User login

Meta-analysis demonstrates better survival outcomes with breast-conserving surgery vs mastectomy

Key clinical point: Women with early-stage invasive breast cancer (BC) who underwent breast-conserving surgery with radiotherapy (BCS) had better overall survival (OS) than those who underwent mastectomy.

Major finding: Compared with mastectomy, BCS was associated with improved OS in the overall population of patients with early-stage invasive BC (relative risk [RR] 0.64; 95% CI 0.55-0.74), with stronger effects observed in women followed-up for <10 years (RR 0.54; 95% CI 0.46-0.64).

Study details: Findings are from a meta-analysis of 30 studies including 1,802,128 women with early-stage invasive BC, of which 1,075,563 and 744,565 patients underwent BCS and mastectomy, respectively, and were followed-up for 4-20 years.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any external funding. Dr. Chatterjee declared serving as a consultant for 3M and Royal.

Source: De la Cruz Ku G et al. Does breast-conserving surgery with radiotherapy have a better survival than mastectomy? A meta-analysis of more than 1,500,000 patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2022 (Jul 25). Doi: 10.1245/s10434-022-12133-8

Key clinical point: Women with early-stage invasive breast cancer (BC) who underwent breast-conserving surgery with radiotherapy (BCS) had better overall survival (OS) than those who underwent mastectomy.

Major finding: Compared with mastectomy, BCS was associated with improved OS in the overall population of patients with early-stage invasive BC (relative risk [RR] 0.64; 95% CI 0.55-0.74), with stronger effects observed in women followed-up for <10 years (RR 0.54; 95% CI 0.46-0.64).

Study details: Findings are from a meta-analysis of 30 studies including 1,802,128 women with early-stage invasive BC, of which 1,075,563 and 744,565 patients underwent BCS and mastectomy, respectively, and were followed-up for 4-20 years.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any external funding. Dr. Chatterjee declared serving as a consultant for 3M and Royal.

Source: De la Cruz Ku G et al. Does breast-conserving surgery with radiotherapy have a better survival than mastectomy? A meta-analysis of more than 1,500,000 patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2022 (Jul 25). Doi: 10.1245/s10434-022-12133-8

Key clinical point: Women with early-stage invasive breast cancer (BC) who underwent breast-conserving surgery with radiotherapy (BCS) had better overall survival (OS) than those who underwent mastectomy.

Major finding: Compared with mastectomy, BCS was associated with improved OS in the overall population of patients with early-stage invasive BC (relative risk [RR] 0.64; 95% CI 0.55-0.74), with stronger effects observed in women followed-up for <10 years (RR 0.54; 95% CI 0.46-0.64).

Study details: Findings are from a meta-analysis of 30 studies including 1,802,128 women with early-stage invasive BC, of which 1,075,563 and 744,565 patients underwent BCS and mastectomy, respectively, and were followed-up for 4-20 years.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any external funding. Dr. Chatterjee declared serving as a consultant for 3M and Royal.

Source: De la Cruz Ku G et al. Does breast-conserving surgery with radiotherapy have a better survival than mastectomy? A meta-analysis of more than 1,500,000 patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2022 (Jul 25). Doi: 10.1245/s10434-022-12133-8

Childbirth does not impact survival in women with previously treated BC

Key clinical point: A live birth (LB) after the diagnosis of breast cancer (BC) does not have a negative impact on a woman’s overall survival.

Major finding: Compared with women with no subsequent LB after BC diagnosis, the overall cohort of women with subsequent LB (hazard ratio [HR] 0.65; P = .002), women with only 1 subsequent LB (HR 0.73; P = .033), women with subsequent LB and no prior history of pregnancy (HR 0.56; P = .003), and women with LB within 5 years of BC diagnosis (HR 0.66; P = .006) had improved survival.

Study details: Findings are from a survival analysis in a national cohort of 5181 women diagnosed with BC at the age of 20-39 years, of which 290 had ≥1 LB and 1682 had no LB after BC diagnosis.

Disclosures: This study was partly supported by the MRC Centre for Reproductive Health, UK. Two authors declared serving as consultants or receiving speaker honoraria from several sources.

Source: Anderson RA et al. Survival after breast cancer in women with a subsequent live birth: Influence of age at diagnosis and interval to subsequent pregnancy. Eur J Cancer. 2022;173:113-122 (Jul 19). Doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2022.06.048

Key clinical point: A live birth (LB) after the diagnosis of breast cancer (BC) does not have a negative impact on a woman’s overall survival.

Major finding: Compared with women with no subsequent LB after BC diagnosis, the overall cohort of women with subsequent LB (hazard ratio [HR] 0.65; P = .002), women with only 1 subsequent LB (HR 0.73; P = .033), women with subsequent LB and no prior history of pregnancy (HR 0.56; P = .003), and women with LB within 5 years of BC diagnosis (HR 0.66; P = .006) had improved survival.

Study details: Findings are from a survival analysis in a national cohort of 5181 women diagnosed with BC at the age of 20-39 years, of which 290 had ≥1 LB and 1682 had no LB after BC diagnosis.

Disclosures: This study was partly supported by the MRC Centre for Reproductive Health, UK. Two authors declared serving as consultants or receiving speaker honoraria from several sources.

Source: Anderson RA et al. Survival after breast cancer in women with a subsequent live birth: Influence of age at diagnosis and interval to subsequent pregnancy. Eur J Cancer. 2022;173:113-122 (Jul 19). Doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2022.06.048

Key clinical point: A live birth (LB) after the diagnosis of breast cancer (BC) does not have a negative impact on a woman’s overall survival.

Major finding: Compared with women with no subsequent LB after BC diagnosis, the overall cohort of women with subsequent LB (hazard ratio [HR] 0.65; P = .002), women with only 1 subsequent LB (HR 0.73; P = .033), women with subsequent LB and no prior history of pregnancy (HR 0.56; P = .003), and women with LB within 5 years of BC diagnosis (HR 0.66; P = .006) had improved survival.

Study details: Findings are from a survival analysis in a national cohort of 5181 women diagnosed with BC at the age of 20-39 years, of which 290 had ≥1 LB and 1682 had no LB after BC diagnosis.

Disclosures: This study was partly supported by the MRC Centre for Reproductive Health, UK. Two authors declared serving as consultants or receiving speaker honoraria from several sources.

