User login

CAG Clinical Practice Guideline: Vaccination in patients with IBD

The Canadian Association of Gastroenterology (CAG) has published a two-part clinical practice guideline for immunizing patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) that covers both live and inactivated vaccines across pediatric and adult patients.

The guideline, which has been endorsed by the American Gastroenterological Association, is composed of recommendations drawn from a broader body of data than prior publications on the same topic, according to Eric I. Benchimol, MD, PhD, of the University of Ottawa and the University of Toronto, and colleagues.

“Previous guidelines on immunizations of patients with IBD considered only the limited available evidence of vaccine safety and effectiveness in IBD populations, and failed to consider the ample evidence available in the general population or in other immune-mediated inflammatory diseases when assessing the certainty of evidence or developing their recommendations,” they wrote in Gastroenterology.

Part 1: Live vaccine recommendations

The first part of the guideline includes seven recommendations for use of live vaccines in patients with IBD.

In this area, decision-making is largely dependent upon use of immunosuppressive therapy, which the investigators defined as “corticosteroids, thiopurines, biologics, small molecules such as JAK [Janus kinase] inhibitors, and combinations thereof,” with the caveat that “there is no standard definition of immunosuppression,” and “the degree to which immunosuppressive therapy causes clinically significant immunosuppression generally is dose related and varies by drug.”

Before offering specific recommendations, Dr. Benchimol and colleagues provided three general principles to abide by: 1. Clinicians should review each patient’s history of immunization and vaccine-preventable diseases at diagnosis and on a routine basis; 2. Appropriate vaccinations should ideally be given prior to starting immunosuppressive therapy; and 3. Immunosuppressive therapy (when urgently needed) should not be delayed so that immunizations can be given in advance.

“[Delaying therapy] could lead to more anticipated harms than benefits, due to the risk of progression of the inflammatory activity and resulting complications,” the investigators wrote.

Specific recommendations in the guideline address measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR); and varicella. Both vaccines are recommended for susceptible pediatric and adult patients not taking immunosuppressive therapy. In contrast, neither vaccine is recommended for immunosuppressed patients of any age. Certainty of evidence ranged from very low to moderate.

Concerning vaccination within the first 6 months of life for infants born of mothers taking biologics, the expert panel did not reach a consensus.

“[T]he group was unable to recommend for or against their routine use because the desirable and undesirable effects were closely balanced and the evidence on safety outcomes was insufficient to justify a recommendation,” wrote Dr. Benchimol and colleagues. “Health care providers should be cautious with the administration of live vaccines in the first year of life in the infants of mothers using biologics. These infants should be evaluated by clinicians with expertise in the impact of exposure to monoclonal antibody biologics in utero.”

Part 2: Inactivated vaccine recommendations

The second part of the guideline, by lead author Jennifer L. Jones, MD, of Dalhousie University, Queen Elizabeth II Health Sciences Center, Halifax, N.S., and colleagues, provides 15 recommendations for giving inactivated vaccines to patients with IBD.

The panel considered eight vaccines: Haemophilus influenzae type B (Hib); herpes zoster (HZ); hepatitis B; influenza; Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcal vaccine); Neisseria meningitidis (meningococcal vaccine); human papillomavirus (HPV); and diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis.

Generally, the above vaccines are recommended on an age-appropriate basis, regardless of immunosuppression status, albeit with varying levels of confidence. For example, the Hib vaccine is strongly recommended for pediatric patients 5 years and younger, whereas the same recommendation for older children and adults is conditional.

For several patient populations and vaccines, the guideline panel did not reach a consensus, including use of double-dose hepatitis B vaccine for immunosuppressed adults, timing seasonal flu shots with dosing of biologics, use of pneumococcal vaccines in nonimmunosuppressed patents without a risk factor for pneumococcal disease, use of meningococcal vaccines in adults not at risk for invasive meningococcal disease, and use of HPV vaccine in patients aged 27-45 years.

While immunosuppressive therapy is not a contraindication for giving inactivated vaccines, Dr. Jones and colleagues noted that immunosuppression may hinder vaccine responses.

“Given that patients with IBD on immunosuppressive therapy may have lower immune response to vaccine, further research will be needed to assess the safety and effectiveness of high-dose vs. standard-dose vaccination strategy,” they wrote, also noting that more work is needed to determine if accelerated vaccinations strategies may be feasible prior to initiation of immunosuppressive therapy.

Because of a lack of evidence, the guideline panel did not issue IBD-specific recommendations for vaccines against SARS-CoV-2; however, Dr. Jones and colleagues suggested that clinicians reference a CAG publication on the subject published earlier this year.

The guideline was supported by grants to the Canadian Association of Gastroenterology from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research’s Institute of Nutrition, Metabolism and Diabetes; and CANImmunize. Dr. Benchimol disclosed additional relationships with the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Crohn’s and Colitis Canada; and the Canadian Child Health Clinician Scientist Program.

The Canadian Association of Gastroenterology (CAG) has published a two-part clinical practice guideline for immunizing patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) that covers both live and inactivated vaccines across pediatric and adult patients.

The guideline, which has been endorsed by the American Gastroenterological Association, is composed of recommendations drawn from a broader body of data than prior publications on the same topic, according to Eric I. Benchimol, MD, PhD, of the University of Ottawa and the University of Toronto, and colleagues.

“Previous guidelines on immunizations of patients with IBD considered only the limited available evidence of vaccine safety and effectiveness in IBD populations, and failed to consider the ample evidence available in the general population or in other immune-mediated inflammatory diseases when assessing the certainty of evidence or developing their recommendations,” they wrote in Gastroenterology.

Part 1: Live vaccine recommendations

The first part of the guideline includes seven recommendations for use of live vaccines in patients with IBD.

In this area, decision-making is largely dependent upon use of immunosuppressive therapy, which the investigators defined as “corticosteroids, thiopurines, biologics, small molecules such as JAK [Janus kinase] inhibitors, and combinations thereof,” with the caveat that “there is no standard definition of immunosuppression,” and “the degree to which immunosuppressive therapy causes clinically significant immunosuppression generally is dose related and varies by drug.”

Before offering specific recommendations, Dr. Benchimol and colleagues provided three general principles to abide by: 1. Clinicians should review each patient’s history of immunization and vaccine-preventable diseases at diagnosis and on a routine basis; 2. Appropriate vaccinations should ideally be given prior to starting immunosuppressive therapy; and 3. Immunosuppressive therapy (when urgently needed) should not be delayed so that immunizations can be given in advance.

“[Delaying therapy] could lead to more anticipated harms than benefits, due to the risk of progression of the inflammatory activity and resulting complications,” the investigators wrote.

Specific recommendations in the guideline address measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR); and varicella. Both vaccines are recommended for susceptible pediatric and adult patients not taking immunosuppressive therapy. In contrast, neither vaccine is recommended for immunosuppressed patients of any age. Certainty of evidence ranged from very low to moderate.

Concerning vaccination within the first 6 months of life for infants born of mothers taking biologics, the expert panel did not reach a consensus.

“[T]he group was unable to recommend for or against their routine use because the desirable and undesirable effects were closely balanced and the evidence on safety outcomes was insufficient to justify a recommendation,” wrote Dr. Benchimol and colleagues. “Health care providers should be cautious with the administration of live vaccines in the first year of life in the infants of mothers using biologics. These infants should be evaluated by clinicians with expertise in the impact of exposure to monoclonal antibody biologics in utero.”

Part 2: Inactivated vaccine recommendations

The second part of the guideline, by lead author Jennifer L. Jones, MD, of Dalhousie University, Queen Elizabeth II Health Sciences Center, Halifax, N.S., and colleagues, provides 15 recommendations for giving inactivated vaccines to patients with IBD.

The panel considered eight vaccines: Haemophilus influenzae type B (Hib); herpes zoster (HZ); hepatitis B; influenza; Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcal vaccine); Neisseria meningitidis (meningococcal vaccine); human papillomavirus (HPV); and diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis.

Generally, the above vaccines are recommended on an age-appropriate basis, regardless of immunosuppression status, albeit with varying levels of confidence. For example, the Hib vaccine is strongly recommended for pediatric patients 5 years and younger, whereas the same recommendation for older children and adults is conditional.

