User login

The finding is the latest in a series of benefits researchers have linked to the surgery, not all of which appear to directly result from weight loss.

“It has an incredible impact on hyperlipidemia and hypertension,” said Luis Felipe Okida, MD, from Cleveland Clinic Florida, Weston. “Those are the main risk factors for aortic dissection.”

He presented the finding at the virtual American Congress of Surgeons Clinical Congress 2020. The study was also published online in the Journal of the American College of Surgeons.

Although uncommon, acute aortic dissection proves fatal to half the people it strikes if patients do not receive treatment within 72 hours, Dr. Okida said in an interview.

To learn whether there is an association between bariatric surgery and risk for aortic dissection, Dr. Okida and colleagues analyzed data from the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) database from 2010 to 2015. The NIS comprises about 20% of hospital inpatient admissions in the United States.

Among the patients in the sample, 296,041 adults had undergone bariatric surgery, and 2,004,804 adults had obesity (body mass index ≥35 kg/m2) but had never undergone bariatric surgery. This latter group represented the control group.

Among the control group, 1,411 patients (.070%) experienced aortic dissection; among the bariatric surgery group, 94 patients (0.032%) experienced aortic dissection. This was a statistically significant difference (P < .0001).

The groups differed significantly in many ways. The mean age of the patients in the control group was 54.4 years, which was a mean of 2.5 years older than the bariatric surgery group. Additionally, the control group included a higher percentage of women and a lower percentage of White persons.

Those in the control group were also more likely to have a history of tobacco use, hypertension (64.2% vs. 48.9% in the surgery group), hyperlipidemia (32.7% vs. 18.3%), diabetes, aortic aneurysm (20.6% vs. 12.0%), and bicuspid aortic valves but were less likely to have Marfan/Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

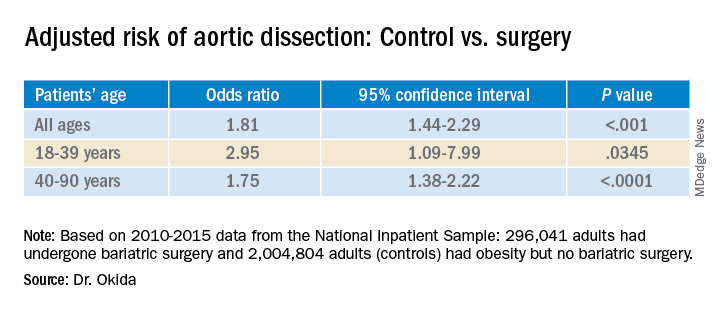

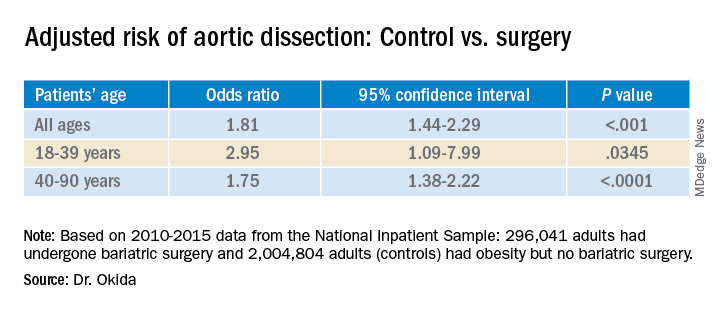

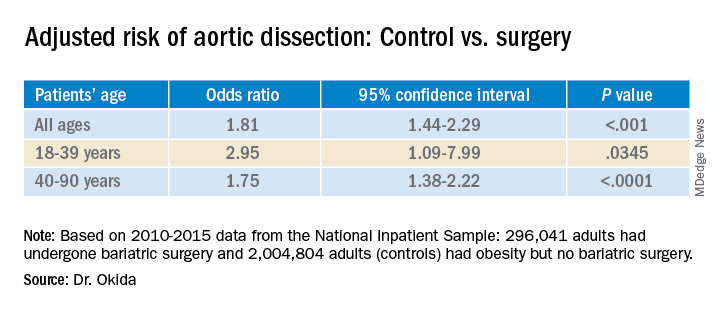

A multivariate analysis showed that gender, age, history of tobacco use, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and Marfan/Ehlers-Danlos syndrome were associated with an increased risk for aortic dissection. Diabetes was associated with a lower risk. All of these findings had previously been reported in the literature, Dr. Okida said, but the reasons for the negative association with diabetes is not well understood.

The association between the surgery and aortic dissection applied to younger patients as well as older ones.

