User login

Commentary: Diet and Colorectal Cancer, September 2022

This month's journal articles in the field of colorectal cancer research lack the cachet of some of the high-profile dispatches we discussed in previous editions of Clinical Edge. Nonetheless, there are several interesting reports this month.

The first is a clinical trial report that came out of China investigating the possible synergistic effect of high-dose vitamin C with chemotherapy in the first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC). The study was based on preclinical data that showed a synergistic increase in cancer cell death with chemotherapy plus high-dose vitamin C in in vitro models. Wang and colleagues randomly assigned 442 treatment-naive patients with mCRC to receive folinic acid, fluorouracil, and oxaliplatin (FOLFOX) and bevacizumab with or without 1.5 g/kg vitamin C intravenously on days 1-3 of each chemotherapy cycle.

The study's primary endpoint was progression-free survival (PFS), and patients were stratified on the basis of tumor sidedness and use of bevacizumab. PFS for the intention-to-treat group was unaffected by use of vitamin C (hazard ratio [HR] 0.86; 95% CI 0.70-1.05; P = .1). However, patients whose tumors harbored RAS mutations had a PFS that was significantly improved in the vitamin C arm (9.2 vs 7.8 months; HR 0.67; 95% CI 0.50-0.91; P = .01). Additionally, treatment-related adverse events were no more common in the treatment arm than in the control arm. Although I seldom draw clinical conclusions from subgroup analyses, I find it comforting to know that high-dose vitamin C is at least safe and potentially helpful for some patients. Many of my patients through the years have asked me about the utility of high-dose vitamin C. At least I can now inform them that the treatment is unlikely to cause physical harm or substantially decrease the efficacy of chemotherapy.

The second article I will discuss focuses on dietary fat intake and its potential effects on mortality and cancer progression in patients with mCRC. Using a food-frequency questionnaire, the authors of the study assessed the diets of 1194 patients who had been part of a previous cooperative group study for patients with treatment-naive mCRC (Van Blarigan et al). Over a median follow-up of 6.1 years, patients with the highest median intake of vegetable fats (23.5% kcal/d; interquartile range [IQR] 21.6%-25.7% kcal/d) vs the lowest intake (11.6% kcal/d; IQR 10.1%-12.7% kcal/d) showed a lower risk for all-cause mortality (adjusted HR 0.79; 95% CI 0.63-1.00) and cancer progression or death (adjusted HR 0.71; 95% CI 0.57-0.88). Although this study's results were not unexpected given data that have been published in the past, it builds on previous work as it shows the specific benefits of vegetable fats vis-à-vis animal fats, which are detrimental to survival. Oncologists continue to benefit from these studies because they allow us to give more specific dietary recommendations for high fat-containing vegan foods, such as avocados, olives, and nuts.

This month's journal articles in the field of colorectal cancer research lack the cachet of some of the high-profile dispatches we discussed in previous editions of Clinical Edge. Nonetheless, there are several interesting reports this month.

The first is a clinical trial report that came out of China investigating the possible synergistic effect of high-dose vitamin C with chemotherapy in the first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC). The study was based on preclinical data that showed a synergistic increase in cancer cell death with chemotherapy plus high-dose vitamin C in in vitro models. Wang and colleagues randomly assigned 442 treatment-naive patients with mCRC to receive folinic acid, fluorouracil, and oxaliplatin (FOLFOX) and bevacizumab with or without 1.5 g/kg vitamin C intravenously on days 1-3 of each chemotherapy cycle.

The study's primary endpoint was progression-free survival (PFS), and patients were stratified on the basis of tumor sidedness and use of bevacizumab. PFS for the intention-to-treat group was unaffected by use of vitamin C (hazard ratio [HR] 0.86; 95% CI 0.70-1.05; P = .1). However, patients whose tumors harbored RAS mutations had a PFS that was significantly improved in the vitamin C arm (9.2 vs 7.8 months; HR 0.67; 95% CI 0.50-0.91; P = .01). Additionally, treatment-related adverse events were no more common in the treatment arm than in the control arm. Although I seldom draw clinical conclusions from subgroup analyses, I find it comforting to know that high-dose vitamin C is at least safe and potentially helpful for some patients. Many of my patients through the years have asked me about the utility of high-dose vitamin C. At least I can now inform them that the treatment is unlikely to cause physical harm or substantially decrease the efficacy of chemotherapy.

The second article I will discuss focuses on dietary fat intake and its potential effects on mortality and cancer progression in patients with mCRC. Using a food-frequency questionnaire, the authors of the study assessed the diets of 1194 patients who had been part of a previous cooperative group study for patients with treatment-naive mCRC (Van Blarigan et al). Over a median follow-up of 6.1 years, patients with the highest median intake of vegetable fats (23.5% kcal/d; interquartile range [IQR] 21.6%-25.7% kcal/d) vs the lowest intake (11.6% kcal/d; IQR 10.1%-12.7% kcal/d) showed a lower risk for all-cause mortality (adjusted HR 0.79; 95% CI 0.63-1.00) and cancer progression or death (adjusted HR 0.71; 95% CI 0.57-0.88). Although this study's results were not unexpected given data that have been published in the past, it builds on previous work as it shows the specific benefits of vegetable fats vis-à-vis animal fats, which are detrimental to survival. Oncologists continue to benefit from these studies because they allow us to give more specific dietary recommendations for high fat-containing vegan foods, such as avocados, olives, and nuts.

This month's journal articles in the field of colorectal cancer research lack the cachet of some of the high-profile dispatches we discussed in previous editions of Clinical Edge. Nonetheless, there are several interesting reports this month.

The first is a clinical trial report that came out of China investigating the possible synergistic effect of high-dose vitamin C with chemotherapy in the first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC). The study was based on preclinical data that showed a synergistic increase in cancer cell death with chemotherapy plus high-dose vitamin C in in vitro models. Wang and colleagues randomly assigned 442 treatment-naive patients with mCRC to receive folinic acid, fluorouracil, and oxaliplatin (FOLFOX) and bevacizumab with or without 1.5 g/kg vitamin C intravenously on days 1-3 of each chemotherapy cycle.

The study's primary endpoint was progression-free survival (PFS), and patients were stratified on the basis of tumor sidedness and use of bevacizumab. PFS for the intention-to-treat group was unaffected by use of vitamin C (hazard ratio [HR] 0.86; 95% CI 0.70-1.05; P = .1). However, patients whose tumors harbored RAS mutations had a PFS that was significantly improved in the vitamin C arm (9.2 vs 7.8 months; HR 0.67; 95% CI 0.50-0.91; P = .01). Additionally, treatment-related adverse events were no more common in the treatment arm than in the control arm. Although I seldom draw clinical conclusions from subgroup analyses, I find it comforting to know that high-dose vitamin C is at least safe and potentially helpful for some patients. Many of my patients through the years have asked me about the utility of high-dose vitamin C. At least I can now inform them that the treatment is unlikely to cause physical harm or substantially decrease the efficacy of chemotherapy.

The second article I will discuss focuses on dietary fat intake and its potential effects on mortality and cancer progression in patients with mCRC. Using a food-frequency questionnaire, the authors of the study assessed the diets of 1194 patients who had been part of a previous cooperative group study for patients with treatment-naive mCRC (Van Blarigan et al). Over a median follow-up of 6.1 years, patients with the highest median intake of vegetable fats (23.5% kcal/d; interquartile range [IQR] 21.6%-25.7% kcal/d) vs the lowest intake (11.6% kcal/d; IQR 10.1%-12.7% kcal/d) showed a lower risk for all-cause mortality (adjusted HR 0.79; 95% CI 0.63-1.00) and cancer progression or death (adjusted HR 0.71; 95% CI 0.57-0.88). Although this study's results were not unexpected given data that have been published in the past, it builds on previous work as it shows the specific benefits of vegetable fats vis-à-vis animal fats, which are detrimental to survival. Oncologists continue to benefit from these studies because they allow us to give more specific dietary recommendations for high fat-containing vegan foods, such as avocados, olives, and nuts.

COMMENT & CONTROVERSY

How common is IUD perforation, expulsion, and malposition?

