User login

Widespread Hyperkeratotic Papules in a Transplant Recipient

The Diagnosis: Trichodysplasia Spinulosa

Trichodysplasia spinulosa has been described in case reports over the last several decades, with its causative virus trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus (TSPyV) identified in 2010 by van der Meijden et al.1 Trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus is a small, nonenveloped, double-stranded DNA virus in the Polyomaviridae family, among several other known cutaneous polyomaviruses including Merkel cell polyomavirus, human polyomavirus (HPyV) 6, HPyV7, HPyV10, and possibly HPyV13.2 The primary target of TSPyV is follicular keratinocytes, and it is believed to cause trichodysplasia spinulosa by primary infection rather than by reactivation. Trichodysplasia spinulosa presents in immunosuppressed patients as a folliculocentric eruption of papules with keratinous spines on the face, often with concurrent alopecia, eventually spreading to the trunk and extremities.3 The diagnosis often is clinical, but a biopsy may be performed for histopathologic confirmation. Alternatively, lesional spicules can be painlessly collected manually and submitted for viral polymerase chain reaction (PCR).4 The diagnosis of trichodysplasia spinulosa can be difficult due to similarities with other more common conditions such as keratosis pilaris, milia, filiform warts, or lichen spinulosus.

Similar to trichodysplasia spinulosa, keratosis pilaris also presents with folliculocentric and often erythematous papules.5 Keratosis pilaris most frequently affects the posterior upper arms and thighs but also may affect the cheeks, as seen in trichodysplasia spinulosa. Differentiation between the 2 diagnoses can be made on a clinical basis, as keratosis pilaris lacks the characteristic keratinous spines and often spares the central face and nose, locations that commonly are affected in trichodysplasia spinulosa.3

Milia typically appear as white to yellow papules, often on the cheeks, eyelids, nose, and chin.6 Given their predilection for the face, milia can appear similarly to trichodysplasia spinulosa. Differentiation can be made clinically, as milia typically are not as numerous as the spiculed papules seen in trichodysplasia spinulosa. Morphologically, milia will present as smooth, dome-shaped papules as opposed to the keratinous spicules seen in trichodysplasia spinulosa. The diagnosis of milia can be confirmed by incision and removal of the white chalky keratin core, a feature absent in trichodysplasia spinulosa.

Filiform warts are benign epidermal proliferations caused by human papillomavirus infection that manifest as flesh-colored, verrucous, hyperkeratotic papules.7 They can appear on virtually any skin surface, including the face, and thus may be mistaken for trichodysplasia spinulosa. Close inspection usually will reveal tiny black dots that represent thrombosed capillaries, a feature lacking in trichodysplasia spinulosa. In long-standing lesions or immunocompromised patients, confluent verrucous plaques may develop.8 Diagnosis of filiform warts can be confirmed with biopsy, which will demonstrate a compact stratum corneum, coarse hypergranulosis, and papillomatosis curving inward, while biopsy of a trichodysplasia spinulosa lesion would show polyomavirus infection of the hair follicle and characteristic eosinophilic inclusion bodies.9

Lichen spinulosus may appear as multiple folliculocentric scaly papules with hairlike horny spines.10 Lichen spinulosus differs from trichodysplasia spinulosa in that it commonly appears on the neck, abdomen, trochanteric region, arms, elbows, or knees. Lichen spinulosus also classically appears as a concrete cluster of papules, often localized to a certain region, in contrast to trichodysplasia spinulosa, which will be widespread, often spreading over time. Finally, clinical history may help differentiate the 2 entities. Lichen spinulosus most often appears in children and adolescents and often has an indolent course, typically resolving during puberty, while trichodysplasia spinulosa is seen in immunocompromised patients.

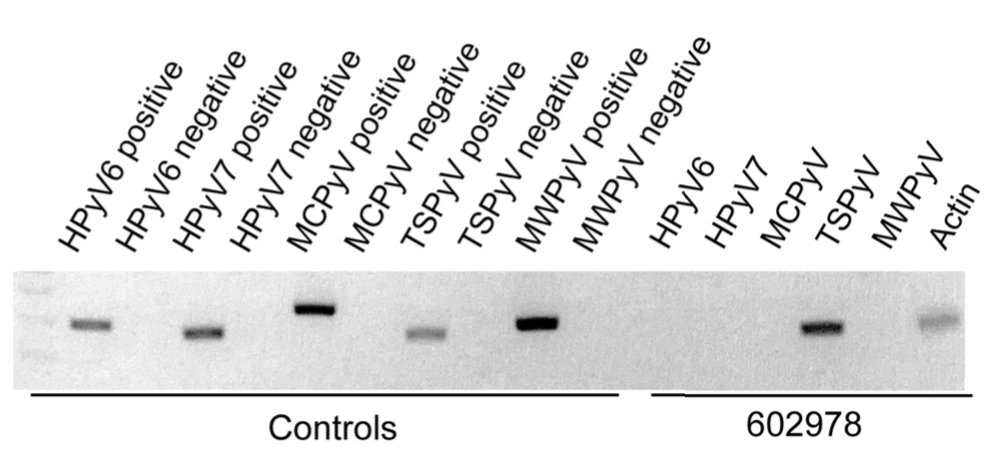

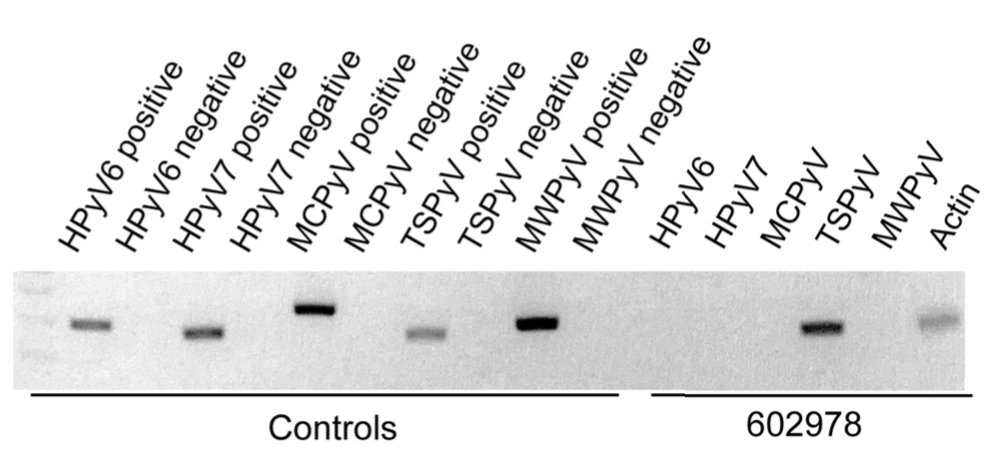

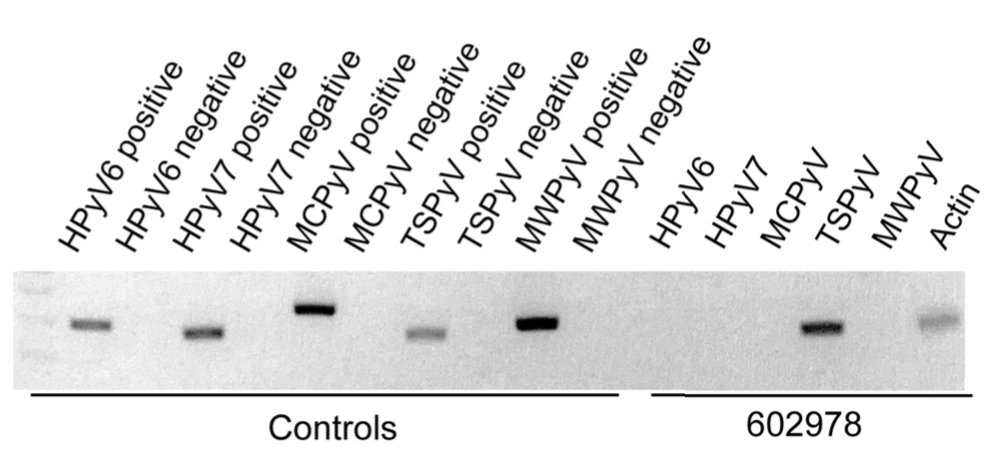

In our patient, the dermatology team made a diagnosis of trichodysplasia spinulosa based on the characteristic clinical presentation, which was confirmed after approximately 10 lesional spicules were removed by tissue forceps and submitted for PCR analysis showing TSPyV (Figure). Two other cases utilized spicule PCR analysis for confirmation of TSPyV.11,12 This technique may represent a viable option for diagnostic confirmation in pediatric cases.

