User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Popularity of virtual conferences may mean a permanent shift

Fifteen days. That’s how much time the American College of Cardiology (ACC) had to convert its annual conference, scheduled for the end of March this year in Chicago, into a virtual meeting for the estimated 17,000 people who had planned to attend.

Because of the coronavirus pandemic, Illinois announced restrictions on the size of gatherings on March 13, causing the ACC to pivot to an online-only model.

“One big advantage was that we already had all of our content planned,” Janice Sibley, the ACC’s executive vice president of education, told Medscape Medical News. “We knew who the faculty would be for different sessions, and many of them had already planned their slides.”

But determining how to present those hundreds of presentations at an online conference, not to mention addressing the logistics related to registrations, tech platforms, exhibit hall sponsors, and other aspects of an annual meeting, would be no small task.

But according to a Medscape poll, many physicians think that, while the virtual experience is worthwhile and getting better, it’s never going to be the same as spending several days on site, immersed in the experience of an annual meeting.

As one respondent commented, “I miss the intellectual excitement, the electricity in the room, when there is a live presentation that announces a major breakthrough.”

Large medical societies have an advantage

As ACC rapidly prepared for its virtual conference, the society first refunded all registration and expo fees and worked with the vendor partners to resolve the cancellation of rental space, food and beverage services, and decorating. Then they organized a team of 15 people split into three groups. One group focused on the intellectual, scientific, and educational elements of the virtual conference. They chose 24 sessions to livestream and decided to prerecord the rest for on-demand access, limiting the number of presenters they needed to train for online presentation.

A second team focused on business and worked with industry partners on how to translate a large expo into digital offerings. They developed virtual pages, advertisements, promotions, and industry-sponsored education.

The third team’s focus, Ms. Sibley said, was most critical, and the hardest: addressing socio-emotional needs.

“That group was responsible for trying to create the buzz and excitement we would have had at the event,” she said, “pivoting that experience we would have had in a live event to a virtual environment. What we were worried about was, would anyone even come?”

But ACC built it, and they did indeed come. Within a half hour of the opening session, nearly 13,000 people logged on from around the world. “It worked beautifully,” Ms. Sibley said.

By the end of the 3-day event, approximately 34,000 unique visitors had logged in for live or prerecorded sessions. Although ACC worried at first about technical glitches and bandwidth needs, everything ran smoothly. By 90 days after the meeting, 63,000 unique users had logged in to access the conference content.

ACC was among the first organizations forced to switch from an in-person to all-online meeting, but dozens of other organizations have now done the same, discovering the benefits and drawbacks of a virtual environment while experimenting with different formats and offerings. Talks with a few large medical societies about the experience revealed several common themes, including the following:

- Finding new ways to attract and measure attendance.

- Ensuring the actual scientific content was as robust online as in person.

- Realizing the value of social media in enhancing the socio-emotional experience.

- Believing that virtual meetings will become a permanent fixture in a future of “hybrid” conferences.

New ways of attracting and measuring attendance

Previous ways to measure meeting attendance were straightforward: number of registrations and number of people physically walking into sessions. An online conference, however, offers dozens of ways to measure attendance. While the number of registrations remained one tool – and all the organizations interviewed reported record numbers of registrations – organizations also used other metrics to measure success, such as “participation,” “engagement,” and “viewing time.”

ACC defined “participation” as a unique user logging in, and it defined “engagement” as sticking around for a while, possibly using chat functions or discussing the content on social media. The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) annual conference in May, which attracted more than 44,000 registered attendees, also measured total content views – more than 2.5 million during the meeting – and monitored social media. More than 8,800 Twitter users posted more than 45,000 tweets with the #ASCO20 hashtag during the meeting, generating 750 million likes, shares, and comments. The European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) annual congress registered a record 18,700 delegates – up from 14,500 in 2019 – but it also measured attendance by average viewing time and visits by congress day and by category.

Organizations shifted fee structures as well. While ACC refunded fees for its first online meeting, it has since developed tiers to match fees to anticipated value, such as charging more for livestreamed sessions that allow interactivity than for viewing recordings. ASCO offered a one-time fee waiver for members plus free registration to cancer survivors and caregivers, discounted registration for patient advocates, and reduced fees for other categories. But adjusting how to measure attendance and charge for events were the easy parts of transitioning to online.

Priority for having robust content

The biggest difficulty for most organizations was the short time they had to move online, with a host of challenges accompanying the switch, said the executive director of EULAR, Julia Rautenstrauch, DrMed. These included technical requirements, communication, training, finances, legal issues, compliance rules, and other logistics.

“The year 2020 will be remembered for being the year of unexpected transformation,” said a spokesperson from European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO), who declined to be named. “The number of fundamental questions we had to ask ourselves is pages long. The solutions we have implemented so far have been successful, but we won’t rest on our laurels.”

ASCO had an advantage in the pivot, despite only 6 weeks to make the switch, because they already had a robust online platform to build on. “We weren’t starting from scratch, but we were sure changing the way we prepared,” ASCO CEO Clifford Hudis, MD, said.

All of the organizations made the breadth and quality of scientific and educational content a top priority, and those who have already hosted meetings this year report positive feedback.

“The rating of the scientific content was excellent, and the event did indeed fulfill the educational goals and expected learning outcomes for the vast majority of delegates,” EULAR’s Dr. Rautenstrauch said.

“Our goal, when we went into this, was that, in the future when somebody looks back at ASCO20, they should not be able to tell that it was a different year from any other in terms of the science,” Dr. Hudis said.

Missing out on networking and social interaction

Even when logistics run smoothly, virtual conferences must overcome two other challenges: the loss of in-person interactions and the potential for “Zoom burnout.”

“You do miss that human contact, the unsaid reactions in the room when you’re speaking or providing a controversial statement, even the facial expression or seeing people lean in or being distracted,” Ms. Sibley said.

Taher Modarressi, MD, an endocrinologist with Diabetes and Endocrine Associates of Hunterdon in Flemington, N.J., said all the digital conferences he has attended were missing those key social elements: “seeing old friends, sideline discussions that generate new ideas, and meeting new colleagues. However, this has been partly alleviated with the robust rise of social media and ‘MedTwitter,’ in particular, where these discussions and interactions continue.”

To attempt to meet that need for social interaction, societies came up with a variety of options. EULAR offered chatrooms, “Meet the Expert” sessions, and other virtual opportunities for live interaction. ASCO hosted discussion groups with subsets of participants, such as virtual meetings with oncology fellows, and it plans to offer networking sessions and “poster walks” during future meetings.

“The value of an in-person meeting is connecting with people, exchanging ideas over coffee, and making new contacts,” ASCO’s Dr. Hudis said. While virtual meetings lose many of those personal interactions, knowledge can also be shared with more people, he said.

The key to combating digital fatigue is focusing on opportunities for interactivity, ACC’s Ms. Sibley said. “When you are creating a virtual environment, it’s important that you offer choices.” Online learners tend to have shorter attention spans than in-person learners, so people need opportunities to flip between sessions, like flipping between TV channels. Different engagement options are also essential, such as chat functions on the video platforms, asking questions of presenters orally or in writing, and using the familiar hashtags for social media discussion.

“We set up all those different ways to interact, and you allow the user to choose,” Ms. Sibley said.

Some conferences, however, had less time or fewer resources to adjust to a virtual format and couldn’t make up for the lost social interaction. Andy Bowman, MD, a neonatologist in Lubbock, Tex., was supposed to attend the Neonatal & Pediatric Airborne Transport Conference sponsored by International Biomed in the spring, but it was canceled at the last minute. Several weeks later, the organizers released videos of scheduled speakers giving their talks, but it was less engaging and too easy to get distracted, Dr. Bowman said.

