User login

The Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management® is an independent, peer-reviewed journal offering evidence-based, practical information for improving the quality, safety, and value of health care.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

As costs for neurologic drugs rise, adherence to therapy drops

For their study, published online Feb. 19 in Neurology, Brian C. Callaghan, MD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and colleagues looked at claims records from a large national private insurer to identify new cases of dementia, Parkinson’s disease, and neuropathy between 2001 and 2016, along with pharmacy records following diagnoses.

The researchers identified more than 52,000 patients with neuropathy on gabapentinoids and another 5,000 treated with serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors for the same. They also identified some 20,000 patients with dementia taking cholinesterase inhibitors, and 3,000 with Parkinson’s disease taking dopamine agonists. Dr. Callaghan and colleagues compared patient adherence over 6 months for pairs of drugs in the same class with similar or equal efficacy, but with different costs to the patient.

Such cost differences can be stark: The researchers noted that the average 2016 out-of-pocket cost for 30 days of pregabalin, a drug used in the treatment of peripheral neuropathy, was $65.70, compared with $8.40 for gabapentin. With two common dementia drugs the difference was even more pronounced: $79.30 for rivastigmine compared with $3.10 for donepezil, both cholinesterase inhibitors with similar efficacy and tolerability.

Dr. Callaghan and colleagues found that such cost differences bore significantly on patient adherence. An increase of $50 in patient costs was seen decreasing adherence by 9% for neuropathy patients on gabapentinoids (adjusted incidence rate ratio [IRR] 0.91, 0.89-0.93) and by 12% for dementia patients on cholinesterase inhibitors (adjusted IRR 0.88, 0.86-0.91, P less than .05 for both). Similar price-linked decreases were seen for neuropathy patients on SNRIs and Parkinson’s patients on dopamine agonists, but the differences did not reach statistical significance.

Black, Asian, and Hispanic patients saw greater drops in adherence than did white patients associated with the same out-of-pocket cost differences, leading the researchers to note that special care should be taken in prescribing decisions for these populations.

“When choosing among medications with differential [out-of-pocket] costs, prescribing the medication with lower [out-of-pocket] expense will likely improve medication adherence while reducing overall costs,” Dr. Callaghan and colleagues wrote in their analysis. “For example, prescribing gabapentin or venlafaxine to patients with newly diagnosed neuropathy is likely to lead to higher adherence compared with pregabalin or duloxetine, and therefore, there is a higher likelihood of relief from neuropathic pain.” The researchers noted that while combination pills and extended-release formulations may be marketed as a way to increase adherence, the higher out-of-pocket costs of such medicines could offset any adherence benefit.

Dr. Callaghan and his colleagues described as strengths of their study its large sample and statistical approach that “allowed us to best estimate the causal relationship between [out-of-pocket] costs and medication adherence by limiting selection bias, residual confounding, and the confounding inherent to medication choice.” Nonadherence – patients who never filled a prescription after diagnosis – was not captured in the study.

The American Academy of Neurology funded the study. Two of its authors reported financial conflicts of interest in the form of compensation from pharmaceutical or device companies. Its lead author, Dr. Callaghan, reported funding for a device maker and performing medical legal consultations.

SOURCE: Reynolds EL et al. Neurology. 2020 Feb 19. doi/10.1212/WNL.0000000000009039.

For their study, published online Feb. 19 in Neurology, Brian C. Callaghan, MD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and colleagues looked at claims records from a large national private insurer to identify new cases of dementia, Parkinson’s disease, and neuropathy between 2001 and 2016, along with pharmacy records following diagnoses.

The researchers identified more than 52,000 patients with neuropathy on gabapentinoids and another 5,000 treated with serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors for the same. They also identified some 20,000 patients with dementia taking cholinesterase inhibitors, and 3,000 with Parkinson’s disease taking dopamine agonists. Dr. Callaghan and colleagues compared patient adherence over 6 months for pairs of drugs in the same class with similar or equal efficacy, but with different costs to the patient.

Such cost differences can be stark: The researchers noted that the average 2016 out-of-pocket cost for 30 days of pregabalin, a drug used in the treatment of peripheral neuropathy, was $65.70, compared with $8.40 for gabapentin. With two common dementia drugs the difference was even more pronounced: $79.30 for rivastigmine compared with $3.10 for donepezil, both cholinesterase inhibitors with similar efficacy and tolerability.

Dr. Callaghan and colleagues found that such cost differences bore significantly on patient adherence. An increase of $50 in patient costs was seen decreasing adherence by 9% for neuropathy patients on gabapentinoids (adjusted incidence rate ratio [IRR] 0.91, 0.89-0.93) and by 12% for dementia patients on cholinesterase inhibitors (adjusted IRR 0.88, 0.86-0.91, P less than .05 for both). Similar price-linked decreases were seen for neuropathy patients on SNRIs and Parkinson’s patients on dopamine agonists, but the differences did not reach statistical significance.

Black, Asian, and Hispanic patients saw greater drops in adherence than did white patients associated with the same out-of-pocket cost differences, leading the researchers to note that special care should be taken in prescribing decisions for these populations.

“When choosing among medications with differential [out-of-pocket] costs, prescribing the medication with lower [out-of-pocket] expense will likely improve medication adherence while reducing overall costs,” Dr. Callaghan and colleagues wrote in their analysis. “For example, prescribing gabapentin or venlafaxine to patients with newly diagnosed neuropathy is likely to lead to higher adherence compared with pregabalin or duloxetine, and therefore, there is a higher likelihood of relief from neuropathic pain.” The researchers noted that while combination pills and extended-release formulations may be marketed as a way to increase adherence, the higher out-of-pocket costs of such medicines could offset any adherence benefit.

Dr. Callaghan and his colleagues described as strengths of their study its large sample and statistical approach that “allowed us to best estimate the causal relationship between [out-of-pocket] costs and medication adherence by limiting selection bias, residual confounding, and the confounding inherent to medication choice.” Nonadherence – patients who never filled a prescription after diagnosis – was not captured in the study.

The American Academy of Neurology funded the study. Two of its authors reported financial conflicts of interest in the form of compensation from pharmaceutical or device companies. Its lead author, Dr. Callaghan, reported funding for a device maker and performing medical legal consultations.

SOURCE: Reynolds EL et al. Neurology. 2020 Feb 19. doi/10.1212/WNL.0000000000009039.

For their study, published online Feb. 19 in Neurology, Brian C. Callaghan, MD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and colleagues looked at claims records from a large national private insurer to identify new cases of dementia, Parkinson’s disease, and neuropathy between 2001 and 2016, along with pharmacy records following diagnoses.

The researchers identified more than 52,000 patients with neuropathy on gabapentinoids and another 5,000 treated with serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors for the same. They also identified some 20,000 patients with dementia taking cholinesterase inhibitors, and 3,000 with Parkinson’s disease taking dopamine agonists. Dr. Callaghan and colleagues compared patient adherence over 6 months for pairs of drugs in the same class with similar or equal efficacy, but with different costs to the patient.

Such cost differences can be stark: The researchers noted that the average 2016 out-of-pocket cost for 30 days of pregabalin, a drug used in the treatment of peripheral neuropathy, was $65.70, compared with $8.40 for gabapentin. With two common dementia drugs the difference was even more pronounced: $79.30 for rivastigmine compared with $3.10 for donepezil, both cholinesterase inhibitors with similar efficacy and tolerability.

Dr. Callaghan and colleagues found that such cost differences bore significantly on patient adherence. An increase of $50 in patient costs was seen decreasing adherence by 9% for neuropathy patients on gabapentinoids (adjusted incidence rate ratio [IRR] 0.91, 0.89-0.93) and by 12% for dementia patients on cholinesterase inhibitors (adjusted IRR 0.88, 0.86-0.91, P less than .05 for both). Similar price-linked decreases were seen for neuropathy patients on SNRIs and Parkinson’s patients on dopamine agonists, but the differences did not reach statistical significance.

Black, Asian, and Hispanic patients saw greater drops in adherence than did white patients associated with the same out-of-pocket cost differences, leading the researchers to note that special care should be taken in prescribing decisions for these populations.

“When choosing among medications with differential [out-of-pocket] costs, prescribing the medication with lower [out-of-pocket] expense will likely improve medication adherence while reducing overall costs,” Dr. Callaghan and colleagues wrote in their analysis. “For example, prescribing gabapentin or venlafaxine to patients with newly diagnosed neuropathy is likely to lead to higher adherence compared with pregabalin or duloxetine, and therefore, there is a higher likelihood of relief from neuropathic pain.” The researchers noted that while combination pills and extended-release formulations may be marketed as a way to increase adherence, the higher out-of-pocket costs of such medicines could offset any adherence benefit.

