User login

Nowhere to run and nowhere to hide

Not surprisingly, the pandemic has torn at the already fraying fabric of many families. Cooped up away from friends and the emotional relief valve of school, even children who had been relatively easy to manage in the past have posed disciplinary challenges beyond their parents’ abilities to cope.

In a recent study from the Parenting in Context Lab of the University of Michigan (“Child Discipline During the Covid-19 Pandemic,” Family Snapshots: Life During the Pandemic, American Academy of Pediatrics, June 8 2021) researchers found that one in six parents surveyed (n = 3,000 adults) admitted to spanking. Nearly half of the parents said that they had yelled at or threatened their children.

Five out of six parents reported using what the investigators described as less harsh “positive discipline measures.” Three-quarters of these parents used “explaining” as a strategy and nearly the same number used either time-outs or sent the children to their rooms.

Again, not surprisingly, parents who had experienced at least one adverse childhood experience (ACE) were more than twice as likely to spank. And parents who reported an episode of intimate partner violence (IPV) were more likely to resort to a harsh discipline strategy (yelling, threatening, or spanking).

Over my professional career I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about discipline and I have attempted to summarize my thoughts in a book titled, “How to Say No to Your Toddler” (Simon and Schuster, 2003), that has been published in four languages. Based on my observations, trying to explain to a misbehaving child the error of his ways is generally parental time not well spent. A well-structured time-out, preferably in a separate room with a door closed, is the most effective and safest discipline strategy.

However, as in all of my books, this advice on discipline was colored by the families in my practice and the audience for which I was writing, primarily middle class and upper middle class, reasonably affluent parents who buy books. These are usually folks who have homes in which children often have their own rooms, or where at least there are multiple rooms with doors – spaces to escape when tensions rise. Few of these parents have endured ACEs. Few have they experienced – nor have their children witnessed – IPV.

My advice that parents make only threats that can be safely carried, out such as time-out, and to always follow up on threats and promises, is valid regardless of a family’s socioeconomic situation. However, when it comes to choosing a consequence, my standard recommendation of a time-out can be difficult to follow for a family of six living in a three-room apartment, particularly during pandemic-dictated restrictions and lockdowns.

Of course there are alternatives to time-outs in a separate space, including an extended hug in a parental lap, but these responses require that the parents have been able to compose themselves well enough, and that they have the time. One of the important benefits of time-outs is that they can provide parents the time and space to reassess the situation and consider their role in the conflict. The bottom line is that a time-out is the safest and most effective form of discipline, but it requires space and a parent relatively unburdened of financial or emotional stress. Families without these luxuries are left with few alternatives other than physical or verbal abuse.

The AAP’s Family Snapshot concludes with the observation that “pediatricians and pediatric health care providers can continue to play an important role in supporting positive discipline strategies.” That is a difficult assignment even in prepandemic times, but for those of you working with families who lack the space and time to defuse disciplinary tensions, it is a heroic task.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

Not surprisingly, the pandemic has torn at the already fraying fabric of many families. Cooped up away from friends and the emotional relief valve of school, even children who had been relatively easy to manage in the past have posed disciplinary challenges beyond their parents’ abilities to cope.

In a recent study from the Parenting in Context Lab of the University of Michigan (“Child Discipline During the Covid-19 Pandemic,” Family Snapshots: Life During the Pandemic, American Academy of Pediatrics, June 8 2021) researchers found that one in six parents surveyed (n = 3,000 adults) admitted to spanking. Nearly half of the parents said that they had yelled at or threatened their children.

Five out of six parents reported using what the investigators described as less harsh “positive discipline measures.” Three-quarters of these parents used “explaining” as a strategy and nearly the same number used either time-outs or sent the children to their rooms.

Again, not surprisingly, parents who had experienced at least one adverse childhood experience (ACE) were more than twice as likely to spank. And parents who reported an episode of intimate partner violence (IPV) were more likely to resort to a harsh discipline strategy (yelling, threatening, or spanking).

Over my professional career I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about discipline and I have attempted to summarize my thoughts in a book titled, “How to Say No to Your Toddler” (Simon and Schuster, 2003), that has been published in four languages. Based on my observations, trying to explain to a misbehaving child the error of his ways is generally parental time not well spent. A well-structured time-out, preferably in a separate room with a door closed, is the most effective and safest discipline strategy.

However, as in all of my books, this advice on discipline was colored by the families in my practice and the audience for which I was writing, primarily middle class and upper middle class, reasonably affluent parents who buy books. These are usually folks who have homes in which children often have their own rooms, or where at least there are multiple rooms with doors – spaces to escape when tensions rise. Few of these parents have endured ACEs. Few have they experienced – nor have their children witnessed – IPV.

My advice that parents make only threats that can be safely carried, out such as time-out, and to always follow up on threats and promises, is valid regardless of a family’s socioeconomic situation. However, when it comes to choosing a consequence, my standard recommendation of a time-out can be difficult to follow for a family of six living in a three-room apartment, particularly during pandemic-dictated restrictions and lockdowns.

Of course there are alternatives to time-outs in a separate space, including an extended hug in a parental lap, but these responses require that the parents have been able to compose themselves well enough, and that they have the time. One of the important benefits of time-outs is that they can provide parents the time and space to reassess the situation and consider their role in the conflict. The bottom line is that a time-out is the safest and most effective form of discipline, but it requires space and a parent relatively unburdened of financial or emotional stress. Families without these luxuries are left with few alternatives other than physical or verbal abuse.

The AAP’s Family Snapshot concludes with the observation that “pediatricians and pediatric health care providers can continue to play an important role in supporting positive discipline strategies.” That is a difficult assignment even in prepandemic times, but for those of you working with families who lack the space and time to defuse disciplinary tensions, it is a heroic task.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

Not surprisingly, the pandemic has torn at the already fraying fabric of many families. Cooped up away from friends and the emotional relief valve of school, even children who had been relatively easy to manage in the past have posed disciplinary challenges beyond their parents’ abilities to cope.

In a recent study from the Parenting in Context Lab of the University of Michigan (“Child Discipline During the Covid-19 Pandemic,” Family Snapshots: Life During the Pandemic, American Academy of Pediatrics, June 8 2021) researchers found that one in six parents surveyed (n = 3,000 adults) admitted to spanking. Nearly half of the parents said that they had yelled at or threatened their children.

Five out of six parents reported using what the investigators described as less harsh “positive discipline measures.” Three-quarters of these parents used “explaining” as a strategy and nearly the same number used either time-outs or sent the children to their rooms.

Again, not surprisingly, parents who had experienced at least one adverse childhood experience (ACE) were more than twice as likely to spank. And parents who reported an episode of intimate partner violence (IPV) were more likely to resort to a harsh discipline strategy (yelling, threatening, or spanking).

Over my professional career I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about discipline and I have attempted to summarize my thoughts in a book titled, “How to Say No to Your Toddler” (Simon and Schuster, 2003), that has been published in four languages. Based on my observations, trying to explain to a misbehaving child the error of his ways is generally parental time not well spent. A well-structured time-out, preferably in a separate room with a door closed, is the most effective and safest discipline strategy.

However, as in all of my books, this advice on discipline was colored by the families in my practice and the audience for which I was writing, primarily middle class and upper middle class, reasonably affluent parents who buy books. These are usually folks who have homes in which children often have their own rooms, or where at least there are multiple rooms with doors – spaces to escape when tensions rise. Few of these parents have endured ACEs. Few have they experienced – nor have their children witnessed – IPV.

My advice that parents make only threats that can be safely carried, out such as time-out, and to always follow up on threats and promises, is valid regardless of a family’s socioeconomic situation. However, when it comes to choosing a consequence, my standard recommendation of a time-out can be difficult to follow for a family of six living in a three-room apartment, particularly during pandemic-dictated restrictions and lockdowns.

Of course there are alternatives to time-outs in a separate space, including an extended hug in a parental lap, but these responses require that the parents have been able to compose themselves well enough, and that they have the time. One of the important benefits of time-outs is that they can provide parents the time and space to reassess the situation and consider their role in the conflict. The bottom line is that a time-out is the safest and most effective form of discipline, but it requires space and a parent relatively unburdened of financial or emotional stress. Families without these luxuries are left with few alternatives other than physical or verbal abuse.

