User login

Closing your practice

“I might have to close my office,” a colleague wrote me recently. “I can’t find reliable medical assistants; no one good applies. Sad, but oh, well.”

A paucity of good employees is just one of many reasons given by physicians who have decided to close up shop. (See my recent column, “Finding Employees During a Pandemic”).

to address in order to ensure a smooth exit.

First, this cannot (and should not) be a hasty process. You will need at least a year to do it correctly, because there is a lot to do.

Once you have settled on a closing date, inform your attorney. If the firm you are using does not have experience in medical practice sales or closures, ask them to recommend one that does. You will need expert legal guidance during many of the steps that follow.

Next, review all of your contracts and leases. Most of them cannot be terminated at the drop of a hat. Facility and equipment leases may require a year’s notice, or even longer. Contracts with managed care, maintenance, cleaning, and hazardous waste disposal companies, and others such as answering services and website managers, should be reviewed to determine what sort of advance notice you will need to give.

Another step to take well in advance is to contact your malpractice insurance carrier. Most carriers have specific guidelines for when to notify your patients – and that notification will vary from carrier to carrier, state to state, and situation to situation. If you have a claims-made policy, you also need to inquire about the necessity of purchasing “tail” coverage, which will protect you in the event of a lawsuit after your practice has closed. Many carriers include tail coverage at no charge if you are retiring completely, but if you expect to do part-time, locum tenens, or volunteer medical work, you will need to pay for it.

Once you have the basics nailed down, notify your employees. You will want them to hear the news from you, not through the grapevine, and certainly not from your patients. You may be worried that some will quit, but keeping them in the dark will not prevent that, as they will find out soon enough. Besides, if you help them by assisting in finding them new employment, they will most likely help you by staying to the end.

At this point, you should also begin thinking about disposition of your patients’ records. You can’t just shred them, much as you might be tempted. Your attorney and malpractice carrier will guide you in how long they must be retained; 7-10 years is typical in many states, but it could be longer in yours. Unless you are selling part or all of your practice to another physician, you will have to designate someone else to be the legal custodian of the records and obtain a written custodial agreement from that person or organization.

Once that is arranged, you can notify your patients. Send them a letter or e-mail (or both) informing them of the date that you intend to close the practice. Let them know where their records will be kept, who to contact for a copy, and that their written consent will be required to obtain it. Some states also require that a notice be placed in the local newspaper or online, including the date of closure and how to request records.

This is also the time to inform all your third-party payers, including Medicare and Medicaid if applicable, any hospitals where you have privileges, and referring physicians. Notify any business concerns not notified already, such as utilities and other ancillary services. Your state medical board and the Drug Enforcement Agency will need to know as well. Contact a liquidator or used equipment dealer to arrange for disposal of any office equipment that has resale value. It is also a good time to decide how you will handle patient collections that trickle in after closing, and where mail should be forwarded.

As the closing date approaches, determine how to properly dispose of any medications you have on-hand. Your state may have requirements for disposal of controlled substances, and possibly for noncontrolled pharmaceuticals as well. Check your state’s controlled substances reporting system and other applicable regulators. Once the office is closed, don’t forget to shred any blank prescription pads and dissolve your corporation, if you have one.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

“I might have to close my office,” a colleague wrote me recently. “I can’t find reliable medical assistants; no one good applies. Sad, but oh, well.”

A paucity of good employees is just one of many reasons given by physicians who have decided to close up shop. (See my recent column, “Finding Employees During a Pandemic”).

to address in order to ensure a smooth exit.

First, this cannot (and should not) be a hasty process. You will need at least a year to do it correctly, because there is a lot to do.

Once you have settled on a closing date, inform your attorney. If the firm you are using does not have experience in medical practice sales or closures, ask them to recommend one that does. You will need expert legal guidance during many of the steps that follow.

Next, review all of your contracts and leases. Most of them cannot be terminated at the drop of a hat. Facility and equipment leases may require a year’s notice, or even longer. Contracts with managed care, maintenance, cleaning, and hazardous waste disposal companies, and others such as answering services and website managers, should be reviewed to determine what sort of advance notice you will need to give.

Another step to take well in advance is to contact your malpractice insurance carrier. Most carriers have specific guidelines for when to notify your patients – and that notification will vary from carrier to carrier, state to state, and situation to situation. If you have a claims-made policy, you also need to inquire about the necessity of purchasing “tail” coverage, which will protect you in the event of a lawsuit after your practice has closed. Many carriers include tail coverage at no charge if you are retiring completely, but if you expect to do part-time, locum tenens, or volunteer medical work, you will need to pay for it.

Once you have the basics nailed down, notify your employees. You will want them to hear the news from you, not through the grapevine, and certainly not from your patients. You may be worried that some will quit, but keeping them in the dark will not prevent that, as they will find out soon enough. Besides, if you help them by assisting in finding them new employment, they will most likely help you by staying to the end.

At this point, you should also begin thinking about disposition of your patients’ records. You can’t just shred them, much as you might be tempted. Your attorney and malpractice carrier will guide you in how long they must be retained; 7-10 years is typical in many states, but it could be longer in yours. Unless you are selling part or all of your practice to another physician, you will have to designate someone else to be the legal custodian of the records and obtain a written custodial agreement from that person or organization.

Once that is arranged, you can notify your patients. Send them a letter or e-mail (or both) informing them of the date that you intend to close the practice. Let them know where their records will be kept, who to contact for a copy, and that their written consent will be required to obtain it. Some states also require that a notice be placed in the local newspaper or online, including the date of closure and how to request records.

This is also the time to inform all your third-party payers, including Medicare and Medicaid if applicable, any hospitals where you have privileges, and referring physicians. Notify any business concerns not notified already, such as utilities and other ancillary services. Your state medical board and the Drug Enforcement Agency will need to know as well. Contact a liquidator or used equipment dealer to arrange for disposal of any office equipment that has resale value. It is also a good time to decide how you will handle patient collections that trickle in after closing, and where mail should be forwarded.

As the closing date approaches, determine how to properly dispose of any medications you have on-hand. Your state may have requirements for disposal of controlled substances, and possibly for noncontrolled pharmaceuticals as well. Check your state’s controlled substances reporting system and other applicable regulators. Once the office is closed, don’t forget to shred any blank prescription pads and dissolve your corporation, if you have one.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

“I might have to close my office,” a colleague wrote me recently. “I can’t find reliable medical assistants; no one good applies. Sad, but oh, well.”

A paucity of good employees is just one of many reasons given by physicians who have decided to close up shop. (See my recent column, “Finding Employees During a Pandemic”).

to address in order to ensure a smooth exit.

First, this cannot (and should not) be a hasty process. You will need at least a year to do it correctly, because there is a lot to do.

Once you have settled on a closing date, inform your attorney. If the firm you are using does not have experience in medical practice sales or closures, ask them to recommend one that does. You will need expert legal guidance during many of the steps that follow.

Next, review all of your contracts and leases. Most of them cannot be terminated at the drop of a hat. Facility and equipment leases may require a year’s notice, or even longer. Contracts with managed care, maintenance, cleaning, and hazardous waste disposal companies, and others such as answering services and website managers, should be reviewed to determine what sort of advance notice you will need to give.

Another step to take well in advance is to contact your malpractice insurance carrier. Most carriers have specific guidelines for when to notify your patients – and that notification will vary from carrier to carrier, state to state, and situation to situation. If you have a claims-made policy, you also need to inquire about the necessity of purchasing “tail” coverage, which will protect you in the event of a lawsuit after your practice has closed. Many carriers include tail coverage at no charge if you are retiring completely, but if you expect to do part-time, locum tenens, or volunteer medical work, you will need to pay for it.

Once you have the basics nailed down, notify your employees. You will want them to hear the news from you, not through the grapevine, and certainly not from your patients. You may be worried that some will quit, but keeping them in the dark will not prevent that, as they will find out soon enough. Besides, if you help them by assisting in finding them new employment, they will most likely help you by staying to the end.

