User login

Long-term antidepressant use tied to an increase in CVD, mortality risk

The investigators drew on 10-year data from the UK Biobank on over 220,000 adults and compared the risk of developing adverse health outcomes among those taking antidepressants with the risk among those who were not taking antidepressants.

After adjusting for preexisting risk factors, they found that 10-year antidepressant use was associated with a twofold higher risk of CHD, an almost-twofold higher risk of CVD as well as CVD mortality, a higher risk of cerebrovascular disease, and more than double the risk of all-cause mortality.

On the other hand, at 10 years, antidepressant use was associated with a 23% lower risk of developing hypertension and a 32% lower risk of diabetes.

The main culprits were mirtazapine, venlafaxine, duloxetine, and trazodone, although SSRIs were also tied to increased risk.

“Our message for clinicians is that prescribing of antidepressants in the long term may not be harm free [and] we hope that this study will help doctors and patients have more informed conversations when they weigh up the potential risks and benefits of treatments for depression,” study investigator Narinder Bansal, MD, honorary research fellow, Centre for Academic Health and Centre for Academic Primary Care, University of Bristol (England), said in a news release.

“Regardless of whether the drugs are the underlying cause of these problems, our findings emphasize the importance of proactive cardiovascular monitoring and prevention in patients who have depression and are on antidepressants, given that both have been associated with higher risks,” she added.

The study was published online in the British Journal of Psychiatry Open.

Monitoring of CVD risk ‘critical’

Antidepressants are among the most widely prescribed drugs; 70 million prescriptions were dispensed in 2018 alone, representing a doubling of prescriptions for these agents in a decade, the investigators noted. “This striking rise in prescribing is attributed to long-term treatment rather than an increased incidence of depression.”

Most trials that have assessed antidepressant efficacy have been “poorly suited to examining adverse outcomes.” One reason for this is that many of the trials are short-term studies. Since depression is “strongly associated” with CVD risk factors, “careful assessment of the long-term cardiometabolic effects of antidepressant treatment is critical.”

Moreover, information about “a wide range of prospectively measured confounders ... is needed to provide robust estimates of the risks associated with long-term antidepressant use,” the authors noted.

The researchers examined the association between antidepressant use and four cardiometabolic morbidity outcomes – diabetes, hypertension, cerebrovascular disease, and CHD. In addition, they assessed two mortality outcomes – CVD mortality and all-cause mortality. Participants were divided into cohorts on the basis of outcome of interest.

The dataset contains detailed information on socioeconomic status, demographics, anthropometric, behavioral, and biochemical risk factors, disability, and health status and is linked to datasets of primary care records and deaths.

The study included 222,121 participants whose data had been linked to primary care records during 2018 (median age of participants, 56-57 years). About half were women, and 96% were of White ethnicity.

Participants were excluded if they had been prescribed antidepressants 12 months or less before baseline, if they had previously been diagnosed for the outcome of interest, if they had been previously prescribed psychotropic drugs, if they used cardiometabolic drugs at baseline, or if they had undergone treatment with antidepressant polytherapy.

Potential confounders included age, gender, body mass index, waist/hip ratio, smoking and alcohol intake status, physical activity, parental history of outcome, biochemical and hematologic biomarkers, socioeconomic status, and long-term illness, disability, or infirmity.

Mechanism unclear

By the end of the 5- and 10-year follow-up periods, an average of 8% and 6% of participants in each cohort, respectively, had been prescribed an antidepressant. SSRIs constituted the most commonly prescribed class (80%-82%), and citalopram was the most commonly prescribed SSRI (46%-47%). Mirtazapine was the most frequently prescribed non-SSRI antidepressant (44%-46%).

At 5 years, any antidepressant use was associated with an increased risk for diabetes, CHD, and all-cause mortality, but the findings were attenuated after further adjustment for confounders. In fact, SSRIs were associated with a reduced risk of diabetes at 5 years (hazard ratio, 0.64; 95% confidence interval, 0.49-0.83).

At 10 years, SSRIs were associated with an increased risk of cerebrovascular disease, CVD mortality, and all-cause mortality; non-SSRIs were associated with an increased risk of CHD, CVD, and all-cause mortality.

On the other hand, SSRIs were associated with a decrease in risk of diabetes and hypertension at 10 years (HR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.53-0.87; and HR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.66-0.89, respectively).

“While we have taken into account a wide range of pre-existing risk factors for cardiovascular disease, including those that are linked to depression such as excess weight, smoking, and low physical activity, it is difficult to fully control for the effects of depression in this kind of study, partly because there is considerable variability in the recording of depression severity in primary care,” said Dr. Bansal.

“This is important because many people taking antidepressants such as mirtazapine, venlafaxine, duloxetine and trazodone may have a more severe depression. This makes it difficult to fully separate the effects of the depression from the effects of medication,” she said.

Further research “is needed to assess whether the associations we have seen are genuinely due to the drugs; and, if so, why this might be,” she added.

Strengths, limitations

Commenting on the study, Roger McIntyre, MD, professor of psychiatry and pharmacology and head of the mood disorders psychopharmacology unit at the University of Toronto,, discussed the strengths and weaknesses of the study.

The UK Biobank is a “well-described, well-phenotyped dataset of good quality,” said Dr. McIntyre, chairperson and executive director of the Brain and Cognitive Discover Foundation, Toronto, who was not involved with the study. Another strength is the “impressive number of variables the database contains, which enabled the authors to go much deeper into the topics.”

A “significant limitation” is the confounding that is inherent to the disorder itself – “people with depression have a much higher intrinsic risk of CVD, [cerebrovascular disease], and cardiovascular mortality,” Dr. McIntyre noted.

The researchers did not adjust for trauma or childhood maltreatment, “which are the biggest risk factors for both depression and CVD; and drug and alcohol misuse were also not accounted for.”

Additionally, “to determine whether something is an association or potentially causative, it must satisfy the Bradford-Hill criteria,” said Dr. McIntyre. “Since we’re moving more toward using these big databases and because we depend on them to give us long-term perspectives, we would want to see coherent, compelling Bradford-Hill criteria regarding causation. If you don’t have any, that’s fine too, but then it’s important to make clear that there is no clear causative line, just an association.”

The research was funded by the National Institute of Health Research School for Primary Care Research and was supported by the NI Biomedical Research Centre at University Hospitals Bristol and Weston NHS Foundation Trust and the University of Bristol. Dr. McIntyre has received research grant support from CI/GACD/National Natural Science Foundation of China and the Milken Institute and speaker/consultation fees from numerous companies. Dr. McIntyre is a CEO of Braxia Scientific.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The investigators drew on 10-year data from the UK Biobank on over 220,000 adults and compared the risk of developing adverse health outcomes among those taking antidepressants with the risk among those who were not taking antidepressants.

After adjusting for preexisting risk factors, they found that 10-year antidepressant use was associated with a twofold higher risk of CHD, an almost-twofold higher risk of CVD as well as CVD mortality, a higher risk of cerebrovascular disease, and more than double the risk of all-cause mortality.

On the other hand, at 10 years, antidepressant use was associated with a 23% lower risk of developing hypertension and a 32% lower risk of diabetes.

The main culprits were mirtazapine, venlafaxine, duloxetine, and trazodone, although SSRIs were also tied to increased risk.

“Our message for clinicians is that prescribing of antidepressants in the long term may not be harm free [and] we hope that this study will help doctors and patients have more informed conversations when they weigh up the potential risks and benefits of treatments for depression,” study investigator Narinder Bansal, MD, honorary research fellow, Centre for Academic Health and Centre for Academic Primary Care, University of Bristol (England), said in a news release.

“Regardless of whether the drugs are the underlying cause of these problems, our findings emphasize the importance of proactive cardiovascular monitoring and prevention in patients who have depression and are on antidepressants, given that both have been associated with higher risks,” she added.

The study was published online in the British Journal of Psychiatry Open.

Monitoring of CVD risk ‘critical’

Antidepressants are among the most widely prescribed drugs; 70 million prescriptions were dispensed in 2018 alone, representing a doubling of prescriptions for these agents in a decade, the investigators noted. “This striking rise in prescribing is attributed to long-term treatment rather than an increased incidence of depression.”

Most trials that have assessed antidepressant efficacy have been “poorly suited to examining adverse outcomes.” One reason for this is that many of the trials are short-term studies. Since depression is “strongly associated” with CVD risk factors, “careful assessment of the long-term cardiometabolic effects of antidepressant treatment is critical.”

Moreover, information about “a wide range of prospectively measured confounders ... is needed to provide robust estimates of the risks associated with long-term antidepressant use,” the authors noted.

The researchers examined the association between antidepressant use and four cardiometabolic morbidity outcomes – diabetes, hypertension, cerebrovascular disease, and CHD. In addition, they assessed two mortality outcomes – CVD mortality and all-cause mortality. Participants were divided into cohorts on the basis of outcome of interest.

The dataset contains detailed information on socioeconomic status, demographics, anthropometric, behavioral, and biochemical risk factors, disability, and health status and is linked to datasets of primary care records and deaths.

The study included 222,121 participants whose data had been linked to primary care records during 2018 (median age of participants, 56-57 years). About half were women, and 96% were of White ethnicity.

Participants were excluded if they had been prescribed antidepressants 12 months or less before baseline, if they had previously been diagnosed for the outcome of interest, if they had been previously prescribed psychotropic drugs, if they used cardiometabolic drugs at baseline, or if they had undergone treatment with antidepressant polytherapy.

Potential confounders included age, gender, body mass index, waist/hip ratio, smoking and alcohol intake status, physical activity, parental history of outcome, biochemical and hematologic biomarkers, socioeconomic status, and long-term illness, disability, or infirmity.

Mechanism unclear

By the end of the 5- and 10-year follow-up periods, an average of 8% and 6% of participants in each cohort, respectively, had been prescribed an antidepressant. SSRIs constituted the most commonly prescribed class (80%-82%), and citalopram was the most commonly prescribed SSRI (46%-47%). Mirtazapine was the most frequently prescribed non-SSRI antidepressant (44%-46%).

At 5 years, any antidepressant use was associated with an increased risk for diabetes, CHD, and all-cause mortality, but the findings were attenuated after further adjustment for confounders. In fact, SSRIs were associated with a reduced risk of diabetes at 5 years (hazard ratio, 0.64; 95% confidence interval, 0.49-0.83).

At 10 years, SSRIs were associated with an increased risk of cerebrovascular disease, CVD mortality, and all-cause mortality; non-SSRIs were associated with an increased risk of CHD, CVD, and all-cause mortality.

On the other hand, SSRIs were associated with a decrease in risk of diabetes and hypertension at 10 years (HR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.53-0.87; and HR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.66-0.89, respectively).

“While we have taken into account a wide range of pre-existing risk factors for cardiovascular disease, including those that are linked to depression such as excess weight, smoking, and low physical activity, it is difficult to fully control for the effects of depression in this kind of study, partly because there is considerable variability in the recording of depression severity in primary care,” said Dr. Bansal.

