User login

Ensifentrine for COPD: Out of reach for many?

Ensifentrine (Ohtuvayre), a novel medication for the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration, has been shown to reduce COPD exacerbations and may improve the quality of life for patients, but these potential benefits come at an unreasonably high annual cost, authors of a cost and effectiveness analysis say.

Ensifentrine is a first-in-class selective dual inhibitor of both phosphodiesterase 3 (PDE-3) and PDE-4, combining both bronchodilator and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory effects in a single molecule. The drug is delivered through a standard jet nebulizer.

In the phase 3 ENHANCE 1 and 2 trials, ensifentrine significantly improved lung function based on the primary outcome of average forced expiratory volume in 1 second within 0-12 hours of administration, compared with placebo. In addition, patients were reported to tolerate the inhaled treatment well, with similar proportions of ensifentrine- and placebo-assigned patients reporting treatment-emergent adverse events. The most common treatment-emergent adverse events were nasopharyngitis, hypertension, and back pain, reported in < 3% of the ensifentrine group.

High cost barrier

But as authors of the analysis from the Boston, Massachusetts–based Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER) found, the therapeutic edge offered by ensifentrine is outweighed by the annual wholesale acquisition cost that its maker, Vernona Pharma, has established: $35,400, which far exceeds the estimated health-benefit price of $7,500-$12,700, according to ICER. ICER is an independent, nonprofit research institute that conducts evidence-based reviews of healthcare interventions, including prescription drugs, other treatments, and diagnostic tests.

“Current evidence shows that ensifentrine decreases COPD exacerbations when used in combination with some current inhaled therapies, but there are uncertainties about how much benefit it may add to unstudied combinations of inhaled treatments,” said David Rind, MD, chief medical officer of ICER in a statement.

In an interview, Dr. Rind noted that the high price of ensifentrine may lead payers to restrict access to an otherwise promising new therapy. “Obviously many drugs in the US are overpriced, and this one, too, looks like it is overpriced. That causes ongoing financial toxicity for individual patients and it causes problems for the entire US health system, because when we pay too much for drugs we don’t have money for other things. So I’m worried about the fact that this price is too high compared to the benefit it provides.”

As previously reported, as many as one in six persons with COPD in the United States miss or delay COPD medication doses because of high drug costs. “I think that the pricing they chose is going to cause lots of barriers to people getting access and that insurance companies will throw up barriers. Primary care physicians like me won’t even try to get approval for a drug like this given the hoops we will be made to jump through, and so fewer people will get this drug,” Dr. Rind said. He pointed out that a lower wholesale acquisition cost could encourage higher-volume sales, affording the drugmaker a comparable profit with the higher-cost but lower-volume option.

Good drug, high price

An independent appraisal committee for ICER determined that “current evidence is adequate to demonstrate a net health benefit for ensifentrine added to maintenance therapy when compared to maintenance therapy alone.”

But ICER also issued an access and affordability alert “to signal to stakeholders and policymakers that the amount of added healthcare costs associated with a new service may be difficult for the health system to absorb over the short term without displacing other needed services.” ICER recommends that payers should include coverage for smoking cessation therapies, and that drug manufacturers “set prices that will foster affordability and good access for all patients by aligning prices with the patient-centered therapeutic value of their treatments.”

“This looks like a pretty good drug,” Dr. Rind said. “It looks quite safe and I think there will be a lot of patients, particularly those who are having frequent exacerbations, who this would be appropriate for, particularly once they’ve maxed out existing therapies, but maybe even earlier than that. And if the price comes down to the point that patients can really access this and providers can access it, people really should look at this as a potential therapy.”

Drug not yet available?

However, providers have not yet had direct experience with the new medication. “We haven’t been able to prescribe it yet,” said Corinne Young, MSN, FNP-C, FCCP, director of Advance Practice Provider and Clinical Services for Colorado Springs Pulmonary Consultants, president and founder of the Association of Pulmonary Advance Practice Providers, and a member of the CHEST Physician Editorial Board.

She learned “they were going to release it to select specialty pharmacies in the 3rd quarter of 2024. But all the ones we call do not have it and no one knows who does. They haven’t sent any reps into the field in my area so we don’t have any points of contact either,” she said.

Verona Pharma stated it anticipates ensifentrine to be available in the third quarter of 2024 “through an exclusive network of accredited specialty pharmacies.”

Funding for the ICER report came from nonprofit foundations. No funding came from health insurers, pharmacy benefit managers, or life science companies. Dr. Rind had no relevant disclosures.

Ensifentrine (Ohtuvayre), a novel medication for the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration, has been shown to reduce COPD exacerbations and may improve the quality of life for patients, but these potential benefits come at an unreasonably high annual cost, authors of a cost and effectiveness analysis say.

Ensifentrine is a first-in-class selective dual inhibitor of both phosphodiesterase 3 (PDE-3) and PDE-4, combining both bronchodilator and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory effects in a single molecule. The drug is delivered through a standard jet nebulizer.

In the phase 3 ENHANCE 1 and 2 trials, ensifentrine significantly improved lung function based on the primary outcome of average forced expiratory volume in 1 second within 0-12 hours of administration, compared with placebo. In addition, patients were reported to tolerate the inhaled treatment well, with similar proportions of ensifentrine- and placebo-assigned patients reporting treatment-emergent adverse events. The most common treatment-emergent adverse events were nasopharyngitis, hypertension, and back pain, reported in < 3% of the ensifentrine group.

High cost barrier

But as authors of the analysis from the Boston, Massachusetts–based Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER) found, the therapeutic edge offered by ensifentrine is outweighed by the annual wholesale acquisition cost that its maker, Vernona Pharma, has established: $35,400, which far exceeds the estimated health-benefit price of $7,500-$12,700, according to ICER. ICER is an independent, nonprofit research institute that conducts evidence-based reviews of healthcare interventions, including prescription drugs, other treatments, and diagnostic tests.

“Current evidence shows that ensifentrine decreases COPD exacerbations when used in combination with some current inhaled therapies, but there are uncertainties about how much benefit it may add to unstudied combinations of inhaled treatments,” said David Rind, MD, chief medical officer of ICER in a statement.

In an interview, Dr. Rind noted that the high price of ensifentrine may lead payers to restrict access to an otherwise promising new therapy. “Obviously many drugs in the US are overpriced, and this one, too, looks like it is overpriced. That causes ongoing financial toxicity for individual patients and it causes problems for the entire US health system, because when we pay too much for drugs we don’t have money for other things. So I’m worried about the fact that this price is too high compared to the benefit it provides.”

As previously reported, as many as one in six persons with COPD in the United States miss or delay COPD medication doses because of high drug costs. “I think that the pricing they chose is going to cause lots of barriers to people getting access and that insurance companies will throw up barriers. Primary care physicians like me won’t even try to get approval for a drug like this given the hoops we will be made to jump through, and so fewer people will get this drug,” Dr. Rind said. He pointed out that a lower wholesale acquisition cost could encourage higher-volume sales, affording the drugmaker a comparable profit with the higher-cost but lower-volume option.

Good drug, high price

An independent appraisal committee for ICER determined that “current evidence is adequate to demonstrate a net health benefit for ensifentrine added to maintenance therapy when compared to maintenance therapy alone.”

But ICER also issued an access and affordability alert “to signal to stakeholders and policymakers that the amount of added healthcare costs associated with a new service may be difficult for the health system to absorb over the short term without displacing other needed services.” ICER recommends that payers should include coverage for smoking cessation therapies, and that drug manufacturers “set prices that will foster affordability and good access for all patients by aligning prices with the patient-centered therapeutic value of their treatments.”

“This looks like a pretty good drug,” Dr. Rind said. “It looks quite safe and I think there will be a lot of patients, particularly those who are having frequent exacerbations, who this would be appropriate for, particularly once they’ve maxed out existing therapies, but maybe even earlier than that. And if the price comes down to the point that patients can really access this and providers can access it, people really should look at this as a potential therapy.”

Drug not yet available?

However, providers have not yet had direct experience with the new medication. “We haven’t been able to prescribe it yet,” said Corinne Young, MSN, FNP-C, FCCP, director of Advance Practice Provider and Clinical Services for Colorado Springs Pulmonary Consultants, president and founder of the Association of Pulmonary Advance Practice Providers, and a member of the CHEST Physician Editorial Board.

She learned “they were going to release it to select specialty pharmacies in the 3rd quarter of 2024. But all the ones we call do not have it and no one knows who does. They haven’t sent any reps into the field in my area so we don’t have any points of contact either,” she said.

Verona Pharma stated it anticipates ensifentrine to be available in the third quarter of 2024 “through an exclusive network of accredited specialty pharmacies.”

Funding for the ICER report came from nonprofit foundations. No funding came from health insurers, pharmacy benefit managers, or life science companies. Dr. Rind had no relevant disclosures.

Ensifentrine (Ohtuvayre), a novel medication for the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration, has been shown to reduce COPD exacerbations and may improve the quality of life for patients, but these potential benefits come at an unreasonably high annual cost, authors of a cost and effectiveness analysis say.

