User login

Use of oral contraception in adolescence raises risk of major depression in adulthood

Key clinical point: Adolescent oral contraceptive use was associated with a significant increase in risk of major depressive disorder in young adulthood; the results may help inform choices for contraceptive methods.

Major finding: Use of oral contraceptives at age 16-19 years was significantly associated with an episode of major depressive disorder at age 20-25 years (odds ratio 1.41, P < .001). The association was slightly higher among young women with no previous history of major depressive disorder.

Study details: The data come from a prospective cohort study of 725 women who participated in the Tracking Adolescents’ Individual Lives (TRAILS) study in Denmark. Use of OCs at ages 16-19 years was assessed as a predictor of major depressive disorder at ages 20-25 years based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV oriented Lifetime Depression Assessment Self-Report and the Composite International Diagnostic Interview.

Disclosures: The larger TRAILS study was supported by Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research NWO, the Dutch Ministry of Justice, the European Science Foundation, the European Research Council, Biobanking and Biomolecular Resources Research Infrastructure, the Gratama Foundation, the Jan Dekker Foundation, the participating universities, and Accare Centre for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. This specific study was also supported by the Feodor Lynen Research Fellowship from the Alexander von Humboldt-Foundation and a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Project Grant awarded to study authors. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Anderl C et al. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2021 Jul 12. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13476.

Key clinical point: Adolescent oral contraceptive use was associated with a significant increase in risk of major depressive disorder in young adulthood; the results may help inform choices for contraceptive methods.

Major finding: Use of oral contraceptives at age 16-19 years was significantly associated with an episode of major depressive disorder at age 20-25 years (odds ratio 1.41, P < .001). The association was slightly higher among young women with no previous history of major depressive disorder.

Study details: The data come from a prospective cohort study of 725 women who participated in the Tracking Adolescents’ Individual Lives (TRAILS) study in Denmark. Use of OCs at ages 16-19 years was assessed as a predictor of major depressive disorder at ages 20-25 years based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV oriented Lifetime Depression Assessment Self-Report and the Composite International Diagnostic Interview.

Disclosures: The larger TRAILS study was supported by Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research NWO, the Dutch Ministry of Justice, the European Science Foundation, the European Research Council, Biobanking and Biomolecular Resources Research Infrastructure, the Gratama Foundation, the Jan Dekker Foundation, the participating universities, and Accare Centre for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. This specific study was also supported by the Feodor Lynen Research Fellowship from the Alexander von Humboldt-Foundation and a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Project Grant awarded to study authors. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Anderl C et al. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2021 Jul 12. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13476.

Key clinical point: Adolescent oral contraceptive use was associated with a significant increase in risk of major depressive disorder in young adulthood; the results may help inform choices for contraceptive methods.

Major finding: Use of oral contraceptives at age 16-19 years was significantly associated with an episode of major depressive disorder at age 20-25 years (odds ratio 1.41, P < .001). The association was slightly higher among young women with no previous history of major depressive disorder.

Study details: The data come from a prospective cohort study of 725 women who participated in the Tracking Adolescents’ Individual Lives (TRAILS) study in Denmark. Use of OCs at ages 16-19 years was assessed as a predictor of major depressive disorder at ages 20-25 years based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV oriented Lifetime Depression Assessment Self-Report and the Composite International Diagnostic Interview.

Disclosures: The larger TRAILS study was supported by Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research NWO, the Dutch Ministry of Justice, the European Science Foundation, the European Research Council, Biobanking and Biomolecular Resources Research Infrastructure, the Gratama Foundation, the Jan Dekker Foundation, the participating universities, and Accare Centre for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. This specific study was also supported by the Feodor Lynen Research Fellowship from the Alexander von Humboldt-Foundation and a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Project Grant awarded to study authors. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Anderl C et al. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2021 Jul 12. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13476.

Uterine sound sparing technique raises satisfaction with IUD placement

Key clinical point: A uterine sound-sparing approach significantly increased patient satisfaction with IUD insertion compared to a trans-abdominal ultrasound guided approach.

Major finding: The VAS scores for patient satisfaction were significantly higher in women who underwent IUD placement with the USSA approach compared to the TVS approach (7.80 vs 5.45, P = .0001). Significantly lower VAS pain scores and significantly shorter duration of insertion also were reported in the USSA group compared to the TVS group (P = .001 and P = .0001, respectively).

Study details: The data come from a randomized, open-label study of multiparous women who requested copper IUD insertion for birth control; 44 women underwent placement with the trans-abdominal ultrasound (TAS) guided approach and 44 with the uterine sound-sparing approach (USSA).

Disclosures: The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Ali MK et al. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2021 Apr 15. doi: 10.1080/13625187.2021.1900565.

Key clinical point: A uterine sound-sparing approach significantly increased patient satisfaction with IUD insertion compared to a trans-abdominal ultrasound guided approach.

Major finding: The VAS scores for patient satisfaction were significantly higher in women who underwent IUD placement with the USSA approach compared to the TVS approach (7.80 vs 5.45, P = .0001). Significantly lower VAS pain scores and significantly shorter duration of insertion also were reported in the USSA group compared to the TVS group (P = .001 and P = .0001, respectively).

Study details: The data come from a randomized, open-label study of multiparous women who requested copper IUD insertion for birth control; 44 women underwent placement with the trans-abdominal ultrasound (TAS) guided approach and 44 with the uterine sound-sparing approach (USSA).

Disclosures: The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Ali MK et al. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2021 Apr 15. doi: 10.1080/13625187.2021.1900565.

Key clinical point: A uterine sound-sparing approach significantly increased patient satisfaction with IUD insertion compared to a trans-abdominal ultrasound guided approach.

Major finding: The VAS scores for patient satisfaction were significantly higher in women who underwent IUD placement with the USSA approach compared to the TVS approach (7.80 vs 5.45, P = .0001). Significantly lower VAS pain scores and significantly shorter duration of insertion also were reported in the USSA group compared to the TVS group (P = .001 and P = .0001, respectively).

Study details: The data come from a randomized, open-label study of multiparous women who requested copper IUD insertion for birth control; 44 women underwent placement with the trans-abdominal ultrasound (TAS) guided approach and 44 with the uterine sound-sparing approach (USSA).

Disclosures: The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Ali MK et al. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2021 Apr 15. doi: 10.1080/13625187.2021.1900565.

Hormone-containing IUDs fail to raise risk of precancerous cervical lesions

Key clinical point: Users of hormone-containing intrauterine (HIUD) devices had no significant increase in risk of developing precancerous cervical lesions than women who used other contraceptives.

Major finding: Women who used hormone-containing IUDs had the same risk as users of copper IUDs (CIUD) of developing cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 3+ (CIN3+) with adjusted relative risk of 1.08 over 5 years. The risk of CIN3+ was lower for the HIUD group and CIUD group compared to users of oral contraceptives (aRR 0.63 and aRR 0.58, respectively).

Study details: The data come from a population-based cohort study of women aged 26-50 years in Denmark, using registry data from 2008 to 2011; the study population included 60,551 users of HIUDs, 30,303 users of CIUDs, and 165,627 users of oral contraceptives.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the A.P. Møller Foundation for the Advancement of Medical Science, the Else and Mogens Wedell-Wedellborgs Fund, the Direktør Emil C. Hertz og Hustru Inger Hertz Fund, and the Fund for Development of Evidence Based Medicine in Private Specialized Practices. Lead author Dr. Skortengaard had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Skortengaard M et al. Hum Reprod. 2021 Jun 18. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deab066.

Key clinical point: Users of hormone-containing intrauterine (HIUD) devices had no significant increase in risk of developing precancerous cervical lesions than women who used other contraceptives.

Major finding: Women who used hormone-containing IUDs had the same risk as users of copper IUDs (CIUD) of developing cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 3+ (CIN3+) with adjusted relative risk of 1.08 over 5 years. The risk of CIN3+ was lower for the HIUD group and CIUD group compared to users of oral contraceptives (aRR 0.63 and aRR 0.58, respectively).

Study details: The data come from a population-based cohort study of women aged 26-50 years in Denmark, using registry data from 2008 to 2011; the study population included 60,551 users of HIUDs, 30,303 users of CIUDs, and 165,627 users of oral contraceptives.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the A.P. Møller Foundation for the Advancement of Medical Science, the Else and Mogens Wedell-Wedellborgs Fund, the Direktør Emil C. Hertz og Hustru Inger Hertz Fund, and the Fund for Development of Evidence Based Medicine in Private Specialized Practices. Lead author Dr. Skortengaard had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Skortengaard M et al. Hum Reprod. 2021 Jun 18. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deab066.

Key clinical point: Users of hormone-containing intrauterine (HIUD) devices had no significant increase in risk of developing precancerous cervical lesions than women who used other contraceptives.

Major finding: Women who used hormone-containing IUDs had the same risk as users of copper IUDs (CIUD) of developing cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 3+ (CIN3+) with adjusted relative risk of 1.08 over 5 years. The risk of CIN3+ was lower for the HIUD group and CIUD group compared to users of oral contraceptives (aRR 0.63 and aRR 0.58, respectively).

Study details: The data come from a population-based cohort study of women aged 26-50 years in Denmark, using registry data from 2008 to 2011; the study population included 60,551 users of HIUDs, 30,303 users of CIUDs, and 165,627 users of oral contraceptives.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the A.P. Møller Foundation for the Advancement of Medical Science, the Else and Mogens Wedell-Wedellborgs Fund, the Direktør Emil C. Hertz og Hustru Inger Hertz Fund, and the Fund for Development of Evidence Based Medicine in Private Specialized Practices. Lead author Dr. Skortengaard had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Skortengaard M et al. Hum Reprod. 2021 Jun 18. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deab066.

Contraceptive use lowers levels of anti-Müllerian hormone compared with non-use

Key clinical point: Current use of hormonal contraceptives was associated with lower mean levels of anti-Müllerian hormone compared to levels in women not on contraceptives; the data may guide clinicians in counseling women to continue their contraceptives during evaluation of ovarian reserve.

Major finding: Compared to women not using any contraceptives, mean anti-Müllerian hormone levels were significantly lower in women using a combined oral contraceptive pill (23.68%), vaginal ring (22.07%), hormonal intrauterine device (6.73%), implant (23.44%), or progestin-only pill (14.80%).

Study details: The data come from a cross-sectional study of 27,125 women aged 20-46 years in the United States. The researchers used dried blood spot cards or venipuncture to assess anti-Müllerian hormone levels.

Disclosures: Modern Fertility, manufacturer of the tests used in the study, paid salaries and consulting fees to the study authors. Lead author Dr. Hariton is a paid consultant for Modern Fertility, has stock options in the company, and his spouse is a Modern Fertility employee.

Source: Hariton E et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021 Jun 12. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.06.052.

Key clinical point: Current use of hormonal contraceptives was associated with lower mean levels of anti-Müllerian hormone compared to levels in women not on contraceptives; the data may guide clinicians in counseling women to continue their contraceptives during evaluation of ovarian reserve.

Major finding: Compared to women not using any contraceptives, mean anti-Müllerian hormone levels were significantly lower in women using a combined oral contraceptive pill (23.68%), vaginal ring (22.07%), hormonal intrauterine device (6.73%), implant (23.44%), or progestin-only pill (14.80%).

Study details: The data come from a cross-sectional study of 27,125 women aged 20-46 years in the United States. The researchers used dried blood spot cards or venipuncture to assess anti-Müllerian hormone levels.

Disclosures: Modern Fertility, manufacturer of the tests used in the study, paid salaries and consulting fees to the study authors. Lead author Dr. Hariton is a paid consultant for Modern Fertility, has stock options in the company, and his spouse is a Modern Fertility employee.

Source: Hariton E et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021 Jun 12. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.06.052.

Key clinical point: Current use of hormonal contraceptives was associated with lower mean levels of anti-Müllerian hormone compared to levels in women not on contraceptives; the data may guide clinicians in counseling women to continue their contraceptives during evaluation of ovarian reserve.

Major finding: Compared to women not using any contraceptives, mean anti-Müllerian hormone levels were significantly lower in women using a combined oral contraceptive pill (23.68%), vaginal ring (22.07%), hormonal intrauterine device (6.73%), implant (23.44%), or progestin-only pill (14.80%).

Study details: The data come from a cross-sectional study of 27,125 women aged 20-46 years in the United States. The researchers used dried blood spot cards or venipuncture to assess anti-Müllerian hormone levels.

Disclosures: Modern Fertility, manufacturer of the tests used in the study, paid salaries and consulting fees to the study authors. Lead author Dr. Hariton is a paid consultant for Modern Fertility, has stock options in the company, and his spouse is a Modern Fertility employee.

Source: Hariton E et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021 Jun 12. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.06.052.

IUD users report low pregnancy rates after placement for emergency contraception

Key clinical point: Pregnancy rates were low following placement of an IUD for emergency contraception, including among women who resumed intercourse within days of IUD placement without backup contraception.

Major finding: No pregnancies were reported among 138 women who received levonorgestrel IUS or among 148 who received copper IUDs who reported intercourse within 7 days of placement, regardless of use of backup contraception.

Study details: The data come from a secondary analysis of 518 participants in a randomized controlled trial of IUDs for emergency contraception; participants received a 52 mg levonorgestrel intrauterine system (IUS) or 380 mm2 copper IUD.

Disclosures: The study was supported in part by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Development, the University of Utah Population Health Research (PHR) Foundation, with funding in part from the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health. The Division of Family Planning in the University of Utah's Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology receives research funding from Bayer Women's Health Care, Merck & Co. Inc., Cooper Surgical, Sebela Pharmaceuticals, Femasys, and Medicines 360. Lead author Dr. Fay had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Fay KE et al. Contraception. 2021 Jun 21. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2021.06.011.