ROBERT L. BARBIERI, MD (APRIL 2022)

The seriousness of IUD embedment

I appreciated Dr. Barbieri’s comprehensive review of clinical problems regarding the intrauterine device (IUD). It is interesting that, in spite of your mention of IUD embedment in the myometrium, other publications regarding this phenomenon are seemingly absent (except for ours).1 Whether or not there is associated pain (and sometimes there is not), in our experience its removal can result in IUD fracture. As you stated, it is true that 3D transvaginal sonography perfectly enables this visualization, yet it is surprising that others have not experienced what we have. Nonetheless, it is encouraging to see that IUD embedment is seriously mentioned.

- Fernandez CM, Levine EM, Cabiya M, et al. Intrauterine device embedment resulting in its fracture: a case series. Arch Obstet Gynecol. 2021;2:1-4.

Elliot Levine, MD

Chicago, Illinois

Dr. Barbieri responds

I thank Dr. Levine for highlighting the important issue of IUD fracture and providing a reference to a case series of IUD fractures. Although such fracture is not common, when it does occur it may require a hysteroscopic procedure to remove all pieces of the IUD. In the cited case series, fracture was more commonly observed with the copper IUD than with the LNG-IUD. With regard to IUD malposition, 4 publications reviewed in my recent editorial describe the problem of an IUD arm embedded in the myometrium.1-4

References

- Benacerraf BR, Shipp TD, Bromley B. Three-dimensional ultrasound detection of abnormally located intrauterine contraceptive devices which are a source of pelvic pain and abnormal bleeding. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2009;34:110-115.

- Braaten KP, Benson CB, Maurer R, et al. Malpositioned intrauterine contraceptive devices: risk factors, outcomes and future pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:1014-1020.

- Gerkowicz SA, Fiorentino DG, Kovacs AP, et al. Uterine structural abnormality and intrauterine device malposition: analysis of ultrasonographic and demographic variables of 517 patients. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220:183.e1-e8.

- Connolly CT, Fox NS. Incidence and risk factors for a malpositioned intrauterine device detected on three-dimensional ultrasound within eight weeks of placement. J Ultrasound Med. September 27, 2021.

Will NAAT replace microscopy for the identification of organisms causing vaginitis?

ROBERT L. BARBIERI, MD (MARCH 2022)

Follow-up questions on NAAT testing

The sensitivity of NAAT testing, as outlined in Dr. Barbieri’s editorial, is undoubtedly better than the clinical methods most clinicians are using. I appreciate the frustration we providers often experience in drawing conclusions for patients based on the Amsel criteria for bacterial vaginitis (BV). I am surprised by the low sensitivity of microscopy for yeast vaginitis. My follow-up questions are:

- Have the NAATs referenced been validated in clinical trials and proven to improve patient outcomes?

- Will the proposal to begin empiric therapy for both yeast vaginitis and BV in combination while waiting for NAAT results lead to an increase of resistant strains?

- What is the cost of NAAT for vaginitis, and is this cost effective in routine practice?

- Can NAATs be utilized to detect resistant strains of yeast or Gardnerella sp?

Alan Paul Gehrich, MD (COL, MC ret.)

Bethesda, Maryland

Dr. Barbieri responds

I thank Dr. Gehrich for raising the important issue of what is the optimal endpoint to assess the clinical utility of NAAT testing for vaginitis. Most studies of the use of NAAT to diagnose the cause of vaginitis focus on comparing NAAT results to standard clinical practice (microscopy and pH), and to a “gold standard.” In most studies the gold standards are Nugent scoring with Amsel criteria to resolve intermediate Nugent scores for bacterial vaginosis, culture for Candida, and culture for Trichomonas vaginalis. It is clear from multiple studies that NAAT provides superior sensitivity and specificity compared with standard clinical practice.1-3 As noted in the editorial, in a study of 466 patients with symptoms of vaginitis, standard office approaches to the diagnosis of vaginitis resulted in the failure to identify the correct infection in a large number of cases.4 For the diagnosis of BV, clinicians missed 42% of the cases identified by NAAT. For the diagnosis of Candida, clinicians missed 46% of the cases identified by NAAT. For the diagnosis of T vaginalis, clinicians missed 72% of the cases identified by NAAT. This resulted in clinicians not appropriately treating many infections detected by NAAT.

NAAT does provide information about the presence of Candida glabrata and Candida krusei, organisms which may be resistant to fluconazole. I agree with Dr. Gehrich that the optimal use of NAAT testing in practice is poorly studied with regard to treatment between sample collection and NAAT results. Cost of testing is a complex issue. Standard microscopy is relatively inexpensive, but performs poorly in clinical practice, resulting in misdiagnosis. NAAT testing is expensive but correctly identifies causes of vaginitis.

References

- Schwebke JR, Gaydos CA, Hyirjesy P, et al. Diagnostic performance of a molecular test versus clinician assessment of vaginitis. J Clin Microbiol. 2018;56:e00252-18.

- Broache M, Cammarata CL, Stonebraker E, et al. Performance of vaginal panel assay compared with clinical diagnosis of vaginitis. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;138:853-859.

- Schwebke JR, Taylor SN, Ackerman N, et al. Clinical validation of the Aptima bacterial vaginosis and Aptima Candida/Trichomonas vaginalis assays: results from a prospective multi-center study. J Clin Microbiol. 2020;58:e01643-19. 4

- Gaydos CA, Beqaj S, Schwebke JR, et al. Clinical validation of a test for the diagnosis of vaginitis. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:181-189.

How common is IUD perforation, expulsion, and malposition?

ROBERT L. BARBIERI, MD (APRIL 2022)

The seriousness of IUD embedment

I appreciated Dr. Barbieri’s comprehensive review of clinical problems regarding the intrauterine device (IUD). It is interesting that, in spite of your mention of IUD embedment in the myometrium, other publications regarding this phenomenon are seemingly absent (except for ours).1 Whether or not there is associated pain (and sometimes there is not), in our experience its removal can result in IUD fracture. As you stated, it is true that 3D transvaginal sonography perfectly enables this visualization, yet it is surprising that others have not experienced what we have. Nonetheless, it is encouraging to see that IUD embedment is seriously mentioned.

- Fernandez CM, Levine EM, Cabiya M, et al. Intrauterine device embedment resulting in its fracture: a case series. Arch Obstet Gynecol. 2021;2:1-4.

Elliot Levine, MD

Chicago, Illinois

Dr. Barbieri responds

I thank Dr. Levine for highlighting the important issue of IUD fracture and providing a reference to a case series of IUD fractures. Although such fracture is not common, when it does occur it may require a hysteroscopic procedure to remove all pieces of the IUD. In the cited case series, fracture was more commonly observed with the copper IUD than with the LNG-IUD. With regard to IUD malposition, 4 publications reviewed in my recent editorial describe the problem of an IUD arm embedded in the myometrium.1-4

References

- Benacerraf BR, Shipp TD, Bromley B. Three-dimensional ultrasound detection of abnormally located intrauterine contraceptive devices which are a source of pelvic pain and abnormal bleeding. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2009;34:110-115.

- Braaten KP, Benson CB, Maurer R, et al. Malpositioned intrauterine contraceptive devices: risk factors, outcomes and future pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:1014-1020.

- Gerkowicz SA, Fiorentino DG, Kovacs AP, et al. Uterine structural abnormality and intrauterine device malposition: analysis of ultrasonographic and demographic variables of 517 patients. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220:183.e1-e8.

- Connolly CT, Fox NS. Incidence and risk factors for a malpositioned intrauterine device detected on three-dimensional ultrasound within eight weeks of placement. J Ultrasound Med. September 27, 2021.

Will NAAT replace microscopy for the identification of organisms causing vaginitis?

ROBERT L. BARBIERI, MD (MARCH 2022)

Follow-up questions on NAAT testing

The sensitivity of NAAT testing, as outlined in Dr. Barbieri’s editorial, is undoubtedly better than the clinical methods most clinicians are using. I appreciate the frustration we providers often experience in drawing conclusions for patients based on the Amsel criteria for bacterial vaginitis (BV). I am surprised by the low sensitivity of microscopy for yeast vaginitis. My follow-up questions are:

- Have the NAATs referenced been validated in clinical trials and proven to improve patient outcomes?

- Will the proposal to begin empiric therapy for both yeast vaginitis and BV in combination while waiting for NAAT results lead to an increase of resistant strains?

