User login

Contemporary psychiatry: A SWOT analysis

Editor’s note: This article was adapted with permission from a version originally published in the Ohio Psychiatric Physician Association’s newsletter, Insight Matters, Fall 2022.

Acknowledging and analyzing strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT) is an important tactic many organizations use to develop a strategic plan to grow, move forward, and thrive. A SWOT analysis can provide a “big picture” view of the status and the desired future directions not only for companies but for medical disciplines such as psychiatry. So here are my perspectives on psychiatry’s strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats. It is a work in progress, and I welcome (and encourage) you to send additional items or comments to me at [email protected].

Strengths

- The American Psychiatric Association (APA) is the oldest medical professional organization, established in 1844 (3 years before the American Medical Association)1

- Strong organizational structure and governance, and a “big tent” with several tiers of membership

- Effective, member-driven District Branches

- The medical identity at the core of psychiatry—we are psychiatric physicians2

- Escalating number of senior medical students choosing psychiatry as a career, far more than a decade ago

- High demand for psychiatrists in all settings around the country

- Increased compensation for psychiatrists (market forces of supply and demand)

- Psychiatry is continuously evolving and reinventing itself: seismic shifts in etiopathogenesis, disease conceptualization, terminology, and therapies (4 major shifts over the past century)3

- An abundant body of evidence supporting that all psychiatric disorders are brain disorders and transdiagnostic in nature4

- Many vibrant subspecialty societies

- Substantial number of Tier 1, evidence-based treatments

- Novel mechanisms of action and treatment strategies are being introduced on a regular basis for psychotic and mood disorders5,6

- Advances in neuromodulation techniques to treat a wide spectrum of psychiatric disorders, including electroconvulsive therapy, transcranial magnetic stimulation, vagus nerve stimulation, transcranial direct current stimulation, deep brain stimulation, cranial electric stimulation, epidural cortical stimulation, focused ultrasound, low field magnetic stimulation, magnetic seizure therapy, and near infrared light therapy, with mechanisms that are electric, ultrasound, magnetic, or optical7,8

- Psychiatric physicians develop wisdom by practicing psychiatry (ie, they become more empathic, tolerant of ambiguity, prosocial, introspective, aware of one’s strengths and limitations). Neuroplasticity in the frontal cortex is triggered by conducting psychotherapy9

Weaknesses

- Shrinking workforce due to a static number of residency training slots for 40 years10

- High rate of retirement by aging psychiatrists

- Persistent stigma around mental disorders despite massive scientific and medical advances11

- Still no real parity! We need succinct laws with “teeth”12

- Demedicalization in the public sector, referring to psychiatric physicians as “providers” and labeling patients as “clients”2

- Not enough graduating residents choosing to do subspecialty fellowships (especially geriatric, addiction, psychosomatic psychiatry) to meet escalating societal needs

- Very low presence in rural areas (both psychiatrists and psychiatric hospitals)

- Persistent APA member apathy: only 10% to 15% vote in the APA national elections or volunteer to serve on committees

- Widespread member dissatisfaction with maintenance of certification

- Neuroscience advances are not being translated fast enough for practical clinical applications

- Many in the public at large do not realize psychiatric symptoms are generated from anomalous brain circuits or that psychiatric disorders are highly genetic but also have environmental and epigenetic etiologies

- The DSM diagnostic system needs a paradigm shift: it is still based on a menu of clinical signs and symptoms and is devoid of objective diagnostic measures such as biomarkers4

- Neuroscience literacy among busy psychiatric practitioners is insufficient at a time of explosive growth in basic and clinical neuroscience13

- No effective treatment for alcohol or substance use disorders despite their very high morbidity and mortality

- Major psychiatric disorders are still associated with significant disability (schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, anxiety disorders, eating disorders, substance use disorders)

- Suicide rate (other than opioid deaths) has continued to rise in the past 3 decades14

Opportunities

- Potentially momentous clinical applications of the neuroscience breakthroughs

- Collaborative care with primary care physicians and increasing colocalization

- Dramatic increase in public awareness about the importance of mental health due to the COVID-19 pandemic15

- Powerful new data management tools, including machine learning, artificial intelligence, super computers, big data, deep learning, nanotechnology, and metabolomics, all of which are expediting neurobiological discoveries16

- The potential of reclassifying psychiatric disorders as neurological disorders, which will improve reimbursement for patient health care and reduce stigma17

- Emergence of new mechanisms of action of disease etiology, such as microbiota, mitochondrial dysfunction, permeable blood-brain barrier, and neuroimmune dysregulation18,19

- The advent and growth of “precision psychiatry”20

- The tremendous potential of molecular genetics and gene therapy for psychiatric disorders, most of which are genetic in etiology

- Expanding applications of neuroimaging techniques, including morphological, spectroscopic, functional, diffusion tensor imaging, and receptor imaging21

- Epigenetic advances in neuropsychiatric disorders

- Remarkably powerful research methods, such as pluripotent cells (producing neurons from skin cells), optogenetics (activating genes with light), gene-wide association studies, CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats, which serve as genetic scissors to remove and replace abnormal genes), and brain connectomics22

- Psychiatry should develop and promote an “annual mental health checkup” for all age groups, similar to an annual physical exam23

- Focus on the social determinants of health

- Address the unmet mental health needs of individuals who are members of minority groups

- Lobby ferociously for a much larger budget for the National Institute of Mental Health to advance funding for research of serious psychiatric brain disorders

- Remind Congress continuously that the cost of mental illness is $700 billion annually and costs can only be reduced by funding neurobiological research1

- Partner with the pharmaceutical industry instead of demonizing them. They are the only entity that develops medication for psychiatry, where 80% of disorders have no FDA-approved drugs.24 Without the pharmaceutical industry and the help of medications, many psychiatric patients would still be institutionalized and unable to lead a normal life. We must recognize the contributions of pharmaceutical companies to the health of our patients, similar to the warp speed development of vaccines for the deadly coronavirus

- Psychiatric clinicians must refer patients to clinical trials because without patients enrolling in FDA studies, no drug developments can take place

- Many “out-of-the-box” therapies are being developed, such as antiapoptotic therapy, microglia inhibition, mitochondrial repair, white matter fiber remyelination, neuroprotection, and reversing N-methyl-

d -aspartate receptor hypofunction25 - The emerging evidence that psychotherapy is in fact a biological treatment that induces brain changes (neuroplasticity) and can modulate the immune system26

- Druggable genes, providing innovative new medications27

- Reposition psychedelics as revolutionary new treatments28

- Emphasize measurement-based care (rating scales), which can upgrade patient care29

- Because psychosis is associated with brain tissue loss, just like heart attacks are associated with myocardium destruction, psychiatrists must act like cardiologists30 and treat psychotic episodes urgently, like a stroke,31 to reduce the duration of untreated psychosis and improve patient outcomes

Threats

- Antipsychiatry cults continue to disparage and attack psychiatry32

- Health delivery systems are replacing psychiatric physicians with nurse practitioners to lower costs, regardless of quality and experience, and they inappropriately lump them together as “providers”2

- Psychologists continue to seek prescribing privileges with absurdly sketchy, predominantly online training supervised by other psychologists33

- Many legislators and policymakers, as well as the public, still don’t understand the difference between psychiatrists and psychologists, and the extensively disparate medical training in quality and quantity

- A dearth of psychiatric physician-scientists because very few residents are pursuing research fellowships after training34

- Disproportionate emphasis on clinical care and generating clinical revenue (relative value units) in academic institutions, with fewer tenure-track faculty members having protected time to write grants for federal or foundation grants to support their salaries and research operations35

- Meager financial support for teaching in psychiatry departments

- Many seriously psychiatrically ill persons do not have access to psychiatric medical care (and often to primary care as well)

- Many in the public falsely believe psychiatric disorders are hopeless and untreatable, which perpetuates stigma

- Long-acting injectable antipsychotic formulations are not used early enough in patients with psychosis, who are known to have a high nonadherence rate with oral medications following discharge from their first hospitalization. This leads to many recurrences with multiple devastating consequences, including progressive brain tissue loss, treatment resistance, disability, incarceration, and suicide36

- Many clinicians do not have full-text access to all studies indexed in PubMed, which is vital for lifelong learning in a rapidly growing medical discipline such as psychiatry

- Psychiatrists are often unable to prescribe medications shortly after they are approved by the FDA due to the insurance companies’ outrageous preauthorization racket that enforces a fail-first policy with cheaper generics, even if generic medications are associated with safety and tolerability problems37

- The continued use of decades-old first-generation antipsychotic medications despite 32 published studies reporting their neurotoxicity and the death of brain cells38

Using this analysis to benefit our patients

Despite its strengths, psychiatry must overcome its weaknesses, fend off its threats, and exploit its many opportunities. The only way to do that is for psychiatrists to unify and for the APA to provide inspired leadership to achieve the aspirational goals of our field. However, we must adopt “moonshot thinking”39 to magnify the Ss, diminish the Ws, exploit the Os, and stave off the Ts of our SWOT, thereby attaining all our cherished and lofty goals. Ultimately, the greatest beneficiaries will be our patients.

1. Nasrallah HA. 20 reasons to celebrate our APA membership. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(1):6-9.

2. Nasrallah HA. We are physicians, not providers, and we treat patients, not clients! Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(2):5-8.

3. Nasrallah HA. From bedlam to biomarkers: the transformation of psychiatry’s terminology reflects its 4 conceptual earthquakes. Current Psychiatry. 2015;14(1):5-7.

4. Nasrallah HA. Re-inventing the DSM as a transdiagnostic model: psychiatric disorders are extensively interconnected. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2021;33(3):148-150.

5. Nasrallah HA. Psychopharmacology 3.0. Current Psychiatry. 2081;17(11):4-7.

6. Nasrallah HA. Reversing depression: a plethora of therapeutic strategies and mechanisms. Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(8):4-6.