“There is a noticeable decrease in energy – you can’t look around to feed off other’s reactions when a speaker says something off the wall, or new, or contrary to expectations,” he said. He also especially missed the social interactions, such as “missing out on the chance encounters in the hallway or seeing the same face in back-to-back sessions and figuring out you have shared interest.” He was also sorry to miss the expo because neonatal transport requires a lot of specialty equipment, and he appreciates the chance to actually touch and see it in person.

Advantages of an online meeting

Despite the challenges, online meetings can overcome obstacles of in-person meetings, particularly for those in low- and middle-income countries, such as travel and registration costs, the hardships of being away from practice, and visa restrictions.

“You really have the potential to broaden your reach,” Ms. Sibley said, noting that people in 157 countries participated in ACC.20.

Another advantage is keeping the experience available to people after the livestreamed event.

“Virtual events have demonstrated the potential for a more democratic conference world, expanding the dissemination of information to a much wider community of stakeholders,” ESMO’s spokesperson said.

Not traveling can actually mean getting more out of the conference, said Atisha Patel Manhas, MD, a hematologist/oncologist in Dallas, who attended ASCO. “I have really enjoyed the access aspect – on the virtual platform there is so much more content available to you, and travel time doesn’t cut into conference time,” she said, though she also missed the interaction with colleagues.

Others found that virtual conferences provided more engagement than in-person conferences. Marwah Abdalla, MD, MPH, an assistant professor of medicine and director of education for the Cardiac Intensive Care Unit at Columbia University Medical Center, New York, felt that moderated Q&A sessions offered more interaction among participants. She attended and spoke on a panel during virtual SLEEP 2020, a joint meeting of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) and the Sleep Research Society (SRS).

“Usually during in-person sessions, only a few questions are possible, and participants rarely have an opportunity to discuss the presentations within the session due to time limits,” Dr. Abdalla said. “Because the conference presentations can also be viewed asynchronously, participants have been able to comment on lectures and continue the discussion offline, either via social media or via email.” She acknowledged drawbacks of the virtual experience, such as an inability to socialize in person and participate in activities but appreciated the new opportunities to network and learn from international colleagues who would not have been able to attend in person.

Ritu Thamman, MD, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, pointed out that many institutions have cut their travel budgets, and physicians would be unable to attend in-person conferences for financial or other reasons. She especially appreciated that the European Society of Cardiology had no registration fee for ESC 2020 and made their content free for all of September, which led to more than 100,000 participants.

“That meant anyone anywhere could learn,” she said. “It makes it much more diverse and more egalitarian. That feels like a good step in the right direction for all of us.”

Dr. Modarressi, who found ESC “exhilarating,” similarly noted the benefit of such an equitably accessible conference. “Decreasing barriers and improving access to top-line results and up-to-date information has always been a challenge to the global health community,” he said, noting that the map of attendance for the virtual meeting was “astonishing.”

Given these benefits, organizers said they expect a future of hybrid conferences: physical meetings for those able to attend in person and virtual ones for those who cannot.

“We also expect that the hybrid congress will cater to the needs of people on-site by allowing them additional access to more scientific content than by physical attendance alone,” Dr. Rautenstrauch said.

Everyone has been in reactive mode this year, Ms. Sibley said, but the future looks bright as they seek ways to overcome challenges such as socio-emotional needs and virtual expo spaces.

“We’ve been thrust into the virtual world much faster than we expected, but we’re finding it’s opening more opportunities than we had live,” Ms. Sibley said. “This has catapulted us, for better or worse, into a new way to deliver education and other types of information.

“I think, if we’re smart, we’ll continue to think of ways this can augment our live environment and not replace it.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Fifteen days. That’s how much time the American College of Cardiology (ACC) had to convert its annual conference, scheduled for the end of March this year in Chicago, into a virtual meeting for the estimated 17,000 people who had planned to attend.

Because of the coronavirus pandemic, Illinois announced restrictions on the size of gatherings on March 13, causing the ACC to pivot to an online-only model.

“One big advantage was that we already had all of our content planned,” Janice Sibley, the ACC’s executive vice president of education, told Medscape Medical News. “We knew who the faculty would be for different sessions, and many of them had already planned their slides.”

But determining how to present those hundreds of presentations at an online conference, not to mention addressing the logistics related to registrations, tech platforms, exhibit hall sponsors, and other aspects of an annual meeting, would be no small task.

But according to a Medscape poll, many physicians think that, while the virtual experience is worthwhile and getting better, it’s never going to be the same as spending several days on site, immersed in the experience of an annual meeting.

As one respondent commented, “I miss the intellectual excitement, the electricity in the room, when there is a live presentation that announces a major breakthrough.”

Large medical societies have an advantage

As ACC rapidly prepared for its virtual conference, the society first refunded all registration and expo fees and worked with the vendor partners to resolve the cancellation of rental space, food and beverage services, and decorating. Then they organized a team of 15 people split into three groups. One group focused on the intellectual, scientific, and educational elements of the virtual conference. They chose 24 sessions to livestream and decided to prerecord the rest for on-demand access, limiting the number of presenters they needed to train for online presentation.

A second team focused on business and worked with industry partners on how to translate a large expo into digital offerings. They developed virtual pages, advertisements, promotions, and industry-sponsored education.

The third team’s focus, Ms. Sibley said, was most critical, and the hardest: addressing socio-emotional needs.

“That group was responsible for trying to create the buzz and excitement we would have had at the event,” she said, “pivoting that experience we would have had in a live event to a virtual environment. What we were worried about was, would anyone even come?”

But ACC built it, and they did indeed come. Within a half hour of the opening session, nearly 13,000 people logged on from around the world. “It worked beautifully,” Ms. Sibley said.

By the end of the 3-day event, approximately 34,000 unique visitors had logged in for live or prerecorded sessions. Although ACC worried at first about technical glitches and bandwidth needs, everything ran smoothly. By 90 days after the meeting, 63,000 unique users had logged in to access the conference content.

ACC was among the first organizations forced to switch from an in-person to all-online meeting, but dozens of other organizations have now done the same, discovering the benefits and drawbacks of a virtual environment while experimenting with different formats and offerings. Talks with a few large medical societies about the experience revealed several common themes, including the following:

- Finding new ways to attract and measure attendance.

- Ensuring the actual scientific content was as robust online as in person.

- Realizing the value of social media in enhancing the socio-emotional experience.

- Believing that virtual meetings will become a permanent fixture in a future of “hybrid” conferences.

New ways of attracting and measuring attendance

Previous ways to measure meeting attendance were straightforward: number of registrations and number of people physically walking into sessions. An online conference, however, offers dozens of ways to measure attendance. While the number of registrations remained one tool – and all the organizations interviewed reported record numbers of registrations – organizations also used other metrics to measure success, such as “participation,” “engagement,” and “viewing time.”

ACC defined “participation” as a unique user logging in, and it defined “engagement” as sticking around for a while, possibly using chat functions or discussing the content on social media. The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) annual conference in May, which attracted more than 44,000 registered attendees, also measured total content views – more than 2.5 million during the meeting – and monitored social media. More than 8,800 Twitter users posted more than 45,000 tweets with the #ASCO20 hashtag during the meeting, generating 750 million likes, shares, and comments. The European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) annual congress registered a record 18,700 delegates – up from 14,500 in 2019 – but it also measured attendance by average viewing time and visits by congress day and by category.

Organizations shifted fee structures as well. While ACC refunded fees for its first online meeting, it has since developed tiers to match fees to anticipated value, such as charging more for livestreamed sessions that allow interactivity than for viewing recordings. ASCO offered a one-time fee waiver for members plus free registration to cancer survivors and caregivers, discounted registration for patient advocates, and reduced fees for other categories. But adjusting how to measure attendance and charge for events were the easy parts of transitioning to online.

Priority for having robust content

The biggest difficulty for most organizations was the short time they had to move online, with a host of challenges accompanying the switch, said the executive director of EULAR, Julia Rautenstrauch, DrMed. These included technical requirements, communication, training, finances, legal issues, compliance rules, and other logistics.

