User login

FDA-cleared panties could reduce STI risk during oral sex

.

The underwear, sold as Lorals for Protection, are single-use, vanilla-scented, natural latex panties that cover the genitals and anus and block the transfer of bodily fluids during oral sex, according to the company website. They sell in packages of four for $25.

The FDA didn’t run human clinical trials but granted authorization after the company gave it data about the product, The New York Times reported.

“The FDA’s authorization of this product gives people another option to protect against STIs during oral sex,” said Courtney Lias, PhD, director of the FDA office that led the review of the underwear.

Previously, the FDA authorized oral dams to prevent the spread of STIs during oral sex. Oral dams, sometimes called oral sex condoms, are thin latex barriers that go between one partner’s mouth and the other person’s genitals. The dams haven’t been widely used, partly because a person has to hold the dam in place during sex, unlike the panties.

“They’re extremely unpopular,” Jeanne Marrazzo, MD, director of the division of infectious diseases at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, told the Times. “I mean, honestly, could there be anything less sexy than a dental dam?”Melanie Cristol said she came up with the idea for the panties after discovering on her 2014 honeymoon that she had an infection that could be sexually transmitted.

“I wanted to feel sexy and confident and use something that was made with my body and actual sex in mind,” she told the Times.

The panties are made of material about as thin as a condom and form a seal on the thigh to keep fluids inside, she said.

Dr. Marrazzo said the panties are an advancement because there are few options for safe oral sex. She noted that some teenagers have their first sexual experience with oral sex and that the panties could reduce anxiety for people of all ages.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

.

The underwear, sold as Lorals for Protection, are single-use, vanilla-scented, natural latex panties that cover the genitals and anus and block the transfer of bodily fluids during oral sex, according to the company website. They sell in packages of four for $25.

The FDA didn’t run human clinical trials but granted authorization after the company gave it data about the product, The New York Times reported.

“The FDA’s authorization of this product gives people another option to protect against STIs during oral sex,” said Courtney Lias, PhD, director of the FDA office that led the review of the underwear.

Previously, the FDA authorized oral dams to prevent the spread of STIs during oral sex. Oral dams, sometimes called oral sex condoms, are thin latex barriers that go between one partner’s mouth and the other person’s genitals. The dams haven’t been widely used, partly because a person has to hold the dam in place during sex, unlike the panties.

“They’re extremely unpopular,” Jeanne Marrazzo, MD, director of the division of infectious diseases at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, told the Times. “I mean, honestly, could there be anything less sexy than a dental dam?”Melanie Cristol said she came up with the idea for the panties after discovering on her 2014 honeymoon that she had an infection that could be sexually transmitted.

“I wanted to feel sexy and confident and use something that was made with my body and actual sex in mind,” she told the Times.

The panties are made of material about as thin as a condom and form a seal on the thigh to keep fluids inside, she said.

Dr. Marrazzo said the panties are an advancement because there are few options for safe oral sex. She noted that some teenagers have their first sexual experience with oral sex and that the panties could reduce anxiety for people of all ages.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

.

The underwear, sold as Lorals for Protection, are single-use, vanilla-scented, natural latex panties that cover the genitals and anus and block the transfer of bodily fluids during oral sex, according to the company website. They sell in packages of four for $25.

The FDA didn’t run human clinical trials but granted authorization after the company gave it data about the product, The New York Times reported.

“The FDA’s authorization of this product gives people another option to protect against STIs during oral sex,” said Courtney Lias, PhD, director of the FDA office that led the review of the underwear.

Previously, the FDA authorized oral dams to prevent the spread of STIs during oral sex. Oral dams, sometimes called oral sex condoms, are thin latex barriers that go between one partner’s mouth and the other person’s genitals. The dams haven’t been widely used, partly because a person has to hold the dam in place during sex, unlike the panties.

“They’re extremely unpopular,” Jeanne Marrazzo, MD, director of the division of infectious diseases at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, told the Times. “I mean, honestly, could there be anything less sexy than a dental dam?”Melanie Cristol said she came up with the idea for the panties after discovering on her 2014 honeymoon that she had an infection that could be sexually transmitted.

“I wanted to feel sexy and confident and use something that was made with my body and actual sex in mind,” she told the Times.

The panties are made of material about as thin as a condom and form a seal on the thigh to keep fluids inside, she said.

Dr. Marrazzo said the panties are an advancement because there are few options for safe oral sex. She noted that some teenagers have their first sexual experience with oral sex and that the panties could reduce anxiety for people of all ages.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Psychosocial Barriers and Their Impact on Hepatocellular Carcinoma Care in US Veterans: Tumor Board Model of Care

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) remains a major global health problem and is the third leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide.1 Management of HCC is complex; as it largely occurs in the background of chronic liver disease, its management must simultaneously address challenges related to the patient’s tumor burden, as well as their underlying liver dysfunction and performance status. HCC is universally fatal without treatment, with a 5-year survival < 10%.2 However, if detected early HCC is potentially curable, with treatments such as hepatic resection, ablation, and/or liver transplantation, which are associated with 5-year survival rates as high as 70%.2 HCC-specific palliative treatments, including intra-arterial therapies (eg, trans-arterial chemoembolization, radioembolization) and systemic chemotherapy, have also been shown to prolong survival in patients with advanced HCC. Therefore, a key driver of patient survival is receipt of HCC-specific therapy.

There is rising incidence and mortality related to HCC in the US veteran population, largely attributed to acquisition of chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection decades prior.3 There is also a high prevalence of psychosocial barriers in this population, such as low socioeconomic status, homelessness, alcohol and substance use disorders, and psychiatric disorders which can negatively influence receipt of medical treatment, including cancer care.4,5 Given the complexity of managing HCC, as well as the plethora of potential treatment options available, it is widely accepted that a multidisciplinary team approach, such as the multidisciplinary tumor board (MDTB) provides optimal care to patients with HCC.2,6 The aim of the present study was to identify in a population of veterans diagnosed with HCC the prevalence of psychosocial barriers to care and assess their impact and the role of an MDTB on receipt of HCC-specific care.

Methods

In June 2007, a joint institutional MDTB was established for patients with primary liver tumors receiving care at the William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans’ Hospital (WSMMVH) in Madison, Wisconsin. As we have described elsewhere, individual cases with their corresponding imaging studies were reviewed at a weekly conference attended by transplant hepatologists, medical oncologists, hepatobiliary and transplant surgeons, pathologists, diagnostic and interventional radiologists, and nurse coordinators.6 Potential therapies offered included surgical resection, liver transplantation (LT), thermal ablation, intra-arterial therapies (chemo and/or radioembolization), systemic chemotherapy, stereotactic radiation, and best supportive care. Decisions regarding the appropriate treatment modality were made based on patient factors, review of their cross-sectional imaging studies and/or histopathology, and context of their underlying liver dysfunction. The tumor board discussion was summarized in meeting minutes as well as tumor board encounters recorded in each patient’s health record. Although patients with benign tumors were presented at the MDTB, only patients with a diagnosis of HCC were included in this study.

A database analysis was conducted of all veteran patients with HCC managed through the WSMMVH MDTB, since its inception up to December 31, 2016, with follow-up until December 31, 2018. Data for analysis included demographics, laboratory parameters at time of diagnosis and treatment, imaging findings, histopathology and/or surgical pathology, treatment rendered, and follow-up information. The primary outcome measured in this study included receipt of any therapy and secondarily, patient survival.

Discrete variables were analyzed with χ2 statistics or Fisher exact test and continuous variables with the student t test. Multivariable analyses were carried out with logistic regression. Variables with a P < .05 were considered statistically significant. Analyses were carried out using IBM SPSS v24.0.

As a quality-improvement initiative for the care and management of veterans with HCC, this study was determined to be exempt from review by the WSMMVH and University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health Institutional Review Board.

Results

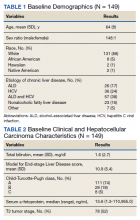

From January 1, 2007, through December 31, 2016, 149 patients with HCC were managed through the MDTB. Baseline demographic data, Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) score and Child-Turcotte-Pugh class, and baseline HCC characteristics of the cohort are shown in Tables 1 and 2.

