User login

Handheld device highly sensitive in detecting amblyopia; can be used in children as young as 2 years of age

A handheld vision screening device to test for amblyopia and strabismus has been found to have a sensitivity of 100%, a specificity of 85%, and a median acquisition time of 28 seconds, according to a study published in the Journal of American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus.

The prospective study involved 300 children recruited from two Kaiser Permanente Southern California pediatric clinics. The patients, aged 24-72 months, were first screened by trained research staff for amblyopia and strabismus using the device, called the Pediatric Vision Scanner (PVS). They were subsequently screened by a pediatric ophthalmologist who was masked to the previous screening results and who then performed a comprehensive eye examination.

With the gold-standard ophthalmologist examination, six children (2%) were identified as having amblyopia and/or strabismus. Using the PVS, all six children with amblyopia and/or strabismus were identified, yielding 100% sensitivity. PVS findings were normal for 45 children (15%), yielding a specificity rate of 85%. The positive predictive value was 26.0% (95% confidence interval, 12.4%-32.4%), and the negative predictive value was 100% (95% CI, 97.1%-100%).

The findings suggest that the device could be used to screen for amblyopia, according to Shaival S. Shah, MD, the study’s first author, who is a pediatric ophthalmologist and regional section lead of pediatric ophthalmology, Southern California Permanente Medical Group.

“A strength of this device is that it is user friendly and easy to use and very quick, which is essential when working with young children,” said Dr. Shah in an interview. He noted that the device could be used for children as young as 2 years.

Dr. Shah pointed out that the children were recruited from a pediatrician’s office and reflect more of a “real-world setting” than had they been recruited from a pediatric ophthalmology clinic.

Dr. Shah added that, with a negative predictive value of 100%, the device is highly reliable at informing the clinician that amblyopia is not present. “It did have a positive predictive value of 26%, which needs to be considered when deciding one’s vision screening strategy,” he said.

A limitation of the study is that there was no head-to-head comparison with another screening device, noted Dr. Shah. “While it may have been more useful to include another vision screening device to have a head-to-head comparison, we did not do this to limit complexity and cost.”

Michael J. Wan, MD, FRCSC, pediatric ophthalmologist, Sick Kids Hospital, Toronto, and assistant professor at the University of Toronto, told this news organization that the device has multiple strengths, including quick acquisition time and excellent detection rate of amblyopia and strabismus in children as young as 2 years.

“It is highly reliable at informing the clinician that amblyopia is not present,” said Dr. Wan, who was not involved in the study. “The PVS uses an elegant mechanism to test for amblyopia directly (as opposed to other screening devices, which only detect risk factors). This study demonstrates the impressive diagnostic accuracy of this approach. With a study population of 300 children, the PVS had a sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 85% (over 90% in cooperative children). This means that the PVS would detect essentially all cases of amblyopia and strabismus while minimizing the number of unnecessary referrals and examinations.”

He added that, although the study included children as young as 2 years, only 2.5% of the children were unable to complete the PVS test. “Detecting amblyopia in children at an age when treatment is still effective has been a longstanding goal in pediatric ophthalmology,” said Dr. Wan, who described the technology as user friendly. “Based on this study, the search for an accurate and practical pediatric vision screening device appears to be over.”

Dr. Wan said it would be useful to replicate this study with a different population to confirm the findings.

Dr. Shah and Dr. Wan disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A handheld vision screening device to test for amblyopia and strabismus has been found to have a sensitivity of 100%, a specificity of 85%, and a median acquisition time of 28 seconds, according to a study published in the Journal of American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus.

The prospective study involved 300 children recruited from two Kaiser Permanente Southern California pediatric clinics. The patients, aged 24-72 months, were first screened by trained research staff for amblyopia and strabismus using the device, called the Pediatric Vision Scanner (PVS). They were subsequently screened by a pediatric ophthalmologist who was masked to the previous screening results and who then performed a comprehensive eye examination.

With the gold-standard ophthalmologist examination, six children (2%) were identified as having amblyopia and/or strabismus. Using the PVS, all six children with amblyopia and/or strabismus were identified, yielding 100% sensitivity. PVS findings were normal for 45 children (15%), yielding a specificity rate of 85%. The positive predictive value was 26.0% (95% confidence interval, 12.4%-32.4%), and the negative predictive value was 100% (95% CI, 97.1%-100%).

The findings suggest that the device could be used to screen for amblyopia, according to Shaival S. Shah, MD, the study’s first author, who is a pediatric ophthalmologist and regional section lead of pediatric ophthalmology, Southern California Permanente Medical Group.

“A strength of this device is that it is user friendly and easy to use and very quick, which is essential when working with young children,” said Dr. Shah in an interview. He noted that the device could be used for children as young as 2 years.

Dr. Shah pointed out that the children were recruited from a pediatrician’s office and reflect more of a “real-world setting” than had they been recruited from a pediatric ophthalmology clinic.

Dr. Shah added that, with a negative predictive value of 100%, the device is highly reliable at informing the clinician that amblyopia is not present. “It did have a positive predictive value of 26%, which needs to be considered when deciding one’s vision screening strategy,” he said.

A limitation of the study is that there was no head-to-head comparison with another screening device, noted Dr. Shah. “While it may have been more useful to include another vision screening device to have a head-to-head comparison, we did not do this to limit complexity and cost.”

Michael J. Wan, MD, FRCSC, pediatric ophthalmologist, Sick Kids Hospital, Toronto, and assistant professor at the University of Toronto, told this news organization that the device has multiple strengths, including quick acquisition time and excellent detection rate of amblyopia and strabismus in children as young as 2 years.

“It is highly reliable at informing the clinician that amblyopia is not present,” said Dr. Wan, who was not involved in the study. “The PVS uses an elegant mechanism to test for amblyopia directly (as opposed to other screening devices, which only detect risk factors). This study demonstrates the impressive diagnostic accuracy of this approach. With a study population of 300 children, the PVS had a sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 85% (over 90% in cooperative children). This means that the PVS would detect essentially all cases of amblyopia and strabismus while minimizing the number of unnecessary referrals and examinations.”

He added that, although the study included children as young as 2 years, only 2.5% of the children were unable to complete the PVS test. “Detecting amblyopia in children at an age when treatment is still effective has been a longstanding goal in pediatric ophthalmology,” said Dr. Wan, who described the technology as user friendly. “Based on this study, the search for an accurate and practical pediatric vision screening device appears to be over.”

Dr. Wan said it would be useful to replicate this study with a different population to confirm the findings.

Dr. Shah and Dr. Wan disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A handheld vision screening device to test for amblyopia and strabismus has been found to have a sensitivity of 100%, a specificity of 85%, and a median acquisition time of 28 seconds, according to a study published in the Journal of American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus.

The prospective study involved 300 children recruited from two Kaiser Permanente Southern California pediatric clinics. The patients, aged 24-72 months, were first screened by trained research staff for amblyopia and strabismus using the device, called the Pediatric Vision Scanner (PVS). They were subsequently screened by a pediatric ophthalmologist who was masked to the previous screening results and who then performed a comprehensive eye examination.

With the gold-standard ophthalmologist examination, six children (2%) were identified as having amblyopia and/or strabismus. Using the PVS, all six children with amblyopia and/or strabismus were identified, yielding 100% sensitivity. PVS findings were normal for 45 children (15%), yielding a specificity rate of 85%. The positive predictive value was 26.0% (95% confidence interval, 12.4%-32.4%), and the negative predictive value was 100% (95% CI, 97.1%-100%).

The findings suggest that the device could be used to screen for amblyopia, according to Shaival S. Shah, MD, the study’s first author, who is a pediatric ophthalmologist and regional section lead of pediatric ophthalmology, Southern California Permanente Medical Group.

“A strength of this device is that it is user friendly and easy to use and very quick, which is essential when working with young children,” said Dr. Shah in an interview. He noted that the device could be used for children as young as 2 years.

Dr. Shah pointed out that the children were recruited from a pediatrician’s office and reflect more of a “real-world setting” than had they been recruited from a pediatric ophthalmology clinic.

Dr. Shah added that, with a negative predictive value of 100%, the device is highly reliable at informing the clinician that amblyopia is not present. “It did have a positive predictive value of 26%, which needs to be considered when deciding one’s vision screening strategy,” he said.

