User login

Spesolimab speeds lesion clearance in generalized pustular psoriasis

GPP is a life-threatening skin condition involving the widespread eruption of sterile pustules, with a clinical course that “can be relapsing with recurrent flares or persistent with intermittent flares,” Hervé Bachelez, MD, of the Université de Paris and coauthors wrote. GPP patients are often hospitalized, and mortality ranges from 2% to 16% from causes that include sepsis and cardiorespiratory failure.

“The role of the interleukin-36 pathway in GPP is supported by the finding of loss-of-function mutations in the interleukin-36 receptor antagonist gene (IL36RN) and associated genes (CARD14, AP1S3, SERPINA3, and MPO) and by the overexpression of interleukin-36 cytokines in GPP skin lesions,” therefore, IL-36 is a potential treatment target to manage flares, they explained.

In the multicenter, double-blind trial, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, the researchers randomized 35 adults with GPP flares to a single 900-mg intravenous dose of spesolimab and 18 to placebo. Patients in both groups could receive an open-label dose of spesolimab after day 8; all patients were followed for 12 weeks.

The primary study endpoint was the Generalized Pustular Psoriasis Physician Global Assessment (GPPGA) pustulation subscore of 0 at 1 week after treatment. The GPPGA ranges from 0 (no visible pustules) to 4 (severe pustules). At baseline, 46% spesolimab patients and 39% placebo patients had a GPPGA pustulation subscore of 3, and 37% and 33%, respectively, had a pustulation subscore of 4.

After 1 week, 54% of the spesolimab patients had no visible pustules, compared with 6% of placebo patients; the difference was statistically significant (P < .001). The main secondary endpoint was a score of 0 or 1 (clear or almost clear skin) on the GPPGA total score after 1 week. Significantly more spesolimab patients had GPPGA total scores of 0 or 1, compared with placebo patients (43% vs. 11%, respectively; P = .02).

Overall, 6 of 35 spesolimab patients (17%) and 6% of those in the placebo groups developed infections during the first week, and 24 of 51 patients (47%) who had received spesolimab at any point during the study developed infections by week 12. Infections included urinary tract infections (three cases), influenza (three), otitis externa (two), folliculitis (two), upper respiratory tract infection (two), and pustule (two).

In the first week, 6% of spesolimab patients and none of the placebo patients reported serious adverse events; at week 12, 12% of patients who had received at least one spesolimab dose reported a serious adverse event. In addition, antidrug antibodies were identified in 23 (46%) of the 50 patients who received at least one dose of spesolimab.

“Symptoms that were observed in two patients who received spesolimab were reported as a drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS),” the authors noted. One patient had a RegiSCAR (European Registry of Severe Cutaneous Adverse Reactions) score and the other had a score of 3; a score below 2 indicates no DRESS, and a score of 2 or 3 indicates “possible DRESS,” they added.

“Because 15 of the 18 patients who were assigned to the placebo group received open-label spesolimab, the effect of spesolimab as compared with that of placebo could not be determined after week 1,” the researchers noted.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the short randomization period and small study population, the researchers noted. However, the effect sizes for both the primary and secondary endpoints were large, which strengthened the results.

The results support data from previous studies suggesting a role for IL-36 in the pathogenesis of GPP, and support the need for longer and larger studies of the safety and effectiveness of spesolimab for GPP patients, they concluded.

No FDA-approved therapy

“GPP is a very rare but devastating life-threatening disease that presents with the sudden onset of pustules throughout the skin,” Joel Gelfand, MD, professor of dermatology and director of the psoriasis and phototherapy center at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said in an interview. “Without rapid treatment, GPP can result in death. Currently there are no [Food and Drug Administration]–approved treatments for this orphan disease.”

Dr. Gelfand said he was surprised by the degree of efficacy and the speed of the patient response to spesolimab, compared with placebo, which he described as “truly remarkable.” Based on the current study results, “spesolimab offers a tremendous step forward for our patients,” he added.

Looking ahead, Dr. Gelfand noted that “longer-term studies with a comparator, such as a biologic that targets IL-17, would be helpful to more fully understand the safety, efficacy, and role that spesolimab will have in real-world patients.”

On Dec. 15, Boehringer Ingelheim announced that the FDA had granted priority review for spesolimab for treating GPP flares.

The study was supported by Boehringer Ingelheim. Lead author Dr. Bachelez had no financial conflicts to disclose. Several authors are employees of Boehringer Ingelheim. Dr. Gelfand is a consultant for the study sponsor Boehringer Ingelheim and has received research grants from Boehringer Ingelheim to his institution to support an investigator-initiated study. He also disclosed serving as a consultant and receiving research grants from other manufacturers of psoriasis products.

GPP is a life-threatening skin condition involving the widespread eruption of sterile pustules, with a clinical course that “can be relapsing with recurrent flares or persistent with intermittent flares,” Hervé Bachelez, MD, of the Université de Paris and coauthors wrote. GPP patients are often hospitalized, and mortality ranges from 2% to 16% from causes that include sepsis and cardiorespiratory failure.

“The role of the interleukin-36 pathway in GPP is supported by the finding of loss-of-function mutations in the interleukin-36 receptor antagonist gene (IL36RN) and associated genes (CARD14, AP1S3, SERPINA3, and MPO) and by the overexpression of interleukin-36 cytokines in GPP skin lesions,” therefore, IL-36 is a potential treatment target to manage flares, they explained.

In the multicenter, double-blind trial, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, the researchers randomized 35 adults with GPP flares to a single 900-mg intravenous dose of spesolimab and 18 to placebo. Patients in both groups could receive an open-label dose of spesolimab after day 8; all patients were followed for 12 weeks.

The primary study endpoint was the Generalized Pustular Psoriasis Physician Global Assessment (GPPGA) pustulation subscore of 0 at 1 week after treatment. The GPPGA ranges from 0 (no visible pustules) to 4 (severe pustules). At baseline, 46% spesolimab patients and 39% placebo patients had a GPPGA pustulation subscore of 3, and 37% and 33%, respectively, had a pustulation subscore of 4.

After 1 week, 54% of the spesolimab patients had no visible pustules, compared with 6% of placebo patients; the difference was statistically significant (P < .001). The main secondary endpoint was a score of 0 or 1 (clear or almost clear skin) on the GPPGA total score after 1 week. Significantly more spesolimab patients had GPPGA total scores of 0 or 1, compared with placebo patients (43% vs. 11%, respectively; P = .02).

Overall, 6 of 35 spesolimab patients (17%) and 6% of those in the placebo groups developed infections during the first week, and 24 of 51 patients (47%) who had received spesolimab at any point during the study developed infections by week 12. Infections included urinary tract infections (three cases), influenza (three), otitis externa (two), folliculitis (two), upper respiratory tract infection (two), and pustule (two).

In the first week, 6% of spesolimab patients and none of the placebo patients reported serious adverse events; at week 12, 12% of patients who had received at least one spesolimab dose reported a serious adverse event. In addition, antidrug antibodies were identified in 23 (46%) of the 50 patients who received at least one dose of spesolimab.

“Symptoms that were observed in two patients who received spesolimab were reported as a drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS),” the authors noted. One patient had a RegiSCAR (European Registry of Severe Cutaneous Adverse Reactions) score and the other had a score of 3; a score below 2 indicates no DRESS, and a score of 2 or 3 indicates “possible DRESS,” they added.

“Because 15 of the 18 patients who were assigned to the placebo group received open-label spesolimab, the effect of spesolimab as compared with that of placebo could not be determined after week 1,” the researchers noted.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the short randomization period and small study population, the researchers noted. However, the effect sizes for both the primary and secondary endpoints were large, which strengthened the results.

The results support data from previous studies suggesting a role for IL-36 in the pathogenesis of GPP, and support the need for longer and larger studies of the safety and effectiveness of spesolimab for GPP patients, they concluded.

No FDA-approved therapy

“GPP is a very rare but devastating life-threatening disease that presents with the sudden onset of pustules throughout the skin,” Joel Gelfand, MD, professor of dermatology and director of the psoriasis and phototherapy center at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said in an interview. “Without rapid treatment, GPP can result in death. Currently there are no [Food and Drug Administration]–approved treatments for this orphan disease.”

Dr. Gelfand said he was surprised by the degree of efficacy and the speed of the patient response to spesolimab, compared with placebo, which he described as “truly remarkable.” Based on the current study results, “spesolimab offers a tremendous step forward for our patients,” he added.

