User login

Indications and techniques for multifetal pregnancy reduction

Multifetal pregnancy reduction (MPR) was developed in the 1980s in the wake of significant increases in the incidence of triplets and other higher-order multiples emanating from assisted reproductive technologies (ART). It was offered to reduce fetal number and improve outcomes for remaining fetuses by reducing rates of preterm delivery, fetal growth restriction, and other adverse perinatal outcomes, as well as maternal complications such as preeclampsia and postpartum hemorrhage.

In recent years, improvements in ART – mainly changes in ovulation induction practices and limitations in the number of embryos implanted to two at most – have reversed the increase in higher-order multiples. However, with intrauterine insemination, higher-order multiples still occur, and even without any reproductive assistance, the reality is that multiple pregnancies – particularly twins – continue to exist. In 2018, twins comprised about 3% of births in the United States.1

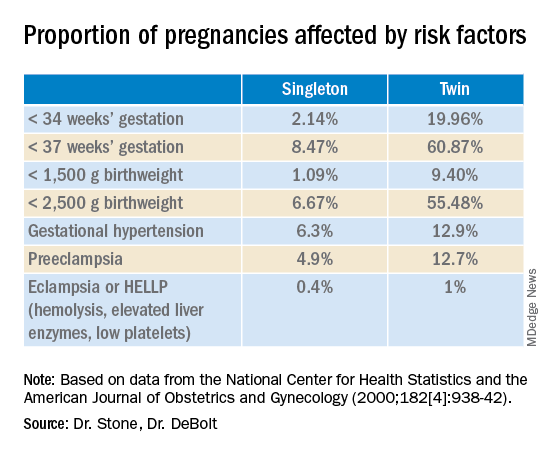

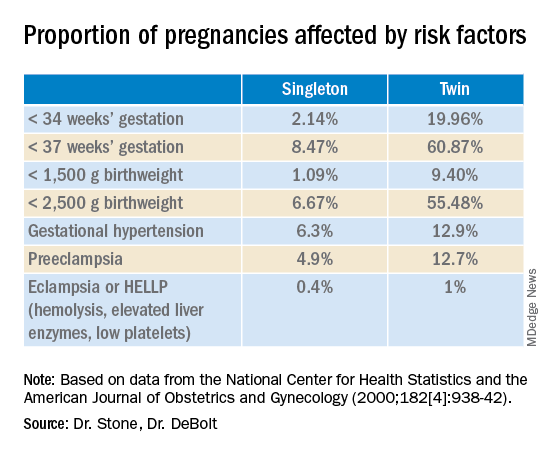

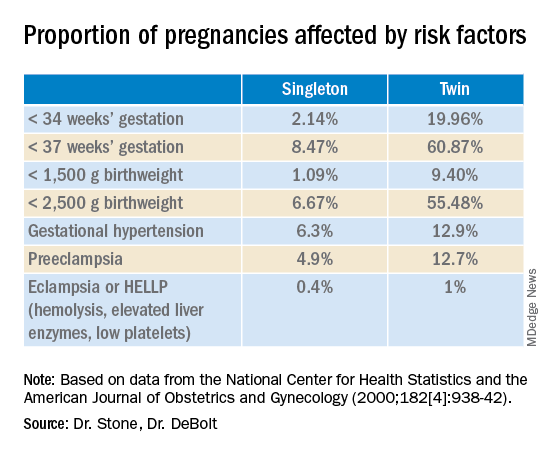

Twin pregnancies have a significantly higher risk than singleton gestations of preterm birth, maternal complications, and neonatal morbidity and mortality. The pregnancies are complicated more often by preterm premature rupture of membranes, fetal growth restriction, and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.

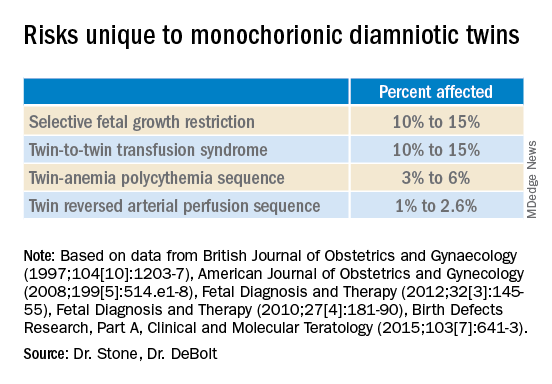

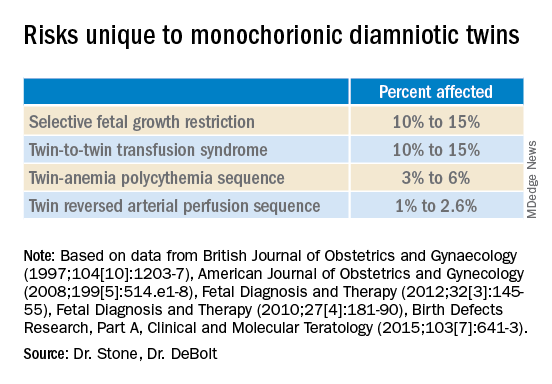

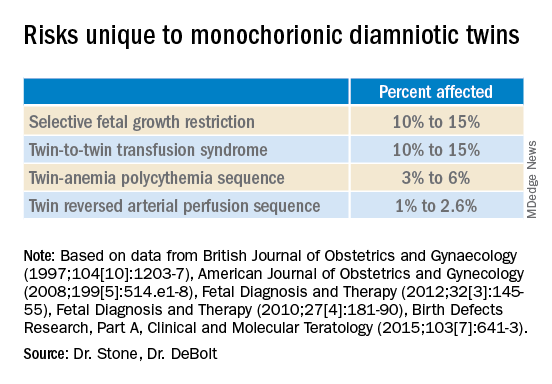

Monochorionic diamniotic twin pregnancies face additional, unique risks of twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome, twin reversed arterial perfusion sequence, and twin-anemia polycythemia sequence. These pregnancies account for about 20% of all twin gestations, and decades of experience with ART have shown us that monochorionic diamniotic gestations occur at a higher rate after in-vitro fertilization.

Although advances have improved the outcomes of multiple births, risks remain and elective MPR is still very relevant for twin gestations. Patients routinely receive counseling about the risks of twin gestations, but they often are not made aware of the option of elective fetal reduction.

We have offered elective reduction (of nonanomalous fetuses) to a singleton for almost 30 years and have published several reports documenting that MPR in dichorionic diamniotic pregnancies reduces the risk of preterm delivery and other complications without increasing the risk of pregnancy loss.