Source: Anderson RA et al. Survival after breast cancer in women with a subsequent live birth: Influence of age at diagnosis and interval to subsequent pregnancy. Eur J Cancer. 2022;173:113-122 (Jul 19). Doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2022.06.048

ER+ BC: Long-term benefits of endocrine therapy in premenopausal women

Key clinical point: Adjuvant endocrine therapy (ET) for 2 years showed a long-term (20 years) advantage in premenopausal women with estrogen receptor-positive (ER+) breast cancer (BC), with differential treatment benefit observed in genomic high-risk vs low-risk tumors.

Major finding: Goserelin (hazard ratio [HR] 0.49; 95% CI 0.32-0.75), tamoxifen (HR 0.57; 95% CI 0.38-0.87), and combined goserelin-tamoxifen (HR 0.63; 95% CI 0.42-0.94) vs no adjuvant ET improved long-term distant recurrence-free interval in the overall cohort of patients, with tamoxifen and goserelin benefitting genomic low-risk (HR 0.24; 95% CI 0.10-0.60) and high-risk (HR 0.24; 95% CI 0.10-0.54) patients, respectively.

Study details: Findings are from the secondary analysis of the Stockholm trial including 584 premenopausal patients with ER+ BC who were randomly assigned to receive goserelin, tamoxifen, combined goserelin-tamoxifen, or no adjuvant ET for 2 years.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Swedish Research Council and other sources. Some authors declared serving as consultants or advisors or leaders for, being employees or stockowners of, or receiving research funding, honoraria, travel, or accommodation expense from several sources.

Source: Johansson A et al. Twenty-year benefit from adjuvant goserelin and tamoxifen in premenopausal patients with breast cancer in a controlled randomized clinical trial. J Clin Oncol. 2022 (Jul 21). Doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.02844

Key clinical point: Adjuvant endocrine therapy (ET) for 2 years showed a long-term (20 years) advantage in premenopausal women with estrogen receptor-positive (ER+) breast cancer (BC), with differential treatment benefit observed in genomic high-risk vs low-risk tumors.

Major finding: Goserelin (hazard ratio [HR] 0.49; 95% CI 0.32-0.75), tamoxifen (HR 0.57; 95% CI 0.38-0.87), and combined goserelin-tamoxifen (HR 0.63; 95% CI 0.42-0.94) vs no adjuvant ET improved long-term distant recurrence-free interval in the overall cohort of patients, with tamoxifen and goserelin benefitting genomic low-risk (HR 0.24; 95% CI 0.10-0.60) and high-risk (HR 0.24; 95% CI 0.10-0.54) patients, respectively.

Study details: Findings are from the secondary analysis of the Stockholm trial including 584 premenopausal patients with ER+ BC who were randomly assigned to receive goserelin, tamoxifen, combined goserelin-tamoxifen, or no adjuvant ET for 2 years.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Swedish Research Council and other sources. Some authors declared serving as consultants or advisors or leaders for, being employees or stockowners of, or receiving research funding, honoraria, travel, or accommodation expense from several sources.

Source: Johansson A et al. Twenty-year benefit from adjuvant goserelin and tamoxifen in premenopausal patients with breast cancer in a controlled randomized clinical trial. J Clin Oncol. 2022 (Jul 21). Doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.02844

Key clinical point: Adjuvant endocrine therapy (ET) for 2 years showed a long-term (20 years) advantage in premenopausal women with estrogen receptor-positive (ER+) breast cancer (BC), with differential treatment benefit observed in genomic high-risk vs low-risk tumors.

Major finding: Goserelin (hazard ratio [HR] 0.49; 95% CI 0.32-0.75), tamoxifen (HR 0.57; 95% CI 0.38-0.87), and combined goserelin-tamoxifen (HR 0.63; 95% CI 0.42-0.94) vs no adjuvant ET improved long-term distant recurrence-free interval in the overall cohort of patients, with tamoxifen and goserelin benefitting genomic low-risk (HR 0.24; 95% CI 0.10-0.60) and high-risk (HR 0.24; 95% CI 0.10-0.54) patients, respectively.

Study details: Findings are from the secondary analysis of the Stockholm trial including 584 premenopausal patients with ER+ BC who were randomly assigned to receive goserelin, tamoxifen, combined goserelin-tamoxifen, or no adjuvant ET for 2 years.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Swedish Research Council and other sources. Some authors declared serving as consultants or advisors or leaders for, being employees or stockowners of, or receiving research funding, honoraria, travel, or accommodation expense from several sources.

Source: Johansson A et al. Twenty-year benefit from adjuvant goserelin and tamoxifen in premenopausal patients with breast cancer in a controlled randomized clinical trial. J Clin Oncol. 2022 (Jul 21). Doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.02844

Early-stage ER+ BC: No recurrence or mortality with systemic or vaginal hormone therapy

Key clinical point: Vaginal estrogen therapy (VET) or menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) did not increase the risk for recurrence/mortality in postmenopausal women with early-stage, estrogen receptor-positive (ER+) BC; however, the recurrence risk was higher in patients receiving aromatase inhibitors (AI)+VET.

Major finding: The recurrence risk among women receiving VET (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 1.08; 95% CI 0.89-1.32) or MHT (aHR 1.05; 95% CI 0.62-1.78) was similar to that among never-users of hormone therapy; however, the risk was elevated in patients receiving VET+AI (aHR 1.39; 95% CI 1.04-1.85). Neither VET (aHR 0.78; 95% CI 0.71-0.87) nor MHT (aHR 0.94; 95% CI 0.70-1.26) was associated with increased overall mortality, irrespective of the receipt of AI.

Study details: Findings are from an observational cohort study including 8461 postmenopausal women with early-stage, invasive, nonmetastatic, ER+ BC who received no endocrine treatment or 5-year adjuvant endocrine therapy.

Disclosures: This study was supported by Breast Friends, a part of the Danish Cancer Society. Some authors declared receiving support, honoraria, or institutional grants from several sources.

Source: Cold S et al. Systemic or vaginal hormone therapy after early breast cancer: A Danish observational cohort study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2022 (Jul 20). Doi: 10.1093/jnci/djac112

Key clinical point: Vaginal estrogen therapy (VET) or menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) did not increase the risk for recurrence/mortality in postmenopausal women with early-stage, estrogen receptor-positive (ER+) BC; however, the recurrence risk was higher in patients receiving aromatase inhibitors (AI)+VET.

Major finding: The recurrence risk among women receiving VET (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 1.08; 95% CI 0.89-1.32) or MHT (aHR 1.05; 95% CI 0.62-1.78) was similar to that among never-users of hormone therapy; however, the risk was elevated in patients receiving VET+AI (aHR 1.39; 95% CI 1.04-1.85). Neither VET (aHR 0.78; 95% CI 0.71-0.87) nor MHT (aHR 0.94; 95% CI 0.70-1.26) was associated with increased overall mortality, irrespective of the receipt of AI.

