User login

Depression: Think outside of the box for diagnosis, treatment

In the treatment of depression, clinicians are commonly dealing with a mix of comorbidities that are more complex than just depression, and as such, effective treatment options may likewise require thinking outside of the box – and beyond the definitions of the DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision).

“The DSM-5 isn’t handed to us on tablets from Mount Sinai,” said Charles B. Nemeroff, MD, PhD, professor and chair in the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the Mulva Clinic for the Neurosciences at the University of Texas at Austin. He spoke at the 21st Annual Psychopharmacology Update presented by Current Psychiatry and the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists.

“Our patients don’t fall into these very convenient buckets,” Dr. Nemeroff said. “The problem with depression is patients have very high rates of morbidity and comorbidity.”

The array of potential psychiatric comorbidities that are common in depression is somewhat staggering: As many as 70% of patients also have social anxiety disorder; 67% of patients have obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD); up to 65% of patients have panic disorder; 48% of patients have posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD); and 42% have generalized anxiety disorder, Dr. Nemeroff said.

And while the DSM-5 may have all those bases covered, in real world clinical practice, cracking the code of each patient’s unique and often more complicated psychiatric profile – and how to best manage it – can be a challenge. But Dr. Nemeroff said important clues can guide the clinician’s path.

A key starting point is making sure to gauge the severity of the patient’s core depression with one of the validated depression scales – whether it’s the self-reported Beck Depression Inventory, the clinician-rated Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression, the clinician-rated Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale, or the Inventory of Depressive Symptoms, clinicians should pick one and track the score with each visit, Dr. Nemeroff advised.

“It doesn’t matter which tool you prefer – most tend to like the Beck Depression Scale, but the bottom line is that you have to get a measure of severity at every visit,” he said.

Among the most important comorbidities to identify as soon as possible is bipolar disorder, due to the potential worsening of the condition that can occur among those patients if treated with antidepressants, Dr. Nemeroff said.

“The question of whether the patient is bipolar should always be in the back of your mind,” he cautioned. “And if patients have been started on antidepressants, the clues may become evident very quickly.”

The most important indicator that the patient has bipolar disorder “is if they tell you that they were prescribed an antidepressant and it resulted in an increase in what we know to be hypomania – they may describe it as agitation or an inability to sleep,” Dr. Nemeroff said.

Of note, the effect is much more common with SNRIs [serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors] than SSRIs [selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors], he said.

“The effect is particularly notable with venlafaxine,” he said. “But SNRIs all have the propensity to switch people with depression into hypomania, but only patients who have bipolar disorder.”

“If you give a patient 150 mg of venlafaxine and they switch to developing hypomania, you now have the diagnosis of bipolar disorder, and you can treat them appropriately.”

Other important clues of bipolarity in depressed patients include:

- Family history: Most cases are genetically driven.

- Earlier age of onset (younger than age 25): “If the patient tells you they were depressed prepuberty, you should be thinking about the possibility of bipolar disorder, as it often presents as depression in childhood.”

- Psychotic features: As many as 80% of patients with psychotic depression end up being bipolar, Dr. Nemeroff said.

- Atypical depression: For example, depression with hypersomnia, or having an increased appetite instead of decreased, or a high amount of anxiety.

Remission should be the goal of treatment, and Dr. Nemeroff said that in efforts to accomplish that with the help of medications, psychiatrists may need to think “outside of the box” – or beyond the label.

“Many practitioners become slaves to the PDR [Physicians’ Desk Reference],” he said. “It is only a guide to what the clinical trials show, and not a mandate in terms of dosing.”

“There’s often strong data in the literature that supports going to a higher dose, if necessary, and I have [plenty] of patients, for instance, on 450 or 600 mg of venlafaxine who had not responded to 150 or even 300 mg.”

Treatment resistance

When patients continue to fail to respond, regardless of dosing or medication adjustments, Dr. Nemeroff suggested that clinicians should consider the potential important reasons. For instance, in addition to comorbid psychiatric conditions, practitioners should determine if there are medical conditions that they are not aware of.

“Does the patient have an underlying medical condition, such as thyroid dysfunction, early Parkinson’s disease, or even something like cancer?” he said.

There is also the inevitable question of whether the patient is indeed taking the medication. “We know that 30% of our patients do not follow their prescriptions, so of course that’s an important question to ask,” Dr. Nemeroff said.

Finally, while some pharmacogenomic tests are emerging with the suggestion of identifying which patients may or may not respond to certain drugs, Dr. Nemeroff says he’s seen little convincing evidence of their benefits.

“We have a problem in this field in that we don’t have the kinds of markers that they do in oncology, so we’re left with having to generally play trial and error,” he said.

“But when it comes to these pharmacogenomic tests, there’s just no ‘there there’,” he asserted. “From what I’ve seen so far, it’s frankly neuro-mythology.”

Dr. Nemeroff disclosed that he receives grant/research support from the National Institutes of Health and serves as a consultant for and/or on the advisory boards of multiple pharmaceutical companies.

The Psychopharmacology Update was sponsored by Medscape Live. Medscape Live and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

In the treatment of depression, clinicians are commonly dealing with a mix of comorbidities that are more complex than just depression, and as such, effective treatment options may likewise require thinking outside of the box – and beyond the definitions of the DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision).

“The DSM-5 isn’t handed to us on tablets from Mount Sinai,” said Charles B. Nemeroff, MD, PhD, professor and chair in the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the Mulva Clinic for the Neurosciences at the University of Texas at Austin. He spoke at the 21st Annual Psychopharmacology Update presented by Current Psychiatry and the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists.

“Our patients don’t fall into these very convenient buckets,” Dr. Nemeroff said. “The problem with depression is patients have very high rates of morbidity and comorbidity.”

The array of potential psychiatric comorbidities that are common in depression is somewhat staggering: As many as 70% of patients also have social anxiety disorder; 67% of patients have obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD); up to 65% of patients have panic disorder; 48% of patients have posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD); and 42% have generalized anxiety disorder, Dr. Nemeroff said.

And while the DSM-5 may have all those bases covered, in real world clinical practice, cracking the code of each patient’s unique and often more complicated psychiatric profile – and how to best manage it – can be a challenge. But Dr. Nemeroff said important clues can guide the clinician’s path.

A key starting point is making sure to gauge the severity of the patient’s core depression with one of the validated depression scales – whether it’s the self-reported Beck Depression Inventory, the clinician-rated Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression, the clinician-rated Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale, or the Inventory of Depressive Symptoms, clinicians should pick one and track the score with each visit, Dr. Nemeroff advised.

“It doesn’t matter which tool you prefer – most tend to like the Beck Depression Scale, but the bottom line is that you have to get a measure of severity at every visit,” he said.

Among the most important comorbidities to identify as soon as possible is bipolar disorder, due to the potential worsening of the condition that can occur among those patients if treated with antidepressants, Dr. Nemeroff said.

“The question of whether the patient is bipolar should always be in the back of your mind,” he cautioned. “And if patients have been started on antidepressants, the clues may become evident very quickly.”

The most important indicator that the patient has bipolar disorder “is if they tell you that they were prescribed an antidepressant and it resulted in an increase in what we know to be hypomania – they may describe it as agitation or an inability to sleep,” Dr. Nemeroff said.

Of note, the effect is much more common with SNRIs [serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors] than SSRIs [selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors], he said.

“The effect is particularly notable with venlafaxine,” he said. “But SNRIs all have the propensity to switch people with depression into hypomania, but only patients who have bipolar disorder.”

“If you give a patient 150 mg of venlafaxine and they switch to developing hypomania, you now have the diagnosis of bipolar disorder, and you can treat them appropriately.”

Other important clues of bipolarity in depressed patients include:

- Family history: Most cases are genetically driven.

- Earlier age of onset (younger than age 25): “If the patient tells you they were depressed prepuberty, you should be thinking about the possibility of bipolar disorder, as it often presents as depression in childhood.”