The AAP’s Family Snapshot concludes with the observation that “pediatricians and pediatric health care providers can continue to play an important role in supporting positive discipline strategies.” That is a difficult assignment even in prepandemic times, but for those of you working with families who lack the space and time to defuse disciplinary tensions, it is a heroic task.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

Genetic testing for neurofibromatosis 1: An imperfect science

According to Peter Kannu, MB, ChB, DCH, PhD, a definitive diagnosis of NF1 can be made in most children using National Institutes of Health criteria published in 1988, which include the presence of two of the following:

- Six or more café au lait macules over 5 mm in diameter in prepubertal individuals and over 15 mm in greatest diameter in postpubertal individuals

- Two or more neurofibromas of any type or one plexiform neurofibroma

- Freckling in the axillary or inguinal regions

- Two or more Lisch nodules

- Optic glioma

- A distinctive osseous lesion such as sphenoid dysplasia or thinning of long bone cortex, with or without pseudarthrosis

- Having a first-degree relative with NF1

For example, in the case of an 8-year-old child who presents with multiple café au lait macules, axillary and inguinal freckling, Lisch nodules, and an optic glioma, “the diagnosis is secure and genetic testing is not going to change clinical management or surveillance,” Dr. Kannu, a clinical geneticist at the University of Alberta, Edmonton, said during the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “The only reason for genetic testing in this situation is so that we know the mutation in order to inform reproductive risk counseling in the future.”

However, while a diagnosis of NF1 may be suspected in a 6- to 12-month-old presenting with only café au lait macules, “the diagnosis is not secure because the clinical criteria cannot be met. In this situation, a genetic test can speed up the diagnosis,” he added. “Or, if the test is negative, it can decrease your suspicion for NF1 and you wouldn’t refer the child on to an NF1 screening clinic for intensive surveillance.”

Dr. Kannu based his remarks largely on his 5 years working at the multidisciplinary Genodermatoses Clinic at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto. Founded in 2015, the clinic is a “one-stop shop” designed to reduce the wait time for diagnosis and management and the number of hospital visits. The team – composed of a dermatologist, medical geneticist, genetic counselor, residents, and fellows – meets to review the charts of each patient before the appointment, and decides on a preliminary management plan. All children are then seen by one of the trainees in the clinic who devises a differential diagnosis that is presented to staff physicians, at which point genetic testing is decided on. A genetics counselor handles follow-up for those who do have genetic testing.

In 2018, Dr. Kannu and colleagues conducted an informal review of 300 patients who had been seen in the clinic. The mean age at referral was about 6 years, 51% were female, and the top three referral sources were pediatricians (51%), dermatologists (18%), and family physicians (18%). Of the 300 children, 84 (28%) were confirmed to have a diagnosis of NF1. Two patients were diagnosed with NF2 and 5% of the total cohort was diagnosed with mosaic NF1 (MNF1), “which is higher than what you would expect based on the incidence of MNF1 in the literature,” he said.

He separates genetic tests for NF1 into one of two categories: Conventional testing, which is offered by most labs in North America; and comprehensive testing, which is offered by the medical genomics lab at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. Conventional testing focuses on the exons, “the protein coding regions of the gene where most of the mutations lie,” he said. “The test also sequences about 20 base pairs or so of the intron exon boundary and may pick up some intronic mutations. But this test will not detect anything that’s hidden deep in the intronic region.”

Comprehensive testing, meanwhile, checks for mutations in both introns and exons.

Dr. Kannu and colleagues published a case of a paraspinal ganglioneuroma in the proband of a large family with mild cutaneous manifestations of NF1, carrying a deep NF1 intronic mutation. “The clinicians were suspicious that this was NF1, rightly so. The diagnosis was only confirmed after we sent samples to the University of Alabama lab where the deep intronic mutation was found,” he said.

The other situation where conventional genetic testing may be negative is in the case of MNF1, where there “are mutations in some cells but not all cells,” Dr. Kannu explained. “It may only be present in the melanocytes of the skin but not present in the lymphocytes in the blood. Mosaicism is characterized by the regional distribution of pigmentary or other NF1 associated findings. Mosaicism may be detected in the blood if it’s more than 20%. Anything less than that is not detected with conventional genetic testing using DNA from blood and requires extracting DNA from a punch biopsy sample of a café au lait macule.”

The differential diagnosis of café au lait macules includes several conditions associated mutations in the RAS pathway. “Neurofibromin is a key signal of molecules which regulates the activation of RAS,” Dr. Kannu said. “A close binding partner of NF1 is SPRED 1. We know that mutations in this gene cause Legius syndrome, a condition which presents with multiple café au lait macules.”

Two key receptors in the RAS pathway include EGFR and KITL, he continued. Mutations in the EGFR receptor cause a rare condition known as neonatal skin and bowel disease, while mutations in the KITL receptor cause familial progressive hyperpigmentation with or without hypopigmentation. “Looking into the pathway and focusing downstream of RAS, we have genes such as RAF and CBL, which are mutated in Noonan syndrome,” he said. “Further along in the pathway you have mutations in PTEN, which cause Cowden syndrome, and mutations in TSC1 and TSC2, which cause tuberous sclerosis. Mutations in any of these genes can also present with café au lait macules.”

During a question-and-answer session Dr. Kannu was asked to comment about revised diagnostic criteria for NF1 based on an international consensus recommendation, such as changes in the eye that require a formal opthalmologic examination, which were recently published.

“We are understanding more about the phenotype,” he said. “If you fulfill diagnostic criteria for NF1, the main reasons for doing genetic testing are, one, if the family wants to know that information, and two, it informs our reproductive risk counseling. Genotype-phenotype correlations do exist in NF1 but they’re not very robust, so that information is not clinically useful.”

Dr. Kannu disclosed that he has been an advisory board member for Ipsen, Novartis, and Alexion. He has also been a primary investigator for QED and Clementia.

According to Peter Kannu, MB, ChB, DCH, PhD, a definitive diagnosis of NF1 can be made in most children using National Institutes of Health criteria published in 1988, which include the presence of two of the following:

- Six or more café au lait macules over 5 mm in diameter in prepubertal individuals and over 15 mm in greatest diameter in postpubertal individuals

- Two or more neurofibromas of any type or one plexiform neurofibroma

- Freckling in the axillary or inguinal regions

- Two or more Lisch nodules

- Optic glioma

- A distinctive osseous lesion such as sphenoid dysplasia or thinning of long bone cortex, with or without pseudarthrosis

- Having a first-degree relative with NF1

For example, in the case of an 8-year-old child who presents with multiple café au lait macules, axillary and inguinal freckling, Lisch nodules, and an optic glioma, “the diagnosis is secure and genetic testing is not going to change clinical management or surveillance,” Dr. Kannu, a clinical geneticist at the University of Alberta, Edmonton, said during the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “The only reason for genetic testing in this situation is so that we know the mutation in order to inform reproductive risk counseling in the future.”

However, while a diagnosis of NF1 may be suspected in a 6- to 12-month-old presenting with only café au lait macules, “the diagnosis is not secure because the clinical criteria cannot be met. In this situation, a genetic test can speed up the diagnosis,” he added. “Or, if the test is negative, it can decrease your suspicion for NF1 and you wouldn’t refer the child on to an NF1 screening clinic for intensive surveillance.”

Dr. Kannu based his remarks largely on his 5 years working at the multidisciplinary Genodermatoses Clinic at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto. Founded in 2015, the clinic is a “one-stop shop” designed to reduce the wait time for diagnosis and management and the number of hospital visits. The team – composed of a dermatologist, medical geneticist, genetic counselor, residents, and fellows – meets to review the charts of each patient before the appointment, and decides on a preliminary management plan. All children are then seen by one of the trainees in the clinic who devises a differential diagnosis that is presented to staff physicians, at which point genetic testing is decided on. A genetics counselor handles follow-up for those who do have genetic testing.

In 2018, Dr. Kannu and colleagues conducted an informal review of 300 patients who had been seen in the clinic. The mean age at referral was about 6 years, 51% were female, and the top three referral sources were pediatricians (51%), dermatologists (18%), and family physicians (18%). Of the 300 children, 84 (28%) were confirmed to have a diagnosis of NF1. Two patients were diagnosed with NF2 and 5% of the total cohort was diagnosed with mosaic NF1 (MNF1), “which is higher than what you would expect based on the incidence of MNF1 in the literature,” he said.

