User login

PCI after TAVR mostly succeeds, some risks identified

Coronary angiography and percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) can be performed successfully after transcatheter aortic valve replacement in most cases, according to data drawn from an international registry that has collected more than 400 such cases.

Overall, reaccess coronary angiography was successful in about 99% of cases with type of prosthesis identified as the most important variable in predicting success, according to a multicenter investigating team led by Won-Keun Kim, MD, director of structural heart disease, Kerckhoff Heart Center, Bad Nauheim, Germany.

By type of prosthesis, Dr. Kim was referring to long versus short stent-frame prostheses (SFP). In the case of angiography of the right coronary artery, for example, success was achieved in 99.6% of those with a short SFP and 95.9% of those with a long SFP (P = .005).

The study was published online in JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions.

Based on these and previous data, “prosthetic choice will be the main decisive factor that affects coronary reaccess, and this decision is in the hands of the TAVR operator,” said Dr. Kim in an interview.

This does not preclude use of a long SFP in TAVR. For patients with increased likelihood of eventually requiring a coronary intervention after TAVR, such as those undergoing the procedure at a relatively young age, a short device appears to be preferable, but Dr. Kim emphasized that it is not the only consideration.

When performing TAVR, “the highest priority is to accomplish a safe procedure with a good immediate outcome,” he said, pointing out that angiographic reaccess and PCI are successfully achieved in most patients whether fitted with a short or long SFP.

“If for any reason I assume that the immediate outcome [after TAVR] might be better using a long SFP, I would not hesitate to use a long SFP,” said Dr. Kim, giving such examples as a need for resheathing or precise positioning.

Coronary reaccess has low relative priority

“Coronary reaccess is an important issue and there is an increasing awareness of this, but it has a lower priority” than optimizing TAVR success,” Dr. Kim explained.

The analysis of coronary angiographic reaccess was based on 449 TAVR patients from 25 sites who required reaccess angiography. The indication in most cases was an acute coronary syndrome, mostly non–ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI, 79%). Of the remaining patients, about half had STEMIs and half had other acute cardiovascular situations. The median time interval from TAVR to need for coronary angiography was 311 days.

In all but 2.7%, diagnostic catheterization was performed initially. It was successful in 98.3% of the procedures in the right coronary artery, 99.3% of the left coronary artery, and 97.3% overall.

Of the 60% who underwent PCI, 9% were considered unsuccessful. The reasons included lack of reflow in eight cases and coronary access issues in six cases. A variety of other issues accounted for the remaining seven cases.

Technical success was achieved in 91.4% of native arteries. In the six cases in which engagement of the culprit vessel with a guiding catheter failed, three were converted to urgent coronary bypass grafting and three died in the hospital. Neither selective versus unselective guiding-catheter engagement nor long versus short SFP related to PCI success, but PCI was performed less commonly in the native coronary arteries of TAVR patients with a long rather than short SFP (49% vs. 57%).

The 30-day all-cause mortality in this series was 12.2%. The independent predictors were a history of diabetes and the occurrence of cardiogenic shock. In the PCI subgroup, these factors plus PCI success predicted 30-day mortality.

Strategies to improve reaccess not resolved

When performing TAVR, other factors that might influence subsequent PCI success includes commissural alignment and positioning, according to Dr. Kim. But he cautioned that there are a number of potential controversies when weighing how to improve chances of post-TAVR angiographic reaccess without compromising the success of valve replacement.

“Lower positioning facilitates coronary access, but unfortunately will increase rates of conduction disturbances,” he noted.

Overall, one of the main messages from this analysis is that “the fear of impaired coronary access [after TAVR] may well be disproportionate to the reality,” according to Neal S. Kleiman, MD, an interventional cardiologist at Houston Methodist DeBakey Heart and Vascular Center. Dr. Kleiman wrote an editorial on the registry findings in the same issue of JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions).

Yet, he agreed that the issue of angiographic reaccess after TAVR cannot be ignored. Although reaccess after TAVR has so far been “surprisingly rare,” Dr. Kleiman expects cases to increase as more younger patients undergo TAVR. He suggested that interventionalists will need consider this issue when performing TAVR, a point he reemphasized in an interview.

“It is still a concern when recommending TAVR to a patient and still poses challenges to device manufacturers,” said Dr. Kleiman, suggesting that “a new set of skills” will be required to perform TAVR that will optimize subsequent angiographic access and PCI.

Dr. Kim agreed. Ultimately, other challenges, such as PCI performed after TAVR-in-TAVR placement, are likely to further complicate this issue, but he, too, is looking to new devices to minimize the problems.

“It would be desirable to modify the design, especially of long SFPs, to improve access for PCI, and there are ongoing efforts of the manufacturers to achieve this,” Dr. Kim said.

Dr. Kim reported financial relationships with Abbot, Boston Scientific, Edwards Lifesciences, Medtronic, and Meril Lifesciences. Dr. Kleiman reported financial relationships with Abbott, Boston Scientific, Edwards Lifesciences, and Medtronic.

Coronary angiography and percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) can be performed successfully after transcatheter aortic valve replacement in most cases, according to data drawn from an international registry that has collected more than 400 such cases.

Overall, reaccess coronary angiography was successful in about 99% of cases with type of prosthesis identified as the most important variable in predicting success, according to a multicenter investigating team led by Won-Keun Kim, MD, director of structural heart disease, Kerckhoff Heart Center, Bad Nauheim, Germany.

By type of prosthesis, Dr. Kim was referring to long versus short stent-frame prostheses (SFP). In the case of angiography of the right coronary artery, for example, success was achieved in 99.6% of those with a short SFP and 95.9% of those with a long SFP (P = .005).

The study was published online in JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions.

Based on these and previous data, “prosthetic choice will be the main decisive factor that affects coronary reaccess, and this decision is in the hands of the TAVR operator,” said Dr. Kim in an interview.

This does not preclude use of a long SFP in TAVR. For patients with increased likelihood of eventually requiring a coronary intervention after TAVR, such as those undergoing the procedure at a relatively young age, a short device appears to be preferable, but Dr. Kim emphasized that it is not the only consideration.

When performing TAVR, “the highest priority is to accomplish a safe procedure with a good immediate outcome,” he said, pointing out that angiographic reaccess and PCI are successfully achieved in most patients whether fitted with a short or long SFP.

“If for any reason I assume that the immediate outcome [after TAVR] might be better using a long SFP, I would not hesitate to use a long SFP,” said Dr. Kim, giving such examples as a need for resheathing or precise positioning.

Coronary reaccess has low relative priority

“Coronary reaccess is an important issue and there is an increasing awareness of this, but it has a lower priority” than optimizing TAVR success,” Dr. Kim explained.

The analysis of coronary angiographic reaccess was based on 449 TAVR patients from 25 sites who required reaccess angiography. The indication in most cases was an acute coronary syndrome, mostly non–ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI, 79%). Of the remaining patients, about half had STEMIs and half had other acute cardiovascular situations. The median time interval from TAVR to need for coronary angiography was 311 days.

In all but 2.7%, diagnostic catheterization was performed initially. It was successful in 98.3% of the procedures in the right coronary artery, 99.3% of the left coronary artery, and 97.3% overall.

Of the 60% who underwent PCI, 9% were considered unsuccessful. The reasons included lack of reflow in eight cases and coronary access issues in six cases. A variety of other issues accounted for the remaining seven cases.

Technical success was achieved in 91.4% of native arteries. In the six cases in which engagement of the culprit vessel with a guiding catheter failed, three were converted to urgent coronary bypass grafting and three died in the hospital. Neither selective versus unselective guiding-catheter engagement nor long versus short SFP related to PCI success, but PCI was performed less commonly in the native coronary arteries of TAVR patients with a long rather than short SFP (49% vs. 57%).

The 30-day all-cause mortality in this series was 12.2%. The independent predictors were a history of diabetes and the occurrence of cardiogenic shock. In the PCI subgroup, these factors plus PCI success predicted 30-day mortality.

Strategies to improve reaccess not resolved

When performing TAVR, other factors that might influence subsequent PCI success includes commissural alignment and positioning, according to Dr. Kim. But he cautioned that there are a number of potential controversies when weighing how to improve chances of post-TAVR angiographic reaccess without compromising the success of valve replacement.

“Lower positioning facilitates coronary access, but unfortunately will increase rates of conduction disturbances,” he noted.

Overall, one of the main messages from this analysis is that “the fear of impaired coronary access [after TAVR] may well be disproportionate to the reality,” according to Neal S. Kleiman, MD, an interventional cardiologist at Houston Methodist DeBakey Heart and Vascular Center. Dr. Kleiman wrote an editorial on the registry findings in the same issue of JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions).

Yet, he agreed that the issue of angiographic reaccess after TAVR cannot be ignored. Although reaccess after TAVR has so far been “surprisingly rare,” Dr. Kleiman expects cases to increase as more younger patients undergo TAVR. He suggested that interventionalists will need consider this issue when performing TAVR, a point he reemphasized in an interview.

