User login

The Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management® is an independent, peer-reviewed journal offering evidence-based, practical information for improving the quality, safety, and value of health care.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Refining your approach to hypothyroidism treatment

CASE

A 38-year-old woman presents for a routine physical. Other than urgent care visits for 1 episode of influenza and 2 upper respiratory illnesses, she has not seen a physician for a physical in 5 years. She denies any significant medical history. She takes naproxen occasionally for chronic right knee pain. She does not use tobacco or alcohol. Recently, she has started using a meal replacement shake at lunchtime for weight management. She performs aerobic exercise 30 to 40 minutes per day, 5 days per week. Her family history is significant for type 2 diabetes mellitus, arthritis, heart disease, and hyperlipidemia on her mother’s side. She is single, is not currently sexually active, works as a pharmacy technician, and has no children. A high-risk human papillomavirus test was normal 4 years ago.

A review of systems is notable for a 20-pound weight gain over the past year, worsening heartburn over the past 2 weeks, and chronic knee pain, which is greater in the right knee than the left. She denies weakness, fatigue, nausea, diarrhea, constipation, or abdominal pain. Vital signs reveal a blood pressure of 146/88 mm Hg, a heart rate of 63 bpm, a temperature of 98°F (36.7°C), a respiratory rate of 16, a height of 5’7’’ (1.7 m), a weight of 217 lbs (98.4 kg), and a peripheral capillary oxygen saturation (SpO2) of 99% on room air. The physical exam reveals a body mass index (BMI) of 34, warm dry skin, and coarse brittle hair.

Lab results reveal a thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level of 11.17 mIU/L (reference range, 0.45-4.5 mIU/L) and a free thyroxine (T4) of 0.58 ng/dL (reference range, 0.8-2.8 ng/dL). A basic metabolic panel and hemoglobin A1C level are normal.

What would you recommend?

In the United States, the prevalence of overt hypothyroidism (defined as a TSH level > 4.5 mIU/L and a low free T4) among people ≥ 12 years of age was estimated at 0.3% based on National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data from 1999-2002.1 Subclinical hypothyroidism (TSH level > 4.5 mIU/L but < 10 mIU/L and a normal T4 level) is even more common, with an estimated prevalence of 3.4%.1 Hypothyroidism is more common in females and occurs more frequently in Caucasian Americans and Mexican Americans than in African Americans.1

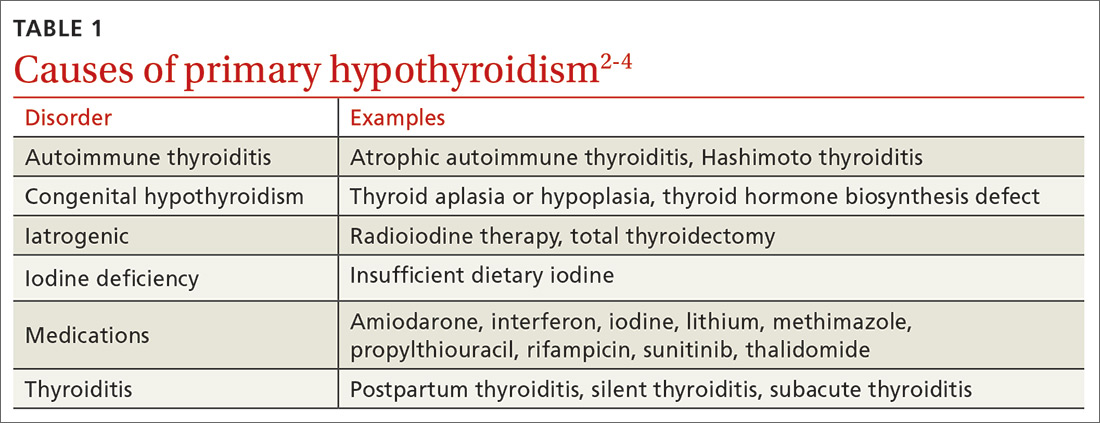

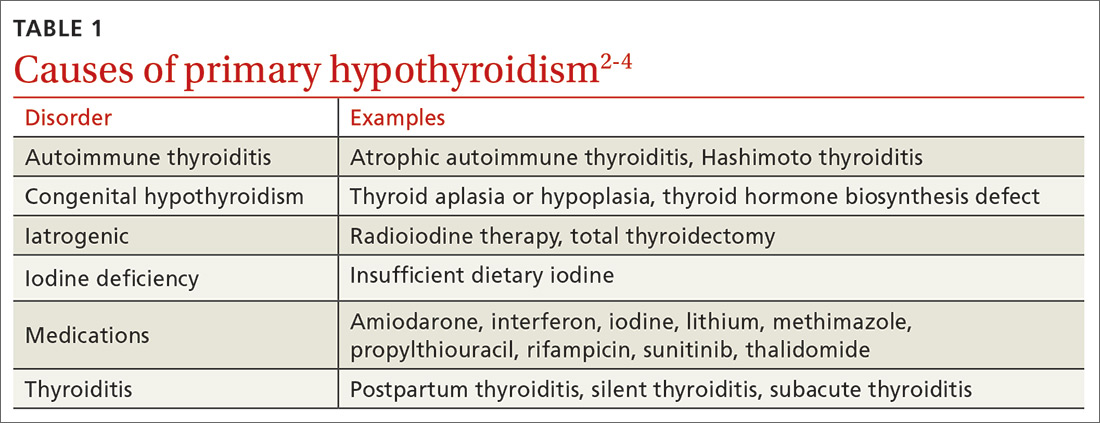

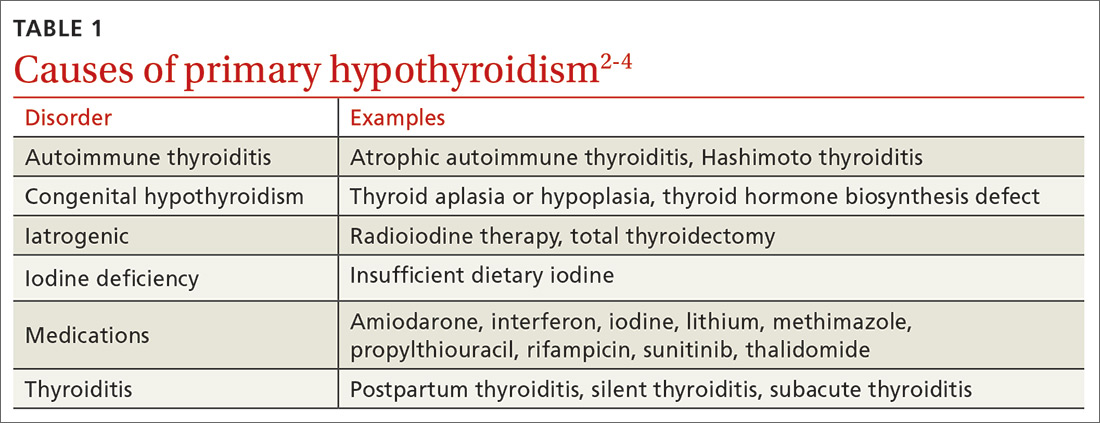

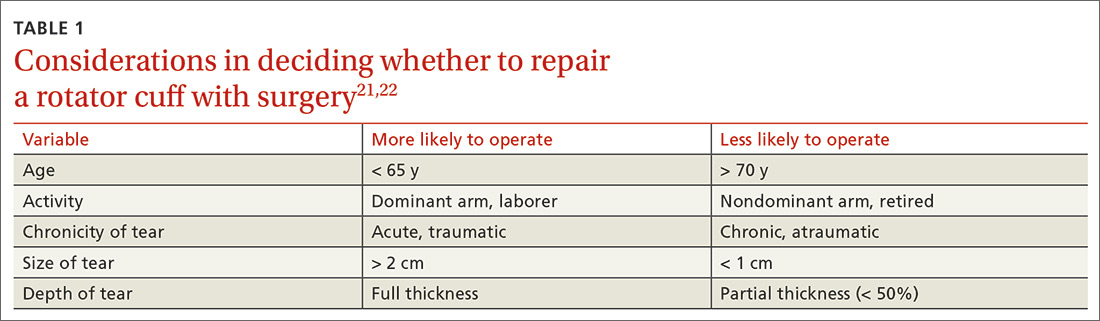

The most common etiologies of hypothyroidism include autoimmune thyroiditis (eg, Hashimoto thyroiditis, atrophic autoimmune thyroiditis) and iatrogenic causes (eg, after radioactive iodine ablation or thyroidectomy) (TABLE 1).2-4

