User login

Higher rates of PTSD, BPD in transgender vs. cisgender psych patients

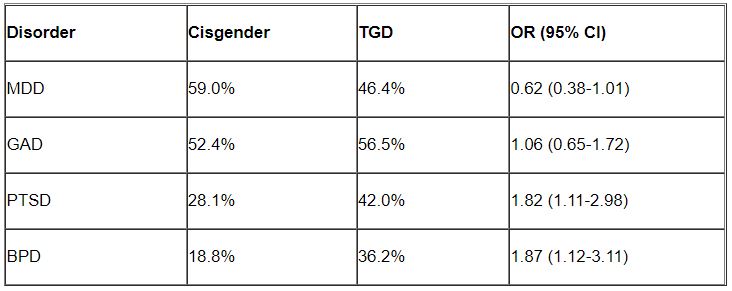

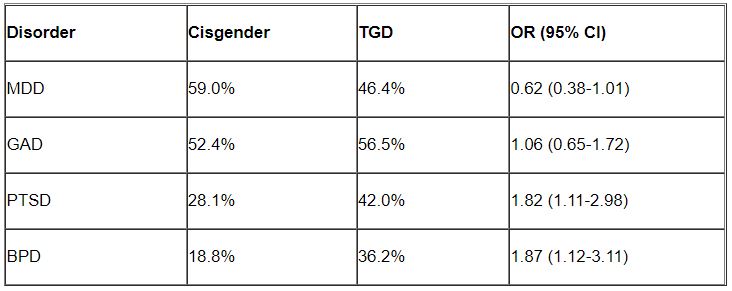

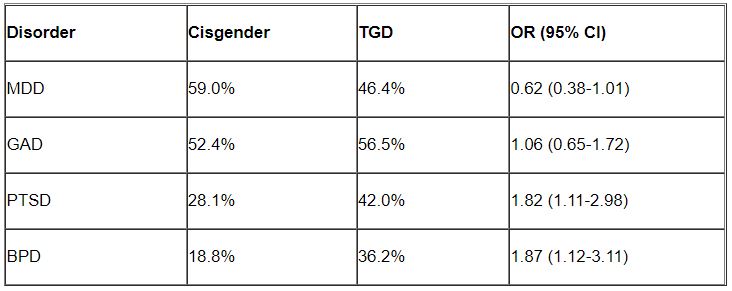

Although mood disorders, depression, and anxiety were the most common diagnoses in both TGD and cisgender patients, “when we compared the diagnostic profiles [of TGD patients] to those of cisgender patients, we found an increased prevalence of PTSD and BPD,” study investigator Mark Zimmerman, MD, professor of psychiatry and human behavior, Brown University, Providence, R.I., told this news organization.

“What we concluded is that psychiatric programs that wish to treat TGD patients should either have or should develop expertise in treating PTSD and BPD, not just mood and anxiety disorders,” Dr. Zimmerman said.

The study was published online September 26 in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

‘Piecemeal literature’

TGD individuals “experience high rates of various forms of psychopathology in general and when compared with cisgender persons,” the investigators note.

They point out that most empirical evidence has relied upon the use of brief, unstructured psychodiagnostic assessment measures and assessment of a “limited constellation of psychiatric symptoms domains,” resulting in a “piecemeal literature wherein each piece of research documents elevations in one – or a few – diagnostic domains.”

Studies pointing to broader psychosocial health variables have often relied upon self-reported measures. In addition, in studies that utilized a structured interview approach, none “used a formal interview procedure to assess psychiatric diagnoses” and most focused only on a “limited number of psychiatric conditions based on self-reports of past diagnosis.”

The goal of the current study was to use semistructured interviews administered by professionals to compare the diagnostic profiles of a samples of TGD and cisgender patients who presented for treatment at a single naturalistic, clinically acute setting – a partial hospital program.

Dr. Zimmerman said that there was an additional motive for conducting the study. “There has been discussion in the field as to whether or not transgender or gender-diverse individuals all have borderline personality disorder, but that hasn’t been our clinical impression.”

Rather, Dr. Zimmerman and colleagues believe TGD people “may have had more difficult childhoods and more difficult adjustments in society because of societal attitudes and have to deal with that stress, whether it be microaggressions or overt bullying and aggression.” The study was designed to investigate this issue.

In addition, studies conducted in primary care programs in individuals seeking gender-affirming surgery have “reported a limited number of psychiatric diagnoses, but we were wondering whether, amongst psychiatric patients specifically, there were differences in diagnostic profiles between transgender and gender-diverse patients and cisgender patients. If so, what might the implications be for providing care for this population?”

TGD not synonymous with borderline

To investigate, the researchers administered semistructured diagnostic interviews for DSM-IV disorders to 2,212 psychiatric patients (66% cisgender women, 30.8% cisgender men, 3.1% TGD; mean [standard deviation] age 36.7 [14.4] years) presenting to the Rhode Island Hospital Department of Psychiatry Partial Hospital Program between April 2014 and January 2021.

Patients also completed a demographic questionnaire including their assigned sex at birth and their current gender identity.

Most patients (44.9%) were single, followed by 23.5% who were married, 14.1% living in a relationship as if married, 12.0% divorced, 3.6% separated, and 1.9% widowed.

Almost three-quarters of participants (73.2%) identified as White, followed by Hispanic (10.7%), Black (6.7%), “other” or a combination of racial/ethnic backgrounds (6.6%), and Asian (2.7%).

There were no differences between cisgender and TGD groups in terms of race or education, but the TGD patients were significantly younger compared with their cisgender counterparts and were significantly more likely to have never been married.

The average number of psychiatric diagnoses in the sample was 3.05 (± 1.73), with TGD patients having a larger number of psychiatric diagnoses than did their cisgender peers (an average of 3.54 ± 1.88 vs. 3.04 ± 1.72, respectively; t = 2.37; P = .02).

Major depressive disorder (MDD) and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) were the most common disorders among both cisgender and TGD patients. However, after controlling for age, the researchers found that TGD patients were significantly more likely than were the cisgender patients to be diagnosed with PTSD and BPD (P < .05 for both).

“Of note, only about one-third of the TGD individuals were diagnosed with BPD, so it is important to realize that transgender or gender-diverse identity is not synonymous with BPD, as some have suggested,” noted Dr. Zimmerman, who is also the director of the outpatient division at the Partial Hospital Program, Rhode Island Hospital.

A representative sample?

Commenting on the study, Jack Drescher, MD, distinguished life fellow of the American Psychiatric Association and clinical professor of psychiatry, Columbia University, New York, called the findings “interesting” but noted that a limitation of the study is that it included “a patient population with likely more severe psychiatric illness, since they were all day hospital patients.”

The question is whether similar findings would be obtained in a less severely ill population, said Dr. Drescher, who is also a senior consulting analyst for sexuality and gender at Columbia University and was not involved with the study. “The patients in the study may not be representative of the general population, either cisgender or transgender.”

Dr. Drescher was “not surprised” by the finding regarding PTSD because the finding “is consistent with our understanding of the kinds of traumas that transgender people go through in day-to-day life.”

He noted that some people misunderstand the diagnostic criterion in BPD of identity confusion and think that because people with gender dysphoria may be confused about their identity, it means that all people who are transgender have borderline personality disorder, “but that’s not true.”

Dr. Zimmerman agreed. “The vast majority of individuals with BPD do not have a transgender or gender-diverse identity, and TGD should not be equated with BPD,” he said.

No source of study funding was disclosed. Dr. Zimmerman and coauthors and Dr. Drescher report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Although mood disorders, depression, and anxiety were the most common diagnoses in both TGD and cisgender patients, “when we compared the diagnostic profiles [of TGD patients] to those of cisgender patients, we found an increased prevalence of PTSD and BPD,” study investigator Mark Zimmerman, MD, professor of psychiatry and human behavior, Brown University, Providence, R.I., told this news organization.

“What we concluded is that psychiatric programs that wish to treat TGD patients should either have or should develop expertise in treating PTSD and BPD, not just mood and anxiety disorders,” Dr. Zimmerman said.