“It is still a concern when recommending TAVR to a patient and still poses challenges to device manufacturers,” said Dr. Kleiman, suggesting that “a new set of skills” will be required to perform TAVR that will optimize subsequent angiographic access and PCI.

Dr. Kim agreed. Ultimately, other challenges, such as PCI performed after TAVR-in-TAVR placement, are likely to further complicate this issue, but he, too, is looking to new devices to minimize the problems.

“It would be desirable to modify the design, especially of long SFPs, to improve access for PCI, and there are ongoing efforts of the manufacturers to achieve this,” Dr. Kim said.

Dr. Kim reported financial relationships with Abbot, Boston Scientific, Edwards Lifesciences, Medtronic, and Meril Lifesciences. Dr. Kleiman reported financial relationships with Abbott, Boston Scientific, Edwards Lifesciences, and Medtronic.

Coronary angiography and percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) can be performed successfully after transcatheter aortic valve replacement in most cases, according to data drawn from an international registry that has collected more than 400 such cases.

Overall, reaccess coronary angiography was successful in about 99% of cases with type of prosthesis identified as the most important variable in predicting success, according to a multicenter investigating team led by Won-Keun Kim, MD, director of structural heart disease, Kerckhoff Heart Center, Bad Nauheim, Germany.

By type of prosthesis, Dr. Kim was referring to long versus short stent-frame prostheses (SFP). In the case of angiography of the right coronary artery, for example, success was achieved in 99.6% of those with a short SFP and 95.9% of those with a long SFP (P = .005).

The study was published online in JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions.

Based on these and previous data, “prosthetic choice will be the main decisive factor that affects coronary reaccess, and this decision is in the hands of the TAVR operator,” said Dr. Kim in an interview.

This does not preclude use of a long SFP in TAVR. For patients with increased likelihood of eventually requiring a coronary intervention after TAVR, such as those undergoing the procedure at a relatively young age, a short device appears to be preferable, but Dr. Kim emphasized that it is not the only consideration.

When performing TAVR, “the highest priority is to accomplish a safe procedure with a good immediate outcome,” he said, pointing out that angiographic reaccess and PCI are successfully achieved in most patients whether fitted with a short or long SFP.

“If for any reason I assume that the immediate outcome [after TAVR] might be better using a long SFP, I would not hesitate to use a long SFP,” said Dr. Kim, giving such examples as a need for resheathing or precise positioning.

Coronary reaccess has low relative priority

“Coronary reaccess is an important issue and there is an increasing awareness of this, but it has a lower priority” than optimizing TAVR success,” Dr. Kim explained.

The analysis of coronary angiographic reaccess was based on 449 TAVR patients from 25 sites who required reaccess angiography. The indication in most cases was an acute coronary syndrome, mostly non–ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI, 79%). Of the remaining patients, about half had STEMIs and half had other acute cardiovascular situations. The median time interval from TAVR to need for coronary angiography was 311 days.

In all but 2.7%, diagnostic catheterization was performed initially. It was successful in 98.3% of the procedures in the right coronary artery, 99.3% of the left coronary artery, and 97.3% overall.

Of the 60% who underwent PCI, 9% were considered unsuccessful. The reasons included lack of reflow in eight cases and coronary access issues in six cases. A variety of other issues accounted for the remaining seven cases.

Technical success was achieved in 91.4% of native arteries. In the six cases in which engagement of the culprit vessel with a guiding catheter failed, three were converted to urgent coronary bypass grafting and three died in the hospital. Neither selective versus unselective guiding-catheter engagement nor long versus short SFP related to PCI success, but PCI was performed less commonly in the native coronary arteries of TAVR patients with a long rather than short SFP (49% vs. 57%).

The 30-day all-cause mortality in this series was 12.2%. The independent predictors were a history of diabetes and the occurrence of cardiogenic shock. In the PCI subgroup, these factors plus PCI success predicted 30-day mortality.

Strategies to improve reaccess not resolved

When performing TAVR, other factors that might influence subsequent PCI success includes commissural alignment and positioning, according to Dr. Kim. But he cautioned that there are a number of potential controversies when weighing how to improve chances of post-TAVR angiographic reaccess without compromising the success of valve replacement.

“Lower positioning facilitates coronary access, but unfortunately will increase rates of conduction disturbances,” he noted.

Overall, one of the main messages from this analysis is that “the fear of impaired coronary access [after TAVR] may well be disproportionate to the reality,” according to Neal S. Kleiman, MD, an interventional cardiologist at Houston Methodist DeBakey Heart and Vascular Center. Dr. Kleiman wrote an editorial on the registry findings in the same issue of JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions).

Yet, he agreed that the issue of angiographic reaccess after TAVR cannot be ignored. Although reaccess after TAVR has so far been “surprisingly rare,” Dr. Kleiman expects cases to increase as more younger patients undergo TAVR. He suggested that interventionalists will need consider this issue when performing TAVR, a point he reemphasized in an interview.

“It is still a concern when recommending TAVR to a patient and still poses challenges to device manufacturers,” said Dr. Kleiman, suggesting that “a new set of skills” will be required to perform TAVR that will optimize subsequent angiographic access and PCI.

Dr. Kim agreed. Ultimately, other challenges, such as PCI performed after TAVR-in-TAVR placement, are likely to further complicate this issue, but he, too, is looking to new devices to minimize the problems.

“It would be desirable to modify the design, especially of long SFPs, to improve access for PCI, and there are ongoing efforts of the manufacturers to achieve this,” Dr. Kim said.

Dr. Kim reported financial relationships with Abbot, Boston Scientific, Edwards Lifesciences, Medtronic, and Meril Lifesciences. Dr. Kleiman reported financial relationships with Abbott, Boston Scientific, Edwards Lifesciences, and Medtronic.

FROM JACC: CARDIOVASCULAR INTERVENTIONS

Pharmacologic and electrical cardioversion of acute Afib reduces hospital admissions

Background: Atrial fibrillation (Afib) is the most common arrhythmia requiring treatment in the ED. There is a paucity of literature regarding the management of acute (onset < 48 h) atrial fibrillation in this setting and no conclusive evidence exists regarding the superiority of pharmacologic vs. electrical cardioversion.

Study design: Multicenter, single-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial.

Setting: 11 Canadian academic medical centers.

Synopsis: In this trial of 396 patients with acute Afib, half were randomly assigned to pharmacologic cardioversion with procainamide infusion (followed by DC cardioversion, if unsuccessful), while half were given a placebo infusion then DC cardioversion. The primary outcome was conversion to sinus rhythm, with maintenance of sinus rhythm at 30 minutes. A secondary protocol evaluated the difference in efficacy between anterolateral (AL) and anteroposterior (AP) pad placement

The “drug-shock” group achieved and maintained sinus rhythm in 96% of cases, compared to 92% in the “placebo-shock” group (statistically insignificant difference). The procainamide infusion alone achieved and maintained sinus rhythm in 52% of recipients, who thereby avoided the need for procedural sedation and monitoring. Notably, only 2% of patients in the study required admission to the hospital. Pad placement was equally efficacious in the AL or AP positions. The most common adverse event observed was transient hypotension during infusion of procainamide. No strokes were observed in either arm. Follow-up ECGs obtained 14 days later showed that 95% of patients remained in sinus rhythm.

Bottom line: Pharmacologic cardioversion with procainamide infusion and/or electrical cardioversion is a safe and efficacious initial management strategy for acute atrial fibrillation, and all but eliminates the need for hospital admission.

Citation: Stiell IG et al. Electrical versus pharmacological cardioversion for emergency department patients with acute atrial fibrillation (RAFF2): a partial factorial randomized trial. Lancet. 2020 Feb 1;395(10221):339-49.

Dr. Lawson is assistant professor of medicine, section of hospital medicine, at the University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville.

Background: Atrial fibrillation (Afib) is the most common arrhythmia requiring treatment in the ED. There is a paucity of literature regarding the management of acute (onset < 48 h) atrial fibrillation in this setting and no conclusive evidence exists regarding the superiority of pharmacologic vs. electrical cardioversion.

Study design: Multicenter, single-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial.

Setting: 11 Canadian academic medical centers.

Synopsis: In this trial of 396 patients with acute Afib, half were randomly assigned to pharmacologic cardioversion with procainamide infusion (followed by DC cardioversion, if unsuccessful), while half were given a placebo infusion then DC cardioversion. The primary outcome was conversion to sinus rhythm, with maintenance of sinus rhythm at 30 minutes. A secondary protocol evaluated the difference in efficacy between anterolateral (AL) and anteroposterior (AP) pad placement

The “drug-shock” group achieved and maintained sinus rhythm in 96% of cases, compared to 92% in the “placebo-shock” group (statistically insignificant difference). The procainamide infusion alone achieved and maintained sinus rhythm in 52% of recipients, who thereby avoided the need for procedural sedation and monitoring. Notably, only 2% of patients in the study required admission to the hospital. Pad placement was equally efficacious in the AL or AP positions. The most common adverse event observed was transient hypotension during infusion of procainamide. No strokes were observed in either arm. Follow-up ECGs obtained 14 days later showed that 95% of patients remained in sinus rhythm.