- Psychotic features: As many as 80% of patients with psychotic depression end up being bipolar, Dr. Nemeroff said.

- Atypical depression: For example, depression with hypersomnia, or having an increased appetite instead of decreased, or a high amount of anxiety.

Remission should be the goal of treatment, and Dr. Nemeroff said that in efforts to accomplish that with the help of medications, psychiatrists may need to think “outside of the box” – or beyond the label.

“Many practitioners become slaves to the PDR [Physicians’ Desk Reference],” he said. “It is only a guide to what the clinical trials show, and not a mandate in terms of dosing.”

“There’s often strong data in the literature that supports going to a higher dose, if necessary, and I have [plenty] of patients, for instance, on 450 or 600 mg of venlafaxine who had not responded to 150 or even 300 mg.”

Treatment resistance

When patients continue to fail to respond, regardless of dosing or medication adjustments, Dr. Nemeroff suggested that clinicians should consider the potential important reasons. For instance, in addition to comorbid psychiatric conditions, practitioners should determine if there are medical conditions that they are not aware of.

“Does the patient have an underlying medical condition, such as thyroid dysfunction, early Parkinson’s disease, or even something like cancer?” he said.

There is also the inevitable question of whether the patient is indeed taking the medication. “We know that 30% of our patients do not follow their prescriptions, so of course that’s an important question to ask,” Dr. Nemeroff said.

Finally, while some pharmacogenomic tests are emerging with the suggestion of identifying which patients may or may not respond to certain drugs, Dr. Nemeroff says he’s seen little convincing evidence of their benefits.

“We have a problem in this field in that we don’t have the kinds of markers that they do in oncology, so we’re left with having to generally play trial and error,” he said.

“But when it comes to these pharmacogenomic tests, there’s just no ‘there there’,” he asserted. “From what I’ve seen so far, it’s frankly neuro-mythology.”

Dr. Nemeroff disclosed that he receives grant/research support from the National Institutes of Health and serves as a consultant for and/or on the advisory boards of multiple pharmaceutical companies.

The Psychopharmacology Update was sponsored by Medscape Live. Medscape Live and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

In the treatment of depression, clinicians are commonly dealing with a mix of comorbidities that are more complex than just depression, and as such, effective treatment options may likewise require thinking outside of the box – and beyond the definitions of the DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision).

“The DSM-5 isn’t handed to us on tablets from Mount Sinai,” said Charles B. Nemeroff, MD, PhD, professor and chair in the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the Mulva Clinic for the Neurosciences at the University of Texas at Austin. He spoke at the 21st Annual Psychopharmacology Update presented by Current Psychiatry and the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists.

“Our patients don’t fall into these very convenient buckets,” Dr. Nemeroff said. “The problem with depression is patients have very high rates of morbidity and comorbidity.”

The array of potential psychiatric comorbidities that are common in depression is somewhat staggering: As many as 70% of patients also have social anxiety disorder; 67% of patients have obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD); up to 65% of patients have panic disorder; 48% of patients have posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD); and 42% have generalized anxiety disorder, Dr. Nemeroff said.

And while the DSM-5 may have all those bases covered, in real world clinical practice, cracking the code of each patient’s unique and often more complicated psychiatric profile – and how to best manage it – can be a challenge. But Dr. Nemeroff said important clues can guide the clinician’s path.

A key starting point is making sure to gauge the severity of the patient’s core depression with one of the validated depression scales – whether it’s the self-reported Beck Depression Inventory, the clinician-rated Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression, the clinician-rated Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale, or the Inventory of Depressive Symptoms, clinicians should pick one and track the score with each visit, Dr. Nemeroff advised.

“It doesn’t matter which tool you prefer – most tend to like the Beck Depression Scale, but the bottom line is that you have to get a measure of severity at every visit,” he said.

Among the most important comorbidities to identify as soon as possible is bipolar disorder, due to the potential worsening of the condition that can occur among those patients if treated with antidepressants, Dr. Nemeroff said.

“The question of whether the patient is bipolar should always be in the back of your mind,” he cautioned. “And if patients have been started on antidepressants, the clues may become evident very quickly.”

The most important indicator that the patient has bipolar disorder “is if they tell you that they were prescribed an antidepressant and it resulted in an increase in what we know to be hypomania – they may describe it as agitation or an inability to sleep,” Dr. Nemeroff said.

Of note, the effect is much more common with SNRIs [serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors] than SSRIs [selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors], he said.

“The effect is particularly notable with venlafaxine,” he said. “But SNRIs all have the propensity to switch people with depression into hypomania, but only patients who have bipolar disorder.”

“If you give a patient 150 mg of venlafaxine and they switch to developing hypomania, you now have the diagnosis of bipolar disorder, and you can treat them appropriately.”

Other important clues of bipolarity in depressed patients include:

- Family history: Most cases are genetically driven.

- Earlier age of onset (younger than age 25): “If the patient tells you they were depressed prepuberty, you should be thinking about the possibility of bipolar disorder, as it often presents as depression in childhood.”

- Psychotic features: As many as 80% of patients with psychotic depression end up being bipolar, Dr. Nemeroff said.

- Atypical depression: For example, depression with hypersomnia, or having an increased appetite instead of decreased, or a high amount of anxiety.

Remission should be the goal of treatment, and Dr. Nemeroff said that in efforts to accomplish that with the help of medications, psychiatrists may need to think “outside of the box” – or beyond the label.

“Many practitioners become slaves to the PDR [Physicians’ Desk Reference],” he said. “It is only a guide to what the clinical trials show, and not a mandate in terms of dosing.”

“There’s often strong data in the literature that supports going to a higher dose, if necessary, and I have [plenty] of patients, for instance, on 450 or 600 mg of venlafaxine who had not responded to 150 or even 300 mg.”

Treatment resistance

When patients continue to fail to respond, regardless of dosing or medication adjustments, Dr. Nemeroff suggested that clinicians should consider the potential important reasons. For instance, in addition to comorbid psychiatric conditions, practitioners should determine if there are medical conditions that they are not aware of.

“Does the patient have an underlying medical condition, such as thyroid dysfunction, early Parkinson’s disease, or even something like cancer?” he said.

There is also the inevitable question of whether the patient is indeed taking the medication. “We know that 30% of our patients do not follow their prescriptions, so of course that’s an important question to ask,” Dr. Nemeroff said.

Finally, while some pharmacogenomic tests are emerging with the suggestion of identifying which patients may or may not respond to certain drugs, Dr. Nemeroff says he’s seen little convincing evidence of their benefits.

“We have a problem in this field in that we don’t have the kinds of markers that they do in oncology, so we’re left with having to generally play trial and error,” he said.

“But when it comes to these pharmacogenomic tests, there’s just no ‘there there’,” he asserted. “From what I’ve seen so far, it’s frankly neuro-mythology.”

Dr. Nemeroff disclosed that he receives grant/research support from the National Institutes of Health and serves as a consultant for and/or on the advisory boards of multiple pharmaceutical companies.

The Psychopharmacology Update was sponsored by Medscape Live. Medscape Live and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

FROM PSYCHOPHARMACOLOGY UPDATE

Serum trace metals relate to lower risk of sleep disorders

, based on data from 3,660 individuals.

Previous research has shown an association between trace metals and sleep and sleep patterns, but data on the impact of serum trace metals on sleep disorders have been limited, wrote Ming-Gang Deng, MD, of Wuhan (China) University and colleagues.

In a study published in the Journal of Affective Disorders, the researchers reviewed data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2011-2016 to calculate the odds ratios of sleep disorders and serum zinc (Zn), copper (Cu), and selenium (Se). The study population included adults aged 18 years and older, with an average age of 47.6 years. Approximately half of the participants were men, and the majority was non-Hispanic white. Serum Zn, Cu, and Se were identified at the Environmental Health Sciences Laboratory of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Environmental Health. The lower limits of detection for Zn, Cu, and Se were 2.9 mcg/dL, 2.5 mcg/dL, and 4.5 mcg/L, respectively. Sleep disorders were assessed based on self-reports of discussions with health professionals about sleep disorders, and via the Sleep Disorder Questionnaire.