At this point, you should also begin thinking about disposition of your patients’ records. You can’t just shred them, much as you might be tempted. Your attorney and malpractice carrier will guide you in how long they must be retained; 7-10 years is typical in many states, but it could be longer in yours. Unless you are selling part or all of your practice to another physician, you will have to designate someone else to be the legal custodian of the records and obtain a written custodial agreement from that person or organization.

Once that is arranged, you can notify your patients. Send them a letter or e-mail (or both) informing them of the date that you intend to close the practice. Let them know where their records will be kept, who to contact for a copy, and that their written consent will be required to obtain it. Some states also require that a notice be placed in the local newspaper or online, including the date of closure and how to request records.

This is also the time to inform all your third-party payers, including Medicare and Medicaid if applicable, any hospitals where you have privileges, and referring physicians. Notify any business concerns not notified already, such as utilities and other ancillary services. Your state medical board and the Drug Enforcement Agency will need to know as well. Contact a liquidator or used equipment dealer to arrange for disposal of any office equipment that has resale value. It is also a good time to decide how you will handle patient collections that trickle in after closing, and where mail should be forwarded.

As the closing date approaches, determine how to properly dispose of any medications you have on-hand. Your state may have requirements for disposal of controlled substances, and possibly for noncontrolled pharmaceuticals as well. Check your state’s controlled substances reporting system and other applicable regulators. Once the office is closed, don’t forget to shred any blank prescription pads and dissolve your corporation, if you have one.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

A very strange place to find a tooth

A nose for the tooth

Have you ever had a stuffy nose that just wouldn’t go away? Those irritating head colds have nothing on the stuffy nose a man in New York recently had to go through. A stuffy nose to top all stuffy noses. One stuffy nose to rule them all, as it were.

This man went to a Mount Sinai clinic with difficulty breathing through his right nostril, a problem that had been going on for years. Let us repeat that: A stuffy nose that lasted for years. The exam revealed a white mass jutting through the back of the septum and a CT scan confirmed the diagnosis. Perhaps you’ve already guessed, since the headline does give things away. Yes, this man had a tooth growing into his nose.

The problem was a half-inch-long ectopic tooth. Ectopic teeth are rare, occurring in less than 1% of people, but an ectopic tooth growing backward into the nasal cavity? Well, that’s so uncommon that this man got a case report in the New England Journal of Medicine.

This story does have a happy ending. Not all ectopic teeth need to be treated, but this one really did have to go. The offending tooth was surgically removed and, at a 3-month follow-up, the stuffy nose issue was completely resolved. So our friend gets the best of both worlds: His issue gets cured and he gets a case report in a major medical publication. If that’s not living the dream, we don’t know what is, and that’s the tooth.

Lettuce recommend you a sleep aid

Lettuce is great for many things. The star in a salad? Of course. The fresh element in a BLT? Yep. A sleep aid? According to a TikTok hack with almost 5 million views, the pinch hitter in a sandwich is switching leagues to be used like a tea for faster sleep. But, does it really work? Researchers say yes and no, according to a recent report at Tyla.com.

Studies conducted in 2013 and 2017 pointed toward a compound called lactucin, which is found in the plant’s n-butanol fraction. In the 2013 study, mice that received n-butanol fraction fell asleep faster and stayed asleep longer. In 2017, researchers found that lettuce made mice sleep longer and helped protect against cell inflammation and damage.

OK, so it works on mice. But what about humans? In the TikTok video, user Shapla Hoque pours hot water on a few lettuce leaves in a mug with a peppermint tea bag (for flavor). After 10 minutes, when the leaves are soaked and soggy, she removes them and drinks the lettuce tea. By the end of the video she’s visibly drowsy and ready to crash. Does this hold water?

Here’s the no. Dr. Charlotte Norton of the Slimming Clinic told Tyla.com that yeah, there are some properties in lettuce that will help you fall asleep, such as lactucarium, which is prominent in romaine. But you would need a massive amount of lettuce to get any effect. The TikTok video, she said, is an example of the placebo effect.

Brains get a rise out of Viagra

A lot of medications are used off label. Antidepressants for COVID have taken the cake recently, but here’s a new one: Viagra for Alzheimer’s disease.

Although there’s no definite link yet between the two, neuron models derived from induced pluripotent stem cells from patients with Alzheimer’s suggest that sildenafil increases neurite growth and decreases phospho-tau expression, Jiansong Fang, PhD, of the Cleveland Clinic, and associates said in Nature Aging.

Their research is an attempt to find untapped sources of new treatments among existing drugs. They began the search with 1,600 approved drugs and focused on those that target the buildup of beta amyloid and tau proteins in the brain, according to the Daily Beast.

Since sildenafil is obviously for men, more research will need to be done on how this drug affects women. Don’t start stocking up just yet.

Omicron is not a social-distancing robot

COVID, safe to say, has not been your typical, run-of-the-mill pandemic. People have protested social distancing. People have protested lockdowns. People have protested mask mandates. People have protested vaccine mandates. People have protested people protesting vaccine mandates.

Someone used a fake arm to get a COVID vaccine card. People have tried to reverse their COVID vaccinations. People had COVID contamination parties.

The common denominator? People. Humans. Maybe what we need is a nonhuman intervention. To fight COVID, we need a hero. A robotic hero.

And where can we find such a hero? The University of Maryland, of course, where computer scientists and engineers are working on an autonomous mobile robot to enforce indoor social-distancing rules.

Their robot can detect lapses in social distancing using cameras, both thermal and visual, along with a LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) sensor. It then sorts the offenders into various groups depending on whether they are standing still or moving and predicts their future movement using a state-of-the-art hybrid collision avoidance method known as Frozone, Adarsh Jagan Sathyamoorthy and associates explained in PLOS One.

“Once it reaches the breach, the robot encourages people to move apart via text that appears on a mounted display,” ScienceDaily said.

Maybe you were expecting a Terminator-type robot coming to enforce social distancing requirements rather than a simple text message. Let’s just hope that all COVID guidelines are followed, including social distancing, so the pandemic will finally end and won’t “be back.”

A nose for the tooth

Have you ever had a stuffy nose that just wouldn’t go away? Those irritating head colds have nothing on the stuffy nose a man in New York recently had to go through. A stuffy nose to top all stuffy noses. One stuffy nose to rule them all, as it were.

This man went to a Mount Sinai clinic with difficulty breathing through his right nostril, a problem that had been going on for years. Let us repeat that: A stuffy nose that lasted for years. The exam revealed a white mass jutting through the back of the septum and a CT scan confirmed the diagnosis. Perhaps you’ve already guessed, since the headline does give things away. Yes, this man had a tooth growing into his nose.

The problem was a half-inch-long ectopic tooth. Ectopic teeth are rare, occurring in less than 1% of people, but an ectopic tooth growing backward into the nasal cavity? Well, that’s so uncommon that this man got a case report in the New England Journal of Medicine.

This story does have a happy ending. Not all ectopic teeth need to be treated, but this one really did have to go. The offending tooth was surgically removed and, at a 3-month follow-up, the stuffy nose issue was completely resolved. So our friend gets the best of both worlds: His issue gets cured and he gets a case report in a major medical publication. If that’s not living the dream, we don’t know what is, and that’s the tooth.

Lettuce recommend you a sleep aid

Lettuce is great for many things. The star in a salad? Of course. The fresh element in a BLT? Yep. A sleep aid? According to a TikTok hack with almost 5 million views, the pinch hitter in a sandwich is switching leagues to be used like a tea for faster sleep. But, does it really work? Researchers say yes and no, according to a recent report at Tyla.com.

Studies conducted in 2013 and 2017 pointed toward a compound called lactucin, which is found in the plant’s n-butanol fraction. In the 2013 study, mice that received n-butanol fraction fell asleep faster and stayed asleep longer. In 2017, researchers found that lettuce made mice sleep longer and helped protect against cell inflammation and damage.

OK, so it works on mice. But what about humans? In the TikTok video, user Shapla Hoque pours hot water on a few lettuce leaves in a mug with a peppermint tea bag (for flavor). After 10 minutes, when the leaves are soaked and soggy, she removes them and drinks the lettuce tea. By the end of the video she’s visibly drowsy and ready to crash. Does this hold water?