7. Rosa MA, Lisanby SH. Somatic treatments for mood disorders. Psychopharmacology. 2012;37(1):102-116.

8. Nasrallah HA. Optimal psychiatric treatment: target the brain and avoid the body. Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(12):3-6.

9. Nasrallah HA. Does psychiatry practice make us wise? Current Psychiatry. 2009;8(10):12-14.

10. Buckley PF, Nasrallah HA. The psychiatry workforce pool is shrinking. What are we doing about it? Current Psychiatry. 2016;15(9):23-24,95.

11. Nasrallah HA. A psychiatric manifesto: stigma is hate speech and a hate crime. Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(6):6-8.

12. Nasrallah HA. The travesty of disparity and non-parity. Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(1):8,19.

13. Nasrallah HA. Advancing clinical neuroscience literacy among psychiatric practitioners. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(9):17-18.

14. Nasrallah HA. The scourge of societal anosognosia about the mentally ill. Current Psychiatry. 2016;15(6):19-24.

15. Nasrallah HA. 10 silver linings of the COVID-19 pandemic. Insight Matters. 2021;45:3-4.

16. Kalenderian H, Nasrallah HA. Artificial intelligence in psychiatry. Current Psychiatry. 2019:18(8):33-38.

17. Nasrallah HA. Let’s tear down the silos and re-unify psychiatry and neurology! Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(8):8-9.

18. Nasrallah HA. It takes guts to be mentally ill: microbiota and psychopathology. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(9):4-6.

19. Schrenk DA, Nasrallah HA. Faulty fences: blood-brain barrier dysfunction in schizophrenia. Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(10):28-32.

20. Nasrallah HA. The dawn of precision psychiatry. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(12):7-8,11.

21. Nasrallah HA. Today’s psychiatric neuroscience advances were science fiction during my residency. Current Psychiatry 2021;20(4):5-7,12,24.

22. Nasrallah HA. Transformative advances are unfolding in psychiatry. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(9):10-12.

23. Nasrallah HA. I have a dream…for psychiatry. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(11):12-14.

24. Devulapalli KK, Nasrallah HA. An analysis of the high psychotropic off-label use in psychiatric disorders: the majority of psychiatric diagnoses have no approved drug. Asian J Psychiatry. 2009;2(1):29-36.

25. Nasrallah HA. Transformative advances are unfolding in psychiatry. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(9):10-12.

26. Nasrallah HA. Repositioning psychotherapy as a neurobiological intervention. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(12):18-19.

27. Nasrallah HA. Druggable genes, promiscuous drugs, repurposed medications. Current Psychiatry. 2016;15(5):23,27.

28. Nasrallah HA. Long overdue: measurement-based psychiatric practice. Current Psychiatry. 2009;8(4):14-16.

29. Nasrallah HA. Maddening therapies: how hallucinogens morphed into novel treatments. Current Psychiatry. 2017:16(1):19-21.

30. Nasrallah HA. For first episode psychosis, psychiatrists should behave like cardiologists. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(8):4-7.

31. Nasrallah HA, Roque A. FAST and RAPID: acronyms to prevent brain damage in stroke and psychosis. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(8):6-8.

32. Nasrallah HA. The antipsychiatry movement: who and why. Current Psychiatry. 2011;10(12):4,6,53.

33. Nasrallah HA. Prescribing is the culmination of extensive medical training and psychologists do not qualify. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(6):11-12,14-16.

34. Fenton W, James R, Insel T. Psychiatry residency training, the physician-scientist, and the future of psychiatry. Acad Psychiatry. 2004;28(4):263-266.

35. Balon R, Morreale MK. The precipitous decline of academic medicine in the United States. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2020;32(4):225-227.

36. Nasrallah HA. 10 devastating consequences of psychotic relapses. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(5):9-12.

37. Nasrallah HA. Pre-authorization is illegal, unethical, and adversely disrupts patient care. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(4):5-11.

38. Nasrallah HA, Chen AT. Multiple neurotoxic effects of haloperidol resulting in neuronal death. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2017;29(3):195-202.

39. Nasrallah HA. It’s time for moonshot thinking in psychiatry. Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(2):8-10.

Editor’s note: This article was adapted with permission from a version originally published in the Ohio Psychiatric Physician Association’s newsletter, Insight Matters, Fall 2022.

Acknowledging and analyzing strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT) is an important tactic many organizations use to develop a strategic plan to grow, move forward, and thrive. A SWOT analysis can provide a “big picture” view of the status and the desired future directions not only for companies but for medical disciplines such as psychiatry. So here are my perspectives on psychiatry’s strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats. It is a work in progress, and I welcome (and encourage) you to send additional items or comments to me at [email protected].

Strengths

- The American Psychiatric Association (APA) is the oldest medical professional organization, established in 1844 (3 years before the American Medical Association)1

- Strong organizational structure and governance, and a “big tent” with several tiers of membership

- Effective, member-driven District Branches

- The medical identity at the core of psychiatry—we are psychiatric physicians2

- Escalating number of senior medical students choosing psychiatry as a career, far more than a decade ago

- High demand for psychiatrists in all settings around the country

- Increased compensation for psychiatrists (market forces of supply and demand)

- Psychiatry is continuously evolving and reinventing itself: seismic shifts in etiopathogenesis, disease conceptualization, terminology, and therapies (4 major shifts over the past century)3

- An abundant body of evidence supporting that all psychiatric disorders are brain disorders and transdiagnostic in nature4

- Many vibrant subspecialty societies

- Substantial number of Tier 1, evidence-based treatments

- Novel mechanisms of action and treatment strategies are being introduced on a regular basis for psychotic and mood disorders5,6

- Advances in neuromodulation techniques to treat a wide spectrum of psychiatric disorders, including electroconvulsive therapy, transcranial magnetic stimulation, vagus nerve stimulation, transcranial direct current stimulation, deep brain stimulation, cranial electric stimulation, epidural cortical stimulation, focused ultrasound, low field magnetic stimulation, magnetic seizure therapy, and near infrared light therapy, with mechanisms that are electric, ultrasound, magnetic, or optical7,8

- Psychiatric physicians develop wisdom by practicing psychiatry (ie, they become more empathic, tolerant of ambiguity, prosocial, introspective, aware of one’s strengths and limitations). Neuroplasticity in the frontal cortex is triggered by conducting psychotherapy9

Weaknesses

- Shrinking workforce due to a static number of residency training slots for 40 years10

- High rate of retirement by aging psychiatrists

- Persistent stigma around mental disorders despite massive scientific and medical advances11

- Still no real parity! We need succinct laws with “teeth”12

- Demedicalization in the public sector, referring to psychiatric physicians as “providers” and labeling patients as “clients”2

- Not enough graduating residents choosing to do subspecialty fellowships (especially geriatric, addiction, psychosomatic psychiatry) to meet escalating societal needs

- Very low presence in rural areas (both psychiatrists and psychiatric hospitals)

- Persistent APA member apathy: only 10% to 15% vote in the APA national elections or volunteer to serve on committees

- Widespread member dissatisfaction with maintenance of certification

- Neuroscience advances are not being translated fast enough for practical clinical applications

- Many in the public at large do not realize psychiatric symptoms are generated from anomalous brain circuits or that psychiatric disorders are highly genetic but also have environmental and epigenetic etiologies

- The DSM diagnostic system needs a paradigm shift: it is still based on a menu of clinical signs and symptoms and is devoid of objective diagnostic measures such as biomarkers4

- Neuroscience literacy among busy psychiatric practitioners is insufficient at a time of explosive growth in basic and clinical neuroscience13

- No effective treatment for alcohol or substance use disorders despite their very high morbidity and mortality

- Major psychiatric disorders are still associated with significant disability (schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, anxiety disorders, eating disorders, substance use disorders)

- Suicide rate (other than opioid deaths) has continued to rise in the past 3 decades14

Opportunities

- Potentially momentous clinical applications of the neuroscience breakthroughs

- Collaborative care with primary care physicians and increasing colocalization

- Dramatic increase in public awareness about the importance of mental health due to the COVID-19 pandemic15

- Powerful new data management tools, including machine learning, artificial intelligence, super computers, big data, deep learning, nanotechnology, and metabolomics, all of which are expediting neurobiological discoveries16

- The potential of reclassifying psychiatric disorders as neurological disorders, which will improve reimbursement for patient health care and reduce stigma17

- Emergence of new mechanisms of action of disease etiology, such as microbiota, mitochondrial dysfunction, permeable blood-brain barrier, and neuroimmune dysregulation18,19

- The advent and growth of “precision psychiatry”20

- The tremendous potential of molecular genetics and gene therapy for psychiatric disorders, most of which are genetic in etiology

- Expanding applications of neuroimaging techniques, including morphological, spectroscopic, functional, diffusion tensor imaging, and receptor imaging21

- Epigenetic advances in neuropsychiatric disorders

- Remarkably powerful research methods, such as pluripotent cells (producing neurons from skin cells), optogenetics (activating genes with light), gene-wide association studies, CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats, which serve as genetic scissors to remove and replace abnormal genes), and brain connectomics22

- Psychiatry should develop and promote an “annual mental health checkup” for all age groups, similar to an annual physical exam23

- Focus on the social determinants of health

- Address the unmet mental health needs of individuals who are members of minority groups

- Lobby ferociously for a much larger budget for the National Institute of Mental Health to advance funding for research of serious psychiatric brain disorders

- Remind Congress continuously that the cost of mental illness is $700 billion annually and costs can only be reduced by funding neurobiological research1

- Partner with the pharmaceutical industry instead of demonizing them. They are the only entity that develops medication for psychiatry, where 80% of disorders have no FDA-approved drugs.24 Without the pharmaceutical industry and the help of medications, many psychiatric patients would still be institutionalized and unable to lead a normal life. We must recognize the contributions of pharmaceutical companies to the health of our patients, similar to the warp speed development of vaccines for the deadly coronavirus

- Psychiatric clinicians must refer patients to clinical trials because without patients enrolling in FDA studies, no drug developments can take place

