User login

Fever following cesarean delivery: What are your steps for management?

CASE Woman who has undergone recent cesarean delivery

A 23-year-old woman had a primary cesarean delivery 72 hours ago due to an arrest of dilation at 6 cm. She was in labor for 22 hours, and her membranes were ruptured for 18 hours. She had 10 internal vaginal examinations, and the duration of internal fetal monitoring was 12 hours; 24 hours after delivery, she developed a fever of 39°C, in association with lower abdominal pain and tenderness. She was presumptively treated for endometritis with cefepime; 48 hours after the initiation of antibiotics, she remains febrile and symptomatic.

- What are the most likely causes of her persistent fever?

- What should be the next steps in her evaluation?

Cesarean delivery background

Cesarean delivery is now the most common major operation performed in US hospitals. Cesarean delivery rates hover between 25% and 30% in most medical centers in the United States.1 The most common postoperative complication of cesarean delivery is infection. Infection typically takes 1 of 3 forms: endometritis (organ space infection), wound infection (surgical site infection), and urinary tract infection (UTI).1 This article will review the initial differential diagnosis, evaluation, and management of the patient with a postoperative fever and also will describe the appropriate assessment and treatment of the patient who has a persistent postoperative fever despite therapy. The article will also highlight key interventions that help to prevent postoperative infections.

Initial evaluation of the febrile patient

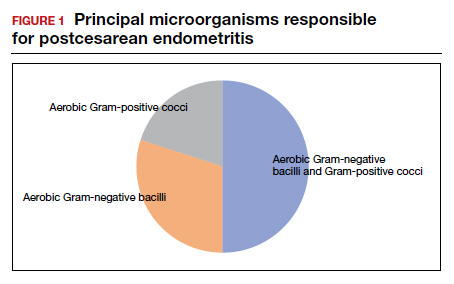

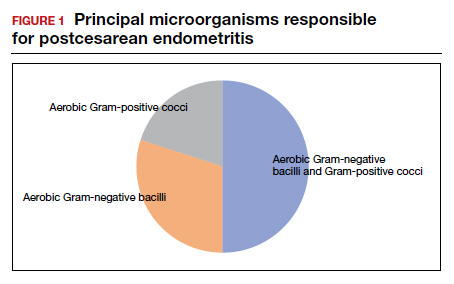

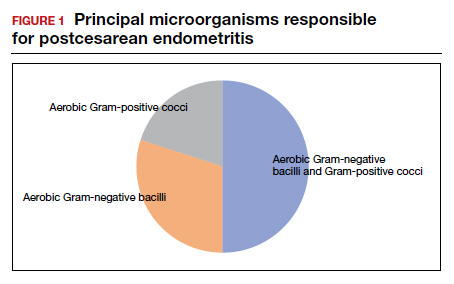

In the first 24 to 48 hours after cesarean delivery, the most common cause of fever is endometritis (organ space infection). This condition is a polymicrobial, mixed aerobic-anaerobic infection (FIGURE). The principal pathogens include anaerobic gram-positive cocci (

The major risk factors for postcesarean endometritis are extended duration of labor and ruptured membranes, multiple internal vaginal examinations, invasive fetal monitoring, and pre-existing colonization with group B Streptococcus and/or the organisms that cause bacterial vaginosis. Affected patients typically have a fever in the range of 38 to 39°C, tachycardia, mild tachypnea, lower abdominal pain and tenderness, and purulent lochia in some individuals.1

Differential for postoperative fever

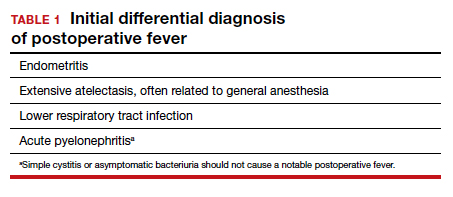

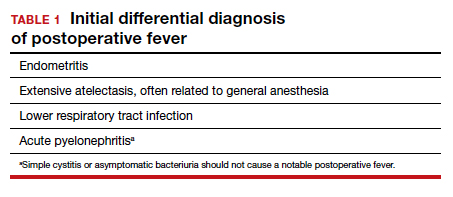

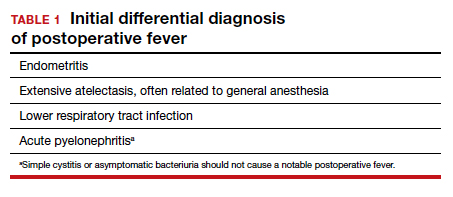

The initial differential diagnosis of postoperative fever is relatively limited (TABLE 1). In addition to endometritis, it includes extensive atelectasis, perhaps resulting from general anesthesia; lower respiratory tract infection, either viral influenza or bacterial pneumonia; and acute pyelonephritis. A simple infection of the bladder (cystitis or asymptomatic bacteriuria) should not cause a substantial temperature elevation and systemic symptoms.1

Differentiation between these entities usually is possible based on physical examination and a few laboratory tests. The peripheral white blood cell count usually is elevated, and a left shift may be evident. If a respiratory tract infection is suspected, chest radiography is indicated. A urine culture should be obtained if acute pyelonephritis strongly is considered. Lower genital tract cultures are rarely of value, and uncontaminated upper tract cultures are difficult to obtain. I do not believe that blood cultures should be performed as a matter of routine. They are expensive, and the results are often not available until after the patient has cleared her infection and left the hospital. However, I would obtain blood cultures in patients who meet one of these criteria1,2:

- They are immunocompromised (eg, HIV infection).

- They have a cardiac or vascular prosthesis and, thus, are at increased risk of complications related to bacteremia.

- They seem critically ill at the onset of evaluation.

- They fail to respond appropriately to initial therapy.

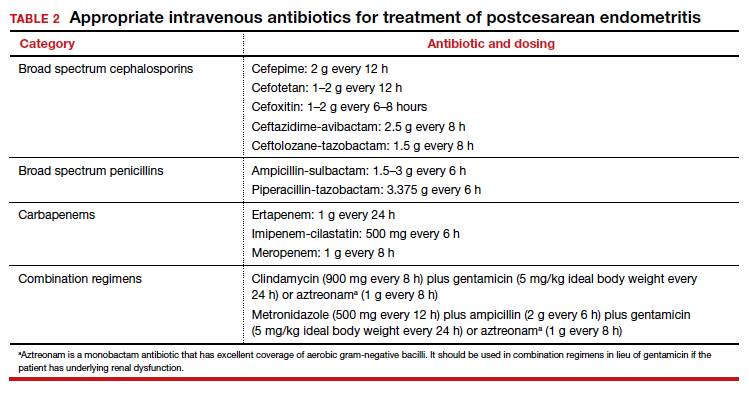

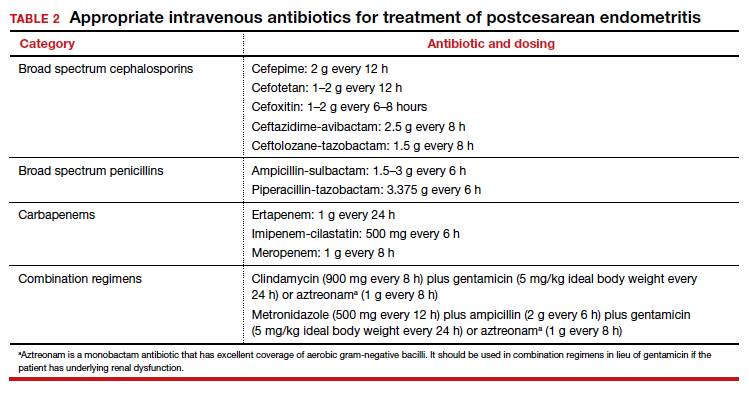

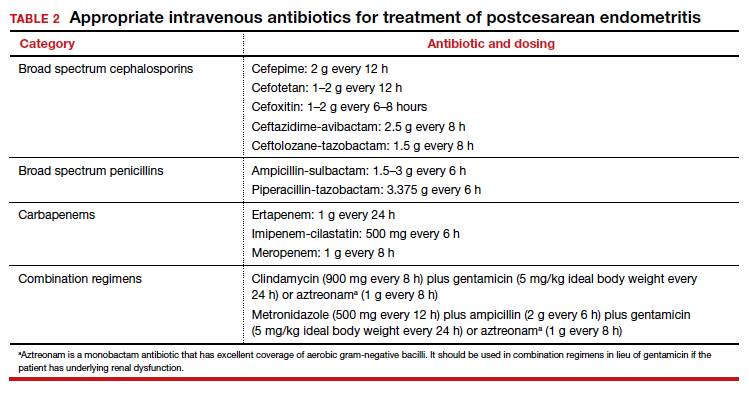

The cornerstone of therapy is broad spectrum antibiotics that target the multiple organisms responsible for endometritis.3 There are several single agents and several combination antibiotic regimens that provide excellent coverage against the usual pelvic pathogens (TABLE 2). I personally favor the generic combination regimen (clindamycin plus gentamicin) because it is relatively inexpensive and has been very well validated in multiple studies. In patients who have underlying renal dysfunction, aztreonam can be substituted for gentamicin.

Approximately 90% of patients will show clear evidence of clinical improvement (ie, decrease in temperature and resolution of abdominopelvic pain) within 48 hours of starting antibiotics. Patients should then continue therapy until they have been afebrile and asymptomatic for approximately 24 hours. At that point, antibiotics should be discontinued, and the patient can be discharged. With rare exceptions, there is no indication for administration of oral antibiotics on an outpatient basis.1,4

Continue to: Persistent postoperative fever...

