User login

IL-17 inhibitors associated with higher treatment persistence in PsA

Key clinical point: Interleukin-17 (IL-17) inhibitors were associated with higher treatment persistence than tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors or IL-12/23 inhibitors in patients with psoriatic arthritis (PsA) who initiated treatment with biologics.

Major finding: Treatment persistence was higher with IL-17 inhibitors than TNF inhibitors (weighted hazard ratio [HR] 0.70; P < .001) or IL-12/23 inhibitor (weighted HR 0.69; P < .001); however, IL-12/23 and TNF inhibitors showed similar persistence (P = .70).

Study details: This nationwide cohort study included 16,892 adults with psoriasis and 6531 adults with PsA who initiated first-line treatment with TNF, IL-12/23, or IL-17 inhibitors.

Disclosures: The study did not report any source of funding. P Claudepierre reported receiving consulting fees and serving as an investigator for several pharmaceutical companies.

Source: Vegas LP et al. Long-term persistence of first-line biologics for patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis in the french health insurance database. JAMA Dermatol. 2022 (Mar 23). Doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.0364

Key clinical point: Interleukin-17 (IL-17) inhibitors were associated with higher treatment persistence than tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors or IL-12/23 inhibitors in patients with psoriatic arthritis (PsA) who initiated treatment with biologics.

Major finding: Treatment persistence was higher with IL-17 inhibitors than TNF inhibitors (weighted hazard ratio [HR] 0.70; P < .001) or IL-12/23 inhibitor (weighted HR 0.69; P < .001); however, IL-12/23 and TNF inhibitors showed similar persistence (P = .70).

Study details: This nationwide cohort study included 16,892 adults with psoriasis and 6531 adults with PsA who initiated first-line treatment with TNF, IL-12/23, or IL-17 inhibitors.

Disclosures: The study did not report any source of funding. P Claudepierre reported receiving consulting fees and serving as an investigator for several pharmaceutical companies.

Source: Vegas LP et al. Long-term persistence of first-line biologics for patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis in the french health insurance database. JAMA Dermatol. 2022 (Mar 23). Doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.0364

Key clinical point: Interleukin-17 (IL-17) inhibitors were associated with higher treatment persistence than tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors or IL-12/23 inhibitors in patients with psoriatic arthritis (PsA) who initiated treatment with biologics.

Major finding: Treatment persistence was higher with IL-17 inhibitors than TNF inhibitors (weighted hazard ratio [HR] 0.70; P < .001) or IL-12/23 inhibitor (weighted HR 0.69; P < .001); however, IL-12/23 and TNF inhibitors showed similar persistence (P = .70).

Study details: This nationwide cohort study included 16,892 adults with psoriasis and 6531 adults with PsA who initiated first-line treatment with TNF, IL-12/23, or IL-17 inhibitors.

Disclosures: The study did not report any source of funding. P Claudepierre reported receiving consulting fees and serving as an investigator for several pharmaceutical companies.

Source: Vegas LP et al. Long-term persistence of first-line biologics for patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis in the french health insurance database. JAMA Dermatol. 2022 (Mar 23). Doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.0364

Clinical Edge Journal Scan Commentary: Type 2 DM May 2022

Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) is common in elderly adults with type 2 diabetes (T2D), and these individuals are at high risk for frailty and cognitive impairment. Empagliflozin has been shown to reduce cardiovascular death or hospitalization for heart failure in individuals with HFpEF with or without diabetes, but little is known about the impact of empagliflozin on cognition in patients with diabetes and HFpEF. In a prospective observation study of 162 frail older adults with T2D and HFpEF, Mone and colleagues reported that after receiving empagliflozin for 1 month, there was a significant improvement in the Montreal Cognitive Assessment score, but no improvement was seen with metformin or insulin. Although the study was limited by its observational design, small sample size, and short follow-up, it indicates that improved cognition may be another unexpected benefit of empagliflozin in patients with HFpEF.

The Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD) study continues to provide valuable information for the management of T2D. ACCORD Lipid had previously shown that fenofibrate vs. placebo added to simvastatin did not reduce major atherosclerotic cardiovascular events in about 5500 patients with T2D who were at high risk for cardiovascular disease. Ferreira and colleagues have now reported that fenofibrate in ACCORD Lipid reduced hospitalization for heart failure or cardiovascular death by 18%, with the benefit predominantly in those treated with standard glucose-lowering therapy. This analysis was done post hoc and is hypothesis-generating for fenofibrate reducing HF-related events. The soon to be completed PROMINENT study of pemafibrate includes a secondary composite cardiovascular outcome with hospitalization for heart failure as a component, so more information regarding the impact of fibrates on heart failure will be available soon.

Diabetes is associated with a threefold greater risk for stroke and microvascular disease. In another analysis of ACCORD, Kaze and colleagues reported that a higher urine albumin‐to‐creatinine ratio and a lower estimated glomerular filtration rate were each independently associated with an increased risk for stroke. Although further adequately powered studies are required, this analysis suggests that prevention of kidney disease and its progression may help mitigate the risk for stroke in people with T2D.

People with severe mental illness (SMI), such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or depression, are at increased risk for T2D, but it is unknown whether they are more likely to develop the complications of diabetes. Scheuer and colleagues published data from a large nationwide registry in Denmark. They found that, compared with people without SMI, people with SMI were more likely to develop nephropathy or cardiovascular disease, have an amputation, and that the nephropathy and cardiovascular disease occurred at younger ages in those with SMI. Although there are limitations with registry data, this study supports diabetes guidelines that recommend cardiorenal protection with sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors and glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists in patients with T2D who are at high risk for nephropathy progression and cardiovascular disease. Because this study suggests that SMI along with T2D confers greater risk for nephropathy and cardiovascular disease at younger ages, perhaps we should consider these cardiorenal protective agents early on in persons with T2D and SMI.

Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) is common in elderly adults with type 2 diabetes (T2D), and these individuals are at high risk for frailty and cognitive impairment. Empagliflozin has been shown to reduce cardiovascular death or hospitalization for heart failure in individuals with HFpEF with or without diabetes, but little is known about the impact of empagliflozin on cognition in patients with diabetes and HFpEF. In a prospective observation study of 162 frail older adults with T2D and HFpEF, Mone and colleagues reported that after receiving empagliflozin for 1 month, there was a significant improvement in the Montreal Cognitive Assessment score, but no improvement was seen with metformin or insulin. Although the study was limited by its observational design, small sample size, and short follow-up, it indicates that improved cognition may be another unexpected benefit of empagliflozin in patients with HFpEF.

The Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD) study continues to provide valuable information for the management of T2D. ACCORD Lipid had previously shown that fenofibrate vs. placebo added to simvastatin did not reduce major atherosclerotic cardiovascular events in about 5500 patients with T2D who were at high risk for cardiovascular disease. Ferreira and colleagues have now reported that fenofibrate in ACCORD Lipid reduced hospitalization for heart failure or cardiovascular death by 18%, with the benefit predominantly in those treated with standard glucose-lowering therapy. This analysis was done post hoc and is hypothesis-generating for fenofibrate reducing HF-related events. The soon to be completed PROMINENT study of pemafibrate includes a secondary composite cardiovascular outcome with hospitalization for heart failure as a component, so more information regarding the impact of fibrates on heart failure will be available soon.

Diabetes is associated with a threefold greater risk for stroke and microvascular disease. In another analysis of ACCORD, Kaze and colleagues reported that a higher urine albumin‐to‐creatinine ratio and a lower estimated glomerular filtration rate were each independently associated with an increased risk for stroke. Although further adequately powered studies are required, this analysis suggests that prevention of kidney disease and its progression may help mitigate the risk for stroke in people with T2D.

People with severe mental illness (SMI), such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or depression, are at increased risk for T2D, but it is unknown whether they are more likely to develop the complications of diabetes. Scheuer and colleagues published data from a large nationwide registry in Denmark. They found that, compared with people without SMI, people with SMI were more likely to develop nephropathy or cardiovascular disease, have an amputation, and that the nephropathy and cardiovascular disease occurred at younger ages in those with SMI. Although there are limitations with registry data, this study supports diabetes guidelines that recommend cardiorenal protection with sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors and glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists in patients with T2D who are at high risk for nephropathy progression and cardiovascular disease. Because this study suggests that SMI along with T2D confers greater risk for nephropathy and cardiovascular disease at younger ages, perhaps we should consider these cardiorenal protective agents early on in persons with T2D and SMI.

Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) is common in elderly adults with type 2 diabetes (T2D), and these individuals are at high risk for frailty and cognitive impairment. Empagliflozin has been shown to reduce cardiovascular death or hospitalization for heart failure in individuals with HFpEF with or without diabetes, but little is known about the impact of empagliflozin on cognition in patients with diabetes and HFpEF. In a prospective observation study of 162 frail older adults with T2D and HFpEF, Mone and colleagues reported that after receiving empagliflozin for 1 month, there was a significant improvement in the Montreal Cognitive Assessment score, but no improvement was seen with metformin or insulin. Although the study was limited by its observational design, small sample size, and short follow-up, it indicates that improved cognition may be another unexpected benefit of empagliflozin in patients with HFpEF.

The Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD) study continues to provide valuable information for the management of T2D. ACCORD Lipid had previously shown that fenofibrate vs. placebo added to simvastatin did not reduce major atherosclerotic cardiovascular events in about 5500 patients with T2D who were at high risk for cardiovascular disease. Ferreira and colleagues have now reported that fenofibrate in ACCORD Lipid reduced hospitalization for heart failure or cardiovascular death by 18%, with the benefit predominantly in those treated with standard glucose-lowering therapy. This analysis was done post hoc and is hypothesis-generating for fenofibrate reducing HF-related events. The soon to be completed PROMINENT study of pemafibrate includes a secondary composite cardiovascular outcome with hospitalization for heart failure as a component, so more information regarding the impact of fibrates on heart failure will be available soon.

Diabetes is associated with a threefold greater risk for stroke and microvascular disease. In another analysis of ACCORD, Kaze and colleagues reported that a higher urine albumin‐to‐creatinine ratio and a lower estimated glomerular filtration rate were each independently associated with an increased risk for stroke. Although further adequately powered studies are required, this analysis suggests that prevention of kidney disease and its progression may help mitigate the risk for stroke in people with T2D.

People with severe mental illness (SMI), such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or depression, are at increased risk for T2D, but it is unknown whether they are more likely to develop the complications of diabetes. Scheuer and colleagues published data from a large nationwide registry in Denmark. They found that, compared with people without SMI, people with SMI were more likely to develop nephropathy or cardiovascular disease, have an amputation, and that the nephropathy and cardiovascular disease occurred at younger ages in those with SMI. Although there are limitations with registry data, this study supports diabetes guidelines that recommend cardiorenal protection with sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors and glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists in patients with T2D who are at high risk for nephropathy progression and cardiovascular disease. Because this study suggests that SMI along with T2D confers greater risk for nephropathy and cardiovascular disease at younger ages, perhaps we should consider these cardiorenal protective agents early on in persons with T2D and SMI.