Here’s the no. Dr. Charlotte Norton of the Slimming Clinic told Tyla.com that yeah, there are some properties in lettuce that will help you fall asleep, such as lactucarium, which is prominent in romaine. But you would need a massive amount of lettuce to get any effect. The TikTok video, she said, is an example of the placebo effect.

Brains get a rise out of Viagra

A lot of medications are used off label. Antidepressants for COVID have taken the cake recently, but here’s a new one: Viagra for Alzheimer’s disease.

Although there’s no definite link yet between the two, neuron models derived from induced pluripotent stem cells from patients with Alzheimer’s suggest that sildenafil increases neurite growth and decreases phospho-tau expression, Jiansong Fang, PhD, of the Cleveland Clinic, and associates said in Nature Aging.

Their research is an attempt to find untapped sources of new treatments among existing drugs. They began the search with 1,600 approved drugs and focused on those that target the buildup of beta amyloid and tau proteins in the brain, according to the Daily Beast.

Since sildenafil is obviously for men, more research will need to be done on how this drug affects women. Don’t start stocking up just yet.

Omicron is not a social-distancing robot

COVID, safe to say, has not been your typical, run-of-the-mill pandemic. People have protested social distancing. People have protested lockdowns. People have protested mask mandates. People have protested vaccine mandates. People have protested people protesting vaccine mandates.

Someone used a fake arm to get a COVID vaccine card. People have tried to reverse their COVID vaccinations. People had COVID contamination parties.

The common denominator? People. Humans. Maybe what we need is a nonhuman intervention. To fight COVID, we need a hero. A robotic hero.

And where can we find such a hero? The University of Maryland, of course, where computer scientists and engineers are working on an autonomous mobile robot to enforce indoor social-distancing rules.

Their robot can detect lapses in social distancing using cameras, both thermal and visual, along with a LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) sensor. It then sorts the offenders into various groups depending on whether they are standing still or moving and predicts their future movement using a state-of-the-art hybrid collision avoidance method known as Frozone, Adarsh Jagan Sathyamoorthy and associates explained in PLOS One.

“Once it reaches the breach, the robot encourages people to move apart via text that appears on a mounted display,” ScienceDaily said.

Maybe you were expecting a Terminator-type robot coming to enforce social distancing requirements rather than a simple text message. Let’s just hope that all COVID guidelines are followed, including social distancing, so the pandemic will finally end and won’t “be back.”

A nose for the tooth

Have you ever had a stuffy nose that just wouldn’t go away? Those irritating head colds have nothing on the stuffy nose a man in New York recently had to go through. A stuffy nose to top all stuffy noses. One stuffy nose to rule them all, as it were.

This man went to a Mount Sinai clinic with difficulty breathing through his right nostril, a problem that had been going on for years. Let us repeat that: A stuffy nose that lasted for years. The exam revealed a white mass jutting through the back of the septum and a CT scan confirmed the diagnosis. Perhaps you’ve already guessed, since the headline does give things away. Yes, this man had a tooth growing into his nose.

The problem was a half-inch-long ectopic tooth. Ectopic teeth are rare, occurring in less than 1% of people, but an ectopic tooth growing backward into the nasal cavity? Well, that’s so uncommon that this man got a case report in the New England Journal of Medicine.

This story does have a happy ending. Not all ectopic teeth need to be treated, but this one really did have to go. The offending tooth was surgically removed and, at a 3-month follow-up, the stuffy nose issue was completely resolved. So our friend gets the best of both worlds: His issue gets cured and he gets a case report in a major medical publication. If that’s not living the dream, we don’t know what is, and that’s the tooth.

Lettuce recommend you a sleep aid

Lettuce is great for many things. The star in a salad? Of course. The fresh element in a BLT? Yep. A sleep aid? According to a TikTok hack with almost 5 million views, the pinch hitter in a sandwich is switching leagues to be used like a tea for faster sleep. But, does it really work? Researchers say yes and no, according to a recent report at Tyla.com.

Studies conducted in 2013 and 2017 pointed toward a compound called lactucin, which is found in the plant’s n-butanol fraction. In the 2013 study, mice that received n-butanol fraction fell asleep faster and stayed asleep longer. In 2017, researchers found that lettuce made mice sleep longer and helped protect against cell inflammation and damage.

OK, so it works on mice. But what about humans? In the TikTok video, user Shapla Hoque pours hot water on a few lettuce leaves in a mug with a peppermint tea bag (for flavor). After 10 minutes, when the leaves are soaked and soggy, she removes them and drinks the lettuce tea. By the end of the video she’s visibly drowsy and ready to crash. Does this hold water?

Here’s the no. Dr. Charlotte Norton of the Slimming Clinic told Tyla.com that yeah, there are some properties in lettuce that will help you fall asleep, such as lactucarium, which is prominent in romaine. But you would need a massive amount of lettuce to get any effect. The TikTok video, she said, is an example of the placebo effect.

Brains get a rise out of Viagra

A lot of medications are used off label. Antidepressants for COVID have taken the cake recently, but here’s a new one: Viagra for Alzheimer’s disease.

Although there’s no definite link yet between the two, neuron models derived from induced pluripotent stem cells from patients with Alzheimer’s suggest that sildenafil increases neurite growth and decreases phospho-tau expression, Jiansong Fang, PhD, of the Cleveland Clinic, and associates said in Nature Aging.

Their research is an attempt to find untapped sources of new treatments among existing drugs. They began the search with 1,600 approved drugs and focused on those that target the buildup of beta amyloid and tau proteins in the brain, according to the Daily Beast.

Since sildenafil is obviously for men, more research will need to be done on how this drug affects women. Don’t start stocking up just yet.

Omicron is not a social-distancing robot

COVID, safe to say, has not been your typical, run-of-the-mill pandemic. People have protested social distancing. People have protested lockdowns. People have protested mask mandates. People have protested vaccine mandates. People have protested people protesting vaccine mandates.

Someone used a fake arm to get a COVID vaccine card. People have tried to reverse their COVID vaccinations. People had COVID contamination parties.

The common denominator? People. Humans. Maybe what we need is a nonhuman intervention. To fight COVID, we need a hero. A robotic hero.

And where can we find such a hero? The University of Maryland, of course, where computer scientists and engineers are working on an autonomous mobile robot to enforce indoor social-distancing rules.

Their robot can detect lapses in social distancing using cameras, both thermal and visual, along with a LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) sensor. It then sorts the offenders into various groups depending on whether they are standing still or moving and predicts their future movement using a state-of-the-art hybrid collision avoidance method known as Frozone, Adarsh Jagan Sathyamoorthy and associates explained in PLOS One.

“Once it reaches the breach, the robot encourages people to move apart via text that appears on a mounted display,” ScienceDaily said.

Maybe you were expecting a Terminator-type robot coming to enforce social distancing requirements rather than a simple text message. Let’s just hope that all COVID guidelines are followed, including social distancing, so the pandemic will finally end and won’t “be back.”

Vaccine protection drops against Omicron, making boosters crucial

A raft of new

The new studies, from teams of researchers in Germany, South Africa, Sweden, and the drug company Pfizer, showed 25 to 40-fold drops in the ability of antibodies created by two doses of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine to neutralize the virus.

But there seemed to be a bright spot in the studies too. The virus didn’t completely escape the immunity from the vaccines, and giving a third, booster dose appeared to restore antibodies to a level that’s been associated with protection against variants in the past.

“One of the silver linings of this pandemic so far is that mRNA vaccines manufactured based on the ancestral SARS-CoV-2 continue to work in the laboratory and, importantly, in real life against variant strains,” said Hana El Sahly, MD, professor of molecular virology and microbiology at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. “The strains so far vary by their degree of being neutralized by the antibodies from these vaccines, but they are being neutralized nonetheless.”

Dr. El Sahly points out that the Beta variant was associated with a 10-fold drop in antibodies, but two doses of the vaccines still protected against it.

President Biden hailed the study results as good news.