The study was published online September 26 in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

‘Piecemeal literature’

TGD individuals “experience high rates of various forms of psychopathology in general and when compared with cisgender persons,” the investigators note.

They point out that most empirical evidence has relied upon the use of brief, unstructured psychodiagnostic assessment measures and assessment of a “limited constellation of psychiatric symptoms domains,” resulting in a “piecemeal literature wherein each piece of research documents elevations in one – or a few – diagnostic domains.”

Studies pointing to broader psychosocial health variables have often relied upon self-reported measures. In addition, in studies that utilized a structured interview approach, none “used a formal interview procedure to assess psychiatric diagnoses” and most focused only on a “limited number of psychiatric conditions based on self-reports of past diagnosis.”

The goal of the current study was to use semistructured interviews administered by professionals to compare the diagnostic profiles of a samples of TGD and cisgender patients who presented for treatment at a single naturalistic, clinically acute setting – a partial hospital program.

Dr. Zimmerman said that there was an additional motive for conducting the study. “There has been discussion in the field as to whether or not transgender or gender-diverse individuals all have borderline personality disorder, but that hasn’t been our clinical impression.”

Rather, Dr. Zimmerman and colleagues believe TGD people “may have had more difficult childhoods and more difficult adjustments in society because of societal attitudes and have to deal with that stress, whether it be microaggressions or overt bullying and aggression.” The study was designed to investigate this issue.

In addition, studies conducted in primary care programs in individuals seeking gender-affirming surgery have “reported a limited number of psychiatric diagnoses, but we were wondering whether, amongst psychiatric patients specifically, there were differences in diagnostic profiles between transgender and gender-diverse patients and cisgender patients. If so, what might the implications be for providing care for this population?”

TGD not synonymous with borderline

To investigate, the researchers administered semistructured diagnostic interviews for DSM-IV disorders to 2,212 psychiatric patients (66% cisgender women, 30.8% cisgender men, 3.1% TGD; mean [standard deviation] age 36.7 [14.4] years) presenting to the Rhode Island Hospital Department of Psychiatry Partial Hospital Program between April 2014 and January 2021.

Patients also completed a demographic questionnaire including their assigned sex at birth and their current gender identity.

Most patients (44.9%) were single, followed by 23.5% who were married, 14.1% living in a relationship as if married, 12.0% divorced, 3.6% separated, and 1.9% widowed.

Almost three-quarters of participants (73.2%) identified as White, followed by Hispanic (10.7%), Black (6.7%), “other” or a combination of racial/ethnic backgrounds (6.6%), and Asian (2.7%).

There were no differences between cisgender and TGD groups in terms of race or education, but the TGD patients were significantly younger compared with their cisgender counterparts and were significantly more likely to have never been married.

The average number of psychiatric diagnoses in the sample was 3.05 (± 1.73), with TGD patients having a larger number of psychiatric diagnoses than did their cisgender peers (an average of 3.54 ± 1.88 vs. 3.04 ± 1.72, respectively; t = 2.37; P = .02).

Major depressive disorder (MDD) and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) were the most common disorders among both cisgender and TGD patients. However, after controlling for age, the researchers found that TGD patients were significantly more likely than were the cisgender patients to be diagnosed with PTSD and BPD (P < .05 for both).

“Of note, only about one-third of the TGD individuals were diagnosed with BPD, so it is important to realize that transgender or gender-diverse identity is not synonymous with BPD, as some have suggested,” noted Dr. Zimmerman, who is also the director of the outpatient division at the Partial Hospital Program, Rhode Island Hospital.

A representative sample?

Commenting on the study, Jack Drescher, MD, distinguished life fellow of the American Psychiatric Association and clinical professor of psychiatry, Columbia University, New York, called the findings “interesting” but noted that a limitation of the study is that it included “a patient population with likely more severe psychiatric illness, since they were all day hospital patients.”

The question is whether similar findings would be obtained in a less severely ill population, said Dr. Drescher, who is also a senior consulting analyst for sexuality and gender at Columbia University and was not involved with the study. “The patients in the study may not be representative of the general population, either cisgender or transgender.”

Dr. Drescher was “not surprised” by the finding regarding PTSD because the finding “is consistent with our understanding of the kinds of traumas that transgender people go through in day-to-day life.”

He noted that some people misunderstand the diagnostic criterion in BPD of identity confusion and think that because people with gender dysphoria may be confused about their identity, it means that all people who are transgender have borderline personality disorder, “but that’s not true.”

Dr. Zimmerman agreed. “The vast majority of individuals with BPD do not have a transgender or gender-diverse identity, and TGD should not be equated with BPD,” he said.

No source of study funding was disclosed. Dr. Zimmerman and coauthors and Dr. Drescher report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Although mood disorders, depression, and anxiety were the most common diagnoses in both TGD and cisgender patients, “when we compared the diagnostic profiles [of TGD patients] to those of cisgender patients, we found an increased prevalence of PTSD and BPD,” study investigator Mark Zimmerman, MD, professor of psychiatry and human behavior, Brown University, Providence, R.I., told this news organization.

“What we concluded is that psychiatric programs that wish to treat TGD patients should either have or should develop expertise in treating PTSD and BPD, not just mood and anxiety disorders,” Dr. Zimmerman said.

The study was published online September 26 in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

‘Piecemeal literature’

TGD individuals “experience high rates of various forms of psychopathology in general and when compared with cisgender persons,” the investigators note.

They point out that most empirical evidence has relied upon the use of brief, unstructured psychodiagnostic assessment measures and assessment of a “limited constellation of psychiatric symptoms domains,” resulting in a “piecemeal literature wherein each piece of research documents elevations in one – or a few – diagnostic domains.”

Studies pointing to broader psychosocial health variables have often relied upon self-reported measures. In addition, in studies that utilized a structured interview approach, none “used a formal interview procedure to assess psychiatric diagnoses” and most focused only on a “limited number of psychiatric conditions based on self-reports of past diagnosis.”

The goal of the current study was to use semistructured interviews administered by professionals to compare the diagnostic profiles of a samples of TGD and cisgender patients who presented for treatment at a single naturalistic, clinically acute setting – a partial hospital program.

Dr. Zimmerman said that there was an additional motive for conducting the study. “There has been discussion in the field as to whether or not transgender or gender-diverse individuals all have borderline personality disorder, but that hasn’t been our clinical impression.”

Rather, Dr. Zimmerman and colleagues believe TGD people “may have had more difficult childhoods and more difficult adjustments in society because of societal attitudes and have to deal with that stress, whether it be microaggressions or overt bullying and aggression.” The study was designed to investigate this issue.

In addition, studies conducted in primary care programs in individuals seeking gender-affirming surgery have “reported a limited number of psychiatric diagnoses, but we were wondering whether, amongst psychiatric patients specifically, there were differences in diagnostic profiles between transgender and gender-diverse patients and cisgender patients. If so, what might the implications be for providing care for this population?”

TGD not synonymous with borderline

To investigate, the researchers administered semistructured diagnostic interviews for DSM-IV disorders to 2,212 psychiatric patients (66% cisgender women, 30.8% cisgender men, 3.1% TGD; mean [standard deviation] age 36.7 [14.4] years) presenting to the Rhode Island Hospital Department of Psychiatry Partial Hospital Program between April 2014 and January 2021.

Patients also completed a demographic questionnaire including their assigned sex at birth and their current gender identity.

Most patients (44.9%) were single, followed by 23.5% who were married, 14.1% living in a relationship as if married, 12.0% divorced, 3.6% separated, and 1.9% widowed.

Almost three-quarters of participants (73.2%) identified as White, followed by Hispanic (10.7%), Black (6.7%), “other” or a combination of racial/ethnic backgrounds (6.6%), and Asian (2.7%).

There were no differences between cisgender and TGD groups in terms of race or education, but the TGD patients were significantly younger compared with their cisgender counterparts and were significantly more likely to have never been married.

The average number of psychiatric diagnoses in the sample was 3.05 (± 1.73), with TGD patients having a larger number of psychiatric diagnoses than did their cisgender peers (an average of 3.54 ± 1.88 vs. 3.04 ± 1.72, respectively; t = 2.37; P = .02).