Initiating thyroid hormone replacement

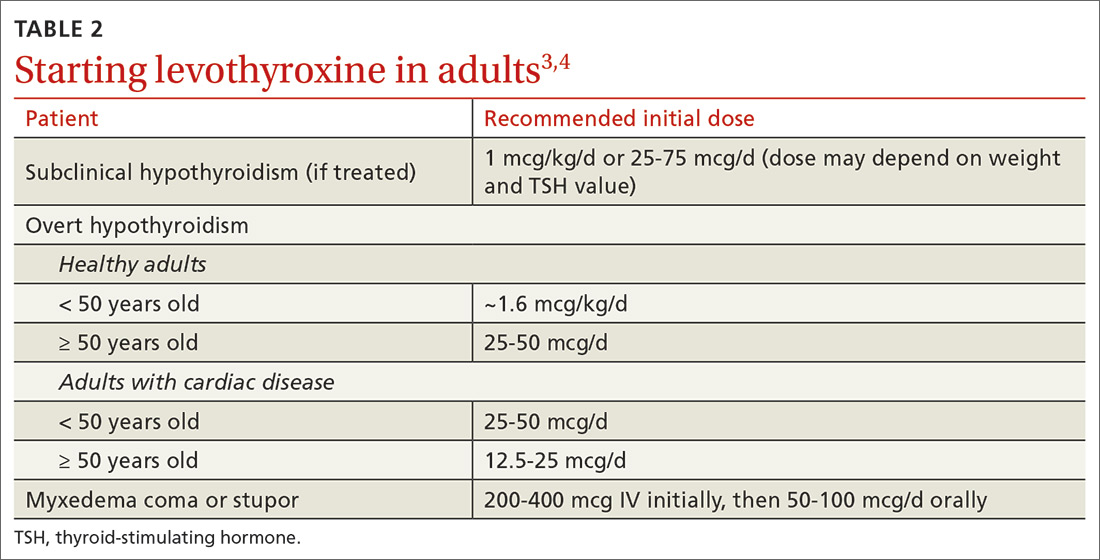

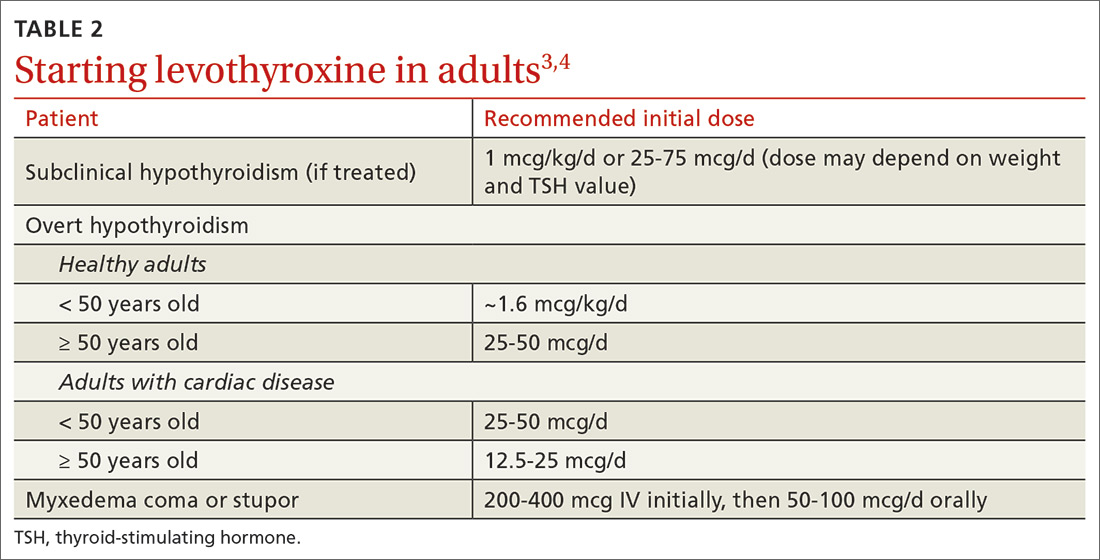

Factors to consider when starting a patient on thyroid hormone replacement include age, weight, symptom severity, TSH level, goal TSH value, adverse effects from thyroid supplements, history of cardiac disease, and, for women of child-bearing age, the desire for pregnancy vs the use of contraceptives. Most adult patients < 50 years with overt hypothyroidism can begin a weight-based dose of levothyroxine: ~1.6 mcg/kg/d (based on ideal body weight).3

Continue to: For adults with cardiac disease...

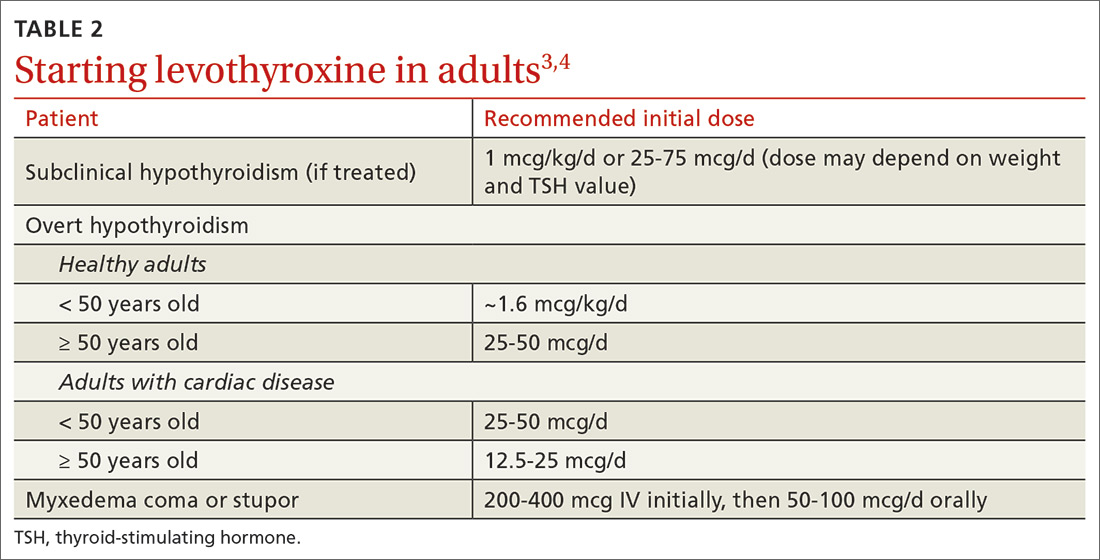

For adults with cardiac disease, the risk of over-replacement limits initial dosing to 25 to 50 mcg/d for patients < 50 years (12.5-25 mcg/d; ≥ 50 years).3 For adults with subclinical hypothyroidism, it is reasonable to begin therapy at a lower daily dose (eg, 25-75 mcg/d) depending on baseline TSH level, symptoms (the patient may be asymptomatic), and the presence of cardiac disease (TABLE 23,4). Consider treatment in patients with subclinical hypothyroidism particularly when patients have a goiter or dyslipidemia and in women contemplating pregnancy in the near future. Elderly patients may require a dose 20% to 25% lower than younger adults because of decreased body mass.3

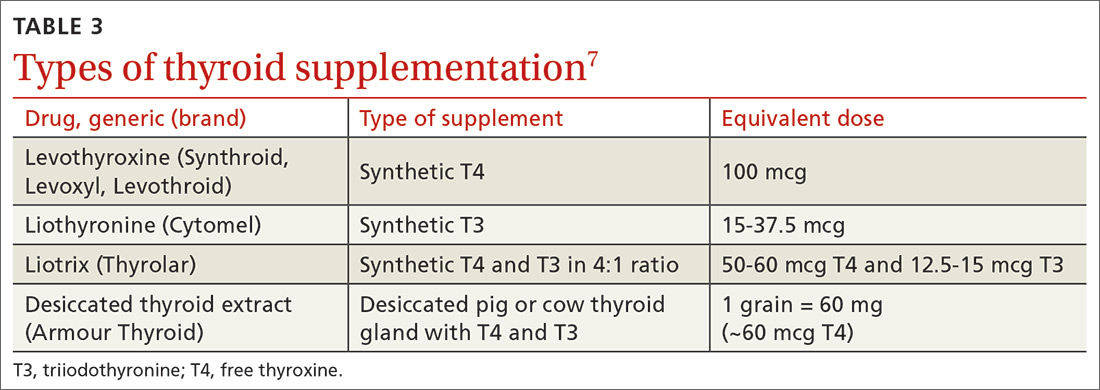

Levothyroxine is considered first-line therapy for hypothyroidism because of its low cost, dose consistency, low risk of allergic reactions, and potential to cause fewer cardiac adverse effects than triiodothyronine (T3) products such as desiccated thyroid extract.5 Although data have not shown an absolute increase in cardiovascular adverse effects, T3 products have a higher T3 vs T4 ratio, giving them a theoretically increased risk.5,6 Desiccated thyroid extract also has been associated with allergic reactions.5

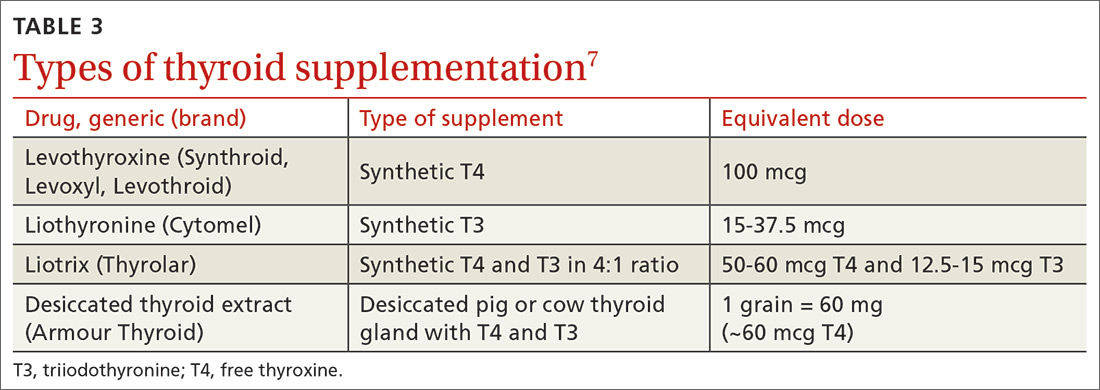

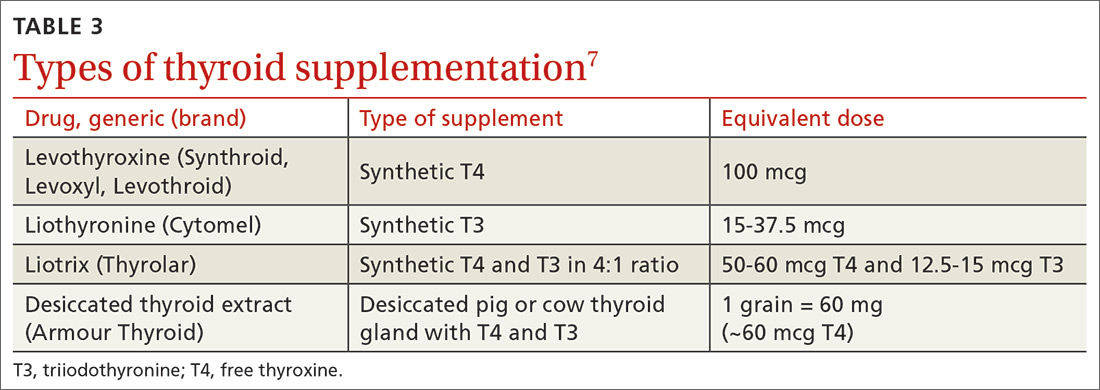

Use of liothyronine alone or in combination with levothyroxine lacks evidence and guideline support.4 Furthermore, it is dosed twice daily, which makes it less convenient, and concerns still exist that there may be an increase in cardiovascular adverse effects.4,6 See TABLE 37 for a summary of available products and their equivalent doses.

Maintaining patients on therapy

The maintenance phase begins once hypothyroidism is diagnosed and treatment is initiated. This phase includes regular monitoring with laboratory studies, office visits, and as-needed adjustments in hormone replacement dosing. The frequency at which all of these occur is variable and based on a number of factors including the patient’s other medical conditions, use of other medications including over-the-counter agents, the patient’s age, weight changes, and pregnancy status.3,4,8 In general, dosage adjustments of 12.5 to 25 mcg can be made at 6- to 8-week intervals based on repeat TSH measurements, patient symptoms, and comorbidities.3

Once a patient is symptomatically stable and laboratory values have normalized, the recommended frequency of laboratory evaluation and office visits is every 12 months, barring significant changes in any of the factors mentioned above. At each visit, physicians should perform medication (including supplements) reconciliation and discuss any health condition updates. Changes to the therapy plan, including frequency or timing of laboratory tests, may be necessary if patients begin taking medications that alter the absorption or function of levothyroxine (eg, steroids).

