User login

Move away from the screen ...

“Go outside and play!”

How often have you said that to your kids (or grandkids)? For that matter, how often did you hear it when you were a kid?

A lot, if memory serves me correctly. Some of it was just my mom wanting me out of the house, some of it an innate realization on her part that too much time spent planted in front of the TV was bad for you. (When I was a kid, Brady Bunch reruns kicked off my summer day at 8:00 a.m.).

The idea that too much time in front of a screen can be bad is nothing new. Regrettably, some of this ancient wisdom has been lost in the eons since I was a kid.

Does this surprise you?

Humans, like all primates, are a social species. We’ve benefited from the combined power of our minds to leave caves, harness nature, and build civilizations. But this has a cost, and perhaps the social media screen has been a tipping point for mental health.

I’m not knocking the basic idea. Share a joke with a friend, see pictures of the new baby, hear out about a new job. That’s fine. The trouble is that it’s gone beyond that. A lot of it is perfectly innocuous ... but a lot isn’t.

As it’s evolved, social media has also become the home of anger. Political and otherwise. It’s so much easier to post memes making fun of other people and their viewpoints than to speak to them in person. Trolls and bots lurk everywhere to get you riled up – things you wouldn’t be encountering if you were talking to your neighbor at the fence or a friend on the phone.

Recent trends on TikTok included students bragging about things they’d stolen from their high schools and people boasting of having “ripped off” Six Flags amusement parks with an annual membership loophole (the latter resulted in park management canceling the plan). How do such things benefit anyone (beyond those posting them getting clicks)?

I’m pretty sure they do nothing to make you feel good, or happy, or positive in any way. And that’s not even counting the political nastiness, cheap shots, and conspiracy theories that drown out rational thought.

Unfortunately, social media in today’s forms is addictive. Seeing one good thing from a friend gives you a dopamine boost, and this drives you to overlook all the bad things the screen does. Like the meth addict who lives for the high, and ignores all the negative aspects – loss of money, family, a home, teeth – that it brings.

So it’s not a surprise that walking away from it for a week made people happier and gave them time to do things that were more important than staring at a screen. Though I do wonder how many of the subjects ended up going back to it, forgetting about the benefits they’d just experienced.

When Frank Zappa released “I’m the Slime” in 1973, it was about television. But today the song is far closer to describing what social media has become than he could have ever imagined. (He died in 1993, never knowing how accurate he’d become).

We encourage our patients to exercise. The benefits of doing so are beyond question. But maybe it’s time to point out not only the good things that come from exercise, but also those that come from turning off the screen in order to do so.

As my mother said: “Go outside and play!”

It’s good for the body and sanity, and both are important.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

“Go outside and play!”

How often have you said that to your kids (or grandkids)? For that matter, how often did you hear it when you were a kid?

A lot, if memory serves me correctly. Some of it was just my mom wanting me out of the house, some of it an innate realization on her part that too much time spent planted in front of the TV was bad for you. (When I was a kid, Brady Bunch reruns kicked off my summer day at 8:00 a.m.).

The idea that too much time in front of a screen can be bad is nothing new. Regrettably, some of this ancient wisdom has been lost in the eons since I was a kid.

Does this surprise you?

Humans, like all primates, are a social species. We’ve benefited from the combined power of our minds to leave caves, harness nature, and build civilizations. But this has a cost, and perhaps the social media screen has been a tipping point for mental health.

I’m not knocking the basic idea. Share a joke with a friend, see pictures of the new baby, hear out about a new job. That’s fine. The trouble is that it’s gone beyond that. A lot of it is perfectly innocuous ... but a lot isn’t.

As it’s evolved, social media has also become the home of anger. Political and otherwise. It’s so much easier to post memes making fun of other people and their viewpoints than to speak to them in person. Trolls and bots lurk everywhere to get you riled up – things you wouldn’t be encountering if you were talking to your neighbor at the fence or a friend on the phone.

Recent trends on TikTok included students bragging about things they’d stolen from their high schools and people boasting of having “ripped off” Six Flags amusement parks with an annual membership loophole (the latter resulted in park management canceling the plan). How do such things benefit anyone (beyond those posting them getting clicks)?

I’m pretty sure they do nothing to make you feel good, or happy, or positive in any way. And that’s not even counting the political nastiness, cheap shots, and conspiracy theories that drown out rational thought.

Unfortunately, social media in today’s forms is addictive. Seeing one good thing from a friend gives you a dopamine boost, and this drives you to overlook all the bad things the screen does. Like the meth addict who lives for the high, and ignores all the negative aspects – loss of money, family, a home, teeth – that it brings.

So it’s not a surprise that walking away from it for a week made people happier and gave them time to do things that were more important than staring at a screen. Though I do wonder how many of the subjects ended up going back to it, forgetting about the benefits they’d just experienced.

When Frank Zappa released “I’m the Slime” in 1973, it was about television. But today the song is far closer to describing what social media has become than he could have ever imagined. (He died in 1993, never knowing how accurate he’d become).

We encourage our patients to exercise. The benefits of doing so are beyond question. But maybe it’s time to point out not only the good things that come from exercise, but also those that come from turning off the screen in order to do so.

As my mother said: “Go outside and play!”

It’s good for the body and sanity, and both are important.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

“Go outside and play!”

How often have you said that to your kids (or grandkids)? For that matter, how often did you hear it when you were a kid?

A lot, if memory serves me correctly. Some of it was just my mom wanting me out of the house, some of it an innate realization on her part that too much time spent planted in front of the TV was bad for you. (When I was a kid, Brady Bunch reruns kicked off my summer day at 8:00 a.m.).

The idea that too much time in front of a screen can be bad is nothing new. Regrettably, some of this ancient wisdom has been lost in the eons since I was a kid.

Does this surprise you?

Humans, like all primates, are a social species. We’ve benefited from the combined power of our minds to leave caves, harness nature, and build civilizations. But this has a cost, and perhaps the social media screen has been a tipping point for mental health.

I’m not knocking the basic idea. Share a joke with a friend, see pictures of the new baby, hear out about a new job. That’s fine. The trouble is that it’s gone beyond that. A lot of it is perfectly innocuous ... but a lot isn’t.

As it’s evolved, social media has also become the home of anger. Political and otherwise. It’s so much easier to post memes making fun of other people and their viewpoints than to speak to them in person. Trolls and bots lurk everywhere to get you riled up – things you wouldn’t be encountering if you were talking to your neighbor at the fence or a friend on the phone.

Recent trends on TikTok included students bragging about things they’d stolen from their high schools and people boasting of having “ripped off” Six Flags amusement parks with an annual membership loophole (the latter resulted in park management canceling the plan). How do such things benefit anyone (beyond those posting them getting clicks)?

I’m pretty sure they do nothing to make you feel good, or happy, or positive in any way. And that’s not even counting the political nastiness, cheap shots, and conspiracy theories that drown out rational thought.

Unfortunately, social media in today’s forms is addictive. Seeing one good thing from a friend gives you a dopamine boost, and this drives you to overlook all the bad things the screen does. Like the meth addict who lives for the high, and ignores all the negative aspects – loss of money, family, a home, teeth – that it brings.

So it’s not a surprise that walking away from it for a week made people happier and gave them time to do things that were more important than staring at a screen. Though I do wonder how many of the subjects ended up going back to it, forgetting about the benefits they’d just experienced.

When Frank Zappa released “I’m the Slime” in 1973, it was about television. But today the song is far closer to describing what social media has become than he could have ever imagined. (He died in 1993, never knowing how accurate he’d become).

We encourage our patients to exercise. The benefits of doing so are beyond question. But maybe it’s time to point out not only the good things that come from exercise, but also those that come from turning off the screen in order to do so.

As my mother said: “Go outside and play!”

It’s good for the body and sanity, and both are important.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Abaloparatide works in ‘ignored population’: Men with osteoporosis

San Diego – The anabolic osteoporosis treatment abaloparatide (Tymlos, Radius Health) works in men as well as women, new data indicate.

Findings from the Abaloparatide for the Treatment of Men With Osteoporosis (ATOM) randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study were presented last week at the American Association of Clinical Endocrinology (AACE) Annual Meeting 2022.

Abaloparatide, a subcutaneously administered parathyroid-hormone–related protein (PTHrP) analog, resulted in significant increases in bone mineral density by 12 months at the lumbar spine, total hip, and femoral neck, compared with placebo in men with osteoporosis, with no significant adverse effects.