“That Pfizer lab report came back saying that the expectation is that the existing vaccines protect against Omicron. But if you get the booster, you’re really in good shape. And so that’s very encouraging,” he said in a press briefing Dec. 8.

More research needed

Other scientists, however, stressed that these studies are from lab tests, and don’t necessarily reflect what will happen with Omicron in the real world. They cautioned about a worldwide push for boosters with so many countries still struggling to give first doses of vaccines.

Soumya Swaminathan, MD, chief scientist for the World Health Organization, stressed in a press briefing Dec. 8 that the results from the four studies varied widely, showing dips in neutralizing activity with Omicron that ranged from 5-fold to 40-fold.

The types of lab tests that were run were different, too, and involved small numbers of blood samples from patients.

She stressed that immunity depends not just on neutralizing antibodies, which act as a first line of defense when a virus invades, but also on B cells and T cells, and so far, tests show that these crucial components — which are important for preventing severe disease and death — had been less impacted than antibodies.

“So, I think it’s premature to conclude that this reduction in neutralizing activity would result in a significant reduction in vaccine effectiveness,” she said.

Whether or not these first-generation vaccines will be enough to stop Omicron, though, remains to be seen. A study of the Pfizer, Moderna, and AstraZeneca vaccines, led by German physician Sandra Ciesek, MD, who directs the Institute of Medical Virology at the University of Frankfurt, shows a booster didn’t appear to hold up well over time.

Dr. Ciesek and her team exposed Omicron viruses to the antibodies of volunteers who had been boosted with the Pfizer vaccine 3 months prior.

She also compared the results to what happened to those same 3-month antibody levels against Delta variant viruses. She found only a 25% neutralization of Omicron compared with a 95% neutralization of Delta. That represented about a 37-fold reduction in the ability of the antibodies to neutralize Omicron vs Delta.

“The data confirm that developing a vaccine adapted for Omicron makes sense,” she tweeted as part of a long thread she posted on her results.

Retool the vaccines?

Both Pfizer and Moderna are retooling their vaccines to better match them to the changes in the Omicron variant. In a press release, Pfizer said it could start deliveries of that updated vaccine by March, pending U.S. Food and Drug Administration authorization.

“What the booster really does in neutralizing Omicron right now, they don’t know, they have no idea,” said Peter Palese, PhD, chair of the department of microbiology at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York City.

Dr. Palese said he was definitely concerned about a possible Omicron wave.

“There are four major sites on the spike protein targeted by antibodies from the vaccines, and all four sites have mutations,” he said. “All these important antigenic sites are changed.

“If Omicron becomes the new Delta, and the old vaccines really aren’t good enough, then we have to make new Omicron vaccines. Then we have to revaccinate everybody twice,” he said, and the costs could be staggering. “I am worried.”

Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, PhD, director general of the WHO, urged countries to move quickly.

“Don’t wait. Act now,” he said, even before all the science is in hand. “All of us, every government, every individual should use all the tools we have right now,” to drive down transmission, increase testing and surveillance, and share scientific findings.

“We can prevent Omicron [from] becoming a global crisis right now,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A raft of new

The new studies, from teams of researchers in Germany, South Africa, Sweden, and the drug company Pfizer, showed 25 to 40-fold drops in the ability of antibodies created by two doses of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine to neutralize the virus.

But there seemed to be a bright spot in the studies too. The virus didn’t completely escape the immunity from the vaccines, and giving a third, booster dose appeared to restore antibodies to a level that’s been associated with protection against variants in the past.

“One of the silver linings of this pandemic so far is that mRNA vaccines manufactured based on the ancestral SARS-CoV-2 continue to work in the laboratory and, importantly, in real life against variant strains,” said Hana El Sahly, MD, professor of molecular virology and microbiology at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. “The strains so far vary by their degree of being neutralized by the antibodies from these vaccines, but they are being neutralized nonetheless.”

Dr. El Sahly points out that the Beta variant was associated with a 10-fold drop in antibodies, but two doses of the vaccines still protected against it.

President Biden hailed the study results as good news.

“That Pfizer lab report came back saying that the expectation is that the existing vaccines protect against Omicron. But if you get the booster, you’re really in good shape. And so that’s very encouraging,” he said in a press briefing Dec. 8.

More research needed

Other scientists, however, stressed that these studies are from lab tests, and don’t necessarily reflect what will happen with Omicron in the real world. They cautioned about a worldwide push for boosters with so many countries still struggling to give first doses of vaccines.

Soumya Swaminathan, MD, chief scientist for the World Health Organization, stressed in a press briefing Dec. 8 that the results from the four studies varied widely, showing dips in neutralizing activity with Omicron that ranged from 5-fold to 40-fold.

The types of lab tests that were run were different, too, and involved small numbers of blood samples from patients.

She stressed that immunity depends not just on neutralizing antibodies, which act as a first line of defense when a virus invades, but also on B cells and T cells, and so far, tests show that these crucial components — which are important for preventing severe disease and death — had been less impacted than antibodies.

“So, I think it’s premature to conclude that this reduction in neutralizing activity would result in a significant reduction in vaccine effectiveness,” she said.

Whether or not these first-generation vaccines will be enough to stop Omicron, though, remains to be seen. A study of the Pfizer, Moderna, and AstraZeneca vaccines, led by German physician Sandra Ciesek, MD, who directs the Institute of Medical Virology at the University of Frankfurt, shows a booster didn’t appear to hold up well over time.

Dr. Ciesek and her team exposed Omicron viruses to the antibodies of volunteers who had been boosted with the Pfizer vaccine 3 months prior.

She also compared the results to what happened to those same 3-month antibody levels against Delta variant viruses. She found only a 25% neutralization of Omicron compared with a 95% neutralization of Delta. That represented about a 37-fold reduction in the ability of the antibodies to neutralize Omicron vs Delta.

“The data confirm that developing a vaccine adapted for Omicron makes sense,” she tweeted as part of a long thread she posted on her results.

Retool the vaccines?

Both Pfizer and Moderna are retooling their vaccines to better match them to the changes in the Omicron variant. In a press release, Pfizer said it could start deliveries of that updated vaccine by March, pending U.S. Food and Drug Administration authorization.

“What the booster really does in neutralizing Omicron right now, they don’t know, they have no idea,” said Peter Palese, PhD, chair of the department of microbiology at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York City.

Dr. Palese said he was definitely concerned about a possible Omicron wave.

“There are four major sites on the spike protein targeted by antibodies from the vaccines, and all four sites have mutations,” he said. “All these important antigenic sites are changed.

“If Omicron becomes the new Delta, and the old vaccines really aren’t good enough, then we have to make new Omicron vaccines. Then we have to revaccinate everybody twice,” he said, and the costs could be staggering. “I am worried.”

Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, PhD, director general of the WHO, urged countries to move quickly.

“Don’t wait. Act now,” he said, even before all the science is in hand. “All of us, every government, every individual should use all the tools we have right now,” to drive down transmission, increase testing and surveillance, and share scientific findings.

“We can prevent Omicron [from] becoming a global crisis right now,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A raft of new

The new studies, from teams of researchers in Germany, South Africa, Sweden, and the drug company Pfizer, showed 25 to 40-fold drops in the ability of antibodies created by two doses of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine to neutralize the virus.

But there seemed to be a bright spot in the studies too. The virus didn’t completely escape the immunity from the vaccines, and giving a third, booster dose appeared to restore antibodies to a level that’s been associated with protection against variants in the past.

“One of the silver linings of this pandemic so far is that mRNA vaccines manufactured based on the ancestral SARS-CoV-2 continue to work in the laboratory and, importantly, in real life against variant strains,” said Hana El Sahly, MD, professor of molecular virology and microbiology at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. “The strains so far vary by their degree of being neutralized by the antibodies from these vaccines, but they are being neutralized nonetheless.”

Dr. El Sahly points out that the Beta variant was associated with a 10-fold drop in antibodies, but two doses of the vaccines still protected against it.

President Biden hailed the study results as good news.