Dr. Callaghan and his colleagues described as strengths of their study its large sample and statistical approach that “allowed us to best estimate the causal relationship between [out-of-pocket] costs and medication adherence by limiting selection bias, residual confounding, and the confounding inherent to medication choice.” Nonadherence – patients who never filled a prescription after diagnosis – was not captured in the study.

The American Academy of Neurology funded the study. Two of its authors reported financial conflicts of interest in the form of compensation from pharmaceutical or device companies. Its lead author, Dr. Callaghan, reported funding for a device maker and performing medical legal consultations.

SOURCE: Reynolds EL et al. Neurology. 2020 Feb 19. doi/10.1212/WNL.0000000000009039.

FROM NEUROLOGY

Early cognitive screening is key for schizophrenia spectrum disorder

, compared with a group of controls, results from a novel study show.

“Based on these findings, we recommend that neurocognitive assessment should be performed as early as possible after illness onset,” researchers led by Lars Helldin, MD, PhD, of the department of psychiatry at NU Health-Care Hospital, Region Västra Götaland, Sweden, wrote in a study published in Schizophrenia Research: Cognition (2020 Jun doi: 10.1016/j.scog.2020.100172). “Early identification of cognitive risk factors for poor real-life functional outcome is necessary in order to alert the clinical and rehabilitation services about patients in need of extra care.”

For the study, 291 men and women suffering from schizophrenia spectrum disorder (SSD) and 302 controls underwent assessment with a series of comprehensive neurocognitive tests, including the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF), the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), the Specific Level of Functioning Scale (SLOF), the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT), and the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST). The researchers found that the neurocognitive function of the SSD patients was significantly lower than that of the healthy controls on all assessments, with very large effect sizes. “There was considerable diversity within each group, as subgroups of patients scored higher than the control mean and subgroups of controls scored lower than the patient mean, particularly on tests of working memory, verbal learning and memory, and executive function,” wrote Dr. Helldin and associates.

As for the WSCT score, the cognitively intact group had a significantly lower PANSS negative symptom level (P less than .01), a lower PANSS general pathology level (P less than .05), and a lower PANSS total symptom level (P less than .01). As for the WAIS Vocabulary score, the patient group with a higher score than the controls had a significantly lower PANSS negative symptom level (P less than .05).

“Here, we have linked neurocognitive heterogeneity to functional outcome differences, and suggest that personalized treatment with emphasis on practical daily skills may be of great significance especially for those with large baseline cognitive deficits,” the researchers concluded. “Such efforts are imperative not only in order to reduce personal suffering and increase quality of life for the patients, but also to reduce the enormous society level economic costs of functional deficits.”

The study was funded by the Regional Health Authority, VG Region, Sweden. The authors reported having no financial disclosures.

, compared with a group of controls, results from a novel study show.

“Based on these findings, we recommend that neurocognitive assessment should be performed as early as possible after illness onset,” researchers led by Lars Helldin, MD, PhD, of the department of psychiatry at NU Health-Care Hospital, Region Västra Götaland, Sweden, wrote in a study published in Schizophrenia Research: Cognition (2020 Jun doi: 10.1016/j.scog.2020.100172). “Early identification of cognitive risk factors for poor real-life functional outcome is necessary in order to alert the clinical and rehabilitation services about patients in need of extra care.”

For the study, 291 men and women suffering from schizophrenia spectrum disorder (SSD) and 302 controls underwent assessment with a series of comprehensive neurocognitive tests, including the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF), the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), the Specific Level of Functioning Scale (SLOF), the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT), and the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST). The researchers found that the neurocognitive function of the SSD patients was significantly lower than that of the healthy controls on all assessments, with very large effect sizes. “There was considerable diversity within each group, as subgroups of patients scored higher than the control mean and subgroups of controls scored lower than the patient mean, particularly on tests of working memory, verbal learning and memory, and executive function,” wrote Dr. Helldin and associates.

As for the WSCT score, the cognitively intact group had a significantly lower PANSS negative symptom level (P less than .01), a lower PANSS general pathology level (P less than .05), and a lower PANSS total symptom level (P less than .01). As for the WAIS Vocabulary score, the patient group with a higher score than the controls had a significantly lower PANSS negative symptom level (P less than .05).

“Here, we have linked neurocognitive heterogeneity to functional outcome differences, and suggest that personalized treatment with emphasis on practical daily skills may be of great significance especially for those with large baseline cognitive deficits,” the researchers concluded. “Such efforts are imperative not only in order to reduce personal suffering and increase quality of life for the patients, but also to reduce the enormous society level economic costs of functional deficits.”

The study was funded by the Regional Health Authority, VG Region, Sweden. The authors reported having no financial disclosures.

, compared with a group of controls, results from a novel study show.

“Based on these findings, we recommend that neurocognitive assessment should be performed as early as possible after illness onset,” researchers led by Lars Helldin, MD, PhD, of the department of psychiatry at NU Health-Care Hospital, Region Västra Götaland, Sweden, wrote in a study published in Schizophrenia Research: Cognition (2020 Jun doi: 10.1016/j.scog.2020.100172). “Early identification of cognitive risk factors for poor real-life functional outcome is necessary in order to alert the clinical and rehabilitation services about patients in need of extra care.”

For the study, 291 men and women suffering from schizophrenia spectrum disorder (SSD) and 302 controls underwent assessment with a series of comprehensive neurocognitive tests, including the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF), the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), the Specific Level of Functioning Scale (SLOF), the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT), and the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST). The researchers found that the neurocognitive function of the SSD patients was significantly lower than that of the healthy controls on all assessments, with very large effect sizes. “There was considerable diversity within each group, as subgroups of patients scored higher than the control mean and subgroups of controls scored lower than the patient mean, particularly on tests of working memory, verbal learning and memory, and executive function,” wrote Dr. Helldin and associates.

As for the WSCT score, the cognitively intact group had a significantly lower PANSS negative symptom level (P less than .01), a lower PANSS general pathology level (P less than .05), and a lower PANSS total symptom level (P less than .01). As for the WAIS Vocabulary score, the patient group with a higher score than the controls had a significantly lower PANSS negative symptom level (P less than .05).

“Here, we have linked neurocognitive heterogeneity to functional outcome differences, and suggest that personalized treatment with emphasis on practical daily skills may be of great significance especially for those with large baseline cognitive deficits,” the researchers concluded. “Such efforts are imperative not only in order to reduce personal suffering and increase quality of life for the patients, but also to reduce the enormous society level economic costs of functional deficits.”

The study was funded by the Regional Health Authority, VG Region, Sweden. The authors reported having no financial disclosures.

FROM SCHIZOPHRENIA RESEARCH: COGNITION

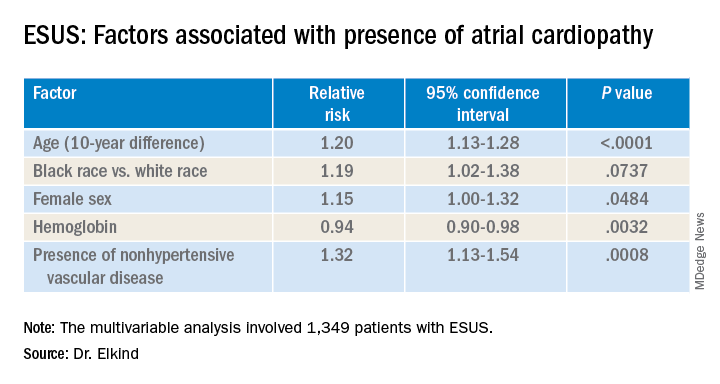

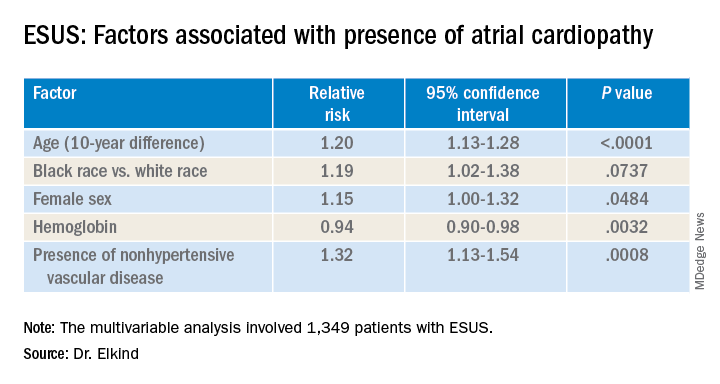

ARCADIA: Predicting risk of atrial cardiopathy poststroke

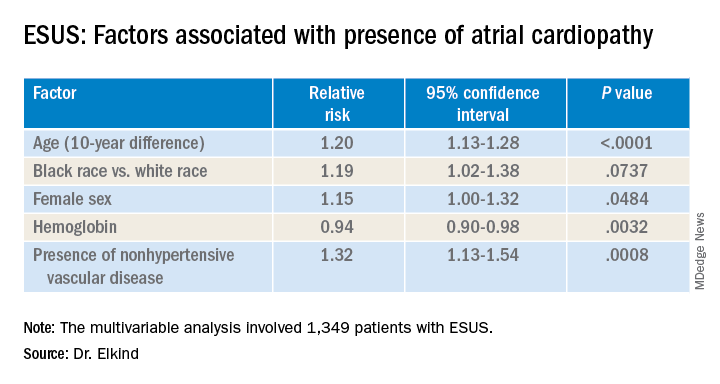

LOS ANGELES – Older age, female sex, black race, relative anemia, and a history of cardiovascular disease are associated with greater risk for atrial cardiopathy among people who experienced an embolic stroke of undetermined source (ESUS), new evidence suggests.