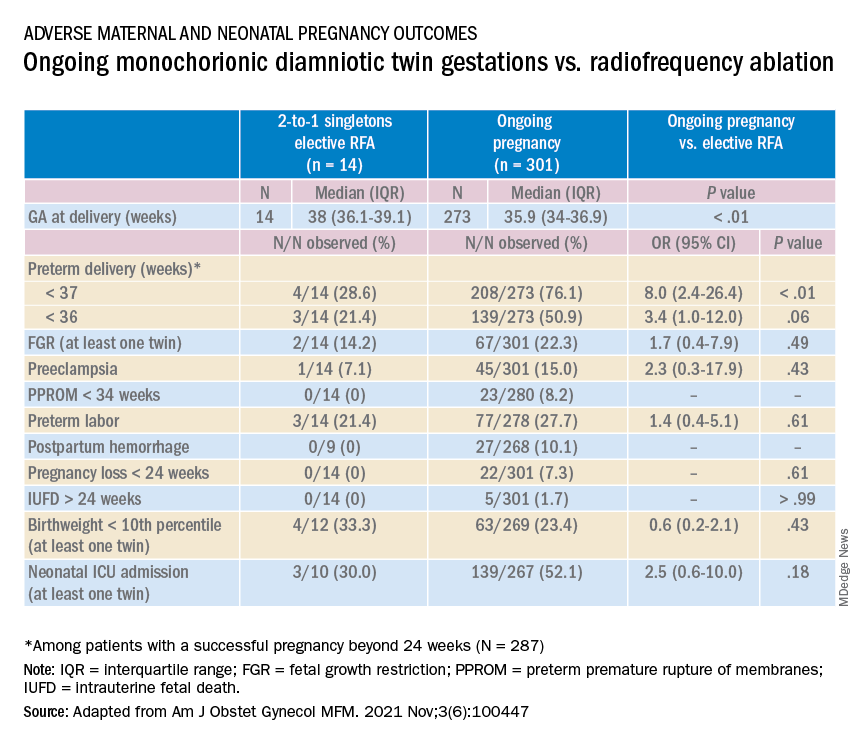

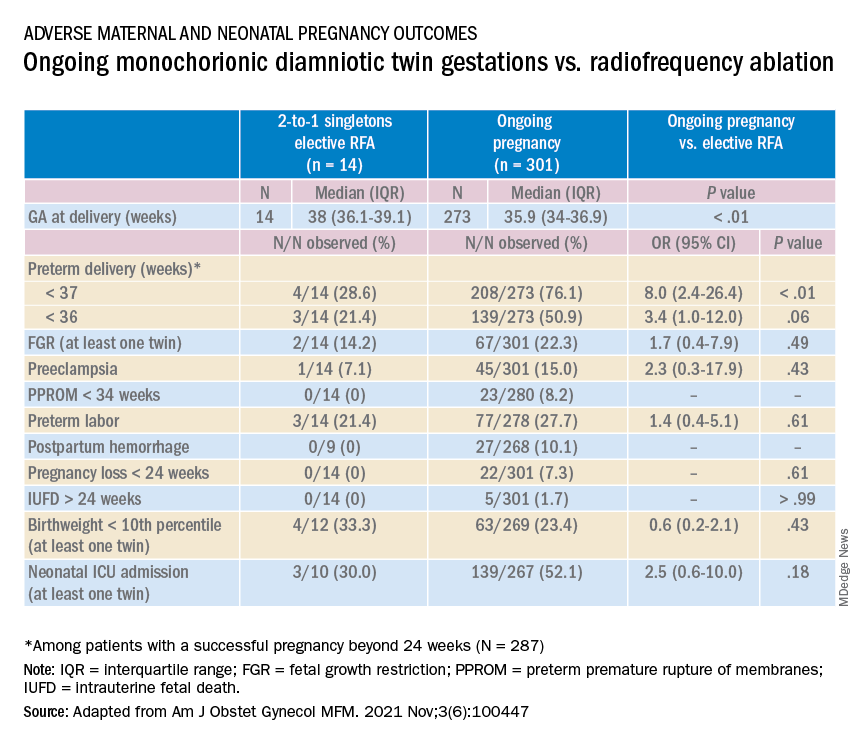

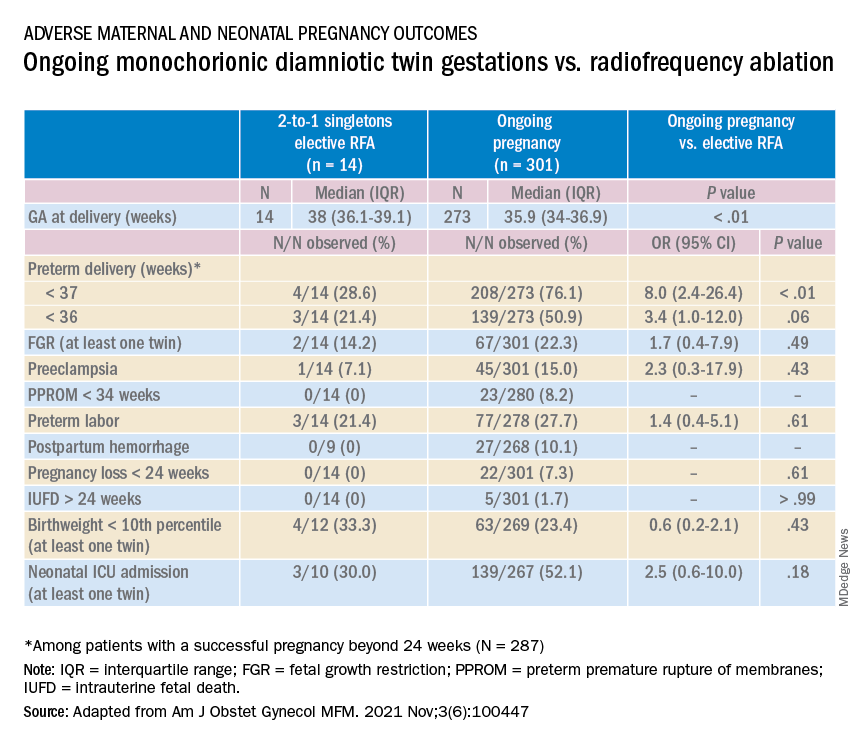

Most recently, we also published data comparing the outcomes of patients with monochorionic diamniotic gestations who underwent elective MPR by radiofrequency ablation (RFA) vs. those with ongoing monochorionic diamniotic gestations.2 While the numbers were small, the data show significantly lower rates of preterm birth without an increased risk of pregnancy loss.

Experience with dichorionic diamniotic twins, genetic testing

Our most recent review3 of outcomes in dichorionic diamniotic gestations covered 855 patients, 29% of whom underwent planned elective MPR at less than 15 weeks, and 71% of whom had ongoing twin gestations. Those with ongoing twin gestations had adjusted odds ratios of preterm delivery at less than 37 weeks and less than 34 weeks of 5.62 and 2.22, respectively (adjustments controlled for maternal characteristics such as maternal age, BMI, use of chorionic villus sampling [CVS], and history of preterm birth).

Ongoing twin pregnancies were also more likely to have preeclampsia (AOR, 3.33), preterm premature rupture of membranes (3.86), and low birthweight (under the 5th and 10th percentiles). There were no significant differences in the rate of unintended pregnancy loss (2.4% vs. 2.3%), and rates for total pregnancy loss at less than 24 weeks and less than 20 weeks were similar.

An important issue in the consideration of MPR is that prenatal diagnosis of chromosomal abnormalities is very safe in twins. Multiple gestations are at greater risk of chromosomal abnormalities, so performing MPR selectively – if a chromosomally abnormal fetus is present – is desirable for many parents.

A recent meta-analysis and systematic review of studies reporting fetal loss following amniocentesis or CVS in twin pregnancies found an exceedingly low risk of loss. Procedure-related fetal loss (the primary outcome) was lower than previously reported, and the rate of fetal loss before 24 weeks gestation or within 4 weeks after the procedure (secondary outcomes), did not differ from the background risk in twin pregnancies not undergoing invasive prenatal testing.4

Our data have shown no significant differences in pregnancy loss between patients who underwent CVS prior to MPR and those who did not. Looking specifically at reduction to a singleton gestation, patients who underwent CVS prior to MPR had a fourfold reduction in loss.5 Therefore, we counsel patients that CVS provides useful information – especially now with the common use of chromosomal microarray – at almost negligible risk.

MPR for monochorionic diamniotic twins

Most of the literature on MPR from twin to singleton gestations reports on intrathoracic potassium chloride injection used in dichorionic diamniotic twins.

MPR in monochorionic diamniotic twins is reserved in the United States for monochorionic pregnancies in which there are severe fetal anomalies, severe growth restriction, or other significant complications. It is performed in such cases around 20 weeks gestation. However, given the significant risks of monochorionic twin pregnancies, we also have been offering MPR electively and earlier in pregnancy. While many modalities of intrafetal cord occlusion exist, RFA at the cord insertion site into the fetal abdomen is our preferred technique.

In our retrospective review of 315 monochorionic diamniotic twin gestations, the 14 patients who had RFA electively had no pregnancy losses and a significantly lower rate of preterm birth at less than 37-weeks gestation, compared with 301 ongoing monochorionic diamniotic twin pregnancies (29% vs. 76%).5 Reduction with RFA, performed at a mean gestational age of 15 weeks, also eliminated the risks unique to monochorionic twins, such as twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome and twin-anemia polycythemia sequence. (Of the ongoing twin gestations, 12% required medically indicated RFA, fetoscopic laser ablation, and/or amnioreduction; 4% had unintended loss of one fetus; and 4% had unintended loss of both fetuses before 24 weeks’ gestation. Fewer than 70% of the ongoing twin gestations had none of the significant adverse outcomes unique to monochorionic twins.)

Interestingly, there were still a couple of cases of fetal growth restriction in patients who underwent elective MPR – a rate higher than that seen in singleton gestations – most likely because of the early timing of the procedure.

Our numbers of MPRs in this review were small, but the data offer at least preliminary evidence that planned elective RFA before 17 weeks gestation may be offered to patients who do not want to assume the risks of monochorionic diamniotic twin pregnancies.

Counseling in twin pregnancies

We perform thorough, early assessments of fetal anatomy in our twin pregnancies, and we undertake thorough medical and obstetrical histories to uncover birth complications or medical conditions that would increase risks of preeclampsia, preterm birth, fetal growth restriction, and other complications.

Because monochorionic gestations are at particularly high risk for heart defects, we also routinely perform fetal echocardiography in these pregnancies.

Genetic testing is offered to all twin pregnancies, and as mentioned above, we especially counsel those considering MPR that such testing provides useful information.

Patients are made aware of the option of MPR and receive nondirective counseling. It is the patient’s choice. We recognize that elective termination is a controversial procedure, but we believe that the option of MPR should be available to patients who want to improve outcomes for their pregnancy.

When anomalies are discovered and selective termination is chosen, we usually try to perform MPR as early as possible. After 16 weeks, we’ve found, the rate of pregnancy loss increases slightly.

Dr. Stone is the Ellen and Howard C. Katz Chairman’s Chair, and Dr. DeBolt is a clinical fellow in maternal-fetal medicine, in the Raquel and Jaime Gilinski Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Science at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

References

1. Martin JA and Osterman MJK. National Center of Health Statistics. NCHS Data Brief, 2019;no 351.

2. Manasa GR et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2021;3:100447.

3. Vieira LA et al. Am J. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221:253.e1-8.

4. Di Mascio et al. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2020 Nov;56(5):647-55.

5. Ferrara L et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Oct;199(4):408.e1-4.

Multifetal pregnancy reduction (MPR) was developed in the 1980s in the wake of significant increases in the incidence of triplets and other higher-order multiples emanating from assisted reproductive technologies (ART). It was offered to reduce fetal number and improve outcomes for remaining fetuses by reducing rates of preterm delivery, fetal growth restriction, and other adverse perinatal outcomes, as well as maternal complications such as preeclampsia and postpartum hemorrhage.