Bottom line: Pharmacologic cardioversion with procainamide infusion and/or electrical cardioversion is a safe and efficacious initial management strategy for acute atrial fibrillation, and all but eliminates the need for hospital admission.

Citation: Stiell IG et al. Electrical versus pharmacological cardioversion for emergency department patients with acute atrial fibrillation (RAFF2): a partial factorial randomized trial. Lancet. 2020 Feb 1;395(10221):339-49.

Dr. Lawson is assistant professor of medicine, section of hospital medicine, at the University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville.

Background: Atrial fibrillation (Afib) is the most common arrhythmia requiring treatment in the ED. There is a paucity of literature regarding the management of acute (onset < 48 h) atrial fibrillation in this setting and no conclusive evidence exists regarding the superiority of pharmacologic vs. electrical cardioversion.

Study design: Multicenter, single-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial.

Setting: 11 Canadian academic medical centers.

Synopsis: In this trial of 396 patients with acute Afib, half were randomly assigned to pharmacologic cardioversion with procainamide infusion (followed by DC cardioversion, if unsuccessful), while half were given a placebo infusion then DC cardioversion. The primary outcome was conversion to sinus rhythm, with maintenance of sinus rhythm at 30 minutes. A secondary protocol evaluated the difference in efficacy between anterolateral (AL) and anteroposterior (AP) pad placement

The “drug-shock” group achieved and maintained sinus rhythm in 96% of cases, compared to 92% in the “placebo-shock” group (statistically insignificant difference). The procainamide infusion alone achieved and maintained sinus rhythm in 52% of recipients, who thereby avoided the need for procedural sedation and monitoring. Notably, only 2% of patients in the study required admission to the hospital. Pad placement was equally efficacious in the AL or AP positions. The most common adverse event observed was transient hypotension during infusion of procainamide. No strokes were observed in either arm. Follow-up ECGs obtained 14 days later showed that 95% of patients remained in sinus rhythm.

Bottom line: Pharmacologic cardioversion with procainamide infusion and/or electrical cardioversion is a safe and efficacious initial management strategy for acute atrial fibrillation, and all but eliminates the need for hospital admission.

Citation: Stiell IG et al. Electrical versus pharmacological cardioversion for emergency department patients with acute atrial fibrillation (RAFF2): a partial factorial randomized trial. Lancet. 2020 Feb 1;395(10221):339-49.

Dr. Lawson is assistant professor of medicine, section of hospital medicine, at the University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville.

Animal-assisted therapy could boost patients’ mental health

For me, vacation planning brings with it a bit of anxiety and stress – particularly as we navigate the many uncertainties around COVID-19.

Not only must my husband and I think about our own safety, we also have to make sure that our beloved dog, Samson, gets the proper care while we are away.

My husband adopted Samson, an 11-year-old mixed-breed rescue, when he was just a year old. He’s an important part of our family.

So, when booking our hotel room and flights, we also had to find someone we trust to care for Samson in our absence. Family members are not always an option, so we often rely on pet-sitting apps. We looked through profile after profile, contacted sitters, and interrogated them as if we were looking for care for a tiny human.

Eventually, we found a service that allows owners to use a mobile app that provides updates about how their pets are faring. While we were away, the sitter sent daily photos and videos of Samson that put our minds at ease.

As a registered nurse who works in an ICU, my own anxiety about leaving Samson reminded me about my patients’ reservations about leaving their pets during hospitalizations. Many of them share the same kinds of anxieties when they are separated from their beloved pets. Hospital visits are rarely planned. I have cared for patients who expressed concerns about their pets being home alone and needing to coordinate pet care. In some cases – to alleviate those patients’ anxieties – I have helped them contact friends and family members to assist with care.

Pets’ popularity grows in U.S.

According to the 2019-2020 National Pet Owners Survey, about 67% of U.S. households own a pet – which translates to about 84.9 million homes. During the height of COVID, Americans also acquired a greater number of smaller pets.1 In addition, when social restrictions increased, the demand for dog adoptions and the desire to serve as foster owners rose significantly.2 Last Chance Animal Rescue of Waldorf, Md., reportedly saw the adoption of dogs rise from 30%-40% in 2020. Another animal rescue operation, Lucky Dog, of Arlington, Va., in 2020 helped about 3,385 pets find adoption, up from about 1,800 in 2019.3 About two-thirds of all American households and roughly half of elderly individuals own pets.4

I am not surprised by those numbers. In my nursing practice, I face many stress-related factors, such as alternating day and night shifts, 12-hour shifts, strenuous physical work, and the psychological strain of attending to ill and dying patients. Interacting with Samson helps relieve that stress. The motion of petting Samson helps calm my heart rate and decreases my anxiety. In addition, Samson makes me smile – and excites almost all the people I interact with while he’s around. Of course, I’m not objective, but I view Samson’s impact on people as a symbol of the power of animal-assisted therapy (AAT).

AAT, defined as “the positive interaction between an animal and a patient within a therapeutic framework,”has proven to be an effective intervention for adults with intellectual disabilities who experience anxiety in an observational study.5 The intervention also has helped reduce cortisol levels in a study of nurses in physical medicine, internal medicine, and long-term care.6 Since most patient hospital stays are unplanned, there is a need to introduce AAT into hospital care. This would lessen anxiety in patients concerning their pets’ welfare.

We know that long-term hospital stays often cause adverse psychosocial effects on patients. Such stays can result in “hospitalization syndrome,” which is characterized by a gradual loss of cognition and orientation, an unwillingness to maintain contact with others or to engage in group therapy, and a loss of interest in their surroundings.7 The common causes for this syndrome are infection, medication, isolation, response to surgery, and dehydration. A consequence can be a permanent change in cognitive function or psychological impairment. However, my experience of practicing nursing for years has led me to discover that pets as an external stimulus can prevent the syndrome’s onset. This is because a large percentage of hospitalized patients have pets, and contact with a pet reminds them of home and the memories they share at home.

Introducing animal therapy into health care facilities could boost patients’ mental health – and ease their anxiety – by acting as a bridge between their present circumstances and the lives they have outside the establishment.

References

1. American Pet Owners Association. Will the COVID Pet Spike Last? State of the industry presentation. 2021 Mar 24.

2. Morgan L et al. Humanit Soc Sci Comm. 2020 Nov 24;7(144). doi: 10.1057/S41599-020-00649-x.

3. Hedgpeth D. So many pets have been adopted during the pandemic that shelters are running out. Washington Post. 2021 Jan 6.

4. Cherniack EP and Cherniack AR. Curr Gerontol Geriatr Res. 2014. doi: 10.1155/2014/623203.

5. Giuliani F and Jacquemettaz M. Eur J Integ Med. 2017 Sep;14;13-9.

6. Machová K et al. Int J Environ Res and Public Health. 2019 Oct;16(19):3670.

7. Machová K et al. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2012 Apr;16(8):1362.

Ms. Scott is a registered nurse specializing in critical care and also has experience in nursing leadership. She has 8 years of experience in cardiothoracic ICUs. Ms. Scott received a bachelor of science in nursing degree from Queens University of Charlotte (N.C.), and a master of business administration in health care administration from the University of North Alabama, Florence. She has no conflicts of interest.

For me, vacation planning brings with it a bit of anxiety and stress – particularly as we navigate the many uncertainties around COVID-19.

Not only must my husband and I think about our own safety, we also have to make sure that our beloved dog, Samson, gets the proper care while we are away.

My husband adopted Samson, an 11-year-old mixed-breed rescue, when he was just a year old. He’s an important part of our family.

So, when booking our hotel room and flights, we also had to find someone we trust to care for Samson in our absence. Family members are not always an option, so we often rely on pet-sitting apps. We looked through profile after profile, contacted sitters, and interrogated them as if we were looking for care for a tiny human.

Eventually, we found a service that allows owners to use a mobile app that provides updates about how their pets are faring. While we were away, the sitter sent daily photos and videos of Samson that put our minds at ease.

As a registered nurse who works in an ICU, my own anxiety about leaving Samson reminded me about my patients’ reservations about leaving their pets during hospitalizations. Many of them share the same kinds of anxieties when they are separated from their beloved pets. Hospital visits are rarely planned. I have cared for patients who expressed concerns about their pets being home alone and needing to coordinate pet care. In some cases – to alleviate those patients’ anxieties – I have helped them contact friends and family members to assist with care.

Pets’ popularity grows in U.S.