“That Pfizer lab report came back saying that the expectation is that the existing vaccines protect against Omicron. But if you get the booster, you’re really in good shape. And so that’s very encouraging,” he said in a press briefing Dec. 8.

More research needed

Other scientists, however, stressed that these studies are from lab tests, and don’t necessarily reflect what will happen with Omicron in the real world. They cautioned about a worldwide push for boosters with so many countries still struggling to give first doses of vaccines.

Soumya Swaminathan, MD, chief scientist for the World Health Organization, stressed in a press briefing Dec. 8 that the results from the four studies varied widely, showing dips in neutralizing activity with Omicron that ranged from 5-fold to 40-fold.

The types of lab tests that were run were different, too, and involved small numbers of blood samples from patients.

She stressed that immunity depends not just on neutralizing antibodies, which act as a first line of defense when a virus invades, but also on B cells and T cells, and so far, tests show that these crucial components — which are important for preventing severe disease and death — had been less impacted than antibodies.

“So, I think it’s premature to conclude that this reduction in neutralizing activity would result in a significant reduction in vaccine effectiveness,” she said.

Whether or not these first-generation vaccines will be enough to stop Omicron, though, remains to be seen. A study of the Pfizer, Moderna, and AstraZeneca vaccines, led by German physician Sandra Ciesek, MD, who directs the Institute of Medical Virology at the University of Frankfurt, shows a booster didn’t appear to hold up well over time.

Dr. Ciesek and her team exposed Omicron viruses to the antibodies of volunteers who had been boosted with the Pfizer vaccine 3 months prior.

She also compared the results to what happened to those same 3-month antibody levels against Delta variant viruses. She found only a 25% neutralization of Omicron compared with a 95% neutralization of Delta. That represented about a 37-fold reduction in the ability of the antibodies to neutralize Omicron vs Delta.

“The data confirm that developing a vaccine adapted for Omicron makes sense,” she tweeted as part of a long thread she posted on her results.

Retool the vaccines?

Both Pfizer and Moderna are retooling their vaccines to better match them to the changes in the Omicron variant. In a press release, Pfizer said it could start deliveries of that updated vaccine by March, pending U.S. Food and Drug Administration authorization.

“What the booster really does in neutralizing Omicron right now, they don’t know, they have no idea,” said Peter Palese, PhD, chair of the department of microbiology at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York City.

Dr. Palese said he was definitely concerned about a possible Omicron wave.

“There are four major sites on the spike protein targeted by antibodies from the vaccines, and all four sites have mutations,” he said. “All these important antigenic sites are changed.

“If Omicron becomes the new Delta, and the old vaccines really aren’t good enough, then we have to make new Omicron vaccines. Then we have to revaccinate everybody twice,” he said, and the costs could be staggering. “I am worried.”

Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, PhD, director general of the WHO, urged countries to move quickly.

“Don’t wait. Act now,” he said, even before all the science is in hand. “All of us, every government, every individual should use all the tools we have right now,” to drive down transmission, increase testing and surveillance, and share scientific findings.

“We can prevent Omicron [from] becoming a global crisis right now,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A sun distributed rash

The photo distribution and annular quality of this patient’s rash, combined with his positive autoimmune work-up, led to a diagnosis of subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE), a nonscarring subtype of cutaneous lupus erythematosus.

SCLE is a chronic and relapsing condition that may manifest as either a papulosquamous or annular eruption.1 It most commonly affects areas of sun exposure such as the shoulders, upper back, and extensor surfaces of the arms. This disorder typically affects young or middle-aged women between the ages of 30 and 40 years.

The differential diagnosis of this eruption includes dermatomyositis, polymorphous light eruption, psoriasis, tinea corporis, and other photodermatoses. The etiology of SCLE is multifactorial and may include a genetic susceptibility in combination with environmental triggers that provoke an autoimmune response to sunlight.1 There is strong evidence linking drug-induced SCLE with proton pump inhibitors, anticonvulsants, beta-blockers, terbinafine, and immune modulators.2

As many as 70% of patients with SCLE have positive anti-Ro/SSA autoantibodies, and this is most often associated with Sjogren syndrome.1 Interestingly, SCLE patients often exhibit symptoms that overlap with Sjogren syndrome. Systemic involvement is rare in SCLE, and if present, these symptoms are usually limited to arthritis and myalgia.

Treatment of SCLE includes photo-protective behaviors, topical corticosteroids/calcineurin inhibitors, and systemic therapies such as hydroxychloroquine (first-line), methotrexate, and mycophenolate mofetil (second-line).2

Our patient was started on hydroxychloroquine 200 mg orally bid, with complete resolution of the lesions at his 2 month–follow-up appointment. This case emphasizes the importance of distinguishing SCLE from other subtypes of lupus erythematosus as the prognostic course and treatment varies between these conditions.

Photos courtesy of Kriti Mishra, MD. Text courtesy of Jaimie Lin, BS, Kriti Mishra, MD, Department of Dermatology, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

1. Okon LG, Werth VP. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus: diagnosis and treatment. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2013;27:391-404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.berh.2013.07.008

2. Jatwani S, Hearth Holmes MP. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. 2021. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2021.

The photo distribution and annular quality of this patient’s rash, combined with his positive autoimmune work-up, led to a diagnosis of subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE), a nonscarring subtype of cutaneous lupus erythematosus.

SCLE is a chronic and relapsing condition that may manifest as either a papulosquamous or annular eruption.1 It most commonly affects areas of sun exposure such as the shoulders, upper back, and extensor surfaces of the arms. This disorder typically affects young or middle-aged women between the ages of 30 and 40 years.

The differential diagnosis of this eruption includes dermatomyositis, polymorphous light eruption, psoriasis, tinea corporis, and other photodermatoses. The etiology of SCLE is multifactorial and may include a genetic susceptibility in combination with environmental triggers that provoke an autoimmune response to sunlight.1 There is strong evidence linking drug-induced SCLE with proton pump inhibitors, anticonvulsants, beta-blockers, terbinafine, and immune modulators.2

As many as 70% of patients with SCLE have positive anti-Ro/SSA autoantibodies, and this is most often associated with Sjogren syndrome.1 Interestingly, SCLE patients often exhibit symptoms that overlap with Sjogren syndrome. Systemic involvement is rare in SCLE, and if present, these symptoms are usually limited to arthritis and myalgia.

Treatment of SCLE includes photo-protective behaviors, topical corticosteroids/calcineurin inhibitors, and systemic therapies such as hydroxychloroquine (first-line), methotrexate, and mycophenolate mofetil (second-line).2

Our patient was started on hydroxychloroquine 200 mg orally bid, with complete resolution of the lesions at his 2 month–follow-up appointment. This case emphasizes the importance of distinguishing SCLE from other subtypes of lupus erythematosus as the prognostic course and treatment varies between these conditions.

Photos courtesy of Kriti Mishra, MD. Text courtesy of Jaimie Lin, BS, Kriti Mishra, MD, Department of Dermatology, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

The photo distribution and annular quality of this patient’s rash, combined with his positive autoimmune work-up, led to a diagnosis of subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE), a nonscarring subtype of cutaneous lupus erythematosus.

SCLE is a chronic and relapsing condition that may manifest as either a papulosquamous or annular eruption.1 It most commonly affects areas of sun exposure such as the shoulders, upper back, and extensor surfaces of the arms. This disorder typically affects young or middle-aged women between the ages of 30 and 40 years.

The differential diagnosis of this eruption includes dermatomyositis, polymorphous light eruption, psoriasis, tinea corporis, and other photodermatoses. The etiology of SCLE is multifactorial and may include a genetic susceptibility in combination with environmental triggers that provoke an autoimmune response to sunlight.1 There is strong evidence linking drug-induced SCLE with proton pump inhibitors, anticonvulsants, beta-blockers, terbinafine, and immune modulators.2

As many as 70% of patients with SCLE have positive anti-Ro/SSA autoantibodies, and this is most often associated with Sjogren syndrome.1 Interestingly, SCLE patients often exhibit symptoms that overlap with Sjogren syndrome. Systemic involvement is rare in SCLE, and if present, these symptoms are usually limited to arthritis and myalgia.