Continue to: To maximize absorption...

To maximize absorption, providers should review with patients the optimal way to take thyroid hormones. Levothyroxine is approximately 70% to 80% absorbed under ideal conditions, which means taking it in the morning at least 30 to 60 minutes before eating or 3 to 4 hours after the last meal of the day.3,9-13 Of note, TSH levels may increase slightly in patients taking proton pump inhibitors, but this does not usually require a dose increase of thyroid hormone.11 Given that some supplements, particularly iron and calcium, can interfere with absorption, it is recommended to maintain a 3- to 4-hour gap between taking those supplements and taking levothyroxine.12-14 For those patients unable or unwilling to adhere to these recommendations, an increase in levothyroxine dose may be required in order to compensate for the decreased absorption.

Don’t adjust hormone therapy based on clinical presentation alone. While clinical symptoms are important, it is not recommended to adjust hormone therapy based solely on clinical presentation. Common hypothyroid symptoms of dry skin, edema, weight gain, and fatigue may be caused by other medical conditions. While indices including Achilles reflex time and basal metabolic rate have shown some correlation to thyroid dysfunction, there has been limited evidence to show that longitudinal index changes reflect subtle changes in thyroid hormone levels.3

The most recent guidelines from the American Thyroid Association recommend that, “Symptoms should be followed, but considered in the context of serum thyrotropin values, relevant comorbidities, and other potential causes.”3

Special populations/circumstances to keep in mind

Malabsorption conditions. When a higher than expected weight-based dose of levothyroxine is required, physicians should review administration timing, adherence, and comorbid medical conditions that can affect absorption.

Several studies, for example, have demonstrated the impact of Helicobacter pylori gastritis on levothyroxine absorption and subsequent TSH levels.15-17 In one nonrandomized prospective study, patients with H pylori and hypothyroidism who were previously thought to be unresponsive to levothyroxine therapy had a decrease in average TSH level from 30.5 mIU/L to 4.2 mIU/L after H pylori was eradicated.15 Autoimmune atrophic gastritis and celiac disease, both of which are more common in those with other autoimmune diseases, are also associated with the need for higher than expected levothyroxine doses.17,18

Continue to: A history of gastric bypass surgery...

A history of gastric bypass surgery alone is not considered a risk factor for poor absorption of thyroid hormone, given that the majority of levothyroxine absorption occurs in the ileum.19,20 However, advancing age (> 70 years) and extreme obesity (BMI > 40) are independent risk factors for decreased levothyroxine absorption.20,21

Women of reproductive age and pregnant women. Overt untreated or undertreated hypothyroidism can be associated with increased risk of maternal and fetal complications including decreased fertility, miscarriage, preterm delivery, lower birth rates, and infant cognitive deficits.3,22 Therefore, the main focus should be optimization of thyroid hormone levels prior to and during pregnancy.3,4,8,22 Thyroid hormone replacement needs to be increased during pregnancy in approximately 50% to 85% of women using thyroid replacement prior to pregnancy, but the dose requirements vary based on the underlying etiology of thyroid dysfunction.

One initial option for patients on a stable dose before pregnancy is to increase their daily dose by a half tablet (1.5 × daily dose) immediately after home confirmation of pregnancy, until finer dose adjustments (usually increases of 25%-60% ) can be made by a physician. Experts recommend that a TSH level be obtained every 4 weeks until mid-gestation and then at least once around 30 weeks’ gestation to ensure specific targets are being met with dose adjustments.22 Optimal thyrotropin reference ranges during conception and pregnancy can be found in the literature.23

Patients who have positive antibodies and normal thyroid function tests. Patients who are screened for thyroid disorders may demonstrate normal thyroid function (ie, euthyroid) with TSH, free T4, and, if checked, free T3, all within normal ranges. Despite these normal lab results, patients may have additional test results that demonstrate positive thyroid autoantibodies including thyroglobulin antibodies and/or thyroid peroxidase antibodies. Thyroid autoimmunity itself has been associated with a range of other autoimmune conditions as well as an increased risk of thyroid cancer in those with Hashimoto thyroiditis.24 Two studies showed that prophylactic treatment of euthyroid patients with levothyroxine led to a reduction in antibody levels and a lower TSH level.25,26 However, no studies have focused on patient-oriented outcomes such as hospitalizations, quality of life, or symptoms. If the patient remains asymptomatic, we recommend no treatment, but that the patient’s TSH levels be monitored every 12 months.27

Elderly patients. Population data have shown that TSH increases normally with age, with a TSH level of 7.5 mIU/L being the upper limit of normal for a population of healthy adults > 80 years of age.28,29 Overall, studies have failed to show any benefit in treating elderly patients with subclinical hypothyroidism unless their TSH level exceeds 10 mIU/L.6,21 The one exception is elderly patients with heart failure in whom untreated subclinical hypothyroidism has been shown to be associated with higher mortality.30

Continue to: Elderly patients are at higher risk...

Elderly patients are at higher risk for adverse effects of thyroid over-replacement, including atrial fibrillation and osteoporosis. While there have been no randomized trials examining target TSH levels in this population, a reasonable recommendation is a goal TSH level of 4 to 6 mIU/L for elderly patients ≥ 70 years.4

CASE

As a result of the patient’s elevated TSH level and symptoms of hypothyroidism, you start levothyroxine 150 mcg/d by mouth, counsel her on potential adverse effects, and schedule a follow-up visit with another TSH check in 6 weeks.

Follow-up laboratory studies 6 weeks later reveal a TSH level of 5.86 mIU/L (reference range, 0.45-4.5 mIU/L) and a free T4 level of 0.74 ng/dL (reference range, 0.8-2.8 ng/dL). Based on those results, you increase the dose of levothyroxine to 175 mcg/d.

At her follow-up visit 12 weeks after initial presentation, her TSH level is 3.85 mIU/L. She reports feeling better overall with less fatigue, and she has lost 5 pounds since her last visit. You recommend she continue levothyroxine 175 mcg/d after reviewing medication compliance with the patient and ensuring she is indeed taking it in the morning, at least 30 minutes prior to eating. With improved but not resolved symptoms, she agrees to follow-up with repeat TSH laboratory studies in 6 weeks to determine whether further dose adjustments are necessary. Given that she is of reproductive age and her TSH level is suboptimal for pregnancy, you caution her about heightened pregnancy/fetal risks with a suboptimal TSH and recommend that she use reliable contraception.

CORRESPONDENCE

Christopher Bunt, MD, FAAFP, 5 Charleston Center Drive, Suite 263, MSC 192,Charleston, SC 29425; [email protected]

1. Aoki Y, Belin RM, Clickner R, et al. Serum TSH and total T4 in the United States population and their association with participant characteristics: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES 1999-2002). Thyroid. 2007;17:1211-1223.

2. Vaidya B, Pearce SH. Management of hypothyroidism in adults. BMJ. 2008;337:a801.

3. Garber JR, Cobin RH, Gharib H, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for hypothyroidism in adults: cosponsored by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and the American Thyroid Association. Endocr Pract. 2012;18:988-1028.

4. Jonklaas J, Bianco AC, Bauer AJ, et al. Guidelines for the treatment of hypothyroidism: prepared by the American Thyroid Association task force on thyroid hormone replacement. Thyroid. 2014;24:1670-1751.

5. Toft AD. Thyroxine therapy. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:174-180.

6. Floriani C, Gencer B, Collet TH, et al. Subclinical thyroid dysfunction and cardiovascular diseases: 2016 update. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:503-507.

7. Lexi-Comp, Inc. (Lexi-Drugs®). https://online.lexi.com/lco/action/login. Accessed July 7, 2017.

8. Okosieme O, Gilbert J, Abraham P, et al. Management of primary hypothyroidism: statement by the British Thyroid Association Executive Committee. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2016;84:799-808.

9. Fish LH, Schwartz HL, Cavanaugh J, et al. Replacement dose, metabolism, and bioavailability of levothyroxine in the treatment of hypothyroidism. Role of triiodothyronine in pituitary feedback in humans. N Engl J Med. 1987;316:764-770.

10. John-Kalarickal J, Pearlman G, Carlson HE. New medications which decrease levothyroxine absorption. Thyroid. 2007;17:763-765.

11. Sachmechi I, Reich DM, Aninyei M, et al. Effect of proton pump inhibitors on serum thyroid-stimulating hormone level in euthyroid patients treated with levothyroxine for hypothyroidism. Endocr Pract. 2007;13:345-349.

12. Sperber AD, Liel Y. Evidence for interference with the intestinal absorption of levothyroxine sodium by aluminum hydroxide. Arch Intern Med. 1992;152:183-184.

13. Zamfirescu I, Carlson HE. Absorption of levothyroxine when coadministered with various calcium formulations. Thyroid. 2011;21:483-486.

14. Campbell NR, Hasinoff BB, Stalts H, et al. Ferrous sulfate reduces thyroxine efficacy in patients with hypothyroidism. Ann Intern Med. 1992;117:1010-1013.

15. Bugdaci MS, Zuhur SS, Sokmen M, et al. The role of Helicobacter pylori in patients with hypothyroidism in whom could not be achieved normal thyrotropin levels despite treatment with high doses of thyroxine. Helicobacter. 2011;16:124-130.

16. Centanni M, Gargano L, Canettieri G, et al. Thyroxine in goiter, Helicobacter pylori infection, and chronic gastritis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1787-1795.

17. Centanni M, Marignani M, Gargano L, et al. Atrophic body gastritis in patients with autoimmune thyroid disease: an underdiagnosed association. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:1726-1730.

18. Collins D, Wilcox R, Nathan M, et al. Celiac disease and hypothyroidism. Am J Med. 2012;125:278-282.

19. Azizi F, Belur R, Albano J. Malabsorption of thyroid hormones after jejunoileal bypass for obesity. Ann Intern Med. 1979;90:941-942.

20. Gkotsina M, Michalaki M, Mamali I, et al. Improved levothyroxine pharmacokinetics after bariatric surgery. Thyroid. 2013;23:414-419.