Ensifentrine is a first-in-class selective dual inhibitor of both phosphodiesterase 3 (PDE-3) and PDE-4, combining both bronchodilator and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory effects in a single molecule. The drug is delivered through a standard jet nebulizer.

In the phase 3 ENHANCE 1 and 2 trials, ensifentrine significantly improved lung function based on the primary outcome of average forced expiratory volume in 1 second within 0-12 hours of administration, compared with placebo. In addition, patients were reported to tolerate the inhaled treatment well, with similar proportions of ensifentrine- and placebo-assigned patients reporting treatment-emergent adverse events. The most common treatment-emergent adverse events were nasopharyngitis, hypertension, and back pain, reported in < 3% of the ensifentrine group.

High cost barrier

But as authors of the analysis from the Boston, Massachusetts–based Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER) found, the therapeutic edge offered by ensifentrine is outweighed by the annual wholesale acquisition cost that its maker, Vernona Pharma, has established: $35,400, which far exceeds the estimated health-benefit price of $7,500-$12,700, according to ICER. ICER is an independent, nonprofit research institute that conducts evidence-based reviews of healthcare interventions, including prescription drugs, other treatments, and diagnostic tests.

“Current evidence shows that ensifentrine decreases COPD exacerbations when used in combination with some current inhaled therapies, but there are uncertainties about how much benefit it may add to unstudied combinations of inhaled treatments,” said David Rind, MD, chief medical officer of ICER in a statement.

In an interview, Dr. Rind noted that the high price of ensifentrine may lead payers to restrict access to an otherwise promising new therapy. “Obviously many drugs in the US are overpriced, and this one, too, looks like it is overpriced. That causes ongoing financial toxicity for individual patients and it causes problems for the entire US health system, because when we pay too much for drugs we don’t have money for other things. So I’m worried about the fact that this price is too high compared to the benefit it provides.”

As previously reported, as many as one in six persons with COPD in the United States miss or delay COPD medication doses because of high drug costs. “I think that the pricing they chose is going to cause lots of barriers to people getting access and that insurance companies will throw up barriers. Primary care physicians like me won’t even try to get approval for a drug like this given the hoops we will be made to jump through, and so fewer people will get this drug,” Dr. Rind said. He pointed out that a lower wholesale acquisition cost could encourage higher-volume sales, affording the drugmaker a comparable profit with the higher-cost but lower-volume option.

Good drug, high price

An independent appraisal committee for ICER determined that “current evidence is adequate to demonstrate a net health benefit for ensifentrine added to maintenance therapy when compared to maintenance therapy alone.”

But ICER also issued an access and affordability alert “to signal to stakeholders and policymakers that the amount of added healthcare costs associated with a new service may be difficult for the health system to absorb over the short term without displacing other needed services.” ICER recommends that payers should include coverage for smoking cessation therapies, and that drug manufacturers “set prices that will foster affordability and good access for all patients by aligning prices with the patient-centered therapeutic value of their treatments.”

“This looks like a pretty good drug,” Dr. Rind said. “It looks quite safe and I think there will be a lot of patients, particularly those who are having frequent exacerbations, who this would be appropriate for, particularly once they’ve maxed out existing therapies, but maybe even earlier than that. And if the price comes down to the point that patients can really access this and providers can access it, people really should look at this as a potential therapy.”

Drug not yet available?

However, providers have not yet had direct experience with the new medication. “We haven’t been able to prescribe it yet,” said Corinne Young, MSN, FNP-C, FCCP, director of Advance Practice Provider and Clinical Services for Colorado Springs Pulmonary Consultants, president and founder of the Association of Pulmonary Advance Practice Providers, and a member of the CHEST Physician Editorial Board.

She learned “they were going to release it to select specialty pharmacies in the 3rd quarter of 2024. But all the ones we call do not have it and no one knows who does. They haven’t sent any reps into the field in my area so we don’t have any points of contact either,” she said.

Verona Pharma stated it anticipates ensifentrine to be available in the third quarter of 2024 “through an exclusive network of accredited specialty pharmacies.”

Funding for the ICER report came from nonprofit foundations. No funding came from health insurers, pharmacy benefit managers, or life science companies. Dr. Rind had no relevant disclosures.

The language of AI and its applications in health care

AI is a group of nonhuman techniques that utilize automated learning methods to extract information from datasets through generalization, classification, prediction, and association. In other words, AI is the simulation of human intelligence processes by machines. The branches of AI include natural language processing, speech recognition, machine vision, and expert systems. AI can make clinical care more efficient; however, many find its confusing terminology to be a barrier.1 This article provides concise definitions of AI terms and is intended to help physicians better understand how AI methods can be applied to clinical care. The clinical application of natural language processing and machine vision applications are more clinically intuitive than the roles of machine learning algorithms.

Machine learning and algorithms

Machine learning is a branch of AI that uses data and algorithms to mimic human reasoning through classification, pattern recognition, and prediction. Supervised and unsupervised machine-learning algorithms can analyze data and recognize undetected associations and relationships.

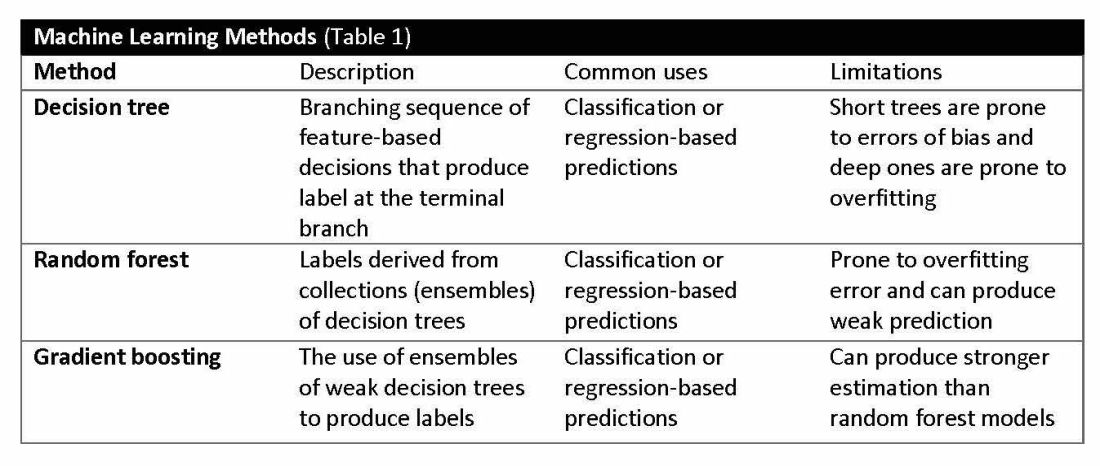

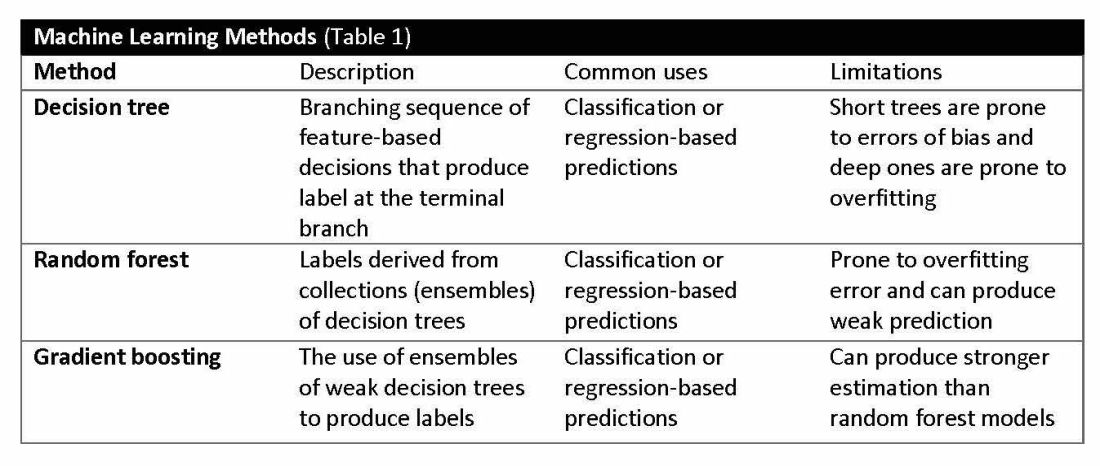

Supervised learning involves training models to make predictions using data sets that have correct outcome parameters called labels using predictive fields called features. Machine learning uses iterative analysis including random forest, decision tree, and gradient boosting methods that minimize predictive error metrics (see Table 1). This approach is widely used to improve diagnoses, predict disease progression or exacerbation, and personalize treatment plan modifications.

Supervised machine learning methods can be particularly effective for processing large volumes of medical information to identify patterns and make accurate predictions. In contrast, unsupervised learning techniques can analyze unlabeled data and help clinicians uncover hidden patterns or undetected groupings. Techniques including clustering, exploratory analysis, and anomaly detection are common applications. Both of these machine-learning approaches can be used to extract novel and helpful insights.

