are available in the public domain to assess a variety of symptoms related to impaired mental health. These tools can be used to quickly evaluate for mood, suicidal ideation or behavior, anxiety, sleep, substance use, pain, trauma, memory, and cognition (TABLE). Individuals with poor mental health incur high health care costs. Those suffering from anxiety and posttraumatic stress have more outpatient and emergency department visits and hospitalizations than patients without these disorders,1,2 although use of mental health care services has been related to a decrease in the overutilization of health care services in general.3

Here we review several screening tools that can help you to identify symptoms of mental illnesses and thus, provide prompt early intervention, including referrals to psychological and psychiatric services.

Mood disorders

Most patients with mood disorders are treated in primary care settings.4 Quickly measuring patients’ mood symptoms can expedite treatment for those who need it. Many primary care clinics use the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) to screen for depression.5 The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) has recommended screening for depression with adequate systems to ensure accurate diagnoses, effective treatment, and follow-up. Although the USPSTF did not specially endorse screening for bipolar disorder, it followed that recommendation with the qualifying statement, “positive screening results [for depression] should lead to additional assessment that considers severity of depression and comorbid psychological problems, alternate diagnoses, and medical conditions.”6 Thus, following a positive screen result for depression, consider using a screening tool for mood disorders to provide diagnostic clarification.

The Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ) is a validated 15-item, self-administered questionnaire that takes only 5 minutes to use in screening adult patients for bipolar I disorder.7 The MDQ assesses specific behaviors related to bipolar disorder, symptom co-occurrence, and functional impairment. The MDQ has low sensitivity (58%) but good specificity (93%) in a primary care setting.8 However, the MDQ is not a diagnostic instrument. A positive screen result should prompt a more thorough clinical evaluation, if necessary, by a professional trained in psychiatric disorders.

We recommend completing the MDQ prior to prescribing antidepressants. You can also monitor a patient’s response to treatment with serial MDQ testing. The MDQ is useful, too, when a patient has unclear mood symptoms that may have features overlapping with bipolar disorder. Furthermore, we recommend screening for bipolar disorder with every patient who reports symptoms of depression, given that some pharmacologic treatments (predominately selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) can induce mania in patients who actually have unrecognized bipolar disorder.9

Continue to: Suicide...

Suicide

Suicide is the 10th leading cause of death among the general population. All demographic groups are impacted by suicide; however, the most vulnerable are men ages 45 to 64 years.10 Given the imminent risk to individuals who experience suicidal ideation, properly assessing and targeting suicidal risk is paramount.

The Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) can be completed in an interview format or as a patient self-report. Versions of the C-SSRS are available for children, adolescents, and adults. It can be used in practice with any patient who may be at risk for suicide. Specifically, consider using the C-SSRS when a patient scores 1 or greater on the PHQ-9 or when risk is revealed with another brief screening tool that includes suicidal ideation.

The C-SSRS covers 10 categories related to suicidal ideation and behavior that the clinician explores with questions requiring only Yes/No responses. The C-SSRS demonstrates moderate-to-strong internal consistency and reliability, and it has shown a high degree of sensitivity (95%) and specificity (95%) for suicidal ideation.11

Anxiety and physiologic arousal

Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) is one of the most common anxiety disorders, with an estimated prevalence of 2.8% to 8.5% among primary care patients.12 Brief, validated screening tools such as the Generalized Anxiety Disorder–7 item (GAD-7) scale can be effective in identifying anxiety and other related disorders in primary care settings.

The GAD-7 comprises 7 items inquiring about symptoms experienced in the past 2 weeks. Scores range from 0 to 21, with cutoffs of 5, 10, and 15 indicating mild, moderate, and severe anxiety, respectively. This questionnaire is appropriate for use with adults and has strong specificity, internal consistency, and test-retest reliability.12 Specificity and sensitivity of the GAD-7 are maximized at a cutoff score of 10 or greater, both exceeding 80%.12 The GAD-7 can be used when patients report symptoms of anxiety or when one needs to screen for anxiety with new patients or more clearly understand symptoms among patients who have complex mental health concerns.

The Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders (SCARED) is a 41-item self-report measure of anxiety for children ages 8 to 18. The SCARED questionnaire yields an overall anxiety score, as well as subscales for panic disorder or significant somatic symptoms, generalized anxiety disorder, separation anxiety, social anxiety disorder, and significant school avoidance.13 There is also a 5-item version of the SCARED, which can be useful for brief screening in fast-paced settings when no anxiety disorder is suspected, or for children who may have anxiety but exhibit reduced verbal capacity. The SCARED has been found to have moderate sensitivity (81.8%) and specificity (52%) for diagnosing anxiety disorders in a community sample, with an optimal cutoff point of 22 on the total scale.14

Sleep

Sleep concerns are common, with the prevalence of insomnia among adults in the United States estimated to be 19.2%.15 The importance of assessing these concerns cannot be overstated, and primary care providers are the ones patients consult most often.16 The gold standard in assessing sleep disorders is a structured clinical interview, polysomnography, sleep diary, and actigraphy (home-based monitoring of movement through a device, often worn on the wrist).17,18 However, this work-up is expensive, time-intensive, and impractical in integrated care settings; thus the need for a brief, self-report screening tool to guide further assessment and intervention.

The Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) assesses patients’ perceptions of their insomnia. The ISI was developed to aid both in the clinical evaluation of patients with insomnia and to measure treatment outcomes. Administration of the ISI takes approximately 5 minutes, and scoring takes less than 1 minute.

The ISI is composed of 7 items that measure the severity of sleep onset and sleep maintenance difficulties, satisfaction with current sleep, impact on daily functioning, impairment observable to others, and degree of distress caused by the sleep problems. Each item is scored on a 0 to 4 Likert-type scale, and the individual items are summed for a total score of 0 to 28, with higher scores suggesting more severe insomnia. Evidence-based guidelines recommend cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) as the first-line treatment for adults with primary insomnia.19

Several validation studies have found the ISI to be a reliable measure of perceived insomnia severity, and one that is sensitive to changes in patients’ perceptions of treatment outcomes.20,21 An additional validation study confirmed that in primary care settings, a cutoff score of 14 should be used to indicate the likely presence of clinical insomnia22 and to guide further assessment and intervention.

The percentage of insomniac patients correctly identified with the ISI was 82.2%, with moderate sensitivity (82.4%) and specificity (82.1%).22 A positive predictive value of 70% was found, meaning that an insomnia disorder is probable when the ISI total score is 14 or higher; conversely, the negative predictive value was 90.2%.

Continue to: Substance use and pain...

Substance use and pain

The evaluation of alcohol and drug use is an integral part of assessing risky health behaviors. The 10-item Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT) is a self-report tool developed by the World Health Organization.23,24 Validated in medical settings, scores of 8 or higher suggest problematic drinking.25,26 The AUDIT has demonstrated high specificity (94%) and moderate sensitivity (81%) in primary care settings.27 The AUDIT-C (items 1, 2, and 3 of the AUDIT) has also demonstrated comparable sensitivity, although slightly lower specificity, than the full AUDIT, suggesting that this 3-question screen can also be used in primary care settings.27

Opioid medications, frequently prescribed for chronic pain, present serious risks for many patients. The Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain–Revised (SOAPP-R) is a 24-item self-reporting scale that can be completed in approximately 10 minutes.28 A score of 18 or higher has identified 81% of patients at high risk for opioid misuse in a clinical setting, with moderate specificity (68%). Although other factors should be considered when assessing risk of opioid misuse, the SOAPP-R is a helpful and quick addition to an opioid risk assessment.

The CRAFFT Screening Tool for Adolescent Substance Use is administered by the clinician for youths ages 14 to 21. The first 3 questions ask about use of alcohol, marijuana, or other substances during the past 12 months. What follows are questions related to the young person’s specific experiences with substances in relation to Cars, Relaxation, being Alone, Forgetting, Family/Friends, and Trouble (CRAFFT). The CRAFFT has shown moderate sensitivity (76%) and good specificity (94%) for identifying any problem with substance use.29 These measures may be administered to clarify or confirm substance use patterns (ie, duration, frequency), or to determine the severity of problems related to substance use (ie, social or legal problems).