Atrial cardiopathy is a suspected cause of ESUS independent of atrial fibrillation. However, clinical predictors to help physicians identify which ESUS patients are at increased risk remain unknown.

The risk for atrial cardiopathy was 34% higher for women versus men with ESUS in this analysis. In addition, black participants had a 29% increased risk, compared with others, and each 10 years of age increased risk for atrial cardiopathy by 30% in an univariable analysis.

“Modest effects of these associations suggest that all ESUS patients, regardless of underlying demographic and risk factors, may have atrial cardiopathy,” principal investigator Mitchell S.V. Elkind, MD, of Columbia University, New York, said when presenting results at the 2020 International Stroke Conference, sponsored by the American Heart Association.

For this reason, he added, all people with ESUS should be considered for recruitment into the ongoing ARCADIA (AtRial Cardiopathy and Antithrombotic Drugs In Prevention After Cryptogenic Stroke) trial, of which he is one of the principal investigators.

ESUS is a heterogeneous condition, and some patients may be responsive to anticoagulants and some might not, Elkind said. This observation “led us to consider alternative ways for ischemic disease to lead to stroke. We would hypothesize that the underlying atrium can be a risk for stroke by itself.”

Not yet available is the primary efficacy outcome of the multicenter, randomized ARCADIA trial comparing apixaban with aspirin in reducing risk for recurrent stroke of any type. However, Dr. Elkind and colleagues have recruited 1,505 patients to date, enough to analyze factors that predict risk for recurrent stroke among people with evidence of atrial cardiopathy.

All ARCADIA participants are 45 years of age or older and have no history of atrial fibrillation. Atrial cardiopathy was defined by presence of at least one of three biomarkers: N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), P wave terminal force velocity, or evidence of a left atrial diameter of 3 cm/m2 or larger on echocardiography.

Of the 1,349 ARCADIA participants eligible for the current analysis, approximately one-third met one or more of these criteria for atrial cardiopathy.

Those with atrial cardiopathy were “more likely to be black and be women, and tended to have shorter time from stroke to screening,” Dr. Elkind said. In addition, heart failure, hypertension, and peripheral artery disease were more common in those with atrial cardiopathy. This group also was more likely to have an elevation in creatinine and lower hemoglobin and hematocrit levels.

“Heart disease, ischemic heart disease and non-hypertensive vascular disease were significant risk factors” for recurrent stroke in the study, Dr. Elkind added.

Elkind said that, surprisingly, there was no independent association between the time to measurement of NT-proBNP and risk, suggesting that this biomarker “does not rise simply in response to stroke, but reflects a stable condition.”

The multicenter ARCADIA trial is recruiting additional participants at 142 sites now, Dr. Elkind said, “and we are still looking for more sites.”

Which comes first?

“He is looking at what the predictors are for cardiopathy in these patients, which is fascinating for all of us,” session moderator Michelle Christina Johansen, MD, assistant professor of neurology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, said in an interview when asked to comment.

There is always the conundrum of what came first — the chicken or the egg, Johansen said. Do these patients have stroke that then somehow led to a state that predisposes them to have atrial cardiopathy? Or, rather, was it an atrial cardiopathy state independent of atrial fibrillation that then led to stroke?

“That is why looking at predictors in this population is of such interest,” she said. The study could help identify a subgroup of patients at higher risk for atrial cardiopathy and guide clinical decision-making when patients present with ESUS.

“One of the things I found interesting was that he found that atrial cardiopathy patients were older [a mean 69 years]. This was amazing, because ESUS patients in general tend to be younger,” Dr. Johansen said.

“And there is about a 4-5% risk of recurrence with these patients. So. it was interesting that prior stroke or [transient ischemic attack] was not associated.”*

The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the BMS-Pfizer Alliance, and Roche provide funding for ARCADIA. Dr. Elkind and Dr. Johansen disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

SOURCE: Elkind M et al. ISC 2020, Abstract 26.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

*Correction, 4/28/20: An earlier version of this article misstated the risk of recurrence.

LOS ANGELES – Older age, female sex, black race, relative anemia, and a history of cardiovascular disease are associated with greater risk for atrial cardiopathy among people who experienced an embolic stroke of undetermined source (ESUS), new evidence suggests.

Atrial cardiopathy is a suspected cause of ESUS independent of atrial fibrillation. However, clinical predictors to help physicians identify which ESUS patients are at increased risk remain unknown.

The risk for atrial cardiopathy was 34% higher for women versus men with ESUS in this analysis. In addition, black participants had a 29% increased risk, compared with others, and each 10 years of age increased risk for atrial cardiopathy by 30% in an univariable analysis.

“Modest effects of these associations suggest that all ESUS patients, regardless of underlying demographic and risk factors, may have atrial cardiopathy,” principal investigator Mitchell S.V. Elkind, MD, of Columbia University, New York, said when presenting results at the 2020 International Stroke Conference, sponsored by the American Heart Association.

For this reason, he added, all people with ESUS should be considered for recruitment into the ongoing ARCADIA (AtRial Cardiopathy and Antithrombotic Drugs In Prevention After Cryptogenic Stroke) trial, of which he is one of the principal investigators.

ESUS is a heterogeneous condition, and some patients may be responsive to anticoagulants and some might not, Elkind said. This observation “led us to consider alternative ways for ischemic disease to lead to stroke. We would hypothesize that the underlying atrium can be a risk for stroke by itself.”

Not yet available is the primary efficacy outcome of the multicenter, randomized ARCADIA trial comparing apixaban with aspirin in reducing risk for recurrent stroke of any type. However, Dr. Elkind and colleagues have recruited 1,505 patients to date, enough to analyze factors that predict risk for recurrent stroke among people with evidence of atrial cardiopathy.

All ARCADIA participants are 45 years of age or older and have no history of atrial fibrillation. Atrial cardiopathy was defined by presence of at least one of three biomarkers: N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), P wave terminal force velocity, or evidence of a left atrial diameter of 3 cm/m2 or larger on echocardiography.

Of the 1,349 ARCADIA participants eligible for the current analysis, approximately one-third met one or more of these criteria for atrial cardiopathy.

Those with atrial cardiopathy were “more likely to be black and be women, and tended to have shorter time from stroke to screening,” Dr. Elkind said. In addition, heart failure, hypertension, and peripheral artery disease were more common in those with atrial cardiopathy. This group also was more likely to have an elevation in creatinine and lower hemoglobin and hematocrit levels.

“Heart disease, ischemic heart disease and non-hypertensive vascular disease were significant risk factors” for recurrent stroke in the study, Dr. Elkind added.

Elkind said that, surprisingly, there was no independent association between the time to measurement of NT-proBNP and risk, suggesting that this biomarker “does not rise simply in response to stroke, but reflects a stable condition.”

The multicenter ARCADIA trial is recruiting additional participants at 142 sites now, Dr. Elkind said, “and we are still looking for more sites.”

Which comes first?

“He is looking at what the predictors are for cardiopathy in these patients, which is fascinating for all of us,” session moderator Michelle Christina Johansen, MD, assistant professor of neurology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, said in an interview when asked to comment.

There is always the conundrum of what came first — the chicken or the egg, Johansen said. Do these patients have stroke that then somehow led to a state that predisposes them to have atrial cardiopathy? Or, rather, was it an atrial cardiopathy state independent of atrial fibrillation that then led to stroke?

“That is why looking at predictors in this population is of such interest,” she said. The study could help identify a subgroup of patients at higher risk for atrial cardiopathy and guide clinical decision-making when patients present with ESUS.

“One of the things I found interesting was that he found that atrial cardiopathy patients were older [a mean 69 years]. This was amazing, because ESUS patients in general tend to be younger,” Dr. Johansen said.