Persistent postoperative fever

Resistant microorganism

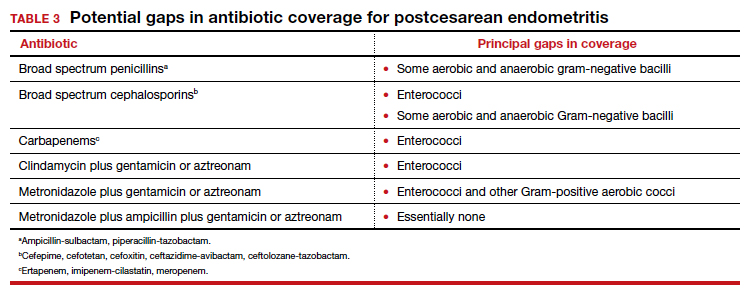

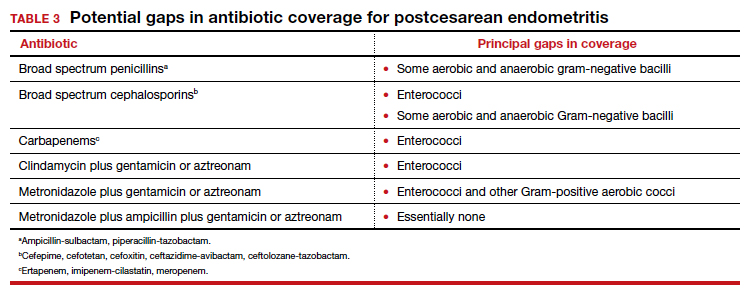

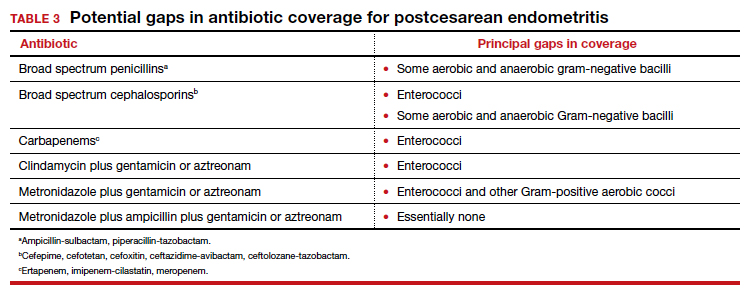

The most common cause of a persistent fever after initiating antibiotic therapy is a resistant microorganism. There are potential gaps in coverage for the antibiotic regimens commonly used to treat postcesarean endometritis (TABLE 3).1,4 Assuming there is no other obvious cause for treatment failure, I recommend that therapy be changed to the triple combination of metronidazole plus ampicillin plus gentamicin (or aztreonam). The first drug provides superb coverage against anaerobes; the second covers enterococci. Gentamicin or aztreonam cover virtually all aerobic Gram-negative bacilli likely to cause postcesarean infection. I prefer metronidazole rather than clindamycin in this regimen because, unlike clindamycin, it is less likely to trigger diarrhea when used in combination with ampicillin. The 3-drug regimen should be continued until the patient has been afebrile and asymptomatic for approximately 24 hours.1,3,4

Wound infection

The second most common reason for a poor response to initial antibiotic therapy is a wound (surgical site) infection. Wound infections are caused by many of the same pelvic pathogens responsible for endometritis combined with skin flora, notably Streptococcus and Staphylococcus species, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).1,4

Wound infections typically take one of two forms. The first is an actual incisional abscess. The patient is febrile; the margins of the wound are warm, indurated, erythematous, and tender; and purulent material drains from the incision. In this situation, the wound should be opened widely to drain the purulent collection. The fascia should then be probed to be certain that dehiscence has not occurred. In addition, intravenous vancomycin (1 g every 12 h) should be included in the antibiotic regimen to ensure adequate coverage of hospital-acquired MRSA.1,4

The second common presentation of a wound infection is cellulitis. The patient is febrile, and there is a spreading area of erythema, warmth, and exquisite tenderness extending from the edges of the incision; however, no purulent drainage is apparent. In this second scenario, the wound should not be opened, but intravenous vancomycin should be added to the treatment regimen.1,3,4

A third and very rare form of wound infection is necrotizing fasciitis. In affected patients, the margins of the wound are darkened and necrotic rather than erythematous and indurated. Two other key physical findings are crepitance and loss of sensation along the margins of the wound. Necrotizing fasciitis is truly a life-threatening emergency and requires immediate and extensive debridement of the devitalized tissue, combined with broad spectrum therapy with antibiotics that provide excellent coverage against anaerobes, aerobic streptococci (particularly group A streptococci), and staphylococci. The requirement for debridement may be so extensive that a skin graft subsequently is necessary to close the defect.1,4

Continue to: Unusual causes of persistent postoperative fever...

Unusual causes of persistent postoperative fever

If a resistant microorganism and wound infection can be excluded, the clinician then must begin a diligent search for “zebras” (ie, uncommon but potentially serious causes of persistent fever).1,4 One possible cause is a pelvic abscess. These purulent collections typically form in the retrovesicle space as a result of infection of a hematoma that formed between the posterior bladder wall and the lower uterine segment, in the leaves of the broad ligament, or in the posterior cul-de-sac. The abscess may or may not be palpable. The patient’s peripheral white blood cell count usually is elevated, with a preponderance of neutrophils. The best imaging test for an abscess is a computed tomography (CT) scan. Abscesses require drainage, which usually can be accomplished by insertion of a percutaneous drain under ultrasonographic or CT guidance.

A second unusual cause of persistent fever is septic pelvic vein thrombophlebitis. The infected venous emboli usually are present in the ovarian veins, with the right side predominant. The patient’s peripheral white blood cell count usually is elevated, and the infected clots are best imaged by CT scan with contrast or magnetic resonance angiography. The appropriate treatment is continuation of broad-spectrum antibiotics and administration of therapeutic doses of parenteral anticoagulants such as enoxaparin or unfractionated heparin.

A third explanation for persistent fever is retained products of conception. This diagnosis is best made by ultrasonography. The placental fragments should be removed by sharp curettage.

A fourth consideration when evaluating the patient with persistent fever is an allergic drug reaction. In most instances, the increase in the patient’s temperature will correspond with administration of the offending antibiotic(s). Affected patients typically have an increased number of eosinophils in their peripheral white blood cell count. The appropriate management of drug fever is discontinuation of antibiotics.

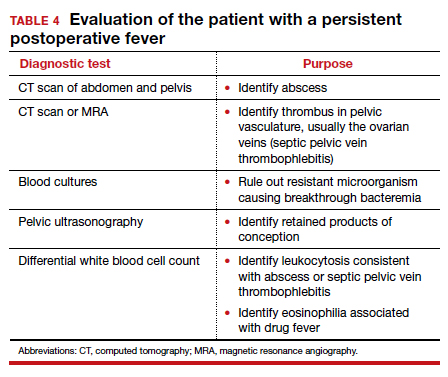

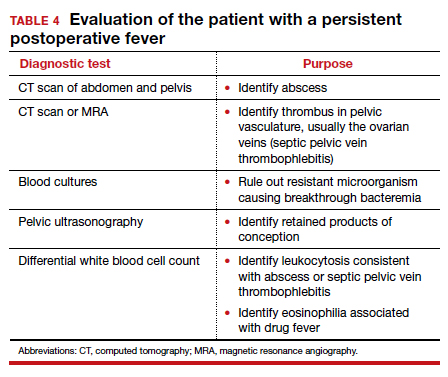

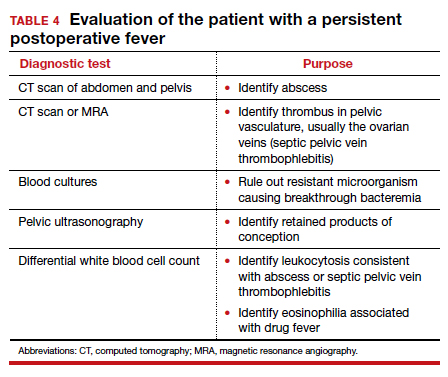

A final and distinctly unusual consideration is recrudescence of a connective tissue disorder such as systemic lupus erythematosus. The best test to confirm this diagnosis is the serum complement assay, which will demonstrate a decreased serum concentration of complement, reflecting consumption of this serum protein during the inflammatory process. The correct management for this condition is administration of a short course of systemic glucocorticoids. TABLE 4 summarizes a simple, systematic plan for evaluation of the patient with a persistent postoperative fever.

Preventive measures

We all remember the simple but profound statement by Benjamin Franklin, “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.” That folksy adage rings true with respect to postoperative infection because this complication extends hospital stay, increases hospital expense, and causes considerable discomfort and inconvenience for the patient. Therefore, we would do well to prevent as many instances of postoperative infection as possible.

Endometritis

On the basis of well-designed, prospective, randomized trials (Level 1 evidence), 3 interventions have proven effective in reducing the frequency of postcesarean endometritis. The first is irrigation of the vaginal canal preoperatively with an iodophor solution.5,6 The second is preoperative administration of systemic antibiotics.7-9 The combination of cefazolin (2 g IV within 30 minutes of incision) plus azithromycin (500 mg IV over 1 hour prior to incision) is superior to cefazolin alone.10,11 The third important preventive measure is removing the placenta by traction on the umbilical cord rather than by manual extraction.12,13

Wound infection

Several interventions are of proven effectiveness in reducing the frequency of postcesarean wound (surgical site) infection. The first is removal of hair at the incision site by clipping rather than by shaving (Level 2 evidence).14 The second is cleansing of the skin with chlorhexidine rather than iodophor (Level 1 evidence).15 The third is closing of the deep subcutaneous layer of the incision if it exceeds 2 cm in depth (Level 1 evidence).16,17 The fourth is closure of the skin with subcutaneous sutures rather than staples (Level 1 evidence).18 The monofilament suture poliglecaprone 25 is superior to the multifilament suture polyglactin 910 for this purpose (Level 1 evidence).19 Finally, in obese patients (body mass index >30 kg/m2), application of a negative pressure wound vacuum dressing may offer additional protection against infection (Level 1 evidence).20 Such dressings are too expensive, however, to be used routinely in all patients.