Management of gastroparesis in 2022

Introduction

Patients presenting with the symptoms of gastroparesis (Gp) are commonly seen in gastroenterology practice.

Presentation

Patients with foregut symptoms of Gp have characteristic presentations, with nausea, vomiting/retching, and abdominal pain often associated with bloating and distension, early satiety, anorexia, and heartburn. Mid- and hindgut gastrointestinal and/or urinary symptoms may be seen in patients with Gp as well.

The precise epidemiology of gastroparesis syndromes (GpS) is unknown. Classic gastroparesis, defined as delayed gastric emptying without known mechanical obstruction, has a prevalence of about 10 per 100,000 population in men and 30 per 100,000 in women with women being affected 3 to 4 times more than men.1,2 Some risk factors for GpS, such as diabetes mellitus (DM) in up to 5% of patients with Type 1 DM, are known.3 Caucasians have the highest prevalence of GpS, followed by African Americans.4,5

The classic definition of Gp has blurred with the realization that patients may have symptoms of Gp without delayed solid gastric emptying. Some patients have been described as having chronic unexplained nausea and vomiting or gastroparesis like syndrome.6 More recently the NIH Gastroparesis Consortium has proposed that disorders like functional dyspepsia may be a spectrum of the two disorders and classic Gp.7 Using this broadened definition, the number of patients with Gp symptoms is much greater, found in 10% or more of the U.S. population.8 For this discussion, GpS is used to encompass this spectrum of disorders.

The etiology of GpS is often unknown for a given patient, but clues to etiology exist in what is known about pathophysiology. Types of Gp are described as being idiopathic, diabetic, or postsurgical, each of which may have varying pathophysiology. Many patients with mild-to-moderate GpS symptoms are effectively treated with out-patient therapies; other patients may be refractory to available treatments. Refractory GpS patients have a high burden of illness affecting them, their families, providers, hospitals, and payers.

Pathophysiology

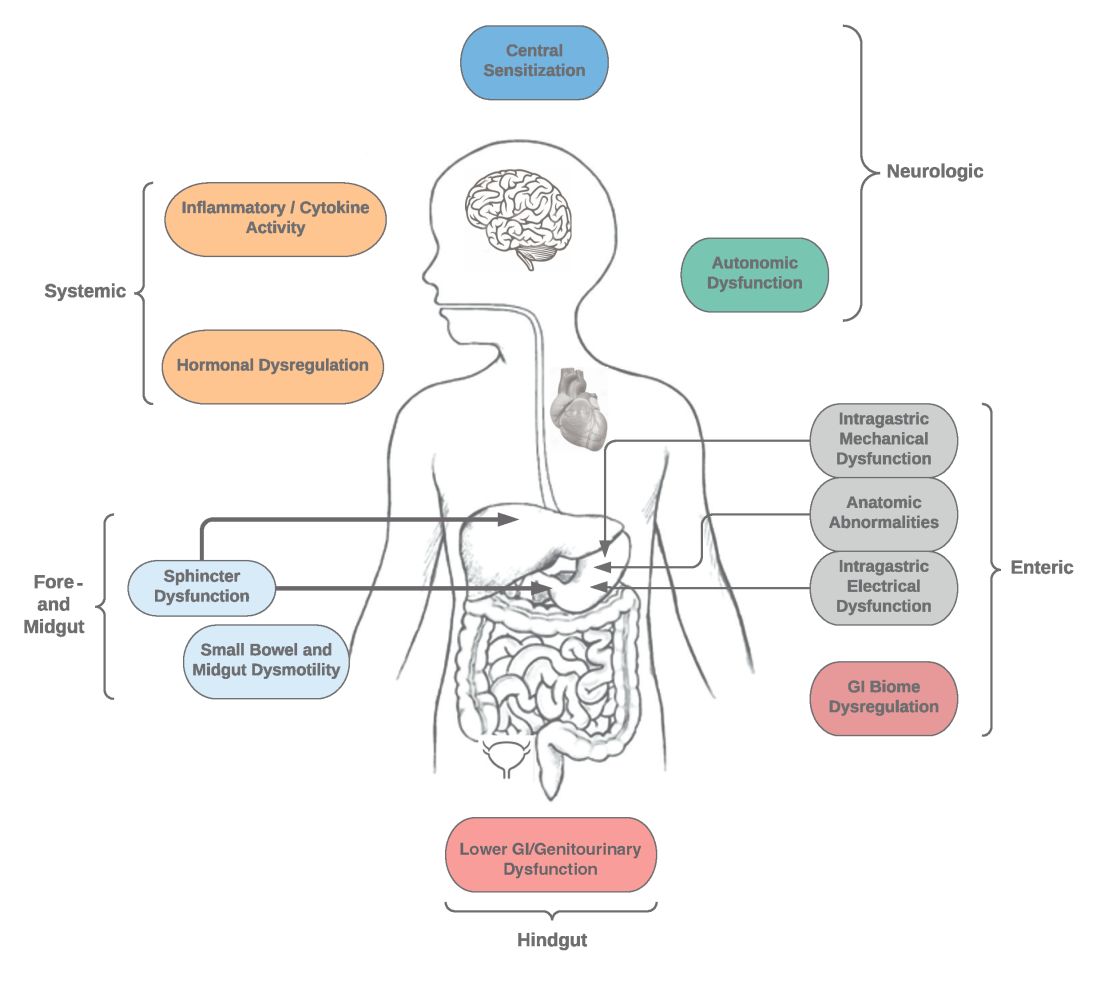

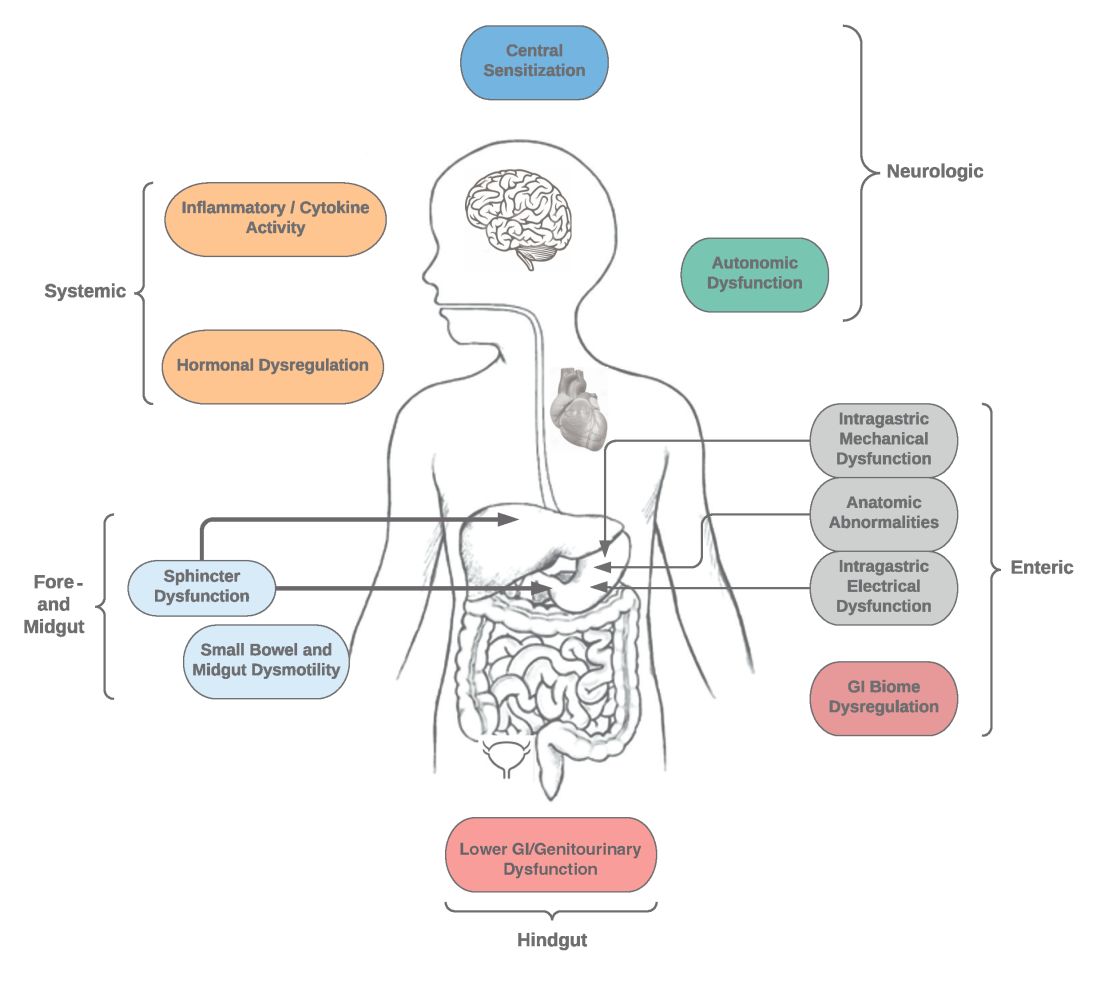

Specific types of gastroparesis syndromes have variable pathophysiology (Figure 1). In some cases, like GpS associated with DM, pathophysiology is partially related to diabetic autonomic dysfunction. GpS are multifactorial, however, and rather than focusing on subtypes, this discussion focuses on shared pathophysiology. Understanding pathophysiology is key to determining treatment options and potential future targets for therapy.

Intragastric mechanical dysfunction, both proximal (fundic relaxation and accommodation and/or lack of fundic contractility) and distal stomach (antral hypomotility) may be involved. Additionally, intragastric electrical disturbances in frequency, amplitude, and propagation of gastric electrical waves can be seen with low/high resolution gastric mapping.

Both gastroesophageal and gastropyloric sphincter dysfunction may be seen. Esophageal dysfunction is frequently seen but is not always categorized in GpS. Pyloric dysfunction is increasingly a focus of both diagnosis and therapy. GI anatomic abnormalities can be identified with gastric biopsies of full thickness muscle and mucosa. CD117/interstitial cells of Cajal, neural fibers, inflammatory and other cells can be evaluated by light microscopy, electron microscopy, and special staining techniques.

Small bowel, mid-, and hindgut dysmotility involvement has often been associated with pathologies of intragastric motility. Not only GI but genitourinary dysfunction may be associated with fore- and mid-gut dysfunction in GpS. Equally well described are abnormalities of the autonomic and sensory nervous system, which have recently been better quantified. Serologic measures, such as channelopathies and other antibody mediated abnormalities, have been recently noted.