“This is important because many people taking antidepressants such as mirtazapine, venlafaxine, duloxetine and trazodone may have a more severe depression. This makes it difficult to fully separate the effects of the depression from the effects of medication,” she said.

Further research “is needed to assess whether the associations we have seen are genuinely due to the drugs; and, if so, why this might be,” she added.

Strengths, limitations

Commenting on the study, Roger McIntyre, MD, professor of psychiatry and pharmacology and head of the mood disorders psychopharmacology unit at the University of Toronto,, discussed the strengths and weaknesses of the study.

The UK Biobank is a “well-described, well-phenotyped dataset of good quality,” said Dr. McIntyre, chairperson and executive director of the Brain and Cognitive Discover Foundation, Toronto, who was not involved with the study. Another strength is the “impressive number of variables the database contains, which enabled the authors to go much deeper into the topics.”

A “significant limitation” is the confounding that is inherent to the disorder itself – “people with depression have a much higher intrinsic risk of CVD, [cerebrovascular disease], and cardiovascular mortality,” Dr. McIntyre noted.

The researchers did not adjust for trauma or childhood maltreatment, “which are the biggest risk factors for both depression and CVD; and drug and alcohol misuse were also not accounted for.”

Additionally, “to determine whether something is an association or potentially causative, it must satisfy the Bradford-Hill criteria,” said Dr. McIntyre. “Since we’re moving more toward using these big databases and because we depend on them to give us long-term perspectives, we would want to see coherent, compelling Bradford-Hill criteria regarding causation. If you don’t have any, that’s fine too, but then it’s important to make clear that there is no clear causative line, just an association.”

The research was funded by the National Institute of Health Research School for Primary Care Research and was supported by the NI Biomedical Research Centre at University Hospitals Bristol and Weston NHS Foundation Trust and the University of Bristol. Dr. McIntyre has received research grant support from CI/GACD/National Natural Science Foundation of China and the Milken Institute and speaker/consultation fees from numerous companies. Dr. McIntyre is a CEO of Braxia Scientific.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The investigators drew on 10-year data from the UK Biobank on over 220,000 adults and compared the risk of developing adverse health outcomes among those taking antidepressants with the risk among those who were not taking antidepressants.

After adjusting for preexisting risk factors, they found that 10-year antidepressant use was associated with a twofold higher risk of CHD, an almost-twofold higher risk of CVD as well as CVD mortality, a higher risk of cerebrovascular disease, and more than double the risk of all-cause mortality.

On the other hand, at 10 years, antidepressant use was associated with a 23% lower risk of developing hypertension and a 32% lower risk of diabetes.

The main culprits were mirtazapine, venlafaxine, duloxetine, and trazodone, although SSRIs were also tied to increased risk.

“Our message for clinicians is that prescribing of antidepressants in the long term may not be harm free [and] we hope that this study will help doctors and patients have more informed conversations when they weigh up the potential risks and benefits of treatments for depression,” study investigator Narinder Bansal, MD, honorary research fellow, Centre for Academic Health and Centre for Academic Primary Care, University of Bristol (England), said in a news release.

“Regardless of whether the drugs are the underlying cause of these problems, our findings emphasize the importance of proactive cardiovascular monitoring and prevention in patients who have depression and are on antidepressants, given that both have been associated with higher risks,” she added.

The study was published online in the British Journal of Psychiatry Open.

Monitoring of CVD risk ‘critical’

Antidepressants are among the most widely prescribed drugs; 70 million prescriptions were dispensed in 2018 alone, representing a doubling of prescriptions for these agents in a decade, the investigators noted. “This striking rise in prescribing is attributed to long-term treatment rather than an increased incidence of depression.”

Most trials that have assessed antidepressant efficacy have been “poorly suited to examining adverse outcomes.” One reason for this is that many of the trials are short-term studies. Since depression is “strongly associated” with CVD risk factors, “careful assessment of the long-term cardiometabolic effects of antidepressant treatment is critical.”

Moreover, information about “a wide range of prospectively measured confounders ... is needed to provide robust estimates of the risks associated with long-term antidepressant use,” the authors noted.

The researchers examined the association between antidepressant use and four cardiometabolic morbidity outcomes – diabetes, hypertension, cerebrovascular disease, and CHD. In addition, they assessed two mortality outcomes – CVD mortality and all-cause mortality. Participants were divided into cohorts on the basis of outcome of interest.

The dataset contains detailed information on socioeconomic status, demographics, anthropometric, behavioral, and biochemical risk factors, disability, and health status and is linked to datasets of primary care records and deaths.

The study included 222,121 participants whose data had been linked to primary care records during 2018 (median age of participants, 56-57 years). About half were women, and 96% were of White ethnicity.

Participants were excluded if they had been prescribed antidepressants 12 months or less before baseline, if they had previously been diagnosed for the outcome of interest, if they had been previously prescribed psychotropic drugs, if they used cardiometabolic drugs at baseline, or if they had undergone treatment with antidepressant polytherapy.

Potential confounders included age, gender, body mass index, waist/hip ratio, smoking and alcohol intake status, physical activity, parental history of outcome, biochemical and hematologic biomarkers, socioeconomic status, and long-term illness, disability, or infirmity.

Mechanism unclear

By the end of the 5- and 10-year follow-up periods, an average of 8% and 6% of participants in each cohort, respectively, had been prescribed an antidepressant. SSRIs constituted the most commonly prescribed class (80%-82%), and citalopram was the most commonly prescribed SSRI (46%-47%). Mirtazapine was the most frequently prescribed non-SSRI antidepressant (44%-46%).

At 5 years, any antidepressant use was associated with an increased risk for diabetes, CHD, and all-cause mortality, but the findings were attenuated after further adjustment for confounders. In fact, SSRIs were associated with a reduced risk of diabetes at 5 years (hazard ratio, 0.64; 95% confidence interval, 0.49-0.83).

At 10 years, SSRIs were associated with an increased risk of cerebrovascular disease, CVD mortality, and all-cause mortality; non-SSRIs were associated with an increased risk of CHD, CVD, and all-cause mortality.

On the other hand, SSRIs were associated with a decrease in risk of diabetes and hypertension at 10 years (HR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.53-0.87; and HR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.66-0.89, respectively).

“While we have taken into account a wide range of pre-existing risk factors for cardiovascular disease, including those that are linked to depression such as excess weight, smoking, and low physical activity, it is difficult to fully control for the effects of depression in this kind of study, partly because there is considerable variability in the recording of depression severity in primary care,” said Dr. Bansal.

“This is important because many people taking antidepressants such as mirtazapine, venlafaxine, duloxetine and trazodone may have a more severe depression. This makes it difficult to fully separate the effects of the depression from the effects of medication,” she said.

Further research “is needed to assess whether the associations we have seen are genuinely due to the drugs; and, if so, why this might be,” she added.

Strengths, limitations

Commenting on the study, Roger McIntyre, MD, professor of psychiatry and pharmacology and head of the mood disorders psychopharmacology unit at the University of Toronto,, discussed the strengths and weaknesses of the study.

The UK Biobank is a “well-described, well-phenotyped dataset of good quality,” said Dr. McIntyre, chairperson and executive director of the Brain and Cognitive Discover Foundation, Toronto, who was not involved with the study. Another strength is the “impressive number of variables the database contains, which enabled the authors to go much deeper into the topics.”

A “significant limitation” is the confounding that is inherent to the disorder itself – “people with depression have a much higher intrinsic risk of CVD, [cerebrovascular disease], and cardiovascular mortality,” Dr. McIntyre noted.

The researchers did not adjust for trauma or childhood maltreatment, “which are the biggest risk factors for both depression and CVD; and drug and alcohol misuse were also not accounted for.”

Additionally, “to determine whether something is an association or potentially causative, it must satisfy the Bradford-Hill criteria,” said Dr. McIntyre. “Since we’re moving more toward using these big databases and because we depend on them to give us long-term perspectives, we would want to see coherent, compelling Bradford-Hill criteria regarding causation. If you don’t have any, that’s fine too, but then it’s important to make clear that there is no clear causative line, just an association.”

The research was funded by the National Institute of Health Research School for Primary Care Research and was supported by the NI Biomedical Research Centre at University Hospitals Bristol and Weston NHS Foundation Trust and the University of Bristol. Dr. McIntyre has received research grant support from CI/GACD/National Natural Science Foundation of China and the Milken Institute and speaker/consultation fees from numerous companies. Dr. McIntyre is a CEO of Braxia Scientific.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE BRITISH JOURNAL OF PSYCHIATRY OPEN

Critical Care Network

Palliative and End-of-Life Care Section

Time-limited trials of critical care

Many patients die in the ICU, often after long courses of aggressive interventions, with potentially nonbeneficial treatments. Surrogate decision makers are tasked with decisions to initiate or forgo treatments based on recommendations from clinicians in the face of prognostic uncertainty and emotional duress. A strategy that has been adopted by ICU clinicians to address this has been proposing a “time-limited trial” (TLT) of ICU-specific interventions. A TLT involves clinicians partnering with patients and their surrogate decision makers in a shared decision-making model, proposing initiation of treatments for a set time, evaluating for specific measures of what is considered beneficial, and deciding to continue treatment or stop if without benefit. with palliative care teams (Vink EE, et al. Intensive Care Med. 2018;44:1369). Recent research about TLT in the ICU has found that when executed well, TLTs can improve quality of care and provide patients with the care they desire and can benefit from (Vink, et al). Additionally, the use of an education intervention for ICU clinicians regarding protocolled TLT interventions was associated with improved quality of family meetings, and, importantly, a reduced intensity and duration of ICU treatments (Chang DW, et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181[6]:786).

Bradley Hayward, MD

Member-at-Large

Palliative and End-of-Life Care Section

Time-limited trials of critical care

Many patients die in the ICU, often after long courses of aggressive interventions, with potentially nonbeneficial treatments. Surrogate decision makers are tasked with decisions to initiate or forgo treatments based on recommendations from clinicians in the face of prognostic uncertainty and emotional duress. A strategy that has been adopted by ICU clinicians to address this has been proposing a “time-limited trial” (TLT) of ICU-specific interventions. A TLT involves clinicians partnering with patients and their surrogate decision makers in a shared decision-making model, proposing initiation of treatments for a set time, evaluating for specific measures of what is considered beneficial, and deciding to continue treatment or stop if without benefit. with palliative care teams (Vink EE, et al. Intensive Care Med. 2018;44:1369). Recent research about TLT in the ICU has found that when executed well, TLTs can improve quality of care and provide patients with the care they desire and can benefit from (Vink, et al). Additionally, the use of an education intervention for ICU clinicians regarding protocolled TLT interventions was associated with improved quality of family meetings, and, importantly, a reduced intensity and duration of ICU treatments (Chang DW, et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181[6]:786).

