User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Step right up, folks, for a public dissection

The greatest autopsy on Earth?

The LOTME staff would like to apologize in advance. The following item contains historical facts.

P.T. Barnum is a rather controversial figure in American history. The greatest show on Earth was certainly popular in its day. However, Barnum got his start in 1835 by leasing a slave named Joyce Heth, an elderly Black woman who told vivid stories of caring for a young George Washington. He toured her around the country, advertising her as a 160-year-old woman who served as George Washington’s nanny. When Ms. Heth died the next year, Barnum sold tickets to the autopsy, charging the equivalent of $30 in today’s money.

When a doctor announced that Ms. Heth was actually 75-80 when she died, it caused great controversy in the press and ruined Barnum’s career. Wait, no, that’s not right. The opposite, actually. He weathered the storm, built his famous circus, and never again committed a hoax.

It’s difficult to quantify how wrong publicly dissecting a person and charging people to see said dissection is, but that was almost 200 years ago. At the very least, we can say that such terrible behavior is firmly in the distant past.

Oh wait.

David Saunders, a 98-year-old veteran of World War II and the Korean War, donated his body to science. His body, however, was purchased by DeathScience.org from a medical lab – with the buyer supposedly misleading the medical lab about its intentions, which was for use at the traveling Oddities and Curiosities Expo. Tickets went for up to $500 each to witness the public autopsy of Mr. Saunders’ body, which took place at a Marriott in Portland, Ore. It promised to be an exciting, all-day event from 9 a.m. to 4 p.m., with a break for lunch, of course. You can’t have an autopsy without a catered lunch.

Another public autopsy event was scheduled in Seattle but canceled after news of the first event broke. Oh, and for that extra little kick, Mr. Saunders died from COVID-19, meaning that all those paying customers were exposed.

P.T. Barnum is probably rolling over in his grave right now. His autopsy tickets were a bargain.

Go ahead, have that soda before math

We should all know by now that sugary drinks are bad, even artificially sweetened ones. It might not always stop us from drinking them, but we know the deal. But what if sugary drinks like soda could be helpful for girls in school?

You read that right. We said girls. A soda before class might have boys bouncing off the walls, but not girls. A recent study showed that not only was girls’ behavior unaffected by having a sugary drink, their math skills even improved.

Researchers analyzed the behavior of 4- to 6-year-old children before and after having a sugary drink. The sugar rush was actually calming for girls and helped them perform better with numerical skills, but the opposite was true for boys. “Our study is the first to provide large-scale experimental evidence on the impact of sugary drinks on preschool children. The results clearly indicate a causal impact of sugary drinks on children’s behavior and test scores,” Fritz Schiltz, PhD, said in a written statement.

This probably isn’t the green light to have as many sugary drinks as you want, but it might be interesting to see how your work is affected after a soda.

Chicken nuggets and the meat paradox

Two young children are fighting over the last chicken nugget when an adult comes in to see what’s going on.

Liam: Vegetable!

Olivia: Meat!

Liam: Chicken nuggets are vegetables!

Olivia: No, dorkface! They’re meat.

Caregiver: Good news, kids. You’re both right.

Olivia: How can we both be right?

At this point, a woman enters the room. She’s wearing a white lab coat, so she must be a scientist.

Dr. Scientist: You can’t both be right, Olivia. You are being fed a serving of the meat paradox. That’s why Liam here doesn’t know that chicken nuggets are made of chicken, which is a form of meat. Sadly, he’s not the only one.

In a recent study, scientists from Furman University in Greenville, S.C., found that 38% of 176 children aged 4-7 years thought that chicken nuggets were vegetables and more than 46% identified French fries as animal based.

Olivia: Did our caregiver lie to us, Dr. Scientist?

Dr. Scientist: Yes, Olivia. The researchers I mentioned explained that “many people experience unease while eating meat. Omnivores eat foods that entail animal suffering and death while at the same time endorsing the compassionate treatment of animals.” That’s the meat paradox.

Liam: What else did they say, Dr. Scientist?

Dr. Scientist: Over 70% of those children said that cows and pigs were not edible and 5% thought that cats and horses were. The investigators wrote “that children and youth should be viewed as agents of environmental change” in the future, but suggested that parents need to bring honesty to the table.

Caregiver: How did you get in here anyway? And how do you know their names?

Dr. Scientist: I’ve been rooting through your garbage for years. All in the name of science, of course.

Bedtimes aren’t just for children

There are multiple ways to prevent heart disease, but what if it could be as easy as switching your bedtime? A recent study in European Heart Journal–Digital Health suggests that there’s a sweet spot when it comes to sleep timing.

Through smartwatch-like devices, researchers measured the sleep-onset and wake-up times for 7 days in 88,026 participants aged 43-79 years. After 5.7 years of follow-up to see if anyone had a heart attack, stroke, or any other cardiovascular event, 3.6% developed some kind of cardiovascular disease.

Those who went to bed between 10 p.m. and 11 p.m. had a lower risk of developing heart disease. The risk was 25% higher for subjects who went to bed at midnight or later, 24% higher for bedtimes before 10 p.m., and 12% higher for bedtimes between 11 p.m. and midnight.

So, why can you go to bed before “The Tonight Show” and lower your cardiovascular risk but not before the nightly news? Well, it has something to do with your body’s natural clock.

“The optimum time to go to sleep is at a specific point in the body’s 24-hour cycle and deviations may be detrimental to health. The riskiest time was after midnight, potentially because it may reduce the likelihood of seeing morning light, which resets the body clock,” said study author Dr. David Plans of the University of Exeter, England.

Although a sleep schedule is preferred, it isn’t realistic all the time for those in certain occupations who might have to resort to other methods to keep their circadian clocks ticking optimally for their health. But if all it takes is prescribing a sleep time to reduce heart disease on a massive scale it would make a great “low-cost public health target.”

So bedtimes aren’t just for children.

The greatest autopsy on Earth?

The LOTME staff would like to apologize in advance. The following item contains historical facts.

P.T. Barnum is a rather controversial figure in American history. The greatest show on Earth was certainly popular in its day. However, Barnum got his start in 1835 by leasing a slave named Joyce Heth, an elderly Black woman who told vivid stories of caring for a young George Washington. He toured her around the country, advertising her as a 160-year-old woman who served as George Washington’s nanny. When Ms. Heth died the next year, Barnum sold tickets to the autopsy, charging the equivalent of $30 in today’s money.

When a doctor announced that Ms. Heth was actually 75-80 when she died, it caused great controversy in the press and ruined Barnum’s career. Wait, no, that’s not right. The opposite, actually. He weathered the storm, built his famous circus, and never again committed a hoax.

It’s difficult to quantify how wrong publicly dissecting a person and charging people to see said dissection is, but that was almost 200 years ago. At the very least, we can say that such terrible behavior is firmly in the distant past.

Oh wait.

David Saunders, a 98-year-old veteran of World War II and the Korean War, donated his body to science. His body, however, was purchased by DeathScience.org from a medical lab – with the buyer supposedly misleading the medical lab about its intentions, which was for use at the traveling Oddities and Curiosities Expo. Tickets went for up to $500 each to witness the public autopsy of Mr. Saunders’ body, which took place at a Marriott in Portland, Ore. It promised to be an exciting, all-day event from 9 a.m. to 4 p.m., with a break for lunch, of course. You can’t have an autopsy without a catered lunch.

Another public autopsy event was scheduled in Seattle but canceled after news of the first event broke. Oh, and for that extra little kick, Mr. Saunders died from COVID-19, meaning that all those paying customers were exposed.

P.T. Barnum is probably rolling over in his grave right now. His autopsy tickets were a bargain.

Go ahead, have that soda before math

We should all know by now that sugary drinks are bad, even artificially sweetened ones. It might not always stop us from drinking them, but we know the deal. But what if sugary drinks like soda could be helpful for girls in school?

You read that right. We said girls. A soda before class might have boys bouncing off the walls, but not girls. A recent study showed that not only was girls’ behavior unaffected by having a sugary drink, their math skills even improved.

Researchers analyzed the behavior of 4- to 6-year-old children before and after having a sugary drink. The sugar rush was actually calming for girls and helped them perform better with numerical skills, but the opposite was true for boys. “Our study is the first to provide large-scale experimental evidence on the impact of sugary drinks on preschool children. The results clearly indicate a causal impact of sugary drinks on children’s behavior and test scores,” Fritz Schiltz, PhD, said in a written statement.

This probably isn’t the green light to have as many sugary drinks as you want, but it might be interesting to see how your work is affected after a soda.

Chicken nuggets and the meat paradox

Two young children are fighting over the last chicken nugget when an adult comes in to see what’s going on.

Liam: Vegetable!

Olivia: Meat!

Liam: Chicken nuggets are vegetables!

Olivia: No, dorkface! They’re meat.

Caregiver: Good news, kids. You’re both right.

Olivia: How can we both be right?

At this point, a woman enters the room. She’s wearing a white lab coat, so she must be a scientist.

Dr. Scientist: You can’t both be right, Olivia. You are being fed a serving of the meat paradox. That’s why Liam here doesn’t know that chicken nuggets are made of chicken, which is a form of meat. Sadly, he’s not the only one.

In a recent study, scientists from Furman University in Greenville, S.C., found that 38% of 176 children aged 4-7 years thought that chicken nuggets were vegetables and more than 46% identified French fries as animal based.