The utility of machine learning analyses depends on the size and accuracy of the available datasets. Small datasets can limit usability, while large datasets require substantial computational power. Predictive models are generated using training datasets and evaluated using separate evaluation datasets. Deep learning models, a subset of machine learning, can automatically readjust themselves to maintain or improve accuracy when analyzing new observations that include accurate labels.

Challenges of algorithms and calibration

Machine learning algorithms vary in complexity and accuracy. For example, a simple logistic regression model using time, date, latitude, and indoor/outdoor location can accurately recommend sunscreen application. This model identifies when solar radiation is high enough to warrant sunscreen use, avoiding unnecessary recommendations during nighttime hours or indoor locations. A more complex model might suffer from model overfitting and inappropriately suggest sunscreen before a tanning salon visit.

Complex machine learning models, like support vector machine (SVM) and decision tree methods, are useful when many features have predictive power. SVMs are useful for small but complex datasets. Features are manipulated in a multidimensional space to maximize the “margins” separating 2 groups. Decision tree analyses are useful when more than 2 groups are being analyzed. SVM and decision tree models can also lose accuracy by data overfitting.

Consider the development of an SVM analysis to predict whether an individual is a fellow or a senior faculty member. One could use high gray hair density feature values to identify senior faculty. When this algorithm is applied to an individual with alopecia, no amount of model adjustment can achieve high levels of discrimination because no hair is present. Rather than overfitting the model by adding more nonpredictive features, individuals with alopecia are analyzed by their own algorithm (tree) that uses the skin wrinkle/solar damage rather than the gray hair density feature.

Decision tree ensemble algorithms like random forest and gradient boosting use feature-based decision trees to process and classify data. Random forests are robust, scalable, and versatile, providing classifications and predictions while protecting against inaccurate data and outliers and have the advantage of being able to handle both categorical and continuous features. Gradient boosting, which uses an ensemble of weak decision trees, often outperforms random forests when individual trees perform only slightly better than random chance. This method incrementally builds the model by optimizing the residual errors of previous trees, leading to more accurate predictions.

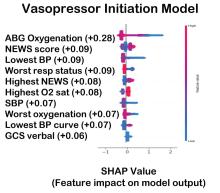

In practice, gradient boosting can be used to fine-tune diagnostic models, improving their precision and reliability. A recent example of how gradient boosting of random forest predictions yielded highly accurate predictions for unplanned vasopressor initiation and intubation events 2 to 4 hours before an ICU adult became unstable.2

Assessing the accuracy of algorithms

The value of the data set is directly related to the accuracy of its labels. Traditional methods that measure model performance, such as sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values (PPV and NPV), have important limitations. They provide little insight into how a complex model made its prediction. Understanding which individual features drive model accuracy is key to fostering trust in model predictions. This can be done by comparing model output with and without including individual features. The results of all possible combinations are aggregated according to feature importance, which is summarized in the Shapley value for each model feature. Higher values indicate greater relative importance. SHAP plots help identify how much and how often specific features change the model output, presenting values of individual model estimates with and without a specific feature (see Figure 1).

Promoting AI use

AI and machine learning algorithms are coming to patient care. Understanding the language of AI helps caregivers integrate these tools into their practices. The science of AI faces serious challenges. Algorithms must be recalibrated to keep pace as therapies advance, disease prevalence changes, and our population ages. AI must address new challenges as they confront those suffering from respiratory diseases. This resource encourages clinicians with novel approaches by using AI methodologies to advance their development. We can better address future health care needs by promoting the equitable use of AI technologies, especially among socially disadvantaged developers.

References

1. Lilly CM, Soni AV, Dunlap D, et al. Advancing point of care testing by application of machine learning techniques and artificial intelligence. Chest. 2024 (in press).

2. Lilly CM, Kirk D, Pessach IM, et al. Application of machine learning models to biomedical and information system signals from critically ill adults. Chest. 2024;165(5):1139-1148.

AI is a group of nonhuman techniques that utilize automated learning methods to extract information from datasets through generalization, classification, prediction, and association. In other words, AI is the simulation of human intelligence processes by machines. The branches of AI include natural language processing, speech recognition, machine vision, and expert systems. AI can make clinical care more efficient; however, many find its confusing terminology to be a barrier.1 This article provides concise definitions of AI terms and is intended to help physicians better understand how AI methods can be applied to clinical care. The clinical application of natural language processing and machine vision applications are more clinically intuitive than the roles of machine learning algorithms.

Machine learning and algorithms

Machine learning is a branch of AI that uses data and algorithms to mimic human reasoning through classification, pattern recognition, and prediction. Supervised and unsupervised machine-learning algorithms can analyze data and recognize undetected associations and relationships.

Supervised learning involves training models to make predictions using data sets that have correct outcome parameters called labels using predictive fields called features. Machine learning uses iterative analysis including random forest, decision tree, and gradient boosting methods that minimize predictive error metrics (see Table 1). This approach is widely used to improve diagnoses, predict disease progression or exacerbation, and personalize treatment plan modifications.

Supervised machine learning methods can be particularly effective for processing large volumes of medical information to identify patterns and make accurate predictions. In contrast, unsupervised learning techniques can analyze unlabeled data and help clinicians uncover hidden patterns or undetected groupings. Techniques including clustering, exploratory analysis, and anomaly detection are common applications. Both of these machine-learning approaches can be used to extract novel and helpful insights.

The utility of machine learning analyses depends on the size and accuracy of the available datasets. Small datasets can limit usability, while large datasets require substantial computational power. Predictive models are generated using training datasets and evaluated using separate evaluation datasets. Deep learning models, a subset of machine learning, can automatically readjust themselves to maintain or improve accuracy when analyzing new observations that include accurate labels.

Challenges of algorithms and calibration

Machine learning algorithms vary in complexity and accuracy. For example, a simple logistic regression model using time, date, latitude, and indoor/outdoor location can accurately recommend sunscreen application. This model identifies when solar radiation is high enough to warrant sunscreen use, avoiding unnecessary recommendations during nighttime hours or indoor locations. A more complex model might suffer from model overfitting and inappropriately suggest sunscreen before a tanning salon visit.

Complex machine learning models, like support vector machine (SVM) and decision tree methods, are useful when many features have predictive power. SVMs are useful for small but complex datasets. Features are manipulated in a multidimensional space to maximize the “margins” separating 2 groups. Decision tree analyses are useful when more than 2 groups are being analyzed. SVM and decision tree models can also lose accuracy by data overfitting.

Consider the development of an SVM analysis to predict whether an individual is a fellow or a senior faculty member. One could use high gray hair density feature values to identify senior faculty. When this algorithm is applied to an individual with alopecia, no amount of model adjustment can achieve high levels of discrimination because no hair is present. Rather than overfitting the model by adding more nonpredictive features, individuals with alopecia are analyzed by their own algorithm (tree) that uses the skin wrinkle/solar damage rather than the gray hair density feature.

Decision tree ensemble algorithms like random forest and gradient boosting use feature-based decision trees to process and classify data. Random forests are robust, scalable, and versatile, providing classifications and predictions while protecting against inaccurate data and outliers and have the advantage of being able to handle both categorical and continuous features. Gradient boosting, which uses an ensemble of weak decision trees, often outperforms random forests when individual trees perform only slightly better than random chance. This method incrementally builds the model by optimizing the residual errors of previous trees, leading to more accurate predictions.

In practice, gradient boosting can be used to fine-tune diagnostic models, improving their precision and reliability. A recent example of how gradient boosting of random forest predictions yielded highly accurate predictions for unplanned vasopressor initiation and intubation events 2 to 4 hours before an ICU adult became unstable.2

Assessing the accuracy of algorithms

The value of the data set is directly related to the accuracy of its labels. Traditional methods that measure model performance, such as sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values (PPV and NPV), have important limitations. They provide little insight into how a complex model made its prediction. Understanding which individual features drive model accuracy is key to fostering trust in model predictions. This can be done by comparing model output with and without including individual features. The results of all possible combinations are aggregated according to feature importance, which is summarized in the Shapley value for each model feature. Higher values indicate greater relative importance. SHAP plots help identify how much and how often specific features change the model output, presenting values of individual model estimates with and without a specific feature (see Figure 1).

Promoting AI use

AI and machine learning algorithms are coming to patient care. Understanding the language of AI helps caregivers integrate these tools into their practices. The science of AI faces serious challenges. Algorithms must be recalibrated to keep pace as therapies advance, disease prevalence changes, and our population ages. AI must address new challenges as they confront those suffering from respiratory diseases. This resource encourages clinicians with novel approaches by using AI methodologies to advance their development. We can better address future health care needs by promoting the equitable use of AI technologies, especially among socially disadvantaged developers.

References

1. Lilly CM, Soni AV, Dunlap D, et al. Advancing point of care testing by application of machine learning techniques and artificial intelligence. Chest. 2024 (in press).

2. Lilly CM, Kirk D, Pessach IM, et al. Application of machine learning models to biomedical and information system signals from critically ill adults. Chest. 2024;165(5):1139-1148.