Study details: Findings are from an observational cohort study including 8461 postmenopausal women with early-stage, invasive, nonmetastatic, ER+ BC who received no endocrine treatment or 5-year adjuvant endocrine therapy.

Disclosures: This study was supported by Breast Friends, a part of the Danish Cancer Society. Some authors declared receiving support, honoraria, or institutional grants from several sources.

Source: Cold S et al. Systemic or vaginal hormone therapy after early breast cancer: A Danish observational cohort study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2022 (Jul 20). Doi: 10.1093/jnci/djac112

Key clinical point: Vaginal estrogen therapy (VET) or menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) did not increase the risk for recurrence/mortality in postmenopausal women with early-stage, estrogen receptor-positive (ER+) BC; however, the recurrence risk was higher in patients receiving aromatase inhibitors (AI)+VET.

Major finding: The recurrence risk among women receiving VET (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 1.08; 95% CI 0.89-1.32) or MHT (aHR 1.05; 95% CI 0.62-1.78) was similar to that among never-users of hormone therapy; however, the risk was elevated in patients receiving VET+AI (aHR 1.39; 95% CI 1.04-1.85). Neither VET (aHR 0.78; 95% CI 0.71-0.87) nor MHT (aHR 0.94; 95% CI 0.70-1.26) was associated with increased overall mortality, irrespective of the receipt of AI.

Study details: Findings are from an observational cohort study including 8461 postmenopausal women with early-stage, invasive, nonmetastatic, ER+ BC who received no endocrine treatment or 5-year adjuvant endocrine therapy.

Disclosures: This study was supported by Breast Friends, a part of the Danish Cancer Society. Some authors declared receiving support, honoraria, or institutional grants from several sources.

Source: Cold S et al. Systemic or vaginal hormone therapy after early breast cancer: A Danish observational cohort study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2022 (Jul 20). Doi: 10.1093/jnci/djac112

ER+ HER2− early BC: Patients with PEPI 0-1/pCR can safely skip adjuvant chemotherapy

Key clinical point: Postmenopausal patients with estrogen receptor-positive (ER+), human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative (HER2−) breast cancer (BC) who achieve a preoperative endocrine prognostic index (PEPI) score of 0-1/pathological complete response (pCR) with only neoadjuvant endocrine therapy (NET) can be safely treated without adjuvant chemotherapy.

Major finding: After a median follow-up of 60 months, the 5-year recurrence-free survival (RFS) improved significantly in patients who had PEPI 0-1/pCR without chemotherapy vs PEPI ≥2 (hazard ratio 0.18; P = .028). In patients who had PEPI ≥2, the 5-year RFS was similar regardless of the receipt of adjuvant chemotherapy (P = .432).

Study details: Findings are from a phase 2 trial including 352 postmenopausal women with early-stage, strongly ER+ and HER2− BC who received NET for 4 months before surgery; after surgery, patients with PEPI 0-1/pCR and PEPI ≥2 were recommended only adjuvant ET and adjuvant ET±chemotherapy, respectively.

Disclosures: This study was supported by Novartis. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Wang X et al. Neoadjuvant endocrine therapy for strongly hormone receptor-positive and HER2-negative early breast cancer: results of a prospective multi-center study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2022 (Aug 2(. Doi: 10.1007/s10549-022-06686-1

Key clinical point: Postmenopausal patients with estrogen receptor-positive (ER+), human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative (HER2−) breast cancer (BC) who achieve a preoperative endocrine prognostic index (PEPI) score of 0-1/pathological complete response (pCR) with only neoadjuvant endocrine therapy (NET) can be safely treated without adjuvant chemotherapy.

Major finding: After a median follow-up of 60 months, the 5-year recurrence-free survival (RFS) improved significantly in patients who had PEPI 0-1/pCR without chemotherapy vs PEPI ≥2 (hazard ratio 0.18; P = .028). In patients who had PEPI ≥2, the 5-year RFS was similar regardless of the receipt of adjuvant chemotherapy (P = .432).

Study details: Findings are from a phase 2 trial including 352 postmenopausal women with early-stage, strongly ER+ and HER2− BC who received NET for 4 months before surgery; after surgery, patients with PEPI 0-1/pCR and PEPI ≥2 were recommended only adjuvant ET and adjuvant ET±chemotherapy, respectively.

Disclosures: This study was supported by Novartis. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Wang X et al. Neoadjuvant endocrine therapy for strongly hormone receptor-positive and HER2-negative early breast cancer: results of a prospective multi-center study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2022 (Aug 2(. Doi: 10.1007/s10549-022-06686-1

Key clinical point: Postmenopausal patients with estrogen receptor-positive (ER+), human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative (HER2−) breast cancer (BC) who achieve a preoperative endocrine prognostic index (PEPI) score of 0-1/pathological complete response (pCR) with only neoadjuvant endocrine therapy (NET) can be safely treated without adjuvant chemotherapy.

Major finding: After a median follow-up of 60 months, the 5-year recurrence-free survival (RFS) improved significantly in patients who had PEPI 0-1/pCR without chemotherapy vs PEPI ≥2 (hazard ratio 0.18; P = .028). In patients who had PEPI ≥2, the 5-year RFS was similar regardless of the receipt of adjuvant chemotherapy (P = .432).

Study details: Findings are from a phase 2 trial including 352 postmenopausal women with early-stage, strongly ER+ and HER2− BC who received NET for 4 months before surgery; after surgery, patients with PEPI 0-1/pCR and PEPI ≥2 were recommended only adjuvant ET and adjuvant ET±chemotherapy, respectively.

Disclosures: This study was supported by Novartis. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Wang X et al. Neoadjuvant endocrine therapy for strongly hormone receptor-positive and HER2-negative early breast cancer: results of a prospective multi-center study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2022 (Aug 2(. Doi: 10.1007/s10549-022-06686-1

Oral paclitaxel+encequidar offers a possible alternative to IV paclitaxel in metastatic BC

Key clinical point: Patients with metastatic breast cancer (BC) who received oral paclitaxel plus encequidar to facilitate the absorption of oral paclitaxel showed higher confirmed tumor response compared with 3 weekly intravenous (IV) paclitaxel doses.

Major finding: Confirmed tumor response rate improved significantly with oral paclitaxel+encequidar vs IV paclitaxel (36% vs 23%; P = .011). The incidence of grade ≥2 neuropathy (31% vs 8%) and grade 2 alopecia (48% vs 29%) were higher with IV paclitaxel vs oral paclitaxel+encequidar; however, the incidence of grade ≥3 gastrointestinal disorders (11.7% vs 3.7%) was higher with oral paclitaxel+encequidar vs IV paclitaxel.