A limitation of the study is that there was no head-to-head comparison with another screening device, noted Dr. Shah. “While it may have been more useful to include another vision screening device to have a head-to-head comparison, we did not do this to limit complexity and cost.”

Michael J. Wan, MD, FRCSC, pediatric ophthalmologist, Sick Kids Hospital, Toronto, and assistant professor at the University of Toronto, told this news organization that the device has multiple strengths, including quick acquisition time and excellent detection rate of amblyopia and strabismus in children as young as 2 years.

“It is highly reliable at informing the clinician that amblyopia is not present,” said Dr. Wan, who was not involved in the study. “The PVS uses an elegant mechanism to test for amblyopia directly (as opposed to other screening devices, which only detect risk factors). This study demonstrates the impressive diagnostic accuracy of this approach. With a study population of 300 children, the PVS had a sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 85% (over 90% in cooperative children). This means that the PVS would detect essentially all cases of amblyopia and strabismus while minimizing the number of unnecessary referrals and examinations.”

He added that, although the study included children as young as 2 years, only 2.5% of the children were unable to complete the PVS test. “Detecting amblyopia in children at an age when treatment is still effective has been a longstanding goal in pediatric ophthalmology,” said Dr. Wan, who described the technology as user friendly. “Based on this study, the search for an accurate and practical pediatric vision screening device appears to be over.”

Dr. Wan said it would be useful to replicate this study with a different population to confirm the findings.

Dr. Shah and Dr. Wan disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FDA clears first mobile rapid test for concussion

, the company has announced.

Eye-Sync is a virtual reality eye-tracking platform that provides objective measurements to aid in the assessment of concussion. It’s the first mobile, rapid test for concussion that has been cleared by the FDA, the company said.

As reported by this news organization, Eye-Sync received breakthrough designation from the FDA for this indication in March 2019.

The FDA initially cleared the Eye-Sync platform for recording, viewing, and analyzing eye movements to help clinicians identify visual tracking impairment.

The Eye-Sync technology uses a series of 60-second eye tracking assessments, neurocognitive batteries, symptom inventories, and standardized patient inventories to identify the type and severity of impairment after concussion.

“The platform generates customizable and interpretive reports that support clinical decision making and offers visual and vestibular therapies to remedy deficits and monitor improvement over time,” the company said.

In support of the application for use in concussion, SyncThink enrolled 1,655 children and adults into a clinical study that collected comprehensive patient and concussion-related data for over 12 months.

The company used these data to develop proprietary algorithms and deep learning models to identify a positive or negative indication of concussion.

The study showed that Eye-Sinc had sensitivity greater than 82% and specificity greater than 93%, “thereby providing clinicians with significant and actionable data when evaluating individuals with concussion,” the company said in a news release.

“The outcome of this study very clearly shows the effectiveness of our technology at detecting concussion and definitively demonstrates the clinical utility of Eye-Sinc,” SyncThink Chief Clinical Officer Scott Anderson said in the release.

“It also shows that the future of concussion diagnosis is no longer purely symptom-based but that of a technology driven multi-modal approach,” Mr. Anderson said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, the company has announced.

Eye-Sync is a virtual reality eye-tracking platform that provides objective measurements to aid in the assessment of concussion. It’s the first mobile, rapid test for concussion that has been cleared by the FDA, the company said.

As reported by this news organization, Eye-Sync received breakthrough designation from the FDA for this indication in March 2019.

The FDA initially cleared the Eye-Sync platform for recording, viewing, and analyzing eye movements to help clinicians identify visual tracking impairment.

The Eye-Sync technology uses a series of 60-second eye tracking assessments, neurocognitive batteries, symptom inventories, and standardized patient inventories to identify the type and severity of impairment after concussion.

“The platform generates customizable and interpretive reports that support clinical decision making and offers visual and vestibular therapies to remedy deficits and monitor improvement over time,” the company said.

In support of the application for use in concussion, SyncThink enrolled 1,655 children and adults into a clinical study that collected comprehensive patient and concussion-related data for over 12 months.

The company used these data to develop proprietary algorithms and deep learning models to identify a positive or negative indication of concussion.

The study showed that Eye-Sinc had sensitivity greater than 82% and specificity greater than 93%, “thereby providing clinicians with significant and actionable data when evaluating individuals with concussion,” the company said in a news release.

“The outcome of this study very clearly shows the effectiveness of our technology at detecting concussion and definitively demonstrates the clinical utility of Eye-Sinc,” SyncThink Chief Clinical Officer Scott Anderson said in the release.

“It also shows that the future of concussion diagnosis is no longer purely symptom-based but that of a technology driven multi-modal approach,” Mr. Anderson said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, the company has announced.

Eye-Sync is a virtual reality eye-tracking platform that provides objective measurements to aid in the assessment of concussion. It’s the first mobile, rapid test for concussion that has been cleared by the FDA, the company said.

As reported by this news organization, Eye-Sync received breakthrough designation from the FDA for this indication in March 2019.

The FDA initially cleared the Eye-Sync platform for recording, viewing, and analyzing eye movements to help clinicians identify visual tracking impairment.

The Eye-Sync technology uses a series of 60-second eye tracking assessments, neurocognitive batteries, symptom inventories, and standardized patient inventories to identify the type and severity of impairment after concussion.

“The platform generates customizable and interpretive reports that support clinical decision making and offers visual and vestibular therapies to remedy deficits and monitor improvement over time,” the company said.

In support of the application for use in concussion, SyncThink enrolled 1,655 children and adults into a clinical study that collected comprehensive patient and concussion-related data for over 12 months.

The company used these data to develop proprietary algorithms and deep learning models to identify a positive or negative indication of concussion.

The study showed that Eye-Sinc had sensitivity greater than 82% and specificity greater than 93%, “thereby providing clinicians with significant and actionable data when evaluating individuals with concussion,” the company said in a news release.

“The outcome of this study very clearly shows the effectiveness of our technology at detecting concussion and definitively demonstrates the clinical utility of Eye-Sinc,” SyncThink Chief Clinical Officer Scott Anderson said in the release.

“It also shows that the future of concussion diagnosis is no longer purely symptom-based but that of a technology driven multi-modal approach,” Mr. Anderson said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Racism a strong factor in Black women’s high rate of premature births, study finds

Dr. Paula Braveman, director of the Center on Social Disparities in Health at the University of California, San Francisco, says her latest research revealed an “astounding” level of evidence that racism is a decisive “upstream” cause of higher rates of preterm birth among Black women.

The tipping point for Dr. Paula Braveman came when a longtime patient of hers at a community clinic in San Francisco’s Mission District slipped past the front desk and knocked on her office door to say goodbye. He wouldn’t be coming to the clinic anymore, he told her, because he could no longer afford it.

It was a decisive moment for Dr. Braveman, who decided she wanted not only to heal ailing patients but also to advocate for policies that would help them be healthier when they arrived at her clinic. In the nearly four decades since, Dr. Braveman has dedicated herself to studying the “social determinants of health” – how the spaces where we live, work, play and learn, and the relationships we have in those places influence how healthy we are.

As director of the Center on Social Disparities in Health at the University of California, San Francisco, Dr. Braveman has studied the link between neighborhood wealth and children’s health, and how access to insurance influences prenatal care. A longtime advocate of translating research into policy, she has collaborated on major health initiatives with the health department in San Francisco, the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the World Health Organization.

Dr. Braveman has a particular interest in maternal and infant health. Her latest research reviews what’s known about the persistent gap in preterm birth rates between Black and White women in the United States. Black women are about 1.6 times as likely as White women to give birth more than three weeks before the due date. That statistic bears alarming and costly health consequences, as infants born prematurely are at higher risk for breathing, heart, and brain abnormalities, among other complications.

Dr. Braveman coauthored the review with a group of experts convened by the March of Dimes that included geneticists, clinicians, epidemiologists, biomedical experts, and neurologists. They examined more than two dozen suspected causes of preterm births – including quality of prenatal care, environmental toxics, chronic stress, poverty and obesity – and determined that racism, directly or indirectly, best explained the racial disparities in preterm birth rates.

(Note: In the review, the authors make extensive use of the terms “upstream” and “downstream” to describe what determines people’s health. A downstream risk is the condition or factor most directly responsible for a health outcome, while an upstream factor is what causes or fuels the downstream risk – and often what needs to change to prevent someone from becoming sick. For example, a person living near drinking water polluted with toxic chemicals might get sick from drinking the water. The downstream fix would be telling individuals to use filters. The upstream solution would be to stop the dumping of toxic chemicals.)