“And there is about a 4-5% risk of recurrence with these patients. So. it was interesting that prior stroke or [transient ischemic attack] was not associated.”*

The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the BMS-Pfizer Alliance, and Roche provide funding for ARCADIA. Dr. Elkind and Dr. Johansen disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

SOURCE: Elkind M et al. ISC 2020, Abstract 26.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

*Correction, 4/28/20: An earlier version of this article misstated the risk of recurrence.

LOS ANGELES – Older age, female sex, black race, relative anemia, and a history of cardiovascular disease are associated with greater risk for atrial cardiopathy among people who experienced an embolic stroke of undetermined source (ESUS), new evidence suggests.

Atrial cardiopathy is a suspected cause of ESUS independent of atrial fibrillation. However, clinical predictors to help physicians identify which ESUS patients are at increased risk remain unknown.

The risk for atrial cardiopathy was 34% higher for women versus men with ESUS in this analysis. In addition, black participants had a 29% increased risk, compared with others, and each 10 years of age increased risk for atrial cardiopathy by 30% in an univariable analysis.

“Modest effects of these associations suggest that all ESUS patients, regardless of underlying demographic and risk factors, may have atrial cardiopathy,” principal investigator Mitchell S.V. Elkind, MD, of Columbia University, New York, said when presenting results at the 2020 International Stroke Conference, sponsored by the American Heart Association.

For this reason, he added, all people with ESUS should be considered for recruitment into the ongoing ARCADIA (AtRial Cardiopathy and Antithrombotic Drugs In Prevention After Cryptogenic Stroke) trial, of which he is one of the principal investigators.

ESUS is a heterogeneous condition, and some patients may be responsive to anticoagulants and some might not, Elkind said. This observation “led us to consider alternative ways for ischemic disease to lead to stroke. We would hypothesize that the underlying atrium can be a risk for stroke by itself.”

Not yet available is the primary efficacy outcome of the multicenter, randomized ARCADIA trial comparing apixaban with aspirin in reducing risk for recurrent stroke of any type. However, Dr. Elkind and colleagues have recruited 1,505 patients to date, enough to analyze factors that predict risk for recurrent stroke among people with evidence of atrial cardiopathy.

All ARCADIA participants are 45 years of age or older and have no history of atrial fibrillation. Atrial cardiopathy was defined by presence of at least one of three biomarkers: N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), P wave terminal force velocity, or evidence of a left atrial diameter of 3 cm/m2 or larger on echocardiography.

Of the 1,349 ARCADIA participants eligible for the current analysis, approximately one-third met one or more of these criteria for atrial cardiopathy.

Those with atrial cardiopathy were “more likely to be black and be women, and tended to have shorter time from stroke to screening,” Dr. Elkind said. In addition, heart failure, hypertension, and peripheral artery disease were more common in those with atrial cardiopathy. This group also was more likely to have an elevation in creatinine and lower hemoglobin and hematocrit levels.

“Heart disease, ischemic heart disease and non-hypertensive vascular disease were significant risk factors” for recurrent stroke in the study, Dr. Elkind added.

Elkind said that, surprisingly, there was no independent association between the time to measurement of NT-proBNP and risk, suggesting that this biomarker “does not rise simply in response to stroke, but reflects a stable condition.”

The multicenter ARCADIA trial is recruiting additional participants at 142 sites now, Dr. Elkind said, “and we are still looking for more sites.”

Which comes first?

“He is looking at what the predictors are for cardiopathy in these patients, which is fascinating for all of us,” session moderator Michelle Christina Johansen, MD, assistant professor of neurology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, said in an interview when asked to comment.

There is always the conundrum of what came first — the chicken or the egg, Johansen said. Do these patients have stroke that then somehow led to a state that predisposes them to have atrial cardiopathy? Or, rather, was it an atrial cardiopathy state independent of atrial fibrillation that then led to stroke?

“That is why looking at predictors in this population is of such interest,” she said. The study could help identify a subgroup of patients at higher risk for atrial cardiopathy and guide clinical decision-making when patients present with ESUS.

“One of the things I found interesting was that he found that atrial cardiopathy patients were older [a mean 69 years]. This was amazing, because ESUS patients in general tend to be younger,” Dr. Johansen said.

“And there is about a 4-5% risk of recurrence with these patients. So. it was interesting that prior stroke or [transient ischemic attack] was not associated.”*

The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the BMS-Pfizer Alliance, and Roche provide funding for ARCADIA. Dr. Elkind and Dr. Johansen disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

SOURCE: Elkind M et al. ISC 2020, Abstract 26.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

*Correction, 4/28/20: An earlier version of this article misstated the risk of recurrence.

REPORTING FROM ISC 2020

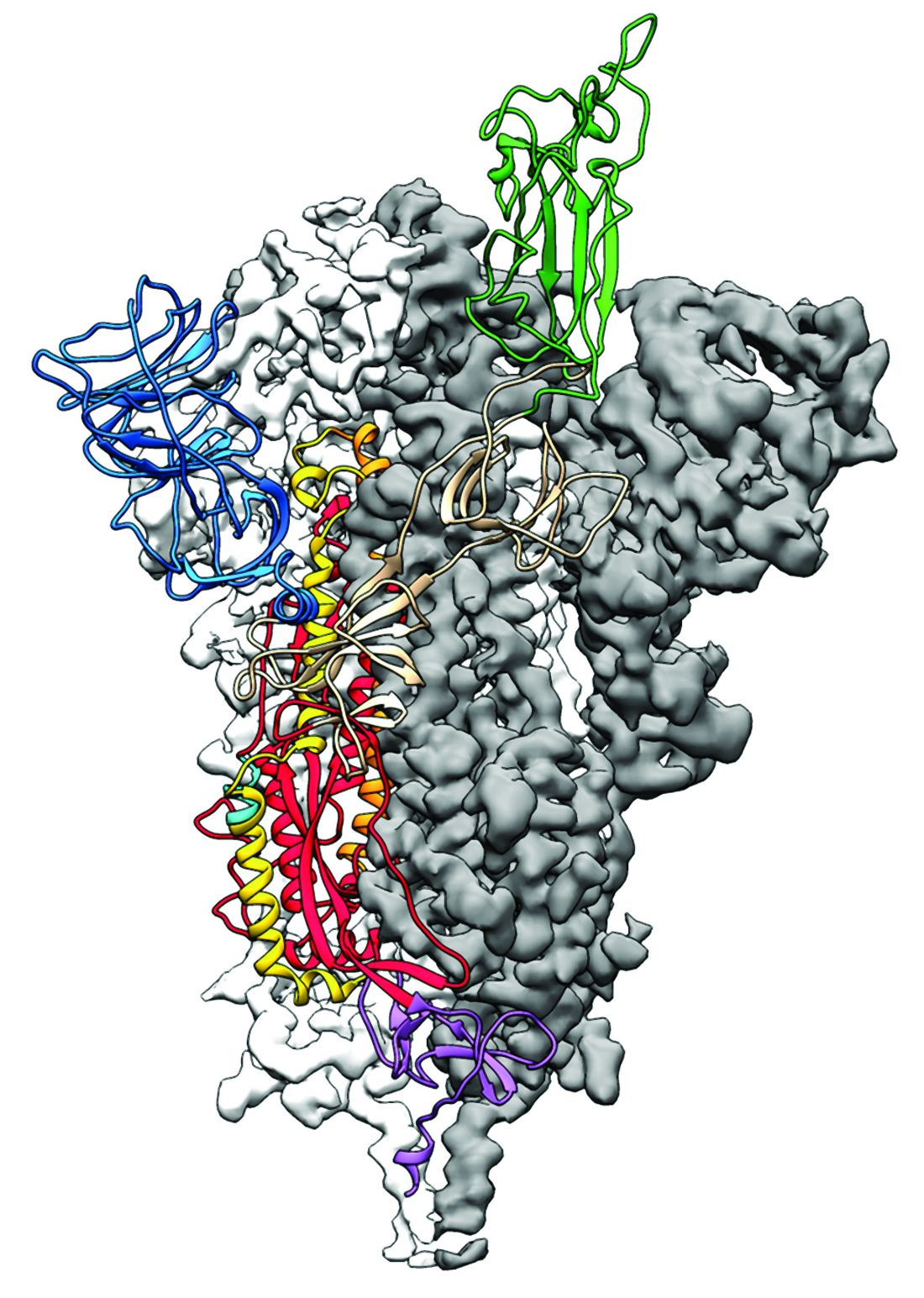

2019-nCoV: Structure, characteristics of key potential therapy target determined

Researchers have identified the structure of a protein that could turn out to be a potential vaccine target for the 2019-nCoV.