Although some articles have examined the molecular and biologic features of trichodysplasia spinulosa, literature on clinical presentation and management is limited to isolated case reports with no comprehensive studies to establish a standardized treatment. Of these reports, oral valganciclovir 900 mg daily, topical retinoids, cidofovir cream 1% to 3%, and decreasing or altering the immunosuppressive regimen all have been noted to provide clinical improvement.13,14 Other therapies including leflunomide and routine manual extraction of spicules also have shown effectiveness in the treatment of trichodysplasia spinulosa.15

In our patient, treatment included decreasing immunosuppression, as she was getting recurrent sinus and upper respiratory infections. Mycophenolate mofetil was discontinued, and the patient was continued solely on tacrolimus therapy. She demonstrated notable improvement after 3 months, with approximately 50% clearance of the eruption. A mutual decision was made at that visit to initiate therapy with compounded cidofovir cream 1% daily to the lesions until the next follow-up visit. Unfortunately, the patient did not return for her scheduled dermatology visits and was lost to long-term follow-up.

Acknowledgment

We thank Richard C. Wang, MD, PhD (Dallas, Texas), for his dermatologic expertise and assistance in analysis of lesional samples for TSPyV.

- van der Meijden E, Janssens RWA, Lauber C, et al. Discovery of a new human polyomavirus associated with trichodysplasia spinulosa in an immunocompromised patient. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:E1001024.

- Sheu JC, Tran J, Rady PL, et al. Polyomaviruses of the skin: integrating molecular and clinical advances in an emerging class of viruses. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:1302-1311.

- Sperling LC, Tomaszewski MM, Thomas DA. Viral-associated trichodysplasia in patients who are immunocompromised. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:318-322.

- Wu JH, Nguyen HP, Rady PL, et al. Molecular insight into the viral biology and clinical features of trichodysplasia spinulosa. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174:490-498.

- Hwang S, Schwartz RA. Keratosis pilaris: a common follicular hyperkeratosis. Cutis. 2008;82:177-180.

- Berk DR, Bayliss SJ. Milia: a review and classification. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:1050-1063.

- Micali G, Dall'Oglio F, Nasca MR, et al. Management of cutaneous warts: an evidence-based approach. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2004;5:311-317.

- Bolognia J, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018.

- Elston DM, Ferringer T, Ko CJ. Dermatopathology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2018.

- Tilly JJ, Drolet BA, Esterly NB. Lichenoid eruptions in children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:606-624.

- Chamseddin BH, Tran BAPD, Lee EE, et al. Trichodysplasia spinulosa in a child: identification of trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus in skin, serum, and urine. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36:723-724.

- Sonstegard A, Grossman M, Garg A. Trichodysplasia spinulosa in a kidney transplant recipient. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:105.

- Leitenberger JJ, Abdelmalek M, Wang RC, et al. Two cases of trichodysplasia spinulosa responsive to compounded topical cidofovir 3% cream. JAAD Case Rep. 2015;1:S33-S35.

- DeCrescenzo AJ, Philips RC, Wilkerson MG. Trichodysplasia spinulosa: a rare complication of immunosuppression. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:307-309.

- Nguyen KD, Chamseddin BH, Cockerell CJ, et al. The biology and clinical features of cutaneous polyomaviruses. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139:285-292.

The Diagnosis: Trichodysplasia Spinulosa

Trichodysplasia spinulosa has been described in case reports over the last several decades, with its causative virus trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus (TSPyV) identified in 2010 by van der Meijden et al.1 Trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus is a small, nonenveloped, double-stranded DNA virus in the Polyomaviridae family, among several other known cutaneous polyomaviruses including Merkel cell polyomavirus, human polyomavirus (HPyV) 6, HPyV7, HPyV10, and possibly HPyV13.2 The primary target of TSPyV is follicular keratinocytes, and it is believed to cause trichodysplasia spinulosa by primary infection rather than by reactivation. Trichodysplasia spinulosa presents in immunosuppressed patients as a folliculocentric eruption of papules with keratinous spines on the face, often with concurrent alopecia, eventually spreading to the trunk and extremities.3 The diagnosis often is clinical, but a biopsy may be performed for histopathologic confirmation. Alternatively, lesional spicules can be painlessly collected manually and submitted for viral polymerase chain reaction (PCR).4 The diagnosis of trichodysplasia spinulosa can be difficult due to similarities with other more common conditions such as keratosis pilaris, milia, filiform warts, or lichen spinulosus.

Similar to trichodysplasia spinulosa, keratosis pilaris also presents with folliculocentric and often erythematous papules.5 Keratosis pilaris most frequently affects the posterior upper arms and thighs but also may affect the cheeks, as seen in trichodysplasia spinulosa. Differentiation between the 2 diagnoses can be made on a clinical basis, as keratosis pilaris lacks the characteristic keratinous spines and often spares the central face and nose, locations that commonly are affected in trichodysplasia spinulosa.3

Milia typically appear as white to yellow papules, often on the cheeks, eyelids, nose, and chin.6 Given their predilection for the face, milia can appear similarly to trichodysplasia spinulosa. Differentiation can be made clinically, as milia typically are not as numerous as the spiculed papules seen in trichodysplasia spinulosa. Morphologically, milia will present as smooth, dome-shaped papules as opposed to the keratinous spicules seen in trichodysplasia spinulosa. The diagnosis of milia can be confirmed by incision and removal of the white chalky keratin core, a feature absent in trichodysplasia spinulosa.

Filiform warts are benign epidermal proliferations caused by human papillomavirus infection that manifest as flesh-colored, verrucous, hyperkeratotic papules.7 They can appear on virtually any skin surface, including the face, and thus may be mistaken for trichodysplasia spinulosa. Close inspection usually will reveal tiny black dots that represent thrombosed capillaries, a feature lacking in trichodysplasia spinulosa. In long-standing lesions or immunocompromised patients, confluent verrucous plaques may develop.8 Diagnosis of filiform warts can be confirmed with biopsy, which will demonstrate a compact stratum corneum, coarse hypergranulosis, and papillomatosis curving inward, while biopsy of a trichodysplasia spinulosa lesion would show polyomavirus infection of the hair follicle and characteristic eosinophilic inclusion bodies.9

Lichen spinulosus may appear as multiple folliculocentric scaly papules with hairlike horny spines.10 Lichen spinulosus differs from trichodysplasia spinulosa in that it commonly appears on the neck, abdomen, trochanteric region, arms, elbows, or knees. Lichen spinulosus also classically appears as a concrete cluster of papules, often localized to a certain region, in contrast to trichodysplasia spinulosa, which will be widespread, often spreading over time. Finally, clinical history may help differentiate the 2 entities. Lichen spinulosus most often appears in children and adolescents and often has an indolent course, typically resolving during puberty, while trichodysplasia spinulosa is seen in immunocompromised patients.

In our patient, the dermatology team made a diagnosis of trichodysplasia spinulosa based on the characteristic clinical presentation, which was confirmed after approximately 10 lesional spicules were removed by tissue forceps and submitted for PCR analysis showing TSPyV (Figure). Two other cases utilized spicule PCR analysis for confirmation of TSPyV.11,12 This technique may represent a viable option for diagnostic confirmation in pediatric cases.

Although some articles have examined the molecular and biologic features of trichodysplasia spinulosa, literature on clinical presentation and management is limited to isolated case reports with no comprehensive studies to establish a standardized treatment. Of these reports, oral valganciclovir 900 mg daily, topical retinoids, cidofovir cream 1% to 3%, and decreasing or altering the immunosuppressive regimen all have been noted to provide clinical improvement.13,14 Other therapies including leflunomide and routine manual extraction of spicules also have shown effectiveness in the treatment of trichodysplasia spinulosa.15

In our patient, treatment included decreasing immunosuppression, as she was getting recurrent sinus and upper respiratory infections. Mycophenolate mofetil was discontinued, and the patient was continued solely on tacrolimus therapy. She demonstrated notable improvement after 3 months, with approximately 50% clearance of the eruption. A mutual decision was made at that visit to initiate therapy with compounded cidofovir cream 1% daily to the lesions until the next follow-up visit. Unfortunately, the patient did not return for her scheduled dermatology visits and was lost to long-term follow-up.

Acknowledgment

We thank Richard C. Wang, MD, PhD (Dallas, Texas), for his dermatologic expertise and assistance in analysis of lesional samples for TSPyV.