AI is a group of nonhuman techniques that utilize automated learning methods to extract information from datasets through generalization, classification, prediction, and association. In other words, AI is the simulation of human intelligence processes by machines. The branches of AI include natural language processing, speech recognition, machine vision, and expert systems. AI can make clinical care more efficient; however, many find its confusing terminology to be a barrier.1 This article provides concise definitions of AI terms and is intended to help physicians better understand how AI methods can be applied to clinical care. The clinical application of natural language processing and machine vision applications are more clinically intuitive than the roles of machine learning algorithms.

Machine learning and algorithms

Machine learning is a branch of AI that uses data and algorithms to mimic human reasoning through classification, pattern recognition, and prediction. Supervised and unsupervised machine-learning algorithms can analyze data and recognize undetected associations and relationships.

Supervised learning involves training models to make predictions using data sets that have correct outcome parameters called labels using predictive fields called features. Machine learning uses iterative analysis including random forest, decision tree, and gradient boosting methods that minimize predictive error metrics (see Table 1). This approach is widely used to improve diagnoses, predict disease progression or exacerbation, and personalize treatment plan modifications.

Supervised machine learning methods can be particularly effective for processing large volumes of medical information to identify patterns and make accurate predictions. In contrast, unsupervised learning techniques can analyze unlabeled data and help clinicians uncover hidden patterns or undetected groupings. Techniques including clustering, exploratory analysis, and anomaly detection are common applications. Both of these machine-learning approaches can be used to extract novel and helpful insights.

The utility of machine learning analyses depends on the size and accuracy of the available datasets. Small datasets can limit usability, while large datasets require substantial computational power. Predictive models are generated using training datasets and evaluated using separate evaluation datasets. Deep learning models, a subset of machine learning, can automatically readjust themselves to maintain or improve accuracy when analyzing new observations that include accurate labels.

Challenges of algorithms and calibration

Machine learning algorithms vary in complexity and accuracy. For example, a simple logistic regression model using time, date, latitude, and indoor/outdoor location can accurately recommend sunscreen application. This model identifies when solar radiation is high enough to warrant sunscreen use, avoiding unnecessary recommendations during nighttime hours or indoor locations. A more complex model might suffer from model overfitting and inappropriately suggest sunscreen before a tanning salon visit.

Complex machine learning models, like support vector machine (SVM) and decision tree methods, are useful when many features have predictive power. SVMs are useful for small but complex datasets. Features are manipulated in a multidimensional space to maximize the “margins” separating 2 groups. Decision tree analyses are useful when more than 2 groups are being analyzed. SVM and decision tree models can also lose accuracy by data overfitting.

Consider the development of an SVM analysis to predict whether an individual is a fellow or a senior faculty member. One could use high gray hair density feature values to identify senior faculty. When this algorithm is applied to an individual with alopecia, no amount of model adjustment can achieve high levels of discrimination because no hair is present. Rather than overfitting the model by adding more nonpredictive features, individuals with alopecia are analyzed by their own algorithm (tree) that uses the skin wrinkle/solar damage rather than the gray hair density feature.

Decision tree ensemble algorithms like random forest and gradient boosting use feature-based decision trees to process and classify data. Random forests are robust, scalable, and versatile, providing classifications and predictions while protecting against inaccurate data and outliers and have the advantage of being able to handle both categorical and continuous features. Gradient boosting, which uses an ensemble of weak decision trees, often outperforms random forests when individual trees perform only slightly better than random chance. This method incrementally builds the model by optimizing the residual errors of previous trees, leading to more accurate predictions.

In practice, gradient boosting can be used to fine-tune diagnostic models, improving their precision and reliability. A recent example of how gradient boosting of random forest predictions yielded highly accurate predictions for unplanned vasopressor initiation and intubation events 2 to 4 hours before an ICU adult became unstable.2

Assessing the accuracy of algorithms

The value of the data set is directly related to the accuracy of its labels. Traditional methods that measure model performance, such as sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values (PPV and NPV), have important limitations. They provide little insight into how a complex model made its prediction. Understanding which individual features drive model accuracy is key to fostering trust in model predictions. This can be done by comparing model output with and without including individual features. The results of all possible combinations are aggregated according to feature importance, which is summarized in the Shapley value for each model feature. Higher values indicate greater relative importance. SHAP plots help identify how much and how often specific features change the model output, presenting values of individual model estimates with and without a specific feature (see Figure 1).

Promoting AI use

AI and machine learning algorithms are coming to patient care. Understanding the language of AI helps caregivers integrate these tools into their practices. The science of AI faces serious challenges. Algorithms must be recalibrated to keep pace as therapies advance, disease prevalence changes, and our population ages. AI must address new challenges as they confront those suffering from respiratory diseases. This resource encourages clinicians with novel approaches by using AI methodologies to advance their development. We can better address future health care needs by promoting the equitable use of AI technologies, especially among socially disadvantaged developers.

References

1. Lilly CM, Soni AV, Dunlap D, et al. Advancing point of care testing by application of machine learning techniques and artificial intelligence. Chest. 2024 (in press).

2. Lilly CM, Kirk D, Pessach IM, et al. Application of machine learning models to biomedical and information system signals from critically ill adults. Chest. 2024;165(5):1139-1148.