He separates genetic tests for NF1 into one of two categories: Conventional testing, which is offered by most labs in North America; and comprehensive testing, which is offered by the medical genomics lab at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. Conventional testing focuses on the exons, “the protein coding regions of the gene where most of the mutations lie,” he said. “The test also sequences about 20 base pairs or so of the intron exon boundary and may pick up some intronic mutations. But this test will not detect anything that’s hidden deep in the intronic region.”

Comprehensive testing, meanwhile, checks for mutations in both introns and exons.

Dr. Kannu and colleagues published a case of a paraspinal ganglioneuroma in the proband of a large family with mild cutaneous manifestations of NF1, carrying a deep NF1 intronic mutation. “The clinicians were suspicious that this was NF1, rightly so. The diagnosis was only confirmed after we sent samples to the University of Alabama lab where the deep intronic mutation was found,” he said.

The other situation where conventional genetic testing may be negative is in the case of MNF1, where there “are mutations in some cells but not all cells,” Dr. Kannu explained. “It may only be present in the melanocytes of the skin but not present in the lymphocytes in the blood. Mosaicism is characterized by the regional distribution of pigmentary or other NF1 associated findings. Mosaicism may be detected in the blood if it’s more than 20%. Anything less than that is not detected with conventional genetic testing using DNA from blood and requires extracting DNA from a punch biopsy sample of a café au lait macule.”

The differential diagnosis of café au lait macules includes several conditions associated mutations in the RAS pathway. “Neurofibromin is a key signal of molecules which regulates the activation of RAS,” Dr. Kannu said. “A close binding partner of NF1 is SPRED 1. We know that mutations in this gene cause Legius syndrome, a condition which presents with multiple café au lait macules.”

Two key receptors in the RAS pathway include EGFR and KITL, he continued. Mutations in the EGFR receptor cause a rare condition known as neonatal skin and bowel disease, while mutations in the KITL receptor cause familial progressive hyperpigmentation with or without hypopigmentation. “Looking into the pathway and focusing downstream of RAS, we have genes such as RAF and CBL, which are mutated in Noonan syndrome,” he said. “Further along in the pathway you have mutations in PTEN, which cause Cowden syndrome, and mutations in TSC1 and TSC2, which cause tuberous sclerosis. Mutations in any of these genes can also present with café au lait macules.”

During a question-and-answer session Dr. Kannu was asked to comment about revised diagnostic criteria for NF1 based on an international consensus recommendation, such as changes in the eye that require a formal opthalmologic examination, which were recently published.

“We are understanding more about the phenotype,” he said. “If you fulfill diagnostic criteria for NF1, the main reasons for doing genetic testing are, one, if the family wants to know that information, and two, it informs our reproductive risk counseling. Genotype-phenotype correlations do exist in NF1 but they’re not very robust, so that information is not clinically useful.”

Dr. Kannu disclosed that he has been an advisory board member for Ipsen, Novartis, and Alexion. He has also been a primary investigator for QED and Clementia.

According to Peter Kannu, MB, ChB, DCH, PhD, a definitive diagnosis of NF1 can be made in most children using National Institutes of Health criteria published in 1988, which include the presence of two of the following:

- Six or more café au lait macules over 5 mm in diameter in prepubertal individuals and over 15 mm in greatest diameter in postpubertal individuals

- Two or more neurofibromas of any type or one plexiform neurofibroma

- Freckling in the axillary or inguinal regions

- Two or more Lisch nodules

- Optic glioma

- A distinctive osseous lesion such as sphenoid dysplasia or thinning of long bone cortex, with or without pseudarthrosis

- Having a first-degree relative with NF1

For example, in the case of an 8-year-old child who presents with multiple café au lait macules, axillary and inguinal freckling, Lisch nodules, and an optic glioma, “the diagnosis is secure and genetic testing is not going to change clinical management or surveillance,” Dr. Kannu, a clinical geneticist at the University of Alberta, Edmonton, said during the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “The only reason for genetic testing in this situation is so that we know the mutation in order to inform reproductive risk counseling in the future.”

However, while a diagnosis of NF1 may be suspected in a 6- to 12-month-old presenting with only café au lait macules, “the diagnosis is not secure because the clinical criteria cannot be met. In this situation, a genetic test can speed up the diagnosis,” he added. “Or, if the test is negative, it can decrease your suspicion for NF1 and you wouldn’t refer the child on to an NF1 screening clinic for intensive surveillance.”

Dr. Kannu based his remarks largely on his 5 years working at the multidisciplinary Genodermatoses Clinic at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto. Founded in 2015, the clinic is a “one-stop shop” designed to reduce the wait time for diagnosis and management and the number of hospital visits. The team – composed of a dermatologist, medical geneticist, genetic counselor, residents, and fellows – meets to review the charts of each patient before the appointment, and decides on a preliminary management plan. All children are then seen by one of the trainees in the clinic who devises a differential diagnosis that is presented to staff physicians, at which point genetic testing is decided on. A genetics counselor handles follow-up for those who do have genetic testing.

In 2018, Dr. Kannu and colleagues conducted an informal review of 300 patients who had been seen in the clinic. The mean age at referral was about 6 years, 51% were female, and the top three referral sources were pediatricians (51%), dermatologists (18%), and family physicians (18%). Of the 300 children, 84 (28%) were confirmed to have a diagnosis of NF1. Two patients were diagnosed with NF2 and 5% of the total cohort was diagnosed with mosaic NF1 (MNF1), “which is higher than what you would expect based on the incidence of MNF1 in the literature,” he said.

He separates genetic tests for NF1 into one of two categories: Conventional testing, which is offered by most labs in North America; and comprehensive testing, which is offered by the medical genomics lab at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. Conventional testing focuses on the exons, “the protein coding regions of the gene where most of the mutations lie,” he said. “The test also sequences about 20 base pairs or so of the intron exon boundary and may pick up some intronic mutations. But this test will not detect anything that’s hidden deep in the intronic region.”

Comprehensive testing, meanwhile, checks for mutations in both introns and exons.

Dr. Kannu and colleagues published a case of a paraspinal ganglioneuroma in the proband of a large family with mild cutaneous manifestations of NF1, carrying a deep NF1 intronic mutation. “The clinicians were suspicious that this was NF1, rightly so. The diagnosis was only confirmed after we sent samples to the University of Alabama lab where the deep intronic mutation was found,” he said.

The other situation where conventional genetic testing may be negative is in the case of MNF1, where there “are mutations in some cells but not all cells,” Dr. Kannu explained. “It may only be present in the melanocytes of the skin but not present in the lymphocytes in the blood. Mosaicism is characterized by the regional distribution of pigmentary or other NF1 associated findings. Mosaicism may be detected in the blood if it’s more than 20%. Anything less than that is not detected with conventional genetic testing using DNA from blood and requires extracting DNA from a punch biopsy sample of a café au lait macule.”

The differential diagnosis of café au lait macules includes several conditions associated mutations in the RAS pathway. “Neurofibromin is a key signal of molecules which regulates the activation of RAS,” Dr. Kannu said. “A close binding partner of NF1 is SPRED 1. We know that mutations in this gene cause Legius syndrome, a condition which presents with multiple café au lait macules.”

Two key receptors in the RAS pathway include EGFR and KITL, he continued. Mutations in the EGFR receptor cause a rare condition known as neonatal skin and bowel disease, while mutations in the KITL receptor cause familial progressive hyperpigmentation with or without hypopigmentation. “Looking into the pathway and focusing downstream of RAS, we have genes such as RAF and CBL, which are mutated in Noonan syndrome,” he said. “Further along in the pathway you have mutations in PTEN, which cause Cowden syndrome, and mutations in TSC1 and TSC2, which cause tuberous sclerosis. Mutations in any of these genes can also present with café au lait macules.”

During a question-and-answer session Dr. Kannu was asked to comment about revised diagnostic criteria for NF1 based on an international consensus recommendation, such as changes in the eye that require a formal opthalmologic examination, which were recently published.

“We are understanding more about the phenotype,” he said. “If you fulfill diagnostic criteria for NF1, the main reasons for doing genetic testing are, one, if the family wants to know that information, and two, it informs our reproductive risk counseling. Genotype-phenotype correlations do exist in NF1 but they’re not very robust, so that information is not clinically useful.”

Dr. Kannu disclosed that he has been an advisory board member for Ipsen, Novartis, and Alexion. He has also been a primary investigator for QED and Clementia.