There was a high prevalence of psychosocial barriers in our study cohort, including alcohol or substance use disorder, mental illness diagnosis, and low socioeconomic status (Table 3). The mean distance traveled to WSMMVH for HCC-specific care was 206 km. Fifty patients in the cohort utilized travel assistance and 33 patients accessed lodging assistance.

HCC Treatments

There was a high rate of receipt of treatment in our study cohort with 127 (85%) patients receiving at least one HCC-specific therapy. Care was individualized and coordinated through our institutional MDTB, with both curative and palliative treatment modalities utilized (Table 4).

Curative treatment, which includes LT, ablation, or resection, was offered to 78 (52%) patients who were within T2 stage. Of these 78 patients who were potential candidates for LT as a curative treatment for HCC, 31 were not deemed suitable transplant candidates. Psychosocial barriers precluded consideration for LT in 7 of the 31 patients due to active substance use, homelessness in 1 patient, and severe mental illness in 3 patients. Medical comorbidities, advanced patient age, and patient preference accounted for the remainder.

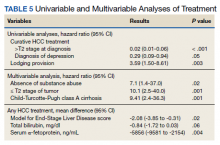

In a univariate analysis of the cohort of 149 patients, factors that decreased the likelihood of receipt of curative HCC therapy included T2 stage or higher at diagnosis and a diagnosis of depression, whereas provision for lodging was associated with increased likelihood of receiving HCC-specific care (Table 5). Other factors that influenced receipt of any treatment included patient’s MELD score, total bilirubin, and serum α-fetoprotein, a surrogate marker for tumor stage. In the multivariable analysis, predictors of receiving curative therapy included absence of substance use, within T2 stage of tumor, and Child-Turcotte-Pugh class A cirrhosis. The presence of psychosocial barriers apart from substance use did not predict a lower chance of receiving curative HCC therapy (including homelessness, distance traveled to center, mental health disorder, and low income).

Median survival was 727 (95% CI, 488-966) days from diagnosis. Survival from HCC diagnosis in study cohort was 72% at 1 year, 50% at 2 years, 39% at 3 years, and 36% at 5 years. Death occurred in 71 (48%) patients; HCC accounted for death in 52 (73%) patients, complications of end-stage liver disease in 13 (18%) patients, and other causes for the remainder of patients.

Discussion

Increases in prevalence and mortality related to cirrhosis and HCC have been reported among the US veteran population.3 This is in large part attributable to the burden of chronic HCV infection in this population. As mirrored in the US population in general, we may be at a turning point regarding the gradual increase in prevalence in HCC.7 The prevalence of cirrhosis and viral-related HCC related to HCV infection will decline with availability of effective antiviral therapy. Alcoholic liver disease remains a main etiological factor for development of cirrhosis and HCC. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is becoming a more prevalent cause for development of cirrhosis, indication for liver transplantation, and development of HCC, and indeed may lead to HCC even in the absence of cirrhosis.8

HCC remains a challenging clinical problem.2 As the vast majority of cases arise in the context of cirrhosis, management of HCC not only must address the cancer stage at diagnosis, but also the patient’s underlying liver dysfunction and performance status. Receipt of HCC-specific therapy is a key driver of patient outcome, with curative therapies available for those diagnosed with early-stage disease. We and others have shown that a multidisciplinary approach to coordinate, individualize, and optimize care for these complex patients can improve the rate of treatment utilization, reduce treatment delays, and improve patient survival.6,9,10

Patient psychosocial barriers, such as low socioeconomic status, homelessness, alcohol and substance use, and psychiatric disorders, are more prevalent among the veteran population and have the potential to negatively influence successful health care delivery. One retrospective study of 100 veterans at a US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical center treated for HCC from 2009 to 2014 showed a majority of the patients lived on a meager income, a high prevalence of homelessness, substance use history in 96% of their cohort, and psychiatric illness in 65% of patients.11 Other studies have documented similar findings in the veteran population, with alcohol, substance use, as well as other uncontrolled comorbidities as barriers to providing care, such as antiviral therapy for chronic HCV infection.12

Herein, we present a cohort of veterans with HCC managed through our MDTB from 2007 to 2016, for whom chronic HCV infection and/or alcoholic liver disease were the main causes of cirrhosis. Our cohort had a high burden of alcohol and substance use disorders while other psychiatric illnesses were also common. Our cohort includes patients who were poor, and even some veterans who lacked a stable home. This profile of poverty and social deprivation among veterans is matched in national data.13-15 Using a tumor board model of nurse navigation and multidisciplinary care, we were able to provide travel and lodging assistance to 50 (34%) and 33 (22%) patients, respectively, in order to facilitate their care.

Our data demonstrate that the impact of psychosocial barriers on our capacity to deliver care varies with the nature of the treatment under consideration: curative vs cancer control. For example, active substance use disorder, homelessness, and severe established mental illness were often considered insurmountable when the treatment in question was LT. Nevertheless, despite the high prevalence in our study group of barriers, such as lack of transport while living far from a VA medical center, or alcohol use disorder, a curative treatment with either LT, tumor ablation, or resection could be offered to over half of our cohort. When noncurative therapies are included, most patients (85%) received HCC-specific care, with good relative survival.

Our reported high receipt of HCC-specific care and patient survival is in contrast to previously reported low rates of HCC-specific care in in a national survey of management of 1296 veteran patients infected with HCV who developed HCC from 1998 to 2006. In this population, HCC-specific treatment was provided to 34%.16 However our data are consistent with our previously published data of patients with HCC managed through an institutional MDTB.6 Indeed, as shown by a univariate analysis in our present study, individualizing care to address modifiable patient barriers, such as providing provisions for lodging if needed, was associated with an increased likelihood of receiving HCC-specific care. On the other hand, advanced tumor stage (> T2) at diagnosis and a diagnosis of depression, which was the most common psychiatric diagnosis in our cohort, were both associated with decreased likelihood of receiving HCC-specific care. Clinical factors such as MELD score, total bilirubin, and serum AFP all affected the likelihood of providing HCC-specific care. In a multivariate analysis, factors that predicted ability to receive curative therapy included absence of substance use, T2 stage of tumor, and Child-Turcotte-Pugh class A cirrhosis. This is expected as patients with HCC within T2 stage (or Milan criteria) with compensated cirrhosis are most likely to receive curative therapies, such as resection, ablation, or LT.2

Conclusions

Our study demonstrates a high burden of psychosocial challenges in veterans with HCC. These accounted for a significant barrier to receive HCC-specific care. Despite the presence of these patient barriers, high rates of HCC-specific treatment are attainable through individualization and coordination of patient care in the context of a MDTB model with nurse navigation. Provision of targeted social support to ameliorate these modifiable factors improves patient outcomes.

1. McGlynn KA, Petrick JL, El-Serag HB. Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2021;73(suppl 1):4-13. doi:10.1002/hep.31288.

2. Marrero JA, Kulik LM, Sirlin CB, et al. Diagnosis, staging, and management of hepatocellular carcinoma: 2018 practice guidance by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2018;68(2):723-750. doi:10.1002/hep.29913

3. Beste LA, Leipertz SL, Green PK, Dominitz JA, Ross D, Ioannou GN. Trends in burden of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma by underlying liver disease in US veterans, 2001-2013. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(6):1471-e18. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2015.07.056

4. Kazis LE, Miller DR, Clark J, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients served by the Department of Veterans Affairs: results from the Veterans Health Study. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(6):626-632. doi:10.1001/archinte.158.6.626

5. Slind LM, Keating TM, Fisher AG, Rose TG. A patient navigation model for veterans traveling for cancer care. Fed Pract. 2016;33(suppl 1):40S-45S.