21. Hennessey JV, Espaillat R. Diagnosis and management of subclinical hypothyroidism in elderly adults: a review of the literature. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:1663-1673.

22. Alexander EK, Pearce EN, Brent GA, et al. 2017 Guidelines of the American Thyroid Association for the diagnosis and management of thyroid disease during pregnancy and the postpartum. Thyroid. 2017;27:315-389.

23. Carney LA, Quinlan JD, West JM. Thyroid disease in pregnancy. Am Fam Physician. 2014;89:273-278.

24. Fröhlich E, Wahl R. Thyroid autoimmunity: role of anti-thyroid antibodies in thyroid and extra-thyroidal diseases. Front Immunol. 2017;8:521.

25. Aksoy DY, Kerimoglu U, Okur H, et al. Effects of prophylactic thyroid hormone replacement in euthyroid Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Endocr J. 2005;52:337-343.

26. Padberg S, Heller K, Usadel KH, et al. One-year prophylactic treatment of euthyroid Hashimoto’s thyroiditis patients with levothyroxine: is there a benefit? Thyroid. 2001;11:249-255.

27. Rugge B, Balshem H, Sehgal R, et al. Screening and Treatment of Subclinical Hypothyroidism or Hyperthyroidism [Internet]. Comparative Effectiveness Reviews, No. 24. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; October 2011. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK83492/. Accessed February 21, 2020.

28. Hollowell JG, Staehling NW, Flanders WD, et al. Serum TSH, T(4), and thyroid antibodies in the United States population (1988 to 1994): National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III). J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:489-499.

29. Surks MI, Hollowell JG. Age-specific distribution of serum thyrotropin and antithyroid antibodies in the US population: implications for the prevalence of subclinical hypothyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:4575-4582.

30. Pasqualetti G, Tognini S, Polini A, et al. Is subclinical hypothyroidism a cardiovascular risk factor in the elderly? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:2256-2266.

CASE

A 38-year-old woman presents for a routine physical. Other than urgent care visits for 1 episode of influenza and 2 upper respiratory illnesses, she has not seen a physician for a physical in 5 years. She denies any significant medical history. She takes naproxen occasionally for chronic right knee pain. She does not use tobacco or alcohol. Recently, she has started using a meal replacement shake at lunchtime for weight management. She performs aerobic exercise 30 to 40 minutes per day, 5 days per week. Her family history is significant for type 2 diabetes mellitus, arthritis, heart disease, and hyperlipidemia on her mother’s side. She is single, is not currently sexually active, works as a pharmacy technician, and has no children. A high-risk human papillomavirus test was normal 4 years ago.

A review of systems is notable for a 20-pound weight gain over the past year, worsening heartburn over the past 2 weeks, and chronic knee pain, which is greater in the right knee than the left. She denies weakness, fatigue, nausea, diarrhea, constipation, or abdominal pain. Vital signs reveal a blood pressure of 146/88 mm Hg, a heart rate of 63 bpm, a temperature of 98°F (36.7°C), a respiratory rate of 16, a height of 5’7’’ (1.7 m), a weight of 217 lbs (98.4 kg), and a peripheral capillary oxygen saturation (SpO2) of 99% on room air. The physical exam reveals a body mass index (BMI) of 34, warm dry skin, and coarse brittle hair.

Lab results reveal a thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level of 11.17 mIU/L (reference range, 0.45-4.5 mIU/L) and a free thyroxine (T4) of 0.58 ng/dL (reference range, 0.8-2.8 ng/dL). A basic metabolic panel and hemoglobin A1C level are normal.

What would you recommend?

In the United States, the prevalence of overt hypothyroidism (defined as a TSH level > 4.5 mIU/L and a low free T4) among people ≥ 12 years of age was estimated at 0.3% based on National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data from 1999-2002.1 Subclinical hypothyroidism (TSH level > 4.5 mIU/L but < 10 mIU/L and a normal T4 level) is even more common, with an estimated prevalence of 3.4%.1 Hypothyroidism is more common in females and occurs more frequently in Caucasian Americans and Mexican Americans than in African Americans.1

The most common etiologies of hypothyroidism include autoimmune thyroiditis (eg, Hashimoto thyroiditis, atrophic autoimmune thyroiditis) and iatrogenic causes (eg, after radioactive iodine ablation or thyroidectomy) (TABLE 1).2-4

Initiating thyroid hormone replacement

Factors to consider when starting a patient on thyroid hormone replacement include age, weight, symptom severity, TSH level, goal TSH value, adverse effects from thyroid supplements, history of cardiac disease, and, for women of child-bearing age, the desire for pregnancy vs the use of contraceptives. Most adult patients < 50 years with overt hypothyroidism can begin a weight-based dose of levothyroxine: ~1.6 mcg/kg/d (based on ideal body weight).3

Continue to: For adults with cardiac disease...

For adults with cardiac disease, the risk of over-replacement limits initial dosing to 25 to 50 mcg/d for patients < 50 years (12.5-25 mcg/d; ≥ 50 years).3 For adults with subclinical hypothyroidism, it is reasonable to begin therapy at a lower daily dose (eg, 25-75 mcg/d) depending on baseline TSH level, symptoms (the patient may be asymptomatic), and the presence of cardiac disease (TABLE 23,4). Consider treatment in patients with subclinical hypothyroidism particularly when patients have a goiter or dyslipidemia and in women contemplating pregnancy in the near future. Elderly patients may require a dose 20% to 25% lower than younger adults because of decreased body mass.3

Levothyroxine is considered first-line therapy for hypothyroidism because of its low cost, dose consistency, low risk of allergic reactions, and potential to cause fewer cardiac adverse effects than triiodothyronine (T3) products such as desiccated thyroid extract.5 Although data have not shown an absolute increase in cardiovascular adverse effects, T3 products have a higher T3 vs T4 ratio, giving them a theoretically increased risk.5,6 Desiccated thyroid extract also has been associated with allergic reactions.5

Use of liothyronine alone or in combination with levothyroxine lacks evidence and guideline support.4 Furthermore, it is dosed twice daily, which makes it less convenient, and concerns still exist that there may be an increase in cardiovascular adverse effects.4,6 See TABLE 37 for a summary of available products and their equivalent doses.

Maintaining patients on therapy

The maintenance phase begins once hypothyroidism is diagnosed and treatment is initiated. This phase includes regular monitoring with laboratory studies, office visits, and as-needed adjustments in hormone replacement dosing. The frequency at which all of these occur is variable and based on a number of factors including the patient’s other medical conditions, use of other medications including over-the-counter agents, the patient’s age, weight changes, and pregnancy status.3,4,8 In general, dosage adjustments of 12.5 to 25 mcg can be made at 6- to 8-week intervals based on repeat TSH measurements, patient symptoms, and comorbidities.3

Once a patient is symptomatically stable and laboratory values have normalized, the recommended frequency of laboratory evaluation and office visits is every 12 months, barring significant changes in any of the factors mentioned above. At each visit, physicians should perform medication (including supplements) reconciliation and discuss any health condition updates. Changes to the therapy plan, including frequency or timing of laboratory tests, may be necessary if patients begin taking medications that alter the absorption or function of levothyroxine (eg, steroids).

Continue to: To maximize absorption...

To maximize absorption, providers should review with patients the optimal way to take thyroid hormones. Levothyroxine is approximately 70% to 80% absorbed under ideal conditions, which means taking it in the morning at least 30 to 60 minutes before eating or 3 to 4 hours after the last meal of the day.3,9-13 Of note, TSH levels may increase slightly in patients taking proton pump inhibitors, but this does not usually require a dose increase of thyroid hormone.11 Given that some supplements, particularly iron and calcium, can interfere with absorption, it is recommended to maintain a 3- to 4-hour gap between taking those supplements and taking levothyroxine.12-14 For those patients unable or unwilling to adhere to these recommendations, an increase in levothyroxine dose may be required in order to compensate for the decreased absorption.

Don’t adjust hormone therapy based on clinical presentation alone. While clinical symptoms are important, it is not recommended to adjust hormone therapy based solely on clinical presentation. Common hypothyroid symptoms of dry skin, edema, weight gain, and fatigue may be caused by other medical conditions. While indices including Achilles reflex time and basal metabolic rate have shown some correlation to thyroid dysfunction, there has been limited evidence to show that longitudinal index changes reflect subtle changes in thyroid hormone levels.3

The most recent guidelines from the American Thyroid Association recommend that, “Symptoms should be followed, but considered in the context of serum thyrotropin values, relevant comorbidities, and other potential causes.”3

Special populations/circumstances to keep in mind

Malabsorption conditions. When a higher than expected weight-based dose of levothyroxine is required, physicians should review administration timing, adherence, and comorbid medical conditions that can affect absorption.

Several studies, for example, have demonstrated the impact of Helicobacter pylori gastritis on levothyroxine absorption and subsequent TSH levels.15-17 In one nonrandomized prospective study, patients with H pylori and hypothyroidism who were previously thought to be unresponsive to levothyroxine therapy had a decrease in average TSH level from 30.5 mIU/L to 4.2 mIU/L after H pylori was eradicated.15 Autoimmune atrophic gastritis and celiac disease, both of which are more common in those with other autoimmune diseases, are also associated with the need for higher than expected levothyroxine doses.17,18

Continue to: A history of gastric bypass surgery...

A history of gastric bypass surgery alone is not considered a risk factor for poor absorption of thyroid hormone, given that the majority of levothyroxine absorption occurs in the ileum.19,20 However, advancing age (> 70 years) and extreme obesity (BMI > 40) are independent risk factors for decreased levothyroxine absorption.20,21

Women of reproductive age and pregnant women. Overt untreated or undertreated hypothyroidism can be associated with increased risk of maternal and fetal complications including decreased fertility, miscarriage, preterm delivery, lower birth rates, and infant cognitive deficits.3,22 Therefore, the main focus should be optimization of thyroid hormone levels prior to and during pregnancy.3,4,8,22 Thyroid hormone replacement needs to be increased during pregnancy in approximately 50% to 85% of women using thyroid replacement prior to pregnancy, but the dose requirements vary based on the underlying etiology of thyroid dysfunction.