For several patient populations and vaccines, the guideline panel did not reach a consensus, including use of double-dose hepatitis B vaccine for immunosuppressed adults, timing seasonal flu shots with dosing of biologics, use of pneumococcal vaccines in nonimmunosuppressed patents without a risk factor for pneumococcal disease, use of meningococcal vaccines in adults not at risk for invasive meningococcal disease, and use of HPV vaccine in patients aged 27-45 years.

While immunosuppressive therapy is not a contraindication for giving inactivated vaccines, Dr. Jones and colleagues noted that immunosuppression may hinder vaccine responses.

“Given that patients with IBD on immunosuppressive therapy may have lower immune response to vaccine, further research will be needed to assess the safety and effectiveness of high-dose vs. standard-dose vaccination strategy,” they wrote, also noting that more work is needed to determine if accelerated vaccinations strategies may be feasible prior to initiation of immunosuppressive therapy.

Because of a lack of evidence, the guideline panel did not issue IBD-specific recommendations for vaccines against SARS-CoV-2; however, Dr. Jones and colleagues suggested that clinicians reference a CAG publication on the subject published earlier this year.

The guideline was supported by grants to the Canadian Association of Gastroenterology from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research’s Institute of Nutrition, Metabolism and Diabetes; and CANImmunize. Dr. Benchimol disclosed additional relationships with the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Crohn’s and Colitis Canada; and the Canadian Child Health Clinician Scientist Program.

The Canadian Association of Gastroenterology (CAG) has published a two-part clinical practice guideline for immunizing patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) that covers both live and inactivated vaccines across pediatric and adult patients.

The guideline, which has been endorsed by the American Gastroenterological Association, is composed of recommendations drawn from a broader body of data than prior publications on the same topic, according to Eric I. Benchimol, MD, PhD, of the University of Ottawa and the University of Toronto, and colleagues.

“Previous guidelines on immunizations of patients with IBD considered only the limited available evidence of vaccine safety and effectiveness in IBD populations, and failed to consider the ample evidence available in the general population or in other immune-mediated inflammatory diseases when assessing the certainty of evidence or developing their recommendations,” they wrote in Gastroenterology.

Part 1: Live vaccine recommendations

The first part of the guideline includes seven recommendations for use of live vaccines in patients with IBD.

In this area, decision-making is largely dependent upon use of immunosuppressive therapy, which the investigators defined as “corticosteroids, thiopurines, biologics, small molecules such as JAK [Janus kinase] inhibitors, and combinations thereof,” with the caveat that “there is no standard definition of immunosuppression,” and “the degree to which immunosuppressive therapy causes clinically significant immunosuppression generally is dose related and varies by drug.”

Before offering specific recommendations, Dr. Benchimol and colleagues provided three general principles to abide by: 1. Clinicians should review each patient’s history of immunization and vaccine-preventable diseases at diagnosis and on a routine basis; 2. Appropriate vaccinations should ideally be given prior to starting immunosuppressive therapy; and 3. Immunosuppressive therapy (when urgently needed) should not be delayed so that immunizations can be given in advance.

“[Delaying therapy] could lead to more anticipated harms than benefits, due to the risk of progression of the inflammatory activity and resulting complications,” the investigators wrote.

Specific recommendations in the guideline address measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR); and varicella. Both vaccines are recommended for susceptible pediatric and adult patients not taking immunosuppressive therapy. In contrast, neither vaccine is recommended for immunosuppressed patients of any age. Certainty of evidence ranged from very low to moderate.

Concerning vaccination within the first 6 months of life for infants born of mothers taking biologics, the expert panel did not reach a consensus.

“[T]he group was unable to recommend for or against their routine use because the desirable and undesirable effects were closely balanced and the evidence on safety outcomes was insufficient to justify a recommendation,” wrote Dr. Benchimol and colleagues. “Health care providers should be cautious with the administration of live vaccines in the first year of life in the infants of mothers using biologics. These infants should be evaluated by clinicians with expertise in the impact of exposure to monoclonal antibody biologics in utero.”

Part 2: Inactivated vaccine recommendations

The second part of the guideline, by lead author Jennifer L. Jones, MD, of Dalhousie University, Queen Elizabeth II Health Sciences Center, Halifax, N.S., and colleagues, provides 15 recommendations for giving inactivated vaccines to patients with IBD.

The panel considered eight vaccines: Haemophilus influenzae type B (Hib); herpes zoster (HZ); hepatitis B; influenza; Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcal vaccine); Neisseria meningitidis (meningococcal vaccine); human papillomavirus (HPV); and diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis.

Generally, the above vaccines are recommended on an age-appropriate basis, regardless of immunosuppression status, albeit with varying levels of confidence. For example, the Hib vaccine is strongly recommended for pediatric patients 5 years and younger, whereas the same recommendation for older children and adults is conditional.

For several patient populations and vaccines, the guideline panel did not reach a consensus, including use of double-dose hepatitis B vaccine for immunosuppressed adults, timing seasonal flu shots with dosing of biologics, use of pneumococcal vaccines in nonimmunosuppressed patents without a risk factor for pneumococcal disease, use of meningococcal vaccines in adults not at risk for invasive meningococcal disease, and use of HPV vaccine in patients aged 27-45 years.

While immunosuppressive therapy is not a contraindication for giving inactivated vaccines, Dr. Jones and colleagues noted that immunosuppression may hinder vaccine responses.

“Given that patients with IBD on immunosuppressive therapy may have lower immune response to vaccine, further research will be needed to assess the safety and effectiveness of high-dose vs. standard-dose vaccination strategy,” they wrote, also noting that more work is needed to determine if accelerated vaccinations strategies may be feasible prior to initiation of immunosuppressive therapy.

Because of a lack of evidence, the guideline panel did not issue IBD-specific recommendations for vaccines against SARS-CoV-2; however, Dr. Jones and colleagues suggested that clinicians reference a CAG publication on the subject published earlier this year.

The guideline was supported by grants to the Canadian Association of Gastroenterology from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research’s Institute of Nutrition, Metabolism and Diabetes; and CANImmunize. Dr. Benchimol disclosed additional relationships with the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Crohn’s and Colitis Canada; and the Canadian Child Health Clinician Scientist Program.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Short-term approach is best for seizure prevention after intracerebral hemorrhage

(sICH), new research shows.

Investigators created a model that simulated common clinical scenarios to compare four antiseizure drug strategies – conservative, moderate, aggressive, and risk-guided. They used the 2HELPS2B score as a risk stratification tool to guide clinical decisions.

The investigators found that the short-term, early-seizure prophylaxis strategies “dominated” long-term therapy under most clinical scenarios, underscoring the importance of early discontinuation of antiseizure drug therapy.

“The main message here was that strategies that involved long-term antiseizure drug prescription (moderate and aggressive) fail to provide better outcomes in most clinical scenarios, when compared with strategies using short-term prophylaxis (conservative and risk-guided),” senior investigator Lidia M.V.R. Moura, MD, MPH, assistant professor of neurology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in an interview.

The study was published online July 26 in JAMA Neurology.

Common complication

“Acute asymptomatic seizures [early seizures ≤7 days after stroke] are a common complication of sICH,” the authors noted.

Potential safety concerns have prompted recommendations against the use of antiseizure medications for primary prophylaxis. However, approximately 40% of U.S. patients with sICH do receive prophylactic levetiracetam before seizure development. For these patients, the duration of prophylaxis varies widely.

“Because seizure risk is a key determinant of which patient groups might benefit most from different prophylaxis strategies, validated tools for predicting early ... and late ... seizure risks could aid physicians in treatment decisions. However, no clinical trials or prospective studies have evaluated the net benefit of various strategies after sICH,” the investigators noted.

“Our patients who were survivors of an intracerebral hemorrhage motivated us to conduct the study,” said Dr. Moura, who is also director of the MGH NeuroValue Laboratory. “Some would come to the clinic with a long list of medications; some of them were taking antiseizure drugs for many years, but they never had a documented seizure.” These patients did not know why they had been taking an antiseizure drug for so long.

“In these conversations, we noted so much variability in indications and variability in patient access to specialty care to make treatment decisions. We noted that the evidence behind our current guidelines on seizure management was limited,” she added.

Dr. Moura and colleagues were “committed to improve outcome for people with neurological conditions by leveraging research methods that can help guide providers and systems, especially when data from clinical trials is lacking,” so they “decided to compare different strategies head to head using available data and generate evidence that could be used in situations with many trade-offs in risks and benefits.”