Looking ahead, Dr. Gelfand noted that “longer-term studies with a comparator, such as a biologic that targets IL-17, would be helpful to more fully understand the safety, efficacy, and role that spesolimab will have in real-world patients.”

On Dec. 15, Boehringer Ingelheim announced that the FDA had granted priority review for spesolimab for treating GPP flares.

The study was supported by Boehringer Ingelheim. Lead author Dr. Bachelez had no financial conflicts to disclose. Several authors are employees of Boehringer Ingelheim. Dr. Gelfand is a consultant for the study sponsor Boehringer Ingelheim and has received research grants from Boehringer Ingelheim to his institution to support an investigator-initiated study. He also disclosed serving as a consultant and receiving research grants from other manufacturers of psoriasis products.

GPP is a life-threatening skin condition involving the widespread eruption of sterile pustules, with a clinical course that “can be relapsing with recurrent flares or persistent with intermittent flares,” Hervé Bachelez, MD, of the Université de Paris and coauthors wrote. GPP patients are often hospitalized, and mortality ranges from 2% to 16% from causes that include sepsis and cardiorespiratory failure.

“The role of the interleukin-36 pathway in GPP is supported by the finding of loss-of-function mutations in the interleukin-36 receptor antagonist gene (IL36RN) and associated genes (CARD14, AP1S3, SERPINA3, and MPO) and by the overexpression of interleukin-36 cytokines in GPP skin lesions,” therefore, IL-36 is a potential treatment target to manage flares, they explained.

In the multicenter, double-blind trial, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, the researchers randomized 35 adults with GPP flares to a single 900-mg intravenous dose of spesolimab and 18 to placebo. Patients in both groups could receive an open-label dose of spesolimab after day 8; all patients were followed for 12 weeks.

The primary study endpoint was the Generalized Pustular Psoriasis Physician Global Assessment (GPPGA) pustulation subscore of 0 at 1 week after treatment. The GPPGA ranges from 0 (no visible pustules) to 4 (severe pustules). At baseline, 46% spesolimab patients and 39% placebo patients had a GPPGA pustulation subscore of 3, and 37% and 33%, respectively, had a pustulation subscore of 4.

After 1 week, 54% of the spesolimab patients had no visible pustules, compared with 6% of placebo patients; the difference was statistically significant (P < .001). The main secondary endpoint was a score of 0 or 1 (clear or almost clear skin) on the GPPGA total score after 1 week. Significantly more spesolimab patients had GPPGA total scores of 0 or 1, compared with placebo patients (43% vs. 11%, respectively; P = .02).

Overall, 6 of 35 spesolimab patients (17%) and 6% of those in the placebo groups developed infections during the first week, and 24 of 51 patients (47%) who had received spesolimab at any point during the study developed infections by week 12. Infections included urinary tract infections (three cases), influenza (three), otitis externa (two), folliculitis (two), upper respiratory tract infection (two), and pustule (two).

In the first week, 6% of spesolimab patients and none of the placebo patients reported serious adverse events; at week 12, 12% of patients who had received at least one spesolimab dose reported a serious adverse event. In addition, antidrug antibodies were identified in 23 (46%) of the 50 patients who received at least one dose of spesolimab.

“Symptoms that were observed in two patients who received spesolimab were reported as a drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS),” the authors noted. One patient had a RegiSCAR (European Registry of Severe Cutaneous Adverse Reactions) score and the other had a score of 3; a score below 2 indicates no DRESS, and a score of 2 or 3 indicates “possible DRESS,” they added.

“Because 15 of the 18 patients who were assigned to the placebo group received open-label spesolimab, the effect of spesolimab as compared with that of placebo could not be determined after week 1,” the researchers noted.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the short randomization period and small study population, the researchers noted. However, the effect sizes for both the primary and secondary endpoints were large, which strengthened the results.

The results support data from previous studies suggesting a role for IL-36 in the pathogenesis of GPP, and support the need for longer and larger studies of the safety and effectiveness of spesolimab for GPP patients, they concluded.

No FDA-approved therapy

“GPP is a very rare but devastating life-threatening disease that presents with the sudden onset of pustules throughout the skin,” Joel Gelfand, MD, professor of dermatology and director of the psoriasis and phototherapy center at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said in an interview. “Without rapid treatment, GPP can result in death. Currently there are no [Food and Drug Administration]–approved treatments for this orphan disease.”

Dr. Gelfand said he was surprised by the degree of efficacy and the speed of the patient response to spesolimab, compared with placebo, which he described as “truly remarkable.” Based on the current study results, “spesolimab offers a tremendous step forward for our patients,” he added.

Looking ahead, Dr. Gelfand noted that “longer-term studies with a comparator, such as a biologic that targets IL-17, would be helpful to more fully understand the safety, efficacy, and role that spesolimab will have in real-world patients.”

On Dec. 15, Boehringer Ingelheim announced that the FDA had granted priority review for spesolimab for treating GPP flares.

The study was supported by Boehringer Ingelheim. Lead author Dr. Bachelez had no financial conflicts to disclose. Several authors are employees of Boehringer Ingelheim. Dr. Gelfand is a consultant for the study sponsor Boehringer Ingelheim and has received research grants from Boehringer Ingelheim to his institution to support an investigator-initiated study. He also disclosed serving as a consultant and receiving research grants from other manufacturers of psoriasis products.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

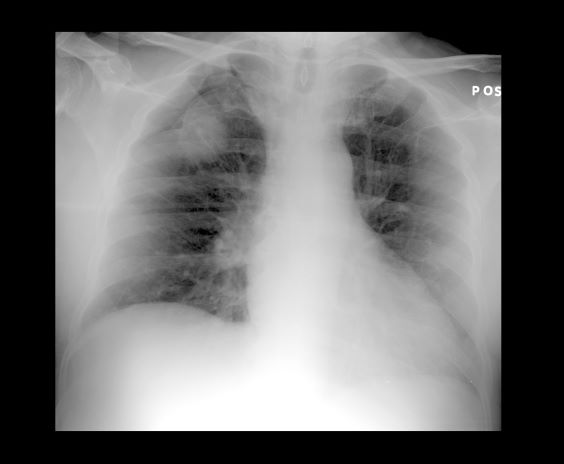

Complaints of incomplete bladder emptying

Many patients with nonmetastatic prostate cancer are asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis due to widespread routine screening. When localized symptoms do occur, they may include urinary frequency, decreased urine stream, urinary urgency, and hematuria. An increasing proportion of patients with localized disease are asymptomatic, however; such signs and symptoms may well be related to age-associated prostate enlargement or other conditions. Nevertheless, men over the age of 50 years who present with urinary symptoms should be screened for prostate cancer using DRE and PSA. Benign prostatic hyperplasia, for example, can manifest in urinary symptoms and even elevate PSA. Acute prostatitis, on the other hand, presents as a urinary tract infection.

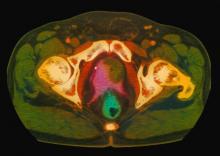

Because this patient showed elevated PSA levels, albeit with normal DRE findings, needle biopsy of the prostate is indicated for tissue diagnosis, usually performed with transrectal ultrasound. A pathologic evaluation of the biopsy specimen will determine the patient's Gleason score. PSA density (amount of PSA per gram of prostate tissue) and PSA doubling time should be collected as well. As seen in the present case, MRI can be used to assess lesions concerning for prostate cancer prior to biopsy. Lesions are then assigned Prostate Imaging–Reporting and Data System (PI-RADS) scores depending on their location within the prostatic zones. Imaging is also useful in staging and active surveillance. Staging is based on the tumor, node, and metastasis (TNM), with clinically localized prostate cancers including any T, N0, M0, NX, or MX cases. The clinician should pursue genetic testing to determine the presence of high-risk germline mutations.

The NCCN Guidelines recommend that for clinically localized prostate cancer, approaches include watchful waiting, active surveillance, radical prostatectomy, and radiation therapy. For asymptomatic patients who are older and/or have other serious comorbidities, active surveillance is often suggested. Radical prostatectomy is typically reserved for patients with a life expectancy of 10 years or more. Pelvic lymph node dissection may be performed on the basis of probability of nodal metastasis. Radiotherapy is also potentially curative in localized prostate cancer and may be delivered via brachytherapy, proton radiation, or external beam radiation therapy (EBRT). EBRT techniques include intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) and hypofractionated, image-guided stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT).