Suspected for many years, immune dysregulation has now been documented in patients with GpS. Further investigation, including genetic dysregulation of immune measures, is ongoing. Other mechanisms include systemic and local inflammation, hormonal abnormalities, macro- and micronutrient deficiencies, dysregulation in GI microbiome, and physical frailty. The above factors may play a role in the pathophysiology of GpS, and it is likely that many of these are involved with a given patient presenting for care.9

Diagnosis of GpS

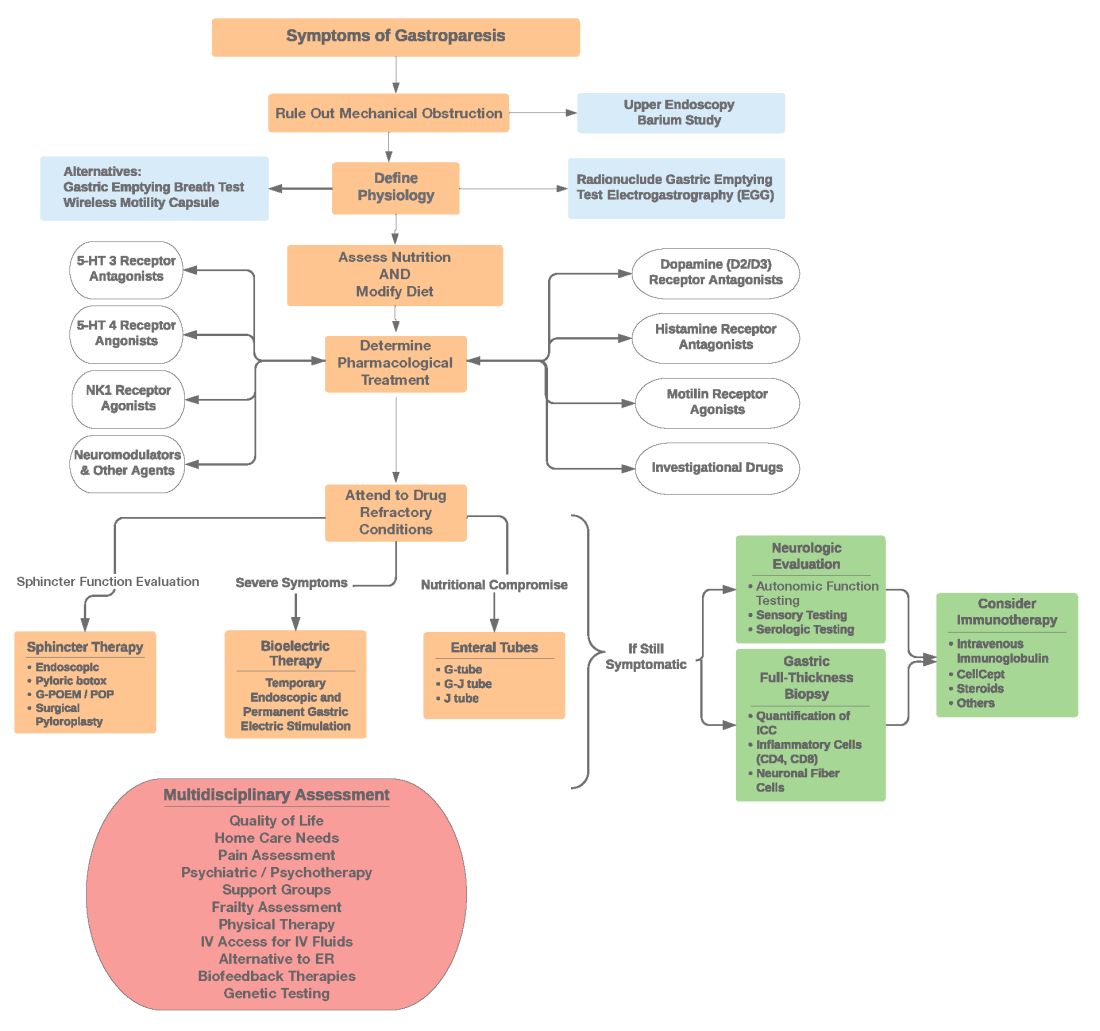

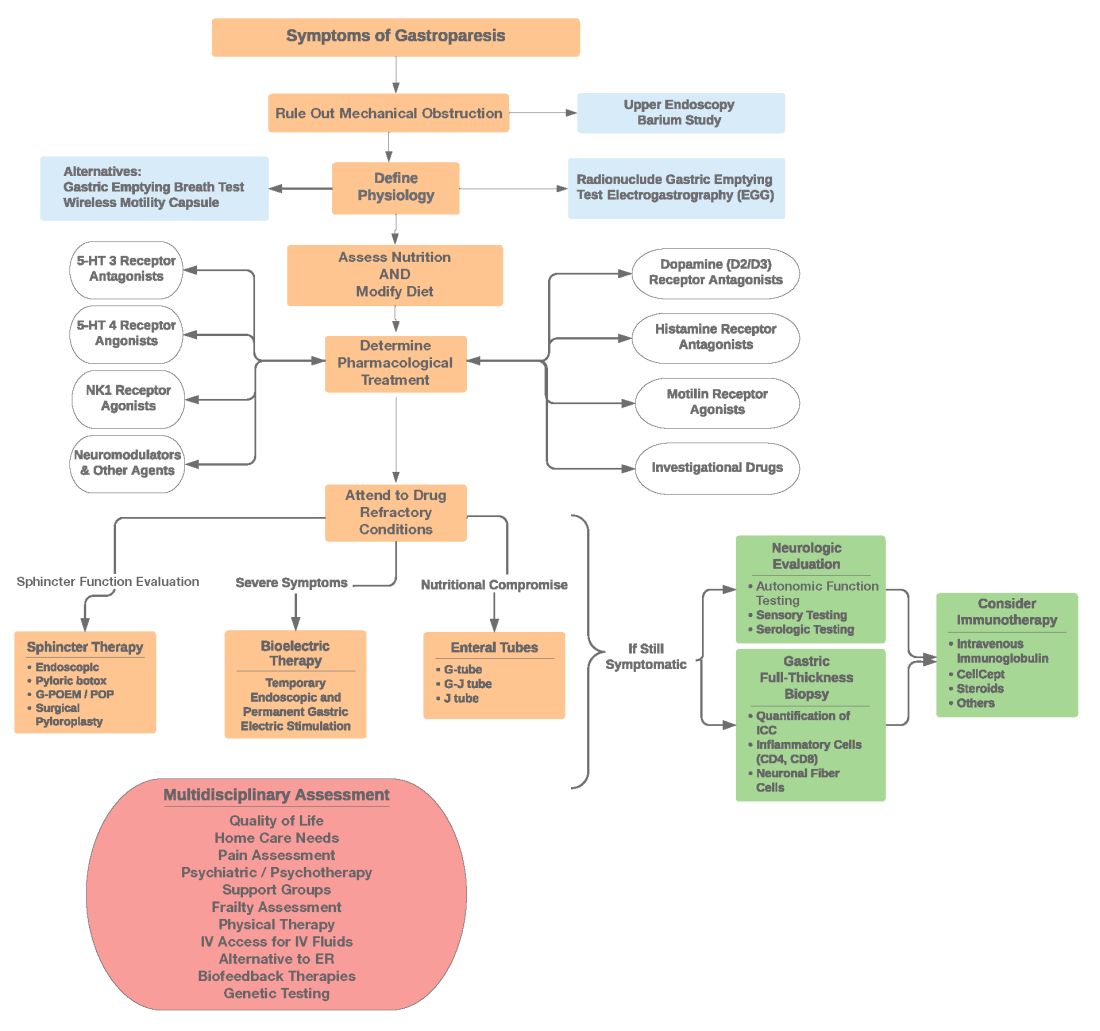

Diagnosis of GpS is often delayed and can be challenging; various tools have been developed, but not all are used. A diagnostic approach for patients with symptoms of Gp is listed below, and Figure 2 details a diagnostic approach and treatment options for symptomatic patients.

Symptom Assessment: Initially Gp symptoms can be assessed using Food and Drug Administration–approved patient-reported outcomes, including frequency and severity of nausea, vomiting, anorexia/early satiety, bloating/distention, and abdominal pain on a 0-4, 0-5 or 0-10 scale. The Gastrointestinal Cardinal Symptom Index or visual analog scales can also be used. It is also important to evaluate midgut and hindgut symptoms.9-11

Mechanical obstruction assessment: Mechanical obstruction can be ruled out using upper endoscopy or barium studies.

Physiologic testing: The most common is radionuclide gastric emptying testing (GET). Compliance with guidelines, standardization, and consistency of GETs is vital to help with an accurate diagnosis. Currently, two consensus recommendations for the standardized performance of GETs exist.12,13 Breath testing is FDA approved in the United States and can be used as an alternative. Wireless motility capsule testing can be complimentary.

Gastric dysrhythmias assessment: Assessment of gastric dysrhythmias can be performed in outpatient settings using cutaneous electrogastrogram, currently available in many referral centers. Most patients with GpS have an underlying gastric electrical abnormality.14,15

Sphincter dysfunction assessment: Both proximal and distal sphincter abnormalities have been described for many years and are of particular interest recently. Use of the functional luminal imaging probe (FLIP) shows patients with GpS may have decreased sphincter distensibility when examining the comparisons of the cross-sectional area relative to pressure Using this information, sphincter therapies can be offered.16-18

Other testing: Neurologic and autonomic testing, along with psychosocial, genetic and frailty assessments, are helpful to explore.19 Nutritional evaluation can be done using standardized scales, such as subjective global assessment and serologic testing for micronutrient deficiency or electrical impedance.20

Treatment of GpS

Therapies for GpS can be viewed as the five D’s: Diet, Drug, Disruption, Devices, and Details.

Diet and nutrition: The mainstay treatment of GpS remains dietary modification. The most common recommendation is to limit meal size, often with increased meal frequency, as well as nutrient composition, in areas that may retard gastric emptying. In addition, some patients with GpS report intolerances of specific foods, such as specific carbohydrates. Nutritional consultation can assist patients with meals tailored for their current nutritional needs. Nutritional supplementation is widely used for patients with GpS.20

Pharmacological treatment: The next tier of treatment for GpS is drugs. Review of a patient’s medications is important to minimize drugs that may retard gastric emptying such as opiates and GLP-1 agonists. A full discussion of medications is beyond the scope of this article, but classes of drugs available include: prokinetics, antiemetics, neuromodulators, and investigational agents.

There is only one approved prokinetic medication for gastroparesis – the dopamine blocker metoclopramide – and most providers are aware of metoclopramide’s limitations in terms of potential side effects, such as the risk of tardive dyskinesia and labeling on duration of therapy, with a maximum of 12 weeks recommended. Alternative prokinetics, such as domperidone, are not easily available in the United States; some mediations approved for other indications, such as the 5-HT drug prucalopride, are sometimes given for GpS off-label. Antiemetics such as promethazine and ondansetron are frequently used for symptomatic control in GpS. Despite lack of positive controlled trials in Gp, neuromodulator drugs, such as tricyclic or tetracyclic antidepressants like amitriptyline or mirtazapine are often used; their efficacy is more proven in the functional dyspepsia area. Other drugs such as the NK-1 drug aprepitant have been studied in Gp and are sometimes used off-label. Drugs such as scopolamine and related compounds can also provide symptomatic relief, as can the tetrahydrocannabinol-containing drug, dronabinol. New pharmacologic agents for GpS include investigational drugs such as ghrelin agonists and several novel compounds, none of which are currently FDA approved.21,22

Fortunately, the majority of patients with GpS respond to conservative therapies, such as dietary changes and/or medications. The last part of the section on treatment of GpS includes patients that are diet and drug refractory. Patients in this group are often referred to gastroenterologists and can be complex, time consuming, and frustrating to provide care for. Many of these patients are eventually seen in referral centers, and some travel great distances and have considerable medical expenses.