KHN spoke with Dr. Braveman about the study and its findings. The excerpts have been edited for length and style.

Q: You have been studying the issue of preterm birth and racial disparities for so long. Were there any findings from this review that surprised you?

The process of systematically going through all of the risk factors that are written about in the literature and then seeing how the story of racism was an upstream determinant for virtually all of them. That was kind of astounding.

The other thing that was very impressive: When we looked at the idea that genetic factors could be the cause of the Black-White disparity in preterm birth. The genetics experts in the group, and there were three or four of them, concluded from the evidence that genetic factors might influence the disparity in preterm birth, but at most the effect would be very small, very small indeed. This could not account for the greater rate of preterm birth among Black women compared to White women.

Q: You were looking to identify not just what causes preterm birth but also to explain racial differences in rates of preterm birth. Are there examples of factors that can influence preterm birth that don’t explain racial disparities?

It does look like there are genetic components to preterm birth, but they don’t explain the Black-White disparity in preterm birth. Another example is having an early elective C-section. That’s one of the problems contributing to avoidable preterm birth, but it doesn’t look like that’s really contributing to the Black-White disparity in preterm birth.

Q: You and your colleagues listed exactly one upstream cause of preterm birth: racism. How would you characterize the certainty that racism is a decisive upstream cause of higher rates of preterm birth among Black women?

It makes me think of this saying: A randomized clinical trial wouldn’t be necessary to give certainty about the importance of having a parachute on if you jump from a plane. To me, at this point, it is close to that.

Going through that paper – and we worked on that paper over a three- or four-year period, so there was a lot of time to think about it – I don’t see how the evidence that we have could be explained otherwise.

Q: What did you learn about how a mother’s broader lifetime experience of racism might affect birth outcomes versus what she experienced within the medical establishment during pregnancy?

There were many ways that experiencing racial discrimination would affect a woman’s pregnancy, but one major way would be through pathways and biological mechanisms involved in stress and stress physiology. In neuroscience, what’s been clear is that a chronic stressor seems to be more damaging to health than an acute stressor.

So it doesn’t make much sense to be looking only during pregnancy. But that’s where most of that research has been done: stress during pregnancy and racial discrimination, and its role in birth outcomes. Very few studies have looked at experiences of racial discrimination across the life course.

My colleagues and I have published a paper where we asked African American women about their experiences of racism, and we didn’t even define what we meant. Women did not talk a lot about the experiences of racism during pregnancy from their medical providers; they talked about the lifetime experience and particularly experiences going back to childhood. And they talked about having to worry, and constant vigilance, so that even if they’re not experiencing an incident, their antennae have to be out to be prepared in case an incident does occur.

Putting all of it together with what we know about stress physiology, I would put my money on the lifetime experiences being so much more important than experiences during pregnancy. There isn’t enough known about preterm birth, but from what is known, inflammation is involved, immune dysfunction, and that’s what stress leads to. The neuroscientists have shown us that chronic stress produces inflammation and immune system dysfunction.

Q: What policies do you think are most important at this stage for reducing preterm birth for Black women?

I wish I could just say one policy or two policies, but I think it does get back to the need to dismantle racism in our society. In all of its manifestations. That’s unfortunate, not to be able to say, “Oh, here, I have this magic bullet, and if you just go with that, that will solve the problem.”

If you take the conclusions of this study seriously, you say, well, policies to just go after these downstream factors are not going to work. It’s up to the upstream investment in trying to achieve a more equitable and less racist society. Ultimately, I think that’s the take-home, and it’s a tall, tall order.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

Dr. Paula Braveman, director of the Center on Social Disparities in Health at the University of California, San Francisco, says her latest research revealed an “astounding” level of evidence that racism is a decisive “upstream” cause of higher rates of preterm birth among Black women.

The tipping point for Dr. Paula Braveman came when a longtime patient of hers at a community clinic in San Francisco’s Mission District slipped past the front desk and knocked on her office door to say goodbye. He wouldn’t be coming to the clinic anymore, he told her, because he could no longer afford it.

It was a decisive moment for Dr. Braveman, who decided she wanted not only to heal ailing patients but also to advocate for policies that would help them be healthier when they arrived at her clinic. In the nearly four decades since, Dr. Braveman has dedicated herself to studying the “social determinants of health” – how the spaces where we live, work, play and learn, and the relationships we have in those places influence how healthy we are.

As director of the Center on Social Disparities in Health at the University of California, San Francisco, Dr. Braveman has studied the link between neighborhood wealth and children’s health, and how access to insurance influences prenatal care. A longtime advocate of translating research into policy, she has collaborated on major health initiatives with the health department in San Francisco, the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the World Health Organization.

Dr. Braveman has a particular interest in maternal and infant health. Her latest research reviews what’s known about the persistent gap in preterm birth rates between Black and White women in the United States. Black women are about 1.6 times as likely as White women to give birth more than three weeks before the due date. That statistic bears alarming and costly health consequences, as infants born prematurely are at higher risk for breathing, heart, and brain abnormalities, among other complications.

Dr. Braveman coauthored the review with a group of experts convened by the March of Dimes that included geneticists, clinicians, epidemiologists, biomedical experts, and neurologists. They examined more than two dozen suspected causes of preterm births – including quality of prenatal care, environmental toxics, chronic stress, poverty and obesity – and determined that racism, directly or indirectly, best explained the racial disparities in preterm birth rates.

(Note: In the review, the authors make extensive use of the terms “upstream” and “downstream” to describe what determines people’s health. A downstream risk is the condition or factor most directly responsible for a health outcome, while an upstream factor is what causes or fuels the downstream risk – and often what needs to change to prevent someone from becoming sick. For example, a person living near drinking water polluted with toxic chemicals might get sick from drinking the water. The downstream fix would be telling individuals to use filters. The upstream solution would be to stop the dumping of toxic chemicals.)

KHN spoke with Dr. Braveman about the study and its findings. The excerpts have been edited for length and style.

Q: You have been studying the issue of preterm birth and racial disparities for so long. Were there any findings from this review that surprised you?

The process of systematically going through all of the risk factors that are written about in the literature and then seeing how the story of racism was an upstream determinant for virtually all of them. That was kind of astounding.

The other thing that was very impressive: When we looked at the idea that genetic factors could be the cause of the Black-White disparity in preterm birth. The genetics experts in the group, and there were three or four of them, concluded from the evidence that genetic factors might influence the disparity in preterm birth, but at most the effect would be very small, very small indeed. This could not account for the greater rate of preterm birth among Black women compared to White women.

Q: You were looking to identify not just what causes preterm birth but also to explain racial differences in rates of preterm birth. Are there examples of factors that can influence preterm birth that don’t explain racial disparities?

It does look like there are genetic components to preterm birth, but they don’t explain the Black-White disparity in preterm birth. Another example is having an early elective C-section. That’s one of the problems contributing to avoidable preterm birth, but it doesn’t look like that’s really contributing to the Black-White disparity in preterm birth.

Q: You and your colleagues listed exactly one upstream cause of preterm birth: racism. How would you characterize the certainty that racism is a decisive upstream cause of higher rates of preterm birth among Black women?

It makes me think of this saying: A randomized clinical trial wouldn’t be necessary to give certainty about the importance of having a parachute on if you jump from a plane. To me, at this point, it is close to that.

Going through that paper – and we worked on that paper over a three- or four-year period, so there was a lot of time to think about it – I don’t see how the evidence that we have could be explained otherwise.

Q: What did you learn about how a mother’s broader lifetime experience of racism might affect birth outcomes versus what she experienced within the medical establishment during pregnancy?

There were many ways that experiencing racial discrimination would affect a woman’s pregnancy, but one major way would be through pathways and biological mechanisms involved in stress and stress physiology. In neuroscience, what’s been clear is that a chronic stressor seems to be more damaging to health than an acute stressor.

So it doesn’t make much sense to be looking only during pregnancy. But that’s where most of that research has been done: stress during pregnancy and racial discrimination, and its role in birth outcomes. Very few studies have looked at experiences of racial discrimination across the life course.

My colleagues and I have published a paper where we asked African American women about their experiences of racism, and we didn’t even define what we meant. Women did not talk a lot about the experiences of racism during pregnancy from their medical providers; they talked about the lifetime experience and particularly experiences going back to childhood. And they talked about having to worry, and constant vigilance, so that even if they’re not experiencing an incident, their antennae have to be out to be prepared in case an incident does occur.