Chad R. Tracy, MD, Professor; Director, Minimally Invasive Surgery, Department of Urology, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City, Iowa

Chad R. Tracy, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a consultant for: Cvico Medical Solutions

Many patients with nonmetastatic prostate cancer are asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis due to widespread routine screening. When localized symptoms do occur, they may include urinary frequency, decreased urine stream, urinary urgency, and hematuria. An increasing proportion of patients with localized disease are asymptomatic, however; such signs and symptoms may well be related to age-associated prostate enlargement or other conditions. Nevertheless, men over the age of 50 years who present with urinary symptoms should be screened for prostate cancer using DRE and PSA. Benign prostatic hyperplasia, for example, can manifest in urinary symptoms and even elevate PSA. Acute prostatitis, on the other hand, presents as a urinary tract infection.

Because this patient showed elevated PSA levels, albeit with normal DRE findings, needle biopsy of the prostate is indicated for tissue diagnosis, usually performed with transrectal ultrasound. A pathologic evaluation of the biopsy specimen will determine the patient's Gleason score. PSA density (amount of PSA per gram of prostate tissue) and PSA doubling time should be collected as well. As seen in the present case, MRI can be used to assess lesions concerning for prostate cancer prior to biopsy. Lesions are then assigned Prostate Imaging–Reporting and Data System (PI-RADS) scores depending on their location within the prostatic zones. Imaging is also useful in staging and active surveillance. Staging is based on the tumor, node, and metastasis (TNM), with clinically localized prostate cancers including any T, N0, M0, NX, or MX cases. The clinician should pursue genetic testing to determine the presence of high-risk germline mutations.

The NCCN Guidelines recommend that for clinically localized prostate cancer, approaches include watchful waiting, active surveillance, radical prostatectomy, and radiation therapy. For asymptomatic patients who are older and/or have other serious comorbidities, active surveillance is often suggested. Radical prostatectomy is typically reserved for patients with a life expectancy of 10 years or more. Pelvic lymph node dissection may be performed on the basis of probability of nodal metastasis. Radiotherapy is also potentially curative in localized prostate cancer and may be delivered via brachytherapy, proton radiation, or external beam radiation therapy (EBRT). EBRT techniques include intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) and hypofractionated, image-guided stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT).

Chad R. Tracy, MD, Professor; Director, Minimally Invasive Surgery, Department of Urology, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City, Iowa

Chad R. Tracy, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a consultant for: Cvico Medical Solutions

Many patients with nonmetastatic prostate cancer are asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis due to widespread routine screening. When localized symptoms do occur, they may include urinary frequency, decreased urine stream, urinary urgency, and hematuria. An increasing proportion of patients with localized disease are asymptomatic, however; such signs and symptoms may well be related to age-associated prostate enlargement or other conditions. Nevertheless, men over the age of 50 years who present with urinary symptoms should be screened for prostate cancer using DRE and PSA. Benign prostatic hyperplasia, for example, can manifest in urinary symptoms and even elevate PSA. Acute prostatitis, on the other hand, presents as a urinary tract infection.

Because this patient showed elevated PSA levels, albeit with normal DRE findings, needle biopsy of the prostate is indicated for tissue diagnosis, usually performed with transrectal ultrasound. A pathologic evaluation of the biopsy specimen will determine the patient's Gleason score. PSA density (amount of PSA per gram of prostate tissue) and PSA doubling time should be collected as well. As seen in the present case, MRI can be used to assess lesions concerning for prostate cancer prior to biopsy. Lesions are then assigned Prostate Imaging–Reporting and Data System (PI-RADS) scores depending on their location within the prostatic zones. Imaging is also useful in staging and active surveillance. Staging is based on the tumor, node, and metastasis (TNM), with clinically localized prostate cancers including any T, N0, M0, NX, or MX cases. The clinician should pursue genetic testing to determine the presence of high-risk germline mutations.

The NCCN Guidelines recommend that for clinically localized prostate cancer, approaches include watchful waiting, active surveillance, radical prostatectomy, and radiation therapy. For asymptomatic patients who are older and/or have other serious comorbidities, active surveillance is often suggested. Radical prostatectomy is typically reserved for patients with a life expectancy of 10 years or more. Pelvic lymph node dissection may be performed on the basis of probability of nodal metastasis. Radiotherapy is also potentially curative in localized prostate cancer and may be delivered via brachytherapy, proton radiation, or external beam radiation therapy (EBRT). EBRT techniques include intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) and hypofractionated, image-guided stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT).

Chad R. Tracy, MD, Professor; Director, Minimally Invasive Surgery, Department of Urology, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City, Iowa

Chad R. Tracy, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a consultant for: Cvico Medical Solutions

A 61-year-old man presents with complaints of frequent urination and incomplete bladder emptying. He also has been feeling fatigued but cannot tell if this is because his symptoms are worse at night and he has not been sleeping well. Despite a family history of atrial fibrillation, he reports no significant medical history beyond appendicitis many years ago. The patient underwent a prostate cancer screening about 18 months ago, which was normal. During a recent office visit, digital rectal examination (DRE) was normal, but prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels were elevated at 10.2 ng/mL. An MRI is performed as part of the workup.

Are we failing to diagnose and treat the many faces of catatonia?

I had seen many new and exciting presentations of psychopathology during my intern year, yet one patient was uniquely memorable. When stable, he worked as a counselor, though for any number of reasons (eg, missing a dose of medication, smoking marijuana) his manic symptoms would emerge quickly, the disease rearing its ugly head within hours. He would become extremely hyperactive, elated, disinhibited (running naked in the streets), and grandiose (believing he was working for the president). He would be escorted to our psychiatric emergency department (ED) by police, who would have to resort to handcuffing him. His symptoms were described by ED and inpatient nursing staff and residents as “disorganized,” “psychotic,” “agitated,”’ or “combative.” He would receive large doses of intramuscular (IM) haloperidol, chlorpromazine, and diphenhydramine in desperate attempts to rein in his mania. Frustratingly—and paradoxically— this would make him more confused, disoriented, restless, and hyperactive, and often led to the need for restraints.

This behavior persisted for days until an attending I was working with assessed him. The attending observed that the patient did not know his current location, day of the week or month, or how he ended up in the hospital. He observed this patient intermittently staring, making abnormal repetitive movements with his arms and hands, occasionally freezing, making impulsive movements, and becoming combative without provocation. His heart rate and temperature were elevated; he was diaphoretic, especially after receiving parenteral antipsychotics. The attending, a pupil of Max Fink, made the diagnosis: delirious mania, a form of catatonia.1,2 Resolution was quick and complete after 6 bilateral electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) sessions.

Catatonia, a neuropsychiatric phenomenon characterized by abnormal speech, movement, and affect, has undergone numerous paradigm shifts since it was recognized by Karl Ludwig Kahlbaum in 1874.3 Shortly after Kahlbaum, Emil Kraepelin held the belief that catatonia was a subtype of dementia praecox, or what is now known as schizophrenia.4 Due to this, patients were likely receiving less-than-optimal treatments, because their catatonia was being diagnosed as acute psychosis. Finally, in DSM-5, catatonia was unshackled from the constraints of schizophrenia and is now an entity of its own.5 However, catatonia is often met with incertitude (despite being present in up to 15% of inpatients),1 with its treatment typically delayed or not even pursued. This is amplified because many forms of catatonia are often misdiagnosed as disorders that are more common or better understood.

Potential catatonia presentations

Delirious mania. Patients with delirious mania typically present with acute delirium, severe paranoia, hyperactivity, and visual/auditory hallucinations.2,6,7 They usually have excited catatonic signs, such as excessive movement, combativeness, impulsivity, stereotypy, and echophenomena. Unfortunately, the catatonia is overshadowed by extreme psychotic and manic symptoms, or delirium (for which an underlying medical cause is usually not found). As was the case for the patient I described earlier, large doses of IM antipsychotics usually are administered, which can cause neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) or precipitate seizures.8

Neuroleptic malignant syndrome. NMS is marked by fever, elevated blood pressure and heart rate, lead-pipe rigidity, parkinsonian features, altered mental status, and lab abnormalities (elevated liver enzymes or creatinine phosphokinase). This syndrome is preceded by the administration of an antipsychotic. It has features of catatonia that include mutism, negativism, and posturing.9 NMS is commonly interpreted as a subtype of malignant catatonia. Some argue that the diagnosis of malignant catatonia yields a more favorable outcome because it leads to more effective treatments (ie, benzodiazepines and ECT as opposed to dopamine agonists and dantrolene).10 Because NMS has much overlap with serotonin syndrome and drug-induced parkinsonism, initiation of benzodiazepines and ECT often is delayed.11

Retarded catatonia. This version of catatonia usually is well recognized. The typical presentation is a patient who does not speak (mutism) or move (stupor), stares, becomes withdrawn (does not eat or drink), or maintains abnormal posturing. Retarded catatonia can be confused with a major depressive episode or hypoactive delirium.