- Many “out-of-the-box” therapies are being developed, such as antiapoptotic therapy, microglia inhibition, mitochondrial repair, white matter fiber remyelination, neuroprotection, and reversing N-methyl-

d -aspartate receptor hypofunction25 - The emerging evidence that psychotherapy is in fact a biological treatment that induces brain changes (neuroplasticity) and can modulate the immune system26

- Druggable genes, providing innovative new medications27

- Reposition psychedelics as revolutionary new treatments28

- Emphasize measurement-based care (rating scales), which can upgrade patient care29

- Because psychosis is associated with brain tissue loss, just like heart attacks are associated with myocardium destruction, psychiatrists must act like cardiologists30 and treat psychotic episodes urgently, like a stroke,31 to reduce the duration of untreated psychosis and improve patient outcomes

Threats

- Antipsychiatry cults continue to disparage and attack psychiatry32

- Health delivery systems are replacing psychiatric physicians with nurse practitioners to lower costs, regardless of quality and experience, and they inappropriately lump them together as “providers”2

- Psychologists continue to seek prescribing privileges with absurdly sketchy, predominantly online training supervised by other psychologists33

- Many legislators and policymakers, as well as the public, still don’t understand the difference between psychiatrists and psychologists, and the extensively disparate medical training in quality and quantity

- A dearth of psychiatric physician-scientists because very few residents are pursuing research fellowships after training34

- Disproportionate emphasis on clinical care and generating clinical revenue (relative value units) in academic institutions, with fewer tenure-track faculty members having protected time to write grants for federal or foundation grants to support their salaries and research operations35

- Meager financial support for teaching in psychiatry departments

- Many seriously psychiatrically ill persons do not have access to psychiatric medical care (and often to primary care as well)

- Many in the public falsely believe psychiatric disorders are hopeless and untreatable, which perpetuates stigma

- Long-acting injectable antipsychotic formulations are not used early enough in patients with psychosis, who are known to have a high nonadherence rate with oral medications following discharge from their first hospitalization. This leads to many recurrences with multiple devastating consequences, including progressive brain tissue loss, treatment resistance, disability, incarceration, and suicide36

- Many clinicians do not have full-text access to all studies indexed in PubMed, which is vital for lifelong learning in a rapidly growing medical discipline such as psychiatry

- Psychiatrists are often unable to prescribe medications shortly after they are approved by the FDA due to the insurance companies’ outrageous preauthorization racket that enforces a fail-first policy with cheaper generics, even if generic medications are associated with safety and tolerability problems37

- The continued use of decades-old first-generation antipsychotic medications despite 32 published studies reporting their neurotoxicity and the death of brain cells38

Using this analysis to benefit our patients

Despite its strengths, psychiatry must overcome its weaknesses, fend off its threats, and exploit its many opportunities. The only way to do that is for psychiatrists to unify and for the APA to provide inspired leadership to achieve the aspirational goals of our field. However, we must adopt “moonshot thinking”39 to magnify the Ss, diminish the Ws, exploit the Os, and stave off the Ts of our SWOT, thereby attaining all our cherished and lofty goals. Ultimately, the greatest beneficiaries will be our patients.

Editor’s note: This article was adapted with permission from a version originally published in the Ohio Psychiatric Physician Association’s newsletter, Insight Matters, Fall 2022.

Acknowledging and analyzing strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT) is an important tactic many organizations use to develop a strategic plan to grow, move forward, and thrive. A SWOT analysis can provide a “big picture” view of the status and the desired future directions not only for companies but for medical disciplines such as psychiatry. So here are my perspectives on psychiatry’s strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats. It is a work in progress, and I welcome (and encourage) you to send additional items or comments to me at [email protected].

Strengths

- The American Psychiatric Association (APA) is the oldest medical professional organization, established in 1844 (3 years before the American Medical Association)1

- Strong organizational structure and governance, and a “big tent” with several tiers of membership

- Effective, member-driven District Branches

- The medical identity at the core of psychiatry—we are psychiatric physicians2

- Escalating number of senior medical students choosing psychiatry as a career, far more than a decade ago

- High demand for psychiatrists in all settings around the country

- Increased compensation for psychiatrists (market forces of supply and demand)

- Psychiatry is continuously evolving and reinventing itself: seismic shifts in etiopathogenesis, disease conceptualization, terminology, and therapies (4 major shifts over the past century)3

- An abundant body of evidence supporting that all psychiatric disorders are brain disorders and transdiagnostic in nature4

- Many vibrant subspecialty societies

- Substantial number of Tier 1, evidence-based treatments

- Novel mechanisms of action and treatment strategies are being introduced on a regular basis for psychotic and mood disorders5,6

- Advances in neuromodulation techniques to treat a wide spectrum of psychiatric disorders, including electroconvulsive therapy, transcranial magnetic stimulation, vagus nerve stimulation, transcranial direct current stimulation, deep brain stimulation, cranial electric stimulation, epidural cortical stimulation, focused ultrasound, low field magnetic stimulation, magnetic seizure therapy, and near infrared light therapy, with mechanisms that are electric, ultrasound, magnetic, or optical7,8

- Psychiatric physicians develop wisdom by practicing psychiatry (ie, they become more empathic, tolerant of ambiguity, prosocial, introspective, aware of one’s strengths and limitations). Neuroplasticity in the frontal cortex is triggered by conducting psychotherapy9

Weaknesses

- Shrinking workforce due to a static number of residency training slots for 40 years10

- High rate of retirement by aging psychiatrists

- Persistent stigma around mental disorders despite massive scientific and medical advances11

- Still no real parity! We need succinct laws with “teeth”12

- Demedicalization in the public sector, referring to psychiatric physicians as “providers” and labeling patients as “clients”2

- Not enough graduating residents choosing to do subspecialty fellowships (especially geriatric, addiction, psychosomatic psychiatry) to meet escalating societal needs

- Very low presence in rural areas (both psychiatrists and psychiatric hospitals)

- Persistent APA member apathy: only 10% to 15% vote in the APA national elections or volunteer to serve on committees

- Widespread member dissatisfaction with maintenance of certification

- Neuroscience advances are not being translated fast enough for practical clinical applications

- Many in the public at large do not realize psychiatric symptoms are generated from anomalous brain circuits or that psychiatric disorders are highly genetic but also have environmental and epigenetic etiologies

- The DSM diagnostic system needs a paradigm shift: it is still based on a menu of clinical signs and symptoms and is devoid of objective diagnostic measures such as biomarkers4

- Neuroscience literacy among busy psychiatric practitioners is insufficient at a time of explosive growth in basic and clinical neuroscience13

- No effective treatment for alcohol or substance use disorders despite their very high morbidity and mortality

- Major psychiatric disorders are still associated with significant disability (schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, anxiety disorders, eating disorders, substance use disorders)

- Suicide rate (other than opioid deaths) has continued to rise in the past 3 decades14

Opportunities

- Potentially momentous clinical applications of the neuroscience breakthroughs

- Collaborative care with primary care physicians and increasing colocalization

- Dramatic increase in public awareness about the importance of mental health due to the COVID-19 pandemic15

- Powerful new data management tools, including machine learning, artificial intelligence, super computers, big data, deep learning, nanotechnology, and metabolomics, all of which are expediting neurobiological discoveries16

- The potential of reclassifying psychiatric disorders as neurological disorders, which will improve reimbursement for patient health care and reduce stigma17

- Emergence of new mechanisms of action of disease etiology, such as microbiota, mitochondrial dysfunction, permeable blood-brain barrier, and neuroimmune dysregulation18,19

- The advent and growth of “precision psychiatry”20

- The tremendous potential of molecular genetics and gene therapy for psychiatric disorders, most of which are genetic in etiology

- Expanding applications of neuroimaging techniques, including morphological, spectroscopic, functional, diffusion tensor imaging, and receptor imaging21

- Epigenetic advances in neuropsychiatric disorders

- Remarkably powerful research methods, such as pluripotent cells (producing neurons from skin cells), optogenetics (activating genes with light), gene-wide association studies, CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats, which serve as genetic scissors to remove and replace abnormal genes), and brain connectomics22

- Psychiatry should develop and promote an “annual mental health checkup” for all age groups, similar to an annual physical exam23

- Focus on the social determinants of health

- Address the unmet mental health needs of individuals who are members of minority groups

- Lobby ferociously for a much larger budget for the National Institute of Mental Health to advance funding for research of serious psychiatric brain disorders

- Remind Congress continuously that the cost of mental illness is $700 billion annually and costs can only be reduced by funding neurobiological research1

- Partner with the pharmaceutical industry instead of demonizing them. They are the only entity that develops medication for psychiatry, where 80% of disorders have no FDA-approved drugs.24 Without the pharmaceutical industry and the help of medications, many psychiatric patients would still be institutionalized and unable to lead a normal life. We must recognize the contributions of pharmaceutical companies to the health of our patients, similar to the warp speed development of vaccines for the deadly coronavirus

- Psychiatric clinicians must refer patients to clinical trials because without patients enrolling in FDA studies, no drug developments can take place

- Many “out-of-the-box” therapies are being developed, such as antiapoptotic therapy, microglia inhibition, mitochondrial repair, white matter fiber remyelination, neuroprotection, and reversing N-methyl-

d -aspartate receptor hypofunction25 - The emerging evidence that psychotherapy is in fact a biological treatment that induces brain changes (neuroplasticity) and can modulate the immune system26

- Druggable genes, providing innovative new medications27

- Reposition psychedelics as revolutionary new treatments28

- Emphasize measurement-based care (rating scales), which can upgrade patient care29

- Because psychosis is associated with brain tissue loss, just like heart attacks are associated with myocardium destruction, psychiatrists must act like cardiologists30 and treat psychotic episodes urgently, like a stroke,31 to reduce the duration of untreated psychosis and improve patient outcomes

Threats

- Antipsychiatry cults continue to disparage and attack psychiatry32

- Health delivery systems are replacing psychiatric physicians with nurse practitioners to lower costs, regardless of quality and experience, and they inappropriately lump them together as “providers”2