One initial option for patients on a stable dose before pregnancy is to increase their daily dose by a half tablet (1.5 × daily dose) immediately after home confirmation of pregnancy, until finer dose adjustments (usually increases of 25%-60% ) can be made by a physician. Experts recommend that a TSH level be obtained every 4 weeks until mid-gestation and then at least once around 30 weeks’ gestation to ensure specific targets are being met with dose adjustments.22 Optimal thyrotropin reference ranges during conception and pregnancy can be found in the literature.23

Patients who have positive antibodies and normal thyroid function tests. Patients who are screened for thyroid disorders may demonstrate normal thyroid function (ie, euthyroid) with TSH, free T4, and, if checked, free T3, all within normal ranges. Despite these normal lab results, patients may have additional test results that demonstrate positive thyroid autoantibodies including thyroglobulin antibodies and/or thyroid peroxidase antibodies. Thyroid autoimmunity itself has been associated with a range of other autoimmune conditions as well as an increased risk of thyroid cancer in those with Hashimoto thyroiditis.24 Two studies showed that prophylactic treatment of euthyroid patients with levothyroxine led to a reduction in antibody levels and a lower TSH level.25,26 However, no studies have focused on patient-oriented outcomes such as hospitalizations, quality of life, or symptoms. If the patient remains asymptomatic, we recommend no treatment, but that the patient’s TSH levels be monitored every 12 months.27

Elderly patients. Population data have shown that TSH increases normally with age, with a TSH level of 7.5 mIU/L being the upper limit of normal for a population of healthy adults > 80 years of age.28,29 Overall, studies have failed to show any benefit in treating elderly patients with subclinical hypothyroidism unless their TSH level exceeds 10 mIU/L.6,21 The one exception is elderly patients with heart failure in whom untreated subclinical hypothyroidism has been shown to be associated with higher mortality.30

Continue to: Elderly patients are at higher risk...

Elderly patients are at higher risk for adverse effects of thyroid over-replacement, including atrial fibrillation and osteoporosis. While there have been no randomized trials examining target TSH levels in this population, a reasonable recommendation is a goal TSH level of 4 to 6 mIU/L for elderly patients ≥ 70 years.4

CASE

As a result of the patient’s elevated TSH level and symptoms of hypothyroidism, you start levothyroxine 150 mcg/d by mouth, counsel her on potential adverse effects, and schedule a follow-up visit with another TSH check in 6 weeks.

Follow-up laboratory studies 6 weeks later reveal a TSH level of 5.86 mIU/L (reference range, 0.45-4.5 mIU/L) and a free T4 level of 0.74 ng/dL (reference range, 0.8-2.8 ng/dL). Based on those results, you increase the dose of levothyroxine to 175 mcg/d.

At her follow-up visit 12 weeks after initial presentation, her TSH level is 3.85 mIU/L. She reports feeling better overall with less fatigue, and she has lost 5 pounds since her last visit. You recommend she continue levothyroxine 175 mcg/d after reviewing medication compliance with the patient and ensuring she is indeed taking it in the morning, at least 30 minutes prior to eating. With improved but not resolved symptoms, she agrees to follow-up with repeat TSH laboratory studies in 6 weeks to determine whether further dose adjustments are necessary. Given that she is of reproductive age and her TSH level is suboptimal for pregnancy, you caution her about heightened pregnancy/fetal risks with a suboptimal TSH and recommend that she use reliable contraception.

CORRESPONDENCE

Christopher Bunt, MD, FAAFP, 5 Charleston Center Drive, Suite 263, MSC 192,Charleston, SC 29425; [email protected]

CASE

A 38-year-old woman presents for a routine physical. Other than urgent care visits for 1 episode of influenza and 2 upper respiratory illnesses, she has not seen a physician for a physical in 5 years. She denies any significant medical history. She takes naproxen occasionally for chronic right knee pain. She does not use tobacco or alcohol. Recently, she has started using a meal replacement shake at lunchtime for weight management. She performs aerobic exercise 30 to 40 minutes per day, 5 days per week. Her family history is significant for type 2 diabetes mellitus, arthritis, heart disease, and hyperlipidemia on her mother’s side. She is single, is not currently sexually active, works as a pharmacy technician, and has no children. A high-risk human papillomavirus test was normal 4 years ago.

A review of systems is notable for a 20-pound weight gain over the past year, worsening heartburn over the past 2 weeks, and chronic knee pain, which is greater in the right knee than the left. She denies weakness, fatigue, nausea, diarrhea, constipation, or abdominal pain. Vital signs reveal a blood pressure of 146/88 mm Hg, a heart rate of 63 bpm, a temperature of 98°F (36.7°C), a respiratory rate of 16, a height of 5’7’’ (1.7 m), a weight of 217 lbs (98.4 kg), and a peripheral capillary oxygen saturation (SpO2) of 99% on room air. The physical exam reveals a body mass index (BMI) of 34, warm dry skin, and coarse brittle hair.

Lab results reveal a thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level of 11.17 mIU/L (reference range, 0.45-4.5 mIU/L) and a free thyroxine (T4) of 0.58 ng/dL (reference range, 0.8-2.8 ng/dL). A basic metabolic panel and hemoglobin A1C level are normal.

What would you recommend?

In the United States, the prevalence of overt hypothyroidism (defined as a TSH level > 4.5 mIU/L and a low free T4) among people ≥ 12 years of age was estimated at 0.3% based on National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data from 1999-2002.1 Subclinical hypothyroidism (TSH level > 4.5 mIU/L but < 10 mIU/L and a normal T4 level) is even more common, with an estimated prevalence of 3.4%.1 Hypothyroidism is more common in females and occurs more frequently in Caucasian Americans and Mexican Americans than in African Americans.1

The most common etiologies of hypothyroidism include autoimmune thyroiditis (eg, Hashimoto thyroiditis, atrophic autoimmune thyroiditis) and iatrogenic causes (eg, after radioactive iodine ablation or thyroidectomy) (TABLE 1).2-4

Initiating thyroid hormone replacement

Factors to consider when starting a patient on thyroid hormone replacement include age, weight, symptom severity, TSH level, goal TSH value, adverse effects from thyroid supplements, history of cardiac disease, and, for women of child-bearing age, the desire for pregnancy vs the use of contraceptives. Most adult patients < 50 years with overt hypothyroidism can begin a weight-based dose of levothyroxine: ~1.6 mcg/kg/d (based on ideal body weight).3

Continue to: For adults with cardiac disease...

For adults with cardiac disease, the risk of over-replacement limits initial dosing to 25 to 50 mcg/d for patients < 50 years (12.5-25 mcg/d; ≥ 50 years).3 For adults with subclinical hypothyroidism, it is reasonable to begin therapy at a lower daily dose (eg, 25-75 mcg/d) depending on baseline TSH level, symptoms (the patient may be asymptomatic), and the presence of cardiac disease (TABLE 23,4). Consider treatment in patients with subclinical hypothyroidism particularly when patients have a goiter or dyslipidemia and in women contemplating pregnancy in the near future. Elderly patients may require a dose 20% to 25% lower than younger adults because of decreased body mass.3

Levothyroxine is considered first-line therapy for hypothyroidism because of its low cost, dose consistency, low risk of allergic reactions, and potential to cause fewer cardiac adverse effects than triiodothyronine (T3) products such as desiccated thyroid extract.5 Although data have not shown an absolute increase in cardiovascular adverse effects, T3 products have a higher T3 vs T4 ratio, giving them a theoretically increased risk.5,6 Desiccated thyroid extract also has been associated with allergic reactions.5

Use of liothyronine alone or in combination with levothyroxine lacks evidence and guideline support.4 Furthermore, it is dosed twice daily, which makes it less convenient, and concerns still exist that there may be an increase in cardiovascular adverse effects.4,6 See TABLE 37 for a summary of available products and their equivalent doses.

Maintaining patients on therapy

The maintenance phase begins once hypothyroidism is diagnosed and treatment is initiated. This phase includes regular monitoring with laboratory studies, office visits, and as-needed adjustments in hormone replacement dosing. The frequency at which all of these occur is variable and based on a number of factors including the patient’s other medical conditions, use of other medications including over-the-counter agents, the patient’s age, weight changes, and pregnancy status.3,4,8 In general, dosage adjustments of 12.5 to 25 mcg can be made at 6- to 8-week intervals based on repeat TSH measurements, patient symptoms, and comorbidities.3

Once a patient is symptomatically stable and laboratory values have normalized, the recommended frequency of laboratory evaluation and office visits is every 12 months, barring significant changes in any of the factors mentioned above. At each visit, physicians should perform medication (including supplements) reconciliation and discuss any health condition updates. Changes to the therapy plan, including frequency or timing of laboratory tests, may be necessary if patients begin taking medications that alter the absorption or function of levothyroxine (eg, steroids).

Continue to: To maximize absorption...

To maximize absorption, providers should review with patients the optimal way to take thyroid hormones. Levothyroxine is approximately 70% to 80% absorbed under ideal conditions, which means taking it in the morning at least 30 to 60 minutes before eating or 3 to 4 hours after the last meal of the day.3,9-13 Of note, TSH levels may increase slightly in patients taking proton pump inhibitors, but this does not usually require a dose increase of thyroid hormone.11 Given that some supplements, particularly iron and calcium, can interfere with absorption, it is recommended to maintain a 3- to 4-hour gap between taking those supplements and taking levothyroxine.12-14 For those patients unable or unwilling to adhere to these recommendations, an increase in levothyroxine dose may be required in order to compensate for the decreased absorption.

Don’t adjust hormone therapy based on clinical presentation alone. While clinical symptoms are important, it is not recommended to adjust hormone therapy based solely on clinical presentation. Common hypothyroid symptoms of dry skin, edema, weight gain, and fatigue may be caused by other medical conditions. While indices including Achilles reflex time and basal metabolic rate have shown some correlation to thyroid dysfunction, there has been limited evidence to show that longitudinal index changes reflect subtle changes in thyroid hormone levels.3

The most recent guidelines from the American Thyroid Association recommend that, “Symptoms should be followed, but considered in the context of serum thyrotropin values, relevant comorbidities, and other potential causes.”3

Special populations/circumstances to keep in mind

Malabsorption conditions. When a higher than expected weight-based dose of levothyroxine is required, physicians should review administration timing, adherence, and comorbid medical conditions that can affect absorption.

Several studies, for example, have demonstrated the impact of Helicobacter pylori gastritis on levothyroxine absorption and subsequent TSH levels.15-17 In one nonrandomized prospective study, patients with H pylori and hypothyroidism who were previously thought to be unresponsive to levothyroxine therapy had a decrease in average TSH level from 30.5 mIU/L to 4.2 mIU/L after H pylori was eradicated.15 Autoimmune atrophic gastritis and celiac disease, both of which are more common in those with other autoimmune diseases, are also associated with the need for higher than expected levothyroxine doses.17,18

Continue to: A history of gastric bypass surgery...