Study details: Findings are from the open-label, phase 3 study including 402 postmenopausal women with metastatic BC who were randomly assigned to receive oral paclitaxel+encequidar or IV paclitaxel.

Disclosures: This study was supported by Athenex, Inc. Four authors declared being employees and owning stocks in Athenex, and the other authors reported ties with several sources, including Athenex.

Source: Rugo HS et al. Open-label, randomized, multicenter, phase III study comparing oral paclitaxel plus encequidar versus intravenous paclitaxel in patients with metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2022 (Jul 20). Doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.02953

Key clinical point: Patients with metastatic breast cancer (BC) who received oral paclitaxel plus encequidar to facilitate the absorption of oral paclitaxel showed higher confirmed tumor response compared with 3 weekly intravenous (IV) paclitaxel doses.

Major finding: Confirmed tumor response rate improved significantly with oral paclitaxel+encequidar vs IV paclitaxel (36% vs 23%; P = .011). The incidence of grade ≥2 neuropathy (31% vs 8%) and grade 2 alopecia (48% vs 29%) were higher with IV paclitaxel vs oral paclitaxel+encequidar; however, the incidence of grade ≥3 gastrointestinal disorders (11.7% vs 3.7%) was higher with oral paclitaxel+encequidar vs IV paclitaxel.

Study details: Findings are from the open-label, phase 3 study including 402 postmenopausal women with metastatic BC who were randomly assigned to receive oral paclitaxel+encequidar or IV paclitaxel.

Disclosures: This study was supported by Athenex, Inc. Four authors declared being employees and owning stocks in Athenex, and the other authors reported ties with several sources, including Athenex.

Source: Rugo HS et al. Open-label, randomized, multicenter, phase III study comparing oral paclitaxel plus encequidar versus intravenous paclitaxel in patients with metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2022 (Jul 20). Doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.02953

Key clinical point: Patients with metastatic breast cancer (BC) who received oral paclitaxel plus encequidar to facilitate the absorption of oral paclitaxel showed higher confirmed tumor response compared with 3 weekly intravenous (IV) paclitaxel doses.

Major finding: Confirmed tumor response rate improved significantly with oral paclitaxel+encequidar vs IV paclitaxel (36% vs 23%; P = .011). The incidence of grade ≥2 neuropathy (31% vs 8%) and grade 2 alopecia (48% vs 29%) were higher with IV paclitaxel vs oral paclitaxel+encequidar; however, the incidence of grade ≥3 gastrointestinal disorders (11.7% vs 3.7%) was higher with oral paclitaxel+encequidar vs IV paclitaxel.

Study details: Findings are from the open-label, phase 3 study including 402 postmenopausal women with metastatic BC who were randomly assigned to receive oral paclitaxel+encequidar or IV paclitaxel.

Disclosures: This study was supported by Athenex, Inc. Four authors declared being employees and owning stocks in Athenex, and the other authors reported ties with several sources, including Athenex.

Source: Rugo HS et al. Open-label, randomized, multicenter, phase III study comparing oral paclitaxel plus encequidar versus intravenous paclitaxel in patients with metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2022 (Jul 20). Doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.02953

ERBB2-positive BC: Adding atezolizumab to PATH shows acceptable pCR rate in phase 2

Key clinical point: Neoadjuvant atezolizumab plus docetaxel, trastuzumab, and pertuzumab (PATH) demonstrated an acceptable pathological complete response (pCR) rate and a modest safety profile in patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (ERBB2)-positive early breast cancer (BC).

Major finding: Rate of pCR was 61% in the overall cohort and was higher in patients with hormone receptor-negative vs -positive subtype (77% vs 44%), stages IIA and IIB vs stage III BC (69% and 70% vs 39% respectively), and positive vs negative programmed cell death 1 expression (100% vs 53%). Few patients reported grade ≥3 neutropenia (12%) and febrile neutropenia (8%).

Study details: Findings are from a single-arm phase 2 trial including 67 patients with ERBB2-positive stage II/III BC who initiated 6 cycles of PATH+atezolizumab every 3 weeks.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea, and other sources. The authors declared serving on advisory boards or receiving personal fees, grants, honoraria, consulting fees, or nonfinancial support from several sources.

Source: Ahn HK et al. Response rate and safety of a neoadjuvant pertuzumab, atezolizumab, docetaxel, and trastuzumab regimen for patients with ERBB2-positive stage II/III breast cancer: The neo-PATH phase 2 nonrandomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2022 (Jul 7). Doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2022.2310

Key clinical point: Neoadjuvant atezolizumab plus docetaxel, trastuzumab, and pertuzumab (PATH) demonstrated an acceptable pathological complete response (pCR) rate and a modest safety profile in patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (ERBB2)-positive early breast cancer (BC).

Major finding: Rate of pCR was 61% in the overall cohort and was higher in patients with hormone receptor-negative vs -positive subtype (77% vs 44%), stages IIA and IIB vs stage III BC (69% and 70% vs 39% respectively), and positive vs negative programmed cell death 1 expression (100% vs 53%). Few patients reported grade ≥3 neutropenia (12%) and febrile neutropenia (8%).

Study details: Findings are from a single-arm phase 2 trial including 67 patients with ERBB2-positive stage II/III BC who initiated 6 cycles of PATH+atezolizumab every 3 weeks.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea, and other sources. The authors declared serving on advisory boards or receiving personal fees, grants, honoraria, consulting fees, or nonfinancial support from several sources.

Source: Ahn HK et al. Response rate and safety of a neoadjuvant pertuzumab, atezolizumab, docetaxel, and trastuzumab regimen for patients with ERBB2-positive stage II/III breast cancer: The neo-PATH phase 2 nonrandomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2022 (Jul 7). Doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2022.2310

Key clinical point: Neoadjuvant atezolizumab plus docetaxel, trastuzumab, and pertuzumab (PATH) demonstrated an acceptable pathological complete response (pCR) rate and a modest safety profile in patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (ERBB2)-positive early breast cancer (BC).

Major finding: Rate of pCR was 61% in the overall cohort and was higher in patients with hormone receptor-negative vs -positive subtype (77% vs 44%), stages IIA and IIB vs stage III BC (69% and 70% vs 39% respectively), and positive vs negative programmed cell death 1 expression (100% vs 53%). Few patients reported grade ≥3 neutropenia (12%) and febrile neutropenia (8%).