To investigate, the researchers used a simulation model and decision analysis to compare four treatment strategies on the basis of type of therapy (primary vs. secondary prophylaxis), timing of event (early vs. late seizures), and duration of therapy (1-week [short-term] versus indefinite [long-term] therapy).

These four strategies were as follows:

- Conservative: short-term (7-day) secondary early-seizure prophylaxis with long-term therapy after late seizure

- Moderate: long-term secondary early-seizure prophylaxis or late-seizure therapy

- Aggressive: long-term primary prophylaxis

- Risk-guided: short-term secondary early-seizure prophylaxis among low-risk patients (2HELPS2b score, 0), short-term primary prophylaxis among patients at higher risk (2HELPS2B score ≥1), and long-term secondary therapy for late seizure

The decision tree’s outcome measure was the number of expected quality-adjusted life-years.

Primary prophylaxis was defined as “treatment initiated immediately on hospital admission.” Secondary prophylaxis was defined as “treatment started after a seizure” and was subdivided into secondary early-seizure prophylaxis, defined as treatment started after a seizure occurring in the first 7 days after the stroke, or secondary late-seizure therapy, defined as treatment started or restarted after a seizure occurring after the first poststroke week.

Incorporate early-risk stratification tool

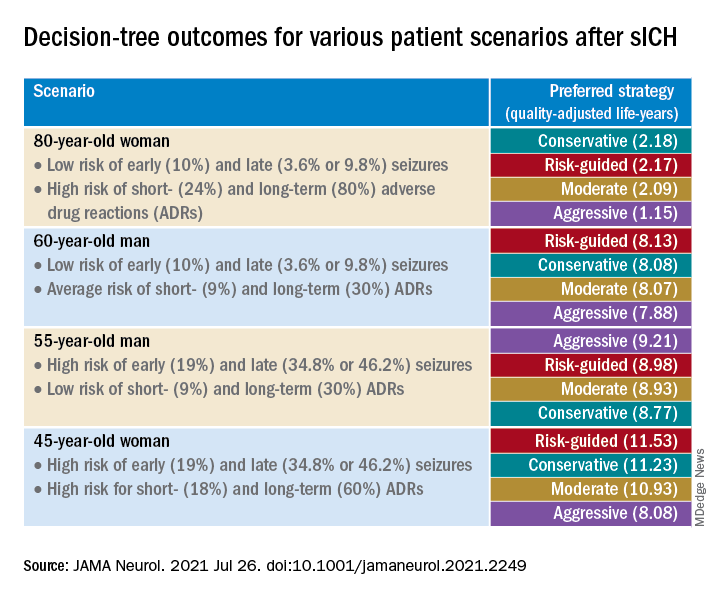

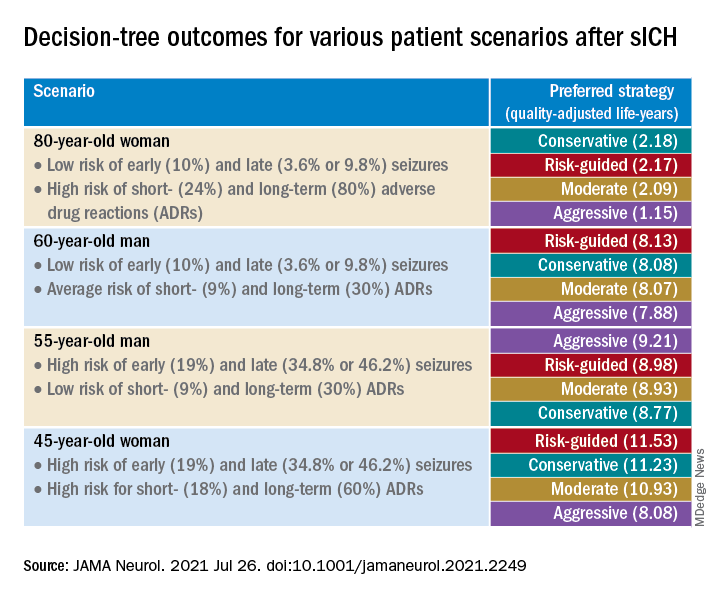

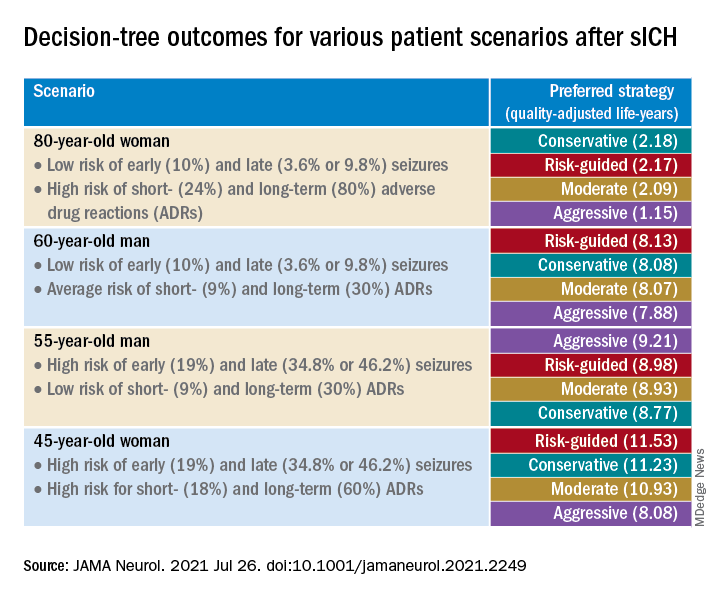

The researchers created four common clinical scenarios and then applied the decision-making model to each. They found that the preferred strategies differed, depending on the particular scenario.

Sensitivity analyses revealed that short-term strategies, including the conservative and risk-guided approaches, were preferable in most cases, with the risk-guided strategy performing comparably or even better than alternative strategies in most cases.

“Our findings suggest that a strategy that incorporates an early-seizure risk stratification tool [2HELPS2B] is favored over alternative strategies in most settings,” Dr. Moura commented.

“Current services with rapidly available EEG may consider using a 1-hour screening with EEG upon admission for all patients presenting with sICH to risk-stratify those patients, using the 2HELPS2B tool,” she continued. “If EEG is unavailable for early-seizure risk stratification, the conservative strategy seems most reasonable.”

‘Potential fallacies’

Commenting on the study, José Biller, MD, professor and chairman, department of neurology, Loyola University Chicago, Maywood, Ill., called it a “well-written and intriguing contribution [to the field], with potential fallacies.”

The bottom line, he said, is that only a randomized, long-term, prospective, multicenter, high-quality study with larger cohorts can prove or disprove the investigators’ assumption.

The authors acknowledged that a limitation of the study was the use of published literature to obtain data to estimate model parameters and that they did not account for other possible factors that might modify some parameter estimates.

Nevertheless, Dr. Moura said the findings have important practical implications because they “highlight the importance of discontinuing antiseizure medications that were started during a hospitalization for sICH in patients that only had an early seizure.”

It is “of great importance for all providers to reassess the indication of antiseizure medications. Those drugs are not free of risks and can impact the patient’s health and quality of life,” she added.

The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Moura reported receiving funding from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the NIH, and the Epilepsy Foundation of America (Epilepsy Learning Healthcare System) as the director of the data coordinating center. Dr. Biller is the editor-in-chief of the Journal of Stroke and Cerebrovascular Diseases and a section editor of UpToDate.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

(sICH), new research shows.

Investigators created a model that simulated common clinical scenarios to compare four antiseizure drug strategies – conservative, moderate, aggressive, and risk-guided. They used the 2HELPS2B score as a risk stratification tool to guide clinical decisions.

The investigators found that the short-term, early-seizure prophylaxis strategies “dominated” long-term therapy under most clinical scenarios, underscoring the importance of early discontinuation of antiseizure drug therapy.

“The main message here was that strategies that involved long-term antiseizure drug prescription (moderate and aggressive) fail to provide better outcomes in most clinical scenarios, when compared with strategies using short-term prophylaxis (conservative and risk-guided),” senior investigator Lidia M.V.R. Moura, MD, MPH, assistant professor of neurology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in an interview.

The study was published online July 26 in JAMA Neurology.