Bradley Hayward, MD

Member-at-Large

Palliative and End-of-Life Care Section

Time-limited trials of critical care

Many patients die in the ICU, often after long courses of aggressive interventions, with potentially nonbeneficial treatments. Surrogate decision makers are tasked with decisions to initiate or forgo treatments based on recommendations from clinicians in the face of prognostic uncertainty and emotional duress. A strategy that has been adopted by ICU clinicians to address this has been proposing a “time-limited trial” (TLT) of ICU-specific interventions. A TLT involves clinicians partnering with patients and their surrogate decision makers in a shared decision-making model, proposing initiation of treatments for a set time, evaluating for specific measures of what is considered beneficial, and deciding to continue treatment or stop if without benefit. with palliative care teams (Vink EE, et al. Intensive Care Med. 2018;44:1369). Recent research about TLT in the ICU has found that when executed well, TLTs can improve quality of care and provide patients with the care they desire and can benefit from (Vink, et al). Additionally, the use of an education intervention for ICU clinicians regarding protocolled TLT interventions was associated with improved quality of family meetings, and, importantly, a reduced intensity and duration of ICU treatments (Chang DW, et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181[6]:786).

Bradley Hayward, MD

Member-at-Large

Expert makes the case for not subtyping patients with rosacea

. At least they should be, according to Julie C. Harper, MD.

“How many people with papules and pustules don’t also have redness?” Dr. Harper, who practices in Birmingham, Ala., said at Medscape Live’s annual Coastal Dermatology Symposium. “If we’re not careful, and we try to classify a person into a subtype of rosacea, we end up treating only part of their rosacea; we don’t treat all of it. We have seen this in the literature,” she added.

“The idea now is to take a phenotypic approach to rosacea. What we mean by that is that you look at the patient, you document every part of rosacea that you see, and you treat according to that,” she continued. “That person with papules and pustules may also have phyma and ocular disease. They may have telangiectasia and persistent background erythema. They may also have flushing.”

Dr. Harper incorporates the mnemonic “STOP” to her visits with rosacea patients.

S stands for: Identify signs and symptoms of the condition. “Listen to the patient for symptoms,” she advised. “We’ve learned to listen to darker skinned patients for what they tell us about erythema, for example, because we may not be able to see it, yet they are experiencing it. They may also have symptomatic burning, itching, and stinging.”

T stands for: Discuss triggers. “Ask patients, ‘what is it that makes your rosacea worse?’ That’s different for everyone,” she said.

O stands for: Agree on a treatment outcome. “Ask, ‘what is it that really bothers you? Are you bothered by the bumps? The redness?’ ” she said.

“The P stands for: Develop a plan that addresses all of that,” she said.

Different treatments for different rosacea symptoms

No one-size-fits-all treatment exists for rosacea. Options that work well for papules and pustules aren’t effective for redness. Similarly, products that work for redness don’t work for telangiectasia.

“Different lesions and signs of rosacea will likely require multiple modes of treatment,” Dr. Harper said. “So, when you evaluate your rosacea patients, if they’re doing great, don’t change their regimen. But if you see somebody who is not well controlled, is there an opportunity for you to come in and add something to that regimen that may make them better? Maybe so.”

Treatment options indicated for papules and pustules include ivermectin, metronidazole, azelaic acid, sodium sulfacetamide/sulfur, modified release doxycycline, minocycline foam, and encapsulated benzoyl peroxide.

Options indicated for persistent background erythema include brimonidine and oxymetazoline, while device-based treatments include the pulsed dye laser, the KTP laser, intense pulsed light, and electrosurgery.

Anti-inflammatory action for pustules and papules

A relatively new product indicated for pustules and papules is minocycline 1.5% foam, the only minocycline that is FDA approved to treat rosacea.

“There is no oral minocycline product approved for rosacea yet,” Dr. Harper said. “There is not a known bacterial pathogen in rosacea. Tetracyclines likely work in rosacea by inhibiting neutrophil chemotaxis, inhibiting MMP and thus KLK-5 and LL-37, inhibiting pro-inflammatory cytokines, downregulating reactive oxygen species, and inhibiting angiogenesis.”

In two 12-week, phase 3 randomized studies of 1,522 patients with moderate to severe rosacea, participants were assigned to receive minocycline 5% foam or a vehicle that contained mineral oil and coconut oil.

At week 12, about 50% of patients who received minocycline 5% foam were clear, compared with about 40% of those in the vehicle arm. Also, the reduction of lesion count was about 63% for patients in the treatment group, compared with a reduction of about 54% in the vehicle arm.

Dr. Harper characterized the 63% reduction as “pretty good, but is it good enough or fast enough? I don’t think so, so even with a great drug like this, I would use something else. You can use two medications sometimes to get people better faster. There’s room to bring in something for that background erythema.”

Minocycline 1.5% foam is colored yellow and may stain fabric. “It contains coconut oil, soybean oil, and light mineral oil,” she said. “Most people prefer to use this at bedtime, but you don’t have to.”

Another treatment option is 5% microencapsulated benzoyl peroxide cream, which is FDA approved for inflammatory lesions of rosacea.

“What’s the mechanism of action? Probably not being antimicrobial,” Dr. Harper said. “I think it’s probably at least in part anti-inflammatory, because we have some data to show that it’s killing Demodex [mites]. If Demodex [are] a trigger of inflammation, and we can lessen Demodex, then we could lessen the inflammatory response after that.”

The drug’s approval was based on data from two positive, identical phase 3 randomized, double-blind, multicenter, 12-week clinical trials that evaluated its safety compared with vehicle in 733 people with inflammatory lesions of rosacea (NCT03564119 and NCT03448939).

At week 12, inflammatory lesions of rosacea were reduced by nearly 70% in both trials among those who received 5% microencapsulated benzoyl peroxide cream, compared with 38%-46% among those who received the vehicle. Also, nearly 50% of subjects in the treatment groups were clear or almost clear at 12 weeks, compared with 38%-46% of those who received the vehicle.

Dr. Harper added that about one-quarter of patients in the treatment group of the trials were clear or almost clear by week 4. “That’s pretty fast,” she said, noting that the product’s microencapsulated shell acts as a fenestrated barrier. “It has little openings, which means that it takes a while for the drug to work itself out,” she said. “I think of it as being like a speed bump for benzoyl peroxide delivery. It has to get through this little maze before it lands on the skin. We think that is what has helped with tolerability.”

Oral sarecycline, a narrow spectrum tetracycline that was FDA approved for acne in 2018, may also benefit rosacea patients. In a 12-week, investigator-blinded pilot study, 72 patients with papulopustular rosacea were assigned to receive sarecycline, while 25 received a multivitamin.

By week 12, 75% of patients in the sarecycline group were clear, compared with 16% of those in the multivitamin group, while the inflammatory lesion counts dropped from baseline by 80% and 60%, respectively. Studies of sarecycline for acne have demonstrated similar rates of vertigo, dizziness, and sunburn to those of placebo.

“There were also low rates of gastrointestinal disturbances,” Dr. Harper said. “That’s important in rosacea, because there is no bacterial pathogen.”

Dr. Harper disclosed that she serves as an advisor or consultant for Almirall, BioPharmX, Cassiopeia, Cutanea, Cutera, Dermira, EPI, Galderma, LaRoche-Posay, Ortho, Vyne, Sol Gel, and Sun. She also serves as a speaker or member of a speakers bureau for Almirall, EPI, Galderma, Ortho, and Vyne.

Medscape Live and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

. At least they should be, according to Julie C. Harper, MD.

“How many people with papules and pustules don’t also have redness?” Dr. Harper, who practices in Birmingham, Ala., said at Medscape Live’s annual Coastal Dermatology Symposium. “If we’re not careful, and we try to classify a person into a subtype of rosacea, we end up treating only part of their rosacea; we don’t treat all of it. We have seen this in the literature,” she added.

“The idea now is to take a phenotypic approach to rosacea. What we mean by that is that you look at the patient, you document every part of rosacea that you see, and you treat according to that,” she continued. “That person with papules and pustules may also have phyma and ocular disease. They may have telangiectasia and persistent background erythema. They may also have flushing.”

Dr. Harper incorporates the mnemonic “STOP” to her visits with rosacea patients.

S stands for: Identify signs and symptoms of the condition. “Listen to the patient for symptoms,” she advised. “We’ve learned to listen to darker skinned patients for what they tell us about erythema, for example, because we may not be able to see it, yet they are experiencing it. They may also have symptomatic burning, itching, and stinging.”

T stands for: Discuss triggers. “Ask patients, ‘what is it that makes your rosacea worse?’ That’s different for everyone,” she said.

O stands for: Agree on a treatment outcome. “Ask, ‘what is it that really bothers you? Are you bothered by the bumps? The redness?’ ” she said.

“The P stands for: Develop a plan that addresses all of that,” she said.

Different treatments for different rosacea symptoms

No one-size-fits-all treatment exists for rosacea. Options that work well for papules and pustules aren’t effective for redness. Similarly, products that work for redness don’t work for telangiectasia.

“Different lesions and signs of rosacea will likely require multiple modes of treatment,” Dr. Harper said. “So, when you evaluate your rosacea patients, if they’re doing great, don’t change their regimen. But if you see somebody who is not well controlled, is there an opportunity for you to come in and add something to that regimen that may make them better? Maybe so.”

Treatment options indicated for papules and pustules include ivermectin, metronidazole, azelaic acid, sodium sulfacetamide/sulfur, modified release doxycycline, minocycline foam, and encapsulated benzoyl peroxide.

Options indicated for persistent background erythema include brimonidine and oxymetazoline, while device-based treatments include the pulsed dye laser, the KTP laser, intense pulsed light, and electrosurgery.

Anti-inflammatory action for pustules and papules

A relatively new product indicated for pustules and papules is minocycline 1.5% foam, the only minocycline that is FDA approved to treat rosacea.

“There is no oral minocycline product approved for rosacea yet,” Dr. Harper said. “There is not a known bacterial pathogen in rosacea. Tetracyclines likely work in rosacea by inhibiting neutrophil chemotaxis, inhibiting MMP and thus KLK-5 and LL-37, inhibiting pro-inflammatory cytokines, downregulating reactive oxygen species, and inhibiting angiogenesis.”

In two 12-week, phase 3 randomized studies of 1,522 patients with moderate to severe rosacea, participants were assigned to receive minocycline 5% foam or a vehicle that contained mineral oil and coconut oil.

At week 12, about 50% of patients who received minocycline 5% foam were clear, compared with about 40% of those in the vehicle arm. Also, the reduction of lesion count was about 63% for patients in the treatment group, compared with a reduction of about 54% in the vehicle arm.

Dr. Harper characterized the 63% reduction as “pretty good, but is it good enough or fast enough? I don’t think so, so even with a great drug like this, I would use something else. You can use two medications sometimes to get people better faster. There’s room to bring in something for that background erythema.”

Minocycline 1.5% foam is colored yellow and may stain fabric. “It contains coconut oil, soybean oil, and light mineral oil,” she said. “Most people prefer to use this at bedtime, but you don’t have to.”

Another treatment option is 5% microencapsulated benzoyl peroxide cream, which is FDA approved for inflammatory lesions of rosacea.