Putting all of it together with what we know about stress physiology, I would put my money on the lifetime experiences being so much more important than experiences during pregnancy. There isn’t enough known about preterm birth, but from what is known, inflammation is involved, immune dysfunction, and that’s what stress leads to. The neuroscientists have shown us that chronic stress produces inflammation and immune system dysfunction.

Q: What policies do you think are most important at this stage for reducing preterm birth for Black women?

I wish I could just say one policy or two policies, but I think it does get back to the need to dismantle racism in our society. In all of its manifestations. That’s unfortunate, not to be able to say, “Oh, here, I have this magic bullet, and if you just go with that, that will solve the problem.”

If you take the conclusions of this study seriously, you say, well, policies to just go after these downstream factors are not going to work. It’s up to the upstream investment in trying to achieve a more equitable and less racist society. Ultimately, I think that’s the take-home, and it’s a tall, tall order.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

Dr. Paula Braveman, director of the Center on Social Disparities in Health at the University of California, San Francisco, says her latest research revealed an “astounding” level of evidence that racism is a decisive “upstream” cause of higher rates of preterm birth among Black women.

The tipping point for Dr. Paula Braveman came when a longtime patient of hers at a community clinic in San Francisco’s Mission District slipped past the front desk and knocked on her office door to say goodbye. He wouldn’t be coming to the clinic anymore, he told her, because he could no longer afford it.

It was a decisive moment for Dr. Braveman, who decided she wanted not only to heal ailing patients but also to advocate for policies that would help them be healthier when they arrived at her clinic. In the nearly four decades since, Dr. Braveman has dedicated herself to studying the “social determinants of health” – how the spaces where we live, work, play and learn, and the relationships we have in those places influence how healthy we are.

As director of the Center on Social Disparities in Health at the University of California, San Francisco, Dr. Braveman has studied the link between neighborhood wealth and children’s health, and how access to insurance influences prenatal care. A longtime advocate of translating research into policy, she has collaborated on major health initiatives with the health department in San Francisco, the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the World Health Organization.

Dr. Braveman has a particular interest in maternal and infant health. Her latest research reviews what’s known about the persistent gap in preterm birth rates between Black and White women in the United States. Black women are about 1.6 times as likely as White women to give birth more than three weeks before the due date. That statistic bears alarming and costly health consequences, as infants born prematurely are at higher risk for breathing, heart, and brain abnormalities, among other complications.

Dr. Braveman coauthored the review with a group of experts convened by the March of Dimes that included geneticists, clinicians, epidemiologists, biomedical experts, and neurologists. They examined more than two dozen suspected causes of preterm births – including quality of prenatal care, environmental toxics, chronic stress, poverty and obesity – and determined that racism, directly or indirectly, best explained the racial disparities in preterm birth rates.

(Note: In the review, the authors make extensive use of the terms “upstream” and “downstream” to describe what determines people’s health. A downstream risk is the condition or factor most directly responsible for a health outcome, while an upstream factor is what causes or fuels the downstream risk – and often what needs to change to prevent someone from becoming sick. For example, a person living near drinking water polluted with toxic chemicals might get sick from drinking the water. The downstream fix would be telling individuals to use filters. The upstream solution would be to stop the dumping of toxic chemicals.)

KHN spoke with Dr. Braveman about the study and its findings. The excerpts have been edited for length and style.

Q: You have been studying the issue of preterm birth and racial disparities for so long. Were there any findings from this review that surprised you?

The process of systematically going through all of the risk factors that are written about in the literature and then seeing how the story of racism was an upstream determinant for virtually all of them. That was kind of astounding.

The other thing that was very impressive: When we looked at the idea that genetic factors could be the cause of the Black-White disparity in preterm birth. The genetics experts in the group, and there were three or four of them, concluded from the evidence that genetic factors might influence the disparity in preterm birth, but at most the effect would be very small, very small indeed. This could not account for the greater rate of preterm birth among Black women compared to White women.

Q: You were looking to identify not just what causes preterm birth but also to explain racial differences in rates of preterm birth. Are there examples of factors that can influence preterm birth that don’t explain racial disparities?

It does look like there are genetic components to preterm birth, but they don’t explain the Black-White disparity in preterm birth. Another example is having an early elective C-section. That’s one of the problems contributing to avoidable preterm birth, but it doesn’t look like that’s really contributing to the Black-White disparity in preterm birth.

Q: You and your colleagues listed exactly one upstream cause of preterm birth: racism. How would you characterize the certainty that racism is a decisive upstream cause of higher rates of preterm birth among Black women?

It makes me think of this saying: A randomized clinical trial wouldn’t be necessary to give certainty about the importance of having a parachute on if you jump from a plane. To me, at this point, it is close to that.

Going through that paper – and we worked on that paper over a three- or four-year period, so there was a lot of time to think about it – I don’t see how the evidence that we have could be explained otherwise.

Q: What did you learn about how a mother’s broader lifetime experience of racism might affect birth outcomes versus what she experienced within the medical establishment during pregnancy?

There were many ways that experiencing racial discrimination would affect a woman’s pregnancy, but one major way would be through pathways and biological mechanisms involved in stress and stress physiology. In neuroscience, what’s been clear is that a chronic stressor seems to be more damaging to health than an acute stressor.

So it doesn’t make much sense to be looking only during pregnancy. But that’s where most of that research has been done: stress during pregnancy and racial discrimination, and its role in birth outcomes. Very few studies have looked at experiences of racial discrimination across the life course.

My colleagues and I have published a paper where we asked African American women about their experiences of racism, and we didn’t even define what we meant. Women did not talk a lot about the experiences of racism during pregnancy from their medical providers; they talked about the lifetime experience and particularly experiences going back to childhood. And they talked about having to worry, and constant vigilance, so that even if they’re not experiencing an incident, their antennae have to be out to be prepared in case an incident does occur.

Putting all of it together with what we know about stress physiology, I would put my money on the lifetime experiences being so much more important than experiences during pregnancy. There isn’t enough known about preterm birth, but from what is known, inflammation is involved, immune dysfunction, and that’s what stress leads to. The neuroscientists have shown us that chronic stress produces inflammation and immune system dysfunction.

Q: What policies do you think are most important at this stage for reducing preterm birth for Black women?

I wish I could just say one policy or two policies, but I think it does get back to the need to dismantle racism in our society. In all of its manifestations. That’s unfortunate, not to be able to say, “Oh, here, I have this magic bullet, and if you just go with that, that will solve the problem.”

If you take the conclusions of this study seriously, you say, well, policies to just go after these downstream factors are not going to work. It’s up to the upstream investment in trying to achieve a more equitable and less racist society. Ultimately, I think that’s the take-home, and it’s a tall, tall order.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

FDA approves first CAR T-cell for adult ALL: For patients with R/R B-cell disease

The therapy is the first chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell treatment approved for adults with ALL.

This is a “meaningful advance,” because “roughly half of all adults with B-ALL will relapse on currently available therapies,” said Bijal Shah, MD, of Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, Fla., in a press statement from the manufacturer, Kite.

“A single infusion of Tecartus has demonstrated durable responses, suggesting the potential for long-term remission and a new approach to care,” he added.

“Roughly half of all cases actually occur in adults, and unlike pediatric ALL, adult ALL has historically had a poor prognosis,” said Lee Greenberger, PhD, chief scientific officer at the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, in the statement. The median overall survival (OS) is only about 8 months in this setting with current treatments, according to the company.

The new FDA approval, which is the fourth indication for brexucabtagene autoleucel, is based on results from ZUMA-3, a multicenter, single-arm study of 71 patients, with 54 efficacy-evaluable patients.

Efficacy was established on the basis of complete remission (CR) rate within 3 months after infusion and the duration of CR (DOCR). Twenty-eight (51.9%) of evaluable patients achieved CR, with a median follow-up for responders of 7.1 months. The median DOCR was not reached.

The median time to CR was 56 days. All 54 efficacy-evaluable patients had potential follow-up for 10 or more months with a median actual follow-up time of 12.3 months.

Among the 54 patients, the median time from leukapheresis to product delivery was 16 days and the median time from leukapheresis to infusion was 29 days.