FROM SPD 2021

C. Diff eradication not necessary for clinical cure of recurrent infections with fecal transplant

It’s not necessary to completely eradicate all Clostridioides difficile to successfully treat recurrent C. difficile infections with fecal microbiota transplant (FMT), according to a study presented online July 12 at the European Congress of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases.

C. difficile colonization persisted for 3 weeks after FMT in about one-quarter of patients, but it’s not clear whether this is a persistent infection, a newly acquired infection, or partial persistence of a mixed infection, said Elisabeth Terveer, MD, a medical microbiologist at Leiden (the Netherlands) University Medical Center. In addition, “82% of patients with detectable C. diff do not relapse, so it’s absolutely not necessary for a cure,” she said.

Several mechanisms explain why FMT is a highly effective therapy for recurrent C. difficile infections, including restoration of bacterial metabolism in the gut, immune modulation, and direct competition between bacteria, Dr. Terveer said, but it’s less clear whether eradication of C. difficile spores is among these mechanisms.

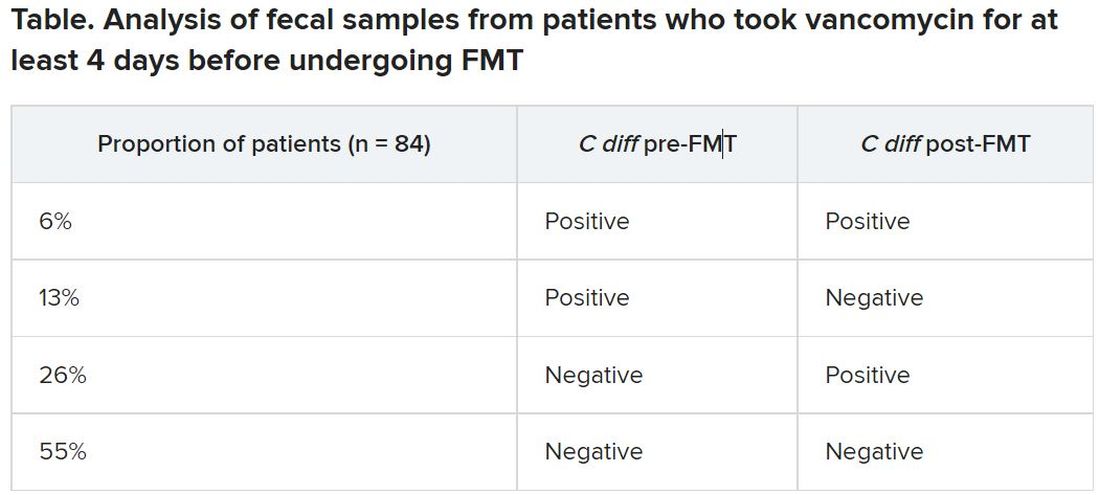

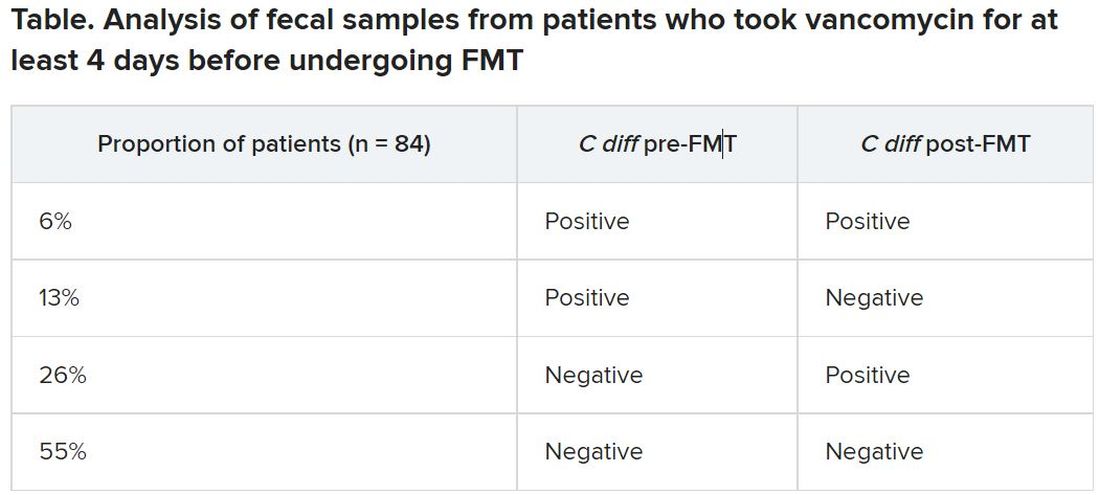

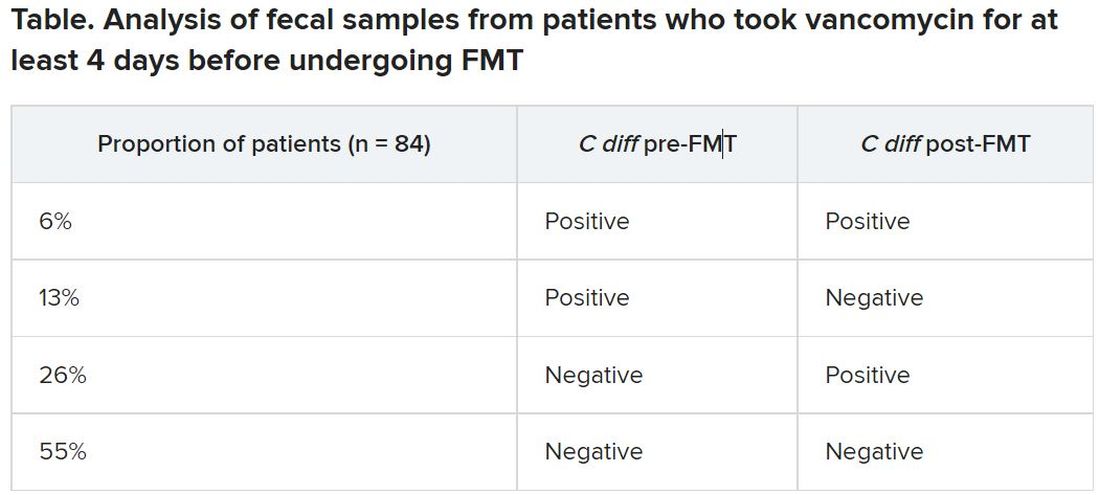

Between May 2016 and April 2020, the researchers analyzed fecal samples from 84 patients who took vancomycin for at least 4 days before undergoing FMT. The researchers took fecal samples from patients before FMT and 3 weeks after FMT to culture them and the donor samples for presence of C. difficile, and they assessed clinical outcomes at 3 weeks and 6 months after FMT.

After antibiotic treatment but prior to FMT, 19% of patients (n = 16) still had a toxigenic C. difficile culture while the other 81% had a negative culture. None of the donor samples had a positive C. difficile culture. After FMT treatment, five patients who had a positive pre-FMT culture remained positive, and the other 11 were negative. Among the 81% of patients (n = 68) who had a negative culture just before FMT, 22 had a positive culture and 46 had a negative culture after FMT. Overall, 26% of patients post FMT had a positive C. difficile culture, a finding that was 10-fold higher than another study that assessed C. difficile with PCR testing, Dr. Terveer said.

The clinical cure rate after FMT was 94%, and five patients had relapses within 2 months of their FMT. These relapses were more prevalent in patients with a positive C. difficile culture prior to FMT (odds ratio [OR], 7.6; P = .045) and a positive C. difficile culture after FMT (OR, 13.6; P = .016). Still, 82% of patients who had a positive C. difficile culture post FMT remained clinically cured 2 months later.

It’s unclear why 19% of patients had a positive culture after their antibiotic pretreatment prior to FMT, Dr. Terveer said, but it may be because the pretreatment was of such a short duration.

“I think the advice should be: Give a full anti–C. diff antibiotic course to treat the C. diff infection, and then give FMT afterward to restore the microbiota and prevent further relapses,” Dr. Terveer told attendees.

Dimitri Drekonja, MD, chief of the Minneapolis VA Infectious Disease Section, said the findings were not necessarily surprising, but it would have been interesting for the researchers to have conducted DNA sequencing of the patients’ fecal samples post FMT to see what the biological diversity looked like.