Catatonia in autism spectrum disorder. Historically, co-occurring catatonia and autism spectrum disorder (ASD) was believed to be extremely rare. However, recent retrospective studies have found that up to 17% of patients with ASD older than age 15 have catatonia.12 Many pediatric psychiatrists fail to recognize catatonia; in 1 study, only 2 patients (of 18) were correctly identified as having catatonia.13 The catatonic signs may vary, but the core features include withdrawal (children may need a feeding tube), decreased communication and/or worsening psychomotor slowing, agitation, or stereotypical movements, which can manifest as worsening self-injurious behavior.14,15

An approach to treatment

Regardless of the etiology or presentation, first-line treatment for catatonia is benzodiazepines and/or ECT. A lorazepam challenge is used for diagnostic clarification; if effective, lorazepam can be titrated until symptoms fully resolve.16,17 Doses >20 mg have been reported as effective and well-tolerated, without the feared sedation and respiratory depression.6 An unsuccessful lorazepam challenge does not rule out catatonia. If benzodiazepine therapy fails or the patient requires immediate symptom relief, ECT is the most effective treatment. Many clinicians use a bilateral electrode placement with high-energy dosing and frequent sessions until the catatonia resolves.1,18

In my experience, catatonia in all its forms remains poorly recognized, with its treatment questioned. Residents—especially those in psychiatry—must understand that catatonia can result in systemic illness or death.

1. Fink M. Expanding the catatonia tent: recognizing electroconvulsive therapy responsive syndromes. J ECT. 2021;37(2):77-79.

2. Fink M. Delirious mania. Bipolar Disord. 1999;1(1):54-60.

3. Starkstein SE, Goldar JC, Hodgkiss A. Karl Ludwig Kahlbaum’s concept of catatonia. Hist Psychiatry. 1995;6(22 Pt 2):201-207.

4. Jain A, Mitra P. Catatonic schizophrenia. StatPearls Publishing. Last updated July 31, 2021. Accessed December 9, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK563222/

5. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

6. Karmacharya R, England ML, Ongür D. Delirious mania: clinical features and treatment response. J Affect Disord. 2008;109(3):312-316.

7. Jacobowski NL, Heckers S, Bobo WV. Delirious mania: detection, diagnosis, and clinical management in the acute setting. J Psychiatr Pract. 2013;19(1):15-28.

8. Fink M. Electroconvulsive Therapy: A Guide for Professionals and Their Patients. Oxford University Press; 2009.

9. Francis A, Yacoub A. Catatonia and neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2008:231; author reply 232-233.

10. Fink M. Hidden in plain sight: catatonia in pediatrics: “An editorial comment to Shorter E. “Making childhood catatonia visible (Separate from competing diagnoses”, (1) Dhossche D, Ross CA, Stoppelbein L. ‘The role of deprivation, abuse, and trauma in pediatric catatonia without a clear medical cause’, (2) Ghaziuddin N, Dhossche D, Marcotte K. ‘Retrospective chart review of catatonia in child and adolescent psychiatric patients’ (3)”. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2012;125(1):11-12.

11. Perry PJ, Wilborn CA. Serotonin syndrome vs neuroleptic malignant syndrome: a contrast of causes, diagnoses, and management. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2012;24(2):155-162.

12. Wing L, Shah A. Catatonia in autistic spectrum disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;176:357-362.

13. Ghaziuddin N, Dhossche D, Marcotte K. Retrospective chart review of catatonia in child and adolescent psychiatric patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2012;125(1):33-38.

14. Wachtel LE, Hermida A, Dhossche DM. Maintenance electroconvulsive therapy in autistic catatonia: a case series review. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2010;34(4):581-587.

15. Wachtel LE. The multiple faces of catatonia in autism spectrum disorders: descriptive clinical experience of 22 patients over 12 years. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2019;28(4):471-480.

16. Bush G, Fink M, Petrides G, et al. Catatonia. I. Rating scale and standardized examination. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1996;93(2):129-136.

17. Bush G, Fink M, Petrides G, et al. Catatonia. II. Treatment with lorazepam and electroconvulsive therapy. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1996;93(2):137-143.

18. Fink M, Kellner CH, McCall WV. Optimizing ECT technique in treating catatonia. J ECT. 2016;32(3):149-150.

I had seen many new and exciting presentations of psychopathology during my intern year, yet one patient was uniquely memorable. When stable, he worked as a counselor, though for any number of reasons (eg, missing a dose of medication, smoking marijuana) his manic symptoms would emerge quickly, the disease rearing its ugly head within hours. He would become extremely hyperactive, elated, disinhibited (running naked in the streets), and grandiose (believing he was working for the president). He would be escorted to our psychiatric emergency department (ED) by police, who would have to resort to handcuffing him. His symptoms were described by ED and inpatient nursing staff and residents as “disorganized,” “psychotic,” “agitated,”’ or “combative.” He would receive large doses of intramuscular (IM) haloperidol, chlorpromazine, and diphenhydramine in desperate attempts to rein in his mania. Frustratingly—and paradoxically— this would make him more confused, disoriented, restless, and hyperactive, and often led to the need for restraints.

This behavior persisted for days until an attending I was working with assessed him. The attending observed that the patient did not know his current location, day of the week or month, or how he ended up in the hospital. He observed this patient intermittently staring, making abnormal repetitive movements with his arms and hands, occasionally freezing, making impulsive movements, and becoming combative without provocation. His heart rate and temperature were elevated; he was diaphoretic, especially after receiving parenteral antipsychotics. The attending, a pupil of Max Fink, made the diagnosis: delirious mania, a form of catatonia.1,2 Resolution was quick and complete after 6 bilateral electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) sessions.

Catatonia, a neuropsychiatric phenomenon characterized by abnormal speech, movement, and affect, has undergone numerous paradigm shifts since it was recognized by Karl Ludwig Kahlbaum in 1874.3 Shortly after Kahlbaum, Emil Kraepelin held the belief that catatonia was a subtype of dementia praecox, or what is now known as schizophrenia.4 Due to this, patients were likely receiving less-than-optimal treatments, because their catatonia was being diagnosed as acute psychosis. Finally, in DSM-5, catatonia was unshackled from the constraints of schizophrenia and is now an entity of its own.5 However, catatonia is often met with incertitude (despite being present in up to 15% of inpatients),1 with its treatment typically delayed or not even pursued. This is amplified because many forms of catatonia are often misdiagnosed as disorders that are more common or better understood.

Potential catatonia presentations

Delirious mania. Patients with delirious mania typically present with acute delirium, severe paranoia, hyperactivity, and visual/auditory hallucinations.2,6,7 They usually have excited catatonic signs, such as excessive movement, combativeness, impulsivity, stereotypy, and echophenomena. Unfortunately, the catatonia is overshadowed by extreme psychotic and manic symptoms, or delirium (for which an underlying medical cause is usually not found). As was the case for the patient I described earlier, large doses of IM antipsychotics usually are administered, which can cause neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) or precipitate seizures.8

Neuroleptic malignant syndrome. NMS is marked by fever, elevated blood pressure and heart rate, lead-pipe rigidity, parkinsonian features, altered mental status, and lab abnormalities (elevated liver enzymes or creatinine phosphokinase). This syndrome is preceded by the administration of an antipsychotic. It has features of catatonia that include mutism, negativism, and posturing.9 NMS is commonly interpreted as a subtype of malignant catatonia. Some argue that the diagnosis of malignant catatonia yields a more favorable outcome because it leads to more effective treatments (ie, benzodiazepines and ECT as opposed to dopamine agonists and dantrolene).10 Because NMS has much overlap with serotonin syndrome and drug-induced parkinsonism, initiation of benzodiazepines and ECT often is delayed.11

Retarded catatonia. This version of catatonia usually is well recognized. The typical presentation is a patient who does not speak (mutism) or move (stupor), stares, becomes withdrawn (does not eat or drink), or maintains abnormal posturing. Retarded catatonia can be confused with a major depressive episode or hypoactive delirium.