Common complication

“Acute asymptomatic seizures [early seizures ≤7 days after stroke] are a common complication of sICH,” the authors noted.

Potential safety concerns have prompted recommendations against the use of antiseizure medications for primary prophylaxis. However, approximately 40% of U.S. patients with sICH do receive prophylactic levetiracetam before seizure development. For these patients, the duration of prophylaxis varies widely.

“Because seizure risk is a key determinant of which patient groups might benefit most from different prophylaxis strategies, validated tools for predicting early ... and late ... seizure risks could aid physicians in treatment decisions. However, no clinical trials or prospective studies have evaluated the net benefit of various strategies after sICH,” the investigators noted.

“Our patients who were survivors of an intracerebral hemorrhage motivated us to conduct the study,” said Dr. Moura, who is also director of the MGH NeuroValue Laboratory. “Some would come to the clinic with a long list of medications; some of them were taking antiseizure drugs for many years, but they never had a documented seizure.” These patients did not know why they had been taking an antiseizure drug for so long.

“In these conversations, we noted so much variability in indications and variability in patient access to specialty care to make treatment decisions. We noted that the evidence behind our current guidelines on seizure management was limited,” she added.

Dr. Moura and colleagues were “committed to improve outcome for people with neurological conditions by leveraging research methods that can help guide providers and systems, especially when data from clinical trials is lacking,” so they “decided to compare different strategies head to head using available data and generate evidence that could be used in situations with many trade-offs in risks and benefits.”

To investigate, the researchers used a simulation model and decision analysis to compare four treatment strategies on the basis of type of therapy (primary vs. secondary prophylaxis), timing of event (early vs. late seizures), and duration of therapy (1-week [short-term] versus indefinite [long-term] therapy).

These four strategies were as follows:

- Conservative: short-term (7-day) secondary early-seizure prophylaxis with long-term therapy after late seizure

- Moderate: long-term secondary early-seizure prophylaxis or late-seizure therapy

- Aggressive: long-term primary prophylaxis

- Risk-guided: short-term secondary early-seizure prophylaxis among low-risk patients (2HELPS2b score, 0), short-term primary prophylaxis among patients at higher risk (2HELPS2B score ≥1), and long-term secondary therapy for late seizure

The decision tree’s outcome measure was the number of expected quality-adjusted life-years.

Primary prophylaxis was defined as “treatment initiated immediately on hospital admission.” Secondary prophylaxis was defined as “treatment started after a seizure” and was subdivided into secondary early-seizure prophylaxis, defined as treatment started after a seizure occurring in the first 7 days after the stroke, or secondary late-seizure therapy, defined as treatment started or restarted after a seizure occurring after the first poststroke week.

Incorporate early-risk stratification tool

The researchers created four common clinical scenarios and then applied the decision-making model to each. They found that the preferred strategies differed, depending on the particular scenario.

Sensitivity analyses revealed that short-term strategies, including the conservative and risk-guided approaches, were preferable in most cases, with the risk-guided strategy performing comparably or even better than alternative strategies in most cases.

“Our findings suggest that a strategy that incorporates an early-seizure risk stratification tool [2HELPS2B] is favored over alternative strategies in most settings,” Dr. Moura commented.

“Current services with rapidly available EEG may consider using a 1-hour screening with EEG upon admission for all patients presenting with sICH to risk-stratify those patients, using the 2HELPS2B tool,” she continued. “If EEG is unavailable for early-seizure risk stratification, the conservative strategy seems most reasonable.”

‘Potential fallacies’

Commenting on the study, José Biller, MD, professor and chairman, department of neurology, Loyola University Chicago, Maywood, Ill., called it a “well-written and intriguing contribution [to the field], with potential fallacies.”

The bottom line, he said, is that only a randomized, long-term, prospective, multicenter, high-quality study with larger cohorts can prove or disprove the investigators’ assumption.

The authors acknowledged that a limitation of the study was the use of published literature to obtain data to estimate model parameters and that they did not account for other possible factors that might modify some parameter estimates.

Nevertheless, Dr. Moura said the findings have important practical implications because they “highlight the importance of discontinuing antiseizure medications that were started during a hospitalization for sICH in patients that only had an early seizure.”

It is “of great importance for all providers to reassess the indication of antiseizure medications. Those drugs are not free of risks and can impact the patient’s health and quality of life,” she added.

The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Moura reported receiving funding from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the NIH, and the Epilepsy Foundation of America (Epilepsy Learning Healthcare System) as the director of the data coordinating center. Dr. Biller is the editor-in-chief of the Journal of Stroke and Cerebrovascular Diseases and a section editor of UpToDate.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

(sICH), new research shows.

Investigators created a model that simulated common clinical scenarios to compare four antiseizure drug strategies – conservative, moderate, aggressive, and risk-guided. They used the 2HELPS2B score as a risk stratification tool to guide clinical decisions.

The investigators found that the short-term, early-seizure prophylaxis strategies “dominated” long-term therapy under most clinical scenarios, underscoring the importance of early discontinuation of antiseizure drug therapy.

“The main message here was that strategies that involved long-term antiseizure drug prescription (moderate and aggressive) fail to provide better outcomes in most clinical scenarios, when compared with strategies using short-term prophylaxis (conservative and risk-guided),” senior investigator Lidia M.V.R. Moura, MD, MPH, assistant professor of neurology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in an interview.

The study was published online July 26 in JAMA Neurology.

Common complication

“Acute asymptomatic seizures [early seizures ≤7 days after stroke] are a common complication of sICH,” the authors noted.

Potential safety concerns have prompted recommendations against the use of antiseizure medications for primary prophylaxis. However, approximately 40% of U.S. patients with sICH do receive prophylactic levetiracetam before seizure development. For these patients, the duration of prophylaxis varies widely.

“Because seizure risk is a key determinant of which patient groups might benefit most from different prophylaxis strategies, validated tools for predicting early ... and late ... seizure risks could aid physicians in treatment decisions. However, no clinical trials or prospective studies have evaluated the net benefit of various strategies after sICH,” the investigators noted.

“Our patients who were survivors of an intracerebral hemorrhage motivated us to conduct the study,” said Dr. Moura, who is also director of the MGH NeuroValue Laboratory. “Some would come to the clinic with a long list of medications; some of them were taking antiseizure drugs for many years, but they never had a documented seizure.” These patients did not know why they had been taking an antiseizure drug for so long.

“In these conversations, we noted so much variability in indications and variability in patient access to specialty care to make treatment decisions. We noted that the evidence behind our current guidelines on seizure management was limited,” she added.

Dr. Moura and colleagues were “committed to improve outcome for people with neurological conditions by leveraging research methods that can help guide providers and systems, especially when data from clinical trials is lacking,” so they “decided to compare different strategies head to head using available data and generate evidence that could be used in situations with many trade-offs in risks and benefits.”

To investigate, the researchers used a simulation model and decision analysis to compare four treatment strategies on the basis of type of therapy (primary vs. secondary prophylaxis), timing of event (early vs. late seizures), and duration of therapy (1-week [short-term] versus indefinite [long-term] therapy).

These four strategies were as follows:

- Conservative: short-term (7-day) secondary early-seizure prophylaxis with long-term therapy after late seizure

- Moderate: long-term secondary early-seizure prophylaxis or late-seizure therapy

- Aggressive: long-term primary prophylaxis

- Risk-guided: short-term secondary early-seizure prophylaxis among low-risk patients (2HELPS2b score, 0), short-term primary prophylaxis among patients at higher risk (2HELPS2B score ≥1), and long-term secondary therapy for late seizure

The decision tree’s outcome measure was the number of expected quality-adjusted life-years.

Primary prophylaxis was defined as “treatment initiated immediately on hospital admission.” Secondary prophylaxis was defined as “treatment started after a seizure” and was subdivided into secondary early-seizure prophylaxis, defined as treatment started after a seizure occurring in the first 7 days after the stroke, or secondary late-seizure therapy, defined as treatment started or restarted after a seizure occurring after the first poststroke week.

Incorporate early-risk stratification tool

The researchers created four common clinical scenarios and then applied the decision-making model to each. They found that the preferred strategies differed, depending on the particular scenario.

Sensitivity analyses revealed that short-term strategies, including the conservative and risk-guided approaches, were preferable in most cases, with the risk-guided strategy performing comparably or even better than alternative strategies in most cases.