“Osteoporosis is underdiagnosed in men. Abaloparatide is another option for an ignored population,” presenter Neil Binkley, MD, of the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health Madison, said in an interview.

Abaloparatide was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2017 for the treatment of postmenopausal women at high risk for fracture due to a history of osteoporotic fracture or multiple fracture risk factors, or who haven’t responded to or are intolerant of other osteoporosis therapies.

While postmenopausal women have mainly been the focus in osteoporosis, men account for approximately 30% of the societal burden of osteoporosis and have greater fracture-related morbidity and mortality than women.

About one in four men over the age of 50 years will have a fragility fracture in their lifetime. Yet, they’re far less likely to be diagnosed or to be included in osteoporosis treatment trials, Dr. Binkley noted.

Asked to comment, session moderator Thanh D. Hoang, DO, told this news organization, “I think it’s a great option to treat osteoporosis, and now we have evidence for treating osteoporosis in men. Mostly the data have come from postmenopausal women.”

Screen men with hypogonadism or those taking steroids

“This new medication is an addition to the very limited number of treatments that we have when patients don’t respond to [initial] medications. To have another anabolic bone-forming medication is very, very good,” said Dr. Hoang, who is professor and program director of the Endocrinology Fellowship Program at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, Maryland.

Radius Health filed a Supplemental New Drug Application with the FDA for abaloparatide (Tymlos) subcutaneous injection in men with osteoporosis at high risk for fracture in February. There is a 10-month review period.

Dr. Binkley advises bone screening for men who have conditions such as hypogonadism or who are taking glucocorticoids or chemotherapeutics.

But, he added, “I think that if we did nothing else good in the osteoporosis field, if we treated people after they fractured that would be a huge step forward. Even with a normal T score, when those people fracture, they [often] don’t have normal bone mineral density ... That’s a group of people we’re ignoring still. They’re not getting diagnosed, and they’re not getting treated.”

ATOM Study: Significant BMD increases at key sites

The approval of abaloparatide in women was based on the phase 3, 18-week ACTIVE trial of more than 2,000 high-risk women, in whom abaloparatide was associated with an 86% reduction in vertebral fracture incidence, compared with placebo, and also significantly greater reductions in nonvertebral fractures, compared with both placebo and teriparatide (Forteo, Eli Lilly).

The ATOM study involved a total of 228 men aged 40-85 years with primary or hypogonadism-associated osteoporosis randomized 2:1 to receive subcutaneous 80 μg abaloparatide or injected placebo daily for 12 months. All had T scores (based on male reference range) of ≤ −2.5 at the lumbar spine or hip, or ≤ −1.5 and with radiologic vertebral fracture or a history of low trauma nonvertebral fracture in the past 5 years, or T score ≤ −2.0 if older than 65 years.

Increases in bone mineral density from baseline were significantly greater with abaloparatide compared with placebo at the lumbar spine, total hip, and femoral neck at 3, 6, and 12 months. Mean percentage changes at 12 months were 8.5%, 2.1%, and 3.0%, for the three locations, respectively, compared with 1.2%, 0.01%, and 0.2% for placebo (all P ≤ .0001).

Three fractures occurred in those receiving placebo and one with abaloparatide.

For markers of bone turnover, median serum procollagen type I N-terminal propeptide (s-PINP) was 111.2 ng/mL after 1 month of abaloparatide treatment and 85.7 ng/mL at month 12. Median serum carboxy-terminal cross-linking telopeptide of type I collagen (s-CTX) was 0.48 ng/mL at month 6 and 0.45 ng/mL at month 12 in the abaloparatide group. Geometric mean relative to baseline s-PINP and s-CTX increased significantly at months 3, 6, and 12 (all P < .001 for relative treatment effect of abaloparatide vs. placebo).

The most commonly reported treatment-emergent adverse events were injection site erythema (12.8% vs. 5.1%), nasopharyngitis (8.7% vs. 7.6%), dizziness (8.7% vs. 1.3%), and arthralgia (6.7% vs. 1.3%), with abaloparatide versus placebo. Serious treatment-emergent adverse event rates were similar in both groups (5.4% vs. 5.1%). There was one death in the abaloparatide group, which was deemed unrelated to the drug.

Dr. Binkley has reported receiving consulting fees from Amgen and research support from Radius. Dr. Hoang has reported disclosures with Acella Pharmaceuticals and Horizon Therapeutics (no financial compensation).

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

San Diego – The anabolic osteoporosis treatment abaloparatide (Tymlos, Radius Health) works in men as well as women, new data indicate.

Findings from the Abaloparatide for the Treatment of Men With Osteoporosis (ATOM) randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study were presented last week at the American Association of Clinical Endocrinology (AACE) Annual Meeting 2022.

Abaloparatide, a subcutaneously administered parathyroid-hormone–related protein (PTHrP) analog, resulted in significant increases in bone mineral density by 12 months at the lumbar spine, total hip, and femoral neck, compared with placebo in men with osteoporosis, with no significant adverse effects.

“Osteoporosis is underdiagnosed in men. Abaloparatide is another option for an ignored population,” presenter Neil Binkley, MD, of the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health Madison, said in an interview.

Abaloparatide was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2017 for the treatment of postmenopausal women at high risk for fracture due to a history of osteoporotic fracture or multiple fracture risk factors, or who haven’t responded to or are intolerant of other osteoporosis therapies.

While postmenopausal women have mainly been the focus in osteoporosis, men account for approximately 30% of the societal burden of osteoporosis and have greater fracture-related morbidity and mortality than women.

About one in four men over the age of 50 years will have a fragility fracture in their lifetime. Yet, they’re far less likely to be diagnosed or to be included in osteoporosis treatment trials, Dr. Binkley noted.

Asked to comment, session moderator Thanh D. Hoang, DO, told this news organization, “I think it’s a great option to treat osteoporosis, and now we have evidence for treating osteoporosis in men. Mostly the data have come from postmenopausal women.”

Screen men with hypogonadism or those taking steroids

“This new medication is an addition to the very limited number of treatments that we have when patients don’t respond to [initial] medications. To have another anabolic bone-forming medication is very, very good,” said Dr. Hoang, who is professor and program director of the Endocrinology Fellowship Program at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, Maryland.

Radius Health filed a Supplemental New Drug Application with the FDA for abaloparatide (Tymlos) subcutaneous injection in men with osteoporosis at high risk for fracture in February. There is a 10-month review period.

Dr. Binkley advises bone screening for men who have conditions such as hypogonadism or who are taking glucocorticoids or chemotherapeutics.

But, he added, “I think that if we did nothing else good in the osteoporosis field, if we treated people after they fractured that would be a huge step forward. Even with a normal T score, when those people fracture, they [often] don’t have normal bone mineral density ... That’s a group of people we’re ignoring still. They’re not getting diagnosed, and they’re not getting treated.”

ATOM Study: Significant BMD increases at key sites

The approval of abaloparatide in women was based on the phase 3, 18-week ACTIVE trial of more than 2,000 high-risk women, in whom abaloparatide was associated with an 86% reduction in vertebral fracture incidence, compared with placebo, and also significantly greater reductions in nonvertebral fractures, compared with both placebo and teriparatide (Forteo, Eli Lilly).

The ATOM study involved a total of 228 men aged 40-85 years with primary or hypogonadism-associated osteoporosis randomized 2:1 to receive subcutaneous 80 μg abaloparatide or injected placebo daily for 12 months. All had T scores (based on male reference range) of ≤ −2.5 at the lumbar spine or hip, or ≤ −1.5 and with radiologic vertebral fracture or a history of low trauma nonvertebral fracture in the past 5 years, or T score ≤ −2.0 if older than 65 years.

Increases in bone mineral density from baseline were significantly greater with abaloparatide compared with placebo at the lumbar spine, total hip, and femoral neck at 3, 6, and 12 months. Mean percentage changes at 12 months were 8.5%, 2.1%, and 3.0%, for the three locations, respectively, compared with 1.2%, 0.01%, and 0.2% for placebo (all P ≤ .0001).

Three fractures occurred in those receiving placebo and one with abaloparatide.

