User login

Write an exercise Rx to improve patients' cardiorespiratory fitness

It is well-known that per capita health care spending in the United States is more than twice the average in other developed countries1; nevertheless, the overall health care ranking of the US is near the bottom compared to other countries in this group.2 Much of the reason for this poor relative showing lies in the fact that the US has employed a somewhat traditional fee-for-service health care model that does not incentivize efforts to promote health and wellness or prevent chronic disease. The paradigm of promoting physical activity for its disease-preventing and treatment benefits has not been well-integrated in the US health care system.

In this article, we endeavor to provide better understanding of the barriers that keep family physicians from routinely promoting physical activity in clinical practice; define tools and resources that can be used in the clinical setting to promote physical activity; and delineate areas for future work.

Glaring hole in US physical activity education

Many primary care physicians feel underprepared to prescribe or motivate patients to exercise. The reason for that lack of preparedness likely relates to a medical education system that does not spend time preparing physicians to perform this critical task. A study showed that, on average, medical schools require only 8 hours of physical activity education in their curriculum during the 4 years of schooling.3 Likewise, the average primary care residency program offers only 3 hours of didactic training on physical activity, nutrition, and obesity.4 The problem extends to sports medicine fellowship training, in which a 2019 survey showed that 63% of fellows were never taught how to write an exercise prescription in their training program.5

Without education on physical activity, medical students, residents, and fellows are woefully underprepared to realize the therapeutic value of physical activity in patient care, comprehend current physical activity guidelines, appropriately motivate patients to engage in exercise, and competently discuss exercise prescriptions in different disease states. Throughout their training, it is imperative for medical professionals to be educated on the social determinants of health, which include the conditions in which people live, work, and play. These environmental variables can contribute to health inequities that create additional barriers to improvement in physical fitness.6

National guidelines on physical activity

The 2018 National Physical Activity Guidelines detail recommendations for children, adolescents, adults, and special populations.7 The guidelines define physical activity as bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that result in energy expenditure above resting baseline levels, and includes all types, intensities, and domains of activity. Exercise is a subset of physical activity characterized as planned, structured, repetitive, and designed to improve or maintain physical fitness, physical performance, or health.

Highlights from the 2018 guidelines include7:

- Preschool-aged children (3 to 5 years of age) should be physically active throughout the day, with as much as 3 hours per day of physical activity of all intensities—light, moderate, and vigorous.

- Older children and adolescents (6 to 17 years) should accumulate 60 minutes per day of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity, including aerobic, muscle-strengthening, and bone-strengthening activities.

- Adults of all ages should achieve approximately 150 to 300 minutes of moderate or 75 to 150 minutes of vigorous physical activity (or an equivalent combination) per week, along with at least 2 days per week of muscle-strengthening activities. Other types of physical activity include flexibility, balance, bone-strengthening, and mind–body exercises.

3-step framework for enhancing physical activity counseling

Merely knowing that physical activity is healthy is not enough, during a patient encounter, to increase the level of physical activity. Therefore, it is imperative to learn and adopt a framework that has proved to yield successful outcomes. The Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) framework, which has predominantly been used to change patient behavior related to alcohol and substance use, is now being utilized by some providers to promote physical activity.8 We apply the SBIRT approach in this article, although research is lacking on its clinical utility and outcome measures.

Continue to: SBIRT

SBIRT: Screening

An office visit provides an opportunity to understand a patient’s level of physical activity. Often, understanding a patient’s baseline level of activity is only asked during a thorough social history, which might not be performed during patient encounters. As physical activity is the primary determinant of cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF), some health care systems have begun delineating physical activity levels as a vital sign to ensure that the assessment of physical activity is a standard part of every clinical encounter. At a minimum, this serves as a prompt and provides an opportunity to start a conversation around improving physical activity levels when guidelines are not being met.

The exercise vital sign. Assessment and documentation of physical activity in the electronic health record are not yet standardized; however, Kaiser Permanente health plans have implemented the exercise vital sign, or EVS, in its HealthConnect (Epic Systems) electronic health record. The EVS incorporates information about a patient’s:

- days per week of moderate-to-strenuous exercise (eg, a brisk walk)

- minutes per day, on average, of exercise at this level.

The physical activity vital sign. Intermountain Healthcare implemented the physical activity vital sign, or PAVS, in its iCentra (Cerner Corp.) electronic health record. The 3-question PAVS assessment asks:

- On average, how many days of the week do you perform physical activity or exercise?

- On average, how many total minutes of physical activity or exercise do you perform on those days?

- How would you describe the intensity of your physical activity or exercise: Light (ie, a casual walk)? Moderate (a brisk walk)? Or vigorous (jogging)?

PAVS includes a fourth data point: The physician–user documents whether the patient was counseled to start, increase, maintain, or modify physical activity or exercise.

EVS and the PAVS have demonstrated validity.9-11

Continue to: Cardiorespiratory fitness as a vital sign

Cardiorespiratory fitness as a vital sign. In 2016, the American Heart Association (AHA) asserted the importance of assessing CRF as a clinical vital sign.12 CRF is commonly expressed as maximal oxygen consumption (VO2max = O2 mL/kg/min) and measured through cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET), considered the gold standard by combining conventional graded exercise testing with ventilatory expired gas analysis. CPET is more objective and precise than equations estimating CRF that are derived from peak work rate. AHA recommended that efforts to improve CRF should become standard in clinical encounters, explaining that even a small increase in CRF (eg, 1 or 2 metabolic equivalentsa [METs]) is associated with a considerably (10% to 30%) lower rate of adverse cardiovascular events.12

De Souza de Silva and colleagues revealed an association between each 1-MET increase in CRF and per-person annual health care cost savings (adjusted for age and presence of cardiovascular disease) of $3272 (normal-weight patients), $4252 (overweight), and $6103 (obese).13 In its 2016 scientific statement on CRF as a vital sign, AHA listed several methods of estimating CRF and concluded that, although CPET involves a higher level of training, proficiency, equipment, and, therefore, cost, the independent and additive information obtained justifies its use in many patients.12

CASE

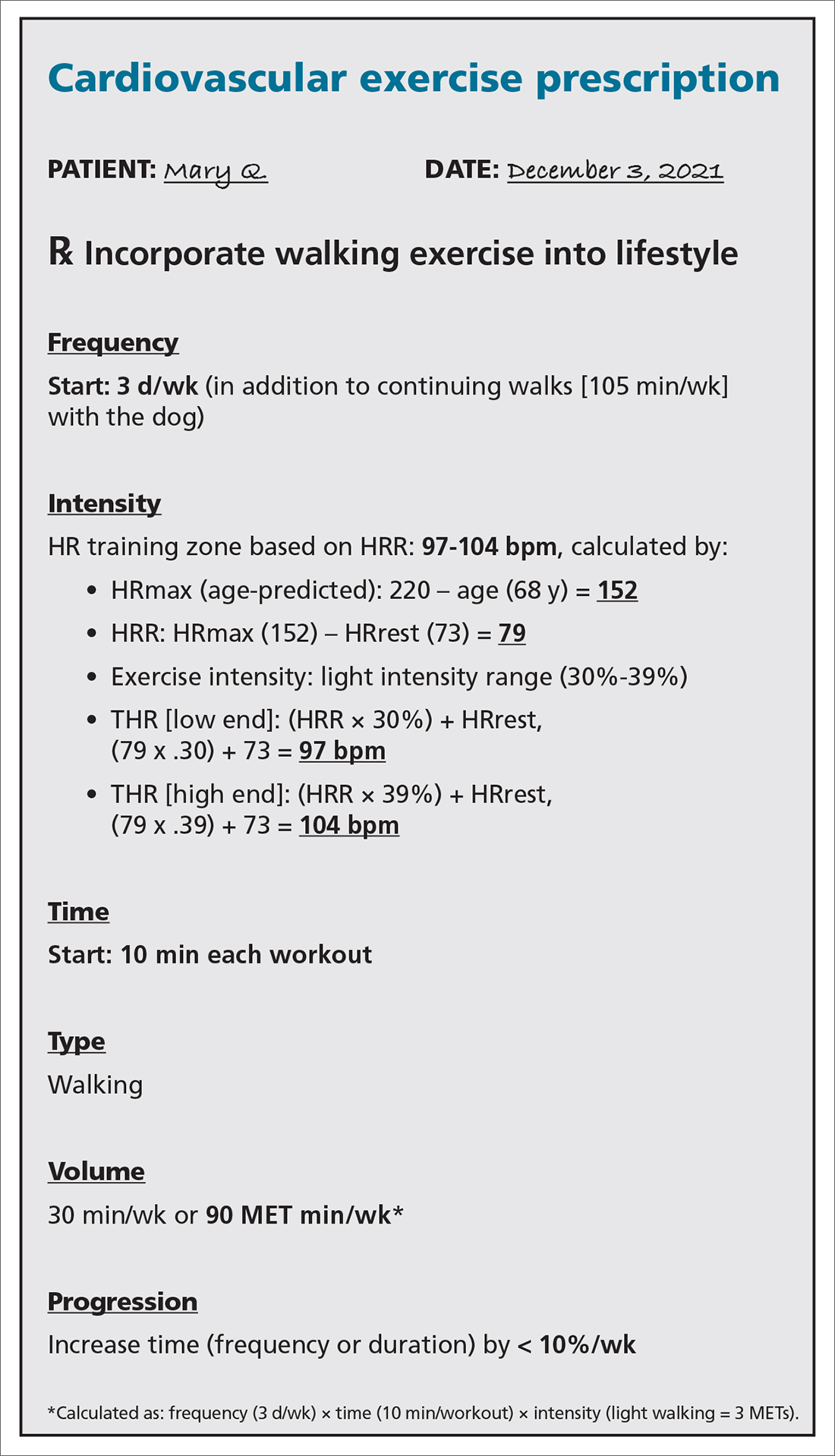

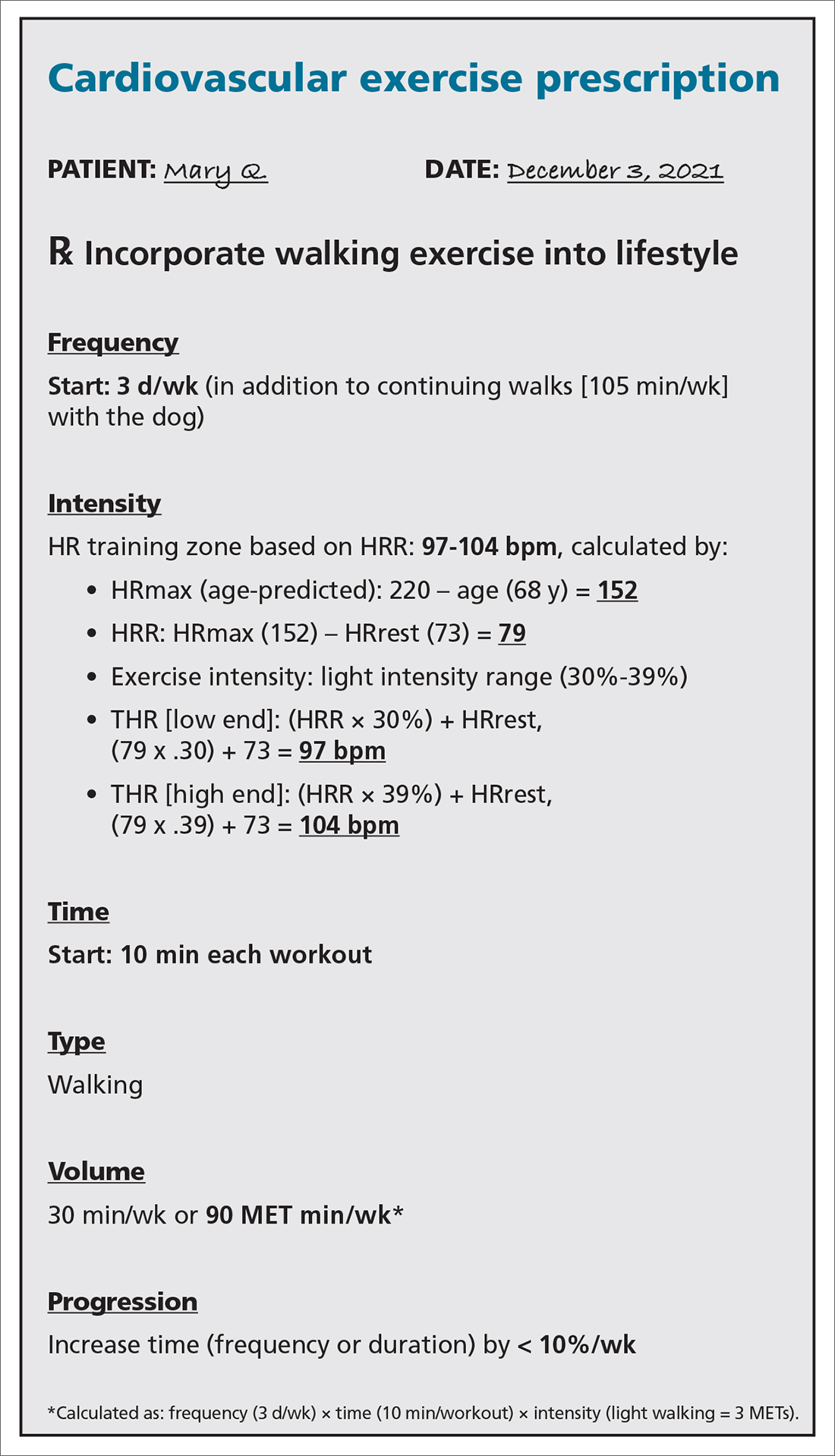

Mary Q, 68 years of age, presents for an annual well-woman examination. Body mass index is 32; resting heart rate (HR), 73 bpm; and blood pressure, 126/74 mm Hg. She reports being inactive, except for light walking every day with her dog around the neighborhood, which takes them approximately 15 minutes. She denies any history or signs and symptoms of cardiovascular, metabolic, or renal disease.