“Our findings suggest that a strategy that incorporates an early-seizure risk stratification tool [2HELPS2B] is favored over alternative strategies in most settings,” Dr. Moura commented.

“Current services with rapidly available EEG may consider using a 1-hour screening with EEG upon admission for all patients presenting with sICH to risk-stratify those patients, using the 2HELPS2B tool,” she continued. “If EEG is unavailable for early-seizure risk stratification, the conservative strategy seems most reasonable.”

‘Potential fallacies’

Commenting on the study, José Biller, MD, professor and chairman, department of neurology, Loyola University Chicago, Maywood, Ill., called it a “well-written and intriguing contribution [to the field], with potential fallacies.”

The bottom line, he said, is that only a randomized, long-term, prospective, multicenter, high-quality study with larger cohorts can prove or disprove the investigators’ assumption.

The authors acknowledged that a limitation of the study was the use of published literature to obtain data to estimate model parameters and that they did not account for other possible factors that might modify some parameter estimates.

Nevertheless, Dr. Moura said the findings have important practical implications because they “highlight the importance of discontinuing antiseizure medications that were started during a hospitalization for sICH in patients that only had an early seizure.”

It is “of great importance for all providers to reassess the indication of antiseizure medications. Those drugs are not free of risks and can impact the patient’s health and quality of life,” she added.

The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Moura reported receiving funding from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the NIH, and the Epilepsy Foundation of America (Epilepsy Learning Healthcare System) as the director of the data coordinating center. Dr. Biller is the editor-in-chief of the Journal of Stroke and Cerebrovascular Diseases and a section editor of UpToDate.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Major musculoskeletal surgery in children with medically complex conditions

A review of the International Committee’s guide

The International Committee on Perioperative Care for Children with Medical Complexity developed an online guide, “Deciding on and Preparing for Major Musculoskeletal Surgery in Children with Cerebral Palsy, Neurodevelopmental Disorders, and Other Medically Complex Conditions,” published on Dec. 20, 2020, detailing how to prepare pediatric patients with medical complexity prior to musculoskeletal surgery. The guide was developed from a dearth of information regarding optimal care practices for these patients.

The multidisciplinary committee included members from orthopedic surgery, general pediatrics, pediatric hospital medicine, anesthesiology, critical care medicine, pain medicine, physiotherapy, developmental and behavioral pediatrics, and families of children with cerebral palsy. Mirna Giordano, MD, FAAP, FHM, associate professor of pediatrics at Columbia University, New York, and International Committee member, helped develop these recommendations to “improve quality of care in the perioperative period for children with medical complexities and neurodisabilities all over the world.”

The guide meticulously details the steps required to successfully prepare for an operation and postoperative recovery. It includes an algorithm and comprehensive assessment plan that can be implemented to assess and optimize the child’s health and wellbeing prior to surgery. It encourages shared decision making and highlights the need for ongoing, open communication between providers, patients, and families to set goals and expectations, discuss potential complications, and describe outcomes and the recovery process.

The module elaborates on several key factors that must be evaluated and addressed long before surgery to ensure success. Baseline nutrition is critical and must be evaluated with body composition and anthropometric measurements. Respiratory health must be assessed with consideration of pulmonology consultation, specific testing, and ventilator or assistive-device optimization. Moreover, children with innate muscular weakness or restrictive lung disease should have baseline physiology evaluated in anticipation of potential postoperative complications, including atelectasis, hypoventilation, and pneumonia. Coexisting chronic medical conditions must also be optimized in anticipation of expected deviations from baseline.

In anticipation of peri- and postoperative care, the medical team should also be aware of details surrounding patients’ indwelling medical devices, such as cardiac implantable devices and tracheostomies. Particular attention should be paid to baclofen pumps, as malfunction or mistitration can lead to periprocedural hypotension or withdrawal.

Of paramount importance is understanding how the child appears and responds when in pain or discomfort, especially for a child with limited verbal communication. The module provides pain assessment tools, tailored to verbal and nonverbal patients in both the inpatient and outpatient settings. The module also shares guidance on establishing communication and goals with the family and within the care team on how the child appears when in distress and how he/she/they respond to pain medications. The pain plan should encompass both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic therapeutics. Furthermore, as pain and discomfort may present from multiple sources, not limited to the regions involved in the procedure, understanding how the child responds to urinary retention, constipation, dyspnea, and uncomfortable positions is important to care. Postoperative immobilization must also be addressed as it may lead to pressure injury, manifesting as behavioral changes.

The module also presents laboratory testing as part of the preoperative health assessment. It details the utility or lack thereof of several common practices and provides recommendations on components that should be part of each patient’s assessment. It also contains videos showcased from the Courage Parents Network on family and provider perceptions of spinal fusion.

Family and social assessments must not be neglected prior to surgery, as these areas may also affect surgical outcomes. The module shares several screening tools that care team members can use to screen for family and social issues. Challenges to discharge planning are also discussed, including how to approach transportation, medical equipment, and school transitions needs.

The module is available for review in OPEN Pediatrics (www.openpediatrics.org), an online community for pediatric health professionals who share peer-reviewed best practices. “Our aim is to disseminate the recommendations as widely as possible to bring about the maximum good to the most,” Dr. Giordano said. The International Committee on Perioperative Care for Children with Medical Complexity is planning further guides regarding perioperative care, particularly for intraoperative and postoperative considerations.

Dr. Tantoco is a med-peds hospitalist at Northwestern Memorial Hospital and Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, and instructor of medicine (hospital medicine) and pediatrics in Northwestern University, in Chicago. She is also a member of the SHM Pediatrics Special Interest Group Executive Committee. Dr. Bhasin is a med-peds hospitalist at Northwestern Memorial Hospital and Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital, and assistant professor of medicine (hospital medicine) and pediatrics in Northwestern University.

A review of the International Committee’s guide

A review of the International Committee’s guide

The International Committee on Perioperative Care for Children with Medical Complexity developed an online guide, “Deciding on and Preparing for Major Musculoskeletal Surgery in Children with Cerebral Palsy, Neurodevelopmental Disorders, and Other Medically Complex Conditions,” published on Dec. 20, 2020, detailing how to prepare pediatric patients with medical complexity prior to musculoskeletal surgery. The guide was developed from a dearth of information regarding optimal care practices for these patients.

The multidisciplinary committee included members from orthopedic surgery, general pediatrics, pediatric hospital medicine, anesthesiology, critical care medicine, pain medicine, physiotherapy, developmental and behavioral pediatrics, and families of children with cerebral palsy. Mirna Giordano, MD, FAAP, FHM, associate professor of pediatrics at Columbia University, New York, and International Committee member, helped develop these recommendations to “improve quality of care in the perioperative period for children with medical complexities and neurodisabilities all over the world.”

The guide meticulously details the steps required to successfully prepare for an operation and postoperative recovery. It includes an algorithm and comprehensive assessment plan that can be implemented to assess and optimize the child’s health and wellbeing prior to surgery. It encourages shared decision making and highlights the need for ongoing, open communication between providers, patients, and families to set goals and expectations, discuss potential complications, and describe outcomes and the recovery process.

The module elaborates on several key factors that must be evaluated and addressed long before surgery to ensure success. Baseline nutrition is critical and must be evaluated with body composition and anthropometric measurements. Respiratory health must be assessed with consideration of pulmonology consultation, specific testing, and ventilator or assistive-device optimization. Moreover, children with innate muscular weakness or restrictive lung disease should have baseline physiology evaluated in anticipation of potential postoperative complications, including atelectasis, hypoventilation, and pneumonia. Coexisting chronic medical conditions must also be optimized in anticipation of expected deviations from baseline.

In anticipation of peri- and postoperative care, the medical team should also be aware of details surrounding patients’ indwelling medical devices, such as cardiac implantable devices and tracheostomies. Particular attention should be paid to baclofen pumps, as malfunction or mistitration can lead to periprocedural hypotension or withdrawal.

Of paramount importance is understanding how the child appears and responds when in pain or discomfort, especially for a child with limited verbal communication. The module provides pain assessment tools, tailored to verbal and nonverbal patients in both the inpatient and outpatient settings. The module also shares guidance on establishing communication and goals with the family and within the care team on how the child appears when in distress and how he/she/they respond to pain medications. The pain plan should encompass both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic therapeutics. Furthermore, as pain and discomfort may present from multiple sources, not limited to the regions involved in the procedure, understanding how the child responds to urinary retention, constipation, dyspnea, and uncomfortable positions is important to care. Postoperative immobilization must also be addressed as it may lead to pressure injury, manifesting as behavioral changes.