Key clinical point: Pregnancy rates were low following placement of an IUD for emergency contraception, including among women who resumed intercourse within days of IUD placement without backup contraception.

Major finding: No pregnancies were reported among 138 women who received levonorgestrel IUS or among 148 who received copper IUDs who reported intercourse within 7 days of placement, regardless of use of backup contraception.

Study details: The data come from a secondary analysis of 518 participants in a randomized controlled trial of IUDs for emergency contraception; participants received a 52 mg levonorgestrel intrauterine system (IUS) or 380 mm2 copper IUD.

Disclosures: The study was supported in part by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Development, the University of Utah Population Health Research (PHR) Foundation, with funding in part from the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health. The Division of Family Planning in the University of Utah's Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology receives research funding from Bayer Women's Health Care, Merck & Co. Inc., Cooper Surgical, Sebela Pharmaceuticals, Femasys, and Medicines 360. Lead author Dr. Fay had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Fay KE et al. Contraception. 2021 Jun 21. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2021.06.011.

Key clinical point: Pregnancy rates were low following placement of an IUD for emergency contraception, including among women who resumed intercourse within days of IUD placement without backup contraception.

Major finding: No pregnancies were reported among 138 women who received levonorgestrel IUS or among 148 who received copper IUDs who reported intercourse within 7 days of placement, regardless of use of backup contraception.

Study details: The data come from a secondary analysis of 518 participants in a randomized controlled trial of IUDs for emergency contraception; participants received a 52 mg levonorgestrel intrauterine system (IUS) or 380 mm2 copper IUD.

Disclosures: The study was supported in part by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Development, the University of Utah Population Health Research (PHR) Foundation, with funding in part from the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health. The Division of Family Planning in the University of Utah's Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology receives research funding from Bayer Women's Health Care, Merck & Co. Inc., Cooper Surgical, Sebela Pharmaceuticals, Femasys, and Medicines 360. Lead author Dr. Fay had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Fay KE et al. Contraception. 2021 Jun 21. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2021.06.011.

Women report high satisfaction with post-Cesarean IUDs

Key clinical point: Rates of continuation and satisfaction were high among women who underwent placement of IUDs during cesarean deliveries, with two cases of infection and no cases of perforation or pregnancy reported.

Major finding: Rates of IUD continuation were 92% at 6 weeks and 71.5% at 6 months; and approximately 85% and 76% of the women reported satisfaction with the devices at 6 weeks and 6 months, respectively.

Study details: The data come from a prospective, observational study of 158 women in Brazil who received copper IUDs during cesarean deliveries, with follow-up at 6 weeks and 6 months after IUD placement.

Disclosures: The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Uchoa de Albuquerque C et al. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2021 Jun 29. doi: 10.1080/13625187.2021.1943739.

Key clinical point: Rates of continuation and satisfaction were high among women who underwent placement of IUDs during cesarean deliveries, with two cases of infection and no cases of perforation or pregnancy reported.

Major finding: Rates of IUD continuation were 92% at 6 weeks and 71.5% at 6 months; and approximately 85% and 76% of the women reported satisfaction with the devices at 6 weeks and 6 months, respectively.

Study details: The data come from a prospective, observational study of 158 women in Brazil who received copper IUDs during cesarean deliveries, with follow-up at 6 weeks and 6 months after IUD placement.

Disclosures: The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Uchoa de Albuquerque C et al. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2021 Jun 29. doi: 10.1080/13625187.2021.1943739.

Key clinical point: Rates of continuation and satisfaction were high among women who underwent placement of IUDs during cesarean deliveries, with two cases of infection and no cases of perforation or pregnancy reported.

Major finding: Rates of IUD continuation were 92% at 6 weeks and 71.5% at 6 months; and approximately 85% and 76% of the women reported satisfaction with the devices at 6 weeks and 6 months, respectively.

Study details: The data come from a prospective, observational study of 158 women in Brazil who received copper IUDs during cesarean deliveries, with follow-up at 6 weeks and 6 months after IUD placement.

Disclosures: The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Uchoa de Albuquerque C et al. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2021 Jun 29. doi: 10.1080/13625187.2021.1943739.

Are you at legal risk for speaking at conferences?

When Jerry Gardner, MD, and a junior colleague received the acceptance notification for their abstract to be presented at Digestive Diseases Week® (DDW) 2021, a clause in the mandatory participation agreement gave Dr. Gardner pause. It required his colleague, as the submitting author, to completely accept any and all legal responsibility for any claims that might arise out of their presentation.

The clause was a red flag to Dr. Gardner, president of Science for Organizations, a Mill Valley, Calif.–based consulting firm. The gastroenterologist and former head of the digestive diseases branch at the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases – who has made hundreds of presentations and had participated in DDW for 40 years – had never encountered such a broad indemnity clause.

This news organization investigated just how risky it is to make a presentation at a conference – more than a dozen professional societies were contacted. Although DDW declined to discuss its agreement, Houston health care attorney Rachel V. Rose said that Dr. Gardner was smart to be cautious. “I would not sign that agreement. I have never seen anything that broad and all encompassing,” she said.

The DDW requirement “means that participants must put themselves at great potential financial risk in order to present their work,” Dr. Gardner said. He added that he and his colleague would not have submitted an abstract had they known about the indemnification clause up front.

Dr. Gardner advised his colleague not to sign the DDW agreement. She did not, and both missed the meeting.

Speakers ‘have to be careful’

Dr. Gardner may be an exception. How many doctors are willing to forgo a presentation because of a concern about something in an agreement?

John Mandrola, MD, said he operates under the assumption that if he does not sign the agreement, then he won’t be able to give his presentation. He admits that he generally just signs them and is careful with his presentations. “I’ve never really paid much attention to them,” said Dr. Mandrola, a cardiac electrophysiologist in Louisville, Ky., and chief cardiology correspondent for Medscape.

Not everyone takes that approach. “I do think that people read them, but they also take them with a grain of salt,” said E. Magnus Ohman, MBBS, professor of medicine at Duke University, Durham, N.C. He said he’s pragmatic and regards the agreements as a necessary evil in a litigious nation. Speakers “have to be careful, obviously,” Dr. Ohman said in an interview.

Some argue that the requirements are not only fair but also understandable. David Johnson, MD, a former president of the American College of Gastroenterology, said he has never had questions about agreements for meetings he has been involved with. “To me, this is not anything other than standard operating procedure,” he said.

Presenters participate by invitation, noted Dr. Johnson, a professor of medicine and chief of gastroenterology at the Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, who is a contributor to this news organization. “If they stand up and do something egregious, I would concur that the society should not be liable,” he said.

Big asks, big secrecy

Even for those who generally agree with Dr. Johnson’s position, it may be hard to completely understand what’s at stake without an attorney.

Although many declined to discuss their policies, a handful of professional societies provided their agreements for review. In general, the agreements appear to offer broad protection and rights to the organizers and large liability exposure for the participants. Participants are charged with a wide range of responsibilities, such as ensuring against copyright violations and intellectual property infringement, and that they also agree to unlimited use of their presentations and their name and likeness.

The American Academy of Neurology, which held its meeting virtually in 2021, required participants to indemnify the organization against all “losses, expenses, damages, or liabilities,” including “reasonable attorneys’ fees.” Federal employees, however, could opt out of indemnification.

The American Society of Clinical Oncology said that it does not usually require indemnification from its meeting participants. However, a spokesperson noted that ASCO did require participants at its 2021 virtual meeting to abide by the terms of use for content posted to the ASCO website. Those terms specify that users agree to indemnify ASCO from damages related to posts.

The American Psychiatric Association said it does not require any indemnification but did not make its agreement available. The American Academy of Pediatrics also said it did not require indemnification but would not share its agreement.

An American Diabetes Association spokesperson said that “every association is different in what they ask or require from speakers,” but would not share its requirements.

The American Academy of Family Physicians, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American College of Physicians, and the Endocrine Society all declined to participate.

The organizations that withheld agreements “probably don’t want anybody picking apart their documents,” said Kyle Claussen, CEO of the Resolve Physician Agency, which reviews employment contracts and other contracts for physicians. “The more fair a document, the more likely they would be willing to disclose that, because they have nothing to hide,” he said.

‘It’s all on you’

Requiring indemnification for any and all aspects of a presentation appears to be increasingly common, said the attorneys interviewed for this article. As organizations repackage meeting presentations for sale, they put the content further out into the world and for a longer period, which increases liability exposure.

“If I’m the attorney for DDW, I certainly think I’d want to have this in place,” said Mr. Claussen.

“It’s good business sense for them because it reduces their risk,” said Courtney H. A. Thompson, an attorney with Fredrikson & Byron in Minneapolis, who advises regional and national corporations and ad agencies on advertising, marketing, and trademark law. She also works with clients who speak at meetings and who thus encounter meeting agreements.

Ms. Thompson said indemnity clauses have become fairly common over the past decade, especially as more companies and organizations have sought to protect trademarks, copyrights, and intellectual property and to minimize litigation costs.

A conference organizer “doesn’t want a third party to come after them for intellectual property, privacy, or publicity right infringement based on the participation of the customer or, in this case, the speaker,” said Ms. Thompson.

The agreements also reflect America’s litigation-prone culture.

Dean Fanelli, a patent attorney in the Washington, D.C., office of Cooley LLP, said the agreements he’s been asked to sign as a speaker increasingly seem “overly lawyerly.”

Two decades ago, a speaker might have been asked to sign a paragraph or a one-page form. Now “they often look more like formalized legal agreements,” Mr. Fanelli told this news organization.

The DDW agreement, for instance, ran four pages and contained 21 detailed clauses.

The increasingly complicated agreements “are a little over the top,” said Mr. Fanelli. But as an attorney who works with clients in the pharmaceutical industry, he said he understands that meeting organizers want to protect their rights.

DDW’s main indemnification clause requires the participant to indemnify DDW and its agents, directors, and employees “against any and all claims, demands, causes of action, losses, damages, liabilities, costs, and expenses,” including attorneys’ fees “arising out of a claim, action or proceeding” based on a breach or “alleged breach” by the participant.

“You’re releasing this information to them and then you’re also giving them blanket indemnity back, saying if there’s any type of intellectual property violation on your end – if you’ve included any type of work that’s protected, if this causes any problems – it’s all on you,” said Mr. Claussen.

Other potential pitfalls

Aside from indemnification, participation agreements can contain other potentially worrisome clauses, including onerous terms for cancellation and reuse of content without remuneration.

DDW requires royalty-free licensing of a speaker’s content; the organization can reproduce it in perpetuity without royalties. Many organizations have such a clause in their agreements, including the AAN and the American College of Cardiology.

ASCO’s general authorization form for meeting participants requires that they assign to ASCO rights to their content “perpetually, irrevocably, worldwide and royalty free.” Participants can contact the organization if they seek to opt out, but it’s not clear whether ASCO grants such requests.

Participants in the upcoming American Heart Association annual meeting can deny permission to record their presentation. But if they allow recording and do not agree to assign all rights and copyright ownership to the AHA, the work will be excluded from publication in the meeting program, e-posters, and the meeting supplement in Circulation.

Mr. Claussen said granting royalty-free rights presents a conundrum. Having content reproduced in various formats “might be better for your personal brand,” but it’s not likely to result in any direct compensation and could increase liability exposure, he said.

How presenters must prepare

Mr. Claussen and Ms. Rose said speakers should be vigilant about their own rights and responsibilities, including ensuring that they do not violate copyrights or infringe on intellectual property rights.

“I would recommend that folks be meticulous about what is in their slide deck and materials,” said Ms. Thompson. He said that presenters should be sure they have the right to share material. Technologies crawl the internet seeking out infringement, which often leads to cease and desist letters from attorneys, she said.

It’s better to head off such a letter, Ms. Thompson said. “You need to defend it whether or not it’s a viable claim,” and that can be costly, she said.

Both Ms. Thompson and Mr. Fanelli also warn about disclosing anything that might be considered a trade secret. Many agreements prohibit presenters from engaging in commercial promotion, but if a talk includes information about a drug or device, the manufacturer will want to review the presentation before it’s made public, said Mr. Fanelli.

Many organizations prohibit attendees from photographing, recording, or tweeting at meetings and often require speakers to warn the audience about doing so. DDW goes further by holding presenters liable if someone violates the rule.

“That’s a huge problem,” said Dr. Mandrola. He noted that although it might be easy to police journalists attending a meeting, “it seems hard to enforce that rule amongst just regular attendees.”

Accept or negotiate?

Individuals who submit work to an organization might feel they must sign an agreement as is, especially if they are looking to advance their career or expand knowledge by presenting work at a meeting. But some attorneys said it might be possible to negotiate with meeting organizers.

“My personal opinion is that it never hurts to ask,” said Ms. Thompson. If she were speaking at a legal conference, she would mark up a contract and “see what happens.” The more times pushback is accepted – say, if it works with three out of five speaking engagements – the more it reduces overall liability exposure.

Mr. Fanelli, however, said that although he always reads over an agreement, he typically signs without negotiating. “I don’t usually worry about it because I’m just trying to talk at a particular seminar,” he said.

Prospective presenters “have to weigh that balance – do you want to talk at a seminar, or are you concerned about the legal issues?” said Mr. Fanelli.

If in doubt, talk with a lawyer.

“If you ever have a question on whether or not you should consult an attorney, the answer is always yes,” said Mr. Claussen. It would be “an ounce of prevention,” especially if it’s just a short agreement, he said.