According to the 2019-2020 National Pet Owners Survey, about 67% of U.S. households own a pet – which translates to about 84.9 million homes. During the height of COVID, Americans also acquired a greater number of smaller pets.1 In addition, when social restrictions increased, the demand for dog adoptions and the desire to serve as foster owners rose significantly.2 Last Chance Animal Rescue of Waldorf, Md., reportedly saw the adoption of dogs rise from 30%-40% in 2020. Another animal rescue operation, Lucky Dog, of Arlington, Va., in 2020 helped about 3,385 pets find adoption, up from about 1,800 in 2019.3 About two-thirds of all American households and roughly half of elderly individuals own pets.4

I am not surprised by those numbers. In my nursing practice, I face many stress-related factors, such as alternating day and night shifts, 12-hour shifts, strenuous physical work, and the psychological strain of attending to ill and dying patients. Interacting with Samson helps relieve that stress. The motion of petting Samson helps calm my heart rate and decreases my anxiety. In addition, Samson makes me smile – and excites almost all the people I interact with while he’s around. Of course, I’m not objective, but I view Samson’s impact on people as a symbol of the power of animal-assisted therapy (AAT).

AAT, defined as “the positive interaction between an animal and a patient within a therapeutic framework,”has proven to be an effective intervention for adults with intellectual disabilities who experience anxiety in an observational study.5 The intervention also has helped reduce cortisol levels in a study of nurses in physical medicine, internal medicine, and long-term care.6 Since most patient hospital stays are unplanned, there is a need to introduce AAT into hospital care. This would lessen anxiety in patients concerning their pets’ welfare.

We know that long-term hospital stays often cause adverse psychosocial effects on patients. Such stays can result in “hospitalization syndrome,” which is characterized by a gradual loss of cognition and orientation, an unwillingness to maintain contact with others or to engage in group therapy, and a loss of interest in their surroundings.7 The common causes for this syndrome are infection, medication, isolation, response to surgery, and dehydration. A consequence can be a permanent change in cognitive function or psychological impairment. However, my experience of practicing nursing for years has led me to discover that pets as an external stimulus can prevent the syndrome’s onset. This is because a large percentage of hospitalized patients have pets, and contact with a pet reminds them of home and the memories they share at home.

Introducing animal therapy into health care facilities could boost patients’ mental health – and ease their anxiety – by acting as a bridge between their present circumstances and the lives they have outside the establishment.

References

1. American Pet Owners Association. Will the COVID Pet Spike Last? State of the industry presentation. 2021 Mar 24.

2. Morgan L et al. Humanit Soc Sci Comm. 2020 Nov 24;7(144). doi: 10.1057/S41599-020-00649-x.

3. Hedgpeth D. So many pets have been adopted during the pandemic that shelters are running out. Washington Post. 2021 Jan 6.

4. Cherniack EP and Cherniack AR. Curr Gerontol Geriatr Res. 2014. doi: 10.1155/2014/623203.

5. Giuliani F and Jacquemettaz M. Eur J Integ Med. 2017 Sep;14;13-9.

6. Machová K et al. Int J Environ Res and Public Health. 2019 Oct;16(19):3670.

7. Machová K et al. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2012 Apr;16(8):1362.

Ms. Scott is a registered nurse specializing in critical care and also has experience in nursing leadership. She has 8 years of experience in cardiothoracic ICUs. Ms. Scott received a bachelor of science in nursing degree from Queens University of Charlotte (N.C.), and a master of business administration in health care administration from the University of North Alabama, Florence. She has no conflicts of interest.

For me, vacation planning brings with it a bit of anxiety and stress – particularly as we navigate the many uncertainties around COVID-19.

Not only must my husband and I think about our own safety, we also have to make sure that our beloved dog, Samson, gets the proper care while we are away.

My husband adopted Samson, an 11-year-old mixed-breed rescue, when he was just a year old. He’s an important part of our family.

So, when booking our hotel room and flights, we also had to find someone we trust to care for Samson in our absence. Family members are not always an option, so we often rely on pet-sitting apps. We looked through profile after profile, contacted sitters, and interrogated them as if we were looking for care for a tiny human.

Eventually, we found a service that allows owners to use a mobile app that provides updates about how their pets are faring. While we were away, the sitter sent daily photos and videos of Samson that put our minds at ease.

As a registered nurse who works in an ICU, my own anxiety about leaving Samson reminded me about my patients’ reservations about leaving their pets during hospitalizations. Many of them share the same kinds of anxieties when they are separated from their beloved pets. Hospital visits are rarely planned. I have cared for patients who expressed concerns about their pets being home alone and needing to coordinate pet care. In some cases – to alleviate those patients’ anxieties – I have helped them contact friends and family members to assist with care.

Pets’ popularity grows in U.S.

According to the 2019-2020 National Pet Owners Survey, about 67% of U.S. households own a pet – which translates to about 84.9 million homes. During the height of COVID, Americans also acquired a greater number of smaller pets.1 In addition, when social restrictions increased, the demand for dog adoptions and the desire to serve as foster owners rose significantly.2 Last Chance Animal Rescue of Waldorf, Md., reportedly saw the adoption of dogs rise from 30%-40% in 2020. Another animal rescue operation, Lucky Dog, of Arlington, Va., in 2020 helped about 3,385 pets find adoption, up from about 1,800 in 2019.3 About two-thirds of all American households and roughly half of elderly individuals own pets.4

I am not surprised by those numbers. In my nursing practice, I face many stress-related factors, such as alternating day and night shifts, 12-hour shifts, strenuous physical work, and the psychological strain of attending to ill and dying patients. Interacting with Samson helps relieve that stress. The motion of petting Samson helps calm my heart rate and decreases my anxiety. In addition, Samson makes me smile – and excites almost all the people I interact with while he’s around. Of course, I’m not objective, but I view Samson’s impact on people as a symbol of the power of animal-assisted therapy (AAT).

AAT, defined as “the positive interaction between an animal and a patient within a therapeutic framework,”has proven to be an effective intervention for adults with intellectual disabilities who experience anxiety in an observational study.5 The intervention also has helped reduce cortisol levels in a study of nurses in physical medicine, internal medicine, and long-term care.6 Since most patient hospital stays are unplanned, there is a need to introduce AAT into hospital care. This would lessen anxiety in patients concerning their pets’ welfare.

We know that long-term hospital stays often cause adverse psychosocial effects on patients. Such stays can result in “hospitalization syndrome,” which is characterized by a gradual loss of cognition and orientation, an unwillingness to maintain contact with others or to engage in group therapy, and a loss of interest in their surroundings.7 The common causes for this syndrome are infection, medication, isolation, response to surgery, and dehydration. A consequence can be a permanent change in cognitive function or psychological impairment. However, my experience of practicing nursing for years has led me to discover that pets as an external stimulus can prevent the syndrome’s onset. This is because a large percentage of hospitalized patients have pets, and contact with a pet reminds them of home and the memories they share at home.

Introducing animal therapy into health care facilities could boost patients’ mental health – and ease their anxiety – by acting as a bridge between their present circumstances and the lives they have outside the establishment.

References

1. American Pet Owners Association. Will the COVID Pet Spike Last? State of the industry presentation. 2021 Mar 24.

2. Morgan L et al. Humanit Soc Sci Comm. 2020 Nov 24;7(144). doi: 10.1057/S41599-020-00649-x.

3. Hedgpeth D. So many pets have been adopted during the pandemic that shelters are running out. Washington Post. 2021 Jan 6.

4. Cherniack EP and Cherniack AR. Curr Gerontol Geriatr Res. 2014. doi: 10.1155/2014/623203.

5. Giuliani F and Jacquemettaz M. Eur J Integ Med. 2017 Sep;14;13-9.

6. Machová K et al. Int J Environ Res and Public Health. 2019 Oct;16(19):3670.

7. Machová K et al. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2012 Apr;16(8):1362.

Ms. Scott is a registered nurse specializing in critical care and also has experience in nursing leadership. She has 8 years of experience in cardiothoracic ICUs. Ms. Scott received a bachelor of science in nursing degree from Queens University of Charlotte (N.C.), and a master of business administration in health care administration from the University of North Alabama, Florence. She has no conflicts of interest.

Vertebral fractures still a risk with low-dose oral glucocorticoids for RA

Patients with rheumatoid arthritis currently being treated with low doses of oral glucocorticoids (GCs) had a 59% increased risk of sustaining a vertebral fracture when compared with past users, results of a retrospective cohort study have shown.

Although the overall risk of an osteoporotic fracture was not increased when comparing current and past GC users, with a hazard ratio of 1.14 (95% confidence interval, 0.98-1.33), the HR for sustaining a spinal fracture was 1.59 (95% CI, 1.11-2.29).

“Clinicians should be aware that, even in RA patients who receive low daily glucocorticoid doses, the risk of clinical vertebral fracture is increased,” Shahab Abtahi, MD, of Maastricht (the Netherlands) University and coauthors reported in Rheumatology.

This is important considering around a quarter of RA patients are treated with GCs in the United Kingdom in accordance with European recommendations, they observed.