“The year 2020 will be remembered for being the year of unexpected transformation,” said a spokesperson from European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO), who declined to be named. “The number of fundamental questions we had to ask ourselves is pages long. The solutions we have implemented so far have been successful, but we won’t rest on our laurels.”

ASCO had an advantage in the pivot, despite only 6 weeks to make the switch, because they already had a robust online platform to build on. “We weren’t starting from scratch, but we were sure changing the way we prepared,” ASCO CEO Clifford Hudis, MD, said.

All of the organizations made the breadth and quality of scientific and educational content a top priority, and those who have already hosted meetings this year report positive feedback.

“The rating of the scientific content was excellent, and the event did indeed fulfill the educational goals and expected learning outcomes for the vast majority of delegates,” EULAR’s Dr. Rautenstrauch said.

“Our goal, when we went into this, was that, in the future when somebody looks back at ASCO20, they should not be able to tell that it was a different year from any other in terms of the science,” Dr. Hudis said.

Missing out on networking and social interaction

Even when logistics run smoothly, virtual conferences must overcome two other challenges: the loss of in-person interactions and the potential for “Zoom burnout.”

“You do miss that human contact, the unsaid reactions in the room when you’re speaking or providing a controversial statement, even the facial expression or seeing people lean in or being distracted,” Ms. Sibley said.

Taher Modarressi, MD, an endocrinologist with Diabetes and Endocrine Associates of Hunterdon in Flemington, N.J., said all the digital conferences he has attended were missing those key social elements: “seeing old friends, sideline discussions that generate new ideas, and meeting new colleagues. However, this has been partly alleviated with the robust rise of social media and ‘MedTwitter,’ in particular, where these discussions and interactions continue.”

To attempt to meet that need for social interaction, societies came up with a variety of options. EULAR offered chatrooms, “Meet the Expert” sessions, and other virtual opportunities for live interaction. ASCO hosted discussion groups with subsets of participants, such as virtual meetings with oncology fellows, and it plans to offer networking sessions and “poster walks” during future meetings.

“The value of an in-person meeting is connecting with people, exchanging ideas over coffee, and making new contacts,” ASCO’s Dr. Hudis said. While virtual meetings lose many of those personal interactions, knowledge can also be shared with more people, he said.

The key to combating digital fatigue is focusing on opportunities for interactivity, ACC’s Ms. Sibley said. “When you are creating a virtual environment, it’s important that you offer choices.” Online learners tend to have shorter attention spans than in-person learners, so people need opportunities to flip between sessions, like flipping between TV channels. Different engagement options are also essential, such as chat functions on the video platforms, asking questions of presenters orally or in writing, and using the familiar hashtags for social media discussion.

“We set up all those different ways to interact, and you allow the user to choose,” Ms. Sibley said.

Some conferences, however, had less time or fewer resources to adjust to a virtual format and couldn’t make up for the lost social interaction. Andy Bowman, MD, a neonatologist in Lubbock, Tex., was supposed to attend the Neonatal & Pediatric Airborne Transport Conference sponsored by International Biomed in the spring, but it was canceled at the last minute. Several weeks later, the organizers released videos of scheduled speakers giving their talks, but it was less engaging and too easy to get distracted, Dr. Bowman said.

“There is a noticeable decrease in energy – you can’t look around to feed off other’s reactions when a speaker says something off the wall, or new, or contrary to expectations,” he said. He also especially missed the social interactions, such as “missing out on the chance encounters in the hallway or seeing the same face in back-to-back sessions and figuring out you have shared interest.” He was also sorry to miss the expo because neonatal transport requires a lot of specialty equipment, and he appreciates the chance to actually touch and see it in person.

Advantages of an online meeting

Despite the challenges, online meetings can overcome obstacles of in-person meetings, particularly for those in low- and middle-income countries, such as travel and registration costs, the hardships of being away from practice, and visa restrictions.

“You really have the potential to broaden your reach,” Ms. Sibley said, noting that people in 157 countries participated in ACC.20.

Another advantage is keeping the experience available to people after the livestreamed event.

“Virtual events have demonstrated the potential for a more democratic conference world, expanding the dissemination of information to a much wider community of stakeholders,” ESMO’s spokesperson said.

Not traveling can actually mean getting more out of the conference, said Atisha Patel Manhas, MD, a hematologist/oncologist in Dallas, who attended ASCO. “I have really enjoyed the access aspect – on the virtual platform there is so much more content available to you, and travel time doesn’t cut into conference time,” she said, though she also missed the interaction with colleagues.

Others found that virtual conferences provided more engagement than in-person conferences. Marwah Abdalla, MD, MPH, an assistant professor of medicine and director of education for the Cardiac Intensive Care Unit at Columbia University Medical Center, New York, felt that moderated Q&A sessions offered more interaction among participants. She attended and spoke on a panel during virtual SLEEP 2020, a joint meeting of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) and the Sleep Research Society (SRS).

“Usually during in-person sessions, only a few questions are possible, and participants rarely have an opportunity to discuss the presentations within the session due to time limits,” Dr. Abdalla said. “Because the conference presentations can also be viewed asynchronously, participants have been able to comment on lectures and continue the discussion offline, either via social media or via email.” She acknowledged drawbacks of the virtual experience, such as an inability to socialize in person and participate in activities but appreciated the new opportunities to network and learn from international colleagues who would not have been able to attend in person.

Ritu Thamman, MD, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, pointed out that many institutions have cut their travel budgets, and physicians would be unable to attend in-person conferences for financial or other reasons. She especially appreciated that the European Society of Cardiology had no registration fee for ESC 2020 and made their content free for all of September, which led to more than 100,000 participants.

“That meant anyone anywhere could learn,” she said. “It makes it much more diverse and more egalitarian. That feels like a good step in the right direction for all of us.”

Dr. Modarressi, who found ESC “exhilarating,” similarly noted the benefit of such an equitably accessible conference. “Decreasing barriers and improving access to top-line results and up-to-date information has always been a challenge to the global health community,” he said, noting that the map of attendance for the virtual meeting was “astonishing.”

Given these benefits, organizers said they expect a future of hybrid conferences: physical meetings for those able to attend in person and virtual ones for those who cannot.

“We also expect that the hybrid congress will cater to the needs of people on-site by allowing them additional access to more scientific content than by physical attendance alone,” Dr. Rautenstrauch said.

Everyone has been in reactive mode this year, Ms. Sibley said, but the future looks bright as they seek ways to overcome challenges such as socio-emotional needs and virtual expo spaces.

“We’ve been thrust into the virtual world much faster than we expected, but we’re finding it’s opening more opportunities than we had live,” Ms. Sibley said. “This has catapulted us, for better or worse, into a new way to deliver education and other types of information.

“I think, if we’re smart, we’ll continue to think of ways this can augment our live environment and not replace it.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Fifteen days. That’s how much time the American College of Cardiology (ACC) had to convert its annual conference, scheduled for the end of March this year in Chicago, into a virtual meeting for the estimated 17,000 people who had planned to attend.

Because of the coronavirus pandemic, Illinois announced restrictions on the size of gatherings on March 13, causing the ACC to pivot to an online-only model.

“One big advantage was that we already had all of our content planned,” Janice Sibley, the ACC’s executive vice president of education, told Medscape Medical News. “We knew who the faculty would be for different sessions, and many of them had already planned their slides.”

But determining how to present those hundreds of presentations at an online conference, not to mention addressing the logistics related to registrations, tech platforms, exhibit hall sponsors, and other aspects of an annual meeting, would be no small task.

But according to a Medscape poll, many physicians think that, while the virtual experience is worthwhile and getting better, it’s never going to be the same as spending several days on site, immersed in the experience of an annual meeting.

As one respondent commented, “I miss the intellectual excitement, the electricity in the room, when there is a live presentation that announces a major breakthrough.”