Trauma and PTSD

Approximately 7.7 million adults per year will experience posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms, although PTSD can affect individuals of any age.30 Given the impact that trauma can have, assess for PTSD in patients who have a history of trauma or who otherwise seem to be at risk. The Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist (PCL-5) is a 20-item self-report questionnaire that screens for symptoms directly from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5) criteria for PTSD. One limitation is that the questionnaire is only validated for adults ages 18 years or older. Completion of the PCL-5 takes 5 to 10 minutes. The PCL-5 has strong internal consistency reliability (94%) and test-retest reliability (82%).31 With a cutoff score of 33 or higher, the sensitivity and specificity have been shown to be moderately high (74.5% and 70.6%, respectively).32

The Child and Adolescent Trauma Screen (CATS) is used to assess for potentially traumatic events and PTSD symptoms in children and adolescents. These symptoms are based on the DSM-5, and therefore the CATS can act as a useful diagnostic aid. The CATS is also available in Spanish, with both caregiver-report (for children ages 3-6 years or 7-17 years) and self-report (for ages 7-17 years) versions. Practical use of the PCL-5 and the CATS involves screening for PTSD symptoms, supporting a provisional diagnosis of PTSD, and monitoring PTSD symptom changes during and after treatment.

Memory and cognition

Cognitive screening is a first step in evaluating possible dementia and other neuropsychological disorders. The importance of brief cognitive screening in primary care cannot be understated, especially for an aging patient population. Although the Mini Mental Status Exam (MMSE) has been widely used among health care providers and researchers, we recommend the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA).

The MoCA is a simple, standalone cognitive screening tool validated for adults ages 55 to 85 years.33 The MoCA addresses many important cognitive domains, fits on one page, and can be administered by a trained provider in 10 minutes. Research also suggests that it has strong test-retest reliability and positive and negative predictive values for mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer dementia, and it has been found to be more sensitive than the MMSE.34 We additionally recommend the MoCA as it measures several cognitive skills that are not addressed on the MMSE, including verbal fluency and abstraction.34 Scores below 25 are suggestive of cognitive impairment and should lead to a referral for neuropsychological testing.

The MoCA’s sensitivity for detecting cognitive impairment is high (94%), and specificity is low (42%).35 To ensure consistency and accuracy in administering the MoCA, certification is now required via an online training program through www.mocatest.org.

Adapting these screening tools to practice

These tools are not meant to be used at every appointment. Every practice is different, and each clinic or physician can tailor the use of these screening tools to the needs of the patient population, as concerns arise, or in collaboration with other providers. Additionally, these screening tools can be used in both integrated care and in private practice, to prompt a more thorough assessment or to aid in—and inform—treatment. Although some physicians choose to administer certain screening tools at each clinic visit, knowing about the availability of other tools can be useful in assessing various issues. The FIGURE can be used to aid in the clinical decision-making process.

Many screening tools are available in the public domain to assess a variety of symptoms related to impaired mental health. These tools can be used to quickly evaluate for mood, suicidal ideation or behavior, anxiety, sleep, substance use, pain, trauma, memory, and cognition (TABLE). Individuals with poor mental health incur high health care costs. Those suffering from anxiety and posttraumatic stress have more outpatient and emergency department visits and hospitalizations than patients without these disorders,1,2 although use of mental health care services has been related to a decrease in the overutilization of health care services in general.3

Here we review several screening tools that can help you to identify symptoms of mental illnesses and thus, provide prompt early intervention, including referrals to psychological and psychiatric services.

Mood disorders

Most patients with mood disorders are treated in primary care settings.4 Quickly measuring patients’ mood symptoms can expedite treatment for those who need it. Many primary care clinics use the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) to screen for depression.5 The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) has recommended screening for depression with adequate systems to ensure accurate diagnoses, effective treatment, and follow-up. Although the USPSTF did not specially endorse screening for bipolar disorder, it followed that recommendation with the qualifying statement, “positive screening results [for depression] should lead to additional assessment that considers severity of depression and comorbid psychological problems, alternate diagnoses, and medical conditions.”6 Thus, following a positive screen result for depression, consider using a screening tool for mood disorders to provide diagnostic clarification.

The Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ) is a validated 15-item, self-administered questionnaire that takes only 5 minutes to use in screening adult patients for bipolar I disorder.7 The MDQ assesses specific behaviors related to bipolar disorder, symptom co-occurrence, and functional impairment. The MDQ has low sensitivity (58%) but good specificity (93%) in a primary care setting.8 However, the MDQ is not a diagnostic instrument. A positive screen result should prompt a more thorough clinical evaluation, if necessary, by a professional trained in psychiatric disorders.