Conflicting randomized and observational findings on whether or not osteoporotic fractures might be linked to the use of low-dose GCs prompted Dr. Abtahi and associates to see if there were any signals in real-world data. To do so, they used data one of the world’s largest primary care databases – the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD), which consists of anonymized patient data from a network of primary care practices across the United Kingdom.

Altogether, the records of more than 15,000 patients with RA aged 50 years and older who were held in the CRPD between 1997 and 2017 were pulled for analysis, and just half (n = 7,039) were receiving or had received GC therapy. Low-dose GC therapy was defined as a prednisolone equivalent dose (PED) of 7.5 mg or less per day.

The use of low-dose GCs use during three key time periods was considered: within the past 6 months (current users), within the past 7-12 months (recent users), and within the past year (past users).

The analyses involved time-dependent Cox proportional-hazards models to look for associations between GC use and all types of osteoporotic fracture, including the risk for incident hip, vertebral, humeral, forearm, pelvis, and rib fractures. They were adjusted for various lifestyle parameters, comorbidities, and the use of other medications.

“Current GC use was further broken down into subcategories based on average daily and cumulative dose,” Dr. Abtahi observed. As might be expected, doses even lower than 7.5 mg or less PED did not increase the chance of any osteoporotic fracture but there was an increased risk for some types with higher average daily doses, notably at the hip and pelvis, as well as the spine.

“Low-dose oral GC therapy was associated with an increased risk of clinical vertebral fracture, while the risk of other individual OP fracture sites was not increased,” said the team, adding that the main results remained unchanged regardless of short- or long-term use.

“We know that vertebral fracture risk is markedly increased in RA, and it is well known that GC therapy in particular affects trabecular bone, which is abundantly present in lumbar vertebrae,” Dr. Abtahi wrote.

“Therefore, we can hypothesize that the beneficial effect of low-dose GC therapy on suppressing the background inflammation of RA could probably be enough to offset its negative effect on bone synthesis in most fracture sites but not in vertebrae,” they suggested.

One of the limitations of the study is that the researchers lacked data on the disease activity of the patients or if they were being treated with biologic therapy. This means that confounding by disease severity might be an issue with only those with higher disease activity being treated with GCs and thus were at higher risk for fractures.

“Another limitation was a potential misclassification of exposure with oral GCs, as we had only prescribing information from CPRD, which is roughly two steps behind actual drug use by patients,” the researchers conceded. The average duration of GC use was estimated at 3.7 years, which is an indication of actual use.

A detection bias may also be involved with regard to vertebral fractures, with complaints of back pain maybe being discussed more often when prescribing GCs, leading to more referrals for possible fracture assessment.

Dr. Abtahi and a fellow coauthor disclosed receiving research and other funding from several pharmaceutical companies unrelated to this study. All other coauthors had no conflicts of interest.

Patients with rheumatoid arthritis currently being treated with low doses of oral glucocorticoids (GCs) had a 59% increased risk of sustaining a vertebral fracture when compared with past users, results of a retrospective cohort study have shown.

Although the overall risk of an osteoporotic fracture was not increased when comparing current and past GC users, with a hazard ratio of 1.14 (95% confidence interval, 0.98-1.33), the HR for sustaining a spinal fracture was 1.59 (95% CI, 1.11-2.29).

“Clinicians should be aware that, even in RA patients who receive low daily glucocorticoid doses, the risk of clinical vertebral fracture is increased,” Shahab Abtahi, MD, of Maastricht (the Netherlands) University and coauthors reported in Rheumatology.

This is important considering around a quarter of RA patients are treated with GCs in the United Kingdom in accordance with European recommendations, they observed.

Conflicting randomized and observational findings on whether or not osteoporotic fractures might be linked to the use of low-dose GCs prompted Dr. Abtahi and associates to see if there were any signals in real-world data. To do so, they used data one of the world’s largest primary care databases – the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD), which consists of anonymized patient data from a network of primary care practices across the United Kingdom.

Altogether, the records of more than 15,000 patients with RA aged 50 years and older who were held in the CRPD between 1997 and 2017 were pulled for analysis, and just half (n = 7,039) were receiving or had received GC therapy. Low-dose GC therapy was defined as a prednisolone equivalent dose (PED) of 7.5 mg or less per day.

The use of low-dose GCs use during three key time periods was considered: within the past 6 months (current users), within the past 7-12 months (recent users), and within the past year (past users).

The analyses involved time-dependent Cox proportional-hazards models to look for associations between GC use and all types of osteoporotic fracture, including the risk for incident hip, vertebral, humeral, forearm, pelvis, and rib fractures. They were adjusted for various lifestyle parameters, comorbidities, and the use of other medications.

“Current GC use was further broken down into subcategories based on average daily and cumulative dose,” Dr. Abtahi observed. As might be expected, doses even lower than 7.5 mg or less PED did not increase the chance of any osteoporotic fracture but there was an increased risk for some types with higher average daily doses, notably at the hip and pelvis, as well as the spine.

“Low-dose oral GC therapy was associated with an increased risk of clinical vertebral fracture, while the risk of other individual OP fracture sites was not increased,” said the team, adding that the main results remained unchanged regardless of short- or long-term use.

“We know that vertebral fracture risk is markedly increased in RA, and it is well known that GC therapy in particular affects trabecular bone, which is abundantly present in lumbar vertebrae,” Dr. Abtahi wrote.

“Therefore, we can hypothesize that the beneficial effect of low-dose GC therapy on suppressing the background inflammation of RA could probably be enough to offset its negative effect on bone synthesis in most fracture sites but not in vertebrae,” they suggested.

One of the limitations of the study is that the researchers lacked data on the disease activity of the patients or if they were being treated with biologic therapy. This means that confounding by disease severity might be an issue with only those with higher disease activity being treated with GCs and thus were at higher risk for fractures.

“Another limitation was a potential misclassification of exposure with oral GCs, as we had only prescribing information from CPRD, which is roughly two steps behind actual drug use by patients,” the researchers conceded. The average duration of GC use was estimated at 3.7 years, which is an indication of actual use.

A detection bias may also be involved with regard to vertebral fractures, with complaints of back pain maybe being discussed more often when prescribing GCs, leading to more referrals for possible fracture assessment.

Dr. Abtahi and a fellow coauthor disclosed receiving research and other funding from several pharmaceutical companies unrelated to this study. All other coauthors had no conflicts of interest.

Patients with rheumatoid arthritis currently being treated with low doses of oral glucocorticoids (GCs) had a 59% increased risk of sustaining a vertebral fracture when compared with past users, results of a retrospective cohort study have shown.

Although the overall risk of an osteoporotic fracture was not increased when comparing current and past GC users, with a hazard ratio of 1.14 (95% confidence interval, 0.98-1.33), the HR for sustaining a spinal fracture was 1.59 (95% CI, 1.11-2.29).

“Clinicians should be aware that, even in RA patients who receive low daily glucocorticoid doses, the risk of clinical vertebral fracture is increased,” Shahab Abtahi, MD, of Maastricht (the Netherlands) University and coauthors reported in Rheumatology.

This is important considering around a quarter of RA patients are treated with GCs in the United Kingdom in accordance with European recommendations, they observed.

Conflicting randomized and observational findings on whether or not osteoporotic fractures might be linked to the use of low-dose GCs prompted Dr. Abtahi and associates to see if there were any signals in real-world data. To do so, they used data one of the world’s largest primary care databases – the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD), which consists of anonymized patient data from a network of primary care practices across the United Kingdom.

Altogether, the records of more than 15,000 patients with RA aged 50 years and older who were held in the CRPD between 1997 and 2017 were pulled for analysis, and just half (n = 7,039) were receiving or had received GC therapy. Low-dose GC therapy was defined as a prednisolone equivalent dose (PED) of 7.5 mg or less per day.

The use of low-dose GCs use during three key time periods was considered: within the past 6 months (current users), within the past 7-12 months (recent users), and within the past year (past users).

The analyses involved time-dependent Cox proportional-hazards models to look for associations between GC use and all types of osteoporotic fracture, including the risk for incident hip, vertebral, humeral, forearm, pelvis, and rib fractures. They were adjusted for various lifestyle parameters, comorbidities, and the use of other medications.

“Current GC use was further broken down into subcategories based on average daily and cumulative dose,” Dr. Abtahi observed. As might be expected, doses even lower than 7.5 mg or less PED did not increase the chance of any osteoporotic fracture but there was an increased risk for some types with higher average daily doses, notably at the hip and pelvis, as well as the spine.

“Low-dose oral GC therapy was associated with an increased risk of clinical vertebral fracture, while the risk of other individual OP fracture sites was not increased,” said the team, adding that the main results remained unchanged regardless of short- or long-term use.

“We know that vertebral fracture risk is markedly increased in RA, and it is well known that GC therapy in particular affects trabecular bone, which is abundantly present in lumbar vertebrae,” Dr. Abtahi wrote.

“Therefore, we can hypothesize that the beneficial effect of low-dose GC therapy on suppressing the background inflammation of RA could probably be enough to offset its negative effect on bone synthesis in most fracture sites but not in vertebrae,” they suggested.