The Diagnosis: Trichodysplasia Spinulosa

Trichodysplasia spinulosa has been described in case reports over the last several decades, with its causative virus trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus (TSPyV) identified in 2010 by van der Meijden et al.1 Trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus is a small, nonenveloped, double-stranded DNA virus in the Polyomaviridae family, among several other known cutaneous polyomaviruses including Merkel cell polyomavirus, human polyomavirus (HPyV) 6, HPyV7, HPyV10, and possibly HPyV13.2 The primary target of TSPyV is follicular keratinocytes, and it is believed to cause trichodysplasia spinulosa by primary infection rather than by reactivation. Trichodysplasia spinulosa presents in immunosuppressed patients as a folliculocentric eruption of papules with keratinous spines on the face, often with concurrent alopecia, eventually spreading to the trunk and extremities.3 The diagnosis often is clinical, but a biopsy may be performed for histopathologic confirmation. Alternatively, lesional spicules can be painlessly collected manually and submitted for viral polymerase chain reaction (PCR).4 The diagnosis of trichodysplasia spinulosa can be difficult due to similarities with other more common conditions such as keratosis pilaris, milia, filiform warts, or lichen spinulosus.

Similar to trichodysplasia spinulosa, keratosis pilaris also presents with folliculocentric and often erythematous papules.5 Keratosis pilaris most frequently affects the posterior upper arms and thighs but also may affect the cheeks, as seen in trichodysplasia spinulosa. Differentiation between the 2 diagnoses can be made on a clinical basis, as keratosis pilaris lacks the characteristic keratinous spines and often spares the central face and nose, locations that commonly are affected in trichodysplasia spinulosa.3

Milia typically appear as white to yellow papules, often on the cheeks, eyelids, nose, and chin.6 Given their predilection for the face, milia can appear similarly to trichodysplasia spinulosa. Differentiation can be made clinically, as milia typically are not as numerous as the spiculed papules seen in trichodysplasia spinulosa. Morphologically, milia will present as smooth, dome-shaped papules as opposed to the keratinous spicules seen in trichodysplasia spinulosa. The diagnosis of milia can be confirmed by incision and removal of the white chalky keratin core, a feature absent in trichodysplasia spinulosa.

Filiform warts are benign epidermal proliferations caused by human papillomavirus infection that manifest as flesh-colored, verrucous, hyperkeratotic papules.7 They can appear on virtually any skin surface, including the face, and thus may be mistaken for trichodysplasia spinulosa. Close inspection usually will reveal tiny black dots that represent thrombosed capillaries, a feature lacking in trichodysplasia spinulosa. In long-standing lesions or immunocompromised patients, confluent verrucous plaques may develop.8 Diagnosis of filiform warts can be confirmed with biopsy, which will demonstrate a compact stratum corneum, coarse hypergranulosis, and papillomatosis curving inward, while biopsy of a trichodysplasia spinulosa lesion would show polyomavirus infection of the hair follicle and characteristic eosinophilic inclusion bodies.9

Lichen spinulosus may appear as multiple folliculocentric scaly papules with hairlike horny spines.10 Lichen spinulosus differs from trichodysplasia spinulosa in that it commonly appears on the neck, abdomen, trochanteric region, arms, elbows, or knees. Lichen spinulosus also classically appears as a concrete cluster of papules, often localized to a certain region, in contrast to trichodysplasia spinulosa, which will be widespread, often spreading over time. Finally, clinical history may help differentiate the 2 entities. Lichen spinulosus most often appears in children and adolescents and often has an indolent course, typically resolving during puberty, while trichodysplasia spinulosa is seen in immunocompromised patients.

In our patient, the dermatology team made a diagnosis of trichodysplasia spinulosa based on the characteristic clinical presentation, which was confirmed after approximately 10 lesional spicules were removed by tissue forceps and submitted for PCR analysis showing TSPyV (Figure). Two other cases utilized spicule PCR analysis for confirmation of TSPyV.11,12 This technique may represent a viable option for diagnostic confirmation in pediatric cases.

Although some articles have examined the molecular and biologic features of trichodysplasia spinulosa, literature on clinical presentation and management is limited to isolated case reports with no comprehensive studies to establish a standardized treatment. Of these reports, oral valganciclovir 900 mg daily, topical retinoids, cidofovir cream 1% to 3%, and decreasing or altering the immunosuppressive regimen all have been noted to provide clinical improvement.13,14 Other therapies including leflunomide and routine manual extraction of spicules also have shown effectiveness in the treatment of trichodysplasia spinulosa.15

In our patient, treatment included decreasing immunosuppression, as she was getting recurrent sinus and upper respiratory infections. Mycophenolate mofetil was discontinued, and the patient was continued solely on tacrolimus therapy. She demonstrated notable improvement after 3 months, with approximately 50% clearance of the eruption. A mutual decision was made at that visit to initiate therapy with compounded cidofovir cream 1% daily to the lesions until the next follow-up visit. Unfortunately, the patient did not return for her scheduled dermatology visits and was lost to long-term follow-up.

Acknowledgment

We thank Richard C. Wang, MD, PhD (Dallas, Texas), for his dermatologic expertise and assistance in analysis of lesional samples for TSPyV.

- van der Meijden E, Janssens RWA, Lauber C, et al. Discovery of a new human polyomavirus associated with trichodysplasia spinulosa in an immunocompromised patient. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:E1001024.

- Sheu JC, Tran J, Rady PL, et al. Polyomaviruses of the skin: integrating molecular and clinical advances in an emerging class of viruses. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:1302-1311.

- Sperling LC, Tomaszewski MM, Thomas DA. Viral-associated trichodysplasia in patients who are immunocompromised. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:318-322.

- Wu JH, Nguyen HP, Rady PL, et al. Molecular insight into the viral biology and clinical features of trichodysplasia spinulosa. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174:490-498.

- Hwang S, Schwartz RA. Keratosis pilaris: a common follicular hyperkeratosis. Cutis. 2008;82:177-180.

- Berk DR, Bayliss SJ. Milia: a review and classification. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:1050-1063.

- Micali G, Dall'Oglio F, Nasca MR, et al. Management of cutaneous warts: an evidence-based approach. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2004;5:311-317.

- Bolognia J, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018.

- Elston DM, Ferringer T, Ko CJ. Dermatopathology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2018.

- Tilly JJ, Drolet BA, Esterly NB. Lichenoid eruptions in children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:606-624.

- Chamseddin BH, Tran BAPD, Lee EE, et al. Trichodysplasia spinulosa in a child: identification of trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus in skin, serum, and urine. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36:723-724.

- Sonstegard A, Grossman M, Garg A. Trichodysplasia spinulosa in a kidney transplant recipient. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:105.

- Leitenberger JJ, Abdelmalek M, Wang RC, et al. Two cases of trichodysplasia spinulosa responsive to compounded topical cidofovir 3% cream. JAAD Case Rep. 2015;1:S33-S35.

- DeCrescenzo AJ, Philips RC, Wilkerson MG. Trichodysplasia spinulosa: a rare complication of immunosuppression. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:307-309.

- Nguyen KD, Chamseddin BH, Cockerell CJ, et al. The biology and clinical features of cutaneous polyomaviruses. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139:285-292.

- van der Meijden E, Janssens RWA, Lauber C, et al. Discovery of a new human polyomavirus associated with trichodysplasia spinulosa in an immunocompromised patient. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:E1001024.

- Sheu JC, Tran J, Rady PL, et al. Polyomaviruses of the skin: integrating molecular and clinical advances in an emerging class of viruses. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:1302-1311.

- Sperling LC, Tomaszewski MM, Thomas DA. Viral-associated trichodysplasia in patients who are immunocompromised. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:318-322.

- Wu JH, Nguyen HP, Rady PL, et al. Molecular insight into the viral biology and clinical features of trichodysplasia spinulosa. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174:490-498.

- Hwang S, Schwartz RA. Keratosis pilaris: a common follicular hyperkeratosis. Cutis. 2008;82:177-180.

- Berk DR, Bayliss SJ. Milia: a review and classification. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:1050-1063.

- Micali G, Dall'Oglio F, Nasca MR, et al. Management of cutaneous warts: an evidence-based approach. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2004;5:311-317.

- Bolognia J, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018.

- Elston DM, Ferringer T, Ko CJ. Dermatopathology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2018.

- Tilly JJ, Drolet BA, Esterly NB. Lichenoid eruptions in children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:606-624.

- Chamseddin BH, Tran BAPD, Lee EE, et al. Trichodysplasia spinulosa in a child: identification of trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus in skin, serum, and urine. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36:723-724.

- Sonstegard A, Grossman M, Garg A. Trichodysplasia spinulosa in a kidney transplant recipient. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:105.