6. Agarwal PD, Phillips P, Hillman L, et al. Multidisciplinary management of hepatocellular carcinoma improves access to therapy and patient survival. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;51(9):845-849. doi:10.1097/MCG.0000000000000825

7. White DL, Thrift AP, Kanwal F, Davila J, El-Serag HB. Incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in all 50 United States, From 2000 Through 2012. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(4):812-820.e5. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2016.11.020

8. Kanwal F, Kramer JR, Mapakshi S, et al. Risk of hepatocellular cancer in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(6):1828-1837.e2. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2018.08.024

9. Yopp AC, Mansour JC, Beg MS, et al. Establishment of a multidisciplinary hepatocellular carcinoma clinic is associated with improved clinical outcome. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(4):1287-1295. doi:10.1245/s10434-013-3413-8

10. Chang TT, Sawhney R, Monto A, et al. Implementation of a multidisciplinary treatment team for hepatocellular cancer at a Veterans Affairs Medical Center improves survival. HPB (Oxford). 2008;10(6):405-411. doi:10.1080/13651820802356572

11. Hwa KJ, Dua MM, Wren SM, Visser BC. Missing the obvious: psychosocial obstacles in veterans with hepatocellular carcinoma. HPB (Oxford). 2015;17(12):1124-1129. doi:10.1111/hpb.12508

12. Taylor J, Carr-Lopez S, Robinson A, et al. Determinants of treatment eligibility in veterans with hepatitis C viral infection. Clin Ther. 2017;39(1):130-137. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2016.11.019

13. Fargo J, Metraux S, Byrne T, et al. Prevalence and risk of homelessness among US veterans. Prev Chronic Dis. 2012;9:E45.

14. Tsai J, Rosenheck RA. Risk factors for homelessness among US veterans. Epidemiol Rev. 2015;37:177-195. doi:10.1093/epirev/mxu004

15. Tsai J, Link B, Rosenheck RA, Pietrzak RH. Homelessness among a nationally representative sample of US veterans: prevalence, service utilization, and correlates. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2016;51(6):907-916. doi:10.1007/s00127-016-1210-y

16. Davila JA, Kramer JR, Duan Z, et al. Referral and receipt of treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma in United States veterans: effect of patient and nonpatient factors. Hepatology. 2013;57(5):1858-1868. doi:10.1002/hep.26287

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) remains a major global health problem and is the third leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide.1 Management of HCC is complex; as it largely occurs in the background of chronic liver disease, its management must simultaneously address challenges related to the patient’s tumor burden, as well as their underlying liver dysfunction and performance status. HCC is universally fatal without treatment, with a 5-year survival < 10%.2 However, if detected early HCC is potentially curable, with treatments such as hepatic resection, ablation, and/or liver transplantation, which are associated with 5-year survival rates as high as 70%.2 HCC-specific palliative treatments, including intra-arterial therapies (eg, trans-arterial chemoembolization, radioembolization) and systemic chemotherapy, have also been shown to prolong survival in patients with advanced HCC. Therefore, a key driver of patient survival is receipt of HCC-specific therapy.

There is rising incidence and mortality related to HCC in the US veteran population, largely attributed to acquisition of chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection decades prior.3 There is also a high prevalence of psychosocial barriers in this population, such as low socioeconomic status, homelessness, alcohol and substance use disorders, and psychiatric disorders which can negatively influence receipt of medical treatment, including cancer care.4,5 Given the complexity of managing HCC, as well as the plethora of potential treatment options available, it is widely accepted that a multidisciplinary team approach, such as the multidisciplinary tumor board (MDTB) provides optimal care to patients with HCC.2,6 The aim of the present study was to identify in a population of veterans diagnosed with HCC the prevalence of psychosocial barriers to care and assess their impact and the role of an MDTB on receipt of HCC-specific care.

Methods

In June 2007, a joint institutional MDTB was established for patients with primary liver tumors receiving care at the William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans’ Hospital (WSMMVH) in Madison, Wisconsin. As we have described elsewhere, individual cases with their corresponding imaging studies were reviewed at a weekly conference attended by transplant hepatologists, medical oncologists, hepatobiliary and transplant surgeons, pathologists, diagnostic and interventional radiologists, and nurse coordinators.6 Potential therapies offered included surgical resection, liver transplantation (LT), thermal ablation, intra-arterial therapies (chemo and/or radioembolization), systemic chemotherapy, stereotactic radiation, and best supportive care. Decisions regarding the appropriate treatment modality were made based on patient factors, review of their cross-sectional imaging studies and/or histopathology, and context of their underlying liver dysfunction. The tumor board discussion was summarized in meeting minutes as well as tumor board encounters recorded in each patient’s health record. Although patients with benign tumors were presented at the MDTB, only patients with a diagnosis of HCC were included in this study.

A database analysis was conducted of all veteran patients with HCC managed through the WSMMVH MDTB, since its inception up to December 31, 2016, with follow-up until December 31, 2018. Data for analysis included demographics, laboratory parameters at time of diagnosis and treatment, imaging findings, histopathology and/or surgical pathology, treatment rendered, and follow-up information. The primary outcome measured in this study included receipt of any therapy and secondarily, patient survival.

Discrete variables were analyzed with χ2 statistics or Fisher exact test and continuous variables with the student t test. Multivariable analyses were carried out with logistic regression. Variables with a P < .05 were considered statistically significant. Analyses were carried out using IBM SPSS v24.0.

As a quality-improvement initiative for the care and management of veterans with HCC, this study was determined to be exempt from review by the WSMMVH and University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health Institutional Review Board.

Results

From January 1, 2007, through December 31, 2016, 149 patients with HCC were managed through the MDTB. Baseline demographic data, Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) score and Child-Turcotte-Pugh class, and baseline HCC characteristics of the cohort are shown in Tables 1 and 2.

There was a high prevalence of psychosocial barriers in our study cohort, including alcohol or substance use disorder, mental illness diagnosis, and low socioeconomic status (Table 3). The mean distance traveled to WSMMVH for HCC-specific care was 206 km. Fifty patients in the cohort utilized travel assistance and 33 patients accessed lodging assistance.

HCC Treatments

There was a high rate of receipt of treatment in our study cohort with 127 (85%) patients receiving at least one HCC-specific therapy. Care was individualized and coordinated through our institutional MDTB, with both curative and palliative treatment modalities utilized (Table 4).

Curative treatment, which includes LT, ablation, or resection, was offered to 78 (52%) patients who were within T2 stage. Of these 78 patients who were potential candidates for LT as a curative treatment for HCC, 31 were not deemed suitable transplant candidates. Psychosocial barriers precluded consideration for LT in 7 of the 31 patients due to active substance use, homelessness in 1 patient, and severe mental illness in 3 patients. Medical comorbidities, advanced patient age, and patient preference accounted for the remainder.

In a univariate analysis of the cohort of 149 patients, factors that decreased the likelihood of receipt of curative HCC therapy included T2 stage or higher at diagnosis and a diagnosis of depression, whereas provision for lodging was associated with increased likelihood of receiving HCC-specific care (Table 5). Other factors that influenced receipt of any treatment included patient’s MELD score, total bilirubin, and serum α-fetoprotein, a surrogate marker for tumor stage. In the multivariable analysis, predictors of receiving curative therapy included absence of substance use, within T2 stage of tumor, and Child-Turcotte-Pugh class A cirrhosis. The presence of psychosocial barriers apart from substance use did not predict a lower chance of receiving curative HCC therapy (including homelessness, distance traveled to center, mental health disorder, and low income).

Median survival was 727 (95% CI, 488-966) days from diagnosis. Survival from HCC diagnosis in study cohort was 72% at 1 year, 50% at 2 years, 39% at 3 years, and 36% at 5 years. Death occurred in 71 (48%) patients; HCC accounted for death in 52 (73%) patients, complications of end-stage liver disease in 13 (18%) patients, and other causes for the remainder of patients.