- Psychologists continue to seek prescribing privileges with absurdly sketchy, predominantly online training supervised by other psychologists33

- Many legislators and policymakers, as well as the public, still don’t understand the difference between psychiatrists and psychologists, and the extensively disparate medical training in quality and quantity

- A dearth of psychiatric physician-scientists because very few residents are pursuing research fellowships after training34

- Disproportionate emphasis on clinical care and generating clinical revenue (relative value units) in academic institutions, with fewer tenure-track faculty members having protected time to write grants for federal or foundation grants to support their salaries and research operations35

- Meager financial support for teaching in psychiatry departments

- Many seriously psychiatrically ill persons do not have access to psychiatric medical care (and often to primary care as well)

- Many in the public falsely believe psychiatric disorders are hopeless and untreatable, which perpetuates stigma

- Long-acting injectable antipsychotic formulations are not used early enough in patients with psychosis, who are known to have a high nonadherence rate with oral medications following discharge from their first hospitalization. This leads to many recurrences with multiple devastating consequences, including progressive brain tissue loss, treatment resistance, disability, incarceration, and suicide36

- Many clinicians do not have full-text access to all studies indexed in PubMed, which is vital for lifelong learning in a rapidly growing medical discipline such as psychiatry

- Psychiatrists are often unable to prescribe medications shortly after they are approved by the FDA due to the insurance companies’ outrageous preauthorization racket that enforces a fail-first policy with cheaper generics, even if generic medications are associated with safety and tolerability problems37

- The continued use of decades-old first-generation antipsychotic medications despite 32 published studies reporting their neurotoxicity and the death of brain cells38

Using this analysis to benefit our patients

Despite its strengths, psychiatry must overcome its weaknesses, fend off its threats, and exploit its many opportunities. The only way to do that is for psychiatrists to unify and for the APA to provide inspired leadership to achieve the aspirational goals of our field. However, we must adopt “moonshot thinking”39 to magnify the Ss, diminish the Ws, exploit the Os, and stave off the Ts of our SWOT, thereby attaining all our cherished and lofty goals. Ultimately, the greatest beneficiaries will be our patients.

1. Nasrallah HA. 20 reasons to celebrate our APA membership. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(1):6-9.

2. Nasrallah HA. We are physicians, not providers, and we treat patients, not clients! Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(2):5-8.

3. Nasrallah HA. From bedlam to biomarkers: the transformation of psychiatry’s terminology reflects its 4 conceptual earthquakes. Current Psychiatry. 2015;14(1):5-7.

4. Nasrallah HA. Re-inventing the DSM as a transdiagnostic model: psychiatric disorders are extensively interconnected. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2021;33(3):148-150.

5. Nasrallah HA. Psychopharmacology 3.0. Current Psychiatry. 2081;17(11):4-7.

6. Nasrallah HA. Reversing depression: a plethora of therapeutic strategies and mechanisms. Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(8):4-6.

7. Rosa MA, Lisanby SH. Somatic treatments for mood disorders. Psychopharmacology. 2012;37(1):102-116.

8. Nasrallah HA. Optimal psychiatric treatment: target the brain and avoid the body. Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(12):3-6.

9. Nasrallah HA. Does psychiatry practice make us wise? Current Psychiatry. 2009;8(10):12-14.

10. Buckley PF, Nasrallah HA. The psychiatry workforce pool is shrinking. What are we doing about it? Current Psychiatry. 2016;15(9):23-24,95.

11. Nasrallah HA. A psychiatric manifesto: stigma is hate speech and a hate crime. Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(6):6-8.

12. Nasrallah HA. The travesty of disparity and non-parity. Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(1):8,19.

13. Nasrallah HA. Advancing clinical neuroscience literacy among psychiatric practitioners. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(9):17-18.

14. Nasrallah HA. The scourge of societal anosognosia about the mentally ill. Current Psychiatry. 2016;15(6):19-24.

15. Nasrallah HA. 10 silver linings of the COVID-19 pandemic. Insight Matters. 2021;45:3-4.

16. Kalenderian H, Nasrallah HA. Artificial intelligence in psychiatry. Current Psychiatry. 2019:18(8):33-38.

17. Nasrallah HA. Let’s tear down the silos and re-unify psychiatry and neurology! Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(8):8-9.

18. Nasrallah HA. It takes guts to be mentally ill: microbiota and psychopathology. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(9):4-6.

19. Schrenk DA, Nasrallah HA. Faulty fences: blood-brain barrier dysfunction in schizophrenia. Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(10):28-32.

20. Nasrallah HA. The dawn of precision psychiatry. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(12):7-8,11.

21. Nasrallah HA. Today’s psychiatric neuroscience advances were science fiction during my residency. Current Psychiatry 2021;20(4):5-7,12,24.

22. Nasrallah HA. Transformative advances are unfolding in psychiatry. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(9):10-12.

23. Nasrallah HA. I have a dream…for psychiatry. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(11):12-14.

24. Devulapalli KK, Nasrallah HA. An analysis of the high psychotropic off-label use in psychiatric disorders: the majority of psychiatric diagnoses have no approved drug. Asian J Psychiatry. 2009;2(1):29-36.

25. Nasrallah HA. Transformative advances are unfolding in psychiatry. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(9):10-12.

26. Nasrallah HA. Repositioning psychotherapy as a neurobiological intervention. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(12):18-19.

27. Nasrallah HA. Druggable genes, promiscuous drugs, repurposed medications. Current Psychiatry. 2016;15(5):23,27.

28. Nasrallah HA. Long overdue: measurement-based psychiatric practice. Current Psychiatry. 2009;8(4):14-16.

29. Nasrallah HA. Maddening therapies: how hallucinogens morphed into novel treatments. Current Psychiatry. 2017:16(1):19-21.

30. Nasrallah HA. For first episode psychosis, psychiatrists should behave like cardiologists. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(8):4-7.

31. Nasrallah HA, Roque A. FAST and RAPID: acronyms to prevent brain damage in stroke and psychosis. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(8):6-8.

32. Nasrallah HA. The antipsychiatry movement: who and why. Current Psychiatry. 2011;10(12):4,6,53.

33. Nasrallah HA. Prescribing is the culmination of extensive medical training and psychologists do not qualify. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(6):11-12,14-16.

34. Fenton W, James R, Insel T. Psychiatry residency training, the physician-scientist, and the future of psychiatry. Acad Psychiatry. 2004;28(4):263-266.

35. Balon R, Morreale MK. The precipitous decline of academic medicine in the United States. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2020;32(4):225-227.

36. Nasrallah HA. 10 devastating consequences of psychotic relapses. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(5):9-12.

37. Nasrallah HA. Pre-authorization is illegal, unethical, and adversely disrupts patient care. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(4):5-11.

38. Nasrallah HA, Chen AT. Multiple neurotoxic effects of haloperidol resulting in neuronal death. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2017;29(3):195-202.

39. Nasrallah HA. It’s time for moonshot thinking in psychiatry. Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(2):8-10.

1. Nasrallah HA. 20 reasons to celebrate our APA membership. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(1):6-9.

2. Nasrallah HA. We are physicians, not providers, and we treat patients, not clients! Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(2):5-8.

3. Nasrallah HA. From bedlam to biomarkers: the transformation of psychiatry’s terminology reflects its 4 conceptual earthquakes. Current Psychiatry. 2015;14(1):5-7.

4. Nasrallah HA. Re-inventing the DSM as a transdiagnostic model: psychiatric disorders are extensively interconnected. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2021;33(3):148-150.

5. Nasrallah HA. Psychopharmacology 3.0. Current Psychiatry. 2081;17(11):4-7.

6. Nasrallah HA. Reversing depression: a plethora of therapeutic strategies and mechanisms. Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(8):4-6.

7. Rosa MA, Lisanby SH. Somatic treatments for mood disorders. Psychopharmacology. 2012;37(1):102-116.

8. Nasrallah HA. Optimal psychiatric treatment: target the brain and avoid the body. Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(12):3-6.

9. Nasrallah HA. Does psychiatry practice make us wise? Current Psychiatry. 2009;8(10):12-14.

10. Buckley PF, Nasrallah HA. The psychiatry workforce pool is shrinking. What are we doing about it? Current Psychiatry. 2016;15(9):23-24,95.

11. Nasrallah HA. A psychiatric manifesto: stigma is hate speech and a hate crime. Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(6):6-8.

12. Nasrallah HA. The travesty of disparity and non-parity. Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(1):8,19.

13. Nasrallah HA. Advancing clinical neuroscience literacy among psychiatric practitioners. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(9):17-18.

14. Nasrallah HA. The scourge of societal anosognosia about the mentally ill. Current Psychiatry. 2016;15(6):19-24.

15. Nasrallah HA. 10 silver linings of the COVID-19 pandemic. Insight Matters. 2021;45:3-4.

16. Kalenderian H, Nasrallah HA. Artificial intelligence in psychiatry. Current Psychiatry. 2019:18(8):33-38.

17. Nasrallah HA. Let’s tear down the silos and re-unify psychiatry and neurology! Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(8):8-9.

18. Nasrallah HA. It takes guts to be mentally ill: microbiota and psychopathology. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(9):4-6.

19. Schrenk DA, Nasrallah HA. Faulty fences: blood-brain barrier dysfunction in schizophrenia. Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(10):28-32.

20. Nasrallah HA. The dawn of precision psychiatry. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(12):7-8,11.

21. Nasrallah HA. Today’s psychiatric neuroscience advances were science fiction during my residency. Current Psychiatry 2021;20(4):5-7,12,24.

22. Nasrallah HA. Transformative advances are unfolding in psychiatry. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(9):10-12.

23. Nasrallah HA. I have a dream…for psychiatry. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(11):12-14.

24. Devulapalli KK, Nasrallah HA. An analysis of the high psychotropic off-label use in psychiatric disorders: the majority of psychiatric diagnoses have no approved drug. Asian J Psychiatry. 2009;2(1):29-36.

25. Nasrallah HA. Transformative advances are unfolding in psychiatry. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(9):10-12.