Olivia: Did our caregiver lie to us, Dr. Scientist?

Dr. Scientist: Yes, Olivia. The researchers I mentioned explained that “many people experience unease while eating meat. Omnivores eat foods that entail animal suffering and death while at the same time endorsing the compassionate treatment of animals.” That’s the meat paradox.

Liam: What else did they say, Dr. Scientist?

Dr. Scientist: Over 70% of those children said that cows and pigs were not edible and 5% thought that cats and horses were. The investigators wrote “that children and youth should be viewed as agents of environmental change” in the future, but suggested that parents need to bring honesty to the table.

Caregiver: How did you get in here anyway? And how do you know their names?

Dr. Scientist: I’ve been rooting through your garbage for years. All in the name of science, of course.

Bedtimes aren’t just for children

There are multiple ways to prevent heart disease, but what if it could be as easy as switching your bedtime? A recent study in European Heart Journal–Digital Health suggests that there’s a sweet spot when it comes to sleep timing.

Through smartwatch-like devices, researchers measured the sleep-onset and wake-up times for 7 days in 88,026 participants aged 43-79 years. After 5.7 years of follow-up to see if anyone had a heart attack, stroke, or any other cardiovascular event, 3.6% developed some kind of cardiovascular disease.

Those who went to bed between 10 p.m. and 11 p.m. had a lower risk of developing heart disease. The risk was 25% higher for subjects who went to bed at midnight or later, 24% higher for bedtimes before 10 p.m., and 12% higher for bedtimes between 11 p.m. and midnight.

So, why can you go to bed before “The Tonight Show” and lower your cardiovascular risk but not before the nightly news? Well, it has something to do with your body’s natural clock.

“The optimum time to go to sleep is at a specific point in the body’s 24-hour cycle and deviations may be detrimental to health. The riskiest time was after midnight, potentially because it may reduce the likelihood of seeing morning light, which resets the body clock,” said study author Dr. David Plans of the University of Exeter, England.

Although a sleep schedule is preferred, it isn’t realistic all the time for those in certain occupations who might have to resort to other methods to keep their circadian clocks ticking optimally for their health. But if all it takes is prescribing a sleep time to reduce heart disease on a massive scale it would make a great “low-cost public health target.”

So bedtimes aren’t just for children.

The greatest autopsy on Earth?

The LOTME staff would like to apologize in advance. The following item contains historical facts.

P.T. Barnum is a rather controversial figure in American history. The greatest show on Earth was certainly popular in its day. However, Barnum got his start in 1835 by leasing a slave named Joyce Heth, an elderly Black woman who told vivid stories of caring for a young George Washington. He toured her around the country, advertising her as a 160-year-old woman who served as George Washington’s nanny. When Ms. Heth died the next year, Barnum sold tickets to the autopsy, charging the equivalent of $30 in today’s money.

When a doctor announced that Ms. Heth was actually 75-80 when she died, it caused great controversy in the press and ruined Barnum’s career. Wait, no, that’s not right. The opposite, actually. He weathered the storm, built his famous circus, and never again committed a hoax.

It’s difficult to quantify how wrong publicly dissecting a person and charging people to see said dissection is, but that was almost 200 years ago. At the very least, we can say that such terrible behavior is firmly in the distant past.

Oh wait.

David Saunders, a 98-year-old veteran of World War II and the Korean War, donated his body to science. His body, however, was purchased by DeathScience.org from a medical lab – with the buyer supposedly misleading the medical lab about its intentions, which was for use at the traveling Oddities and Curiosities Expo. Tickets went for up to $500 each to witness the public autopsy of Mr. Saunders’ body, which took place at a Marriott in Portland, Ore. It promised to be an exciting, all-day event from 9 a.m. to 4 p.m., with a break for lunch, of course. You can’t have an autopsy without a catered lunch.

Another public autopsy event was scheduled in Seattle but canceled after news of the first event broke. Oh, and for that extra little kick, Mr. Saunders died from COVID-19, meaning that all those paying customers were exposed.

P.T. Barnum is probably rolling over in his grave right now. His autopsy tickets were a bargain.

Go ahead, have that soda before math

We should all know by now that sugary drinks are bad, even artificially sweetened ones. It might not always stop us from drinking them, but we know the deal. But what if sugary drinks like soda could be helpful for girls in school?

You read that right. We said girls. A soda before class might have boys bouncing off the walls, but not girls. A recent study showed that not only was girls’ behavior unaffected by having a sugary drink, their math skills even improved.

Researchers analyzed the behavior of 4- to 6-year-old children before and after having a sugary drink. The sugar rush was actually calming for girls and helped them perform better with numerical skills, but the opposite was true for boys. “Our study is the first to provide large-scale experimental evidence on the impact of sugary drinks on preschool children. The results clearly indicate a causal impact of sugary drinks on children’s behavior and test scores,” Fritz Schiltz, PhD, said in a written statement.

This probably isn’t the green light to have as many sugary drinks as you want, but it might be interesting to see how your work is affected after a soda.

Chicken nuggets and the meat paradox

Two young children are fighting over the last chicken nugget when an adult comes in to see what’s going on.

Liam: Vegetable!

Olivia: Meat!

Liam: Chicken nuggets are vegetables!

Olivia: No, dorkface! They’re meat.

Caregiver: Good news, kids. You’re both right.

Olivia: How can we both be right?

At this point, a woman enters the room. She’s wearing a white lab coat, so she must be a scientist.

Dr. Scientist: You can’t both be right, Olivia. You are being fed a serving of the meat paradox. That’s why Liam here doesn’t know that chicken nuggets are made of chicken, which is a form of meat. Sadly, he’s not the only one.

In a recent study, scientists from Furman University in Greenville, S.C., found that 38% of 176 children aged 4-7 years thought that chicken nuggets were vegetables and more than 46% identified French fries as animal based.

Olivia: Did our caregiver lie to us, Dr. Scientist?

Dr. Scientist: Yes, Olivia. The researchers I mentioned explained that “many people experience unease while eating meat. Omnivores eat foods that entail animal suffering and death while at the same time endorsing the compassionate treatment of animals.” That’s the meat paradox.

Liam: What else did they say, Dr. Scientist?

Dr. Scientist: Over 70% of those children said that cows and pigs were not edible and 5% thought that cats and horses were. The investigators wrote “that children and youth should be viewed as agents of environmental change” in the future, but suggested that parents need to bring honesty to the table.

Caregiver: How did you get in here anyway? And how do you know their names?

Dr. Scientist: I’ve been rooting through your garbage for years. All in the name of science, of course.

Bedtimes aren’t just for children

There are multiple ways to prevent heart disease, but what if it could be as easy as switching your bedtime? A recent study in European Heart Journal–Digital Health suggests that there’s a sweet spot when it comes to sleep timing.

Through smartwatch-like devices, researchers measured the sleep-onset and wake-up times for 7 days in 88,026 participants aged 43-79 years. After 5.7 years of follow-up to see if anyone had a heart attack, stroke, or any other cardiovascular event, 3.6% developed some kind of cardiovascular disease.

Those who went to bed between 10 p.m. and 11 p.m. had a lower risk of developing heart disease. The risk was 25% higher for subjects who went to bed at midnight or later, 24% higher for bedtimes before 10 p.m., and 12% higher for bedtimes between 11 p.m. and midnight.

So, why can you go to bed before “The Tonight Show” and lower your cardiovascular risk but not before the nightly news? Well, it has something to do with your body’s natural clock.

“The optimum time to go to sleep is at a specific point in the body’s 24-hour cycle and deviations may be detrimental to health. The riskiest time was after midnight, potentially because it may reduce the likelihood of seeing morning light, which resets the body clock,” said study author Dr. David Plans of the University of Exeter, England.

Although a sleep schedule is preferred, it isn’t realistic all the time for those in certain occupations who might have to resort to other methods to keep their circadian clocks ticking optimally for their health. But if all it takes is prescribing a sleep time to reduce heart disease on a massive scale it would make a great “low-cost public health target.”

So bedtimes aren’t just for children.

Should you tell your doctor that you’re a doctor?

The question drew spirited debate when urologist Ashley Winter, MD, made a simple, straightforward request on Twitter: “If you are a doctor & you come to an appointment please tell me you are a doctor, not because I will treat you differently but because it’s easier to speak in jargon.”

She later added, “This doesn’t’ mean I would be less patient-focused or emotional with a physician or other [healthcare worker]. Just means that, instead of saying ‘you will have a catheter draining your urine to a bag,’ I can say, ‘you will have a Foley.’ ”

The Tweet followed an encounter with a patient who told Dr. Winter that he was a doctor only after she had gone to some length explaining a surgical procedure in lay terms.

“I explained the surgery, obviously assuming he was an intelligent adult, but using fully layman’s terms,” she said in an interview. The patient then told her that he was a doctor. “I guess I felt this embarrassment — I wouldn’t have treated him differently, but I just could have discussed the procedure with him in more professional terms.”

“To some extent, it was my own fault,” she commented in an interview. “I didn’t take the time to ask [about his work] at the beginning of the consultation, but that’s a fine line, also,” added Dr. Winter, a urologist and sexual medicine physician in Portland, Ore.