Discussion

Increases in prevalence and mortality related to cirrhosis and HCC have been reported among the US veteran population.3 This is in large part attributable to the burden of chronic HCV infection in this population. As mirrored in the US population in general, we may be at a turning point regarding the gradual increase in prevalence in HCC.7 The prevalence of cirrhosis and viral-related HCC related to HCV infection will decline with availability of effective antiviral therapy. Alcoholic liver disease remains a main etiological factor for development of cirrhosis and HCC. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is becoming a more prevalent cause for development of cirrhosis, indication for liver transplantation, and development of HCC, and indeed may lead to HCC even in the absence of cirrhosis.8

HCC remains a challenging clinical problem.2 As the vast majority of cases arise in the context of cirrhosis, management of HCC not only must address the cancer stage at diagnosis, but also the patient’s underlying liver dysfunction and performance status. Receipt of HCC-specific therapy is a key driver of patient outcome, with curative therapies available for those diagnosed with early-stage disease. We and others have shown that a multidisciplinary approach to coordinate, individualize, and optimize care for these complex patients can improve the rate of treatment utilization, reduce treatment delays, and improve patient survival.6,9,10

Patient psychosocial barriers, such as low socioeconomic status, homelessness, alcohol and substance use, and psychiatric disorders, are more prevalent among the veteran population and have the potential to negatively influence successful health care delivery. One retrospective study of 100 veterans at a US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical center treated for HCC from 2009 to 2014 showed a majority of the patients lived on a meager income, a high prevalence of homelessness, substance use history in 96% of their cohort, and psychiatric illness in 65% of patients.11 Other studies have documented similar findings in the veteran population, with alcohol, substance use, as well as other uncontrolled comorbidities as barriers to providing care, such as antiviral therapy for chronic HCV infection.12

Herein, we present a cohort of veterans with HCC managed through our MDTB from 2007 to 2016, for whom chronic HCV infection and/or alcoholic liver disease were the main causes of cirrhosis. Our cohort had a high burden of alcohol and substance use disorders while other psychiatric illnesses were also common. Our cohort includes patients who were poor, and even some veterans who lacked a stable home. This profile of poverty and social deprivation among veterans is matched in national data.13-15 Using a tumor board model of nurse navigation and multidisciplinary care, we were able to provide travel and lodging assistance to 50 (34%) and 33 (22%) patients, respectively, in order to facilitate their care.

Our data demonstrate that the impact of psychosocial barriers on our capacity to deliver care varies with the nature of the treatment under consideration: curative vs cancer control. For example, active substance use disorder, homelessness, and severe established mental illness were often considered insurmountable when the treatment in question was LT. Nevertheless, despite the high prevalence in our study group of barriers, such as lack of transport while living far from a VA medical center, or alcohol use disorder, a curative treatment with either LT, tumor ablation, or resection could be offered to over half of our cohort. When noncurative therapies are included, most patients (85%) received HCC-specific care, with good relative survival.

Our reported high receipt of HCC-specific care and patient survival is in contrast to previously reported low rates of HCC-specific care in in a national survey of management of 1296 veteran patients infected with HCV who developed HCC from 1998 to 2006. In this population, HCC-specific treatment was provided to 34%.16 However our data are consistent with our previously published data of patients with HCC managed through an institutional MDTB.6 Indeed, as shown by a univariate analysis in our present study, individualizing care to address modifiable patient barriers, such as providing provisions for lodging if needed, was associated with an increased likelihood of receiving HCC-specific care. On the other hand, advanced tumor stage (> T2) at diagnosis and a diagnosis of depression, which was the most common psychiatric diagnosis in our cohort, were both associated with decreased likelihood of receiving HCC-specific care. Clinical factors such as MELD score, total bilirubin, and serum AFP all affected the likelihood of providing HCC-specific care. In a multivariate analysis, factors that predicted ability to receive curative therapy included absence of substance use, T2 stage of tumor, and Child-Turcotte-Pugh class A cirrhosis. This is expected as patients with HCC within T2 stage (or Milan criteria) with compensated cirrhosis are most likely to receive curative therapies, such as resection, ablation, or LT.2

Conclusions

Our study demonstrates a high burden of psychosocial challenges in veterans with HCC. These accounted for a significant barrier to receive HCC-specific care. Despite the presence of these patient barriers, high rates of HCC-specific treatment are attainable through individualization and coordination of patient care in the context of a MDTB model with nurse navigation. Provision of targeted social support to ameliorate these modifiable factors improves patient outcomes.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) remains a major global health problem and is the third leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide.1 Management of HCC is complex; as it largely occurs in the background of chronic liver disease, its management must simultaneously address challenges related to the patient’s tumor burden, as well as their underlying liver dysfunction and performance status. HCC is universally fatal without treatment, with a 5-year survival < 10%.2 However, if detected early HCC is potentially curable, with treatments such as hepatic resection, ablation, and/or liver transplantation, which are associated with 5-year survival rates as high as 70%.2 HCC-specific palliative treatments, including intra-arterial therapies (eg, trans-arterial chemoembolization, radioembolization) and systemic chemotherapy, have also been shown to prolong survival in patients with advanced HCC. Therefore, a key driver of patient survival is receipt of HCC-specific therapy.

There is rising incidence and mortality related to HCC in the US veteran population, largely attributed to acquisition of chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection decades prior.3 There is also a high prevalence of psychosocial barriers in this population, such as low socioeconomic status, homelessness, alcohol and substance use disorders, and psychiatric disorders which can negatively influence receipt of medical treatment, including cancer care.4,5 Given the complexity of managing HCC, as well as the plethora of potential treatment options available, it is widely accepted that a multidisciplinary team approach, such as the multidisciplinary tumor board (MDTB) provides optimal care to patients with HCC.2,6 The aim of the present study was to identify in a population of veterans diagnosed with HCC the prevalence of psychosocial barriers to care and assess their impact and the role of an MDTB on receipt of HCC-specific care.

Methods

In June 2007, a joint institutional MDTB was established for patients with primary liver tumors receiving care at the William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans’ Hospital (WSMMVH) in Madison, Wisconsin. As we have described elsewhere, individual cases with their corresponding imaging studies were reviewed at a weekly conference attended by transplant hepatologists, medical oncologists, hepatobiliary and transplant surgeons, pathologists, diagnostic and interventional radiologists, and nurse coordinators.6 Potential therapies offered included surgical resection, liver transplantation (LT), thermal ablation, intra-arterial therapies (chemo and/or radioembolization), systemic chemotherapy, stereotactic radiation, and best supportive care. Decisions regarding the appropriate treatment modality were made based on patient factors, review of their cross-sectional imaging studies and/or histopathology, and context of their underlying liver dysfunction. The tumor board discussion was summarized in meeting minutes as well as tumor board encounters recorded in each patient’s health record. Although patients with benign tumors were presented at the MDTB, only patients with a diagnosis of HCC were included in this study.

A database analysis was conducted of all veteran patients with HCC managed through the WSMMVH MDTB, since its inception up to December 31, 2016, with follow-up until December 31, 2018. Data for analysis included demographics, laboratory parameters at time of diagnosis and treatment, imaging findings, histopathology and/or surgical pathology, treatment rendered, and follow-up information. The primary outcome measured in this study included receipt of any therapy and secondarily, patient survival.

Discrete variables were analyzed with χ2 statistics or Fisher exact test and continuous variables with the student t test. Multivariable analyses were carried out with logistic regression. Variables with a P < .05 were considered statistically significant. Analyses were carried out using IBM SPSS v24.0.

As a quality-improvement initiative for the care and management of veterans with HCC, this study was determined to be exempt from review by the WSMMVH and University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health Institutional Review Board.

Results

From January 1, 2007, through December 31, 2016, 149 patients with HCC were managed through the MDTB. Baseline demographic data, Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) score and Child-Turcotte-Pugh class, and baseline HCC characteristics of the cohort are shown in Tables 1 and 2.

There was a high prevalence of psychosocial barriers in our study cohort, including alcohol or substance use disorder, mental illness diagnosis, and low socioeconomic status (Table 3). The mean distance traveled to WSMMVH for HCC-specific care was 206 km. Fifty patients in the cohort utilized travel assistance and 33 patients accessed lodging assistance.

HCC Treatments

There was a high rate of receipt of treatment in our study cohort with 127 (85%) patients receiving at least one HCC-specific therapy. Care was individualized and coordinated through our institutional MDTB, with both curative and palliative treatment modalities utilized (Table 4).

Curative treatment, which includes LT, ablation, or resection, was offered to 78 (52%) patients who were within T2 stage. Of these 78 patients who were potential candidates for LT as a curative treatment for HCC, 31 were not deemed suitable transplant candidates. Psychosocial barriers precluded consideration for LT in 7 of the 31 patients due to active substance use, homelessness in 1 patient, and severe mental illness in 3 patients. Medical comorbidities, advanced patient age, and patient preference accounted for the remainder.