After adjusting for sociodemographic, behavioral characteristics, and health characteristics, adults in the highest tertiles of serum Zn had a 30% reduced risk of sleep disorders, compared with those in the lowest tertiles of serum Zn (odds ratio, 0.70; P = .035). In measures of trace metals ratios, serum Zn/Cu and Zn/Se also were significantly associated with reduced risk of sleep disorders for individuals in the highest tertiles, compared with those in the lowest tertiles (OR, 0.62 and OR, 0.68, respectively).

However, serum Cu, Se and Cu/Se were not associated with sleep disorder risk.

Sociodemographic factors included age, sex, race, education level, family income level; behavioral characteristics included smoking, alcohol consumption, physical activity, and caffeine intake.

The researchers also used a restricted cubic spline model to examine the dose-response relationships between serum trace metals, serum trace metals ratios, and sleep disorders. In this analysis, higher levels of serum Zn, Zn/Cu, and Zn/Se were related to reduced risk of sleep disorders, while no significant association appeared between serum Cu, Se, or Cu/Se and sleep disorders risk.

The findings showing a lack of association between Se and sleep disorders were not consistent with previous studies, the researchers wrote in their discussion. Previous research has shown that a higher Se was less likely to be associated with trouble falling asleep, and has shown a potential treatment effect of Se on obstructive sleep apnea, they said.

“Although serum Cu and Se levels were not correlated to sleep disorders in our study, the Zn/Cu and Zn/Se may provide some novel insights,” they wrote. For example, Zn/Cu has been used as a predictor of several clinical complications related to an increased risk of sleep disorders including cardiovascular disease, cancer, and major depressive disorder, they noted.

The findings were limited by several factors including the cross-sectional design, use of self-reports, and the inability to examine relationships between trace metals and specific sleep disorder symptoms, such as restless legs syndrome, insomnia, and obstructive sleep apnea, the researchers noted.

However, the results were strengthened by the large national sample, and support data from previous studies, they said.

“The inverse associations of serum Zn, and Zn/Cu, Zn/Se with sleep disorders enlightened us that increasing Zn intake may be an excellent approach to prevent sleep disorders due to its benefits from these three aspects,” they concluded.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

, based on data from 3,660 individuals.

Previous research has shown an association between trace metals and sleep and sleep patterns, but data on the impact of serum trace metals on sleep disorders have been limited, wrote Ming-Gang Deng, MD, of Wuhan (China) University and colleagues.

In a study published in the Journal of Affective Disorders, the researchers reviewed data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2011-2016 to calculate the odds ratios of sleep disorders and serum zinc (Zn), copper (Cu), and selenium (Se). The study population included adults aged 18 years and older, with an average age of 47.6 years. Approximately half of the participants were men, and the majority was non-Hispanic white. Serum Zn, Cu, and Se were identified at the Environmental Health Sciences Laboratory of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Environmental Health. The lower limits of detection for Zn, Cu, and Se were 2.9 mcg/dL, 2.5 mcg/dL, and 4.5 mcg/L, respectively. Sleep disorders were assessed based on self-reports of discussions with health professionals about sleep disorders, and via the Sleep Disorder Questionnaire.

After adjusting for sociodemographic, behavioral characteristics, and health characteristics, adults in the highest tertiles of serum Zn had a 30% reduced risk of sleep disorders, compared with those in the lowest tertiles of serum Zn (odds ratio, 0.70; P = .035). In measures of trace metals ratios, serum Zn/Cu and Zn/Se also were significantly associated with reduced risk of sleep disorders for individuals in the highest tertiles, compared with those in the lowest tertiles (OR, 0.62 and OR, 0.68, respectively).

However, serum Cu, Se and Cu/Se were not associated with sleep disorder risk.

Sociodemographic factors included age, sex, race, education level, family income level; behavioral characteristics included smoking, alcohol consumption, physical activity, and caffeine intake.

The researchers also used a restricted cubic spline model to examine the dose-response relationships between serum trace metals, serum trace metals ratios, and sleep disorders. In this analysis, higher levels of serum Zn, Zn/Cu, and Zn/Se were related to reduced risk of sleep disorders, while no significant association appeared between serum Cu, Se, or Cu/Se and sleep disorders risk.

The findings showing a lack of association between Se and sleep disorders were not consistent with previous studies, the researchers wrote in their discussion. Previous research has shown that a higher Se was less likely to be associated with trouble falling asleep, and has shown a potential treatment effect of Se on obstructive sleep apnea, they said.

“Although serum Cu and Se levels were not correlated to sleep disorders in our study, the Zn/Cu and Zn/Se may provide some novel insights,” they wrote. For example, Zn/Cu has been used as a predictor of several clinical complications related to an increased risk of sleep disorders including cardiovascular disease, cancer, and major depressive disorder, they noted.

The findings were limited by several factors including the cross-sectional design, use of self-reports, and the inability to examine relationships between trace metals and specific sleep disorder symptoms, such as restless legs syndrome, insomnia, and obstructive sleep apnea, the researchers noted.

However, the results were strengthened by the large national sample, and support data from previous studies, they said.

“The inverse associations of serum Zn, and Zn/Cu, Zn/Se with sleep disorders enlightened us that increasing Zn intake may be an excellent approach to prevent sleep disorders due to its benefits from these three aspects,” they concluded.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

, based on data from 3,660 individuals.

Previous research has shown an association between trace metals and sleep and sleep patterns, but data on the impact of serum trace metals on sleep disorders have been limited, wrote Ming-Gang Deng, MD, of Wuhan (China) University and colleagues.

In a study published in the Journal of Affective Disorders, the researchers reviewed data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2011-2016 to calculate the odds ratios of sleep disorders and serum zinc (Zn), copper (Cu), and selenium (Se). The study population included adults aged 18 years and older, with an average age of 47.6 years. Approximately half of the participants were men, and the majority was non-Hispanic white. Serum Zn, Cu, and Se were identified at the Environmental Health Sciences Laboratory of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Environmental Health. The lower limits of detection for Zn, Cu, and Se were 2.9 mcg/dL, 2.5 mcg/dL, and 4.5 mcg/L, respectively. Sleep disorders were assessed based on self-reports of discussions with health professionals about sleep disorders, and via the Sleep Disorder Questionnaire.

After adjusting for sociodemographic, behavioral characteristics, and health characteristics, adults in the highest tertiles of serum Zn had a 30% reduced risk of sleep disorders, compared with those in the lowest tertiles of serum Zn (odds ratio, 0.70; P = .035). In measures of trace metals ratios, serum Zn/Cu and Zn/Se also were significantly associated with reduced risk of sleep disorders for individuals in the highest tertiles, compared with those in the lowest tertiles (OR, 0.62 and OR, 0.68, respectively).

However, serum Cu, Se and Cu/Se were not associated with sleep disorder risk.

Sociodemographic factors included age, sex, race, education level, family income level; behavioral characteristics included smoking, alcohol consumption, physical activity, and caffeine intake.

The researchers also used a restricted cubic spline model to examine the dose-response relationships between serum trace metals, serum trace metals ratios, and sleep disorders. In this analysis, higher levels of serum Zn, Zn/Cu, and Zn/Se were related to reduced risk of sleep disorders, while no significant association appeared between serum Cu, Se, or Cu/Se and sleep disorders risk.

The findings showing a lack of association between Se and sleep disorders were not consistent with previous studies, the researchers wrote in their discussion. Previous research has shown that a higher Se was less likely to be associated with trouble falling asleep, and has shown a potential treatment effect of Se on obstructive sleep apnea, they said.

“Although serum Cu and Se levels were not correlated to sleep disorders in our study, the Zn/Cu and Zn/Se may provide some novel insights,” they wrote. For example, Zn/Cu has been used as a predictor of several clinical complications related to an increased risk of sleep disorders including cardiovascular disease, cancer, and major depressive disorder, they noted.