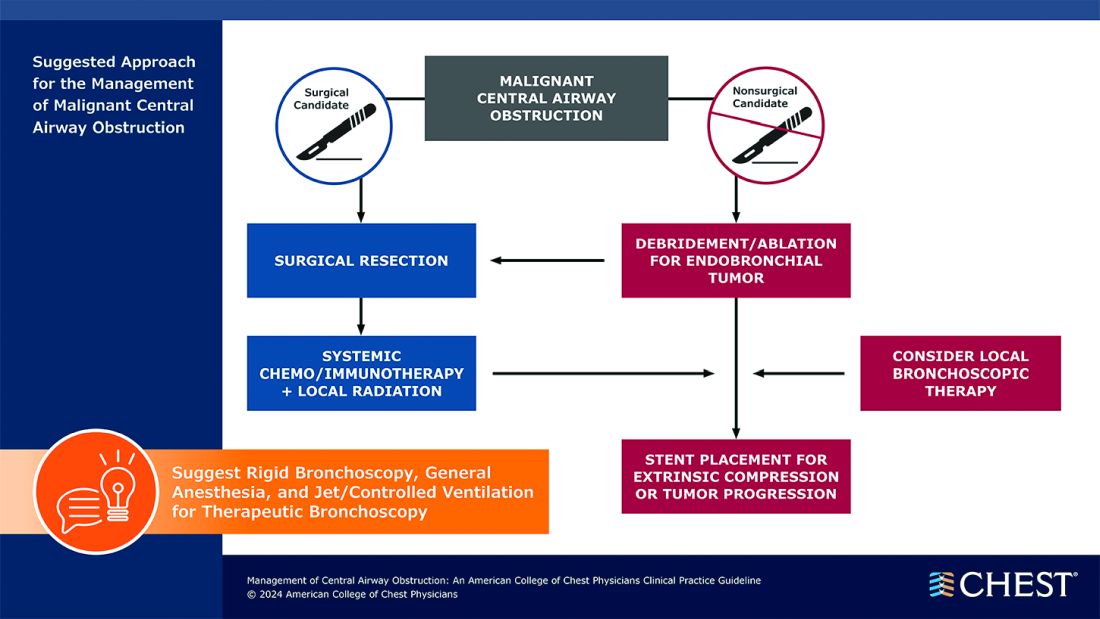

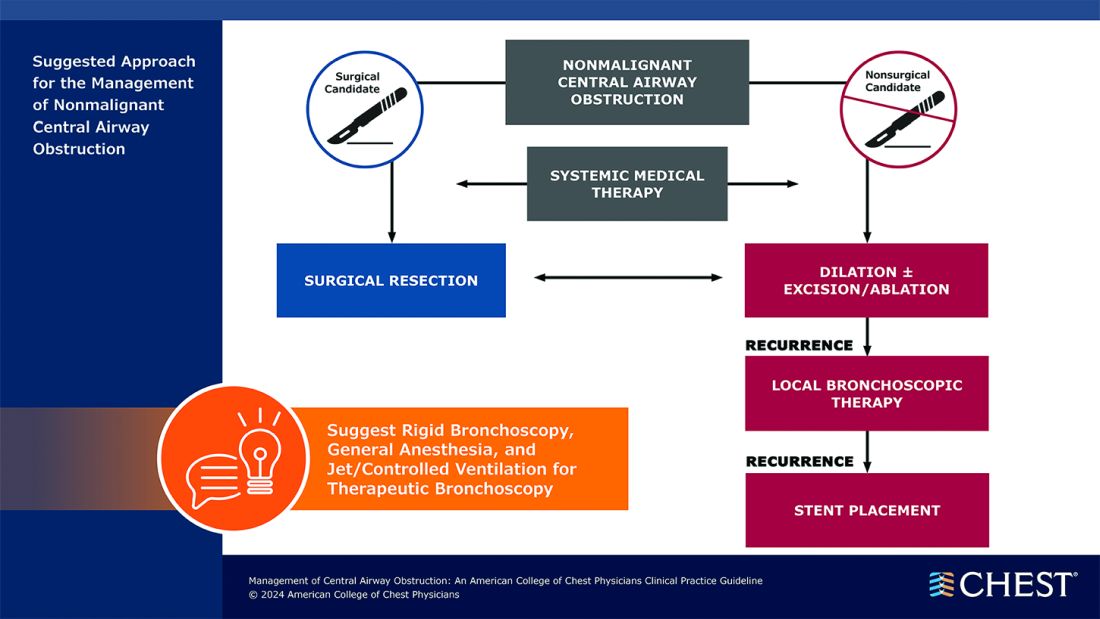

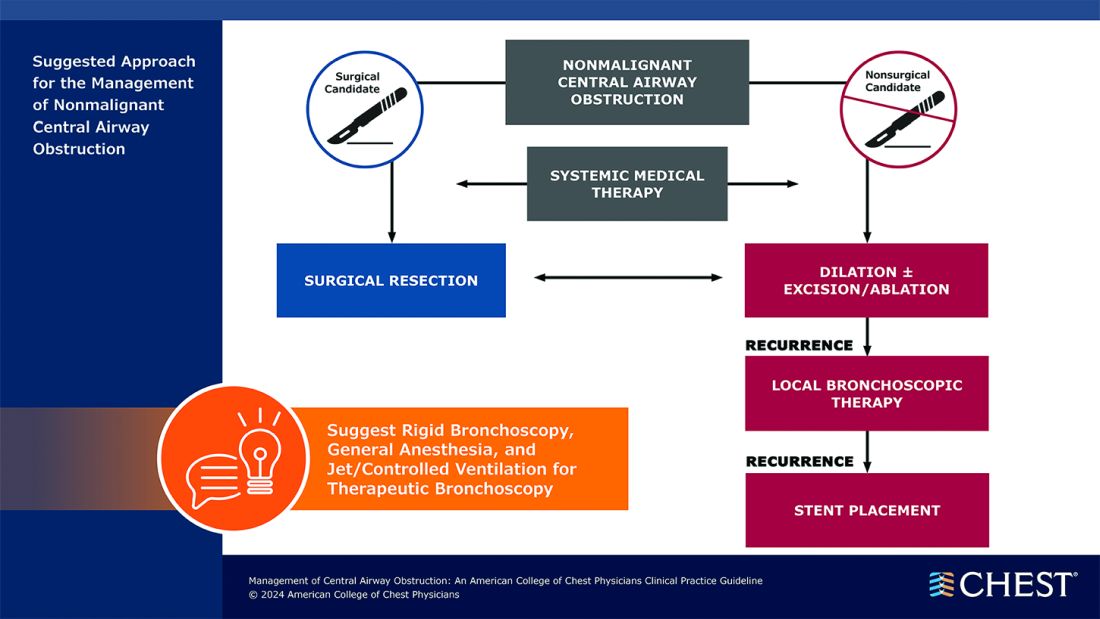

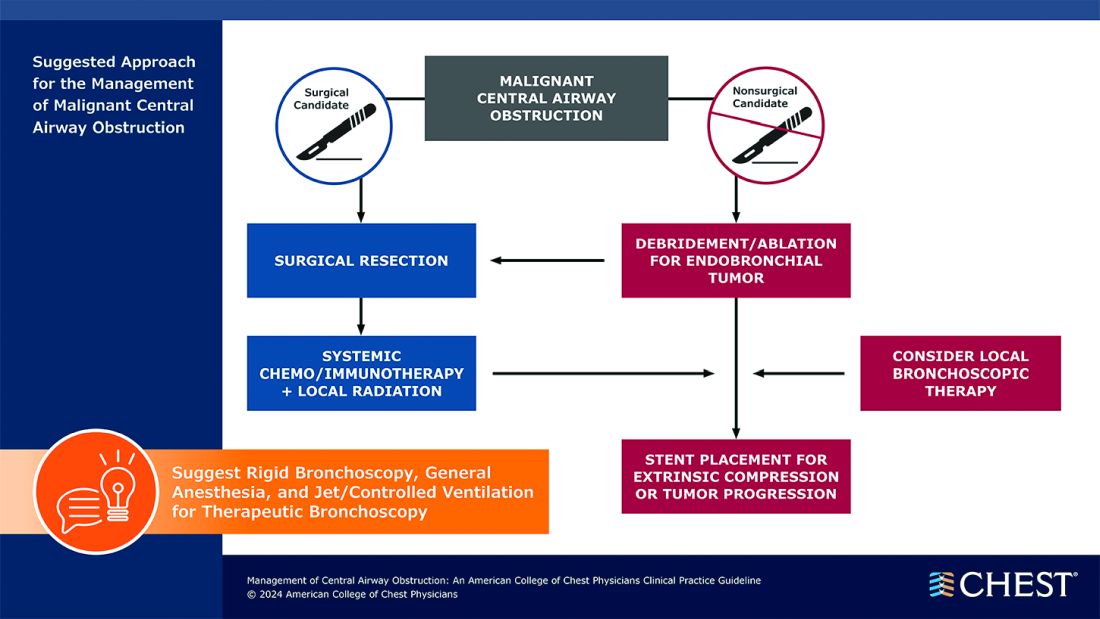

CHEST releases new guideline on management of central airway obstruction

CHEST recently released a new clinical guideline on central airway obstruction (CAO).

“Central airway obstruction is associated with a poor prognosis, and the management of CAO is highly variable dependent on the provider expertise and local resources. By releasing this guideline, the panel hopes to standardize the definition of CAO and provide guidance for the management of patients to optimize care and improve outcomes,” said Kamran Mahmood, MD, MPH, FCCP, lead author on the guideline. “The guideline recommendations are developed using GRADE methodology and based on thorough evidence review and expert input. But the quality of overall evidence is very low, and the panel calls for well-designed studies and randomized controlled trials for the management of CAO.”

CAO can be caused by a variety of malignant and nonmalignant disorders, and multiple specialists may be involved in the care, including pulmonologists, interventional pulmonologists, radiologists, anesthesiologists, oncologists, radiation oncologists, thoracic surgeons and otolaryngologists, etc. The panel recommends shared decision-making with the patients and a multidisciplinary approach to manage CAO.

Below, you’ll find flowcharts outlining the suggested treatments for patients with a malignant or nonmalignant CAO.

Visit www.chestnet.org/CAO-guideline to download the flowcharts and access the complete guideline.

CHEST recently released a new clinical guideline on central airway obstruction (CAO).

“Central airway obstruction is associated with a poor prognosis, and the management of CAO is highly variable dependent on the provider expertise and local resources. By releasing this guideline, the panel hopes to standardize the definition of CAO and provide guidance for the management of patients to optimize care and improve outcomes,” said Kamran Mahmood, MD, MPH, FCCP, lead author on the guideline. “The guideline recommendations are developed using GRADE methodology and based on thorough evidence review and expert input. But the quality of overall evidence is very low, and the panel calls for well-designed studies and randomized controlled trials for the management of CAO.”

CAO can be caused by a variety of malignant and nonmalignant disorders, and multiple specialists may be involved in the care, including pulmonologists, interventional pulmonologists, radiologists, anesthesiologists, oncologists, radiation oncologists, thoracic surgeons and otolaryngologists, etc. The panel recommends shared decision-making with the patients and a multidisciplinary approach to manage CAO.

Below, you’ll find flowcharts outlining the suggested treatments for patients with a malignant or nonmalignant CAO.

Visit www.chestnet.org/CAO-guideline to download the flowcharts and access the complete guideline.

CHEST recently released a new clinical guideline on central airway obstruction (CAO).

“Central airway obstruction is associated with a poor prognosis, and the management of CAO is highly variable dependent on the provider expertise and local resources. By releasing this guideline, the panel hopes to standardize the definition of CAO and provide guidance for the management of patients to optimize care and improve outcomes,” said Kamran Mahmood, MD, MPH, FCCP, lead author on the guideline. “The guideline recommendations are developed using GRADE methodology and based on thorough evidence review and expert input. But the quality of overall evidence is very low, and the panel calls for well-designed studies and randomized controlled trials for the management of CAO.”

CAO can be caused by a variety of malignant and nonmalignant disorders, and multiple specialists may be involved in the care, including pulmonologists, interventional pulmonologists, radiologists, anesthesiologists, oncologists, radiation oncologists, thoracic surgeons and otolaryngologists, etc. The panel recommends shared decision-making with the patients and a multidisciplinary approach to manage CAO.

Below, you’ll find flowcharts outlining the suggested treatments for patients with a malignant or nonmalignant CAO.

Visit www.chestnet.org/CAO-guideline to download the flowcharts and access the complete guideline.

Are Beta-Blockers Needed Post MI? No, Even After the ABYSS Trial

The ABYSS trial found that interruption of beta-blocker therapy in patients after myocardial infarction (MI) was not noninferior to continuing the drugs.

I will argue why I think it is okay to stop beta-blockers after MI — despite this conclusion. The results of ABYSS are, in fact, similar to REDUCE-AMI, which compared beta-blocker use or nonuse immediately after MI, and found no difference in a composite endpoint of death or MI.

The ABYSS Trial

ABYSS investigators randomly assigned nearly 3700 patients who had MI and were prescribed a beta-blocker to either continue (control arm) or stop (active arm) the drug at 1 year.