“One school of thought has been that you have to repopulate the normal diverse microbiota of the colon” with FMT, and the other “is that you need to get rid of the C. diff that›s there,” Dr. Drekonja, who was not involved in the study, said in an interview. “I think more people think it’s the diverse microbiota because if it’s just getting rid of C. diff, we can get do that with antibiotics – but that gets rid of the other organisms.”

As long as you have a diverse microbiota post FMT, Dr. Drekonja said, then “having a few residual organisms, even if they get magnified in the culture process, is probably not that big a deal.”

But there’s a third school of thought that Dr. Drekonja said he himself falls into: “I don’t really care how it works, just that in well-done trials, it does work.” As long as large, robust, well-blinded trials show that FMT works, “I’m open to all sorts of ideas of what the mechanism is,” he said. “The main thing is that it does or doesn’t work.”

These findings basically reinforce current guidance not to test patients’ stools if they are asymptomatic, Dr. Drekonja said. In the past, clinicians sometimes tested patients’ stool after therapy to ensure the C. difficile was eradicated, regardless of whether the patient had symptoms of infection, he said.

“We’ve since become much more attuned that there are lots of people who have detectable C. diff in their stool without any symptoms,” whether detectable by culture or PCR, Dr. Drekonja said. “Generally, if you’re doing well and you’re not having diarrhea, don’t test, and if someone does test and finds it, pretend you didn’t see the test,” he advised. “This is a big part of diagnostic stewardship, which is: You don’t go testing people who are doing well.”

The Netherlands Donor Feces Bank used in the research is funded by a grant from Vedanta Biosciences. Dr. Drekonja had no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It’s not necessary to completely eradicate all Clostridioides difficile to successfully treat recurrent C. difficile infections with fecal microbiota transplant (FMT), according to a study presented online July 12 at the European Congress of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases.

C. difficile colonization persisted for 3 weeks after FMT in about one-quarter of patients, but it’s not clear whether this is a persistent infection, a newly acquired infection, or partial persistence of a mixed infection, said Elisabeth Terveer, MD, a medical microbiologist at Leiden (the Netherlands) University Medical Center. In addition, “82% of patients with detectable C. diff do not relapse, so it’s absolutely not necessary for a cure,” she said.

Several mechanisms explain why FMT is a highly effective therapy for recurrent C. difficile infections, including restoration of bacterial metabolism in the gut, immune modulation, and direct competition between bacteria, Dr. Terveer said, but it’s less clear whether eradication of C. difficile spores is among these mechanisms.

Between May 2016 and April 2020, the researchers analyzed fecal samples from 84 patients who took vancomycin for at least 4 days before undergoing FMT. The researchers took fecal samples from patients before FMT and 3 weeks after FMT to culture them and the donor samples for presence of C. difficile, and they assessed clinical outcomes at 3 weeks and 6 months after FMT.

After antibiotic treatment but prior to FMT, 19% of patients (n = 16) still had a toxigenic C. difficile culture while the other 81% had a negative culture. None of the donor samples had a positive C. difficile culture. After FMT treatment, five patients who had a positive pre-FMT culture remained positive, and the other 11 were negative. Among the 81% of patients (n = 68) who had a negative culture just before FMT, 22 had a positive culture and 46 had a negative culture after FMT. Overall, 26% of patients post FMT had a positive C. difficile culture, a finding that was 10-fold higher than another study that assessed C. difficile with PCR testing, Dr. Terveer said.

The clinical cure rate after FMT was 94%, and five patients had relapses within 2 months of their FMT. These relapses were more prevalent in patients with a positive C. difficile culture prior to FMT (odds ratio [OR], 7.6; P = .045) and a positive C. difficile culture after FMT (OR, 13.6; P = .016). Still, 82% of patients who had a positive C. difficile culture post FMT remained clinically cured 2 months later.

It’s unclear why 19% of patients had a positive culture after their antibiotic pretreatment prior to FMT, Dr. Terveer said, but it may be because the pretreatment was of such a short duration.

“I think the advice should be: Give a full anti–C. diff antibiotic course to treat the C. diff infection, and then give FMT afterward to restore the microbiota and prevent further relapses,” Dr. Terveer told attendees.

Dimitri Drekonja, MD, chief of the Minneapolis VA Infectious Disease Section, said the findings were not necessarily surprising, but it would have been interesting for the researchers to have conducted DNA sequencing of the patients’ fecal samples post FMT to see what the biological diversity looked like.

“One school of thought has been that you have to repopulate the normal diverse microbiota of the colon” with FMT, and the other “is that you need to get rid of the C. diff that›s there,” Dr. Drekonja, who was not involved in the study, said in an interview. “I think more people think it’s the diverse microbiota because if it’s just getting rid of C. diff, we can get do that with antibiotics – but that gets rid of the other organisms.”

As long as you have a diverse microbiota post FMT, Dr. Drekonja said, then “having a few residual organisms, even if they get magnified in the culture process, is probably not that big a deal.”

But there’s a third school of thought that Dr. Drekonja said he himself falls into: “I don’t really care how it works, just that in well-done trials, it does work.” As long as large, robust, well-blinded trials show that FMT works, “I’m open to all sorts of ideas of what the mechanism is,” he said. “The main thing is that it does or doesn’t work.”

These findings basically reinforce current guidance not to test patients’ stools if they are asymptomatic, Dr. Drekonja said. In the past, clinicians sometimes tested patients’ stool after therapy to ensure the C. difficile was eradicated, regardless of whether the patient had symptoms of infection, he said.

“We’ve since become much more attuned that there are lots of people who have detectable C. diff in their stool without any symptoms,” whether detectable by culture or PCR, Dr. Drekonja said. “Generally, if you’re doing well and you’re not having diarrhea, don’t test, and if someone does test and finds it, pretend you didn’t see the test,” he advised. “This is a big part of diagnostic stewardship, which is: You don’t go testing people who are doing well.”

The Netherlands Donor Feces Bank used in the research is funded by a grant from Vedanta Biosciences. Dr. Drekonja had no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It’s not necessary to completely eradicate all Clostridioides difficile to successfully treat recurrent C. difficile infections with fecal microbiota transplant (FMT), according to a study presented online July 12 at the European Congress of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases.

C. difficile colonization persisted for 3 weeks after FMT in about one-quarter of patients, but it’s not clear whether this is a persistent infection, a newly acquired infection, or partial persistence of a mixed infection, said Elisabeth Terveer, MD, a medical microbiologist at Leiden (the Netherlands) University Medical Center. In addition, “82% of patients with detectable C. diff do not relapse, so it’s absolutely not necessary for a cure,” she said.

Several mechanisms explain why FMT is a highly effective therapy for recurrent C. difficile infections, including restoration of bacterial metabolism in the gut, immune modulation, and direct competition between bacteria, Dr. Terveer said, but it’s less clear whether eradication of C. difficile spores is among these mechanisms.

Between May 2016 and April 2020, the researchers analyzed fecal samples from 84 patients who took vancomycin for at least 4 days before undergoing FMT. The researchers took fecal samples from patients before FMT and 3 weeks after FMT to culture them and the donor samples for presence of C. difficile, and they assessed clinical outcomes at 3 weeks and 6 months after FMT.

After antibiotic treatment but prior to FMT, 19% of patients (n = 16) still had a toxigenic C. difficile culture while the other 81% had a negative culture. None of the donor samples had a positive C. difficile culture. After FMT treatment, five patients who had a positive pre-FMT culture remained positive, and the other 11 were negative. Among the 81% of patients (n = 68) who had a negative culture just before FMT, 22 had a positive culture and 46 had a negative culture after FMT. Overall, 26% of patients post FMT had a positive C. difficile culture, a finding that was 10-fold higher than another study that assessed C. difficile with PCR testing, Dr. Terveer said.

The clinical cure rate after FMT was 94%, and five patients had relapses within 2 months of their FMT. These relapses were more prevalent in patients with a positive C. difficile culture prior to FMT (odds ratio [OR], 7.6; P = .045) and a positive C. difficile culture after FMT (OR, 13.6; P = .016). Still, 82% of patients who had a positive C. difficile culture post FMT remained clinically cured 2 months later.

It’s unclear why 19% of patients had a positive culture after their antibiotic pretreatment prior to FMT, Dr. Terveer said, but it may be because the pretreatment was of such a short duration.

“I think the advice should be: Give a full anti–C. diff antibiotic course to treat the C. diff infection, and then give FMT afterward to restore the microbiota and prevent further relapses,” Dr. Terveer told attendees.