Study details: Findings are from a single-arm phase 2 trial including 67 patients with ERBB2-positive stage II/III BC who initiated 6 cycles of PATH+atezolizumab every 3 weeks.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea, and other sources. The authors declared serving on advisory boards or receiving personal fees, grants, honoraria, consulting fees, or nonfinancial support from several sources.

Source: Ahn HK et al. Response rate and safety of a neoadjuvant pertuzumab, atezolizumab, docetaxel, and trastuzumab regimen for patients with ERBB2-positive stage II/III breast cancer: The neo-PATH phase 2 nonrandomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2022 (Jul 7). Doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2022.2310

TNBC: First-line nab-paclitaxel+cisplatin effective and safe in phase 3

Key clinical point: In patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), first-line treatment with nanoparticle albumin-bound (nab)-paclitaxel+cisplatin significantly reduced the risk for disease progression/death compared with gemcitabine+cisplatin, with both the combinations showing a consistent safety profile.

Major finding: Progression-free survival (stratified hazard ratio 0.67; P = .004) and objective response rate (81.1% vs 56.3%; P < .001) improved significantly in patients receiving nab-paclitaxel+cisplatin vs gemcitabine+cisplatin. Grade ≥3 only neuropathy (19% vs 0%) and nausea and vomiting (6% vs 1%) were higher in the nab-paclitaxel+cisplatin vs gemcitabine+cisplatin arm, whereas grade ≥3 thrombocytopenia (29.4% vs 3.9%) was more common in the gemcitabine+cisplatin vs nab-paclitaxel+cisplatin arm.

Study details: Findings are from an open-label phase 3 study including 254 patients with untreated metastatic TNBC who were randomly assigned to receive nab-paclitaxel+cisplatin or gemcitabine+cisplatin.

Disclosures: This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Wang B et al. A randomized phase 3 trial of gemcitabine or nab-paclitaxel combined with cisplatin as first-line treatment in patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. Nat Commun. 2022;13:4025 (Jul 12). Doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-31704-7

Key clinical point: In patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), first-line treatment with nanoparticle albumin-bound (nab)-paclitaxel+cisplatin significantly reduced the risk for disease progression/death compared with gemcitabine+cisplatin, with both the combinations showing a consistent safety profile.

Major finding: Progression-free survival (stratified hazard ratio 0.67; P = .004) and objective response rate (81.1% vs 56.3%; P < .001) improved significantly in patients receiving nab-paclitaxel+cisplatin vs gemcitabine+cisplatin. Grade ≥3 only neuropathy (19% vs 0%) and nausea and vomiting (6% vs 1%) were higher in the nab-paclitaxel+cisplatin vs gemcitabine+cisplatin arm, whereas grade ≥3 thrombocytopenia (29.4% vs 3.9%) was more common in the gemcitabine+cisplatin vs nab-paclitaxel+cisplatin arm.

Study details: Findings are from an open-label phase 3 study including 254 patients with untreated metastatic TNBC who were randomly assigned to receive nab-paclitaxel+cisplatin or gemcitabine+cisplatin.

Disclosures: This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Wang B et al. A randomized phase 3 trial of gemcitabine or nab-paclitaxel combined with cisplatin as first-line treatment in patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. Nat Commun. 2022;13:4025 (Jul 12). Doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-31704-7

Key clinical point: In patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), first-line treatment with nanoparticle albumin-bound (nab)-paclitaxel+cisplatin significantly reduced the risk for disease progression/death compared with gemcitabine+cisplatin, with both the combinations showing a consistent safety profile.

Major finding: Progression-free survival (stratified hazard ratio 0.67; P = .004) and objective response rate (81.1% vs 56.3%; P < .001) improved significantly in patients receiving nab-paclitaxel+cisplatin vs gemcitabine+cisplatin. Grade ≥3 only neuropathy (19% vs 0%) and nausea and vomiting (6% vs 1%) were higher in the nab-paclitaxel+cisplatin vs gemcitabine+cisplatin arm, whereas grade ≥3 thrombocytopenia (29.4% vs 3.9%) was more common in the gemcitabine+cisplatin vs nab-paclitaxel+cisplatin arm.

Study details: Findings are from an open-label phase 3 study including 254 patients with untreated metastatic TNBC who were randomly assigned to receive nab-paclitaxel+cisplatin or gemcitabine+cisplatin.

Disclosures: This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Wang B et al. A randomized phase 3 trial of gemcitabine or nab-paclitaxel combined with cisplatin as first-line treatment in patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. Nat Commun. 2022;13:4025 (Jul 12). Doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-31704-7

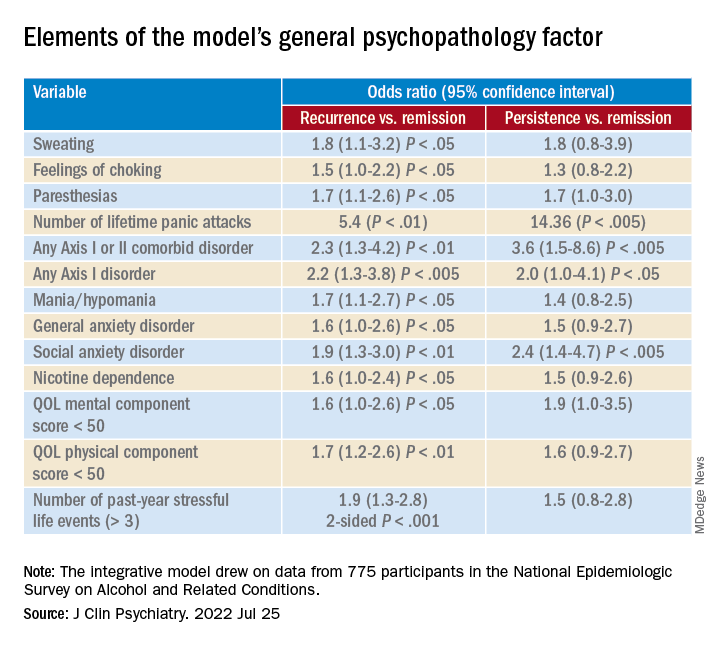

New panic disorder model flags risk for recurrence, persistence

Investigators based in France and the United States analyzed data for almost 800 patients with DSM-IV–diagnosed PD.

Results showed that having a “general psychopathology factor,” defined as the shared effects of all comorbid conditions, or PD liability, significantly and independently predicted 3-year recurrence or persistence of PD symptoms.

Having a lower physical health-related quality of life (QOL), a greater number of stressful life events, and not seeking treatment at baseline were also significant and independent predictors.