“What’s the mechanism of action? Probably not being antimicrobial,” Dr. Harper said. “I think it’s probably at least in part anti-inflammatory, because we have some data to show that it’s killing Demodex [mites]. If Demodex [are] a trigger of inflammation, and we can lessen Demodex, then we could lessen the inflammatory response after that.”

The drug’s approval was based on data from two positive, identical phase 3 randomized, double-blind, multicenter, 12-week clinical trials that evaluated its safety compared with vehicle in 733 people with inflammatory lesions of rosacea (NCT03564119 and NCT03448939).

At week 12, inflammatory lesions of rosacea were reduced by nearly 70% in both trials among those who received 5% microencapsulated benzoyl peroxide cream, compared with 38%-46% among those who received the vehicle. Also, nearly 50% of subjects in the treatment groups were clear or almost clear at 12 weeks, compared with 38%-46% of those who received the vehicle.

Dr. Harper added that about one-quarter of patients in the treatment group of the trials were clear or almost clear by week 4. “That’s pretty fast,” she said, noting that the product’s microencapsulated shell acts as a fenestrated barrier. “It has little openings, which means that it takes a while for the drug to work itself out,” she said. “I think of it as being like a speed bump for benzoyl peroxide delivery. It has to get through this little maze before it lands on the skin. We think that is what has helped with tolerability.”

Oral sarecycline, a narrow spectrum tetracycline that was FDA approved for acne in 2018, may also benefit rosacea patients. In a 12-week, investigator-blinded pilot study, 72 patients with papulopustular rosacea were assigned to receive sarecycline, while 25 received a multivitamin.

By week 12, 75% of patients in the sarecycline group were clear, compared with 16% of those in the multivitamin group, while the inflammatory lesion counts dropped from baseline by 80% and 60%, respectively. Studies of sarecycline for acne have demonstrated similar rates of vertigo, dizziness, and sunburn to those of placebo.

“There were also low rates of gastrointestinal disturbances,” Dr. Harper said. “That’s important in rosacea, because there is no bacterial pathogen.”

Dr. Harper disclosed that she serves as an advisor or consultant for Almirall, BioPharmX, Cassiopeia, Cutanea, Cutera, Dermira, EPI, Galderma, LaRoche-Posay, Ortho, Vyne, Sol Gel, and Sun. She also serves as a speaker or member of a speakers bureau for Almirall, EPI, Galderma, Ortho, and Vyne.

Medscape Live and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

. At least they should be, according to Julie C. Harper, MD.

“How many people with papules and pustules don’t also have redness?” Dr. Harper, who practices in Birmingham, Ala., said at Medscape Live’s annual Coastal Dermatology Symposium. “If we’re not careful, and we try to classify a person into a subtype of rosacea, we end up treating only part of their rosacea; we don’t treat all of it. We have seen this in the literature,” she added.

“The idea now is to take a phenotypic approach to rosacea. What we mean by that is that you look at the patient, you document every part of rosacea that you see, and you treat according to that,” she continued. “That person with papules and pustules may also have phyma and ocular disease. They may have telangiectasia and persistent background erythema. They may also have flushing.”

Dr. Harper incorporates the mnemonic “STOP” to her visits with rosacea patients.

S stands for: Identify signs and symptoms of the condition. “Listen to the patient for symptoms,” she advised. “We’ve learned to listen to darker skinned patients for what they tell us about erythema, for example, because we may not be able to see it, yet they are experiencing it. They may also have symptomatic burning, itching, and stinging.”

T stands for: Discuss triggers. “Ask patients, ‘what is it that makes your rosacea worse?’ That’s different for everyone,” she said.

O stands for: Agree on a treatment outcome. “Ask, ‘what is it that really bothers you? Are you bothered by the bumps? The redness?’ ” she said.

“The P stands for: Develop a plan that addresses all of that,” she said.

Different treatments for different rosacea symptoms

No one-size-fits-all treatment exists for rosacea. Options that work well for papules and pustules aren’t effective for redness. Similarly, products that work for redness don’t work for telangiectasia.

“Different lesions and signs of rosacea will likely require multiple modes of treatment,” Dr. Harper said. “So, when you evaluate your rosacea patients, if they’re doing great, don’t change their regimen. But if you see somebody who is not well controlled, is there an opportunity for you to come in and add something to that regimen that may make them better? Maybe so.”

Treatment options indicated for papules and pustules include ivermectin, metronidazole, azelaic acid, sodium sulfacetamide/sulfur, modified release doxycycline, minocycline foam, and encapsulated benzoyl peroxide.

Options indicated for persistent background erythema include brimonidine and oxymetazoline, while device-based treatments include the pulsed dye laser, the KTP laser, intense pulsed light, and electrosurgery.

Anti-inflammatory action for pustules and papules

A relatively new product indicated for pustules and papules is minocycline 1.5% foam, the only minocycline that is FDA approved to treat rosacea.

“There is no oral minocycline product approved for rosacea yet,” Dr. Harper said. “There is not a known bacterial pathogen in rosacea. Tetracyclines likely work in rosacea by inhibiting neutrophil chemotaxis, inhibiting MMP and thus KLK-5 and LL-37, inhibiting pro-inflammatory cytokines, downregulating reactive oxygen species, and inhibiting angiogenesis.”

In two 12-week, phase 3 randomized studies of 1,522 patients with moderate to severe rosacea, participants were assigned to receive minocycline 5% foam or a vehicle that contained mineral oil and coconut oil.

At week 12, about 50% of patients who received minocycline 5% foam were clear, compared with about 40% of those in the vehicle arm. Also, the reduction of lesion count was about 63% for patients in the treatment group, compared with a reduction of about 54% in the vehicle arm.

Dr. Harper characterized the 63% reduction as “pretty good, but is it good enough or fast enough? I don’t think so, so even with a great drug like this, I would use something else. You can use two medications sometimes to get people better faster. There’s room to bring in something for that background erythema.”

Minocycline 1.5% foam is colored yellow and may stain fabric. “It contains coconut oil, soybean oil, and light mineral oil,” she said. “Most people prefer to use this at bedtime, but you don’t have to.”

Another treatment option is 5% microencapsulated benzoyl peroxide cream, which is FDA approved for inflammatory lesions of rosacea.

“What’s the mechanism of action? Probably not being antimicrobial,” Dr. Harper said. “I think it’s probably at least in part anti-inflammatory, because we have some data to show that it’s killing Demodex [mites]. If Demodex [are] a trigger of inflammation, and we can lessen Demodex, then we could lessen the inflammatory response after that.”

The drug’s approval was based on data from two positive, identical phase 3 randomized, double-blind, multicenter, 12-week clinical trials that evaluated its safety compared with vehicle in 733 people with inflammatory lesions of rosacea (NCT03564119 and NCT03448939).

At week 12, inflammatory lesions of rosacea were reduced by nearly 70% in both trials among those who received 5% microencapsulated benzoyl peroxide cream, compared with 38%-46% among those who received the vehicle. Also, nearly 50% of subjects in the treatment groups were clear or almost clear at 12 weeks, compared with 38%-46% of those who received the vehicle.

Dr. Harper added that about one-quarter of patients in the treatment group of the trials were clear or almost clear by week 4. “That’s pretty fast,” she said, noting that the product’s microencapsulated shell acts as a fenestrated barrier. “It has little openings, which means that it takes a while for the drug to work itself out,” she said. “I think of it as being like a speed bump for benzoyl peroxide delivery. It has to get through this little maze before it lands on the skin. We think that is what has helped with tolerability.”

Oral sarecycline, a narrow spectrum tetracycline that was FDA approved for acne in 2018, may also benefit rosacea patients. In a 12-week, investigator-blinded pilot study, 72 patients with papulopustular rosacea were assigned to receive sarecycline, while 25 received a multivitamin.

By week 12, 75% of patients in the sarecycline group were clear, compared with 16% of those in the multivitamin group, while the inflammatory lesion counts dropped from baseline by 80% and 60%, respectively. Studies of sarecycline for acne have demonstrated similar rates of vertigo, dizziness, and sunburn to those of placebo.

“There were also low rates of gastrointestinal disturbances,” Dr. Harper said. “That’s important in rosacea, because there is no bacterial pathogen.”

Dr. Harper disclosed that she serves as an advisor or consultant for Almirall, BioPharmX, Cassiopeia, Cutanea, Cutera, Dermira, EPI, Galderma, LaRoche-Posay, Ortho, Vyne, Sol Gel, and Sun. She also serves as a speaker or member of a speakers bureau for Almirall, EPI, Galderma, Ortho, and Vyne.

Medscape Live and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

FROM MEDSCAPE LIVE COASTAL DERM

Advances in Insulin Therapy for Type 2 Diabetes From EASD 2022

Dr Anne Peters, of the Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California, reports on the latest research on insulin therapy in adults with type 2 diabetes, presented at the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD).

Dr Peters highlights a clinical study evaluating whether bedtime is optimal for the administration of neutral protamine Hagedorn (NPH) insulin, also known as isophane insulin. The results indicate that titration of NPH plays an important role in avoiding nocturnal hypoglycemia.

Next, Dr Peters discusses the ONWARDS 2 study, a phase 3a trial looking at once-weekly insulin icodec vs once-daily insulin degludec in basal insulin–treated type 2 diabetes. The trial found insulin icodec to be superior to insulin degludec in reducing A1c.

Dr Peters also examines the SoliMix trial, which compared iGlarLixi once daily to twice-daily premix BIAsp 30 in suboptimally controlled type 2 diabetes. The trial evaluated whether patients currently on a basal-bolus regimen would have an equal or more effective response to once-a-day combination therapy. Results showed that iGlarLixi provided better glycemic control and weight benefit than the twice-daily BlAsp 30.

Finally, Dr Peters evaluates a study that looked at switching from a basal-bolus insulin treatment to insulin degludec + liraglutide combination. The combination proved at least as effective as the basal-bolus approach.

--

Anne L. Peters, MD, Professor, Department of Clinical Medicine, Clinical Scholar, Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California; Director, USC Clinical Diabetes Programs, University of Southern California Westside Center for Diabetes, Los Angeles, California

Anne L. Peters, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or a trustee for: AstraZeneca; Lilly; NovoNordisk; Abbott; Vertex; Zealand; ShouTi

Received research grant from: Insulet; Dexcom; Abbott

Received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from: AstraZeneca; Lilly; NovoNordisk; Abbott; Vertex; Zealand; ShouTi; Insulet; Dexcom

Stock options from: Teladoc; Omada Health (not even close to 5% equity)

Dr Anne Peters, of the Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California, reports on the latest research on insulin therapy in adults with type 2 diabetes, presented at the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD).

Dr Peters highlights a clinical study evaluating whether bedtime is optimal for the administration of neutral protamine Hagedorn (NPH) insulin, also known as isophane insulin. The results indicate that titration of NPH plays an important role in avoiding nocturnal hypoglycemia.

Next, Dr Peters discusses the ONWARDS 2 study, a phase 3a trial looking at once-weekly insulin icodec vs once-daily insulin degludec in basal insulin–treated type 2 diabetes. The trial found insulin icodec to be superior to insulin degludec in reducing A1c.