“You know that patient is there because they want care from you and it’s not necessarily always at the forefront of importance to be asking them what they do for their work, but alternatively, if you don’t ask then you put them in this position where they have to find a way to go ahead and tell you.”

Several people chimed in on the thread to voice their thoughts on the matter. Some commiserated with Dr. Winter’s experience:

“I took care of a retired cardiologist in the hospital as a second-year resident and honest to god he let me ramble on ‘explaining’ his echo result and never told me. I found out a couple days later and wanted to die,” posted @MaddyAndrewsMD.

Another recalled a similarly embarrassing experience when she “went on and on” discussing headaches with a patient whose husband “was in the corner smirking.”

“They told my attending later [that the] husband was a retired FM doc who practiced medicine longer than I’ve been alive. I wanted to die,” posted @JSinghDO.

Many on the thread, though, were doctors and other healthcare professionals speaking as patients. Some said they didn’t want to disclose their status as a healthcare provider because they felt it affected the care they received.

For example, @drhelenrainford commented: “In my experience my care is less ‘caring’ when they know I am a [doctor]. I get spoken to like they are discussing a patient with me — no empathy just facts and difficult results just blurted out without consideration. Awful awful time as an inpatient …but that’s another story!”

@Dr_B_Ring said: “Nope – You and I speak different jargon – I would want you to speak to me like a human that doesn’t know your jargon. My ego would get in the way of asking about the acronyms I don’t know if you knew I was a fellow physician.”

Conversely, @lozzlemcfozzle said: “Honestly I prefer not to tell my Doctors — I’ve found people skip explanations assuming I ‘know,’ or seem a little nervous when I tell them!”

Others said they felt uncomfortable — pretentious, even — in announcing their status, or worried that they might come across as expecting special care.

“It’s such a tough needle to thread. Want to tell people early but not come off as demanding special treatment, but don’t want to wait too long and it seems like a trap,” said @MDaware.

Twitter user @MsBabyCatcher wrote: “I have a hard time doing this because I don’t want people to think I’m being pretentious or going to micromanage/dictate care.”

Replying to @MsBabyCatcher, @RedStethoscope wrote: “I used to think this too until I got [very poor] care a few times, and was advised by other doctor moms to ‘play the doctor card.’ I have gotten better/more compassionate care by making sure it’s clear that I’m a physician (which is junk, but here we are).”

Several of those responding used the words “tricky” and “awkward,” suggesting a common theme for doctors presenting as patients.

“I struggle with this. My 5-year-old broke her arm this weekend, we spent hours in the ED, of my own hospital, I never mentioned it because I didn’t want to get preferential care. But as they were explaining her type of fracture, it felt awkward and inefficient,” said @lindsay_petty.

To avoid the awkwardness, a number of respondents said they purposefully use medical jargon to open up a conversation rather than just offering up the information that they are a doctor.

Still others offered suggestions on how to broach the subject more directly when presenting as a patient:

‘”Just FYI I’m a X doc but I’m here because I really want your help and advice!” That’s what I usually do,” wrote @drcakefm.

@BeeSting14618 Tweeted: “I usually say ‘I know some of this but I’m here because I want YOUR guidance. Also I may ask dumb questions, and I’ll tell you if a question is asking your opinion or making a request.’”

A few others injected a bit of humor: “I just do the 14-part handshake that only doctors know. Is that not customary?” quipped @Branmiz25.

“Ah yes, that transmits the entire [history of present illness],” replied Dr. Winter.

Jokes aside, the topic is obviously one that touched on a shared experience among healthcare providers, Dr. Winter commented. The Twitter thread she started just “blew up.”

That’s typically a sign that the Tweet is relatable for a lot of people, she said.

“It’s definitely something that all of us as care providers and as patients understand. It’s a funny, awkward thing that can really change an interaction, so we probably all feel pretty strongly about our experiences related to that,” she added.

The debate begs the question: Is there a duty or ethical reason to disclose?

“I definitely think it is very reasonable to disclose that one is a medical professional to another doctor,” medical ethicist Charlotte Blease, PhD, said in an interview. “There are good reasons to believe doing so might make a difference to the quality of communication and transparency.”

If the ability to use medical terminology or jargon more freely improves patient understanding, autonomy, and shared decision-making, then it may be of benefit, said Dr. Blease, a Keane OpenNotes Scholar at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston.

“Since doctors should strive to communicate effectively with every patient and to respect their unique needs and level of understanding, then I see no reason to deny that one is a medic,” she added.”

Knowing how to share the information is another story.

“This is something that affects all of us as physicians — we’re going to be patients at some point, right?” Dr. Winter commented. “But I don’t think how to disclose that is something that was ever brought up in my medical training.”

“Maybe there should just be a discussion of this one day when people are in medical school — maybe in a professionalism course — to broach this topic or look at if there’s any literature on outcomes related to disclosure of status or what are best practices,” she suggested.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The question drew spirited debate when urologist Ashley Winter, MD, made a simple, straightforward request on Twitter: “If you are a doctor & you come to an appointment please tell me you are a doctor, not because I will treat you differently but because it’s easier to speak in jargon.”

She later added, “This doesn’t’ mean I would be less patient-focused or emotional with a physician or other [healthcare worker]. Just means that, instead of saying ‘you will have a catheter draining your urine to a bag,’ I can say, ‘you will have a Foley.’ ”

The Tweet followed an encounter with a patient who told Dr. Winter that he was a doctor only after she had gone to some length explaining a surgical procedure in lay terms.

“I explained the surgery, obviously assuming he was an intelligent adult, but using fully layman’s terms,” she said in an interview. The patient then told her that he was a doctor. “I guess I felt this embarrassment — I wouldn’t have treated him differently, but I just could have discussed the procedure with him in more professional terms.”

“To some extent, it was my own fault,” she commented in an interview. “I didn’t take the time to ask [about his work] at the beginning of the consultation, but that’s a fine line, also,” added Dr. Winter, a urologist and sexual medicine physician in Portland, Ore.

“You know that patient is there because they want care from you and it’s not necessarily always at the forefront of importance to be asking them what they do for their work, but alternatively, if you don’t ask then you put them in this position where they have to find a way to go ahead and tell you.”

Several people chimed in on the thread to voice their thoughts on the matter. Some commiserated with Dr. Winter’s experience:

“I took care of a retired cardiologist in the hospital as a second-year resident and honest to god he let me ramble on ‘explaining’ his echo result and never told me. I found out a couple days later and wanted to die,” posted @MaddyAndrewsMD.

Another recalled a similarly embarrassing experience when she “went on and on” discussing headaches with a patient whose husband “was in the corner smirking.”

“They told my attending later [that the] husband was a retired FM doc who practiced medicine longer than I’ve been alive. I wanted to die,” posted @JSinghDO.

Many on the thread, though, were doctors and other healthcare professionals speaking as patients. Some said they didn’t want to disclose their status as a healthcare provider because they felt it affected the care they received.

For example, @drhelenrainford commented: “In my experience my care is less ‘caring’ when they know I am a [doctor]. I get spoken to like they are discussing a patient with me — no empathy just facts and difficult results just blurted out without consideration. Awful awful time as an inpatient …but that’s another story!”

@Dr_B_Ring said: “Nope – You and I speak different jargon – I would want you to speak to me like a human that doesn’t know your jargon. My ego would get in the way of asking about the acronyms I don’t know if you knew I was a fellow physician.”

Conversely, @lozzlemcfozzle said: “Honestly I prefer not to tell my Doctors — I’ve found people skip explanations assuming I ‘know,’ or seem a little nervous when I tell them!”

Others said they felt uncomfortable — pretentious, even — in announcing their status, or worried that they might come across as expecting special care.

“It’s such a tough needle to thread. Want to tell people early but not come off as demanding special treatment, but don’t want to wait too long and it seems like a trap,” said @MDaware.

Twitter user @MsBabyCatcher wrote: “I have a hard time doing this because I don’t want people to think I’m being pretentious or going to micromanage/dictate care.”

Replying to @MsBabyCatcher, @RedStethoscope wrote: “I used to think this too until I got [very poor] care a few times, and was advised by other doctor moms to ‘play the doctor card.’ I have gotten better/more compassionate care by making sure it’s clear that I’m a physician (which is junk, but here we are).”

Several of those responding used the words “tricky” and “awkward,” suggesting a common theme for doctors presenting as patients.

“I struggle with this. My 5-year-old broke her arm this weekend, we spent hours in the ED, of my own hospital, I never mentioned it because I didn’t want to get preferential care. But as they were explaining her type of fracture, it felt awkward and inefficient,” said @lindsay_petty.

To avoid the awkwardness, a number of respondents said they purposefully use medical jargon to open up a conversation rather than just offering up the information that they are a doctor.

Still others offered suggestions on how to broach the subject more directly when presenting as a patient:

‘”Just FYI I’m a X doc but I’m here because I really want your help and advice!” That’s what I usually do,” wrote @drcakefm.

@BeeSting14618 Tweeted: “I usually say ‘I know some of this but I’m here because I want YOUR guidance. Also I may ask dumb questions, and I’ll tell you if a question is asking your opinion or making a request.’”

A few others injected a bit of humor: “I just do the 14-part handshake that only doctors know. Is that not customary?” quipped @Branmiz25.

“Ah yes, that transmits the entire [history of present illness],” replied Dr. Winter.