In recent years, improvements in ART – mainly changes in ovulation induction practices and limitations in the number of embryos implanted to two at most – have reversed the increase in higher-order multiples. However, with intrauterine insemination, higher-order multiples still occur, and even without any reproductive assistance, the reality is that multiple pregnancies – particularly twins – continue to exist. In 2018, twins comprised about 3% of births in the United States.1

Twin pregnancies have a significantly higher risk than singleton gestations of preterm birth, maternal complications, and neonatal morbidity and mortality. The pregnancies are complicated more often by preterm premature rupture of membranes, fetal growth restriction, and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.

Monochorionic diamniotic twin pregnancies face additional, unique risks of twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome, twin reversed arterial perfusion sequence, and twin-anemia polycythemia sequence. These pregnancies account for about 20% of all twin gestations, and decades of experience with ART have shown us that monochorionic diamniotic gestations occur at a higher rate after in-vitro fertilization.

Although advances have improved the outcomes of multiple births, risks remain and elective MPR is still very relevant for twin gestations. Patients routinely receive counseling about the risks of twin gestations, but they often are not made aware of the option of elective fetal reduction.

We have offered elective reduction (of nonanomalous fetuses) to a singleton for almost 30 years and have published several reports documenting that MPR in dichorionic diamniotic pregnancies reduces the risk of preterm delivery and other complications without increasing the risk of pregnancy loss.

Most recently, we also published data comparing the outcomes of patients with monochorionic diamniotic gestations who underwent elective MPR by radiofrequency ablation (RFA) vs. those with ongoing monochorionic diamniotic gestations.2 While the numbers were small, the data show significantly lower rates of preterm birth without an increased risk of pregnancy loss.

Experience with dichorionic diamniotic twins, genetic testing

Our most recent review3 of outcomes in dichorionic diamniotic gestations covered 855 patients, 29% of whom underwent planned elective MPR at less than 15 weeks, and 71% of whom had ongoing twin gestations. Those with ongoing twin gestations had adjusted odds ratios of preterm delivery at less than 37 weeks and less than 34 weeks of 5.62 and 2.22, respectively (adjustments controlled for maternal characteristics such as maternal age, BMI, use of chorionic villus sampling [CVS], and history of preterm birth).

Ongoing twin pregnancies were also more likely to have preeclampsia (AOR, 3.33), preterm premature rupture of membranes (3.86), and low birthweight (under the 5th and 10th percentiles). There were no significant differences in the rate of unintended pregnancy loss (2.4% vs. 2.3%), and rates for total pregnancy loss at less than 24 weeks and less than 20 weeks were similar.

An important issue in the consideration of MPR is that prenatal diagnosis of chromosomal abnormalities is very safe in twins. Multiple gestations are at greater risk of chromosomal abnormalities, so performing MPR selectively – if a chromosomally abnormal fetus is present – is desirable for many parents.

A recent meta-analysis and systematic review of studies reporting fetal loss following amniocentesis or CVS in twin pregnancies found an exceedingly low risk of loss. Procedure-related fetal loss (the primary outcome) was lower than previously reported, and the rate of fetal loss before 24 weeks gestation or within 4 weeks after the procedure (secondary outcomes), did not differ from the background risk in twin pregnancies not undergoing invasive prenatal testing.4

Our data have shown no significant differences in pregnancy loss between patients who underwent CVS prior to MPR and those who did not. Looking specifically at reduction to a singleton gestation, patients who underwent CVS prior to MPR had a fourfold reduction in loss.5 Therefore, we counsel patients that CVS provides useful information – especially now with the common use of chromosomal microarray – at almost negligible risk.

MPR for monochorionic diamniotic twins

Most of the literature on MPR from twin to singleton gestations reports on intrathoracic potassium chloride injection used in dichorionic diamniotic twins.

MPR in monochorionic diamniotic twins is reserved in the United States for monochorionic pregnancies in which there are severe fetal anomalies, severe growth restriction, or other significant complications. It is performed in such cases around 20 weeks gestation. However, given the significant risks of monochorionic twin pregnancies, we also have been offering MPR electively and earlier in pregnancy. While many modalities of intrafetal cord occlusion exist, RFA at the cord insertion site into the fetal abdomen is our preferred technique.

In our retrospective review of 315 monochorionic diamniotic twin gestations, the 14 patients who had RFA electively had no pregnancy losses and a significantly lower rate of preterm birth at less than 37-weeks gestation, compared with 301 ongoing monochorionic diamniotic twin pregnancies (29% vs. 76%).5 Reduction with RFA, performed at a mean gestational age of 15 weeks, also eliminated the risks unique to monochorionic twins, such as twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome and twin-anemia polycythemia sequence. (Of the ongoing twin gestations, 12% required medically indicated RFA, fetoscopic laser ablation, and/or amnioreduction; 4% had unintended loss of one fetus; and 4% had unintended loss of both fetuses before 24 weeks’ gestation. Fewer than 70% of the ongoing twin gestations had none of the significant adverse outcomes unique to monochorionic twins.)

Interestingly, there were still a couple of cases of fetal growth restriction in patients who underwent elective MPR – a rate higher than that seen in singleton gestations – most likely because of the early timing of the procedure.

Our numbers of MPRs in this review were small, but the data offer at least preliminary evidence that planned elective RFA before 17 weeks gestation may be offered to patients who do not want to assume the risks of monochorionic diamniotic twin pregnancies.

Counseling in twin pregnancies

We perform thorough, early assessments of fetal anatomy in our twin pregnancies, and we undertake thorough medical and obstetrical histories to uncover birth complications or medical conditions that would increase risks of preeclampsia, preterm birth, fetal growth restriction, and other complications.

Because monochorionic gestations are at particularly high risk for heart defects, we also routinely perform fetal echocardiography in these pregnancies.

Genetic testing is offered to all twin pregnancies, and as mentioned above, we especially counsel those considering MPR that such testing provides useful information.

Patients are made aware of the option of MPR and receive nondirective counseling. It is the patient’s choice. We recognize that elective termination is a controversial procedure, but we believe that the option of MPR should be available to patients who want to improve outcomes for their pregnancy.

When anomalies are discovered and selective termination is chosen, we usually try to perform MPR as early as possible. After 16 weeks, we’ve found, the rate of pregnancy loss increases slightly.

Dr. Stone is the Ellen and Howard C. Katz Chairman’s Chair, and Dr. DeBolt is a clinical fellow in maternal-fetal medicine, in the Raquel and Jaime Gilinski Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Science at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

References

1. Martin JA and Osterman MJK. National Center of Health Statistics. NCHS Data Brief, 2019;no 351.

2. Manasa GR et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2021;3:100447.

3. Vieira LA et al. Am J. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221:253.e1-8.

4. Di Mascio et al. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2020 Nov;56(5):647-55.

5. Ferrara L et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Oct;199(4):408.e1-4.

Multifetal pregnancy reduction (MPR) was developed in the 1980s in the wake of significant increases in the incidence of triplets and other higher-order multiples emanating from assisted reproductive technologies (ART). It was offered to reduce fetal number and improve outcomes for remaining fetuses by reducing rates of preterm delivery, fetal growth restriction, and other adverse perinatal outcomes, as well as maternal complications such as preeclampsia and postpartum hemorrhage.

In recent years, improvements in ART – mainly changes in ovulation induction practices and limitations in the number of embryos implanted to two at most – have reversed the increase in higher-order multiples. However, with intrauterine insemination, higher-order multiples still occur, and even without any reproductive assistance, the reality is that multiple pregnancies – particularly twins – continue to exist. In 2018, twins comprised about 3% of births in the United States.1

Twin pregnancies have a significantly higher risk than singleton gestations of preterm birth, maternal complications, and neonatal morbidity and mortality. The pregnancies are complicated more often by preterm premature rupture of membranes, fetal growth restriction, and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.

Monochorionic diamniotic twin pregnancies face additional, unique risks of twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome, twin reversed arterial perfusion sequence, and twin-anemia polycythemia sequence. These pregnancies account for about 20% of all twin gestations, and decades of experience with ART have shown us that monochorionic diamniotic gestations occur at a higher rate after in-vitro fertilization.

Although advances have improved the outcomes of multiple births, risks remain and elective MPR is still very relevant for twin gestations. Patients routinely receive counseling about the risks of twin gestations, but they often are not made aware of the option of elective fetal reduction.

We have offered elective reduction (of nonanomalous fetuses) to a singleton for almost 30 years and have published several reports documenting that MPR in dichorionic diamniotic pregnancies reduces the risk of preterm delivery and other complications without increasing the risk of pregnancy loss.

Most recently, we also published data comparing the outcomes of patients with monochorionic diamniotic gestations who underwent elective MPR by radiofrequency ablation (RFA) vs. those with ongoing monochorionic diamniotic gestations.2 While the numbers were small, the data show significantly lower rates of preterm birth without an increased risk of pregnancy loss.