You consider 3 questions before taking next steps regarding increasing Ms. Q’s activity level:

- What is her PAVS?

- Does she need medical clearance before starting an exercise program?

- What would an evidence-based cardiovascular exercise prescription for Ms. Q look like?

SBIRT: Brief intervention

When a patient does not meet the recommended level of physical activity, you have an opportunity to deliver a brief intervention. To do this effectively, you must have adequate understanding of the patient’s receptivity for change. The transtheoretical, or Stages of Change, model proposes that a person typically goes through 5 stages of growth—pre-contemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance—in the process of lifestyle modification. This model highlights the different approaches to exercise adoption and maintenance that need to be taken, based on a given patient’s stage at the moment.

Continue to: Using this framework...

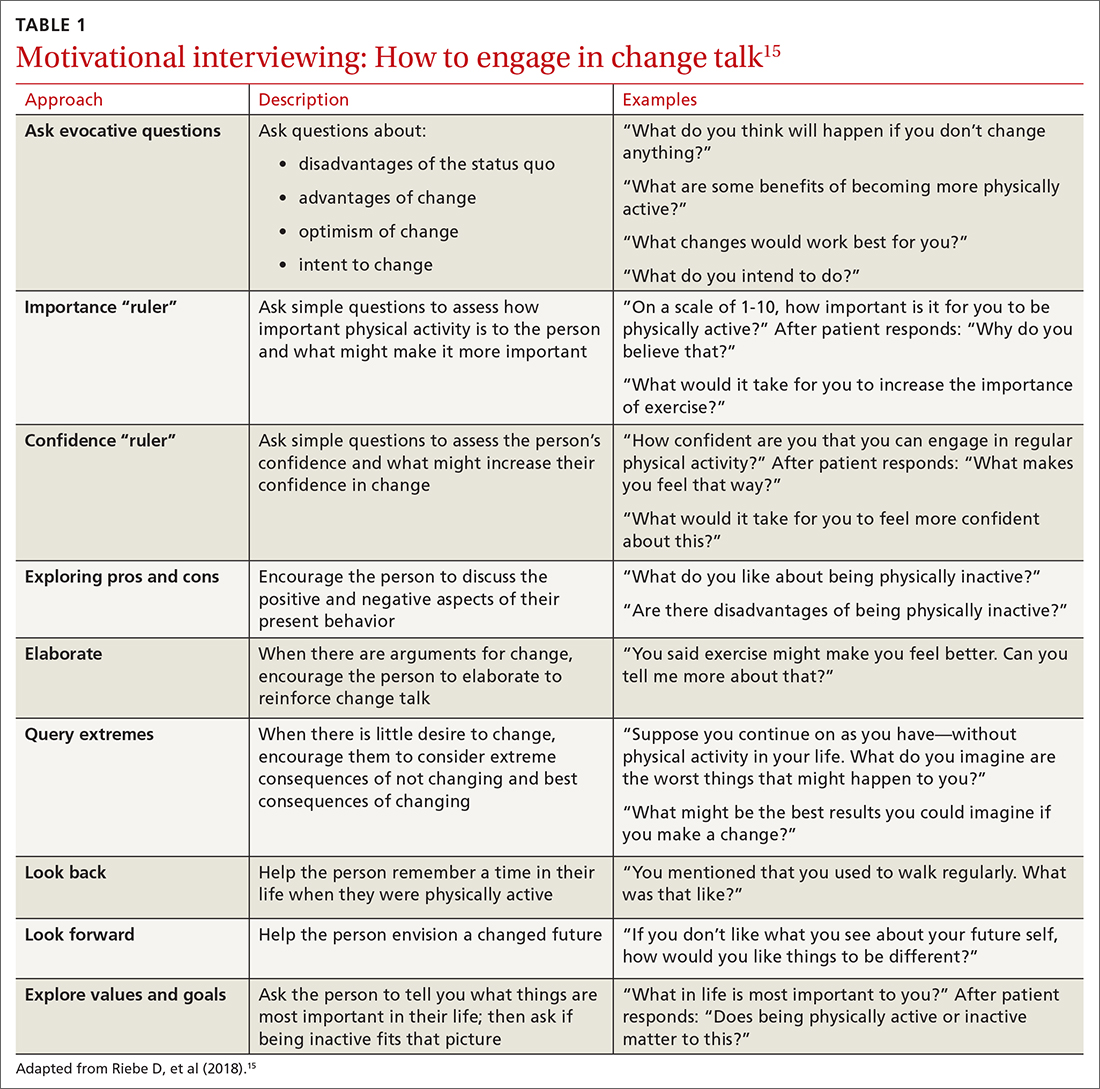

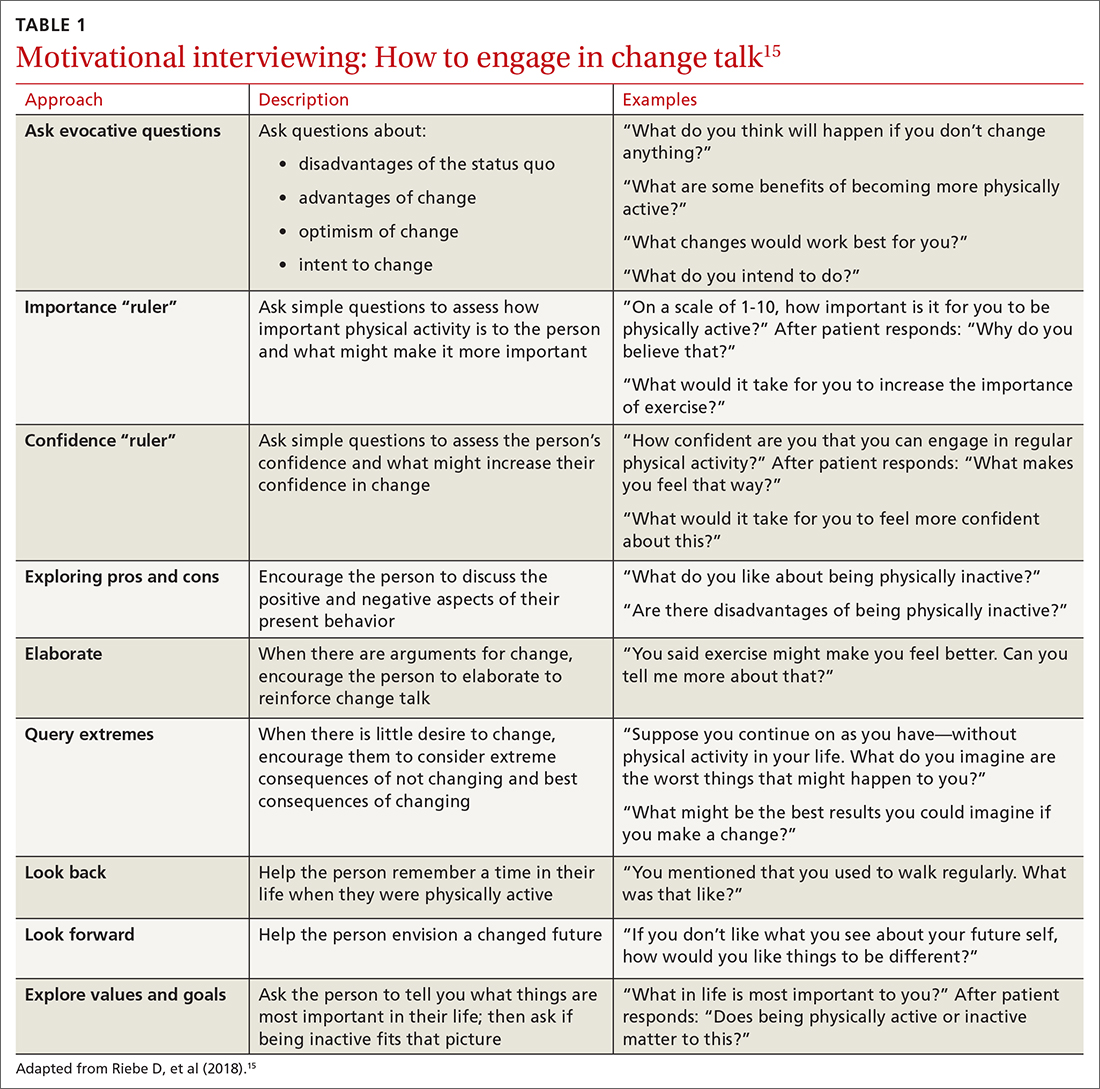

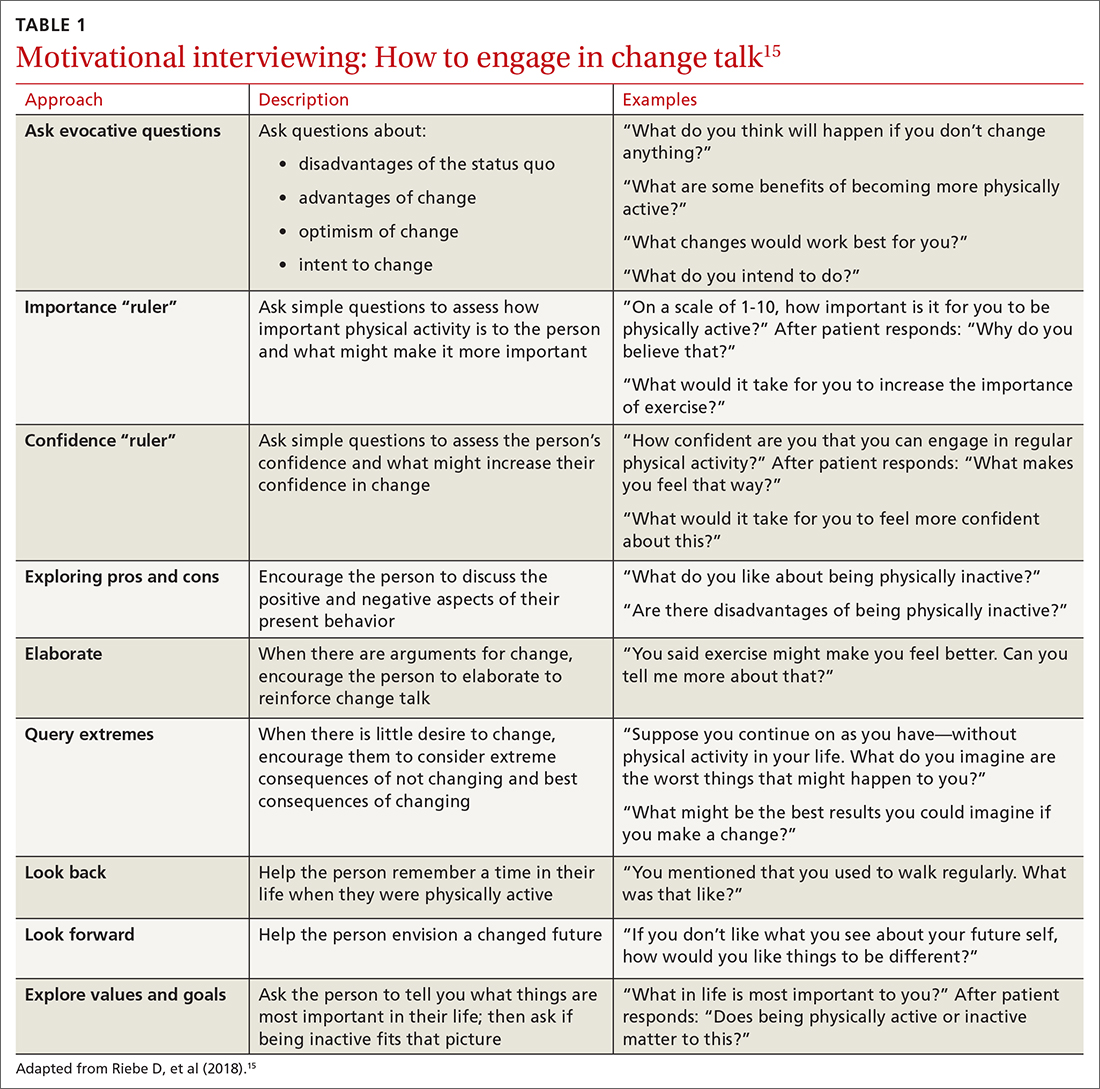

Using this framework, you can help patients realize intrinsic motivation that can facilitate progression through each stage, utilizing techniques such as motivational interviewing—so-called change talk—to increase self-efficacy.14TABLE 115 provides examples of motivational interviewing techniques that can be used during a patient encounter to improve health behaviors, such as physical activity.