A history of gastric bypass surgery alone is not considered a risk factor for poor absorption of thyroid hormone, given that the majority of levothyroxine absorption occurs in the ileum.19,20 However, advancing age (> 70 years) and extreme obesity (BMI > 40) are independent risk factors for decreased levothyroxine absorption.20,21

Women of reproductive age and pregnant women. Overt untreated or undertreated hypothyroidism can be associated with increased risk of maternal and fetal complications including decreased fertility, miscarriage, preterm delivery, lower birth rates, and infant cognitive deficits.3,22 Therefore, the main focus should be optimization of thyroid hormone levels prior to and during pregnancy.3,4,8,22 Thyroid hormone replacement needs to be increased during pregnancy in approximately 50% to 85% of women using thyroid replacement prior to pregnancy, but the dose requirements vary based on the underlying etiology of thyroid dysfunction.

One initial option for patients on a stable dose before pregnancy is to increase their daily dose by a half tablet (1.5 × daily dose) immediately after home confirmation of pregnancy, until finer dose adjustments (usually increases of 25%-60% ) can be made by a physician. Experts recommend that a TSH level be obtained every 4 weeks until mid-gestation and then at least once around 30 weeks’ gestation to ensure specific targets are being met with dose adjustments.22 Optimal thyrotropin reference ranges during conception and pregnancy can be found in the literature.23

Patients who have positive antibodies and normal thyroid function tests. Patients who are screened for thyroid disorders may demonstrate normal thyroid function (ie, euthyroid) with TSH, free T4, and, if checked, free T3, all within normal ranges. Despite these normal lab results, patients may have additional test results that demonstrate positive thyroid autoantibodies including thyroglobulin antibodies and/or thyroid peroxidase antibodies. Thyroid autoimmunity itself has been associated with a range of other autoimmune conditions as well as an increased risk of thyroid cancer in those with Hashimoto thyroiditis.24 Two studies showed that prophylactic treatment of euthyroid patients with levothyroxine led to a reduction in antibody levels and a lower TSH level.25,26 However, no studies have focused on patient-oriented outcomes such as hospitalizations, quality of life, or symptoms. If the patient remains asymptomatic, we recommend no treatment, but that the patient’s TSH levels be monitored every 12 months.27

Elderly patients. Population data have shown that TSH increases normally with age, with a TSH level of 7.5 mIU/L being the upper limit of normal for a population of healthy adults > 80 years of age.28,29 Overall, studies have failed to show any benefit in treating elderly patients with subclinical hypothyroidism unless their TSH level exceeds 10 mIU/L.6,21 The one exception is elderly patients with heart failure in whom untreated subclinical hypothyroidism has been shown to be associated with higher mortality.30

Continue to: Elderly patients are at higher risk...

Elderly patients are at higher risk for adverse effects of thyroid over-replacement, including atrial fibrillation and osteoporosis. While there have been no randomized trials examining target TSH levels in this population, a reasonable recommendation is a goal TSH level of 4 to 6 mIU/L for elderly patients ≥ 70 years.4

CASE

As a result of the patient’s elevated TSH level and symptoms of hypothyroidism, you start levothyroxine 150 mcg/d by mouth, counsel her on potential adverse effects, and schedule a follow-up visit with another TSH check in 6 weeks.

Follow-up laboratory studies 6 weeks later reveal a TSH level of 5.86 mIU/L (reference range, 0.45-4.5 mIU/L) and a free T4 level of 0.74 ng/dL (reference range, 0.8-2.8 ng/dL). Based on those results, you increase the dose of levothyroxine to 175 mcg/d.

At her follow-up visit 12 weeks after initial presentation, her TSH level is 3.85 mIU/L. She reports feeling better overall with less fatigue, and she has lost 5 pounds since her last visit. You recommend she continue levothyroxine 175 mcg/d after reviewing medication compliance with the patient and ensuring she is indeed taking it in the morning, at least 30 minutes prior to eating. With improved but not resolved symptoms, she agrees to follow-up with repeat TSH laboratory studies in 6 weeks to determine whether further dose adjustments are necessary. Given that she is of reproductive age and her TSH level is suboptimal for pregnancy, you caution her about heightened pregnancy/fetal risks with a suboptimal TSH and recommend that she use reliable contraception.

CORRESPONDENCE

Christopher Bunt, MD, FAAFP, 5 Charleston Center Drive, Suite 263, MSC 192,Charleston, SC 29425; [email protected]

1. Aoki Y, Belin RM, Clickner R, et al. Serum TSH and total T4 in the United States population and their association with participant characteristics: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES 1999-2002). Thyroid. 2007;17:1211-1223.

2. Vaidya B, Pearce SH. Management of hypothyroidism in adults. BMJ. 2008;337:a801.

3. Garber JR, Cobin RH, Gharib H, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for hypothyroidism in adults: cosponsored by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and the American Thyroid Association. Endocr Pract. 2012;18:988-1028.

4. Jonklaas J, Bianco AC, Bauer AJ, et al. Guidelines for the treatment of hypothyroidism: prepared by the American Thyroid Association task force on thyroid hormone replacement. Thyroid. 2014;24:1670-1751.

5. Toft AD. Thyroxine therapy. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:174-180.

6. Floriani C, Gencer B, Collet TH, et al. Subclinical thyroid dysfunction and cardiovascular diseases: 2016 update. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:503-507.

7. Lexi-Comp, Inc. (Lexi-Drugs®). https://online.lexi.com/lco/action/login. Accessed July 7, 2017.

8. Okosieme O, Gilbert J, Abraham P, et al. Management of primary hypothyroidism: statement by the British Thyroid Association Executive Committee. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2016;84:799-808.

9. Fish LH, Schwartz HL, Cavanaugh J, et al. Replacement dose, metabolism, and bioavailability of levothyroxine in the treatment of hypothyroidism. Role of triiodothyronine in pituitary feedback in humans. N Engl J Med. 1987;316:764-770.

10. John-Kalarickal J, Pearlman G, Carlson HE. New medications which decrease levothyroxine absorption. Thyroid. 2007;17:763-765.

11. Sachmechi I, Reich DM, Aninyei M, et al. Effect of proton pump inhibitors on serum thyroid-stimulating hormone level in euthyroid patients treated with levothyroxine for hypothyroidism. Endocr Pract. 2007;13:345-349.

12. Sperber AD, Liel Y. Evidence for interference with the intestinal absorption of levothyroxine sodium by aluminum hydroxide. Arch Intern Med. 1992;152:183-184.

13. Zamfirescu I, Carlson HE. Absorption of levothyroxine when coadministered with various calcium formulations. Thyroid. 2011;21:483-486.

14. Campbell NR, Hasinoff BB, Stalts H, et al. Ferrous sulfate reduces thyroxine efficacy in patients with hypothyroidism. Ann Intern Med. 1992;117:1010-1013.

15. Bugdaci MS, Zuhur SS, Sokmen M, et al. The role of Helicobacter pylori in patients with hypothyroidism in whom could not be achieved normal thyrotropin levels despite treatment with high doses of thyroxine. Helicobacter. 2011;16:124-130.

16. Centanni M, Gargano L, Canettieri G, et al. Thyroxine in goiter, Helicobacter pylori infection, and chronic gastritis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1787-1795.

17. Centanni M, Marignani M, Gargano L, et al. Atrophic body gastritis in patients with autoimmune thyroid disease: an underdiagnosed association. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:1726-1730.

18. Collins D, Wilcox R, Nathan M, et al. Celiac disease and hypothyroidism. Am J Med. 2012;125:278-282.

19. Azizi F, Belur R, Albano J. Malabsorption of thyroid hormones after jejunoileal bypass for obesity. Ann Intern Med. 1979;90:941-942.

20. Gkotsina M, Michalaki M, Mamali I, et al. Improved levothyroxine pharmacokinetics after bariatric surgery. Thyroid. 2013;23:414-419.

21. Hennessey JV, Espaillat R. Diagnosis and management of subclinical hypothyroidism in elderly adults: a review of the literature. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:1663-1673.

22. Alexander EK, Pearce EN, Brent GA, et al. 2017 Guidelines of the American Thyroid Association for the diagnosis and management of thyroid disease during pregnancy and the postpartum. Thyroid. 2017;27:315-389.

23. Carney LA, Quinlan JD, West JM. Thyroid disease in pregnancy. Am Fam Physician. 2014;89:273-278.

24. Fröhlich E, Wahl R. Thyroid autoimmunity: role of anti-thyroid antibodies in thyroid and extra-thyroidal diseases. Front Immunol. 2017;8:521.

25. Aksoy DY, Kerimoglu U, Okur H, et al. Effects of prophylactic thyroid hormone replacement in euthyroid Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Endocr J. 2005;52:337-343.

26. Padberg S, Heller K, Usadel KH, et al. One-year prophylactic treatment of euthyroid Hashimoto’s thyroiditis patients with levothyroxine: is there a benefit? Thyroid. 2001;11:249-255.

27. Rugge B, Balshem H, Sehgal R, et al. Screening and Treatment of Subclinical Hypothyroidism or Hyperthyroidism [Internet]. Comparative Effectiveness Reviews, No. 24. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; October 2011. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK83492/. Accessed February 21, 2020.

28. Hollowell JG, Staehling NW, Flanders WD, et al. Serum TSH, T(4), and thyroid antibodies in the United States population (1988 to 1994): National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III). J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:489-499.

29. Surks MI, Hollowell JG. Age-specific distribution of serum thyrotropin and antithyroid antibodies in the US population: implications for the prevalence of subclinical hypothyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:4575-4582.

30. Pasqualetti G, Tognini S, Polini A, et al. Is subclinical hypothyroidism a cardiovascular risk factor in the elderly? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:2256-2266.

1. Aoki Y, Belin RM, Clickner R, et al. Serum TSH and total T4 in the United States population and their association with participant characteristics: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES 1999-2002). Thyroid. 2007;17:1211-1223.

2. Vaidya B, Pearce SH. Management of hypothyroidism in adults. BMJ. 2008;337:a801.

3. Garber JR, Cobin RH, Gharib H, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for hypothyroidism in adults: cosponsored by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and the American Thyroid Association. Endocr Pract. 2012;18:988-1028.

4. Jonklaas J, Bianco AC, Bauer AJ, et al. Guidelines for the treatment of hypothyroidism: prepared by the American Thyroid Association task force on thyroid hormone replacement. Thyroid. 2014;24:1670-1751.