Pylorus-directed therapies: The recent renewed interest in pyloric dysfunction in patients with Gp symptoms has led to a great deal of clinical activity. Gastropyloric dysfunction in Gp has been documented for decades, originally in diabetic patients with autonomic and enteric neuropathy. The use of botulinum toxin in upper- and lower-gastric sphincters has led to continuing use of this therapy for patients with GpS. Despite initial negative controlled trials of botulinum toxin in the pyloric sphincter, newer studies indicate that physiologic measures, such as the FLIP, may help with patient selection. Other disruptive pyloric therapies, including pyloromyotomy, per oral pyloromyotomy, and gastric peroral endoscopic myotomy, are supported by open-label use, despite a lack of published positive controlled trials.17

Bioelectric therapy: Another approach for patients with symptomatic drug refractory GpS is bioelectric device therapies, which can be delivered several ways, including directly to the stomach or to the spinal cord or the vagus nerve in the neck or ear, as well as by electro-acupuncture. High-frequency, low-energy gastric electrical stimulation (GES) is the best studied. First done in 1992 as an experimental therapy, GES was investigational from 1995 to 2000, when it became FDA approved as a humanitarian-use device. GES has been used in over 10,000 patients worldwide; only a small number (greater than 700 study patients) have been in controlled trials. Nine controlled trials of GES have been primarily positive, and durability for over 10 years has been shown. Temporary GES can also be performed endoscopically, although that is an off-label procedure. It has been shown to predict long-term therapy outcome.23-26

Nutritional support: Nutritional abnormalities in some cases of GpS lead to consideration of enteral tubes, starting with a trial of feeding with an N-J tube placed endoscopically. An N-J trial is most often performed in patients who have macro-malnutrition and weight loss but can be considered for other highly symptomatic patients. Other endoscopic tubes can be PEG or PEG-J or direct PEJ tubes. Some patients may require surgical placement of enteral tubes, presenting an opportunity for a small bowel or gastric full-thickness biopsy. Enteral tubes are sometimes used for decompression in highly symptomatic patients.27

For patients presenting with neurological symptoms, findings and serologic abnormalities have led to interest in immunotherapies. One is intravenous immunoglobulin, given parenterally. Several open-label studies have been published, the most recent one with 47 patients showing better response if glutamic acid decarboxylase–65 antibodies were present and with longer therapeutic dosing.28 Drawbacks to immunotherapies like intravenous immunoglobulin are cost and requiring parenteral access.

Other evaluation/treatments for drug refractory patients can be detailed as follows: First, an overall quality of life assessment can be helpful, especially one that includes impact of GpS on the patients and family. Nutritional considerations, which may not have been fully assessed, can be examined in more detail. Frailty assessments may show the need for physical therapy. Assessment for home care needs may indicate, in severe patients, needs for IV fluids at home, either enteral or parenteral, if nutrition is not adequate. Psychosocial and/or psychiatric assessments may lead to the need for medications, psychotherapy, and/or support groups. Lastly, an assessment of overall health status may lead to approaches for minimizing visits to emergency rooms and hospitalizations.29,30

Conclusion

Patients with Gp symptoms are becoming increasingly recognized and referred to gastroenterologists. Better understandings of the pathophysiology of the spectrum of gastroparesis syndromes, assisted by innovations in diagnosis, have led to expansion of existing and new therapeutic approaches. Fortunately, most patients can benefit from a standardized diagnostic approach and directed noninvasive therapies. Patients with refractory gastroparesis symptoms, often with complex issues referred to gastroenterologists, remain a challenge, and novel approaches may improve their quality of life.

Dr. Mathur is a GI motility research fellow at the University of Louisville, Ky. He reports no conflicts of interest. Dr. Abell is the Arthur M. Schoen, MD, Chair in Gastroenterology at the University of Louisville. His main funding is NIH GpCRC and NIH Definitive Evaluation of Gastric Dysrhythmia. He is an investigator for Cindome, Vanda, Allergan, and Neurogastrx; a consultant for Censa, Nuvaira, and Takeda; a speaker for Takeda and Medtronic; and a reviewer for UpToDate. He is also the founder of ADEPT-GI, which holds IP related to mucosal stimulation and autonomic and enteric profiling.

References

1. Jung HK et al. Gastroenterology. 2009;136(4):1225-33.

2. Ye Y et al. Gut. 2021;70(4):644-53.

3. Oshima T et al. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021;27(1):46-54.

4. Soykan I et al. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43(11):2398-404.

5. Syed AR et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2020;54(1):50-4.

6.Pasricha PJ et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9(7):567-76.e1-4.

7. Pasricha PJ et al. Gastroenterology. 2021;160(6):2006-17.

8. Almario CV et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(11):1701-10.

9. Abell TL et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2021 Apr;66(4):1127-41.

10. Abell TL et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2019;31(3):e13534.

11. Elmasry M et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021 Oct 26;e14274.

12. Maurer AH et al. J Nucl Med. 2020;61(3):11N-7N.

13. Abell TL et al. J Nucl Med Technol. 2008 Mar;36(1):44-54.

14. Shine A et al. Neuromodulation. 2022 Feb 16;S1094-7159(21)06986-5.

15. O’Grady G et al. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2021;321(5):G527-g42.

16. Saadi M et al. Rev Gastroenterol Mex (Engl Ed). Oct-Dec 2018;83(4):375-84.

17. Kamal F et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2022;55(2):168-77.

18. Harberson J et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55(2):359-70.

19. Winston J. Gastrointestinal Disorders. 2021;3(2):78-83.

20. Parkman HP et al. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(2):486-98, 98.e1-7.

21. Heckroth M et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2021;55(4):279-99.

22. Camilleri M. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(1):19-24.

23. Payne SC et al. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16(2):89-105.

24. Ducrotte P et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(3):506-14.e2.

25. Burlen J et al. Gastroenterology Res. 2018;11(5):349-54.

26. Hedjoudje A et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020;32(11):e13949.

27. Petrov RV et al. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2020;49(3):539-56.

28. Gala K et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2021 Dec 31. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001655.

29. Abell TL et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2006;18(4):263-83.

30. Camilleri M et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(1):18-37.

Introduction

Patients presenting with the symptoms of gastroparesis (Gp) are commonly seen in gastroenterology practice.

Presentation

Patients with foregut symptoms of Gp have characteristic presentations, with nausea, vomiting/retching, and abdominal pain often associated with bloating and distension, early satiety, anorexia, and heartburn. Mid- and hindgut gastrointestinal and/or urinary symptoms may be seen in patients with Gp as well.

The precise epidemiology of gastroparesis syndromes (GpS) is unknown. Classic gastroparesis, defined as delayed gastric emptying without known mechanical obstruction, has a prevalence of about 10 per 100,000 population in men and 30 per 100,000 in women with women being affected 3 to 4 times more than men.1,2 Some risk factors for GpS, such as diabetes mellitus (DM) in up to 5% of patients with Type 1 DM, are known.3 Caucasians have the highest prevalence of GpS, followed by African Americans.4,5

The classic definition of Gp has blurred with the realization that patients may have symptoms of Gp without delayed solid gastric emptying. Some patients have been described as having chronic unexplained nausea and vomiting or gastroparesis like syndrome.6 More recently the NIH Gastroparesis Consortium has proposed that disorders like functional dyspepsia may be a spectrum of the two disorders and classic Gp.7 Using this broadened definition, the number of patients with Gp symptoms is much greater, found in 10% or more of the U.S. population.8 For this discussion, GpS is used to encompass this spectrum of disorders.

The etiology of GpS is often unknown for a given patient, but clues to etiology exist in what is known about pathophysiology. Types of Gp are described as being idiopathic, diabetic, or postsurgical, each of which may have varying pathophysiology. Many patients with mild-to-moderate GpS symptoms are effectively treated with out-patient therapies; other patients may be refractory to available treatments. Refractory GpS patients have a high burden of illness affecting them, their families, providers, hospitals, and payers.

Pathophysiology

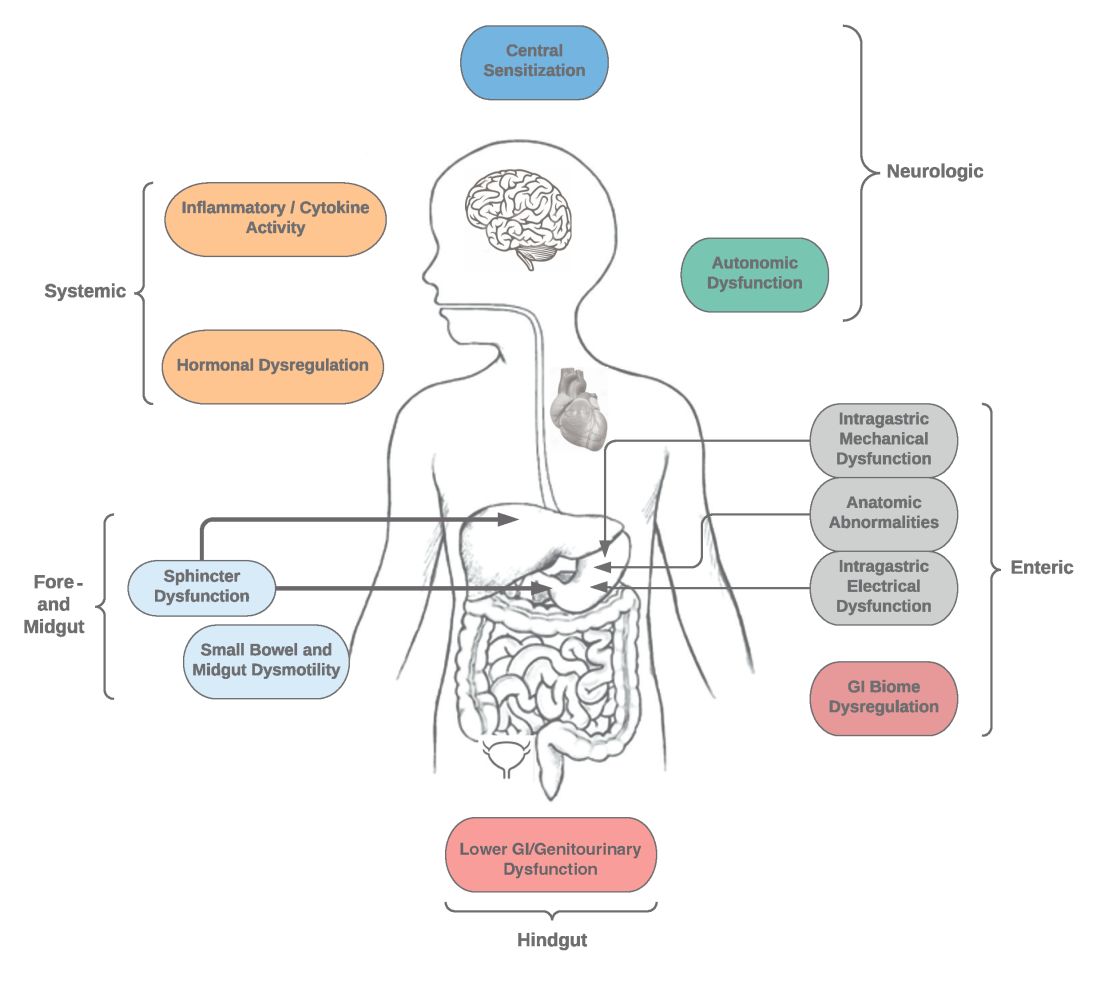

Specific types of gastroparesis syndromes have variable pathophysiology (Figure 1). In some cases, like GpS associated with DM, pathophysiology is partially related to diabetic autonomic dysfunction. GpS are multifactorial, however, and rather than focusing on subtypes, this discussion focuses on shared pathophysiology. Understanding pathophysiology is key to determining treatment options and potential future targets for therapy.