26. Nasrallah HA. Repositioning psychotherapy as a neurobiological intervention. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(12):18-19.

27. Nasrallah HA. Druggable genes, promiscuous drugs, repurposed medications. Current Psychiatry. 2016;15(5):23,27.

28. Nasrallah HA. Long overdue: measurement-based psychiatric practice. Current Psychiatry. 2009;8(4):14-16.

29. Nasrallah HA. Maddening therapies: how hallucinogens morphed into novel treatments. Current Psychiatry. 2017:16(1):19-21.

30. Nasrallah HA. For first episode psychosis, psychiatrists should behave like cardiologists. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(8):4-7.

31. Nasrallah HA, Roque A. FAST and RAPID: acronyms to prevent brain damage in stroke and psychosis. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(8):6-8.

32. Nasrallah HA. The antipsychiatry movement: who and why. Current Psychiatry. 2011;10(12):4,6,53.

33. Nasrallah HA. Prescribing is the culmination of extensive medical training and psychologists do not qualify. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(6):11-12,14-16.

34. Fenton W, James R, Insel T. Psychiatry residency training, the physician-scientist, and the future of psychiatry. Acad Psychiatry. 2004;28(4):263-266.

35. Balon R, Morreale MK. The precipitous decline of academic medicine in the United States. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2020;32(4):225-227.

36. Nasrallah HA. 10 devastating consequences of psychotic relapses. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(5):9-12.

37. Nasrallah HA. Pre-authorization is illegal, unethical, and adversely disrupts patient care. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(4):5-11.

38. Nasrallah HA, Chen AT. Multiple neurotoxic effects of haloperidol resulting in neuronal death. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2017;29(3):195-202.

39. Nasrallah HA. It’s time for moonshot thinking in psychiatry. Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(2):8-10.

From debate to stalemate and hate: An epidemic of intellectual constipation

Groupthink is hazardous, especially when perfused with religious fervor. It can lead to adopting irrational thinking1 and aversion to new ideas or facts. Tenaciously clinging to 1 ideology as “the absolute truth” precludes an open-minded, constructive debate with any other point of view.

Three historical examples come to mind:

- The discovery of chlorpromazine in 1952 was a scientifically and clinically seismic and transformational event for the treatment of psychosis, which for centuries had been dogmatically deemed irreversible. Jean Delay, MD, the French psychiatrist and co-discoverer of chlorpromazine, was the first physician to witness the magical and dazzling dissolution of delusions and hallucinations in chronically institutionalized patients with psychosis.2 He published his landmark clinical observations and then traveled to the United States to share the great news and present his findings at a large psychiatric conference, hoping to enthrall American psychiatrists with the historic breakthrough in treating psychosis. This was an era in which psychoanalysis dominated American psychiatry (despite its dearth of empirical evidence). Dr. Delay was shocked when the audience of psychoanalysts booed him for saying that psychosis can be treated with a medication instead of with psychoanalysis (which, in the most intense groupthink in the history of psychiatry, they all believed was the only therapy for psychosis). Deeply disheartened, Dr. Delay returned to France and never returned to the United States. This groupthink was a prime example of intellectual constipation. Since then, not surprisingly, psychopharmacology grew meteorically while psychoanalysis declined precipitously.

- The monoamine hypothesis of depression, first propagated 60 years ago, became a groupthink dogma among psychiatric researchers for the next several decades, stultifying broader antidepressant medication development by focusing only on monoamines (eg, serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine). More recently, researchers have become more open-minded, and the monoamine hypothesis has taken a backseat to innovative new models of antidepressant therapy based on advances in the pathophysiology of depression, such as glutamatergic, opioid, and sigma pathways as well as neuroplasticity models.3 The consequence of groupthink in antidepressant research was a half-century delay in the development of effective alternative treatments that could have helped millions of patients recover from a life-threatening brain disorder such as major depressive disorder.

- Peptic ulcer and its serious gastritis were long believed to be due to stress and increased stomach acidity. So the groupthink gastroenterologists mocked 2 Australian researchers, Barry Marshall and Robin Warren, when they proposed that peptic ulcer may be due to an infection with a bacterium called Helicobacter pylori, and published their data demonstrating it.4 Marshall and Warren had the last laugh when they were awarded the 2005 Nobel Prize in Medicine and Physiology. It is ironic that even gastroenterologists are not immune to the affliction of intellectual constipation!

Intellectual constipation’s effects on youth

The principle of a civilized debate of contrarian ideas must be inculcated early, especially during college years. Youth should be mentored about not cowering into an ideological cocoon and shun listening to different or opposing points of view.5 Institutions of higher learning are incubators of future leaders. They must provide their young students with a wide diversity of ideas and philosophies and encourage them to critique those ideas, not “shelter” or isolate them from any ideas. Youth need to recognize that the complex societies in which we all live and work are not placid or unidimensional but a hotbed of clashing ideas and perspectives. An open-minded approach to education will inoculate young minds from developing intellectual constipation in adulthood.

Avoiding or insulating oneself from the ideas of others—no matter how disagreeable—leads to cognitive cowardice and behavioral intolerance. Healthy and vibrant debate is necessary as an inoculation against extremism, hate, paranoia, and, ultimately, violence. Psychiatrists help patients to self-reflect, gain insight, and consider changing their view of themselves and the world to help them grow into mature and resilient individuals. But for the millions of people with intellectual constipation, a potent cerebral enema comprised of a salubrious concoction of insight, common sense, and compromise may be the prescription to forestall lethal intellectual ileus.

1. Nasrallah HA. Irrational beliefs: a ubiquitous human trait. Current Psychiatry. 2007;6(2):15-16.

2. Ban TA. Fifty years chlorpromazine: a historical perspective. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2007;3(4):495-500.

3. Boku S, Nakagawa S, Toda H, et al. Neural basis of major depressive disorder: beyond monoamine hypothesis. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2018;72(1):3-12.

4. Warren JR, Marshall B. Unidentified curved bacilli on gastric epithelium in active chronic gastritis. Lancet. 1983;1(8336):1273-1275.

5. Lukianoff G, Haidt J. The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas Are Setting Up a Generation for Failure. Penguin Books; 2018.

Groupthink is hazardous, especially when perfused with religious fervor. It can lead to adopting irrational thinking1 and aversion to new ideas or facts. Tenaciously clinging to 1 ideology as “the absolute truth” precludes an open-minded, constructive debate with any other point of view.

Three historical examples come to mind:

- The discovery of chlorpromazine in 1952 was a scientifically and clinically seismic and transformational event for the treatment of psychosis, which for centuries had been dogmatically deemed irreversible. Jean Delay, MD, the French psychiatrist and co-discoverer of chlorpromazine, was the first physician to witness the magical and dazzling dissolution of delusions and hallucinations in chronically institutionalized patients with psychosis.2 He published his landmark clinical observations and then traveled to the United States to share the great news and present his findings at a large psychiatric conference, hoping to enthrall American psychiatrists with the historic breakthrough in treating psychosis. This was an era in which psychoanalysis dominated American psychiatry (despite its dearth of empirical evidence). Dr. Delay was shocked when the audience of psychoanalysts booed him for saying that psychosis can be treated with a medication instead of with psychoanalysis (which, in the most intense groupthink in the history of psychiatry, they all believed was the only therapy for psychosis). Deeply disheartened, Dr. Delay returned to France and never returned to the United States. This groupthink was a prime example of intellectual constipation. Since then, not surprisingly, psychopharmacology grew meteorically while psychoanalysis declined precipitously.

- The monoamine hypothesis of depression, first propagated 60 years ago, became a groupthink dogma among psychiatric researchers for the next several decades, stultifying broader antidepressant medication development by focusing only on monoamines (eg, serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine). More recently, researchers have become more open-minded, and the monoamine hypothesis has taken a backseat to innovative new models of antidepressant therapy based on advances in the pathophysiology of depression, such as glutamatergic, opioid, and sigma pathways as well as neuroplasticity models.3 The consequence of groupthink in antidepressant research was a half-century delay in the development of effective alternative treatments that could have helped millions of patients recover from a life-threatening brain disorder such as major depressive disorder.

- Peptic ulcer and its serious gastritis were long believed to be due to stress and increased stomach acidity. So the groupthink gastroenterologists mocked 2 Australian researchers, Barry Marshall and Robin Warren, when they proposed that peptic ulcer may be due to an infection with a bacterium called Helicobacter pylori, and published their data demonstrating it.4 Marshall and Warren had the last laugh when they were awarded the 2005 Nobel Prize in Medicine and Physiology. It is ironic that even gastroenterologists are not immune to the affliction of intellectual constipation!

Intellectual constipation’s effects on youth

The principle of a civilized debate of contrarian ideas must be inculcated early, especially during college years. Youth should be mentored about not cowering into an ideological cocoon and shun listening to different or opposing points of view.5 Institutions of higher learning are incubators of future leaders. They must provide their young students with a wide diversity of ideas and philosophies and encourage them to critique those ideas, not “shelter” or isolate them from any ideas. Youth need to recognize that the complex societies in which we all live and work are not placid or unidimensional but a hotbed of clashing ideas and perspectives. An open-minded approach to education will inoculate young minds from developing intellectual constipation in adulthood.

Avoiding or insulating oneself from the ideas of others—no matter how disagreeable—leads to cognitive cowardice and behavioral intolerance. Healthy and vibrant debate is necessary as an inoculation against extremism, hate, paranoia, and, ultimately, violence. Psychiatrists help patients to self-reflect, gain insight, and consider changing their view of themselves and the world to help them grow into mature and resilient individuals. But for the millions of people with intellectual constipation, a potent cerebral enema comprised of a salubrious concoction of insight, common sense, and compromise may be the prescription to forestall lethal intellectual ileus.

Groupthink is hazardous, especially when perfused with religious fervor. It can lead to adopting irrational thinking1 and aversion to new ideas or facts. Tenaciously clinging to 1 ideology as “the absolute truth” precludes an open-minded, constructive debate with any other point of view.