5. Toft AD. Thyroxine therapy. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:174-180.

6. Floriani C, Gencer B, Collet TH, et al. Subclinical thyroid dysfunction and cardiovascular diseases: 2016 update. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:503-507.

7. Lexi-Comp, Inc. (Lexi-Drugs®). https://online.lexi.com/lco/action/login. Accessed July 7, 2017.

8. Okosieme O, Gilbert J, Abraham P, et al. Management of primary hypothyroidism: statement by the British Thyroid Association Executive Committee. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2016;84:799-808.

9. Fish LH, Schwartz HL, Cavanaugh J, et al. Replacement dose, metabolism, and bioavailability of levothyroxine in the treatment of hypothyroidism. Role of triiodothyronine in pituitary feedback in humans. N Engl J Med. 1987;316:764-770.

10. John-Kalarickal J, Pearlman G, Carlson HE. New medications which decrease levothyroxine absorption. Thyroid. 2007;17:763-765.

11. Sachmechi I, Reich DM, Aninyei M, et al. Effect of proton pump inhibitors on serum thyroid-stimulating hormone level in euthyroid patients treated with levothyroxine for hypothyroidism. Endocr Pract. 2007;13:345-349.

12. Sperber AD, Liel Y. Evidence for interference with the intestinal absorption of levothyroxine sodium by aluminum hydroxide. Arch Intern Med. 1992;152:183-184.

13. Zamfirescu I, Carlson HE. Absorption of levothyroxine when coadministered with various calcium formulations. Thyroid. 2011;21:483-486.

14. Campbell NR, Hasinoff BB, Stalts H, et al. Ferrous sulfate reduces thyroxine efficacy in patients with hypothyroidism. Ann Intern Med. 1992;117:1010-1013.

15. Bugdaci MS, Zuhur SS, Sokmen M, et al. The role of Helicobacter pylori in patients with hypothyroidism in whom could not be achieved normal thyrotropin levels despite treatment with high doses of thyroxine. Helicobacter. 2011;16:124-130.

16. Centanni M, Gargano L, Canettieri G, et al. Thyroxine in goiter, Helicobacter pylori infection, and chronic gastritis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1787-1795.

17. Centanni M, Marignani M, Gargano L, et al. Atrophic body gastritis in patients with autoimmune thyroid disease: an underdiagnosed association. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:1726-1730.

18. Collins D, Wilcox R, Nathan M, et al. Celiac disease and hypothyroidism. Am J Med. 2012;125:278-282.

19. Azizi F, Belur R, Albano J. Malabsorption of thyroid hormones after jejunoileal bypass for obesity. Ann Intern Med. 1979;90:941-942.

20. Gkotsina M, Michalaki M, Mamali I, et al. Improved levothyroxine pharmacokinetics after bariatric surgery. Thyroid. 2013;23:414-419.

21. Hennessey JV, Espaillat R. Diagnosis and management of subclinical hypothyroidism in elderly adults: a review of the literature. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:1663-1673.

22. Alexander EK, Pearce EN, Brent GA, et al. 2017 Guidelines of the American Thyroid Association for the diagnosis and management of thyroid disease during pregnancy and the postpartum. Thyroid. 2017;27:315-389.

23. Carney LA, Quinlan JD, West JM. Thyroid disease in pregnancy. Am Fam Physician. 2014;89:273-278.

24. Fröhlich E, Wahl R. Thyroid autoimmunity: role of anti-thyroid antibodies in thyroid and extra-thyroidal diseases. Front Immunol. 2017;8:521.

25. Aksoy DY, Kerimoglu U, Okur H, et al. Effects of prophylactic thyroid hormone replacement in euthyroid Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Endocr J. 2005;52:337-343.

26. Padberg S, Heller K, Usadel KH, et al. One-year prophylactic treatment of euthyroid Hashimoto’s thyroiditis patients with levothyroxine: is there a benefit? Thyroid. 2001;11:249-255.

27. Rugge B, Balshem H, Sehgal R, et al. Screening and Treatment of Subclinical Hypothyroidism or Hyperthyroidism [Internet]. Comparative Effectiveness Reviews, No. 24. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; October 2011. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK83492/. Accessed February 21, 2020.

28. Hollowell JG, Staehling NW, Flanders WD, et al. Serum TSH, T(4), and thyroid antibodies in the United States population (1988 to 1994): National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III). J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:489-499.

29. Surks MI, Hollowell JG. Age-specific distribution of serum thyrotropin and antithyroid antibodies in the US population: implications for the prevalence of subclinical hypothyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:4575-4582.

30. Pasqualetti G, Tognini S, Polini A, et al. Is subclinical hypothyroidism a cardiovascular risk factor in the elderly? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:2256-2266.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

› Prescribe levothyroxine 1.6 mcg/kg/d for healthy adult patients < 50 years of age with overt hypothyroidism. B

› Consider lower initial doses of levothyroxine in patients with cardiac disease (12.5-50 mcg/d) or subclinical hypothyroidism (25-75 mcg/d). B

› Titrate levothyroxine by 12.5 to 25 mcg/d at 6- to 8-week intervals based on thyroid-stimulating hormone measurements, comorbidities, and symptoms. C

› Closely monitor and provide thyroid supplementation to female patients who are pregnant or of reproductive age with concomitant hypothyroidism. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Intervention improves antibiotics use in UTIs

A multifaceted intervention significantly changed clinicians’ use of antibiotics to treat urinary tract infections (UTIs) in children, according to data from more than 2,000 cases observed between January 2014 and September 2018.

“Changing clinicians’ antibiotic prescribing practices can be challenging; barriers to change include lack of awareness of new evidence, competing clinical demands, and concern about treatment failure,” wrote Matthew F. Daley, MD, of Kaiser Permanente Colorado, Aurora, and colleagues in Pediatrics.

To promote judicious antibiotic use, the researchers designed an intervention including the development of new local UTI guidelines; a live, case-based educational session; emailed knowledge assessments before and after the session; and a specific UTI order set in the EHR.

The researchers divided the study period into a preintervention period (January 1, 2014, to April 25, 2017) and a postintervention period (April 26, 2017, to September 30, 2018). They collected data on 2,142 incident outpatient UTIs; 1,636 from the preintervention period and 506 from the postintervention period. The patients were younger than 18 years and older than 60 days, and children with complicated urologic or neurologic conditions were excluded.

(P less than .0001). In particular, the use of first-line, narrow spectrum cephalexin increased significantly from 29% during the preintervention period to 53% during the postintervention period (P less than .0001). In addition, use of broad spectrum cefixime decreased from 17% during the preintervention period to 3% during the postintervention period (P less than .0001). These changes in prescribing patterns continued through the end of the study period, the researchers said.

The study was limited by several factors, notably that “the interrupted time-series design prevents us from inferring that the intervention caused the observed change in practice,” the researchers wrote. However, other factors including the immediate change in prescribing patterns after the intervention, multiple time points, large sample size, and consistent UTI case mix support the impact of the intervention, they suggested. Although the results might not translate completely to other settings, “developing a UTI-specific EHR order set is relatively straightforward” and might be applied elsewhere, they noted.

“Despite the limitations inherent in a nonexperimental study design, the methods and interventions developed in the current study may be informative to other learning health systems and other content areas when conducting organization-wide quality improvement initiatives,” they concluded.

The study was supported by unrestricted internal resources from the Colorado Permanente Medical Group. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Daley MF et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Mar 3. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-2503.

A multifaceted intervention significantly changed clinicians’ use of antibiotics to treat urinary tract infections (UTIs) in children, according to data from more than 2,000 cases observed between January 2014 and September 2018.

“Changing clinicians’ antibiotic prescribing practices can be challenging; barriers to change include lack of awareness of new evidence, competing clinical demands, and concern about treatment failure,” wrote Matthew F. Daley, MD, of Kaiser Permanente Colorado, Aurora, and colleagues in Pediatrics.

To promote judicious antibiotic use, the researchers designed an intervention including the development of new local UTI guidelines; a live, case-based educational session; emailed knowledge assessments before and after the session; and a specific UTI order set in the EHR.

The researchers divided the study period into a preintervention period (January 1, 2014, to April 25, 2017) and a postintervention period (April 26, 2017, to September 30, 2018). They collected data on 2,142 incident outpatient UTIs; 1,636 from the preintervention period and 506 from the postintervention period. The patients were younger than 18 years and older than 60 days, and children with complicated urologic or neurologic conditions were excluded.

(P less than .0001). In particular, the use of first-line, narrow spectrum cephalexin increased significantly from 29% during the preintervention period to 53% during the postintervention period (P less than .0001). In addition, use of broad spectrum cefixime decreased from 17% during the preintervention period to 3% during the postintervention period (P less than .0001). These changes in prescribing patterns continued through the end of the study period, the researchers said.

The study was limited by several factors, notably that “the interrupted time-series design prevents us from inferring that the intervention caused the observed change in practice,” the researchers wrote. However, other factors including the immediate change in prescribing patterns after the intervention, multiple time points, large sample size, and consistent UTI case mix support the impact of the intervention, they suggested. Although the results might not translate completely to other settings, “developing a UTI-specific EHR order set is relatively straightforward” and might be applied elsewhere, they noted.

“Despite the limitations inherent in a nonexperimental study design, the methods and interventions developed in the current study may be informative to other learning health systems and other content areas when conducting organization-wide quality improvement initiatives,” they concluded.

The study was supported by unrestricted internal resources from the Colorado Permanente Medical Group. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Daley MF et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Mar 3. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-2503.

A multifaceted intervention significantly changed clinicians’ use of antibiotics to treat urinary tract infections (UTIs) in children, according to data from more than 2,000 cases observed between January 2014 and September 2018.

“Changing clinicians’ antibiotic prescribing practices can be challenging; barriers to change include lack of awareness of new evidence, competing clinical demands, and concern about treatment failure,” wrote Matthew F. Daley, MD, of Kaiser Permanente Colorado, Aurora, and colleagues in Pediatrics.

To promote judicious antibiotic use, the researchers designed an intervention including the development of new local UTI guidelines; a live, case-based educational session; emailed knowledge assessments before and after the session; and a specific UTI order set in the EHR.

The researchers divided the study period into a preintervention period (January 1, 2014, to April 25, 2017) and a postintervention period (April 26, 2017, to September 30, 2018). They collected data on 2,142 incident outpatient UTIs; 1,636 from the preintervention period and 506 from the postintervention period. The patients were younger than 18 years and older than 60 days, and children with complicated urologic or neurologic conditions were excluded.