Experience with dichorionic diamniotic twins, genetic testing

Our most recent review3 of outcomes in dichorionic diamniotic gestations covered 855 patients, 29% of whom underwent planned elective MPR at less than 15 weeks, and 71% of whom had ongoing twin gestations. Those with ongoing twin gestations had adjusted odds ratios of preterm delivery at less than 37 weeks and less than 34 weeks of 5.62 and 2.22, respectively (adjustments controlled for maternal characteristics such as maternal age, BMI, use of chorionic villus sampling [CVS], and history of preterm birth).

Ongoing twin pregnancies were also more likely to have preeclampsia (AOR, 3.33), preterm premature rupture of membranes (3.86), and low birthweight (under the 5th and 10th percentiles). There were no significant differences in the rate of unintended pregnancy loss (2.4% vs. 2.3%), and rates for total pregnancy loss at less than 24 weeks and less than 20 weeks were similar.

An important issue in the consideration of MPR is that prenatal diagnosis of chromosomal abnormalities is very safe in twins. Multiple gestations are at greater risk of chromosomal abnormalities, so performing MPR selectively – if a chromosomally abnormal fetus is present – is desirable for many parents.

A recent meta-analysis and systematic review of studies reporting fetal loss following amniocentesis or CVS in twin pregnancies found an exceedingly low risk of loss. Procedure-related fetal loss (the primary outcome) was lower than previously reported, and the rate of fetal loss before 24 weeks gestation or within 4 weeks after the procedure (secondary outcomes), did not differ from the background risk in twin pregnancies not undergoing invasive prenatal testing.4

Our data have shown no significant differences in pregnancy loss between patients who underwent CVS prior to MPR and those who did not. Looking specifically at reduction to a singleton gestation, patients who underwent CVS prior to MPR had a fourfold reduction in loss.5 Therefore, we counsel patients that CVS provides useful information – especially now with the common use of chromosomal microarray – at almost negligible risk.

MPR for monochorionic diamniotic twins

Most of the literature on MPR from twin to singleton gestations reports on intrathoracic potassium chloride injection used in dichorionic diamniotic twins.

MPR in monochorionic diamniotic twins is reserved in the United States for monochorionic pregnancies in which there are severe fetal anomalies, severe growth restriction, or other significant complications. It is performed in such cases around 20 weeks gestation. However, given the significant risks of monochorionic twin pregnancies, we also have been offering MPR electively and earlier in pregnancy. While many modalities of intrafetal cord occlusion exist, RFA at the cord insertion site into the fetal abdomen is our preferred technique.

In our retrospective review of 315 monochorionic diamniotic twin gestations, the 14 patients who had RFA electively had no pregnancy losses and a significantly lower rate of preterm birth at less than 37-weeks gestation, compared with 301 ongoing monochorionic diamniotic twin pregnancies (29% vs. 76%).5 Reduction with RFA, performed at a mean gestational age of 15 weeks, also eliminated the risks unique to monochorionic twins, such as twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome and twin-anemia polycythemia sequence. (Of the ongoing twin gestations, 12% required medically indicated RFA, fetoscopic laser ablation, and/or amnioreduction; 4% had unintended loss of one fetus; and 4% had unintended loss of both fetuses before 24 weeks’ gestation. Fewer than 70% of the ongoing twin gestations had none of the significant adverse outcomes unique to monochorionic twins.)

Interestingly, there were still a couple of cases of fetal growth restriction in patients who underwent elective MPR – a rate higher than that seen in singleton gestations – most likely because of the early timing of the procedure.

Our numbers of MPRs in this review were small, but the data offer at least preliminary evidence that planned elective RFA before 17 weeks gestation may be offered to patients who do not want to assume the risks of monochorionic diamniotic twin pregnancies.

Counseling in twin pregnancies

We perform thorough, early assessments of fetal anatomy in our twin pregnancies, and we undertake thorough medical and obstetrical histories to uncover birth complications or medical conditions that would increase risks of preeclampsia, preterm birth, fetal growth restriction, and other complications.

Because monochorionic gestations are at particularly high risk for heart defects, we also routinely perform fetal echocardiography in these pregnancies.

Genetic testing is offered to all twin pregnancies, and as mentioned above, we especially counsel those considering MPR that such testing provides useful information.

Patients are made aware of the option of MPR and receive nondirective counseling. It is the patient’s choice. We recognize that elective termination is a controversial procedure, but we believe that the option of MPR should be available to patients who want to improve outcomes for their pregnancy.

When anomalies are discovered and selective termination is chosen, we usually try to perform MPR as early as possible. After 16 weeks, we’ve found, the rate of pregnancy loss increases slightly.

Dr. Stone is the Ellen and Howard C. Katz Chairman’s Chair, and Dr. DeBolt is a clinical fellow in maternal-fetal medicine, in the Raquel and Jaime Gilinski Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Science at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

References

1. Martin JA and Osterman MJK. National Center of Health Statistics. NCHS Data Brief, 2019;no 351.

2. Manasa GR et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2021;3:100447.

3. Vieira LA et al. Am J. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221:253.e1-8.

4. Di Mascio et al. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2020 Nov;56(5):647-55.

5. Ferrara L et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Oct;199(4):408.e1-4.

Managing maternal mortality with multifetal pregnancy reduction

For over 2 years, the world has reeled from the COVID-19 pandemic. Life has changed dramatically, priorities have been re-examined, and the collective approach to health care has shifted tremendously. While concerns regarding coronavirus and its variants are warranted, another “pandemic” is ravaging the world and has yet to be fully addressed: pregnancy-related maternal mortality.

The rate of pregnancy-related deaths in the United States is unconscionable. Compared with other developed nations – such as Germany, the United Kingdom, and Canada – we lag far behind. Data published in 2020 showed that the rate of maternal deaths per 100,000 live births in the United States was 17.4, more than double that of France (8.7 deaths per 100,000 live births),1 the country with the next-highest rate. Americans like being first – first to invent the light bulb, first to perform a successful solid organ xenotransplantation, first to go to the moon – but holding “first place” in maternal mortality is not something we should wish to maintain.

Ob.gyns. have long raised the alarm regarding the exceedingly high rates of pregnancy-related deaths in the United States. While there have been many advances in antenatal care to reduce these severe adverse events – improvements in surveillance and data reporting, maternal-focused telemedicine services, multidisciplinary care team models, and numerous research initiatives by federal and nonprofit organizations2 – the recent wave of legislation restricting reproductive choice may also have the unintended consequence of further increasing the rate of pregnancy-related maternal morbidity and mortality.3

While we have an obligation to provide our maternal and fetal patients with the best possible care, under some circumstances, that care may require prioritizing the mother’s health above all else.

To discuss the judicious use of multifetal pregnancy reduction, we have invited Dr. Joanne Stone, The Ellen and Howard C. Katz Chairman’s Chair, and Dr. Chelsea DeBolt, clinical fellow in maternal-fetal medicine, both in the Raquel and Jaime Gilinski Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Science at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is executive vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. He is the medical editor of this column. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Contact him at [email protected].

References

1. Tikkanen R et al. The Commonwealth Fund. Nov 2020. doi: 10.26099/411v-9255

2. Ahn R et al. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(11 Suppl):S3-10. doi: 10.7326/M19-3258.

3. Pabayo R et al. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(11):3773. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17113773.

For over 2 years, the world has reeled from the COVID-19 pandemic. Life has changed dramatically, priorities have been re-examined, and the collective approach to health care has shifted tremendously. While concerns regarding coronavirus and its variants are warranted, another “pandemic” is ravaging the world and has yet to be fully addressed: pregnancy-related maternal mortality.

The rate of pregnancy-related deaths in the United States is unconscionable. Compared with other developed nations – such as Germany, the United Kingdom, and Canada – we lag far behind. Data published in 2020 showed that the rate of maternal deaths per 100,000 live births in the United States was 17.4, more than double that of France (8.7 deaths per 100,000 live births),1 the country with the next-highest rate. Americans like being first – first to invent the light bulb, first to perform a successful solid organ xenotransplantation, first to go to the moon – but holding “first place” in maternal mortality is not something we should wish to maintain.

Ob.gyns. have long raised the alarm regarding the exceedingly high rates of pregnancy-related deaths in the United States. While there have been many advances in antenatal care to reduce these severe adverse events – improvements in surveillance and data reporting, maternal-focused telemedicine services, multidisciplinary care team models, and numerous research initiatives by federal and nonprofit organizations2 – the recent wave of legislation restricting reproductive choice may also have the unintended consequence of further increasing the rate of pregnancy-related maternal morbidity and mortality.3

While we have an obligation to provide our maternal and fetal patients with the best possible care, under some circumstances, that care may require prioritizing the mother’s health above all else.

To discuss the judicious use of multifetal pregnancy reduction, we have invited Dr. Joanne Stone, The Ellen and Howard C. Katz Chairman’s Chair, and Dr. Chelsea DeBolt, clinical fellow in maternal-fetal medicine, both in the Raquel and Jaime Gilinski Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Science at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is executive vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. He is the medical editor of this column. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Contact him at [email protected].

References

1. Tikkanen R et al. The Commonwealth Fund. Nov 2020. doi: 10.26099/411v-9255

2. Ahn R et al. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(11 Suppl):S3-10. doi: 10.7326/M19-3258.

3. Pabayo R et al. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(11):3773. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17113773.