Jokes aside, the topic is obviously one that touched on a shared experience among healthcare providers, Dr. Winter commented. The Twitter thread she started just “blew up.”

That’s typically a sign that the Tweet is relatable for a lot of people, she said.

“It’s definitely something that all of us as care providers and as patients understand. It’s a funny, awkward thing that can really change an interaction, so we probably all feel pretty strongly about our experiences related to that,” she added.

The debate begs the question: Is there a duty or ethical reason to disclose?

“I definitely think it is very reasonable to disclose that one is a medical professional to another doctor,” medical ethicist Charlotte Blease, PhD, said in an interview. “There are good reasons to believe doing so might make a difference to the quality of communication and transparency.”

If the ability to use medical terminology or jargon more freely improves patient understanding, autonomy, and shared decision-making, then it may be of benefit, said Dr. Blease, a Keane OpenNotes Scholar at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston.

“Since doctors should strive to communicate effectively with every patient and to respect their unique needs and level of understanding, then I see no reason to deny that one is a medic,” she added.”

Knowing how to share the information is another story.

“This is something that affects all of us as physicians — we’re going to be patients at some point, right?” Dr. Winter commented. “But I don’t think how to disclose that is something that was ever brought up in my medical training.”

“Maybe there should just be a discussion of this one day when people are in medical school — maybe in a professionalism course — to broach this topic or look at if there’s any literature on outcomes related to disclosure of status or what are best practices,” she suggested.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The question drew spirited debate when urologist Ashley Winter, MD, made a simple, straightforward request on Twitter: “If you are a doctor & you come to an appointment please tell me you are a doctor, not because I will treat you differently but because it’s easier to speak in jargon.”

She later added, “This doesn’t’ mean I would be less patient-focused or emotional with a physician or other [healthcare worker]. Just means that, instead of saying ‘you will have a catheter draining your urine to a bag,’ I can say, ‘you will have a Foley.’ ”

The Tweet followed an encounter with a patient who told Dr. Winter that he was a doctor only after she had gone to some length explaining a surgical procedure in lay terms.

“I explained the surgery, obviously assuming he was an intelligent adult, but using fully layman’s terms,” she said in an interview. The patient then told her that he was a doctor. “I guess I felt this embarrassment — I wouldn’t have treated him differently, but I just could have discussed the procedure with him in more professional terms.”

“To some extent, it was my own fault,” she commented in an interview. “I didn’t take the time to ask [about his work] at the beginning of the consultation, but that’s a fine line, also,” added Dr. Winter, a urologist and sexual medicine physician in Portland, Ore.

“You know that patient is there because they want care from you and it’s not necessarily always at the forefront of importance to be asking them what they do for their work, but alternatively, if you don’t ask then you put them in this position where they have to find a way to go ahead and tell you.”

Several people chimed in on the thread to voice their thoughts on the matter. Some commiserated with Dr. Winter’s experience:

“I took care of a retired cardiologist in the hospital as a second-year resident and honest to god he let me ramble on ‘explaining’ his echo result and never told me. I found out a couple days later and wanted to die,” posted @MaddyAndrewsMD.

Another recalled a similarly embarrassing experience when she “went on and on” discussing headaches with a patient whose husband “was in the corner smirking.”

“They told my attending later [that the] husband was a retired FM doc who practiced medicine longer than I’ve been alive. I wanted to die,” posted @JSinghDO.

Many on the thread, though, were doctors and other healthcare professionals speaking as patients. Some said they didn’t want to disclose their status as a healthcare provider because they felt it affected the care they received.

For example, @drhelenrainford commented: “In my experience my care is less ‘caring’ when they know I am a [doctor]. I get spoken to like they are discussing a patient with me — no empathy just facts and difficult results just blurted out without consideration. Awful awful time as an inpatient …but that’s another story!”

@Dr_B_Ring said: “Nope – You and I speak different jargon – I would want you to speak to me like a human that doesn’t know your jargon. My ego would get in the way of asking about the acronyms I don’t know if you knew I was a fellow physician.”

Conversely, @lozzlemcfozzle said: “Honestly I prefer not to tell my Doctors — I’ve found people skip explanations assuming I ‘know,’ or seem a little nervous when I tell them!”

Others said they felt uncomfortable — pretentious, even — in announcing their status, or worried that they might come across as expecting special care.

“It’s such a tough needle to thread. Want to tell people early but not come off as demanding special treatment, but don’t want to wait too long and it seems like a trap,” said @MDaware.

Twitter user @MsBabyCatcher wrote: “I have a hard time doing this because I don’t want people to think I’m being pretentious or going to micromanage/dictate care.”

Replying to @MsBabyCatcher, @RedStethoscope wrote: “I used to think this too until I got [very poor] care a few times, and was advised by other doctor moms to ‘play the doctor card.’ I have gotten better/more compassionate care by making sure it’s clear that I’m a physician (which is junk, but here we are).”

Several of those responding used the words “tricky” and “awkward,” suggesting a common theme for doctors presenting as patients.

“I struggle with this. My 5-year-old broke her arm this weekend, we spent hours in the ED, of my own hospital, I never mentioned it because I didn’t want to get preferential care. But as they were explaining her type of fracture, it felt awkward and inefficient,” said @lindsay_petty.

To avoid the awkwardness, a number of respondents said they purposefully use medical jargon to open up a conversation rather than just offering up the information that they are a doctor.

Still others offered suggestions on how to broach the subject more directly when presenting as a patient:

‘”Just FYI I’m a X doc but I’m here because I really want your help and advice!” That’s what I usually do,” wrote @drcakefm.

@BeeSting14618 Tweeted: “I usually say ‘I know some of this but I’m here because I want YOUR guidance. Also I may ask dumb questions, and I’ll tell you if a question is asking your opinion or making a request.’”

A few others injected a bit of humor: “I just do the 14-part handshake that only doctors know. Is that not customary?” quipped @Branmiz25.

“Ah yes, that transmits the entire [history of present illness],” replied Dr. Winter.

Jokes aside, the topic is obviously one that touched on a shared experience among healthcare providers, Dr. Winter commented. The Twitter thread she started just “blew up.”

That’s typically a sign that the Tweet is relatable for a lot of people, she said.

“It’s definitely something that all of us as care providers and as patients understand. It’s a funny, awkward thing that can really change an interaction, so we probably all feel pretty strongly about our experiences related to that,” she added.

The debate begs the question: Is there a duty or ethical reason to disclose?

“I definitely think it is very reasonable to disclose that one is a medical professional to another doctor,” medical ethicist Charlotte Blease, PhD, said in an interview. “There are good reasons to believe doing so might make a difference to the quality of communication and transparency.”

If the ability to use medical terminology or jargon more freely improves patient understanding, autonomy, and shared decision-making, then it may be of benefit, said Dr. Blease, a Keane OpenNotes Scholar at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston.

“Since doctors should strive to communicate effectively with every patient and to respect their unique needs and level of understanding, then I see no reason to deny that one is a medic,” she added.”

Knowing how to share the information is another story.

“This is something that affects all of us as physicians — we’re going to be patients at some point, right?” Dr. Winter commented. “But I don’t think how to disclose that is something that was ever brought up in my medical training.”

“Maybe there should just be a discussion of this one day when people are in medical school — maybe in a professionalism course — to broach this topic or look at if there’s any literature on outcomes related to disclosure of status or what are best practices,” she suggested.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Liraglutide effective against weight regain after gastric bypass

The glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist liraglutide (Saxenda, Novo Nordisk) was safe and effective for treating weight regain after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), in a randomized controlled trial.

That is, 132 patients who had lost at least 25% of their initial weight after RYGB and then gained at least 10% back were randomized 2:1 to receive liraglutide plus frequent lifestyle advice from a registered dietitian or lifestyle advice alone.

After a year, 69%, 48%, and 24% of patients who had received liraglutide lost at least 5%, 10%, and 15% of their study entry weight, respectively. In contrast, only 5% of patients in the control group lost at least 5% of their weight and none lost at least 10% of their weight.

“Liraglutide 3.0 mg/day, with lifestyle modification, was significantly more effective than placebo in treating weight regain after RYGB without increased risk of serious adverse events,” Holly F. Lofton, MD, summarized this week in an oral session at ObesityWeek®, the annual meeting of The Obesity Society.

Dr. Lofton, a clinical associate professor of surgery and medicine, and director, weight management program, NYU, Langone Health, explained to this news organization that she initiated the study after attending a “packed” session about post bariatric surgery weight regain at a prior American Society of Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery conference.

“The lecturers recommended conservative measures (such as reiterating the diet recommendations, exercise, [and] counseling), and revisional surgeries,” she said in an email, but at the time “there was no literature that provided direction on which pharmacotherapies are best for this population.”

It was known that decreases in endogenous GLP-1 levels coincide with weight regain, and liraglutide (Saxenda) was the only GLP-1 agonist approved for chronic weight management at the time, so she devised the current study protocol.

The findings are especially helpful for patients who are not candidates for bariatric surgery revisions, she noted. Further research is needed to investigate the effect of newer GLP-1 agonists, such as semaglutide (Wegovy), on weight regain following different types of bariatric surgery.

Asked to comment, Wendy C. King, PhD, who was not involved with this research, said that more than two-thirds of patients treated with 3 mg/day subcutaneous liraglutide injections in the current study lost at least 5% of their initial weight a year later, and 20% of them attained a weight as low as, or lower than, their lowest weight after bariatric surgery (nadir weight).