Major depressive disorder (MDD) and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) were the most common disorders among both cisgender and TGD patients. However, after controlling for age, the researchers found that TGD patients were significantly more likely than were the cisgender patients to be diagnosed with PTSD and BPD (P < .05 for both).

“Of note, only about one-third of the TGD individuals were diagnosed with BPD, so it is important to realize that transgender or gender-diverse identity is not synonymous with BPD, as some have suggested,” noted Dr. Zimmerman, who is also the director of the outpatient division at the Partial Hospital Program, Rhode Island Hospital.

A representative sample?

Commenting on the study, Jack Drescher, MD, distinguished life fellow of the American Psychiatric Association and clinical professor of psychiatry, Columbia University, New York, called the findings “interesting” but noted that a limitation of the study is that it included “a patient population with likely more severe psychiatric illness, since they were all day hospital patients.”

The question is whether similar findings would be obtained in a less severely ill population, said Dr. Drescher, who is also a senior consulting analyst for sexuality and gender at Columbia University and was not involved with the study. “The patients in the study may not be representative of the general population, either cisgender or transgender.”

Dr. Drescher was “not surprised” by the finding regarding PTSD because the finding “is consistent with our understanding of the kinds of traumas that transgender people go through in day-to-day life.”

He noted that some people misunderstand the diagnostic criterion in BPD of identity confusion and think that because people with gender dysphoria may be confused about their identity, it means that all people who are transgender have borderline personality disorder, “but that’s not true.”

Dr. Zimmerman agreed. “The vast majority of individuals with BPD do not have a transgender or gender-diverse identity, and TGD should not be equated with BPD,” he said.

No source of study funding was disclosed. Dr. Zimmerman and coauthors and Dr. Drescher report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JOURNAL OF CLINICAL PSYCHIATRY

Resection of infected sacrohysteropexy mesh

Pain in Cancer Survivors: Assess, Monitor, and Ask for Help

SAN DIEGO—As patients with cancer live longer, pain is going to become an even bigger challenge for clinicians, a palliative care specialist told cancer specialists in a presentation at the annual meeting of the Association of VA Hematology/Oncology (AVAHO) in September, and decisions about treatment are becoming more complicated amid the opioid epidemic.

Fortunately, guidelines and clinical experience offer helpful insight into the best practices, said hematologist/oncologist Andrea Ruskin, MD, medical director of palliative care at Veterans Administration (VA) Connecticut Healthcare System (VACHS).

As Ruskin pointed out, two-thirds of newly diagnosed cancer patients are living for at least 5 years, “but with this progress comes challenges.” More than one-third (37%) of cancer survivors report cancer pain, 21% have noncancer pain, and 45% have both. About 5% to 8% of VA cancer survivors use opioids for the long term, she said, although there have been few studies in this population.

Among patients with head and neck cancer, specifically, chronic pain affects 45%, and severe pain affects 11%. Subclinical PTSD, depression, anxiety, and low quality of life are common in this population. “We may cure them, but they have a lot of issues going forward.”

One key strategy is to perform a comprehensive pain assessment at the first visit, and then address pain at every subsequent visit. She recommended a physician resource from the American Society of Clinical Oncology, and a template may be useful to provide helpful questions, Ruskin said.

At VACHS certain questions are routine. “Is pain interfering with your function? Sometimes people say it’s always a 10, but it’s not affecting function at all. Ask if the medicine is working. And how are they taking it? Sometimes they say, ‘I’m taking that for sleep,’ and we say ‘No, Mr. Smith, that is not a sleep medication.’”

Be aware that some patients may use nonmedical opioids, she said. And set expectations early on. “Safe opioid use starts with the very first prescription,” she said. “If I have somebody with myeloma or head and neck cancer, I make it very clear that my goal is that we want you off the opioids after the radiation or once the disease is in remission. I really make an effort at the very beginning to make sure that we're all on the same page.”

As you continue to see a patient, consider ordering urine tests, she said, not as a punitive measure but to make sure you’re offering the safest and most effective treatment. “We don’t do it to say ‘no, no, no.’ We do it for safety and to make sure they’re not getting meds elsewhere.”

What are the best practices when pain doesn’t go away? Should they stay on opioids? According to Ruskin, few evidence-based guidelines address the “more nuanced care” that patients need when their pain lasts for months or years.

But there are useful resources. Ruskin highlighted the National Comprehensive Cancer Network’s survivorship guidelines, and she summarized a few of the available painkiller options. “Opioids are great, and adjuvants are so-so. They work in some people, but we definitely have room for improvement.”

What if patients have persistent opioid use after cancer recovery? “I try to taper if I can, and I try to explain why I’m tapering. It could take months or years to taper patients,” she said. And consider transitioning the patient to buprenorphine, a drug that treats both pain and opioid use disorder, if appropriate. “You don’t need a waiver if you use it for pain. It’s definitely something we’re using more of.”

One important step is to bring in colleagues to help. Psychologists, chiropractors, physical therapists, physiatrists, and pain pharmacists can all be helpful, she said. “Learn about your VA resources and who can partner with you to help these complicated patients. They’re all at your fingertips.”

SAN DIEGO—As patients with cancer live longer, pain is going to become an even bigger challenge for clinicians, a palliative care specialist told cancer specialists in a presentation at the annual meeting of the Association of VA Hematology/Oncology (AVAHO) in September, and decisions about treatment are becoming more complicated amid the opioid epidemic.

Fortunately, guidelines and clinical experience offer helpful insight into the best practices, said hematologist/oncologist Andrea Ruskin, MD, medical director of palliative care at Veterans Administration (VA) Connecticut Healthcare System (VACHS).

As Ruskin pointed out, two-thirds of newly diagnosed cancer patients are living for at least 5 years, “but with this progress comes challenges.” More than one-third (37%) of cancer survivors report cancer pain, 21% have noncancer pain, and 45% have both. About 5% to 8% of VA cancer survivors use opioids for the long term, she said, although there have been few studies in this population.

Among patients with head and neck cancer, specifically, chronic pain affects 45%, and severe pain affects 11%. Subclinical PTSD, depression, anxiety, and low quality of life are common in this population. “We may cure them, but they have a lot of issues going forward.”

One key strategy is to perform a comprehensive pain assessment at the first visit, and then address pain at every subsequent visit. She recommended a physician resource from the American Society of Clinical Oncology, and a template may be useful to provide helpful questions, Ruskin said.

At VACHS certain questions are routine. “Is pain interfering with your function? Sometimes people say it’s always a 10, but it’s not affecting function at all. Ask if the medicine is working. And how are they taking it? Sometimes they say, ‘I’m taking that for sleep,’ and we say ‘No, Mr. Smith, that is not a sleep medication.’”

Be aware that some patients may use nonmedical opioids, she said. And set expectations early on. “Safe opioid use starts with the very first prescription,” she said. “If I have somebody with myeloma or head and neck cancer, I make it very clear that my goal is that we want you off the opioids after the radiation or once the disease is in remission. I really make an effort at the very beginning to make sure that we're all on the same page.”

As you continue to see a patient, consider ordering urine tests, she said, not as a punitive measure but to make sure you’re offering the safest and most effective treatment. “We don’t do it to say ‘no, no, no.’ We do it for safety and to make sure they’re not getting meds elsewhere.”

What are the best practices when pain doesn’t go away? Should they stay on opioids? According to Ruskin, few evidence-based guidelines address the “more nuanced care” that patients need when their pain lasts for months or years.

But there are useful resources. Ruskin highlighted the National Comprehensive Cancer Network’s survivorship guidelines, and she summarized a few of the available painkiller options. “Opioids are great, and adjuvants are so-so. They work in some people, but we definitely have room for improvement.”

What if patients have persistent opioid use after cancer recovery? “I try to taper if I can, and I try to explain why I’m tapering. It could take months or years to taper patients,” she said. And consider transitioning the patient to buprenorphine, a drug that treats both pain and opioid use disorder, if appropriate. “You don’t need a waiver if you use it for pain. It’s definitely something we’re using more of.”