For over 2 years, the world has reeled from the COVID-19 pandemic. Life has changed dramatically, priorities have been re-examined, and the collective approach to health care has shifted tremendously. While concerns regarding coronavirus and its variants are warranted, another “pandemic” is ravaging the world and has yet to be fully addressed: pregnancy-related maternal mortality.

The rate of pregnancy-related deaths in the United States is unconscionable. Compared with other developed nations – such as Germany, the United Kingdom, and Canada – we lag far behind. Data published in 2020 showed that the rate of maternal deaths per 100,000 live births in the United States was 17.4, more than double that of France (8.7 deaths per 100,000 live births),1 the country with the next-highest rate. Americans like being first – first to invent the light bulb, first to perform a successful solid organ xenotransplantation, first to go to the moon – but holding “first place” in maternal mortality is not something we should wish to maintain.

Ob.gyns. have long raised the alarm regarding the exceedingly high rates of pregnancy-related deaths in the United States. While there have been many advances in antenatal care to reduce these severe adverse events – improvements in surveillance and data reporting, maternal-focused telemedicine services, multidisciplinary care team models, and numerous research initiatives by federal and nonprofit organizations2 – the recent wave of legislation restricting reproductive choice may also have the unintended consequence of further increasing the rate of pregnancy-related maternal morbidity and mortality.3

While we have an obligation to provide our maternal and fetal patients with the best possible care, under some circumstances, that care may require prioritizing the mother’s health above all else.

To discuss the judicious use of multifetal pregnancy reduction, we have invited Dr. Joanne Stone, The Ellen and Howard C. Katz Chairman’s Chair, and Dr. Chelsea DeBolt, clinical fellow in maternal-fetal medicine, both in the Raquel and Jaime Gilinski Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Science at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is executive vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. He is the medical editor of this column. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Contact him at [email protected].

References

1. Tikkanen R et al. The Commonwealth Fund. Nov 2020. doi: 10.26099/411v-9255

2. Ahn R et al. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(11 Suppl):S3-10. doi: 10.7326/M19-3258.

3. Pabayo R et al. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(11):3773. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17113773.

New combination med for severe mental illness tied to less weight gain

, new research suggests. However, at least one expert says the weight difference between the two drugs is of “questionable clinical benefit.”

Last year, the Food and Drug Administration approved the drug for the treatment of adults with schizophrenia or bipolar I disorder, as a maintenance monotherapy or as either monotherapy or an adjunct to lithium or valproate for acute manic or mixed episodes.

In the ENLIGHTEN-Early trial, researchers examined weight-gain profiles of more than 400 patients with early schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, or bipolar I disorder.

Results showed those given combination treatment gained just over half the amount of weight as those given monotherapy. They were also 36% less likely to gain at least 10% of their body weight during the 12-week treatment period.

They indicate that the weight-mitigating effects shown with olanzapine plus samidorphan are “consistent, regardless of the stage of illness,” Dr. Kahn added.

He presented the findings at the annual congress of the Schizophrenia International Research Society.

Potential benefit

“Early intervention with antipsychotic treatment is critical in shaping the course of treatment and the disease trajectory,” coinvestigator Christine Graham, PhD, with Alkermes, which manufactures the drug, told this news organization.

Olanzapine is a “highly effective antipsychotic, but it’s really avoided a lot in this population,” Dr. Graham said. Therefore, patients “could really stand to benefit” from a combination that delivers the same amount of antipsychotic effect, but “reduces the propensity” for clinically significant weight gain, she added.

Dr. Kahn noted in his meeting presentation that antipsychotics are the “cornerstone” of the treatment of serious mental illness, but that “many are associated with concerning weight gain and cardiometabolic effects.”

While olanzapine is an effective medication, it has “one of the highest weight gain” profiles of the available antipsychotics and patients early on in their illness are “especially vulnerable,” Dr. Kahn said.

Previous studies have shown the combination of olanzapine plus samidorphan is similarly effective as olanzapine, but is associated with less weight gain.

To determine its impact in recent-onset illness, the current researchers screened patients with schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, or bipolar I disorder. The patients were aged 16-39 years and had an initial onset of active phase symptoms less than 4 years previously. They had less than 24 weeks’ cumulative lifetime exposure to antipsychotics.

Participants were randomly assigned to receive olanzapine plus samidorphan or olanzapine alone for 12 weeks, and then followed up for safety assessment for a further 4 weeks.

A total of 426 patients were recruited and 76.5% completed the study. The mean age was 25.8 years, 66.2% were men, 66.4% were White, and 28.2% were Black.

The mean body mass index at baseline was 23.69 kg/m2. The most common diagnosis among the participants was schizophrenia (62.9%) followed by bipolar I disorder (21.6%).

Less weight gain

Results of the 12-week study showed a significant difference in percent change in body weight from baseline between the two treatment groups, with a gain of 4.91% for the olanzapine plus samidorphan group vs. 6.77% for the olanzapine-alone group (between-group difference, 1.87%; P = .012).

Dr. Kahn noted this equates to an average weight gain of 2.8 kg (6.2 pounds) with olanzapine plus samidorphan and a gain of about 5 kg (11pounds) with olanzapine.

“It’s not a huge difference, but it’s certainly a significant one,” he said. “I also think it’s clinically important and significant.”

The reduction in weight gain compared with olanzapine was even maintained in patients assigned to olanzapine plus samidorphan who dropped out and did not complete the study, Dr. Kahn reported. “No one really had a weight gain,” he said.

In contrast, patients in the olanzapine groups who dropped out of the study had weight gain larger than their counterparts who stayed in it.

Further analysis showed the proportion of patients who gained 10% or more of their body weight by week 12 was 21.9% for those receiving olanzapine plus samidorphan vs. 30.4% for those receiving just olanzapine (odds ratio, 0.64; P = .075).

As expected, the improvement in Clinical Global Impression–Severity scale scores was almost identical between the olanzapine + samidorphan and olanzapine-only groups.

For safety, Dr. Kahn said the adverse event rates were “very, very similar” between the two treatment arms, which was a pattern that was repeated for serious AEs. This led him to note that “nothing out of the ordinary” was observed.

Clinical impact 'questionable'

Commenting on the study, Laura LaChance, MD, a psychiatrist at St. Mary’s Hospital Centre, McGill University, Montreal, said the actual amount of weight loss shown in the study “is of questionable clinical significance.”

On the other hand, Dr. LaChance said she has achieved “better results with metformin, which has a great safety profile and is cheap and widely available.

“Cost is always a concern in patients with psychotic disorders,” she concluded.

The study was funded by Alkermes. Dr. Kahn reported having relationships with Alkermes, Angelini, Janssen, Sunovion, Otsuka, Merck, Minerva Neuroscience, Roche, and Teva. Dr. Graham is an employee of Alkermes.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research suggests. However, at least one expert says the weight difference between the two drugs is of “questionable clinical benefit.”

Last year, the Food and Drug Administration approved the drug for the treatment of adults with schizophrenia or bipolar I disorder, as a maintenance monotherapy or as either monotherapy or an adjunct to lithium or valproate for acute manic or mixed episodes.

In the ENLIGHTEN-Early trial, researchers examined weight-gain profiles of more than 400 patients with early schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, or bipolar I disorder.

Results showed those given combination treatment gained just over half the amount of weight as those given monotherapy. They were also 36% less likely to gain at least 10% of their body weight during the 12-week treatment period.

They indicate that the weight-mitigating effects shown with olanzapine plus samidorphan are “consistent, regardless of the stage of illness,” Dr. Kahn added.

He presented the findings at the annual congress of the Schizophrenia International Research Society.

Potential benefit

“Early intervention with antipsychotic treatment is critical in shaping the course of treatment and the disease trajectory,” coinvestigator Christine Graham, PhD, with Alkermes, which manufactures the drug, told this news organization.

Olanzapine is a “highly effective antipsychotic, but it’s really avoided a lot in this population,” Dr. Graham said. Therefore, patients “could really stand to benefit” from a combination that delivers the same amount of antipsychotic effect, but “reduces the propensity” for clinically significant weight gain, she added.

Dr. Kahn noted in his meeting presentation that antipsychotics are the “cornerstone” of the treatment of serious mental illness, but that “many are associated with concerning weight gain and cardiometabolic effects.”

While olanzapine is an effective medication, it has “one of the highest weight gain” profiles of the available antipsychotics and patients early on in their illness are “especially vulnerable,” Dr. Kahn said.

Previous studies have shown the combination of olanzapine plus samidorphan is similarly effective as olanzapine, but is associated with less weight gain.

To determine its impact in recent-onset illness, the current researchers screened patients with schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, or bipolar I disorder. The patients were aged 16-39 years and had an initial onset of active phase symptoms less than 4 years previously. They had less than 24 weeks’ cumulative lifetime exposure to antipsychotics.

Participants were randomly assigned to receive olanzapine plus samidorphan or olanzapine alone for 12 weeks, and then followed up for safety assessment for a further 4 weeks.

A total of 426 patients were recruited and 76.5% completed the study. The mean age was 25.8 years, 66.2% were men, 66.4% were White, and 28.2% were Black.

The mean body mass index at baseline was 23.69 kg/m2. The most common diagnosis among the participants was schizophrenia (62.9%) followed by bipolar I disorder (21.6%).