We recommend completing the MDQ prior to prescribing antidepressants. You can also monitor a patient’s response to treatment with serial MDQ testing. The MDQ is useful, too, when a patient has unclear mood symptoms that may have features overlapping with bipolar disorder. Furthermore, we recommend screening for bipolar disorder with every patient who reports symptoms of depression, given that some pharmacologic treatments (predominately selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) can induce mania in patients who actually have unrecognized bipolar disorder.9

Continue to: Suicide...

Suicide

Suicide is the 10th leading cause of death among the general population. All demographic groups are impacted by suicide; however, the most vulnerable are men ages 45 to 64 years.10 Given the imminent risk to individuals who experience suicidal ideation, properly assessing and targeting suicidal risk is paramount.

The Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) can be completed in an interview format or as a patient self-report. Versions of the C-SSRS are available for children, adolescents, and adults. It can be used in practice with any patient who may be at risk for suicide. Specifically, consider using the C-SSRS when a patient scores 1 or greater on the PHQ-9 or when risk is revealed with another brief screening tool that includes suicidal ideation.

The C-SSRS covers 10 categories related to suicidal ideation and behavior that the clinician explores with questions requiring only Yes/No responses. The C-SSRS demonstrates moderate-to-strong internal consistency and reliability, and it has shown a high degree of sensitivity (95%) and specificity (95%) for suicidal ideation.11

Anxiety and physiologic arousal

Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) is one of the most common anxiety disorders, with an estimated prevalence of 2.8% to 8.5% among primary care patients.12 Brief, validated screening tools such as the Generalized Anxiety Disorder–7 item (GAD-7) scale can be effective in identifying anxiety and other related disorders in primary care settings.

The GAD-7 comprises 7 items inquiring about symptoms experienced in the past 2 weeks. Scores range from 0 to 21, with cutoffs of 5, 10, and 15 indicating mild, moderate, and severe anxiety, respectively. This questionnaire is appropriate for use with adults and has strong specificity, internal consistency, and test-retest reliability.12 Specificity and sensitivity of the GAD-7 are maximized at a cutoff score of 10 or greater, both exceeding 80%.12 The GAD-7 can be used when patients report symptoms of anxiety or when one needs to screen for anxiety with new patients or more clearly understand symptoms among patients who have complex mental health concerns.

The Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders (SCARED) is a 41-item self-report measure of anxiety for children ages 8 to 18. The SCARED questionnaire yields an overall anxiety score, as well as subscales for panic disorder or significant somatic symptoms, generalized anxiety disorder, separation anxiety, social anxiety disorder, and significant school avoidance.13 There is also a 5-item version of the SCARED, which can be useful for brief screening in fast-paced settings when no anxiety disorder is suspected, or for children who may have anxiety but exhibit reduced verbal capacity. The SCARED has been found to have moderate sensitivity (81.8%) and specificity (52%) for diagnosing anxiety disorders in a community sample, with an optimal cutoff point of 22 on the total scale.14

Sleep

Sleep concerns are common, with the prevalence of insomnia among adults in the United States estimated to be 19.2%.15 The importance of assessing these concerns cannot be overstated, and primary care providers are the ones patients consult most often.16 The gold standard in assessing sleep disorders is a structured clinical interview, polysomnography, sleep diary, and actigraphy (home-based monitoring of movement through a device, often worn on the wrist).17,18 However, this work-up is expensive, time-intensive, and impractical in integrated care settings; thus the need for a brief, self-report screening tool to guide further assessment and intervention.

The Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) assesses patients’ perceptions of their insomnia. The ISI was developed to aid both in the clinical evaluation of patients with insomnia and to measure treatment outcomes. Administration of the ISI takes approximately 5 minutes, and scoring takes less than 1 minute.