- Leitenberger JJ, Abdelmalek M, Wang RC, et al. Two cases of trichodysplasia spinulosa responsive to compounded topical cidofovir 3% cream. JAAD Case Rep. 2015;1:S33-S35.

- DeCrescenzo AJ, Philips RC, Wilkerson MG. Trichodysplasia spinulosa: a rare complication of immunosuppression. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:307-309.

- Nguyen KD, Chamseddin BH, Cockerell CJ, et al. The biology and clinical features of cutaneous polyomaviruses. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139:285-292.

A 4-year-old girl with a history of cardiac transplantation 1 year prior for dilated cardiomyopathy presented to the dermatology consultation service with widespread hyperkeratotic papules of 2 months’ duration. The eruption initially had appeared on the face with subsequent involvement of the trunk and extremities. Her immunosuppressive medications included oral tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil. No over-the-counter or prescription treatments had been used for the eruption; the patient’s mother had been manually extracting the spicules from the nose, cheeks, and forehead with tweezers. The lesions were asymptomatic with only mild follicular erythema. Physical examination revealed multiple folliculocentric keratinous spicules on the nose, cheeks, forehead (top), trunk (bottom), arms, and legs.

How to improve our response to COVID’s mental tolls

We have no way of precisely knowing how many lives might have been saved, and how much grief and loneliness spared and economic ruin contained during COVID-19 if we had risen to its myriad challenges in a timely fashion. However, I feel we can safely say that the United States deserves to be graded with an “F” for its management of the pandemic.

To render this grade, we need only to read the countless verified reports of how critically needed public health measures were not taken soon enough, or sufficiently, to substantially mitigate human and societal suffering.

This began with the failure to protect doctors, nurses, and technicians, who did not have the personal protective equipment needed to prevent infection and spare risk to their loved ones. It soon extended to the country’s failure to adequately protect all its citizens and residents. COVID-19 then rained its grievous consequences disproportionately upon people of color, those living in poverty, and those with housing and food insecurity – those already greatly foreclosed from opportunities to exit from their circumstances.

We all have heard, “Fool me once, shame on you; fool me twice, shame on me.”

Bear witness, colleagues and friends: It will be our shared shame if we too continue to fail in our response to COVID-19. But failure need not happen because protecting ourselves and our country is a solvable problem; complex and demanding for sure, but solvable.

To battle trauma, we must first define it

The sine qua non of a disaster is its psychic and social trauma. I asked Maureen Sayres Van Niel, MD, chair of the American Psychiatric Association’s Minority and Underrepresented Caucus and a former steering committee member of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, to define trauma. She said, “It is [the product of] a catastrophic, unexpected event over which we have little control, with grave consequences to the lives and psychological functioning of those individuals and groups affected.”

The COVID-19 pandemic is a massively amplified traumatic event because of the virulence and contagious properties of the virus and its variants; the absence of end date on the horizon; its effect as a proverbial ax that disproportionately falls on the majority of the populace experiencing racial and social inequities; and the ironic yet necessary imperative to distance ourselves from those we care about and who care about us.

Four interdependent factors drive the magnitude of the traumatic impact of a disaster: the degree of exposure to the life-threatening event; the duration and threat of recurrence; an individual’s preexisting (natural and human-made) trauma and mental and addictive disorders; and the adequacy of family and fundamental resources such as housing, food, safety, and access to health care (the social dimensions of health and mental health). These factors underline the “who,” “what,” “where,” and “how” of what should have been (and continue to be) an effective public health response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Yet existing categories that we have used to predict risk for trauma no longer hold. The gravity, prevalence, and persistence of COVID-19’s horrors erase any differences among victims, witnesses, and bystanders. Dr Sayres Van Niel asserts that we have a “collective, national trauma.” In April, the Kaiser Family Foundation’s Vaccine Monitor reported that 24% of U.S. adults had a close friend or family member who died of COVID-19. That’s 82 million Americans! Our country has eclipsed individual victimization and trauma because we are all in its maw.

Vital lessons from the past

In a previous column, I described my role as New York City’s mental health commissioner after 9/11 and the many lessons we learned during that multiyear process. Our work served as a template for other disasters to follow, such as Hurricane Sandy. Its value to COVID-19 is equally apparent.

We learned that those most at risk of developing symptomatic, functionally impairing mental illness had prior traumatic experiences (for example, from childhood abuse or neglect, violence, war, and forced displacement from their native land) and/or a preexisting mental or substance use disorder.

Once these individuals and communities were identified, we could prioritize their treatment and care. Doing so required mobilizing both inner and external (social) resources, which can be used before disaster strikes or in its wake.

For individuals, adaptive resources include developing any of a number of mind-body activities (for example, meditation, mindfulness, slow breathing, and yoga); sufficient but not necessarily excessive levels of exercise (as has been said, if exercise were a pill, it would be the most potent of medicines); nourishing diets; sleep, nature’s restorative state; and perhaps most important, attachment and human connection to people who care about you and whom you care about and trust.

This does not necessarily mean holding or following an institutional religion or belonging to house of worship (though, of course, that melds and augments faith with community). For a great many, myself included, there is spirituality, the belief in a greater power, which need not be a God yet instills a sense of the vastness, universality, and continuity of life.

For communities, adaptive resources include safe homes and neighborhoods; diminishing housing and food insecurity; education, including pre-K; employment, with a livable wage; ridding human interactions of the endless, so-called microaggressions (which are not micro at all, because they accrue) of race, ethnic, class, and age discrimination and injustice; and ready access to quality and affordable health care, now more than ever for the rising tide of mental and substance use disorders that COVID-19 has unleashed.

Every gain we make to ablate racism, social injustice, discrimination, and widely and deeply spread resource and opportunity inequities means more cohesion among the members of our collective tribe. Greater cohesion, a love for thy neighbor, and equity (in action, not polemics) will fuel the resilience we will need to withstand more of COVID-19’s ongoing trauma; that of other, inescapable disasters and losses; and the wear and tear of everyday life. The rewards of equity are priceless and include the dignity that derives from fairness and justice – given and received.

An unprecedented disaster requires a bold response

My, what a list. But to me, the encompassing nature of what’s needed means that we can make differences anywhere, everywhere, and in countless and continuous ways.

The measure of any society is in how it cares for those who are foreclosed, through no fault of their own, from what we all want: a life safe from violence, secure in housing and food, with loving relationships and the pride that comes of making contributions, each in our own, wonderfully unique way.

Where will we all be in a year, 2, or 3 from now? Prepared, or not? Emotionally inoculated, or not? Better equipped, or not? As divided, or more cohesive?

Well, I imagine that depends on each and every one of us.

Lloyd I. Sederer, MD, is a psychiatrist, public health doctor, and writer. He is an adjunct professor at the Columbia University School of Public Health, director of Columbia Psychiatry Media, chief medical officer of Bongo Media, and chair of the advisory board of Get Help. He has been chief medical officer of McLean Hospital, a Harvard teaching hospital; mental health commissioner of New York City (in the Bloomberg administration); and chief medical officer of the New York State Office of Mental Health, the nation’s largest state mental health agency.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

We have no way of precisely knowing how many lives might have been saved, and how much grief and loneliness spared and economic ruin contained during COVID-19 if we had risen to its myriad challenges in a timely fashion. However, I feel we can safely say that the United States deserves to be graded with an “F” for its management of the pandemic.

To render this grade, we need only to read the countless verified reports of how critically needed public health measures were not taken soon enough, or sufficiently, to substantially mitigate human and societal suffering.

This began with the failure to protect doctors, nurses, and technicians, who did not have the personal protective equipment needed to prevent infection and spare risk to their loved ones. It soon extended to the country’s failure to adequately protect all its citizens and residents. COVID-19 then rained its grievous consequences disproportionately upon people of color, those living in poverty, and those with housing and food insecurity – those already greatly foreclosed from opportunities to exit from their circumstances.

We all have heard, “Fool me once, shame on you; fool me twice, shame on me.”

Bear witness, colleagues and friends: It will be our shared shame if we too continue to fail in our response to COVID-19. But failure need not happen because protecting ourselves and our country is a solvable problem; complex and demanding for sure, but solvable.

To battle trauma, we must first define it

The sine qua non of a disaster is its psychic and social trauma. I asked Maureen Sayres Van Niel, MD, chair of the American Psychiatric Association’s Minority and Underrepresented Caucus and a former steering committee member of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, to define trauma. She said, “It is [the product of] a catastrophic, unexpected event over which we have little control, with grave consequences to the lives and psychological functioning of those individuals and groups affected.”