One important step is to bring in colleagues to help. Psychologists, chiropractors, physical therapists, physiatrists, and pain pharmacists can all be helpful, she said. “Learn about your VA resources and who can partner with you to help these complicated patients. They’re all at your fingertips.”

SAN DIEGO—As patients with cancer live longer, pain is going to become an even bigger challenge for clinicians, a palliative care specialist told cancer specialists in a presentation at the annual meeting of the Association of VA Hematology/Oncology (AVAHO) in September, and decisions about treatment are becoming more complicated amid the opioid epidemic.

Fortunately, guidelines and clinical experience offer helpful insight into the best practices, said hematologist/oncologist Andrea Ruskin, MD, medical director of palliative care at Veterans Administration (VA) Connecticut Healthcare System (VACHS).

As Ruskin pointed out, two-thirds of newly diagnosed cancer patients are living for at least 5 years, “but with this progress comes challenges.” More than one-third (37%) of cancer survivors report cancer pain, 21% have noncancer pain, and 45% have both. About 5% to 8% of VA cancer survivors use opioids for the long term, she said, although there have been few studies in this population.

Among patients with head and neck cancer, specifically, chronic pain affects 45%, and severe pain affects 11%. Subclinical PTSD, depression, anxiety, and low quality of life are common in this population. “We may cure them, but they have a lot of issues going forward.”

One key strategy is to perform a comprehensive pain assessment at the first visit, and then address pain at every subsequent visit. She recommended a physician resource from the American Society of Clinical Oncology, and a template may be useful to provide helpful questions, Ruskin said.

At VACHS certain questions are routine. “Is pain interfering with your function? Sometimes people say it’s always a 10, but it’s not affecting function at all. Ask if the medicine is working. And how are they taking it? Sometimes they say, ‘I’m taking that for sleep,’ and we say ‘No, Mr. Smith, that is not a sleep medication.’”

Be aware that some patients may use nonmedical opioids, she said. And set expectations early on. “Safe opioid use starts with the very first prescription,” she said. “If I have somebody with myeloma or head and neck cancer, I make it very clear that my goal is that we want you off the opioids after the radiation or once the disease is in remission. I really make an effort at the very beginning to make sure that we're all on the same page.”

As you continue to see a patient, consider ordering urine tests, she said, not as a punitive measure but to make sure you’re offering the safest and most effective treatment. “We don’t do it to say ‘no, no, no.’ We do it for safety and to make sure they’re not getting meds elsewhere.”

What are the best practices when pain doesn’t go away? Should they stay on opioids? According to Ruskin, few evidence-based guidelines address the “more nuanced care” that patients need when their pain lasts for months or years.

But there are useful resources. Ruskin highlighted the National Comprehensive Cancer Network’s survivorship guidelines, and she summarized a few of the available painkiller options. “Opioids are great, and adjuvants are so-so. They work in some people, but we definitely have room for improvement.”

What if patients have persistent opioid use after cancer recovery? “I try to taper if I can, and I try to explain why I’m tapering. It could take months or years to taper patients,” she said. And consider transitioning the patient to buprenorphine, a drug that treats both pain and opioid use disorder, if appropriate. “You don’t need a waiver if you use it for pain. It’s definitely something we’re using more of.”

One important step is to bring in colleagues to help. Psychologists, chiropractors, physical therapists, physiatrists, and pain pharmacists can all be helpful, she said. “Learn about your VA resources and who can partner with you to help these complicated patients. They’re all at your fingertips.”

HCC surveillance screening increased slightly with invitations, reminders

Mailing invitations for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) surveillance screening to patients with cirrhosis increased ultrasound uptake by 13 percentage points, but the majority of patients still did not receive the recommended semiannual screenings, according to findings published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

“These data highlight the need for more intensive interventions to further increase surveillance,” wrote Amit Singal, MD, of University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center and Parkland Health Hospital System in Dallas, and colleagues. “The underuse of HCC surveillance has been attributed to a combination of patient- and provider-level barriers, which can serve as future additional intervention targets.” These include transportation and financial barriers and possibly new blood-based screening modalities when they become available, thereby removing the need for a separate ultrasound appointment.

According to one study, more than 90% of hepatocellular carcinoma cases occur in people with chronic liver disease, and the cancer is a leading cause of death in those with compensated cirrhosis. Multiple medical associations therefore recommend an abdominal ultrasound every 6 months with or without alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) for surveillance in at-risk patients, including anyone with cirrhosis of any kind, but too few patients receive these surveillance ultrasounds, the authors write.

The researchers therefore conducted a pragmatic randomized clinical trial from March 2018 to September 2019 to compare surveillance ultrasound uptake for two groups of people with cirrhosis: 1,436 people who were mailed invitations to get a surveillance ultrasound and 1,436 people who received usual care, with surveillance recommended only at usual visits. The patients all received care at one of three health systems: a tertiary care referral center, a safety net health system, and a Veterans Affairs medical center. The primary outcome was semiannual surveillance in the patients over 1 year.

The researchers identified patients using ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes for cirrhosis and cirrhosis complications, as well as those with suspected but undocumented cirrhosis based on electronic medical record notes such as an elevated Fibrosis-4 index. They confirmed the diagnoses with chart review, confirmed that the patients had at least one outpatient visit in the previous year, and excluded those in whom surveillance is not recommended, who lacked contact information, or who spoke a language besides English or Spanish.

The mailing was a one-page letter in English and Spanish, written at a low literacy level, that explained hepatocellular carcinoma risk and recommended surveillance. Those who didn’t respond to the mailed invitation within 2 weeks received a reminder call to undergo surveillance, and those who scheduled an ultrasound received a reminder call about a week before the visit. Primary and subspecialty providers were blinded to the patients’ study arm assignments.

“We conducted the study as a pragmatic trial whereby patients in either arm could also be offered HCC surveillance by primary or specialty care providers during clinic visits,” the researchers wrote. “The frequency of the clinic visits and provider discussions regarding HCC surveillance were conducted per usual care and not dictated by the study protocol.”

Two-thirds of the patients (67.7%) were men, with a median age of 61.2 years. Just over a third (37.0%) were white, 31.9% were Hispanic, and 27.6% were Black. More than half the patients had hepatitis C (56.4%), 18.1% had alcohol-related liver disease, 14.5% had nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, and 2.4% had hepatitis B. Most of the patients had compensated cirrhosis, including 36.7% with ascites and 17.1% with hepatic encephalopathy.

Nearly a quarter of the patients in the outreach arm (23%) could not be contacted or lacked working phone numbers, but they remained in the intent-to-screen analysis. Just over a third of the patients who received mailed outreach (35.1%; 95% confidence interval, 32.6%-37.6%) received semiannual surveillance, compared to 21.9% (95% CI, 19.8%-24.2%) of the usual-care patients. The increased surveillance in the outreach group applied to most subgroups, including race/ethnicity and cirrhosis severity based on the Child-Turcotte-Pugh class.

“However, we observed site-level differences in the intervention effect, with significant increases in semiannual surveillance at the VA and safety net health systems (both P < .001) but not at the tertiary care referral center (P = .52),” the authors wrote. “In a post hoc subgroup analysis among patients with at least 1 primary care or gastroenterology outpatient visit during the study period, mailed outreach continued to increase semiannual surveillance, compared with usual care (46.8% vs. 32.7%; P < .001).”

Despite the improved rates from the intervention, the majority of patients still did not receive semiannual surveillance across all three sites, and almost 30% underwent no surveillance the entire year.

The research was funded by the National Cancer Institute, the Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas, and the Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness and Safety. Dr. Singal has consulted for or served on the advisory boards of Bayer, FujiFilm Medical Sciences, Exact Sciences, Roche, Glycotest, and GRAIL. The other authors had no industry disclosures.

Hepatocellular carcinoma is a deadly cancer that is usually incurable unless detected at an early stage through regular surveillance. Current American guidelines support 6-monthly abdominal ultrasonography, with or without serum alpha-fetoprotein, for HCC surveillance in at-risk patients, such as those with cirrhosis. However, even in such a high-risk group, the uptake of and adherence to surveillance are far from satisfactory. This study by Dr. Singal and colleagues is therefore important and practical. Randomized controlled trials in HCC surveillance are rare. The authors clearly demonstrate that an outreach program comprising mail invitations followed by phone contacts if there was no response could increase the surveillance uptake by more than 10%.