Of the 17 study patients who did reach efficacy evaluation, 6 did not receive the agent because of manufacturing failure, 8 were not treated because of adverse events following leukapheresis, 2 underwent leukapheresis and received lymphodepleting chemotherapy but were not treated with the drug, and 1 treated patient was not evaluable for efficacy, per the prescribing information.

Among all patients treated with brexucabtagene autoleucel at its target dose, grade 3 or higher cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and neurologic events occurred in 26% and 35% of patients, respectively, and were generally well managed, according to the company.

The most common adverse reactions (≥20%) among ALL patients are fever, CRS, hypotension, encephalopathy, tachycardia, nausea, chills, headache, fatigue, febrile neutropenia, diarrhea, musculoskeletal pain, hypoxia, rash, edema, tremor, infection with pathogen unspecified, constipation, decreased appetite, and vomiting.

The prescribing information includes a boxed warning about the risks of CRS and neurologic toxicities; the drug is approved with a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) because of these risks.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The therapy is the first chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell treatment approved for adults with ALL.

This is a “meaningful advance,” because “roughly half of all adults with B-ALL will relapse on currently available therapies,” said Bijal Shah, MD, of Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, Fla., in a press statement from the manufacturer, Kite.

“A single infusion of Tecartus has demonstrated durable responses, suggesting the potential for long-term remission and a new approach to care,” he added.

“Roughly half of all cases actually occur in adults, and unlike pediatric ALL, adult ALL has historically had a poor prognosis,” said Lee Greenberger, PhD, chief scientific officer at the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, in the statement. The median overall survival (OS) is only about 8 months in this setting with current treatments, according to the company.

The new FDA approval, which is the fourth indication for brexucabtagene autoleucel, is based on results from ZUMA-3, a multicenter, single-arm study of 71 patients, with 54 efficacy-evaluable patients.

Efficacy was established on the basis of complete remission (CR) rate within 3 months after infusion and the duration of CR (DOCR). Twenty-eight (51.9%) of evaluable patients achieved CR, with a median follow-up for responders of 7.1 months. The median DOCR was not reached.

The median time to CR was 56 days. All 54 efficacy-evaluable patients had potential follow-up for 10 or more months with a median actual follow-up time of 12.3 months.

Among the 54 patients, the median time from leukapheresis to product delivery was 16 days and the median time from leukapheresis to infusion was 29 days.

Of the 17 study patients who did reach efficacy evaluation, 6 did not receive the agent because of manufacturing failure, 8 were not treated because of adverse events following leukapheresis, 2 underwent leukapheresis and received lymphodepleting chemotherapy but were not treated with the drug, and 1 treated patient was not evaluable for efficacy, per the prescribing information.

Among all patients treated with brexucabtagene autoleucel at its target dose, grade 3 or higher cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and neurologic events occurred in 26% and 35% of patients, respectively, and were generally well managed, according to the company.

The most common adverse reactions (≥20%) among ALL patients are fever, CRS, hypotension, encephalopathy, tachycardia, nausea, chills, headache, fatigue, febrile neutropenia, diarrhea, musculoskeletal pain, hypoxia, rash, edema, tremor, infection with pathogen unspecified, constipation, decreased appetite, and vomiting.

The prescribing information includes a boxed warning about the risks of CRS and neurologic toxicities; the drug is approved with a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) because of these risks.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The therapy is the first chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell treatment approved for adults with ALL.

This is a “meaningful advance,” because “roughly half of all adults with B-ALL will relapse on currently available therapies,” said Bijal Shah, MD, of Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, Fla., in a press statement from the manufacturer, Kite.

“A single infusion of Tecartus has demonstrated durable responses, suggesting the potential for long-term remission and a new approach to care,” he added.

“Roughly half of all cases actually occur in adults, and unlike pediatric ALL, adult ALL has historically had a poor prognosis,” said Lee Greenberger, PhD, chief scientific officer at the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, in the statement. The median overall survival (OS) is only about 8 months in this setting with current treatments, according to the company.

The new FDA approval, which is the fourth indication for brexucabtagene autoleucel, is based on results from ZUMA-3, a multicenter, single-arm study of 71 patients, with 54 efficacy-evaluable patients.

Efficacy was established on the basis of complete remission (CR) rate within 3 months after infusion and the duration of CR (DOCR). Twenty-eight (51.9%) of evaluable patients achieved CR, with a median follow-up for responders of 7.1 months. The median DOCR was not reached.

The median time to CR was 56 days. All 54 efficacy-evaluable patients had potential follow-up for 10 or more months with a median actual follow-up time of 12.3 months.

Among the 54 patients, the median time from leukapheresis to product delivery was 16 days and the median time from leukapheresis to infusion was 29 days.

Of the 17 study patients who did reach efficacy evaluation, 6 did not receive the agent because of manufacturing failure, 8 were not treated because of adverse events following leukapheresis, 2 underwent leukapheresis and received lymphodepleting chemotherapy but were not treated with the drug, and 1 treated patient was not evaluable for efficacy, per the prescribing information.

Among all patients treated with brexucabtagene autoleucel at its target dose, grade 3 or higher cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and neurologic events occurred in 26% and 35% of patients, respectively, and were generally well managed, according to the company.

The most common adverse reactions (≥20%) among ALL patients are fever, CRS, hypotension, encephalopathy, tachycardia, nausea, chills, headache, fatigue, febrile neutropenia, diarrhea, musculoskeletal pain, hypoxia, rash, edema, tremor, infection with pathogen unspecified, constipation, decreased appetite, and vomiting.

The prescribing information includes a boxed warning about the risks of CRS and neurologic toxicities; the drug is approved with a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) because of these risks.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