Catatonia in autism spectrum disorder. Historically, co-occurring catatonia and autism spectrum disorder (ASD) was believed to be extremely rare. However, recent retrospective studies have found that up to 17% of patients with ASD older than age 15 have catatonia.12 Many pediatric psychiatrists fail to recognize catatonia; in 1 study, only 2 patients (of 18) were correctly identified as having catatonia.13 The catatonic signs may vary, but the core features include withdrawal (children may need a feeding tube), decreased communication and/or worsening psychomotor slowing, agitation, or stereotypical movements, which can manifest as worsening self-injurious behavior.14,15

An approach to treatment

Regardless of the etiology or presentation, first-line treatment for catatonia is benzodiazepines and/or ECT. A lorazepam challenge is used for diagnostic clarification; if effective, lorazepam can be titrated until symptoms fully resolve.16,17 Doses >20 mg have been reported as effective and well-tolerated, without the feared sedation and respiratory depression.6 An unsuccessful lorazepam challenge does not rule out catatonia. If benzodiazepine therapy fails or the patient requires immediate symptom relief, ECT is the most effective treatment. Many clinicians use a bilateral electrode placement with high-energy dosing and frequent sessions until the catatonia resolves.1,18

In my experience, catatonia in all its forms remains poorly recognized, with its treatment questioned. Residents—especially those in psychiatry—must understand that catatonia can result in systemic illness or death.

I had seen many new and exciting presentations of psychopathology during my intern year, yet one patient was uniquely memorable. When stable, he worked as a counselor, though for any number of reasons (eg, missing a dose of medication, smoking marijuana) his manic symptoms would emerge quickly, the disease rearing its ugly head within hours. He would become extremely hyperactive, elated, disinhibited (running naked in the streets), and grandiose (believing he was working for the president). He would be escorted to our psychiatric emergency department (ED) by police, who would have to resort to handcuffing him. His symptoms were described by ED and inpatient nursing staff and residents as “disorganized,” “psychotic,” “agitated,”’ or “combative.” He would receive large doses of intramuscular (IM) haloperidol, chlorpromazine, and diphenhydramine in desperate attempts to rein in his mania. Frustratingly—and paradoxically— this would make him more confused, disoriented, restless, and hyperactive, and often led to the need for restraints.

This behavior persisted for days until an attending I was working with assessed him. The attending observed that the patient did not know his current location, day of the week or month, or how he ended up in the hospital. He observed this patient intermittently staring, making abnormal repetitive movements with his arms and hands, occasionally freezing, making impulsive movements, and becoming combative without provocation. His heart rate and temperature were elevated; he was diaphoretic, especially after receiving parenteral antipsychotics. The attending, a pupil of Max Fink, made the diagnosis: delirious mania, a form of catatonia.1,2 Resolution was quick and complete after 6 bilateral electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) sessions.

Catatonia, a neuropsychiatric phenomenon characterized by abnormal speech, movement, and affect, has undergone numerous paradigm shifts since it was recognized by Karl Ludwig Kahlbaum in 1874.3 Shortly after Kahlbaum, Emil Kraepelin held the belief that catatonia was a subtype of dementia praecox, or what is now known as schizophrenia.4 Due to this, patients were likely receiving less-than-optimal treatments, because their catatonia was being diagnosed as acute psychosis. Finally, in DSM-5, catatonia was unshackled from the constraints of schizophrenia and is now an entity of its own.5 However, catatonia is often met with incertitude (despite being present in up to 15% of inpatients),1 with its treatment typically delayed or not even pursued. This is amplified because many forms of catatonia are often misdiagnosed as disorders that are more common or better understood.

Potential catatonia presentations

Delirious mania. Patients with delirious mania typically present with acute delirium, severe paranoia, hyperactivity, and visual/auditory hallucinations.2,6,7 They usually have excited catatonic signs, such as excessive movement, combativeness, impulsivity, stereotypy, and echophenomena. Unfortunately, the catatonia is overshadowed by extreme psychotic and manic symptoms, or delirium (for which an underlying medical cause is usually not found). As was the case for the patient I described earlier, large doses of IM antipsychotics usually are administered, which can cause neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) or precipitate seizures.8

Neuroleptic malignant syndrome. NMS is marked by fever, elevated blood pressure and heart rate, lead-pipe rigidity, parkinsonian features, altered mental status, and lab abnormalities (elevated liver enzymes or creatinine phosphokinase). This syndrome is preceded by the administration of an antipsychotic. It has features of catatonia that include mutism, negativism, and posturing.9 NMS is commonly interpreted as a subtype of malignant catatonia. Some argue that the diagnosis of malignant catatonia yields a more favorable outcome because it leads to more effective treatments (ie, benzodiazepines and ECT as opposed to dopamine agonists and dantrolene).10 Because NMS has much overlap with serotonin syndrome and drug-induced parkinsonism, initiation of benzodiazepines and ECT often is delayed.11

Retarded catatonia. This version of catatonia usually is well recognized. The typical presentation is a patient who does not speak (mutism) or move (stupor), stares, becomes withdrawn (does not eat or drink), or maintains abnormal posturing. Retarded catatonia can be confused with a major depressive episode or hypoactive delirium.

Catatonia in autism spectrum disorder. Historically, co-occurring catatonia and autism spectrum disorder (ASD) was believed to be extremely rare. However, recent retrospective studies have found that up to 17% of patients with ASD older than age 15 have catatonia.12 Many pediatric psychiatrists fail to recognize catatonia; in 1 study, only 2 patients (of 18) were correctly identified as having catatonia.13 The catatonic signs may vary, but the core features include withdrawal (children may need a feeding tube), decreased communication and/or worsening psychomotor slowing, agitation, or stereotypical movements, which can manifest as worsening self-injurious behavior.14,15

An approach to treatment

Regardless of the etiology or presentation, first-line treatment for catatonia is benzodiazepines and/or ECT. A lorazepam challenge is used for diagnostic clarification; if effective, lorazepam can be titrated until symptoms fully resolve.16,17 Doses >20 mg have been reported as effective and well-tolerated, without the feared sedation and respiratory depression.6 An unsuccessful lorazepam challenge does not rule out catatonia. If benzodiazepine therapy fails or the patient requires immediate symptom relief, ECT is the most effective treatment. Many clinicians use a bilateral electrode placement with high-energy dosing and frequent sessions until the catatonia resolves.1,18

In my experience, catatonia in all its forms remains poorly recognized, with its treatment questioned. Residents—especially those in psychiatry—must understand that catatonia can result in systemic illness or death.

1. Fink M. Expanding the catatonia tent: recognizing electroconvulsive therapy responsive syndromes. J ECT. 2021;37(2):77-79.

2. Fink M. Delirious mania. Bipolar Disord. 1999;1(1):54-60.

3. Starkstein SE, Goldar JC, Hodgkiss A. Karl Ludwig Kahlbaum’s concept of catatonia. Hist Psychiatry. 1995;6(22 Pt 2):201-207.

4. Jain A, Mitra P. Catatonic schizophrenia. StatPearls Publishing. Last updated July 31, 2021. Accessed December 9, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK563222/

5. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

6. Karmacharya R, England ML, Ongür D. Delirious mania: clinical features and treatment response. J Affect Disord. 2008;109(3):312-316.

7. Jacobowski NL, Heckers S, Bobo WV. Delirious mania: detection, diagnosis, and clinical management in the acute setting. J Psychiatr Pract. 2013;19(1):15-28.

8. Fink M. Electroconvulsive Therapy: A Guide for Professionals and Their Patients. Oxford University Press; 2009.

9. Francis A, Yacoub A. Catatonia and neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2008:231; author reply 232-233.

10. Fink M. Hidden in plain sight: catatonia in pediatrics: “An editorial comment to Shorter E. “Making childhood catatonia visible (Separate from competing diagnoses”, (1) Dhossche D, Ross CA, Stoppelbein L. ‘The role of deprivation, abuse, and trauma in pediatric catatonia without a clear medical cause’, (2) Ghaziuddin N, Dhossche D, Marcotte K. ‘Retrospective chart review of catatonia in child and adolescent psychiatric patients’ (3)”. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2012;125(1):11-12.

11. Perry PJ, Wilborn CA. Serotonin syndrome vs neuroleptic malignant syndrome: a contrast of causes, diagnoses, and management. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2012;24(2):155-162.

12. Wing L, Shah A. Catatonia in autistic spectrum disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;176:357-362.

13. Ghaziuddin N, Dhossche D, Marcotte K. Retrospective chart review of catatonia in child and adolescent psychiatric patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2012;125(1):33-38.

14. Wachtel LE, Hermida A, Dhossche DM. Maintenance electroconvulsive therapy in autistic catatonia: a case series review. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2010;34(4):581-587.