“This integrative model could help clinicians to identify individuals at high risk of recurrence or persistence of panic disorder and provide content for future research,” Valentin Scheer, MD, MPH, a resident in psychiatry at AP-HP, Assistance Publique, Hôpitaux de Paris, and colleagues wrote.

The findings were published online in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

Integration needed

PD is a disabling disorder with a “chronic course” – and a recurrence rate ranging from 25% to 50%, the investigators noted.

“Because of the heterogeneous course of PD, there is a need to develop a comprehensive predictive model of recurrence or persistence,” they wrote. This could “help practitioners adapt therapeutic strategies and develop prevention strategies in high-risk individuals.”

Most previous studies that have investigated risk factors for PD recurrence and persistence have relied on clinical samples, often with limited sample sizes.

Moreover, each risk factor, when considered individually, accounts for only a “small proportion” of the variance in risk, the researchers noted. The co-occurrence of these risk factors “suggests the need to combine them into a broad multivariable model.”

However, currently proposed integrative models do not identify independent predictors or mitigate the influence of confounding variables. To fill this gap, the investigators conducted a study using structural equation modeling “to take into account multiple correlations across predictors.”

They drew on data from 775 participants (mean age, 40 years) in the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). For the current analysis, they examined two waves of NESARC (2001-2002 and 2004-2005) to “build a comprehensive model” of the 3-year recurrence or persistence of PD.

The researchers used a “latent variable approach” that simultaneously examined the effect of the following five groups of potential predictors of recurrence or persistence: PD severity, severity of comorbidity, family history of psychiatric disorders, sociodemographic characteristics, and treatment-seeking behavior.

They also distinguished between risk factors responsible for recurrence and those responsible for persistence.

Psychiatric diagnoses were determined on the basis of the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV. Participants also completed Version 2 of the Short Form 12-Item Health Survey, which assesses both mental and physical QOL over the previous 4 weeks.

Early treatment needed

Among participants with a 12-month diagnosis of PD at wave 1, 13% had persistent PD and 27.6% had recurrent PD during the 3-year period. The mean duration of illness was 9.5 years.

A greater number of lifetime panic attacks, the presence of any Axis I or II comorbid disorder, and any Axis I disorder, especially social anxiety disorder, were significantly associated with 3-year risk for recurrence and for persistence.

Sweating, choking, paresthesias, the comorbid disorders of mania/hypomania and general anxiety disorder, nicotine dependence, lower mental and physical QOL scores, and exposure to a greater number of stressful life events in the previous year were all significantly associated with 3-year risk for recurrence.

Only variables shown with a P value were statistically significant, “with the a priori fixed at .05,” the researchers noted.

A combination of psychopathology factors, such as the shared effect of all comorbid psychiatric conditions, PD liability, lower physical health-related QOL, more life stressors during the past year, and not seeking treatment at baseline “significantly and independently” predicted recurrence or persistence of symptoms between the two waves (all Ps < .05), the investigators reported.

One study limitation cited was that several psychiatric disorders known to be associated with PD recurrence or persistence, such as borderline personality disorder, were not examined. Additionally, the study used a 3-year follow-up period – and the results might have differed for other follow-up time frames, the researchers noted.

Nevertheless, the findings constitute a “comprehensive model” to predict recurrence and persistence of PD, they wrote. Moreover, early treatment-seeking behavior “should be promoted, as it may reduce the risk of recurrence.”

Not much new?

Commenting on the study, Peter Roy-Byrne, MD, professor of psychiatry, University of Washington, Seattle, noted, “there is not much that is new here.”

Dr. Roy-Byrne, who was not involved with the study, said that a “general theme for years has been that more severe illness, whether you measure it by greater number of other Axis I disorders or symptom severity or a general psychopathology factor, usually predicts worse outcome – here codified as persistence and recurrence.”

Greater stress and reluctance to seek treatment may also predict worse outcomes, he noted.

In addition, the study “did not examine another very important factor: the degree of social connection/social support that someone has,” Dr. Roy-Byrne said. However, “perhaps some of this was contained in specific life events.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

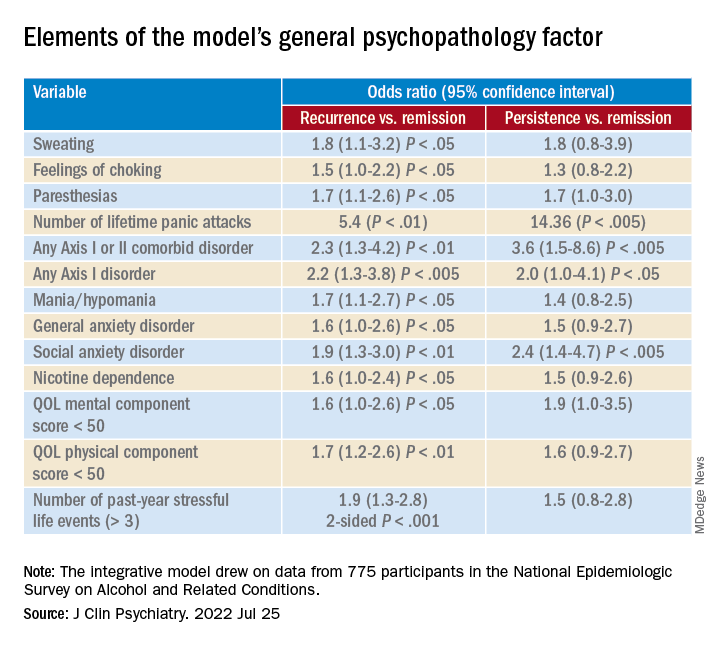

Investigators based in France and the United States analyzed data for almost 800 patients with DSM-IV–diagnosed PD.

Results showed that having a “general psychopathology factor,” defined as the shared effects of all comorbid conditions, or PD liability, significantly and independently predicted 3-year recurrence or persistence of PD symptoms.

Having a lower physical health-related quality of life (QOL), a greater number of stressful life events, and not seeking treatment at baseline were also significant and independent predictors.

“This integrative model could help clinicians to identify individuals at high risk of recurrence or persistence of panic disorder and provide content for future research,” Valentin Scheer, MD, MPH, a resident in psychiatry at AP-HP, Assistance Publique, Hôpitaux de Paris, and colleagues wrote.

The findings were published online in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

Integration needed

PD is a disabling disorder with a “chronic course” – and a recurrence rate ranging from 25% to 50%, the investigators noted.