As is typical of other coronaviruses, 2019-nCoV makes use of a densely glycosylated spike protein to gain entry into host cells. The spike protein is a trimeric class I fusion protein that exists in a metastable prefusion conformation that undergoes a dramatic structural rearrangement to fuse the viral membrane with the host-cell membrane, according to Daniel Wrapp of the University of Texas at Austin and colleagues.

The researchers performed a study to synthesize and determine the 3-D structure of the spike protein because it is a logical target for vaccine development and for the development of targeted therapeutics for COVID-19, the disease caused by the virus.

“As soon as we knew this was a coronavirus, we felt we had to jump at it,” senior author Jason S. McLellan, PhD, associate professor of molecular science, said in a press release from the University, “because we could be one of the first ones to get this structure. We knew exactly what mutations to put into this because we’ve already shown these mutations work for a bunch of other coronaviruses.”

Because recent reports by other researchers demonstrated that 2019-nCoV and SARS-CoV spike proteins share the same functional host-cell receptor–angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), Dr. McLellan and his colleagues examined the relation between the two viruses. They found biophysical and structural evidence that the 2019-nCoV spike protein binds ACE2 with higher affinity than the closely related SARS-CoV spike protein. “The high affinity of 2019-nCoV S for human ACE2 may contribute to the apparent ease with which 2019-nCoV can spread from human-to-human; however, additional studies are needed to investigate this possibility,” the researchers wrote.

Focusing their attention on the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of the 2019-nCoV spike protein, they tested several published SARS-CoV RBD-specific monoclonal antibodies against it and found that these antibodies showed no appreciable binding to 2019-nCoV spike protein, which suggests limited antibody cross-reactivity. For this reason, they suggested that future antibody isolation and therapeutic design efforts will benefit from specifically using 2019-nCoV spike proteins as probes.

“This information will support precision vaccine design and discovery of anti-viral therapeutics, accelerating medical countermeasure development,” they concluded.

The research was supported in part by an National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases grant and by intramural funding from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Four authors are inventors on US patent application No. 62/412,703 (Prefusion Coronavirus Spike Proteins and Their Use) and all are inventors on US patent application No. 62/972,886 (2019-nCoV Vaccine).

SOURCE: Wrapp D et al. Science. 2020 Feb 19. doi: 10.1126/science.abb2507.

Researchers have identified the structure of a protein that could turn out to be a potential vaccine target for the 2019-nCoV.

As is typical of other coronaviruses, 2019-nCoV makes use of a densely glycosylated spike protein to gain entry into host cells. The spike protein is a trimeric class I fusion protein that exists in a metastable prefusion conformation that undergoes a dramatic structural rearrangement to fuse the viral membrane with the host-cell membrane, according to Daniel Wrapp of the University of Texas at Austin and colleagues.

The researchers performed a study to synthesize and determine the 3-D structure of the spike protein because it is a logical target for vaccine development and for the development of targeted therapeutics for COVID-19, the disease caused by the virus.

“As soon as we knew this was a coronavirus, we felt we had to jump at it,” senior author Jason S. McLellan, PhD, associate professor of molecular science, said in a press release from the University, “because we could be one of the first ones to get this structure. We knew exactly what mutations to put into this because we’ve already shown these mutations work for a bunch of other coronaviruses.”

Because recent reports by other researchers demonstrated that 2019-nCoV and SARS-CoV spike proteins share the same functional host-cell receptor–angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), Dr. McLellan and his colleagues examined the relation between the two viruses. They found biophysical and structural evidence that the 2019-nCoV spike protein binds ACE2 with higher affinity than the closely related SARS-CoV spike protein. “The high affinity of 2019-nCoV S for human ACE2 may contribute to the apparent ease with which 2019-nCoV can spread from human-to-human; however, additional studies are needed to investigate this possibility,” the researchers wrote.

Focusing their attention on the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of the 2019-nCoV spike protein, they tested several published SARS-CoV RBD-specific monoclonal antibodies against it and found that these antibodies showed no appreciable binding to 2019-nCoV spike protein, which suggests limited antibody cross-reactivity. For this reason, they suggested that future antibody isolation and therapeutic design efforts will benefit from specifically using 2019-nCoV spike proteins as probes.

“This information will support precision vaccine design and discovery of anti-viral therapeutics, accelerating medical countermeasure development,” they concluded.

The research was supported in part by an National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases grant and by intramural funding from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Four authors are inventors on US patent application No. 62/412,703 (Prefusion Coronavirus Spike Proteins and Their Use) and all are inventors on US patent application No. 62/972,886 (2019-nCoV Vaccine).

SOURCE: Wrapp D et al. Science. 2020 Feb 19. doi: 10.1126/science.abb2507.

Researchers have identified the structure of a protein that could turn out to be a potential vaccine target for the 2019-nCoV.

As is typical of other coronaviruses, 2019-nCoV makes use of a densely glycosylated spike protein to gain entry into host cells. The spike protein is a trimeric class I fusion protein that exists in a metastable prefusion conformation that undergoes a dramatic structural rearrangement to fuse the viral membrane with the host-cell membrane, according to Daniel Wrapp of the University of Texas at Austin and colleagues.

The researchers performed a study to synthesize and determine the 3-D structure of the spike protein because it is a logical target for vaccine development and for the development of targeted therapeutics for COVID-19, the disease caused by the virus.

“As soon as we knew this was a coronavirus, we felt we had to jump at it,” senior author Jason S. McLellan, PhD, associate professor of molecular science, said in a press release from the University, “because we could be one of the first ones to get this structure. We knew exactly what mutations to put into this because we’ve already shown these mutations work for a bunch of other coronaviruses.”

Because recent reports by other researchers demonstrated that 2019-nCoV and SARS-CoV spike proteins share the same functional host-cell receptor–angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), Dr. McLellan and his colleagues examined the relation between the two viruses. They found biophysical and structural evidence that the 2019-nCoV spike protein binds ACE2 with higher affinity than the closely related SARS-CoV spike protein. “The high affinity of 2019-nCoV S for human ACE2 may contribute to the apparent ease with which 2019-nCoV can spread from human-to-human; however, additional studies are needed to investigate this possibility,” the researchers wrote.

Focusing their attention on the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of the 2019-nCoV spike protein, they tested several published SARS-CoV RBD-specific monoclonal antibodies against it and found that these antibodies showed no appreciable binding to 2019-nCoV spike protein, which suggests limited antibody cross-reactivity. For this reason, they suggested that future antibody isolation and therapeutic design efforts will benefit from specifically using 2019-nCoV spike proteins as probes.

“This information will support precision vaccine design and discovery of anti-viral therapeutics, accelerating medical countermeasure development,” they concluded.

The research was supported in part by an National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases grant and by intramural funding from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Four authors are inventors on US patent application No. 62/412,703 (Prefusion Coronavirus Spike Proteins and Their Use) and all are inventors on US patent application No. 62/972,886 (2019-nCoV Vaccine).

SOURCE: Wrapp D et al. Science. 2020 Feb 19. doi: 10.1126/science.abb2507.

FROM SCIENCE

Shingles vaccine linked to lower stroke risk

LOS ANGELES – Prevention of shingles with the Zoster Vaccine Live may reduce the risk of subsequent stroke among older adults as well, the first study to examine this association suggests. Shingles vaccination was linked to a 20% decrease in stroke risk in people younger than 80 years of age in the large Medicare cohort study. Older participants showed a 10% reduced risk, according to data released in advance of formal presentation at this week’s International Stroke Conference, sponsored by the American Heart Association.

Reductions were seen for both ischemic and hemorrhagic events.

“Our findings might encourage people age 50 or older to get vaccinated against shingles and to prevent shingles-associated stroke risk,” Quanhe Yang, PhD, lead study author and senior scientist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said in an interview.

Dr. Yang and colleagues evaluated the only shingles vaccine available at the time of the study, Zoster Vaccine Live (Zostavax). However, the CDC now calls an adjuvanted, nonlive recombinant vaccine (Shingrix) the preferred shingles vaccine for healthy adults aged 50 years and older. Shingrix was approved in 2017. Zostavax, approved in 2006, can still be used in healthy adults aged 60 years and older, the agency states.

A reduction in inflammation from Zoster Vaccine Live may be the mechanism by which stroke risk is reduced, Dr. Yang said. The newer vaccine, which the CDC notes is more than 90% effective, might provide even greater protection against stroke, although more research is needed, he added.

Interestingly, prior research suggested that, once a person develops shingles, it may be too late. Dr. Yang and colleagues showed vaccination or antiviral treatment after a shingles episode was not effective at reducing stroke risk in research presented at the 2019 International Stroke Conference.

Shingles can present as a painful reactivation of chickenpox, also known as the varicella-zoster virus. Shingles is also common; Dr. Yang estimated one in three people who had chickenpox will develop the condition at some point in their lifetime. In addition, researchers have linked shingles to an elevated risk of stroke.