Patients had to have a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) at least 40%; the median was 60%.

The composite primary endpoint included death, MI, stroke, or hospitalization for any cardiovascular reason. ABYSS authors chose a noninferiority design. The assumption must have been that the interruption arm offered an easier option for patients — eg, fewer pills.

Over 3 years, a primary endpoint occurred in 23.8% of the interruption group vs 21.1% in the continuation group.

In ABYSS, the noninferiority margin was set at a 3% absolute risk increase. The 2.7% absolute risk increase had an upper bound of the 95% CI (worst case) of 5.5% leading to the not-noninferior conclusion (5.5% exceeds the noninferiority margins).

More simply stated, the primary outcome event rate was higher in the interruption arm.

Does This Mean we Should Continue Beta-Blockers in Post-MI Patients?

This led some to conclude that we should continue beta-blockers. I disagree. To properly interpret the ABYSS trial, you must consider trial procedures, components of the primary endpoint, and then compare ABYSS with REDUCE-AMI.

It’s also reasonable to have extremely pessimistic prior beliefs about post-MI beta-blockade because the evidence establishing benefit comes from trials conducted before urgent revascularization became the standard therapy.

ABYSS was a pragmatic open-label trial. The core problem with this design is that one of the components of the primary outcome (hospitalization for cardiovascular reasons) requires clinical judgment — and is therefore susceptible to bias, particularly in an open-label trial.

This becomes apparent when we look at the components of the primary outcome in the two arms of the trial (interrupt vs continue):

- For death, the rates were 4.1 and 4.0%

- For MI, the rates were 2.5 and 2.4%

- For stroke, the rates were 1.0% in both arms

- For CV hospitalization, the rates were 18.9% vs 16.6%

The higher rate CV hospitalization alone drove the results of ABYSS. Death, MI, and stroke rates were nearly identical.

The most common reason for admission to the hospital in this category was for angiography. In fact, the rate of angiography was 2.3% higher in the interruption arm — identical to the rate increase in the CV hospitalization component of the primary endpoint.

The results of ABYSS, therefore, were driven by higher rates of angiography in the interrupt arm.

You need not imply malfeasance to speculate that patients who had their beta-blocker stopped might be treated differently regarding hospital admissions or angiography than those who stayed on beta-blockers. Researchers from Imperial College London called such a bias in unblinded trials “subtraction anxiety and faith healing.”

Had the ABYSS investigators chosen the simpler, less bias-prone endpoints of death, MI, or stroke, their results would have been the same as REDUCE-AMI.

My Final Two Conclusions

I would conclude that interruption of beta-blockers at 1 year vs continuation in post-MI patients did not lead to an increase in death, MI, or stroke.

ABYSS, therefore, is consistent with REDUCE-AMI. Taken together, along with the pessimistic priors, these are important findings because they allow us to stop a medicine and reduce the work of being a patient.

My second conclusion concerns ways of knowing in medicine. I’ve long felt that randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are the best way to sort out causation. This idea led me to the believe that medicine should have more RCTs rather than follow expert opinion or therapeutic fashion.

I’ve now modified my love of RCTs — a little. The ABYSS trial is yet another example of the need to be super careful with their design.

Something as seemingly simple as choosing what to measure can alter the way clinicians interpret and use the data.

So, let’s have (slightly) more trials, but we should be really careful in their design. Slow and careful is the best way to practice medicine. And it’s surely the best way to do research as well.

Dr. Mandrola, clinical electrophysiologist, Baptist Medical Associates, Louisville, Kentucky, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The ABYSS trial found that interruption of beta-blocker therapy in patients after myocardial infarction (MI) was not noninferior to continuing the drugs.

I will argue why I think it is okay to stop beta-blockers after MI — despite this conclusion. The results of ABYSS are, in fact, similar to REDUCE-AMI, which compared beta-blocker use or nonuse immediately after MI, and found no difference in a composite endpoint of death or MI.

The ABYSS Trial

ABYSS investigators randomly assigned nearly 3700 patients who had MI and were prescribed a beta-blocker to either continue (control arm) or stop (active arm) the drug at 1 year.

Patients had to have a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) at least 40%; the median was 60%.

The composite primary endpoint included death, MI, stroke, or hospitalization for any cardiovascular reason. ABYSS authors chose a noninferiority design. The assumption must have been that the interruption arm offered an easier option for patients — eg, fewer pills.

Over 3 years, a primary endpoint occurred in 23.8% of the interruption group vs 21.1% in the continuation group.

In ABYSS, the noninferiority margin was set at a 3% absolute risk increase. The 2.7% absolute risk increase had an upper bound of the 95% CI (worst case) of 5.5% leading to the not-noninferior conclusion (5.5% exceeds the noninferiority margins).

More simply stated, the primary outcome event rate was higher in the interruption arm.

Does This Mean we Should Continue Beta-Blockers in Post-MI Patients?

This led some to conclude that we should continue beta-blockers. I disagree. To properly interpret the ABYSS trial, you must consider trial procedures, components of the primary endpoint, and then compare ABYSS with REDUCE-AMI.

It’s also reasonable to have extremely pessimistic prior beliefs about post-MI beta-blockade because the evidence establishing benefit comes from trials conducted before urgent revascularization became the standard therapy.

ABYSS was a pragmatic open-label trial. The core problem with this design is that one of the components of the primary outcome (hospitalization for cardiovascular reasons) requires clinical judgment — and is therefore susceptible to bias, particularly in an open-label trial.

This becomes apparent when we look at the components of the primary outcome in the two arms of the trial (interrupt vs continue):

- For death, the rates were 4.1 and 4.0%

- For MI, the rates were 2.5 and 2.4%

- For stroke, the rates were 1.0% in both arms

- For CV hospitalization, the rates were 18.9% vs 16.6%

The higher rate CV hospitalization alone drove the results of ABYSS. Death, MI, and stroke rates were nearly identical.

The most common reason for admission to the hospital in this category was for angiography. In fact, the rate of angiography was 2.3% higher in the interruption arm — identical to the rate increase in the CV hospitalization component of the primary endpoint.

The results of ABYSS, therefore, were driven by higher rates of angiography in the interrupt arm.

You need not imply malfeasance to speculate that patients who had their beta-blocker stopped might be treated differently regarding hospital admissions or angiography than those who stayed on beta-blockers. Researchers from Imperial College London called such a bias in unblinded trials “subtraction anxiety and faith healing.”

Had the ABYSS investigators chosen the simpler, less bias-prone endpoints of death, MI, or stroke, their results would have been the same as REDUCE-AMI.

My Final Two Conclusions

I would conclude that interruption of beta-blockers at 1 year vs continuation in post-MI patients did not lead to an increase in death, MI, or stroke.

ABYSS, therefore, is consistent with REDUCE-AMI. Taken together, along with the pessimistic priors, these are important findings because they allow us to stop a medicine and reduce the work of being a patient.

My second conclusion concerns ways of knowing in medicine. I’ve long felt that randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are the best way to sort out causation. This idea led me to the believe that medicine should have more RCTs rather than follow expert opinion or therapeutic fashion.

I’ve now modified my love of RCTs — a little. The ABYSS trial is yet another example of the need to be super careful with their design.

Something as seemingly simple as choosing what to measure can alter the way clinicians interpret and use the data.

So, let’s have (slightly) more trials, but we should be really careful in their design. Slow and careful is the best way to practice medicine. And it’s surely the best way to do research as well.

Dr. Mandrola, clinical electrophysiologist, Baptist Medical Associates, Louisville, Kentucky, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The ABYSS trial found that interruption of beta-blocker therapy in patients after myocardial infarction (MI) was not noninferior to continuing the drugs.

I will argue why I think it is okay to stop beta-blockers after MI — despite this conclusion. The results of ABYSS are, in fact, similar to REDUCE-AMI, which compared beta-blocker use or nonuse immediately after MI, and found no difference in a composite endpoint of death or MI.

The ABYSS Trial

ABYSS investigators randomly assigned nearly 3700 patients who had MI and were prescribed a beta-blocker to either continue (control arm) or stop (active arm) the drug at 1 year.

Patients had to have a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) at least 40%; the median was 60%.

The composite primary endpoint included death, MI, stroke, or hospitalization for any cardiovascular reason. ABYSS authors chose a noninferiority design. The assumption must have been that the interruption arm offered an easier option for patients — eg, fewer pills.

Over 3 years, a primary endpoint occurred in 23.8% of the interruption group vs 21.1% in the continuation group.

In ABYSS, the noninferiority margin was set at a 3% absolute risk increase. The 2.7% absolute risk increase had an upper bound of the 95% CI (worst case) of 5.5% leading to the not-noninferior conclusion (5.5% exceeds the noninferiority margins).

More simply stated, the primary outcome event rate was higher in the interruption arm.

Does This Mean we Should Continue Beta-Blockers in Post-MI Patients?

This led some to conclude that we should continue beta-blockers. I disagree. To properly interpret the ABYSS trial, you must consider trial procedures, components of the primary endpoint, and then compare ABYSS with REDUCE-AMI.