- What is the cost of NAAT for vaginitis, and is this cost effective in routine practice?

- Can NAATs be utilized to detect resistant strains of yeast or Gardnerella sp?

Alan Paul Gehrich, MD (COL, MC ret.)

Bethesda, Maryland

Dr. Barbieri responds

I thank Dr. Gehrich for raising the important issue of what is the optimal endpoint to assess the clinical utility of NAAT testing for vaginitis. Most studies of the use of NAAT to diagnose the cause of vaginitis focus on comparing NAAT results to standard clinical practice (microscopy and pH), and to a “gold standard.” In most studies the gold standards are Nugent scoring with Amsel criteria to resolve intermediate Nugent scores for bacterial vaginosis, culture for Candida, and culture for Trichomonas vaginalis. It is clear from multiple studies that NAAT provides superior sensitivity and specificity compared with standard clinical practice.1-3 As noted in the editorial, in a study of 466 patients with symptoms of vaginitis, standard office approaches to the diagnosis of vaginitis resulted in the failure to identify the correct infection in a large number of cases.4 For the diagnosis of BV, clinicians missed 42% of the cases identified by NAAT. For the diagnosis of Candida, clinicians missed 46% of the cases identified by NAAT. For the diagnosis of T vaginalis, clinicians missed 72% of the cases identified by NAAT. This resulted in clinicians not appropriately treating many infections detected by NAAT.

NAAT does provide information about the presence of Candida glabrata and Candida krusei, organisms which may be resistant to fluconazole. I agree with Dr. Gehrich that the optimal use of NAAT testing in practice is poorly studied with regard to treatment between sample collection and NAAT results. Cost of testing is a complex issue. Standard microscopy is relatively inexpensive, but performs poorly in clinical practice, resulting in misdiagnosis. NAAT testing is expensive but correctly identifies causes of vaginitis.

References

- Schwebke JR, Gaydos CA, Hyirjesy P, et al. Diagnostic performance of a molecular test versus clinician assessment of vaginitis. J Clin Microbiol. 2018;56:e00252-18.

- Broache M, Cammarata CL, Stonebraker E, et al. Performance of vaginal panel assay compared with clinical diagnosis of vaginitis. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;138:853-859.

- Schwebke JR, Taylor SN, Ackerman N, et al. Clinical validation of the Aptima bacterial vaginosis and Aptima Candida/Trichomonas vaginalis assays: results from a prospective multi-center study. J Clin Microbiol. 2020;58:e01643-19. 4

- Gaydos CA, Beqaj S, Schwebke JR, et al. Clinical validation of a test for the diagnosis of vaginitis. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:181-189.

How common is IUD perforation, expulsion, and malposition?

ROBERT L. BARBIERI, MD (APRIL 2022)

The seriousness of IUD embedment

I appreciated Dr. Barbieri’s comprehensive review of clinical problems regarding the intrauterine device (IUD). It is interesting that, in spite of your mention of IUD embedment in the myometrium, other publications regarding this phenomenon are seemingly absent (except for ours).1 Whether or not there is associated pain (and sometimes there is not), in our experience its removal can result in IUD fracture. As you stated, it is true that 3D transvaginal sonography perfectly enables this visualization, yet it is surprising that others have not experienced what we have. Nonetheless, it is encouraging to see that IUD embedment is seriously mentioned.

- Fernandez CM, Levine EM, Cabiya M, et al. Intrauterine device embedment resulting in its fracture: a case series. Arch Obstet Gynecol. 2021;2:1-4.

Elliot Levine, MD

Chicago, Illinois

Dr. Barbieri responds

I thank Dr. Levine for highlighting the important issue of IUD fracture and providing a reference to a case series of IUD fractures. Although such fracture is not common, when it does occur it may require a hysteroscopic procedure to remove all pieces of the IUD. In the cited case series, fracture was more commonly observed with the copper IUD than with the LNG-IUD. With regard to IUD malposition, 4 publications reviewed in my recent editorial describe the problem of an IUD arm embedded in the myometrium.1-4

References

- Benacerraf BR, Shipp TD, Bromley B. Three-dimensional ultrasound detection of abnormally located intrauterine contraceptive devices which are a source of pelvic pain and abnormal bleeding. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2009;34:110-115.

- Braaten KP, Benson CB, Maurer R, et al. Malpositioned intrauterine contraceptive devices: risk factors, outcomes and future pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:1014-1020.

- Gerkowicz SA, Fiorentino DG, Kovacs AP, et al. Uterine structural abnormality and intrauterine device malposition: analysis of ultrasonographic and demographic variables of 517 patients. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220:183.e1-e8.

- Connolly CT, Fox NS. Incidence and risk factors for a malpositioned intrauterine device detected on three-dimensional ultrasound within eight weeks of placement. J Ultrasound Med. September 27, 2021.

Will NAAT replace microscopy for the identification of organisms causing vaginitis?

ROBERT L. BARBIERI, MD (MARCH 2022)

Follow-up questions on NAAT testing

The sensitivity of NAAT testing, as outlined in Dr. Barbieri’s editorial, is undoubtedly better than the clinical methods most clinicians are using. I appreciate the frustration we providers often experience in drawing conclusions for patients based on the Amsel criteria for bacterial vaginitis (BV). I am surprised by the low sensitivity of microscopy for yeast vaginitis. My follow-up questions are:

- Have the NAATs referenced been validated in clinical trials and proven to improve patient outcomes?

- Will the proposal to begin empiric therapy for both yeast vaginitis and BV in combination while waiting for NAAT results lead to an increase of resistant strains?

- What is the cost of NAAT for vaginitis, and is this cost effective in routine practice?

- Can NAATs be utilized to detect resistant strains of yeast or Gardnerella sp?

Alan Paul Gehrich, MD (COL, MC ret.)

Bethesda, Maryland

Dr. Barbieri responds

I thank Dr. Gehrich for raising the important issue of what is the optimal endpoint to assess the clinical utility of NAAT testing for vaginitis. Most studies of the use of NAAT to diagnose the cause of vaginitis focus on comparing NAAT results to standard clinical practice (microscopy and pH), and to a “gold standard.” In most studies the gold standards are Nugent scoring with Amsel criteria to resolve intermediate Nugent scores for bacterial vaginosis, culture for Candida, and culture for Trichomonas vaginalis. It is clear from multiple studies that NAAT provides superior sensitivity and specificity compared with standard clinical practice.1-3 As noted in the editorial, in a study of 466 patients with symptoms of vaginitis, standard office approaches to the diagnosis of vaginitis resulted in the failure to identify the correct infection in a large number of cases.4 For the diagnosis of BV, clinicians missed 42% of the cases identified by NAAT. For the diagnosis of Candida, clinicians missed 46% of the cases identified by NAAT. For the diagnosis of T vaginalis, clinicians missed 72% of the cases identified by NAAT. This resulted in clinicians not appropriately treating many infections detected by NAAT.

NAAT does provide information about the presence of Candida glabrata and Candida krusei, organisms which may be resistant to fluconazole. I agree with Dr. Gehrich that the optimal use of NAAT testing in practice is poorly studied with regard to treatment between sample collection and NAAT results. Cost of testing is a complex issue. Standard microscopy is relatively inexpensive, but performs poorly in clinical practice, resulting in misdiagnosis. NAAT testing is expensive but correctly identifies causes of vaginitis.

References

- Schwebke JR, Gaydos CA, Hyirjesy P, et al. Diagnostic performance of a molecular test versus clinician assessment of vaginitis. J Clin Microbiol. 2018;56:e00252-18.

- Broache M, Cammarata CL, Stonebraker E, et al. Performance of vaginal panel assay compared with clinical diagnosis of vaginitis. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;138:853-859.

- Schwebke JR, Taylor SN, Ackerman N, et al. Clinical validation of the Aptima bacterial vaginosis and Aptima Candida/Trichomonas vaginalis assays: results from a prospective multi-center study. J Clin Microbiol. 2020;58:e01643-19. 4

- Gaydos CA, Beqaj S, Schwebke JR, et al. Clinical validation of a test for the diagnosis of vaginitis. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:181-189.