Urinary tract infection

The most important measures for preventing postoperative UTIs are identifying and clearing asymptomatic bacteriuria prior to delivery, inserting the urinary catheter prior to surgery using strict sterile technique, and removing the catheter as soon as possible after surgery, ideally within 12 hours.1,4

CASE Resolved

The 2 most likely causes for this patient’s poor response to initial therapy are resistant microorganism and wound infection. If a wound infection can be excluded by physical examination, the patient’s antibiotic regimen should be changed to metronidazole plus ampicillin plus gentamicin (or aztreonam). If an incisional abscess is identified, the incision should be opened and drained, and vancomycin should be added to the treatment regimen. If a wound cellulitis is evident, the incision should not be opened, but vancomycin should be added to the treatment regimen to enhance coverage against aerobic Streptococcus and Staphylococcus species. ●

- Duff WP. Maternal and perinatal infection in pregnancy: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al, eds. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2020:1124-1146.

- Locksmith GJ, Duff P. Assessment of the value of routine blood cultures in the evaluation and treatment of patients with chorioamnionitis. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 1994;2:111-114.

- Duff P. Antibiotic selection in obstetric patients. Infect Dis Clin N Am. 1997;11:1-12.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Creasy RK, Resnik R, Iams, JD, et al, eds. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

- Haas DM, Morgan S, Contreras K. Vaginal preparation with antiseptic solution before cesarean section for preventing postoperative infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;12:CD007892.

- Caissutti C, Saccone G, Zullo F, et al. Vaginal cleansing before cesarean delivery. a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:527-538.

- Sullivan SA, Smith T, Change E, et al. Administration of cefazolin prior to skin incision is superior to cefazolin at cord clamping in preventing postcesarean infectious morbidity; a randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:455.e1-455.e5.

- Tita ATN, Hauth JC, Grimes A, et al. Decreasing incidence of postcesarean endometritis with extended-spectrum antibiotic prophylaxis. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:51-56.

- Tita ATN, Owen J, Stamm AM, et al. Impact of extended-spectrum antibiotic prophylaxis on incidence of postcesarean surgical wound infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199: 303.e1-303.e3.

- Tita ATN, Szchowski JM, Boggess K, et al. Two antibiotics before cesarean delivery reduce infection rates further than one agent. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1231-1241.

- Harper LM, Kilgore M, Szychowski JM, et al. Economic evaluation of adjunctive azithromycin prophylaxis for cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:328-334.

- Lasley DS, Eblen A, Yancey MK, et al. The effect of placental removal method on the incidence of postcesarean infections. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176:1250-1254.

- Anorlu RI, Maholwana B, Hofmeyr GJ. Methods of delivering the placenta at cesarean section. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;3:CD004737.

- Cruse PJ, Foord R. A five-year prospective study of 23,649 surgical wounds. Arch Surg. 1973;107:206-209.

- Tuuli MG, Liu J, Stout MJ, et al. A randomized trial comparing skin antiseptic agents at cesarean delivery. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:657-665.

- Del Valle GO, Combs P, Qualls C, et al. Does closure of camper fascia reduce the incidence of post-cesarean superficial wound disruption? Obstet Gynecol. 1992;80:1013-1016.

- Chelmow D. Rodriguez EJ, Sabatini MM. Suture closure of subcutaneous fat and wound disruption after cesarean delivery: a meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103:974-980.

- Tuuli MG, Rampersod RM, Carbone JF, et al. Staples compared with subcuticular suture for skin closure after cesarean delivery. a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:682-690.

- Buresch AM, Arsdale AV, Ferzli M, et al. Comparison of subcuticular suture type for skin closure after cesarean delivery. a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:521-526.

- Yu L, Kronen RJ, Simon LE, et al. Prophylactic negative-pressure wound therapy after cesarean is associated with reduced risk of surgical site infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218:200-210.

CASE Woman who has undergone recent cesarean delivery

A 23-year-old woman had a primary cesarean delivery 72 hours ago due to an arrest of dilation at 6 cm. She was in labor for 22 hours, and her membranes were ruptured for 18 hours. She had 10 internal vaginal examinations, and the duration of internal fetal monitoring was 12 hours; 24 hours after delivery, she developed a fever of 39°C, in association with lower abdominal pain and tenderness. She was presumptively treated for endometritis with cefepime; 48 hours after the initiation of antibiotics, she remains febrile and symptomatic.

- What are the most likely causes of her persistent fever?

- What should be the next steps in her evaluation?

Cesarean delivery background

Cesarean delivery is now the most common major operation performed in US hospitals. Cesarean delivery rates hover between 25% and 30% in most medical centers in the United States.1 The most common postoperative complication of cesarean delivery is infection. Infection typically takes 1 of 3 forms: endometritis (organ space infection), wound infection (surgical site infection), and urinary tract infection (UTI).1 This article will review the initial differential diagnosis, evaluation, and management of the patient with a postoperative fever and also will describe the appropriate assessment and treatment of the patient who has a persistent postoperative fever despite therapy. The article will also highlight key interventions that help to prevent postoperative infections.

Initial evaluation of the febrile patient

In the first 24 to 48 hours after cesarean delivery, the most common cause of fever is endometritis (organ space infection). This condition is a polymicrobial, mixed aerobic-anaerobic infection (FIGURE). The principal pathogens include anaerobic gram-positive cocci (

The major risk factors for postcesarean endometritis are extended duration of labor and ruptured membranes, multiple internal vaginal examinations, invasive fetal monitoring, and pre-existing colonization with group B Streptococcus and/or the organisms that cause bacterial vaginosis. Affected patients typically have a fever in the range of 38 to 39°C, tachycardia, mild tachypnea, lower abdominal pain and tenderness, and purulent lochia in some individuals.1

Differential for postoperative fever

The initial differential diagnosis of postoperative fever is relatively limited (TABLE 1). In addition to endometritis, it includes extensive atelectasis, perhaps resulting from general anesthesia; lower respiratory tract infection, either viral influenza or bacterial pneumonia; and acute pyelonephritis. A simple infection of the bladder (cystitis or asymptomatic bacteriuria) should not cause a substantial temperature elevation and systemic symptoms.1

Differentiation between these entities usually is possible based on physical examination and a few laboratory tests. The peripheral white blood cell count usually is elevated, and a left shift may be evident. If a respiratory tract infection is suspected, chest radiography is indicated. A urine culture should be obtained if acute pyelonephritis strongly is considered. Lower genital tract cultures are rarely of value, and uncontaminated upper tract cultures are difficult to obtain. I do not believe that blood cultures should be performed as a matter of routine. They are expensive, and the results are often not available until after the patient has cleared her infection and left the hospital. However, I would obtain blood cultures in patients who meet one of these criteria1,2:

- They are immunocompromised (eg, HIV infection).

- They have a cardiac or vascular prosthesis and, thus, are at increased risk of complications related to bacteremia.

- They seem critically ill at the onset of evaluation.

- They fail to respond appropriately to initial therapy.

The cornerstone of therapy is broad spectrum antibiotics that target the multiple organisms responsible for endometritis.3 There are several single agents and several combination antibiotic regimens that provide excellent coverage against the usual pelvic pathogens (TABLE 2). I personally favor the generic combination regimen (clindamycin plus gentamicin) because it is relatively inexpensive and has been very well validated in multiple studies. In patients who have underlying renal dysfunction, aztreonam can be substituted for gentamicin.

Approximately 90% of patients will show clear evidence of clinical improvement (ie, decrease in temperature and resolution of abdominopelvic pain) within 48 hours of starting antibiotics. Patients should then continue therapy until they have been afebrile and asymptomatic for approximately 24 hours. At that point, antibiotics should be discontinued, and the patient can be discharged. With rare exceptions, there is no indication for administration of oral antibiotics on an outpatient basis.1,4

Continue to: Persistent postoperative fever...

Persistent postoperative fever

Resistant microorganism

The most common cause of a persistent fever after initiating antibiotic therapy is a resistant microorganism. There are potential gaps in coverage for the antibiotic regimens commonly used to treat postcesarean endometritis (TABLE 3).1,4 Assuming there is no other obvious cause for treatment failure, I recommend that therapy be changed to the triple combination of metronidazole plus ampicillin plus gentamicin (or aztreonam). The first drug provides superb coverage against anaerobes; the second covers enterococci. Gentamicin or aztreonam cover virtually all aerobic Gram-negative bacilli likely to cause postcesarean infection. I prefer metronidazole rather than clindamycin in this regimen because, unlike clindamycin, it is less likely to trigger diarrhea when used in combination with ampicillin. The 3-drug regimen should be continued until the patient has been afebrile and asymptomatic for approximately 24 hours.1,3,4

Wound infection

The second most common reason for a poor response to initial antibiotic therapy is a wound (surgical site) infection. Wound infections are caused by many of the same pelvic pathogens responsible for endometritis combined with skin flora, notably Streptococcus and Staphylococcus species, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).1,4

Wound infections typically take one of two forms. The first is an actual incisional abscess. The patient is febrile; the margins of the wound are warm, indurated, erythematous, and tender; and purulent material drains from the incision. In this situation, the wound should be opened widely to drain the purulent collection. The fascia should then be probed to be certain that dehiscence has not occurred. In addition, intravenous vancomycin (1 g every 12 h) should be included in the antibiotic regimen to ensure adequate coverage of hospital-acquired MRSA.1,4

The second common presentation of a wound infection is cellulitis. The patient is febrile, and there is a spreading area of erythema, warmth, and exquisite tenderness extending from the edges of the incision; however, no purulent drainage is apparent. In this second scenario, the wound should not be opened, but intravenous vancomycin should be added to the treatment regimen.1,3,4

A third and very rare form of wound infection is necrotizing fasciitis. In affected patients, the margins of the wound are darkened and necrotic rather than erythematous and indurated. Two other key physical findings are crepitance and loss of sensation along the margins of the wound. Necrotizing fasciitis is truly a life-threatening emergency and requires immediate and extensive debridement of the devitalized tissue, combined with broad spectrum therapy with antibiotics that provide excellent coverage against anaerobes, aerobic streptococci (particularly group A streptococci), and staphylococci. The requirement for debridement may be so extensive that a skin graft subsequently is necessary to close the defect.1,4

Continue to: Unusual causes of persistent postoperative fever...