“Because of the heterogeneous course of PD, there is a need to develop a comprehensive predictive model of recurrence or persistence,” they wrote. This could “help practitioners adapt therapeutic strategies and develop prevention strategies in high-risk individuals.”

Most previous studies that have investigated risk factors for PD recurrence and persistence have relied on clinical samples, often with limited sample sizes.

Moreover, each risk factor, when considered individually, accounts for only a “small proportion” of the variance in risk, the researchers noted. The co-occurrence of these risk factors “suggests the need to combine them into a broad multivariable model.”

However, currently proposed integrative models do not identify independent predictors or mitigate the influence of confounding variables. To fill this gap, the investigators conducted a study using structural equation modeling “to take into account multiple correlations across predictors.”

They drew on data from 775 participants (mean age, 40 years) in the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). For the current analysis, they examined two waves of NESARC (2001-2002 and 2004-2005) to “build a comprehensive model” of the 3-year recurrence or persistence of PD.

The researchers used a “latent variable approach” that simultaneously examined the effect of the following five groups of potential predictors of recurrence or persistence: PD severity, severity of comorbidity, family history of psychiatric disorders, sociodemographic characteristics, and treatment-seeking behavior.

They also distinguished between risk factors responsible for recurrence and those responsible for persistence.

Psychiatric diagnoses were determined on the basis of the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV. Participants also completed Version 2 of the Short Form 12-Item Health Survey, which assesses both mental and physical QOL over the previous 4 weeks.

Early treatment needed

Among participants with a 12-month diagnosis of PD at wave 1, 13% had persistent PD and 27.6% had recurrent PD during the 3-year period. The mean duration of illness was 9.5 years.

A greater number of lifetime panic attacks, the presence of any Axis I or II comorbid disorder, and any Axis I disorder, especially social anxiety disorder, were significantly associated with 3-year risk for recurrence and for persistence.

Sweating, choking, paresthesias, the comorbid disorders of mania/hypomania and general anxiety disorder, nicotine dependence, lower mental and physical QOL scores, and exposure to a greater number of stressful life events in the previous year were all significantly associated with 3-year risk for recurrence.

Only variables shown with a P value were statistically significant, “with the a priori fixed at .05,” the researchers noted.

A combination of psychopathology factors, such as the shared effect of all comorbid psychiatric conditions, PD liability, lower physical health-related QOL, more life stressors during the past year, and not seeking treatment at baseline “significantly and independently” predicted recurrence or persistence of symptoms between the two waves (all Ps < .05), the investigators reported.

One study limitation cited was that several psychiatric disorders known to be associated with PD recurrence or persistence, such as borderline personality disorder, were not examined. Additionally, the study used a 3-year follow-up period – and the results might have differed for other follow-up time frames, the researchers noted.

Nevertheless, the findings constitute a “comprehensive model” to predict recurrence and persistence of PD, they wrote. Moreover, early treatment-seeking behavior “should be promoted, as it may reduce the risk of recurrence.”

Not much new?

Commenting on the study, Peter Roy-Byrne, MD, professor of psychiatry, University of Washington, Seattle, noted, “there is not much that is new here.”

Dr. Roy-Byrne, who was not involved with the study, said that a “general theme for years has been that more severe illness, whether you measure it by greater number of other Axis I disorders or symptom severity or a general psychopathology factor, usually predicts worse outcome – here codified as persistence and recurrence.”

Greater stress and reluctance to seek treatment may also predict worse outcomes, he noted.

In addition, the study “did not examine another very important factor: the degree of social connection/social support that someone has,” Dr. Roy-Byrne said. However, “perhaps some of this was contained in specific life events.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

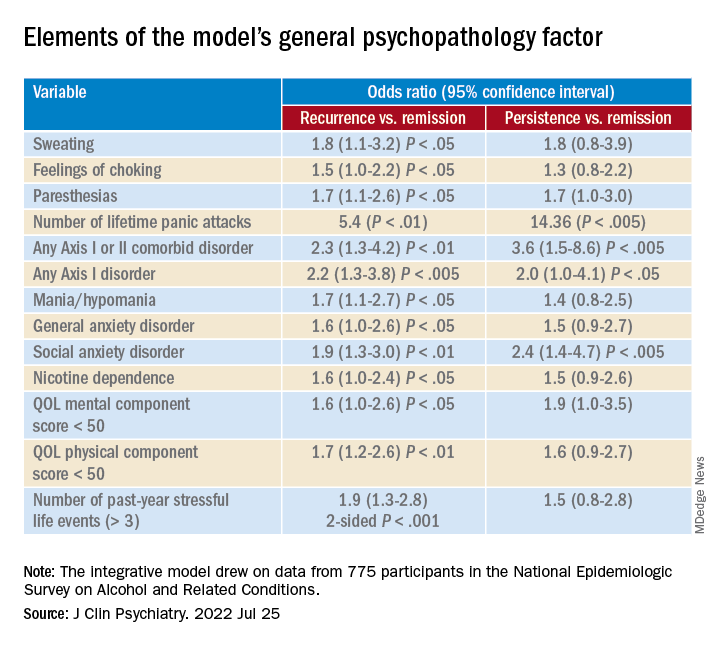

Investigators based in France and the United States analyzed data for almost 800 patients with DSM-IV–diagnosed PD.

Results showed that having a “general psychopathology factor,” defined as the shared effects of all comorbid conditions, or PD liability, significantly and independently predicted 3-year recurrence or persistence of PD symptoms.

Having a lower physical health-related quality of life (QOL), a greater number of stressful life events, and not seeking treatment at baseline were also significant and independent predictors.

“This integrative model could help clinicians to identify individuals at high risk of recurrence or persistence of panic disorder and provide content for future research,” Valentin Scheer, MD, MPH, a resident in psychiatry at AP-HP, Assistance Publique, Hôpitaux de Paris, and colleagues wrote.

The findings were published online in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

Integration needed

PD is a disabling disorder with a “chronic course” – and a recurrence rate ranging from 25% to 50%, the investigators noted.

“Because of the heterogeneous course of PD, there is a need to develop a comprehensive predictive model of recurrence or persistence,” they wrote. This could “help practitioners adapt therapeutic strategies and develop prevention strategies in high-risk individuals.”

Most previous studies that have investigated risk factors for PD recurrence and persistence have relied on clinical samples, often with limited sample sizes.

Moreover, each risk factor, when considered individually, accounts for only a “small proportion” of the variance in risk, the researchers noted. The co-occurrence of these risk factors “suggests the need to combine them into a broad multivariable model.”

However, currently proposed integrative models do not identify independent predictors or mitigate the influence of confounding variables. To fill this gap, the investigators conducted a study using structural equation modeling “to take into account multiple correlations across predictors.”