The module also presents laboratory testing as part of the preoperative health assessment. It details the utility or lack thereof of several common practices and provides recommendations on components that should be part of each patient’s assessment. It also contains videos showcased from the Courage Parents Network on family and provider perceptions of spinal fusion.

Family and social assessments must not be neglected prior to surgery, as these areas may also affect surgical outcomes. The module shares several screening tools that care team members can use to screen for family and social issues. Challenges to discharge planning are also discussed, including how to approach transportation, medical equipment, and school transitions needs.

The module is available for review in OPEN Pediatrics (www.openpediatrics.org), an online community for pediatric health professionals who share peer-reviewed best practices. “Our aim is to disseminate the recommendations as widely as possible to bring about the maximum good to the most,” Dr. Giordano said. The International Committee on Perioperative Care for Children with Medical Complexity is planning further guides regarding perioperative care, particularly for intraoperative and postoperative considerations.

Dr. Tantoco is a med-peds hospitalist at Northwestern Memorial Hospital and Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, and instructor of medicine (hospital medicine) and pediatrics in Northwestern University, in Chicago. She is also a member of the SHM Pediatrics Special Interest Group Executive Committee. Dr. Bhasin is a med-peds hospitalist at Northwestern Memorial Hospital and Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital, and assistant professor of medicine (hospital medicine) and pediatrics in Northwestern University.

The International Committee on Perioperative Care for Children with Medical Complexity developed an online guide, “Deciding on and Preparing for Major Musculoskeletal Surgery in Children with Cerebral Palsy, Neurodevelopmental Disorders, and Other Medically Complex Conditions,” published on Dec. 20, 2020, detailing how to prepare pediatric patients with medical complexity prior to musculoskeletal surgery. The guide was developed from a dearth of information regarding optimal care practices for these patients.

The multidisciplinary committee included members from orthopedic surgery, general pediatrics, pediatric hospital medicine, anesthesiology, critical care medicine, pain medicine, physiotherapy, developmental and behavioral pediatrics, and families of children with cerebral palsy. Mirna Giordano, MD, FAAP, FHM, associate professor of pediatrics at Columbia University, New York, and International Committee member, helped develop these recommendations to “improve quality of care in the perioperative period for children with medical complexities and neurodisabilities all over the world.”

The guide meticulously details the steps required to successfully prepare for an operation and postoperative recovery. It includes an algorithm and comprehensive assessment plan that can be implemented to assess and optimize the child’s health and wellbeing prior to surgery. It encourages shared decision making and highlights the need for ongoing, open communication between providers, patients, and families to set goals and expectations, discuss potential complications, and describe outcomes and the recovery process.

The module elaborates on several key factors that must be evaluated and addressed long before surgery to ensure success. Baseline nutrition is critical and must be evaluated with body composition and anthropometric measurements. Respiratory health must be assessed with consideration of pulmonology consultation, specific testing, and ventilator or assistive-device optimization. Moreover, children with innate muscular weakness or restrictive lung disease should have baseline physiology evaluated in anticipation of potential postoperative complications, including atelectasis, hypoventilation, and pneumonia. Coexisting chronic medical conditions must also be optimized in anticipation of expected deviations from baseline.

In anticipation of peri- and postoperative care, the medical team should also be aware of details surrounding patients’ indwelling medical devices, such as cardiac implantable devices and tracheostomies. Particular attention should be paid to baclofen pumps, as malfunction or mistitration can lead to periprocedural hypotension or withdrawal.

Of paramount importance is understanding how the child appears and responds when in pain or discomfort, especially for a child with limited verbal communication. The module provides pain assessment tools, tailored to verbal and nonverbal patients in both the inpatient and outpatient settings. The module also shares guidance on establishing communication and goals with the family and within the care team on how the child appears when in distress and how he/she/they respond to pain medications. The pain plan should encompass both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic therapeutics. Furthermore, as pain and discomfort may present from multiple sources, not limited to the regions involved in the procedure, understanding how the child responds to urinary retention, constipation, dyspnea, and uncomfortable positions is important to care. Postoperative immobilization must also be addressed as it may lead to pressure injury, manifesting as behavioral changes.

The module also presents laboratory testing as part of the preoperative health assessment. It details the utility or lack thereof of several common practices and provides recommendations on components that should be part of each patient’s assessment. It also contains videos showcased from the Courage Parents Network on family and provider perceptions of spinal fusion.

Family and social assessments must not be neglected prior to surgery, as these areas may also affect surgical outcomes. The module shares several screening tools that care team members can use to screen for family and social issues. Challenges to discharge planning are also discussed, including how to approach transportation, medical equipment, and school transitions needs.

The module is available for review in OPEN Pediatrics (www.openpediatrics.org), an online community for pediatric health professionals who share peer-reviewed best practices. “Our aim is to disseminate the recommendations as widely as possible to bring about the maximum good to the most,” Dr. Giordano said. The International Committee on Perioperative Care for Children with Medical Complexity is planning further guides regarding perioperative care, particularly for intraoperative and postoperative considerations.

Dr. Tantoco is a med-peds hospitalist at Northwestern Memorial Hospital and Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, and instructor of medicine (hospital medicine) and pediatrics in Northwestern University, in Chicago. She is also a member of the SHM Pediatrics Special Interest Group Executive Committee. Dr. Bhasin is a med-peds hospitalist at Northwestern Memorial Hospital and Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital, and assistant professor of medicine (hospital medicine) and pediatrics in Northwestern University.

Ultraprocessed foods comprise most of the calories for youths

In the 2 decades from 1999 to 2018, ultraprocessed foods consistently accounted for the majority of energy intake by American young people, a large cross-sectional study of National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data shows.

In young people aged 2-19 years, the estimated percentage of total energy from consumption of ultraprocessed foods increased from 61.4% to 67.0%, for a difference of 5.6% (95% confidence interval [CI] 3.5-7.7, P < .001 for trend), according to Lu Wang, PhD, MPH, a postdoctoral fellow at the Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy at Tufts University in Boston, and colleagues.

In contrast, total energy from non- or minimally processed foods decreased from 28.8% to 23.5% (difference −5.3%, 95% CI, −7.5 to −3.2, P < .001 for trend).

“The estimated percentage of energy consumed from ultraprocessed foods increased from 1999 to 2018, with an increasing trend in ready-to-heat and -eat mixed dishes and a decreasing trend in sugar-sweetened beverages,” the authors wrote. The report was published online Aug. 10 in JAMA.

The findings held regardless of the educational and socioeconomic status of the children’s parents.

Significant disparities by race and ethnicity emerged, however, with the ultraprocessed food phenomenon more marked in non-Hispanic Black youths and Mexican-American youths than in their non-Hispanic White counterparts. “Targeted marketing of junk foods toward racial/ethnic minority youths may partly contribute to such differences,” the authors wrote. “However, persistently lower consumption of ultraprocessed foods among Mexican-American youths may reflect more home cooking among Hispanic families.”

Among non-Hispanic Black youths consumption rose from 62.2% to 72.5% (difference 10.3%, 95% CI, 6.8-13.8) and among Mexican-American youths from 55.8% to 63.5% (difference 7.6%, 95% CI, 4.4-10.9). In non-Hispanic White youths intake rose from 63.4% to 68.6% (difference 5.2%, 95% CI, 2.1-8.3, P = .04 for trends).

In addition, a higher consumption of ultraprocessed foods among school-aged youths than among preschool children aged 2-5 years may reflect increased marketing, availability, and selection of ultraprocessed foods for older youths, the authors noted.

Food processing, with its potential adverse effects, may need to be considered as a food dimension in addition to nutrients and food groups in future dietary recommendations and food policies, they added.

“An increasing number of studies are showing a link between ultraprocessed food consumption and adverse health outcomes in children,” corresponding author Fang Fang Zhang, MD, PhD, Neely Family Professor and associate professor at Tufts’ Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy, said in an interview. “Health care providers can play a larger role in encouraging patients – and their parents – to replace unhealthy ultraprocessed foods such as ultraprocessed sweet bakery products with healthy unprocessed or minimally processed foods in their diet such as less processed whole grains. “

In Dr. Zhang’s view, teachers also have a part to play in promoting nutrition literacy. “Schools can play an important role in empowering children with knowledge and skills to make healthy food choices,” she said. “Nutrition literacy should be an integral part of the health education curriculum in all K-12 schools.”