“In elderly patients, the main risk factor for aortic dissection is hypertension, and in younger patients, below 40 years old, the main risk factors are diseases of the collagen and diseases of the aorta,” said Dr. Okida during his presentation. “But these younger patients still have a high prevalence of hypertension, and that’s why bariatric surgery is beneficial.”

Although the finding regarding risk for aortic dissection supports the value of bariatric surgery, it does not in itself provide justification for undergoing the procedure. “It’s not even one of the comorbidities that insurance companies would recognize as key in approving this procedure,” said senior author Emanuele Lo Menzo, MD, PhD, also from the Cleveland Clinic Florida.

“I don’t think a physician would ever recommend this procedure specifically to avoid aortic dissection,” he said in an interview. “It’s sort of an extended benefit.”

The study raises interesting questions about the effects of the surgery, said Shanu Kothari, MD, president-elect of the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery.

“We’ve known for a long time that patients with chronic obesity who undergo weight-loss surgery live longer than those who don’t,” he said in an interview. “They have less cardiovascular disease and cancer. Is this one more reason that they live longer?”

Bariatric surgery produces benefits for people with diabetes the day after the surgery, long before patients lose weight as a result of the procedure, Dr. Kothari said.

The effects on metabolism are complex, he added. Besides caloric restriction, they include changes in bile salt absorption and the gut microbiome, which in turn can affect hormones and inflammation.

A key question is how long after the surgery the risk for aortic dissection starts to decline, said Dr. Kothari.

The study could not answer such questions, and Dr. Okida could not find any previous studies that explored the association. He also couldn’t find any study that examined whether weight loss by other means might also reduce the risk for aortic dissection.

Dr. Okida, Dr. Lo Menzo, and Dr. Kothari disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The finding is the latest in a series of benefits researchers have linked to the surgery, not all of which appear to directly result from weight loss.

“It has an incredible impact on hyperlipidemia and hypertension,” said Luis Felipe Okida, MD, from Cleveland Clinic Florida, Weston. “Those are the main risk factors for aortic dissection.”

He presented the finding at the virtual American Congress of Surgeons Clinical Congress 2020. The study was also published online in the Journal of the American College of Surgeons.

Although uncommon, acute aortic dissection proves fatal to half the people it strikes if patients do not receive treatment within 72 hours, Dr. Okida said in an interview.

To learn whether there is an association between bariatric surgery and risk for aortic dissection, Dr. Okida and colleagues analyzed data from the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) database from 2010 to 2015. The NIS comprises about 20% of hospital inpatient admissions in the United States.

Among the patients in the sample, 296,041 adults had undergone bariatric surgery, and 2,004,804 adults had obesity (body mass index ≥35 kg/m2) but had never undergone bariatric surgery. This latter group represented the control group.

Among the control group, 1,411 patients (.070%) experienced aortic dissection; among the bariatric surgery group, 94 patients (0.032%) experienced aortic dissection. This was a statistically significant difference (P < .0001).

The groups differed significantly in many ways. The mean age of the patients in the control group was 54.4 years, which was a mean of 2.5 years older than the bariatric surgery group. Additionally, the control group included a higher percentage of women and a lower percentage of White persons.

Those in the control group were also more likely to have a history of tobacco use, hypertension (64.2% vs. 48.9% in the surgery group), hyperlipidemia (32.7% vs. 18.3%), diabetes, aortic aneurysm (20.6% vs. 12.0%), and bicuspid aortic valves but were less likely to have Marfan/Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

A multivariate analysis showed that gender, age, history of tobacco use, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and Marfan/Ehlers-Danlos syndrome were associated with an increased risk for aortic dissection. Diabetes was associated with a lower risk. All of these findings had previously been reported in the literature, Dr. Okida said, but the reasons for the negative association with diabetes is not well understood.

The association between the surgery and aortic dissection applied to younger patients as well as older ones.

“In elderly patients, the main risk factor for aortic dissection is hypertension, and in younger patients, below 40 years old, the main risk factors are diseases of the collagen and diseases of the aorta,” said Dr. Okida during his presentation. “But these younger patients still have a high prevalence of hypertension, and that’s why bariatric surgery is beneficial.”

Although the finding regarding risk for aortic dissection supports the value of bariatric surgery, it does not in itself provide justification for undergoing the procedure. “It’s not even one of the comorbidities that insurance companies would recognize as key in approving this procedure,” said senior author Emanuele Lo Menzo, MD, PhD, also from the Cleveland Clinic Florida.

“I don’t think a physician would ever recommend this procedure specifically to avoid aortic dissection,” he said in an interview. “It’s sort of an extended benefit.”

The study raises interesting questions about the effects of the surgery, said Shanu Kothari, MD, president-elect of the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery.