“The fact that both groups received lifestyle counseling from registered dietitians for just over a year, but only patients in the liraglutide group lost weight, on average, speaks to the difficulty of losing weight following weight regain post–bariatric surgery,” added Dr. King, an associate professor of epidemiology at the University of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

This study “provides data that may help clinicians and patients understand the potential effect of adding liraglutide 3.0 mg/day to their weight loss efforts,” she told this news organization in an email.

However, “given that 42% of those on liraglutide reported gastrointestinal-related side effects, patients should also be counseled on this potential outcome and given suggestions for how to minimize such side effects,” Dr. King suggested.

Weight regain common, repeat surgery entails risk

Weight regain is common even years after bariatric surgery. Repeat surgery entails some risk, and lifestyle approaches alone are rarely successful in reversing weight regain, Dr. Lofton told the audience.

The researchers enrolled 132 adults who had a mean weight of 134 kg (295 pounds) when they underwent RYGB, and who lost at least 25% of their initial weight (mean weight loss of 38%) after the surgery, but who also regained at least 10% of their initial weight.

At enrollment of the current study (baseline), the patients had had RYGB 18 months to 10 years earlier (mean 5.7 years earlier) and now had a mean weight of 99 kg (218 pounds) and a mean BMI of 35.6 kg/m2. None of the patients had diabetes.

The patients were randomized to receive liraglutide (n = 89, 84% women) or placebo (n = 43, 88% women) for 56 weeks.

They were a mean age of 48 years, and about 59% were White and 25% were Black.

All patients had clinic visits every 3 months where they received lifestyle counseling from a registered dietitian.

At 12 months, patients in the liraglutide group had lost a mean of 8.8% of their baseline weight, whereas those in the placebo group had gained a mean of 1.48% of their baseline weight.

There were no significant between-group differences in cardiometabolic variables.

None of the patients in the control group attained a weight that was as low as their nadir weight after RYGB.

The rates of nausea (25%), constipation (16%), and abdominal pain (10%) in the liraglutide group were higher than in the placebo group (7%, 14%, and 5%, respectively) but similar to rates of gastrointestinal side effects in other trials of this agent.

Dr. Lofton has disclosed receiving consulting fees and being on a speaker bureau for Novo Nordisk and receiving research funds from Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, and Novo Nordisk. Dr. King has reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist liraglutide (Saxenda, Novo Nordisk) was safe and effective for treating weight regain after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), in a randomized controlled trial.

That is, 132 patients who had lost at least 25% of their initial weight after RYGB and then gained at least 10% back were randomized 2:1 to receive liraglutide plus frequent lifestyle advice from a registered dietitian or lifestyle advice alone.

After a year, 69%, 48%, and 24% of patients who had received liraglutide lost at least 5%, 10%, and 15% of their study entry weight, respectively. In contrast, only 5% of patients in the control group lost at least 5% of their weight and none lost at least 10% of their weight.

“Liraglutide 3.0 mg/day, with lifestyle modification, was significantly more effective than placebo in treating weight regain after RYGB without increased risk of serious adverse events,” Holly F. Lofton, MD, summarized this week in an oral session at ObesityWeek®, the annual meeting of The Obesity Society.

Dr. Lofton, a clinical associate professor of surgery and medicine, and director, weight management program, NYU, Langone Health, explained to this news organization that she initiated the study after attending a “packed” session about post bariatric surgery weight regain at a prior American Society of Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery conference.

“The lecturers recommended conservative measures (such as reiterating the diet recommendations, exercise, [and] counseling), and revisional surgeries,” she said in an email, but at the time “there was no literature that provided direction on which pharmacotherapies are best for this population.”

It was known that decreases in endogenous GLP-1 levels coincide with weight regain, and liraglutide (Saxenda) was the only GLP-1 agonist approved for chronic weight management at the time, so she devised the current study protocol.

The findings are especially helpful for patients who are not candidates for bariatric surgery revisions, she noted. Further research is needed to investigate the effect of newer GLP-1 agonists, such as semaglutide (Wegovy), on weight regain following different types of bariatric surgery.

Asked to comment, Wendy C. King, PhD, who was not involved with this research, said that more than two-thirds of patients treated with 3 mg/day subcutaneous liraglutide injections in the current study lost at least 5% of their initial weight a year later, and 20% of them attained a weight as low as, or lower than, their lowest weight after bariatric surgery (nadir weight).

“The fact that both groups received lifestyle counseling from registered dietitians for just over a year, but only patients in the liraglutide group lost weight, on average, speaks to the difficulty of losing weight following weight regain post–bariatric surgery,” added Dr. King, an associate professor of epidemiology at the University of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

This study “provides data that may help clinicians and patients understand the potential effect of adding liraglutide 3.0 mg/day to their weight loss efforts,” she told this news organization in an email.

However, “given that 42% of those on liraglutide reported gastrointestinal-related side effects, patients should also be counseled on this potential outcome and given suggestions for how to minimize such side effects,” Dr. King suggested.

Weight regain common, repeat surgery entails risk

Weight regain is common even years after bariatric surgery. Repeat surgery entails some risk, and lifestyle approaches alone are rarely successful in reversing weight regain, Dr. Lofton told the audience.

The researchers enrolled 132 adults who had a mean weight of 134 kg (295 pounds) when they underwent RYGB, and who lost at least 25% of their initial weight (mean weight loss of 38%) after the surgery, but who also regained at least 10% of their initial weight.

At enrollment of the current study (baseline), the patients had had RYGB 18 months to 10 years earlier (mean 5.7 years earlier) and now had a mean weight of 99 kg (218 pounds) and a mean BMI of 35.6 kg/m2. None of the patients had diabetes.

The patients were randomized to receive liraglutide (n = 89, 84% women) or placebo (n = 43, 88% women) for 56 weeks.

They were a mean age of 48 years, and about 59% were White and 25% were Black.

All patients had clinic visits every 3 months where they received lifestyle counseling from a registered dietitian.

At 12 months, patients in the liraglutide group had lost a mean of 8.8% of their baseline weight, whereas those in the placebo group had gained a mean of 1.48% of their baseline weight.

There were no significant between-group differences in cardiometabolic variables.

None of the patients in the control group attained a weight that was as low as their nadir weight after RYGB.

The rates of nausea (25%), constipation (16%), and abdominal pain (10%) in the liraglutide group were higher than in the placebo group (7%, 14%, and 5%, respectively) but similar to rates of gastrointestinal side effects in other trials of this agent.

Dr. Lofton has disclosed receiving consulting fees and being on a speaker bureau for Novo Nordisk and receiving research funds from Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, and Novo Nordisk. Dr. King has reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist liraglutide (Saxenda, Novo Nordisk) was safe and effective for treating weight regain after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), in a randomized controlled trial.

That is, 132 patients who had lost at least 25% of their initial weight after RYGB and then gained at least 10% back were randomized 2:1 to receive liraglutide plus frequent lifestyle advice from a registered dietitian or lifestyle advice alone.

After a year, 69%, 48%, and 24% of patients who had received liraglutide lost at least 5%, 10%, and 15% of their study entry weight, respectively. In contrast, only 5% of patients in the control group lost at least 5% of their weight and none lost at least 10% of their weight.

“Liraglutide 3.0 mg/day, with lifestyle modification, was significantly more effective than placebo in treating weight regain after RYGB without increased risk of serious adverse events,” Holly F. Lofton, MD, summarized this week in an oral session at ObesityWeek®, the annual meeting of The Obesity Society.

Dr. Lofton, a clinical associate professor of surgery and medicine, and director, weight management program, NYU, Langone Health, explained to this news organization that she initiated the study after attending a “packed” session about post bariatric surgery weight regain at a prior American Society of Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery conference.

“The lecturers recommended conservative measures (such as reiterating the diet recommendations, exercise, [and] counseling), and revisional surgeries,” she said in an email, but at the time “there was no literature that provided direction on which pharmacotherapies are best for this population.”

It was known that decreases in endogenous GLP-1 levels coincide with weight regain, and liraglutide (Saxenda) was the only GLP-1 agonist approved for chronic weight management at the time, so she devised the current study protocol.

The findings are especially helpful for patients who are not candidates for bariatric surgery revisions, she noted. Further research is needed to investigate the effect of newer GLP-1 agonists, such as semaglutide (Wegovy), on weight regain following different types of bariatric surgery.

Asked to comment, Wendy C. King, PhD, who was not involved with this research, said that more than two-thirds of patients treated with 3 mg/day subcutaneous liraglutide injections in the current study lost at least 5% of their initial weight a year later, and 20% of them attained a weight as low as, or lower than, their lowest weight after bariatric surgery (nadir weight).

“The fact that both groups received lifestyle counseling from registered dietitians for just over a year, but only patients in the liraglutide group lost weight, on average, speaks to the difficulty of losing weight following weight regain post–bariatric surgery,” added Dr. King, an associate professor of epidemiology at the University of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

This study “provides data that may help clinicians and patients understand the potential effect of adding liraglutide 3.0 mg/day to their weight loss efforts,” she told this news organization in an email.