Writing the exercise prescription

A patient who wants to increase their level of physical activity should be offered a formal exercise prescription, which has been shown to increase the level of physical activity, particularly in older patients. In fact, a study conducted in Spain in the practices of family physicians found that older patients who received a physical activity prescription increased their activity by 131 minutes per week; and compared to control patients, they doubled the minutes per week devoted to moderate or vigorous physical activity.16

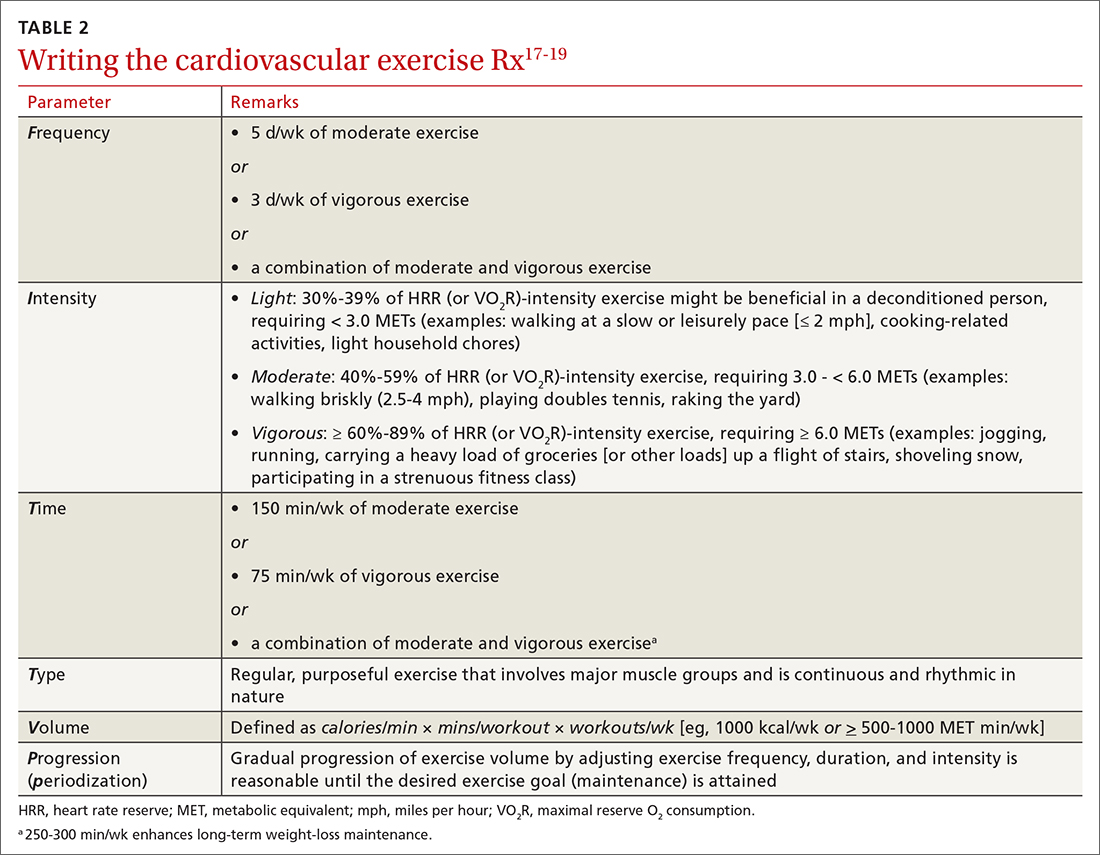

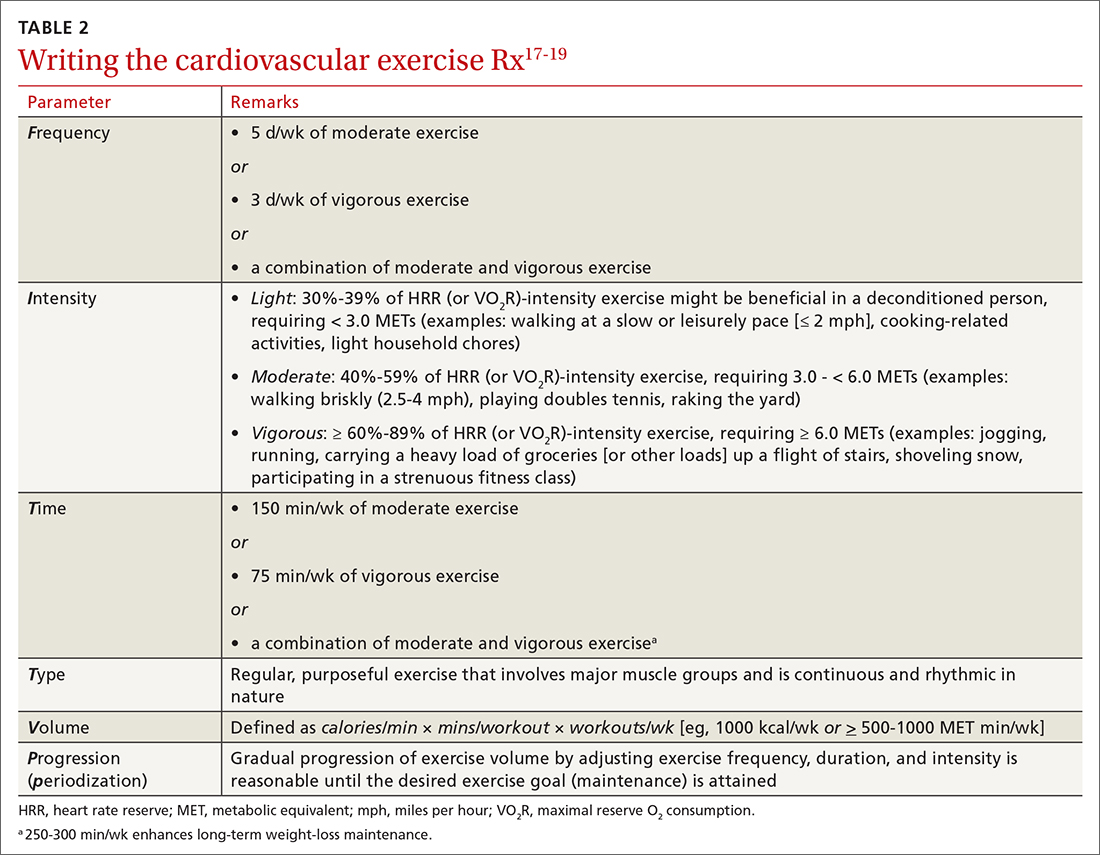

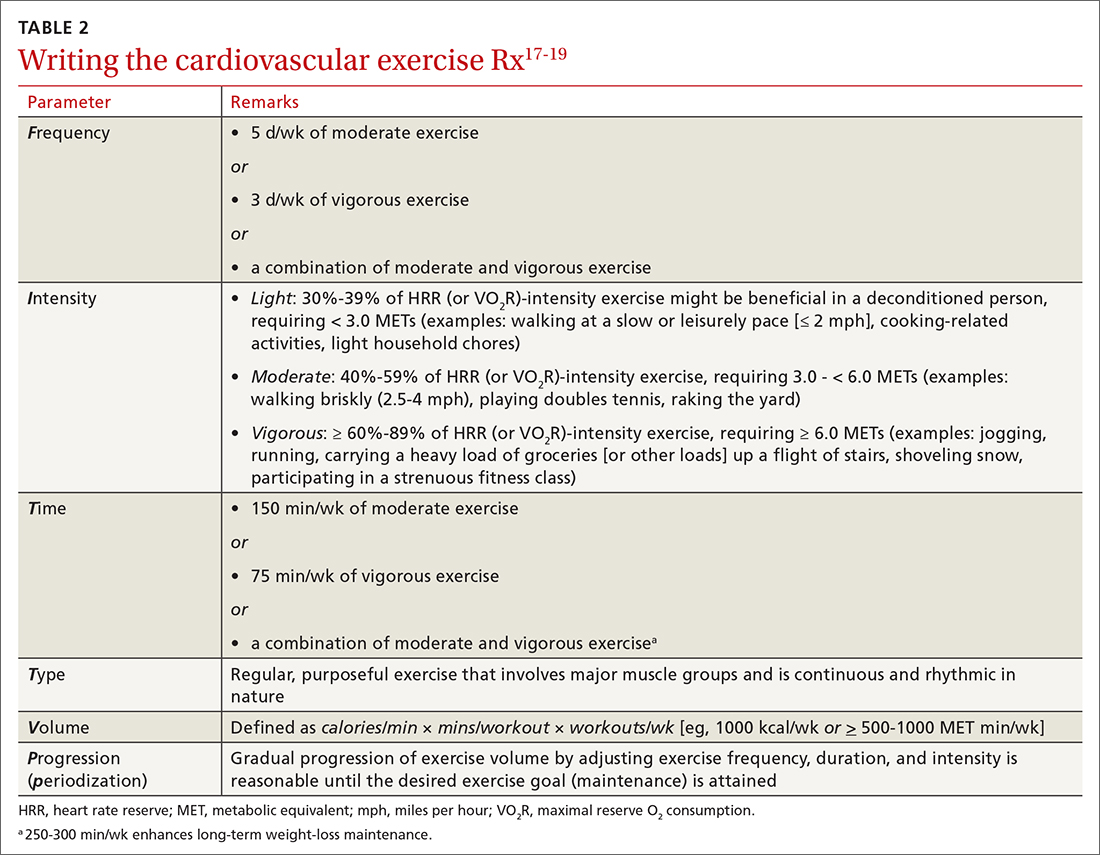

FITT-VP. The basics of a cardiovascular exercise prescription can be found in the FITT-VP (Frequency, Intensity, Time, Type, Volume, and [monitoring of] Progression) framework (TABLE 217-19). For most patients, this model includes 3 to 5 days per week of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity for 30 to 60 minutes per session. For patients with established chronic disease, physical activity provides health benefits but might require modification. Disease-specific patient handouts for exercise can be downloaded, at no cost, through the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) “Exercise Is Medicine” program, which can be found at: www.exerciseismedicine.org/support_page.php/rx-for-health-series.

Determining intensity level. Although CPET is the gold standard for determining a patient’s target intensity level, such a test might be impracticable for a given patient. Surrogate markers of target intensity level can be obtained by measuring maximum HR (HRmax), using a well-known equation20:

HRmax = 220 – age

which is then multiplied by intensity range:

- light: 30%-39%

- moderate: 40%-59%

- vigorous: 60%-89%

or, more preferably, by calculating the HR training zone while accounting for HR at rest (HRrest). This is accomplished by calculating the HR reserve (HRR) (ie, HRR = HRmax – HRrest) and then calculating the target heart rate (THR)21:

THR = [HRR × %intensity] + HRrest

Continue to: The THR calculation...

The THR calculation is performed twice, once with a lower %intensity and again with a higher %intensity to develop a training zone based on HRR.

The HRR equation is more accurate than calculating HRmax from 220 – age, because HRR accounts for resting HR, which is often lower in people who are better conditioned.

Another method of calculating intensity for patients who are beginning a physical activity program is the rating of perceived exertion (RPE), which is graded on a scale of 6 to 20: Moderate exercise correlates with an RPE of 12 to 13 (“somewhat hard”); vigorous exercise correlates with an RPE of 14 to 16 (“hard”). By adding a zero to the rating on the RPE scale, the corresponding HR in a healthy adult can be estimated when they are performing an activity at that perceived intensity.22 Moderate exercise therefore correlates with a HR of 120 and 130 bpm.

The so-called talk test can also guide exercise intensity: Light-intensity activity correlates with an ability to sing; moderate-intensity physical activity likely allows the patient to still hold a conversation; and vigorous-intensity activity correlates with an inability to carry on a conversation while exercising.

An exercise prescription should be accompanied by a patient-derived goal, which can be reassessed during a follow-up visit. So-called SMART goals (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-bound) are tools to help patients set personalized and realistic expectations for physical activity. Meeting the goal of approximately 150 to 300 minutes of moderate or 75 to 150 minutes of vigorous physical activity (or an equivalent combination) per week is ideal, but a patient needs to start where they are, at the moment, and gradually increase activity by setting what for them are realistic and sustainable goals.

Continue to: CASE

CASE

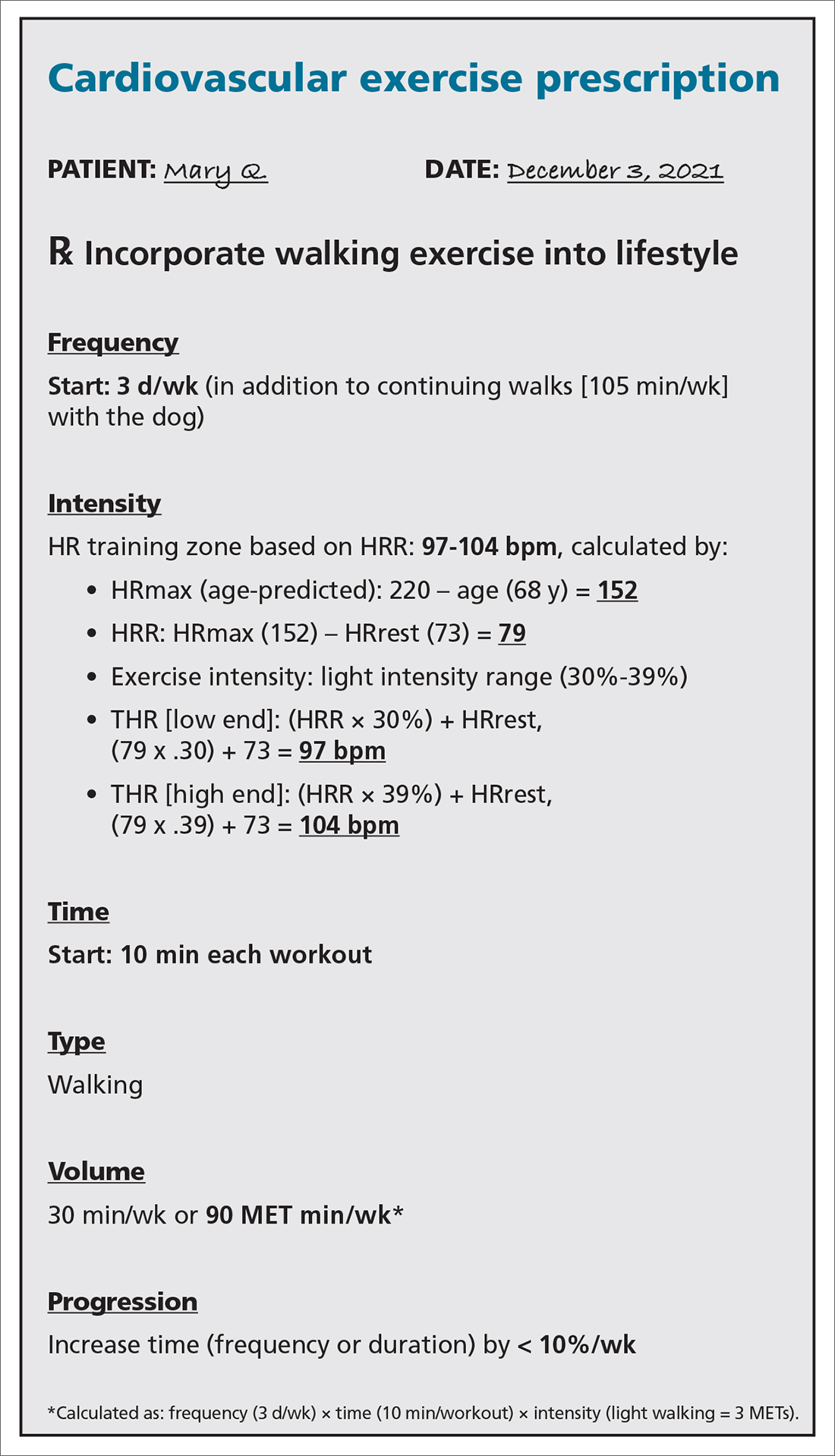

With a PAVS of 105 minutes (ie, 15 minutes per day × 7 days) of weekly light-to-moderate exercise walking her dog, Ms. Q does not satisfy current physical activity guidelines. She needs an exercise prescription to incorporate into her lifestyle (see “Cardiovascular exercise prescription,” at left).