To assess the vaccine’s protective effect on stroke, Dr. Yang and colleagues reviewed health records for 1.38 million Medicare recipients. All participants were aged 66 years or older, had no history of stroke at baseline, and received the Zoster Vaccine Live during 2008-2016. The investigators compared the stroke rate in this vaccinated group with the rate in a matched control group of the same number of Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries who did not receive the vaccination. They adjusted their analysis for age, sex, race, medications, and comorbidities.

The overall decrease of 16% in stroke risk associated with vaccination included a 12% drop in hemorrhagic stroke and 18% decrease in ischemic stroke over a median follow-up of 3.9 years follow-up (interquartile range, 2.7-5.4).

The adjusted hazard ratios comparing the vaccinated with control groups were 0.84 (95% confidence interval, 0.83-0.85) for all stroke; 0.82 (95% CI, 0.81-0.83) for acute ischemic stroke; and 0.88 (95% CI, 0.84-0.91) for hemorrhagic stroke.

The vaccinated group experienced 42,267 stroke events during that time. This rate included 33,510 acute ischemic strokes and 4,318 hemorrhagic strokes. At the same time, 48,139 strokes occurred in the control group. The breakdown included 39,334 ischemic and 4,713 hemorrhagic events.

“Approximately 1 million people in the United States get shingles each year, yet there is a vaccine to help prevent it,” Dr. Yang stated in a news release. “Our study results may encourage people ages 50 and older to follow the recommendation and get vaccinated against shingles. You are reducing the risk of shingles, and at the same time, you may be reducing your risk of stroke.”

“Further studies are needed to confirm our findings of association between Zostavax vaccine and risk of stroke,” Dr. Yang said.

Because the CDC Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommended Shingrix vaccine only for healthy adults 50 years and older in 2017, there were insufficient data in Medicare to study the association between that vaccine and risk of stroke at the time of the current study.

“However, two doses of Shingrix are more than 90% effective at preventing shingles and postherpetic neuralgia, and higher than that of Zostavax,” Dr. Yang said.

‘Very intriguing’ research

“This is a very interesting study,” Ralph L. Sacco, MD, past president of the American Heart Association, said in a video commentary released in advance of the conference. It was a very large sample, he noted, and those older than age 60 years who had the vaccine were protected with a lower risk for both ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke.

“So it is very intriguing,” added Dr. Sacco, chairman of the department of neurology at the University of Miami. “We know things like shingles can increase inflammation and increase the risk of stroke,” Dr. Sacco said, “but this is the first time in a very large Medicare database that it was shown that those who had the vaccine had a lower risk of stroke.”

The CDC funded this study. Dr. Yang and Dr. Sacco have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

SOURCE: Yang Q et al. ISC 2020, Abstract TP493.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

LOS ANGELES – Prevention of shingles with the Zoster Vaccine Live may reduce the risk of subsequent stroke among older adults as well, the first study to examine this association suggests. Shingles vaccination was linked to a 20% decrease in stroke risk in people younger than 80 years of age in the large Medicare cohort study. Older participants showed a 10% reduced risk, according to data released in advance of formal presentation at this week’s International Stroke Conference, sponsored by the American Heart Association.

Reductions were seen for both ischemic and hemorrhagic events.

“Our findings might encourage people age 50 or older to get vaccinated against shingles and to prevent shingles-associated stroke risk,” Quanhe Yang, PhD, lead study author and senior scientist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said in an interview.

Dr. Yang and colleagues evaluated the only shingles vaccine available at the time of the study, Zoster Vaccine Live (Zostavax). However, the CDC now calls an adjuvanted, nonlive recombinant vaccine (Shingrix) the preferred shingles vaccine for healthy adults aged 50 years and older. Shingrix was approved in 2017. Zostavax, approved in 2006, can still be used in healthy adults aged 60 years and older, the agency states.

A reduction in inflammation from Zoster Vaccine Live may be the mechanism by which stroke risk is reduced, Dr. Yang said. The newer vaccine, which the CDC notes is more than 90% effective, might provide even greater protection against stroke, although more research is needed, he added.

Interestingly, prior research suggested that, once a person develops shingles, it may be too late. Dr. Yang and colleagues showed vaccination or antiviral treatment after a shingles episode was not effective at reducing stroke risk in research presented at the 2019 International Stroke Conference.

Shingles can present as a painful reactivation of chickenpox, also known as the varicella-zoster virus. Shingles is also common; Dr. Yang estimated one in three people who had chickenpox will develop the condition at some point in their lifetime. In addition, researchers have linked shingles to an elevated risk of stroke.

To assess the vaccine’s protective effect on stroke, Dr. Yang and colleagues reviewed health records for 1.38 million Medicare recipients. All participants were aged 66 years or older, had no history of stroke at baseline, and received the Zoster Vaccine Live during 2008-2016. The investigators compared the stroke rate in this vaccinated group with the rate in a matched control group of the same number of Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries who did not receive the vaccination. They adjusted their analysis for age, sex, race, medications, and comorbidities.

The overall decrease of 16% in stroke risk associated with vaccination included a 12% drop in hemorrhagic stroke and 18% decrease in ischemic stroke over a median follow-up of 3.9 years follow-up (interquartile range, 2.7-5.4).

The adjusted hazard ratios comparing the vaccinated with control groups were 0.84 (95% confidence interval, 0.83-0.85) for all stroke; 0.82 (95% CI, 0.81-0.83) for acute ischemic stroke; and 0.88 (95% CI, 0.84-0.91) for hemorrhagic stroke.

The vaccinated group experienced 42,267 stroke events during that time. This rate included 33,510 acute ischemic strokes and 4,318 hemorrhagic strokes. At the same time, 48,139 strokes occurred in the control group. The breakdown included 39,334 ischemic and 4,713 hemorrhagic events.

“Approximately 1 million people in the United States get shingles each year, yet there is a vaccine to help prevent it,” Dr. Yang stated in a news release. “Our study results may encourage people ages 50 and older to follow the recommendation and get vaccinated against shingles. You are reducing the risk of shingles, and at the same time, you may be reducing your risk of stroke.”

“Further studies are needed to confirm our findings of association between Zostavax vaccine and risk of stroke,” Dr. Yang said.

Because the CDC Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommended Shingrix vaccine only for healthy adults 50 years and older in 2017, there were insufficient data in Medicare to study the association between that vaccine and risk of stroke at the time of the current study.

“However, two doses of Shingrix are more than 90% effective at preventing shingles and postherpetic neuralgia, and higher than that of Zostavax,” Dr. Yang said.

‘Very intriguing’ research

“This is a very interesting study,” Ralph L. Sacco, MD, past president of the American Heart Association, said in a video commentary released in advance of the conference. It was a very large sample, he noted, and those older than age 60 years who had the vaccine were protected with a lower risk for both ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke.

“So it is very intriguing,” added Dr. Sacco, chairman of the department of neurology at the University of Miami. “We know things like shingles can increase inflammation and increase the risk of stroke,” Dr. Sacco said, “but this is the first time in a very large Medicare database that it was shown that those who had the vaccine had a lower risk of stroke.”

The CDC funded this study. Dr. Yang and Dr. Sacco have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

SOURCE: Yang Q et al. ISC 2020, Abstract TP493.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

LOS ANGELES – Prevention of shingles with the Zoster Vaccine Live may reduce the risk of subsequent stroke among older adults as well, the first study to examine this association suggests. Shingles vaccination was linked to a 20% decrease in stroke risk in people younger than 80 years of age in the large Medicare cohort study. Older participants showed a 10% reduced risk, according to data released in advance of formal presentation at this week’s International Stroke Conference, sponsored by the American Heart Association.

Reductions were seen for both ischemic and hemorrhagic events.

“Our findings might encourage people age 50 or older to get vaccinated against shingles and to prevent shingles-associated stroke risk,” Quanhe Yang, PhD, lead study author and senior scientist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said in an interview.

Dr. Yang and colleagues evaluated the only shingles vaccine available at the time of the study, Zoster Vaccine Live (Zostavax). However, the CDC now calls an adjuvanted, nonlive recombinant vaccine (Shingrix) the preferred shingles vaccine for healthy adults aged 50 years and older. Shingrix was approved in 2017. Zostavax, approved in 2006, can still be used in healthy adults aged 60 years and older, the agency states.

A reduction in inflammation from Zoster Vaccine Live may be the mechanism by which stroke risk is reduced, Dr. Yang said. The newer vaccine, which the CDC notes is more than 90% effective, might provide even greater protection against stroke, although more research is needed, he added.