Treatment of SCLE includes photo-protective behaviors, topical corticosteroids/calcineurin inhibitors, and systemic therapies such as hydroxychloroquine (first-line), methotrexate, and mycophenolate mofetil (second-line).2

Our patient was started on hydroxychloroquine 200 mg orally bid, with complete resolution of the lesions at his 2 month–follow-up appointment. This case emphasizes the importance of distinguishing SCLE from other subtypes of lupus erythematosus as the prognostic course and treatment varies between these conditions.

Photos courtesy of Kriti Mishra, MD. Text courtesy of Jaimie Lin, BS, Kriti Mishra, MD, Department of Dermatology, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

1. Okon LG, Werth VP. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus: diagnosis and treatment. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2013;27:391-404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.berh.2013.07.008

2. Jatwani S, Hearth Holmes MP. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. 2021. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2021.

1. Okon LG, Werth VP. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus: diagnosis and treatment. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2013;27:391-404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.berh.2013.07.008

2. Jatwani S, Hearth Holmes MP. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. 2021. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2021.

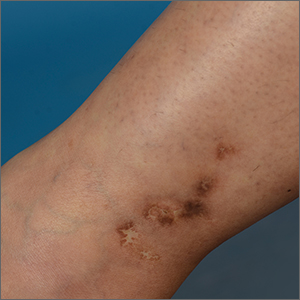

White ankle scars

A 42-year-old woman presented to our dermatology center with white scars on both of her ankles. She first noticed the lesions 2 years prior; they were initially erythematous and painful, even when she was at rest. Her past medical history included 3 spontaneous term miscarriages. She denied any prolonged standing or trauma.

On examination, atrophic porcelain-white stellate scars were visible with surrounding hyperpigmentation on the medial aspect of both ankles (FIGURE 1A & 1B). There were no tender erythematous nodules,

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Atrophie blanche

Atrophie blanche is a morphologic feature described as porcelain-white stellate scars with surrounding telangiectasia and hyperpigmentation. The lesions are typically found over the peri-malleolar region and are sequelae of healed erythematous and painful ulcers. The lesions arise from upper dermal, small vessel, thrombotic vasculopathy leading to ischemic rest pain; if left untreated, atrophic white scars eventually develop.

A sign of venous insufficiency or thrombotic vasculopathy

Atrophie blanche may develop following healing of an ulcer due to venous insufficiency or small vessel thrombotic vasculopathy.1 The incidence of thrombotic vasculopathy is 1:100,000 with a female predominance, and up to 50% of cases are associated with procoagulant conditions.2 Thrombotic vasculopathy can be due to an inherited or acquired thrombophilia.1

Causes of hereditary thrombophilia include Factor V Leiden/prothrombin mutations, anti-thrombin III/protein C/protein S deficiencies, dysfibrinogenemia, and hyperhomocysteinemia.

Acquired thrombophilia arises from underlying prothrombotic states associated with the Virchow triad: hypercoagulability, blood flow stasis, and endothelial injury. The use of oral contraceptives or hormone replacement therapy, presence of malignancy, and antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) are causes of acquired thrombophilia.2

Obtaining a careful history is crucial

Thorough history-taking and physical examination are required to determine the underlying cause of atrophie blanche.

Continue to: Chronic venous insufficiency

Chronic venous insufficiency is more likely in patients with a history of prolonged standing, obesity, or previous injury/surgery to leg veins. Physical examination would reveal hyperpigmentation, telangiectasia, varicose veins, pedal edema, and venous ulcers.3

Inherited thrombophilia may be at work in patients with a family history of arterial and venous thrombosis (eg, stroke, acute coronary syndrome, or deep vein thromboses).

Acquired thrombophilia should be suspected if there is a history of recurrent miscarriages or malignancy.4 Given our patient’s history of miscarriages, we ordered further lab work and found that she had elevated anticardiolipin levels (> 40 U/mL) fulfilling the revised Sapporo criteria5 for APS.

Thrombophilia or chronic venous insufficiency? In a patient with a history suggestive of thrombophilia, further work-up should be done before attributing atrophie blanche to healed venous ulcers from chronic venous insufficiency. A skin lesion biopsy could reveal classic changes of thrombotic vasculopathy subjacent to the ulcer, including intraluminal thrombosis, endothelial proliferation, and subintimal hyaline degeneration, as opposed to dermal changes consistent with venous stasis, such as increased siderophages, hemosiderin deposition, erythrocyte extravasation, dermal fibrosis, and adipocytic damage.

Differential diagnosis includes atrophic scarring

The differential diagnosis for hypopigmented atrophic macules and plaques over the lower limbs include atrophic scarring from previous trauma, guttate morphea, extra-genital lichen sclerosus, and tuberculoid leprosy.

Continue to: Atrophic scarring

Atrophic scarring occurs only after trauma.

Guttate morphea lesions are sclerotic and may be depressed.

Extra-genital lichen sclerosus is characterized by polygonal, shiny, ivory-white sclerotic lesions with or without follicular plugging.

Tuberculoid leprosy involves loss of nociception, hypotrichosis, and palpable thickened regional nerves (eg, great auricular, sural, or ulnar nerve).

Treatment requires long-term anticoagulation

Our patient had APS and the mainstay of treatment is long-term systemic anticoagulation along with attentive wound care.6 Warfarin is preferred over a direct oral anticoagulant as it is more effective in the prevention of recurrent thrombosis in patients with APS.7

Our patient was started on warfarin. Since APS may occur as a primary condition or in the setting of a systemic disease, such as systemic lupus erythematosus, she was referred to a rheumatologist.

1. Alavi A, Hafner J, Dutz JP, et al. Atrophie blanche: is it associated with venous disease or livedoid vasculopathy? Adv Skin Wound Care. 2014;27:518-24. doi: 10.1097/01.ASW.0000455098.98684.95

2. Di Giacomo TB, Hussein TP, Souza DG, et al. Frequency of thrombophilia determinant factors in patients with livedoid vasculopathy and treatment with anticoagulant drugs—a prospective study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:1340-1346. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03646.x

3. Millan SB, Gan R, Townsend PE. Venous ulcers: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2019;100:298-305.

4. Armstrong EM, Bellone JM, Hornsby LB, et al. Acquired thrombophilia. J Pharm Pract. 2014;27:234-242. doi: 10.1177/0897190014530424

5. Miyakis S, Lockshin MD, Atsumi T, et al. International consensus statement on an update of the classification criteria for definite antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:295-306. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01753.x

6. Stevens SM, Woller SC, Bauer KA, et al. Guidance for the evaluation and treatment of hereditary and acquired thrombophilia. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2016;41:154-164. doi: 10.1007/s11239-015-1316-1

7. Cohen H, Hunt BJ, Efthymiou M, et al. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin to treat patients with thrombotic antiphospholipid syndrome, with or without systemic lupus erythematosus (RAPS): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 2/3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Haematol. 2016;3:e426-e436. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(16)30079-5

A 42-year-old woman presented to our dermatology center with white scars on both of her ankles. She first noticed the lesions 2 years prior; they were initially erythematous and painful, even when she was at rest. Her past medical history included 3 spontaneous term miscarriages. She denied any prolonged standing or trauma.

On examination, atrophic porcelain-white stellate scars were visible with surrounding hyperpigmentation on the medial aspect of both ankles (FIGURE 1A & 1B). There were no tender erythematous nodules,

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Atrophie blanche

Atrophie blanche is a morphologic feature described as porcelain-white stellate scars with surrounding telangiectasia and hyperpigmentation. The lesions are typically found over the peri-malleolar region and are sequelae of healed erythematous and painful ulcers. The lesions arise from upper dermal, small vessel, thrombotic vasculopathy leading to ischemic rest pain; if left untreated, atrophic white scars eventually develop.