First, based on ACSM pre-participation guidelines, Ms. Q does not need medical clearance before initiating light-to-moderate exercise and gradually progressing to vigorous-intensity exercise.

Second, in addition to walking the dog for 105 minutes a week, you:

- advise her to start walking for 10 minutes, 3 times per week, at a pace that keeps her HR at 97-104 bpm.

- encourage her to gradually increase the frequency or duration of her walks by no more than 10% per week.

SBIRT: Referral for treatment

When referring a patient to a fitness program or professional, it is essential to consider their preferences, resources, and environment.23 Community fitness partners are often an excellent referral option for a patient seeking guidance or structure for their exercise program. Using the ACSM ProFinder service, (www.acsm.org/get-stay-certified/find-a-pro) you can search for exercise professionals who have achieved the College’s Gold Standard credential.

Gym memberships or fitness programs might be part of the extra coverage offered by Medicare Advantage Plans, other Medicare health plans, or Medicare Supplement Insurance (Medigap) plans.24

Continue to: CASE

CASE

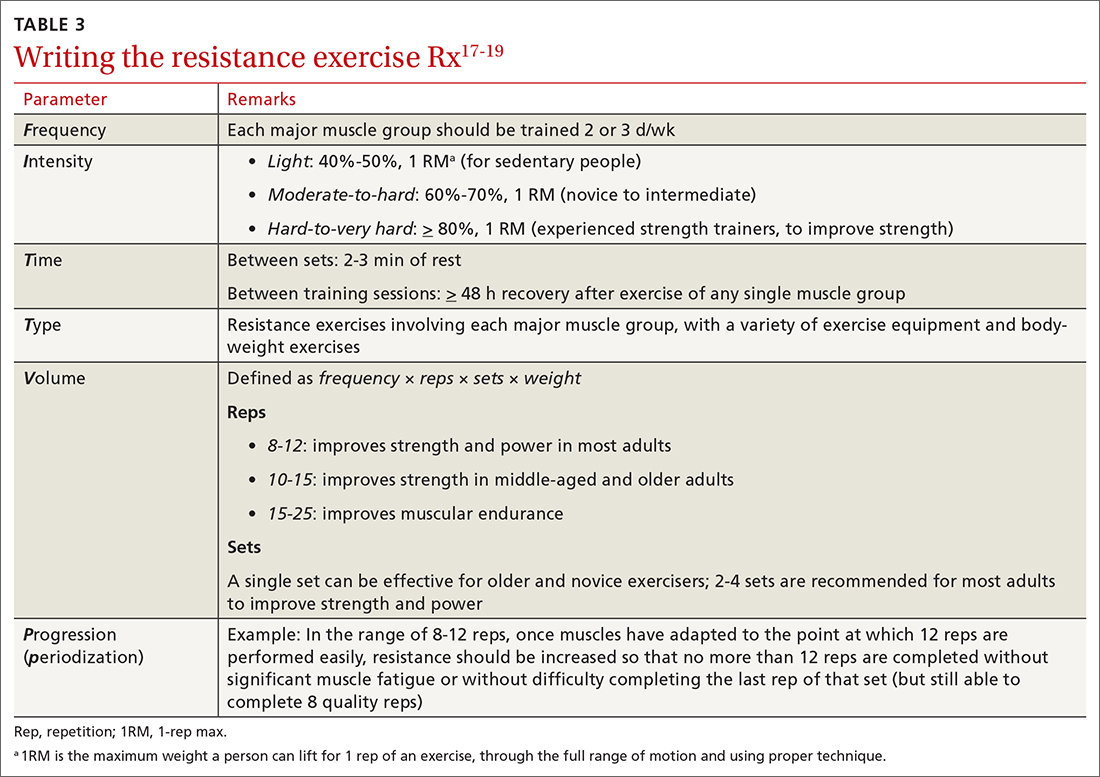

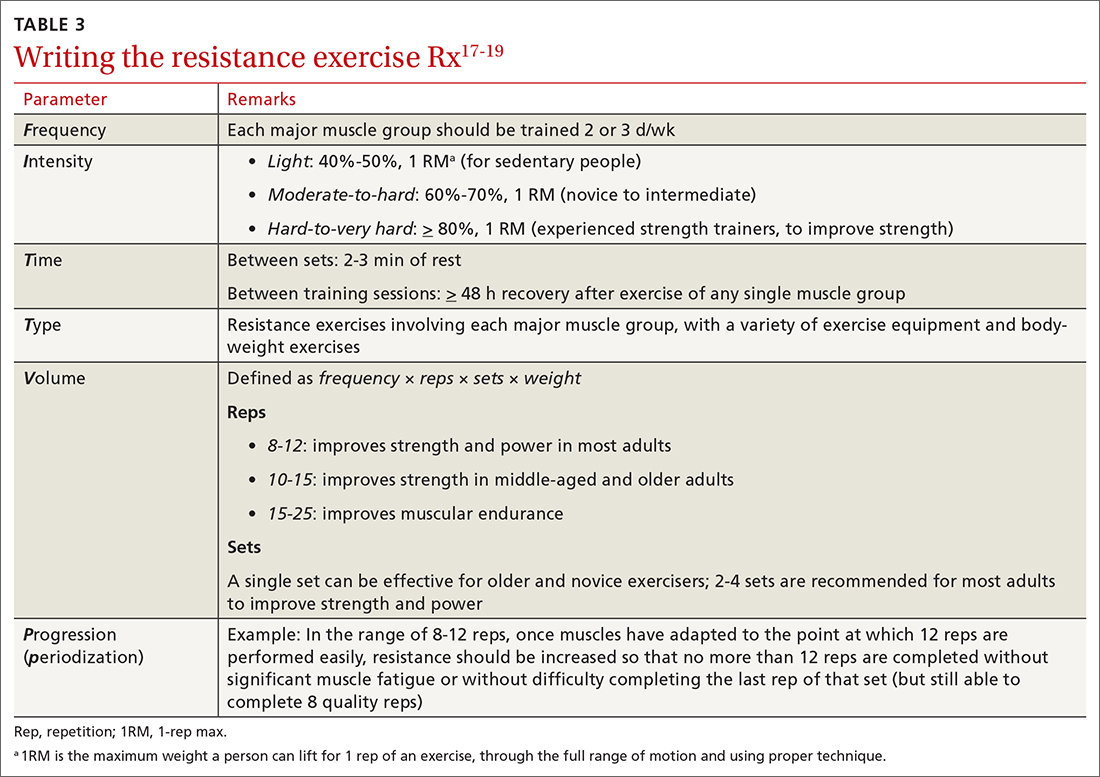

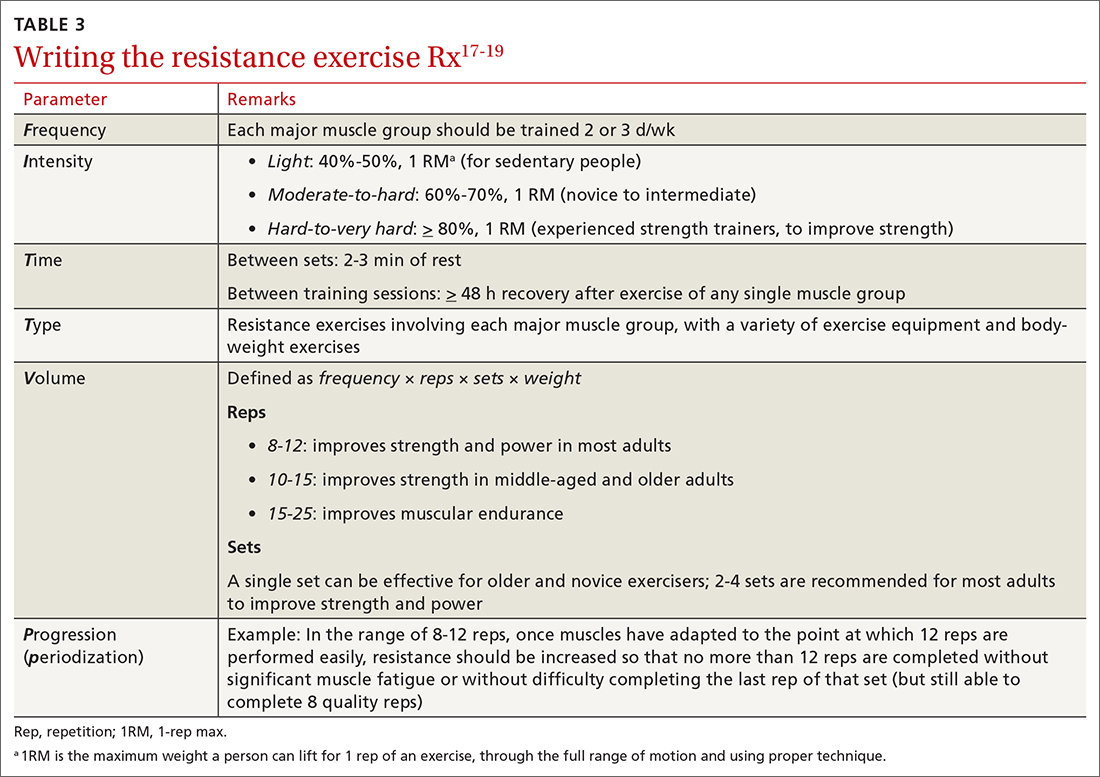

After providing Ms. Q with her exercise prescription, you refer her to a local gym that participates in the Silver Sneakers fitness and wellness program (for adults ≥ 65 years of age in eligible Medicare plans) to determine whether she qualifies to begin resistance and flexibility training, for which you will write a second exercise prescription (TABLE 317-19).

Pre-participation screening

Updated 2015 ACSM exercise pre-participation health screening recommendations attempt to decrease possible barriers to people who are becoming more physically active, by minimizing unnecessary referral to health care providers before they change their level of physical activity. ACSM recommendations on exercise clearance include this guidance25:

- For a patient who is asymptomatic and already physically active—regardless of whether they have known cardiovascular, metabolic, or renal disease—medical clearance is unnecessary for moderate-intensity exercise.

- Any patient who has been physically active and asymptomatic but who becomes symptomatic during exercise should immediately discontinue such activity and undergo medical evaluation.

- For a patient who is inactive, asymptomatic, and who does not have known cardiovascular, metabolic, or renal disease, medical clearance for light- or moderate-intensity exercise is unnecessary.

- For inactive, asymptomatic patients who have known cardiovascular, metabolic, or renal disease, medical clearance is recommended.

Digital health

Smartwatches and health apps (eg, CardioCoach, Fitbit, Garmin Connect, Nike Training Club, Strava, and Training Peaks) can provide workouts and offer patients the ability to collect information and even connect with other users through social media platforms. This information can be synced to Apple Health platforms for iPhones (www.apple.com/ios/health/) or through Google Fit (www.google.com/fit/) on Android devices. Primary care physicians who become familiar with health apps might find them useful for select patients who want to use technology to improve their physical activity level.

However, data on the value of using digital apps for increasing physical activity, in relation to their cost, are limited. Additional research is needed to assess their validity.