Dr. Ohman, however, said that he believed “it would be fairly costly” and potentially unwieldy. “You can’t litigate everything in life,” he added.

As for Dr. Gardner, he said he would not be as likely to attend DDW in the future if he has to agree to cover any and all liability. “I can’t conceive of ever agreeing to personally indemnify DDW in order to make a presentation at the annual meeting,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

When Jerry Gardner, MD, and a junior colleague received the acceptance notification for their abstract to be presented at Digestive Diseases Week® (DDW) 2021, a clause in the mandatory participation agreement gave Dr. Gardner pause. It required his colleague, as the submitting author, to completely accept any and all legal responsibility for any claims that might arise out of their presentation.

The clause was a red flag to Dr. Gardner, president of Science for Organizations, a Mill Valley, Calif.–based consulting firm. The gastroenterologist and former head of the digestive diseases branch at the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases – who has made hundreds of presentations and had participated in DDW for 40 years – had never encountered such a broad indemnity clause.

This news organization investigated just how risky it is to make a presentation at a conference – more than a dozen professional societies were contacted. Although DDW declined to discuss its agreement, Houston health care attorney Rachel V. Rose said that Dr. Gardner was smart to be cautious. “I would not sign that agreement. I have never seen anything that broad and all encompassing,” she said.

The DDW requirement “means that participants must put themselves at great potential financial risk in order to present their work,” Dr. Gardner said. He added that he and his colleague would not have submitted an abstract had they known about the indemnification clause up front.

Dr. Gardner advised his colleague not to sign the DDW agreement. She did not, and both missed the meeting.

Speakers ‘have to be careful’

Dr. Gardner may be an exception. How many doctors are willing to forgo a presentation because of a concern about something in an agreement?

John Mandrola, MD, said he operates under the assumption that if he does not sign the agreement, then he won’t be able to give his presentation. He admits that he generally just signs them and is careful with his presentations. “I’ve never really paid much attention to them,” said Dr. Mandrola, a cardiac electrophysiologist in Louisville, Ky., and chief cardiology correspondent for Medscape.

Not everyone takes that approach. “I do think that people read them, but they also take them with a grain of salt,” said E. Magnus Ohman, MBBS, professor of medicine at Duke University, Durham, N.C. He said he’s pragmatic and regards the agreements as a necessary evil in a litigious nation. Speakers “have to be careful, obviously,” Dr. Ohman said in an interview.

Some argue that the requirements are not only fair but also understandable. David Johnson, MD, a former president of the American College of Gastroenterology, said he has never had questions about agreements for meetings he has been involved with. “To me, this is not anything other than standard operating procedure,” he said.

Presenters participate by invitation, noted Dr. Johnson, a professor of medicine and chief of gastroenterology at the Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, who is a contributor to this news organization. “If they stand up and do something egregious, I would concur that the society should not be liable,” he said.

Big asks, big secrecy

Even for those who generally agree with Dr. Johnson’s position, it may be hard to completely understand what’s at stake without an attorney.

Although many declined to discuss their policies, a handful of professional societies provided their agreements for review. In general, the agreements appear to offer broad protection and rights to the organizers and large liability exposure for the participants. Participants are charged with a wide range of responsibilities, such as ensuring against copyright violations and intellectual property infringement, and that they also agree to unlimited use of their presentations and their name and likeness.

The American Academy of Neurology, which held its meeting virtually in 2021, required participants to indemnify the organization against all “losses, expenses, damages, or liabilities,” including “reasonable attorneys’ fees.” Federal employees, however, could opt out of indemnification.

The American Society of Clinical Oncology said that it does not usually require indemnification from its meeting participants. However, a spokesperson noted that ASCO did require participants at its 2021 virtual meeting to abide by the terms of use for content posted to the ASCO website. Those terms specify that users agree to indemnify ASCO from damages related to posts.

The American Psychiatric Association said it does not require any indemnification but did not make its agreement available. The American Academy of Pediatrics also said it did not require indemnification but would not share its agreement.

An American Diabetes Association spokesperson said that “every association is different in what they ask or require from speakers,” but would not share its requirements.

The American Academy of Family Physicians, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American College of Physicians, and the Endocrine Society all declined to participate.

The organizations that withheld agreements “probably don’t want anybody picking apart their documents,” said Kyle Claussen, CEO of the Resolve Physician Agency, which reviews employment contracts and other contracts for physicians. “The more fair a document, the more likely they would be willing to disclose that, because they have nothing to hide,” he said.

‘It’s all on you’

Requiring indemnification for any and all aspects of a presentation appears to be increasingly common, said the attorneys interviewed for this article. As organizations repackage meeting presentations for sale, they put the content further out into the world and for a longer period, which increases liability exposure.

“If I’m the attorney for DDW, I certainly think I’d want to have this in place,” said Mr. Claussen.

“It’s good business sense for them because it reduces their risk,” said Courtney H. A. Thompson, an attorney with Fredrikson & Byron in Minneapolis, who advises regional and national corporations and ad agencies on advertising, marketing, and trademark law. She also works with clients who speak at meetings and who thus encounter meeting agreements.

Ms. Thompson said indemnity clauses have become fairly common over the past decade, especially as more companies and organizations have sought to protect trademarks, copyrights, and intellectual property and to minimize litigation costs.

A conference organizer “doesn’t want a third party to come after them for intellectual property, privacy, or publicity right infringement based on the participation of the customer or, in this case, the speaker,” said Ms. Thompson.

The agreements also reflect America’s litigation-prone culture.

Dean Fanelli, a patent attorney in the Washington, D.C., office of Cooley LLP, said the agreements he’s been asked to sign as a speaker increasingly seem “overly lawyerly.”

Two decades ago, a speaker might have been asked to sign a paragraph or a one-page form. Now “they often look more like formalized legal agreements,” Mr. Fanelli told this news organization.

The DDW agreement, for instance, ran four pages and contained 21 detailed clauses.

The increasingly complicated agreements “are a little over the top,” said Mr. Fanelli. But as an attorney who works with clients in the pharmaceutical industry, he said he understands that meeting organizers want to protect their rights.

DDW’s main indemnification clause requires the participant to indemnify DDW and its agents, directors, and employees “against any and all claims, demands, causes of action, losses, damages, liabilities, costs, and expenses,” including attorneys’ fees “arising out of a claim, action or proceeding” based on a breach or “alleged breach” by the participant.

“You’re releasing this information to them and then you’re also giving them blanket indemnity back, saying if there’s any type of intellectual property violation on your end – if you’ve included any type of work that’s protected, if this causes any problems – it’s all on you,” said Mr. Claussen.

Other potential pitfalls

Aside from indemnification, participation agreements can contain other potentially worrisome clauses, including onerous terms for cancellation and reuse of content without remuneration.

DDW requires royalty-free licensing of a speaker’s content; the organization can reproduce it in perpetuity without royalties. Many organizations have such a clause in their agreements, including the AAN and the American College of Cardiology.

ASCO’s general authorization form for meeting participants requires that they assign to ASCO rights to their content “perpetually, irrevocably, worldwide and royalty free.” Participants can contact the organization if they seek to opt out, but it’s not clear whether ASCO grants such requests.

Participants in the upcoming American Heart Association annual meeting can deny permission to record their presentation. But if they allow recording and do not agree to assign all rights and copyright ownership to the AHA, the work will be excluded from publication in the meeting program, e-posters, and the meeting supplement in Circulation.

Mr. Claussen said granting royalty-free rights presents a conundrum. Having content reproduced in various formats “might be better for your personal brand,” but it’s not likely to result in any direct compensation and could increase liability exposure, he said.

How presenters must prepare

Mr. Claussen and Ms. Rose said speakers should be vigilant about their own rights and responsibilities, including ensuring that they do not violate copyrights or infringe on intellectual property rights.

“I would recommend that folks be meticulous about what is in their slide deck and materials,” said Ms. Thompson. He said that presenters should be sure they have the right to share material. Technologies crawl the internet seeking out infringement, which often leads to cease and desist letters from attorneys, she said.

It’s better to head off such a letter, Ms. Thompson said. “You need to defend it whether or not it’s a viable claim,” and that can be costly, she said.

Both Ms. Thompson and Mr. Fanelli also warn about disclosing anything that might be considered a trade secret. Many agreements prohibit presenters from engaging in commercial promotion, but if a talk includes information about a drug or device, the manufacturer will want to review the presentation before it’s made public, said Mr. Fanelli.

Many organizations prohibit attendees from photographing, recording, or tweeting at meetings and often require speakers to warn the audience about doing so. DDW goes further by holding presenters liable if someone violates the rule.

“That’s a huge problem,” said Dr. Mandrola. He noted that although it might be easy to police journalists attending a meeting, “it seems hard to enforce that rule amongst just regular attendees.”

Accept or negotiate?

Individuals who submit work to an organization might feel they must sign an agreement as is, especially if they are looking to advance their career or expand knowledge by presenting work at a meeting. But some attorneys said it might be possible to negotiate with meeting organizers.

“My personal opinion is that it never hurts to ask,” said Ms. Thompson. If she were speaking at a legal conference, she would mark up a contract and “see what happens.” The more times pushback is accepted – say, if it works with three out of five speaking engagements – the more it reduces overall liability exposure.

Mr. Fanelli, however, said that although he always reads over an agreement, he typically signs without negotiating. “I don’t usually worry about it because I’m just trying to talk at a particular seminar,” he said.

Prospective presenters “have to weigh that balance – do you want to talk at a seminar, or are you concerned about the legal issues?” said Mr. Fanelli.

If in doubt, talk with a lawyer.

“If you ever have a question on whether or not you should consult an attorney, the answer is always yes,” said Mr. Claussen. It would be “an ounce of prevention,” especially if it’s just a short agreement, he said.

Dr. Ohman, however, said that he believed “it would be fairly costly” and potentially unwieldy. “You can’t litigate everything in life,” he added.

As for Dr. Gardner, he said he would not be as likely to attend DDW in the future if he has to agree to cover any and all liability. “I can’t conceive of ever agreeing to personally indemnify DDW in order to make a presentation at the annual meeting,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

When Jerry Gardner, MD, and a junior colleague received the acceptance notification for their abstract to be presented at Digestive Diseases Week® (DDW) 2021, a clause in the mandatory participation agreement gave Dr. Gardner pause. It required his colleague, as the submitting author, to completely accept any and all legal responsibility for any claims that might arise out of their presentation.

The clause was a red flag to Dr. Gardner, president of Science for Organizations, a Mill Valley, Calif.–based consulting firm. The gastroenterologist and former head of the digestive diseases branch at the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases – who has made hundreds of presentations and had participated in DDW for 40 years – had never encountered such a broad indemnity clause.

This news organization investigated just how risky it is to make a presentation at a conference – more than a dozen professional societies were contacted. Although DDW declined to discuss its agreement, Houston health care attorney Rachel V. Rose said that Dr. Gardner was smart to be cautious. “I would not sign that agreement. I have never seen anything that broad and all encompassing,” she said.

The DDW requirement “means that participants must put themselves at great potential financial risk in order to present their work,” Dr. Gardner said. He added that he and his colleague would not have submitted an abstract had they known about the indemnification clause up front.

Dr. Gardner advised his colleague not to sign the DDW agreement. She did not, and both missed the meeting.

Speakers ‘have to be careful’

Dr. Gardner may be an exception. How many doctors are willing to forgo a presentation because of a concern about something in an agreement?

John Mandrola, MD, said he operates under the assumption that if he does not sign the agreement, then he won’t be able to give his presentation. He admits that he generally just signs them and is careful with his presentations. “I’ve never really paid much attention to them,” said Dr. Mandrola, a cardiac electrophysiologist in Louisville, Ky., and chief cardiology correspondent for Medscape.

Not everyone takes that approach. “I do think that people read them, but they also take them with a grain of salt,” said E. Magnus Ohman, MBBS, professor of medicine at Duke University, Durham, N.C. He said he’s pragmatic and regards the agreements as a necessary evil in a litigious nation. Speakers “have to be careful, obviously,” Dr. Ohman said in an interview.

Some argue that the requirements are not only fair but also understandable. David Johnson, MD, a former president of the American College of Gastroenterology, said he has never had questions about agreements for meetings he has been involved with. “To me, this is not anything other than standard operating procedure,” he said.

Presenters participate by invitation, noted Dr. Johnson, a professor of medicine and chief of gastroenterology at the Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, who is a contributor to this news organization. “If they stand up and do something egregious, I would concur that the society should not be liable,” he said.

Big asks, big secrecy

Even for those who generally agree with Dr. Johnson’s position, it may be hard to completely understand what’s at stake without an attorney.

Although many declined to discuss their policies, a handful of professional societies provided their agreements for review. In general, the agreements appear to offer broad protection and rights to the organizers and large liability exposure for the participants. Participants are charged with a wide range of responsibilities, such as ensuring against copyright violations and intellectual property infringement, and that they also agree to unlimited use of their presentations and their name and likeness.

The American Academy of Neurology, which held its meeting virtually in 2021, required participants to indemnify the organization against all “losses, expenses, damages, or liabilities,” including “reasonable attorneys’ fees.” Federal employees, however, could opt out of indemnification.

The American Society of Clinical Oncology said that it does not usually require indemnification from its meeting participants. However, a spokesperson noted that ASCO did require participants at its 2021 virtual meeting to abide by the terms of use for content posted to the ASCO website. Those terms specify that users agree to indemnify ASCO from damages related to posts.

The American Psychiatric Association said it does not require any indemnification but did not make its agreement available. The American Academy of Pediatrics also said it did not require indemnification but would not share its agreement.