For markers of bone turnover, median serum procollagen type I N-terminal propeptide (s-PINP) was 111.2 ng/mL after 1 month of abaloparatide treatment and 85.7 ng/mL at month 12. Median serum carboxy-terminal cross-linking telopeptide of type I collagen (s-CTX) was 0.48 ng/mL at month 6 and 0.45 ng/mL at month 12 in the abaloparatide group. Geometric mean relative to baseline s-PINP and s-CTX increased significantly at months 3, 6, and 12 (all P < .001 for relative treatment effect of abaloparatide vs. placebo).

The most commonly reported treatment-emergent adverse events were injection site erythema (12.8% vs. 5.1%), nasopharyngitis (8.7% vs. 7.6%), dizziness (8.7% vs. 1.3%), and arthralgia (6.7% vs. 1.3%), with abaloparatide versus placebo. Serious treatment-emergent adverse event rates were similar in both groups (5.4% vs. 5.1%). There was one death in the abaloparatide group, which was deemed unrelated to the drug.

Dr. Binkley has reported receiving consulting fees from Amgen and research support from Radius. Dr. Hoang has reported disclosures with Acella Pharmaceuticals and Horizon Therapeutics (no financial compensation).

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

San Diego – The anabolic osteoporosis treatment abaloparatide (Tymlos, Radius Health) works in men as well as women, new data indicate.

Findings from the Abaloparatide for the Treatment of Men With Osteoporosis (ATOM) randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study were presented last week at the American Association of Clinical Endocrinology (AACE) Annual Meeting 2022.

Abaloparatide, a subcutaneously administered parathyroid-hormone–related protein (PTHrP) analog, resulted in significant increases in bone mineral density by 12 months at the lumbar spine, total hip, and femoral neck, compared with placebo in men with osteoporosis, with no significant adverse effects.

“Osteoporosis is underdiagnosed in men. Abaloparatide is another option for an ignored population,” presenter Neil Binkley, MD, of the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health Madison, said in an interview.

Abaloparatide was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2017 for the treatment of postmenopausal women at high risk for fracture due to a history of osteoporotic fracture or multiple fracture risk factors, or who haven’t responded to or are intolerant of other osteoporosis therapies.

While postmenopausal women have mainly been the focus in osteoporosis, men account for approximately 30% of the societal burden of osteoporosis and have greater fracture-related morbidity and mortality than women.

About one in four men over the age of 50 years will have a fragility fracture in their lifetime. Yet, they’re far less likely to be diagnosed or to be included in osteoporosis treatment trials, Dr. Binkley noted.

Asked to comment, session moderator Thanh D. Hoang, DO, told this news organization, “I think it’s a great option to treat osteoporosis, and now we have evidence for treating osteoporosis in men. Mostly the data have come from postmenopausal women.”

Screen men with hypogonadism or those taking steroids

“This new medication is an addition to the very limited number of treatments that we have when patients don’t respond to [initial] medications. To have another anabolic bone-forming medication is very, very good,” said Dr. Hoang, who is professor and program director of the Endocrinology Fellowship Program at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, Maryland.

Radius Health filed a Supplemental New Drug Application with the FDA for abaloparatide (Tymlos) subcutaneous injection in men with osteoporosis at high risk for fracture in February. There is a 10-month review period.

Dr. Binkley advises bone screening for men who have conditions such as hypogonadism or who are taking glucocorticoids or chemotherapeutics.

But, he added, “I think that if we did nothing else good in the osteoporosis field, if we treated people after they fractured that would be a huge step forward. Even with a normal T score, when those people fracture, they [often] don’t have normal bone mineral density ... That’s a group of people we’re ignoring still. They’re not getting diagnosed, and they’re not getting treated.”

ATOM Study: Significant BMD increases at key sites

The approval of abaloparatide in women was based on the phase 3, 18-week ACTIVE trial of more than 2,000 high-risk women, in whom abaloparatide was associated with an 86% reduction in vertebral fracture incidence, compared with placebo, and also significantly greater reductions in nonvertebral fractures, compared with both placebo and teriparatide (Forteo, Eli Lilly).

The ATOM study involved a total of 228 men aged 40-85 years with primary or hypogonadism-associated osteoporosis randomized 2:1 to receive subcutaneous 80 μg abaloparatide or injected placebo daily for 12 months. All had T scores (based on male reference range) of ≤ −2.5 at the lumbar spine or hip, or ≤ −1.5 and with radiologic vertebral fracture or a history of low trauma nonvertebral fracture in the past 5 years, or T score ≤ −2.0 if older than 65 years.

Increases in bone mineral density from baseline were significantly greater with abaloparatide compared with placebo at the lumbar spine, total hip, and femoral neck at 3, 6, and 12 months. Mean percentage changes at 12 months were 8.5%, 2.1%, and 3.0%, for the three locations, respectively, compared with 1.2%, 0.01%, and 0.2% for placebo (all P ≤ .0001).

Three fractures occurred in those receiving placebo and one with abaloparatide.

For markers of bone turnover, median serum procollagen type I N-terminal propeptide (s-PINP) was 111.2 ng/mL after 1 month of abaloparatide treatment and 85.7 ng/mL at month 12. Median serum carboxy-terminal cross-linking telopeptide of type I collagen (s-CTX) was 0.48 ng/mL at month 6 and 0.45 ng/mL at month 12 in the abaloparatide group. Geometric mean relative to baseline s-PINP and s-CTX increased significantly at months 3, 6, and 12 (all P < .001 for relative treatment effect of abaloparatide vs. placebo).

The most commonly reported treatment-emergent adverse events were injection site erythema (12.8% vs. 5.1%), nasopharyngitis (8.7% vs. 7.6%), dizziness (8.7% vs. 1.3%), and arthralgia (6.7% vs. 1.3%), with abaloparatide versus placebo. Serious treatment-emergent adverse event rates were similar in both groups (5.4% vs. 5.1%). There was one death in the abaloparatide group, which was deemed unrelated to the drug.

Dr. Binkley has reported receiving consulting fees from Amgen and research support from Radius. Dr. Hoang has reported disclosures with Acella Pharmaceuticals and Horizon Therapeutics (no financial compensation).

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AT AACE 2022

Neuropsychiatric risks of COVID-19: New data

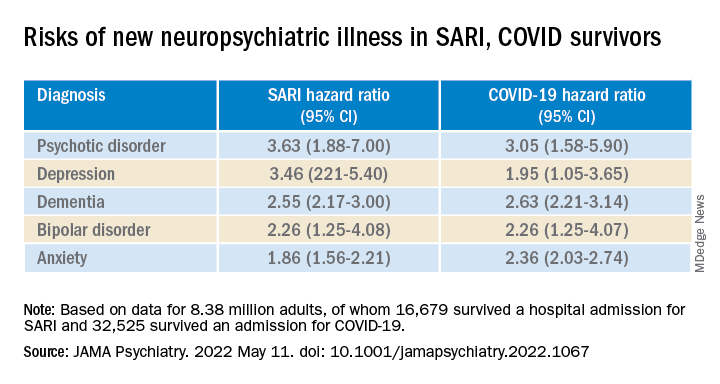

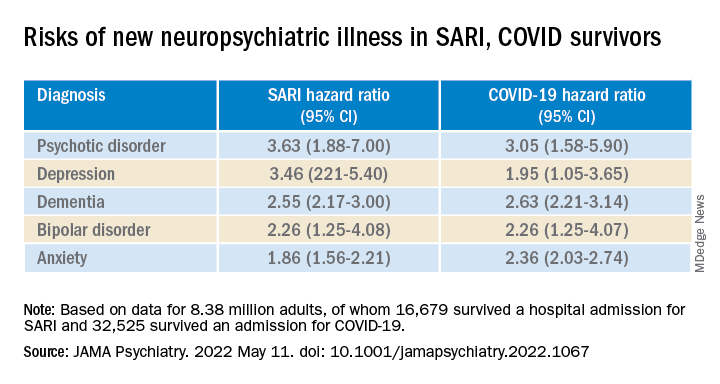

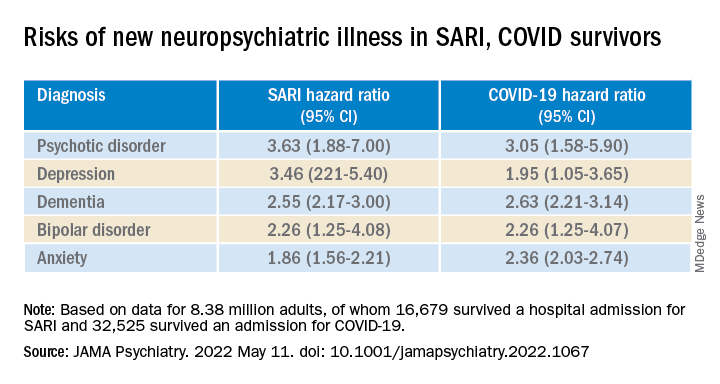

The neuropsychiatric ramifications of severe COVID-19 infection appear to be no different than for other severe acute respiratory infections (SARI).