It’s also reasonable to have extremely pessimistic prior beliefs about post-MI beta-blockade because the evidence establishing benefit comes from trials conducted before urgent revascularization became the standard therapy.

ABYSS was a pragmatic open-label trial. The core problem with this design is that one of the components of the primary outcome (hospitalization for cardiovascular reasons) requires clinical judgment — and is therefore susceptible to bias, particularly in an open-label trial.

This becomes apparent when we look at the components of the primary outcome in the two arms of the trial (interrupt vs continue):

- For death, the rates were 4.1 and 4.0%

- For MI, the rates were 2.5 and 2.4%

- For stroke, the rates were 1.0% in both arms

- For CV hospitalization, the rates were 18.9% vs 16.6%

The higher rate CV hospitalization alone drove the results of ABYSS. Death, MI, and stroke rates were nearly identical.

The most common reason for admission to the hospital in this category was for angiography. In fact, the rate of angiography was 2.3% higher in the interruption arm — identical to the rate increase in the CV hospitalization component of the primary endpoint.

The results of ABYSS, therefore, were driven by higher rates of angiography in the interrupt arm.

You need not imply malfeasance to speculate that patients who had their beta-blocker stopped might be treated differently regarding hospital admissions or angiography than those who stayed on beta-blockers. Researchers from Imperial College London called such a bias in unblinded trials “subtraction anxiety and faith healing.”

Had the ABYSS investigators chosen the simpler, less bias-prone endpoints of death, MI, or stroke, their results would have been the same as REDUCE-AMI.

My Final Two Conclusions

I would conclude that interruption of beta-blockers at 1 year vs continuation in post-MI patients did not lead to an increase in death, MI, or stroke.

ABYSS, therefore, is consistent with REDUCE-AMI. Taken together, along with the pessimistic priors, these are important findings because they allow us to stop a medicine and reduce the work of being a patient.

My second conclusion concerns ways of knowing in medicine. I’ve long felt that randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are the best way to sort out causation. This idea led me to the believe that medicine should have more RCTs rather than follow expert opinion or therapeutic fashion.

I’ve now modified my love of RCTs — a little. The ABYSS trial is yet another example of the need to be super careful with their design.

Something as seemingly simple as choosing what to measure can alter the way clinicians interpret and use the data.

So, let’s have (slightly) more trials, but we should be really careful in their design. Slow and careful is the best way to practice medicine. And it’s surely the best way to do research as well.

Dr. Mandrola, clinical electrophysiologist, Baptist Medical Associates, Louisville, Kentucky, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

First-Time Fathers Experience Period of High Psychological Risk

Anxiety and stress during fatherhood receive less research attention than do anxiety and stress during motherhood.

Longitudinal data tracking the evolution of men’s mental health following the birth of the first child are even rarer, especially in the French population. Only two studies of the subject have been conducted. They were dedicated solely to paternal depression and limited to the first 4 months post partum. Better understanding of the risk in the population can not only help identify public health issues, but also aid in defining targeted preventive approaches.

French researchers in epidemiology and public health sought to expand our knowledge of the mental health trajectories of new fathers using 9 years of data from the CONSTANCES cohort. Within this cohort, participants filled out self-administered questionnaires annually. They declared their parental status and the presence of mental illnesses. They also completed questionnaires to assess mental health, such as the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale for depression and the General Health Questionnaire for depressive, anxious, and somatic disorders. Thresholds for each score were established to characterize the severity of symptoms. In addition, the researchers analyzed all factors (eg, sociodemographic, psychosocial, lifestyle, professional, family, or cultural) that potentially are associated with poor mental health and were available within the questionnaires.

The study included 6299 men who had their first child and for whom at least one mental health measure was collected during the follow-up period. These men had an average age of 38 years at inclusion, 88% lived with a partner, and 85% were employed. Overall, 7.9% of this male cohort self-reported a mental illness during the study, with 5.6% of illnesses occurring before the child’s birth and 9.7% after. Anxiety affected 6.5% of the cohort, and it was more pronounced after the birth than before (7.8% after vs 4.9% before).

The rate of clinically significant symptoms averaged 23.2% during the study period, increasing from 18.3% to 25.2% after the birth. The discrepancy between the self-declared diagnosis by new fathers and the symptom-related score highlights underreporting or insufficient awareness among men.

After conducting a latent class analysis, the researchers identified three homogeneous subgroups of men who had comparable mental health trajectories over time. The first group (90.3% of the cohort) maintained a constant and low risk for mental illnesses. The second (4.1%) presented a high and generally constant risk over time. Finally, 5.6% of the cohort had a temporarily high risk in the 2-4 years surrounding the birth.

The risk factors associated with being at a transiently high risk for mental illness were, in order of descending significance, not having a job, having had at least one negative experience during childhood, forgoing healthcare for financial reasons, and being aged 35-39 years (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] between 3.01 and 1.61). The risk factors associated with a high and constant mental illness risk were, in order of descending significance, being aged 60 years or older, not having a job, not living with a partner, being aged 40-44 years, and having other children in the following years (AOR between 3.79 and 1.85).

The authors noted that the risk factors for mental health challenges associated with fatherhood do not imply causality, the meaning of which would also need further study. They contended that French fathers, who on average are entitled to 2 weeks of paid paternity leave, may struggle to manage their time, professional responsibilities, and parenting duties. Consequently, they may experience dissatisfaction and difficulty seeking support, assistance, or a mental health diagnosis, especially in the face of a mental health risk to which they are less attuned than women.

This story was translated from Univadis France, which is part of the Medscape Professional Network, using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Anxiety and stress during fatherhood receive less research attention than do anxiety and stress during motherhood.

Longitudinal data tracking the evolution of men’s mental health following the birth of the first child are even rarer, especially in the French population. Only two studies of the subject have been conducted. They were dedicated solely to paternal depression and limited to the first 4 months post partum. Better understanding of the risk in the population can not only help identify public health issues, but also aid in defining targeted preventive approaches.

French researchers in epidemiology and public health sought to expand our knowledge of the mental health trajectories of new fathers using 9 years of data from the CONSTANCES cohort. Within this cohort, participants filled out self-administered questionnaires annually. They declared their parental status and the presence of mental illnesses. They also completed questionnaires to assess mental health, such as the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale for depression and the General Health Questionnaire for depressive, anxious, and somatic disorders. Thresholds for each score were established to characterize the severity of symptoms. In addition, the researchers analyzed all factors (eg, sociodemographic, psychosocial, lifestyle, professional, family, or cultural) that potentially are associated with poor mental health and were available within the questionnaires.

The study included 6299 men who had their first child and for whom at least one mental health measure was collected during the follow-up period. These men had an average age of 38 years at inclusion, 88% lived with a partner, and 85% were employed. Overall, 7.9% of this male cohort self-reported a mental illness during the study, with 5.6% of illnesses occurring before the child’s birth and 9.7% after. Anxiety affected 6.5% of the cohort, and it was more pronounced after the birth than before (7.8% after vs 4.9% before).

The rate of clinically significant symptoms averaged 23.2% during the study period, increasing from 18.3% to 25.2% after the birth. The discrepancy between the self-declared diagnosis by new fathers and the symptom-related score highlights underreporting or insufficient awareness among men.

After conducting a latent class analysis, the researchers identified three homogeneous subgroups of men who had comparable mental health trajectories over time. The first group (90.3% of the cohort) maintained a constant and low risk for mental illnesses. The second (4.1%) presented a high and generally constant risk over time. Finally, 5.6% of the cohort had a temporarily high risk in the 2-4 years surrounding the birth.

The risk factors associated with being at a transiently high risk for mental illness were, in order of descending significance, not having a job, having had at least one negative experience during childhood, forgoing healthcare for financial reasons, and being aged 35-39 years (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] between 3.01 and 1.61). The risk factors associated with a high and constant mental illness risk were, in order of descending significance, being aged 60 years or older, not having a job, not living with a partner, being aged 40-44 years, and having other children in the following years (AOR between 3.79 and 1.85).

The authors noted that the risk factors for mental health challenges associated with fatherhood do not imply causality, the meaning of which would also need further study. They contended that French fathers, who on average are entitled to 2 weeks of paid paternity leave, may struggle to manage their time, professional responsibilities, and parenting duties. Consequently, they may experience dissatisfaction and difficulty seeking support, assistance, or a mental health diagnosis, especially in the face of a mental health risk to which they are less attuned than women.

This story was translated from Univadis France, which is part of the Medscape Professional Network, using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Anxiety and stress during fatherhood receive less research attention than do anxiety and stress during motherhood.

Longitudinal data tracking the evolution of men’s mental health following the birth of the first child are even rarer, especially in the French population. Only two studies of the subject have been conducted. They were dedicated solely to paternal depression and limited to the first 4 months post partum. Better understanding of the risk in the population can not only help identify public health issues, but also aid in defining targeted preventive approaches.