The ISI is composed of 7 items that measure the severity of sleep onset and sleep maintenance difficulties, satisfaction with current sleep, impact on daily functioning, impairment observable to others, and degree of distress caused by the sleep problems. Each item is scored on a 0 to 4 Likert-type scale, and the individual items are summed for a total score of 0 to 28, with higher scores suggesting more severe insomnia. Evidence-based guidelines recommend cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) as the first-line treatment for adults with primary insomnia.19

Several validation studies have found the ISI to be a reliable measure of perceived insomnia severity, and one that is sensitive to changes in patients’ perceptions of treatment outcomes.20,21 An additional validation study confirmed that in primary care settings, a cutoff score of 14 should be used to indicate the likely presence of clinical insomnia22 and to guide further assessment and intervention.

The percentage of insomniac patients correctly identified with the ISI was 82.2%, with moderate sensitivity (82.4%) and specificity (82.1%).22 A positive predictive value of 70% was found, meaning that an insomnia disorder is probable when the ISI total score is 14 or higher; conversely, the negative predictive value was 90.2%.

Continue to: Substance use and pain...

Substance use and pain

The evaluation of alcohol and drug use is an integral part of assessing risky health behaviors. The 10-item Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT) is a self-report tool developed by the World Health Organization.23,24 Validated in medical settings, scores of 8 or higher suggest problematic drinking.25,26 The AUDIT has demonstrated high specificity (94%) and moderate sensitivity (81%) in primary care settings.27 The AUDIT-C (items 1, 2, and 3 of the AUDIT) has also demonstrated comparable sensitivity, although slightly lower specificity, than the full AUDIT, suggesting that this 3-question screen can also be used in primary care settings.27

Opioid medications, frequently prescribed for chronic pain, present serious risks for many patients. The Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain–Revised (SOAPP-R) is a 24-item self-reporting scale that can be completed in approximately 10 minutes.28 A score of 18 or higher has identified 81% of patients at high risk for opioid misuse in a clinical setting, with moderate specificity (68%). Although other factors should be considered when assessing risk of opioid misuse, the SOAPP-R is a helpful and quick addition to an opioid risk assessment.

The CRAFFT Screening Tool for Adolescent Substance Use is administered by the clinician for youths ages 14 to 21. The first 3 questions ask about use of alcohol, marijuana, or other substances during the past 12 months. What follows are questions related to the young person’s specific experiences with substances in relation to Cars, Relaxation, being Alone, Forgetting, Family/Friends, and Trouble (CRAFFT). The CRAFFT has shown moderate sensitivity (76%) and good specificity (94%) for identifying any problem with substance use.29 These measures may be administered to clarify or confirm substance use patterns (ie, duration, frequency), or to determine the severity of problems related to substance use (ie, social or legal problems).

Trauma and PTSD

Approximately 7.7 million adults per year will experience posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms, although PTSD can affect individuals of any age.30 Given the impact that trauma can have, assess for PTSD in patients who have a history of trauma or who otherwise seem to be at risk. The Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist (PCL-5) is a 20-item self-report questionnaire that screens for symptoms directly from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5) criteria for PTSD. One limitation is that the questionnaire is only validated for adults ages 18 years or older. Completion of the PCL-5 takes 5 to 10 minutes. The PCL-5 has strong internal consistency reliability (94%) and test-retest reliability (82%).31 With a cutoff score of 33 or higher, the sensitivity and specificity have been shown to be moderately high (74.5% and 70.6%, respectively).32

The Child and Adolescent Trauma Screen (CATS) is used to assess for potentially traumatic events and PTSD symptoms in children and adolescents. These symptoms are based on the DSM-5, and therefore the CATS can act as a useful diagnostic aid. The CATS is also available in Spanish, with both caregiver-report (for children ages 3-6 years or 7-17 years) and self-report (for ages 7-17 years) versions. Practical use of the PCL-5 and the CATS involves screening for PTSD symptoms, supporting a provisional diagnosis of PTSD, and monitoring PTSD symptom changes during and after treatment.

Memory and cognition

Cognitive screening is a first step in evaluating possible dementia and other neuropsychological disorders. The importance of brief cognitive screening in primary care cannot be understated, especially for an aging patient population. Although the Mini Mental Status Exam (MMSE) has been widely used among health care providers and researchers, we recommend the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA).

The MoCA is a simple, standalone cognitive screening tool validated for adults ages 55 to 85 years.33 The MoCA addresses many important cognitive domains, fits on one page, and can be administered by a trained provider in 10 minutes. Research also suggests that it has strong test-retest reliability and positive and negative predictive values for mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer dementia, and it has been found to be more sensitive than the MMSE.34 We additionally recommend the MoCA as it measures several cognitive skills that are not addressed on the MMSE, including verbal fluency and abstraction.34 Scores below 25 are suggestive of cognitive impairment and should lead to a referral for neuropsychological testing.