Unusual causes of persistent postoperative fever

If a resistant microorganism and wound infection can be excluded, the clinician then must begin a diligent search for “zebras” (ie, uncommon but potentially serious causes of persistent fever).1,4 One possible cause is a pelvic abscess. These purulent collections typically form in the retrovesicle space as a result of infection of a hematoma that formed between the posterior bladder wall and the lower uterine segment, in the leaves of the broad ligament, or in the posterior cul-de-sac. The abscess may or may not be palpable. The patient’s peripheral white blood cell count usually is elevated, with a preponderance of neutrophils. The best imaging test for an abscess is a computed tomography (CT) scan. Abscesses require drainage, which usually can be accomplished by insertion of a percutaneous drain under ultrasonographic or CT guidance.

A second unusual cause of persistent fever is septic pelvic vein thrombophlebitis. The infected venous emboli usually are present in the ovarian veins, with the right side predominant. The patient’s peripheral white blood cell count usually is elevated, and the infected clots are best imaged by CT scan with contrast or magnetic resonance angiography. The appropriate treatment is continuation of broad-spectrum antibiotics and administration of therapeutic doses of parenteral anticoagulants such as enoxaparin or unfractionated heparin.

A third explanation for persistent fever is retained products of conception. This diagnosis is best made by ultrasonography. The placental fragments should be removed by sharp curettage.

A fourth consideration when evaluating the patient with persistent fever is an allergic drug reaction. In most instances, the increase in the patient’s temperature will correspond with administration of the offending antibiotic(s). Affected patients typically have an increased number of eosinophils in their peripheral white blood cell count. The appropriate management of drug fever is discontinuation of antibiotics.

A final and distinctly unusual consideration is recrudescence of a connective tissue disorder such as systemic lupus erythematosus. The best test to confirm this diagnosis is the serum complement assay, which will demonstrate a decreased serum concentration of complement, reflecting consumption of this serum protein during the inflammatory process. The correct management for this condition is administration of a short course of systemic glucocorticoids. TABLE 4 summarizes a simple, systematic plan for evaluation of the patient with a persistent postoperative fever.

Preventive measures

We all remember the simple but profound statement by Benjamin Franklin, “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.” That folksy adage rings true with respect to postoperative infection because this complication extends hospital stay, increases hospital expense, and causes considerable discomfort and inconvenience for the patient. Therefore, we would do well to prevent as many instances of postoperative infection as possible.

Endometritis

On the basis of well-designed, prospective, randomized trials (Level 1 evidence), 3 interventions have proven effective in reducing the frequency of postcesarean endometritis. The first is irrigation of the vaginal canal preoperatively with an iodophor solution.5,6 The second is preoperative administration of systemic antibiotics.7-9 The combination of cefazolin (2 g IV within 30 minutes of incision) plus azithromycin (500 mg IV over 1 hour prior to incision) is superior to cefazolin alone.10,11 The third important preventive measure is removing the placenta by traction on the umbilical cord rather than by manual extraction.12,13

Wound infection

Several interventions are of proven effectiveness in reducing the frequency of postcesarean wound (surgical site) infection. The first is removal of hair at the incision site by clipping rather than by shaving (Level 2 evidence).14 The second is cleansing of the skin with chlorhexidine rather than iodophor (Level 1 evidence).15 The third is closing of the deep subcutaneous layer of the incision if it exceeds 2 cm in depth (Level 1 evidence).16,17 The fourth is closure of the skin with subcutaneous sutures rather than staples (Level 1 evidence).18 The monofilament suture poliglecaprone 25 is superior to the multifilament suture polyglactin 910 for this purpose (Level 1 evidence).19 Finally, in obese patients (body mass index >30 kg/m2), application of a negative pressure wound vacuum dressing may offer additional protection against infection (Level 1 evidence).20 Such dressings are too expensive, however, to be used routinely in all patients.

Urinary tract infection

The most important measures for preventing postoperative UTIs are identifying and clearing asymptomatic bacteriuria prior to delivery, inserting the urinary catheter prior to surgery using strict sterile technique, and removing the catheter as soon as possible after surgery, ideally within 12 hours.1,4

CASE Resolved

The 2 most likely causes for this patient’s poor response to initial therapy are resistant microorganism and wound infection. If a wound infection can be excluded by physical examination, the patient’s antibiotic regimen should be changed to metronidazole plus ampicillin plus gentamicin (or aztreonam). If an incisional abscess is identified, the incision should be opened and drained, and vancomycin should be added to the treatment regimen. If a wound cellulitis is evident, the incision should not be opened, but vancomycin should be added to the treatment regimen to enhance coverage against aerobic Streptococcus and Staphylococcus species. ●

CASE Woman who has undergone recent cesarean delivery

A 23-year-old woman had a primary cesarean delivery 72 hours ago due to an arrest of dilation at 6 cm. She was in labor for 22 hours, and her membranes were ruptured for 18 hours. She had 10 internal vaginal examinations, and the duration of internal fetal monitoring was 12 hours; 24 hours after delivery, she developed a fever of 39°C, in association with lower abdominal pain and tenderness. She was presumptively treated for endometritis with cefepime; 48 hours after the initiation of antibiotics, she remains febrile and symptomatic.

- What are the most likely causes of her persistent fever?

- What should be the next steps in her evaluation?

Cesarean delivery background

Cesarean delivery is now the most common major operation performed in US hospitals. Cesarean delivery rates hover between 25% and 30% in most medical centers in the United States.1 The most common postoperative complication of cesarean delivery is infection. Infection typically takes 1 of 3 forms: endometritis (organ space infection), wound infection (surgical site infection), and urinary tract infection (UTI).1 This article will review the initial differential diagnosis, evaluation, and management of the patient with a postoperative fever and also will describe the appropriate assessment and treatment of the patient who has a persistent postoperative fever despite therapy. The article will also highlight key interventions that help to prevent postoperative infections.

Initial evaluation of the febrile patient

In the first 24 to 48 hours after cesarean delivery, the most common cause of fever is endometritis (organ space infection). This condition is a polymicrobial, mixed aerobic-anaerobic infection (FIGURE). The principal pathogens include anaerobic gram-positive cocci (

The major risk factors for postcesarean endometritis are extended duration of labor and ruptured membranes, multiple internal vaginal examinations, invasive fetal monitoring, and pre-existing colonization with group B Streptococcus and/or the organisms that cause bacterial vaginosis. Affected patients typically have a fever in the range of 38 to 39°C, tachycardia, mild tachypnea, lower abdominal pain and tenderness, and purulent lochia in some individuals.1

Differential for postoperative fever

The initial differential diagnosis of postoperative fever is relatively limited (TABLE 1). In addition to endometritis, it includes extensive atelectasis, perhaps resulting from general anesthesia; lower respiratory tract infection, either viral influenza or bacterial pneumonia; and acute pyelonephritis. A simple infection of the bladder (cystitis or asymptomatic bacteriuria) should not cause a substantial temperature elevation and systemic symptoms.1

Differentiation between these entities usually is possible based on physical examination and a few laboratory tests. The peripheral white blood cell count usually is elevated, and a left shift may be evident. If a respiratory tract infection is suspected, chest radiography is indicated. A urine culture should be obtained if acute pyelonephritis strongly is considered. Lower genital tract cultures are rarely of value, and uncontaminated upper tract cultures are difficult to obtain. I do not believe that blood cultures should be performed as a matter of routine. They are expensive, and the results are often not available until after the patient has cleared her infection and left the hospital. However, I would obtain blood cultures in patients who meet one of these criteria1,2:

- They are immunocompromised (eg, HIV infection).

- They have a cardiac or vascular prosthesis and, thus, are at increased risk of complications related to bacteremia.

- They seem critically ill at the onset of evaluation.

- They fail to respond appropriately to initial therapy.

The cornerstone of therapy is broad spectrum antibiotics that target the multiple organisms responsible for endometritis.3 There are several single agents and several combination antibiotic regimens that provide excellent coverage against the usual pelvic pathogens (TABLE 2). I personally favor the generic combination regimen (clindamycin plus gentamicin) because it is relatively inexpensive and has been very well validated in multiple studies. In patients who have underlying renal dysfunction, aztreonam can be substituted for gentamicin.

Approximately 90% of patients will show clear evidence of clinical improvement (ie, decrease in temperature and resolution of abdominopelvic pain) within 48 hours of starting antibiotics. Patients should then continue therapy until they have been afebrile and asymptomatic for approximately 24 hours. At that point, antibiotics should be discontinued, and the patient can be discharged. With rare exceptions, there is no indication for administration of oral antibiotics on an outpatient basis.1,4

Continue to: Persistent postoperative fever...