In a univariate analysis of the cohort of 149 patients, factors that decreased the likelihood of receipt of curative HCC therapy included T2 stage or higher at diagnosis and a diagnosis of depression, whereas provision for lodging was associated with increased likelihood of receiving HCC-specific care (Table 5). Other factors that influenced receipt of any treatment included patient’s MELD score, total bilirubin, and serum α-fetoprotein, a surrogate marker for tumor stage. In the multivariable analysis, predictors of receiving curative therapy included absence of substance use, within T2 stage of tumor, and Child-Turcotte-Pugh class A cirrhosis. The presence of psychosocial barriers apart from substance use did not predict a lower chance of receiving curative HCC therapy (including homelessness, distance traveled to center, mental health disorder, and low income).

Median survival was 727 (95% CI, 488-966) days from diagnosis. Survival from HCC diagnosis in study cohort was 72% at 1 year, 50% at 2 years, 39% at 3 years, and 36% at 5 years. Death occurred in 71 (48%) patients; HCC accounted for death in 52 (73%) patients, complications of end-stage liver disease in 13 (18%) patients, and other causes for the remainder of patients.

Discussion

Increases in prevalence and mortality related to cirrhosis and HCC have been reported among the US veteran population.3 This is in large part attributable to the burden of chronic HCV infection in this population. As mirrored in the US population in general, we may be at a turning point regarding the gradual increase in prevalence in HCC.7 The prevalence of cirrhosis and viral-related HCC related to HCV infection will decline with availability of effective antiviral therapy. Alcoholic liver disease remains a main etiological factor for development of cirrhosis and HCC. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is becoming a more prevalent cause for development of cirrhosis, indication for liver transplantation, and development of HCC, and indeed may lead to HCC even in the absence of cirrhosis.8

HCC remains a challenging clinical problem.2 As the vast majority of cases arise in the context of cirrhosis, management of HCC not only must address the cancer stage at diagnosis, but also the patient’s underlying liver dysfunction and performance status. Receipt of HCC-specific therapy is a key driver of patient outcome, with curative therapies available for those diagnosed with early-stage disease. We and others have shown that a multidisciplinary approach to coordinate, individualize, and optimize care for these complex patients can improve the rate of treatment utilization, reduce treatment delays, and improve patient survival.6,9,10

Patient psychosocial barriers, such as low socioeconomic status, homelessness, alcohol and substance use, and psychiatric disorders, are more prevalent among the veteran population and have the potential to negatively influence successful health care delivery. One retrospective study of 100 veterans at a US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical center treated for HCC from 2009 to 2014 showed a majority of the patients lived on a meager income, a high prevalence of homelessness, substance use history in 96% of their cohort, and psychiatric illness in 65% of patients.11 Other studies have documented similar findings in the veteran population, with alcohol, substance use, as well as other uncontrolled comorbidities as barriers to providing care, such as antiviral therapy for chronic HCV infection.12

Herein, we present a cohort of veterans with HCC managed through our MDTB from 2007 to 2016, for whom chronic HCV infection and/or alcoholic liver disease were the main causes of cirrhosis. Our cohort had a high burden of alcohol and substance use disorders while other psychiatric illnesses were also common. Our cohort includes patients who were poor, and even some veterans who lacked a stable home. This profile of poverty and social deprivation among veterans is matched in national data.13-15 Using a tumor board model of nurse navigation and multidisciplinary care, we were able to provide travel and lodging assistance to 50 (34%) and 33 (22%) patients, respectively, in order to facilitate their care.

Our data demonstrate that the impact of psychosocial barriers on our capacity to deliver care varies with the nature of the treatment under consideration: curative vs cancer control. For example, active substance use disorder, homelessness, and severe established mental illness were often considered insurmountable when the treatment in question was LT. Nevertheless, despite the high prevalence in our study group of barriers, such as lack of transport while living far from a VA medical center, or alcohol use disorder, a curative treatment with either LT, tumor ablation, or resection could be offered to over half of our cohort. When noncurative therapies are included, most patients (85%) received HCC-specific care, with good relative survival.

Our reported high receipt of HCC-specific care and patient survival is in contrast to previously reported low rates of HCC-specific care in in a national survey of management of 1296 veteran patients infected with HCV who developed HCC from 1998 to 2006. In this population, HCC-specific treatment was provided to 34%.16 However our data are consistent with our previously published data of patients with HCC managed through an institutional MDTB.6 Indeed, as shown by a univariate analysis in our present study, individualizing care to address modifiable patient barriers, such as providing provisions for lodging if needed, was associated with an increased likelihood of receiving HCC-specific care. On the other hand, advanced tumor stage (> T2) at diagnosis and a diagnosis of depression, which was the most common psychiatric diagnosis in our cohort, were both associated with decreased likelihood of receiving HCC-specific care. Clinical factors such as MELD score, total bilirubin, and serum AFP all affected the likelihood of providing HCC-specific care. In a multivariate analysis, factors that predicted ability to receive curative therapy included absence of substance use, T2 stage of tumor, and Child-Turcotte-Pugh class A cirrhosis. This is expected as patients with HCC within T2 stage (or Milan criteria) with compensated cirrhosis are most likely to receive curative therapies, such as resection, ablation, or LT.2

Conclusions

Our study demonstrates a high burden of psychosocial challenges in veterans with HCC. These accounted for a significant barrier to receive HCC-specific care. Despite the presence of these patient barriers, high rates of HCC-specific treatment are attainable through individualization and coordination of patient care in the context of a MDTB model with nurse navigation. Provision of targeted social support to ameliorate these modifiable factors improves patient outcomes.

1. McGlynn KA, Petrick JL, El-Serag HB. Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2021;73(suppl 1):4-13. doi:10.1002/hep.31288.

2. Marrero JA, Kulik LM, Sirlin CB, et al. Diagnosis, staging, and management of hepatocellular carcinoma: 2018 practice guidance by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2018;68(2):723-750. doi:10.1002/hep.29913

3. Beste LA, Leipertz SL, Green PK, Dominitz JA, Ross D, Ioannou GN. Trends in burden of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma by underlying liver disease in US veterans, 2001-2013. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(6):1471-e18. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2015.07.056

4. Kazis LE, Miller DR, Clark J, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients served by the Department of Veterans Affairs: results from the Veterans Health Study. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(6):626-632. doi:10.1001/archinte.158.6.626

5. Slind LM, Keating TM, Fisher AG, Rose TG. A patient navigation model for veterans traveling for cancer care. Fed Pract. 2016;33(suppl 1):40S-45S.

6. Agarwal PD, Phillips P, Hillman L, et al. Multidisciplinary management of hepatocellular carcinoma improves access to therapy and patient survival. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;51(9):845-849. doi:10.1097/MCG.0000000000000825

7. White DL, Thrift AP, Kanwal F, Davila J, El-Serag HB. Incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in all 50 United States, From 2000 Through 2012. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(4):812-820.e5. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2016.11.020

8. Kanwal F, Kramer JR, Mapakshi S, et al. Risk of hepatocellular cancer in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(6):1828-1837.e2. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2018.08.024

9. Yopp AC, Mansour JC, Beg MS, et al. Establishment of a multidisciplinary hepatocellular carcinoma clinic is associated with improved clinical outcome. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(4):1287-1295. doi:10.1245/s10434-013-3413-8

10. Chang TT, Sawhney R, Monto A, et al. Implementation of a multidisciplinary treatment team for hepatocellular cancer at a Veterans Affairs Medical Center improves survival. HPB (Oxford). 2008;10(6):405-411. doi:10.1080/13651820802356572

11. Hwa KJ, Dua MM, Wren SM, Visser BC. Missing the obvious: psychosocial obstacles in veterans with hepatocellular carcinoma. HPB (Oxford). 2015;17(12):1124-1129. doi:10.1111/hpb.12508

12. Taylor J, Carr-Lopez S, Robinson A, et al. Determinants of treatment eligibility in veterans with hepatitis C viral infection. Clin Ther. 2017;39(1):130-137. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2016.11.019

13. Fargo J, Metraux S, Byrne T, et al. Prevalence and risk of homelessness among US veterans. Prev Chronic Dis. 2012;9:E45.