This suggests that disease severity, rather than pathogen, is the most relevant factor in new-onset neuropsychiatric illness, the investigators note.

The risk of new-onset neuropsychological illness after severe COVID-19 infection are “substantial, but similar to those after other severe respiratory infections,” study investigator Peter Watkinson, MD, Nuffield Department of Clinical Neurosciences, University of Oxford, and John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, England, told this news organization.

The study was published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

Significant mental health burden

Research has shown a significant burden of neuropsychological illness after severe COVID-19 infection. However, it’s unclear how this risk compares to SARI.

To investigate, Dr. Watkinson and colleagues evaluated electronic health record data on more than 8.3 million adults, including 16,679 (0.02%) who survived a hospital admission for SARI and 32,525 (0.03%) who survived a hospital stay for COVID-19.

Compared with the remaining population, risks of new anxiety disorder, dementia, psychotic disorder, depression, and bipolar disorder diagnoses were significantly and similarly increased in adults surviving hospitalization for either COVID-19 or SARI.

Compared with the wider population, survivors of severe SARI or COVID-19 were also at increased risk of starting treatment with antidepressants, hypnotics/anxiolytics, or antipsychotics.

When comparing survivors of SARI hospitalization to survivors of COVID-19 hospitalization, no significant differences were observed in the postdischarge rates of new-onset anxiety disorder, dementia, depression, or bipolar affective disorder.

The SARI and COVID groups also did not differ in terms of their postdischarge risks of antidepressant or hypnotic/anxiolytic use, but the COVID survivors had a 20% lower risk of starting an antipsychotic.

“In this cohort study, SARI were found to be associated with significant postacute neuropsychiatric morbidity, for which COVID-19 is not distinctly different,” Dr. Watkinson and colleagues write.

“These results may help refine our understanding of the post–severe COVID-19 phenotype and may inform post-discharge support for patients requiring hospital-based and intensive care for SARI regardless of causative pathogen,” they write.

Caveats, cautionary notes

Kevin McConway, PhD, emeritus professor of applied statistics at the Open University in Milton Keynes, England, described the study as “impressive.” However, he pointed out that the study’s observational design is a limitation.

“One can never be absolutely certain about the interpretation of findings of an observational study. What the research can’t tell us is what caused the increased psychiatric risks for people hospitalized with COVID-19 or some other serious respiratory disease,” Dr. McConway said.

“It can’t tell us what might happen in the future, when, we all hope, many fewer are being hospitalized with COVID-19 than was the case in those first two waves, and the current backlog of provision of some health services has decreased,” he added.

“So we can’t just say that, in general, serious COVID-19 has much the same neuropsychiatric consequences as other very serious respiratory illness. Maybe it does, maybe it doesn’t,” Dr. McConway cautioned.

Max Taquet, PhD, with the University of Oxford, noted that the study is limited to hospitalized adult patients, leaving open the question of risk in nonhospitalized individuals – which is the overwhelming majority of patients with COVID-19 – or in children.

Whether the neuropsychiatric risks have remained the same since the emergence of the Omicron variant also remains “an open question since all patients in this study were diagnosed before July 2021,” Dr. Taquet said in statement.

The study was funded by the Wellcome Trust, the John Fell Oxford University Press Research Fund, the Oxford Wellcome Institutional Strategic Support Fund and Cancer Research UK, through the Cancer Research UK Oxford Centre. Dr. Watkinson disclosed grants from the National Institute for Health Research and Sensyne Health outside the submitted work; and serving as chief medical officer for Sensyne Health prior to this work, as well as holding shares in the company. Dr. McConway is a trustee of the UK Science Media Centre and a member of its advisory committee. His comments were provided in his capacity as an independent professional statistician. Dr. Taquet has worked on similar studies trying to identify, quantify, and specify the neurological and psychiatric consequences of COVID-19.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The neuropsychiatric ramifications of severe COVID-19 infection appear to be no different than for other severe acute respiratory infections (SARI).

This suggests that disease severity, rather than pathogen, is the most relevant factor in new-onset neuropsychiatric illness, the investigators note.

The risk of new-onset neuropsychological illness after severe COVID-19 infection are “substantial, but similar to those after other severe respiratory infections,” study investigator Peter Watkinson, MD, Nuffield Department of Clinical Neurosciences, University of Oxford, and John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, England, told this news organization.

The study was published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

Significant mental health burden

Research has shown a significant burden of neuropsychological illness after severe COVID-19 infection. However, it’s unclear how this risk compares to SARI.

To investigate, Dr. Watkinson and colleagues evaluated electronic health record data on more than 8.3 million adults, including 16,679 (0.02%) who survived a hospital admission for SARI and 32,525 (0.03%) who survived a hospital stay for COVID-19.

Compared with the remaining population, risks of new anxiety disorder, dementia, psychotic disorder, depression, and bipolar disorder diagnoses were significantly and similarly increased in adults surviving hospitalization for either COVID-19 or SARI.

Compared with the wider population, survivors of severe SARI or COVID-19 were also at increased risk of starting treatment with antidepressants, hypnotics/anxiolytics, or antipsychotics.

When comparing survivors of SARI hospitalization to survivors of COVID-19 hospitalization, no significant differences were observed in the postdischarge rates of new-onset anxiety disorder, dementia, depression, or bipolar affective disorder.

The SARI and COVID groups also did not differ in terms of their postdischarge risks of antidepressant or hypnotic/anxiolytic use, but the COVID survivors had a 20% lower risk of starting an antipsychotic.

“In this cohort study, SARI were found to be associated with significant postacute neuropsychiatric morbidity, for which COVID-19 is not distinctly different,” Dr. Watkinson and colleagues write.

“These results may help refine our understanding of the post–severe COVID-19 phenotype and may inform post-discharge support for patients requiring hospital-based and intensive care for SARI regardless of causative pathogen,” they write.

Caveats, cautionary notes

Kevin McConway, PhD, emeritus professor of applied statistics at the Open University in Milton Keynes, England, described the study as “impressive.” However, he pointed out that the study’s observational design is a limitation.

“One can never be absolutely certain about the interpretation of findings of an observational study. What the research can’t tell us is what caused the increased psychiatric risks for people hospitalized with COVID-19 or some other serious respiratory disease,” Dr. McConway said.

“It can’t tell us what might happen in the future, when, we all hope, many fewer are being hospitalized with COVID-19 than was the case in those first two waves, and the current backlog of provision of some health services has decreased,” he added.

“So we can’t just say that, in general, serious COVID-19 has much the same neuropsychiatric consequences as other very serious respiratory illness. Maybe it does, maybe it doesn’t,” Dr. McConway cautioned.

Max Taquet, PhD, with the University of Oxford, noted that the study is limited to hospitalized adult patients, leaving open the question of risk in nonhospitalized individuals – which is the overwhelming majority of patients with COVID-19 – or in children.

Whether the neuropsychiatric risks have remained the same since the emergence of the Omicron variant also remains “an open question since all patients in this study were diagnosed before July 2021,” Dr. Taquet said in statement.

The study was funded by the Wellcome Trust, the John Fell Oxford University Press Research Fund, the Oxford Wellcome Institutional Strategic Support Fund and Cancer Research UK, through the Cancer Research UK Oxford Centre. Dr. Watkinson disclosed grants from the National Institute for Health Research and Sensyne Health outside the submitted work; and serving as chief medical officer for Sensyne Health prior to this work, as well as holding shares in the company. Dr. McConway is a trustee of the UK Science Media Centre and a member of its advisory committee. His comments were provided in his capacity as an independent professional statistician. Dr. Taquet has worked on similar studies trying to identify, quantify, and specify the neurological and psychiatric consequences of COVID-19.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The neuropsychiatric ramifications of severe COVID-19 infection appear to be no different than for other severe acute respiratory infections (SARI).

This suggests that disease severity, rather than pathogen, is the most relevant factor in new-onset neuropsychiatric illness, the investigators note.