An American Diabetes Association spokesperson said that “every association is different in what they ask or require from speakers,” but would not share its requirements.

The American Academy of Family Physicians, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American College of Physicians, and the Endocrine Society all declined to participate.

The organizations that withheld agreements “probably don’t want anybody picking apart their documents,” said Kyle Claussen, CEO of the Resolve Physician Agency, which reviews employment contracts and other contracts for physicians. “The more fair a document, the more likely they would be willing to disclose that, because they have nothing to hide,” he said.

‘It’s all on you’

Requiring indemnification for any and all aspects of a presentation appears to be increasingly common, said the attorneys interviewed for this article. As organizations repackage meeting presentations for sale, they put the content further out into the world and for a longer period, which increases liability exposure.

“If I’m the attorney for DDW, I certainly think I’d want to have this in place,” said Mr. Claussen.

“It’s good business sense for them because it reduces their risk,” said Courtney H. A. Thompson, an attorney with Fredrikson & Byron in Minneapolis, who advises regional and national corporations and ad agencies on advertising, marketing, and trademark law. She also works with clients who speak at meetings and who thus encounter meeting agreements.

Ms. Thompson said indemnity clauses have become fairly common over the past decade, especially as more companies and organizations have sought to protect trademarks, copyrights, and intellectual property and to minimize litigation costs.

A conference organizer “doesn’t want a third party to come after them for intellectual property, privacy, or publicity right infringement based on the participation of the customer or, in this case, the speaker,” said Ms. Thompson.

The agreements also reflect America’s litigation-prone culture.

Dean Fanelli, a patent attorney in the Washington, D.C., office of Cooley LLP, said the agreements he’s been asked to sign as a speaker increasingly seem “overly lawyerly.”

Two decades ago, a speaker might have been asked to sign a paragraph or a one-page form. Now “they often look more like formalized legal agreements,” Mr. Fanelli told this news organization.

The DDW agreement, for instance, ran four pages and contained 21 detailed clauses.

The increasingly complicated agreements “are a little over the top,” said Mr. Fanelli. But as an attorney who works with clients in the pharmaceutical industry, he said he understands that meeting organizers want to protect their rights.

DDW’s main indemnification clause requires the participant to indemnify DDW and its agents, directors, and employees “against any and all claims, demands, causes of action, losses, damages, liabilities, costs, and expenses,” including attorneys’ fees “arising out of a claim, action or proceeding” based on a breach or “alleged breach” by the participant.

“You’re releasing this information to them and then you’re also giving them blanket indemnity back, saying if there’s any type of intellectual property violation on your end – if you’ve included any type of work that’s protected, if this causes any problems – it’s all on you,” said Mr. Claussen.

Other potential pitfalls

Aside from indemnification, participation agreements can contain other potentially worrisome clauses, including onerous terms for cancellation and reuse of content without remuneration.

DDW requires royalty-free licensing of a speaker’s content; the organization can reproduce it in perpetuity without royalties. Many organizations have such a clause in their agreements, including the AAN and the American College of Cardiology.

ASCO’s general authorization form for meeting participants requires that they assign to ASCO rights to their content “perpetually, irrevocably, worldwide and royalty free.” Participants can contact the organization if they seek to opt out, but it’s not clear whether ASCO grants such requests.

Participants in the upcoming American Heart Association annual meeting can deny permission to record their presentation. But if they allow recording and do not agree to assign all rights and copyright ownership to the AHA, the work will be excluded from publication in the meeting program, e-posters, and the meeting supplement in Circulation.

Mr. Claussen said granting royalty-free rights presents a conundrum. Having content reproduced in various formats “might be better for your personal brand,” but it’s not likely to result in any direct compensation and could increase liability exposure, he said.

How presenters must prepare

Mr. Claussen and Ms. Rose said speakers should be vigilant about their own rights and responsibilities, including ensuring that they do not violate copyrights or infringe on intellectual property rights.

“I would recommend that folks be meticulous about what is in their slide deck and materials,” said Ms. Thompson. He said that presenters should be sure they have the right to share material. Technologies crawl the internet seeking out infringement, which often leads to cease and desist letters from attorneys, she said.

It’s better to head off such a letter, Ms. Thompson said. “You need to defend it whether or not it’s a viable claim,” and that can be costly, she said.

Both Ms. Thompson and Mr. Fanelli also warn about disclosing anything that might be considered a trade secret. Many agreements prohibit presenters from engaging in commercial promotion, but if a talk includes information about a drug or device, the manufacturer will want to review the presentation before it’s made public, said Mr. Fanelli.

Many organizations prohibit attendees from photographing, recording, or tweeting at meetings and often require speakers to warn the audience about doing so. DDW goes further by holding presenters liable if someone violates the rule.

“That’s a huge problem,” said Dr. Mandrola. He noted that although it might be easy to police journalists attending a meeting, “it seems hard to enforce that rule amongst just regular attendees.”

Accept or negotiate?

Individuals who submit work to an organization might feel they must sign an agreement as is, especially if they are looking to advance their career or expand knowledge by presenting work at a meeting. But some attorneys said it might be possible to negotiate with meeting organizers.

“My personal opinion is that it never hurts to ask,” said Ms. Thompson. If she were speaking at a legal conference, she would mark up a contract and “see what happens.” The more times pushback is accepted – say, if it works with three out of five speaking engagements – the more it reduces overall liability exposure.

Mr. Fanelli, however, said that although he always reads over an agreement, he typically signs without negotiating. “I don’t usually worry about it because I’m just trying to talk at a particular seminar,” he said.

Prospective presenters “have to weigh that balance – do you want to talk at a seminar, or are you concerned about the legal issues?” said Mr. Fanelli.

If in doubt, talk with a lawyer.

“If you ever have a question on whether or not you should consult an attorney, the answer is always yes,” said Mr. Claussen. It would be “an ounce of prevention,” especially if it’s just a short agreement, he said.

Dr. Ohman, however, said that he believed “it would be fairly costly” and potentially unwieldy. “You can’t litigate everything in life,” he added.

As for Dr. Gardner, he said he would not be as likely to attend DDW in the future if he has to agree to cover any and all liability. “I can’t conceive of ever agreeing to personally indemnify DDW in order to make a presentation at the annual meeting,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Clinical Edge Journal Scan Commentary: Contraception August 2021

Levonorgestrel intrauterine devices (LNG IUD) are a hot topic in contraceptive research. A recent study on LNG IUDs published by Fay KE et al evaluated pregnancy rates in US women who received LNG or copper IUDs for emergency contraception and reported intercourse within 7 days of insertion. Zero pregnancies were reported in women who resumed intercourse within 7 days of IUD insertion for both the LNG IUD and copper IUD, even in women who had multiple unprotected sexual encounters. LNG IUDs are more readily accessible and better tolerated than their copper IUD counterparts, and expanding their use will only continue to improve access to reliable contraception. Women often resume penetrative intercourse shortly after initiating new contraceptive method despite counseling. Patients can be reassured that placement of a LNG IUD appears to provide immediate contraceptive benefit.

A new estrogen is on the market for use in combined oral contraceptive pills (COC). Estetrol is a natural estrogen produced by the human fetal liver only found in circulation during pregnancy. Estetrol was previously studied for use in menopausal hormone therapy as it acts as a mixed agonist and antagonist, offering a potential improved side effect profile with less activity in the breast and liver. Estetrol (15 mg) was combined with 3 mg of drospirinone for a novel combined oral contraceptive option in a study by Gemzell-Danielsson K et al. The pregnancy rate was similar to traditional COCs, demonstrating good contraceptive efficacy. Bleeding patterns and side effects were similar to traditional COCs, and one case of venous thromboembolism was reported in the large study population. A phase III trial with similar results has been completed and this new oral contraceptive formulation recently received FDA approval and is now marketed as Nextstellis. This new oral contraceptive pill hopefully represents a novel option for women who desire COCs with a low androgenic profile and VTE risk or have failed other COC formulations.

Women are increasingly delaying childbearing, utilizing a variety of contraceptive options to avoid pregnancy. Many proactively seek to determine their fertility potential and clinicians often utilize anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) as the standard biomarker for assessing ovarian reserve, as it is cycle independent and can be drawn at any time during a woman’s clinical assessment. Hormonal contraception suppresses ovulation by gonadotropin suppression as a means of contraceptive action, and thus could impact an AMH value. A fascinating study by Hariton E et al looked at all contraceptive options and their impact on AMH values. AMH levels were significantly lower in women using COCs, implants, progestin-only pills, and vaginal rings compared to patients not using contraceptives, and AMH levels were slightly lower in women using hormonal IUDs. These results help clinicians counsel patients on expectations for AMH levels while on contraceptives and can guide future research to generate contraceptive-specific ranges. Women using contraceptives should be counseled to retest after stopping if AMH levels are low.

Levonorgestrel intrauterine devices (LNG IUD) are a hot topic in contraceptive research. A recent study on LNG IUDs published by Fay KE et al evaluated pregnancy rates in US women who received LNG or copper IUDs for emergency contraception and reported intercourse within 7 days of insertion. Zero pregnancies were reported in women who resumed intercourse within 7 days of IUD insertion for both the LNG IUD and copper IUD, even in women who had multiple unprotected sexual encounters. LNG IUDs are more readily accessible and better tolerated than their copper IUD counterparts, and expanding their use will only continue to improve access to reliable contraception. Women often resume penetrative intercourse shortly after initiating new contraceptive method despite counseling. Patients can be reassured that placement of a LNG IUD appears to provide immediate contraceptive benefit.

A new estrogen is on the market for use in combined oral contraceptive pills (COC). Estetrol is a natural estrogen produced by the human fetal liver only found in circulation during pregnancy. Estetrol was previously studied for use in menopausal hormone therapy as it acts as a mixed agonist and antagonist, offering a potential improved side effect profile with less activity in the breast and liver. Estetrol (15 mg) was combined with 3 mg of drospirinone for a novel combined oral contraceptive option in a study by Gemzell-Danielsson K et al. The pregnancy rate was similar to traditional COCs, demonstrating good contraceptive efficacy. Bleeding patterns and side effects were similar to traditional COCs, and one case of venous thromboembolism was reported in the large study population. A phase III trial with similar results has been completed and this new oral contraceptive formulation recently received FDA approval and is now marketed as Nextstellis. This new oral contraceptive pill hopefully represents a novel option for women who desire COCs with a low androgenic profile and VTE risk or have failed other COC formulations.

Women are increasingly delaying childbearing, utilizing a variety of contraceptive options to avoid pregnancy. Many proactively seek to determine their fertility potential and clinicians often utilize anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) as the standard biomarker for assessing ovarian reserve, as it is cycle independent and can be drawn at any time during a woman’s clinical assessment. Hormonal contraception suppresses ovulation by gonadotropin suppression as a means of contraceptive action, and thus could impact an AMH value. A fascinating study by Hariton E et al looked at all contraceptive options and their impact on AMH values. AMH levels were significantly lower in women using COCs, implants, progestin-only pills, and vaginal rings compared to patients not using contraceptives, and AMH levels were slightly lower in women using hormonal IUDs. These results help clinicians counsel patients on expectations for AMH levels while on contraceptives and can guide future research to generate contraceptive-specific ranges. Women using contraceptives should be counseled to retest after stopping if AMH levels are low.

Levonorgestrel intrauterine devices (LNG IUD) are a hot topic in contraceptive research. A recent study on LNG IUDs published by Fay KE et al evaluated pregnancy rates in US women who received LNG or copper IUDs for emergency contraception and reported intercourse within 7 days of insertion. Zero pregnancies were reported in women who resumed intercourse within 7 days of IUD insertion for both the LNG IUD and copper IUD, even in women who had multiple unprotected sexual encounters. LNG IUDs are more readily accessible and better tolerated than their copper IUD counterparts, and expanding their use will only continue to improve access to reliable contraception. Women often resume penetrative intercourse shortly after initiating new contraceptive method despite counseling. Patients can be reassured that placement of a LNG IUD appears to provide immediate contraceptive benefit.

A new estrogen is on the market for use in combined oral contraceptive pills (COC). Estetrol is a natural estrogen produced by the human fetal liver only found in circulation during pregnancy. Estetrol was previously studied for use in menopausal hormone therapy as it acts as a mixed agonist and antagonist, offering a potential improved side effect profile with less activity in the breast and liver. Estetrol (15 mg) was combined with 3 mg of drospirinone for a novel combined oral contraceptive option in a study by Gemzell-Danielsson K et al. The pregnancy rate was similar to traditional COCs, demonstrating good contraceptive efficacy. Bleeding patterns and side effects were similar to traditional COCs, and one case of venous thromboembolism was reported in the large study population. A phase III trial with similar results has been completed and this new oral contraceptive formulation recently received FDA approval and is now marketed as Nextstellis. This new oral contraceptive pill hopefully represents a novel option for women who desire COCs with a low androgenic profile and VTE risk or have failed other COC formulations.

Women are increasingly delaying childbearing, utilizing a variety of contraceptive options to avoid pregnancy. Many proactively seek to determine their fertility potential and clinicians often utilize anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) as the standard biomarker for assessing ovarian reserve, as it is cycle independent and can be drawn at any time during a woman’s clinical assessment. Hormonal contraception suppresses ovulation by gonadotropin suppression as a means of contraceptive action, and thus could impact an AMH value. A fascinating study by Hariton E et al looked at all contraceptive options and their impact on AMH values. AMH levels were significantly lower in women using COCs, implants, progestin-only pills, and vaginal rings compared to patients not using contraceptives, and AMH levels were slightly lower in women using hormonal IUDs. These results help clinicians counsel patients on expectations for AMH levels while on contraceptives and can guide future research to generate contraceptive-specific ranges. Women using contraceptives should be counseled to retest after stopping if AMH levels are low.