Dr Peters also examines the SoliMix trial, which compared iGlarLixi once daily to twice-daily premix BIAsp 30 in suboptimally controlled type 2 diabetes. The trial evaluated whether patients currently on a basal-bolus regimen would have an equal or more effective response to once-a-day combination therapy. Results showed that iGlarLixi provided better glycemic control and weight benefit than the twice-daily BlAsp 30.

Finally, Dr Peters evaluates a study that looked at switching from a basal-bolus insulin treatment to insulin degludec + liraglutide combination. The combination proved at least as effective as the basal-bolus approach.

--

Anne L. Peters, MD, Professor, Department of Clinical Medicine, Clinical Scholar, Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California; Director, USC Clinical Diabetes Programs, University of Southern California Westside Center for Diabetes, Los Angeles, California

Anne L. Peters, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or a trustee for: AstraZeneca; Lilly; NovoNordisk; Abbott; Vertex; Zealand; ShouTi

Received research grant from: Insulet; Dexcom; Abbott

Received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from: AstraZeneca; Lilly; NovoNordisk; Abbott; Vertex; Zealand; ShouTi; Insulet; Dexcom

Stock options from: Teladoc; Omada Health (not even close to 5% equity)

Dr Anne Peters, of the Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California, reports on the latest research on insulin therapy in adults with type 2 diabetes, presented at the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD).

Dr Peters highlights a clinical study evaluating whether bedtime is optimal for the administration of neutral protamine Hagedorn (NPH) insulin, also known as isophane insulin. The results indicate that titration of NPH plays an important role in avoiding nocturnal hypoglycemia.

Next, Dr Peters discusses the ONWARDS 2 study, a phase 3a trial looking at once-weekly insulin icodec vs once-daily insulin degludec in basal insulin–treated type 2 diabetes. The trial found insulin icodec to be superior to insulin degludec in reducing A1c.

Dr Peters also examines the SoliMix trial, which compared iGlarLixi once daily to twice-daily premix BIAsp 30 in suboptimally controlled type 2 diabetes. The trial evaluated whether patients currently on a basal-bolus regimen would have an equal or more effective response to once-a-day combination therapy. Results showed that iGlarLixi provided better glycemic control and weight benefit than the twice-daily BlAsp 30.

Finally, Dr Peters evaluates a study that looked at switching from a basal-bolus insulin treatment to insulin degludec + liraglutide combination. The combination proved at least as effective as the basal-bolus approach.

--

Anne L. Peters, MD, Professor, Department of Clinical Medicine, Clinical Scholar, Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California; Director, USC Clinical Diabetes Programs, University of Southern California Westside Center for Diabetes, Los Angeles, California

Anne L. Peters, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or a trustee for: AstraZeneca; Lilly; NovoNordisk; Abbott; Vertex; Zealand; ShouTi

Received research grant from: Insulet; Dexcom; Abbott

Received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from: AstraZeneca; Lilly; NovoNordisk; Abbott; Vertex; Zealand; ShouTi; Insulet; Dexcom

Stock options from: Teladoc; Omada Health (not even close to 5% equity)

PCCM diversity grant recipient looks to inhibit platelet endothelial interactions via NEDD9 to improve acute lung injury

In February, The American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST), the American Thoracic Society, and the American Lung Association announced a partnership with the prestigious Harold Amos Medical Faculty Development Program (AMFDP), a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation initiative, to sponsor a scholar in pulmonary and critical care medicine.

George Alba, MD, is a pulmonary and critical care physician investigator at Massachusetts General Hospital. Dr. Alba studied English Literature and Biology as an undergraduate at Washington University in St. Louis, where he worked in a developmental biology laboratory; earned his MD at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine, where he graduated AOA with Distinction in Medical Education; and then completed both Internal Medicine and Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine training at Massachusetts General Hospital.

During his fellowship, Dr. Alba specialized in pulmonary and critical care medicine because he appreciated the variety that comes with working in the intensive care unit.

“I love the medical complexity, the physiology, and the decision-making,” said Dr. Alba. “I’ve always enjoyed all aspects of clinical medicine, so it was hard to choose a path, but the benefit of the ICU is that it allows me to take care of a spectrum of medical illness across all subspecialties.”

He continued, “What I loved about pulmonary, specifically, was that I could see patients in the hospital and in the ICU, perform procedures, and still have a longitudinal relationship with patients in the clinic, which gave me a very flexible, wide grasp of medicine.”

Growing up in a close-knit Cuban family and community, Dr. Alba was raised speaking Spanish at home and learned English primarily in school. Being bilingual helped him in medicine greatly: in clinic, in the hospital, and in the ICU, he is able to communicate directly with Spanish-speaking patients and their families. This became critically important during the COVID-19 pandemic when Chelsea, a primarily Hispanic community in Boston, was disproportionately impacted. The patients greatly benefited from Spanish-speaking clinicians to communicate with their family members who were unable to visit due to the infection control policies in place.

As an instructor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and pulmonary and critical care physician at Massachusetts General, Dr. Alba is actively engaged in clinical care, teaching, and research focusing primarily on mechanisms of pulmonary vascular dysfunction in lung disease.

Dr. Alba’s AMFDP award project is titled “Pulmonary Endothelial NEDD9 and Acute Lung Injury,” and through the proposed scientific aims, he looks to advance NEDD9 antagonism as a potential therapeutic target in acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS.) He is being co-mentored by Bradley Maron, MD, a pulmonary vascular disease researcher at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and Eric Schmidt, MD, an endothelial biologist and expert in animal models of acute lung injury at Massachusetts General Hospital.

This is especially relevant research during the COVID-19 pandemic, as patients with severe lung injury frequently develop clotting in the lung blood vessels. Dr. Alba’s prior work demonstrated that NEDD9 is a pulmonary endothelial protein that is upregulated by hypoxia, that it binds to activated platelets to promote platelet adhesion and clotting, and that inhibition of NEDD9-platelet interactions with a custom antibody can decrease clotting in the lungs of animals. He recently showed that pulmonary endothelial NEDD9 is increased in patients with ARDS who demonstrate blood vessel clotting.

Now, Dr. Alba seeks to use a custom-made anti-NEDD9 antibody to block platelet adhesion in animal models of ARDS to decrease the extent of lung injury. While aspirin and anticoagulants have been unhelpful in treating ARDS in prior trials, Dr. Alba believes that circulating pulmonary endothelial protein NEDD9 can serve as a biomarker to identify subgroups of ARDS who may benefit from earlier targeted antithrombotic therapy.

Dr. Alba hopes that one day the anti-NEDD9 antibody may become one such therapeutic option for patients. The AMFDP will help support his ongoing work.

“Growing up, I saw through my father’s example how education unlocks opportunities. Our community came together to help him on this path. Now a retired doctor of osteopathy in neonatology, he inspired me to pursue a career in medicine,” said Dr. Alba. “This award comes at a critical time in my junior faculty career: It allows me to continue pursuing my research in a meaningful way while also gaining new skills that will be critical for my ongoing career development.”

Dr. Alba continued, “Programs like the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation initiative that specifically try to increase the number of individuals traditionally underrepresented in academia are key and would not be possible without the support of groups like CHEST, the American Lung Association, and the American Thoracic Society.

These programs help folks who may have other external barriers to being in academia, including socioeconomic pressures, lack of resources

Dr. Alba is also committed to paying it forward: “I want to ensure that the type of invested mentorship I experienced to help get me this far is not a matter of serendipity for the fortunate few, but rather a standard for all students and trainees, especially those from underrepresented backgrounds.”

In February, The American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST), the American Thoracic Society, and the American Lung Association announced a partnership with the prestigious Harold Amos Medical Faculty Development Program (AMFDP), a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation initiative, to sponsor a scholar in pulmonary and critical care medicine.

George Alba, MD, is a pulmonary and critical care physician investigator at Massachusetts General Hospital. Dr. Alba studied English Literature and Biology as an undergraduate at Washington University in St. Louis, where he worked in a developmental biology laboratory; earned his MD at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine, where he graduated AOA with Distinction in Medical Education; and then completed both Internal Medicine and Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine training at Massachusetts General Hospital.

During his fellowship, Dr. Alba specialized in pulmonary and critical care medicine because he appreciated the variety that comes with working in the intensive care unit.

“I love the medical complexity, the physiology, and the decision-making,” said Dr. Alba. “I’ve always enjoyed all aspects of clinical medicine, so it was hard to choose a path, but the benefit of the ICU is that it allows me to take care of a spectrum of medical illness across all subspecialties.”

He continued, “What I loved about pulmonary, specifically, was that I could see patients in the hospital and in the ICU, perform procedures, and still have a longitudinal relationship with patients in the clinic, which gave me a very flexible, wide grasp of medicine.”

Growing up in a close-knit Cuban family and community, Dr. Alba was raised speaking Spanish at home and learned English primarily in school. Being bilingual helped him in medicine greatly: in clinic, in the hospital, and in the ICU, he is able to communicate directly with Spanish-speaking patients and their families. This became critically important during the COVID-19 pandemic when Chelsea, a primarily Hispanic community in Boston, was disproportionately impacted. The patients greatly benefited from Spanish-speaking clinicians to communicate with their family members who were unable to visit due to the infection control policies in place.

As an instructor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and pulmonary and critical care physician at Massachusetts General, Dr. Alba is actively engaged in clinical care, teaching, and research focusing primarily on mechanisms of pulmonary vascular dysfunction in lung disease.

Dr. Alba’s AMFDP award project is titled “Pulmonary Endothelial NEDD9 and Acute Lung Injury,” and through the proposed scientific aims, he looks to advance NEDD9 antagonism as a potential therapeutic target in acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS.) He is being co-mentored by Bradley Maron, MD, a pulmonary vascular disease researcher at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and Eric Schmidt, MD, an endothelial biologist and expert in animal models of acute lung injury at Massachusetts General Hospital.

This is especially relevant research during the COVID-19 pandemic, as patients with severe lung injury frequently develop clotting in the lung blood vessels. Dr. Alba’s prior work demonstrated that NEDD9 is a pulmonary endothelial protein that is upregulated by hypoxia, that it binds to activated platelets to promote platelet adhesion and clotting, and that inhibition of NEDD9-platelet interactions with a custom antibody can decrease clotting in the lungs of animals. He recently showed that pulmonary endothelial NEDD9 is increased in patients with ARDS who demonstrate blood vessel clotting.

Now, Dr. Alba seeks to use a custom-made anti-NEDD9 antibody to block platelet adhesion in animal models of ARDS to decrease the extent of lung injury. While aspirin and anticoagulants have been unhelpful in treating ARDS in prior trials, Dr. Alba believes that circulating pulmonary endothelial protein NEDD9 can serve as a biomarker to identify subgroups of ARDS who may benefit from earlier targeted antithrombotic therapy.

Dr. Alba hopes that one day the anti-NEDD9 antibody may become one such therapeutic option for patients. The AMFDP will help support his ongoing work.