Intragastric mechanical dysfunction, both proximal (fundic relaxation and accommodation and/or lack of fundic contractility) and distal stomach (antral hypomotility) may be involved. Additionally, intragastric electrical disturbances in frequency, amplitude, and propagation of gastric electrical waves can be seen with low/high resolution gastric mapping.

Both gastroesophageal and gastropyloric sphincter dysfunction may be seen. Esophageal dysfunction is frequently seen but is not always categorized in GpS. Pyloric dysfunction is increasingly a focus of both diagnosis and therapy. GI anatomic abnormalities can be identified with gastric biopsies of full thickness muscle and mucosa. CD117/interstitial cells of Cajal, neural fibers, inflammatory and other cells can be evaluated by light microscopy, electron microscopy, and special staining techniques.

Small bowel, mid-, and hindgut dysmotility involvement has often been associated with pathologies of intragastric motility. Not only GI but genitourinary dysfunction may be associated with fore- and mid-gut dysfunction in GpS. Equally well described are abnormalities of the autonomic and sensory nervous system, which have recently been better quantified. Serologic measures, such as channelopathies and other antibody mediated abnormalities, have been recently noted.

Suspected for many years, immune dysregulation has now been documented in patients with GpS. Further investigation, including genetic dysregulation of immune measures, is ongoing. Other mechanisms include systemic and local inflammation, hormonal abnormalities, macro- and micronutrient deficiencies, dysregulation in GI microbiome, and physical frailty. The above factors may play a role in the pathophysiology of GpS, and it is likely that many of these are involved with a given patient presenting for care.9

Diagnosis of GpS

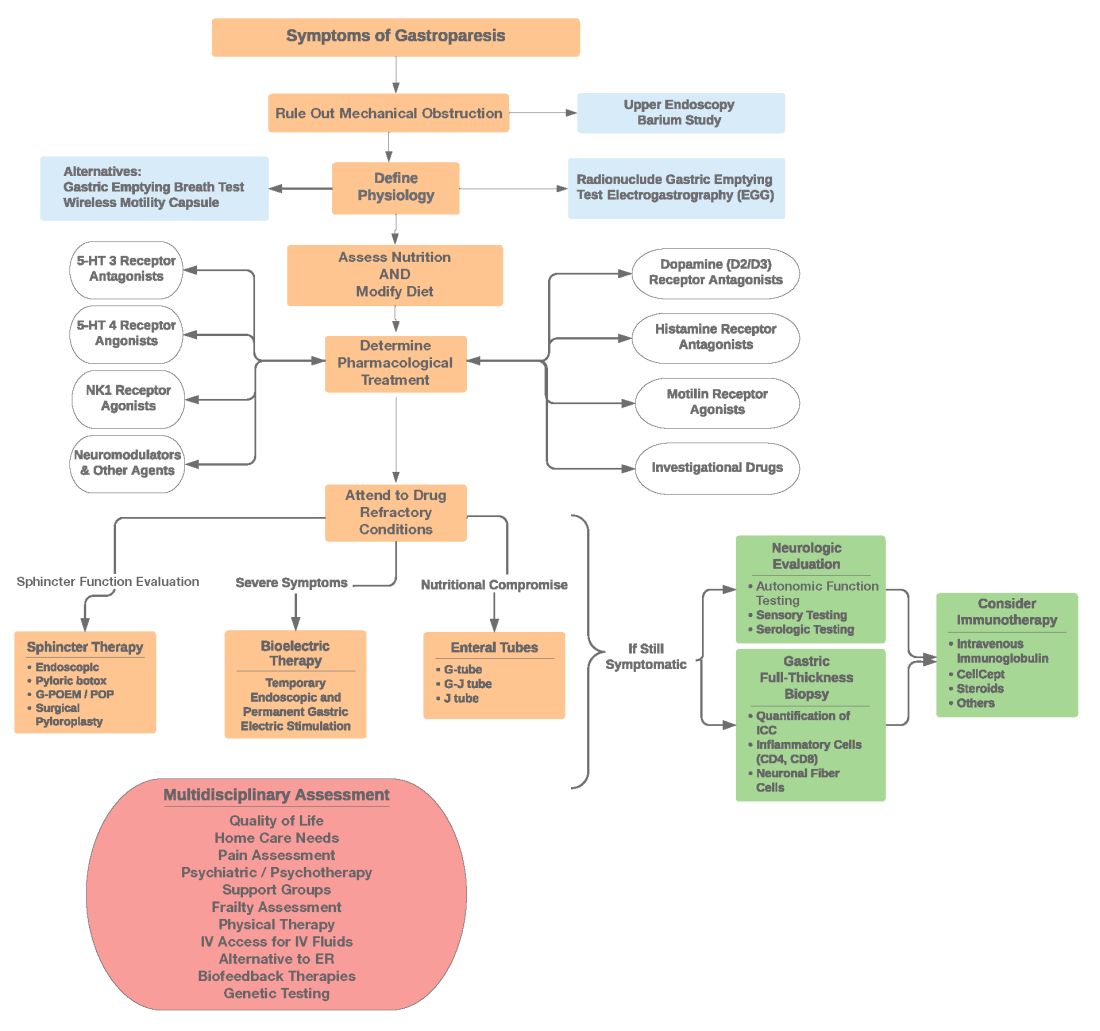

Diagnosis of GpS is often delayed and can be challenging; various tools have been developed, but not all are used. A diagnostic approach for patients with symptoms of Gp is listed below, and Figure 2 details a diagnostic approach and treatment options for symptomatic patients.

Symptom Assessment: Initially Gp symptoms can be assessed using Food and Drug Administration–approved patient-reported outcomes, including frequency and severity of nausea, vomiting, anorexia/early satiety, bloating/distention, and abdominal pain on a 0-4, 0-5 or 0-10 scale. The Gastrointestinal Cardinal Symptom Index or visual analog scales can also be used. It is also important to evaluate midgut and hindgut symptoms.9-11

Mechanical obstruction assessment: Mechanical obstruction can be ruled out using upper endoscopy or barium studies.

Physiologic testing: The most common is radionuclide gastric emptying testing (GET). Compliance with guidelines, standardization, and consistency of GETs is vital to help with an accurate diagnosis. Currently, two consensus recommendations for the standardized performance of GETs exist.12,13 Breath testing is FDA approved in the United States and can be used as an alternative. Wireless motility capsule testing can be complimentary.

Gastric dysrhythmias assessment: Assessment of gastric dysrhythmias can be performed in outpatient settings using cutaneous electrogastrogram, currently available in many referral centers. Most patients with GpS have an underlying gastric electrical abnormality.14,15

Sphincter dysfunction assessment: Both proximal and distal sphincter abnormalities have been described for many years and are of particular interest recently. Use of the functional luminal imaging probe (FLIP) shows patients with GpS may have decreased sphincter distensibility when examining the comparisons of the cross-sectional area relative to pressure Using this information, sphincter therapies can be offered.16-18

Other testing: Neurologic and autonomic testing, along with psychosocial, genetic and frailty assessments, are helpful to explore.19 Nutritional evaluation can be done using standardized scales, such as subjective global assessment and serologic testing for micronutrient deficiency or electrical impedance.20

Treatment of GpS

Therapies for GpS can be viewed as the five D’s: Diet, Drug, Disruption, Devices, and Details.

Diet and nutrition: The mainstay treatment of GpS remains dietary modification. The most common recommendation is to limit meal size, often with increased meal frequency, as well as nutrient composition, in areas that may retard gastric emptying. In addition, some patients with GpS report intolerances of specific foods, such as specific carbohydrates. Nutritional consultation can assist patients with meals tailored for their current nutritional needs. Nutritional supplementation is widely used for patients with GpS.20

Pharmacological treatment: The next tier of treatment for GpS is drugs. Review of a patient’s medications is important to minimize drugs that may retard gastric emptying such as opiates and GLP-1 agonists. A full discussion of medications is beyond the scope of this article, but classes of drugs available include: prokinetics, antiemetics, neuromodulators, and investigational agents.

There is only one approved prokinetic medication for gastroparesis – the dopamine blocker metoclopramide – and most providers are aware of metoclopramide’s limitations in terms of potential side effects, such as the risk of tardive dyskinesia and labeling on duration of therapy, with a maximum of 12 weeks recommended. Alternative prokinetics, such as domperidone, are not easily available in the United States; some mediations approved for other indications, such as the 5-HT drug prucalopride, are sometimes given for GpS off-label. Antiemetics such as promethazine and ondansetron are frequently used for symptomatic control in GpS. Despite lack of positive controlled trials in Gp, neuromodulator drugs, such as tricyclic or tetracyclic antidepressants like amitriptyline or mirtazapine are often used; their efficacy is more proven in the functional dyspepsia area. Other drugs such as the NK-1 drug aprepitant have been studied in Gp and are sometimes used off-label. Drugs such as scopolamine and related compounds can also provide symptomatic relief, as can the tetrahydrocannabinol-containing drug, dronabinol. New pharmacologic agents for GpS include investigational drugs such as ghrelin agonists and several novel compounds, none of which are currently FDA approved.21,22

Fortunately, the majority of patients with GpS respond to conservative therapies, such as dietary changes and/or medications. The last part of the section on treatment of GpS includes patients that are diet and drug refractory. Patients in this group are often referred to gastroenterologists and can be complex, time consuming, and frustrating to provide care for. Many of these patients are eventually seen in referral centers, and some travel great distances and have considerable medical expenses.