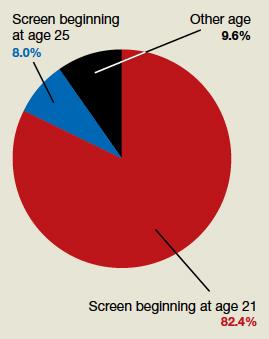

At what age do ObGyns recommend their patients begin cervical cancer screening?

In their peer-to-peer interview, “Cervical cancer: A path to eradication,” (OBG Manag. May 2022;34:30-34.) David G. Mutch, MD, and Warner Huh, MD, discussed the varying guidelines for cervical cancer screening. Dr. Huh pointed out that the 2020 guidelines for the American Cancer Society recommend cervical cancer screening to begin at age 25 years, although the current guidelines for the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists continue to recommend age 21. He noted that “the rate of cervical cancer is extremely low under age 25, and other countries like the United Kingdom already” screen beginning at age 25. OBG Management followed up with a poll for readers to ask: “Guidelines vary on what age to begin screening for cervical cancer. What age do you typically recommend for patients?”

A total of 187 readers cast their vote:

82.4% (154 readers) said age 21

8.0% (15 readers) said age 25

9.6% (18 readers) said other age

In their peer-to-peer interview, “Cervical cancer: A path to eradication,” (OBG Manag. May 2022;34:30-34.) David G. Mutch, MD, and Warner Huh, MD, discussed the varying guidelines for cervical cancer screening. Dr. Huh pointed out that the 2020 guidelines for the American Cancer Society recommend cervical cancer screening to begin at age 25 years, although the current guidelines for the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists continue to recommend age 21. He noted that “the rate of cervical cancer is extremely low under age 25, and other countries like the United Kingdom already” screen beginning at age 25. OBG Management followed up with a poll for readers to ask: “Guidelines vary on what age to begin screening for cervical cancer. What age do you typically recommend for patients?”

A total of 187 readers cast their vote:

82.4% (154 readers) said age 21

8.0% (15 readers) said age 25

9.6% (18 readers) said other age

In their peer-to-peer interview, “Cervical cancer: A path to eradication,” (OBG Manag. May 2022;34:30-34.) David G. Mutch, MD, and Warner Huh, MD, discussed the varying guidelines for cervical cancer screening. Dr. Huh pointed out that the 2020 guidelines for the American Cancer Society recommend cervical cancer screening to begin at age 25 years, although the current guidelines for the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists continue to recommend age 21. He noted that “the rate of cervical cancer is extremely low under age 25, and other countries like the United Kingdom already” screen beginning at age 25. OBG Management followed up with a poll for readers to ask: “Guidelines vary on what age to begin screening for cervical cancer. What age do you typically recommend for patients?”

A total of 187 readers cast their vote:

82.4% (154 readers) said age 21

8.0% (15 readers) said age 25

9.6% (18 readers) said other age

Well-child visits rise, but disparities remain

Adherence to well-child visits in the United States increased overall over a 10-year period, but a gap of up to 20% persisted between the highest and lowest adherence groups, reflecting disparities by race and ethnicity, poverty level, geography, and insurance status.

Well-child visits are recommended to provide children with preventive health and development services, ensure immunizations, and allow parents to discuss health concerns, wrote Salam Abdus, PhD, and Thomas M. Selden, PhD, of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, Md.

“We know from prior studies that as of 2008, well-child visits were trending upward, but often fell short of recommendations among key socioeconomic groups,” they wrote.

To examine recent trends in well-child visits, the researchers conducted a cross-sectional study of data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) on children aged 0 to 18 years. The findings were published in JAMA Pediatrics.

The study population included 19,018 children in 2006 and 2007 and 17,533 children in 2016 and 2017.

Adherence was defined as the ratio of reported well-child visits divided by the recommended number of visits in a calendar year.

Overall, the mean adherence increased from 47.9% in 2006-2007 to 62.3% in 2016-2017.

However, significant gaps persisted across race and ethnicity. Notably, adherence in the Hispanic population increased by nearly 22% between the study dates, compared to a 15.3% increase among White non-Hispanic children. However, Hispanic children still trailed White children overall in 2016-2017 (58% vs. 67.8%).

The smallest increase in adherence occurred among Black non-Hispanic children (5.6%) which further widened the gap between Black and White non-Hispanic children in 2016-2017 (52.5% vs. 67.8%).

Adherence rates increased similarly for children with public and private insurance (15.5% and 13.9%, respectively), but the adherence rates for uninsured children remained stable. Adherence in 2016-2017 for children with private, public, and no insurance were 66.3%, 58.7%, and 31.1%.

Also, despite overall increases in adherence across regions, a gap of more than 20% separated the region with the highest adherence (Northeast) from the lowest (West) in both the 2006-2007 and 2016-2017 periods (69.3% vs. 38.4%, and 79.3% vs. 55.2%, respectively).

The findings show an increase in well-child visits that spanned a time period of increased recommendations, economic changes, and the impact of the Affordable Care Act, but unaddressed disparities remain, the researchers noted.

Reducing disparities and improving adherence, “will require the combined efforts of researchers, policymakers, and clinicians to improve our understanding of adherence, to implement policies improving access to care, and to increase health care professional engagement with disadvantaged communities,” they concluded.

Overall increases are encouraging, but barriers need attention

“Demographic data are critical to determine which groups of children need the most support for recommended well child care,” Susan Boulter, MD, of the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hanover, N.H., said in an interview. In the current study, “it was encouraging to see how either public or private insurance significantly increased the percentage of children receiving well child care,” she said.

The level of increased adherence to AAP-recommended guidelines for well-child visits was surprising, said Dr. Boulter. The overall increase is likely attributable in part to the increased coverage for well-child visits in the wake of the Affordable Care Act, as the study authors mention, she said.

“The gains experienced by Hispanic families were especially encouraging,” she added.

However, ongoing barriers to well-child care include “lack of adequate provider numbers and mix, transportation difficulties for patients, and lack of child care and time away from work for parents so they can complete the recommended well child visit schedule,” Dr. Boulter noted. “Provider schedules and locations of care should be improved so families would have easier access. Also, social media should have more positive well-child messages to counteract the negative messaging.”

More research is needed to examine the impact of COVID-19 on well-child visits, Dr. Boulter emphasized. “Most likely, the percentages in all groups will have changed since COVID-19 has impacted office practices,” she said. “Anxiety about COVID-19 transmissibility in the pediatric office decreased routine office visits, and skepticism about vaccines, including vaccine refusal, has significantly changed the percentage of children who have received the AAP recommended vaccines,” she explained. Ideally, the study authors will review the MEPS data again to examine changes since the COVID-19 pandemic began, she told this news organization.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Boulter had no financial conflicts to disclose and serves on the editorial advisory board of Pediatric News.

Adherence to well-child visits in the United States increased overall over a 10-year period, but a gap of up to 20% persisted between the highest and lowest adherence groups, reflecting disparities by race and ethnicity, poverty level, geography, and insurance status.

Well-child visits are recommended to provide children with preventive health and development services, ensure immunizations, and allow parents to discuss health concerns, wrote Salam Abdus, PhD, and Thomas M. Selden, PhD, of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, Md.

“We know from prior studies that as of 2008, well-child visits were trending upward, but often fell short of recommendations among key socioeconomic groups,” they wrote.

To examine recent trends in well-child visits, the researchers conducted a cross-sectional study of data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) on children aged 0 to 18 years. The findings were published in JAMA Pediatrics.

The study population included 19,018 children in 2006 and 2007 and 17,533 children in 2016 and 2017.

Adherence was defined as the ratio of reported well-child visits divided by the recommended number of visits in a calendar year.

Overall, the mean adherence increased from 47.9% in 2006-2007 to 62.3% in 2016-2017.

However, significant gaps persisted across race and ethnicity. Notably, adherence in the Hispanic population increased by nearly 22% between the study dates, compared to a 15.3% increase among White non-Hispanic children. However, Hispanic children still trailed White children overall in 2016-2017 (58% vs. 67.8%).

The smallest increase in adherence occurred among Black non-Hispanic children (5.6%) which further widened the gap between Black and White non-Hispanic children in 2016-2017 (52.5% vs. 67.8%).