Interestingly, prior research suggested that, once a person develops shingles, it may be too late. Dr. Yang and colleagues showed vaccination or antiviral treatment after a shingles episode was not effective at reducing stroke risk in research presented at the 2019 International Stroke Conference.

Shingles can present as a painful reactivation of chickenpox, also known as the varicella-zoster virus. Shingles is also common; Dr. Yang estimated one in three people who had chickenpox will develop the condition at some point in their lifetime. In addition, researchers have linked shingles to an elevated risk of stroke.

To assess the vaccine’s protective effect on stroke, Dr. Yang and colleagues reviewed health records for 1.38 million Medicare recipients. All participants were aged 66 years or older, had no history of stroke at baseline, and received the Zoster Vaccine Live during 2008-2016. The investigators compared the stroke rate in this vaccinated group with the rate in a matched control group of the same number of Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries who did not receive the vaccination. They adjusted their analysis for age, sex, race, medications, and comorbidities.

The overall decrease of 16% in stroke risk associated with vaccination included a 12% drop in hemorrhagic stroke and 18% decrease in ischemic stroke over a median follow-up of 3.9 years follow-up (interquartile range, 2.7-5.4).

The adjusted hazard ratios comparing the vaccinated with control groups were 0.84 (95% confidence interval, 0.83-0.85) for all stroke; 0.82 (95% CI, 0.81-0.83) for acute ischemic stroke; and 0.88 (95% CI, 0.84-0.91) for hemorrhagic stroke.

The vaccinated group experienced 42,267 stroke events during that time. This rate included 33,510 acute ischemic strokes and 4,318 hemorrhagic strokes. At the same time, 48,139 strokes occurred in the control group. The breakdown included 39,334 ischemic and 4,713 hemorrhagic events.

“Approximately 1 million people in the United States get shingles each year, yet there is a vaccine to help prevent it,” Dr. Yang stated in a news release. “Our study results may encourage people ages 50 and older to follow the recommendation and get vaccinated against shingles. You are reducing the risk of shingles, and at the same time, you may be reducing your risk of stroke.”

“Further studies are needed to confirm our findings of association between Zostavax vaccine and risk of stroke,” Dr. Yang said.

Because the CDC Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommended Shingrix vaccine only for healthy adults 50 years and older in 2017, there were insufficient data in Medicare to study the association between that vaccine and risk of stroke at the time of the current study.

“However, two doses of Shingrix are more than 90% effective at preventing shingles and postherpetic neuralgia, and higher than that of Zostavax,” Dr. Yang said.

‘Very intriguing’ research

“This is a very interesting study,” Ralph L. Sacco, MD, past president of the American Heart Association, said in a video commentary released in advance of the conference. It was a very large sample, he noted, and those older than age 60 years who had the vaccine were protected with a lower risk for both ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke.

“So it is very intriguing,” added Dr. Sacco, chairman of the department of neurology at the University of Miami. “We know things like shingles can increase inflammation and increase the risk of stroke,” Dr. Sacco said, “but this is the first time in a very large Medicare database that it was shown that those who had the vaccine had a lower risk of stroke.”

The CDC funded this study. Dr. Yang and Dr. Sacco have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

SOURCE: Yang Q et al. ISC 2020, Abstract TP493.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

REPORTING FROM ISC 2020

Stroke risk tied to diabetic retinopathy may not be modifiable

LOS ANGELES – Evidence continues to mount that diabetic retinopathy predicts elevated risk for stroke.

In a new study with nearly 3,000 people, those with diabetic retinopathy were 60% more likely than others with diabetes to develop an incident stroke over time. Investigators also found that addressing glucose, lipids, and blood pressure levels did not mitigate this risk in this secondary analysis of the ACCORD Eye Study.

“We are not surprised with the finding that diabetic retinopathy increases the risk of stroke — as diabetic retinopathy is common microvascular disease that is an established risk factor for cardiovascular disease,” lead author Ka-Ho Wong, BS, MBA, said in an interview.

However, “we were surprised that none of the trial interventions mitigated this risk, in particular the intensive blood pressure reduction, because hypertension is the most important cause of microvascular disease,” he said. Mr. Wong is clinical research coordinator and lab manager of the de Havenon Lab at the University of Utah Health Hospitals and Clinics in Salt Lake City.

The study findings were released Feb. 12, 2020, in advance of formal presentation at the International Stroke Conference sponsored by the American Heart Association.

Common predictor of vascular disease

Diabetic retinopathy is the most common complication of diabetes mellitus, affecting up to 50% of people living with type 1 and type 2 diabetes. In addition, previous research suggests that macrovascular diabetes complications, including stroke, could share a common or synergistic pathway.

This small vessel damage in the eye also has been linked to an increased risk of adverse cardiac events, including heart failure, as previously reported by Medscape Medical News.

To find out more, Mr. Wong and colleagues analyzed 2,828 participants in the Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD) Eye Study. They compared the stroke risk between 874 people with diabetic retinopathy and another 1,954 diabetics without this complication. The average age was 62 years and 62% were men.

Diabetic neuropathy at baseline was diagnosed using the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study Severity Scale using seven-field stereoscopic fundus photographs.

A total of 117 participants experienced a stroke during a mean follow-up of 5.4 years.

The investigators found that diabetic retinopathy was more common among patients who had a stroke (41%) versus 31% of those without a stroke (P = .016). The link between diabetic retinopathy and stroke remained in an analysis adjusted for multiple factors, including baseline age, gender, race, total cholesterol, A1c, smoking, and more. Risk remained elevated, with a hazard ratio of 1.60 (95% confidence interval, 1.10-2.32; P = .015).

Regarding the potential for modifying this risk, the association was unaffected among participants randomly assigned to the ACCORD glucose intervention (P = .305), lipid intervention (P = .546), or blood pressure intervention (P = .422).

The study was a secondary analysis, so information on stroke type and location were unavailable.

The big picture

“Diabetic retinopathy is associated with an increased risk of stroke, which suggests that the microvascular pathology inherent to diabetic retinopathy has larger cardiovascular implications,” the researchers noted.

Despite these findings, the researchers suggest that patients with diabetic retinopathy receive aggressive medical management to try to reduce their stroke risk.

“It’s important for everyone with diabetes to maintain good blood glucose control, and those with established diabetic retinopathy should pay particular attention to meeting all the stroke prevention guidelines that are established by the American Stroke Association,” said Mr. Wong.

“Patients with established diabetic retinopathy should pay particular attention to meeting all stroke prevention guidelines established by the [American Heart Association],” he added.

Mr. Wong and colleagues would like to expand on these findings. Pending grant application and funding support, they propose conducting a prospective, observational trial in stroke patients with baseline diabetic retinopathy. One aim would be to identify the most common mechanisms leading to stroke in this population, “which would have important implications for prevention efforts,” he said.

Consistent Findings

“The results of the study showing that having diabetic retinopathy is also associated with an increase in stroke really isn’t surprising. There have been other studies, population-based studies, done in the past, that have found a similar relationship,” Larry B. Goldstein, MD, said in a video commentary on the findings.

“The results are actually quite consistent with several other studies that have evaluated the same relationship,” added Dr. Goldstein, who is chair of the department of neurology and codirector of the Kentucky Neuroscience Institute, University of Kentucky HealthCare, Lexington.

Mr. Wong and Dr. Goldstein have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. The NIH’s National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke funded the study.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

LOS ANGELES – Evidence continues to mount that diabetic retinopathy predicts elevated risk for stroke.

In a new study with nearly 3,000 people, those with diabetic retinopathy were 60% more likely than others with diabetes to develop an incident stroke over time. Investigators also found that addressing glucose, lipids, and blood pressure levels did not mitigate this risk in this secondary analysis of the ACCORD Eye Study.

“We are not surprised with the finding that diabetic retinopathy increases the risk of stroke — as diabetic retinopathy is common microvascular disease that is an established risk factor for cardiovascular disease,” lead author Ka-Ho Wong, BS, MBA, said in an interview.

However, “we were surprised that none of the trial interventions mitigated this risk, in particular the intensive blood pressure reduction, because hypertension is the most important cause of microvascular disease,” he said. Mr. Wong is clinical research coordinator and lab manager of the de Havenon Lab at the University of Utah Health Hospitals and Clinics in Salt Lake City.

The study findings were released Feb. 12, 2020, in advance of formal presentation at the International Stroke Conference sponsored by the American Heart Association.

Common predictor of vascular disease

Diabetic retinopathy is the most common complication of diabetes mellitus, affecting up to 50% of people living with type 1 and type 2 diabetes. In addition, previous research suggests that macrovascular diabetes complications, including stroke, could share a common or synergistic pathway.

This small vessel damage in the eye also has been linked to an increased risk of adverse cardiac events, including heart failure, as previously reported by Medscape Medical News.