The risk of new-onset neuropsychological illness after severe COVID-19 infection are “substantial, but similar to those after other severe respiratory infections,” study investigator Peter Watkinson, MD, Nuffield Department of Clinical Neurosciences, University of Oxford, and John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, England, told this news organization.

The study was published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

Significant mental health burden

Research has shown a significant burden of neuropsychological illness after severe COVID-19 infection. However, it’s unclear how this risk compares to SARI.

To investigate, Dr. Watkinson and colleagues evaluated electronic health record data on more than 8.3 million adults, including 16,679 (0.02%) who survived a hospital admission for SARI and 32,525 (0.03%) who survived a hospital stay for COVID-19.

Compared with the remaining population, risks of new anxiety disorder, dementia, psychotic disorder, depression, and bipolar disorder diagnoses were significantly and similarly increased in adults surviving hospitalization for either COVID-19 or SARI.

Compared with the wider population, survivors of severe SARI or COVID-19 were also at increased risk of starting treatment with antidepressants, hypnotics/anxiolytics, or antipsychotics.

When comparing survivors of SARI hospitalization to survivors of COVID-19 hospitalization, no significant differences were observed in the postdischarge rates of new-onset anxiety disorder, dementia, depression, or bipolar affective disorder.

The SARI and COVID groups also did not differ in terms of their postdischarge risks of antidepressant or hypnotic/anxiolytic use, but the COVID survivors had a 20% lower risk of starting an antipsychotic.

“In this cohort study, SARI were found to be associated with significant postacute neuropsychiatric morbidity, for which COVID-19 is not distinctly different,” Dr. Watkinson and colleagues write.

“These results may help refine our understanding of the post–severe COVID-19 phenotype and may inform post-discharge support for patients requiring hospital-based and intensive care for SARI regardless of causative pathogen,” they write.

Caveats, cautionary notes

Kevin McConway, PhD, emeritus professor of applied statistics at the Open University in Milton Keynes, England, described the study as “impressive.” However, he pointed out that the study’s observational design is a limitation.

“One can never be absolutely certain about the interpretation of findings of an observational study. What the research can’t tell us is what caused the increased psychiatric risks for people hospitalized with COVID-19 or some other serious respiratory disease,” Dr. McConway said.

“It can’t tell us what might happen in the future, when, we all hope, many fewer are being hospitalized with COVID-19 than was the case in those first two waves, and the current backlog of provision of some health services has decreased,” he added.

“So we can’t just say that, in general, serious COVID-19 has much the same neuropsychiatric consequences as other very serious respiratory illness. Maybe it does, maybe it doesn’t,” Dr. McConway cautioned.

Max Taquet, PhD, with the University of Oxford, noted that the study is limited to hospitalized adult patients, leaving open the question of risk in nonhospitalized individuals – which is the overwhelming majority of patients with COVID-19 – or in children.

Whether the neuropsychiatric risks have remained the same since the emergence of the Omicron variant also remains “an open question since all patients in this study were diagnosed before July 2021,” Dr. Taquet said in statement.

The study was funded by the Wellcome Trust, the John Fell Oxford University Press Research Fund, the Oxford Wellcome Institutional Strategic Support Fund and Cancer Research UK, through the Cancer Research UK Oxford Centre. Dr. Watkinson disclosed grants from the National Institute for Health Research and Sensyne Health outside the submitted work; and serving as chief medical officer for Sensyne Health prior to this work, as well as holding shares in the company. Dr. McConway is a trustee of the UK Science Media Centre and a member of its advisory committee. His comments were provided in his capacity as an independent professional statistician. Dr. Taquet has worked on similar studies trying to identify, quantify, and specify the neurological and psychiatric consequences of COVID-19.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Clozapine and cancer risk in schizophrenia patients: New data

Long-term treatment with clozapine is associated with a small but significant risk of hematological malignancies in individuals with schizophrenia, new research shows.

The study was published online in The Lancet Psychiatry.

An unresolved issue

Clozapine is more effective than other antipsychotics for managing symptoms and suicidal behavior in schizophrenia, with the lowest mortality, compared with other antipsychotics, but its use is restricted in many countries, the researchers note.

Reports of nine deaths associated with clozapine use – eight due to agranulocytosis and one due to leukemia – in southwestern Finland in 1975 resulted in worldwide withdrawal of the drug. In 1990, clozapine was relaunched with stipulations for strict blood count control. The cumulative incidence of clozapine-induced agranulocytosis or severe neutropenia is estimated at about 0.9%.

Several small studies from Australia, Denmark, and the United States, and a large pharmacovigilance study, suggest that clozapine treatment might be associated with an increased risk of hematological malignancies.

“Previous studies have suggested a possible risk of hematological malignancies associated with clozapine, but due to methodological issues, the question had remained unsettled,” said Dr. Tiihonen.

Finland has among the highest rates of clozapine use in the world, where 20% of schizophrenia cases are treated with the drug. In most other countries, clozapine use is less than half of that, in Finland largely because of agranulocytosis concerns.

To examine the risk of hematological malignancies associated with long-term use of clozapine and other antipsychotics, the investigators conducted a large prospective case-control and cohort study that used data from Finnish national registers and included all patients with schizophrenia.

“Unlike previous studies, we employed prospectively gathered data from a nationwide cohort [including all patients with schizophrenia], had a long follow-up time, and studied the dose-response of the risk of hematological malignancies,” Dr. Tiihonen noted.

The nested case-control study was constructed by individually matching cases of lymphoid and hematopoietic tissue malignancy and pairing them with up to 10 matched controls with schizophrenia but without cancer.

Inclusion criteria were restricted to malignancies diagnosed on a histological basis. Individuals outside the ages of 18-85 years were excluded, as were those with a previous malignancy. Analyses were done using conditional logistic regression adjusted for comorbid conditions.

Patient education, vigilant monitoring

The case-control analysis was based on 516 patients with a first-time diagnosis of lymphoid and hematopoietic tissue malignancy from 2000-2017 and diagnosed after first diagnosis of schizophrenia.

Of these, 102 patients were excluded because of a diagnosis with no histological basis, five were excluded because of age, and 34 for a previous malignancy, resulting in 375 patients with malignancies matched with 10 controls for a total of 3,743 study participants.

Of the 375 patients with hematological malignancies (305 had lymphoma, 42 leukemia, 22 myeloma, six unspecified) in 2000-2017, 208 (55%) were men and 167 (45%) were women. Ethnicity data were not available.

Compared with non-use of clozapine, clozapine use was associated with increased odds of hematological malignancies in a dose-response manner (adjusted odds ratio, 3.35; 95% confidence interval, 2.22-5.05] for ≥ 5,000 defined daily dose cumulative exposure (P < .0001).

Exposure to other antipsychotic medications was not associated with increased odds of hematological malignancies. A complementary analysis showed that the clozapine-related risk increase was specific to hematological malignancies only.

Over 17 years follow-up of the base cohort, 37 deaths occurred due to hematological malignancy among patients exposed to clozapine in 26 patients with ongoing use at the time they were diagnosed with malignancy and in 11 patients who did not use clozapine at the exact time of their cancer diagnosis. Only three deaths occurred due to agranulocytosis, the investigators report.

The use of a nationwide registry for the study makes it “unlikely” that there were any undiagnosed/unreported malignancies, the researchers note. This, plus the “robust dose-response finding, and additional analysis showing no substantial difference in odds of other cancers between users of clozapine versus other antipsychotics suggest the association is causal, and not attributable to surveillance bias,” they write.

These findings, the investigators note, suggest patients taking clozapine and their caregivers need to be educated about the signs of hematological malignancies. Furthermore, they call for mental health providers to be “vigilant” in monitoring for potential signs and symptoms of hematological malignancy in patients taking the drug.

A ‘vital’ medication

Commenting on the findings, Stephen Marder, MD, professor of psychiatry and biobehavioral sciences and vice chair of the department of psychiatry at UCLA, noted the link between clozapine and agranulocytosis.

“Clozapine has been previously associated with agranulocytosis. Over the years that seemed to be the main concern of clinicians. The monitoring system for agranulocytosis has been a burden on the system and for patients, but not really a significant cause for concern with the safety of the drug,” said Dr. Marder, who is also director of the VISN 22 Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center for the Department of Veterans Affairs and director of the section on psychosis at the UCLA Neuropsychiatric Institute.