Adherence rates increased similarly for children with public and private insurance (15.5% and 13.9%, respectively), but the adherence rates for uninsured children remained stable. Adherence in 2016-2017 for children with private, public, and no insurance were 66.3%, 58.7%, and 31.1%.

Also, despite overall increases in adherence across regions, a gap of more than 20% separated the region with the highest adherence (Northeast) from the lowest (West) in both the 2006-2007 and 2016-2017 periods (69.3% vs. 38.4%, and 79.3% vs. 55.2%, respectively).

The findings show an increase in well-child visits that spanned a time period of increased recommendations, economic changes, and the impact of the Affordable Care Act, but unaddressed disparities remain, the researchers noted.

Reducing disparities and improving adherence, “will require the combined efforts of researchers, policymakers, and clinicians to improve our understanding of adherence, to implement policies improving access to care, and to increase health care professional engagement with disadvantaged communities,” they concluded.

Overall increases are encouraging, but barriers need attention

“Demographic data are critical to determine which groups of children need the most support for recommended well child care,” Susan Boulter, MD, of the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hanover, N.H., said in an interview. In the current study, “it was encouraging to see how either public or private insurance significantly increased the percentage of children receiving well child care,” she said.

The level of increased adherence to AAP-recommended guidelines for well-child visits was surprising, said Dr. Boulter. The overall increase is likely attributable in part to the increased coverage for well-child visits in the wake of the Affordable Care Act, as the study authors mention, she said.

“The gains experienced by Hispanic families were especially encouraging,” she added.

However, ongoing barriers to well-child care include “lack of adequate provider numbers and mix, transportation difficulties for patients, and lack of child care and time away from work for parents so they can complete the recommended well child visit schedule,” Dr. Boulter noted. “Provider schedules and locations of care should be improved so families would have easier access. Also, social media should have more positive well-child messages to counteract the negative messaging.”

More research is needed to examine the impact of COVID-19 on well-child visits, Dr. Boulter emphasized. “Most likely, the percentages in all groups will have changed since COVID-19 has impacted office practices,” she said. “Anxiety about COVID-19 transmissibility in the pediatric office decreased routine office visits, and skepticism about vaccines, including vaccine refusal, has significantly changed the percentage of children who have received the AAP recommended vaccines,” she explained. Ideally, the study authors will review the MEPS data again to examine changes since the COVID-19 pandemic began, she told this news organization.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Boulter had no financial conflicts to disclose and serves on the editorial advisory board of Pediatric News.

Adherence to well-child visits in the United States increased overall over a 10-year period, but a gap of up to 20% persisted between the highest and lowest adherence groups, reflecting disparities by race and ethnicity, poverty level, geography, and insurance status.

Well-child visits are recommended to provide children with preventive health and development services, ensure immunizations, and allow parents to discuss health concerns, wrote Salam Abdus, PhD, and Thomas M. Selden, PhD, of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, Md.

“We know from prior studies that as of 2008, well-child visits were trending upward, but often fell short of recommendations among key socioeconomic groups,” they wrote.

To examine recent trends in well-child visits, the researchers conducted a cross-sectional study of data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) on children aged 0 to 18 years. The findings were published in JAMA Pediatrics.

The study population included 19,018 children in 2006 and 2007 and 17,533 children in 2016 and 2017.

Adherence was defined as the ratio of reported well-child visits divided by the recommended number of visits in a calendar year.

Overall, the mean adherence increased from 47.9% in 2006-2007 to 62.3% in 2016-2017.

However, significant gaps persisted across race and ethnicity. Notably, adherence in the Hispanic population increased by nearly 22% between the study dates, compared to a 15.3% increase among White non-Hispanic children. However, Hispanic children still trailed White children overall in 2016-2017 (58% vs. 67.8%).

The smallest increase in adherence occurred among Black non-Hispanic children (5.6%) which further widened the gap between Black and White non-Hispanic children in 2016-2017 (52.5% vs. 67.8%).

Adherence rates increased similarly for children with public and private insurance (15.5% and 13.9%, respectively), but the adherence rates for uninsured children remained stable. Adherence in 2016-2017 for children with private, public, and no insurance were 66.3%, 58.7%, and 31.1%.

Also, despite overall increases in adherence across regions, a gap of more than 20% separated the region with the highest adherence (Northeast) from the lowest (West) in both the 2006-2007 and 2016-2017 periods (69.3% vs. 38.4%, and 79.3% vs. 55.2%, respectively).

The findings show an increase in well-child visits that spanned a time period of increased recommendations, economic changes, and the impact of the Affordable Care Act, but unaddressed disparities remain, the researchers noted.

Reducing disparities and improving adherence, “will require the combined efforts of researchers, policymakers, and clinicians to improve our understanding of adherence, to implement policies improving access to care, and to increase health care professional engagement with disadvantaged communities,” they concluded.

Overall increases are encouraging, but barriers need attention

“Demographic data are critical to determine which groups of children need the most support for recommended well child care,” Susan Boulter, MD, of the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hanover, N.H., said in an interview. In the current study, “it was encouraging to see how either public or private insurance significantly increased the percentage of children receiving well child care,” she said.

The level of increased adherence to AAP-recommended guidelines for well-child visits was surprising, said Dr. Boulter. The overall increase is likely attributable in part to the increased coverage for well-child visits in the wake of the Affordable Care Act, as the study authors mention, she said.

“The gains experienced by Hispanic families were especially encouraging,” she added.

However, ongoing barriers to well-child care include “lack of adequate provider numbers and mix, transportation difficulties for patients, and lack of child care and time away from work for parents so they can complete the recommended well child visit schedule,” Dr. Boulter noted. “Provider schedules and locations of care should be improved so families would have easier access. Also, social media should have more positive well-child messages to counteract the negative messaging.”

More research is needed to examine the impact of COVID-19 on well-child visits, Dr. Boulter emphasized. “Most likely, the percentages in all groups will have changed since COVID-19 has impacted office practices,” she said. “Anxiety about COVID-19 transmissibility in the pediatric office decreased routine office visits, and skepticism about vaccines, including vaccine refusal, has significantly changed the percentage of children who have received the AAP recommended vaccines,” she explained. Ideally, the study authors will review the MEPS data again to examine changes since the COVID-19 pandemic began, she told this news organization.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Boulter had no financial conflicts to disclose and serves on the editorial advisory board of Pediatric News.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

Preparing for back to school amid monkeypox outbreak and ever-changing COVID landscape

Unlike last school year, there are now vaccines available for all over the age of 6 months, and home rapid antigen tests are more readily available. Additionally, many have now been exposed either by infection or vaccination to the virus.

The CDC has removed the recommendations for maintaining cohorts in the K-12 population. This changing landscape along with differing levels of personal risk make it challenging to counsel families about what to expect in terms of COVID this year.

The best defense that we currently have against COVID is the vaccine. Although it seems that many are susceptible to the virus despite the vaccine, those who have been vaccinated are less susceptible to serious disease, including young children.

As older children may be heading to college, it is important

to encourage them to isolate when they have symptoms, even when they test negative for COVID as we would all like to avoid being sick in general.

Additionally, they should pay attention to the COVID risk level in their area and wear masks, particularly when indoors, as the levels increase. College students should have a plan for where they can isolate when not feeling well. If anyone does test positive for COVID, they should follow the most recent quarantine guidelines, including wearing a well fitted mask when they do begin returning to activities.

Monkeypox

We now have a new health concern for this school year.

Monkeypox has come onto the scene with information changing as rapidly as information previously did for COVID. With this virus, we must particularly counsel those heading away to college to be careful to limit their exposure to this disease.

Dormitories and other congregate settings are high-risk locations for the spread of monkeypox. Particularly, students headed to stay in dormitories should be counseled about avoiding:

- sexual activity with those with lesions consistent with monkeypox;

- sharing eating and drinking utensils; and

- sleeping in the same bed as or sharing bedding or towels with anyone with a diagnosis of or lesions consistent with monkeypox.

Additionally, as with prevention of all infections, it is important to frequently wash hands or use alcohol-based sanitizer before eating, and avoid touching the face after using the restroom.

Guidance for those eligible for vaccines against monkeypox seems to be quickly changing as well.