Less weight gain

Results of the 12-week study showed a significant difference in percent change in body weight from baseline between the two treatment groups, with a gain of 4.91% for the olanzapine plus samidorphan group vs. 6.77% for the olanzapine-alone group (between-group difference, 1.87%; P = .012).

Dr. Kahn noted this equates to an average weight gain of 2.8 kg (6.2 pounds) with olanzapine plus samidorphan and a gain of about 5 kg (11pounds) with olanzapine.

“It’s not a huge difference, but it’s certainly a significant one,” he said. “I also think it’s clinically important and significant.”

The reduction in weight gain compared with olanzapine was even maintained in patients assigned to olanzapine plus samidorphan who dropped out and did not complete the study, Dr. Kahn reported. “No one really had a weight gain,” he said.

In contrast, patients in the olanzapine groups who dropped out of the study had weight gain larger than their counterparts who stayed in it.

Further analysis showed the proportion of patients who gained 10% or more of their body weight by week 12 was 21.9% for those receiving olanzapine plus samidorphan vs. 30.4% for those receiving just olanzapine (odds ratio, 0.64; P = .075).

As expected, the improvement in Clinical Global Impression–Severity scale scores was almost identical between the olanzapine + samidorphan and olanzapine-only groups.

For safety, Dr. Kahn said the adverse event rates were “very, very similar” between the two treatment arms, which was a pattern that was repeated for serious AEs. This led him to note that “nothing out of the ordinary” was observed.

Clinical impact 'questionable'

Commenting on the study, Laura LaChance, MD, a psychiatrist at St. Mary’s Hospital Centre, McGill University, Montreal, said the actual amount of weight loss shown in the study “is of questionable clinical significance.”

On the other hand, Dr. LaChance said she has achieved “better results with metformin, which has a great safety profile and is cheap and widely available.

“Cost is always a concern in patients with psychotic disorders,” she concluded.

The study was funded by Alkermes. Dr. Kahn reported having relationships with Alkermes, Angelini, Janssen, Sunovion, Otsuka, Merck, Minerva Neuroscience, Roche, and Teva. Dr. Graham is an employee of Alkermes.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research suggests. However, at least one expert says the weight difference between the two drugs is of “questionable clinical benefit.”

Last year, the Food and Drug Administration approved the drug for the treatment of adults with schizophrenia or bipolar I disorder, as a maintenance monotherapy or as either monotherapy or an adjunct to lithium or valproate for acute manic or mixed episodes.

In the ENLIGHTEN-Early trial, researchers examined weight-gain profiles of more than 400 patients with early schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, or bipolar I disorder.

Results showed those given combination treatment gained just over half the amount of weight as those given monotherapy. They were also 36% less likely to gain at least 10% of their body weight during the 12-week treatment period.

They indicate that the weight-mitigating effects shown with olanzapine plus samidorphan are “consistent, regardless of the stage of illness,” Dr. Kahn added.

He presented the findings at the annual congress of the Schizophrenia International Research Society.

Potential benefit

“Early intervention with antipsychotic treatment is critical in shaping the course of treatment and the disease trajectory,” coinvestigator Christine Graham, PhD, with Alkermes, which manufactures the drug, told this news organization.

Olanzapine is a “highly effective antipsychotic, but it’s really avoided a lot in this population,” Dr. Graham said. Therefore, patients “could really stand to benefit” from a combination that delivers the same amount of antipsychotic effect, but “reduces the propensity” for clinically significant weight gain, she added.

Dr. Kahn noted in his meeting presentation that antipsychotics are the “cornerstone” of the treatment of serious mental illness, but that “many are associated with concerning weight gain and cardiometabolic effects.”

While olanzapine is an effective medication, it has “one of the highest weight gain” profiles of the available antipsychotics and patients early on in their illness are “especially vulnerable,” Dr. Kahn said.

Previous studies have shown the combination of olanzapine plus samidorphan is similarly effective as olanzapine, but is associated with less weight gain.

To determine its impact in recent-onset illness, the current researchers screened patients with schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, or bipolar I disorder. The patients were aged 16-39 years and had an initial onset of active phase symptoms less than 4 years previously. They had less than 24 weeks’ cumulative lifetime exposure to antipsychotics.

Participants were randomly assigned to receive olanzapine plus samidorphan or olanzapine alone for 12 weeks, and then followed up for safety assessment for a further 4 weeks.

A total of 426 patients were recruited and 76.5% completed the study. The mean age was 25.8 years, 66.2% were men, 66.4% were White, and 28.2% were Black.

The mean body mass index at baseline was 23.69 kg/m2. The most common diagnosis among the participants was schizophrenia (62.9%) followed by bipolar I disorder (21.6%).

Less weight gain

Results of the 12-week study showed a significant difference in percent change in body weight from baseline between the two treatment groups, with a gain of 4.91% for the olanzapine plus samidorphan group vs. 6.77% for the olanzapine-alone group (between-group difference, 1.87%; P = .012).

Dr. Kahn noted this equates to an average weight gain of 2.8 kg (6.2 pounds) with olanzapine plus samidorphan and a gain of about 5 kg (11pounds) with olanzapine.

“It’s not a huge difference, but it’s certainly a significant one,” he said. “I also think it’s clinically important and significant.”

The reduction in weight gain compared with olanzapine was even maintained in patients assigned to olanzapine plus samidorphan who dropped out and did not complete the study, Dr. Kahn reported. “No one really had a weight gain,” he said.

In contrast, patients in the olanzapine groups who dropped out of the study had weight gain larger than their counterparts who stayed in it.

Further analysis showed the proportion of patients who gained 10% or more of their body weight by week 12 was 21.9% for those receiving olanzapine plus samidorphan vs. 30.4% for those receiving just olanzapine (odds ratio, 0.64; P = .075).

As expected, the improvement in Clinical Global Impression–Severity scale scores was almost identical between the olanzapine + samidorphan and olanzapine-only groups.

For safety, Dr. Kahn said the adverse event rates were “very, very similar” between the two treatment arms, which was a pattern that was repeated for serious AEs. This led him to note that “nothing out of the ordinary” was observed.

Clinical impact 'questionable'

Commenting on the study, Laura LaChance, MD, a psychiatrist at St. Mary’s Hospital Centre, McGill University, Montreal, said the actual amount of weight loss shown in the study “is of questionable clinical significance.”

On the other hand, Dr. LaChance said she has achieved “better results with metformin, which has a great safety profile and is cheap and widely available.

“Cost is always a concern in patients with psychotic disorders,” she concluded.

The study was funded by Alkermes. Dr. Kahn reported having relationships with Alkermes, Angelini, Janssen, Sunovion, Otsuka, Merck, Minerva Neuroscience, Roche, and Teva. Dr. Graham is an employee of Alkermes.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM SIRS 2022

How effective are sterilization procedures? Study raises questions

Women opt for sterilization for a variety of reasons, but the goal is the same: to avoid getting pregnant.

But a head-to-head study of two forms of female sterilization has found surprisingly high rates of failure with the procedures.

The study compared the effectiveness of hysteroscopic sterilization, a nonincisional procedure, and minimally invasive laparoscopic sterilization. Although both methods prevented pregnancy in the vast majority of women, each was associated with more than a 6% failure rate 5 years after the procedure.

That figure is “much higher than expected,” said Aileen Gariepy, MD, MPH, the director of complex family planning at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, who led the study.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists reported that the chance of pregnancy after sterilization is less than 1%, Dr. Gariepy said. “Women and pregnancy-capable people considering sterilization should be informed that, after the procedure, they have at least a 6% – not 1% – chance of pregnancy in the next 5 years.”

The study was published in Fertility and Sterility.

For laparoscopic sterilization, surgeons close or sever the fallopian tubes to prevent eggs from reaching the uterus and becoming fertilized.

Hysteroscopic sterilization involves the implantation of small, flexible metal coils into each fallopian tube, a process that produces inflammation and scarring that in turn prevents pregnancy. This method, called Essure and formerly marketed by Bayer, received approval by the Food and Drug Administration in 2002. But the agency received thousands of reports of adverse events with Essure, prompting regulators in 2016 to add a boxed warning to the product label about the risk for adverse events, including perforation, migration of the coils, allergic reactions, and pain.

Bayer pulled Essure from the market in 2019, citing decreased sales of the product. Some women did not have the device removed, however, and questions remain about its effectiveness, according to the researchers.

In the new study, Dr. Gariepy and colleagues examined Medicaid claims for 5906 hysteroscopic and 23,965 laparoscopic sterilizations performed in California between 2008 and 2014. They excluded sterilizations that were performed immediately after delivery, which involve a different approach.

The average age of the women in the study was 33 years.

The study found that, 5 years after the sterilization procedure, 6% of women in either group had become pregnant.

Despite the surprising new data, Chailee Moss, MD, an assistant professor of gynecology and obstetrics at Johns Hopkins University Medical Center, Baltimore, said she did not think the study would significantly affect the way she counsels her patients.

The main reason, she said, is that the study relied on an analysis of medical claims, which “is likely inferior to careful review of individual patient records or prospective collection of clinical data.” Home pregnancy tests may easily be excluded from such data and that patients can undergo ultrasound and termination procedures that would likely not be included in the data the researchers analyzed.