The MoCA’s sensitivity for detecting cognitive impairment is high (94%), and specificity is low (42%).35 To ensure consistency and accuracy in administering the MoCA, certification is now required via an online training program through www.mocatest.org.

Adapting these screening tools to practice

These tools are not meant to be used at every appointment. Every practice is different, and each clinic or physician can tailor the use of these screening tools to the needs of the patient population, as concerns arise, or in collaboration with other providers. Additionally, these screening tools can be used in both integrated care and in private practice, to prompt a more thorough assessment or to aid in—and inform—treatment. Although some physicians choose to administer certain screening tools at each clinic visit, knowing about the availability of other tools can be useful in assessing various issues. The FIGURE can be used to aid in the clinical decision-making process.

- Robinson RL, Grabner M, Palli SR, et al. Covariates of depression and high utilizers of healthcare: impact on resource use and costs. J Psychosom Res. 2016,85:35-43.

- Fogarty CT, Sharma S, Chetty VK, et al. Mental health conditions are associated with increased health care utilization among urban family medicine patients. J Am Board Fam Med. 2008,21:398-407.

- Weissman JD, Russell D, Beasley J, et al. Relationships between adult emotional states and indicators of health care utilization: findings from the National Health Interview Survey 2006–2014. J Psychosom Res. 2016,91:75-81.

- Haddad M, Walters P. Mood disorders in primary care. Psychiatry. 2009,8:71-75.

- Mitchell AJ, Yadegarfar M, Gill J, et al. Case finding and screening clinical utility of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9 and PHQ-2) for depression in primary care: a diagnostic metaanalysis of 40 studies. BJPsych Open. 2016,2:127-138.

- Siu AL and US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for depression in adults. JAMA. 2016;315:380-387.

- Hirschfeld RM, Williams JB, Spitzer RL, et al. Development and validation of a screening instrument for bipolar spectrum disorder: the Mood Disorder Questionnaire. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1873-1875.

- Hirschfeld RM, Cass AR, Holt DC, et al. Screening for bipolar disorder in patients treated for depression in a family medicine clinic. J Am Board Fam Med. 2005;18:233-239.

- Das AK, Olfson M, Gameroff MJ, et al. Screening for bipolar disorder in a primary care practice. JAMA. 2005;293:956-963.

- CDC. Suicide mortality in the United States, 1999-2017. www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db330.htm. Accessed October 23, 2020.

- Viguera AC, Milano N, Ralston L, et al. Comparison of electronic screening for suicidal risk with Patient Health Questionnaire Item 9 and the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale in an outpatient psychiatric clinic. Psychosomatics. 2015;56:460-469.

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092-1097.

- Birmaher B, Khetarpal S, Brent D, et al. The Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED): scale construction and psychometric characteristics. J Am Acad Chil Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:545-553.

- DeSousa DA, Salum GA, Isolan LR, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED): a community-based study. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2013;44:391-399.

- Ford ES, Cunningham TJ, Giles WH, et al. Trends in insomnia and excessive daytime sleepiness among U.S. adults from 2002 to 2012. Sleep Med. 2015;16:372-378.

- Morin CM, LeBlanc M, Daley M, et al. Epidemiology of insomnia: prevalence, self-help treatments, consultations, and determinants of help-seeking behaviors. Sleep Med. 2006;7:123-130.

- Buysse DJ, Ancoli-Israel S, Edinger JD, et al. Recommendations for a standard research assessment of insomnia. Sleep. 2006;29:1155-1173.

- Martin JL, Hakim AD. Wrist actigraphy. Chest. 2011;139:1514-1527.

- Riemann D, Baglioni C, Bassetti C, et al. European guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of insomnia. J Sleep Res. 2017;26:675-700.

- Bastien CH, Vallières A, Morin CM. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med. 2001;2:297-307.

- Wong ML, Lau KNT, Espie CA, et al. Psychometric properties of the Sleep Condition Indicator and Insomnia Severity Index in the evaluation of insomnia disorder. Sleep Med. 2017;33:76-81.