At the time of this article, CDC guidance recommends the vaccine against monkeypox for:

- those considered to be at high risk for it, including those identified by public health officials as a contact of someone with monkeypox;

- those who are aware that a sexual partner had a diagnosis of monkeypox within the past 2 weeks;

- those with multiple sex partners in the past 2 weeks in an area with known monkeypox; and

- those whose jobs may expose them to monkeypox.

Currently, the CDC recommends the vaccine JYNNEOS, a two-dose vaccine that reaches maximum protection after fourteen days. Ultimately, guidance is likely to continue to quickly change for both COVID-19 and Monkeypox throughout the fall. It is possible that new vaccinations will become available, and families and physicians alike will have many questions.

Primary care offices should ensure that someone is keeping up to date with the latest guidance to share with the office so that physicians may share accurate information with their patients.

Families should be counseled that we anticipate information about monkeypox, particularly related to vaccinations, to continue to change, as it has during all stages of the COVID pandemic.

As always, patients should be reminded to continue regular routine vaccinations, including the annual influenza vaccine.

Dr. Wheat is a family physician at Erie Family Health Center and program director of Northwestern University’s McGaw Family Medicine residency program, both in Chicago. Dr. Wheat serves on the editorial advisory board of Family Practice News. You can contact her at [email protected].

Unlike last school year, there are now vaccines available for all over the age of 6 months, and home rapid antigen tests are more readily available. Additionally, many have now been exposed either by infection or vaccination to the virus.

The CDC has removed the recommendations for maintaining cohorts in the K-12 population. This changing landscape along with differing levels of personal risk make it challenging to counsel families about what to expect in terms of COVID this year.

The best defense that we currently have against COVID is the vaccine. Although it seems that many are susceptible to the virus despite the vaccine, those who have been vaccinated are less susceptible to serious disease, including young children.

As older children may be heading to college, it is important

to encourage them to isolate when they have symptoms, even when they test negative for COVID as we would all like to avoid being sick in general.

Additionally, they should pay attention to the COVID risk level in their area and wear masks, particularly when indoors, as the levels increase. College students should have a plan for where they can isolate when not feeling well. If anyone does test positive for COVID, they should follow the most recent quarantine guidelines, including wearing a well fitted mask when they do begin returning to activities.

Monkeypox

We now have a new health concern for this school year.

Monkeypox has come onto the scene with information changing as rapidly as information previously did for COVID. With this virus, we must particularly counsel those heading away to college to be careful to limit their exposure to this disease.

Dormitories and other congregate settings are high-risk locations for the spread of monkeypox. Particularly, students headed to stay in dormitories should be counseled about avoiding:

- sexual activity with those with lesions consistent with monkeypox;

- sharing eating and drinking utensils; and

- sleeping in the same bed as or sharing bedding or towels with anyone with a diagnosis of or lesions consistent with monkeypox.

Additionally, as with prevention of all infections, it is important to frequently wash hands or use alcohol-based sanitizer before eating, and avoid touching the face after using the restroom.

Guidance for those eligible for vaccines against monkeypox seems to be quickly changing as well.

At the time of this article, CDC guidance recommends the vaccine against monkeypox for:

- those considered to be at high risk for it, including those identified by public health officials as a contact of someone with monkeypox;

- those who are aware that a sexual partner had a diagnosis of monkeypox within the past 2 weeks;

- those with multiple sex partners in the past 2 weeks in an area with known monkeypox; and

- those whose jobs may expose them to monkeypox.

Currently, the CDC recommends the vaccine JYNNEOS, a two-dose vaccine that reaches maximum protection after fourteen days. Ultimately, guidance is likely to continue to quickly change for both COVID-19 and Monkeypox throughout the fall. It is possible that new vaccinations will become available, and families and physicians alike will have many questions.

Primary care offices should ensure that someone is keeping up to date with the latest guidance to share with the office so that physicians may share accurate information with their patients.

Families should be counseled that we anticipate information about monkeypox, particularly related to vaccinations, to continue to change, as it has during all stages of the COVID pandemic.

As always, patients should be reminded to continue regular routine vaccinations, including the annual influenza vaccine.

Dr. Wheat is a family physician at Erie Family Health Center and program director of Northwestern University’s McGaw Family Medicine residency program, both in Chicago. Dr. Wheat serves on the editorial advisory board of Family Practice News. You can contact her at [email protected].

Unlike last school year, there are now vaccines available for all over the age of 6 months, and home rapid antigen tests are more readily available. Additionally, many have now been exposed either by infection or vaccination to the virus.

The CDC has removed the recommendations for maintaining cohorts in the K-12 population. This changing landscape along with differing levels of personal risk make it challenging to counsel families about what to expect in terms of COVID this year.

The best defense that we currently have against COVID is the vaccine. Although it seems that many are susceptible to the virus despite the vaccine, those who have been vaccinated are less susceptible to serious disease, including young children.

As older children may be heading to college, it is important

to encourage them to isolate when they have symptoms, even when they test negative for COVID as we would all like to avoid being sick in general.

Additionally, they should pay attention to the COVID risk level in their area and wear masks, particularly when indoors, as the levels increase. College students should have a plan for where they can isolate when not feeling well. If anyone does test positive for COVID, they should follow the most recent quarantine guidelines, including wearing a well fitted mask when they do begin returning to activities.

Monkeypox

We now have a new health concern for this school year.

Monkeypox has come onto the scene with information changing as rapidly as information previously did for COVID. With this virus, we must particularly counsel those heading away to college to be careful to limit their exposure to this disease.

Dormitories and other congregate settings are high-risk locations for the spread of monkeypox. Particularly, students headed to stay in dormitories should be counseled about avoiding:

- sexual activity with those with lesions consistent with monkeypox;

- sharing eating and drinking utensils; and

- sleeping in the same bed as or sharing bedding or towels with anyone with a diagnosis of or lesions consistent with monkeypox.

Additionally, as with prevention of all infections, it is important to frequently wash hands or use alcohol-based sanitizer before eating, and avoid touching the face after using the restroom.

Guidance for those eligible for vaccines against monkeypox seems to be quickly changing as well.

At the time of this article, CDC guidance recommends the vaccine against monkeypox for:

- those considered to be at high risk for it, including those identified by public health officials as a contact of someone with monkeypox;

- those who are aware that a sexual partner had a diagnosis of monkeypox within the past 2 weeks;

- those with multiple sex partners in the past 2 weeks in an area with known monkeypox; and

- those whose jobs may expose them to monkeypox.

Currently, the CDC recommends the vaccine JYNNEOS, a two-dose vaccine that reaches maximum protection after fourteen days. Ultimately, guidance is likely to continue to quickly change for both COVID-19 and Monkeypox throughout the fall. It is possible that new vaccinations will become available, and families and physicians alike will have many questions.

Primary care offices should ensure that someone is keeping up to date with the latest guidance to share with the office so that physicians may share accurate information with their patients.

Families should be counseled that we anticipate information about monkeypox, particularly related to vaccinations, to continue to change, as it has during all stages of the COVID pandemic.

As always, patients should be reminded to continue regular routine vaccinations, including the annual influenza vaccine.

Dr. Wheat is a family physician at Erie Family Health Center and program director of Northwestern University’s McGaw Family Medicine residency program, both in Chicago. Dr. Wheat serves on the editorial advisory board of Family Practice News. You can contact her at [email protected].

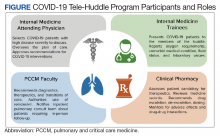

Implementation of a Virtual Huddle to Support Patient Care During the COVID-19 Pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic challenged hospital medicine teams to care for patients with complex respiratory needs, comply with evolving protocols, and remain abreast of new therapies.1,2 Pulmonary and critical care medicine (PCCM) faculty grappled with similar issues, acknowledging that their critical care expertise could be beneficial outside of the intensive care unit (ICU). Clinical pharmacists managed the procurement, allocation, and monitoring of complex (and sometimes limited) pharmacologic therapies. Although strategies used by health care systems to prepare and restructure for COVID-19 are reported, processes to enhance multidisciplinary care are limited.3,4 Therefore, we developed the COVID-19 Tele-Huddle Program using video conference to support hospital medicine teams caring for patients with COVID-19 and high disease severity.