Dimitri Drekonja, MD, chief of the Minneapolis VA Infectious Disease Section, said the findings were not necessarily surprising, but it would have been interesting for the researchers to have conducted DNA sequencing of the patients’ fecal samples post FMT to see what the biological diversity looked like.

“One school of thought has been that you have to repopulate the normal diverse microbiota of the colon” with FMT, and the other “is that you need to get rid of the C. diff that›s there,” Dr. Drekonja, who was not involved in the study, said in an interview. “I think more people think it’s the diverse microbiota because if it’s just getting rid of C. diff, we can get do that with antibiotics – but that gets rid of the other organisms.”

As long as you have a diverse microbiota post FMT, Dr. Drekonja said, then “having a few residual organisms, even if they get magnified in the culture process, is probably not that big a deal.”

But there’s a third school of thought that Dr. Drekonja said he himself falls into: “I don’t really care how it works, just that in well-done trials, it does work.” As long as large, robust, well-blinded trials show that FMT works, “I’m open to all sorts of ideas of what the mechanism is,” he said. “The main thing is that it does or doesn’t work.”

These findings basically reinforce current guidance not to test patients’ stools if they are asymptomatic, Dr. Drekonja said. In the past, clinicians sometimes tested patients’ stool after therapy to ensure the C. difficile was eradicated, regardless of whether the patient had symptoms of infection, he said.

“We’ve since become much more attuned that there are lots of people who have detectable C. diff in their stool without any symptoms,” whether detectable by culture or PCR, Dr. Drekonja said. “Generally, if you’re doing well and you’re not having diarrhea, don’t test, and if someone does test and finds it, pretend you didn’t see the test,” he advised. “This is a big part of diagnostic stewardship, which is: You don’t go testing people who are doing well.”

The Netherlands Donor Feces Bank used in the research is funded by a grant from Vedanta Biosciences. Dr. Drekonja had no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Mayo, Cleveland Clinics top latest U.S. News & World Report hospital rankings

This year’s expanded report debuts new ratings for seven “important procedures and conditions to help patients, in consultation with their doctors, narrow down their choice of hospital based on the specific type of care they need,” Ben Harder, managing editor and chief of health analysis, said in a news release.

With new ratings for myocardial infarction, stroke, hip fracture, and back surgery (spinal fusion), the report now ranks 17 procedures and conditions.

Also new to the 2021 report, which marks the 32nd edition, is a look at racial disparities in health care and the inclusion of health equity measures alongside the hospital rankings.

The new measures examine whether the patients each hospital has treated reflect the racial and ethnic diversity of the surrounding community, among other aspects of health equity.

“At roughly four out of five hospitals, we found that the community’s minority residents were underrepresented among patients receiving services such as joint replacement, cancer surgery and common heart procedures,” Mr. Harder said.

“Against this backdrop, however, we found important exceptions – hospitals that provide care to a disproportionate share of their community’s minority residents. These metrics are just a beginning; we aim to expand on our measurement of health equity in the future,” Mr. Harder added.

Mayo and Cleveland Clinic remain tops

Following the Mayo Clinic, the Cleveland Clinic once again takes the No. 2 spot in the magazine’s latest annual honor roll of best hospitals, which highlights hospitals that deliver exceptional treatment across multiple areas of care.

UCLA Medical Center, Los Angeles, holds the No. 3 spot in 2021. In 2020, UCLA Medical Center and New York–Presbyterian Hospital–Columbia and Cornell, New York, sat in a tie at No. 4.

In 2021, Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, which held the No. 3 spot in 2020, drops to No. 4, while Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston takes the No. 5 spot, up from No. 6 in 2020.

Rounding out the top 10 (in order) are Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles; New York–Presbyterian Hospital–Columbia and Cornell, New York; NYU Langone Hospitals, New York; UCSF Medical Center, San Francisco; and Northwestern Memorial Hospital, Chicago.

2021-2022 Best Hospitals honor roll

1. Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

2. Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland

3. UCLA Medical Center, Los Angeles

4. Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore

5. Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston

6. Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, San Francisco

7. New York–Presbyterian Hospital–Columbia and Cornell, New York

8. NYU Langone Hospitals, New York

9. UCSF Medical Center, San Francisco

10. Northwestern Memorial Hospital, Chicago

11. University of Michigan Hospitals–Michigan Medicine, Ann Arbor.

12. Stanford Health Care–Stanford Hospital, Palo Alto, Calif.

13. Hospitals of the University of Pennsylvania–Penn Presbyterian, Philadelphia

14. Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston

15. Mayo Clinic–Phoenix, Phoenix

16. Houston Methodist Hospital, Houston

17. (tie) Barnes-Jewish Hospital, St. Louis

17. (tie) Mount Sinai Hospital, New York Rush University Medical Center, Chicago

19. Rush University Medical Center, Chicago

20. Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn.

For the 2021-2022 rankings and ratings, the magazine compared more than 4,750 hospitals nationwide in 15 specialties and 17 procedures and conditions.

At least 2,039 hospitals received a high performance rating in at least one of the services rated; 11 hospitals received high performance in all 17. A total of 175 hospitals were nationally ranked in at least one specialty

For specialty rankings, the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center continues to hold the No. 1 spot in cancer care, the Hospital for Special Surgery continues to be No. 1 in orthopedics, and the Cleveland Clinic continues to be No. 1 in cardiology and heart surgery.

Top five for cancer

1. University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston

2. Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York

3. Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

4. Dana-Farber/Brigham & Women’s Cancer Center, Boston

5. Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland

Top five for cardiology and heart surgery

1. Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland

2. Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

3. Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles

4. New York–Presbyterian Hospital–Columbia and Cornell, New York

5. NYU Langone Hospitals, New York

Top five for orthopedics

1. Hospital for Special Surgery, New York

2. Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

3. Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles

4. NYU Langone Orthopedic Hospital, New York

5. UCLA Medical Center, Los Angeles

The magazine noted that data for the 2021-2022 Best Hospitals rankings and ratings were not affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, which began after the end of the data collection period.

The methodologies used in determining the rankings are based largely on objective measures, such as risk-adjusted survival, discharge-to-home rates, volume, and quality of nursing, among other care-related indicators.

The full report is available online.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This year’s expanded report debuts new ratings for seven “important procedures and conditions to help patients, in consultation with their doctors, narrow down their choice of hospital based on the specific type of care they need,” Ben Harder, managing editor and chief of health analysis, said in a news release.

With new ratings for myocardial infarction, stroke, hip fracture, and back surgery (spinal fusion), the report now ranks 17 procedures and conditions.

Also new to the 2021 report, which marks the 32nd edition, is a look at racial disparities in health care and the inclusion of health equity measures alongside the hospital rankings.

The new measures examine whether the patients each hospital has treated reflect the racial and ethnic diversity of the surrounding community, among other aspects of health equity.

“At roughly four out of five hospitals, we found that the community’s minority residents were underrepresented among patients receiving services such as joint replacement, cancer surgery and common heart procedures,” Mr. Harder said.

“Against this backdrop, however, we found important exceptions – hospitals that provide care to a disproportionate share of their community’s minority residents. These metrics are just a beginning; we aim to expand on our measurement of health equity in the future,” Mr. Harder added.

Mayo and Cleveland Clinic remain tops

Following the Mayo Clinic, the Cleveland Clinic once again takes the No. 2 spot in the magazine’s latest annual honor roll of best hospitals, which highlights hospitals that deliver exceptional treatment across multiple areas of care.

UCLA Medical Center, Los Angeles, holds the No. 3 spot in 2021. In 2020, UCLA Medical Center and New York–Presbyterian Hospital–Columbia and Cornell, New York, sat in a tie at No. 4.

In 2021, Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, which held the No. 3 spot in 2020, drops to No. 4, while Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston takes the No. 5 spot, up from No. 6 in 2020.

Rounding out the top 10 (in order) are Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles; New York–Presbyterian Hospital–Columbia and Cornell, New York; NYU Langone Hospitals, New York; UCSF Medical Center, San Francisco; and Northwestern Memorial Hospital, Chicago.