14. Tsai J, Rosenheck RA. Risk factors for homelessness among US veterans. Epidemiol Rev. 2015;37:177-195. doi:10.1093/epirev/mxu004

15. Tsai J, Link B, Rosenheck RA, Pietrzak RH. Homelessness among a nationally representative sample of US veterans: prevalence, service utilization, and correlates. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2016;51(6):907-916. doi:10.1007/s00127-016-1210-y

16. Davila JA, Kramer JR, Duan Z, et al. Referral and receipt of treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma in United States veterans: effect of patient and nonpatient factors. Hepatology. 2013;57(5):1858-1868. doi:10.1002/hep.26287

1. McGlynn KA, Petrick JL, El-Serag HB. Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2021;73(suppl 1):4-13. doi:10.1002/hep.31288.

2. Marrero JA, Kulik LM, Sirlin CB, et al. Diagnosis, staging, and management of hepatocellular carcinoma: 2018 practice guidance by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2018;68(2):723-750. doi:10.1002/hep.29913

3. Beste LA, Leipertz SL, Green PK, Dominitz JA, Ross D, Ioannou GN. Trends in burden of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma by underlying liver disease in US veterans, 2001-2013. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(6):1471-e18. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2015.07.056

4. Kazis LE, Miller DR, Clark J, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients served by the Department of Veterans Affairs: results from the Veterans Health Study. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(6):626-632. doi:10.1001/archinte.158.6.626

5. Slind LM, Keating TM, Fisher AG, Rose TG. A patient navigation model for veterans traveling for cancer care. Fed Pract. 2016;33(suppl 1):40S-45S.

6. Agarwal PD, Phillips P, Hillman L, et al. Multidisciplinary management of hepatocellular carcinoma improves access to therapy and patient survival. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;51(9):845-849. doi:10.1097/MCG.0000000000000825

7. White DL, Thrift AP, Kanwal F, Davila J, El-Serag HB. Incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in all 50 United States, From 2000 Through 2012. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(4):812-820.e5. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2016.11.020

8. Kanwal F, Kramer JR, Mapakshi S, et al. Risk of hepatocellular cancer in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(6):1828-1837.e2. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2018.08.024

9. Yopp AC, Mansour JC, Beg MS, et al. Establishment of a multidisciplinary hepatocellular carcinoma clinic is associated with improved clinical outcome. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(4):1287-1295. doi:10.1245/s10434-013-3413-8

10. Chang TT, Sawhney R, Monto A, et al. Implementation of a multidisciplinary treatment team for hepatocellular cancer at a Veterans Affairs Medical Center improves survival. HPB (Oxford). 2008;10(6):405-411. doi:10.1080/13651820802356572

11. Hwa KJ, Dua MM, Wren SM, Visser BC. Missing the obvious: psychosocial obstacles in veterans with hepatocellular carcinoma. HPB (Oxford). 2015;17(12):1124-1129. doi:10.1111/hpb.12508

12. Taylor J, Carr-Lopez S, Robinson A, et al. Determinants of treatment eligibility in veterans with hepatitis C viral infection. Clin Ther. 2017;39(1):130-137. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2016.11.019

13. Fargo J, Metraux S, Byrne T, et al. Prevalence and risk of homelessness among US veterans. Prev Chronic Dis. 2012;9:E45.

14. Tsai J, Rosenheck RA. Risk factors for homelessness among US veterans. Epidemiol Rev. 2015;37:177-195. doi:10.1093/epirev/mxu004

15. Tsai J, Link B, Rosenheck RA, Pietrzak RH. Homelessness among a nationally representative sample of US veterans: prevalence, service utilization, and correlates. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2016;51(6):907-916. doi:10.1007/s00127-016-1210-y

16. Davila JA, Kramer JR, Duan Z, et al. Referral and receipt of treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma in United States veterans: effect of patient and nonpatient factors. Hepatology. 2013;57(5):1858-1868. doi:10.1002/hep.26287

Women with lung cancer live longer than men

“In this first Australian prospective study of lung cancer survival comparing men and women, we found that men had a 43% greater risk of dying from their lung cancer than women,” comments lead author Xue Qin Yu, PhD, the Daffodil Centre, the University of Sydney, and colleagues.

“[However], when all prognostic factors were considered together, most of the survival differential disappeared,” they add.

“These results suggest that sex differences in lung cancer survival can be largely explained by known prognostic factors,” Dr. Yu and colleagues emphasize.

The study was published in the May issue of the Journal of Thoracic Oncology.

The ‘45 and up’ study

The findings come from the Sax Institute’s 45 and Up Study, an ongoing trial involving over 267,000 participants aged 45 years and older living in New South Wales, Australia. Patients were recruited to the study between 2006 and 2009. At the time of recruitment, patients were cancer free.

A total of 1,130 participants were diagnosed with having lung cancer during follow-up – 488 women and 642 men. Compared with men, women were, on average, younger at the time of diagnosis, had fewer comorbidities, and were more likely to be never-smokers or to have been exposed to passive smoke.

Women were also more likely to be diagnosed with adenocarcinoma than men and to receive surgery within 6 months of their diagnosis.

“Lung cancer survival was significantly higher for women,” the authors report, at a median of 1.28 years versus 0.77 years for men (P < .0001).

Within each subgroup of major prognostic factors – histologic subtype, cancer stage, cancer treatment, and smoking status – women again survived significantly longer than men.

Interestingly, the authors note that “women with adenocarcinoma had significantly better survival than men with adenocarcinoma independent of smoking status,” (P = .0009). This suggests that sex differences in tumor biology may play a role in explaining the sex survival differential between men and women, they commented. That said, never-smokers had a 16% lower risk for lung cancer death than ever-smokers after adjusting for age, the authors point out.

The authors also note that approximately half of the disparity in survival between the sexes could be explained by differences in the receipt of anticancer therapy within 6 months of the diagnosis. “This could partly be due to a lower proportion of men having surgery within 6 months than women,” investigators speculate, at 17% versus 25%, respectively.

Men were also older than women at the time of diagnosis, were less likely to be never-smokers, and had more comorbidities, all of which might also have prevented them from having surgery. Women with lung cancer may also respond better to chemotherapy than men, although the sex disparity in survival persisted even among patients who did not receive any treatment for their cancer within 6 months of their diagnosis, investigators point out.

Furthermore, “smoking history at baseline was identified as a significant contributing factor to the sex survival disparity, explaining approximately 28% of the overall disparity,” Dr. Yu and colleagues observe.

Only 8% of men diagnosed with lung cancer were never-smokers, compared with 23% of women. The authors note that never-smokers are more likely to receive aggressive or complete treatment and respond well to treatment.

Similarly, tumor-related factors together explained about one-quarter of the overall sex disparity in survival.

Screening guidelines

Commenting on the findings in an accompanying editorial, Claudia Poleri, MD, Hospital María Ferrer, Buenos Aires, says that this Australian study provides “valuable information.”

“The risk of dying from lung cancer was significantly higher for men than for women,” she writes. “Differences in treatment-related factors explained 50% of the sex survival differential, followed by lifestyle and tumor-related factors (28% and 26%, respectively).

“Nevertheless, these differences alone do not explain the higher survival in women,” she comments.

“Does it matter to analyze the differences by sex in lung cancer?” Dr. Poleri asks in the editorial, and then answers herself: “It matters.”

“It is necessary to implement screening programs and build artificial intelligence diagnostic algorithms considering the role of sex and gender equity to ensure that innovative technologies do not induce disparities in clinical care,” she writes.

“It is crucial to conduct education and health public programs that consider these differences, optimizing the use of available resources, [and] it is essential to improve the accuracy of research design and clinical trials,” she adds.

Dr. Yu and Dr. Poleri declared no relevant financial interests.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“In this first Australian prospective study of lung cancer survival comparing men and women, we found that men had a 43% greater risk of dying from their lung cancer than women,” comments lead author Xue Qin Yu, PhD, the Daffodil Centre, the University of Sydney, and colleagues.