The COVID-19 pandemic is a massively amplified traumatic event because of the virulence and contagious properties of the virus and its variants; the absence of end date on the horizon; its effect as a proverbial ax that disproportionately falls on the majority of the populace experiencing racial and social inequities; and the ironic yet necessary imperative to distance ourselves from those we care about and who care about us.

Four interdependent factors drive the magnitude of the traumatic impact of a disaster: the degree of exposure to the life-threatening event; the duration and threat of recurrence; an individual’s preexisting (natural and human-made) trauma and mental and addictive disorders; and the adequacy of family and fundamental resources such as housing, food, safety, and access to health care (the social dimensions of health and mental health). These factors underline the “who,” “what,” “where,” and “how” of what should have been (and continue to be) an effective public health response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Yet existing categories that we have used to predict risk for trauma no longer hold. The gravity, prevalence, and persistence of COVID-19’s horrors erase any differences among victims, witnesses, and bystanders. Dr Sayres Van Niel asserts that we have a “collective, national trauma.” In April, the Kaiser Family Foundation’s Vaccine Monitor reported that 24% of U.S. adults had a close friend or family member who died of COVID-19. That’s 82 million Americans! Our country has eclipsed individual victimization and trauma because we are all in its maw.

Vital lessons from the past

In a previous column, I described my role as New York City’s mental health commissioner after 9/11 and the many lessons we learned during that multiyear process. Our work served as a template for other disasters to follow, such as Hurricane Sandy. Its value to COVID-19 is equally apparent.

We learned that those most at risk of developing symptomatic, functionally impairing mental illness had prior traumatic experiences (for example, from childhood abuse or neglect, violence, war, and forced displacement from their native land) and/or a preexisting mental or substance use disorder.

Once these individuals and communities were identified, we could prioritize their treatment and care. Doing so required mobilizing both inner and external (social) resources, which can be used before disaster strikes or in its wake.

For individuals, adaptive resources include developing any of a number of mind-body activities (for example, meditation, mindfulness, slow breathing, and yoga); sufficient but not necessarily excessive levels of exercise (as has been said, if exercise were a pill, it would be the most potent of medicines); nourishing diets; sleep, nature’s restorative state; and perhaps most important, attachment and human connection to people who care about you and whom you care about and trust.

This does not necessarily mean holding or following an institutional religion or belonging to house of worship (though, of course, that melds and augments faith with community). For a great many, myself included, there is spirituality, the belief in a greater power, which need not be a God yet instills a sense of the vastness, universality, and continuity of life.

For communities, adaptive resources include safe homes and neighborhoods; diminishing housing and food insecurity; education, including pre-K; employment, with a livable wage; ridding human interactions of the endless, so-called microaggressions (which are not micro at all, because they accrue) of race, ethnic, class, and age discrimination and injustice; and ready access to quality and affordable health care, now more than ever for the rising tide of mental and substance use disorders that COVID-19 has unleashed.

Every gain we make to ablate racism, social injustice, discrimination, and widely and deeply spread resource and opportunity inequities means more cohesion among the members of our collective tribe. Greater cohesion, a love for thy neighbor, and equity (in action, not polemics) will fuel the resilience we will need to withstand more of COVID-19’s ongoing trauma; that of other, inescapable disasters and losses; and the wear and tear of everyday life. The rewards of equity are priceless and include the dignity that derives from fairness and justice – given and received.

An unprecedented disaster requires a bold response

My, what a list. But to me, the encompassing nature of what’s needed means that we can make differences anywhere, everywhere, and in countless and continuous ways.

The measure of any society is in how it cares for those who are foreclosed, through no fault of their own, from what we all want: a life safe from violence, secure in housing and food, with loving relationships and the pride that comes of making contributions, each in our own, wonderfully unique way.

Where will we all be in a year, 2, or 3 from now? Prepared, or not? Emotionally inoculated, or not? Better equipped, or not? As divided, or more cohesive?

Well, I imagine that depends on each and every one of us.

Lloyd I. Sederer, MD, is a psychiatrist, public health doctor, and writer. He is an adjunct professor at the Columbia University School of Public Health, director of Columbia Psychiatry Media, chief medical officer of Bongo Media, and chair of the advisory board of Get Help. He has been chief medical officer of McLean Hospital, a Harvard teaching hospital; mental health commissioner of New York City (in the Bloomberg administration); and chief medical officer of the New York State Office of Mental Health, the nation’s largest state mental health agency.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

We have no way of precisely knowing how many lives might have been saved, and how much grief and loneliness spared and economic ruin contained during COVID-19 if we had risen to its myriad challenges in a timely fashion. However, I feel we can safely say that the United States deserves to be graded with an “F” for its management of the pandemic.

To render this grade, we need only to read the countless verified reports of how critically needed public health measures were not taken soon enough, or sufficiently, to substantially mitigate human and societal suffering.

This began with the failure to protect doctors, nurses, and technicians, who did not have the personal protective equipment needed to prevent infection and spare risk to their loved ones. It soon extended to the country’s failure to adequately protect all its citizens and residents. COVID-19 then rained its grievous consequences disproportionately upon people of color, those living in poverty, and those with housing and food insecurity – those already greatly foreclosed from opportunities to exit from their circumstances.

We all have heard, “Fool me once, shame on you; fool me twice, shame on me.”

Bear witness, colleagues and friends: It will be our shared shame if we too continue to fail in our response to COVID-19. But failure need not happen because protecting ourselves and our country is a solvable problem; complex and demanding for sure, but solvable.

To battle trauma, we must first define it

The sine qua non of a disaster is its psychic and social trauma. I asked Maureen Sayres Van Niel, MD, chair of the American Psychiatric Association’s Minority and Underrepresented Caucus and a former steering committee member of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, to define trauma. She said, “It is [the product of] a catastrophic, unexpected event over which we have little control, with grave consequences to the lives and psychological functioning of those individuals and groups affected.”

The COVID-19 pandemic is a massively amplified traumatic event because of the virulence and contagious properties of the virus and its variants; the absence of end date on the horizon; its effect as a proverbial ax that disproportionately falls on the majority of the populace experiencing racial and social inequities; and the ironic yet necessary imperative to distance ourselves from those we care about and who care about us.

Four interdependent factors drive the magnitude of the traumatic impact of a disaster: the degree of exposure to the life-threatening event; the duration and threat of recurrence; an individual’s preexisting (natural and human-made) trauma and mental and addictive disorders; and the adequacy of family and fundamental resources such as housing, food, safety, and access to health care (the social dimensions of health and mental health). These factors underline the “who,” “what,” “where,” and “how” of what should have been (and continue to be) an effective public health response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Yet existing categories that we have used to predict risk for trauma no longer hold. The gravity, prevalence, and persistence of COVID-19’s horrors erase any differences among victims, witnesses, and bystanders. Dr Sayres Van Niel asserts that we have a “collective, national trauma.” In April, the Kaiser Family Foundation’s Vaccine Monitor reported that 24% of U.S. adults had a close friend or family member who died of COVID-19. That’s 82 million Americans! Our country has eclipsed individual victimization and trauma because we are all in its maw.

Vital lessons from the past

In a previous column, I described my role as New York City’s mental health commissioner after 9/11 and the many lessons we learned during that multiyear process. Our work served as a template for other disasters to follow, such as Hurricane Sandy. Its value to COVID-19 is equally apparent.

We learned that those most at risk of developing symptomatic, functionally impairing mental illness had prior traumatic experiences (for example, from childhood abuse or neglect, violence, war, and forced displacement from their native land) and/or a preexisting mental or substance use disorder.

Once these individuals and communities were identified, we could prioritize their treatment and care. Doing so required mobilizing both inner and external (social) resources, which can be used before disaster strikes or in its wake.

For individuals, adaptive resources include developing any of a number of mind-body activities (for example, meditation, mindfulness, slow breathing, and yoga); sufficient but not necessarily excessive levels of exercise (as has been said, if exercise were a pill, it would be the most potent of medicines); nourishing diets; sleep, nature’s restorative state; and perhaps most important, attachment and human connection to people who care about you and whom you care about and trust.

This does not necessarily mean holding or following an institutional religion or belonging to house of worship (though, of course, that melds and augments faith with community). For a great many, myself included, there is spirituality, the belief in a greater power, which need not be a God yet instills a sense of the vastness, universality, and continuity of life.

For communities, adaptive resources include safe homes and neighborhoods; diminishing housing and food insecurity; education, including pre-K; employment, with a livable wage; ridding human interactions of the endless, so-called microaggressions (which are not micro at all, because they accrue) of race, ethnic, class, and age discrimination and injustice; and ready access to quality and affordable health care, now more than ever for the rising tide of mental and substance use disorders that COVID-19 has unleashed.