15. Wachtel LE. The multiple faces of catatonia in autism spectrum disorders: descriptive clinical experience of 22 patients over 12 years. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2019;28(4):471-480.

16. Bush G, Fink M, Petrides G, et al. Catatonia. I. Rating scale and standardized examination. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1996;93(2):129-136.

17. Bush G, Fink M, Petrides G, et al. Catatonia. II. Treatment with lorazepam and electroconvulsive therapy. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1996;93(2):137-143.

18. Fink M, Kellner CH, McCall WV. Optimizing ECT technique in treating catatonia. J ECT. 2016;32(3):149-150.

1. Fink M. Expanding the catatonia tent: recognizing electroconvulsive therapy responsive syndromes. J ECT. 2021;37(2):77-79.

2. Fink M. Delirious mania. Bipolar Disord. 1999;1(1):54-60.

3. Starkstein SE, Goldar JC, Hodgkiss A. Karl Ludwig Kahlbaum’s concept of catatonia. Hist Psychiatry. 1995;6(22 Pt 2):201-207.

4. Jain A, Mitra P. Catatonic schizophrenia. StatPearls Publishing. Last updated July 31, 2021. Accessed December 9, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK563222/

5. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

6. Karmacharya R, England ML, Ongür D. Delirious mania: clinical features and treatment response. J Affect Disord. 2008;109(3):312-316.

7. Jacobowski NL, Heckers S, Bobo WV. Delirious mania: detection, diagnosis, and clinical management in the acute setting. J Psychiatr Pract. 2013;19(1):15-28.

8. Fink M. Electroconvulsive Therapy: A Guide for Professionals and Their Patients. Oxford University Press; 2009.

9. Francis A, Yacoub A. Catatonia and neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2008:231; author reply 232-233.

10. Fink M. Hidden in plain sight: catatonia in pediatrics: “An editorial comment to Shorter E. “Making childhood catatonia visible (Separate from competing diagnoses”, (1) Dhossche D, Ross CA, Stoppelbein L. ‘The role of deprivation, abuse, and trauma in pediatric catatonia without a clear medical cause’, (2) Ghaziuddin N, Dhossche D, Marcotte K. ‘Retrospective chart review of catatonia in child and adolescent psychiatric patients’ (3)”. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2012;125(1):11-12.

11. Perry PJ, Wilborn CA. Serotonin syndrome vs neuroleptic malignant syndrome: a contrast of causes, diagnoses, and management. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2012;24(2):155-162.

12. Wing L, Shah A. Catatonia in autistic spectrum disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;176:357-362.

13. Ghaziuddin N, Dhossche D, Marcotte K. Retrospective chart review of catatonia in child and adolescent psychiatric patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2012;125(1):33-38.

14. Wachtel LE, Hermida A, Dhossche DM. Maintenance electroconvulsive therapy in autistic catatonia: a case series review. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2010;34(4):581-587.

15. Wachtel LE. The multiple faces of catatonia in autism spectrum disorders: descriptive clinical experience of 22 patients over 12 years. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2019;28(4):471-480.

16. Bush G, Fink M, Petrides G, et al. Catatonia. I. Rating scale and standardized examination. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1996;93(2):129-136.

17. Bush G, Fink M, Petrides G, et al. Catatonia. II. Treatment with lorazepam and electroconvulsive therapy. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1996;93(2):137-143.

18. Fink M, Kellner CH, McCall WV. Optimizing ECT technique in treating catatonia. J ECT. 2016;32(3):149-150.

Boy presents with abdominal cramping

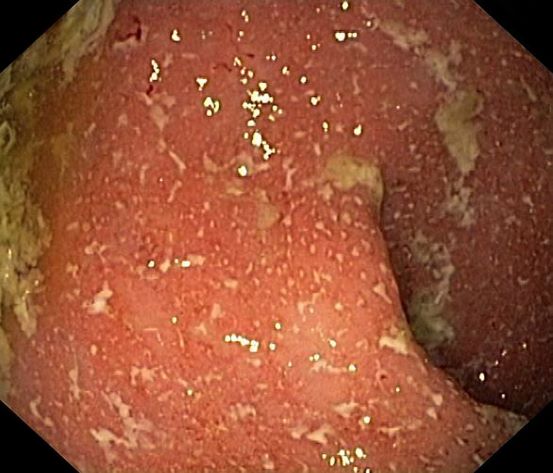

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is an autoimmune-related inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). It typically develops in the rectum and extends to involve the large intestine. Pediatric UC can have a more severe phenotype than adult disease and may affect a child's pubertal development, bone mineral density, nutrition levels, and social life. It is currently theorized that the age at diagnosis and sex of the patient do not predict disease activity.

UC disease can announce itself as mild, moderate, or severe, and the Pediatric Ulcerative Colitis Activity Index (PUCAI) endoscopic grading is used as a clinical scoring system. The most common presenting symptoms are rectal bleeding, diarrhea, and abdominal pain; among children, the presentation can vary.

Crohns disease, another IBD, must be carefully ruled out of the differential. Colonoscopy represents the first-line approach in the diagnosis of IBD. The findings that would suggest Crohns disease are sparing of the rectal mucosa, aphthous ulceration, and noncontiguous (or skip) lesions. Micronutrient and vitamin levels are usually low in Crohns disease. And although weight loss, perineal disease, fistulae, and obstruction are commonly seen in the context of Crohns disease, they are uncommon or rare in UC. Bleeding is observed much more frequently in UC.

During UC workup, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein level often serve as markers of disease activity. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) test is frequently used with suspected UC (though this measure may not correlate with disease activity). In addition, a broad metabolic panel should be performed, along with stool cultures, to rule out infection.

The goals of pediatric UC management are to maintain control of the disease, extend periods of remission, and reduce long-term damage caused by inflammation, all while potentially allowing the patient to function as normally as possible. Anti-inflammatory therapy with 5-aminosalicylic acid agents, such as sulfasalazine and mesalamine, is foundational to treatment. Acute flares of UC in the pediatric population are usually responsive to corticosteroids, but these regimens should be short-term only. Immunomodulatory agents, tumor necrosis factor inhibitors, and newer therapies such as monoclonal antibodies are also used during flares, but only a minority of patients will require these therapies. These are also considered treatment alternatives for patients who are steroid-dependent or steroid-refractory.

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, Professor, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is an autoimmune-related inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). It typically develops in the rectum and extends to involve the large intestine. Pediatric UC can have a more severe phenotype than adult disease and may affect a child's pubertal development, bone mineral density, nutrition levels, and social life. It is currently theorized that the age at diagnosis and sex of the patient do not predict disease activity.

UC disease can announce itself as mild, moderate, or severe, and the Pediatric Ulcerative Colitis Activity Index (PUCAI) endoscopic grading is used as a clinical scoring system. The most common presenting symptoms are rectal bleeding, diarrhea, and abdominal pain; among children, the presentation can vary.

Crohns disease, another IBD, must be carefully ruled out of the differential. Colonoscopy represents the first-line approach in the diagnosis of IBD. The findings that would suggest Crohns disease are sparing of the rectal mucosa, aphthous ulceration, and noncontiguous (or skip) lesions. Micronutrient and vitamin levels are usually low in Crohns disease. And although weight loss, perineal disease, fistulae, and obstruction are commonly seen in the context of Crohns disease, they are uncommon or rare in UC. Bleeding is observed much more frequently in UC.

During UC workup, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein level often serve as markers of disease activity. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) test is frequently used with suspected UC (though this measure may not correlate with disease activity). In addition, a broad metabolic panel should be performed, along with stool cultures, to rule out infection.

The goals of pediatric UC management are to maintain control of the disease, extend periods of remission, and reduce long-term damage caused by inflammation, all while potentially allowing the patient to function as normally as possible. Anti-inflammatory therapy with 5-aminosalicylic acid agents, such as sulfasalazine and mesalamine, is foundational to treatment. Acute flares of UC in the pediatric population are usually responsive to corticosteroids, but these regimens should be short-term only. Immunomodulatory agents, tumor necrosis factor inhibitors, and newer therapies such as monoclonal antibodies are also used during flares, but only a minority of patients will require these therapies. These are also considered treatment alternatives for patients who are steroid-dependent or steroid-refractory.

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, Professor, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is an autoimmune-related inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). It typically develops in the rectum and extends to involve the large intestine. Pediatric UC can have a more severe phenotype than adult disease and may affect a child's pubertal development, bone mineral density, nutrition levels, and social life. It is currently theorized that the age at diagnosis and sex of the patient do not predict disease activity.