However, “given that 42% of those on liraglutide reported gastrointestinal-related side effects, patients should also be counseled on this potential outcome and given suggestions for how to minimize such side effects,” Dr. King suggested.

Weight regain common, repeat surgery entails risk

Weight regain is common even years after bariatric surgery. Repeat surgery entails some risk, and lifestyle approaches alone are rarely successful in reversing weight regain, Dr. Lofton told the audience.

The researchers enrolled 132 adults who had a mean weight of 134 kg (295 pounds) when they underwent RYGB, and who lost at least 25% of their initial weight (mean weight loss of 38%) after the surgery, but who also regained at least 10% of their initial weight.

At enrollment of the current study (baseline), the patients had had RYGB 18 months to 10 years earlier (mean 5.7 years earlier) and now had a mean weight of 99 kg (218 pounds) and a mean BMI of 35.6 kg/m2. None of the patients had diabetes.

The patients were randomized to receive liraglutide (n = 89, 84% women) or placebo (n = 43, 88% women) for 56 weeks.

They were a mean age of 48 years, and about 59% were White and 25% were Black.

All patients had clinic visits every 3 months where they received lifestyle counseling from a registered dietitian.

At 12 months, patients in the liraglutide group had lost a mean of 8.8% of their baseline weight, whereas those in the placebo group had gained a mean of 1.48% of their baseline weight.

There were no significant between-group differences in cardiometabolic variables.

None of the patients in the control group attained a weight that was as low as their nadir weight after RYGB.

The rates of nausea (25%), constipation (16%), and abdominal pain (10%) in the liraglutide group were higher than in the placebo group (7%, 14%, and 5%, respectively) but similar to rates of gastrointestinal side effects in other trials of this agent.

Dr. Lofton has disclosed receiving consulting fees and being on a speaker bureau for Novo Nordisk and receiving research funds from Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, and Novo Nordisk. Dr. King has reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM OBESITY WEEK 2021