Every gain we make to ablate racism, social injustice, discrimination, and widely and deeply spread resource and opportunity inequities means more cohesion among the members of our collective tribe. Greater cohesion, a love for thy neighbor, and equity (in action, not polemics) will fuel the resilience we will need to withstand more of COVID-19’s ongoing trauma; that of other, inescapable disasters and losses; and the wear and tear of everyday life. The rewards of equity are priceless and include the dignity that derives from fairness and justice – given and received.

An unprecedented disaster requires a bold response

My, what a list. But to me, the encompassing nature of what’s needed means that we can make differences anywhere, everywhere, and in countless and continuous ways.

The measure of any society is in how it cares for those who are foreclosed, through no fault of their own, from what we all want: a life safe from violence, secure in housing and food, with loving relationships and the pride that comes of making contributions, each in our own, wonderfully unique way.

Where will we all be in a year, 2, or 3 from now? Prepared, or not? Emotionally inoculated, or not? Better equipped, or not? As divided, or more cohesive?

Well, I imagine that depends on each and every one of us.

Lloyd I. Sederer, MD, is a psychiatrist, public health doctor, and writer. He is an adjunct professor at the Columbia University School of Public Health, director of Columbia Psychiatry Media, chief medical officer of Bongo Media, and chair of the advisory board of Get Help. He has been chief medical officer of McLean Hospital, a Harvard teaching hospital; mental health commissioner of New York City (in the Bloomberg administration); and chief medical officer of the New York State Office of Mental Health, the nation’s largest state mental health agency.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Addressing an uncharted front in the war on COVID-19: Vaccination during pregnancy

In December 2020, the US Food and Drug Administration’s Emergency Use Authorization of the first COVID-19 vaccine presented us with a new tactic in the war against SARS-COV-2—and a new dilemma for obstetricians. What we had learned about COVID-19 infection in pregnancy by that point was alarming. While the vast majority (>90%) of pregnant women who contract COVID-19 recover without requiring hospitalization, pregnant women are at increased risk for severe illness and mechanical ventilation when compared with their nonpregnant counterparts.1 Vertical transmission to the fetus is a rare event, but the increased risk of preterm birth, miscarriage, and preeclampsia makes the fetus a second victim in many cases.2 Moreover, much is still unknown about the long-term impact of severe illness on maternal and fetal health.

Gaining vaccine approval

The COVID-19 vaccine, with its high efficacy rates in the nonpregnant adult population, presents an opportunity to reduce maternal morbidity related to this devastating illness. But unlike other vaccines, such as the flu shot and TDAP, results from prospective studies on COVID-19 vaccination of expectant women are pending. Under the best of circumstances, gaining acceptance of any vaccine during pregnancy faces barriers such as vaccine hesitancy and a general concern from pregnant women about the effect of medical interventions on the fetus. There is no reason to expect that either the mRNA vaccines or the replication-incompetent adenovirus recombinant vector vaccine could cause harm to the developing fetus, but the fact that currently available COVID-19 vaccines use newer technologies complicates the decision for many women.

Nevertheless, what we do know now is much more than we did in December, particularly when it comes to the mRNA vaccines. To date, observational studies of women who received the mRNA vaccine in pregnancy have shown no increased risk of adverse maternal, fetal, or obstetric outcomes.3 Emerging data also indicate that antibodies to the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein—the target of all 3 vaccines—is present in cord blood, potentially protecting the infant in the first months of life from contracting COVID-19 if the mother receives the vaccine during pregnancy.4,5

Our approach to counseling

How can we best help our patients navigate the risks and benefits of the COVID-19 vaccine? First, by acknowledging the obvious: We are in the midst of a pandemic with high rates of community spread, which makes COVID-19 different from any other vaccine-preventable disease at this time. Providing patients with a structure for making an educated decision is essential, taking into account (1) what we know about COVID-19 infection during pregnancy, (2) what we know about vaccine efficacy and safety to date, and (3) individual factors such as:

- The presence of comorbidities such as obesity, heart disease, respiratory disease, and diabetes.

- Potential exposures—“Do you have children in school or daycare? Do childcare providers or other workers come to your home? What is your occupation?”

- The ability to take precautions (social distancing, wearing a mask, etc)

All things considered, the decision to accept the COVID-19 vaccine or not ultimately belongs to the patient. Given disease prevalence and the latest information on vaccine safety in pregnancy, I have been advising my patients in the second trimester or beyond to receive the vaccine with the caveat that delaying the vaccine until the postpartum period is a completely valid alternative. The most important gift we can offer our patients is to arm them with the necessary information so that they can make the choice best for them and their family as we continue to fight this war on COVID-19.

- Allotey J, Stallings E, Bonet M, et al. Clinical manifestations, risk factors and maternal and perinatal outcomes of coronavirus disease 2019 in pregnancy: living systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020;370:m3320. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3320.

- Soheili M, Moradi G, Baradaran HR, et al. Clinical manifestation and maternal complications and neonatal outcomes in pregnant women with COVID-19: a comprehensive evidence synthesis and meta-analysis. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. February 18, 2021. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2021.1888923.

- Shimabukuro TT, Kim SY, Myers TR, et al. Preliminary findings of mRNA Covid-19 vaccine safety in pregnant persons. N Engl J Med. April 21, 2021. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2104983.

- Mithal LB, Otero S, Shanes ED, et al. Cord blood antibodies following maternal COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;S0002-9378(21)00215-5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.03.035.

- Rottenstreich A, Zarbiv G, Oiknine-Djian E, et al. Efficient maternofetal transplacental transfer of anti- SARS-CoV-2 spike antibodies after antenatal SARS-CoV-2 BNT162b2 mRNA vaccination. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;ciab266. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab266.

In December 2020, the US Food and Drug Administration’s Emergency Use Authorization of the first COVID-19 vaccine presented us with a new tactic in the war against SARS-COV-2—and a new dilemma for obstetricians. What we had learned about COVID-19 infection in pregnancy by that point was alarming. While the vast majority (>90%) of pregnant women who contract COVID-19 recover without requiring hospitalization, pregnant women are at increased risk for severe illness and mechanical ventilation when compared with their nonpregnant counterparts.1 Vertical transmission to the fetus is a rare event, but the increased risk of preterm birth, miscarriage, and preeclampsia makes the fetus a second victim in many cases.2 Moreover, much is still unknown about the long-term impact of severe illness on maternal and fetal health.

Gaining vaccine approval

The COVID-19 vaccine, with its high efficacy rates in the nonpregnant adult population, presents an opportunity to reduce maternal morbidity related to this devastating illness. But unlike other vaccines, such as the flu shot and TDAP, results from prospective studies on COVID-19 vaccination of expectant women are pending. Under the best of circumstances, gaining acceptance of any vaccine during pregnancy faces barriers such as vaccine hesitancy and a general concern from pregnant women about the effect of medical interventions on the fetus. There is no reason to expect that either the mRNA vaccines or the replication-incompetent adenovirus recombinant vector vaccine could cause harm to the developing fetus, but the fact that currently available COVID-19 vaccines use newer technologies complicates the decision for many women.

Nevertheless, what we do know now is much more than we did in December, particularly when it comes to the mRNA vaccines. To date, observational studies of women who received the mRNA vaccine in pregnancy have shown no increased risk of adverse maternal, fetal, or obstetric outcomes.3 Emerging data also indicate that antibodies to the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein—the target of all 3 vaccines—is present in cord blood, potentially protecting the infant in the first months of life from contracting COVID-19 if the mother receives the vaccine during pregnancy.4,5

Our approach to counseling

How can we best help our patients navigate the risks and benefits of the COVID-19 vaccine? First, by acknowledging the obvious: We are in the midst of a pandemic with high rates of community spread, which makes COVID-19 different from any other vaccine-preventable disease at this time. Providing patients with a structure for making an educated decision is essential, taking into account (1) what we know about COVID-19 infection during pregnancy, (2) what we know about vaccine efficacy and safety to date, and (3) individual factors such as:

- The presence of comorbidities such as obesity, heart disease, respiratory disease, and diabetes.

- Potential exposures—“Do you have children in school or daycare? Do childcare providers or other workers come to your home? What is your occupation?”

- The ability to take precautions (social distancing, wearing a mask, etc)

All things considered, the decision to accept the COVID-19 vaccine or not ultimately belongs to the patient. Given disease prevalence and the latest information on vaccine safety in pregnancy, I have been advising my patients in the second trimester or beyond to receive the vaccine with the caveat that delaying the vaccine until the postpartum period is a completely valid alternative. The most important gift we can offer our patients is to arm them with the necessary information so that they can make the choice best for them and their family as we continue to fight this war on COVID-19.