“[However], when all prognostic factors were considered together, most of the survival differential disappeared,” they add.

“These results suggest that sex differences in lung cancer survival can be largely explained by known prognostic factors,” Dr. Yu and colleagues emphasize.

The study was published in the May issue of the Journal of Thoracic Oncology.

The ‘45 and up’ study

The findings come from the Sax Institute’s 45 and Up Study, an ongoing trial involving over 267,000 participants aged 45 years and older living in New South Wales, Australia. Patients were recruited to the study between 2006 and 2009. At the time of recruitment, patients were cancer free.

A total of 1,130 participants were diagnosed with having lung cancer during follow-up – 488 women and 642 men. Compared with men, women were, on average, younger at the time of diagnosis, had fewer comorbidities, and were more likely to be never-smokers or to have been exposed to passive smoke.

Women were also more likely to be diagnosed with adenocarcinoma than men and to receive surgery within 6 months of their diagnosis.

“Lung cancer survival was significantly higher for women,” the authors report, at a median of 1.28 years versus 0.77 years for men (P < .0001).

Within each subgroup of major prognostic factors – histologic subtype, cancer stage, cancer treatment, and smoking status – women again survived significantly longer than men.

Interestingly, the authors note that “women with adenocarcinoma had significantly better survival than men with adenocarcinoma independent of smoking status,” (P = .0009). This suggests that sex differences in tumor biology may play a role in explaining the sex survival differential between men and women, they commented. That said, never-smokers had a 16% lower risk for lung cancer death than ever-smokers after adjusting for age, the authors point out.

The authors also note that approximately half of the disparity in survival between the sexes could be explained by differences in the receipt of anticancer therapy within 6 months of the diagnosis. “This could partly be due to a lower proportion of men having surgery within 6 months than women,” investigators speculate, at 17% versus 25%, respectively.

Men were also older than women at the time of diagnosis, were less likely to be never-smokers, and had more comorbidities, all of which might also have prevented them from having surgery. Women with lung cancer may also respond better to chemotherapy than men, although the sex disparity in survival persisted even among patients who did not receive any treatment for their cancer within 6 months of their diagnosis, investigators point out.

Furthermore, “smoking history at baseline was identified as a significant contributing factor to the sex survival disparity, explaining approximately 28% of the overall disparity,” Dr. Yu and colleagues observe.

Only 8% of men diagnosed with lung cancer were never-smokers, compared with 23% of women. The authors note that never-smokers are more likely to receive aggressive or complete treatment and respond well to treatment.

Similarly, tumor-related factors together explained about one-quarter of the overall sex disparity in survival.

Screening guidelines

Commenting on the findings in an accompanying editorial, Claudia Poleri, MD, Hospital María Ferrer, Buenos Aires, says that this Australian study provides “valuable information.”

“The risk of dying from lung cancer was significantly higher for men than for women,” she writes. “Differences in treatment-related factors explained 50% of the sex survival differential, followed by lifestyle and tumor-related factors (28% and 26%, respectively).

“Nevertheless, these differences alone do not explain the higher survival in women,” she comments.

“Does it matter to analyze the differences by sex in lung cancer?” Dr. Poleri asks in the editorial, and then answers herself: “It matters.”

“It is necessary to implement screening programs and build artificial intelligence diagnostic algorithms considering the role of sex and gender equity to ensure that innovative technologies do not induce disparities in clinical care,” she writes.

“It is crucial to conduct education and health public programs that consider these differences, optimizing the use of available resources, [and] it is essential to improve the accuracy of research design and clinical trials,” she adds.

Dr. Yu and Dr. Poleri declared no relevant financial interests.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“In this first Australian prospective study of lung cancer survival comparing men and women, we found that men had a 43% greater risk of dying from their lung cancer than women,” comments lead author Xue Qin Yu, PhD, the Daffodil Centre, the University of Sydney, and colleagues.

“[However], when all prognostic factors were considered together, most of the survival differential disappeared,” they add.

“These results suggest that sex differences in lung cancer survival can be largely explained by known prognostic factors,” Dr. Yu and colleagues emphasize.

The study was published in the May issue of the Journal of Thoracic Oncology.

The ‘45 and up’ study

The findings come from the Sax Institute’s 45 and Up Study, an ongoing trial involving over 267,000 participants aged 45 years and older living in New South Wales, Australia. Patients were recruited to the study between 2006 and 2009. At the time of recruitment, patients were cancer free.

A total of 1,130 participants were diagnosed with having lung cancer during follow-up – 488 women and 642 men. Compared with men, women were, on average, younger at the time of diagnosis, had fewer comorbidities, and were more likely to be never-smokers or to have been exposed to passive smoke.

Women were also more likely to be diagnosed with adenocarcinoma than men and to receive surgery within 6 months of their diagnosis.

“Lung cancer survival was significantly higher for women,” the authors report, at a median of 1.28 years versus 0.77 years for men (P < .0001).

Within each subgroup of major prognostic factors – histologic subtype, cancer stage, cancer treatment, and smoking status – women again survived significantly longer than men.

Interestingly, the authors note that “women with adenocarcinoma had significantly better survival than men with adenocarcinoma independent of smoking status,” (P = .0009). This suggests that sex differences in tumor biology may play a role in explaining the sex survival differential between men and women, they commented. That said, never-smokers had a 16% lower risk for lung cancer death than ever-smokers after adjusting for age, the authors point out.

The authors also note that approximately half of the disparity in survival between the sexes could be explained by differences in the receipt of anticancer therapy within 6 months of the diagnosis. “This could partly be due to a lower proportion of men having surgery within 6 months than women,” investigators speculate, at 17% versus 25%, respectively.

Men were also older than women at the time of diagnosis, were less likely to be never-smokers, and had more comorbidities, all of which might also have prevented them from having surgery. Women with lung cancer may also respond better to chemotherapy than men, although the sex disparity in survival persisted even among patients who did not receive any treatment for their cancer within 6 months of their diagnosis, investigators point out.

Furthermore, “smoking history at baseline was identified as a significant contributing factor to the sex survival disparity, explaining approximately 28% of the overall disparity,” Dr. Yu and colleagues observe.

Only 8% of men diagnosed with lung cancer were never-smokers, compared with 23% of women. The authors note that never-smokers are more likely to receive aggressive or complete treatment and respond well to treatment.

Similarly, tumor-related factors together explained about one-quarter of the overall sex disparity in survival.

Screening guidelines

Commenting on the findings in an accompanying editorial, Claudia Poleri, MD, Hospital María Ferrer, Buenos Aires, says that this Australian study provides “valuable information.”

“The risk of dying from lung cancer was significantly higher for men than for women,” she writes. “Differences in treatment-related factors explained 50% of the sex survival differential, followed by lifestyle and tumor-related factors (28% and 26%, respectively).

“Nevertheless, these differences alone do not explain the higher survival in women,” she comments.

“Does it matter to analyze the differences by sex in lung cancer?” Dr. Poleri asks in the editorial, and then answers herself: “It matters.”

“It is necessary to implement screening programs and build artificial intelligence diagnostic algorithms considering the role of sex and gender equity to ensure that innovative technologies do not induce disparities in clinical care,” she writes.

“It is crucial to conduct education and health public programs that consider these differences, optimizing the use of available resources, [and] it is essential to improve the accuracy of research design and clinical trials,” she adds.

Dr. Yu and Dr. Poleri declared no relevant financial interests.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THORACIC ONCOLOGY

New data support electroconvulsive therapy for severe depression

Advocates and users of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) have received further scientific backing:

The patient cohort comprised 27,231 men and 40,096 women who had been treated as inpatients. The average age was 45.1 years (range: 18-103 years), and 4,982 patients received ECT. The primary endpoint was death by suicide within 365 days of hospital discharge. The secondary endpoints were death not by suicide and total mortality. The cause-specific hazard ratio (csHR) was calculated for patients with ECT, compared with patients without ECT.

In the propensity score-weighted analysis, ECT was linked to a significantly reduced suicide risk (csHR: 0.53; 95% confidence interval, 0.31-0.92). According to the calculations, ECT was associated with a significantly decreased total mortality risk (hazard ratio, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.58-0.97). However, this was not the case for death from causes other than suicide.