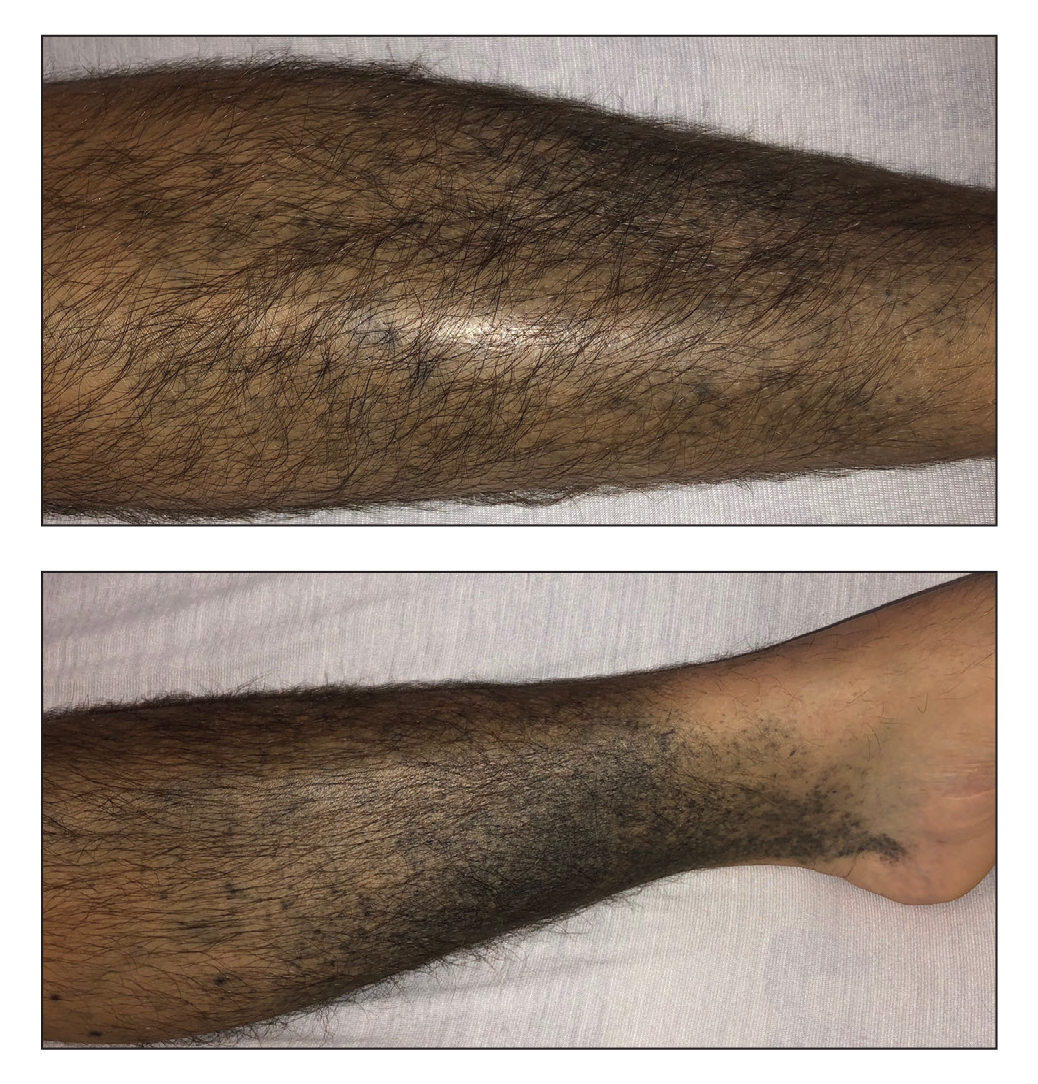

Chronic Hyperpigmented Patches on the Legs

The Diagnosis: Drug-Induced Hyperpigmentation

Additional history provided by the patient’s caretaker elucidated an extensive list of medications including chlorpromazine and minocycline, among several others. The caretaker revealed that the patient began treatment for acne vulgaris 2 years prior; despite the acne resolving, therapy was not discontinued. The blue-gray and brown pigmentation on our patient’s shins likely was attributed to a medication he was taking.

Both chlorpromazine and minocycline, among many other medications, are known to cause abnormal pigmentation of the skin.1 Minocycline is a tetracycline antibiotic prescribed for acne and other inflammatory cutaneous conditions. It is highly lipophilic, allowing it to reach high drug concentrations in the skin and nail unit.2 Patients taking minocycline long term and at high doses are at greatest risk for pigment deposition.3,4

Minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation is classified into 3 types. Type I describes blue-black deposition of pigment in acne scars and areas of inflammation, typically on facial skin.1,5 Histologically, type I stains positive for Perls Prussian blue, indicating an increased deposition of iron as hemosiderin,1 which likely occurs because minocycline is thought to play a role in defective clearance of hemosiderin from the dermis of injured tissue.5 Type II hyperpigmentation presents as bluegray pigment on the lower legs and occasionally the arms.6,7 Type II stains positive for both Perls Prussian blue and Fontana-Masson, demonstrating hemosiderin and melanin, respectively.6 The third form of hyperpigmentation results in diffuse, dark brown to gray pigmentation with a predilection for sun-exposed areas.8 Histology of type III shows increased pigment in the basal portion of the epidermis and brown-black pigment in macrophages of the dermis. Type III stains positive for Fontana-Masson and negative for Perls Prussian blue. The etiology of hyperpigmentation has been suspected to be caused by minocycline stimulating melanin production and/or deposition of minocycline-melanin complexes in dermal macrophages after a certain drug level; this largely is seen in patients receiving 100 to 200 mg daily as early as 1 year into treatment.8

Chlorpromazine is a typical antipsychotic that causes abnormal skin pigmentation in sun-exposed areas due to increased melanogenesis.9 Similar to type III minocyclineinduced hyperpigmentation, a histologic specimen may stain positive for Fontana-Masson yet negative for Perls Prussian blue. Lal et al10 demonstrated complete resolution of abnormal skin pigmentation within 5 years after stopping chlorpromazine. In contrast, minocyclineinduced hyperpigmentation may be permanent in some cases. There is substantial clinical and histologic overlap for drug-induced hyperpigmentation etiologies; it would behoove the clinician to focus on the most common locations affected and the generalized coloration.

Treatment of minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation includes the use of Q-switched lasers, specifically Q-switched ruby and Q-switched alexandrite.11 The use of the Q-switched Nd:YAG laser appears to be ineffective at clearing minocycline-induced pigmentation.7,11 In our patient, minocycline was discontinued immediately. Due to the patient’s critical condition, he deferred all other therapy. Erythema dyschromicum perstans, also referred to as ashy dermatosis, is an idiopathic form of hyperpigmentation.12 Lesions start as blue-gray to ashy gray macules, occasionally surrounded by a slightly erythematous, raised border.

Erythema dyschromicum perstans typically presents on the trunk, face, and arms of patients with Fitzpatrick skin types III and IV; it is considered a variant of lichen planus actinicus.12 Histologically, erythema dyschromicum perstans may mimic lichen planus pigmentosus (LPP); however, subtle differences exist to distinguish the 2 conditions. Erythema dyschromicum perstans demonstrates a mild lichenoid infiltrate, focal basal vacuolization at the dermoepidermal junction, and melanophage deposition.13 In contrast, LPP demonstrates pigmentary incontinence and a more severe inflammatory infiltrate. A perifollicular infiltrate and fibrosis also can be seen in LPP, which may explain the frontal fibrosing alopecia that often precedes LPP.13

Addison disease, also known as primary adrenal insufficiency, can cause diffuse hyperpigmentation in the skin, mucosae, and nail beds. The pigmentation is prominent in regions of naturally increased pigmentation, such as the flexural surfaces and intertriginous areas.14 Patients with adrenal insufficiency will have accompanying weight loss, hypotension, and fatigue, among other symptoms related to deficiency of cortisol and aldosterone. Skin biopsy shows acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, focal parakeratosis, spongiosis, superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, basal melanin deposition, and superficial dermal macrophages.15

Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis is an uncommon dermatosis that presents with multiple hyperpigmented macules and papules that coalesce to form patches and plaques centrally with reticulation in the periphery.16 Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis commonly presents on the upper trunk, axillae, and neck, though involvement can include flexural surfaces as well as the lower trunk and legs.16,17 Biopsy demonstrates undulating hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, acanthosis, and negative fungal staining.16

Pretibial myxedema most commonly is associated with Graves disease and presents as well-defined thickening and induration with overlying pink or purple-brown papules in the pretibial region.18 An acral surface and mucin deposition within the entire dermis may be appreciated on histology with staining for colloidal iron or Alcian blue.

- Fenske NA, Millns JL, Greer KE. Minocycline-induced pigmentation at sites of cutaneous inflammation. JAMA. 1980;244:1103-1106. doi:10.1001/jama.1980.03310100021021

- Snodgrass A, Motaparthi K. Systemic antibacterial agents. In: Wolverton SE, Wu JJ, eds. Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2020:69-98.

- Eisen D, Hakim MD. Minocycline-induced pigmentation. incidence, prevention and management. Drug Saf. 1998;18:431-440. doi:10.2165/00002018-199818060-00004

- Goulden V, Glass D, Cunliffe WJ. Safety of long-term high-dose minocycline in the treatment of acne. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:693-695. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1996.tb06972.x

- Basler RS, Kohnen PW. Localized hemosiderosis as a sequela of acne. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:1695-1697.

- Ridgway HA, Sonnex TS, Kennedy CT, et al. Hyperpigmentation associated with oral minocycline. Br J Dermatol. 1982;107:95-102. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1982.tb00296.x

- Nisar MS, Iyer K, Brodell RT, et al. Minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation: comparison of 3 Q-switched lasers to reverse its effects. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2013;6:159-162. doi:10.2147/CCID.S42166

- Simons JJ, Morales A. Minocycline and generalized cutaneous pigmentation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;3:244-247. doi:10.1016/s0190 -9622(80)80186-1

- Perry TL, Culling CF, Berry K, et al. 7-Hydroxychlorpromazine: potential toxic drug metabolite in psychiatric patients. Science. 1964;146:81-83. doi:10.1126/science.146.3640.81

- Lal S, Bloom D, Silver B, et al. Replacement of chlorpromazine with other neuroleptics: effect on abnormal skin pigmentation and ocular changes. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 1993;18:173-177.

- Tsao H, Busam K, Barnhill RL, et al. Treatment of minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation with the Q-switched ruby laser. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:1250-1251.