None of these can work if chronic liver disease and cirrhosis are not diagnosed in the first place. Disease awareness, access to care (and racial discrepancies), and clinical care pathways are hurdles we need to overcome in order to make an impact on HCC mortality at the population level.

Vincent Wong, MD, is an academic hepatologist at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. He does not have relevant conflicts of interest in this article.

Hepatocellular carcinoma is a deadly cancer that is usually incurable unless detected at an early stage through regular surveillance. Current American guidelines support 6-monthly abdominal ultrasonography, with or without serum alpha-fetoprotein, for HCC surveillance in at-risk patients, such as those with cirrhosis. However, even in such a high-risk group, the uptake of and adherence to surveillance are far from satisfactory. This study by Dr. Singal and colleagues is therefore important and practical. Randomized controlled trials in HCC surveillance are rare. The authors clearly demonstrate that an outreach program comprising mail invitations followed by phone contacts if there was no response could increase the surveillance uptake by more than 10%.

None of these can work if chronic liver disease and cirrhosis are not diagnosed in the first place. Disease awareness, access to care (and racial discrepancies), and clinical care pathways are hurdles we need to overcome in order to make an impact on HCC mortality at the population level.

Vincent Wong, MD, is an academic hepatologist at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. He does not have relevant conflicts of interest in this article.

Hepatocellular carcinoma is a deadly cancer that is usually incurable unless detected at an early stage through regular surveillance. Current American guidelines support 6-monthly abdominal ultrasonography, with or without serum alpha-fetoprotein, for HCC surveillance in at-risk patients, such as those with cirrhosis. However, even in such a high-risk group, the uptake of and adherence to surveillance are far from satisfactory. This study by Dr. Singal and colleagues is therefore important and practical. Randomized controlled trials in HCC surveillance are rare. The authors clearly demonstrate that an outreach program comprising mail invitations followed by phone contacts if there was no response could increase the surveillance uptake by more than 10%.

None of these can work if chronic liver disease and cirrhosis are not diagnosed in the first place. Disease awareness, access to care (and racial discrepancies), and clinical care pathways are hurdles we need to overcome in order to make an impact on HCC mortality at the population level.

Vincent Wong, MD, is an academic hepatologist at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. He does not have relevant conflicts of interest in this article.

Mailing invitations for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) surveillance screening to patients with cirrhosis increased ultrasound uptake by 13 percentage points, but the majority of patients still did not receive the recommended semiannual screenings, according to findings published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

“These data highlight the need for more intensive interventions to further increase surveillance,” wrote Amit Singal, MD, of University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center and Parkland Health Hospital System in Dallas, and colleagues. “The underuse of HCC surveillance has been attributed to a combination of patient- and provider-level barriers, which can serve as future additional intervention targets.” These include transportation and financial barriers and possibly new blood-based screening modalities when they become available, thereby removing the need for a separate ultrasound appointment.

According to one study, more than 90% of hepatocellular carcinoma cases occur in people with chronic liver disease, and the cancer is a leading cause of death in those with compensated cirrhosis. Multiple medical associations therefore recommend an abdominal ultrasound every 6 months with or without alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) for surveillance in at-risk patients, including anyone with cirrhosis of any kind, but too few patients receive these surveillance ultrasounds, the authors write.

The researchers therefore conducted a pragmatic randomized clinical trial from March 2018 to September 2019 to compare surveillance ultrasound uptake for two groups of people with cirrhosis: 1,436 people who were mailed invitations to get a surveillance ultrasound and 1,436 people who received usual care, with surveillance recommended only at usual visits. The patients all received care at one of three health systems: a tertiary care referral center, a safety net health system, and a Veterans Affairs medical center. The primary outcome was semiannual surveillance in the patients over 1 year.

The researchers identified patients using ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes for cirrhosis and cirrhosis complications, as well as those with suspected but undocumented cirrhosis based on electronic medical record notes such as an elevated Fibrosis-4 index. They confirmed the diagnoses with chart review, confirmed that the patients had at least one outpatient visit in the previous year, and excluded those in whom surveillance is not recommended, who lacked contact information, or who spoke a language besides English or Spanish.

The mailing was a one-page letter in English and Spanish, written at a low literacy level, that explained hepatocellular carcinoma risk and recommended surveillance. Those who didn’t respond to the mailed invitation within 2 weeks received a reminder call to undergo surveillance, and those who scheduled an ultrasound received a reminder call about a week before the visit. Primary and subspecialty providers were blinded to the patients’ study arm assignments.

“We conducted the study as a pragmatic trial whereby patients in either arm could also be offered HCC surveillance by primary or specialty care providers during clinic visits,” the researchers wrote. “The frequency of the clinic visits and provider discussions regarding HCC surveillance were conducted per usual care and not dictated by the study protocol.”

Two-thirds of the patients (67.7%) were men, with a median age of 61.2 years. Just over a third (37.0%) were white, 31.9% were Hispanic, and 27.6% were Black. More than half the patients had hepatitis C (56.4%), 18.1% had alcohol-related liver disease, 14.5% had nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, and 2.4% had hepatitis B. Most of the patients had compensated cirrhosis, including 36.7% with ascites and 17.1% with hepatic encephalopathy.

Nearly a quarter of the patients in the outreach arm (23%) could not be contacted or lacked working phone numbers, but they remained in the intent-to-screen analysis. Just over a third of the patients who received mailed outreach (35.1%; 95% confidence interval, 32.6%-37.6%) received semiannual surveillance, compared to 21.9% (95% CI, 19.8%-24.2%) of the usual-care patients. The increased surveillance in the outreach group applied to most subgroups, including race/ethnicity and cirrhosis severity based on the Child-Turcotte-Pugh class.

“However, we observed site-level differences in the intervention effect, with significant increases in semiannual surveillance at the VA and safety net health systems (both P < .001) but not at the tertiary care referral center (P = .52),” the authors wrote. “In a post hoc subgroup analysis among patients with at least 1 primary care or gastroenterology outpatient visit during the study period, mailed outreach continued to increase semiannual surveillance, compared with usual care (46.8% vs. 32.7%; P < .001).”

Despite the improved rates from the intervention, the majority of patients still did not receive semiannual surveillance across all three sites, and almost 30% underwent no surveillance the entire year.

The research was funded by the National Cancer Institute, the Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas, and the Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness and Safety. Dr. Singal has consulted for or served on the advisory boards of Bayer, FujiFilm Medical Sciences, Exact Sciences, Roche, Glycotest, and GRAIL. The other authors had no industry disclosures.

Mailing invitations for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) surveillance screening to patients with cirrhosis increased ultrasound uptake by 13 percentage points, but the majority of patients still did not receive the recommended semiannual screenings, according to findings published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

“These data highlight the need for more intensive interventions to further increase surveillance,” wrote Amit Singal, MD, of University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center and Parkland Health Hospital System in Dallas, and colleagues. “The underuse of HCC surveillance has been attributed to a combination of patient- and provider-level barriers, which can serve as future additional intervention targets.” These include transportation and financial barriers and possibly new blood-based screening modalities when they become available, thereby removing the need for a separate ultrasound appointment.

According to one study, more than 90% of hepatocellular carcinoma cases occur in people with chronic liver disease, and the cancer is a leading cause of death in those with compensated cirrhosis. Multiple medical associations therefore recommend an abdominal ultrasound every 6 months with or without alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) for surveillance in at-risk patients, including anyone with cirrhosis of any kind, but too few patients receive these surveillance ultrasounds, the authors write.

The researchers therefore conducted a pragmatic randomized clinical trial from March 2018 to September 2019 to compare surveillance ultrasound uptake for two groups of people with cirrhosis: 1,436 people who were mailed invitations to get a surveillance ultrasound and 1,436 people who received usual care, with surveillance recommended only at usual visits. The patients all received care at one of three health systems: a tertiary care referral center, a safety net health system, and a Veterans Affairs medical center. The primary outcome was semiannual surveillance in the patients over 1 year.