In fact, he noted recent research, including studies from this group that used large databases from Finland, which showed that clozapine was actually associated with a lower mortality risk than other antipsychotics.

The fact that the study showed prolonged use of clozapine at high doses was associated with a “very small” risk of hematological abnormalities does not undermine its standing as “the most effective antipsychotic [that is] associated with a lower risk of death,” said Dr. Marder.

“On the other hand,” he added, “it does suggest that clinicians should tell patients about it and, when they review the blood monitoring, they look at things beyond the neutrophil count” that may suggest malignancy.

“Clozapine has a vital role as the most effective antipsychotic drug and the only drug that has an indication for treatment-resistant schizophrenia and schizophrenia associated with suicidality,” said Dr. Marder.

The study was funded by the Finnish Ministry of Social Affairs and Health through the developmental fund for Niuvanniemi Hospital and by the Academy of Finland. Dr. Tiihonen and Dr. Marder have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Long-term treatment with clozapine is associated with a small but significant risk of hematological malignancies in individuals with schizophrenia, new research shows.

The study was published online in The Lancet Psychiatry.

An unresolved issue

Clozapine is more effective than other antipsychotics for managing symptoms and suicidal behavior in schizophrenia, with the lowest mortality, compared with other antipsychotics, but its use is restricted in many countries, the researchers note.

Reports of nine deaths associated with clozapine use – eight due to agranulocytosis and one due to leukemia – in southwestern Finland in 1975 resulted in worldwide withdrawal of the drug. In 1990, clozapine was relaunched with stipulations for strict blood count control. The cumulative incidence of clozapine-induced agranulocytosis or severe neutropenia is estimated at about 0.9%.

Several small studies from Australia, Denmark, and the United States, and a large pharmacovigilance study, suggest that clozapine treatment might be associated with an increased risk of hematological malignancies.

“Previous studies have suggested a possible risk of hematological malignancies associated with clozapine, but due to methodological issues, the question had remained unsettled,” said Dr. Tiihonen.

Finland has among the highest rates of clozapine use in the world, where 20% of schizophrenia cases are treated with the drug. In most other countries, clozapine use is less than half of that, in Finland largely because of agranulocytosis concerns.

To examine the risk of hematological malignancies associated with long-term use of clozapine and other antipsychotics, the investigators conducted a large prospective case-control and cohort study that used data from Finnish national registers and included all patients with schizophrenia.

“Unlike previous studies, we employed prospectively gathered data from a nationwide cohort [including all patients with schizophrenia], had a long follow-up time, and studied the dose-response of the risk of hematological malignancies,” Dr. Tiihonen noted.

The nested case-control study was constructed by individually matching cases of lymphoid and hematopoietic tissue malignancy and pairing them with up to 10 matched controls with schizophrenia but without cancer.

Inclusion criteria were restricted to malignancies diagnosed on a histological basis. Individuals outside the ages of 18-85 years were excluded, as were those with a previous malignancy. Analyses were done using conditional logistic regression adjusted for comorbid conditions.

Patient education, vigilant monitoring

The case-control analysis was based on 516 patients with a first-time diagnosis of lymphoid and hematopoietic tissue malignancy from 2000-2017 and diagnosed after first diagnosis of schizophrenia.

Of these, 102 patients were excluded because of a diagnosis with no histological basis, five were excluded because of age, and 34 for a previous malignancy, resulting in 375 patients with malignancies matched with 10 controls for a total of 3,743 study participants.

Of the 375 patients with hematological malignancies (305 had lymphoma, 42 leukemia, 22 myeloma, six unspecified) in 2000-2017, 208 (55%) were men and 167 (45%) were women. Ethnicity data were not available.

Compared with non-use of clozapine, clozapine use was associated with increased odds of hematological malignancies in a dose-response manner (adjusted odds ratio, 3.35; 95% confidence interval, 2.22-5.05] for ≥ 5,000 defined daily dose cumulative exposure (P < .0001).

Exposure to other antipsychotic medications was not associated with increased odds of hematological malignancies. A complementary analysis showed that the clozapine-related risk increase was specific to hematological malignancies only.

Over 17 years follow-up of the base cohort, 37 deaths occurred due to hematological malignancy among patients exposed to clozapine in 26 patients with ongoing use at the time they were diagnosed with malignancy and in 11 patients who did not use clozapine at the exact time of their cancer diagnosis. Only three deaths occurred due to agranulocytosis, the investigators report.

The use of a nationwide registry for the study makes it “unlikely” that there were any undiagnosed/unreported malignancies, the researchers note. This, plus the “robust dose-response finding, and additional analysis showing no substantial difference in odds of other cancers between users of clozapine versus other antipsychotics suggest the association is causal, and not attributable to surveillance bias,” they write.

These findings, the investigators note, suggest patients taking clozapine and their caregivers need to be educated about the signs of hematological malignancies. Furthermore, they call for mental health providers to be “vigilant” in monitoring for potential signs and symptoms of hematological malignancy in patients taking the drug.

A ‘vital’ medication

Commenting on the findings, Stephen Marder, MD, professor of psychiatry and biobehavioral sciences and vice chair of the department of psychiatry at UCLA, noted the link between clozapine and agranulocytosis.

“Clozapine has been previously associated with agranulocytosis. Over the years that seemed to be the main concern of clinicians. The monitoring system for agranulocytosis has been a burden on the system and for patients, but not really a significant cause for concern with the safety of the drug,” said Dr. Marder, who is also director of the VISN 22 Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center for the Department of Veterans Affairs and director of the section on psychosis at the UCLA Neuropsychiatric Institute.

In fact, he noted recent research, including studies from this group that used large databases from Finland, which showed that clozapine was actually associated with a lower mortality risk than other antipsychotics.

The fact that the study showed prolonged use of clozapine at high doses was associated with a “very small” risk of hematological abnormalities does not undermine its standing as “the most effective antipsychotic [that is] associated with a lower risk of death,” said Dr. Marder.

“On the other hand,” he added, “it does suggest that clinicians should tell patients about it and, when they review the blood monitoring, they look at things beyond the neutrophil count” that may suggest malignancy.

“Clozapine has a vital role as the most effective antipsychotic drug and the only drug that has an indication for treatment-resistant schizophrenia and schizophrenia associated with suicidality,” said Dr. Marder.

The study was funded by the Finnish Ministry of Social Affairs and Health through the developmental fund for Niuvanniemi Hospital and by the Academy of Finland. Dr. Tiihonen and Dr. Marder have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Long-term treatment with clozapine is associated with a small but significant risk of hematological malignancies in individuals with schizophrenia, new research shows.

The study was published online in The Lancet Psychiatry.

An unresolved issue

Clozapine is more effective than other antipsychotics for managing symptoms and suicidal behavior in schizophrenia, with the lowest mortality, compared with other antipsychotics, but its use is restricted in many countries, the researchers note.

Reports of nine deaths associated with clozapine use – eight due to agranulocytosis and one due to leukemia – in southwestern Finland in 1975 resulted in worldwide withdrawal of the drug. In 1990, clozapine was relaunched with stipulations for strict blood count control. The cumulative incidence of clozapine-induced agranulocytosis or severe neutropenia is estimated at about 0.9%.

Several small studies from Australia, Denmark, and the United States, and a large pharmacovigilance study, suggest that clozapine treatment might be associated with an increased risk of hematological malignancies.

“Previous studies have suggested a possible risk of hematological malignancies associated with clozapine, but due to methodological issues, the question had remained unsettled,” said Dr. Tiihonen.

Finland has among the highest rates of clozapine use in the world, where 20% of schizophrenia cases are treated with the drug. In most other countries, clozapine use is less than half of that, in Finland largely because of agranulocytosis concerns.

To examine the risk of hematological malignancies associated with long-term use of clozapine and other antipsychotics, the investigators conducted a large prospective case-control and cohort study that used data from Finnish national registers and included all patients with schizophrenia.

“Unlike previous studies, we employed prospectively gathered data from a nationwide cohort [including all patients with schizophrenia], had a long follow-up time, and studied the dose-response of the risk of hematological malignancies,” Dr. Tiihonen noted.

The nested case-control study was constructed by individually matching cases of lymphoid and hematopoietic tissue malignancy and pairing them with up to 10 matched controls with schizophrenia but without cancer.

Inclusion criteria were restricted to malignancies diagnosed on a histological basis. Individuals outside the ages of 18-85 years were excluded, as were those with a previous malignancy. Analyses were done using conditional logistic regression adjusted for comorbid conditions.