Billing and coding

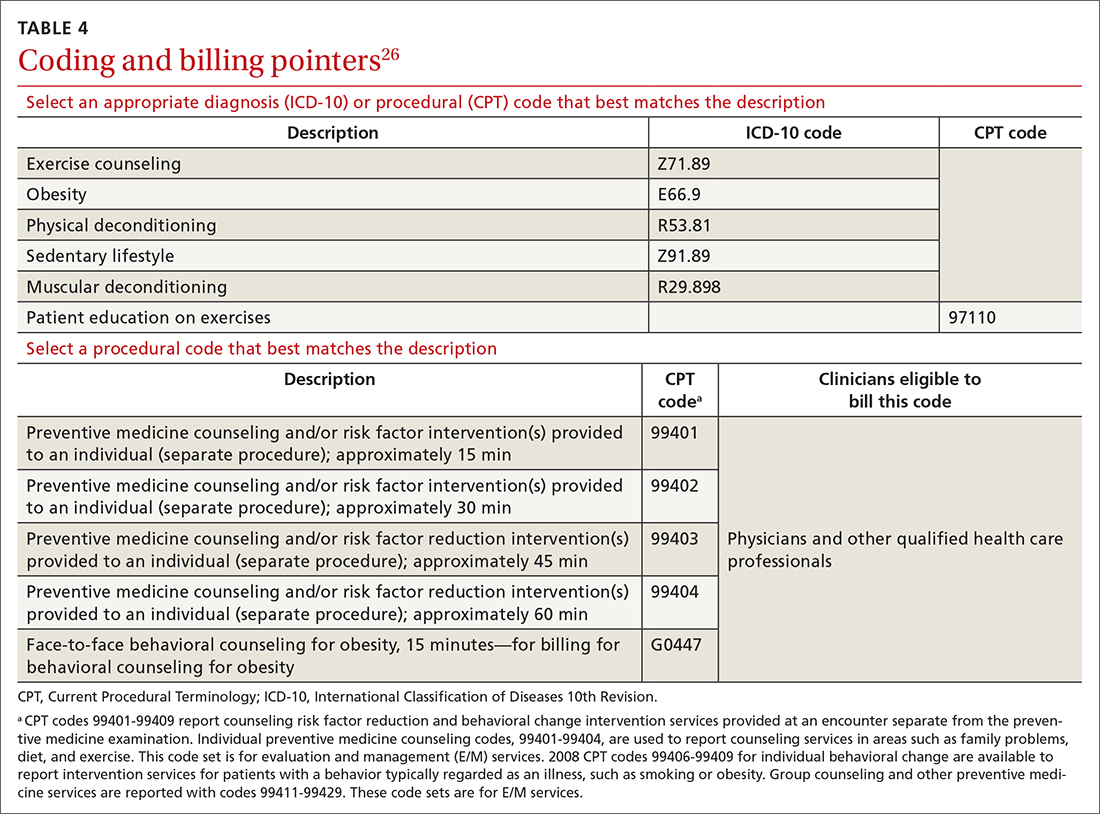

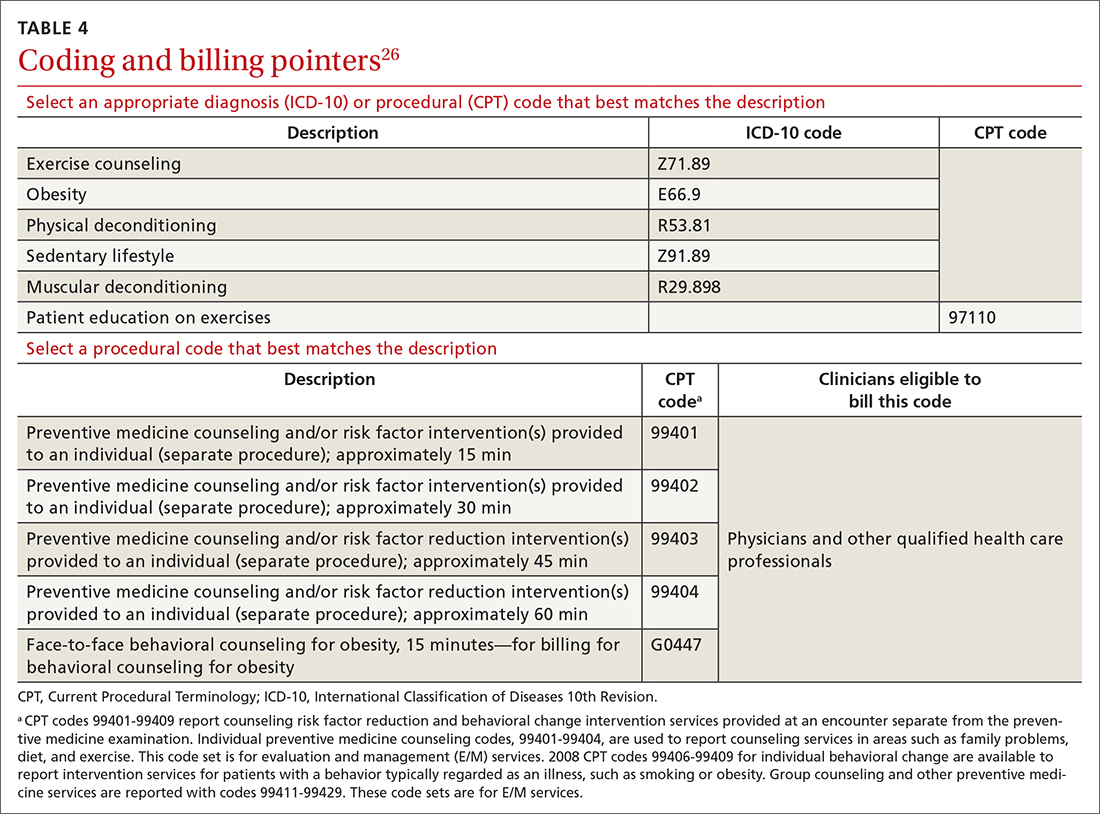

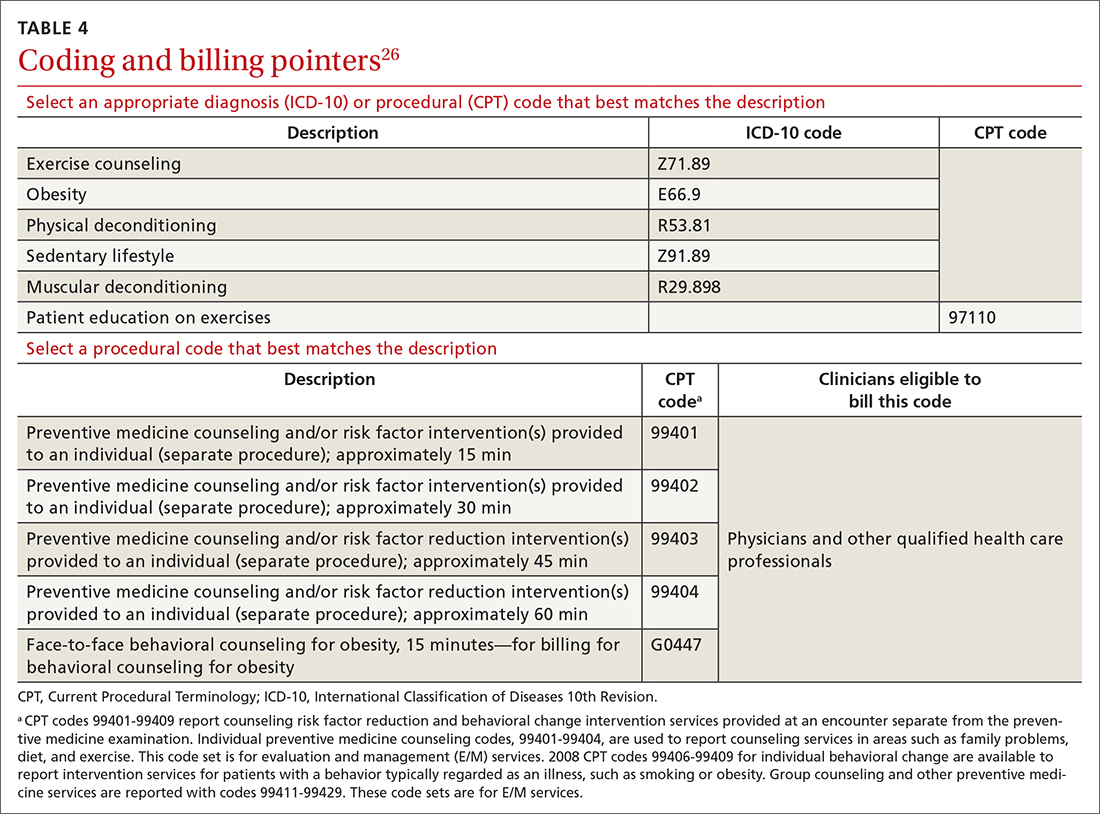

For most patients, the physical activity assessment, prescription, and referral are performed in the context of treating another condition (eg, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, obesity, depression) or during a preventive health examination, and are typically covered without additional charge to the patient. An evaluation and management visit for an established patient could be used to bill if > 50% of the office visit was spent face-to-face with a physician, with patient counseling and coordination of care.

Continue to: Physicians and physical therapists...

Physicians and physical therapists can use the therapeutic exercise code (Current Procedural Terminology code 97110) when teaching patients exercises to develop muscle strength and endurance, joint range of motion, and flexibility26 (TABLE 426).

Conclusion

Physical activity and CRF are strong predictors of premature mortality, even compared to other risk factors, such as cigarette smoking, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and type 2 diabetes.27 Brief physical activity assessment and counseling is an efficient, effective, and cost-effective means to increase physical activity, and presents a unique opportunity for you to encourage lifestyle-based strategies for reducing cardiovascular risk.28

However, it is essential to meet patients where they are before trying to have them progress; it is therefore imperative to assess the individual patient’s level of activity using PAVS. With that information in hand, you can personalize physical activity advice; determine readiness for change and potential barriers for change; assist the patient in setting SMART goals; and arrange follow-up to assess adherence to the exercise prescription. Encourage the patient to call their health insurance plan to determine whether a gym membership or fitness program is covered.

Research is needed to evaluate the value of using digital apps, in light of their cost, to increase physical activity and improve CRF in a clinical setting. Prospective trials should be initiated to determine how routine implementation of CRF assessment in primary care alters the trajectory of clinical care. It is hoped that future research will answer the question: Would such an approach improve clinical outcomes and reduce health care expenditures?12

a Defined as O2 consumed while sitting at rest; equivalent to 3.5 mL of O2 × kg of body weight × min.

CORRESPONDENCE

Matthew Kampert, DO, MS, Sports Medicine, 5555 Transportation Boulevard, Cleveland, OH 44125; [email protected]

1. Papanicolas I, Woskie LR, Jha AK. Health care spending in the United States and other high-income countries. JAMA. 2018;319:1024-1039. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.1150

2. Tikkanen R, Abrams MK. U.S. health care from a global perspective, 2019: higher spending, worse outcomes? The Commonwealth Fund Website. January 30, 2020. Accessed November 16, 2021. www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2020/jan/us-health-care-global-perspective-2019

3. Stoutenberg M, Stasi S, Stamatakis E, et al. Physical activity training in US medical schools: preparing future physicians to engage in primary prevention. Phys Sportsmed. 2015;43:388-394. doi: 10.1080/00913847.2015.1084868

4. Antognoli EL, Seeholzer EL, Gullett H, et al. Primary care resident training for obesity, nutrition, and physical activity counseling: a mixed-methods study. Health Promot Pract. 2017;18:672-680. doi: 10.1177/1524839916658025

5. Asif IM, Drezner JA. Sports and exercise medicine education in the USA: call to action. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54:195-196. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2019-101104

6. Douglas JA, Briones MD, Bauer EZ, et al. Social and environmental determinants of physical activity in urban parks: testing a neighborhood disorder model. Prev Med. 2018;109:119-124. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.01.013

7. 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee. 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Scientific Report. Washington, DC: US Department of Health & Human Services; 2018. Accessed November 15, 2021. https://health.gov/sites/default/files/2019-09/PAG_Advisory_Committee_Report.pdf

8. Avis JL, Cave AL, Donaldson S, et al. Working with parents to prevent childhood obesity: protocol for a primary care-based ehealth study. JMIR Res Protoc. 2015;4:e35. doi:10.2196/resprot.4147

9. Ball TJ, Joy EA, Gren LH, et al. Concurrent validity of a self-reported physical activity ‘vital sign’ questionnaire with adult primary care patients. Prev Chronic Dis. 2016;13:e16. doi: 10.5888/pcd13.150228

10. Ball TJ, Joy EA, Gren LH, et al. Predictive validity of an adult physical activity “vital sign” recorded in electronic health records. J Phys Act Health. 2016;13:403-408. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2015-0210

11. Coleman KJ, Ngor E, Reynolds K, et al. Initial validation of an exercise “vital sign” in electronic medical records. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012;44:2071-2076. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3182630ec1

12. Ross R, Blair SN, Arena R, et al; ; ; ; ; ; . Importance of assessing cardiorespiratory fitness in clinical practice: a case for fitness as a clinical vital sign: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;134:e653-e699. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000461

13. de Souza de Silva CG, Kokkinos PP, Doom R, et al. Association between cardiorespiratory fitness, obesity, and health care costs: The Veterans Exercise Testing Study. Int J Obes (Lond). 2019;43:2225-2232. doi: 10.1038/s41366-018-0257-0

14. Prochaska JO, Velicer WF. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. Am J Health Promot. 1997;12:38-48. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-12.1.38

15. Riebe D, Ehrman JK, Liguori G, et al. Methods for evoking change talk. In: ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription. 10th ed. Wolters Kluwer; 2018.

16. Grandes G, Sanchez A, Sanchez-Pinilla RO, et al. Effectiveness of physical activity advice and prescription by physicians in routine primary care: a cluster randomized trial. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:694-701. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.23

17. McNeill LH, Kreuter MW, Subramanian SV. Social environment and physical activity: a review of concepts and evidence. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63:1011-1022. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.03.012

18. Garber CE, Blissmer BE, Deschenes MR, et al; American College of Sports Medicine. Quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: Guidance for prescribing exercise. Position stand. Med Sci Sport Exerc. 2011;43:1334-1359. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318213fefb

19. Donnelly JE, Blair SN, Jakicic JM, et al; American College of Sports Medicine. Appropriate physical activity intervention strategies for weight loss and prevention of weight regain for adults. Position stand. Med Sci Sport Exerc. 2009;41:459-471. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181949333

20. Fox SM 3rd, Naughton JP, Haskell WL. Physical activity and the prevention of coronary heart disease. Ann Clin Res. 1971;3:404-432.

21. Karvonen MJ, Kentala E, Mustala O. The effects of training on heart rate; a longitudinal study. Ann Med Exp Biol Fenn. 1957;35:307-315.

22. The Borg RPE scale. In: Borg G. Borg’s Perceived Exertion and Pain Scales. Human Kinetics; 1998:29-38.

23. Ratamess NA, Alvar BA, Evetoch TK, et al; American College of Sports Medicine. Progression models in resistance training for healthy adults. Position stand. Med Sci Sport Exerc. 2009;41:687-708. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181915670

24. Gym memberships & fitness programs. Medicare.gov. Baltimore, MD: US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Accessed November 16, 2021. www.medicare.gov/coverage/gym-memberships-fitness-programs

25. Riebe D, Franklin BA, Thompson PD, et al. Updating ACSM’s recommendations for exercise preparticipation health screening. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2015;47:2473-2479. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000664

26. Physical Activity Related Current Procedural Terminology (CPT®) Codes. Physical Activity Alliance website. Accessed November 16, 2021. https://paamovewithus.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/PAA-Physical-Activity-CPT-Codes-Nov-2020-AMA-Approved-Final-1.pdf

27. Blair SN. Physical inactivity: the biggest public health problem of the 21st century Br J Sports Med. 2009;43:1-2.

28. Vuori IM, Lavie CJ, Blair SN. Physical activity promotion in the health care system. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88:1446-1461. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.08.020

It is well-known that per capita health care spending in the United States is more than twice the average in other developed countries1; nevertheless, the overall health care ranking of the US is near the bottom compared to other countries in this group.2 Much of the reason for this poor relative showing lies in the fact that the US has employed a somewhat traditional fee-for-service health care model that does not incentivize efforts to promote health and wellness or prevent chronic disease. The paradigm of promoting physical activity for its disease-preventing and treatment benefits has not been well-integrated in the US health care system.