Large medical societies have an advantage

As ACC rapidly prepared for its virtual conference, the society first refunded all registration and expo fees and worked with the vendor partners to resolve the cancellation of rental space, food and beverage services, and decorating. Then they organized a team of 15 people split into three groups. One group focused on the intellectual, scientific, and educational elements of the virtual conference. They chose 24 sessions to livestream and decided to prerecord the rest for on-demand access, limiting the number of presenters they needed to train for online presentation.

A second team focused on business and worked with industry partners on how to translate a large expo into digital offerings. They developed virtual pages, advertisements, promotions, and industry-sponsored education.

The third team’s focus, Ms. Sibley said, was most critical, and the hardest: addressing socio-emotional needs.

“That group was responsible for trying to create the buzz and excitement we would have had at the event,” she said, “pivoting that experience we would have had in a live event to a virtual environment. What we were worried about was, would anyone even come?”

But ACC built it, and they did indeed come. Within a half hour of the opening session, nearly 13,000 people logged on from around the world. “It worked beautifully,” Ms. Sibley said.

By the end of the 3-day event, approximately 34,000 unique visitors had logged in for live or prerecorded sessions. Although ACC worried at first about technical glitches and bandwidth needs, everything ran smoothly. By 90 days after the meeting, 63,000 unique users had logged in to access the conference content.

ACC was among the first organizations forced to switch from an in-person to all-online meeting, but dozens of other organizations have now done the same, discovering the benefits and drawbacks of a virtual environment while experimenting with different formats and offerings. Talks with a few large medical societies about the experience revealed several common themes, including the following:

- Finding new ways to attract and measure attendance.

- Ensuring the actual scientific content was as robust online as in person.

- Realizing the value of social media in enhancing the socio-emotional experience.

- Believing that virtual meetings will become a permanent fixture in a future of “hybrid” conferences.

New ways of attracting and measuring attendance

Previous ways to measure meeting attendance were straightforward: number of registrations and number of people physically walking into sessions. An online conference, however, offers dozens of ways to measure attendance. While the number of registrations remained one tool – and all the organizations interviewed reported record numbers of registrations – organizations also used other metrics to measure success, such as “participation,” “engagement,” and “viewing time.”

ACC defined “participation” as a unique user logging in, and it defined “engagement” as sticking around for a while, possibly using chat functions or discussing the content on social media. The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) annual conference in May, which attracted more than 44,000 registered attendees, also measured total content views – more than 2.5 million during the meeting – and monitored social media. More than 8,800 Twitter users posted more than 45,000 tweets with the #ASCO20 hashtag during the meeting, generating 750 million likes, shares, and comments. The European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) annual congress registered a record 18,700 delegates – up from 14,500 in 2019 – but it also measured attendance by average viewing time and visits by congress day and by category.

Organizations shifted fee structures as well. While ACC refunded fees for its first online meeting, it has since developed tiers to match fees to anticipated value, such as charging more for livestreamed sessions that allow interactivity than for viewing recordings. ASCO offered a one-time fee waiver for members plus free registration to cancer survivors and caregivers, discounted registration for patient advocates, and reduced fees for other categories. But adjusting how to measure attendance and charge for events were the easy parts of transitioning to online.

Priority for having robust content

The biggest difficulty for most organizations was the short time they had to move online, with a host of challenges accompanying the switch, said the executive director of EULAR, Julia Rautenstrauch, DrMed. These included technical requirements, communication, training, finances, legal issues, compliance rules, and other logistics.

“The year 2020 will be remembered for being the year of unexpected transformation,” said a spokesperson from European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO), who declined to be named. “The number of fundamental questions we had to ask ourselves is pages long. The solutions we have implemented so far have been successful, but we won’t rest on our laurels.”

ASCO had an advantage in the pivot, despite only 6 weeks to make the switch, because they already had a robust online platform to build on. “We weren’t starting from scratch, but we were sure changing the way we prepared,” ASCO CEO Clifford Hudis, MD, said.

All of the organizations made the breadth and quality of scientific and educational content a top priority, and those who have already hosted meetings this year report positive feedback.

“The rating of the scientific content was excellent, and the event did indeed fulfill the educational goals and expected learning outcomes for the vast majority of delegates,” EULAR’s Dr. Rautenstrauch said.

“Our goal, when we went into this, was that, in the future when somebody looks back at ASCO20, they should not be able to tell that it was a different year from any other in terms of the science,” Dr. Hudis said.

Missing out on networking and social interaction

Even when logistics run smoothly, virtual conferences must overcome two other challenges: the loss of in-person interactions and the potential for “Zoom burnout.”

“You do miss that human contact, the unsaid reactions in the room when you’re speaking or providing a controversial statement, even the facial expression or seeing people lean in or being distracted,” Ms. Sibley said.

Taher Modarressi, MD, an endocrinologist with Diabetes and Endocrine Associates of Hunterdon in Flemington, N.J., said all the digital conferences he has attended were missing those key social elements: “seeing old friends, sideline discussions that generate new ideas, and meeting new colleagues. However, this has been partly alleviated with the robust rise of social media and ‘MedTwitter,’ in particular, where these discussions and interactions continue.”

To attempt to meet that need for social interaction, societies came up with a variety of options. EULAR offered chatrooms, “Meet the Expert” sessions, and other virtual opportunities for live interaction. ASCO hosted discussion groups with subsets of participants, such as virtual meetings with oncology fellows, and it plans to offer networking sessions and “poster walks” during future meetings.

“The value of an in-person meeting is connecting with people, exchanging ideas over coffee, and making new contacts,” ASCO’s Dr. Hudis said. While virtual meetings lose many of those personal interactions, knowledge can also be shared with more people, he said.

The key to combating digital fatigue is focusing on opportunities for interactivity, ACC’s Ms. Sibley said. “When you are creating a virtual environment, it’s important that you offer choices.” Online learners tend to have shorter attention spans than in-person learners, so people need opportunities to flip between sessions, like flipping between TV channels. Different engagement options are also essential, such as chat functions on the video platforms, asking questions of presenters orally or in writing, and using the familiar hashtags for social media discussion.

“We set up all those different ways to interact, and you allow the user to choose,” Ms. Sibley said.

Some conferences, however, had less time or fewer resources to adjust to a virtual format and couldn’t make up for the lost social interaction. Andy Bowman, MD, a neonatologist in Lubbock, Tex., was supposed to attend the Neonatal & Pediatric Airborne Transport Conference sponsored by International Biomed in the spring, but it was canceled at the last minute. Several weeks later, the organizers released videos of scheduled speakers giving their talks, but it was less engaging and too easy to get distracted, Dr. Bowman said.

“There is a noticeable decrease in energy – you can’t look around to feed off other’s reactions when a speaker says something off the wall, or new, or contrary to expectations,” he said. He also especially missed the social interactions, such as “missing out on the chance encounters in the hallway or seeing the same face in back-to-back sessions and figuring out you have shared interest.” He was also sorry to miss the expo because neonatal transport requires a lot of specialty equipment, and he appreciates the chance to actually touch and see it in person.

Advantages of an online meeting

Despite the challenges, online meetings can overcome obstacles of in-person meetings, particularly for those in low- and middle-income countries, such as travel and registration costs, the hardships of being away from practice, and visa restrictions.

“You really have the potential to broaden your reach,” Ms. Sibley said, noting that people in 157 countries participated in ACC.20.

Another advantage is keeping the experience available to people after the livestreamed event.

“Virtual events have demonstrated the potential for a more democratic conference world, expanding the dissemination of information to a much wider community of stakeholders,” ESMO’s spokesperson said.

Not traveling can actually mean getting more out of the conference, said Atisha Patel Manhas, MD, a hematologist/oncologist in Dallas, who attended ASCO. “I have really enjoyed the access aspect – on the virtual platform there is so much more content available to you, and travel time doesn’t cut into conference time,” she said, though she also missed the interaction with colleagues.