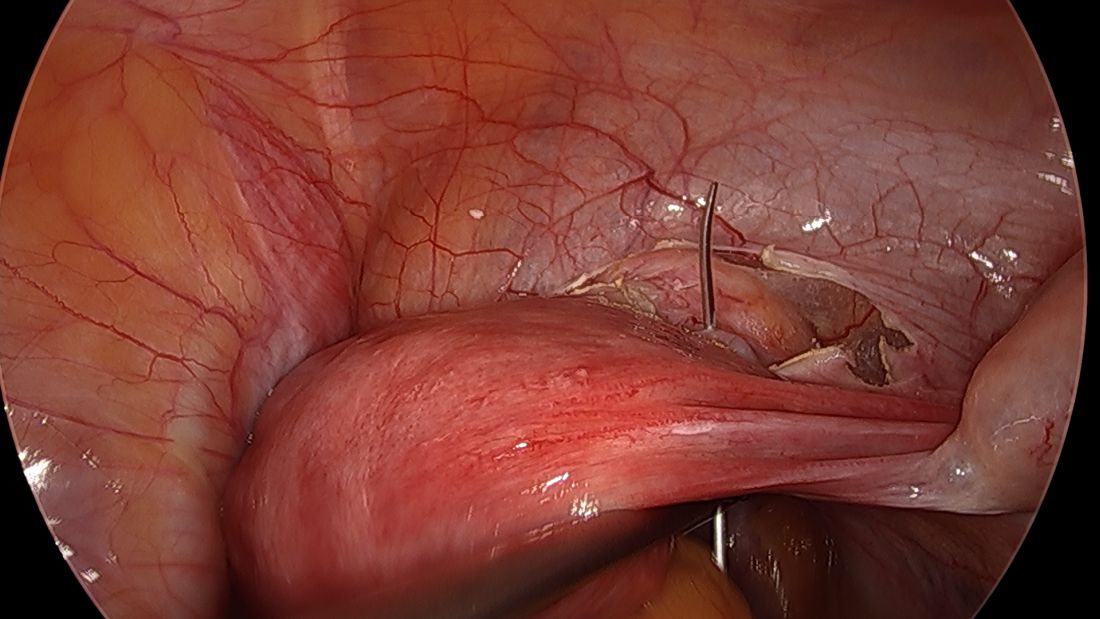

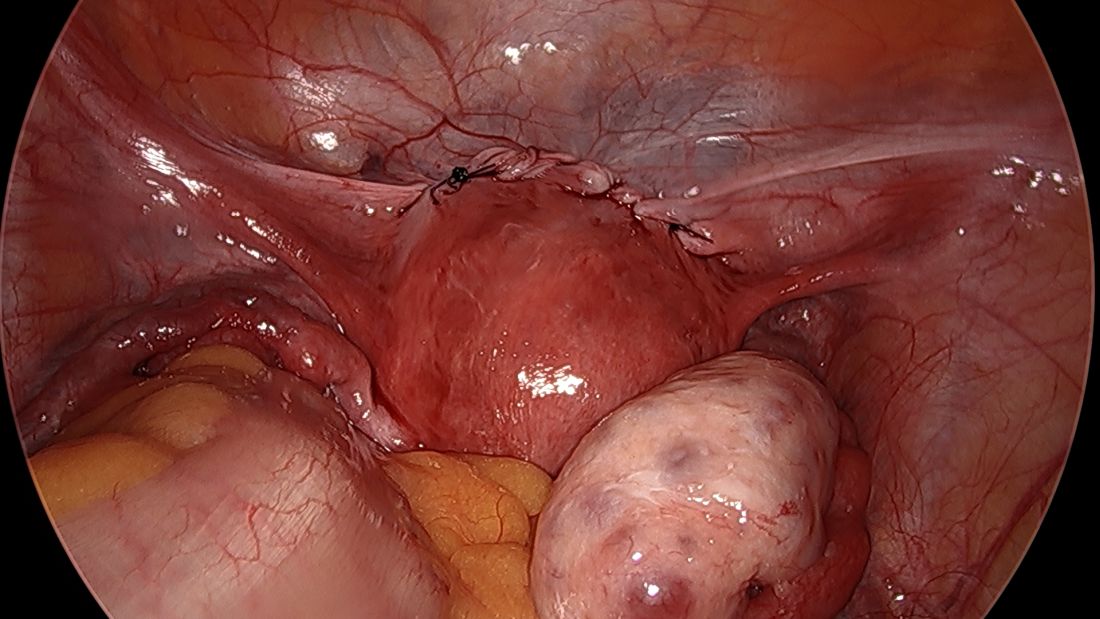

Laparoscopic abdominal cerclage: An effective, patient-sought approach for cervical insufficiency

Cervical insufficiency is an important cause of preterm birth and complicates up to 1% of pregnancies. It is typically diagnosed as painless cervical dilation without contractions, often in the second trimester at around 16-18 weeks, but the clinical presentation can be variable. In some cases, a rescue cerclage can be placed to prevent second trimester loss or preterm birth.

A recent landmark randomized controlled trial of abdominal vs. vaginal cerclage – the MAVRIC trial (Multicentre Abdominal vs. Vaginal Randomized Intervention of Cerclage)1 published in 2020 – has offered significant validation for the belief that an abdominal approach is the preferred approach for patients with cervical insufficiency and a prior failed vaginal cerclage.

Obstetricians traditionally have had a high threshold for placement of an abdominal cerclage given the need for cesarean delivery and the morbidity of an open procedure. Laparoscopic abdominal cerclage has lowered this threshold and is increasingly the preferred method for cerclage placement. Reported complication rates are generally lower than for open abdominal cerclage, and neonatal survival rates are similar or improved.

In our experience, the move toward laparoscopic abdominal cerclage is largely a patient-driven shift. Since 2007, at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, we have performed over 150 laparoscopic abdominal cerclage placements. The majority of patients had at least one prior second-trimester loss (many of them had multiple losses), with many having also failed a transvaginal cerclage.

In an analysis of 137 of these cases published recently in Fertility and Sterility, the neonatal survival rate was 93.8% in the 80 pregnancies that followed and extended beyond the first trimester, and the mean gestational age at delivery was 36.9 weeks.2 (First trimester losses are typically excluded from the denominator because they are unlikely to be the result of cervical insufficiency.)

History and outcomes data

The vaginal cerclage has long been a mainstay of therapy because it is a simple procedure. The McDonald technique, described in the 1950s, uses a simple purse string suture at the cervico-vaginal juncture, and the Shirodkar approach, also described in the 1950s, involves placing the cerclage higher on the cervix, as close to the internal os as possible. The Shirodkar technique is more complex, requiring more dissection, and is used less often than the McDonald approach.

The abdominal cerclage, first reported in 1965,3 is placed higher on the cervix, right near the juncture of the lower uterine segment and the cervix, and has generally been thought to provide optimal integrity. It is this point of placement – right at the juncture where membranes begin protruding into the cervix as it shortens and softens – that offers the strongest defense against cervical insufficiency.

The laparoscopic abdominal approach has been gaining popularity since it was first reported in 1998.4 Its traditional indication has been after a prior failed vaginal cerclage or when the cervix is too short to place a vaginal cerclage – as a result of a congenital anomaly or cervical conization, for instance.

Some of my patients have had one pregnancy loss in which cervical insufficiency was suspected and have sought laparoscopic abdominal cerclage without attempting a vaginal cerclage. Data to support this scenario are unavailable, but given the psychological trauma of pregnancy loss and the minimally invasive and low-risk nature of laparoscopic abdominal cerclage, I have been inclined to agree to preventive laparoscopic abdominal procedures without a trial of a vaginal cerclage. I believe this is a reasonable option.

The recently published MAVRIC trial included only abdominal cerclages performed using an open approach, but it provides good data for the scenario in which a vaginal cerclage has failed.

The rates of preterm birth at less than 32 weeks were significantly lower with abdominal cerclage than with low vaginal cerclage (McDonald technique) or high vaginal cerclage (Shirodkar technique) (8% vs. 33%, and 8% vs. 38%). No neonatal deaths occurred.

The analysis covered 111 women who conceived and had known pregnancy outcomes, out of 139 who were recruited and randomized. Cerclage placement occurred either between 10 and 16 weeks of gestation for vaginal cerclages and at 14 weeks for abdominal cerclages or before conception for those assigned to receive an abdominal or high vaginal cerclage.

Reviews of the literature done by our group1 and others have found equivalent outcomes between abdominal cerclages placed through laparotomy and through laparoscopy. The largest systematic review analyzed 31 studies involving 1,844 patients and found that neonatal survival rates were significantly greater in the laparoscopic group (97% vs. 90%), as were rates of deliveries after 34 weeks of gestation (83% vs. 76%).5

The better outcomes in the laparoscopic group may at least partly reflect improved laparoscopic surgeon techniques and improvements in neonatal care over time. At the minimum, we can conclude that neonatal outcomes are at least equivalent when an abdominal cerclage is placed through laparotomy or with a minimally invasive approach.