“We’ve known for a long time that patients with chronic obesity who undergo weight-loss surgery live longer than those who don’t,” he said in an interview. “They have less cardiovascular disease and cancer. Is this one more reason that they live longer?”

Bariatric surgery produces benefits for people with diabetes the day after the surgery, long before patients lose weight as a result of the procedure, Dr. Kothari said.

The effects on metabolism are complex, he added. Besides caloric restriction, they include changes in bile salt absorption and the gut microbiome, which in turn can affect hormones and inflammation.

A key question is how long after the surgery the risk for aortic dissection starts to decline, said Dr. Kothari.

The study could not answer such questions, and Dr. Okida could not find any previous studies that explored the association. He also couldn’t find any study that examined whether weight loss by other means might also reduce the risk for aortic dissection.

Dr. Okida, Dr. Lo Menzo, and Dr. Kothari disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The finding is the latest in a series of benefits researchers have linked to the surgery, not all of which appear to directly result from weight loss.

“It has an incredible impact on hyperlipidemia and hypertension,” said Luis Felipe Okida, MD, from Cleveland Clinic Florida, Weston. “Those are the main risk factors for aortic dissection.”

He presented the finding at the virtual American Congress of Surgeons Clinical Congress 2020. The study was also published online in the Journal of the American College of Surgeons.

Although uncommon, acute aortic dissection proves fatal to half the people it strikes if patients do not receive treatment within 72 hours, Dr. Okida said in an interview.

To learn whether there is an association between bariatric surgery and risk for aortic dissection, Dr. Okida and colleagues analyzed data from the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) database from 2010 to 2015. The NIS comprises about 20% of hospital inpatient admissions in the United States.

Among the patients in the sample, 296,041 adults had undergone bariatric surgery, and 2,004,804 adults had obesity (body mass index ≥35 kg/m2) but had never undergone bariatric surgery. This latter group represented the control group.

Among the control group, 1,411 patients (.070%) experienced aortic dissection; among the bariatric surgery group, 94 patients (0.032%) experienced aortic dissection. This was a statistically significant difference (P < .0001).

The groups differed significantly in many ways. The mean age of the patients in the control group was 54.4 years, which was a mean of 2.5 years older than the bariatric surgery group. Additionally, the control group included a higher percentage of women and a lower percentage of White persons.

Those in the control group were also more likely to have a history of tobacco use, hypertension (64.2% vs. 48.9% in the surgery group), hyperlipidemia (32.7% vs. 18.3%), diabetes, aortic aneurysm (20.6% vs. 12.0%), and bicuspid aortic valves but were less likely to have Marfan/Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

A multivariate analysis showed that gender, age, history of tobacco use, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and Marfan/Ehlers-Danlos syndrome were associated with an increased risk for aortic dissection. Diabetes was associated with a lower risk. All of these findings had previously been reported in the literature, Dr. Okida said, but the reasons for the negative association with diabetes is not well understood.

The association between the surgery and aortic dissection applied to younger patients as well as older ones.

“In elderly patients, the main risk factor for aortic dissection is hypertension, and in younger patients, below 40 years old, the main risk factors are diseases of the collagen and diseases of the aorta,” said Dr. Okida during his presentation. “But these younger patients still have a high prevalence of hypertension, and that’s why bariatric surgery is beneficial.”

Although the finding regarding risk for aortic dissection supports the value of bariatric surgery, it does not in itself provide justification for undergoing the procedure. “It’s not even one of the comorbidities that insurance companies would recognize as key in approving this procedure,” said senior author Emanuele Lo Menzo, MD, PhD, also from the Cleveland Clinic Florida.

“I don’t think a physician would ever recommend this procedure specifically to avoid aortic dissection,” he said in an interview. “It’s sort of an extended benefit.”

The study raises interesting questions about the effects of the surgery, said Shanu Kothari, MD, president-elect of the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery.

“We’ve known for a long time that patients with chronic obesity who undergo weight-loss surgery live longer than those who don’t,” he said in an interview. “They have less cardiovascular disease and cancer. Is this one more reason that they live longer?”

Bariatric surgery produces benefits for people with diabetes the day after the surgery, long before patients lose weight as a result of the procedure, Dr. Kothari said.

The effects on metabolism are complex, he added. Besides caloric restriction, they include changes in bile salt absorption and the gut microbiome, which in turn can affect hormones and inflammation.

A key question is how long after the surgery the risk for aortic dissection starts to decline, said Dr. Kothari.

The study could not answer such questions, and Dr. Okida could not find any previous studies that explored the association. He also couldn’t find any study that examined whether weight loss by other means might also reduce the risk for aortic dissection.

Dr. Okida, Dr. Lo Menzo, and Dr. Kothari disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.