Others found that virtual conferences provided more engagement than in-person conferences. Marwah Abdalla, MD, MPH, an assistant professor of medicine and director of education for the Cardiac Intensive Care Unit at Columbia University Medical Center, New York, felt that moderated Q&A sessions offered more interaction among participants. She attended and spoke on a panel during virtual SLEEP 2020, a joint meeting of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) and the Sleep Research Society (SRS).

“Usually during in-person sessions, only a few questions are possible, and participants rarely have an opportunity to discuss the presentations within the session due to time limits,” Dr. Abdalla said. “Because the conference presentations can also be viewed asynchronously, participants have been able to comment on lectures and continue the discussion offline, either via social media or via email.” She acknowledged drawbacks of the virtual experience, such as an inability to socialize in person and participate in activities but appreciated the new opportunities to network and learn from international colleagues who would not have been able to attend in person.

Ritu Thamman, MD, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, pointed out that many institutions have cut their travel budgets, and physicians would be unable to attend in-person conferences for financial or other reasons. She especially appreciated that the European Society of Cardiology had no registration fee for ESC 2020 and made their content free for all of September, which led to more than 100,000 participants.

“That meant anyone anywhere could learn,” she said. “It makes it much more diverse and more egalitarian. That feels like a good step in the right direction for all of us.”

Dr. Modarressi, who found ESC “exhilarating,” similarly noted the benefit of such an equitably accessible conference. “Decreasing barriers and improving access to top-line results and up-to-date information has always been a challenge to the global health community,” he said, noting that the map of attendance for the virtual meeting was “astonishing.”

Given these benefits, organizers said they expect a future of hybrid conferences: physical meetings for those able to attend in person and virtual ones for those who cannot.

“We also expect that the hybrid congress will cater to the needs of people on-site by allowing them additional access to more scientific content than by physical attendance alone,” Dr. Rautenstrauch said.

Everyone has been in reactive mode this year, Ms. Sibley said, but the future looks bright as they seek ways to overcome challenges such as socio-emotional needs and virtual expo spaces.

“We’ve been thrust into the virtual world much faster than we expected, but we’re finding it’s opening more opportunities than we had live,” Ms. Sibley said. “This has catapulted us, for better or worse, into a new way to deliver education and other types of information.

“I think, if we’re smart, we’ll continue to think of ways this can augment our live environment and not replace it.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Brazil confirms death of volunteer in COVID-19 vaccine trial

The Brazilian National Health Surveillance Agency (Anvisa) announced Oct. 21 that it is investigating data received on the death of a volunteer in a clinical trial of the COVID-19 vaccine developed by Oxford University and the pharmaceutical company AstraZeneca.

In an email sent to Medscape Medical News, the agency states that it was formally informed of the death on October 19. It has already received data regarding the investigation of the case, which is now being conducted by the Brazilian International Security Assessment Committee.

The identity of the volunteer and cause of death have not yet been confirmed by any official source linked to the study. In the email, Anvisa reiterated that “according to national and international regulations on good clinical practices, data on clinical research volunteers must be kept confidential, in accordance with the principles of confidentiality, human dignity, and protection of participants.”

A report in the Brazilian newspaper O Globo, however, states that the patient who died is a 28-year-old doctor, recently graduated, who worked on the front line of combating COVID-19 in three hospitals in Rio de Janeiro. . Due to the study design, it is impossible to know whether the volunteer received the vaccine or placebo.

It is imperative to wait for the results of the investigations, said Sergio Cimerman, MD, the scientific coordinator of the Brazilian Society of Infectious Diseases (SBI), because death is possible during any vaccine trial, even more so in cases in which the final goal is to immunize the population in record time.

“It is precisely the phase 3 study that assesses efficacy and safety so that the vaccine can be used for the entire population. We cannot let ourselves lose hope, and we must move forward, as safely as possible, in search of an ideal vaccine,” said Cimerman, who works at the Instituto de Infectologia Emílio Ribas and is also an advisor to the Portuguese edition of Medscape.

This article was translated and adapted from the Portuguese edition of Medscape.

The Brazilian National Health Surveillance Agency (Anvisa) announced Oct. 21 that it is investigating data received on the death of a volunteer in a clinical trial of the COVID-19 vaccine developed by Oxford University and the pharmaceutical company AstraZeneca.

In an email sent to Medscape Medical News, the agency states that it was formally informed of the death on October 19. It has already received data regarding the investigation of the case, which is now being conducted by the Brazilian International Security Assessment Committee.

The identity of the volunteer and cause of death have not yet been confirmed by any official source linked to the study. In the email, Anvisa reiterated that “according to national and international regulations on good clinical practices, data on clinical research volunteers must be kept confidential, in accordance with the principles of confidentiality, human dignity, and protection of participants.”

A report in the Brazilian newspaper O Globo, however, states that the patient who died is a 28-year-old doctor, recently graduated, who worked on the front line of combating COVID-19 in three hospitals in Rio de Janeiro. . Due to the study design, it is impossible to know whether the volunteer received the vaccine or placebo.

It is imperative to wait for the results of the investigations, said Sergio Cimerman, MD, the scientific coordinator of the Brazilian Society of Infectious Diseases (SBI), because death is possible during any vaccine trial, even more so in cases in which the final goal is to immunize the population in record time.

“It is precisely the phase 3 study that assesses efficacy and safety so that the vaccine can be used for the entire population. We cannot let ourselves lose hope, and we must move forward, as safely as possible, in search of an ideal vaccine,” said Cimerman, who works at the Instituto de Infectologia Emílio Ribas and is also an advisor to the Portuguese edition of Medscape.

This article was translated and adapted from the Portuguese edition of Medscape.

The Brazilian National Health Surveillance Agency (Anvisa) announced Oct. 21 that it is investigating data received on the death of a volunteer in a clinical trial of the COVID-19 vaccine developed by Oxford University and the pharmaceutical company AstraZeneca.

In an email sent to Medscape Medical News, the agency states that it was formally informed of the death on October 19. It has already received data regarding the investigation of the case, which is now being conducted by the Brazilian International Security Assessment Committee.

The identity of the volunteer and cause of death have not yet been confirmed by any official source linked to the study. In the email, Anvisa reiterated that “according to national and international regulations on good clinical practices, data on clinical research volunteers must be kept confidential, in accordance with the principles of confidentiality, human dignity, and protection of participants.”

A report in the Brazilian newspaper O Globo, however, states that the patient who died is a 28-year-old doctor, recently graduated, who worked on the front line of combating COVID-19 in three hospitals in Rio de Janeiro. . Due to the study design, it is impossible to know whether the volunteer received the vaccine or placebo.

It is imperative to wait for the results of the investigations, said Sergio Cimerman, MD, the scientific coordinator of the Brazilian Society of Infectious Diseases (SBI), because death is possible during any vaccine trial, even more so in cases in which the final goal is to immunize the population in record time.

“It is precisely the phase 3 study that assesses efficacy and safety so that the vaccine can be used for the entire population. We cannot let ourselves lose hope, and we must move forward, as safely as possible, in search of an ideal vaccine,” said Cimerman, who works at the Instituto de Infectologia Emílio Ribas and is also an advisor to the Portuguese edition of Medscape.

This article was translated and adapted from the Portuguese edition of Medscape.

Outpatient visits rebound for most specialties to pre-COVID-19 levels

, according to new data.

Overall visits plunged by almost 60% at the low point in late March and did not start recovering until late June, when visits were still off by 10%. Visits began to rise again – by 2% over the March 1 baseline – around Labor Day.

As of Oct. 4, visits had returned to that March 1 baseline, which was slightly higher than in late February, according to data analyzed by Harvard University, the Commonwealth Fund, and the healthcare technology company Phreesia, which helps medical practices with patient registration, insurance verification, and payments, and has data on 50,000 providers in all 50 states.

The study was published online by the Commonwealth Fund.