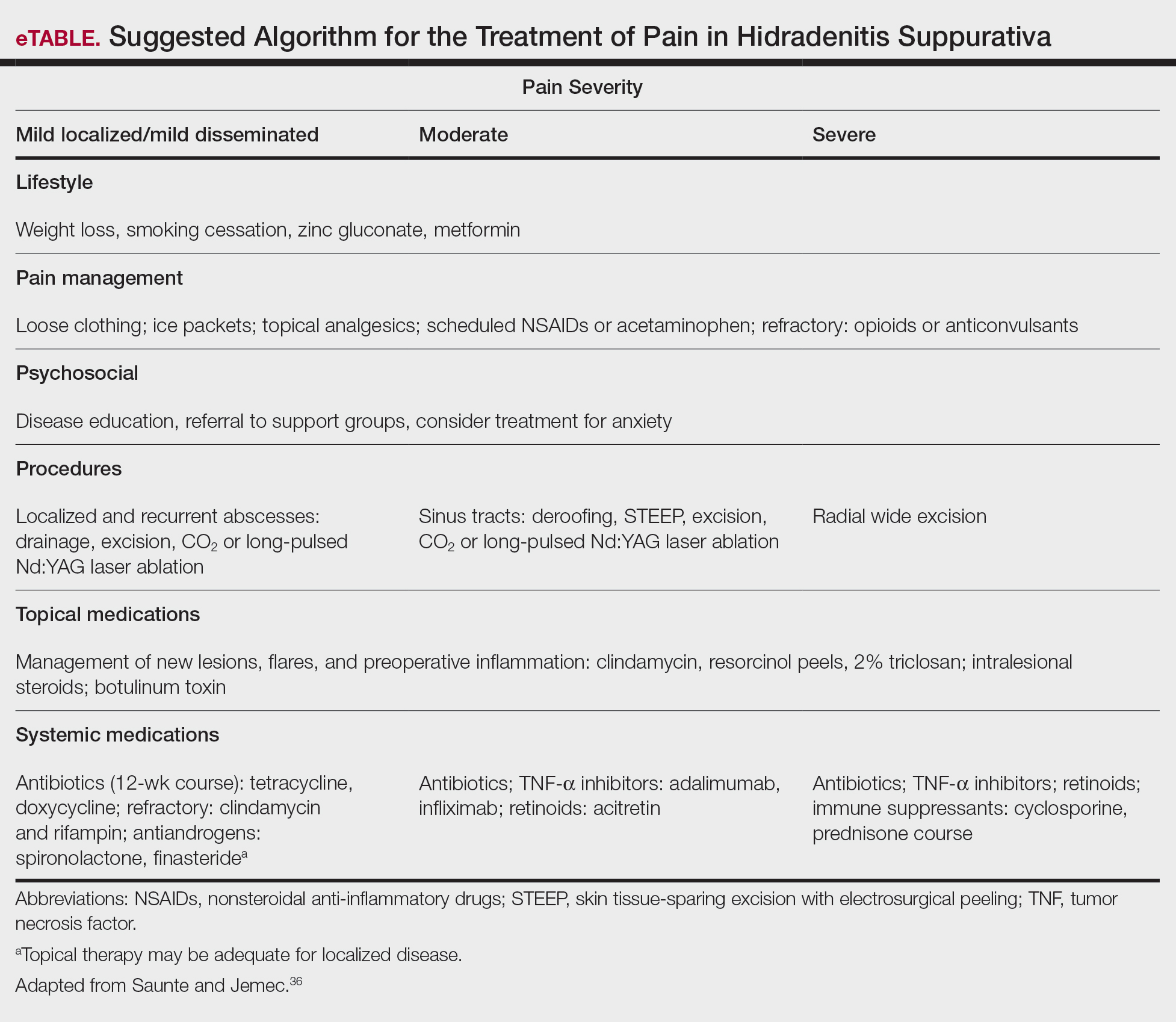

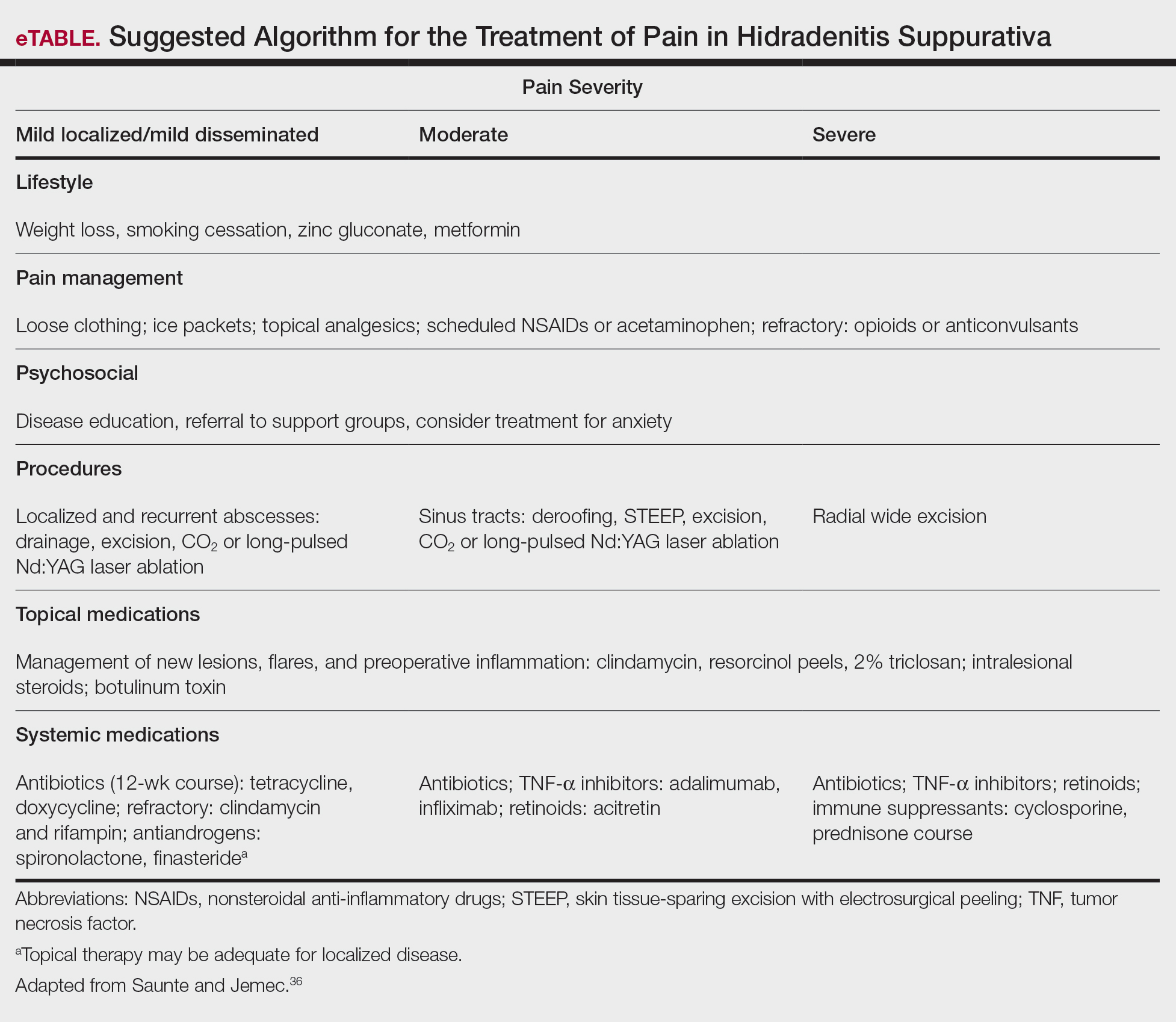

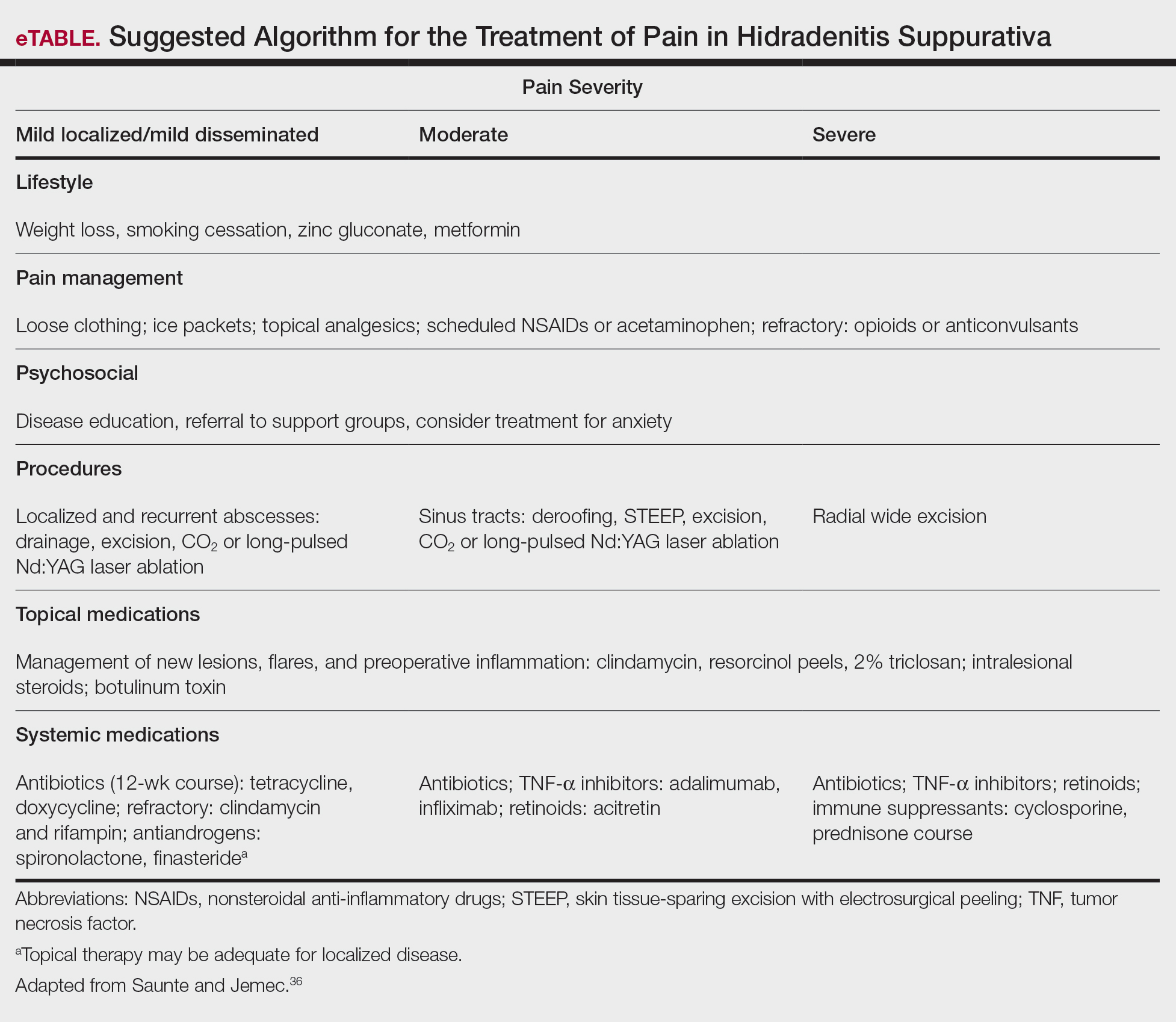

Management of Acute and Chronic Pain Associated With Hidradenitis Suppurativa: A Comprehensive Review of Pharmacologic and Therapeutic Considerations in Clinical Practice

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory, androgen gland disorder characterized by recurrent rupture of the hair follicles with a vigorous inflammatory response. This response results in abscess formation and development of draining sinus tracts and hypertrophic fibrous scars.1,2 Pain, discomfort, and odorous discharge from the recalcitrant lesions have a profound impact on patient quality of life.3,4

The morbidity and disease burden associated with HS are particularly underestimated, as patients frequently report debilitating pain that often is overlooked.5,6 Additionally, the quality and intensity of perceived pain are compounded by frequently associated depression and anxiety.7-9 Pain has been reported by patients with HS to be the highest cause of morbidity, despite the disfiguring nature of the disease and its associated psychosocial distress.7,10 Nonetheless, HS lacks an accepted pain management algorithm similar to those that have been developed for the treatment of other acute or chronic pain disorders, such as back pain and sickle cell disease.4,11-13

Given the lack of formal studies regarding pain management in patients with HS, clinicians are limited to general pain guidelines, expert opinion, small trials, and patient preference.3 Furthermore, effective pain management in HS necessitates the treatment of both chronic pain affecting daily function and acute pain present during disease flares, surgical interventions, and dressing changes.3 The result is a wide array of strategies used for HS-associated pain.3,4

Epidemiology and Pathophysiology

Hidradenitis suppurativa historically has been an overlooked and underdiagnosed disease, which limits epidemiology data.5 Current estimates are that HS affects approximately 1% of the general population; however, prevalence rates range from 0.03% to 4.1%.14-16

The exact etiology of HS remains unclear, but it is thought that genetic factors, immune dysregulation, and environmental/behavioral influences all contribute to its pathophysiology.1,17 Up to 40% of patients with HS report a positive family history of the disease.18-20 Hidradenitis suppurativa has been associated with other inflammatory disease states, such as inflammatory bowel disease, spondyloarthropathies, and pyoderma gangrenosum.16,21,22

It is thought that HS is the result of some defect in keratin clearance that leads to follicular hyperkeratinization and occlusion.1 Resultant rupture of pilosebaceous units and spillage of contents (including keratin and bacteria) into the surrounding dermis triggers a vigorous inflammatory response. Sinus tracts and fistulas become the targets of bacterial colonization, biofilm formation, and secondary infection. The result is suppuration and extension of the lesions as well as sustained chronic inflammation.23,24

Although the etiology of HS is complex, several modifiable risk factors for the disease have been identified, most prominently cigarette smoking and obesity. Approximately 70% of patients with HS smoke cigarettes.2,15,25,26 Obesity has a well-known association with HS, and it is possible that weight reduction lowers disease severity.27-30

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

Establishing a diagnosis of HS necessitates recognition of disease morphology, topography, and chronicity. Hidradenitis suppurativa most commonly occurs in the axillae, inguinal and anogenital region, perineal region, and inframammary region.5,31 A typical history involves a prolonged disease course with recurrent lesions and intermittent periods of improvement or remission. Primary lesions are deep, inflamed, painful, and sterile. Ultimately, these lesions rupture and track subcutaneously.15,25 Intercommunicating sinus tracts form from multiple recurrent nodules in close proximity and may ultimately lead to fibrotic scarring and local architectural distortion.32 The Hurley staging system helps to guide treatment interventions based on disease severity. Approach to pain management is discussed below.

Pain Management in HS: General Principles

Pain management is complex for clinicians, as there are limited studies from which to draw treatment recommendations. Incomplete understanding of the etiology and pathophysiology of the disease contributes to the lack of established management guidelines.

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms hidradenitis, suppurativa, pain, and management revealed 61 different results dating back to 1980, 52 of which had been published in the last 5 years. When the word acute was added to the search, there were only 6 results identified. These results clearly reflect a better understanding of HS-mediated pain as well as clinical unmet needs and evolving strategies in pain management therapeutics. However, many of these studies reflect therapies focused on the mediation or modulation of HS pathogenesis rather than potential pain management therapies.

In addition, the heterogenous nature of the pain experience in HS poses a challenge for clinicians. Patients may experience multiple pain types concurrently, including inflammatory, noninflammatory, nociceptive, neuropathic, and ischemic, as well as pain related to arthritis.3,33,34 Pain perception is further complicated by the observation that patients with HS have high rates of psychiatric comorbidities such as depression and anxiety, both of which profoundly alter perception of both the strength and quality of pain.7,8,22,35 A suggested algorithm for treatment of pain in HS is described in the eTable.36

Chronicity is a hallmark of HS. Patients experience a prolonged disease course involving acute painful exacerbations superimposed on chronic pain that affects all aspects of daily life. Changes in self-perception, daily living activities, mood state, physical functioning, and physical comfort frequently are reported to have a major impact on quality of life.1,3,37

In 2018, Thorlacius et al38 created a multistakeholder consensus on a core outcome set of domains detailing what to measure in clinical trials for HS. The authors hoped that the routine adoption of these core domains would promote the collection of consistent and relevant information, bolster the strength of evidence synthesis, and minimize the risk for outcome reporting bias among studies.38 It is important to ascertain the patient’s description of his/her pain to distinguish between stimulus-dependent nociceptive pain vs spontaneous neuropathic pain.3,7,10 The most common pain descriptors used by patients are “shooting,” “itchy,” “blinding,” “cutting,” and “exhausting.”10 In addition to obtaining descriptive factors, it is important for the clinician to obtain information on the timing of the pain, whether or not the pain is relieved with spontaneous or surgical drainage, and if the patient is experiencing chronic background pain secondary to scarring or skin contraction.3 With the routine utilization of a consistent set of core domains, advances in our understanding of the different elements of HS pain, and increased provider awareness of the disease, the future of pain management in patients with HS seems promising.