- Gagnon C, Bélanger L, Ivers H, et al. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index in primary care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2013;26:701-710.

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, et al. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO Collaborative Project on Early Detection of Persons with Harmful Alcohol Consumption. Addiction. 1993;88:791-804.

- Selin KH. Test-retest reliability of the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test in a general population sample. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:1428-1435.

- Bohn MJ, Babor TF, Kranzler HR. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): validation of a screening instrument for use in medical settings. J Stud Alcohol. 1995;56:423-432.

- Conigrave KM, Hall WD, Saunders JB. The AUDIT questionnaire: choosing a cut-off score. Addiction. 1995;90:1349-1356.

- Gomez A, Conde A, Santana JM, et al. Diagnostic usefulness of brief versions of Alcohol Use Identification Test (AUDIT) for detecting hazardous drinkers in primary care settings. J Stud Alcohol. 2005;66:305-308.

- Butler SF, Fernandez K, Benoit C, et al. Validation of the revised Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain (SOAPPR). J Pain. 2008;9:360-372.

- Knight JR, Sherritt L, Shrier LA, et al. Validity of the CRAFFT substance abuse screening test among adolescent clinic patients. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:607-614.

- DHHS. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). https://archives.nih.gov/asites/report/09-09-2019/report.nih.gov/nihfactsheets/ViewFactSheetfdf8.html?csid=58&key=P#P. Accessed October 23,2020.

- Blevins CA, Weathers FW, Davis MT, et al. The Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): development and initial psychometric evaluation. J Trauma Stress. 2015;28:489-498.

- Verhey R, Chilbanda D, Gibson L, et al. Validation of the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist- 5 (PCL-5) in a primary care population with high HIV prevalence in Zimbabwe. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18:109.

- Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:695-699.

- Stewart S, O’Riley A, Edelstein B, et al. A preliminary comparison of three cognitive screening instruments in long term care: the MMSE, SLUMS, and MoCA. Clin Gerontol. 2012;35:57-75.

- Godefroy O, Fickl A, Roussel M, et al. Is the Montreal Cognitive Assessment superior to the Mini-Mental State Examination to detect poststroke cognitive impairment? A study with neuropsychological evaluation. Stroke. 2011;42:1712-1716.

- Robinson RL, Grabner M, Palli SR, et al. Covariates of depression and high utilizers of healthcare: impact on resource use and costs. J Psychosom Res. 2016,85:35-43.

- Fogarty CT, Sharma S, Chetty VK, et al. Mental health conditions are associated with increased health care utilization among urban family medicine patients. J Am Board Fam Med. 2008,21:398-407.

- Weissman JD, Russell D, Beasley J, et al. Relationships between adult emotional states and indicators of health care utilization: findings from the National Health Interview Survey 2006–2014. J Psychosom Res. 2016,91:75-81.

- Haddad M, Walters P. Mood disorders in primary care. Psychiatry. 2009,8:71-75.

- Mitchell AJ, Yadegarfar M, Gill J, et al. Case finding and screening clinical utility of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9 and PHQ-2) for depression in primary care: a diagnostic metaanalysis of 40 studies. BJPsych Open. 2016,2:127-138.

- Siu AL and US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for depression in adults. JAMA. 2016;315:380-387.

- Hirschfeld RM, Williams JB, Spitzer RL, et al. Development and validation of a screening instrument for bipolar spectrum disorder: the Mood Disorder Questionnaire. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1873-1875.

- Hirschfeld RM, Cass AR, Holt DC, et al. Screening for bipolar disorder in patients treated for depression in a family medicine clinic. J Am Board Fam Med. 2005;18:233-239.

- Das AK, Olfson M, Gameroff MJ, et al. Screening for bipolar disorder in a primary care practice. JAMA. 2005;293:956-963.

- CDC. Suicide mortality in the United States, 1999-2017. www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db330.htm. Accessed October 23, 2020.

- Viguera AC, Milano N, Ralston L, et al. Comparison of electronic screening for suicidal risk with Patient Health Questionnaire Item 9 and the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale in an outpatient psychiatric clinic. Psychosomatics. 2015;56:460-469.

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092-1097.

- Birmaher B, Khetarpal S, Brent D, et al. The Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED): scale construction and psychometric characteristics. J Am Acad Chil Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:545-553.