The findings were limited by several factors including the cross-sectional design, use of self-reports, and the inability to examine relationships between trace metals and specific sleep disorder symptoms, such as restless legs syndrome, insomnia, and obstructive sleep apnea, the researchers noted.

However, the results were strengthened by the large national sample, and support data from previous studies, they said.

“The inverse associations of serum Zn, and Zn/Cu, Zn/Se with sleep disorders enlightened us that increasing Zn intake may be an excellent approach to prevent sleep disorders due to its benefits from these three aspects,” they concluded.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF AFFECTIVE DISORDERS

COVID isolated people. Long COVID makes it worse

A year ago in December, mapping specialist Whitney Tyshynski, 35, was working out 5 days a week with a personal trainer near her home in Alberta, Canada, doing 5k trail runs, lifting heavy weights, and feeling good. Then, in January she got COVID-19. The symptoms never went away.

Nowadays, Ms. Tyshynski needs a walker to retrieve her mail, a half-block trip she can’t make without fear of fainting. Because she gets dizzy when she drives, she rarely goes anywhere in her car. Going for a dog walk with a friend means sitting in a car and watching the friend and the dogs in an open field. And since fainting at Costco during the summer, she’s afraid to shop by herself.

Because she lives alone and her closest relatives are an hour and a half away, Ms. Tyshynski is dependent on friends. But she’s reluctant to lean on them because they already have trouble understanding how debilitating her lingering symptoms can be.

“I’ve had people pretty much insinuate that I’m lazy,” she says.

There’s no question that COVID-19 cut people off from one another. But for those like Ms. Tyshynski who have long COVID, that disconnect has never ended. that the condition is real.

At worst, as Ms. Tyshynski has discovered, people don’t take it seriously and accuse those who have it of exaggerating their health woes. In that way, long COVID can be as isolating as the original illness.

“Isolation in long COVID comes in various forms and it’s not primarily just that physical isolation,” says Yochai Re’em, MD, a psychiatrist in private practice in New York who has experienced long COVID and blogs about the condition for Psychology Today. “A different yet equally challenging type of isolation is the emotional isolation, where you need more emotional support, connection with other people who can appreciate what it is you are going through without putting their own needs and desires onto you – and that can be hard to find.”

It’s hard to find in part because of what Dr. Re’em sees as a collective belief that anyone who feels bad should be able to get better by exercising, researching, or going to a doctor.

“Society thinks you need to take some kind of action and usually that’s a physical action,” he says. “And that attitude is tremendously problematic in this illness because of the postexertional malaise that people experience: When people exert themselves, their symptoms get worse. And so the action that people take can’t be that traditional action that we’re used to taking in our society.”

Long COVID patients often have their feelings invalidated not just by friends, loved ones, and extended family, but by health care providers. That can heighten feelings of isolation, particularly for people who live alone, says Jordan Anderson, DO, a neuropsychiatrist and assistant professor of psychiatry at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland.

The first patients Dr. Anderson saw as part of OHSU’s long COVID program contracted the virus in February 2020. Because the program addresses both the physical and mental health components of the condition, Dr. Anderson has seen a lot of people whose emotional challenges are similar to those Ms. Tyshynski faces.

“I think there’s a lack of understanding that leads to people just not necessarily taking it seriously,” he says. “Plus, the symptoms of long COVID do wax and wane. They’re not static. So people can be feeling pretty good one day and be feeling terrible the next. There’s some predictability to it, but it’s not absolutely predictable. It can be difficult for people to understand.”

Both Dr. Anderson and Dr. Re’em stress that long COVID patients need to prioritize their own energy regardless of what they’re being told by those who don’t understand the illness. Dr. Anderson offers to speak to his patients’ spouses to educate them about the realities of the condition because, he says, “any kind of lack of awareness or understanding in a family member or close support could potentially isolate the person struggling with long COVID.”

Depending on how open-minded and motivated a friend or relative is, they might develop more empathy with time and education, Dr. Re’em says. But for others, dealing with a confusing, unfamiliar chronic illness can be overwhelming and provoke anxiety.

“The hopelessness is too much for them to sit with, so instead they say things like ‘just push through it,’ or ‘just do X, Y, and Z,’ because psychologically it’s too much for them to take on that burden,” he says.

The good news is that there are plenty of web-based support groups for people with long COVID, including Body Politic (which Dr. Re’em is affiliated with), Survivor Corps, and on Facebook. “The patient community with this illness is tremendous, absolutely tremendous,” Dr. Re’em says. “Those people can be found and they can support each other.”

Some long COVID clinics run groups, as do individual practitioners such as Dr. Re’em, although those can be challenging to join. For instance, Dr. Re’em’s are only for New York state residents.

The key to finding a group is to be patient, because finding the right one takes time and energy.

“There are support groups that exist, but they are not as prevalent as I would like them to be,” Dr. Anderson says.

OHSU had an educational support group run by a social worker affiliated with the long COVID hub, but when the social worker left the program, the program was put on hold.

There’s a psychotherapy group operating out of the psychiatry department, but the patients are recruited exclusively from Dr. Anderson’s clinic and access is limited.

“The services exist, but I think that generally they’re sparse and pretty geographically dependent,” Dr. Anderson says. “I think you’d probably more likely be able to find something like this in a city or an area that has an academic institution or a place with a lot of resources rather than out in a rural community.”

Ms. Tyshynski opted not to join a group for fear it would increase the depression and anxiety that she had even before developing long COVID. When she and her family joined a cancer support group when her father was ill, she found it more depressing than helpful. Where she has found support is from the cofounder of the animal rescue society where she volunteers, a woman who has had long COVID for more than 2 years and has been a source of comfort and advice.

It’s one of the rare reminders Ms. Tyshynski has that even though she may live alone, she’s not completely alone. “Other people are going through this, too,” she says. “It helps to remember that.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

A year ago in December, mapping specialist Whitney Tyshynski, 35, was working out 5 days a week with a personal trainer near her home in Alberta, Canada, doing 5k trail runs, lifting heavy weights, and feeling good. Then, in January she got COVID-19. The symptoms never went away.

Nowadays, Ms. Tyshynski needs a walker to retrieve her mail, a half-block trip she can’t make without fear of fainting. Because she gets dizzy when she drives, she rarely goes anywhere in her car. Going for a dog walk with a friend means sitting in a car and watching the friend and the dogs in an open field. And since fainting at Costco during the summer, she’s afraid to shop by herself.

Because she lives alone and her closest relatives are an hour and a half away, Ms. Tyshynski is dependent on friends. But she’s reluctant to lean on them because they already have trouble understanding how debilitating her lingering symptoms can be.

“I’ve had people pretty much insinuate that I’m lazy,” she says.

There’s no question that COVID-19 cut people off from one another. But for those like Ms. Tyshynski who have long COVID, that disconnect has never ended. that the condition is real.

At worst, as Ms. Tyshynski has discovered, people don’t take it seriously and accuse those who have it of exaggerating their health woes. In that way, long COVID can be as isolating as the original illness.

“Isolation in long COVID comes in various forms and it’s not primarily just that physical isolation,” says Yochai Re’em, MD, a psychiatrist in private practice in New York who has experienced long COVID and blogs about the condition for Psychology Today. “A different yet equally challenging type of isolation is the emotional isolation, where you need more emotional support, connection with other people who can appreciate what it is you are going through without putting their own needs and desires onto you – and that can be hard to find.”

It’s hard to find in part because of what Dr. Re’em sees as a collective belief that anyone who feels bad should be able to get better by exercising, researching, or going to a doctor.

“Society thinks you need to take some kind of action and usually that’s a physical action,” he says. “And that attitude is tremendously problematic in this illness because of the postexertional malaise that people experience: When people exert themselves, their symptoms get worse. And so the action that people take can’t be that traditional action that we’re used to taking in our society.”

Long COVID patients often have their feelings invalidated not just by friends, loved ones, and extended family, but by health care providers. That can heighten feelings of isolation, particularly for people who live alone, says Jordan Anderson, DO, a neuropsychiatrist and assistant professor of psychiatry at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland.