In-person visits are still down 6% from the March 1 baseline. Telemedicine visits – which surged in mid-April to account for some 13%-14% of visits – have subsided to 6% of visits.

Many states reopened businesses and lifted travel restrictions in early September, benefiting medical practices in some areas. But clinicians in some regions are still facing rising COVID-19 cases, as well as “the challenges of keeping patients and clinicians safe while also maintaining revenue,” wrote the report authors.

Some specialties are still hard hit. For the week starting Oct. 4, visits to pulmonologists were off 20% from March 1. Otolaryngology visits were down 17%, and behavioral health visits were down 14%. Cardiology, allergy/immunology, neurology, gastroenterology, and endocrinology also saw drops of 5%-10% from March.

Patients were flocking to dermatologists, however. Visits were up 17% over baseline. Primary care also was popular, with a 13% increase over March 1.

At the height of the pandemic shutdown in late March, Medicare beneficiaries stayed away from doctors the most. Visits dipped 63%, compared with 56% for the commercially insured, and 52% for those on Medicaid. Now, Medicare visits are up 3% over baseline, while Medicaid visits are down 1% and commercially insured visits have risen 1% from March.

The over-65 age group did not have the steepest drop in visits when analyzed by age. Children aged 3-17 years saw the biggest decline at the height of the shutdown. Infants to 5-year-olds have still not returned to prepandemic visit levels. Those visits are off by 10%-18%. The 65-and-older group is up 4% from March.

Larger practices – with more than six clinicians – have seen the biggest rebound, after having had the largest dip in visits, from a decline of 53% in late March to a 14% rise over that baseline. Practices with fewer than five clinicians are still 6% down from the March baseline.

Wide variation in telemedicine use

The researchers reported a massive gap in the percentage of various specialties that are using telemedicine. At the top end are behavioral health specialists, where 41% of visits are by telemedicine.

The next-closest specialty is endocrinology, which has 14% of visits via telemedicine, on par with rheumatology, neurology, and gastroenterology. At the low end: ophthalmology, with zero virtual visits; otolaryngology (1%), orthopedics (1%), surgery (2%), and dermatology and ob.gyn., both at 3%.

Smaller practices – with fewer than five clinicians – never adopted telemedicine at the rate of the larger practices. During the mid-April peak, about 10% of the smaller practices were using telemedicine in adult primary care practices, compared with 19% of those primary care practices with more than six clinicians.

The gap persists. Currently, 9% of the larger practices are using telemedicine, compared with 4% of small practices.

One-third of all provider organizations analyzed never-adopted telemedicine. And while use continues, it is now mostly minimal. At the April peak, 35% of the practices with telemedicine reported heavy use – that is, in more than 20% of visits. In September, 9% said they had such heavy use.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

, according to new data.

Overall visits plunged by almost 60% at the low point in late March and did not start recovering until late June, when visits were still off by 10%. Visits began to rise again – by 2% over the March 1 baseline – around Labor Day.

As of Oct. 4, visits had returned to that March 1 baseline, which was slightly higher than in late February, according to data analyzed by Harvard University, the Commonwealth Fund, and the healthcare technology company Phreesia, which helps medical practices with patient registration, insurance verification, and payments, and has data on 50,000 providers in all 50 states.

The study was published online by the Commonwealth Fund.

In-person visits are still down 6% from the March 1 baseline. Telemedicine visits – which surged in mid-April to account for some 13%-14% of visits – have subsided to 6% of visits.

Many states reopened businesses and lifted travel restrictions in early September, benefiting medical practices in some areas. But clinicians in some regions are still facing rising COVID-19 cases, as well as “the challenges of keeping patients and clinicians safe while also maintaining revenue,” wrote the report authors.

Some specialties are still hard hit. For the week starting Oct. 4, visits to pulmonologists were off 20% from March 1. Otolaryngology visits were down 17%, and behavioral health visits were down 14%. Cardiology, allergy/immunology, neurology, gastroenterology, and endocrinology also saw drops of 5%-10% from March.

Patients were flocking to dermatologists, however. Visits were up 17% over baseline. Primary care also was popular, with a 13% increase over March 1.

At the height of the pandemic shutdown in late March, Medicare beneficiaries stayed away from doctors the most. Visits dipped 63%, compared with 56% for the commercially insured, and 52% for those on Medicaid. Now, Medicare visits are up 3% over baseline, while Medicaid visits are down 1% and commercially insured visits have risen 1% from March.

The over-65 age group did not have the steepest drop in visits when analyzed by age. Children aged 3-17 years saw the biggest decline at the height of the shutdown. Infants to 5-year-olds have still not returned to prepandemic visit levels. Those visits are off by 10%-18%. The 65-and-older group is up 4% from March.

Larger practices – with more than six clinicians – have seen the biggest rebound, after having had the largest dip in visits, from a decline of 53% in late March to a 14% rise over that baseline. Practices with fewer than five clinicians are still 6% down from the March baseline.

Wide variation in telemedicine use

The researchers reported a massive gap in the percentage of various specialties that are using telemedicine. At the top end are behavioral health specialists, where 41% of visits are by telemedicine.

The next-closest specialty is endocrinology, which has 14% of visits via telemedicine, on par with rheumatology, neurology, and gastroenterology. At the low end: ophthalmology, with zero virtual visits; otolaryngology (1%), orthopedics (1%), surgery (2%), and dermatology and ob.gyn., both at 3%.

Smaller practices – with fewer than five clinicians – never adopted telemedicine at the rate of the larger practices. During the mid-April peak, about 10% of the smaller practices were using telemedicine in adult primary care practices, compared with 19% of those primary care practices with more than six clinicians.

The gap persists. Currently, 9% of the larger practices are using telemedicine, compared with 4% of small practices.

One-third of all provider organizations analyzed never-adopted telemedicine. And while use continues, it is now mostly minimal. At the April peak, 35% of the practices with telemedicine reported heavy use – that is, in more than 20% of visits. In September, 9% said they had such heavy use.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

, according to new data.

Overall visits plunged by almost 60% at the low point in late March and did not start recovering until late June, when visits were still off by 10%. Visits began to rise again – by 2% over the March 1 baseline – around Labor Day.

As of Oct. 4, visits had returned to that March 1 baseline, which was slightly higher than in late February, according to data analyzed by Harvard University, the Commonwealth Fund, and the healthcare technology company Phreesia, which helps medical practices with patient registration, insurance verification, and payments, and has data on 50,000 providers in all 50 states.

The study was published online by the Commonwealth Fund.

In-person visits are still down 6% from the March 1 baseline. Telemedicine visits – which surged in mid-April to account for some 13%-14% of visits – have subsided to 6% of visits.

Many states reopened businesses and lifted travel restrictions in early September, benefiting medical practices in some areas. But clinicians in some regions are still facing rising COVID-19 cases, as well as “the challenges of keeping patients and clinicians safe while also maintaining revenue,” wrote the report authors.

Some specialties are still hard hit. For the week starting Oct. 4, visits to pulmonologists were off 20% from March 1. Otolaryngology visits were down 17%, and behavioral health visits were down 14%. Cardiology, allergy/immunology, neurology, gastroenterology, and endocrinology also saw drops of 5%-10% from March.

Patients were flocking to dermatologists, however. Visits were up 17% over baseline. Primary care also was popular, with a 13% increase over March 1.

At the height of the pandemic shutdown in late March, Medicare beneficiaries stayed away from doctors the most. Visits dipped 63%, compared with 56% for the commercially insured, and 52% for those on Medicaid. Now, Medicare visits are up 3% over baseline, while Medicaid visits are down 1% and commercially insured visits have risen 1% from March.

The over-65 age group did not have the steepest drop in visits when analyzed by age. Children aged 3-17 years saw the biggest decline at the height of the shutdown. Infants to 5-year-olds have still not returned to prepandemic visit levels. Those visits are off by 10%-18%. The 65-and-older group is up 4% from March.