“Growing up, I saw through my father’s example how education unlocks opportunities. Our community came together to help him on this path. Now a retired doctor of osteopathy in neonatology, he inspired me to pursue a career in medicine,” said Dr. Alba. “This award comes at a critical time in my junior faculty career: It allows me to continue pursuing my research in a meaningful way while also gaining new skills that will be critical for my ongoing career development.”

Dr. Alba continued, “Programs like the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation initiative that specifically try to increase the number of individuals traditionally underrepresented in academia are key and would not be possible without the support of groups like CHEST, the American Lung Association, and the American Thoracic Society.

These programs help folks who may have other external barriers to being in academia, including socioeconomic pressures, lack of resources

Dr. Alba is also committed to paying it forward: “I want to ensure that the type of invested mentorship I experienced to help get me this far is not a matter of serendipity for the fortunate few, but rather a standard for all students and trainees, especially those from underrepresented backgrounds.”

In February, The American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST), the American Thoracic Society, and the American Lung Association announced a partnership with the prestigious Harold Amos Medical Faculty Development Program (AMFDP), a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation initiative, to sponsor a scholar in pulmonary and critical care medicine.

George Alba, MD, is a pulmonary and critical care physician investigator at Massachusetts General Hospital. Dr. Alba studied English Literature and Biology as an undergraduate at Washington University in St. Louis, where he worked in a developmental biology laboratory; earned his MD at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine, where he graduated AOA with Distinction in Medical Education; and then completed both Internal Medicine and Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine training at Massachusetts General Hospital.

During his fellowship, Dr. Alba specialized in pulmonary and critical care medicine because he appreciated the variety that comes with working in the intensive care unit.

“I love the medical complexity, the physiology, and the decision-making,” said Dr. Alba. “I’ve always enjoyed all aspects of clinical medicine, so it was hard to choose a path, but the benefit of the ICU is that it allows me to take care of a spectrum of medical illness across all subspecialties.”

He continued, “What I loved about pulmonary, specifically, was that I could see patients in the hospital and in the ICU, perform procedures, and still have a longitudinal relationship with patients in the clinic, which gave me a very flexible, wide grasp of medicine.”

Growing up in a close-knit Cuban family and community, Dr. Alba was raised speaking Spanish at home and learned English primarily in school. Being bilingual helped him in medicine greatly: in clinic, in the hospital, and in the ICU, he is able to communicate directly with Spanish-speaking patients and their families. This became critically important during the COVID-19 pandemic when Chelsea, a primarily Hispanic community in Boston, was disproportionately impacted. The patients greatly benefited from Spanish-speaking clinicians to communicate with their family members who were unable to visit due to the infection control policies in place.

As an instructor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and pulmonary and critical care physician at Massachusetts General, Dr. Alba is actively engaged in clinical care, teaching, and research focusing primarily on mechanisms of pulmonary vascular dysfunction in lung disease.

Dr. Alba’s AMFDP award project is titled “Pulmonary Endothelial NEDD9 and Acute Lung Injury,” and through the proposed scientific aims, he looks to advance NEDD9 antagonism as a potential therapeutic target in acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS.) He is being co-mentored by Bradley Maron, MD, a pulmonary vascular disease researcher at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and Eric Schmidt, MD, an endothelial biologist and expert in animal models of acute lung injury at Massachusetts General Hospital.

This is especially relevant research during the COVID-19 pandemic, as patients with severe lung injury frequently develop clotting in the lung blood vessels. Dr. Alba’s prior work demonstrated that NEDD9 is a pulmonary endothelial protein that is upregulated by hypoxia, that it binds to activated platelets to promote platelet adhesion and clotting, and that inhibition of NEDD9-platelet interactions with a custom antibody can decrease clotting in the lungs of animals. He recently showed that pulmonary endothelial NEDD9 is increased in patients with ARDS who demonstrate blood vessel clotting.

Now, Dr. Alba seeks to use a custom-made anti-NEDD9 antibody to block platelet adhesion in animal models of ARDS to decrease the extent of lung injury. While aspirin and anticoagulants have been unhelpful in treating ARDS in prior trials, Dr. Alba believes that circulating pulmonary endothelial protein NEDD9 can serve as a biomarker to identify subgroups of ARDS who may benefit from earlier targeted antithrombotic therapy.

Dr. Alba hopes that one day the anti-NEDD9 antibody may become one such therapeutic option for patients. The AMFDP will help support his ongoing work.

“Growing up, I saw through my father’s example how education unlocks opportunities. Our community came together to help him on this path. Now a retired doctor of osteopathy in neonatology, he inspired me to pursue a career in medicine,” said Dr. Alba. “This award comes at a critical time in my junior faculty career: It allows me to continue pursuing my research in a meaningful way while also gaining new skills that will be critical for my ongoing career development.”

Dr. Alba continued, “Programs like the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation initiative that specifically try to increase the number of individuals traditionally underrepresented in academia are key and would not be possible without the support of groups like CHEST, the American Lung Association, and the American Thoracic Society.

These programs help folks who may have other external barriers to being in academia, including socioeconomic pressures, lack of resources

Dr. Alba is also committed to paying it forward: “I want to ensure that the type of invested mentorship I experienced to help get me this far is not a matter of serendipity for the fortunate few, but rather a standard for all students and trainees, especially those from underrepresented backgrounds.”