2021-2022 Best Hospitals honor roll

1. Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

2. Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland

3. UCLA Medical Center, Los Angeles

4. Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore

5. Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston

6. Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, San Francisco

7. New York–Presbyterian Hospital–Columbia and Cornell, New York

8. NYU Langone Hospitals, New York

9. UCSF Medical Center, San Francisco

10. Northwestern Memorial Hospital, Chicago

11. University of Michigan Hospitals–Michigan Medicine, Ann Arbor.

12. Stanford Health Care–Stanford Hospital, Palo Alto, Calif.

13. Hospitals of the University of Pennsylvania–Penn Presbyterian, Philadelphia

14. Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston

15. Mayo Clinic–Phoenix, Phoenix

16. Houston Methodist Hospital, Houston

17. (tie) Barnes-Jewish Hospital, St. Louis

17. (tie) Mount Sinai Hospital, New York Rush University Medical Center, Chicago

19. Rush University Medical Center, Chicago

20. Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn.

For the 2021-2022 rankings and ratings, the magazine compared more than 4,750 hospitals nationwide in 15 specialties and 17 procedures and conditions.

At least 2,039 hospitals received a high performance rating in at least one of the services rated; 11 hospitals received high performance in all 17. A total of 175 hospitals were nationally ranked in at least one specialty

For specialty rankings, the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center continues to hold the No. 1 spot in cancer care, the Hospital for Special Surgery continues to be No. 1 in orthopedics, and the Cleveland Clinic continues to be No. 1 in cardiology and heart surgery.

Top five for cancer

1. University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston

2. Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York

3. Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

4. Dana-Farber/Brigham & Women’s Cancer Center, Boston

5. Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland

Top five for cardiology and heart surgery

1. Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland

2. Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

3. Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles

4. New York–Presbyterian Hospital–Columbia and Cornell, New York

5. NYU Langone Hospitals, New York

Top five for orthopedics

1. Hospital for Special Surgery, New York

2. Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

3. Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles

4. NYU Langone Orthopedic Hospital, New York

5. UCLA Medical Center, Los Angeles

The magazine noted that data for the 2021-2022 Best Hospitals rankings and ratings were not affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, which began after the end of the data collection period.

The methodologies used in determining the rankings are based largely on objective measures, such as risk-adjusted survival, discharge-to-home rates, volume, and quality of nursing, among other care-related indicators.

The full report is available online.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This year’s expanded report debuts new ratings for seven “important procedures and conditions to help patients, in consultation with their doctors, narrow down their choice of hospital based on the specific type of care they need,” Ben Harder, managing editor and chief of health analysis, said in a news release.

With new ratings for myocardial infarction, stroke, hip fracture, and back surgery (spinal fusion), the report now ranks 17 procedures and conditions.

Also new to the 2021 report, which marks the 32nd edition, is a look at racial disparities in health care and the inclusion of health equity measures alongside the hospital rankings.

The new measures examine whether the patients each hospital has treated reflect the racial and ethnic diversity of the surrounding community, among other aspects of health equity.

“At roughly four out of five hospitals, we found that the community’s minority residents were underrepresented among patients receiving services such as joint replacement, cancer surgery and common heart procedures,” Mr. Harder said.

“Against this backdrop, however, we found important exceptions – hospitals that provide care to a disproportionate share of their community’s minority residents. These metrics are just a beginning; we aim to expand on our measurement of health equity in the future,” Mr. Harder added.

Mayo and Cleveland Clinic remain tops

Following the Mayo Clinic, the Cleveland Clinic once again takes the No. 2 spot in the magazine’s latest annual honor roll of best hospitals, which highlights hospitals that deliver exceptional treatment across multiple areas of care.

UCLA Medical Center, Los Angeles, holds the No. 3 spot in 2021. In 2020, UCLA Medical Center and New York–Presbyterian Hospital–Columbia and Cornell, New York, sat in a tie at No. 4.

In 2021, Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, which held the No. 3 spot in 2020, drops to No. 4, while Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston takes the No. 5 spot, up from No. 6 in 2020.

Rounding out the top 10 (in order) are Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles; New York–Presbyterian Hospital–Columbia and Cornell, New York; NYU Langone Hospitals, New York; UCSF Medical Center, San Francisco; and Northwestern Memorial Hospital, Chicago.

2021-2022 Best Hospitals honor roll

1. Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

2. Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland

3. UCLA Medical Center, Los Angeles

4. Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore

5. Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston

6. Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, San Francisco

7. New York–Presbyterian Hospital–Columbia and Cornell, New York

8. NYU Langone Hospitals, New York

9. UCSF Medical Center, San Francisco

10. Northwestern Memorial Hospital, Chicago

11. University of Michigan Hospitals–Michigan Medicine, Ann Arbor.

12. Stanford Health Care–Stanford Hospital, Palo Alto, Calif.

13. Hospitals of the University of Pennsylvania–Penn Presbyterian, Philadelphia

14. Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston

15. Mayo Clinic–Phoenix, Phoenix

16. Houston Methodist Hospital, Houston

17. (tie) Barnes-Jewish Hospital, St. Louis

17. (tie) Mount Sinai Hospital, New York Rush University Medical Center, Chicago

19. Rush University Medical Center, Chicago

20. Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn.

For the 2021-2022 rankings and ratings, the magazine compared more than 4,750 hospitals nationwide in 15 specialties and 17 procedures and conditions.

At least 2,039 hospitals received a high performance rating in at least one of the services rated; 11 hospitals received high performance in all 17. A total of 175 hospitals were nationally ranked in at least one specialty

For specialty rankings, the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center continues to hold the No. 1 spot in cancer care, the Hospital for Special Surgery continues to be No. 1 in orthopedics, and the Cleveland Clinic continues to be No. 1 in cardiology and heart surgery.

Top five for cancer

1. University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston

2. Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York

3. Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

4. Dana-Farber/Brigham & Women’s Cancer Center, Boston

5. Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland

Top five for cardiology and heart surgery

1. Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland

2. Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

3. Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles

4. New York–Presbyterian Hospital–Columbia and Cornell, New York

5. NYU Langone Hospitals, New York

Top five for orthopedics

1. Hospital for Special Surgery, New York

2. Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

3. Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles

4. NYU Langone Orthopedic Hospital, New York

5. UCLA Medical Center, Los Angeles

The magazine noted that data for the 2021-2022 Best Hospitals rankings and ratings were not affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, which began after the end of the data collection period.

The methodologies used in determining the rankings are based largely on objective measures, such as risk-adjusted survival, discharge-to-home rates, volume, and quality of nursing, among other care-related indicators.

The full report is available online.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AMA, 55 other groups urge health care vax mandate

As COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations, and deaths mount again across the country, the American Medical Association (AMA), the American Nursing Association, and 54 other

This injunction, issued July 26, covers everyone in healthcare, Emanuel Ezekiel, MD, PhD, chair of the department of medical ethics and health policy at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and the organizer of the joint statement, said in an interview.

That includes not only hospitals, but also physician offices, ambulatory surgery centers, home care agencies, skilled nursing facilities, pharmacies, laboratories, and imaging centers, he said.

The exhortation to get vaccinated also extends to federal and state healthcare facilities, including those of the military health system — TRICARE and the Department of Veterans Affairs — which instituted a mandate the same day.

The American Hospital Association (AHA) and other hospital groups recently said they supported hospitals and health systems that required their personnel to get vaccinated. Several dozen healthcare organizations have already done so, including some of the nation’s largest health systems.

A substantial fraction of U.S. healthcare workers have not yet gotten vaccinated, although how many are unvaccinated is unclear. An analysis by WebMD and Medscape Medical News estimated that 25% of hospital workers who had contact with patients were unvaccinated at the end of May.

More than 38% of nursing workers were not fully vaccinated by July 11, according to an analysis of Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services data by LeadingAge, which was cited by the Washington Post. And more than 40% of nursing home employees have not been fully vaccinated, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The joint statement did not give any indication of how many employees of physician practices have failed to get COVID shots. However, a recent AMA survey shows that 96% of physicians have been fully vaccinated.

Ethical commitment

The main reason for vaccine mandates, according to the healthcare associations’ statement, is “the ethical commitment to put patients as well as residents of long-term care facilities first and take all steps necessary to ensure their health and well-being.”

In addition, the statement noted, vaccination can protect healthcare workers and their families from getting COVID-19.

The statement also pointed out that many healthcare and long-term care organizations already require vaccinations for influenza, hepatitis B, and pertussis.

Workers who have certain medical conditions should be exempt from the vaccination mandates, the statement added.

While recognizing the “historical mistrust of health care institutions” among some healthcare workers, the statement said, “We must continue to address workers’ concerns, engage with marginalized populations, and work with trusted messengers to improve vaccine acceptance.”