In this article, we endeavor to provide better understanding of the barriers that keep family physicians from routinely promoting physical activity in clinical practice; define tools and resources that can be used in the clinical setting to promote physical activity; and delineate areas for future work.

Glaring hole in US physical activity education

Many primary care physicians feel underprepared to prescribe or motivate patients to exercise. The reason for that lack of preparedness likely relates to a medical education system that does not spend time preparing physicians to perform this critical task. A study showed that, on average, medical schools require only 8 hours of physical activity education in their curriculum during the 4 years of schooling.3 Likewise, the average primary care residency program offers only 3 hours of didactic training on physical activity, nutrition, and obesity.4 The problem extends to sports medicine fellowship training, in which a 2019 survey showed that 63% of fellows were never taught how to write an exercise prescription in their training program.5

Without education on physical activity, medical students, residents, and fellows are woefully underprepared to realize the therapeutic value of physical activity in patient care, comprehend current physical activity guidelines, appropriately motivate patients to engage in exercise, and competently discuss exercise prescriptions in different disease states. Throughout their training, it is imperative for medical professionals to be educated on the social determinants of health, which include the conditions in which people live, work, and play. These environmental variables can contribute to health inequities that create additional barriers to improvement in physical fitness.6

National guidelines on physical activity

The 2018 National Physical Activity Guidelines detail recommendations for children, adolescents, adults, and special populations.7 The guidelines define physical activity as bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that result in energy expenditure above resting baseline levels, and includes all types, intensities, and domains of activity. Exercise is a subset of physical activity characterized as planned, structured, repetitive, and designed to improve or maintain physical fitness, physical performance, or health.

Highlights from the 2018 guidelines include7:

- Preschool-aged children (3 to 5 years of age) should be physically active throughout the day, with as much as 3 hours per day of physical activity of all intensities—light, moderate, and vigorous.

- Older children and adolescents (6 to 17 years) should accumulate 60 minutes per day of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity, including aerobic, muscle-strengthening, and bone-strengthening activities.

- Adults of all ages should achieve approximately 150 to 300 minutes of moderate or 75 to 150 minutes of vigorous physical activity (or an equivalent combination) per week, along with at least 2 days per week of muscle-strengthening activities. Other types of physical activity include flexibility, balance, bone-strengthening, and mind–body exercises.

3-step framework for enhancing physical activity counseling

Merely knowing that physical activity is healthy is not enough, during a patient encounter, to increase the level of physical activity. Therefore, it is imperative to learn and adopt a framework that has proved to yield successful outcomes. The Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) framework, which has predominantly been used to change patient behavior related to alcohol and substance use, is now being utilized by some providers to promote physical activity.8 We apply the SBIRT approach in this article, although research is lacking on its clinical utility and outcome measures.

Continue to: SBIRT

SBIRT: Screening

An office visit provides an opportunity to understand a patient’s level of physical activity. Often, understanding a patient’s baseline level of activity is only asked during a thorough social history, which might not be performed during patient encounters. As physical activity is the primary determinant of cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF), some health care systems have begun delineating physical activity levels as a vital sign to ensure that the assessment of physical activity is a standard part of every clinical encounter. At a minimum, this serves as a prompt and provides an opportunity to start a conversation around improving physical activity levels when guidelines are not being met.

The exercise vital sign. Assessment and documentation of physical activity in the electronic health record are not yet standardized; however, Kaiser Permanente health plans have implemented the exercise vital sign, or EVS, in its HealthConnect (Epic Systems) electronic health record. The EVS incorporates information about a patient’s:

- days per week of moderate-to-strenuous exercise (eg, a brisk walk)

- minutes per day, on average, of exercise at this level.

The physical activity vital sign. Intermountain Healthcare implemented the physical activity vital sign, or PAVS, in its iCentra (Cerner Corp.) electronic health record. The 3-question PAVS assessment asks:

- On average, how many days of the week do you perform physical activity or exercise?

- On average, how many total minutes of physical activity or exercise do you perform on those days?

- How would you describe the intensity of your physical activity or exercise: Light (ie, a casual walk)? Moderate (a brisk walk)? Or vigorous (jogging)?

PAVS includes a fourth data point: The physician–user documents whether the patient was counseled to start, increase, maintain, or modify physical activity or exercise.

EVS and the PAVS have demonstrated validity.9-11

Continue to: Cardiorespiratory fitness as a vital sign

Cardiorespiratory fitness as a vital sign. In 2016, the American Heart Association (AHA) asserted the importance of assessing CRF as a clinical vital sign.12 CRF is commonly expressed as maximal oxygen consumption (VO2max = O2 mL/kg/min) and measured through cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET), considered the gold standard by combining conventional graded exercise testing with ventilatory expired gas analysis. CPET is more objective and precise than equations estimating CRF that are derived from peak work rate. AHA recommended that efforts to improve CRF should become standard in clinical encounters, explaining that even a small increase in CRF (eg, 1 or 2 metabolic equivalentsa [METs]) is associated with a considerably (10% to 30%) lower rate of adverse cardiovascular events.12

De Souza de Silva and colleagues revealed an association between each 1-MET increase in CRF and per-person annual health care cost savings (adjusted for age and presence of cardiovascular disease) of $3272 (normal-weight patients), $4252 (overweight), and $6103 (obese).13 In its 2016 scientific statement on CRF as a vital sign, AHA listed several methods of estimating CRF and concluded that, although CPET involves a higher level of training, proficiency, equipment, and, therefore, cost, the independent and additive information obtained justifies its use in many patients.12

CASE

Mary Q, 68 years of age, presents for an annual well-woman examination. Body mass index is 32; resting heart rate (HR), 73 bpm; and blood pressure, 126/74 mm Hg. She reports being inactive, except for light walking every day with her dog around the neighborhood, which takes them approximately 15 minutes. She denies any history or signs and symptoms of cardiovascular, metabolic, or renal disease.

You consider 3 questions before taking next steps regarding increasing Ms. Q’s activity level:

- What is her PAVS?

- Does she need medical clearance before starting an exercise program?

- What would an evidence-based cardiovascular exercise prescription for Ms. Q look like?

SBIRT: Brief intervention

When a patient does not meet the recommended level of physical activity, you have an opportunity to deliver a brief intervention. To do this effectively, you must have adequate understanding of the patient’s receptivity for change. The transtheoretical, or Stages of Change, model proposes that a person typically goes through 5 stages of growth—pre-contemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance—in the process of lifestyle modification. This model highlights the different approaches to exercise adoption and maintenance that need to be taken, based on a given patient’s stage at the moment.

Continue to: Using this framework...

Using this framework, you can help patients realize intrinsic motivation that can facilitate progression through each stage, utilizing techniques such as motivational interviewing—so-called change talk—to increase self-efficacy.14TABLE 115 provides examples of motivational interviewing techniques that can be used during a patient encounter to improve health behaviors, such as physical activity.

Writing the exercise prescription

A patient who wants to increase their level of physical activity should be offered a formal exercise prescription, which has been shown to increase the level of physical activity, particularly in older patients. In fact, a study conducted in Spain in the practices of family physicians found that older patients who received a physical activity prescription increased their activity by 131 minutes per week; and compared to control patients, they doubled the minutes per week devoted to moderate or vigorous physical activity.16

FITT-VP. The basics of a cardiovascular exercise prescription can be found in the FITT-VP (Frequency, Intensity, Time, Type, Volume, and [monitoring of] Progression) framework (TABLE 217-19). For most patients, this model includes 3 to 5 days per week of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity for 30 to 60 minutes per session. For patients with established chronic disease, physical activity provides health benefits but might require modification. Disease-specific patient handouts for exercise can be downloaded, at no cost, through the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) “Exercise Is Medicine” program, which can be found at: www.exerciseismedicine.org/support_page.php/rx-for-health-series.

Determining intensity level. Although CPET is the gold standard for determining a patient’s target intensity level, such a test might be impracticable for a given patient. Surrogate markers of target intensity level can be obtained by measuring maximum HR (HRmax), using a well-known equation20:

HRmax = 220 – age

which is then multiplied by intensity range:

- light: 30%-39%

- moderate: 40%-59%

- vigorous: 60%-89%

or, more preferably, by calculating the HR training zone while accounting for HR at rest (HRrest). This is accomplished by calculating the HR reserve (HRR) (ie, HRR = HRmax – HRrest) and then calculating the target heart rate (THR)21:

THR = [HRR × %intensity] + HRrest

Continue to: The THR calculation...

The THR calculation is performed twice, once with a lower %intensity and again with a higher %intensity to develop a training zone based on HRR.

The HRR equation is more accurate than calculating HRmax from 220 – age, because HRR accounts for resting HR, which is often lower in people who are better conditioned.

Another method of calculating intensity for patients who are beginning a physical activity program is the rating of perceived exertion (RPE), which is graded on a scale of 6 to 20: Moderate exercise correlates with an RPE of 12 to 13 (“somewhat hard”); vigorous exercise correlates with an RPE of 14 to 16 (“hard”). By adding a zero to the rating on the RPE scale, the corresponding HR in a healthy adult can be estimated when they are performing an activity at that perceived intensity.22 Moderate exercise therefore correlates with a HR of 120 and 130 bpm.

The so-called talk test can also guide exercise intensity: Light-intensity activity correlates with an ability to sing; moderate-intensity physical activity likely allows the patient to still hold a conversation; and vigorous-intensity activity correlates with an inability to carry on a conversation while exercising.

An exercise prescription should be accompanied by a patient-derived goal, which can be reassessed during a follow-up visit. So-called SMART goals (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-bound) are tools to help patients set personalized and realistic expectations for physical activity. Meeting the goal of approximately 150 to 300 minutes of moderate or 75 to 150 minutes of vigorous physical activity (or an equivalent combination) per week is ideal, but a patient needs to start where they are, at the moment, and gradually increase activity by setting what for them are realistic and sustainable goals.

Continue to: CASE

CASE

With a PAVS of 105 minutes (ie, 15 minutes per day × 7 days) of weekly light-to-moderate exercise walking her dog, Ms. Q does not satisfy current physical activity guidelines. She needs an exercise prescription to incorporate into her lifestyle (see “Cardiovascular exercise prescription,” at left).

First, based on ACSM pre-participation guidelines, Ms. Q does not need medical clearance before initiating light-to-moderate exercise and gradually progressing to vigorous-intensity exercise.

Second, in addition to walking the dog for 105 minutes a week, you:

- advise her to start walking for 10 minutes, 3 times per week, at a pace that keeps her HR at 97-104 bpm.

- encourage her to gradually increase the frequency or duration of her walks by no more than 10% per week.

SBIRT: Referral for treatment

When referring a patient to a fitness program or professional, it is essential to consider their preferences, resources, and environment.23 Community fitness partners are often an excellent referral option for a patient seeking guidance or structure for their exercise program. Using the ACSM ProFinder service, (www.acsm.org/get-stay-certified/find-a-pro) you can search for exercise professionals who have achieved the College’s Gold Standard credential.

Gym memberships or fitness programs might be part of the extra coverage offered by Medicare Advantage Plans, other Medicare health plans, or Medicare Supplement Insurance (Medigap) plans.24

Continue to: CASE

CASE

After providing Ms. Q with her exercise prescription, you refer her to a local gym that participates in the Silver Sneakers fitness and wellness program (for adults ≥ 65 years of age in eligible Medicare plans) to determine whether she qualifies to begin resistance and flexibility training, for which you will write a second exercise prescription (TABLE 317-19).

Pre-participation screening

Updated 2015 ACSM exercise pre-participation health screening recommendations attempt to decrease possible barriers to people who are becoming more physically active, by minimizing unnecessary referral to health care providers before they change their level of physical activity. ACSM recommendations on exercise clearance include this guidance25:

- For a patient who is asymptomatic and already physically active—regardless of whether they have known cardiovascular, metabolic, or renal disease—medical clearance is unnecessary for moderate-intensity exercise.

- Any patient who has been physically active and asymptomatic but who becomes symptomatic during exercise should immediately discontinue such activity and undergo medical evaluation.

- For a patient who is inactive, asymptomatic, and who does not have known cardiovascular, metabolic, or renal disease, medical clearance for light- or moderate-intensity exercise is unnecessary.

- For inactive, asymptomatic patients who have known cardiovascular, metabolic, or renal disease, medical clearance is recommended.

Digital health

Smartwatches and health apps (eg, CardioCoach, Fitbit, Garmin Connect, Nike Training Club, Strava, and Training Peaks) can provide workouts and offer patients the ability to collect information and even connect with other users through social media platforms. This information can be synced to Apple Health platforms for iPhones (www.apple.com/ios/health/) or through Google Fit (www.google.com/fit/) on Android devices. Primary care physicians who become familiar with health apps might find them useful for select patients who want to use technology to improve their physical activity level.

However, data on the value of using digital apps for increasing physical activity, in relation to their cost, are limited. Additional research is needed to assess their validity.

Billing and coding

For most patients, the physical activity assessment, prescription, and referral are performed in the context of treating another condition (eg, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, obesity, depression) or during a preventive health examination, and are typically covered without additional charge to the patient. An evaluation and management visit for an established patient could be used to bill if > 50% of the office visit was spent face-to-face with a physician, with patient counseling and coordination of care.

Continue to: Physicians and physical therapists...

Physicians and physical therapists can use the therapeutic exercise code (Current Procedural Terminology code 97110) when teaching patients exercises to develop muscle strength and endurance, joint range of motion, and flexibility26 (TABLE 426).