UC disease can announce itself as mild, moderate, or severe, and the Pediatric Ulcerative Colitis Activity Index (PUCAI) endoscopic grading is used as a clinical scoring system. The most common presenting symptoms are rectal bleeding, diarrhea, and abdominal pain; among children, the presentation can vary.

Crohns disease, another IBD, must be carefully ruled out of the differential. Colonoscopy represents the first-line approach in the diagnosis of IBD. The findings that would suggest Crohns disease are sparing of the rectal mucosa, aphthous ulceration, and noncontiguous (or skip) lesions. Micronutrient and vitamin levels are usually low in Crohns disease. And although weight loss, perineal disease, fistulae, and obstruction are commonly seen in the context of Crohns disease, they are uncommon or rare in UC. Bleeding is observed much more frequently in UC.

During UC workup, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein level often serve as markers of disease activity. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) test is frequently used with suspected UC (though this measure may not correlate with disease activity). In addition, a broad metabolic panel should be performed, along with stool cultures, to rule out infection.

The goals of pediatric UC management are to maintain control of the disease, extend periods of remission, and reduce long-term damage caused by inflammation, all while potentially allowing the patient to function as normally as possible. Anti-inflammatory therapy with 5-aminosalicylic acid agents, such as sulfasalazine and mesalamine, is foundational to treatment. Acute flares of UC in the pediatric population are usually responsive to corticosteroids, but these regimens should be short-term only. Immunomodulatory agents, tumor necrosis factor inhibitors, and newer therapies such as monoclonal antibodies are also used during flares, but only a minority of patients will require these therapies. These are also considered treatment alternatives for patients who are steroid-dependent or steroid-refractory.

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, Professor, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships

A 5-year-old boy presents with abdominal cramping and bloody stools over the course of 2 days. His mother explains that the onset of diarrhea was insidious. Because the patient has a sensitive stomach, she tries to keep his diet relatively bland, but she worries about what he eats at school. He is slightly underweight for his age group. The family has not traveled recently. The patient does not have a fever, but skin turgor is decreased. There is no evidence of fistulae or abscesses. His complete blood cell count is 10.6 g/dL.

Decreased visual acuity and paresthesia

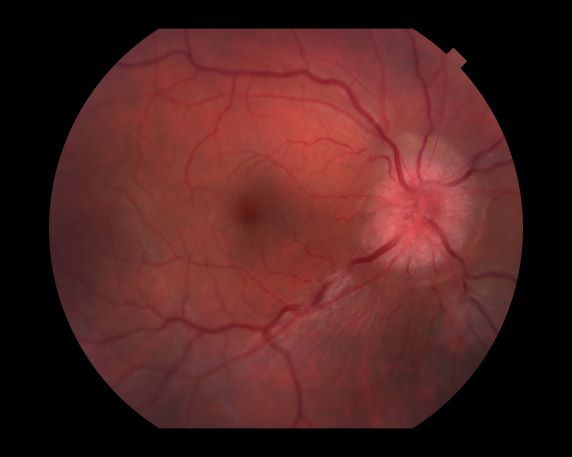

All of the above conditions can have ophthalmic manifestations, but the majority of optic neuritis cases seen in clinical practice are either sporadic or MS related. Optic neuritis is the first demyelinating event in approximately 20% of patients with MS. It develops in approximately 40% of MS patients during the course of their disease.

Optic neuritis is characterized by loss of vision (or loss of color vision) in the affected eye and pain on movement of the eye (painful ophthalmoplegia). Less often, patients with optic neuritis may describe phosphenes (transient flashes of light or black squares) lasting from hours to months. Phosphenes may occur before or during an optic neuritis event or even several months after recovery.

The diagnosis of optic neuritis is usually made clinically, with direct imaging of the optic nerves showing evidence of optic disc swelling with blurred margins. The real contribution of imaging in the setting of optic neuritis, however, is made by imaging of the brain, not of the optic nerves themselves. MRI of the brain provides information that can change the management of optic neuritis and yields prognostic information regarding the patient's future risk of developing MS. The most valuable predictor of the development of subsequent MS is the presence of white matter abnormalities. Between 27% and 70% of patients (in various studies) with isolated optic neuritis showed abnormal MRI brain findings, as defined by the presence of two or more white matter lesions on T2-weighted images. Patients with two or more lesions may have up to an 80% chance of meeting criteria for MS within the next 5 years.

A gradual recovery of visual acuity with time is characteristic of optic neuritis, although permanent residual deficits in color vision and contrast and brightness sensitivity are common. The symptoms of optic neuritis will usually resolve without medical treatment, although continuing to take regular MS disease-modulating medication is usually helpful. An intravenous steroid or oral prednisone is sometimes recommended to speed recovery. A 3- to 5-day course of high-dose (1 g) IV methylprednisolone, followed by a rapid oral taper of prednisone, has been shown to provide rapid recovery of symptoms in the acute phase. However, IV steroids do little to affect the ultimate visual acuity in patients with optic neuritis.

Typically, patients begin to recover 2-4 weeks after the onset of the vision loss. The optic nerve may take up to 6-12 months to heal completely, but most patients recover as much vision as they are going to within the first few months.

For patients with optic neuritis whose brain lesions on MRI indicate a high risk of developing clinically definite MS, treatment with immunomodulators may be considered. IV immunoglobulin treatment of acute optic neuritis has been shown to have no beneficial effect. In severe cases, plasma exchange may be considered.

Krupa Pandey, MD, Director, Multiple Sclerosis Center, Department of Neurology & Neuroscience Institute, Hackensack University Medical Center; Neurologist, Department of Neurology, Hackensack Meridian Health, Hackensack, NJ.

Krupa Pandey, MD, has serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Bristol-Myers Squibb; Biogen; Alexion; Genentech; Sanofi-Genzyme.

All of the above conditions can have ophthalmic manifestations, but the majority of optic neuritis cases seen in clinical practice are either sporadic or MS related. Optic neuritis is the first demyelinating event in approximately 20% of patients with MS. It develops in approximately 40% of MS patients during the course of their disease.

Optic neuritis is characterized by loss of vision (or loss of color vision) in the affected eye and pain on movement of the eye (painful ophthalmoplegia). Less often, patients with optic neuritis may describe phosphenes (transient flashes of light or black squares) lasting from hours to months. Phosphenes may occur before or during an optic neuritis event or even several months after recovery.

The diagnosis of optic neuritis is usually made clinically, with direct imaging of the optic nerves showing evidence of optic disc swelling with blurred margins. The real contribution of imaging in the setting of optic neuritis, however, is made by imaging of the brain, not of the optic nerves themselves. MRI of the brain provides information that can change the management of optic neuritis and yields prognostic information regarding the patient's future risk of developing MS. The most valuable predictor of the development of subsequent MS is the presence of white matter abnormalities. Between 27% and 70% of patients (in various studies) with isolated optic neuritis showed abnormal MRI brain findings, as defined by the presence of two or more white matter lesions on T2-weighted images. Patients with two or more lesions may have up to an 80% chance of meeting criteria for MS within the next 5 years.

A gradual recovery of visual acuity with time is characteristic of optic neuritis, although permanent residual deficits in color vision and contrast and brightness sensitivity are common. The symptoms of optic neuritis will usually resolve without medical treatment, although continuing to take regular MS disease-modulating medication is usually helpful. An intravenous steroid or oral prednisone is sometimes recommended to speed recovery. A 3- to 5-day course of high-dose (1 g) IV methylprednisolone, followed by a rapid oral taper of prednisone, has been shown to provide rapid recovery of symptoms in the acute phase. However, IV steroids do little to affect the ultimate visual acuity in patients with optic neuritis.

Typically, patients begin to recover 2-4 weeks after the onset of the vision loss. The optic nerve may take up to 6-12 months to heal completely, but most patients recover as much vision as they are going to within the first few months.

For patients with optic neuritis whose brain lesions on MRI indicate a high risk of developing clinically definite MS, treatment with immunomodulators may be considered. IV immunoglobulin treatment of acute optic neuritis has been shown to have no beneficial effect. In severe cases, plasma exchange may be considered.

Krupa Pandey, MD, Director, Multiple Sclerosis Center, Department of Neurology & Neuroscience Institute, Hackensack University Medical Center; Neurologist, Department of Neurology, Hackensack Meridian Health, Hackensack, NJ.

Krupa Pandey, MD, has serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Bristol-Myers Squibb; Biogen; Alexion; Genentech; Sanofi-Genzyme.