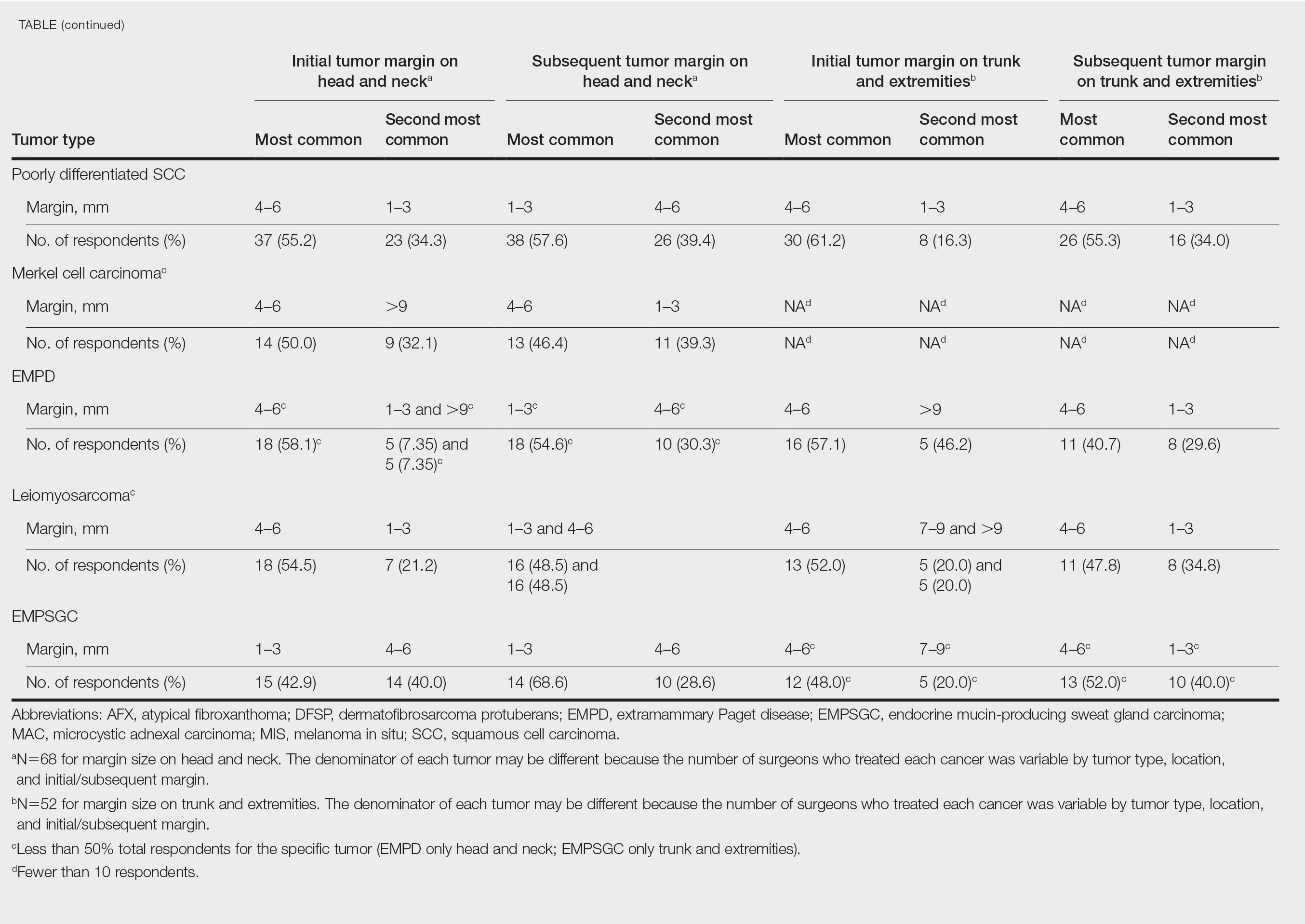

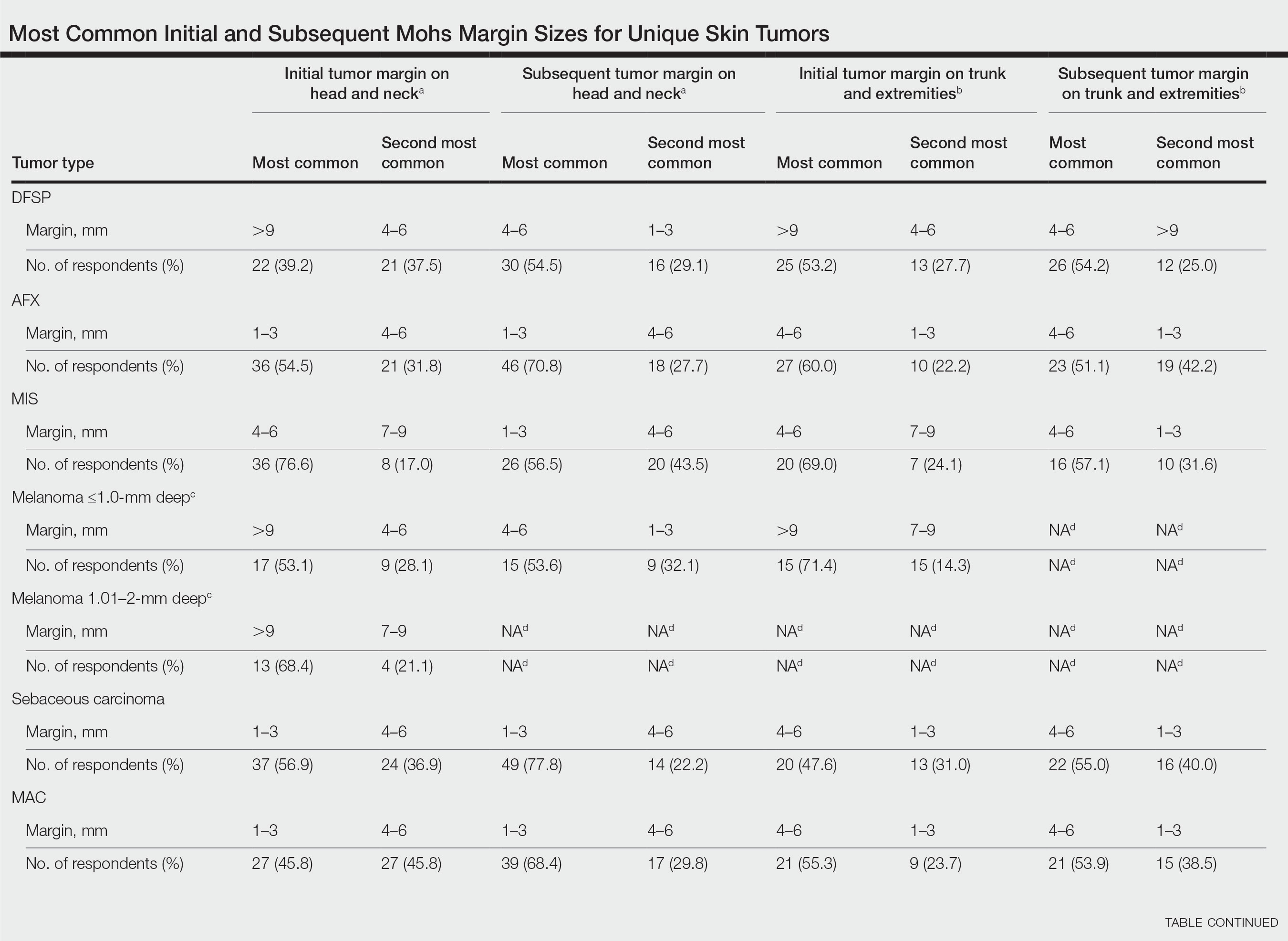

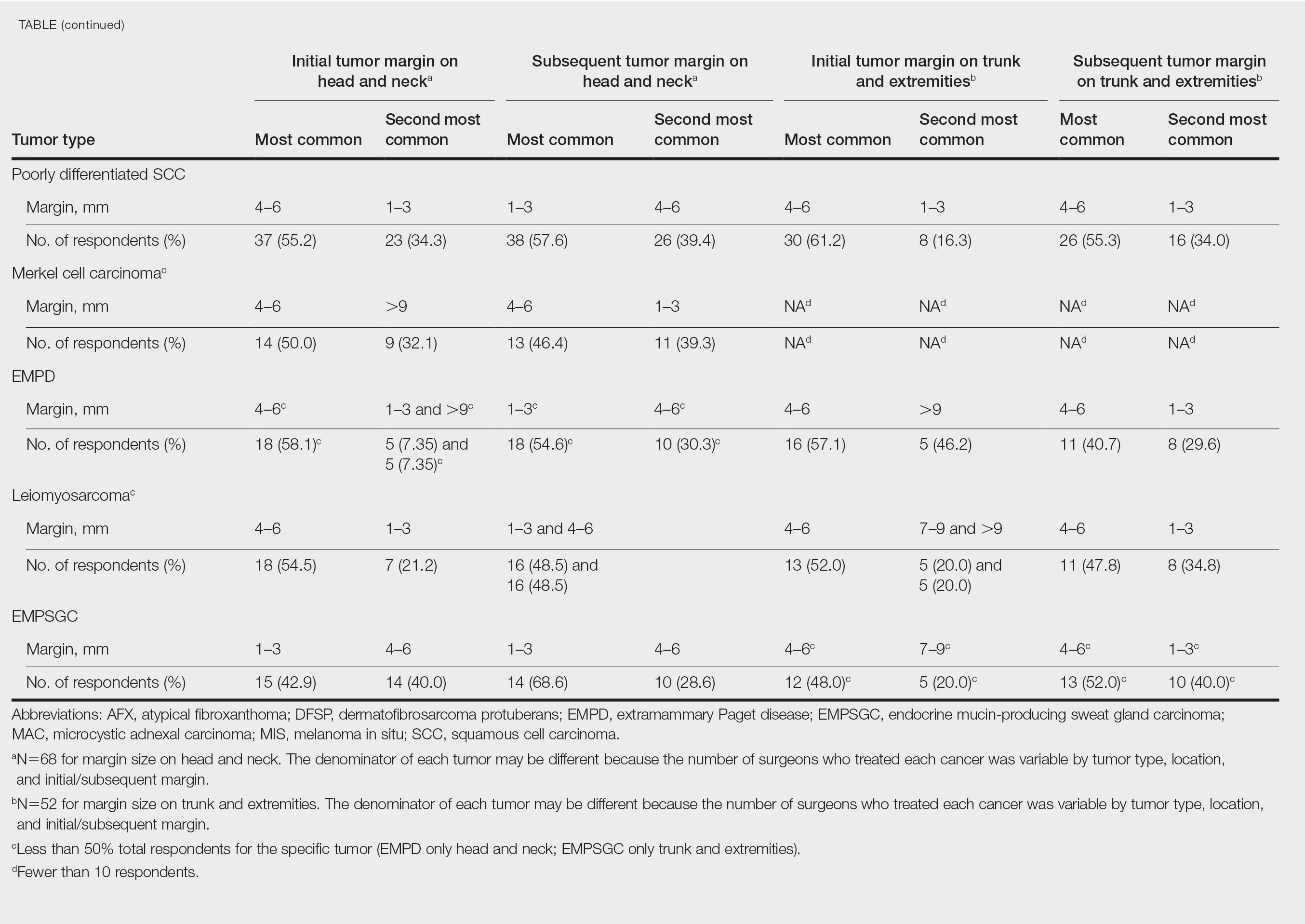

Margin Size for Unique Skin Tumors Treated With Mohs Micrographic Surgery: A Survey of Practice Patterns