There has been some skepticism about the legality of requiring healthcare workers to get vaccinated as a condition of employment, partly because the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has not yet fully authorized any of the COVID-19 vaccines.

But in June, a federal judge turned down a legal challenge to Houston Methodist’s vaccination mandate.

“It is critical that all people in the health care workforce get vaccinated against COVID-19 for the safety of our patients and our colleagues. With more than 300 million doses administered in the United States and nearly 4 billion doses administered worldwide, we know the vaccines are safe and highly effective at preventing severe illness and death from COVID-19.

“Increased vaccinations among health care personnel will not only reduce the spread of COVID-19 but also reduce the harmful toll this virus is taking within the health care workforce and those we are striving to serve,” Susan Bailey, MD, immediate past president of the AMA, said in a news release.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

As COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations, and deaths mount again across the country, the American Medical Association (AMA), the American Nursing Association, and 54 other

This injunction, issued July 26, covers everyone in healthcare, Emanuel Ezekiel, MD, PhD, chair of the department of medical ethics and health policy at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and the organizer of the joint statement, said in an interview.

That includes not only hospitals, but also physician offices, ambulatory surgery centers, home care agencies, skilled nursing facilities, pharmacies, laboratories, and imaging centers, he said.

The exhortation to get vaccinated also extends to federal and state healthcare facilities, including those of the military health system — TRICARE and the Department of Veterans Affairs — which instituted a mandate the same day.

The American Hospital Association (AHA) and other hospital groups recently said they supported hospitals and health systems that required their personnel to get vaccinated. Several dozen healthcare organizations have already done so, including some of the nation’s largest health systems.

A substantial fraction of U.S. healthcare workers have not yet gotten vaccinated, although how many are unvaccinated is unclear. An analysis by WebMD and Medscape Medical News estimated that 25% of hospital workers who had contact with patients were unvaccinated at the end of May.

More than 38% of nursing workers were not fully vaccinated by July 11, according to an analysis of Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services data by LeadingAge, which was cited by the Washington Post. And more than 40% of nursing home employees have not been fully vaccinated, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The joint statement did not give any indication of how many employees of physician practices have failed to get COVID shots. However, a recent AMA survey shows that 96% of physicians have been fully vaccinated.

Ethical commitment

The main reason for vaccine mandates, according to the healthcare associations’ statement, is “the ethical commitment to put patients as well as residents of long-term care facilities first and take all steps necessary to ensure their health and well-being.”

In addition, the statement noted, vaccination can protect healthcare workers and their families from getting COVID-19.

The statement also pointed out that many healthcare and long-term care organizations already require vaccinations for influenza, hepatitis B, and pertussis.

Workers who have certain medical conditions should be exempt from the vaccination mandates, the statement added.

While recognizing the “historical mistrust of health care institutions” among some healthcare workers, the statement said, “We must continue to address workers’ concerns, engage with marginalized populations, and work with trusted messengers to improve vaccine acceptance.”

There has been some skepticism about the legality of requiring healthcare workers to get vaccinated as a condition of employment, partly because the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has not yet fully authorized any of the COVID-19 vaccines.

But in June, a federal judge turned down a legal challenge to Houston Methodist’s vaccination mandate.

“It is critical that all people in the health care workforce get vaccinated against COVID-19 for the safety of our patients and our colleagues. With more than 300 million doses administered in the United States and nearly 4 billion doses administered worldwide, we know the vaccines are safe and highly effective at preventing severe illness and death from COVID-19.

“Increased vaccinations among health care personnel will not only reduce the spread of COVID-19 but also reduce the harmful toll this virus is taking within the health care workforce and those we are striving to serve,” Susan Bailey, MD, immediate past president of the AMA, said in a news release.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

As COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations, and deaths mount again across the country, the American Medical Association (AMA), the American Nursing Association, and 54 other

This injunction, issued July 26, covers everyone in healthcare, Emanuel Ezekiel, MD, PhD, chair of the department of medical ethics and health policy at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and the organizer of the joint statement, said in an interview.

That includes not only hospitals, but also physician offices, ambulatory surgery centers, home care agencies, skilled nursing facilities, pharmacies, laboratories, and imaging centers, he said.

The exhortation to get vaccinated also extends to federal and state healthcare facilities, including those of the military health system — TRICARE and the Department of Veterans Affairs — which instituted a mandate the same day.

The American Hospital Association (AHA) and other hospital groups recently said they supported hospitals and health systems that required their personnel to get vaccinated. Several dozen healthcare organizations have already done so, including some of the nation’s largest health systems.

A substantial fraction of U.S. healthcare workers have not yet gotten vaccinated, although how many are unvaccinated is unclear. An analysis by WebMD and Medscape Medical News estimated that 25% of hospital workers who had contact with patients were unvaccinated at the end of May.

More than 38% of nursing workers were not fully vaccinated by July 11, according to an analysis of Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services data by LeadingAge, which was cited by the Washington Post. And more than 40% of nursing home employees have not been fully vaccinated, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The joint statement did not give any indication of how many employees of physician practices have failed to get COVID shots. However, a recent AMA survey shows that 96% of physicians have been fully vaccinated.

Ethical commitment

The main reason for vaccine mandates, according to the healthcare associations’ statement, is “the ethical commitment to put patients as well as residents of long-term care facilities first and take all steps necessary to ensure their health and well-being.”

In addition, the statement noted, vaccination can protect healthcare workers and their families from getting COVID-19.

The statement also pointed out that many healthcare and long-term care organizations already require vaccinations for influenza, hepatitis B, and pertussis.

Workers who have certain medical conditions should be exempt from the vaccination mandates, the statement added.

While recognizing the “historical mistrust of health care institutions” among some healthcare workers, the statement said, “We must continue to address workers’ concerns, engage with marginalized populations, and work with trusted messengers to improve vaccine acceptance.”

There has been some skepticism about the legality of requiring healthcare workers to get vaccinated as a condition of employment, partly because the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has not yet fully authorized any of the COVID-19 vaccines.

But in June, a federal judge turned down a legal challenge to Houston Methodist’s vaccination mandate.

“It is critical that all people in the health care workforce get vaccinated against COVID-19 for the safety of our patients and our colleagues. With more than 300 million doses administered in the United States and nearly 4 billion doses administered worldwide, we know the vaccines are safe and highly effective at preventing severe illness and death from COVID-19.

“Increased vaccinations among health care personnel will not only reduce the spread of COVID-19 but also reduce the harmful toll this virus is taking within the health care workforce and those we are striving to serve,” Susan Bailey, MD, immediate past president of the AMA, said in a news release.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Time’s little reminders

I don’t see anyone under 18. After all, I’m not a child neurologist.

People will occasionally argue with this policy, claiming that it’s too rigid. Why not 17½? I know that some adult neurologists do see teenagers.

But not me. It’s easier to just have a solid line and stick by it.

So, by habit, I often note someone’s birthday on the schedule to make sure they’re old enough to see me. And, over the years, this has made me realize the passage of time more than a lot of things.

Not much changes in my office. I’ve been in the same building since 2013, had the same furniture for longer, and the same staff since 2004. So it’s easy to lose track of how long I’ve been doing this.

But when I started out I didn’t see anyone born after 1979. Today that’s crept up to 2003. How the hell did that happen?

With that came the even more sobering realization that my kids are now all old enough to be my patients.

Time flies by in this world. You do the same thing day in and day out, and suddenly you’re 20 years older and starting to think about retirement.

We all see ourselves in the mirror each day, but rarely notice the changes. Watching patients grow older, seeing the minimum birth year for them advance, even being surprised when a drug I thought had just come out is now generic – those are the reminders of time’s passage that get my attention at work.

Not that it’s a bad thing. After 20 years I still enjoy this job, and it allows me to support my family. I can’t ask for much more than that.

But each morning I scan through the names and birthdays on my schedule, and am amazed when I think about how clearly I remember my first day of medical school, college, and even high school like it had just happened.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I don’t see anyone under 18. After all, I’m not a child neurologist.

People will occasionally argue with this policy, claiming that it’s too rigid. Why not 17½? I know that some adult neurologists do see teenagers.

But not me. It’s easier to just have a solid line and stick by it.

So, by habit, I often note someone’s birthday on the schedule to make sure they’re old enough to see me. And, over the years, this has made me realize the passage of time more than a lot of things.