Persistent postoperative fever

Resistant microorganism

The most common cause of a persistent fever after initiating antibiotic therapy is a resistant microorganism. There are potential gaps in coverage for the antibiotic regimens commonly used to treat postcesarean endometritis (TABLE 3).1,4 Assuming there is no other obvious cause for treatment failure, I recommend that therapy be changed to the triple combination of metronidazole plus ampicillin plus gentamicin (or aztreonam). The first drug provides superb coverage against anaerobes; the second covers enterococci. Gentamicin or aztreonam cover virtually all aerobic Gram-negative bacilli likely to cause postcesarean infection. I prefer metronidazole rather than clindamycin in this regimen because, unlike clindamycin, it is less likely to trigger diarrhea when used in combination with ampicillin. The 3-drug regimen should be continued until the patient has been afebrile and asymptomatic for approximately 24 hours.1,3,4

Wound infection

The second most common reason for a poor response to initial antibiotic therapy is a wound (surgical site) infection. Wound infections are caused by many of the same pelvic pathogens responsible for endometritis combined with skin flora, notably Streptococcus and Staphylococcus species, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).1,4

Wound infections typically take one of two forms. The first is an actual incisional abscess. The patient is febrile; the margins of the wound are warm, indurated, erythematous, and tender; and purulent material drains from the incision. In this situation, the wound should be opened widely to drain the purulent collection. The fascia should then be probed to be certain that dehiscence has not occurred. In addition, intravenous vancomycin (1 g every 12 h) should be included in the antibiotic regimen to ensure adequate coverage of hospital-acquired MRSA.1,4

The second common presentation of a wound infection is cellulitis. The patient is febrile, and there is a spreading area of erythema, warmth, and exquisite tenderness extending from the edges of the incision; however, no purulent drainage is apparent. In this second scenario, the wound should not be opened, but intravenous vancomycin should be added to the treatment regimen.1,3,4

A third and very rare form of wound infection is necrotizing fasciitis. In affected patients, the margins of the wound are darkened and necrotic rather than erythematous and indurated. Two other key physical findings are crepitance and loss of sensation along the margins of the wound. Necrotizing fasciitis is truly a life-threatening emergency and requires immediate and extensive debridement of the devitalized tissue, combined with broad spectrum therapy with antibiotics that provide excellent coverage against anaerobes, aerobic streptococci (particularly group A streptococci), and staphylococci. The requirement for debridement may be so extensive that a skin graft subsequently is necessary to close the defect.1,4

Continue to: Unusual causes of persistent postoperative fever...

Unusual causes of persistent postoperative fever

If a resistant microorganism and wound infection can be excluded, the clinician then must begin a diligent search for “zebras” (ie, uncommon but potentially serious causes of persistent fever).1,4 One possible cause is a pelvic abscess. These purulent collections typically form in the retrovesicle space as a result of infection of a hematoma that formed between the posterior bladder wall and the lower uterine segment, in the leaves of the broad ligament, or in the posterior cul-de-sac. The abscess may or may not be palpable. The patient’s peripheral white blood cell count usually is elevated, with a preponderance of neutrophils. The best imaging test for an abscess is a computed tomography (CT) scan. Abscesses require drainage, which usually can be accomplished by insertion of a percutaneous drain under ultrasonographic or CT guidance.

A second unusual cause of persistent fever is septic pelvic vein thrombophlebitis. The infected venous emboli usually are present in the ovarian veins, with the right side predominant. The patient’s peripheral white blood cell count usually is elevated, and the infected clots are best imaged by CT scan with contrast or magnetic resonance angiography. The appropriate treatment is continuation of broad-spectrum antibiotics and administration of therapeutic doses of parenteral anticoagulants such as enoxaparin or unfractionated heparin.

A third explanation for persistent fever is retained products of conception. This diagnosis is best made by ultrasonography. The placental fragments should be removed by sharp curettage.

A fourth consideration when evaluating the patient with persistent fever is an allergic drug reaction. In most instances, the increase in the patient’s temperature will correspond with administration of the offending antibiotic(s). Affected patients typically have an increased number of eosinophils in their peripheral white blood cell count. The appropriate management of drug fever is discontinuation of antibiotics.

A final and distinctly unusual consideration is recrudescence of a connective tissue disorder such as systemic lupus erythematosus. The best test to confirm this diagnosis is the serum complement assay, which will demonstrate a decreased serum concentration of complement, reflecting consumption of this serum protein during the inflammatory process. The correct management for this condition is administration of a short course of systemic glucocorticoids. TABLE 4 summarizes a simple, systematic plan for evaluation of the patient with a persistent postoperative fever.

Preventive measures

We all remember the simple but profound statement by Benjamin Franklin, “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.” That folksy adage rings true with respect to postoperative infection because this complication extends hospital stay, increases hospital expense, and causes considerable discomfort and inconvenience for the patient. Therefore, we would do well to prevent as many instances of postoperative infection as possible.

Endometritis

On the basis of well-designed, prospective, randomized trials (Level 1 evidence), 3 interventions have proven effective in reducing the frequency of postcesarean endometritis. The first is irrigation of the vaginal canal preoperatively with an iodophor solution.5,6 The second is preoperative administration of systemic antibiotics.7-9 The combination of cefazolin (2 g IV within 30 minutes of incision) plus azithromycin (500 mg IV over 1 hour prior to incision) is superior to cefazolin alone.10,11 The third important preventive measure is removing the placenta by traction on the umbilical cord rather than by manual extraction.12,13

Wound infection

Several interventions are of proven effectiveness in reducing the frequency of postcesarean wound (surgical site) infection. The first is removal of hair at the incision site by clipping rather than by shaving (Level 2 evidence).14 The second is cleansing of the skin with chlorhexidine rather than iodophor (Level 1 evidence).15 The third is closing of the deep subcutaneous layer of the incision if it exceeds 2 cm in depth (Level 1 evidence).16,17 The fourth is closure of the skin with subcutaneous sutures rather than staples (Level 1 evidence).18 The monofilament suture poliglecaprone 25 is superior to the multifilament suture polyglactin 910 for this purpose (Level 1 evidence).19 Finally, in obese patients (body mass index >30 kg/m2), application of a negative pressure wound vacuum dressing may offer additional protection against infection (Level 1 evidence).20 Such dressings are too expensive, however, to be used routinely in all patients.

Urinary tract infection

The most important measures for preventing postoperative UTIs are identifying and clearing asymptomatic bacteriuria prior to delivery, inserting the urinary catheter prior to surgery using strict sterile technique, and removing the catheter as soon as possible after surgery, ideally within 12 hours.1,4

CASE Resolved

The 2 most likely causes for this patient’s poor response to initial therapy are resistant microorganism and wound infection. If a wound infection can be excluded by physical examination, the patient’s antibiotic regimen should be changed to metronidazole plus ampicillin plus gentamicin (or aztreonam). If an incisional abscess is identified, the incision should be opened and drained, and vancomycin should be added to the treatment regimen. If a wound cellulitis is evident, the incision should not be opened, but vancomycin should be added to the treatment regimen to enhance coverage against aerobic Streptococcus and Staphylococcus species. ●

- Duff WP. Maternal and perinatal infection in pregnancy: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al, eds. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2020:1124-1146.

- Locksmith GJ, Duff P. Assessment of the value of routine blood cultures in the evaluation and treatment of patients with chorioamnionitis. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 1994;2:111-114.

- Duff P. Antibiotic selection in obstetric patients. Infect Dis Clin N Am. 1997;11:1-12.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Creasy RK, Resnik R, Iams, JD, et al, eds. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

- Haas DM, Morgan S, Contreras K. Vaginal preparation with antiseptic solution before cesarean section for preventing postoperative infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;12:CD007892.

- Caissutti C, Saccone G, Zullo F, et al. Vaginal cleansing before cesarean delivery. a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:527-538.

- Sullivan SA, Smith T, Change E, et al. Administration of cefazolin prior to skin incision is superior to cefazolin at cord clamping in preventing postcesarean infectious morbidity; a randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:455.e1-455.e5.

- Tita ATN, Hauth JC, Grimes A, et al. Decreasing incidence of postcesarean endometritis with extended-spectrum antibiotic prophylaxis. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:51-56.

- Tita ATN, Owen J, Stamm AM, et al. Impact of extended-spectrum antibiotic prophylaxis on incidence of postcesarean surgical wound infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199: 303.e1-303.e3.

- Tita ATN, Szchowski JM, Boggess K, et al. Two antibiotics before cesarean delivery reduce infection rates further than one agent. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1231-1241.

- Harper LM, Kilgore M, Szychowski JM, et al. Economic evaluation of adjunctive azithromycin prophylaxis for cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:328-334.

- Lasley DS, Eblen A, Yancey MK, et al. The effect of placental removal method on the incidence of postcesarean infections. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176:1250-1254.

- Anorlu RI, Maholwana B, Hofmeyr GJ. Methods of delivering the placenta at cesarean section. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;3:CD004737.

- Cruse PJ, Foord R. A five-year prospective study of 23,649 surgical wounds. Arch Surg. 1973;107:206-209.

- Tuuli MG, Liu J, Stout MJ, et al. A randomized trial comparing skin antiseptic agents at cesarean delivery. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:657-665.

- Del Valle GO, Combs P, Qualls C, et al. Does closure of camper fascia reduce the incidence of post-cesarean superficial wound disruption? Obstet Gynecol. 1992;80:1013-1016.

- Chelmow D. Rodriguez EJ, Sabatini MM. Suture closure of subcutaneous fat and wound disruption after cesarean delivery: a meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103:974-980.

- Tuuli MG, Rampersod RM, Carbone JF, et al. Staples compared with subcuticular suture for skin closure after cesarean delivery. a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:682-690.