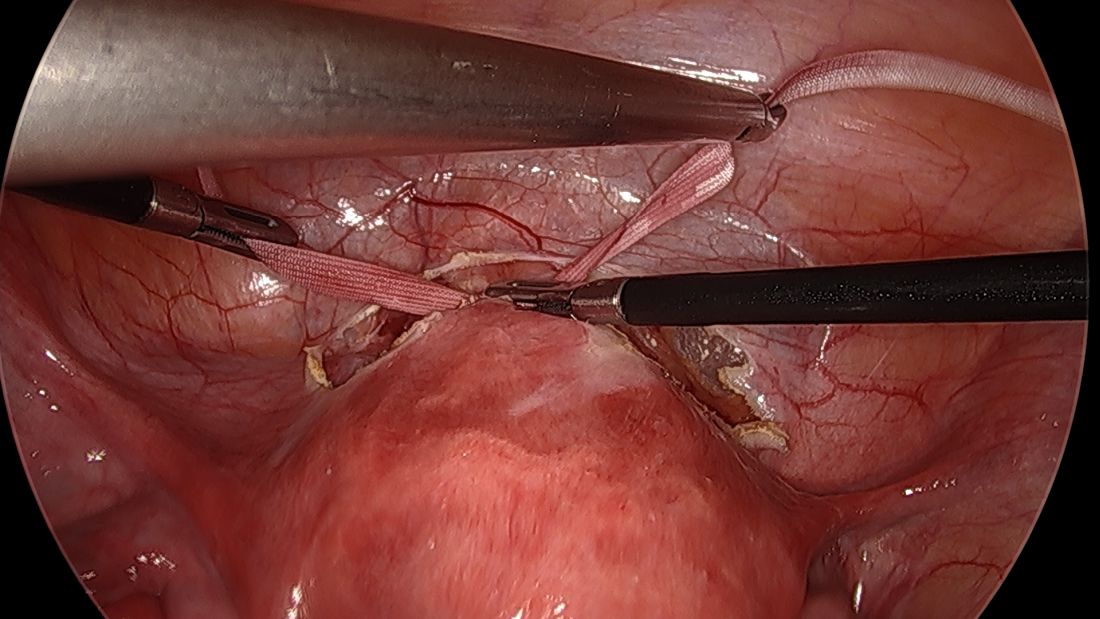

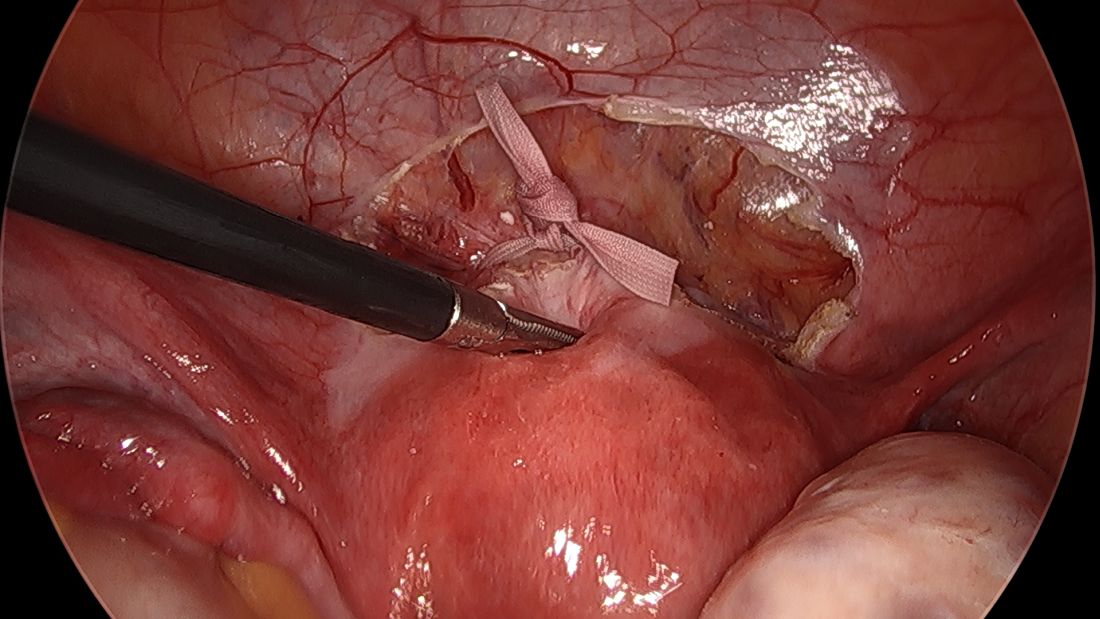

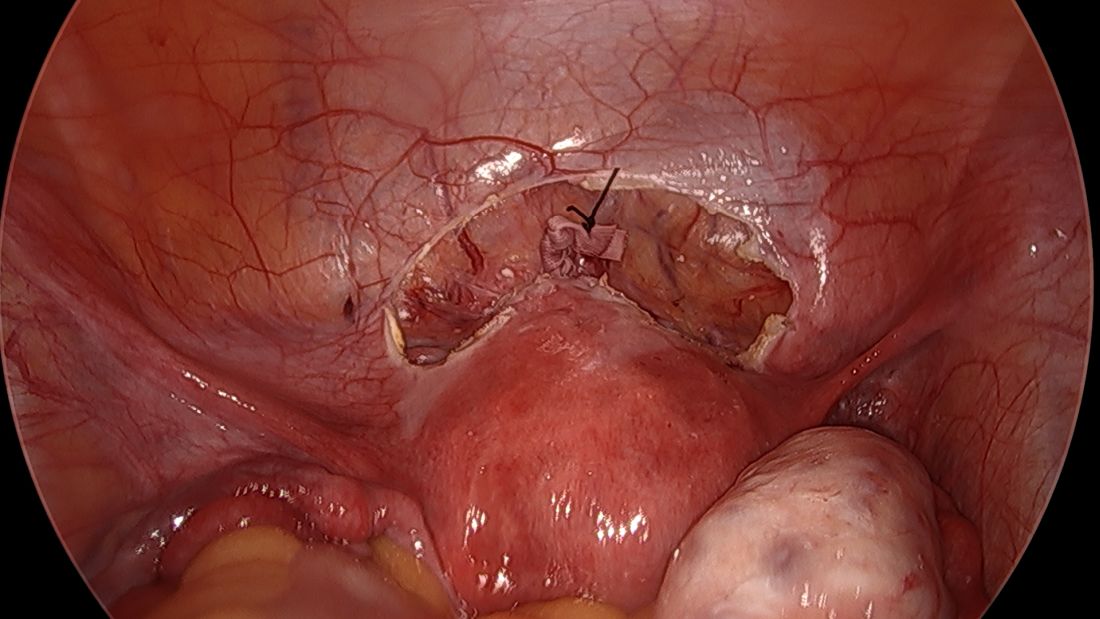

Our technique

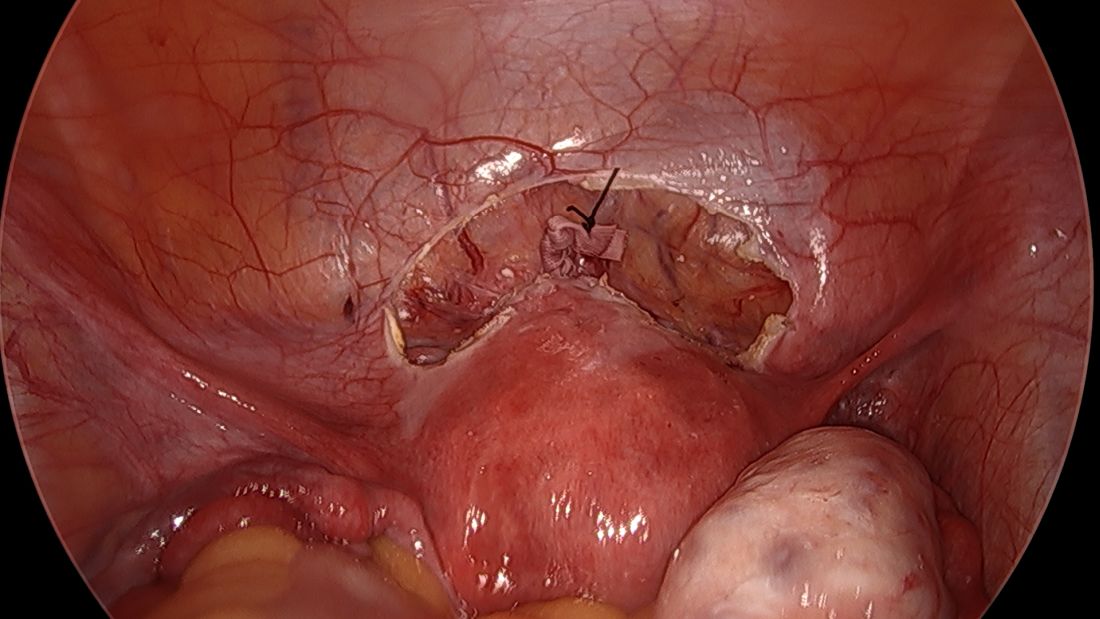

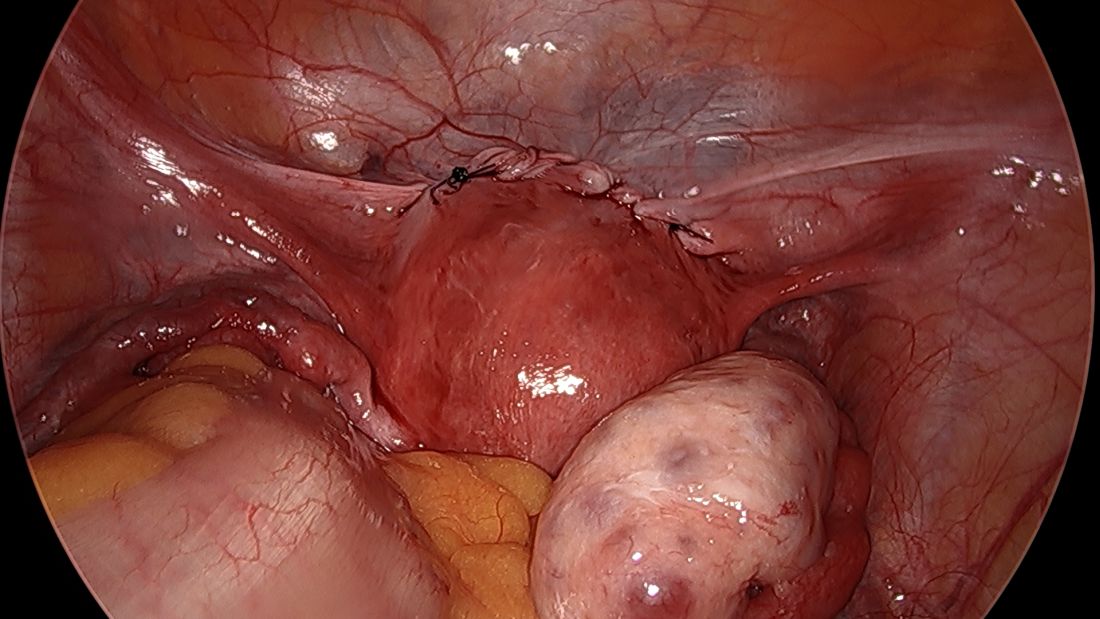

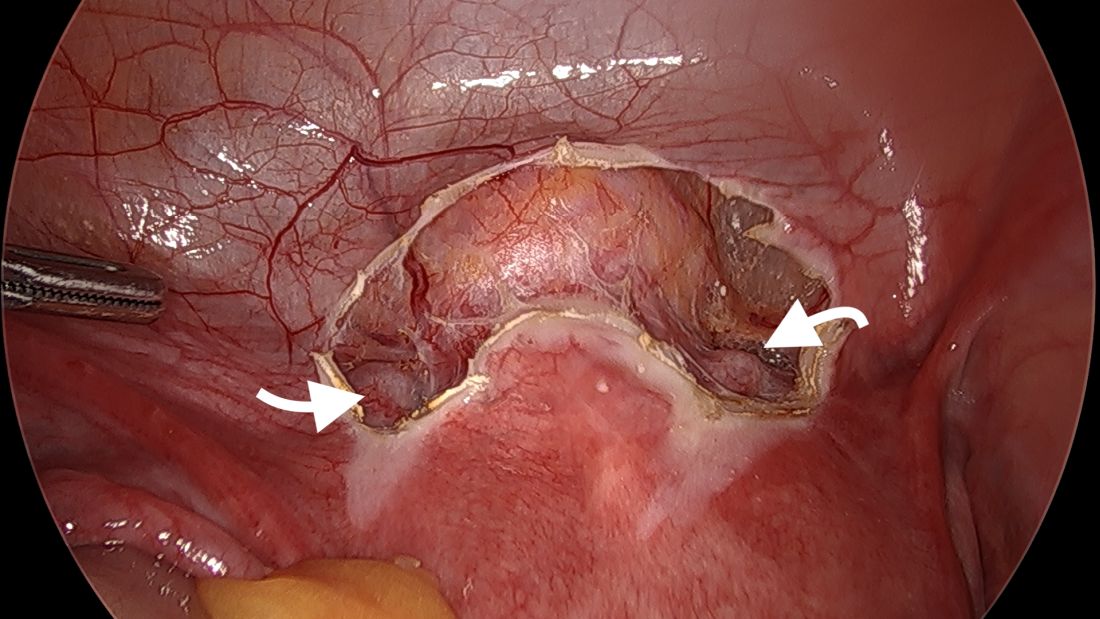

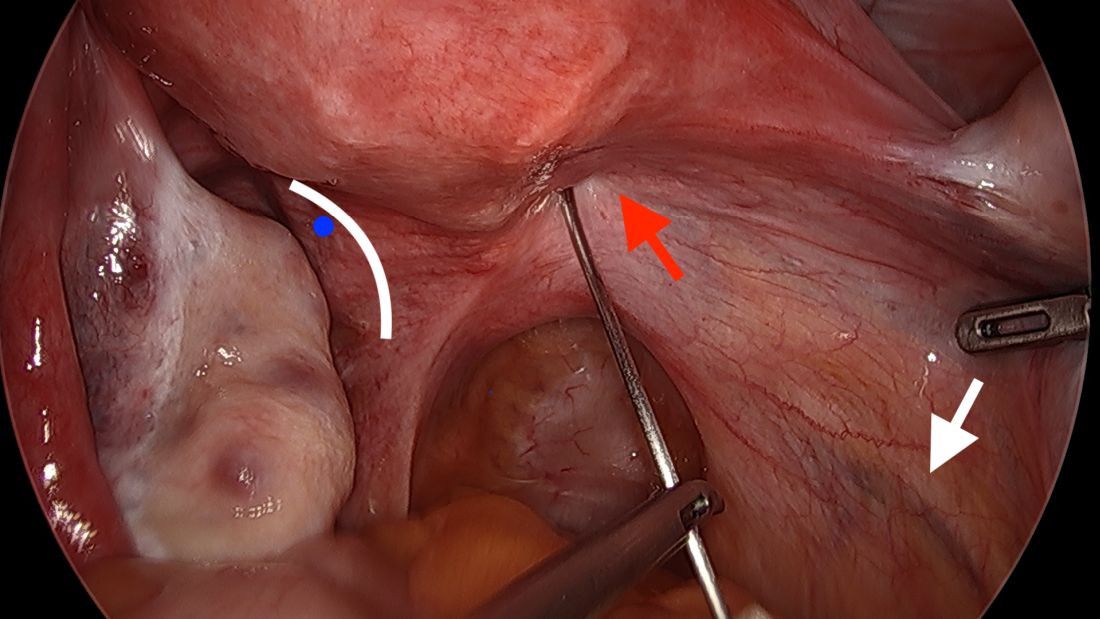

Laparoscopic cerclages are much more easily placed – and with less risk of surgical complications or blood loss – in patients who are not pregnant. Postconception cerclage placement also carries a unique, small risk of fetal loss (estimated to occur in 1.2% of laparoscopic cases and 3% of open cases). 1 We therefore prefer to perform the procedure before pregnancy, though we do place abdominal cerclages in early pregnancy as well. (Approximately 10% of the 137 patients in our analysis were pregnant at the time of cerclage placement. 1 )

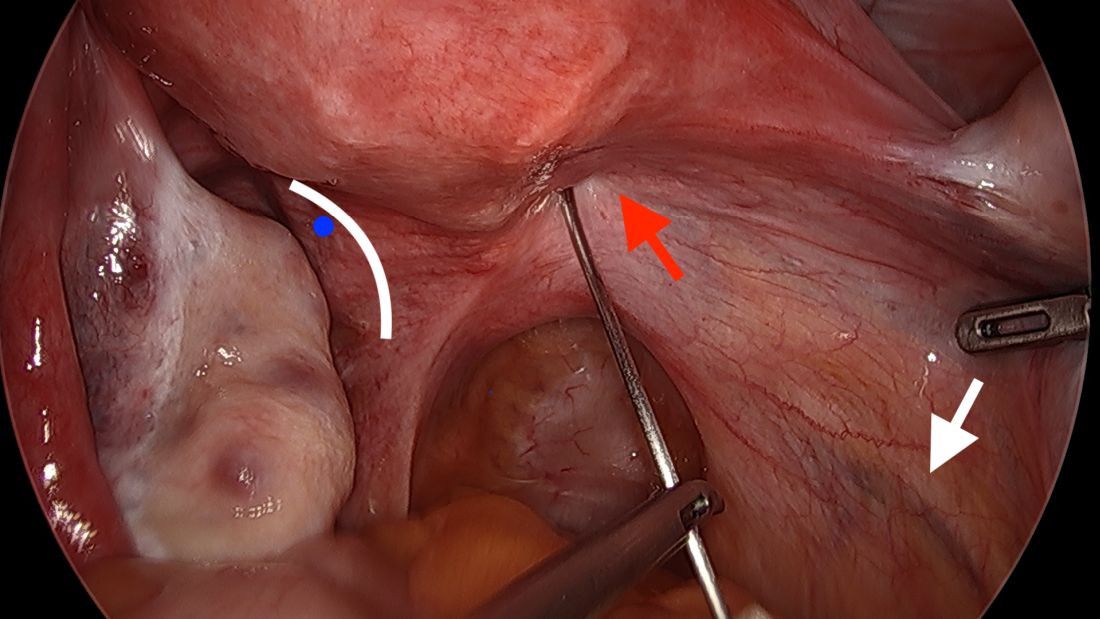

The procedure, described here for the nonpregnant patient, typically requires 3-4 ports. My preference is to use a 10-mm scope at the umbilicus, two 5-mm ipsilateral ports, and an additional 5-mm port for my assistant. We generally use a uterine manipulator to help with dissection and facilitate the correct angulation of the suture needle.