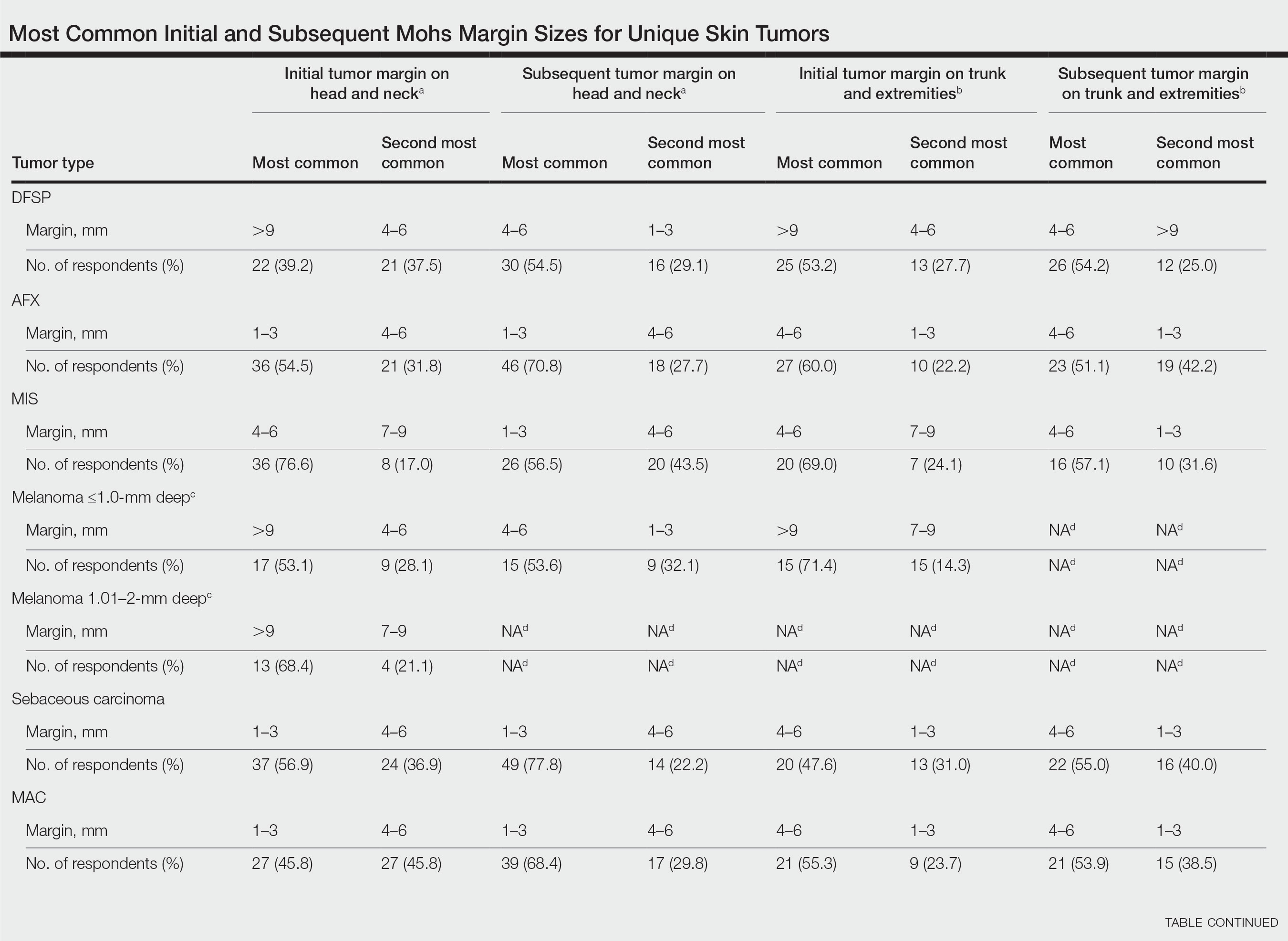

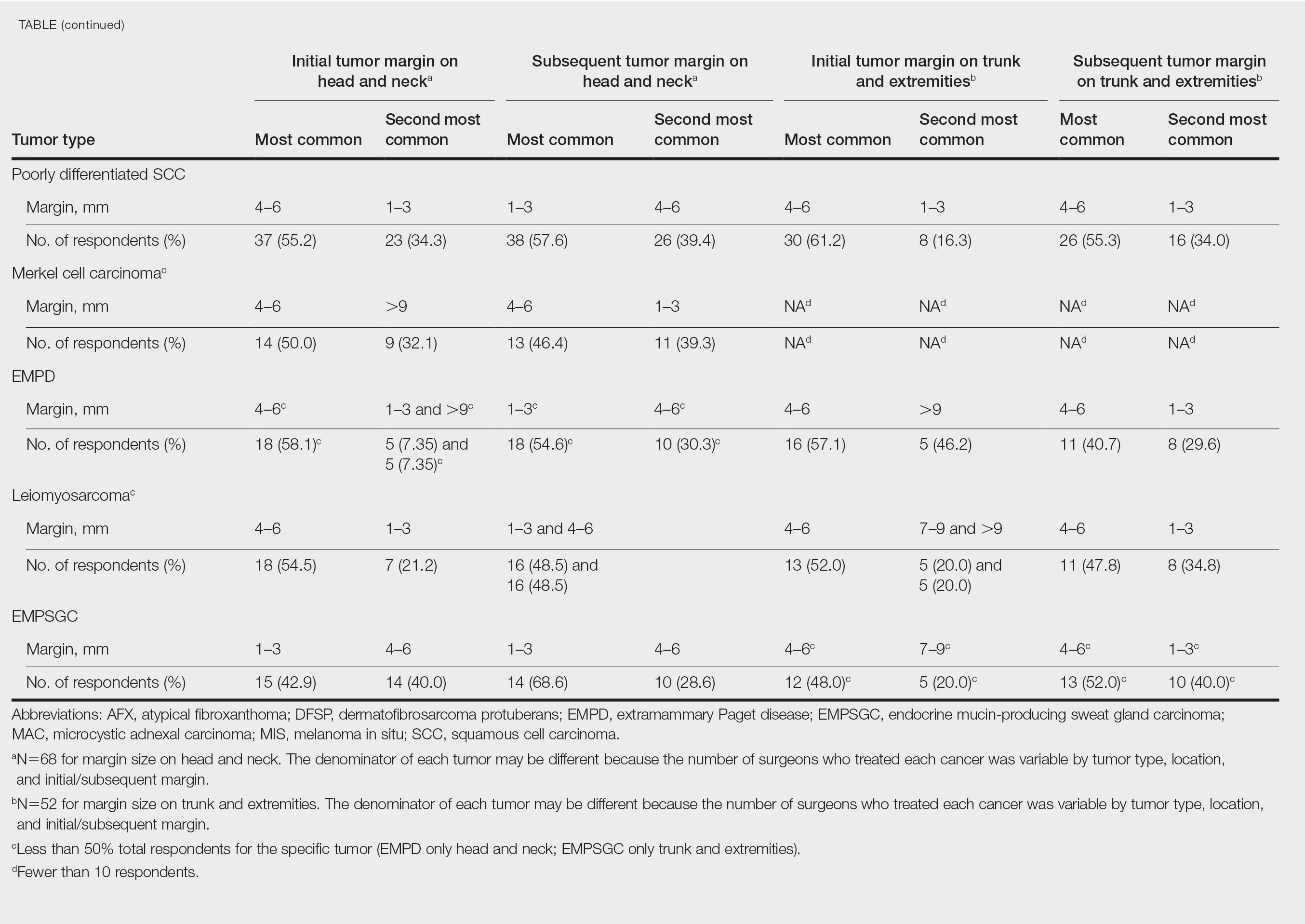

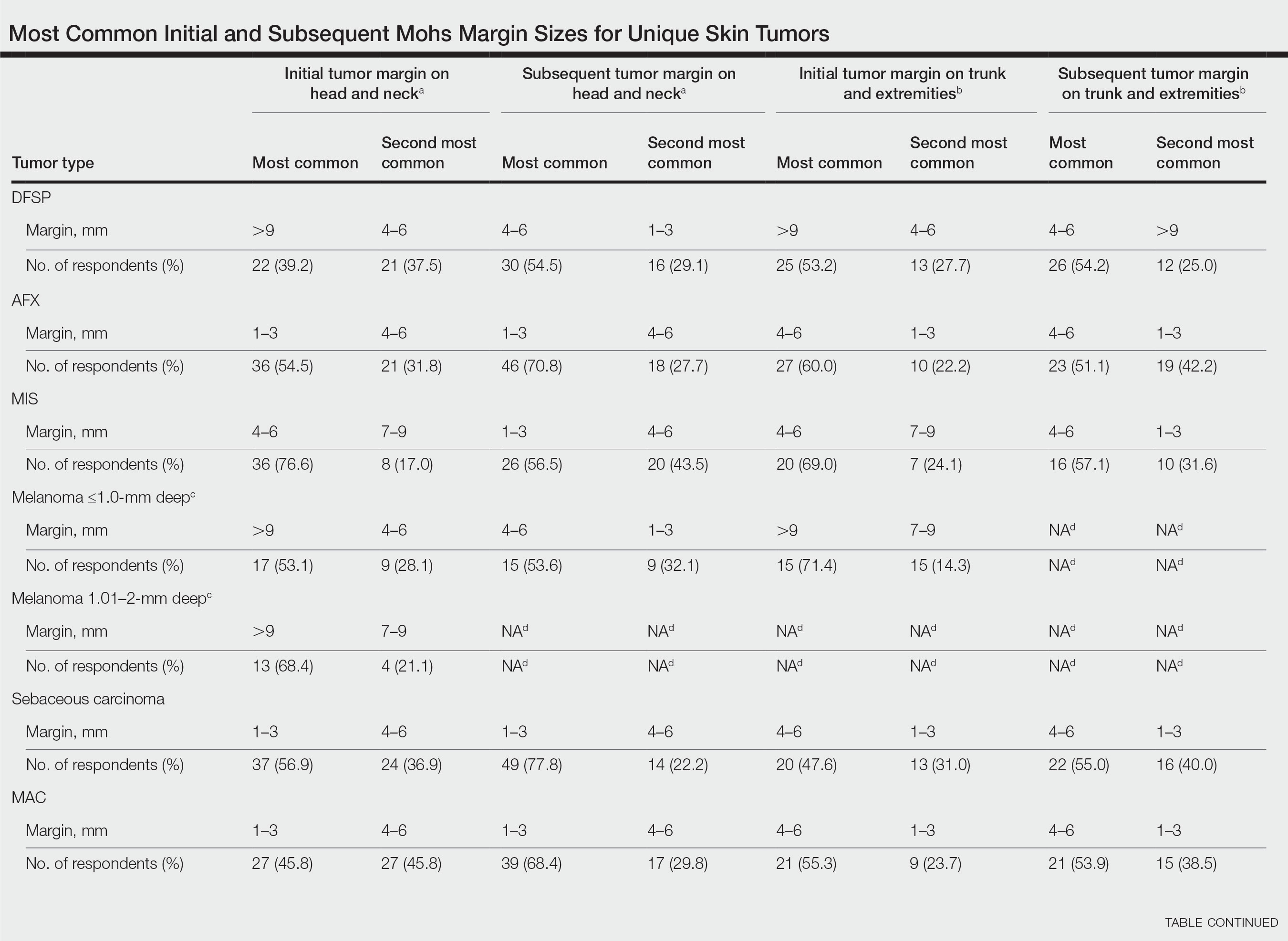

Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) is most commonly used for the surgical management of squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) and basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) in high-risk locations. The ability for 100% margin evaluation with MMS also has shown lower recurrence rates compared with wide local excision for less common and/or more aggressive tumors. However, there is a lack of standardization on initial and subsequent margin size when treating these less common skin tumors, such as dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP), atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX), and sebaceous carcinoma.

Because Mohs surgeons must balance normal tissue preservation with the importance of tumor clearance in the context of comprehensive margin control, we aimed to assess the practice patterns of Mohs surgeons regarding margin size for these unique tumors. The average margin size for each Mohs layer has been reported to be 1 to 3 mm for BCC compared with 3 to 6 mm or larger for other skin cancers, such as melanoma in situ (MIS).1-3 We hypothesized that the initial margin size would vary among surgeons and likely be greater for more aggressive and rarer malignancies as well as for lesions on the trunk and extremities.

Methods

A descriptive survey was created using SurveyMonkey and distributed to members of the American College of Mohs Surgery (ACMS). Survey participants and their responses were anonymous. Demographic information on survey participants was collected in addition to initial and subsequent MMS margin size for DFSP, AFX, MIS, invasive melanoma, sebaceous carcinoma, microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC), poorly differentiated SCC, Merkel cell carcinoma, extramammary Paget disease, leiomyosarcoma, and endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma. Survey participants were asked to choose from a range of margin sizes: 1 to 3 mm, 4 to 6 mm, 7 to 9 mm, and greater than 9 mm. This study was approved by the University of Texas Southwest Medical Center (Dallas, Texas) institutional review board.

Results

Eighty-seven respondents from the ACMS listserve completed the survey (response rate <10%). Of these, 58 respondents (66.7%) reported practicing for more than 5 years, and 58 (66.7%) were male. Practice setting was primarily private/community (71.3% [62/87]), and survey respondents were located across the United States. More than 50% of survey respondents treated the following tumors on the head and neck in their respective practices: DFSP (80.9% [55/68]), AFX (95.6% [65/68]), MIS (67.7% [46/68]), sebaceous carcinoma (92.7% [63/68]), MAC (83.8% [57/68]), poorly differentiated SCC (97.1% [66/68]), and endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma (51.5% [35/68]). More than 50% of survey respondents treated the following tumors on the trunk and extremities: DFSP (90.3% [47/52]), AFX (86.4% [45/52]), MIS (55.8% [29/52]), sebaceous carcinoma (80.8% [42/52]), MAC (73.1% [38/52]), poorly differentiated SCC (94.2% [49/52]), and extramammary Paget disease (53.9% [28/52]). Invasive melanoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, and leiomyosarcoma were overall less commonly treated.

In general, respondent Mohs surgeons were more likely to take larger initial and subsequent margins for tumors treated on the trunk and extremities compared with the head and neck (Table). In addition, initial margin size often was larger than the 1- to 3-mm margin commonly used in Mohs surgery for BCCs and less aggressive SCCs (Table). A larger initial margin size (>9 mm) and subsequent margin size (4–6 mm) was more commonly reported for certain tumors known to be more aggressive and/or have extensive subclinical extension, such as DFSP and invasive melanoma. Of note, most respondents performed 4- to 6-mm margins (37/67 [55.2%]) for poorly differentiated SCC. Overall, there was a high range of margin size variability among Mohs surgeons for these unique and/or more aggressive skin tumors.

Comment

Given that no guidelines exist on margins with MMS for less commonly treated skin tumors, this study helps give Mohs surgeons perspective on current practice patterns for both initial and subsequent Mohs margin sizes. High margin-size variability among Mohs surgeons is expected, as surgeons also need to account for high-risk features of the tumor or specific locations where tissue sparing is critical. Overall, Mohs surgeons are more likely to take larger initial margins for these less common skin tumors compared with BCCs or SCCs. Initial margin size was consistently larger on the trunk and extremities where tissue sparing often is less critical.

Our survey was limited by a small sample size and incomplete response of the ACMS membership. In addition, most respondents practiced in a private/community setting, which may have led to bias, as academic centers may manage rare malignancies more commonly and/or have increased access to immunostains and multispecialty care. Future registries for rare skin malignancies will hopefully be developed that will allow for further consensus on standardized margins. Additional studies on the average number of stages required to clear these less common tumors also are warranted.

- Muller FM, Dawe RS, Moseley H, et al. Randomized comparison of Mohs micrographic surgery and surgical excision for small nodular basal cell carcinoma: tissue‐sparing outcome. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1349-1354.

- van Loo E, Mosterd K, Krekels GA, et al. Surgical excision versus Mohs’ micrographic surgery for basal cell carcinoma of the face: a randomised clinical trial with 10 year follow-up. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50:3011-3020.