Dr. Moss added that the study was limited to California and that the researchers could not determine pregnancy rates for women who moved out of the state and thus received pregnancy care elsewhere. Nor did the authors account for the use of assistive reproductive technology, which can facilitate pregnancy after sterilization despite the success of the original procedure.

Dr. Gariepy, however, said the study may in fact have undercounted pregnancies and that the failure rates might be even higher than 6%, noting that California is “one of the largest, most populous and most diverse states” in terms of race, ethnicity, and other factors, making the new findings highly generalizable.

“I agree that study results should be confirmed by new nationwide study to determine risk of pregnancy after different sterilization methods,” she said. “Nevertheless, this retrospective cohort study delivers a strong signal that doctors and patients need to know about.”

Dr. Gariepy is on the board of directors of the Society of Family Planning. Dr. Moss has received research funding from Merck.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Women opt for sterilization for a variety of reasons, but the goal is the same: to avoid getting pregnant.

But a head-to-head study of two forms of female sterilization has found surprisingly high rates of failure with the procedures.

The study compared the effectiveness of hysteroscopic sterilization, a nonincisional procedure, and minimally invasive laparoscopic sterilization. Although both methods prevented pregnancy in the vast majority of women, each was associated with more than a 6% failure rate 5 years after the procedure.

That figure is “much higher than expected,” said Aileen Gariepy, MD, MPH, the director of complex family planning at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, who led the study.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists reported that the chance of pregnancy after sterilization is less than 1%, Dr. Gariepy said. “Women and pregnancy-capable people considering sterilization should be informed that, after the procedure, they have at least a 6% – not 1% – chance of pregnancy in the next 5 years.”

The study was published in Fertility and Sterility.

For laparoscopic sterilization, surgeons close or sever the fallopian tubes to prevent eggs from reaching the uterus and becoming fertilized.

Hysteroscopic sterilization involves the implantation of small, flexible metal coils into each fallopian tube, a process that produces inflammation and scarring that in turn prevents pregnancy. This method, called Essure and formerly marketed by Bayer, received approval by the Food and Drug Administration in 2002. But the agency received thousands of reports of adverse events with Essure, prompting regulators in 2016 to add a boxed warning to the product label about the risk for adverse events, including perforation, migration of the coils, allergic reactions, and pain.

Bayer pulled Essure from the market in 2019, citing decreased sales of the product. Some women did not have the device removed, however, and questions remain about its effectiveness, according to the researchers.

In the new study, Dr. Gariepy and colleagues examined Medicaid claims for 5906 hysteroscopic and 23,965 laparoscopic sterilizations performed in California between 2008 and 2014. They excluded sterilizations that were performed immediately after delivery, which involve a different approach.

The average age of the women in the study was 33 years.

The study found that, 5 years after the sterilization procedure, 6% of women in either group had become pregnant.

Despite the surprising new data, Chailee Moss, MD, an assistant professor of gynecology and obstetrics at Johns Hopkins University Medical Center, Baltimore, said she did not think the study would significantly affect the way she counsels her patients.

The main reason, she said, is that the study relied on an analysis of medical claims, which “is likely inferior to careful review of individual patient records or prospective collection of clinical data.” Home pregnancy tests may easily be excluded from such data and that patients can undergo ultrasound and termination procedures that would likely not be included in the data the researchers analyzed.

Dr. Moss added that the study was limited to California and that the researchers could not determine pregnancy rates for women who moved out of the state and thus received pregnancy care elsewhere. Nor did the authors account for the use of assistive reproductive technology, which can facilitate pregnancy after sterilization despite the success of the original procedure.

Dr. Gariepy, however, said the study may in fact have undercounted pregnancies and that the failure rates might be even higher than 6%, noting that California is “one of the largest, most populous and most diverse states” in terms of race, ethnicity, and other factors, making the new findings highly generalizable.

“I agree that study results should be confirmed by new nationwide study to determine risk of pregnancy after different sterilization methods,” she said. “Nevertheless, this retrospective cohort study delivers a strong signal that doctors and patients need to know about.”

Dr. Gariepy is on the board of directors of the Society of Family Planning. Dr. Moss has received research funding from Merck.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Women opt for sterilization for a variety of reasons, but the goal is the same: to avoid getting pregnant.

But a head-to-head study of two forms of female sterilization has found surprisingly high rates of failure with the procedures.

The study compared the effectiveness of hysteroscopic sterilization, a nonincisional procedure, and minimally invasive laparoscopic sterilization. Although both methods prevented pregnancy in the vast majority of women, each was associated with more than a 6% failure rate 5 years after the procedure.

That figure is “much higher than expected,” said Aileen Gariepy, MD, MPH, the director of complex family planning at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, who led the study.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists reported that the chance of pregnancy after sterilization is less than 1%, Dr. Gariepy said. “Women and pregnancy-capable people considering sterilization should be informed that, after the procedure, they have at least a 6% – not 1% – chance of pregnancy in the next 5 years.”

The study was published in Fertility and Sterility.

For laparoscopic sterilization, surgeons close or sever the fallopian tubes to prevent eggs from reaching the uterus and becoming fertilized.

Hysteroscopic sterilization involves the implantation of small, flexible metal coils into each fallopian tube, a process that produces inflammation and scarring that in turn prevents pregnancy. This method, called Essure and formerly marketed by Bayer, received approval by the Food and Drug Administration in 2002. But the agency received thousands of reports of adverse events with Essure, prompting regulators in 2016 to add a boxed warning to the product label about the risk for adverse events, including perforation, migration of the coils, allergic reactions, and pain.

Bayer pulled Essure from the market in 2019, citing decreased sales of the product. Some women did not have the device removed, however, and questions remain about its effectiveness, according to the researchers.

In the new study, Dr. Gariepy and colleagues examined Medicaid claims for 5906 hysteroscopic and 23,965 laparoscopic sterilizations performed in California between 2008 and 2014. They excluded sterilizations that were performed immediately after delivery, which involve a different approach.

The average age of the women in the study was 33 years.

The study found that, 5 years after the sterilization procedure, 6% of women in either group had become pregnant.

Despite the surprising new data, Chailee Moss, MD, an assistant professor of gynecology and obstetrics at Johns Hopkins University Medical Center, Baltimore, said she did not think the study would significantly affect the way she counsels her patients.

The main reason, she said, is that the study relied on an analysis of medical claims, which “is likely inferior to careful review of individual patient records or prospective collection of clinical data.” Home pregnancy tests may easily be excluded from such data and that patients can undergo ultrasound and termination procedures that would likely not be included in the data the researchers analyzed.

Dr. Moss added that the study was limited to California and that the researchers could not determine pregnancy rates for women who moved out of the state and thus received pregnancy care elsewhere. Nor did the authors account for the use of assistive reproductive technology, which can facilitate pregnancy after sterilization despite the success of the original procedure.

Dr. Gariepy, however, said the study may in fact have undercounted pregnancies and that the failure rates might be even higher than 6%, noting that California is “one of the largest, most populous and most diverse states” in terms of race, ethnicity, and other factors, making the new findings highly generalizable.

“I agree that study results should be confirmed by new nationwide study to determine risk of pregnancy after different sterilization methods,” she said. “Nevertheless, this retrospective cohort study delivers a strong signal that doctors and patients need to know about.”

Dr. Gariepy is on the board of directors of the Society of Family Planning. Dr. Moss has received research funding from Merck.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM FERTILITY AND STERILITY

Second-trimester blood test predicts preterm birth

A new blood test performed in the second trimester could help identify pregnancies at risk of early and very early spontaneous preterm birth (sPTB), based on a prospective cohort trial.

The cell-free RNA (cfRNA) profiling tool could guide patient and provider decision-making, while the underlying research illuminates biological pathways that may facilitate novel interventions, reported lead author Joan Camunas-Soler, PhD, of Mirvie, South San Francisco, and colleagues.

“Given the complex etiology of this heterogeneous syndrome, it would be advantageous to develop predictive tests that provide insight on the specific pathophysiology leading to preterm birth for each particular pregnancy,” Dr. Camunas-Soler and colleagues wrote in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. “Such an approach could inform the development of preventive treatments and targeted therapeutics that are currently lacking/difficult to implement due to the heterogeneous etiology of sPTB.”

Currently, the best predictor of sPTB is previous sPTB, according to the investigators. Although a combination approach that incorporates cervical length and fetal fibronectin in cervicovaginal fluid is “of use,” they noted, “this is not standard of care in the U.S.A. nor recommended by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists or the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.” Existing molecular tests lack clinical data and may be inaccurate across diverse patient populations, they added.

The present study aimed to address these shortcomings by creating a second-trimester blood test for predicting sPTB. To identify relevant biomarkers, the investigators compared RNA profiles that were differentially expressed in three types of cases: term birth, early sPTB, and very early sPTB.

Among 242 women who contributed second-trimester blood samples for analysis, 194 went on to have a term birth. Of the remaining 48 women who gave birth spontaneously before 35 weeks’ gestation, 32 delivered between 25 and 35 weeks (early sPTB), while 16 delivered before 25 weeks’ gestation (very early sPTB). Slightly more than half of the patients were White, about one-third were Black, approximately 10% were Asian, and the remainder were of unknown race/ethnicity. Cases of preeclampsia were excluded.