The first patients Dr. Anderson saw as part of OHSU’s long COVID program contracted the virus in February 2020. Because the program addresses both the physical and mental health components of the condition, Dr. Anderson has seen a lot of people whose emotional challenges are similar to those Ms. Tyshynski faces.

“I think there’s a lack of understanding that leads to people just not necessarily taking it seriously,” he says. “Plus, the symptoms of long COVID do wax and wane. They’re not static. So people can be feeling pretty good one day and be feeling terrible the next. There’s some predictability to it, but it’s not absolutely predictable. It can be difficult for people to understand.”

Both Dr. Anderson and Dr. Re’em stress that long COVID patients need to prioritize their own energy regardless of what they’re being told by those who don’t understand the illness. Dr. Anderson offers to speak to his patients’ spouses to educate them about the realities of the condition because, he says, “any kind of lack of awareness or understanding in a family member or close support could potentially isolate the person struggling with long COVID.”

Depending on how open-minded and motivated a friend or relative is, they might develop more empathy with time and education, Dr. Re’em says. But for others, dealing with a confusing, unfamiliar chronic illness can be overwhelming and provoke anxiety.

“The hopelessness is too much for them to sit with, so instead they say things like ‘just push through it,’ or ‘just do X, Y, and Z,’ because psychologically it’s too much for them to take on that burden,” he says.

The good news is that there are plenty of web-based support groups for people with long COVID, including Body Politic (which Dr. Re’em is affiliated with), Survivor Corps, and on Facebook. “The patient community with this illness is tremendous, absolutely tremendous,” Dr. Re’em says. “Those people can be found and they can support each other.”

Some long COVID clinics run groups, as do individual practitioners such as Dr. Re’em, although those can be challenging to join. For instance, Dr. Re’em’s are only for New York state residents.

The key to finding a group is to be patient, because finding the right one takes time and energy.

“There are support groups that exist, but they are not as prevalent as I would like them to be,” Dr. Anderson says.

OHSU had an educational support group run by a social worker affiliated with the long COVID hub, but when the social worker left the program, the program was put on hold.

There’s a psychotherapy group operating out of the psychiatry department, but the patients are recruited exclusively from Dr. Anderson’s clinic and access is limited.

“The services exist, but I think that generally they’re sparse and pretty geographically dependent,” Dr. Anderson says. “I think you’d probably more likely be able to find something like this in a city or an area that has an academic institution or a place with a lot of resources rather than out in a rural community.”

Ms. Tyshynski opted not to join a group for fear it would increase the depression and anxiety that she had even before developing long COVID. When she and her family joined a cancer support group when her father was ill, she found it more depressing than helpful. Where she has found support is from the cofounder of the animal rescue society where she volunteers, a woman who has had long COVID for more than 2 years and has been a source of comfort and advice.

It’s one of the rare reminders Ms. Tyshynski has that even though she may live alone, she’s not completely alone. “Other people are going through this, too,” she says. “It helps to remember that.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

A year ago in December, mapping specialist Whitney Tyshynski, 35, was working out 5 days a week with a personal trainer near her home in Alberta, Canada, doing 5k trail runs, lifting heavy weights, and feeling good. Then, in January she got COVID-19. The symptoms never went away.

Nowadays, Ms. Tyshynski needs a walker to retrieve her mail, a half-block trip she can’t make without fear of fainting. Because she gets dizzy when she drives, she rarely goes anywhere in her car. Going for a dog walk with a friend means sitting in a car and watching the friend and the dogs in an open field. And since fainting at Costco during the summer, she’s afraid to shop by herself.

Because she lives alone and her closest relatives are an hour and a half away, Ms. Tyshynski is dependent on friends. But she’s reluctant to lean on them because they already have trouble understanding how debilitating her lingering symptoms can be.

“I’ve had people pretty much insinuate that I’m lazy,” she says.

There’s no question that COVID-19 cut people off from one another. But for those like Ms. Tyshynski who have long COVID, that disconnect has never ended. that the condition is real.

At worst, as Ms. Tyshynski has discovered, people don’t take it seriously and accuse those who have it of exaggerating their health woes. In that way, long COVID can be as isolating as the original illness.

“Isolation in long COVID comes in various forms and it’s not primarily just that physical isolation,” says Yochai Re’em, MD, a psychiatrist in private practice in New York who has experienced long COVID and blogs about the condition for Psychology Today. “A different yet equally challenging type of isolation is the emotional isolation, where you need more emotional support, connection with other people who can appreciate what it is you are going through without putting their own needs and desires onto you – and that can be hard to find.”

It’s hard to find in part because of what Dr. Re’em sees as a collective belief that anyone who feels bad should be able to get better by exercising, researching, or going to a doctor.

“Society thinks you need to take some kind of action and usually that’s a physical action,” he says. “And that attitude is tremendously problematic in this illness because of the postexertional malaise that people experience: When people exert themselves, their symptoms get worse. And so the action that people take can’t be that traditional action that we’re used to taking in our society.”

Long COVID patients often have their feelings invalidated not just by friends, loved ones, and extended family, but by health care providers. That can heighten feelings of isolation, particularly for people who live alone, says Jordan Anderson, DO, a neuropsychiatrist and assistant professor of psychiatry at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland.

The first patients Dr. Anderson saw as part of OHSU’s long COVID program contracted the virus in February 2020. Because the program addresses both the physical and mental health components of the condition, Dr. Anderson has seen a lot of people whose emotional challenges are similar to those Ms. Tyshynski faces.

“I think there’s a lack of understanding that leads to people just not necessarily taking it seriously,” he says. “Plus, the symptoms of long COVID do wax and wane. They’re not static. So people can be feeling pretty good one day and be feeling terrible the next. There’s some predictability to it, but it’s not absolutely predictable. It can be difficult for people to understand.”

Both Dr. Anderson and Dr. Re’em stress that long COVID patients need to prioritize their own energy regardless of what they’re being told by those who don’t understand the illness. Dr. Anderson offers to speak to his patients’ spouses to educate them about the realities of the condition because, he says, “any kind of lack of awareness or understanding in a family member or close support could potentially isolate the person struggling with long COVID.”

Depending on how open-minded and motivated a friend or relative is, they might develop more empathy with time and education, Dr. Re’em says. But for others, dealing with a confusing, unfamiliar chronic illness can be overwhelming and provoke anxiety.

“The hopelessness is too much for them to sit with, so instead they say things like ‘just push through it,’ or ‘just do X, Y, and Z,’ because psychologically it’s too much for them to take on that burden,” he says.

The good news is that there are plenty of web-based support groups for people with long COVID, including Body Politic (which Dr. Re’em is affiliated with), Survivor Corps, and on Facebook. “The patient community with this illness is tremendous, absolutely tremendous,” Dr. Re’em says. “Those people can be found and they can support each other.”

Some long COVID clinics run groups, as do individual practitioners such as Dr. Re’em, although those can be challenging to join. For instance, Dr. Re’em’s are only for New York state residents.

The key to finding a group is to be patient, because finding the right one takes time and energy.

“There are support groups that exist, but they are not as prevalent as I would like them to be,” Dr. Anderson says.

OHSU had an educational support group run by a social worker affiliated with the long COVID hub, but when the social worker left the program, the program was put on hold.

There’s a psychotherapy group operating out of the psychiatry department, but the patients are recruited exclusively from Dr. Anderson’s clinic and access is limited.

“The services exist, but I think that generally they’re sparse and pretty geographically dependent,” Dr. Anderson says. “I think you’d probably more likely be able to find something like this in a city or an area that has an academic institution or a place with a lot of resources rather than out in a rural community.”

Ms. Tyshynski opted not to join a group for fear it would increase the depression and anxiety that she had even before developing long COVID. When she and her family joined a cancer support group when her father was ill, she found it more depressing than helpful. Where she has found support is from the cofounder of the animal rescue society where she volunteers, a woman who has had long COVID for more than 2 years and has been a source of comfort and advice.