- Knox JM, Dodge BG, Freeman RG. Erythema dyschromicum perstans. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:262-272. doi:10.1001 /archderm.1968.01610090034006

- Rutnin S, Udompanich S, Pratumchart N, et al. Ashy dermatosis and lichen planus pigmentosus: the histopathological differences. Biomed Res Int. 2019;2019:5829185. doi:10.1155/2019/5829185

- Montgomery H, O’Leary PA. Pigmentation of the skin in Addison’s disease, acanthosis nigricans and hemochromatosis. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1930;21:970-984. doi:10.1001 /archderm.1930.01440120072005

- Fernandez-Flores A, Cassarino DS. Histopathologic findings of cutaneous hyperpigmentation in Addison disease and immunostain of the melanocytic population. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:924-927. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000000937

- Davis MD, Weenig RH, Camilleri MJ. Confluent and reticulate papillomatosis (Gougerot-Carteaud syndrome): a minocycline-responsive dermatosis without evidence for yeast in pathogenesis. a study of 39 patients and a proposal of diagnostic criteria. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:287-293. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06955.x

- Jo S, Park HS, Cho S, et al. Updated diagnosis criteria for confluent and reticulated papillomatosis: a case report. Ann Dermatol. 2014; 26:409-410. doi:10.5021/ad.2014.26.3.409

- Lause M, Kamboj A, Fernandez Faith E. Dermatologic manifestations of endocrine disorders. Transl Pediatr. 2017;6:300-312. doi:10.21037 /tp.2017.09.08

The Diagnosis: Drug-Induced Hyperpigmentation

Additional history provided by the patient’s caretaker elucidated an extensive list of medications including chlorpromazine and minocycline, among several others. The caretaker revealed that the patient began treatment for acne vulgaris 2 years prior; despite the acne resolving, therapy was not discontinued. The blue-gray and brown pigmentation on our patient’s shins likely was attributed to a medication he was taking.

Both chlorpromazine and minocycline, among many other medications, are known to cause abnormal pigmentation of the skin.1 Minocycline is a tetracycline antibiotic prescribed for acne and other inflammatory cutaneous conditions. It is highly lipophilic, allowing it to reach high drug concentrations in the skin and nail unit.2 Patients taking minocycline long term and at high doses are at greatest risk for pigment deposition.3,4

Minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation is classified into 3 types. Type I describes blue-black deposition of pigment in acne scars and areas of inflammation, typically on facial skin.1,5 Histologically, type I stains positive for Perls Prussian blue, indicating an increased deposition of iron as hemosiderin,1 which likely occurs because minocycline is thought to play a role in defective clearance of hemosiderin from the dermis of injured tissue.5 Type II hyperpigmentation presents as bluegray pigment on the lower legs and occasionally the arms.6,7 Type II stains positive for both Perls Prussian blue and Fontana-Masson, demonstrating hemosiderin and melanin, respectively.6 The third form of hyperpigmentation results in diffuse, dark brown to gray pigmentation with a predilection for sun-exposed areas.8 Histology of type III shows increased pigment in the basal portion of the epidermis and brown-black pigment in macrophages of the dermis. Type III stains positive for Fontana-Masson and negative for Perls Prussian blue. The etiology of hyperpigmentation has been suspected to be caused by minocycline stimulating melanin production and/or deposition of minocycline-melanin complexes in dermal macrophages after a certain drug level; this largely is seen in patients receiving 100 to 200 mg daily as early as 1 year into treatment.8

Chlorpromazine is a typical antipsychotic that causes abnormal skin pigmentation in sun-exposed areas due to increased melanogenesis.9 Similar to type III minocyclineinduced hyperpigmentation, a histologic specimen may stain positive for Fontana-Masson yet negative for Perls Prussian blue. Lal et al10 demonstrated complete resolution of abnormal skin pigmentation within 5 years after stopping chlorpromazine. In contrast, minocyclineinduced hyperpigmentation may be permanent in some cases. There is substantial clinical and histologic overlap for drug-induced hyperpigmentation etiologies; it would behoove the clinician to focus on the most common locations affected and the generalized coloration.

Treatment of minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation includes the use of Q-switched lasers, specifically Q-switched ruby and Q-switched alexandrite.11 The use of the Q-switched Nd:YAG laser appears to be ineffective at clearing minocycline-induced pigmentation.7,11 In our patient, minocycline was discontinued immediately. Due to the patient’s critical condition, he deferred all other therapy. Erythema dyschromicum perstans, also referred to as ashy dermatosis, is an idiopathic form of hyperpigmentation.12 Lesions start as blue-gray to ashy gray macules, occasionally surrounded by a slightly erythematous, raised border.

Erythema dyschromicum perstans typically presents on the trunk, face, and arms of patients with Fitzpatrick skin types III and IV; it is considered a variant of lichen planus actinicus.12 Histologically, erythema dyschromicum perstans may mimic lichen planus pigmentosus (LPP); however, subtle differences exist to distinguish the 2 conditions. Erythema dyschromicum perstans demonstrates a mild lichenoid infiltrate, focal basal vacuolization at the dermoepidermal junction, and melanophage deposition.13 In contrast, LPP demonstrates pigmentary incontinence and a more severe inflammatory infiltrate. A perifollicular infiltrate and fibrosis also can be seen in LPP, which may explain the frontal fibrosing alopecia that often precedes LPP.13

Addison disease, also known as primary adrenal insufficiency, can cause diffuse hyperpigmentation in the skin, mucosae, and nail beds. The pigmentation is prominent in regions of naturally increased pigmentation, such as the flexural surfaces and intertriginous areas.14 Patients with adrenal insufficiency will have accompanying weight loss, hypotension, and fatigue, among other symptoms related to deficiency of cortisol and aldosterone. Skin biopsy shows acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, focal parakeratosis, spongiosis, superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, basal melanin deposition, and superficial dermal macrophages.15

Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis is an uncommon dermatosis that presents with multiple hyperpigmented macules and papules that coalesce to form patches and plaques centrally with reticulation in the periphery.16 Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis commonly presents on the upper trunk, axillae, and neck, though involvement can include flexural surfaces as well as the lower trunk and legs.16,17 Biopsy demonstrates undulating hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, acanthosis, and negative fungal staining.16

Pretibial myxedema most commonly is associated with Graves disease and presents as well-defined thickening and induration with overlying pink or purple-brown papules in the pretibial region.18 An acral surface and mucin deposition within the entire dermis may be appreciated on histology with staining for colloidal iron or Alcian blue.

The Diagnosis: Drug-Induced Hyperpigmentation

Additional history provided by the patient’s caretaker elucidated an extensive list of medications including chlorpromazine and minocycline, among several others. The caretaker revealed that the patient began treatment for acne vulgaris 2 years prior; despite the acne resolving, therapy was not discontinued. The blue-gray and brown pigmentation on our patient’s shins likely was attributed to a medication he was taking.

Both chlorpromazine and minocycline, among many other medications, are known to cause abnormal pigmentation of the skin.1 Minocycline is a tetracycline antibiotic prescribed for acne and other inflammatory cutaneous conditions. It is highly lipophilic, allowing it to reach high drug concentrations in the skin and nail unit.2 Patients taking minocycline long term and at high doses are at greatest risk for pigment deposition.3,4

Minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation is classified into 3 types. Type I describes blue-black deposition of pigment in acne scars and areas of inflammation, typically on facial skin.1,5 Histologically, type I stains positive for Perls Prussian blue, indicating an increased deposition of iron as hemosiderin,1 which likely occurs because minocycline is thought to play a role in defective clearance of hemosiderin from the dermis of injured tissue.5 Type II hyperpigmentation presents as bluegray pigment on the lower legs and occasionally the arms.6,7 Type II stains positive for both Perls Prussian blue and Fontana-Masson, demonstrating hemosiderin and melanin, respectively.6 The third form of hyperpigmentation results in diffuse, dark brown to gray pigmentation with a predilection for sun-exposed areas.8 Histology of type III shows increased pigment in the basal portion of the epidermis and brown-black pigment in macrophages of the dermis. Type III stains positive for Fontana-Masson and negative for Perls Prussian blue. The etiology of hyperpigmentation has been suspected to be caused by minocycline stimulating melanin production and/or deposition of minocycline-melanin complexes in dermal macrophages after a certain drug level; this largely is seen in patients receiving 100 to 200 mg daily as early as 1 year into treatment.8

Chlorpromazine is a typical antipsychotic that causes abnormal skin pigmentation in sun-exposed areas due to increased melanogenesis.9 Similar to type III minocyclineinduced hyperpigmentation, a histologic specimen may stain positive for Fontana-Masson yet negative for Perls Prussian blue. Lal et al10 demonstrated complete resolution of abnormal skin pigmentation within 5 years after stopping chlorpromazine. In contrast, minocyclineinduced hyperpigmentation may be permanent in some cases. There is substantial clinical and histologic overlap for drug-induced hyperpigmentation etiologies; it would behoove the clinician to focus on the most common locations affected and the generalized coloration.