All of the above conditions can have ophthalmic manifestations, but the majority of optic neuritis cases seen in clinical practice are either sporadic or MS related. Optic neuritis is the first demyelinating event in approximately 20% of patients with MS. It develops in approximately 40% of MS patients during the course of their disease.

Optic neuritis is characterized by loss of vision (or loss of color vision) in the affected eye and pain on movement of the eye (painful ophthalmoplegia). Less often, patients with optic neuritis may describe phosphenes (transient flashes of light or black squares) lasting from hours to months. Phosphenes may occur before or during an optic neuritis event or even several months after recovery.

The diagnosis of optic neuritis is usually made clinically, with direct imaging of the optic nerves showing evidence of optic disc swelling with blurred margins. The real contribution of imaging in the setting of optic neuritis, however, is made by imaging of the brain, not of the optic nerves themselves. MRI of the brain provides information that can change the management of optic neuritis and yields prognostic information regarding the patient's future risk of developing MS. The most valuable predictor of the development of subsequent MS is the presence of white matter abnormalities. Between 27% and 70% of patients (in various studies) with isolated optic neuritis showed abnormal MRI brain findings, as defined by the presence of two or more white matter lesions on T2-weighted images. Patients with two or more lesions may have up to an 80% chance of meeting criteria for MS within the next 5 years.

A gradual recovery of visual acuity with time is characteristic of optic neuritis, although permanent residual deficits in color vision and contrast and brightness sensitivity are common. The symptoms of optic neuritis will usually resolve without medical treatment, although continuing to take regular MS disease-modulating medication is usually helpful. An intravenous steroid or oral prednisone is sometimes recommended to speed recovery. A 3- to 5-day course of high-dose (1 g) IV methylprednisolone, followed by a rapid oral taper of prednisone, has been shown to provide rapid recovery of symptoms in the acute phase. However, IV steroids do little to affect the ultimate visual acuity in patients with optic neuritis.

Typically, patients begin to recover 2-4 weeks after the onset of the vision loss. The optic nerve may take up to 6-12 months to heal completely, but most patients recover as much vision as they are going to within the first few months.

For patients with optic neuritis whose brain lesions on MRI indicate a high risk of developing clinically definite MS, treatment with immunomodulators may be considered. IV immunoglobulin treatment of acute optic neuritis has been shown to have no beneficial effect. In severe cases, plasma exchange may be considered.

Krupa Pandey, MD, Director, Multiple Sclerosis Center, Department of Neurology & Neuroscience Institute, Hackensack University Medical Center; Neurologist, Department of Neurology, Hackensack Meridian Health, Hackensack, NJ.

Krupa Pandey, MD, has serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Bristol-Myers Squibb; Biogen; Alexion; Genentech; Sanofi-Genzyme.

A 44-year-old woman presents with decreased visual acuity, painful ophthalmoplegia, photophobia, and paresthesia of the left hand. The patient's ocular history was unremarkable. Her medical history was significant only for recurrent urinary tract infections. She did not have a history of neurologic problems and reported that she did not have dizziness, tingling, tremors, sensory changes, speech changes, or focal weaknesses. Besides current use of naproxen, she said she was not taking any other medications. Her family ocular history was significant for glaucoma in her father and paternal grandfather. Her maternal grandfather died at age 58 of multiple sclerosis (MS).

How do digital technologies affect young people’s mental health?

Editor’s note: Readers’ Forum is a department for correspondence from readers that is not in response to articles published in

For almost all of us, “screen time”—time spent using a device with a screen such as a smartphone, computer, television, or video game console—has become a large part of our daily lives. This is very much the case for children and adolescents. In the United States, children ages 8 to 12 years spend an average of 4 to 6 hours each day watching or using screens, and teens spend up to 9 hours.1 Because young people are continually adopting newer forms of entertainment and technologies, new digital technologies are an ongoing source of concern for parents and clinicians alike.2 Studies have suggested that excessive screen time is associated with numerous psychiatric symptoms and disorders, including poor sleep, weight gain, anxiety, depression, and attention-deficit/hyperactive disorder.3,4 However, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis found that individuals’ self-reports of media use were rarely an accurate reflection of their actual, logged media use, and that measures of problematic media use had an even weaker association with usage logs.5 Therefore, it is crucial to have an accurate understanding of how children and adolescents are affected by new technologies. In this article, we discuss a recent study that investigated variations in adolescents’ mental health over time, and the association of their mental health and their use of digital technologies.

Results were mixed

Vuorre et al6 conducted a study to examine a possible shift in the associations between adolescents’ technology use and mental health outcomes. To investigate whether technology engagement and mental health outcomes changed over time, these researchers evaluated the impact not only of smartphones and social media, but also of television, which in the mid- to late-20th century elicited comparable levels of academic, public, and policy concern about its potential impact on child development. They analyzed data from 3 large-scale studies of adolescents living in the United States (Monitoring the Future and Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System) and the United Kingdom (Understanding Society) that included a total of 430,561 participants.

The results were mixed across types of technology and mental health outcomes. Television and social media were found to have a direct correlation with conduct problems and emotional problems. Suicidal ideation and behavior were associated with digital device use; however, no correlation was found between depression and technology use. Regarding social media use, researchers found that its association with conduct problems remained stable, decreased with depression, and increased with emotional problems. The magnitudes of the observed changes over time were small. These researchers concluded there is “little evidence for increases in the associations between adolescents’ technology engagement and mental health [problems]” and “drawing firm conclusions about changes in ... associations with mental health may be premature.”6

Future directions

The study by Vuorre et al6 has opened the door to better analysis of the association between screen use and mental health outcomes. More robust, detailed studies are required to fully understand the varying impact of technologies on the lives of children and adolescents. Collaborative efforts by technology companies and researchers can help to determine the impact of technology on young people’s mental health.

1. American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. Screen time and children. Updated February 2020. Accessed October 7, 2021. http://www.aacap.org/AACAP/Families_and_Youth/Facts_for_Families/FFF-Guide/Children-And-Watching-TV-054.aspx

2. Orben A. The Sisyphean cycle of technology panics. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2020;15(5):1143-1157.

3. Paulich KN, Ross JM, Lessem JM, et al. Screen time and early adolescent mental health, academic, and social outcomes in 9- and 10-year old children: utilizing the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study. PLoS One. 2021;16(9):e0256591. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0256591

4. Twenge JM, Campbell WK. Associations between screen time and lower psychological well-being among children and adolescents: evidence from a population-based study. Prev Med Rep. 2018;12:271-283. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2018.10.003

5. Parry DA, Davidson BI, Sewall CJR, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of discrepancies between logged and self-reported digital media use. Nat Hum Behav. 2021;5(11):1535-1547.

6. Vuorre M, Orben A, Przybylski AK. There is no evidence that associations between adolescents’ digital technology engagement and mental health problems have increased. Clin Psychol Sci. 2021;9(5):823-835.

Editor’s note: Readers’ Forum is a department for correspondence from readers that is not in response to articles published in

For almost all of us, “screen time”—time spent using a device with a screen such as a smartphone, computer, television, or video game console—has become a large part of our daily lives. This is very much the case for children and adolescents. In the United States, children ages 8 to 12 years spend an average of 4 to 6 hours each day watching or using screens, and teens spend up to 9 hours.1 Because young people are continually adopting newer forms of entertainment and technologies, new digital technologies are an ongoing source of concern for parents and clinicians alike.2 Studies have suggested that excessive screen time is associated with numerous psychiatric symptoms and disorders, including poor sleep, weight gain, anxiety, depression, and attention-deficit/hyperactive disorder.3,4 However, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis found that individuals’ self-reports of media use were rarely an accurate reflection of their actual, logged media use, and that measures of problematic media use had an even weaker association with usage logs.5 Therefore, it is crucial to have an accurate understanding of how children and adolescents are affected by new technologies. In this article, we discuss a recent study that investigated variations in adolescents’ mental health over time, and the association of their mental health and their use of digital technologies.

Results were mixed

Vuorre et al6 conducted a study to examine a possible shift in the associations between adolescents’ technology use and mental health outcomes. To investigate whether technology engagement and mental health outcomes changed over time, these researchers evaluated the impact not only of smartphones and social media, but also of television, which in the mid- to late-20th century elicited comparable levels of academic, public, and policy concern about its potential impact on child development. They analyzed data from 3 large-scale studies of adolescents living in the United States (Monitoring the Future and Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System) and the United Kingdom (Understanding Society) that included a total of 430,561 participants.