The researchers identified patients using ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes for cirrhosis and cirrhosis complications, as well as those with suspected but undocumented cirrhosis based on electronic medical record notes such as an elevated Fibrosis-4 index. They confirmed the diagnoses with chart review, confirmed that the patients had at least one outpatient visit in the previous year, and excluded those in whom surveillance is not recommended, who lacked contact information, or who spoke a language besides English or Spanish.

The mailing was a one-page letter in English and Spanish, written at a low literacy level, that explained hepatocellular carcinoma risk and recommended surveillance. Those who didn’t respond to the mailed invitation within 2 weeks received a reminder call to undergo surveillance, and those who scheduled an ultrasound received a reminder call about a week before the visit. Primary and subspecialty providers were blinded to the patients’ study arm assignments.

“We conducted the study as a pragmatic trial whereby patients in either arm could also be offered HCC surveillance by primary or specialty care providers during clinic visits,” the researchers wrote. “The frequency of the clinic visits and provider discussions regarding HCC surveillance were conducted per usual care and not dictated by the study protocol.”

Two-thirds of the patients (67.7%) were men, with a median age of 61.2 years. Just over a third (37.0%) were white, 31.9% were Hispanic, and 27.6% were Black. More than half the patients had hepatitis C (56.4%), 18.1% had alcohol-related liver disease, 14.5% had nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, and 2.4% had hepatitis B. Most of the patients had compensated cirrhosis, including 36.7% with ascites and 17.1% with hepatic encephalopathy.

Nearly a quarter of the patients in the outreach arm (23%) could not be contacted or lacked working phone numbers, but they remained in the intent-to-screen analysis. Just over a third of the patients who received mailed outreach (35.1%; 95% confidence interval, 32.6%-37.6%) received semiannual surveillance, compared to 21.9% (95% CI, 19.8%-24.2%) of the usual-care patients. The increased surveillance in the outreach group applied to most subgroups, including race/ethnicity and cirrhosis severity based on the Child-Turcotte-Pugh class.

“However, we observed site-level differences in the intervention effect, with significant increases in semiannual surveillance at the VA and safety net health systems (both P < .001) but not at the tertiary care referral center (P = .52),” the authors wrote. “In a post hoc subgroup analysis among patients with at least 1 primary care or gastroenterology outpatient visit during the study period, mailed outreach continued to increase semiannual surveillance, compared with usual care (46.8% vs. 32.7%; P < .001).”

Despite the improved rates from the intervention, the majority of patients still did not receive semiannual surveillance across all three sites, and almost 30% underwent no surveillance the entire year.

The research was funded by the National Cancer Institute, the Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas, and the Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness and Safety. Dr. Singal has consulted for or served on the advisory boards of Bayer, FujiFilm Medical Sciences, Exact Sciences, Roche, Glycotest, and GRAIL. The other authors had no industry disclosures.

REPORTING FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Should health care be a right?

Is health care a human right?

This year voters in Oregon are being asked to decide that.

It brings up some interesting questions. Should it be a right? Food, water, shelter, and oxygen aren’t, as far as I know, considered such. So why health care?

Probably the main argument against the idea is that, if it’s a right, shouldn’t the government (and therefore taxpayers) be tasked with paying for it all?

Good question, and not one that I can answer. If my neighbor refuses to buy insurance, then has a health crisis he can’t afford, why should I have to pay for his obstinacy and lack of foresight? Isn’t it his problem?

Of course, the truth is that not everyone can afford health care, or insurance. They ain’t cheap. Even if you get coverage through your job, part of your earnings, and part of the company’s profits, are being taken out to pay for it.

This raises the question of whether health care is something that should be rationed only to the working, successfully retired, or wealthy. Heaven knows I have plenty of patients tell me that. Their point is that if you’re not contributing to society, why should society contribute to you?

One even said that our distant ancestors didn’t see an issue with this: If you were unable to hunt, or outrun a cave lion, you probably weren’t helping the rest of the tribe anyway and deserved what happened to you.

Perhaps true, but we aren’t our distant ancestors. Over the millennia we’ve developed into a remarkably social, and increasingly interconnected, species. Somewhat paradoxically we often care more about famines on the other side of the world than we do in our own cities. If you’re going to use the argument of “we didn’t used to do this,” we also didn’t used to have cars, planes, or computers, but I don’t see anyone giving them up.

Another thing to keep in mind is that we are all paying for the uninsured under pretty much any system of health care there is. Whether it’s through taxes, insurance premiums, or both, our own costs go up to pay the bills of those who don’t have coverage. So in that respect the financial aspect of declaring it a right probably doesn’t change the de facto truth of the situation. It just makes it more official-ish.

Maybe the statement has more philosophical or political meaning than it does practical. If it passes it may change a lot of things, or nothing at all, depending how it’s legally interpreted.

Like so many things, we won’t know where it goes unless it happens. And even then it’s uncertain where it will lead.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Is health care a human right?

This year voters in Oregon are being asked to decide that.

It brings up some interesting questions. Should it be a right? Food, water, shelter, and oxygen aren’t, as far as I know, considered such. So why health care?

Probably the main argument against the idea is that, if it’s a right, shouldn’t the government (and therefore taxpayers) be tasked with paying for it all?

Good question, and not one that I can answer. If my neighbor refuses to buy insurance, then has a health crisis he can’t afford, why should I have to pay for his obstinacy and lack of foresight? Isn’t it his problem?

Of course, the truth is that not everyone can afford health care, or insurance. They ain’t cheap. Even if you get coverage through your job, part of your earnings, and part of the company’s profits, are being taken out to pay for it.

This raises the question of whether health care is something that should be rationed only to the working, successfully retired, or wealthy. Heaven knows I have plenty of patients tell me that. Their point is that if you’re not contributing to society, why should society contribute to you?

One even said that our distant ancestors didn’t see an issue with this: If you were unable to hunt, or outrun a cave lion, you probably weren’t helping the rest of the tribe anyway and deserved what happened to you.

Perhaps true, but we aren’t our distant ancestors. Over the millennia we’ve developed into a remarkably social, and increasingly interconnected, species. Somewhat paradoxically we often care more about famines on the other side of the world than we do in our own cities. If you’re going to use the argument of “we didn’t used to do this,” we also didn’t used to have cars, planes, or computers, but I don’t see anyone giving them up.

Another thing to keep in mind is that we are all paying for the uninsured under pretty much any system of health care there is. Whether it’s through taxes, insurance premiums, or both, our own costs go up to pay the bills of those who don’t have coverage. So in that respect the financial aspect of declaring it a right probably doesn’t change the de facto truth of the situation. It just makes it more official-ish.

Maybe the statement has more philosophical or political meaning than it does practical. If it passes it may change a lot of things, or nothing at all, depending how it’s legally interpreted.

Like so many things, we won’t know where it goes unless it happens. And even then it’s uncertain where it will lead.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Is health care a human right?

This year voters in Oregon are being asked to decide that.

It brings up some interesting questions. Should it be a right? Food, water, shelter, and oxygen aren’t, as far as I know, considered such. So why health care?

Probably the main argument against the idea is that, if it’s a right, shouldn’t the government (and therefore taxpayers) be tasked with paying for it all?

Good question, and not one that I can answer. If my neighbor refuses to buy insurance, then has a health crisis he can’t afford, why should I have to pay for his obstinacy and lack of foresight? Isn’t it his problem?

Of course, the truth is that not everyone can afford health care, or insurance. They ain’t cheap. Even if you get coverage through your job, part of your earnings, and part of the company’s profits, are being taken out to pay for it.

This raises the question of whether health care is something that should be rationed only to the working, successfully retired, or wealthy. Heaven knows I have plenty of patients tell me that. Their point is that if you’re not contributing to society, why should society contribute to you?

One even said that our distant ancestors didn’t see an issue with this: If you were unable to hunt, or outrun a cave lion, you probably weren’t helping the rest of the tribe anyway and deserved what happened to you.