One of the limitations of the study is that the researchers lacked data on the disease activity of the patients or if they were being treated with biologic therapy. This means that confounding by disease severity might be an issue with only those with higher disease activity being treated with GCs and thus were at higher risk for fractures.

“Another limitation was a potential misclassification of exposure with oral GCs, as we had only prescribing information from CPRD, which is roughly two steps behind actual drug use by patients,” the researchers conceded. The average duration of GC use was estimated at 3.7 years, which is an indication of actual use.

A detection bias may also be involved with regard to vertebral fractures, with complaints of back pain maybe being discussed more often when prescribing GCs, leading to more referrals for possible fracture assessment.

Dr. Abtahi and a fellow coauthor disclosed receiving research and other funding from several pharmaceutical companies unrelated to this study. All other coauthors had no conflicts of interest.

FROM RHEUMATOLOGY

Cycling linked to longer life in people with type 2 diabetes

Bicycle riding may help people with diabetes live longer, new research suggests.

Among more than 7,000 adults with diabetes in 10 Western European countries followed for about 15 years, those who cycled regularly were significantly less likely to die of any cause or of cardiovascular causes, even after accounting for differences in factors such as sex, age, educational level, diet, comorbidities, and other physical activities.

“The association between cycling and all-cause and CVD [cardiovascular disease] mortality in this study of person[s] with diabetes was of the same magnitude and direction as observed in the healthy population,” wrote Mathias Ried-Larsen, PhD, of the Centre for Physical Activity Research, Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen, and colleagues. The findings were published online July 19, 2021, in JAMA Internal Medicine.

In an accompanying Editor’s Note, JAMA Internal Medicine editor Rita F. Redberg, MD, and two deputy editors said that the new data add to previous studies showing benefits of cycling, compared with other physical activities. “The analysis from Ried-Larsen and colleagues strengthens the epidemiologic data on cycling and strongly suggests that it may contribute directly to longer and healthier lives,” they wrote.

Dr. Redberg, of the University of California, San Francisco, told this news organization: “I think the number of cyclists grew greatly during pandemic, when there was little auto traffic, and people did not want to take public transportation. Cities that add bike lanes, especially protected bike lanes, see an increase in cyclists. I think Americans can cycle more, would enjoy cycling more, and would live longer [by] cycling, to work and for pleasure.”

Dr. Redberg disclosed that she is “an avid cyclist and am currently on a bike ride in Glacier National Park. ... This group [Climate Ride] raises money for more bike lanes, promotes climate change awareness, has paid for solar panels at Glacier, and more.”

However, Dr. Redberg and colleagues also “recognize that cycling requires fitness, a good sense of balance, and the means to purchase a bicycle. We also understand that regular cycling requires living in an area where it is reasonably safe, and we celebrate the installation of more bike lanes, particularly protected lanes, in many cities around the world.”

But, despite the limitations of an observational study and possible selection bias of people who are able to cycle, “it is important to share this evidence for the potentially large health benefits of cycling, which almost surely generalize to persons without diabetes.”

Cycling tied to lower all-cause and CVD mortality

The prospective cohort study included 7,459 adults with diabetes from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. All were assessed during 1992-1998 and again in 1996-2011, with a mean follow-up of roughly 15 years. During that time, there were 1,673 deaths from all causes, with 811 attributed to CVD.

Compared with no cycling, those who reported any cycling had a 24% lower risk of death from any cause over a 5-year period, after adjustment for confounders and for other physical activity. The greatest risk reduction was seen in those who reported cycling between 150-299 minutes per week, particularly in CVD mortality.

In a subanalysis of 5,423 individuals with 10.7 years of follow-up, there were 975 all-cause deaths and 429 from CVD. Individuals who began or continued cycling during follow-up experienced reductions of about 35% for both all-cause and CVD mortality, compared with those who never cycled.

Dr. Redberg and colleagues added that “there are environmental benefits to increasing the use of cycling for commuting and other transport because cycling helps to decrease the adverse environmental and health effects of automobile exhaust.”

They concluded: “As avid and/or aspiring cyclists ourselves, we are sold on the mental and physical benefits of getting to work and seeing the world on two wheels, self-propelled, and think it is well worth a try.”

The study work was supported by the Health Research Fund of Instituto de Salud Carlos III; the Spanish regional governments of Andalucía, Asturias, Basque Country, Murcia, and Navarra; and the Catalan Institute of Oncology. The Centre for Physical Activity Research is supported by a grant from TrygFonden. Dr. Ried-Larsen reported personal fees from Novo Nordisk. Dr. Redberg reported receiving grants from Arnold Ventures; the Greenwall Foundation; and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Bicycle riding may help people with diabetes live longer, new research suggests.

Among more than 7,000 adults with diabetes in 10 Western European countries followed for about 15 years, those who cycled regularly were significantly less likely to die of any cause or of cardiovascular causes, even after accounting for differences in factors such as sex, age, educational level, diet, comorbidities, and other physical activities.

“The association between cycling and all-cause and CVD [cardiovascular disease] mortality in this study of person[s] with diabetes was of the same magnitude and direction as observed in the healthy population,” wrote Mathias Ried-Larsen, PhD, of the Centre for Physical Activity Research, Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen, and colleagues. The findings were published online July 19, 2021, in JAMA Internal Medicine.

In an accompanying Editor’s Note, JAMA Internal Medicine editor Rita F. Redberg, MD, and two deputy editors said that the new data add to previous studies showing benefits of cycling, compared with other physical activities. “The analysis from Ried-Larsen and colleagues strengthens the epidemiologic data on cycling and strongly suggests that it may contribute directly to longer and healthier lives,” they wrote.

Dr. Redberg, of the University of California, San Francisco, told this news organization: “I think the number of cyclists grew greatly during pandemic, when there was little auto traffic, and people did not want to take public transportation. Cities that add bike lanes, especially protected bike lanes, see an increase in cyclists. I think Americans can cycle more, would enjoy cycling more, and would live longer [by] cycling, to work and for pleasure.”

Dr. Redberg disclosed that she is “an avid cyclist and am currently on a bike ride in Glacier National Park. ... This group [Climate Ride] raises money for more bike lanes, promotes climate change awareness, has paid for solar panels at Glacier, and more.”

However, Dr. Redberg and colleagues also “recognize that cycling requires fitness, a good sense of balance, and the means to purchase a bicycle. We also understand that regular cycling requires living in an area where it is reasonably safe, and we celebrate the installation of more bike lanes, particularly protected lanes, in many cities around the world.”

But, despite the limitations of an observational study and possible selection bias of people who are able to cycle, “it is important to share this evidence for the potentially large health benefits of cycling, which almost surely generalize to persons without diabetes.”

Cycling tied to lower all-cause and CVD mortality

The prospective cohort study included 7,459 adults with diabetes from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. All were assessed during 1992-1998 and again in 1996-2011, with a mean follow-up of roughly 15 years. During that time, there were 1,673 deaths from all causes, with 811 attributed to CVD.

Compared with no cycling, those who reported any cycling had a 24% lower risk of death from any cause over a 5-year period, after adjustment for confounders and for other physical activity. The greatest risk reduction was seen in those who reported cycling between 150-299 minutes per week, particularly in CVD mortality.

In a subanalysis of 5,423 individuals with 10.7 years of follow-up, there were 975 all-cause deaths and 429 from CVD. Individuals who began or continued cycling during follow-up experienced reductions of about 35% for both all-cause and CVD mortality, compared with those who never cycled.

Dr. Redberg and colleagues added that “there are environmental benefits to increasing the use of cycling for commuting and other transport because cycling helps to decrease the adverse environmental and health effects of automobile exhaust.”

They concluded: “As avid and/or aspiring cyclists ourselves, we are sold on the mental and physical benefits of getting to work and seeing the world on two wheels, self-propelled, and think it is well worth a try.”

The study work was supported by the Health Research Fund of Instituto de Salud Carlos III; the Spanish regional governments of Andalucía, Asturias, Basque Country, Murcia, and Navarra; and the Catalan Institute of Oncology. The Centre for Physical Activity Research is supported by a grant from TrygFonden. Dr. Ried-Larsen reported personal fees from Novo Nordisk. Dr. Redberg reported receiving grants from Arnold Ventures; the Greenwall Foundation; and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Bicycle riding may help people with diabetes live longer, new research suggests.

Among more than 7,000 adults with diabetes in 10 Western European countries followed for about 15 years, those who cycled regularly were significantly less likely to die of any cause or of cardiovascular causes, even after accounting for differences in factors such as sex, age, educational level, diet, comorbidities, and other physical activities.

“The association between cycling and all-cause and CVD [cardiovascular disease] mortality in this study of person[s] with diabetes was of the same magnitude and direction as observed in the healthy population,” wrote Mathias Ried-Larsen, PhD, of the Centre for Physical Activity Research, Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen, and colleagues. The findings were published online July 19, 2021, in JAMA Internal Medicine.