- DeSousa DA, Salum GA, Isolan LR, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED): a community-based study. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2013;44:391-399.

- Ford ES, Cunningham TJ, Giles WH, et al. Trends in insomnia and excessive daytime sleepiness among U.S. adults from 2002 to 2012. Sleep Med. 2015;16:372-378.

- Morin CM, LeBlanc M, Daley M, et al. Epidemiology of insomnia: prevalence, self-help treatments, consultations, and determinants of help-seeking behaviors. Sleep Med. 2006;7:123-130.

- Buysse DJ, Ancoli-Israel S, Edinger JD, et al. Recommendations for a standard research assessment of insomnia. Sleep. 2006;29:1155-1173.

- Martin JL, Hakim AD. Wrist actigraphy. Chest. 2011;139:1514-1527.

- Riemann D, Baglioni C, Bassetti C, et al. European guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of insomnia. J Sleep Res. 2017;26:675-700.

- Bastien CH, Vallières A, Morin CM. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med. 2001;2:297-307.

- Wong ML, Lau KNT, Espie CA, et al. Psychometric properties of the Sleep Condition Indicator and Insomnia Severity Index in the evaluation of insomnia disorder. Sleep Med. 2017;33:76-81.

- Gagnon C, Bélanger L, Ivers H, et al. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index in primary care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2013;26:701-710.

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, et al. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO Collaborative Project on Early Detection of Persons with Harmful Alcohol Consumption. Addiction. 1993;88:791-804.

- Selin KH. Test-retest reliability of the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test in a general population sample. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:1428-1435.

- Bohn MJ, Babor TF, Kranzler HR. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): validation of a screening instrument for use in medical settings. J Stud Alcohol. 1995;56:423-432.

- Conigrave KM, Hall WD, Saunders JB. The AUDIT questionnaire: choosing a cut-off score. Addiction. 1995;90:1349-1356.

- Gomez A, Conde A, Santana JM, et al. Diagnostic usefulness of brief versions of Alcohol Use Identification Test (AUDIT) for detecting hazardous drinkers in primary care settings. J Stud Alcohol. 2005;66:305-308.

- Butler SF, Fernandez K, Benoit C, et al. Validation of the revised Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain (SOAPPR). J Pain. 2008;9:360-372.

- Knight JR, Sherritt L, Shrier LA, et al. Validity of the CRAFFT substance abuse screening test among adolescent clinic patients. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:607-614.

- DHHS. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). https://archives.nih.gov/asites/report/09-09-2019/report.nih.gov/nihfactsheets/ViewFactSheetfdf8.html?csid=58&key=P#P. Accessed October 23,2020.

- Blevins CA, Weathers FW, Davis MT, et al. The Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): development and initial psychometric evaluation. J Trauma Stress. 2015;28:489-498.

- Verhey R, Chilbanda D, Gibson L, et al. Validation of the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist- 5 (PCL-5) in a primary care population with high HIV prevalence in Zimbabwe. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18:109.

- Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:695-699.

- Stewart S, O’Riley A, Edelstein B, et al. A preliminary comparison of three cognitive screening instruments in long term care: the MMSE, SLUMS, and MoCA. Clin Gerontol. 2012;35:57-75.

- Godefroy O, Fickl A, Roussel M, et al. Is the Montreal Cognitive Assessment superior to the Mini-Mental State Examination to detect poststroke cognitive impairment? A study with neuropsychological evaluation. Stroke. 2011;42:1712-1716.

Hidden Basal Cell Carcinoma in the Intergluteal Crease

Practice Gap

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common cancer, and its incidence is on the rise.1 The risk of this skin cancer is increased when there is a history of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) or BCC.2 Basal cell carcinoma often is found in sun-exposed areas, most commonly due to a history of intense sunburn.3 Other risk factors include male gender and increased age.4

Eighty percent to 85% of BCCs present on the head and neck5; however, BCC also can occur in unusual locations. When BCC presents in areas such as the perianal region, it is found to be larger than when found in more common areas,6 likely because neoplasms in this sensitive area often are overlooked. Literature on BCC of the intergluteal crease is limited.7 Being educated on the existence of BCC in this sensitive area can aid proper diagnosis.

The Technique and Case