Three historical examples come to mind:

- The discovery of chlorpromazine in 1952 was a scientifically and clinically seismic and transformational event for the treatment of psychosis, which for centuries had been dogmatically deemed irreversible. Jean Delay, MD, the French psychiatrist and co-discoverer of chlorpromazine, was the first physician to witness the magical and dazzling dissolution of delusions and hallucinations in chronically institutionalized patients with psychosis.2 He published his landmark clinical observations and then traveled to the United States to share the great news and present his findings at a large psychiatric conference, hoping to enthrall American psychiatrists with the historic breakthrough in treating psychosis. This was an era in which psychoanalysis dominated American psychiatry (despite its dearth of empirical evidence). Dr. Delay was shocked when the audience of psychoanalysts booed him for saying that psychosis can be treated with a medication instead of with psychoanalysis (which, in the most intense groupthink in the history of psychiatry, they all believed was the only therapy for psychosis). Deeply disheartened, Dr. Delay returned to France and never returned to the United States. This groupthink was a prime example of intellectual constipation. Since then, not surprisingly, psychopharmacology grew meteorically while psychoanalysis declined precipitously.

- The monoamine hypothesis of depression, first propagated 60 years ago, became a groupthink dogma among psychiatric researchers for the next several decades, stultifying broader antidepressant medication development by focusing only on monoamines (eg, serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine). More recently, researchers have become more open-minded, and the monoamine hypothesis has taken a backseat to innovative new models of antidepressant therapy based on advances in the pathophysiology of depression, such as glutamatergic, opioid, and sigma pathways as well as neuroplasticity models.3 The consequence of groupthink in antidepressant research was a half-century delay in the development of effective alternative treatments that could have helped millions of patients recover from a life-threatening brain disorder such as major depressive disorder.

- Peptic ulcer and its serious gastritis were long believed to be due to stress and increased stomach acidity. So the groupthink gastroenterologists mocked 2 Australian researchers, Barry Marshall and Robin Warren, when they proposed that peptic ulcer may be due to an infection with a bacterium called Helicobacter pylori, and published their data demonstrating it.4 Marshall and Warren had the last laugh when they were awarded the 2005 Nobel Prize in Medicine and Physiology. It is ironic that even gastroenterologists are not immune to the affliction of intellectual constipation!

Intellectual constipation’s effects on youth

The principle of a civilized debate of contrarian ideas must be inculcated early, especially during college years. Youth should be mentored about not cowering into an ideological cocoon and shun listening to different or opposing points of view.5 Institutions of higher learning are incubators of future leaders. They must provide their young students with a wide diversity of ideas and philosophies and encourage them to critique those ideas, not “shelter” or isolate them from any ideas. Youth need to recognize that the complex societies in which we all live and work are not placid or unidimensional but a hotbed of clashing ideas and perspectives. An open-minded approach to education will inoculate young minds from developing intellectual constipation in adulthood.

Avoiding or insulating oneself from the ideas of others—no matter how disagreeable—leads to cognitive cowardice and behavioral intolerance. Healthy and vibrant debate is necessary as an inoculation against extremism, hate, paranoia, and, ultimately, violence. Psychiatrists help patients to self-reflect, gain insight, and consider changing their view of themselves and the world to help them grow into mature and resilient individuals. But for the millions of people with intellectual constipation, a potent cerebral enema comprised of a salubrious concoction of insight, common sense, and compromise may be the prescription to forestall lethal intellectual ileus.

1. Nasrallah HA. Irrational beliefs: a ubiquitous human trait. Current Psychiatry. 2007;6(2):15-16.

2. Ban TA. Fifty years chlorpromazine: a historical perspective. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2007;3(4):495-500.

3. Boku S, Nakagawa S, Toda H, et al. Neural basis of major depressive disorder: beyond monoamine hypothesis. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2018;72(1):3-12.

4. Warren JR, Marshall B. Unidentified curved bacilli on gastric epithelium in active chronic gastritis. Lancet. 1983;1(8336):1273-1275.

5. Lukianoff G, Haidt J. The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas Are Setting Up a Generation for Failure. Penguin Books; 2018.

1. Nasrallah HA. Irrational beliefs: a ubiquitous human trait. Current Psychiatry. 2007;6(2):15-16.

2. Ban TA. Fifty years chlorpromazine: a historical perspective. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2007;3(4):495-500.

3. Boku S, Nakagawa S, Toda H, et al. Neural basis of major depressive disorder: beyond monoamine hypothesis. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2018;72(1):3-12.

4. Warren JR, Marshall B. Unidentified curved bacilli on gastric epithelium in active chronic gastritis. Lancet. 1983;1(8336):1273-1275.

5. Lukianoff G, Haidt J. The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas Are Setting Up a Generation for Failure. Penguin Books; 2018.

Positive psychotherapy: Core principles

In a time of great national and global upheaval, increasing social problems, migration, climate crisis, globalization, and increasingly multicultural societies, our patients and their needs are unique, diverse, and changing. We need a new understanding of mental health to be able to adequately meet the demands of an ever-changing world. Treatment exclusively with psychotropic medications or years of psychoanalysis will not meet these needs.

Psychiatrists and psychotherapists feel (and actually have) a social responsibility, particularly in a multifaceted global society. Psychotherapeutic interventions may contribute to a more peaceful society1 by reducing individuals’ inner stress, solving (unconscious) conflicts, and conveying a humanistic worldview. As an integrative and transcultural method, positive psychotherapy has been applied for more than 45 years in more than 60 countries and is an active force within a “positive mental health movement.”2

The term “positive psychotherapy” describes 2 different approaches3: positive psychotherapy (1977) by Nossrat Peseschkian,4 which is a humanistic psychodynamic approach, and positive psychotherapy (2006) by Martin E.P. Seligman, Tayyab Rashid, and Acacia C. Parks,5 which is a more cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT)–based approach. This article focuses on the first approach.

Why ‘positive’ psychotherapy?

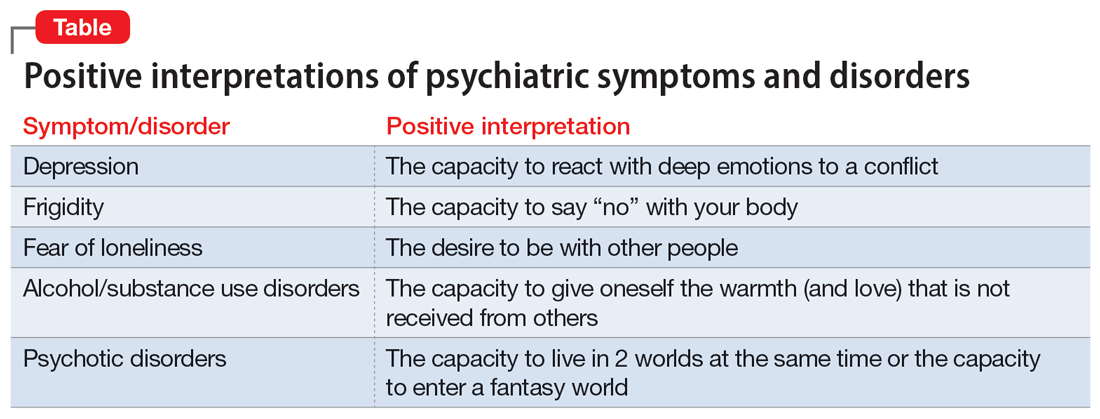

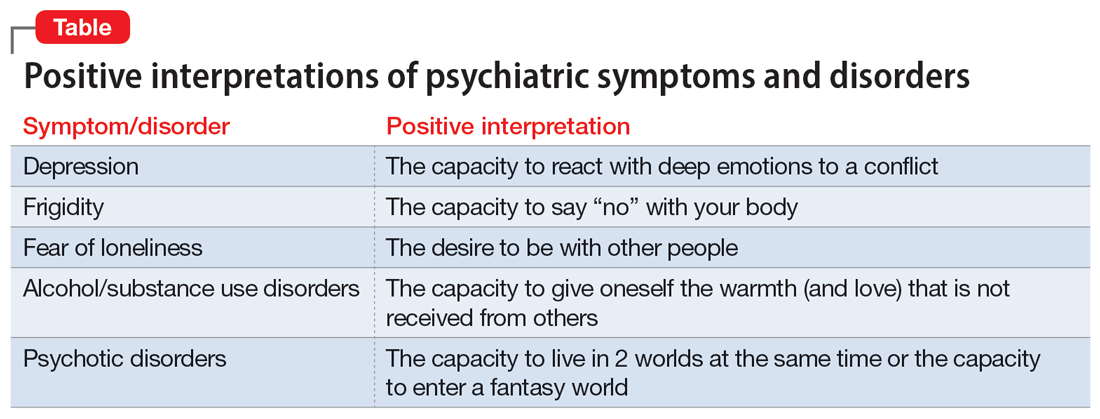

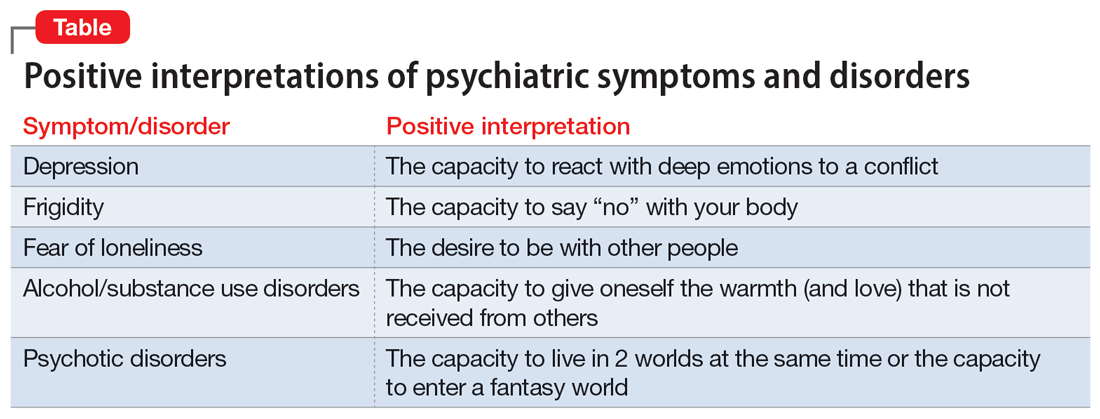

The term “positive” implies that positive psychotherapy focuses on the patient’s possibilities and capacities. Symptoms and disorders are seen as capacities to react to a conflict. The Latin term “positum” or “positivus” is applied in its original meaning—the factual, the given, the actual. Factual and given are not only the disorder, the symptoms, and the problems but also the capacity to become healthy and/or cope with this situation. This positive meaning confronts the patient (and the therapist) with a lesser-known aspect of the illness, but one that is just as important for the understanding and clinical treatment of the affliction: its function, its meaning, and, consequently, its positive aspects.6

Positive psychotherapy is a humanistic psychodynamic psychotherapy approach developed by Nossrat Peseschkian (1933-2010).4,7 Positive psychotherapy has been developed since the 1970s in the clinical setting with neurotic and psychosomatic patients. It integrates approaches of the 4 main modalities of psychotherapy:

- a humanistic view of human beings

- a systemic approach toward culture, work, and environment

- a psychodynamic understanding of disorders

- a practical, goal-oriented approach with some cognitive-behavioral techniques.