In an accompanying Editor’s Note, JAMA Internal Medicine editor Rita F. Redberg, MD, and two deputy editors said that the new data add to previous studies showing benefits of cycling, compared with other physical activities. “The analysis from Ried-Larsen and colleagues strengthens the epidemiologic data on cycling and strongly suggests that it may contribute directly to longer and healthier lives,” they wrote.

Dr. Redberg, of the University of California, San Francisco, told this news organization: “I think the number of cyclists grew greatly during pandemic, when there was little auto traffic, and people did not want to take public transportation. Cities that add bike lanes, especially protected bike lanes, see an increase in cyclists. I think Americans can cycle more, would enjoy cycling more, and would live longer [by] cycling, to work and for pleasure.”

Dr. Redberg disclosed that she is “an avid cyclist and am currently on a bike ride in Glacier National Park. ... This group [Climate Ride] raises money for more bike lanes, promotes climate change awareness, has paid for solar panels at Glacier, and more.”

However, Dr. Redberg and colleagues also “recognize that cycling requires fitness, a good sense of balance, and the means to purchase a bicycle. We also understand that regular cycling requires living in an area where it is reasonably safe, and we celebrate the installation of more bike lanes, particularly protected lanes, in many cities around the world.”

But, despite the limitations of an observational study and possible selection bias of people who are able to cycle, “it is important to share this evidence for the potentially large health benefits of cycling, which almost surely generalize to persons without diabetes.”

Cycling tied to lower all-cause and CVD mortality

The prospective cohort study included 7,459 adults with diabetes from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. All were assessed during 1992-1998 and again in 1996-2011, with a mean follow-up of roughly 15 years. During that time, there were 1,673 deaths from all causes, with 811 attributed to CVD.

Compared with no cycling, those who reported any cycling had a 24% lower risk of death from any cause over a 5-year period, after adjustment for confounders and for other physical activity. The greatest risk reduction was seen in those who reported cycling between 150-299 minutes per week, particularly in CVD mortality.

In a subanalysis of 5,423 individuals with 10.7 years of follow-up, there were 975 all-cause deaths and 429 from CVD. Individuals who began or continued cycling during follow-up experienced reductions of about 35% for both all-cause and CVD mortality, compared with those who never cycled.

Dr. Redberg and colleagues added that “there are environmental benefits to increasing the use of cycling for commuting and other transport because cycling helps to decrease the adverse environmental and health effects of automobile exhaust.”

They concluded: “As avid and/or aspiring cyclists ourselves, we are sold on the mental and physical benefits of getting to work and seeing the world on two wheels, self-propelled, and think it is well worth a try.”

The study work was supported by the Health Research Fund of Instituto de Salud Carlos III; the Spanish regional governments of Andalucía, Asturias, Basque Country, Murcia, and Navarra; and the Catalan Institute of Oncology. The Centre for Physical Activity Research is supported by a grant from TrygFonden. Dr. Ried-Larsen reported personal fees from Novo Nordisk. Dr. Redberg reported receiving grants from Arnold Ventures; the Greenwall Foundation; and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

FROM JAMA INTERNAL MEDICINE

Long COVID seen in patients with severe and mild disease

Findings from the cohort, composed of 113 COVID-19 survivors who developed ARDS after admission to a single center before to April 16, 2020, were presented online at the 31st European Congress of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases by Judit Aranda, MD, from Complex Hospitalari Moisés Broggi in Barcelona.

Median age of the participants was 64 years, and 70% were male. At least one persistent symptom was experienced during follow-up by 81% of the cohort, with 45% reporting shortness of breath, 50% reporting muscle pain, 43% reporting memory impairment, and 46% reporting physical weakness of at least 5 on a 10-point scale.

Of the 104 participants who completed a 6-minute walk test, 30% had a decrease in oxygen saturation level of at least 4%, and 5% had an initial or final level below 88%. Of the 46 participants who underwent a pulmonary function test, 15% had a forced expiratory volume in 1 second below 70%.

And of the 49% of participants with pathologic findings on chest x-ray, most were bilateral interstitial infiltrates (88%).

In addition, more than 90% of participants developed depression, anxiety, or PTSD, Dr. Aranda reported.

Not the whole picture

This study shows that sicker people – “those in intensive care units with acute respiratory distress syndrome” – are “more likely to be struggling with more severe symptoms,” said Christopher Terndrup, MD, from the division of general internal medicine and geriatrics at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland.

But a Swiss study, also presented at the meeting, “shows how even mild COVID cases can lead to debilitating symptoms,” Dr. Terndrup said in an interview.

The investigation of long-term COVID symptoms in outpatients was presented online by Florian Desgranges, MD, from Lausanne (Switzerland) University Hospital. He and his colleagues found that more than half of those with a mild to moderate disease had persistent symptoms at least 3 months after diagnosis.

The prevalence of long COVID has varied in previous research, from 15% in a study of health care workers, to 46% in a study of patients with mild COVID, 52% in a study of young COVID outpatients, and 76% in a study of patients hospitalized with COVID.

Dr. Desgranges and colleagues evaluated patients seen in an ED or outpatient clinic from February to April 2020.