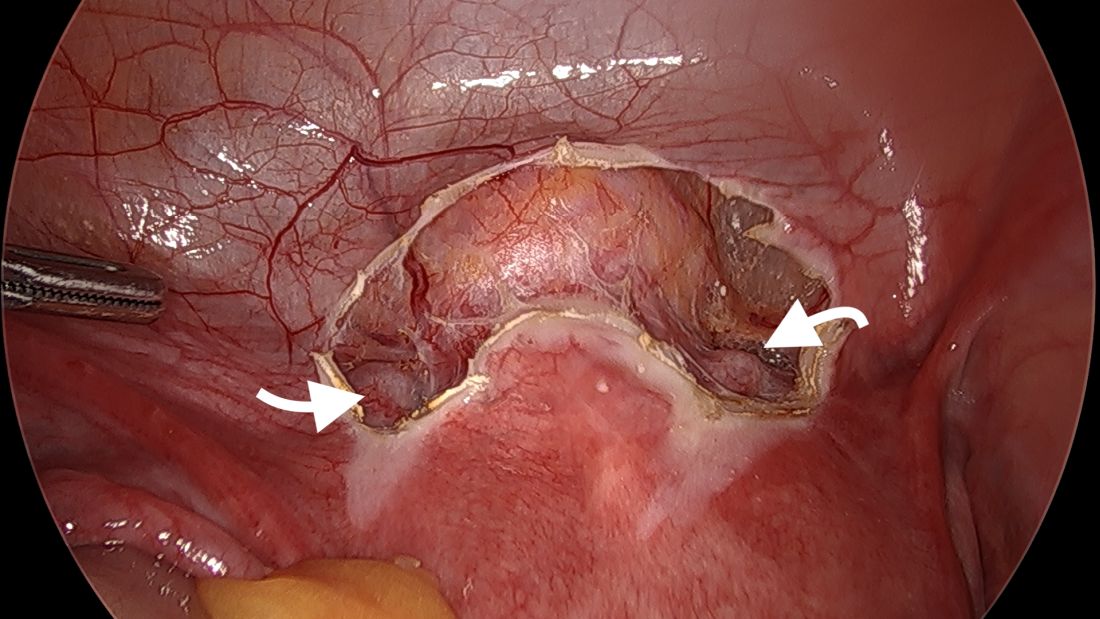

We start by opening the vesicouterine peritoneum to dissect the uterine arteries anteriorly and to move the bladder slightly caudad. It is not a significant dissection.