(P less than .0001). In particular, the use of first-line, narrow spectrum cephalexin increased significantly from 29% during the preintervention period to 53% during the postintervention period (P less than .0001). In addition, use of broad spectrum cefixime decreased from 17% during the preintervention period to 3% during the postintervention period (P less than .0001). These changes in prescribing patterns continued through the end of the study period, the researchers said.

The study was limited by several factors, notably that “the interrupted time-series design prevents us from inferring that the intervention caused the observed change in practice,” the researchers wrote. However, other factors including the immediate change in prescribing patterns after the intervention, multiple time points, large sample size, and consistent UTI case mix support the impact of the intervention, they suggested. Although the results might not translate completely to other settings, “developing a UTI-specific EHR order set is relatively straightforward” and might be applied elsewhere, they noted.

“Despite the limitations inherent in a nonexperimental study design, the methods and interventions developed in the current study may be informative to other learning health systems and other content areas when conducting organization-wide quality improvement initiatives,” they concluded.

The study was supported by unrestricted internal resources from the Colorado Permanente Medical Group. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Daley MF et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Mar 3. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-2503.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point: After an educational intervention, approximately 62% of clinicians prescribed first-line antibiotics, up from 43% before the intervention.

Major finding: Cephalexin use increased from 29% before the intervention to 53% after the intervention.

Study details: The data come from a review of 2,142 incident outpatient cases of urinary tract infection in patients aged older than 60 days up to 18 years.

Disclosures: The study was supported by unrestricted internal resources from the Colorado Permanente Medical Group. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Daley MF et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Mar 3. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-2503.

Washington State grapples with coronavirus outbreak

As the first COVID-19 outbreak in the United States emerges in Washington State, the city of Seattle, King County, and Washington State health officials provided the beginnings of a roadmap for how the region will address the rapidly evolving health crisis.

Health officials announced that four new cases were reported over the weekend in King County, Wash. There have now been 10 hospitalizations and 6 COVID-19 deaths at Evergreen Health, Kirkland, Wash. Of the deaths, five were King County residents and one was a resident of Snohomish County. Three patients died on March 1; all were in their 70s or 80s with comorbidities. Two had been residents of the Life Care senior residential facility that is at the center of the Kirkland outbreak. The number of cases in Washington now totals 18, with four cases in Snohomish County and the balance in neighboring King County.

Approximately 29 cases are under investigation with test results pending; a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) team is on-site.

Speaking at a news conference March 2, officials sought to strike a balance between giving the community a realistic appraisal of the likely scope of the COVID-19 outbreak and avoiding sparking a panic.

“This is a complex and unprecedented challenge nationally, globally, and locally. The vast majority of the infected have mild or moderate disease and do not need hospitalization,” said Jeffrey Duchin, MD, health officer and chief, Communicable Disease EPI/Immunization Section, Public Health, Seattle and King County, and a professor of infectious diseases at the University of Washington, Seattle. “On the other hand, it’s obvious that this infection can cause very serious disease in people who are older and have underlying health conditions. We expect cases to continue to increase. We are taking the situation extremely seriously; the risk for all of us becoming infected is increasing. ...There is the potential for many to become ill at the same time.”

Among the measures being taken immediately are the purchase by King County of a hotel to house individuals who require isolation and those who are convalescing from the virus. Officials are also placing a number of prefabricated stand-alone housing units on public grounds in Seattle, with the recognition that the area has a large transient and homeless community. The stand-alone units will house homeless individuals who need isolation, treatment, or recuperation but who aren’t ill enough to be hospitalized.

Dr. Duchin said that testing capacity is ramping up rapidly in Washington State: The state lab can now accommodate up to about 200 tests daily, and expects to be able to do up to 1,000 daily soon. The University of Washington’s testing capacity will come online March 2 or 3 as a testing facility with similar initial and future peak testing capacities.

The testing strategy will continue to include very ill individuals with pneumonia or other respiratory illness of unknown etiology, but will also expand to include less ill people. This shift is being made in accordance with a shift in CDC guidelines, because of increased testing capacity, and to provide a better picture of the severity, scope, geography, and timing of the current COVID-19 outbreak in the greater Seattle area.

No school closures or cancellation of gatherings are currently recommended by public health authorities. There are currently no COVID-19 cases in Washington schools. The expectation is that any recommendations regarding closures will be re-evaluated as the outbreak progresses.

Repeatedly, officials asked the general public to employ basic measures such as handwashing and avoidance of touching the face, and to spare masks for the ill and for those who care for them. “The vast majority of people will not have serious illness. In turn we need to do everything we can to help those health care workers. I’m asking the public to do things like save the masks for our health care workers. …We need assets for our front-line health care workers and also for those who may be needing them,” said King County Health Department director Patty Hayes, RN, MN.

Now is also the time for households to initiate basic emergency preparedness measures, such as having adequate food and medication, and to make arrangements for childcare in the event of school closures, said several officials.

“We can decrease the impact on our health care system by reducing our individual risk. We are making individual- and community-level recommendations to limit the spread of disease. These are very similar to what we recommend for influenza,” said Dr. Duchin.

Ettore Palazzo, MD, chief medical and quality officer at EvergreenHealth, gave a sense of how the hospital is coping with being Ground Zero for COVID-19 in the United States. “We have made adjustments for airborne precautions,” he said, including transforming the entire critical care unit to a negative pressure unit. “We have these capabilities in other parts of the hospital as well.” Staff are working hard, but thus far staffing has kept pace with demand, he said, but all are feeling the strain already.

Dr. Duchin made the point that Washington is relatively well equipped to handle the increasingly likely scenario of a large spike in coronavirus cases, since it’s part of the Northwest Healthcare Response Network. The network is planning for sharing resources such as staff, respirators, and intensive care unit beds as circumstances warrant.

“What you just heard illustrates the challenge of this disease,” said Dr. Duchin, summing up. “The public health service and clinical health care delivery systems don’t have the capacity to track down every case in the community. I’m guessing we will see more cases of coronavirus than we see of influenza. At some point we will be shifting from counting every case” to focusing on outbreaks and the critically ill in hospitals, he said.

“We are still trying to contain the outbreak, but we are at the same time pivoting to a more community-based approach,” similar to the approach with influenza, said Dr. Duchin.

A summary of deaths and ongoing cases, drawn from the press release, is below:

The four new cases are:

• A male in his 50s, hospitalized at Highline Hospital. He has no known exposures. He is in stable but critical condition. He had no underlying health conditions.

• A male in his 70s, a resident of Life Care, hospitalized at EvergreenHealth in Kirkland. The man had underlying health conditions, and died March 1.

• A female in her 70s, a resident of Life Care, hospitalized at EvergreenHealth in Kirkland. The woman had underlying health conditions, and died March 1.

• A female in her 80s, a resident of Life Care, was hospitalized at EvergreenHealth. She is in critical condition.

In addition, a woman in her 80s, who was already reported as in critical condition at Evergreen, has died. She died on March 1.

Ten other cases, already reported earlier by Public Health, include:

• A female in her 80s, hospitalized at EvergreenHealth in Kirkland. This person has now died, and is reported as such above.

• A female in her 90s, hospitalized at EvergreenHealth in Kirkland. The woman has underlying health conditions, and is in critical condition.

• A male in his 70s, hospitalized at EvergreenHealth in Kirkland. The man has underlying health conditions, and is in critical condition.

• A male in his 70s was hospitalized at EvergreenHealth. He had underlying health conditions and died on Feb. 29.

• A man in his 60s, hospitalized at Valley Medical Center in Renton.

• A man in 60s, hospitalized at Virginia Mason Medical Center.

• A woman in her 50s, who had traveled to South Korea; recovering at home.

• A woman in her 70s, who was a resident of Life Care in Kirkland, hospitalized at EvergreenHealth.

• A woman in her 40s, employed by Life Care, who is hospitalized at Overlake Medical Center.

• A man in his 50s, who was hospitalized and died at EvergreenHealth.

As the first COVID-19 outbreak in the United States emerges in Washington State, the city of Seattle, King County, and Washington State health officials provided the beginnings of a roadmap for how the region will address the rapidly evolving health crisis.

Health officials announced that four new cases were reported over the weekend in King County, Wash. There have now been 10 hospitalizations and 6 COVID-19 deaths at Evergreen Health, Kirkland, Wash. Of the deaths, five were King County residents and one was a resident of Snohomish County. Three patients died on March 1; all were in their 70s or 80s with comorbidities. Two had been residents of the Life Care senior residential facility that is at the center of the Kirkland outbreak. The number of cases in Washington now totals 18, with four cases in Snohomish County and the balance in neighboring King County.

Approximately 29 cases are under investigation with test results pending; a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) team is on-site.

Speaking at a news conference March 2, officials sought to strike a balance between giving the community a realistic appraisal of the likely scope of the COVID-19 outbreak and avoiding sparking a panic.

“This is a complex and unprecedented challenge nationally, globally, and locally. The vast majority of the infected have mild or moderate disease and do not need hospitalization,” said Jeffrey Duchin, MD, health officer and chief, Communicable Disease EPI/Immunization Section, Public Health, Seattle and King County, and a professor of infectious diseases at the University of Washington, Seattle. “On the other hand, it’s obvious that this infection can cause very serious disease in people who are older and have underlying health conditions. We expect cases to continue to increase. We are taking the situation extremely seriously; the risk for all of us becoming infected is increasing. ...There is the potential for many to become ill at the same time.”

Among the measures being taken immediately are the purchase by King County of a hotel to house individuals who require isolation and those who are convalescing from the virus. Officials are also placing a number of prefabricated stand-alone housing units on public grounds in Seattle, with the recognition that the area has a large transient and homeless community. The stand-alone units will house homeless individuals who need isolation, treatment, or recuperation but who aren’t ill enough to be hospitalized.

Dr. Duchin said that testing capacity is ramping up rapidly in Washington State: The state lab can now accommodate up to about 200 tests daily, and expects to be able to do up to 1,000 daily soon. The University of Washington’s testing capacity will come online March 2 or 3 as a testing facility with similar initial and future peak testing capacities.

The testing strategy will continue to include very ill individuals with pneumonia or other respiratory illness of unknown etiology, but will also expand to include less ill people. This shift is being made in accordance with a shift in CDC guidelines, because of increased testing capacity, and to provide a better picture of the severity, scope, geography, and timing of the current COVID-19 outbreak in the greater Seattle area.

No school closures or cancellation of gatherings are currently recommended by public health authorities. There are currently no COVID-19 cases in Washington schools. The expectation is that any recommendations regarding closures will be re-evaluated as the outbreak progresses.