- Buresch AM, Arsdale AV, Ferzli M, et al. Comparison of subcuticular suture type for skin closure after cesarean delivery. a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:521-526.

- Yu L, Kronen RJ, Simon LE, et al. Prophylactic negative-pressure wound therapy after cesarean is associated with reduced risk of surgical site infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218:200-210.

- Duff WP. Maternal and perinatal infection in pregnancy: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al, eds. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2020:1124-1146.

- Locksmith GJ, Duff P. Assessment of the value of routine blood cultures in the evaluation and treatment of patients with chorioamnionitis. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 1994;2:111-114.

- Duff P. Antibiotic selection in obstetric patients. Infect Dis Clin N Am. 1997;11:1-12.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Creasy RK, Resnik R, Iams, JD, et al, eds. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

- Haas DM, Morgan S, Contreras K. Vaginal preparation with antiseptic solution before cesarean section for preventing postoperative infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;12:CD007892.

- Caissutti C, Saccone G, Zullo F, et al. Vaginal cleansing before cesarean delivery. a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:527-538.

- Sullivan SA, Smith T, Change E, et al. Administration of cefazolin prior to skin incision is superior to cefazolin at cord clamping in preventing postcesarean infectious morbidity; a randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:455.e1-455.e5.

- Tita ATN, Hauth JC, Grimes A, et al. Decreasing incidence of postcesarean endometritis with extended-spectrum antibiotic prophylaxis. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:51-56.

- Tita ATN, Owen J, Stamm AM, et al. Impact of extended-spectrum antibiotic prophylaxis on incidence of postcesarean surgical wound infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199: 303.e1-303.e3.

- Tita ATN, Szchowski JM, Boggess K, et al. Two antibiotics before cesarean delivery reduce infection rates further than one agent. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1231-1241.

- Harper LM, Kilgore M, Szychowski JM, et al. Economic evaluation of adjunctive azithromycin prophylaxis for cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:328-334.

- Lasley DS, Eblen A, Yancey MK, et al. The effect of placental removal method on the incidence of postcesarean infections. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176:1250-1254.

- Anorlu RI, Maholwana B, Hofmeyr GJ. Methods of delivering the placenta at cesarean section. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;3:CD004737.

- Cruse PJ, Foord R. A five-year prospective study of 23,649 surgical wounds. Arch Surg. 1973;107:206-209.

- Tuuli MG, Liu J, Stout MJ, et al. A randomized trial comparing skin antiseptic agents at cesarean delivery. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:657-665.

- Del Valle GO, Combs P, Qualls C, et al. Does closure of camper fascia reduce the incidence of post-cesarean superficial wound disruption? Obstet Gynecol. 1992;80:1013-1016.

- Chelmow D. Rodriguez EJ, Sabatini MM. Suture closure of subcutaneous fat and wound disruption after cesarean delivery: a meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103:974-980.

- Tuuli MG, Rampersod RM, Carbone JF, et al. Staples compared with subcuticular suture for skin closure after cesarean delivery. a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:682-690.

- Buresch AM, Arsdale AV, Ferzli M, et al. Comparison of subcuticular suture type for skin closure after cesarean delivery. a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:521-526.

- Yu L, Kronen RJ, Simon LE, et al. Prophylactic negative-pressure wound therapy after cesarean is associated with reduced risk of surgical site infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218:200-210.

Does prophylactic manual rotation of OP and OT positions in early second stage of labor decrease operative vaginal and/or CDs?

Blanc J, Castel P, Mauviel F, et al. Prophylactic manual rotation of occiput posterior and transverse positions to decrease operative delivery: the PROPOP randomized clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;225:444.e1-444.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.05.020.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Occiput posterior or occiput transverse positions are reported at a rate of 20% in labor, with 5% persistent at the time of delivery. These lead to a higher risk of maternal complications, such as cesarean delivery (CD), prolonged second stage, severe perineal lacerations, postpartum hemorrhage, chorioamnionitis, and operative vaginal delivery.

Several options are available for rotation to occiput anterior (OA) to increase the likelihood of spontaneous delivery. These include instrument (which requires forceps or vacuum experience in rotation), maternal positioning changes, or manual rotation. Timing of manual rotation can be at full dilation (“prophylactic”) or at failure to progress (“therapeutic”), with the latter less likely to succeed.

Although the existing literature is somewhat limited, both the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine recommend consideration of manual rotation to reduce the rate of operative delivery. A recent study by Blanc and colleagues sought to add to the evidence for the effectiveness of manual rotation in reducing operative delivery.

Details of the study

The multicenter, open-label, randomized clinical trial included 257 patients at 4 French hospitals (2 academic, 2 community). The 126 patients in the intervention group underwent a trial of prophylactic manual rotation, while the 131 in the standard group had no trial of prophylactic manual rotation. The study’s primary objective was to determine the effect of prophylactic manual rotation on operative delivery (vaginal or cesarean). The hypothesis was that manual rotation would decrease the risk of operative delivery.

The inclusion criteria were patients with a singleton pregnancy at more than 37 weeks, epidural anesthesia, and OP or OT presentation (confirmed by ultrasonography) in the early second stage of labor at diagnosis of full dilation. Manual rotation was attempted using the previously described Tarnier and Chantreiul technique, and all investigators were trained in this technique at the beginning of the study using a mannequin.

The primary outcome was vaginal or cesarean operative delivery. Secondary outcomes included length of the second stage of labor as well as maternal and neonatal complications.

Results. The intervention group had a significantly lower rate of operative delivery (29.4%) compared with the standard group (41.2%). Length of the second stage was also lower in the intervention group (146.7 minutes) compared with that of the standard group (164.4 minutes). The 5-minute Apgar score was reported as significantly higher in the intervention group as well (9.8 vs 9.6). There were no other differences between the groups in either maternal or neonatal complications.

Study strengths and limitations

The strengths of this study included randomization and no loss to follow-up. The 4 different study sites with different levels of care and acuity added to the generalizability of the results. Given the potential for inaccuracy of digital exam for fetal head positioning, the use of ultrasonography for confirmation of the OP or OT position is a study strength. Additional strengths are the prestudy training in the maneuver using simulation and the high level of success in the rotations (89.7%).

The study’s main limitation is that it was not double blinded; therefore, bias in management was a possibility. Additionally, the study looked only at short-term outcomes for the delivery itself and not at the potential long-term pelvic floor outcomes. The authors reported that the study was underpowered for operative vaginal delivery and cesarean delivery separately, as well as the secondary outcomes. Other limitations were the high frequency of operative vaginal delivery, low rate of consent for the study, and lack of patient satisfaction data. ●

In this study, a trial of prophylactic manual rotation of the occiput posterior or occiput transverse presentation decreased the rate of operative delivery and reduced the length of the second stage of labor without differences in maternal or neonatal complications. Obstetrical providers should consider this strategy to resolve the OP or OT presentation prior to performing an operative vaginal delivery or cesarean delivery. Simulation training in this maneuver may be a useful adjunct for both trainees and providers unfamiliar with the procedure.

JAIMEY M. PAULI, MD

Blanc J, Castel P, Mauviel F, et al. Prophylactic manual rotation of occiput posterior and transverse positions to decrease operative delivery: the PROPOP randomized clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;225:444.e1-444.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.05.020.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Occiput posterior or occiput transverse positions are reported at a rate of 20% in labor, with 5% persistent at the time of delivery. These lead to a higher risk of maternal complications, such as cesarean delivery (CD), prolonged second stage, severe perineal lacerations, postpartum hemorrhage, chorioamnionitis, and operative vaginal delivery.

Several options are available for rotation to occiput anterior (OA) to increase the likelihood of spontaneous delivery. These include instrument (which requires forceps or vacuum experience in rotation), maternal positioning changes, or manual rotation. Timing of manual rotation can be at full dilation (“prophylactic”) or at failure to progress (“therapeutic”), with the latter less likely to succeed.

Although the existing literature is somewhat limited, both the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine recommend consideration of manual rotation to reduce the rate of operative delivery. A recent study by Blanc and colleagues sought to add to the evidence for the effectiveness of manual rotation in reducing operative delivery.

Details of the study

The multicenter, open-label, randomized clinical trial included 257 patients at 4 French hospitals (2 academic, 2 community). The 126 patients in the intervention group underwent a trial of prophylactic manual rotation, while the 131 in the standard group had no trial of prophylactic manual rotation. The study’s primary objective was to determine the effect of prophylactic manual rotation on operative delivery (vaginal or cesarean). The hypothesis was that manual rotation would decrease the risk of operative delivery.

The inclusion criteria were patients with a singleton pregnancy at more than 37 weeks, epidural anesthesia, and OP or OT presentation (confirmed by ultrasonography) in the early second stage of labor at diagnosis of full dilation. Manual rotation was attempted using the previously described Tarnier and Chantreiul technique, and all investigators were trained in this technique at the beginning of the study using a mannequin.

The primary outcome was vaginal or cesarean operative delivery. Secondary outcomes included length of the second stage of labor as well as maternal and neonatal complications.

Results. The intervention group had a significantly lower rate of operative delivery (29.4%) compared with the standard group (41.2%). Length of the second stage was also lower in the intervention group (146.7 minutes) compared with that of the standard group (164.4 minutes). The 5-minute Apgar score was reported as significantly higher in the intervention group as well (9.8 vs 9.6). There were no other differences between the groups in either maternal or neonatal complications.

Study strengths and limitations

The strengths of this study included randomization and no loss to follow-up. The 4 different study sites with different levels of care and acuity added to the generalizability of the results. Given the potential for inaccuracy of digital exam for fetal head positioning, the use of ultrasonography for confirmation of the OP or OT position is a study strength. Additional strengths are the prestudy training in the maneuver using simulation and the high level of success in the rotations (89.7%).