They drew on data from 775 participants (mean age, 40 years) in the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). For the current analysis, they examined two waves of NESARC (2001-2002 and 2004-2005) to “build a comprehensive model” of the 3-year recurrence or persistence of PD.

The researchers used a “latent variable approach” that simultaneously examined the effect of the following five groups of potential predictors of recurrence or persistence: PD severity, severity of comorbidity, family history of psychiatric disorders, sociodemographic characteristics, and treatment-seeking behavior.

They also distinguished between risk factors responsible for recurrence and those responsible for persistence.

Psychiatric diagnoses were determined on the basis of the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV. Participants also completed Version 2 of the Short Form 12-Item Health Survey, which assesses both mental and physical QOL over the previous 4 weeks.

Early treatment needed

Among participants with a 12-month diagnosis of PD at wave 1, 13% had persistent PD and 27.6% had recurrent PD during the 3-year period. The mean duration of illness was 9.5 years.

A greater number of lifetime panic attacks, the presence of any Axis I or II comorbid disorder, and any Axis I disorder, especially social anxiety disorder, were significantly associated with 3-year risk for recurrence and for persistence.

Sweating, choking, paresthesias, the comorbid disorders of mania/hypomania and general anxiety disorder, nicotine dependence, lower mental and physical QOL scores, and exposure to a greater number of stressful life events in the previous year were all significantly associated with 3-year risk for recurrence.

Only variables shown with a P value were statistically significant, “with the a priori fixed at .05,” the researchers noted.

A combination of psychopathology factors, such as the shared effect of all comorbid psychiatric conditions, PD liability, lower physical health-related QOL, more life stressors during the past year, and not seeking treatment at baseline “significantly and independently” predicted recurrence or persistence of symptoms between the two waves (all Ps < .05), the investigators reported.

One study limitation cited was that several psychiatric disorders known to be associated with PD recurrence or persistence, such as borderline personality disorder, were not examined. Additionally, the study used a 3-year follow-up period – and the results might have differed for other follow-up time frames, the researchers noted.

Nevertheless, the findings constitute a “comprehensive model” to predict recurrence and persistence of PD, they wrote. Moreover, early treatment-seeking behavior “should be promoted, as it may reduce the risk of recurrence.”

Not much new?

Commenting on the study, Peter Roy-Byrne, MD, professor of psychiatry, University of Washington, Seattle, noted, “there is not much that is new here.”

Dr. Roy-Byrne, who was not involved with the study, said that a “general theme for years has been that more severe illness, whether you measure it by greater number of other Axis I disorders or symptom severity or a general psychopathology factor, usually predicts worse outcome – here codified as persistence and recurrence.”

Greater stress and reluctance to seek treatment may also predict worse outcomes, he noted.

In addition, the study “did not examine another very important factor: the degree of social connection/social support that someone has,” Dr. Roy-Byrne said. However, “perhaps some of this was contained in specific life events.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL PSYCHIATRY

Bed boost after WBI reduces local recurrence of ductal carcinoma in situ in the breast

Key clinical point: In patients with ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), tumor bed boost after postoperative whole breast irradiation (WBI) reduced local recurrence but with higher toxicity. Hypofractionated WBI was as effective as conventional WBI.

Major finding: The 5-year free-from-local-recurrence rates improved significantly with vs without tumor bed boost after postoperative WBI (hazard ratio 0.47; P < .001) and did not worsen with hypofractionated vs conventional WBI (P = .85). The rates of grade ≥2 breast pain (P = .003) and induration (P < .001) were higher with vs without tumor bed boost.

Study details: Findings are from a multicenter, phase 3 study including 1608 adult women with unilateral, non-low-risk DCIS who underwent breast-conserving surgery and were randomly assigned to receive WBI (conventional or hypofractionated) with or without tumor bed boost.

Disclosures: This study was funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia and other sources. Some authors declared receiving research grants, funding, or non-direct financial support from several sources.

Source: Chua BH et al. Radiation doses and fractionation schedules in non-low-risk ductal carcinoma in situ in the breast (BIG 3–07/TROG 07.01): A randomised, factorial, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 study Lancet. 2022;400(10350):431-440 (Aug 6). Doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01246-6

Key clinical point: In patients with ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), tumor bed boost after postoperative whole breast irradiation (WBI) reduced local recurrence but with higher toxicity. Hypofractionated WBI was as effective as conventional WBI.

Major finding: The 5-year free-from-local-recurrence rates improved significantly with vs without tumor bed boost after postoperative WBI (hazard ratio 0.47; P < .001) and did not worsen with hypofractionated vs conventional WBI (P = .85). The rates of grade ≥2 breast pain (P = .003) and induration (P < .001) were higher with vs without tumor bed boost.

Study details: Findings are from a multicenter, phase 3 study including 1608 adult women with unilateral, non-low-risk DCIS who underwent breast-conserving surgery and were randomly assigned to receive WBI (conventional or hypofractionated) with or without tumor bed boost.

Disclosures: This study was funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia and other sources. Some authors declared receiving research grants, funding, or non-direct financial support from several sources.

Source: Chua BH et al. Radiation doses and fractionation schedules in non-low-risk ductal carcinoma in situ in the breast (BIG 3–07/TROG 07.01): A randomised, factorial, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 study Lancet. 2022;400(10350):431-440 (Aug 6). Doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01246-6

Key clinical point: In patients with ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), tumor bed boost after postoperative whole breast irradiation (WBI) reduced local recurrence but with higher toxicity. Hypofractionated WBI was as effective as conventional WBI.

Major finding: The 5-year free-from-local-recurrence rates improved significantly with vs without tumor bed boost after postoperative WBI (hazard ratio 0.47; P < .001) and did not worsen with hypofractionated vs conventional WBI (P = .85). The rates of grade ≥2 breast pain (P = .003) and induration (P < .001) were higher with vs without tumor bed boost.

Study details: Findings are from a multicenter, phase 3 study including 1608 adult women with unilateral, non-low-risk DCIS who underwent breast-conserving surgery and were randomly assigned to receive WBI (conventional or hypofractionated) with or without tumor bed boost.

Disclosures: This study was funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia and other sources. Some authors declared receiving research grants, funding, or non-direct financial support from several sources.

Source: Chua BH et al. Radiation doses and fractionation schedules in non-low-risk ductal carcinoma in situ in the breast (BIG 3–07/TROG 07.01): A randomised, factorial, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 study Lancet. 2022;400(10350):431-440 (Aug 6). Doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01246-6