Perhaps true, but we aren’t our distant ancestors. Over the millennia we’ve developed into a remarkably social, and increasingly interconnected, species. Somewhat paradoxically we often care more about famines on the other side of the world than we do in our own cities. If you’re going to use the argument of “we didn’t used to do this,” we also didn’t used to have cars, planes, or computers, but I don’t see anyone giving them up.

Another thing to keep in mind is that we are all paying for the uninsured under pretty much any system of health care there is. Whether it’s through taxes, insurance premiums, or both, our own costs go up to pay the bills of those who don’t have coverage. So in that respect the financial aspect of declaring it a right probably doesn’t change the de facto truth of the situation. It just makes it more official-ish.

Maybe the statement has more philosophical or political meaning than it does practical. If it passes it may change a lot of things, or nothing at all, depending how it’s legally interpreted.

Like so many things, we won’t know where it goes unless it happens. And even then it’s uncertain where it will lead.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Sex-linked IL-22 activity may affect NAFLD outcomes

Interleukin-22 may mitigate nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)–related fibrosis in females but not males, suggesting a sex-linked hepatoprotective pathway, according to investigators.

These differences between men and women should be considered when conducting clinical trials for IL-22–targeting therapies, reported lead author Mohamed N. Abdelnabi, MSc, of the Centre de Recherche du Centre Hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal and colleagues.

“IL-22 is a pleiotropic cytokine with both inflammatory and protective effects during injury and repair in various tissues including the liver,” the investigators wrote in Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology, noting that IL-22 activity has been linked with both antifibrotic and profibrotic outcomes in previous preclinical studies. “These different observations highlight the dual nature of IL-22 that likely is dictated by multiple factors including the tissue involved, pathologic environment, endogenous vs. exogenous IL-22 level, and the time of exposure.”

Prior research has left some questions unanswered, the investigators noted, because many studies have relied on exogenous administration of IL-22 in mouse models, some of which lack all the metabolic abnormalities observed in human disease. Furthermore, these mice were all male, which has prevented detection of possible sex-linked differences in IL-22–related pathophysiology, they added.

To address these gaps, the investigators conducted a series of experiments involving men and women with NAFLD, plus mice of both sexes with NAFLD induced by a high-fat diet, both wild-type and with knock-out of the IL-22 receptor.

Human data

To characterize IL-22 activity in men versus women with NAFLD, the investigators first analyzed two publicly available microarray datasets. These revealed notably increased expression of hepatic IL-22 mRNA in the livers of females compared with males. Supporting this finding, liver biopsies from 11 men and 9 women with NAFLD with similar levels of fibrosis showed significantly increased IL-22–producing cells in female patients compared with male patients.

“These results suggest a sexual dimorphic expression of IL-22 in the context of NAFLD,” the investigators wrote.

Mouse data

Echoing the human data, the livers of female wild-type mice with NAFLD had significantly greater IL-22 expression than male mice at both mRNA and protein levels.

Next, the investigators explored the effects of IL-22–receptor knockout. In addition to NAFLD, these knockout mice developed weight gain and metabolic alterations, especially insulin resistance, supporting previous work that highlighted the protective role of IL-22 against these outcomes. More relevant to the present study, female knockout mice had significantly worse hepatic liver injury, apoptosis, inflammation, and fibrosis than male knockout mice, suggesting that IL-22 signaling confers hepatoprotection in females but not males.

“These observations may suggest a regulation of IL-22 expression by the female sex hormone estrogen,” the investigators wrote. “Indeed, estrogen is known to modulate inflammatory responses in NAFLD, but the underlying mechanisms remain undefined. ... Further in vivo studies are warranted to investigate whether endogenous estrogen regulates hepatic IL-22 expression in the context of NAFLD.”

In the meantime, the present data may steer drug development.

“These findings should be considered in clinical trials testing IL-22–based therapeutic approaches in treatment of female vs. male subjects with NAFLD,” the investigators concluded.

The study was partially funded by the Canadian Liver Foundation and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Bourse d’Exemption des Droits de Scolarité Supplémentaires from the Université de Montréal, the Canadian Network on Hepatitis, and others. The investigators disclosed no competing interests.

The cytokine interleukin-22 has potential as a therapeutic for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, as it has been shown to decrease fat accumulation in hepatocytes and has various other liver protective effects such as prevention of cell death, enhancement of proliferation, and, importantly, reduction of liver fibrosis progression. Indeed, a recombinant derivative of IL22 has been studied in a clinical trial of alcoholic liver disease and has been found to be safe. However, the beneficial effect of this cytokine is context dependent. High levels of IL22 increased inflammation or fibrosis in hepatitis B infection and in toxic injury models in mouse models.

This is in line with observations that progression to cirrhosis in NAFLD is greater after menopause. On the other hand, women are more likely to develop cirrhosis than men despite higher levels of IL22, indicating more factors are at play in the progression of NAFLD. Overall, this report should alert investigators to consider the sex-specific effects of emerging therapies for NAFLD. Future IL22-based trials must include sex-based subgroup analyses.

Kirk Wangensteen, MD, PhD, is with the department of medicine, division of gastroenterology and hepatology at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. He declares no relevant conflicts of interest.

The cytokine interleukin-22 has potential as a therapeutic for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, as it has been shown to decrease fat accumulation in hepatocytes and has various other liver protective effects such as prevention of cell death, enhancement of proliferation, and, importantly, reduction of liver fibrosis progression. Indeed, a recombinant derivative of IL22 has been studied in a clinical trial of alcoholic liver disease and has been found to be safe. However, the beneficial effect of this cytokine is context dependent. High levels of IL22 increased inflammation or fibrosis in hepatitis B infection and in toxic injury models in mouse models.

This is in line with observations that progression to cirrhosis in NAFLD is greater after menopause. On the other hand, women are more likely to develop cirrhosis than men despite higher levels of IL22, indicating more factors are at play in the progression of NAFLD. Overall, this report should alert investigators to consider the sex-specific effects of emerging therapies for NAFLD. Future IL22-based trials must include sex-based subgroup analyses.

Kirk Wangensteen, MD, PhD, is with the department of medicine, division of gastroenterology and hepatology at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. He declares no relevant conflicts of interest.

The cytokine interleukin-22 has potential as a therapeutic for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, as it has been shown to decrease fat accumulation in hepatocytes and has various other liver protective effects such as prevention of cell death, enhancement of proliferation, and, importantly, reduction of liver fibrosis progression. Indeed, a recombinant derivative of IL22 has been studied in a clinical trial of alcoholic liver disease and has been found to be safe. However, the beneficial effect of this cytokine is context dependent. High levels of IL22 increased inflammation or fibrosis in hepatitis B infection and in toxic injury models in mouse models.

This is in line with observations that progression to cirrhosis in NAFLD is greater after menopause. On the other hand, women are more likely to develop cirrhosis than men despite higher levels of IL22, indicating more factors are at play in the progression of NAFLD. Overall, this report should alert investigators to consider the sex-specific effects of emerging therapies for NAFLD. Future IL22-based trials must include sex-based subgroup analyses.

Kirk Wangensteen, MD, PhD, is with the department of medicine, division of gastroenterology and hepatology at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. He declares no relevant conflicts of interest.

Interleukin-22 may mitigate nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)–related fibrosis in females but not males, suggesting a sex-linked hepatoprotective pathway, according to investigators.

These differences between men and women should be considered when conducting clinical trials for IL-22–targeting therapies, reported lead author Mohamed N. Abdelnabi, MSc, of the Centre de Recherche du Centre Hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal and colleagues.

“IL-22 is a pleiotropic cytokine with both inflammatory and protective effects during injury and repair in various tissues including the liver,” the investigators wrote in Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology, noting that IL-22 activity has been linked with both antifibrotic and profibrotic outcomes in previous preclinical studies. “These different observations highlight the dual nature of IL-22 that likely is dictated by multiple factors including the tissue involved, pathologic environment, endogenous vs. exogenous IL-22 level, and the time of exposure.”

Prior research has left some questions unanswered, the investigators noted, because many studies have relied on exogenous administration of IL-22 in mouse models, some of which lack all the metabolic abnormalities observed in human disease. Furthermore, these mice were all male, which has prevented detection of possible sex-linked differences in IL-22–related pathophysiology, they added.