Program Description

The Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center (MEDVAMC) in Houston, Texas, is a 349-bed, level 1A federal health care facility serving more than 113,000 veterans in southeast Texas.5 The COVID-19 Tele-Huddle Program took place over a 4-week period from July 6 to August 2, 2020. By the end of the 4-week period, there was a decline in the number of COVID patient admissions and thus the need for the huddle. Participation in the huddle also declined, likely reflecting the end of the surge and an increase in knowledge about COVID management acquired by the teams. Each COVID-19 Tele-Huddle Program consultation session consisted of at least 1 member from each hospital medicine team, 1 to 2 PCCM faculty members, and 1 to 2 clinical pharmacy specialists (Figure). The consultation team members included 4 PCCM faculty members and 2 clinical pharmacy specialists. The internal medicine (IM) participants included 10 ward teams with a total of 20 interns (PGY1), 12 upper-level residents (PGY2 and PGY 3), and 10 attending physicians.

The COVID-19 Tele-Huddle Program was a daily (including weekends) video conference. The hospital medicine team members joined the huddle from team workrooms, using webcams supplied by the MEDVAMC information technology department. The COVID-19 Tele-Huddle Program consultation team members joined remotely. Each hospital medicine team joined the huddle at a pre-assigned 15- to 30-minute time allotment, which varied based on patient volume. Participation in the huddle was mandatory for the first week and became optional thereafter. This was in recognition of the steep learning curve and provided the teams both basic knowledge of COVID management and a shared understanding of when a multidisciplinary consultation would be critical. Mandatory daily participation was challenging due to the pressures of patient volume during the surge.

COVID-19 patients with high disease severity were discussed during huddles based on specific criteria: all newly admitted COVID-19 patients, patients requiring step-down level of care, those with increasing oxygen requirements, and/or patients requiring authorization of remdesivir therapy, which required clinical pharmacy authorization at MEDVAMC. The hospital medicine teams reported the patients’ oxygen requirements, comorbid medical conditions, current and prior therapies, fluid status, and relevant laboratory values. A dashboard using the Premier Inc. TheraDoc clinical decision support system was developed to display patient vital signs, laboratory values, and medications. The PCCM faculty and clinical pharmacists listened to inpatient medicine teams presentations and used the dashboard and radiographic images to formulate clinical decisions. Discussion of a patient at the huddle did not preclude in-person consultation at any time.

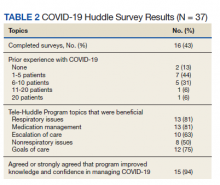

Tele-Huddles were not recorded, and all protected health information discussed was accessed through the electronic health record using a secure network. Data on length of the meeting, number of patients discussed, and management decisions were recorded daily in a spreadsheet. At the end of the 4-week surge, participants in the program completed a survey, which assessed participant demographics, prior experience with COVID-19, and satisfaction with the program based on a series of agree/disagree questions.

Program Metrics

During the COVID-19 Tele-Huddle Program 4-week evaluation period, 323 encounters were discussed with 117 unique patients with COVID-19. A median (IQR) of 5 (4-8) hospital medicine teams discussed 15 (9-18) patients. The COVID-19 Tele-Huddle Program lasted a median (IQR) 74 (53-94) minutes. A mean (SD) 27% (13) of patients with COVID-19 admitted to the acute care services were discussed.

The multidisciplinary team provided 247 chest X-ray interpretations, 82 diagnostic recommendations, 206 therapeutic recommendations, and 32 transition of care recommendations (Table 1). A total of 55 (47%) patients were given remdesivir with first dose authorized by clinical pharmacy and given within a median (IQR) 6 (3-10) hours after the order was placed. Oxygen therapy, including titration and de-escalation of high-flow nasal cannula and noninvasive positive pressure ventilation (NIPPV), was used for 26 (22.2%) patients. Additional interventions included the review of imaging, the assessment of volume status to guide diuretic recommendations, and the discussion of goals of care.

Of the participating IM trainees and attendings, 16 of 37 (43%) completed the user survey (Table 2). Prior experience with COVID-19 patients varied, with 7 of 16 respondents indicating experience with ≥ 5 patients with COVID-19 prior to the intervention period. Respondents believed that the huddle was helpful in management of respiratory issues (13 of 16), management of medications (13 of 16), escalation of care to ICU (10 of 16), and management of nonrespiratory issues (8 of 16) and goals of care (12 of 16). Fifteen of 16 participants strongly agreed or agreed that the COVID-19 Tele-Huddle Program improved their knowledge and confidence in managing patients. One participant commented, “Getting interdisciplinary help on COVID patients has really helped our team feel confident in our decisions about some of these very complex patients.” Another respondent commented, “Reliability was very helpful for planning how to discuss updates with our patients rather than the formal consultative process.”

Discussion

During the unprecedented COVID-19 pandemic, health care systems have been challenged to manage a large volume of patients, often with high disease severity, in non-ICU settings. This surge in cases has placed strain on hospital medicine teams. There is a subset of patients with COVID-19 with high disease severity that may be managed safely by hospital medicine teams, provided the accessibility and support of consultants, such as PCCM faculty and clinical pharmacists.

Huddles are defined as functional groups of people focused on enhancing communication and care coordination to benefit patient safety. While often brief in nature, huddles can encompass a variety of structures, agendas, and outcome measures.6,7 We implemented a modified huddle using video conferencing to provide important aspects of critical care for patients with COVID-19. Face-to-face evaluation of about 15 patients each day would have strained an already burdened PCCM faculty who were providing additional critical care services as part of the surge response. Conversion of in-person consultations to the COVID-19 Tele-Huddle Program allowed for mitigation of COVID-19 transmission risk for additional clinicians, conservation of personal protective equipment, and more effective communication between acute inpatient practitioners and clinical services. The huddle model expedited the authorization and delivery of therapeutics, including remdesivir, which was prescribed for many patients discussed. Clinical pharmacists provided a review of all medications with input on escalation, de-escalation, dosing, drug-drug interactions, and emergency use authorization therapies.

Our experience resonates with previously described advantages of a huddle model, including the reliability of the consultation, empowerment for all members with a de-emphasis on hierarchy and accountability expected by all.8 The huddle provided situational awareness about patients that may require escalation of care to the ICU and/or further goals of care conversations. Assistance with these transitions of care was highly appreciated by the hospital medicine teams who voiced that these decisions were quite challenging. COVID-19 patients at risk for decompensation were referred for in-person consultation and follow-up if required.

addition, the COVID-19 Tele-Huddle Program allowed for a safe and dependable venue for IM trainees and attending physicians to voice questions and concerns about their patients. We observed the development of a shared mental model among all huddle participants, in the face of a steep learning curve on the management of patients with complex respiratory needs. This was reflected in the survey: Most respondents reported improved knowledge and confidence in managing these patients. Situational awareness that arose from the huddle provided the PCCM faculty the opportunity to guide the inpatient ward teams on next steps whether it be escalation to the ICU and/or further goals of care conversations. Facilitation of transitions of care were voiced as challenging decisions faced by the inpatient ward teams, and there was appreciation for additional support from the PCCM faculty in making these difficult decisions.

Challenges and Opportunities

This was a single-center experience caring for veterans. Challenges with having virtual huddles during the COVID-19 surge involved both time for the health care practitioners and technology. This was recognized early by the educational leaders at our facility, and headsets and cameras were purchased for the team rooms and made available as quickly as possible. Another limitation was the unpredictability and variability of patient volume for specific teams that sometimes would affect the efficiency of the huddle. The number of teams who attended the COVID-19 huddle was highest for the first 2 weeks (maximum of 9 teams) but declined to a nadir of 3 at the end of the month. This reflected the increase in knowledge about COVID-19 and respiratory disease that the teams acquired initially as well as a decline in COVID-19 patient admissions over those weeks.

The COVID-19 Tele-Huddle Program model also can be expanded to include other frontline clinicians, including nurses and respiratory therapists. For example, case management huddles were performed in a similar way during the COVID-19 surge to allow for efficient and effective multidisciplinary conversations about patients

Conclusions

Given the rise of telemedicine and availability of video conferencing services, virtual huddles can be implemented in institutions with appropriate staff and remote access to health records. Multidisciplinary consultation services using video conferencing can serve as an adjunct to the traditional, in-person consultation service model for patients with complex needs.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge all of the Baylor Internal Medicine house staff and internal medicine attendings who participated in our huddle and more importantly, cared for our veterans during this COVID-19 surge.