The study’s main limitation is that it was not double blinded; therefore, bias in management was a possibility. Additionally, the study looked only at short-term outcomes for the delivery itself and not at the potential long-term pelvic floor outcomes. The authors reported that the study was underpowered for operative vaginal delivery and cesarean delivery separately, as well as the secondary outcomes. Other limitations were the high frequency of operative vaginal delivery, low rate of consent for the study, and lack of patient satisfaction data. ●

In this study, a trial of prophylactic manual rotation of the occiput posterior or occiput transverse presentation decreased the rate of operative delivery and reduced the length of the second stage of labor without differences in maternal or neonatal complications. Obstetrical providers should consider this strategy to resolve the OP or OT presentation prior to performing an operative vaginal delivery or cesarean delivery. Simulation training in this maneuver may be a useful adjunct for both trainees and providers unfamiliar with the procedure.

JAIMEY M. PAULI, MD

Blanc J, Castel P, Mauviel F, et al. Prophylactic manual rotation of occiput posterior and transverse positions to decrease operative delivery: the PROPOP randomized clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;225:444.e1-444.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.05.020.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Occiput posterior or occiput transverse positions are reported at a rate of 20% in labor, with 5% persistent at the time of delivery. These lead to a higher risk of maternal complications, such as cesarean delivery (CD), prolonged second stage, severe perineal lacerations, postpartum hemorrhage, chorioamnionitis, and operative vaginal delivery.

Several options are available for rotation to occiput anterior (OA) to increase the likelihood of spontaneous delivery. These include instrument (which requires forceps or vacuum experience in rotation), maternal positioning changes, or manual rotation. Timing of manual rotation can be at full dilation (“prophylactic”) or at failure to progress (“therapeutic”), with the latter less likely to succeed.

Although the existing literature is somewhat limited, both the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine recommend consideration of manual rotation to reduce the rate of operative delivery. A recent study by Blanc and colleagues sought to add to the evidence for the effectiveness of manual rotation in reducing operative delivery.

Details of the study

The multicenter, open-label, randomized clinical trial included 257 patients at 4 French hospitals (2 academic, 2 community). The 126 patients in the intervention group underwent a trial of prophylactic manual rotation, while the 131 in the standard group had no trial of prophylactic manual rotation. The study’s primary objective was to determine the effect of prophylactic manual rotation on operative delivery (vaginal or cesarean). The hypothesis was that manual rotation would decrease the risk of operative delivery.

The inclusion criteria were patients with a singleton pregnancy at more than 37 weeks, epidural anesthesia, and OP or OT presentation (confirmed by ultrasonography) in the early second stage of labor at diagnosis of full dilation. Manual rotation was attempted using the previously described Tarnier and Chantreiul technique, and all investigators were trained in this technique at the beginning of the study using a mannequin.

The primary outcome was vaginal or cesarean operative delivery. Secondary outcomes included length of the second stage of labor as well as maternal and neonatal complications.

Results. The intervention group had a significantly lower rate of operative delivery (29.4%) compared with the standard group (41.2%). Length of the second stage was also lower in the intervention group (146.7 minutes) compared with that of the standard group (164.4 minutes). The 5-minute Apgar score was reported as significantly higher in the intervention group as well (9.8 vs 9.6). There were no other differences between the groups in either maternal or neonatal complications.

Study strengths and limitations

The strengths of this study included randomization and no loss to follow-up. The 4 different study sites with different levels of care and acuity added to the generalizability of the results. Given the potential for inaccuracy of digital exam for fetal head positioning, the use of ultrasonography for confirmation of the OP or OT position is a study strength. Additional strengths are the prestudy training in the maneuver using simulation and the high level of success in the rotations (89.7%).

The study’s main limitation is that it was not double blinded; therefore, bias in management was a possibility. Additionally, the study looked only at short-term outcomes for the delivery itself and not at the potential long-term pelvic floor outcomes. The authors reported that the study was underpowered for operative vaginal delivery and cesarean delivery separately, as well as the secondary outcomes. Other limitations were the high frequency of operative vaginal delivery, low rate of consent for the study, and lack of patient satisfaction data. ●

In this study, a trial of prophylactic manual rotation of the occiput posterior or occiput transverse presentation decreased the rate of operative delivery and reduced the length of the second stage of labor without differences in maternal or neonatal complications. Obstetrical providers should consider this strategy to resolve the OP or OT presentation prior to performing an operative vaginal delivery or cesarean delivery. Simulation training in this maneuver may be a useful adjunct for both trainees and providers unfamiliar with the procedure.

JAIMEY M. PAULI, MD

Reduce the use of perioperative opioids with a multimodal pain management strategy

Opioid-related deaths are a major cause of mortality in the United States. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported 72,151 and 93,331 drug overdose deaths in 2019 and 2020, respectively, and drug overdose deaths have continued to increase in 2021.1 The majority of drug overdose deaths are due to opioids. There are many factors contributing to this rise, including an incredibly high rate of opioid prescriptions in this country.2 The CDC reported that in 3.6% of US counties, there are more opioid prescriptions filled each year than number of residents in the county.3 The consumption of opioids per person in the US is approximately four times greater than countries with excellent health outcomes, including Sweden, Netherlands, Norway, and the United Kingdom.4 Some US physicians have opioid prescribing practices that are inconsistent with good medical practice in other countries, prescribing powerful opioids and an excessive number of pills per opioid prescription.2 We must continue to evolve our clinical practices to reduce opioid use while continually improving patient outcomes.

Cesarean birth is one of the most common major surgical procedures performed in the United States. The National Center for Health Statistics reported that in 2020 there were approximately 1,150,000 US cesarean births.5 Following cesarean birth, patients who were previously naïve to opioid medications were reported to have a 0.33% to 2.2% probability of transitioning to the persistent use of opioid prescriptions.6-8 Predictors of persistent opioid use after cesarean birth included a history of tobacco use, back pain, migraine headaches, and antidepressant or benzodiazepine use.6 The use of cesarean birth pain management protocols that prioritize multimodal analgesia and opioid sparing is warranted.