Patient education, vigilant monitoring

The case-control analysis was based on 516 patients with a first-time diagnosis of lymphoid and hematopoietic tissue malignancy from 2000-2017 and diagnosed after first diagnosis of schizophrenia.

Of these, 102 patients were excluded because of a diagnosis with no histological basis, five were excluded because of age, and 34 for a previous malignancy, resulting in 375 patients with malignancies matched with 10 controls for a total of 3,743 study participants.

Of the 375 patients with hematological malignancies (305 had lymphoma, 42 leukemia, 22 myeloma, six unspecified) in 2000-2017, 208 (55%) were men and 167 (45%) were women. Ethnicity data were not available.

Compared with non-use of clozapine, clozapine use was associated with increased odds of hematological malignancies in a dose-response manner (adjusted odds ratio, 3.35; 95% confidence interval, 2.22-5.05] for ≥ 5,000 defined daily dose cumulative exposure (P < .0001).

Exposure to other antipsychotic medications was not associated with increased odds of hematological malignancies. A complementary analysis showed that the clozapine-related risk increase was specific to hematological malignancies only.

Over 17 years follow-up of the base cohort, 37 deaths occurred due to hematological malignancy among patients exposed to clozapine in 26 patients with ongoing use at the time they were diagnosed with malignancy and in 11 patients who did not use clozapine at the exact time of their cancer diagnosis. Only three deaths occurred due to agranulocytosis, the investigators report.

The use of a nationwide registry for the study makes it “unlikely” that there were any undiagnosed/unreported malignancies, the researchers note. This, plus the “robust dose-response finding, and additional analysis showing no substantial difference in odds of other cancers between users of clozapine versus other antipsychotics suggest the association is causal, and not attributable to surveillance bias,” they write.

These findings, the investigators note, suggest patients taking clozapine and their caregivers need to be educated about the signs of hematological malignancies. Furthermore, they call for mental health providers to be “vigilant” in monitoring for potential signs and symptoms of hematological malignancy in patients taking the drug.

A ‘vital’ medication

Commenting on the findings, Stephen Marder, MD, professor of psychiatry and biobehavioral sciences and vice chair of the department of psychiatry at UCLA, noted the link between clozapine and agranulocytosis.

“Clozapine has been previously associated with agranulocytosis. Over the years that seemed to be the main concern of clinicians. The monitoring system for agranulocytosis has been a burden on the system and for patients, but not really a significant cause for concern with the safety of the drug,” said Dr. Marder, who is also director of the VISN 22 Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center for the Department of Veterans Affairs and director of the section on psychosis at the UCLA Neuropsychiatric Institute.

In fact, he noted recent research, including studies from this group that used large databases from Finland, which showed that clozapine was actually associated with a lower mortality risk than other antipsychotics.

The fact that the study showed prolonged use of clozapine at high doses was associated with a “very small” risk of hematological abnormalities does not undermine its standing as “the most effective antipsychotic [that is] associated with a lower risk of death,” said Dr. Marder.

“On the other hand,” he added, “it does suggest that clinicians should tell patients about it and, when they review the blood monitoring, they look at things beyond the neutrophil count” that may suggest malignancy.

“Clozapine has a vital role as the most effective antipsychotic drug and the only drug that has an indication for treatment-resistant schizophrenia and schizophrenia associated with suicidality,” said Dr. Marder.

The study was funded by the Finnish Ministry of Social Affairs and Health through the developmental fund for Niuvanniemi Hospital and by the Academy of Finland. Dr. Tiihonen and Dr. Marder have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE LANCET PSYCHIATRY

Experts urge stopping melanoma trial because of failure and harm

New

The approach seemed promising, given the efficacy of PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors in metastatic melanoma, and the relatively short response times to BRAF and MEK inhibitors could potentially be supplemented by longer response times associated with PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors. The two categories also have different mechanisms of action and nonoverlapping toxicities, which led to an expectation that the combination would be well tolerated.

But the new study joins two previous randomized, controlled trials that also failed to show much clinical benefit. IMspire150 assigned BRAF V600–mutated melanoma patients to vemurafenib and cobimetinib plus the anti–PD-L1 antibody atezolizumab or placebo. The treatment arm had a small benefit in progression-free survival (hazard ratio, 0.78), which led to Food and Drug Administration approval of the combination, though there was no significant difference when the two cohorts were assessed by an independent review committee. The KEYNOTE-022 trial examined dabrafenib plus trametinib with or without the anti–PD-1 antibody pembrolizumab, and found no difference in investigator-assessed progression free survival.

The new study was published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology. In an accompanying editorial, Margaret K. Callahan, MD, PhD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, and Paul B. Chapman, MD, of Weill Cornell Medicine, both in New York, speculated that the toxicity of the triplet combination might explain the latest failure, since patients in the triplet arm had more treatment interruptions and dose reductions than the doublet arm (32% received full-dose dabrafenib vs. 54% in the doublet arm), which may have undermined efficacy.

Citing the fact that there are now three randomized, controlled trials with discouraging results, “we believe that there are sufficient data now to be confident that the addition of anti–PD-1 or anti–PD-L1 antibodies to combination RAFi [RAF inhibitors] plus MEKi [MEK inhibitors] is not associated with a significant clinical benefit and should not be studied further in melanoma.

Moreover, “there is some evidence of harm,” the editorial authors wrote. “As the additional toxicity of triplet combination limited the delivery of combination RAFi plus MEKi therapy in COMBI-I. Focus should turn instead to optimizing doses and schedules of combination RAFi plus MEKi and checkpoint inhibitors, developing treatment strategies to overcome resistance to these therapies, and determining how best to sequence combination RAFi plus MEKi therapy and checkpoint inhibitors. Regarding the latter point, there are several sequential therapy trials currently underway in previously untreated patients with BRAF V600–mutated melanoma.”

In the study, patients were randomized to receive dabrafenib and trametinib plus the anti–PD receptor–1 antibody spartalizumab or placebo. After a median follow-up of 27.2 months, mean progression-free survival was 16.2 months in the spartalizumab arm and 12.0 months in the placebo arm (HR, 0.82; P = .042). The spartalizumab group had a 69% objective response rate versus 64% in the placebo group. 55% of the spartalizumab group experienced grade 3 or higher treatment-related adverse events, compared with 33% in the placebo group.

“These results do not support broad use of first-line immunotherapy plus targeted therapy combination, but they provide additional data toward understanding the optimal application of these therapeutic classes in patients with BRAF V600–mutant metastatic melanoma,” the authors of the study wrote.

The study was funded by F Hoffmann–La Roche and Genentech. Dr. Callahan has been employed at Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, and Kleo Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Callahan has consulted for or advised AstraZeneca, Moderna Therapeutics, Merck, and Immunocore. Dr. Chapman has stock or ownership interest in Rgenix; has consulted for or advised Merck, Pfizer, and Black Diamond Therapeutics; and has received research funding from Genentech.

New

The approach seemed promising, given the efficacy of PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors in metastatic melanoma, and the relatively short response times to BRAF and MEK inhibitors could potentially be supplemented by longer response times associated with PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors. The two categories also have different mechanisms of action and nonoverlapping toxicities, which led to an expectation that the combination would be well tolerated.

But the new study joins two previous randomized, controlled trials that also failed to show much clinical benefit. IMspire150 assigned BRAF V600–mutated melanoma patients to vemurafenib and cobimetinib plus the anti–PD-L1 antibody atezolizumab or placebo. The treatment arm had a small benefit in progression-free survival (hazard ratio, 0.78), which led to Food and Drug Administration approval of the combination, though there was no significant difference when the two cohorts were assessed by an independent review committee. The KEYNOTE-022 trial examined dabrafenib plus trametinib with or without the anti–PD-1 antibody pembrolizumab, and found no difference in investigator-assessed progression free survival.

The new study was published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology. In an accompanying editorial, Margaret K. Callahan, MD, PhD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, and Paul B. Chapman, MD, of Weill Cornell Medicine, both in New York, speculated that the toxicity of the triplet combination might explain the latest failure, since patients in the triplet arm had more treatment interruptions and dose reductions than the doublet arm (32% received full-dose dabrafenib vs. 54% in the doublet arm), which may have undermined efficacy.