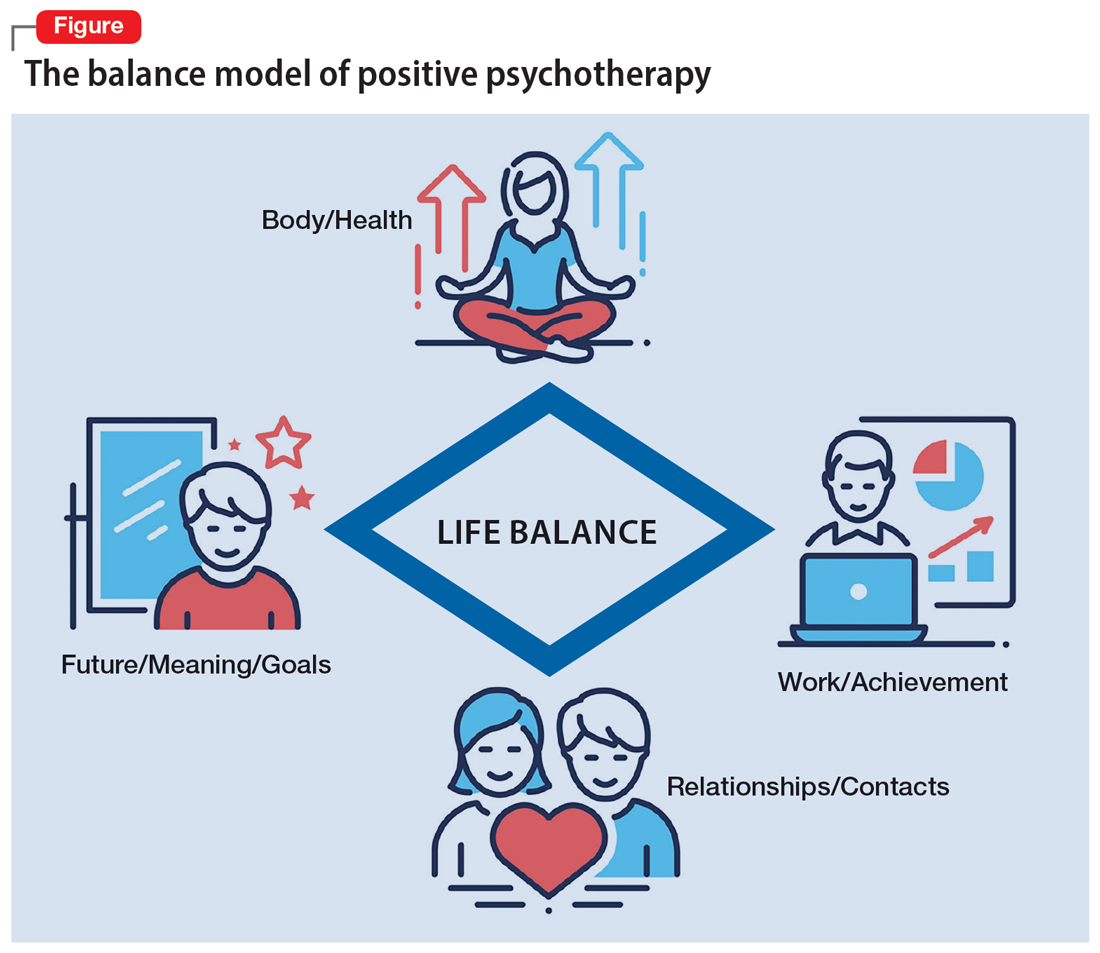

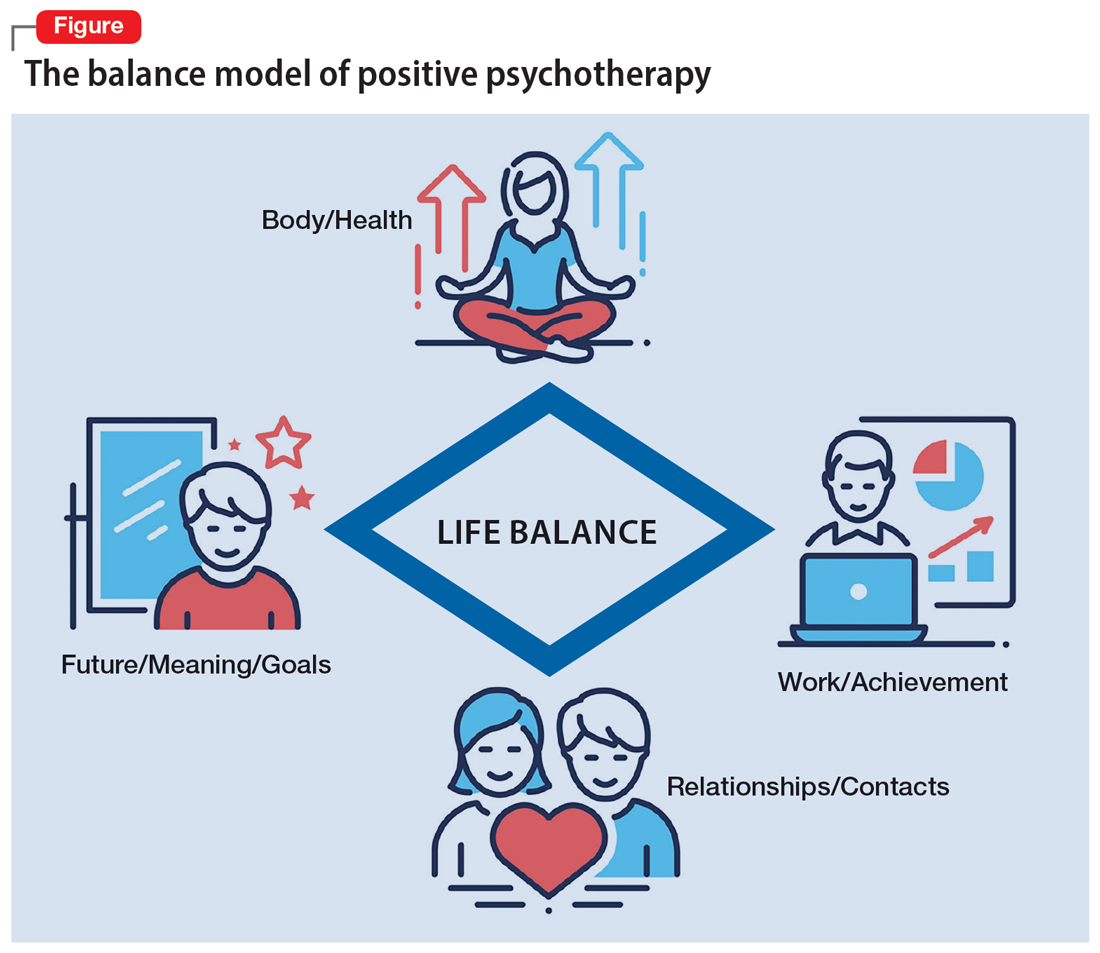

The concept of balance

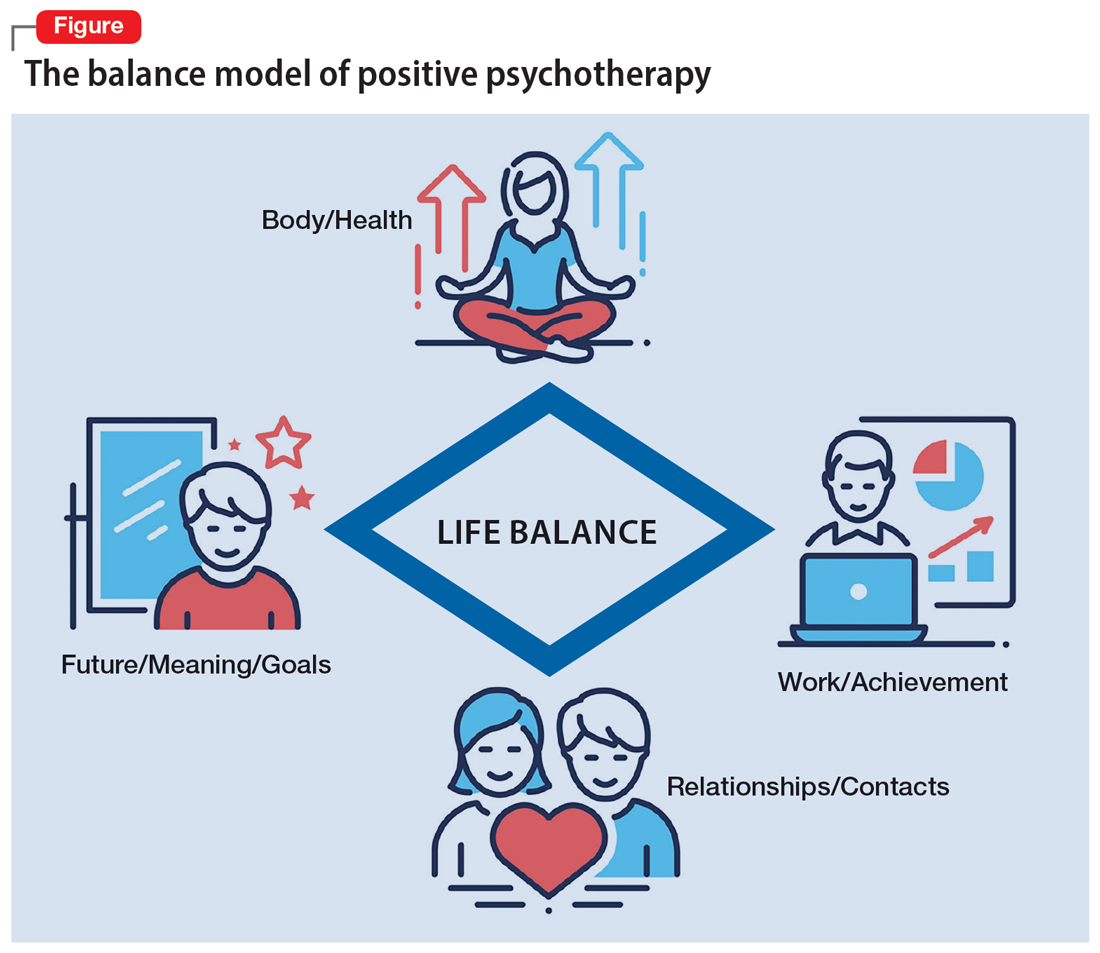

Based on a humanistic view of human beings and the resources every patient possesses, a key concept of positive psychotherapy is the importance of balance in one’s life. The balance model (Figure) is the core of positive psychotherapy and is applied in clinical and nonclinical settings. This model is based on the concept that there are 4 main areas of life in which a human being lives and functions. These areas influence one’s satisfaction in life, one’s feelings of self-worth, and the way one deals with conflicts and challenges. Although all 4 capacities are latent in every human being, depending on one`s education, environment, and zeitgeist, some will be more developed than others. Our life energies, activities, and reactions belong to these 4 areas of life:

- physical: eating, tenderness, sexuality, sleep, relaxation, sports, appearance, clothing

- achievement: work, job, career, money

- relationships: partner, family, friends, acquaintances and strangers, community life

- meaning and future: existential questions, spirituality, religious practices, future plans, fantasy.

A goal of treatment is to help the patient recognize their own resources and mobilize them with the goal of bringing them into a dynamic equilibrium. This goal places value on a balanced distribution of energy (25% to each area), not of time. According to positive psychotherapy, a person does not become ill because one sphere of life is overemphasized but because of the areas that have been neglected. In the case vignette described in the Box, the problem is not the patient’s work but that his physical health, family and friends, and existential questions are being neglected. That the therapist is not critical from the start of treatment is a constructive experience for the patient and is important and fruitful for building the relationship between the therapist and the patient. Instead of emphasizing the deficits or the disorders, the patient and his family hear that he has neglected other areas of life and not developed them yet.

Box

Mr. M, a 52-year-old manager, is “sent” by his wife to see a psychotherapist. “My wife says I am married to my job, and I should spend more time with her and the children. I understand this, but I love my job. It is no stress for me, but a few minutes at home, and I feel totally stressed out,” he says. During the first interview, the therapist asks Mr. M to draw his energy distribution in the balance model (Figure), and it becomes clear he spends more than 80% of his time and energy on his job.

That is not such a surprise for him. But after some explanation, the therapist tells him that he should continue to do so and that it is an ability to be able to spend so much time every day for his job. Mr. M says, “You are the first person to tell me that it is good that I am working so much. I expected you, like all the others, to tell me I must reduce my working hours immediately, go on vacation, etc.”

Continue to: The balance model...

The balance model also embodies the 4 potential sources of self-esteem. Usually, only 1 or 2 areas provide self-esteem, but in the therapeutic process a patient can learn to uncover the neglected areas so that their self-esteem will have additional pillars of support. By emphasizing how therapy can help to develop one’s self-esteem, many patients can be motivated for the therapeutic process. The balance model, with its concept of devoting 25% of one’s energy to each sphere of life, gives the patient a clear vision about their life and how they can be healthy over the long run by avoiding one-sidedness.8

The transcultural approach

In positive psychotherapy, the term “transcultural” (or cross-cultural) means not only consideration of cultural factors when the therapist and patient come from diverse cultural backgrounds (intercultural psychotherapy or “migrant psychotherapy”) but specifically the consideration of cultural factors in every therapeutic relationship, as a therapeutic attitude and consequently as a sociopolitical dimension of our thinking and behavior. This consideration of the uniqueness of each person, of the relativity of human behavior, and of “unity in diversity” is an essential reason positive psychotherapy is not a “Western” method in the sense of “psychological colonization.”9 Rather, this approach is a culture-sensitive method that can be modified to adapt to particular cultures and life situations.

Transcultural positive psychotherapy begins with answering 2 questions: “How are people different?” and “What do all people have in common?”4 During the therapeutic process, the therapist gives examples from other cultures to the patient to help them relativize their own perspective and broaden their repertoire of behavior.

The use of stories, tales, proverbs, and anecdotes