Larger practices – with more than six clinicians – have seen the biggest rebound, after having had the largest dip in visits, from a decline of 53% in late March to a 14% rise over that baseline. Practices with fewer than five clinicians are still 6% down from the March baseline.

Wide variation in telemedicine use

The researchers reported a massive gap in the percentage of various specialties that are using telemedicine. At the top end are behavioral health specialists, where 41% of visits are by telemedicine.

The next-closest specialty is endocrinology, which has 14% of visits via telemedicine, on par with rheumatology, neurology, and gastroenterology. At the low end: ophthalmology, with zero virtual visits; otolaryngology (1%), orthopedics (1%), surgery (2%), and dermatology and ob.gyn., both at 3%.

Smaller practices – with fewer than five clinicians – never adopted telemedicine at the rate of the larger practices. During the mid-April peak, about 10% of the smaller practices were using telemedicine in adult primary care practices, compared with 19% of those primary care practices with more than six clinicians.

The gap persists. Currently, 9% of the larger practices are using telemedicine, compared with 4% of small practices.

One-third of all provider organizations analyzed never-adopted telemedicine. And while use continues, it is now mostly minimal. At the April peak, 35% of the practices with telemedicine reported heavy use – that is, in more than 20% of visits. In September, 9% said they had such heavy use.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Scrubs ad that insulted women and DOs pulled after outcry

A video that advertised scrubs but denigrated women and DOs has been removed from the company’s website after fierce backlash.

On Tuesday Kevin Klauer, DO, EJD, directed this tweet to the medical uniform company Figs: “@wearfigs REMOVE YOUR DO offensive web ad immediately or the @AOAforDOs will proceed promptly with a defamation lawsuit on behalf of our members and profession.”

Also on Tuesday, the American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine demanded a public apology.

The video ad featured a woman carrying a “Medical Terminology for Dummies” book upside down while modeling the pink scrubs from all angles and dancing. At one point in the ad, the camera zooms in on the badge clipped to her waistband that read “DO.”

Agnieszka Solberg, MD, a vascular and interventional radiologist and assistant clinical professor at the University of North Dakota in Grand Forks, was among those voicing pointed criticism on social media.

“This was another hit for our DO colleagues,” she said in an interview, emphasizing that MDs and DOs provide the same level of care.

AACOM tweeted: “We are outraged women physicians & doctors of osteopathic medicine are still attacked in ignorant marketing campaigns. A company like @wearfigs should be ashamed for promoting these stereotypes. We demand the respect we’ve earned AND a public apology.”

Dr. Solberg says this is not the first offense by the company. She said she had stopped buying the company’s scrubs a year ago because the ads “have been portraying female providers as dumb and silly. This was the final straw.”

She said the timing of the ad is suspect as DOs had been swept into a storm of negativity earlier this month, as Medscape Medical News reported, when some questioned the qualifications of President Donald Trump’s physician, Sean Conley, who is a DO.

The scrubs ad ignited criticism across specialties, provider levels, and genders.

Jessica K. Willett, MD, tweeted: “As women physicians in 2020, we still struggle to be taken seriously compared to our male counterparts, as we battle stereotypes like THIS EXACT ONE. We expect the brands we support to reflect the badasses we are.”

The company responded to her tweet: “Thank you so much for the feedback! Totally not our intent – we’re taking down both the men’s and women’s versions of this ASAP! I really appreciate you taking the time to share this.”

The company did not respond to a request for comment but issued an apology on social media: “A lot of you guys have pointed out an insensitive video we had on our site – we are incredibly sorry for any hurt this has caused you, especially our female DOs (who are amazing!) FIGS is a female founded company whose only mission is to make you guys feel awesome.”

The Los Angeles–based company, which Forbes estimated will make $250 million in sales this year, was founded by co-CEOs Heather Hasson and Trina Spear.

A med student wrote on Twitter: “As a female and a DO student, how would I ever “feel awesome” about myself knowing that this is how you view me??? And how you want others to view me??? Women and DO’s have fought stereotypes way too long for you to go ahead and put this out there. Do better.”

Even the company’s apology was tinged with disrespect, some noted, with the use of “you guys” and for what it didn’t include.

As Liesl Young, MD, tweeted: “We are not “guys”, we are women. MD = DO. We stand together.”

Dr. Solberg said the apology came across as an apology that feelings were hurt. It should have detailed the changes the company would make to prevent another incident and address the processes that led to the video.

Dr. Solberg said she is seeing something positive come from the whole incident in that, “women are taking up the torch of feminism in such a volatile and divisive time.”

Dr. Solberg reported no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A video that advertised scrubs but denigrated women and DOs has been removed from the company’s website after fierce backlash.

On Tuesday Kevin Klauer, DO, EJD, directed this tweet to the medical uniform company Figs: “@wearfigs REMOVE YOUR DO offensive web ad immediately or the @AOAforDOs will proceed promptly with a defamation lawsuit on behalf of our members and profession.”

Also on Tuesday, the American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine demanded a public apology.

The video ad featured a woman carrying a “Medical Terminology for Dummies” book upside down while modeling the pink scrubs from all angles and dancing. At one point in the ad, the camera zooms in on the badge clipped to her waistband that read “DO.”

Agnieszka Solberg, MD, a vascular and interventional radiologist and assistant clinical professor at the University of North Dakota in Grand Forks, was among those voicing pointed criticism on social media.

“This was another hit for our DO colleagues,” she said in an interview, emphasizing that MDs and DOs provide the same level of care.

AACOM tweeted: “We are outraged women physicians & doctors of osteopathic medicine are still attacked in ignorant marketing campaigns. A company like @wearfigs should be ashamed for promoting these stereotypes. We demand the respect we’ve earned AND a public apology.”

Dr. Solberg says this is not the first offense by the company. She said she had stopped buying the company’s scrubs a year ago because the ads “have been portraying female providers as dumb and silly. This was the final straw.”

She said the timing of the ad is suspect as DOs had been swept into a storm of negativity earlier this month, as Medscape Medical News reported, when some questioned the qualifications of President Donald Trump’s physician, Sean Conley, who is a DO.

The scrubs ad ignited criticism across specialties, provider levels, and genders.

Jessica K. Willett, MD, tweeted: “As women physicians in 2020, we still struggle to be taken seriously compared to our male counterparts, as we battle stereotypes like THIS EXACT ONE. We expect the brands we support to reflect the badasses we are.”

The company responded to her tweet: “Thank you so much for the feedback! Totally not our intent – we’re taking down both the men’s and women’s versions of this ASAP! I really appreciate you taking the time to share this.”

The company did not respond to a request for comment but issued an apology on social media: “A lot of you guys have pointed out an insensitive video we had on our site – we are incredibly sorry for any hurt this has caused you, especially our female DOs (who are amazing!) FIGS is a female founded company whose only mission is to make you guys feel awesome.”

The Los Angeles–based company, which Forbes estimated will make $250 million in sales this year, was founded by co-CEOs Heather Hasson and Trina Spear.

A med student wrote on Twitter: “As a female and a DO student, how would I ever “feel awesome” about myself knowing that this is how you view me??? And how you want others to view me??? Women and DO’s have fought stereotypes way too long for you to go ahead and put this out there. Do better.”

Even the company’s apology was tinged with disrespect, some noted, with the use of “you guys” and for what it didn’t include.

As Liesl Young, MD, tweeted: “We are not “guys”, we are women. MD = DO. We stand together.”

Dr. Solberg said the apology came across as an apology that feelings were hurt. It should have detailed the changes the company would make to prevent another incident and address the processes that led to the video.

Dr. Solberg said she is seeing something positive come from the whole incident in that, “women are taking up the torch of feminism in such a volatile and divisive time.”

Dr. Solberg reported no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A video that advertised scrubs but denigrated women and DOs has been removed from the company’s website after fierce backlash.