To address these gaps, the investigators conducted a series of experiments involving men and women with NAFLD, plus mice of both sexes with NAFLD induced by a high-fat diet, both wild-type and with knock-out of the IL-22 receptor.

Human data

To characterize IL-22 activity in men versus women with NAFLD, the investigators first analyzed two publicly available microarray datasets. These revealed notably increased expression of hepatic IL-22 mRNA in the livers of females compared with males. Supporting this finding, liver biopsies from 11 men and 9 women with NAFLD with similar levels of fibrosis showed significantly increased IL-22–producing cells in female patients compared with male patients.

“These results suggest a sexual dimorphic expression of IL-22 in the context of NAFLD,” the investigators wrote.

Mouse data

Echoing the human data, the livers of female wild-type mice with NAFLD had significantly greater IL-22 expression than male mice at both mRNA and protein levels.

Next, the investigators explored the effects of IL-22–receptor knockout. In addition to NAFLD, these knockout mice developed weight gain and metabolic alterations, especially insulin resistance, supporting previous work that highlighted the protective role of IL-22 against these outcomes. More relevant to the present study, female knockout mice had significantly worse hepatic liver injury, apoptosis, inflammation, and fibrosis than male knockout mice, suggesting that IL-22 signaling confers hepatoprotection in females but not males.

“These observations may suggest a regulation of IL-22 expression by the female sex hormone estrogen,” the investigators wrote. “Indeed, estrogen is known to modulate inflammatory responses in NAFLD, but the underlying mechanisms remain undefined. ... Further in vivo studies are warranted to investigate whether endogenous estrogen regulates hepatic IL-22 expression in the context of NAFLD.”

In the meantime, the present data may steer drug development.

“These findings should be considered in clinical trials testing IL-22–based therapeutic approaches in treatment of female vs. male subjects with NAFLD,” the investigators concluded.

The study was partially funded by the Canadian Liver Foundation and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Bourse d’Exemption des Droits de Scolarité Supplémentaires from the Université de Montréal, the Canadian Network on Hepatitis, and others. The investigators disclosed no competing interests.

Interleukin-22 may mitigate nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)–related fibrosis in females but not males, suggesting a sex-linked hepatoprotective pathway, according to investigators.

These differences between men and women should be considered when conducting clinical trials for IL-22–targeting therapies, reported lead author Mohamed N. Abdelnabi, MSc, of the Centre de Recherche du Centre Hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal and colleagues.

“IL-22 is a pleiotropic cytokine with both inflammatory and protective effects during injury and repair in various tissues including the liver,” the investigators wrote in Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology, noting that IL-22 activity has been linked with both antifibrotic and profibrotic outcomes in previous preclinical studies. “These different observations highlight the dual nature of IL-22 that likely is dictated by multiple factors including the tissue involved, pathologic environment, endogenous vs. exogenous IL-22 level, and the time of exposure.”

Prior research has left some questions unanswered, the investigators noted, because many studies have relied on exogenous administration of IL-22 in mouse models, some of which lack all the metabolic abnormalities observed in human disease. Furthermore, these mice were all male, which has prevented detection of possible sex-linked differences in IL-22–related pathophysiology, they added.

To address these gaps, the investigators conducted a series of experiments involving men and women with NAFLD, plus mice of both sexes with NAFLD induced by a high-fat diet, both wild-type and with knock-out of the IL-22 receptor.

Human data

To characterize IL-22 activity in men versus women with NAFLD, the investigators first analyzed two publicly available microarray datasets. These revealed notably increased expression of hepatic IL-22 mRNA in the livers of females compared with males. Supporting this finding, liver biopsies from 11 men and 9 women with NAFLD with similar levels of fibrosis showed significantly increased IL-22–producing cells in female patients compared with male patients.

“These results suggest a sexual dimorphic expression of IL-22 in the context of NAFLD,” the investigators wrote.

Mouse data

Echoing the human data, the livers of female wild-type mice with NAFLD had significantly greater IL-22 expression than male mice at both mRNA and protein levels.

Next, the investigators explored the effects of IL-22–receptor knockout. In addition to NAFLD, these knockout mice developed weight gain and metabolic alterations, especially insulin resistance, supporting previous work that highlighted the protective role of IL-22 against these outcomes. More relevant to the present study, female knockout mice had significantly worse hepatic liver injury, apoptosis, inflammation, and fibrosis than male knockout mice, suggesting that IL-22 signaling confers hepatoprotection in females but not males.

“These observations may suggest a regulation of IL-22 expression by the female sex hormone estrogen,” the investigators wrote. “Indeed, estrogen is known to modulate inflammatory responses in NAFLD, but the underlying mechanisms remain undefined. ... Further in vivo studies are warranted to investigate whether endogenous estrogen regulates hepatic IL-22 expression in the context of NAFLD.”

In the meantime, the present data may steer drug development.

“These findings should be considered in clinical trials testing IL-22–based therapeutic approaches in treatment of female vs. male subjects with NAFLD,” the investigators concluded.

The study was partially funded by the Canadian Liver Foundation and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Bourse d’Exemption des Droits de Scolarité Supplémentaires from the Université de Montréal, the Canadian Network on Hepatitis, and others. The investigators disclosed no competing interests.

FROM CELLULAR AND MOLECULAR GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Children and COVID: Weekly cases can’t sustain downward trend

New COVID-19 cases in children inched up in late October, just 1 week after dipping to their lowest level in more than a year, and some measures of pediatric emergency visits and hospital admissions rose as well.

There was an 8% increase in the number of cases for the week of Oct. 21-27, compared with the previous week, but this week’s total was still below 25,000, and the overall trend since the beginning of September is still one of decline, based on data from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

A similar increase can be seen for hospitalizations with confirmed COVID. The rate for children aged 0-17 years fell from 0.44 admissions per 100,000 population at the end of August to 0.16 per 100,000 on Oct. 23. Hospitalizations have since ticked up to 0.17 per 100,000, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Emergency department visits with diagnosed COVID among children aged 16-17 years, as a percentage of all ED visits, rose from 0.6% on Oct. 21 to 0.8% on Oct. 26. ED visits for 12- to 15-year-olds rose from 0.6% to 0.7% at about the same time, with both increases coming after declines that started in late August. No such increase has occurred yet among children aged 0-11 years, the CDC reported on its COVID Data Tracker.

One small milestone reached in the past week involved the proportion of all COVID cases that have occurred in children. The total number of child cases as of Oct. 27 was almost 14.9 million, which represents 18.3% of cases in all Americans, according to the AAP and CHA. That figure had been sitting at 18.4% since mid-August after reaching as high as 19.0% during the spring.

The CDC puts total COVID-related hospital admissions for children aged 0-17 at 163,588 since Aug. 1, 2020, which is 3.0% of all U.S. admissions. Total pediatric deaths number 1,843, or just about 0.2% of all COVID-related fatalities since the start of the pandemic, the CDC data show.

The latest vaccination figures show that 71.3% of children aged 12-17 years have received at least one dose, as have 38.8% of 5- to 11-year-olds, 8.4% of 2- to 4-year-olds, and 5.5% of those under age 2. Full vaccination by age group looks like this: 60.9% (12-17 years), 31.7% (5-11 years), 3.7% (2-4 years), and 2.1% (<2 years), the CDC reported. Almost 30% of children aged 12-17 have gotten a first booster dose, as have 16% of 5- to 11-year-olds.

New COVID-19 cases in children inched up in late October, just 1 week after dipping to their lowest level in more than a year, and some measures of pediatric emergency visits and hospital admissions rose as well.

There was an 8% increase in the number of cases for the week of Oct. 21-27, compared with the previous week, but this week’s total was still below 25,000, and the overall trend since the beginning of September is still one of decline, based on data from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

A similar increase can be seen for hospitalizations with confirmed COVID. The rate for children aged 0-17 years fell from 0.44 admissions per 100,000 population at the end of August to 0.16 per 100,000 on Oct. 23. Hospitalizations have since ticked up to 0.17 per 100,000, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.