A sign of venous insufficiency or thrombotic vasculopathy

Atrophie blanche may develop following healing of an ulcer due to venous insufficiency or small vessel thrombotic vasculopathy.1 The incidence of thrombotic vasculopathy is 1:100,000 with a female predominance, and up to 50% of cases are associated with procoagulant conditions.2 Thrombotic vasculopathy can be due to an inherited or acquired thrombophilia.1

Causes of hereditary thrombophilia include Factor V Leiden/prothrombin mutations, anti-thrombin III/protein C/protein S deficiencies, dysfibrinogenemia, and hyperhomocysteinemia.

Acquired thrombophilia arises from underlying prothrombotic states associated with the Virchow triad: hypercoagulability, blood flow stasis, and endothelial injury. The use of oral contraceptives or hormone replacement therapy, presence of malignancy, and antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) are causes of acquired thrombophilia.2

Obtaining a careful history is crucial

Thorough history-taking and physical examination are required to determine the underlying cause of atrophie blanche.

Continue to: Chronic venous insufficiency

Chronic venous insufficiency is more likely in patients with a history of prolonged standing, obesity, or previous injury/surgery to leg veins. Physical examination would reveal hyperpigmentation, telangiectasia, varicose veins, pedal edema, and venous ulcers.3

Inherited thrombophilia may be at work in patients with a family history of arterial and venous thrombosis (eg, stroke, acute coronary syndrome, or deep vein thromboses).

Acquired thrombophilia should be suspected if there is a history of recurrent miscarriages or malignancy.4 Given our patient’s history of miscarriages, we ordered further lab work and found that she had elevated anticardiolipin levels (> 40 U/mL) fulfilling the revised Sapporo criteria5 for APS.

Thrombophilia or chronic venous insufficiency? In a patient with a history suggestive of thrombophilia, further work-up should be done before attributing atrophie blanche to healed venous ulcers from chronic venous insufficiency. A skin lesion biopsy could reveal classic changes of thrombotic vasculopathy subjacent to the ulcer, including intraluminal thrombosis, endothelial proliferation, and subintimal hyaline degeneration, as opposed to dermal changes consistent with venous stasis, such as increased siderophages, hemosiderin deposition, erythrocyte extravasation, dermal fibrosis, and adipocytic damage.

Differential diagnosis includes atrophic scarring

The differential diagnosis for hypopigmented atrophic macules and plaques over the lower limbs include atrophic scarring from previous trauma, guttate morphea, extra-genital lichen sclerosus, and tuberculoid leprosy.

Continue to: Atrophic scarring

Atrophic scarring occurs only after trauma.

Guttate morphea lesions are sclerotic and may be depressed.

Extra-genital lichen sclerosus is characterized by polygonal, shiny, ivory-white sclerotic lesions with or without follicular plugging.

Tuberculoid leprosy involves loss of nociception, hypotrichosis, and palpable thickened regional nerves (eg, great auricular, sural, or ulnar nerve).

Treatment requires long-term anticoagulation

Our patient had APS and the mainstay of treatment is long-term systemic anticoagulation along with attentive wound care.6 Warfarin is preferred over a direct oral anticoagulant as it is more effective in the prevention of recurrent thrombosis in patients with APS.7

Our patient was started on warfarin. Since APS may occur as a primary condition or in the setting of a systemic disease, such as systemic lupus erythematosus, she was referred to a rheumatologist.

A 42-year-old woman presented to our dermatology center with white scars on both of her ankles. She first noticed the lesions 2 years prior; they were initially erythematous and painful, even when she was at rest. Her past medical history included 3 spontaneous term miscarriages. She denied any prolonged standing or trauma.

On examination, atrophic porcelain-white stellate scars were visible with surrounding hyperpigmentation on the medial aspect of both ankles (FIGURE 1A & 1B). There were no tender erythematous nodules,

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Atrophie blanche

Atrophie blanche is a morphologic feature described as porcelain-white stellate scars with surrounding telangiectasia and hyperpigmentation. The lesions are typically found over the peri-malleolar region and are sequelae of healed erythematous and painful ulcers. The lesions arise from upper dermal, small vessel, thrombotic vasculopathy leading to ischemic rest pain; if left untreated, atrophic white scars eventually develop.

A sign of venous insufficiency or thrombotic vasculopathy

Atrophie blanche may develop following healing of an ulcer due to venous insufficiency or small vessel thrombotic vasculopathy.1 The incidence of thrombotic vasculopathy is 1:100,000 with a female predominance, and up to 50% of cases are associated with procoagulant conditions.2 Thrombotic vasculopathy can be due to an inherited or acquired thrombophilia.1

Causes of hereditary thrombophilia include Factor V Leiden/prothrombin mutations, anti-thrombin III/protein C/protein S deficiencies, dysfibrinogenemia, and hyperhomocysteinemia.

Acquired thrombophilia arises from underlying prothrombotic states associated with the Virchow triad: hypercoagulability, blood flow stasis, and endothelial injury. The use of oral contraceptives or hormone replacement therapy, presence of malignancy, and antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) are causes of acquired thrombophilia.2

Obtaining a careful history is crucial

Thorough history-taking and physical examination are required to determine the underlying cause of atrophie blanche.

Continue to: Chronic venous insufficiency

Chronic venous insufficiency is more likely in patients with a history of prolonged standing, obesity, or previous injury/surgery to leg veins. Physical examination would reveal hyperpigmentation, telangiectasia, varicose veins, pedal edema, and venous ulcers.3

Inherited thrombophilia may be at work in patients with a family history of arterial and venous thrombosis (eg, stroke, acute coronary syndrome, or deep vein thromboses).

Acquired thrombophilia should be suspected if there is a history of recurrent miscarriages or malignancy.4 Given our patient’s history of miscarriages, we ordered further lab work and found that she had elevated anticardiolipin levels (> 40 U/mL) fulfilling the revised Sapporo criteria5 for APS.

Thrombophilia or chronic venous insufficiency? In a patient with a history suggestive of thrombophilia, further work-up should be done before attributing atrophie blanche to healed venous ulcers from chronic venous insufficiency. A skin lesion biopsy could reveal classic changes of thrombotic vasculopathy subjacent to the ulcer, including intraluminal thrombosis, endothelial proliferation, and subintimal hyaline degeneration, as opposed to dermal changes consistent with venous stasis, such as increased siderophages, hemosiderin deposition, erythrocyte extravasation, dermal fibrosis, and adipocytic damage.

Differential diagnosis includes atrophic scarring

The differential diagnosis for hypopigmented atrophic macules and plaques over the lower limbs include atrophic scarring from previous trauma, guttate morphea, extra-genital lichen sclerosus, and tuberculoid leprosy.

Continue to: Atrophic scarring

Atrophic scarring occurs only after trauma.

Guttate morphea lesions are sclerotic and may be depressed.

Extra-genital lichen sclerosus is characterized by polygonal, shiny, ivory-white sclerotic lesions with or without follicular plugging.

Tuberculoid leprosy involves loss of nociception, hypotrichosis, and palpable thickened regional nerves (eg, great auricular, sural, or ulnar nerve).

Treatment requires long-term anticoagulation

Our patient had APS and the mainstay of treatment is long-term systemic anticoagulation along with attentive wound care.6 Warfarin is preferred over a direct oral anticoagulant as it is more effective in the prevention of recurrent thrombosis in patients with APS.7

Our patient was started on warfarin. Since APS may occur as a primary condition or in the setting of a systemic disease, such as systemic lupus erythematosus, she was referred to a rheumatologist.