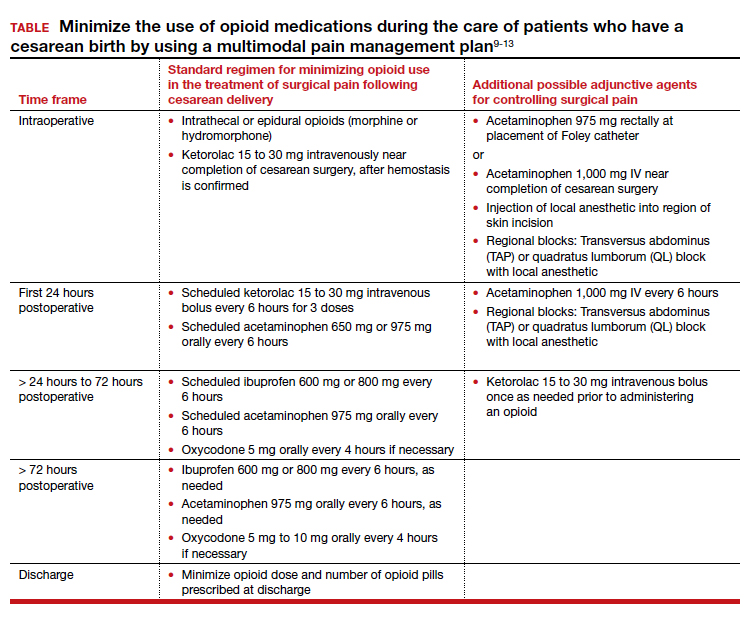

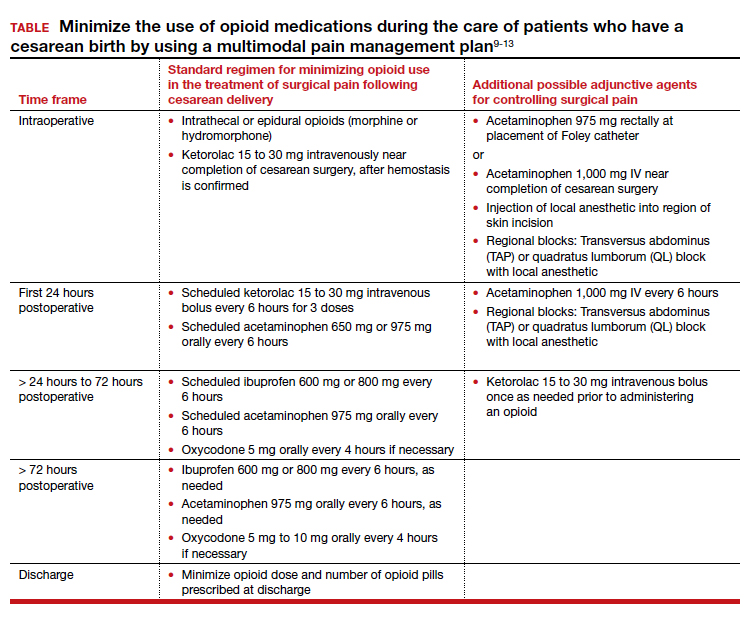

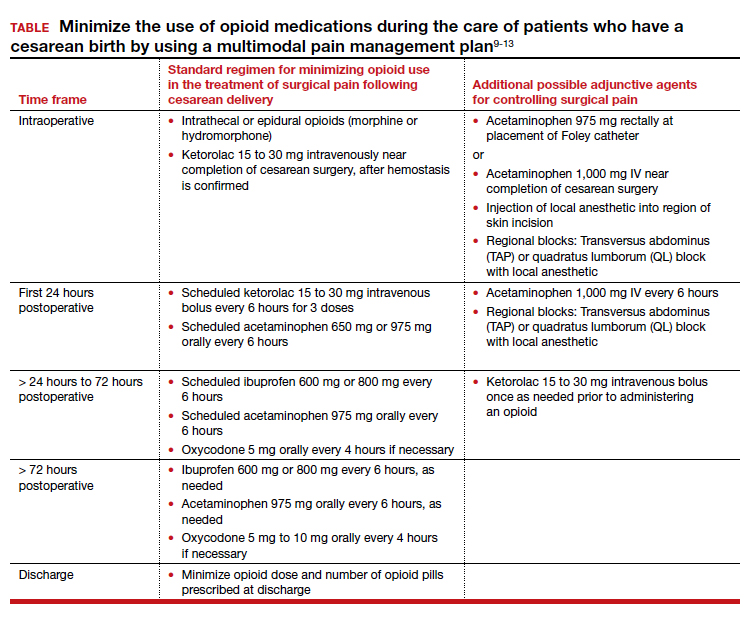

Multimodal pain management protocols for cesarean birth have been shown to reduce the use of opioid medications in the hospital and at discharge without a clinically significant increase in pain scores or a reduction in patient satisfaction (TABLE).9-13 For example, Holland and colleagues9 reported that the implementation of a multimodal pain management protocol reduced the percent of patients using oral opioids during hospitalization for cesarean birth from 68% to 45%, pre- and post-intervention, respectively. Mehraban and colleagues12 reported that the percent of patients using opioids during hospitalization for cesarean birth was reduced from 45% preintervention to 18% postintervention. In addition, these studies showed that multimodal pain management protocols for cesarean birth also reduced opioid prescribing at discharge. Holland and colleagues9 reported that the percent of patients provided an opioid prescription at discharge was reduced from 91% to 40%, pre- and post-intervention, respectively. Mehraban and colleagues12 reported that the percent of patients who took opioids after discharge was reduced from 24% preintervention to 9% postintervention. These studies were not randomized controlled clinical trials, but they do provide strong evidence that a focused intervention to reduce opioid medications in the management of pain after cesarean surgery can be successful without decreasing patient satisfaction or increasing reported pain scores. In these studies, it is likely that the influence, enthusiasm, and commitment of the study leaders to the change process contributed to the success of these opioid-sparing pain management programs.

Continue to: Key features of a multimodal analgesia intervention for cesarean surgery...

Key features of a multimodal analgesia intervention for cesarean surgery

Fundamental inclusions of multimodal analgesia for cesarean surgery include:

- exquisite attention to pain control during the surgical procedure by both the anesthesiologist and surgeon, with prioritization of spinal anesthesia that includes morphine and fentanyl

- regularly scheduled administration of intravenous ketorolac during the first 24 hours postcesarean

- regularly scheduled administration of both acetaminophen and ibuprofen, rather than “as needed” dosing

- using analgesics that work through different molecular pathways (ibuprofen and acetaminophen) (See Table.).

The significance of neuraxial and truncal nerve blockade for post-cesarean delivery pain control

Administration of a long-acting intrathecal opioid such as morphine lengthens time to first analgesic request after surgery and lowers 24-hour post‒cesarean delivery opioid requirement.14 If a patient requires general anesthesia and receives no spinal opioid, a transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block or quadratus lumborum (QL) block for postpartum pain control can lower associated postpartum opioid consumption. However, TAP or QL blocks confer no additional benefit to patients who receive spinal morphine,15 nor do they confer added benefit when combined with a multimodal pain management regimen postdelivery vs the multimodal regimen alone.16). TAP blocks administered to patients with severe breakthrough pain after spinal anesthesia help to lower opioid consumption.17 Further research is warranted on the use of TAP, QL, or other truncal blocks to spare opioid requirement after cesarean delivery in women with chronic pain, opioid use disorder, or those undergoing higher-complexity surgery such as cesarean hysterectomy for placenta accreta spectrum.

NSAIDs: Potential adverse effects

As we decrease the use of opioid medications and increase the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), we should reflect on the potential adverse effects of NSAID treatment in some patients. Specifically, the impact of ketorolac on hypertension, platelet function, and breastfeeding warrant consideration.

In the past, some studies reported that NSAID treatment is associated with a modest increase in blood pressure (BP), with a mean increase of 5 mm Hg.18 However, multiple recent studies report that in women with preeclampsia with and without severe features, postpartum administration of ibuprofen and ketorolac did not increase BP or delay resolution of hypertension.19-22 In a meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies comparing the effects of ibuprofen and acetaminophen on BP, neither medication was associated with an increase in BP.19 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists supports the use of NSAIDs as one component of multimodal analgesia to help reduce the use of opioids.23

NSAIDs can inhibit platelet function and this effect is of clinical concern for people with platelet defects. However, a meta-analysis of clinical trials reported no difference in bleeding between surgical patients administered ketorolac or control participants.24 Alternative opioid-sparing adjuncts (TAP or QL blocks) may be considered for patients who cannot receive ketorolac based on a history of platelet deficiency. Furthermore, patients with ongoing coagulation defects after surgery from severe postpartum hemorrhage, hyperfibrinolysis, disseminated intravascular coagulation, or dilutional coagulopathy may have both limited platelet reserves and acute kidney injury. The need to postpone the initiation of NSAIDs in such patients should prompt alternate options such as TAP or QL blocks or dosing of an indwelling epidural when possible, in conjunction with acetaminophen. Patients who have a contraindication to ketorolac due to peptic ulcer disease or renal insufficiency may also benefit from TAP and QL blocks after cesarean delivery, although more studies are needed in these patients.

Both ketorolac and ibuprofen transfer to breast milk. The relative infant dose for ketorolac and ibuprofen is very low—0.2% and 0.9%, respectively.25,26 The World Health Organization advises that ibuprofen is compatible with breastfeeding.27 Of interest, in an enhanced recovery after cesarean clinical trial, scheduled ketorolac administration resulted in more mothers exclusively breastfeeding at discharge compared with “as needed” ketorolac treatment, 67% versus 48%, respectively; P = .046.28

Conclusion

Many factors influence a person’s experience of their surgery, including their pain symptoms. Factors that modulate a person’s perception of pain following surgery include their personality, social supports, and genetic factors. The technical skill of the anesthesiologist, surgeon, and nurses, and the confidence of the patient in the surgical care team are important factors influencing a person’s global experience of their surgery, including their experience of pain. Patients’ expectations regarding postoperative pain and psychological distress surrounding surgery may also influence their pain experience. Assuring patients that their pain will be addressed adequately, and helping them manage peripartum anxiety, also may favorably impact their pain experience.

Following a surgical procedure, a surgeon’s top goal is the full recovery of the patient to normal activity as soon as possible with as few complications as possible. Persistent opioid dependence is a serious long-term complication of surgery. Decades ago, most heroin users reported that heroin was the first opioid they used. However, the gateway drug to heroin use has evolved. In a recent study, 75% of heroin users reported that the first opioid they used was a prescription opioid.29 In managing surgical pain we want to minimize the use of opioids and reduce the risk of persistent opioid use following discharge. We believe that implementing a multimodal approach to the management of pain with additional targeted therapy for patients at risk for higher opioid requirement will reduce the perioperative and postdischarge use of opioid analgesics. ●

- Drug overdose deaths in the U.S. up 30% in 2020. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention web- site. July 14, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs /pressroom/nchs_press_releases/2021/20210714 .htm. Last reviewed July 14, 2021

- Jani M, Girard N, Bates DW, et al. Opioid prescribing among new users for non-cancer pain in the USA, Canada, UK, and Taiwan: a population-based cohort study. PLoS Med. 2021;18:e1003829.

- U.S. opioid dispensing rate maps. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www. cdc.gov/drugoverdose/rxrate-maps/index.html. Last reviewed November 10, 2021.

- Richards GC, Aronson JK, Mahtani KR, et al. Global, regional, and national consumption of controlled opioids: a cross-sectional study of 214 countries and non-metropolitan areas. British J Pain. 2021. https://doi .org/10.1177/20494637211013052.

- Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Osterman MJK. Births: Provisional data for 2020. Vital Statistics Rapid Release; no 12. Hyattsville MD: National Center for Health Statistics. May 2021.

- Bateman BT, Franklin JM, Bykov K, et al. Persistent opioid use following cesarean delivery: patterns and predictors among opioid-naïve women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215:353.e1-e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.03.016.

- Osmundson SS, Wiese AD, Min JY, et al. Delivery type, opioid prescribing and the risk of persistent opioid use after delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220:405-407. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.10.026.

- Peahl AF, Dalton VK, Montgomery JR, et al. Rates of new persistent opioid use after vaginal or cesarean birth among U.S. women. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;e197863. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.7863.

- Holland E, Bateman BT, Cole N, et al. Evaluation of a quality improvement intervention that eliminated routine use of opioids after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:91-97. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003010.

- Smith AM, Young P, Blosser CC, et al. Multimodal stepwise approach to reducing in-hospital opioid use after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:700-706. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003156.

- Herbert KA, Yuraschevich M, Fuller M, et al. Impact of multimodeal analgesic protocol modification on opioid consumption after cesarean delivery: a retrospective cohort study. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2021;3:1-7. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2020.1863364.

- Mehraban SS, Suddle R, Mehraban S, et al. Opioid-free multimodal analgesia pathway to decrease opioid utilization after cesarean delivery. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2021;47:873-881. doi: 10.1111/jog.14582.

- Meyer MF, Broman AT, Gnadt SE, et al. A standardized post-cesarean analgesia regimen reduces postpartum opioid use. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2021;26:1-8. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2021.1970132.