Conclusion

Physical activity and CRF are strong predictors of premature mortality, even compared to other risk factors, such as cigarette smoking, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and type 2 diabetes.27 Brief physical activity assessment and counseling is an efficient, effective, and cost-effective means to increase physical activity, and presents a unique opportunity for you to encourage lifestyle-based strategies for reducing cardiovascular risk.28

However, it is essential to meet patients where they are before trying to have them progress; it is therefore imperative to assess the individual patient’s level of activity using PAVS. With that information in hand, you can personalize physical activity advice; determine readiness for change and potential barriers for change; assist the patient in setting SMART goals; and arrange follow-up to assess adherence to the exercise prescription. Encourage the patient to call their health insurance plan to determine whether a gym membership or fitness program is covered.

Research is needed to evaluate the value of using digital apps, in light of their cost, to increase physical activity and improve CRF in a clinical setting. Prospective trials should be initiated to determine how routine implementation of CRF assessment in primary care alters the trajectory of clinical care. It is hoped that future research will answer the question: Would such an approach improve clinical outcomes and reduce health care expenditures?12

a Defined as O2 consumed while sitting at rest; equivalent to 3.5 mL of O2 × kg of body weight × min.

CORRESPONDENCE

Matthew Kampert, DO, MS, Sports Medicine, 5555 Transportation Boulevard, Cleveland, OH 44125; [email protected]

It is well-known that per capita health care spending in the United States is more than twice the average in other developed countries1; nevertheless, the overall health care ranking of the US is near the bottom compared to other countries in this group.2 Much of the reason for this poor relative showing lies in the fact that the US has employed a somewhat traditional fee-for-service health care model that does not incentivize efforts to promote health and wellness or prevent chronic disease. The paradigm of promoting physical activity for its disease-preventing and treatment benefits has not been well-integrated in the US health care system.

In this article, we endeavor to provide better understanding of the barriers that keep family physicians from routinely promoting physical activity in clinical practice; define tools and resources that can be used in the clinical setting to promote physical activity; and delineate areas for future work.

Glaring hole in US physical activity education

Many primary care physicians feel underprepared to prescribe or motivate patients to exercise. The reason for that lack of preparedness likely relates to a medical education system that does not spend time preparing physicians to perform this critical task. A study showed that, on average, medical schools require only 8 hours of physical activity education in their curriculum during the 4 years of schooling.3 Likewise, the average primary care residency program offers only 3 hours of didactic training on physical activity, nutrition, and obesity.4 The problem extends to sports medicine fellowship training, in which a 2019 survey showed that 63% of fellows were never taught how to write an exercise prescription in their training program.5

Without education on physical activity, medical students, residents, and fellows are woefully underprepared to realize the therapeutic value of physical activity in patient care, comprehend current physical activity guidelines, appropriately motivate patients to engage in exercise, and competently discuss exercise prescriptions in different disease states. Throughout their training, it is imperative for medical professionals to be educated on the social determinants of health, which include the conditions in which people live, work, and play. These environmental variables can contribute to health inequities that create additional barriers to improvement in physical fitness.6

National guidelines on physical activity

The 2018 National Physical Activity Guidelines detail recommendations for children, adolescents, adults, and special populations.7 The guidelines define physical activity as bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that result in energy expenditure above resting baseline levels, and includes all types, intensities, and domains of activity. Exercise is a subset of physical activity characterized as planned, structured, repetitive, and designed to improve or maintain physical fitness, physical performance, or health.

Highlights from the 2018 guidelines include7:

- Preschool-aged children (3 to 5 years of age) should be physically active throughout the day, with as much as 3 hours per day of physical activity of all intensities—light, moderate, and vigorous.

- Older children and adolescents (6 to 17 years) should accumulate 60 minutes per day of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity, including aerobic, muscle-strengthening, and bone-strengthening activities.

- Adults of all ages should achieve approximately 150 to 300 minutes of moderate or 75 to 150 minutes of vigorous physical activity (or an equivalent combination) per week, along with at least 2 days per week of muscle-strengthening activities. Other types of physical activity include flexibility, balance, bone-strengthening, and mind–body exercises.

3-step framework for enhancing physical activity counseling

Merely knowing that physical activity is healthy is not enough, during a patient encounter, to increase the level of physical activity. Therefore, it is imperative to learn and adopt a framework that has proved to yield successful outcomes. The Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) framework, which has predominantly been used to change patient behavior related to alcohol and substance use, is now being utilized by some providers to promote physical activity.8 We apply the SBIRT approach in this article, although research is lacking on its clinical utility and outcome measures.

Continue to: SBIRT

SBIRT: Screening

An office visit provides an opportunity to understand a patient’s level of physical activity. Often, understanding a patient’s baseline level of activity is only asked during a thorough social history, which might not be performed during patient encounters. As physical activity is the primary determinant of cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF), some health care systems have begun delineating physical activity levels as a vital sign to ensure that the assessment of physical activity is a standard part of every clinical encounter. At a minimum, this serves as a prompt and provides an opportunity to start a conversation around improving physical activity levels when guidelines are not being met.

The exercise vital sign. Assessment and documentation of physical activity in the electronic health record are not yet standardized; however, Kaiser Permanente health plans have implemented the exercise vital sign, or EVS, in its HealthConnect (Epic Systems) electronic health record. The EVS incorporates information about a patient’s:

- days per week of moderate-to-strenuous exercise (eg, a brisk walk)

- minutes per day, on average, of exercise at this level.

The physical activity vital sign. Intermountain Healthcare implemented the physical activity vital sign, or PAVS, in its iCentra (Cerner Corp.) electronic health record. The 3-question PAVS assessment asks:

- On average, how many days of the week do you perform physical activity or exercise?

- On average, how many total minutes of physical activity or exercise do you perform on those days?

- How would you describe the intensity of your physical activity or exercise: Light (ie, a casual walk)? Moderate (a brisk walk)? Or vigorous (jogging)?

PAVS includes a fourth data point: The physician–user documents whether the patient was counseled to start, increase, maintain, or modify physical activity or exercise.

EVS and the PAVS have demonstrated validity.9-11

Continue to: Cardiorespiratory fitness as a vital sign

Cardiorespiratory fitness as a vital sign. In 2016, the American Heart Association (AHA) asserted the importance of assessing CRF as a clinical vital sign.12 CRF is commonly expressed as maximal oxygen consumption (VO2max = O2 mL/kg/min) and measured through cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET), considered the gold standard by combining conventional graded exercise testing with ventilatory expired gas analysis. CPET is more objective and precise than equations estimating CRF that are derived from peak work rate. AHA recommended that efforts to improve CRF should become standard in clinical encounters, explaining that even a small increase in CRF (eg, 1 or 2 metabolic equivalentsa [METs]) is associated with a considerably (10% to 30%) lower rate of adverse cardiovascular events.12

De Souza de Silva and colleagues revealed an association between each 1-MET increase in CRF and per-person annual health care cost savings (adjusted for age and presence of cardiovascular disease) of $3272 (normal-weight patients), $4252 (overweight), and $6103 (obese).13 In its 2016 scientific statement on CRF as a vital sign, AHA listed several methods of estimating CRF and concluded that, although CPET involves a higher level of training, proficiency, equipment, and, therefore, cost, the independent and additive information obtained justifies its use in many patients.12

CASE

Mary Q, 68 years of age, presents for an annual well-woman examination. Body mass index is 32; resting heart rate (HR), 73 bpm; and blood pressure, 126/74 mm Hg. She reports being inactive, except for light walking every day with her dog around the neighborhood, which takes them approximately 15 minutes. She denies any history or signs and symptoms of cardiovascular, metabolic, or renal disease.

You consider 3 questions before taking next steps regarding increasing Ms. Q’s activity level:

- What is her PAVS?

- Does she need medical clearance before starting an exercise program?

- What would an evidence-based cardiovascular exercise prescription for Ms. Q look like?

SBIRT: Brief intervention

When a patient does not meet the recommended level of physical activity, you have an opportunity to deliver a brief intervention. To do this effectively, you must have adequate understanding of the patient’s receptivity for change. The transtheoretical, or Stages of Change, model proposes that a person typically goes through 5 stages of growth—pre-contemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance—in the process of lifestyle modification. This model highlights the different approaches to exercise adoption and maintenance that need to be taken, based on a given patient’s stage at the moment.

Continue to: Using this framework...

Using this framework, you can help patients realize intrinsic motivation that can facilitate progression through each stage, utilizing techniques such as motivational interviewing—so-called change talk—to increase self-efficacy.14TABLE 115 provides examples of motivational interviewing techniques that can be used during a patient encounter to improve health behaviors, such as physical activity.

Writing the exercise prescription

A patient who wants to increase their level of physical activity should be offered a formal exercise prescription, which has been shown to increase the level of physical activity, particularly in older patients. In fact, a study conducted in Spain in the practices of family physicians found that older patients who received a physical activity prescription increased their activity by 131 minutes per week; and compared to control patients, they doubled the minutes per week devoted to moderate or vigorous physical activity.16

FITT-VP. The basics of a cardiovascular exercise prescription can be found in the FITT-VP (Frequency, Intensity, Time, Type, Volume, and [monitoring of] Progression) framework (TABLE 217-19). For most patients, this model includes 3 to 5 days per week of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity for 30 to 60 minutes per session. For patients with established chronic disease, physical activity provides health benefits but might require modification. Disease-specific patient handouts for exercise can be downloaded, at no cost, through the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) “Exercise Is Medicine” program, which can be found at: www.exerciseismedicine.org/support_page.php/rx-for-health-series.

Determining intensity level. Although CPET is the gold standard for determining a patient’s target intensity level, such a test might be impracticable for a given patient. Surrogate markers of target intensity level can be obtained by measuring maximum HR (HRmax), using a well-known equation20:

HRmax = 220 – age

which is then multiplied by intensity range:

- light: 30%-39%

- moderate: 40%-59%

- vigorous: 60%-89%

or, more preferably, by calculating the HR training zone while accounting for HR at rest (HRrest). This is accomplished by calculating the HR reserve (HRR) (ie, HRR = HRmax – HRrest) and then calculating the target heart rate (THR)21:

THR = [HRR × %intensity] + HRrest

Continue to: The THR calculation...

The THR calculation is performed twice, once with a lower %intensity and again with a higher %intensity to develop a training zone based on HRR.

The HRR equation is more accurate than calculating HRmax from 220 – age, because HRR accounts for resting HR, which is often lower in people who are better conditioned.

Another method of calculating intensity for patients who are beginning a physical activity program is the rating of perceived exertion (RPE), which is graded on a scale of 6 to 20: Moderate exercise correlates with an RPE of 12 to 13 (“somewhat hard”); vigorous exercise correlates with an RPE of 14 to 16 (“hard”). By adding a zero to the rating on the RPE scale, the corresponding HR in a healthy adult can be estimated when they are performing an activity at that perceived intensity.22 Moderate exercise therefore correlates with a HR of 120 and 130 bpm.

The so-called talk test can also guide exercise intensity: Light-intensity activity correlates with an ability to sing; moderate-intensity physical activity likely allows the patient to still hold a conversation; and vigorous-intensity activity correlates with an inability to carry on a conversation while exercising.

An exercise prescription should be accompanied by a patient-derived goal, which can be reassessed during a follow-up visit. So-called SMART goals (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-bound) are tools to help patients set personalized and realistic expectations for physical activity. Meeting the goal of approximately 150 to 300 minutes of moderate or 75 to 150 minutes of vigorous physical activity (or an equivalent combination) per week is ideal, but a patient needs to start where they are, at the moment, and gradually increase activity by setting what for them are realistic and sustainable goals.

Continue to: CASE

CASE

With a PAVS of 105 minutes (ie, 15 minutes per day × 7 days) of weekly light-to-moderate exercise walking her dog, Ms. Q does not satisfy current physical activity guidelines. She needs an exercise prescription to incorporate into her lifestyle (see “Cardiovascular exercise prescription,” at left).

First, based on ACSM pre-participation guidelines, Ms. Q does not need medical clearance before initiating light-to-moderate exercise and gradually progressing to vigorous-intensity exercise.

Second, in addition to walking the dog for 105 minutes a week, you:

- advise her to start walking for 10 minutes, 3 times per week, at a pace that keeps her HR at 97-104 bpm.

- encourage her to gradually increase the frequency or duration of her walks by no more than 10% per week.

SBIRT: Referral for treatment

When referring a patient to a fitness program or professional, it is essential to consider their preferences, resources, and environment.23 Community fitness partners are often an excellent referral option for a patient seeking guidance or structure for their exercise program. Using the ACSM ProFinder service, (www.acsm.org/get-stay-certified/find-a-pro) you can search for exercise professionals who have achieved the College’s Gold Standard credential.

Gym memberships or fitness programs might be part of the extra coverage offered by Medicare Advantage Plans, other Medicare health plans, or Medicare Supplement Insurance (Medigap) plans.24

Continue to: CASE

CASE

After providing Ms. Q with her exercise prescription, you refer her to a local gym that participates in the Silver Sneakers fitness and wellness program (for adults ≥ 65 years of age in eligible Medicare plans) to determine whether she qualifies to begin resistance and flexibility training, for which you will write a second exercise prescription (TABLE 317-19).

Pre-participation screening

Updated 2015 ACSM exercise pre-participation health screening recommendations attempt to decrease possible barriers to people who are becoming more physically active, by minimizing unnecessary referral to health care providers before they change their level of physical activity. ACSM recommendations on exercise clearance include this guidance25:

- For a patient who is asymptomatic and already physically active—regardless of whether they have known cardiovascular, metabolic, or renal disease—medical clearance is unnecessary for moderate-intensity exercise.

- Any patient who has been physically active and asymptomatic but who becomes symptomatic during exercise should immediately discontinue such activity and undergo medical evaluation.

- For a patient who is inactive, asymptomatic, and who does not have known cardiovascular, metabolic, or renal disease, medical clearance for light- or moderate-intensity exercise is unnecessary.