It’s one of the rare reminders Ms. Tyshynski has that even though she may live alone, she’s not completely alone. “Other people are going through this, too,” she says. “It helps to remember that.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

FDA approves first-in-class drug for HIV

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved the medication lenacapavir (Sunlenca) for adults living with multidrug resistant HIV-1 infection. .

“Following today’s decision from the FDA, lenacapavir helps to fill a critical unmet need for people with complex prior treatment histories and offers physicians a long-awaited twice-yearly option for these patients who otherwise have limited therapy choices,” said site principal investigator Sorana Segal-Maurer, MD, a professor of clinical medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, in a statement.

HIV drug regimens generally consist of two or three HIV medicines combined in a daily pill. In 2021, the FDA approved the first injectable complete drug regimen for HIV-1, Cabenuva, which can be administered monthly or every other month. Lenacapavir is administered only twice annually, but it is also combined with other antiretrovirals. The injections and oral tablets of lenacapavir are estimated to cost $42,250 in the first year of treatment and then $39,000 annually in the subsequent years, Reuters reported.

Lenacapavir is the first of a new class of drug called capsid inhibitors to be FDA-approved for treating HIV-1. The drug blocks the HIV-1 virus’s protein shell and interferes with essential steps of the virus’s evolution. The approval, announced today, was based on a multicenter clinical trial of 72 patients with multidrug resistant HIV-1 infection. After a year of the medication, 30 (83%) of the 36 patients randomly assigned to take lenacapavir, in combination with other HIV medications, had undetectable viral loads.

“Today’s approval ushers in a new class of antiretroviral drugs that may help patients with HIV who have run out of treatment options,” said Debra Birnkrant, MD, director of the division of antivirals in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, in a press release. “The availability of new classes of antiretroviral medications may possibly help these patients live longer, healthier lives.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved the medication lenacapavir (Sunlenca) for adults living with multidrug resistant HIV-1 infection. .

“Following today’s decision from the FDA, lenacapavir helps to fill a critical unmet need for people with complex prior treatment histories and offers physicians a long-awaited twice-yearly option for these patients who otherwise have limited therapy choices,” said site principal investigator Sorana Segal-Maurer, MD, a professor of clinical medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, in a statement.

HIV drug regimens generally consist of two or three HIV medicines combined in a daily pill. In 2021, the FDA approved the first injectable complete drug regimen for HIV-1, Cabenuva, which can be administered monthly or every other month. Lenacapavir is administered only twice annually, but it is also combined with other antiretrovirals. The injections and oral tablets of lenacapavir are estimated to cost $42,250 in the first year of treatment and then $39,000 annually in the subsequent years, Reuters reported.

Lenacapavir is the first of a new class of drug called capsid inhibitors to be FDA-approved for treating HIV-1. The drug blocks the HIV-1 virus’s protein shell and interferes with essential steps of the virus’s evolution. The approval, announced today, was based on a multicenter clinical trial of 72 patients with multidrug resistant HIV-1 infection. After a year of the medication, 30 (83%) of the 36 patients randomly assigned to take lenacapavir, in combination with other HIV medications, had undetectable viral loads.

“Today’s approval ushers in a new class of antiretroviral drugs that may help patients with HIV who have run out of treatment options,” said Debra Birnkrant, MD, director of the division of antivirals in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, in a press release. “The availability of new classes of antiretroviral medications may possibly help these patients live longer, healthier lives.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved the medication lenacapavir (Sunlenca) for adults living with multidrug resistant HIV-1 infection. .

“Following today’s decision from the FDA, lenacapavir helps to fill a critical unmet need for people with complex prior treatment histories and offers physicians a long-awaited twice-yearly option for these patients who otherwise have limited therapy choices,” said site principal investigator Sorana Segal-Maurer, MD, a professor of clinical medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, in a statement.

HIV drug regimens generally consist of two or three HIV medicines combined in a daily pill. In 2021, the FDA approved the first injectable complete drug regimen for HIV-1, Cabenuva, which can be administered monthly or every other month. Lenacapavir is administered only twice annually, but it is also combined with other antiretrovirals. The injections and oral tablets of lenacapavir are estimated to cost $42,250 in the first year of treatment and then $39,000 annually in the subsequent years, Reuters reported.

Lenacapavir is the first of a new class of drug called capsid inhibitors to be FDA-approved for treating HIV-1. The drug blocks the HIV-1 virus’s protein shell and interferes with essential steps of the virus’s evolution. The approval, announced today, was based on a multicenter clinical trial of 72 patients with multidrug resistant HIV-1 infection. After a year of the medication, 30 (83%) of the 36 patients randomly assigned to take lenacapavir, in combination with other HIV medications, had undetectable viral loads.

“Today’s approval ushers in a new class of antiretroviral drugs that may help patients with HIV who have run out of treatment options,” said Debra Birnkrant, MD, director of the division of antivirals in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, in a press release. “The availability of new classes of antiretroviral medications may possibly help these patients live longer, healthier lives.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID update: ASH experts discuss thrombosis, immunity

NEW ORLEANS –

In a presidential symposium at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, La Jolla Institute of Immunology scientist Shane Crotty, PhD, explained that COVID-19 has a “superpower” that allows it to be “extraordinarily stealthy.”

The virus, he said, can sneak past the body’s innate immune system, which normally responds to viral invaders within minutes to hours. “This is why you have people with high viral loads who are presymptomatic. Their innate immune system hasn’t even recognized that these people are infected.”

The adaptive immune system kicks in later. As Dr. Crotty noted, adaptive immunity is composed of three branches: B cells (the source of antibodies), CD4 “helper” T cells, and CD8 “killer” T cells. In the first year of COVID-19, his team tracked 188 subjects post infection in what he said was the largest study of its kind ever for any viral infection.

“In 8 months, 95% of people who had been infected still had measurable immune memory. In fact, most of them had multiple different compartments of immune memory still detectable, and it was likely that these individuals would still have that memory years into the future. Based on that, we made the prediction that most people who have had COVID-19 would likely be protected from reinfection – at least by severe infections – for 3 years into the future. That prediction has widely held up even in the presence of variants which weren’t around at the time.”

How do vaccines fit into the immunity picture? Dr. Crotty’s lab has tracked subjects who received 4 vaccines – Moderna, Pfizer/BioNTech, Janssen/Johnson & Johnson, and Novavax. Researchers found that the mRNA vaccines, Moderna and Pfizer/BioNTech, “are fantastic at eliciting neutralizing antibodies quickly, but then they drop off rapidly at two doses and actually continue to drop for 10 months.”

Still, he said, “when we take a look at 6 months, actually the vaccines are doing pretty incredibly well. If we compare them to an average infected individual, the mRNA vaccines all have higher neutralizing antibody titers.”

What’s happening? According to Dr. Crotty, B cells are “making guesses about what other variants might look like.” But he said research suggests that an important component of this process – germinal centers – aren’t made in some vaccinated people who are immunocompromised. (Germinal centers have been described as “microbial boot camps” for B cells.)

The good news, Dr. Crotty noted, is that a greater understanding of how COVID-19 penetrates various layers of adaptive immune defenses will lead to better ways to protect the immunocompromised. “If you think about immunity in this layered defense way, there are various ways that it could be enhanced for individuals in different categories,” he said.

Hematologist Beverley J. Hunt, MD, OBE, of St. Thomas’ Hospital/King’s Healthcare Partners in London, spoke at the ASH presidential symposium about blood clots and COVID-19. As she noted, concern arose about vaccine-related blood clots. A British team “managed quickly to come up with a diagnostic criteria,” she said. “We looked at nearly 300 patients and essentially came up with a scoring system.”

The diagnostic criteria was based on an analysis of definite or probable cases of vaccine-induced immune thrombocytopenia and thrombosis (VITT) – all related to the AstraZeneca vaccine. The criteria appeared in a 2021 study in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The report’s data didn’t allow it to compare the efficacy of anticoagulants. However, Dr. Hunt noted that clinicians turned to plasma exchange in patients with low platelet counts and extensive thrombosis. The report stated “survival after plasma exchange was 90%, considerably better than would be predicted given the baseline characteristics.”