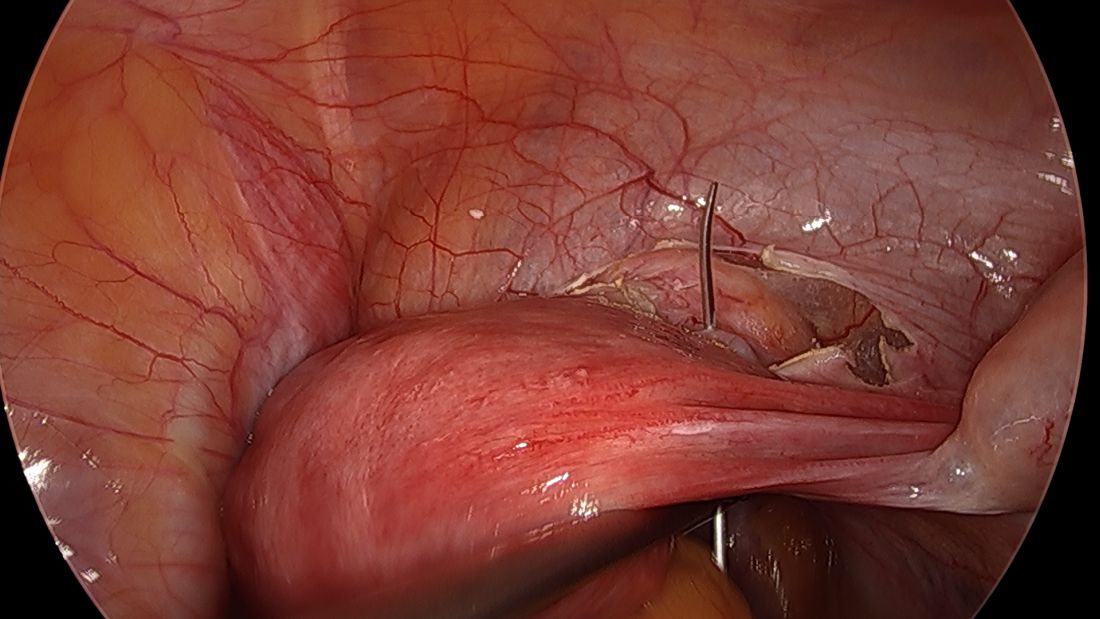

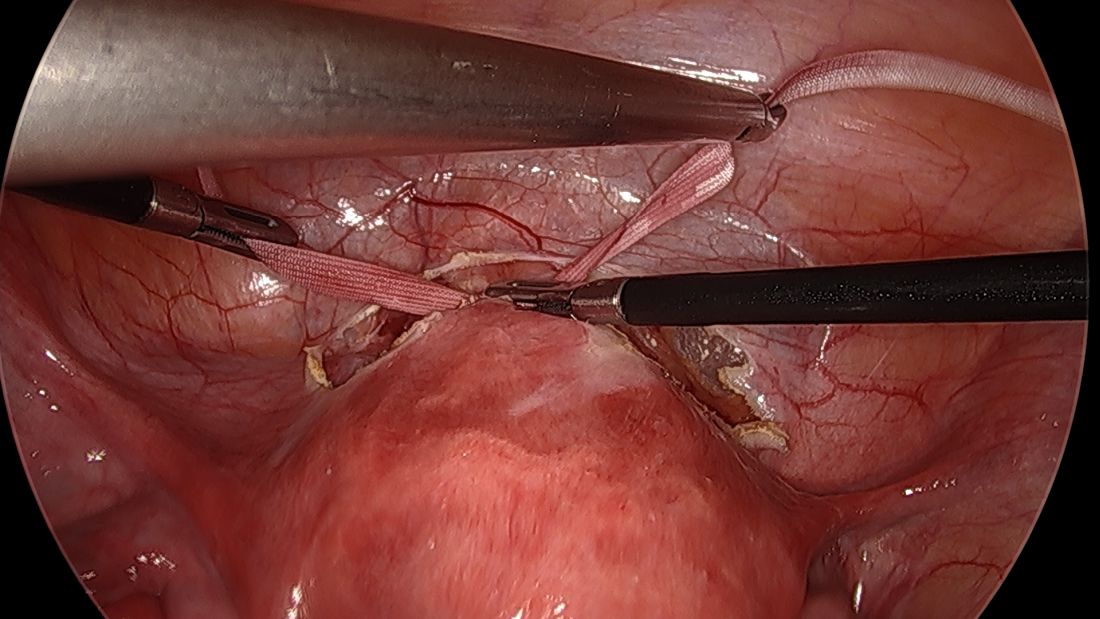

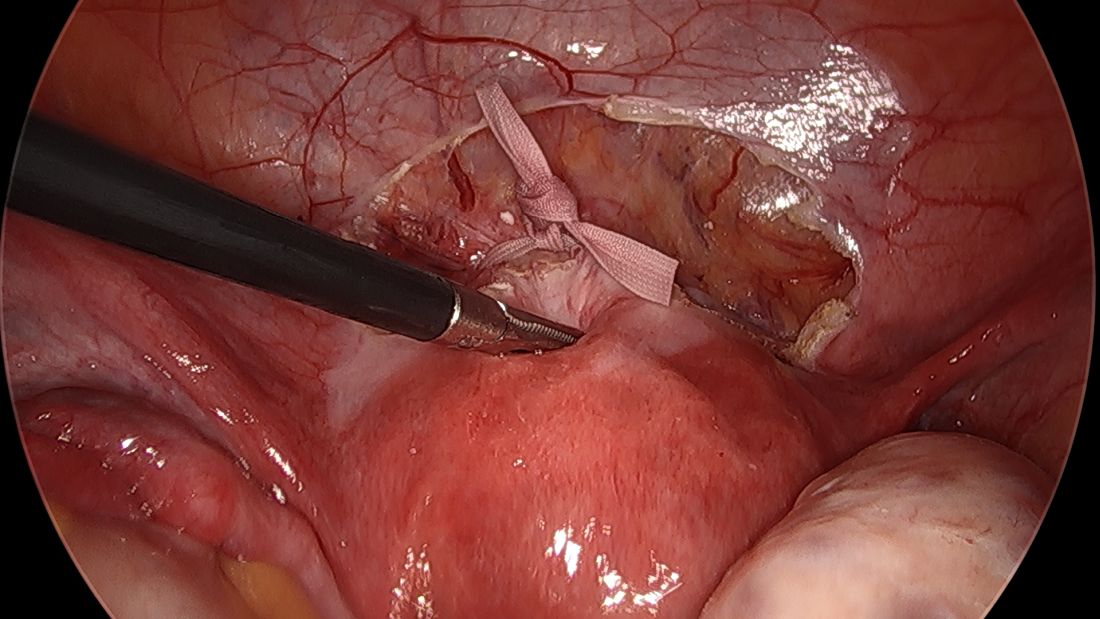

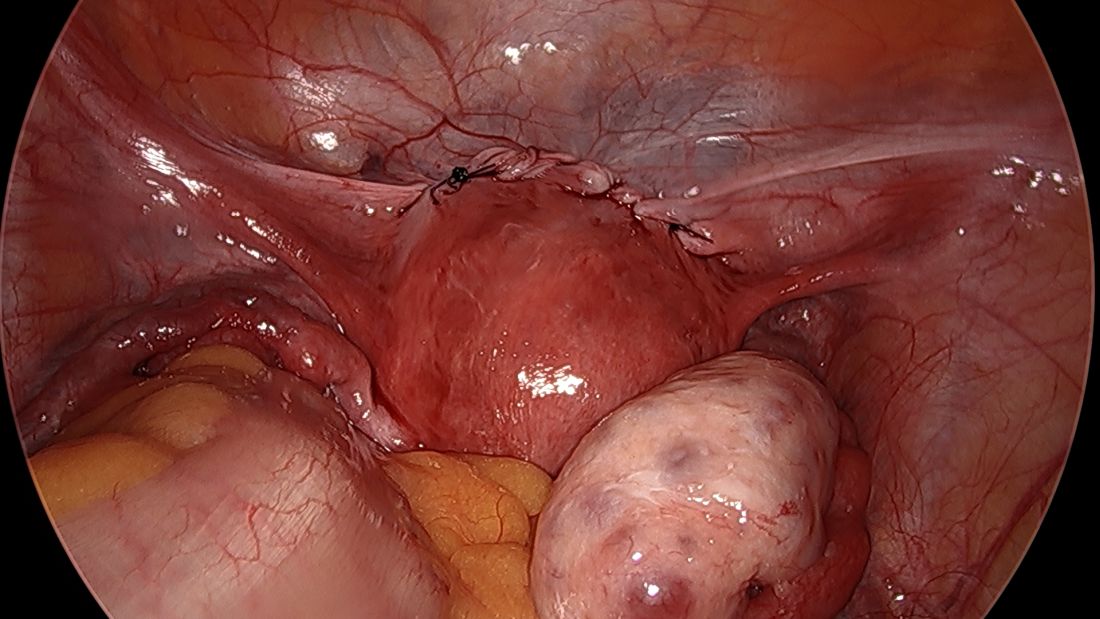

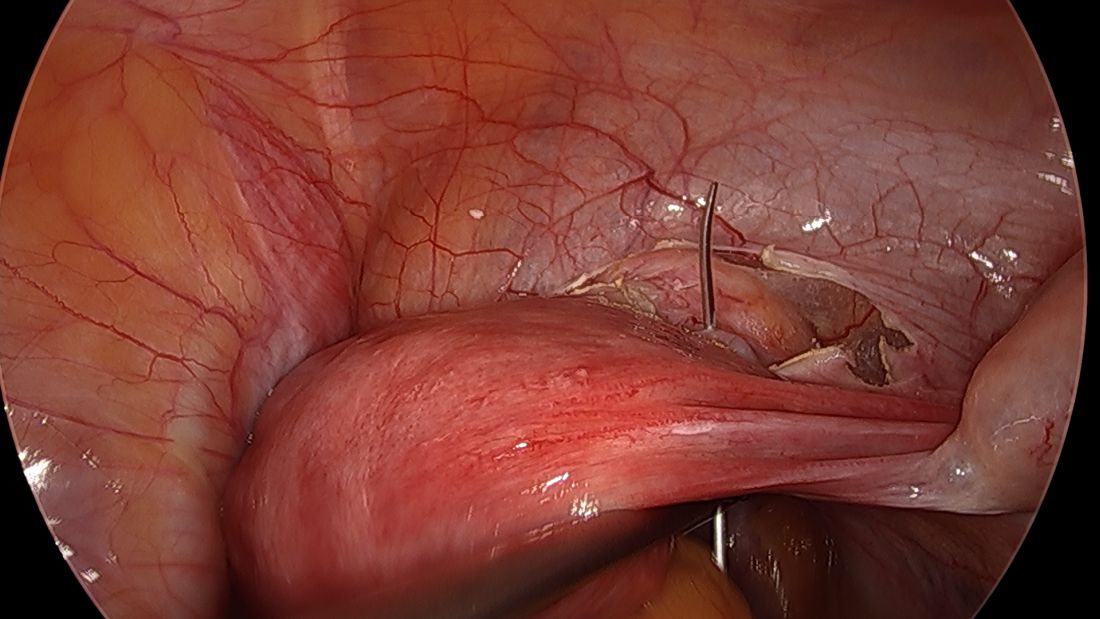

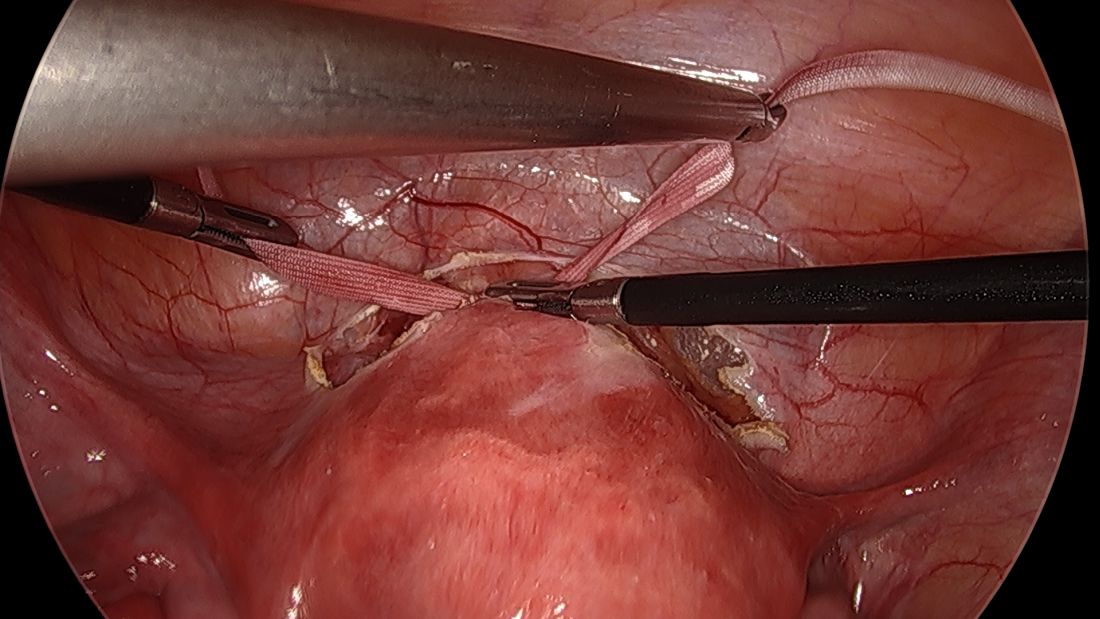

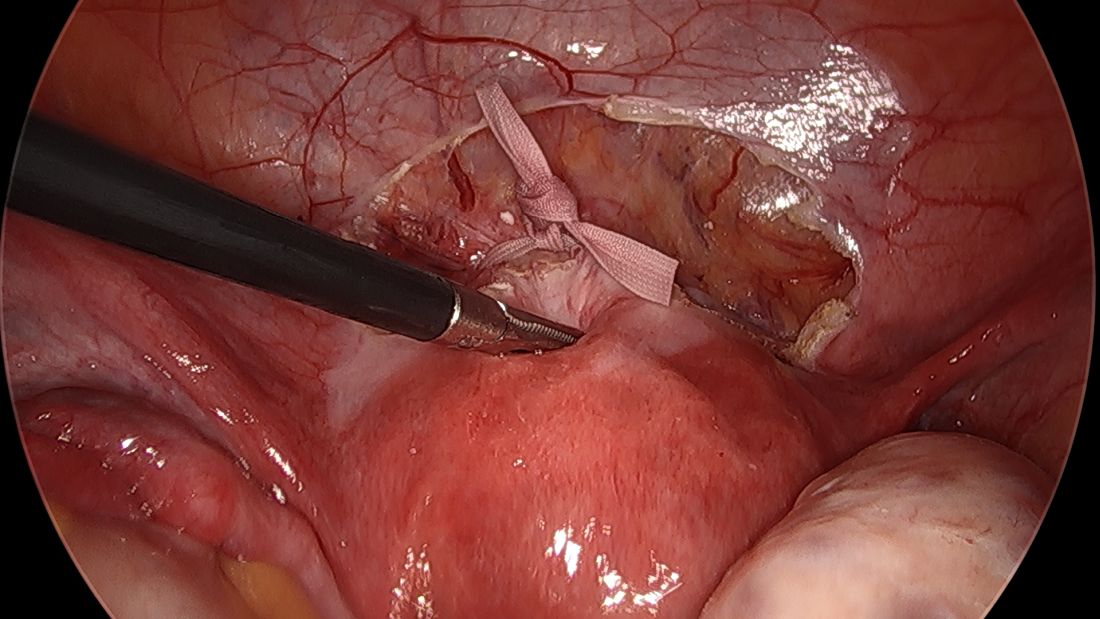

For suturing, we use 5-mm Mersilene polyester tape with blunt-tip needles – the same tape that is commonly used for vaginal cerclages. The needles (which probably are unnecessarily long for laparoscopic cerclages) are straightened out prior to insertion with robust needle holders.

The posterior broad ligament is not opened prior to insertion of the needle, as opening the broad ligament risks possible vessel injury and adds complexity.

Direct insertion of the needle simplifies the procedure and has not led to any complications thus far.

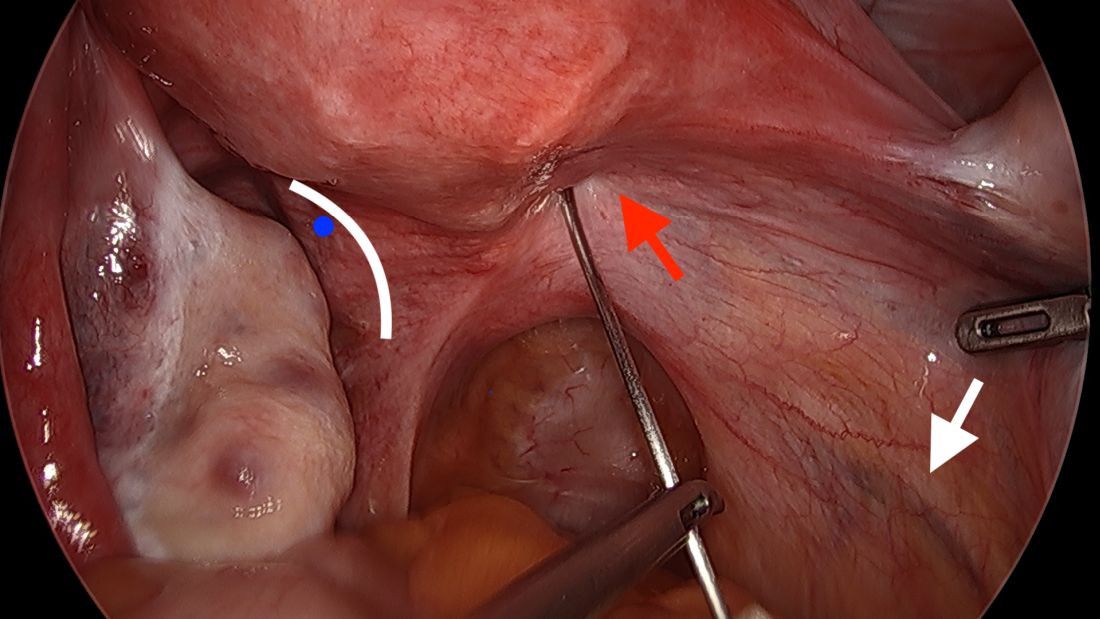

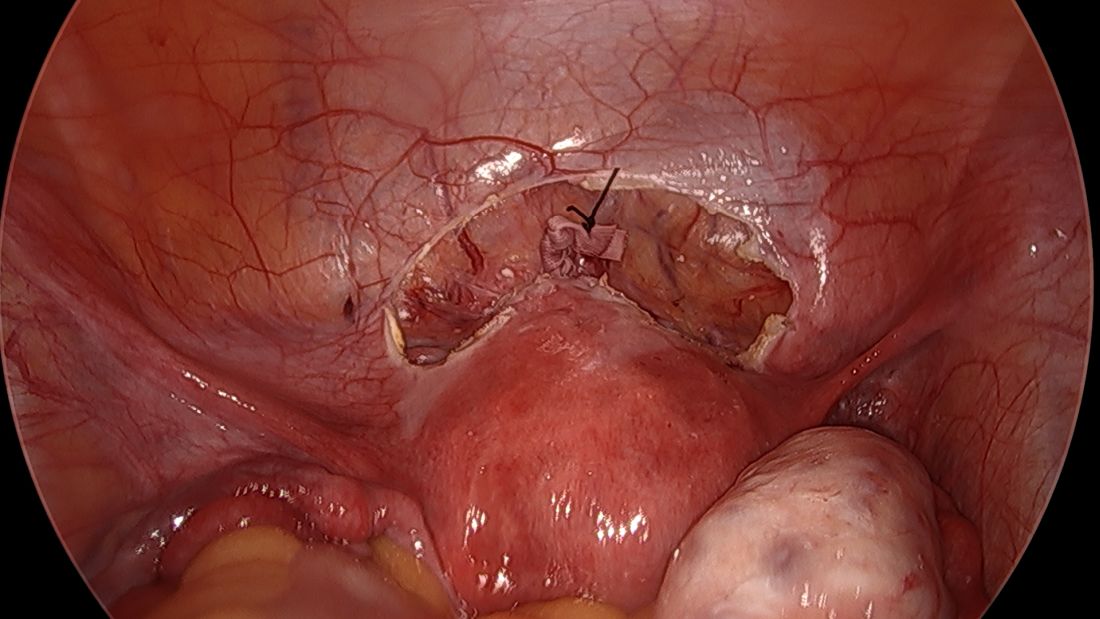

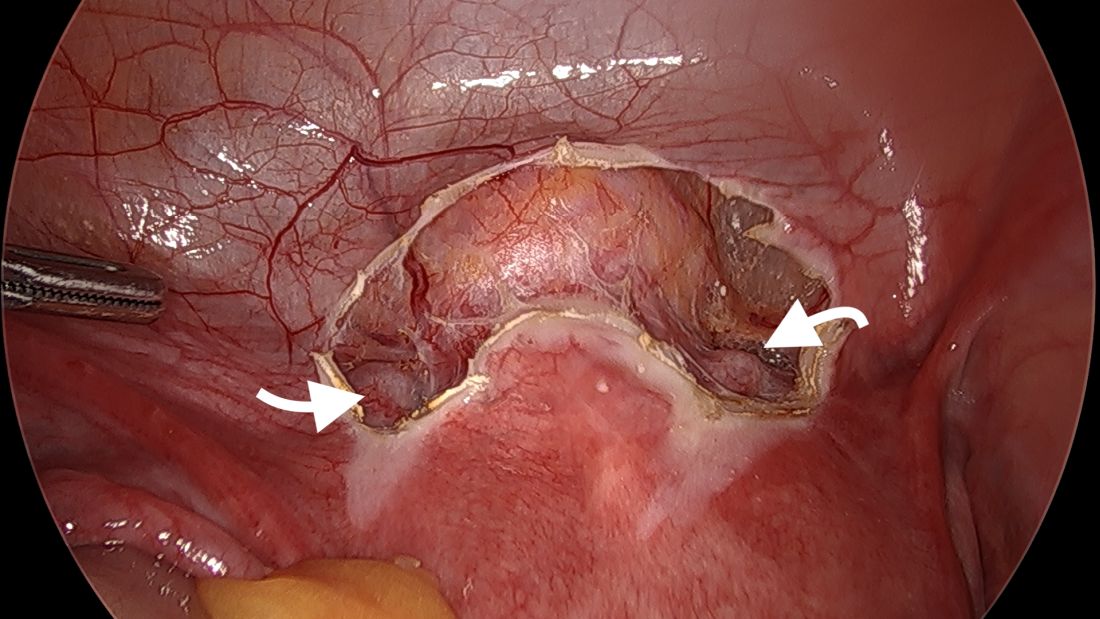

We prefer to insert the suture posteriorly at the level of the internal os just above the insertion of the uterosacral ligaments. It is helpful to view the uterus and cervix as an hourglass, with the level of the internal os is at the narrowest point of the hourglass.

The suture is passed carefully between the uterine vessels and the cervical stroma. The uterine artery should be lateral to placement of the needle, and the uterosacral ligament should be below. The surgeon should see a pulsation of the uterine artery. The use of blunt needles is advantageous because, especially when newer to the procedure, the surgeon can place the needle in slightly more medial than may be deemed necessary so as to avert the uterine vessels, then adjust placement slightly more laterally if resistance is met.