- For inactive, asymptomatic patients who have known cardiovascular, metabolic, or renal disease, medical clearance is recommended.

Digital health

Smartwatches and health apps (eg, CardioCoach, Fitbit, Garmin Connect, Nike Training Club, Strava, and Training Peaks) can provide workouts and offer patients the ability to collect information and even connect with other users through social media platforms. This information can be synced to Apple Health platforms for iPhones (www.apple.com/ios/health/) or through Google Fit (www.google.com/fit/) on Android devices. Primary care physicians who become familiar with health apps might find them useful for select patients who want to use technology to improve their physical activity level.

However, data on the value of using digital apps for increasing physical activity, in relation to their cost, are limited. Additional research is needed to assess their validity.

Billing and coding

For most patients, the physical activity assessment, prescription, and referral are performed in the context of treating another condition (eg, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, obesity, depression) or during a preventive health examination, and are typically covered without additional charge to the patient. An evaluation and management visit for an established patient could be used to bill if > 50% of the office visit was spent face-to-face with a physician, with patient counseling and coordination of care.

Continue to: Physicians and physical therapists...

Physicians and physical therapists can use the therapeutic exercise code (Current Procedural Terminology code 97110) when teaching patients exercises to develop muscle strength and endurance, joint range of motion, and flexibility26 (TABLE 426).

Conclusion

Physical activity and CRF are strong predictors of premature mortality, even compared to other risk factors, such as cigarette smoking, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and type 2 diabetes.27 Brief physical activity assessment and counseling is an efficient, effective, and cost-effective means to increase physical activity, and presents a unique opportunity for you to encourage lifestyle-based strategies for reducing cardiovascular risk.28

However, it is essential to meet patients where they are before trying to have them progress; it is therefore imperative to assess the individual patient’s level of activity using PAVS. With that information in hand, you can personalize physical activity advice; determine readiness for change and potential barriers for change; assist the patient in setting SMART goals; and arrange follow-up to assess adherence to the exercise prescription. Encourage the patient to call their health insurance plan to determine whether a gym membership or fitness program is covered.

Research is needed to evaluate the value of using digital apps, in light of their cost, to increase physical activity and improve CRF in a clinical setting. Prospective trials should be initiated to determine how routine implementation of CRF assessment in primary care alters the trajectory of clinical care. It is hoped that future research will answer the question: Would such an approach improve clinical outcomes and reduce health care expenditures?12

a Defined as O2 consumed while sitting at rest; equivalent to 3.5 mL of O2 × kg of body weight × min.

CORRESPONDENCE

Matthew Kampert, DO, MS, Sports Medicine, 5555 Transportation Boulevard, Cleveland, OH 44125; [email protected]

1. Papanicolas I, Woskie LR, Jha AK. Health care spending in the United States and other high-income countries. JAMA. 2018;319:1024-1039. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.1150

2. Tikkanen R, Abrams MK. U.S. health care from a global perspective, 2019: higher spending, worse outcomes? The Commonwealth Fund Website. January 30, 2020. Accessed November 16, 2021. www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2020/jan/us-health-care-global-perspective-2019

3. Stoutenberg M, Stasi S, Stamatakis E, et al. Physical activity training in US medical schools: preparing future physicians to engage in primary prevention. Phys Sportsmed. 2015;43:388-394. doi: 10.1080/00913847.2015.1084868

4. Antognoli EL, Seeholzer EL, Gullett H, et al. Primary care resident training for obesity, nutrition, and physical activity counseling: a mixed-methods study. Health Promot Pract. 2017;18:672-680. doi: 10.1177/1524839916658025

5. Asif IM, Drezner JA. Sports and exercise medicine education in the USA: call to action. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54:195-196. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2019-101104

6. Douglas JA, Briones MD, Bauer EZ, et al. Social and environmental determinants of physical activity in urban parks: testing a neighborhood disorder model. Prev Med. 2018;109:119-124. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.01.013

7. 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee. 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Scientific Report. Washington, DC: US Department of Health & Human Services; 2018. Accessed November 15, 2021. https://health.gov/sites/default/files/2019-09/PAG_Advisory_Committee_Report.pdf

8. Avis JL, Cave AL, Donaldson S, et al. Working with parents to prevent childhood obesity: protocol for a primary care-based ehealth study. JMIR Res Protoc. 2015;4:e35. doi:10.2196/resprot.4147

9. Ball TJ, Joy EA, Gren LH, et al. Concurrent validity of a self-reported physical activity ‘vital sign’ questionnaire with adult primary care patients. Prev Chronic Dis. 2016;13:e16. doi: 10.5888/pcd13.150228

10. Ball TJ, Joy EA, Gren LH, et al. Predictive validity of an adult physical activity “vital sign” recorded in electronic health records. J Phys Act Health. 2016;13:403-408. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2015-0210

11. Coleman KJ, Ngor E, Reynolds K, et al. Initial validation of an exercise “vital sign” in electronic medical records. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012;44:2071-2076. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3182630ec1

12. Ross R, Blair SN, Arena R, et al; ; ; ; ; ; . Importance of assessing cardiorespiratory fitness in clinical practice: a case for fitness as a clinical vital sign: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;134:e653-e699. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000461

13. de Souza de Silva CG, Kokkinos PP, Doom R, et al. Association between cardiorespiratory fitness, obesity, and health care costs: The Veterans Exercise Testing Study. Int J Obes (Lond). 2019;43:2225-2232. doi: 10.1038/s41366-018-0257-0

14. Prochaska JO, Velicer WF. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. Am J Health Promot. 1997;12:38-48. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-12.1.38

15. Riebe D, Ehrman JK, Liguori G, et al. Methods for evoking change talk. In: ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription. 10th ed. Wolters Kluwer; 2018.

16. Grandes G, Sanchez A, Sanchez-Pinilla RO, et al. Effectiveness of physical activity advice and prescription by physicians in routine primary care: a cluster randomized trial. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:694-701. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.23

17. McNeill LH, Kreuter MW, Subramanian SV. Social environment and physical activity: a review of concepts and evidence. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63:1011-1022. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.03.012

18. Garber CE, Blissmer BE, Deschenes MR, et al; American College of Sports Medicine. Quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: Guidance for prescribing exercise. Position stand. Med Sci Sport Exerc. 2011;43:1334-1359. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318213fefb

19. Donnelly JE, Blair SN, Jakicic JM, et al; American College of Sports Medicine. Appropriate physical activity intervention strategies for weight loss and prevention of weight regain for adults. Position stand. Med Sci Sport Exerc. 2009;41:459-471. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181949333

20. Fox SM 3rd, Naughton JP, Haskell WL. Physical activity and the prevention of coronary heart disease. Ann Clin Res. 1971;3:404-432.

21. Karvonen MJ, Kentala E, Mustala O. The effects of training on heart rate; a longitudinal study. Ann Med Exp Biol Fenn. 1957;35:307-315.

22. The Borg RPE scale. In: Borg G. Borg’s Perceived Exertion and Pain Scales. Human Kinetics; 1998:29-38.

23. Ratamess NA, Alvar BA, Evetoch TK, et al; American College of Sports Medicine. Progression models in resistance training for healthy adults. Position stand. Med Sci Sport Exerc. 2009;41:687-708. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181915670

24. Gym memberships & fitness programs. Medicare.gov. Baltimore, MD: US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Accessed November 16, 2021. www.medicare.gov/coverage/gym-memberships-fitness-programs

25. Riebe D, Franklin BA, Thompson PD, et al. Updating ACSM’s recommendations for exercise preparticipation health screening. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2015;47:2473-2479. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000664

26. Physical Activity Related Current Procedural Terminology (CPT®) Codes. Physical Activity Alliance website. Accessed November 16, 2021. https://paamovewithus.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/PAA-Physical-Activity-CPT-Codes-Nov-2020-AMA-Approved-Final-1.pdf

27. Blair SN. Physical inactivity: the biggest public health problem of the 21st century Br J Sports Med. 2009;43:1-2.

28. Vuori IM, Lavie CJ, Blair SN. Physical activity promotion in the health care system. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88:1446-1461. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.08.020

1. Papanicolas I, Woskie LR, Jha AK. Health care spending in the United States and other high-income countries. JAMA. 2018;319:1024-1039. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.1150

2. Tikkanen R, Abrams MK. U.S. health care from a global perspective, 2019: higher spending, worse outcomes? The Commonwealth Fund Website. January 30, 2020. Accessed November 16, 2021. www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2020/jan/us-health-care-global-perspective-2019

3. Stoutenberg M, Stasi S, Stamatakis E, et al. Physical activity training in US medical schools: preparing future physicians to engage in primary prevention. Phys Sportsmed. 2015;43:388-394. doi: 10.1080/00913847.2015.1084868

4. Antognoli EL, Seeholzer EL, Gullett H, et al. Primary care resident training for obesity, nutrition, and physical activity counseling: a mixed-methods study. Health Promot Pract. 2017;18:672-680. doi: 10.1177/1524839916658025

5. Asif IM, Drezner JA. Sports and exercise medicine education in the USA: call to action. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54:195-196. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2019-101104

6. Douglas JA, Briones MD, Bauer EZ, et al. Social and environmental determinants of physical activity in urban parks: testing a neighborhood disorder model. Prev Med. 2018;109:119-124. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.01.013

7. 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee. 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Scientific Report. Washington, DC: US Department of Health & Human Services; 2018. Accessed November 15, 2021. https://health.gov/sites/default/files/2019-09/PAG_Advisory_Committee_Report.pdf

8. Avis JL, Cave AL, Donaldson S, et al. Working with parents to prevent childhood obesity: protocol for a primary care-based ehealth study. JMIR Res Protoc. 2015;4:e35. doi:10.2196/resprot.4147

9. Ball TJ, Joy EA, Gren LH, et al. Concurrent validity of a self-reported physical activity ‘vital sign’ questionnaire with adult primary care patients. Prev Chronic Dis. 2016;13:e16. doi: 10.5888/pcd13.150228

10. Ball TJ, Joy EA, Gren LH, et al. Predictive validity of an adult physical activity “vital sign” recorded in electronic health records. J Phys Act Health. 2016;13:403-408. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2015-0210

11. Coleman KJ, Ngor E, Reynolds K, et al. Initial validation of an exercise “vital sign” in electronic medical records. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012;44:2071-2076. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3182630ec1

12. Ross R, Blair SN, Arena R, et al; ; ; ; ; ; . Importance of assessing cardiorespiratory fitness in clinical practice: a case for fitness as a clinical vital sign: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;134:e653-e699. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000461

13. de Souza de Silva CG, Kokkinos PP, Doom R, et al. Association between cardiorespiratory fitness, obesity, and health care costs: The Veterans Exercise Testing Study. Int J Obes (Lond). 2019;43:2225-2232. doi: 10.1038/s41366-018-0257-0

14. Prochaska JO, Velicer WF. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. Am J Health Promot. 1997;12:38-48. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-12.1.38

15. Riebe D, Ehrman JK, Liguori G, et al. Methods for evoking change talk. In: ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription. 10th ed. Wolters Kluwer; 2018.

16. Grandes G, Sanchez A, Sanchez-Pinilla RO, et al. Effectiveness of physical activity advice and prescription by physicians in routine primary care: a cluster randomized trial. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:694-701. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.23

17. McNeill LH, Kreuter MW, Subramanian SV. Social environment and physical activity: a review of concepts and evidence. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63:1011-1022. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.03.012

18. Garber CE, Blissmer BE, Deschenes MR, et al; American College of Sports Medicine. Quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: Guidance for prescribing exercise. Position stand. Med Sci Sport Exerc. 2011;43:1334-1359. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318213fefb

19. Donnelly JE, Blair SN, Jakicic JM, et al; American College of Sports Medicine. Appropriate physical activity intervention strategies for weight loss and prevention of weight regain for adults. Position stand. Med Sci Sport Exerc. 2009;41:459-471. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181949333

20. Fox SM 3rd, Naughton JP, Haskell WL. Physical activity and the prevention of coronary heart disease. Ann Clin Res. 1971;3:404-432.

21. Karvonen MJ, Kentala E, Mustala O. The effects of training on heart rate; a longitudinal study. Ann Med Exp Biol Fenn. 1957;35:307-315.

22. The Borg RPE scale. In: Borg G. Borg’s Perceived Exertion and Pain Scales. Human Kinetics; 1998:29-38.

23. Ratamess NA, Alvar BA, Evetoch TK, et al; American College of Sports Medicine. Progression models in resistance training for healthy adults. Position stand. Med Sci Sport Exerc. 2009;41:687-708. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181915670

24. Gym memberships & fitness programs. Medicare.gov. Baltimore, MD: US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Accessed November 16, 2021. www.medicare.gov/coverage/gym-memberships-fitness-programs

25. Riebe D, Franklin BA, Thompson PD, et al. Updating ACSM’s recommendations for exercise preparticipation health screening. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2015;47:2473-2479. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000664

26. Physical Activity Related Current Procedural Terminology (CPT®) Codes. Physical Activity Alliance website. Accessed November 16, 2021. https://paamovewithus.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/PAA-Physical-Activity-CPT-Codes-Nov-2020-AMA-Approved-Final-1.pdf

27. Blair SN. Physical inactivity: the biggest public health problem of the 21st century Br J Sports Med. 2009;43:1-2.

28. Vuori IM, Lavie CJ, Blair SN. Physical activity promotion in the health care system. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88:1446-1461. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.08.020

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

› Encourage children and adolescents (6 to 17 years of age) to engage in 60 min of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity, including aerobic, muscle-strengthening, and bone-strengthening endeavors on most, if not all, days of the week. A

› Encourage adults to perform approximately 150 to 300 min of moderate or 75 to 150 min of vigorous physical activity (or an equivalent combination) per week, along with moderate-intensity muscle-strengthening activities on ≥ 2 days per week. A

› Counsel patients that even a small (eg, 1-2 metabolic equivalents) increase in cardiorespiratory fitness is associated with a 10% to 30% lower rate of adverse events. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series