A special technique of positive psychotherapy is the therapeutic use of stories, tales, proverbs, and anecdotes.10 Often stories from other cultures are used because they offer another perspective when the patient sees none. This has been shown to be highly effective in psychiatric settings, especially in group settings. Psychiatric patients can often easily relate to the images created by stories. In psychiatry and psychotherapy, stories can be a means of changing a patient’s point of view. Such narratives can free up the listener’s feelings and thoughts and often lead to “Aha!” moments. The mirror function of storytelling leads to identification. In the narratives, the reader or listener recognizes themself as well as their needs and situation. They can reflect on the stories without personally becoming the focus of these reflections and remember their own experiences. Stories present solutions that can be models against which one’s own approach can be compared but that also leave room for broader interpretation. Storytelling is particularly useful in bringing about change in patients who are holding fast to old and outworn ideas.

The positive interpretation of disorders

Positive psychotherapy is based on a humanistic view that every human being is good by nature and endowed with unique capacities.11 This positive perspective leads not only to a new quality of relationship between the therapist and patient but also to a new perspective on disorders (Table). Thus, disorders can be “interpreted” in a positive way6: What does the patient unconsciously want to express with their symptoms? What is the function of their disorder? The positive process brings with it a change in perspective to all those concerned: the patient, their family, and the therapist/physician. In this way, one moves from the symptom (which is the disorder and often already has been very thoroughly examined) to the conflict (and the function of the disorder). The positive interpretations are only offered to the patient (“What do you say to this explanation?” “Can you apply this to your own situation?”).

Continue to: This process also helps us...

This process also helps us focus on the “true” patient, who often is not our patient. The patient who comes to us functions as a symptom carrier and can be seen as the “weakest link” in the family chain. The “real patient” is often sitting at home. The positive interpretation of illnesses confronts the patient with the possible function and psychodynamic meaning of their illness for themself and their social milieu, encouraging the patient (and their family) to see their abilities and not merely the pathological aspects.12

Fields of application of positive psychotherapy

As a method positioned between manualized CBT and process-oriented analytical psychotherapy, positive psychotherapy pursues a semi-structured approach in diagnostics (first interview), treatment, posttherapeutic self-help, and training. Positive psychotherapy is applied for the treatment of mood (affective), neurotic, stress-related, and somatoform disorders; behavioral syndromes; and, to some extent, personality disorders. Positive psychotherapy has been employed successfully side-by-side with classical individual therapy as well as in the settings of couple, family, and group therapy.13

What makes positive psychotherapy attractive for mental health professionals?

- As a method that integrates the 4 main modalities of psychotherapy, it does not engage in the conflicts between different schools but combines effective elements into a single approach.

- As an integrative approach, it adjusts to the patient and not vice versa. It gives the therapist the possibility of focusing more on either the actual problems (supportive approach) or the basic conflict (psychodynamic approach).

- It uses vocabulary and terms that can be understood by patients from all strata of society.

- As a culturally sensitive method, it can be applied to patients from different cultures and does not require cultural adaptation.

- As a psychodynamic method, it does not stop after early life conflicts have become more conscious but helps the patient to apply the gained insights using practical techniques.

- It starts with positive affirmations and encouragement but does not later “forget” the unconscious conflicts that have led to disorders. It is not perceived as superficial.

- As a method originally coming from psychiatry and medical practice, it builds a bridge between a scientific basis and psychotherapeutic insights. It favors the biopsychosocial approach.

Bottom Line

Positive psychotherapy combines humanistic, systemic, psychodynamic, and cognitive-behavioral aspects. It is based on a resource-oriented view of human beings in which disorders are interpreted as capacities to react in a specific and unique way to life events and circumstances. Positive psychotherapy can be applied in psychiatry and psychotherapy. This short-term method is easily understood by patients from diverse cultures and social backgrounds.

Related Resources

- Peseschkian H, Remmers A. Positive psychotherapy: an introduction. In: Messias E, Peseschkian H, Cagande C, eds. Positive Psychiatry, Psychotherapy and Psychology. Springer; 2020:11-32. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-33264-8_2

- Tritt K, Loew T, Meyer M, et al. Positive psychotherapy: effectiveness of an interdisciplinary approach. Eur J Psychiatry. 1999;13(4):231-241.

- World Association for Positive and Transcultural Psychotherapy. http://www.positum.org

1. Mackenthun G. Passt Psychotherapie an ‚die Gesellschaft’ an? Dynamische Psychiatrie. 1991;24(5-6):326-333.