The gene discovery and modeling process revealed 25 distinct genes that were significantly associated with early sPTB, offering a risk model with a sensitivity of 76% and a specificity of 72% (area under the curve, 0.80; 95% confidence interval, 0.72-0.87). Very early sPTB was associated with a set of 39 genes, giving a model with a sensitivity of 64% and a specificity of 80% (area under the curve = 0.76; 95% CI, 0.63-0.87).

Characterization of the two RNA profiles offered a glimpse into the underlying biological processes driving preterm birth. The genes predicting early sPTB are largely responsible for extracellular matrix degradation and remodeling, which could, “in terms of mechanism, reflect ongoing processes associated with cervical shortening, a feature often detected some weeks prior to sPTB,” the investigators wrote. In contrast, genes associated with very early sPTB are linked with insulinlike growth factor transport, which drives fetal growth and placentation. These findings could lead to development of pathway-specific interventions, Dr. Camunas-Soler and colleagues suggested.

According to coauthor Michal A. Elovitz, MD, the Hilarie L. Morgan and Mitchell L. Morgan President’s Distinguished Professor in Women’s Health at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and chief medical advisor at Mirvie, the proprietary RNA platform moves beyond “unreliable and at times biased clinical factors such as race, BMI, and maternal age” to offer a “precision-based approach to pregnancy health.”

Excluding traditional risk factors also “promises more equitable care than the use of broad sociodemographic factors that often result in bias,” she added, noting that this may help address the higher rate of pregnancy complications among Black patients.

When asked about the potential for false-positive results, considering reported specificity rates of 72%-80%, Dr. Elovitz suggested that such concerns among pregnant women are an “unfortunate misconception.”

“It is not reflective of what women want regarding knowledge about the health of their pregnancy,” she said in a written comment. “Rather than be left in the dark, women want to be prepared for what is to come in their pregnancy journey.”

In support of this statement, Dr. Elovitz cited a recent study involving women with preeclampsia and other hypertensive disorders in pregnancy. A questionnaire showed that women appreciated pregnancy risk models when making decisions, and reported that they would have greater peace of mind if such tests were available.

Laura Jelliffe-Pawlowski, PhD, of the University of California, San Francisco, California Preterm Birth Initiative, supported Dr. Elovitz’s viewpoint.

“If you talk to women who have delivered preterm most (but not all) say that they would have wanted to know their risk so they could have been better prepared,” she said in a written comment. “I think we need to shift the narrative to empowerment away from fear.”

Dr. Jelliffe-Pawlowski, who holds a patent for a separate test predicting preterm birth, said that the Mirvie RNA platform is “promising,” although she expressed concern that excluding patients with preeclampsia – representing approximately 4% of pregnancies in the United States – may have clouded accuracy results.

“What is unclear is how the test would perform more generally when a sample of all pregnancies was included,” she said. “Without that information, it is hard to compare their findings with other predictive models without such exclusions.”

Regardless of the model used, Dr. Jelliffe-Pawlowski said that more research is needed to determine best clinical responses when risk of sPTB is increased.

“Ultimately we want to connect action with results,” she said. “Okay, so [a woman] is at high risk for delivering preterm – now what? There is a lot of untapped potential once you start to focus more with women and birthing people you know have a high likelihood of preterm birth.”

The study was supported by Mirvie, Tommy’s Charity, and the National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre. The investigators disclosed financial relationships with Mirvie, including equity interest and/or intellectual property rights. Cohort contributors were remunerated for sample collection and/or shipping. Dr. Jelliffe-Pawlowski holds a patent for a different preterm birth prediction blood test.

*This story was updated on 4/26/2022.

A new blood test performed in the second trimester could help identify pregnancies at risk of early and very early spontaneous preterm birth (sPTB), based on a prospective cohort trial.

The cell-free RNA (cfRNA) profiling tool could guide patient and provider decision-making, while the underlying research illuminates biological pathways that may facilitate novel interventions, reported lead author Joan Camunas-Soler, PhD, of Mirvie, South San Francisco, and colleagues.

“Given the complex etiology of this heterogeneous syndrome, it would be advantageous to develop predictive tests that provide insight on the specific pathophysiology leading to preterm birth for each particular pregnancy,” Dr. Camunas-Soler and colleagues wrote in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. “Such an approach could inform the development of preventive treatments and targeted therapeutics that are currently lacking/difficult to implement due to the heterogeneous etiology of sPTB.”

Currently, the best predictor of sPTB is previous sPTB, according to the investigators. Although a combination approach that incorporates cervical length and fetal fibronectin in cervicovaginal fluid is “of use,” they noted, “this is not standard of care in the U.S.A. nor recommended by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists or the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.” Existing molecular tests lack clinical data and may be inaccurate across diverse patient populations, they added.

The present study aimed to address these shortcomings by creating a second-trimester blood test for predicting sPTB. To identify relevant biomarkers, the investigators compared RNA profiles that were differentially expressed in three types of cases: term birth, early sPTB, and very early sPTB.

Among 242 women who contributed second-trimester blood samples for analysis, 194 went on to have a term birth. Of the remaining 48 women who gave birth spontaneously before 35 weeks’ gestation, 32 delivered between 25 and 35 weeks (early sPTB), while 16 delivered before 25 weeks’ gestation (very early sPTB). Slightly more than half of the patients were White, about one-third were Black, approximately 10% were Asian, and the remainder were of unknown race/ethnicity. Cases of preeclampsia were excluded.

The gene discovery and modeling process revealed 25 distinct genes that were significantly associated with early sPTB, offering a risk model with a sensitivity of 76% and a specificity of 72% (area under the curve, 0.80; 95% confidence interval, 0.72-0.87). Very early sPTB was associated with a set of 39 genes, giving a model with a sensitivity of 64% and a specificity of 80% (area under the curve = 0.76; 95% CI, 0.63-0.87).

Characterization of the two RNA profiles offered a glimpse into the underlying biological processes driving preterm birth. The genes predicting early sPTB are largely responsible for extracellular matrix degradation and remodeling, which could, “in terms of mechanism, reflect ongoing processes associated with cervical shortening, a feature often detected some weeks prior to sPTB,” the investigators wrote. In contrast, genes associated with very early sPTB are linked with insulinlike growth factor transport, which drives fetal growth and placentation. These findings could lead to development of pathway-specific interventions, Dr. Camunas-Soler and colleagues suggested.

According to coauthor Michal A. Elovitz, MD, the Hilarie L. Morgan and Mitchell L. Morgan President’s Distinguished Professor in Women’s Health at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and chief medical advisor at Mirvie, the proprietary RNA platform moves beyond “unreliable and at times biased clinical factors such as race, BMI, and maternal age” to offer a “precision-based approach to pregnancy health.”

Excluding traditional risk factors also “promises more equitable care than the use of broad sociodemographic factors that often result in bias,” she added, noting that this may help address the higher rate of pregnancy complications among Black patients.

When asked about the potential for false-positive results, considering reported specificity rates of 72%-80%, Dr. Elovitz suggested that such concerns among pregnant women are an “unfortunate misconception.”

“It is not reflective of what women want regarding knowledge about the health of their pregnancy,” she said in a written comment. “Rather than be left in the dark, women want to be prepared for what is to come in their pregnancy journey.”

In support of this statement, Dr. Elovitz cited a recent study involving women with preeclampsia and other hypertensive disorders in pregnancy. A questionnaire showed that women appreciated pregnancy risk models when making decisions, and reported that they would have greater peace of mind if such tests were available.

Laura Jelliffe-Pawlowski, PhD, of the University of California, San Francisco, California Preterm Birth Initiative, supported Dr. Elovitz’s viewpoint.

“If you talk to women who have delivered preterm most (but not all) say that they would have wanted to know their risk so they could have been better prepared,” she said in a written comment. “I think we need to shift the narrative to empowerment away from fear.”

Dr. Jelliffe-Pawlowski, who holds a patent for a separate test predicting preterm birth, said that the Mirvie RNA platform is “promising,” although she expressed concern that excluding patients with preeclampsia – representing approximately 4% of pregnancies in the United States – may have clouded accuracy results.

“What is unclear is how the test would perform more generally when a sample of all pregnancies was included,” she said. “Without that information, it is hard to compare their findings with other predictive models without such exclusions.”

Regardless of the model used, Dr. Jelliffe-Pawlowski said that more research is needed to determine best clinical responses when risk of sPTB is increased.

“Ultimately we want to connect action with results,” she said. “Okay, so [a woman] is at high risk for delivering preterm – now what? There is a lot of untapped potential once you start to focus more with women and birthing people you know have a high likelihood of preterm birth.”

The study was supported by Mirvie, Tommy’s Charity, and the National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre. The investigators disclosed financial relationships with Mirvie, including equity interest and/or intellectual property rights. Cohort contributors were remunerated for sample collection and/or shipping. Dr. Jelliffe-Pawlowski holds a patent for a different preterm birth prediction blood test.

*This story was updated on 4/26/2022.

A new blood test performed in the second trimester could help identify pregnancies at risk of early and very early spontaneous preterm birth (sPTB), based on a prospective cohort trial.

The cell-free RNA (cfRNA) profiling tool could guide patient and provider decision-making, while the underlying research illuminates biological pathways that may facilitate novel interventions, reported lead author Joan Camunas-Soler, PhD, of Mirvie, South San Francisco, and colleagues.