Commenting on the study but not involved in it, Michelle Katzow, MD, a pediatrician/obesity medicine specialist and assistant professor at the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research in Manhasset, N.Y., said the work highlights an often overlooked aspect of the modern American diet that may well be contributing to poor health outcomes in young people.

“It suggests that even as the science advances and we learn more about the adverse health effects of ultraprocessed foods, public health efforts to improve nutrition and food quality in children have not been successful,” she said in an interview. “This is because it is so hard for public health advocates to compete with the food industry, which stands to really benefit financially from hooking kids on processed foods that are not good for their health.”

Dr. Katzow added that the observed racial/ethnic disparities are not surprising in light of a growing body of evidence that racism exists in food marketing. “We need to put forward policies that regulate the food industry, particularly in relation to its most susceptible targets, our kids.”

Study details

The serial cross-sectional analysis used 24-hour dietary recall data from a nationally representative sample from 10 NHANES cycles for the range of 1999-2000 to 2017-2018. The weighted mean age of the cohort was 10.7 years and 49.1% were girls.

Among the subgroups of ultraprocessed foods, the estimated percentage of energy from ready-to-heat and ready-to-eat mixed dishes increased from 2.2% to 11.2% (difference 8.9%; 95%, CI, 7.7-10.2).

Energy from sweets and sweet snacks increased from 10.7% to 12.9% (difference 2.3%; 95% CI, 1.0-3.6), but the estimated percentage of energy decreased for sugar-sweetened beverages from 10.8% to 5.3% (difference −5.5%; 95% CI, −6.5 to −4.5).

In other categories, estimated energy intake from processed fats and oils, condiments, and sauces fell from 7.1% to 4.0% (difference −3.1%; 95% CI, −3.7 to −2.6, all P < .05 for trend).

Not surprisingly, ultraprocessed foods had an overall poorer nutrient profile than that of nonultraprocessed, although they often contained less saturated fat, and they also contained more carbohydrates, mostly from low-quality sources with added sugars and low levels of dietary fiber and protein.

And despite a higher total folate content in ultraprocessed foods because of fortification, higher-level consumers took in less total folate owing to their lower consumption of whole foods.

The authors cautioned that in addition to poor nutrient profiles, processing itself may harm health by changing the physical structure and chemical composition of food, which could lead to elevated glycemic response and reduced satiety. Furthermore, recent research has linked food additives such as emulsifiers, stabilizers, and artificial sweeteners to adverse metabolomic effects and obesity risk. Pointing to the recent success of efforts to reduce consumption of sugary beverages, Dr. Zhang said, “We need to mobilize the same energy and level of commitment when it comes to other unhealthy ultraprocessed foods such as cakes, cookies, doughnuts, and brownies.”

The trends identified by the Tufts study “are concerning and potentially have major public health significance,” according to an accompanying JAMA editorial.

“Better dietary assessment methods are needed to document trends and understand the unique role of ultraprocessed foods to inform future evidence-based policy and dietary recommendations,” wrote Katie A. Meyer, ScD, and Lindsey Smith Taillie, PhD, of the Gillings School of Global Public Health at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill.

The editorialists share the authors’ view that “a conceptual advancement would be to consider the level and characteristics of processing as just one of multiple dimensions (including nutrients and food groups) used to classify foods as healthy or unhealthy.” They pointed out that the Pan American Health Organization already recommends targeting products that are ultraprocessed and high in concerning add-in nutrients.

They cautioned, however, that the classification of ultraprocessed foods will not be easy because it requires data on a full list of ingredients, and the effects of processing generally cannot be separated from the composite nutrients of ultraprocessed foods.

This presents a challenge for national food consumption research “given that most large epidemiological studies rely on food frequency questionnaires that lack the information necessary to classify processing levels,” they wrote.

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health and the São Paulo Research Foundation. Coauthor Dariush Mozaffarian, MD, a cardiologist at Tufts University, disclosed support from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, and the Rockefeller Foundation as well as personal fees from several commercial companies. He has served on several scientific advisory boards and received royalties from UpToDate, all outside of the submitted work. Dr. Meyer reported a grant from choline manufacturer Balchem. Dr. Taillie reported funding from Bloomberg Philanthropies. Dr. Zhang had no disclosures. Dr. Katzow disclosed no competing interests.

In the 2 decades from 1999 to 2018, ultraprocessed foods consistently accounted for the majority of energy intake by American young people, a large cross-sectional study of National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data shows.

In young people aged 2-19 years, the estimated percentage of total energy from consumption of ultraprocessed foods increased from 61.4% to 67.0%, for a difference of 5.6% (95% confidence interval [CI] 3.5-7.7, P < .001 for trend), according to Lu Wang, PhD, MPH, a postdoctoral fellow at the Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy at Tufts University in Boston, and colleagues.

In contrast, total energy from non- or minimally processed foods decreased from 28.8% to 23.5% (difference −5.3%, 95% CI, −7.5 to −3.2, P < .001 for trend).

“The estimated percentage of energy consumed from ultraprocessed foods increased from 1999 to 2018, with an increasing trend in ready-to-heat and -eat mixed dishes and a decreasing trend in sugar-sweetened beverages,” the authors wrote. The report was published online Aug. 10 in JAMA.

The findings held regardless of the educational and socioeconomic status of the children’s parents.

Significant disparities by race and ethnicity emerged, however, with the ultraprocessed food phenomenon more marked in non-Hispanic Black youths and Mexican-American youths than in their non-Hispanic White counterparts. “Targeted marketing of junk foods toward racial/ethnic minority youths may partly contribute to such differences,” the authors wrote. “However, persistently lower consumption of ultraprocessed foods among Mexican-American youths may reflect more home cooking among Hispanic families.”

Among non-Hispanic Black youths consumption rose from 62.2% to 72.5% (difference 10.3%, 95% CI, 6.8-13.8) and among Mexican-American youths from 55.8% to 63.5% (difference 7.6%, 95% CI, 4.4-10.9). In non-Hispanic White youths intake rose from 63.4% to 68.6% (difference 5.2%, 95% CI, 2.1-8.3, P = .04 for trends).

In addition, a higher consumption of ultraprocessed foods among school-aged youths than among preschool children aged 2-5 years may reflect increased marketing, availability, and selection of ultraprocessed foods for older youths, the authors noted.

Food processing, with its potential adverse effects, may need to be considered as a food dimension in addition to nutrients and food groups in future dietary recommendations and food policies, they added.

“An increasing number of studies are showing a link between ultraprocessed food consumption and adverse health outcomes in children,” corresponding author Fang Fang Zhang, MD, PhD, Neely Family Professor and associate professor at Tufts’ Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy, said in an interview. “Health care providers can play a larger role in encouraging patients – and their parents – to replace unhealthy ultraprocessed foods such as ultraprocessed sweet bakery products with healthy unprocessed or minimally processed foods in their diet such as less processed whole grains. “

In Dr. Zhang’s view, teachers also have a part to play in promoting nutrition literacy. “Schools can play an important role in empowering children with knowledge and skills to make healthy food choices,” she said. “Nutrition literacy should be an integral part of the health education curriculum in all K-12 schools.”

Commenting on the study but not involved in it, Michelle Katzow, MD, a pediatrician/obesity medicine specialist and assistant professor at the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research in Manhasset, N.Y., said the work highlights an often overlooked aspect of the modern American diet that may well be contributing to poor health outcomes in young people.

“It suggests that even as the science advances and we learn more about the adverse health effects of ultraprocessed foods, public health efforts to improve nutrition and food quality in children have not been successful,” she said in an interview. “This is because it is so hard for public health advocates to compete with the food industry, which stands to really benefit financially from hooking kids on processed foods that are not good for their health.”

Dr. Katzow added that the observed racial/ethnic disparities are not surprising in light of a growing body of evidence that racism exists in food marketing. “We need to put forward policies that regulate the food industry, particularly in relation to its most susceptible targets, our kids.”

Study details

The serial cross-sectional analysis used 24-hour dietary recall data from a nationally representative sample from 10 NHANES cycles for the range of 1999-2000 to 2017-2018. The weighted mean age of the cohort was 10.7 years and 49.1% were girls.