Acute and Perioperative Pain Management

Acute Pain Management—The pain in HS can range from mild to excruciating.3,7 The difference between acute and chronic pain in this condition may be hard to delineate, as patients may have intense acute flares on top of a baseline level of chronic pain.3,7,14 These factors, in combination with various pain types of differing etiologies, make the treatment of HS-associated pain a therapeutic challenge.

The first-line treatments for acute pain in HS are oral acetaminophen, oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and topical analgesics.3 These treatment modalities are especially helpful for nociceptive pain, which often is described as having an aching or tender quality.3 Topical treatment for acute pain episodes includes diclofenac gel and liposomal lidocaine cream.39 Topical lidocaine in particular has the benefit of being rapid acting, and its effect can last 1 to 2 hours. Ketamine has been anecdotally used as a topical treatment. Treatment options for neuropathic pain include topical amitriptyline, gabapentin, and pregabalin.39 Dressings and ice packs may be used in cases of mild acute pain, depending on patient preference.3

First-line therapies may not provide adequate pain control in many patients.3,40,41 Should the first-line treatments fail, oral opiates can be considered as a treatment option, especially if the patient has a history of recurrent pain unresponsive to milder methods of pain control.3,40,41 However, prudence should be exercised, as patients with HS have a higher risk for opioid abuse, and referral to a pain specialist is advisable.40 Generally, use of opioids should be limited to the smallest period of time possible.40,41 Codeine can be used as a first opioid option, with hydromorphone available as an alternative.41

Pain caused by inflamed abscesses and nodules can be treated with either intralesional corticosteroids or incision and drainage. Intralesional triamcinolone has been found to cause substantial pain relief within 1 day of injection in patients with HS.3,42

Prompt discussion about the remitting course of HS will prepare patients for flares. Although the therapies discussed here aim to reduce the clinical severity and inflammation associated with HS, achieving pain-free remission can be challenging. Barriers to developing a long-term treatment regimen include intolerable side effects or simply nonresponsive disease.36,43

Management of Perioperative Pain—Medical treatment of HS often yields only transient or mild results. Hurley stage II or III lesions typically require surgical removal of affected tissues.32,44-46 Surgery may dramatically reduce the primary disease burden and provide substantial pain relief.3,4,44 Complete resection of the affected tissue by wide excision is the most common surgical procedure used.46-48 However, various tissue-sparing techniques, such as skin-tissue-sparing excision with electrosurgical peeling, also have been utilized. Tissue-sparing surgical techniques may lead to shorter healing times and less postoperative pain.48

There currently is little guidance available on the perioperative management of pain as it relates to surgical procedures for HS. The pain experienced from surgery varies based on the area and location of affected tissue; extent of disease; surgical technique used; and whether primary closure, closure by secondary intention, or skin grafting is utilized.47,49 Medical treatment aimed at reducing inflammation prior to surgical intervention may improve postoperative pain and complications.

The use of general vs local anesthesia during surgery depends on the extent of the disease and the amount of tissue being removed; however, the use of local anesthesia has been associated with a higher recurrence of disease, possibly owing to less aggressive tissue removal.50 Intraoperatively, the injection of 0.5% bupivacaine around the wound edges may lead to less postoperative pain.3,48 Postoperative pain usually is managed with acetaminophen and NSAIDs.48 In cases of severe postoperative pain, short- and long-acting opioid oxycodone preparations may be used. The combination of diclofenac and tramadol also has been used postoperatively.3 Patients who do not undergo extensive surgery often can leave the hospital the same day.

Effective strategies for mitigating HS-associated pain must address the chronic pain component of the disease. Long-term management involves lifestyle modifications and pharmacologic agents.

Chronic Pain Management

Although HS is not a curable disease, there are treatments available to minimize symptoms. Long-term management of HS is essential to minimize the effects of chronic pain and physical scarring associated with inflammation.31 In one study from the French Society of Dermatology, pain reported by patients with HS was directly associated with severity and duration of disease, emotional symptoms, and reduced functionality.51 For these reasons, many treatments for HS target reducing clinical severity and achieving remission, often defined as more than 6 months without any recurrence of lesions.52 In addition to lifestyle management, therapies available to manage HS include topical and systemic medications as well as procedures such as surgical excision.36,43,52,53

Lifestyle Modifications

Regardless of the severity of HS, all patients may benefit from basic education on the pathogenesis of the disease.36 The associations with smoking and obesity have been well documented, and treatment of these comorbid conditions is indicated.36,43,52 For example, in relation to obesity, the use of metformin is very well tolerated and seems to positively impact HS symptoms.43 Several studies have suggested that weight reduction lowers disease severity.28-30 Patients should be counseled on the importance of smoking cessation and weight loss.

Finally, the emotional impact of HS is not to be discounted, both the physical and social discomfort as well as the chronicity of the disease and frustration with treatment.51 Chronic pain has been associated with increased rates of depression, and 43% of patients with HS specifically have been diagnosed with major depressive disorder.7 For these reasons, clinician guidance, social support, and websites can improve patient understanding of the disease, adherence to treatment, and comorbid anxiety and depression.52

Topical Therapy

Topical therapy generally is limited to mild disease and is geared at decreasing inflammation or superimposed infection.36,52 Some of the earliest therapies used were topical antibiotics.43 Topical clindamycin has been shown to be as effective as oral tetracyclines in reducing the number of abscesses, but neither treatment substantially reduces pain associated with smaller nodules.54 Intralesional corticosteroids such as triamcinolone acetonide have been shown to decrease both patient-reported pain and physician-assessed severity within 1 to 7 days.42 Routine injection, however, is not a feasible means of long-term treatment both because of inconvenience and the potential adverse effects of corticosteroids.36,52 Both topical clindamycin and intralesional steroids are helpful in reducing inflammation prior to planned surgical intervention.36,52,53

Newer topical therapies include resorcinol peels and combination antimicrobials, such as 2% triclosan and oral zinc gluconate.52,53 Data surrounding the use of resorcinol in mild to moderate HS are promising and have shown decreased severity of both new and long-standing nodules. Fifteen-percent resorcinol peels are helpful tools that allow for self-administration by patients during exacerbations to decrease pain and flare duration.55,56 In a 2016 clinical trial, a combination of oral zinc gluconate with topical triclosan was shown to reduce flare-ups and nodules in mild HS.57 Oral zinc alone may have anti-inflammatory properties and generally is well tolerated.43,53 Topical therapies have a role in reducing HS-associated pain but often are limited to milder disease.

Systemic Agents

Several therapeutic options exist for the treatment of HS; however, a detailed description of their mechanisms and efficacies is beyond the scope of this review, which is focused on pain. Briefly, these systemic agents include antibiotics, retinoids, corticosteroids, antiandrogens, and biologics.43,52,53

Treatment with antibiotics such as tetracyclines or a combination of clindamycin plus rifampin has been shown to produce complete remission in 60% to 80% of users; however, this treatment requires more than 6 months of antibiotic therapy, which can be difficult to tolerate.52,53,58 Relapse is common after antibiotic cessation.2,43,52 Antibiotics have demonstrated efficacy during acute flares and in reducing inflammatory activity prior to surgery.52

Retinoids have been utilized in the treatment of HS because of their action on sebaceous glands and hair follicles.43,53 Acitretin has been shown to be the most effective oral retinoid available in the United States.43 Unfortunately, many of the studies investigating the use of retinoids for treatment of HS are limited by small sample size.36,43,52

Because HS is predominantly an inflammatory condition, immunosuppressants have been adapted to manage patients when antibiotics and topicals have failed. Systemic steroids rarely are used for long-term therapy because of the severe side effects and are preferred only for acute management.36,52 Cyclosporine and dapsone have demonstrated efficacy in treating moderate to severe HS, whereas methotrexate and colchicine have shown little efficacy.52 Both cyclosporine and dapsone are difficult to tolerate, require laboratory monitoring, and lead to only conservative improvement rather than remission in most patients.43

Immune dysregulation in HS involves elevated levels of proinflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), which is a key mediator of inflammation and a stimulator of other inflammatory cytokines.59,60 The first approved biologic treatment of HS was adalimumab, a TNF-α inhibitor, which showed a 50% reduction in total abscess and inflammatory nodule count in 60% of patients with moderate to severe HS.61-63 Of course, TNF-α inhibitor therapy is not without risks, specifically those of infection.43,53,61,62 Maintenance therapy may be required if patients relapse.53,61

Various interleukin inhibitors also have emerged as potential therapies for HS, such as ustekinumab and anakinra.36,64 Both have been subject to numerous small case trials that have reported improvements in clinical severity and pain; however, both drugs were associated with a fair number of nonresponders.36,64,65

Surgical Procedures