“Now we’re following up,” Dr. Hunt said. One question to answer: Is long-term anticoagulation helpful? “We have many patients,” she said, “who are taking an anti-platelet factor out of habit.”

Dr. Crotty and Dr. Hunt report no disclosures. This reporter is a paid participant in a COVID vaccine study run by Dr. Crotty’s lab.

NEW ORLEANS –

In a presidential symposium at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, La Jolla Institute of Immunology scientist Shane Crotty, PhD, explained that COVID-19 has a “superpower” that allows it to be “extraordinarily stealthy.”

The virus, he said, can sneak past the body’s innate immune system, which normally responds to viral invaders within minutes to hours. “This is why you have people with high viral loads who are presymptomatic. Their innate immune system hasn’t even recognized that these people are infected.”

The adaptive immune system kicks in later. As Dr. Crotty noted, adaptive immunity is composed of three branches: B cells (the source of antibodies), CD4 “helper” T cells, and CD8 “killer” T cells. In the first year of COVID-19, his team tracked 188 subjects post infection in what he said was the largest study of its kind ever for any viral infection.

“In 8 months, 95% of people who had been infected still had measurable immune memory. In fact, most of them had multiple different compartments of immune memory still detectable, and it was likely that these individuals would still have that memory years into the future. Based on that, we made the prediction that most people who have had COVID-19 would likely be protected from reinfection – at least by severe infections – for 3 years into the future. That prediction has widely held up even in the presence of variants which weren’t around at the time.”

How do vaccines fit into the immunity picture? Dr. Crotty’s lab has tracked subjects who received 4 vaccines – Moderna, Pfizer/BioNTech, Janssen/Johnson & Johnson, and Novavax. Researchers found that the mRNA vaccines, Moderna and Pfizer/BioNTech, “are fantastic at eliciting neutralizing antibodies quickly, but then they drop off rapidly at two doses and actually continue to drop for 10 months.”

Still, he said, “when we take a look at 6 months, actually the vaccines are doing pretty incredibly well. If we compare them to an average infected individual, the mRNA vaccines all have higher neutralizing antibody titers.”

What’s happening? According to Dr. Crotty, B cells are “making guesses about what other variants might look like.” But he said research suggests that an important component of this process – germinal centers – aren’t made in some vaccinated people who are immunocompromised. (Germinal centers have been described as “microbial boot camps” for B cells.)

The good news, Dr. Crotty noted, is that a greater understanding of how COVID-19 penetrates various layers of adaptive immune defenses will lead to better ways to protect the immunocompromised. “If you think about immunity in this layered defense way, there are various ways that it could be enhanced for individuals in different categories,” he said.

Hematologist Beverley J. Hunt, MD, OBE, of St. Thomas’ Hospital/King’s Healthcare Partners in London, spoke at the ASH presidential symposium about blood clots and COVID-19. As she noted, concern arose about vaccine-related blood clots. A British team “managed quickly to come up with a diagnostic criteria,” she said. “We looked at nearly 300 patients and essentially came up with a scoring system.”

The diagnostic criteria was based on an analysis of definite or probable cases of vaccine-induced immune thrombocytopenia and thrombosis (VITT) – all related to the AstraZeneca vaccine. The criteria appeared in a 2021 study in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The report’s data didn’t allow it to compare the efficacy of anticoagulants. However, Dr. Hunt noted that clinicians turned to plasma exchange in patients with low platelet counts and extensive thrombosis. The report stated “survival after plasma exchange was 90%, considerably better than would be predicted given the baseline characteristics.”

“Now we’re following up,” Dr. Hunt said. One question to answer: Is long-term anticoagulation helpful? “We have many patients,” she said, “who are taking an anti-platelet factor out of habit.”

Dr. Crotty and Dr. Hunt report no disclosures. This reporter is a paid participant in a COVID vaccine study run by Dr. Crotty’s lab.

NEW ORLEANS –

In a presidential symposium at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, La Jolla Institute of Immunology scientist Shane Crotty, PhD, explained that COVID-19 has a “superpower” that allows it to be “extraordinarily stealthy.”

The virus, he said, can sneak past the body’s innate immune system, which normally responds to viral invaders within minutes to hours. “This is why you have people with high viral loads who are presymptomatic. Their innate immune system hasn’t even recognized that these people are infected.”

The adaptive immune system kicks in later. As Dr. Crotty noted, adaptive immunity is composed of three branches: B cells (the source of antibodies), CD4 “helper” T cells, and CD8 “killer” T cells. In the first year of COVID-19, his team tracked 188 subjects post infection in what he said was the largest study of its kind ever for any viral infection.

“In 8 months, 95% of people who had been infected still had measurable immune memory. In fact, most of them had multiple different compartments of immune memory still detectable, and it was likely that these individuals would still have that memory years into the future. Based on that, we made the prediction that most people who have had COVID-19 would likely be protected from reinfection – at least by severe infections – for 3 years into the future. That prediction has widely held up even in the presence of variants which weren’t around at the time.”

How do vaccines fit into the immunity picture? Dr. Crotty’s lab has tracked subjects who received 4 vaccines – Moderna, Pfizer/BioNTech, Janssen/Johnson & Johnson, and Novavax. Researchers found that the mRNA vaccines, Moderna and Pfizer/BioNTech, “are fantastic at eliciting neutralizing antibodies quickly, but then they drop off rapidly at two doses and actually continue to drop for 10 months.”

Still, he said, “when we take a look at 6 months, actually the vaccines are doing pretty incredibly well. If we compare them to an average infected individual, the mRNA vaccines all have higher neutralizing antibody titers.”

What’s happening? According to Dr. Crotty, B cells are “making guesses about what other variants might look like.” But he said research suggests that an important component of this process – germinal centers – aren’t made in some vaccinated people who are immunocompromised. (Germinal centers have been described as “microbial boot camps” for B cells.)

The good news, Dr. Crotty noted, is that a greater understanding of how COVID-19 penetrates various layers of adaptive immune defenses will lead to better ways to protect the immunocompromised. “If you think about immunity in this layered defense way, there are various ways that it could be enhanced for individuals in different categories,” he said.

Hematologist Beverley J. Hunt, MD, OBE, of St. Thomas’ Hospital/King’s Healthcare Partners in London, spoke at the ASH presidential symposium about blood clots and COVID-19. As she noted, concern arose about vaccine-related blood clots. A British team “managed quickly to come up with a diagnostic criteria,” she said. “We looked at nearly 300 patients and essentially came up with a scoring system.”

The diagnostic criteria was based on an analysis of definite or probable cases of vaccine-induced immune thrombocytopenia and thrombosis (VITT) – all related to the AstraZeneca vaccine. The criteria appeared in a 2021 study in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The report’s data didn’t allow it to compare the efficacy of anticoagulants. However, Dr. Hunt noted that clinicians turned to plasma exchange in patients with low platelet counts and extensive thrombosis. The report stated “survival after plasma exchange was 90%, considerably better than would be predicted given the baseline characteristics.”

“Now we’re following up,” Dr. Hunt said. One question to answer: Is long-term anticoagulation helpful? “We have many patients,” she said, “who are taking an anti-platelet factor out of habit.”

Dr. Crotty and Dr. Hunt report no disclosures. This reporter is a paid participant in a COVID vaccine study run by Dr. Crotty’s lab.