Citing the fact that there are now three randomized, controlled trials with discouraging results, “we believe that there are sufficient data now to be confident that the addition of anti–PD-1 or anti–PD-L1 antibodies to combination RAFi [RAF inhibitors] plus MEKi [MEK inhibitors] is not associated with a significant clinical benefit and should not be studied further in melanoma.

Moreover, “there is some evidence of harm,” the editorial authors wrote. “As the additional toxicity of triplet combination limited the delivery of combination RAFi plus MEKi therapy in COMBI-I. Focus should turn instead to optimizing doses and schedules of combination RAFi plus MEKi and checkpoint inhibitors, developing treatment strategies to overcome resistance to these therapies, and determining how best to sequence combination RAFi plus MEKi therapy and checkpoint inhibitors. Regarding the latter point, there are several sequential therapy trials currently underway in previously untreated patients with BRAF V600–mutated melanoma.”

In the study, patients were randomized to receive dabrafenib and trametinib plus the anti–PD receptor–1 antibody spartalizumab or placebo. After a median follow-up of 27.2 months, mean progression-free survival was 16.2 months in the spartalizumab arm and 12.0 months in the placebo arm (HR, 0.82; P = .042). The spartalizumab group had a 69% objective response rate versus 64% in the placebo group. 55% of the spartalizumab group experienced grade 3 or higher treatment-related adverse events, compared with 33% in the placebo group.

“These results do not support broad use of first-line immunotherapy plus targeted therapy combination, but they provide additional data toward understanding the optimal application of these therapeutic classes in patients with BRAF V600–mutant metastatic melanoma,” the authors of the study wrote.

The study was funded by F Hoffmann–La Roche and Genentech. Dr. Callahan has been employed at Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, and Kleo Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Callahan has consulted for or advised AstraZeneca, Moderna Therapeutics, Merck, and Immunocore. Dr. Chapman has stock or ownership interest in Rgenix; has consulted for or advised Merck, Pfizer, and Black Diamond Therapeutics; and has received research funding from Genentech.

New

The approach seemed promising, given the efficacy of PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors in metastatic melanoma, and the relatively short response times to BRAF and MEK inhibitors could potentially be supplemented by longer response times associated with PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors. The two categories also have different mechanisms of action and nonoverlapping toxicities, which led to an expectation that the combination would be well tolerated.

But the new study joins two previous randomized, controlled trials that also failed to show much clinical benefit. IMspire150 assigned BRAF V600–mutated melanoma patients to vemurafenib and cobimetinib plus the anti–PD-L1 antibody atezolizumab or placebo. The treatment arm had a small benefit in progression-free survival (hazard ratio, 0.78), which led to Food and Drug Administration approval of the combination, though there was no significant difference when the two cohorts were assessed by an independent review committee. The KEYNOTE-022 trial examined dabrafenib plus trametinib with or without the anti–PD-1 antibody pembrolizumab, and found no difference in investigator-assessed progression free survival.

The new study was published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology. In an accompanying editorial, Margaret K. Callahan, MD, PhD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, and Paul B. Chapman, MD, of Weill Cornell Medicine, both in New York, speculated that the toxicity of the triplet combination might explain the latest failure, since patients in the triplet arm had more treatment interruptions and dose reductions than the doublet arm (32% received full-dose dabrafenib vs. 54% in the doublet arm), which may have undermined efficacy.

Citing the fact that there are now three randomized, controlled trials with discouraging results, “we believe that there are sufficient data now to be confident that the addition of anti–PD-1 or anti–PD-L1 antibodies to combination RAFi [RAF inhibitors] plus MEKi [MEK inhibitors] is not associated with a significant clinical benefit and should not be studied further in melanoma.

Moreover, “there is some evidence of harm,” the editorial authors wrote. “As the additional toxicity of triplet combination limited the delivery of combination RAFi plus MEKi therapy in COMBI-I. Focus should turn instead to optimizing doses and schedules of combination RAFi plus MEKi and checkpoint inhibitors, developing treatment strategies to overcome resistance to these therapies, and determining how best to sequence combination RAFi plus MEKi therapy and checkpoint inhibitors. Regarding the latter point, there are several sequential therapy trials currently underway in previously untreated patients with BRAF V600–mutated melanoma.”

In the study, patients were randomized to receive dabrafenib and trametinib plus the anti–PD receptor–1 antibody spartalizumab or placebo. After a median follow-up of 27.2 months, mean progression-free survival was 16.2 months in the spartalizumab arm and 12.0 months in the placebo arm (HR, 0.82; P = .042). The spartalizumab group had a 69% objective response rate versus 64% in the placebo group. 55% of the spartalizumab group experienced grade 3 or higher treatment-related adverse events, compared with 33% in the placebo group.

“These results do not support broad use of first-line immunotherapy plus targeted therapy combination, but they provide additional data toward understanding the optimal application of these therapeutic classes in patients with BRAF V600–mutant metastatic melanoma,” the authors of the study wrote.

The study was funded by F Hoffmann–La Roche and Genentech. Dr. Callahan has been employed at Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, and Kleo Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Callahan has consulted for or advised AstraZeneca, Moderna Therapeutics, Merck, and Immunocore. Dr. Chapman has stock or ownership interest in Rgenix; has consulted for or advised Merck, Pfizer, and Black Diamond Therapeutics; and has received research funding from Genentech.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Quadruple-negative breast cancer associated with poorest outcomes

and face a poorer prognosis than patients with PD-L1–positive tumors, according to a study presented at ESMO Breast Cancer 2022, a meeting of the European Society for Medical Oncology.

“The newly distinct quadruple negative breast cancer subtype could be considered the breast cancer subtype with the poorest outcome,” wrote the authors, who were led by Loay Kassem, MD, a clinical oncology consultant at Cairo (Egypt) University.

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) accounts for 15%-20% of all breast cancers. It tends to be more aggressive and difficult to treat than other subtypes.

Prior research has shown the expression of PD-L1 in tumors is predictive of immunotherapy response in patients with metastatic TNBC. The checkpoint inhibitor pembrolizumab (Keytruda, Merck) was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2021 for high-risk, early-stage, triple-negative breast cancer in combination with neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and then continued as a single treatment after surgery.

To determine whether PD-L1 expression could also predict response to chemotherapy in with nonmetastatic TNBC, the researchers conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of 19 studies that included a total of 2,319 patients with nonmetastatic TBNC. The team examined whether PD-L1 expression could predict pathological complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. PD-L1–positive TNBC were found to be significantly associated with a higher probability of achieving a pathological complete response with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Long-term studies have shown that PD-L1 positivity was associated with better disease-free survival and overall survival than PD-L1–negative patients.

The researchers also examined RNA sequence data, which showed that PD-L1 expression was indicative of higher levels of expression of key immune-related genes that mediate response to chemotherapy in TNBC.

Dr. Kassem and colleagues suggest that quadruple-negative breast cancer defined by a lack of PD-L1 expression is a distinct subtype of breast cancer associated with the poorest outcomes. Another quadruple-negative breast cancer – a subtype of TNBC where patients lack expression of the androgen receptor, has also been associated with more aggressive disease and poorer response to treatment.

The authors report no funding or conflicts of interest.

and face a poorer prognosis than patients with PD-L1–positive tumors, according to a study presented at ESMO Breast Cancer 2022, a meeting of the European Society for Medical Oncology.

“The newly distinct quadruple negative breast cancer subtype could be considered the breast cancer subtype with the poorest outcome,” wrote the authors, who were led by Loay Kassem, MD, a clinical oncology consultant at Cairo (Egypt) University.

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) accounts for 15%-20% of all breast cancers. It tends to be more aggressive and difficult to treat than other subtypes.

Prior research has shown the expression of PD-L1 in tumors is predictive of immunotherapy response in patients with metastatic TNBC. The checkpoint inhibitor pembrolizumab (Keytruda, Merck) was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2021 for high-risk, early-stage, triple-negative breast cancer in combination with neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and then continued as a single treatment after surgery.

To determine whether PD-L1 expression could also predict response to chemotherapy in with nonmetastatic TNBC, the researchers conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of 19 studies that included a total of 2,319 patients with nonmetastatic TBNC. The team examined whether PD-L1 expression could predict pathological complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. PD-L1–positive TNBC were found to be significantly associated with a higher probability of achieving a pathological complete response with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Long-term studies have shown that PD-L1 positivity was associated with better disease-free survival and overall survival than PD-L1–negative patients.