Pylorus-directed therapies: The recent renewed interest in pyloric dysfunction in patients with Gp symptoms has led to a great deal of clinical activity. Gastropyloric dysfunction in Gp has been documented for decades, originally in diabetic patients with autonomic and enteric neuropathy. The use of botulinum toxin in upper- and lower-gastric sphincters has led to continuing use of this therapy for patients with GpS. Despite initial negative controlled trials of botulinum toxin in the pyloric sphincter, newer studies indicate that physiologic measures, such as the FLIP, may help with patient selection. Other disruptive pyloric therapies, including pyloromyotomy, per oral pyloromyotomy, and gastric peroral endoscopic myotomy, are supported by open-label use, despite a lack of published positive controlled trials.17

Bioelectric therapy: Another approach for patients with symptomatic drug refractory GpS is bioelectric device therapies, which can be delivered several ways, including directly to the stomach or to the spinal cord or the vagus nerve in the neck or ear, as well as by electro-acupuncture. High-frequency, low-energy gastric electrical stimulation (GES) is the best studied. First done in 1992 as an experimental therapy, GES was investigational from 1995 to 2000, when it became FDA approved as a humanitarian-use device. GES has been used in over 10,000 patients worldwide; only a small number (greater than 700 study patients) have been in controlled trials. Nine controlled trials of GES have been primarily positive, and durability for over 10 years has been shown. Temporary GES can also be performed endoscopically, although that is an off-label procedure. It has been shown to predict long-term therapy outcome.23-26

Nutritional support: Nutritional abnormalities in some cases of GpS lead to consideration of enteral tubes, starting with a trial of feeding with an N-J tube placed endoscopically. An N-J trial is most often performed in patients who have macro-malnutrition and weight loss but can be considered for other highly symptomatic patients. Other endoscopic tubes can be PEG or PEG-J or direct PEJ tubes. Some patients may require surgical placement of enteral tubes, presenting an opportunity for a small bowel or gastric full-thickness biopsy. Enteral tubes are sometimes used for decompression in highly symptomatic patients.27

For patients presenting with neurological symptoms, findings and serologic abnormalities have led to interest in immunotherapies. One is intravenous immunoglobulin, given parenterally. Several open-label studies have been published, the most recent one with 47 patients showing better response if glutamic acid decarboxylase–65 antibodies were present and with longer therapeutic dosing.28 Drawbacks to immunotherapies like intravenous immunoglobulin are cost and requiring parenteral access.

Other evaluation/treatments for drug refractory patients can be detailed as follows: First, an overall quality of life assessment can be helpful, especially one that includes impact of GpS on the patients and family. Nutritional considerations, which may not have been fully assessed, can be examined in more detail. Frailty assessments may show the need for physical therapy. Assessment for home care needs may indicate, in severe patients, needs for IV fluids at home, either enteral or parenteral, if nutrition is not adequate. Psychosocial and/or psychiatric assessments may lead to the need for medications, psychotherapy, and/or support groups. Lastly, an assessment of overall health status may lead to approaches for minimizing visits to emergency rooms and hospitalizations.29,30

Conclusion

Patients with Gp symptoms are becoming increasingly recognized and referred to gastroenterologists. Better understandings of the pathophysiology of the spectrum of gastroparesis syndromes, assisted by innovations in diagnosis, have led to expansion of existing and new therapeutic approaches. Fortunately, most patients can benefit from a standardized diagnostic approach and directed noninvasive therapies. Patients with refractory gastroparesis symptoms, often with complex issues referred to gastroenterologists, remain a challenge, and novel approaches may improve their quality of life.

Dr. Mathur is a GI motility research fellow at the University of Louisville, Ky. He reports no conflicts of interest. Dr. Abell is the Arthur M. Schoen, MD, Chair in Gastroenterology at the University of Louisville. His main funding is NIH GpCRC and NIH Definitive Evaluation of Gastric Dysrhythmia. He is an investigator for Cindome, Vanda, Allergan, and Neurogastrx; a consultant for Censa, Nuvaira, and Takeda; a speaker for Takeda and Medtronic; and a reviewer for UpToDate. He is also the founder of ADEPT-GI, which holds IP related to mucosal stimulation and autonomic and enteric profiling.

References

1. Jung HK et al. Gastroenterology. 2009;136(4):1225-33.

2. Ye Y et al. Gut. 2021;70(4):644-53.

3. Oshima T et al. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021;27(1):46-54.

4. Soykan I et al. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43(11):2398-404.

5. Syed AR et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2020;54(1):50-4.

6.Pasricha PJ et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9(7):567-76.e1-4.

7. Pasricha PJ et al. Gastroenterology. 2021;160(6):2006-17.

8. Almario CV et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(11):1701-10.

9. Abell TL et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2021 Apr;66(4):1127-41.

10. Abell TL et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2019;31(3):e13534.

11. Elmasry M et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021 Oct 26;e14274.

12. Maurer AH et al. J Nucl Med. 2020;61(3):11N-7N.

13. Abell TL et al. J Nucl Med Technol. 2008 Mar;36(1):44-54.

14. Shine A et al. Neuromodulation. 2022 Feb 16;S1094-7159(21)06986-5.

15. O’Grady G et al. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2021;321(5):G527-g42.

16. Saadi M et al. Rev Gastroenterol Mex (Engl Ed). Oct-Dec 2018;83(4):375-84.

17. Kamal F et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2022;55(2):168-77.

18. Harberson J et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55(2):359-70.

19. Winston J. Gastrointestinal Disorders. 2021;3(2):78-83.

20. Parkman HP et al. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(2):486-98, 98.e1-7.

21. Heckroth M et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2021;55(4):279-99.

22. Camilleri M. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(1):19-24.

23. Payne SC et al. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16(2):89-105.

24. Ducrotte P et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(3):506-14.e2.

25. Burlen J et al. Gastroenterology Res. 2018;11(5):349-54.

26. Hedjoudje A et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020;32(11):e13949.

27. Petrov RV et al. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2020;49(3):539-56.

28. Gala K et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2021 Dec 31. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001655.

29. Abell TL et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2006;18(4):263-83.

30. Camilleri M et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(1):18-37.

Introduction

Patients presenting with the symptoms of gastroparesis (Gp) are commonly seen in gastroenterology practice.

Presentation

Patients with foregut symptoms of Gp have characteristic presentations, with nausea, vomiting/retching, and abdominal pain often associated with bloating and distension, early satiety, anorexia, and heartburn. Mid- and hindgut gastrointestinal and/or urinary symptoms may be seen in patients with Gp as well.

The precise epidemiology of gastroparesis syndromes (GpS) is unknown. Classic gastroparesis, defined as delayed gastric emptying without known mechanical obstruction, has a prevalence of about 10 per 100,000 population in men and 30 per 100,000 in women with women being affected 3 to 4 times more than men.1,2 Some risk factors for GpS, such as diabetes mellitus (DM) in up to 5% of patients with Type 1 DM, are known.3 Caucasians have the highest prevalence of GpS, followed by African Americans.4,5

The classic definition of Gp has blurred with the realization that patients may have symptoms of Gp without delayed solid gastric emptying. Some patients have been described as having chronic unexplained nausea and vomiting or gastroparesis like syndrome.6 More recently the NIH Gastroparesis Consortium has proposed that disorders like functional dyspepsia may be a spectrum of the two disorders and classic Gp.7 Using this broadened definition, the number of patients with Gp symptoms is much greater, found in 10% or more of the U.S. population.8 For this discussion, GpS is used to encompass this spectrum of disorders.

The etiology of GpS is often unknown for a given patient, but clues to etiology exist in what is known about pathophysiology. Types of Gp are described as being idiopathic, diabetic, or postsurgical, each of which may have varying pathophysiology. Many patients with mild-to-moderate GpS symptoms are effectively treated with out-patient therapies; other patients may be refractory to available treatments. Refractory GpS patients have a high burden of illness affecting them, their families, providers, hospitals, and payers.

Pathophysiology

Specific types of gastroparesis syndromes have variable pathophysiology (Figure 1). In some cases, like GpS associated with DM, pathophysiology is partially related to diabetic autonomic dysfunction. GpS are multifactorial, however, and rather than focusing on subtypes, this discussion focuses on shared pathophysiology. Understanding pathophysiology is key to determining treatment options and potential future targets for therapy.

Intragastric mechanical dysfunction, both proximal (fundic relaxation and accommodation and/or lack of fundic contractility) and distal stomach (antral hypomotility) may be involved. Additionally, intragastric electrical disturbances in frequency, amplitude, and propagation of gastric electrical waves can be seen with low/high resolution gastric mapping.

Both gastroesophageal and gastropyloric sphincter dysfunction may be seen. Esophageal dysfunction is frequently seen but is not always categorized in GpS. Pyloric dysfunction is increasingly a focus of both diagnosis and therapy. GI anatomic abnormalities can be identified with gastric biopsies of full thickness muscle and mucosa. CD117/interstitial cells of Cajal, neural fibers, inflammatory and other cells can be evaluated by light microscopy, electron microscopy, and special staining techniques.

Small bowel, mid-, and hindgut dysmotility involvement has often been associated with pathologies of intragastric motility. Not only GI but genitourinary dysfunction may be associated with fore- and mid-gut dysfunction in GpS. Equally well described are abnormalities of the autonomic and sensory nervous system, which have recently been better quantified. Serologic measures, such as channelopathies and other antibody mediated abnormalities, have been recently noted.

Suspected for many years, immune dysregulation has now been documented in patients with GpS. Further investigation, including genetic dysregulation of immune measures, is ongoing. Other mechanisms include systemic and local inflammation, hormonal abnormalities, macro- and micronutrient deficiencies, dysregulation in GI microbiome, and physical frailty. The above factors may play a role in the pathophysiology of GpS, and it is likely that many of these are involved with a given patient presenting for care.9

Diagnosis of GpS

Diagnosis of GpS is often delayed and can be challenging; various tools have been developed, but not all are used. A diagnostic approach for patients with symptoms of Gp is listed below, and Figure 2 details a diagnostic approach and treatment options for symptomatic patients.

Symptom Assessment: Initially Gp symptoms can be assessed using Food and Drug Administration–approved patient-reported outcomes, including frequency and severity of nausea, vomiting, anorexia/early satiety, bloating/distention, and abdominal pain on a 0-4, 0-5 or 0-10 scale. The Gastrointestinal Cardinal Symptom Index or visual analog scales can also be used. It is also important to evaluate midgut and hindgut symptoms.9-11

Mechanical obstruction assessment: Mechanical obstruction can be ruled out using upper endoscopy or barium studies.

Physiologic testing: The most common is radionuclide gastric emptying testing (GET). Compliance with guidelines, standardization, and consistency of GETs is vital to help with an accurate diagnosis. Currently, two consensus recommendations for the standardized performance of GETs exist.12,13 Breath testing is FDA approved in the United States and can be used as an alternative. Wireless motility capsule testing can be complimentary.