The authors, led by Tyler S. Kaster, PhD, a psychiatrist at Temerty Centre for Therapeutic Brain Intervention, Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, Toronto, concluded that this study underlines the importance of ECT, in particular for people with severe depression.

A well-tested therapy

ECT has been used for decades as a substantial tool for the treatment of patients with severe mental illnesses. Over the past 15 years, new methods for the treatment of severely depressed patients have been tested, such as vagus nerve stimulation, transcranial magnetic stimulation, and intranasal administration of esketamine. However, in a recent review paper in the New England Journal of Medicine, American psychiatrists Randall T. Espinoza, MD, MPH, University of California, Los Angeles, and Charles H. Kellner, MD, University of South Carolina, Charleston, reported that none of these therapies had proven to be an indisputable substitute for ECT for people with severe depression.

Significant clinical benefits

According to these American psychiatrists, the benefit of ECT has been proven many times, and several studies demonstrate the effect on the risk for suicide. Moreover, quality of life is improved, and the rate of new hospital admissions is lowered. ECT can rapidly improve depressive, psychotic, and catatonic symptoms and reduce suicidal urges for certain patient groups.

Studies on ECT involving patients with treatment-refractory depression have shown response rates of 60%-80% and pooled remission rates of 50%-60%. High response rates for ECT have even been reported for patients with psychotic depression or catatonia. In one study that recruited patients with treatment-refractory schizophrenia, the ECT efficacy rates were between 40% and 70%. In some Asian countries, schizophrenia is the main indication for ECT.

Good safety profile

Overall, the psychiatrists consider ECT to be a safe and tolerable therapy. The estimated death rate is around 2.1 deaths per 100,000 treatments. The most common complications are acute cardiopulmonary events, which are estimated to occur in less than 1% of treatments. Rare serious adverse events linked to ECT are arrhythmias, shortness of breath, aspiration, and prolonged seizures. The common but mild side effects are headaches, jaw pain, myalgia, nausea, and vomiting after the procedure, as well as fatigue.

Concerns regarding cognitive impairment still represent an obstacle for the use of ECT. However, in today’s practice, ECT leads to fewer cognitive side effects than previous treatments. The authors stated that it is not possible to predict how an individual patient will be affected, but most patients have only mild or moderate cognitive side effects that generally abate days to weeks after an ECT course has ended.

However, retrograde amnesia linked to ECT can last over a year. In rare cases, acute confusion or delirium can develop that requires interruption or discontinuation of treatment. No indications of structural brain damage after ECT have been detected in neuropathological testing. A Danish cohort study involving 168,015 patients with depression, of whom 3.1% had at least one ECT treatment, did not find a link between ECT with a mean period of almost 5 years and increased onset of dementia.

Bad reputation

Dr. Espinoza and Dr. Kellner criticized the fact that, despite its proven efficacy and safety, ECT is used too little. This judgment is nothing new. Psychiatrists have been complaining for years that this procedure is used too little, including Eric Slade, MD, from the University of Baltimore, in 2017 and German professors Andreas Fallgatter, MD, and Urban Wiesing, MD, PhD, in 2018. Dr. Wiesing and Dr. Fallgatter attribute the low level of use to the fact that ECT is labor-intensive, compared with pharmacotherapy.

Another reason is clearly the bad reputation of this method. However, ECT’s poor image, which has only increased over time, is not a convincing argument to forego today’s ECT as a treatment for patients with severe mental illnesses. According to Dr. Fallgatter and Dr. Wiesing, even the risk of misuse of this method is “not a sufficient argument for categorical refusal, rather for caution at best.” They argued that otherwise, “modern medicine would have to renounce many more therapies.”

This article was translated from Univadis Germany.

Advocates and users of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) have received further scientific backing:

The patient cohort comprised 27,231 men and 40,096 women who had been treated as inpatients. The average age was 45.1 years (range: 18-103 years), and 4,982 patients received ECT. The primary endpoint was death by suicide within 365 days of hospital discharge. The secondary endpoints were death not by suicide and total mortality. The cause-specific hazard ratio (csHR) was calculated for patients with ECT, compared with patients without ECT.

In the propensity score-weighted analysis, ECT was linked to a significantly reduced suicide risk (csHR: 0.53; 95% confidence interval, 0.31-0.92). According to the calculations, ECT was associated with a significantly decreased total mortality risk (hazard ratio, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.58-0.97). However, this was not the case for death from causes other than suicide.

The authors, led by Tyler S. Kaster, PhD, a psychiatrist at Temerty Centre for Therapeutic Brain Intervention, Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, Toronto, concluded that this study underlines the importance of ECT, in particular for people with severe depression.

A well-tested therapy

ECT has been used for decades as a substantial tool for the treatment of patients with severe mental illnesses. Over the past 15 years, new methods for the treatment of severely depressed patients have been tested, such as vagus nerve stimulation, transcranial magnetic stimulation, and intranasal administration of esketamine. However, in a recent review paper in the New England Journal of Medicine, American psychiatrists Randall T. Espinoza, MD, MPH, University of California, Los Angeles, and Charles H. Kellner, MD, University of South Carolina, Charleston, reported that none of these therapies had proven to be an indisputable substitute for ECT for people with severe depression.

Significant clinical benefits

According to these American psychiatrists, the benefit of ECT has been proven many times, and several studies demonstrate the effect on the risk for suicide. Moreover, quality of life is improved, and the rate of new hospital admissions is lowered. ECT can rapidly improve depressive, psychotic, and catatonic symptoms and reduce suicidal urges for certain patient groups.

Studies on ECT involving patients with treatment-refractory depression have shown response rates of 60%-80% and pooled remission rates of 50%-60%. High response rates for ECT have even been reported for patients with psychotic depression or catatonia. In one study that recruited patients with treatment-refractory schizophrenia, the ECT efficacy rates were between 40% and 70%. In some Asian countries, schizophrenia is the main indication for ECT.

Good safety profile

Overall, the psychiatrists consider ECT to be a safe and tolerable therapy. The estimated death rate is around 2.1 deaths per 100,000 treatments. The most common complications are acute cardiopulmonary events, which are estimated to occur in less than 1% of treatments. Rare serious adverse events linked to ECT are arrhythmias, shortness of breath, aspiration, and prolonged seizures. The common but mild side effects are headaches, jaw pain, myalgia, nausea, and vomiting after the procedure, as well as fatigue.

Concerns regarding cognitive impairment still represent an obstacle for the use of ECT. However, in today’s practice, ECT leads to fewer cognitive side effects than previous treatments. The authors stated that it is not possible to predict how an individual patient will be affected, but most patients have only mild or moderate cognitive side effects that generally abate days to weeks after an ECT course has ended.

However, retrograde amnesia linked to ECT can last over a year. In rare cases, acute confusion or delirium can develop that requires interruption or discontinuation of treatment. No indications of structural brain damage after ECT have been detected in neuropathological testing. A Danish cohort study involving 168,015 patients with depression, of whom 3.1% had at least one ECT treatment, did not find a link between ECT with a mean period of almost 5 years and increased onset of dementia.

Bad reputation

Dr. Espinoza and Dr. Kellner criticized the fact that, despite its proven efficacy and safety, ECT is used too little. This judgment is nothing new. Psychiatrists have been complaining for years that this procedure is used too little, including Eric Slade, MD, from the University of Baltimore, in 2017 and German professors Andreas Fallgatter, MD, and Urban Wiesing, MD, PhD, in 2018. Dr. Wiesing and Dr. Fallgatter attribute the low level of use to the fact that ECT is labor-intensive, compared with pharmacotherapy.

Another reason is clearly the bad reputation of this method. However, ECT’s poor image, which has only increased over time, is not a convincing argument to forego today’s ECT as a treatment for patients with severe mental illnesses. According to Dr. Fallgatter and Dr. Wiesing, even the risk of misuse of this method is “not a sufficient argument for categorical refusal, rather for caution at best.” They argued that otherwise, “modern medicine would have to renounce many more therapies.”

This article was translated from Univadis Germany.