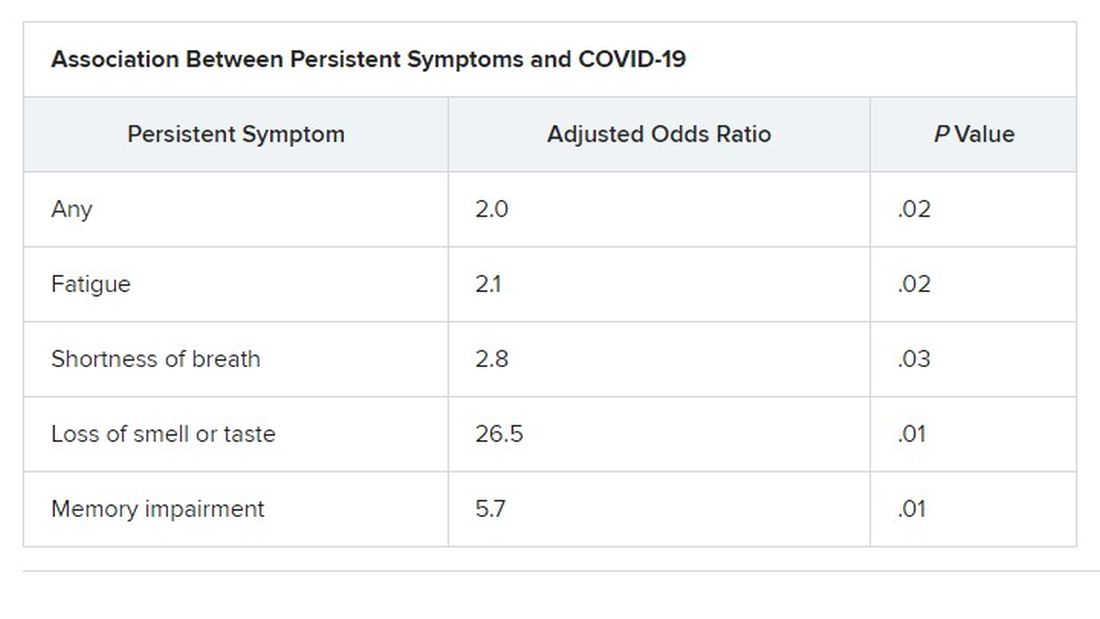

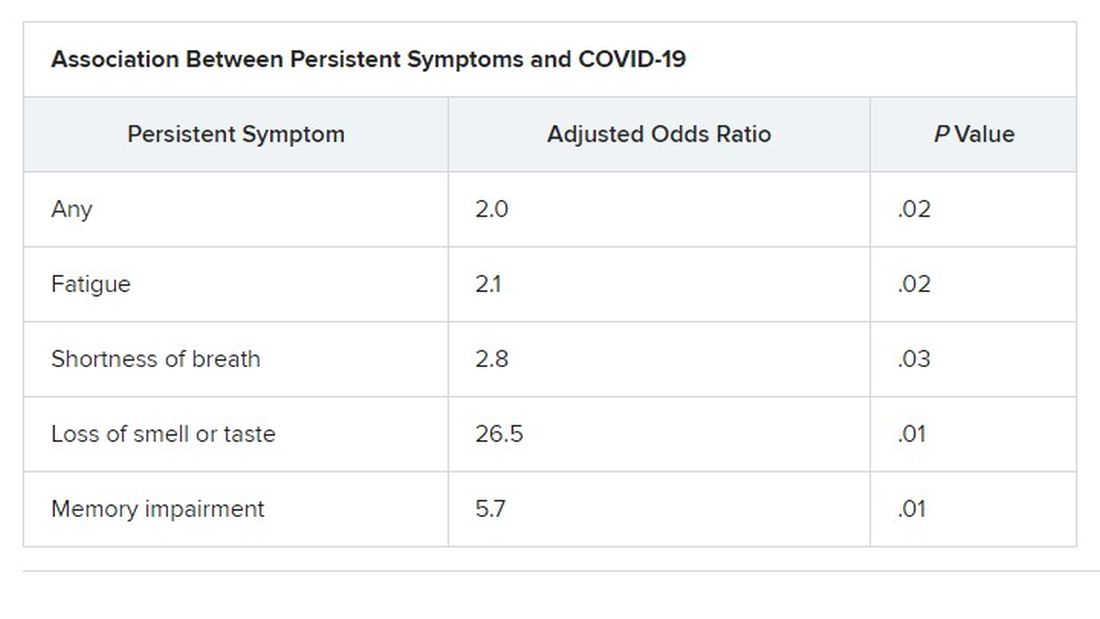

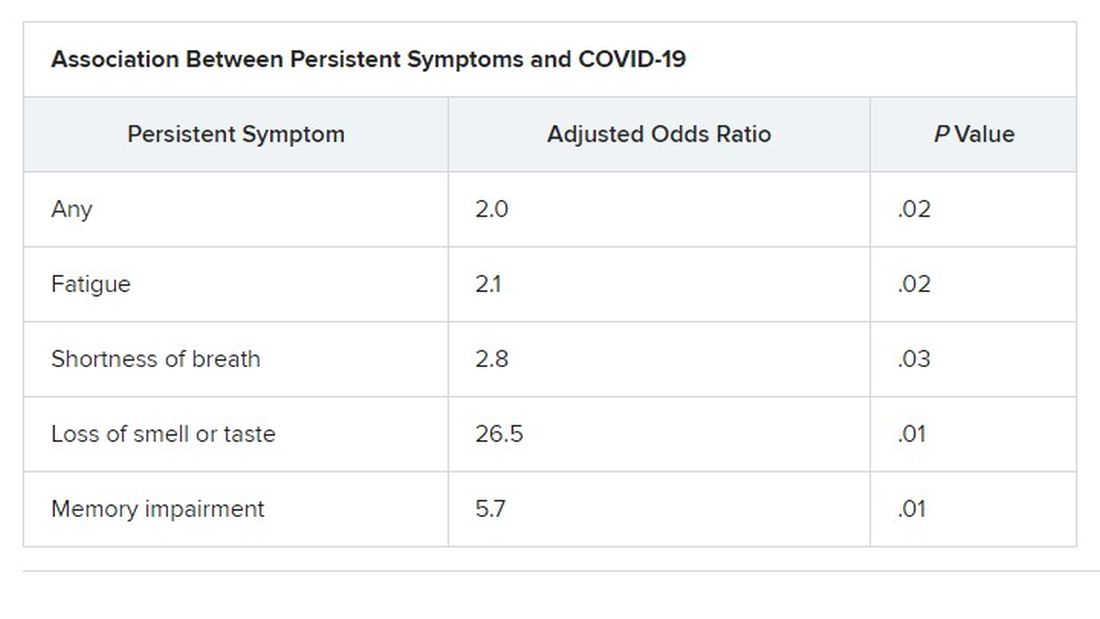

The 418 patients with a confirmed COVID-19 diagnosis were compared with a control group of 89 patients who presented to the same centers during the same time frame with similar symptoms – cough, shortness of breath, or fever – but had a negative SARS-CoV-2 test.

The number of patients with comorbidities was similar in the COVID and control groups (34% vs. 36%), as was median age (41 vs. 36 years) and the prevalence of women (62% vs 64%), but the proportion of health care workers was lower in the COVID group (64% vs 82%; P =.006).

Symptoms that persisted for at least 3 months were more common in the COVID than in the control group (53% vs. 37%). And patients in the COVID group reported more symptoms than those in the control group after adjustment for age, gender, smoking status, comorbidities, and timing of the survey phone call.

Levels of sleeping problems and headache were similar in the two groups.

“We have to remember that with COVID-19 came the psychosocial changes of the pandemic situation” Dr. Desgranges said.

This study suggests that some long-COVID symptoms – such as the fatigue, headache, and sleep disorders reported in the control group – could be related to the pandemic itself, which has caused psychosocial distress, Dr. Terndrup said.

Another study that looked at outpatients “has some fantastic long-term follow-up data, and shows that many patients are still engaging in rehabilitation programs nearly a year after their diagnosis,” he explained.

The COVID HOME study

That prospective longitudinal COVID HOME study, which assessed long-term symptoms in people who were never hospitalized for COVID, was presented online by Adriana Tami, MD, PhD, from the University Medical Center Groningen (the Netherlands).

The researchers visited the homes of patients to collect data, blood samples, and perform polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing 1, 2, and 3 weeks after a diagnosis of COVID-19. If their PCR test was still positive, testing continued until week 6 or a negative test. In addition, participants completed questionnaires at week 2 and at months 3, 6 and 12 to assess fatigue, quality of life, and symptoms of depression and anxiety.

Three-month follow-up data were available for 134 of the 276 people initially enrolled in the study. Questionnaires were completed by 85 participants at 3 months, 62 participants at 6 months, and 10 participants at 12 months.

At least 40% of participants reported long-lasting symptoms at some point during follow-up, and at least 30% said they didn’t feel fully recovered at 12 months. The most common symptom was persistent fatigue, reported at 3, 6, and 12 months by at least 44% of participants. Other common symptoms – reported by at least 20% of respondents at 3, 6, and 12 months – were headache, mental or neurologic symptoms, and sleep disorders, shortness of breath, lack of smell or taste, and severe fatigue.

“We have a high proportion of nonhospitalized individuals who suffer from long COVID after more than 12 months,” Dr. Tami concluded, adding that the study is ongoing. “We have other variables that we want to look at, including duration viral shedding and serological results and variants.”

“These cohort studies are very helpful, but they can lead to inaccurate conclusions,” Dr. Terndrup cautioned.

They only provide pieces of the big picture, but they “do add to a growing body of knowledge about a significant portion of COVID patients still struggling with symptoms long after their initial infection. The symptoms can be quite variable but are dominated by both physical and mental fatigue, and tend to be worse in patients who were sicker at initial infection,” he said in an interview.

As a whole, these studies reinforce the need for treatment programs to help patients who suffer from long COVID, he added, but “I advise caution to folks suffering out there who seek ‘miracle cures’; across the world, we are collaborating to find solutions that are safe and effective.”

We are in desperate need of an equity lens in these studies.

“There is still a great deal to learn about long COVID,” said Dr. Terndrup. Data on underrepresented populations – such as Black, Indigenous, and people of color – are lacking from these and others studies, he explained. “We are in desperate need of an equity lens in these studies,” particularly in the United States, where there are “significant disparities” in the treatment of different populations.

However, “I do hope that this work can lead to a better understanding of how other viral infections can cause long-lasting symptoms,” said Dr. Terndrup.

“We have long proposed that after acute presentation, some microbes can cause chronic symptoms, like fatigue and widespread pain. Perhaps we can learn how to better care for these patients after learning from COVID’s significant impact on our societies across the globe.”

Dr. Aranda and Dr. Desgranges have disclosed no relevant financial relationships or study funding. The study by Dr. Tami’s team was funded by the University Medical Center Groningen Organization for Health Research and Development, and Connecting European Cohorts to Increase Common and Effective Response to SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic. Dr. Terndrup disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Findings from the cohort, composed of 113 COVID-19 survivors who developed ARDS after admission to a single center before to April 16, 2020, were presented online at the 31st European Congress of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases by Judit Aranda, MD, from Complex Hospitalari Moisés Broggi in Barcelona.

Median age of the participants was 64 years, and 70% were male. At least one persistent symptom was experienced during follow-up by 81% of the cohort, with 45% reporting shortness of breath, 50% reporting muscle pain, 43% reporting memory impairment, and 46% reporting physical weakness of at least 5 on a 10-point scale.

Of the 104 participants who completed a 6-minute walk test, 30% had a decrease in oxygen saturation level of at least 4%, and 5% had an initial or final level below 88%. Of the 46 participants who underwent a pulmonary function test, 15% had a forced expiratory volume in 1 second below 70%.

And of the 49% of participants with pathologic findings on chest x-ray, most were bilateral interstitial infiltrates (88%).

In addition, more than 90% of participants developed depression, anxiety, or PTSD, Dr. Aranda reported.

Not the whole picture

This study shows that sicker people – “those in intensive care units with acute respiratory distress syndrome” – are “more likely to be struggling with more severe symptoms,” said Christopher Terndrup, MD, from the division of general internal medicine and geriatrics at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland.

But a Swiss study, also presented at the meeting, “shows how even mild COVID cases can lead to debilitating symptoms,” Dr. Terndrup said in an interview.

The investigation of long-term COVID symptoms in outpatients was presented online by Florian Desgranges, MD, from Lausanne (Switzerland) University Hospital. He and his colleagues found that more than half of those with a mild to moderate disease had persistent symptoms at least 3 months after diagnosis.