To find out more, Mr. Wong and colleagues analyzed 2,828 participants in the Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD) Eye Study. They compared the stroke risk between 874 people with diabetic retinopathy and another 1,954 diabetics without this complication. The average age was 62 years and 62% were men.

Diabetic neuropathy at baseline was diagnosed using the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study Severity Scale using seven-field stereoscopic fundus photographs.

A total of 117 participants experienced a stroke during a mean follow-up of 5.4 years.

The investigators found that diabetic retinopathy was more common among patients who had a stroke (41%) versus 31% of those without a stroke (P = .016). The link between diabetic retinopathy and stroke remained in an analysis adjusted for multiple factors, including baseline age, gender, race, total cholesterol, A1c, smoking, and more. Risk remained elevated, with a hazard ratio of 1.60 (95% confidence interval, 1.10-2.32; P = .015).

Regarding the potential for modifying this risk, the association was unaffected among participants randomly assigned to the ACCORD glucose intervention (P = .305), lipid intervention (P = .546), or blood pressure intervention (P = .422).

The study was a secondary analysis, so information on stroke type and location were unavailable.

The big picture

“Diabetic retinopathy is associated with an increased risk of stroke, which suggests that the microvascular pathology inherent to diabetic retinopathy has larger cardiovascular implications,” the researchers noted.

Despite these findings, the researchers suggest that patients with diabetic retinopathy receive aggressive medical management to try to reduce their stroke risk.

“It’s important for everyone with diabetes to maintain good blood glucose control, and those with established diabetic retinopathy should pay particular attention to meeting all the stroke prevention guidelines that are established by the American Stroke Association,” said Mr. Wong.

“Patients with established diabetic retinopathy should pay particular attention to meeting all stroke prevention guidelines established by the [American Heart Association],” he added.

Mr. Wong and colleagues would like to expand on these findings. Pending grant application and funding support, they propose conducting a prospective, observational trial in stroke patients with baseline diabetic retinopathy. One aim would be to identify the most common mechanisms leading to stroke in this population, “which would have important implications for prevention efforts,” he said.

Consistent Findings

“The results of the study showing that having diabetic retinopathy is also associated with an increase in stroke really isn’t surprising. There have been other studies, population-based studies, done in the past, that have found a similar relationship,” Larry B. Goldstein, MD, said in a video commentary on the findings.

“The results are actually quite consistent with several other studies that have evaluated the same relationship,” added Dr. Goldstein, who is chair of the department of neurology and codirector of the Kentucky Neuroscience Institute, University of Kentucky HealthCare, Lexington.

Mr. Wong and Dr. Goldstein have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. The NIH’s National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke funded the study.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

LOS ANGELES – Evidence continues to mount that diabetic retinopathy predicts elevated risk for stroke.

In a new study with nearly 3,000 people, those with diabetic retinopathy were 60% more likely than others with diabetes to develop an incident stroke over time. Investigators also found that addressing glucose, lipids, and blood pressure levels did not mitigate this risk in this secondary analysis of the ACCORD Eye Study.

“We are not surprised with the finding that diabetic retinopathy increases the risk of stroke — as diabetic retinopathy is common microvascular disease that is an established risk factor for cardiovascular disease,” lead author Ka-Ho Wong, BS, MBA, said in an interview.

However, “we were surprised that none of the trial interventions mitigated this risk, in particular the intensive blood pressure reduction, because hypertension is the most important cause of microvascular disease,” he said. Mr. Wong is clinical research coordinator and lab manager of the de Havenon Lab at the University of Utah Health Hospitals and Clinics in Salt Lake City.

The study findings were released Feb. 12, 2020, in advance of formal presentation at the International Stroke Conference sponsored by the American Heart Association.

Common predictor of vascular disease

Diabetic retinopathy is the most common complication of diabetes mellitus, affecting up to 50% of people living with type 1 and type 2 diabetes. In addition, previous research suggests that macrovascular diabetes complications, including stroke, could share a common or synergistic pathway.

This small vessel damage in the eye also has been linked to an increased risk of adverse cardiac events, including heart failure, as previously reported by Medscape Medical News.

To find out more, Mr. Wong and colleagues analyzed 2,828 participants in the Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD) Eye Study. They compared the stroke risk between 874 people with diabetic retinopathy and another 1,954 diabetics without this complication. The average age was 62 years and 62% were men.

Diabetic neuropathy at baseline was diagnosed using the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study Severity Scale using seven-field stereoscopic fundus photographs.

A total of 117 participants experienced a stroke during a mean follow-up of 5.4 years.

The investigators found that diabetic retinopathy was more common among patients who had a stroke (41%) versus 31% of those without a stroke (P = .016). The link between diabetic retinopathy and stroke remained in an analysis adjusted for multiple factors, including baseline age, gender, race, total cholesterol, A1c, smoking, and more. Risk remained elevated, with a hazard ratio of 1.60 (95% confidence interval, 1.10-2.32; P = .015).

Regarding the potential for modifying this risk, the association was unaffected among participants randomly assigned to the ACCORD glucose intervention (P = .305), lipid intervention (P = .546), or blood pressure intervention (P = .422).

The study was a secondary analysis, so information on stroke type and location were unavailable.

The big picture

“Diabetic retinopathy is associated with an increased risk of stroke, which suggests that the microvascular pathology inherent to diabetic retinopathy has larger cardiovascular implications,” the researchers noted.

Despite these findings, the researchers suggest that patients with diabetic retinopathy receive aggressive medical management to try to reduce their stroke risk.

“It’s important for everyone with diabetes to maintain good blood glucose control, and those with established diabetic retinopathy should pay particular attention to meeting all the stroke prevention guidelines that are established by the American Stroke Association,” said Mr. Wong.

“Patients with established diabetic retinopathy should pay particular attention to meeting all stroke prevention guidelines established by the [American Heart Association],” he added.

Mr. Wong and colleagues would like to expand on these findings. Pending grant application and funding support, they propose conducting a prospective, observational trial in stroke patients with baseline diabetic retinopathy. One aim would be to identify the most common mechanisms leading to stroke in this population, “which would have important implications for prevention efforts,” he said.

Consistent Findings

“The results of the study showing that having diabetic retinopathy is also associated with an increase in stroke really isn’t surprising. There have been other studies, population-based studies, done in the past, that have found a similar relationship,” Larry B. Goldstein, MD, said in a video commentary on the findings.

“The results are actually quite consistent with several other studies that have evaluated the same relationship,” added Dr. Goldstein, who is chair of the department of neurology and codirector of the Kentucky Neuroscience Institute, University of Kentucky HealthCare, Lexington.

Mr. Wong and Dr. Goldstein have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. The NIH’s National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke funded the study.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

REPORTING FROM ISC 2020

Doctors look to existing drugs in coronavirus fight

COVID-19, the infection caused by the newly identified coronavirus, is a currently a disease with no pharmaceutical weapons against it. There’s no vaccine to prevent it, and no drugs can treat it.

But researchers are racing to change that. A vaccine could be ready to test as soon as April. More than two dozen studies have already been registered on ClinicalTrials.gov, a website that tracks research. These studies aim to test everything from traditional Chinese medicine to vitamin C, stem cells, steroids, and medications that fight other viruses, like the flu and HIV. The hope is that something about how these repurposed remedies work will help patients who are desperately ill with no other prospects.

Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, says this is all part of the playbook for brand-new diseases. “There’s a lot of empiric guessing,” he says. “They’re going to propose a whole lot of drugs that already exist. They’re going to say, here’s the data that shows it blocks the virus” in a test tube. But test tubes aren’t people, and many drugs that seem to work in a lab won’t end up helping patients.

Coronaviruses are especially hard to stop once they invade the body. Unlike many other kinds of viruses, they have a fail-safe against tampering – a “proofreader” that constantly inspects their code, looking for errors, including the potentially life-saving errors that drugs could introduce.

Dr. Fauci said that researchers will be able to make better guesses about how to help people when they can try drugs in animals. “We don’t have an animal model yet of the new coronavirus. When we do get an animal model, that will be a big boon to drugs because then, you can clearly test them in a physiological way, whether they work,” he says.

Looking to drugs for HIV and flu

One of the drugs already under study is the combination of two HIV medications: lopinavir and ritonavir (Kaletra). Kaletra stops viruses by interfering with the enzymes they need to infect cells, called proteases.

One study being done at the Guangzhou Eighth People’s Hospital in China is testing Kaletra against Arbidol, an antiviral drug approved in China and Russia to treat the flu. Two groups of patients will take the medications along with standard care. A third group in the study will receive only standard care, typically supportive therapy with oxygen and IV fluids that are meant to support the body so the immune system can fight off a virus on its own.