Treatment of minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation includes the use of Q-switched lasers, specifically Q-switched ruby and Q-switched alexandrite.11 The use of the Q-switched Nd:YAG laser appears to be ineffective at clearing minocycline-induced pigmentation.7,11 In our patient, minocycline was discontinued immediately. Due to the patient’s critical condition, he deferred all other therapy. Erythema dyschromicum perstans, also referred to as ashy dermatosis, is an idiopathic form of hyperpigmentation.12 Lesions start as blue-gray to ashy gray macules, occasionally surrounded by a slightly erythematous, raised border.

Erythema dyschromicum perstans typically presents on the trunk, face, and arms of patients with Fitzpatrick skin types III and IV; it is considered a variant of lichen planus actinicus.12 Histologically, erythema dyschromicum perstans may mimic lichen planus pigmentosus (LPP); however, subtle differences exist to distinguish the 2 conditions. Erythema dyschromicum perstans demonstrates a mild lichenoid infiltrate, focal basal vacuolization at the dermoepidermal junction, and melanophage deposition.13 In contrast, LPP demonstrates pigmentary incontinence and a more severe inflammatory infiltrate. A perifollicular infiltrate and fibrosis also can be seen in LPP, which may explain the frontal fibrosing alopecia that often precedes LPP.13

Addison disease, also known as primary adrenal insufficiency, can cause diffuse hyperpigmentation in the skin, mucosae, and nail beds. The pigmentation is prominent in regions of naturally increased pigmentation, such as the flexural surfaces and intertriginous areas.14 Patients with adrenal insufficiency will have accompanying weight loss, hypotension, and fatigue, among other symptoms related to deficiency of cortisol and aldosterone. Skin biopsy shows acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, focal parakeratosis, spongiosis, superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, basal melanin deposition, and superficial dermal macrophages.15

Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis is an uncommon dermatosis that presents with multiple hyperpigmented macules and papules that coalesce to form patches and plaques centrally with reticulation in the periphery.16 Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis commonly presents on the upper trunk, axillae, and neck, though involvement can include flexural surfaces as well as the lower trunk and legs.16,17 Biopsy demonstrates undulating hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, acanthosis, and negative fungal staining.16

Pretibial myxedema most commonly is associated with Graves disease and presents as well-defined thickening and induration with overlying pink or purple-brown papules in the pretibial region.18 An acral surface and mucin deposition within the entire dermis may be appreciated on histology with staining for colloidal iron or Alcian blue.

- Fenske NA, Millns JL, Greer KE. Minocycline-induced pigmentation at sites of cutaneous inflammation. JAMA. 1980;244:1103-1106. doi:10.1001/jama.1980.03310100021021

- Snodgrass A, Motaparthi K. Systemic antibacterial agents. In: Wolverton SE, Wu JJ, eds. Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2020:69-98.

- Eisen D, Hakim MD. Minocycline-induced pigmentation. incidence, prevention and management. Drug Saf. 1998;18:431-440. doi:10.2165/00002018-199818060-00004

- Goulden V, Glass D, Cunliffe WJ. Safety of long-term high-dose minocycline in the treatment of acne. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:693-695. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1996.tb06972.x

- Basler RS, Kohnen PW. Localized hemosiderosis as a sequela of acne. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:1695-1697.

- Ridgway HA, Sonnex TS, Kennedy CT, et al. Hyperpigmentation associated with oral minocycline. Br J Dermatol. 1982;107:95-102. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1982.tb00296.x

- Nisar MS, Iyer K, Brodell RT, et al. Minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation: comparison of 3 Q-switched lasers to reverse its effects. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2013;6:159-162. doi:10.2147/CCID.S42166

- Simons JJ, Morales A. Minocycline and generalized cutaneous pigmentation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;3:244-247. doi:10.1016/s0190 -9622(80)80186-1

- Perry TL, Culling CF, Berry K, et al. 7-Hydroxychlorpromazine: potential toxic drug metabolite in psychiatric patients. Science. 1964;146:81-83. doi:10.1126/science.146.3640.81

- Lal S, Bloom D, Silver B, et al. Replacement of chlorpromazine with other neuroleptics: effect on abnormal skin pigmentation and ocular changes. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 1993;18:173-177.

- Tsao H, Busam K, Barnhill RL, et al. Treatment of minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation with the Q-switched ruby laser. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:1250-1251.

- Knox JM, Dodge BG, Freeman RG. Erythema dyschromicum perstans. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:262-272. doi:10.1001 /archderm.1968.01610090034006

- Rutnin S, Udompanich S, Pratumchart N, et al. Ashy dermatosis and lichen planus pigmentosus: the histopathological differences. Biomed Res Int. 2019;2019:5829185. doi:10.1155/2019/5829185

- Montgomery H, O’Leary PA. Pigmentation of the skin in Addison’s disease, acanthosis nigricans and hemochromatosis. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1930;21:970-984. doi:10.1001 /archderm.1930.01440120072005

- Fernandez-Flores A, Cassarino DS. Histopathologic findings of cutaneous hyperpigmentation in Addison disease and immunostain of the melanocytic population. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:924-927. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000000937

- Davis MD, Weenig RH, Camilleri MJ. Confluent and reticulate papillomatosis (Gougerot-Carteaud syndrome): a minocycline-responsive dermatosis without evidence for yeast in pathogenesis. a study of 39 patients and a proposal of diagnostic criteria. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:287-293. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06955.x

- Jo S, Park HS, Cho S, et al. Updated diagnosis criteria for confluent and reticulated papillomatosis: a case report. Ann Dermatol. 2014; 26:409-410. doi:10.5021/ad.2014.26.3.409

- Lause M, Kamboj A, Fernandez Faith E. Dermatologic manifestations of endocrine disorders. Transl Pediatr. 2017;6:300-312. doi:10.21037 /tp.2017.09.08

- Fenske NA, Millns JL, Greer KE. Minocycline-induced pigmentation at sites of cutaneous inflammation. JAMA. 1980;244:1103-1106. doi:10.1001/jama.1980.03310100021021

- Snodgrass A, Motaparthi K. Systemic antibacterial agents. In: Wolverton SE, Wu JJ, eds. Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2020:69-98.

- Eisen D, Hakim MD. Minocycline-induced pigmentation. incidence, prevention and management. Drug Saf. 1998;18:431-440. doi:10.2165/00002018-199818060-00004

- Goulden V, Glass D, Cunliffe WJ. Safety of long-term high-dose minocycline in the treatment of acne. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:693-695. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1996.tb06972.x

- Basler RS, Kohnen PW. Localized hemosiderosis as a sequela of acne. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:1695-1697.

- Ridgway HA, Sonnex TS, Kennedy CT, et al. Hyperpigmentation associated with oral minocycline. Br J Dermatol. 1982;107:95-102. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1982.tb00296.x

- Nisar MS, Iyer K, Brodell RT, et al. Minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation: comparison of 3 Q-switched lasers to reverse its effects. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2013;6:159-162. doi:10.2147/CCID.S42166

- Simons JJ, Morales A. Minocycline and generalized cutaneous pigmentation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;3:244-247. doi:10.1016/s0190 -9622(80)80186-1

- Perry TL, Culling CF, Berry K, et al. 7-Hydroxychlorpromazine: potential toxic drug metabolite in psychiatric patients. Science. 1964;146:81-83. doi:10.1126/science.146.3640.81

- Lal S, Bloom D, Silver B, et al. Replacement of chlorpromazine with other neuroleptics: effect on abnormal skin pigmentation and ocular changes. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 1993;18:173-177.

- Tsao H, Busam K, Barnhill RL, et al. Treatment of minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation with the Q-switched ruby laser. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:1250-1251.

- Knox JM, Dodge BG, Freeman RG. Erythema dyschromicum perstans. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:262-272. doi:10.1001 /archderm.1968.01610090034006

- Rutnin S, Udompanich S, Pratumchart N, et al. Ashy dermatosis and lichen planus pigmentosus: the histopathological differences. Biomed Res Int. 2019;2019:5829185. doi:10.1155/2019/5829185

- Montgomery H, O’Leary PA. Pigmentation of the skin in Addison’s disease, acanthosis nigricans and hemochromatosis. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1930;21:970-984. doi:10.1001 /archderm.1930.01440120072005