In December 2020, the US Food and Drug Administration’s Emergency Use Authorization of the first COVID-19 vaccine presented us with a new tactic in the war against SARS-COV-2—and a new dilemma for obstetricians. What we had learned about COVID-19 infection in pregnancy by that point was alarming. While the vast majority (>90%) of pregnant women who contract COVID-19 recover without requiring hospitalization, pregnant women are at increased risk for severe illness and mechanical ventilation when compared with their nonpregnant counterparts.1 Vertical transmission to the fetus is a rare event, but the increased risk of preterm birth, miscarriage, and preeclampsia makes the fetus a second victim in many cases.2 Moreover, much is still unknown about the long-term impact of severe illness on maternal and fetal health.

Gaining vaccine approval

The COVID-19 vaccine, with its high efficacy rates in the nonpregnant adult population, presents an opportunity to reduce maternal morbidity related to this devastating illness. But unlike other vaccines, such as the flu shot and TDAP, results from prospective studies on COVID-19 vaccination of expectant women are pending. Under the best of circumstances, gaining acceptance of any vaccine during pregnancy faces barriers such as vaccine hesitancy and a general concern from pregnant women about the effect of medical interventions on the fetus. There is no reason to expect that either the mRNA vaccines or the replication-incompetent adenovirus recombinant vector vaccine could cause harm to the developing fetus, but the fact that currently available COVID-19 vaccines use newer technologies complicates the decision for many women.

Nevertheless, what we do know now is much more than we did in December, particularly when it comes to the mRNA vaccines. To date, observational studies of women who received the mRNA vaccine in pregnancy have shown no increased risk of adverse maternal, fetal, or obstetric outcomes.3 Emerging data also indicate that antibodies to the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein—the target of all 3 vaccines—is present in cord blood, potentially protecting the infant in the first months of life from contracting COVID-19 if the mother receives the vaccine during pregnancy.4,5

Our approach to counseling

How can we best help our patients navigate the risks and benefits of the COVID-19 vaccine? First, by acknowledging the obvious: We are in the midst of a pandemic with high rates of community spread, which makes COVID-19 different from any other vaccine-preventable disease at this time. Providing patients with a structure for making an educated decision is essential, taking into account (1) what we know about COVID-19 infection during pregnancy, (2) what we know about vaccine efficacy and safety to date, and (3) individual factors such as:

- The presence of comorbidities such as obesity, heart disease, respiratory disease, and diabetes.

- Potential exposures—“Do you have children in school or daycare? Do childcare providers or other workers come to your home? What is your occupation?”

- The ability to take precautions (social distancing, wearing a mask, etc)

All things considered, the decision to accept the COVID-19 vaccine or not ultimately belongs to the patient. Given disease prevalence and the latest information on vaccine safety in pregnancy, I have been advising my patients in the second trimester or beyond to receive the vaccine with the caveat that delaying the vaccine until the postpartum period is a completely valid alternative. The most important gift we can offer our patients is to arm them with the necessary information so that they can make the choice best for them and their family as we continue to fight this war on COVID-19.

- Allotey J, Stallings E, Bonet M, et al. Clinical manifestations, risk factors and maternal and perinatal outcomes of coronavirus disease 2019 in pregnancy: living systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020;370:m3320. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3320.

- Soheili M, Moradi G, Baradaran HR, et al. Clinical manifestation and maternal complications and neonatal outcomes in pregnant women with COVID-19: a comprehensive evidence synthesis and meta-analysis. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. February 18, 2021. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2021.1888923.

- Shimabukuro TT, Kim SY, Myers TR, et al. Preliminary findings of mRNA Covid-19 vaccine safety in pregnant persons. N Engl J Med. April 21, 2021. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2104983.

- Mithal LB, Otero S, Shanes ED, et al. Cord blood antibodies following maternal COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;S0002-9378(21)00215-5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.03.035.

- Rottenstreich A, Zarbiv G, Oiknine-Djian E, et al. Efficient maternofetal transplacental transfer of anti- SARS-CoV-2 spike antibodies after antenatal SARS-CoV-2 BNT162b2 mRNA vaccination. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;ciab266. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab266.

- Allotey J, Stallings E, Bonet M, et al. Clinical manifestations, risk factors and maternal and perinatal outcomes of coronavirus disease 2019 in pregnancy: living systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020;370:m3320. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3320.

- Soheili M, Moradi G, Baradaran HR, et al. Clinical manifestation and maternal complications and neonatal outcomes in pregnant women with COVID-19: a comprehensive evidence synthesis and meta-analysis. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. February 18, 2021. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2021.1888923.

- Shimabukuro TT, Kim SY, Myers TR, et al. Preliminary findings of mRNA Covid-19 vaccine safety in pregnant persons. N Engl J Med. April 21, 2021. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2104983.

- Mithal LB, Otero S, Shanes ED, et al. Cord blood antibodies following maternal COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;S0002-9378(21)00215-5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.03.035.

- Rottenstreich A, Zarbiv G, Oiknine-Djian E, et al. Efficient maternofetal transplacental transfer of anti- SARS-CoV-2 spike antibodies after antenatal SARS-CoV-2 BNT162b2 mRNA vaccination. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;ciab266. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab266.

Self-harm is a leading cause of death for new moms

Death by self-harm through suicide or overdose is a leading cause of death for women in the first year post partum, data indicate. Many of these deaths may be preventable, said Adrienne Griffen, MPP, executive director of the Maternal Mental Health Leadership Alliance.

Ms. Griffen discussed these findings and ways clinicians may be able to help at the 2021 virtual meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Women “visit a health care provider an average of 25 times during a healthy pregnancy and first year of baby’s life,” she said. “Obstetric and primary care providers who serve pregnant and postpartum women are uniquely positioned to intervene effectively to screen and assess women for mental health disorders.”

To that end, clinicians should discuss mental health “early and often,” Ms. Griffen said.

“Asking about mental health issues and suicide will not cause women to think these thoughts,” she said. “We cannot wait for women to raise their hand and ask for help because by the time they do that, they needed help many weeks ago.”

For example, a doctor might tell a patient: “Your mental health is just as important as your physical health, and anxiety and depression are the most common complications of pregnancy and childbirth,” Ms. Griffen suggested. “Every time I see you, I’m going to ask you how you are doing, and we’ll do a formal screening assessment periodically over the course of the pregnancy. … Your job is to answer us honestly so that we can connect you with resources as soon as possible to minimize the impact on you and your baby.”

Although the obstetric provider should introduce this topic, a nurse, lactation consultant, or social worker may conduct screenings and help patients who are experiencing distress, she said.

During the past decade, several medical associations have issued new guidance around screening new mothers for anxiety and depression. One recent ACOG committee opinion recommends screening for depression at least once during pregnancy and once post partum, and encourages doctors to initiate medical therapy if possible and provide resources and referrals.

Another committee opinion suggests that doctors should have contact with a patient between 2 and 3 weeks post partum, primarily to assess for mental health.

Limited data

In discussing maternal suicide statistics, Ms. Griffen focused on data from Maternal Mortality Review Committees (MMRCs).

Two other sources of data about maternal mortality – the National Vital Statistics System and the Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System – do not include information about suicide, which may be a reason this cause of death is not discussed more often, Ms. Griffen noted.

MMRCs, on the other hand, include information about suicide and self-harm. About half of the states in the United States have these multidisciplinary committees. Committee members review deaths of all women during pregnancy or within 1 year of pregnancy. Members consider a range of clinical and nonclinical data, including reports from social services and police, to try to understand the circumstances of each death.

A report that examined pregnancy-related deaths using data from 14 U.S. MMRCs between 2008 and 2017 showed that mental health conditions were the leading cause of death for non-Hispanic White women. In all, 34% of pregnancy-related suicide deaths had a documented prior suicide attempt, and the majority of suicides happened in the late postpartum time frame (43-365 days post partum).

Some physicians cite a lack of education, time, reimbursement, or referral resources as barriers to maternal mental health screening and treatment, but there may be useful options available, Ms. Griffen said. Postpartum Support International provides resources for physicians, as well as mothers. The National Curriculum in Reproductive Psychiatry and the Seleni Institute also have educational resources.

Some states have psychiatry access programs, where psychiatrists educate obstetricians, family physicians, and pediatricians about how to assess for and treat maternal mental health issues, Ms. Griffen noted.

Self care, social support, and talk therapy may help patients. “Sometimes medication is needed, but a combination of all of these things … can help women recover from maternal mental health conditions,” Ms. Griffen said.