Among the subgroups of ultraprocessed foods, the estimated percentage of energy from ready-to-heat and ready-to-eat mixed dishes increased from 2.2% to 11.2% (difference 8.9%; 95%, CI, 7.7-10.2).

Energy from sweets and sweet snacks increased from 10.7% to 12.9% (difference 2.3%; 95% CI, 1.0-3.6), but the estimated percentage of energy decreased for sugar-sweetened beverages from 10.8% to 5.3% (difference −5.5%; 95% CI, −6.5 to −4.5).

In other categories, estimated energy intake from processed fats and oils, condiments, and sauces fell from 7.1% to 4.0% (difference −3.1%; 95% CI, −3.7 to −2.6, all P < .05 for trend).

Not surprisingly, ultraprocessed foods had an overall poorer nutrient profile than that of nonultraprocessed, although they often contained less saturated fat, and they also contained more carbohydrates, mostly from low-quality sources with added sugars and low levels of dietary fiber and protein.

And despite a higher total folate content in ultraprocessed foods because of fortification, higher-level consumers took in less total folate owing to their lower consumption of whole foods.

The authors cautioned that in addition to poor nutrient profiles, processing itself may harm health by changing the physical structure and chemical composition of food, which could lead to elevated glycemic response and reduced satiety. Furthermore, recent research has linked food additives such as emulsifiers, stabilizers, and artificial sweeteners to adverse metabolomic effects and obesity risk. Pointing to the recent success of efforts to reduce consumption of sugary beverages, Dr. Zhang said, “We need to mobilize the same energy and level of commitment when it comes to other unhealthy ultraprocessed foods such as cakes, cookies, doughnuts, and brownies.”

The trends identified by the Tufts study “are concerning and potentially have major public health significance,” according to an accompanying JAMA editorial.

“Better dietary assessment methods are needed to document trends and understand the unique role of ultraprocessed foods to inform future evidence-based policy and dietary recommendations,” wrote Katie A. Meyer, ScD, and Lindsey Smith Taillie, PhD, of the Gillings School of Global Public Health at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill.

The editorialists share the authors’ view that “a conceptual advancement would be to consider the level and characteristics of processing as just one of multiple dimensions (including nutrients and food groups) used to classify foods as healthy or unhealthy.” They pointed out that the Pan American Health Organization already recommends targeting products that are ultraprocessed and high in concerning add-in nutrients.

They cautioned, however, that the classification of ultraprocessed foods will not be easy because it requires data on a full list of ingredients, and the effects of processing generally cannot be separated from the composite nutrients of ultraprocessed foods.

This presents a challenge for national food consumption research “given that most large epidemiological studies rely on food frequency questionnaires that lack the information necessary to classify processing levels,” they wrote.

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health and the São Paulo Research Foundation. Coauthor Dariush Mozaffarian, MD, a cardiologist at Tufts University, disclosed support from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, and the Rockefeller Foundation as well as personal fees from several commercial companies. He has served on several scientific advisory boards and received royalties from UpToDate, all outside of the submitted work. Dr. Meyer reported a grant from choline manufacturer Balchem. Dr. Taillie reported funding from Bloomberg Philanthropies. Dr. Zhang had no disclosures. Dr. Katzow disclosed no competing interests.

In the 2 decades from 1999 to 2018, ultraprocessed foods consistently accounted for the majority of energy intake by American young people, a large cross-sectional study of National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data shows.

In young people aged 2-19 years, the estimated percentage of total energy from consumption of ultraprocessed foods increased from 61.4% to 67.0%, for a difference of 5.6% (95% confidence interval [CI] 3.5-7.7, P < .001 for trend), according to Lu Wang, PhD, MPH, a postdoctoral fellow at the Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy at Tufts University in Boston, and colleagues.

In contrast, total energy from non- or minimally processed foods decreased from 28.8% to 23.5% (difference −5.3%, 95% CI, −7.5 to −3.2, P < .001 for trend).

“The estimated percentage of energy consumed from ultraprocessed foods increased from 1999 to 2018, with an increasing trend in ready-to-heat and -eat mixed dishes and a decreasing trend in sugar-sweetened beverages,” the authors wrote. The report was published online Aug. 10 in JAMA.

The findings held regardless of the educational and socioeconomic status of the children’s parents.

Significant disparities by race and ethnicity emerged, however, with the ultraprocessed food phenomenon more marked in non-Hispanic Black youths and Mexican-American youths than in their non-Hispanic White counterparts. “Targeted marketing of junk foods toward racial/ethnic minority youths may partly contribute to such differences,” the authors wrote. “However, persistently lower consumption of ultraprocessed foods among Mexican-American youths may reflect more home cooking among Hispanic families.”

Among non-Hispanic Black youths consumption rose from 62.2% to 72.5% (difference 10.3%, 95% CI, 6.8-13.8) and among Mexican-American youths from 55.8% to 63.5% (difference 7.6%, 95% CI, 4.4-10.9). In non-Hispanic White youths intake rose from 63.4% to 68.6% (difference 5.2%, 95% CI, 2.1-8.3, P = .04 for trends).

In addition, a higher consumption of ultraprocessed foods among school-aged youths than among preschool children aged 2-5 years may reflect increased marketing, availability, and selection of ultraprocessed foods for older youths, the authors noted.

Food processing, with its potential adverse effects, may need to be considered as a food dimension in addition to nutrients and food groups in future dietary recommendations and food policies, they added.

“An increasing number of studies are showing a link between ultraprocessed food consumption and adverse health outcomes in children,” corresponding author Fang Fang Zhang, MD, PhD, Neely Family Professor and associate professor at Tufts’ Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy, said in an interview. “Health care providers can play a larger role in encouraging patients – and their parents – to replace unhealthy ultraprocessed foods such as ultraprocessed sweet bakery products with healthy unprocessed or minimally processed foods in their diet such as less processed whole grains. “

In Dr. Zhang’s view, teachers also have a part to play in promoting nutrition literacy. “Schools can play an important role in empowering children with knowledge and skills to make healthy food choices,” she said. “Nutrition literacy should be an integral part of the health education curriculum in all K-12 schools.”

Commenting on the study but not involved in it, Michelle Katzow, MD, a pediatrician/obesity medicine specialist and assistant professor at the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research in Manhasset, N.Y., said the work highlights an often overlooked aspect of the modern American diet that may well be contributing to poor health outcomes in young people.

“It suggests that even as the science advances and we learn more about the adverse health effects of ultraprocessed foods, public health efforts to improve nutrition and food quality in children have not been successful,” she said in an interview. “This is because it is so hard for public health advocates to compete with the food industry, which stands to really benefit financially from hooking kids on processed foods that are not good for their health.”

Dr. Katzow added that the observed racial/ethnic disparities are not surprising in light of a growing body of evidence that racism exists in food marketing. “We need to put forward policies that regulate the food industry, particularly in relation to its most susceptible targets, our kids.”

Study details

The serial cross-sectional analysis used 24-hour dietary recall data from a nationally representative sample from 10 NHANES cycles for the range of 1999-2000 to 2017-2018. The weighted mean age of the cohort was 10.7 years and 49.1% were girls.

Among the subgroups of ultraprocessed foods, the estimated percentage of energy from ready-to-heat and ready-to-eat mixed dishes increased from 2.2% to 11.2% (difference 8.9%; 95%, CI, 7.7-10.2).

Energy from sweets and sweet snacks increased from 10.7% to 12.9% (difference 2.3%; 95% CI, 1.0-3.6), but the estimated percentage of energy decreased for sugar-sweetened beverages from 10.8% to 5.3% (difference −5.5%; 95% CI, −6.5 to −4.5).

In other categories, estimated energy intake from processed fats and oils, condiments, and sauces fell from 7.1% to 4.0% (difference −3.1%; 95% CI, −3.7 to −2.6, all P < .05 for trend).

Not surprisingly, ultraprocessed foods had an overall poorer nutrient profile than that of nonultraprocessed, although they often contained less saturated fat, and they also contained more carbohydrates, mostly from low-quality sources with added sugars and low levels of dietary fiber and protein.

And despite a higher total folate content in ultraprocessed foods because of fortification, higher-level consumers took in less total folate owing to their lower consumption of whole foods.