French researchers in epidemiology and public health sought to expand our knowledge of the mental health trajectories of new fathers using 9 years of data from the CONSTANCES cohort. Within this cohort, participants filled out self-administered questionnaires annually. They declared their parental status and the presence of mental illnesses. They also completed questionnaires to assess mental health, such as the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale for depression and the General Health Questionnaire for depressive, anxious, and somatic disorders. Thresholds for each score were established to characterize the severity of symptoms. In addition, the researchers analyzed all factors (eg, sociodemographic, psychosocial, lifestyle, professional, family, or cultural) that potentially are associated with poor mental health and were available within the questionnaires.

The study included 6299 men who had their first child and for whom at least one mental health measure was collected during the follow-up period. These men had an average age of 38 years at inclusion, 88% lived with a partner, and 85% were employed. Overall, 7.9% of this male cohort self-reported a mental illness during the study, with 5.6% of illnesses occurring before the child’s birth and 9.7% after. Anxiety affected 6.5% of the cohort, and it was more pronounced after the birth than before (7.8% after vs 4.9% before).

The rate of clinically significant symptoms averaged 23.2% during the study period, increasing from 18.3% to 25.2% after the birth. The discrepancy between the self-declared diagnosis by new fathers and the symptom-related score highlights underreporting or insufficient awareness among men.

After conducting a latent class analysis, the researchers identified three homogeneous subgroups of men who had comparable mental health trajectories over time. The first group (90.3% of the cohort) maintained a constant and low risk for mental illnesses. The second (4.1%) presented a high and generally constant risk over time. Finally, 5.6% of the cohort had a temporarily high risk in the 2-4 years surrounding the birth.

The risk factors associated with being at a transiently high risk for mental illness were, in order of descending significance, not having a job, having had at least one negative experience during childhood, forgoing healthcare for financial reasons, and being aged 35-39 years (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] between 3.01 and 1.61). The risk factors associated with a high and constant mental illness risk were, in order of descending significance, being aged 60 years or older, not having a job, not living with a partner, being aged 40-44 years, and having other children in the following years (AOR between 3.79 and 1.85).

The authors noted that the risk factors for mental health challenges associated with fatherhood do not imply causality, the meaning of which would also need further study. They contended that French fathers, who on average are entitled to 2 weeks of paid paternity leave, may struggle to manage their time, professional responsibilities, and parenting duties. Consequently, they may experience dissatisfaction and difficulty seeking support, assistance, or a mental health diagnosis, especially in the face of a mental health risk to which they are less attuned than women.

This story was translated from Univadis France, which is part of the Medscape Professional Network, using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Setbacks Identified After Stopping Beta-Blockers

LONDON — It may not be advisable for patients with a history of myocardial infarction and preserved left ventricular function to discontinue long-term beta-blocker therapy, warn investigators.

In the randomized ABYSS trial, although there was no difference in death, MI, or stroke between patients who discontinued and those who continued taking beta-blockers, those who stopped taking the drugs had a higher rate of cardiovascular hospitalization.

Discontinuation was also associated with an increase in blood pressure and heart rate, without any improvement in quality of life.

The results, which were simultaneously published online in The New England Journal of Medicine, call into question current guidelines, which suggest that beta-blockers may be discontinued after 1 year in certain patient groups.

Beta-blockers have long been considered the standard of care for patients after MI, but trials showing the benefit of these drugs were conducted before the modern era of myocardial reperfusion and pharmacotherapy, which have led to sharp decreases in the risk for heart failure and for death after MI, Dr. Silvain explained.

This has led to questions about the add-on benefits of lifelong beta-blocker treatment for patients with MI and a preserved left ventricular ejection fraction and no other primary indication for beta-blocker therapy.

The ABYSS Trial

To explore this issue, the open-label, non-inferiority ABYSS trial randomly assigned 3698 patients with a history of MI to the discontinuation or continuation of beta-blocker treatment. All study participants had a left ventricular ejection fraction of at least 40%, were receiving long-term beta-blocker treatment, and had experienced no cardiovascular event in the previous 6 months.

At a median follow-up of 3 years, the primary endpoint — a composite of death, MI, stroke, and hospitalization for cardiovascular reasons — occurred more often in the discontinuation group than in the continuation group (23.8% vs 21.1%; hazard ratio, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.01-1.33). This did not meet the criteria for non-inferiority of discontinuation, compared with continuation, of beta-blocker therapy (P for non-inferiority = .44).

The difference in event rates between the two groups was driven by cardiovascular hospitalizations, which occurred more often in the discontinuation group than in the continuation group (18.9% vs 16.6%).

Other key results showed that there was no difference in quality of life between the two groups.

However, 6 months after randomization, there were increases in blood pressure and heart rate in the discontinuation group. Systolic blood pressure increased by 3.7 mm Hg and diastolic blood pressure increased by 3.9 mm Hg. Resting heart rate increased by 9.8 beats per minute.

“We were not able to show the non-inferiority of stopping beta-blockers in terms of cardiovascular events, [but we] showed a safety signal with this strategy of an increase in blood pressure and heart rate, with no improvement in quality of life,” Dr. Sylvain said.

“While recent guidelines suggest it may be reasonable to stop beta-blockers in this population, after these results, I will not be stopping these drugs if they are being well tolerated,” he said.

Sylvain said he was surprised that there was not an improvement in quality of life in the group that discontinued beta-blockers. “We are always told that beta-blockers have many side effects, so we expected to see an improvement in quality of life in the patients who stopped these drugs.”

One possible reason for the lack of improvement in quality of life is that the trial participants had been taking beta-blockers for several years. “We may have, therefore, selected patients who tolerate these drugs quite well. Those who had tolerance issues had probably already stopped taking them,” he explained.

In addition, the patient population had relatively high quality-of-life scores at baseline. “They were well treated and the therapies they were taking were well tolerated, so maybe it is difficult to improve quality of life further,” he said.

The REDUCE-AMI Trial

The ABYSS results appear at first to differ from results from the recent REDUCE-AMI trial, which failed to show the superiority of beta-blocker therapy, compared with no beta-blocker therapy, in acute MI patients with preserved ejection fraction.

But the REDUCE-AMI primary endpoint was a composite of death from any cause or new myocardial infarction; it did not include cardiovascular hospitalization, which was the main driver of the difference in outcomes in the ABYSS study, Dr. Sylvain pointed out.

“We showed an increase in coronary cases of hospitalization with stopping beta-blockers, and you have to remember that beta-blockers were developed to reduce coronary disease,” he said.

‘Slightly Inconclusive’

Jane Armitage, MBBS, University of Oxford, England, the ABYSS discussant for the ESC HOTLINE session, pointed out some limitations of the study, which led her to report that the result was “slightly inconclusive.”

The open-label design may have allowed some bias regarding the cardiovascular hospitalization endpoint, she said.

“The decision whether to admit a patient to [the] hospital is somewhat subjective and could be influenced by a physician’s knowledge of treatment allocation. That is why, ideally, we prefer blinded trials. I think there are questions there,” she explained.

She also questioned whether the non-inferiority margin could have been increased, given the higher-than-expected event rate.

More data on this issue will come from several trials that are currently ongoing, Dr. Armitage said.

The ABYSS and REDUCE-AMI trials together suggest that it is safe, with respect to serious cardiac events, to stop beta-blocker treatment in MI patients with preserved ejection fraction, writes Tomas Jernberg, MD, PhD, from the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm, Sweden, in an accompanying editorial.

However, “because of the anti-ischemic effects of beta-blockers, an interruption may increase the risk of recurrent angina and the need for rehospitalization,” he adds.

“It is prudent to wait for the results of additional ongoing trials of beta-blockers involving patients with MI and a preserved left ventricular ejection fraction before definitively updating guidelines,” Dr. Jernberg concludes.

The ABYSS trial was funded by the French Ministry of Health and the ACTION Study Group. Dr. Sylvain, Dr. Armitage, and Dr. Jernberg report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

LONDON — It may not be advisable for patients with a history of myocardial infarction and preserved left ventricular function to discontinue long-term beta-blocker therapy, warn investigators.

In the randomized ABYSS trial, although there was no difference in death, MI, or stroke between patients who discontinued and those who continued taking beta-blockers, those who stopped taking the drugs had a higher rate of cardiovascular hospitalization.

Discontinuation was also associated with an increase in blood pressure and heart rate, without any improvement in quality of life.

The results, which were simultaneously published online in The New England Journal of Medicine, call into question current guidelines, which suggest that beta-blockers may be discontinued after 1 year in certain patient groups.

Beta-blockers have long been considered the standard of care for patients after MI, but trials showing the benefit of these drugs were conducted before the modern era of myocardial reperfusion and pharmacotherapy, which have led to sharp decreases in the risk for heart failure and for death after MI, Dr. Silvain explained.

This has led to questions about the add-on benefits of lifelong beta-blocker treatment for patients with MI and a preserved left ventricular ejection fraction and no other primary indication for beta-blocker therapy.

The ABYSS Trial

To explore this issue, the open-label, non-inferiority ABYSS trial randomly assigned 3698 patients with a history of MI to the discontinuation or continuation of beta-blocker treatment. All study participants had a left ventricular ejection fraction of at least 40%, were receiving long-term beta-blocker treatment, and had experienced no cardiovascular event in the previous 6 months.