On Tuesday Kevin Klauer, DO, EJD, directed this tweet to the medical uniform company Figs: “@wearfigs REMOVE YOUR DO offensive web ad immediately or the @AOAforDOs will proceed promptly with a defamation lawsuit on behalf of our members and profession.”

Also on Tuesday, the American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine demanded a public apology.

The video ad featured a woman carrying a “Medical Terminology for Dummies” book upside down while modeling the pink scrubs from all angles and dancing. At one point in the ad, the camera zooms in on the badge clipped to her waistband that read “DO.”

Agnieszka Solberg, MD, a vascular and interventional radiologist and assistant clinical professor at the University of North Dakota in Grand Forks, was among those voicing pointed criticism on social media.

“This was another hit for our DO colleagues,” she said in an interview, emphasizing that MDs and DOs provide the same level of care.

AACOM tweeted: “We are outraged women physicians & doctors of osteopathic medicine are still attacked in ignorant marketing campaigns. A company like @wearfigs should be ashamed for promoting these stereotypes. We demand the respect we’ve earned AND a public apology.”

Dr. Solberg says this is not the first offense by the company. She said she had stopped buying the company’s scrubs a year ago because the ads “have been portraying female providers as dumb and silly. This was the final straw.”

She said the timing of the ad is suspect as DOs had been swept into a storm of negativity earlier this month, as Medscape Medical News reported, when some questioned the qualifications of President Donald Trump’s physician, Sean Conley, who is a DO.

The scrubs ad ignited criticism across specialties, provider levels, and genders.

Jessica K. Willett, MD, tweeted: “As women physicians in 2020, we still struggle to be taken seriously compared to our male counterparts, as we battle stereotypes like THIS EXACT ONE. We expect the brands we support to reflect the badasses we are.”

The company responded to her tweet: “Thank you so much for the feedback! Totally not our intent – we’re taking down both the men’s and women’s versions of this ASAP! I really appreciate you taking the time to share this.”

The company did not respond to a request for comment but issued an apology on social media: “A lot of you guys have pointed out an insensitive video we had on our site – we are incredibly sorry for any hurt this has caused you, especially our female DOs (who are amazing!) FIGS is a female founded company whose only mission is to make you guys feel awesome.”

The Los Angeles–based company, which Forbes estimated will make $250 million in sales this year, was founded by co-CEOs Heather Hasson and Trina Spear.

A med student wrote on Twitter: “As a female and a DO student, how would I ever “feel awesome” about myself knowing that this is how you view me??? And how you want others to view me??? Women and DO’s have fought stereotypes way too long for you to go ahead and put this out there. Do better.”

Even the company’s apology was tinged with disrespect, some noted, with the use of “you guys” and for what it didn’t include.

As Liesl Young, MD, tweeted: “We are not “guys”, we are women. MD = DO. We stand together.”

Dr. Solberg said the apology came across as an apology that feelings were hurt. It should have detailed the changes the company would make to prevent another incident and address the processes that led to the video.

Dr. Solberg said she is seeing something positive come from the whole incident in that, “women are taking up the torch of feminism in such a volatile and divisive time.”

Dr. Solberg reported no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Bariatric surgery tied to lower aortic dissection risk

The finding is the latest in a series of benefits researchers have linked to the surgery, not all of which appear to directly result from weight loss.

“It has an incredible impact on hyperlipidemia and hypertension,” said Luis Felipe Okida, MD, from Cleveland Clinic Florida, Weston. “Those are the main risk factors for aortic dissection.”

He presented the finding at the virtual American Congress of Surgeons Clinical Congress 2020. The study was also published online in the Journal of the American College of Surgeons.

Although uncommon, acute aortic dissection proves fatal to half the people it strikes if patients do not receive treatment within 72 hours, Dr. Okida said in an interview.

To learn whether there is an association between bariatric surgery and risk for aortic dissection, Dr. Okida and colleagues analyzed data from the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) database from 2010 to 2015. The NIS comprises about 20% of hospital inpatient admissions in the United States.

Among the patients in the sample, 296,041 adults had undergone bariatric surgery, and 2,004,804 adults had obesity (body mass index ≥35 kg/m2) but had never undergone bariatric surgery. This latter group represented the control group.

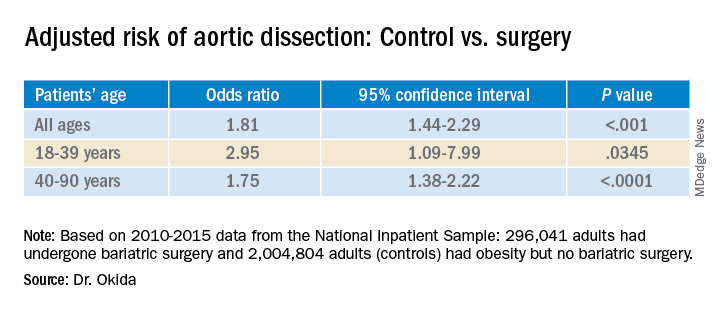

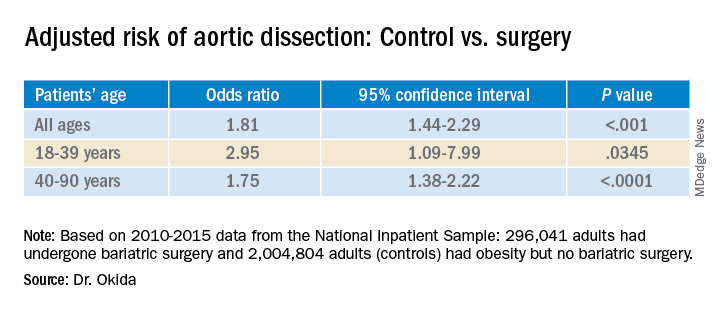

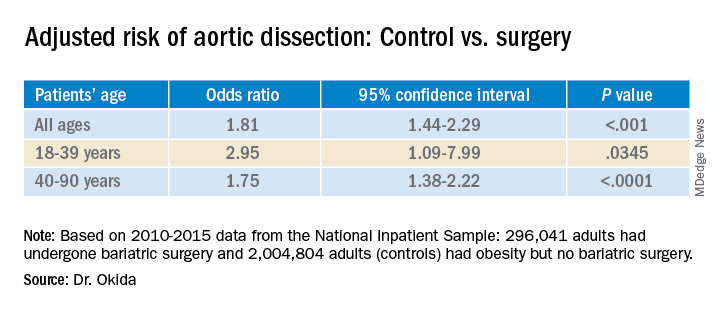

Among the control group, 1,411 patients (.070%) experienced aortic dissection; among the bariatric surgery group, 94 patients (0.032%) experienced aortic dissection. This was a statistically significant difference (P < .0001).

The groups differed significantly in many ways. The mean age of the patients in the control group was 54.4 years, which was a mean of 2.5 years older than the bariatric surgery group. Additionally, the control group included a higher percentage of women and a lower percentage of White persons.

Those in the control group were also more likely to have a history of tobacco use, hypertension (64.2% vs. 48.9% in the surgery group), hyperlipidemia (32.7% vs. 18.3%), diabetes, aortic aneurysm (20.6% vs. 12.0%), and bicuspid aortic valves but were less likely to have Marfan/Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

A multivariate analysis showed that gender, age, history of tobacco use, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and Marfan/Ehlers-Danlos syndrome were associated with an increased risk for aortic dissection. Diabetes was associated with a lower risk. All of these findings had previously been reported in the literature, Dr. Okida said, but the reasons for the negative association with diabetes is not well understood.

The association between the surgery and aortic dissection applied to younger patients as well as older ones.

“In elderly patients, the main risk factor for aortic dissection is hypertension, and in younger patients, below 40 years old, the main risk factors are diseases of the collagen and diseases of the aorta,” said Dr. Okida during his presentation. “But these younger patients still have a high prevalence of hypertension, and that’s why bariatric surgery is beneficial.”