AT ASH 2022

Abdominal pain and constipation

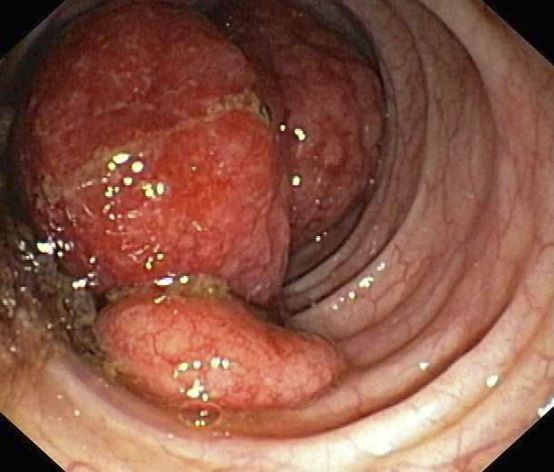

This patient's clinical presentation and endoscopy findings are consistent with a diagnosis of recurrent MCL presenting as a colonic mass.

MCL is an aggressive type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma that accounts for approximately 5%-7% of all lymphomas. Nearly 80% of patients have extranodal involvement at initial presentation, occurring in sites such as the bone marrow, spleen, Waldeyer ring, and the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Secondary GI involvement in MCL (involving nodal and/or other extranodal tissue) is common and may be detected at diagnosis and/or relapse. In several retrospective studies, the prevalence of secondary GI involvement in MCL ranged from 15% to 30%. However, in later studies, routine endoscopies in patients with untreated MCL showed GI involvement in up to 90% of patients, despite most patients not reporting GI symptoms.

The colon is the most commonly involved GI site; however, both the upper and lower GI tract from the stomach to the colon can be involved. Lymphomatous polyposis is the most common endoscopic presentation of MCL, but polyp, mass, or even normal-appearing mucosa may also be seen.

New and emerging treatment options are helping to improve survival in patients with relapsed/refractory MCL. According to National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines, the preferred second-line and subsequent regimens are:

• Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitors:

o Acalabrutinib

o Ibrutinib ± rituximab

o Zanubrutinib

• Lenalidomide + rituximab (if BTK inhibitor is contraindicated)

Other regimens that may be useful in certain circumstances are:

• Bendamustine + rituximab (if not previously given)

• Bendamustine + rituximab + cytarabine (RBAC500) (if not previously given)

• Bortezomib ± rituximab

• RDHA (rituximab, dexamethasone, cytarabine) + platinum (carboplatin, cisplatin, or oxaliplatin) (if not previously given)

• GemOx (gemcitabine, oxaliplatin) + rituximab

• Ibrutinib, lenalidomide, rituximab (category 2B)

• Ibrutinib + venetoclax

• Venetoclax, lenalidomide, rituximab (category 2B)

• Venetoclax ± rituximab

Brexucabtagene autoleucel is suggested as third-line therapy, after chemoimmunotherapy and treatment with a BTK inhibitor.

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, Assistant Professor of Internal Medicine - Clinical, Division of Hematology, The Ohio State University James Comprehensive Cancer Center, Columbus, OH.

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received research grant from: AstraZeneca; Morphosys; Incyte; Recordati.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

This patient's clinical presentation and endoscopy findings are consistent with a diagnosis of recurrent MCL presenting as a colonic mass.

MCL is an aggressive type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma that accounts for approximately 5%-7% of all lymphomas. Nearly 80% of patients have extranodal involvement at initial presentation, occurring in sites such as the bone marrow, spleen, Waldeyer ring, and the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Secondary GI involvement in MCL (involving nodal and/or other extranodal tissue) is common and may be detected at diagnosis and/or relapse. In several retrospective studies, the prevalence of secondary GI involvement in MCL ranged from 15% to 30%. However, in later studies, routine endoscopies in patients with untreated MCL showed GI involvement in up to 90% of patients, despite most patients not reporting GI symptoms.

The colon is the most commonly involved GI site; however, both the upper and lower GI tract from the stomach to the colon can be involved. Lymphomatous polyposis is the most common endoscopic presentation of MCL, but polyp, mass, or even normal-appearing mucosa may also be seen.

New and emerging treatment options are helping to improve survival in patients with relapsed/refractory MCL. According to National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines, the preferred second-line and subsequent regimens are:

• Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitors:

o Acalabrutinib

o Ibrutinib ± rituximab

o Zanubrutinib

• Lenalidomide + rituximab (if BTK inhibitor is contraindicated)

Other regimens that may be useful in certain circumstances are:

• Bendamustine + rituximab (if not previously given)

• Bendamustine + rituximab + cytarabine (RBAC500) (if not previously given)

• Bortezomib ± rituximab

• RDHA (rituximab, dexamethasone, cytarabine) + platinum (carboplatin, cisplatin, or oxaliplatin) (if not previously given)

• GemOx (gemcitabine, oxaliplatin) + rituximab

• Ibrutinib, lenalidomide, rituximab (category 2B)

• Ibrutinib + venetoclax

• Venetoclax, lenalidomide, rituximab (category 2B)

• Venetoclax ± rituximab

Brexucabtagene autoleucel is suggested as third-line therapy, after chemoimmunotherapy and treatment with a BTK inhibitor.

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, Assistant Professor of Internal Medicine - Clinical, Division of Hematology, The Ohio State University James Comprehensive Cancer Center, Columbus, OH.

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received research grant from: AstraZeneca; Morphosys; Incyte; Recordati.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

This patient's clinical presentation and endoscopy findings are consistent with a diagnosis of recurrent MCL presenting as a colonic mass.

MCL is an aggressive type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma that accounts for approximately 5%-7% of all lymphomas. Nearly 80% of patients have extranodal involvement at initial presentation, occurring in sites such as the bone marrow, spleen, Waldeyer ring, and the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Secondary GI involvement in MCL (involving nodal and/or other extranodal tissue) is common and may be detected at diagnosis and/or relapse. In several retrospective studies, the prevalence of secondary GI involvement in MCL ranged from 15% to 30%. However, in later studies, routine endoscopies in patients with untreated MCL showed GI involvement in up to 90% of patients, despite most patients not reporting GI symptoms.

The colon is the most commonly involved GI site; however, both the upper and lower GI tract from the stomach to the colon can be involved. Lymphomatous polyposis is the most common endoscopic presentation of MCL, but polyp, mass, or even normal-appearing mucosa may also be seen.

New and emerging treatment options are helping to improve survival in patients with relapsed/refractory MCL. According to National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines, the preferred second-line and subsequent regimens are:

• Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitors:

o Acalabrutinib

o Ibrutinib ± rituximab

o Zanubrutinib

• Lenalidomide + rituximab (if BTK inhibitor is contraindicated)

Other regimens that may be useful in certain circumstances are:

• Bendamustine + rituximab (if not previously given)

• Bendamustine + rituximab + cytarabine (RBAC500) (if not previously given)

• Bortezomib ± rituximab

• RDHA (rituximab, dexamethasone, cytarabine) + platinum (carboplatin, cisplatin, or oxaliplatin) (if not previously given)

• GemOx (gemcitabine, oxaliplatin) + rituximab

• Ibrutinib, lenalidomide, rituximab (category 2B)

• Ibrutinib + venetoclax

• Venetoclax, lenalidomide, rituximab (category 2B)

• Venetoclax ± rituximab

Brexucabtagene autoleucel is suggested as third-line therapy, after chemoimmunotherapy and treatment with a BTK inhibitor.

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, Assistant Professor of Internal Medicine - Clinical, Division of Hematology, The Ohio State University James Comprehensive Cancer Center, Columbus, OH.

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received research grant from: AstraZeneca; Morphosys; Incyte; Recordati.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 55-year-old White woman presents with complaints of left-sided abdominal pain and constipation of 10-day duration. The patient's prior medical history is notable for mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) treated 2 years earlier with RDHA (rituximab, dexamethasone, cytarabine) + platinum (carboplatin, cisplatin, or oxaliplatin) followed by autologous stem cell transplantation. No lymphadenopathy is noted on physical examination. Abdominal examination reveals abdominal distension, normal bowel sounds, and left lower quadrant tenderness to palpation without guarding, rigidity, or hepatosplenomegaly. Laboratory test results including CBC are within normal range. Endoscopy reveals a growth in the colon, as shown in the image.

Cochrane Review bolsters case that emollients don’t prevent AD

associated with early use of emollients.