Gastric dysrhythmias assessment: Assessment of gastric dysrhythmias can be performed in outpatient settings using cutaneous electrogastrogram, currently available in many referral centers. Most patients with GpS have an underlying gastric electrical abnormality.14,15

Sphincter dysfunction assessment: Both proximal and distal sphincter abnormalities have been described for many years and are of particular interest recently. Use of the functional luminal imaging probe (FLIP) shows patients with GpS may have decreased sphincter distensibility when examining the comparisons of the cross-sectional area relative to pressure Using this information, sphincter therapies can be offered.16-18

Other testing: Neurologic and autonomic testing, along with psychosocial, genetic and frailty assessments, are helpful to explore.19 Nutritional evaluation can be done using standardized scales, such as subjective global assessment and serologic testing for micronutrient deficiency or electrical impedance.20

Treatment of GpS

Therapies for GpS can be viewed as the five D’s: Diet, Drug, Disruption, Devices, and Details.

Diet and nutrition: The mainstay treatment of GpS remains dietary modification. The most common recommendation is to limit meal size, often with increased meal frequency, as well as nutrient composition, in areas that may retard gastric emptying. In addition, some patients with GpS report intolerances of specific foods, such as specific carbohydrates. Nutritional consultation can assist patients with meals tailored for their current nutritional needs. Nutritional supplementation is widely used for patients with GpS.20

Pharmacological treatment: The next tier of treatment for GpS is drugs. Review of a patient’s medications is important to minimize drugs that may retard gastric emptying such as opiates and GLP-1 agonists. A full discussion of medications is beyond the scope of this article, but classes of drugs available include: prokinetics, antiemetics, neuromodulators, and investigational agents.

There is only one approved prokinetic medication for gastroparesis – the dopamine blocker metoclopramide – and most providers are aware of metoclopramide’s limitations in terms of potential side effects, such as the risk of tardive dyskinesia and labeling on duration of therapy, with a maximum of 12 weeks recommended. Alternative prokinetics, such as domperidone, are not easily available in the United States; some mediations approved for other indications, such as the 5-HT drug prucalopride, are sometimes given for GpS off-label. Antiemetics such as promethazine and ondansetron are frequently used for symptomatic control in GpS. Despite lack of positive controlled trials in Gp, neuromodulator drugs, such as tricyclic or tetracyclic antidepressants like amitriptyline or mirtazapine are often used; their efficacy is more proven in the functional dyspepsia area. Other drugs such as the NK-1 drug aprepitant have been studied in Gp and are sometimes used off-label. Drugs such as scopolamine and related compounds can also provide symptomatic relief, as can the tetrahydrocannabinol-containing drug, dronabinol. New pharmacologic agents for GpS include investigational drugs such as ghrelin agonists and several novel compounds, none of which are currently FDA approved.21,22

Fortunately, the majority of patients with GpS respond to conservative therapies, such as dietary changes and/or medications. The last part of the section on treatment of GpS includes patients that are diet and drug refractory. Patients in this group are often referred to gastroenterologists and can be complex, time consuming, and frustrating to provide care for. Many of these patients are eventually seen in referral centers, and some travel great distances and have considerable medical expenses.

Pylorus-directed therapies: The recent renewed interest in pyloric dysfunction in patients with Gp symptoms has led to a great deal of clinical activity. Gastropyloric dysfunction in Gp has been documented for decades, originally in diabetic patients with autonomic and enteric neuropathy. The use of botulinum toxin in upper- and lower-gastric sphincters has led to continuing use of this therapy for patients with GpS. Despite initial negative controlled trials of botulinum toxin in the pyloric sphincter, newer studies indicate that physiologic measures, such as the FLIP, may help with patient selection. Other disruptive pyloric therapies, including pyloromyotomy, per oral pyloromyotomy, and gastric peroral endoscopic myotomy, are supported by open-label use, despite a lack of published positive controlled trials.17

Bioelectric therapy: Another approach for patients with symptomatic drug refractory GpS is bioelectric device therapies, which can be delivered several ways, including directly to the stomach or to the spinal cord or the vagus nerve in the neck or ear, as well as by electro-acupuncture. High-frequency, low-energy gastric electrical stimulation (GES) is the best studied. First done in 1992 as an experimental therapy, GES was investigational from 1995 to 2000, when it became FDA approved as a humanitarian-use device. GES has been used in over 10,000 patients worldwide; only a small number (greater than 700 study patients) have been in controlled trials. Nine controlled trials of GES have been primarily positive, and durability for over 10 years has been shown. Temporary GES can also be performed endoscopically, although that is an off-label procedure. It has been shown to predict long-term therapy outcome.23-26

Nutritional support: Nutritional abnormalities in some cases of GpS lead to consideration of enteral tubes, starting with a trial of feeding with an N-J tube placed endoscopically. An N-J trial is most often performed in patients who have macro-malnutrition and weight loss but can be considered for other highly symptomatic patients. Other endoscopic tubes can be PEG or PEG-J or direct PEJ tubes. Some patients may require surgical placement of enteral tubes, presenting an opportunity for a small bowel or gastric full-thickness biopsy. Enteral tubes are sometimes used for decompression in highly symptomatic patients.27

For patients presenting with neurological symptoms, findings and serologic abnormalities have led to interest in immunotherapies. One is intravenous immunoglobulin, given parenterally. Several open-label studies have been published, the most recent one with 47 patients showing better response if glutamic acid decarboxylase–65 antibodies were present and with longer therapeutic dosing.28 Drawbacks to immunotherapies like intravenous immunoglobulin are cost and requiring parenteral access.

Other evaluation/treatments for drug refractory patients can be detailed as follows: First, an overall quality of life assessment can be helpful, especially one that includes impact of GpS on the patients and family. Nutritional considerations, which may not have been fully assessed, can be examined in more detail. Frailty assessments may show the need for physical therapy. Assessment for home care needs may indicate, in severe patients, needs for IV fluids at home, either enteral or parenteral, if nutrition is not adequate. Psychosocial and/or psychiatric assessments may lead to the need for medications, psychotherapy, and/or support groups. Lastly, an assessment of overall health status may lead to approaches for minimizing visits to emergency rooms and hospitalizations.29,30

Conclusion

Patients with Gp symptoms are becoming increasingly recognized and referred to gastroenterologists. Better understandings of the pathophysiology of the spectrum of gastroparesis syndromes, assisted by innovations in diagnosis, have led to expansion of existing and new therapeutic approaches. Fortunately, most patients can benefit from a standardized diagnostic approach and directed noninvasive therapies. Patients with refractory gastroparesis symptoms, often with complex issues referred to gastroenterologists, remain a challenge, and novel approaches may improve their quality of life.

Dr. Mathur is a GI motility research fellow at the University of Louisville, Ky. He reports no conflicts of interest. Dr. Abell is the Arthur M. Schoen, MD, Chair in Gastroenterology at the University of Louisville. His main funding is NIH GpCRC and NIH Definitive Evaluation of Gastric Dysrhythmia. He is an investigator for Cindome, Vanda, Allergan, and Neurogastrx; a consultant for Censa, Nuvaira, and Takeda; a speaker for Takeda and Medtronic; and a reviewer for UpToDate. He is also the founder of ADEPT-GI, which holds IP related to mucosal stimulation and autonomic and enteric profiling.

References

1. Jung HK et al. Gastroenterology. 2009;136(4):1225-33.

2. Ye Y et al. Gut. 2021;70(4):644-53.

3. Oshima T et al. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021;27(1):46-54.

4. Soykan I et al. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43(11):2398-404.

5. Syed AR et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2020;54(1):50-4.

6.Pasricha PJ et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9(7):567-76.e1-4.

7. Pasricha PJ et al. Gastroenterology. 2021;160(6):2006-17.

8. Almario CV et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(11):1701-10.

9. Abell TL et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2021 Apr;66(4):1127-41.

10. Abell TL et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2019;31(3):e13534.

11. Elmasry M et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021 Oct 26;e14274.

12. Maurer AH et al. J Nucl Med. 2020;61(3):11N-7N.

13. Abell TL et al. J Nucl Med Technol. 2008 Mar;36(1):44-54.

14. Shine A et al. Neuromodulation. 2022 Feb 16;S1094-7159(21)06986-5.

15. O’Grady G et al. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2021;321(5):G527-g42.

16. Saadi M et al. Rev Gastroenterol Mex (Engl Ed). Oct-Dec 2018;83(4):375-84.

17. Kamal F et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2022;55(2):168-77.

18. Harberson J et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55(2):359-70.

19. Winston J. Gastrointestinal Disorders. 2021;3(2):78-83.

20. Parkman HP et al. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(2):486-98, 98.e1-7.

21. Heckroth M et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2021;55(4):279-99.

22. Camilleri M. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(1):19-24.

23. Payne SC et al. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16(2):89-105.

24. Ducrotte P et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(3):506-14.e2.

25. Burlen J et al. Gastroenterology Res. 2018;11(5):349-54.

26. Hedjoudje A et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020;32(11):e13949.

27. Petrov RV et al. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2020;49(3):539-56.

28. Gala K et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2021 Dec 31. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001655.

29. Abell TL et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2006;18(4):263-83.

30. Camilleri M et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(1):18-37.

Study points to causal role for Lp(a) in atrial fibrillation

Although lipoprotein(a) is causally related to coronary artery disease and aortic valve stenosis – two known risk factors for atrial fibrillation (AFib) – evidence linking Lp(a) to a causal role in the development of AFib has been lukewarm at best.

A recent Mendelian randomization study showed only a nominally significant effect of Lp(a) on AFib, whereas an ARIC substudy showed high levels of Lp(a) to be associated with elevated ischemic stroke risk but not incident AFib.

A new study that adds the heft of Mendelian randomization to large observational and genetic analyses, however, implicates Lp(a) as a potential causal mediator of AFib, independent of its known effects on atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD).

“Why this is exciting is because it shows that Lp(a) has effects beyond the arteries and beyond the aortic valve, and that provides two things,” senior author Guillaume Paré, MD, MSc, Population Health Research Institute, Hamilton, Ontario, told this news organization.

“First, it provides a potential means to decrease the risk, because there are all these Lp(a) inhibitors in development,” he said. “But I think the other thing is that it just points to a new pathway that leads to atrial fibrillation development that could potentially be targeted with other drugs when it’s better understood. We don’t pretend that we understand the biology there, but it opens this possibility.”

The results were published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Using data from 435,579 participants in the UK Biobank, the researchers identified 20,432 cases of incident AFib over a median of 11 years of follow-up. They also constructed a genetic risk score for Lp(a) using genetic variants within 500 kb of the LPA gene.

After common AFib risk factors were controlled for, results showed a 3% increased risk for incident AFib per 50 nmol/L increase in Lp(a) at enrollment (hazard ratio, 1.03; 95% confidence interval, 1.02-1.05).

A Mendelian randomization analysis showed a similar association between genetically predicted Lp(a) and AFib (odds ratio, 1.03; 95% CI, 1.02-1.05).

To replicate the results, the investigators performed separate Mendelian randomization analyses using publicly available genome-wide association study (GWAS) statistics from the largest GWAS of AFib involving more than 1 million participants and from the FinnGen cohort involving more than 114,000 Finnish residents.

The analyses showed a 3% increase in risk for AFib in the genome-wide study (OR, 1.03; 95% CI, 1.02-1.05) and an 8% increase in risk in the Finnish study (OR, 1.08; 95% CI, 1.04-1.12) per 50 nmol/L increase in Lp(a).