1. Alavi A, Hafner J, Dutz JP, et al. Atrophie blanche: is it associated with venous disease or livedoid vasculopathy? Adv Skin Wound Care. 2014;27:518-24. doi: 10.1097/01.ASW.0000455098.98684.95

2. Di Giacomo TB, Hussein TP, Souza DG, et al. Frequency of thrombophilia determinant factors in patients with livedoid vasculopathy and treatment with anticoagulant drugs—a prospective study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:1340-1346. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03646.x

3. Millan SB, Gan R, Townsend PE. Venous ulcers: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2019;100:298-305.

4. Armstrong EM, Bellone JM, Hornsby LB, et al. Acquired thrombophilia. J Pharm Pract. 2014;27:234-242. doi: 10.1177/0897190014530424

5. Miyakis S, Lockshin MD, Atsumi T, et al. International consensus statement on an update of the classification criteria for definite antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:295-306. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01753.x

6. Stevens SM, Woller SC, Bauer KA, et al. Guidance for the evaluation and treatment of hereditary and acquired thrombophilia. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2016;41:154-164. doi: 10.1007/s11239-015-1316-1

7. Cohen H, Hunt BJ, Efthymiou M, et al. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin to treat patients with thrombotic antiphospholipid syndrome, with or without systemic lupus erythematosus (RAPS): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 2/3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Haematol. 2016;3:e426-e436. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(16)30079-5

1. Alavi A, Hafner J, Dutz JP, et al. Atrophie blanche: is it associated with venous disease or livedoid vasculopathy? Adv Skin Wound Care. 2014;27:518-24. doi: 10.1097/01.ASW.0000455098.98684.95

2. Di Giacomo TB, Hussein TP, Souza DG, et al. Frequency of thrombophilia determinant factors in patients with livedoid vasculopathy and treatment with anticoagulant drugs—a prospective study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:1340-1346. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03646.x

3. Millan SB, Gan R, Townsend PE. Venous ulcers: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2019;100:298-305.

4. Armstrong EM, Bellone JM, Hornsby LB, et al. Acquired thrombophilia. J Pharm Pract. 2014;27:234-242. doi: 10.1177/0897190014530424

5. Miyakis S, Lockshin MD, Atsumi T, et al. International consensus statement on an update of the classification criteria for definite antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:295-306. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01753.x

6. Stevens SM, Woller SC, Bauer KA, et al. Guidance for the evaluation and treatment of hereditary and acquired thrombophilia. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2016;41:154-164. doi: 10.1007/s11239-015-1316-1

7. Cohen H, Hunt BJ, Efthymiou M, et al. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin to treat patients with thrombotic antiphospholipid syndrome, with or without systemic lupus erythematosus (RAPS): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 2/3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Haematol. 2016;3:e426-e436. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(16)30079-5

25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration is key to analyzing vitamin D’s effects

The recent Practice Alert by Dr. Campos-Outcalt, “How to proceed when it comes to vitamin D” (J Fam Pract. 2021;70:289-292) claimed that the value of vitamin D supplements for prevention is nil or still unknown.1 Most of the references cited in support of this statement were centered on randomized controlled trials (RCTs) based on vitamin D dose rather than achieved 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] concentration. Since the health effects of vitamin D supplementation are correlated with 25(OH)D concentration, the latter should be used to evaluate the results of vitamin D RCTs—a point I made in my 2018 article on the topic.2

For example, in the Vitamin D and Type 2 Diabetes (D2d) Study, in which participants in the treatment arm received 4000 IU/d vitamin D3, there was no reduced rate of progression from prediabetes to diabetes. However, when 25(OH)D concentrations were analyzed for those in the vitamin D arm during the trial, the risk was found to be reduced by 25% (hazard ratio [HR] = 0.75; 95% CI, 0.68-0.82) per 10 ng/mL increase in 25(OH)D.3

Another trial, the Harvard-led VITamin D and OmegA-3 TriaL (VITAL), enrolled more than 25,000 participants, with the treatment arm receiving 2000 IU/d vitamin D3.4 There were no significant reductions in incidence of either cancer or cardiovascular disease for the entire group. The mean baseline 25(OH)D concentration for those for whom values were provided was 31 ng/mL (32.2 ng/mL for White participants, 24.9 ng/mL for Black participants). However, there were ~25% reductions in cancer risk among Black participants (who had lower 25(OH)D concentrations than White participants) and those with a body mass index < 25. A posthoc analysis suggested a possible benefit related to the rate of total cancer deaths.

A recent article reported the results of long-term vitamin D supplementation among Veterans Health Administration patients who had an initial 25(OH)D concentration of < 20 ng/mL.5 For those who were treated with vitamin D and achieved a 25(OH)D concentration of > 30 ng/mL (compared to those who were untreated and had an average concentration of < 20 ng/mL), the risk of myocardial infarction was 27% lower (HR = 0.73; 95% CI, 0.55-0.96) and the risk of all-cause mortality was reduced by 39% (HR = 0.61; 95% CI, 0.56-0.67).

An analysis of SARS-CoV-2 positivity examined data for more than 190,000 patients in the United States who had serum 25(OH)D concentration measurements taken up to 1 year prior to their SARS-CoV-2 test. Positivity rates were 12.5% (95% CI, 12.2%-12.8%) for those with a 25(OH)D concentration < 20 ng/mL vs 5.9% (95% CI, 5.5%-6.4%) for those with a 25(OH)D concentration ≥55 ng/mL.6

Thus, there are significant benefits of vitamin D supplementation to achieve a 25(OH)D concentration of 30 to 60 ng/mL for important health outcomes.

Continue to: Author's Response

Author's response

I appreciate the letter from Dr. Grant in response to my previous Practice Alert, as it provides an opportunity to make some important points about assessment of scientific evidence and drawing conclusions based on sound methodology. There is an overabundance of scientific literature published, much of which is of questionable quality, meaning a “study” or 2 can be found to support any preconceived point of view.

In 2011, the Institute of Medicine (now the National Academy of Medicine) published a series of recommendations on how trustworthy recommendations and guidelines should be produced.1,2 Key among the steps recommended is a full assessment of the totality of the literature on the subject by an independent, nonconflicted panel. This should be based on a systematic review that includes standard search methods to find all pertinent articles, an assessment of the quality of each study using standardized tools, and an overall assessment of the quality of the evidence. A high-quality systematic review meeting these standards was the basis for my review article on vitamin D.3

To challenge the findings of the unproven benefits of vitamin D, Dr. Grant cited 4 studies to support the purported benefit of achieving a specific serum 25(OH)D level to prevent cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancer, and COVID-19. After reading these studies, I would not consider any of them a “game changer.”

The first study was restricted to those with prediabetes, had limited follow-up (mean of 2.5 years), and found different results for those with the same 25(OH)D concentrations in the placebo and treatment groups.4 The second study was a large, well-conducted clinical trial that found no benefit of vitamin D supplementation in preventing cancer and cardiovascular disease.5 While Dr. Grant claims that benefits were found for some subgroups, I could locate only the statistics on cancer incidence in Black participants, and the confidence intervals showed no statistically significant benefit. It is always questionable to look at multiple outcomes in multiple subgroups without a prior hypothesis because of the likely occurrence of chance findings in so many comparisons. The third was a retrospective observational study with all the potential biases and challenges to validity that such studies present.6 A single study, especially 1 with observational methods, almost never conclusively settles a point.

The role of vitamin D in the prevention or treatment of COVID-19 is an aspect that was not covered in the systematic review by the US Preventive Services Task Force. The study on this issuecited by Dr. Grant was a large retrospective observational study that found an inverse relationship between serum 25(OH)D levels and SARS-CoV-2 positivity rates.7 This is 1 observational study with interesting results. However, I believe the conclusion of the National Institutes of Health is currently still the correct one: “There is insufficient evidence to recommend either for or against the use of vitamin D for the prevention or treatment of COVID-19.”8

With time and further research, Dr. Grant may eventually prove to be correct on specific points. However, when challenging a high-quality systematic review, one must assess the quality of the studies used while also placing them in context of the totality of the literature.

Doug Campos-Outcalt, MD, MPA

Phoenix, AZ

References

1. Institute of Medicine. Finding What Works in Health Care. The National Academy Press, 2011.

2. Institute of Medicine. Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust. The National Academy Press, 2011.

3. Kahwati LC, LeBlanc E, Weber RP, et al. Screening for vitamin D deficiency in adults; updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2021;325:1443-1463. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.26498

4. Dawson-Hughes B, Staten MA, Knowler WC, et al. Intratrial exposure to vitamin D and new-onset diabetes among adults with prediabetes: a secondary analysis from the Vitamin D and Type 2 Diabetes (D2d) Study. Diabetes Care. 2020;43:2916-2922. doi: 10.2337/dc20-1765