Need to intervene

Although medical societies have emphasized the importance of maternal mental health screening and treatment in recent years, the risk of self-harm has been a concern for obstetricians and gynecologists long before then, said Marc Alan Landsberg, MD, a member of the meeting’s scientific committee who moderated the session.

“We have been talking about this at ACOG for a long time,” Dr. Landsberg said in an interview.

The presentation highlighted why obstetricians, gynecologists, and other doctors who deliver babies and care for women post partum “have got to screen these people,” he said. The finding that 34% of pregnancy-related suicide deaths had a prior suicide attempt indicates that clinicians may be able to identify these patients, Dr. Landsberg said. Suicide and overdose are leading causes of death in the first year post partum and “probably 100% of these are preventable,” he said.

As a first step, screening may be relatively simple. The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale, highlighted during the talk, is an easy and quick tool to use, Dr. Landsberg said. It contains 10 items and assesses for anxiety and depression. It also specifically asks about suicide.

Ms. Griffen and Dr. Landsberg had no conflicts of interest.

Death by self-harm through suicide or overdose is a leading cause of death for women in the first year post partum, data indicate. Many of these deaths may be preventable, said Adrienne Griffen, MPP, executive director of the Maternal Mental Health Leadership Alliance.

Ms. Griffen discussed these findings and ways clinicians may be able to help at the 2021 virtual meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Women “visit a health care provider an average of 25 times during a healthy pregnancy and first year of baby’s life,” she said. “Obstetric and primary care providers who serve pregnant and postpartum women are uniquely positioned to intervene effectively to screen and assess women for mental health disorders.”

To that end, clinicians should discuss mental health “early and often,” Ms. Griffen said.

“Asking about mental health issues and suicide will not cause women to think these thoughts,” she said. “We cannot wait for women to raise their hand and ask for help because by the time they do that, they needed help many weeks ago.”

For example, a doctor might tell a patient: “Your mental health is just as important as your physical health, and anxiety and depression are the most common complications of pregnancy and childbirth,” Ms. Griffen suggested. “Every time I see you, I’m going to ask you how you are doing, and we’ll do a formal screening assessment periodically over the course of the pregnancy. … Your job is to answer us honestly so that we can connect you with resources as soon as possible to minimize the impact on you and your baby.”

Although the obstetric provider should introduce this topic, a nurse, lactation consultant, or social worker may conduct screenings and help patients who are experiencing distress, she said.

During the past decade, several medical associations have issued new guidance around screening new mothers for anxiety and depression. One recent ACOG committee opinion recommends screening for depression at least once during pregnancy and once post partum, and encourages doctors to initiate medical therapy if possible and provide resources and referrals.

Another committee opinion suggests that doctors should have contact with a patient between 2 and 3 weeks post partum, primarily to assess for mental health.

Limited data

In discussing maternal suicide statistics, Ms. Griffen focused on data from Maternal Mortality Review Committees (MMRCs).

Two other sources of data about maternal mortality – the National Vital Statistics System and the Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System – do not include information about suicide, which may be a reason this cause of death is not discussed more often, Ms. Griffen noted.

MMRCs, on the other hand, include information about suicide and self-harm. About half of the states in the United States have these multidisciplinary committees. Committee members review deaths of all women during pregnancy or within 1 year of pregnancy. Members consider a range of clinical and nonclinical data, including reports from social services and police, to try to understand the circumstances of each death.

A report that examined pregnancy-related deaths using data from 14 U.S. MMRCs between 2008 and 2017 showed that mental health conditions were the leading cause of death for non-Hispanic White women. In all, 34% of pregnancy-related suicide deaths had a documented prior suicide attempt, and the majority of suicides happened in the late postpartum time frame (43-365 days post partum).

Some physicians cite a lack of education, time, reimbursement, or referral resources as barriers to maternal mental health screening and treatment, but there may be useful options available, Ms. Griffen said. Postpartum Support International provides resources for physicians, as well as mothers. The National Curriculum in Reproductive Psychiatry and the Seleni Institute also have educational resources.

Some states have psychiatry access programs, where psychiatrists educate obstetricians, family physicians, and pediatricians about how to assess for and treat maternal mental health issues, Ms. Griffen noted.

Self care, social support, and talk therapy may help patients. “Sometimes medication is needed, but a combination of all of these things … can help women recover from maternal mental health conditions,” Ms. Griffen said.

Need to intervene

Although medical societies have emphasized the importance of maternal mental health screening and treatment in recent years, the risk of self-harm has been a concern for obstetricians and gynecologists long before then, said Marc Alan Landsberg, MD, a member of the meeting’s scientific committee who moderated the session.

“We have been talking about this at ACOG for a long time,” Dr. Landsberg said in an interview.

The presentation highlighted why obstetricians, gynecologists, and other doctors who deliver babies and care for women post partum “have got to screen these people,” he said. The finding that 34% of pregnancy-related suicide deaths had a prior suicide attempt indicates that clinicians may be able to identify these patients, Dr. Landsberg said. Suicide and overdose are leading causes of death in the first year post partum and “probably 100% of these are preventable,” he said.

As a first step, screening may be relatively simple. The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale, highlighted during the talk, is an easy and quick tool to use, Dr. Landsberg said. It contains 10 items and assesses for anxiety and depression. It also specifically asks about suicide.

Ms. Griffen and Dr. Landsberg had no conflicts of interest.

Death by self-harm through suicide or overdose is a leading cause of death for women in the first year post partum, data indicate. Many of these deaths may be preventable, said Adrienne Griffen, MPP, executive director of the Maternal Mental Health Leadership Alliance.

Ms. Griffen discussed these findings and ways clinicians may be able to help at the 2021 virtual meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Women “visit a health care provider an average of 25 times during a healthy pregnancy and first year of baby’s life,” she said. “Obstetric and primary care providers who serve pregnant and postpartum women are uniquely positioned to intervene effectively to screen and assess women for mental health disorders.”

To that end, clinicians should discuss mental health “early and often,” Ms. Griffen said.

“Asking about mental health issues and suicide will not cause women to think these thoughts,” she said. “We cannot wait for women to raise their hand and ask for help because by the time they do that, they needed help many weeks ago.”

For example, a doctor might tell a patient: “Your mental health is just as important as your physical health, and anxiety and depression are the most common complications of pregnancy and childbirth,” Ms. Griffen suggested. “Every time I see you, I’m going to ask you how you are doing, and we’ll do a formal screening assessment periodically over the course of the pregnancy. … Your job is to answer us honestly so that we can connect you with resources as soon as possible to minimize the impact on you and your baby.”

Although the obstetric provider should introduce this topic, a nurse, lactation consultant, or social worker may conduct screenings and help patients who are experiencing distress, she said.

During the past decade, several medical associations have issued new guidance around screening new mothers for anxiety and depression. One recent ACOG committee opinion recommends screening for depression at least once during pregnancy and once post partum, and encourages doctors to initiate medical therapy if possible and provide resources and referrals.

Another committee opinion suggests that doctors should have contact with a patient between 2 and 3 weeks post partum, primarily to assess for mental health.

Limited data

In discussing maternal suicide statistics, Ms. Griffen focused on data from Maternal Mortality Review Committees (MMRCs).

Two other sources of data about maternal mortality – the National Vital Statistics System and the Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System – do not include information about suicide, which may be a reason this cause of death is not discussed more often, Ms. Griffen noted.

MMRCs, on the other hand, include information about suicide and self-harm. About half of the states in the United States have these multidisciplinary committees. Committee members review deaths of all women during pregnancy or within 1 year of pregnancy. Members consider a range of clinical and nonclinical data, including reports from social services and police, to try to understand the circumstances of each death.

A report that examined pregnancy-related deaths using data from 14 U.S. MMRCs between 2008 and 2017 showed that mental health conditions were the leading cause of death for non-Hispanic White women. In all, 34% of pregnancy-related suicide deaths had a documented prior suicide attempt, and the majority of suicides happened in the late postpartum time frame (43-365 days post partum).

Some physicians cite a lack of education, time, reimbursement, or referral resources as barriers to maternal mental health screening and treatment, but there may be useful options available, Ms. Griffen said. Postpartum Support International provides resources for physicians, as well as mothers. The National Curriculum in Reproductive Psychiatry and the Seleni Institute also have educational resources.

Some states have psychiatry access programs, where psychiatrists educate obstetricians, family physicians, and pediatricians about how to assess for and treat maternal mental health issues, Ms. Griffen noted.

Self care, social support, and talk therapy may help patients. “Sometimes medication is needed, but a combination of all of these things … can help women recover from maternal mental health conditions,” Ms. Griffen said.

Need to intervene