1. Heymann DL, Shindo N; WHO Scientific and Technical Advisory Group for Infectious Hazards. COVID-19: what is next for public health?. Lancet. 2020;395(10224):542-545. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30374-3

2. Dichter JR, Kanter RK, Dries D, et al; Task Force for Mass Critical Care. System-level planning, coordination, and communication: care of the critically ill and injured during pandemics and disasters: CHEST consensus statement. Chest. 2014;146(suppl 4):e87S-e102S. doi:10.1378/chest.14-0738

3. Chowdhury JM, Patel M, Zheng M, Abramian O, Criner GJ. Mobilization and preparation of a large urban academic center during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020;17(8):922-925. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.202003-259PS

4. Uppal A, Silvestri DM, Siegler M, et al. Critical care and emergency department response at the epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(8):1443-1449. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00901

5. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center- Houston, Texas. Accessed December 10, 2020. https://www.houston.va.gov/about

6. Provost SM, Lanham HJ, Leykum LK, McDaniel RR Jr, Pugh J. Health care huddles: managing complexity to achieve high reliability. Health Care Manage Rev. 2015;40(1):2-12. doi:10.1097/HMR.0000000000000009

7. Franklin BJ, Gandhi TK, Bates DW, et al. Impact of multidisciplinary team huddles on patient safety: a systematic review and proposed taxonomy. BMJ Qual Saf. 2020;29(10):1-2. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2019-009911

8. Goldenhar LM, Brady PW, Sutcliffe KM, Muething SE. Huddling for high reliability and situation awareness. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22(11):899-906. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001467

The COVID-19 pandemic challenged hospital medicine teams to care for patients with complex respiratory needs, comply with evolving protocols, and remain abreast of new therapies.1,2 Pulmonary and critical care medicine (PCCM) faculty grappled with similar issues, acknowledging that their critical care expertise could be beneficial outside of the intensive care unit (ICU). Clinical pharmacists managed the procurement, allocation, and monitoring of complex (and sometimes limited) pharmacologic therapies. Although strategies used by health care systems to prepare and restructure for COVID-19 are reported, processes to enhance multidisciplinary care are limited.3,4 Therefore, we developed the COVID-19 Tele-Huddle Program using video conference to support hospital medicine teams caring for patients with COVID-19 and high disease severity.

Program Description

The Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center (MEDVAMC) in Houston, Texas, is a 349-bed, level 1A federal health care facility serving more than 113,000 veterans in southeast Texas.5 The COVID-19 Tele-Huddle Program took place over a 4-week period from July 6 to August 2, 2020. By the end of the 4-week period, there was a decline in the number of COVID patient admissions and thus the need for the huddle. Participation in the huddle also declined, likely reflecting the end of the surge and an increase in knowledge about COVID management acquired by the teams. Each COVID-19 Tele-Huddle Program consultation session consisted of at least 1 member from each hospital medicine team, 1 to 2 PCCM faculty members, and 1 to 2 clinical pharmacy specialists (Figure). The consultation team members included 4 PCCM faculty members and 2 clinical pharmacy specialists. The internal medicine (IM) participants included 10 ward teams with a total of 20 interns (PGY1), 12 upper-level residents (PGY2 and PGY 3), and 10 attending physicians.

The COVID-19 Tele-Huddle Program was a daily (including weekends) video conference. The hospital medicine team members joined the huddle from team workrooms, using webcams supplied by the MEDVAMC information technology department. The COVID-19 Tele-Huddle Program consultation team members joined remotely. Each hospital medicine team joined the huddle at a pre-assigned 15- to 30-minute time allotment, which varied based on patient volume. Participation in the huddle was mandatory for the first week and became optional thereafter. This was in recognition of the steep learning curve and provided the teams both basic knowledge of COVID management and a shared understanding of when a multidisciplinary consultation would be critical. Mandatory daily participation was challenging due to the pressures of patient volume during the surge.

COVID-19 patients with high disease severity were discussed during huddles based on specific criteria: all newly admitted COVID-19 patients, patients requiring step-down level of care, those with increasing oxygen requirements, and/or patients requiring authorization of remdesivir therapy, which required clinical pharmacy authorization at MEDVAMC. The hospital medicine teams reported the patients’ oxygen requirements, comorbid medical conditions, current and prior therapies, fluid status, and relevant laboratory values. A dashboard using the Premier Inc. TheraDoc clinical decision support system was developed to display patient vital signs, laboratory values, and medications. The PCCM faculty and clinical pharmacists listened to inpatient medicine teams presentations and used the dashboard and radiographic images to formulate clinical decisions. Discussion of a patient at the huddle did not preclude in-person consultation at any time.

Tele-Huddles were not recorded, and all protected health information discussed was accessed through the electronic health record using a secure network. Data on length of the meeting, number of patients discussed, and management decisions were recorded daily in a spreadsheet. At the end of the 4-week surge, participants in the program completed a survey, which assessed participant demographics, prior experience with COVID-19, and satisfaction with the program based on a series of agree/disagree questions.

Program Metrics

During the COVID-19 Tele-Huddle Program 4-week evaluation period, 323 encounters were discussed with 117 unique patients with COVID-19. A median (IQR) of 5 (4-8) hospital medicine teams discussed 15 (9-18) patients. The COVID-19 Tele-Huddle Program lasted a median (IQR) 74 (53-94) minutes. A mean (SD) 27% (13) of patients with COVID-19 admitted to the acute care services were discussed.

The multidisciplinary team provided 247 chest X-ray interpretations, 82 diagnostic recommendations, 206 therapeutic recommendations, and 32 transition of care recommendations (Table 1). A total of 55 (47%) patients were given remdesivir with first dose authorized by clinical pharmacy and given within a median (IQR) 6 (3-10) hours after the order was placed. Oxygen therapy, including titration and de-escalation of high-flow nasal cannula and noninvasive positive pressure ventilation (NIPPV), was used for 26 (22.2%) patients. Additional interventions included the review of imaging, the assessment of volume status to guide diuretic recommendations, and the discussion of goals of care.

Of the participating IM trainees and attendings, 16 of 37 (43%) completed the user survey (Table 2). Prior experience with COVID-19 patients varied, with 7 of 16 respondents indicating experience with ≥ 5 patients with COVID-19 prior to the intervention period. Respondents believed that the huddle was helpful in management of respiratory issues (13 of 16), management of medications (13 of 16), escalation of care to ICU (10 of 16), and management of nonrespiratory issues (8 of 16) and goals of care (12 of 16). Fifteen of 16 participants strongly agreed or agreed that the COVID-19 Tele-Huddle Program improved their knowledge and confidence in managing patients. One participant commented, “Getting interdisciplinary help on COVID patients has really helped our team feel confident in our decisions about some of these very complex patients.” Another respondent commented, “Reliability was very helpful for planning how to discuss updates with our patients rather than the formal consultative process.”

Discussion

During the unprecedented COVID-19 pandemic, health care systems have been challenged to manage a large volume of patients, often with high disease severity, in non-ICU settings. This surge in cases has placed strain on hospital medicine teams. There is a subset of patients with COVID-19 with high disease severity that may be managed safely by hospital medicine teams, provided the accessibility and support of consultants, such as PCCM faculty and clinical pharmacists.

Huddles are defined as functional groups of people focused on enhancing communication and care coordination to benefit patient safety. While often brief in nature, huddles can encompass a variety of structures, agendas, and outcome measures.6,7 We implemented a modified huddle using video conferencing to provide important aspects of critical care for patients with COVID-19. Face-to-face evaluation of about 15 patients each day would have strained an already burdened PCCM faculty who were providing additional critical care services as part of the surge response. Conversion of in-person consultations to the COVID-19 Tele-Huddle Program allowed for mitigation of COVID-19 transmission risk for additional clinicians, conservation of personal protective equipment, and more effective communication between acute inpatient practitioners and clinical services. The huddle model expedited the authorization and delivery of therapeutics, including remdesivir, which was prescribed for many patients discussed. Clinical pharmacists provided a review of all medications with input on escalation, de-escalation, dosing, drug-drug interactions, and emergency use authorization therapies.