There was no evidence that the effect of observed or genetically predicted Lp(a) was modified by prevalent ischemic heart disease or aortic stenosis.

Further, MR analyses revealed no risk effect of low-density-lipoprotein cholesterol or triglycerides on AFib.

Notably, only 39% of Lp(a) was mediated through ASCVD, suggesting that Lp(a) partly influences AFib independent of its known effect on ASCVD.

“To me, the eureka moment is when we repeated the same analysis for LDL cholesterol and it had absolutely no association with AFib,” Dr. Paré said. “Because up to that point, there was always this lingering doubt that, well, it’s because of coronary artery disease, and that’s logical. But the signal is completely flat with LDL, and we see this strong signal with Lp(a).”

Another ‘red flag’

Erin D. Michos, MD, MHS, senior author of the ARIC substudy and associate director of preventive cardiology at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, said the findings are “another red flag that lipoprotein(a) is a marker we need to pay attention to and potentially needs treatment.”

“The fact that it was Mendelian randomization does suggest that there’s a causal role,” she said. “I think the relationship is relatively modest compared to its known risk for stroke, ASCVD, coronary disease, and aortic stenosis, ... which may be why we didn’t see it in the ARIC cohort with 12,000 participants. You needed to have a million participants and 60,000 cases to see an effect here.”

Dr. Michos said she hopes the findings encourage increased testing, particularly with multiple potential treatments currently in the pipeline. She pointed out that the researchers estimated that the experimental antisense agent pelacarsen, which lowers Lp(a) by about 80%, would translate into about an 8% reduction in AFib risk, or “the same effect as 2 kg of weight loss or a 5 mm Hg reduction in blood pressure, which we do think are meaningful.”

Adding to this point in an accompanying editorial, Daniel Seung Kim, MD, PhD, and Abha Khandelwal, MD, MS, Stanford University School of Medicine, California, say that “moreover, reduction of Lp(a) levels would have multifactorial effects on CAD, cerebrovascular/peripheral artery disease, and AS risk.

“Therefore, approaches to reduce Lp(a) should be prioritized to further reduce the morbidity and mortality of a rapidly aging population,” they write.

The editorialists also join the researchers in calling for inclusion of AFib as a secondary outcome in ongoing Lp(a) trials, in addition to cerebrovascular disease and peripheral vascular disease.

Unanswered questions

As to what’s driving the risk effect of Lp(a), first author Pedrum Mohammadi-Shemirani, PhD, also from the Population Health Research Institute, explained that in aortic stenosis, “mechanical stress increases endothelial permeability, allowing Lp(a) to infiltrate valvular tissue and induce gene expression that results in microcalcifications and cell death.”

“So, in theory, a similar sort of mechanism could be at play in atrial tissue that may lead to damage and the electrical remodeling that causes atrial fibrillation,” he told this news organization.

Dr. Mohammadi-Shemirani also noted that Lp(a) has proinflammatory properties, but added that any potential mechanisms are “speculative and require further research to disentangle.”

Dr. Paré and colleagues say follow-up studies are also warranted, noting that generalizability of the results may be limited because AFib cases were found using electronic health records in the population-scale cohorts and because few UK Biobank participants were of non-European ancestry and Lp(a) levels vary among ethnic groups.

Another limitation is that the number of kringle IV type 2 domain repeats within the LPA gene, the largest contributor to genetic variation in Lp(a), could not be directly measured. Still, 71.4% of the variation in Lp(a) was explained using the genetic risk score alone, they say.

Dr. Paré holds the Canada Research Chair in Genetic and Molecular Epidemiology and Cisco Systems Professorship in Integrated Health Biosystems. Dr. Mohammadi-Shemirani is supported by the Frederick Banting and Charles Best Canada Graduate Scholarship from the Canadian Institute of Health Research. Dr. Michos reports consulting for Novartis and serving on advisory boards for Novartis, AstraZeneca, Bayer, and Boehringer Ingelheim. Dr. Kim reports grant support from the National Institutes of Health and the American Heart Association. Dr. Khandelwal serves on the advisory board of Amgen and has received funding from Novartis CTQJ and Akcea.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Although lipoprotein(a) is causally related to coronary artery disease and aortic valve stenosis – two known risk factors for atrial fibrillation (AFib) – evidence linking Lp(a) to a causal role in the development of AFib has been lukewarm at best.

A recent Mendelian randomization study showed only a nominally significant effect of Lp(a) on AFib, whereas an ARIC substudy showed high levels of Lp(a) to be associated with elevated ischemic stroke risk but not incident AFib.

A new study that adds the heft of Mendelian randomization to large observational and genetic analyses, however, implicates Lp(a) as a potential causal mediator of AFib, independent of its known effects on atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD).

“Why this is exciting is because it shows that Lp(a) has effects beyond the arteries and beyond the aortic valve, and that provides two things,” senior author Guillaume Paré, MD, MSc, Population Health Research Institute, Hamilton, Ontario, told this news organization.

“First, it provides a potential means to decrease the risk, because there are all these Lp(a) inhibitors in development,” he said. “But I think the other thing is that it just points to a new pathway that leads to atrial fibrillation development that could potentially be targeted with other drugs when it’s better understood. We don’t pretend that we understand the biology there, but it opens this possibility.”

The results were published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Using data from 435,579 participants in the UK Biobank, the researchers identified 20,432 cases of incident AFib over a median of 11 years of follow-up. They also constructed a genetic risk score for Lp(a) using genetic variants within 500 kb of the LPA gene.

After common AFib risk factors were controlled for, results showed a 3% increased risk for incident AFib per 50 nmol/L increase in Lp(a) at enrollment (hazard ratio, 1.03; 95% confidence interval, 1.02-1.05).

A Mendelian randomization analysis showed a similar association between genetically predicted Lp(a) and AFib (odds ratio, 1.03; 95% CI, 1.02-1.05).

To replicate the results, the investigators performed separate Mendelian randomization analyses using publicly available genome-wide association study (GWAS) statistics from the largest GWAS of AFib involving more than 1 million participants and from the FinnGen cohort involving more than 114,000 Finnish residents.

The analyses showed a 3% increase in risk for AFib in the genome-wide study (OR, 1.03; 95% CI, 1.02-1.05) and an 8% increase in risk in the Finnish study (OR, 1.08; 95% CI, 1.04-1.12) per 50 nmol/L increase in Lp(a).

There was no evidence that the effect of observed or genetically predicted Lp(a) was modified by prevalent ischemic heart disease or aortic stenosis.

Further, MR analyses revealed no risk effect of low-density-lipoprotein cholesterol or triglycerides on AFib.

Notably, only 39% of Lp(a) was mediated through ASCVD, suggesting that Lp(a) partly influences AFib independent of its known effect on ASCVD.

“To me, the eureka moment is when we repeated the same analysis for LDL cholesterol and it had absolutely no association with AFib,” Dr. Paré said. “Because up to that point, there was always this lingering doubt that, well, it’s because of coronary artery disease, and that’s logical. But the signal is completely flat with LDL, and we see this strong signal with Lp(a).”

Another ‘red flag’

Erin D. Michos, MD, MHS, senior author of the ARIC substudy and associate director of preventive cardiology at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, said the findings are “another red flag that lipoprotein(a) is a marker we need to pay attention to and potentially needs treatment.”

“The fact that it was Mendelian randomization does suggest that there’s a causal role,” she said. “I think the relationship is relatively modest compared to its known risk for stroke, ASCVD, coronary disease, and aortic stenosis, ... which may be why we didn’t see it in the ARIC cohort with 12,000 participants. You needed to have a million participants and 60,000 cases to see an effect here.”

Dr. Michos said she hopes the findings encourage increased testing, particularly with multiple potential treatments currently in the pipeline. She pointed out that the researchers estimated that the experimental antisense agent pelacarsen, which lowers Lp(a) by about 80%, would translate into about an 8% reduction in AFib risk, or “the same effect as 2 kg of weight loss or a 5 mm Hg reduction in blood pressure, which we do think are meaningful.”

Adding to this point in an accompanying editorial, Daniel Seung Kim, MD, PhD, and Abha Khandelwal, MD, MS, Stanford University School of Medicine, California, say that “moreover, reduction of Lp(a) levels would have multifactorial effects on CAD, cerebrovascular/peripheral artery disease, and AS risk.

“Therefore, approaches to reduce Lp(a) should be prioritized to further reduce the morbidity and mortality of a rapidly aging population,” they write.

The editorialists also join the researchers in calling for inclusion of AFib as a secondary outcome in ongoing Lp(a) trials, in addition to cerebrovascular disease and peripheral vascular disease.

Unanswered questions

As to what’s driving the risk effect of Lp(a), first author Pedrum Mohammadi-Shemirani, PhD, also from the Population Health Research Institute, explained that in aortic stenosis, “mechanical stress increases endothelial permeability, allowing Lp(a) to infiltrate valvular tissue and induce gene expression that results in microcalcifications and cell death.”

“So, in theory, a similar sort of mechanism could be at play in atrial tissue that may lead to damage and the electrical remodeling that causes atrial fibrillation,” he told this news organization.

Dr. Mohammadi-Shemirani also noted that Lp(a) has proinflammatory properties, but added that any potential mechanisms are “speculative and require further research to disentangle.”

Dr. Paré and colleagues say follow-up studies are also warranted, noting that generalizability of the results may be limited because AFib cases were found using electronic health records in the population-scale cohorts and because few UK Biobank participants were of non-European ancestry and Lp(a) levels vary among ethnic groups.

Another limitation is that the number of kringle IV type 2 domain repeats within the LPA gene, the largest contributor to genetic variation in Lp(a), could not be directly measured. Still, 71.4% of the variation in Lp(a) was explained using the genetic risk score alone, they say.

Dr. Paré holds the Canada Research Chair in Genetic and Molecular Epidemiology and Cisco Systems Professorship in Integrated Health Biosystems. Dr. Mohammadi-Shemirani is supported by the Frederick Banting and Charles Best Canada Graduate Scholarship from the Canadian Institute of Health Research. Dr. Michos reports consulting for Novartis and serving on advisory boards for Novartis, AstraZeneca, Bayer, and Boehringer Ingelheim. Dr. Kim reports grant support from the National Institutes of Health and the American Heart Association. Dr. Khandelwal serves on the advisory board of Amgen and has received funding from Novartis CTQJ and Akcea.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Although lipoprotein(a) is causally related to coronary artery disease and aortic valve stenosis – two known risk factors for atrial fibrillation (AFib) – evidence linking Lp(a) to a causal role in the development of AFib has been lukewarm at best.

A recent Mendelian randomization study showed only a nominally significant effect of Lp(a) on AFib, whereas an ARIC substudy showed high levels of Lp(a) to be associated with elevated ischemic stroke risk but not incident AFib.

A new study that adds the heft of Mendelian randomization to large observational and genetic analyses, however, implicates Lp(a) as a potential causal mediator of AFib, independent of its known effects on atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD).